User login

Analysis boosts fluvoxamine for COVID, but what’s the evidence?

a new systematic review and meta-analysis has found. But outside experts differ over whether the evidence from just three studies is strong enough to warrant adding the drug to the COVID-19 armamentarium.

The report, published online in JAMA Network Open, looked at three studies and estimated that the drug could reduce the relative risk of hospitalization by around 25% (likelihood of moderate effect, 81.6%-91.8%), depending on the type of analysis used.

“This research might be valuable, but the jury remains out until several other adequately powered and designed trials are completed,” said infectious disease specialist Carl J. Fichtenbaum, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, who’s familiar with the findings. “I’m not sure how useful this is given we have several antiviral agents available. Why would we choose this over Paxlovid, remdesivir, or molnupiravir?”

According to Dr. Fichtenbaum, researchers began focusing on fluvoxamine after case reports about patients improving while on the medication. This led to further interest, he said, boosted by the drug’s known ability to dampen the immune system.

A Silicon Valley investor and antivaccine activist named Steve Kirsch has been pushing the drug along with the debunked treatment hydroxychloroquine. He’s accused the government of a cover-up of fluvoxamine’s worth, according to MIT Technology Review, and he wrote a commentary that referred to the drug as “the fast, easy, safe, simple, low-cost solution to COVID that works 100% of the time that nobody wants to talk about.”

For the new analysis, researchers examined three randomized clinical trials with a total of 2,196 participants. The most extensive trial, the TOGETHER study in Brazil (n = 1,497), focused on an unusual outcome: It linked the drug to a 32% reduction in relative risk of patients with COVID-19 being hospitalized in an ED for fewer than 6 hours or transferred to a tertiary hospital because of the disease.

Another study, the STOP COVID 2 trial in the United States and Canada (n = 547), was stopped because too few patients could be recruited to provide useful results. The initial phase of this trial, STOP COVID 1 (n = 152), was also included in the analysis.

All participants in the three studies were unvaccinated. Their median age was 46-50 years, 55%-72% were women, and 44%-56% were obese. Most were multiracial due to the high number of participants from Brazil.

“In the Bayesian analyses, the pooled risk ratio in favor of fluvoxamine was 0.78 (95% confidence interval, 0.58-1.08) for the weakly neutral prior and 0.73 (95% CI, 0.53-1.01) for the moderately optimistic prior,” the researchers reported, referring to a reduction in risk of hospitalization. “In the frequentist meta-analysis, the pooled risk ratio in favor of fluvoxamine was 0.75 (95% CI, 0.58-0.97; I2, 0.2%).”

Two of the authors of the new analysis were also coauthors of the TOGETHER trial and both STOP COVID trials.

Corresponding author Emily G. McDonald, MD, division of experimental medicine at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview that the findings show fluvoxamine “very likely reduces hospitalization in high-risk outpatient adults with COVID-19. This effect varies depending on your baseline risk of developing complications in the first place.”

Dr. McDonald added that “fluvoxamine is an option to reduce hospitalizations in high-risk adults. It is likely effective, is inexpensive, and has a long safety track record.” She also noted that “not all countries have access to Paxlovid, and some people have drug interactions that preclude its use. Existing monoclonals are not effective with newer variants.”

The drug’s apparent anti-inflammatory properties seem to be key, she said. According to her, the next steps should be “testing lower doses to see if they remain effective, following patients long term to see what impact there is on long COVID symptoms, testing related medications in the drug class to see if they also show an effect, and testing in vaccinated people and with newer variants.”

In an interview, biostatistician James Watson, PhD, of the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit, Bangkok, Thailand, and Nuffield department of medicine, University of Oxford, England, said the findings of the analysis are “not overwhelming data.”

He noted the TOGETHER study’s unusual focus on ED visits that latest fewer than 6 hours, which he described as “not a very objective endpoint.” The new meta-analysis focused instead on “outcome data on emergency department visits lasting more than 24 hours and used this as a more representative proxy for hospital admission than an ED visit alone.”

Dr. Fichtenbaum also highlighted the odd endpoint. “Most of us would have chosen something like use of oxygen, requirement for ventilation, or death,” he said. “There are many reasons why people go to the ED. This endpoint is not very strong.”

He also noted that the three studies “are very different in design and endpoints.”

Jeffrey S. Morris, PhD, a biostatistician at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, offered a different perspective about the findings in an interview. “There’s good evidence that it helps some,” he said, and may reduce hospitalizations by 10%. “If the pill is super cheap and toxicity is very acceptable, it’s not adding additional risk. Most clinicians would say that: ‘If I’m reducing risk by 10%, it’s worthwhile.’ ”

No funding was reported. Two authors report having a patent application filed by Washington University for methods of treating COVID-19 during the conduct of the study. Dr. Watson is an investigator for studies analyzing antiviral drugs and Prozac as COVID-19 treatments. Dr. Fichtenbaum and Dr. Morris disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a new systematic review and meta-analysis has found. But outside experts differ over whether the evidence from just three studies is strong enough to warrant adding the drug to the COVID-19 armamentarium.

The report, published online in JAMA Network Open, looked at three studies and estimated that the drug could reduce the relative risk of hospitalization by around 25% (likelihood of moderate effect, 81.6%-91.8%), depending on the type of analysis used.

“This research might be valuable, but the jury remains out until several other adequately powered and designed trials are completed,” said infectious disease specialist Carl J. Fichtenbaum, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, who’s familiar with the findings. “I’m not sure how useful this is given we have several antiviral agents available. Why would we choose this over Paxlovid, remdesivir, or molnupiravir?”

According to Dr. Fichtenbaum, researchers began focusing on fluvoxamine after case reports about patients improving while on the medication. This led to further interest, he said, boosted by the drug’s known ability to dampen the immune system.

A Silicon Valley investor and antivaccine activist named Steve Kirsch has been pushing the drug along with the debunked treatment hydroxychloroquine. He’s accused the government of a cover-up of fluvoxamine’s worth, according to MIT Technology Review, and he wrote a commentary that referred to the drug as “the fast, easy, safe, simple, low-cost solution to COVID that works 100% of the time that nobody wants to talk about.”

For the new analysis, researchers examined three randomized clinical trials with a total of 2,196 participants. The most extensive trial, the TOGETHER study in Brazil (n = 1,497), focused on an unusual outcome: It linked the drug to a 32% reduction in relative risk of patients with COVID-19 being hospitalized in an ED for fewer than 6 hours or transferred to a tertiary hospital because of the disease.

Another study, the STOP COVID 2 trial in the United States and Canada (n = 547), was stopped because too few patients could be recruited to provide useful results. The initial phase of this trial, STOP COVID 1 (n = 152), was also included in the analysis.

All participants in the three studies were unvaccinated. Their median age was 46-50 years, 55%-72% were women, and 44%-56% were obese. Most were multiracial due to the high number of participants from Brazil.

“In the Bayesian analyses, the pooled risk ratio in favor of fluvoxamine was 0.78 (95% confidence interval, 0.58-1.08) for the weakly neutral prior and 0.73 (95% CI, 0.53-1.01) for the moderately optimistic prior,” the researchers reported, referring to a reduction in risk of hospitalization. “In the frequentist meta-analysis, the pooled risk ratio in favor of fluvoxamine was 0.75 (95% CI, 0.58-0.97; I2, 0.2%).”

Two of the authors of the new analysis were also coauthors of the TOGETHER trial and both STOP COVID trials.

Corresponding author Emily G. McDonald, MD, division of experimental medicine at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview that the findings show fluvoxamine “very likely reduces hospitalization in high-risk outpatient adults with COVID-19. This effect varies depending on your baseline risk of developing complications in the first place.”

Dr. McDonald added that “fluvoxamine is an option to reduce hospitalizations in high-risk adults. It is likely effective, is inexpensive, and has a long safety track record.” She also noted that “not all countries have access to Paxlovid, and some people have drug interactions that preclude its use. Existing monoclonals are not effective with newer variants.”

The drug’s apparent anti-inflammatory properties seem to be key, she said. According to her, the next steps should be “testing lower doses to see if they remain effective, following patients long term to see what impact there is on long COVID symptoms, testing related medications in the drug class to see if they also show an effect, and testing in vaccinated people and with newer variants.”

In an interview, biostatistician James Watson, PhD, of the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit, Bangkok, Thailand, and Nuffield department of medicine, University of Oxford, England, said the findings of the analysis are “not overwhelming data.”

He noted the TOGETHER study’s unusual focus on ED visits that latest fewer than 6 hours, which he described as “not a very objective endpoint.” The new meta-analysis focused instead on “outcome data on emergency department visits lasting more than 24 hours and used this as a more representative proxy for hospital admission than an ED visit alone.”

Dr. Fichtenbaum also highlighted the odd endpoint. “Most of us would have chosen something like use of oxygen, requirement for ventilation, or death,” he said. “There are many reasons why people go to the ED. This endpoint is not very strong.”

He also noted that the three studies “are very different in design and endpoints.”

Jeffrey S. Morris, PhD, a biostatistician at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, offered a different perspective about the findings in an interview. “There’s good evidence that it helps some,” he said, and may reduce hospitalizations by 10%. “If the pill is super cheap and toxicity is very acceptable, it’s not adding additional risk. Most clinicians would say that: ‘If I’m reducing risk by 10%, it’s worthwhile.’ ”

No funding was reported. Two authors report having a patent application filed by Washington University for methods of treating COVID-19 during the conduct of the study. Dr. Watson is an investigator for studies analyzing antiviral drugs and Prozac as COVID-19 treatments. Dr. Fichtenbaum and Dr. Morris disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a new systematic review and meta-analysis has found. But outside experts differ over whether the evidence from just three studies is strong enough to warrant adding the drug to the COVID-19 armamentarium.

The report, published online in JAMA Network Open, looked at three studies and estimated that the drug could reduce the relative risk of hospitalization by around 25% (likelihood of moderate effect, 81.6%-91.8%), depending on the type of analysis used.

“This research might be valuable, but the jury remains out until several other adequately powered and designed trials are completed,” said infectious disease specialist Carl J. Fichtenbaum, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, who’s familiar with the findings. “I’m not sure how useful this is given we have several antiviral agents available. Why would we choose this over Paxlovid, remdesivir, or molnupiravir?”

According to Dr. Fichtenbaum, researchers began focusing on fluvoxamine after case reports about patients improving while on the medication. This led to further interest, he said, boosted by the drug’s known ability to dampen the immune system.

A Silicon Valley investor and antivaccine activist named Steve Kirsch has been pushing the drug along with the debunked treatment hydroxychloroquine. He’s accused the government of a cover-up of fluvoxamine’s worth, according to MIT Technology Review, and he wrote a commentary that referred to the drug as “the fast, easy, safe, simple, low-cost solution to COVID that works 100% of the time that nobody wants to talk about.”

For the new analysis, researchers examined three randomized clinical trials with a total of 2,196 participants. The most extensive trial, the TOGETHER study in Brazil (n = 1,497), focused on an unusual outcome: It linked the drug to a 32% reduction in relative risk of patients with COVID-19 being hospitalized in an ED for fewer than 6 hours or transferred to a tertiary hospital because of the disease.

Another study, the STOP COVID 2 trial in the United States and Canada (n = 547), was stopped because too few patients could be recruited to provide useful results. The initial phase of this trial, STOP COVID 1 (n = 152), was also included in the analysis.

All participants in the three studies were unvaccinated. Their median age was 46-50 years, 55%-72% were women, and 44%-56% were obese. Most were multiracial due to the high number of participants from Brazil.

“In the Bayesian analyses, the pooled risk ratio in favor of fluvoxamine was 0.78 (95% confidence interval, 0.58-1.08) for the weakly neutral prior and 0.73 (95% CI, 0.53-1.01) for the moderately optimistic prior,” the researchers reported, referring to a reduction in risk of hospitalization. “In the frequentist meta-analysis, the pooled risk ratio in favor of fluvoxamine was 0.75 (95% CI, 0.58-0.97; I2, 0.2%).”

Two of the authors of the new analysis were also coauthors of the TOGETHER trial and both STOP COVID trials.

Corresponding author Emily G. McDonald, MD, division of experimental medicine at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview that the findings show fluvoxamine “very likely reduces hospitalization in high-risk outpatient adults with COVID-19. This effect varies depending on your baseline risk of developing complications in the first place.”

Dr. McDonald added that “fluvoxamine is an option to reduce hospitalizations in high-risk adults. It is likely effective, is inexpensive, and has a long safety track record.” She also noted that “not all countries have access to Paxlovid, and some people have drug interactions that preclude its use. Existing monoclonals are not effective with newer variants.”

The drug’s apparent anti-inflammatory properties seem to be key, she said. According to her, the next steps should be “testing lower doses to see if they remain effective, following patients long term to see what impact there is on long COVID symptoms, testing related medications in the drug class to see if they also show an effect, and testing in vaccinated people and with newer variants.”

In an interview, biostatistician James Watson, PhD, of the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit, Bangkok, Thailand, and Nuffield department of medicine, University of Oxford, England, said the findings of the analysis are “not overwhelming data.”

He noted the TOGETHER study’s unusual focus on ED visits that latest fewer than 6 hours, which he described as “not a very objective endpoint.” The new meta-analysis focused instead on “outcome data on emergency department visits lasting more than 24 hours and used this as a more representative proxy for hospital admission than an ED visit alone.”

Dr. Fichtenbaum also highlighted the odd endpoint. “Most of us would have chosen something like use of oxygen, requirement for ventilation, or death,” he said. “There are many reasons why people go to the ED. This endpoint is not very strong.”

He also noted that the three studies “are very different in design and endpoints.”

Jeffrey S. Morris, PhD, a biostatistician at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, offered a different perspective about the findings in an interview. “There’s good evidence that it helps some,” he said, and may reduce hospitalizations by 10%. “If the pill is super cheap and toxicity is very acceptable, it’s not adding additional risk. Most clinicians would say that: ‘If I’m reducing risk by 10%, it’s worthwhile.’ ”

No funding was reported. Two authors report having a patent application filed by Washington University for methods of treating COVID-19 during the conduct of the study. Dr. Watson is an investigator for studies analyzing antiviral drugs and Prozac as COVID-19 treatments. Dr. Fichtenbaum and Dr. Morris disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

COVID cases rising in about half of states

About half the states have reported increases in COVID cases fueled by the Omicron subvariant, Axios reported. Alaska, Vermont, and Rhode Island had the highest increases, with more than 20 new cases per 100,000 people.

Nationally, the statistics are encouraging, with the 7-day average of daily cases around 26,000 on April 6, down from around 41,000 on March 6, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The number of deaths has dropped to an average of around 600 a day, down 34% from 2 weeks ago.

National health officials have said some spots would have a lot of COVID cases.

“Looking across the country, we see that 95% of counties are reporting low COVID-19 community levels, which represent over 97% of the U.S. population,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said April 5 at a White House news briefing.

“If we look more closely at the local level, we find a handful of counties where we are seeing increases in both cases and markers of more severe disease, like hospitalizations and in-patient bed capacity, which have resulted in an increased COVID-19 community level in some areas.”

Meanwhile, the Commonwealth Fund issued a report April 8 saying the U.S. vaccine program had prevented an estimated 2.2 million deaths and 17 million hospitalizations.

If the vaccine program didn’t exist, the United States would have had another 66 million COVID infections and spent about $900 billion more on health care, the foundation said.

The United States has reported about 982,000 COVID-related deaths so far with about 80 million COVID cases, according to the CDC.

“Our findings highlight the profound and ongoing impact of the vaccination program in reducing infections, hospitalizations, and deaths,” the Commonwealth Fund said.

“Investing in vaccination programs also has produced substantial cost savings – approximately the size of one-fifth of annual national health expenditures – by dramatically reducing the amount spent on COVID-19 hospitalizations.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

About half the states have reported increases in COVID cases fueled by the Omicron subvariant, Axios reported. Alaska, Vermont, and Rhode Island had the highest increases, with more than 20 new cases per 100,000 people.

Nationally, the statistics are encouraging, with the 7-day average of daily cases around 26,000 on April 6, down from around 41,000 on March 6, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The number of deaths has dropped to an average of around 600 a day, down 34% from 2 weeks ago.

National health officials have said some spots would have a lot of COVID cases.

“Looking across the country, we see that 95% of counties are reporting low COVID-19 community levels, which represent over 97% of the U.S. population,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said April 5 at a White House news briefing.

“If we look more closely at the local level, we find a handful of counties where we are seeing increases in both cases and markers of more severe disease, like hospitalizations and in-patient bed capacity, which have resulted in an increased COVID-19 community level in some areas.”

Meanwhile, the Commonwealth Fund issued a report April 8 saying the U.S. vaccine program had prevented an estimated 2.2 million deaths and 17 million hospitalizations.

If the vaccine program didn’t exist, the United States would have had another 66 million COVID infections and spent about $900 billion more on health care, the foundation said.

The United States has reported about 982,000 COVID-related deaths so far with about 80 million COVID cases, according to the CDC.

“Our findings highlight the profound and ongoing impact of the vaccination program in reducing infections, hospitalizations, and deaths,” the Commonwealth Fund said.

“Investing in vaccination programs also has produced substantial cost savings – approximately the size of one-fifth of annual national health expenditures – by dramatically reducing the amount spent on COVID-19 hospitalizations.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

About half the states have reported increases in COVID cases fueled by the Omicron subvariant, Axios reported. Alaska, Vermont, and Rhode Island had the highest increases, with more than 20 new cases per 100,000 people.

Nationally, the statistics are encouraging, with the 7-day average of daily cases around 26,000 on April 6, down from around 41,000 on March 6, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The number of deaths has dropped to an average of around 600 a day, down 34% from 2 weeks ago.

National health officials have said some spots would have a lot of COVID cases.

“Looking across the country, we see that 95% of counties are reporting low COVID-19 community levels, which represent over 97% of the U.S. population,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, said April 5 at a White House news briefing.

“If we look more closely at the local level, we find a handful of counties where we are seeing increases in both cases and markers of more severe disease, like hospitalizations and in-patient bed capacity, which have resulted in an increased COVID-19 community level in some areas.”

Meanwhile, the Commonwealth Fund issued a report April 8 saying the U.S. vaccine program had prevented an estimated 2.2 million deaths and 17 million hospitalizations.

If the vaccine program didn’t exist, the United States would have had another 66 million COVID infections and spent about $900 billion more on health care, the foundation said.

The United States has reported about 982,000 COVID-related deaths so far with about 80 million COVID cases, according to the CDC.

“Our findings highlight the profound and ongoing impact of the vaccination program in reducing infections, hospitalizations, and deaths,” the Commonwealth Fund said.

“Investing in vaccination programs also has produced substantial cost savings – approximately the size of one-fifth of annual national health expenditures – by dramatically reducing the amount spent on COVID-19 hospitalizations.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Study finds discrepancies in biopsy decisions, diagnoses based on skin type

BOSTON – compared with White patients, new research shows.

“Our findings suggest diagnostic biases based on skin color exist in dermatology practice,” lead author Loren Krueger, MD, assistant professor in the department of dermatology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, said at the Annual Skin of Color Society Scientific Symposium. “A lower likelihood of biopsy of malignancy in darker skin types could contribute to disparities in cutaneous malignancies,” she added.

Disparities in dermatologic care among Black patients, compared with White patients, have been well documented. Recent evidence includes a 2020 study that showed significant shortcomings among medical students in correctly diagnosing squamous cell carcinoma, urticaria, and atopic dermatitis for patients with skin of color.

“It’s no secret that our images do not accurately or in the right quantity include skin of color,” Dr. Krueger said. “Yet few papers talk about how these biases actually impact our care. Importantly, this study demonstrates that diagnostic bias develops as early as the medical student level.”

To further investigate the role of skin color in the assessment of neoplastic and inflammatory skin conditions and decisions to perform biopsy, Dr. Krueger and her colleagues surveyed 144 dermatology residents and attending dermatologists to evaluate their clinical decisionmaking skills in assessing skin conditions for patients with lighter skin and those with darker skin. Almost 80% (113) provided complete responses and were included in the study.

For the survey, participants were shown photos of 10 neoplastic and 10 inflammatory skin conditions. Each image was matched in lighter (skin types I-II) and darker (skin types IV-VI) skinned patients in random order. Participants were asked to identify the suspected underlying etiology (neoplastic–benign, neoplastic–malignant, papulosquamous, lichenoid, infectious, bullous, or no suspected etiology) and whether they would choose to perform biopsy for the pictured condition.

Overall, their responses showed a slightly higher probability of recommending a biopsy for patients with skin types IV-V (odds ratio, 1.18; P = .054).

However, respondents were more than twice as likely to recommend a biopsy for benign neoplasms for patients with skin of color, compared with those with lighter skin types (OR, 2.57; P < .0001). They were significantly less likely to recommend a biopsy for a malignant neoplasm for patients with skin of color (OR, 0.42; P < .0001).

In addition, the correct etiology was much more commonly missed in diagnosing patients with skin of color, even after adjusting for years in dermatology practice (OR, 0.569; P < .0001).

Conversely, respondents were significantly less likely to recommend a biopsy for benign neoplasms and were more likely to recommend a biopsy for malignant neoplasms among White patients. Etiology was more commonly correct.

The findings underscore that “for skin of color patients, you’re more likely to have a benign neoplasm biopsied, you’re less likely to have a malignant neoplasm biopsied, and more often, your etiology may be missed,” Dr. Krueger said at the meeting.

Of note, while 45% of respondents were dermatology residents or fellows, 20.4% had 1-5 years of experience, and about 28% had 10 to more than 25 years of experience.

And while 75% of the dermatology residents, fellows, and attendings were White, there was no difference in the probability of correctly identifying the underlying etiology in dark or light skin types based on the provider’s self-identified race.

Importantly, the patterns in the study of diagnostic discrepancies are reflected in broader dermatologic outcomes. The 5-year melanoma survival rate is 74.1% among Black patients and 92.9% among White patients. Dr. Krueger referred to data showing that only 52.6% of Black patients have stage I melanoma at diagnosis, whereas among White patients, the rate is much higher, at 75.9%.

“We know skin malignancy can be more aggressive and late-stage in skin of color populations, leading to increased morbidity and later stage at initial diagnosis,” Dr. Krueger told this news organization. “We routinely attribute this to limited access to care and lack of awareness on skin malignancy. However, we have no evidence on how we, as dermatologists, may be playing a role.”

Furthermore, the decision to perform biopsy or not can affect the size and stage at diagnosis of a cutaneous malignancy, she noted.

Key changes needed to prevent the disparities – and their implications – should start at the training level, she emphasized. “I would love to see increased photo representation in training materials – this is a great place to start,” Dr. Krueger said.

In addition, “encouraging medical students, residents, and dermatologists to learn from skin of color experts is vital,” she said. “We should also provide hands-on experience and training with diverse patient populations.”

The first step to addressing biases “is to acknowledge they exist,” Dr. Krueger added. “I am hopeful this inspires others to continue to investigate these biases, as well as how we can eliminate them.”

The study was funded by the Rudin Resident Research Award. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BOSTON – compared with White patients, new research shows.

“Our findings suggest diagnostic biases based on skin color exist in dermatology practice,” lead author Loren Krueger, MD, assistant professor in the department of dermatology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, said at the Annual Skin of Color Society Scientific Symposium. “A lower likelihood of biopsy of malignancy in darker skin types could contribute to disparities in cutaneous malignancies,” she added.

Disparities in dermatologic care among Black patients, compared with White patients, have been well documented. Recent evidence includes a 2020 study that showed significant shortcomings among medical students in correctly diagnosing squamous cell carcinoma, urticaria, and atopic dermatitis for patients with skin of color.

“It’s no secret that our images do not accurately or in the right quantity include skin of color,” Dr. Krueger said. “Yet few papers talk about how these biases actually impact our care. Importantly, this study demonstrates that diagnostic bias develops as early as the medical student level.”

To further investigate the role of skin color in the assessment of neoplastic and inflammatory skin conditions and decisions to perform biopsy, Dr. Krueger and her colleagues surveyed 144 dermatology residents and attending dermatologists to evaluate their clinical decisionmaking skills in assessing skin conditions for patients with lighter skin and those with darker skin. Almost 80% (113) provided complete responses and were included in the study.

For the survey, participants were shown photos of 10 neoplastic and 10 inflammatory skin conditions. Each image was matched in lighter (skin types I-II) and darker (skin types IV-VI) skinned patients in random order. Participants were asked to identify the suspected underlying etiology (neoplastic–benign, neoplastic–malignant, papulosquamous, lichenoid, infectious, bullous, or no suspected etiology) and whether they would choose to perform biopsy for the pictured condition.

Overall, their responses showed a slightly higher probability of recommending a biopsy for patients with skin types IV-V (odds ratio, 1.18; P = .054).

However, respondents were more than twice as likely to recommend a biopsy for benign neoplasms for patients with skin of color, compared with those with lighter skin types (OR, 2.57; P < .0001). They were significantly less likely to recommend a biopsy for a malignant neoplasm for patients with skin of color (OR, 0.42; P < .0001).

In addition, the correct etiology was much more commonly missed in diagnosing patients with skin of color, even after adjusting for years in dermatology practice (OR, 0.569; P < .0001).

Conversely, respondents were significantly less likely to recommend a biopsy for benign neoplasms and were more likely to recommend a biopsy for malignant neoplasms among White patients. Etiology was more commonly correct.

The findings underscore that “for skin of color patients, you’re more likely to have a benign neoplasm biopsied, you’re less likely to have a malignant neoplasm biopsied, and more often, your etiology may be missed,” Dr. Krueger said at the meeting.

Of note, while 45% of respondents were dermatology residents or fellows, 20.4% had 1-5 years of experience, and about 28% had 10 to more than 25 years of experience.

And while 75% of the dermatology residents, fellows, and attendings were White, there was no difference in the probability of correctly identifying the underlying etiology in dark or light skin types based on the provider’s self-identified race.

Importantly, the patterns in the study of diagnostic discrepancies are reflected in broader dermatologic outcomes. The 5-year melanoma survival rate is 74.1% among Black patients and 92.9% among White patients. Dr. Krueger referred to data showing that only 52.6% of Black patients have stage I melanoma at diagnosis, whereas among White patients, the rate is much higher, at 75.9%.

“We know skin malignancy can be more aggressive and late-stage in skin of color populations, leading to increased morbidity and later stage at initial diagnosis,” Dr. Krueger told this news organization. “We routinely attribute this to limited access to care and lack of awareness on skin malignancy. However, we have no evidence on how we, as dermatologists, may be playing a role.”

Furthermore, the decision to perform biopsy or not can affect the size and stage at diagnosis of a cutaneous malignancy, she noted.

Key changes needed to prevent the disparities – and their implications – should start at the training level, she emphasized. “I would love to see increased photo representation in training materials – this is a great place to start,” Dr. Krueger said.

In addition, “encouraging medical students, residents, and dermatologists to learn from skin of color experts is vital,” she said. “We should also provide hands-on experience and training with diverse patient populations.”

The first step to addressing biases “is to acknowledge they exist,” Dr. Krueger added. “I am hopeful this inspires others to continue to investigate these biases, as well as how we can eliminate them.”

The study was funded by the Rudin Resident Research Award. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BOSTON – compared with White patients, new research shows.

“Our findings suggest diagnostic biases based on skin color exist in dermatology practice,” lead author Loren Krueger, MD, assistant professor in the department of dermatology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, said at the Annual Skin of Color Society Scientific Symposium. “A lower likelihood of biopsy of malignancy in darker skin types could contribute to disparities in cutaneous malignancies,” she added.

Disparities in dermatologic care among Black patients, compared with White patients, have been well documented. Recent evidence includes a 2020 study that showed significant shortcomings among medical students in correctly diagnosing squamous cell carcinoma, urticaria, and atopic dermatitis for patients with skin of color.

“It’s no secret that our images do not accurately or in the right quantity include skin of color,” Dr. Krueger said. “Yet few papers talk about how these biases actually impact our care. Importantly, this study demonstrates that diagnostic bias develops as early as the medical student level.”

To further investigate the role of skin color in the assessment of neoplastic and inflammatory skin conditions and decisions to perform biopsy, Dr. Krueger and her colleagues surveyed 144 dermatology residents and attending dermatologists to evaluate their clinical decisionmaking skills in assessing skin conditions for patients with lighter skin and those with darker skin. Almost 80% (113) provided complete responses and were included in the study.

For the survey, participants were shown photos of 10 neoplastic and 10 inflammatory skin conditions. Each image was matched in lighter (skin types I-II) and darker (skin types IV-VI) skinned patients in random order. Participants were asked to identify the suspected underlying etiology (neoplastic–benign, neoplastic–malignant, papulosquamous, lichenoid, infectious, bullous, or no suspected etiology) and whether they would choose to perform biopsy for the pictured condition.

Overall, their responses showed a slightly higher probability of recommending a biopsy for patients with skin types IV-V (odds ratio, 1.18; P = .054).

However, respondents were more than twice as likely to recommend a biopsy for benign neoplasms for patients with skin of color, compared with those with lighter skin types (OR, 2.57; P < .0001). They were significantly less likely to recommend a biopsy for a malignant neoplasm for patients with skin of color (OR, 0.42; P < .0001).

In addition, the correct etiology was much more commonly missed in diagnosing patients with skin of color, even after adjusting for years in dermatology practice (OR, 0.569; P < .0001).

Conversely, respondents were significantly less likely to recommend a biopsy for benign neoplasms and were more likely to recommend a biopsy for malignant neoplasms among White patients. Etiology was more commonly correct.

The findings underscore that “for skin of color patients, you’re more likely to have a benign neoplasm biopsied, you’re less likely to have a malignant neoplasm biopsied, and more often, your etiology may be missed,” Dr. Krueger said at the meeting.

Of note, while 45% of respondents were dermatology residents or fellows, 20.4% had 1-5 years of experience, and about 28% had 10 to more than 25 years of experience.

And while 75% of the dermatology residents, fellows, and attendings were White, there was no difference in the probability of correctly identifying the underlying etiology in dark or light skin types based on the provider’s self-identified race.

Importantly, the patterns in the study of diagnostic discrepancies are reflected in broader dermatologic outcomes. The 5-year melanoma survival rate is 74.1% among Black patients and 92.9% among White patients. Dr. Krueger referred to data showing that only 52.6% of Black patients have stage I melanoma at diagnosis, whereas among White patients, the rate is much higher, at 75.9%.

“We know skin malignancy can be more aggressive and late-stage in skin of color populations, leading to increased morbidity and later stage at initial diagnosis,” Dr. Krueger told this news organization. “We routinely attribute this to limited access to care and lack of awareness on skin malignancy. However, we have no evidence on how we, as dermatologists, may be playing a role.”

Furthermore, the decision to perform biopsy or not can affect the size and stage at diagnosis of a cutaneous malignancy, she noted.

Key changes needed to prevent the disparities – and their implications – should start at the training level, she emphasized. “I would love to see increased photo representation in training materials – this is a great place to start,” Dr. Krueger said.

In addition, “encouraging medical students, residents, and dermatologists to learn from skin of color experts is vital,” she said. “We should also provide hands-on experience and training with diverse patient populations.”

The first step to addressing biases “is to acknowledge they exist,” Dr. Krueger added. “I am hopeful this inspires others to continue to investigate these biases, as well as how we can eliminate them.”

The study was funded by the Rudin Resident Research Award. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ulcerating Nodule on the Foot

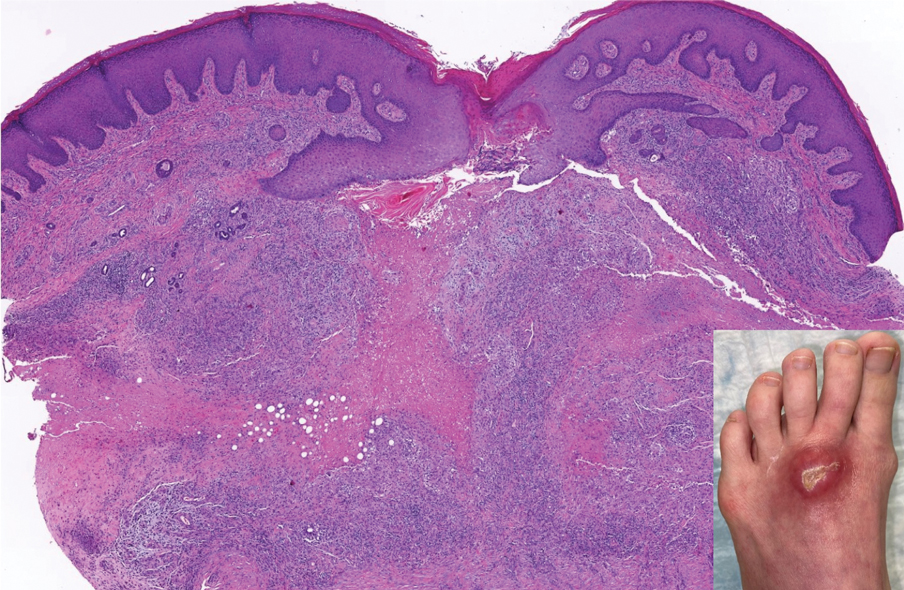

The Diagnosis: Perforating Rheumatoid Nodule

Perforating rheumatoid nodule (RN) is a variant of RN that demonstrates necrobiotic material extruding through the epidermis via the process of transepidermal elimination.1 The necrobiotic material contains fibrin and often harbors karyorrhectic debris. The pathogenesis of RN remains unclear; possible mechanisms include a small vessel vasculitis or mechanical trauma inciting a localized aggregation of inflammatory products and rheumatoid factor complexes. This induces macrophage activation, fibrin deposition, and necrosis.2 The majority of patients with RNs have detectable rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated protein in the blood.3 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and will develop in 30% to 40% of RA patients.4,5 They typically are associated with advanced RA but may precede the onset of clinically severe RA in 5% to 10% of patients.5 Rheumatoid nodules generally range in size from 2 mm to 5 cm and are slightly more prevalent in men than in women. They present as firm painless masses typically on the extensor surfaces of the hands and olecranon process but can occur over any tendinous or ligamentlike structure.6,7 Perforating RNs are most common on areas subjected to pressure or repeated trauma, such as the sacrum.

The diagnosis usually is clinical; however, in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, RN can be distinguished by its histologic appearance. Rheumatoid nodules demonstrate granulomatous palisading necrobiosis with a central zone of highly eosinophilic fibrinoid necrobiosis surrounded by palisading mononuclear cells and an outer zone of granulation tissue. There may be a mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate predominantly composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes in the background.

Rheumatoid nodules typically do not require treatment; however, perforation is known to increase the risk for infection, and surgical excision generally is indicated for prophylaxis against infection, though nodules may recur in the excision area.1,3,8 Alternatively, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and intralesional corticosteroids may effectively reduce the size of RNs. The differential diagnosis for perforating RNs includes epithelioid sarcoma, perforating granuloma annulare, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, and necrobiosis lipoidica.

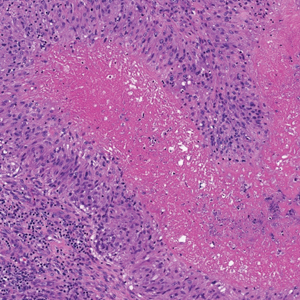

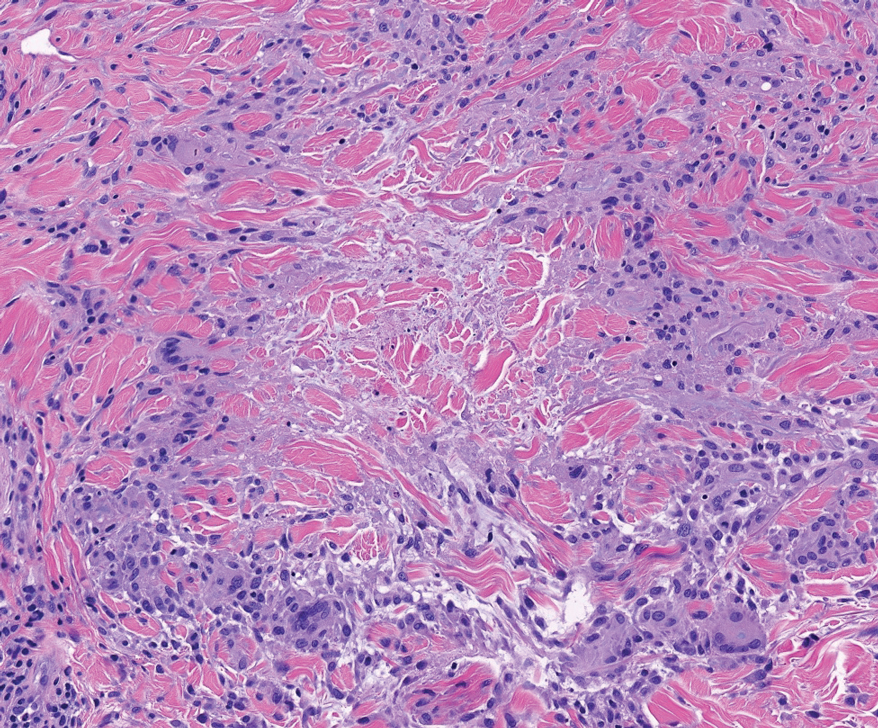

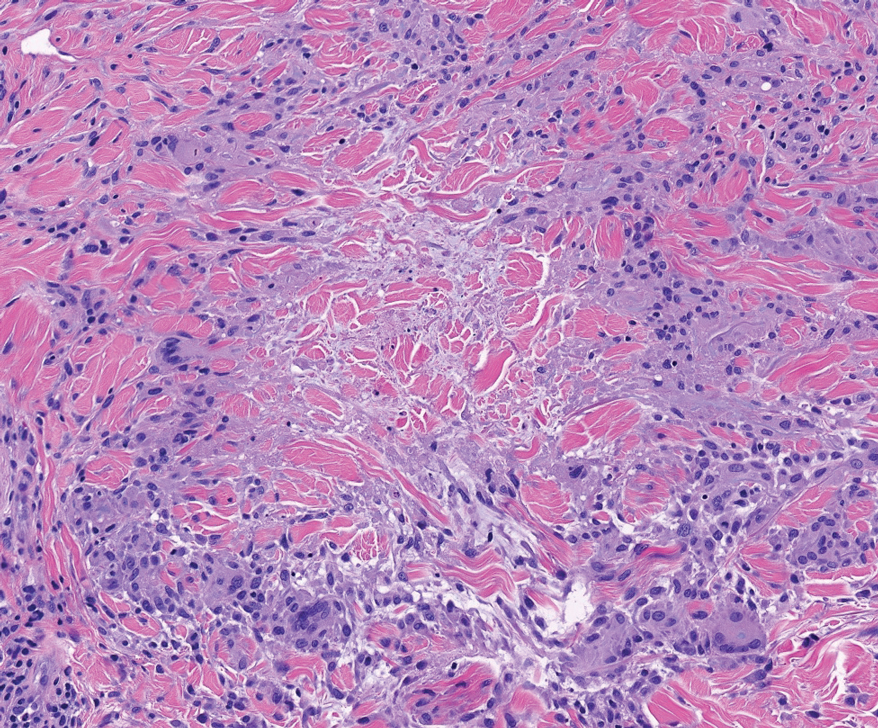

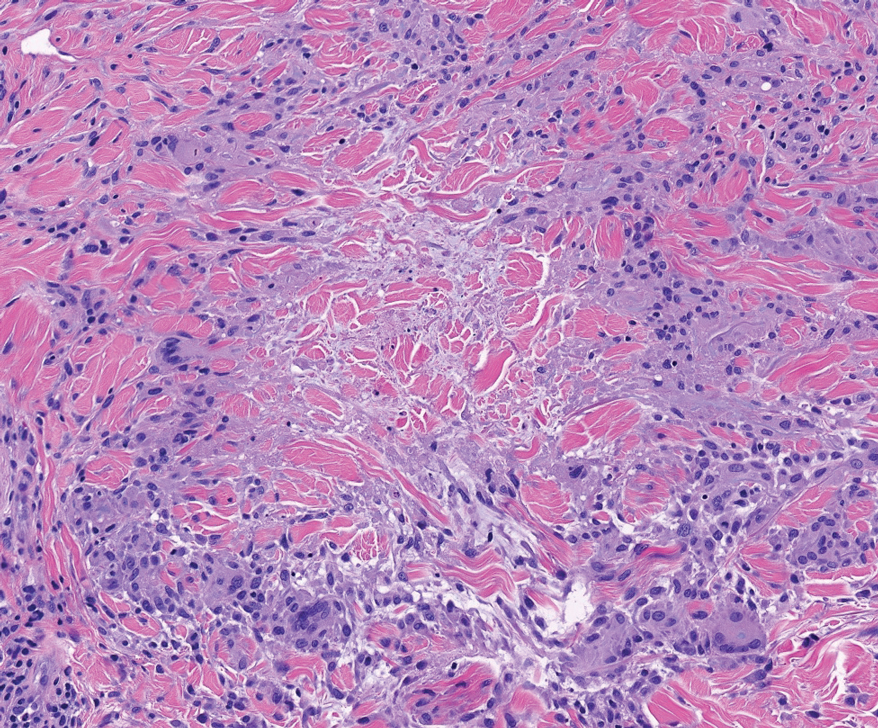

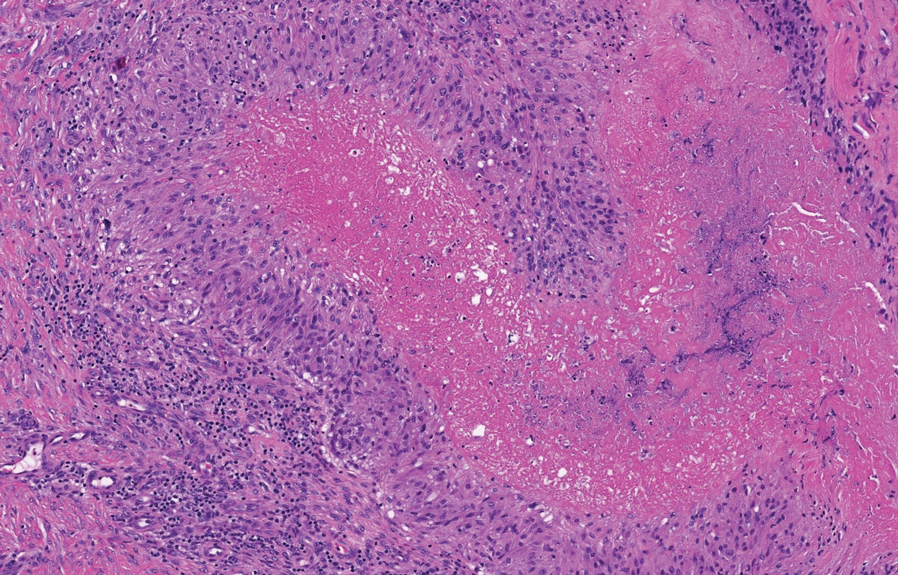

Epithelioid sarcoma is a malignant soft tissue tumor typically found on the upper extremities of adolescent or young adult males. They usually present as hard tender nodules that commonly ulcerate. Epithelioid sarcoma makes up less than 1% of soft tissue sarcomas.9 Although rare, they present a diagnostic pitfall, as the histology may mimic an inflammatory palisaded granulomatous dermatitis similar to RN and granuloma annulare, thus a high index of suspicion is required to not overlook this aggressive malignancy. Histology is typified by nodular aggregates of epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and often with central zones of necrosis (Figure 1). Epithelioid sarcoma displays immunoreactivity to cytokeratin, CD34, and epithelial membrane antigen, but loss of integrase interactor 1 expression. Cytologic abnormalities such as pleomorphism and hyperchromatism can be helpful in distinguishing between epithelioid sarcoma and RN.

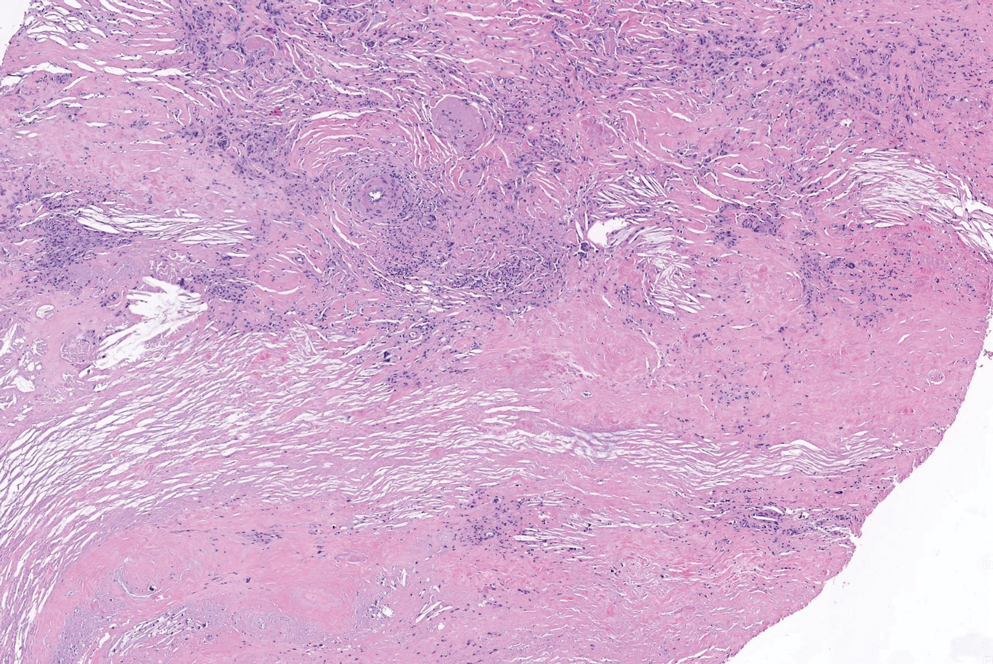

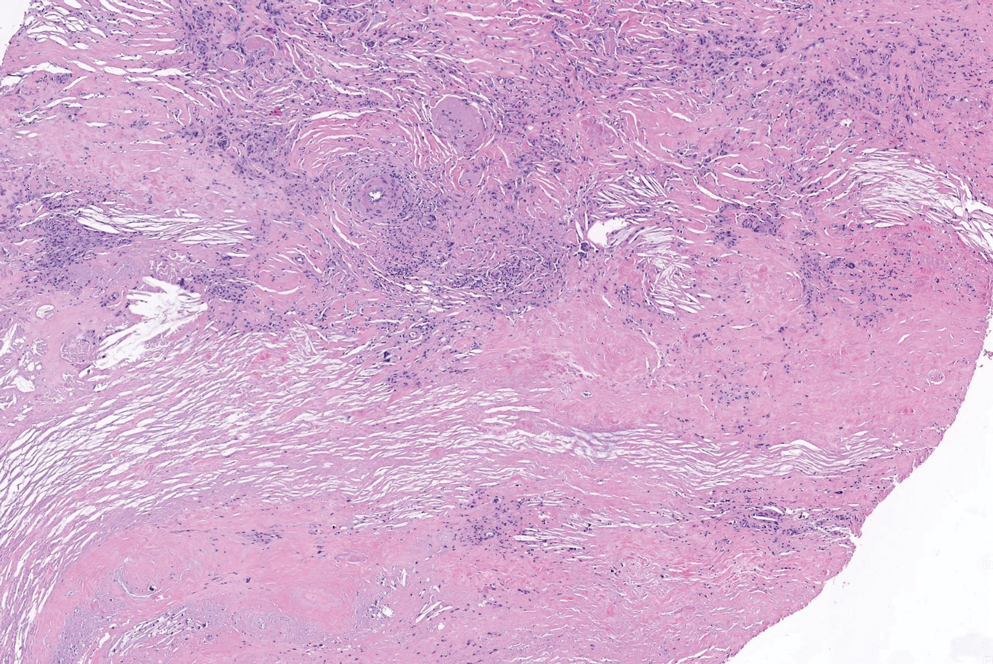

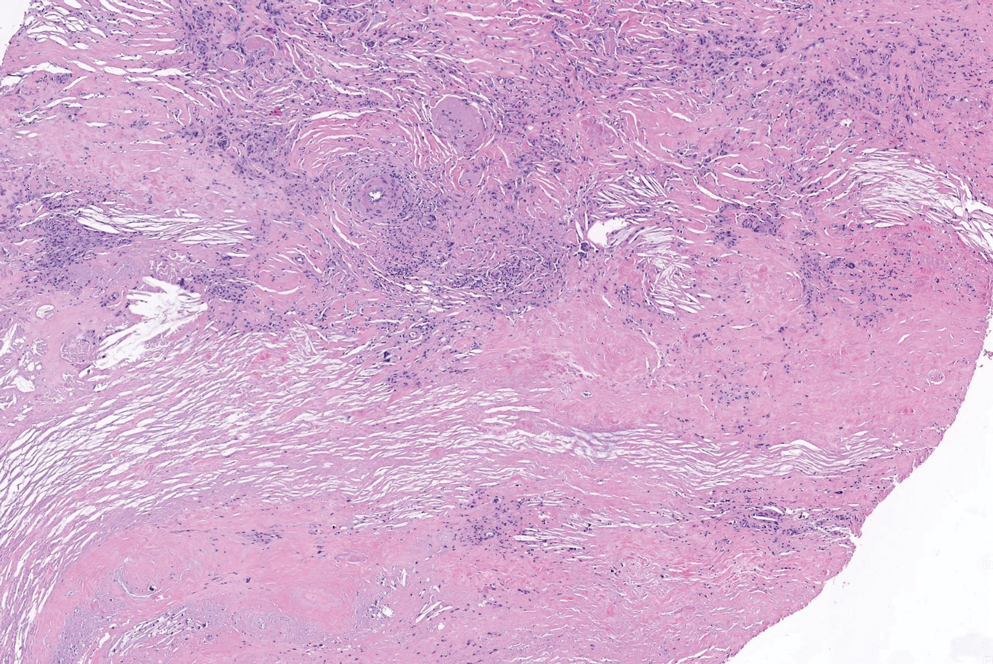

Perforating granuloma annulare is a rare subtype of granuloma annulare that presents with flesh- to red-colored papules that develop central crust or scale. Perforating granuloma annulare composes approximately 5% of granuloma annulare cases. Perforating granuloma annulare can develop on any region of the body but has an affinity for the extensor surfaces of the extremities. It most frequently occurs in young women and rarely presents as a single lesion.10 Granuloma annulare typically is not associated with joint pain, and thus it differs from most cases of RNs. Histologically, it presents with an inflammatory palisading granuloma. There may be overlying epidermal thinning or parakeratosis, which can progress to perforation and extrusion of necrobiotic material. In comparison with RN, perforating granuloma annulare displays mucin deposition in the necrobiotic zones in lieu of fibrin (Figure 2).10,11

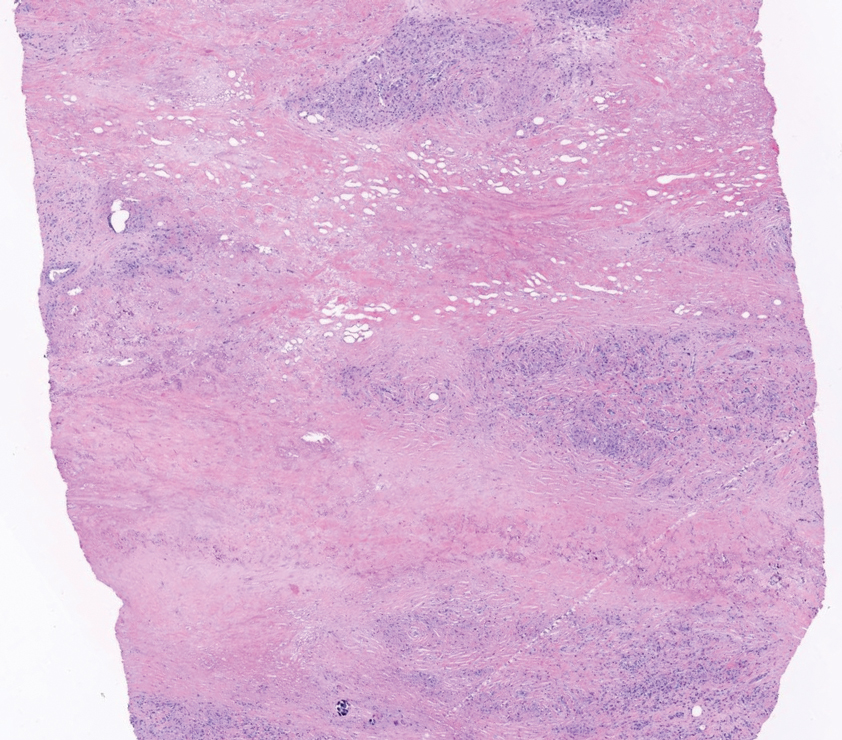

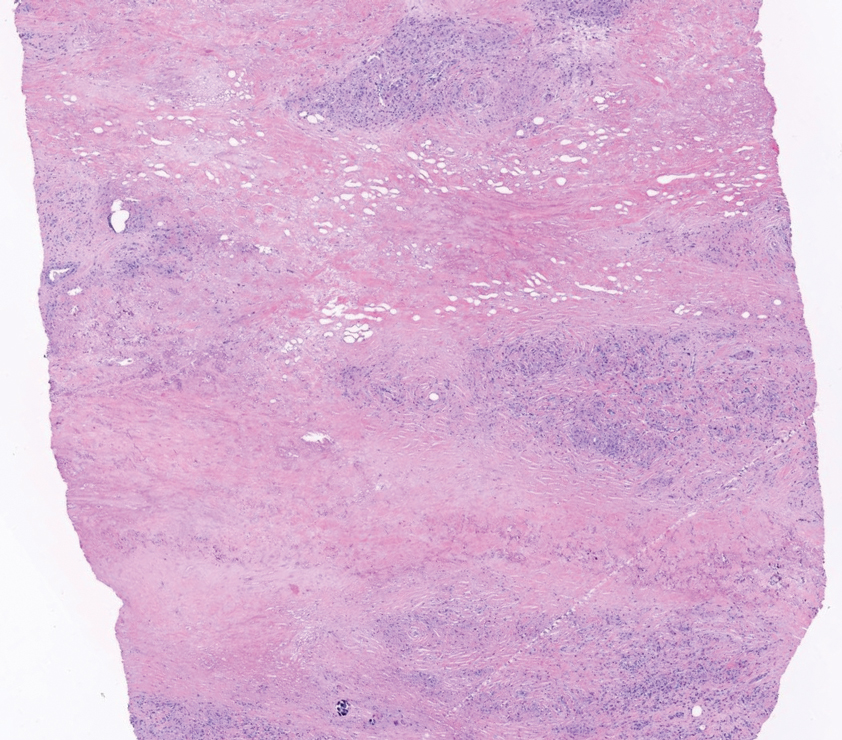

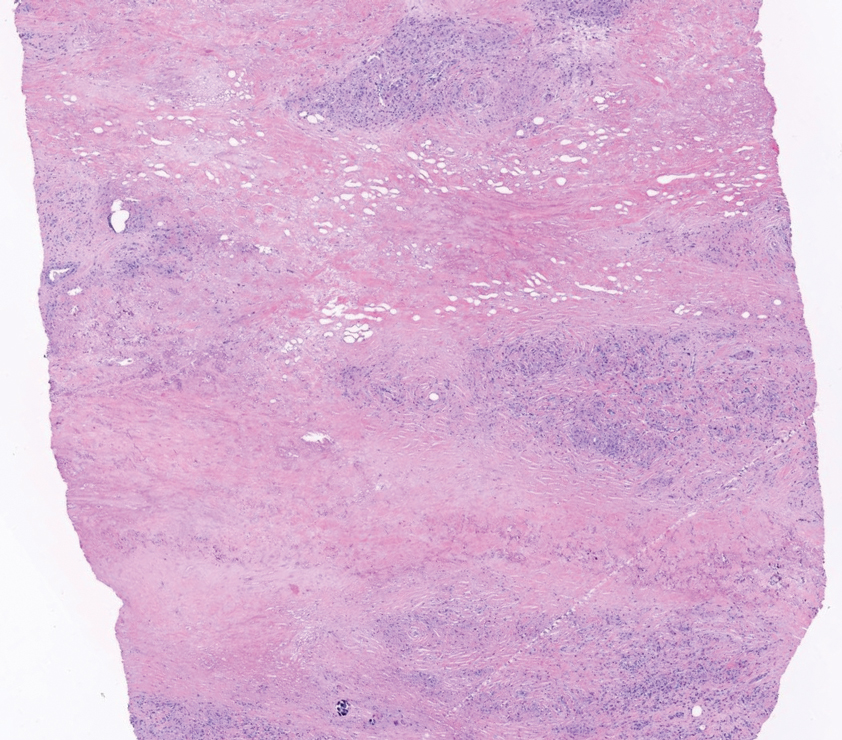

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a rare chronic form of non-Langerhans histiocytosis that characteristically presents with yellow or violaceous indurated plaques and nodules in a periorbital distribution. It often is associated with monoclonal gammopathy of IgG-κ. Lesions will ulcerate in 40% to 50% of patients.12 The mean age at presentation is in the sixth decade of life, and it is moderately predominant in females.13 Histopathology demonstrates palisading granulomatous formations with a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and zones of necrobiosis in the mid dermis extending into the panniculus. Characteristic histologic features that are variably present in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma but typically absent in RN include neutrophilic debris, cholesterol clefts, and Touton or foreign body giant cells (Figure 3).13

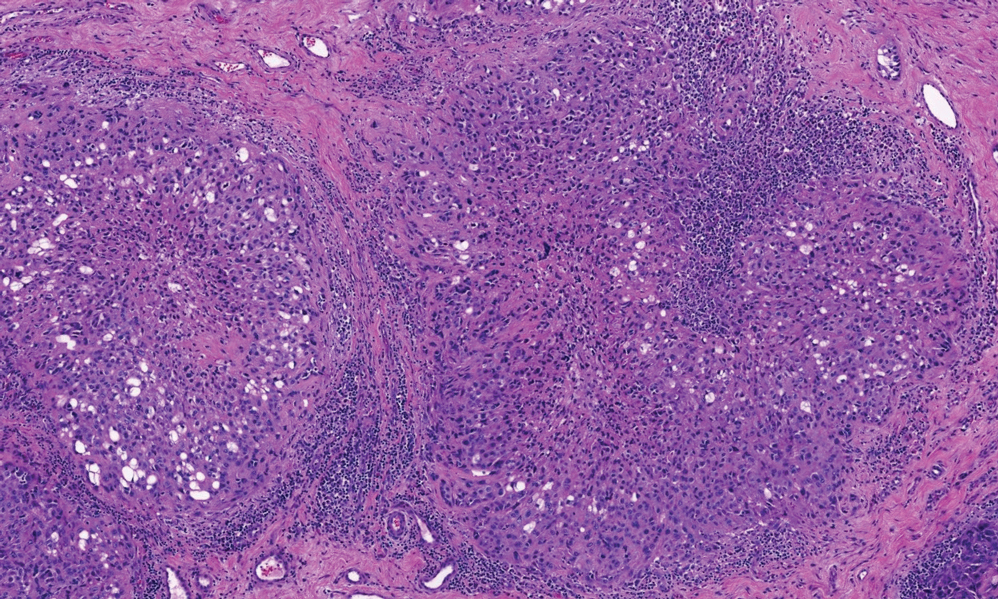

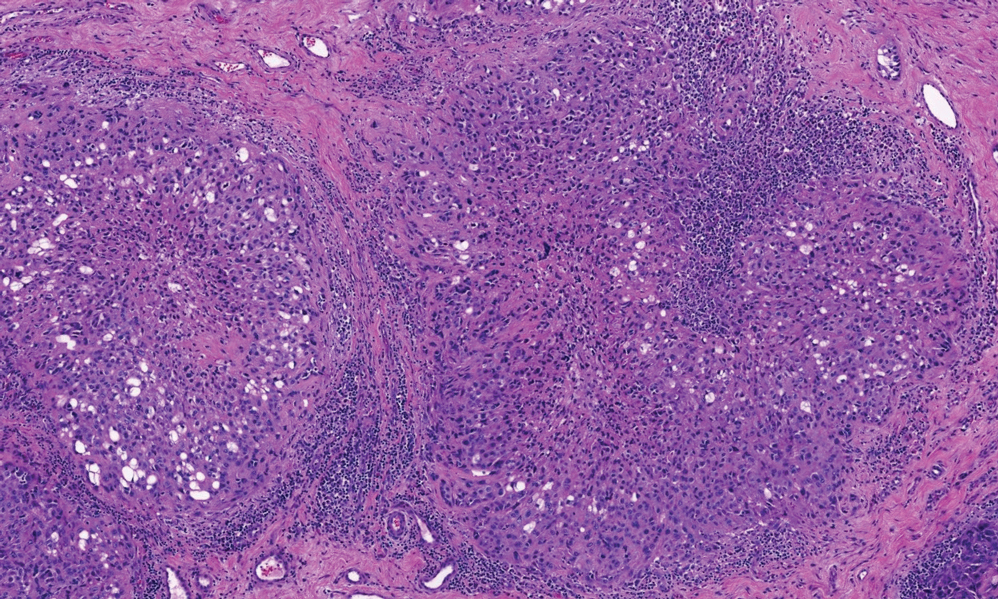

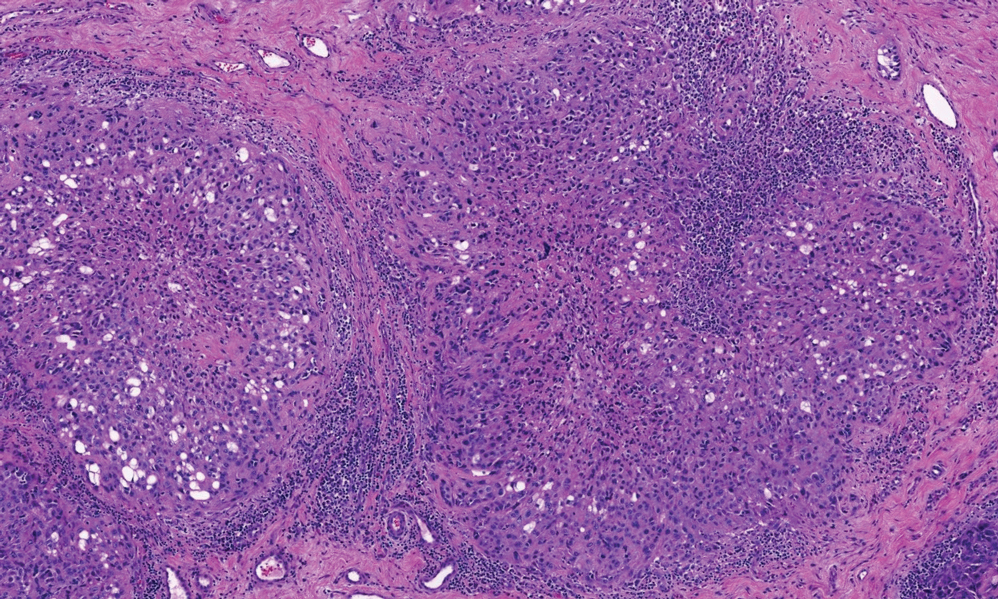

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease characterized by well-demarcated, atrophic, yellow-brown plaques on the pretibial surfaces. It typically presents in the third decade of life in women, and most cases are associated with diabetes mellitus types 1 or 2 or autoimmune conditions.14 Necrobiosis lipoidica begins as asymptomatic papules that enlarge progressively over months to years. They can become pruritic or painful and often develop ulceration. Histopathology shows horizontal zones of palisading histiocytes with intervening necrobiosis. An inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells also may be present (Figure 4).

- Horn RT Jr, Goette DK. Perforating rheumatoid nodule. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:696-697.

- Tilstra JS, Lienesch DW. Rheumatoid nodules. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:361-371. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.004

- Kaye BR, Kaye RL, Bobrove A. Rheumatoid nodules. review of the spectrum of associated conditions and proposal of a new classification, with a report of four seronegative cases. Am J Med. 1984;76:279-292. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(84)90787-3

- Nyhäll-Wåhlin BM, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF, et al; BARFOT study group. Smoking is a strong risk factor for rheumatoid nodules in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:601-606. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.039172

- Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, Crowson CS, et al. Occurrence of extraarticular disease manifestations is associated with excess mortality in a community-based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:62-67.

- Bang S, Kim Y, Jang K, et al. Clinicopathologic features of rheumatoid nodules: a retrospective analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:3041-3048. doi:10.1007/s10067-019-04668-1

- Chaganti S, Joshy S, Hariharan K, et al. Rheumatoid nodule presenting as Morton’s neuroma. J Orthop Traumatol. 2013;14:219-222. doi:10.1007/s10195-012-0215-x

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-212. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.023

- de Visscher SA, van Ginkel RJ, Wobbes T, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: still an only surgically curable disease. Cancer. 2006;107:606-612. doi:10.1002/cncr.22037

- Penas PF, Jones-Caballero M, Fraga J, et al. Perforating granuloma annulare. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:340-348. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-4362.1997.00047.x

- Gale M, Gilbert E, Blumenthal D. Isolated rheumatoid nodules: a diagnostic dilemma. Case Rep Med. 2015;2015:352352. doi:10.1155/2015/352352

- Wood AJ, Wagner MV, Abbott JJ, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a review of 17 cases with emphasis on clinical and pathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:279-284. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.583

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter crosssectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4221

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

The Diagnosis: Perforating Rheumatoid Nodule

Perforating rheumatoid nodule (RN) is a variant of RN that demonstrates necrobiotic material extruding through the epidermis via the process of transepidermal elimination.1 The necrobiotic material contains fibrin and often harbors karyorrhectic debris. The pathogenesis of RN remains unclear; possible mechanisms include a small vessel vasculitis or mechanical trauma inciting a localized aggregation of inflammatory products and rheumatoid factor complexes. This induces macrophage activation, fibrin deposition, and necrosis.2 The majority of patients with RNs have detectable rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated protein in the blood.3 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and will develop in 30% to 40% of RA patients.4,5 They typically are associated with advanced RA but may precede the onset of clinically severe RA in 5% to 10% of patients.5 Rheumatoid nodules generally range in size from 2 mm to 5 cm and are slightly more prevalent in men than in women. They present as firm painless masses typically on the extensor surfaces of the hands and olecranon process but can occur over any tendinous or ligamentlike structure.6,7 Perforating RNs are most common on areas subjected to pressure or repeated trauma, such as the sacrum.

The diagnosis usually is clinical; however, in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, RN can be distinguished by its histologic appearance. Rheumatoid nodules demonstrate granulomatous palisading necrobiosis with a central zone of highly eosinophilic fibrinoid necrobiosis surrounded by palisading mononuclear cells and an outer zone of granulation tissue. There may be a mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate predominantly composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes in the background.

Rheumatoid nodules typically do not require treatment; however, perforation is known to increase the risk for infection, and surgical excision generally is indicated for prophylaxis against infection, though nodules may recur in the excision area.1,3,8 Alternatively, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and intralesional corticosteroids may effectively reduce the size of RNs. The differential diagnosis for perforating RNs includes epithelioid sarcoma, perforating granuloma annulare, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, and necrobiosis lipoidica.

Epithelioid sarcoma is a malignant soft tissue tumor typically found on the upper extremities of adolescent or young adult males. They usually present as hard tender nodules that commonly ulcerate. Epithelioid sarcoma makes up less than 1% of soft tissue sarcomas.9 Although rare, they present a diagnostic pitfall, as the histology may mimic an inflammatory palisaded granulomatous dermatitis similar to RN and granuloma annulare, thus a high index of suspicion is required to not overlook this aggressive malignancy. Histology is typified by nodular aggregates of epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and often with central zones of necrosis (Figure 1). Epithelioid sarcoma displays immunoreactivity to cytokeratin, CD34, and epithelial membrane antigen, but loss of integrase interactor 1 expression. Cytologic abnormalities such as pleomorphism and hyperchromatism can be helpful in distinguishing between epithelioid sarcoma and RN.

Perforating granuloma annulare is a rare subtype of granuloma annulare that presents with flesh- to red-colored papules that develop central crust or scale. Perforating granuloma annulare composes approximately 5% of granuloma annulare cases. Perforating granuloma annulare can develop on any region of the body but has an affinity for the extensor surfaces of the extremities. It most frequently occurs in young women and rarely presents as a single lesion.10 Granuloma annulare typically is not associated with joint pain, and thus it differs from most cases of RNs. Histologically, it presents with an inflammatory palisading granuloma. There may be overlying epidermal thinning or parakeratosis, which can progress to perforation and extrusion of necrobiotic material. In comparison with RN, perforating granuloma annulare displays mucin deposition in the necrobiotic zones in lieu of fibrin (Figure 2).10,11

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a rare chronic form of non-Langerhans histiocytosis that characteristically presents with yellow or violaceous indurated plaques and nodules in a periorbital distribution. It often is associated with monoclonal gammopathy of IgG-κ. Lesions will ulcerate in 40% to 50% of patients.12 The mean age at presentation is in the sixth decade of life, and it is moderately predominant in females.13 Histopathology demonstrates palisading granulomatous formations with a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and zones of necrobiosis in the mid dermis extending into the panniculus. Characteristic histologic features that are variably present in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma but typically absent in RN include neutrophilic debris, cholesterol clefts, and Touton or foreign body giant cells (Figure 3).13

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease characterized by well-demarcated, atrophic, yellow-brown plaques on the pretibial surfaces. It typically presents in the third decade of life in women, and most cases are associated with diabetes mellitus types 1 or 2 or autoimmune conditions.14 Necrobiosis lipoidica begins as asymptomatic papules that enlarge progressively over months to years. They can become pruritic or painful and often develop ulceration. Histopathology shows horizontal zones of palisading histiocytes with intervening necrobiosis. An inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells also may be present (Figure 4).

The Diagnosis: Perforating Rheumatoid Nodule

Perforating rheumatoid nodule (RN) is a variant of RN that demonstrates necrobiotic material extruding through the epidermis via the process of transepidermal elimination.1 The necrobiotic material contains fibrin and often harbors karyorrhectic debris. The pathogenesis of RN remains unclear; possible mechanisms include a small vessel vasculitis or mechanical trauma inciting a localized aggregation of inflammatory products and rheumatoid factor complexes. This induces macrophage activation, fibrin deposition, and necrosis.2 The majority of patients with RNs have detectable rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated protein in the blood.3 Rheumatoid nodules are the most common cutaneous manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and will develop in 30% to 40% of RA patients.4,5 They typically are associated with advanced RA but may precede the onset of clinically severe RA in 5% to 10% of patients.5 Rheumatoid nodules generally range in size from 2 mm to 5 cm and are slightly more prevalent in men than in women. They present as firm painless masses typically on the extensor surfaces of the hands and olecranon process but can occur over any tendinous or ligamentlike structure.6,7 Perforating RNs are most common on areas subjected to pressure or repeated trauma, such as the sacrum.

The diagnosis usually is clinical; however, in cases of diagnostic uncertainty, RN can be distinguished by its histologic appearance. Rheumatoid nodules demonstrate granulomatous palisading necrobiosis with a central zone of highly eosinophilic fibrinoid necrobiosis surrounded by palisading mononuclear cells and an outer zone of granulation tissue. There may be a mixed chronic inflammatory infiltrate predominantly composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes in the background.

Rheumatoid nodules typically do not require treatment; however, perforation is known to increase the risk for infection, and surgical excision generally is indicated for prophylaxis against infection, though nodules may recur in the excision area.1,3,8 Alternatively, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and intralesional corticosteroids may effectively reduce the size of RNs. The differential diagnosis for perforating RNs includes epithelioid sarcoma, perforating granuloma annulare, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, and necrobiosis lipoidica.

Epithelioid sarcoma is a malignant soft tissue tumor typically found on the upper extremities of adolescent or young adult males. They usually present as hard tender nodules that commonly ulcerate. Epithelioid sarcoma makes up less than 1% of soft tissue sarcomas.9 Although rare, they present a diagnostic pitfall, as the histology may mimic an inflammatory palisaded granulomatous dermatitis similar to RN and granuloma annulare, thus a high index of suspicion is required to not overlook this aggressive malignancy. Histology is typified by nodular aggregates of epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and often with central zones of necrosis (Figure 1). Epithelioid sarcoma displays immunoreactivity to cytokeratin, CD34, and epithelial membrane antigen, but loss of integrase interactor 1 expression. Cytologic abnormalities such as pleomorphism and hyperchromatism can be helpful in distinguishing between epithelioid sarcoma and RN.

Perforating granuloma annulare is a rare subtype of granuloma annulare that presents with flesh- to red-colored papules that develop central crust or scale. Perforating granuloma annulare composes approximately 5% of granuloma annulare cases. Perforating granuloma annulare can develop on any region of the body but has an affinity for the extensor surfaces of the extremities. It most frequently occurs in young women and rarely presents as a single lesion.10 Granuloma annulare typically is not associated with joint pain, and thus it differs from most cases of RNs. Histologically, it presents with an inflammatory palisading granuloma. There may be overlying epidermal thinning or parakeratosis, which can progress to perforation and extrusion of necrobiotic material. In comparison with RN, perforating granuloma annulare displays mucin deposition in the necrobiotic zones in lieu of fibrin (Figure 2).10,11

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma is a rare chronic form of non-Langerhans histiocytosis that characteristically presents with yellow or violaceous indurated plaques and nodules in a periorbital distribution. It often is associated with monoclonal gammopathy of IgG-κ. Lesions will ulcerate in 40% to 50% of patients.12 The mean age at presentation is in the sixth decade of life, and it is moderately predominant in females.13 Histopathology demonstrates palisading granulomatous formations with a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and zones of necrobiosis in the mid dermis extending into the panniculus. Characteristic histologic features that are variably present in necrobiotic xanthogranuloma but typically absent in RN include neutrophilic debris, cholesterol clefts, and Touton or foreign body giant cells (Figure 3).13

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare chronic granulomatous disease characterized by well-demarcated, atrophic, yellow-brown plaques on the pretibial surfaces. It typically presents in the third decade of life in women, and most cases are associated with diabetes mellitus types 1 or 2 or autoimmune conditions.14 Necrobiosis lipoidica begins as asymptomatic papules that enlarge progressively over months to years. They can become pruritic or painful and often develop ulceration. Histopathology shows horizontal zones of palisading histiocytes with intervening necrobiosis. An inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells also may be present (Figure 4).

- Horn RT Jr, Goette DK. Perforating rheumatoid nodule. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:696-697.

- Tilstra JS, Lienesch DW. Rheumatoid nodules. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:361-371. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.004

- Kaye BR, Kaye RL, Bobrove A. Rheumatoid nodules. review of the spectrum of associated conditions and proposal of a new classification, with a report of four seronegative cases. Am J Med. 1984;76:279-292. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(84)90787-3

- Nyhäll-Wåhlin BM, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF, et al; BARFOT study group. Smoking is a strong risk factor for rheumatoid nodules in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:601-606. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.039172

- Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, Crowson CS, et al. Occurrence of extraarticular disease manifestations is associated with excess mortality in a community-based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:62-67.

- Bang S, Kim Y, Jang K, et al. Clinicopathologic features of rheumatoid nodules: a retrospective analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:3041-3048. doi:10.1007/s10067-019-04668-1

- Chaganti S, Joshy S, Hariharan K, et al. Rheumatoid nodule presenting as Morton’s neuroma. J Orthop Traumatol. 2013;14:219-222. doi:10.1007/s10195-012-0215-x

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-212. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.023

- de Visscher SA, van Ginkel RJ, Wobbes T, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: still an only surgically curable disease. Cancer. 2006;107:606-612. doi:10.1002/cncr.22037

- Penas PF, Jones-Caballero M, Fraga J, et al. Perforating granuloma annulare. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:340-348. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-4362.1997.00047.x

- Gale M, Gilbert E, Blumenthal D. Isolated rheumatoid nodules: a diagnostic dilemma. Case Rep Med. 2015;2015:352352. doi:10.1155/2015/352352

- Wood AJ, Wagner MV, Abbott JJ, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a review of 17 cases with emphasis on clinical and pathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:279-284. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.583

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter crosssectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4221

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

- Horn RT Jr, Goette DK. Perforating rheumatoid nodule. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:696-697.

- Tilstra JS, Lienesch DW. Rheumatoid nodules. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:361-371. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.004

- Kaye BR, Kaye RL, Bobrove A. Rheumatoid nodules. review of the spectrum of associated conditions and proposal of a new classification, with a report of four seronegative cases. Am J Med. 1984;76:279-292. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(84)90787-3

- Nyhäll-Wåhlin BM, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF, et al; BARFOT study group. Smoking is a strong risk factor for rheumatoid nodules in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:601-606. doi:10.1136/ard.2005.039172

- Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, Crowson CS, et al. Occurrence of extraarticular disease manifestations is associated with excess mortality in a community-based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:62-67.

- Bang S, Kim Y, Jang K, et al. Clinicopathologic features of rheumatoid nodules: a retrospective analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38:3041-3048. doi:10.1007/s10067-019-04668-1

- Chaganti S, Joshy S, Hariharan K, et al. Rheumatoid nodule presenting as Morton’s neuroma. J Orthop Traumatol. 2013;14:219-222. doi:10.1007/s10195-012-0215-x

- Sayah A, English JC 3rd. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:191-209; quiz 210-212. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.023

- de Visscher SA, van Ginkel RJ, Wobbes T, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma: still an only surgically curable disease. Cancer. 2006;107:606-612. doi:10.1002/cncr.22037

- Penas PF, Jones-Caballero M, Fraga J, et al. Perforating granuloma annulare. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:340-348. doi:10.1046 /j.1365-4362.1997.00047.x

- Gale M, Gilbert E, Blumenthal D. Isolated rheumatoid nodules: a diagnostic dilemma. Case Rep Med. 2015;2015:352352. doi:10.1155/2015/352352

- Wood AJ, Wagner MV, Abbott JJ, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: a review of 17 cases with emphasis on clinical and pathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:279-284. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.583

- Nelson CA, Zhong CS, Hashemi DA, et al. A multicenter crosssectional study and systematic review of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with proposed diagnostic criteria. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:270-279. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.4221

- Sibbald C, Reid S, Alavi A. Necrobiosis lipoidica. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:343-360. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.003

A 59-year-old woman with a history of joint pain presented with a foot nodule that developed over the course of 2 years. Physical examination revealed a firm, mobile, mildly tender, 3-cm, deep red nodule on the dorsal aspect of the left foot (top [inset]) with an overlying central epidermal defect and thick keratinaceous debris. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable. Empiric treatments with oral antibiotics and intralesional corticosteroids were unsuccessful. Incisional biopsy was performed for histologic review, and tissue culture studies were negative.

TNF inhibitor treatment models promote personalized care in ankylosing spondylitis

A small number of patient and physician-reported outcomes, as well as laboratory and clinical factors, may help to predict the response of patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) to treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors when they have never taken them before, according to an analysis of data from nearly 2,000 individuals in 10 clinical trials.

TNF inhibitors are recommended for patients with AS whose symptoms persist despite use of NSAIDs, Runsheng Wang, MD, adjunct assistant professor at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, and a practicing rheumatologist at Garden State Rheumatology Consultants, Union, N.J., and colleagues wrote. Randomized, controlled clinical trials have shown that TNF inhibitors are effective in treating AS, but approximately half of patients fail to achieve notable improvement, which suggests the need for a predictive model.

“In clinical practice, before starting a treatment, physicians and patients want to know how likely a patient would be to respond to the treatment, particularly when more than one treatment option is available,” Dr. Wang said in an interview. “In this study, we developed predictive models that can potentially answer this question.”

The results suggest that the models in the study can be used to personalize clinical decision-making for patients with AS, whether to promote confidence in choosing a TNF inhibitor or to terminate treatment in nonresponders who had a higher probability of nonresponse at baseline, the researchers wrote. Similar models for other biologic treatments can help prioritize treatment options.

The predictive models are practical for clinical use because the variables in the reduced models – can be collected easily during patient visits, Dr. Wang explained. However, data from clinical practice are needed to further validate the study findings.

In a retrospective cohort study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers analyzed data from 10 randomized, controlled clinical trials of TNF inhibitor treatment in patients with active AS conducted during 2002-2016. The study population included 1,899 adults with active AS who received an originator TNF inhibitor for at least 12 weeks, and the training set included 1,207 individuals. In the training set, the mean age of the participants was 39 years, and 75% were men.

The outcomes included major response and no response based on change in AS Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) from baseline to 12 weeks, and the researchers used machine-learning algorithms to estimate the probability of major response or no response. Major response was defined as a decrease in ASDAS of 2.0 or greater; no response was defined as a decrease in ASDAS of less than 1.1.

In the training set, a total of 407 patients (33.7%) had a major response, and 414 (34.3%) had no response.

The key features in the full, 21-variable model that increased the probability of a major response were higher C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, higher patient global assessment (PGA) of disease activity, and Bath AS Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) question 2 scores. (Question 2 asks for the overall level of back, hip, or neck pain associated with AS.) The probability of a major response decreased with higher body mass index and Bath AS Functional Index (BASFI) scores.

The key features in the model that increased the probability of no response were older age and higher BASFI scores. The probability of no response decreased with higher CRP levels, higher BASDAI question 2 scores, and higher PGA scores.

Overall, the researchers found that models using smaller subsets of variables (three or five variables in total) that would be easier to gather clinically yielded similar predictive performance.

The models were externally validated in a testing set of 692 individuals. Baseline characteristics were similar in the testing and training sets. In the testing set, the full models demonstrated moderate to high accuracy of 0.71 in the random forest model for major response and 0.76 in the random forest model for no response, with similar results in the reduced models.

At a prevalence of 25% for major response, the positive predictive values (PPVs) for random forest and logistic regression models ranged from 0.49 to 0.60, and the negative predictive values (NPVs) ranged from 0.82 to 0.84. At a prevalence of 25% for no response, PPVs ranged from 0.61 to 0.77, and NPVs ranged from 0.81 to 0.83.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of data on smoking, which has been linked both to shorter treatment adherence and worse response to TNF inhibitors; the inclusion of only TNF inhibitor–naive patients; and the exclusion of NSAIDs from the models, the researchers wrote.

Dr. Wang disclosed support from the Rheumatology Research Foundation. The study’s two other authors disclosed receiving support from the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The study was based on an analysis of data from AbbVie and Pfizer that were made available through Vivli.

A small number of patient and physician-reported outcomes, as well as laboratory and clinical factors, may help to predict the response of patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) to treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors when they have never taken them before, according to an analysis of data from nearly 2,000 individuals in 10 clinical trials.

TNF inhibitors are recommended for patients with AS whose symptoms persist despite use of NSAIDs, Runsheng Wang, MD, adjunct assistant professor at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, and a practicing rheumatologist at Garden State Rheumatology Consultants, Union, N.J., and colleagues wrote. Randomized, controlled clinical trials have shown that TNF inhibitors are effective in treating AS, but approximately half of patients fail to achieve notable improvement, which suggests the need for a predictive model.

“In clinical practice, before starting a treatment, physicians and patients want to know how likely a patient would be to respond to the treatment, particularly when more than one treatment option is available,” Dr. Wang said in an interview. “In this study, we developed predictive models that can potentially answer this question.”

The results suggest that the models in the study can be used to personalize clinical decision-making for patients with AS, whether to promote confidence in choosing a TNF inhibitor or to terminate treatment in nonresponders who had a higher probability of nonresponse at baseline, the researchers wrote. Similar models for other biologic treatments can help prioritize treatment options.

The predictive models are practical for clinical use because the variables in the reduced models – can be collected easily during patient visits, Dr. Wang explained. However, data from clinical practice are needed to further validate the study findings.

In a retrospective cohort study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers analyzed data from 10 randomized, controlled clinical trials of TNF inhibitor treatment in patients with active AS conducted during 2002-2016. The study population included 1,899 adults with active AS who received an originator TNF inhibitor for at least 12 weeks, and the training set included 1,207 individuals. In the training set, the mean age of the participants was 39 years, and 75% were men.

The outcomes included major response and no response based on change in AS Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) from baseline to 12 weeks, and the researchers used machine-learning algorithms to estimate the probability of major response or no response. Major response was defined as a decrease in ASDAS of 2.0 or greater; no response was defined as a decrease in ASDAS of less than 1.1.

In the training set, a total of 407 patients (33.7%) had a major response, and 414 (34.3%) had no response.

The key features in the full, 21-variable model that increased the probability of a major response were higher C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, higher patient global assessment (PGA) of disease activity, and Bath AS Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) question 2 scores. (Question 2 asks for the overall level of back, hip, or neck pain associated with AS.) The probability of a major response decreased with higher body mass index and Bath AS Functional Index (BASFI) scores.

The key features in the model that increased the probability of no response were older age and higher BASFI scores. The probability of no response decreased with higher CRP levels, higher BASDAI question 2 scores, and higher PGA scores.

Overall, the researchers found that models using smaller subsets of variables (three or five variables in total) that would be easier to gather clinically yielded similar predictive performance.

The models were externally validated in a testing set of 692 individuals. Baseline characteristics were similar in the testing and training sets. In the testing set, the full models demonstrated moderate to high accuracy of 0.71 in the random forest model for major response and 0.76 in the random forest model for no response, with similar results in the reduced models.

At a prevalence of 25% for major response, the positive predictive values (PPVs) for random forest and logistic regression models ranged from 0.49 to 0.60, and the negative predictive values (NPVs) ranged from 0.82 to 0.84. At a prevalence of 25% for no response, PPVs ranged from 0.61 to 0.77, and NPVs ranged from 0.81 to 0.83.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the lack of data on smoking, which has been linked both to shorter treatment adherence and worse response to TNF inhibitors; the inclusion of only TNF inhibitor–naive patients; and the exclusion of NSAIDs from the models, the researchers wrote.

Dr. Wang disclosed support from the Rheumatology Research Foundation. The study’s two other authors disclosed receiving support from the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The study was based on an analysis of data from AbbVie and Pfizer that were made available through Vivli.

A small number of patient and physician-reported outcomes, as well as laboratory and clinical factors, may help to predict the response of patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) to treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors when they have never taken them before, according to an analysis of data from nearly 2,000 individuals in 10 clinical trials.

TNF inhibitors are recommended for patients with AS whose symptoms persist despite use of NSAIDs, Runsheng Wang, MD, adjunct assistant professor at Columbia University Medical Center, New York, and a practicing rheumatologist at Garden State Rheumatology Consultants, Union, N.J., and colleagues wrote. Randomized, controlled clinical trials have shown that TNF inhibitors are effective in treating AS, but approximately half of patients fail to achieve notable improvement, which suggests the need for a predictive model.

“In clinical practice, before starting a treatment, physicians and patients want to know how likely a patient would be to respond to the treatment, particularly when more than one treatment option is available,” Dr. Wang said in an interview. “In this study, we developed predictive models that can potentially answer this question.”

The results suggest that the models in the study can be used to personalize clinical decision-making for patients with AS, whether to promote confidence in choosing a TNF inhibitor or to terminate treatment in nonresponders who had a higher probability of nonresponse at baseline, the researchers wrote. Similar models for other biologic treatments can help prioritize treatment options.

The predictive models are practical for clinical use because the variables in the reduced models – can be collected easily during patient visits, Dr. Wang explained. However, data from clinical practice are needed to further validate the study findings.

In a retrospective cohort study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers analyzed data from 10 randomized, controlled clinical trials of TNF inhibitor treatment in patients with active AS conducted during 2002-2016. The study population included 1,899 adults with active AS who received an originator TNF inhibitor for at least 12 weeks, and the training set included 1,207 individuals. In the training set, the mean age of the participants was 39 years, and 75% were men.

The outcomes included major response and no response based on change in AS Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) from baseline to 12 weeks, and the researchers used machine-learning algorithms to estimate the probability of major response or no response. Major response was defined as a decrease in ASDAS of 2.0 or greater; no response was defined as a decrease in ASDAS of less than 1.1.

In the training set, a total of 407 patients (33.7%) had a major response, and 414 (34.3%) had no response.

The key features in the full, 21-variable model that increased the probability of a major response were higher C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, higher patient global assessment (PGA) of disease activity, and Bath AS Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) question 2 scores. (Question 2 asks for the overall level of back, hip, or neck pain associated with AS.) The probability of a major response decreased with higher body mass index and Bath AS Functional Index (BASFI) scores.