User login

Poverty-related stress linked to aggressive head and neck cancer

A humanized mouse model suggests that head and neck cancer growth may stem from chronic stress. The study found that animals had immunophenotypic changes and a greater propensity towards tumor growth and metastasis.

Other studies have shown this may be caused by the lack of access to health care services or poor quality care. but the difference remains even after adjusting for these factors, according to researchers writing in Head and Neck.

Led by Heather A. Himburg, PhD, associate professor of radiation oncology with the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, researchers conducted a study of head and neck cancer models in which tumor cells were implanted into a mouse with a humanized immune system.

Their theory was that psychosocial stress may contribute to the growth of head and neck tumors. The stress of poverty, social deprivation and social isolation can lead to the up-regulation of proinflammatory markers in circulating blood leukocytes, and this has been tied to worse outcomes in hematologic malignancies and breast cancer. Many such studies examined social adversity and found an association with greater tumor growth rates and treatment resistance.

Other researchers have used mouse models to study the phenomenon, but the results have been inconclusive. For example, some research linked the beta-adrenergic pathway to head and neck cancer, but clinical trials of beta-blockers showed no benefit, and even potential harm, for patients with head and neck cancers. Those results imply that this pathway does not drive tumor growth and metastasis in the presence of chronic stress.

Previous research used immunocompromised or nonhumanized mice. However, neither type of model reproduces the human tumor microenvironment, which may contribute to ensuing clinical failures. In the new study, researchers describe results from a preclinical model created using a human head and neck cancer xenograft in a mouse with a humanized immune system.

How the study was conducted

The animals were randomly assigned to normal housing of two or three animals from the same litter to a cage, or social isolation from littermates. There were five male and five female animals in each arm, and the animals were housed in their separate conditions for 4 weeks before tumor implantation.

The isolated animals experienced increased growth and metastasis of the xenografts, compared with controls. The results are consistent with findings in immunodeficient or syngeneic mice, but the humanized nature of the new model could lead to better translation of findings into clinical studies. “The humanized model system in this study demonstrated the presence of both human myeloid and lymphoid lineages as well as expression of at least 40 human cytokines. These data indicate that our model is likely to well-represent the human condition and better predict human clinical responses as compared to both immunodeficient and syngeneic models,” the authors wrote.

The researchers also found that chronic stress may act through an immunoregulatory effect, since there was greater human immune infiltrate into the tumors of stressed animals. Increased presence of regulatory components like myeloid-derived suppressor cells or regulatory T cells, or eroded function of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, might explain this finding. The researchers also identified a proinflammatory change in peripheral blood monocular cells in the stressed group. When they analyzed samples from patients who were low income earners of less than $45,000 in annual household income, they found a similar pattern. “This suggests that chronic socioeconomic stress may induce a similar proinflammatory immune state as our chronic stress model system,” the authors wrote.

Tumors were also different between the two groups of mice. Tumors in stressed animals had a higher percentage of cancer stem cells, which is associated with more aggressive tumors and worse disease-free survival. The researchers suggested that up-regulated levels of the chemokine SDF-1 seen in the stressed animals may be driving the higher proportion of stem cells through its effects on the CXCR4 receptor, which is expressed by stem cells in various organs and may cause migration, proliferation, and cell survival.

The study was funded by an endowment from Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin and a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

A humanized mouse model suggests that head and neck cancer growth may stem from chronic stress. The study found that animals had immunophenotypic changes and a greater propensity towards tumor growth and metastasis.

Other studies have shown this may be caused by the lack of access to health care services or poor quality care. but the difference remains even after adjusting for these factors, according to researchers writing in Head and Neck.

Led by Heather A. Himburg, PhD, associate professor of radiation oncology with the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, researchers conducted a study of head and neck cancer models in which tumor cells were implanted into a mouse with a humanized immune system.

Their theory was that psychosocial stress may contribute to the growth of head and neck tumors. The stress of poverty, social deprivation and social isolation can lead to the up-regulation of proinflammatory markers in circulating blood leukocytes, and this has been tied to worse outcomes in hematologic malignancies and breast cancer. Many such studies examined social adversity and found an association with greater tumor growth rates and treatment resistance.

Other researchers have used mouse models to study the phenomenon, but the results have been inconclusive. For example, some research linked the beta-adrenergic pathway to head and neck cancer, but clinical trials of beta-blockers showed no benefit, and even potential harm, for patients with head and neck cancers. Those results imply that this pathway does not drive tumor growth and metastasis in the presence of chronic stress.

Previous research used immunocompromised or nonhumanized mice. However, neither type of model reproduces the human tumor microenvironment, which may contribute to ensuing clinical failures. In the new study, researchers describe results from a preclinical model created using a human head and neck cancer xenograft in a mouse with a humanized immune system.

How the study was conducted

The animals were randomly assigned to normal housing of two or three animals from the same litter to a cage, or social isolation from littermates. There were five male and five female animals in each arm, and the animals were housed in their separate conditions for 4 weeks before tumor implantation.

The isolated animals experienced increased growth and metastasis of the xenografts, compared with controls. The results are consistent with findings in immunodeficient or syngeneic mice, but the humanized nature of the new model could lead to better translation of findings into clinical studies. “The humanized model system in this study demonstrated the presence of both human myeloid and lymphoid lineages as well as expression of at least 40 human cytokines. These data indicate that our model is likely to well-represent the human condition and better predict human clinical responses as compared to both immunodeficient and syngeneic models,” the authors wrote.

The researchers also found that chronic stress may act through an immunoregulatory effect, since there was greater human immune infiltrate into the tumors of stressed animals. Increased presence of regulatory components like myeloid-derived suppressor cells or regulatory T cells, or eroded function of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, might explain this finding. The researchers also identified a proinflammatory change in peripheral blood monocular cells in the stressed group. When they analyzed samples from patients who were low income earners of less than $45,000 in annual household income, they found a similar pattern. “This suggests that chronic socioeconomic stress may induce a similar proinflammatory immune state as our chronic stress model system,” the authors wrote.

Tumors were also different between the two groups of mice. Tumors in stressed animals had a higher percentage of cancer stem cells, which is associated with more aggressive tumors and worse disease-free survival. The researchers suggested that up-regulated levels of the chemokine SDF-1 seen in the stressed animals may be driving the higher proportion of stem cells through its effects on the CXCR4 receptor, which is expressed by stem cells in various organs and may cause migration, proliferation, and cell survival.

The study was funded by an endowment from Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin and a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

A humanized mouse model suggests that head and neck cancer growth may stem from chronic stress. The study found that animals had immunophenotypic changes and a greater propensity towards tumor growth and metastasis.

Other studies have shown this may be caused by the lack of access to health care services or poor quality care. but the difference remains even after adjusting for these factors, according to researchers writing in Head and Neck.

Led by Heather A. Himburg, PhD, associate professor of radiation oncology with the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, researchers conducted a study of head and neck cancer models in which tumor cells were implanted into a mouse with a humanized immune system.

Their theory was that psychosocial stress may contribute to the growth of head and neck tumors. The stress of poverty, social deprivation and social isolation can lead to the up-regulation of proinflammatory markers in circulating blood leukocytes, and this has been tied to worse outcomes in hematologic malignancies and breast cancer. Many such studies examined social adversity and found an association with greater tumor growth rates and treatment resistance.

Other researchers have used mouse models to study the phenomenon, but the results have been inconclusive. For example, some research linked the beta-adrenergic pathway to head and neck cancer, but clinical trials of beta-blockers showed no benefit, and even potential harm, for patients with head and neck cancers. Those results imply that this pathway does not drive tumor growth and metastasis in the presence of chronic stress.

Previous research used immunocompromised or nonhumanized mice. However, neither type of model reproduces the human tumor microenvironment, which may contribute to ensuing clinical failures. In the new study, researchers describe results from a preclinical model created using a human head and neck cancer xenograft in a mouse with a humanized immune system.

How the study was conducted

The animals were randomly assigned to normal housing of two or three animals from the same litter to a cage, or social isolation from littermates. There were five male and five female animals in each arm, and the animals were housed in their separate conditions for 4 weeks before tumor implantation.

The isolated animals experienced increased growth and metastasis of the xenografts, compared with controls. The results are consistent with findings in immunodeficient or syngeneic mice, but the humanized nature of the new model could lead to better translation of findings into clinical studies. “The humanized model system in this study demonstrated the presence of both human myeloid and lymphoid lineages as well as expression of at least 40 human cytokines. These data indicate that our model is likely to well-represent the human condition and better predict human clinical responses as compared to both immunodeficient and syngeneic models,” the authors wrote.

The researchers also found that chronic stress may act through an immunoregulatory effect, since there was greater human immune infiltrate into the tumors of stressed animals. Increased presence of regulatory components like myeloid-derived suppressor cells or regulatory T cells, or eroded function of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, might explain this finding. The researchers also identified a proinflammatory change in peripheral blood monocular cells in the stressed group. When they analyzed samples from patients who were low income earners of less than $45,000 in annual household income, they found a similar pattern. “This suggests that chronic socioeconomic stress may induce a similar proinflammatory immune state as our chronic stress model system,” the authors wrote.

Tumors were also different between the two groups of mice. Tumors in stressed animals had a higher percentage of cancer stem cells, which is associated with more aggressive tumors and worse disease-free survival. The researchers suggested that up-regulated levels of the chemokine SDF-1 seen in the stressed animals may be driving the higher proportion of stem cells through its effects on the CXCR4 receptor, which is expressed by stem cells in various organs and may cause migration, proliferation, and cell survival.

The study was funded by an endowment from Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin and a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM HEAD & NECK

Steroids counter ataxia telangiectasia

SEATTLE –

The disease is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the ATM gene, which is critical to the response to cellular insults such as DNA breaks, oxidative damage, and other forms of stress. The result is clinical manifestations that range from a suppressed immune system to organ damage and neurological symptoms that typically lead patients to be wheelchair bound by their teenage years.

“It’s really multisystem and a very, very difficult disease for people to live with,” Howard M. Lederman, MD, PhD, said in an interview. Dr. Lederman is a coauthor of the study, which was presented by Stefan Zielen, PhD, professor at the University of Goethe, at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Various therapies have been developed to improve immunodeficiency, lung disease, and some of the other clinical aspects of the condition, but there is no treatment for its neurological effects. “There’s not really been a good animal model, which has been a big problem in trying to test drugs and design treatment trials,” said Dr. Lederman, professor of pediatrics and medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The new results may change that. “In the children under the age of 9, there was really a very clear slowdown in the neurodegeneration, and specifically the time that it took for them to lose the ability to ambulate. It’s very exciting, because it’s the first time that anybody has really shown in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, large phase 3 study that any drug has been able to do this. And there were really no steroid side effects, which is the other really remarkable thing about this study,” said Dr. Lederman.

The therapy grew out of a study by researchers in Italy who treated pediatric ataxia telangiectasia patients with corticosteroids and found some transitory improvements in gross motor function, but concerns about long-term exposure to steroids limited its application. EryDel, which specializes in encapsulating therapeutics in red blood cells, became interested and developed a formulation using the patient’s own red blood cells infused with DSP. Reinfused to the patients, the red blood cells slowly release the steroid.

It isn’t clear how dexamethasone works. There are data suggesting that it might lead to transcription of small pieces of the ATM protein, “but that has really not been nailed down in any way at this point. Corticosteroids act on all kinds of cells in all kinds of ways, and so there might be a little bit of this so-called mini-ATM that’s produced, but that may or may not be related to the way in which corticosteroids have a beneficial effect on the rate of neurodegeneration,” said Dr. Lederman.

The treatment process is not easy. Children must have 50-60 cc of blood removed. Red blood cells treated to become porous are exposed to DSP, and then resealed. Then the cells are reinfused. “The whole process takes from beginning to end probably about 3 hours, with a really experienced team of people doing it. And it’s limiting because it’s not easy to put in an IV and take 50 or 60 cc of blood out of children much younger than 5 or 6. The process is now being modified to see whether we could do it with 20 to 30 cc instead,” said Dr. Lederman.

A ‘promising and impressive’ study

The study is promising, according to Nicholas Johnson, MD, who comoderated the session where the study was presented. “They were able to show a slower rate of neurological degeneration or duration on both the lower and higher dose compared with the placebo. This is promising and impressive, in the sense that it’s a really large (trial) for a rare condition,” Dr. Johnson, vice chair of research at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, said in an interview.

The study included 164 patients Europe, Australia, Israel, Tunisia, India, and the United States, who received 5-10 mg dexamethasone, 14-22 mg DSP, or placebo. Mean ages in each group ranged from 9.6 to 10.4 years.

In an intention-to-treat analysis, modified International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale (mICARS) scores trended toward improvement in the low-dose (–1.37; P = .0847) and high-dose groups (–1.40; P = .0765) when determined by central raters during the COVID-19 pandemic. There was also a trend toward improvement when determined by local raters in the low dose group (–1.73; P = .0720) and a statistically significant change in the high dose group (–2.11; P = .0277). The researchers noted some inconsistency between local and central raters, due to inconsistency of videography and language challenges for central raters.

An intention-to-treat analysis of a subgroup of 89 patients age 6-9, who were compared with natural history data from 245 patients, found a deterioration of mICARS of 3.7 per year, compared with 0.92 in the high-dose group, for a reduction of 75% (P = .020). In the high-dose group, 51.7% had a minimal or significant improvement compared with baseline according to the Clinical Global Impression of Change, as did 29.0% on low dose, and 27.6% in the placebo group.

SEATTLE –

The disease is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the ATM gene, which is critical to the response to cellular insults such as DNA breaks, oxidative damage, and other forms of stress. The result is clinical manifestations that range from a suppressed immune system to organ damage and neurological symptoms that typically lead patients to be wheelchair bound by their teenage years.

“It’s really multisystem and a very, very difficult disease for people to live with,” Howard M. Lederman, MD, PhD, said in an interview. Dr. Lederman is a coauthor of the study, which was presented by Stefan Zielen, PhD, professor at the University of Goethe, at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Various therapies have been developed to improve immunodeficiency, lung disease, and some of the other clinical aspects of the condition, but there is no treatment for its neurological effects. “There’s not really been a good animal model, which has been a big problem in trying to test drugs and design treatment trials,” said Dr. Lederman, professor of pediatrics and medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The new results may change that. “In the children under the age of 9, there was really a very clear slowdown in the neurodegeneration, and specifically the time that it took for them to lose the ability to ambulate. It’s very exciting, because it’s the first time that anybody has really shown in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, large phase 3 study that any drug has been able to do this. And there were really no steroid side effects, which is the other really remarkable thing about this study,” said Dr. Lederman.

The therapy grew out of a study by researchers in Italy who treated pediatric ataxia telangiectasia patients with corticosteroids and found some transitory improvements in gross motor function, but concerns about long-term exposure to steroids limited its application. EryDel, which specializes in encapsulating therapeutics in red blood cells, became interested and developed a formulation using the patient’s own red blood cells infused with DSP. Reinfused to the patients, the red blood cells slowly release the steroid.

It isn’t clear how dexamethasone works. There are data suggesting that it might lead to transcription of small pieces of the ATM protein, “but that has really not been nailed down in any way at this point. Corticosteroids act on all kinds of cells in all kinds of ways, and so there might be a little bit of this so-called mini-ATM that’s produced, but that may or may not be related to the way in which corticosteroids have a beneficial effect on the rate of neurodegeneration,” said Dr. Lederman.

The treatment process is not easy. Children must have 50-60 cc of blood removed. Red blood cells treated to become porous are exposed to DSP, and then resealed. Then the cells are reinfused. “The whole process takes from beginning to end probably about 3 hours, with a really experienced team of people doing it. And it’s limiting because it’s not easy to put in an IV and take 50 or 60 cc of blood out of children much younger than 5 or 6. The process is now being modified to see whether we could do it with 20 to 30 cc instead,” said Dr. Lederman.

A ‘promising and impressive’ study

The study is promising, according to Nicholas Johnson, MD, who comoderated the session where the study was presented. “They were able to show a slower rate of neurological degeneration or duration on both the lower and higher dose compared with the placebo. This is promising and impressive, in the sense that it’s a really large (trial) for a rare condition,” Dr. Johnson, vice chair of research at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, said in an interview.

The study included 164 patients Europe, Australia, Israel, Tunisia, India, and the United States, who received 5-10 mg dexamethasone, 14-22 mg DSP, or placebo. Mean ages in each group ranged from 9.6 to 10.4 years.

In an intention-to-treat analysis, modified International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale (mICARS) scores trended toward improvement in the low-dose (–1.37; P = .0847) and high-dose groups (–1.40; P = .0765) when determined by central raters during the COVID-19 pandemic. There was also a trend toward improvement when determined by local raters in the low dose group (–1.73; P = .0720) and a statistically significant change in the high dose group (–2.11; P = .0277). The researchers noted some inconsistency between local and central raters, due to inconsistency of videography and language challenges for central raters.

An intention-to-treat analysis of a subgroup of 89 patients age 6-9, who were compared with natural history data from 245 patients, found a deterioration of mICARS of 3.7 per year, compared with 0.92 in the high-dose group, for a reduction of 75% (P = .020). In the high-dose group, 51.7% had a minimal or significant improvement compared with baseline according to the Clinical Global Impression of Change, as did 29.0% on low dose, and 27.6% in the placebo group.

SEATTLE –

The disease is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in the ATM gene, which is critical to the response to cellular insults such as DNA breaks, oxidative damage, and other forms of stress. The result is clinical manifestations that range from a suppressed immune system to organ damage and neurological symptoms that typically lead patients to be wheelchair bound by their teenage years.

“It’s really multisystem and a very, very difficult disease for people to live with,” Howard M. Lederman, MD, PhD, said in an interview. Dr. Lederman is a coauthor of the study, which was presented by Stefan Zielen, PhD, professor at the University of Goethe, at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Various therapies have been developed to improve immunodeficiency, lung disease, and some of the other clinical aspects of the condition, but there is no treatment for its neurological effects. “There’s not really been a good animal model, which has been a big problem in trying to test drugs and design treatment trials,” said Dr. Lederman, professor of pediatrics and medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The new results may change that. “In the children under the age of 9, there was really a very clear slowdown in the neurodegeneration, and specifically the time that it took for them to lose the ability to ambulate. It’s very exciting, because it’s the first time that anybody has really shown in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, large phase 3 study that any drug has been able to do this. And there were really no steroid side effects, which is the other really remarkable thing about this study,” said Dr. Lederman.

The therapy grew out of a study by researchers in Italy who treated pediatric ataxia telangiectasia patients with corticosteroids and found some transitory improvements in gross motor function, but concerns about long-term exposure to steroids limited its application. EryDel, which specializes in encapsulating therapeutics in red blood cells, became interested and developed a formulation using the patient’s own red blood cells infused with DSP. Reinfused to the patients, the red blood cells slowly release the steroid.

It isn’t clear how dexamethasone works. There are data suggesting that it might lead to transcription of small pieces of the ATM protein, “but that has really not been nailed down in any way at this point. Corticosteroids act on all kinds of cells in all kinds of ways, and so there might be a little bit of this so-called mini-ATM that’s produced, but that may or may not be related to the way in which corticosteroids have a beneficial effect on the rate of neurodegeneration,” said Dr. Lederman.

The treatment process is not easy. Children must have 50-60 cc of blood removed. Red blood cells treated to become porous are exposed to DSP, and then resealed. Then the cells are reinfused. “The whole process takes from beginning to end probably about 3 hours, with a really experienced team of people doing it. And it’s limiting because it’s not easy to put in an IV and take 50 or 60 cc of blood out of children much younger than 5 or 6. The process is now being modified to see whether we could do it with 20 to 30 cc instead,” said Dr. Lederman.

A ‘promising and impressive’ study

The study is promising, according to Nicholas Johnson, MD, who comoderated the session where the study was presented. “They were able to show a slower rate of neurological degeneration or duration on both the lower and higher dose compared with the placebo. This is promising and impressive, in the sense that it’s a really large (trial) for a rare condition,” Dr. Johnson, vice chair of research at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, said in an interview.

The study included 164 patients Europe, Australia, Israel, Tunisia, India, and the United States, who received 5-10 mg dexamethasone, 14-22 mg DSP, or placebo. Mean ages in each group ranged from 9.6 to 10.4 years.

In an intention-to-treat analysis, modified International Cooperative Ataxia Rating Scale (mICARS) scores trended toward improvement in the low-dose (–1.37; P = .0847) and high-dose groups (–1.40; P = .0765) when determined by central raters during the COVID-19 pandemic. There was also a trend toward improvement when determined by local raters in the low dose group (–1.73; P = .0720) and a statistically significant change in the high dose group (–2.11; P = .0277). The researchers noted some inconsistency between local and central raters, due to inconsistency of videography and language challenges for central raters.

An intention-to-treat analysis of a subgroup of 89 patients age 6-9, who were compared with natural history data from 245 patients, found a deterioration of mICARS of 3.7 per year, compared with 0.92 in the high-dose group, for a reduction of 75% (P = .020). In the high-dose group, 51.7% had a minimal or significant improvement compared with baseline according to the Clinical Global Impression of Change, as did 29.0% on low dose, and 27.6% in the placebo group.

AT AAN 2022

Postpartum HCV treatment rare in infected mothers with opioid use disorder

Despite the availability of effective direct-acting antivirals, very few a mothers with opioid use disorder (OUD) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) during pregnancy received follow-up care or treatment for the infection within 6 months of giving birth, a retrospective study of Medicaid maternity patients found.

The study pooled data on 23,780 Medicaid-enrolled pregnant women with OUD who had a live or stillbirth during 2016-2019 and were followed for 6 months after delivery. Among these women – drawn from six states in the Medicaid Outcomes Distributed Research Network – the pooled average probability of HCV testing during pregnancy was 70.3% (95% confidence interval, 61.5%-79.1%). Of these, 30.9% (95% CI, 23.8%-38%) tested positive. At 60 days postpartum, just 3.2% (95% CI, 2.6%-3.8%) had a follow-up visit or treatment for HCV. In a subset of patients followed for 6 months, only 5.9% (95% CI, 4.9%-6.9%) had any HCV follow-up visit or medication within 6 months of delivery.

While HCV screening and diagnosis rates varied across states, postpartum follow-up rates were universally low. The results suggest a need to improve the cascade of postpartum care for HCV and, ultimately perhaps, introduce antenatal HCV treatment, as is currently given safely for HIV, if current clinical research establishes safety, according to Marian P. Jarlenski, PhD, MPH, an associate professor of public health policy and management at the University of Pittsburgh. The study was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

HCV infection has risen substantially in people of reproductive age in tandem with an increase in OUDs. HCV is transmitted from an infected mother to her baby in about 6% of cases, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which in 2020 expanded its HCV screening recommendations to include all pregnant women. Currently no treatment for HCV during pregnancy has been approved.

In light of those recent recommendations, Dr. Jarlenski said in an interview that her group was “interested in looking at high-risk screened people and estimating what proportion received follow-up care and treatment for HCV. What is the promise of screening? The promise is that you can treat. Otherwise why screen?”

She acknowledged, however, that the postpartum period is a challenging time for a mother to seek health information or care for herself, whether she’s a new parent or has other children in the home. Nevertheless, the low rate of follow-up and treatment was unexpected. “Even the 70% rate of screening was low – we felt it should have been closer to 100% – but the follow-up rate was surprisingly low,” Dr. Jarlenski said.

Mishka Terplan, MD, MPH, medical director of Friends Research Institute in Baltimore, was not surprised at the low follow-up rate. “The cascade of care for hep C is demoralizing,” said Dr. Terplan, who was not involved in the study. “We know that hep C is syndemic with OUD and other opioid crises and we know that screening is effective for identifying hep C and that antiviral medications are now more effective and less toxic than ever before. But despite this, we’re failing pregnant women and their kids at every step along the cascade. We do a better job with initial testing than with the follow-up testing. We do a horrible job with postpartum medication initiation.”

He pointed to the systemic challenges mothers face in getting postpartum HCV care. “They may be transferred to a subspecialist for treatment, and this transfer is compounded by issues of insurance coverage and eligibility.” With the onus on new mothers to submit the paperwork, “the idea that mothers would be able to initiate much less continue postpartum treatment is absurd,” Dr. Terplan said.

He added that the children born to HCV-positive mothers need surveillance as well, but data suggest that the rates of newborn testing are also low. “There’s a preventable public health burden in all of this.”

The obvious way to increase eradicative therapy would be to treat women while they are getting antenatal care. A small phase 1 trial found that all pregnant participants who were HCV positive and given antivirals in their second trimester were safely treated and gave birth to healthy babies.

“If larger trials prove this treatment is safe and effective, then these results should be communicated to care providers and pregnant patients,” Dr. Jarlenski said. Otherwise, the public health potential of universal screening in pregnancy will not be realized.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse and by the Delaware Division of Medicaid and Medical Assistance and the University of Delaware, Center for Community Research & Service. Dr. Jarlenski disclosed no competing interests. One coauthor disclosed grant funding through her institution from Gilead Sciences and Organon unrelated to this work. Dr. Terplan reported no relevant competing interests.

Despite the availability of effective direct-acting antivirals, very few a mothers with opioid use disorder (OUD) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) during pregnancy received follow-up care or treatment for the infection within 6 months of giving birth, a retrospective study of Medicaid maternity patients found.

The study pooled data on 23,780 Medicaid-enrolled pregnant women with OUD who had a live or stillbirth during 2016-2019 and were followed for 6 months after delivery. Among these women – drawn from six states in the Medicaid Outcomes Distributed Research Network – the pooled average probability of HCV testing during pregnancy was 70.3% (95% confidence interval, 61.5%-79.1%). Of these, 30.9% (95% CI, 23.8%-38%) tested positive. At 60 days postpartum, just 3.2% (95% CI, 2.6%-3.8%) had a follow-up visit or treatment for HCV. In a subset of patients followed for 6 months, only 5.9% (95% CI, 4.9%-6.9%) had any HCV follow-up visit or medication within 6 months of delivery.

While HCV screening and diagnosis rates varied across states, postpartum follow-up rates were universally low. The results suggest a need to improve the cascade of postpartum care for HCV and, ultimately perhaps, introduce antenatal HCV treatment, as is currently given safely for HIV, if current clinical research establishes safety, according to Marian P. Jarlenski, PhD, MPH, an associate professor of public health policy and management at the University of Pittsburgh. The study was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

HCV infection has risen substantially in people of reproductive age in tandem with an increase in OUDs. HCV is transmitted from an infected mother to her baby in about 6% of cases, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which in 2020 expanded its HCV screening recommendations to include all pregnant women. Currently no treatment for HCV during pregnancy has been approved.

In light of those recent recommendations, Dr. Jarlenski said in an interview that her group was “interested in looking at high-risk screened people and estimating what proportion received follow-up care and treatment for HCV. What is the promise of screening? The promise is that you can treat. Otherwise why screen?”

She acknowledged, however, that the postpartum period is a challenging time for a mother to seek health information or care for herself, whether she’s a new parent or has other children in the home. Nevertheless, the low rate of follow-up and treatment was unexpected. “Even the 70% rate of screening was low – we felt it should have been closer to 100% – but the follow-up rate was surprisingly low,” Dr. Jarlenski said.

Mishka Terplan, MD, MPH, medical director of Friends Research Institute in Baltimore, was not surprised at the low follow-up rate. “The cascade of care for hep C is demoralizing,” said Dr. Terplan, who was not involved in the study. “We know that hep C is syndemic with OUD and other opioid crises and we know that screening is effective for identifying hep C and that antiviral medications are now more effective and less toxic than ever before. But despite this, we’re failing pregnant women and their kids at every step along the cascade. We do a better job with initial testing than with the follow-up testing. We do a horrible job with postpartum medication initiation.”

He pointed to the systemic challenges mothers face in getting postpartum HCV care. “They may be transferred to a subspecialist for treatment, and this transfer is compounded by issues of insurance coverage and eligibility.” With the onus on new mothers to submit the paperwork, “the idea that mothers would be able to initiate much less continue postpartum treatment is absurd,” Dr. Terplan said.

He added that the children born to HCV-positive mothers need surveillance as well, but data suggest that the rates of newborn testing are also low. “There’s a preventable public health burden in all of this.”

The obvious way to increase eradicative therapy would be to treat women while they are getting antenatal care. A small phase 1 trial found that all pregnant participants who were HCV positive and given antivirals in their second trimester were safely treated and gave birth to healthy babies.

“If larger trials prove this treatment is safe and effective, then these results should be communicated to care providers and pregnant patients,” Dr. Jarlenski said. Otherwise, the public health potential of universal screening in pregnancy will not be realized.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse and by the Delaware Division of Medicaid and Medical Assistance and the University of Delaware, Center for Community Research & Service. Dr. Jarlenski disclosed no competing interests. One coauthor disclosed grant funding through her institution from Gilead Sciences and Organon unrelated to this work. Dr. Terplan reported no relevant competing interests.

Despite the availability of effective direct-acting antivirals, very few a mothers with opioid use disorder (OUD) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) during pregnancy received follow-up care or treatment for the infection within 6 months of giving birth, a retrospective study of Medicaid maternity patients found.

The study pooled data on 23,780 Medicaid-enrolled pregnant women with OUD who had a live or stillbirth during 2016-2019 and were followed for 6 months after delivery. Among these women – drawn from six states in the Medicaid Outcomes Distributed Research Network – the pooled average probability of HCV testing during pregnancy was 70.3% (95% confidence interval, 61.5%-79.1%). Of these, 30.9% (95% CI, 23.8%-38%) tested positive. At 60 days postpartum, just 3.2% (95% CI, 2.6%-3.8%) had a follow-up visit or treatment for HCV. In a subset of patients followed for 6 months, only 5.9% (95% CI, 4.9%-6.9%) had any HCV follow-up visit or medication within 6 months of delivery.

While HCV screening and diagnosis rates varied across states, postpartum follow-up rates were universally low. The results suggest a need to improve the cascade of postpartum care for HCV and, ultimately perhaps, introduce antenatal HCV treatment, as is currently given safely for HIV, if current clinical research establishes safety, according to Marian P. Jarlenski, PhD, MPH, an associate professor of public health policy and management at the University of Pittsburgh. The study was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

HCV infection has risen substantially in people of reproductive age in tandem with an increase in OUDs. HCV is transmitted from an infected mother to her baby in about 6% of cases, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which in 2020 expanded its HCV screening recommendations to include all pregnant women. Currently no treatment for HCV during pregnancy has been approved.

In light of those recent recommendations, Dr. Jarlenski said in an interview that her group was “interested in looking at high-risk screened people and estimating what proportion received follow-up care and treatment for HCV. What is the promise of screening? The promise is that you can treat. Otherwise why screen?”

She acknowledged, however, that the postpartum period is a challenging time for a mother to seek health information or care for herself, whether she’s a new parent or has other children in the home. Nevertheless, the low rate of follow-up and treatment was unexpected. “Even the 70% rate of screening was low – we felt it should have been closer to 100% – but the follow-up rate was surprisingly low,” Dr. Jarlenski said.

Mishka Terplan, MD, MPH, medical director of Friends Research Institute in Baltimore, was not surprised at the low follow-up rate. “The cascade of care for hep C is demoralizing,” said Dr. Terplan, who was not involved in the study. “We know that hep C is syndemic with OUD and other opioid crises and we know that screening is effective for identifying hep C and that antiviral medications are now more effective and less toxic than ever before. But despite this, we’re failing pregnant women and their kids at every step along the cascade. We do a better job with initial testing than with the follow-up testing. We do a horrible job with postpartum medication initiation.”

He pointed to the systemic challenges mothers face in getting postpartum HCV care. “They may be transferred to a subspecialist for treatment, and this transfer is compounded by issues of insurance coverage and eligibility.” With the onus on new mothers to submit the paperwork, “the idea that mothers would be able to initiate much less continue postpartum treatment is absurd,” Dr. Terplan said.

He added that the children born to HCV-positive mothers need surveillance as well, but data suggest that the rates of newborn testing are also low. “There’s a preventable public health burden in all of this.”

The obvious way to increase eradicative therapy would be to treat women while they are getting antenatal care. A small phase 1 trial found that all pregnant participants who were HCV positive and given antivirals in their second trimester were safely treated and gave birth to healthy babies.

“If larger trials prove this treatment is safe and effective, then these results should be communicated to care providers and pregnant patients,” Dr. Jarlenski said. Otherwise, the public health potential of universal screening in pregnancy will not be realized.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse and by the Delaware Division of Medicaid and Medical Assistance and the University of Delaware, Center for Community Research & Service. Dr. Jarlenski disclosed no competing interests. One coauthor disclosed grant funding through her institution from Gilead Sciences and Organon unrelated to this work. Dr. Terplan reported no relevant competing interests.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Restless legs syndrome occurs often in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy

Patients with X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), a neurodegenerative disease, often experience gait and balance problems, as well as leg discomfort, sleep disturbances, and pain, wrote John W. Winkelman, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues. Restless legs syndrome (RLS) has been associated with neurological conditions including Parkinson’s disease, but the prevalence of RLS in ALD patients has not been examined, they said.

In a pilot study published in Sleep Medicine, the researchers identified 21 women and 11 men with ALD who were treated at a single center. The median age of the patients was 45.9 years. Twenty-seven patients had symptoms of myelopathy, with a median age of onset of 34 years.

The researchers assessed RLS severity using questionnaires and the Hopkins Telephone Diagnostic Interview (HTDI), a validated RLS assessment tool. They also reviewed patients’ charts for data on neurological examinations, functional gait measures, and laboratory assessments. Functional gait assessments included the 25-Foot Walk test (25-FW), the Timed Up and Go test (TUG), and Six Minute Walk test (6MW).

Thirteen patients (10 women and 3 men) met criteria for RLS based on the HTDI. The median age of RLS onset was 35 years. Six RLS patients (46.2%) reported using medication to relieve symptoms, and eight RLS patients had a history of antidepressant use.

In addition, six patients with RLS reported a history of anemia or iron deficiency. Ferritin levels were available for 14 patients: 8 women with RLS and 4 women and 2 men without RLS; the mean ferritin levels were 74.0 mcg/L in RLS patients and 99.5 mcg/L in those without RLS.

Of the seven ALD patients with brain lesions, all were men, only two were diagnosed with RLS, and all seven cases were mild, the researchers noted.

Overall, patients with RLS had more neurological signs and symptoms than those without RLS; the most significant were pain and gait difficulty. However, patients with RLS also were more likely than were those without RLS to report spasticity, muscle weakness, impaired coordination, hyperreflexia, impaired sensation, and paraesthesia, as well as bladder, bowel, and erectile dysfunction.

The 40.6% prevalence of RLS in patients with ALD is notably higher than that of the general population, in which the prevalence of RLS is 5%-10%, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

“Consistent with patterns observed in the general population, risk factors for RLS in this cohort of adults with ALD included female gender, increased age, lower iron indices, and use of serotonergic antidepressants,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the small size and the possible contribution of antidepressant use to the high rate of RLS, the researchers noted.

“Awareness of RLS in patients with ALD would allow for its effective treatment, which may improve the functional impairments as well as quality of life, mood, and anxiety issues in those with ALD,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding.

Dr. Winkelman disclosed ties with Advance Medical, Avadel, Disc Medicine, Eisai, Emalex, Idorsia, Noctrix, UpToDate, and Merck Pharmaceuticals, as well as research support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Baszucki Brain Research Foundation. The study also was supported by grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the European Leukodystrophy Association, the Arrivederci Foundation, the Leblang Foundation, and the Hammer Family Fund Journal Preproof for ALD Research and Therapies for Women.

Patients with X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), a neurodegenerative disease, often experience gait and balance problems, as well as leg discomfort, sleep disturbances, and pain, wrote John W. Winkelman, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues. Restless legs syndrome (RLS) has been associated with neurological conditions including Parkinson’s disease, but the prevalence of RLS in ALD patients has not been examined, they said.

In a pilot study published in Sleep Medicine, the researchers identified 21 women and 11 men with ALD who were treated at a single center. The median age of the patients was 45.9 years. Twenty-seven patients had symptoms of myelopathy, with a median age of onset of 34 years.

The researchers assessed RLS severity using questionnaires and the Hopkins Telephone Diagnostic Interview (HTDI), a validated RLS assessment tool. They also reviewed patients’ charts for data on neurological examinations, functional gait measures, and laboratory assessments. Functional gait assessments included the 25-Foot Walk test (25-FW), the Timed Up and Go test (TUG), and Six Minute Walk test (6MW).

Thirteen patients (10 women and 3 men) met criteria for RLS based on the HTDI. The median age of RLS onset was 35 years. Six RLS patients (46.2%) reported using medication to relieve symptoms, and eight RLS patients had a history of antidepressant use.

In addition, six patients with RLS reported a history of anemia or iron deficiency. Ferritin levels were available for 14 patients: 8 women with RLS and 4 women and 2 men without RLS; the mean ferritin levels were 74.0 mcg/L in RLS patients and 99.5 mcg/L in those without RLS.

Of the seven ALD patients with brain lesions, all were men, only two were diagnosed with RLS, and all seven cases were mild, the researchers noted.

Overall, patients with RLS had more neurological signs and symptoms than those without RLS; the most significant were pain and gait difficulty. However, patients with RLS also were more likely than were those without RLS to report spasticity, muscle weakness, impaired coordination, hyperreflexia, impaired sensation, and paraesthesia, as well as bladder, bowel, and erectile dysfunction.

The 40.6% prevalence of RLS in patients with ALD is notably higher than that of the general population, in which the prevalence of RLS is 5%-10%, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

“Consistent with patterns observed in the general population, risk factors for RLS in this cohort of adults with ALD included female gender, increased age, lower iron indices, and use of serotonergic antidepressants,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the small size and the possible contribution of antidepressant use to the high rate of RLS, the researchers noted.

“Awareness of RLS in patients with ALD would allow for its effective treatment, which may improve the functional impairments as well as quality of life, mood, and anxiety issues in those with ALD,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding.

Dr. Winkelman disclosed ties with Advance Medical, Avadel, Disc Medicine, Eisai, Emalex, Idorsia, Noctrix, UpToDate, and Merck Pharmaceuticals, as well as research support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Baszucki Brain Research Foundation. The study also was supported by grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the European Leukodystrophy Association, the Arrivederci Foundation, the Leblang Foundation, and the Hammer Family Fund Journal Preproof for ALD Research and Therapies for Women.

Patients with X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD), a neurodegenerative disease, often experience gait and balance problems, as well as leg discomfort, sleep disturbances, and pain, wrote John W. Winkelman, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and colleagues. Restless legs syndrome (RLS) has been associated with neurological conditions including Parkinson’s disease, but the prevalence of RLS in ALD patients has not been examined, they said.

In a pilot study published in Sleep Medicine, the researchers identified 21 women and 11 men with ALD who were treated at a single center. The median age of the patients was 45.9 years. Twenty-seven patients had symptoms of myelopathy, with a median age of onset of 34 years.

The researchers assessed RLS severity using questionnaires and the Hopkins Telephone Diagnostic Interview (HTDI), a validated RLS assessment tool. They also reviewed patients’ charts for data on neurological examinations, functional gait measures, and laboratory assessments. Functional gait assessments included the 25-Foot Walk test (25-FW), the Timed Up and Go test (TUG), and Six Minute Walk test (6MW).

Thirteen patients (10 women and 3 men) met criteria for RLS based on the HTDI. The median age of RLS onset was 35 years. Six RLS patients (46.2%) reported using medication to relieve symptoms, and eight RLS patients had a history of antidepressant use.

In addition, six patients with RLS reported a history of anemia or iron deficiency. Ferritin levels were available for 14 patients: 8 women with RLS and 4 women and 2 men without RLS; the mean ferritin levels were 74.0 mcg/L in RLS patients and 99.5 mcg/L in those without RLS.

Of the seven ALD patients with brain lesions, all were men, only two were diagnosed with RLS, and all seven cases were mild, the researchers noted.

Overall, patients with RLS had more neurological signs and symptoms than those without RLS; the most significant were pain and gait difficulty. However, patients with RLS also were more likely than were those without RLS to report spasticity, muscle weakness, impaired coordination, hyperreflexia, impaired sensation, and paraesthesia, as well as bladder, bowel, and erectile dysfunction.

The 40.6% prevalence of RLS in patients with ALD is notably higher than that of the general population, in which the prevalence of RLS is 5%-10%, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

“Consistent with patterns observed in the general population, risk factors for RLS in this cohort of adults with ALD included female gender, increased age, lower iron indices, and use of serotonergic antidepressants,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the small size and the possible contribution of antidepressant use to the high rate of RLS, the researchers noted.

“Awareness of RLS in patients with ALD would allow for its effective treatment, which may improve the functional impairments as well as quality of life, mood, and anxiety issues in those with ALD,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding.

Dr. Winkelman disclosed ties with Advance Medical, Avadel, Disc Medicine, Eisai, Emalex, Idorsia, Noctrix, UpToDate, and Merck Pharmaceuticals, as well as research support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Baszucki Brain Research Foundation. The study also was supported by grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the European Leukodystrophy Association, the Arrivederci Foundation, the Leblang Foundation, and the Hammer Family Fund Journal Preproof for ALD Research and Therapies for Women.

FROM SLEEP MEDICINE

Pneumonia shows strong connection to chronic otitis media

Individuals with a prior diagnosis of pneumonia were significantly more likely to develop chronic otitis media (COM) than were those without a history of pneumonia, based on data from a nationwide cohort study of more than 100,000 patients.

“Recently, middle ear diseases, including COM, have been recognized as respiratory tract diseases beyond the pathophysiological concepts of ventilation dysfunction, with recurrent infection that occurs from anatomically adjacent structures such as the middle ear, mastoid cavity, and eustachian tube,” but the potential link between pneumonia and chronic otitis media and adults in particular has not been examined, wrote Sung Kyun Kim, MD, of Hallym University, Dongtan, South Korea, and colleagues.

In a study recently published in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases, the researchers identified 23,436 adults with COM and 93,744 controls aged 40 years and older from a Korean health insurance database between 2002 and 2015.

The overall incidence of pneumonia in the study population was significantly higher in the COM group compared with controls (9.3% vs. 7.2%, P <.001). The odds ratios of pneumonia were significantly higher in the COM group compared with controls, and a history of pneumonia increased the odds of COM regardless of sex and across all ages.

Pneumonia was defined as when a patient had a diagnosis of pneumonia based on ICD-10 codes and underwent a chest x-ray or chest CT scan. Chronic otitis media was defined as when a patient had a diagnosis based on ICD-10 codes at least two times with one of the following conditions: chronic serous otitis media, chronic mucoid otitis media, other chronic nonsuppurative otitis media, unspecified nonsuppurative otitis media, chronic tubotympanic suppurative otitis media, chronic atticoantral suppurative otitis media, other chronic suppurative otitis media, or unspecified suppurative otitis media.

Age groups were divided into 5-year intervals, and patients were classified into income groups and rural vs. urban residence.

In a further sensitivity analysis, individuals who were diagnosed with pneumonia five or more times before the index date had a significantly higher odds ratio for COM compared with those with less than five diagnoses of pneumonia (adjusted odds ratio, 1.34; P < .001).

Microbiome dysbiosis may explain part of the connection between pneumonia and COM, the researchers wrote in their discussion. Pathogens in the lungs can prompt changes in the microbiome dynamics, as might the use of antibiotics, they said. In addition, “Mucus plugging in the airway caused by pneumonia induces hypoxic conditions and leads to the expression of inflammatory markers in the eustachian tube and middle ear mucosa,” they noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective design and lack of data on microbiological cultures for antibiotic susceptibility, radiologic findings on the severity of pneumonia, results of pulmonary function tests, and hearing thresholds, the researchers noted. Other limitations were the exclusion of the frequency of upper respiratory infections and antibiotic use due to lack of data, they said.

However, the results show an association between pneumonia diagnoses and increased incidence of COM, which suggests a novel perspective that “infection of the lower respiratory tract may affect the function of the eustachian tube and the middle ear to later cause COM,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Individuals with a prior diagnosis of pneumonia were significantly more likely to develop chronic otitis media (COM) than were those without a history of pneumonia, based on data from a nationwide cohort study of more than 100,000 patients.

“Recently, middle ear diseases, including COM, have been recognized as respiratory tract diseases beyond the pathophysiological concepts of ventilation dysfunction, with recurrent infection that occurs from anatomically adjacent structures such as the middle ear, mastoid cavity, and eustachian tube,” but the potential link between pneumonia and chronic otitis media and adults in particular has not been examined, wrote Sung Kyun Kim, MD, of Hallym University, Dongtan, South Korea, and colleagues.

In a study recently published in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases, the researchers identified 23,436 adults with COM and 93,744 controls aged 40 years and older from a Korean health insurance database between 2002 and 2015.

The overall incidence of pneumonia in the study population was significantly higher in the COM group compared with controls (9.3% vs. 7.2%, P <.001). The odds ratios of pneumonia were significantly higher in the COM group compared with controls, and a history of pneumonia increased the odds of COM regardless of sex and across all ages.

Pneumonia was defined as when a patient had a diagnosis of pneumonia based on ICD-10 codes and underwent a chest x-ray or chest CT scan. Chronic otitis media was defined as when a patient had a diagnosis based on ICD-10 codes at least two times with one of the following conditions: chronic serous otitis media, chronic mucoid otitis media, other chronic nonsuppurative otitis media, unspecified nonsuppurative otitis media, chronic tubotympanic suppurative otitis media, chronic atticoantral suppurative otitis media, other chronic suppurative otitis media, or unspecified suppurative otitis media.

Age groups were divided into 5-year intervals, and patients were classified into income groups and rural vs. urban residence.

In a further sensitivity analysis, individuals who were diagnosed with pneumonia five or more times before the index date had a significantly higher odds ratio for COM compared with those with less than five diagnoses of pneumonia (adjusted odds ratio, 1.34; P < .001).

Microbiome dysbiosis may explain part of the connection between pneumonia and COM, the researchers wrote in their discussion. Pathogens in the lungs can prompt changes in the microbiome dynamics, as might the use of antibiotics, they said. In addition, “Mucus plugging in the airway caused by pneumonia induces hypoxic conditions and leads to the expression of inflammatory markers in the eustachian tube and middle ear mucosa,” they noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective design and lack of data on microbiological cultures for antibiotic susceptibility, radiologic findings on the severity of pneumonia, results of pulmonary function tests, and hearing thresholds, the researchers noted. Other limitations were the exclusion of the frequency of upper respiratory infections and antibiotic use due to lack of data, they said.

However, the results show an association between pneumonia diagnoses and increased incidence of COM, which suggests a novel perspective that “infection of the lower respiratory tract may affect the function of the eustachian tube and the middle ear to later cause COM,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Individuals with a prior diagnosis of pneumonia were significantly more likely to develop chronic otitis media (COM) than were those without a history of pneumonia, based on data from a nationwide cohort study of more than 100,000 patients.

“Recently, middle ear diseases, including COM, have been recognized as respiratory tract diseases beyond the pathophysiological concepts of ventilation dysfunction, with recurrent infection that occurs from anatomically adjacent structures such as the middle ear, mastoid cavity, and eustachian tube,” but the potential link between pneumonia and chronic otitis media and adults in particular has not been examined, wrote Sung Kyun Kim, MD, of Hallym University, Dongtan, South Korea, and colleagues.

In a study recently published in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases, the researchers identified 23,436 adults with COM and 93,744 controls aged 40 years and older from a Korean health insurance database between 2002 and 2015.

The overall incidence of pneumonia in the study population was significantly higher in the COM group compared with controls (9.3% vs. 7.2%, P <.001). The odds ratios of pneumonia were significantly higher in the COM group compared with controls, and a history of pneumonia increased the odds of COM regardless of sex and across all ages.

Pneumonia was defined as when a patient had a diagnosis of pneumonia based on ICD-10 codes and underwent a chest x-ray or chest CT scan. Chronic otitis media was defined as when a patient had a diagnosis based on ICD-10 codes at least two times with one of the following conditions: chronic serous otitis media, chronic mucoid otitis media, other chronic nonsuppurative otitis media, unspecified nonsuppurative otitis media, chronic tubotympanic suppurative otitis media, chronic atticoantral suppurative otitis media, other chronic suppurative otitis media, or unspecified suppurative otitis media.

Age groups were divided into 5-year intervals, and patients were classified into income groups and rural vs. urban residence.

In a further sensitivity analysis, individuals who were diagnosed with pneumonia five or more times before the index date had a significantly higher odds ratio for COM compared with those with less than five diagnoses of pneumonia (adjusted odds ratio, 1.34; P < .001).

Microbiome dysbiosis may explain part of the connection between pneumonia and COM, the researchers wrote in their discussion. Pathogens in the lungs can prompt changes in the microbiome dynamics, as might the use of antibiotics, they said. In addition, “Mucus plugging in the airway caused by pneumonia induces hypoxic conditions and leads to the expression of inflammatory markers in the eustachian tube and middle ear mucosa,” they noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective design and lack of data on microbiological cultures for antibiotic susceptibility, radiologic findings on the severity of pneumonia, results of pulmonary function tests, and hearing thresholds, the researchers noted. Other limitations were the exclusion of the frequency of upper respiratory infections and antibiotic use due to lack of data, they said.

However, the results show an association between pneumonia diagnoses and increased incidence of COM, which suggests a novel perspective that “infection of the lower respiratory tract may affect the function of the eustachian tube and the middle ear to later cause COM,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES

How common is IUD perforation, expulsion, and malposition?

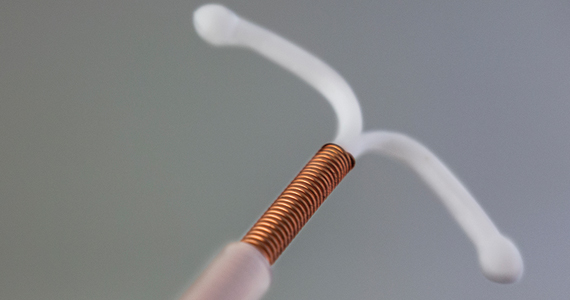

The medicated intrauterine devices (IUDs), including the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (LNG-IUD) (Mirena, Kyleena, Skyla, and Liletta) and the copper IUD (Cu-IUD; Paragard), are remarkably effective contraceptives. For the 52-mg LNG-IUD (Mirena, Liletta) the pregnancy rate over 6 years of use averaged less than 0.2% per year.1,2 For the Cu-IUD, the pregnancy rate over 10 years of use averaged 0.5% per year for the first 3 years of use and 0.2% per year over the following 7 years of use.3 IUD perforation of the uterus, expulsion, and malposition are recognized complications of IUD use. Our understanding of the prevalence and management of malpositioned IUDs is evolving and the main focus of this editorial.

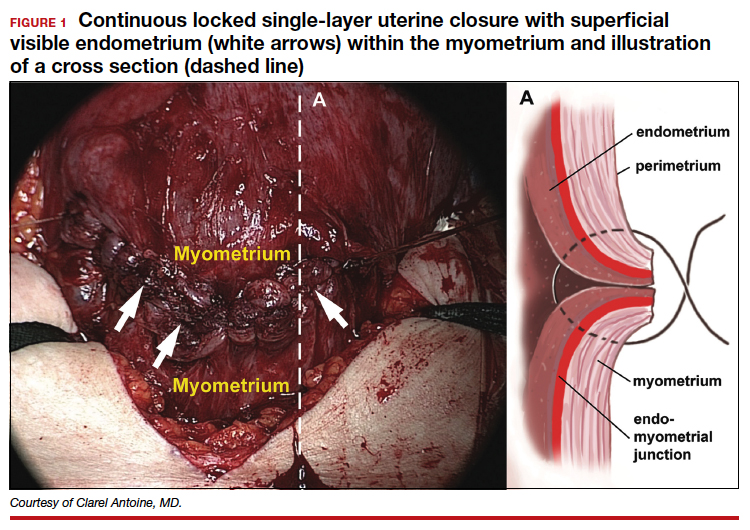

Complete and partial uterus perforation

A complete uterine perforation occurs when the entire IUD is outside the walls of the uterus. A partial uterine perforation occurs when the IUD is outside the uterine cavity, but a portion of the IUD remains in the myometrium. When uterine perforation is suspected, ultrasound can determine if the IUD is properly sited within the uterus. If ultrasonography does not detect the IUD within the uterus, an x-ray of the pelvis and abdomen should be obtained to determine if the IUD is in the peritoneal cavity. If both an ultrasound and a pelvic-abdominal x-ray do not detect the IUD, the IUD was probably expelled from the patient.

Uterine perforation is uncommon and occurs once in every 500 to 1,000 insertions in non-breastfeeding women.4-8 The most common symptoms reported by patients with a perforated IUD are pain and/or bleeding.8 Investigators in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices (EURAS) enrolled more than 60,000 patients who had an IUD insertion and followed them for 12 months with more than 39,000 followed for up to 60 months.7,8 The uterine perforation rate per 1,000 IUD insertions in non-breastfeeding women with 60 months of follow-up was 1.6 for the LNG-IUD and 0.8 for the Cu-IUD.8 The rate of uterine perforation was much higher in women who are breastfeeding or recently postpartum. In the EURAS study after 60 months of follow-up, the perforation rate per 1,000 insertions among breastfeeding women was 7.9 for the LNG-IUS and 4.7 for the Cu-IUD.8

Remarkably very few IUD perforations were detected at the time of insertion, including only 2% of the LNG-IUD insertions and 17% of the Cu-IUD insertions.8 Many perforations were not detected until more than 12 months following insertion, including 32% of the LNG-IUD insertions and 22% of the Cu-IUD insertions.8 Obviously, an IUD that has completely perforated the uterus and resides in the peritoneal cavity is not an effective contraceptive. For some patients, the IUD perforation was initially diagnosed after they became pregnant, and imaging studies to locate the IUD and assess the pregnancy were initiated. Complete perforation is usually treated with laparoscopy to remove the IUD and reduce the risk of injury to intra-abdominal organs.

Patients with an IUD partial perforation may present with pelvic pain or abnormal uterine bleeding.9 An ultrasound study to explore the cause of the presenting symptom may detect the partial perforation. It is estimated that approximately 20% of cases of IUD perforation are partial perforation.9 Over time, a partial perforation may progress to a complete perforation. In some cases of partial perforation, the IUD string may still be visible in the cervix, and the IUD may be removed by pulling on the strings.8 Hysteroscopy and/or laparoscopy may be needed to remove a partially perforated IUD. Following a partial or complete IUD perforation, if the patient desires to continue with IUD contraception, it would be wise to insert a new IUD under ultrasound guidance or assess proper placement with a postplacement ultrasound.

Continue to: Expulsion...

Expulsion

IUD expulsion occurs in approximately 3% to 11% of patients.10-13 The age of the patient influences the rate of expulsion. In a study of 2,748 patients with a Cu-IUD, the rate of expulsion by age for patients <20 years, 20–24 years, 25–29 years, 30–34 years, and ≥35 years was 8.2%, 3.2%, 3.0%, 2.3%, and 1.8%, respectively.10 In this study, age did not influence the rate of IUD removal for pelvic pain or abnormal bleeding, which was 4% to 5% across all age groups.10 In a study of 5,403 patients with an IUD, the rate of IUD expulsion by age for patients <20 years, 20–29 years, and 30–45 years was 14.6%, 7.3%, and 7.2%, respectively.12 In this study, the 3-year cumulative rate of expulsion was 10.2%.12 There was no statistically significant difference in the 3-year cumulative rate of expulsion for the 52-mg LNG-IUD (10.1%) and Cu-IUD (10.7%).12

The majority of patients who have an IUD expulsion recognize the event and seek additional contraception care. A few patients first recognize the IUD expulsion when they become pregnant, and imaging studies detect no IUD in the uterus or the peritoneal cavity. In a study of more than 17,000 patients using an LNG-IUD, 108 pregnancies were reported. Seven pregnancies occurred in patients who did not realize their IUD was expelled.14 Patients who have had an IUD expulsion and receive a new IUD are at increased risk for re-expulsion. For these patients, reinsertion of an IUD could be performed under ultrasound guidance to ensure and document optimal initial IUD position within the uterus, or ultrasound can be obtained postinsertion to document appropriate IUD position.

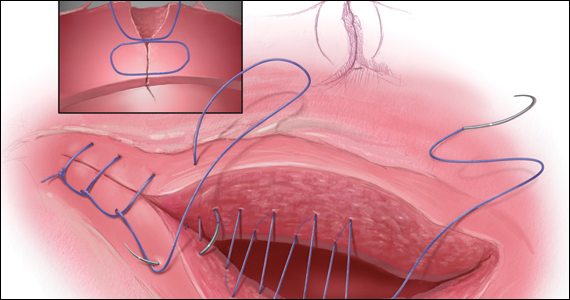

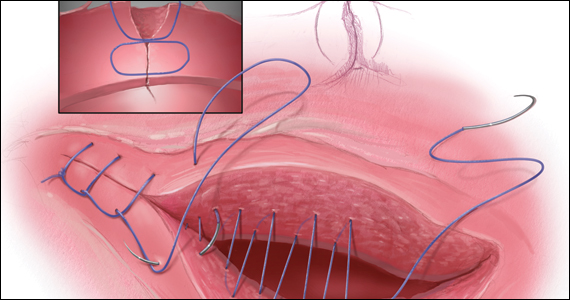

Malposition—prevalence and management

Our understanding of the prevalence and management of a malpositioned IUD is evolving. For the purposes of this discussion a malpositioned IUD is defined as being in the uterus, but not properly positioned within the uterine cavity. Perforation into the peritoneal cavity and complete expulsion of an IUD are considered separate entities. However, a malpositioned IUD within the uterus may eventually perforate the uterus or be expelled from the body. For example, an IUD embedded in the uterine wall may eventually work its way through the wall and become perforated, residing in the peritoneal cavity. An IUD with the stem in the cervix below the internal os may eventually be expelled from the uterus and leave the body through the vagina.

High-quality ultrasonography, including 2-dimensional (2-D) ultrasound with videoclips or 3-dimensional (3-D) ultrasound with coronal views, has greatly advanced our understanding of the prevalence and characteristics of a malpositioned IUD.15-18 Ultrasound features of an IUD correctly placed within the uterus include:

- the IUD is in the uterus

- the shaft is in the midline of the uterine cavity

- the shaft of the IUD is not in the endocervix

- the IUD arms are at a 90-degree angle from the shaft

- the top of the IUD is within 2 cm of the fundus

- the IUD is not rotated outside of the cornual plane, inverted or transverse.

Ultrasound imaging has identified multiple types of malpositioned IUDs, including:

- IUD embedded in the myometrium—a portion of the IUD is embedded in the uterine wall

- low-lying IUD—the IUD is low in the uterine cavity but not in the endocervix

- IUD in the endocervix—the stem is in the endocervical canal

- rotated—the IUD is rotated outside the cornual plane

- malpositioned arms—the arms are not at a 90-degree angle to the stem

- the IUD is inverted, transverse, or laterally displaced.

IUD malposition is highly prevalent and has been identified in 10% to 20% of convenience cohorts in which an ultrasound study was performed.15-18

Benacerraf, Shipp, and Bromley were among the first experts to use ultrasound to detect the high prevalence of malpositioned IUDs among a convenience sample of 167 patients with an IUD undergoing ultrasound for a variety of indications. Using 3-D ultrasound, including reconstructed coronal views, they identified 28 patients (17%) with a malpositioned IUD based on the detection of the IUD “poking into the substance of the uterus or cervix.” Among the patients with a malpositioned IUD, the principal indication for the ultrasound study was pelvic pain (39%) or abnormal uterine bleeding (36%). Among women with a normally sited IUD, pelvic pain (19%) or abnormal uterine bleeding (15%) were less often the principal indication for the ultrasound.15 The malpositioned IUD was removed in 21 of the 28 cases and the symptoms of pelvic pain or abnormal bleeding resolved in 20 of the 21 patients.15

Other investigators have confirmed the observation that IUD malposition is common.16-18 In a retrospective study of 1,748 pelvic ultrasounds performed for any indication where an IUD was present, after excluding 13 patients who were determined to have expelled their IUD (13) and 13 patients with a perforated IUD, 156 patients (8.9%) were diagnosed as having a malpositioned IUD.16 IUD malposition was diagnosed when the IUD was in the uterus but positioned in the lower uterine segment, cervix, rotated or embedded in the uterus. An IUD in the lower uterine segment or cervix was detected in 133 patients, representing 85% of cases. Among these cases, 29 IUDs were also embedded and/or rotated, indicating that some IUDs have multiple causes of the malposition. Twenty-one IUDs were near the fundus but embedded and/or rotated. Controls with a normally-sited IUD were selected for comparison to the case group. Among IUD users, the identification of suspected adenomyosis on the ultrasound was associated with an increased risk of IUD malposition (odds ratio [OR], 3.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08-8.52).16 In this study, removal of a malpositioned LNG-IUD, without initiating a highly reliable contraceptive was associated with an increased risk of pregnancy. It is important to initiate a highly reliable form of contraception if the plan is to remove a malpositioned IUD.16,19

In a study of 1,253 pelvic ultrasounds performed for any indication where an IUD was identified in the uterus, 263 IUDs (19%) were determined to be malpositioned.17 In this study the location of the malpositioned IUDs included17:

- the lower uterine segment not extending into the cervix (38%)

- in the lower uterine segment extending into the cervix (22%)

- in the cervix (26%)

- rotated axis of the IUD (12%)

- other (2%).

Among the 236 malpositioned IUDs, 24% appeared to be embedded in the uterine wall.17 Compared with patients with a normally-sited IUD on ultrasound, patients with a malpositioned IUD more frequently reported vaginal bleeding (30% vs 19%; P<.005) and pelvic pain (43% vs 30%; P<.002), similar to the findings in the Benacerraf et al. study.14

Connolly and Fox18 designed an innovative study to determine the rate of malpositioned IUDs using 2-D ultrasound to ensure proper IUD placement at the time of insertion with a follow-up 3-D ultrasound 8 weeks after insertion to assess IUD position within the uterus. At the 8-week 3-D ultrasound, among 763 women, 16.6% of the IUDs were malpositioned.18 In this study, IUD position was determined to be correct if all the following features were identified:

- the IUD shaft was in the midline of the uterine cavity

- the IUD arms were at 90 degrees from the stem

- the top of the IUD was within 3 to 4 mm of the fundus

- the IUD was not rotated, inverted or transverse.

IUD malpositions were categorized as:

- embedded in the uterine wall

- low in the uterine cavity

- in the endocervical canal

- misaligned

- perforated

- expulsed.

At the 8-week follow-up, 636 patients (83.4%) had an IUD that was correctly positioned.18 In 127 patients (16.6%) IUD malposition was identified, with some patients having more than one type of malposition. The types of malposition identified were:

- embedded in the myometrium (54%)

- misaligned, including rotated, laterally displaced, inverted, transverse or arms not deployed (47%)

- low in the uterine cavity (39%)

- in the endocervical canal (14%)

- perforated (3%)

- expulsion (0%).

Recall that all of these patients had a 2-D ultrasound at the time of insertion that identified the IUD as correctly placed. This suggests that during the 8 weeks following IUD placement there were changes in the location of the IUD or that 2-D ultrasound has lower sensitivity than 3-D ultrasound to detect malposition. Of note, at the 8-week follow-up, bleeding or pain was reported by 36% of the patients with a malpositioned IUD and 20% of patients with a correctly positioned IUD.17 Sixty-seven of the 127 malpositioned IUDs “required” removal, but the precise reasons for the removals were not delineated. The investigators concluded that 3-D ultrasonography is useful for the detection of IUD malposition and could be considered as part of ongoing IUD care, if symptoms of pain or bleeding occur.18

Continue to: IUD malposition following postplacental insertion...

IUD malposition following postplacental insertion