User login

Coating repels blood and bacteria

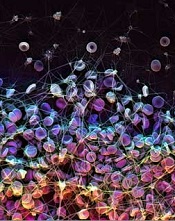

to form a blood clot

Credit: James Weaver

Researchers have developed a coating that can prevent blood and bacteria from adhering to the surface of medical devices.

The coating repelled blood from more than 20 medically relevant substrates, suppressed biofilm formation, and prevented coagulation in an animal model for at least 8 hours.

The researchers believe this technology could reduce the use of anticoagulants and help prevent thrombotic occlusion and biofouling of medical devices.

The idea for the coating evolved from a surface technology known as “slippery liquid-infused porous surfaces (SLIPS),” which was developed by Joanna Aizenberg, PhD, of Harvard University’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering.

Inspired by the slippery surface of the carnivorous pitcher plant, which enables the plant to capture insects, SLIPS can repel nearly any material. The liquid layer on the surface provides a barrier to everything from ice to crude oil and blood.

“Traditional SLIPS uses porous, textured surface substrates to immobilize the liquid layer, whereas medical surfaces are mostly flat and smooth,” Dr Aizenberg said. “So we further adapted our approach by capitalizing on the natural roughness of chemically modified surfaces of medical devices.”

She and her colleagues described this work in Nature Biotechnology.

The researchers developed a super-repellent coating that can be adhered to existing, approved medical devices. In a 2-step surface-coating process, they chemically attached a monolayer of perfluorocarbon, which is similar to Teflon.

Then, they added a layer of liquid perfluorocarbon, which is widely used in medicine for applications such as liquid ventilation for infants with breathing challenges, blood substitution, and eye surgery. The team calls the tethered perfluorocarbon plus the liquid layer a “tethered-liquid perfluorocarbon surface (TLP)”.

TLP worked seamlessly when coated on more than 20 different medical surfaces, including plastics, glasses, and metals.

The researchers also implanted medical-grade tubing and catheters coated with TLP in large blood vessels in pigs, and the coating prevented blood from clotting for at least 8 hours without the use of anticoagulants.

TLP-treated medical tubing was stored for more than a year under normal temperature and humidity conditions and still prevented clot formation, repelling fibrin and platelets.

The TLP surface remained stable under the full range of clinically relevant physiological shear stresses, or rates of blood flow seen in catheters and central lines, all the way up to dialysis machines.

When the bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa were grown in TLP-coated medical tubing for more than 6 weeks, less than 1 in a billion bacteria were able to adhere. Central lines coated with TLP significantly reduced sepsis from central-line associated bloodstream infections.

Out of curiosity, the researchers even tested a TLP-coated surface with a gecko, whose footpads contain hair-like structures with tremendous adhesive strength. And the gecko was unable to hold on.

“We were wonderfully surprised by how well the TLP coating worked, particularly in vivo without heparin,” said Anna Waterhouse, PhD, of the Wyss Institute.

“Usually, the blood will start to clot within an hour in the extracorporeal circuit, so our experiments really demonstrate the clinical relevance of this new coating.” ![]()

to form a blood clot

Credit: James Weaver

Researchers have developed a coating that can prevent blood and bacteria from adhering to the surface of medical devices.

The coating repelled blood from more than 20 medically relevant substrates, suppressed biofilm formation, and prevented coagulation in an animal model for at least 8 hours.

The researchers believe this technology could reduce the use of anticoagulants and help prevent thrombotic occlusion and biofouling of medical devices.

The idea for the coating evolved from a surface technology known as “slippery liquid-infused porous surfaces (SLIPS),” which was developed by Joanna Aizenberg, PhD, of Harvard University’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering.

Inspired by the slippery surface of the carnivorous pitcher plant, which enables the plant to capture insects, SLIPS can repel nearly any material. The liquid layer on the surface provides a barrier to everything from ice to crude oil and blood.

“Traditional SLIPS uses porous, textured surface substrates to immobilize the liquid layer, whereas medical surfaces are mostly flat and smooth,” Dr Aizenberg said. “So we further adapted our approach by capitalizing on the natural roughness of chemically modified surfaces of medical devices.”

She and her colleagues described this work in Nature Biotechnology.

The researchers developed a super-repellent coating that can be adhered to existing, approved medical devices. In a 2-step surface-coating process, they chemically attached a monolayer of perfluorocarbon, which is similar to Teflon.

Then, they added a layer of liquid perfluorocarbon, which is widely used in medicine for applications such as liquid ventilation for infants with breathing challenges, blood substitution, and eye surgery. The team calls the tethered perfluorocarbon plus the liquid layer a “tethered-liquid perfluorocarbon surface (TLP)”.

TLP worked seamlessly when coated on more than 20 different medical surfaces, including plastics, glasses, and metals.

The researchers also implanted medical-grade tubing and catheters coated with TLP in large blood vessels in pigs, and the coating prevented blood from clotting for at least 8 hours without the use of anticoagulants.

TLP-treated medical tubing was stored for more than a year under normal temperature and humidity conditions and still prevented clot formation, repelling fibrin and platelets.

The TLP surface remained stable under the full range of clinically relevant physiological shear stresses, or rates of blood flow seen in catheters and central lines, all the way up to dialysis machines.

When the bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa were grown in TLP-coated medical tubing for more than 6 weeks, less than 1 in a billion bacteria were able to adhere. Central lines coated with TLP significantly reduced sepsis from central-line associated bloodstream infections.

Out of curiosity, the researchers even tested a TLP-coated surface with a gecko, whose footpads contain hair-like structures with tremendous adhesive strength. And the gecko was unable to hold on.

“We were wonderfully surprised by how well the TLP coating worked, particularly in vivo without heparin,” said Anna Waterhouse, PhD, of the Wyss Institute.

“Usually, the blood will start to clot within an hour in the extracorporeal circuit, so our experiments really demonstrate the clinical relevance of this new coating.” ![]()

to form a blood clot

Credit: James Weaver

Researchers have developed a coating that can prevent blood and bacteria from adhering to the surface of medical devices.

The coating repelled blood from more than 20 medically relevant substrates, suppressed biofilm formation, and prevented coagulation in an animal model for at least 8 hours.

The researchers believe this technology could reduce the use of anticoagulants and help prevent thrombotic occlusion and biofouling of medical devices.

The idea for the coating evolved from a surface technology known as “slippery liquid-infused porous surfaces (SLIPS),” which was developed by Joanna Aizenberg, PhD, of Harvard University’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering.

Inspired by the slippery surface of the carnivorous pitcher plant, which enables the plant to capture insects, SLIPS can repel nearly any material. The liquid layer on the surface provides a barrier to everything from ice to crude oil and blood.

“Traditional SLIPS uses porous, textured surface substrates to immobilize the liquid layer, whereas medical surfaces are mostly flat and smooth,” Dr Aizenberg said. “So we further adapted our approach by capitalizing on the natural roughness of chemically modified surfaces of medical devices.”

She and her colleagues described this work in Nature Biotechnology.

The researchers developed a super-repellent coating that can be adhered to existing, approved medical devices. In a 2-step surface-coating process, they chemically attached a monolayer of perfluorocarbon, which is similar to Teflon.

Then, they added a layer of liquid perfluorocarbon, which is widely used in medicine for applications such as liquid ventilation for infants with breathing challenges, blood substitution, and eye surgery. The team calls the tethered perfluorocarbon plus the liquid layer a “tethered-liquid perfluorocarbon surface (TLP)”.

TLP worked seamlessly when coated on more than 20 different medical surfaces, including plastics, glasses, and metals.

The researchers also implanted medical-grade tubing and catheters coated with TLP in large blood vessels in pigs, and the coating prevented blood from clotting for at least 8 hours without the use of anticoagulants.

TLP-treated medical tubing was stored for more than a year under normal temperature and humidity conditions and still prevented clot formation, repelling fibrin and platelets.

The TLP surface remained stable under the full range of clinically relevant physiological shear stresses, or rates of blood flow seen in catheters and central lines, all the way up to dialysis machines.

When the bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa were grown in TLP-coated medical tubing for more than 6 weeks, less than 1 in a billion bacteria were able to adhere. Central lines coated with TLP significantly reduced sepsis from central-line associated bloodstream infections.

Out of curiosity, the researchers even tested a TLP-coated surface with a gecko, whose footpads contain hair-like structures with tremendous adhesive strength. And the gecko was unable to hold on.

“We were wonderfully surprised by how well the TLP coating worked, particularly in vivo without heparin,” said Anna Waterhouse, PhD, of the Wyss Institute.

“Usually, the blood will start to clot within an hour in the extracorporeal circuit, so our experiments really demonstrate the clinical relevance of this new coating.” ![]()

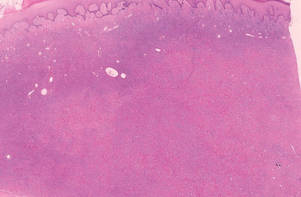

System can detect sepsis early

Credit: CDC

An early warning and response system can predict a patient’s likelihood of developing sepsis, according to research published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

The system uses lab and vital-sign data in the electronic health record of hospital inpatients to identify those at risk for sepsis.

In a multi-hospital study, the system allowed for a marked increase in sepsis identification and care, transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU), and an indication of fewer deaths due to sepsis.

Craig A. Umscheid, MD, of Penn Medicine in Philadelphia, and his colleagues developed the system using 4575 patients admitted to the University of Pennsylvania Health System in October 2011.

The system monitored lab values and vital signs in real time. If a patient had 4 or more predefined abnormalities at any single time, an electronic communication was sent to the provider, nurse, and rapid response coordinator, who performed an immediate bedside patient evaluation.

The researchers validated the effectiveness of the system during a pre-implementation period from June to September 2012, when data on admitted patients was evaluated and alerts triggered in a database, but no notifications were sent to providers on the ground.

Outcomes in that control period were then compared to a post-implementation period from June to September 2013. The total number of patients included in both periods was 31,093.

In the pre- and post-implementation periods, 4% of patient visits triggered the alert. Analysis revealed that 90% of those patients received bedside evaluations by the care team within 30 minutes of the alert being issued.

The system resulted in a 2- to 3-fold increase in orders for tests that could help identify the presence of sepsis and a 1.5- to 2-fold increase in the administration of antibiotics and intravenous fluids.

The system prompted an increase of more than 50% in the proportion of patients quickly transferred to the ICU and a 50% increase in documentation of sepsis in the patients’ electronic health record.

There was a lower death rate from sepsis and an increase in the number of patients successfully discharged home in the post-implementation period. But these rates were not significantly different from those in the pre-implementation period.

“Our study is the first we’re aware of that was implemented throughout a multihospital health system,” Dr Umscheid said.

“Previous studies that have examined the impact of sepsis prediction tools at other institutions have only taken place on a limited number of inpatient wards. The varied patient populations, clinical staffing, practice models, and practice cultures across our health system increases the generalizability of our findings to other healthcare settings.”

Dr Umscheid also noted that the system could help triage patients for suitability of ICU transfer.

“By better identifying those with sepsis requiring advanced care,” he said, “the tool can help screen out patients not needing the inevitably limited number of ICU beds.” ![]()

Credit: CDC

An early warning and response system can predict a patient’s likelihood of developing sepsis, according to research published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

The system uses lab and vital-sign data in the electronic health record of hospital inpatients to identify those at risk for sepsis.

In a multi-hospital study, the system allowed for a marked increase in sepsis identification and care, transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU), and an indication of fewer deaths due to sepsis.

Craig A. Umscheid, MD, of Penn Medicine in Philadelphia, and his colleagues developed the system using 4575 patients admitted to the University of Pennsylvania Health System in October 2011.

The system monitored lab values and vital signs in real time. If a patient had 4 or more predefined abnormalities at any single time, an electronic communication was sent to the provider, nurse, and rapid response coordinator, who performed an immediate bedside patient evaluation.

The researchers validated the effectiveness of the system during a pre-implementation period from June to September 2012, when data on admitted patients was evaluated and alerts triggered in a database, but no notifications were sent to providers on the ground.

Outcomes in that control period were then compared to a post-implementation period from June to September 2013. The total number of patients included in both periods was 31,093.

In the pre- and post-implementation periods, 4% of patient visits triggered the alert. Analysis revealed that 90% of those patients received bedside evaluations by the care team within 30 minutes of the alert being issued.

The system resulted in a 2- to 3-fold increase in orders for tests that could help identify the presence of sepsis and a 1.5- to 2-fold increase in the administration of antibiotics and intravenous fluids.

The system prompted an increase of more than 50% in the proportion of patients quickly transferred to the ICU and a 50% increase in documentation of sepsis in the patients’ electronic health record.

There was a lower death rate from sepsis and an increase in the number of patients successfully discharged home in the post-implementation period. But these rates were not significantly different from those in the pre-implementation period.

“Our study is the first we’re aware of that was implemented throughout a multihospital health system,” Dr Umscheid said.

“Previous studies that have examined the impact of sepsis prediction tools at other institutions have only taken place on a limited number of inpatient wards. The varied patient populations, clinical staffing, practice models, and practice cultures across our health system increases the generalizability of our findings to other healthcare settings.”

Dr Umscheid also noted that the system could help triage patients for suitability of ICU transfer.

“By better identifying those with sepsis requiring advanced care,” he said, “the tool can help screen out patients not needing the inevitably limited number of ICU beds.” ![]()

Credit: CDC

An early warning and response system can predict a patient’s likelihood of developing sepsis, according to research published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

The system uses lab and vital-sign data in the electronic health record of hospital inpatients to identify those at risk for sepsis.

In a multi-hospital study, the system allowed for a marked increase in sepsis identification and care, transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU), and an indication of fewer deaths due to sepsis.

Craig A. Umscheid, MD, of Penn Medicine in Philadelphia, and his colleagues developed the system using 4575 patients admitted to the University of Pennsylvania Health System in October 2011.

The system monitored lab values and vital signs in real time. If a patient had 4 or more predefined abnormalities at any single time, an electronic communication was sent to the provider, nurse, and rapid response coordinator, who performed an immediate bedside patient evaluation.

The researchers validated the effectiveness of the system during a pre-implementation period from June to September 2012, when data on admitted patients was evaluated and alerts triggered in a database, but no notifications were sent to providers on the ground.

Outcomes in that control period were then compared to a post-implementation period from June to September 2013. The total number of patients included in both periods was 31,093.

In the pre- and post-implementation periods, 4% of patient visits triggered the alert. Analysis revealed that 90% of those patients received bedside evaluations by the care team within 30 minutes of the alert being issued.

The system resulted in a 2- to 3-fold increase in orders for tests that could help identify the presence of sepsis and a 1.5- to 2-fold increase in the administration of antibiotics and intravenous fluids.

The system prompted an increase of more than 50% in the proportion of patients quickly transferred to the ICU and a 50% increase in documentation of sepsis in the patients’ electronic health record.

There was a lower death rate from sepsis and an increase in the number of patients successfully discharged home in the post-implementation period. But these rates were not significantly different from those in the pre-implementation period.

“Our study is the first we’re aware of that was implemented throughout a multihospital health system,” Dr Umscheid said.

“Previous studies that have examined the impact of sepsis prediction tools at other institutions have only taken place on a limited number of inpatient wards. The varied patient populations, clinical staffing, practice models, and practice cultures across our health system increases the generalizability of our findings to other healthcare settings.”

Dr Umscheid also noted that the system could help triage patients for suitability of ICU transfer.

“By better identifying those with sepsis requiring advanced care,” he said, “the tool can help screen out patients not needing the inevitably limited number of ICU beds.” ![]()

FDA approves drug for nausea, vomiting

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved Akynzeo to treat nausea and vomiting in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Akynzeo is a capsule consisting of two drugs, netupitant and palonosetron.

Palonosetron prevents nausea and vomiting in the acute phase—within the first 24 hours of chemotherapy initiation.

Netupitant prevents nausea and vomiting in the acute phase and the delayed phase—25 to 120 hours after chemotherapy began.

Akynzeo’s effectiveness was established in two clinical trials of 1720 cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Patients were randomized to receive Akynzeo or oral palonosetron.

The trials were designed to measure whether the drugs prevented any vomiting episodes in the acute, delayed, and overall phases after the start of chemotherapy.

Most Akynzeo-treated patients did not experience any vomiting or require rescue medication for nausea during the acute (98.5%), delayed (90.4%), and overall phases (89.6%).

The same was true for patients who received palonosetron, although percentages were lower—89.7%, 80.1%, and 76.5%, respectively.

The second trial showed similar results.

Common side effects of Akynzeo in the clinical trials were headache, asthenia, fatigue, dyspepsia, and constipation.

Akynzeo is distributed and marketed by Eisai Inc., under license from Helsinn Healthcare S.A. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved Akynzeo to treat nausea and vomiting in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Akynzeo is a capsule consisting of two drugs, netupitant and palonosetron.

Palonosetron prevents nausea and vomiting in the acute phase—within the first 24 hours of chemotherapy initiation.

Netupitant prevents nausea and vomiting in the acute phase and the delayed phase—25 to 120 hours after chemotherapy began.

Akynzeo’s effectiveness was established in two clinical trials of 1720 cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Patients were randomized to receive Akynzeo or oral palonosetron.

The trials were designed to measure whether the drugs prevented any vomiting episodes in the acute, delayed, and overall phases after the start of chemotherapy.

Most Akynzeo-treated patients did not experience any vomiting or require rescue medication for nausea during the acute (98.5%), delayed (90.4%), and overall phases (89.6%).

The same was true for patients who received palonosetron, although percentages were lower—89.7%, 80.1%, and 76.5%, respectively.

The second trial showed similar results.

Common side effects of Akynzeo in the clinical trials were headache, asthenia, fatigue, dyspepsia, and constipation.

Akynzeo is distributed and marketed by Eisai Inc., under license from Helsinn Healthcare S.A. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved Akynzeo to treat nausea and vomiting in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Akynzeo is a capsule consisting of two drugs, netupitant and palonosetron.

Palonosetron prevents nausea and vomiting in the acute phase—within the first 24 hours of chemotherapy initiation.

Netupitant prevents nausea and vomiting in the acute phase and the delayed phase—25 to 120 hours after chemotherapy began.

Akynzeo’s effectiveness was established in two clinical trials of 1720 cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Patients were randomized to receive Akynzeo or oral palonosetron.

The trials were designed to measure whether the drugs prevented any vomiting episodes in the acute, delayed, and overall phases after the start of chemotherapy.

Most Akynzeo-treated patients did not experience any vomiting or require rescue medication for nausea during the acute (98.5%), delayed (90.4%), and overall phases (89.6%).

The same was true for patients who received palonosetron, although percentages were lower—89.7%, 80.1%, and 76.5%, respectively.

The second trial showed similar results.

Common side effects of Akynzeo in the clinical trials were headache, asthenia, fatigue, dyspepsia, and constipation.

Akynzeo is distributed and marketed by Eisai Inc., under license from Helsinn Healthcare S.A. ![]()

Product News: 04 2014

Keytruda

Merck & Co, Inc, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Keytruda (pembrolizumab) for the treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma and disease progression following ipilimumab and, if BRAF V600–mutation positive, a BRAF inhibitor. Keytruda is the first anti-PD-1 (programmed death receptor-1) therapy in the United States and is approved as a breakthrough therapy based on tumor response rate and durability of response. It works by increasing the ability of the body’s immune system to fight advanced melanoma. It blocks the interaction between PD-1 and its ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2) and may affect both tumor cells and healthy cells. For more information, visit www.keytruda.com.

Otezla

Celgene Corporation obtains US Food and Drug Administration approval for Otezla (apremilast), an oral, selective inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4 for the treatment of adult patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy. Otezla is associated with an increase in adverse reactions of depression. Patients, their caregivers, and families should be advised of the need to be alert for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts, or other mood changes. Otezla also is approved for patients with active psoriatic arthritis. For more information, visit www.otezla.com.

Papaya Enzyme Cleanser

Revision Skincare introduces the Papaya Enzyme Cleanser, an energizing facial wash formulated with a unique extract derived from papayas to nourish skin with a multitude of vitamins and minerals. The Papaya Enzyme Cleanser, available exclusively through physicians, helps patients achieve naturally vibrant skin. For more information, visit www.revisionskincare.com.

Pigmentclar

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique launches Pigmentclar Intensive Dark Spot Correcting Serum and Pigmentclar SPF 30 Daily Dark Spot Correcting Moisturizer to target multiple stages of dark spot development, leaving patients with a brighter, more even skin tone. The products are formulated to correct dark spots that are underlying, visible, or recurrent. Phe-resorcinol helps reduce excess melanin at the early stages of production, lipohydroxy acid enables cell-by-cell exfoliation, and niacinamide reduces melanin transfer from one cell to another. Both products can be purchased over-the-counter at select retailers, physicians’ offices, and online. For more information, visit www.laroche-posay.us.

Regenacyn

Oculus Innovative Sciences, Inc, introduces Regenacyn Advanced Scar Management Hydrogel to improve the texture, color, softness, and overall appearance of scars. Formulated with Microcyn technology, Regenacyn is intended for the management of old and new hypertrophic and keloid scars of various sizes, shapes, and locations resulting from burns, general surgical procedures, and trauma wounds. Regenacyn is physician dispensed by plastic surgeons and obstetricians/gynecologists. For more information, visit www.oculusis.com/regenacyn-hydrogel.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Keytruda

Merck & Co, Inc, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Keytruda (pembrolizumab) for the treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma and disease progression following ipilimumab and, if BRAF V600–mutation positive, a BRAF inhibitor. Keytruda is the first anti-PD-1 (programmed death receptor-1) therapy in the United States and is approved as a breakthrough therapy based on tumor response rate and durability of response. It works by increasing the ability of the body’s immune system to fight advanced melanoma. It blocks the interaction between PD-1 and its ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2) and may affect both tumor cells and healthy cells. For more information, visit www.keytruda.com.

Otezla

Celgene Corporation obtains US Food and Drug Administration approval for Otezla (apremilast), an oral, selective inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4 for the treatment of adult patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy. Otezla is associated with an increase in adverse reactions of depression. Patients, their caregivers, and families should be advised of the need to be alert for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts, or other mood changes. Otezla also is approved for patients with active psoriatic arthritis. For more information, visit www.otezla.com.

Papaya Enzyme Cleanser

Revision Skincare introduces the Papaya Enzyme Cleanser, an energizing facial wash formulated with a unique extract derived from papayas to nourish skin with a multitude of vitamins and minerals. The Papaya Enzyme Cleanser, available exclusively through physicians, helps patients achieve naturally vibrant skin. For more information, visit www.revisionskincare.com.

Pigmentclar

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique launches Pigmentclar Intensive Dark Spot Correcting Serum and Pigmentclar SPF 30 Daily Dark Spot Correcting Moisturizer to target multiple stages of dark spot development, leaving patients with a brighter, more even skin tone. The products are formulated to correct dark spots that are underlying, visible, or recurrent. Phe-resorcinol helps reduce excess melanin at the early stages of production, lipohydroxy acid enables cell-by-cell exfoliation, and niacinamide reduces melanin transfer from one cell to another. Both products can be purchased over-the-counter at select retailers, physicians’ offices, and online. For more information, visit www.laroche-posay.us.

Regenacyn

Oculus Innovative Sciences, Inc, introduces Regenacyn Advanced Scar Management Hydrogel to improve the texture, color, softness, and overall appearance of scars. Formulated with Microcyn technology, Regenacyn is intended for the management of old and new hypertrophic and keloid scars of various sizes, shapes, and locations resulting from burns, general surgical procedures, and trauma wounds. Regenacyn is physician dispensed by plastic surgeons and obstetricians/gynecologists. For more information, visit www.oculusis.com/regenacyn-hydrogel.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Keytruda

Merck & Co, Inc, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Keytruda (pembrolizumab) for the treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma and disease progression following ipilimumab and, if BRAF V600–mutation positive, a BRAF inhibitor. Keytruda is the first anti-PD-1 (programmed death receptor-1) therapy in the United States and is approved as a breakthrough therapy based on tumor response rate and durability of response. It works by increasing the ability of the body’s immune system to fight advanced melanoma. It blocks the interaction between PD-1 and its ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2) and may affect both tumor cells and healthy cells. For more information, visit www.keytruda.com.

Otezla

Celgene Corporation obtains US Food and Drug Administration approval for Otezla (apremilast), an oral, selective inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 4 for the treatment of adult patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy. Otezla is associated with an increase in adverse reactions of depression. Patients, their caregivers, and families should be advised of the need to be alert for the emergence or worsening of depression, suicidal thoughts, or other mood changes. Otezla also is approved for patients with active psoriatic arthritis. For more information, visit www.otezla.com.

Papaya Enzyme Cleanser

Revision Skincare introduces the Papaya Enzyme Cleanser, an energizing facial wash formulated with a unique extract derived from papayas to nourish skin with a multitude of vitamins and minerals. The Papaya Enzyme Cleanser, available exclusively through physicians, helps patients achieve naturally vibrant skin. For more information, visit www.revisionskincare.com.

Pigmentclar

La Roche-Posay Laboratoire Dermatologique launches Pigmentclar Intensive Dark Spot Correcting Serum and Pigmentclar SPF 30 Daily Dark Spot Correcting Moisturizer to target multiple stages of dark spot development, leaving patients with a brighter, more even skin tone. The products are formulated to correct dark spots that are underlying, visible, or recurrent. Phe-resorcinol helps reduce excess melanin at the early stages of production, lipohydroxy acid enables cell-by-cell exfoliation, and niacinamide reduces melanin transfer from one cell to another. Both products can be purchased over-the-counter at select retailers, physicians’ offices, and online. For more information, visit www.laroche-posay.us.

Regenacyn

Oculus Innovative Sciences, Inc, introduces Regenacyn Advanced Scar Management Hydrogel to improve the texture, color, softness, and overall appearance of scars. Formulated with Microcyn technology, Regenacyn is intended for the management of old and new hypertrophic and keloid scars of various sizes, shapes, and locations resulting from burns, general surgical procedures, and trauma wounds. Regenacyn is physician dispensed by plastic surgeons and obstetricians/gynecologists. For more information, visit www.oculusis.com/regenacyn-hydrogel.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Errata

Due to a submission error, an acknowledgment was missing from the July 2014 article “The Great Mimickers of Rosacea” (Cutis. 2014;94:39-45).

Acknowledgements—The authors thank Jennifer Rullan, MD, San Diego, California, and Jose Gonzalez-Chavez, MD, San Juan, Puerto Rico, for their assistance.

Also, the order of the authors was incorrect in the July 2014 e-only article “Lepromatous Leprosy Associated With Erythema Nodosum Leprosum” (Cutis. 2014;94:E19-E20). The correct order is:

Azeen Sadeghian, MD

These articles have been corrected online.

Due to a submission error, an acknowledgment was missing from the July 2014 article “The Great Mimickers of Rosacea” (Cutis. 2014;94:39-45).

Acknowledgements—The authors thank Jennifer Rullan, MD, San Diego, California, and Jose Gonzalez-Chavez, MD, San Juan, Puerto Rico, for their assistance.

Also, the order of the authors was incorrect in the July 2014 e-only article “Lepromatous Leprosy Associated With Erythema Nodosum Leprosum” (Cutis. 2014;94:E19-E20). The correct order is:

Azeen Sadeghian, MD

These articles have been corrected online.

Due to a submission error, an acknowledgment was missing from the July 2014 article “The Great Mimickers of Rosacea” (Cutis. 2014;94:39-45).

Acknowledgements—The authors thank Jennifer Rullan, MD, San Diego, California, and Jose Gonzalez-Chavez, MD, San Juan, Puerto Rico, for their assistance.

Also, the order of the authors was incorrect in the July 2014 e-only article “Lepromatous Leprosy Associated With Erythema Nodosum Leprosum” (Cutis. 2014;94:E19-E20). The correct order is:

Azeen Sadeghian, MD

These articles have been corrected online.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis to 2-Octyl Cyanoacrylate

Cyanoacrylates are widely used in adhesive products, with applications ranging from household products to nail and beauty salons and even dentistry. A topical skin adhesive containing 2-octyl cyanoacrylate was approved in 1998 for topical application for closure of skin edges of wounds from surgical incisions.1 Usually cyanoacrylates are not strong sensitizers, and despite their extensive use, there have been relatively few reports of associated allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).2-5 We report 4 cases of ACD to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate used in postsurgical wound closures as confirmed by patch tests.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 33-year-old woman presented with an intensely pruritic peri-incisional rash on the lower back and right buttock of 1 week’s duration. The eruption started roughly 1 week following surgical implantation of a spinal cord stimulator for treatment of chronic back pain. Both incisions made during the implantation were closed with 2-octyl cyanoacrylate. The patient denied any prior exposure to topical skin adhesives or any history of contact dermatitis to nickel or other materials. The patient did not dress the wounds and did not apply topical agents to the area.

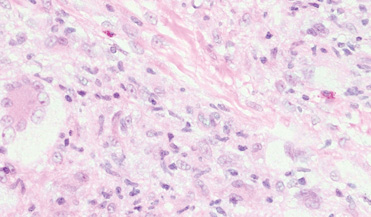

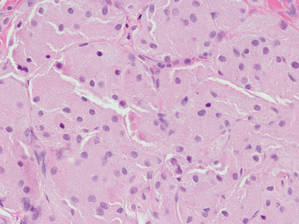

Physical examination revealed 6- to 8-cm linear surgical scars on the midline lumbar back and superior right buttock with surrounding excoriated erythematous papules coalescing into plaques consistent with acute eczematous dermatitis (Figure 1). Similar papules and plaques were scattered across the abdomen and chest. She was given triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily and hydroxyzine pamoate 25 mg 3 times daily for itching. The surgical wounds healed within 2 weeks of presentation with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation surrounding the scars.

|

|

| Figure 1. Surgical scars with surrounding excoriated erythematous papules coalescing into plaques on the midline lumbar back (A) and superior right buttock (B). | |

Six weeks later she underwent patch testing to confirm the diagnosis. She was screened using the North American Contact Dermatitis Group standard 65-allergen series and a miscellaneous tray including hardware obtained from the spinal cord stimulator device manufacturer. A use test to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate also was performed. At 96 hours, true positives included cinnamic aldehyde (1+), nickel (1+), bacitracin (1+), fragrance mix (2+), disperse blue dyes 106 and 124 (2+), and 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (3+)(1+=weak positive; 2+=strong positive; 3+=extreme reaction). There was no response to any components of the device. The pattern of dermatitis and positive patch-test results strongly supported the diagnosis of ACD to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate.

Patients 2, 3, and 4

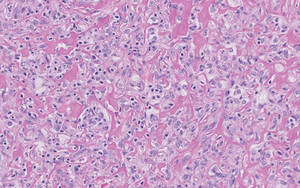

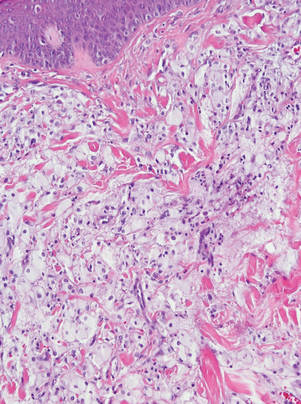

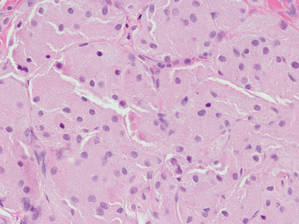

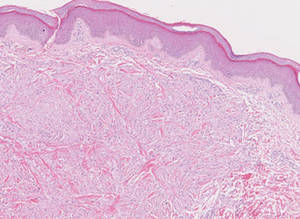

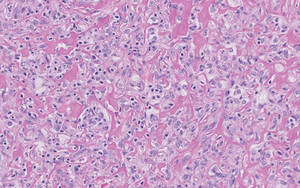

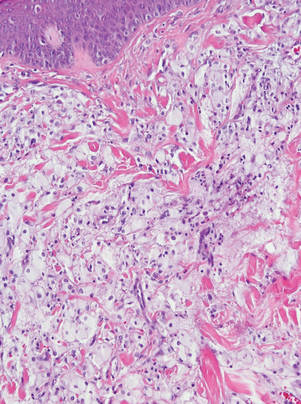

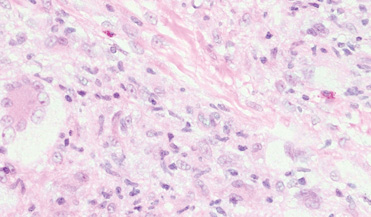

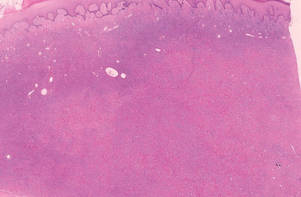

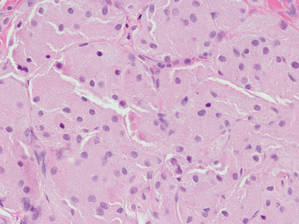

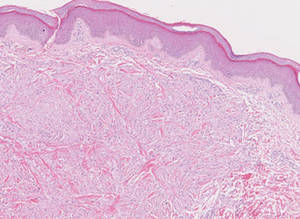

Three patients—a 65-year-old woman, a 35-year-old woman, and a 44-year-old woman—presented to us with eczematous dermatitis at laparoscopic portal sites that were closed with 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (Figures 2 and 3). They presented approximately 1 week following laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, laparoscopic left hepatectomy, and laparoscopic cholecystectomy, respectively. None of these 3 patients had been using any topical medications. All of them had a positive reaction (2+) to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate on use testing. Interestingly, use tests for 2 other cyanoacrylates containing 2-butyl cyanoacrylate were negative in 2 patients.

|

| Figure 2. Acute eczematous plaques at wound closures. |

|

| Figure 3. Coalescing acute eczematous plaques focused at wound closures. |

Although patient 1 reported no prior exposure to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate, these 3 additional patients reported prior exposure with no reaction. Other possible contact allergens associated with wound closure included iodine, topical antibiotics, and dressing tape.

Comment

Contact allergies to acrylates are not uncommon. In a series of 275 patients, Kanerva et al6 found that 17.5% of patients had an allergic reaction to at least 1 acrylate or methacrylate. In the same series, no allergic reactions to cyanoacrylates were noted.6 The role of methacrylates in the development of occupational ACD and irritant dermatitis has been well characterized among dentists, orthopedic surgeons, beauticians, and industrial workers who are commonly exposed to these agents.7-12 Partially because of their longer carbon chains, cyanoacrylates have reduced toxicity and improved bonding strength as well as flexibility. Given their availability and the ease and speed of their use, skin adhesives have become widely used in the closure of surgical wounds.13-16

Postoperative contact dermatitis is problematic, as patients are exposed to many potential allergens during surgery. In our clinical practice, the most common allergens causing ACD associated with surgery are iodine, topical antibiotics (ie, bacitracin, neomycin), tape adhesives, suture materials, and less commonly surgical hardware. Although they are rarely reported, contact allergies to skin adhesives such as cyanoacrylates are of particular importance because they may complicate surgical wounds, leading to dehiscence, infection, and scarring, among other complications. In our patients, there were no adverse outcomes in wound healing with the exception of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Under ideal conditions, 2-octyl cyanoacrylate generally is not a strong sensitizer; however, application to open wounds or thinner skin such as the eyelids may permit exposure of antigen-presenting cells to cyanoacrylate monomers, thereby initiating sensitization. Postsurgical occlusive dressings, which often are left in place for 7 to 14 days, also may contribute to sensitization. The role of the degradation of skin adhesive products in the development of contact dermatitis is unknown.

Management of ACD from skin adhesives should involve the immediate removal of any remaining adhesive. One manufacturer recommends removal of the product using acetone or petroleum jelly.1 In our experience, rubbing the adhesive with 2×2-in gauze pads or using forceps have been successful methods for removal. The use of petroleum jelly prior to rubbing with gauze also can aid in removal of the adhesive. Warm water soaks and soap also may be helpful but are not expected to immediately loosen the bond. A mid-potency steroid ointment such as triamcinolone may be effective in treating dermatitis, though the use of higher-potency steroids such as clobetasol may be needed for severe reactions.1,2

As members of the cyano group, cyanoacrylates are highly reactive molecules that polymerize and rapidly bind to the stratum corneum when they come in contact with traces of water. During polymerization, the individual constituents or monomer cyanoacrylate molecules are joined into a polymer chain, which should be trapped by keratinocytes and not reach immunomodulators2,10; however, as postulated during the first report of contact dermatitis, an arid environment could delay polymerization and increase the risk of sensitization.2 The first report was made in Las Vegas, Nevada,2 and our cases presented in San Antonio, Texas.

There currently are 2 main cutaneous adhesives containing cyanoacrylate on the market, including 2-octyl cyanoacrylate and 2-butyl cyanoacrylate. These products are known by various trade names and differ primarily in the length of the carbon chain in the cyanoacrylate. A dye is added to allow better visibility of the glue during application, and a plasticizer increases viscosity and accelerates polymerization. The 2 most widely used products contain the same dye (D&C Violet No. 2) and similar but proprietary plasticizers.

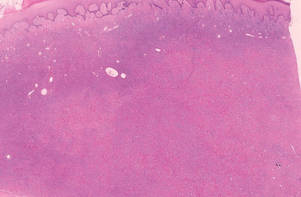

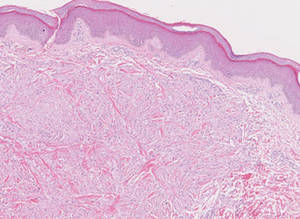

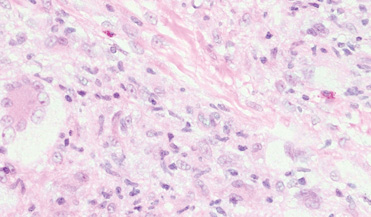

Although plasticizers and dyes may be potential contact allergens, we postulated that the cyanoacrylate was the responsible sensitizer in our cases. Because the individual ingredients were not readily available for use testing, we devised a logical method to attempt to determine the specific component of the skin adhesive that was responsible for contact sensitization (Figure 4). Patients 3 and 4 in our series were tested using this method and were found to be sensitive to the product containing 2-octyl cyanoacrylate but not the products containing 2-butyl cyanoacrylate.

Conclusion

Given the many advantages of cyanoacrylates, it is likely that their use in skin adhesive products will continue to increase. Our 4 patients may represent a rise in the incidence of ACD associated with increased use of skin adhesives, but it is important to look critically at this agent when patients present with postoperative pruritus in the absence of topical bacitracin or neomycin use and surgical dressing irritation. By using the technique we described, it is possible to identify the component responsible for the reaction; however, in the future, the exact mechanisms of sensitization and the specific components should be further elucidated by researchers working in conjunction with the manufacturers. Use testing on abraded skin and/or under occlusive dressings more closely mimics the initial exposure and may have a role in determining true allergy.

1. Dermabond Advanced [package insert]. San Lorenzo, PR: Ethicon, LLC; 2013.

2. Hivnor CM, Hudkins ML. Allergic contact dermatitis after postsurgical repair with 2-octyl cyanoacrylate. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:814-815.

3. Perry AW, Sosin M. Severe allergic reaction to Dermabond. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29:314-316.

4. El-Dars LD, Chaudhury W, Hughes TM, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to Dermabond after orthopaedic joint replacement. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:315-317.

5. Howard BK, Hudkins ML. Contact dermatitis from Dermabond. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:E252-E253.

6. Kanerva L, Jolanki R, Estlander T. 10 years of patch testing with the (meth)acrylate series. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;37:255-258.

7. Belsito DV. Contact dermatitis to ethyl-cyanoacrylate-containing glue. Contact Dermatitis. 1987;17:234-236.

8. Leggat PA, Kedjarune U, Smith DR. Toxicity of cyanoacrylate adhesives and their occupational impacts for dental staff. Ind Health. 2004;42:207-211.

9. Conde-Salazar L, Rojo S, Guimaraens D. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis from cyanoacrylate. Am J Contact Dermat. 1998;9:188-189.

10. Aalto-Korte K, Alanko K, Kuuliala O, et al. Occupational methacrylate and acrylate allergy from glues. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:340-346.

11. Tomb RR, Lepoittevin JP, Durepaire F, et al. Ectopic contact dermatitis from ethyl cyanoacrylate instant adhesives. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;28:206-208.

12. Dragu A, Unglaub F, Schwarz S, et al. Foreign body reaction after usage of tissue adhesives for skin closure: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129:167-169.

13. Eaglstein WH, Sullivan T. Cyanoacrylates for skin closure. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:193-198.

14. Singer AJ, Quinn JV, Hollander JE. The cyanoacrylate topical skin adhesives. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:490-496.

15. Singer AJ, Thode HC Jr. A review of the literature on octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive. Am J Surg. 2004;187:238-248.

16. Calnan CD. Cyanoacrylate dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1979;5:165-167.

Cyanoacrylates are widely used in adhesive products, with applications ranging from household products to nail and beauty salons and even dentistry. A topical skin adhesive containing 2-octyl cyanoacrylate was approved in 1998 for topical application for closure of skin edges of wounds from surgical incisions.1 Usually cyanoacrylates are not strong sensitizers, and despite their extensive use, there have been relatively few reports of associated allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).2-5 We report 4 cases of ACD to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate used in postsurgical wound closures as confirmed by patch tests.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 33-year-old woman presented with an intensely pruritic peri-incisional rash on the lower back and right buttock of 1 week’s duration. The eruption started roughly 1 week following surgical implantation of a spinal cord stimulator for treatment of chronic back pain. Both incisions made during the implantation were closed with 2-octyl cyanoacrylate. The patient denied any prior exposure to topical skin adhesives or any history of contact dermatitis to nickel or other materials. The patient did not dress the wounds and did not apply topical agents to the area.

Physical examination revealed 6- to 8-cm linear surgical scars on the midline lumbar back and superior right buttock with surrounding excoriated erythematous papules coalescing into plaques consistent with acute eczematous dermatitis (Figure 1). Similar papules and plaques were scattered across the abdomen and chest. She was given triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily and hydroxyzine pamoate 25 mg 3 times daily for itching. The surgical wounds healed within 2 weeks of presentation with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation surrounding the scars.

|

|

| Figure 1. Surgical scars with surrounding excoriated erythematous papules coalescing into plaques on the midline lumbar back (A) and superior right buttock (B). | |

Six weeks later she underwent patch testing to confirm the diagnosis. She was screened using the North American Contact Dermatitis Group standard 65-allergen series and a miscellaneous tray including hardware obtained from the spinal cord stimulator device manufacturer. A use test to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate also was performed. At 96 hours, true positives included cinnamic aldehyde (1+), nickel (1+), bacitracin (1+), fragrance mix (2+), disperse blue dyes 106 and 124 (2+), and 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (3+)(1+=weak positive; 2+=strong positive; 3+=extreme reaction). There was no response to any components of the device. The pattern of dermatitis and positive patch-test results strongly supported the diagnosis of ACD to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate.

Patients 2, 3, and 4

Three patients—a 65-year-old woman, a 35-year-old woman, and a 44-year-old woman—presented to us with eczematous dermatitis at laparoscopic portal sites that were closed with 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (Figures 2 and 3). They presented approximately 1 week following laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, laparoscopic left hepatectomy, and laparoscopic cholecystectomy, respectively. None of these 3 patients had been using any topical medications. All of them had a positive reaction (2+) to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate on use testing. Interestingly, use tests for 2 other cyanoacrylates containing 2-butyl cyanoacrylate were negative in 2 patients.

|

| Figure 2. Acute eczematous plaques at wound closures. |

|

| Figure 3. Coalescing acute eczematous plaques focused at wound closures. |

Although patient 1 reported no prior exposure to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate, these 3 additional patients reported prior exposure with no reaction. Other possible contact allergens associated with wound closure included iodine, topical antibiotics, and dressing tape.

Comment

Contact allergies to acrylates are not uncommon. In a series of 275 patients, Kanerva et al6 found that 17.5% of patients had an allergic reaction to at least 1 acrylate or methacrylate. In the same series, no allergic reactions to cyanoacrylates were noted.6 The role of methacrylates in the development of occupational ACD and irritant dermatitis has been well characterized among dentists, orthopedic surgeons, beauticians, and industrial workers who are commonly exposed to these agents.7-12 Partially because of their longer carbon chains, cyanoacrylates have reduced toxicity and improved bonding strength as well as flexibility. Given their availability and the ease and speed of their use, skin adhesives have become widely used in the closure of surgical wounds.13-16

Postoperative contact dermatitis is problematic, as patients are exposed to many potential allergens during surgery. In our clinical practice, the most common allergens causing ACD associated with surgery are iodine, topical antibiotics (ie, bacitracin, neomycin), tape adhesives, suture materials, and less commonly surgical hardware. Although they are rarely reported, contact allergies to skin adhesives such as cyanoacrylates are of particular importance because they may complicate surgical wounds, leading to dehiscence, infection, and scarring, among other complications. In our patients, there were no adverse outcomes in wound healing with the exception of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Under ideal conditions, 2-octyl cyanoacrylate generally is not a strong sensitizer; however, application to open wounds or thinner skin such as the eyelids may permit exposure of antigen-presenting cells to cyanoacrylate monomers, thereby initiating sensitization. Postsurgical occlusive dressings, which often are left in place for 7 to 14 days, also may contribute to sensitization. The role of the degradation of skin adhesive products in the development of contact dermatitis is unknown.

Management of ACD from skin adhesives should involve the immediate removal of any remaining adhesive. One manufacturer recommends removal of the product using acetone or petroleum jelly.1 In our experience, rubbing the adhesive with 2×2-in gauze pads or using forceps have been successful methods for removal. The use of petroleum jelly prior to rubbing with gauze also can aid in removal of the adhesive. Warm water soaks and soap also may be helpful but are not expected to immediately loosen the bond. A mid-potency steroid ointment such as triamcinolone may be effective in treating dermatitis, though the use of higher-potency steroids such as clobetasol may be needed for severe reactions.1,2

As members of the cyano group, cyanoacrylates are highly reactive molecules that polymerize and rapidly bind to the stratum corneum when they come in contact with traces of water. During polymerization, the individual constituents or monomer cyanoacrylate molecules are joined into a polymer chain, which should be trapped by keratinocytes and not reach immunomodulators2,10; however, as postulated during the first report of contact dermatitis, an arid environment could delay polymerization and increase the risk of sensitization.2 The first report was made in Las Vegas, Nevada,2 and our cases presented in San Antonio, Texas.

There currently are 2 main cutaneous adhesives containing cyanoacrylate on the market, including 2-octyl cyanoacrylate and 2-butyl cyanoacrylate. These products are known by various trade names and differ primarily in the length of the carbon chain in the cyanoacrylate. A dye is added to allow better visibility of the glue during application, and a plasticizer increases viscosity and accelerates polymerization. The 2 most widely used products contain the same dye (D&C Violet No. 2) and similar but proprietary plasticizers.

Although plasticizers and dyes may be potential contact allergens, we postulated that the cyanoacrylate was the responsible sensitizer in our cases. Because the individual ingredients were not readily available for use testing, we devised a logical method to attempt to determine the specific component of the skin adhesive that was responsible for contact sensitization (Figure 4). Patients 3 and 4 in our series were tested using this method and were found to be sensitive to the product containing 2-octyl cyanoacrylate but not the products containing 2-butyl cyanoacrylate.

Conclusion

Given the many advantages of cyanoacrylates, it is likely that their use in skin adhesive products will continue to increase. Our 4 patients may represent a rise in the incidence of ACD associated with increased use of skin adhesives, but it is important to look critically at this agent when patients present with postoperative pruritus in the absence of topical bacitracin or neomycin use and surgical dressing irritation. By using the technique we described, it is possible to identify the component responsible for the reaction; however, in the future, the exact mechanisms of sensitization and the specific components should be further elucidated by researchers working in conjunction with the manufacturers. Use testing on abraded skin and/or under occlusive dressings more closely mimics the initial exposure and may have a role in determining true allergy.

Cyanoacrylates are widely used in adhesive products, with applications ranging from household products to nail and beauty salons and even dentistry. A topical skin adhesive containing 2-octyl cyanoacrylate was approved in 1998 for topical application for closure of skin edges of wounds from surgical incisions.1 Usually cyanoacrylates are not strong sensitizers, and despite their extensive use, there have been relatively few reports of associated allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).2-5 We report 4 cases of ACD to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate used in postsurgical wound closures as confirmed by patch tests.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 33-year-old woman presented with an intensely pruritic peri-incisional rash on the lower back and right buttock of 1 week’s duration. The eruption started roughly 1 week following surgical implantation of a spinal cord stimulator for treatment of chronic back pain. Both incisions made during the implantation were closed with 2-octyl cyanoacrylate. The patient denied any prior exposure to topical skin adhesives or any history of contact dermatitis to nickel or other materials. The patient did not dress the wounds and did not apply topical agents to the area.

Physical examination revealed 6- to 8-cm linear surgical scars on the midline lumbar back and superior right buttock with surrounding excoriated erythematous papules coalescing into plaques consistent with acute eczematous dermatitis (Figure 1). Similar papules and plaques were scattered across the abdomen and chest. She was given triamcinolone acetonide ointment 0.1% twice daily and hydroxyzine pamoate 25 mg 3 times daily for itching. The surgical wounds healed within 2 weeks of presentation with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation surrounding the scars.

|

|

| Figure 1. Surgical scars with surrounding excoriated erythematous papules coalescing into plaques on the midline lumbar back (A) and superior right buttock (B). | |

Six weeks later she underwent patch testing to confirm the diagnosis. She was screened using the North American Contact Dermatitis Group standard 65-allergen series and a miscellaneous tray including hardware obtained from the spinal cord stimulator device manufacturer. A use test to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate also was performed. At 96 hours, true positives included cinnamic aldehyde (1+), nickel (1+), bacitracin (1+), fragrance mix (2+), disperse blue dyes 106 and 124 (2+), and 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (3+)(1+=weak positive; 2+=strong positive; 3+=extreme reaction). There was no response to any components of the device. The pattern of dermatitis and positive patch-test results strongly supported the diagnosis of ACD to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate.

Patients 2, 3, and 4

Three patients—a 65-year-old woman, a 35-year-old woman, and a 44-year-old woman—presented to us with eczematous dermatitis at laparoscopic portal sites that were closed with 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (Figures 2 and 3). They presented approximately 1 week following laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication, laparoscopic left hepatectomy, and laparoscopic cholecystectomy, respectively. None of these 3 patients had been using any topical medications. All of them had a positive reaction (2+) to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate on use testing. Interestingly, use tests for 2 other cyanoacrylates containing 2-butyl cyanoacrylate were negative in 2 patients.

|

| Figure 2. Acute eczematous plaques at wound closures. |

|

| Figure 3. Coalescing acute eczematous plaques focused at wound closures. |

Although patient 1 reported no prior exposure to 2-octyl cyanoacrylate, these 3 additional patients reported prior exposure with no reaction. Other possible contact allergens associated with wound closure included iodine, topical antibiotics, and dressing tape.

Comment

Contact allergies to acrylates are not uncommon. In a series of 275 patients, Kanerva et al6 found that 17.5% of patients had an allergic reaction to at least 1 acrylate or methacrylate. In the same series, no allergic reactions to cyanoacrylates were noted.6 The role of methacrylates in the development of occupational ACD and irritant dermatitis has been well characterized among dentists, orthopedic surgeons, beauticians, and industrial workers who are commonly exposed to these agents.7-12 Partially because of their longer carbon chains, cyanoacrylates have reduced toxicity and improved bonding strength as well as flexibility. Given their availability and the ease and speed of their use, skin adhesives have become widely used in the closure of surgical wounds.13-16

Postoperative contact dermatitis is problematic, as patients are exposed to many potential allergens during surgery. In our clinical practice, the most common allergens causing ACD associated with surgery are iodine, topical antibiotics (ie, bacitracin, neomycin), tape adhesives, suture materials, and less commonly surgical hardware. Although they are rarely reported, contact allergies to skin adhesives such as cyanoacrylates are of particular importance because they may complicate surgical wounds, leading to dehiscence, infection, and scarring, among other complications. In our patients, there were no adverse outcomes in wound healing with the exception of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Under ideal conditions, 2-octyl cyanoacrylate generally is not a strong sensitizer; however, application to open wounds or thinner skin such as the eyelids may permit exposure of antigen-presenting cells to cyanoacrylate monomers, thereby initiating sensitization. Postsurgical occlusive dressings, which often are left in place for 7 to 14 days, also may contribute to sensitization. The role of the degradation of skin adhesive products in the development of contact dermatitis is unknown.

Management of ACD from skin adhesives should involve the immediate removal of any remaining adhesive. One manufacturer recommends removal of the product using acetone or petroleum jelly.1 In our experience, rubbing the adhesive with 2×2-in gauze pads or using forceps have been successful methods for removal. The use of petroleum jelly prior to rubbing with gauze also can aid in removal of the adhesive. Warm water soaks and soap also may be helpful but are not expected to immediately loosen the bond. A mid-potency steroid ointment such as triamcinolone may be effective in treating dermatitis, though the use of higher-potency steroids such as clobetasol may be needed for severe reactions.1,2

As members of the cyano group, cyanoacrylates are highly reactive molecules that polymerize and rapidly bind to the stratum corneum when they come in contact with traces of water. During polymerization, the individual constituents or monomer cyanoacrylate molecules are joined into a polymer chain, which should be trapped by keratinocytes and not reach immunomodulators2,10; however, as postulated during the first report of contact dermatitis, an arid environment could delay polymerization and increase the risk of sensitization.2 The first report was made in Las Vegas, Nevada,2 and our cases presented in San Antonio, Texas.

There currently are 2 main cutaneous adhesives containing cyanoacrylate on the market, including 2-octyl cyanoacrylate and 2-butyl cyanoacrylate. These products are known by various trade names and differ primarily in the length of the carbon chain in the cyanoacrylate. A dye is added to allow better visibility of the glue during application, and a plasticizer increases viscosity and accelerates polymerization. The 2 most widely used products contain the same dye (D&C Violet No. 2) and similar but proprietary plasticizers.

Although plasticizers and dyes may be potential contact allergens, we postulated that the cyanoacrylate was the responsible sensitizer in our cases. Because the individual ingredients were not readily available for use testing, we devised a logical method to attempt to determine the specific component of the skin adhesive that was responsible for contact sensitization (Figure 4). Patients 3 and 4 in our series were tested using this method and were found to be sensitive to the product containing 2-octyl cyanoacrylate but not the products containing 2-butyl cyanoacrylate.

Conclusion

Given the many advantages of cyanoacrylates, it is likely that their use in skin adhesive products will continue to increase. Our 4 patients may represent a rise in the incidence of ACD associated with increased use of skin adhesives, but it is important to look critically at this agent when patients present with postoperative pruritus in the absence of topical bacitracin or neomycin use and surgical dressing irritation. By using the technique we described, it is possible to identify the component responsible for the reaction; however, in the future, the exact mechanisms of sensitization and the specific components should be further elucidated by researchers working in conjunction with the manufacturers. Use testing on abraded skin and/or under occlusive dressings more closely mimics the initial exposure and may have a role in determining true allergy.

1. Dermabond Advanced [package insert]. San Lorenzo, PR: Ethicon, LLC; 2013.

2. Hivnor CM, Hudkins ML. Allergic contact dermatitis after postsurgical repair with 2-octyl cyanoacrylate. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:814-815.

3. Perry AW, Sosin M. Severe allergic reaction to Dermabond. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29:314-316.

4. El-Dars LD, Chaudhury W, Hughes TM, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to Dermabond after orthopaedic joint replacement. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:315-317.

5. Howard BK, Hudkins ML. Contact dermatitis from Dermabond. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:E252-E253.

6. Kanerva L, Jolanki R, Estlander T. 10 years of patch testing with the (meth)acrylate series. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;37:255-258.

7. Belsito DV. Contact dermatitis to ethyl-cyanoacrylate-containing glue. Contact Dermatitis. 1987;17:234-236.

8. Leggat PA, Kedjarune U, Smith DR. Toxicity of cyanoacrylate adhesives and their occupational impacts for dental staff. Ind Health. 2004;42:207-211.

9. Conde-Salazar L, Rojo S, Guimaraens D. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis from cyanoacrylate. Am J Contact Dermat. 1998;9:188-189.

10. Aalto-Korte K, Alanko K, Kuuliala O, et al. Occupational methacrylate and acrylate allergy from glues. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:340-346.

11. Tomb RR, Lepoittevin JP, Durepaire F, et al. Ectopic contact dermatitis from ethyl cyanoacrylate instant adhesives. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;28:206-208.

12. Dragu A, Unglaub F, Schwarz S, et al. Foreign body reaction after usage of tissue adhesives for skin closure: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129:167-169.

13. Eaglstein WH, Sullivan T. Cyanoacrylates for skin closure. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:193-198.

14. Singer AJ, Quinn JV, Hollander JE. The cyanoacrylate topical skin adhesives. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:490-496.

15. Singer AJ, Thode HC Jr. A review of the literature on octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive. Am J Surg. 2004;187:238-248.

16. Calnan CD. Cyanoacrylate dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1979;5:165-167.

1. Dermabond Advanced [package insert]. San Lorenzo, PR: Ethicon, LLC; 2013.

2. Hivnor CM, Hudkins ML. Allergic contact dermatitis after postsurgical repair with 2-octyl cyanoacrylate. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:814-815.

3. Perry AW, Sosin M. Severe allergic reaction to Dermabond. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29:314-316.

4. El-Dars LD, Chaudhury W, Hughes TM, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to Dermabond after orthopaedic joint replacement. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:315-317.

5. Howard BK, Hudkins ML. Contact dermatitis from Dermabond. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:E252-E253.

6. Kanerva L, Jolanki R, Estlander T. 10 years of patch testing with the (meth)acrylate series. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;37:255-258.

7. Belsito DV. Contact dermatitis to ethyl-cyanoacrylate-containing glue. Contact Dermatitis. 1987;17:234-236.

8. Leggat PA, Kedjarune U, Smith DR. Toxicity of cyanoacrylate adhesives and their occupational impacts for dental staff. Ind Health. 2004;42:207-211.

9. Conde-Salazar L, Rojo S, Guimaraens D. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis from cyanoacrylate. Am J Contact Dermat. 1998;9:188-189.

10. Aalto-Korte K, Alanko K, Kuuliala O, et al. Occupational methacrylate and acrylate allergy from glues. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:340-346.

11. Tomb RR, Lepoittevin JP, Durepaire F, et al. Ectopic contact dermatitis from ethyl cyanoacrylate instant adhesives. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;28:206-208.

12. Dragu A, Unglaub F, Schwarz S, et al. Foreign body reaction after usage of tissue adhesives for skin closure: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129:167-169.

13. Eaglstein WH, Sullivan T. Cyanoacrylates for skin closure. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:193-198.

14. Singer AJ, Quinn JV, Hollander JE. The cyanoacrylate topical skin adhesives. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:490-496.

15. Singer AJ, Thode HC Jr. A review of the literature on octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive. Am J Surg. 2004;187:238-248.

16. Calnan CD. Cyanoacrylate dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1979;5:165-167.

Practice Points

- It is important for physicians to recognize that skin adhesives are a potential source of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) in a postsurgical setting.

- There are 3 primary components of skin adhesives that are potential contactants, including a cyanoacrylate, a plasticizer, and a dye.

- Treatment of ACD to skin adhesives is straightforward, including removal of any remaining adhesive and applying topical steroids.

First drug-coated angioplasty balloon approved for PAD

A drug-coated angioplasty balloon catheter has been approved for treating peripheral artery disease, the first such device approved for this use, the Food and Drug Administration announced on October 10.

The device is the Lutonix 035 Drug Coated Balloon Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty Catheter (Lutonix DCB), manufactured by Lutonix; its outer surface is coated with paclitaxel, “which may help to prevent” restenosis after the angioplasty procedure, according to the FDA statement announcing the approval. “The clinical data show that Lutonix DCB may be more effective than traditional balloon angioplasty at helping to prevent further blockage in the artery,” Dr. William Maisel, deputy director for science and chief scientist in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

Approval was based on the results of three clinical trials and nonclinical testing:

• A randomized, multicenter study of 101 people in Europe, which found that after 6 months, no further treatment for PAD was needed in almost 72% of the patients treated with Lutonix DCB, compared with almost 50% of those treated with conventional balloon angioplasty.

• A single-blind, multicenter, randomized study of 476 people in the United States and Europe, which found that 65% of those randomized to treatment with Lutonix DCB had no restenosis at 12 months, compared with roughly 53% of those randomized to treatment with conventional balloon angioplasty.

• A single-arm, ongoing study that is further evaluating safety and effectiveness in 657 people treated with the device in the United States and Europe, which, at the time of approval, “show that there have been no unanticipated device- or drug-related adverse events,” the FDA said.

These studies also indicated that the safety of Lutonix DCB was comparable to conventional balloon angioplasty. The most common major adverse events included additional intervention, pain as a result of poor blood flow, narrowing of arteries that were not treated, chest pain, and abnormal growth of tissue.

Contraindications include women who are breastfeeding, pregnant, or plan to become pregnant; and men who plan to father children.

The company is required by the FDA to conduct two postapproval studies, the ongoing 5-year study of 657 patients, and a randomized, single-blind, multicenter study that will evaluate safety and effectiveness of the device in women in the United States, “due to differences in observed outcomes in this group as compared to outcomes for the general study population,” according to the FDA.

The device was reviewed at an FDA advisory panel meeting in June.

A drug-coated angioplasty balloon catheter has been approved for treating peripheral artery disease, the first such device approved for this use, the Food and Drug Administration announced on October 10.

The device is the Lutonix 035 Drug Coated Balloon Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty Catheter (Lutonix DCB), manufactured by Lutonix; its outer surface is coated with paclitaxel, “which may help to prevent” restenosis after the angioplasty procedure, according to the FDA statement announcing the approval. “The clinical data show that Lutonix DCB may be more effective than traditional balloon angioplasty at helping to prevent further blockage in the artery,” Dr. William Maisel, deputy director for science and chief scientist in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

Approval was based on the results of three clinical trials and nonclinical testing:

• A randomized, multicenter study of 101 people in Europe, which found that after 6 months, no further treatment for PAD was needed in almost 72% of the patients treated with Lutonix DCB, compared with almost 50% of those treated with conventional balloon angioplasty.

• A single-blind, multicenter, randomized study of 476 people in the United States and Europe, which found that 65% of those randomized to treatment with Lutonix DCB had no restenosis at 12 months, compared with roughly 53% of those randomized to treatment with conventional balloon angioplasty.

• A single-arm, ongoing study that is further evaluating safety and effectiveness in 657 people treated with the device in the United States and Europe, which, at the time of approval, “show that there have been no unanticipated device- or drug-related adverse events,” the FDA said.

These studies also indicated that the safety of Lutonix DCB was comparable to conventional balloon angioplasty. The most common major adverse events included additional intervention, pain as a result of poor blood flow, narrowing of arteries that were not treated, chest pain, and abnormal growth of tissue.

Contraindications include women who are breastfeeding, pregnant, or plan to become pregnant; and men who plan to father children.

The company is required by the FDA to conduct two postapproval studies, the ongoing 5-year study of 657 patients, and a randomized, single-blind, multicenter study that will evaluate safety and effectiveness of the device in women in the United States, “due to differences in observed outcomes in this group as compared to outcomes for the general study population,” according to the FDA.

The device was reviewed at an FDA advisory panel meeting in June.

A drug-coated angioplasty balloon catheter has been approved for treating peripheral artery disease, the first such device approved for this use, the Food and Drug Administration announced on October 10.

The device is the Lutonix 035 Drug Coated Balloon Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty Catheter (Lutonix DCB), manufactured by Lutonix; its outer surface is coated with paclitaxel, “which may help to prevent” restenosis after the angioplasty procedure, according to the FDA statement announcing the approval. “The clinical data show that Lutonix DCB may be more effective than traditional balloon angioplasty at helping to prevent further blockage in the artery,” Dr. William Maisel, deputy director for science and chief scientist in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

Approval was based on the results of three clinical trials and nonclinical testing:

• A randomized, multicenter study of 101 people in Europe, which found that after 6 months, no further treatment for PAD was needed in almost 72% of the patients treated with Lutonix DCB, compared with almost 50% of those treated with conventional balloon angioplasty.

• A single-blind, multicenter, randomized study of 476 people in the United States and Europe, which found that 65% of those randomized to treatment with Lutonix DCB had no restenosis at 12 months, compared with roughly 53% of those randomized to treatment with conventional balloon angioplasty.

• A single-arm, ongoing study that is further evaluating safety and effectiveness in 657 people treated with the device in the United States and Europe, which, at the time of approval, “show that there have been no unanticipated device- or drug-related adverse events,” the FDA said.

These studies also indicated that the safety of Lutonix DCB was comparable to conventional balloon angioplasty. The most common major adverse events included additional intervention, pain as a result of poor blood flow, narrowing of arteries that were not treated, chest pain, and abnormal growth of tissue.

Contraindications include women who are breastfeeding, pregnant, or plan to become pregnant; and men who plan to father children.

The company is required by the FDA to conduct two postapproval studies, the ongoing 5-year study of 657 patients, and a randomized, single-blind, multicenter study that will evaluate safety and effectiveness of the device in women in the United States, “due to differences in observed outcomes in this group as compared to outcomes for the general study population,” according to the FDA.

The device was reviewed at an FDA advisory panel meeting in June.

Topical Therapy for Acne in Women: Is There a Role for Clindamycin Phosphate–Benzoyl Peroxide Gel?

The management of acne vulgaris (AV) in women has been the subject of considerable attention over the last few years. It has become increasingly recognized that a greater number of patient encounters in dermatology offices involve women with AV who are beyond their adolescent years. Overall, it is estimated that up to approximately 22% of women in the United States are affected by AV, with approximately half of women in their 20s and one-third of women in their 30s reporting some degree of AV.1-4 Among women, the disease shows no predilection for certain skin types or ethnicities, can start during the preteenaged or adolescent years, can persist or recur in adulthood (persistent acne, 75%), or can start in adulthood (late-onset acne, 25%) in females with minimal or no history of AV occurring earlier in life.3,5-7 In the subpopulation of adult women, AV occurs at a time when many expect to be far beyond this “teenage affliction.” Women who are affected commonly express feeling embarrassed and frustrated.5-8