User login

Primary Care Medical Services for Homeless Veterans

On a single night in 2012, 62,619 veterans experienced homelessness.1 With high rates of illness, as well as alcohol, tobacco, and other drug (ATOD) use among homeless adults, ending veteran homelessness is a signature initiative of the VA.2-4 However, despite increasing efforts to improve health care for homeless individuals, little is known about best practices in homeless-focused primary care.2,5

With an age-adjusted mortality that is 2 to 10 times higher than that of their housed counterparts, homeless veterans pose a formidable challenge for primary care providers (PCPs).6,7 The complexity of homeless persons’ primary care needs is compounded by poor social support and the need to navigate priorities (eg, shelter) that compete with medical care.6,8,9 Moreover, veterans may face unique vulnerabilities conferred by military-specific experiences.2,10

As of 2012, only 2 VA facilities had primary care clinics tailored to the needs of homeless veterans. McGuire and colleagues built a system of colocated primary care, mental health, and homeless services for mentally ill veterans in Los Angeles, California.11 Over 18 months, this clinic facilitated greater primary and preventive care delivery, though the population’s physical health status did not improve.11 More recently, O’Toole and colleagues implemented a homeless-focused primary care clinic in Providence, Rhode Island.6 Compared with a historical sample of homeless veterans in traditional VA primary care, veterans in this homeless-tailored clinic had greater improvements in some chronic disease outcomes.6 This clinic also decreased nonacute emergency department (ED) use and hospitalizations for general medical conditions.6

Despite these promising outcomes, the VA lacked a nationwide homeless-focused primary care initiative. In 2012 the VA Office of Homeless Programs and the Office of Primary Care Operations funded a national demonstration project to create Homeless Patient-Aligned Care Teams (HPACTs)—primary care medical clinics for homeless veterans—at 32 facilities. This demonstration project guided HPACTs to tailor clinical and social services to homeless veterans’ needs, establish processes to identify and refer appropriate veterans, and integrate distinct services.

There were no explicit instructions that detailed HPACT structure. Because new VA programs must fit local contextual factors, including infrastructure, space, personnel, and institutional/community resources, different models of homeless-focused primary care have evolved.

This article is a case study of HPACTs at 3 of the 32 participating VA facilities, each reflecting a distinct community and organizational context. In light of projected HPACT expansion and concerns that current services are better tailored to sheltered homeless veterans than to their unsheltered peers, there is particular importance to detailed clinic descriptions that vividly portray the intricate relationships between service design and populations served.1

METHODS

VA HPACTs established in May 2012 at 3 facilities were examined: Birmingham VAMC in Alabama (BIR), West Los Angeles VAMC in California (WLA), and VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System in Pennsylvania (PIT). Prior to this demonstration project, each facility offered a range of housing/social services and traditional primary care for veterans. These sites are a geographically diverse convenience sample that emerged from existing homeless-focused collaborations among the authors and represent geographically diverse HPACTs.

The national director of VA Homeless Programs formally determined that this comparison constitutes a VA operations activity that is not research.12 This activity was exempt from Institutional Review Board review.

Study Design

Timed at an early stage of HPACT implementation, this project had 3 aims: (1) To identify noteworthy similarities and/or differences among the initial HPACT clinic structures; (2) To compare and contrast the patient characteristics of veterans enrolled in each of these clinics; and (3) To use these data to inform ongoing HPACT service design.

HPACT program evaluation data are not presented. Rather, a nascent system of care is illustrated that contributes to the limited literature concerning the design and implementation of homeless-focused primary care. Such organizational profiles inform novel program delivery and hold particular utility for heterogeneous populations who are difficult to engage in care.13,14

Authors at each site independently developed lists of variables that fell within the 3 guiding principles of this demonstration project. These variables were compiled and iteratively reduced to a consolidated table that assessed each clinic, including location, operating hours, methods of patient identification and referral, and linkages to distinct services (eg, primary care, mental health, addiction, and social services).

This table also became a guide for HPACT directors to generate narrative clinic descriptions. Characteristics of VA medical homes that are embraced regardless of patients’ housing status (eg, patient-centered, team-based care) were also incorporated into these descriptions.15

Patient Characteristics

The VA electronic health record (EHR) was used to identify all patients enrolled in HPACTs at BIR, WLA, and PIT from May 1, 2012 (clinic inception), through September 30, 2012. Authors developed a standardized template for EHR review and coined the first HPACT record as the patient’s index visit. This record was used to code initial housing status, demographics, and acute medical conditions diagnosed/treated. If housing status was not recorded at the index visit, the first preceding informative record was used.

Records for 6 months preceding the index visit were used to identify the presence or absence of common medical conditions, psychiatric diagnoses, and ATOD abuse or dependence. Medical conditions were identified from a list of common outpatient diagnoses from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, supplemented by common conditions among homeless men.16-18 The EHR problem list (a list of diagnoses, by patient) was used to obtain diagnoses, supplemented by notes from inpatient admissions/discharges, as well as ED, primary care, and subspecialty consultations within 6 months preceding the index visit. Prior VA health care use was ascertained from the EHR review of the same 6-month window, reflecting ED visits, inpatient admissions, primary care visits, subspecialty visits, and individual/group therapy for ATOD or other mental health problems. Data were used to generate site-specific descriptive statistics.

RESULTS

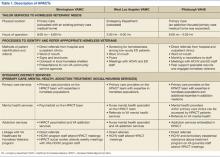

Like all VA hospital-based clinics, a universal EHR captured all medical and social service notes, orders, medications, and administrative records. All facilities had on-site EDs, medical/mental health specialty care, and pharmacies. Social services, including benefits counseling and housing services, were available on site. Table 1 summarizes the HPACT structures at BIR, WLA, and PIT.

Birmingham

The BIR HPACT was devised as a new homeless-focused team located within a VA primary care clinic where other providers continued to see primary care patients. Staff and space were reallocated for this HPACT, which recruited patients in 4 ways: (1) the facility’s primary homeless program, Healthcare for Homeless Veterans, referred patients who previously sought VA housing but who required primary care; (2) an outreach specialist sought homeless veterans in shelters and on the streets; (3) HPACT staff marketed the clinic with presentations and flyers to other VA services and non-VA community agencies; and (4) a referral mechanism within the EHR.

A nurse practitioner was the PCP at this site, supervised by an academic internist experienced in the care of underserved populations, and the HPACT director, a physician certified in internal and addiction medicine. Patients at the BIR HPACT also received care from a social worker, registered nurse, licensed practical nurse, and psychiatrist who received all or a portion of their salaries from this demonstration project. This clinic accommodated walk-in appointments during business hours. Clinicians discussed clinical cases daily, and the full clinical and administrative team met weekly. To promote service integration, HPACT staff attended meetings of the BIR general primary care and Healthcare for Homeless Veterans programs, and vice versa.

West Los Angeles

At WLA, a previously established Homeless Screening Clinic that offered integrated social and medical services for homeless veterans with mental illness was already available during business hours and located within the site’s mental health program.11 However, because ED use for homeless veterans peaked after hours, the new WLA HPACT was established within the WLA ED.

During WLA HPACT hours (3 weekday evenings/week), routine nursing triage occurred for all patients who presented to the ED. However, distinct from other times of day, veterans who were triaged with low-acuity and who were appropriate for outpatient care were given a self-administered, 4-item questionnaire to identify patients who were homeless or at risk for becoming homeless. Veterans who were identified with this screening tool were offered the choice of an ED or HPACT visit. Veterans who chose the latter were assigned to the queue for an HPACT primary care visit instead of the ED.

A physician led the clinical team, with additional services from a mental health clinical nurse specialist and clerks who worked with homeless and/or mental health patients during business hours and provided part-time HPACT coverage. When needed, additional services were provided from colocated ED nurses and social workers. Providers were chosen for their aptitude in culturally responsive communication.

Patients who chose to be seen in HPACT received a primary care visit that also addressed the reason for ED presentation. HPACT staff worked collaboratively, with interdisciplinary team huddles that preceded each clinic session and ended each patient visit. Referrals and social service needs were tracked and monitored by the PCP. Specialty care referrals were also tracked and facilitated when possible with direct communication between HPACT providers and specialty services. Meetings with daytime Homeless Screening Clinic and ED staff facilitated cross-departmental collaborations that helped veterans prepare for and retain housing.

Pittsburgh

The HPACT at PIT evolved from an existing PACT that provided primary care-based addiction services.2 That team included an internist credentialed in addiction medicine and experienced in homeless health care, nurse practitioner, nurse care manager, nursing assistant, and clerks. At this site, HPACT providers had subspecialty expertise in the assessment and treatment of ATOD use, certification to prescribe buprenorphine for outpatient opioid detoxification and/or maintenance, and experience engaging homeless and other vulnerable veterans. The existing colocated clinic included 2 additional addiction medicine clinicians and a physician assistant experienced in ATOD use. The PIT HPACT was not restricted to patients with ATOD use.

At PIT, HPACT care was provided during business hours in a flexible model that allowed for walk-in visits. Providers from the existing addiction-focused PACT identified and referred homeless veterans, as well as patients deemed at-risk for becoming homeless. In addition, other homeless veterans who did not have a PCP could be referred through e-consults placed by any VA staff member. If a referred homeless veteran was already enrolled on a PCP’s panel, HPACT facilitated reengagement with the existing provider. Near the end of this data collection period, a peer support specialist also began community outreach to engage both enrolled and potential HPACT patients.

Patient Characteristics

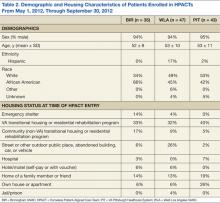

Table 2 presents the demographic and housing characteristics of enrolled HPACT patients at BIR, WLA, and PIT from May 1, 2012, to September 30, 2012. Each site had a similar number of patients (n = 35/47/43 at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively). Across sites, most patients were male and African American or white. The majority of patients at each site were housed in VA transitional housing/residential rehabilitation programs (33%/32%/40% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively). Fewer patients were unsheltered (on the streets or other places not meant for sleeping), though WLA had the most unsheltered patients (26%) compared with BIR (6%) and PIT (2%). BIR had more patients from emergency shelters (14%) than did the other 2 sites (4% at WLA and 0% at PIT). PIT had the most domiciled patients in houses/apartments (26%, compared with 6% each at BIR and WLA), but who were at risk for homelessness.

Table 3 summarizes the diagnoses and VA health care use patterns of these cohorts. In the first week of HPACT care, WLA addressed the most acute medical conditions (81% of patients had≥ 1 common condition), followed by BIR (54%) and PIT (23%). Among chronic conditions, chronic pain was diagnosed in 51% of patients at BIR, 30% of patients at WLA, and 12% of patients at PIT. Hepatitis C diagnoses were most common at WLA (36%), similar at PIT (33%), and lower at BIR (17%). Overall, chronic medical diagnoses were most common among patients at BIR (91%), followed by WLA (85%), and PIT (60%).

Among mental health diagnoses, mood disorders were the most prevalent across sites (49%/55%/42% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively), followed by posttraumatic stress disorder (17%/21%/9% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively). WLA had more patients with psychosis (19%) than did the other 2 sites (7% at PIT and 0% at BIR). Overall, mental illness was common among HPACT patients across sites (60%/72%/72% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively).

Health care use in the 6 months before HPACT enrollment differed between sites. BIR and PIT had similar rates of ED/urgent care use (46% and 47% sought care over the prior 6 months, respectively), but WLA had the highest rate (62%). However, inpatient admission rates were lowest at WLA (13%) and again similar at BIR (23%) and PIT (26%). BIR patients had the most VA primary care exposure before HPACT entry (71% obtained primary care in the past 6 months), followed by WLA (38%) and PIT (18%). Mental health specialty care was also highest at BIR (60%), followed by PIT (56%), then WLA (39%)

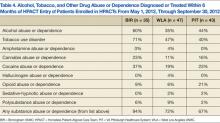

Table 4 presents the prevalence of ATOD abuse or dependence among HPACT patients in the6 months before clinic enrollment. The most commonly misused substances were alcohol (60%/35%/44% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively), tobacco (71%/47%/40% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively), and cocaine (37%/19%/23% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively). PIT had the highest percentages of patients with opioid misuse (21%), followed by BIR (9%) and WLA (6%). Overall, these disorders were prevalent across sites, highest at BIR (94%) and similar at WLA (72%) and PIT (67%).

DISCUSSION

In this case report of early HPACT implementation, strikingly different models of homeless-focused primary care at the geographically distinct facilities were found. The lack of a gold standard primary care medical home for homeless persons—compounded by contrasting local contextual features—led to distinct clinic designs. BIR capitalized on primary care needs among veterans who previously sought housing and relied on the available space within an operating primary care clinic. As WLA already offered primary care for homeless veterans that was colocated with mental health services, the HPACT at this site was devised as an after-hours clinic colocated with the ED.11 At PIT, an existing primary care team with addiction expertise expanded its role to include a focus on homelessness, without needing new space or staff.

The initial HPACT patient cohorts likely reflected these contrasting clinic structures. That is, at WLA, the higher rates of unsheltered patients, prevalence of acute medical conditions and psychotic disorders, and greater ED use was likely driven by ED colocation. The physical location of this site’s HPACT may also speak to greater future decreases in ED use. At BIR, the use of a dedicated HPACT community outreach worker likely led to greater recruitment from emergency shelters. However, the clinic mainly recruited veterans who had previously engaged in VA mainstream primary care services and individuals with ATOD use. At PIT, higher rates of psychotherapy were likely facilitated by the HPACT’s placement within an addiction treatment setting, which may favor psychosocial rehabilitation. The distinctly higher rate of patients with opioid misuse at PIT likely paralleled the ATOD expertise of its providers and/or buprenorphine availability.

The more challenging questions surround the implementation of the current clinic models to address the needs of these patient cohorts and possible avenues to improve each clinic. High rates of chronic medical illness, mental illness, and ATOD use are well known in the homeless veteran and general populations.2,9 Within these 3 HPACTs, the high rates of medical/mental illness and ATOD use speak favorably about the clinics’ respective recruitment strategies; ie, normative homeless populations with high rates of illness are enrolling in these clinics. However, current service integration practices may be enhanced with the specific knowledge gained from this examination. For example, the very high rates of mood and anxiety disorders at each site suggest a role for an embedded mental health provider with prescribing privileges (the model adopted by BIR) as opposed to mental health referrals used at WLA and PIT. There may also be a role for cognitive behavioral therapy services within these clinics. Similarly, the high rates of ATOD (especially alcohol, tobacco, and cocaine) misuse suggest a role for addiction medicine training among the PCPs (the PIT model) as well as psychosocial rehabilitation for ATOD use within the HPACTs. High rates of chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes, hepatitis C, and hypertension elucidate possible roles for specialty care integration and/or chronic disease management programs tailored to the homeless.

Comparing the housing status of these cohorts can help in the design of future homeless-tailored primary care operations and improve these HPACTs. Most patients across sites lived in VA transitional housing/residential rehabilitation programs. As such, current referral practices at these 3 HPACTs proved sufficient in recruiting this subpopulation of homeless veterans. However, in light of national data showing that the count of unsheltered homeless veterans has not declined as rapidly as the count of homeless veterans overall, the higher numbers of veterans recruited from interim sheltering arrangements suggest a need for enhanced outreach to unsheltered individuals.1 WLA data suggest that linkages to EDs can advance this objective. BIR data show that targeted outreach in shelters can engage this high-risk, transiently sheltered subpopulation in primary care. At the time of this project, PIT just began using a peer support specialist for outreach to unsheltered veterans. It will be important to evaluate the outcomes of this new referral strategy.

Limitations

These exploratory findings—though from a small convenience sample within a nascent, growing program—generated critical and detailed information to guide ongoing policies and service design. However, these findings have limitations. First, though this research contributes to limited existing literature about the operational design of homeless-focused primary care, no outcome data were included. Although a comprehensive evaluation of all HPACT sites is a distinct and useful endeavor, this project instead offers a rapid, detailed illustration of 3 early-stage clinics. Though smaller in scope, this effort informs other facilities developing homeless-focused primary care initiatives and the larger demonstration project.

Second, a convenience sample of 3 urban facilities with strong academic ties and community commitment to providing services for homeless persons was presented. It may be difficult to translate these findings to communities with fewer resources.

Third, EHR review was used to determine patient demographics, diagnoses, and patterns of health care use. Though EHR review offers detailed information that is unavailable from administrative data, EHR is subject to variations in documentation patterns.

Last, differing characteristics of the homeless veteran population in each city may interact with contrasting HPACT structures to influence the characteristics of patients served. For example, though the data suggest that linkages with the ED may facilitate greater recruitment of unsheltered veterans in WLA, Los Angeles is known to have particularly high rates of unsheltered individuals.1

CONCLUSIONS

Clinicians, administrators, and researchers in the safety net may benefit from the experience implementing new clinics to recruit and engage homeless veterans in primary care. In a relatively nascent field with few accepted models of care, this paper offers detailed descriptions of newly developed homeless-focused primary care clinics at 3 VA facilities, which can inform other sites undertaking similar initiatives. This study highlights the wide range of approaches to building such clinics, with important variations in structural characteristics such as clinic location and operating hours, as well as within the intricacies of service integration patterns.

Within primary care clinics for homeless adults, this study suggests a role for embedded mental health (medication management and psychotherapy) and substance abuse services, chronic disease management programs tailored to this vulnerable population, and the role of linkages to the ED or community-based outreach to recruit unsheltered homeless patients. To pave a path toward identifying an evidence-based model of homeless-focused primary care, future studies are needed to study nationwide HPACT outcomes, including health status, patient satisfaction, quality of life, housing, and cost-effectiveness.

Acknowledgements

This work was undertaken in part by the VA’s PACT Demonstration Laboratory initiative, supporting and evaluating VA’s transition to a patient-centered medical home. Funding for the PACT Demonstration Laboratory initiative was provided by the VA Office of Patient Care Services. This project received support from the VISN 22 VA Assessment and Improvement Lab for Patient Centered Care (VAIL-PCC) (XVA 65-018; PI: Rubenstein).

Dr. Gabrielian was supported in part by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations, Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment. Drs. Gelberg and Andersen were supported in part by NIDA DA 022445. Dr. Andersen received additional support from the UCLA/DREW Project EXPORT, National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, P20MD000148/P20MD000182. Dr. Broyles was supported by a Career Development Award (CDA 10–014) from the VA Health Services Research & Development service. Dr. Kertesz was supported through funding of VISN 7.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Cortes A, Henry M, de la Cruz RJ, Brown S. The 2012 Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness: Volume I of the 2012 Annual Homeless Assessment Report. Washington, DC: The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development; 2012.

2. Balshem H, Christensen V, Tuepker A, Kansagara D. A Critical Review of the Literature Regarding Homelessness Among Veterans. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research & Development Service; 2011. VA-ESP Project #05-225.

3. O’Toole TP, Pirraglia PA, Dosa D, et al; Primary Care-Special Populations Treatment Team. Building care systems to improve access for high-risk and vulnerable veteran populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(suppl 2):683-688.

4. Opening Doors: Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness. Washington, DC: The United States Interagency Council on Homelessness; 2010.

5. Nakashima J, McGuire J, Berman S, Daniels W. Developing programs for homeless veterans: Understanding driving forces in implementation. Soc Work Health Care. 2004;40(2):1-12.

6. O’Toole TP, Buckel L, Bourgault C, et al. Applying the chronic care model to homeless veterans: Effect of a population approach to primary care on utilization and clinical outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2493-2499.

7. Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Kasprow WJ. Determinants of receipt of ambulatory medical care in a national sample of mentally ill homeless veterans. Med Care. 2003;41(2):275-287.

8. Irene Wong YL, Stanhope V. Conceptualizing community: A comparison of neighborhood characteristics of supportive housing for persons with psychiatric and developmental disabilities. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(8):1376-1387.

9. Gelberg L, Gallagher TC, Andersen RM, Koegel P. Competing priorities as a barrier to medical care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(2):217-220.

10. Hamilton AB, Poza I, Washington DL. “Homelessness and trauma go hand-in-hand”: Pathways to homelessness among women veterans. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21(suppl 4):S203-S209.

11. McGuire J, Gelberg L, Blue-Howells J, Rosenheck RA. Access to primary care for homeless veterans with serious mental illness or substance abuse: A follow-up evaluation of co-located primary care and homeless social services. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36(4):255-264.

12. VHA Operations Activities That May Constitute Research. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration; 2011. VHA Handbook 1058.05.

13. Resnick SG, Armstrong M, Sperrazza M, Harkness L, Rosenheck RA. A model of consumer-provider partnership: Vet-to-Vet. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;28(2):185-187.

14. Hogan TP, Wakefield B, Nazi KM, Houston TK, Weaver FM. Promoting access through complementary eHealth technologies: Recommendations for VA’s Home Telehealth and personal health record programs. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(suppl 2):628-635.

15. Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(7):e263-e272.

16. Hsiao CJ, Cherry DK, Beatty PC, Rechtsteiner EA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2007 summary. Natl Health Stat Report. 2010;3(27):1-32.

17. Hwang SW, Orav EJ, O’Connell JJ, Lebow JM, Brennan TA. Causes of death in homeless adults in Boston. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(8):625-628.

18. Hwang SW, Tolomiczenko G, Kouyoumdjian FG, Garner RE. Interventions to improve the health of the homeless: A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(4):311-319.

On a single night in 2012, 62,619 veterans experienced homelessness.1 With high rates of illness, as well as alcohol, tobacco, and other drug (ATOD) use among homeless adults, ending veteran homelessness is a signature initiative of the VA.2-4 However, despite increasing efforts to improve health care for homeless individuals, little is known about best practices in homeless-focused primary care.2,5

With an age-adjusted mortality that is 2 to 10 times higher than that of their housed counterparts, homeless veterans pose a formidable challenge for primary care providers (PCPs).6,7 The complexity of homeless persons’ primary care needs is compounded by poor social support and the need to navigate priorities (eg, shelter) that compete with medical care.6,8,9 Moreover, veterans may face unique vulnerabilities conferred by military-specific experiences.2,10

As of 2012, only 2 VA facilities had primary care clinics tailored to the needs of homeless veterans. McGuire and colleagues built a system of colocated primary care, mental health, and homeless services for mentally ill veterans in Los Angeles, California.11 Over 18 months, this clinic facilitated greater primary and preventive care delivery, though the population’s physical health status did not improve.11 More recently, O’Toole and colleagues implemented a homeless-focused primary care clinic in Providence, Rhode Island.6 Compared with a historical sample of homeless veterans in traditional VA primary care, veterans in this homeless-tailored clinic had greater improvements in some chronic disease outcomes.6 This clinic also decreased nonacute emergency department (ED) use and hospitalizations for general medical conditions.6

Despite these promising outcomes, the VA lacked a nationwide homeless-focused primary care initiative. In 2012 the VA Office of Homeless Programs and the Office of Primary Care Operations funded a national demonstration project to create Homeless Patient-Aligned Care Teams (HPACTs)—primary care medical clinics for homeless veterans—at 32 facilities. This demonstration project guided HPACTs to tailor clinical and social services to homeless veterans’ needs, establish processes to identify and refer appropriate veterans, and integrate distinct services.

There were no explicit instructions that detailed HPACT structure. Because new VA programs must fit local contextual factors, including infrastructure, space, personnel, and institutional/community resources, different models of homeless-focused primary care have evolved.

This article is a case study of HPACTs at 3 of the 32 participating VA facilities, each reflecting a distinct community and organizational context. In light of projected HPACT expansion and concerns that current services are better tailored to sheltered homeless veterans than to their unsheltered peers, there is particular importance to detailed clinic descriptions that vividly portray the intricate relationships between service design and populations served.1

METHODS

VA HPACTs established in May 2012 at 3 facilities were examined: Birmingham VAMC in Alabama (BIR), West Los Angeles VAMC in California (WLA), and VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System in Pennsylvania (PIT). Prior to this demonstration project, each facility offered a range of housing/social services and traditional primary care for veterans. These sites are a geographically diverse convenience sample that emerged from existing homeless-focused collaborations among the authors and represent geographically diverse HPACTs.

The national director of VA Homeless Programs formally determined that this comparison constitutes a VA operations activity that is not research.12 This activity was exempt from Institutional Review Board review.

Study Design

Timed at an early stage of HPACT implementation, this project had 3 aims: (1) To identify noteworthy similarities and/or differences among the initial HPACT clinic structures; (2) To compare and contrast the patient characteristics of veterans enrolled in each of these clinics; and (3) To use these data to inform ongoing HPACT service design.

HPACT program evaluation data are not presented. Rather, a nascent system of care is illustrated that contributes to the limited literature concerning the design and implementation of homeless-focused primary care. Such organizational profiles inform novel program delivery and hold particular utility for heterogeneous populations who are difficult to engage in care.13,14

Authors at each site independently developed lists of variables that fell within the 3 guiding principles of this demonstration project. These variables were compiled and iteratively reduced to a consolidated table that assessed each clinic, including location, operating hours, methods of patient identification and referral, and linkages to distinct services (eg, primary care, mental health, addiction, and social services).

This table also became a guide for HPACT directors to generate narrative clinic descriptions. Characteristics of VA medical homes that are embraced regardless of patients’ housing status (eg, patient-centered, team-based care) were also incorporated into these descriptions.15

Patient Characteristics

The VA electronic health record (EHR) was used to identify all patients enrolled in HPACTs at BIR, WLA, and PIT from May 1, 2012 (clinic inception), through September 30, 2012. Authors developed a standardized template for EHR review and coined the first HPACT record as the patient’s index visit. This record was used to code initial housing status, demographics, and acute medical conditions diagnosed/treated. If housing status was not recorded at the index visit, the first preceding informative record was used.

Records for 6 months preceding the index visit were used to identify the presence or absence of common medical conditions, psychiatric diagnoses, and ATOD abuse or dependence. Medical conditions were identified from a list of common outpatient diagnoses from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, supplemented by common conditions among homeless men.16-18 The EHR problem list (a list of diagnoses, by patient) was used to obtain diagnoses, supplemented by notes from inpatient admissions/discharges, as well as ED, primary care, and subspecialty consultations within 6 months preceding the index visit. Prior VA health care use was ascertained from the EHR review of the same 6-month window, reflecting ED visits, inpatient admissions, primary care visits, subspecialty visits, and individual/group therapy for ATOD or other mental health problems. Data were used to generate site-specific descriptive statistics.

RESULTS

Like all VA hospital-based clinics, a universal EHR captured all medical and social service notes, orders, medications, and administrative records. All facilities had on-site EDs, medical/mental health specialty care, and pharmacies. Social services, including benefits counseling and housing services, were available on site. Table 1 summarizes the HPACT structures at BIR, WLA, and PIT.

Birmingham

The BIR HPACT was devised as a new homeless-focused team located within a VA primary care clinic where other providers continued to see primary care patients. Staff and space were reallocated for this HPACT, which recruited patients in 4 ways: (1) the facility’s primary homeless program, Healthcare for Homeless Veterans, referred patients who previously sought VA housing but who required primary care; (2) an outreach specialist sought homeless veterans in shelters and on the streets; (3) HPACT staff marketed the clinic with presentations and flyers to other VA services and non-VA community agencies; and (4) a referral mechanism within the EHR.

A nurse practitioner was the PCP at this site, supervised by an academic internist experienced in the care of underserved populations, and the HPACT director, a physician certified in internal and addiction medicine. Patients at the BIR HPACT also received care from a social worker, registered nurse, licensed practical nurse, and psychiatrist who received all or a portion of their salaries from this demonstration project. This clinic accommodated walk-in appointments during business hours. Clinicians discussed clinical cases daily, and the full clinical and administrative team met weekly. To promote service integration, HPACT staff attended meetings of the BIR general primary care and Healthcare for Homeless Veterans programs, and vice versa.

West Los Angeles

At WLA, a previously established Homeless Screening Clinic that offered integrated social and medical services for homeless veterans with mental illness was already available during business hours and located within the site’s mental health program.11 However, because ED use for homeless veterans peaked after hours, the new WLA HPACT was established within the WLA ED.

During WLA HPACT hours (3 weekday evenings/week), routine nursing triage occurred for all patients who presented to the ED. However, distinct from other times of day, veterans who were triaged with low-acuity and who were appropriate for outpatient care were given a self-administered, 4-item questionnaire to identify patients who were homeless or at risk for becoming homeless. Veterans who were identified with this screening tool were offered the choice of an ED or HPACT visit. Veterans who chose the latter were assigned to the queue for an HPACT primary care visit instead of the ED.

A physician led the clinical team, with additional services from a mental health clinical nurse specialist and clerks who worked with homeless and/or mental health patients during business hours and provided part-time HPACT coverage. When needed, additional services were provided from colocated ED nurses and social workers. Providers were chosen for their aptitude in culturally responsive communication.

Patients who chose to be seen in HPACT received a primary care visit that also addressed the reason for ED presentation. HPACT staff worked collaboratively, with interdisciplinary team huddles that preceded each clinic session and ended each patient visit. Referrals and social service needs were tracked and monitored by the PCP. Specialty care referrals were also tracked and facilitated when possible with direct communication between HPACT providers and specialty services. Meetings with daytime Homeless Screening Clinic and ED staff facilitated cross-departmental collaborations that helped veterans prepare for and retain housing.

Pittsburgh

The HPACT at PIT evolved from an existing PACT that provided primary care-based addiction services.2 That team included an internist credentialed in addiction medicine and experienced in homeless health care, nurse practitioner, nurse care manager, nursing assistant, and clerks. At this site, HPACT providers had subspecialty expertise in the assessment and treatment of ATOD use, certification to prescribe buprenorphine for outpatient opioid detoxification and/or maintenance, and experience engaging homeless and other vulnerable veterans. The existing colocated clinic included 2 additional addiction medicine clinicians and a physician assistant experienced in ATOD use. The PIT HPACT was not restricted to patients with ATOD use.

At PIT, HPACT care was provided during business hours in a flexible model that allowed for walk-in visits. Providers from the existing addiction-focused PACT identified and referred homeless veterans, as well as patients deemed at-risk for becoming homeless. In addition, other homeless veterans who did not have a PCP could be referred through e-consults placed by any VA staff member. If a referred homeless veteran was already enrolled on a PCP’s panel, HPACT facilitated reengagement with the existing provider. Near the end of this data collection period, a peer support specialist also began community outreach to engage both enrolled and potential HPACT patients.

Patient Characteristics

Table 2 presents the demographic and housing characteristics of enrolled HPACT patients at BIR, WLA, and PIT from May 1, 2012, to September 30, 2012. Each site had a similar number of patients (n = 35/47/43 at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively). Across sites, most patients were male and African American or white. The majority of patients at each site were housed in VA transitional housing/residential rehabilitation programs (33%/32%/40% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively). Fewer patients were unsheltered (on the streets or other places not meant for sleeping), though WLA had the most unsheltered patients (26%) compared with BIR (6%) and PIT (2%). BIR had more patients from emergency shelters (14%) than did the other 2 sites (4% at WLA and 0% at PIT). PIT had the most domiciled patients in houses/apartments (26%, compared with 6% each at BIR and WLA), but who were at risk for homelessness.

Table 3 summarizes the diagnoses and VA health care use patterns of these cohorts. In the first week of HPACT care, WLA addressed the most acute medical conditions (81% of patients had≥ 1 common condition), followed by BIR (54%) and PIT (23%). Among chronic conditions, chronic pain was diagnosed in 51% of patients at BIR, 30% of patients at WLA, and 12% of patients at PIT. Hepatitis C diagnoses were most common at WLA (36%), similar at PIT (33%), and lower at BIR (17%). Overall, chronic medical diagnoses were most common among patients at BIR (91%), followed by WLA (85%), and PIT (60%).

Among mental health diagnoses, mood disorders were the most prevalent across sites (49%/55%/42% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively), followed by posttraumatic stress disorder (17%/21%/9% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively). WLA had more patients with psychosis (19%) than did the other 2 sites (7% at PIT and 0% at BIR). Overall, mental illness was common among HPACT patients across sites (60%/72%/72% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively).

Health care use in the 6 months before HPACT enrollment differed between sites. BIR and PIT had similar rates of ED/urgent care use (46% and 47% sought care over the prior 6 months, respectively), but WLA had the highest rate (62%). However, inpatient admission rates were lowest at WLA (13%) and again similar at BIR (23%) and PIT (26%). BIR patients had the most VA primary care exposure before HPACT entry (71% obtained primary care in the past 6 months), followed by WLA (38%) and PIT (18%). Mental health specialty care was also highest at BIR (60%), followed by PIT (56%), then WLA (39%)

Table 4 presents the prevalence of ATOD abuse or dependence among HPACT patients in the6 months before clinic enrollment. The most commonly misused substances were alcohol (60%/35%/44% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively), tobacco (71%/47%/40% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively), and cocaine (37%/19%/23% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively). PIT had the highest percentages of patients with opioid misuse (21%), followed by BIR (9%) and WLA (6%). Overall, these disorders were prevalent across sites, highest at BIR (94%) and similar at WLA (72%) and PIT (67%).

DISCUSSION

In this case report of early HPACT implementation, strikingly different models of homeless-focused primary care at the geographically distinct facilities were found. The lack of a gold standard primary care medical home for homeless persons—compounded by contrasting local contextual features—led to distinct clinic designs. BIR capitalized on primary care needs among veterans who previously sought housing and relied on the available space within an operating primary care clinic. As WLA already offered primary care for homeless veterans that was colocated with mental health services, the HPACT at this site was devised as an after-hours clinic colocated with the ED.11 At PIT, an existing primary care team with addiction expertise expanded its role to include a focus on homelessness, without needing new space or staff.

The initial HPACT patient cohorts likely reflected these contrasting clinic structures. That is, at WLA, the higher rates of unsheltered patients, prevalence of acute medical conditions and psychotic disorders, and greater ED use was likely driven by ED colocation. The physical location of this site’s HPACT may also speak to greater future decreases in ED use. At BIR, the use of a dedicated HPACT community outreach worker likely led to greater recruitment from emergency shelters. However, the clinic mainly recruited veterans who had previously engaged in VA mainstream primary care services and individuals with ATOD use. At PIT, higher rates of psychotherapy were likely facilitated by the HPACT’s placement within an addiction treatment setting, which may favor psychosocial rehabilitation. The distinctly higher rate of patients with opioid misuse at PIT likely paralleled the ATOD expertise of its providers and/or buprenorphine availability.

The more challenging questions surround the implementation of the current clinic models to address the needs of these patient cohorts and possible avenues to improve each clinic. High rates of chronic medical illness, mental illness, and ATOD use are well known in the homeless veteran and general populations.2,9 Within these 3 HPACTs, the high rates of medical/mental illness and ATOD use speak favorably about the clinics’ respective recruitment strategies; ie, normative homeless populations with high rates of illness are enrolling in these clinics. However, current service integration practices may be enhanced with the specific knowledge gained from this examination. For example, the very high rates of mood and anxiety disorders at each site suggest a role for an embedded mental health provider with prescribing privileges (the model adopted by BIR) as opposed to mental health referrals used at WLA and PIT. There may also be a role for cognitive behavioral therapy services within these clinics. Similarly, the high rates of ATOD (especially alcohol, tobacco, and cocaine) misuse suggest a role for addiction medicine training among the PCPs (the PIT model) as well as psychosocial rehabilitation for ATOD use within the HPACTs. High rates of chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes, hepatitis C, and hypertension elucidate possible roles for specialty care integration and/or chronic disease management programs tailored to the homeless.

Comparing the housing status of these cohorts can help in the design of future homeless-tailored primary care operations and improve these HPACTs. Most patients across sites lived in VA transitional housing/residential rehabilitation programs. As such, current referral practices at these 3 HPACTs proved sufficient in recruiting this subpopulation of homeless veterans. However, in light of national data showing that the count of unsheltered homeless veterans has not declined as rapidly as the count of homeless veterans overall, the higher numbers of veterans recruited from interim sheltering arrangements suggest a need for enhanced outreach to unsheltered individuals.1 WLA data suggest that linkages to EDs can advance this objective. BIR data show that targeted outreach in shelters can engage this high-risk, transiently sheltered subpopulation in primary care. At the time of this project, PIT just began using a peer support specialist for outreach to unsheltered veterans. It will be important to evaluate the outcomes of this new referral strategy.

Limitations

These exploratory findings—though from a small convenience sample within a nascent, growing program—generated critical and detailed information to guide ongoing policies and service design. However, these findings have limitations. First, though this research contributes to limited existing literature about the operational design of homeless-focused primary care, no outcome data were included. Although a comprehensive evaluation of all HPACT sites is a distinct and useful endeavor, this project instead offers a rapid, detailed illustration of 3 early-stage clinics. Though smaller in scope, this effort informs other facilities developing homeless-focused primary care initiatives and the larger demonstration project.

Second, a convenience sample of 3 urban facilities with strong academic ties and community commitment to providing services for homeless persons was presented. It may be difficult to translate these findings to communities with fewer resources.

Third, EHR review was used to determine patient demographics, diagnoses, and patterns of health care use. Though EHR review offers detailed information that is unavailable from administrative data, EHR is subject to variations in documentation patterns.

Last, differing characteristics of the homeless veteran population in each city may interact with contrasting HPACT structures to influence the characteristics of patients served. For example, though the data suggest that linkages with the ED may facilitate greater recruitment of unsheltered veterans in WLA, Los Angeles is known to have particularly high rates of unsheltered individuals.1

CONCLUSIONS

Clinicians, administrators, and researchers in the safety net may benefit from the experience implementing new clinics to recruit and engage homeless veterans in primary care. In a relatively nascent field with few accepted models of care, this paper offers detailed descriptions of newly developed homeless-focused primary care clinics at 3 VA facilities, which can inform other sites undertaking similar initiatives. This study highlights the wide range of approaches to building such clinics, with important variations in structural characteristics such as clinic location and operating hours, as well as within the intricacies of service integration patterns.

Within primary care clinics for homeless adults, this study suggests a role for embedded mental health (medication management and psychotherapy) and substance abuse services, chronic disease management programs tailored to this vulnerable population, and the role of linkages to the ED or community-based outreach to recruit unsheltered homeless patients. To pave a path toward identifying an evidence-based model of homeless-focused primary care, future studies are needed to study nationwide HPACT outcomes, including health status, patient satisfaction, quality of life, housing, and cost-effectiveness.

Acknowledgements

This work was undertaken in part by the VA’s PACT Demonstration Laboratory initiative, supporting and evaluating VA’s transition to a patient-centered medical home. Funding for the PACT Demonstration Laboratory initiative was provided by the VA Office of Patient Care Services. This project received support from the VISN 22 VA Assessment and Improvement Lab for Patient Centered Care (VAIL-PCC) (XVA 65-018; PI: Rubenstein).

Dr. Gabrielian was supported in part by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations, Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment. Drs. Gelberg and Andersen were supported in part by NIDA DA 022445. Dr. Andersen received additional support from the UCLA/DREW Project EXPORT, National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, P20MD000148/P20MD000182. Dr. Broyles was supported by a Career Development Award (CDA 10–014) from the VA Health Services Research & Development service. Dr. Kertesz was supported through funding of VISN 7.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

On a single night in 2012, 62,619 veterans experienced homelessness.1 With high rates of illness, as well as alcohol, tobacco, and other drug (ATOD) use among homeless adults, ending veteran homelessness is a signature initiative of the VA.2-4 However, despite increasing efforts to improve health care for homeless individuals, little is known about best practices in homeless-focused primary care.2,5

With an age-adjusted mortality that is 2 to 10 times higher than that of their housed counterparts, homeless veterans pose a formidable challenge for primary care providers (PCPs).6,7 The complexity of homeless persons’ primary care needs is compounded by poor social support and the need to navigate priorities (eg, shelter) that compete with medical care.6,8,9 Moreover, veterans may face unique vulnerabilities conferred by military-specific experiences.2,10

As of 2012, only 2 VA facilities had primary care clinics tailored to the needs of homeless veterans. McGuire and colleagues built a system of colocated primary care, mental health, and homeless services for mentally ill veterans in Los Angeles, California.11 Over 18 months, this clinic facilitated greater primary and preventive care delivery, though the population’s physical health status did not improve.11 More recently, O’Toole and colleagues implemented a homeless-focused primary care clinic in Providence, Rhode Island.6 Compared with a historical sample of homeless veterans in traditional VA primary care, veterans in this homeless-tailored clinic had greater improvements in some chronic disease outcomes.6 This clinic also decreased nonacute emergency department (ED) use and hospitalizations for general medical conditions.6

Despite these promising outcomes, the VA lacked a nationwide homeless-focused primary care initiative. In 2012 the VA Office of Homeless Programs and the Office of Primary Care Operations funded a national demonstration project to create Homeless Patient-Aligned Care Teams (HPACTs)—primary care medical clinics for homeless veterans—at 32 facilities. This demonstration project guided HPACTs to tailor clinical and social services to homeless veterans’ needs, establish processes to identify and refer appropriate veterans, and integrate distinct services.

There were no explicit instructions that detailed HPACT structure. Because new VA programs must fit local contextual factors, including infrastructure, space, personnel, and institutional/community resources, different models of homeless-focused primary care have evolved.

This article is a case study of HPACTs at 3 of the 32 participating VA facilities, each reflecting a distinct community and organizational context. In light of projected HPACT expansion and concerns that current services are better tailored to sheltered homeless veterans than to their unsheltered peers, there is particular importance to detailed clinic descriptions that vividly portray the intricate relationships between service design and populations served.1

METHODS

VA HPACTs established in May 2012 at 3 facilities were examined: Birmingham VAMC in Alabama (BIR), West Los Angeles VAMC in California (WLA), and VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System in Pennsylvania (PIT). Prior to this demonstration project, each facility offered a range of housing/social services and traditional primary care for veterans. These sites are a geographically diverse convenience sample that emerged from existing homeless-focused collaborations among the authors and represent geographically diverse HPACTs.

The national director of VA Homeless Programs formally determined that this comparison constitutes a VA operations activity that is not research.12 This activity was exempt from Institutional Review Board review.

Study Design

Timed at an early stage of HPACT implementation, this project had 3 aims: (1) To identify noteworthy similarities and/or differences among the initial HPACT clinic structures; (2) To compare and contrast the patient characteristics of veterans enrolled in each of these clinics; and (3) To use these data to inform ongoing HPACT service design.

HPACT program evaluation data are not presented. Rather, a nascent system of care is illustrated that contributes to the limited literature concerning the design and implementation of homeless-focused primary care. Such organizational profiles inform novel program delivery and hold particular utility for heterogeneous populations who are difficult to engage in care.13,14

Authors at each site independently developed lists of variables that fell within the 3 guiding principles of this demonstration project. These variables were compiled and iteratively reduced to a consolidated table that assessed each clinic, including location, operating hours, methods of patient identification and referral, and linkages to distinct services (eg, primary care, mental health, addiction, and social services).

This table also became a guide for HPACT directors to generate narrative clinic descriptions. Characteristics of VA medical homes that are embraced regardless of patients’ housing status (eg, patient-centered, team-based care) were also incorporated into these descriptions.15

Patient Characteristics

The VA electronic health record (EHR) was used to identify all patients enrolled in HPACTs at BIR, WLA, and PIT from May 1, 2012 (clinic inception), through September 30, 2012. Authors developed a standardized template for EHR review and coined the first HPACT record as the patient’s index visit. This record was used to code initial housing status, demographics, and acute medical conditions diagnosed/treated. If housing status was not recorded at the index visit, the first preceding informative record was used.

Records for 6 months preceding the index visit were used to identify the presence or absence of common medical conditions, psychiatric diagnoses, and ATOD abuse or dependence. Medical conditions were identified from a list of common outpatient diagnoses from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, supplemented by common conditions among homeless men.16-18 The EHR problem list (a list of diagnoses, by patient) was used to obtain diagnoses, supplemented by notes from inpatient admissions/discharges, as well as ED, primary care, and subspecialty consultations within 6 months preceding the index visit. Prior VA health care use was ascertained from the EHR review of the same 6-month window, reflecting ED visits, inpatient admissions, primary care visits, subspecialty visits, and individual/group therapy for ATOD or other mental health problems. Data were used to generate site-specific descriptive statistics.

RESULTS

Like all VA hospital-based clinics, a universal EHR captured all medical and social service notes, orders, medications, and administrative records. All facilities had on-site EDs, medical/mental health specialty care, and pharmacies. Social services, including benefits counseling and housing services, were available on site. Table 1 summarizes the HPACT structures at BIR, WLA, and PIT.

Birmingham

The BIR HPACT was devised as a new homeless-focused team located within a VA primary care clinic where other providers continued to see primary care patients. Staff and space were reallocated for this HPACT, which recruited patients in 4 ways: (1) the facility’s primary homeless program, Healthcare for Homeless Veterans, referred patients who previously sought VA housing but who required primary care; (2) an outreach specialist sought homeless veterans in shelters and on the streets; (3) HPACT staff marketed the clinic with presentations and flyers to other VA services and non-VA community agencies; and (4) a referral mechanism within the EHR.

A nurse practitioner was the PCP at this site, supervised by an academic internist experienced in the care of underserved populations, and the HPACT director, a physician certified in internal and addiction medicine. Patients at the BIR HPACT also received care from a social worker, registered nurse, licensed practical nurse, and psychiatrist who received all or a portion of their salaries from this demonstration project. This clinic accommodated walk-in appointments during business hours. Clinicians discussed clinical cases daily, and the full clinical and administrative team met weekly. To promote service integration, HPACT staff attended meetings of the BIR general primary care and Healthcare for Homeless Veterans programs, and vice versa.

West Los Angeles

At WLA, a previously established Homeless Screening Clinic that offered integrated social and medical services for homeless veterans with mental illness was already available during business hours and located within the site’s mental health program.11 However, because ED use for homeless veterans peaked after hours, the new WLA HPACT was established within the WLA ED.

During WLA HPACT hours (3 weekday evenings/week), routine nursing triage occurred for all patients who presented to the ED. However, distinct from other times of day, veterans who were triaged with low-acuity and who were appropriate for outpatient care were given a self-administered, 4-item questionnaire to identify patients who were homeless or at risk for becoming homeless. Veterans who were identified with this screening tool were offered the choice of an ED or HPACT visit. Veterans who chose the latter were assigned to the queue for an HPACT primary care visit instead of the ED.

A physician led the clinical team, with additional services from a mental health clinical nurse specialist and clerks who worked with homeless and/or mental health patients during business hours and provided part-time HPACT coverage. When needed, additional services were provided from colocated ED nurses and social workers. Providers were chosen for their aptitude in culturally responsive communication.

Patients who chose to be seen in HPACT received a primary care visit that also addressed the reason for ED presentation. HPACT staff worked collaboratively, with interdisciplinary team huddles that preceded each clinic session and ended each patient visit. Referrals and social service needs were tracked and monitored by the PCP. Specialty care referrals were also tracked and facilitated when possible with direct communication between HPACT providers and specialty services. Meetings with daytime Homeless Screening Clinic and ED staff facilitated cross-departmental collaborations that helped veterans prepare for and retain housing.

Pittsburgh

The HPACT at PIT evolved from an existing PACT that provided primary care-based addiction services.2 That team included an internist credentialed in addiction medicine and experienced in homeless health care, nurse practitioner, nurse care manager, nursing assistant, and clerks. At this site, HPACT providers had subspecialty expertise in the assessment and treatment of ATOD use, certification to prescribe buprenorphine for outpatient opioid detoxification and/or maintenance, and experience engaging homeless and other vulnerable veterans. The existing colocated clinic included 2 additional addiction medicine clinicians and a physician assistant experienced in ATOD use. The PIT HPACT was not restricted to patients with ATOD use.

At PIT, HPACT care was provided during business hours in a flexible model that allowed for walk-in visits. Providers from the existing addiction-focused PACT identified and referred homeless veterans, as well as patients deemed at-risk for becoming homeless. In addition, other homeless veterans who did not have a PCP could be referred through e-consults placed by any VA staff member. If a referred homeless veteran was already enrolled on a PCP’s panel, HPACT facilitated reengagement with the existing provider. Near the end of this data collection period, a peer support specialist also began community outreach to engage both enrolled and potential HPACT patients.

Patient Characteristics

Table 2 presents the demographic and housing characteristics of enrolled HPACT patients at BIR, WLA, and PIT from May 1, 2012, to September 30, 2012. Each site had a similar number of patients (n = 35/47/43 at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively). Across sites, most patients were male and African American or white. The majority of patients at each site were housed in VA transitional housing/residential rehabilitation programs (33%/32%/40% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively). Fewer patients were unsheltered (on the streets or other places not meant for sleeping), though WLA had the most unsheltered patients (26%) compared with BIR (6%) and PIT (2%). BIR had more patients from emergency shelters (14%) than did the other 2 sites (4% at WLA and 0% at PIT). PIT had the most domiciled patients in houses/apartments (26%, compared with 6% each at BIR and WLA), but who were at risk for homelessness.

Table 3 summarizes the diagnoses and VA health care use patterns of these cohorts. In the first week of HPACT care, WLA addressed the most acute medical conditions (81% of patients had≥ 1 common condition), followed by BIR (54%) and PIT (23%). Among chronic conditions, chronic pain was diagnosed in 51% of patients at BIR, 30% of patients at WLA, and 12% of patients at PIT. Hepatitis C diagnoses were most common at WLA (36%), similar at PIT (33%), and lower at BIR (17%). Overall, chronic medical diagnoses were most common among patients at BIR (91%), followed by WLA (85%), and PIT (60%).

Among mental health diagnoses, mood disorders were the most prevalent across sites (49%/55%/42% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively), followed by posttraumatic stress disorder (17%/21%/9% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively). WLA had more patients with psychosis (19%) than did the other 2 sites (7% at PIT and 0% at BIR). Overall, mental illness was common among HPACT patients across sites (60%/72%/72% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively).

Health care use in the 6 months before HPACT enrollment differed between sites. BIR and PIT had similar rates of ED/urgent care use (46% and 47% sought care over the prior 6 months, respectively), but WLA had the highest rate (62%). However, inpatient admission rates were lowest at WLA (13%) and again similar at BIR (23%) and PIT (26%). BIR patients had the most VA primary care exposure before HPACT entry (71% obtained primary care in the past 6 months), followed by WLA (38%) and PIT (18%). Mental health specialty care was also highest at BIR (60%), followed by PIT (56%), then WLA (39%)

Table 4 presents the prevalence of ATOD abuse or dependence among HPACT patients in the6 months before clinic enrollment. The most commonly misused substances were alcohol (60%/35%/44% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively), tobacco (71%/47%/40% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively), and cocaine (37%/19%/23% at BIR/WLA/PIT, respectively). PIT had the highest percentages of patients with opioid misuse (21%), followed by BIR (9%) and WLA (6%). Overall, these disorders were prevalent across sites, highest at BIR (94%) and similar at WLA (72%) and PIT (67%).

DISCUSSION

In this case report of early HPACT implementation, strikingly different models of homeless-focused primary care at the geographically distinct facilities were found. The lack of a gold standard primary care medical home for homeless persons—compounded by contrasting local contextual features—led to distinct clinic designs. BIR capitalized on primary care needs among veterans who previously sought housing and relied on the available space within an operating primary care clinic. As WLA already offered primary care for homeless veterans that was colocated with mental health services, the HPACT at this site was devised as an after-hours clinic colocated with the ED.11 At PIT, an existing primary care team with addiction expertise expanded its role to include a focus on homelessness, without needing new space or staff.

The initial HPACT patient cohorts likely reflected these contrasting clinic structures. That is, at WLA, the higher rates of unsheltered patients, prevalence of acute medical conditions and psychotic disorders, and greater ED use was likely driven by ED colocation. The physical location of this site’s HPACT may also speak to greater future decreases in ED use. At BIR, the use of a dedicated HPACT community outreach worker likely led to greater recruitment from emergency shelters. However, the clinic mainly recruited veterans who had previously engaged in VA mainstream primary care services and individuals with ATOD use. At PIT, higher rates of psychotherapy were likely facilitated by the HPACT’s placement within an addiction treatment setting, which may favor psychosocial rehabilitation. The distinctly higher rate of patients with opioid misuse at PIT likely paralleled the ATOD expertise of its providers and/or buprenorphine availability.

The more challenging questions surround the implementation of the current clinic models to address the needs of these patient cohorts and possible avenues to improve each clinic. High rates of chronic medical illness, mental illness, and ATOD use are well known in the homeless veteran and general populations.2,9 Within these 3 HPACTs, the high rates of medical/mental illness and ATOD use speak favorably about the clinics’ respective recruitment strategies; ie, normative homeless populations with high rates of illness are enrolling in these clinics. However, current service integration practices may be enhanced with the specific knowledge gained from this examination. For example, the very high rates of mood and anxiety disorders at each site suggest a role for an embedded mental health provider with prescribing privileges (the model adopted by BIR) as opposed to mental health referrals used at WLA and PIT. There may also be a role for cognitive behavioral therapy services within these clinics. Similarly, the high rates of ATOD (especially alcohol, tobacco, and cocaine) misuse suggest a role for addiction medicine training among the PCPs (the PIT model) as well as psychosocial rehabilitation for ATOD use within the HPACTs. High rates of chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes, hepatitis C, and hypertension elucidate possible roles for specialty care integration and/or chronic disease management programs tailored to the homeless.

Comparing the housing status of these cohorts can help in the design of future homeless-tailored primary care operations and improve these HPACTs. Most patients across sites lived in VA transitional housing/residential rehabilitation programs. As such, current referral practices at these 3 HPACTs proved sufficient in recruiting this subpopulation of homeless veterans. However, in light of national data showing that the count of unsheltered homeless veterans has not declined as rapidly as the count of homeless veterans overall, the higher numbers of veterans recruited from interim sheltering arrangements suggest a need for enhanced outreach to unsheltered individuals.1 WLA data suggest that linkages to EDs can advance this objective. BIR data show that targeted outreach in shelters can engage this high-risk, transiently sheltered subpopulation in primary care. At the time of this project, PIT just began using a peer support specialist for outreach to unsheltered veterans. It will be important to evaluate the outcomes of this new referral strategy.

Limitations

These exploratory findings—though from a small convenience sample within a nascent, growing program—generated critical and detailed information to guide ongoing policies and service design. However, these findings have limitations. First, though this research contributes to limited existing literature about the operational design of homeless-focused primary care, no outcome data were included. Although a comprehensive evaluation of all HPACT sites is a distinct and useful endeavor, this project instead offers a rapid, detailed illustration of 3 early-stage clinics. Though smaller in scope, this effort informs other facilities developing homeless-focused primary care initiatives and the larger demonstration project.

Second, a convenience sample of 3 urban facilities with strong academic ties and community commitment to providing services for homeless persons was presented. It may be difficult to translate these findings to communities with fewer resources.

Third, EHR review was used to determine patient demographics, diagnoses, and patterns of health care use. Though EHR review offers detailed information that is unavailable from administrative data, EHR is subject to variations in documentation patterns.

Last, differing characteristics of the homeless veteran population in each city may interact with contrasting HPACT structures to influence the characteristics of patients served. For example, though the data suggest that linkages with the ED may facilitate greater recruitment of unsheltered veterans in WLA, Los Angeles is known to have particularly high rates of unsheltered individuals.1

CONCLUSIONS

Clinicians, administrators, and researchers in the safety net may benefit from the experience implementing new clinics to recruit and engage homeless veterans in primary care. In a relatively nascent field with few accepted models of care, this paper offers detailed descriptions of newly developed homeless-focused primary care clinics at 3 VA facilities, which can inform other sites undertaking similar initiatives. This study highlights the wide range of approaches to building such clinics, with important variations in structural characteristics such as clinic location and operating hours, as well as within the intricacies of service integration patterns.

Within primary care clinics for homeless adults, this study suggests a role for embedded mental health (medication management and psychotherapy) and substance abuse services, chronic disease management programs tailored to this vulnerable population, and the role of linkages to the ED or community-based outreach to recruit unsheltered homeless patients. To pave a path toward identifying an evidence-based model of homeless-focused primary care, future studies are needed to study nationwide HPACT outcomes, including health status, patient satisfaction, quality of life, housing, and cost-effectiveness.

Acknowledgements

This work was undertaken in part by the VA’s PACT Demonstration Laboratory initiative, supporting and evaluating VA’s transition to a patient-centered medical home. Funding for the PACT Demonstration Laboratory initiative was provided by the VA Office of Patient Care Services. This project received support from the VISN 22 VA Assessment and Improvement Lab for Patient Centered Care (VAIL-PCC) (XVA 65-018; PI: Rubenstein).

Dr. Gabrielian was supported in part by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations, Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment. Drs. Gelberg and Andersen were supported in part by NIDA DA 022445. Dr. Andersen received additional support from the UCLA/DREW Project EXPORT, National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities, P20MD000148/P20MD000182. Dr. Broyles was supported by a Career Development Award (CDA 10–014) from the VA Health Services Research & Development service. Dr. Kertesz was supported through funding of VISN 7.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Cortes A, Henry M, de la Cruz RJ, Brown S. The 2012 Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness: Volume I of the 2012 Annual Homeless Assessment Report. Washington, DC: The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development; 2012.

2. Balshem H, Christensen V, Tuepker A, Kansagara D. A Critical Review of the Literature Regarding Homelessness Among Veterans. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research & Development Service; 2011. VA-ESP Project #05-225.

3. O’Toole TP, Pirraglia PA, Dosa D, et al; Primary Care-Special Populations Treatment Team. Building care systems to improve access for high-risk and vulnerable veteran populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(suppl 2):683-688.

4. Opening Doors: Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness. Washington, DC: The United States Interagency Council on Homelessness; 2010.

5. Nakashima J, McGuire J, Berman S, Daniels W. Developing programs for homeless veterans: Understanding driving forces in implementation. Soc Work Health Care. 2004;40(2):1-12.

6. O’Toole TP, Buckel L, Bourgault C, et al. Applying the chronic care model to homeless veterans: Effect of a population approach to primary care on utilization and clinical outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2493-2499.

7. Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Kasprow WJ. Determinants of receipt of ambulatory medical care in a national sample of mentally ill homeless veterans. Med Care. 2003;41(2):275-287.

8. Irene Wong YL, Stanhope V. Conceptualizing community: A comparison of neighborhood characteristics of supportive housing for persons with psychiatric and developmental disabilities. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(8):1376-1387.

9. Gelberg L, Gallagher TC, Andersen RM, Koegel P. Competing priorities as a barrier to medical care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(2):217-220.

10. Hamilton AB, Poza I, Washington DL. “Homelessness and trauma go hand-in-hand”: Pathways to homelessness among women veterans. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21(suppl 4):S203-S209.

11. McGuire J, Gelberg L, Blue-Howells J, Rosenheck RA. Access to primary care for homeless veterans with serious mental illness or substance abuse: A follow-up evaluation of co-located primary care and homeless social services. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36(4):255-264.

12. VHA Operations Activities That May Constitute Research. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration; 2011. VHA Handbook 1058.05.

13. Resnick SG, Armstrong M, Sperrazza M, Harkness L, Rosenheck RA. A model of consumer-provider partnership: Vet-to-Vet. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;28(2):185-187.

14. Hogan TP, Wakefield B, Nazi KM, Houston TK, Weaver FM. Promoting access through complementary eHealth technologies: Recommendations for VA’s Home Telehealth and personal health record programs. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(suppl 2):628-635.

15. Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, et al. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(7):e263-e272.

16. Hsiao CJ, Cherry DK, Beatty PC, Rechtsteiner EA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2007 summary. Natl Health Stat Report. 2010;3(27):1-32.

17. Hwang SW, Orav EJ, O’Connell JJ, Lebow JM, Brennan TA. Causes of death in homeless adults in Boston. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(8):625-628.

18. Hwang SW, Tolomiczenko G, Kouyoumdjian FG, Garner RE. Interventions to improve the health of the homeless: A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(4):311-319.

1. Cortes A, Henry M, de la Cruz RJ, Brown S. The 2012 Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness: Volume I of the 2012 Annual Homeless Assessment Report. Washington, DC: The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development; 2012.