User login

ICD-10 Codes: More Specificity With More Characters

As I have mentioned in prior columns, the key to success with International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) coding will be additional specificity, which will come in the form of more characters to communicate with payors and statisticians regarding the services that have been provided during the office visit. The addition of characters will permit more information about the visit to be delivered in the code.

Some of these additional characters will be required to submit the code for processing. Specifically look out for codes that communicate accidents or injury. Some common circumstances for dermatologists will be lacerations, abrasions, laceration repairs, and burns. The structure of the ICD-10-CM codes is outlined below to explain circumstances in which the increased number of characters will be most important for dermatologists.

The ICD-10-CM codes will be 3 to 7 characters long.1 The first 3 characters are the general categories. For example, L70 is the 3-character category for acne and L40 is the category for psoriasis. The next 3 characters (ie, characters 4–6) correspond to the related etiology (ie, the cause, set of causes, manner of causation of a disease or condition), anatomic site, severity, and other vital clinical details.1

Take the case of a burn on the hand. With the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, a first-degree burn on the back of the hand is coded with 5 characters (944.16).2 According to the ICD-10-CM coding system, the code for an initial visit for a first-degree burn on the back of the hand would include 7 characters (T23.169A).1 There will be times when the sixth character may not be necessary; in these instances, an X must be placed in this position as a placeholder, but the absence of a sixth character does not negate the need for a seventh. Thankfully, the seventh character can only be 1 of 3 letters. As illustrated above in the code for a first-degree burn on the back of the hand, the A designates an initial encounter; a D would designate a follow-up visit for this burn, and an S would represent a sequela from the initial burn, such as a postinflammatory change, which would have its own code.1

Conclusion

To be reimbursed, appropriate ICD-10-CM codes must be used. Be sure to master the structure of these codes before the October 1, 2015, compliance deadline; plan now for a training and testing period.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. ICD-10-CM Tabular List of Diseases and Injuries. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/ICD10/downloads/6_I10tab2010.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed September 18, 2014.

2. ICD-9 code lookup. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/staticpages/icd-9-code-lookup.aspx. Accessed September 18, 2014.

As I have mentioned in prior columns, the key to success with International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) coding will be additional specificity, which will come in the form of more characters to communicate with payors and statisticians regarding the services that have been provided during the office visit. The addition of characters will permit more information about the visit to be delivered in the code.

Some of these additional characters will be required to submit the code for processing. Specifically look out for codes that communicate accidents or injury. Some common circumstances for dermatologists will be lacerations, abrasions, laceration repairs, and burns. The structure of the ICD-10-CM codes is outlined below to explain circumstances in which the increased number of characters will be most important for dermatologists.

The ICD-10-CM codes will be 3 to 7 characters long.1 The first 3 characters are the general categories. For example, L70 is the 3-character category for acne and L40 is the category for psoriasis. The next 3 characters (ie, characters 4–6) correspond to the related etiology (ie, the cause, set of causes, manner of causation of a disease or condition), anatomic site, severity, and other vital clinical details.1

Take the case of a burn on the hand. With the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, a first-degree burn on the back of the hand is coded with 5 characters (944.16).2 According to the ICD-10-CM coding system, the code for an initial visit for a first-degree burn on the back of the hand would include 7 characters (T23.169A).1 There will be times when the sixth character may not be necessary; in these instances, an X must be placed in this position as a placeholder, but the absence of a sixth character does not negate the need for a seventh. Thankfully, the seventh character can only be 1 of 3 letters. As illustrated above in the code for a first-degree burn on the back of the hand, the A designates an initial encounter; a D would designate a follow-up visit for this burn, and an S would represent a sequela from the initial burn, such as a postinflammatory change, which would have its own code.1

Conclusion

To be reimbursed, appropriate ICD-10-CM codes must be used. Be sure to master the structure of these codes before the October 1, 2015, compliance deadline; plan now for a training and testing period.

As I have mentioned in prior columns, the key to success with International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) coding will be additional specificity, which will come in the form of more characters to communicate with payors and statisticians regarding the services that have been provided during the office visit. The addition of characters will permit more information about the visit to be delivered in the code.

Some of these additional characters will be required to submit the code for processing. Specifically look out for codes that communicate accidents or injury. Some common circumstances for dermatologists will be lacerations, abrasions, laceration repairs, and burns. The structure of the ICD-10-CM codes is outlined below to explain circumstances in which the increased number of characters will be most important for dermatologists.

The ICD-10-CM codes will be 3 to 7 characters long.1 The first 3 characters are the general categories. For example, L70 is the 3-character category for acne and L40 is the category for psoriasis. The next 3 characters (ie, characters 4–6) correspond to the related etiology (ie, the cause, set of causes, manner of causation of a disease or condition), anatomic site, severity, and other vital clinical details.1

Take the case of a burn on the hand. With the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, a first-degree burn on the back of the hand is coded with 5 characters (944.16).2 According to the ICD-10-CM coding system, the code for an initial visit for a first-degree burn on the back of the hand would include 7 characters (T23.169A).1 There will be times when the sixth character may not be necessary; in these instances, an X must be placed in this position as a placeholder, but the absence of a sixth character does not negate the need for a seventh. Thankfully, the seventh character can only be 1 of 3 letters. As illustrated above in the code for a first-degree burn on the back of the hand, the A designates an initial encounter; a D would designate a follow-up visit for this burn, and an S would represent a sequela from the initial burn, such as a postinflammatory change, which would have its own code.1

Conclusion

To be reimbursed, appropriate ICD-10-CM codes must be used. Be sure to master the structure of these codes before the October 1, 2015, compliance deadline; plan now for a training and testing period.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. ICD-10-CM Tabular List of Diseases and Injuries. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/ICD10/downloads/6_I10tab2010.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed September 18, 2014.

2. ICD-9 code lookup. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/staticpages/icd-9-code-lookup.aspx. Accessed September 18, 2014.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. ICD-10-CM Tabular List of Diseases and Injuries. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/ICD10/downloads/6_I10tab2010.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed September 18, 2014.

2. ICD-9 code lookup. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/staticpages/icd-9-code-lookup.aspx. Accessed September 18, 2014.

Practice Points

- The addition of characters in International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes will permit more information about the visit to be communicated to payors and statisticians.

- Codes with ICD-10-CM will be 3 to 7 characters long and indicate the disease category, followed by the related etiology, anatomic site, severity, and other vital clinical details. The last character is 1 of 3 letters to indicate if the visit is an initial encounter, subsequent encounter, or sequela.

Confronting aspirin unresponsiveness in congenital heart surgery

Thrombosis occurs in up to 15% of pediatric patients following cardiac surgery, and is associated with increased mortality. Although aspirin is commonly administered to pediatric patients after high-risk congenital cardiac surgery to reduce thrombosis risk, aspirin responsiveness is rarely assessed, according to Dr. Sirisha Emani and colleagues .

“In our observational study, aspirin unresponsiveness occurred in approximately 11% of patients undergoing specific high-risk cardiac procedures, and postoperative thrombosis was associated with aspirin unresponsiveness in this patient population,” said Dr. Emani.

In order to determine whether inadequate response to aspirin was associated with increased risk of thrombosis following high-risk procedures, the researchers performed a prospective analysis of 62 patients undergoing congenital cardiac surgical procedures involving placement of prosthetic material into the circulation or coronary artery manipulation who received aspirin.

Response to aspirin was determined using the Verify Now system at least 48 hours following administration. Patients were prospectively monitored for development of thrombosis events by imaging (echocardiogram, cardiac catheterization, MRI) and review of clinical events (shunt thrombosis, stroke, or limb ischemia) until the time of hospital discharge.

Aspirin responsiveness was tested a median of 2 days after initiation of therapy. The rate of aspirin unresponsiveness (Aspirin Responsive Unit, ARU greater than 550) was 7/62 (11.3%) in all patients and was highest in patients less than 5 kg who received 20.25 mg aspirin. Thrombosis events were demonstrated in 7 patients (11.3%). Thrombosis was observed in 6 (86%) of 7 patients who were unresponsive to aspirin as opposed to 1 (2%) of 54 patients who were responsive to aspirin, a significant difference. In two neonates who were unresponsive at 20.25 and 40.5 mg of aspirin, increase in dosage to 40.5 and 81 mg, respectively, resulted in an aspirin response, suggesting insufficiency rather than true unresponsiveness.

“Monitoring of aspirin therapy and consideration of dose adjustment or alternative agents for unresponsive patients may be justified and warrants further investigation in a prospective trial,” concluded Dr. Emani.

|

Dr. Robert Jaquiss |

Aspirin is sometimes used in pediatric cardiac surgical patients with either therapeutic or prophylactic intent, and the anticipated anti-platelet activity is simply assumed to follow. This study demonstrates that in children, this assumption may be flawed in as many as 11% of patients. Furthermore, in those patients in whom the assumption of efficacy was wrong, thrombosis was alarmingly common. This information should be of concern to physicians and surgeons who prescribe aspirin for children with cardiovascular abnormalities, and certainly merits further study.

Dr. Robert Jaquiss is chief of pediatric heart surgery, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.

|

Dr. Robert Jaquiss |

Aspirin is sometimes used in pediatric cardiac surgical patients with either therapeutic or prophylactic intent, and the anticipated anti-platelet activity is simply assumed to follow. This study demonstrates that in children, this assumption may be flawed in as many as 11% of patients. Furthermore, in those patients in whom the assumption of efficacy was wrong, thrombosis was alarmingly common. This information should be of concern to physicians and surgeons who prescribe aspirin for children with cardiovascular abnormalities, and certainly merits further study.

Dr. Robert Jaquiss is chief of pediatric heart surgery, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.

|

Dr. Robert Jaquiss |

Aspirin is sometimes used in pediatric cardiac surgical patients with either therapeutic or prophylactic intent, and the anticipated anti-platelet activity is simply assumed to follow. This study demonstrates that in children, this assumption may be flawed in as many as 11% of patients. Furthermore, in those patients in whom the assumption of efficacy was wrong, thrombosis was alarmingly common. This information should be of concern to physicians and surgeons who prescribe aspirin for children with cardiovascular abnormalities, and certainly merits further study.

Dr. Robert Jaquiss is chief of pediatric heart surgery, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C.

Thrombosis occurs in up to 15% of pediatric patients following cardiac surgery, and is associated with increased mortality. Although aspirin is commonly administered to pediatric patients after high-risk congenital cardiac surgery to reduce thrombosis risk, aspirin responsiveness is rarely assessed, according to Dr. Sirisha Emani and colleagues .

“In our observational study, aspirin unresponsiveness occurred in approximately 11% of patients undergoing specific high-risk cardiac procedures, and postoperative thrombosis was associated with aspirin unresponsiveness in this patient population,” said Dr. Emani.

In order to determine whether inadequate response to aspirin was associated with increased risk of thrombosis following high-risk procedures, the researchers performed a prospective analysis of 62 patients undergoing congenital cardiac surgical procedures involving placement of prosthetic material into the circulation or coronary artery manipulation who received aspirin.

Response to aspirin was determined using the Verify Now system at least 48 hours following administration. Patients were prospectively monitored for development of thrombosis events by imaging (echocardiogram, cardiac catheterization, MRI) and review of clinical events (shunt thrombosis, stroke, or limb ischemia) until the time of hospital discharge.

Aspirin responsiveness was tested a median of 2 days after initiation of therapy. The rate of aspirin unresponsiveness (Aspirin Responsive Unit, ARU greater than 550) was 7/62 (11.3%) in all patients and was highest in patients less than 5 kg who received 20.25 mg aspirin. Thrombosis events were demonstrated in 7 patients (11.3%). Thrombosis was observed in 6 (86%) of 7 patients who were unresponsive to aspirin as opposed to 1 (2%) of 54 patients who were responsive to aspirin, a significant difference. In two neonates who were unresponsive at 20.25 and 40.5 mg of aspirin, increase in dosage to 40.5 and 81 mg, respectively, resulted in an aspirin response, suggesting insufficiency rather than true unresponsiveness.

“Monitoring of aspirin therapy and consideration of dose adjustment or alternative agents for unresponsive patients may be justified and warrants further investigation in a prospective trial,” concluded Dr. Emani.

Thrombosis occurs in up to 15% of pediatric patients following cardiac surgery, and is associated with increased mortality. Although aspirin is commonly administered to pediatric patients after high-risk congenital cardiac surgery to reduce thrombosis risk, aspirin responsiveness is rarely assessed, according to Dr. Sirisha Emani and colleagues .

“In our observational study, aspirin unresponsiveness occurred in approximately 11% of patients undergoing specific high-risk cardiac procedures, and postoperative thrombosis was associated with aspirin unresponsiveness in this patient population,” said Dr. Emani.

In order to determine whether inadequate response to aspirin was associated with increased risk of thrombosis following high-risk procedures, the researchers performed a prospective analysis of 62 patients undergoing congenital cardiac surgical procedures involving placement of prosthetic material into the circulation or coronary artery manipulation who received aspirin.

Response to aspirin was determined using the Verify Now system at least 48 hours following administration. Patients were prospectively monitored for development of thrombosis events by imaging (echocardiogram, cardiac catheterization, MRI) and review of clinical events (shunt thrombosis, stroke, or limb ischemia) until the time of hospital discharge.

Aspirin responsiveness was tested a median of 2 days after initiation of therapy. The rate of aspirin unresponsiveness (Aspirin Responsive Unit, ARU greater than 550) was 7/62 (11.3%) in all patients and was highest in patients less than 5 kg who received 20.25 mg aspirin. Thrombosis events were demonstrated in 7 patients (11.3%). Thrombosis was observed in 6 (86%) of 7 patients who were unresponsive to aspirin as opposed to 1 (2%) of 54 patients who were responsive to aspirin, a significant difference. In two neonates who were unresponsive at 20.25 and 40.5 mg of aspirin, increase in dosage to 40.5 and 81 mg, respectively, resulted in an aspirin response, suggesting insufficiency rather than true unresponsiveness.

“Monitoring of aspirin therapy and consideration of dose adjustment or alternative agents for unresponsive patients may be justified and warrants further investigation in a prospective trial,” concluded Dr. Emani.

Private Practice Will Survive But Patient Billing Will Not

For many years I have advised physicians that aggressive management of accounts receivable is the key to financial health for any private practice. In the current health care reform climate, it has become more important than ever. A crucial step toward proper management of accounts receivable in the age of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act is minimization, if not outright elimination, of patient billing, which is a hallowed yet obsolete tradition in private practice. Billing, in effect, is extending free credit to patients, and independent physicians can no longer afford it.

Some physicians of a traditional bent cling to the idea that accepting credit cards or even asking for payment at the time of service smacks of “storekeeping.” They feel more comfortable billing patients for outstanding balances but complain that their bills often are ignored; with each passing day following treatment in your office, the likelihood decreases that a patient will pay the bill.

Patient billing also is expensive. When you total the costs of materials, postage, and staff labor, each bill can cost anywhere from $2 to $10 or more. Every minute the office staff spends producing and mailing bills is time not spent on more productive work. Billing services are an alternative, but they also are expensive, and those bills get ignored too. Requiring immediate payment may seem distasteful to some physicians, but for physicians who wish to keep their office private and independent, it is rapidly becoming the only viable option.

Health Savings Accounts

Private practices will need to become increasingly flexible in how they accept payments as the population continues to age. This flexibility becomes increasingly important as more and more patients rely on health savings accounts (HSAs). Enrollment in these specialized, tax-deductible, tax-free accounts has increased 10-fold over the last decade.1 Private practice physicians will want to accommodate for HSAs as much as possible.

A few credit companies are already promoting cards to finance HSAs and other private-pay portions of health care expenses, such as The HELPcard (www.helpcard.com). Major credit card companies also have begun to appreciate this largely untapped segment of potential business for them. Soon you may begin receiving help from them in setting up creative payment plans for your patients. Some financial institutions have even begun creating medical credit and debit cards called health benefit cards that are designed specifically for use at physicians’ offices.2

Credit and Debit Cards

Credit and debit cards eliminate many of the problems associated with patient billing. They allow you to collect more fees at the time of service while you still have the patient’s attention and the service you provided is still appreciated.

Charging to a credit or debit card also reduces the chances of a balance owed falling through the cracks, getting lost in the mail, or getting embezzled, and it cannot bounce so it is better than a check. Card payments also can improve your practice’s cash flow, which is always a welcome benefit. Additionally, if a patient is delinquent in paying a credit card bill, it is the credit card company’s problem, not yours.

Credit cards also offer more payment flexibility for patients. In the case of a large balance, offer your patient the option of charging all of the services to a credit card, which he/she can then pay off in affordable monthly installments. Your practice will get reimbursed in full, even as the patient is paying it off slowly, and the patient is able to pay off the debt at a pace that makes sense for his/her finances.

Payment Policies

Beyond simply accepting credit cards, the next step is one that every hotel, rental car agency, and many other businesses have used for years: Retain a card number in each patient’s file, and bill balances as they come in.

Every new patient in my office receives a letter at his/her first visit explaining our policy: We will keep a credit card number on file and use it to bill any outstanding balances after third parties pay their portion. At the bottom of the letter is a brief statement of consent for the patient to sign, along with a place to write the credit card number and expiration date. This policy also comes in handy for patients who claim to have come to the office without cash, a checkbook, credit cards, or any other method of payment. In such situations, my office manager can say, “No problem, we have your credit card information on file!”

Do patients object to this policy? Some do, mostly older patients. But when we explain that we are doing nothing different than hotels do at check-in and that this policy also will work to their advantage by decreasing the number of bills they receive and checks they must write, most come around. Make it an option at first if you wish; then, when everyone is accustomed, you can make it a mandatory policy. My office manager has the authority to make exceptions on a case-by-case basis when necessary.

Do patients worry about confidentiality or unauthorized use? Most individuals do not worry when they use a credit card at a restaurant, hotel, or the Internet. Guard your patients’ financial information as carefully as their medical information. If you have electronic health records, the patient’s credit card number can go in the medical chart. Otherwise use a separate portable filing system that can be locked up each night.

Does this policy work? In only 1 year, my total accounts receivable dropped by nearly 50%; after another year they stabilized at 30% to 35% of prior levels and have remained there ever since, which was a source of consternation for our new accountant who we hired shortly thereafter. “Something must be wrong,” he said nervously after his first look at our books. “Accounts receivable totals are never that low in a medical office with your level of volume.” His eyes widened as I explained our system. “Why doesn’t every private practice do that?” he asked. Why, indeed.

Final Thoughts

The business of health care delivery is currently being rocked at its foundations, as I have been detailing in this column. Without considerable adaptation to these fundamental changes, a private practice can do little more than survive, and even that will take luck. A crucial component of adaptation involves doing more of what we do best, treating patients. Leave the business of extending credit to the banks and credit card companies.

1. Stroud M. Making the most of that shiny new HSA. Reuters. April 19, 2012. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/04/19/us-healthcare-savings-idU BRE83I0ZI20120419. Accessed September 16, 2014.

2. Prater C. Is there a health care debit card in your future? CreditCards.com Web site. http://www.credit cards.com/credit-card-news/payment-cards-health-care-expenses-1271.php. Published April 14, 2009. Accessed September 16, 2014.

For many years I have advised physicians that aggressive management of accounts receivable is the key to financial health for any private practice. In the current health care reform climate, it has become more important than ever. A crucial step toward proper management of accounts receivable in the age of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act is minimization, if not outright elimination, of patient billing, which is a hallowed yet obsolete tradition in private practice. Billing, in effect, is extending free credit to patients, and independent physicians can no longer afford it.

Some physicians of a traditional bent cling to the idea that accepting credit cards or even asking for payment at the time of service smacks of “storekeeping.” They feel more comfortable billing patients for outstanding balances but complain that their bills often are ignored; with each passing day following treatment in your office, the likelihood decreases that a patient will pay the bill.

Patient billing also is expensive. When you total the costs of materials, postage, and staff labor, each bill can cost anywhere from $2 to $10 or more. Every minute the office staff spends producing and mailing bills is time not spent on more productive work. Billing services are an alternative, but they also are expensive, and those bills get ignored too. Requiring immediate payment may seem distasteful to some physicians, but for physicians who wish to keep their office private and independent, it is rapidly becoming the only viable option.

Health Savings Accounts

Private practices will need to become increasingly flexible in how they accept payments as the population continues to age. This flexibility becomes increasingly important as more and more patients rely on health savings accounts (HSAs). Enrollment in these specialized, tax-deductible, tax-free accounts has increased 10-fold over the last decade.1 Private practice physicians will want to accommodate for HSAs as much as possible.

A few credit companies are already promoting cards to finance HSAs and other private-pay portions of health care expenses, such as The HELPcard (www.helpcard.com). Major credit card companies also have begun to appreciate this largely untapped segment of potential business for them. Soon you may begin receiving help from them in setting up creative payment plans for your patients. Some financial institutions have even begun creating medical credit and debit cards called health benefit cards that are designed specifically for use at physicians’ offices.2

Credit and Debit Cards

Credit and debit cards eliminate many of the problems associated with patient billing. They allow you to collect more fees at the time of service while you still have the patient’s attention and the service you provided is still appreciated.

Charging to a credit or debit card also reduces the chances of a balance owed falling through the cracks, getting lost in the mail, or getting embezzled, and it cannot bounce so it is better than a check. Card payments also can improve your practice’s cash flow, which is always a welcome benefit. Additionally, if a patient is delinquent in paying a credit card bill, it is the credit card company’s problem, not yours.

Credit cards also offer more payment flexibility for patients. In the case of a large balance, offer your patient the option of charging all of the services to a credit card, which he/she can then pay off in affordable monthly installments. Your practice will get reimbursed in full, even as the patient is paying it off slowly, and the patient is able to pay off the debt at a pace that makes sense for his/her finances.

Payment Policies

Beyond simply accepting credit cards, the next step is one that every hotel, rental car agency, and many other businesses have used for years: Retain a card number in each patient’s file, and bill balances as they come in.

Every new patient in my office receives a letter at his/her first visit explaining our policy: We will keep a credit card number on file and use it to bill any outstanding balances after third parties pay their portion. At the bottom of the letter is a brief statement of consent for the patient to sign, along with a place to write the credit card number and expiration date. This policy also comes in handy for patients who claim to have come to the office without cash, a checkbook, credit cards, or any other method of payment. In such situations, my office manager can say, “No problem, we have your credit card information on file!”

Do patients object to this policy? Some do, mostly older patients. But when we explain that we are doing nothing different than hotels do at check-in and that this policy also will work to their advantage by decreasing the number of bills they receive and checks they must write, most come around. Make it an option at first if you wish; then, when everyone is accustomed, you can make it a mandatory policy. My office manager has the authority to make exceptions on a case-by-case basis when necessary.

Do patients worry about confidentiality or unauthorized use? Most individuals do not worry when they use a credit card at a restaurant, hotel, or the Internet. Guard your patients’ financial information as carefully as their medical information. If you have electronic health records, the patient’s credit card number can go in the medical chart. Otherwise use a separate portable filing system that can be locked up each night.

Does this policy work? In only 1 year, my total accounts receivable dropped by nearly 50%; after another year they stabilized at 30% to 35% of prior levels and have remained there ever since, which was a source of consternation for our new accountant who we hired shortly thereafter. “Something must be wrong,” he said nervously after his first look at our books. “Accounts receivable totals are never that low in a medical office with your level of volume.” His eyes widened as I explained our system. “Why doesn’t every private practice do that?” he asked. Why, indeed.

Final Thoughts

The business of health care delivery is currently being rocked at its foundations, as I have been detailing in this column. Without considerable adaptation to these fundamental changes, a private practice can do little more than survive, and even that will take luck. A crucial component of adaptation involves doing more of what we do best, treating patients. Leave the business of extending credit to the banks and credit card companies.

For many years I have advised physicians that aggressive management of accounts receivable is the key to financial health for any private practice. In the current health care reform climate, it has become more important than ever. A crucial step toward proper management of accounts receivable in the age of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act is minimization, if not outright elimination, of patient billing, which is a hallowed yet obsolete tradition in private practice. Billing, in effect, is extending free credit to patients, and independent physicians can no longer afford it.

Some physicians of a traditional bent cling to the idea that accepting credit cards or even asking for payment at the time of service smacks of “storekeeping.” They feel more comfortable billing patients for outstanding balances but complain that their bills often are ignored; with each passing day following treatment in your office, the likelihood decreases that a patient will pay the bill.

Patient billing also is expensive. When you total the costs of materials, postage, and staff labor, each bill can cost anywhere from $2 to $10 or more. Every minute the office staff spends producing and mailing bills is time not spent on more productive work. Billing services are an alternative, but they also are expensive, and those bills get ignored too. Requiring immediate payment may seem distasteful to some physicians, but for physicians who wish to keep their office private and independent, it is rapidly becoming the only viable option.

Health Savings Accounts

Private practices will need to become increasingly flexible in how they accept payments as the population continues to age. This flexibility becomes increasingly important as more and more patients rely on health savings accounts (HSAs). Enrollment in these specialized, tax-deductible, tax-free accounts has increased 10-fold over the last decade.1 Private practice physicians will want to accommodate for HSAs as much as possible.

A few credit companies are already promoting cards to finance HSAs and other private-pay portions of health care expenses, such as The HELPcard (www.helpcard.com). Major credit card companies also have begun to appreciate this largely untapped segment of potential business for them. Soon you may begin receiving help from them in setting up creative payment plans for your patients. Some financial institutions have even begun creating medical credit and debit cards called health benefit cards that are designed specifically for use at physicians’ offices.2

Credit and Debit Cards

Credit and debit cards eliminate many of the problems associated with patient billing. They allow you to collect more fees at the time of service while you still have the patient’s attention and the service you provided is still appreciated.

Charging to a credit or debit card also reduces the chances of a balance owed falling through the cracks, getting lost in the mail, or getting embezzled, and it cannot bounce so it is better than a check. Card payments also can improve your practice’s cash flow, which is always a welcome benefit. Additionally, if a patient is delinquent in paying a credit card bill, it is the credit card company’s problem, not yours.

Credit cards also offer more payment flexibility for patients. In the case of a large balance, offer your patient the option of charging all of the services to a credit card, which he/she can then pay off in affordable monthly installments. Your practice will get reimbursed in full, even as the patient is paying it off slowly, and the patient is able to pay off the debt at a pace that makes sense for his/her finances.

Payment Policies

Beyond simply accepting credit cards, the next step is one that every hotel, rental car agency, and many other businesses have used for years: Retain a card number in each patient’s file, and bill balances as they come in.

Every new patient in my office receives a letter at his/her first visit explaining our policy: We will keep a credit card number on file and use it to bill any outstanding balances after third parties pay their portion. At the bottom of the letter is a brief statement of consent for the patient to sign, along with a place to write the credit card number and expiration date. This policy also comes in handy for patients who claim to have come to the office without cash, a checkbook, credit cards, or any other method of payment. In such situations, my office manager can say, “No problem, we have your credit card information on file!”

Do patients object to this policy? Some do, mostly older patients. But when we explain that we are doing nothing different than hotels do at check-in and that this policy also will work to their advantage by decreasing the number of bills they receive and checks they must write, most come around. Make it an option at first if you wish; then, when everyone is accustomed, you can make it a mandatory policy. My office manager has the authority to make exceptions on a case-by-case basis when necessary.

Do patients worry about confidentiality or unauthorized use? Most individuals do not worry when they use a credit card at a restaurant, hotel, or the Internet. Guard your patients’ financial information as carefully as their medical information. If you have electronic health records, the patient’s credit card number can go in the medical chart. Otherwise use a separate portable filing system that can be locked up each night.

Does this policy work? In only 1 year, my total accounts receivable dropped by nearly 50%; after another year they stabilized at 30% to 35% of prior levels and have remained there ever since, which was a source of consternation for our new accountant who we hired shortly thereafter. “Something must be wrong,” he said nervously after his first look at our books. “Accounts receivable totals are never that low in a medical office with your level of volume.” His eyes widened as I explained our system. “Why doesn’t every private practice do that?” he asked. Why, indeed.

Final Thoughts

The business of health care delivery is currently being rocked at its foundations, as I have been detailing in this column. Without considerable adaptation to these fundamental changes, a private practice can do little more than survive, and even that will take luck. A crucial component of adaptation involves doing more of what we do best, treating patients. Leave the business of extending credit to the banks and credit card companies.

1. Stroud M. Making the most of that shiny new HSA. Reuters. April 19, 2012. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/04/19/us-healthcare-savings-idU BRE83I0ZI20120419. Accessed September 16, 2014.

2. Prater C. Is there a health care debit card in your future? CreditCards.com Web site. http://www.credit cards.com/credit-card-news/payment-cards-health-care-expenses-1271.php. Published April 14, 2009. Accessed September 16, 2014.

1. Stroud M. Making the most of that shiny new HSA. Reuters. April 19, 2012. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/04/19/us-healthcare-savings-idU BRE83I0ZI20120419. Accessed September 16, 2014.

2. Prater C. Is there a health care debit card in your future? CreditCards.com Web site. http://www.credit cards.com/credit-card-news/payment-cards-health-care-expenses-1271.php. Published April 14, 2009. Accessed September 16, 2014.

Practice Points

- Aggressive management of accounts receivable is the key to the financial health of any private practice. Physicians must become increasingly flexible in how they accept payments as the population continues to age.

- Consider requiring patients to supply a credit card or debit card to bill for outstanding balances after third parties pay their portion.

- Accommodate health savings accounts and health benefit cards.

Methotrexate: Finding the Right Starting Dose

Decades of experience have narrowed the most effective dose of methotrexate (MTX) for rheumatoid arthritis to somewhere between 15 mg and 25 mg per week. However, experience has also suggested that early and rapid control of the disease activity minimizes damage. The result has been a quicker escalation of MTX dosing, with a starting dose of 10 mg to 15 mg per week and escalating by 5 mg every month, rather than the more traditional 5 mg every 3 months.

But researchers from Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research in Chandigarh, India, point out that the recommendation to start with the higher dose of 15 mg is based on “weak evidence.” What’s more, they say, only a limited number of studies had compared fixed MTX doses head-to-head, and of those studies, many are 20 to 30 years old. No study had compared starting doses of 7.5 mg and 15 mg MTX, the researchers say.

Starting higher may have some benefits of efficacy, but that higher dose can also lead to adverse effects (AEs), intolerance, and withdrawal from therapy, say the researchers. They decided to find a balance between efficacy, speed, and tolerability by comparing 2 dosage regimens of oral MTX, starting at either 7.5 mgor 15 mg per week and escalating 2.5 mg every 2 weeks over 12 weeks, to a possible maximum of 25 mg per week. In group one, 47 patients were started on the lower dose, reaching a mean dose at 12 weeks of 17.3 mg per week. In group two, 53 patients were started on the higher dose and reached a mean dose of 23.6 mg per week. In patients who completed the study, the mean doses were 19.2 mg per week and 24.5 mg per week, respectively (P < .001).

Nine patients withdrew from group 1, and 7 patients withdrew from group 2. The numbers withdrawing from each group due to AEs were not statistically significant (P = .9). However, group 2 had a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting (42%, vs 19% in group 1), although the severity and duration of nausea were similar in both groups. There were no significant differences in frequency of cytopenia (P = .09) or transaminitis (P = .08). There was no difference in disease activity at weeks 4, 8, or 12.

The researchers say one limitation of their study is the short duration. They chose 12 weeks, because guidelines had suggested 3 months as a decision point, when other drugs could be added if the patient did not respond to MTX. However, they note that the European League Against Rheumatism 2013 update now specifies that the 3-month period relates “solely to assessing improvements” and says it takes 6 months to see maximal efficacy. The researchers, agreeing with this, say they found “a relatively poor response” by week 12. Indeed, they say, in view of the relatively slow decline in disease activity, future studies might benefit from extending the follow-up period to 24 weeks.

Source

Dhir V, Singla M, Gupta N, et al. Clin Ther. 2014;36(7):1005-1015.

doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.05.063.

Decades of experience have narrowed the most effective dose of methotrexate (MTX) for rheumatoid arthritis to somewhere between 15 mg and 25 mg per week. However, experience has also suggested that early and rapid control of the disease activity minimizes damage. The result has been a quicker escalation of MTX dosing, with a starting dose of 10 mg to 15 mg per week and escalating by 5 mg every month, rather than the more traditional 5 mg every 3 months.

But researchers from Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research in Chandigarh, India, point out that the recommendation to start with the higher dose of 15 mg is based on “weak evidence.” What’s more, they say, only a limited number of studies had compared fixed MTX doses head-to-head, and of those studies, many are 20 to 30 years old. No study had compared starting doses of 7.5 mg and 15 mg MTX, the researchers say.

Starting higher may have some benefits of efficacy, but that higher dose can also lead to adverse effects (AEs), intolerance, and withdrawal from therapy, say the researchers. They decided to find a balance between efficacy, speed, and tolerability by comparing 2 dosage regimens of oral MTX, starting at either 7.5 mgor 15 mg per week and escalating 2.5 mg every 2 weeks over 12 weeks, to a possible maximum of 25 mg per week. In group one, 47 patients were started on the lower dose, reaching a mean dose at 12 weeks of 17.3 mg per week. In group two, 53 patients were started on the higher dose and reached a mean dose of 23.6 mg per week. In patients who completed the study, the mean doses were 19.2 mg per week and 24.5 mg per week, respectively (P < .001).

Nine patients withdrew from group 1, and 7 patients withdrew from group 2. The numbers withdrawing from each group due to AEs were not statistically significant (P = .9). However, group 2 had a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting (42%, vs 19% in group 1), although the severity and duration of nausea were similar in both groups. There were no significant differences in frequency of cytopenia (P = .09) or transaminitis (P = .08). There was no difference in disease activity at weeks 4, 8, or 12.

The researchers say one limitation of their study is the short duration. They chose 12 weeks, because guidelines had suggested 3 months as a decision point, when other drugs could be added if the patient did not respond to MTX. However, they note that the European League Against Rheumatism 2013 update now specifies that the 3-month period relates “solely to assessing improvements” and says it takes 6 months to see maximal efficacy. The researchers, agreeing with this, say they found “a relatively poor response” by week 12. Indeed, they say, in view of the relatively slow decline in disease activity, future studies might benefit from extending the follow-up period to 24 weeks.

Source

Dhir V, Singla M, Gupta N, et al. Clin Ther. 2014;36(7):1005-1015.

doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.05.063.

Decades of experience have narrowed the most effective dose of methotrexate (MTX) for rheumatoid arthritis to somewhere between 15 mg and 25 mg per week. However, experience has also suggested that early and rapid control of the disease activity minimizes damage. The result has been a quicker escalation of MTX dosing, with a starting dose of 10 mg to 15 mg per week and escalating by 5 mg every month, rather than the more traditional 5 mg every 3 months.

But researchers from Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research in Chandigarh, India, point out that the recommendation to start with the higher dose of 15 mg is based on “weak evidence.” What’s more, they say, only a limited number of studies had compared fixed MTX doses head-to-head, and of those studies, many are 20 to 30 years old. No study had compared starting doses of 7.5 mg and 15 mg MTX, the researchers say.

Starting higher may have some benefits of efficacy, but that higher dose can also lead to adverse effects (AEs), intolerance, and withdrawal from therapy, say the researchers. They decided to find a balance between efficacy, speed, and tolerability by comparing 2 dosage regimens of oral MTX, starting at either 7.5 mgor 15 mg per week and escalating 2.5 mg every 2 weeks over 12 weeks, to a possible maximum of 25 mg per week. In group one, 47 patients were started on the lower dose, reaching a mean dose at 12 weeks of 17.3 mg per week. In group two, 53 patients were started on the higher dose and reached a mean dose of 23.6 mg per week. In patients who completed the study, the mean doses were 19.2 mg per week and 24.5 mg per week, respectively (P < .001).

Nine patients withdrew from group 1, and 7 patients withdrew from group 2. The numbers withdrawing from each group due to AEs were not statistically significant (P = .9). However, group 2 had a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting (42%, vs 19% in group 1), although the severity and duration of nausea were similar in both groups. There were no significant differences in frequency of cytopenia (P = .09) or transaminitis (P = .08). There was no difference in disease activity at weeks 4, 8, or 12.

The researchers say one limitation of their study is the short duration. They chose 12 weeks, because guidelines had suggested 3 months as a decision point, when other drugs could be added if the patient did not respond to MTX. However, they note that the European League Against Rheumatism 2013 update now specifies that the 3-month period relates “solely to assessing improvements” and says it takes 6 months to see maximal efficacy. The researchers, agreeing with this, say they found “a relatively poor response” by week 12. Indeed, they say, in view of the relatively slow decline in disease activity, future studies might benefit from extending the follow-up period to 24 weeks.

Source

Dhir V, Singla M, Gupta N, et al. Clin Ther. 2014;36(7):1005-1015.

doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.05.063.

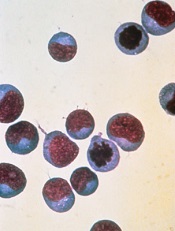

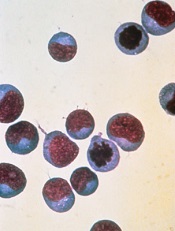

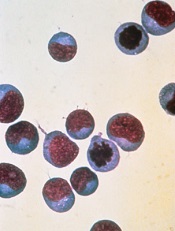

Physical changes in RBCs remain a mystery

During their approximately 100-day lifespan in the bloodstream, red blood cells (RBCs) lose membrane surface area, volume, and hemoglobin content.

A study published in PLOS Computational Biology shows that, of these 3 changes, only surface-area loss can be explained by RBCs shedding small, hemoglobin-containing vesicles budding off their cells’ membrane.

Therefore, an unknown process must be primarily responsible for loss of RBC volume and hemoglobin reduction.

Roy Malka, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues noted that variations in RBCs’ mean volume and hemoglobin content are associated with important clinical conditions, but the mechanisms controlling these physical characteristics are not well understood.

Vesicle shedding was thought to be the most important mechanism, but the researchers found evidence to suggest that a dominant role for vesicle shedding would violate empirical geometric and biophysical constraints.

So they concluded that an unknown mechanism must control loss of RBC volume and hemoglobin reduction. And this mechanism is likely responsible for 60% to 90% of volume loss and hemoglobin reduction.

The group’s work combined mathematical modeling of the mechanism that changes the physical properties of RBCs, clinical measurements of both cellular volume and hemoglobin content, and data from a new system for characterizing the non-water cellular mass of individual cells.

The researchers said the quantitative characterization of RBC loss processes will help focus future research into the molecular mechanisms of RBC maturation. And it may ultimately help in the early detection of clinical conditions where the RBC maturation pattern is altered. ![]()

During their approximately 100-day lifespan in the bloodstream, red blood cells (RBCs) lose membrane surface area, volume, and hemoglobin content.

A study published in PLOS Computational Biology shows that, of these 3 changes, only surface-area loss can be explained by RBCs shedding small, hemoglobin-containing vesicles budding off their cells’ membrane.

Therefore, an unknown process must be primarily responsible for loss of RBC volume and hemoglobin reduction.

Roy Malka, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues noted that variations in RBCs’ mean volume and hemoglobin content are associated with important clinical conditions, but the mechanisms controlling these physical characteristics are not well understood.

Vesicle shedding was thought to be the most important mechanism, but the researchers found evidence to suggest that a dominant role for vesicle shedding would violate empirical geometric and biophysical constraints.

So they concluded that an unknown mechanism must control loss of RBC volume and hemoglobin reduction. And this mechanism is likely responsible for 60% to 90% of volume loss and hemoglobin reduction.

The group’s work combined mathematical modeling of the mechanism that changes the physical properties of RBCs, clinical measurements of both cellular volume and hemoglobin content, and data from a new system for characterizing the non-water cellular mass of individual cells.

The researchers said the quantitative characterization of RBC loss processes will help focus future research into the molecular mechanisms of RBC maturation. And it may ultimately help in the early detection of clinical conditions where the RBC maturation pattern is altered. ![]()

During their approximately 100-day lifespan in the bloodstream, red blood cells (RBCs) lose membrane surface area, volume, and hemoglobin content.

A study published in PLOS Computational Biology shows that, of these 3 changes, only surface-area loss can be explained by RBCs shedding small, hemoglobin-containing vesicles budding off their cells’ membrane.

Therefore, an unknown process must be primarily responsible for loss of RBC volume and hemoglobin reduction.

Roy Malka, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues noted that variations in RBCs’ mean volume and hemoglobin content are associated with important clinical conditions, but the mechanisms controlling these physical characteristics are not well understood.

Vesicle shedding was thought to be the most important mechanism, but the researchers found evidence to suggest that a dominant role for vesicle shedding would violate empirical geometric and biophysical constraints.

So they concluded that an unknown mechanism must control loss of RBC volume and hemoglobin reduction. And this mechanism is likely responsible for 60% to 90% of volume loss and hemoglobin reduction.

The group’s work combined mathematical modeling of the mechanism that changes the physical properties of RBCs, clinical measurements of both cellular volume and hemoglobin content, and data from a new system for characterizing the non-water cellular mass of individual cells.

The researchers said the quantitative characterization of RBC loss processes will help focus future research into the molecular mechanisms of RBC maturation. And it may ultimately help in the early detection of clinical conditions where the RBC maturation pattern is altered. ![]()

FDA approves drug for untreated MCL

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved bortezomib (Velcade) for use in previously untreated patients with mantle cell

lymphoma (MCL).

This is the first drug to be approved in the US for previously untreated patients with MCL.

The approval extends the utility of bortezomib beyond relapsed or refractory MCL, for which it has been approved since 2006.

The new approval is based on results of a phase 3 trial.

The study was a comparison of VcR-CAP (bortezomib, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone) and R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) in 487 patients newly diagnosed with stage II, III, or IV MCL.

Survival and response

VcR-CAP demonstrated a 59% relative improvement in the study’s primary endpoint of progression-free survival. At a median follow-up of 40 months, the median progression-free survival was 25 months in the VcR-CAP arm and 14 months in the R-CHOP arm (hazard ratio [HR]=0.63, P<0.001).

However, there was no significant improvement in overall survival. The median overall survival was not reached in the VcR-CAP arm and was 56.3 months in the R-CHOP arm (HR=0.80; P=0.173).

Patients in the VcR-CAP arm had a higher rate of complete response/unconfirmed complete response than those in the R-CHOP arm—53% and 42%, respectively (P=0.007). But there was no significant difference in overall response—92% and 90%, respectively (P=0.275).

The time to progression was significantly longer in the VcR-CAP arm—30.5 months, compared to 16.1 months in the R-CHOP arm (HR=0.58; P<0.001). And the median time to subsequent treatment was significantly longer in the VcR-CAP arm—44.5 months vs 24.8 months (HR 0.50; P<0.001).

Adverse events

VcR-CAP was associated with additional but manageable toxicity compared to R-CHOP.

Serious adverse events were reported in 38% of patients in the VcR-CAP arm and 30% in the R-CHOP arm. Grade 3 or higher adverse events were reported in 93% and 85%, respectively.

There were similar rates of all-grade peripheral neuropathy between the VcR-CAP arm and the R-CHOP arm—30% and 29%, respectively. But the rate of grade 3 or higher peripheral neuropathy was significantly higher in the VcR-CAP arm—7.5% vs 4.1%.

The incidence of all-grade thrombocytopenia was substantially higher in the VcR-CAP arm than the R-CHOP arm—72% and 19%, respectively. But there was no significant difference in bleeding events—6% and 5%, respectively.

The incidence of all-grade neutropenia was 88% in the VcR-CAP arm and 74% in the R-CHOP arm. The rate of grade 3 or higher febrile neutropenia was 14% and 15%, respectively, and the rate of infection was 60% and 46%, respectively.

These data were presented at ASCO 2014 as abstract 8500.

Bortezomib is marketed as Velcade by Millennium/Takeda and Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies. Millennium is responsible for commercialization in the US, and Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies are responsible for commercialization in the rest of the world.

For more details on the drug, visit www.velcade.com. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved bortezomib (Velcade) for use in previously untreated patients with mantle cell

lymphoma (MCL).

This is the first drug to be approved in the US for previously untreated patients with MCL.

The approval extends the utility of bortezomib beyond relapsed or refractory MCL, for which it has been approved since 2006.

The new approval is based on results of a phase 3 trial.

The study was a comparison of VcR-CAP (bortezomib, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone) and R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) in 487 patients newly diagnosed with stage II, III, or IV MCL.

Survival and response

VcR-CAP demonstrated a 59% relative improvement in the study’s primary endpoint of progression-free survival. At a median follow-up of 40 months, the median progression-free survival was 25 months in the VcR-CAP arm and 14 months in the R-CHOP arm (hazard ratio [HR]=0.63, P<0.001).

However, there was no significant improvement in overall survival. The median overall survival was not reached in the VcR-CAP arm and was 56.3 months in the R-CHOP arm (HR=0.80; P=0.173).

Patients in the VcR-CAP arm had a higher rate of complete response/unconfirmed complete response than those in the R-CHOP arm—53% and 42%, respectively (P=0.007). But there was no significant difference in overall response—92% and 90%, respectively (P=0.275).

The time to progression was significantly longer in the VcR-CAP arm—30.5 months, compared to 16.1 months in the R-CHOP arm (HR=0.58; P<0.001). And the median time to subsequent treatment was significantly longer in the VcR-CAP arm—44.5 months vs 24.8 months (HR 0.50; P<0.001).

Adverse events

VcR-CAP was associated with additional but manageable toxicity compared to R-CHOP.

Serious adverse events were reported in 38% of patients in the VcR-CAP arm and 30% in the R-CHOP arm. Grade 3 or higher adverse events were reported in 93% and 85%, respectively.

There were similar rates of all-grade peripheral neuropathy between the VcR-CAP arm and the R-CHOP arm—30% and 29%, respectively. But the rate of grade 3 or higher peripheral neuropathy was significantly higher in the VcR-CAP arm—7.5% vs 4.1%.

The incidence of all-grade thrombocytopenia was substantially higher in the VcR-CAP arm than the R-CHOP arm—72% and 19%, respectively. But there was no significant difference in bleeding events—6% and 5%, respectively.

The incidence of all-grade neutropenia was 88% in the VcR-CAP arm and 74% in the R-CHOP arm. The rate of grade 3 or higher febrile neutropenia was 14% and 15%, respectively, and the rate of infection was 60% and 46%, respectively.

These data were presented at ASCO 2014 as abstract 8500.

Bortezomib is marketed as Velcade by Millennium/Takeda and Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies. Millennium is responsible for commercialization in the US, and Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies are responsible for commercialization in the rest of the world.

For more details on the drug, visit www.velcade.com. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved bortezomib (Velcade) for use in previously untreated patients with mantle cell

lymphoma (MCL).

This is the first drug to be approved in the US for previously untreated patients with MCL.

The approval extends the utility of bortezomib beyond relapsed or refractory MCL, for which it has been approved since 2006.

The new approval is based on results of a phase 3 trial.

The study was a comparison of VcR-CAP (bortezomib, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone) and R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) in 487 patients newly diagnosed with stage II, III, or IV MCL.

Survival and response

VcR-CAP demonstrated a 59% relative improvement in the study’s primary endpoint of progression-free survival. At a median follow-up of 40 months, the median progression-free survival was 25 months in the VcR-CAP arm and 14 months in the R-CHOP arm (hazard ratio [HR]=0.63, P<0.001).

However, there was no significant improvement in overall survival. The median overall survival was not reached in the VcR-CAP arm and was 56.3 months in the R-CHOP arm (HR=0.80; P=0.173).

Patients in the VcR-CAP arm had a higher rate of complete response/unconfirmed complete response than those in the R-CHOP arm—53% and 42%, respectively (P=0.007). But there was no significant difference in overall response—92% and 90%, respectively (P=0.275).

The time to progression was significantly longer in the VcR-CAP arm—30.5 months, compared to 16.1 months in the R-CHOP arm (HR=0.58; P<0.001). And the median time to subsequent treatment was significantly longer in the VcR-CAP arm—44.5 months vs 24.8 months (HR 0.50; P<0.001).

Adverse events

VcR-CAP was associated with additional but manageable toxicity compared to R-CHOP.

Serious adverse events were reported in 38% of patients in the VcR-CAP arm and 30% in the R-CHOP arm. Grade 3 or higher adverse events were reported in 93% and 85%, respectively.

There were similar rates of all-grade peripheral neuropathy between the VcR-CAP arm and the R-CHOP arm—30% and 29%, respectively. But the rate of grade 3 or higher peripheral neuropathy was significantly higher in the VcR-CAP arm—7.5% vs 4.1%.

The incidence of all-grade thrombocytopenia was substantially higher in the VcR-CAP arm than the R-CHOP arm—72% and 19%, respectively. But there was no significant difference in bleeding events—6% and 5%, respectively.

The incidence of all-grade neutropenia was 88% in the VcR-CAP arm and 74% in the R-CHOP arm. The rate of grade 3 or higher febrile neutropenia was 14% and 15%, respectively, and the rate of infection was 60% and 46%, respectively.

These data were presented at ASCO 2014 as abstract 8500.

Bortezomib is marketed as Velcade by Millennium/Takeda and Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies. Millennium is responsible for commercialization in the US, and Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies are responsible for commercialization in the rest of the world.

For more details on the drug, visit www.velcade.com. ![]()

No need to switch antibiotics, study shows

Staphylococcus

infectionCredit: Bill Branson

New research suggests the antibiotic vancomycin is still effective in treating Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream (SAB) infections, despite increases in minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values.

Researchers found no difference in mortality between patients with low-vancomycin MIC and those with high-vancomycin MIC.

So it seems physicians can continue using vancomycin when MIC values are elevated but within the susceptible range, rather than

switching to newer antibiotics.

Andre Kalil, MD, of the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, and his colleagues described this research in JAMA.

In recent years, physicians treating Staphylococcus infections with vancomycin have seen an increase in the MIC, the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial agent that inhibits the growth of a microorganism.

MIC values lower than 4 mg/L suggest Staphylococcus is susceptible to vancomycin. However, when the MIC value exceeds 1.5 mg/L, some physicians have taken it as an indication that vancomycin may not be working at maximum effectiveness.

Some reports have suggested that elevations in vancomycin MIC values may be associated with increased treatment failure and death.

To determine the effectiveness of vancomycin, Dr Kalil and his colleagues analyzed data from 38 studies covering 8291 episodes of SAB infection.

The team evaluated the association between vancomycin MIC elevation and mortality. Among all SAB infections studied, the overall mortality was 26.1%.

The adjusted absolute risk of mortality did not differ significantly between patients with high-vancomycin MIC and those with low-vancomycin MIC—26.8% and 25.8%, respectively.

In studies that included only methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections, the mortality among SAB episodes in patients with high-vancomycin MIC was 27.6%, compared with a mortality of 27.4% among patients with low-vancomycin MIC.

“The study provides strong evidence that vancomycin remains highly useful,” Dr Kalil said. “Even though vancomycin is an older drug, it is still killing staph very efficiently. There are newer antibiotics available to treat Staphylococcus aureus infections, but this study demonstrates that physicians don’t necessarily need to switch to these new drugs when the MIC is increased but still within the susceptible range.”

“The prevention of a rapid switch to newer drugs has another great benefit to our patients—less unnecessary exposure to these drugs, which will translate into less development of antibiotic resistance.”

Dr Kalil said the study may have implications for clinical practice and public health.

The results suggest standards for vancomycin MIC likely do not need to be lowered, routine differentiation of MIC values between 1 mg/L and 2 mg/L appears unnecessary, and the use of alternative drugs may not be required for Staphylococcus aureus isolates with elevated but susceptible vancomycin MIC values. ![]()

Staphylococcus

infectionCredit: Bill Branson

New research suggests the antibiotic vancomycin is still effective in treating Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream (SAB) infections, despite increases in minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values.

Researchers found no difference in mortality between patients with low-vancomycin MIC and those with high-vancomycin MIC.

So it seems physicians can continue using vancomycin when MIC values are elevated but within the susceptible range, rather than

switching to newer antibiotics.

Andre Kalil, MD, of the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, and his colleagues described this research in JAMA.

In recent years, physicians treating Staphylococcus infections with vancomycin have seen an increase in the MIC, the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial agent that inhibits the growth of a microorganism.

MIC values lower than 4 mg/L suggest Staphylococcus is susceptible to vancomycin. However, when the MIC value exceeds 1.5 mg/L, some physicians have taken it as an indication that vancomycin may not be working at maximum effectiveness.

Some reports have suggested that elevations in vancomycin MIC values may be associated with increased treatment failure and death.

To determine the effectiveness of vancomycin, Dr Kalil and his colleagues analyzed data from 38 studies covering 8291 episodes of SAB infection.

The team evaluated the association between vancomycin MIC elevation and mortality. Among all SAB infections studied, the overall mortality was 26.1%.

The adjusted absolute risk of mortality did not differ significantly between patients with high-vancomycin MIC and those with low-vancomycin MIC—26.8% and 25.8%, respectively.

In studies that included only methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections, the mortality among SAB episodes in patients with high-vancomycin MIC was 27.6%, compared with a mortality of 27.4% among patients with low-vancomycin MIC.

“The study provides strong evidence that vancomycin remains highly useful,” Dr Kalil said. “Even though vancomycin is an older drug, it is still killing staph very efficiently. There are newer antibiotics available to treat Staphylococcus aureus infections, but this study demonstrates that physicians don’t necessarily need to switch to these new drugs when the MIC is increased but still within the susceptible range.”

“The prevention of a rapid switch to newer drugs has another great benefit to our patients—less unnecessary exposure to these drugs, which will translate into less development of antibiotic resistance.”

Dr Kalil said the study may have implications for clinical practice and public health.

The results suggest standards for vancomycin MIC likely do not need to be lowered, routine differentiation of MIC values between 1 mg/L and 2 mg/L appears unnecessary, and the use of alternative drugs may not be required for Staphylococcus aureus isolates with elevated but susceptible vancomycin MIC values. ![]()

Staphylococcus

infectionCredit: Bill Branson

New research suggests the antibiotic vancomycin is still effective in treating Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream (SAB) infections, despite increases in minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values.

Researchers found no difference in mortality between patients with low-vancomycin MIC and those with high-vancomycin MIC.

So it seems physicians can continue using vancomycin when MIC values are elevated but within the susceptible range, rather than

switching to newer antibiotics.

Andre Kalil, MD, of the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, and his colleagues described this research in JAMA.

In recent years, physicians treating Staphylococcus infections with vancomycin have seen an increase in the MIC, the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial agent that inhibits the growth of a microorganism.

MIC values lower than 4 mg/L suggest Staphylococcus is susceptible to vancomycin. However, when the MIC value exceeds 1.5 mg/L, some physicians have taken it as an indication that vancomycin may not be working at maximum effectiveness.

Some reports have suggested that elevations in vancomycin MIC values may be associated with increased treatment failure and death.

To determine the effectiveness of vancomycin, Dr Kalil and his colleagues analyzed data from 38 studies covering 8291 episodes of SAB infection.

The team evaluated the association between vancomycin MIC elevation and mortality. Among all SAB infections studied, the overall mortality was 26.1%.

The adjusted absolute risk of mortality did not differ significantly between patients with high-vancomycin MIC and those with low-vancomycin MIC—26.8% and 25.8%, respectively.

In studies that included only methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections, the mortality among SAB episodes in patients with high-vancomycin MIC was 27.6%, compared with a mortality of 27.4% among patients with low-vancomycin MIC.

“The study provides strong evidence that vancomycin remains highly useful,” Dr Kalil said. “Even though vancomycin is an older drug, it is still killing staph very efficiently. There are newer antibiotics available to treat Staphylococcus aureus infections, but this study demonstrates that physicians don’t necessarily need to switch to these new drugs when the MIC is increased but still within the susceptible range.”

“The prevention of a rapid switch to newer drugs has another great benefit to our patients—less unnecessary exposure to these drugs, which will translate into less development of antibiotic resistance.”

Dr Kalil said the study may have implications for clinical practice and public health.

The results suggest standards for vancomycin MIC likely do not need to be lowered, routine differentiation of MIC values between 1 mg/L and 2 mg/L appears unnecessary, and the use of alternative drugs may not be required for Staphylococcus aureus isolates with elevated but susceptible vancomycin MIC values. ![]()

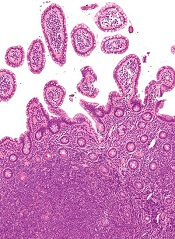

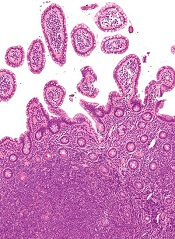

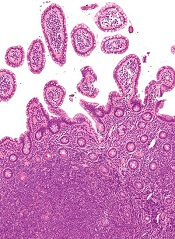

New insight into T-cell development

Credit: NIAID

A fundamental theory about how the thymus “educates” T cells appears to be wrong, according to research published in Nature Communications.

It’s known that stem cells leave the bone marrow and travel to the thymus to become one of two CD4 T-cell types: effector cells or regulatory T cells (Tregs).

One widely held concept of why the cells become one type or the other is that they are exposed to different ligands in the thymus, said Leszek Ignatowicz, PhD, of Georgia Regents University in Augusta.

But when he and his colleagues limited the cells’ exposure to only one ligand, the same mix of T cells still emerged.

“We asked a simple question, ‘Is it going to affect their development,’ and the answer was ‘no,’” Dr Ignatowicz said. “The cells still mature in the thymus, so something else must be determining it.”

The finding provides more insight into immunity that could one day enable a new approach to vaccines that steer the thymus to produce more of whatever T-cell type a patient needs: more effector cells if they have an infection or cancer, more Tregs if they have autoimmune diseases such as arthritis and multiple sclerosis.

“We could help steer the education process in the desired direction,” Dr Ignatowicz said.

To uncover their findings, he and his colleagues studied two types of mice, each expressing a single ligand in the thymus. The researchers thought one would prompt strong ligand binding and favor Treg development, and the other would favor a weaker ligand bond and effector cell development.

The mix of resulting T cells was the same as if both were exposed to the usual thousands of ligands, although the experiment did reveal one difference.

Ligands—and, eventually, bacteria and other invaders—get the attention of T cells by activating their receptors. Both CD4 T-cell types generally have the same receptors, but they are organized differently.

The researchers found that as long as the binding was weak, as it was in the first mouse, there was a lot of overlap in the receptors the ligand bound to in both T-cell types. However, in the second mouse, where the ligand prompted strong binding, there was far less overlap.

“We are now trying to find what causes that difference,” Dr Ignatowicz said. ![]()

Credit: NIAID

A fundamental theory about how the thymus “educates” T cells appears to be wrong, according to research published in Nature Communications.

It’s known that stem cells leave the bone marrow and travel to the thymus to become one of two CD4 T-cell types: effector cells or regulatory T cells (Tregs).

One widely held concept of why the cells become one type or the other is that they are exposed to different ligands in the thymus, said Leszek Ignatowicz, PhD, of Georgia Regents University in Augusta.

But when he and his colleagues limited the cells’ exposure to only one ligand, the same mix of T cells still emerged.

“We asked a simple question, ‘Is it going to affect their development,’ and the answer was ‘no,’” Dr Ignatowicz said. “The cells still mature in the thymus, so something else must be determining it.”

The finding provides more insight into immunity that could one day enable a new approach to vaccines that steer the thymus to produce more of whatever T-cell type a patient needs: more effector cells if they have an infection or cancer, more Tregs if they have autoimmune diseases such as arthritis and multiple sclerosis.

“We could help steer the education process in the desired direction,” Dr Ignatowicz said.

To uncover their findings, he and his colleagues studied two types of mice, each expressing a single ligand in the thymus. The researchers thought one would prompt strong ligand binding and favor Treg development, and the other would favor a weaker ligand bond and effector cell development.

The mix of resulting T cells was the same as if both were exposed to the usual thousands of ligands, although the experiment did reveal one difference.

Ligands—and, eventually, bacteria and other invaders—get the attention of T cells by activating their receptors. Both CD4 T-cell types generally have the same receptors, but they are organized differently.

The researchers found that as long as the binding was weak, as it was in the first mouse, there was a lot of overlap in the receptors the ligand bound to in both T-cell types. However, in the second mouse, where the ligand prompted strong binding, there was far less overlap.

“We are now trying to find what causes that difference,” Dr Ignatowicz said. ![]()

Credit: NIAID

A fundamental theory about how the thymus “educates” T cells appears to be wrong, according to research published in Nature Communications.

It’s known that stem cells leave the bone marrow and travel to the thymus to become one of two CD4 T-cell types: effector cells or regulatory T cells (Tregs).

One widely held concept of why the cells become one type or the other is that they are exposed to different ligands in the thymus, said Leszek Ignatowicz, PhD, of Georgia Regents University in Augusta.

But when he and his colleagues limited the cells’ exposure to only one ligand, the same mix of T cells still emerged.

“We asked a simple question, ‘Is it going to affect their development,’ and the answer was ‘no,’” Dr Ignatowicz said. “The cells still mature in the thymus, so something else must be determining it.”

The finding provides more insight into immunity that could one day enable a new approach to vaccines that steer the thymus to produce more of whatever T-cell type a patient needs: more effector cells if they have an infection or cancer, more Tregs if they have autoimmune diseases such as arthritis and multiple sclerosis.

“We could help steer the education process in the desired direction,” Dr Ignatowicz said.

To uncover their findings, he and his colleagues studied two types of mice, each expressing a single ligand in the thymus. The researchers thought one would prompt strong ligand binding and favor Treg development, and the other would favor a weaker ligand bond and effector cell development.

The mix of resulting T cells was the same as if both were exposed to the usual thousands of ligands, although the experiment did reveal one difference.

Ligands—and, eventually, bacteria and other invaders—get the attention of T cells by activating their receptors. Both CD4 T-cell types generally have the same receptors, but they are organized differently.