User login

Interventions Effective in Preventing Hospital Readmissions

Clinical question: Which interventions are most effective to prevent 30-day readmissions in medical or surgical patients?

Background: Preventing early readmissions has become a national priority. This study set out to determine which intervention had the largest impact on the prevention of early readmission.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Forty-seven studies in multiple locations.

Synopsis: This study evaluated 47 randomized trials that assessed the effectiveness of peri-discharge interventions on the risk of all-cause or unplanned 30-day readmissions for medical and surgical patients. Outcomes included unplanned readmissions, all-cause readmissions, and a composite of unplanned and all-cause readmissions plus out-of-hospital deaths.

The included studies reported up to seven methods of preventing readmissions, including involvement of case management, home visits, education of patients, and self-care support. In 42 trials reporting readmission rates, the pooled relative risk of readmission was 0.82 (95 % CI, 0.73-0.91; P<0.001) within 30 days.

Multiple subgroup analyses noted that the most effective interventions on hospital readmission were those that were more complex and those that sought to augment patient capacity to access and enact dependable post-discharge care.

Limitations included single-center academic studies, lack of standard for dealing with missing data, existence of publication bias, and differing methods used to evaluate intervention effects.

Bottom line: This study was the largest of its kind, to date, and suggests that the interventions analyzed in this study, although complex (e.g. enhancing capacity for self-care at home), were efficacious in reducing 30-day readmissions.

Citation: Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095-1107.

Clinical question: Which interventions are most effective to prevent 30-day readmissions in medical or surgical patients?

Background: Preventing early readmissions has become a national priority. This study set out to determine which intervention had the largest impact on the prevention of early readmission.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Forty-seven studies in multiple locations.

Synopsis: This study evaluated 47 randomized trials that assessed the effectiveness of peri-discharge interventions on the risk of all-cause or unplanned 30-day readmissions for medical and surgical patients. Outcomes included unplanned readmissions, all-cause readmissions, and a composite of unplanned and all-cause readmissions plus out-of-hospital deaths.

The included studies reported up to seven methods of preventing readmissions, including involvement of case management, home visits, education of patients, and self-care support. In 42 trials reporting readmission rates, the pooled relative risk of readmission was 0.82 (95 % CI, 0.73-0.91; P<0.001) within 30 days.

Multiple subgroup analyses noted that the most effective interventions on hospital readmission were those that were more complex and those that sought to augment patient capacity to access and enact dependable post-discharge care.

Limitations included single-center academic studies, lack of standard for dealing with missing data, existence of publication bias, and differing methods used to evaluate intervention effects.

Bottom line: This study was the largest of its kind, to date, and suggests that the interventions analyzed in this study, although complex (e.g. enhancing capacity for self-care at home), were efficacious in reducing 30-day readmissions.

Citation: Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095-1107.

Clinical question: Which interventions are most effective to prevent 30-day readmissions in medical or surgical patients?

Background: Preventing early readmissions has become a national priority. This study set out to determine which intervention had the largest impact on the prevention of early readmission.

Study design: Meta-analysis.

Setting: Forty-seven studies in multiple locations.

Synopsis: This study evaluated 47 randomized trials that assessed the effectiveness of peri-discharge interventions on the risk of all-cause or unplanned 30-day readmissions for medical and surgical patients. Outcomes included unplanned readmissions, all-cause readmissions, and a composite of unplanned and all-cause readmissions plus out-of-hospital deaths.

The included studies reported up to seven methods of preventing readmissions, including involvement of case management, home visits, education of patients, and self-care support. In 42 trials reporting readmission rates, the pooled relative risk of readmission was 0.82 (95 % CI, 0.73-0.91; P<0.001) within 30 days.

Multiple subgroup analyses noted that the most effective interventions on hospital readmission were those that were more complex and those that sought to augment patient capacity to access and enact dependable post-discharge care.

Limitations included single-center academic studies, lack of standard for dealing with missing data, existence of publication bias, and differing methods used to evaluate intervention effects.

Bottom line: This study was the largest of its kind, to date, and suggests that the interventions analyzed in this study, although complex (e.g. enhancing capacity for self-care at home), were efficacious in reducing 30-day readmissions.

Citation: Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095-1107.

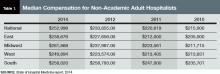

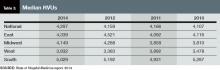

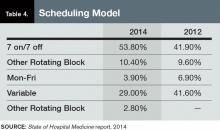

New State of Hospital Medicine Report Better Than Ever

For the last six months or so, not a week has gone by in which someone hasn’t asked me when the new SHM survey report will be released. The anticipation level is high, and rightly so. This will be the first new look at hospitalist practice characteristics in two years, and boy, have they been an eventful two years!

On behalf of SHM and the SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC), I’m thrilled to introduce SHM’s 2014 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SOHM) and the resumption of the monthly “Survey Insights” article written by PAC members. Here are a few key things you should know about the new SOHM report:

- The content is more wide-ranging than ever. SHM leaves the collection of hospitalist compensation and productivity data to the Medical Group Management Association—SHM licenses compensation and production data from MGMA and has incorporated it into the new SOHM report—but covers just about every other aspect of hospitalist group structure and operations imaginable. In addition to traditional questions regarding scope of services, staffing and scheduling models, and financial support, this year’s report includes new information about hospitalist back-up staffing plans, how academic hospitalist time is allocated, accountable care organization participation, electronic health record use, and the presence of other hospital-focused practice specialties.

—Leslie Flores, MHA

- The number of survey participants is larger than ever. This year SHM received eligible responses from 499 different hospitalist groups, an increase of about 7% over 2012. Respondents continue to represent all employer/ownership models and geographic regions, in roughly similar proportions to previous surveys. And we continue to get good participation by both academic and nonacademic hospital medicine groups. This means we have more—and more reliable—information than ever for different subgroups of hospitalists.

- The report is more accessible and easier to read than it has ever been. This year SHM has produced the SOHM report in full color, with professional layout and graphics; it’s a pleasure to read compared to previous versions. And, for the first time, SHM is making available a web-based version of the full report, so that you can refer to it anywhere and at any time.

As a consultant, I refer to my copy of the SOHM report almost every day and find it indispensable as a source of context when offering advice to my clients. And I’m always interested to see the diverse ways in which hospitalist groups across the country use survey information to make decisions about how to run their practices and to explain their environments to hospital leaders and other stakeholders.

I encourage you to obtain a copy of the SOHM report and review it carefully; you’ll almost certainly find more than one interesting and useful tidbit of information. Use the report to assess how your practice compares to your peers, but always keep in mind that surveys don’t tell you what should be—they only tell you what currently is. New best practices not reflected in survey data are emerging all the time, and the ways others do things won’t always be right for your group’s unique situation and needs. Whether you are partners or employees, you and your colleagues “own” the success of your practice and are the best judges of what is right for you.

Leslie Flores is a PAC member and partner of Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants.

For the last six months or so, not a week has gone by in which someone hasn’t asked me when the new SHM survey report will be released. The anticipation level is high, and rightly so. This will be the first new look at hospitalist practice characteristics in two years, and boy, have they been an eventful two years!

On behalf of SHM and the SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC), I’m thrilled to introduce SHM’s 2014 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SOHM) and the resumption of the monthly “Survey Insights” article written by PAC members. Here are a few key things you should know about the new SOHM report:

- The content is more wide-ranging than ever. SHM leaves the collection of hospitalist compensation and productivity data to the Medical Group Management Association—SHM licenses compensation and production data from MGMA and has incorporated it into the new SOHM report—but covers just about every other aspect of hospitalist group structure and operations imaginable. In addition to traditional questions regarding scope of services, staffing and scheduling models, and financial support, this year’s report includes new information about hospitalist back-up staffing plans, how academic hospitalist time is allocated, accountable care organization participation, electronic health record use, and the presence of other hospital-focused practice specialties.

—Leslie Flores, MHA

- The number of survey participants is larger than ever. This year SHM received eligible responses from 499 different hospitalist groups, an increase of about 7% over 2012. Respondents continue to represent all employer/ownership models and geographic regions, in roughly similar proportions to previous surveys. And we continue to get good participation by both academic and nonacademic hospital medicine groups. This means we have more—and more reliable—information than ever for different subgroups of hospitalists.

- The report is more accessible and easier to read than it has ever been. This year SHM has produced the SOHM report in full color, with professional layout and graphics; it’s a pleasure to read compared to previous versions. And, for the first time, SHM is making available a web-based version of the full report, so that you can refer to it anywhere and at any time.

As a consultant, I refer to my copy of the SOHM report almost every day and find it indispensable as a source of context when offering advice to my clients. And I’m always interested to see the diverse ways in which hospitalist groups across the country use survey information to make decisions about how to run their practices and to explain their environments to hospital leaders and other stakeholders.

I encourage you to obtain a copy of the SOHM report and review it carefully; you’ll almost certainly find more than one interesting and useful tidbit of information. Use the report to assess how your practice compares to your peers, but always keep in mind that surveys don’t tell you what should be—they only tell you what currently is. New best practices not reflected in survey data are emerging all the time, and the ways others do things won’t always be right for your group’s unique situation and needs. Whether you are partners or employees, you and your colleagues “own” the success of your practice and are the best judges of what is right for you.

Leslie Flores is a PAC member and partner of Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants.

For the last six months or so, not a week has gone by in which someone hasn’t asked me when the new SHM survey report will be released. The anticipation level is high, and rightly so. This will be the first new look at hospitalist practice characteristics in two years, and boy, have they been an eventful two years!

On behalf of SHM and the SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC), I’m thrilled to introduce SHM’s 2014 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SOHM) and the resumption of the monthly “Survey Insights” article written by PAC members. Here are a few key things you should know about the new SOHM report:

- The content is more wide-ranging than ever. SHM leaves the collection of hospitalist compensation and productivity data to the Medical Group Management Association—SHM licenses compensation and production data from MGMA and has incorporated it into the new SOHM report—but covers just about every other aspect of hospitalist group structure and operations imaginable. In addition to traditional questions regarding scope of services, staffing and scheduling models, and financial support, this year’s report includes new information about hospitalist back-up staffing plans, how academic hospitalist time is allocated, accountable care organization participation, electronic health record use, and the presence of other hospital-focused practice specialties.

—Leslie Flores, MHA

- The number of survey participants is larger than ever. This year SHM received eligible responses from 499 different hospitalist groups, an increase of about 7% over 2012. Respondents continue to represent all employer/ownership models and geographic regions, in roughly similar proportions to previous surveys. And we continue to get good participation by both academic and nonacademic hospital medicine groups. This means we have more—and more reliable—information than ever for different subgroups of hospitalists.

- The report is more accessible and easier to read than it has ever been. This year SHM has produced the SOHM report in full color, with professional layout and graphics; it’s a pleasure to read compared to previous versions. And, for the first time, SHM is making available a web-based version of the full report, so that you can refer to it anywhere and at any time.

As a consultant, I refer to my copy of the SOHM report almost every day and find it indispensable as a source of context when offering advice to my clients. And I’m always interested to see the diverse ways in which hospitalist groups across the country use survey information to make decisions about how to run their practices and to explain their environments to hospital leaders and other stakeholders.

I encourage you to obtain a copy of the SOHM report and review it carefully; you’ll almost certainly find more than one interesting and useful tidbit of information. Use the report to assess how your practice compares to your peers, but always keep in mind that surveys don’t tell you what should be—they only tell you what currently is. New best practices not reflected in survey data are emerging all the time, and the ways others do things won’t always be right for your group’s unique situation and needs. Whether you are partners or employees, you and your colleagues “own” the success of your practice and are the best judges of what is right for you.

Leslie Flores is a PAC member and partner of Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants.

9 Ways Hospitals Can Use Electronic Health Records to Reduce Readmissions

Editor’s note: Second in a two-part series from SHM’s Information Technology committee offering practical recommendations for improving electronic health records (EHRs) to reduce readmissions. The first article appeared in the September issue of The Hospitalist.

Discharge Coach

Recommendation: Use EHR workflows to support discharge coaches.

David Ling, MD, is the chief medical information officer at Mary Washington Healthcare in Fredericksburg, Va. His team has applied Project Red functionality to use discharge coaches to improve transitions with EHR support. This intervention reduced readmissions to 7% from 11% from 2011 to 2012; there were no other initiatives during this time.

During this trial, a nurse functioned as discharge advocate, and clinical pharmacists called the patients within 72 hours of discharge. Nursing discharge advocates arranged follow-up appointments, reviewed medication reconciliation, and conducted patient education.

Patients were triaged to the service based on a diagnosis of heart failure, pneumonia, MI, or LACE (length of stay, acuity of admission, Charlson index [modified], number of ER visits in the last six months) risk stratification score greater than eight. The discharge advocate then reviewed prior encounters and determined educational needs.

Patient education was handled using care notes. The discharge advocate was the last person to review the discharge medication list. Pending labs were populated by the discharge advocate.

EHR support of this process required putting all of the discharge-related information in one spot in the EHR to make sure that all processes were completed by the multidisciplinary team prior to discharge.

—Noah Finkel, MD, FHM, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center

Patient-Centric Discharge Instructions

Recommendation: Support EHR build, create patient-centric multidisciplinary discharge paperwork.

At Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass., Noah Finkel, MD, and his colleague, Daniela Urma, MD, knew they had a problem with discharge. Paperwork and medication lists were incomplete and illegible. They knew they could not wait until the transition to Epic EHR to solve their problems.

In-house technical expertise created a program called “discharge assistant.” Discharge instructions are added to a common form for all members of the multidisciplinary team. A discharge medication list is imported at discharge from the outpatient EHR. The program allows the provider to note whether a medication is new, changed, or the same, and to add comments and indications to each medication. All of the standard elements of discharge planning are included (i.e., diet, wound care, return to work, diagnosis list, and who to call for specific problems).

The form cannot be completed and printed without all of the required elements included. The primary benefits of this program are legibility, completeness, and multidisciplinary data entry.

Coordination of Post-Discharge Appointments and Tests Prior to Discharge

Recommendation: Support coordination of care with electronic means of scheduling post-discharge care prior to discharge.

Aroop Pal, MD, FACP, FHM, program director of the Transitions of Care Services at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, knows that there are many barriers to coordination of care with outside providers prior to discharge. If patients are discharged during normal business hours, the discharging provider may have to schedule these appointments and tests. A patient discharged after hours may be sent back to his or her PCP with a note requesting specific follow-ups.

Kansas University initiatives to improve scheduling have allowed its team to keep readmission rates below 13%, despite being the primary teaching hospital for the state of Kansas.

The process involved submission of scheduling requests, via EHR, to dedicated schedulers who would make the appointments in real time. The schedulers would notify the primary team, who would communicate with the patient. This system reduced the time to make the appointment and improved scheduler and physician satisfaction.

Medication Compliance after Discharge

Recommendation: Reduce technical and financial barriers to communication of medication list and medication compliance at home.

Sriram Vissa, MD, FACP, FHM, is medical director for informatics and co-practice group leader of the hospitalists for DePaul Hospital, SSM Healthcare, in Bridgeton, Mo. His hospital has improved medication compliance through improved medication reconciliation, improved clarity of discharge instructions, and better pharmacy integration. These interventions and others have reduced readmission rates to 12.81% at 30 days.

Barriers to compliance include procurement, financial issues, health literacy, clarity of instructions, medication lists to primary physicians, and patient portals. The EHR allows insurance integration to make sure that the patient can afford the prescribed medication An electronic connection to an on-site pharmacy makes sure that medications are delivered to the patient’s room prior to discharge. Medication lists are routed to PCPs via continuity of care functionality, which complies with meaningful use stage 2.

Also, the patient portal allows inpatient providers to ask questions about medications or discharge instructions.

Dr. Finkel is a hospitalist at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass., and a member of SHM’s Health IT Committee.

Editor’s note: Second in a two-part series from SHM’s Information Technology committee offering practical recommendations for improving electronic health records (EHRs) to reduce readmissions. The first article appeared in the September issue of The Hospitalist.

Discharge Coach

Recommendation: Use EHR workflows to support discharge coaches.

David Ling, MD, is the chief medical information officer at Mary Washington Healthcare in Fredericksburg, Va. His team has applied Project Red functionality to use discharge coaches to improve transitions with EHR support. This intervention reduced readmissions to 7% from 11% from 2011 to 2012; there were no other initiatives during this time.

During this trial, a nurse functioned as discharge advocate, and clinical pharmacists called the patients within 72 hours of discharge. Nursing discharge advocates arranged follow-up appointments, reviewed medication reconciliation, and conducted patient education.

Patients were triaged to the service based on a diagnosis of heart failure, pneumonia, MI, or LACE (length of stay, acuity of admission, Charlson index [modified], number of ER visits in the last six months) risk stratification score greater than eight. The discharge advocate then reviewed prior encounters and determined educational needs.

Patient education was handled using care notes. The discharge advocate was the last person to review the discharge medication list. Pending labs were populated by the discharge advocate.

EHR support of this process required putting all of the discharge-related information in one spot in the EHR to make sure that all processes were completed by the multidisciplinary team prior to discharge.

—Noah Finkel, MD, FHM, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center

Patient-Centric Discharge Instructions

Recommendation: Support EHR build, create patient-centric multidisciplinary discharge paperwork.

At Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass., Noah Finkel, MD, and his colleague, Daniela Urma, MD, knew they had a problem with discharge. Paperwork and medication lists were incomplete and illegible. They knew they could not wait until the transition to Epic EHR to solve their problems.

In-house technical expertise created a program called “discharge assistant.” Discharge instructions are added to a common form for all members of the multidisciplinary team. A discharge medication list is imported at discharge from the outpatient EHR. The program allows the provider to note whether a medication is new, changed, or the same, and to add comments and indications to each medication. All of the standard elements of discharge planning are included (i.e., diet, wound care, return to work, diagnosis list, and who to call for specific problems).

The form cannot be completed and printed without all of the required elements included. The primary benefits of this program are legibility, completeness, and multidisciplinary data entry.

Coordination of Post-Discharge Appointments and Tests Prior to Discharge

Recommendation: Support coordination of care with electronic means of scheduling post-discharge care prior to discharge.

Aroop Pal, MD, FACP, FHM, program director of the Transitions of Care Services at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, knows that there are many barriers to coordination of care with outside providers prior to discharge. If patients are discharged during normal business hours, the discharging provider may have to schedule these appointments and tests. A patient discharged after hours may be sent back to his or her PCP with a note requesting specific follow-ups.

Kansas University initiatives to improve scheduling have allowed its team to keep readmission rates below 13%, despite being the primary teaching hospital for the state of Kansas.

The process involved submission of scheduling requests, via EHR, to dedicated schedulers who would make the appointments in real time. The schedulers would notify the primary team, who would communicate with the patient. This system reduced the time to make the appointment and improved scheduler and physician satisfaction.

Medication Compliance after Discharge

Recommendation: Reduce technical and financial barriers to communication of medication list and medication compliance at home.

Sriram Vissa, MD, FACP, FHM, is medical director for informatics and co-practice group leader of the hospitalists for DePaul Hospital, SSM Healthcare, in Bridgeton, Mo. His hospital has improved medication compliance through improved medication reconciliation, improved clarity of discharge instructions, and better pharmacy integration. These interventions and others have reduced readmission rates to 12.81% at 30 days.

Barriers to compliance include procurement, financial issues, health literacy, clarity of instructions, medication lists to primary physicians, and patient portals. The EHR allows insurance integration to make sure that the patient can afford the prescribed medication An electronic connection to an on-site pharmacy makes sure that medications are delivered to the patient’s room prior to discharge. Medication lists are routed to PCPs via continuity of care functionality, which complies with meaningful use stage 2.

Also, the patient portal allows inpatient providers to ask questions about medications or discharge instructions.

Dr. Finkel is a hospitalist at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass., and a member of SHM’s Health IT Committee.

Editor’s note: Second in a two-part series from SHM’s Information Technology committee offering practical recommendations for improving electronic health records (EHRs) to reduce readmissions. The first article appeared in the September issue of The Hospitalist.

Discharge Coach

Recommendation: Use EHR workflows to support discharge coaches.

David Ling, MD, is the chief medical information officer at Mary Washington Healthcare in Fredericksburg, Va. His team has applied Project Red functionality to use discharge coaches to improve transitions with EHR support. This intervention reduced readmissions to 7% from 11% from 2011 to 2012; there were no other initiatives during this time.

During this trial, a nurse functioned as discharge advocate, and clinical pharmacists called the patients within 72 hours of discharge. Nursing discharge advocates arranged follow-up appointments, reviewed medication reconciliation, and conducted patient education.

Patients were triaged to the service based on a diagnosis of heart failure, pneumonia, MI, or LACE (length of stay, acuity of admission, Charlson index [modified], number of ER visits in the last six months) risk stratification score greater than eight. The discharge advocate then reviewed prior encounters and determined educational needs.

Patient education was handled using care notes. The discharge advocate was the last person to review the discharge medication list. Pending labs were populated by the discharge advocate.

EHR support of this process required putting all of the discharge-related information in one spot in the EHR to make sure that all processes were completed by the multidisciplinary team prior to discharge.

—Noah Finkel, MD, FHM, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center

Patient-Centric Discharge Instructions

Recommendation: Support EHR build, create patient-centric multidisciplinary discharge paperwork.

At Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass., Noah Finkel, MD, and his colleague, Daniela Urma, MD, knew they had a problem with discharge. Paperwork and medication lists were incomplete and illegible. They knew they could not wait until the transition to Epic EHR to solve their problems.

In-house technical expertise created a program called “discharge assistant.” Discharge instructions are added to a common form for all members of the multidisciplinary team. A discharge medication list is imported at discharge from the outpatient EHR. The program allows the provider to note whether a medication is new, changed, or the same, and to add comments and indications to each medication. All of the standard elements of discharge planning are included (i.e., diet, wound care, return to work, diagnosis list, and who to call for specific problems).

The form cannot be completed and printed without all of the required elements included. The primary benefits of this program are legibility, completeness, and multidisciplinary data entry.

Coordination of Post-Discharge Appointments and Tests Prior to Discharge

Recommendation: Support coordination of care with electronic means of scheduling post-discharge care prior to discharge.

Aroop Pal, MD, FACP, FHM, program director of the Transitions of Care Services at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, knows that there are many barriers to coordination of care with outside providers prior to discharge. If patients are discharged during normal business hours, the discharging provider may have to schedule these appointments and tests. A patient discharged after hours may be sent back to his or her PCP with a note requesting specific follow-ups.

Kansas University initiatives to improve scheduling have allowed its team to keep readmission rates below 13%, despite being the primary teaching hospital for the state of Kansas.

The process involved submission of scheduling requests, via EHR, to dedicated schedulers who would make the appointments in real time. The schedulers would notify the primary team, who would communicate with the patient. This system reduced the time to make the appointment and improved scheduler and physician satisfaction.

Medication Compliance after Discharge

Recommendation: Reduce technical and financial barriers to communication of medication list and medication compliance at home.

Sriram Vissa, MD, FACP, FHM, is medical director for informatics and co-practice group leader of the hospitalists for DePaul Hospital, SSM Healthcare, in Bridgeton, Mo. His hospital has improved medication compliance through improved medication reconciliation, improved clarity of discharge instructions, and better pharmacy integration. These interventions and others have reduced readmission rates to 12.81% at 30 days.

Barriers to compliance include procurement, financial issues, health literacy, clarity of instructions, medication lists to primary physicians, and patient portals. The EHR allows insurance integration to make sure that the patient can afford the prescribed medication An electronic connection to an on-site pharmacy makes sure that medications are delivered to the patient’s room prior to discharge. Medication lists are routed to PCPs via continuity of care functionality, which complies with meaningful use stage 2.

Also, the patient portal allows inpatient providers to ask questions about medications or discharge instructions.

Dr. Finkel is a hospitalist at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass., and a member of SHM’s Health IT Committee.

Society of Hospital Medicine Event Dates, Deadlines

Nov. 3-6

Leadership Academy

Demand continues for SHM’s Leadership Academy in Honolulu. The first course, “Leadership Foundations,” is sold out, but (as of press time) registration is still open for the Advanced Leadership courses: “Influential Management” and “Mastering Teamwork.”

SHM also is accepting registrations to be placed on a waiting list for “Leadership Foundations.”

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership.

Dec. 17

Master in Hospital Medicine

The Master in Hospital Medicine (MHM) designation is the “Hall of Fame” for the specialty. Do you know a hospitalist who deserves the designation? Make sure your nomination is in by December 17.

To submit a nomination, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/fellows.

Jan. 9, 2015

Deadline for FHM, SFHM Application

It’s not too early to start working on your FHM or SFHM applications. Applications require letters of recommendation and self-assessments, so procrastinators might find themselves missing the deadline.

Feb. 2, 2015

Early Registration Deadline for HM15

Start planning today for Hospital Medicine 2015 in National Harbor, Md., just minutes from Washington, D.C. HM15 will set the stage for all of hospital medicine next year and will include new educational sessions specifically geared toward medical students, residents, and hospitalists just starting their careers.

During the annual meeting, SHM will be organizing its next “Hospitalists on the Hill” event, in which a delegation of hospitalists will talk with lawmakers in Congress about the policies that affect care for hospitalized patients. To register: www.hospitalmedicine2015.org.

Nov. 3-6

Leadership Academy

Demand continues for SHM’s Leadership Academy in Honolulu. The first course, “Leadership Foundations,” is sold out, but (as of press time) registration is still open for the Advanced Leadership courses: “Influential Management” and “Mastering Teamwork.”

SHM also is accepting registrations to be placed on a waiting list for “Leadership Foundations.”

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership.

Dec. 17

Master in Hospital Medicine

The Master in Hospital Medicine (MHM) designation is the “Hall of Fame” for the specialty. Do you know a hospitalist who deserves the designation? Make sure your nomination is in by December 17.

To submit a nomination, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/fellows.

Jan. 9, 2015

Deadline for FHM, SFHM Application

It’s not too early to start working on your FHM or SFHM applications. Applications require letters of recommendation and self-assessments, so procrastinators might find themselves missing the deadline.

Feb. 2, 2015

Early Registration Deadline for HM15

Start planning today for Hospital Medicine 2015 in National Harbor, Md., just minutes from Washington, D.C. HM15 will set the stage for all of hospital medicine next year and will include new educational sessions specifically geared toward medical students, residents, and hospitalists just starting their careers.

During the annual meeting, SHM will be organizing its next “Hospitalists on the Hill” event, in which a delegation of hospitalists will talk with lawmakers in Congress about the policies that affect care for hospitalized patients. To register: www.hospitalmedicine2015.org.

Nov. 3-6

Leadership Academy

Demand continues for SHM’s Leadership Academy in Honolulu. The first course, “Leadership Foundations,” is sold out, but (as of press time) registration is still open for the Advanced Leadership courses: “Influential Management” and “Mastering Teamwork.”

SHM also is accepting registrations to be placed on a waiting list for “Leadership Foundations.”

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/leadership.

Dec. 17

Master in Hospital Medicine

The Master in Hospital Medicine (MHM) designation is the “Hall of Fame” for the specialty. Do you know a hospitalist who deserves the designation? Make sure your nomination is in by December 17.

To submit a nomination, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/fellows.

Jan. 9, 2015

Deadline for FHM, SFHM Application

It’s not too early to start working on your FHM or SFHM applications. Applications require letters of recommendation and self-assessments, so procrastinators might find themselves missing the deadline.

Feb. 2, 2015

Early Registration Deadline for HM15

Start planning today for Hospital Medicine 2015 in National Harbor, Md., just minutes from Washington, D.C. HM15 will set the stage for all of hospital medicine next year and will include new educational sessions specifically geared toward medical students, residents, and hospitalists just starting their careers.

During the annual meeting, SHM will be organizing its next “Hospitalists on the Hill” event, in which a delegation of hospitalists will talk with lawmakers in Congress about the policies that affect care for hospitalized patients. To register: www.hospitalmedicine2015.org.

Society of Hospital Medicine Fellows Webinar Available

Interested in becoming a Fellow in Hospital Medicine (FHM) or a Senior Fellow in Hospital Medicine (SFHM) but missed last month’s webinar? It’s now archived at www.hospitalmedicine.org/fellows so you can make your application the best it can be.

Interested in becoming a Fellow in Hospital Medicine (FHM) or a Senior Fellow in Hospital Medicine (SFHM) but missed last month’s webinar? It’s now archived at www.hospitalmedicine.org/fellows so you can make your application the best it can be.

Interested in becoming a Fellow in Hospital Medicine (FHM) or a Senior Fellow in Hospital Medicine (SFHM) but missed last month’s webinar? It’s now archived at www.hospitalmedicine.org/fellows so you can make your application the best it can be.

Society of Hospital Medicine Membership Ambassador Program Offers Perks

Do you know someone who should be a part of the hospital medicine movement but hasn’t joined SHM? Now you can both win: Your colleague can enjoy all the benefits of SHM membership, and you can receive credits against your future dues. Plus, you’ll get the chance to win free registration to HM15.

Now through December 31, all active SHM members can earn dues credits and special recognition for recruiting new physician, allied health, or affiliate members. Active members will be eligible for:

- A $35 credit toward 2015-2016 dues when recruiting one new member;

- A $50 credit toward 2015-2016 dues when recruiting two to four new members;

- A $75 credit toward 2015-2016 dues when recruiting five to nine new members; or

- A $125 credit toward 2015-2016 dues when recruiting 10+ new members.

For EVERY member recruited, individuals will receive one entry into a grand prize drawing to receive complimentary registration to Hospital Medicine 2015 in National Harbor, Md.

For details, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/membership.

Do you know someone who should be a part of the hospital medicine movement but hasn’t joined SHM? Now you can both win: Your colleague can enjoy all the benefits of SHM membership, and you can receive credits against your future dues. Plus, you’ll get the chance to win free registration to HM15.

Now through December 31, all active SHM members can earn dues credits and special recognition for recruiting new physician, allied health, or affiliate members. Active members will be eligible for:

- A $35 credit toward 2015-2016 dues when recruiting one new member;

- A $50 credit toward 2015-2016 dues when recruiting two to four new members;

- A $75 credit toward 2015-2016 dues when recruiting five to nine new members; or

- A $125 credit toward 2015-2016 dues when recruiting 10+ new members.

For EVERY member recruited, individuals will receive one entry into a grand prize drawing to receive complimentary registration to Hospital Medicine 2015 in National Harbor, Md.

For details, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/membership.

Do you know someone who should be a part of the hospital medicine movement but hasn’t joined SHM? Now you can both win: Your colleague can enjoy all the benefits of SHM membership, and you can receive credits against your future dues. Plus, you’ll get the chance to win free registration to HM15.

Now through December 31, all active SHM members can earn dues credits and special recognition for recruiting new physician, allied health, or affiliate members. Active members will be eligible for:

- A $35 credit toward 2015-2016 dues when recruiting one new member;

- A $50 credit toward 2015-2016 dues when recruiting two to four new members;

- A $75 credit toward 2015-2016 dues when recruiting five to nine new members; or

- A $125 credit toward 2015-2016 dues when recruiting 10+ new members.

For EVERY member recruited, individuals will receive one entry into a grand prize drawing to receive complimentary registration to Hospital Medicine 2015 in National Harbor, Md.

For details, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/membership.

Get Involved in Hospital Medicine Movement

As the hospital medicine specialty continues to grow, hospitalists often ask: “How can I get involved?”

Getting involved in the hospital medicine movement and contributing to SHM’s goal of helping hospitalists provide exceptional care to hospitalized patients is easy—and it can start today.

A: Awards

Nominating a colleague—or yourself—for one of SHM’s seven awards is a great way to share your successes with the rest of the specialty. It also generates national recognition for the people and practices that make hospital medicine great.

This year, SHM will be awarding seven awards:

- Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement;

- Excellence in Research;

- Excellence in Hospital Medicine for Non-Physicians;

- Excellence in Teaching;

- Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine;

- Clinical Excellence; and

- Excellence in Humanitarian Services.

Award winners will be recognized onstage at HM15 in National Harbor, Md.

For more information or to nominate yourself or someone else for an award, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/awards. But don’t wait. The deadline for award submissions is Oct. 13.

B: Board

Are you ready to take a national leadership position within hospital medicine? SHM’s board of directors guides the specialty and helps ensure that SHM provides hospitalists with the tools and education they need to be the best caregivers possible.

Any SHM member in good standing is eligible to become a board member. Four seats are open for the three-year term starting in 2015.

Recently, the SHM Board of Directors oversaw the creation and publication of the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group,” a formative set of principles that were published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine and now help hospital medicine groups across the country evaluate their performance.

The board will continue to take on major projects like the key characteristics; if you would like to nominate yourself or someone else, visit the “Board of Directors” section of “About SHM” on www.hospitalmedicine.org.

But don’t wait long. Nominations are due Oct. 22.

C: Committees

Committees are the engines of change for hospital medicine. They guide SHM’s policy initiatives, address pressing quality improvement issues for hospitalists, and serve as the point of engagement for many of SHM’s important audiences, including nurse practitioners, physician assistants, family medicine practitioners, and physicians in training.

With more than 20 committees ranging in topics from information technology to support for SHM’s local chapters, there is bound to be one that could benefit from your passion and expertise.

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/committees.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president for communications.

As the hospital medicine specialty continues to grow, hospitalists often ask: “How can I get involved?”

Getting involved in the hospital medicine movement and contributing to SHM’s goal of helping hospitalists provide exceptional care to hospitalized patients is easy—and it can start today.

A: Awards

Nominating a colleague—or yourself—for one of SHM’s seven awards is a great way to share your successes with the rest of the specialty. It also generates national recognition for the people and practices that make hospital medicine great.

This year, SHM will be awarding seven awards:

- Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement;

- Excellence in Research;

- Excellence in Hospital Medicine for Non-Physicians;

- Excellence in Teaching;

- Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine;

- Clinical Excellence; and

- Excellence in Humanitarian Services.

Award winners will be recognized onstage at HM15 in National Harbor, Md.

For more information or to nominate yourself or someone else for an award, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/awards. But don’t wait. The deadline for award submissions is Oct. 13.

B: Board

Are you ready to take a national leadership position within hospital medicine? SHM’s board of directors guides the specialty and helps ensure that SHM provides hospitalists with the tools and education they need to be the best caregivers possible.

Any SHM member in good standing is eligible to become a board member. Four seats are open for the three-year term starting in 2015.

Recently, the SHM Board of Directors oversaw the creation and publication of the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group,” a formative set of principles that were published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine and now help hospital medicine groups across the country evaluate their performance.

The board will continue to take on major projects like the key characteristics; if you would like to nominate yourself or someone else, visit the “Board of Directors” section of “About SHM” on www.hospitalmedicine.org.

But don’t wait long. Nominations are due Oct. 22.

C: Committees

Committees are the engines of change for hospital medicine. They guide SHM’s policy initiatives, address pressing quality improvement issues for hospitalists, and serve as the point of engagement for many of SHM’s important audiences, including nurse practitioners, physician assistants, family medicine practitioners, and physicians in training.

With more than 20 committees ranging in topics from information technology to support for SHM’s local chapters, there is bound to be one that could benefit from your passion and expertise.

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/committees.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president for communications.

As the hospital medicine specialty continues to grow, hospitalists often ask: “How can I get involved?”

Getting involved in the hospital medicine movement and contributing to SHM’s goal of helping hospitalists provide exceptional care to hospitalized patients is easy—and it can start today.

A: Awards

Nominating a colleague—or yourself—for one of SHM’s seven awards is a great way to share your successes with the rest of the specialty. It also generates national recognition for the people and practices that make hospital medicine great.

This year, SHM will be awarding seven awards:

- Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement;

- Excellence in Research;

- Excellence in Hospital Medicine for Non-Physicians;

- Excellence in Teaching;

- Outstanding Service in Hospital Medicine;

- Clinical Excellence; and

- Excellence in Humanitarian Services.

Award winners will be recognized onstage at HM15 in National Harbor, Md.

For more information or to nominate yourself or someone else for an award, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/awards. But don’t wait. The deadline for award submissions is Oct. 13.

B: Board

Are you ready to take a national leadership position within hospital medicine? SHM’s board of directors guides the specialty and helps ensure that SHM provides hospitalists with the tools and education they need to be the best caregivers possible.

Any SHM member in good standing is eligible to become a board member. Four seats are open for the three-year term starting in 2015.

Recently, the SHM Board of Directors oversaw the creation and publication of the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group,” a formative set of principles that were published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine and now help hospital medicine groups across the country evaluate their performance.

The board will continue to take on major projects like the key characteristics; if you would like to nominate yourself or someone else, visit the “Board of Directors” section of “About SHM” on www.hospitalmedicine.org.

But don’t wait long. Nominations are due Oct. 22.

C: Committees

Committees are the engines of change for hospital medicine. They guide SHM’s policy initiatives, address pressing quality improvement issues for hospitalists, and serve as the point of engagement for many of SHM’s important audiences, including nurse practitioners, physician assistants, family medicine practitioners, and physicians in training.

With more than 20 committees ranging in topics from information technology to support for SHM’s local chapters, there is bound to be one that could benefit from your passion and expertise.

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/committees.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president for communications.

Better Prescription Practices Can Curb Antibiotic Resistance

Overuse of antibiotics is fueling antimicrobial resistance, posing a threat to people around the world and prompting increased attention to antibiotic stewardship practices. Good stewardship requires hospitals and clinicians to adopt coordinated interventions that focus on reducing inappropriate antibiotic prescribing while remaining focused on the health of patients.

Although it can seem overwhelming to physicians with busy workloads and sick patients to engage in these practices, not addressing the issue of responsible antibiotic prescribing is putting patients at risk.

“We know development of resistance is complicated,” says Arjun Srinivasan, MD, FSHEA, associate director for the CDC’s Healthcare Associated Infection Prevention Program and medical director of Get Smart for Healthcare in the CDC’s division of Healthcare Quality Promotion. Dr. Srinivasan is one of the authors of a recent CDC report on antibiotic prescribing practices across the U.S. “Nonetheless, we know that overuse of antibiotics leads to increases in resistance. We also know that if we can improve the way we prescribe them, we can reduce antibiotic resistance.”

The CDC recommends that hospitals adopt, at a minimum, the following antibiotic stewardship checklist:

- Commit leadership: Dedicate necessary human, financial, and information technology resources.

- Create accountability: Appoint a single leader responsible for program outcomes. Physicians have proven successful in this role.

- Provide drug expertise: Appoint a single pharmacist leader to support improved prescribing.

- Act: Take at least one prescribing improvement action, such as requiring reassessment within 48 hours to check drug choice, dose, and duration.

- Track: Monitor prescribing and antibiotic resistance patterns.

- Report: Regularly report to staff on prescribing and resistance patterns, as well as steps to improve.

- Educate: Offer education about antibiotic resistance and improving prescribing practices.

- Work with other healthcare facilities to prevent infections, transmission, and resistance.

These practices are not just the domain of infectious disease clinicians, either, says Neil Fishman, MD, chief patient safety officer and associate chief medical officer at the University of Pennsylvania Health System and past president of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. In 1992, Dr. Fishman helped establish an antibiotic stewardship program at Penn, working with infectious disease staff to identify and adopt best practices tailored to their needs.

Their efforts have shown promise in improving the health of their patients, he says, and many institutions that adopt stewardship programs typically see cost savings, too.

“These programs do usually end up decreasing drug costs but also increasing the quality of care,”

Dr. Fishman says. “If you can cut out 30% of unnecessary drugs, you cut drug costs. To me, that meets the true definition of value in healthcare.”

In one study that looked at stewardship-related cost reduction, primarily among larger healthcare settings, the average annual savings from reduced inappropriate antibiotic prescribing ranged from $200,000 to $900,000.

The recent CDC report, to which Dr. Srinivasan contributed, was published March 4 in Vital Signs. The study found that as many as a third of antibiotics prescribed are done so inappropriately. According to experts, hospitals and other healthcare institutions need to develop processes and standards to assist physicians in efforts to be responsible antibiotic prescribers.

“Sometimes, when you’re focusing on other issues, antibiotics are a bit of an afterthought,” says Scott Flanders, MD, FACP, MHM, professor of internal medicine and director of hospital medicine at University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor.

“If there is not a checklist of processes [and] things are not accounted for in a systematic way, it doesn’t happen.”

Dr. Flanders and colleague Sanjay Saint, MD, MPH, the University of Michigan George Dock Collegiate professor of internal medicine and associate chief of medicine at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, recently published an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine in which they recommend the following:

- Antimicrobial stewardship programs, which aim to develop guidelines and implement programs that help optimize antibiotic use among hospitalized patients, should partner with front-line clinicians to tackle the problem.

- Clinicians should better document aspects of antibiotic use that can be shared with other providers caring for the same patient throughout his or her hospital stay and after discharge.

- Clinicians should take an “antibiotic time-out” after 48-72 hours of a patient’s use of antibiotics to reassess the use of these drugs.

- Treatment and its duration should be in line with evidence-based guidelines, and institutions should work to clearly identify appropriate treatment duration.

- Improved diagnostic tests should be available to physicians.

- Target diagnostic error by working to improve how physicians think when considering whether to provide antibiotics.

- Develop performance measures that highlight common conditions in which antibiotics are overprescribed, to shine a brighter light on the problem.

“I think we can make a lot of progress,” Dr. Flanders says. “The problem is complex; it developed over decades, and any solutions are unlikely to solve the problem immediately. But there are several examples of institutions and hospitals making significant inroads in a short period of time.” —KAT

Overuse of antibiotics is fueling antimicrobial resistance, posing a threat to people around the world and prompting increased attention to antibiotic stewardship practices. Good stewardship requires hospitals and clinicians to adopt coordinated interventions that focus on reducing inappropriate antibiotic prescribing while remaining focused on the health of patients.

Although it can seem overwhelming to physicians with busy workloads and sick patients to engage in these practices, not addressing the issue of responsible antibiotic prescribing is putting patients at risk.

“We know development of resistance is complicated,” says Arjun Srinivasan, MD, FSHEA, associate director for the CDC’s Healthcare Associated Infection Prevention Program and medical director of Get Smart for Healthcare in the CDC’s division of Healthcare Quality Promotion. Dr. Srinivasan is one of the authors of a recent CDC report on antibiotic prescribing practices across the U.S. “Nonetheless, we know that overuse of antibiotics leads to increases in resistance. We also know that if we can improve the way we prescribe them, we can reduce antibiotic resistance.”

The CDC recommends that hospitals adopt, at a minimum, the following antibiotic stewardship checklist:

- Commit leadership: Dedicate necessary human, financial, and information technology resources.

- Create accountability: Appoint a single leader responsible for program outcomes. Physicians have proven successful in this role.

- Provide drug expertise: Appoint a single pharmacist leader to support improved prescribing.

- Act: Take at least one prescribing improvement action, such as requiring reassessment within 48 hours to check drug choice, dose, and duration.

- Track: Monitor prescribing and antibiotic resistance patterns.

- Report: Regularly report to staff on prescribing and resistance patterns, as well as steps to improve.

- Educate: Offer education about antibiotic resistance and improving prescribing practices.

- Work with other healthcare facilities to prevent infections, transmission, and resistance.

These practices are not just the domain of infectious disease clinicians, either, says Neil Fishman, MD, chief patient safety officer and associate chief medical officer at the University of Pennsylvania Health System and past president of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. In 1992, Dr. Fishman helped establish an antibiotic stewardship program at Penn, working with infectious disease staff to identify and adopt best practices tailored to their needs.

Their efforts have shown promise in improving the health of their patients, he says, and many institutions that adopt stewardship programs typically see cost savings, too.

“These programs do usually end up decreasing drug costs but also increasing the quality of care,”

Dr. Fishman says. “If you can cut out 30% of unnecessary drugs, you cut drug costs. To me, that meets the true definition of value in healthcare.”

In one study that looked at stewardship-related cost reduction, primarily among larger healthcare settings, the average annual savings from reduced inappropriate antibiotic prescribing ranged from $200,000 to $900,000.

The recent CDC report, to which Dr. Srinivasan contributed, was published March 4 in Vital Signs. The study found that as many as a third of antibiotics prescribed are done so inappropriately. According to experts, hospitals and other healthcare institutions need to develop processes and standards to assist physicians in efforts to be responsible antibiotic prescribers.

“Sometimes, when you’re focusing on other issues, antibiotics are a bit of an afterthought,” says Scott Flanders, MD, FACP, MHM, professor of internal medicine and director of hospital medicine at University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor.

“If there is not a checklist of processes [and] things are not accounted for in a systematic way, it doesn’t happen.”

Dr. Flanders and colleague Sanjay Saint, MD, MPH, the University of Michigan George Dock Collegiate professor of internal medicine and associate chief of medicine at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, recently published an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine in which they recommend the following:

- Antimicrobial stewardship programs, which aim to develop guidelines and implement programs that help optimize antibiotic use among hospitalized patients, should partner with front-line clinicians to tackle the problem.

- Clinicians should better document aspects of antibiotic use that can be shared with other providers caring for the same patient throughout his or her hospital stay and after discharge.

- Clinicians should take an “antibiotic time-out” after 48-72 hours of a patient’s use of antibiotics to reassess the use of these drugs.

- Treatment and its duration should be in line with evidence-based guidelines, and institutions should work to clearly identify appropriate treatment duration.

- Improved diagnostic tests should be available to physicians.

- Target diagnostic error by working to improve how physicians think when considering whether to provide antibiotics.

- Develop performance measures that highlight common conditions in which antibiotics are overprescribed, to shine a brighter light on the problem.

“I think we can make a lot of progress,” Dr. Flanders says. “The problem is complex; it developed over decades, and any solutions are unlikely to solve the problem immediately. But there are several examples of institutions and hospitals making significant inroads in a short period of time.” —KAT

Overuse of antibiotics is fueling antimicrobial resistance, posing a threat to people around the world and prompting increased attention to antibiotic stewardship practices. Good stewardship requires hospitals and clinicians to adopt coordinated interventions that focus on reducing inappropriate antibiotic prescribing while remaining focused on the health of patients.

Although it can seem overwhelming to physicians with busy workloads and sick patients to engage in these practices, not addressing the issue of responsible antibiotic prescribing is putting patients at risk.

“We know development of resistance is complicated,” says Arjun Srinivasan, MD, FSHEA, associate director for the CDC’s Healthcare Associated Infection Prevention Program and medical director of Get Smart for Healthcare in the CDC’s division of Healthcare Quality Promotion. Dr. Srinivasan is one of the authors of a recent CDC report on antibiotic prescribing practices across the U.S. “Nonetheless, we know that overuse of antibiotics leads to increases in resistance. We also know that if we can improve the way we prescribe them, we can reduce antibiotic resistance.”

The CDC recommends that hospitals adopt, at a minimum, the following antibiotic stewardship checklist:

- Commit leadership: Dedicate necessary human, financial, and information technology resources.

- Create accountability: Appoint a single leader responsible for program outcomes. Physicians have proven successful in this role.

- Provide drug expertise: Appoint a single pharmacist leader to support improved prescribing.

- Act: Take at least one prescribing improvement action, such as requiring reassessment within 48 hours to check drug choice, dose, and duration.

- Track: Monitor prescribing and antibiotic resistance patterns.

- Report: Regularly report to staff on prescribing and resistance patterns, as well as steps to improve.

- Educate: Offer education about antibiotic resistance and improving prescribing practices.

- Work with other healthcare facilities to prevent infections, transmission, and resistance.

These practices are not just the domain of infectious disease clinicians, either, says Neil Fishman, MD, chief patient safety officer and associate chief medical officer at the University of Pennsylvania Health System and past president of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. In 1992, Dr. Fishman helped establish an antibiotic stewardship program at Penn, working with infectious disease staff to identify and adopt best practices tailored to their needs.

Their efforts have shown promise in improving the health of their patients, he says, and many institutions that adopt stewardship programs typically see cost savings, too.

“These programs do usually end up decreasing drug costs but also increasing the quality of care,”

Dr. Fishman says. “If you can cut out 30% of unnecessary drugs, you cut drug costs. To me, that meets the true definition of value in healthcare.”

In one study that looked at stewardship-related cost reduction, primarily among larger healthcare settings, the average annual savings from reduced inappropriate antibiotic prescribing ranged from $200,000 to $900,000.

The recent CDC report, to which Dr. Srinivasan contributed, was published March 4 in Vital Signs. The study found that as many as a third of antibiotics prescribed are done so inappropriately. According to experts, hospitals and other healthcare institutions need to develop processes and standards to assist physicians in efforts to be responsible antibiotic prescribers.

“Sometimes, when you’re focusing on other issues, antibiotics are a bit of an afterthought,” says Scott Flanders, MD, FACP, MHM, professor of internal medicine and director of hospital medicine at University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor.

“If there is not a checklist of processes [and] things are not accounted for in a systematic way, it doesn’t happen.”

Dr. Flanders and colleague Sanjay Saint, MD, MPH, the University of Michigan George Dock Collegiate professor of internal medicine and associate chief of medicine at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, recently published an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine in which they recommend the following:

- Antimicrobial stewardship programs, which aim to develop guidelines and implement programs that help optimize antibiotic use among hospitalized patients, should partner with front-line clinicians to tackle the problem.

- Clinicians should better document aspects of antibiotic use that can be shared with other providers caring for the same patient throughout his or her hospital stay and after discharge.

- Clinicians should take an “antibiotic time-out” after 48-72 hours of a patient’s use of antibiotics to reassess the use of these drugs.

- Treatment and its duration should be in line with evidence-based guidelines, and institutions should work to clearly identify appropriate treatment duration.

- Improved diagnostic tests should be available to physicians.

- Target diagnostic error by working to improve how physicians think when considering whether to provide antibiotics.

- Develop performance measures that highlight common conditions in which antibiotics are overprescribed, to shine a brighter light on the problem.

“I think we can make a lot of progress,” Dr. Flanders says. “The problem is complex; it developed over decades, and any solutions are unlikely to solve the problem immediately. But there are several examples of institutions and hospitals making significant inroads in a short period of time.” —KAT

Hospitalists Adopt Strategies to Become More Responsible Prescribers of Antibiotics

A recent CDC study found that nearly a third of antibiotics might be inappropriately prescribed.1 The report also found wide variation in antibiotic prescribing practices for patients in similar treatment areas in hospitals across the country.

Across the globe, antibiotic resistance has become a daunting threat. Some public health officials have labeled it a crisis, and improper prescribing and use of antibiotics is at least partly to blame, experts say.

“We’re dangerously close to a pre-antibiotic era where we don’t have antibiotics to treat common infections,” says Neil Fishman, MD, chief patient safety officer and associate chief medical officer at the University of Pennsylvania Health System and past president of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. “We are seeing more and more infections, usually hospital-based, caused by bacterial resistance to most, if not all, of the antibiotics that we have.”

It’s an issue hospitalists around the country are championing.

“I think for a long time there’s been a misperception that antibiotic stewardship is at odds with hospitalists, who are managing very busy patient loads and managing inpatient prescribing,” says Arjun Srinivasan, MD, FSHEA, associate director for the CDC’s Healthcare Associated Infection Prevention Program and medical director of Get Smart for Healthcare in the division of Healthcare Quality Promotion at the CDC. Dr. Srinivasan is one of the authors of the new CDC study.

But “they have taken that ball and run with it,” says Dr. Srinivasan, who has worked with the Society of Hospital Medicine to address antibiotic resistance issues.

The goals of the study, published in the CDC’s Vital Signs on March 4, 2014, were to evaluate the extent and rationale for the prescribing of antibiotics in U.S. hospitals, while demonstrating opportunities for improvement in prescribing practices.

—Neil Fishman, MD, chief patient safety officer and associate chief medical officer at the University of Pennsylvania Health System

Study authors analyzed data from the Truven Health MarketScan Hospital Drug Database and the CDC’s Emerging Infection Program and, using a model based on the data, demonstrated that a 30% reduction in broad-spectrum antibiotics use would decrease Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) by 26%. Overall antibiotic use would drop by 5%.

According to the CDC, antibiotics are among the most frequent causes of adverse drug events among hospitalized patients in the U.S., and complications like CDI can be deadly. In fact, 250,000 hospitalized patients are infected with CDI each year, resulting in 14,000 deaths.

“We’re really at a critical juncture in healthcare now,” Dr. Fishman says. “The field of stewardship has evolved mainly in academic tertiary care settings. The CDC report is timely because it highlights the necessity of making sure antibiotics are used appropriately in all healthcare settings.”

Take a Break

One of the ways in which hospitalists have addressed the need for more appropriate antibiotic prescribing in their institutions is the practice of an “antibiotic time-out.”

“After some point, when the dust settles at about 48-72 hours, you can evaluate the patient’s progress, evaluate their studies, [and] you may have culture results,” says Scott Flanders, MD, FACP, MHM, professor of internal medicine and director of hospital medicine at the University of Michigan Medical School in Ann Arbor. At that point, physicians can decide whether to maintain a patient on the original antibiotic, alter the duration of treatment, or take them off the treatment altogether.

Dr. Flanders and a colleague published an editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine that coincided with the CDC report.2 A 2007 study published in Clinical Infectious Diseases found that the choice of antibiotic agent or duration of treatment can be incorrect in as many as half of all cases in which antibiotics are prescribed.3

Dr. Flanders, a past president of SHM who has worked extensively with the CDC and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, was behind the development of the time-out strategy. Dr. Srinivasan says the clinical utility of the method was “eye-opening.”

The strategy, which has taken hold among hospital groups the CDC has worked with, has demonstrated that stewardship and patient management are not at odds, Dr. Srinivasan says. Despite patient sign-outs and hand-offs, the time-out strategy allows any clinician to track a patient’s antibiotic status and reevaluate the treatment plan.

Having a process is critical to more responsible prescribing practices, Dr. Flanders says. He attributes much of the variability in antibiotics prescribing among similar departments at hospitals across the country to a lack of standards, though he noted that variability in patient populations undoubtedly plays a role.

Lack of Stats

The CDC report showed up to a threefold difference in the number of antibiotics prescribed to patients in similar hospital settings at hospitals across the country. The reasons for this are not known, Dr. Fishman says.

“The main reason we don’t know is we don’t have a good mechanism in the U.S. right now to monitor antibiotics use,” he explains. “We don’t have a way for healthcare facilities to benchmark their use.”

Without good strategies to monitor and develop more responsible antibiotics prescription practices, Dr. Flanders believes many physicians find themselves trapped by the “chagrin” of not prescribing.

“Patients often enter the hospital without a clear diagnosis,” he says. “They are quite ill. They may have a serious bacterial infection, and, in diagnosing them, we can’t guess wrong and make the decision to withhold antibiotics, only to find out later the patient is infected.

“We know delays increase mortality, and that’s not an acceptable option.”

—Scott Flanders, MD, FACP, MHM, professor of internal medicine, director of hospital medicine, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, past president, SHM

Beyond the Bedside

Many physicians fail to consider the bigger societal implications when prescribing antibiotics for sick patients in their charge, because their responsibility is, first and foremost, to that individual. But, Dr. Srinivasan says, “good antibiotic stewardship is beneficial to the patient lying in the bed in front of you, because every day we are confronted with C. diff. infections, adverse drug events, all of these issues.”

Strategies and processes help hospitalists make the best decision for their patients at the time they require care, while providing room for adaptation and the improvements that serve all patients.

Some institutions use interventions like prospective audit and feedback monitoring to help physicians become more responsible antibiotic prescribers, says Dr. Fishman, who worked with infectious disease specialists at the University of Pennsylvania in the early 1990s to develop a stewardship program there.

“In our institution, we see better outcomes—lower complications—usually associated with a decreased length of stay, at least in the ICU for critically ill patients—and increased cure rates,” he says.

Stewardship efforts take investment on the part of the hospital. Dr. Fishman cited a recent study at the Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania that looked at whether a particular education strategy the hospital implemented actually led to improvements.4

“It was successful in intervening in this problem [of inappropriate prescribing] in pediatricians, but it did take ongoing education of both healthcare providers and patients,” he says, noting that large financial and time investments are necessary for the ongoing training and follow-up that is necessary.

And patients need to be educated, too.

“It takes a minute to write that prescription and probably 15 or 20 minutes not to write it,” Dr. Fishman says. “We need to educate patients about potential complications of antibiotics use, as well as the signs and symptoms of infection.”

The CDC report is a call to action for all healthcare providers to consider how they can become better antibiotic stewards. There are very few new antibiotics on the market and little in the pipeline. All providers must do what they can to preserve the antibiotics we currently have, Dr. Fishman says.

“There is opportunity, and I think hospitalists are up to the challenge,” Dr. Flanders says. “They are doing lots of work to improve quality across lots of domains in their hospitals. I think this is an area where attention is deserved.”

Kelly April Tyrrell is a freelance writer in Madison, Wis.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Vital signs: improving antibiotic use among hospitalized patients. Available at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6309a4.htm?s_cid=mm6309a4_w. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- Flanders SA, Saint S. Why does antrimicrobial overuse in hospitalized patients persist? JAMA Internal Medicine online. Available at: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1838720. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, et al. Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Available at: http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/44/2/159.full. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks A, et al. Effect of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention on broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing by primary care pediatricians. JAMA. 2013;309(22):2345-2352.

A recent CDC study found that nearly a third of antibiotics might be inappropriately prescribed.1 The report also found wide variation in antibiotic prescribing practices for patients in similar treatment areas in hospitals across the country.

Across the globe, antibiotic resistance has become a daunting threat. Some public health officials have labeled it a crisis, and improper prescribing and use of antibiotics is at least partly to blame, experts say.

“We’re dangerously close to a pre-antibiotic era where we don’t have antibiotics to treat common infections,” says Neil Fishman, MD, chief patient safety officer and associate chief medical officer at the University of Pennsylvania Health System and past president of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. “We are seeing more and more infections, usually hospital-based, caused by bacterial resistance to most, if not all, of the antibiotics that we have.”

It’s an issue hospitalists around the country are championing.