User login

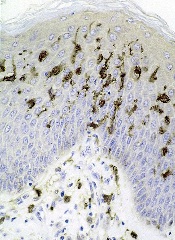

Studies have shown that dendritic cells (DCs) can contribute to tumor growth and help shield the tumor from the immune system in colon, stomach, breast, and prostate cancer.

Now, researchers have found evidence suggesting this phenomenon also occurs in Myc-driven lymphomas.

The team has also identified the molecular mechanism that induces the immune cells to promote tumor growth.

They reported these findings in Nature Communications.

Uta Höpken, PhD, of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in Berlin, Germany, and her colleagues investigated how DCs drive tumor in mouse models of Eµ-Myc lymphoma.

The team began by depleting DCs in these mice and found that tumor growth was delayed—the first clue that DCs are indeed associated with lymphoma growth.

Next, the researchers found that, after contact with lymphoma cells, the DCs increasingly secrete immunomodulatory cytokines and growth factors. The cytokine secretion takes place in the spleen and lymph nodes.

Dr Höpken and her colleagues previously demonstrated that various forms of lymphoma cells settle in the lymph nodes and in the spleen, where they create their own survival niche. This process is regulated by selective cytokines and growth factors the researchers identified a few years ago.

“In these niches, almost everything is already there that the lymphoma cells as malignant B cells need to survive, including blood vessels and connective tissue cells [stromal cells],” Dr Höpken said. “The survival substances secreted by the DCs optimize the niche so that the tumors can grow better.”

This also means the DCs prevent the T lymphocytes from exercising their defensive function. Normally, healthy B or T cells settle in the respective B- or T-cell niches of the spleen and the lymph nodes to be made fit for immune defense.

“What is paradoxical is that the mouse lymphoma cells we studied—malignant B cells—found their survival niche in the T-cell zones of the lymph nodes and the spleen and not in the B-cell zones,” Dr Höpken said.

After making contact with the lymphoma cells, the DCs increasingly upregulate C/EBPβ, a transcription factor that promotes the production of cytokines that mediate inflammation.

The researchers found that C/EBPβ regulates DCs. Without it, the cells could not secrete inflammatory cytokines. C/EBPβ also indirectly blocks apoptosis in the lymphoma cells, allowing the cancer cells to grow unchecked.

The team pointed out that, even if their model of Eµ-Myc lymphoma is not entirely comparable to B-cell lymphomas in humans, it shows that lymphoma cells and DCs interact—a previously unknown molecular mechanism.

Furthermore, these findings may have clinical applications. The researchers noted that the immunomodulatory agent lenalidomide induces downregulation of C/EBPβ, which is secreted by cancer cells.

So Dr Höpken and her colleagues believe it might be appropriate to approve the use of lenalidomide for patients with Myc B-cell lymphoma, as an addition to their existing treatment, to strengthen their immune defense. ![]()

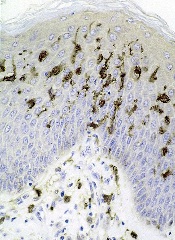

Studies have shown that dendritic cells (DCs) can contribute to tumor growth and help shield the tumor from the immune system in colon, stomach, breast, and prostate cancer.

Now, researchers have found evidence suggesting this phenomenon also occurs in Myc-driven lymphomas.

The team has also identified the molecular mechanism that induces the immune cells to promote tumor growth.

They reported these findings in Nature Communications.

Uta Höpken, PhD, of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in Berlin, Germany, and her colleagues investigated how DCs drive tumor in mouse models of Eµ-Myc lymphoma.

The team began by depleting DCs in these mice and found that tumor growth was delayed—the first clue that DCs are indeed associated with lymphoma growth.

Next, the researchers found that, after contact with lymphoma cells, the DCs increasingly secrete immunomodulatory cytokines and growth factors. The cytokine secretion takes place in the spleen and lymph nodes.

Dr Höpken and her colleagues previously demonstrated that various forms of lymphoma cells settle in the lymph nodes and in the spleen, where they create their own survival niche. This process is regulated by selective cytokines and growth factors the researchers identified a few years ago.

“In these niches, almost everything is already there that the lymphoma cells as malignant B cells need to survive, including blood vessels and connective tissue cells [stromal cells],” Dr Höpken said. “The survival substances secreted by the DCs optimize the niche so that the tumors can grow better.”

This also means the DCs prevent the T lymphocytes from exercising their defensive function. Normally, healthy B or T cells settle in the respective B- or T-cell niches of the spleen and the lymph nodes to be made fit for immune defense.

“What is paradoxical is that the mouse lymphoma cells we studied—malignant B cells—found their survival niche in the T-cell zones of the lymph nodes and the spleen and not in the B-cell zones,” Dr Höpken said.

After making contact with the lymphoma cells, the DCs increasingly upregulate C/EBPβ, a transcription factor that promotes the production of cytokines that mediate inflammation.

The researchers found that C/EBPβ regulates DCs. Without it, the cells could not secrete inflammatory cytokines. C/EBPβ also indirectly blocks apoptosis in the lymphoma cells, allowing the cancer cells to grow unchecked.

The team pointed out that, even if their model of Eµ-Myc lymphoma is not entirely comparable to B-cell lymphomas in humans, it shows that lymphoma cells and DCs interact—a previously unknown molecular mechanism.

Furthermore, these findings may have clinical applications. The researchers noted that the immunomodulatory agent lenalidomide induces downregulation of C/EBPβ, which is secreted by cancer cells.

So Dr Höpken and her colleagues believe it might be appropriate to approve the use of lenalidomide for patients with Myc B-cell lymphoma, as an addition to their existing treatment, to strengthen their immune defense. ![]()

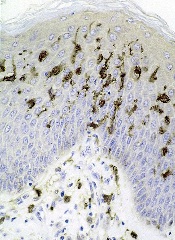

Studies have shown that dendritic cells (DCs) can contribute to tumor growth and help shield the tumor from the immune system in colon, stomach, breast, and prostate cancer.

Now, researchers have found evidence suggesting this phenomenon also occurs in Myc-driven lymphomas.

The team has also identified the molecular mechanism that induces the immune cells to promote tumor growth.

They reported these findings in Nature Communications.

Uta Höpken, PhD, of the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in Berlin, Germany, and her colleagues investigated how DCs drive tumor in mouse models of Eµ-Myc lymphoma.

The team began by depleting DCs in these mice and found that tumor growth was delayed—the first clue that DCs are indeed associated with lymphoma growth.

Next, the researchers found that, after contact with lymphoma cells, the DCs increasingly secrete immunomodulatory cytokines and growth factors. The cytokine secretion takes place in the spleen and lymph nodes.

Dr Höpken and her colleagues previously demonstrated that various forms of lymphoma cells settle in the lymph nodes and in the spleen, where they create their own survival niche. This process is regulated by selective cytokines and growth factors the researchers identified a few years ago.

“In these niches, almost everything is already there that the lymphoma cells as malignant B cells need to survive, including blood vessels and connective tissue cells [stromal cells],” Dr Höpken said. “The survival substances secreted by the DCs optimize the niche so that the tumors can grow better.”

This also means the DCs prevent the T lymphocytes from exercising their defensive function. Normally, healthy B or T cells settle in the respective B- or T-cell niches of the spleen and the lymph nodes to be made fit for immune defense.

“What is paradoxical is that the mouse lymphoma cells we studied—malignant B cells—found their survival niche in the T-cell zones of the lymph nodes and the spleen and not in the B-cell zones,” Dr Höpken said.

After making contact with the lymphoma cells, the DCs increasingly upregulate C/EBPβ, a transcription factor that promotes the production of cytokines that mediate inflammation.

The researchers found that C/EBPβ regulates DCs. Without it, the cells could not secrete inflammatory cytokines. C/EBPβ also indirectly blocks apoptosis in the lymphoma cells, allowing the cancer cells to grow unchecked.

The team pointed out that, even if their model of Eµ-Myc lymphoma is not entirely comparable to B-cell lymphomas in humans, it shows that lymphoma cells and DCs interact—a previously unknown molecular mechanism.

Furthermore, these findings may have clinical applications. The researchers noted that the immunomodulatory agent lenalidomide induces downregulation of C/EBPβ, which is secreted by cancer cells.

So Dr Höpken and her colleagues believe it might be appropriate to approve the use of lenalidomide for patients with Myc B-cell lymphoma, as an addition to their existing treatment, to strengthen their immune defense. ![]()