User login

What are cancer survivors’ needs and how well are they being met?

ABSTRACT

Purpose This study sought to identify the needs and unmet needs of the growing number of adult cancer survivors.

Methods Vermont survivor advocates partnered with academic researchers to create a survivor registry and conduct a cross-sectional survey of cancer-related needs and unmet needs of adult survivors. The mailed survey addressed 53 specific needs in 5 domains based on prior research, contributions from the research partners, and pilot testing. Results were summarized by computing proportions who reported having needs met or unmet.

Results Survey participants included 1668 of 2005 individuals invited from the survivor registry (83%); 65.7% were ages 60 or older and 61.9% were women. These participants had received their diagnosis 2 to 16 years earlier; 77.5% had been diagnosed ≥5 years previously; 30.2% had at least one unmet need in the emotional, social, and spiritual (e) domain; just 14.4% had at least one unmet need in the economic and legal domain. The most commonly identified individual unmet needs were in the e and the information (i) domains and included “help reducing stress” (14.8% of all respondents) and “information about possible after effects of treatment” (14.4%).

Conclusions Most needs of these longer-term survivors were met, but substantial proportions of survivors identified unmet needs. Unmet needs such as information about late and long-term adverse effects of treatment could be met within clinical care with a cancer survivor care plan, but some survivors may require referral to services focused on stress and coping.

Following a successful course of treatment for cancer, many patients return to or remain in the care of their primary care physician (PCP). What often goes unrecognized, however, are these cancer survivors’ unique needs—physical, psychological, social, spiritual, economic, and legal—and the informational and professional services available to address them.1,2

Increased cancer survival creates new needs. There are already >12 million cancer survivors in the United States and >30 million worldwide.3 As baby boomers age, the number of cancers diagnosed over the next 45 years will double4 and improved diagnosis and treatments are already prolonging survivors’ lives. With the greater number of cancer survivors and longer survival time, a cancer survivorship advocacy community has developed to help identify and address the concerns, needs, and benefits of having lived with, through, and beyond a cancer diagnosis.

The purpose of our study. Some of these areas of need have been studied extensively with childhood survivors, breast cancer survivors, and, more recently, prostate cancer survivors. However, few studies have examined adult survivors from all cancer types5-9 or have had cohorts large enough to yield meaningful information.5,7-9 The aim of this study was to describe the needs of adult survivors of all cancer types in a general population from Vermont and to determine whether these needs were met. The results of this study can help identify the services needed by cancer survivors.

METHODS

Population and sample

In November 2009, we invited all survivors listed in a cancer survivor registry to complete a 12-page survey. The registry10 was created as part of the Cancer Survivor Community Study, a community-based participatory research project funded by the National Cancer Institute. The study’s Steering Committee was comprised of cancer survivors, cancer registrars, and researchers. We identified and invited cancer survivors from 4 hospital registries in northwest and central Vermont to participate. Registry participants who indicated willingness to enroll in research studies received an invitation letter and informed consent form, the 12-page survey, and an addressed and stamped return envelope. We obtained Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval for these procedures at the University of Vermont and at local hospital IRBs.

Instrument development

A working group from the Steering Committee reviewed a range of available instruments to assess cancer survivors’ needs.9,11-15 We determined that the survey most relevant to our objectives was the Cancer Survivors’ Unmet Needs (CaSun) instrument.13 Because CaSun was developed in Australia, we carefully examined each question for appropriateness to our target audience. We eliminated several questions that we thought less important, added questions from other instruments, and simplified the survey format. Survivors from the Steering Committee pilot tested the draft questionnaire to identify awkward wording or concepts.

We piloted the revised draft using a standardized feedback form with cancer survivors who were not connected to our project and not enrolled in the survivor registry, and with residents at a senior center. Students and a teacher from an Adult Basic Education program helped to ensure easy readability. Our final instrument had 53 questions about needs in 5 domains. Questions within each domain completed the lead-in, “Since your cancer diagnosis, did you need....” We asked participants to check only 1 of the 3 boxes to the right of each question to indicate that there was no need in that area, that there was a need and it was met, or that there was a need and it was not met. We obtained self-reported demographic data during enrollment in the registry.

Data analysis

We summarized data by computing the percent of survivors who reported having each need (either met or unmet) and the percent for whom the need was unmet. The latter was computed both as a percent of all survivors and as a percent of those who had the need. We also calculated the percentage of survivors that had at least one need and at least one unmet need in each domain, as well as the average number of needs per survivor in each domain. We used SPSS for Unix, Release 6.1 (AIX 3.2)(IBM, Armonk, New York).

RESULTS

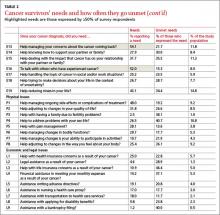

Of the 2005 cancer survivors invited into the study, 1668 responded, yielding a participation rate of 83%. TABLE 1 describes the self-reported demographic and cancer characteristics of participants in this study. Most respondents were female, ≥60 years old, urban dwellers, married or with a partner, well educated, and had household incomes of ≥$50,000. There were more breast cancer survivors than survivors of other cancers, and 14.6% of all survivors reported being diagnosed with more than one cancer. Cancer was diagnosed at stages 1 or 2 for 78.3% of the participants; 61.9% reported having undergone ≥2 treatment regimens.

The survey addressed needs in 5 domains: access to care and services (A); information (I); emotional, social, and spiritual (E); physical (P); and economic and legal (L). More than 80% of respondents reported having at least one need in the A, I, and E domains. The E domain had the most survivors with at least one unmet need (N=503), followed by the I (N=410) and P (N=375) domains.

Identifying unmet needs. TABLE 2 shows results for the specific questions within the domains in the order they were asked. Most participants who had a need also had it met. However, some needs that were not commonly reported were deemed unmet by a large proportion of those who expressed the need. For example, the A need for “A case manager to whom you could go to find out about services whenever they were needed” (A5) was reported by only 29.1% of survivors. But 32.1% of those reporting the need said it was unmet, which corresponds to 9.4% of all study participants having the need unmet. Similarly, the need for “More information about complementary and alternative medicine” (I3) was reported by about a quarter of the study population, 41.4% of whom (9.8% of all participants) reported it as unmet. In the P domain, the need for “Help to address problems with your sex life” (P4) was reported by only 26.5% of the respondents; yet 40.7% of those reporting the need had it unmet. Similarly, in the L domain, “Help with life insurance concerns as a result of your cancer” (L3) was only reported by 10.9% of the participants but was unmet for 46.4% of those who reported the need, or 5% of all study participants.

Most commonly expressed needs. TABLE 2 also identifies 12 needs reported by ≥50% of participants. Three of these needs were in the A domain, 6 in the I domain, and 3 in the E domain. The 2 most common needs related to A: the need “To feel like you were managing your health together with the medical team” (A3) was reported by 68.6% and was viewed as unmet by 5.2% of all respondents; the need for “Access to screening for recurrence or other cancers” (A7) was reported by 63.8% of the survivors but was deemed unmet by only 3.1% of all the respondents. “More information about possible after effects of your treatment” (I5) was a need for 63.2% that went unmet in 22.9% (14.4% of all participants). “Help managing your concerns about the cancer coming back” (E13) was reported as a need by 54.1% and as unmet by 11.8% of all participants.

The rank order of 7 unmet needs reported by ≥10% of the participants is shown in TABLE 3. Four of the 7 unmet needs were in the E domain. The most common unmet need in this domain was “Help reducing stress in your life” (E19).

Only 3 needs were both commonly reported and also unmet for at least 10% of the participants: “More information about possible after effects of your treatment” (I5), “More information about possible side effects of your treatment” (I4), and “Help managing your concerns about the cancer coming back” (E13).

DISCUSSION

The survey instrument we used to assess the needs of cancer survivors in a large community-based registry included a detailed list of potential needs generated, in part, by representatives of the survivor community. Most cancer survivor needs mentioned in this survey were met. However, some needs were not met for substantial proportions of respondents and should be examined carefully to determine whether services could be improved to better address them. This study was planned and implemented by researchers and cancer survivors using community-based participatory principles to learn about local needs. The results of this study may be generalizable to similar populations of survivors and will inform the survivorship goals for the Vermont State Cancer Plan and future Vermont Cancer Survivor Network activities.

Acting on patients’ expressed needs. Over 80% of participants had needs in the A, I, and E domains. The most commonly reported need was in the A domain, “To feel like you were managing your health together with the medical team” (A3). It was also a top need in other studies that asked this question.16,17 A cancer diagnosis may cause patients to feel out of control. Participation in the management of their health may help them gain a greater sense of control. PCP accommodation of expressed patient preferences may be an important part of a cancer survivor’s long-term adaptation to the disease.

Six of the 12 most frequently reported needs and 2 frequently reported unmet needs were in the I domain. Communication of information increases patients’ involvement in decision-making and enables them to cope better during diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up.18 “More information about possible after effects of your treatment” and “More information about possible side effects of your treatment” were reported by a high proportion of participants, and many also reported these needs as unmet. In another study about health-related information needs of survivors, 52% wanted more information about “What late and long-term side effects of cancer treatment are expected”19; and in a 2005 review of information needs, 12% of survivors reported similar needs.20 Two recent articles also noted such needs in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors.21,22 Based on current evidence, it would be advisable to discuss anticipated effects of treatment with patients not only at the outset but also at the end of treatment, and to write it in a cancer survivor care plan.

Individual needs that were not met for at least 10% of respondents, regardless of how common the need (TABLE 3), provided additional insights. Among these 7 needs, 3 also were reported as a need by more than 50% of respondents (TABLE 2), and 4 by <50%, indicating that some less common needs are not being met adequately. Among these 7 prominent unmet needs, 4 were E Issues (TABLE 3) and 2 were I Issues.

Unmet needs are an opportunity to improve care. In our study and in others, E needs were most likely to be unmet.17,23-26 Among the 4 common unmet E needs, 2 (E19 and E11) focused on generalized stress and worry, and one (E15) focused on concern about illness impact on family members or partners. Although these issues may be challenging to address successfully in a typical clinical environment, others have confirmed the importance of these needs and proposed ways to meet them.27 The fourth most common unmet E need focused on concern about cancer recurrence, also a prominent need found in other studies.15-17 These needs might be addressed more adequately in the course of usual clinical care by PCPs or specialists. In fact, the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer 2012 standards now require psychosocial distress screening and the provision of referral for psychosocial services.24 Our results are consistent in many respects with prior studies of needs reported by cancer survivors in other countries. The CaSUN survey developed by Hodgkinson et al13 has been applied to several survivor populations in Australia. In a diverse survivor sample, specific E, I, and A issues were frequently reported as unmet needs.13 The most prominent unmet needs in a gynecologic cancer sample using CaSUN focused on emotional and social issues such as worry, stress, coping, and relationships with, and expectations of, others.25

Barg et al23 conducted a survey of unmet needs in the United States using a detailed list based on prior survivor research and targeting individuals in a cancer registry. The most prominent area of need expressed was “emotional,” similar to the high rank of E needs in our study. In contrast to our study, however, physical and financial issues also were prominent. The latter variances might be explained by differences in access to care, or perhaps the study’s low response rate (23.8%). A similar survey reported by Campbell et al12 identified needs in the emotional domain as the most cited unmet survivor needs based on psychometrically developed subscales of a 152-item survey (29% response rate).

These results from several studies, including ours, call for more detailed exploration of the E needs of long-term cancer survivors. A useful framework developed by Stein et al28 accounts for factors contributing to cancer stress and burden as well as resources available to survivors (intrapersonal, social, informational, and tangible services), with the interactions between these 2 domains determining how well a survivor will be able to cope. There clearly is a role for development of more effective communication channels and focused services to meet survivor needs.

The list of most common unmet needs in TABLE 3 also includes a focus on “problems with your sex life” (P4). This is an area that may be difficult to address in a cancer care setting because of the focus on disease management. Primary care providers might be better prepared to address this issue because they likely encounter similar issues among the wide range of patients they serve. However, a recent study reported that only 46% of internists were somewhat or likely to initiate a discussion about sexuality with cancer survivors.29 Some additional preparation for physicians to address this need might be warranted.

The proportion in this sample reporting needs for access to, or information about, complementary and alternative medicine services fell below the thresholds chosen to designate common needs in this study. Although reported use is relatively common among cancer survivor in several studies,30-32 it appears that in our survivor sample, those who were interested in these approaches encountered only moderate barriers.

Study limitations. We invited participants from a registry unlikely to include cancer survivors with lower educational attainment or from rural locations9—that is, our participants were less likely to have challenges in obtaining appropriate services and information. This sample limitation therefore likely underestimates the overall level of needs among cancer survivors.

This was a cross-sectional assessment of perceived needs among a diverse group of survivors, which may have overlooked needs that were met but only after considerable effort on the part of survivors. Longitudinal studies would provide more complete accounts of how readily needs are met and the changes in needs at different times in the continuum of care.

The Vermont population is less diverse racially and ethnically, but not with respect to household income or educational attainment, than the overall US population. Access to health care also is relatively high in Vermont compared with many other states. According to a 2009 Vermont Household Health Insurance Survey, only 7.6% of Vermonters are uninsured.33

CORRESPONDENCE

Berta Geller, EdD, University of Vermont, Health Promotion Research/Family Medicine, 1 South Prospect Street, Burlington, VT 05401-3444; [email protected]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Anne Dorwaldt, Kathy Howe, Mark Bowman and John Mace at the University of Vermont, and the Cancer Survivor Community Study Steering Committee for their contributions to the successful completion of this study. We also thank the cancer survivors who participated in the pilot testing and the overall survey.

1. Potosky A, Han PK, Rowland J, et al. Differences between primary care physicians’ and oncologists’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1403-1410.

2. Rowland J. Survivorship research: past, present, and future. In: Chang AE, Ganz PA, Hayes DF, et al, eds. Oncology: An Evidence-Based Approach. New York, NY: Springer; 2005:1753-1767.

3. Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, et al. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1893-1907.

4. Hewitt ME, Greenfield S, Stovall E, eds. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005.

5. Hawkins NA, Smith T, Zhao L, et al. Health-related behavior change after cancer: results of the American Cancer Society’s studies of cancer survivors (SCS). J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:20-32.

6. Katz ML, Reiter PL, Corbin S, et al. Are rural Ohio Appalachia cancer survivors needs different than urban cancer survivors? J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:140-148.

7. Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, Clauser S, et al. Burden of illness in cancer survivors: findings from a population-based national sample. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1322-1330.

8. Sanson-Fisher R, Girgis A, Boyes A, et al; Supportive Care Review Group. The unmet supportive care needs of patients with cancer. Cancer. 2000;88:226-237.

9. Smith T, Stein KD, Mehta CC, et al. The rationale, design, and implementation of the American Cancer Society’s studies of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2007;109:1-12.

10. Geller BM, Mace J, Vacek P, et al. Are cancer survivors willing to participate in research? J Community Health. 2011;36: 772-778.

11. Crespi CM, Ganz PA, Petersen L, et al. Refinement and psychometric evaluation of the impact of cancer scale. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1530-1541.

12. Campbell HS, Sanson-Fisher R, Turner D, et al. Psychometric properties of cancer survivors’ unmet needs survey. Support Care Cancer. 2010;19:221-230.

13. Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, et al. The development and evaluation of a measure to assess cancer survivors’ unmet supportive care needs: the CaSUN (Cancer Survivors’ Unmet Needs measure). Psychooncology. 2007;16:796-804.

14. Zebrack BJ, Ganz PA, Bernaards CA, et al. Assessing the impact of cancer: development of a new instrument for long-term survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;15:407-421.

15. Arora NK, Hesse BW, Rimer BK, et al. Frustrated and confused: the American public rates its cancer-related information-seeking experiences. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:223-228.

16. Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, et al. Breast cancer survivors’ supportive care needs 2-10 years after diagnosis. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:515-523.

17. Harrison SE, Watson EK, Ward AM, et al. Primary health and supportive care needs of long-term cancer survivors: a questionnaire study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2091-2098.

18. Rutten LJ, Squiers L, Treiman K. Requests for information by family and friends of cancer patients calling the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Information Service. Psychooncology. 2006;15:664-672.

19. Beckjord EB, Arora NK, McLaughlin W, et al. Health-related information needs in a large and diverse sample of adult cancer survivors: implications for cancer care. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2:179-189.

20. Rutten LJ, Arora NK, Bakos AD, et al. Information needs and sources of information among cancer patients: a systematic review of research (1980-2003). Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57:250-261.

21. Zebrack BJ, Block R, Hayes-Lattin B, et al. Psychosocial service use and unmet need among recently diagnosed adolescent and youg adult patients. Cancer. 2013;119:201-214.

22. Keegan TH, Lichtensztajn DY, Kato I, et al. Unmet adolescent and young adult cancer survivors information and service needs: a population-based cancer registry study. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:239-250.

23. Barg KF, Cronholm PF, Straton JB, et al. Unmet psychosocial needs of Pennsylvanians with cancer: 1996-2005. Cancer. 2007;110:631-639.

24. American College of Surgeons. Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2011.

25. Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Fuchs A, et al. Long-term survival from gynecologic cancer: psychosocial outcomes, supportive care needs and positive outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104:381-389.

26. Houts PS, Yasko JM, Kahn SB, et al. Unmet psychological, social, and economic needs of persons with cancer in Pennsylvania. Cancer. 1986;58:2355-2361.

27. Holland JC, Reznik I. Pathways for psychosocial care of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2005;104(11 suppl):2624-2637.

28. Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(11 suppl):2577-2592.

29. Park ER, Bober SL, Campbell EG, et al. General: Internist communication about sexual function with cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(suppl 2):S407-S411.

30. Girgis A, Adams J, Sibbritt D. The use of complementary and alternative therapies by patients with cancer. Oncol Res. 2005;15:281-289.

31. Gansler T, Kaw C, Crammer C, et al. A population-based study of prevalence of complementary methods use by cancer survivors: a report from the American Cancer Society’s studies of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2008;113:1048-1057.

32. Fouladbakhsh JM, Stommel M. Gender, symptom experience, and use of complementary and alternative medicine practices among cancer survivors in the U.S. cancer population. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37:E7-E15.

33. Vermont Department of Financial Regulation. Vermont Household Health Insurance Survey (VHHIS). Vermont Department of Financial Regulation Web site. Available at: http://www.dfr.vermont.gov/insurance/health-insurance/vermont-household-health-insurance-survey-vhhis. Accessed July 15, 2014.

ABSTRACT

Purpose This study sought to identify the needs and unmet needs of the growing number of adult cancer survivors.

Methods Vermont survivor advocates partnered with academic researchers to create a survivor registry and conduct a cross-sectional survey of cancer-related needs and unmet needs of adult survivors. The mailed survey addressed 53 specific needs in 5 domains based on prior research, contributions from the research partners, and pilot testing. Results were summarized by computing proportions who reported having needs met or unmet.

Results Survey participants included 1668 of 2005 individuals invited from the survivor registry (83%); 65.7% were ages 60 or older and 61.9% were women. These participants had received their diagnosis 2 to 16 years earlier; 77.5% had been diagnosed ≥5 years previously; 30.2% had at least one unmet need in the emotional, social, and spiritual (e) domain; just 14.4% had at least one unmet need in the economic and legal domain. The most commonly identified individual unmet needs were in the e and the information (i) domains and included “help reducing stress” (14.8% of all respondents) and “information about possible after effects of treatment” (14.4%).

Conclusions Most needs of these longer-term survivors were met, but substantial proportions of survivors identified unmet needs. Unmet needs such as information about late and long-term adverse effects of treatment could be met within clinical care with a cancer survivor care plan, but some survivors may require referral to services focused on stress and coping.

Following a successful course of treatment for cancer, many patients return to or remain in the care of their primary care physician (PCP). What often goes unrecognized, however, are these cancer survivors’ unique needs—physical, psychological, social, spiritual, economic, and legal—and the informational and professional services available to address them.1,2

Increased cancer survival creates new needs. There are already >12 million cancer survivors in the United States and >30 million worldwide.3 As baby boomers age, the number of cancers diagnosed over the next 45 years will double4 and improved diagnosis and treatments are already prolonging survivors’ lives. With the greater number of cancer survivors and longer survival time, a cancer survivorship advocacy community has developed to help identify and address the concerns, needs, and benefits of having lived with, through, and beyond a cancer diagnosis.

The purpose of our study. Some of these areas of need have been studied extensively with childhood survivors, breast cancer survivors, and, more recently, prostate cancer survivors. However, few studies have examined adult survivors from all cancer types5-9 or have had cohorts large enough to yield meaningful information.5,7-9 The aim of this study was to describe the needs of adult survivors of all cancer types in a general population from Vermont and to determine whether these needs were met. The results of this study can help identify the services needed by cancer survivors.

METHODS

Population and sample

In November 2009, we invited all survivors listed in a cancer survivor registry to complete a 12-page survey. The registry10 was created as part of the Cancer Survivor Community Study, a community-based participatory research project funded by the National Cancer Institute. The study’s Steering Committee was comprised of cancer survivors, cancer registrars, and researchers. We identified and invited cancer survivors from 4 hospital registries in northwest and central Vermont to participate. Registry participants who indicated willingness to enroll in research studies received an invitation letter and informed consent form, the 12-page survey, and an addressed and stamped return envelope. We obtained Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval for these procedures at the University of Vermont and at local hospital IRBs.

Instrument development

A working group from the Steering Committee reviewed a range of available instruments to assess cancer survivors’ needs.9,11-15 We determined that the survey most relevant to our objectives was the Cancer Survivors’ Unmet Needs (CaSun) instrument.13 Because CaSun was developed in Australia, we carefully examined each question for appropriateness to our target audience. We eliminated several questions that we thought less important, added questions from other instruments, and simplified the survey format. Survivors from the Steering Committee pilot tested the draft questionnaire to identify awkward wording or concepts.

We piloted the revised draft using a standardized feedback form with cancer survivors who were not connected to our project and not enrolled in the survivor registry, and with residents at a senior center. Students and a teacher from an Adult Basic Education program helped to ensure easy readability. Our final instrument had 53 questions about needs in 5 domains. Questions within each domain completed the lead-in, “Since your cancer diagnosis, did you need....” We asked participants to check only 1 of the 3 boxes to the right of each question to indicate that there was no need in that area, that there was a need and it was met, or that there was a need and it was not met. We obtained self-reported demographic data during enrollment in the registry.

Data analysis

We summarized data by computing the percent of survivors who reported having each need (either met or unmet) and the percent for whom the need was unmet. The latter was computed both as a percent of all survivors and as a percent of those who had the need. We also calculated the percentage of survivors that had at least one need and at least one unmet need in each domain, as well as the average number of needs per survivor in each domain. We used SPSS for Unix, Release 6.1 (AIX 3.2)(IBM, Armonk, New York).

RESULTS

Of the 2005 cancer survivors invited into the study, 1668 responded, yielding a participation rate of 83%. TABLE 1 describes the self-reported demographic and cancer characteristics of participants in this study. Most respondents were female, ≥60 years old, urban dwellers, married or with a partner, well educated, and had household incomes of ≥$50,000. There were more breast cancer survivors than survivors of other cancers, and 14.6% of all survivors reported being diagnosed with more than one cancer. Cancer was diagnosed at stages 1 or 2 for 78.3% of the participants; 61.9% reported having undergone ≥2 treatment regimens.

The survey addressed needs in 5 domains: access to care and services (A); information (I); emotional, social, and spiritual (E); physical (P); and economic and legal (L). More than 80% of respondents reported having at least one need in the A, I, and E domains. The E domain had the most survivors with at least one unmet need (N=503), followed by the I (N=410) and P (N=375) domains.

Identifying unmet needs. TABLE 2 shows results for the specific questions within the domains in the order they were asked. Most participants who had a need also had it met. However, some needs that were not commonly reported were deemed unmet by a large proportion of those who expressed the need. For example, the A need for “A case manager to whom you could go to find out about services whenever they were needed” (A5) was reported by only 29.1% of survivors. But 32.1% of those reporting the need said it was unmet, which corresponds to 9.4% of all study participants having the need unmet. Similarly, the need for “More information about complementary and alternative medicine” (I3) was reported by about a quarter of the study population, 41.4% of whom (9.8% of all participants) reported it as unmet. In the P domain, the need for “Help to address problems with your sex life” (P4) was reported by only 26.5% of the respondents; yet 40.7% of those reporting the need had it unmet. Similarly, in the L domain, “Help with life insurance concerns as a result of your cancer” (L3) was only reported by 10.9% of the participants but was unmet for 46.4% of those who reported the need, or 5% of all study participants.

Most commonly expressed needs. TABLE 2 also identifies 12 needs reported by ≥50% of participants. Three of these needs were in the A domain, 6 in the I domain, and 3 in the E domain. The 2 most common needs related to A: the need “To feel like you were managing your health together with the medical team” (A3) was reported by 68.6% and was viewed as unmet by 5.2% of all respondents; the need for “Access to screening for recurrence or other cancers” (A7) was reported by 63.8% of the survivors but was deemed unmet by only 3.1% of all the respondents. “More information about possible after effects of your treatment” (I5) was a need for 63.2% that went unmet in 22.9% (14.4% of all participants). “Help managing your concerns about the cancer coming back” (E13) was reported as a need by 54.1% and as unmet by 11.8% of all participants.

The rank order of 7 unmet needs reported by ≥10% of the participants is shown in TABLE 3. Four of the 7 unmet needs were in the E domain. The most common unmet need in this domain was “Help reducing stress in your life” (E19).

Only 3 needs were both commonly reported and also unmet for at least 10% of the participants: “More information about possible after effects of your treatment” (I5), “More information about possible side effects of your treatment” (I4), and “Help managing your concerns about the cancer coming back” (E13).

DISCUSSION

The survey instrument we used to assess the needs of cancer survivors in a large community-based registry included a detailed list of potential needs generated, in part, by representatives of the survivor community. Most cancer survivor needs mentioned in this survey were met. However, some needs were not met for substantial proportions of respondents and should be examined carefully to determine whether services could be improved to better address them. This study was planned and implemented by researchers and cancer survivors using community-based participatory principles to learn about local needs. The results of this study may be generalizable to similar populations of survivors and will inform the survivorship goals for the Vermont State Cancer Plan and future Vermont Cancer Survivor Network activities.

Acting on patients’ expressed needs. Over 80% of participants had needs in the A, I, and E domains. The most commonly reported need was in the A domain, “To feel like you were managing your health together with the medical team” (A3). It was also a top need in other studies that asked this question.16,17 A cancer diagnosis may cause patients to feel out of control. Participation in the management of their health may help them gain a greater sense of control. PCP accommodation of expressed patient preferences may be an important part of a cancer survivor’s long-term adaptation to the disease.

Six of the 12 most frequently reported needs and 2 frequently reported unmet needs were in the I domain. Communication of information increases patients’ involvement in decision-making and enables them to cope better during diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up.18 “More information about possible after effects of your treatment” and “More information about possible side effects of your treatment” were reported by a high proportion of participants, and many also reported these needs as unmet. In another study about health-related information needs of survivors, 52% wanted more information about “What late and long-term side effects of cancer treatment are expected”19; and in a 2005 review of information needs, 12% of survivors reported similar needs.20 Two recent articles also noted such needs in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors.21,22 Based on current evidence, it would be advisable to discuss anticipated effects of treatment with patients not only at the outset but also at the end of treatment, and to write it in a cancer survivor care plan.

Individual needs that were not met for at least 10% of respondents, regardless of how common the need (TABLE 3), provided additional insights. Among these 7 needs, 3 also were reported as a need by more than 50% of respondents (TABLE 2), and 4 by <50%, indicating that some less common needs are not being met adequately. Among these 7 prominent unmet needs, 4 were E Issues (TABLE 3) and 2 were I Issues.

Unmet needs are an opportunity to improve care. In our study and in others, E needs were most likely to be unmet.17,23-26 Among the 4 common unmet E needs, 2 (E19 and E11) focused on generalized stress and worry, and one (E15) focused on concern about illness impact on family members or partners. Although these issues may be challenging to address successfully in a typical clinical environment, others have confirmed the importance of these needs and proposed ways to meet them.27 The fourth most common unmet E need focused on concern about cancer recurrence, also a prominent need found in other studies.15-17 These needs might be addressed more adequately in the course of usual clinical care by PCPs or specialists. In fact, the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer 2012 standards now require psychosocial distress screening and the provision of referral for psychosocial services.24 Our results are consistent in many respects with prior studies of needs reported by cancer survivors in other countries. The CaSUN survey developed by Hodgkinson et al13 has been applied to several survivor populations in Australia. In a diverse survivor sample, specific E, I, and A issues were frequently reported as unmet needs.13 The most prominent unmet needs in a gynecologic cancer sample using CaSUN focused on emotional and social issues such as worry, stress, coping, and relationships with, and expectations of, others.25

Barg et al23 conducted a survey of unmet needs in the United States using a detailed list based on prior survivor research and targeting individuals in a cancer registry. The most prominent area of need expressed was “emotional,” similar to the high rank of E needs in our study. In contrast to our study, however, physical and financial issues also were prominent. The latter variances might be explained by differences in access to care, or perhaps the study’s low response rate (23.8%). A similar survey reported by Campbell et al12 identified needs in the emotional domain as the most cited unmet survivor needs based on psychometrically developed subscales of a 152-item survey (29% response rate).

These results from several studies, including ours, call for more detailed exploration of the E needs of long-term cancer survivors. A useful framework developed by Stein et al28 accounts for factors contributing to cancer stress and burden as well as resources available to survivors (intrapersonal, social, informational, and tangible services), with the interactions between these 2 domains determining how well a survivor will be able to cope. There clearly is a role for development of more effective communication channels and focused services to meet survivor needs.

The list of most common unmet needs in TABLE 3 also includes a focus on “problems with your sex life” (P4). This is an area that may be difficult to address in a cancer care setting because of the focus on disease management. Primary care providers might be better prepared to address this issue because they likely encounter similar issues among the wide range of patients they serve. However, a recent study reported that only 46% of internists were somewhat or likely to initiate a discussion about sexuality with cancer survivors.29 Some additional preparation for physicians to address this need might be warranted.

The proportion in this sample reporting needs for access to, or information about, complementary and alternative medicine services fell below the thresholds chosen to designate common needs in this study. Although reported use is relatively common among cancer survivor in several studies,30-32 it appears that in our survivor sample, those who were interested in these approaches encountered only moderate barriers.

Study limitations. We invited participants from a registry unlikely to include cancer survivors with lower educational attainment or from rural locations9—that is, our participants were less likely to have challenges in obtaining appropriate services and information. This sample limitation therefore likely underestimates the overall level of needs among cancer survivors.

This was a cross-sectional assessment of perceived needs among a diverse group of survivors, which may have overlooked needs that were met but only after considerable effort on the part of survivors. Longitudinal studies would provide more complete accounts of how readily needs are met and the changes in needs at different times in the continuum of care.

The Vermont population is less diverse racially and ethnically, but not with respect to household income or educational attainment, than the overall US population. Access to health care also is relatively high in Vermont compared with many other states. According to a 2009 Vermont Household Health Insurance Survey, only 7.6% of Vermonters are uninsured.33

CORRESPONDENCE

Berta Geller, EdD, University of Vermont, Health Promotion Research/Family Medicine, 1 South Prospect Street, Burlington, VT 05401-3444; [email protected]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Anne Dorwaldt, Kathy Howe, Mark Bowman and John Mace at the University of Vermont, and the Cancer Survivor Community Study Steering Committee for their contributions to the successful completion of this study. We also thank the cancer survivors who participated in the pilot testing and the overall survey.

ABSTRACT

Purpose This study sought to identify the needs and unmet needs of the growing number of adult cancer survivors.

Methods Vermont survivor advocates partnered with academic researchers to create a survivor registry and conduct a cross-sectional survey of cancer-related needs and unmet needs of adult survivors. The mailed survey addressed 53 specific needs in 5 domains based on prior research, contributions from the research partners, and pilot testing. Results were summarized by computing proportions who reported having needs met or unmet.

Results Survey participants included 1668 of 2005 individuals invited from the survivor registry (83%); 65.7% were ages 60 or older and 61.9% were women. These participants had received their diagnosis 2 to 16 years earlier; 77.5% had been diagnosed ≥5 years previously; 30.2% had at least one unmet need in the emotional, social, and spiritual (e) domain; just 14.4% had at least one unmet need in the economic and legal domain. The most commonly identified individual unmet needs were in the e and the information (i) domains and included “help reducing stress” (14.8% of all respondents) and “information about possible after effects of treatment” (14.4%).

Conclusions Most needs of these longer-term survivors were met, but substantial proportions of survivors identified unmet needs. Unmet needs such as information about late and long-term adverse effects of treatment could be met within clinical care with a cancer survivor care plan, but some survivors may require referral to services focused on stress and coping.

Following a successful course of treatment for cancer, many patients return to or remain in the care of their primary care physician (PCP). What often goes unrecognized, however, are these cancer survivors’ unique needs—physical, psychological, social, spiritual, economic, and legal—and the informational and professional services available to address them.1,2

Increased cancer survival creates new needs. There are already >12 million cancer survivors in the United States and >30 million worldwide.3 As baby boomers age, the number of cancers diagnosed over the next 45 years will double4 and improved diagnosis and treatments are already prolonging survivors’ lives. With the greater number of cancer survivors and longer survival time, a cancer survivorship advocacy community has developed to help identify and address the concerns, needs, and benefits of having lived with, through, and beyond a cancer diagnosis.

The purpose of our study. Some of these areas of need have been studied extensively with childhood survivors, breast cancer survivors, and, more recently, prostate cancer survivors. However, few studies have examined adult survivors from all cancer types5-9 or have had cohorts large enough to yield meaningful information.5,7-9 The aim of this study was to describe the needs of adult survivors of all cancer types in a general population from Vermont and to determine whether these needs were met. The results of this study can help identify the services needed by cancer survivors.

METHODS

Population and sample

In November 2009, we invited all survivors listed in a cancer survivor registry to complete a 12-page survey. The registry10 was created as part of the Cancer Survivor Community Study, a community-based participatory research project funded by the National Cancer Institute. The study’s Steering Committee was comprised of cancer survivors, cancer registrars, and researchers. We identified and invited cancer survivors from 4 hospital registries in northwest and central Vermont to participate. Registry participants who indicated willingness to enroll in research studies received an invitation letter and informed consent form, the 12-page survey, and an addressed and stamped return envelope. We obtained Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval for these procedures at the University of Vermont and at local hospital IRBs.

Instrument development

A working group from the Steering Committee reviewed a range of available instruments to assess cancer survivors’ needs.9,11-15 We determined that the survey most relevant to our objectives was the Cancer Survivors’ Unmet Needs (CaSun) instrument.13 Because CaSun was developed in Australia, we carefully examined each question for appropriateness to our target audience. We eliminated several questions that we thought less important, added questions from other instruments, and simplified the survey format. Survivors from the Steering Committee pilot tested the draft questionnaire to identify awkward wording or concepts.

We piloted the revised draft using a standardized feedback form with cancer survivors who were not connected to our project and not enrolled in the survivor registry, and with residents at a senior center. Students and a teacher from an Adult Basic Education program helped to ensure easy readability. Our final instrument had 53 questions about needs in 5 domains. Questions within each domain completed the lead-in, “Since your cancer diagnosis, did you need....” We asked participants to check only 1 of the 3 boxes to the right of each question to indicate that there was no need in that area, that there was a need and it was met, or that there was a need and it was not met. We obtained self-reported demographic data during enrollment in the registry.

Data analysis

We summarized data by computing the percent of survivors who reported having each need (either met or unmet) and the percent for whom the need was unmet. The latter was computed both as a percent of all survivors and as a percent of those who had the need. We also calculated the percentage of survivors that had at least one need and at least one unmet need in each domain, as well as the average number of needs per survivor in each domain. We used SPSS for Unix, Release 6.1 (AIX 3.2)(IBM, Armonk, New York).

RESULTS

Of the 2005 cancer survivors invited into the study, 1668 responded, yielding a participation rate of 83%. TABLE 1 describes the self-reported demographic and cancer characteristics of participants in this study. Most respondents were female, ≥60 years old, urban dwellers, married or with a partner, well educated, and had household incomes of ≥$50,000. There were more breast cancer survivors than survivors of other cancers, and 14.6% of all survivors reported being diagnosed with more than one cancer. Cancer was diagnosed at stages 1 or 2 for 78.3% of the participants; 61.9% reported having undergone ≥2 treatment regimens.

The survey addressed needs in 5 domains: access to care and services (A); information (I); emotional, social, and spiritual (E); physical (P); and economic and legal (L). More than 80% of respondents reported having at least one need in the A, I, and E domains. The E domain had the most survivors with at least one unmet need (N=503), followed by the I (N=410) and P (N=375) domains.

Identifying unmet needs. TABLE 2 shows results for the specific questions within the domains in the order they were asked. Most participants who had a need also had it met. However, some needs that were not commonly reported were deemed unmet by a large proportion of those who expressed the need. For example, the A need for “A case manager to whom you could go to find out about services whenever they were needed” (A5) was reported by only 29.1% of survivors. But 32.1% of those reporting the need said it was unmet, which corresponds to 9.4% of all study participants having the need unmet. Similarly, the need for “More information about complementary and alternative medicine” (I3) was reported by about a quarter of the study population, 41.4% of whom (9.8% of all participants) reported it as unmet. In the P domain, the need for “Help to address problems with your sex life” (P4) was reported by only 26.5% of the respondents; yet 40.7% of those reporting the need had it unmet. Similarly, in the L domain, “Help with life insurance concerns as a result of your cancer” (L3) was only reported by 10.9% of the participants but was unmet for 46.4% of those who reported the need, or 5% of all study participants.

Most commonly expressed needs. TABLE 2 also identifies 12 needs reported by ≥50% of participants. Three of these needs were in the A domain, 6 in the I domain, and 3 in the E domain. The 2 most common needs related to A: the need “To feel like you were managing your health together with the medical team” (A3) was reported by 68.6% and was viewed as unmet by 5.2% of all respondents; the need for “Access to screening for recurrence or other cancers” (A7) was reported by 63.8% of the survivors but was deemed unmet by only 3.1% of all the respondents. “More information about possible after effects of your treatment” (I5) was a need for 63.2% that went unmet in 22.9% (14.4% of all participants). “Help managing your concerns about the cancer coming back” (E13) was reported as a need by 54.1% and as unmet by 11.8% of all participants.

The rank order of 7 unmet needs reported by ≥10% of the participants is shown in TABLE 3. Four of the 7 unmet needs were in the E domain. The most common unmet need in this domain was “Help reducing stress in your life” (E19).

Only 3 needs were both commonly reported and also unmet for at least 10% of the participants: “More information about possible after effects of your treatment” (I5), “More information about possible side effects of your treatment” (I4), and “Help managing your concerns about the cancer coming back” (E13).

DISCUSSION

The survey instrument we used to assess the needs of cancer survivors in a large community-based registry included a detailed list of potential needs generated, in part, by representatives of the survivor community. Most cancer survivor needs mentioned in this survey were met. However, some needs were not met for substantial proportions of respondents and should be examined carefully to determine whether services could be improved to better address them. This study was planned and implemented by researchers and cancer survivors using community-based participatory principles to learn about local needs. The results of this study may be generalizable to similar populations of survivors and will inform the survivorship goals for the Vermont State Cancer Plan and future Vermont Cancer Survivor Network activities.

Acting on patients’ expressed needs. Over 80% of participants had needs in the A, I, and E domains. The most commonly reported need was in the A domain, “To feel like you were managing your health together with the medical team” (A3). It was also a top need in other studies that asked this question.16,17 A cancer diagnosis may cause patients to feel out of control. Participation in the management of their health may help them gain a greater sense of control. PCP accommodation of expressed patient preferences may be an important part of a cancer survivor’s long-term adaptation to the disease.

Six of the 12 most frequently reported needs and 2 frequently reported unmet needs were in the I domain. Communication of information increases patients’ involvement in decision-making and enables them to cope better during diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up.18 “More information about possible after effects of your treatment” and “More information about possible side effects of your treatment” were reported by a high proportion of participants, and many also reported these needs as unmet. In another study about health-related information needs of survivors, 52% wanted more information about “What late and long-term side effects of cancer treatment are expected”19; and in a 2005 review of information needs, 12% of survivors reported similar needs.20 Two recent articles also noted such needs in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors.21,22 Based on current evidence, it would be advisable to discuss anticipated effects of treatment with patients not only at the outset but also at the end of treatment, and to write it in a cancer survivor care plan.

Individual needs that were not met for at least 10% of respondents, regardless of how common the need (TABLE 3), provided additional insights. Among these 7 needs, 3 also were reported as a need by more than 50% of respondents (TABLE 2), and 4 by <50%, indicating that some less common needs are not being met adequately. Among these 7 prominent unmet needs, 4 were E Issues (TABLE 3) and 2 were I Issues.

Unmet needs are an opportunity to improve care. In our study and in others, E needs were most likely to be unmet.17,23-26 Among the 4 common unmet E needs, 2 (E19 and E11) focused on generalized stress and worry, and one (E15) focused on concern about illness impact on family members or partners. Although these issues may be challenging to address successfully in a typical clinical environment, others have confirmed the importance of these needs and proposed ways to meet them.27 The fourth most common unmet E need focused on concern about cancer recurrence, also a prominent need found in other studies.15-17 These needs might be addressed more adequately in the course of usual clinical care by PCPs or specialists. In fact, the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer 2012 standards now require psychosocial distress screening and the provision of referral for psychosocial services.24 Our results are consistent in many respects with prior studies of needs reported by cancer survivors in other countries. The CaSUN survey developed by Hodgkinson et al13 has been applied to several survivor populations in Australia. In a diverse survivor sample, specific E, I, and A issues were frequently reported as unmet needs.13 The most prominent unmet needs in a gynecologic cancer sample using CaSUN focused on emotional and social issues such as worry, stress, coping, and relationships with, and expectations of, others.25

Barg et al23 conducted a survey of unmet needs in the United States using a detailed list based on prior survivor research and targeting individuals in a cancer registry. The most prominent area of need expressed was “emotional,” similar to the high rank of E needs in our study. In contrast to our study, however, physical and financial issues also were prominent. The latter variances might be explained by differences in access to care, or perhaps the study’s low response rate (23.8%). A similar survey reported by Campbell et al12 identified needs in the emotional domain as the most cited unmet survivor needs based on psychometrically developed subscales of a 152-item survey (29% response rate).

These results from several studies, including ours, call for more detailed exploration of the E needs of long-term cancer survivors. A useful framework developed by Stein et al28 accounts for factors contributing to cancer stress and burden as well as resources available to survivors (intrapersonal, social, informational, and tangible services), with the interactions between these 2 domains determining how well a survivor will be able to cope. There clearly is a role for development of more effective communication channels and focused services to meet survivor needs.

The list of most common unmet needs in TABLE 3 also includes a focus on “problems with your sex life” (P4). This is an area that may be difficult to address in a cancer care setting because of the focus on disease management. Primary care providers might be better prepared to address this issue because they likely encounter similar issues among the wide range of patients they serve. However, a recent study reported that only 46% of internists were somewhat or likely to initiate a discussion about sexuality with cancer survivors.29 Some additional preparation for physicians to address this need might be warranted.

The proportion in this sample reporting needs for access to, or information about, complementary and alternative medicine services fell below the thresholds chosen to designate common needs in this study. Although reported use is relatively common among cancer survivor in several studies,30-32 it appears that in our survivor sample, those who were interested in these approaches encountered only moderate barriers.

Study limitations. We invited participants from a registry unlikely to include cancer survivors with lower educational attainment or from rural locations9—that is, our participants were less likely to have challenges in obtaining appropriate services and information. This sample limitation therefore likely underestimates the overall level of needs among cancer survivors.

This was a cross-sectional assessment of perceived needs among a diverse group of survivors, which may have overlooked needs that were met but only after considerable effort on the part of survivors. Longitudinal studies would provide more complete accounts of how readily needs are met and the changes in needs at different times in the continuum of care.

The Vermont population is less diverse racially and ethnically, but not with respect to household income or educational attainment, than the overall US population. Access to health care also is relatively high in Vermont compared with many other states. According to a 2009 Vermont Household Health Insurance Survey, only 7.6% of Vermonters are uninsured.33

CORRESPONDENCE

Berta Geller, EdD, University of Vermont, Health Promotion Research/Family Medicine, 1 South Prospect Street, Burlington, VT 05401-3444; [email protected]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Anne Dorwaldt, Kathy Howe, Mark Bowman and John Mace at the University of Vermont, and the Cancer Survivor Community Study Steering Committee for their contributions to the successful completion of this study. We also thank the cancer survivors who participated in the pilot testing and the overall survey.

1. Potosky A, Han PK, Rowland J, et al. Differences between primary care physicians’ and oncologists’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1403-1410.

2. Rowland J. Survivorship research: past, present, and future. In: Chang AE, Ganz PA, Hayes DF, et al, eds. Oncology: An Evidence-Based Approach. New York, NY: Springer; 2005:1753-1767.

3. Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, et al. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1893-1907.

4. Hewitt ME, Greenfield S, Stovall E, eds. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005.

5. Hawkins NA, Smith T, Zhao L, et al. Health-related behavior change after cancer: results of the American Cancer Society’s studies of cancer survivors (SCS). J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:20-32.

6. Katz ML, Reiter PL, Corbin S, et al. Are rural Ohio Appalachia cancer survivors needs different than urban cancer survivors? J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:140-148.

7. Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, Clauser S, et al. Burden of illness in cancer survivors: findings from a population-based national sample. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1322-1330.

8. Sanson-Fisher R, Girgis A, Boyes A, et al; Supportive Care Review Group. The unmet supportive care needs of patients with cancer. Cancer. 2000;88:226-237.

9. Smith T, Stein KD, Mehta CC, et al. The rationale, design, and implementation of the American Cancer Society’s studies of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2007;109:1-12.

10. Geller BM, Mace J, Vacek P, et al. Are cancer survivors willing to participate in research? J Community Health. 2011;36: 772-778.

11. Crespi CM, Ganz PA, Petersen L, et al. Refinement and psychometric evaluation of the impact of cancer scale. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1530-1541.

12. Campbell HS, Sanson-Fisher R, Turner D, et al. Psychometric properties of cancer survivors’ unmet needs survey. Support Care Cancer. 2010;19:221-230.

13. Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, et al. The development and evaluation of a measure to assess cancer survivors’ unmet supportive care needs: the CaSUN (Cancer Survivors’ Unmet Needs measure). Psychooncology. 2007;16:796-804.

14. Zebrack BJ, Ganz PA, Bernaards CA, et al. Assessing the impact of cancer: development of a new instrument for long-term survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;15:407-421.

15. Arora NK, Hesse BW, Rimer BK, et al. Frustrated and confused: the American public rates its cancer-related information-seeking experiences. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:223-228.

16. Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, et al. Breast cancer survivors’ supportive care needs 2-10 years after diagnosis. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:515-523.

17. Harrison SE, Watson EK, Ward AM, et al. Primary health and supportive care needs of long-term cancer survivors: a questionnaire study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2091-2098.

18. Rutten LJ, Squiers L, Treiman K. Requests for information by family and friends of cancer patients calling the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Information Service. Psychooncology. 2006;15:664-672.

19. Beckjord EB, Arora NK, McLaughlin W, et al. Health-related information needs in a large and diverse sample of adult cancer survivors: implications for cancer care. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2:179-189.

20. Rutten LJ, Arora NK, Bakos AD, et al. Information needs and sources of information among cancer patients: a systematic review of research (1980-2003). Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57:250-261.

21. Zebrack BJ, Block R, Hayes-Lattin B, et al. Psychosocial service use and unmet need among recently diagnosed adolescent and youg adult patients. Cancer. 2013;119:201-214.

22. Keegan TH, Lichtensztajn DY, Kato I, et al. Unmet adolescent and young adult cancer survivors information and service needs: a population-based cancer registry study. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:239-250.

23. Barg KF, Cronholm PF, Straton JB, et al. Unmet psychosocial needs of Pennsylvanians with cancer: 1996-2005. Cancer. 2007;110:631-639.

24. American College of Surgeons. Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2011.

25. Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Fuchs A, et al. Long-term survival from gynecologic cancer: psychosocial outcomes, supportive care needs and positive outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104:381-389.

26. Houts PS, Yasko JM, Kahn SB, et al. Unmet psychological, social, and economic needs of persons with cancer in Pennsylvania. Cancer. 1986;58:2355-2361.

27. Holland JC, Reznik I. Pathways for psychosocial care of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2005;104(11 suppl):2624-2637.

28. Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(11 suppl):2577-2592.

29. Park ER, Bober SL, Campbell EG, et al. General: Internist communication about sexual function with cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(suppl 2):S407-S411.

30. Girgis A, Adams J, Sibbritt D. The use of complementary and alternative therapies by patients with cancer. Oncol Res. 2005;15:281-289.

31. Gansler T, Kaw C, Crammer C, et al. A population-based study of prevalence of complementary methods use by cancer survivors: a report from the American Cancer Society’s studies of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2008;113:1048-1057.

32. Fouladbakhsh JM, Stommel M. Gender, symptom experience, and use of complementary and alternative medicine practices among cancer survivors in the U.S. cancer population. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37:E7-E15.

33. Vermont Department of Financial Regulation. Vermont Household Health Insurance Survey (VHHIS). Vermont Department of Financial Regulation Web site. Available at: http://www.dfr.vermont.gov/insurance/health-insurance/vermont-household-health-insurance-survey-vhhis. Accessed July 15, 2014.

1. Potosky A, Han PK, Rowland J, et al. Differences between primary care physicians’ and oncologists’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1403-1410.

2. Rowland J. Survivorship research: past, present, and future. In: Chang AE, Ganz PA, Hayes DF, et al, eds. Oncology: An Evidence-Based Approach. New York, NY: Springer; 2005:1753-1767.

3. Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, et al. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1893-1907.

4. Hewitt ME, Greenfield S, Stovall E, eds. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005.

5. Hawkins NA, Smith T, Zhao L, et al. Health-related behavior change after cancer: results of the American Cancer Society’s studies of cancer survivors (SCS). J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:20-32.

6. Katz ML, Reiter PL, Corbin S, et al. Are rural Ohio Appalachia cancer survivors needs different than urban cancer survivors? J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:140-148.

7. Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, Clauser S, et al. Burden of illness in cancer survivors: findings from a population-based national sample. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1322-1330.

8. Sanson-Fisher R, Girgis A, Boyes A, et al; Supportive Care Review Group. The unmet supportive care needs of patients with cancer. Cancer. 2000;88:226-237.

9. Smith T, Stein KD, Mehta CC, et al. The rationale, design, and implementation of the American Cancer Society’s studies of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2007;109:1-12.

10. Geller BM, Mace J, Vacek P, et al. Are cancer survivors willing to participate in research? J Community Health. 2011;36: 772-778.

11. Crespi CM, Ganz PA, Petersen L, et al. Refinement and psychometric evaluation of the impact of cancer scale. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1530-1541.

12. Campbell HS, Sanson-Fisher R, Turner D, et al. Psychometric properties of cancer survivors’ unmet needs survey. Support Care Cancer. 2010;19:221-230.

13. Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, et al. The development and evaluation of a measure to assess cancer survivors’ unmet supportive care needs: the CaSUN (Cancer Survivors’ Unmet Needs measure). Psychooncology. 2007;16:796-804.

14. Zebrack BJ, Ganz PA, Bernaards CA, et al. Assessing the impact of cancer: development of a new instrument for long-term survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;15:407-421.

15. Arora NK, Hesse BW, Rimer BK, et al. Frustrated and confused: the American public rates its cancer-related information-seeking experiences. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:223-228.

16. Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, et al. Breast cancer survivors’ supportive care needs 2-10 years after diagnosis. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:515-523.

17. Harrison SE, Watson EK, Ward AM, et al. Primary health and supportive care needs of long-term cancer survivors: a questionnaire study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2091-2098.

18. Rutten LJ, Squiers L, Treiman K. Requests for information by family and friends of cancer patients calling the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Information Service. Psychooncology. 2006;15:664-672.

19. Beckjord EB, Arora NK, McLaughlin W, et al. Health-related information needs in a large and diverse sample of adult cancer survivors: implications for cancer care. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2:179-189.

20. Rutten LJ, Arora NK, Bakos AD, et al. Information needs and sources of information among cancer patients: a systematic review of research (1980-2003). Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57:250-261.

21. Zebrack BJ, Block R, Hayes-Lattin B, et al. Psychosocial service use and unmet need among recently diagnosed adolescent and youg adult patients. Cancer. 2013;119:201-214.

22. Keegan TH, Lichtensztajn DY, Kato I, et al. Unmet adolescent and young adult cancer survivors information and service needs: a population-based cancer registry study. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:239-250.

23. Barg KF, Cronholm PF, Straton JB, et al. Unmet psychosocial needs of Pennsylvanians with cancer: 1996-2005. Cancer. 2007;110:631-639.

24. American College of Surgeons. Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2011.

25. Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Fuchs A, et al. Long-term survival from gynecologic cancer: psychosocial outcomes, supportive care needs and positive outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104:381-389.

26. Houts PS, Yasko JM, Kahn SB, et al. Unmet psychological, social, and economic needs of persons with cancer in Pennsylvania. Cancer. 1986;58:2355-2361.

27. Holland JC, Reznik I. Pathways for psychosocial care of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2005;104(11 suppl):2624-2637.

28. Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(11 suppl):2577-2592.

29. Park ER, Bober SL, Campbell EG, et al. General: Internist communication about sexual function with cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(suppl 2):S407-S411.

30. Girgis A, Adams J, Sibbritt D. The use of complementary and alternative therapies by patients with cancer. Oncol Res. 2005;15:281-289.

31. Gansler T, Kaw C, Crammer C, et al. A population-based study of prevalence of complementary methods use by cancer survivors: a report from the American Cancer Society’s studies of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2008;113:1048-1057.

32. Fouladbakhsh JM, Stommel M. Gender, symptom experience, and use of complementary and alternative medicine practices among cancer survivors in the U.S. cancer population. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37:E7-E15.

33. Vermont Department of Financial Regulation. Vermont Household Health Insurance Survey (VHHIS). Vermont Department of Financial Regulation Web site. Available at: http://www.dfr.vermont.gov/insurance/health-insurance/vermont-household-health-insurance-survey-vhhis. Accessed July 15, 2014.