User login

Antibiotic Therapy Guidelines for Pediatric Pneumonia Helpful, Not Hurtful

Hospitalists need not fear negative consequences when prescribing guideline-recommended antibiotic therapy for children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), according to a recent study conducted at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC).

"Guideline-recommended therapy for pediatric pneumonia did not result in different outcomes than nonrecommended [largely cephalosporin] therapy," lead author and CCHMC-based hospitalist Joanna Thomson MD, MPH, says in an email to The Hospitalist.

Published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the study followed the outcomes of 168 pediatric inpatients ages 3 months to 18 years who were prescribed empiric guideline-recommended therapy, which advises using an aminopenicillin first rather than a broad-spectrum antibiotic. The study focused on patients’ outcomes, specifically length of stay (LOS), total cost of hospitalization, and inpatient pharmacy costs, and found no difference in LOS or costs for patients treated according to guidelines compared with those whose treatment varied from the recommendations.

"Given growing concerns regarding antimicrobial resistance, it is pretty easy to extrapolate the benefits of using narrow-spectrum therapy, but we wanted to make sure that it wasn't resulting in negative unintended consequences," Dr. Thomson says. "Indeed, use of guideline-recommended therapy did not change our outcomes."

However, most patients hospitalized with CAP do not currently receive guideline-recommended therapy, according to Dr. Thomson. CCHMC had been one of those institutions overprescribing cephalosporin, with nearly 70% of children admitted with pneumonia receiving the antibiotic. That practice has since changed, she notes.

"The majority of hospitalized patients in the U.S. still receive broad-spectrum cephalosporins," Dr. Thomson says. "I suspect that this may partially be due to fears of unintended negative consequences. We should all be good stewards and prescribe guideline-recommended therapy whenever possible."

Visit our website for more information on antibiotic prescription practices.

Hospitalists need not fear negative consequences when prescribing guideline-recommended antibiotic therapy for children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), according to a recent study conducted at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC).

"Guideline-recommended therapy for pediatric pneumonia did not result in different outcomes than nonrecommended [largely cephalosporin] therapy," lead author and CCHMC-based hospitalist Joanna Thomson MD, MPH, says in an email to The Hospitalist.

Published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the study followed the outcomes of 168 pediatric inpatients ages 3 months to 18 years who were prescribed empiric guideline-recommended therapy, which advises using an aminopenicillin first rather than a broad-spectrum antibiotic. The study focused on patients’ outcomes, specifically length of stay (LOS), total cost of hospitalization, and inpatient pharmacy costs, and found no difference in LOS or costs for patients treated according to guidelines compared with those whose treatment varied from the recommendations.

"Given growing concerns regarding antimicrobial resistance, it is pretty easy to extrapolate the benefits of using narrow-spectrum therapy, but we wanted to make sure that it wasn't resulting in negative unintended consequences," Dr. Thomson says. "Indeed, use of guideline-recommended therapy did not change our outcomes."

However, most patients hospitalized with CAP do not currently receive guideline-recommended therapy, according to Dr. Thomson. CCHMC had been one of those institutions overprescribing cephalosporin, with nearly 70% of children admitted with pneumonia receiving the antibiotic. That practice has since changed, she notes.

"The majority of hospitalized patients in the U.S. still receive broad-spectrum cephalosporins," Dr. Thomson says. "I suspect that this may partially be due to fears of unintended negative consequences. We should all be good stewards and prescribe guideline-recommended therapy whenever possible."

Visit our website for more information on antibiotic prescription practices.

Hospitalists need not fear negative consequences when prescribing guideline-recommended antibiotic therapy for children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), according to a recent study conducted at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC).

"Guideline-recommended therapy for pediatric pneumonia did not result in different outcomes than nonrecommended [largely cephalosporin] therapy," lead author and CCHMC-based hospitalist Joanna Thomson MD, MPH, says in an email to The Hospitalist.

Published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, the study followed the outcomes of 168 pediatric inpatients ages 3 months to 18 years who were prescribed empiric guideline-recommended therapy, which advises using an aminopenicillin first rather than a broad-spectrum antibiotic. The study focused on patients’ outcomes, specifically length of stay (LOS), total cost of hospitalization, and inpatient pharmacy costs, and found no difference in LOS or costs for patients treated according to guidelines compared with those whose treatment varied from the recommendations.

"Given growing concerns regarding antimicrobial resistance, it is pretty easy to extrapolate the benefits of using narrow-spectrum therapy, but we wanted to make sure that it wasn't resulting in negative unintended consequences," Dr. Thomson says. "Indeed, use of guideline-recommended therapy did not change our outcomes."

However, most patients hospitalized with CAP do not currently receive guideline-recommended therapy, according to Dr. Thomson. CCHMC had been one of those institutions overprescribing cephalosporin, with nearly 70% of children admitted with pneumonia receiving the antibiotic. That practice has since changed, she notes.

"The majority of hospitalized patients in the U.S. still receive broad-spectrum cephalosporins," Dr. Thomson says. "I suspect that this may partially be due to fears of unintended negative consequences. We should all be good stewards and prescribe guideline-recommended therapy whenever possible."

Visit our website for more information on antibiotic prescription practices.

Brentuximab combinations highly active in Hodgkin lymphoma

Photo courtesy of ASH

SAN FRANCISCO—Two recent studies have shown combination therapy with brentuximab vedotin to be highly active in newly diagnosed patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and in relapsed or refractory patients after frontline therapy.

The first study evaluated brentuximab with ABVD or AVD and the second with bendamustine.

Objective response rates were 95% with ABVD, 96% with AVD, and 96% with bendamustine.

Both studies were presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting, and both were sponsored by Seattle Genetics, Inc., the company developing brentuximab vedotin.

Brentuximab with ABVD or AVD

Standard frontline therapy with ABVD (adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) or AVD (the same regimen without bleomycin) fails to cure up to 30% of patients with HL.

So investigators decided to try a new approach to increase efficacy and reduce toxicity—combining brentuximab with standard therapy.

Joseph M. Connors, MD, of the BC Cancer Agency and University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, presented long-term outcomes of the brentuximab-ABVD combination as abstract 292.*

Phase 1 dose-escalation study

The key initial study of the combination determined the maximum tolerated dose of brentuximab to be 1.2 mg/kg delivered on a 2-week schedule to match the other agents in the ABVD regimen. Brentuximab was delivered for up to 6 cycles.

Of the 50 patients treated, 75% were males with an ECOG status of 0 or 1. Their median age was 32.5 years (range, 18 to 59). Approximately 80% were stage III or IV.

“We learned several key lessons from that initial study,” Dr Connors said. “The first was that when one adds brentuximab vedotin to the full-dose combination ABVD, unacceptable levels of pulmonary toxicity occurred, with 44% of the patients eventually experiencing pulmonary toxicity, typically manifest between the third and sixth cycle of treatment.”

The toxicity resolved in 9 of the 11 patients, but was fatal in 2. The median time to resolution was 2.6 weeks.

Eight patients discontinued bleomycin but were able to complete treatment with AVD and brentuximab.

“When we dropped bleomycin from the combination and shifted to AVD without bleomycin, no patients experienced pulmonary toxicity,” Dr Connors added.

Ultimately, the combination produced a response rate of 95% with ABVD and 96% with AVD.

Long-term follow-up

Investigators then assessed the durability of the response and the time distribution of any relapses.

All but 1 patient was available for follow-up. Patients were followed for a median of 45 months in the ABVD arm and 36 months in the AVD arm.

In the ABVD arm, 22 of 24 patients are living, and all 26 patients in the AVD group are alive. Altogether, there have been 5 relapses—3 in the ABVD arm (occurring at 9, 22, and 23 months) and 2 in the AVD arm (occurring at 7 and 22 months).

The 3-year failure-free survival is 79% with ABVD and 92% with AVD. And the 3-year overall survival is 92% in the ABVD arm and 100% in the AVD arm.

No deaths from HL have occurred, and all 5 relapsed patients have undergone autologous stem cell transplant. One of those has subsequently relapsed.

“So far,” Dr Connors said, “survival has been excellent.” And responses are durable.

“This has encouraged activation of the large, international trial,” Dr Connors said, comparing AVD plus brentuximab to standard ABVD in frontline treatment of HL.

Brentuximab with bendamustine

Brentuximab is also active as a single agent in relapsed/refractory HL, producing a 34% complete response (CR) rate. And the alkylating agent bendamustine produces a 33% CR rate in these patients. Furthermore, both agents have manageable safety profiles and different mechanisms of action.

Investigators therefore hypothesized that brentuximab in combination with bendamustine could induce more CRs in HL patients with relapsed or refractory disease after frontline therapy.

Ann LaCasce, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, presented the data at ASH as abstract 293.*

Ten patients were enrolled in the phase 1 portion of the study to determine the optimal dose level of bendamustine and to assess safety and tolerability.

No dose-limiting toxicities were observed. So the investigators used bendamustine at 90 mg/m2 and brentuximab at 1.8 mg/kg. Patients received a median of 2 cycles (range, 1 to 6) of combination therapy.

Patients had the option to proceed to an autologous stem cell transplant at any time after cycle 2 and could receive brentuximab monotherapy thereafter for up to 16 total doses.

The phase 2 expansion portion enrolled 44 patients and assessed the best response, duration of response, and progression-free survival.

Results

Patients were a median age of 37 years (range, 27 to 51), and 57% were male. Ninety-eight percent were ECOG status 0 or 1, and 54% had stage III or IV disease at diagnosis.

The majority of patients had received ABVD as frontline therapy, Dr LaCasce pointed out.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse event was infusion-related reactions, accounting for 96% of the events. Dyspnea (15%), chills (13%), and flushing (13%) were the most common symptoms, and hypotension requiring vasopressor support also occurred.

Most reactions occurred within 24 hours of the cycle 2 infusion and were considered related to both agents. However, delayed hypersensitivity reactions also occurred, Dr LaCasce said, the most common being rash in 14 patients up to 22 days after infusion.

“Based on the number of infusion-related reactions after 24 patients, the protocol was amended to require mandatory corticosteroids and anthistamine premedication,” Dr LaCasce explained. “[T]his resulted in a significant decrease in the severity of the infusion-related reactions.”

The best clinical response for the 48 evaluable patients was 83% CR and 13% partial remission, for an objective response rate of 96%.

The median progression-free survival has not yet been reached, and the combination has had no negative impact on stem cell mobilization or engraftment to date.

The response rate compares very favorably to historical data, Dr LaCasce said, and the combination represents a promising salvage regimen for HL patients. ![]()

*Data in the presentation differ from the abstract.

Photo courtesy of ASH

SAN FRANCISCO—Two recent studies have shown combination therapy with brentuximab vedotin to be highly active in newly diagnosed patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and in relapsed or refractory patients after frontline therapy.

The first study evaluated brentuximab with ABVD or AVD and the second with bendamustine.

Objective response rates were 95% with ABVD, 96% with AVD, and 96% with bendamustine.

Both studies were presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting, and both were sponsored by Seattle Genetics, Inc., the company developing brentuximab vedotin.

Brentuximab with ABVD or AVD

Standard frontline therapy with ABVD (adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) or AVD (the same regimen without bleomycin) fails to cure up to 30% of patients with HL.

So investigators decided to try a new approach to increase efficacy and reduce toxicity—combining brentuximab with standard therapy.

Joseph M. Connors, MD, of the BC Cancer Agency and University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, presented long-term outcomes of the brentuximab-ABVD combination as abstract 292.*

Phase 1 dose-escalation study

The key initial study of the combination determined the maximum tolerated dose of brentuximab to be 1.2 mg/kg delivered on a 2-week schedule to match the other agents in the ABVD regimen. Brentuximab was delivered for up to 6 cycles.

Of the 50 patients treated, 75% were males with an ECOG status of 0 or 1. Their median age was 32.5 years (range, 18 to 59). Approximately 80% were stage III or IV.

“We learned several key lessons from that initial study,” Dr Connors said. “The first was that when one adds brentuximab vedotin to the full-dose combination ABVD, unacceptable levels of pulmonary toxicity occurred, with 44% of the patients eventually experiencing pulmonary toxicity, typically manifest between the third and sixth cycle of treatment.”

The toxicity resolved in 9 of the 11 patients, but was fatal in 2. The median time to resolution was 2.6 weeks.

Eight patients discontinued bleomycin but were able to complete treatment with AVD and brentuximab.

“When we dropped bleomycin from the combination and shifted to AVD without bleomycin, no patients experienced pulmonary toxicity,” Dr Connors added.

Ultimately, the combination produced a response rate of 95% with ABVD and 96% with AVD.

Long-term follow-up

Investigators then assessed the durability of the response and the time distribution of any relapses.

All but 1 patient was available for follow-up. Patients were followed for a median of 45 months in the ABVD arm and 36 months in the AVD arm.

In the ABVD arm, 22 of 24 patients are living, and all 26 patients in the AVD group are alive. Altogether, there have been 5 relapses—3 in the ABVD arm (occurring at 9, 22, and 23 months) and 2 in the AVD arm (occurring at 7 and 22 months).

The 3-year failure-free survival is 79% with ABVD and 92% with AVD. And the 3-year overall survival is 92% in the ABVD arm and 100% in the AVD arm.

No deaths from HL have occurred, and all 5 relapsed patients have undergone autologous stem cell transplant. One of those has subsequently relapsed.

“So far,” Dr Connors said, “survival has been excellent.” And responses are durable.

“This has encouraged activation of the large, international trial,” Dr Connors said, comparing AVD plus brentuximab to standard ABVD in frontline treatment of HL.

Brentuximab with bendamustine

Brentuximab is also active as a single agent in relapsed/refractory HL, producing a 34% complete response (CR) rate. And the alkylating agent bendamustine produces a 33% CR rate in these patients. Furthermore, both agents have manageable safety profiles and different mechanisms of action.

Investigators therefore hypothesized that brentuximab in combination with bendamustine could induce more CRs in HL patients with relapsed or refractory disease after frontline therapy.

Ann LaCasce, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, presented the data at ASH as abstract 293.*

Ten patients were enrolled in the phase 1 portion of the study to determine the optimal dose level of bendamustine and to assess safety and tolerability.

No dose-limiting toxicities were observed. So the investigators used bendamustine at 90 mg/m2 and brentuximab at 1.8 mg/kg. Patients received a median of 2 cycles (range, 1 to 6) of combination therapy.

Patients had the option to proceed to an autologous stem cell transplant at any time after cycle 2 and could receive brentuximab monotherapy thereafter for up to 16 total doses.

The phase 2 expansion portion enrolled 44 patients and assessed the best response, duration of response, and progression-free survival.

Results

Patients were a median age of 37 years (range, 27 to 51), and 57% were male. Ninety-eight percent were ECOG status 0 or 1, and 54% had stage III or IV disease at diagnosis.

The majority of patients had received ABVD as frontline therapy, Dr LaCasce pointed out.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse event was infusion-related reactions, accounting for 96% of the events. Dyspnea (15%), chills (13%), and flushing (13%) were the most common symptoms, and hypotension requiring vasopressor support also occurred.

Most reactions occurred within 24 hours of the cycle 2 infusion and were considered related to both agents. However, delayed hypersensitivity reactions also occurred, Dr LaCasce said, the most common being rash in 14 patients up to 22 days after infusion.

“Based on the number of infusion-related reactions after 24 patients, the protocol was amended to require mandatory corticosteroids and anthistamine premedication,” Dr LaCasce explained. “[T]his resulted in a significant decrease in the severity of the infusion-related reactions.”

The best clinical response for the 48 evaluable patients was 83% CR and 13% partial remission, for an objective response rate of 96%.

The median progression-free survival has not yet been reached, and the combination has had no negative impact on stem cell mobilization or engraftment to date.

The response rate compares very favorably to historical data, Dr LaCasce said, and the combination represents a promising salvage regimen for HL patients. ![]()

*Data in the presentation differ from the abstract.

Photo courtesy of ASH

SAN FRANCISCO—Two recent studies have shown combination therapy with brentuximab vedotin to be highly active in newly diagnosed patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) and in relapsed or refractory patients after frontline therapy.

The first study evaluated brentuximab with ABVD or AVD and the second with bendamustine.

Objective response rates were 95% with ABVD, 96% with AVD, and 96% with bendamustine.

Both studies were presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting, and both were sponsored by Seattle Genetics, Inc., the company developing brentuximab vedotin.

Brentuximab with ABVD or AVD

Standard frontline therapy with ABVD (adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) or AVD (the same regimen without bleomycin) fails to cure up to 30% of patients with HL.

So investigators decided to try a new approach to increase efficacy and reduce toxicity—combining brentuximab with standard therapy.

Joseph M. Connors, MD, of the BC Cancer Agency and University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, presented long-term outcomes of the brentuximab-ABVD combination as abstract 292.*

Phase 1 dose-escalation study

The key initial study of the combination determined the maximum tolerated dose of brentuximab to be 1.2 mg/kg delivered on a 2-week schedule to match the other agents in the ABVD regimen. Brentuximab was delivered for up to 6 cycles.

Of the 50 patients treated, 75% were males with an ECOG status of 0 or 1. Their median age was 32.5 years (range, 18 to 59). Approximately 80% were stage III or IV.

“We learned several key lessons from that initial study,” Dr Connors said. “The first was that when one adds brentuximab vedotin to the full-dose combination ABVD, unacceptable levels of pulmonary toxicity occurred, with 44% of the patients eventually experiencing pulmonary toxicity, typically manifest between the third and sixth cycle of treatment.”

The toxicity resolved in 9 of the 11 patients, but was fatal in 2. The median time to resolution was 2.6 weeks.

Eight patients discontinued bleomycin but were able to complete treatment with AVD and brentuximab.

“When we dropped bleomycin from the combination and shifted to AVD without bleomycin, no patients experienced pulmonary toxicity,” Dr Connors added.

Ultimately, the combination produced a response rate of 95% with ABVD and 96% with AVD.

Long-term follow-up

Investigators then assessed the durability of the response and the time distribution of any relapses.

All but 1 patient was available for follow-up. Patients were followed for a median of 45 months in the ABVD arm and 36 months in the AVD arm.

In the ABVD arm, 22 of 24 patients are living, and all 26 patients in the AVD group are alive. Altogether, there have been 5 relapses—3 in the ABVD arm (occurring at 9, 22, and 23 months) and 2 in the AVD arm (occurring at 7 and 22 months).

The 3-year failure-free survival is 79% with ABVD and 92% with AVD. And the 3-year overall survival is 92% in the ABVD arm and 100% in the AVD arm.

No deaths from HL have occurred, and all 5 relapsed patients have undergone autologous stem cell transplant. One of those has subsequently relapsed.

“So far,” Dr Connors said, “survival has been excellent.” And responses are durable.

“This has encouraged activation of the large, international trial,” Dr Connors said, comparing AVD plus brentuximab to standard ABVD in frontline treatment of HL.

Brentuximab with bendamustine

Brentuximab is also active as a single agent in relapsed/refractory HL, producing a 34% complete response (CR) rate. And the alkylating agent bendamustine produces a 33% CR rate in these patients. Furthermore, both agents have manageable safety profiles and different mechanisms of action.

Investigators therefore hypothesized that brentuximab in combination with bendamustine could induce more CRs in HL patients with relapsed or refractory disease after frontline therapy.

Ann LaCasce, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, presented the data at ASH as abstract 293.*

Ten patients were enrolled in the phase 1 portion of the study to determine the optimal dose level of bendamustine and to assess safety and tolerability.

No dose-limiting toxicities were observed. So the investigators used bendamustine at 90 mg/m2 and brentuximab at 1.8 mg/kg. Patients received a median of 2 cycles (range, 1 to 6) of combination therapy.

Patients had the option to proceed to an autologous stem cell transplant at any time after cycle 2 and could receive brentuximab monotherapy thereafter for up to 16 total doses.

The phase 2 expansion portion enrolled 44 patients and assessed the best response, duration of response, and progression-free survival.

Results

Patients were a median age of 37 years (range, 27 to 51), and 57% were male. Ninety-eight percent were ECOG status 0 or 1, and 54% had stage III or IV disease at diagnosis.

The majority of patients had received ABVD as frontline therapy, Dr LaCasce pointed out.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse event was infusion-related reactions, accounting for 96% of the events. Dyspnea (15%), chills (13%), and flushing (13%) were the most common symptoms, and hypotension requiring vasopressor support also occurred.

Most reactions occurred within 24 hours of the cycle 2 infusion and were considered related to both agents. However, delayed hypersensitivity reactions also occurred, Dr LaCasce said, the most common being rash in 14 patients up to 22 days after infusion.

“Based on the number of infusion-related reactions after 24 patients, the protocol was amended to require mandatory corticosteroids and anthistamine premedication,” Dr LaCasce explained. “[T]his resulted in a significant decrease in the severity of the infusion-related reactions.”

The best clinical response for the 48 evaluable patients was 83% CR and 13% partial remission, for an objective response rate of 96%.

The median progression-free survival has not yet been reached, and the combination has had no negative impact on stem cell mobilization or engraftment to date.

The response rate compares very favorably to historical data, Dr LaCasce said, and the combination represents a promising salvage regimen for HL patients. ![]()

*Data in the presentation differ from the abstract.

FDA approves pathogen inactivation system for platelets

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets, the first system of its kind to be approved in the US.

It is used to inactivate viruses, bacteria, spirochetes, parasites, and leukocytes in apheresis platelet components.

This can reduce the risk of transfusion-transmitted infection and, potentially, transfusion-associated graft-vs-host disease, although the system cannot inactivate all pathogens.

Certain non-enveloped viruses (such as HAV, HEV, B19, and poliovirus) and Bacillus cereus spores have demonstrated resistance to the INTERCEPT process.

Earlier this week, the FDA approved the INTERCEPT Blood System for plasma (also the first system of its kind to gain FDA approval).

The platelet and plasma systems use the same illumination device, the same active compound (amotosalen), and very similar production steps.

The INTERCEPT systems target a basic biological difference between the therapeutic components of blood. Platelets, plasma, and red blood cells do not require functional DNA or RNA for therapeutic efficacy. But pathogens and white blood cells do, in order to transmit infection.

The INTERCEPT systems use a proprietary molecule that, when activated by UVA light, binds to and blocks the replication of DNA and RNA, preventing nucleic acid replication and rendering the pathogen inactive.

The INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets has been approved in Europe since 2002 and is currently used in 20 countries.

The system was recently made available in the US and its territories under an investigational device exemption study to reduce the risk of transfusion-transmitted dengue and Chikungunya viruses, both of which are epidemic in the Caribbean region, including Puerto Rico, as well as sporadically in the southern US. No approved blood bank screening tests are available for either virus.

Researchers have evaluated INTERCEPT-processed platelets in 10 controlled clinical trials. Details on these trials can be found in the package insert. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets, the first system of its kind to be approved in the US.

It is used to inactivate viruses, bacteria, spirochetes, parasites, and leukocytes in apheresis platelet components.

This can reduce the risk of transfusion-transmitted infection and, potentially, transfusion-associated graft-vs-host disease, although the system cannot inactivate all pathogens.

Certain non-enveloped viruses (such as HAV, HEV, B19, and poliovirus) and Bacillus cereus spores have demonstrated resistance to the INTERCEPT process.

Earlier this week, the FDA approved the INTERCEPT Blood System for plasma (also the first system of its kind to gain FDA approval).

The platelet and plasma systems use the same illumination device, the same active compound (amotosalen), and very similar production steps.

The INTERCEPT systems target a basic biological difference between the therapeutic components of blood. Platelets, plasma, and red blood cells do not require functional DNA or RNA for therapeutic efficacy. But pathogens and white blood cells do, in order to transmit infection.

The INTERCEPT systems use a proprietary molecule that, when activated by UVA light, binds to and blocks the replication of DNA and RNA, preventing nucleic acid replication and rendering the pathogen inactive.

The INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets has been approved in Europe since 2002 and is currently used in 20 countries.

The system was recently made available in the US and its territories under an investigational device exemption study to reduce the risk of transfusion-transmitted dengue and Chikungunya viruses, both of which are epidemic in the Caribbean region, including Puerto Rico, as well as sporadically in the southern US. No approved blood bank screening tests are available for either virus.

Researchers have evaluated INTERCEPT-processed platelets in 10 controlled clinical trials. Details on these trials can be found in the package insert. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets, the first system of its kind to be approved in the US.

It is used to inactivate viruses, bacteria, spirochetes, parasites, and leukocytes in apheresis platelet components.

This can reduce the risk of transfusion-transmitted infection and, potentially, transfusion-associated graft-vs-host disease, although the system cannot inactivate all pathogens.

Certain non-enveloped viruses (such as HAV, HEV, B19, and poliovirus) and Bacillus cereus spores have demonstrated resistance to the INTERCEPT process.

Earlier this week, the FDA approved the INTERCEPT Blood System for plasma (also the first system of its kind to gain FDA approval).

The platelet and plasma systems use the same illumination device, the same active compound (amotosalen), and very similar production steps.

The INTERCEPT systems target a basic biological difference between the therapeutic components of blood. Platelets, plasma, and red blood cells do not require functional DNA or RNA for therapeutic efficacy. But pathogens and white blood cells do, in order to transmit infection.

The INTERCEPT systems use a proprietary molecule that, when activated by UVA light, binds to and blocks the replication of DNA and RNA, preventing nucleic acid replication and rendering the pathogen inactive.

The INTERCEPT Blood System for platelets has been approved in Europe since 2002 and is currently used in 20 countries.

The system was recently made available in the US and its territories under an investigational device exemption study to reduce the risk of transfusion-transmitted dengue and Chikungunya viruses, both of which are epidemic in the Caribbean region, including Puerto Rico, as well as sporadically in the southern US. No approved blood bank screening tests are available for either virus.

Researchers have evaluated INTERCEPT-processed platelets in 10 controlled clinical trials. Details on these trials can be found in the package insert. ![]()

Studies show TRALI underreported, TACO on the decline

Credit: Elise Amendola

Two studies shed new light on the prevalence of transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) and transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) in the US.

The research showed that postoperative TRALI is significantly underreported and more common than previously thought, with an overall rate of 1.4%.

And the rate of TACO is on the decline, but the risk to surgical patients remains high, at 4%, similar to previous TACO estimates in non-surgical patients.

“An accurate understanding of the risks associated with blood transfusions is essential when determining the safety and appropriateness of transfusion therapies for patients,” said Daryl Kor, MD, senior author of both studies and an associate professor at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“Our research provides a greater awareness of the incidence of TRALI and TACO in surgical patients, a population that has been perhaps underrepresented in studies in this area. We believe this to be an important first step in our efforts to prevent these life-threatening transfusion complications.”

Dr Kor and his colleagues described this research in Anesthesiology alongside a related editorial.

In the two retrospective studies, the researchers examined the incidence of TRALI in 3379 patients and TACO in 4070 patients who received blood transfusions during non-cardiac surgery under general anesthesia in 2004 and 2011.

Using a novel algorithm, followed by a rigorous manual review, the team performed a detailed epidemiologic analysis for both complications.

The first study showed that TRALI occurred in 1.4% of surgical patients, with higher rates in specific surgical populations such as those having surgery inside the chest cavity, on major blood vessels, or having an organ transplant. Patients who received larger volumes of blood were also at increased risk.

Previous studies investigating TRALI rates have primarily focused on the critically ill and reported variable incidence rates. Many studies have reported incidences between 0.02% and 0.05%.

The second study showed that TACO occurs in 4.3% of surgical patients, with higher rates associated with increased volume of blood transfused, advanced age, and total intraoperative fluid balance. Again, patients having surgery inside the chest cavity, on major blood vessels, or organ transplants were at the greatest risk.

The study also revealed that the rate of TACO decreased significantly from 2004 to 2011—from 5.5% to 3%. This decline was not fully explained by any of the patient or transfusion characteristics evaluated in the study.

The researchers said future studies are needed to further explore which mechanisms and risk factors are responsible for TACO and TRALI.

“With improved understanding of the mechanisms underlying TRALI and TACO, we may be able to refine the novel electronic algorithms used to screen patients in these studies,” Dr Kor said. “Ultimately, we hope to develop a real-time prediction model for these complications so that we can identify those at greatest risk and perhaps implement strategies to reduce this risk.” ![]()

Credit: Elise Amendola

Two studies shed new light on the prevalence of transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) and transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) in the US.

The research showed that postoperative TRALI is significantly underreported and more common than previously thought, with an overall rate of 1.4%.

And the rate of TACO is on the decline, but the risk to surgical patients remains high, at 4%, similar to previous TACO estimates in non-surgical patients.

“An accurate understanding of the risks associated with blood transfusions is essential when determining the safety and appropriateness of transfusion therapies for patients,” said Daryl Kor, MD, senior author of both studies and an associate professor at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“Our research provides a greater awareness of the incidence of TRALI and TACO in surgical patients, a population that has been perhaps underrepresented in studies in this area. We believe this to be an important first step in our efforts to prevent these life-threatening transfusion complications.”

Dr Kor and his colleagues described this research in Anesthesiology alongside a related editorial.

In the two retrospective studies, the researchers examined the incidence of TRALI in 3379 patients and TACO in 4070 patients who received blood transfusions during non-cardiac surgery under general anesthesia in 2004 and 2011.

Using a novel algorithm, followed by a rigorous manual review, the team performed a detailed epidemiologic analysis for both complications.

The first study showed that TRALI occurred in 1.4% of surgical patients, with higher rates in specific surgical populations such as those having surgery inside the chest cavity, on major blood vessels, or having an organ transplant. Patients who received larger volumes of blood were also at increased risk.

Previous studies investigating TRALI rates have primarily focused on the critically ill and reported variable incidence rates. Many studies have reported incidences between 0.02% and 0.05%.

The second study showed that TACO occurs in 4.3% of surgical patients, with higher rates associated with increased volume of blood transfused, advanced age, and total intraoperative fluid balance. Again, patients having surgery inside the chest cavity, on major blood vessels, or organ transplants were at the greatest risk.

The study also revealed that the rate of TACO decreased significantly from 2004 to 2011—from 5.5% to 3%. This decline was not fully explained by any of the patient or transfusion characteristics evaluated in the study.

The researchers said future studies are needed to further explore which mechanisms and risk factors are responsible for TACO and TRALI.

“With improved understanding of the mechanisms underlying TRALI and TACO, we may be able to refine the novel electronic algorithms used to screen patients in these studies,” Dr Kor said. “Ultimately, we hope to develop a real-time prediction model for these complications so that we can identify those at greatest risk and perhaps implement strategies to reduce this risk.” ![]()

Credit: Elise Amendola

Two studies shed new light on the prevalence of transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) and transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) in the US.

The research showed that postoperative TRALI is significantly underreported and more common than previously thought, with an overall rate of 1.4%.

And the rate of TACO is on the decline, but the risk to surgical patients remains high, at 4%, similar to previous TACO estimates in non-surgical patients.

“An accurate understanding of the risks associated with blood transfusions is essential when determining the safety and appropriateness of transfusion therapies for patients,” said Daryl Kor, MD, senior author of both studies and an associate professor at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“Our research provides a greater awareness of the incidence of TRALI and TACO in surgical patients, a population that has been perhaps underrepresented in studies in this area. We believe this to be an important first step in our efforts to prevent these life-threatening transfusion complications.”

Dr Kor and his colleagues described this research in Anesthesiology alongside a related editorial.

In the two retrospective studies, the researchers examined the incidence of TRALI in 3379 patients and TACO in 4070 patients who received blood transfusions during non-cardiac surgery under general anesthesia in 2004 and 2011.

Using a novel algorithm, followed by a rigorous manual review, the team performed a detailed epidemiologic analysis for both complications.

The first study showed that TRALI occurred in 1.4% of surgical patients, with higher rates in specific surgical populations such as those having surgery inside the chest cavity, on major blood vessels, or having an organ transplant. Patients who received larger volumes of blood were also at increased risk.

Previous studies investigating TRALI rates have primarily focused on the critically ill and reported variable incidence rates. Many studies have reported incidences between 0.02% and 0.05%.

The second study showed that TACO occurs in 4.3% of surgical patients, with higher rates associated with increased volume of blood transfused, advanced age, and total intraoperative fluid balance. Again, patients having surgery inside the chest cavity, on major blood vessels, or organ transplants were at the greatest risk.

The study also revealed that the rate of TACO decreased significantly from 2004 to 2011—from 5.5% to 3%. This decline was not fully explained by any of the patient or transfusion characteristics evaluated in the study.

The researchers said future studies are needed to further explore which mechanisms and risk factors are responsible for TACO and TRALI.

“With improved understanding of the mechanisms underlying TRALI and TACO, we may be able to refine the novel electronic algorithms used to screen patients in these studies,” Dr Kor said. “Ultimately, we hope to develop a real-time prediction model for these complications so that we can identify those at greatest risk and perhaps implement strategies to reduce this risk.” ![]()

NICE backs dabigatran for VTE

Credit: CDC

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has published a final guidance recommending the anticoagulant dabigatran (Pradaxa, Boehringer Ingelheim) as an option for treating and preventing recurrent deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) in adults.

The guidance says dabigatran can provide a benefit for these patients, with cost- and clinical-effectiveness similar to rivaroxaban and added convenience compared to warfarin.

“For many people, using warfarin can be difficult because of the need for frequent tests to see if the blood is clotting properly, and having to adjust the dose of the

drug if it is not,” said Carole Longson, NICE Health Technology Evaluation Centre Director.

“The appraisal committee felt that dabigatran represents a potential benefit for many people who have had a DVT or PE, particularly those who have risk factors for recurrence of a blood clot and who therefore need longer-term treatment. We are pleased, therefore, to be able to recommend dabigatran as a cost-effective option for treating DVT and PE and preventing further episodes in adults.”

NICE expects dabigatran to be available on the National Health Service within 3 months.

Cost considerations

Dabigatran costs £65.90 for a 60-capsule pack of the 150 mg or 110 mg doses (excluding tax) and £2.20 per day of treatment, although costs may vary in different settings.

The most plausible incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for dabigatran compared with warfarin for acute treatment was uncertain.

However, both Boehringer Ingelheim’s and the evidence review group’s exploratory ICER remained in the range that could be considered a cost-effective use of National Health Service resources. That is, both were under £20,000 per quality-adjusted life-year gained (QALY).

Neither Boehringer Ingelheim nor the evidence review group found any significant difference in efficacy between dabigatran and rivaroxaban for acute treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in their indirect comparisons, and the costs were also very similar between these two treatments.

For combined treatment and secondary prevention of VTE, the appraisal committee said the company’s base case ICER for dabigatran compared with warfarin was likely too low (£9973 per QALY gained).

But the evidence review group’s exploratory base case for dabigatran compared with warfarin may have overestimated the ICER (£35,786 per QALY gained). So the ICER probably lies somewhere between these estimates.

Clinical evidence

To assess the clinical effectiveness of dabigatran, the appraisal committee evaluated data from the RECOVER, RE-MEDY, and RESONATE trials.

In the first RE-COVER trial, dabigatran proved noninferior to warfarin for preventing VTE recurrence, and rates of major bleeding were similar between the treatment arms.

However, patients were more likely to discontinue dabigatran due to adverse events. Results from this trial were presented at ASH 2009 and published in NEJM.

The RE-COVER II trial also suggested that dabigatran was noninferior to warfarin for preventing VTE recurrence and related deaths, and dabigatran was associated with a lower rate of major bleeding.

Rates of death, adverse events, and acute coronary syndromes were similar between the treatment arms. Results from this trial were published in Circulation in 2013.

The RE-MEDY and RE-SONATE trials were designed to evaluate dabigatran as extended VTE prophylaxis. Results of both trials were reported in a single NEJM article published in 2013.

The RE-MEDY trial suggested that dabigatran was noninferior to warfarin as extended prophylaxis for recurrent VTE, and warfarin presented a significantly higher risk of bleeding.

Results of the RE-SONATE trial indicated that dabigatran was superior to placebo for preventing recurrent VTE, although the drug significantly increased the risk of major or clinically relevant bleeding. ![]()

Credit: CDC

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has published a final guidance recommending the anticoagulant dabigatran (Pradaxa, Boehringer Ingelheim) as an option for treating and preventing recurrent deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) in adults.

The guidance says dabigatran can provide a benefit for these patients, with cost- and clinical-effectiveness similar to rivaroxaban and added convenience compared to warfarin.

“For many people, using warfarin can be difficult because of the need for frequent tests to see if the blood is clotting properly, and having to adjust the dose of the

drug if it is not,” said Carole Longson, NICE Health Technology Evaluation Centre Director.

“The appraisal committee felt that dabigatran represents a potential benefit for many people who have had a DVT or PE, particularly those who have risk factors for recurrence of a blood clot and who therefore need longer-term treatment. We are pleased, therefore, to be able to recommend dabigatran as a cost-effective option for treating DVT and PE and preventing further episodes in adults.”

NICE expects dabigatran to be available on the National Health Service within 3 months.

Cost considerations

Dabigatran costs £65.90 for a 60-capsule pack of the 150 mg or 110 mg doses (excluding tax) and £2.20 per day of treatment, although costs may vary in different settings.

The most plausible incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for dabigatran compared with warfarin for acute treatment was uncertain.

However, both Boehringer Ingelheim’s and the evidence review group’s exploratory ICER remained in the range that could be considered a cost-effective use of National Health Service resources. That is, both were under £20,000 per quality-adjusted life-year gained (QALY).

Neither Boehringer Ingelheim nor the evidence review group found any significant difference in efficacy between dabigatran and rivaroxaban for acute treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in their indirect comparisons, and the costs were also very similar between these two treatments.

For combined treatment and secondary prevention of VTE, the appraisal committee said the company’s base case ICER for dabigatran compared with warfarin was likely too low (£9973 per QALY gained).

But the evidence review group’s exploratory base case for dabigatran compared with warfarin may have overestimated the ICER (£35,786 per QALY gained). So the ICER probably lies somewhere between these estimates.

Clinical evidence

To assess the clinical effectiveness of dabigatran, the appraisal committee evaluated data from the RECOVER, RE-MEDY, and RESONATE trials.

In the first RE-COVER trial, dabigatran proved noninferior to warfarin for preventing VTE recurrence, and rates of major bleeding were similar between the treatment arms.

However, patients were more likely to discontinue dabigatran due to adverse events. Results from this trial were presented at ASH 2009 and published in NEJM.

The RE-COVER II trial also suggested that dabigatran was noninferior to warfarin for preventing VTE recurrence and related deaths, and dabigatran was associated with a lower rate of major bleeding.

Rates of death, adverse events, and acute coronary syndromes were similar between the treatment arms. Results from this trial were published in Circulation in 2013.

The RE-MEDY and RE-SONATE trials were designed to evaluate dabigatran as extended VTE prophylaxis. Results of both trials were reported in a single NEJM article published in 2013.

The RE-MEDY trial suggested that dabigatran was noninferior to warfarin as extended prophylaxis for recurrent VTE, and warfarin presented a significantly higher risk of bleeding.

Results of the RE-SONATE trial indicated that dabigatran was superior to placebo for preventing recurrent VTE, although the drug significantly increased the risk of major or clinically relevant bleeding. ![]()

Credit: CDC

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has published a final guidance recommending the anticoagulant dabigatran (Pradaxa, Boehringer Ingelheim) as an option for treating and preventing recurrent deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) in adults.

The guidance says dabigatran can provide a benefit for these patients, with cost- and clinical-effectiveness similar to rivaroxaban and added convenience compared to warfarin.

“For many people, using warfarin can be difficult because of the need for frequent tests to see if the blood is clotting properly, and having to adjust the dose of the

drug if it is not,” said Carole Longson, NICE Health Technology Evaluation Centre Director.

“The appraisal committee felt that dabigatran represents a potential benefit for many people who have had a DVT or PE, particularly those who have risk factors for recurrence of a blood clot and who therefore need longer-term treatment. We are pleased, therefore, to be able to recommend dabigatran as a cost-effective option for treating DVT and PE and preventing further episodes in adults.”

NICE expects dabigatran to be available on the National Health Service within 3 months.

Cost considerations

Dabigatran costs £65.90 for a 60-capsule pack of the 150 mg or 110 mg doses (excluding tax) and £2.20 per day of treatment, although costs may vary in different settings.

The most plausible incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for dabigatran compared with warfarin for acute treatment was uncertain.

However, both Boehringer Ingelheim’s and the evidence review group’s exploratory ICER remained in the range that could be considered a cost-effective use of National Health Service resources. That is, both were under £20,000 per quality-adjusted life-year gained (QALY).

Neither Boehringer Ingelheim nor the evidence review group found any significant difference in efficacy between dabigatran and rivaroxaban for acute treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in their indirect comparisons, and the costs were also very similar between these two treatments.

For combined treatment and secondary prevention of VTE, the appraisal committee said the company’s base case ICER for dabigatran compared with warfarin was likely too low (£9973 per QALY gained).

But the evidence review group’s exploratory base case for dabigatran compared with warfarin may have overestimated the ICER (£35,786 per QALY gained). So the ICER probably lies somewhere between these estimates.

Clinical evidence

To assess the clinical effectiveness of dabigatran, the appraisal committee evaluated data from the RECOVER, RE-MEDY, and RESONATE trials.

In the first RE-COVER trial, dabigatran proved noninferior to warfarin for preventing VTE recurrence, and rates of major bleeding were similar between the treatment arms.

However, patients were more likely to discontinue dabigatran due to adverse events. Results from this trial were presented at ASH 2009 and published in NEJM.

The RE-COVER II trial also suggested that dabigatran was noninferior to warfarin for preventing VTE recurrence and related deaths, and dabigatran was associated with a lower rate of major bleeding.

Rates of death, adverse events, and acute coronary syndromes were similar between the treatment arms. Results from this trial were published in Circulation in 2013.

The RE-MEDY and RE-SONATE trials were designed to evaluate dabigatran as extended VTE prophylaxis. Results of both trials were reported in a single NEJM article published in 2013.

The RE-MEDY trial suggested that dabigatran was noninferior to warfarin as extended prophylaxis for recurrent VTE, and warfarin presented a significantly higher risk of bleeding.

Results of the RE-SONATE trial indicated that dabigatran was superior to placebo for preventing recurrent VTE, although the drug significantly increased the risk of major or clinically relevant bleeding. ![]()

Effect of Hospitalist Discontinuity on AE

Although definitions vary, continuity of care can be thought of as the patient's experience of a continuous caring relationship with an identified healthcare professional.[1] Research in ambulatory settings has found that patients who see their primary care physician for a higher proportion of office visits have higher patient satisfaction, better hypertensive control, lower risk of hospitalization, and fewer emergency department visits.[2, 3, 4, 5] Continuity with a single hospital‐based physician is difficult to achieve because of the need to provide care 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Key clinical information may be lost during physician‐to‐physician handoffs (eg, at admission, at the end of rotations on service) during hospitalization. Our research group recently found that lower hospital physician continuity was associated with modestly increased hospital costs, but also a trend toward lower readmissions.[6] We speculated that physicians newly taking over patient care from colleagues reassess diagnoses and treatment plans. This reassessment may identify errors missed by the previous hospital physician. Thus, discontinuity may theoretically help or hinder the provision of safe hospital care.

We sought to examine the relationship between hospital physician continuity and the incidence of adverse events (AEs). We combined data from 2 previously published studies by our research group; one investigated the relationship between hospital physician continuity and costs and 30‐day readmissions, the other assessed the impact of unit‐based interventions on AEs.[6, 7]

METHODS

Setting and Study Design

This retrospective, observational study was conducted at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, an 876‐bed tertiary care teaching hospital in Chicago, Illinois, and was approved by the institutional review board of Northwestern University. Subjects included patients admitted to an adult nonteaching hospitalist service between March 1, 2009 and December 31, 2011. Hospitalists on this service worked without resident physicians in rotations usually lasting 7 consecutive days beginning on Mondays and ending on Sundays. Hospitalists were allowed to switch portions of their schedule with one another, creating the possibility that certain rotations may have been slightly shorter or longer than 7 days. Hospitalists gave verbal sign‐out via telephone to the hospitalist taking over their service on the afternoon of the last day of their rotation. These handoffs customarily involved both hospitalists viewing the electronic health record during the discussion but were not standardized. Night hospitalists performed admissions and cross‐coverage each night from 7 pm to 7 am. Night hospitalists printed history and physicals for day hospitalists, but typically did not give verbal sign‐out on new admissions.

Acquisition of Study Population Data

We identified all patients admitted to the nonteaching hospitalist service using the Northwestern Medicine Enterprise Data Warehouse (EDW), an integrated repository of all clinical and research data sources on the campus. We excluded patients admitted under observation status, those initially admitted to other services (eg, intensive care, general surgery), those discharged from other services, and those cared for by advanced practice providers (ie, nurse practitioners and physician assistants).

Predictor Variables

We identified physicians completing the primary service history and physicals (H&P) and progress notes throughout patients' hospitalizations to calculate 2 measures of continuity: the Number of Physicians Index (NPI), and the Usual Provider of Continuity (UPC) Index.[8, 9] The NPI represented the total number of unique hospitalists completing H&Ps and/or progress notes for a patient. The UPC was calculated as the largest number of notes signed by a single hospitalist divided by the total number of hospitalist notes for a patient. For example, if Dr. John Smith wrote notes on the first 4 days of a patient's hospital stay, and Dr. Mary Jones wrote notes on the following 2 days (total stay=6 days), the NPI would be 2 and the UPC would be 0.67. Therefore, higher NPI and lower UPC designate lower continuity. Significant events occurring during the nighttime were documented in separate notes titled cross‐cover notes. These cross‐cover notes were not included in the calculation of NPI or UPC. In the rare event that 2 or more progress notes were written on the same day, we selected the one used for billing to calculate UPC and NPI.

Outcome Variables

We used AE data from a study we conducted to assess the impact of unit‐based interventions to improve teamwork and patient safety, the methods of which have been previously described.[7] Briefly, we used a 2‐stage medical record review similar to that performed in prior studies.[10, 11, 12, 13] In the first stage, we identified potential AEs using automated queries of the Northwestern Medicine EDW. These queries were based on screening criteria used in the Harvard Medical Practice Study and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Global Trigger Tool.[12, 13] Examples of queries included abnormal laboratory values (eg, international normalized ratio [INR] >6 after hospital day 2 and excluding patients with INR >4 on day 1), administration of rescue medications (eg, naloxone), certain types of incident reports (eg, pressure ulcer), International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) codes indicating hospital‐acquired conditions (eg, venous thromboembolism), and text searches of progress notes and discharge summaries using natural language processing.[14] Prior research by our group confirmed these automated screens identify a similar number of AEs as manual medical record screening.[14] For each patient with 1 or more potential AE, a research nurse performed a medical record abstraction and created a description of each potential AE.

In the second stage, 2 physician researchers independently reviewed each potential AE in a blinded fashion to determine whether or not an AE was present. An AE was defined as injury due to medical management rather than the natural history of the illness,[15] and included injuries that prolonged the hospital stay or produced disability as well as those resulting in transient disability or abnormal lab values.[16] After independent review, physician reviewers discussed discrepancies in their ratings to achieve consensus.

We tested the reliability of medical record abstractions in our prior study by conducting duplicate abstractions and consensus ratings for a randomly selected sample of 294 patients.[7] The inter‐rater reliability was good for determining the presence of AEs (=0.63).

Statistical Analyses

We calculated descriptive statistics for patient characteristics. Primary discharge diagnosis ICD‐9 codes were categorized using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Clinical Classification Software.[17] We created multivariable logistic regression models with the independent variable being the measure of continuity (NPI or UPC) and the dependent variable being experiencing 1 or more AEs. Covariates included patient age, sex, race, payer, night admission, weekend admission, intensive care unit stay, Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS‐DRG) weight, and total number of Elixhauser comorbidities.[18] The length of stay (LOS) was also included as a covariate, as longer LOS increases the probability of discontinuity and may increase the risk for AEs. Because MS‐DRG weight and LOS were highly correlated, we created several models; the first including both as continuous variables, the second including both categorized into quartiles, and a third excluding MS‐DRG weight and including LOS as a continuous variable. Our prior study assessing the impact of unit‐based interventions did not show a statistically significant difference in the pre‐ versus postintervention period, thus we did not include study period as a covariate.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

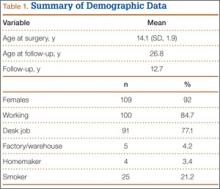

Our analyses included data from 474 hospitalizations. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Patients were a mean 51.118.8 years of age, hospitalized for a mean 3.43.1 days, included 241 (50.8%) women, and 233 (49.2%) persons of nonwhite race. The mean and standard deviation of NPI and UPC were 2.51.0 and 0.60.2. Overall, 47 patients (9.9%) experienced 55 total AEs. AEs included 31 adverse drug events, 6 falls, 5 procedural injuries, 4 manifestations of poor glycemic control, 3 hospital‐acquired infections, 2 episodes of acute renal failure, 1 episode of delirium, 1 pressure ulcer, and 2 categorized as other.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| |

| Mean age (SD), y | 55.1 (18.8) |

| Mean length of stay (SD), d | 3.4 (3.1) |

| Women, n (%) | 241 (50.8) |

| Nonwhite race, n (%) | 233 (49.2) |

| Payer, n (%) | |

| Private | 180 (38) |

| Medicare | 165 (34.8) |

| Medicaid | 47 (9.9) |

| Self‐pay/other | 82 (17.3) |

| Night admission, n (%) | 245 (51.7) |

| Weekend admission, n (%) | 135 (28.5) |

| Intensive care unit stay, n (%) | 18 (3.8) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Diseases of the circulatory system | 95 (20.0) |

| Diseases of the digestive system | 65 (13.7) |

| Diseases of the respiratory system | 49 (10.3) |

| Injury and poisoning | 41 (8.7) |

| Diseases of the skin and soft tissue | 31 (6.5) |

| Symptoms, signs, and ill‐defined conditions and factors influencing health status | 28 (5.9) |

| Endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases and immunity disorders | 25 (5.3) |

| Diseases of the genitourinary system | 24 (5.1) |

| Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 23 (4.9) |

| Diseases of the nervous system | 23 (4.9) |

| Other | 70 (14.8) |

| Mean no. of Elixhauser comorbidities (SD) | 2.3 (1.7) |

| Mean MS‐DRG weight (SD) | 1.0 (1.0) |

| Mean NPI (SD) | 2.5 (1.0) |

| Mean UPC (SD) | 0.6 (0.2) |

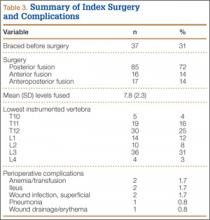

Association Between Continuity and Adverse Events

In unadjusted models, each 1‐unit increase in the NPI (ie, less continuity) was significantly associated with the incidence of 1 or more AEs (odds ratio [OR]=1.75; P<0.001). However, UPC was not associated with incidence of AEs (OR=1.03; P=0.68) (Table 2). Across all adjusted models, neither NPI nor UPC was significantly associated with the incidence of AEs. The direction of the effect of discontinuity on AEs was inconsistent across models. Though all 3 adjusted models using NPI as the independent variable showed a trend toward increased odds of experiencing 1 or more AE with discontinuity, 2 of the 3 models using UPC showed trends in the opposite direction.

| NPI OR (95% CI)* | P Value | UPC OR (95% CI)* | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Unadjusted model | 1.75 (1.332.29) | <0.0001 | 1.03 (0.89‐1.21) | 0.68 | |

| Adjusted models | |||||

| Model 1 | MS‐DRG and LOS continuous | 1.16 (0.781.72) | 0.47 | 0.96 (0.791.14) | 0.60 |

| Model 2 | MS‐DRG and LOS in quartiles | 1.38 (0.981.94) | 0.07 | 1.05 (0.881.26) | 0.59 |

| Model 3 | MS‐DRG dropped, LOS continuous | 1.14 (0.771.70) | 0.51 | 0.95 (0.791.14) | 0.56 |

DISCUSSION

We found that hospitalist physician continuity was not associated with the incidence of AEs. Our findings are somewhat surprising because of the high value placed on continuity of care and patient safety concerns related to handoffs. Key clinical information may be lost when patient care is transitioned to a new hospitalist shortly after admission (eg, from a night hospitalist) or at the end of a rotation. Thus, it is logical to assume that discontinuity inherently increases the risk for harm. On the other hand, a physician newly taking over patient care from another may not be anchored to the initial diagnosis and treatment plan established by the first. This second look could potentially prevent missed/delayed diagnoses and optimize the plan of care.[19] These countervailing forces may explain our findings.

Several other potential explanations for our findings should be considered. First, the quality of handoffs may have been sufficient to overcome the potential for information loss. We feel this is unlikely given that little attention had been dedicated to improving the quality of patient handoffs among hospitalists in our institution. Notably, though a number of studies have evaluated resident physician handoffs, most of the work has focused on night coverage, and little is known about the quality of attending handoffs.[20] Second, access to a fully integrated electronic health record may have assisted hospitalists in complementing information received during handoffs. For example, a hospitalist about to start his or her rotation may have remotely accessed and reviewed patient medical records prior to receiving the phone handoff from the outgoing hospitalist. Third, other efforts to improve patient safety may have reduced the overall risk and provided some resilience in the system. Unit‐based interventions, including structured interdisciplinary rounds and nurse‐physician coleadership, improved teamwork climate and reduced AEs in the study hospital over time.[7]

Another factor to consider relates to the fact that hospital care is provided by teams of clinicians (eg, nurses, specialist physicians, therapists, social workers). Hospital teams are often large and have dynamic team membership. Similar to hospitalists, nurses, physician specialists, and other team members handoff care throughout the course of a patient's hospital stay. Yet, discontinuity for each professional type may occur at different times and frequencies. For example, a patient may be handed off from one hospitalist to another, yet the care continues with the same cardiologist or nurse. Future research should better characterize hospital team complexity (eg, size, relationships among members) and dynamics (eg, continuity for various professional types) and the impact of these factors on patient outcomes.

Our findings are important because hospitalist physician discontinuity is common during hospital stays. Hospital medicine groups vary in their staffing and scheduling models. Policies related to admission distribution and rotation length (consecutive days worked) systematically impact physician continuity. Few studies have evaluated the effect on continuity on hospitalized patient outcomes, and no prior research, to our knowledge, has explored the association of continuity on measures of patient safety.[6, 21, 22] Though our study might suggest that staffing models have little impact on patient safety, as previously mentioned, other team factors may influence patient outcomes.

Our study has several limitations. First, we assessed the impact of continuity on AEs in a single site. Although the 7 days on/7 days off model is the most common scheduling pattern used by adult hospital medicine groups,[23] staffing models and patient safety practices vary across hospitals, potentially limiting the generalizability of our study. Second, continuity can be defined and measured in a variety of ways. We used 2 different measures of physician continuity. As previously mentioned, assessing continuity of other clinicians may allow for a more complete understanding of the potential problems related to fragmentation of care. Third, this study excluded patients who experienced care transitions from other hospitals or other units within the hospital. Patients transferred from other hospitals are often complex, severely ill, and may be at higher risk for loss of key clinical information. Fourth, we used automated screens of an EDW to identify potential AEs. Although our prior research found that this method identified a similar number of AEs as manual medical record review screening, there was poor agreement between the 2 methods. Unfortunately, there is no gold standard to identify AEs. The EDW‐facilitated method allowed us to feasibly screen a larger number of charts, increasing statistical power, and minimized any potential bias that might occur during a manual review to identify potential AEs. Finally, we used data available from 2 prior studies and may have been underpowered to detect a significant association between continuity and AEs due to the relatively low percentage of patients experiencing an AE. In a post hoc power calculation, we estimated that we had 70% power to detect a 33% change in the proportion of patients with 1 or more AE for each 1‐unit increase in NPI, and 80% power to detect a 20% change for each 0.1‐unit decrease in UPC.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we found that hospitalist physician continuity was not associated with the incidence of AEs. We speculate that hospitalist continuity is only 1 of many team factors that may influence patient safety, and that prior efforts within our institution may have reduced our ability to detect an association. Future research should better characterize hospital team complexity and dynamics and the impact of these factors on patient outcomes.

Disclosures

This project was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and an Excellence in Academic Medicine Award, administered by Northwestern Memorial Hospital. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , . What is “continuity of care”? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2006;11:248–250.

- , . Interpersonal continuity of care and care outcomes: a critical review. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:159–166.

- , , , . The association between continuity of care and outcomes: a systematic and critical review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16:947–956.

- , . Interpersonal continuity of care and patient satisfaction: a critical review. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:445–451.

- , , , . Continuity of care in a family practice residency program. Impact on physician satisfaction. J Fam Pract. 1990;31:69–73.

- , , , et al. The impact of hospitalist discontinuity on hospital cost, readmissions, and patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1004–1008.

- , , , et al. Implementation of unit‐based interventions to improve teamwork and patient safety on a medical service [published online ahead of print June 11, 2014]. Am J Med Qual. doi: 10.1177/1062860614538093.

- . Measuring provider continuity in ambulatory care: an assessment of alternative approaches. Med Care. 1979;17:551–565.

- . Defining and measuring interpersonal continuity of care. Ann Fam Med. 2003;1:134–143.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Adverse events in hospitals: national incidence among medical beneficiaries. Available at: http://psnet.ahrq.gov/resource.aspx?resourceID=19811. Published November 2010. Accessed on December 15, 2014.

- , , , et al. “Global trigger tool” shows that adverse events in hospitals may be ten times greater than previously measured. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:581–589.

- , , , et al. A study of medical injury and medical malpractice. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:480–484.

- , , , et al. Incidence and types of adverse events and negligent care in Utah and Colorado. Med Care. 2000;38:261–271.

- , , , et al. Comparison of traditional trigger tool to data warehouse based screening for identifying hospital adverse events. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:130–138.

- , , , et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:370–376.

- , , . Safety of patients isolated for infection control. JAMA. 2003;290:1899–1905.

- HCUP Clinical Classification Software. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed on December 15, 2014.

- , , , . Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27.

- . Does continuity of care matter? No: discontinuity can improve patient care. West J Med. 2001;175:5.

- , , , , , . Hospitalist handoffs: a systematic review and task force recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2009;4:433–440.

- , , , , . The impact of fragmentation of hospitalist care on length of stay. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:335–338.

- , , . The Creating Incentives and Continuity Leading to Efficiency staffing model: a quality improvement initiative in hospital medicine. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:364–371.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. 2014 state of hospital medicine report. Philadelphia, PA: Society of Hospital Medicine; 2014.

Although definitions vary, continuity of care can be thought of as the patient's experience of a continuous caring relationship with an identified healthcare professional.[1] Research in ambulatory settings has found that patients who see their primary care physician for a higher proportion of office visits have higher patient satisfaction, better hypertensive control, lower risk of hospitalization, and fewer emergency department visits.[2, 3, 4, 5] Continuity with a single hospital‐based physician is difficult to achieve because of the need to provide care 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Key clinical information may be lost during physician‐to‐physician handoffs (eg, at admission, at the end of rotations on service) during hospitalization. Our research group recently found that lower hospital physician continuity was associated with modestly increased hospital costs, but also a trend toward lower readmissions.[6] We speculated that physicians newly taking over patient care from colleagues reassess diagnoses and treatment plans. This reassessment may identify errors missed by the previous hospital physician. Thus, discontinuity may theoretically help or hinder the provision of safe hospital care.

We sought to examine the relationship between hospital physician continuity and the incidence of adverse events (AEs). We combined data from 2 previously published studies by our research group; one investigated the relationship between hospital physician continuity and costs and 30‐day readmissions, the other assessed the impact of unit‐based interventions on AEs.[6, 7]

METHODS

Setting and Study Design

This retrospective, observational study was conducted at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, an 876‐bed tertiary care teaching hospital in Chicago, Illinois, and was approved by the institutional review board of Northwestern University. Subjects included patients admitted to an adult nonteaching hospitalist service between March 1, 2009 and December 31, 2011. Hospitalists on this service worked without resident physicians in rotations usually lasting 7 consecutive days beginning on Mondays and ending on Sundays. Hospitalists were allowed to switch portions of their schedule with one another, creating the possibility that certain rotations may have been slightly shorter or longer than 7 days. Hospitalists gave verbal sign‐out via telephone to the hospitalist taking over their service on the afternoon of the last day of their rotation. These handoffs customarily involved both hospitalists viewing the electronic health record during the discussion but were not standardized. Night hospitalists performed admissions and cross‐coverage each night from 7 pm to 7 am. Night hospitalists printed history and physicals for day hospitalists, but typically did not give verbal sign‐out on new admissions.

Acquisition of Study Population Data

We identified all patients admitted to the nonteaching hospitalist service using the Northwestern Medicine Enterprise Data Warehouse (EDW), an integrated repository of all clinical and research data sources on the campus. We excluded patients admitted under observation status, those initially admitted to other services (eg, intensive care, general surgery), those discharged from other services, and those cared for by advanced practice providers (ie, nurse practitioners and physician assistants).

Predictor Variables

We identified physicians completing the primary service history and physicals (H&P) and progress notes throughout patients' hospitalizations to calculate 2 measures of continuity: the Number of Physicians Index (NPI), and the Usual Provider of Continuity (UPC) Index.[8, 9] The NPI represented the total number of unique hospitalists completing H&Ps and/or progress notes for a patient. The UPC was calculated as the largest number of notes signed by a single hospitalist divided by the total number of hospitalist notes for a patient. For example, if Dr. John Smith wrote notes on the first 4 days of a patient's hospital stay, and Dr. Mary Jones wrote notes on the following 2 days (total stay=6 days), the NPI would be 2 and the UPC would be 0.67. Therefore, higher NPI and lower UPC designate lower continuity. Significant events occurring during the nighttime were documented in separate notes titled cross‐cover notes. These cross‐cover notes were not included in the calculation of NPI or UPC. In the rare event that 2 or more progress notes were written on the same day, we selected the one used for billing to calculate UPC and NPI.

Outcome Variables