User login

Do progesterone-only contraceptives lead to more mood changes than other types?

Lower, or comparable depression scores compared with other methods

A retrospective cohort trial compared 298 women on progesterone-only contraception with 6356 women on other or no contraception to examine the association between contraception use and depressive symptoms.1

When surveyed with the Center of Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (using both a 10-question, 30-point questionnaire and a 20-question, 60-point questionnaire), women on progesterone-only contraception demonstrated significantly lower levels of depressive symptoms compared with women using low-efficacy contraception (early withdrawal, spermicides, contraceptive films) or no contraception (mean deviation [MD]=-1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], -2.4 to -0.2). No significant difference was seen in depression scores when compared with women on other forms of hormonal contraception (MD=-0.3; 95% CI, -1.2 to 0.6).

No significant difference in depression and less anhedonia for nonusers

A cross-sectional, population-based trial conducted by survey in Finland in 1997, 2002, and 2007 investigated the link between contraception and mood symptoms. It included 759 women using the progesterone-only levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) and 7036 women on other forms of contraception or none.2

Current LNG-IUS users vs nonusers had no significant difference in diagnosis of depression, as assessed by asking patients if they had been diagnosed with or treated for depression in the previous year of contraception (8.0% vs 7.3%; P>.05); depressive symptoms in the previous year (24% vs 26%; P>.05), or psychological illness (1.9% vs 2.5%; P>.05).

LNG-IUS users reported significantly less anhedonia than nonusers in the previous year (19% vs 22%; P<.05). Moreover, in a partial correlation analysis, LNG-IUS was negatively correlated with anhedonia (r=0.024; P<.05) and symptoms of depression over the previous month (r=0.098; P<.05).

Did relationship satisfaction, rather than contraceptive, influence depression?

A multicenter prospective cohort trial analyzed the effect of the levonorgestrel implant on mood in 267 women followed for 2 years by evaluating depressive symptoms reported from the Mental Health Inventory, a 6-item questionnaire scored 0 to 24.3

The women demonstrated a significant increase in depressive symptom scores from 7.9 at baseline to 8.8 (P=.01). However, the study authors suggested that relationship satisfaction, not method of birth control, was the cause of depressive symptoms. The 62 women who experienced a decrease in relationship satisfaction exhibited a significant increase in depressive symptoms (6.7-10; P=.001) compared with the 156 women who reported an improvement or no change in relationship satisfaction (7.8-8.2; P=.30).

1. Keyes K, Cheslack-Postava K, Westhoff C, et al. Association of hormonal contraception use with reduced levels of depressive symptoms: a national study of sexually active women in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:1378-1388.

2. Toffol E, Heikinheimo O, Koponen P, et al. Further evidence for lack of negative associations between hormonal contraception and mental health. Contraception. 2012;86:470-480.

3. Westhoff C, Truman C, Kalmuss D, et al. Depressive symptoms and Norplant contraceptive implants. Contraception. 1998;57:241-245.

Lower, or comparable depression scores compared with other methods

A retrospective cohort trial compared 298 women on progesterone-only contraception with 6356 women on other or no contraception to examine the association between contraception use and depressive symptoms.1

When surveyed with the Center of Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (using both a 10-question, 30-point questionnaire and a 20-question, 60-point questionnaire), women on progesterone-only contraception demonstrated significantly lower levels of depressive symptoms compared with women using low-efficacy contraception (early withdrawal, spermicides, contraceptive films) or no contraception (mean deviation [MD]=-1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], -2.4 to -0.2). No significant difference was seen in depression scores when compared with women on other forms of hormonal contraception (MD=-0.3; 95% CI, -1.2 to 0.6).

No significant difference in depression and less anhedonia for nonusers

A cross-sectional, population-based trial conducted by survey in Finland in 1997, 2002, and 2007 investigated the link between contraception and mood symptoms. It included 759 women using the progesterone-only levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) and 7036 women on other forms of contraception or none.2

Current LNG-IUS users vs nonusers had no significant difference in diagnosis of depression, as assessed by asking patients if they had been diagnosed with or treated for depression in the previous year of contraception (8.0% vs 7.3%; P>.05); depressive symptoms in the previous year (24% vs 26%; P>.05), or psychological illness (1.9% vs 2.5%; P>.05).

LNG-IUS users reported significantly less anhedonia than nonusers in the previous year (19% vs 22%; P<.05). Moreover, in a partial correlation analysis, LNG-IUS was negatively correlated with anhedonia (r=0.024; P<.05) and symptoms of depression over the previous month (r=0.098; P<.05).

Did relationship satisfaction, rather than contraceptive, influence depression?

A multicenter prospective cohort trial analyzed the effect of the levonorgestrel implant on mood in 267 women followed for 2 years by evaluating depressive symptoms reported from the Mental Health Inventory, a 6-item questionnaire scored 0 to 24.3

The women demonstrated a significant increase in depressive symptom scores from 7.9 at baseline to 8.8 (P=.01). However, the study authors suggested that relationship satisfaction, not method of birth control, was the cause of depressive symptoms. The 62 women who experienced a decrease in relationship satisfaction exhibited a significant increase in depressive symptoms (6.7-10; P=.001) compared with the 156 women who reported an improvement or no change in relationship satisfaction (7.8-8.2; P=.30).

Lower, or comparable depression scores compared with other methods

A retrospective cohort trial compared 298 women on progesterone-only contraception with 6356 women on other or no contraception to examine the association between contraception use and depressive symptoms.1

When surveyed with the Center of Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (using both a 10-question, 30-point questionnaire and a 20-question, 60-point questionnaire), women on progesterone-only contraception demonstrated significantly lower levels of depressive symptoms compared with women using low-efficacy contraception (early withdrawal, spermicides, contraceptive films) or no contraception (mean deviation [MD]=-1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], -2.4 to -0.2). No significant difference was seen in depression scores when compared with women on other forms of hormonal contraception (MD=-0.3; 95% CI, -1.2 to 0.6).

No significant difference in depression and less anhedonia for nonusers

A cross-sectional, population-based trial conducted by survey in Finland in 1997, 2002, and 2007 investigated the link between contraception and mood symptoms. It included 759 women using the progesterone-only levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) and 7036 women on other forms of contraception or none.2

Current LNG-IUS users vs nonusers had no significant difference in diagnosis of depression, as assessed by asking patients if they had been diagnosed with or treated for depression in the previous year of contraception (8.0% vs 7.3%; P>.05); depressive symptoms in the previous year (24% vs 26%; P>.05), or psychological illness (1.9% vs 2.5%; P>.05).

LNG-IUS users reported significantly less anhedonia than nonusers in the previous year (19% vs 22%; P<.05). Moreover, in a partial correlation analysis, LNG-IUS was negatively correlated with anhedonia (r=0.024; P<.05) and symptoms of depression over the previous month (r=0.098; P<.05).

Did relationship satisfaction, rather than contraceptive, influence depression?

A multicenter prospective cohort trial analyzed the effect of the levonorgestrel implant on mood in 267 women followed for 2 years by evaluating depressive symptoms reported from the Mental Health Inventory, a 6-item questionnaire scored 0 to 24.3

The women demonstrated a significant increase in depressive symptom scores from 7.9 at baseline to 8.8 (P=.01). However, the study authors suggested that relationship satisfaction, not method of birth control, was the cause of depressive symptoms. The 62 women who experienced a decrease in relationship satisfaction exhibited a significant increase in depressive symptoms (6.7-10; P=.001) compared with the 156 women who reported an improvement or no change in relationship satisfaction (7.8-8.2; P=.30).

1. Keyes K, Cheslack-Postava K, Westhoff C, et al. Association of hormonal contraception use with reduced levels of depressive symptoms: a national study of sexually active women in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:1378-1388.

2. Toffol E, Heikinheimo O, Koponen P, et al. Further evidence for lack of negative associations between hormonal contraception and mental health. Contraception. 2012;86:470-480.

3. Westhoff C, Truman C, Kalmuss D, et al. Depressive symptoms and Norplant contraceptive implants. Contraception. 1998;57:241-245.

1. Keyes K, Cheslack-Postava K, Westhoff C, et al. Association of hormonal contraception use with reduced levels of depressive symptoms: a national study of sexually active women in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:1378-1388.

2. Toffol E, Heikinheimo O, Koponen P, et al. Further evidence for lack of negative associations between hormonal contraception and mental health. Contraception. 2012;86:470-480.

3. Westhoff C, Truman C, Kalmuss D, et al. Depressive symptoms and Norplant contraceptive implants. Contraception. 1998;57:241-245.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

No. Women taking progesterone-only contraceptives don’t appear to experience more depressive symptoms or mood changes than women on other hormonal contraceptives, and they may experience slightly less depression than women using no contraception (strength of recommendation: B, multiple homogeneous cohorts).

Is an intestinal biopsy necessary when the blood work suggests celiac disease?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 Belgian prospective study of 104 non-IgA–deficient adults and children diagnosed with celiac disease and 537 adults and children without celiac disease evaluated the accuracy of 4 manufacturers’ serologic tests for IgA anti-tTG.1 All patients underwent serologic testing followed by a diagnostic biopsy. A Marsh type 3 or greater lesion on duodenal biopsy was considered diagnostic for celiac disease.

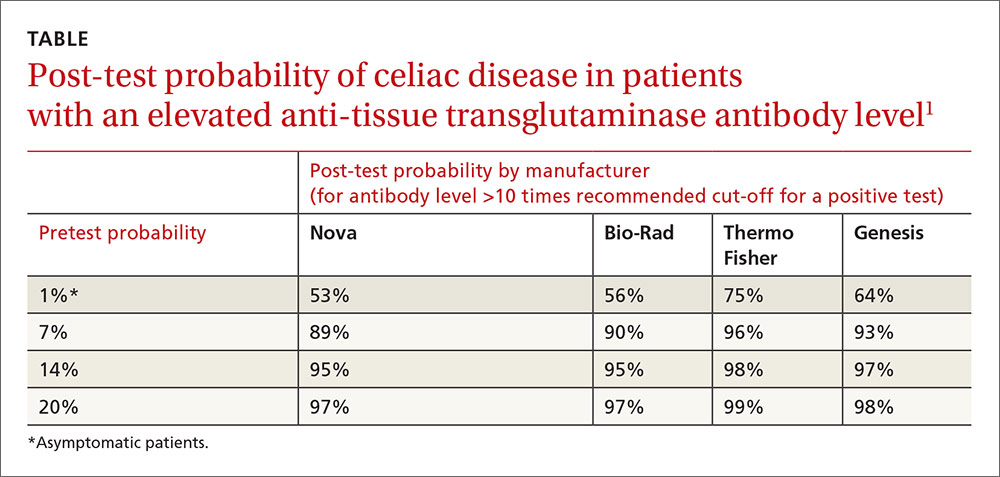

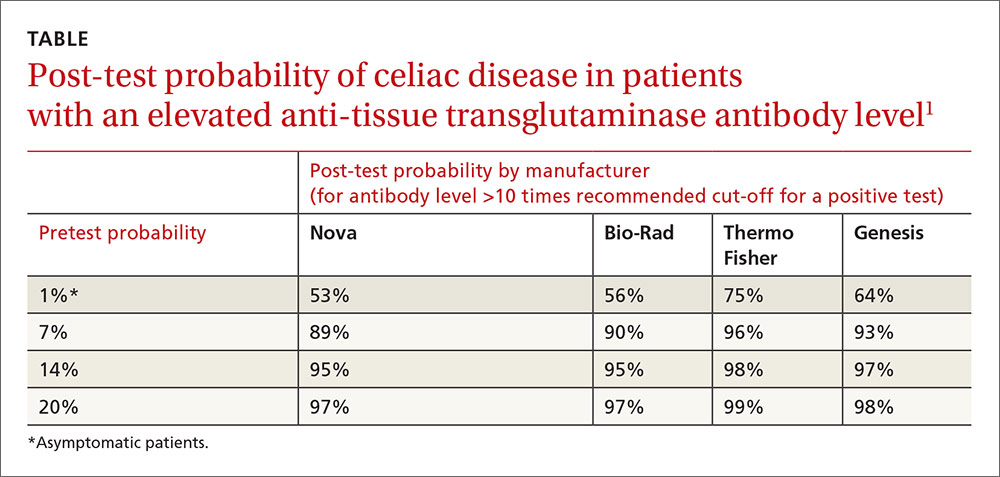

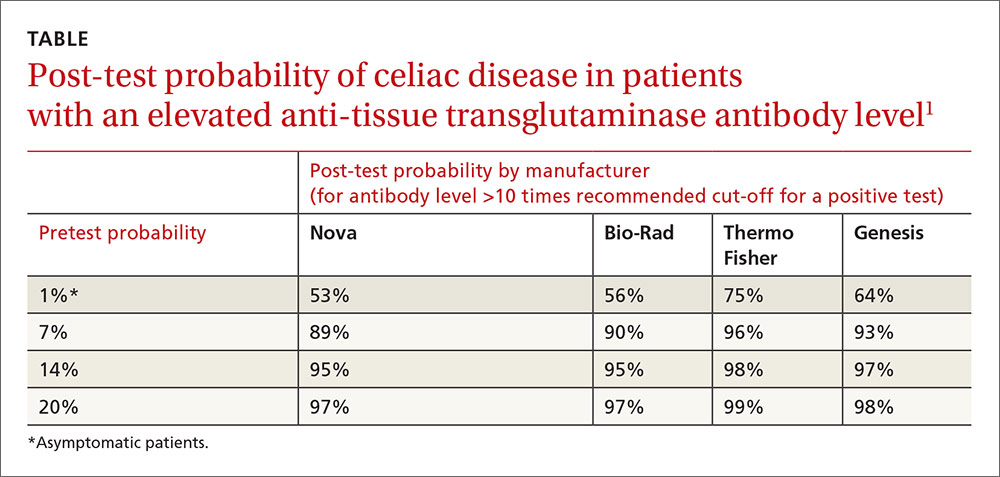

Anti-tTG levels greater than 10 times the manufacturer-recommended level for a positive test (cut-off) were associated with a likelihood ratio of 111 to 294 (depending on the manufacturer) of positive biopsy. Post-test probabilities were calculated based on various pretest probabilities using an anti-tTG level of greater than 10 times the cut-off (TABLE1).

Investigators also obtained IgG anti-DGP levels from 2 of the manufacturers.1 Likelihood ratios increased along with antibody levels. Ratios of 80 and 400, depending on the manufacturer, were found at IgG anti-DGP levels 10-fold greater than the cut-off. Pre- and post-test probabilities weren’t calculated.

Positive predictive value rises with antibody levels

A 2013 retrospective study evaluated the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition’s recommendation to forego intestinal biopsy in non-IgA–deficient, symptomatic children and adolescents with positive IgA anti-tTG levels greater than 10 times the cut-off value, positive EMA, and positive HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8.2

Overall, 153 symptomatic patients referred to the gastroenterology unit met these criteria. The age range was 9 months to 14.6 years (mean 4 years). All but 3 of the patients had Marsh 2 or greater lesions with biopsy-confirmed diagnoses of celiac disease. The remaining 3 developed biopsy-positive celiac disease on follow-up. The positive predictive value of combined serologic testing in this small selected patient population was 100%.

A 2013 retrospective study of 2477 symptomatic adults (older than 18 years) who received diagnostic testing for celiac disease at 2 academic institutions in Cleveland, Ohio, evaluated the predictive value of IgA anti-tTG and EMA. Of the patients, 610 (25%) had abnormal serologic tests, and 240 (39%) underwent endoscopy with biopsy.

A total of 50 patients (21%) had biopsy results consistent with celiac disease, defined as a Marsh 3 lesion or greater.3 An IgA anti-tTG level of 118 U/mL (5.9-fold the upper limit of normal on the test) had a positive predictive value of 86.4% with a false-positive value of 2%. An EMA titer greater than 1:160 when IgA anti-tTG was between 21 and 118 U/mL had a positive predictive value of 83%.

Antibody levels 10 times normal show 100% positive predictive value

A 2008 retrospective study of one manufacturer’s IgA anti-tTG serologic test sought to establish the serologic antibody level at which the positive predictive value was 100%.4 Overall, 148 people, 15 years and older, with a positive IgA anti-tTG before biopsy or within 21 days of biopsy were included.

Of the patients biopsied, 139 (93%) had positive biopsies of Marsh 2 or greater and were diagnosed with celiac disease. Using a cut-off of 3.3 and 6.7 times the upper limit of normal, investigators calculated a positive predictive value of 95% and 98%, respectively.

A cut-off of 10 times the upper limit of normal or greater had a positive predictive value of 100%. The highest level of IgA anti-tTG in a patient who didn’t have celiac disease on biopsy was 7.3 times the upper limit of normal.

1. Vermeersch P, Geboes K, Mariën G, et al. Defining thresholds of antibody levels improves diagnosis of celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:398-403;quiz e32.

2. Klapp G, Masip E, Bolonio M, et al. Celiac disease: The new proposed ESPGHAN diagnostic criteria do work well in a selected population. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:251-256.

3. Wakim-Fleming J, Pagadala MR, Lemyre MS, et al. Diagnosis of celiac disease in adults based on serology test results, without small-bowel biopsy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:511-516.

4. Hill PG, Holmes GK. Coeliac disease: a biopsy is not always necessary for diagnosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:572-577.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 Belgian prospective study of 104 non-IgA–deficient adults and children diagnosed with celiac disease and 537 adults and children without celiac disease evaluated the accuracy of 4 manufacturers’ serologic tests for IgA anti-tTG.1 All patients underwent serologic testing followed by a diagnostic biopsy. A Marsh type 3 or greater lesion on duodenal biopsy was considered diagnostic for celiac disease.

Anti-tTG levels greater than 10 times the manufacturer-recommended level for a positive test (cut-off) were associated with a likelihood ratio of 111 to 294 (depending on the manufacturer) of positive biopsy. Post-test probabilities were calculated based on various pretest probabilities using an anti-tTG level of greater than 10 times the cut-off (TABLE1).

Investigators also obtained IgG anti-DGP levels from 2 of the manufacturers.1 Likelihood ratios increased along with antibody levels. Ratios of 80 and 400, depending on the manufacturer, were found at IgG anti-DGP levels 10-fold greater than the cut-off. Pre- and post-test probabilities weren’t calculated.

Positive predictive value rises with antibody levels

A 2013 retrospective study evaluated the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition’s recommendation to forego intestinal biopsy in non-IgA–deficient, symptomatic children and adolescents with positive IgA anti-tTG levels greater than 10 times the cut-off value, positive EMA, and positive HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8.2

Overall, 153 symptomatic patients referred to the gastroenterology unit met these criteria. The age range was 9 months to 14.6 years (mean 4 years). All but 3 of the patients had Marsh 2 or greater lesions with biopsy-confirmed diagnoses of celiac disease. The remaining 3 developed biopsy-positive celiac disease on follow-up. The positive predictive value of combined serologic testing in this small selected patient population was 100%.

A 2013 retrospective study of 2477 symptomatic adults (older than 18 years) who received diagnostic testing for celiac disease at 2 academic institutions in Cleveland, Ohio, evaluated the predictive value of IgA anti-tTG and EMA. Of the patients, 610 (25%) had abnormal serologic tests, and 240 (39%) underwent endoscopy with biopsy.

A total of 50 patients (21%) had biopsy results consistent with celiac disease, defined as a Marsh 3 lesion or greater.3 An IgA anti-tTG level of 118 U/mL (5.9-fold the upper limit of normal on the test) had a positive predictive value of 86.4% with a false-positive value of 2%. An EMA titer greater than 1:160 when IgA anti-tTG was between 21 and 118 U/mL had a positive predictive value of 83%.

Antibody levels 10 times normal show 100% positive predictive value

A 2008 retrospective study of one manufacturer’s IgA anti-tTG serologic test sought to establish the serologic antibody level at which the positive predictive value was 100%.4 Overall, 148 people, 15 years and older, with a positive IgA anti-tTG before biopsy or within 21 days of biopsy were included.

Of the patients biopsied, 139 (93%) had positive biopsies of Marsh 2 or greater and were diagnosed with celiac disease. Using a cut-off of 3.3 and 6.7 times the upper limit of normal, investigators calculated a positive predictive value of 95% and 98%, respectively.

A cut-off of 10 times the upper limit of normal or greater had a positive predictive value of 100%. The highest level of IgA anti-tTG in a patient who didn’t have celiac disease on biopsy was 7.3 times the upper limit of normal.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 Belgian prospective study of 104 non-IgA–deficient adults and children diagnosed with celiac disease and 537 adults and children without celiac disease evaluated the accuracy of 4 manufacturers’ serologic tests for IgA anti-tTG.1 All patients underwent serologic testing followed by a diagnostic biopsy. A Marsh type 3 or greater lesion on duodenal biopsy was considered diagnostic for celiac disease.

Anti-tTG levels greater than 10 times the manufacturer-recommended level for a positive test (cut-off) were associated with a likelihood ratio of 111 to 294 (depending on the manufacturer) of positive biopsy. Post-test probabilities were calculated based on various pretest probabilities using an anti-tTG level of greater than 10 times the cut-off (TABLE1).

Investigators also obtained IgG anti-DGP levels from 2 of the manufacturers.1 Likelihood ratios increased along with antibody levels. Ratios of 80 and 400, depending on the manufacturer, were found at IgG anti-DGP levels 10-fold greater than the cut-off. Pre- and post-test probabilities weren’t calculated.

Positive predictive value rises with antibody levels

A 2013 retrospective study evaluated the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition’s recommendation to forego intestinal biopsy in non-IgA–deficient, symptomatic children and adolescents with positive IgA anti-tTG levels greater than 10 times the cut-off value, positive EMA, and positive HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8.2

Overall, 153 symptomatic patients referred to the gastroenterology unit met these criteria. The age range was 9 months to 14.6 years (mean 4 years). All but 3 of the patients had Marsh 2 or greater lesions with biopsy-confirmed diagnoses of celiac disease. The remaining 3 developed biopsy-positive celiac disease on follow-up. The positive predictive value of combined serologic testing in this small selected patient population was 100%.

A 2013 retrospective study of 2477 symptomatic adults (older than 18 years) who received diagnostic testing for celiac disease at 2 academic institutions in Cleveland, Ohio, evaluated the predictive value of IgA anti-tTG and EMA. Of the patients, 610 (25%) had abnormal serologic tests, and 240 (39%) underwent endoscopy with biopsy.

A total of 50 patients (21%) had biopsy results consistent with celiac disease, defined as a Marsh 3 lesion or greater.3 An IgA anti-tTG level of 118 U/mL (5.9-fold the upper limit of normal on the test) had a positive predictive value of 86.4% with a false-positive value of 2%. An EMA titer greater than 1:160 when IgA anti-tTG was between 21 and 118 U/mL had a positive predictive value of 83%.

Antibody levels 10 times normal show 100% positive predictive value

A 2008 retrospective study of one manufacturer’s IgA anti-tTG serologic test sought to establish the serologic antibody level at which the positive predictive value was 100%.4 Overall, 148 people, 15 years and older, with a positive IgA anti-tTG before biopsy or within 21 days of biopsy were included.

Of the patients biopsied, 139 (93%) had positive biopsies of Marsh 2 or greater and were diagnosed with celiac disease. Using a cut-off of 3.3 and 6.7 times the upper limit of normal, investigators calculated a positive predictive value of 95% and 98%, respectively.

A cut-off of 10 times the upper limit of normal or greater had a positive predictive value of 100%. The highest level of IgA anti-tTG in a patient who didn’t have celiac disease on biopsy was 7.3 times the upper limit of normal.

1. Vermeersch P, Geboes K, Mariën G, et al. Defining thresholds of antibody levels improves diagnosis of celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:398-403;quiz e32.

2. Klapp G, Masip E, Bolonio M, et al. Celiac disease: The new proposed ESPGHAN diagnostic criteria do work well in a selected population. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:251-256.

3. Wakim-Fleming J, Pagadala MR, Lemyre MS, et al. Diagnosis of celiac disease in adults based on serology test results, without small-bowel biopsy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:511-516.

4. Hill PG, Holmes GK. Coeliac disease: a biopsy is not always necessary for diagnosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:572-577.

1. Vermeersch P, Geboes K, Mariën G, et al. Defining thresholds of antibody levels improves diagnosis of celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:398-403;quiz e32.

2. Klapp G, Masip E, Bolonio M, et al. Celiac disease: The new proposed ESPGHAN diagnostic criteria do work well in a selected population. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:251-256.

3. Wakim-Fleming J, Pagadala MR, Lemyre MS, et al. Diagnosis of celiac disease in adults based on serology test results, without small-bowel biopsy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:511-516.

4. Hill PG, Holmes GK. Coeliac disease: a biopsy is not always necessary for diagnosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:572-577.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

It depends on the antibody levels in the blood work. Symptomatic patients with serologic levels of immunoglobulin A anti-tissue transglutaminase (IgA anti-tTG) or immunoglobulin G anti-deamidated gliadin peptide antibody (IgG anti-DGP) greater than 10 times the upper limits of normal—especially if they also are positive for endomysial antibodies (EMA) and human leukocyte antigen DQ2 (HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8)—may not need an intestinal biopsy to confirm the diagnosis of celiac disease (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, inconsistent or limited-quality cohort studies).

Patients with antibody levels lower than 10 times the upper limits of normal or who are asymptomatic most likely need an intestinal biopsy to confirm the diagnosis (SOR: B, inconsistent or limited-quality cohort studies).

Does vitamin D without calcium reduce fracture risk?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

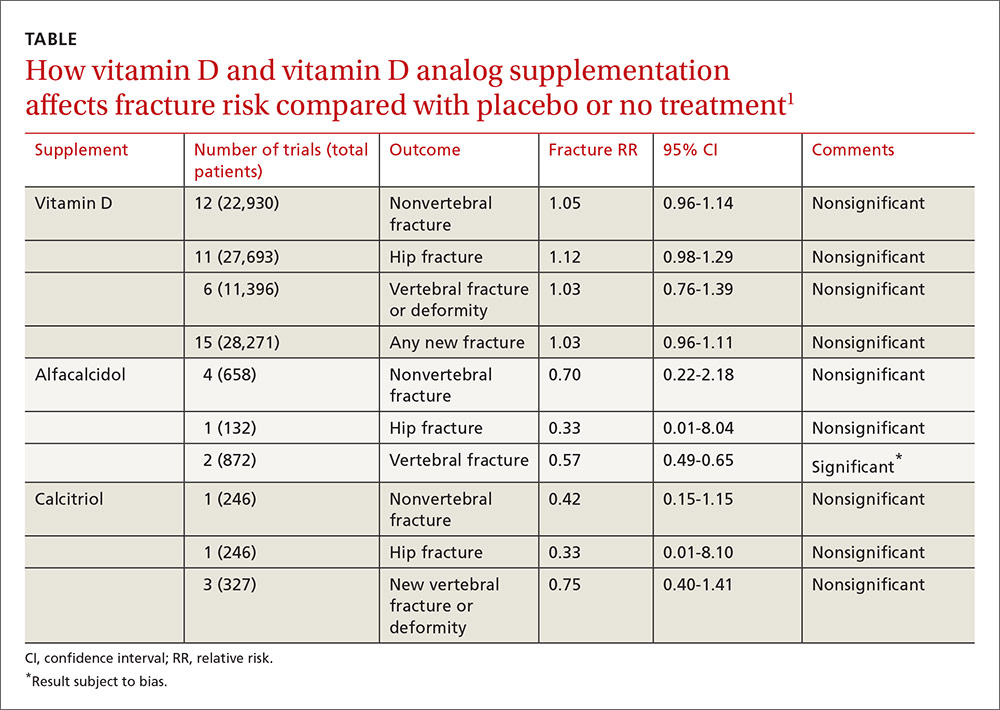

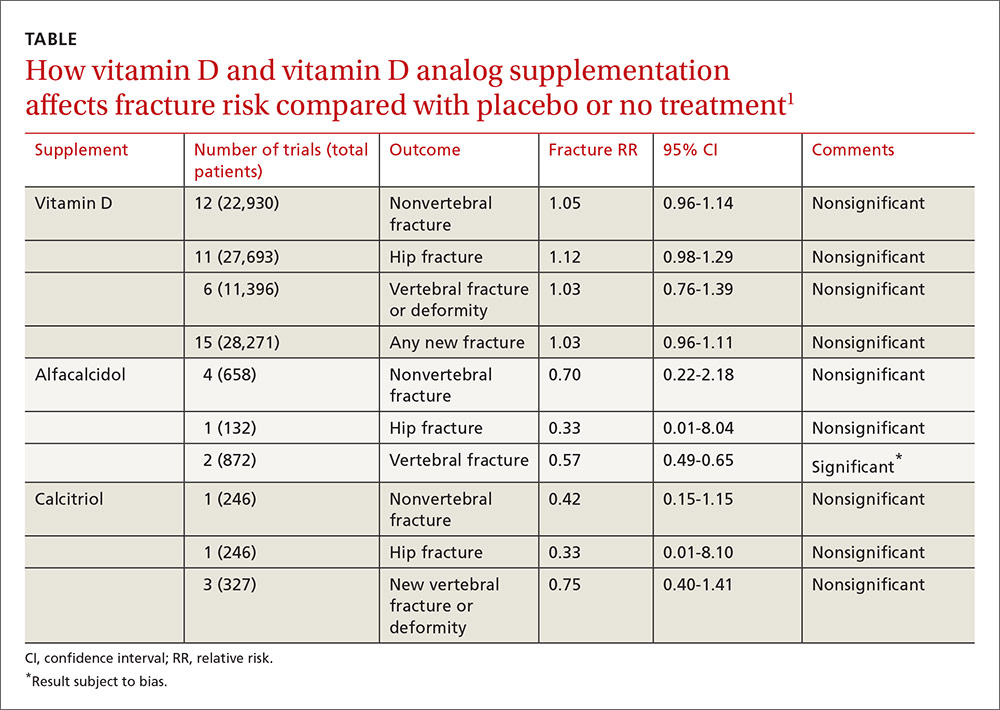

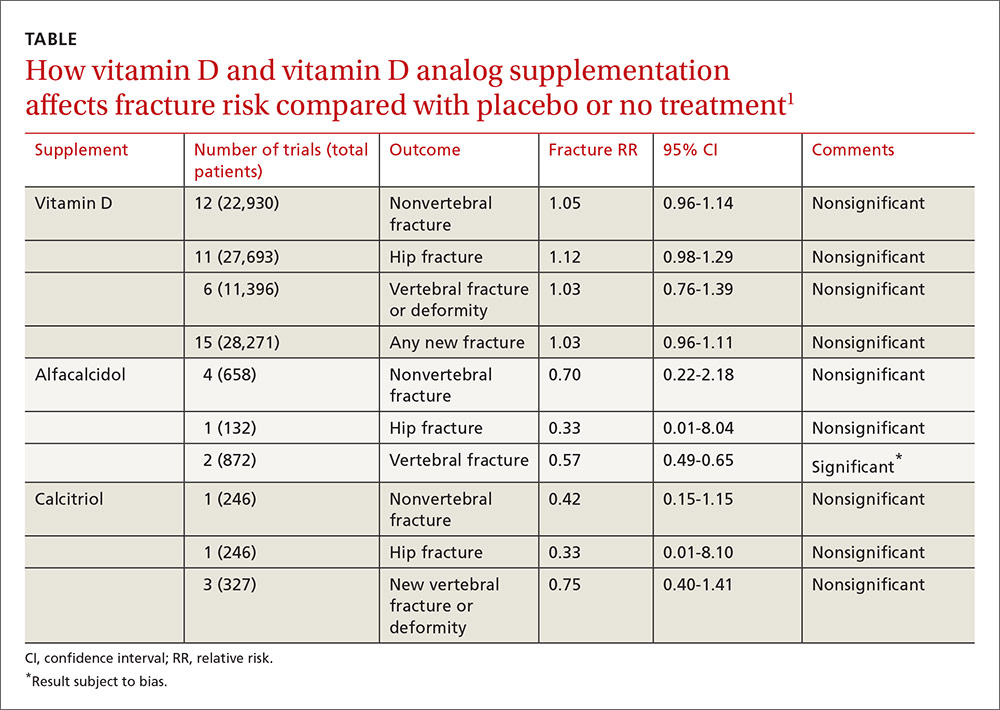

A 2014 meta-analysis of 15 trials (quasi-random and RCT) with a total of 28,271 patients that compared the effect of vitamin D on fracture risk with placebo or no treatment, found no benefit for vitamin D supplementation (TABLE).1 Patients lived in community and nursing home settings and ranged in age from 50 to 85 years; 24% to 100% were female.

Only 3 trials required patients to have had a previous fracture. Exclusions included: diseases affecting bone metabolism, cognitive impairment, drugs affecting bone metabolism (bisphosphonates, selective estrogen receptor modulators, and corticosteroids), renal failure, hypercalcemia, nephrolithiasis, and decreased mobility (recent stroke recovery and Parkinson’s disease).

Formulations of vitamin D included cholecalciferol (D3) 400 to 2000 IU/d for 4 months to 5 years or 100,000 to 500,000 IU every 3 to 12 months for 1 to 5 years; calcifediol (25(OH)D3) 600 IU/d for 4 years; and ergocalciferol (D2) 400 IU/d for 2 years or 3000 to 300,000 IU every 3 to 12 months for 10 months to 3 years.

Vitamin D analogs generally have no benefit either

The same meta-analysis compared vitamin D analogs to placebo or no treatment (8 trials, quasi-random and RCT, 1743 patients) on the risk of fracture, again finding no benefit in all but one case. Included patients were mostly by referral to tertiary or university hospitals and outpatient community settings.

Most of the studies included only a small number of patients (about 200), with the largest study having 740 patients. The age range was 50 to 77 years, and 50% to 100% were female. Most of the trials required patients to have osteoporosis or vitamin D deficiency with a previous vertebral deformity on imaging. Study exclusions included osteomalacia, malabsorption, hyperparathyroidism, active kidney stones, history of hypercalciuria, cancer, incurable disease, dementia, severe chronic illness (renal or liver failure), recent stroke or fracture, and drugs that affect bone metabolism.

Vitamin D analogs were given as alfacalcidol (1-alphahydroxyvitamin D3) 0.5 mcg twice daily or 1 mcg/d for 36 weeks to 2 years or calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) 0.25 to 1 mcg once or twice daily for one to 3 years. Researchers found a significant reduction in vertebral (but not nonvertebral or hip) fractures with alfacalcidol, but the finding occurred in a single trial that was assessed by the authors of the meta-analysis as subject to bias.

Supplementation doesn’t affect mortality, but does have some side effects

Patients taking vitamin D or an analog with or without calcium showed no difference in risk of death compared with patients taking placebo (29 trials, 71,032 patients; relative risk [RR]=0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.93-1.01).

Patients taking vitamin D or an analog were more likely than controls to have mild hypercalcemia, with an average increase of 2.7 mmol/L (21 trials, 17,124 patients; RR=2.28; 95% CI, 1.57-3.31). Patients taking calcitriol had the highest risk (4 trials, 988 patients; RR=4.41; 95% CI, 2.14-9.09).

Gastrointestinal adverse effects (4% increase) and renal calculi or mild renal insufficiency (16% increase) were more common with vitamin D and analogs than placebo (GI adverse effects: 15 trials, 47,761 patients; RR=1.04; 95% CI, 1.00-1.08; renal calculi or mild renal insufficiency: 11 trials, 46,548 patients; RR=1.16; 95% CI, 1.02-1.33).

RECOMMENDATIONS

There are no guidelines recommending vitamin D supplementation without calcium to prevent fracture.

1. Avenell A, Mak JC, O’Connell D. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures in post-menopausal women and older men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD000227.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2014 meta-analysis of 15 trials (quasi-random and RCT) with a total of 28,271 patients that compared the effect of vitamin D on fracture risk with placebo or no treatment, found no benefit for vitamin D supplementation (TABLE).1 Patients lived in community and nursing home settings and ranged in age from 50 to 85 years; 24% to 100% were female.

Only 3 trials required patients to have had a previous fracture. Exclusions included: diseases affecting bone metabolism, cognitive impairment, drugs affecting bone metabolism (bisphosphonates, selective estrogen receptor modulators, and corticosteroids), renal failure, hypercalcemia, nephrolithiasis, and decreased mobility (recent stroke recovery and Parkinson’s disease).

Formulations of vitamin D included cholecalciferol (D3) 400 to 2000 IU/d for 4 months to 5 years or 100,000 to 500,000 IU every 3 to 12 months for 1 to 5 years; calcifediol (25(OH)D3) 600 IU/d for 4 years; and ergocalciferol (D2) 400 IU/d for 2 years or 3000 to 300,000 IU every 3 to 12 months for 10 months to 3 years.

Vitamin D analogs generally have no benefit either

The same meta-analysis compared vitamin D analogs to placebo or no treatment (8 trials, quasi-random and RCT, 1743 patients) on the risk of fracture, again finding no benefit in all but one case. Included patients were mostly by referral to tertiary or university hospitals and outpatient community settings.

Most of the studies included only a small number of patients (about 200), with the largest study having 740 patients. The age range was 50 to 77 years, and 50% to 100% were female. Most of the trials required patients to have osteoporosis or vitamin D deficiency with a previous vertebral deformity on imaging. Study exclusions included osteomalacia, malabsorption, hyperparathyroidism, active kidney stones, history of hypercalciuria, cancer, incurable disease, dementia, severe chronic illness (renal or liver failure), recent stroke or fracture, and drugs that affect bone metabolism.

Vitamin D analogs were given as alfacalcidol (1-alphahydroxyvitamin D3) 0.5 mcg twice daily or 1 mcg/d for 36 weeks to 2 years or calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) 0.25 to 1 mcg once or twice daily for one to 3 years. Researchers found a significant reduction in vertebral (but not nonvertebral or hip) fractures with alfacalcidol, but the finding occurred in a single trial that was assessed by the authors of the meta-analysis as subject to bias.

Supplementation doesn’t affect mortality, but does have some side effects

Patients taking vitamin D or an analog with or without calcium showed no difference in risk of death compared with patients taking placebo (29 trials, 71,032 patients; relative risk [RR]=0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.93-1.01).

Patients taking vitamin D or an analog were more likely than controls to have mild hypercalcemia, with an average increase of 2.7 mmol/L (21 trials, 17,124 patients; RR=2.28; 95% CI, 1.57-3.31). Patients taking calcitriol had the highest risk (4 trials, 988 patients; RR=4.41; 95% CI, 2.14-9.09).

Gastrointestinal adverse effects (4% increase) and renal calculi or mild renal insufficiency (16% increase) were more common with vitamin D and analogs than placebo (GI adverse effects: 15 trials, 47,761 patients; RR=1.04; 95% CI, 1.00-1.08; renal calculi or mild renal insufficiency: 11 trials, 46,548 patients; RR=1.16; 95% CI, 1.02-1.33).

RECOMMENDATIONS

There are no guidelines recommending vitamin D supplementation without calcium to prevent fracture.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2014 meta-analysis of 15 trials (quasi-random and RCT) with a total of 28,271 patients that compared the effect of vitamin D on fracture risk with placebo or no treatment, found no benefit for vitamin D supplementation (TABLE).1 Patients lived in community and nursing home settings and ranged in age from 50 to 85 years; 24% to 100% were female.

Only 3 trials required patients to have had a previous fracture. Exclusions included: diseases affecting bone metabolism, cognitive impairment, drugs affecting bone metabolism (bisphosphonates, selective estrogen receptor modulators, and corticosteroids), renal failure, hypercalcemia, nephrolithiasis, and decreased mobility (recent stroke recovery and Parkinson’s disease).

Formulations of vitamin D included cholecalciferol (D3) 400 to 2000 IU/d for 4 months to 5 years or 100,000 to 500,000 IU every 3 to 12 months for 1 to 5 years; calcifediol (25(OH)D3) 600 IU/d for 4 years; and ergocalciferol (D2) 400 IU/d for 2 years or 3000 to 300,000 IU every 3 to 12 months for 10 months to 3 years.

Vitamin D analogs generally have no benefit either

The same meta-analysis compared vitamin D analogs to placebo or no treatment (8 trials, quasi-random and RCT, 1743 patients) on the risk of fracture, again finding no benefit in all but one case. Included patients were mostly by referral to tertiary or university hospitals and outpatient community settings.

Most of the studies included only a small number of patients (about 200), with the largest study having 740 patients. The age range was 50 to 77 years, and 50% to 100% were female. Most of the trials required patients to have osteoporosis or vitamin D deficiency with a previous vertebral deformity on imaging. Study exclusions included osteomalacia, malabsorption, hyperparathyroidism, active kidney stones, history of hypercalciuria, cancer, incurable disease, dementia, severe chronic illness (renal or liver failure), recent stroke or fracture, and drugs that affect bone metabolism.

Vitamin D analogs were given as alfacalcidol (1-alphahydroxyvitamin D3) 0.5 mcg twice daily or 1 mcg/d for 36 weeks to 2 years or calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) 0.25 to 1 mcg once or twice daily for one to 3 years. Researchers found a significant reduction in vertebral (but not nonvertebral or hip) fractures with alfacalcidol, but the finding occurred in a single trial that was assessed by the authors of the meta-analysis as subject to bias.

Supplementation doesn’t affect mortality, but does have some side effects

Patients taking vitamin D or an analog with or without calcium showed no difference in risk of death compared with patients taking placebo (29 trials, 71,032 patients; relative risk [RR]=0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.93-1.01).

Patients taking vitamin D or an analog were more likely than controls to have mild hypercalcemia, with an average increase of 2.7 mmol/L (21 trials, 17,124 patients; RR=2.28; 95% CI, 1.57-3.31). Patients taking calcitriol had the highest risk (4 trials, 988 patients; RR=4.41; 95% CI, 2.14-9.09).

Gastrointestinal adverse effects (4% increase) and renal calculi or mild renal insufficiency (16% increase) were more common with vitamin D and analogs than placebo (GI adverse effects: 15 trials, 47,761 patients; RR=1.04; 95% CI, 1.00-1.08; renal calculi or mild renal insufficiency: 11 trials, 46,548 patients; RR=1.16; 95% CI, 1.02-1.33).

RECOMMENDATIONS

There are no guidelines recommending vitamin D supplementation without calcium to prevent fracture.

1. Avenell A, Mak JC, O’Connell D. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures in post-menopausal women and older men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD000227.

1. Avenell A, Mak JC, O’Connell D. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures in post-menopausal women and older men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD000227.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

No. Supplemental vitamin D without calcium—in doses averaging as much as 800 IU per day—doesn’t reduce the risk of hip, vertebral, or nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women and older men (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, large, high-quality meta-analysis of randomized or quasi-randomized placebo-controlled trials).

The vitamin D analogs alfacalcidol and calcitriol also don’t reduce hip or nonvertebral fractures (SOR: A, multiple randomized, controlled trials [RCTs]), although alfacalcidol (but not calcitriol) does reduce vertebral fractures by 43% (SOR: B, one RCT and one quasi-randomized trial with potential for bias)

Vitamin D supplementation, with or without calcium, doesn’t affect mortality. It does double the risk of mild hypercalcemia (about 2.7 mmol/L increase), raise the risk of renal calculi or mild renal insufficiency by 16%, and slightly increase (4%) gastrointestinal adverse effects (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs or quasi-randomized trials).

Does breastfeeding affect the risk of childhood obesity?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating infant risk factors for childhood obesity found that breastfeeding was associated with a lower risk of obesity.1 The authors identified 10 trials (primarily from the United States and Europe) with more than 76,000 infants that compared the effect of some breastfeeding in the first year to no breastfeeding. Follow-up ranged from 2 to 14 years (median 6 years).

Having ever breastfed decreased the odds of future overweight (BMI >85th percentile) or obesity (BMI >95th percentile) by 15% (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=0.85; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.74-0.99).

Subsequent studies suggest increased risk with formula feeding

Three large, prospective, longitudinal cohort studies have been published since the meta-analysis. One, which followed 43,367 term infants in Japan, found that formula feeding before 6 months was associated with increased risk of obesity compared with continuous breastfeeding for 6 months.2 Researchers evaluated weight at 7 years and adjusted for child and maternal factors associated with weight gain (AOR for obesity, formula-fed infants=1.8; 95% CI, 1.3-2.6).

A similar prospective longitudinal cohort study of 2868 infants in Australia analyzed maternal breastfeeding diaries and followed children’s weight to age 20 years.3 Introducing a milk other than breast milk before 6 months of age was linked to increased risk of obesity at age 20 (odds ratio [OR]=1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-1.9).

Finally, in a prospective cohort of 568 children in India, 17% of children who breastfed for fewer than 6 months were above the 90th percentile for weight at age 5 years, compared with 10% of children who were breastfed for at least 18 months.4 The result didn’t reach statistical significance, however (P=.08).

Interventions that increase breastfeeding don’t seem to have an impact

An RCT of an intervention to promote breastfeeding didn’t find any effect on subsequent obesity rates. Researchers in Belarus randomized 17,046 mother-infant pairs to breastfeeding promotion, modeled on the UNICEF Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative, or usual care. The intervention increased the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding (at 3 months, 43% vs 6%; at 6 months, 7% vs 0.6%; P values not given).

When researchers evaluated 13,879 children at 11 or 12 years by intention-to-treat analysis, however, they found no difference in mean BMI between the children whose mothers received the intervention and those whose mothers didn’t (BMI difference=0.16; 95% CI, -0.02 to 0.35).5

Introduction of solid foods: Later is better

A systematic review investigated the association between the timing of introducing complementary (solid) foods and childhood obesity in 23 primarily cross-sectional and cohort studies (17 from the United States, Canada, and Europe) with more than 33,000 patients. Follow-up ranged from 4 to 19 years.

Eight of the 21 studies that used BMI as an outcome found that early introduction of complementary foods was associated with a higher childhood BMI. In the largest study (a cohort of 17,561 infants), introducing complementary foods before 3 months was associated with higher risk of obesity at age 5 years than introducing them thereafter (OR=1.3; 95% CI, 1.1-1.6).6 Introduction of solids after 4 months was not associated with childhood obesity.

A systematic review of 10 primarily cross-sectional and cohort studies with more than 3000 infants evaluated associations between the types of complementary foods given and the development of childhood obesity.7 Six of the 10 studies were from Europe and none were from the United States. Follow-up ages ranged from 4 to 11 years.

Outcomes were heterogeneous, and no meta-analysis could be performed. The authors cited 3 studies (total 1174 infants) that found various positive associations between total caloric intake during complementary feeding and childhood obesity. No consistent evidence pointed to increased risk from specific foods or food groups.

Scheduled feeding is linked to rapid infant weight gain

A cohort study evaluated the baseline data of an Australian RCT (on an intervention to promote proper nutrition) in 612 infants, mean age 4.3 months.8 Researchers looked at the relationship between feeding on demand vs scheduled feeding (assessed by parental report) and weight gain in infancy. “Rapid weight gain” was defined as >0.67 change in weight-for-age Z-score between birth and enrollment.

Scheduled feeding was associated with rapid weight gain at a higher rate than feeding on demand (OR=2.3; 95% CI, 1.1-4.6). This study didn’t use childhood obesity as an outcome.

1. Weng SF, Redsell SA, Swift JA, et al. Systematic review and meta-analyses of risk factors for childhood overweight identifiable during infancy. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:1019-1026.

2. Yamakawa M, Yorifuji T, Inoue S, et al. Breastfeeding and obesity among schoolchildren: a national longitudinal survey in Japan. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:919-925.

3. Oddy WH, Mari TA, Huang RC, et al. Early infant feeding and adiposity risk: from infancy to adulthood. Ann Nutr Metab. 2014;64:262-270.

4. Caleyachetty A, Krishnaveni GV, Veena SR, et al. Breast-feeding duration, age of starting solids, and high BMI risk and adiposity in Indian children. Matern Child Nutr. 2013;9:199-216.

5. Martin RM, Patel, R, Kramer MS, et al. Effects of promoting longer-term and exclusive breastfeeding on adiposity and insulin-like growth factor-I at age 11.5 years: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;309:1005-1013.

6. Pearce J, Taylor MA, Langley-Evans SC. Timing of the introduction of complementary feeding and risk of childhood obesity: a systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37:1295-1306.

7. Pearce J, Langley-Evans. The types of food introduced during complementary feeding and risk of childhood obesity: a systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37:477-485.

8. Mihrshahi S, Battistutta D, Magarey A, et al. Determinants of rapid weight gain during infancy: baseline results from the NOURISH randomised controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:99.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating infant risk factors for childhood obesity found that breastfeeding was associated with a lower risk of obesity.1 The authors identified 10 trials (primarily from the United States and Europe) with more than 76,000 infants that compared the effect of some breastfeeding in the first year to no breastfeeding. Follow-up ranged from 2 to 14 years (median 6 years).

Having ever breastfed decreased the odds of future overweight (BMI >85th percentile) or obesity (BMI >95th percentile) by 15% (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=0.85; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.74-0.99).

Subsequent studies suggest increased risk with formula feeding

Three large, prospective, longitudinal cohort studies have been published since the meta-analysis. One, which followed 43,367 term infants in Japan, found that formula feeding before 6 months was associated with increased risk of obesity compared with continuous breastfeeding for 6 months.2 Researchers evaluated weight at 7 years and adjusted for child and maternal factors associated with weight gain (AOR for obesity, formula-fed infants=1.8; 95% CI, 1.3-2.6).

A similar prospective longitudinal cohort study of 2868 infants in Australia analyzed maternal breastfeeding diaries and followed children’s weight to age 20 years.3 Introducing a milk other than breast milk before 6 months of age was linked to increased risk of obesity at age 20 (odds ratio [OR]=1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-1.9).

Finally, in a prospective cohort of 568 children in India, 17% of children who breastfed for fewer than 6 months were above the 90th percentile for weight at age 5 years, compared with 10% of children who were breastfed for at least 18 months.4 The result didn’t reach statistical significance, however (P=.08).

Interventions that increase breastfeeding don’t seem to have an impact

An RCT of an intervention to promote breastfeeding didn’t find any effect on subsequent obesity rates. Researchers in Belarus randomized 17,046 mother-infant pairs to breastfeeding promotion, modeled on the UNICEF Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative, or usual care. The intervention increased the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding (at 3 months, 43% vs 6%; at 6 months, 7% vs 0.6%; P values not given).

When researchers evaluated 13,879 children at 11 or 12 years by intention-to-treat analysis, however, they found no difference in mean BMI between the children whose mothers received the intervention and those whose mothers didn’t (BMI difference=0.16; 95% CI, -0.02 to 0.35).5

Introduction of solid foods: Later is better

A systematic review investigated the association between the timing of introducing complementary (solid) foods and childhood obesity in 23 primarily cross-sectional and cohort studies (17 from the United States, Canada, and Europe) with more than 33,000 patients. Follow-up ranged from 4 to 19 years.

Eight of the 21 studies that used BMI as an outcome found that early introduction of complementary foods was associated with a higher childhood BMI. In the largest study (a cohort of 17,561 infants), introducing complementary foods before 3 months was associated with higher risk of obesity at age 5 years than introducing them thereafter (OR=1.3; 95% CI, 1.1-1.6).6 Introduction of solids after 4 months was not associated with childhood obesity.

A systematic review of 10 primarily cross-sectional and cohort studies with more than 3000 infants evaluated associations between the types of complementary foods given and the development of childhood obesity.7 Six of the 10 studies were from Europe and none were from the United States. Follow-up ages ranged from 4 to 11 years.

Outcomes were heterogeneous, and no meta-analysis could be performed. The authors cited 3 studies (total 1174 infants) that found various positive associations between total caloric intake during complementary feeding and childhood obesity. No consistent evidence pointed to increased risk from specific foods or food groups.

Scheduled feeding is linked to rapid infant weight gain

A cohort study evaluated the baseline data of an Australian RCT (on an intervention to promote proper nutrition) in 612 infants, mean age 4.3 months.8 Researchers looked at the relationship between feeding on demand vs scheduled feeding (assessed by parental report) and weight gain in infancy. “Rapid weight gain” was defined as >0.67 change in weight-for-age Z-score between birth and enrollment.

Scheduled feeding was associated with rapid weight gain at a higher rate than feeding on demand (OR=2.3; 95% CI, 1.1-4.6). This study didn’t use childhood obesity as an outcome.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating infant risk factors for childhood obesity found that breastfeeding was associated with a lower risk of obesity.1 The authors identified 10 trials (primarily from the United States and Europe) with more than 76,000 infants that compared the effect of some breastfeeding in the first year to no breastfeeding. Follow-up ranged from 2 to 14 years (median 6 years).

Having ever breastfed decreased the odds of future overweight (BMI >85th percentile) or obesity (BMI >95th percentile) by 15% (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=0.85; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.74-0.99).

Subsequent studies suggest increased risk with formula feeding

Three large, prospective, longitudinal cohort studies have been published since the meta-analysis. One, which followed 43,367 term infants in Japan, found that formula feeding before 6 months was associated with increased risk of obesity compared with continuous breastfeeding for 6 months.2 Researchers evaluated weight at 7 years and adjusted for child and maternal factors associated with weight gain (AOR for obesity, formula-fed infants=1.8; 95% CI, 1.3-2.6).

A similar prospective longitudinal cohort study of 2868 infants in Australia analyzed maternal breastfeeding diaries and followed children’s weight to age 20 years.3 Introducing a milk other than breast milk before 6 months of age was linked to increased risk of obesity at age 20 (odds ratio [OR]=1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-1.9).

Finally, in a prospective cohort of 568 children in India, 17% of children who breastfed for fewer than 6 months were above the 90th percentile for weight at age 5 years, compared with 10% of children who were breastfed for at least 18 months.4 The result didn’t reach statistical significance, however (P=.08).

Interventions that increase breastfeeding don’t seem to have an impact

An RCT of an intervention to promote breastfeeding didn’t find any effect on subsequent obesity rates. Researchers in Belarus randomized 17,046 mother-infant pairs to breastfeeding promotion, modeled on the UNICEF Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative, or usual care. The intervention increased the prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding (at 3 months, 43% vs 6%; at 6 months, 7% vs 0.6%; P values not given).

When researchers evaluated 13,879 children at 11 or 12 years by intention-to-treat analysis, however, they found no difference in mean BMI between the children whose mothers received the intervention and those whose mothers didn’t (BMI difference=0.16; 95% CI, -0.02 to 0.35).5

Introduction of solid foods: Later is better

A systematic review investigated the association between the timing of introducing complementary (solid) foods and childhood obesity in 23 primarily cross-sectional and cohort studies (17 from the United States, Canada, and Europe) with more than 33,000 patients. Follow-up ranged from 4 to 19 years.

Eight of the 21 studies that used BMI as an outcome found that early introduction of complementary foods was associated with a higher childhood BMI. In the largest study (a cohort of 17,561 infants), introducing complementary foods before 3 months was associated with higher risk of obesity at age 5 years than introducing them thereafter (OR=1.3; 95% CI, 1.1-1.6).6 Introduction of solids after 4 months was not associated with childhood obesity.

A systematic review of 10 primarily cross-sectional and cohort studies with more than 3000 infants evaluated associations between the types of complementary foods given and the development of childhood obesity.7 Six of the 10 studies were from Europe and none were from the United States. Follow-up ages ranged from 4 to 11 years.

Outcomes were heterogeneous, and no meta-analysis could be performed. The authors cited 3 studies (total 1174 infants) that found various positive associations between total caloric intake during complementary feeding and childhood obesity. No consistent evidence pointed to increased risk from specific foods or food groups.

Scheduled feeding is linked to rapid infant weight gain

A cohort study evaluated the baseline data of an Australian RCT (on an intervention to promote proper nutrition) in 612 infants, mean age 4.3 months.8 Researchers looked at the relationship between feeding on demand vs scheduled feeding (assessed by parental report) and weight gain in infancy. “Rapid weight gain” was defined as >0.67 change in weight-for-age Z-score between birth and enrollment.

Scheduled feeding was associated with rapid weight gain at a higher rate than feeding on demand (OR=2.3; 95% CI, 1.1-4.6). This study didn’t use childhood obesity as an outcome.

1. Weng SF, Redsell SA, Swift JA, et al. Systematic review and meta-analyses of risk factors for childhood overweight identifiable during infancy. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:1019-1026.

2. Yamakawa M, Yorifuji T, Inoue S, et al. Breastfeeding and obesity among schoolchildren: a national longitudinal survey in Japan. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:919-925.

3. Oddy WH, Mari TA, Huang RC, et al. Early infant feeding and adiposity risk: from infancy to adulthood. Ann Nutr Metab. 2014;64:262-270.

4. Caleyachetty A, Krishnaveni GV, Veena SR, et al. Breast-feeding duration, age of starting solids, and high BMI risk and adiposity in Indian children. Matern Child Nutr. 2013;9:199-216.

5. Martin RM, Patel, R, Kramer MS, et al. Effects of promoting longer-term and exclusive breastfeeding on adiposity and insulin-like growth factor-I at age 11.5 years: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;309:1005-1013.

6. Pearce J, Taylor MA, Langley-Evans SC. Timing of the introduction of complementary feeding and risk of childhood obesity: a systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37:1295-1306.

7. Pearce J, Langley-Evans. The types of food introduced during complementary feeding and risk of childhood obesity: a systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37:477-485.

8. Mihrshahi S, Battistutta D, Magarey A, et al. Determinants of rapid weight gain during infancy: baseline results from the NOURISH randomised controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:99.

1. Weng SF, Redsell SA, Swift JA, et al. Systematic review and meta-analyses of risk factors for childhood overweight identifiable during infancy. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:1019-1026.

2. Yamakawa M, Yorifuji T, Inoue S, et al. Breastfeeding and obesity among schoolchildren: a national longitudinal survey in Japan. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:919-925.

3. Oddy WH, Mari TA, Huang RC, et al. Early infant feeding and adiposity risk: from infancy to adulthood. Ann Nutr Metab. 2014;64:262-270.

4. Caleyachetty A, Krishnaveni GV, Veena SR, et al. Breast-feeding duration, age of starting solids, and high BMI risk and adiposity in Indian children. Matern Child Nutr. 2013;9:199-216.

5. Martin RM, Patel, R, Kramer MS, et al. Effects of promoting longer-term and exclusive breastfeeding on adiposity and insulin-like growth factor-I at age 11.5 years: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;309:1005-1013.

6. Pearce J, Taylor MA, Langley-Evans SC. Timing of the introduction of complementary feeding and risk of childhood obesity: a systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37:1295-1306.

7. Pearce J, Langley-Evans. The types of food introduced during complementary feeding and risk of childhood obesity: a systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37:477-485.

8. Mihrshahi S, Battistutta D, Magarey A, et al. Determinants of rapid weight gain during infancy: baseline results from the NOURISH randomised controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:99.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes. Ever having breastfed during the first year of life is associated with a 15% lower risk of overweight or obesity over the next 2 to 14 years compared with never having breastfed. Breastfeeding exclusively for 6 months is associated with a 30% to 50% reduction in risk (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analysis of cohort studies and subsequent cohort studies). However, interventions that increase breastfeeding rates during the first 3 to 6 months of life don’t appear to alter body mass index (BMI) at 11 to 12 years of age (SOR: B, randomized clinical trial [RCT]).

Introducing complementary (solid) foods before 3 months is associated with a 30% greater risk of childhood obesity than later introduction; starting solid foods after 4 months isn’t linked to increased obesity. High caloric density of complementary feedings may be associated with greater childhood obesity (SOR: C, systematic reviews of heterogeneous cohort studies).

Scheduled feeding doubles the risk of rapid infant weight gain compared with on-demand feeding, although it’s unclear whether a direct relationship exists between rapid infant weight gain and childhood obesity (SOR: B, cohort study).

Worsening of longstanding headaches, dizziness, visual symptoms • Dx?

THE CASE

A 59-year-old woman from the Democratic Republic of the Congo presented to our family medicine clinic with acute worsening of longstanding headaches. Using a Swahili interpreter, the patient reported a 15-year history of recurrent, intermittent headaches that had been previously diagnosed as migraines. Over the prior 2 months, the headaches had intensified with new symptoms of dizziness, ocular pain, and blurred vision with red flashes. She had no hemiplegia, dysarthria, respiratory symptoms, night sweats, or weight loss. A neurologic exam was negative.

Before immigrating to the United States 14 years earlier, the patient lived for 6 months in a refugee camp in the Congo. At the time of her immigration, she was negative for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and a tuberculosis (TB) skin test was positive. A chest x-ray was normal and she had no respiratory symptoms. Shortly after her immigration, she completed 6 months of isoniazid treatment for latent TB.

THE DIAGNOSIS

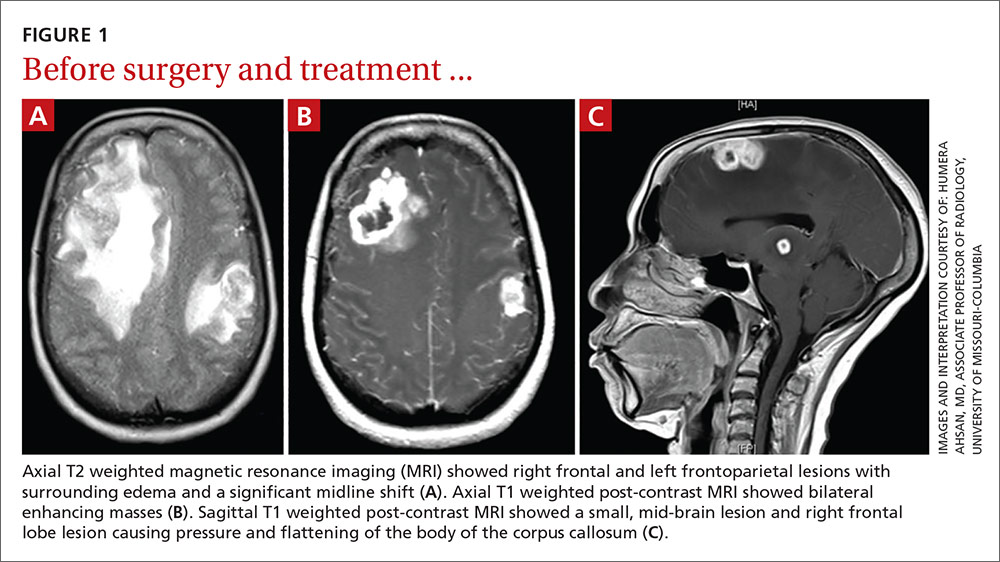

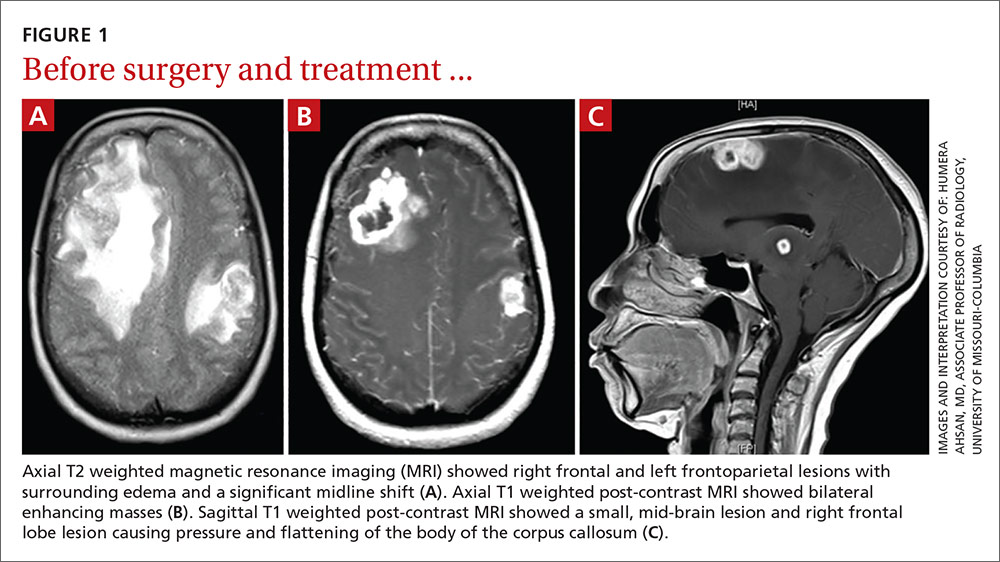

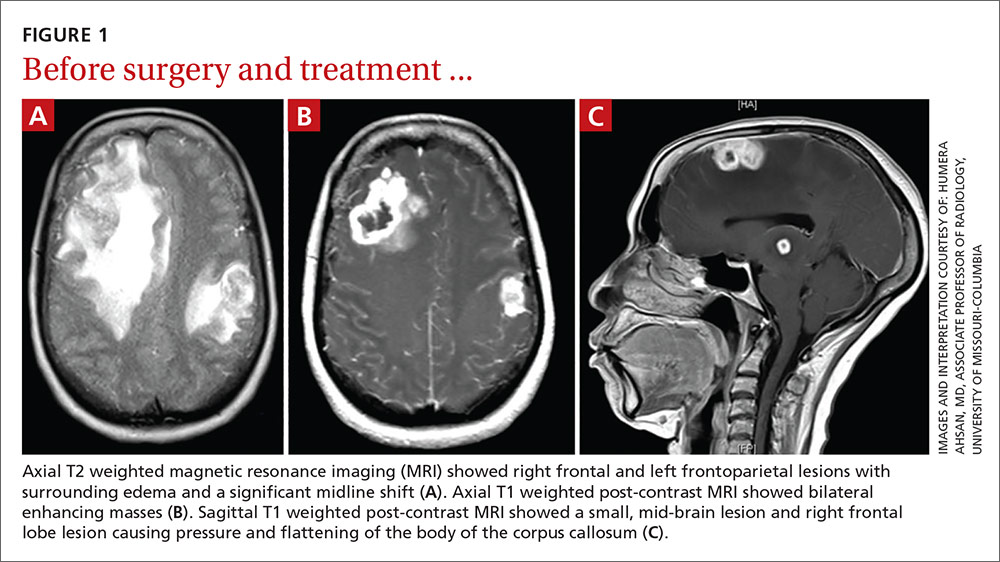

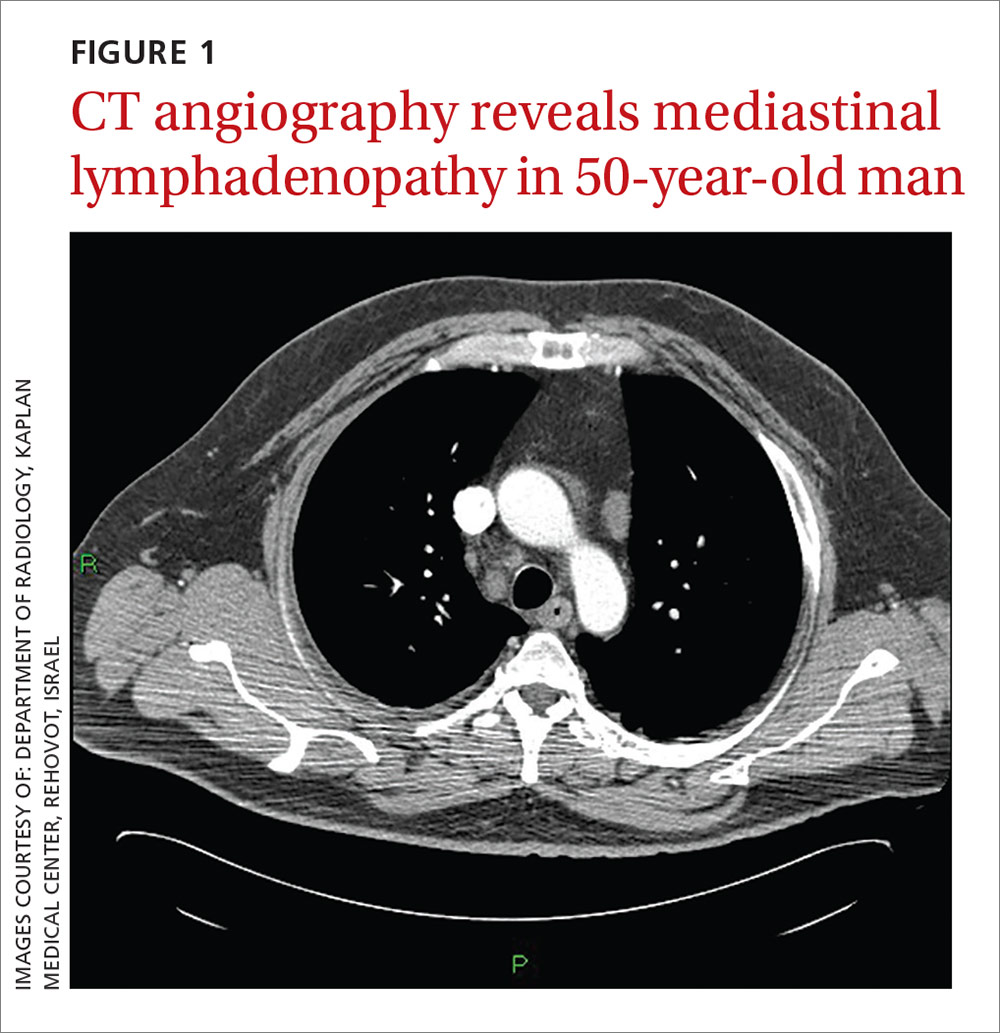

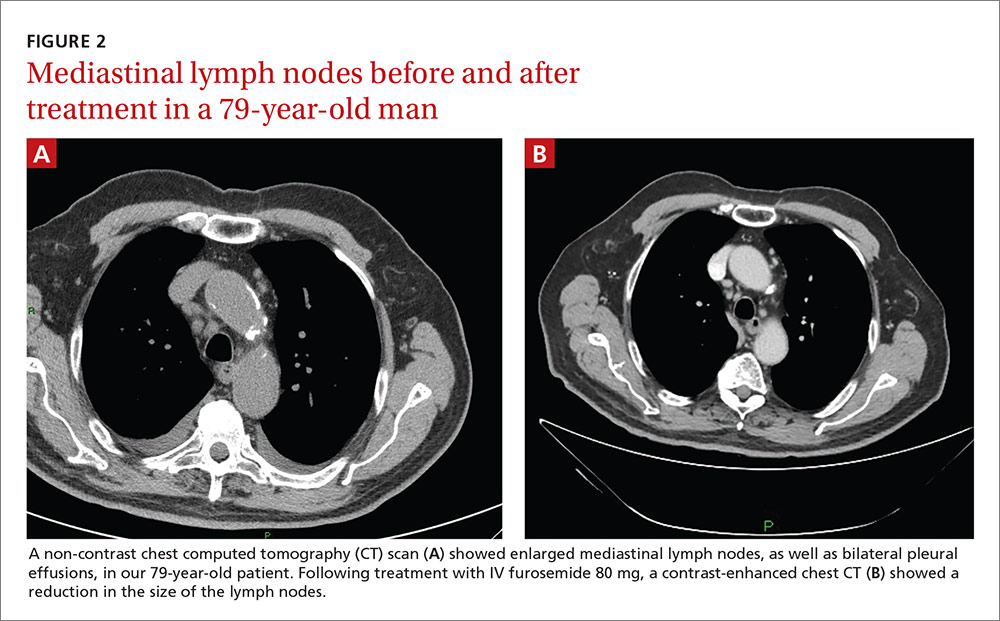

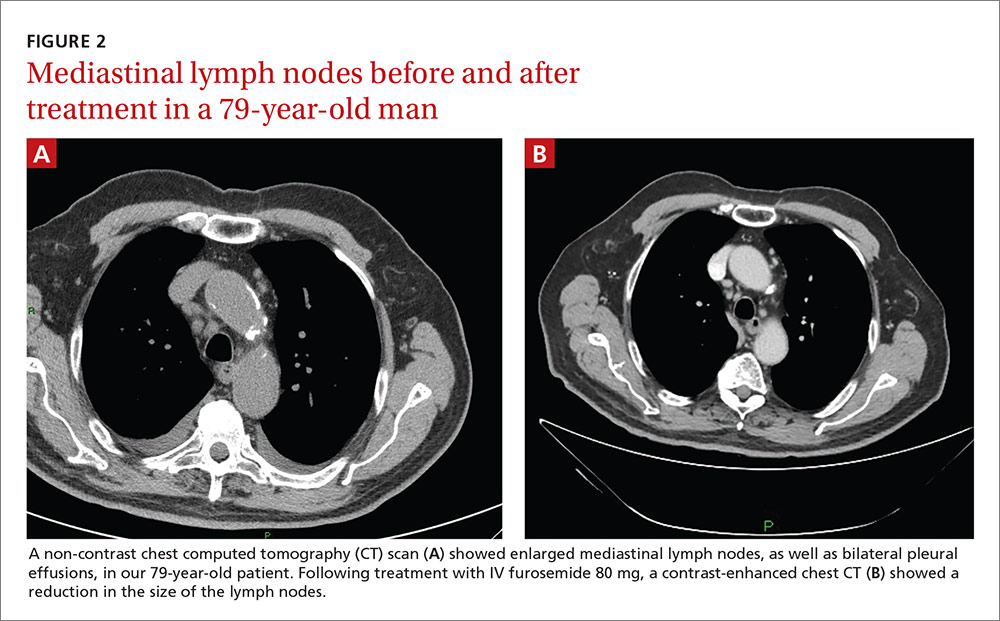

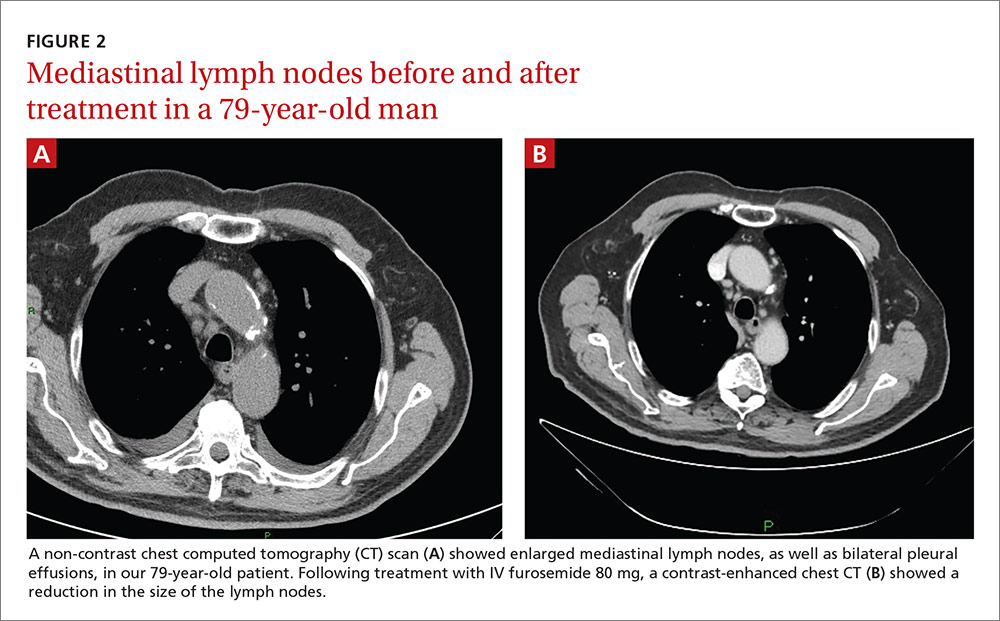

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the patient’s head demonstrated a large right frontal mass. The differential diagnosis included neoplasm, sarcoidosis, or, less likely, an infectious etiology. A contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the brain showed multiple heterogeneous enhancing lesions, with the largest measuring 4.4 cm x 4.6 cm x 3 cm (FIGURE 1). Significant surrounding edema caused a 1.6-cm midline shift, subfalcine herniation, and impending uncal herniation. A CT of the abdomen and chest showed no pulmonary masses or metastatic disease, but did reveal a single 1-cm lymph node in the mediastinum and a 1.2-cm right axillary node.

A craniotomy was performed, which confirmed a large mass adhered to the dura. Surgeons removed the mass en bloc; pathology was consistent with a necrotizing granuloma. Acid-fast bacilli (AFB) staining of 3 specimens was negative. Because the tissue was preserved in formalin, mycobacterial cultures could not be obtained. A cerebrospinal fluid analysis showed lymphocytosis and elevated protein, consistent with neurotuberculosis. Blood testing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis with interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) was negative, as was testing for HIV 1 and 2. In addition, induced sputum was AFB-smear negative, as was an M tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction test.

Despite the negative AFB stain and negative IGRA, the patient’s findings were suspicious for TB, so we began to treat her empirically for neurotuberculosis with a 4-drug regimen (isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol).

In an attempt to confirm the diagnosis of TB and determine sensitivities, we performed a right axillary lymph node biopsy and sent it to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), along with the preserved neural tissue. Using a newly developed technique, the CDC amplified and sequenced mycobacterial DNA from both the central nervous system (CNS) mass and the axillary node, confirming M tuberculosis complex species. Cultures from the axillary node grew pan-sensitive M tuberculosis.

DISCUSSION

About one-third of the world’s population has either active or latent TB.1 In areas where TB is endemic, tuberculomas have accounted for up to 20% of intracranial masses.2 In non-endemic regions, however, they are relatively uncommon. The 3 manifestations of active CNS TB are meningitis, tuberculoma, and abscess.3 The clinical presentation and imaging studies of CNS TB are often indistinguishable from those of patients with malignant neoplasms or metastatic disease. Biopsies may be necessary to distinguish tuberculomas from other intracranial lesions such as pyogenic abscesses or necrotic tumors.4 Mycobacterial cultures were not done on the brain biopsies of our patient because of the high clinical suspicion for neoplasm. Axillary lymph node tissue ultimately confirmed the diagnosis and provided sensitivities.

A diagnosis of CNS tuberculoma without meningitis can be challenging because the clinical presentation is often vague, mild, or even asymptomatic. Constitutional symptoms may include headache, fever, and anorexia.5

In our patient, IGRA testing was also negative. For latent TB, IGRAs are considered to be at least as sensitive as, and considerably more specific than TB skin testing, but their use in CNS TB is less well understood. Studies evaluating IGRA sensitivity for TB meningitis show variable results. In one study, IGRAs were positive in only 50% of culture-confirmed cases of TB meningitis in an HIV-negative population.6

Obtain sputum samples for all patients with extrapulmonary TB

The CDC recommends sputum sampling for all patients with extrapulmonary TB, even in the absence of pulmonary symptoms or radiographic findings, to determine the level of infectivity and potential need for a contact investigation.7

Due to low sensitivity of currently available rapid diagnostic tests and high mortality associated with delayed treatment, initiation of empiric treatment is recommended when the probability of CNS TB is high.5

Treatment duration for CNS tuberculomas is based on one randomized controlled trial,8 a small number of observational studies, a prospective cohort study looking at radiographic resolution,9 and expert opinion. Treatment recommendations often do not distinguish CNS tuberculomas from TB meningitis.10 CNS tuberculomas are commonly treated with a minimum of 12 months of therapy, generally using the same medications and dosages used in the treatment of pulmonary TB, starting with 4 first-line agents: isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. Modification of the treatment regimen may be made once sensitivities are available.10

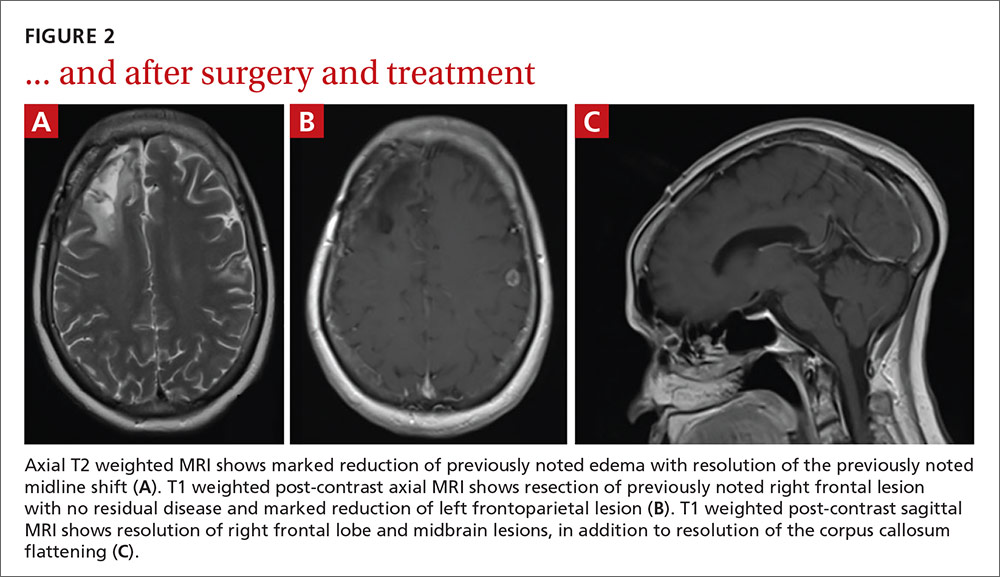

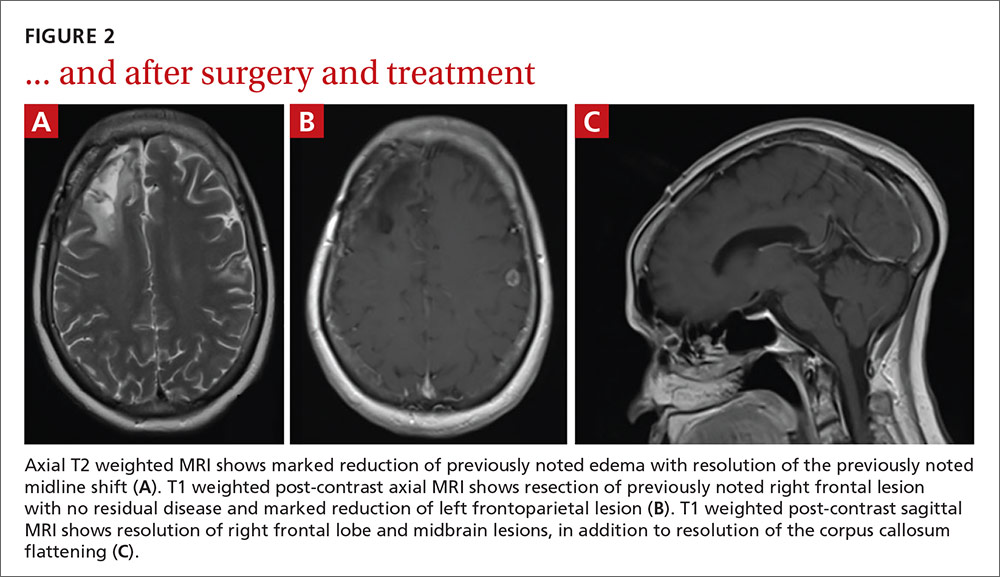

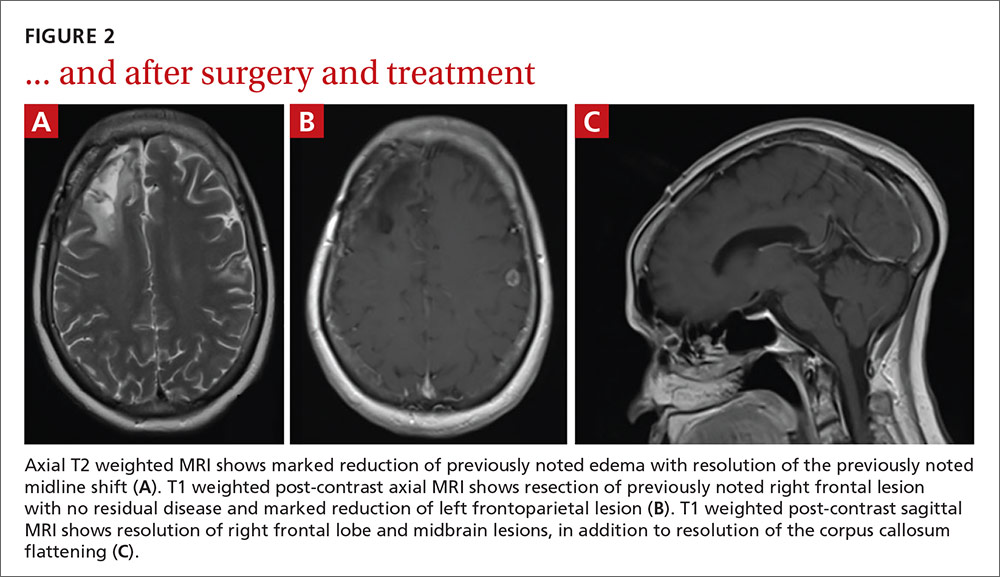

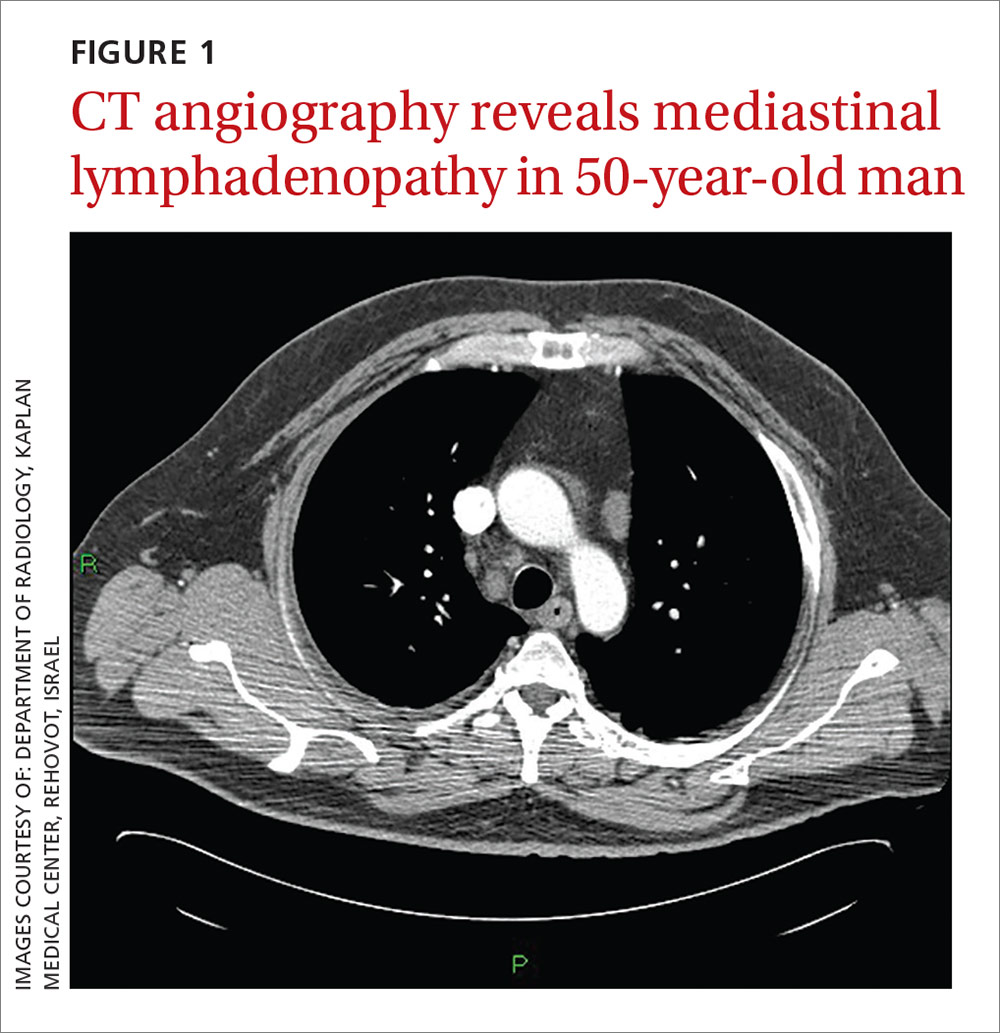

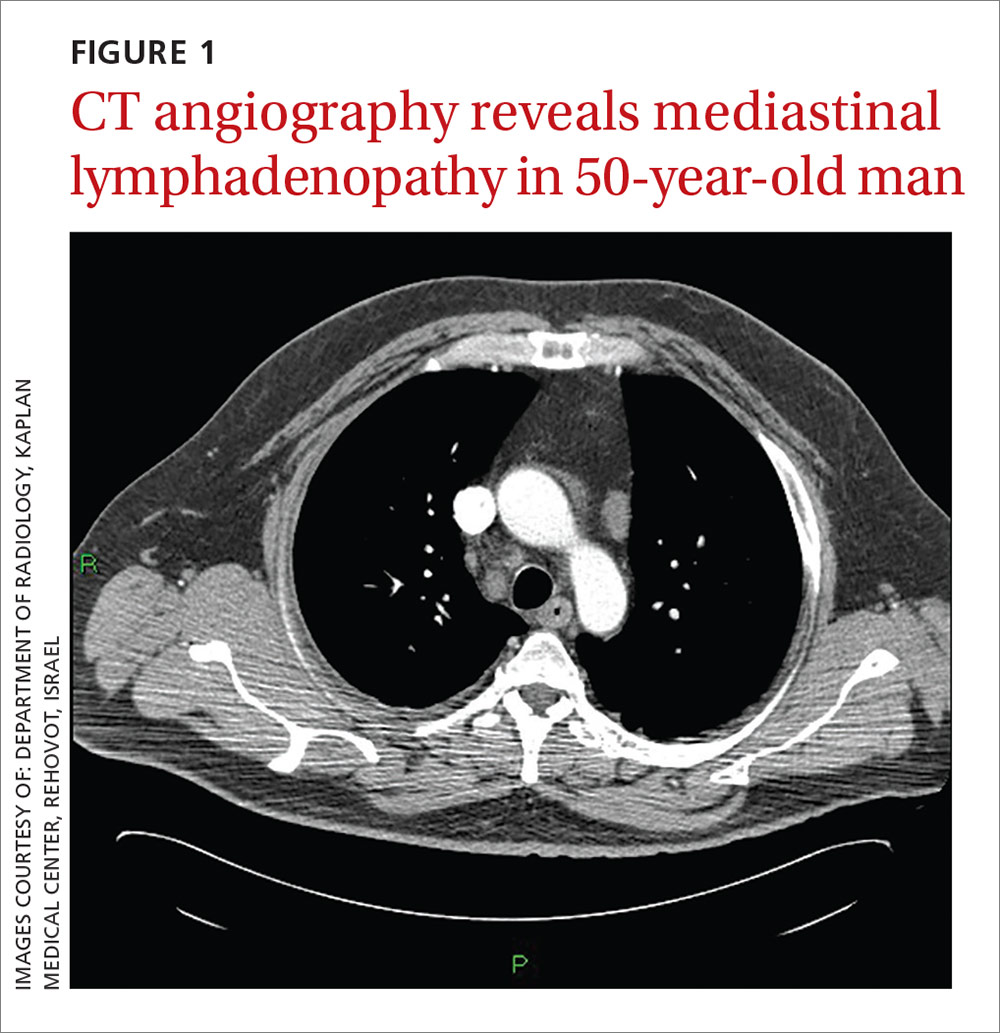

Our patient. After cultures were determined to be pan-sensitive, our patient’s treatment regimen was simplified to rifampin and isoniazid, which she continued for the remainder of her treatment course. Her treatment was discontinued after 18 months when quarterly MRIs showed stabilization of the tuberculomas (FIGURE 2).

Following her surgery, she was started on levetiractam for seizure prophylaxis. She subsequently had a seizure on 2 occasions when the medication was discontinued or decreased, so we chose to continue it. The patient is asymptomatic from her disease with no residual deficits.

THE TAKEAWAY

A change in headache patterns in a patient over the age of 50 is a red flag that warrants imaging. In patients from countries where TB is endemic,11 consider neurotuberculosis in the differential diagnosis of worsening headaches and progressive neurologic symptoms.

A diagnosis of CNS TB can be difficult and requires a high level of clinical suspicion, but early diagnosis and treatment of neurotuberculosis can minimize the high risk of morbidity and mortality. Treatment for TB shouldn’t be withheld in cases in which there’s a strong clinical suspicion for TB, but for which a definitive diagnosis is still pending.

1. World Health Organization. 10 facts on tuberculosis. Available at: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/tuberculosis/en/. Accessed September 19, 2014.

2. Dastur DK, Iyer CG. Pathological analysis of 450 intracranial space-occupying lesions. Ind J Cancer. 1966;3:105-115.

3. Chin JH, Mateen FJ. Central nervous system tuberculosis: Challenges and advances in diagnosis and treatment. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2013;15:631-635.

4. Bayindir C, Mete O, Bilgic B. Retrospective study of 23 pathologically proven cases of central nervous system tuberculomas. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2006;108:353-357.

5. Thwaites G, Fisher M, Hemingway C, et al; British Infection Society. British Infection Society guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis of the central nervous system in adults and children. J Infect. 2009;59:167-187.

6. Simmons CP, Thwaites GE, Quyen NT, et al. Pretreatment intracerebral and peripheral blood immune responses in Vietnamese adults with tuberculous meningitis: diagnostic value and relationship to disease severity and outcome. J Immunol. 2006;176:2007-2014.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Core curriculum on tuberculosis: What the clinician should know. 6th ed. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA; 2013.

8. Rajeswari R, Sivasubramanian S, Balambal R, et al. A controlled clinical trial of short-course chemotherapy for tuberculoma of the brain. Tuber Lung Dis. 1995;76:311-317.

9. Poonnoose SI, Rajshekhar V. Rate of resolution of histologically verified intracranial tuberculomas. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:873-878.

10. American Thoracic Society; CDC; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Treatment of tuberculosis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52:1-77. Erratum in: MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;53:1203.

11. Stop TB Partnership. High burden countries. Available at: http://www.stoptb.org/countries/tbdata.asp. Accessed November 7, 2016.

THE CASE

A 59-year-old woman from the Democratic Republic of the Congo presented to our family medicine clinic with acute worsening of longstanding headaches. Using a Swahili interpreter, the patient reported a 15-year history of recurrent, intermittent headaches that had been previously diagnosed as migraines. Over the prior 2 months, the headaches had intensified with new symptoms of dizziness, ocular pain, and blurred vision with red flashes. She had no hemiplegia, dysarthria, respiratory symptoms, night sweats, or weight loss. A neurologic exam was negative.

Before immigrating to the United States 14 years earlier, the patient lived for 6 months in a refugee camp in the Congo. At the time of her immigration, she was negative for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and a tuberculosis (TB) skin test was positive. A chest x-ray was normal and she had no respiratory symptoms. Shortly after her immigration, she completed 6 months of isoniazid treatment for latent TB.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the patient’s head demonstrated a large right frontal mass. The differential diagnosis included neoplasm, sarcoidosis, or, less likely, an infectious etiology. A contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the brain showed multiple heterogeneous enhancing lesions, with the largest measuring 4.4 cm x 4.6 cm x 3 cm (FIGURE 1). Significant surrounding edema caused a 1.6-cm midline shift, subfalcine herniation, and impending uncal herniation. A CT of the abdomen and chest showed no pulmonary masses or metastatic disease, but did reveal a single 1-cm lymph node in the mediastinum and a 1.2-cm right axillary node.

A craniotomy was performed, which confirmed a large mass adhered to the dura. Surgeons removed the mass en bloc; pathology was consistent with a necrotizing granuloma. Acid-fast bacilli (AFB) staining of 3 specimens was negative. Because the tissue was preserved in formalin, mycobacterial cultures could not be obtained. A cerebrospinal fluid analysis showed lymphocytosis and elevated protein, consistent with neurotuberculosis. Blood testing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis with interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) was negative, as was testing for HIV 1 and 2. In addition, induced sputum was AFB-smear negative, as was an M tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction test.

Despite the negative AFB stain and negative IGRA, the patient’s findings were suspicious for TB, so we began to treat her empirically for neurotuberculosis with a 4-drug regimen (isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol).

In an attempt to confirm the diagnosis of TB and determine sensitivities, we performed a right axillary lymph node biopsy and sent it to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), along with the preserved neural tissue. Using a newly developed technique, the CDC amplified and sequenced mycobacterial DNA from both the central nervous system (CNS) mass and the axillary node, confirming M tuberculosis complex species. Cultures from the axillary node grew pan-sensitive M tuberculosis.

DISCUSSION

About one-third of the world’s population has either active or latent TB.1 In areas where TB is endemic, tuberculomas have accounted for up to 20% of intracranial masses.2 In non-endemic regions, however, they are relatively uncommon. The 3 manifestations of active CNS TB are meningitis, tuberculoma, and abscess.3 The clinical presentation and imaging studies of CNS TB are often indistinguishable from those of patients with malignant neoplasms or metastatic disease. Biopsies may be necessary to distinguish tuberculomas from other intracranial lesions such as pyogenic abscesses or necrotic tumors.4 Mycobacterial cultures were not done on the brain biopsies of our patient because of the high clinical suspicion for neoplasm. Axillary lymph node tissue ultimately confirmed the diagnosis and provided sensitivities.

A diagnosis of CNS tuberculoma without meningitis can be challenging because the clinical presentation is often vague, mild, or even asymptomatic. Constitutional symptoms may include headache, fever, and anorexia.5

In our patient, IGRA testing was also negative. For latent TB, IGRAs are considered to be at least as sensitive as, and considerably more specific than TB skin testing, but their use in CNS TB is less well understood. Studies evaluating IGRA sensitivity for TB meningitis show variable results. In one study, IGRAs were positive in only 50% of culture-confirmed cases of TB meningitis in an HIV-negative population.6

Obtain sputum samples for all patients with extrapulmonary TB

The CDC recommends sputum sampling for all patients with extrapulmonary TB, even in the absence of pulmonary symptoms or radiographic findings, to determine the level of infectivity and potential need for a contact investigation.7

Due to low sensitivity of currently available rapid diagnostic tests and high mortality associated with delayed treatment, initiation of empiric treatment is recommended when the probability of CNS TB is high.5

Treatment duration for CNS tuberculomas is based on one randomized controlled trial,8 a small number of observational studies, a prospective cohort study looking at radiographic resolution,9 and expert opinion. Treatment recommendations often do not distinguish CNS tuberculomas from TB meningitis.10 CNS tuberculomas are commonly treated with a minimum of 12 months of therapy, generally using the same medications and dosages used in the treatment of pulmonary TB, starting with 4 first-line agents: isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. Modification of the treatment regimen may be made once sensitivities are available.10

Our patient. After cultures were determined to be pan-sensitive, our patient’s treatment regimen was simplified to rifampin and isoniazid, which she continued for the remainder of her treatment course. Her treatment was discontinued after 18 months when quarterly MRIs showed stabilization of the tuberculomas (FIGURE 2).

Following her surgery, she was started on levetiractam for seizure prophylaxis. She subsequently had a seizure on 2 occasions when the medication was discontinued or decreased, so we chose to continue it. The patient is asymptomatic from her disease with no residual deficits.

THE TAKEAWAY

A change in headache patterns in a patient over the age of 50 is a red flag that warrants imaging. In patients from countries where TB is endemic,11 consider neurotuberculosis in the differential diagnosis of worsening headaches and progressive neurologic symptoms.

A diagnosis of CNS TB can be difficult and requires a high level of clinical suspicion, but early diagnosis and treatment of neurotuberculosis can minimize the high risk of morbidity and mortality. Treatment for TB shouldn’t be withheld in cases in which there’s a strong clinical suspicion for TB, but for which a definitive diagnosis is still pending.

THE CASE

A 59-year-old woman from the Democratic Republic of the Congo presented to our family medicine clinic with acute worsening of longstanding headaches. Using a Swahili interpreter, the patient reported a 15-year history of recurrent, intermittent headaches that had been previously diagnosed as migraines. Over the prior 2 months, the headaches had intensified with new symptoms of dizziness, ocular pain, and blurred vision with red flashes. She had no hemiplegia, dysarthria, respiratory symptoms, night sweats, or weight loss. A neurologic exam was negative.

Before immigrating to the United States 14 years earlier, the patient lived for 6 months in a refugee camp in the Congo. At the time of her immigration, she was negative for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and a tuberculosis (TB) skin test was positive. A chest x-ray was normal and she had no respiratory symptoms. Shortly after her immigration, she completed 6 months of isoniazid treatment for latent TB.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the patient’s head demonstrated a large right frontal mass. The differential diagnosis included neoplasm, sarcoidosis, or, less likely, an infectious etiology. A contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the brain showed multiple heterogeneous enhancing lesions, with the largest measuring 4.4 cm x 4.6 cm x 3 cm (FIGURE 1). Significant surrounding edema caused a 1.6-cm midline shift, subfalcine herniation, and impending uncal herniation. A CT of the abdomen and chest showed no pulmonary masses or metastatic disease, but did reveal a single 1-cm lymph node in the mediastinum and a 1.2-cm right axillary node.

A craniotomy was performed, which confirmed a large mass adhered to the dura. Surgeons removed the mass en bloc; pathology was consistent with a necrotizing granuloma. Acid-fast bacilli (AFB) staining of 3 specimens was negative. Because the tissue was preserved in formalin, mycobacterial cultures could not be obtained. A cerebrospinal fluid analysis showed lymphocytosis and elevated protein, consistent with neurotuberculosis. Blood testing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis with interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) was negative, as was testing for HIV 1 and 2. In addition, induced sputum was AFB-smear negative, as was an M tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction test.

Despite the negative AFB stain and negative IGRA, the patient’s findings were suspicious for TB, so we began to treat her empirically for neurotuberculosis with a 4-drug regimen (isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol).

In an attempt to confirm the diagnosis of TB and determine sensitivities, we performed a right axillary lymph node biopsy and sent it to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), along with the preserved neural tissue. Using a newly developed technique, the CDC amplified and sequenced mycobacterial DNA from both the central nervous system (CNS) mass and the axillary node, confirming M tuberculosis complex species. Cultures from the axillary node grew pan-sensitive M tuberculosis.

DISCUSSION

About one-third of the world’s population has either active or latent TB.1 In areas where TB is endemic, tuberculomas have accounted for up to 20% of intracranial masses.2 In non-endemic regions, however, they are relatively uncommon. The 3 manifestations of active CNS TB are meningitis, tuberculoma, and abscess.3 The clinical presentation and imaging studies of CNS TB are often indistinguishable from those of patients with malignant neoplasms or metastatic disease. Biopsies may be necessary to distinguish tuberculomas from other intracranial lesions such as pyogenic abscesses or necrotic tumors.4 Mycobacterial cultures were not done on the brain biopsies of our patient because of the high clinical suspicion for neoplasm. Axillary lymph node tissue ultimately confirmed the diagnosis and provided sensitivities.

A diagnosis of CNS tuberculoma without meningitis can be challenging because the clinical presentation is often vague, mild, or even asymptomatic. Constitutional symptoms may include headache, fever, and anorexia.5

In our patient, IGRA testing was also negative. For latent TB, IGRAs are considered to be at least as sensitive as, and considerably more specific than TB skin testing, but their use in CNS TB is less well understood. Studies evaluating IGRA sensitivity for TB meningitis show variable results. In one study, IGRAs were positive in only 50% of culture-confirmed cases of TB meningitis in an HIV-negative population.6

Obtain sputum samples for all patients with extrapulmonary TB

The CDC recommends sputum sampling for all patients with extrapulmonary TB, even in the absence of pulmonary symptoms or radiographic findings, to determine the level of infectivity and potential need for a contact investigation.7

Due to low sensitivity of currently available rapid diagnostic tests and high mortality associated with delayed treatment, initiation of empiric treatment is recommended when the probability of CNS TB is high.5

Treatment duration for CNS tuberculomas is based on one randomized controlled trial,8 a small number of observational studies, a prospective cohort study looking at radiographic resolution,9 and expert opinion. Treatment recommendations often do not distinguish CNS tuberculomas from TB meningitis.10 CNS tuberculomas are commonly treated with a minimum of 12 months of therapy, generally using the same medications and dosages used in the treatment of pulmonary TB, starting with 4 first-line agents: isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. Modification of the treatment regimen may be made once sensitivities are available.10

Our patient. After cultures were determined to be pan-sensitive, our patient’s treatment regimen was simplified to rifampin and isoniazid, which she continued for the remainder of her treatment course. Her treatment was discontinued after 18 months when quarterly MRIs showed stabilization of the tuberculomas (FIGURE 2).

Following her surgery, she was started on levetiractam for seizure prophylaxis. She subsequently had a seizure on 2 occasions when the medication was discontinued or decreased, so we chose to continue it. The patient is asymptomatic from her disease with no residual deficits.

THE TAKEAWAY

A change in headache patterns in a patient over the age of 50 is a red flag that warrants imaging. In patients from countries where TB is endemic,11 consider neurotuberculosis in the differential diagnosis of worsening headaches and progressive neurologic symptoms.