User login

Dapivirine vaginal ring cuts new HIV-1 infections

The dapivirine vaginal ring reduced the rate of new HIV-1 infection by 31% in a phase III clinical trial involving 1,959 high-risk women in sub-Saharan Africa, according to a report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The dapivirine-containing ring is replaced every month and was used in this study for up to 2 years. It was not associated with any safety concerns, said Annalene Nel, MD, PhD, of the International Partnership for Microbicides, Silver Spring, Md., and her associates.

The International Partnership for Microbicides is a nonprofit group that developed the ring, which can be self-inserted and removed and which provides a sustained release of the antiretroviral drug for at least 4 weeks. QPharma of Malmö, Sweden, manufactures the rings and donated the ones used in this study, but was not otherwise involved in the trial.

The study participants were sexually active women aged 18-45 years (mean age, 26) treated at seven research centers in South Africa and Uganda. Almost all of them (98%) had only one male sexual partner. For the purposes of this trial, the women were asked to attend the participating clinics every 4 weeks to have the rings replaced and to provide a plasma sample. This allowed the researchers to measure the residual amount of dapivirine in the used rings and to measure plasma levels of the drug, both of which were indicators of compliance.

A total of 1,307 women were randomly assigned to receive dapivirine rings and 652 to receive placebo rings. At the data cutoff point, 615 women (31.4%) were still in the trial and 761 (38.8%) had completed it; 583 women (29.8%) had discontinued early. All the participants at one medical center were withdrawn by the sponsor because of high rates of protocol violation at that facility and corresponding high rates of patient nonadherence with the device.

The primary efficacy endpoint – the rate of HIV-1 seroconversion during follow-up – was 4.1 per 100 person-years with the dapivirine ring, compared with 6.1 per 100 person-years with the placebo ring. This represents a 31% lower infection rate with the active treatment (hazard ratio, 0.69). A subgroup analysis that excluded participants at the protocol-violating facility showed a seroconversion rate of 3.6 per 100 person-years with the active treatment vs. 5.4 per 100 person-years with the placebo, a 30% reduction in the infection rate, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602046).

The findings were consistent across other subgroup analyses, including those that categorized the participants according to their adherence levels, as measured by plasma levels and residual ring levels of dapivirine.

The cumulative incidence of adverse events was similar between the two study groups (87.4% and 85.7%, respectively), as was the incidence of grade 3 or 4 adverse events. None of the more serious adverse events were judged to be related to the devices. Mild product-related adverse events occurred in 5 women (0.4%) in the dapivirine group and 3 (0.5%) in the placebo group. There also were no significant differences between the two study groups in the incidence of laboratory abnormalities, rates of sexually transmitted and other genital infections, or pregnancy rates.

The study was funded by the International Partnership for Microbicides, which is supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Irish Aid, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, the U.K. Department for International Development, the U.S. Agency for International Development, and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

Dr. Nel reported having no relevant financial disclosures; one of her associates reported ties to Janssen and Johnson & Johnson.

The dapivirine vaginal ring reduced the rate of new HIV-1 infection by 31% in a phase III clinical trial involving 1,959 high-risk women in sub-Saharan Africa, according to a report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The dapivirine-containing ring is replaced every month and was used in this study for up to 2 years. It was not associated with any safety concerns, said Annalene Nel, MD, PhD, of the International Partnership for Microbicides, Silver Spring, Md., and her associates.

The International Partnership for Microbicides is a nonprofit group that developed the ring, which can be self-inserted and removed and which provides a sustained release of the antiretroviral drug for at least 4 weeks. QPharma of Malmö, Sweden, manufactures the rings and donated the ones used in this study, but was not otherwise involved in the trial.

The study participants were sexually active women aged 18-45 years (mean age, 26) treated at seven research centers in South Africa and Uganda. Almost all of them (98%) had only one male sexual partner. For the purposes of this trial, the women were asked to attend the participating clinics every 4 weeks to have the rings replaced and to provide a plasma sample. This allowed the researchers to measure the residual amount of dapivirine in the used rings and to measure plasma levels of the drug, both of which were indicators of compliance.

A total of 1,307 women were randomly assigned to receive dapivirine rings and 652 to receive placebo rings. At the data cutoff point, 615 women (31.4%) were still in the trial and 761 (38.8%) had completed it; 583 women (29.8%) had discontinued early. All the participants at one medical center were withdrawn by the sponsor because of high rates of protocol violation at that facility and corresponding high rates of patient nonadherence with the device.

The primary efficacy endpoint – the rate of HIV-1 seroconversion during follow-up – was 4.1 per 100 person-years with the dapivirine ring, compared with 6.1 per 100 person-years with the placebo ring. This represents a 31% lower infection rate with the active treatment (hazard ratio, 0.69). A subgroup analysis that excluded participants at the protocol-violating facility showed a seroconversion rate of 3.6 per 100 person-years with the active treatment vs. 5.4 per 100 person-years with the placebo, a 30% reduction in the infection rate, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602046).

The findings were consistent across other subgroup analyses, including those that categorized the participants according to their adherence levels, as measured by plasma levels and residual ring levels of dapivirine.

The cumulative incidence of adverse events was similar between the two study groups (87.4% and 85.7%, respectively), as was the incidence of grade 3 or 4 adverse events. None of the more serious adverse events were judged to be related to the devices. Mild product-related adverse events occurred in 5 women (0.4%) in the dapivirine group and 3 (0.5%) in the placebo group. There also were no significant differences between the two study groups in the incidence of laboratory abnormalities, rates of sexually transmitted and other genital infections, or pregnancy rates.

The study was funded by the International Partnership for Microbicides, which is supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Irish Aid, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, the U.K. Department for International Development, the U.S. Agency for International Development, and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

Dr. Nel reported having no relevant financial disclosures; one of her associates reported ties to Janssen and Johnson & Johnson.

The dapivirine vaginal ring reduced the rate of new HIV-1 infection by 31% in a phase III clinical trial involving 1,959 high-risk women in sub-Saharan Africa, according to a report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The dapivirine-containing ring is replaced every month and was used in this study for up to 2 years. It was not associated with any safety concerns, said Annalene Nel, MD, PhD, of the International Partnership for Microbicides, Silver Spring, Md., and her associates.

The International Partnership for Microbicides is a nonprofit group that developed the ring, which can be self-inserted and removed and which provides a sustained release of the antiretroviral drug for at least 4 weeks. QPharma of Malmö, Sweden, manufactures the rings and donated the ones used in this study, but was not otherwise involved in the trial.

The study participants were sexually active women aged 18-45 years (mean age, 26) treated at seven research centers in South Africa and Uganda. Almost all of them (98%) had only one male sexual partner. For the purposes of this trial, the women were asked to attend the participating clinics every 4 weeks to have the rings replaced and to provide a plasma sample. This allowed the researchers to measure the residual amount of dapivirine in the used rings and to measure plasma levels of the drug, both of which were indicators of compliance.

A total of 1,307 women were randomly assigned to receive dapivirine rings and 652 to receive placebo rings. At the data cutoff point, 615 women (31.4%) were still in the trial and 761 (38.8%) had completed it; 583 women (29.8%) had discontinued early. All the participants at one medical center were withdrawn by the sponsor because of high rates of protocol violation at that facility and corresponding high rates of patient nonadherence with the device.

The primary efficacy endpoint – the rate of HIV-1 seroconversion during follow-up – was 4.1 per 100 person-years with the dapivirine ring, compared with 6.1 per 100 person-years with the placebo ring. This represents a 31% lower infection rate with the active treatment (hazard ratio, 0.69). A subgroup analysis that excluded participants at the protocol-violating facility showed a seroconversion rate of 3.6 per 100 person-years with the active treatment vs. 5.4 per 100 person-years with the placebo, a 30% reduction in the infection rate, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602046).

The findings were consistent across other subgroup analyses, including those that categorized the participants according to their adherence levels, as measured by plasma levels and residual ring levels of dapivirine.

The cumulative incidence of adverse events was similar between the two study groups (87.4% and 85.7%, respectively), as was the incidence of grade 3 or 4 adverse events. None of the more serious adverse events were judged to be related to the devices. Mild product-related adverse events occurred in 5 women (0.4%) in the dapivirine group and 3 (0.5%) in the placebo group. There also were no significant differences between the two study groups in the incidence of laboratory abnormalities, rates of sexually transmitted and other genital infections, or pregnancy rates.

The study was funded by the International Partnership for Microbicides, which is supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Irish Aid, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, the U.K. Department for International Development, the U.S. Agency for International Development, and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

Dr. Nel reported having no relevant financial disclosures; one of her associates reported ties to Janssen and Johnson & Johnson.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: The dapivirine vaginal ring reduced the rate of new HIV-1 infection by 31% in a phase III trial involving 1,959 high-risk women in sub-Saharan Africa.

Major finding: The primary efficacy endpoint – the rate of HIV-1 seroconversion during follow-up – was 4.1 per 100 person-years with the dapivirine ring, compared with 6.1 per 100 person-years with the placebo ring.

Data source: A multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled phase III trial involving 1,959 high-risk women in South Africa and Uganda.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the International Partnership for Microbicides, a nonprofit group that developed the dapivirine vaginal ring and is supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Irish Aid, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, the U.K. Department for International Development, the U.S. Agency for International Development, and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. Dr. Nel reported having no relevant financial disclosures; one of her associates reported ties to Janssen and Johnson & Johnson.

Can bioprosthetics work for large airway defects?

Large and complex airway defects that primary repair cannot fully close require alternative surgical approaches and techniques that are far more difficult to perform, but bioprosthetic materials may be an option to repair large tracheal and bronchial defects that has achieved good results, without postoperative death or defect recurrence, in a small cohort of patients at Massachusetts General Hospital, in Boston.

Brooks Udelsman, MD, and his coauthors reported their results of bioprosthetic repair of central airway defects in eight patients in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016 Nov;152:1388-97). “Although our results are derived from a limited number of heterogeneous patients, they suggest that closure of noncircumferential large airway defects with bioprosthetic materials is feasible, safe and reliable,” Dr. Udelsman said. He previously reported the results at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, May 14-18, 2016, in Baltimore.

These complex defects typically exceed 5 cm and can involve communication with the esophagus. For repair of smaller defects, surgeons can use a more conventional approach that involves neck flexion, laryngeal release, airway mobilization, and hilar release, but in larger defects, these techniques increase the risk of too much tension on the anastomosis and dehiscence along with airway failure. Large and complex defects occur in patients who have had a previous airway operation or radiation exposure, requiring alternative strategies, the researchers wrote. “Patients in this rare category should be referred to a high-volume center for careful evaluation by a surgeon experienced in complex airway reconstruction before the decision to abandon primary repair is made,” he said. Among the advantages that bioprosthetic materials have over synthetic materials for airway defect repair are easier handling, minimal immunogenic response, and potential for tissue ingrowth, Dr. Udelsman and his coauthors said.

All eight patients in this study, who underwent repair from 2008 to 2015, had significant comorbidities, including previous surgery of the trachea, esophagus, or thyroid. The etiology of the airway defect included HIV-AIDS–associated esophagitis, malignancy, mesh erosion, and complications from extended intubation. Three patients had previous radiation therapy to the neck or chest. Five patients had defects localized to the membranous tracheal wall, two had defects of the mainstem bronchus or bronchus intermedius, and one patient had a defect of the anterior wall of the trachea.

Dr. Udelsman and his coauthors used both aortic homograft and acellular dermal matrix to repair large defects. Their experience confirmed previous reports of the formation of granulation tissue with aortic autografts, underscoring the importance of frequent bronchoscopy and debridement when necessary. And while previous reports have claimed human acellular dermis resists granulation formation, that wasn’t the case in this study. “The exact histologic basis of bioprosthetic incorporation and reepithelialization in these patients is still elusive and will require further study,” the researchers said.

This study also employed the controversial muscle buttress repair in six patients, which helped, at least theoretically, to secure the repairs when leaks occur, to separate suture lines when both the airway and esophagus were repaired and to support the bioprosthetic material to prevent tissue softening, Dr. Udelsman and his coauthors said.

Postoperative examinations confirmed that the operations successfully closed the airway defects in all eight patients. Long term, most resumed oral intake, but three did not for various reasons: one had a pharyngostomy; another had neurocognitive issues preoperatively; and a third with a tracheoesophageal fistula repair and cervical esophagostomy could resume oral intake but depended on tube feeds to meet caloric needs.

All patients developed granulation at the repair site, two of whom required further debridement and one who underwent balloon dilation. Pneumonia was the most common complication within 30 days of surgery, occurring in two patients. Three patients died within 120 days from metastatic disease, and a fourth patient progressed to end-stage AIDS 6 years after the operation and eventually died.

Dr. Udelsman and his coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

In his invited commentary, Raja Flores, MD, of Mount Sinai Health System in New York said this study demonstrated “modest success” with bioprosthetic materials for repair of large airway deficits – the same level of success he ascribes to human studies of other surgical approaches to large airway deficits (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016 Nov;152:1233-4).

But progress has been slow and animal studies of large airway deficit repair have been “wastefully repetitive” without any advances. “We must build on what these human studies have taught us and not continue unsuccessfully to reinvent the same malfunctioning [airways],” Dr. Flores said.

When surgeons encounter such patients, surgery isn’t necessary for their survival, Dr. Flores said. “T-tubes work just fine.” The goal is to improve their quality of life. “Unless we can provide a reliable, long-lasting solution, an unpredictable life-threatening experimental surgical intervention is not justified to treat a stable, functional patient,” he said.

And while Dr. Udelsman and his colleagues have shown “some progress” in their study, he cautioned surgeons to heed the words of a tracheal surgery pioneer Hermes Grillo, MD, at Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School: “Success has been announced episodically over the decades in each of these categories, but thus far no one replacement method has held for the long term in any safe and practicable manner.” Dr. Flores added: “This still holds true today.”

Dr. Flores reported having no financial disclosures.

In his invited commentary, Raja Flores, MD, of Mount Sinai Health System in New York said this study demonstrated “modest success” with bioprosthetic materials for repair of large airway deficits – the same level of success he ascribes to human studies of other surgical approaches to large airway deficits (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016 Nov;152:1233-4).

But progress has been slow and animal studies of large airway deficit repair have been “wastefully repetitive” without any advances. “We must build on what these human studies have taught us and not continue unsuccessfully to reinvent the same malfunctioning [airways],” Dr. Flores said.

When surgeons encounter such patients, surgery isn’t necessary for their survival, Dr. Flores said. “T-tubes work just fine.” The goal is to improve their quality of life. “Unless we can provide a reliable, long-lasting solution, an unpredictable life-threatening experimental surgical intervention is not justified to treat a stable, functional patient,” he said.

And while Dr. Udelsman and his colleagues have shown “some progress” in their study, he cautioned surgeons to heed the words of a tracheal surgery pioneer Hermes Grillo, MD, at Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School: “Success has been announced episodically over the decades in each of these categories, but thus far no one replacement method has held for the long term in any safe and practicable manner.” Dr. Flores added: “This still holds true today.”

Dr. Flores reported having no financial disclosures.

In his invited commentary, Raja Flores, MD, of Mount Sinai Health System in New York said this study demonstrated “modest success” with bioprosthetic materials for repair of large airway deficits – the same level of success he ascribes to human studies of other surgical approaches to large airway deficits (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016 Nov;152:1233-4).

But progress has been slow and animal studies of large airway deficit repair have been “wastefully repetitive” without any advances. “We must build on what these human studies have taught us and not continue unsuccessfully to reinvent the same malfunctioning [airways],” Dr. Flores said.

When surgeons encounter such patients, surgery isn’t necessary for their survival, Dr. Flores said. “T-tubes work just fine.” The goal is to improve their quality of life. “Unless we can provide a reliable, long-lasting solution, an unpredictable life-threatening experimental surgical intervention is not justified to treat a stable, functional patient,” he said.

And while Dr. Udelsman and his colleagues have shown “some progress” in their study, he cautioned surgeons to heed the words of a tracheal surgery pioneer Hermes Grillo, MD, at Boston’s Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School: “Success has been announced episodically over the decades in each of these categories, but thus far no one replacement method has held for the long term in any safe and practicable manner.” Dr. Flores added: “This still holds true today.”

Dr. Flores reported having no financial disclosures.

Large and complex airway defects that primary repair cannot fully close require alternative surgical approaches and techniques that are far more difficult to perform, but bioprosthetic materials may be an option to repair large tracheal and bronchial defects that has achieved good results, without postoperative death or defect recurrence, in a small cohort of patients at Massachusetts General Hospital, in Boston.

Brooks Udelsman, MD, and his coauthors reported their results of bioprosthetic repair of central airway defects in eight patients in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016 Nov;152:1388-97). “Although our results are derived from a limited number of heterogeneous patients, they suggest that closure of noncircumferential large airway defects with bioprosthetic materials is feasible, safe and reliable,” Dr. Udelsman said. He previously reported the results at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, May 14-18, 2016, in Baltimore.

These complex defects typically exceed 5 cm and can involve communication with the esophagus. For repair of smaller defects, surgeons can use a more conventional approach that involves neck flexion, laryngeal release, airway mobilization, and hilar release, but in larger defects, these techniques increase the risk of too much tension on the anastomosis and dehiscence along with airway failure. Large and complex defects occur in patients who have had a previous airway operation or radiation exposure, requiring alternative strategies, the researchers wrote. “Patients in this rare category should be referred to a high-volume center for careful evaluation by a surgeon experienced in complex airway reconstruction before the decision to abandon primary repair is made,” he said. Among the advantages that bioprosthetic materials have over synthetic materials for airway defect repair are easier handling, minimal immunogenic response, and potential for tissue ingrowth, Dr. Udelsman and his coauthors said.

All eight patients in this study, who underwent repair from 2008 to 2015, had significant comorbidities, including previous surgery of the trachea, esophagus, or thyroid. The etiology of the airway defect included HIV-AIDS–associated esophagitis, malignancy, mesh erosion, and complications from extended intubation. Three patients had previous radiation therapy to the neck or chest. Five patients had defects localized to the membranous tracheal wall, two had defects of the mainstem bronchus or bronchus intermedius, and one patient had a defect of the anterior wall of the trachea.

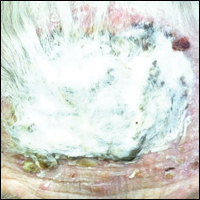

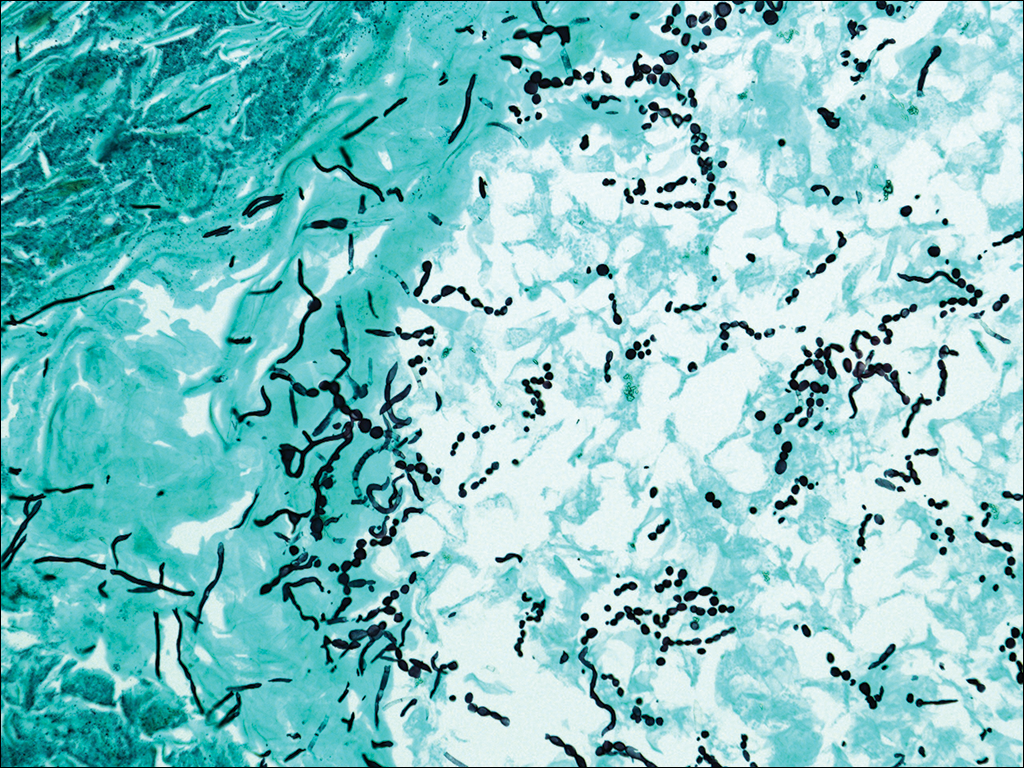

Dr. Udelsman and his coauthors used both aortic homograft and acellular dermal matrix to repair large defects. Their experience confirmed previous reports of the formation of granulation tissue with aortic autografts, underscoring the importance of frequent bronchoscopy and debridement when necessary. And while previous reports have claimed human acellular dermis resists granulation formation, that wasn’t the case in this study. “The exact histologic basis of bioprosthetic incorporation and reepithelialization in these patients is still elusive and will require further study,” the researchers said.

This study also employed the controversial muscle buttress repair in six patients, which helped, at least theoretically, to secure the repairs when leaks occur, to separate suture lines when both the airway and esophagus were repaired and to support the bioprosthetic material to prevent tissue softening, Dr. Udelsman and his coauthors said.

Postoperative examinations confirmed that the operations successfully closed the airway defects in all eight patients. Long term, most resumed oral intake, but three did not for various reasons: one had a pharyngostomy; another had neurocognitive issues preoperatively; and a third with a tracheoesophageal fistula repair and cervical esophagostomy could resume oral intake but depended on tube feeds to meet caloric needs.

All patients developed granulation at the repair site, two of whom required further debridement and one who underwent balloon dilation. Pneumonia was the most common complication within 30 days of surgery, occurring in two patients. Three patients died within 120 days from metastatic disease, and a fourth patient progressed to end-stage AIDS 6 years after the operation and eventually died.

Dr. Udelsman and his coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

Large and complex airway defects that primary repair cannot fully close require alternative surgical approaches and techniques that are far more difficult to perform, but bioprosthetic materials may be an option to repair large tracheal and bronchial defects that has achieved good results, without postoperative death or defect recurrence, in a small cohort of patients at Massachusetts General Hospital, in Boston.

Brooks Udelsman, MD, and his coauthors reported their results of bioprosthetic repair of central airway defects in eight patients in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2016 Nov;152:1388-97). “Although our results are derived from a limited number of heterogeneous patients, they suggest that closure of noncircumferential large airway defects with bioprosthetic materials is feasible, safe and reliable,” Dr. Udelsman said. He previously reported the results at the annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, May 14-18, 2016, in Baltimore.

These complex defects typically exceed 5 cm and can involve communication with the esophagus. For repair of smaller defects, surgeons can use a more conventional approach that involves neck flexion, laryngeal release, airway mobilization, and hilar release, but in larger defects, these techniques increase the risk of too much tension on the anastomosis and dehiscence along with airway failure. Large and complex defects occur in patients who have had a previous airway operation or radiation exposure, requiring alternative strategies, the researchers wrote. “Patients in this rare category should be referred to a high-volume center for careful evaluation by a surgeon experienced in complex airway reconstruction before the decision to abandon primary repair is made,” he said. Among the advantages that bioprosthetic materials have over synthetic materials for airway defect repair are easier handling, minimal immunogenic response, and potential for tissue ingrowth, Dr. Udelsman and his coauthors said.

All eight patients in this study, who underwent repair from 2008 to 2015, had significant comorbidities, including previous surgery of the trachea, esophagus, or thyroid. The etiology of the airway defect included HIV-AIDS–associated esophagitis, malignancy, mesh erosion, and complications from extended intubation. Three patients had previous radiation therapy to the neck or chest. Five patients had defects localized to the membranous tracheal wall, two had defects of the mainstem bronchus or bronchus intermedius, and one patient had a defect of the anterior wall of the trachea.

Dr. Udelsman and his coauthors used both aortic homograft and acellular dermal matrix to repair large defects. Their experience confirmed previous reports of the formation of granulation tissue with aortic autografts, underscoring the importance of frequent bronchoscopy and debridement when necessary. And while previous reports have claimed human acellular dermis resists granulation formation, that wasn’t the case in this study. “The exact histologic basis of bioprosthetic incorporation and reepithelialization in these patients is still elusive and will require further study,” the researchers said.

This study also employed the controversial muscle buttress repair in six patients, which helped, at least theoretically, to secure the repairs when leaks occur, to separate suture lines when both the airway and esophagus were repaired and to support the bioprosthetic material to prevent tissue softening, Dr. Udelsman and his coauthors said.

Postoperative examinations confirmed that the operations successfully closed the airway defects in all eight patients. Long term, most resumed oral intake, but three did not for various reasons: one had a pharyngostomy; another had neurocognitive issues preoperatively; and a third with a tracheoesophageal fistula repair and cervical esophagostomy could resume oral intake but depended on tube feeds to meet caloric needs.

All patients developed granulation at the repair site, two of whom required further debridement and one who underwent balloon dilation. Pneumonia was the most common complication within 30 days of surgery, occurring in two patients. Three patients died within 120 days from metastatic disease, and a fourth patient progressed to end-stage AIDS 6 years after the operation and eventually died.

Dr. Udelsman and his coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Bioprosthetic materials show progress for reconstruction of large airway defects.

Major finding: Airway defects were successfully closed in all patients, with no postoperative deaths or recurrence of airway defect.

Data source: Eight patients who underwent closure of complex central airway defects with bioprosthetic materials between 2008 and 2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Udelsman and coauthors reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Oral Fixed Drug Eruption Due to Tinidazole

To the Editor:

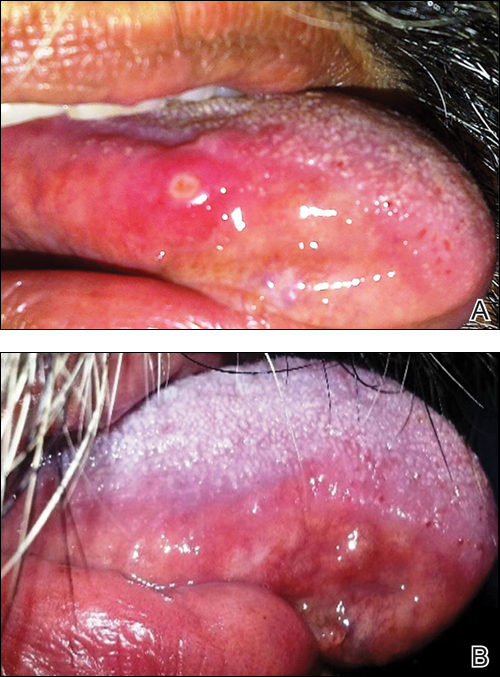

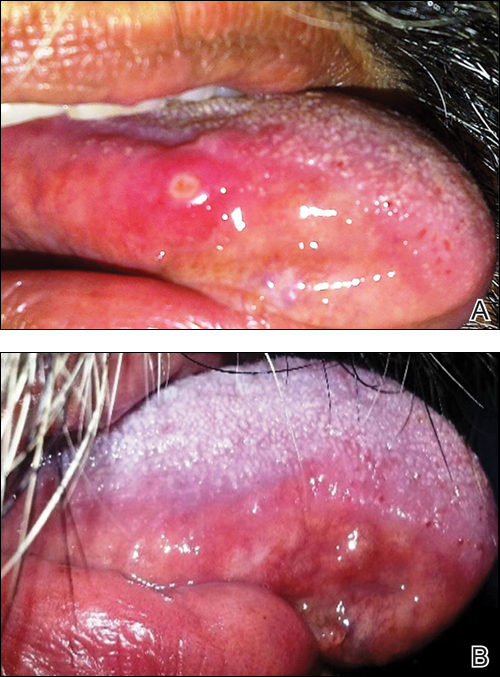

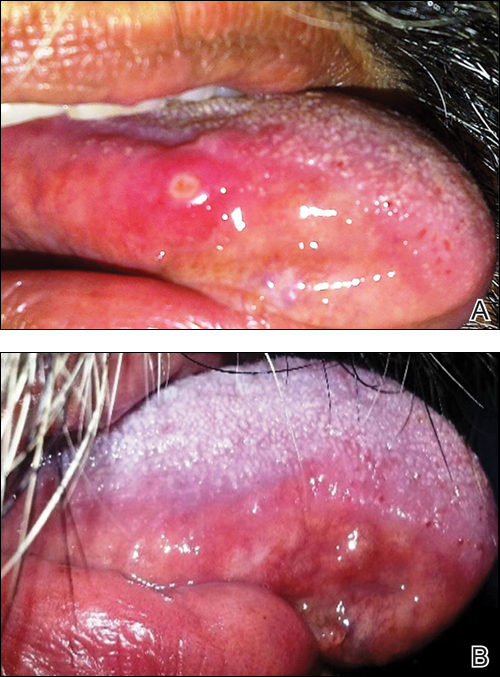

A 50-year-old man presented with a painful ulcer and a burning sensation on the tongue of 2 days’ duration (Figure, A). The ulcer had a yellowish white appearance with erythematous borders. The patient started taking tinidazole 500 mg twice daily 2 days prior, which was prescribed by his primary care physician for an episode of gastroenteritis. He was not taking any other medications and did not smoke or drink. Routine laboratory test results did not reveal any abnormalities. Based on the physical examination as well as the patient’s medical and medication history, a provisional diagnosis of fixed drug eruption (FDE) due to tinidazole was made. Tinidazole was immediately withdrawn and the patient was prescribed beclomethasone dipropionate ointment twice daily to relieve the burning sensation. A punch biopsy of the lesion was recommended; however, the patient opted to wait a week after discontinuing the drug. At follow-up 1 week later, complete healing of the ulcer was observed with no scarring and the burning sensation had resolved (Figure, B). After obtaining informed consent from the patient, an oral challenge test was conducted in the office with 50 mg of tinidazole. Four hours after taking the drug orally, the patient felt a burning sensation and a small ulcerative lesion was observed on the tongue at the same site the next day. The patient was informed of the fixed drug reaction to tinidazole, a drug belonging to the nitroimidazole group, and this information also was conveyed to the patient’s primary care physician.

Tinidazole is a synthetic antiprotozoal and antibacterial agent used primarily in infections such as amebiasis, giardiasis, and trichomoniasis.1 Tinidazole may be a therapeutic alternative to metronidazole. Fixed drug eruption is a distinctive variant of drug eruption with characteristic recurrence at the same site of skin or mucous membranes. It is characterized by onset of round/oval, erythematous, well-defined macules on the skin and/or mucosa associated with itching and burning.1 Fixed drug eruption generally is restricted to the mucous membrane and skin, with the lips, palms, soles, glans penis, and groin area being the most common sites. Intraoral involvement, excluding the lips, of FDE is rare. The tongue is a rare site of an FDE.2 Fixed drug eruption on the tongue has been reported with clarithromycin.3 Dental clinicians have to be aware of the possibility of FDE due to commonly used drugs such tinidazole, which would help in prompt diagnosis of these lesions.

- Prieto A, De Barrio M, Infante S, et al. Recurrent fixed drug eruption due to metronidazole elicited by patch test with tinidazole. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;53:169-170.

- Dhar S, Kanwar AJ. Fixed drug eruption on the tongue of a 4-year-old boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 1995;12:51-52.

- Alonso JC, Melgosa AC, Gonzalo MJ, et al. Fixed drug eruption on the tongue due to clarithromycin. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;53:121-122.

To the Editor:

A 50-year-old man presented with a painful ulcer and a burning sensation on the tongue of 2 days’ duration (Figure, A). The ulcer had a yellowish white appearance with erythematous borders. The patient started taking tinidazole 500 mg twice daily 2 days prior, which was prescribed by his primary care physician for an episode of gastroenteritis. He was not taking any other medications and did not smoke or drink. Routine laboratory test results did not reveal any abnormalities. Based on the physical examination as well as the patient’s medical and medication history, a provisional diagnosis of fixed drug eruption (FDE) due to tinidazole was made. Tinidazole was immediately withdrawn and the patient was prescribed beclomethasone dipropionate ointment twice daily to relieve the burning sensation. A punch biopsy of the lesion was recommended; however, the patient opted to wait a week after discontinuing the drug. At follow-up 1 week later, complete healing of the ulcer was observed with no scarring and the burning sensation had resolved (Figure, B). After obtaining informed consent from the patient, an oral challenge test was conducted in the office with 50 mg of tinidazole. Four hours after taking the drug orally, the patient felt a burning sensation and a small ulcerative lesion was observed on the tongue at the same site the next day. The patient was informed of the fixed drug reaction to tinidazole, a drug belonging to the nitroimidazole group, and this information also was conveyed to the patient’s primary care physician.

Tinidazole is a synthetic antiprotozoal and antibacterial agent used primarily in infections such as amebiasis, giardiasis, and trichomoniasis.1 Tinidazole may be a therapeutic alternative to metronidazole. Fixed drug eruption is a distinctive variant of drug eruption with characteristic recurrence at the same site of skin or mucous membranes. It is characterized by onset of round/oval, erythematous, well-defined macules on the skin and/or mucosa associated with itching and burning.1 Fixed drug eruption generally is restricted to the mucous membrane and skin, with the lips, palms, soles, glans penis, and groin area being the most common sites. Intraoral involvement, excluding the lips, of FDE is rare. The tongue is a rare site of an FDE.2 Fixed drug eruption on the tongue has been reported with clarithromycin.3 Dental clinicians have to be aware of the possibility of FDE due to commonly used drugs such tinidazole, which would help in prompt diagnosis of these lesions.

To the Editor:

A 50-year-old man presented with a painful ulcer and a burning sensation on the tongue of 2 days’ duration (Figure, A). The ulcer had a yellowish white appearance with erythematous borders. The patient started taking tinidazole 500 mg twice daily 2 days prior, which was prescribed by his primary care physician for an episode of gastroenteritis. He was not taking any other medications and did not smoke or drink. Routine laboratory test results did not reveal any abnormalities. Based on the physical examination as well as the patient’s medical and medication history, a provisional diagnosis of fixed drug eruption (FDE) due to tinidazole was made. Tinidazole was immediately withdrawn and the patient was prescribed beclomethasone dipropionate ointment twice daily to relieve the burning sensation. A punch biopsy of the lesion was recommended; however, the patient opted to wait a week after discontinuing the drug. At follow-up 1 week later, complete healing of the ulcer was observed with no scarring and the burning sensation had resolved (Figure, B). After obtaining informed consent from the patient, an oral challenge test was conducted in the office with 50 mg of tinidazole. Four hours after taking the drug orally, the patient felt a burning sensation and a small ulcerative lesion was observed on the tongue at the same site the next day. The patient was informed of the fixed drug reaction to tinidazole, a drug belonging to the nitroimidazole group, and this information also was conveyed to the patient’s primary care physician.

Tinidazole is a synthetic antiprotozoal and antibacterial agent used primarily in infections such as amebiasis, giardiasis, and trichomoniasis.1 Tinidazole may be a therapeutic alternative to metronidazole. Fixed drug eruption is a distinctive variant of drug eruption with characteristic recurrence at the same site of skin or mucous membranes. It is characterized by onset of round/oval, erythematous, well-defined macules on the skin and/or mucosa associated with itching and burning.1 Fixed drug eruption generally is restricted to the mucous membrane and skin, with the lips, palms, soles, glans penis, and groin area being the most common sites. Intraoral involvement, excluding the lips, of FDE is rare. The tongue is a rare site of an FDE.2 Fixed drug eruption on the tongue has been reported with clarithromycin.3 Dental clinicians have to be aware of the possibility of FDE due to commonly used drugs such tinidazole, which would help in prompt diagnosis of these lesions.

- Prieto A, De Barrio M, Infante S, et al. Recurrent fixed drug eruption due to metronidazole elicited by patch test with tinidazole. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;53:169-170.

- Dhar S, Kanwar AJ. Fixed drug eruption on the tongue of a 4-year-old boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 1995;12:51-52.

- Alonso JC, Melgosa AC, Gonzalo MJ, et al. Fixed drug eruption on the tongue due to clarithromycin. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;53:121-122.

- Prieto A, De Barrio M, Infante S, et al. Recurrent fixed drug eruption due to metronidazole elicited by patch test with tinidazole. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;53:169-170.

- Dhar S, Kanwar AJ. Fixed drug eruption on the tongue of a 4-year-old boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 1995;12:51-52.

- Alonso JC, Melgosa AC, Gonzalo MJ, et al. Fixed drug eruption on the tongue due to clarithromycin. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;53:121-122.

Practice Points

- Fixed drug eruption (FDE) is characterized by onset of round/oval, erythematous, well-defined macules on the skin and/or mucosa associated with itching and burning.

- Intraoral involvement of FDE is rare.

- Tinidazole may cause FDE and should be suspected in patients with a spontaneous eruption of macules on mucous membranes.

Sore throat and ear pain

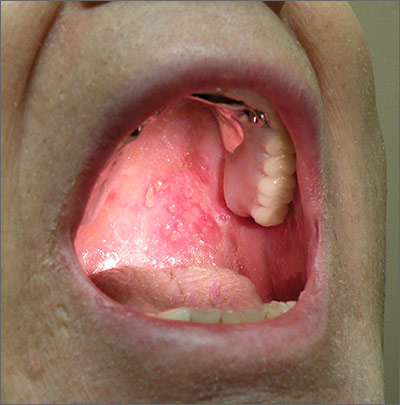

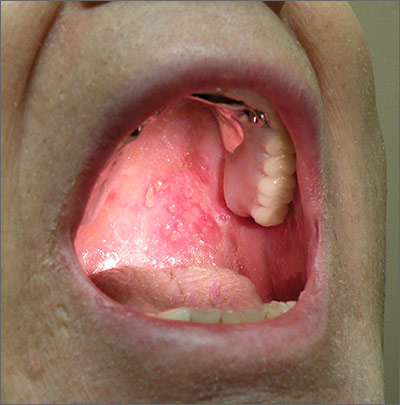

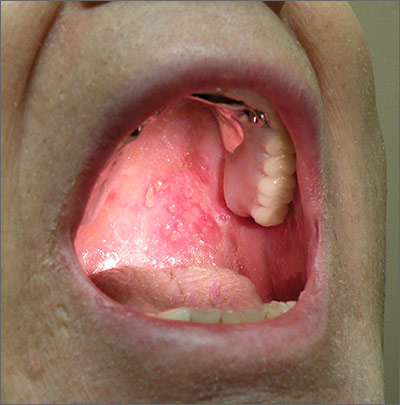

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation, he was given a diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus—also known as Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome typically develop unilateral facial paralysis and erythematous vesicles that appear ipsilaterally on the ear and/or in the mouth. This syndrome is a rare complication of herpes zoster that occurs when latent varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection reactivates and spreads to affect the geniculate ganglion.

An estimated 5 out of every 100,000 people develop Ramsay Hunt syndrome each year in the United States; men and women are equally affected. Any patient who’s had VZV infection runs the risk of developing Ramsay Hunt syndrome, but it most often develops in individuals older than age 60.

Vesicles in the mouth usually develop on the tongue or hard palate. Other symptoms may include tinnitus, hearing loss, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, and nystagmus. Because the symptoms of Ramsay Hunt syndrome suggest a possible infection, the differential diagnosis should include herpes simplex virus type 1, Epstein-Barr virus, group A Streptococcus, and measles.

A diagnosis of Ramsay Hunt syndrome is typically made clinically, but can be confirmed with direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) analysis, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, or viral culture of vesicular exudates. DFA for VZV has an 87% sensitivity. PCR has a higher sensitivity (92%), is widely available, and is the diagnostic test of choice, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Treatment with an oral steroid, such as prednisone, in addition to an antiviral such as acyclovir or valacyclovir, may reduce the likelihood of postherpetic neuralgia and improve facial motor function. However, these benefits have not been demonstrated in randomized controlled trials.

In this case, the FP prescribed oral valacyclovir 1 g 3 times a day for 7 days and oral prednisone 50 mg/d for 5 days for the patient. After one week of treatment, the patient’s symptoms resolved and the vesicles in his mouth crusted over. He did not experience postherpetic neuralgia or have a recurrence.

Adapted from: Moss DA, Crawford P. Sore throat and left ear pain. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:117-119.

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation, he was given a diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus—also known as Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome typically develop unilateral facial paralysis and erythematous vesicles that appear ipsilaterally on the ear and/or in the mouth. This syndrome is a rare complication of herpes zoster that occurs when latent varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection reactivates and spreads to affect the geniculate ganglion.

An estimated 5 out of every 100,000 people develop Ramsay Hunt syndrome each year in the United States; men and women are equally affected. Any patient who’s had VZV infection runs the risk of developing Ramsay Hunt syndrome, but it most often develops in individuals older than age 60.

Vesicles in the mouth usually develop on the tongue or hard palate. Other symptoms may include tinnitus, hearing loss, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, and nystagmus. Because the symptoms of Ramsay Hunt syndrome suggest a possible infection, the differential diagnosis should include herpes simplex virus type 1, Epstein-Barr virus, group A Streptococcus, and measles.

A diagnosis of Ramsay Hunt syndrome is typically made clinically, but can be confirmed with direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) analysis, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, or viral culture of vesicular exudates. DFA for VZV has an 87% sensitivity. PCR has a higher sensitivity (92%), is widely available, and is the diagnostic test of choice, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Treatment with an oral steroid, such as prednisone, in addition to an antiviral such as acyclovir or valacyclovir, may reduce the likelihood of postherpetic neuralgia and improve facial motor function. However, these benefits have not been demonstrated in randomized controlled trials.

In this case, the FP prescribed oral valacyclovir 1 g 3 times a day for 7 days and oral prednisone 50 mg/d for 5 days for the patient. After one week of treatment, the patient’s symptoms resolved and the vesicles in his mouth crusted over. He did not experience postherpetic neuralgia or have a recurrence.

Adapted from: Moss DA, Crawford P. Sore throat and left ear pain. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:117-119.

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation, he was given a diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus—also known as Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Patients with Ramsay Hunt syndrome typically develop unilateral facial paralysis and erythematous vesicles that appear ipsilaterally on the ear and/or in the mouth. This syndrome is a rare complication of herpes zoster that occurs when latent varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection reactivates and spreads to affect the geniculate ganglion.

An estimated 5 out of every 100,000 people develop Ramsay Hunt syndrome each year in the United States; men and women are equally affected. Any patient who’s had VZV infection runs the risk of developing Ramsay Hunt syndrome, but it most often develops in individuals older than age 60.

Vesicles in the mouth usually develop on the tongue or hard palate. Other symptoms may include tinnitus, hearing loss, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, and nystagmus. Because the symptoms of Ramsay Hunt syndrome suggest a possible infection, the differential diagnosis should include herpes simplex virus type 1, Epstein-Barr virus, group A Streptococcus, and measles.

A diagnosis of Ramsay Hunt syndrome is typically made clinically, but can be confirmed with direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) analysis, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, or viral culture of vesicular exudates. DFA for VZV has an 87% sensitivity. PCR has a higher sensitivity (92%), is widely available, and is the diagnostic test of choice, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Treatment with an oral steroid, such as prednisone, in addition to an antiviral such as acyclovir or valacyclovir, may reduce the likelihood of postherpetic neuralgia and improve facial motor function. However, these benefits have not been demonstrated in randomized controlled trials.

In this case, the FP prescribed oral valacyclovir 1 g 3 times a day for 7 days and oral prednisone 50 mg/d for 5 days for the patient. After one week of treatment, the patient’s symptoms resolved and the vesicles in his mouth crusted over. He did not experience postherpetic neuralgia or have a recurrence.

Adapted from: Moss DA, Crawford P. Sore throat and left ear pain. J Fam Pract. 2015;64:117-119.

Sarcoidosis and Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Connection Documented in a Case Series of 3 Patients

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 25% to 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may occur in a variety of forms including macules, papules, plaques, and lupus pernio.1,2 Dermatologists commonly are confronted with the diagnosis and management of sarcoidosis because of its high incidence of cutaneous involvement. Due to the protean nature of the disease, skin biopsy plays a key role in confirming the diagnosis. Histological evidence of noncaseating granulomas in combination with an appropriate clinical and radiographic picture is necessary for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.1,2 Brincker and Wilbek

We describe 3 patients with sarcoidosis who developed squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin, including 2 black patients, which highlights the potential for SCC development.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A black woman in her 60s with a history of sarcoidosis affecting the lungs and skin that was well controlled with biweekly adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneous injections presented with a new dark painful lesion on the right third finger. She reported the lesion had been present for 1 to 2 years prior to the current presentation and was increasing in size. She had no history of prior skin cancers.

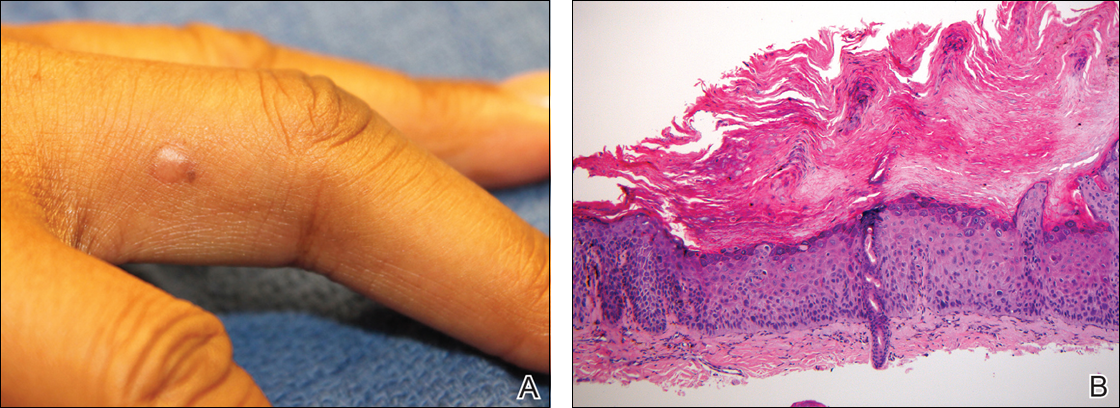

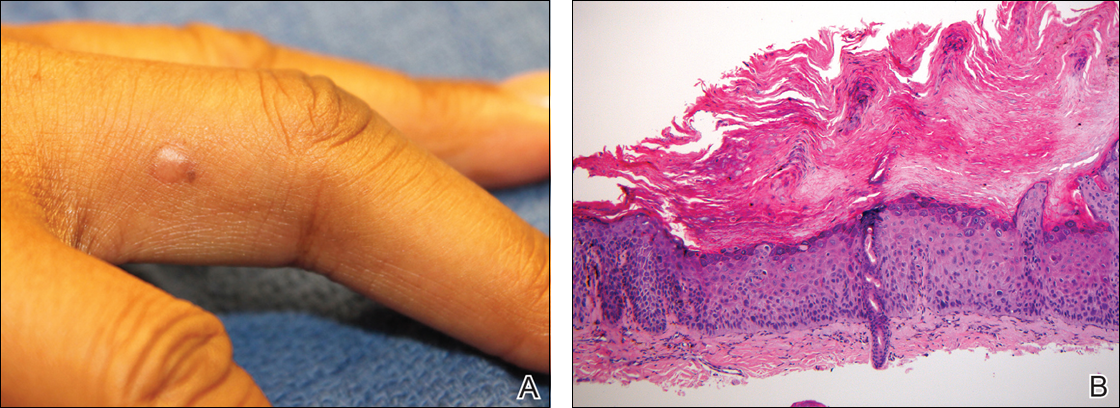

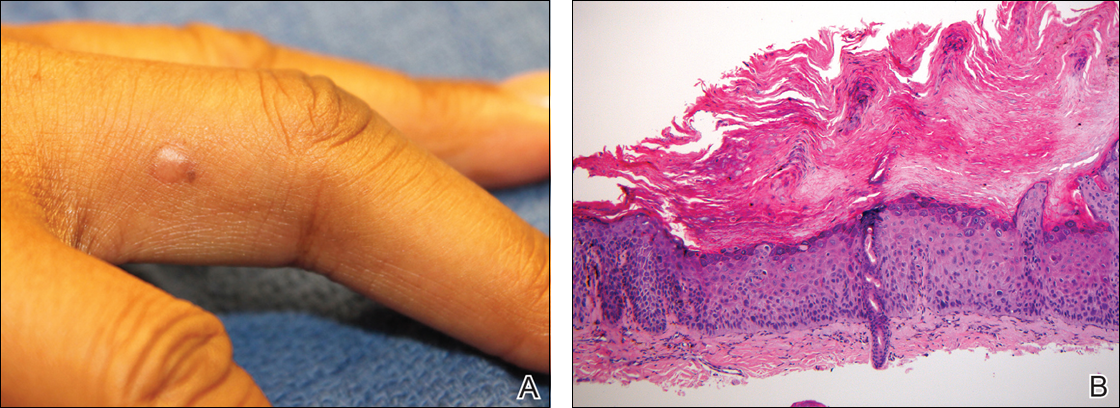

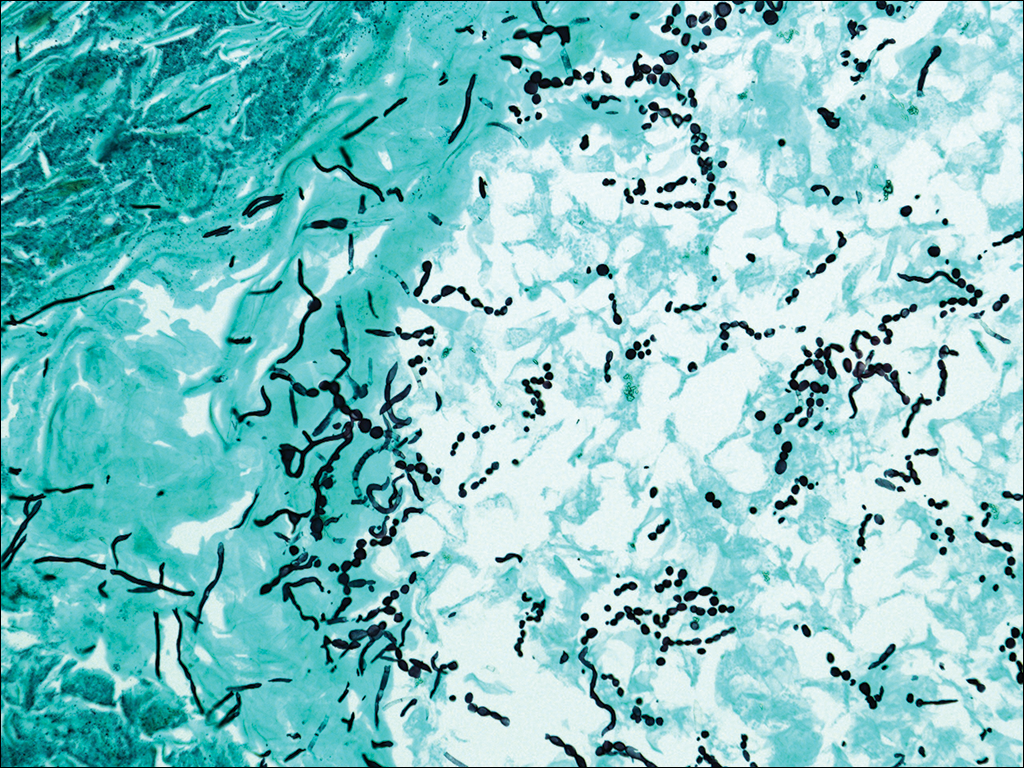

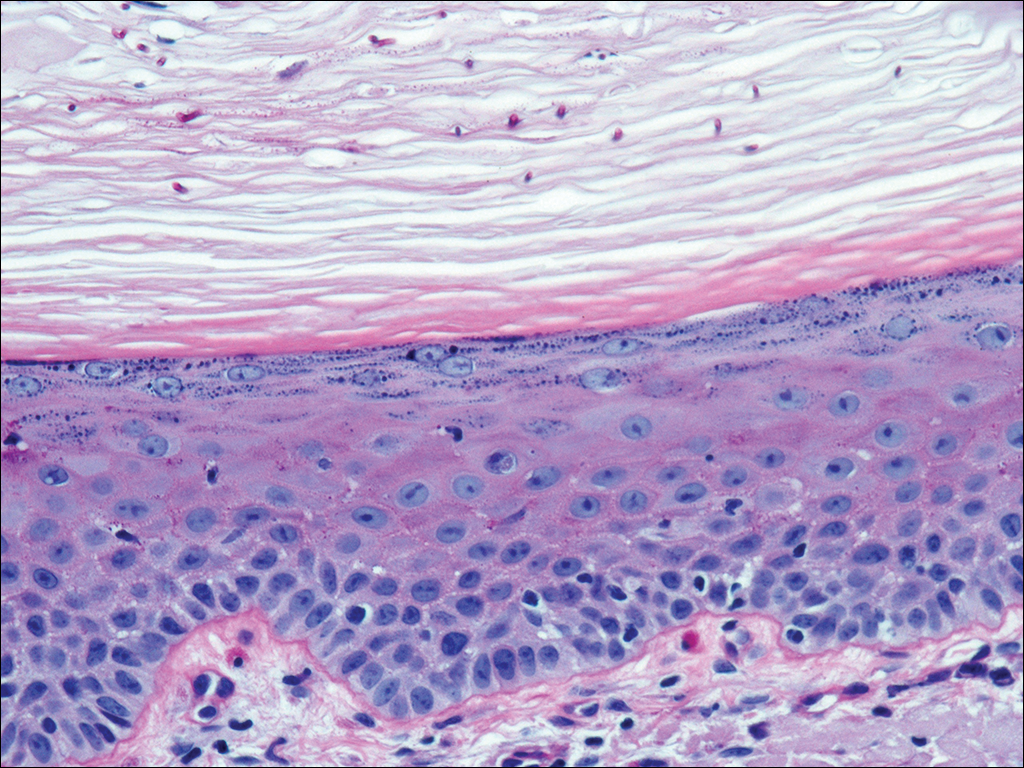

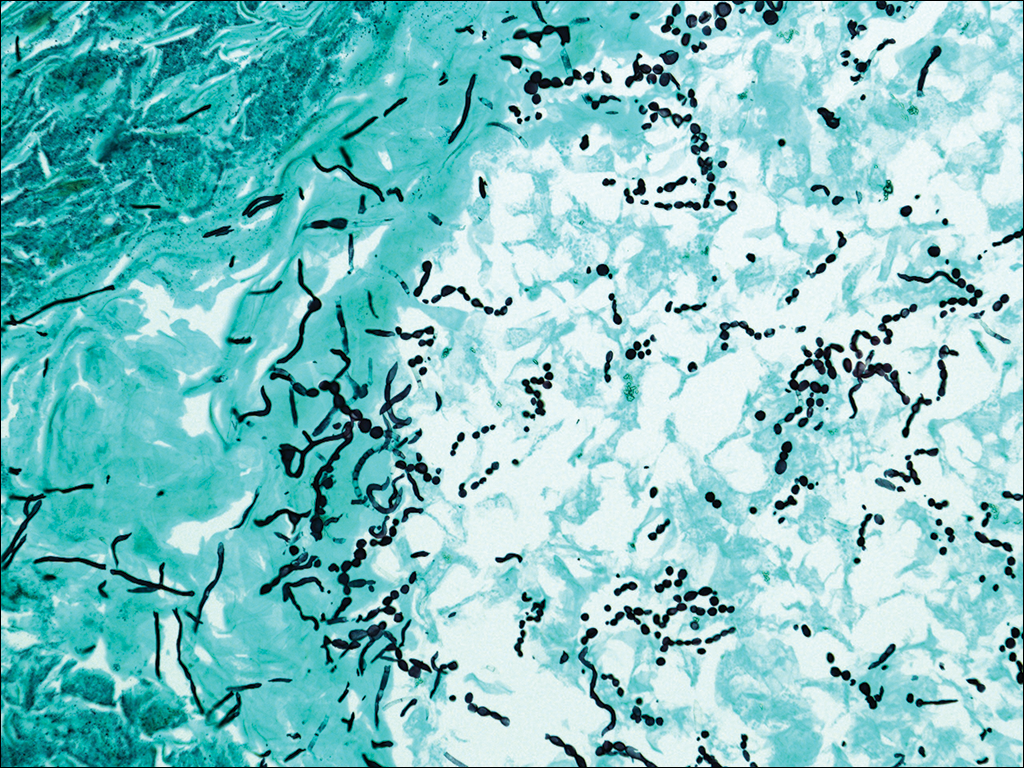

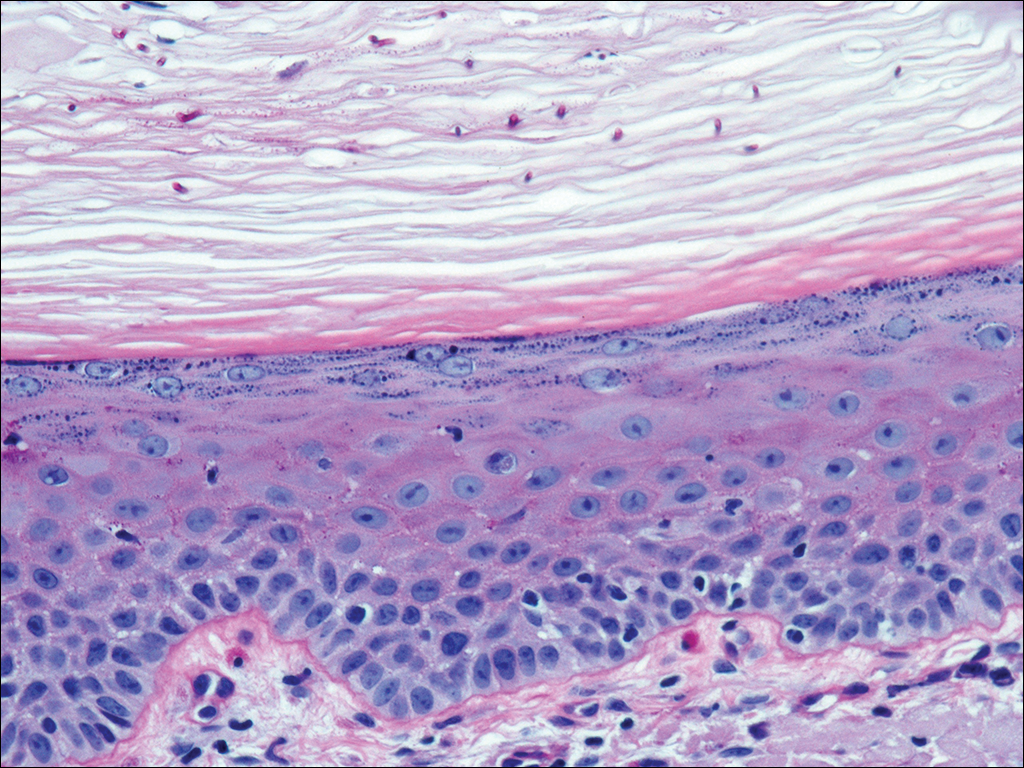

Physical examination revealed a waxy, brown-pigmented papule with overlying scale on the ulnar aspect of the right third digit near the web space (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy revealed atypical keratinocytes involving all layers of the epidermis along with associated parakeratotic scale consistent with a diagnosis of SCC in situ (Figure 1B). Human papillomavirus staining was negative. Due to the location of the lesion, the patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery and the lesion was completely excised.

Patient 2

A black woman in her 60s with a history of cutaneous sarcoidosis that was maintained on minocycline 100 mg twice daily, chloroquine 250 mg daily, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, tretinoin cream 0.025%, and intermittent intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections to the nose, as well as quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, developed a new, growing, asymptomatic, hyperpigmented lesion on the left side of the submandibular neck over a period of a few months. A biopsy was performed and the lesion was found to be an SCC, which subsequently was completely excised.

Patient 3

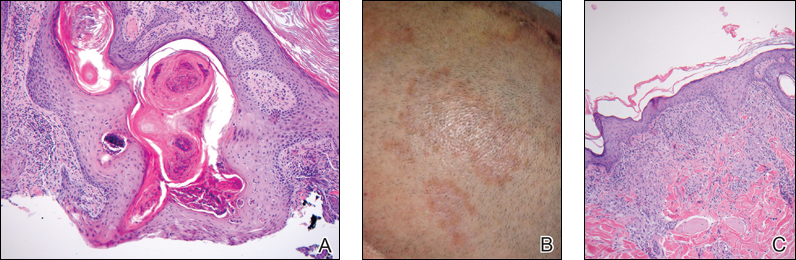

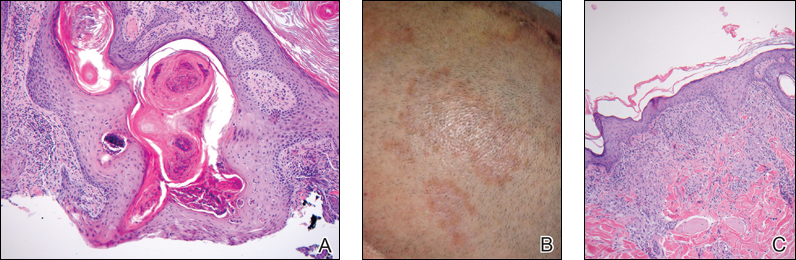

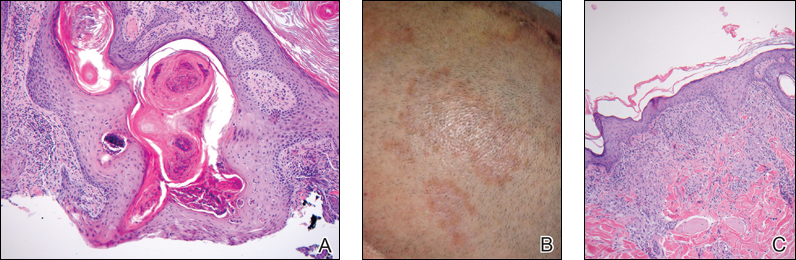

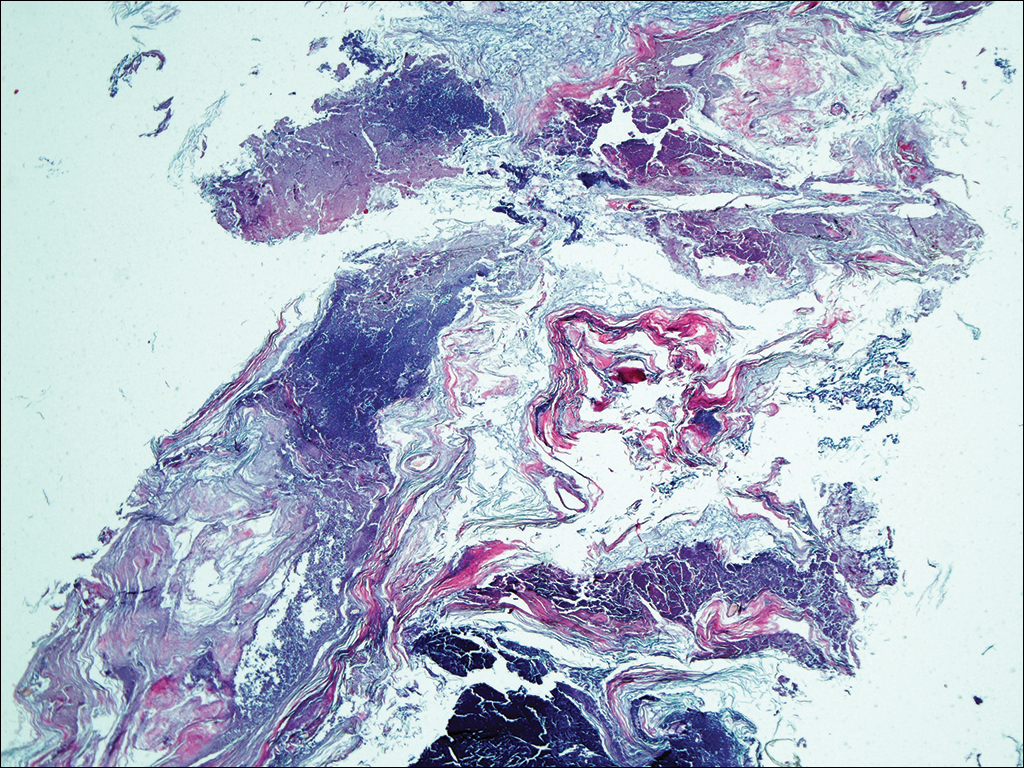

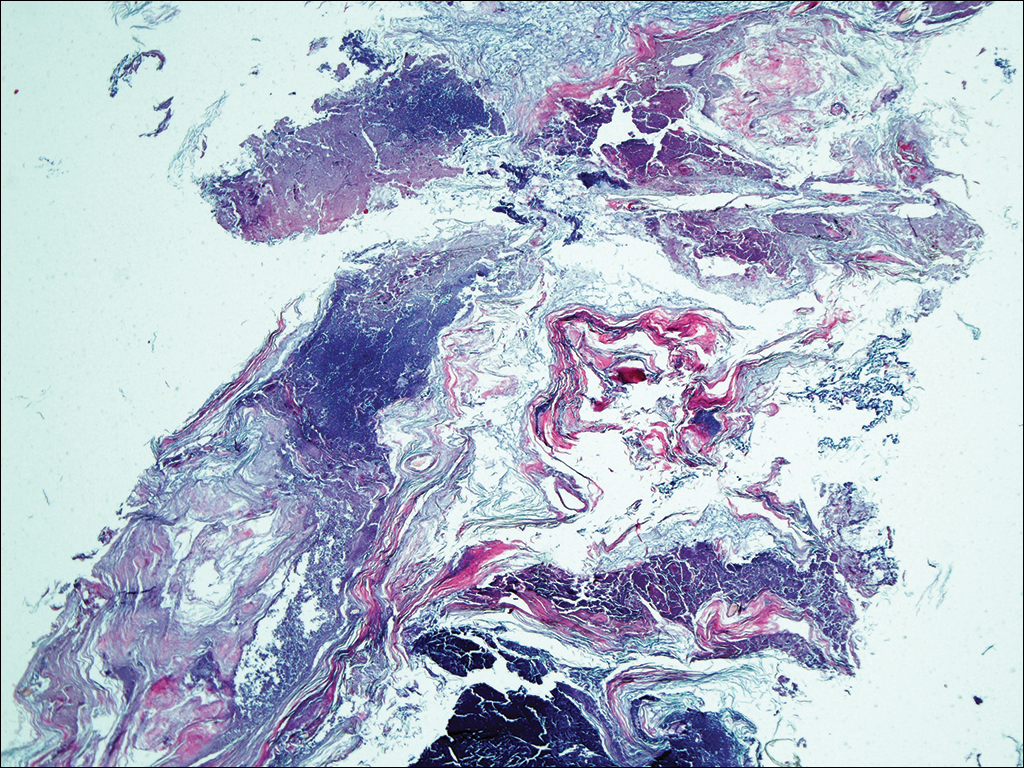

A white man in his 60s with a history of prior quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, remote melanoma, and multiple nonmelanoma skin cancers developed scaly papules on the scalp for months, one that was interpreted by an outside pathologist as an invasive SCC (Figure 2A). He was referred to our institution for Mohs micrographic surgery. On presentation when his scalp was shaved for surgery, he was noted to have several violaceous, annular, thin plaques on the scalp (Figure 2B). A biopsy of an annular plaque demonstrated several areas of granulomatous dermatitis consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis (Figure 2C). The patient had clinical lymphadenopathy of the neck and supraclavicular region. Given the patient’s history, the differential diagnosis for these lesions included metastatic SCC, lymphoma, and sarcoidosis. The patient underwent a positron emission tomography scan, which demonstrated fluorodeoxyglucose-positive regions in both lungs and the right side of the neck. After evaluation by the pulmonary and otorhinolaryngology departments, including a lymph node biopsy, the positron emission tomography–enhancing lesions were ultimately determined to be consistent with sarcoidosis.

The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of the scalp SCC and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the body, clobetasol propionate foam 0.05% for the scalp, and hydroxychloroquine sulfate 400 mg daily for the cutaneous sarcoidosis. His annular scalp lesions resolved, but over the following 12 months the patient had numerous clinically suspicious skin lesions that were biopsied and were consistent with multiple basal cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, and SCC in situ. They were treated with surgery, cryosurgical destruction with liquid nitrogen, and 5-fluorouracil cream.

Over the 3 years subsequent to initial presentation, the patient developed ocular inflammation attributed to his sarcoidosis and atrial fibrillation, which was determined to be unrelated. He also developed 5 scaly hyperkeratotic plaques on the vertex aspect of the scalp. Biopsy of 2 lesions revealed mild keratinocyte atypia and epidermal hyperplasia, favored to represent SCC over pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia overlying associated granulomatous inflammation. These lesions ultimately were believed to represent new SCCs, while biopsies of 2 other lesions revealed isolated granulomatous inflammation that was believed to represent hyperkeratotic cutaneous sarcoidosis clinically resembling his SCCs. The patient was again referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and the malignancies were completely removed, while the cutaneous sarcoidosis was again treated with topical corticosteroids with complete resolution.

Comment

The potential increased risk for malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis has been well documented.3-6 Brincker and Wilbek3 first reported this association after studying 2544 patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis from 1962 to 1971. In particular, they noted a difference between the expected and observed number of cases of malignancy, particularly lung cancer and lymphoma, in the sarcoidosis population.3 In a study of 10,037 hospitalized sarcoidosis patients from 1964 to 2004, Ji et al5 noted a 40% overall increase in the incidence of cancer and found that the risk for malignancy was highest in the year following hospitalization. Interestingly, they found that the risk for developing cutaneous SCC was elevated in sarcoidosis patients even after the first year following hospitalization.5 In a retrospective cohort study examining more than 9000 patients, Askling et al4 also confirmed the increased incidence of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients. Specifically, the authors found a higher than expected occurrence of skin cancer, both melanoma (standardized incidence ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.3) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (standardized incidence ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-3.8) in patients with sarcoidosis.4 Reich et al7 cross-matched 30,000 cases from the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region Tumor Registry against a sarcoidosis registry of 243 cases to evaluate for evidence of linkage between sarcoidosis and malignancy. They concluded that there may be an etiologic relationship between sarcoidosis and malignancy in at least one-quarter of cases in which both are present and hypothesized that granulomas may be the result of a cell-mediated reaction to tumor antigens.7

Few published studies specifically address the incidence of malignancy in patients with primarily cutaneous sarcoidosis. Cutaneous sarcoidosis includes nonspecific lesions, such as erythema nodosum, as well as specific lesions, such as papules, plaques, nodules, and lupus pernio.8 Alexandrescu et al6 evaluated 110 patients with a diagnosis of both sarcoidosis (cutaneous and noncutaneous) and malignancy. Through their analysis, they found that cutaneous sarcoidosis is seen more commonly in patients presenting with sarcoidosis and malignancy (56.4%) than in the total sarcoidosis population (20%–25%). From these findings, the authors concluded that cutaneous sarcoidosis appears to be a subtype of sarcoidosis associated with cancer.6

We report 3 cases that specifically illustrate a link between cutaneous sarcoidosis and an increased risk for cutaneous SCC. Because sarcoidosis commonly affects the skin, patients often present to dermatologists for care. Once the initial diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis is made via biopsy, it is natural to be tempted to attribute any new skin lesions to worsening or active disease; however, as cutaneous sarcoidosis may take on a variety of nonspecific forms, it is important to biopsy any unusual lesions. In our case series, patient 3 presented at several different points with scaly scalp lesions. Upon biopsy, several of these lesions were found to be SCCs, while others demonstrated regions of granulomatous inflammation consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. On further review of pathology during the preparation of this manuscript after the initial diagnoses were made, it was further noted that it is challenging to distinguish granulomatous inflammation with reactive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia from SCC. The fact that these lesions were clinically indistinguishable illustrates the critical importance of appropriate-depth biopsy in this situation, and the histopathologic challenges highlighted herein are important for pathologists to remember.

Patients 1 and 2 were both black women, and the fact that these patients both presented with cutaneous SCCs—one of whom was immunosuppressed due to treatment with adalimumab, the other without systemic immunosuppression—exemplifies the need for comprehensive skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as for biopsies of new or unusual lesions.

The mechanism for the development of malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis is unknown and likely is multifactorial. Multiple theories have been proposed.1,2,5,6,8 Sarcoidosis is marked by the development of granulomas secondary to the interaction between CD4+ T cells and antigen-presenting cells, which is mediated by various cytokines and chemokines, including IL-2 and IFN-γ. Patients with sarcoidosis have been found to have oligoclonal T-cell lineages with a limited receptor repertoire, suggestive of selective immune system activation, as well as a deficiency of certain types of regulatory cells, namely natural killer cells.1,2 This immune dysregulation has been postulated to play an etiologic role in the development of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients.1,2,5 Furthermore, the chronic inflammation found in the organs commonly affected by both sarcoidosis and malignancy is another possible mechanism.6,8 Finally, immunosuppression and mutagenesis secondary to the treatment modalities used in sarcoidosis may be another contributing factor.6

Conclusion

An association between sarcoidosis and malignancy has been suggested for several decades. We specifically report 3 cases of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis who presented with concurrent cutaneous SCCs. Given the varied and often nonspecific nature of cutaneous sarcoidosis, these cases highlight the importance of biopsy when sarcoidosis patients present with new and unusual skin lesions. Additionally, they illustrate the importance of thorough skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as some of the challenges these patients pose for dermatologists.

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirsten AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153-2165.

- Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305:391-399.

- Brincker H, Wilbek E. The incidence of malignant tumours in patients with respiratory sarcoidosis. Br J Cancer. 1974;29:247-251.

- Askling J, Grunewald J, Eklund A, et al. Increased risk for cancer following sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(5, pt 1):1668-1672.

- Ji J, Shu X, Li X, et al. Cancer risk in hospitalized sarcoidosis patients: a follow-up study in Sweden. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1121-1126.

- Alexandrescu DT, Kauffman CL, Ichim TE, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis and malignancy: an association between sarcoidosis with skin manifestations and systemic neoplasia. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:2.

- Reich JM, Mullooly JP, Johnson RE. Linkage analysis of malignancy-associated sarcoidosis. Chest. 1995;107:605-613.

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sarcoidosis and malignancy. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:326-333.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 25% to 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may occur in a variety of forms including macules, papules, plaques, and lupus pernio.1,2 Dermatologists commonly are confronted with the diagnosis and management of sarcoidosis because of its high incidence of cutaneous involvement. Due to the protean nature of the disease, skin biopsy plays a key role in confirming the diagnosis. Histological evidence of noncaseating granulomas in combination with an appropriate clinical and radiographic picture is necessary for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.1,2 Brincker and Wilbek

We describe 3 patients with sarcoidosis who developed squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin, including 2 black patients, which highlights the potential for SCC development.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A black woman in her 60s with a history of sarcoidosis affecting the lungs and skin that was well controlled with biweekly adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneous injections presented with a new dark painful lesion on the right third finger. She reported the lesion had been present for 1 to 2 years prior to the current presentation and was increasing in size. She had no history of prior skin cancers.

Physical examination revealed a waxy, brown-pigmented papule with overlying scale on the ulnar aspect of the right third digit near the web space (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy revealed atypical keratinocytes involving all layers of the epidermis along with associated parakeratotic scale consistent with a diagnosis of SCC in situ (Figure 1B). Human papillomavirus staining was negative. Due to the location of the lesion, the patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery and the lesion was completely excised.

Patient 2

A black woman in her 60s with a history of cutaneous sarcoidosis that was maintained on minocycline 100 mg twice daily, chloroquine 250 mg daily, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, tretinoin cream 0.025%, and intermittent intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections to the nose, as well as quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, developed a new, growing, asymptomatic, hyperpigmented lesion on the left side of the submandibular neck over a period of a few months. A biopsy was performed and the lesion was found to be an SCC, which subsequently was completely excised.

Patient 3

A white man in his 60s with a history of prior quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, remote melanoma, and multiple nonmelanoma skin cancers developed scaly papules on the scalp for months, one that was interpreted by an outside pathologist as an invasive SCC (Figure 2A). He was referred to our institution for Mohs micrographic surgery. On presentation when his scalp was shaved for surgery, he was noted to have several violaceous, annular, thin plaques on the scalp (Figure 2B). A biopsy of an annular plaque demonstrated several areas of granulomatous dermatitis consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis (Figure 2C). The patient had clinical lymphadenopathy of the neck and supraclavicular region. Given the patient’s history, the differential diagnosis for these lesions included metastatic SCC, lymphoma, and sarcoidosis. The patient underwent a positron emission tomography scan, which demonstrated fluorodeoxyglucose-positive regions in both lungs and the right side of the neck. After evaluation by the pulmonary and otorhinolaryngology departments, including a lymph node biopsy, the positron emission tomography–enhancing lesions were ultimately determined to be consistent with sarcoidosis.

The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of the scalp SCC and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the body, clobetasol propionate foam 0.05% for the scalp, and hydroxychloroquine sulfate 400 mg daily for the cutaneous sarcoidosis. His annular scalp lesions resolved, but over the following 12 months the patient had numerous clinically suspicious skin lesions that were biopsied and were consistent with multiple basal cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, and SCC in situ. They were treated with surgery, cryosurgical destruction with liquid nitrogen, and 5-fluorouracil cream.

Over the 3 years subsequent to initial presentation, the patient developed ocular inflammation attributed to his sarcoidosis and atrial fibrillation, which was determined to be unrelated. He also developed 5 scaly hyperkeratotic plaques on the vertex aspect of the scalp. Biopsy of 2 lesions revealed mild keratinocyte atypia and epidermal hyperplasia, favored to represent SCC over pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia overlying associated granulomatous inflammation. These lesions ultimately were believed to represent new SCCs, while biopsies of 2 other lesions revealed isolated granulomatous inflammation that was believed to represent hyperkeratotic cutaneous sarcoidosis clinically resembling his SCCs. The patient was again referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and the malignancies were completely removed, while the cutaneous sarcoidosis was again treated with topical corticosteroids with complete resolution.

Comment

The potential increased risk for malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis has been well documented.3-6 Brincker and Wilbek3 first reported this association after studying 2544 patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis from 1962 to 1971. In particular, they noted a difference between the expected and observed number of cases of malignancy, particularly lung cancer and lymphoma, in the sarcoidosis population.3 In a study of 10,037 hospitalized sarcoidosis patients from 1964 to 2004, Ji et al5 noted a 40% overall increase in the incidence of cancer and found that the risk for malignancy was highest in the year following hospitalization. Interestingly, they found that the risk for developing cutaneous SCC was elevated in sarcoidosis patients even after the first year following hospitalization.5 In a retrospective cohort study examining more than 9000 patients, Askling et al4 also confirmed the increased incidence of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients. Specifically, the authors found a higher than expected occurrence of skin cancer, both melanoma (standardized incidence ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.3) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (standardized incidence ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-3.8) in patients with sarcoidosis.4 Reich et al7 cross-matched 30,000 cases from the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region Tumor Registry against a sarcoidosis registry of 243 cases to evaluate for evidence of linkage between sarcoidosis and malignancy. They concluded that there may be an etiologic relationship between sarcoidosis and malignancy in at least one-quarter of cases in which both are present and hypothesized that granulomas may be the result of a cell-mediated reaction to tumor antigens.7

Few published studies specifically address the incidence of malignancy in patients with primarily cutaneous sarcoidosis. Cutaneous sarcoidosis includes nonspecific lesions, such as erythema nodosum, as well as specific lesions, such as papules, plaques, nodules, and lupus pernio.8 Alexandrescu et al6 evaluated 110 patients with a diagnosis of both sarcoidosis (cutaneous and noncutaneous) and malignancy. Through their analysis, they found that cutaneous sarcoidosis is seen more commonly in patients presenting with sarcoidosis and malignancy (56.4%) than in the total sarcoidosis population (20%–25%). From these findings, the authors concluded that cutaneous sarcoidosis appears to be a subtype of sarcoidosis associated with cancer.6

We report 3 cases that specifically illustrate a link between cutaneous sarcoidosis and an increased risk for cutaneous SCC. Because sarcoidosis commonly affects the skin, patients often present to dermatologists for care. Once the initial diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis is made via biopsy, it is natural to be tempted to attribute any new skin lesions to worsening or active disease; however, as cutaneous sarcoidosis may take on a variety of nonspecific forms, it is important to biopsy any unusual lesions. In our case series, patient 3 presented at several different points with scaly scalp lesions. Upon biopsy, several of these lesions were found to be SCCs, while others demonstrated regions of granulomatous inflammation consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis. On further review of pathology during the preparation of this manuscript after the initial diagnoses were made, it was further noted that it is challenging to distinguish granulomatous inflammation with reactive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia from SCC. The fact that these lesions were clinically indistinguishable illustrates the critical importance of appropriate-depth biopsy in this situation, and the histopathologic challenges highlighted herein are important for pathologists to remember.

Patients 1 and 2 were both black women, and the fact that these patients both presented with cutaneous SCCs—one of whom was immunosuppressed due to treatment with adalimumab, the other without systemic immunosuppression—exemplifies the need for comprehensive skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as for biopsies of new or unusual lesions.

The mechanism for the development of malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis is unknown and likely is multifactorial. Multiple theories have been proposed.1,2,5,6,8 Sarcoidosis is marked by the development of granulomas secondary to the interaction between CD4+ T cells and antigen-presenting cells, which is mediated by various cytokines and chemokines, including IL-2 and IFN-γ. Patients with sarcoidosis have been found to have oligoclonal T-cell lineages with a limited receptor repertoire, suggestive of selective immune system activation, as well as a deficiency of certain types of regulatory cells, namely natural killer cells.1,2 This immune dysregulation has been postulated to play an etiologic role in the development of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients.1,2,5 Furthermore, the chronic inflammation found in the organs commonly affected by both sarcoidosis and malignancy is another possible mechanism.6,8 Finally, immunosuppression and mutagenesis secondary to the treatment modalities used in sarcoidosis may be another contributing factor.6

Conclusion

An association between sarcoidosis and malignancy has been suggested for several decades. We specifically report 3 cases of patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis who presented with concurrent cutaneous SCCs. Given the varied and often nonspecific nature of cutaneous sarcoidosis, these cases highlight the importance of biopsy when sarcoidosis patients present with new and unusual skin lesions. Additionally, they illustrate the importance of thorough skin examinations in sarcoidosis patients as well as some of the challenges these patients pose for dermatologists.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that most commonly affects the lungs, eyes, and skin. Cutaneous involvement is reported in 25% to 35% of patients with sarcoidosis and may occur in a variety of forms including macules, papules, plaques, and lupus pernio.1,2 Dermatologists commonly are confronted with the diagnosis and management of sarcoidosis because of its high incidence of cutaneous involvement. Due to the protean nature of the disease, skin biopsy plays a key role in confirming the diagnosis. Histological evidence of noncaseating granulomas in combination with an appropriate clinical and radiographic picture is necessary for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.1,2 Brincker and Wilbek

We describe 3 patients with sarcoidosis who developed squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin, including 2 black patients, which highlights the potential for SCC development.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A black woman in her 60s with a history of sarcoidosis affecting the lungs and skin that was well controlled with biweekly adalimumab 40 mg subcutaneous injections presented with a new dark painful lesion on the right third finger. She reported the lesion had been present for 1 to 2 years prior to the current presentation and was increasing in size. She had no history of prior skin cancers.

Physical examination revealed a waxy, brown-pigmented papule with overlying scale on the ulnar aspect of the right third digit near the web space (Figure 1A). A shave biopsy revealed atypical keratinocytes involving all layers of the epidermis along with associated parakeratotic scale consistent with a diagnosis of SCC in situ (Figure 1B). Human papillomavirus staining was negative. Due to the location of the lesion, the patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery and the lesion was completely excised.

Patient 2

A black woman in her 60s with a history of cutaneous sarcoidosis that was maintained on minocycline 100 mg twice daily, chloroquine 250 mg daily, tacrolimus ointment 0.1%, tretinoin cream 0.025%, and intermittent intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injections to the nose, as well as quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, developed a new, growing, asymptomatic, hyperpigmented lesion on the left side of the submandibular neck over a period of a few months. A biopsy was performed and the lesion was found to be an SCC, which subsequently was completely excised.

Patient 3

A white man in his 60s with a history of prior quiescent pulmonary sarcoidosis, remote melanoma, and multiple nonmelanoma skin cancers developed scaly papules on the scalp for months, one that was interpreted by an outside pathologist as an invasive SCC (Figure 2A). He was referred to our institution for Mohs micrographic surgery. On presentation when his scalp was shaved for surgery, he was noted to have several violaceous, annular, thin plaques on the scalp (Figure 2B). A biopsy of an annular plaque demonstrated several areas of granulomatous dermatitis consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis (Figure 2C). The patient had clinical lymphadenopathy of the neck and supraclavicular region. Given the patient’s history, the differential diagnosis for these lesions included metastatic SCC, lymphoma, and sarcoidosis. The patient underwent a positron emission tomography scan, which demonstrated fluorodeoxyglucose-positive regions in both lungs and the right side of the neck. After evaluation by the pulmonary and otorhinolaryngology departments, including a lymph node biopsy, the positron emission tomography–enhancing lesions were ultimately determined to be consistent with sarcoidosis.

The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery for treatment of the scalp SCC and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% for the body, clobetasol propionate foam 0.05% for the scalp, and hydroxychloroquine sulfate 400 mg daily for the cutaneous sarcoidosis. His annular scalp lesions resolved, but over the following 12 months the patient had numerous clinically suspicious skin lesions that were biopsied and were consistent with multiple basal cell carcinomas, actinic keratoses, and SCC in situ. They were treated with surgery, cryosurgical destruction with liquid nitrogen, and 5-fluorouracil cream.

Over the 3 years subsequent to initial presentation, the patient developed ocular inflammation attributed to his sarcoidosis and atrial fibrillation, which was determined to be unrelated. He also developed 5 scaly hyperkeratotic plaques on the vertex aspect of the scalp. Biopsy of 2 lesions revealed mild keratinocyte atypia and epidermal hyperplasia, favored to represent SCC over pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia overlying associated granulomatous inflammation. These lesions ultimately were believed to represent new SCCs, while biopsies of 2 other lesions revealed isolated granulomatous inflammation that was believed to represent hyperkeratotic cutaneous sarcoidosis clinically resembling his SCCs. The patient was again referred for Mohs micrographic surgery and the malignancies were completely removed, while the cutaneous sarcoidosis was again treated with topical corticosteroids with complete resolution.

Comment

The potential increased risk for malignancy in patients with sarcoidosis has been well documented.3-6 Brincker and Wilbek3 first reported this association after studying 2544 patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis from 1962 to 1971. In particular, they noted a difference between the expected and observed number of cases of malignancy, particularly lung cancer and lymphoma, in the sarcoidosis population.3 In a study of 10,037 hospitalized sarcoidosis patients from 1964 to 2004, Ji et al5 noted a 40% overall increase in the incidence of cancer and found that the risk for malignancy was highest in the year following hospitalization. Interestingly, they found that the risk for developing cutaneous SCC was elevated in sarcoidosis patients even after the first year following hospitalization.5 In a retrospective cohort study examining more than 9000 patients, Askling et al4 also confirmed the increased incidence of malignancy in sarcoidosis patients. Specifically, the authors found a higher than expected occurrence of skin cancer, both melanoma (standardized incidence ratio, 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.3) and nonmelanoma skin cancer (standardized incidence ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 2.0-3.8) in patients with sarcoidosis.4 Reich et al7 cross-matched 30,000 cases from the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region Tumor Registry against a sarcoidosis registry of 243 cases to evaluate for evidence of linkage between sarcoidosis and malignancy. They concluded that there may be an etiologic relationship between sarcoidosis and malignancy in at least one-quarter of cases in which both are present and hypothesized that granulomas may be the result of a cell-mediated reaction to tumor antigens.7

Few published studies specifically address the incidence of malignancy in patients with primarily cutaneous sarcoidosis. Cutaneous sarcoidosis includes nonspecific lesions, such as erythema nodosum, as well as specific lesions, such as papules, plaques, nodules, and lupus pernio.8 Alexandrescu et al6 evaluated 110 patients with a diagnosis of both sarcoidosis (cutaneous and noncutaneous) and malignancy. Through their analysis, they found that cutaneous sarcoidosis is seen more commonly in patients presenting with sarcoidosis and malignancy (56.4%) than in the total sarcoidosis population (20%–25%). From these findings, the authors concluded that cutaneous sarcoidosis appears to be a subtype of sarcoidosis associated with cancer.6