User login

Improving your approach to nasal obstruction

Nasal obstruction is one of the most common reasons that patients visit their primary care providers.1,2 Often described by patients as nasal congestion or the inability to adequately breathe out of one or both nostrils during the day and/or night, nasal obstruction commonly interferes with a patient’s ability to eat, sleep, and function, thereby significantly impacting quality of life. Overlapping presentations can make discerning the exact cause of nasal obstruction difficult.

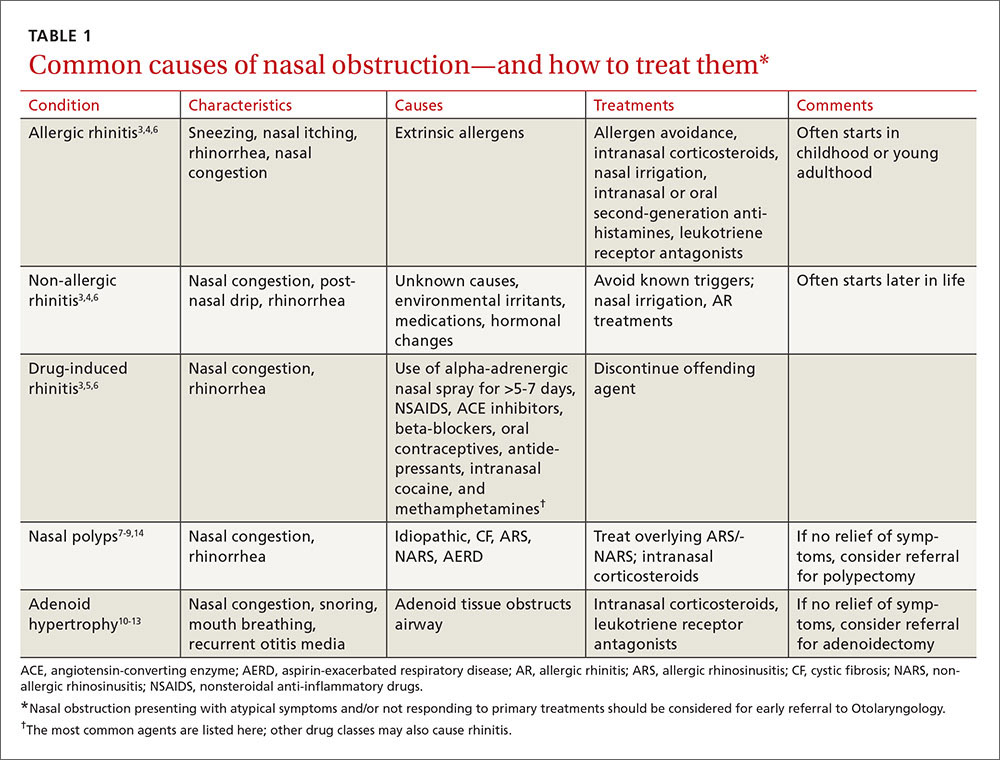

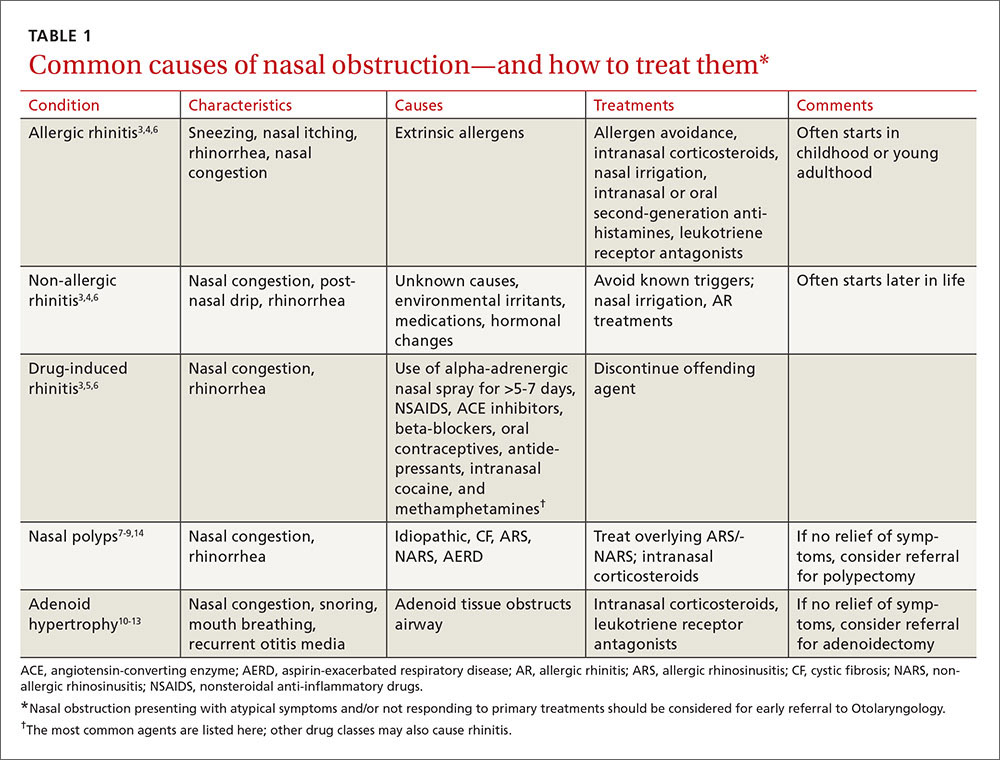

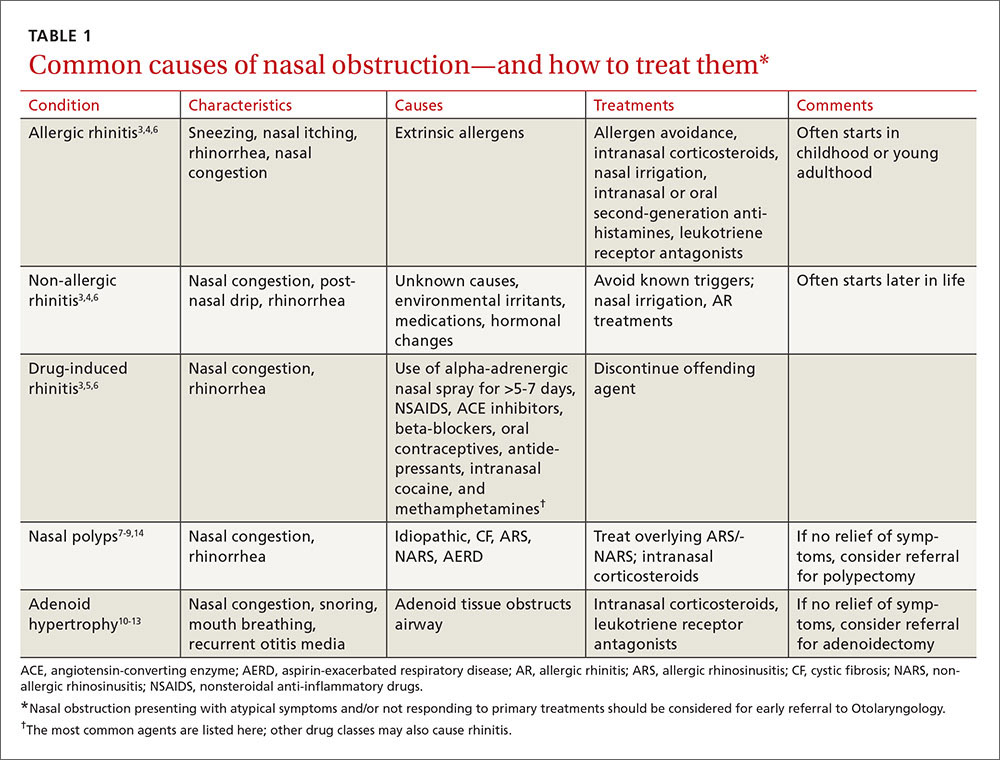

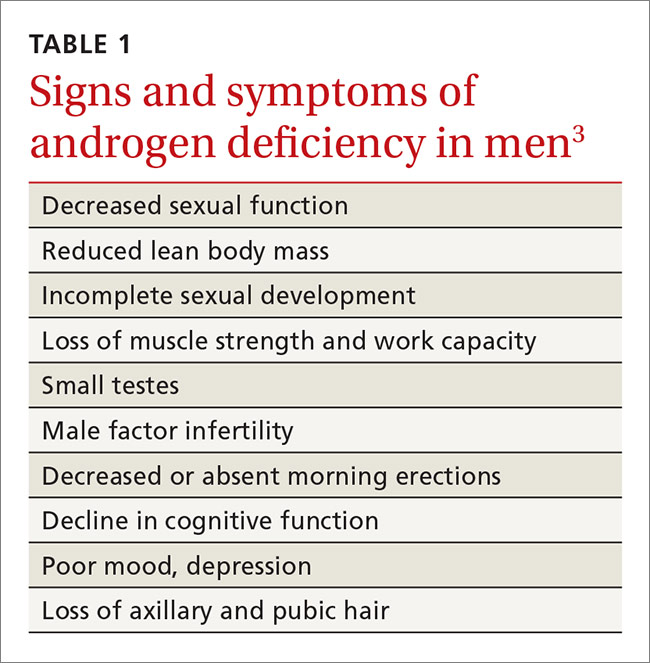

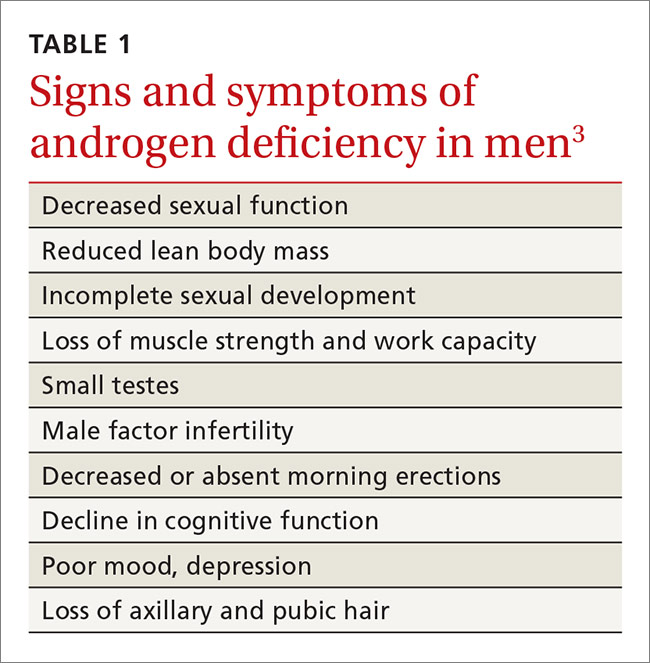

To improve diagnosis and treatment, we review here the evidence-based recommendations for the most common causes of nasal obstruction: rhinitis, rhinosinusitis (RS), drug-induced nasal obstruction, and mechanical/structural abnormalities (TABLE 13-14).

Rhinitis/rhinosinusitis: It all begins with inflammation

Sneezing, rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, and nasal itching are complaints that signal rhinitis, which affects 30 to 60 million people in the United States annually.3 Rhinitis can be allergic, non-allergic, infectious, hormonal, or occupational in nature. All forms of rhinitis share inflammation as the cause of the nasal obstruction. The most common form is allergic rhinitis (AR), which includes seasonal AR and perennial AR. Seasonal AR is typically caused by outdoor allergens and waxes and wanes with pollen seasons. Perennial AR is caused mostly by indoor allergens, such as dust mites, molds, cockroaches, and pet dander; it persists all or most of the year.6 Causes of non-allergic rhinitis (NAR) include environmental irritants such as cigarette smoke, perfume, and car exhaust; medications; and hormonal changes,6 but most causes of NAR are unknown.3,6

While AR can begin at any age, most people develop symptoms in childhood or as young adults, whereas NAR tends to begin later in life. Nasal itching can help to distinguish AR from NAR. NAR symptoms tend to be perennial and include postnasal drainage. If symptoms persist longer than 12 weeks despite treatment, the condition becomes known as chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS).

Treatment of rhinitis: Tiered and often continuous

Treatment of AR and NAR is similar and multitiered beginning with the avoidance of irritants and/or allergens whenever possible, moving on to pharmacotherapy, and, at least for AR, ending with allergen immunotherapy. Treatment is often an ongoing process and typically requires continuous therapy as opposed to treatment on an as-needed basis.3 It is unnecessary to perform allergy testing before making a presumed diagnosis of NAR and starting treatment.6

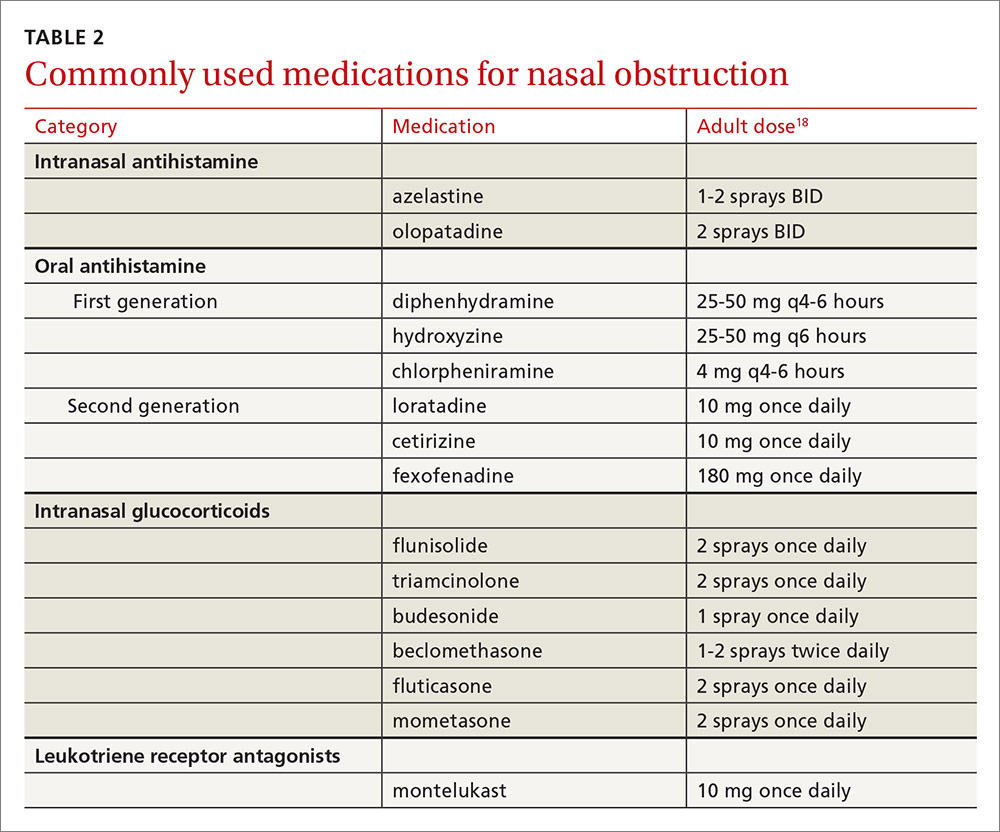

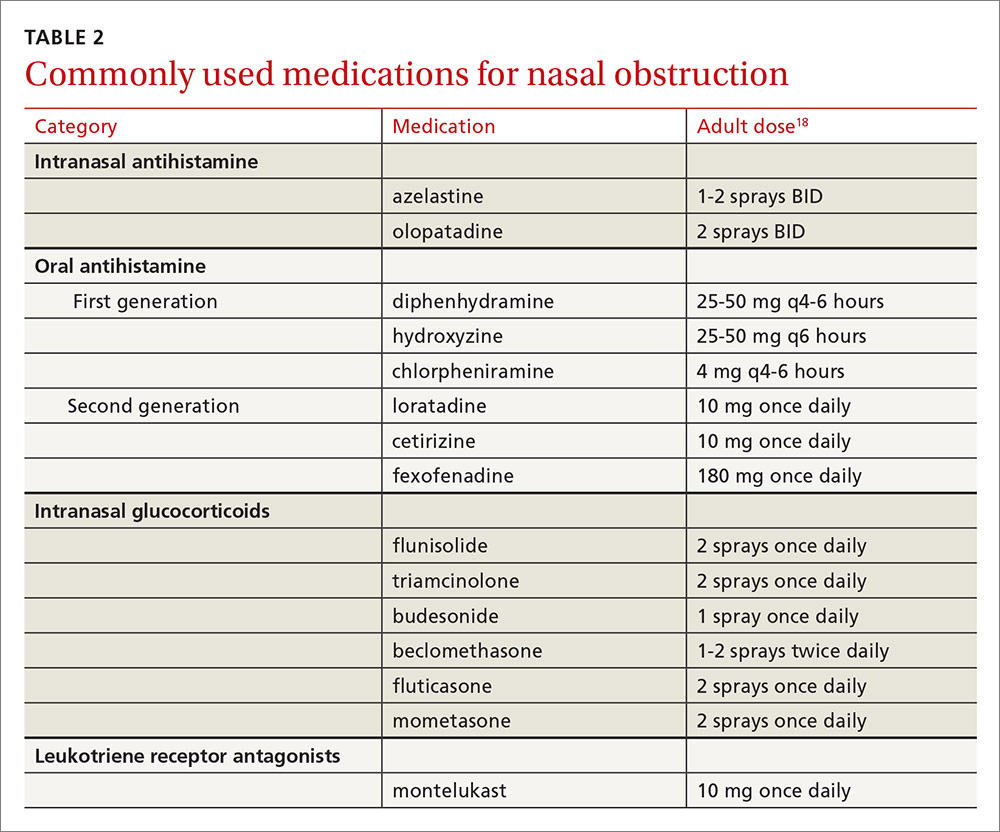

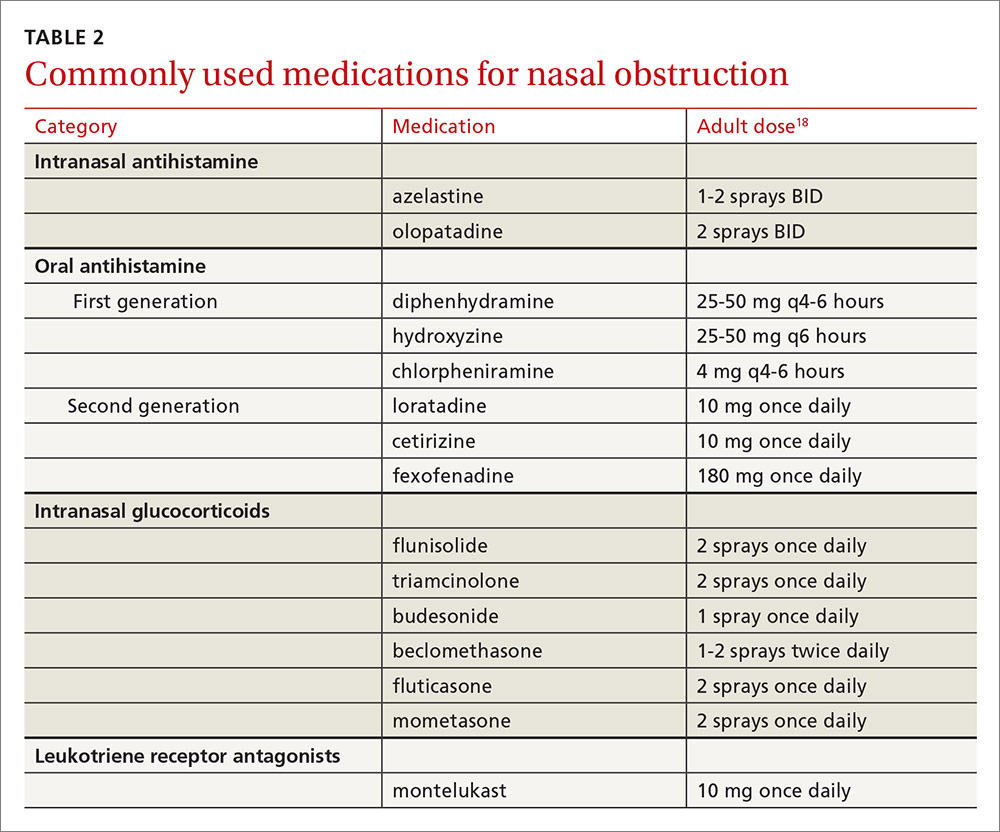

Intranasal corticosteroids. Currently, intranasal glucocorticosteroids (INGCs) are the most effective monotherapy for AR and NAR and have few adverse effects when used at prescribed doses.3,4 For mild to intermittent symptoms, begin with the maximum dosage of an INGC for the patient’s age and proceed with incremental reductions to identify the lowest effective dose.3 If INGCs alone are ineffective, studies have shown that the addition of an intranasal second-generation antihistamine can be of some benefit.3,4 In fact, an INGC and an intranasal antihistamine—along with saline nasal irrigation—is recommended for both AR and NAR resistant to single therapy.3,6,15 If intranasal antihistamines are not an option, oral therapy can be initiated.

Start with second-generation antihistamines and consider LRAs. For oral therapy, start with second-generation antihistamines (loratadine, cetirizine, fexofenadine). First-generation antihistamines (diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, chlorpheniramine), although widely available at relatively low cost, can cause several significant adverse effects including sedation, impaired cognitive function, and agitation in children.3,4 Because second-generation antihistamines have fewer adverse effects, they are recommended as first-line therapy when oral antihistamine therapy is desired, such as for nasal congestion, sneezing, and itchy, watery eyes.

Of note: A 2014 meta-analysis found that a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LRA) (montelukast) had efficacy similar to oral antihistamines for symptom relief in AR, and that LRAs may be better suited to nighttime symptoms (difficulty falling asleep, nighttime awakenings, congestion on awakening), while antihistamines may provide better relief of daytime symptoms (pruritus, rhinorrhea, sneezing).16 Although further head-to-head, double-blind randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are needed to confirm the results and investigate possible gender differences in symptom response, consider an LRA for first-line therapy in patients with AR who have predominantly nighttime symptoms.

What about pregnant women and the elderly?

It is important to consider teratogenicity when selecting medications for pregnant patients, especially during the first trimester.3 Nasal cromolyn has the most reassuring safety profile in pregnancy. Cetirizine, chlorpheniramine, loratadine, diphenhydramine, and tripelennamine may be used in pregnancy. The US Food and Drug Administration considers them to have a low risk of fetal harm, based on human data, whereas it views many other antihistamines as probably safe, based on limited or no human data. Most INGCs are not expected to cause fetal harm, but limited human data are available. Avoid prescribing oral decongestants to women who are in the first trimester of pregnancy due to the risk of gastroschisis in newborns.17

Elderly patients represent another population for which adverse effects must be carefully considered. Allergies in individuals >65 years of age are uncommon. Rhinitis in this age group is often secondary to cholinergic hyperactivity, alpha-adrenergic hyperactivity, or rhinosinusitis. Given elderly patients’ increased susceptibility to the potential adverse central nervous system (CNS) and anticholinergic effects of antihistamines, non-sedating medications are recommended. Oral decongestants also should be used with caution in this population, not only because of CNS effects, but also because of heart and bladder effects3 (TABLE 218).

For drug-induced rhinitis, stop the offending drug and consider an INGC

Several types of medications, both oral and inhaled, are known to cause rhinitis. The use of alpha-adrenergic decongestant sprays for more than 5 to 7 days can induce rebound congestion on withdrawal, known as rhinitis medicamentosa.3 Repeated use of intranasal cocaine and methamphetamines can also result in rebound congestion. Oral medications that can result in rhinitis or congestion include angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta-blockers, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), oral contraceptives, and even antidepressants.3

The treatment for drug-induced rhinitis is termination of the offending agent. INGCs can be used to help decrease inflammation and control symptoms once the offending agent is discontinued.

Mechanical/structural causes of obstruction are wide-ranging

Mechanical/structural causes of nasal obstruction range from foreign bodies to anatomical variations including nasal polyps, a deviated septum, adenoidal hypertrophy, foreign bodies, and tumors. Because more than one etiology may be at work, it is best to first treat any non-mechanical causes of obstruction, such as ARS or NARS.

Nasal polyposis often requires both a medical and surgical approach

Nasal polyps are benign growths arising from the mucosa of the nasal sinuses and nasal cavities and affecting up to 4% of the population.7 Their etiology is unclear, but we do know that nasal polyps result from underlying inflammation.7 Uncommon in children outside of those affected by cystic fibrosis,7 nasal polyposis can be associated with disease processes such as AR and sinusitis. Polyps are also associated with clinical syndromes such as aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD) syndrome, which involves upper and lower respiratory tract symptoms in patients with asthma who have taken aspirin or other NSAIDs.9

Symptoms vary with the location and size of the polyps, but generally include nasal congestion, alteration in smell, and rhinorrhea. The goals of treatment are to restore or improve nasal breathing and olfaction and prevent recurrence.8 This often requires both a medical and surgical approach.

Topical corticosteroids are effective at reducing both the size of polyps and associated symptoms (rhinorrhea, rhinitis).8 And research has shown that steroids reduce the need for both primary and repeat surgical polypectomies.4 Other treatments to consider prior to surgery (if no symptom reduction occurs with INGCs) include systemic (oral) corticosteroids, intra-polyp steroid injections, macrolide antibiotics, and nasal washes.7,14

When symptoms of polyposis are refractory to medical management, functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) is the surgical procedure of choice.3 In addition to refractory symptoms, indications for FESS include the need to correct anatomic deformities believed to be contributing to the persistence of disease and the need to debulk advanced nasal polyposis.3 The principal goal is to restore patency to the ostiomeatal unit.3

Several studies have reported a high success rate for FESS in improving the symptoms of CRS.3,19-23 In a 1992 study, for example, 98% of patients reported improvement following surgery,19 and in a follow-up report approximately 6 years later, 98% of patients continued to report subjective improvement.22

For septal etiologies, consider septoplasty

Deviation of the nasal septum is a common structural etiology for nasal obstruction arising primarily from congenital, genetic, or traumatic causes.24 Turbulent airflow from the septal deviation often causes turbinate hypertrophy, which creates (or exacerbates) the obstructive symptoms from the septal deviation.25

Septoplasty is the most common ear, nose, and throat operation in adults.26 Reduction of nasal symptoms has been reported in up to 89% of patients who receive this surgery, according to one single-center, non-randomized trial.27 Currently, at least one multicenter, randomized trial is underway that aims to develop evidence-based guidelines for septoplasty.26

Septal perforation is another etiology that can present with nasal obstruction symptoms. Causes include traumatic perforation, inflammatory or collagen vascular diseases, infections, overuse of vasoconstrictive medications, and malignancy.28,29 A careful inspection of the nasal septum is necessary to identify a perforation; this may require nasal endoscopy.

Anterior, rather than posterior, perforations are more likely to cause symptoms of nasal obstruction. Posterior perforations rarely require treatment unless malignancy is suspected, in which case referral for biopsy is recommended. Anterior perforations are treated initially with avoidance of any causative agent if, for example, the problem is drug- or medication-induced, and then with humidification and emollients.28,29

For anterior perforations, septal silicone buttons can be used for recalcitrant symptoms. However, observational studies indicate that for long-term symptom resolution, silicone buttons are effective in only about one-third of patients.29

For patients with persistent symptoms despite the above measures, surgical repair with various flap techniques is an option. A meta-analysis of case studies involving various techniques concluded that there is a wide variety of options, and that surgeons must weigh factors such as the characteristics and etiology of the perforation and their own experience and expertise when choosing from among available methods.30 Additional good quality research is necessary before clear recommendations regarding technique can be made.

Adenoid hypertrophy: Consider corticosteroid nasal drops

Adenoid hypertrophy is a common cause of chronic nasal obstruction in children. Although adenoidectomy is commonly performed to correct the problem, current evidence regarding the efficacy of the procedure is inconclusive.10 Evidence demonstrates corticosteroid nasal drops significantly reduce symptoms of nasal obstruction in children and may provide an effective alternative to surgical resection.18 Studies have also demonstrated that treatment with oral LRAs significantly reduces adenoid size and nasal obstruction symptoms.12,13

Foreign bodies: Don’t forget “a mother’s kiss”

Foreign bodies are the most common cause of nasal obstruction in the pediatric population. There is a paucity of high-quality evidence on removal of these objects; however, a number of retrospective reviews and case series support that most objects can be removed in the office or emergency department without otolaryngologic referral.31,32

Techniques for removal include positive pressure, which is best used for smooth or soft objects. Positive pressure techniques include having the patient blow their own nose or having a parent use a mouth-to-mouth–type blowing technique (ie, the “mother’s kiss” method).32 Refer patients to Otolaryngology if the obstruction involves:31

- objects not easily visualized by anterior rhinoscopy

- chronic or impacted objects

- button batteries or magnets

- penetrating or hooked objects

- any object that cannot be removed during an initial attempt.

Nasal tumors: More common in older men

Nasal tumors occur most often in the nasal cavity itself and are more common in men ≥60 years.33 There is no notable racial predominance.33 Other risk factors include human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, tobacco smoke, and occupational exposure to inhaled wood dust, glues, and adhesives.34-37

Benign tumors occurring in the nasal cavity are a diverse group of disorders, including inverted papillomas, squamous papillomas, pyogenic granulomas, and other less common lesions, all of which typically present with nasal obstruction as a symptom. Many of these lesions cause local tissue destruction or have a high incidence of recurrence. These tumors are treated universally with nasoendoscopic resection.38

Malignant nasal tumors are rare but serious causes of nasal obstruction, making up 3% of all head and neck cancers.39 Most nasal cancers present when they are locally advanced and cause unilateral nasal obstruction, lacrimation, and epistaxis. These symptoms are typically refractory to initial medical management and present as CRS. This diagnosis should be suspected in certain patient groups, such as those who have been exposed to wood dust (eg, construction workers or those who work in wood mills).36

Computed tomography is the gold standard imaging method for CRS; however, if nasal cancer is suspected, referral for biopsy and histopathologic examination is necessary for a final diagnosis.39 Because of the nonspecific nature of their initial presentation, many nasal tumors are at an advanced stage and carry a poor prognosis by the time they are diagnosed.39

CORRESPONDENCE

Margaret A. Bayard, MD, MPH, FAAFP, Naval Hospital Camp Pendleton, 200 Mercy Circle, Camp Pendleton, CA 92005; [email protected].

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC’s FastStats on Ambulatory Care Use and Physician Office Visits. Selected patient and provider characteristics for ambulatory care visits to physician offices and hospital outpatient and emergency departments: United States, 2009-2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/combined_tables/AMC_2009-2010_combined_web_table01.pdf. Accessed November 9, 2016.

2. US Census Bureau. Table 158. Visits to office-based physician and hospital outpatient departments, 2006. Available at: http://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2006/compendia/statab/126ed/tables/07s0158.xls. Accessed November 13, 2016.

3. Dykewicz MS, Hamilos DL. Rhinitis and sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:S103-S115.

4. Wallace DV, Dykewicz MS. The diagnosis and management of rhinitis: an updated practice parameter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:S1-S84.

5. Krouse J, Lund V, Fokkens W, et al. Diagnostic strategies in nasal congestion. Int J Gen Med. 2010;3:59-67.

6. Skoner DP. Allergic rhinitis: definition, epidemiology, pathophysiology, detection, and diagnosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:S2-S8.

7. Newton JR, Ah-See KW. A review of nasal polyposis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:507-512.

8. Badia L, Lund V. Topical corticosteroids in nasal polyposis. Drugs. 2001;61:573-578.

9. Fahrenholz JM. Natural history and clinical features of aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2003;24:113-124.

10. van den Aardweg MT, Schilder AG, Herket E, et al. Adenoidectomy for recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD008282.

11. Demirhan H, Aksoy F, Ozturan O, et al. Medical treatment of adenoid hypertrophy with “fluticasone propionate nasal drops”. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74:773-776.

12. Shokouhi F, Jahromi AM, Majidi MR, et al. Montelukast in adenoid hypertrophy: its effect on size and symptoms. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;27:433-448.

13. Goldbart AD, Greenberg-Dotan S, Tai A. Montelukast for children with obstructive sleep apnea: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e575-e580.

14. Moss WJ, Kjos KB, Karnezis TT, et al. Intranasal steroid injections and blindness: our personal experience and a review of the past 60 years. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:796-800.

15. Chusakul S, Warathanasin S, Suksangpanya N, et al. Comparison of buffered and nonbuffered nasal saline irrigations in treating allergic rhinitis. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:53-56.

16. Xu Y, Zhang J, Wang J. The efficacy and safety of selective H1-antihistamine versus leukotriene receptor antagonist for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112815.

17. Werler MM, Sheehan JE, Mitchell AA. Maternal medication use and risks of gastroschisis and small intestinal atresia. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:26-31.

18. Lexi-Comp Online. Available at: online.lexi.com/crlsql/servlet/crlonline. Accessed November 9, 2016.

19. Kennedy DW. Prognostic factors, outcomes and staging in ethmoid sinus surgery. Laryngoscope.1992;102:1-18.

20. Khalil HS, Nunez DA. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD004458.

21. Chambers DW, Davis WE, Cook PR, et al. Long-term outcome analysis of functional endoscopic sinus surgery: correlation of symptoms with endoscopic examination findings and potential prognostic variables. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:504-510.

22. Senior BA, Kennedy DW, Tanabodee J, et al. Long-term results of functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:151-157.

23. Jakobsen J, Svendstrup F. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery in chronic sinusitis—a series of 237 consecutively operated patients. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2000;543:158-161.

24. Aziz T, Biron VL, Ansari K, et al. Measurement tools for the diagnosis of nasal septal deviation: a systematic review. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;43:11.

25. Grutzenmacher S, Robinson DM, Grafe K, et al. First findings concerning airflow in noses with septal deviation and compensatory turbinate hypertrophy—a model study. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2006;68:199-205.

26. van Egmond MMHT, Rovers MM, Hendriks CTM, et al. Effectiveness of septoplasty versus non-surgical management for nasal obstruction due to deviated nasal septum in adults: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:500.

27. Gandomi B, Bayat A, Kazemei T. Outcomes of septoplasty in young adults: the Nasal Obstruction Septoplasty Effectiveness study. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31:189-192.

28. Døsen L, Have R. Silicone button in nasal septal perforation. Long term observations. Rhinology. 2008;46:324-327.

29. Kridel RW. Considerations in the etiology, treatment and repair of septal perforations. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2004;12:435-450.

30. Goh AY, Hussain SS. Different surgical treatments for nasal septal perforation and their outcomes. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:419-426.

31. Mackle T, Conlon B. Foreign bodies of the nose and ears in children. Should these be managed in the accident and emergency setting? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:425-428.

32. Cook S, Burton M, Glasziou P. Efficacy and safety of the “mother’s kiss” technique: a systematic review of case reports and case series. CMAJ. 2012;184:E904-E912.

33. Turner JH, Reh DD. Incidence and survival in patients with sinonasal cancer: a historical analysis of population-based data. Head Neck. 2012;34:877-885.

34. Benninger MS. The impact of cigarette smoking and environmental tobacco smoke on nasal and sinus disease: a review of the literature. Am J Rhinol. 1999:13:435-438.

35. Luce D, Gerin M, Leclerc A, et al. Sinonasal cancer and occupational exposure to formaldehyde and other substances. Int J Cancer. 1993;53:224-231.

36. Mayr SI, Hafizovic K, Waldfahrer F, et al. Characterization of initial clinical symptoms and risk factors for sinonasal adenocarcinomas: results of a case-control study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2010;83;631-638.

37. Syrjänen KJ. HPV infections in benign and malignant sinonasal lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:174-181.

38. Wood JW, Casiano RR. Inverted papillomas and benign nonneoplastic lesions of the nasal cavity. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26:157-163.

39. Eggesbø HB. Imaging of sinonasal tumours. Cancer Imaging. 2012;12:136-152.

Nasal obstruction is one of the most common reasons that patients visit their primary care providers.1,2 Often described by patients as nasal congestion or the inability to adequately breathe out of one or both nostrils during the day and/or night, nasal obstruction commonly interferes with a patient’s ability to eat, sleep, and function, thereby significantly impacting quality of life. Overlapping presentations can make discerning the exact cause of nasal obstruction difficult.

To improve diagnosis and treatment, we review here the evidence-based recommendations for the most common causes of nasal obstruction: rhinitis, rhinosinusitis (RS), drug-induced nasal obstruction, and mechanical/structural abnormalities (TABLE 13-14).

Rhinitis/rhinosinusitis: It all begins with inflammation

Sneezing, rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, and nasal itching are complaints that signal rhinitis, which affects 30 to 60 million people in the United States annually.3 Rhinitis can be allergic, non-allergic, infectious, hormonal, or occupational in nature. All forms of rhinitis share inflammation as the cause of the nasal obstruction. The most common form is allergic rhinitis (AR), which includes seasonal AR and perennial AR. Seasonal AR is typically caused by outdoor allergens and waxes and wanes with pollen seasons. Perennial AR is caused mostly by indoor allergens, such as dust mites, molds, cockroaches, and pet dander; it persists all or most of the year.6 Causes of non-allergic rhinitis (NAR) include environmental irritants such as cigarette smoke, perfume, and car exhaust; medications; and hormonal changes,6 but most causes of NAR are unknown.3,6

While AR can begin at any age, most people develop symptoms in childhood or as young adults, whereas NAR tends to begin later in life. Nasal itching can help to distinguish AR from NAR. NAR symptoms tend to be perennial and include postnasal drainage. If symptoms persist longer than 12 weeks despite treatment, the condition becomes known as chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS).

Treatment of rhinitis: Tiered and often continuous

Treatment of AR and NAR is similar and multitiered beginning with the avoidance of irritants and/or allergens whenever possible, moving on to pharmacotherapy, and, at least for AR, ending with allergen immunotherapy. Treatment is often an ongoing process and typically requires continuous therapy as opposed to treatment on an as-needed basis.3 It is unnecessary to perform allergy testing before making a presumed diagnosis of NAR and starting treatment.6

Intranasal corticosteroids. Currently, intranasal glucocorticosteroids (INGCs) are the most effective monotherapy for AR and NAR and have few adverse effects when used at prescribed doses.3,4 For mild to intermittent symptoms, begin with the maximum dosage of an INGC for the patient’s age and proceed with incremental reductions to identify the lowest effective dose.3 If INGCs alone are ineffective, studies have shown that the addition of an intranasal second-generation antihistamine can be of some benefit.3,4 In fact, an INGC and an intranasal antihistamine—along with saline nasal irrigation—is recommended for both AR and NAR resistant to single therapy.3,6,15 If intranasal antihistamines are not an option, oral therapy can be initiated.

Start with second-generation antihistamines and consider LRAs. For oral therapy, start with second-generation antihistamines (loratadine, cetirizine, fexofenadine). First-generation antihistamines (diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, chlorpheniramine), although widely available at relatively low cost, can cause several significant adverse effects including sedation, impaired cognitive function, and agitation in children.3,4 Because second-generation antihistamines have fewer adverse effects, they are recommended as first-line therapy when oral antihistamine therapy is desired, such as for nasal congestion, sneezing, and itchy, watery eyes.

Of note: A 2014 meta-analysis found that a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LRA) (montelukast) had efficacy similar to oral antihistamines for symptom relief in AR, and that LRAs may be better suited to nighttime symptoms (difficulty falling asleep, nighttime awakenings, congestion on awakening), while antihistamines may provide better relief of daytime symptoms (pruritus, rhinorrhea, sneezing).16 Although further head-to-head, double-blind randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are needed to confirm the results and investigate possible gender differences in symptom response, consider an LRA for first-line therapy in patients with AR who have predominantly nighttime symptoms.

What about pregnant women and the elderly?

It is important to consider teratogenicity when selecting medications for pregnant patients, especially during the first trimester.3 Nasal cromolyn has the most reassuring safety profile in pregnancy. Cetirizine, chlorpheniramine, loratadine, diphenhydramine, and tripelennamine may be used in pregnancy. The US Food and Drug Administration considers them to have a low risk of fetal harm, based on human data, whereas it views many other antihistamines as probably safe, based on limited or no human data. Most INGCs are not expected to cause fetal harm, but limited human data are available. Avoid prescribing oral decongestants to women who are in the first trimester of pregnancy due to the risk of gastroschisis in newborns.17

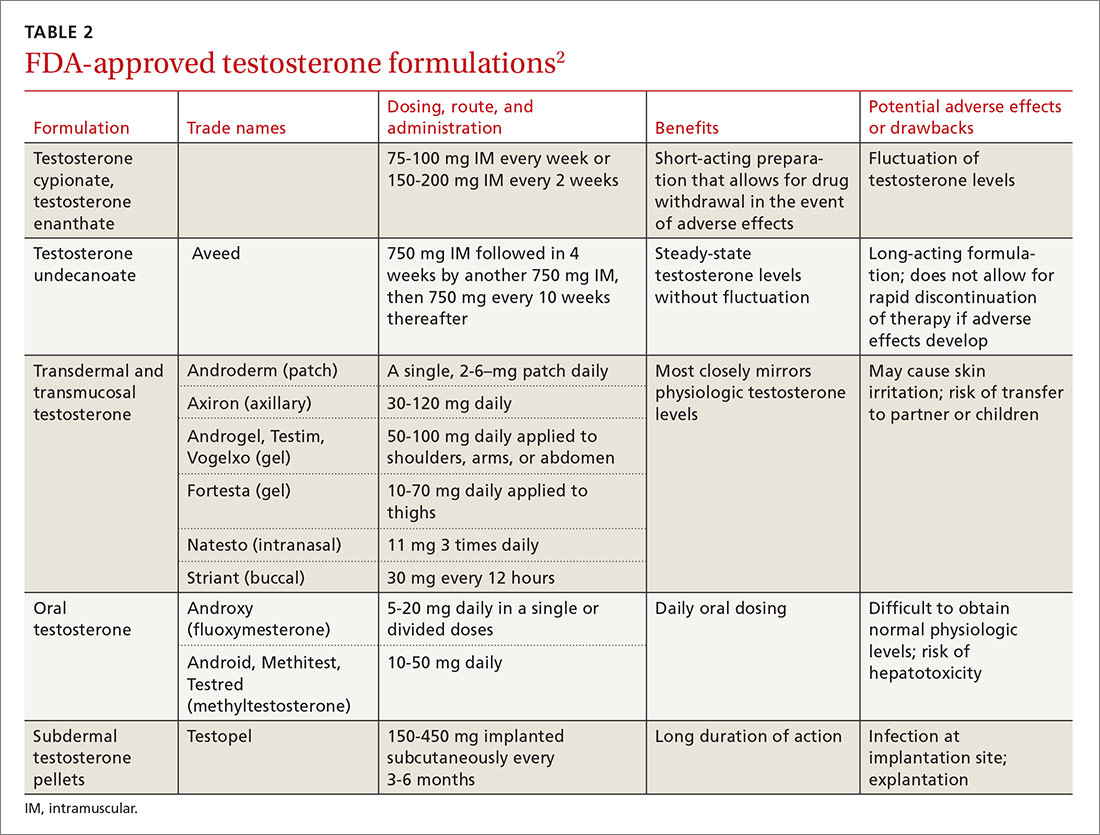

Elderly patients represent another population for which adverse effects must be carefully considered. Allergies in individuals >65 years of age are uncommon. Rhinitis in this age group is often secondary to cholinergic hyperactivity, alpha-adrenergic hyperactivity, or rhinosinusitis. Given elderly patients’ increased susceptibility to the potential adverse central nervous system (CNS) and anticholinergic effects of antihistamines, non-sedating medications are recommended. Oral decongestants also should be used with caution in this population, not only because of CNS effects, but also because of heart and bladder effects3 (TABLE 218).

For drug-induced rhinitis, stop the offending drug and consider an INGC

Several types of medications, both oral and inhaled, are known to cause rhinitis. The use of alpha-adrenergic decongestant sprays for more than 5 to 7 days can induce rebound congestion on withdrawal, known as rhinitis medicamentosa.3 Repeated use of intranasal cocaine and methamphetamines can also result in rebound congestion. Oral medications that can result in rhinitis or congestion include angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta-blockers, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), oral contraceptives, and even antidepressants.3

The treatment for drug-induced rhinitis is termination of the offending agent. INGCs can be used to help decrease inflammation and control symptoms once the offending agent is discontinued.

Mechanical/structural causes of obstruction are wide-ranging

Mechanical/structural causes of nasal obstruction range from foreign bodies to anatomical variations including nasal polyps, a deviated septum, adenoidal hypertrophy, foreign bodies, and tumors. Because more than one etiology may be at work, it is best to first treat any non-mechanical causes of obstruction, such as ARS or NARS.

Nasal polyposis often requires both a medical and surgical approach

Nasal polyps are benign growths arising from the mucosa of the nasal sinuses and nasal cavities and affecting up to 4% of the population.7 Their etiology is unclear, but we do know that nasal polyps result from underlying inflammation.7 Uncommon in children outside of those affected by cystic fibrosis,7 nasal polyposis can be associated with disease processes such as AR and sinusitis. Polyps are also associated with clinical syndromes such as aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD) syndrome, which involves upper and lower respiratory tract symptoms in patients with asthma who have taken aspirin or other NSAIDs.9

Symptoms vary with the location and size of the polyps, but generally include nasal congestion, alteration in smell, and rhinorrhea. The goals of treatment are to restore or improve nasal breathing and olfaction and prevent recurrence.8 This often requires both a medical and surgical approach.

Topical corticosteroids are effective at reducing both the size of polyps and associated symptoms (rhinorrhea, rhinitis).8 And research has shown that steroids reduce the need for both primary and repeat surgical polypectomies.4 Other treatments to consider prior to surgery (if no symptom reduction occurs with INGCs) include systemic (oral) corticosteroids, intra-polyp steroid injections, macrolide antibiotics, and nasal washes.7,14

When symptoms of polyposis are refractory to medical management, functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) is the surgical procedure of choice.3 In addition to refractory symptoms, indications for FESS include the need to correct anatomic deformities believed to be contributing to the persistence of disease and the need to debulk advanced nasal polyposis.3 The principal goal is to restore patency to the ostiomeatal unit.3

Several studies have reported a high success rate for FESS in improving the symptoms of CRS.3,19-23 In a 1992 study, for example, 98% of patients reported improvement following surgery,19 and in a follow-up report approximately 6 years later, 98% of patients continued to report subjective improvement.22

For septal etiologies, consider septoplasty

Deviation of the nasal septum is a common structural etiology for nasal obstruction arising primarily from congenital, genetic, or traumatic causes.24 Turbulent airflow from the septal deviation often causes turbinate hypertrophy, which creates (or exacerbates) the obstructive symptoms from the septal deviation.25

Septoplasty is the most common ear, nose, and throat operation in adults.26 Reduction of nasal symptoms has been reported in up to 89% of patients who receive this surgery, according to one single-center, non-randomized trial.27 Currently, at least one multicenter, randomized trial is underway that aims to develop evidence-based guidelines for septoplasty.26

Septal perforation is another etiology that can present with nasal obstruction symptoms. Causes include traumatic perforation, inflammatory or collagen vascular diseases, infections, overuse of vasoconstrictive medications, and malignancy.28,29 A careful inspection of the nasal septum is necessary to identify a perforation; this may require nasal endoscopy.

Anterior, rather than posterior, perforations are more likely to cause symptoms of nasal obstruction. Posterior perforations rarely require treatment unless malignancy is suspected, in which case referral for biopsy is recommended. Anterior perforations are treated initially with avoidance of any causative agent if, for example, the problem is drug- or medication-induced, and then with humidification and emollients.28,29

For anterior perforations, septal silicone buttons can be used for recalcitrant symptoms. However, observational studies indicate that for long-term symptom resolution, silicone buttons are effective in only about one-third of patients.29

For patients with persistent symptoms despite the above measures, surgical repair with various flap techniques is an option. A meta-analysis of case studies involving various techniques concluded that there is a wide variety of options, and that surgeons must weigh factors such as the characteristics and etiology of the perforation and their own experience and expertise when choosing from among available methods.30 Additional good quality research is necessary before clear recommendations regarding technique can be made.

Adenoid hypertrophy: Consider corticosteroid nasal drops

Adenoid hypertrophy is a common cause of chronic nasal obstruction in children. Although adenoidectomy is commonly performed to correct the problem, current evidence regarding the efficacy of the procedure is inconclusive.10 Evidence demonstrates corticosteroid nasal drops significantly reduce symptoms of nasal obstruction in children and may provide an effective alternative to surgical resection.18 Studies have also demonstrated that treatment with oral LRAs significantly reduces adenoid size and nasal obstruction symptoms.12,13

Foreign bodies: Don’t forget “a mother’s kiss”

Foreign bodies are the most common cause of nasal obstruction in the pediatric population. There is a paucity of high-quality evidence on removal of these objects; however, a number of retrospective reviews and case series support that most objects can be removed in the office or emergency department without otolaryngologic referral.31,32

Techniques for removal include positive pressure, which is best used for smooth or soft objects. Positive pressure techniques include having the patient blow their own nose or having a parent use a mouth-to-mouth–type blowing technique (ie, the “mother’s kiss” method).32 Refer patients to Otolaryngology if the obstruction involves:31

- objects not easily visualized by anterior rhinoscopy

- chronic or impacted objects

- button batteries or magnets

- penetrating or hooked objects

- any object that cannot be removed during an initial attempt.

Nasal tumors: More common in older men

Nasal tumors occur most often in the nasal cavity itself and are more common in men ≥60 years.33 There is no notable racial predominance.33 Other risk factors include human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, tobacco smoke, and occupational exposure to inhaled wood dust, glues, and adhesives.34-37

Benign tumors occurring in the nasal cavity are a diverse group of disorders, including inverted papillomas, squamous papillomas, pyogenic granulomas, and other less common lesions, all of which typically present with nasal obstruction as a symptom. Many of these lesions cause local tissue destruction or have a high incidence of recurrence. These tumors are treated universally with nasoendoscopic resection.38

Malignant nasal tumors are rare but serious causes of nasal obstruction, making up 3% of all head and neck cancers.39 Most nasal cancers present when they are locally advanced and cause unilateral nasal obstruction, lacrimation, and epistaxis. These symptoms are typically refractory to initial medical management and present as CRS. This diagnosis should be suspected in certain patient groups, such as those who have been exposed to wood dust (eg, construction workers or those who work in wood mills).36

Computed tomography is the gold standard imaging method for CRS; however, if nasal cancer is suspected, referral for biopsy and histopathologic examination is necessary for a final diagnosis.39 Because of the nonspecific nature of their initial presentation, many nasal tumors are at an advanced stage and carry a poor prognosis by the time they are diagnosed.39

CORRESPONDENCE

Margaret A. Bayard, MD, MPH, FAAFP, Naval Hospital Camp Pendleton, 200 Mercy Circle, Camp Pendleton, CA 92005; [email protected].

Nasal obstruction is one of the most common reasons that patients visit their primary care providers.1,2 Often described by patients as nasal congestion or the inability to adequately breathe out of one or both nostrils during the day and/or night, nasal obstruction commonly interferes with a patient’s ability to eat, sleep, and function, thereby significantly impacting quality of life. Overlapping presentations can make discerning the exact cause of nasal obstruction difficult.

To improve diagnosis and treatment, we review here the evidence-based recommendations for the most common causes of nasal obstruction: rhinitis, rhinosinusitis (RS), drug-induced nasal obstruction, and mechanical/structural abnormalities (TABLE 13-14).

Rhinitis/rhinosinusitis: It all begins with inflammation

Sneezing, rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, and nasal itching are complaints that signal rhinitis, which affects 30 to 60 million people in the United States annually.3 Rhinitis can be allergic, non-allergic, infectious, hormonal, or occupational in nature. All forms of rhinitis share inflammation as the cause of the nasal obstruction. The most common form is allergic rhinitis (AR), which includes seasonal AR and perennial AR. Seasonal AR is typically caused by outdoor allergens and waxes and wanes with pollen seasons. Perennial AR is caused mostly by indoor allergens, such as dust mites, molds, cockroaches, and pet dander; it persists all or most of the year.6 Causes of non-allergic rhinitis (NAR) include environmental irritants such as cigarette smoke, perfume, and car exhaust; medications; and hormonal changes,6 but most causes of NAR are unknown.3,6

While AR can begin at any age, most people develop symptoms in childhood or as young adults, whereas NAR tends to begin later in life. Nasal itching can help to distinguish AR from NAR. NAR symptoms tend to be perennial and include postnasal drainage. If symptoms persist longer than 12 weeks despite treatment, the condition becomes known as chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS).

Treatment of rhinitis: Tiered and often continuous

Treatment of AR and NAR is similar and multitiered beginning with the avoidance of irritants and/or allergens whenever possible, moving on to pharmacotherapy, and, at least for AR, ending with allergen immunotherapy. Treatment is often an ongoing process and typically requires continuous therapy as opposed to treatment on an as-needed basis.3 It is unnecessary to perform allergy testing before making a presumed diagnosis of NAR and starting treatment.6

Intranasal corticosteroids. Currently, intranasal glucocorticosteroids (INGCs) are the most effective monotherapy for AR and NAR and have few adverse effects when used at prescribed doses.3,4 For mild to intermittent symptoms, begin with the maximum dosage of an INGC for the patient’s age and proceed with incremental reductions to identify the lowest effective dose.3 If INGCs alone are ineffective, studies have shown that the addition of an intranasal second-generation antihistamine can be of some benefit.3,4 In fact, an INGC and an intranasal antihistamine—along with saline nasal irrigation—is recommended for both AR and NAR resistant to single therapy.3,6,15 If intranasal antihistamines are not an option, oral therapy can be initiated.

Start with second-generation antihistamines and consider LRAs. For oral therapy, start with second-generation antihistamines (loratadine, cetirizine, fexofenadine). First-generation antihistamines (diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, chlorpheniramine), although widely available at relatively low cost, can cause several significant adverse effects including sedation, impaired cognitive function, and agitation in children.3,4 Because second-generation antihistamines have fewer adverse effects, they are recommended as first-line therapy when oral antihistamine therapy is desired, such as for nasal congestion, sneezing, and itchy, watery eyes.

Of note: A 2014 meta-analysis found that a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LRA) (montelukast) had efficacy similar to oral antihistamines for symptom relief in AR, and that LRAs may be better suited to nighttime symptoms (difficulty falling asleep, nighttime awakenings, congestion on awakening), while antihistamines may provide better relief of daytime symptoms (pruritus, rhinorrhea, sneezing).16 Although further head-to-head, double-blind randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are needed to confirm the results and investigate possible gender differences in symptom response, consider an LRA for first-line therapy in patients with AR who have predominantly nighttime symptoms.

What about pregnant women and the elderly?

It is important to consider teratogenicity when selecting medications for pregnant patients, especially during the first trimester.3 Nasal cromolyn has the most reassuring safety profile in pregnancy. Cetirizine, chlorpheniramine, loratadine, diphenhydramine, and tripelennamine may be used in pregnancy. The US Food and Drug Administration considers them to have a low risk of fetal harm, based on human data, whereas it views many other antihistamines as probably safe, based on limited or no human data. Most INGCs are not expected to cause fetal harm, but limited human data are available. Avoid prescribing oral decongestants to women who are in the first trimester of pregnancy due to the risk of gastroschisis in newborns.17

Elderly patients represent another population for which adverse effects must be carefully considered. Allergies in individuals >65 years of age are uncommon. Rhinitis in this age group is often secondary to cholinergic hyperactivity, alpha-adrenergic hyperactivity, or rhinosinusitis. Given elderly patients’ increased susceptibility to the potential adverse central nervous system (CNS) and anticholinergic effects of antihistamines, non-sedating medications are recommended. Oral decongestants also should be used with caution in this population, not only because of CNS effects, but also because of heart and bladder effects3 (TABLE 218).

For drug-induced rhinitis, stop the offending drug and consider an INGC

Several types of medications, both oral and inhaled, are known to cause rhinitis. The use of alpha-adrenergic decongestant sprays for more than 5 to 7 days can induce rebound congestion on withdrawal, known as rhinitis medicamentosa.3 Repeated use of intranasal cocaine and methamphetamines can also result in rebound congestion. Oral medications that can result in rhinitis or congestion include angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta-blockers, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), oral contraceptives, and even antidepressants.3

The treatment for drug-induced rhinitis is termination of the offending agent. INGCs can be used to help decrease inflammation and control symptoms once the offending agent is discontinued.

Mechanical/structural causes of obstruction are wide-ranging

Mechanical/structural causes of nasal obstruction range from foreign bodies to anatomical variations including nasal polyps, a deviated septum, adenoidal hypertrophy, foreign bodies, and tumors. Because more than one etiology may be at work, it is best to first treat any non-mechanical causes of obstruction, such as ARS or NARS.

Nasal polyposis often requires both a medical and surgical approach

Nasal polyps are benign growths arising from the mucosa of the nasal sinuses and nasal cavities and affecting up to 4% of the population.7 Their etiology is unclear, but we do know that nasal polyps result from underlying inflammation.7 Uncommon in children outside of those affected by cystic fibrosis,7 nasal polyposis can be associated with disease processes such as AR and sinusitis. Polyps are also associated with clinical syndromes such as aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD) syndrome, which involves upper and lower respiratory tract symptoms in patients with asthma who have taken aspirin or other NSAIDs.9

Symptoms vary with the location and size of the polyps, but generally include nasal congestion, alteration in smell, and rhinorrhea. The goals of treatment are to restore or improve nasal breathing and olfaction and prevent recurrence.8 This often requires both a medical and surgical approach.

Topical corticosteroids are effective at reducing both the size of polyps and associated symptoms (rhinorrhea, rhinitis).8 And research has shown that steroids reduce the need for both primary and repeat surgical polypectomies.4 Other treatments to consider prior to surgery (if no symptom reduction occurs with INGCs) include systemic (oral) corticosteroids, intra-polyp steroid injections, macrolide antibiotics, and nasal washes.7,14

When symptoms of polyposis are refractory to medical management, functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) is the surgical procedure of choice.3 In addition to refractory symptoms, indications for FESS include the need to correct anatomic deformities believed to be contributing to the persistence of disease and the need to debulk advanced nasal polyposis.3 The principal goal is to restore patency to the ostiomeatal unit.3

Several studies have reported a high success rate for FESS in improving the symptoms of CRS.3,19-23 In a 1992 study, for example, 98% of patients reported improvement following surgery,19 and in a follow-up report approximately 6 years later, 98% of patients continued to report subjective improvement.22

For septal etiologies, consider septoplasty

Deviation of the nasal septum is a common structural etiology for nasal obstruction arising primarily from congenital, genetic, or traumatic causes.24 Turbulent airflow from the septal deviation often causes turbinate hypertrophy, which creates (or exacerbates) the obstructive symptoms from the septal deviation.25

Septoplasty is the most common ear, nose, and throat operation in adults.26 Reduction of nasal symptoms has been reported in up to 89% of patients who receive this surgery, according to one single-center, non-randomized trial.27 Currently, at least one multicenter, randomized trial is underway that aims to develop evidence-based guidelines for septoplasty.26

Septal perforation is another etiology that can present with nasal obstruction symptoms. Causes include traumatic perforation, inflammatory or collagen vascular diseases, infections, overuse of vasoconstrictive medications, and malignancy.28,29 A careful inspection of the nasal septum is necessary to identify a perforation; this may require nasal endoscopy.

Anterior, rather than posterior, perforations are more likely to cause symptoms of nasal obstruction. Posterior perforations rarely require treatment unless malignancy is suspected, in which case referral for biopsy is recommended. Anterior perforations are treated initially with avoidance of any causative agent if, for example, the problem is drug- or medication-induced, and then with humidification and emollients.28,29

For anterior perforations, septal silicone buttons can be used for recalcitrant symptoms. However, observational studies indicate that for long-term symptom resolution, silicone buttons are effective in only about one-third of patients.29

For patients with persistent symptoms despite the above measures, surgical repair with various flap techniques is an option. A meta-analysis of case studies involving various techniques concluded that there is a wide variety of options, and that surgeons must weigh factors such as the characteristics and etiology of the perforation and their own experience and expertise when choosing from among available methods.30 Additional good quality research is necessary before clear recommendations regarding technique can be made.

Adenoid hypertrophy: Consider corticosteroid nasal drops

Adenoid hypertrophy is a common cause of chronic nasal obstruction in children. Although adenoidectomy is commonly performed to correct the problem, current evidence regarding the efficacy of the procedure is inconclusive.10 Evidence demonstrates corticosteroid nasal drops significantly reduce symptoms of nasal obstruction in children and may provide an effective alternative to surgical resection.18 Studies have also demonstrated that treatment with oral LRAs significantly reduces adenoid size and nasal obstruction symptoms.12,13

Foreign bodies: Don’t forget “a mother’s kiss”

Foreign bodies are the most common cause of nasal obstruction in the pediatric population. There is a paucity of high-quality evidence on removal of these objects; however, a number of retrospective reviews and case series support that most objects can be removed in the office or emergency department without otolaryngologic referral.31,32

Techniques for removal include positive pressure, which is best used for smooth or soft objects. Positive pressure techniques include having the patient blow their own nose or having a parent use a mouth-to-mouth–type blowing technique (ie, the “mother’s kiss” method).32 Refer patients to Otolaryngology if the obstruction involves:31

- objects not easily visualized by anterior rhinoscopy

- chronic or impacted objects

- button batteries or magnets

- penetrating or hooked objects

- any object that cannot be removed during an initial attempt.

Nasal tumors: More common in older men

Nasal tumors occur most often in the nasal cavity itself and are more common in men ≥60 years.33 There is no notable racial predominance.33 Other risk factors include human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, tobacco smoke, and occupational exposure to inhaled wood dust, glues, and adhesives.34-37

Benign tumors occurring in the nasal cavity are a diverse group of disorders, including inverted papillomas, squamous papillomas, pyogenic granulomas, and other less common lesions, all of which typically present with nasal obstruction as a symptom. Many of these lesions cause local tissue destruction or have a high incidence of recurrence. These tumors are treated universally with nasoendoscopic resection.38

Malignant nasal tumors are rare but serious causes of nasal obstruction, making up 3% of all head and neck cancers.39 Most nasal cancers present when they are locally advanced and cause unilateral nasal obstruction, lacrimation, and epistaxis. These symptoms are typically refractory to initial medical management and present as CRS. This diagnosis should be suspected in certain patient groups, such as those who have been exposed to wood dust (eg, construction workers or those who work in wood mills).36

Computed tomography is the gold standard imaging method for CRS; however, if nasal cancer is suspected, referral for biopsy and histopathologic examination is necessary for a final diagnosis.39 Because of the nonspecific nature of their initial presentation, many nasal tumors are at an advanced stage and carry a poor prognosis by the time they are diagnosed.39

CORRESPONDENCE

Margaret A. Bayard, MD, MPH, FAAFP, Naval Hospital Camp Pendleton, 200 Mercy Circle, Camp Pendleton, CA 92005; [email protected].

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC’s FastStats on Ambulatory Care Use and Physician Office Visits. Selected patient and provider characteristics for ambulatory care visits to physician offices and hospital outpatient and emergency departments: United States, 2009-2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/combined_tables/AMC_2009-2010_combined_web_table01.pdf. Accessed November 9, 2016.

2. US Census Bureau. Table 158. Visits to office-based physician and hospital outpatient departments, 2006. Available at: http://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2006/compendia/statab/126ed/tables/07s0158.xls. Accessed November 13, 2016.

3. Dykewicz MS, Hamilos DL. Rhinitis and sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:S103-S115.

4. Wallace DV, Dykewicz MS. The diagnosis and management of rhinitis: an updated practice parameter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:S1-S84.

5. Krouse J, Lund V, Fokkens W, et al. Diagnostic strategies in nasal congestion. Int J Gen Med. 2010;3:59-67.

6. Skoner DP. Allergic rhinitis: definition, epidemiology, pathophysiology, detection, and diagnosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:S2-S8.

7. Newton JR, Ah-See KW. A review of nasal polyposis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:507-512.

8. Badia L, Lund V. Topical corticosteroids in nasal polyposis. Drugs. 2001;61:573-578.

9. Fahrenholz JM. Natural history and clinical features of aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2003;24:113-124.

10. van den Aardweg MT, Schilder AG, Herket E, et al. Adenoidectomy for recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD008282.

11. Demirhan H, Aksoy F, Ozturan O, et al. Medical treatment of adenoid hypertrophy with “fluticasone propionate nasal drops”. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74:773-776.

12. Shokouhi F, Jahromi AM, Majidi MR, et al. Montelukast in adenoid hypertrophy: its effect on size and symptoms. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;27:433-448.

13. Goldbart AD, Greenberg-Dotan S, Tai A. Montelukast for children with obstructive sleep apnea: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e575-e580.

14. Moss WJ, Kjos KB, Karnezis TT, et al. Intranasal steroid injections and blindness: our personal experience and a review of the past 60 years. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:796-800.

15. Chusakul S, Warathanasin S, Suksangpanya N, et al. Comparison of buffered and nonbuffered nasal saline irrigations in treating allergic rhinitis. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:53-56.

16. Xu Y, Zhang J, Wang J. The efficacy and safety of selective H1-antihistamine versus leukotriene receptor antagonist for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112815.

17. Werler MM, Sheehan JE, Mitchell AA. Maternal medication use and risks of gastroschisis and small intestinal atresia. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:26-31.

18. Lexi-Comp Online. Available at: online.lexi.com/crlsql/servlet/crlonline. Accessed November 9, 2016.

19. Kennedy DW. Prognostic factors, outcomes and staging in ethmoid sinus surgery. Laryngoscope.1992;102:1-18.

20. Khalil HS, Nunez DA. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD004458.

21. Chambers DW, Davis WE, Cook PR, et al. Long-term outcome analysis of functional endoscopic sinus surgery: correlation of symptoms with endoscopic examination findings and potential prognostic variables. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:504-510.

22. Senior BA, Kennedy DW, Tanabodee J, et al. Long-term results of functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:151-157.

23. Jakobsen J, Svendstrup F. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery in chronic sinusitis—a series of 237 consecutively operated patients. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2000;543:158-161.

24. Aziz T, Biron VL, Ansari K, et al. Measurement tools for the diagnosis of nasal septal deviation: a systematic review. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;43:11.

25. Grutzenmacher S, Robinson DM, Grafe K, et al. First findings concerning airflow in noses with septal deviation and compensatory turbinate hypertrophy—a model study. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2006;68:199-205.

26. van Egmond MMHT, Rovers MM, Hendriks CTM, et al. Effectiveness of septoplasty versus non-surgical management for nasal obstruction due to deviated nasal septum in adults: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:500.

27. Gandomi B, Bayat A, Kazemei T. Outcomes of septoplasty in young adults: the Nasal Obstruction Septoplasty Effectiveness study. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31:189-192.

28. Døsen L, Have R. Silicone button in nasal septal perforation. Long term observations. Rhinology. 2008;46:324-327.

29. Kridel RW. Considerations in the etiology, treatment and repair of septal perforations. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2004;12:435-450.

30. Goh AY, Hussain SS. Different surgical treatments for nasal septal perforation and their outcomes. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:419-426.

31. Mackle T, Conlon B. Foreign bodies of the nose and ears in children. Should these be managed in the accident and emergency setting? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:425-428.

32. Cook S, Burton M, Glasziou P. Efficacy and safety of the “mother’s kiss” technique: a systematic review of case reports and case series. CMAJ. 2012;184:E904-E912.

33. Turner JH, Reh DD. Incidence and survival in patients with sinonasal cancer: a historical analysis of population-based data. Head Neck. 2012;34:877-885.

34. Benninger MS. The impact of cigarette smoking and environmental tobacco smoke on nasal and sinus disease: a review of the literature. Am J Rhinol. 1999:13:435-438.

35. Luce D, Gerin M, Leclerc A, et al. Sinonasal cancer and occupational exposure to formaldehyde and other substances. Int J Cancer. 1993;53:224-231.

36. Mayr SI, Hafizovic K, Waldfahrer F, et al. Characterization of initial clinical symptoms and risk factors for sinonasal adenocarcinomas: results of a case-control study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2010;83;631-638.

37. Syrjänen KJ. HPV infections in benign and malignant sinonasal lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:174-181.

38. Wood JW, Casiano RR. Inverted papillomas and benign nonneoplastic lesions of the nasal cavity. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26:157-163.

39. Eggesbø HB. Imaging of sinonasal tumours. Cancer Imaging. 2012;12:136-152.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC’s FastStats on Ambulatory Care Use and Physician Office Visits. Selected patient and provider characteristics for ambulatory care visits to physician offices and hospital outpatient and emergency departments: United States, 2009-2010. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/combined_tables/AMC_2009-2010_combined_web_table01.pdf. Accessed November 9, 2016.

2. US Census Bureau. Table 158. Visits to office-based physician and hospital outpatient departments, 2006. Available at: http://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2006/compendia/statab/126ed/tables/07s0158.xls. Accessed November 13, 2016.

3. Dykewicz MS, Hamilos DL. Rhinitis and sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:S103-S115.

4. Wallace DV, Dykewicz MS. The diagnosis and management of rhinitis: an updated practice parameter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:S1-S84.

5. Krouse J, Lund V, Fokkens W, et al. Diagnostic strategies in nasal congestion. Int J Gen Med. 2010;3:59-67.

6. Skoner DP. Allergic rhinitis: definition, epidemiology, pathophysiology, detection, and diagnosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:S2-S8.

7. Newton JR, Ah-See KW. A review of nasal polyposis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:507-512.

8. Badia L, Lund V. Topical corticosteroids in nasal polyposis. Drugs. 2001;61:573-578.

9. Fahrenholz JM. Natural history and clinical features of aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2003;24:113-124.

10. van den Aardweg MT, Schilder AG, Herket E, et al. Adenoidectomy for recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD008282.

11. Demirhan H, Aksoy F, Ozturan O, et al. Medical treatment of adenoid hypertrophy with “fluticasone propionate nasal drops”. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74:773-776.

12. Shokouhi F, Jahromi AM, Majidi MR, et al. Montelukast in adenoid hypertrophy: its effect on size and symptoms. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;27:433-448.

13. Goldbart AD, Greenberg-Dotan S, Tai A. Montelukast for children with obstructive sleep apnea: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e575-e580.

14. Moss WJ, Kjos KB, Karnezis TT, et al. Intranasal steroid injections and blindness: our personal experience and a review of the past 60 years. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:796-800.

15. Chusakul S, Warathanasin S, Suksangpanya N, et al. Comparison of buffered and nonbuffered nasal saline irrigations in treating allergic rhinitis. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:53-56.

16. Xu Y, Zhang J, Wang J. The efficacy and safety of selective H1-antihistamine versus leukotriene receptor antagonist for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112815.

17. Werler MM, Sheehan JE, Mitchell AA. Maternal medication use and risks of gastroschisis and small intestinal atresia. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:26-31.

18. Lexi-Comp Online. Available at: online.lexi.com/crlsql/servlet/crlonline. Accessed November 9, 2016.

19. Kennedy DW. Prognostic factors, outcomes and staging in ethmoid sinus surgery. Laryngoscope.1992;102:1-18.

20. Khalil HS, Nunez DA. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD004458.

21. Chambers DW, Davis WE, Cook PR, et al. Long-term outcome analysis of functional endoscopic sinus surgery: correlation of symptoms with endoscopic examination findings and potential prognostic variables. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:504-510.

22. Senior BA, Kennedy DW, Tanabodee J, et al. Long-term results of functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:151-157.

23. Jakobsen J, Svendstrup F. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery in chronic sinusitis—a series of 237 consecutively operated patients. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2000;543:158-161.

24. Aziz T, Biron VL, Ansari K, et al. Measurement tools for the diagnosis of nasal septal deviation: a systematic review. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;43:11.

25. Grutzenmacher S, Robinson DM, Grafe K, et al. First findings concerning airflow in noses with septal deviation and compensatory turbinate hypertrophy—a model study. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2006;68:199-205.

26. van Egmond MMHT, Rovers MM, Hendriks CTM, et al. Effectiveness of septoplasty versus non-surgical management for nasal obstruction due to deviated nasal septum in adults: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:500.

27. Gandomi B, Bayat A, Kazemei T. Outcomes of septoplasty in young adults: the Nasal Obstruction Septoplasty Effectiveness study. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31:189-192.

28. Døsen L, Have R. Silicone button in nasal septal perforation. Long term observations. Rhinology. 2008;46:324-327.

29. Kridel RW. Considerations in the etiology, treatment and repair of septal perforations. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2004;12:435-450.

30. Goh AY, Hussain SS. Different surgical treatments for nasal septal perforation and their outcomes. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:419-426.

31. Mackle T, Conlon B. Foreign bodies of the nose and ears in children. Should these be managed in the accident and emergency setting? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:425-428.

32. Cook S, Burton M, Glasziou P. Efficacy and safety of the “mother’s kiss” technique: a systematic review of case reports and case series. CMAJ. 2012;184:E904-E912.

33. Turner JH, Reh DD. Incidence and survival in patients with sinonasal cancer: a historical analysis of population-based data. Head Neck. 2012;34:877-885.

34. Benninger MS. The impact of cigarette smoking and environmental tobacco smoke on nasal and sinus disease: a review of the literature. Am J Rhinol. 1999:13:435-438.

35. Luce D, Gerin M, Leclerc A, et al. Sinonasal cancer and occupational exposure to formaldehyde and other substances. Int J Cancer. 1993;53:224-231.

36. Mayr SI, Hafizovic K, Waldfahrer F, et al. Characterization of initial clinical symptoms and risk factors for sinonasal adenocarcinomas: results of a case-control study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2010;83;631-638.

37. Syrjänen KJ. HPV infections in benign and malignant sinonasal lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:174-181.

38. Wood JW, Casiano RR. Inverted papillomas and benign nonneoplastic lesions of the nasal cavity. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26:157-163.

39. Eggesbø HB. Imaging of sinonasal tumours. Cancer Imaging. 2012;12:136-152.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Consider intranasal corticosteroids for patients with nasal polyps, as they are effective at reducing the size of the polyps and associated symptoms of obstruction, rhinorrhea, and rhinitis. A

› Prescribe intranasal corticosteroids for patients with adenoid hypertrophy. A

› Refer patients with chronic refractory rhinosinusitis for functional endoscopic sinus surgery. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A look at the burden of opioid management in primary care

ABSTRACT

Purpose Pain management with opioids in primary care is challenging. The objective of this study was to identify the number of opioid-related tasks in our clinics and determine whether opioid-related tasks occur more often in a residency setting.

Methods This was a retrospective observational review of an electronic health record (EHR) system to evaluate tasks related to the use of opioids and other controlled substances. Tasks are created in the EHR when patients call the clinic; the task-box system is a means of communication within the EHR. The study setting was 2 university-based family medicine clinics. Clinic 1 has faculty and resident providers in an urban area. Clinic 2 has only faculty providers in a suburban area. We reviewed all tasks recorded in November 2010.

Results A total of 3193 patients were seen at the clinics. In addition, 1028 call-related tasks were created, 220 of which (21.4%) were opioid-related. More than half of the tasks were about chronic (ongoing) patient issues. More than one‑third of the tasks required follow-up phone calls. Multiple logistic regression analysis showed more opioid-related tasks in the residency setting (Clinic 1) compared with the nonresidency setting (Clinic 2), (23.1% vs 16.7%; P<.001). However, multiple logistic regression analysis did not show any correlations between opioid-related tasks and who addressed the tasks or the day tasks were created.

Conclusions Primary care physicians prescribe significant amounts of opioids. Due to the nature of opioid use and abuse, a well-planned protocol customized to the practice or institution is required to streamline this process and decrease the number of unnecessary phone calls and follow-ups.

Pain management with opioids in primary care is challenging,1,2 and many physicians find it unsatisfying and burdensome.3 More than 60 million patient visits for chronic pain occur annually in the United States, consuming large amounts of time and resources.4 Contributing to the challenge is the need to ensure patient safety and satisfaction, as well as staff satisfaction with pain management.5-8 Opioid-related death is a major cause of iatrogenic mortality in the United States:9,10 From 1999 to 2006, fatal opioid-involved intoxications more than tripled from 4000 to 13,800.7

At issue for many providers, as well as patients and staff, is dissatisfaction with current systems in place for managing chronic non-cancer pain with opioids.2,3,8,11 In developing this study, we decided to focus on the systems aspect of care with 2 primary outcome measures in mind. Specifically, we sought to identify the tasks related to managing opioids and other controlled substances in 2 primary care clinics in a university-based family medicine program and to determine what proportion of all routine tasks in these 2 clinics could be attributed to opioid-related issues. With our secondary outcome measures, we sought to compare the number of opioid-related tasks in the residency setting with those in a nonresidency setting, and to identify factors that might be associated with an increase in the number of opioid-related tasks.

METHODS

Setting and design

We conducted a retrospective observational pilot study reviewing our electronic health record (EHR) system (Allscripts TouchWorks) at 2 of our outpatient family medicine clinics at the University of Colorado. When patients call the clinics, or when patient-care-related concerns need to be addressed, an electronic task message is created and sent to the appropriate task box for staff or provider response. The task box system is how staff and providers communicate within the EHR. Each provider has a personal task box, and there are other task boxes in the system (eg, triage, medication refill) for urgent and non-urgent patient care issues.

For example, when a patient calls to request a refill, a medical assistant (MA), care team assistant (CTA), or nurse will create a task for the medication refill box. If the task is urgent, it is marked with a red asterisk and a triage provider will address the task that same day. Non-urgent triage tasks will be addressed by the patient’s primary care provider within 2 to 3 days. Depending on the issue at hand, the task may or may not require phone calls to the patient, pharmacy, or insurance company.

Clinic 1, in urban Denver, has 13 physicians (many of them part-time clinical faculty), one nurse practitioner (NP), one physician assistant (PA), and 18 family medicine residents. Clinic 2, in a suburb of Denver, has 5 physicians (only one is part-time) and one nurse practitioner. Clinic 1 is divided into 3 pods, and each has the same number of attending physicians, residents, and MAs, and either a PA or NP.

We reviewed, one by one, all tasks created from November 1 to 30, 2010. One of the study’s investigators categorized each task according to the following descriptors: who created the task, who addressed the task, what day of the week the task was created, urgency of the task, whether the task required a follow-up phone call, and whether the task was related to opioid/controlled-substance issues. The task was categorized as acute if the issue was related to a condition that had been present for fewer than 3 weeks. Chronic tasks were created for conditions present for ≥3 weeks. At the time the study was completed, our EHR had no portal through which we could communicate with patients.

ANALYSIS

We conducted statistical analyses with the IBM SPSS, version 22.0 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, Illinois). We used descriptive statistics to examine the frequency and percentage for all variables. We used a chi-squared (χ2) test to assess the differences between the 2 clinics, and used a binary multiple logistic regression model to determine possible factors related to opioid-related tasks. P values <.05 were considered statistically significant. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved this study.

RESULTS

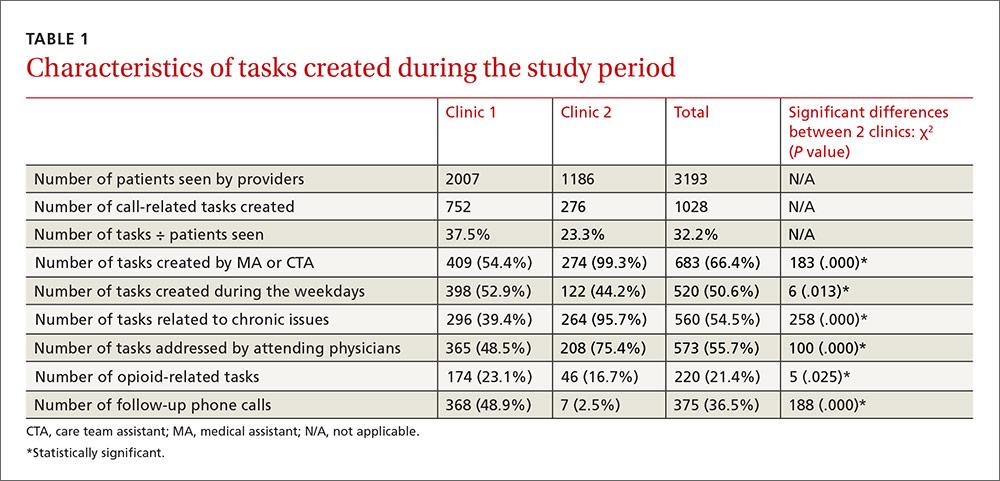

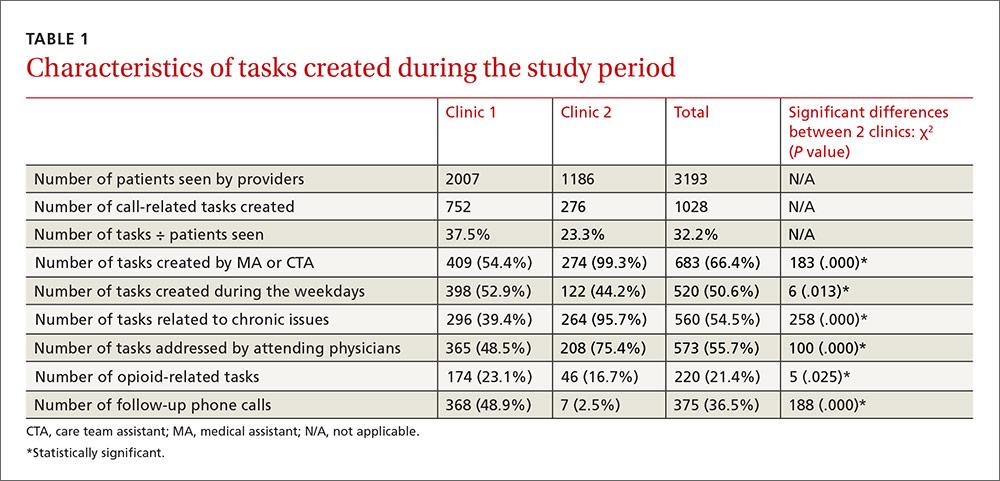

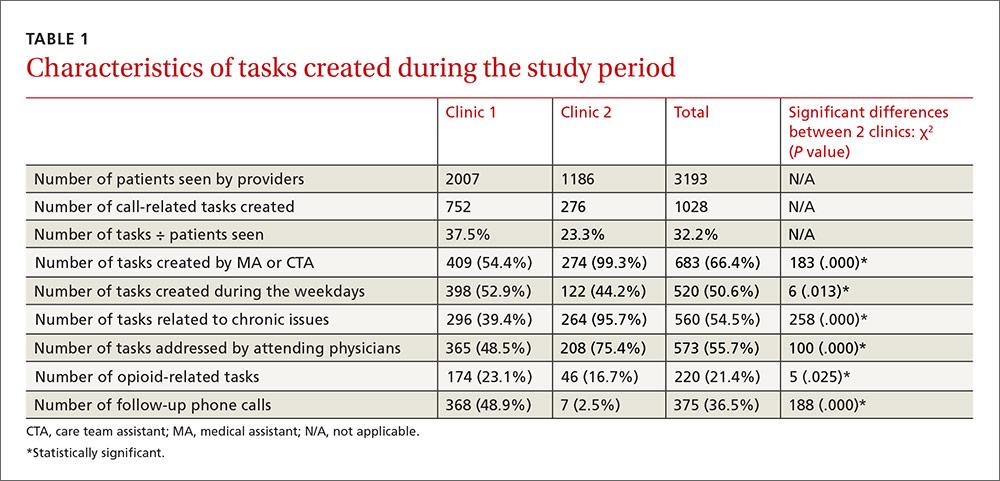

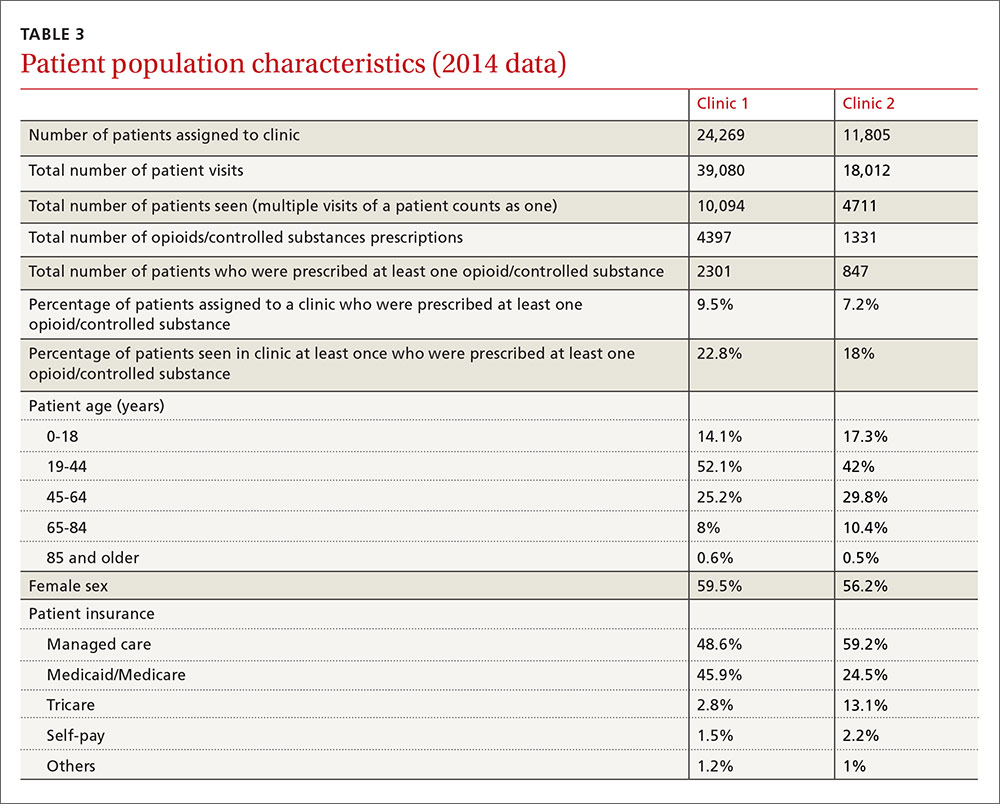

Clinics 1 and 2, respectively, saw 2007 and 1186 patients during the study period (TABLE 1). The additional 1028 tasks generated by phone calls were almost equally distributed among the 3 pods of Clinic 1 (290, 202, and 260) and Clinic 2 (276). For data analysis, we compared Clinic 1 with Clinic 2 and also compared the 3 pods of Clinic 1 individually with Clinic 2. Both approaches produced similar results.

Most tasks (54% for Clinic 1 and 99% for Clinic 2) were created by MAs and CTAs. At Clinic 1, tasks were also created by residents (17%), PA/NPs (8%), attending physicians (7%), and others/clinical nurses (14%). Tasks at Clinic 1 were addressed by attending physicians (49%), residents (25%), PA/NPs (25%), and others (1%). At Clinic 2, tasks were addressed by attending physicians (75%) and PA/NPs (25%). Approximately half of the tasks (51%) in both clinics were created during weekdays, compared with the day after weekends/holidays (28%), the day before weekends/holidays (17%), and during weekends/holidays (4%). Chronic patient issues, acute patient issues, and other issues accounted for 54%, 29%, and 17% of tasks, respectively. Follow-up phone calls to patients, pharmacies, or others occurred in 37% of tasks. Two hundred twenty tasks (21%) in the clinics combined were related to opioids and controlled substances.

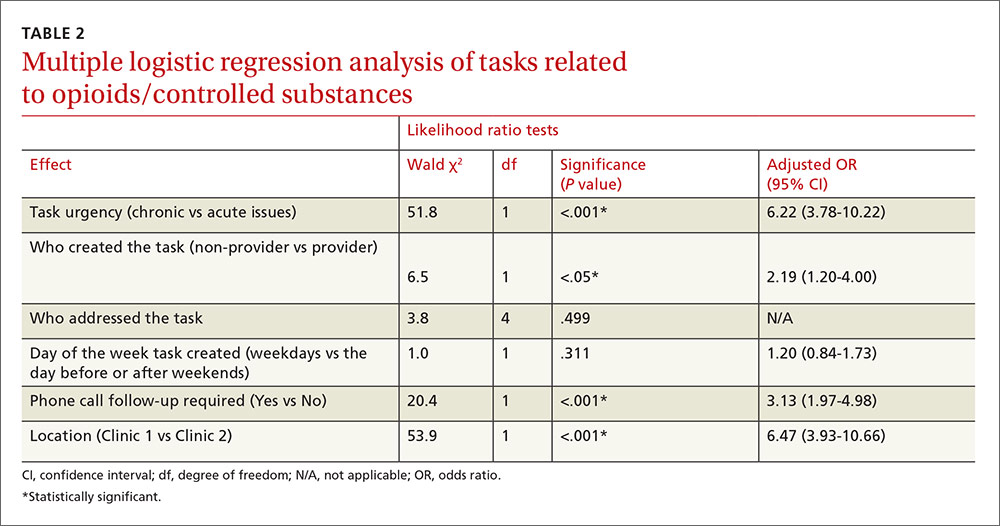

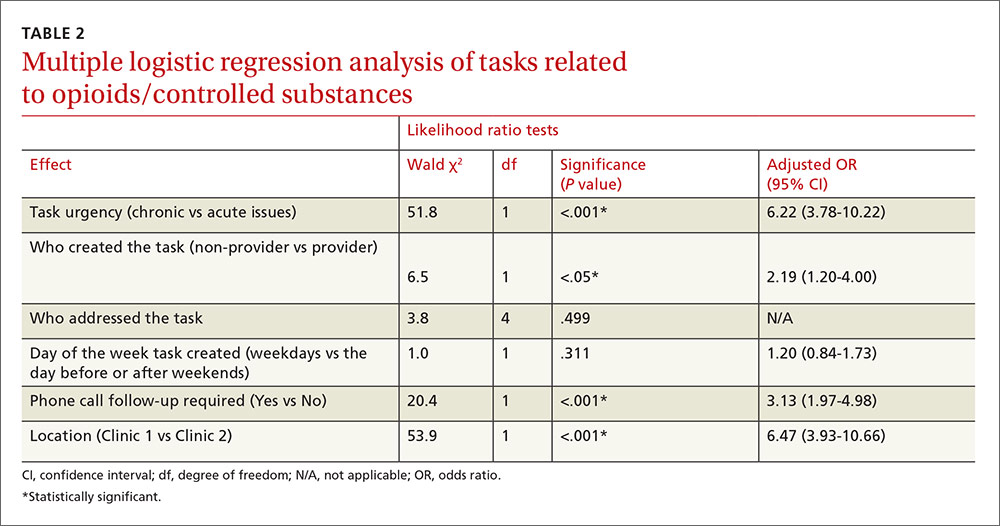

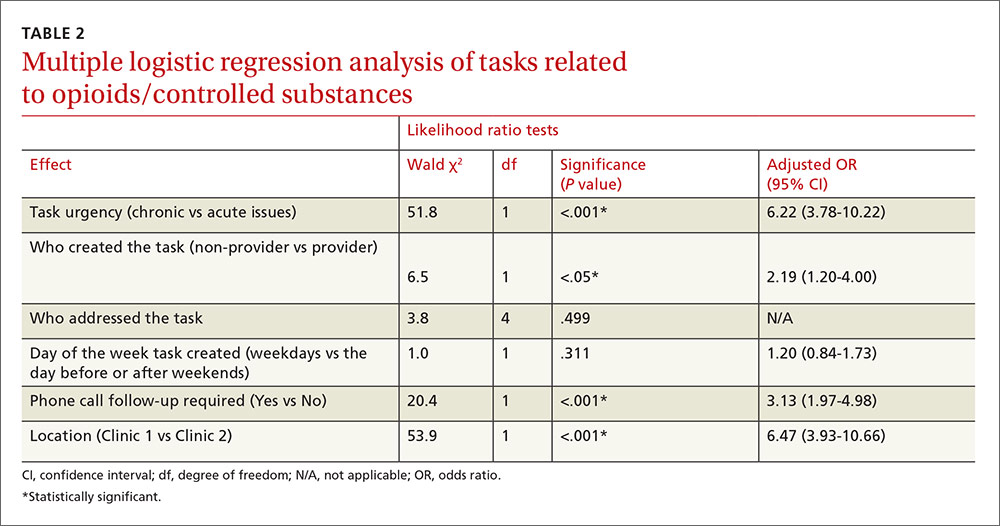

Multiple logistic regression analysis of data from both clinics (TABLE 2) showed more opioid-related tasks in Clinic 1 compared with Clinic 2 (P<.001), and that these tasks were more often related to chronic issues than to acute issues (P<.001). Tasks created by MAs, CTAs, clinical nurses, and others were more likely to be opioid-related compared with the tasks created by attending physicians, residents, NPs, or a PA (25% vs 15%; P<.05). Compared with non-opioid-related tasks, opioid-related tasks required more follow-up phone calls (P<.001). Follow-up phone calls to pharmacies occurred more often with opioid-related tasks than with non-opioid tasks (11% vs 5%), while follow-up phone calls to patients occurred more often for non-opioid related tasks than opioid-related tasks (28% vs 18%). No correlations with task creation were found for who addressed the opioid-related task or the day the task was created.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that our process of handling patient issues related to opioids accounts for a large proportion of all tasks. Dealing with tasks is time consuming, not only for attending physicians and residents but also for clinic nurses and staff. Almost a quarter of clinic tasks were opioid related. As has been shown in previous studies,5-8 chronic pain management with opioids is an unsatisfying task for staff and care providers at our clinics. We also found that tasks created by non-providers were more likely to be opioid-related than were tasks created by providers. This is most likely due to the fact that non-providers cannot write prescriptions and they have to ask providers for further reviews.

Khalid et al found that, compared with attending physicians, residents had more patients on chronic opioids who displayed concerning behaviors, including early refills and refills from multiple providers.13 The higher number of part-time providers at Clinic 1 in our study may have also caused insufficient continuity of care at that site. Nevertheless, this model of practice is used in many academic primary care institutions.4 Another possible reason for the difference could be a lack of resident training on current guidelines for managing opiates for chronic pain.3,13,14 Again, this was a pilot study and we drew no solid conclusion about the reasons for differences between these 2 clinics.

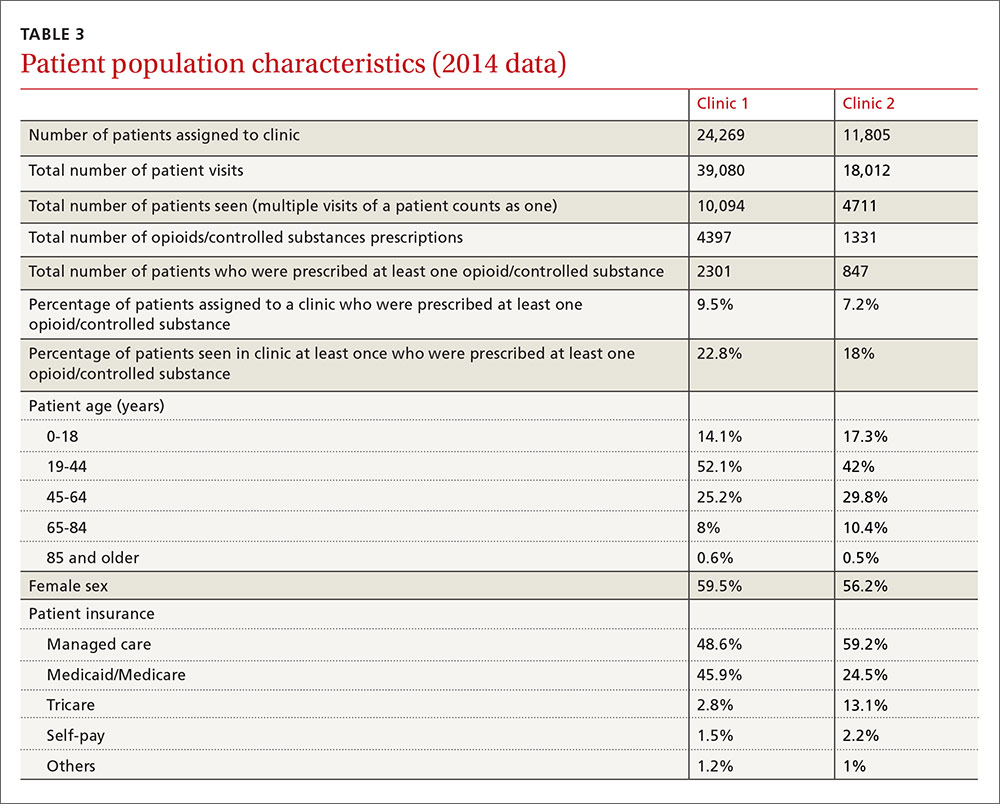

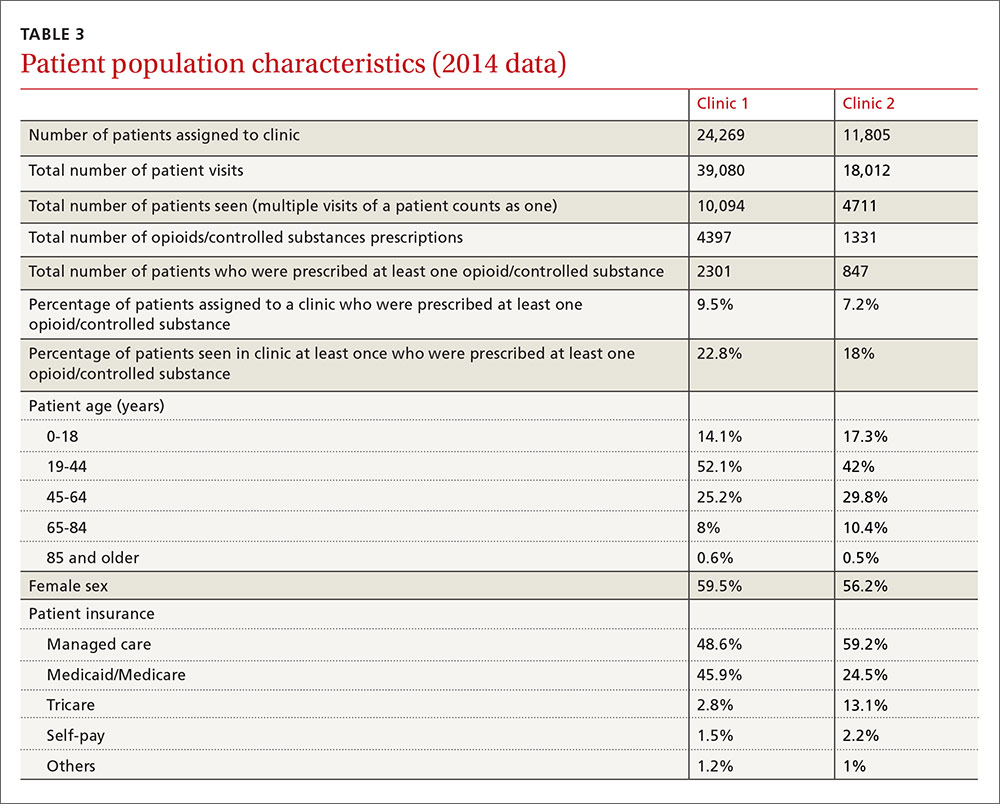

It is obvious, however, that we spend a significant amount of time and resources dealing with chronic pain management. Our institution created an opioid/controlled-substance patient registry about 3 years ago. The data for 2014 showed that 22.8% and 18% of patients seen at least once at Clinic 1 and Clinic 2, respectively, were prescribed opioids/controlled substances (TABLE 3).

Possible solutions to reduce tasks related to opioid management. For both small and large practices, one way to reduce the number of tasks related to opioid management and, therefore, the time allocated to completing those tasks, would be to have a clear protocol to follow.3,4,8,11,14,15 The protocol may include the creation of an opioid/controlled-substance registry and the development and implementation of clinical decision support programs.

We also recommend the dissemination of tools for clinical management at the point of care. These can include a controlled-substance risk assessment tool for aberrant behaviors, a controlled-substance informed consent form, a functional and quality-of-life assessment, electronic clinical-note templates in the EHR, urine drug screening, and routine use of existing state pharmacy prescription drug monitoring programs. Also essential would be the provision of routine educational programs for clinicians regarding chronic pain management based on existing evidence and guidelines. (See “Opioids for chronic pain: The CDC’s 12 recommendations.”) It has been demonstrated that an EHR opioid dashboard or an EHR-based protocol improved adherence to guidelines for prescribing opiates.16

This study has several limitations. First, this was a small pilot study completed over a short period of time, although we believe the findings are likely representative of the prescribing practices in the 2 clinics we evaluated. Second, it was a retrospective study, which was appropriate for evaluating our questions. Third, we were unable to account for other factors that could potentially confound the results, including, but not limited to, the amount of time allocated to each task, and the total number of patients at each clinic who were on opioids for management of chronic pain during the study period. However, due to our recent addition of an opioid/controlled-substance patient registry, we were able to add information for the year 2014 (TABLE 3). Multi-center large scale studies are required to evaluate this further.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Corey Lyon for his editorial assistance.

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, AFW Family Medicine Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected].

1. Smith BH, Torrance N. Management of chronic pain in primary care. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2011;5:137-142.

2. Zgierska A, Miller M, Rabago D. Patient satisfaction, prescription drug abuse, and potential unintended consequences. JAMA. 2012;307:1377-1378.

3. Leverence RR, Williams RL, Potter M, et al; PRIME Net Clinicians. Chronic non-cancer pain: a siren for primary care—a report from the PRImary Care MultiEthnic Network (PRIME Net). J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:551-561.

4. Watkins A, Wasmann S, Dodson L, et al. An evaluation of the care provided to patients prescribed controlled substances for chronic nonmalignant pain at an academic family medicine center. Fam Med. 2004;36:487-489.

5. Brown J, Setnik B, Lee K, et al. Assessment, stratification, and monitoring of the risk for prescription opioid misuse and abuse in the primary care setting. J Opioid Manag. 2011;7:467-483.

6. Duensing L, Eksterowicz N, Macario A, et al. Patient and physician perceptions of treatment of moderate-to-severe chronic pain with oral opioids. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:1579-1585.

7. Webster LR, Cochella S, Dasgupta N, et al. An analysis of the root causes for opioid-related overdose deaths in the United States. Pain Med. 2011;12:S26-S35.

8. Wenghofer EF, Wilson L, Kahan M, et al. Survey of Ontario primary care physicians’ experiences with opioid prescribing. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:324-332.