User login

Getting it right at the end of life

Although the concept of the living will was first proposed in 1969

In contrast, an informal search of PubMed reveals that at least 38 articles on advance directives and end-of-life care have been published during the first 7 months of 2017. And a feature article in this month’s issue of JFP makes one more. Why is there such strong interest now in an issue that seldom arose when I began practice in 1978?

More complex, less personalized medicine. As medical care has become more sophisticated, there is a great deal more we can do to keep people alive as they approach the end of life, and a great many more decisions to be made.

Additionally, people are much less likely today to be cared for in their dying days by a family physician who knows them, their wishes, and their family well. In my early years in small-town practice, I was present when my patients were dying, and I usually knew their family members. Family meetings were easy to arrange, and we quickly came to a consensus about what to do and what not to do. If I was not available, one of my practice partners was. We cared for our patients in the office, nursing home, and hospital. Now, most dying hospitalized patients are cared for by hospitalists who may be meeting the patient for the first time.

Getting more people to participate. Consequently, it is important to understand patients’ wishes for end-of-life care and to document those wishes in writing, using things like a POLST (Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment) form. Although randomized trials support the value of advance care planning, especially in primary care settings,3,4 two-thirds of Americans have not completed an advance directive.5 Rolnick suggests we “delegalize” the process to remove barriers and make it easier for people to execute such documents and integrate them into health care systems.6

Make it part of your office routine. A 70-year-old patient of mine with advanced COPD arrived at his office visit last month with advance directive and POLST forms in hand. We had an excellent, frank conversation, spiced with humor that he supplied, about his wishes for end-of-life care. Just like so many other tasks that we must squeeze into our busy schedules, this is one that we should hard-wire into our office systems and routines.

1. Kutner L. Due process of euthanasia: the living will, a proposal. Indiana Law J. 1969;44:539-554.

2. Schneiderman LJ, Arras JD. Counseling patients to counsel physicians on future care in the event of patient incompetence. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:693-698.

3. Weathers E, O’Caoimh R, Cornally N, et al. Advance care planning: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials conducted with older adults. Maturitas. 2016;91:101-109.

4. Tierney WM, Dexter PR, Gramelspacher GP, et al. The effect of discussions about advance directives on patients’ satisfaction with primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:32-40.

5. Yadav KN, Gabler NB, Cooney E, et al. Approximately one in three US adults completes any type of advance directive for end-of-life care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36:1244-1251.

6. Rolnick JA, Asch DA, Halpern SD. Delegalizing advance directives—facilitating advance care planning. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2105-2107.

Although the concept of the living will was first proposed in 1969

In contrast, an informal search of PubMed reveals that at least 38 articles on advance directives and end-of-life care have been published during the first 7 months of 2017. And a feature article in this month’s issue of JFP makes one more. Why is there such strong interest now in an issue that seldom arose when I began practice in 1978?

More complex, less personalized medicine. As medical care has become more sophisticated, there is a great deal more we can do to keep people alive as they approach the end of life, and a great many more decisions to be made.

Additionally, people are much less likely today to be cared for in their dying days by a family physician who knows them, their wishes, and their family well. In my early years in small-town practice, I was present when my patients were dying, and I usually knew their family members. Family meetings were easy to arrange, and we quickly came to a consensus about what to do and what not to do. If I was not available, one of my practice partners was. We cared for our patients in the office, nursing home, and hospital. Now, most dying hospitalized patients are cared for by hospitalists who may be meeting the patient for the first time.

Getting more people to participate. Consequently, it is important to understand patients’ wishes for end-of-life care and to document those wishes in writing, using things like a POLST (Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment) form. Although randomized trials support the value of advance care planning, especially in primary care settings,3,4 two-thirds of Americans have not completed an advance directive.5 Rolnick suggests we “delegalize” the process to remove barriers and make it easier for people to execute such documents and integrate them into health care systems.6

Make it part of your office routine. A 70-year-old patient of mine with advanced COPD arrived at his office visit last month with advance directive and POLST forms in hand. We had an excellent, frank conversation, spiced with humor that he supplied, about his wishes for end-of-life care. Just like so many other tasks that we must squeeze into our busy schedules, this is one that we should hard-wire into our office systems and routines.

Although the concept of the living will was first proposed in 1969

In contrast, an informal search of PubMed reveals that at least 38 articles on advance directives and end-of-life care have been published during the first 7 months of 2017. And a feature article in this month’s issue of JFP makes one more. Why is there such strong interest now in an issue that seldom arose when I began practice in 1978?

More complex, less personalized medicine. As medical care has become more sophisticated, there is a great deal more we can do to keep people alive as they approach the end of life, and a great many more decisions to be made.

Additionally, people are much less likely today to be cared for in their dying days by a family physician who knows them, their wishes, and their family well. In my early years in small-town practice, I was present when my patients were dying, and I usually knew their family members. Family meetings were easy to arrange, and we quickly came to a consensus about what to do and what not to do. If I was not available, one of my practice partners was. We cared for our patients in the office, nursing home, and hospital. Now, most dying hospitalized patients are cared for by hospitalists who may be meeting the patient for the first time.

Getting more people to participate. Consequently, it is important to understand patients’ wishes for end-of-life care and to document those wishes in writing, using things like a POLST (Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment) form. Although randomized trials support the value of advance care planning, especially in primary care settings,3,4 two-thirds of Americans have not completed an advance directive.5 Rolnick suggests we “delegalize” the process to remove barriers and make it easier for people to execute such documents and integrate them into health care systems.6

Make it part of your office routine. A 70-year-old patient of mine with advanced COPD arrived at his office visit last month with advance directive and POLST forms in hand. We had an excellent, frank conversation, spiced with humor that he supplied, about his wishes for end-of-life care. Just like so many other tasks that we must squeeze into our busy schedules, this is one that we should hard-wire into our office systems and routines.

1. Kutner L. Due process of euthanasia: the living will, a proposal. Indiana Law J. 1969;44:539-554.

2. Schneiderman LJ, Arras JD. Counseling patients to counsel physicians on future care in the event of patient incompetence. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:693-698.

3. Weathers E, O’Caoimh R, Cornally N, et al. Advance care planning: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials conducted with older adults. Maturitas. 2016;91:101-109.

4. Tierney WM, Dexter PR, Gramelspacher GP, et al. The effect of discussions about advance directives on patients’ satisfaction with primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:32-40.

5. Yadav KN, Gabler NB, Cooney E, et al. Approximately one in three US adults completes any type of advance directive for end-of-life care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36:1244-1251.

6. Rolnick JA, Asch DA, Halpern SD. Delegalizing advance directives—facilitating advance care planning. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2105-2107.

1. Kutner L. Due process of euthanasia: the living will, a proposal. Indiana Law J. 1969;44:539-554.

2. Schneiderman LJ, Arras JD. Counseling patients to counsel physicians on future care in the event of patient incompetence. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:693-698.

3. Weathers E, O’Caoimh R, Cornally N, et al. Advance care planning: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials conducted with older adults. Maturitas. 2016;91:101-109.

4. Tierney WM, Dexter PR, Gramelspacher GP, et al. The effect of discussions about advance directives on patients’ satisfaction with primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:32-40.

5. Yadav KN, Gabler NB, Cooney E, et al. Approximately one in three US adults completes any type of advance directive for end-of-life care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36:1244-1251.

6. Rolnick JA, Asch DA, Halpern SD. Delegalizing advance directives—facilitating advance care planning. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2105-2107.

Low-grade fever, erythematous rash in pregnant woman • Dx?

THE CASE

A 31-year-old woman presented to her obstetrician’s office at 16 weeks’ gestation with a 2-day history of low-grade fever and an erythematous rash measuring 1 x 4 cm on her right groin. She had a medical history of a penicillin allergy (urticaria) and her outdoor activities included gardening and picnicking.

We suspected that she was experiencing an allergic reaction and recommended an antihistamine (diphenhydramine). The patient returned 4 days later with new symptoms including headache, photophobia, neck pain, unilateral large joint pain, and periorbital cellulitis, as well as expansion of her rash. She was afebrile and an examination revealed that the 1 x 4 cm rash on her groin had grown; it was now a demarcated erythematous rash with faint central clearing measuring 5 x 8 cm. Right periorbital erythema and nuchal rigidity were also noted.

Because of her expanding rash and nuchal rigidity, we suspected Lyme meningitis and we referred her to the emergency department. Within 24 hours, the rash had spread to her abdomen, thigh, and wrist, and was consistent with erythema migrans.

Laboratory evaluation revealed an increased number of white bloods cells (13.5 million cells/mcL; normal range 4.5-11.0 million cells/mcL), and an increased number of neutrophils (10.8 million cells/mcL; normal range 1.8-8 million cells/mcL), indicating leukocytosis with a left shift. Lab tests also revealed a low hemoglobin level (10.6 g/dL; normal range 12-16 g/dL) and a mean corpuscular volume of 85.6 fL/red cell (normal range 80-100 fL/red cell), indicating microcytic anemia. A lumbar puncture was negative for disseminated Lyme disease by Gram stain, culture, and polymerase chain reaction.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A diagnosis of Lyme disease was confirmed with a positive Lyme titer serology via an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The rash and other symptoms responded promptly to intravenous ceftriaxone 2 g, and the patient was discharged home on oral cefuroxime 500 mg bid for 14 days.

DISCUSSION

Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne illness in the United States, concentrated heavily in the Northeast and upper Midwest.1 The most recent information released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lists Vermont, Maine, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Delaware, New Hampshire, and Minnesota as the states with the highest incidence of Lyme disease.2

The number of reported cases in the United States has increased over the past 2 decades, from approximately 11,000 in 1995 to about 28,000 in 2015.3 Over the past year, we have seen several cases of Lyme disease in the obstetric population of our own practice.

Prompt treatment is crucial. Pregnant women who are acutely infected with Borrelia burgdorferi (the primary cause of Lyme disease) and do not receive treatment have experienced multiple adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm delivery, infants born with rash, and stillbirth.4 Additional concern exists for fetal cardiac anomalies, with data showing that there are twice as many cardiac defects in children born to mothers residing in endemic regions.5

What animal studies have taught us about Lyme disease

The potential causal relationship between Lyme disease and fetal demise was first studied in 2007. This case report involved the stillbirth of a full-term baby from an acutely infected woman who did not receive treatment. She experienced erythema multiforme 6 weeks prior to delivery.6

The vast majority of research on Lyme disease in pregnancy comes from work with mice and dogs. These studies confirmed that acute infection with Lyme disease is associated with an increased risk of adverse fetal outcomes, specifically fetal death.7

Silver et al further researched the association using murine models in the 1980s. They found that fetal death occurred in 12% of acutely infected mice, compared with none of the mice that were chronically infected.7

In 2010, Lakos and Solymosi examined the effects of Lyme disease on pregnancy outcomes in acutely infected women. Seven out of 95 pregnant women acutely infected with B burgdorferi experienced fetal demise, further supporting the association seen in animal experiments.8

Treating pregnant patients

Doxycycline and tetracycline, which are routinely used to treat Lyme disease, are not appropriate in the obstetric population. The CDC recommends up to a 3-week course of antibiotics; the standard regimen is amoxicillin 500 mg by mouth tid. For women who are allergic to penicillin, as was the case with our patient, cefuroxime 500 mg by mouth bid is the treatment of choice.9

Our patient underwent a detailed ultrasound at 21 weeks, which revealed normal fetal anatomy and no evidence of cardiac malformations. The remainder of her pregnancy was uncomplicated, and she gave birth vaginally at 41 weeks to a baby boy weighing 3700 g.

THE TAKEAWAY

There is a need to increase awareness of Lyme disease in pregnancy on a national level. It is the responsibility of every practitioner caring for obstetric patients in endemic regions to address new-onset rash promptly. There have been cases of women who experienced erythema migrans and arthralgias after exposure to a tick bite, later delivering infants with cardiac anomalies such as atrial and ventricular septal defects.10 In obstetric patients acutely infected during the first trimester, a fetal echocardiogram is reasonable, given the demonstrated high potential for fetal cardiac anomalies.

Preventing adverse fetal outcomes requires early treatment with antibiotics. The CDC maintains that there have been no life-threatening adverse fetal effects from Lyme disease seen in women who are appropriately treated, as well as no transmission of Lyme disease in the breast milk of lactating mothers.9

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme disease. Data and statistics. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/. Accessed July 5, 2017.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme disease data tables. Reported cases of Lyme disease by state or locality, 2005-2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/chartstables/reportedcases_statelocality.html. Accessed July 5, 2017.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme disease graphs. Reported cases of Lyme disease by year, United States, 1995-2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/graphs.html. Accessed July 5, 2017.

4. Maraspin V, Cimperman J, Lotric-Furlan S, et al. Erythema migrans in pregnancy. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1999;111:933-940.

5. Strobino BA, Williams CL, Abid S, et al. Lyme disease and pregnancy outcome: a prospective study of two thousand prenatal patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:367-374.

6. Gibbs RS, Roberts DJ. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 27-2007. A 30-year-old pregnant woman with intrauterine fetal death. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:918-925.

7. Silver RM, Yang L, Daynes RA, et al. Fetal outcome in murine Lyme disease. Infect Immun. 1995;63:66-72.

8. Lakos A, Solymosi N. Maternal Lyme borreliosis and pregnancy outcomes. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e494-e498.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ticks and Lyme disease. Pregnancy and Lyme disease. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/resources/toolkit/factsheets/10_508_Lyme%20disease_PregnantWoman_FACTSheet.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2017.

10. O’Brien JM, Martens MG. Lyme disease in pregnancy: a New Jersey medical advisory. MD Advis. 2014;7:24-27.

THE CASE

A 31-year-old woman presented to her obstetrician’s office at 16 weeks’ gestation with a 2-day history of low-grade fever and an erythematous rash measuring 1 x 4 cm on her right groin. She had a medical history of a penicillin allergy (urticaria) and her outdoor activities included gardening and picnicking.

We suspected that she was experiencing an allergic reaction and recommended an antihistamine (diphenhydramine). The patient returned 4 days later with new symptoms including headache, photophobia, neck pain, unilateral large joint pain, and periorbital cellulitis, as well as expansion of her rash. She was afebrile and an examination revealed that the 1 x 4 cm rash on her groin had grown; it was now a demarcated erythematous rash with faint central clearing measuring 5 x 8 cm. Right periorbital erythema and nuchal rigidity were also noted.

Because of her expanding rash and nuchal rigidity, we suspected Lyme meningitis and we referred her to the emergency department. Within 24 hours, the rash had spread to her abdomen, thigh, and wrist, and was consistent with erythema migrans.

Laboratory evaluation revealed an increased number of white bloods cells (13.5 million cells/mcL; normal range 4.5-11.0 million cells/mcL), and an increased number of neutrophils (10.8 million cells/mcL; normal range 1.8-8 million cells/mcL), indicating leukocytosis with a left shift. Lab tests also revealed a low hemoglobin level (10.6 g/dL; normal range 12-16 g/dL) and a mean corpuscular volume of 85.6 fL/red cell (normal range 80-100 fL/red cell), indicating microcytic anemia. A lumbar puncture was negative for disseminated Lyme disease by Gram stain, culture, and polymerase chain reaction.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A diagnosis of Lyme disease was confirmed with a positive Lyme titer serology via an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The rash and other symptoms responded promptly to intravenous ceftriaxone 2 g, and the patient was discharged home on oral cefuroxime 500 mg bid for 14 days.

DISCUSSION

Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne illness in the United States, concentrated heavily in the Northeast and upper Midwest.1 The most recent information released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lists Vermont, Maine, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Delaware, New Hampshire, and Minnesota as the states with the highest incidence of Lyme disease.2

The number of reported cases in the United States has increased over the past 2 decades, from approximately 11,000 in 1995 to about 28,000 in 2015.3 Over the past year, we have seen several cases of Lyme disease in the obstetric population of our own practice.

Prompt treatment is crucial. Pregnant women who are acutely infected with Borrelia burgdorferi (the primary cause of Lyme disease) and do not receive treatment have experienced multiple adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm delivery, infants born with rash, and stillbirth.4 Additional concern exists for fetal cardiac anomalies, with data showing that there are twice as many cardiac defects in children born to mothers residing in endemic regions.5

What animal studies have taught us about Lyme disease

The potential causal relationship between Lyme disease and fetal demise was first studied in 2007. This case report involved the stillbirth of a full-term baby from an acutely infected woman who did not receive treatment. She experienced erythema multiforme 6 weeks prior to delivery.6

The vast majority of research on Lyme disease in pregnancy comes from work with mice and dogs. These studies confirmed that acute infection with Lyme disease is associated with an increased risk of adverse fetal outcomes, specifically fetal death.7

Silver et al further researched the association using murine models in the 1980s. They found that fetal death occurred in 12% of acutely infected mice, compared with none of the mice that were chronically infected.7

In 2010, Lakos and Solymosi examined the effects of Lyme disease on pregnancy outcomes in acutely infected women. Seven out of 95 pregnant women acutely infected with B burgdorferi experienced fetal demise, further supporting the association seen in animal experiments.8

Treating pregnant patients

Doxycycline and tetracycline, which are routinely used to treat Lyme disease, are not appropriate in the obstetric population. The CDC recommends up to a 3-week course of antibiotics; the standard regimen is amoxicillin 500 mg by mouth tid. For women who are allergic to penicillin, as was the case with our patient, cefuroxime 500 mg by mouth bid is the treatment of choice.9

Our patient underwent a detailed ultrasound at 21 weeks, which revealed normal fetal anatomy and no evidence of cardiac malformations. The remainder of her pregnancy was uncomplicated, and she gave birth vaginally at 41 weeks to a baby boy weighing 3700 g.

THE TAKEAWAY

There is a need to increase awareness of Lyme disease in pregnancy on a national level. It is the responsibility of every practitioner caring for obstetric patients in endemic regions to address new-onset rash promptly. There have been cases of women who experienced erythema migrans and arthralgias after exposure to a tick bite, later delivering infants with cardiac anomalies such as atrial and ventricular septal defects.10 In obstetric patients acutely infected during the first trimester, a fetal echocardiogram is reasonable, given the demonstrated high potential for fetal cardiac anomalies.

Preventing adverse fetal outcomes requires early treatment with antibiotics. The CDC maintains that there have been no life-threatening adverse fetal effects from Lyme disease seen in women who are appropriately treated, as well as no transmission of Lyme disease in the breast milk of lactating mothers.9

THE CASE

A 31-year-old woman presented to her obstetrician’s office at 16 weeks’ gestation with a 2-day history of low-grade fever and an erythematous rash measuring 1 x 4 cm on her right groin. She had a medical history of a penicillin allergy (urticaria) and her outdoor activities included gardening and picnicking.

We suspected that she was experiencing an allergic reaction and recommended an antihistamine (diphenhydramine). The patient returned 4 days later with new symptoms including headache, photophobia, neck pain, unilateral large joint pain, and periorbital cellulitis, as well as expansion of her rash. She was afebrile and an examination revealed that the 1 x 4 cm rash on her groin had grown; it was now a demarcated erythematous rash with faint central clearing measuring 5 x 8 cm. Right periorbital erythema and nuchal rigidity were also noted.

Because of her expanding rash and nuchal rigidity, we suspected Lyme meningitis and we referred her to the emergency department. Within 24 hours, the rash had spread to her abdomen, thigh, and wrist, and was consistent with erythema migrans.

Laboratory evaluation revealed an increased number of white bloods cells (13.5 million cells/mcL; normal range 4.5-11.0 million cells/mcL), and an increased number of neutrophils (10.8 million cells/mcL; normal range 1.8-8 million cells/mcL), indicating leukocytosis with a left shift. Lab tests also revealed a low hemoglobin level (10.6 g/dL; normal range 12-16 g/dL) and a mean corpuscular volume of 85.6 fL/red cell (normal range 80-100 fL/red cell), indicating microcytic anemia. A lumbar puncture was negative for disseminated Lyme disease by Gram stain, culture, and polymerase chain reaction.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A diagnosis of Lyme disease was confirmed with a positive Lyme titer serology via an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The rash and other symptoms responded promptly to intravenous ceftriaxone 2 g, and the patient was discharged home on oral cefuroxime 500 mg bid for 14 days.

DISCUSSION

Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne illness in the United States, concentrated heavily in the Northeast and upper Midwest.1 The most recent information released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lists Vermont, Maine, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Delaware, New Hampshire, and Minnesota as the states with the highest incidence of Lyme disease.2

The number of reported cases in the United States has increased over the past 2 decades, from approximately 11,000 in 1995 to about 28,000 in 2015.3 Over the past year, we have seen several cases of Lyme disease in the obstetric population of our own practice.

Prompt treatment is crucial. Pregnant women who are acutely infected with Borrelia burgdorferi (the primary cause of Lyme disease) and do not receive treatment have experienced multiple adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm delivery, infants born with rash, and stillbirth.4 Additional concern exists for fetal cardiac anomalies, with data showing that there are twice as many cardiac defects in children born to mothers residing in endemic regions.5

What animal studies have taught us about Lyme disease

The potential causal relationship between Lyme disease and fetal demise was first studied in 2007. This case report involved the stillbirth of a full-term baby from an acutely infected woman who did not receive treatment. She experienced erythema multiforme 6 weeks prior to delivery.6

The vast majority of research on Lyme disease in pregnancy comes from work with mice and dogs. These studies confirmed that acute infection with Lyme disease is associated with an increased risk of adverse fetal outcomes, specifically fetal death.7

Silver et al further researched the association using murine models in the 1980s. They found that fetal death occurred in 12% of acutely infected mice, compared with none of the mice that were chronically infected.7

In 2010, Lakos and Solymosi examined the effects of Lyme disease on pregnancy outcomes in acutely infected women. Seven out of 95 pregnant women acutely infected with B burgdorferi experienced fetal demise, further supporting the association seen in animal experiments.8

Treating pregnant patients

Doxycycline and tetracycline, which are routinely used to treat Lyme disease, are not appropriate in the obstetric population. The CDC recommends up to a 3-week course of antibiotics; the standard regimen is amoxicillin 500 mg by mouth tid. For women who are allergic to penicillin, as was the case with our patient, cefuroxime 500 mg by mouth bid is the treatment of choice.9

Our patient underwent a detailed ultrasound at 21 weeks, which revealed normal fetal anatomy and no evidence of cardiac malformations. The remainder of her pregnancy was uncomplicated, and she gave birth vaginally at 41 weeks to a baby boy weighing 3700 g.

THE TAKEAWAY

There is a need to increase awareness of Lyme disease in pregnancy on a national level. It is the responsibility of every practitioner caring for obstetric patients in endemic regions to address new-onset rash promptly. There have been cases of women who experienced erythema migrans and arthralgias after exposure to a tick bite, later delivering infants with cardiac anomalies such as atrial and ventricular septal defects.10 In obstetric patients acutely infected during the first trimester, a fetal echocardiogram is reasonable, given the demonstrated high potential for fetal cardiac anomalies.

Preventing adverse fetal outcomes requires early treatment with antibiotics. The CDC maintains that there have been no life-threatening adverse fetal effects from Lyme disease seen in women who are appropriately treated, as well as no transmission of Lyme disease in the breast milk of lactating mothers.9

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme disease. Data and statistics. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/. Accessed July 5, 2017.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme disease data tables. Reported cases of Lyme disease by state or locality, 2005-2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/chartstables/reportedcases_statelocality.html. Accessed July 5, 2017.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme disease graphs. Reported cases of Lyme disease by year, United States, 1995-2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/graphs.html. Accessed July 5, 2017.

4. Maraspin V, Cimperman J, Lotric-Furlan S, et al. Erythema migrans in pregnancy. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1999;111:933-940.

5. Strobino BA, Williams CL, Abid S, et al. Lyme disease and pregnancy outcome: a prospective study of two thousand prenatal patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:367-374.

6. Gibbs RS, Roberts DJ. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 27-2007. A 30-year-old pregnant woman with intrauterine fetal death. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:918-925.

7. Silver RM, Yang L, Daynes RA, et al. Fetal outcome in murine Lyme disease. Infect Immun. 1995;63:66-72.

8. Lakos A, Solymosi N. Maternal Lyme borreliosis and pregnancy outcomes. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e494-e498.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ticks and Lyme disease. Pregnancy and Lyme disease. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/resources/toolkit/factsheets/10_508_Lyme%20disease_PregnantWoman_FACTSheet.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2017.

10. O’Brien JM, Martens MG. Lyme disease in pregnancy: a New Jersey medical advisory. MD Advis. 2014;7:24-27.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme disease. Data and statistics. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/. Accessed July 5, 2017.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme disease data tables. Reported cases of Lyme disease by state or locality, 2005-2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/chartstables/reportedcases_statelocality.html. Accessed July 5, 2017.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme disease graphs. Reported cases of Lyme disease by year, United States, 1995-2015. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/graphs.html. Accessed July 5, 2017.

4. Maraspin V, Cimperman J, Lotric-Furlan S, et al. Erythema migrans in pregnancy. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1999;111:933-940.

5. Strobino BA, Williams CL, Abid S, et al. Lyme disease and pregnancy outcome: a prospective study of two thousand prenatal patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:367-374.

6. Gibbs RS, Roberts DJ. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 27-2007. A 30-year-old pregnant woman with intrauterine fetal death. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:918-925.

7. Silver RM, Yang L, Daynes RA, et al. Fetal outcome in murine Lyme disease. Infect Immun. 1995;63:66-72.

8. Lakos A, Solymosi N. Maternal Lyme borreliosis and pregnancy outcomes. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e494-e498.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ticks and Lyme disease. Pregnancy and Lyme disease. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/resources/toolkit/factsheets/10_508_Lyme%20disease_PregnantWoman_FACTSheet.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2017.

10. O’Brien JM, Martens MG. Lyme disease in pregnancy: a New Jersey medical advisory. MD Advis. 2014;7:24-27.

Progressive hair loss

A 66-year-old white woman presented to her primary care clinic with concerns about hair loss, which began 2 years ago. Recently, she had noticed some “bumps” on her cheeks, as well.

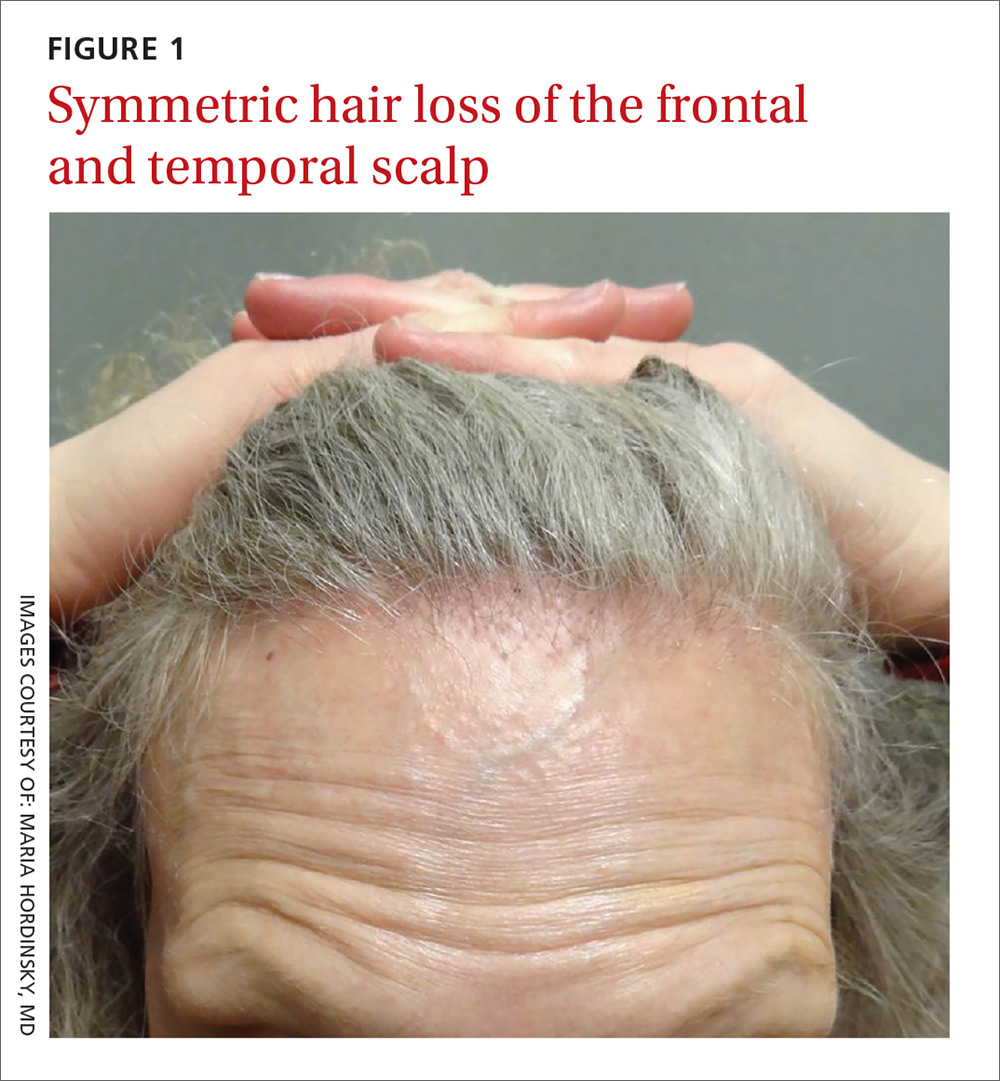

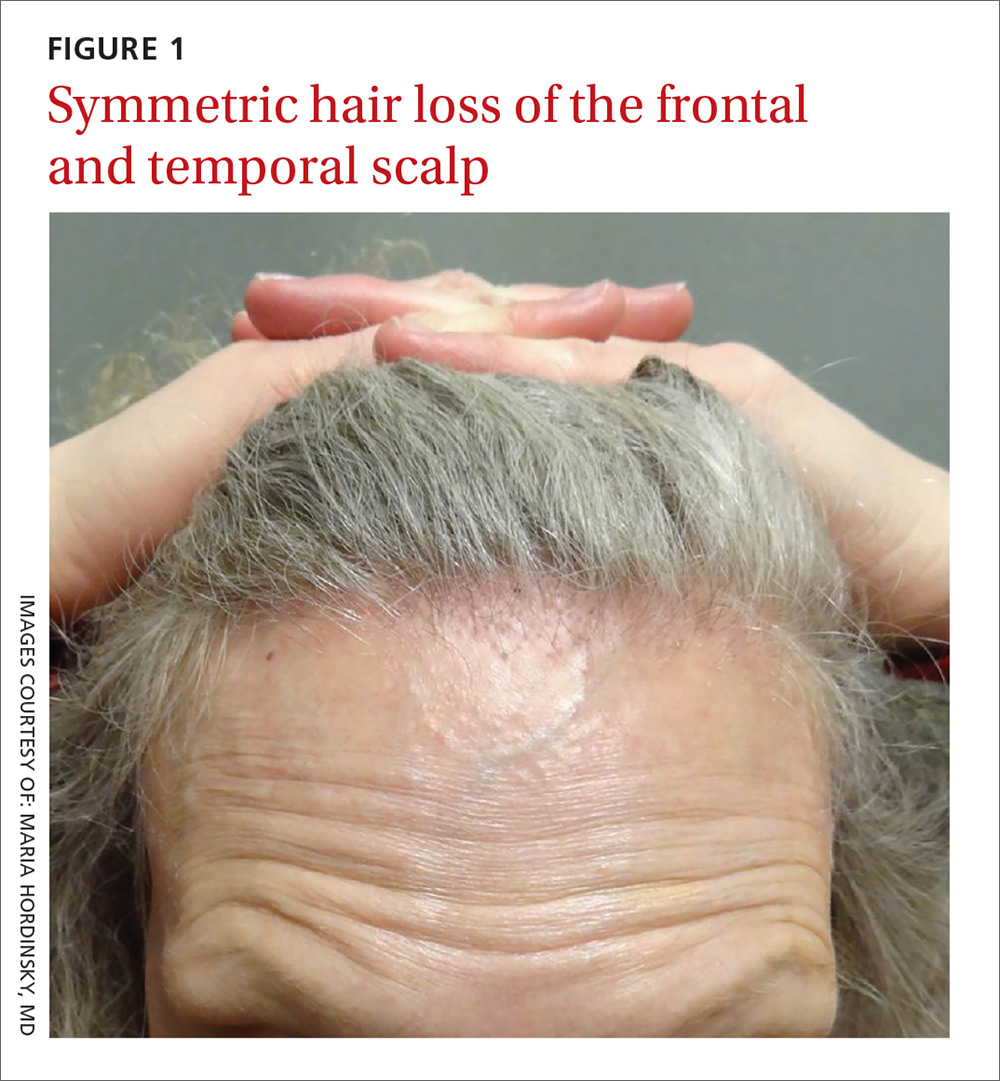

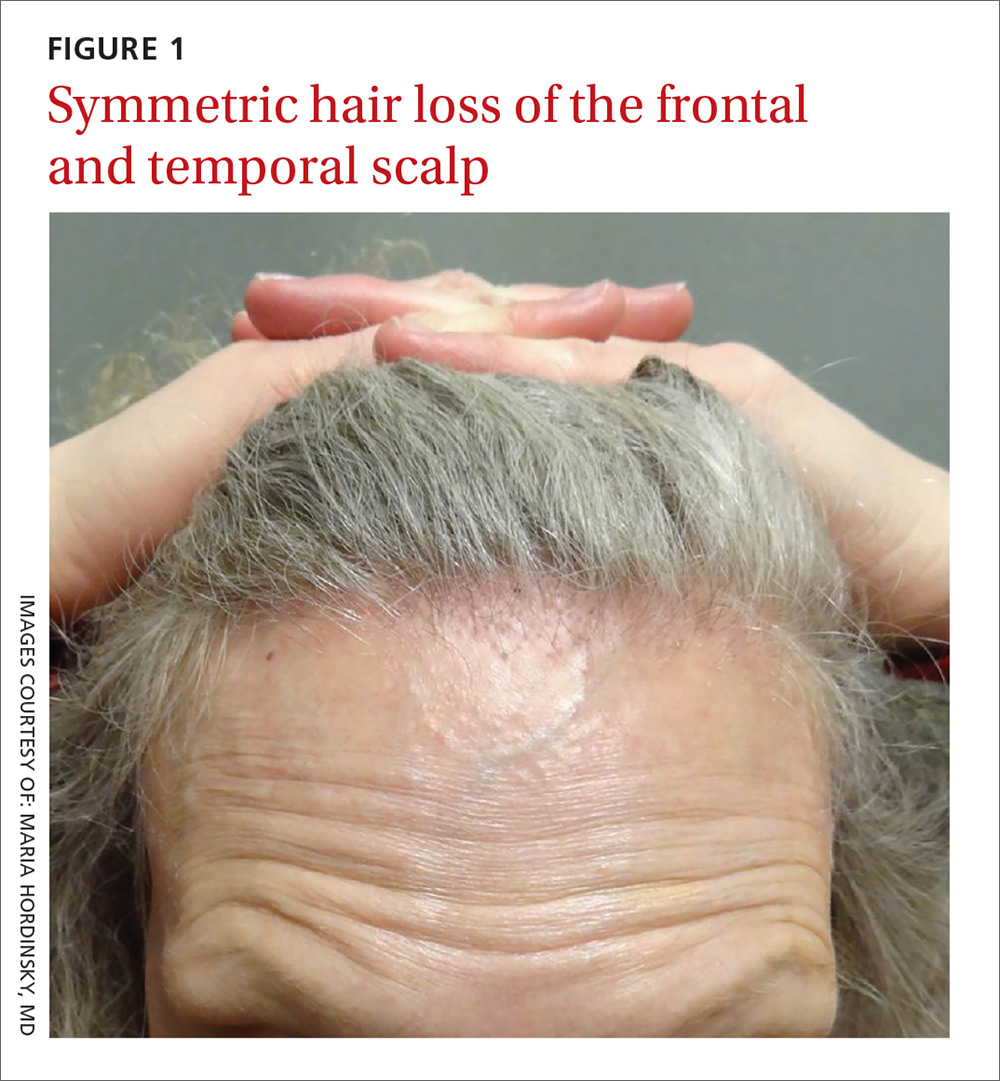

On physical examination, the physician noted hair loss in a symmetric 2-cm band-like distribution across her frontal and temporal scalp (FIGURES 1 and 2). In both areas, there was moderate perifollicular erythema, scale, and what appeared to be scarring.

The patient had lost most of her eyebrow hairs, and had prominent temporal veins (FIGURE 2) and flesh-colored papules on her cheeks. She had no significant medical history, was emotionally stable, and recently had a satisfactory health care maintenance exam. The postmenopausal patient’s last menses was 15 years earlier, and she was not taking hormone replacement.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Frontal fibrosing alopecia

The patient was referred to our dermatology clinic, which specializes in hair loss. Based on the clinical findings, we suspected that this was a case of frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA), a primary lymphocytic cicatricial (scarring) alopecia. A dermatopathologist confirmed the diagnosis via histologic review.

A condition on the rise. The incidence of FFA has been steadily increasing internationally since the condition was first described in 1994.1 Among patients referred to a specialty clinic for hair loss, diagnosis of FFA has increased from 1.6% in 2000 to 17% in 2011.2

FFA is characterized by symmetric band-like hair loss with evidence of scarring in the frontal and temporal regions of the scalp. (The extent of hair loss can be assessed by retracting the patient’s hair and having the patient raise his or her eyebrows and wrinkle the forehead in a surprised look.) FFA is accompanied by eyebrow loss in 73% to 95% of patients.2,3 Mild to severe perifollicular (and possibly more generalized) erythema and scale are usually present. In addition, erythematous or skin-colored papules may appear on the face,3 and marked exaggeration of the temporal veins is a common finding.

Most patients with FFA (83%) are postmenopausal women and nearly all (98.6%) have Fitzpatrick skin type 1 or 2 (white skin that burns easily and doesn’t readily tan).4 Other pertinent findings include the absence of oral lesions, nail changes, or other skin diseases.

A subtype of another condition? Because they are similar histologically, some consider FFA to be a subtype of lichen planopilaris. (See “Scarring alopecia in a woman with psoriasis,” J Fam Pract. 2015;64:E1-E3.)

A punch biopsy to confirm the diagnosis of FFA should be taken from the leading edge of the hair loss and, ideally, reviewed by a dermatopathologist. Histologic examination will reveal a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate (predominantly around the hair follicle where the follicular stem cells reside), resulting in fibrosis and scarring.5

Rule out other causes of hair loss

In addition to confirming the diagnosis with histologic examination, you’ll also need to have ruled out the following conditions in the differential.

Alopecia areata may mimic the ophiasis (band-like) pattern of hair loss seen with FFA, but it is a non-scarring disorder that typically lacks any signs of inflammation.

Female pattern hair loss is characterized by a decrease in hair density and thinning. The condition is non-scarring and usually involves the frontal and vertex (crown) regions of the scalp.

Discoid lupus erythematosus is characterized by circular scarring hair loss with a central patch of inflammation, as well as depigmentation.

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia predominantly affects black women and is characterized by circular hair loss of the vertex, with perifollicular inflammation and scarring.

Traction alopecia can occur in the same location as FFA, but is not usually associated with perifollicular inflammation. This condition can cause scarring if traction has been longstanding and persistent. There is usually a history of certain hairstyles (such as braiding) associated with chronic tension on hair fibers.

Numerous Tx strategies exist, but they are not well studied

Because there are no published randomized clinical trials on treatment for FFA, few evidence-based treatment strategies exist.6 In addition, the prognosis is variable. Experts have employed numerous treatment strategies, including topical and intralesional steroids, immunosuppressive medications, antibiotics, and anti-androgen therapy, with varying results.4,6 For most primary care physicians, it’s best to refer patients to a dermatologist to initiate treatment.

Intralesional steroids such as triamcinolone acetonide (5-10 mg/cc), as well as high-potency topical steroids, are generally helpful to stabilize the disease. There is also some evidence of benefit from oral dutasteride or finasteride at variable doses.6 Immunosuppressants such as hydroxychloroquine may also be used as second-line treatments, although the benefit-to-risk ratio needs to be taken into consideration.7

Early detection is key. In general, treatment should be initiated as soon as possible to prevent disease progression and reduce permanent scarring and hair loss. The Lichen Planopilaris Activity Index7 is a tool that clinicians can use to measure disease severity and track changes in disease activity through patient report of symptoms and measurements of scalp inflammation.

Our patient was started on a regimen of topical high-potency steroids (clobetasol foam, 0.05%), with targeted, intralesional injection of steroids (10 mg/cc of triamcinolone acetonide) to areas with the most inflammation. The patient was advised to use ketoconazole 2% shampoo while showering.

These interventions decreased our patient’s symptoms dramatically. Her scalp erythema and scale improved, but the hair did not regrow. One year later, her hairline was clinically stable with no evidence of disease progression. She continues to see a dermatologist annually.

CORRESPONDENCE

David V. Power, MB, MPH, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota, 516 Delaware St. SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455; [email protected].

1. Kossard S. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: Scarring alopecia in a pattern distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:770-774.

2. MacDonald A, Clark C, Holmes S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a review of 60 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:955-961.

3. Ladizinski B, Bazakas A, Selim MA, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a retrospective review of 19 patients seen at Duke University. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:749-755.

4. Vañó-Galván S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Serrano-Falcón C, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a multicenter review of 355 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:670-678.

5. Poblet E, Jiménez F, Pascual A, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia versus lichen planopilaris: a clinicopathological study. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:375-380.

6. Rácz E, Gho C, Moorman PW, et al. Treatment of frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planopilaris: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1461-1470.

7. Chiang C, Sah D, Cho BK, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and lichen planopilaris: efficacy and introduction of Lichen Planopilaris Activity Index scoring system. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:387-392.

A 66-year-old white woman presented to her primary care clinic with concerns about hair loss, which began 2 years ago. Recently, she had noticed some “bumps” on her cheeks, as well.

On physical examination, the physician noted hair loss in a symmetric 2-cm band-like distribution across her frontal and temporal scalp (FIGURES 1 and 2). In both areas, there was moderate perifollicular erythema, scale, and what appeared to be scarring.

The patient had lost most of her eyebrow hairs, and had prominent temporal veins (FIGURE 2) and flesh-colored papules on her cheeks. She had no significant medical history, was emotionally stable, and recently had a satisfactory health care maintenance exam. The postmenopausal patient’s last menses was 15 years earlier, and she was not taking hormone replacement.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Frontal fibrosing alopecia

The patient was referred to our dermatology clinic, which specializes in hair loss. Based on the clinical findings, we suspected that this was a case of frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA), a primary lymphocytic cicatricial (scarring) alopecia. A dermatopathologist confirmed the diagnosis via histologic review.

A condition on the rise. The incidence of FFA has been steadily increasing internationally since the condition was first described in 1994.1 Among patients referred to a specialty clinic for hair loss, diagnosis of FFA has increased from 1.6% in 2000 to 17% in 2011.2

FFA is characterized by symmetric band-like hair loss with evidence of scarring in the frontal and temporal regions of the scalp. (The extent of hair loss can be assessed by retracting the patient’s hair and having the patient raise his or her eyebrows and wrinkle the forehead in a surprised look.) FFA is accompanied by eyebrow loss in 73% to 95% of patients.2,3 Mild to severe perifollicular (and possibly more generalized) erythema and scale are usually present. In addition, erythematous or skin-colored papules may appear on the face,3 and marked exaggeration of the temporal veins is a common finding.

Most patients with FFA (83%) are postmenopausal women and nearly all (98.6%) have Fitzpatrick skin type 1 or 2 (white skin that burns easily and doesn’t readily tan).4 Other pertinent findings include the absence of oral lesions, nail changes, or other skin diseases.

A subtype of another condition? Because they are similar histologically, some consider FFA to be a subtype of lichen planopilaris. (See “Scarring alopecia in a woman with psoriasis,” J Fam Pract. 2015;64:E1-E3.)

A punch biopsy to confirm the diagnosis of FFA should be taken from the leading edge of the hair loss and, ideally, reviewed by a dermatopathologist. Histologic examination will reveal a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate (predominantly around the hair follicle where the follicular stem cells reside), resulting in fibrosis and scarring.5

Rule out other causes of hair loss

In addition to confirming the diagnosis with histologic examination, you’ll also need to have ruled out the following conditions in the differential.

Alopecia areata may mimic the ophiasis (band-like) pattern of hair loss seen with FFA, but it is a non-scarring disorder that typically lacks any signs of inflammation.

Female pattern hair loss is characterized by a decrease in hair density and thinning. The condition is non-scarring and usually involves the frontal and vertex (crown) regions of the scalp.

Discoid lupus erythematosus is characterized by circular scarring hair loss with a central patch of inflammation, as well as depigmentation.

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia predominantly affects black women and is characterized by circular hair loss of the vertex, with perifollicular inflammation and scarring.

Traction alopecia can occur in the same location as FFA, but is not usually associated with perifollicular inflammation. This condition can cause scarring if traction has been longstanding and persistent. There is usually a history of certain hairstyles (such as braiding) associated with chronic tension on hair fibers.

Numerous Tx strategies exist, but they are not well studied

Because there are no published randomized clinical trials on treatment for FFA, few evidence-based treatment strategies exist.6 In addition, the prognosis is variable. Experts have employed numerous treatment strategies, including topical and intralesional steroids, immunosuppressive medications, antibiotics, and anti-androgen therapy, with varying results.4,6 For most primary care physicians, it’s best to refer patients to a dermatologist to initiate treatment.

Intralesional steroids such as triamcinolone acetonide (5-10 mg/cc), as well as high-potency topical steroids, are generally helpful to stabilize the disease. There is also some evidence of benefit from oral dutasteride or finasteride at variable doses.6 Immunosuppressants such as hydroxychloroquine may also be used as second-line treatments, although the benefit-to-risk ratio needs to be taken into consideration.7

Early detection is key. In general, treatment should be initiated as soon as possible to prevent disease progression and reduce permanent scarring and hair loss. The Lichen Planopilaris Activity Index7 is a tool that clinicians can use to measure disease severity and track changes in disease activity through patient report of symptoms and measurements of scalp inflammation.

Our patient was started on a regimen of topical high-potency steroids (clobetasol foam, 0.05%), with targeted, intralesional injection of steroids (10 mg/cc of triamcinolone acetonide) to areas with the most inflammation. The patient was advised to use ketoconazole 2% shampoo while showering.

These interventions decreased our patient’s symptoms dramatically. Her scalp erythema and scale improved, but the hair did not regrow. One year later, her hairline was clinically stable with no evidence of disease progression. She continues to see a dermatologist annually.

CORRESPONDENCE

David V. Power, MB, MPH, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota, 516 Delaware St. SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455; [email protected].

A 66-year-old white woman presented to her primary care clinic with concerns about hair loss, which began 2 years ago. Recently, she had noticed some “bumps” on her cheeks, as well.

On physical examination, the physician noted hair loss in a symmetric 2-cm band-like distribution across her frontal and temporal scalp (FIGURES 1 and 2). In both areas, there was moderate perifollicular erythema, scale, and what appeared to be scarring.

The patient had lost most of her eyebrow hairs, and had prominent temporal veins (FIGURE 2) and flesh-colored papules on her cheeks. She had no significant medical history, was emotionally stable, and recently had a satisfactory health care maintenance exam. The postmenopausal patient’s last menses was 15 years earlier, and she was not taking hormone replacement.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Frontal fibrosing alopecia

The patient was referred to our dermatology clinic, which specializes in hair loss. Based on the clinical findings, we suspected that this was a case of frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA), a primary lymphocytic cicatricial (scarring) alopecia. A dermatopathologist confirmed the diagnosis via histologic review.

A condition on the rise. The incidence of FFA has been steadily increasing internationally since the condition was first described in 1994.1 Among patients referred to a specialty clinic for hair loss, diagnosis of FFA has increased from 1.6% in 2000 to 17% in 2011.2

FFA is characterized by symmetric band-like hair loss with evidence of scarring in the frontal and temporal regions of the scalp. (The extent of hair loss can be assessed by retracting the patient’s hair and having the patient raise his or her eyebrows and wrinkle the forehead in a surprised look.) FFA is accompanied by eyebrow loss in 73% to 95% of patients.2,3 Mild to severe perifollicular (and possibly more generalized) erythema and scale are usually present. In addition, erythematous or skin-colored papules may appear on the face,3 and marked exaggeration of the temporal veins is a common finding.

Most patients with FFA (83%) are postmenopausal women and nearly all (98.6%) have Fitzpatrick skin type 1 or 2 (white skin that burns easily and doesn’t readily tan).4 Other pertinent findings include the absence of oral lesions, nail changes, or other skin diseases.

A subtype of another condition? Because they are similar histologically, some consider FFA to be a subtype of lichen planopilaris. (See “Scarring alopecia in a woman with psoriasis,” J Fam Pract. 2015;64:E1-E3.)

A punch biopsy to confirm the diagnosis of FFA should be taken from the leading edge of the hair loss and, ideally, reviewed by a dermatopathologist. Histologic examination will reveal a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate (predominantly around the hair follicle where the follicular stem cells reside), resulting in fibrosis and scarring.5

Rule out other causes of hair loss

In addition to confirming the diagnosis with histologic examination, you’ll also need to have ruled out the following conditions in the differential.

Alopecia areata may mimic the ophiasis (band-like) pattern of hair loss seen with FFA, but it is a non-scarring disorder that typically lacks any signs of inflammation.

Female pattern hair loss is characterized by a decrease in hair density and thinning. The condition is non-scarring and usually involves the frontal and vertex (crown) regions of the scalp.

Discoid lupus erythematosus is characterized by circular scarring hair loss with a central patch of inflammation, as well as depigmentation.

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia predominantly affects black women and is characterized by circular hair loss of the vertex, with perifollicular inflammation and scarring.

Traction alopecia can occur in the same location as FFA, but is not usually associated with perifollicular inflammation. This condition can cause scarring if traction has been longstanding and persistent. There is usually a history of certain hairstyles (such as braiding) associated with chronic tension on hair fibers.

Numerous Tx strategies exist, but they are not well studied

Because there are no published randomized clinical trials on treatment for FFA, few evidence-based treatment strategies exist.6 In addition, the prognosis is variable. Experts have employed numerous treatment strategies, including topical and intralesional steroids, immunosuppressive medications, antibiotics, and anti-androgen therapy, with varying results.4,6 For most primary care physicians, it’s best to refer patients to a dermatologist to initiate treatment.

Intralesional steroids such as triamcinolone acetonide (5-10 mg/cc), as well as high-potency topical steroids, are generally helpful to stabilize the disease. There is also some evidence of benefit from oral dutasteride or finasteride at variable doses.6 Immunosuppressants such as hydroxychloroquine may also be used as second-line treatments, although the benefit-to-risk ratio needs to be taken into consideration.7

Early detection is key. In general, treatment should be initiated as soon as possible to prevent disease progression and reduce permanent scarring and hair loss. The Lichen Planopilaris Activity Index7 is a tool that clinicians can use to measure disease severity and track changes in disease activity through patient report of symptoms and measurements of scalp inflammation.

Our patient was started on a regimen of topical high-potency steroids (clobetasol foam, 0.05%), with targeted, intralesional injection of steroids (10 mg/cc of triamcinolone acetonide) to areas with the most inflammation. The patient was advised to use ketoconazole 2% shampoo while showering.

These interventions decreased our patient’s symptoms dramatically. Her scalp erythema and scale improved, but the hair did not regrow. One year later, her hairline was clinically stable with no evidence of disease progression. She continues to see a dermatologist annually.

CORRESPONDENCE

David V. Power, MB, MPH, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota, 516 Delaware St. SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455; [email protected].

1. Kossard S. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: Scarring alopecia in a pattern distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:770-774.

2. MacDonald A, Clark C, Holmes S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a review of 60 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:955-961.

3. Ladizinski B, Bazakas A, Selim MA, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a retrospective review of 19 patients seen at Duke University. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:749-755.

4. Vañó-Galván S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Serrano-Falcón C, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a multicenter review of 355 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:670-678.

5. Poblet E, Jiménez F, Pascual A, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia versus lichen planopilaris: a clinicopathological study. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:375-380.

6. Rácz E, Gho C, Moorman PW, et al. Treatment of frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planopilaris: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1461-1470.

7. Chiang C, Sah D, Cho BK, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and lichen planopilaris: efficacy and introduction of Lichen Planopilaris Activity Index scoring system. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:387-392.

1. Kossard S. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: Scarring alopecia in a pattern distribution. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:770-774.

2. MacDonald A, Clark C, Holmes S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a review of 60 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:955-961.

3. Ladizinski B, Bazakas A, Selim MA, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a retrospective review of 19 patients seen at Duke University. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:749-755.

4. Vañó-Galván S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Serrano-Falcón C, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a multicenter review of 355 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:670-678.

5. Poblet E, Jiménez F, Pascual A, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia versus lichen planopilaris: a clinicopathological study. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:375-380.

6. Rácz E, Gho C, Moorman PW, et al. Treatment of frontal fibrosing alopecia and lichen planopilaris: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1461-1470.

7. Chiang C, Sah D, Cho BK, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and lichen planopilaris: efficacy and introduction of Lichen Planopilaris Activity Index scoring system. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:387-392.

Active 46-year-old man with right-sided visual loss and no family history of stroke • Dx?

THE CASE

A 46-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with sudden-onset right-sided visual loss. He had a history of asthma, but no family history of hypercoagulability, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), or stroke. The patient had an active lifestyle that included scuba diving, mountain biking, and hockey (coaching and playing). The physical examination revealed a right homonymous upper quadrantanopia. The neurologic examination was within normal limits, except for the visual deficit and unequal pupil size. A computerized tomography scan of the patient’s head did not reveal any lesions.

Based on the patient’s clinical picture, the ED physician prescribed alteplase, a tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), and admitted him to the intensive care unit for monitoring.

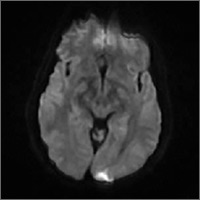

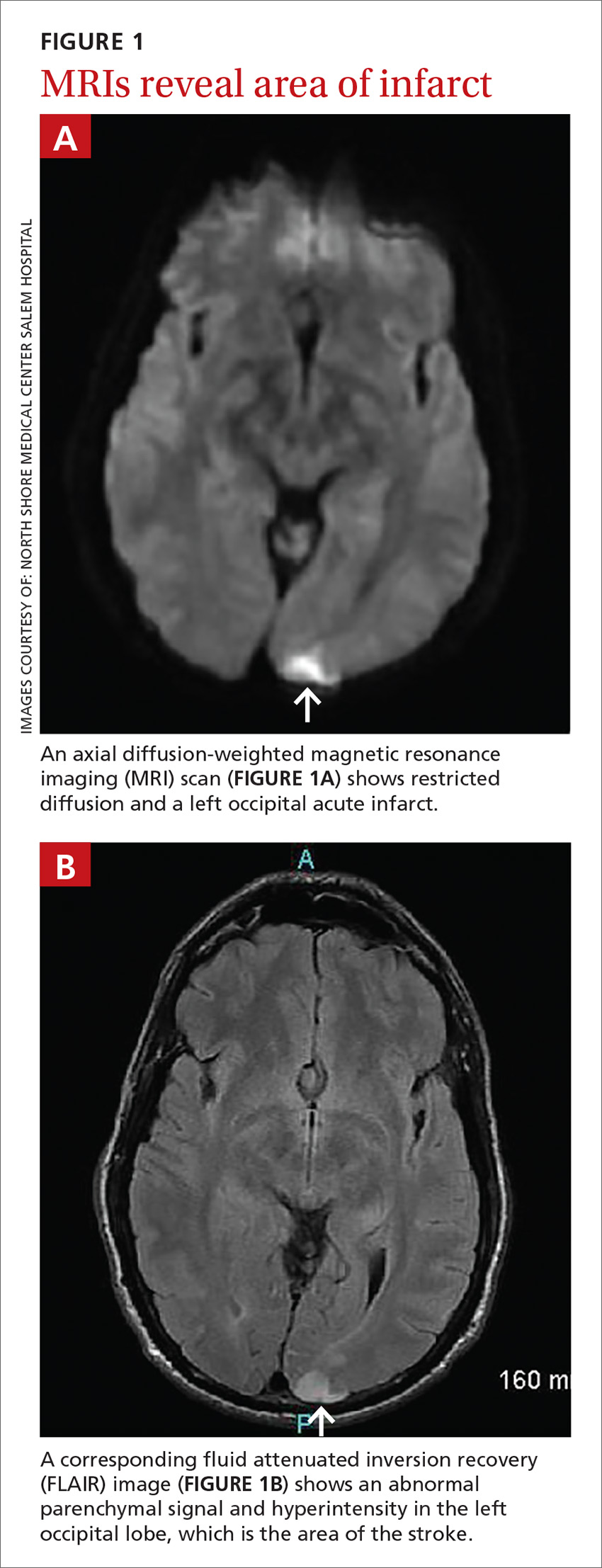

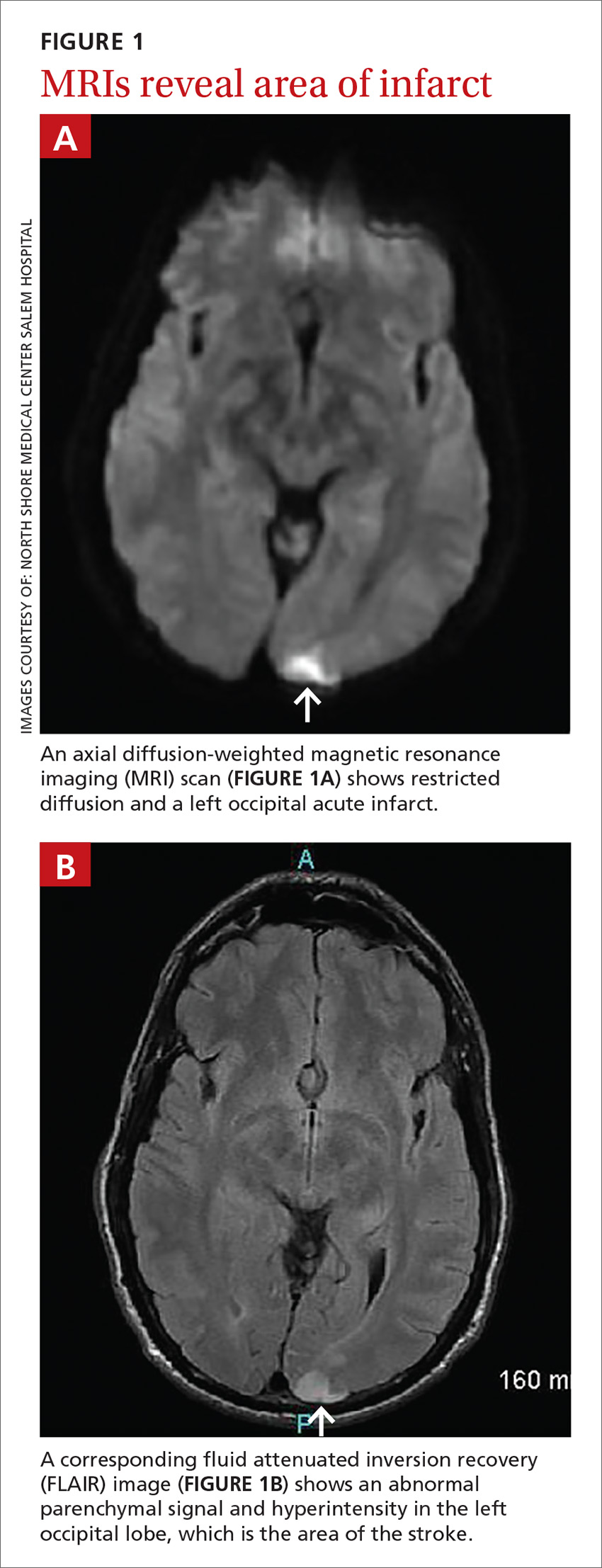

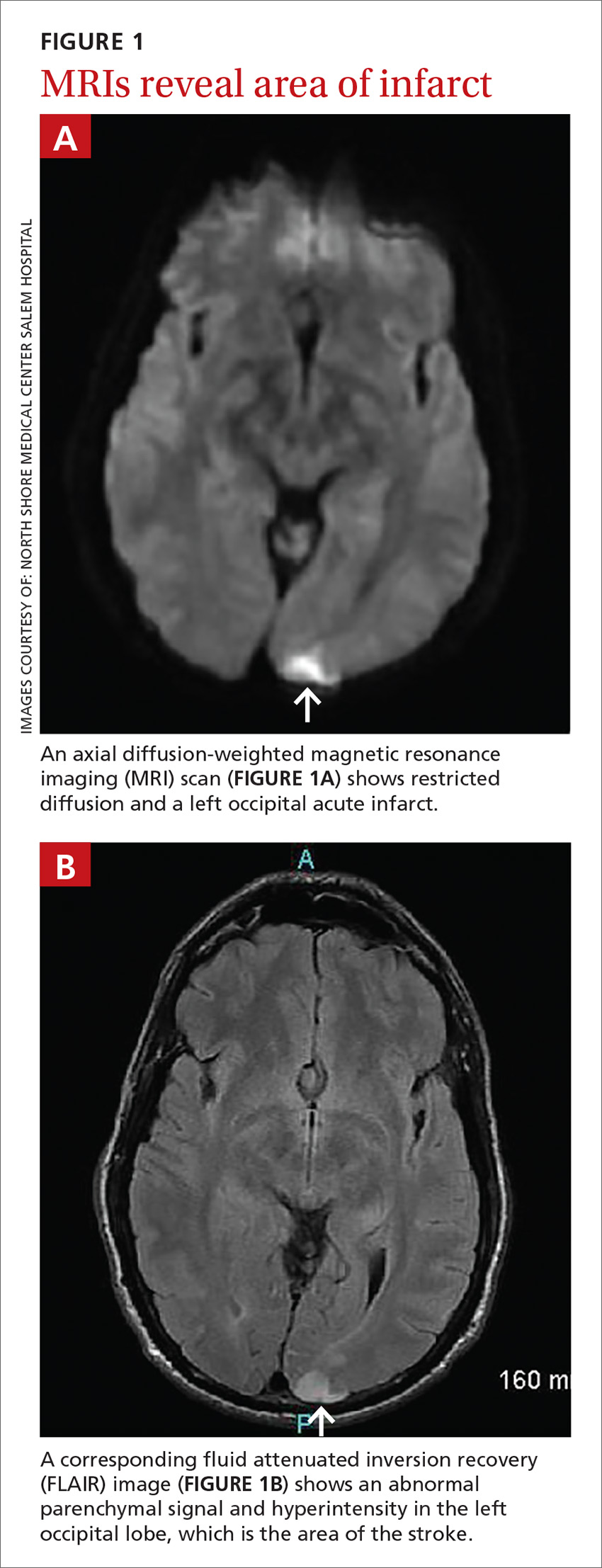

Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed multiple small areas of acute infarct in the posterior circulation territory bilaterally, with involvement of small portions of the bilateral cerebellar hemispheres and parts of the left occipital lobe (FIGURE 1A and 1B).

An electrocardiogram showed no evidence of atrial fibrillation, and hypercoagulability studies were within normal limits. There was no evidence of May-Thurner anatomy, and an ultrasound of the lower extremities showed no DVT.

THE DIAGNOSIS

An echocardiogram with bubble study confirmed a diagnosis of patent foramen ovale (PFO) with bidirectional flow, a normal ejection fraction, and no evidence of left ventricular or left atrial thrombus. We started the patient on the anticoagulant enoxaparin 70 mg bid bridged with warfarin 5 mg/d.

Taking the patient’s active lifestyle into consideration, he was approved for PFO closure by the PFO committee and underwent closure. Following treatment, the patient was left with a residual 2-mm blind spot in the right visual field. At a 2-year follow-up visit, he showed no new focal deficits or recurrent symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Since 1988 when Lechat et al reported increased incidence of PFO in young stroke patients,1 many studies have supported the association between PFO and cryptogenic stroke (CS) in young adults.2 Because it remained controversial as to whether PFO is a risk factor for stroke or transient ischemic attack recurrence,3 researchers investigated PFO closure as a preventive measure to decrease stroke recurrence in patients with both CS and PFO.

A 2012 meta-analysis showed possible benefits of closure compared with medical management using antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapies.4 However, these results were not supported by results of other studies. These include the CLOSURE I trial,5 which compared device closure of PFO with medical therapy, and the RESPECT6 and PC trials,7 which did not show a significant difference in the primary end point of recurrent stroke between patients who received medical therapy and those who had PFO closure.

American Heart Association/American Stroke Association’s 2011 guidelines recommend only antiplatelet therapy for patients with CS and PFO.8 While there is consensus that surgical closure is not better than a medical approach to patients with CS and PFO, cases should be individualized, as a patient’s clinical or social factors may dictate otherwise.

Lifestyle may warrant PFO closure

No previous studies have considered occupation or hobbies as an indication for PFO closure in patients with CS. Our patient’s active lifestyle, particularly his scuba diving and participation in contact sports, made him a poor candidate for anticoagulation. Scuba diving is associated with decompression sickness and air emboli, which can be a mechanism of cerebral ischemia, especially in patients with a right-to-left shunt, such as with PFO.9

We did not observe a strong temporal relationship between diving and stroke in our patient. MRI findings suggested that he had multiple minor embolic events over time, which is consistent with a prior case report.9 This suggested air emboli as a possible source of stroke, in which case, our patient might not benefit from antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case illustrates the importance of a thorough social history and knowledge of the patient’s hobbies, occupation, and preferences in evaluating and treating individuals with CS associated with PFO. The current literature does not provide complete answers to the cause, diagnosis, and management of CS; additional research is needed.

The work-up involved in defining the etiology of stroke includes, but is not limited to, head and brain imaging, an echocardiogram, hypercoagulability tests, and vascular imaging. The work of Sanna et al showed that approximately 12% of patients with CS have atrial fibrillation when monitored over a one-year period, suggesting atrial fibrillation as a possible cause in some cases.10

As the case described here demonstrates, further research is warranted regarding how a patient’s occupation and lifestyle factor into decision-making for patients with PFO.

1. Lechat P, Mas JL, Lascault G, et al. Prevalence of patent foramen ovale in patients with stroke. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1148-1152.

2. Ferro JM, Massaro AR, Mas JL. Aetiological diagnosis of ischaemic stroke in young adults. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:1085-1096.

3. Cotter PE, Belham M, Martin PJ. Stroke in younger patients: the heart of the matter. J Neurol. 2010;257:1777-1787.

4. Kitsios GD, Dahabreh IJ, Abu Dabrh AM, et al. Patent foramen ovale closure and medical treatments for secondary stroke prevention: a systematic review of observational and randomized evidence. Stroke. 2012;43:422-431.

5. Furlan AJ, Reisman M, Massaro J, et al. Closure or medical therapy for cryptogenic stroke with patent foramen ovale. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:991-999.

6. Carroll JD, Saver JL, Thaler DE, et al. Closure of patent foramen ovale versus medical therapy after cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1092-1100.

7. Meier B, Kalesan B, Mattle HP, et al. Percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale in cryptogenic embolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1083-1091.

8. Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:227-276.

9. Menkin M, Schwartzman RJ. Cerebral air embolism. Report of five cases and review of the literature. Arch Neurol. 1977;34:168-170.

10. Sanna T, Diener HC, Passman RS, et al. Cryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2478-2486.

THE CASE

A 46-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with sudden-onset right-sided visual loss. He had a history of asthma, but no family history of hypercoagulability, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), or stroke. The patient had an active lifestyle that included scuba diving, mountain biking, and hockey (coaching and playing). The physical examination revealed a right homonymous upper quadrantanopia. The neurologic examination was within normal limits, except for the visual deficit and unequal pupil size. A computerized tomography scan of the patient’s head did not reveal any lesions.

Based on the patient’s clinical picture, the ED physician prescribed alteplase, a tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), and admitted him to the intensive care unit for monitoring.

Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed multiple small areas of acute infarct in the posterior circulation territory bilaterally, with involvement of small portions of the bilateral cerebellar hemispheres and parts of the left occipital lobe (FIGURE 1A and 1B).

An electrocardiogram showed no evidence of atrial fibrillation, and hypercoagulability studies were within normal limits. There was no evidence of May-Thurner anatomy, and an ultrasound of the lower extremities showed no DVT.

THE DIAGNOSIS

An echocardiogram with bubble study confirmed a diagnosis of patent foramen ovale (PFO) with bidirectional flow, a normal ejection fraction, and no evidence of left ventricular or left atrial thrombus. We started the patient on the anticoagulant enoxaparin 70 mg bid bridged with warfarin 5 mg/d.

Taking the patient’s active lifestyle into consideration, he was approved for PFO closure by the PFO committee and underwent closure. Following treatment, the patient was left with a residual 2-mm blind spot in the right visual field. At a 2-year follow-up visit, he showed no new focal deficits or recurrent symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Since 1988 when Lechat et al reported increased incidence of PFO in young stroke patients,1 many studies have supported the association between PFO and cryptogenic stroke (CS) in young adults.2 Because it remained controversial as to whether PFO is a risk factor for stroke or transient ischemic attack recurrence,3 researchers investigated PFO closure as a preventive measure to decrease stroke recurrence in patients with both CS and PFO.

A 2012 meta-analysis showed possible benefits of closure compared with medical management using antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapies.4 However, these results were not supported by results of other studies. These include the CLOSURE I trial,5 which compared device closure of PFO with medical therapy, and the RESPECT6 and PC trials,7 which did not show a significant difference in the primary end point of recurrent stroke between patients who received medical therapy and those who had PFO closure.

American Heart Association/American Stroke Association’s 2011 guidelines recommend only antiplatelet therapy for patients with CS and PFO.8 While there is consensus that surgical closure is not better than a medical approach to patients with CS and PFO, cases should be individualized, as a patient’s clinical or social factors may dictate otherwise.

Lifestyle may warrant PFO closure

No previous studies have considered occupation or hobbies as an indication for PFO closure in patients with CS. Our patient’s active lifestyle, particularly his scuba diving and participation in contact sports, made him a poor candidate for anticoagulation. Scuba diving is associated with decompression sickness and air emboli, which can be a mechanism of cerebral ischemia, especially in patients with a right-to-left shunt, such as with PFO.9

We did not observe a strong temporal relationship between diving and stroke in our patient. MRI findings suggested that he had multiple minor embolic events over time, which is consistent with a prior case report.9 This suggested air emboli as a possible source of stroke, in which case, our patient might not benefit from antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case illustrates the importance of a thorough social history and knowledge of the patient’s hobbies, occupation, and preferences in evaluating and treating individuals with CS associated with PFO. The current literature does not provide complete answers to the cause, diagnosis, and management of CS; additional research is needed.

The work-up involved in defining the etiology of stroke includes, but is not limited to, head and brain imaging, an echocardiogram, hypercoagulability tests, and vascular imaging. The work of Sanna et al showed that approximately 12% of patients with CS have atrial fibrillation when monitored over a one-year period, suggesting atrial fibrillation as a possible cause in some cases.10

As the case described here demonstrates, further research is warranted regarding how a patient’s occupation and lifestyle factor into decision-making for patients with PFO.

THE CASE

A 46-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with sudden-onset right-sided visual loss. He had a history of asthma, but no family history of hypercoagulability, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), or stroke. The patient had an active lifestyle that included scuba diving, mountain biking, and hockey (coaching and playing). The physical examination revealed a right homonymous upper quadrantanopia. The neurologic examination was within normal limits, except for the visual deficit and unequal pupil size. A computerized tomography scan of the patient’s head did not reveal any lesions.

Based on the patient’s clinical picture, the ED physician prescribed alteplase, a tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), and admitted him to the intensive care unit for monitoring.

Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed multiple small areas of acute infarct in the posterior circulation territory bilaterally, with involvement of small portions of the bilateral cerebellar hemispheres and parts of the left occipital lobe (FIGURE 1A and 1B).

An electrocardiogram showed no evidence of atrial fibrillation, and hypercoagulability studies were within normal limits. There was no evidence of May-Thurner anatomy, and an ultrasound of the lower extremities showed no DVT.

THE DIAGNOSIS

An echocardiogram with bubble study confirmed a diagnosis of patent foramen ovale (PFO) with bidirectional flow, a normal ejection fraction, and no evidence of left ventricular or left atrial thrombus. We started the patient on the anticoagulant enoxaparin 70 mg bid bridged with warfarin 5 mg/d.

Taking the patient’s active lifestyle into consideration, he was approved for PFO closure by the PFO committee and underwent closure. Following treatment, the patient was left with a residual 2-mm blind spot in the right visual field. At a 2-year follow-up visit, he showed no new focal deficits or recurrent symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Since 1988 when Lechat et al reported increased incidence of PFO in young stroke patients,1 many studies have supported the association between PFO and cryptogenic stroke (CS) in young adults.2 Because it remained controversial as to whether PFO is a risk factor for stroke or transient ischemic attack recurrence,3 researchers investigated PFO closure as a preventive measure to decrease stroke recurrence in patients with both CS and PFO.

A 2012 meta-analysis showed possible benefits of closure compared with medical management using antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapies.4 However, these results were not supported by results of other studies. These include the CLOSURE I trial,5 which compared device closure of PFO with medical therapy, and the RESPECT6 and PC trials,7 which did not show a significant difference in the primary end point of recurrent stroke between patients who received medical therapy and those who had PFO closure.

American Heart Association/American Stroke Association’s 2011 guidelines recommend only antiplatelet therapy for patients with CS and PFO.8 While there is consensus that surgical closure is not better than a medical approach to patients with CS and PFO, cases should be individualized, as a patient’s clinical or social factors may dictate otherwise.

Lifestyle may warrant PFO closure

No previous studies have considered occupation or hobbies as an indication for PFO closure in patients with CS. Our patient’s active lifestyle, particularly his scuba diving and participation in contact sports, made him a poor candidate for anticoagulation. Scuba diving is associated with decompression sickness and air emboli, which can be a mechanism of cerebral ischemia, especially in patients with a right-to-left shunt, such as with PFO.9

We did not observe a strong temporal relationship between diving and stroke in our patient. MRI findings suggested that he had multiple minor embolic events over time, which is consistent with a prior case report.9 This suggested air emboli as a possible source of stroke, in which case, our patient might not benefit from antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case illustrates the importance of a thorough social history and knowledge of the patient’s hobbies, occupation, and preferences in evaluating and treating individuals with CS associated with PFO. The current literature does not provide complete answers to the cause, diagnosis, and management of CS; additional research is needed.

The work-up involved in defining the etiology of stroke includes, but is not limited to, head and brain imaging, an echocardiogram, hypercoagulability tests, and vascular imaging. The work of Sanna et al showed that approximately 12% of patients with CS have atrial fibrillation when monitored over a one-year period, suggesting atrial fibrillation as a possible cause in some cases.10

As the case described here demonstrates, further research is warranted regarding how a patient’s occupation and lifestyle factor into decision-making for patients with PFO.

1. Lechat P, Mas JL, Lascault G, et al. Prevalence of patent foramen ovale in patients with stroke. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1148-1152.

2. Ferro JM, Massaro AR, Mas JL. Aetiological diagnosis of ischaemic stroke in young adults. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:1085-1096.

3. Cotter PE, Belham M, Martin PJ. Stroke in younger patients: the heart of the matter. J Neurol. 2010;257:1777-1787.

4. Kitsios GD, Dahabreh IJ, Abu Dabrh AM, et al. Patent foramen ovale closure and medical treatments for secondary stroke prevention: a systematic review of observational and randomized evidence. Stroke. 2012;43:422-431.

5. Furlan AJ, Reisman M, Massaro J, et al. Closure or medical therapy for cryptogenic stroke with patent foramen ovale. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:991-999.

6. Carroll JD, Saver JL, Thaler DE, et al. Closure of patent foramen ovale versus medical therapy after cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1092-1100.

7. Meier B, Kalesan B, Mattle HP, et al. Percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale in cryptogenic embolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1083-1091.

8. Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:227-276.

9. Menkin M, Schwartzman RJ. Cerebral air embolism. Report of five cases and review of the literature. Arch Neurol. 1977;34:168-170.

10. Sanna T, Diener HC, Passman RS, et al. Cryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2478-2486.

1. Lechat P, Mas JL, Lascault G, et al. Prevalence of patent foramen ovale in patients with stroke. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1148-1152.

2. Ferro JM, Massaro AR, Mas JL. Aetiological diagnosis of ischaemic stroke in young adults. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:1085-1096.

3. Cotter PE, Belham M, Martin PJ. Stroke in younger patients: the heart of the matter. J Neurol. 2010;257:1777-1787.

4. Kitsios GD, Dahabreh IJ, Abu Dabrh AM, et al. Patent foramen ovale closure and medical treatments for secondary stroke prevention: a systematic review of observational and randomized evidence. Stroke. 2012;43:422-431.

5. Furlan AJ, Reisman M, Massaro J, et al. Closure or medical therapy for cryptogenic stroke with patent foramen ovale. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:991-999.

6. Carroll JD, Saver JL, Thaler DE, et al. Closure of patent foramen ovale versus medical therapy after cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1092-1100.

7. Meier B, Kalesan B, Mattle HP, et al. Percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale in cryptogenic embolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1083-1091.

8. Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:227-276.

9. Menkin M, Schwartzman RJ. Cerebral air embolism. Report of five cases and review of the literature. Arch Neurol. 1977;34:168-170.

10. Sanna T, Diener HC, Passman RS, et al. Cryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2478-2486.

Radiation therapy: Managing GI tract complications

CASE A 57-year-old man presented for evaluation of painless, intermittent passage of bright red blood per rectum for several months. His bowel habits were otherwise unchanged, averaging 2 soft bowel movements daily without straining. His medical history was significant for radiation therapy for prostate cancer 18 months earlier and a recent finding of mild microcytic anemia. A colonoscopy 7 years ago was negative for polyps, diverticula, or other lesions. He denied any family history of colon cancer or other gastrointestinal disorders. He wanted to know what he could do to stop the bleeding or if further testing would be needed.

Next steps?

Radiation therapy and its effect on the GI tract

In 1895, Dr. Wilhelm Roentgen first introduced the use of x-rays for diagnostic radiographic purposes. A year later, Dr. Emil Gruble made the first attempt to use radiation therapy (XRT) to treat cancer. In 1897, Dr. David Walsh described the first case of XRT-induced tissue injury in the British Medical Journal.1

Since then, XRT has been used extensively to treat cancer, and its delivery techniques have improved and diversified. Like chemotherapy, XRT has its greatest effect on rapidly dividing cells, but as a result, the adverse effects of therapy are also greatest on rapidly dividing normal tissues, as well as others in the radiation field.

A large proportion of cancer patients will receive XRT, yet XRT-related costs account for less than 5% of total cancer care expenditure, suggesting cost effectiveness.2,3 However, even with the great progress achieved in the delivery of XRT, it continues to have its share of acute and chronic complications, among the most common of which is gastrointestinal (GI) tract toxicity. These adverse effects are often first reported to, diagnosed, or treated by the primary care provider, who frequently remains pivotally involved in the patient’s longitudinal care.

Approximately 50% to 75% of patients undergoing XRT will have some degree of GI symptoms of acute injury, but the majority will recover fully within a few weeks following completion of treatment.4-6 However, in about 5% of patients,4-6 there will be long-term consequences of varying degrees that may develop as soon as one year or as long as 10 years after XRT. These can pose substantial challenges for patients, as well as both the primary care provider and consulting specialists.

In the review that follows, we detail the potential acute and chronic complications of XRT on the GI tract and how best to manage them. But first, a word about the related terminology.

Getting a handle on XRT-related injury terminology

The preferred terms used to describe injury to normal tissue as a result of XRT include “XRT-related injury” or “pelvic radiation disease” (when the injury is confined to intrapelvic tissues); organ-specific descriptors such as “radiation enteropathy” or “XRT-induced esophageal stricture” are also used and are acceptable.4,7,8

Terms such as “radiation enteritis” or “radiation proctitis” are considered misnomers since there is no significant histologic inflammation. Indeed, as we will discuss, acute injury is largely due to epithelial cellular injury and cell death (necrosis), while chronic injury is primarily the consequence of ongoing tissue ischemia, fibrosis, and other pathophysiologic processes.

Acute vs chronic XRT-related tissue injury

From a pathobiologic and clinical perspective, XRT-related injury can be categorized as either acute or chronic.8-12 Acute XRT-related injury involves direct cellular necrosis of the epithelial cells and damage (eg, irreparable DNA alterations) to stem cells. This acute injury prevents appropriate cellular regeneration, which results in denuded mucosa, mucosal ulcerations, and even perforation in severe cases.10 Acute injury starts 2 to 3 weeks after initiating XRT and typically resolves within 2 to 3 months following completion of treatment.