User login

FIGHT to remember PTSD

Certain clinical features of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) appear in other psychiatric diagnoses and therefore can confound accurate diagnosis and treatment. PTSD is frequently comorbid with other classes of psychiatric disorders, including mood, personality, substance use, and psychotic disorders, which can further complicate diagnostic clarity. Comorbidity in PTSD is important to recognize because it has been associated with worse treatment outcomes.1

In DSM-5, the updated criteria for PTSD included Criterion D: “Negative alterations in cognitions and mood associated with the traumatic event(s) ….”2 In addition to inability to remember an important aspect of the trau

We created the mnemonic FIGHT to help remember the updated DSM-5 criteria for PTSD when considering the differential diagnosis.

Flight. Avoidant symptoms, including efforts to avoid distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings about the traumatic event, as well as avoidance of external reminders.

Intrusive symptoms, such as distressing dreams, intrusive memories, and physiological distress when exposed to cues.

Gloomy cognitions. Negative cognitions and mood associated with the traumatic event.

Hypervigilance. Alterations in arousal, such as irritability, angry outbursts, reckless behavior, and exaggerated startle response.

Trauma. Exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence.

A diagnosis of PTSD requires ≥1 month of symptoms that cause significant distress or impairment and are not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or medical condition. Specifiers in DSM-5 include with depersonalization or derealization, as well as delayed expression.2

Vigilance in the assessment and treatment of PTSD will aid the clinician and patient in producing better care outcomes.

1. Angstman KB, Marcelin A, Gonzalez CA, et al. The impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on the 6-month outcomes in collaborative care management for depression. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(3):159-164.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

Certain clinical features of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) appear in other psychiatric diagnoses and therefore can confound accurate diagnosis and treatment. PTSD is frequently comorbid with other classes of psychiatric disorders, including mood, personality, substance use, and psychotic disorders, which can further complicate diagnostic clarity. Comorbidity in PTSD is important to recognize because it has been associated with worse treatment outcomes.1

In DSM-5, the updated criteria for PTSD included Criterion D: “Negative alterations in cognitions and mood associated with the traumatic event(s) ….”2 In addition to inability to remember an important aspect of the trau

We created the mnemonic FIGHT to help remember the updated DSM-5 criteria for PTSD when considering the differential diagnosis.

Flight. Avoidant symptoms, including efforts to avoid distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings about the traumatic event, as well as avoidance of external reminders.

Intrusive symptoms, such as distressing dreams, intrusive memories, and physiological distress when exposed to cues.

Gloomy cognitions. Negative cognitions and mood associated with the traumatic event.

Hypervigilance. Alterations in arousal, such as irritability, angry outbursts, reckless behavior, and exaggerated startle response.

Trauma. Exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence.

A diagnosis of PTSD requires ≥1 month of symptoms that cause significant distress or impairment and are not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or medical condition. Specifiers in DSM-5 include with depersonalization or derealization, as well as delayed expression.2

Vigilance in the assessment and treatment of PTSD will aid the clinician and patient in producing better care outcomes.

Certain clinical features of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) appear in other psychiatric diagnoses and therefore can confound accurate diagnosis and treatment. PTSD is frequently comorbid with other classes of psychiatric disorders, including mood, personality, substance use, and psychotic disorders, which can further complicate diagnostic clarity. Comorbidity in PTSD is important to recognize because it has been associated with worse treatment outcomes.1

In DSM-5, the updated criteria for PTSD included Criterion D: “Negative alterations in cognitions and mood associated with the traumatic event(s) ….”2 In addition to inability to remember an important aspect of the trau

We created the mnemonic FIGHT to help remember the updated DSM-5 criteria for PTSD when considering the differential diagnosis.

Flight. Avoidant symptoms, including efforts to avoid distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings about the traumatic event, as well as avoidance of external reminders.

Intrusive symptoms, such as distressing dreams, intrusive memories, and physiological distress when exposed to cues.

Gloomy cognitions. Negative cognitions and mood associated with the traumatic event.

Hypervigilance. Alterations in arousal, such as irritability, angry outbursts, reckless behavior, and exaggerated startle response.

Trauma. Exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence.

A diagnosis of PTSD requires ≥1 month of symptoms that cause significant distress or impairment and are not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or medical condition. Specifiers in DSM-5 include with depersonalization or derealization, as well as delayed expression.2

Vigilance in the assessment and treatment of PTSD will aid the clinician and patient in producing better care outcomes.

1. Angstman KB, Marcelin A, Gonzalez CA, et al. The impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on the 6-month outcomes in collaborative care management for depression. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(3):159-164.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

1. Angstman KB, Marcelin A, Gonzalez CA, et al. The impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on the 6-month outcomes in collaborative care management for depression. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(3):159-164.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

‘Difficult’ patients: How to improve rapport

As psychiatrists, we all come across patients who press our buttons and engender negative feelings, such as anger, frustration, and inadequacy.1 These patients have been referred to as “hateful” or “difficult” because they disrupt the treatment alliance.1,2 We are quick to point our fingers at such patients for making our jobs harder, being noncompliant, resisting the therapeutic alliance, and in general, being “problem patients.”3 However, the physician–patient relationship is a 2-way street. Although our patients knowingly or unknowingly play a role in this dynamic, we could be overlooking our role in adversely affecting this relationship. The following factors influence the physician–patient bond.1,2

Countertransference. We may have negative feelings toward a patient based on our personalities and/or if the patient reminds us of someone we may not like, which could lead us to overprescribe or underprescribe medications, conduct unnecessary medical workups, distance ourselves from the patient, etc. Accepting our disdain for certain patients and understanding why we have these emotions will allow us to better understand them, ensure that we are not impeding the delivery of appropriate clinical care, and improve rapport.

Listening. It may seem obvious that not listening to our patients negatively impacts rapport. However, in today’s technological world, we may not be really listening to our patients even when we think we are. Answering a text message or reading the patient’s electronic medical record while they are talking to us may increase productivity, but doing so also can interfere with our ability to form a therapeutic alliance. Although we may hear what our patients are saying, such distractions can create a hurdle in listening to what they are telling us.

Empathy often is confused for sympathy. Sympathy entails expressing concern and compassion for one’s distress, whereas empathy includes recognizing and sharing the patient’s emotions. Identifying with and understanding our patients’ situations, drives, and feelings allows us to understand what they are experiencing, see why they are reacting in a negative manner, and protect them from unnecessary emotional distress. Empathy can lead us to know what needs to be said and what should be said. It also can demystify a patient’s suffering. Not providing empathy or substituting sympathy can disrupt the therapeutic alliance.

Projective identification. Patients can project intolerable and negative feelings onto us and coerce us into identifying with what has been projected, allowing them to indirectly take control of our emotions. Our subsequent reactions can unsettle the physician–patient relationship. We need to be attuned to this process and recognize what the patient is provoking within us. Once we understand the process, we can realize that this is how they deal with others under similarly stressful conditions, and then react in a more supportive and healthy manner, rather than reviling our patients and negatively impacting the therapeutic relationship.

1. Strous RD, Ulman AM, Kotler M. The hateful patient revisited: relevance for 21st century medicine. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17(6):387-393.

2. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(16):883-887.

3. Boland R. The ‘problem patient’: modest advice for frustrated clinicians. R I Med J (2013). 2014;97(6):29-32.

As psychiatrists, we all come across patients who press our buttons and engender negative feelings, such as anger, frustration, and inadequacy.1 These patients have been referred to as “hateful” or “difficult” because they disrupt the treatment alliance.1,2 We are quick to point our fingers at such patients for making our jobs harder, being noncompliant, resisting the therapeutic alliance, and in general, being “problem patients.”3 However, the physician–patient relationship is a 2-way street. Although our patients knowingly or unknowingly play a role in this dynamic, we could be overlooking our role in adversely affecting this relationship. The following factors influence the physician–patient bond.1,2

Countertransference. We may have negative feelings toward a patient based on our personalities and/or if the patient reminds us of someone we may not like, which could lead us to overprescribe or underprescribe medications, conduct unnecessary medical workups, distance ourselves from the patient, etc. Accepting our disdain for certain patients and understanding why we have these emotions will allow us to better understand them, ensure that we are not impeding the delivery of appropriate clinical care, and improve rapport.

Listening. It may seem obvious that not listening to our patients negatively impacts rapport. However, in today’s technological world, we may not be really listening to our patients even when we think we are. Answering a text message or reading the patient’s electronic medical record while they are talking to us may increase productivity, but doing so also can interfere with our ability to form a therapeutic alliance. Although we may hear what our patients are saying, such distractions can create a hurdle in listening to what they are telling us.

Empathy often is confused for sympathy. Sympathy entails expressing concern and compassion for one’s distress, whereas empathy includes recognizing and sharing the patient’s emotions. Identifying with and understanding our patients’ situations, drives, and feelings allows us to understand what they are experiencing, see why they are reacting in a negative manner, and protect them from unnecessary emotional distress. Empathy can lead us to know what needs to be said and what should be said. It also can demystify a patient’s suffering. Not providing empathy or substituting sympathy can disrupt the therapeutic alliance.

Projective identification. Patients can project intolerable and negative feelings onto us and coerce us into identifying with what has been projected, allowing them to indirectly take control of our emotions. Our subsequent reactions can unsettle the physician–patient relationship. We need to be attuned to this process and recognize what the patient is provoking within us. Once we understand the process, we can realize that this is how they deal with others under similarly stressful conditions, and then react in a more supportive and healthy manner, rather than reviling our patients and negatively impacting the therapeutic relationship.

As psychiatrists, we all come across patients who press our buttons and engender negative feelings, such as anger, frustration, and inadequacy.1 These patients have been referred to as “hateful” or “difficult” because they disrupt the treatment alliance.1,2 We are quick to point our fingers at such patients for making our jobs harder, being noncompliant, resisting the therapeutic alliance, and in general, being “problem patients.”3 However, the physician–patient relationship is a 2-way street. Although our patients knowingly or unknowingly play a role in this dynamic, we could be overlooking our role in adversely affecting this relationship. The following factors influence the physician–patient bond.1,2

Countertransference. We may have negative feelings toward a patient based on our personalities and/or if the patient reminds us of someone we may not like, which could lead us to overprescribe or underprescribe medications, conduct unnecessary medical workups, distance ourselves from the patient, etc. Accepting our disdain for certain patients and understanding why we have these emotions will allow us to better understand them, ensure that we are not impeding the delivery of appropriate clinical care, and improve rapport.

Listening. It may seem obvious that not listening to our patients negatively impacts rapport. However, in today’s technological world, we may not be really listening to our patients even when we think we are. Answering a text message or reading the patient’s electronic medical record while they are talking to us may increase productivity, but doing so also can interfere with our ability to form a therapeutic alliance. Although we may hear what our patients are saying, such distractions can create a hurdle in listening to what they are telling us.

Empathy often is confused for sympathy. Sympathy entails expressing concern and compassion for one’s distress, whereas empathy includes recognizing and sharing the patient’s emotions. Identifying with and understanding our patients’ situations, drives, and feelings allows us to understand what they are experiencing, see why they are reacting in a negative manner, and protect them from unnecessary emotional distress. Empathy can lead us to know what needs to be said and what should be said. It also can demystify a patient’s suffering. Not providing empathy or substituting sympathy can disrupt the therapeutic alliance.

Projective identification. Patients can project intolerable and negative feelings onto us and coerce us into identifying with what has been projected, allowing them to indirectly take control of our emotions. Our subsequent reactions can unsettle the physician–patient relationship. We need to be attuned to this process and recognize what the patient is provoking within us. Once we understand the process, we can realize that this is how they deal with others under similarly stressful conditions, and then react in a more supportive and healthy manner, rather than reviling our patients and negatively impacting the therapeutic relationship.

1. Strous RD, Ulman AM, Kotler M. The hateful patient revisited: relevance for 21st century medicine. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17(6):387-393.

2. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(16):883-887.

3. Boland R. The ‘problem patient’: modest advice for frustrated clinicians. R I Med J (2013). 2014;97(6):29-32.

1. Strous RD, Ulman AM, Kotler M. The hateful patient revisited: relevance for 21st century medicine. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17(6):387-393.

2. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(16):883-887.

3. Boland R. The ‘problem patient’: modest advice for frustrated clinicians. R I Med J (2013). 2014;97(6):29-32.

Understanding childhood cancer in sub-Saharan Africa

Researchers say they have published the most extensive data ever collected on childhood cancer in sub-Saharan Africa.

On the African continent, only South Africa operates a childhood cancer registry on the national level.

Researchers brought together data from 16 of the smaller, local registries, collecting this information for the first time and presenting it in an accessible format.

The data were published in ecancermedicalscience.

Examining the data in context allowed the researchers to notice trends in cancer incidence. For example, they found that, in Blantyre, Malawi’s second-largest city, the cumulative risk of a child developing Burkitt lymphoma is 2 in every thousand.

The researchers called this incidence “remarkable” and noted that the global research community is largely unaware of this.

“Everything starts with awareness,” said study author Cristina Stefan, global clinical leader of oncology for Roche Diagnostics International Ltd of Switzerland and director of the African Medical Research and Innovation Institute.

“It is highly necessary to publicize these data, which, at the moment, represent the best image of the malignant disease in children in the respective regions.”

The researchers also noted that factors such as the prevalence of malaria and the Epstein-Barr virus contribute to the unique epidemiology of childhood cancer in Africa.

“Our colleagues can learn that the patterns and distribution of cancers in Africa are totally different from Europe, and there is a need for further research into the roles of factors such as genetic predispositions and the influence of infections and other comorbidities in the evolution of cancer,” Dr Stefan said.

“We have learned many universal lessons about data collection as we prepared this work. Our hope is that the publication of this monograph will open the forums for future discussions and that the work will be referenced for the better understanding of cancer in children in Africa and used to improve outcomes for children affected there.” ![]()

Researchers say they have published the most extensive data ever collected on childhood cancer in sub-Saharan Africa.

On the African continent, only South Africa operates a childhood cancer registry on the national level.

Researchers brought together data from 16 of the smaller, local registries, collecting this information for the first time and presenting it in an accessible format.

The data were published in ecancermedicalscience.

Examining the data in context allowed the researchers to notice trends in cancer incidence. For example, they found that, in Blantyre, Malawi’s second-largest city, the cumulative risk of a child developing Burkitt lymphoma is 2 in every thousand.

The researchers called this incidence “remarkable” and noted that the global research community is largely unaware of this.

“Everything starts with awareness,” said study author Cristina Stefan, global clinical leader of oncology for Roche Diagnostics International Ltd of Switzerland and director of the African Medical Research and Innovation Institute.

“It is highly necessary to publicize these data, which, at the moment, represent the best image of the malignant disease in children in the respective regions.”

The researchers also noted that factors such as the prevalence of malaria and the Epstein-Barr virus contribute to the unique epidemiology of childhood cancer in Africa.

“Our colleagues can learn that the patterns and distribution of cancers in Africa are totally different from Europe, and there is a need for further research into the roles of factors such as genetic predispositions and the influence of infections and other comorbidities in the evolution of cancer,” Dr Stefan said.

“We have learned many universal lessons about data collection as we prepared this work. Our hope is that the publication of this monograph will open the forums for future discussions and that the work will be referenced for the better understanding of cancer in children in Africa and used to improve outcomes for children affected there.” ![]()

Researchers say they have published the most extensive data ever collected on childhood cancer in sub-Saharan Africa.

On the African continent, only South Africa operates a childhood cancer registry on the national level.

Researchers brought together data from 16 of the smaller, local registries, collecting this information for the first time and presenting it in an accessible format.

The data were published in ecancermedicalscience.

Examining the data in context allowed the researchers to notice trends in cancer incidence. For example, they found that, in Blantyre, Malawi’s second-largest city, the cumulative risk of a child developing Burkitt lymphoma is 2 in every thousand.

The researchers called this incidence “remarkable” and noted that the global research community is largely unaware of this.

“Everything starts with awareness,” said study author Cristina Stefan, global clinical leader of oncology for Roche Diagnostics International Ltd of Switzerland and director of the African Medical Research and Innovation Institute.

“It is highly necessary to publicize these data, which, at the moment, represent the best image of the malignant disease in children in the respective regions.”

The researchers also noted that factors such as the prevalence of malaria and the Epstein-Barr virus contribute to the unique epidemiology of childhood cancer in Africa.

“Our colleagues can learn that the patterns and distribution of cancers in Africa are totally different from Europe, and there is a need for further research into the roles of factors such as genetic predispositions and the influence of infections and other comorbidities in the evolution of cancer,” Dr Stefan said.

“We have learned many universal lessons about data collection as we prepared this work. Our hope is that the publication of this monograph will open the forums for future discussions and that the work will be referenced for the better understanding of cancer in children in Africa and used to improve outcomes for children affected there.” ![]()

Hand and arm pain: A pictorial guide to injections

Primary care physicians are frequently the first to evaluate hand, wrist, and forearm pain in patients, making knowledge of the symptoms, causes, and treatment of common diagnoses in the upper extremities imperative. Primary symptoms usually include pain and/or swelling. While most tendon disorders originating in the hand and wrist are idiopathic in nature, some patients occasionally report having recently performed unusual manual activity or having experienced trauma to the area days or weeks prior. A significant portion of patients are injured as a result of chronic repetitive activities at work.1

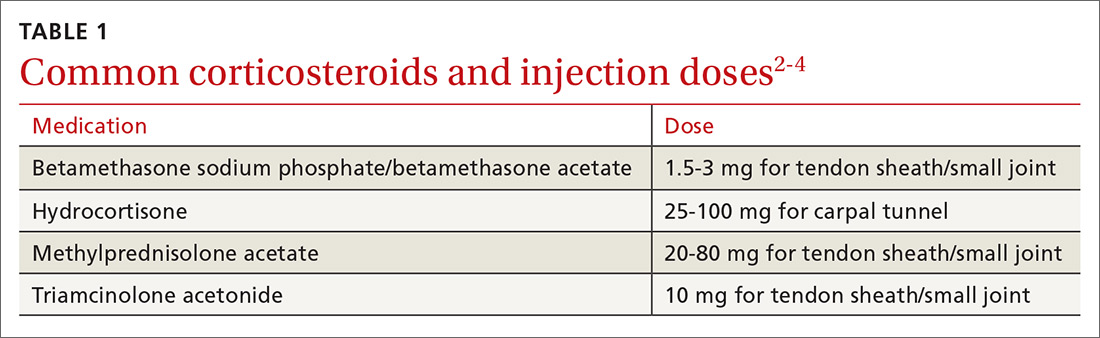

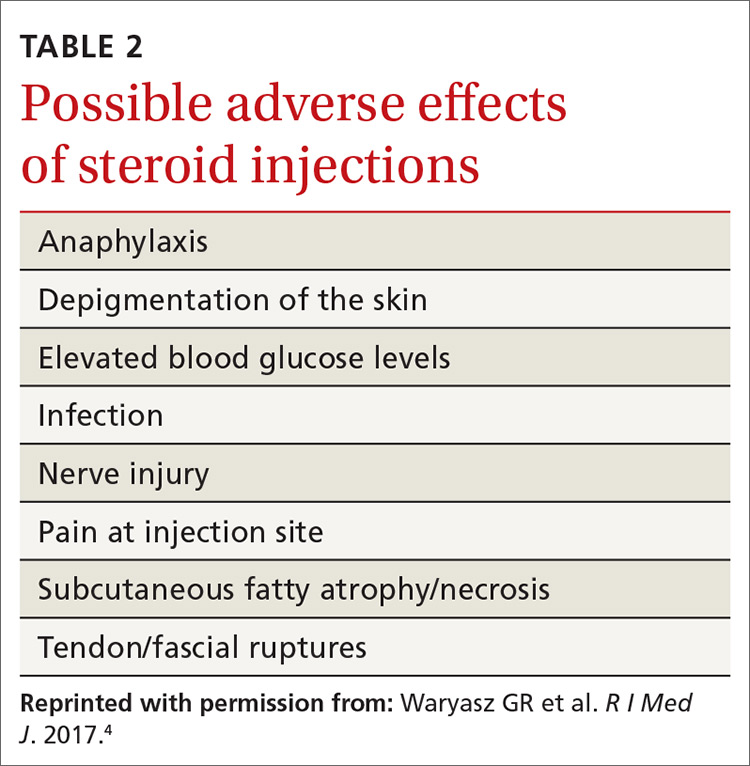

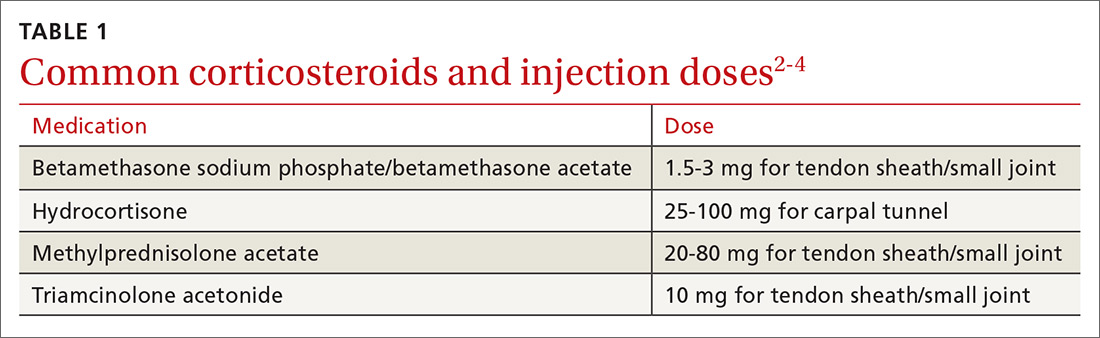

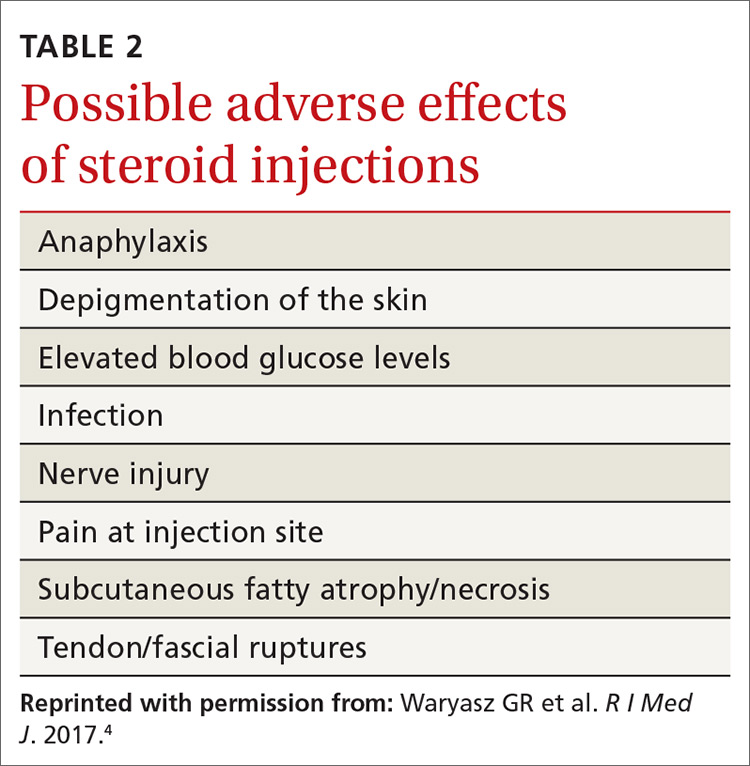

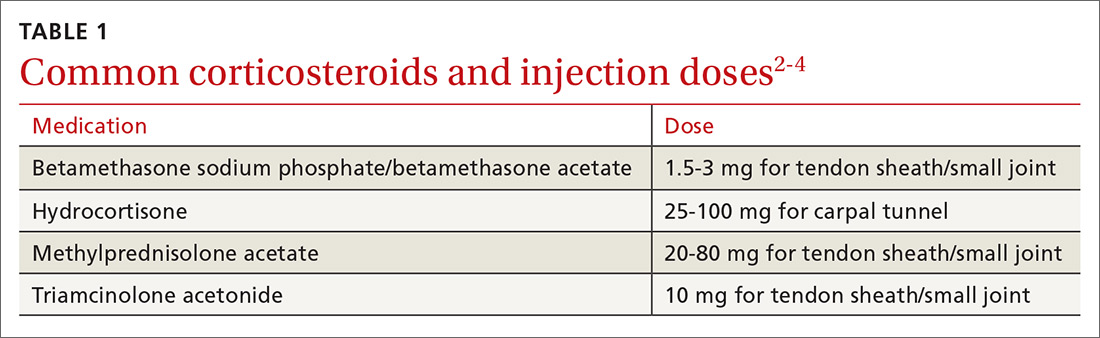

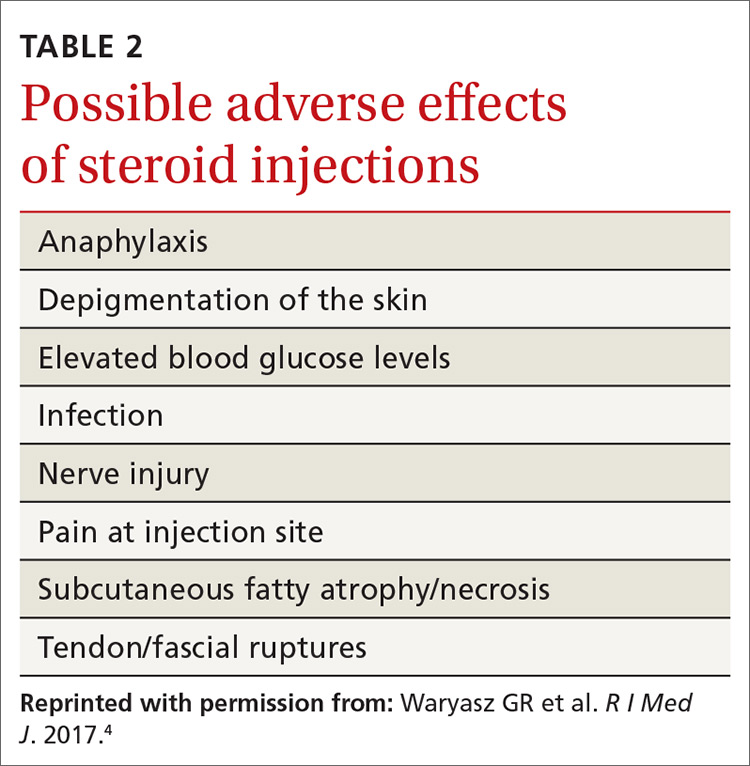

Most diagnoses can be made by pairing your knowledge of hand and forearm anatomy with an understanding of which tender points are indicative of which common conditions. (Care, of course, must be taken to ensure that there is no underlying infection.) Common conditions can often be treated nonsurgically with conservative treatments such as physical therapy, bracing/splinting, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and injections of corticosteroids (eg, betamethasone, hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone, and triamcinolone) (TABLE 12-4) with or without the use of ultrasound. The benefits of corticosteroid injections for these conditions are well studied and documented in the literature, although physicians should always warn patients of the possible adverse effects prior to injection3,5 (TABLE 24).

To help you refine your skills, we review some of the more common hand and forearm conditions you are likely to encounter in the office and provide photos that reveal underlying anatomy so that you can administer injections without, in many cases, the need for ultrasound.

Trigger finger/thumb: New pathophysiologic findings?

Trigger finger most commonly occurs in the dominant hand. It is also more common in women, patients in their 50s, and in individuals with diabetes.6 Trigger finger/thumb is caused by inflammation and constriction of the flexor tendon sheath, which carries the flexor tendons through the palm and into the fingers and thumb. This, in turn, causes irritation of the tendons, sometimes via the formation of tendinous nodules, which may impinge upon the sheath’s “pulley system.”

When the “pulley” is compromised. The retinacular sheath is composed of 5 annular ligaments, or pulleys, that hold the tendons of the fingers close to the bone and allow the fingers to flex properly. The A1 pulley, at the level of the metacarpal head, is the first part of the sheath and is subject to the highest force; high forces may subsequently lead to the finger becoming locked in a flexed, or trigger, position.6 Patients may experience pain in the distal palm at the level of the A1 pulley and clicking of the finger.6

Additionally . . . recent studies show discrete histologic changes in trigger finger tendons, similar to findings with Achilles tendinosis and tendinopathy.7 In trigger finger tendons, collagen type 1A1 and 3A1, aggrecan, and biglycan are up-regulated, while metalloproteinase inhibitor 3 (TIMP-3) and matrix metallopeptidase3 (MMP-3) are down-regulated, a situation also described in Achilles tendinosis.7 This similarity in conditions provides new insight into the pathophysiology of the condition and may help provide future treatments.

Making the Dx: Look for swelling, check for carpal tunnel

During the examination, first look at both hands for swelling, arthropathy, or injury, and note the presence of any joint contractures. Next, examine all of the digits in flexion and extension while noting which ones are triggering, as the problem can occur in multiple digits on one hand. Then palpate the palms over the patient’s metacarpal heads, feeling for tender nodules.

Finally, examine the patient for carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS). A positive Tinel’s sign (shooting pain into the hand when the median nerve in the wrist is percussed), a positive Phalen maneuver (numbness or pain, usually within one minute of full wrist flexion), or thenar muscle wasting are highly indicative of CTS (compression of the median nerve at the transverse carpal ligament in the carpal tunnel). It is important to check for CTS when examining a patient for trigger finger because the 2 conditions frequently co-occur.6 (For more on CTS, see here.)

Treatment: Consider corticosteroids first

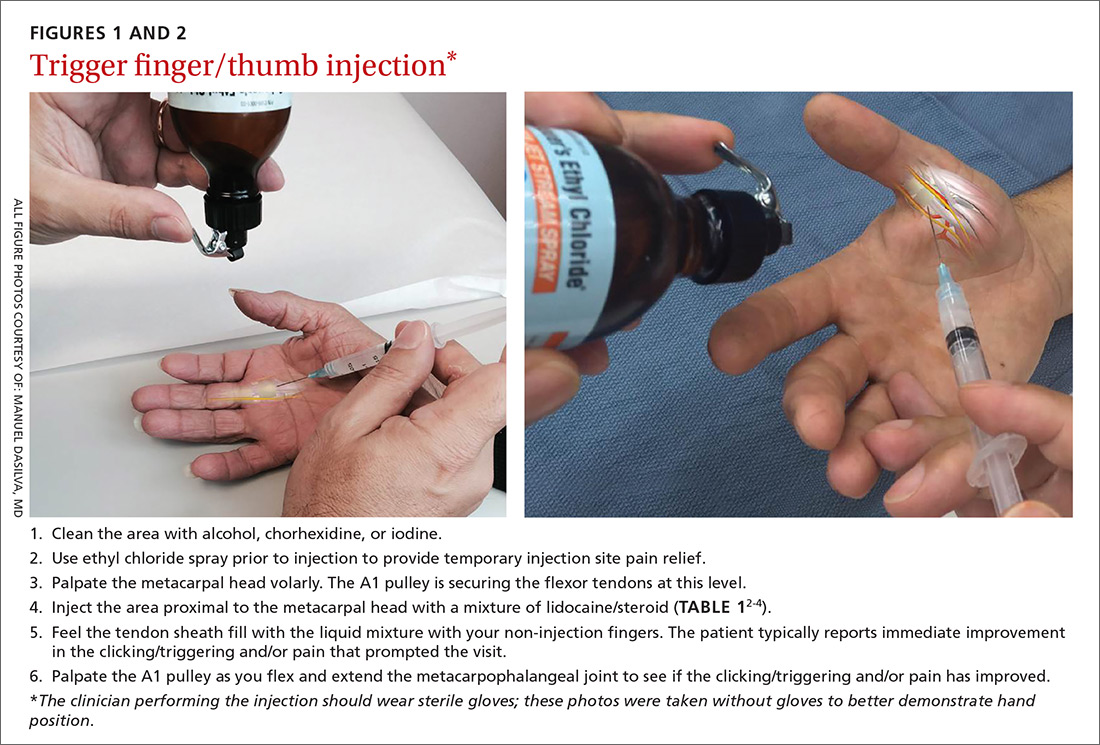

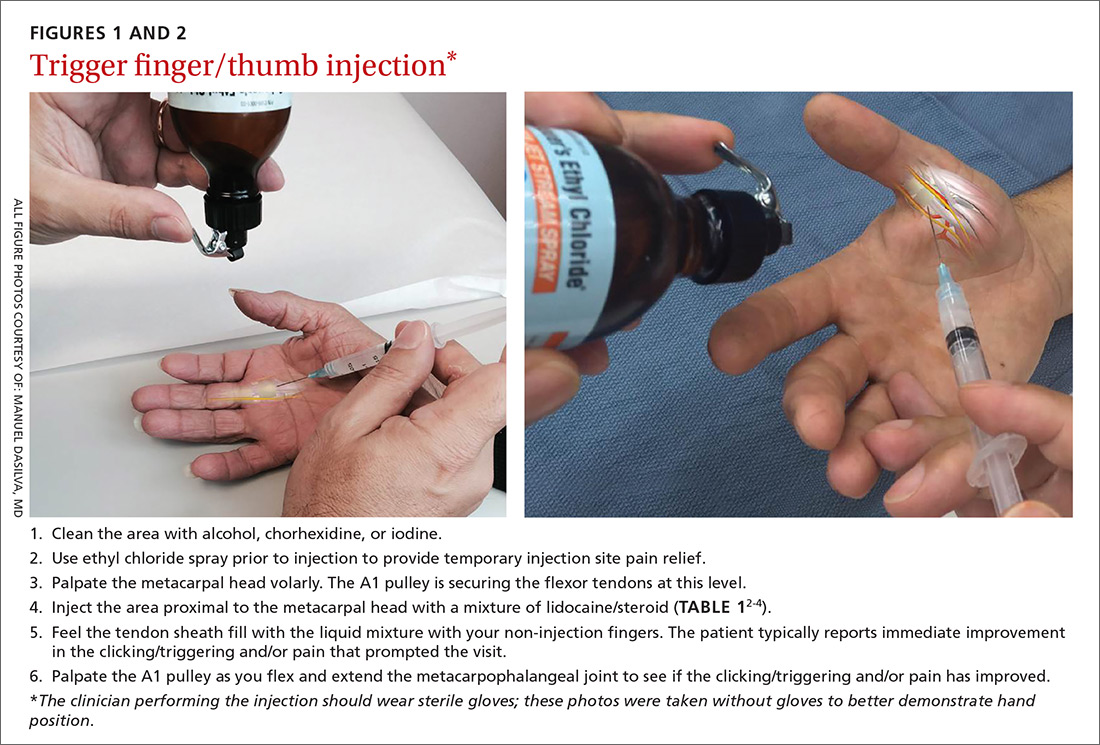

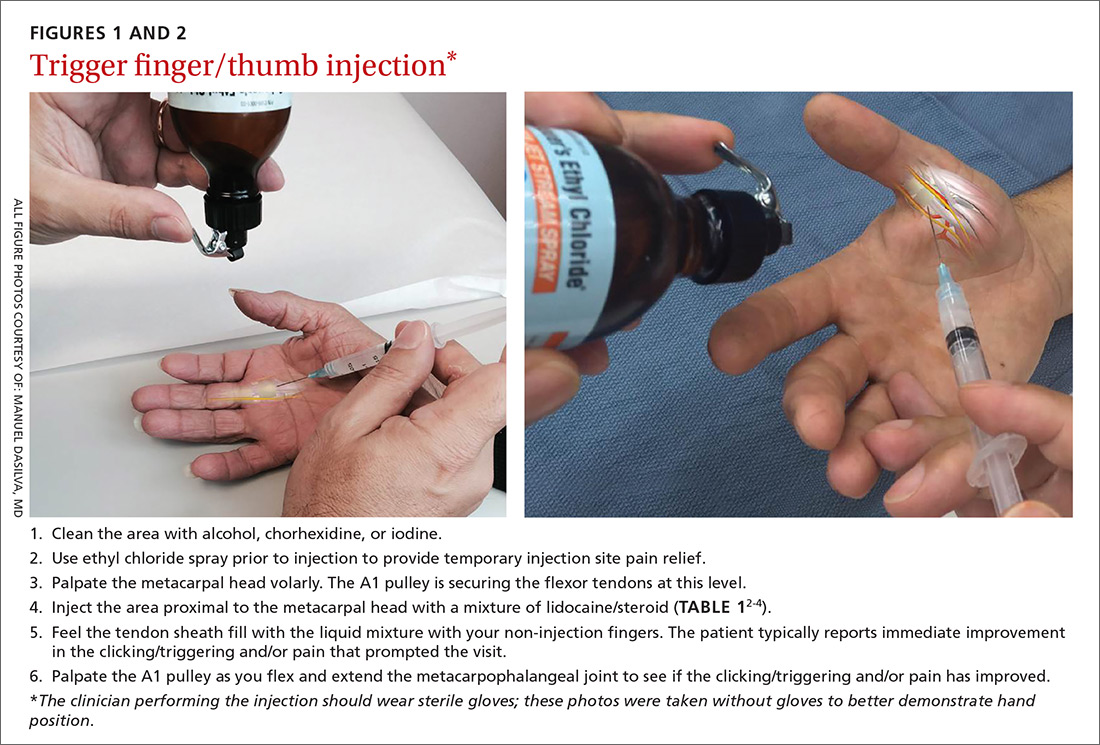

First-line treatment for patients with trigger finger or thumb is a corticosteroid injection into the subcutaneous tissue around the tendon sheath (FIGURES 1 and 2). (For this indication and for the others discussed throughout the article, there isn’t tremendous evidence for one particular type of corticosteroid over another; see TABLE 12-4 for choices.) Up to 57% of cases resolve with one injection, and 86% resolve with 2,8 but keep in mind that it may take up to 2 weeks to achieve the full clinical benefit.

Patients with multiple trigger fingers can be treated with oral corticosteroids (eg, a methylprednisolone dose pack). Peters-Veluthamaningal et al performed a systematic review in 2009 and found 2 randomized controlled trials involving 63 patients (34 received injections of a corticosteroid [either methylprednisolone or betamethasone] and lidocaine and 29 received lidocaine only).2 The corticosteroid/lidocaine combination was more effective at 4 weeks (relative risk [RR]=3.15; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.34 to 7.40).2

If 2 corticosteroid injections 6 weeks apart fail to provide benefit, or the finger is irreversibly locked in flexion, surgical release of the pulley is required and is performed through a palmar incision at the level of the A1 pulley. Complications from this surgery, including nerve damage, are exceedingly rare, but injury can occur, given the proximity of the digital nerves to the A1 pulley.

Patient is a child? Refer children with trigger finger or thumb to a hand surgeon for evaluation and management because the indications for nonoperative treatment in the pediatric population are unclear.9

Carpometacarpal arthritis: Common, with many causes

Osteoarthritis of the first carpometacarpal (CMC) joint is the most common site of arthritis in the hand/wrist region, affecting up to 11% of men and 33% of women in their 50s and 60s.10 Because the CMC joint lacks a bony restraint, it relies on a number of ligaments for stability—the strongest and most important of which is the palmar oblique “beak” ligament.11 A major cause of degenerative arthritis of this joint is attenuation and laxity of these ligaments, leading to abnormal and increased stress loads, which, in turn, can lead to loss of cartilage and bony impingement. While the exact mechanism of this process is not fully understood,10,12 acute or chronic trauma, advanced age, hormonal factors, and genetic factors seem to play a role.11

Many believe there is a relationship between a patient's occupation and the development of CMC arthritis, but studies are inconclusive.13 At risk are secretarial workers, tailors, domestic helpers/cleaners, and individuals whose jobs involve repetitive thumb use and/or insufficient rest of the joint throughout the day.

Making the Dx: Perform the Grind test

A detailed patient history (which is usually void of trauma to the hand) and physical examination are the keys to making the diagnosis of CMC arthritis. A history of pain at the base of the thumb during pinching and gripping tasks is often elucidated. Classically, patients describe pain upon turning keys, opening jars, and gripping doorknobs.11

It's important to focus on the dorsoradial aspect of the thumb during the physical exam and to rule out other causes of pain, such as de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, flexor carpi radialis tendinitis, CTS, and trigger thumb.11 Typical findings include pain with palpation directly over the dorsoradial aspect of the CMC joint and pain with axial loading and upon circumduction during a Grind test of the CMC joint. (The Grind test is performed by moving the metacarpal bone of the thumb in a circle and loading it with gentle axial forces. People with thumb joint arthritis generally experience sudden sharp pain at the CMC joint.)

Radiographic findings can be useful as a diagnostic adjunct, with staging of the disease, and in determining who can benefit from conservative management.11

Treatment: Start with NSAIDs and splinting

Depending on the degree of arthritis, management may include both conservative and surgical options.10 Patient education describing activity modification is useful during all stages of CMC arthritis. Research has shown that avoiding inciting activities, such as key turning, pinching, and grasping, helps to alleviate symptoms.14 Patients may also obtain relief from NSAIDs, especially when they are used in conjunction with activity modification and splinting. NSAIDs, however, do not halt or reverse the disease process; they only reduce inflammation, synovitis, and pain.11

Splinting. Studies have shown splinting of the thumb CMC joint to provide pain relief and to potentially slow disease progression.15 Because splints decrease motion and increase joint stability, they are especially useful for patients with joint hypermobility. The long opponens thumb spica splint is commonly used; it immobilizes the wrist and CMC, while leaving the thumb interphalangeal joint free. Short thumb spica and neoprene splints are also commercially available, and studies have shown that they provide good results.15 Splinting is most beneficial in patients with early-stage disease and may be used for either short-term flares or long-term treatment.11

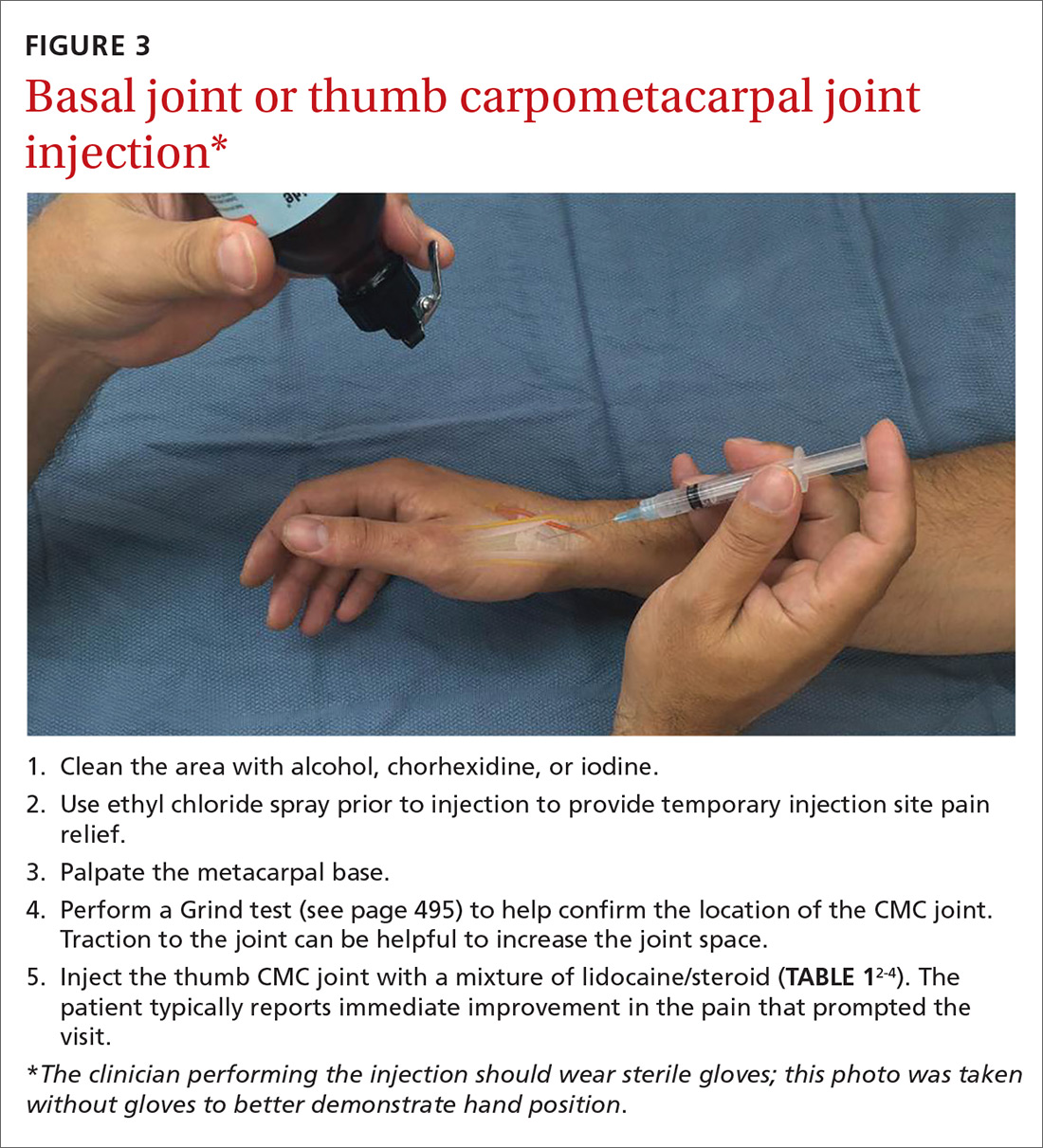

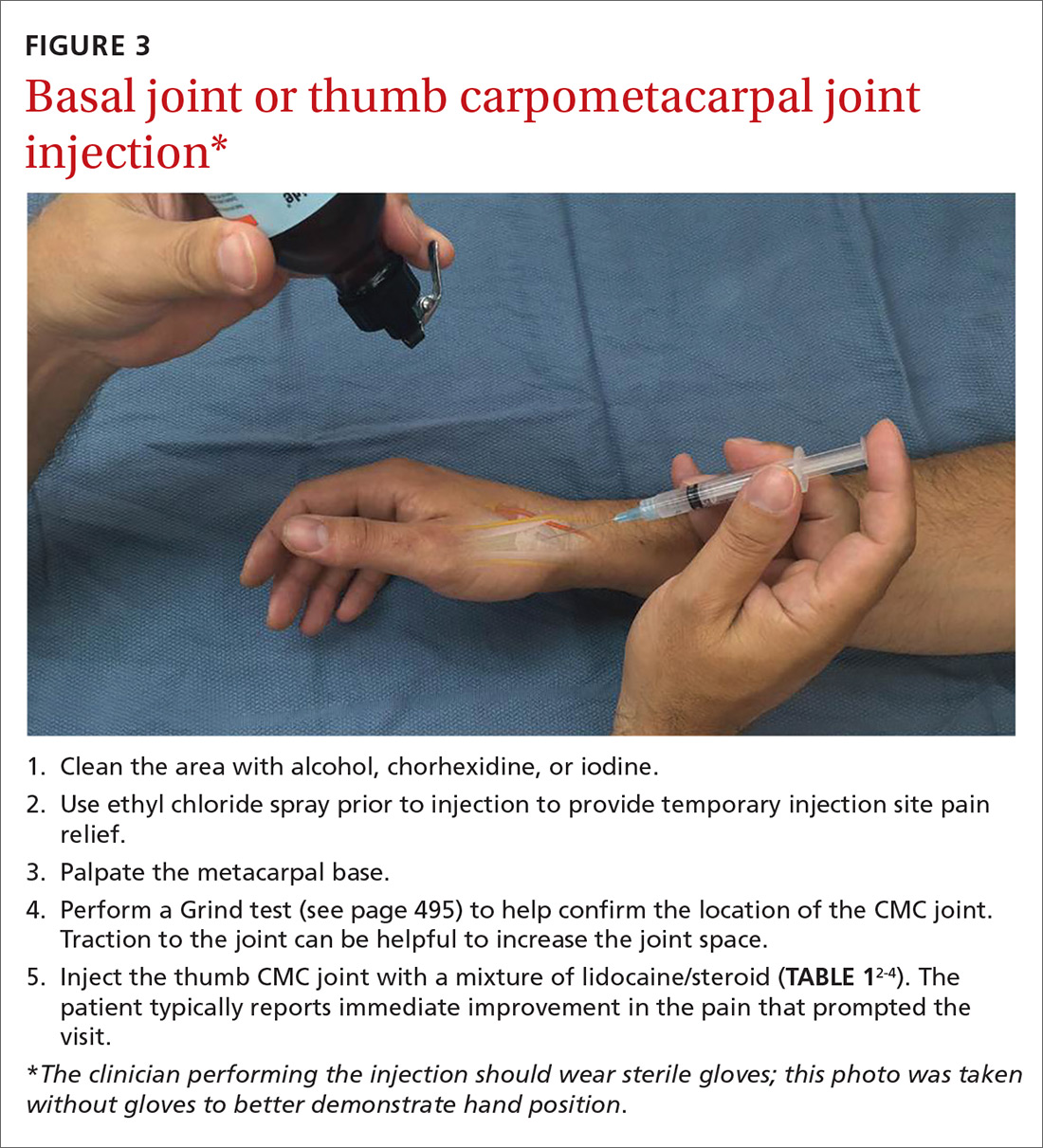

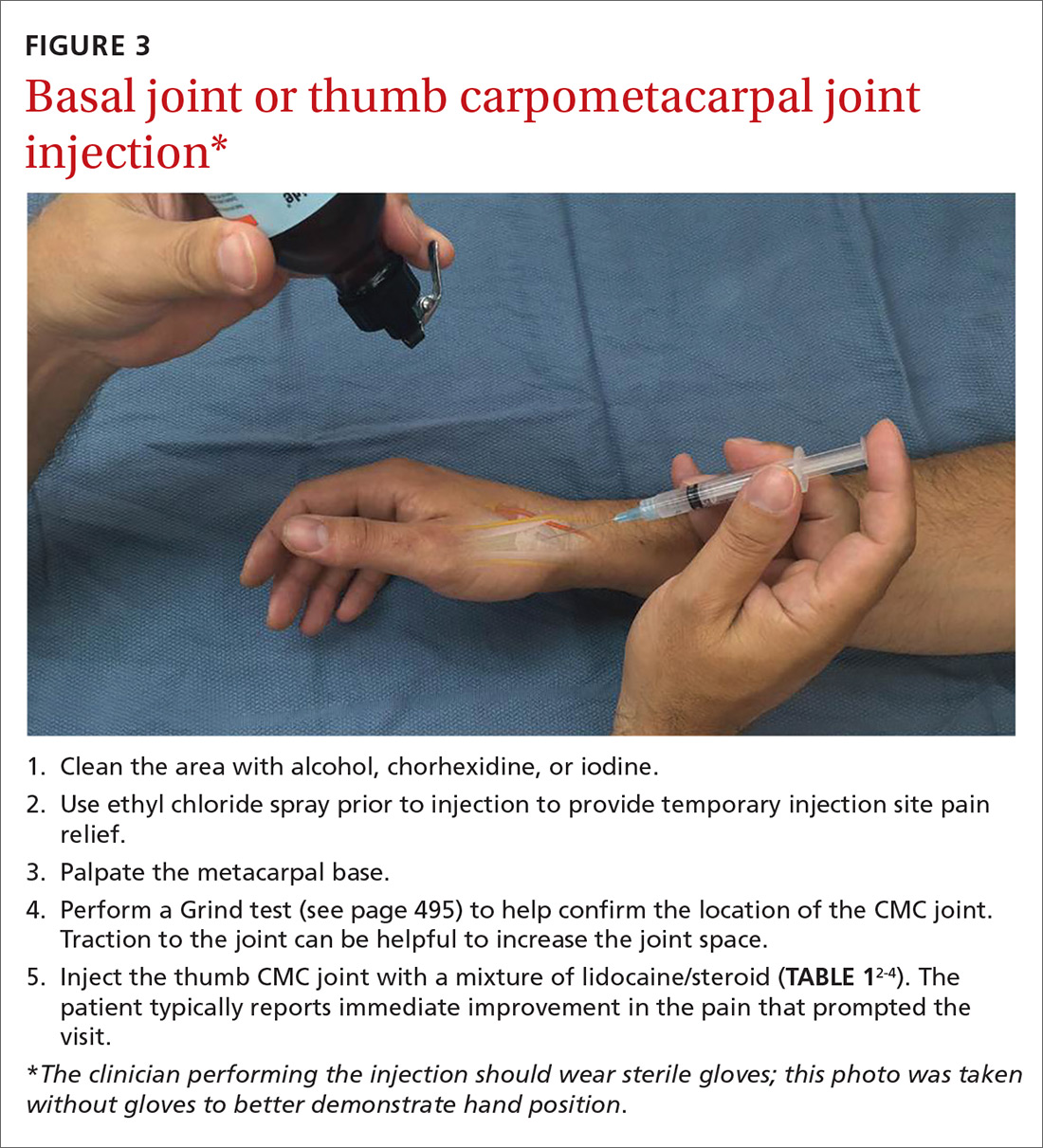

Cortisone injections. For those patients who do not respond to activity modification, NSAIDs, and/or splinting, consider cortisone injections (FIGURE 3). Intra-articular cortisone injections can decrease inflammation and provide good pain relief, especially in patients with early-stage disease. The effectiveness of cortisone injections in patients with more advanced disease is not clear; no benefit has been shown in studies to date.16 Equally unclear is the long-term benefit of injections.11 Patients who do not respond to conservative treatments will often require surgical care.

Carpal tunnel syndrome: Moving slower to surgery

CTS is one of the most common conditions of the upper extremities. Researchers estimate that 491 women per 100,000 person-years and 258 men per 100,000 person-years will develop CTS, with 109 per 100,000 person-years receiving carpal tunnel release surgery.17 Risk factors for the development of CTS include diabetes, hypothyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, pregnancy, obesity, family history, trauma, and occupations that involve repetitive tasks or long hours working at a computer.18

CTS is caused by compression of the median nerve as it passes through the carpal tunnel.19 The elevated pressure in the carpal tunnel restricts epineural blood flow and supply, causing the pain felt with CTS.20 Even after surgical decompression, recurrent or persistent CTS can be a problem.21

Making the Dx: Perform the Phalen maneuver, Durkan’s test

Patients typically present with complaints of weakness, pain, and/or numbness in at least 2 of 4 radial digits (thumb, index, middle, ring).19,22 The most common time of day for patients to have symptoms is at night.21

The diagnostic tools. Tinel’s sign is a useful diagnostic tool when you suspect carpal tunnel syndrome. Tinel’s sign is positive if percussion over the median nerve at the carpal tunnel elicits pain or paresthesia.18

When employing the Phalen maneuver, be certain to have the patient flex his/her wrist to 90 degrees and to document the number of seconds it takes for numbness to present in the fingers. Pain or paresthesia should occur in <60 seconds for the test to be positive.18

Median nerve compression over the carpal tunnel, also known as Durkan’s test, may also elicit symptoms. With Durkan’s test, you apply direct pressure over the transverse carpal ligament. If pain or paresthesia occurs in <30 seconds, the test is positive.18 Often clinicians will combine the Phalen maneuver and Durkan’s test to increase sensitivity and specificity.18 Nerve conduction studies are often performed to confirm the clinical diagnosis.

Is more than one condition at play? It is important to determine whether cervical spine disease and/or peripheral neuropathy is contributing to the patient’s symptoms, along with CTS; patients may have more than one condition contributing to their pain. We routinely check cervical spine motion, tenderness, and nerve compression as part of the exam on a patient with suspected CTS. In the office, a monofilament test or 2-point discrimination test can help make the clinical diagnosis by uncovering decreased sensation in the thumb, index, and/or middle fingers.23

The 5.07 monofilament test is performed with the clinician applying the monofilament to different dermatomal or sensory distributions while the patient has his/her eyes closed. The 2-point discrimination test is performed with a caliper device that measures the distance at which the patient can feel 2 separate stimuli. Often electromyography or nerve conduction studies are necessary.18

Treatment: Pursue nonoperative approaches

A survey of the membership of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand revealed that surgeons are utilizing nonoperative treatments for a longer duration of time and are employing narrowed surgical indications.24 Thus, clinicians are more likely to try splints and steroid injections before proceeding to operative release.24

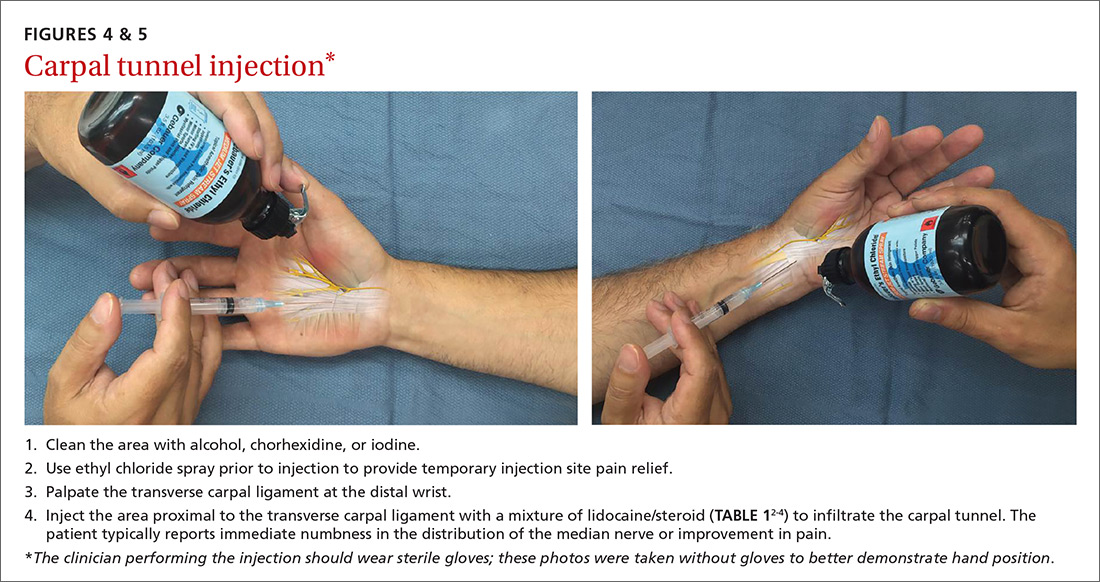

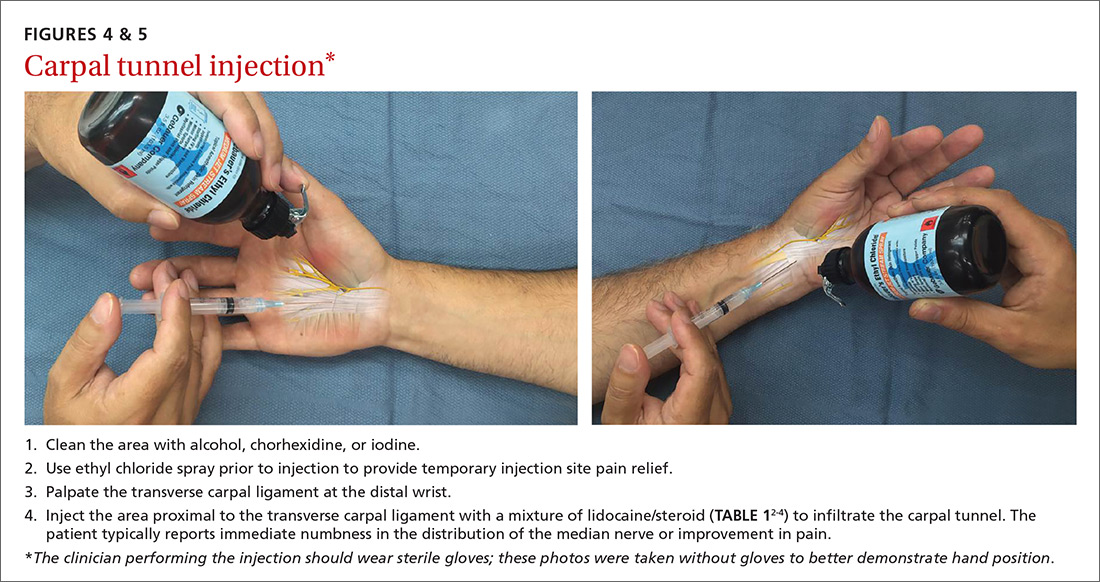

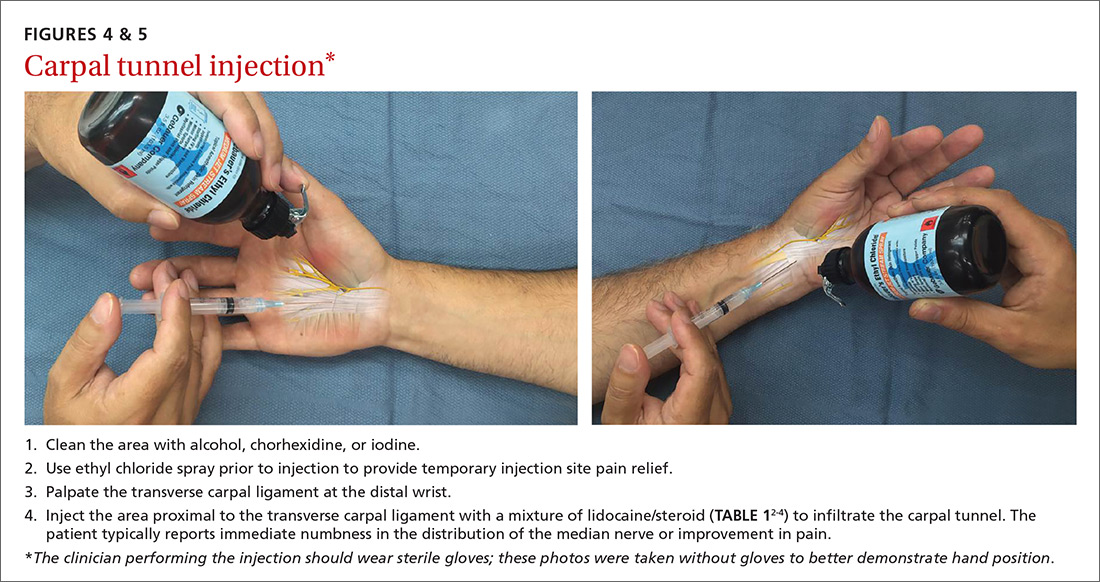

Nonsurgical management. In our practice, we commonly recommend corticosteroid injections (TABLE 12-4) into the carpal tunnel (FIGURES 4 and 5) to patients who are poor candidates for surgery (ie, those who have too many medical comorbidities or wound healing concerns). This is one indication for which you may want to consider ultrasound-guided injections because the improved accuracy may provide symptom relief faster than “blind” or palpation-guided injections.25

A recent randomized controlled trial from Sweden showed that injections of methylprednisolone relieved symptoms in patients with mild to moderate CTS at 10 weeks and reduced the rate of surgery one year after treatment; however, 3 out of 4 patients still went on to have surgery within a year.22 Patients in the study had failed a 2-month trial of splinting and were given either 80 mg or 40 mg of methylprednisolone or saline. There was no statistical difference between the doses of methylprednisolone in preventing surgery at one year. Compared to placebo, the 80-mg methylprednisolone group was less likely to have surgery with an odds ratio of 0.24 (P=.042).22

There is evidence that oral steroids, injected steroids, ultrasound, electromagnetic field therapy, nocturnal splinting, and use of ergonomic keyboards are effective nonoperative modalities in the short term, but evidence is sparse for mid- or long-term use.19 In addition, at least one randomized trial found traditional cupping therapy applied around the shoulder alleviated carpal tunnel symptoms in the short-term.26 Other nonoperative therapies include rest, NSAIDs, extracorporeal shock wave therapy, and activity modification.19,27

Surgical outcomes by either endoscopic, mini-open, or open surgical techniques are typically good.20,21 Surgical release involves cutting the transverse carpal ligament over the carpal tunnel to decompress the median nerve.24 You should inform patients of the risks and inconveniences associated with surgery, including the cost, absence from work, infection, and chronic pain. Patients who have recurrent or persistent symptoms after surgery may have had an incompletely released transverse carpal ligament or there may be no identifiable cause.21 Overall, surgical treatment, combined with physical therapy, seems to be more effective than splinting or NSAIDs for mid- and long-term treatment of CTS.28

De Quervain’s tenosynovitis: Common during pregnancy

De Quervain’s tenosynovitis (radial styloid tenosynovitis) involves painful inflammation of the 2 tendons in the first dorsal compartment of the wrist—the abductor pollicis longus (APL) and the extensor pollicis brevis (EPB). The tendons comprise the radial border of the anatomic snuffbox.

The APL abducts and extends the thumb at the CMC joint, while the EPB extends the thumb proximal phalanx at the metacarpophalangeal joint. These tendons are contained in a synovial sheath that is subject to inflammation and constriction and subsequent wear and damage.29 In addition, the extensor retinaculum in patients with de Quervain’s disease demonstrates increased vascularity and deposition of dense fibrous tissue resulting in thickening of the tendon up to 5 times its normal width.30

As a result, degeneration and thickening of the tendon sheath, as well as radial-sided wrist pain elicited at the first dorsal compartment, are common pathophysiologic and clinical findings.31 Pain is often accompanied by the build-up of protuberances and nodulations of the tendon sheath.

De Quervain’s disease commonly occurs during and after pregnancy.32 Other risk factors include racquet sports, golfing, wrist trauma, and other activities involving repetitive hand and wrist motions.33 Often, however, de Quervain’s is idiopathic.

Making the Dx: Perform a Finkelstein's test

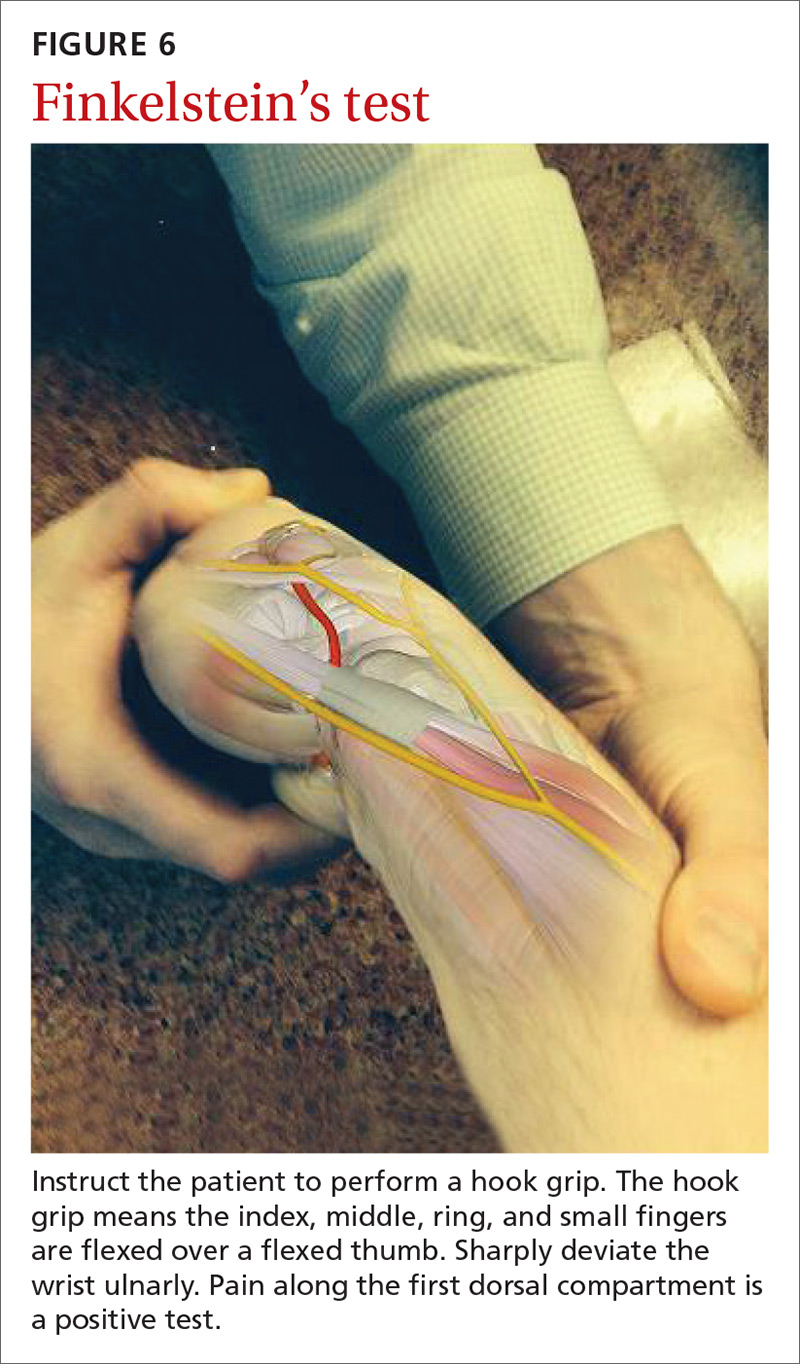

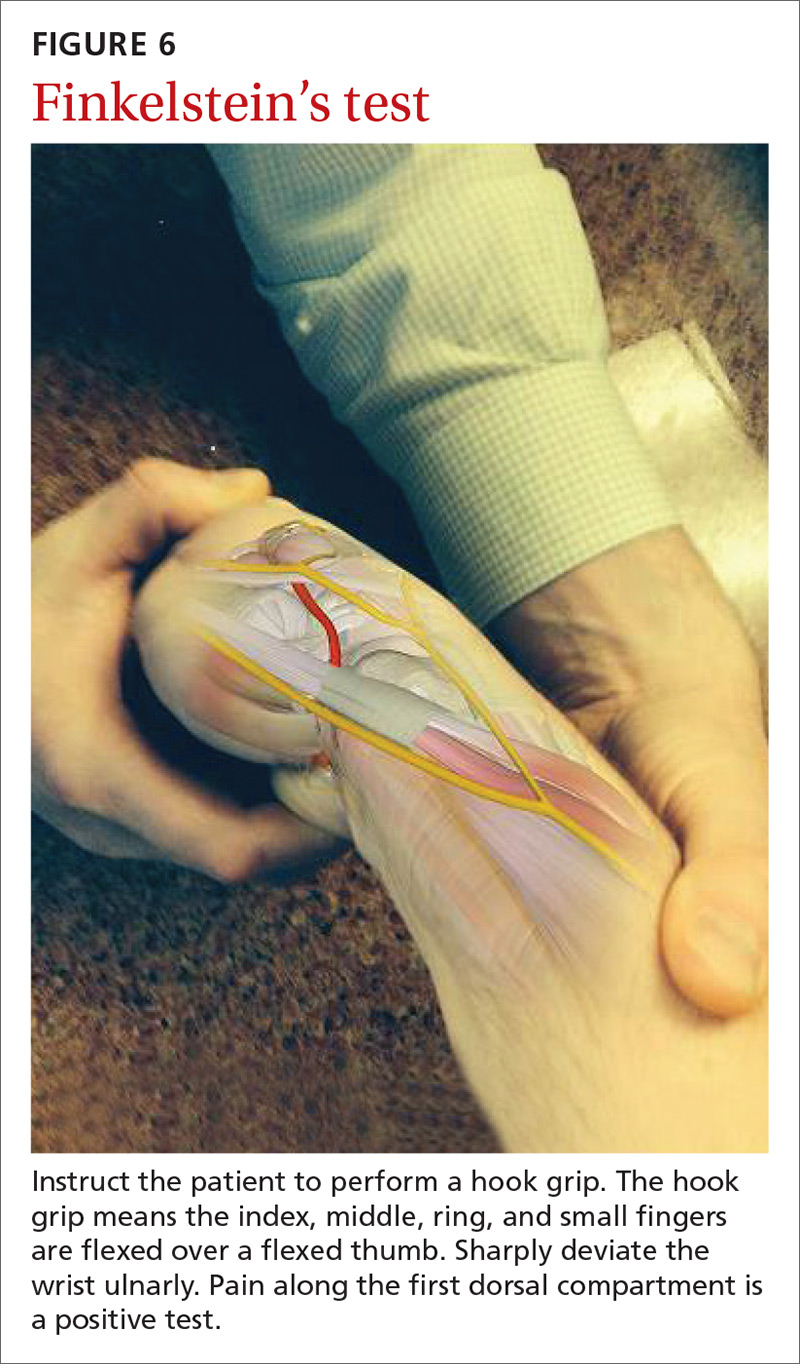

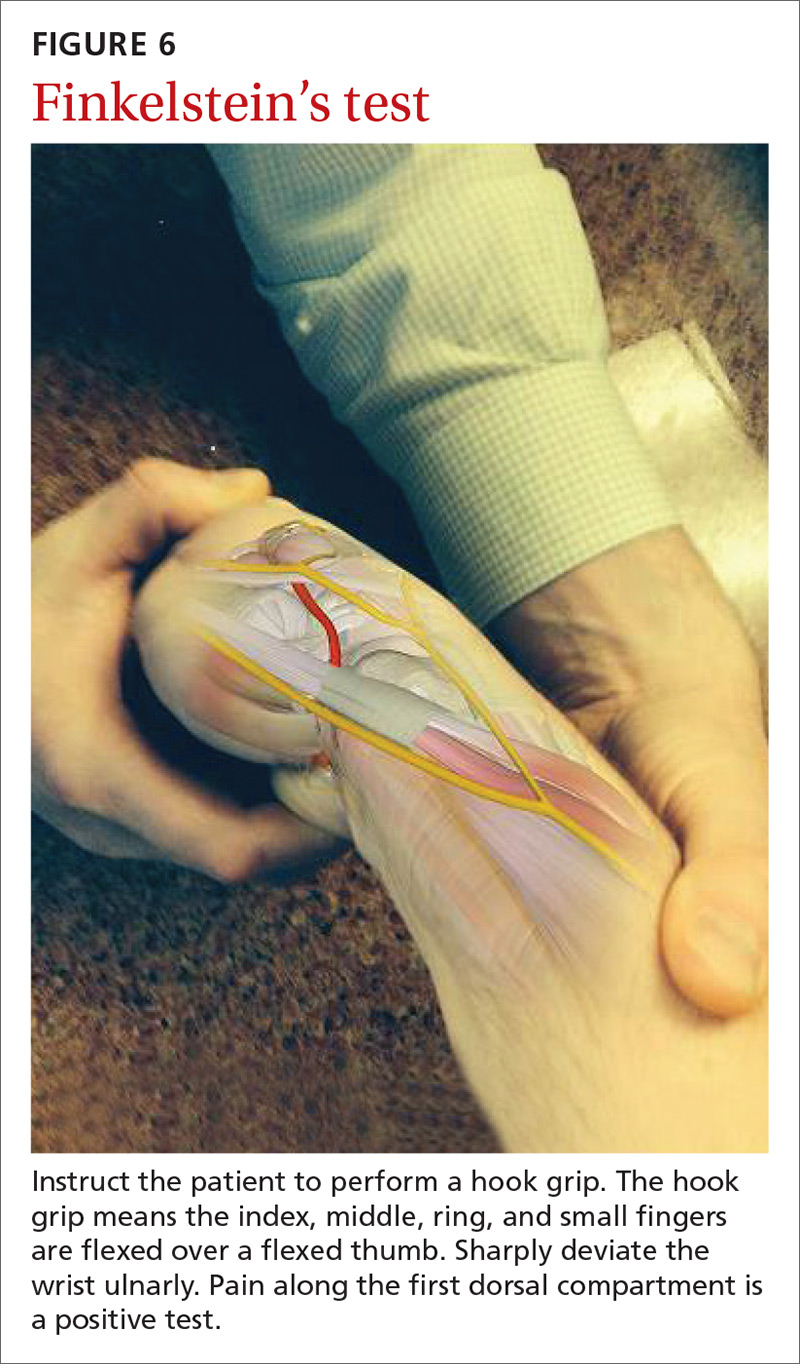

The major finding in patients with de Quervain’s tenosynovitis is a positive Finkelstein's test. To perform Finkelstein's test (FIGURE 6), ask the patient to oppose the thumb into the palm and flex the fingers of the same hand over the thumb. Holding the patient’s fingers around the thumb, ulnarly deviate the wrist. Finkelstein's test puts strain on the APL and EPB, causing pain along the radial border of the wrist and forearm in patients with de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. Since the maneuver can be uncomfortable, complete the exam on the unaffected side for comparison.

Stenosis of the tendon sheath may lead to crepitus over the first dorsal wrist compartment. This should be distinguished from intersection syndrome (tenosynovitis at the intersection of the first and second extensor compartments), which can also present with forearm and wrist crepitus. Patients usually have swelling of the wrist with marked discomfort upon palpation of the radial tendons. An x-ray can be useful to evaluate for CMC or radiocarpal arthritis, which may be an underlying cause.

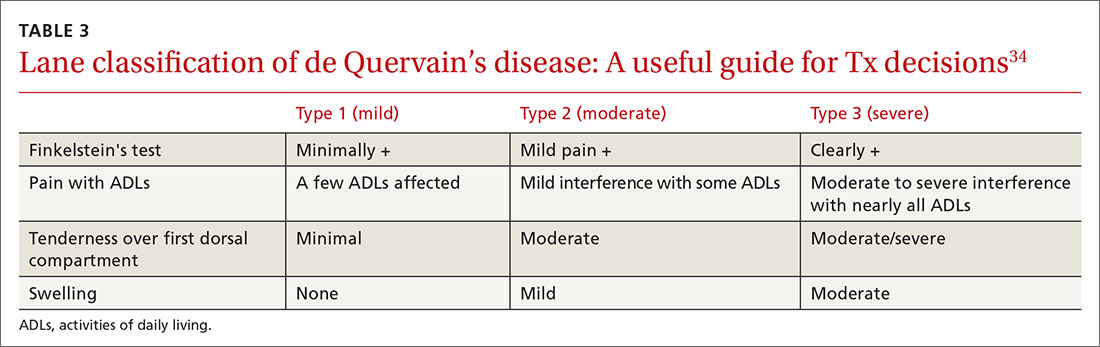

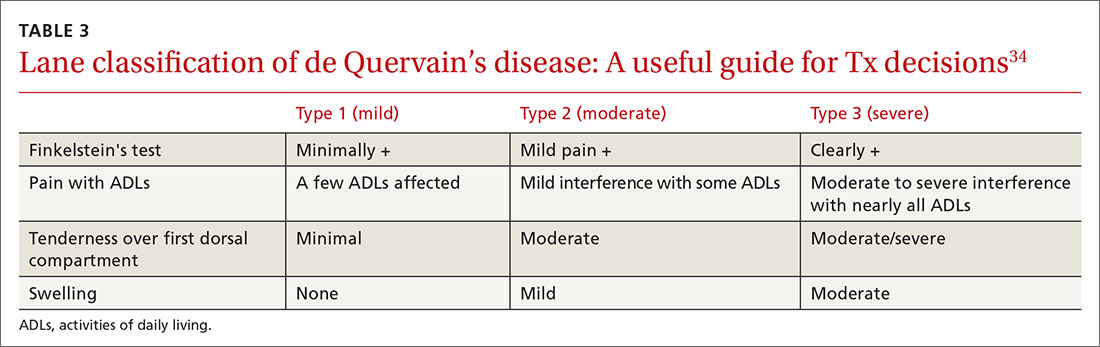

Treatment: Select an approach based on symptom severity

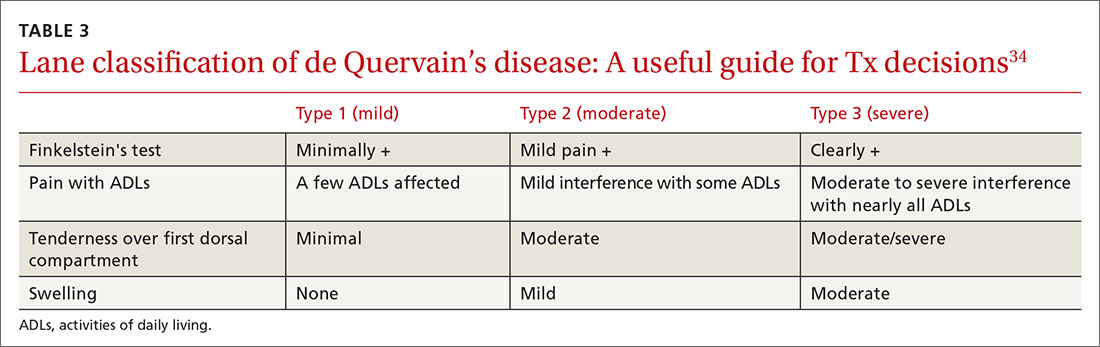

In a retrospective analysis, Lane et al concluded that classification of patients with de Quervain’s disease based on pretreatment symptoms may assist physicians in selecting the most efficacious treatment and in providing prognostic information to their patients (TABLE 334). Patients with mild to moderate (Types 1 and 2) de Quervain’s may benefit from immobilization in a thumb spica splint, rest, NSAIDs, and physical or occupational therapy. If work conditions played a role in causing the symptoms, they need to be addressed to improve outcomes. Types 2 and 3 can be initially treated with a corticosteroid injection, but may eventually require surgery.33

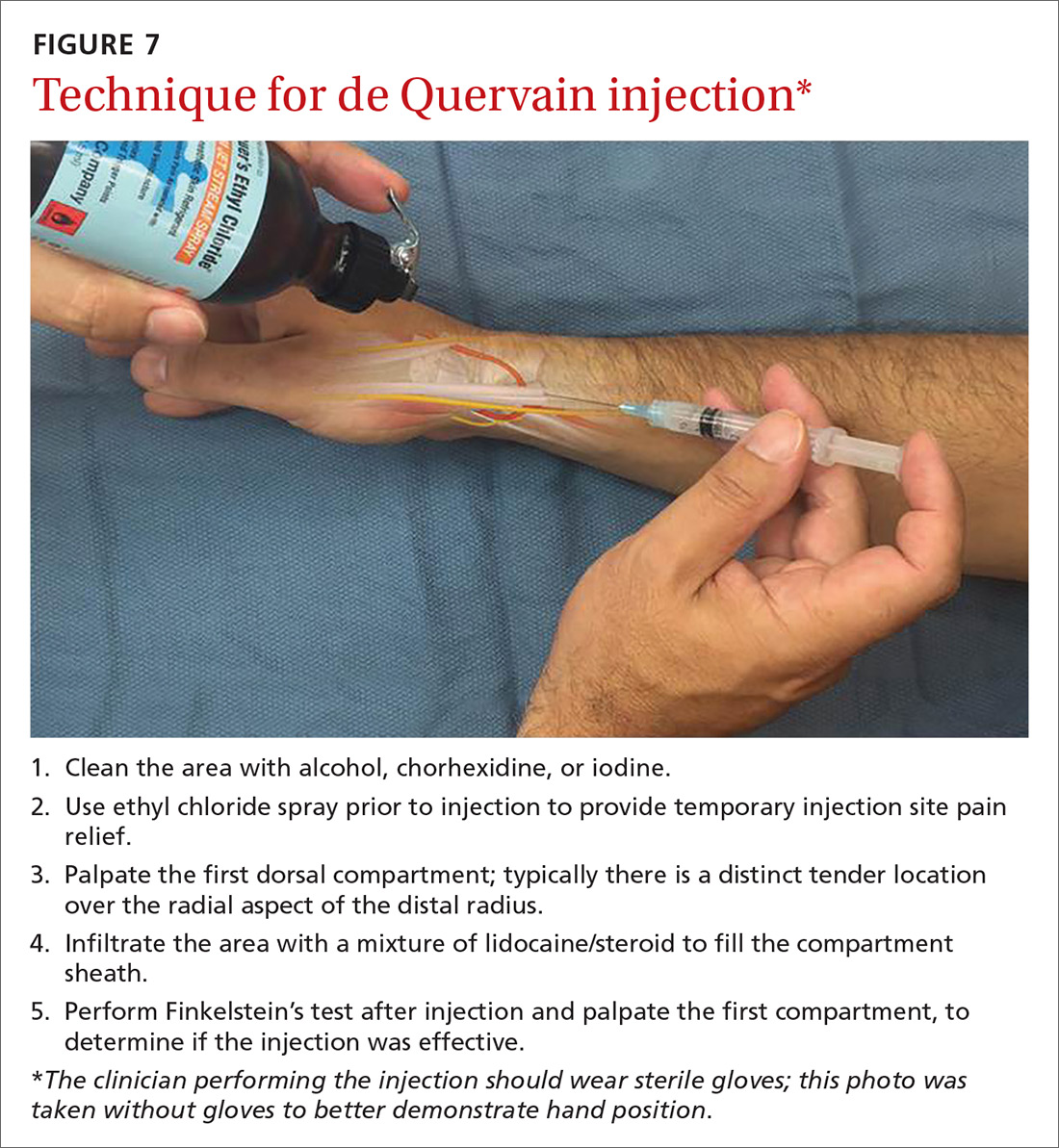

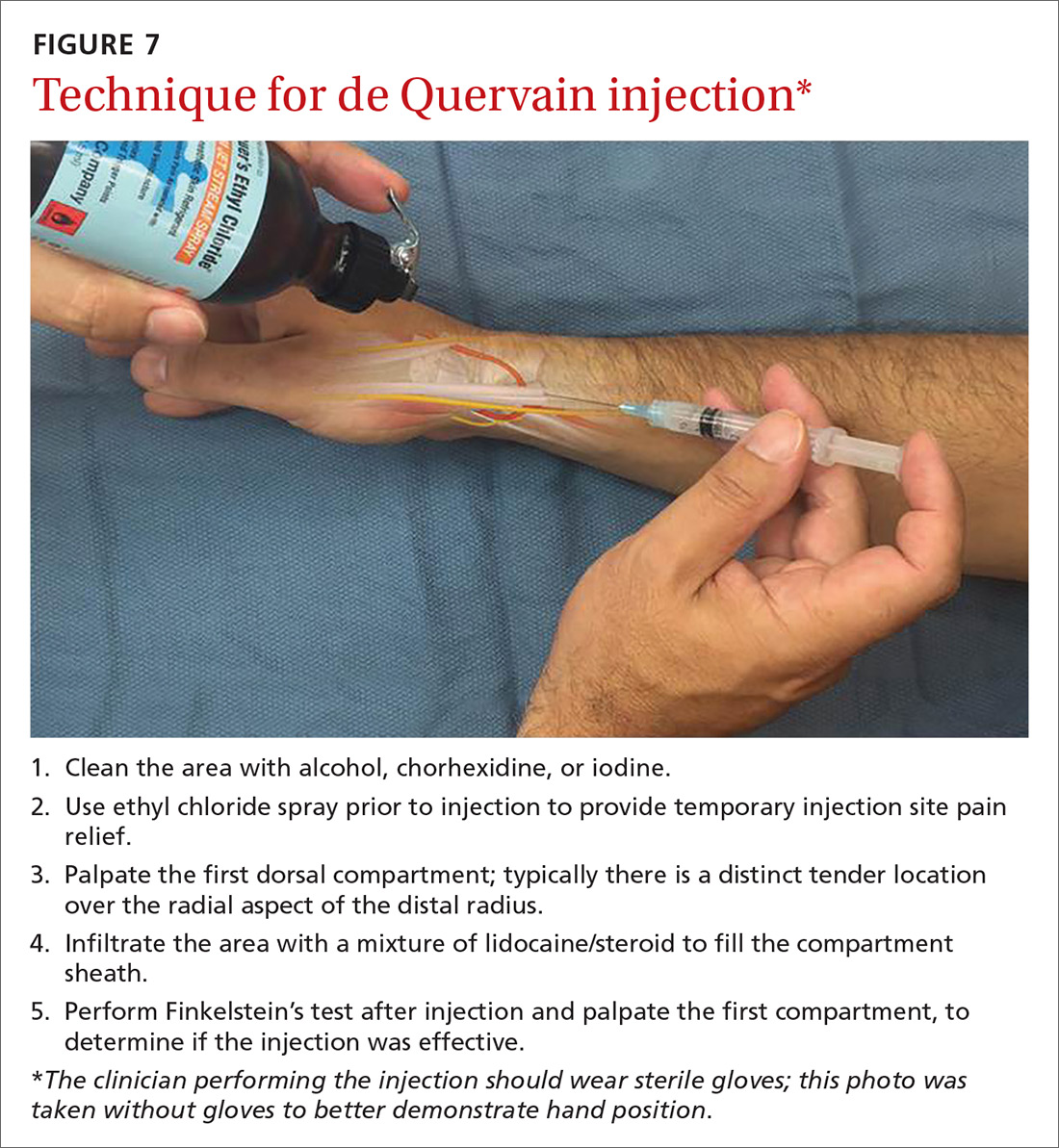

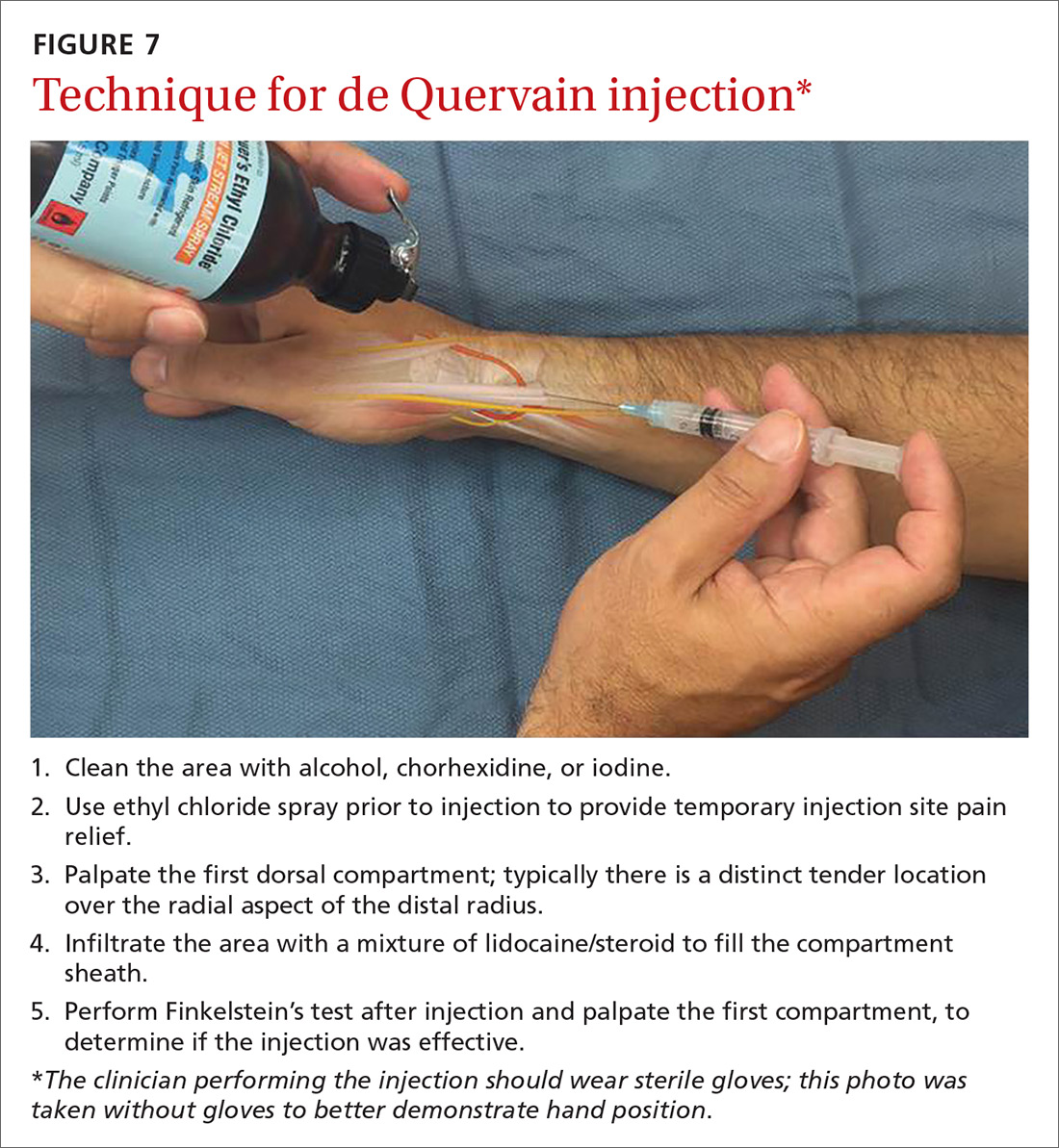

Treatment with NSAIDs or corticosteroid injections (see TABLE 12-4 for choices) in the first compartment of the extensor retinaculum (FIGURE 7) is usually adequate to provide relief. Peters-Veluthamaningal et al performed a systematic review in 2009 and found only one controlled trial of 18 participants (all pregnant or lactating women) who were either injected with corticosteroids or given a thumb spica splint.35 All 9 patients in the injection group had complete pain relief, whereas no one in the splint group had complete resolution of symptoms.35 Typical anatomic placement of corticosteroid injections is shown in FIGURE 7.

More complicated injection methods have been described, but injecting the first dorsal compartment is usually satisfactory. Patients will feel the tendon sheath filling with the injection material. The 2-point technique, implemented by Sawaizumi et al, which involves injecting corticosteroid into 2 points over the EPB and APL tendon in the area of maximum pain and soft tissue thickening, is more effective than the 1-point injection technique.36

Severe, recalcitrant cases. Professional and college athletes may be prone to recalcitrant de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. A 2010 study by Pagonis et al showed that recurrent symptomatic episodes commonly occur in athletes who engage in high-resistance, intense athletic training. In these severe cases, a 4-point injection technique offers better distribution of corticosteroid solution to the first extensor compartment than other methods.37 Consider referring severe cases to a hand surgeon.

Surgical release of the first dorsal compartmental sheath around the tendons serves as a final option for patients who fail conservative treatment. Care should be taken to release both tendons completely, as there may be at least 2 tendon slips of the APL or there may be a distinct EPB sheath dorsally.38

“Tennis elbow”— you don’t have to play tennis to have it

Lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow) is a painful condition involving microtears within the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle and the subsequent development of angiofibroblastic dysplasia.39 According to Regan et al who studied the histopathologic features of 11 patients with lateral epicondylitis, the underlying cause of recalcitrant lateral epicondylitis is, in fact, degenerative, rather than inflammatory.40

Although the condition has been nicknamed “tennis elbow,” only about 5% of tennis players have the condition.41 In tennis players, males are more often affected than females, whereas in the general population, incidence is approximately equal in men and women.41 Lateral epicondylitis occurs between 4 and 7 times more frequently than medial-sided elbow pain.42

Making the Dx: Look for localized pain, normal ROM

The diagnosis of lateral epicondylitis is based upon a history of pain over the lateral epicondyle and findings on physical examination, including local tenderness directly over the lateral epicondyle,43 pain aggravated by resisted wrist extension and radial deviation, pain with resisted middle finger extension, and decreased grip strength or pain aggravated by strong gripping. These findings typically occur in the presence of normal elbow range of motion.

Treatment: Choose from a range of options

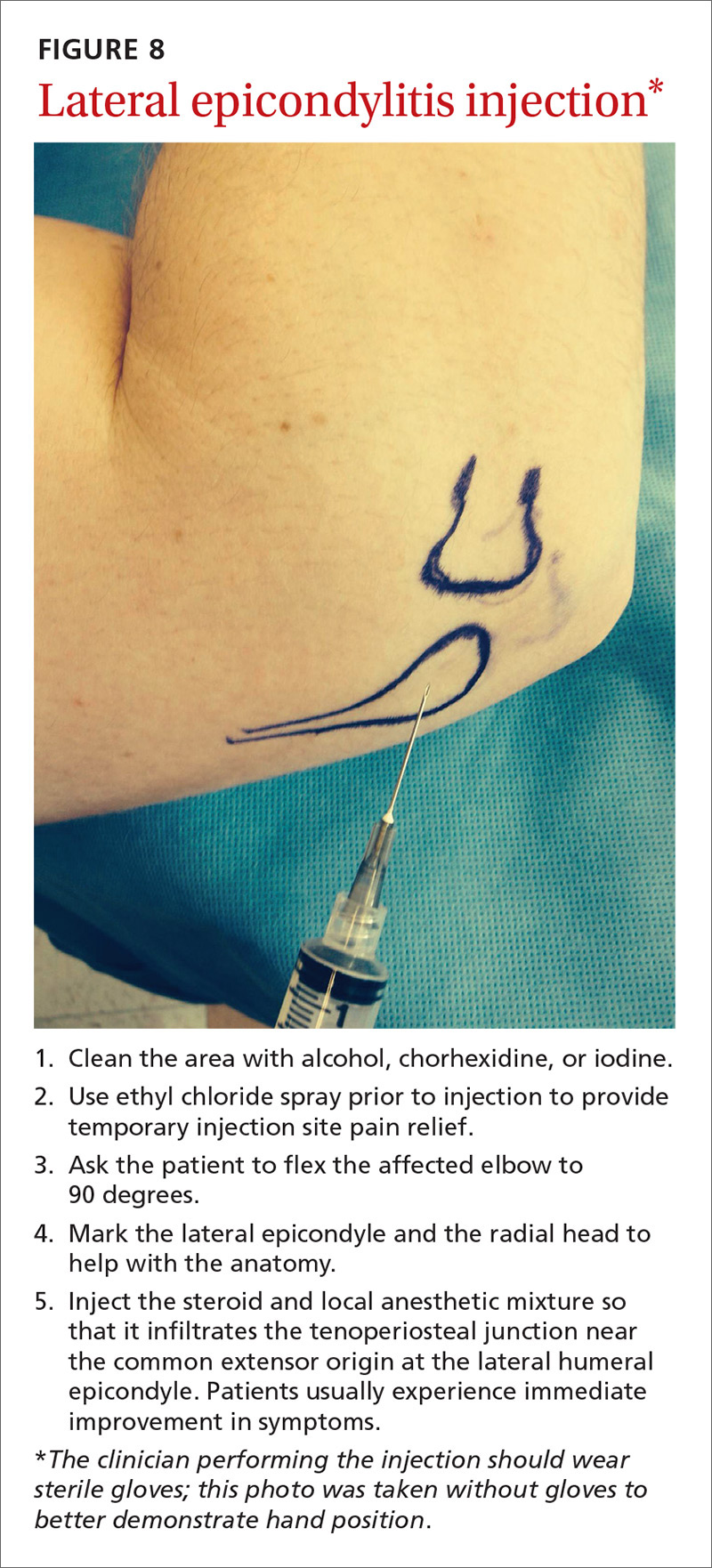

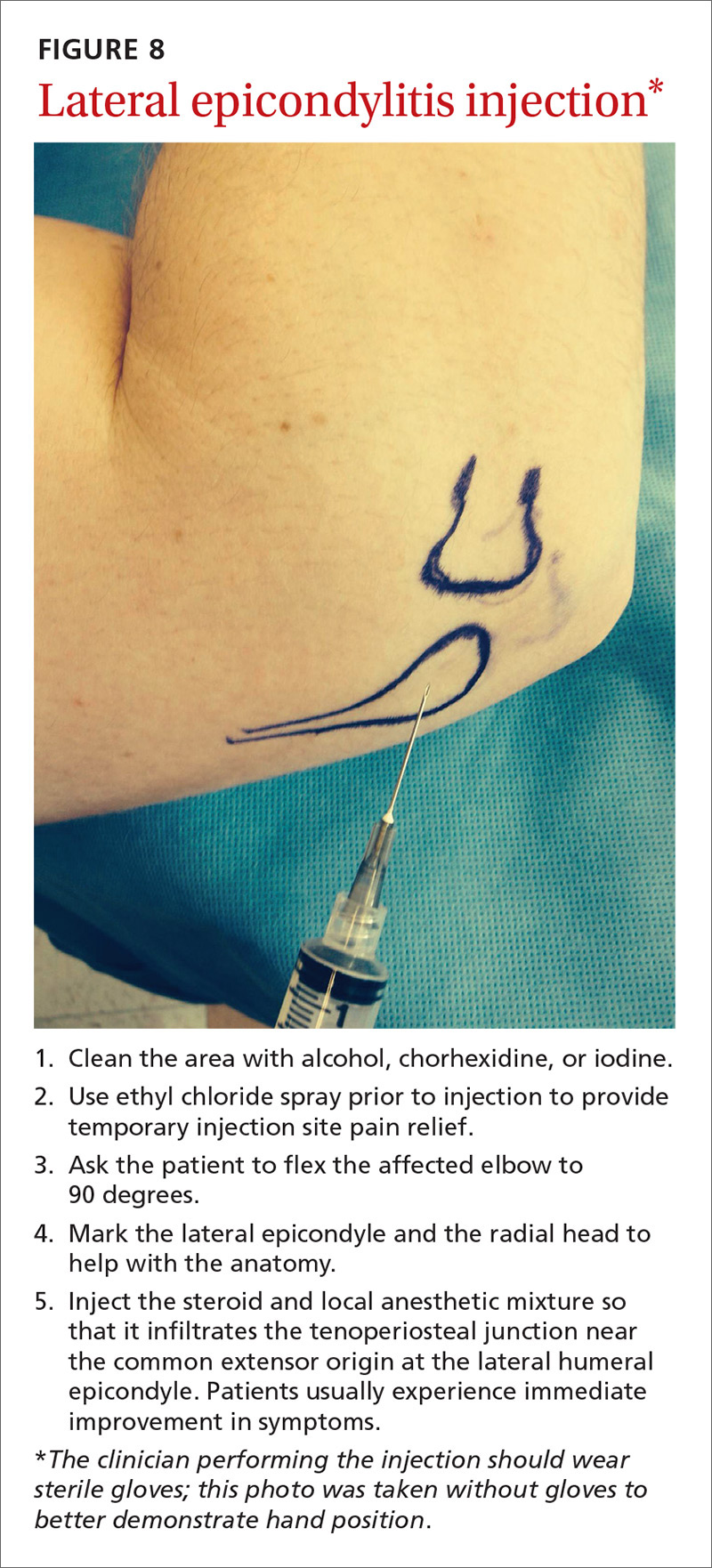

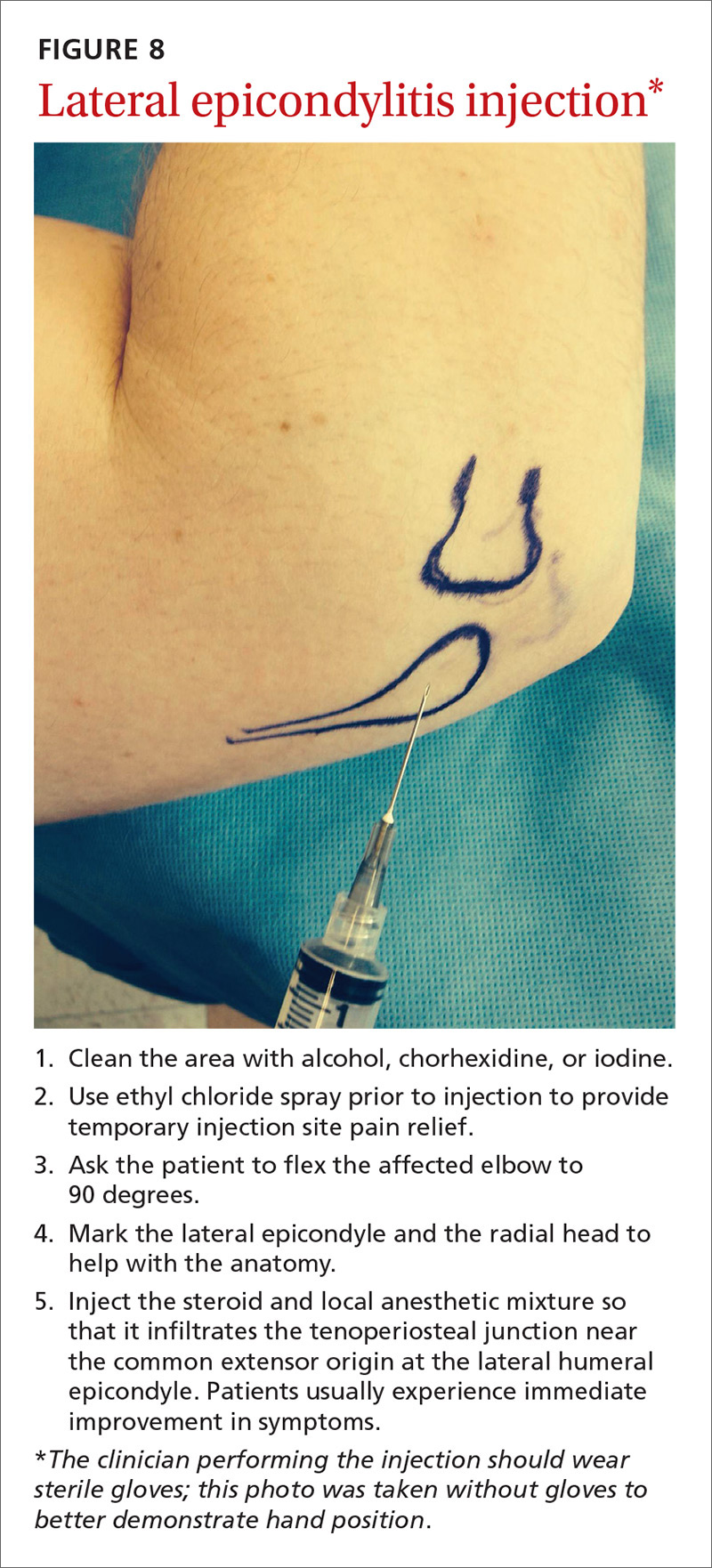

Since lateral epicondylitis was first described, researchers have proposed a wide variety of treatments as initial interventions including rest, activity, equipment modification, NSAIDs, wrist bracing/elbow straps, and physical therapy. If initial treatment does not produce the desired effect, second-line treatments include corticosteroid injections (FIGURE 8), prolotherapy (injection of an irritant, often dextrose; see “Prolotherapy: Can it help your patient?” J Fam Pract. 2015;64:763-768), autologous blood injections, platelet-rich plasma injections (see “Is platelet-rich plasma right for your patient?” J Fam Pract. 2016;65:319-328), and needling of the extensor tendon origin. Refer patients who do not improve after one corticosteroid injection to an orthopedic surgeon for consideration of open or arthroscopic treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Gregory R. Waryasz, MD, Rhode Island Hospital, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, 593 Eddy St., Providence, RI 02903; [email protected].

1. Fitzgibbons PG, Weiss AP. Hand manifestations of diabetes mellitus. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:771-775.

2. Peters-Veluthamaningal C, Van der Windt DA, Winters JC, et al. Corticosteroid injection for trigger finger in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD005617.

3. Cheng J, Abdi S. Complications of joint, tendon, and muscle injections. Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manag. 2007;11:141-147.

4. Waryasz GR, Tambone R, Borenstein TR, et al. A review of anatomical placement of corticosteroid injections for uncommon hand, wrist, and elbow pathologies. R I Med J. 2017;100:31-34.

5. Nepple JJ, Matava MJ. Soft tissue injections in the athlete. Sports Health. 2009;1:396-404.

6. Henton J, Jain A, Medhurst C, et al. Adult trigger finger. BMJ. 2012;345:e5743.

7. Lundin AC, Aspenberg P, Eliasson P. Trigger finger, tendinosis, and intratendinous gene expression. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24:363-368.

8. Sato ES, Gomes Dos Santos JB, Belloti JC, et al. Treatment of trigger finger: randomized clinical trial comparing the methods of corticosteroid injection, percutaneous release and open surgery. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51:93-99.

9. Baek GH, Kim JH, Chug MS, et al. The natural history of pediatric trigger thumb. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:980-985.

10. Gillis J, Calder K, Williams J. Review of thumb carpometacarpal arthritis classification, treatment and outcomes. Can J Plast Surg. 2011;19:134-138.

11. Yao J, Park MJ. Early treatment of degenerative arthritis of the thumb carpometacarpal joint. Hand Clin. 2008;24:251-261.

12. Ladd AL, Weiss AP, Crisco JJ, et al. The thumb carpometacarpal joint: anatomy, hormones, and biomechanics. Instr Course Lect. 2013;62:165-179.

13. Fontana L, Neel S, Claise JM, et al. Osteoarthritis of the thumb carpometacarpal joint in women and occupational risk factors: a case-control study. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32:459-465.

14. Stamm TA, Machold KP, Smolen JS, et al. Joint protection and home hand exercises improve hand function in patients with hand osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:44-49.

15. Weiss S, LaStayo P, Mills A, et al. Prospective analysis of splinting the first carpometacarpal joint: an objective, subjective, and radiographic assessment. J Hand Ther. 2000;13:218-226.

16. Day CS, Gelberman R, Patel AA, et al. Basal joint osteoarthritis of the thumb: a prospective trial of steroid injection and splinting. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29:247-251.

17. Gelfman R, Melton LJ 3rd, Yawn BP, et al. Long-term trends in carpal tunnel syndrome. Neurology. 2009;72:33-41.

18. Wipperman J, Potter L. Carpal tunnel syndrome-try these diagnostic maneuvers. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:726-732.

19. Huisstede BM, Hoogvliet P, Randsdorp MS, et al. Carpal tunnel syndrome. Part I: effectiveness of nonsurgical treatments—a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:981-1004.

20. Mintalucci DJ, Leinberry CF Jr. Open versus endoscopic carpal tunnel release. Orthop Clin North Am. 2012;43:431-437.

21. Soltani AM, Allan BJ, Best MJ, et al. A systematic review of the literature on the outcomes of treatment for recurrent and persistent carpal tunnel syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:114-121.

22. Atroshi I, Flondell M, Hofer M, et al. Methylprednisolone injections for the carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:309-317.

23. Raji P, Ansari NN, Naghdi S, et al. Relationship between Semmes-Weinstein Monofilaments perception test and sensory nerve conduction studies in carpal tunnel syndrome. NeuroRehabilitation. 2014;35:543-552.

24. Leinberry CF, Rivlin M, Maltenfort M, et al. Treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome by members of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand: a 25-year perspective. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:1997-2003.e3.

25. Ustün N, Tok F, Yagz AE, et al. Ultrasound-guided vs. blind steroid injections in carpal tunnel syndrome: a single-blind randomized prospective study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;92:999-1004.

26. Michalsen A, Bock S, Lüdtke R, et al. Effects of traditional cupping therapy in patients with carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain. 2009;10:601-608.

27. Seok H, Kim SH. The effectiveness of extracorporeal shock wave therapy vs. local steroid injection for management of carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;92:327-334.

28. Huisstede BM, Randsdorp MS, Coert JH, et al. Carpal tunnel syndrome. Part II: effectiveness of surgical treatments—a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:1005-1024.

29. Shehab R, Mirabelli MH. Evaluation and diagnosis of wrist pain: a case-based approach. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:568-573.

30. Clarke MT, Lyall HA, Grant JW, et al. The histopathology of de Quervain’s disease. J Hand Surg Br. 1998;23:732-734.

31. Zychowicz MA. A closer look at hand and wrist complaints. Nurse Pract. 2013;38:46-53.

32. Avci S, Yilmaz C, Sayli U. Comparison of nonsurgical treatment measures for de Quervain’s disease of pregnancy and lactation. J Hand Surg Am. 2002;27:322-324.

33. Mani L, Gerr F. Work-related upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders. Prim Care. 2000;27:845-864.

34. Lane LB, Boretz RS, Stuchin SA. Treatment of de Quervain’s disease: role of conservative management. J Hand Surg Br. 2001;26:258-260.

35. Peters-Veluthamaningal C, Van der Windt JC, Winters JC, et al. Corticosteroid injection for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;8:CD005616.

36. Sawaizumi T, Nanno M, Ito H. De Quervain’s disease: efficacy of intra-sheath triamcinolone injection. Int Orthop. 2007;31:265-268.

37. Pagonis T, Ditsios K, Toli P, et al. Improved corticosteroid treatment of recalcitrant de Quervain tenosynovitis with a novel 4-point injection technique. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:398-403.

38. Scheller A, Schuh R, Hönle W, et al. Long-term results of surgical release of de Quervain’s stenosing tenosynovitis. Int Orthop. 2009;33:1301-1303.

39. Nirschl RP, Pettrone FA. Tennis elbow. The surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61:832-839.

40. Regan W, Wold LE, Coonrad R, et al. Microscopic histopathology of chronic refractory lateral epicondylitis. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:746-749.

41. Van Hofwegen C, Baker CL 3rd, Baker CL Jr. Epicondylitis in the athlete’s elbow. Clin Sports Med. 2010;29:577-597.

42. Leach RE, Miller JK. Lateral and medial epicondylitis of the elbow. Clin Sports Med. 1987;6:259-272.

43. Weerakul S, Galassi M. Randomized controlled trial local injection for treatment of lateral epicondylitis, 5 and 10 mg triamcinolone compared. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95 Supp 10:S184-188.

Primary care physicians are frequently the first to evaluate hand, wrist, and forearm pain in patients, making knowledge of the symptoms, causes, and treatment of common diagnoses in the upper extremities imperative. Primary symptoms usually include pain and/or swelling. While most tendon disorders originating in the hand and wrist are idiopathic in nature, some patients occasionally report having recently performed unusual manual activity or having experienced trauma to the area days or weeks prior. A significant portion of patients are injured as a result of chronic repetitive activities at work.1

Most diagnoses can be made by pairing your knowledge of hand and forearm anatomy with an understanding of which tender points are indicative of which common conditions. (Care, of course, must be taken to ensure that there is no underlying infection.) Common conditions can often be treated nonsurgically with conservative treatments such as physical therapy, bracing/splinting, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and injections of corticosteroids (eg, betamethasone, hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone, and triamcinolone) (TABLE 12-4) with or without the use of ultrasound. The benefits of corticosteroid injections for these conditions are well studied and documented in the literature, although physicians should always warn patients of the possible adverse effects prior to injection3,5 (TABLE 24).

To help you refine your skills, we review some of the more common hand and forearm conditions you are likely to encounter in the office and provide photos that reveal underlying anatomy so that you can administer injections without, in many cases, the need for ultrasound.

Trigger finger/thumb: New pathophysiologic findings?

Trigger finger most commonly occurs in the dominant hand. It is also more common in women, patients in their 50s, and in individuals with diabetes.6 Trigger finger/thumb is caused by inflammation and constriction of the flexor tendon sheath, which carries the flexor tendons through the palm and into the fingers and thumb. This, in turn, causes irritation of the tendons, sometimes via the formation of tendinous nodules, which may impinge upon the sheath’s “pulley system.”

When the “pulley” is compromised. The retinacular sheath is composed of 5 annular ligaments, or pulleys, that hold the tendons of the fingers close to the bone and allow the fingers to flex properly. The A1 pulley, at the level of the metacarpal head, is the first part of the sheath and is subject to the highest force; high forces may subsequently lead to the finger becoming locked in a flexed, or trigger, position.6 Patients may experience pain in the distal palm at the level of the A1 pulley and clicking of the finger.6

Additionally . . . recent studies show discrete histologic changes in trigger finger tendons, similar to findings with Achilles tendinosis and tendinopathy.7 In trigger finger tendons, collagen type 1A1 and 3A1, aggrecan, and biglycan are up-regulated, while metalloproteinase inhibitor 3 (TIMP-3) and matrix metallopeptidase3 (MMP-3) are down-regulated, a situation also described in Achilles tendinosis.7 This similarity in conditions provides new insight into the pathophysiology of the condition and may help provide future treatments.

Making the Dx: Look for swelling, check for carpal tunnel

During the examination, first look at both hands for swelling, arthropathy, or injury, and note the presence of any joint contractures. Next, examine all of the digits in flexion and extension while noting which ones are triggering, as the problem can occur in multiple digits on one hand. Then palpate the palms over the patient’s metacarpal heads, feeling for tender nodules.

Finally, examine the patient for carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS). A positive Tinel’s sign (shooting pain into the hand when the median nerve in the wrist is percussed), a positive Phalen maneuver (numbness or pain, usually within one minute of full wrist flexion), or thenar muscle wasting are highly indicative of CTS (compression of the median nerve at the transverse carpal ligament in the carpal tunnel). It is important to check for CTS when examining a patient for trigger finger because the 2 conditions frequently co-occur.6 (For more on CTS, see here.)

Treatment: Consider corticosteroids first

First-line treatment for patients with trigger finger or thumb is a corticosteroid injection into the subcutaneous tissue around the tendon sheath (FIGURES 1 and 2). (For this indication and for the others discussed throughout the article, there isn’t tremendous evidence for one particular type of corticosteroid over another; see TABLE 12-4 for choices.) Up to 57% of cases resolve with one injection, and 86% resolve with 2,8 but keep in mind that it may take up to 2 weeks to achieve the full clinical benefit.

Patients with multiple trigger fingers can be treated with oral corticosteroids (eg, a methylprednisolone dose pack). Peters-Veluthamaningal et al performed a systematic review in 2009 and found 2 randomized controlled trials involving 63 patients (34 received injections of a corticosteroid [either methylprednisolone or betamethasone] and lidocaine and 29 received lidocaine only).2 The corticosteroid/lidocaine combination was more effective at 4 weeks (relative risk [RR]=3.15; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.34 to 7.40).2

If 2 corticosteroid injections 6 weeks apart fail to provide benefit, or the finger is irreversibly locked in flexion, surgical release of the pulley is required and is performed through a palmar incision at the level of the A1 pulley. Complications from this surgery, including nerve damage, are exceedingly rare, but injury can occur, given the proximity of the digital nerves to the A1 pulley.

Patient is a child? Refer children with trigger finger or thumb to a hand surgeon for evaluation and management because the indications for nonoperative treatment in the pediatric population are unclear.9

Carpometacarpal arthritis: Common, with many causes

Osteoarthritis of the first carpometacarpal (CMC) joint is the most common site of arthritis in the hand/wrist region, affecting up to 11% of men and 33% of women in their 50s and 60s.10 Because the CMC joint lacks a bony restraint, it relies on a number of ligaments for stability—the strongest and most important of which is the palmar oblique “beak” ligament.11 A major cause of degenerative arthritis of this joint is attenuation and laxity of these ligaments, leading to abnormal and increased stress loads, which, in turn, can lead to loss of cartilage and bony impingement. While the exact mechanism of this process is not fully understood,10,12 acute or chronic trauma, advanced age, hormonal factors, and genetic factors seem to play a role.11

Many believe there is a relationship between a patient's occupation and the development of CMC arthritis, but studies are inconclusive.13 At risk are secretarial workers, tailors, domestic helpers/cleaners, and individuals whose jobs involve repetitive thumb use and/or insufficient rest of the joint throughout the day.

Making the Dx: Perform the Grind test

A detailed patient history (which is usually void of trauma to the hand) and physical examination are the keys to making the diagnosis of CMC arthritis. A history of pain at the base of the thumb during pinching and gripping tasks is often elucidated. Classically, patients describe pain upon turning keys, opening jars, and gripping doorknobs.11

It's important to focus on the dorsoradial aspect of the thumb during the physical exam and to rule out other causes of pain, such as de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, flexor carpi radialis tendinitis, CTS, and trigger thumb.11 Typical findings include pain with palpation directly over the dorsoradial aspect of the CMC joint and pain with axial loading and upon circumduction during a Grind test of the CMC joint. (The Grind test is performed by moving the metacarpal bone of the thumb in a circle and loading it with gentle axial forces. People with thumb joint arthritis generally experience sudden sharp pain at the CMC joint.)

Radiographic findings can be useful as a diagnostic adjunct, with staging of the disease, and in determining who can benefit from conservative management.11

Treatment: Start with NSAIDs and splinting

Depending on the degree of arthritis, management may include both conservative and surgical options.10 Patient education describing activity modification is useful during all stages of CMC arthritis. Research has shown that avoiding inciting activities, such as key turning, pinching, and grasping, helps to alleviate symptoms.14 Patients may also obtain relief from NSAIDs, especially when they are used in conjunction with activity modification and splinting. NSAIDs, however, do not halt or reverse the disease process; they only reduce inflammation, synovitis, and pain.11

Splinting. Studies have shown splinting of the thumb CMC joint to provide pain relief and to potentially slow disease progression.15 Because splints decrease motion and increase joint stability, they are especially useful for patients with joint hypermobility. The long opponens thumb spica splint is commonly used; it immobilizes the wrist and CMC, while leaving the thumb interphalangeal joint free. Short thumb spica and neoprene splints are also commercially available, and studies have shown that they provide good results.15 Splinting is most beneficial in patients with early-stage disease and may be used for either short-term flares or long-term treatment.11

Cortisone injections. For those patients who do not respond to activity modification, NSAIDs, and/or splinting, consider cortisone injections (FIGURE 3). Intra-articular cortisone injections can decrease inflammation and provide good pain relief, especially in patients with early-stage disease. The effectiveness of cortisone injections in patients with more advanced disease is not clear; no benefit has been shown in studies to date.16 Equally unclear is the long-term benefit of injections.11 Patients who do not respond to conservative treatments will often require surgical care.

Carpal tunnel syndrome: Moving slower to surgery

CTS is one of the most common conditions of the upper extremities. Researchers estimate that 491 women per 100,000 person-years and 258 men per 100,000 person-years will develop CTS, with 109 per 100,000 person-years receiving carpal tunnel release surgery.17 Risk factors for the development of CTS include diabetes, hypothyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, pregnancy, obesity, family history, trauma, and occupations that involve repetitive tasks or long hours working at a computer.18

CTS is caused by compression of the median nerve as it passes through the carpal tunnel.19 The elevated pressure in the carpal tunnel restricts epineural blood flow and supply, causing the pain felt with CTS.20 Even after surgical decompression, recurrent or persistent CTS can be a problem.21

Making the Dx: Perform the Phalen maneuver, Durkan’s test

Patients typically present with complaints of weakness, pain, and/or numbness in at least 2 of 4 radial digits (thumb, index, middle, ring).19,22 The most common time of day for patients to have symptoms is at night.21

The diagnostic tools. Tinel’s sign is a useful diagnostic tool when you suspect carpal tunnel syndrome. Tinel’s sign is positive if percussion over the median nerve at the carpal tunnel elicits pain or paresthesia.18

When employing the Phalen maneuver, be certain to have the patient flex his/her wrist to 90 degrees and to document the number of seconds it takes for numbness to present in the fingers. Pain or paresthesia should occur in <60 seconds for the test to be positive.18

Median nerve compression over the carpal tunnel, also known as Durkan’s test, may also elicit symptoms. With Durkan’s test, you apply direct pressure over the transverse carpal ligament. If pain or paresthesia occurs in <30 seconds, the test is positive.18 Often clinicians will combine the Phalen maneuver and Durkan’s test to increase sensitivity and specificity.18 Nerve conduction studies are often performed to confirm the clinical diagnosis.

Is more than one condition at play? It is important to determine whether cervical spine disease and/or peripheral neuropathy is contributing to the patient’s symptoms, along with CTS; patients may have more than one condition contributing to their pain. We routinely check cervical spine motion, tenderness, and nerve compression as part of the exam on a patient with suspected CTS. In the office, a monofilament test or 2-point discrimination test can help make the clinical diagnosis by uncovering decreased sensation in the thumb, index, and/or middle fingers.23

The 5.07 monofilament test is performed with the clinician applying the monofilament to different dermatomal or sensory distributions while the patient has his/her eyes closed. The 2-point discrimination test is performed with a caliper device that measures the distance at which the patient can feel 2 separate stimuli. Often electromyography or nerve conduction studies are necessary.18

Treatment: Pursue nonoperative approaches

A survey of the membership of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand revealed that surgeons are utilizing nonoperative treatments for a longer duration of time and are employing narrowed surgical indications.24 Thus, clinicians are more likely to try splints and steroid injections before proceeding to operative release.24

Nonsurgical management. In our practice, we commonly recommend corticosteroid injections (TABLE 12-4) into the carpal tunnel (FIGURES 4 and 5) to patients who are poor candidates for surgery (ie, those who have too many medical comorbidities or wound healing concerns). This is one indication for which you may want to consider ultrasound-guided injections because the improved accuracy may provide symptom relief faster than “blind” or palpation-guided injections.25

A recent randomized controlled trial from Sweden showed that injections of methylprednisolone relieved symptoms in patients with mild to moderate CTS at 10 weeks and reduced the rate of surgery one year after treatment; however, 3 out of 4 patients still went on to have surgery within a year.22 Patients in the study had failed a 2-month trial of splinting and were given either 80 mg or 40 mg of methylprednisolone or saline. There was no statistical difference between the doses of methylprednisolone in preventing surgery at one year. Compared to placebo, the 80-mg methylprednisolone group was less likely to have surgery with an odds ratio of 0.24 (P=.042).22

There is evidence that oral steroids, injected steroids, ultrasound, electromagnetic field therapy, nocturnal splinting, and use of ergonomic keyboards are effective nonoperative modalities in the short term, but evidence is sparse for mid- or long-term use.19 In addition, at least one randomized trial found traditional cupping therapy applied around the shoulder alleviated carpal tunnel symptoms in the short-term.26 Other nonoperative therapies include rest, NSAIDs, extracorporeal shock wave therapy, and activity modification.19,27

Surgical outcomes by either endoscopic, mini-open, or open surgical techniques are typically good.20,21 Surgical release involves cutting the transverse carpal ligament over the carpal tunnel to decompress the median nerve.24 You should inform patients of the risks and inconveniences associated with surgery, including the cost, absence from work, infection, and chronic pain. Patients who have recurrent or persistent symptoms after surgery may have had an incompletely released transverse carpal ligament or there may be no identifiable cause.21 Overall, surgical treatment, combined with physical therapy, seems to be more effective than splinting or NSAIDs for mid- and long-term treatment of CTS.28

De Quervain’s tenosynovitis: Common during pregnancy

De Quervain’s tenosynovitis (radial styloid tenosynovitis) involves painful inflammation of the 2 tendons in the first dorsal compartment of the wrist—the abductor pollicis longus (APL) and the extensor pollicis brevis (EPB). The tendons comprise the radial border of the anatomic snuffbox.

The APL abducts and extends the thumb at the CMC joint, while the EPB extends the thumb proximal phalanx at the metacarpophalangeal joint. These tendons are contained in a synovial sheath that is subject to inflammation and constriction and subsequent wear and damage.29 In addition, the extensor retinaculum in patients with de Quervain’s disease demonstrates increased vascularity and deposition of dense fibrous tissue resulting in thickening of the tendon up to 5 times its normal width.30

As a result, degeneration and thickening of the tendon sheath, as well as radial-sided wrist pain elicited at the first dorsal compartment, are common pathophysiologic and clinical findings.31 Pain is often accompanied by the build-up of protuberances and nodulations of the tendon sheath.

De Quervain’s disease commonly occurs during and after pregnancy.32 Other risk factors include racquet sports, golfing, wrist trauma, and other activities involving repetitive hand and wrist motions.33 Often, however, de Quervain’s is idiopathic.

Making the Dx: Perform a Finkelstein's test

The major finding in patients with de Quervain’s tenosynovitis is a positive Finkelstein's test. To perform Finkelstein's test (FIGURE 6), ask the patient to oppose the thumb into the palm and flex the fingers of the same hand over the thumb. Holding the patient’s fingers around the thumb, ulnarly deviate the wrist. Finkelstein's test puts strain on the APL and EPB, causing pain along the radial border of the wrist and forearm in patients with de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. Since the maneuver can be uncomfortable, complete the exam on the unaffected side for comparison.

Stenosis of the tendon sheath may lead to crepitus over the first dorsal wrist compartment. This should be distinguished from intersection syndrome (tenosynovitis at the intersection of the first and second extensor compartments), which can also present with forearm and wrist crepitus. Patients usually have swelling of the wrist with marked discomfort upon palpation of the radial tendons. An x-ray can be useful to evaluate for CMC or radiocarpal arthritis, which may be an underlying cause.

Treatment: Select an approach based on symptom severity

In a retrospective analysis, Lane et al concluded that classification of patients with de Quervain’s disease based on pretreatment symptoms may assist physicians in selecting the most efficacious treatment and in providing prognostic information to their patients (TABLE 334). Patients with mild to moderate (Types 1 and 2) de Quervain’s may benefit from immobilization in a thumb spica splint, rest, NSAIDs, and physical or occupational therapy. If work conditions played a role in causing the symptoms, they need to be addressed to improve outcomes. Types 2 and 3 can be initially treated with a corticosteroid injection, but may eventually require surgery.33

Treatment with NSAIDs or corticosteroid injections (see TABLE 12-4 for choices) in the first compartment of the extensor retinaculum (FIGURE 7) is usually adequate to provide relief. Peters-Veluthamaningal et al performed a systematic review in 2009 and found only one controlled trial of 18 participants (all pregnant or lactating women) who were either injected with corticosteroids or given a thumb spica splint.35 All 9 patients in the injection group had complete pain relief, whereas no one in the splint group had complete resolution of symptoms.35 Typical anatomic placement of corticosteroid injections is shown in FIGURE 7.

More complicated injection methods have been described, but injecting the first dorsal compartment is usually satisfactory. Patients will feel the tendon sheath filling with the injection material. The 2-point technique, implemented by Sawaizumi et al, which involves injecting corticosteroid into 2 points over the EPB and APL tendon in the area of maximum pain and soft tissue thickening, is more effective than the 1-point injection technique.36

Severe, recalcitrant cases. Professional and college athletes may be prone to recalcitrant de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. A 2010 study by Pagonis et al showed that recurrent symptomatic episodes commonly occur in athletes who engage in high-resistance, intense athletic training. In these severe cases, a 4-point injection technique offers better distribution of corticosteroid solution to the first extensor compartment than other methods.37 Consider referring severe cases to a hand surgeon.

Surgical release of the first dorsal compartmental sheath around the tendons serves as a final option for patients who fail conservative treatment. Care should be taken to release both tendons completely, as there may be at least 2 tendon slips of the APL or there may be a distinct EPB sheath dorsally.38

“Tennis elbow”— you don’t have to play tennis to have it

Lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow) is a painful condition involving microtears within the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle and the subsequent development of angiofibroblastic dysplasia.39 According to Regan et al who studied the histopathologic features of 11 patients with lateral epicondylitis, the underlying cause of recalcitrant lateral epicondylitis is, in fact, degenerative, rather than inflammatory.40

Although the condition has been nicknamed “tennis elbow,” only about 5% of tennis players have the condition.41 In tennis players, males are more often affected than females, whereas in the general population, incidence is approximately equal in men and women.41 Lateral epicondylitis occurs between 4 and 7 times more frequently than medial-sided elbow pain.42

Making the Dx: Look for localized pain, normal ROM

The diagnosis of lateral epicondylitis is based upon a history of pain over the lateral epicondyle and findings on physical examination, including local tenderness directly over the lateral epicondyle,43 pain aggravated by resisted wrist extension and radial deviation, pain with resisted middle finger extension, and decreased grip strength or pain aggravated by strong gripping. These findings typically occur in the presence of normal elbow range of motion.

Treatment: Choose from a range of options

Since lateral epicondylitis was first described, researchers have proposed a wide variety of treatments as initial interventions including rest, activity, equipment modification, NSAIDs, wrist bracing/elbow straps, and physical therapy. If initial treatment does not produce the desired effect, second-line treatments include corticosteroid injections (FIGURE 8), prolotherapy (injection of an irritant, often dextrose; see “Prolotherapy: Can it help your patient?” J Fam Pract. 2015;64:763-768), autologous blood injections, platelet-rich plasma injections (see “Is platelet-rich plasma right for your patient?” J Fam Pract. 2016;65:319-328), and needling of the extensor tendon origin. Refer patients who do not improve after one corticosteroid injection to an orthopedic surgeon for consideration of open or arthroscopic treatment.

CORRESPONDENCE

Gregory R. Waryasz, MD, Rhode Island Hospital, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, 593 Eddy St., Providence, RI 02903; [email protected].

Primary care physicians are frequently the first to evaluate hand, wrist, and forearm pain in patients, making knowledge of the symptoms, causes, and treatment of common diagnoses in the upper extremities imperative. Primary symptoms usually include pain and/or swelling. While most tendon disorders originating in the hand and wrist are idiopathic in nature, some patients occasionally report having recently performed unusual manual activity or having experienced trauma to the area days or weeks prior. A significant portion of patients are injured as a result of chronic repetitive activities at work.1

Most diagnoses can be made by pairing your knowledge of hand and forearm anatomy with an understanding of which tender points are indicative of which common conditions. (Care, of course, must be taken to ensure that there is no underlying infection.) Common conditions can often be treated nonsurgically with conservative treatments such as physical therapy, bracing/splinting, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and injections of corticosteroids (eg, betamethasone, hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone, and triamcinolone) (TABLE 12-4) with or without the use of ultrasound. The benefits of corticosteroid injections for these conditions are well studied and documented in the literature, although physicians should always warn patients of the possible adverse effects prior to injection3,5 (TABLE 24).

To help you refine your skills, we review some of the more common hand and forearm conditions you are likely to encounter in the office and provide photos that reveal underlying anatomy so that you can administer injections without, in many cases, the need for ultrasound.

Trigger finger/thumb: New pathophysiologic findings?