User login

Use of Post-Acute Facility Care in Children Hospitalized With Acute Respiratory Illness

Respiratory illness (RI) is one of the most common reasons for pediatric hospitalization.1 Examples of RI include acute illness, such as bronchiolitis, bacterial pneumonia, and asthma, as well as chronic conditions, such as obstructive sleep apnea and chronic respiratory insufficiency. Hospital care for RI includes monitoring and treatment to optimize oxygenation, ventilation, hydration, and other body functions. Most previously healthy children hospitalized with RI stay in the hospital for a limited duration (eg, a few days) because the severity of their illness is short lived and they quickly return to their previous healthy status.2 However, hospital care is increasing for children with fragile and tenuous health due to complex medical conditions.3 RI is a common reason for hospitalization among these children as well and recovery of respiratory health and function can be slow and protracted for some of them.4 Weeks, months, or longer periods of time may be necessary for the children to return to their previous respiratory baseline health and function after hospital discharge; other children may not return to their baseline.5,6

Hospitalized older adults with high-severity RI are routinely streamlined for transfer to post-acute facility care (PAC) shortly (eg, a few days) after acute-care hospitalization. Nearly 70% of elderly Medicare beneficiaries use PAC following a brief length of stay (LOS) in the acute-care hospital.7 It is believed that PAC helps optimize the patients’ health and functional status and relieves the family caregiving burden that would have occurred at home.8-10 PAC use also helps to shorten acute-care hospitalization for RI while avoiding readmission.8-10 In contrast with adult patients, use of PAC for hospitalized children is not routine.11 While PAC use in children is infrequent, RI is one of the most common reasons for acute admission among children who use it.12

For some children with RI, PAC might be positioned to offer a safe, therapeutic, and high-value setting for pulmonary rehabilitation, as well as related medical, nutritional, functional, and family cares.6 PAC, by design, could possibly help some of the children transition back into their homes and communities. As studies continue to emerge that assess the value of PAC in children, it is important to learn more about the use of PAC in children hospitalized with RI. The objectives were to (1) assess which children admitted with RI are the most likely to use PAC services for recovery and (2) estimate how many hospitalized children not using PAC had the same characteristics as those who did.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Population

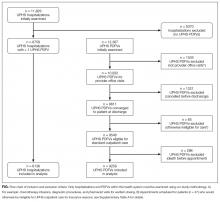

We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of 609,800 hospitalizations for RI occurring from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2015, in 43 freestanding children’s hospitals in the Pediatric Health Information Systems (PHIS) dataset. All hospitals participating in PHIS are members of the Children’s Hospital Association.13 The Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board approved this study with a waiver for informed consent.

RI was identified using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Clinical Classification System (CCS).14 Using diagnosis CCS category 8 (“Diseases of the Respiratory System”) and the procedure CCS category 6 (“Operations on the Respiratory System”), we identified all hospitalizations from the participating hospitals with a principal diagnosis or procedure International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code for an RI.

Main Outcome Measure

Discharge disposition following the acute-care hospitalization for RI was the main outcome measure. We used PHIS uniform disposition coding to classify the discharge disposition as transfer to PAC (ie, rehabilitation facility, skilled nursing facility, etc.) vs all other dispositions (ie, routine to home, against medical advice, etc.).12 The PAC disposition category was derived from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Patient Discharge Status Codes and Hospital Transfer Policies as informed by the National Uniform Billing Committee Official UB-04 Data Specifications Manual, 2008. PAC transfer included disposition to external PAC facilities, as well as to internal, embedded PAC units residing in a few of the acute-care children’s hospitals included in the cohort.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

We assessed patient demographic and clinical characteristics that might correlate with PAC use following acute-care hospitalization for RI. Demographic characteristics included gender, age at admission in years, payer (public, private, and other), and race/ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, other).

Clinical characteristics included chronic conditions (type and number) and assistance with medical technology. Chronic condition and medical technology characteristics were assessed with ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes. PHIS contain up to 41 ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes per hospital discharge record. To identify the presence and number of chronic conditions, we used the AHRQ Chronic Condition Indicator system, which categorizes over 14,000 ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes into chronic vs non-chronic conditions.14,15 Children hospitalized with a chronic condition were further classified as having a complex chronic condition (CCC) using Feudtner and colleagues’ ICD-9-CM diagnosis classification scheme.16 CCCs represent defined diagnosis groupings expected to last longer than 12 months and involving either a single organ system, severe enough to require specialty pediatric care and hospitalization, or multiple organ systems.17,18 Hospitalized children who were assisted with medical technology were identified with ICD-9-CM codes indicating the use of a medical device to manage and treat a chronic illness (eg, ventricular shunt to treat hydrocephalus) or to maintain basic body functions necessary for sustaining life (eg, a tracheostomy tube for breathing).19,20 We distinguished children undergoing tracheotomy during hospitalization using ICD-9-CM procedure codes 31.1 and 31.2.

Acute-Care Hospitalization Characteristics

We also assessed the relationship between acute-care hospitalization characteristics and use of PAC after discharge, including US census region, LOS, use of intensive care, number of medication classes administered, and use of enhanced respiratory support. Enhanced respiratory support was defined as use of continuous or bilevel positive airway pressure (CPAP or BiPAP) or mechanical ventilation during the acute-care hospitalization for RI. These respiratory supports were identified using billing data in PHIS.

Statistical Analysis

In bivariable analysis, we compared demographic, clinical, and hospitalization characteristics of hospitalized children with vs without discharge to PAC using Rao-Scott chi-square tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests as appropriate. In multivariable analysis, we derived a generalized linear mix effects model with fixed effects for demographic, clinical, and hospitalization characteristics that were associated with PAC at P < 0.1 in bivariable analysis (ie, age, gender, race/ethnicity, payer, medical technology, use of intensive care unit [ICU], use of positive pressure or mechanical ventilation, hospital region, LOS, new tracheostomy, existing tracheostomy, other technologies, number of medications, number of chronic conditions [of any complexity], and type of complex chronic conditions). We controlled for clustering of patients within hospitals by including a random intercept for each hospital. We also assessed combinations of patient characteristics on the likelihood of PAC use with classification and regression tree (CART) modeling. Using CART, we determined which characteristic combinations were associated with the highest and lowest use of PAC using binary split and post-pruning, goodness of fit rules.21 All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and R v.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the “party” package. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 609,800 hospitalizations for RI, PAC use after discharge occurred for 2660 (0.4%). RI discharges to PAC accounted for 2.1% (n = 67,405) of hospital days and 2.7% ($280 million) of hospital cost of all RI hospitalizations. For discharges to PAC, the most common RI were pneumonia (29.1% [n = 773]), respiratory failure or insufficiency (unspecified reason; 22.0% [n = 584]), and upper respiratory infection (12.2% [n = 323]).

Demographic Characteristics

Median age at acute-care admission was higher for PAC vs non-PAC discharges (6 years [interquartile range {IQR} 1-15] vs 2 years [0-7], P < 0.001; Table 1). Hispanic patients accounted for a smaller percentage of RI discharges to PAC vs non-PAC (14.1% vs 21.8%, P < 0.001) and a higher percentage to PAC were for patients with public insurance (75.9% vs 62.5, P < 0.001; Table 1).

Clinical Characteristics

A greater percentage of RI hospitalizations discharged to PAC vs not-PAC had ≥1 CCC (94.9% vs 33.5%), including a neuromuscular CCC (57.5% vs 8.9%) or respiratory CCC (62.5% vs 12.0%), P < 0.001 for all (Table 2). A greater percentage discharged to PAC was assisted with medical technology (83.2% vs 15.1%), including respiratory technology (eg, tracheostomy; 53.8% vs 5.4%) and gastrointestinal technology (eg, gastrostomy; 71.9% vs 11.8%), P < 0.001 for all. Of the children with respiratory technology, 14.8% (n = 394) underwent tracheotomy during the acute-care hospitalization. Children discharged to PAC had a higher percentage of multiple chronic conditions. For example, the percentages of children discharged to PAC vs not with ≥7 conditions were 54.5% vs 7.0% (P < 0.001; Table 2). The most common chronic conditions experienced by children discharged to PAC included epilepsy (41.2%), gastroesophageal reflux (36.6%), cerebral palsy (28.2%), and asthma (18.2%).

Hospitalization Characteristics

Acute-care RI hospitalization median LOS was longer for discharges to PAC vs non-PAC (10 days [IQR 4-27] vs 2 days [IQR 1-4], P < 0.001; Table 1). A greater percentage of discharges to PAC were administered medications from multiple classes during the acute-care RI admission (eg, 54.8% vs 13.4% used medications from ≥7 classes, P < 0.001). A greater percentage of discharges to PAC used intensive care services during the acute-care admission (65.6% vs 22.4%, P < 0.001). A greater percentage of discharges to PAC received CPAP (10.6 vs 5.0%), BiPAP (19.8% vs 11.4%), or mechanical ventilation (52.7% vs 9.1%) during the acute-care RI hospitalization (P < 0.001 for all; Table 1).

Multivariable Analysis of the Likelihood of Post-Acute Care Use Following Discharge

In multivariable analysis, the patient characteristics associated with the highest likelihood of discharge to PAC included ≥11 vs no chronic conditions (odds ratio [OR] 11.8 , 95% CI, 8.0-17.2), ≥9 classes vs no classes of medications administered during the acute-care hospitalization (OR 4.8 , 95% CI, 1.8-13.0), and existing tracheostomy (OR 3.0, [95% CI, 2.6-3.5; Figure 2 and eTable). Patient characteristics associated with a more modest likelihood of discharge to PAC included public vs private insurance (OR 1.8, 95% CI, 1.6-2.0), neuromuscular complex chronic condition (OR 1.6, 95% CI, 1.5-1.8), new tracheostomy (OR 1.9, 95% CI, 1.7-2.2), and use of any enhanced respiratory support (ie, CPAP/BiPAP/mechanical ventilation) during the acute-care hospitalization (OR 1.4, 95% CI, 1.3-1.6; Figure 2 and Supplementary Table).

Classification and Regression Tree Analysis

In the CART analysis, the highest percentage (6.3%) of children hospitalized with RI who were discharged to PAC had the following combination of characteristics: ≥6 chronic conditions, ≥7 classes of medications administered, and respiratory technology. Median (IQR) length of acute-care LOS for children with these attributes who were transferred to PAC was 19 (IQR 8-56; range 1-1005) days; LOS remained long (median 13 days [IQR 6-41, range 1-1413]) for children with the same attributes not transferred to PAC (n = 9448). Between these children transferred vs not to PAC, 79.3% vs 65.9% received ICU services; 74.4% vs 73.5% received CPAP, BiPAP, or mechanical ventilation; and 31.0% vs 22.7% underwent tracheotomy during the acute-care hospitalization. Of these children who were not transferred to PAC, 18.9% were discharged to home nursing services.

DISCUSSION

The findings from the present study suggest that patients with RI hospitalization in children’s hospitals who use PAC are medically complex, with high rates of multiple chronic conditions—including cerebral palsy, asthma, chronic respiratory insufficiency, dysphagia, epilepsy, and gastroesophageal reflux—and high rates of technology assistance including enterostomy and tracheostomy. The characteristics of patients most likely to use PAC include long LOS, a large number of chronic conditions, many types of medications administered during the acute-care hospitalization, respiratory technology use, and an underlying neuromuscular condition. Specifically, the highest percentage of children hospitalized with RI who were discharged to PAC had ≥6 chronic conditions, ≥7 classes of medications administered, and respiratory technology. Our analysis suggests that there may be a large population of children with these same characteristics who experienced a prolonged LOS but were not transferred to PAC.

There are several reasons to explain why children hospitalized with RI who rely on medical technology, such as existing tracheostomy, are more likely to use PAC. Tracheostomy often indicates the presence of life-limiting impairment in oxygenation or ventilation, thereby representing a high degree of medical fragility. Tracheostomy, in some cases, offers enhanced ability to assist with RI treatment, including establishment of airway clearance of secretions (ie, suctioning and chest physiotherapy), administration of antimicrobials (eg, nebulized antibiotics), and optimization of ventilation (eg, non-invasive positive airway pressure). However, not all acute-care inpatient clinicians have experience and clinical proficiencies in the care of children with pediatric tracheostomy.23 As a result, a more cautious approach, with prolonged LOS and gradual arrival to hospital discharge, is often taken in the acute-care hospital setting for children with tracheostomy. Tracheostomy care delivered during recovery from RI by trained and experienced teams of providers in the PAC setting may be best positioned to help optimize respiratory health and ensure proper family education and readiness to continue care at home.6

Further investigation is needed of the long LOS in children not transferred to PAC who had similar characteristics to those who were transferred. In hospitalized adult patients with RI, PAC is routinely introduced early in the admission process, with anticipated transfer within a few days into the hospitalization. In the current study, LOS was nearly 2 weeks or longer in many children not transferred to PAC who had similar characteristics to those who were transferred. Perhaps some of the children not transferred experienced long LOS in the acute-care hospital because of a limited number of pediatric PAC beds in their local area. Some families of these children may have been offered but declined use of PAC. PAC may not have been offered to some because illness acuity was too high or there was lack of PAC awareness as a possible setting for recovery.

There are several limitations to this study. PHIS does not contain non-freestanding children’s hospitals; therefore, the study results may generalize best to children’s hospitals. PHIS does not contain information on the amount (eg, number of days used), cost, or treatments provided in PAC. Therefore, we were unable to determine the true reasons why children used PAC services following RI hospitalization (eg, for respiratory rehabilitation vs other reasons, such as epilepsy or nutrition/hydration management). Moreover, we could not assess which children truly used PAC for short-term recovery vs longer-term care because they were unable to reside at home (eg, they were too medically complex). We were unable to assess PAC availability (eg, number of beds) in the surrounding areas of the acute-care hospitals in the PHIS database. Although we assessed use of medical technology, PHIS does not contain data on functional status or activities of daily living, which correlate with the use of PAC in adults. We could not distinguish whether children receiving BiPAP, CPAP, or mechanical ventilation during hospitalization were using it chronically. Although higher PAC use was associated with public insurance, due to absent information on the children’s home, family, and social environment, we were unable to assess whether PAC use was influenced by limited caregiving support or resources.

Data on the type and number of chronic conditions are limited by the ICD-9-CM codes available to distinguish them. Although several patient demographic and clinical characteristics were significantly associated with the use of PAC, significance may have occurred because of the large sample size and consequent robust statistical power. This is why we elected to highlight and discuss the characteristics with the strongest and most clinically meaningful associations (eg, multiple chronic conditions). There may be additional characteristics, including social, familial, and community resources, that are not available to assess in PHIS that could have affected PAC use.

Despite these limitations, the current study suggests that the characteristics of children hospitalized with RI who use PAC for recovery are evident and that there is a large population of children with these characteristics who experienced a prolonged LOS that did not result in transfer to PAC. These findings could be used in subsequent studies to help create the base of a matched cohort of children with similar clinical, demographic, and hospitalization characteristics who used vs didn’t use PAC. Comparison of the functional status, health trajectory, and family and/or social attributes of these 2 groups of children, as well as their post-discharge outcomes and utilization (eg, length of PAC stay, emergency department revisits, and acute-care hospital readmissions), could occur with chart review, clinician and parent interview, and other methods. This body of work might ultimately lead to an assessment of value in PAC and potentially help us understand the need for PAC capacity in various communities. In the meantime, clinicians may find it useful to consider the results of the current study when contemplating PAC use in their hospitalized children with RI, including exploration of health system opportunities of clinical collaboration between acute-care children’s hospitals and PAC facilities. Ultimately, all of this work will generate meaningful knowledge regarding the most appropriate, safe, and cost-effective settings for hospitalized children with RI to regain their health.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Berry was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R21 HS023092-01), the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health, and Franciscan Hospital for Children. The funders were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

1. Friedman B, Berdahl T, Simpson LA, et al. Annual report on health care for children and youth in the United States: focus on trends in hospital use and quality. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(4):263-279. PubMed

2. Srivastava R, Homer CJ. Length of stay for common pediatric conditions: teaching versus nonteaching hospitals. Pediatrics. 2003;112(2):278-281. PubMed

3. Berry JG, Hall M, Hall DE, et al. Inpatient growth and resource use in 28 children’s hospitals: a longitudinal, multi-institutional study. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(2):170-177. PubMed

4. Gold JM, Hall M, Shah SS, et al. Long length of hospital stay in children with medical complexity. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):750-756. PubMed

5. Faultner J. Integrating medical plans within family life. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(10):891-892. PubMed

6. O’Brien JE, Haley SM, Dumas HM, et al. Outcomes of post-acute hospital episodes for young children requiring airway support. Dev Neurorehabil. 2007;10(3):241-247. PubMed

7. Morley M, Bogasky S, Gage B, et al. Medicare post-acute care episodes and payment bundling. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014;4(1):mmrr.004.01.b02. PubMed

8. Mentro AM, Steward DK. Caring for medically fragile children in the home: an alternative theoretical approach. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2002;16(3):161-177. PubMed

9. Thyen U, Kuhlthau K, Perrin JM. Employment, child care, and mental health of mothers caring for children assisted by technology. Pediatrics. 1999;103(6 Pt 1):1235-1242. PubMed

10. Thyen U, Terres NM, Yazdgerdi SR, Perrin JM. Impact of long-term care of children assisted by technology on maternal health. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1998;19(4):273-282. PubMed

11. O’Brien JE, Berry J, Dumas H. Pediatric Post-acute hospital care: striving for identity and value. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(10):548-551. PubMed

12. Berry JG, Hall M, Dumas H, et al. Pediatric hospital discharges to home health and postacute facility care: a national study. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(4):326-333. PubMed

13. Children’s Hospital Association. Pediatric Health Information System. https://childrenshospitals.org/Programs-and-Services/Data-Analytics-and-Research/Pediatric-Analytic-Solutions/Pediatric-Health-Information-System. Accessed June 12, 2017.

14. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Chronic Condition Indicator. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp. Accessed on June 19, 2017.

15. Berry JG, Ash AS, Cohen E, Hasan F, Feudtner C, Hall M. Contributions of children with multiple chronic conditions to pediatric hospitalizations in the United States: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis [published online ahead of print June 20, 2017]. Hosp Pediatr. 2017 Jun 20. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0179. PubMed

16. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. PubMed

17. Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, et al. Children with medical complexity: an emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):529-538. PubMed

18. Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980-1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1 Pt 2):205-209. PubMed

19. Palfrey JS, Walker DK, Haynie M, et al. Technology’s children: report of a statewide census of children dependent on medical supports. Pediatrics. 1991;87(5):611-618. PubMed

20. Feudtner C, Villareale NL, Morray B, Sharp V, Hays RM, Neff JM. Technology-dependency among patients discharged from a children’s hospital: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2005;5(1):8. PubMed

21. Breiman L, Freidman J, Stone CJ, Olshen RA. Classification and Regression Trees. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth International; 1984.

22. Thomson J, Hall M, Ambroggio L, et al. Aspiration and Non-Aspiration Pneumonia in Hospitalized Children With Neurologic Impairment. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20151612. PubMed

23. Berry JG, Goldmann DA, Mandl KD, et al. Health information management and perceptions of the quality of care for children with tracheotomy: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:117. PubMed

Respiratory illness (RI) is one of the most common reasons for pediatric hospitalization.1 Examples of RI include acute illness, such as bronchiolitis, bacterial pneumonia, and asthma, as well as chronic conditions, such as obstructive sleep apnea and chronic respiratory insufficiency. Hospital care for RI includes monitoring and treatment to optimize oxygenation, ventilation, hydration, and other body functions. Most previously healthy children hospitalized with RI stay in the hospital for a limited duration (eg, a few days) because the severity of their illness is short lived and they quickly return to their previous healthy status.2 However, hospital care is increasing for children with fragile and tenuous health due to complex medical conditions.3 RI is a common reason for hospitalization among these children as well and recovery of respiratory health and function can be slow and protracted for some of them.4 Weeks, months, or longer periods of time may be necessary for the children to return to their previous respiratory baseline health and function after hospital discharge; other children may not return to their baseline.5,6

Hospitalized older adults with high-severity RI are routinely streamlined for transfer to post-acute facility care (PAC) shortly (eg, a few days) after acute-care hospitalization. Nearly 70% of elderly Medicare beneficiaries use PAC following a brief length of stay (LOS) in the acute-care hospital.7 It is believed that PAC helps optimize the patients’ health and functional status and relieves the family caregiving burden that would have occurred at home.8-10 PAC use also helps to shorten acute-care hospitalization for RI while avoiding readmission.8-10 In contrast with adult patients, use of PAC for hospitalized children is not routine.11 While PAC use in children is infrequent, RI is one of the most common reasons for acute admission among children who use it.12

For some children with RI, PAC might be positioned to offer a safe, therapeutic, and high-value setting for pulmonary rehabilitation, as well as related medical, nutritional, functional, and family cares.6 PAC, by design, could possibly help some of the children transition back into their homes and communities. As studies continue to emerge that assess the value of PAC in children, it is important to learn more about the use of PAC in children hospitalized with RI. The objectives were to (1) assess which children admitted with RI are the most likely to use PAC services for recovery and (2) estimate how many hospitalized children not using PAC had the same characteristics as those who did.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Population

We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of 609,800 hospitalizations for RI occurring from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2015, in 43 freestanding children’s hospitals in the Pediatric Health Information Systems (PHIS) dataset. All hospitals participating in PHIS are members of the Children’s Hospital Association.13 The Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board approved this study with a waiver for informed consent.

RI was identified using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Clinical Classification System (CCS).14 Using diagnosis CCS category 8 (“Diseases of the Respiratory System”) and the procedure CCS category 6 (“Operations on the Respiratory System”), we identified all hospitalizations from the participating hospitals with a principal diagnosis or procedure International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code for an RI.

Main Outcome Measure

Discharge disposition following the acute-care hospitalization for RI was the main outcome measure. We used PHIS uniform disposition coding to classify the discharge disposition as transfer to PAC (ie, rehabilitation facility, skilled nursing facility, etc.) vs all other dispositions (ie, routine to home, against medical advice, etc.).12 The PAC disposition category was derived from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Patient Discharge Status Codes and Hospital Transfer Policies as informed by the National Uniform Billing Committee Official UB-04 Data Specifications Manual, 2008. PAC transfer included disposition to external PAC facilities, as well as to internal, embedded PAC units residing in a few of the acute-care children’s hospitals included in the cohort.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

We assessed patient demographic and clinical characteristics that might correlate with PAC use following acute-care hospitalization for RI. Demographic characteristics included gender, age at admission in years, payer (public, private, and other), and race/ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, other).

Clinical characteristics included chronic conditions (type and number) and assistance with medical technology. Chronic condition and medical technology characteristics were assessed with ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes. PHIS contain up to 41 ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes per hospital discharge record. To identify the presence and number of chronic conditions, we used the AHRQ Chronic Condition Indicator system, which categorizes over 14,000 ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes into chronic vs non-chronic conditions.14,15 Children hospitalized with a chronic condition were further classified as having a complex chronic condition (CCC) using Feudtner and colleagues’ ICD-9-CM diagnosis classification scheme.16 CCCs represent defined diagnosis groupings expected to last longer than 12 months and involving either a single organ system, severe enough to require specialty pediatric care and hospitalization, or multiple organ systems.17,18 Hospitalized children who were assisted with medical technology were identified with ICD-9-CM codes indicating the use of a medical device to manage and treat a chronic illness (eg, ventricular shunt to treat hydrocephalus) or to maintain basic body functions necessary for sustaining life (eg, a tracheostomy tube for breathing).19,20 We distinguished children undergoing tracheotomy during hospitalization using ICD-9-CM procedure codes 31.1 and 31.2.

Acute-Care Hospitalization Characteristics

We also assessed the relationship between acute-care hospitalization characteristics and use of PAC after discharge, including US census region, LOS, use of intensive care, number of medication classes administered, and use of enhanced respiratory support. Enhanced respiratory support was defined as use of continuous or bilevel positive airway pressure (CPAP or BiPAP) or mechanical ventilation during the acute-care hospitalization for RI. These respiratory supports were identified using billing data in PHIS.

Statistical Analysis

In bivariable analysis, we compared demographic, clinical, and hospitalization characteristics of hospitalized children with vs without discharge to PAC using Rao-Scott chi-square tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests as appropriate. In multivariable analysis, we derived a generalized linear mix effects model with fixed effects for demographic, clinical, and hospitalization characteristics that were associated with PAC at P < 0.1 in bivariable analysis (ie, age, gender, race/ethnicity, payer, medical technology, use of intensive care unit [ICU], use of positive pressure or mechanical ventilation, hospital region, LOS, new tracheostomy, existing tracheostomy, other technologies, number of medications, number of chronic conditions [of any complexity], and type of complex chronic conditions). We controlled for clustering of patients within hospitals by including a random intercept for each hospital. We also assessed combinations of patient characteristics on the likelihood of PAC use with classification and regression tree (CART) modeling. Using CART, we determined which characteristic combinations were associated with the highest and lowest use of PAC using binary split and post-pruning, goodness of fit rules.21 All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and R v.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the “party” package. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 609,800 hospitalizations for RI, PAC use after discharge occurred for 2660 (0.4%). RI discharges to PAC accounted for 2.1% (n = 67,405) of hospital days and 2.7% ($280 million) of hospital cost of all RI hospitalizations. For discharges to PAC, the most common RI were pneumonia (29.1% [n = 773]), respiratory failure or insufficiency (unspecified reason; 22.0% [n = 584]), and upper respiratory infection (12.2% [n = 323]).

Demographic Characteristics

Median age at acute-care admission was higher for PAC vs non-PAC discharges (6 years [interquartile range {IQR} 1-15] vs 2 years [0-7], P < 0.001; Table 1). Hispanic patients accounted for a smaller percentage of RI discharges to PAC vs non-PAC (14.1% vs 21.8%, P < 0.001) and a higher percentage to PAC were for patients with public insurance (75.9% vs 62.5, P < 0.001; Table 1).

Clinical Characteristics

A greater percentage of RI hospitalizations discharged to PAC vs not-PAC had ≥1 CCC (94.9% vs 33.5%), including a neuromuscular CCC (57.5% vs 8.9%) or respiratory CCC (62.5% vs 12.0%), P < 0.001 for all (Table 2). A greater percentage discharged to PAC was assisted with medical technology (83.2% vs 15.1%), including respiratory technology (eg, tracheostomy; 53.8% vs 5.4%) and gastrointestinal technology (eg, gastrostomy; 71.9% vs 11.8%), P < 0.001 for all. Of the children with respiratory technology, 14.8% (n = 394) underwent tracheotomy during the acute-care hospitalization. Children discharged to PAC had a higher percentage of multiple chronic conditions. For example, the percentages of children discharged to PAC vs not with ≥7 conditions were 54.5% vs 7.0% (P < 0.001; Table 2). The most common chronic conditions experienced by children discharged to PAC included epilepsy (41.2%), gastroesophageal reflux (36.6%), cerebral palsy (28.2%), and asthma (18.2%).

Hospitalization Characteristics

Acute-care RI hospitalization median LOS was longer for discharges to PAC vs non-PAC (10 days [IQR 4-27] vs 2 days [IQR 1-4], P < 0.001; Table 1). A greater percentage of discharges to PAC were administered medications from multiple classes during the acute-care RI admission (eg, 54.8% vs 13.4% used medications from ≥7 classes, P < 0.001). A greater percentage of discharges to PAC used intensive care services during the acute-care admission (65.6% vs 22.4%, P < 0.001). A greater percentage of discharges to PAC received CPAP (10.6 vs 5.0%), BiPAP (19.8% vs 11.4%), or mechanical ventilation (52.7% vs 9.1%) during the acute-care RI hospitalization (P < 0.001 for all; Table 1).

Multivariable Analysis of the Likelihood of Post-Acute Care Use Following Discharge

In multivariable analysis, the patient characteristics associated with the highest likelihood of discharge to PAC included ≥11 vs no chronic conditions (odds ratio [OR] 11.8 , 95% CI, 8.0-17.2), ≥9 classes vs no classes of medications administered during the acute-care hospitalization (OR 4.8 , 95% CI, 1.8-13.0), and existing tracheostomy (OR 3.0, [95% CI, 2.6-3.5; Figure 2 and eTable). Patient characteristics associated with a more modest likelihood of discharge to PAC included public vs private insurance (OR 1.8, 95% CI, 1.6-2.0), neuromuscular complex chronic condition (OR 1.6, 95% CI, 1.5-1.8), new tracheostomy (OR 1.9, 95% CI, 1.7-2.2), and use of any enhanced respiratory support (ie, CPAP/BiPAP/mechanical ventilation) during the acute-care hospitalization (OR 1.4, 95% CI, 1.3-1.6; Figure 2 and Supplementary Table).

Classification and Regression Tree Analysis

In the CART analysis, the highest percentage (6.3%) of children hospitalized with RI who were discharged to PAC had the following combination of characteristics: ≥6 chronic conditions, ≥7 classes of medications administered, and respiratory technology. Median (IQR) length of acute-care LOS for children with these attributes who were transferred to PAC was 19 (IQR 8-56; range 1-1005) days; LOS remained long (median 13 days [IQR 6-41, range 1-1413]) for children with the same attributes not transferred to PAC (n = 9448). Between these children transferred vs not to PAC, 79.3% vs 65.9% received ICU services; 74.4% vs 73.5% received CPAP, BiPAP, or mechanical ventilation; and 31.0% vs 22.7% underwent tracheotomy during the acute-care hospitalization. Of these children who were not transferred to PAC, 18.9% were discharged to home nursing services.

DISCUSSION

The findings from the present study suggest that patients with RI hospitalization in children’s hospitals who use PAC are medically complex, with high rates of multiple chronic conditions—including cerebral palsy, asthma, chronic respiratory insufficiency, dysphagia, epilepsy, and gastroesophageal reflux—and high rates of technology assistance including enterostomy and tracheostomy. The characteristics of patients most likely to use PAC include long LOS, a large number of chronic conditions, many types of medications administered during the acute-care hospitalization, respiratory technology use, and an underlying neuromuscular condition. Specifically, the highest percentage of children hospitalized with RI who were discharged to PAC had ≥6 chronic conditions, ≥7 classes of medications administered, and respiratory technology. Our analysis suggests that there may be a large population of children with these same characteristics who experienced a prolonged LOS but were not transferred to PAC.

There are several reasons to explain why children hospitalized with RI who rely on medical technology, such as existing tracheostomy, are more likely to use PAC. Tracheostomy often indicates the presence of life-limiting impairment in oxygenation or ventilation, thereby representing a high degree of medical fragility. Tracheostomy, in some cases, offers enhanced ability to assist with RI treatment, including establishment of airway clearance of secretions (ie, suctioning and chest physiotherapy), administration of antimicrobials (eg, nebulized antibiotics), and optimization of ventilation (eg, non-invasive positive airway pressure). However, not all acute-care inpatient clinicians have experience and clinical proficiencies in the care of children with pediatric tracheostomy.23 As a result, a more cautious approach, with prolonged LOS and gradual arrival to hospital discharge, is often taken in the acute-care hospital setting for children with tracheostomy. Tracheostomy care delivered during recovery from RI by trained and experienced teams of providers in the PAC setting may be best positioned to help optimize respiratory health and ensure proper family education and readiness to continue care at home.6

Further investigation is needed of the long LOS in children not transferred to PAC who had similar characteristics to those who were transferred. In hospitalized adult patients with RI, PAC is routinely introduced early in the admission process, with anticipated transfer within a few days into the hospitalization. In the current study, LOS was nearly 2 weeks or longer in many children not transferred to PAC who had similar characteristics to those who were transferred. Perhaps some of the children not transferred experienced long LOS in the acute-care hospital because of a limited number of pediatric PAC beds in their local area. Some families of these children may have been offered but declined use of PAC. PAC may not have been offered to some because illness acuity was too high or there was lack of PAC awareness as a possible setting for recovery.

There are several limitations to this study. PHIS does not contain non-freestanding children’s hospitals; therefore, the study results may generalize best to children’s hospitals. PHIS does not contain information on the amount (eg, number of days used), cost, or treatments provided in PAC. Therefore, we were unable to determine the true reasons why children used PAC services following RI hospitalization (eg, for respiratory rehabilitation vs other reasons, such as epilepsy or nutrition/hydration management). Moreover, we could not assess which children truly used PAC for short-term recovery vs longer-term care because they were unable to reside at home (eg, they were too medically complex). We were unable to assess PAC availability (eg, number of beds) in the surrounding areas of the acute-care hospitals in the PHIS database. Although we assessed use of medical technology, PHIS does not contain data on functional status or activities of daily living, which correlate with the use of PAC in adults. We could not distinguish whether children receiving BiPAP, CPAP, or mechanical ventilation during hospitalization were using it chronically. Although higher PAC use was associated with public insurance, due to absent information on the children’s home, family, and social environment, we were unable to assess whether PAC use was influenced by limited caregiving support or resources.

Data on the type and number of chronic conditions are limited by the ICD-9-CM codes available to distinguish them. Although several patient demographic and clinical characteristics were significantly associated with the use of PAC, significance may have occurred because of the large sample size and consequent robust statistical power. This is why we elected to highlight and discuss the characteristics with the strongest and most clinically meaningful associations (eg, multiple chronic conditions). There may be additional characteristics, including social, familial, and community resources, that are not available to assess in PHIS that could have affected PAC use.

Despite these limitations, the current study suggests that the characteristics of children hospitalized with RI who use PAC for recovery are evident and that there is a large population of children with these characteristics who experienced a prolonged LOS that did not result in transfer to PAC. These findings could be used in subsequent studies to help create the base of a matched cohort of children with similar clinical, demographic, and hospitalization characteristics who used vs didn’t use PAC. Comparison of the functional status, health trajectory, and family and/or social attributes of these 2 groups of children, as well as their post-discharge outcomes and utilization (eg, length of PAC stay, emergency department revisits, and acute-care hospital readmissions), could occur with chart review, clinician and parent interview, and other methods. This body of work might ultimately lead to an assessment of value in PAC and potentially help us understand the need for PAC capacity in various communities. In the meantime, clinicians may find it useful to consider the results of the current study when contemplating PAC use in their hospitalized children with RI, including exploration of health system opportunities of clinical collaboration between acute-care children’s hospitals and PAC facilities. Ultimately, all of this work will generate meaningful knowledge regarding the most appropriate, safe, and cost-effective settings for hospitalized children with RI to regain their health.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Berry was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R21 HS023092-01), the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health, and Franciscan Hospital for Children. The funders were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Respiratory illness (RI) is one of the most common reasons for pediatric hospitalization.1 Examples of RI include acute illness, such as bronchiolitis, bacterial pneumonia, and asthma, as well as chronic conditions, such as obstructive sleep apnea and chronic respiratory insufficiency. Hospital care for RI includes monitoring and treatment to optimize oxygenation, ventilation, hydration, and other body functions. Most previously healthy children hospitalized with RI stay in the hospital for a limited duration (eg, a few days) because the severity of their illness is short lived and they quickly return to their previous healthy status.2 However, hospital care is increasing for children with fragile and tenuous health due to complex medical conditions.3 RI is a common reason for hospitalization among these children as well and recovery of respiratory health and function can be slow and protracted for some of them.4 Weeks, months, or longer periods of time may be necessary for the children to return to their previous respiratory baseline health and function after hospital discharge; other children may not return to their baseline.5,6

Hospitalized older adults with high-severity RI are routinely streamlined for transfer to post-acute facility care (PAC) shortly (eg, a few days) after acute-care hospitalization. Nearly 70% of elderly Medicare beneficiaries use PAC following a brief length of stay (LOS) in the acute-care hospital.7 It is believed that PAC helps optimize the patients’ health and functional status and relieves the family caregiving burden that would have occurred at home.8-10 PAC use also helps to shorten acute-care hospitalization for RI while avoiding readmission.8-10 In contrast with adult patients, use of PAC for hospitalized children is not routine.11 While PAC use in children is infrequent, RI is one of the most common reasons for acute admission among children who use it.12

For some children with RI, PAC might be positioned to offer a safe, therapeutic, and high-value setting for pulmonary rehabilitation, as well as related medical, nutritional, functional, and family cares.6 PAC, by design, could possibly help some of the children transition back into their homes and communities. As studies continue to emerge that assess the value of PAC in children, it is important to learn more about the use of PAC in children hospitalized with RI. The objectives were to (1) assess which children admitted with RI are the most likely to use PAC services for recovery and (2) estimate how many hospitalized children not using PAC had the same characteristics as those who did.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Population

We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of 609,800 hospitalizations for RI occurring from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2015, in 43 freestanding children’s hospitals in the Pediatric Health Information Systems (PHIS) dataset. All hospitals participating in PHIS are members of the Children’s Hospital Association.13 The Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board approved this study with a waiver for informed consent.

RI was identified using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Clinical Classification System (CCS).14 Using diagnosis CCS category 8 (“Diseases of the Respiratory System”) and the procedure CCS category 6 (“Operations on the Respiratory System”), we identified all hospitalizations from the participating hospitals with a principal diagnosis or procedure International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code for an RI.

Main Outcome Measure

Discharge disposition following the acute-care hospitalization for RI was the main outcome measure. We used PHIS uniform disposition coding to classify the discharge disposition as transfer to PAC (ie, rehabilitation facility, skilled nursing facility, etc.) vs all other dispositions (ie, routine to home, against medical advice, etc.).12 The PAC disposition category was derived from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Patient Discharge Status Codes and Hospital Transfer Policies as informed by the National Uniform Billing Committee Official UB-04 Data Specifications Manual, 2008. PAC transfer included disposition to external PAC facilities, as well as to internal, embedded PAC units residing in a few of the acute-care children’s hospitals included in the cohort.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

We assessed patient demographic and clinical characteristics that might correlate with PAC use following acute-care hospitalization for RI. Demographic characteristics included gender, age at admission in years, payer (public, private, and other), and race/ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, other).

Clinical characteristics included chronic conditions (type and number) and assistance with medical technology. Chronic condition and medical technology characteristics were assessed with ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes. PHIS contain up to 41 ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes per hospital discharge record. To identify the presence and number of chronic conditions, we used the AHRQ Chronic Condition Indicator system, which categorizes over 14,000 ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes into chronic vs non-chronic conditions.14,15 Children hospitalized with a chronic condition were further classified as having a complex chronic condition (CCC) using Feudtner and colleagues’ ICD-9-CM diagnosis classification scheme.16 CCCs represent defined diagnosis groupings expected to last longer than 12 months and involving either a single organ system, severe enough to require specialty pediatric care and hospitalization, or multiple organ systems.17,18 Hospitalized children who were assisted with medical technology were identified with ICD-9-CM codes indicating the use of a medical device to manage and treat a chronic illness (eg, ventricular shunt to treat hydrocephalus) or to maintain basic body functions necessary for sustaining life (eg, a tracheostomy tube for breathing).19,20 We distinguished children undergoing tracheotomy during hospitalization using ICD-9-CM procedure codes 31.1 and 31.2.

Acute-Care Hospitalization Characteristics

We also assessed the relationship between acute-care hospitalization characteristics and use of PAC after discharge, including US census region, LOS, use of intensive care, number of medication classes administered, and use of enhanced respiratory support. Enhanced respiratory support was defined as use of continuous or bilevel positive airway pressure (CPAP or BiPAP) or mechanical ventilation during the acute-care hospitalization for RI. These respiratory supports were identified using billing data in PHIS.

Statistical Analysis

In bivariable analysis, we compared demographic, clinical, and hospitalization characteristics of hospitalized children with vs without discharge to PAC using Rao-Scott chi-square tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests as appropriate. In multivariable analysis, we derived a generalized linear mix effects model with fixed effects for demographic, clinical, and hospitalization characteristics that were associated with PAC at P < 0.1 in bivariable analysis (ie, age, gender, race/ethnicity, payer, medical technology, use of intensive care unit [ICU], use of positive pressure or mechanical ventilation, hospital region, LOS, new tracheostomy, existing tracheostomy, other technologies, number of medications, number of chronic conditions [of any complexity], and type of complex chronic conditions). We controlled for clustering of patients within hospitals by including a random intercept for each hospital. We also assessed combinations of patient characteristics on the likelihood of PAC use with classification and regression tree (CART) modeling. Using CART, we determined which characteristic combinations were associated with the highest and lowest use of PAC using binary split and post-pruning, goodness of fit rules.21 All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and R v.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the “party” package. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 609,800 hospitalizations for RI, PAC use after discharge occurred for 2660 (0.4%). RI discharges to PAC accounted for 2.1% (n = 67,405) of hospital days and 2.7% ($280 million) of hospital cost of all RI hospitalizations. For discharges to PAC, the most common RI were pneumonia (29.1% [n = 773]), respiratory failure or insufficiency (unspecified reason; 22.0% [n = 584]), and upper respiratory infection (12.2% [n = 323]).

Demographic Characteristics

Median age at acute-care admission was higher for PAC vs non-PAC discharges (6 years [interquartile range {IQR} 1-15] vs 2 years [0-7], P < 0.001; Table 1). Hispanic patients accounted for a smaller percentage of RI discharges to PAC vs non-PAC (14.1% vs 21.8%, P < 0.001) and a higher percentage to PAC were for patients with public insurance (75.9% vs 62.5, P < 0.001; Table 1).

Clinical Characteristics

A greater percentage of RI hospitalizations discharged to PAC vs not-PAC had ≥1 CCC (94.9% vs 33.5%), including a neuromuscular CCC (57.5% vs 8.9%) or respiratory CCC (62.5% vs 12.0%), P < 0.001 for all (Table 2). A greater percentage discharged to PAC was assisted with medical technology (83.2% vs 15.1%), including respiratory technology (eg, tracheostomy; 53.8% vs 5.4%) and gastrointestinal technology (eg, gastrostomy; 71.9% vs 11.8%), P < 0.001 for all. Of the children with respiratory technology, 14.8% (n = 394) underwent tracheotomy during the acute-care hospitalization. Children discharged to PAC had a higher percentage of multiple chronic conditions. For example, the percentages of children discharged to PAC vs not with ≥7 conditions were 54.5% vs 7.0% (P < 0.001; Table 2). The most common chronic conditions experienced by children discharged to PAC included epilepsy (41.2%), gastroesophageal reflux (36.6%), cerebral palsy (28.2%), and asthma (18.2%).

Hospitalization Characteristics

Acute-care RI hospitalization median LOS was longer for discharges to PAC vs non-PAC (10 days [IQR 4-27] vs 2 days [IQR 1-4], P < 0.001; Table 1). A greater percentage of discharges to PAC were administered medications from multiple classes during the acute-care RI admission (eg, 54.8% vs 13.4% used medications from ≥7 classes, P < 0.001). A greater percentage of discharges to PAC used intensive care services during the acute-care admission (65.6% vs 22.4%, P < 0.001). A greater percentage of discharges to PAC received CPAP (10.6 vs 5.0%), BiPAP (19.8% vs 11.4%), or mechanical ventilation (52.7% vs 9.1%) during the acute-care RI hospitalization (P < 0.001 for all; Table 1).

Multivariable Analysis of the Likelihood of Post-Acute Care Use Following Discharge

In multivariable analysis, the patient characteristics associated with the highest likelihood of discharge to PAC included ≥11 vs no chronic conditions (odds ratio [OR] 11.8 , 95% CI, 8.0-17.2), ≥9 classes vs no classes of medications administered during the acute-care hospitalization (OR 4.8 , 95% CI, 1.8-13.0), and existing tracheostomy (OR 3.0, [95% CI, 2.6-3.5; Figure 2 and eTable). Patient characteristics associated with a more modest likelihood of discharge to PAC included public vs private insurance (OR 1.8, 95% CI, 1.6-2.0), neuromuscular complex chronic condition (OR 1.6, 95% CI, 1.5-1.8), new tracheostomy (OR 1.9, 95% CI, 1.7-2.2), and use of any enhanced respiratory support (ie, CPAP/BiPAP/mechanical ventilation) during the acute-care hospitalization (OR 1.4, 95% CI, 1.3-1.6; Figure 2 and Supplementary Table).

Classification and Regression Tree Analysis

In the CART analysis, the highest percentage (6.3%) of children hospitalized with RI who were discharged to PAC had the following combination of characteristics: ≥6 chronic conditions, ≥7 classes of medications administered, and respiratory technology. Median (IQR) length of acute-care LOS for children with these attributes who were transferred to PAC was 19 (IQR 8-56; range 1-1005) days; LOS remained long (median 13 days [IQR 6-41, range 1-1413]) for children with the same attributes not transferred to PAC (n = 9448). Between these children transferred vs not to PAC, 79.3% vs 65.9% received ICU services; 74.4% vs 73.5% received CPAP, BiPAP, or mechanical ventilation; and 31.0% vs 22.7% underwent tracheotomy during the acute-care hospitalization. Of these children who were not transferred to PAC, 18.9% were discharged to home nursing services.

DISCUSSION

The findings from the present study suggest that patients with RI hospitalization in children’s hospitals who use PAC are medically complex, with high rates of multiple chronic conditions—including cerebral palsy, asthma, chronic respiratory insufficiency, dysphagia, epilepsy, and gastroesophageal reflux—and high rates of technology assistance including enterostomy and tracheostomy. The characteristics of patients most likely to use PAC include long LOS, a large number of chronic conditions, many types of medications administered during the acute-care hospitalization, respiratory technology use, and an underlying neuromuscular condition. Specifically, the highest percentage of children hospitalized with RI who were discharged to PAC had ≥6 chronic conditions, ≥7 classes of medications administered, and respiratory technology. Our analysis suggests that there may be a large population of children with these same characteristics who experienced a prolonged LOS but were not transferred to PAC.

There are several reasons to explain why children hospitalized with RI who rely on medical technology, such as existing tracheostomy, are more likely to use PAC. Tracheostomy often indicates the presence of life-limiting impairment in oxygenation or ventilation, thereby representing a high degree of medical fragility. Tracheostomy, in some cases, offers enhanced ability to assist with RI treatment, including establishment of airway clearance of secretions (ie, suctioning and chest physiotherapy), administration of antimicrobials (eg, nebulized antibiotics), and optimization of ventilation (eg, non-invasive positive airway pressure). However, not all acute-care inpatient clinicians have experience and clinical proficiencies in the care of children with pediatric tracheostomy.23 As a result, a more cautious approach, with prolonged LOS and gradual arrival to hospital discharge, is often taken in the acute-care hospital setting for children with tracheostomy. Tracheostomy care delivered during recovery from RI by trained and experienced teams of providers in the PAC setting may be best positioned to help optimize respiratory health and ensure proper family education and readiness to continue care at home.6

Further investigation is needed of the long LOS in children not transferred to PAC who had similar characteristics to those who were transferred. In hospitalized adult patients with RI, PAC is routinely introduced early in the admission process, with anticipated transfer within a few days into the hospitalization. In the current study, LOS was nearly 2 weeks or longer in many children not transferred to PAC who had similar characteristics to those who were transferred. Perhaps some of the children not transferred experienced long LOS in the acute-care hospital because of a limited number of pediatric PAC beds in their local area. Some families of these children may have been offered but declined use of PAC. PAC may not have been offered to some because illness acuity was too high or there was lack of PAC awareness as a possible setting for recovery.

There are several limitations to this study. PHIS does not contain non-freestanding children’s hospitals; therefore, the study results may generalize best to children’s hospitals. PHIS does not contain information on the amount (eg, number of days used), cost, or treatments provided in PAC. Therefore, we were unable to determine the true reasons why children used PAC services following RI hospitalization (eg, for respiratory rehabilitation vs other reasons, such as epilepsy or nutrition/hydration management). Moreover, we could not assess which children truly used PAC for short-term recovery vs longer-term care because they were unable to reside at home (eg, they were too medically complex). We were unable to assess PAC availability (eg, number of beds) in the surrounding areas of the acute-care hospitals in the PHIS database. Although we assessed use of medical technology, PHIS does not contain data on functional status or activities of daily living, which correlate with the use of PAC in adults. We could not distinguish whether children receiving BiPAP, CPAP, or mechanical ventilation during hospitalization were using it chronically. Although higher PAC use was associated with public insurance, due to absent information on the children’s home, family, and social environment, we were unable to assess whether PAC use was influenced by limited caregiving support or resources.

Data on the type and number of chronic conditions are limited by the ICD-9-CM codes available to distinguish them. Although several patient demographic and clinical characteristics were significantly associated with the use of PAC, significance may have occurred because of the large sample size and consequent robust statistical power. This is why we elected to highlight and discuss the characteristics with the strongest and most clinically meaningful associations (eg, multiple chronic conditions). There may be additional characteristics, including social, familial, and community resources, that are not available to assess in PHIS that could have affected PAC use.

Despite these limitations, the current study suggests that the characteristics of children hospitalized with RI who use PAC for recovery are evident and that there is a large population of children with these characteristics who experienced a prolonged LOS that did not result in transfer to PAC. These findings could be used in subsequent studies to help create the base of a matched cohort of children with similar clinical, demographic, and hospitalization characteristics who used vs didn’t use PAC. Comparison of the functional status, health trajectory, and family and/or social attributes of these 2 groups of children, as well as their post-discharge outcomes and utilization (eg, length of PAC stay, emergency department revisits, and acute-care hospital readmissions), could occur with chart review, clinician and parent interview, and other methods. This body of work might ultimately lead to an assessment of value in PAC and potentially help us understand the need for PAC capacity in various communities. In the meantime, clinicians may find it useful to consider the results of the current study when contemplating PAC use in their hospitalized children with RI, including exploration of health system opportunities of clinical collaboration between acute-care children’s hospitals and PAC facilities. Ultimately, all of this work will generate meaningful knowledge regarding the most appropriate, safe, and cost-effective settings for hospitalized children with RI to regain their health.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Berry was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R21 HS023092-01), the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health, and Franciscan Hospital for Children. The funders were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

1. Friedman B, Berdahl T, Simpson LA, et al. Annual report on health care for children and youth in the United States: focus on trends in hospital use and quality. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(4):263-279. PubMed

2. Srivastava R, Homer CJ. Length of stay for common pediatric conditions: teaching versus nonteaching hospitals. Pediatrics. 2003;112(2):278-281. PubMed

3. Berry JG, Hall M, Hall DE, et al. Inpatient growth and resource use in 28 children’s hospitals: a longitudinal, multi-institutional study. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(2):170-177. PubMed

4. Gold JM, Hall M, Shah SS, et al. Long length of hospital stay in children with medical complexity. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):750-756. PubMed

5. Faultner J. Integrating medical plans within family life. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(10):891-892. PubMed

6. O’Brien JE, Haley SM, Dumas HM, et al. Outcomes of post-acute hospital episodes for young children requiring airway support. Dev Neurorehabil. 2007;10(3):241-247. PubMed

7. Morley M, Bogasky S, Gage B, et al. Medicare post-acute care episodes and payment bundling. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014;4(1):mmrr.004.01.b02. PubMed

8. Mentro AM, Steward DK. Caring for medically fragile children in the home: an alternative theoretical approach. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2002;16(3):161-177. PubMed

9. Thyen U, Kuhlthau K, Perrin JM. Employment, child care, and mental health of mothers caring for children assisted by technology. Pediatrics. 1999;103(6 Pt 1):1235-1242. PubMed

10. Thyen U, Terres NM, Yazdgerdi SR, Perrin JM. Impact of long-term care of children assisted by technology on maternal health. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1998;19(4):273-282. PubMed

11. O’Brien JE, Berry J, Dumas H. Pediatric Post-acute hospital care: striving for identity and value. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(10):548-551. PubMed

12. Berry JG, Hall M, Dumas H, et al. Pediatric hospital discharges to home health and postacute facility care: a national study. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(4):326-333. PubMed

13. Children’s Hospital Association. Pediatric Health Information System. https://childrenshospitals.org/Programs-and-Services/Data-Analytics-and-Research/Pediatric-Analytic-Solutions/Pediatric-Health-Information-System. Accessed June 12, 2017.

14. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Chronic Condition Indicator. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp. Accessed on June 19, 2017.

15. Berry JG, Ash AS, Cohen E, Hasan F, Feudtner C, Hall M. Contributions of children with multiple chronic conditions to pediatric hospitalizations in the United States: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis [published online ahead of print June 20, 2017]. Hosp Pediatr. 2017 Jun 20. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0179. PubMed

16. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. PubMed

17. Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, et al. Children with medical complexity: an emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):529-538. PubMed

18. Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980-1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1 Pt 2):205-209. PubMed

19. Palfrey JS, Walker DK, Haynie M, et al. Technology’s children: report of a statewide census of children dependent on medical supports. Pediatrics. 1991;87(5):611-618. PubMed

20. Feudtner C, Villareale NL, Morray B, Sharp V, Hays RM, Neff JM. Technology-dependency among patients discharged from a children’s hospital: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2005;5(1):8. PubMed

21. Breiman L, Freidman J, Stone CJ, Olshen RA. Classification and Regression Trees. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth International; 1984.

22. Thomson J, Hall M, Ambroggio L, et al. Aspiration and Non-Aspiration Pneumonia in Hospitalized Children With Neurologic Impairment. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20151612. PubMed

23. Berry JG, Goldmann DA, Mandl KD, et al. Health information management and perceptions of the quality of care for children with tracheotomy: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:117. PubMed

1. Friedman B, Berdahl T, Simpson LA, et al. Annual report on health care for children and youth in the United States: focus on trends in hospital use and quality. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(4):263-279. PubMed

2. Srivastava R, Homer CJ. Length of stay for common pediatric conditions: teaching versus nonteaching hospitals. Pediatrics. 2003;112(2):278-281. PubMed

3. Berry JG, Hall M, Hall DE, et al. Inpatient growth and resource use in 28 children’s hospitals: a longitudinal, multi-institutional study. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(2):170-177. PubMed

4. Gold JM, Hall M, Shah SS, et al. Long length of hospital stay in children with medical complexity. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):750-756. PubMed

5. Faultner J. Integrating medical plans within family life. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(10):891-892. PubMed

6. O’Brien JE, Haley SM, Dumas HM, et al. Outcomes of post-acute hospital episodes for young children requiring airway support. Dev Neurorehabil. 2007;10(3):241-247. PubMed

7. Morley M, Bogasky S, Gage B, et al. Medicare post-acute care episodes and payment bundling. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014;4(1):mmrr.004.01.b02. PubMed

8. Mentro AM, Steward DK. Caring for medically fragile children in the home: an alternative theoretical approach. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2002;16(3):161-177. PubMed

9. Thyen U, Kuhlthau K, Perrin JM. Employment, child care, and mental health of mothers caring for children assisted by technology. Pediatrics. 1999;103(6 Pt 1):1235-1242. PubMed

10. Thyen U, Terres NM, Yazdgerdi SR, Perrin JM. Impact of long-term care of children assisted by technology on maternal health. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1998;19(4):273-282. PubMed

11. O’Brien JE, Berry J, Dumas H. Pediatric Post-acute hospital care: striving for identity and value. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(10):548-551. PubMed

12. Berry JG, Hall M, Dumas H, et al. Pediatric hospital discharges to home health and postacute facility care: a national study. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(4):326-333. PubMed

13. Children’s Hospital Association. Pediatric Health Information System. https://childrenshospitals.org/Programs-and-Services/Data-Analytics-and-Research/Pediatric-Analytic-Solutions/Pediatric-Health-Information-System. Accessed June 12, 2017.

14. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Chronic Condition Indicator. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp. Accessed on June 19, 2017.

15. Berry JG, Ash AS, Cohen E, Hasan F, Feudtner C, Hall M. Contributions of children with multiple chronic conditions to pediatric hospitalizations in the United States: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis [published online ahead of print June 20, 2017]. Hosp Pediatr. 2017 Jun 20. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0179. PubMed

16. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. PubMed

17. Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, et al. Children with medical complexity: an emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):529-538. PubMed

18. Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980-1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1 Pt 2):205-209. PubMed

19. Palfrey JS, Walker DK, Haynie M, et al. Technology’s children: report of a statewide census of children dependent on medical supports. Pediatrics. 1991;87(5):611-618. PubMed

20. Feudtner C, Villareale NL, Morray B, Sharp V, Hays RM, Neff JM. Technology-dependency among patients discharged from a children’s hospital: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2005;5(1):8. PubMed

21. Breiman L, Freidman J, Stone CJ, Olshen RA. Classification and Regression Trees. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth International; 1984.

22. Thomson J, Hall M, Ambroggio L, et al. Aspiration and Non-Aspiration Pneumonia in Hospitalized Children With Neurologic Impairment. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20151612. PubMed

23. Berry JG, Goldmann DA, Mandl KD, et al. Health information management and perceptions of the quality of care for children with tracheotomy: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:117. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

If You Book It, Will They Come? Attendance at Postdischarge Follow-Up Visits Scheduled by Inpatient Providers

Given growing incentives to reduce readmission rates, predischarge checklists and bundles have recommended that inpatient providers schedule postdischarge follow-up visits (PDFVs) for their hospitalized patients.1-4 PDFVs have been linked to lower readmission rates in patients with chronic conditions, including congestive heart failure, psychiatric illnesses, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.5-8 In contrast, the impact of PDFVs on readmissions in hospitalized general medicine populations has been mixed.9-12 Beyond the presence or absence of PDFVs, it may be a patient’s inability to keep scheduled PDFVs that contributes more strongly to preventable readmissions.11

This challenge, dealing with the 12% to 37% of patients who miss their visits (“no-shows”), is not new.13-17 In high-risk patient populations, such as those with substance abuse, diabetes, or human immunodeficiency virus, no-shows (NSs) have been linked to poorer short-term and long-term clinical outcomes.16,18-20 Additionally, NSs pose a challenge for outpatient clinics and the healthcare system at large. The financial cost of NSs ranges from approximately $200 per patient in 2 analyses to $7 million in cumulative lost revenue per year at 1 large academic health system.13,17,21 As such, increasing attendance at PDFVs is a potential target for improving both patient outcomes and clinic productivity.

Most prior PDFV research has focused on readmission risk rather than PDFV attendance as the primary outcome.5-12 However, given the patient-oriented benefits of attending PDFVs and the clinic-oriented benefits of avoiding vacant time slots, NS PDFVs represent an important missed opportunity for our healthcare delivery system. To our knowledge, risk factors for PDFV nonattendance have not yet been systematically studied. The aim of our study was to analyze PDFV nonattendance, particularly NSs and same-day cancellations (SDCs), for hospitalizations and clinics within our healthcare system.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted an observational cohort study of adult patients from 10 medical units at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (a 789-bed quaternary-care hospital within an urban, academic medical system) who were scheduled with at least 1 PDFV. Specifically, the patients included in our analysis were hospitalized on general internal medicine services or medical subspecialty services with discharge dates between April 1, 2014, and March 31, 2015. Hospitalizations included in our study had at least 1 PDFV scheduled with an outpatient provider affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania Health System (UPHS). PDFVs scheduled with unaffiliated providers were not examined.

Each PDFV was requested by a patient’s inpatient care team. Once the care team had determined that a PDFV was clinically warranted, a member of the team (generally a resident, advanced practice provider, medical student, or designee) either called the UPHS clinic to schedule an appointment time or e-mailed the outpatient UPHS provider directly to facilitate a more urgent PDFV appointment time. Once a PDFV time was confirmed, PDFV details (ie, date, time, location, and phone number) were electronically entered into the patient’s discharge instructions by the inpatient care team. At the time of discharge, nurses reviewed these instructions with their patients. All patients left the hospital with a physical copy of these instructions. As part of routine care at our institution, patients then received automated telephone reminders from their UPHS-affiliated outpatient clinic 48 hours prior to each PDFV.

Data Collection

Our study was determined to meet criteria for quality improvement by the University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Review Board. We used our healthcare system’s integrated electronic medical record system to track the dates of initial PDFV requests, the dates of hospitalization, and actual PDFV dates. PDFVs were included if the appointment request was made while a patient was hospitalized, including the day of discharge. Our study methodology only allowed us to investigate PDFVs scheduled with UPHS outpatient providers. We did not review discharge instructions or survey non-UPHS clinics to quantify visits scheduled with other providers, for example, community health centers or external private practices.

Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) office visits with nonproviders, for example, scheduled diagnostic procedures or pharmacist appointments for warfarin dosing; (2) visits cancelled by inpatient providers prior to discharge; (3) visits for patients not otherwise eligible for UPHS outpatient care because of insurance reasons; and (4) visits scheduled for dates after a patient’s death. Our motivation for the third exclusion criterion was the infrequent and irregular process by which PDFVs were authorized for these patients. These patients and their characteristics are described in Supplementary Table 1 in more detail.

For each PDFV, we recorded age, gender, race, insurance status, driving distance, length of stay for index hospitalization, discharging service (general internal medicine vs subspecialty), postdischarge disposition (home, home with home care services such as nursing or physical therapy, or facility), the number of PDFVs scheduled per index hospitalization, PDFV specialty type (oncologic subspecialty, nononcologic medical subspecialty, nononcologic surgical subspecialty, primary care, or other specialty), PDFV season, and PDFV lead time (the number of days between the discharge date and PDFV). We consolidated oncologic specialties into 1 group given the integrated nature of our healthcare system’s comprehensive cancer center. “Other” PDFV specialty subtypes are described in Supplementary Table 2. Driving distances between patient postal codes and our hospital were calculated using Excel VBA Master (Salt Lake City, Utah) and were subsequently categorized into patient-level quartiles for further analysis. For cancelled PDFVs, we collected dates of cancellation relative to the date of the appointment itself.

Study Outcomes

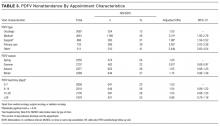

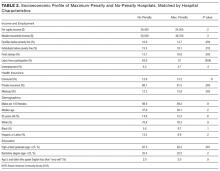

The primary study outcome was PDFV attendance. Each PDFV’s status was categorized by outpatient clinic staff as attended, cancelled, or NS. For cancelled appointments, cancellation dates and reasons (if entered by clinic representatives) were collected. In keeping with prior studies investigating outpatient nonattendance,we calculated collective NS/SDC rates for the variables listed above.17,22-25 We additionally calculated NS/SDC and attendance-as-scheduled rates stratified by the number of PDFVs per patient to assess for a “high-utilizer” effect with regard to PDFV attendance.

Statistical Analysis