User login

New guidelines highlight rapid, interdisciplinary treatment of PANS/PANDAS

Prompt, symptomatic, multidisciplinary treatment is the best way to curtail the symptoms of pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS) and pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS), according to new guidelines.

Clinicians should tailor treatment to symptoms, wrote Margo Thienemann, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and her coauthors in the clinical management section of the guidelines. For example, children with mild psychiatric symptoms might only need cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), while more severe symptoms can merit a slow up-titration of psychoactive medications.

Clinical management of PANS/PANDAS includes psychoeducational, psychotherapeutic, behavioral, family- and school-based, and pharmacologic interventions, Dr. Thienemann and her associates wrote. Starting CBT (exposure-response prevention) has the best chance of halting OCD behaviors. Acutely ill children might not be ready for CBT, but parents still can learn to “hold the line” to avoid accommodating and worsening irrational fears.

Options for psychoactive medications include benzodiazepines for anxiety; aripiprazole, risperidone, olanzapine, haloperidol, or quetiapine for psychosis; and SSRIs, such as fluoxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine for depression and OCD. Severe depression merits both psychotherapy and an SSRI. Antipsychotics are not indicated for OCD unless children are incapacitated and only if their QTc interval does not exceed 450 milliseconds. Because PANS/PANDAS patients can react severely to psychotropics, clinicians should “start low” at about a quarter of a typical dose and “go slow,” gradually titrating up.

It’s best to rule out other medical disorders first when patients refuse or restrict food or fluids. Next, clinicians should assess medical stability and support nutrition and hydration while treating underlying brain inflammation. “Feeding tubes may be necessary, at least during the acute phases of the illness,” the authors wrote. Chronic symptoms can warrant treatments for eating disorders.

Bouts of aggression or irritability are classic and can be especially challenging for families. Parents can refocus the child with toys or by dancing, singing, or acting silly but should also make a safety plan, such as calling 911, if aggressive behaviors are endangering the patient or family members. Pharmacologic options for aggression include diphenhydramine, benzodiazepines, and antipsychotics.

For tics, options include comprehensive behavioral intervention for tics, habit reversal training, and cautiously monitored pharmacotherapy with alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, clonidine, guanfacine, or short-course antipsychotics. Symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder merit classroom accommodations; methylphenidate compounds can be added if needed. For children with sleep disturbances, the best strategy is to focus on sleep hygiene before considering low-dose diphenhydramine, melatonin, cyproheptadine, clonidine, trazodone, or zolpidem. Pain, however, needs early treatment to stop it from becoming refractory. Pain and stiffness after awakening can signal arthritis, enthesitis, or inflammatory back pain and warrant physical therapy and evaluation by a pediatric rheumatologist or pain specialist.

Part II of the guidelines covers immunomodulators. As in other severe brain disorders, early treatment improves outcomes and helps prevent relapses, wrote Jennifer Frankovich, MD, also of Stanford University, and her associates. Clinicians should start second-line therapies if first-line treatment fails. Acute impairment can remit with NSAIDs or a short course of oral corticosteroids, but chronic symptoms often need more aggressive and prolonged immunotherapy. Children with moderate to severe impairment should receive intravenous immunoglobulins, and those with severe, chronic impairment may need bursts of high-dose corticosteroids or longer-term corticosteroids with taper. Patients with extreme or life-threatening impairment should receive first-line therapeutic plasma exchange alone or with intravenous immunoglobulins, high-dose intravenous corticosteroids, and rituximab.

Part III of the guidelines covers infections. Most cases involve group A streptococci (GAS), but other culprits include Mycoplasma pneumoniae and viruses, such as influenza, wrote Michael S. Cooperstock, MD, MPH, of the University of Missouri-Columbia and his associates. They recommend antistreptococcal treatment for “essentially all” newly diagnosed cases. They also suggest secondary antistreptococcal prophylaxis for severe neuropsychiatric symptoms or intermittent exacerbations associated with GAS. “For all other [cases], vigilance for GAS infection in both the patient and close contacts is recommended,” they wrote. “Since any intercurrent infection may induce a symptom flare, close observation with appropriate therapy for any treatable intercurrent infection is warranted.” They also recommend standard childhood immunizations and monitoring vitamin D levels.

The National Institutes of Health supported the research summarized in the guidelines. Dr. Thienemann disclosed grants from Auspex, Shire, Pfizer, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, AstraZeneca, Sunovion, Neurocrine Biosciences, Psyadon, and the PANDAS Network, as well as personal fees from the International OCD Foundation and the Tourette Syndrome Association. Dr. Frankovich and Dr. Cooperstock had no relevant disclosures.

Prompt, symptomatic, multidisciplinary treatment is the best way to curtail the symptoms of pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS) and pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS), according to new guidelines.

Clinicians should tailor treatment to symptoms, wrote Margo Thienemann, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and her coauthors in the clinical management section of the guidelines. For example, children with mild psychiatric symptoms might only need cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), while more severe symptoms can merit a slow up-titration of psychoactive medications.

Clinical management of PANS/PANDAS includes psychoeducational, psychotherapeutic, behavioral, family- and school-based, and pharmacologic interventions, Dr. Thienemann and her associates wrote. Starting CBT (exposure-response prevention) has the best chance of halting OCD behaviors. Acutely ill children might not be ready for CBT, but parents still can learn to “hold the line” to avoid accommodating and worsening irrational fears.

Options for psychoactive medications include benzodiazepines for anxiety; aripiprazole, risperidone, olanzapine, haloperidol, or quetiapine for psychosis; and SSRIs, such as fluoxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine for depression and OCD. Severe depression merits both psychotherapy and an SSRI. Antipsychotics are not indicated for OCD unless children are incapacitated and only if their QTc interval does not exceed 450 milliseconds. Because PANS/PANDAS patients can react severely to psychotropics, clinicians should “start low” at about a quarter of a typical dose and “go slow,” gradually titrating up.

It’s best to rule out other medical disorders first when patients refuse or restrict food or fluids. Next, clinicians should assess medical stability and support nutrition and hydration while treating underlying brain inflammation. “Feeding tubes may be necessary, at least during the acute phases of the illness,” the authors wrote. Chronic symptoms can warrant treatments for eating disorders.

Bouts of aggression or irritability are classic and can be especially challenging for families. Parents can refocus the child with toys or by dancing, singing, or acting silly but should also make a safety plan, such as calling 911, if aggressive behaviors are endangering the patient or family members. Pharmacologic options for aggression include diphenhydramine, benzodiazepines, and antipsychotics.

For tics, options include comprehensive behavioral intervention for tics, habit reversal training, and cautiously monitored pharmacotherapy with alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, clonidine, guanfacine, or short-course antipsychotics. Symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder merit classroom accommodations; methylphenidate compounds can be added if needed. For children with sleep disturbances, the best strategy is to focus on sleep hygiene before considering low-dose diphenhydramine, melatonin, cyproheptadine, clonidine, trazodone, or zolpidem. Pain, however, needs early treatment to stop it from becoming refractory. Pain and stiffness after awakening can signal arthritis, enthesitis, or inflammatory back pain and warrant physical therapy and evaluation by a pediatric rheumatologist or pain specialist.

Part II of the guidelines covers immunomodulators. As in other severe brain disorders, early treatment improves outcomes and helps prevent relapses, wrote Jennifer Frankovich, MD, also of Stanford University, and her associates. Clinicians should start second-line therapies if first-line treatment fails. Acute impairment can remit with NSAIDs or a short course of oral corticosteroids, but chronic symptoms often need more aggressive and prolonged immunotherapy. Children with moderate to severe impairment should receive intravenous immunoglobulins, and those with severe, chronic impairment may need bursts of high-dose corticosteroids or longer-term corticosteroids with taper. Patients with extreme or life-threatening impairment should receive first-line therapeutic plasma exchange alone or with intravenous immunoglobulins, high-dose intravenous corticosteroids, and rituximab.

Part III of the guidelines covers infections. Most cases involve group A streptococci (GAS), but other culprits include Mycoplasma pneumoniae and viruses, such as influenza, wrote Michael S. Cooperstock, MD, MPH, of the University of Missouri-Columbia and his associates. They recommend antistreptococcal treatment for “essentially all” newly diagnosed cases. They also suggest secondary antistreptococcal prophylaxis for severe neuropsychiatric symptoms or intermittent exacerbations associated with GAS. “For all other [cases], vigilance for GAS infection in both the patient and close contacts is recommended,” they wrote. “Since any intercurrent infection may induce a symptom flare, close observation with appropriate therapy for any treatable intercurrent infection is warranted.” They also recommend standard childhood immunizations and monitoring vitamin D levels.

The National Institutes of Health supported the research summarized in the guidelines. Dr. Thienemann disclosed grants from Auspex, Shire, Pfizer, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, AstraZeneca, Sunovion, Neurocrine Biosciences, Psyadon, and the PANDAS Network, as well as personal fees from the International OCD Foundation and the Tourette Syndrome Association. Dr. Frankovich and Dr. Cooperstock had no relevant disclosures.

Prompt, symptomatic, multidisciplinary treatment is the best way to curtail the symptoms of pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS) and pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with streptococcal infection (PANDAS), according to new guidelines.

Clinicians should tailor treatment to symptoms, wrote Margo Thienemann, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University and her coauthors in the clinical management section of the guidelines. For example, children with mild psychiatric symptoms might only need cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), while more severe symptoms can merit a slow up-titration of psychoactive medications.

Clinical management of PANS/PANDAS includes psychoeducational, psychotherapeutic, behavioral, family- and school-based, and pharmacologic interventions, Dr. Thienemann and her associates wrote. Starting CBT (exposure-response prevention) has the best chance of halting OCD behaviors. Acutely ill children might not be ready for CBT, but parents still can learn to “hold the line” to avoid accommodating and worsening irrational fears.

Options for psychoactive medications include benzodiazepines for anxiety; aripiprazole, risperidone, olanzapine, haloperidol, or quetiapine for psychosis; and SSRIs, such as fluoxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine for depression and OCD. Severe depression merits both psychotherapy and an SSRI. Antipsychotics are not indicated for OCD unless children are incapacitated and only if their QTc interval does not exceed 450 milliseconds. Because PANS/PANDAS patients can react severely to psychotropics, clinicians should “start low” at about a quarter of a typical dose and “go slow,” gradually titrating up.

It’s best to rule out other medical disorders first when patients refuse or restrict food or fluids. Next, clinicians should assess medical stability and support nutrition and hydration while treating underlying brain inflammation. “Feeding tubes may be necessary, at least during the acute phases of the illness,” the authors wrote. Chronic symptoms can warrant treatments for eating disorders.

Bouts of aggression or irritability are classic and can be especially challenging for families. Parents can refocus the child with toys or by dancing, singing, or acting silly but should also make a safety plan, such as calling 911, if aggressive behaviors are endangering the patient or family members. Pharmacologic options for aggression include diphenhydramine, benzodiazepines, and antipsychotics.

For tics, options include comprehensive behavioral intervention for tics, habit reversal training, and cautiously monitored pharmacotherapy with alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, clonidine, guanfacine, or short-course antipsychotics. Symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder merit classroom accommodations; methylphenidate compounds can be added if needed. For children with sleep disturbances, the best strategy is to focus on sleep hygiene before considering low-dose diphenhydramine, melatonin, cyproheptadine, clonidine, trazodone, or zolpidem. Pain, however, needs early treatment to stop it from becoming refractory. Pain and stiffness after awakening can signal arthritis, enthesitis, or inflammatory back pain and warrant physical therapy and evaluation by a pediatric rheumatologist or pain specialist.

Part II of the guidelines covers immunomodulators. As in other severe brain disorders, early treatment improves outcomes and helps prevent relapses, wrote Jennifer Frankovich, MD, also of Stanford University, and her associates. Clinicians should start second-line therapies if first-line treatment fails. Acute impairment can remit with NSAIDs or a short course of oral corticosteroids, but chronic symptoms often need more aggressive and prolonged immunotherapy. Children with moderate to severe impairment should receive intravenous immunoglobulins, and those with severe, chronic impairment may need bursts of high-dose corticosteroids or longer-term corticosteroids with taper. Patients with extreme or life-threatening impairment should receive first-line therapeutic plasma exchange alone or with intravenous immunoglobulins, high-dose intravenous corticosteroids, and rituximab.

Part III of the guidelines covers infections. Most cases involve group A streptococci (GAS), but other culprits include Mycoplasma pneumoniae and viruses, such as influenza, wrote Michael S. Cooperstock, MD, MPH, of the University of Missouri-Columbia and his associates. They recommend antistreptococcal treatment for “essentially all” newly diagnosed cases. They also suggest secondary antistreptococcal prophylaxis for severe neuropsychiatric symptoms or intermittent exacerbations associated with GAS. “For all other [cases], vigilance for GAS infection in both the patient and close contacts is recommended,” they wrote. “Since any intercurrent infection may induce a symptom flare, close observation with appropriate therapy for any treatable intercurrent infection is warranted.” They also recommend standard childhood immunizations and monitoring vitamin D levels.

The National Institutes of Health supported the research summarized in the guidelines. Dr. Thienemann disclosed grants from Auspex, Shire, Pfizer, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, AstraZeneca, Sunovion, Neurocrine Biosciences, Psyadon, and the PANDAS Network, as well as personal fees from the International OCD Foundation and the Tourette Syndrome Association. Dr. Frankovich and Dr. Cooperstock had no relevant disclosures.

FROM JOURNAL OF CHILD AND ADOLESCENT PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY

We Want to Know: Eliciting Hospitalized Patients’ Perspectives on Breakdowns in Care

There is growing recognition that patients and family members have critical insights into healthcare experiences. As consumers of healthcare, patient experience is the definitive gauge of whether healthcare is patient centered. In addition, patients may know things about their healthcare that the care team does not. Several studies have demonstrated that patients have knowledge of adverse events and medical errors that are not detected by other methods.1-5 For these reasons, systems designed to elicit patient perspectives of care and detect patient-perceived breakdowns in care could be used to improve healthcare safety and quality, including the patient experience.

Historically, hospitals have relied on patient-initiated reporting via complaints or legal action as the main source of information regarding patient-perceived breakdowns in care. However, many patients are hesitant to speak up about problems or uncertain about how to report concerns.6-8 As a result, healthcare systems often only learn of the most severe breakdowns in care from a subset of activated patients, thus underestimating how widespread patient-perceived breakdowns are.

To overcome these limitations of patient-initiated reporting, hospitals could conduct outreach to patients to actively identify and learn about patient-perceived breakdowns in care. Potential benefits of outreach to patients include more reliable detection of patient-perceived breakdowns in care, identification of a broader range of types of breakdowns commonly experienced by patients, and recognition of problems in real-time when there is more opportunity for redress. Indeed, some hospitals have adopted active outreach programs such as structured nurse manager rounding or postdischarge phone calls.9

It is possible that outreach will not overcome patients’ reluctance to speak up, or patients may not share serious or actionable breakdowns. The manner in which outreach is conducted is likely to influence the information patients are willing to share. Prior studies examining patient perspectives of healthcare have primarily taken a structured approach with close-ended questions or a focus on specific aspects of care.1,10,11 Limited data collected using an open-ended approach suggest patient-perceived breakdowns in care may be very common.2,12,13 However, the impact of such breakdowns on patients has not been well characterized.

In order to design systems that can optimally detect patient-perceived breakdowns in care, additional information is needed to understand whether patients will report breakdowns in response to outreach programs, what types of problems they will report, and how these problems impact them. Understanding such issues will allow healthcare systems to respond to calls by federal health agencies to develop mechanisms for patients to report concerns about breakdowns in care, thereby providing truly patient-centered care.14 Therefore, we undertook this study with the overall goal of describing what may be learned from an open-ended outreach approach that directly asks patients about problems they have encountered during hospitalization. Specifically, we aim to (1) describe the types of problems reported by patients in response to this outreach approach and (2) characterize patients’ perceptions of the impact of these events.

METHODS

Setting

We conducted this study in 2 hospitals between June 2014 and February 2015. One participating hospital is a large, urban, tertiary care medical center serving a predominantly white (78%) patient population in Baltimore, Maryland. The second hospital is a large, inner city, tertiary care medical center serving a predominantly African-American (71%) patient population in Washington, DC.

Three medical-surgical units (MSUs) at each hospital participated. We selected MSUs because MSU patients interact with a variety of clinicians, often have long stays, and are at risk for adverse events. Hospitalists were part of the clinical care team in each of the participating units, serving either as the attending of record or by comanaging patients.

Patient Eligibility

Patients were potentially eligible if they were at least 18 years old, able to speak English or Spanish, and admitted to the hospital for more than 24 hours. Ineligibility criteria included the following: imminent discharge, observation (noninpatient) status, on hospice, on infection precautions (for inpatient interviews only), psychiatric or violence concerns, prisoner status, significant confusion, or inability to provide informed consent.

Eligible patients in each unit were randomized. Interviewers consecutively approached patients according to their random assignment. If a patient was not available, the interviewer proceeded to the next room. Interviewers returned to rooms of missed patients when possible. Recruitment in the unit ended when the recruitment target for that unit was achieved.

Interviewers

Five interviewers conducted interviews. One author (KS) provided interviewer training that included didactic instruction, observation, feedback, and modeling. Interviewers participated in weekly debriefing sessions. One interviewer speaks Spanish fluently and was able to conduct interviews in Spanish. Translator services were available for the other interviewers.

Interview Process

Interviews were conducted in person while the patients were hospitalized or via telephone 7 - 30 days postdischarge. A patient who had completed an interview while hospitalized was not eligible for a postdischarge telephone interview. Family members or friends present at the time of the interviews could also participate in addition to or in lieu of the patients with the patients’ assent. Interviewers obtained verbal, informed consent at the start of each interview.

The interview domains and sample questions were developed specifically for the current study and are listed in Table 1. The goal of the interview was to elicit the patient’s (or family member’s) perception of their care experiences and their perceptions of the consequences of any problems with their care. The interviewer sought to obtain sufficient detail to understand the patient’s concerns and to determine what, if any, action might be needed to remediate problems reported by patients. Interviewers captured patient responses by taking detailed notes on a case report form or by directly entering patient responses using a computer or iPad at the time of interview at the discretion of the interviewer.

We defined a patient-perceived breakdown as something that went wrong during the hospitalization according to the patient. If a patient-perceived breakdown in care was identified, the interviewer attempted to resolve the concern. Some breakdowns had occurred in the past, making further resolution impossible (eg, a long wait in the emergency department). Other breakdowns were active and addressable, such as the patient having clinical questions that had not been answered. In such cases, the interviewer attempted to address the patient’s concerns, typically by working with unit nursing staff. For patients interviewed postdischarge, the interviewer worked to resolve ongoing patient concerns with the assistance of the patient safety, quality, and compliance teams as needed. The interviewer provided a brief narrative summary of all interviews to unit nursing leadership within 24 hours. Positive comments were sent to leadership but not captured systematically for research purposes. Further details of the process of responding to patients’ concerns will be reported elsewhere. All data were entered into REDCap to facilitate data management and reporting.15

The MedStar Health Research Institute Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study.

Categorizing Patients’ Responses: The Patient Experience Coding Tool

Using directed content analysis,16 we deductively created the Patient Experience Coding Tool (PECT) in order to summarize the narrative information captured during the interviews and categorize patient-perceived breakdowns in care. First, we referred to our prior interviews of patients’ views on breakdowns in cancer care6 and surrogate decision-makers’ views on breakdowns in intensive care units13 to create the initial categories. We then applied the resultant framework to the interviews in the present study and refined the categories. This involved applying the categorization to an initial set of interviews to check the sufficiency of the coding categories. We clarified the scope of each category (ie, what types of events fit under each category) and created additional categories (eg, medication-related problems) to capture patient experiences that were not included in the initial framework.

We then coded each interview using the PECT. A minimum of 2 readers reviewed the narrative notes for each interview. The first reader provided an initial categorization; the second reader reviewed the narrative and confirmed or questioned the initial categorization to improve coding accuracy. If a reader was uncertain about the correct categorization, it was discussed by three readers until an agreement was achieved. Because facilities-related problems (eg, food or parking) fall outside the realm of provider-based hospital care, such comments were not the focus of the outreach efforts and were not consistently recorded. Therefore, they were not included in the PECT and are not reported here.

Analyses

We computed simple, descriptive statistics including the number and percentage of patients identifying at least one breakdown, as well as the number and percent reporting each type of breakdown. We also computed the number and percentage of patients reporting any harm and each type of harm. We computed the percentage of patients reporting at least 1 breakdown by hospital, type of interview (postdischarge vs inpatient), selected patient demographic characteristics (eg, gender, age, education, race), and interviewee (patient vs someone other than the patient interviewed or present during the interview) using the chi-square statistic to test the statistical significance of the resulting differences. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.

RESULTS

A total of 979 outreach interviews were conducted. Of these, 349 were conducted via telephone postdischarge, and 630 were conducted in person during hospitalization. The average interview duration was 8.5 minutes for telephone interviews and 12.2 minutes for in-person interviews. Of the patients approached to participate, 67% completed an interview (61% in person, 83% via telephone). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

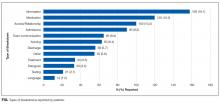

Overall, 386 of 979 interviewees (39.4%) believed they had experienced at least one breakdown in care. The types of patient-perceived breakdowns reported were categorized using the PECT and are summarized in Table 3 and the Figure. The most common concern involved information exchange. Approximately 1 in 10 patients (n = 105, 10.7%) felt that they had not received the information they needed when they needed it. Medication-related concerns were reported by 12.3% (n = 120) of interviewees and predominantly included concerns about what medications were being administered (5.7%) and inadequately treated pain (5.6%). Many of the patients expressing concerns about what medications were administered questioned why they were not receiving their outpatient medications or did not understand why a different medication was being administered, suggesting that many of these instances were related to breakdowns in communication as well. Other relatively common concerns were delays in the admissions process (reported by 9.2% of interviewees), poor team communication (reported by 6.6% of interviewees), healthcare providers with a rude or uncaring manner (reported by 6.3% of interviewees), and problems related to discharge (reported by 5.7% of interviewees).

Of the 386 interviewees who perceived a breakdown in care, 140 (36.3%) perceived harm associated with the event (Table 3). The most common harms were physical (eg, pain; n = 66) and emotional (eg, distress, worry; n = 60). In addition, patients reported instances of damage to relationships with providers (n = 28) resulting in a loss of trust, with participants citing breakdowns as a reason for not coming back to a particular hospital or provider. In other cases, patients believed that breakdowns in care resulted in the need for additional care or a prolonged hospital stay.

We found no difference between the 2 hospitals where the study was conducted in the percentage of interviewees reporting at least 1 breakdown (39.1% vs 39.9%, P = 0.80). We also found no difference between interview method, (ie, in person vs telephone; 40.6% vs 37.2%, respectively, P = 0.30), patient gender (40.6% and 38.8% for men and women, respectively, P = 0.57), race (41.0% and 36.8% for white and black or African-American, respectively, P = 0.20) or between interviewers (P = 0.37). We did identify differences in rates of reporting at least 1 breakdown in care related to age (45.4% of patients aged 60 years or younger vs 34.5% of patients older than 60 years, P < 0.001) and education (32.7% of patients with a high school education or less vs 46.8% of those with at least some college education, P < 0.001). Patients interviewed alone reported fewer breakdowns than if another person was present during the interview or was interviewed in lieu of the patient (37.8% vs 53.4%, P = 0.002). The rate of reporting breakdowns for patients interviewed alone in the hospital is very similar to the rates of those interviewed via telephone (37.8% vs 37.2%). For most types of breakdowns, there were no differences in reporting for in-person vs postdischarge interviews. Discharge-related problems were more frequently reported among patients interviewed postdischarge (8.9% postdischarge vs 4.0% in person, P = 0.002). Patients interviewed in person were more likely to report problems with information exchange compared to patients interviewed postdischarge (17.6% vs 13.5%, respectively; P = 0.09), although this did not reach statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

Through interviews with nearly 1000 patients, we have found that approximately 4 in 10 hospitalized patients believed they experienced a breakdown in care. Not only are patient-perceived breakdowns in care distressingly common, more than one-third of these events resulted in harm according to the patient. Patients reported a diverse range of breakdowns, including problems related to patient experience, as well as breakdowns in technical aspects of medical care. Collectively, these findings illustrate a striking need to identify and address these frequent and potentially harmful breakdowns.

Our findings are consistent with prior studies in which 20% to 50% of patients identified a problem during hospitalization. For example, Weingart et al. interviewed patients in a single general medical unit and found that 20% experienced an adverse event, near miss, or medical error, while nearly 40% experienced what was defined as a service quality incident.2,12 Of note, both our study and the study by Weingart et al. systematically elicited patients’ perspectives of breakdowns in care with explicit questions about problems or breakdowns in care.2,12 Because patients are often reluctant to speak up about problems in care,without such efforts to actively identify problems, providers and leaders are likely to be unaware of the majority of these concerns.6-8 These findings suggest that hospital-based providers should at least consider routinely asking patients about breakdowns in care to identify and respond to patients’ concerns.

Not only are patient-perceived breakdowns common, more than one-third of patients who experienced a breakdown considered it to be harmful. This suggests that our outreach approach identified predominantly nontrivial concerns. We adopted a broad definition of harm that includes emotional distress, damage to the relationship with providers, and life disruption. This differs from other studies examining patient reports of breakdowns in care, in which harm was restricted to physical injury.1,2 We consider this inclusive definition of harm to be a strength of the present study as it provides the most complete picture of the impact of such events on patients. This approach is supported by other studies demonstrating that patients place great emphasis on the psychological consequences of adverse events.17-19 Thus, it is clear from our work and other studies that nonphysical harm is important and warrants concerted efforts to address.

Patients in our study reported a variety of breakdowns, including breakdowns related to patient experience (eg, communication, relationship with providers) and technical aspects of healthcare delivery (eg, diagnosis, treatment). This is consistent with other studies examining patient perspectives of breakdowns in care. Weingart et al.found that hospitalized patients reported a broad range of problems, including adverse events, medical errors, communication breakdowns, and problems with food.2,12 This variety of events suggests a need for integration between the various hospital groups that handle patient-perceived breakdowns, including bedside providers, risk management, patient relations, patient advocates, and quality and safety groups, in order to provide a coordinated and effective response to the full spectrum of patient-perceived breakdowns in care.

Patients in our study were more likely to report breakdowns related to communication and relationships with providers than those related to technical aspects of care. Similarly, Kuzel et al.found that the most common problems cited by patients in the primary care setting were breakdowns in the clinician-patient relationship and access-related problems.17This is not surprising, as patients are likely to have more direct knowledge about communication and interpersonal relationships than about technical aspects of care.

We identified several factors associated with the likelihood of reporting a breakdown in care. Most strikingly, involving a friend or family member in the interview was strongly associated with reporting a breakdown. Other work has also suggested that patients’ friends and family members are an important source of information about safety concerns.20,21 In addition, several patient characteristics were associated with an increased likelihood of reporting a breakdown, including being younger and better educated. These findings highlight the importance of engaging patients’ friends and families in efforts to elicit patient concerns about healthcare, and they confirm recommendations for patients to bring a friend or family member to healthcare encounters.22 In addition, they illustrate the need to better understand how patient characteristics affect perceptions of breakdowns in care and their willingness to speak up, as this could inform efforts to target outreach to especially vulnerable patients.

A strength of this study is the number of interviews completed (almost 1000), which provides a diverse range of patient views and experiences, as evidenced by the demographic characteristics of participants. Interviews were conducted at two hospitals that differ substantially with regard to populations served, further enhancing the generalizability of our findings. Despite the large number of interviews and diverse patient characteristics, patients were drawn from only 3 units at 2 hospitals, which may limit generalizability.

We did not conduct medical record reviews to validate patients’ reports of problems, which may be viewed as a limitation. While such a comparison would be informative, the intent of the current study was to elicit patients’ perceptions of care, including aspects of care that are not typically captured in the medical record, such as communication. Other studies have demonstrated that patients’ reports of medical errors and adverse events tend to differ from providers’ reports of the same subjects.19,23 Therefore, we considered the patients’ perceptions of care to be a useful endpoint in and of itself. We did not determine the extent to which providers were already aware of patients’ concerns or whether they considered patients’ concerns valid. A related limitation is our inability to determine whether the differences we identified in the rates of breakdown reporting based on patient characteristics reflect differences in willingness to report or differences in experiences. Because we included patients in an MSU, it is possible that breakdowns were related to medical care, surgical care, or both. We did not follow patients longitudinally and therefore only captured harm perceived by a patient at the time of the interview. It is possible that patients may have experienced harm later in their hospitalization or following discharge that was not measured. Lastly, we did not measure interrater reliability of the interview coding and therefore do not present the PECT as a validated instrument. These important questions should be targeted for future study.

CONCLUSION

When directly asked about their experiences, almost 4 out of 10 hospitalized patients reported a breakdown in their care, many of which were perceived to be harmful. Not all hospitals will have the resources to implement the intensive approach used in this study to elicit patient-perceived breakdowns. Therefore, further work is needed to develop sustainable methods to overcome patients’ reluctance to report breakdowns in care. Engaging patients’ families and friends may be a particularly fruitful strategy. We offer the PECT as a tool that hospitals could use to summarize a variety of sources of patient feedback such as complaints, responses to surveys, and consumer reviews. Hospitals that effectively encourage patients and their family members to speak up about perceived breakdowns will identify many opportunities to address patient concerns, potentially leading to improved patient safety and experience.

1. Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Weingart SN, et al. Comparing patient-reported hospital adverse events with medical record review: Do patients know something that hospitals do not? Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(2):100-108. PubMed

2. Weingart SN, Pagovich O, Sands DZ, et al. What can hospitalized patients tell us about adverse events? learning from patient-reported incidents. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(9):830-836. PubMed

3. Wetzels R, Wolters R, van Weel C, Wensing M. Mix of methods is needed to identify adverse events in general practice: A prospective observational study. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:35. PubMed

4. Friedman SM, Provan D, Moore S, Hanneman K. Errors, near misses and adverse events in the emergency department: What can patients tell us? CJEM. 2008;10(5):421-427. PubMed

5. Iedema R, Allen S, Britton K, Gallagher TH. What do patients and relatives know about problems and failures in care? BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(3):198-205. PubMed

6. Mazor KM, Roblin DW, Greene SM, et al. Toward patient-centered cancer care: Patient perceptions of problematic events, impact, and response. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(15):1784-1790. PubMed

7. Frosch DL, May SG, Rendle KA, Tietbohl C, Elwyn G. Authoritarian physicians and patients’ fear of being labeled ‘difficult’ among key obstacles to shared decision making. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(5):1030-1038. PubMed

8. Entwistle VA, McCaughan D, Watt IS, et al. Speaking up about safety concerns: Multi-setting qualitative study of patients’ views and experiences. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(6):e33. PubMed

9. Tan M, Lang D. Effectiveness of nurse leader rounding and post-discharge telephone calls in patient satisfaction: A systematic review. JBI database of systematic reviews and implementation reports. 2015;13(7):154-176. PubMed

10. Garbutt J, Bose D, McCawley BA, Burroughs T, Medoff G. Soliciting patient complaints to improve performance. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003;29(3):103-112. PubMed

11. Agoritsas T, Bovier PA, Perneger TV. Patient reports of undesirable events during hospitalization. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(10):922-928. PubMed

12. Weingart SN, Pagovich O, Sands DZ, et al. Patient-reported service quality on a medicine unit. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18(2):95-101. PubMed

13. Fisher KA, Ahmad S, Jackson M, Mazor KM. Surrogate decision makers’ perspectives on preventable breakdowns in care among critically ill patients: A qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(10):1685-1693. PubMed

14. Halpern MT, Roussel AE, Treiman K, Nerz PA, Hatlie MJ, Sheridan S. Designing consumer reporting systems for patient safety events. Final Report (Prepared by RTI International and Consumers Advancing Patient Safety under Contract No. 290-06-00001-5). AHRQ Publication No. 11-0060-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011.

15. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. PubMed

16. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288. PubMed

17. Kuzel AJ, Woolf SH, Gilchrist VJ, et al. Patient reports of preventable problems and harms in primary health care. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(4):333-340. PubMed

18. Sokol-Hessner L, Folcarelli PH, Sands KE. Emotional harm from disrespect: The neglected preventable harm. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(9):550-553. PubMed

19. Masso Guijarro P, Aranaz Andres JM, Mira JJ, Perdiguero E, Aibar C. Adverse events in hospitals: The patient’s point of view. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(2):144-147. PubMed

20. Bardach NS, Lyndon A, Asteria-Penaloza R, Goldman LE, Lin GA, Dudley RA. From the closest observers of patient care: A thematic analysis of online narrative reviews of hospitals. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015. PubMed

21. Schneider EC, Ridgely MS, Quigley DD, et al. Developing and testing the health care safety hotline: A prototype consumer reporting system for patient safety events. Final Report (Prepared by RAND Corporation under contract HHSA2902010000171). Rockvelle, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; May 2016.

22. Shekelle PG, Pronovost PJ, Wachter RM, et al. The top patient safety strategies that can be encouraged for adoption now. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5 Pt 2):365-368. PubMed

23. Lawton R, O’Hara JK, Sheard L, et al. Can staff and patient perspectives on hospital safety predict harm-free care? an analysis of staff and patient survey data and routinely collected outcomes. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(6):369-376. PubMed

There is growing recognition that patients and family members have critical insights into healthcare experiences. As consumers of healthcare, patient experience is the definitive gauge of whether healthcare is patient centered. In addition, patients may know things about their healthcare that the care team does not. Several studies have demonstrated that patients have knowledge of adverse events and medical errors that are not detected by other methods.1-5 For these reasons, systems designed to elicit patient perspectives of care and detect patient-perceived breakdowns in care could be used to improve healthcare safety and quality, including the patient experience.

Historically, hospitals have relied on patient-initiated reporting via complaints or legal action as the main source of information regarding patient-perceived breakdowns in care. However, many patients are hesitant to speak up about problems or uncertain about how to report concerns.6-8 As a result, healthcare systems often only learn of the most severe breakdowns in care from a subset of activated patients, thus underestimating how widespread patient-perceived breakdowns are.

To overcome these limitations of patient-initiated reporting, hospitals could conduct outreach to patients to actively identify and learn about patient-perceived breakdowns in care. Potential benefits of outreach to patients include more reliable detection of patient-perceived breakdowns in care, identification of a broader range of types of breakdowns commonly experienced by patients, and recognition of problems in real-time when there is more opportunity for redress. Indeed, some hospitals have adopted active outreach programs such as structured nurse manager rounding or postdischarge phone calls.9

It is possible that outreach will not overcome patients’ reluctance to speak up, or patients may not share serious or actionable breakdowns. The manner in which outreach is conducted is likely to influence the information patients are willing to share. Prior studies examining patient perspectives of healthcare have primarily taken a structured approach with close-ended questions or a focus on specific aspects of care.1,10,11 Limited data collected using an open-ended approach suggest patient-perceived breakdowns in care may be very common.2,12,13 However, the impact of such breakdowns on patients has not been well characterized.

In order to design systems that can optimally detect patient-perceived breakdowns in care, additional information is needed to understand whether patients will report breakdowns in response to outreach programs, what types of problems they will report, and how these problems impact them. Understanding such issues will allow healthcare systems to respond to calls by federal health agencies to develop mechanisms for patients to report concerns about breakdowns in care, thereby providing truly patient-centered care.14 Therefore, we undertook this study with the overall goal of describing what may be learned from an open-ended outreach approach that directly asks patients about problems they have encountered during hospitalization. Specifically, we aim to (1) describe the types of problems reported by patients in response to this outreach approach and (2) characterize patients’ perceptions of the impact of these events.

METHODS

Setting

We conducted this study in 2 hospitals between June 2014 and February 2015. One participating hospital is a large, urban, tertiary care medical center serving a predominantly white (78%) patient population in Baltimore, Maryland. The second hospital is a large, inner city, tertiary care medical center serving a predominantly African-American (71%) patient population in Washington, DC.

Three medical-surgical units (MSUs) at each hospital participated. We selected MSUs because MSU patients interact with a variety of clinicians, often have long stays, and are at risk for adverse events. Hospitalists were part of the clinical care team in each of the participating units, serving either as the attending of record or by comanaging patients.

Patient Eligibility

Patients were potentially eligible if they were at least 18 years old, able to speak English or Spanish, and admitted to the hospital for more than 24 hours. Ineligibility criteria included the following: imminent discharge, observation (noninpatient) status, on hospice, on infection precautions (for inpatient interviews only), psychiatric or violence concerns, prisoner status, significant confusion, or inability to provide informed consent.

Eligible patients in each unit were randomized. Interviewers consecutively approached patients according to their random assignment. If a patient was not available, the interviewer proceeded to the next room. Interviewers returned to rooms of missed patients when possible. Recruitment in the unit ended when the recruitment target for that unit was achieved.

Interviewers

Five interviewers conducted interviews. One author (KS) provided interviewer training that included didactic instruction, observation, feedback, and modeling. Interviewers participated in weekly debriefing sessions. One interviewer speaks Spanish fluently and was able to conduct interviews in Spanish. Translator services were available for the other interviewers.

Interview Process

Interviews were conducted in person while the patients were hospitalized or via telephone 7 - 30 days postdischarge. A patient who had completed an interview while hospitalized was not eligible for a postdischarge telephone interview. Family members or friends present at the time of the interviews could also participate in addition to or in lieu of the patients with the patients’ assent. Interviewers obtained verbal, informed consent at the start of each interview.

The interview domains and sample questions were developed specifically for the current study and are listed in Table 1. The goal of the interview was to elicit the patient’s (or family member’s) perception of their care experiences and their perceptions of the consequences of any problems with their care. The interviewer sought to obtain sufficient detail to understand the patient’s concerns and to determine what, if any, action might be needed to remediate problems reported by patients. Interviewers captured patient responses by taking detailed notes on a case report form or by directly entering patient responses using a computer or iPad at the time of interview at the discretion of the interviewer.

We defined a patient-perceived breakdown as something that went wrong during the hospitalization according to the patient. If a patient-perceived breakdown in care was identified, the interviewer attempted to resolve the concern. Some breakdowns had occurred in the past, making further resolution impossible (eg, a long wait in the emergency department). Other breakdowns were active and addressable, such as the patient having clinical questions that had not been answered. In such cases, the interviewer attempted to address the patient’s concerns, typically by working with unit nursing staff. For patients interviewed postdischarge, the interviewer worked to resolve ongoing patient concerns with the assistance of the patient safety, quality, and compliance teams as needed. The interviewer provided a brief narrative summary of all interviews to unit nursing leadership within 24 hours. Positive comments were sent to leadership but not captured systematically for research purposes. Further details of the process of responding to patients’ concerns will be reported elsewhere. All data were entered into REDCap to facilitate data management and reporting.15

The MedStar Health Research Institute Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study.

Categorizing Patients’ Responses: The Patient Experience Coding Tool

Using directed content analysis,16 we deductively created the Patient Experience Coding Tool (PECT) in order to summarize the narrative information captured during the interviews and categorize patient-perceived breakdowns in care. First, we referred to our prior interviews of patients’ views on breakdowns in cancer care6 and surrogate decision-makers’ views on breakdowns in intensive care units13 to create the initial categories. We then applied the resultant framework to the interviews in the present study and refined the categories. This involved applying the categorization to an initial set of interviews to check the sufficiency of the coding categories. We clarified the scope of each category (ie, what types of events fit under each category) and created additional categories (eg, medication-related problems) to capture patient experiences that were not included in the initial framework.

We then coded each interview using the PECT. A minimum of 2 readers reviewed the narrative notes for each interview. The first reader provided an initial categorization; the second reader reviewed the narrative and confirmed or questioned the initial categorization to improve coding accuracy. If a reader was uncertain about the correct categorization, it was discussed by three readers until an agreement was achieved. Because facilities-related problems (eg, food or parking) fall outside the realm of provider-based hospital care, such comments were not the focus of the outreach efforts and were not consistently recorded. Therefore, they were not included in the PECT and are not reported here.

Analyses

We computed simple, descriptive statistics including the number and percentage of patients identifying at least one breakdown, as well as the number and percent reporting each type of breakdown. We also computed the number and percentage of patients reporting any harm and each type of harm. We computed the percentage of patients reporting at least 1 breakdown by hospital, type of interview (postdischarge vs inpatient), selected patient demographic characteristics (eg, gender, age, education, race), and interviewee (patient vs someone other than the patient interviewed or present during the interview) using the chi-square statistic to test the statistical significance of the resulting differences. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.

RESULTS

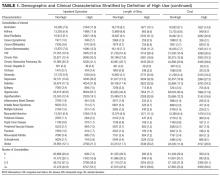

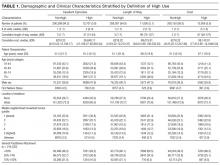

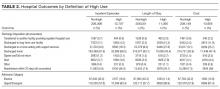

A total of 979 outreach interviews were conducted. Of these, 349 were conducted via telephone postdischarge, and 630 were conducted in person during hospitalization. The average interview duration was 8.5 minutes for telephone interviews and 12.2 minutes for in-person interviews. Of the patients approached to participate, 67% completed an interview (61% in person, 83% via telephone). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

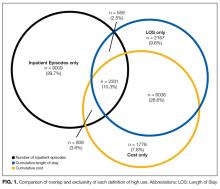

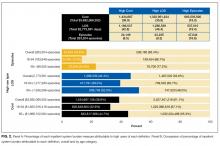

Overall, 386 of 979 interviewees (39.4%) believed they had experienced at least one breakdown in care. The types of patient-perceived breakdowns reported were categorized using the PECT and are summarized in Table 3 and the Figure. The most common concern involved information exchange. Approximately 1 in 10 patients (n = 105, 10.7%) felt that they had not received the information they needed when they needed it. Medication-related concerns were reported by 12.3% (n = 120) of interviewees and predominantly included concerns about what medications were being administered (5.7%) and inadequately treated pain (5.6%). Many of the patients expressing concerns about what medications were administered questioned why they were not receiving their outpatient medications or did not understand why a different medication was being administered, suggesting that many of these instances were related to breakdowns in communication as well. Other relatively common concerns were delays in the admissions process (reported by 9.2% of interviewees), poor team communication (reported by 6.6% of interviewees), healthcare providers with a rude or uncaring manner (reported by 6.3% of interviewees), and problems related to discharge (reported by 5.7% of interviewees).

Of the 386 interviewees who perceived a breakdown in care, 140 (36.3%) perceived harm associated with the event (Table 3). The most common harms were physical (eg, pain; n = 66) and emotional (eg, distress, worry; n = 60). In addition, patients reported instances of damage to relationships with providers (n = 28) resulting in a loss of trust, with participants citing breakdowns as a reason for not coming back to a particular hospital or provider. In other cases, patients believed that breakdowns in care resulted in the need for additional care or a prolonged hospital stay.

We found no difference between the 2 hospitals where the study was conducted in the percentage of interviewees reporting at least 1 breakdown (39.1% vs 39.9%, P = 0.80). We also found no difference between interview method, (ie, in person vs telephone; 40.6% vs 37.2%, respectively, P = 0.30), patient gender (40.6% and 38.8% for men and women, respectively, P = 0.57), race (41.0% and 36.8% for white and black or African-American, respectively, P = 0.20) or between interviewers (P = 0.37). We did identify differences in rates of reporting at least 1 breakdown in care related to age (45.4% of patients aged 60 years or younger vs 34.5% of patients older than 60 years, P < 0.001) and education (32.7% of patients with a high school education or less vs 46.8% of those with at least some college education, P < 0.001). Patients interviewed alone reported fewer breakdowns than if another person was present during the interview or was interviewed in lieu of the patient (37.8% vs 53.4%, P = 0.002). The rate of reporting breakdowns for patients interviewed alone in the hospital is very similar to the rates of those interviewed via telephone (37.8% vs 37.2%). For most types of breakdowns, there were no differences in reporting for in-person vs postdischarge interviews. Discharge-related problems were more frequently reported among patients interviewed postdischarge (8.9% postdischarge vs 4.0% in person, P = 0.002). Patients interviewed in person were more likely to report problems with information exchange compared to patients interviewed postdischarge (17.6% vs 13.5%, respectively; P = 0.09), although this did not reach statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

Through interviews with nearly 1000 patients, we have found that approximately 4 in 10 hospitalized patients believed they experienced a breakdown in care. Not only are patient-perceived breakdowns in care distressingly common, more than one-third of these events resulted in harm according to the patient. Patients reported a diverse range of breakdowns, including problems related to patient experience, as well as breakdowns in technical aspects of medical care. Collectively, these findings illustrate a striking need to identify and address these frequent and potentially harmful breakdowns.

Our findings are consistent with prior studies in which 20% to 50% of patients identified a problem during hospitalization. For example, Weingart et al. interviewed patients in a single general medical unit and found that 20% experienced an adverse event, near miss, or medical error, while nearly 40% experienced what was defined as a service quality incident.2,12 Of note, both our study and the study by Weingart et al. systematically elicited patients’ perspectives of breakdowns in care with explicit questions about problems or breakdowns in care.2,12 Because patients are often reluctant to speak up about problems in care,without such efforts to actively identify problems, providers and leaders are likely to be unaware of the majority of these concerns.6-8 These findings suggest that hospital-based providers should at least consider routinely asking patients about breakdowns in care to identify and respond to patients’ concerns.

Not only are patient-perceived breakdowns common, more than one-third of patients who experienced a breakdown considered it to be harmful. This suggests that our outreach approach identified predominantly nontrivial concerns. We adopted a broad definition of harm that includes emotional distress, damage to the relationship with providers, and life disruption. This differs from other studies examining patient reports of breakdowns in care, in which harm was restricted to physical injury.1,2 We consider this inclusive definition of harm to be a strength of the present study as it provides the most complete picture of the impact of such events on patients. This approach is supported by other studies demonstrating that patients place great emphasis on the psychological consequences of adverse events.17-19 Thus, it is clear from our work and other studies that nonphysical harm is important and warrants concerted efforts to address.

Patients in our study reported a variety of breakdowns, including breakdowns related to patient experience (eg, communication, relationship with providers) and technical aspects of healthcare delivery (eg, diagnosis, treatment). This is consistent with other studies examining patient perspectives of breakdowns in care. Weingart et al.found that hospitalized patients reported a broad range of problems, including adverse events, medical errors, communication breakdowns, and problems with food.2,12 This variety of events suggests a need for integration between the various hospital groups that handle patient-perceived breakdowns, including bedside providers, risk management, patient relations, patient advocates, and quality and safety groups, in order to provide a coordinated and effective response to the full spectrum of patient-perceived breakdowns in care.

Patients in our study were more likely to report breakdowns related to communication and relationships with providers than those related to technical aspects of care. Similarly, Kuzel et al.found that the most common problems cited by patients in the primary care setting were breakdowns in the clinician-patient relationship and access-related problems.17This is not surprising, as patients are likely to have more direct knowledge about communication and interpersonal relationships than about technical aspects of care.

We identified several factors associated with the likelihood of reporting a breakdown in care. Most strikingly, involving a friend or family member in the interview was strongly associated with reporting a breakdown. Other work has also suggested that patients’ friends and family members are an important source of information about safety concerns.20,21 In addition, several patient characteristics were associated with an increased likelihood of reporting a breakdown, including being younger and better educated. These findings highlight the importance of engaging patients’ friends and families in efforts to elicit patient concerns about healthcare, and they confirm recommendations for patients to bring a friend or family member to healthcare encounters.22 In addition, they illustrate the need to better understand how patient characteristics affect perceptions of breakdowns in care and their willingness to speak up, as this could inform efforts to target outreach to especially vulnerable patients.

A strength of this study is the number of interviews completed (almost 1000), which provides a diverse range of patient views and experiences, as evidenced by the demographic characteristics of participants. Interviews were conducted at two hospitals that differ substantially with regard to populations served, further enhancing the generalizability of our findings. Despite the large number of interviews and diverse patient characteristics, patients were drawn from only 3 units at 2 hospitals, which may limit generalizability.

We did not conduct medical record reviews to validate patients’ reports of problems, which may be viewed as a limitation. While such a comparison would be informative, the intent of the current study was to elicit patients’ perceptions of care, including aspects of care that are not typically captured in the medical record, such as communication. Other studies have demonstrated that patients’ reports of medical errors and adverse events tend to differ from providers’ reports of the same subjects.19,23 Therefore, we considered the patients’ perceptions of care to be a useful endpoint in and of itself. We did not determine the extent to which providers were already aware of patients’ concerns or whether they considered patients’ concerns valid. A related limitation is our inability to determine whether the differences we identified in the rates of breakdown reporting based on patient characteristics reflect differences in willingness to report or differences in experiences. Because we included patients in an MSU, it is possible that breakdowns were related to medical care, surgical care, or both. We did not follow patients longitudinally and therefore only captured harm perceived by a patient at the time of the interview. It is possible that patients may have experienced harm later in their hospitalization or following discharge that was not measured. Lastly, we did not measure interrater reliability of the interview coding and therefore do not present the PECT as a validated instrument. These important questions should be targeted for future study.

CONCLUSION

When directly asked about their experiences, almost 4 out of 10 hospitalized patients reported a breakdown in their care, many of which were perceived to be harmful. Not all hospitals will have the resources to implement the intensive approach used in this study to elicit patient-perceived breakdowns. Therefore, further work is needed to develop sustainable methods to overcome patients’ reluctance to report breakdowns in care. Engaging patients’ families and friends may be a particularly fruitful strategy. We offer the PECT as a tool that hospitals could use to summarize a variety of sources of patient feedback such as complaints, responses to surveys, and consumer reviews. Hospitals that effectively encourage patients and their family members to speak up about perceived breakdowns will identify many opportunities to address patient concerns, potentially leading to improved patient safety and experience.

There is growing recognition that patients and family members have critical insights into healthcare experiences. As consumers of healthcare, patient experience is the definitive gauge of whether healthcare is patient centered. In addition, patients may know things about their healthcare that the care team does not. Several studies have demonstrated that patients have knowledge of adverse events and medical errors that are not detected by other methods.1-5 For these reasons, systems designed to elicit patient perspectives of care and detect patient-perceived breakdowns in care could be used to improve healthcare safety and quality, including the patient experience.

Historically, hospitals have relied on patient-initiated reporting via complaints or legal action as the main source of information regarding patient-perceived breakdowns in care. However, many patients are hesitant to speak up about problems or uncertain about how to report concerns.6-8 As a result, healthcare systems often only learn of the most severe breakdowns in care from a subset of activated patients, thus underestimating how widespread patient-perceived breakdowns are.

To overcome these limitations of patient-initiated reporting, hospitals could conduct outreach to patients to actively identify and learn about patient-perceived breakdowns in care. Potential benefits of outreach to patients include more reliable detection of patient-perceived breakdowns in care, identification of a broader range of types of breakdowns commonly experienced by patients, and recognition of problems in real-time when there is more opportunity for redress. Indeed, some hospitals have adopted active outreach programs such as structured nurse manager rounding or postdischarge phone calls.9

It is possible that outreach will not overcome patients’ reluctance to speak up, or patients may not share serious or actionable breakdowns. The manner in which outreach is conducted is likely to influence the information patients are willing to share. Prior studies examining patient perspectives of healthcare have primarily taken a structured approach with close-ended questions or a focus on specific aspects of care.1,10,11 Limited data collected using an open-ended approach suggest patient-perceived breakdowns in care may be very common.2,12,13 However, the impact of such breakdowns on patients has not been well characterized.

In order to design systems that can optimally detect patient-perceived breakdowns in care, additional information is needed to understand whether patients will report breakdowns in response to outreach programs, what types of problems they will report, and how these problems impact them. Understanding such issues will allow healthcare systems to respond to calls by federal health agencies to develop mechanisms for patients to report concerns about breakdowns in care, thereby providing truly patient-centered care.14 Therefore, we undertook this study with the overall goal of describing what may be learned from an open-ended outreach approach that directly asks patients about problems they have encountered during hospitalization. Specifically, we aim to (1) describe the types of problems reported by patients in response to this outreach approach and (2) characterize patients’ perceptions of the impact of these events.

METHODS

Setting

We conducted this study in 2 hospitals between June 2014 and February 2015. One participating hospital is a large, urban, tertiary care medical center serving a predominantly white (78%) patient population in Baltimore, Maryland. The second hospital is a large, inner city, tertiary care medical center serving a predominantly African-American (71%) patient population in Washington, DC.

Three medical-surgical units (MSUs) at each hospital participated. We selected MSUs because MSU patients interact with a variety of clinicians, often have long stays, and are at risk for adverse events. Hospitalists were part of the clinical care team in each of the participating units, serving either as the attending of record or by comanaging patients.

Patient Eligibility

Patients were potentially eligible if they were at least 18 years old, able to speak English or Spanish, and admitted to the hospital for more than 24 hours. Ineligibility criteria included the following: imminent discharge, observation (noninpatient) status, on hospice, on infection precautions (for inpatient interviews only), psychiatric or violence concerns, prisoner status, significant confusion, or inability to provide informed consent.

Eligible patients in each unit were randomized. Interviewers consecutively approached patients according to their random assignment. If a patient was not available, the interviewer proceeded to the next room. Interviewers returned to rooms of missed patients when possible. Recruitment in the unit ended when the recruitment target for that unit was achieved.

Interviewers

Five interviewers conducted interviews. One author (KS) provided interviewer training that included didactic instruction, observation, feedback, and modeling. Interviewers participated in weekly debriefing sessions. One interviewer speaks Spanish fluently and was able to conduct interviews in Spanish. Translator services were available for the other interviewers.

Interview Process

Interviews were conducted in person while the patients were hospitalized or via telephone 7 - 30 days postdischarge. A patient who had completed an interview while hospitalized was not eligible for a postdischarge telephone interview. Family members or friends present at the time of the interviews could also participate in addition to or in lieu of the patients with the patients’ assent. Interviewers obtained verbal, informed consent at the start of each interview.

The interview domains and sample questions were developed specifically for the current study and are listed in Table 1. The goal of the interview was to elicit the patient’s (or family member’s) perception of their care experiences and their perceptions of the consequences of any problems with their care. The interviewer sought to obtain sufficient detail to understand the patient’s concerns and to determine what, if any, action might be needed to remediate problems reported by patients. Interviewers captured patient responses by taking detailed notes on a case report form or by directly entering patient responses using a computer or iPad at the time of interview at the discretion of the interviewer.

We defined a patient-perceived breakdown as something that went wrong during the hospitalization according to the patient. If a patient-perceived breakdown in care was identified, the interviewer attempted to resolve the concern. Some breakdowns had occurred in the past, making further resolution impossible (eg, a long wait in the emergency department). Other breakdowns were active and addressable, such as the patient having clinical questions that had not been answered. In such cases, the interviewer attempted to address the patient’s concerns, typically by working with unit nursing staff. For patients interviewed postdischarge, the interviewer worked to resolve ongoing patient concerns with the assistance of the patient safety, quality, and compliance teams as needed. The interviewer provided a brief narrative summary of all interviews to unit nursing leadership within 24 hours. Positive comments were sent to leadership but not captured systematically for research purposes. Further details of the process of responding to patients’ concerns will be reported elsewhere. All data were entered into REDCap to facilitate data management and reporting.15

The MedStar Health Research Institute Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study.

Categorizing Patients’ Responses: The Patient Experience Coding Tool

Using directed content analysis,16 we deductively created the Patient Experience Coding Tool (PECT) in order to summarize the narrative information captured during the interviews and categorize patient-perceived breakdowns in care. First, we referred to our prior interviews of patients’ views on breakdowns in cancer care6 and surrogate decision-makers’ views on breakdowns in intensive care units13 to create the initial categories. We then applied the resultant framework to the interviews in the present study and refined the categories. This involved applying the categorization to an initial set of interviews to check the sufficiency of the coding categories. We clarified the scope of each category (ie, what types of events fit under each category) and created additional categories (eg, medication-related problems) to capture patient experiences that were not included in the initial framework.

We then coded each interview using the PECT. A minimum of 2 readers reviewed the narrative notes for each interview. The first reader provided an initial categorization; the second reader reviewed the narrative and confirmed or questioned the initial categorization to improve coding accuracy. If a reader was uncertain about the correct categorization, it was discussed by three readers until an agreement was achieved. Because facilities-related problems (eg, food or parking) fall outside the realm of provider-based hospital care, such comments were not the focus of the outreach efforts and were not consistently recorded. Therefore, they were not included in the PECT and are not reported here.

Analyses

We computed simple, descriptive statistics including the number and percentage of patients identifying at least one breakdown, as well as the number and percent reporting each type of breakdown. We also computed the number and percentage of patients reporting any harm and each type of harm. We computed the percentage of patients reporting at least 1 breakdown by hospital, type of interview (postdischarge vs inpatient), selected patient demographic characteristics (eg, gender, age, education, race), and interviewee (patient vs someone other than the patient interviewed or present during the interview) using the chi-square statistic to test the statistical significance of the resulting differences. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.

RESULTS

A total of 979 outreach interviews were conducted. Of these, 349 were conducted via telephone postdischarge, and 630 were conducted in person during hospitalization. The average interview duration was 8.5 minutes for telephone interviews and 12.2 minutes for in-person interviews. Of the patients approached to participate, 67% completed an interview (61% in person, 83% via telephone). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Overall, 386 of 979 interviewees (39.4%) believed they had experienced at least one breakdown in care. The types of patient-perceived breakdowns reported were categorized using the PECT and are summarized in Table 3 and the Figure. The most common concern involved information exchange. Approximately 1 in 10 patients (n = 105, 10.7%) felt that they had not received the information they needed when they needed it. Medication-related concerns were reported by 12.3% (n = 120) of interviewees and predominantly included concerns about what medications were being administered (5.7%) and inadequately treated pain (5.6%). Many of the patients expressing concerns about what medications were administered questioned why they were not receiving their outpatient medications or did not understand why a different medication was being administered, suggesting that many of these instances were related to breakdowns in communication as well. Other relatively common concerns were delays in the admissions process (reported by 9.2% of interviewees), poor team communication (reported by 6.6% of interviewees), healthcare providers with a rude or uncaring manner (reported by 6.3% of interviewees), and problems related to discharge (reported by 5.7% of interviewees).

Of the 386 interviewees who perceived a breakdown in care, 140 (36.3%) perceived harm associated with the event (Table 3). The most common harms were physical (eg, pain; n = 66) and emotional (eg, distress, worry; n = 60). In addition, patients reported instances of damage to relationships with providers (n = 28) resulting in a loss of trust, with participants citing breakdowns as a reason for not coming back to a particular hospital or provider. In other cases, patients believed that breakdowns in care resulted in the need for additional care or a prolonged hospital stay.