User login

Natural and Unnatural Disasters

Between late August and early November of this year, three strong Gulf Coast and Atlantic hurricanes and several intense, fast-moving northern California forest fires claimed more than 285 lives and caused countless additional injuries and illnesses. During the same period, three unnatural disasters—in Las Vegas, New York City (NYC), and now Sutherland Springs, Texas—were responsible for a total of 84 deaths and 558 injuries. Emergency physicians (EPs) and our colleagues helped deal with the aftermath of all of these incidents, saving lives and ameliorating survivors’ pain and suffering. But ironically, preventing future deaths and injuries from natural disasters may be easier than preventing loss of life from depraved human behavior.

An October 9, 2017 Wall Street Journal (WSJ) article by Jeanne Whalen entitled “Training Ground for Military Trauma Experts: U.S. Gun Violence,” describes how military surgeons helped treat victims of the Las Vegas shooting, one of several arrangements across the United States where steady gun violence provides a training ground that experts can then use on the battlefield. The article includes a photograph of Tom Scalea, MD, Chief of the R. Adams Cowley (Maryland) Shock Trauma Center and EM board member, operating with the assistance of an Air Force surgeon “embedded” at the hospital.

Before September 11, 2001, US hospitals looked to military surgeons experienced in treating combat injuries to direct and staff their trauma centers. Now, the military looks to US hospitals to provide their surgeons with experience treating victims of gun violence, explosives, and high-speed vehicular injuries prior to sending them into war zones! In the week before this issue of EM went to press, a terrorist driving a rental truck down an NYC bicycle path killed 8 people and injured 11 near the site of the 1993 and 2001 World Trade Center attacks. Five days later, 26 church worshipers near Austin, Texas lost their lives and 20 more were seriously injured when a lone gunman shot them with an assault rifle.

The gun violence statistics in this country are staggering. According to the nonprofit Gun Violence Archive (GVA; http://www.gunviolencearchive.org/), from January 1 through November 8, 2017 there have been 52,719 incidents resulting in 13,245 deaths and 27,111

The pervasiveness of the gun culture in this country offers little hope of eliminating such incidents in the future, which makes it especially important for all EPs to be skilled in state-of-the-art trauma management. (See parts I and II of “The changing landscape of trauma care” in the July and August 2017 issues of EM [www.mdedge.com/emed-journal]). As Baltimore trauma surgeon Tom Scalea notes in the WSJ article cited earlier, “Mass shooting? That’s every weekend.…it makes me despondent….I don’t have the ability to make that go away. I have the ability to keep as many alive as I can, and we’re pretty good at it.”

As for preventing deaths from natural disasters, more accurate weather forecasting and newer technology offer more hope. Among the 134 storm-related deaths from Hurricane Irma in September, 14 were heat-related after the storm disabled a transformer supplying power to the air conditioning system of a Hollywood, Florida nursing home. A new state law will now require all nursing homes to have adequate backup generators. But for the increasing numbers of older persons with comorbidities, taking multiple medications, and living in hot climates, air conditioning must be considered life support equipment that requires immediate repair or replacement when it fails—or transfer of the residents to a cool facility.

If only we could someday also prevent terrorism and other acts of senseless violence.

*The GVA defines a mass shooting as a single incident resulting in 4 or more people (not including the shooter) shot and/or killed at the same general time and location.

Between late August and early November of this year, three strong Gulf Coast and Atlantic hurricanes and several intense, fast-moving northern California forest fires claimed more than 285 lives and caused countless additional injuries and illnesses. During the same period, three unnatural disasters—in Las Vegas, New York City (NYC), and now Sutherland Springs, Texas—were responsible for a total of 84 deaths and 558 injuries. Emergency physicians (EPs) and our colleagues helped deal with the aftermath of all of these incidents, saving lives and ameliorating survivors’ pain and suffering. But ironically, preventing future deaths and injuries from natural disasters may be easier than preventing loss of life from depraved human behavior.

An October 9, 2017 Wall Street Journal (WSJ) article by Jeanne Whalen entitled “Training Ground for Military Trauma Experts: U.S. Gun Violence,” describes how military surgeons helped treat victims of the Las Vegas shooting, one of several arrangements across the United States where steady gun violence provides a training ground that experts can then use on the battlefield. The article includes a photograph of Tom Scalea, MD, Chief of the R. Adams Cowley (Maryland) Shock Trauma Center and EM board member, operating with the assistance of an Air Force surgeon “embedded” at the hospital.

Before September 11, 2001, US hospitals looked to military surgeons experienced in treating combat injuries to direct and staff their trauma centers. Now, the military looks to US hospitals to provide their surgeons with experience treating victims of gun violence, explosives, and high-speed vehicular injuries prior to sending them into war zones! In the week before this issue of EM went to press, a terrorist driving a rental truck down an NYC bicycle path killed 8 people and injured 11 near the site of the 1993 and 2001 World Trade Center attacks. Five days later, 26 church worshipers near Austin, Texas lost their lives and 20 more were seriously injured when a lone gunman shot them with an assault rifle.

The gun violence statistics in this country are staggering. According to the nonprofit Gun Violence Archive (GVA; http://www.gunviolencearchive.org/), from January 1 through November 8, 2017 there have been 52,719 incidents resulting in 13,245 deaths and 27,111

The pervasiveness of the gun culture in this country offers little hope of eliminating such incidents in the future, which makes it especially important for all EPs to be skilled in state-of-the-art trauma management. (See parts I and II of “The changing landscape of trauma care” in the July and August 2017 issues of EM [www.mdedge.com/emed-journal]). As Baltimore trauma surgeon Tom Scalea notes in the WSJ article cited earlier, “Mass shooting? That’s every weekend.…it makes me despondent….I don’t have the ability to make that go away. I have the ability to keep as many alive as I can, and we’re pretty good at it.”

As for preventing deaths from natural disasters, more accurate weather forecasting and newer technology offer more hope. Among the 134 storm-related deaths from Hurricane Irma in September, 14 were heat-related after the storm disabled a transformer supplying power to the air conditioning system of a Hollywood, Florida nursing home. A new state law will now require all nursing homes to have adequate backup generators. But for the increasing numbers of older persons with comorbidities, taking multiple medications, and living in hot climates, air conditioning must be considered life support equipment that requires immediate repair or replacement when it fails—or transfer of the residents to a cool facility.

If only we could someday also prevent terrorism and other acts of senseless violence.

*The GVA defines a mass shooting as a single incident resulting in 4 or more people (not including the shooter) shot and/or killed at the same general time and location.

Between late August and early November of this year, three strong Gulf Coast and Atlantic hurricanes and several intense, fast-moving northern California forest fires claimed more than 285 lives and caused countless additional injuries and illnesses. During the same period, three unnatural disasters—in Las Vegas, New York City (NYC), and now Sutherland Springs, Texas—were responsible for a total of 84 deaths and 558 injuries. Emergency physicians (EPs) and our colleagues helped deal with the aftermath of all of these incidents, saving lives and ameliorating survivors’ pain and suffering. But ironically, preventing future deaths and injuries from natural disasters may be easier than preventing loss of life from depraved human behavior.

An October 9, 2017 Wall Street Journal (WSJ) article by Jeanne Whalen entitled “Training Ground for Military Trauma Experts: U.S. Gun Violence,” describes how military surgeons helped treat victims of the Las Vegas shooting, one of several arrangements across the United States where steady gun violence provides a training ground that experts can then use on the battlefield. The article includes a photograph of Tom Scalea, MD, Chief of the R. Adams Cowley (Maryland) Shock Trauma Center and EM board member, operating with the assistance of an Air Force surgeon “embedded” at the hospital.

Before September 11, 2001, US hospitals looked to military surgeons experienced in treating combat injuries to direct and staff their trauma centers. Now, the military looks to US hospitals to provide their surgeons with experience treating victims of gun violence, explosives, and high-speed vehicular injuries prior to sending them into war zones! In the week before this issue of EM went to press, a terrorist driving a rental truck down an NYC bicycle path killed 8 people and injured 11 near the site of the 1993 and 2001 World Trade Center attacks. Five days later, 26 church worshipers near Austin, Texas lost their lives and 20 more were seriously injured when a lone gunman shot them with an assault rifle.

The gun violence statistics in this country are staggering. According to the nonprofit Gun Violence Archive (GVA; http://www.gunviolencearchive.org/), from January 1 through November 8, 2017 there have been 52,719 incidents resulting in 13,245 deaths and 27,111

The pervasiveness of the gun culture in this country offers little hope of eliminating such incidents in the future, which makes it especially important for all EPs to be skilled in state-of-the-art trauma management. (See parts I and II of “The changing landscape of trauma care” in the July and August 2017 issues of EM [www.mdedge.com/emed-journal]). As Baltimore trauma surgeon Tom Scalea notes in the WSJ article cited earlier, “Mass shooting? That’s every weekend.…it makes me despondent….I don’t have the ability to make that go away. I have the ability to keep as many alive as I can, and we’re pretty good at it.”

As for preventing deaths from natural disasters, more accurate weather forecasting and newer technology offer more hope. Among the 134 storm-related deaths from Hurricane Irma in September, 14 were heat-related after the storm disabled a transformer supplying power to the air conditioning system of a Hollywood, Florida nursing home. A new state law will now require all nursing homes to have adequate backup generators. But for the increasing numbers of older persons with comorbidities, taking multiple medications, and living in hot climates, air conditioning must be considered life support equipment that requires immediate repair or replacement when it fails—or transfer of the residents to a cool facility.

If only we could someday also prevent terrorism and other acts of senseless violence.

*The GVA defines a mass shooting as a single incident resulting in 4 or more people (not including the shooter) shot and/or killed at the same general time and location.

Back to Basics: An Uncommon, Unrelated Presentation of a Common Disease

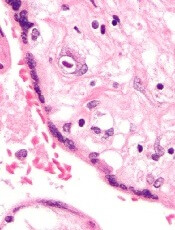

The early initial ulcerative lesion (chancre) caused by Treponema pallidum infection, has a median incubation period of 21 days (primary syphilis). When untreated, secondary syphilis will develop within weeks to months and is characterized by generalized symptoms such as malaise, fevers, headaches, sore throat, and myalgia. However, the most characteristic finding in secondary syphilis remains a rash that is classically identified as symmetric, macular, or papular, and involving the entire trunk and extremities, including the palms and soles.

When secondary syphilis is left untreated, late syphilis or tertiary syphilis can develop, which is characterized by cardiovascular involvement, including aortitis, gummatous syphilis (granulomatous nodules in a variety of organs but typically the skin and bones), or central nervous system involvement.1-3 The following case describes a patient with nondescript symptoms, including malaise and cough, who had a characteristic rash of secondary syphilis that was diagnosed and treated in our Houston-area community hospital.

Case

In late autumn, a 30-year-old man presented to our community ED for evaluation of a cough productive of green sputum along with mild chest discomfort, malaise, and generalized myalgia, which were intermittent over the course of the past month. The patient denied rhinorrhea, fevers, chills, dyspnea, or any other systemic complaints. He also denied any sick contacts, but noted that his influenza vaccine was not up to date.

The patient denied any remote or recent medical or surgical history. He further denied taking any medications, and noted that his only medical allergy was to penicillin. His family history was noncontributory. Regarding his social history, the patient admitted to smoking one pack of cigarettes per day and to a daily alcohol intake of approximately one 6-pack of beer. He also admitted to frequently smoking crystal methamphetamine, which he stated he had last used 2 days prior to presentation. The patient said his current chest pain was similar to prior episodes, noting that when the pain occurred, he would temporarily stop smoking crystal methamphetamine.

Plain chest radiography, electrocardiogram, complete metabolic panel, complete blood count, B-natriuretic peptide, and troponin levels were all unremarkable. Due to the presence and nature of the patient’s rash, a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) screen was also taken, the results of which were reactive.

On further questioning, the patient admitted to having multiple female sexual partners with whom he used barrier protection sporadically. A more detailed physical examination revealed multiple painless ulcerations/chancres over the penile shaft and scrotum, without urethral drainage or inguinal lymphadenopathy. The patient denied dysuria or hematuria.

Since the patient was allergic to penicillin, he was given a single oral dose of azithromycin 2 g, and started on a 2-week course of oral doxycycline 100 mg. Further laboratory studies included gonorrhea and chlamydia cultures, both of which were negative. He was instructed to follow-up with his primary care physician for extended sexually transmitted infection (STI) panel-testing, including HIV, hepatitis, and confirmatory syphilis testing. Unfortunately, it is not known whether the patient complied with discharge instructions as he was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Diagnostic algorithms for syphilis, one of the best studied STIs, have changed with technological advancement, but diagnosis and treatment for the most part has remained mostly the same. The uniqueness of this case is really focused around the patient’s chief complaint. While it is classic to present with malaise, headache, and rash, our patient complained of cough productive of sputum with chest pain—a rare presentation of secondary syphilis. The fortuitous key finding of the truncal rash directed the emergency physician toward the appropriate diagnosis.

Diagnosis

In the ED, where patients such as the one in our case are often lost to follow-up, and consistent infectious disease and primary care follow-up is unavailable, prompt treatment based on history and physical examination alone is recommended. Patients should be tested for syphilis, as well as other STIs including chlamydia, gonorrhea, hepatitis, and HIV as an outpatient. In addition, any partners with whom the patient has had sexual contact within the last 90 days should also undergo STI testing; sexual partners from over 90 days should be notified of the patient’s status and evaluated with testing as indicated.4 All positive test results should be reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).5

Nontreponemal and Treponemal Testing

For patients with clinical signs and symptoms of syphilis, recommended laboratory evaluation includes both nontreponemal and treponemal testing. Nontreponemal tests include RPR, venereal disease research laboratory test, and toluidine red unheated serum test. Treponemal tests include fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption, microhemagglutination test for antibodies to T pallidum, T pallidum particle agglutination assay, T pallidum enzyme immunoassay, and chemiluminescence immunoassay. Patients who test positive for treponemal antibody will typically remain reactive for life.5,6

In the setting of discordant test results, patients with a nonreactive treponemal result are generally considered to be negative for syphilis. Discordant results with a negative nontreponemal test are more complicated, and recommendations are based on symptomatology and repeat testing.5

Treatment

When a patient has a positive nontreponemal and treponemal test, treatment is usually indicated. As with the patient in this case, treatment is always indicated for patients who have no prior history of syphilis. For patients who have a history of treated syphilis, attention must be given to titer levels on previous testing and to patient symptomatology.

The treatment for early (primary and secondary) syphilis in patients with no penicillin allergy is a single dose of penicillin G benzathine intramuscularly, at a dose of 2.4 million U. Alternative regimens include doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 14 days, and azithromycin 2 g orally as a single dose; however, there is an association of treatment failure with azithromycin due to macrolide resistance.5 The patient in this case received empiric treatment targeting syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia.

Conclusion

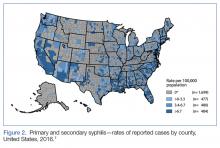

Ten years ago, the rates of primary and secondary syphilis were low, leading the infectious disease community to believe that preventive efforts had been effective. According to the CDC, however, “[current] rates…are the highest they have been in more than 20 years.”5Figure 2 demonstrates the geographic distribution of syphilis cases in the United States in 2016.7

Heightened concern has prompted the CDC to promote the theme “Syphilis Strikes Back” in April 2017, which was STI Awareness Month.8 Identification of disease is critical in the ED, especially when a previously common disease has become uncommon, like the resurgence of syphilis we are now seeing.

1. Clark EG, Danbolt N. The Oslo study of the natural course of untreated syphilis: An epidemiologic investigation based on a re-study of the Boeck-Bruusgaard material. Med Clin North Am. 1964;48:613.

2. Rockwell DH, Yobs AR, Moore MB Jr. The Tuskegee study of untreated syphilis; the 30th year of observation. Arch Intern Med. 1964;114:792-798.

3. Sparling PF, Swartz MN, Musher DM, Healy BP. Clinical manifestations of syphilis. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, et al, eds. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1999:661-684.

4. Birnbaumer DM. Sexually transmitted diseases. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. Vol 2. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2014:1312-1325.

5. Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1-137.

6. Larsen SA. Syphilis. Clin Lab Med. 1989;9(3):545-557.

7. Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Primary and secondary syphilis—rates of reported cases by county, United States, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/figures/33.htm. Updated September 26, 2017. Accessed October 31 2017.]

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STD Awareness Month. Syphilis Strikes Back. https://www.cdc.gov/std/sam/index.htm?s_cid=tw_SAM_17001. Updated April 6, 2017. Accessed October 31, 2017.

The early initial ulcerative lesion (chancre) caused by Treponema pallidum infection, has a median incubation period of 21 days (primary syphilis). When untreated, secondary syphilis will develop within weeks to months and is characterized by generalized symptoms such as malaise, fevers, headaches, sore throat, and myalgia. However, the most characteristic finding in secondary syphilis remains a rash that is classically identified as symmetric, macular, or papular, and involving the entire trunk and extremities, including the palms and soles.

When secondary syphilis is left untreated, late syphilis or tertiary syphilis can develop, which is characterized by cardiovascular involvement, including aortitis, gummatous syphilis (granulomatous nodules in a variety of organs but typically the skin and bones), or central nervous system involvement.1-3 The following case describes a patient with nondescript symptoms, including malaise and cough, who had a characteristic rash of secondary syphilis that was diagnosed and treated in our Houston-area community hospital.

Case

In late autumn, a 30-year-old man presented to our community ED for evaluation of a cough productive of green sputum along with mild chest discomfort, malaise, and generalized myalgia, which were intermittent over the course of the past month. The patient denied rhinorrhea, fevers, chills, dyspnea, or any other systemic complaints. He also denied any sick contacts, but noted that his influenza vaccine was not up to date.

The patient denied any remote or recent medical or surgical history. He further denied taking any medications, and noted that his only medical allergy was to penicillin. His family history was noncontributory. Regarding his social history, the patient admitted to smoking one pack of cigarettes per day and to a daily alcohol intake of approximately one 6-pack of beer. He also admitted to frequently smoking crystal methamphetamine, which he stated he had last used 2 days prior to presentation. The patient said his current chest pain was similar to prior episodes, noting that when the pain occurred, he would temporarily stop smoking crystal methamphetamine.

Plain chest radiography, electrocardiogram, complete metabolic panel, complete blood count, B-natriuretic peptide, and troponin levels were all unremarkable. Due to the presence and nature of the patient’s rash, a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) screen was also taken, the results of which were reactive.

On further questioning, the patient admitted to having multiple female sexual partners with whom he used barrier protection sporadically. A more detailed physical examination revealed multiple painless ulcerations/chancres over the penile shaft and scrotum, without urethral drainage or inguinal lymphadenopathy. The patient denied dysuria or hematuria.

Since the patient was allergic to penicillin, he was given a single oral dose of azithromycin 2 g, and started on a 2-week course of oral doxycycline 100 mg. Further laboratory studies included gonorrhea and chlamydia cultures, both of which were negative. He was instructed to follow-up with his primary care physician for extended sexually transmitted infection (STI) panel-testing, including HIV, hepatitis, and confirmatory syphilis testing. Unfortunately, it is not known whether the patient complied with discharge instructions as he was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Diagnostic algorithms for syphilis, one of the best studied STIs, have changed with technological advancement, but diagnosis and treatment for the most part has remained mostly the same. The uniqueness of this case is really focused around the patient’s chief complaint. While it is classic to present with malaise, headache, and rash, our patient complained of cough productive of sputum with chest pain—a rare presentation of secondary syphilis. The fortuitous key finding of the truncal rash directed the emergency physician toward the appropriate diagnosis.

Diagnosis

In the ED, where patients such as the one in our case are often lost to follow-up, and consistent infectious disease and primary care follow-up is unavailable, prompt treatment based on history and physical examination alone is recommended. Patients should be tested for syphilis, as well as other STIs including chlamydia, gonorrhea, hepatitis, and HIV as an outpatient. In addition, any partners with whom the patient has had sexual contact within the last 90 days should also undergo STI testing; sexual partners from over 90 days should be notified of the patient’s status and evaluated with testing as indicated.4 All positive test results should be reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).5

Nontreponemal and Treponemal Testing

For patients with clinical signs and symptoms of syphilis, recommended laboratory evaluation includes both nontreponemal and treponemal testing. Nontreponemal tests include RPR, venereal disease research laboratory test, and toluidine red unheated serum test. Treponemal tests include fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption, microhemagglutination test for antibodies to T pallidum, T pallidum particle agglutination assay, T pallidum enzyme immunoassay, and chemiluminescence immunoassay. Patients who test positive for treponemal antibody will typically remain reactive for life.5,6

In the setting of discordant test results, patients with a nonreactive treponemal result are generally considered to be negative for syphilis. Discordant results with a negative nontreponemal test are more complicated, and recommendations are based on symptomatology and repeat testing.5

Treatment

When a patient has a positive nontreponemal and treponemal test, treatment is usually indicated. As with the patient in this case, treatment is always indicated for patients who have no prior history of syphilis. For patients who have a history of treated syphilis, attention must be given to titer levels on previous testing and to patient symptomatology.

The treatment for early (primary and secondary) syphilis in patients with no penicillin allergy is a single dose of penicillin G benzathine intramuscularly, at a dose of 2.4 million U. Alternative regimens include doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 14 days, and azithromycin 2 g orally as a single dose; however, there is an association of treatment failure with azithromycin due to macrolide resistance.5 The patient in this case received empiric treatment targeting syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia.

Conclusion

Ten years ago, the rates of primary and secondary syphilis were low, leading the infectious disease community to believe that preventive efforts had been effective. According to the CDC, however, “[current] rates…are the highest they have been in more than 20 years.”5Figure 2 demonstrates the geographic distribution of syphilis cases in the United States in 2016.7

Heightened concern has prompted the CDC to promote the theme “Syphilis Strikes Back” in April 2017, which was STI Awareness Month.8 Identification of disease is critical in the ED, especially when a previously common disease has become uncommon, like the resurgence of syphilis we are now seeing.

The early initial ulcerative lesion (chancre) caused by Treponema pallidum infection, has a median incubation period of 21 days (primary syphilis). When untreated, secondary syphilis will develop within weeks to months and is characterized by generalized symptoms such as malaise, fevers, headaches, sore throat, and myalgia. However, the most characteristic finding in secondary syphilis remains a rash that is classically identified as symmetric, macular, or papular, and involving the entire trunk and extremities, including the palms and soles.

When secondary syphilis is left untreated, late syphilis or tertiary syphilis can develop, which is characterized by cardiovascular involvement, including aortitis, gummatous syphilis (granulomatous nodules in a variety of organs but typically the skin and bones), or central nervous system involvement.1-3 The following case describes a patient with nondescript symptoms, including malaise and cough, who had a characteristic rash of secondary syphilis that was diagnosed and treated in our Houston-area community hospital.

Case

In late autumn, a 30-year-old man presented to our community ED for evaluation of a cough productive of green sputum along with mild chest discomfort, malaise, and generalized myalgia, which were intermittent over the course of the past month. The patient denied rhinorrhea, fevers, chills, dyspnea, or any other systemic complaints. He also denied any sick contacts, but noted that his influenza vaccine was not up to date.

The patient denied any remote or recent medical or surgical history. He further denied taking any medications, and noted that his only medical allergy was to penicillin. His family history was noncontributory. Regarding his social history, the patient admitted to smoking one pack of cigarettes per day and to a daily alcohol intake of approximately one 6-pack of beer. He also admitted to frequently smoking crystal methamphetamine, which he stated he had last used 2 days prior to presentation. The patient said his current chest pain was similar to prior episodes, noting that when the pain occurred, he would temporarily stop smoking crystal methamphetamine.

Plain chest radiography, electrocardiogram, complete metabolic panel, complete blood count, B-natriuretic peptide, and troponin levels were all unremarkable. Due to the presence and nature of the patient’s rash, a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) screen was also taken, the results of which were reactive.

On further questioning, the patient admitted to having multiple female sexual partners with whom he used barrier protection sporadically. A more detailed physical examination revealed multiple painless ulcerations/chancres over the penile shaft and scrotum, without urethral drainage or inguinal lymphadenopathy. The patient denied dysuria or hematuria.

Since the patient was allergic to penicillin, he was given a single oral dose of azithromycin 2 g, and started on a 2-week course of oral doxycycline 100 mg. Further laboratory studies included gonorrhea and chlamydia cultures, both of which were negative. He was instructed to follow-up with his primary care physician for extended sexually transmitted infection (STI) panel-testing, including HIV, hepatitis, and confirmatory syphilis testing. Unfortunately, it is not known whether the patient complied with discharge instructions as he was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

Diagnostic algorithms for syphilis, one of the best studied STIs, have changed with technological advancement, but diagnosis and treatment for the most part has remained mostly the same. The uniqueness of this case is really focused around the patient’s chief complaint. While it is classic to present with malaise, headache, and rash, our patient complained of cough productive of sputum with chest pain—a rare presentation of secondary syphilis. The fortuitous key finding of the truncal rash directed the emergency physician toward the appropriate diagnosis.

Diagnosis

In the ED, where patients such as the one in our case are often lost to follow-up, and consistent infectious disease and primary care follow-up is unavailable, prompt treatment based on history and physical examination alone is recommended. Patients should be tested for syphilis, as well as other STIs including chlamydia, gonorrhea, hepatitis, and HIV as an outpatient. In addition, any partners with whom the patient has had sexual contact within the last 90 days should also undergo STI testing; sexual partners from over 90 days should be notified of the patient’s status and evaluated with testing as indicated.4 All positive test results should be reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).5

Nontreponemal and Treponemal Testing

For patients with clinical signs and symptoms of syphilis, recommended laboratory evaluation includes both nontreponemal and treponemal testing. Nontreponemal tests include RPR, venereal disease research laboratory test, and toluidine red unheated serum test. Treponemal tests include fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption, microhemagglutination test for antibodies to T pallidum, T pallidum particle agglutination assay, T pallidum enzyme immunoassay, and chemiluminescence immunoassay. Patients who test positive for treponemal antibody will typically remain reactive for life.5,6

In the setting of discordant test results, patients with a nonreactive treponemal result are generally considered to be negative for syphilis. Discordant results with a negative nontreponemal test are more complicated, and recommendations are based on symptomatology and repeat testing.5

Treatment

When a patient has a positive nontreponemal and treponemal test, treatment is usually indicated. As with the patient in this case, treatment is always indicated for patients who have no prior history of syphilis. For patients who have a history of treated syphilis, attention must be given to titer levels on previous testing and to patient symptomatology.

The treatment for early (primary and secondary) syphilis in patients with no penicillin allergy is a single dose of penicillin G benzathine intramuscularly, at a dose of 2.4 million U. Alternative regimens include doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for 14 days, and azithromycin 2 g orally as a single dose; however, there is an association of treatment failure with azithromycin due to macrolide resistance.5 The patient in this case received empiric treatment targeting syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia.

Conclusion

Ten years ago, the rates of primary and secondary syphilis were low, leading the infectious disease community to believe that preventive efforts had been effective. According to the CDC, however, “[current] rates…are the highest they have been in more than 20 years.”5Figure 2 demonstrates the geographic distribution of syphilis cases in the United States in 2016.7

Heightened concern has prompted the CDC to promote the theme “Syphilis Strikes Back” in April 2017, which was STI Awareness Month.8 Identification of disease is critical in the ED, especially when a previously common disease has become uncommon, like the resurgence of syphilis we are now seeing.

1. Clark EG, Danbolt N. The Oslo study of the natural course of untreated syphilis: An epidemiologic investigation based on a re-study of the Boeck-Bruusgaard material. Med Clin North Am. 1964;48:613.

2. Rockwell DH, Yobs AR, Moore MB Jr. The Tuskegee study of untreated syphilis; the 30th year of observation. Arch Intern Med. 1964;114:792-798.

3. Sparling PF, Swartz MN, Musher DM, Healy BP. Clinical manifestations of syphilis. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, et al, eds. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1999:661-684.

4. Birnbaumer DM. Sexually transmitted diseases. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. Vol 2. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2014:1312-1325.

5. Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1-137.

6. Larsen SA. Syphilis. Clin Lab Med. 1989;9(3):545-557.

7. Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Primary and secondary syphilis—rates of reported cases by county, United States, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/figures/33.htm. Updated September 26, 2017. Accessed October 31 2017.]

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STD Awareness Month. Syphilis Strikes Back. https://www.cdc.gov/std/sam/index.htm?s_cid=tw_SAM_17001. Updated April 6, 2017. Accessed October 31, 2017.

1. Clark EG, Danbolt N. The Oslo study of the natural course of untreated syphilis: An epidemiologic investigation based on a re-study of the Boeck-Bruusgaard material. Med Clin North Am. 1964;48:613.

2. Rockwell DH, Yobs AR, Moore MB Jr. The Tuskegee study of untreated syphilis; the 30th year of observation. Arch Intern Med. 1964;114:792-798.

3. Sparling PF, Swartz MN, Musher DM, Healy BP. Clinical manifestations of syphilis. In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, et al, eds. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1999:661-684.

4. Birnbaumer DM. Sexually transmitted diseases. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. Vol 2. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2014:1312-1325.

5. Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1-137.

6. Larsen SA. Syphilis. Clin Lab Med. 1989;9(3):545-557.

7. Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Primary and secondary syphilis—rates of reported cases by county, United States, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/figures/33.htm. Updated September 26, 2017. Accessed October 31 2017.]

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STD Awareness Month. Syphilis Strikes Back. https://www.cdc.gov/std/sam/index.htm?s_cid=tw_SAM_17001. Updated April 6, 2017. Accessed October 31, 2017.

Home noninvasive ventilation reduces COPD readmissions

Clinical question: Is there a benefit to home noninvasive ventilation (NIV) following a hospital admission for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation?

Background: Preventing hospital readmission following a COPD exacerbation is a priority; however, the role of NIV in this situation remains uncertain.

Setting: 13 medical centers in the United Kingdom.

Synopsis: Investigators randomized 116 patients with COPD and persistent hypercapnia (paCO2 less than 53) 2-4 weeks following a COPD exacerbation to either home oxygen therapy with NIV or to home oxygen therapy alone. The study’s primary endpoint was a composite of time to readmission or death within 12 months. They found that the median time to this endpoint was significantly longer in the intervention group (1.4 vs. 4.3 months; 95% CI, 0.31-0.77; P = .002) and that the absolute risk reduction was 17.0% (80.4% vs. 63.4%; 95% CI, 0.1%-34.0%). The differences were driven by readmissions, as the mortality rate did not differ significantly between groups, although the study was not powered to evaluate this. Of note, the median NIV settings were 24/4, which constitutes a “high-pressure strategy” which may account for the benefits seen in this study that have been absent in some other trials.

Bottom line: NIV reduced readmissions in patients with COPD and persistent hypercapnia several weeks following an acute exacerbation.

Citation: Murphy PB, Rehal S, Arbane G, et al. Effect of home noninvasive ventilation with oxygen therapy vs. oxygen therapy alone on hospital readmission or death after an acute COPD exacerbation, a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(21):2177-86.

Dr. Herscher is assistant professor, division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine of the Mount Sinai Health System.

Clinical question: Is there a benefit to home noninvasive ventilation (NIV) following a hospital admission for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation?

Background: Preventing hospital readmission following a COPD exacerbation is a priority; however, the role of NIV in this situation remains uncertain.

Setting: 13 medical centers in the United Kingdom.

Synopsis: Investigators randomized 116 patients with COPD and persistent hypercapnia (paCO2 less than 53) 2-4 weeks following a COPD exacerbation to either home oxygen therapy with NIV or to home oxygen therapy alone. The study’s primary endpoint was a composite of time to readmission or death within 12 months. They found that the median time to this endpoint was significantly longer in the intervention group (1.4 vs. 4.3 months; 95% CI, 0.31-0.77; P = .002) and that the absolute risk reduction was 17.0% (80.4% vs. 63.4%; 95% CI, 0.1%-34.0%). The differences were driven by readmissions, as the mortality rate did not differ significantly between groups, although the study was not powered to evaluate this. Of note, the median NIV settings were 24/4, which constitutes a “high-pressure strategy” which may account for the benefits seen in this study that have been absent in some other trials.

Bottom line: NIV reduced readmissions in patients with COPD and persistent hypercapnia several weeks following an acute exacerbation.

Citation: Murphy PB, Rehal S, Arbane G, et al. Effect of home noninvasive ventilation with oxygen therapy vs. oxygen therapy alone on hospital readmission or death after an acute COPD exacerbation, a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(21):2177-86.

Dr. Herscher is assistant professor, division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine of the Mount Sinai Health System.

Clinical question: Is there a benefit to home noninvasive ventilation (NIV) following a hospital admission for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation?

Background: Preventing hospital readmission following a COPD exacerbation is a priority; however, the role of NIV in this situation remains uncertain.

Setting: 13 medical centers in the United Kingdom.

Synopsis: Investigators randomized 116 patients with COPD and persistent hypercapnia (paCO2 less than 53) 2-4 weeks following a COPD exacerbation to either home oxygen therapy with NIV or to home oxygen therapy alone. The study’s primary endpoint was a composite of time to readmission or death within 12 months. They found that the median time to this endpoint was significantly longer in the intervention group (1.4 vs. 4.3 months; 95% CI, 0.31-0.77; P = .002) and that the absolute risk reduction was 17.0% (80.4% vs. 63.4%; 95% CI, 0.1%-34.0%). The differences were driven by readmissions, as the mortality rate did not differ significantly between groups, although the study was not powered to evaluate this. Of note, the median NIV settings were 24/4, which constitutes a “high-pressure strategy” which may account for the benefits seen in this study that have been absent in some other trials.

Bottom line: NIV reduced readmissions in patients with COPD and persistent hypercapnia several weeks following an acute exacerbation.

Citation: Murphy PB, Rehal S, Arbane G, et al. Effect of home noninvasive ventilation with oxygen therapy vs. oxygen therapy alone on hospital readmission or death after an acute COPD exacerbation, a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(21):2177-86.

Dr. Herscher is assistant professor, division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine of the Mount Sinai Health System.

Duodenal Perforation After Endoscopic Procedure

Tension pneumoperitoneum (TPP), also known as hyperacute abdominal compartment syndrome or abdominal tamponade, is a rare condition most commonly associated with gastrointestinal (GI) perforation during endoscopy and iatrogenic insufflation of gas into the peritoneal cavity.1 Other reported causes of TPP include gastric rupture after cardiopulmonary resuscitation, barotrauma during scuba diving, positive pressure ventilation through pleural-peritoneal channels, and spontaneous TPP of uncertain mechanism.1-4

Case Presentation

A 76-year-old male with a history of ischemic cardiomyopathy, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus presented to the VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle, Washington emergency department with painless jaundice, hematemesis, melena, and acute renal failure. On esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), he was found to have an ulcer on the posterior wall of the duodenal bulb. The ulcer was coagulated and injected with epinephrine. The patient’s subsequent hospital course was complicated by worsening liver function, the need for renal replacement therapy, and recurrence of upper GI bleeding that required a transcatheter embolization of 2 separate superior pancreaticoduodenal arteries (SPDA) and the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (IPDA).

Once clinically stable, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed to evaluate for cholangiocarcinoma. A stricture was discovered in the common hepatic duct, brushings were taken, and a 15 cm, 7 Fr stent was placed in the common hepatic duct. The procedure was performed with an Olympus TJF Type Q180V duodenovideoscope (Tokyo, Japan) with an external diameter of 13.7 mm. The patient became hypotensive during the procedure and was treated with phenylephrine and ephedrine boluses. There was no endoscopic evidence of bleeding or bowel trauma.

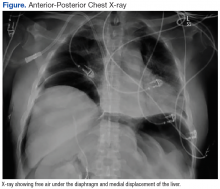

After completion of the procedure, in the recovery area the patient became severely hypotensive and unresponsive. The physical examination was noteworthy for gross abdominal distention. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed severe metabolic and respiratory acidosis. Chest radiography demonstrated massive pneumoperitoneum, low lung volumes, and diaphragmatic compression (Figure).

A diagnosis of tension pneumoperitoneum was made, and as the patient was transported to the operating room he became bradycardic without a pulse, requiring initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The abdomen was decompressed with a 14-gauge needle, followed by insertion of a laparoscopic trocar as a decompressive maneuver. This procedure resulted in return of spontaneous circulation.

An exploratory laparotomy was performed, and a massive rush of air was noted on opening the peritoneum. A pinhole perforation of the anterior wall of the second portion of the duodenum was found along with large-volume bilious ascites. This perforation was repaired with a Graham patch, and the patient was taken to the intensive care unit. Postoperatively, the patient developed disseminated intravascular coagulation, shock liver, and acute respiratory distress syndrome, expiring 10 days later from sequelae of multiorgan failure.

Discussion

In relation to upper GI endoscopic procedures, TPP has been reported after diagnostic EGD, endoscopic sphincterotomy, and submucosal tumor dissection.5-7 During these interventions, clinically apparent or overt iatrogenic perforations can occur either in the stomach or duodenum. These perforations may function as one-way valves that cause massive air accumulation and marked elevation of the diaphragm, which severely decreases lung volumes, pulmonary compliance, and limits gas exchange. Hemodynamically, compression of the inferior vena cava restricts venous return to the heart, resulting in decreased cardiac output.8

Patients with TPP present in acute distress with dyspnea, abdominal pain, and shock. On physical examination the abdomen is markedly distended, tympanic, and rigid. Rectal prolapse and subcutaneous emphysema also may be present.9 Roentographic features of TPP include findings of intraperitoneal air with elevation of the diaphragm, medial displacement of the liver (saddlebag sign), and juxtaposition of air in visceral interfaces, making intra-abdominal structures (spleen and gallbladder) appear more discrete.10 Abdominal computer tomography may show massive pneumoperitoneum with bowel loop compression and centralization of abdominal organs.4

Treatment strategies include emergent decompression either with percutaneous catheter insertion or abdominal drain placement followed by a definitive surgical repair. As with management of tension pneumothorax, treatment should not be delayed while awaiting confirmatory radiologic studies.9 When percutaneous needle decompression is undertaken, it is preferable to use a large bore (14-gauge venous catheter) and to advance a catheter over a needle to minimize the risk of visceral injury with egress of air and return of abdominal organs to their normal anatomical positions. The needle should be inserted directly above or below the umbilicus or in the left or right lower quadrants to avoid solid organ (ie, liver or spleen) injury.

Etiologic possibilities for the duodenal perforation in this case include mechanical trauma from the endoscope and duodenal tissue infarction after embolization of a bleeding duodenal ulcer. The duodenum and pancreatic head have a dual blood supply from the SPDA, a branch of the gastroduodenal artery, and the IPDA, a branch of the superior mesenteric artery.11 After failed endoscopic management of persistent duodenal hemorrhage, the patient underwent synchronous embolization of 2 separate SPDAs and the IPDA. This might have put the first 2 segments of the duodenum at risk for ischemic damage and caused it to perforate at some point during the patient’s hospitalization (as evidenced by the bilious ascitis) or rendered them vulnerable to perforation from intraluminal insufflation during endoscopy.12

During the laparotomy, a pinhole-sized perforation was noted in the anterior wall of the second part of the duodenum, distinct form the duodenal ulcer present on the posterior wall. This perforation likely provided a pathway for the intraluminal gas to escape into the peritoneal cavity, culminating in abdominal tamponade, cardiopulmonary deterioration, and arrest. Needle decompression of the abdominal cavity provided an effective, though temporizing relief of this pressure, enabling return of spontaneous circulation.

This case highlights the need for a high index of suspicion for TPP in a patient with cardiopulmonary compromise and abdominal distension after upper GI endoscopic procedures even in the absence of identifiable perforations. Close coordination among gastroenterologists, anesthesiologists, and surgeons is key in prevention, recognition, and management of this rare but catastrophic complication.

1. Bunni J, Bryson PJ, Higgs SM. Abdominal compartment syndrome caused by tension pneumoperitoneum in a scuba diver. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2012;94(8):e237-e239.

2. Cameron PA, Rosengarten PL, Johnson WR, Dziukas L. Tension pneumoperitoneum after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Med J Aust. 1991;155(1):44-47.

3. Burdett-Smith P, Jaffey L. Tension pneumoperitoneum. J Accid Emerg Med. 1996;13(3):220-221.

4. Joshi D, Ganai B. Radiological features of tension pneumoperitoneum. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015.

5. Rai A, Iftikhar S. Tension pneumothorax complicating diagnostic upper endoscopy: a case report. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(3):845-847.

6. Iyilikci L, Akarsu M, Duran E, et al. Duodenal perforation and bilateral tension pneumothorax following endoscopic sphincterotomy. J Anesth. 2009;23(1):164-165.

7. Siboni S, Bona D, Abate E, Bonavina L. Tension pneumoperitoneum following endoscopic submucosal dissection of leiomyoma of the cardia. Endoscopy. 2010;42(suppl 2):E152.

8. Deenichin GP. Abdominal compartment syndrome. Surg Today. 2008;38(1):5-19.

9. Chiapponi C, Stocker U, Korner M, et al. Emergency percutaneous needle decompression for tension pneumoperitoneum. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:48.

10. Lin BW, Thanassi W. Tension pneumoperitoneum. J Emerg Med. 2010;38(1):57-59.

11. Bell SD, Lau KY, Sniderman KW. Synchronous embolization of the gastroduodenal artery and the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery in patients with massive duodenal hemorrhage. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1995;6(4):531-536.

12. Wang YL, Cheng YS, Liu LZ, He ZH, Ding KH. Emergency transcatheter arterial embolization for patients with acute massive duodenal ulcer hemorrhage. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(34):4765-4770.

Tension pneumoperitoneum (TPP), also known as hyperacute abdominal compartment syndrome or abdominal tamponade, is a rare condition most commonly associated with gastrointestinal (GI) perforation during endoscopy and iatrogenic insufflation of gas into the peritoneal cavity.1 Other reported causes of TPP include gastric rupture after cardiopulmonary resuscitation, barotrauma during scuba diving, positive pressure ventilation through pleural-peritoneal channels, and spontaneous TPP of uncertain mechanism.1-4

Case Presentation

A 76-year-old male with a history of ischemic cardiomyopathy, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus presented to the VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle, Washington emergency department with painless jaundice, hematemesis, melena, and acute renal failure. On esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), he was found to have an ulcer on the posterior wall of the duodenal bulb. The ulcer was coagulated and injected with epinephrine. The patient’s subsequent hospital course was complicated by worsening liver function, the need for renal replacement therapy, and recurrence of upper GI bleeding that required a transcatheter embolization of 2 separate superior pancreaticoduodenal arteries (SPDA) and the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (IPDA).

Once clinically stable, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed to evaluate for cholangiocarcinoma. A stricture was discovered in the common hepatic duct, brushings were taken, and a 15 cm, 7 Fr stent was placed in the common hepatic duct. The procedure was performed with an Olympus TJF Type Q180V duodenovideoscope (Tokyo, Japan) with an external diameter of 13.7 mm. The patient became hypotensive during the procedure and was treated with phenylephrine and ephedrine boluses. There was no endoscopic evidence of bleeding or bowel trauma.

After completion of the procedure, in the recovery area the patient became severely hypotensive and unresponsive. The physical examination was noteworthy for gross abdominal distention. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed severe metabolic and respiratory acidosis. Chest radiography demonstrated massive pneumoperitoneum, low lung volumes, and diaphragmatic compression (Figure).

A diagnosis of tension pneumoperitoneum was made, and as the patient was transported to the operating room he became bradycardic without a pulse, requiring initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The abdomen was decompressed with a 14-gauge needle, followed by insertion of a laparoscopic trocar as a decompressive maneuver. This procedure resulted in return of spontaneous circulation.

An exploratory laparotomy was performed, and a massive rush of air was noted on opening the peritoneum. A pinhole perforation of the anterior wall of the second portion of the duodenum was found along with large-volume bilious ascites. This perforation was repaired with a Graham patch, and the patient was taken to the intensive care unit. Postoperatively, the patient developed disseminated intravascular coagulation, shock liver, and acute respiratory distress syndrome, expiring 10 days later from sequelae of multiorgan failure.

Discussion

In relation to upper GI endoscopic procedures, TPP has been reported after diagnostic EGD, endoscopic sphincterotomy, and submucosal tumor dissection.5-7 During these interventions, clinically apparent or overt iatrogenic perforations can occur either in the stomach or duodenum. These perforations may function as one-way valves that cause massive air accumulation and marked elevation of the diaphragm, which severely decreases lung volumes, pulmonary compliance, and limits gas exchange. Hemodynamically, compression of the inferior vena cava restricts venous return to the heart, resulting in decreased cardiac output.8

Patients with TPP present in acute distress with dyspnea, abdominal pain, and shock. On physical examination the abdomen is markedly distended, tympanic, and rigid. Rectal prolapse and subcutaneous emphysema also may be present.9 Roentographic features of TPP include findings of intraperitoneal air with elevation of the diaphragm, medial displacement of the liver (saddlebag sign), and juxtaposition of air in visceral interfaces, making intra-abdominal structures (spleen and gallbladder) appear more discrete.10 Abdominal computer tomography may show massive pneumoperitoneum with bowel loop compression and centralization of abdominal organs.4

Treatment strategies include emergent decompression either with percutaneous catheter insertion or abdominal drain placement followed by a definitive surgical repair. As with management of tension pneumothorax, treatment should not be delayed while awaiting confirmatory radiologic studies.9 When percutaneous needle decompression is undertaken, it is preferable to use a large bore (14-gauge venous catheter) and to advance a catheter over a needle to minimize the risk of visceral injury with egress of air and return of abdominal organs to their normal anatomical positions. The needle should be inserted directly above or below the umbilicus or in the left or right lower quadrants to avoid solid organ (ie, liver or spleen) injury.

Etiologic possibilities for the duodenal perforation in this case include mechanical trauma from the endoscope and duodenal tissue infarction after embolization of a bleeding duodenal ulcer. The duodenum and pancreatic head have a dual blood supply from the SPDA, a branch of the gastroduodenal artery, and the IPDA, a branch of the superior mesenteric artery.11 After failed endoscopic management of persistent duodenal hemorrhage, the patient underwent synchronous embolization of 2 separate SPDAs and the IPDA. This might have put the first 2 segments of the duodenum at risk for ischemic damage and caused it to perforate at some point during the patient’s hospitalization (as evidenced by the bilious ascitis) or rendered them vulnerable to perforation from intraluminal insufflation during endoscopy.12

During the laparotomy, a pinhole-sized perforation was noted in the anterior wall of the second part of the duodenum, distinct form the duodenal ulcer present on the posterior wall. This perforation likely provided a pathway for the intraluminal gas to escape into the peritoneal cavity, culminating in abdominal tamponade, cardiopulmonary deterioration, and arrest. Needle decompression of the abdominal cavity provided an effective, though temporizing relief of this pressure, enabling return of spontaneous circulation.

This case highlights the need for a high index of suspicion for TPP in a patient with cardiopulmonary compromise and abdominal distension after upper GI endoscopic procedures even in the absence of identifiable perforations. Close coordination among gastroenterologists, anesthesiologists, and surgeons is key in prevention, recognition, and management of this rare but catastrophic complication.

Tension pneumoperitoneum (TPP), also known as hyperacute abdominal compartment syndrome or abdominal tamponade, is a rare condition most commonly associated with gastrointestinal (GI) perforation during endoscopy and iatrogenic insufflation of gas into the peritoneal cavity.1 Other reported causes of TPP include gastric rupture after cardiopulmonary resuscitation, barotrauma during scuba diving, positive pressure ventilation through pleural-peritoneal channels, and spontaneous TPP of uncertain mechanism.1-4

Case Presentation

A 76-year-old male with a history of ischemic cardiomyopathy, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus presented to the VA Puget Sound Health Care System in Seattle, Washington emergency department with painless jaundice, hematemesis, melena, and acute renal failure. On esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), he was found to have an ulcer on the posterior wall of the duodenal bulb. The ulcer was coagulated and injected with epinephrine. The patient’s subsequent hospital course was complicated by worsening liver function, the need for renal replacement therapy, and recurrence of upper GI bleeding that required a transcatheter embolization of 2 separate superior pancreaticoduodenal arteries (SPDA) and the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (IPDA).

Once clinically stable, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed to evaluate for cholangiocarcinoma. A stricture was discovered in the common hepatic duct, brushings were taken, and a 15 cm, 7 Fr stent was placed in the common hepatic duct. The procedure was performed with an Olympus TJF Type Q180V duodenovideoscope (Tokyo, Japan) with an external diameter of 13.7 mm. The patient became hypotensive during the procedure and was treated with phenylephrine and ephedrine boluses. There was no endoscopic evidence of bleeding or bowel trauma.

After completion of the procedure, in the recovery area the patient became severely hypotensive and unresponsive. The physical examination was noteworthy for gross abdominal distention. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed severe metabolic and respiratory acidosis. Chest radiography demonstrated massive pneumoperitoneum, low lung volumes, and diaphragmatic compression (Figure).

A diagnosis of tension pneumoperitoneum was made, and as the patient was transported to the operating room he became bradycardic without a pulse, requiring initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The abdomen was decompressed with a 14-gauge needle, followed by insertion of a laparoscopic trocar as a decompressive maneuver. This procedure resulted in return of spontaneous circulation.

An exploratory laparotomy was performed, and a massive rush of air was noted on opening the peritoneum. A pinhole perforation of the anterior wall of the second portion of the duodenum was found along with large-volume bilious ascites. This perforation was repaired with a Graham patch, and the patient was taken to the intensive care unit. Postoperatively, the patient developed disseminated intravascular coagulation, shock liver, and acute respiratory distress syndrome, expiring 10 days later from sequelae of multiorgan failure.

Discussion

In relation to upper GI endoscopic procedures, TPP has been reported after diagnostic EGD, endoscopic sphincterotomy, and submucosal tumor dissection.5-7 During these interventions, clinically apparent or overt iatrogenic perforations can occur either in the stomach or duodenum. These perforations may function as one-way valves that cause massive air accumulation and marked elevation of the diaphragm, which severely decreases lung volumes, pulmonary compliance, and limits gas exchange. Hemodynamically, compression of the inferior vena cava restricts venous return to the heart, resulting in decreased cardiac output.8

Patients with TPP present in acute distress with dyspnea, abdominal pain, and shock. On physical examination the abdomen is markedly distended, tympanic, and rigid. Rectal prolapse and subcutaneous emphysema also may be present.9 Roentographic features of TPP include findings of intraperitoneal air with elevation of the diaphragm, medial displacement of the liver (saddlebag sign), and juxtaposition of air in visceral interfaces, making intra-abdominal structures (spleen and gallbladder) appear more discrete.10 Abdominal computer tomography may show massive pneumoperitoneum with bowel loop compression and centralization of abdominal organs.4

Treatment strategies include emergent decompression either with percutaneous catheter insertion or abdominal drain placement followed by a definitive surgical repair. As with management of tension pneumothorax, treatment should not be delayed while awaiting confirmatory radiologic studies.9 When percutaneous needle decompression is undertaken, it is preferable to use a large bore (14-gauge venous catheter) and to advance a catheter over a needle to minimize the risk of visceral injury with egress of air and return of abdominal organs to their normal anatomical positions. The needle should be inserted directly above or below the umbilicus or in the left or right lower quadrants to avoid solid organ (ie, liver or spleen) injury.

Etiologic possibilities for the duodenal perforation in this case include mechanical trauma from the endoscope and duodenal tissue infarction after embolization of a bleeding duodenal ulcer. The duodenum and pancreatic head have a dual blood supply from the SPDA, a branch of the gastroduodenal artery, and the IPDA, a branch of the superior mesenteric artery.11 After failed endoscopic management of persistent duodenal hemorrhage, the patient underwent synchronous embolization of 2 separate SPDAs and the IPDA. This might have put the first 2 segments of the duodenum at risk for ischemic damage and caused it to perforate at some point during the patient’s hospitalization (as evidenced by the bilious ascitis) or rendered them vulnerable to perforation from intraluminal insufflation during endoscopy.12

During the laparotomy, a pinhole-sized perforation was noted in the anterior wall of the second part of the duodenum, distinct form the duodenal ulcer present on the posterior wall. This perforation likely provided a pathway for the intraluminal gas to escape into the peritoneal cavity, culminating in abdominal tamponade, cardiopulmonary deterioration, and arrest. Needle decompression of the abdominal cavity provided an effective, though temporizing relief of this pressure, enabling return of spontaneous circulation.

This case highlights the need for a high index of suspicion for TPP in a patient with cardiopulmonary compromise and abdominal distension after upper GI endoscopic procedures even in the absence of identifiable perforations. Close coordination among gastroenterologists, anesthesiologists, and surgeons is key in prevention, recognition, and management of this rare but catastrophic complication.

1. Bunni J, Bryson PJ, Higgs SM. Abdominal compartment syndrome caused by tension pneumoperitoneum in a scuba diver. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2012;94(8):e237-e239.

2. Cameron PA, Rosengarten PL, Johnson WR, Dziukas L. Tension pneumoperitoneum after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Med J Aust. 1991;155(1):44-47.

3. Burdett-Smith P, Jaffey L. Tension pneumoperitoneum. J Accid Emerg Med. 1996;13(3):220-221.

4. Joshi D, Ganai B. Radiological features of tension pneumoperitoneum. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015.

5. Rai A, Iftikhar S. Tension pneumothorax complicating diagnostic upper endoscopy: a case report. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(3):845-847.

6. Iyilikci L, Akarsu M, Duran E, et al. Duodenal perforation and bilateral tension pneumothorax following endoscopic sphincterotomy. J Anesth. 2009;23(1):164-165.

7. Siboni S, Bona D, Abate E, Bonavina L. Tension pneumoperitoneum following endoscopic submucosal dissection of leiomyoma of the cardia. Endoscopy. 2010;42(suppl 2):E152.

8. Deenichin GP. Abdominal compartment syndrome. Surg Today. 2008;38(1):5-19.

9. Chiapponi C, Stocker U, Korner M, et al. Emergency percutaneous needle decompression for tension pneumoperitoneum. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:48.

10. Lin BW, Thanassi W. Tension pneumoperitoneum. J Emerg Med. 2010;38(1):57-59.

11. Bell SD, Lau KY, Sniderman KW. Synchronous embolization of the gastroduodenal artery and the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery in patients with massive duodenal hemorrhage. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1995;6(4):531-536.

12. Wang YL, Cheng YS, Liu LZ, He ZH, Ding KH. Emergency transcatheter arterial embolization for patients with acute massive duodenal ulcer hemorrhage. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(34):4765-4770.

1. Bunni J, Bryson PJ, Higgs SM. Abdominal compartment syndrome caused by tension pneumoperitoneum in a scuba diver. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2012;94(8):e237-e239.

2. Cameron PA, Rosengarten PL, Johnson WR, Dziukas L. Tension pneumoperitoneum after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Med J Aust. 1991;155(1):44-47.

3. Burdett-Smith P, Jaffey L. Tension pneumoperitoneum. J Accid Emerg Med. 1996;13(3):220-221.

4. Joshi D, Ganai B. Radiological features of tension pneumoperitoneum. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015.

5. Rai A, Iftikhar S. Tension pneumothorax complicating diagnostic upper endoscopy: a case report. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(3):845-847.

6. Iyilikci L, Akarsu M, Duran E, et al. Duodenal perforation and bilateral tension pneumothorax following endoscopic sphincterotomy. J Anesth. 2009;23(1):164-165.

7. Siboni S, Bona D, Abate E, Bonavina L. Tension pneumoperitoneum following endoscopic submucosal dissection of leiomyoma of the cardia. Endoscopy. 2010;42(suppl 2):E152.

8. Deenichin GP. Abdominal compartment syndrome. Surg Today. 2008;38(1):5-19.

9. Chiapponi C, Stocker U, Korner M, et al. Emergency percutaneous needle decompression for tension pneumoperitoneum. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:48.

10. Lin BW, Thanassi W. Tension pneumoperitoneum. J Emerg Med. 2010;38(1):57-59.

11. Bell SD, Lau KY, Sniderman KW. Synchronous embolization of the gastroduodenal artery and the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery in patients with massive duodenal hemorrhage. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1995;6(4):531-536.

12. Wang YL, Cheng YS, Liu LZ, He ZH, Ding KH. Emergency transcatheter arterial embolization for patients with acute massive duodenal ulcer hemorrhage. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(34):4765-4770.

FDA approves letermovir as CMV prophylaxis

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the oral and intravenous formulations of letermovir (PREVYMIS™).

Letermovir is a member of a new class of non-nucleoside CMV inhibitors known as 3,4 dihydro-quinazolines.

The FDA approved letermovir as prophylaxis for cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and disease in adult recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCTs) who are CMV-seropositive.

“PREVYMIS is the first new medicine for CMV infection approved in the US in 15 years,” said Roy Baynes, senior vice president, head of clinical development, and chief medical officer of Merck Research Laboratories, the company marketing letermovir.

Letermovir is expected to be available in December. The list price (wholesaler acquisition cost) per day is $195.00 for letermovir tablets and $270.00 for letermovir injections. (Wholesaler acquisition costs do not include discounts that may be paid on the product.)

The recommended dosage of letermovir is 480 mg once daily, initiated as early as day 0 and up to day 28 post-transplant (before or after engraftment) and continued through day 100. If letermovir is co-administered with cyclosporine, the dosage of letermovir should be decreased to 240 mg once daily.

Letermovir is available as 240 mg and 480 mg tablets, which may be administered with or without food. Letermovir is also available as a 240 mg and 480 mg injection for intravenous infusion via a peripheral catheter or central venous line at a constant rate over 1 hour.

For more details on letermovir, see the full prescribing information.

Trial results

The FDA’s approval of letermovir was supported by results of a phase 3 trial of adult recipients of allogeneic HSCTs who were CMV-seropositive. Patients were randomized (2:1) to receive either letermovir (at a dose of 480 mg once-daily, adjusted to 240 mg when co-administered with cyclosporine) or placebo.

Study drug was initiated after HSCT (at any time from day 0 to 28 post-transplant) and continued through week 14 post-transplant. Patients were monitored through week 24 post-HSCT for the primary efficacy endpoint, with continued follow-up through week 48.

Among the 565 treated patients, 34% were engrafted at baseline, and 30% had one or more factors associated with additional risk for CMV reactivation. The most common primary reasons for transplant were acute myeloid leukemia (38%), myelodysplastic syndromes (16%), and lymphoma (12%).

Thirty eight percent of patients in the letermovir arm and 61% in the placebo arm failed prophylaxis.

Reasons for failure (in the letermovir and placebo arms, respectively) included:

- Clinically significant CMV infection—18% vs 42%

- Initiation of PET based on documented CMV viremia—16% vs 40%

- CMV end-organ disease—2% for both

- Study discontinuation before week 24—17% vs 16%

- Missing outcome in week 24 visit window—3% for both.

The stratum-adjusted treatment difference for letermovir vs placebo was -23.5 (95% CI, -32.5, -14.6, P<0.0001).

The Kaplan-Meier event rate for all-cause mortality in the letermovir and placebo arms, respectively, was 12% and 17% at week 24 and 24% and 28% at week 48.

Common adverse events (in the letermovir and placebo arms, respectively) were nausea (27% vs 23%), diarrhea (26% vs 24%), vomiting (19% vs 14%), peripheral edema (14% vs 9%), cough (14% vs 10%), headache (14% vs 9%), fatigue (13% vs 11%), and abdominal pain (12% vs 9%).

The cardiac adverse event rate (regardless of investigator-assessed causality) was 13% in the letermovir arm and 6% in the placebo arm. The most common cardiac adverse events (in the letermovir and placebo arms, respectively) were tachycardia (4% vs 2%) and atrial fibrillation (3% vs 1%).

Results from this trial were presented at the 2017 BMT Tandem Meetings. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the oral and intravenous formulations of letermovir (PREVYMIS™).

Letermovir is a member of a new class of non-nucleoside CMV inhibitors known as 3,4 dihydro-quinazolines.

The FDA approved letermovir as prophylaxis for cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and disease in adult recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCTs) who are CMV-seropositive.

“PREVYMIS is the first new medicine for CMV infection approved in the US in 15 years,” said Roy Baynes, senior vice president, head of clinical development, and chief medical officer of Merck Research Laboratories, the company marketing letermovir.

Letermovir is expected to be available in December. The list price (wholesaler acquisition cost) per day is $195.00 for letermovir tablets and $270.00 for letermovir injections. (Wholesaler acquisition costs do not include discounts that may be paid on the product.)

The recommended dosage of letermovir is 480 mg once daily, initiated as early as day 0 and up to day 28 post-transplant (before or after engraftment) and continued through day 100. If letermovir is co-administered with cyclosporine, the dosage of letermovir should be decreased to 240 mg once daily.

Letermovir is available as 240 mg and 480 mg tablets, which may be administered with or without food. Letermovir is also available as a 240 mg and 480 mg injection for intravenous infusion via a peripheral catheter or central venous line at a constant rate over 1 hour.

For more details on letermovir, see the full prescribing information.

Trial results

The FDA’s approval of letermovir was supported by results of a phase 3 trial of adult recipients of allogeneic HSCTs who were CMV-seropositive. Patients were randomized (2:1) to receive either letermovir (at a dose of 480 mg once-daily, adjusted to 240 mg when co-administered with cyclosporine) or placebo.

Study drug was initiated after HSCT (at any time from day 0 to 28 post-transplant) and continued through week 14 post-transplant. Patients were monitored through week 24 post-HSCT for the primary efficacy endpoint, with continued follow-up through week 48.

Among the 565 treated patients, 34% were engrafted at baseline, and 30% had one or more factors associated with additional risk for CMV reactivation. The most common primary reasons for transplant were acute myeloid leukemia (38%), myelodysplastic syndromes (16%), and lymphoma (12%).

Thirty eight percent of patients in the letermovir arm and 61% in the placebo arm failed prophylaxis.

Reasons for failure (in the letermovir and placebo arms, respectively) included:

- Clinically significant CMV infection—18% vs 42%

- Initiation of PET based on documented CMV viremia—16% vs 40%

- CMV end-organ disease—2% for both

- Study discontinuation before week 24—17% vs 16%

- Missing outcome in week 24 visit window—3% for both.

The stratum-adjusted treatment difference for letermovir vs placebo was -23.5 (95% CI, -32.5, -14.6, P<0.0001).

The Kaplan-Meier event rate for all-cause mortality in the letermovir and placebo arms, respectively, was 12% and 17% at week 24 and 24% and 28% at week 48.

Common adverse events (in the letermovir and placebo arms, respectively) were nausea (27% vs 23%), diarrhea (26% vs 24%), vomiting (19% vs 14%), peripheral edema (14% vs 9%), cough (14% vs 10%), headache (14% vs 9%), fatigue (13% vs 11%), and abdominal pain (12% vs 9%).

The cardiac adverse event rate (regardless of investigator-assessed causality) was 13% in the letermovir arm and 6% in the placebo arm. The most common cardiac adverse events (in the letermovir and placebo arms, respectively) were tachycardia (4% vs 2%) and atrial fibrillation (3% vs 1%).

Results from this trial were presented at the 2017 BMT Tandem Meetings. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the oral and intravenous formulations of letermovir (PREVYMIS™).

Letermovir is a member of a new class of non-nucleoside CMV inhibitors known as 3,4 dihydro-quinazolines.

The FDA approved letermovir as prophylaxis for cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and disease in adult recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCTs) who are CMV-seropositive.

“PREVYMIS is the first new medicine for CMV infection approved in the US in 15 years,” said Roy Baynes, senior vice president, head of clinical development, and chief medical officer of Merck Research Laboratories, the company marketing letermovir.

Letermovir is expected to be available in December. The list price (wholesaler acquisition cost) per day is $195.00 for letermovir tablets and $270.00 for letermovir injections. (Wholesaler acquisition costs do not include discounts that may be paid on the product.)

The recommended dosage of letermovir is 480 mg once daily, initiated as early as day 0 and up to day 28 post-transplant (before or after engraftment) and continued through day 100. If letermovir is co-administered with cyclosporine, the dosage of letermovir should be decreased to 240 mg once daily.

Letermovir is available as 240 mg and 480 mg tablets, which may be administered with or without food. Letermovir is also available as a 240 mg and 480 mg injection for intravenous infusion via a peripheral catheter or central venous line at a constant rate over 1 hour.

For more details on letermovir, see the full prescribing information.

Trial results

The FDA’s approval of letermovir was supported by results of a phase 3 trial of adult recipients of allogeneic HSCTs who were CMV-seropositive. Patients were randomized (2:1) to receive either letermovir (at a dose of 480 mg once-daily, adjusted to 240 mg when co-administered with cyclosporine) or placebo.