User login

Lenalidomide shows clinical activity in relapsed/refractory MCL

Lenalidomide alone and in combination showed “clinically significant activity” and no new safety signals in patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) who had previously failed on ibrutinib, according to findings from a retrospective, observational study.

Michael Wang, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his colleagues enrolled 58 MCL patients across 11 study sites. The patients had a median age of 71 years and 88% of patients had received three or more prior therapies. Most had received ibrutinib as monotherapy and used a lenalidomide-containing therapy next.

The overall response rate was 29% (95% confidence interval, 18%-43%). The rate was similar between patients with MCL refractory to ibrutinib and patients who relapsed/progressed on or following ibrutinib use (32% versus 30%, respectively). There was a 14% complete response, though it varied by subgroup with 8% among MCL patients refractory to ibrutinib and 22% among relapsed/progressed patients. There was a 20-week median duration of response, but 82% of responders were censored so the researchers urged caution in interpreting that finding.

Among the 58 patients, more than 80% reported one or more treatment-emergent adverse events during lenalidomide treatment and 20 patients (34%) had serious events. Nine patients (16%) discontinued the drug because of adverse events.

“Lenalidomide addresses an unmet medical need and widens the therapeutic options in a difficult-to-treat patient population,” the researchers wrote.

Read the full study in the Journal of Hematology Oncology (2017 Nov 2;10[1]:171).

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

Lenalidomide alone and in combination showed “clinically significant activity” and no new safety signals in patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) who had previously failed on ibrutinib, according to findings from a retrospective, observational study.

Michael Wang, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his colleagues enrolled 58 MCL patients across 11 study sites. The patients had a median age of 71 years and 88% of patients had received three or more prior therapies. Most had received ibrutinib as monotherapy and used a lenalidomide-containing therapy next.

The overall response rate was 29% (95% confidence interval, 18%-43%). The rate was similar between patients with MCL refractory to ibrutinib and patients who relapsed/progressed on or following ibrutinib use (32% versus 30%, respectively). There was a 14% complete response, though it varied by subgroup with 8% among MCL patients refractory to ibrutinib and 22% among relapsed/progressed patients. There was a 20-week median duration of response, but 82% of responders were censored so the researchers urged caution in interpreting that finding.

Among the 58 patients, more than 80% reported one or more treatment-emergent adverse events during lenalidomide treatment and 20 patients (34%) had serious events. Nine patients (16%) discontinued the drug because of adverse events.

“Lenalidomide addresses an unmet medical need and widens the therapeutic options in a difficult-to-treat patient population,” the researchers wrote.

Read the full study in the Journal of Hematology Oncology (2017 Nov 2;10[1]:171).

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

Lenalidomide alone and in combination showed “clinically significant activity” and no new safety signals in patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) who had previously failed on ibrutinib, according to findings from a retrospective, observational study.

Michael Wang, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and his colleagues enrolled 58 MCL patients across 11 study sites. The patients had a median age of 71 years and 88% of patients had received three or more prior therapies. Most had received ibrutinib as monotherapy and used a lenalidomide-containing therapy next.

The overall response rate was 29% (95% confidence interval, 18%-43%). The rate was similar between patients with MCL refractory to ibrutinib and patients who relapsed/progressed on or following ibrutinib use (32% versus 30%, respectively). There was a 14% complete response, though it varied by subgroup with 8% among MCL patients refractory to ibrutinib and 22% among relapsed/progressed patients. There was a 20-week median duration of response, but 82% of responders were censored so the researchers urged caution in interpreting that finding.

Among the 58 patients, more than 80% reported one or more treatment-emergent adverse events during lenalidomide treatment and 20 patients (34%) had serious events. Nine patients (16%) discontinued the drug because of adverse events.

“Lenalidomide addresses an unmet medical need and widens the therapeutic options in a difficult-to-treat patient population,” the researchers wrote.

Read the full study in the Journal of Hematology Oncology (2017 Nov 2;10[1]:171).

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

FROM THE JOURNAL OF HEMATOLOGY & ONCOLOGY

Gastrectomy mortality risk increased fivefold with same-day discharge

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has been associated with low mortality, but the mortality is even lower when it includes overnight observation, according to a national database evaluation.

Among patients discharged on the same day, 30-day mortality was 0.1%, but it fell to 0.02% among patients discharged the following day, according to Colette Inaba, MD, a surgery resident at the University of California, Irvine.*

“Surgeons who are considering same-day discharge in sleeve gastrectomy patients should have a low threshold to admit these patients for overnight observation given our findings,” Dr. Inaba reported at an annual meeting presented by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and The Obesity Society.

Same-day discharge has been associated with an increased mortality risk in previously published descriptive institutional reviews, but this is the first study to evaluate this question through analysis of a national database, according to Dr. Inaba. It was based on 37,301 laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy cases performed in 2015 and submitted to the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program database. All participants in this database are accredited bariatric centers.

There were baseline differences between same-day and next-day discharges, but many of these differences conferred the next-day group with higher risk. In particular, the next-day group had significantly higher rates of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and sleep apnea. On average, the procedure time was 13 minutes longer in the next-day versus the same-day discharge groups.

In addition to mortality, 30-day morbidity and need for revisions were compared between the two groups, but there were no significant differences between groups in the rates of these outcomes.

Overall, the baseline demographics of the patients in same-day and next-day groups were comparable, according to Dr. Inaba. She described the population as predominantly female and white with an average body mass index of 45 kg/m2. In this analysis, only primary procedures (excluding redos and revisions) were included.

Relative to the next-day discharge cases, a significantly higher percentage of same-day discharge procedures were performed with a surgical tech or another provider rather than a designated first-assist surgeon, according to Dr. Inaba. For next-day cases, a higher percentage was performed with the participation of fellows or surgical residents. There were fewer swallow studies performed before discharge in the same-day discharge group.

Very similar results were generated by a study evaluating same-day discharge after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, according to John M. Morton, MD, chief of bariatric and minimally invasive surgery, Stanford (Calif.) University. Dr. Morton, first author of the study and moderator of the session in which Dr. Inaba presented the LSG data, reported that same-day discharge in that study was also associated with a trend for an increased risk of serious complications (Ann Surg. 2014;259:286-92).

“Same-day discharge is often reimbursed at a lower rate, so there is less pay and patients are at greater risk of harm,” Dr. Morton said.

The reasons that same-day discharge is associated with higher mortality cannot be derived from the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program database, but, Dr. Inaba said, “Our thought is it is a function of failure to rescue patients from respiratory complications.” She acknowledged that this is a speculative assessment not supported by data, but she suggested that history of sleep apnea might be a particular indication to consider next-day discharge.

Dr. Inaba reports no financial relationships relevant to this topic.

Correction, 12/4/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the 30-day mortality among patients discharged the next day.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has been associated with low mortality, but the mortality is even lower when it includes overnight observation, according to a national database evaluation.

Among patients discharged on the same day, 30-day mortality was 0.1%, but it fell to 0.02% among patients discharged the following day, according to Colette Inaba, MD, a surgery resident at the University of California, Irvine.*

“Surgeons who are considering same-day discharge in sleeve gastrectomy patients should have a low threshold to admit these patients for overnight observation given our findings,” Dr. Inaba reported at an annual meeting presented by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and The Obesity Society.

Same-day discharge has been associated with an increased mortality risk in previously published descriptive institutional reviews, but this is the first study to evaluate this question through analysis of a national database, according to Dr. Inaba. It was based on 37,301 laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy cases performed in 2015 and submitted to the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program database. All participants in this database are accredited bariatric centers.

There were baseline differences between same-day and next-day discharges, but many of these differences conferred the next-day group with higher risk. In particular, the next-day group had significantly higher rates of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and sleep apnea. On average, the procedure time was 13 minutes longer in the next-day versus the same-day discharge groups.

In addition to mortality, 30-day morbidity and need for revisions were compared between the two groups, but there were no significant differences between groups in the rates of these outcomes.

Overall, the baseline demographics of the patients in same-day and next-day groups were comparable, according to Dr. Inaba. She described the population as predominantly female and white with an average body mass index of 45 kg/m2. In this analysis, only primary procedures (excluding redos and revisions) were included.

Relative to the next-day discharge cases, a significantly higher percentage of same-day discharge procedures were performed with a surgical tech or another provider rather than a designated first-assist surgeon, according to Dr. Inaba. For next-day cases, a higher percentage was performed with the participation of fellows or surgical residents. There were fewer swallow studies performed before discharge in the same-day discharge group.

Very similar results were generated by a study evaluating same-day discharge after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, according to John M. Morton, MD, chief of bariatric and minimally invasive surgery, Stanford (Calif.) University. Dr. Morton, first author of the study and moderator of the session in which Dr. Inaba presented the LSG data, reported that same-day discharge in that study was also associated with a trend for an increased risk of serious complications (Ann Surg. 2014;259:286-92).

“Same-day discharge is often reimbursed at a lower rate, so there is less pay and patients are at greater risk of harm,” Dr. Morton said.

The reasons that same-day discharge is associated with higher mortality cannot be derived from the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program database, but, Dr. Inaba said, “Our thought is it is a function of failure to rescue patients from respiratory complications.” She acknowledged that this is a speculative assessment not supported by data, but she suggested that history of sleep apnea might be a particular indication to consider next-day discharge.

Dr. Inaba reports no financial relationships relevant to this topic.

Correction, 12/4/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the 30-day mortality among patients discharged the next day.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has been associated with low mortality, but the mortality is even lower when it includes overnight observation, according to a national database evaluation.

Among patients discharged on the same day, 30-day mortality was 0.1%, but it fell to 0.02% among patients discharged the following day, according to Colette Inaba, MD, a surgery resident at the University of California, Irvine.*

“Surgeons who are considering same-day discharge in sleeve gastrectomy patients should have a low threshold to admit these patients for overnight observation given our findings,” Dr. Inaba reported at an annual meeting presented by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and The Obesity Society.

Same-day discharge has been associated with an increased mortality risk in previously published descriptive institutional reviews, but this is the first study to evaluate this question through analysis of a national database, according to Dr. Inaba. It was based on 37,301 laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy cases performed in 2015 and submitted to the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program database. All participants in this database are accredited bariatric centers.

There were baseline differences between same-day and next-day discharges, but many of these differences conferred the next-day group with higher risk. In particular, the next-day group had significantly higher rates of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and sleep apnea. On average, the procedure time was 13 minutes longer in the next-day versus the same-day discharge groups.

In addition to mortality, 30-day morbidity and need for revisions were compared between the two groups, but there were no significant differences between groups in the rates of these outcomes.

Overall, the baseline demographics of the patients in same-day and next-day groups were comparable, according to Dr. Inaba. She described the population as predominantly female and white with an average body mass index of 45 kg/m2. In this analysis, only primary procedures (excluding redos and revisions) were included.

Relative to the next-day discharge cases, a significantly higher percentage of same-day discharge procedures were performed with a surgical tech or another provider rather than a designated first-assist surgeon, according to Dr. Inaba. For next-day cases, a higher percentage was performed with the participation of fellows or surgical residents. There were fewer swallow studies performed before discharge in the same-day discharge group.

Very similar results were generated by a study evaluating same-day discharge after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, according to John M. Morton, MD, chief of bariatric and minimally invasive surgery, Stanford (Calif.) University. Dr. Morton, first author of the study and moderator of the session in which Dr. Inaba presented the LSG data, reported that same-day discharge in that study was also associated with a trend for an increased risk of serious complications (Ann Surg. 2014;259:286-92).

“Same-day discharge is often reimbursed at a lower rate, so there is less pay and patients are at greater risk of harm,” Dr. Morton said.

The reasons that same-day discharge is associated with higher mortality cannot be derived from the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program database, but, Dr. Inaba said, “Our thought is it is a function of failure to rescue patients from respiratory complications.” She acknowledged that this is a speculative assessment not supported by data, but she suggested that history of sleep apnea might be a particular indication to consider next-day discharge.

Dr. Inaba reports no financial relationships relevant to this topic.

Correction, 12/4/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the 30-day mortality among patients discharged the next day.

AT OBESITY WEEK 2017

Key clinical point: Thirty-day mortality after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is several times higher with same-day discharge relative to an overnight stay.

Major finding: In an analysis of a national database with more than 35,000 cases, the mortality odds ratio for same-day discharge was 5.7 (P = .032) relative to next-day discharge.

Data source: Retrospective database analysis.

Disclosures: Dr. Inaba reports no financial relationships relevant to this topic.

FDA approves letermovir for CMV prophylaxis

The Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 8 approved the use of letermovir (Prevymis) tablets and injections for the prevention of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and disease in adults exposed to the virus who have received an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). This is the first drug to be approved for this purpose. It had previously been granted Breakthrough Therapy and Orphan Drug designation.

CMV infection is a major risk for patients undergoing HSCT, because an estimated 65%-80% of these patients already have been exposed to the virus.

Side effects associated with the use of letermovir include nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, swelling in the arms and legs, cough, headache, tiredness, and abdominal pain. The drug is contraindicated for patients receiving pimozide and ergot alkaloids, or pitavastatin or simvastatin when coadministered with cyclosporine. Prescribing information is available at the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 8 approved the use of letermovir (Prevymis) tablets and injections for the prevention of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and disease in adults exposed to the virus who have received an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). This is the first drug to be approved for this purpose. It had previously been granted Breakthrough Therapy and Orphan Drug designation.

CMV infection is a major risk for patients undergoing HSCT, because an estimated 65%-80% of these patients already have been exposed to the virus.

Side effects associated with the use of letermovir include nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, swelling in the arms and legs, cough, headache, tiredness, and abdominal pain. The drug is contraindicated for patients receiving pimozide and ergot alkaloids, or pitavastatin or simvastatin when coadministered with cyclosporine. Prescribing information is available at the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 8 approved the use of letermovir (Prevymis) tablets and injections for the prevention of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and disease in adults exposed to the virus who have received an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT). This is the first drug to be approved for this purpose. It had previously been granted Breakthrough Therapy and Orphan Drug designation.

CMV infection is a major risk for patients undergoing HSCT, because an estimated 65%-80% of these patients already have been exposed to the virus.

Side effects associated with the use of letermovir include nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, swelling in the arms and legs, cough, headache, tiredness, and abdominal pain. The drug is contraindicated for patients receiving pimozide and ergot alkaloids, or pitavastatin or simvastatin when coadministered with cyclosporine. Prescribing information is available at the FDA website.

OSA home testing less expensive than polysomnography

Home respiratory polygraphy had similar efficacy with substantially lower per-patient cost, compared with traditional polysomnography for diagnosing obstructive sleep apnea, a study showed.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common chronic disease associated with higher risk of cardiovascular disease and traffic accidents and a lower quality of life. Although expensive and time intensive, the polysomnography (PSG) has been the preferred test for diagnosing OSA. Home respiratory polygraphy (HRP) uses portable devices that are less complex than polysomnography and has been shown to have similar effectiveness in diagnosing OSA, compared with PSG, in patients with a high clinical suspicion of OSA. However, there is limited evidence for the cost effectiveness of HRP, compared with PSG (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017 Nov 1;196[9]:1181-90).

The investigators conducted a multicenter, randomized controlled, noninferiority trial and cost-effectiveness analysis comparing PSG with HRP. Inclusion criteria included snoring or observed sleep apnea, Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)of 10 or higher, and no suspicion of alternative causes for daytime sleepiness. Patients with a suspicion for OSA were randomized to polysomnography or respiratory polygraphy protocols. Both arms received counseling on proper sleep hygiene; counseling on weight loss, if overweight; and auto-CPAP titration if continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) was clinically indicated.

Assessment of CPAP compliance or dietary and sleep hygiene compliance was assessed at months 1 and 3. ESS, quality of life measures, well-being measures, 24-hour blood pressure monitoring, auto accidents, and cardiovascular events were assessed at baseline and at month 6.

CPAP treatment was indicated in 68% of the PSG arm, compared with 53% of the HRP arm. After intention-to-treat analysis, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups for ESS improvement (HRP mean, –4.2, vs. PSG mean, –4.9; P = .14). The groups demonstrated similar results for quality of life, blood pressure, polysomnographic assessment at 6 months, CPAP compliance, and rates of cardiovascular events and accidents at follow-up.

The cost-effective analysis demonstrated respiratory polygraphy was less expensive, saving more than 400 euros/patient. “Because the effectiveness (ESS and QALYs [quality-adjusted life-years]) was similar between arms, the HRP protocol is preferable due to its lower cost,” the authors wrote.

In all, 430 patients were randomized to HRP or PSG and consisted mostly of men (70.5%) with a mean body mass index of 30.7 kg/m2. The groups had similar rates of alcohol consumption and hypertension.

Limitations of the study included unblinded randomization to the participants and researchers and the possibility of variability in therapeutic decisions. However, the authors noted that intraobserver variability was minimized by using the Spanish Sleep Network guidelines and centralized assessment.

“[The] HRP management protocol is not inferior to PSG and presents substantially lower costs. Therefore, PSG is not necessary for most patients with suspicion of OSA. This finding could change established clinical practice, with a clear economic benefit,” the authors concluded.

Home respiratory polygraphy continues to impress

This study adds strong evidence to support the use of home respiratory polygraphy for the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in patients without major comorbidities such as severe chronic restrictive or obstructive lung disease, heart failure or unstable cardiovascular disease, major psychiatric diagnoses, and neuromuscular conditions, noted Ching Li Chai-Coetzer, MBBS, PhD, and R.

Doug McEvoy, MBBS, MD, in an accompanying editorial (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017 Nov 1;196[9]:1096-8). However, lower-cost methods to diagnose OSA would still not address unmet needs such as the cost of continuous positive airway pressure and scarcity of sleep physicians to assess patients with OSA, and still may be too expensive for underresourced populations, they said.

Dr. Chai-Coetzer and Dr. McEvoy are affiliated with the Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health at Flinders University and the Sleep Health Service, Southern Adelaide Local Health Network, both in South Australia.

The study was supported by Sociedad Española de Neumología, Air Liquide (Spain), Asociacion de Neumologos del Sur, and Sociedad Extremeña de Neumología. The investigators report no disclosures.

Dr. Chai-Coetzer reported grants from National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and nonfinancial support from Biotech Pharmaceuticals. Dr. McEvoy reported grants and nonfinancial support from Philips Respironics, nonfinancial support from ResMed, and grants from Fisher & Paykel.

Home respiratory polygraphy had similar efficacy with substantially lower per-patient cost, compared with traditional polysomnography for diagnosing obstructive sleep apnea, a study showed.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common chronic disease associated with higher risk of cardiovascular disease and traffic accidents and a lower quality of life. Although expensive and time intensive, the polysomnography (PSG) has been the preferred test for diagnosing OSA. Home respiratory polygraphy (HRP) uses portable devices that are less complex than polysomnography and has been shown to have similar effectiveness in diagnosing OSA, compared with PSG, in patients with a high clinical suspicion of OSA. However, there is limited evidence for the cost effectiveness of HRP, compared with PSG (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017 Nov 1;196[9]:1181-90).

The investigators conducted a multicenter, randomized controlled, noninferiority trial and cost-effectiveness analysis comparing PSG with HRP. Inclusion criteria included snoring or observed sleep apnea, Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)of 10 or higher, and no suspicion of alternative causes for daytime sleepiness. Patients with a suspicion for OSA were randomized to polysomnography or respiratory polygraphy protocols. Both arms received counseling on proper sleep hygiene; counseling on weight loss, if overweight; and auto-CPAP titration if continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) was clinically indicated.

Assessment of CPAP compliance or dietary and sleep hygiene compliance was assessed at months 1 and 3. ESS, quality of life measures, well-being measures, 24-hour blood pressure monitoring, auto accidents, and cardiovascular events were assessed at baseline and at month 6.

CPAP treatment was indicated in 68% of the PSG arm, compared with 53% of the HRP arm. After intention-to-treat analysis, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups for ESS improvement (HRP mean, –4.2, vs. PSG mean, –4.9; P = .14). The groups demonstrated similar results for quality of life, blood pressure, polysomnographic assessment at 6 months, CPAP compliance, and rates of cardiovascular events and accidents at follow-up.

The cost-effective analysis demonstrated respiratory polygraphy was less expensive, saving more than 400 euros/patient. “Because the effectiveness (ESS and QALYs [quality-adjusted life-years]) was similar between arms, the HRP protocol is preferable due to its lower cost,” the authors wrote.

In all, 430 patients were randomized to HRP or PSG and consisted mostly of men (70.5%) with a mean body mass index of 30.7 kg/m2. The groups had similar rates of alcohol consumption and hypertension.

Limitations of the study included unblinded randomization to the participants and researchers and the possibility of variability in therapeutic decisions. However, the authors noted that intraobserver variability was minimized by using the Spanish Sleep Network guidelines and centralized assessment.

“[The] HRP management protocol is not inferior to PSG and presents substantially lower costs. Therefore, PSG is not necessary for most patients with suspicion of OSA. This finding could change established clinical practice, with a clear economic benefit,” the authors concluded.

Home respiratory polygraphy continues to impress

This study adds strong evidence to support the use of home respiratory polygraphy for the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in patients without major comorbidities such as severe chronic restrictive or obstructive lung disease, heart failure or unstable cardiovascular disease, major psychiatric diagnoses, and neuromuscular conditions, noted Ching Li Chai-Coetzer, MBBS, PhD, and R.

Doug McEvoy, MBBS, MD, in an accompanying editorial (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017 Nov 1;196[9]:1096-8). However, lower-cost methods to diagnose OSA would still not address unmet needs such as the cost of continuous positive airway pressure and scarcity of sleep physicians to assess patients with OSA, and still may be too expensive for underresourced populations, they said.

Dr. Chai-Coetzer and Dr. McEvoy are affiliated with the Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health at Flinders University and the Sleep Health Service, Southern Adelaide Local Health Network, both in South Australia.

The study was supported by Sociedad Española de Neumología, Air Liquide (Spain), Asociacion de Neumologos del Sur, and Sociedad Extremeña de Neumología. The investigators report no disclosures.

Dr. Chai-Coetzer reported grants from National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and nonfinancial support from Biotech Pharmaceuticals. Dr. McEvoy reported grants and nonfinancial support from Philips Respironics, nonfinancial support from ResMed, and grants from Fisher & Paykel.

Home respiratory polygraphy had similar efficacy with substantially lower per-patient cost, compared with traditional polysomnography for diagnosing obstructive sleep apnea, a study showed.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common chronic disease associated with higher risk of cardiovascular disease and traffic accidents and a lower quality of life. Although expensive and time intensive, the polysomnography (PSG) has been the preferred test for diagnosing OSA. Home respiratory polygraphy (HRP) uses portable devices that are less complex than polysomnography and has been shown to have similar effectiveness in diagnosing OSA, compared with PSG, in patients with a high clinical suspicion of OSA. However, there is limited evidence for the cost effectiveness of HRP, compared with PSG (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017 Nov 1;196[9]:1181-90).

The investigators conducted a multicenter, randomized controlled, noninferiority trial and cost-effectiveness analysis comparing PSG with HRP. Inclusion criteria included snoring or observed sleep apnea, Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)of 10 or higher, and no suspicion of alternative causes for daytime sleepiness. Patients with a suspicion for OSA were randomized to polysomnography or respiratory polygraphy protocols. Both arms received counseling on proper sleep hygiene; counseling on weight loss, if overweight; and auto-CPAP titration if continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) was clinically indicated.

Assessment of CPAP compliance or dietary and sleep hygiene compliance was assessed at months 1 and 3. ESS, quality of life measures, well-being measures, 24-hour blood pressure monitoring, auto accidents, and cardiovascular events were assessed at baseline and at month 6.

CPAP treatment was indicated in 68% of the PSG arm, compared with 53% of the HRP arm. After intention-to-treat analysis, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups for ESS improvement (HRP mean, –4.2, vs. PSG mean, –4.9; P = .14). The groups demonstrated similar results for quality of life, blood pressure, polysomnographic assessment at 6 months, CPAP compliance, and rates of cardiovascular events and accidents at follow-up.

The cost-effective analysis demonstrated respiratory polygraphy was less expensive, saving more than 400 euros/patient. “Because the effectiveness (ESS and QALYs [quality-adjusted life-years]) was similar between arms, the HRP protocol is preferable due to its lower cost,” the authors wrote.

In all, 430 patients were randomized to HRP or PSG and consisted mostly of men (70.5%) with a mean body mass index of 30.7 kg/m2. The groups had similar rates of alcohol consumption and hypertension.

Limitations of the study included unblinded randomization to the participants and researchers and the possibility of variability in therapeutic decisions. However, the authors noted that intraobserver variability was minimized by using the Spanish Sleep Network guidelines and centralized assessment.

“[The] HRP management protocol is not inferior to PSG and presents substantially lower costs. Therefore, PSG is not necessary for most patients with suspicion of OSA. This finding could change established clinical practice, with a clear economic benefit,” the authors concluded.

Home respiratory polygraphy continues to impress

This study adds strong evidence to support the use of home respiratory polygraphy for the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in patients without major comorbidities such as severe chronic restrictive or obstructive lung disease, heart failure or unstable cardiovascular disease, major psychiatric diagnoses, and neuromuscular conditions, noted Ching Li Chai-Coetzer, MBBS, PhD, and R.

Doug McEvoy, MBBS, MD, in an accompanying editorial (Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017 Nov 1;196[9]:1096-8). However, lower-cost methods to diagnose OSA would still not address unmet needs such as the cost of continuous positive airway pressure and scarcity of sleep physicians to assess patients with OSA, and still may be too expensive for underresourced populations, they said.

Dr. Chai-Coetzer and Dr. McEvoy are affiliated with the Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health at Flinders University and the Sleep Health Service, Southern Adelaide Local Health Network, both in South Australia.

The study was supported by Sociedad Española de Neumología, Air Liquide (Spain), Asociacion de Neumologos del Sur, and Sociedad Extremeña de Neumología. The investigators report no disclosures.

Dr. Chai-Coetzer reported grants from National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and nonfinancial support from Biotech Pharmaceuticals. Dr. McEvoy reported grants and nonfinancial support from Philips Respironics, nonfinancial support from ResMed, and grants from Fisher & Paykel.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF RESPIRATORY AND CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Home obstructive sleep apnea testing was less costly and noninferior to polysomnography.

Major finding: Using respiratory polygraphy instead of polysomnography results in savings of more than 400 euros/patient.

Data source: A multicenter, randomized controlled, noninferiority trial and cost-effectiveness analysis of 430 patients suspected of having OSA.

Disclosures: The study was supported by Sociedad Española de Neumología, Air Liquide (Spain), Asociacion de Neumologos del Sur, and Sociedad Extremeña de Neumología. The authors report no disclosures.

ED visits after bariatric surgery may be difficult to reduce

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – In an evaluation of 633 emergency department visits following bariatric surgery in Michigan over a 1-year period, the vast majority were for complaints amenable to a phone call consultation or treatment in a lower-acuity setting, but few patients would have been satisfied with this type of management, according to an evaluation based on patient interviews presented at Obesity Week 2017.

“Unfortunately, 91% of the patients said that there was nothing the surgical team could have done that would have helped avoid the ED visit,” reported Haley Stevens, quality improvement coordinator at the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The 633 ED visits followed 7,617 bariatric surgeries for a rate of 8.3%. According to Ms. Stevens, this is consistent with the rates of 5%-11% reported previously. Based on clinically abstracted data and patient interviews conducted by trained nurses in a sample of patients involved in these ED visits, it was estimated that 62% were made without any attempt to first contact the surgical team, she reported at an annual meeting presented by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and The Obesity Society.

In the interviews, a variety of reasons were offered for not first contacting the surgical team, according to Ms. Stevens. Most commonly, patients reported that a sense of urgency drove them to the ED. In 18% of cases, the complaint occurred after office hours, leading the patient to believe that the ED was the only option. Another 16% of patients reported that calling the surgeon simply did not occur to them.

“When interviewed, many patients considered the visit necessary and unavoidable even after learning subsequently that the symptoms were not serious,” Ms. Stevens reported.

The primary reasons for the ED visit were nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain, which accounted for 50% of the visits. The next most common reasons were chest pain (8%) and concerns regarding the incision (7%). Only 30% of the ED visits ultimately resulted in a hospital admission, but 60% of the visits resulted in administration of intravenous fluids. Thirty-eight percent of ED visits resulted in oral or intravenous therapy for pain.

Based on the interviews, most patients reported that they visited the ED because they wanted an immediate evaluation of their symptoms, according to Ms. Stevens. She said that the goal in most cases was simply obtaining reassurance. While better patient education about symptoms and recovery might have circumvented patient concerns about nonurgent complaints, Ms. Stevens also suggested that visits to a lower-acuity center, such as an urgent care facility, might provide a lower-cost alternative for reassurance or simple treatments.

As this study represents the first in a series to guide a quality improvement initiative, Ms. Stevens acknowledged that the best solution to reducing unnecessary ED visits is unclear, but she did suggest that multiple strategies might be needed. Based on this and previously published studies evaluating this issue “there is no silver bullet” for reducing ED visits, Ms. Stevens said.

In an animated discussion that followed presentation of these results, others recounting efforts to reduce ED visits following bariatric surgery emphasized the importance of follow-up phone calls or home visits within 2 or 3 days of surgery. According to several of those who commented, these steps allow early identification of problems while providing the type of reassurance that can prevent unnecessary ED visits.

The average cost of an ED visit following bariatric surgery is approximately $1,300, according to Ms. Stevens. For this and other reasons, strategies to reduce ED visits are needed, but Ms. Stevens cautioned that the solutions might not be simple. Based on data from this study, the key may be providing patients with a clear route to the reassurance they need to avoid seeking care for nonurgent issues.

Ms. Stevens reports no financial relationships relevant to this topic.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – In an evaluation of 633 emergency department visits following bariatric surgery in Michigan over a 1-year period, the vast majority were for complaints amenable to a phone call consultation or treatment in a lower-acuity setting, but few patients would have been satisfied with this type of management, according to an evaluation based on patient interviews presented at Obesity Week 2017.

“Unfortunately, 91% of the patients said that there was nothing the surgical team could have done that would have helped avoid the ED visit,” reported Haley Stevens, quality improvement coordinator at the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The 633 ED visits followed 7,617 bariatric surgeries for a rate of 8.3%. According to Ms. Stevens, this is consistent with the rates of 5%-11% reported previously. Based on clinically abstracted data and patient interviews conducted by trained nurses in a sample of patients involved in these ED visits, it was estimated that 62% were made without any attempt to first contact the surgical team, she reported at an annual meeting presented by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and The Obesity Society.

In the interviews, a variety of reasons were offered for not first contacting the surgical team, according to Ms. Stevens. Most commonly, patients reported that a sense of urgency drove them to the ED. In 18% of cases, the complaint occurred after office hours, leading the patient to believe that the ED was the only option. Another 16% of patients reported that calling the surgeon simply did not occur to them.

“When interviewed, many patients considered the visit necessary and unavoidable even after learning subsequently that the symptoms were not serious,” Ms. Stevens reported.

The primary reasons for the ED visit were nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain, which accounted for 50% of the visits. The next most common reasons were chest pain (8%) and concerns regarding the incision (7%). Only 30% of the ED visits ultimately resulted in a hospital admission, but 60% of the visits resulted in administration of intravenous fluids. Thirty-eight percent of ED visits resulted in oral or intravenous therapy for pain.

Based on the interviews, most patients reported that they visited the ED because they wanted an immediate evaluation of their symptoms, according to Ms. Stevens. She said that the goal in most cases was simply obtaining reassurance. While better patient education about symptoms and recovery might have circumvented patient concerns about nonurgent complaints, Ms. Stevens also suggested that visits to a lower-acuity center, such as an urgent care facility, might provide a lower-cost alternative for reassurance or simple treatments.

As this study represents the first in a series to guide a quality improvement initiative, Ms. Stevens acknowledged that the best solution to reducing unnecessary ED visits is unclear, but she did suggest that multiple strategies might be needed. Based on this and previously published studies evaluating this issue “there is no silver bullet” for reducing ED visits, Ms. Stevens said.

In an animated discussion that followed presentation of these results, others recounting efforts to reduce ED visits following bariatric surgery emphasized the importance of follow-up phone calls or home visits within 2 or 3 days of surgery. According to several of those who commented, these steps allow early identification of problems while providing the type of reassurance that can prevent unnecessary ED visits.

The average cost of an ED visit following bariatric surgery is approximately $1,300, according to Ms. Stevens. For this and other reasons, strategies to reduce ED visits are needed, but Ms. Stevens cautioned that the solutions might not be simple. Based on data from this study, the key may be providing patients with a clear route to the reassurance they need to avoid seeking care for nonurgent issues.

Ms. Stevens reports no financial relationships relevant to this topic.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – In an evaluation of 633 emergency department visits following bariatric surgery in Michigan over a 1-year period, the vast majority were for complaints amenable to a phone call consultation or treatment in a lower-acuity setting, but few patients would have been satisfied with this type of management, according to an evaluation based on patient interviews presented at Obesity Week 2017.

“Unfortunately, 91% of the patients said that there was nothing the surgical team could have done that would have helped avoid the ED visit,” reported Haley Stevens, quality improvement coordinator at the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The 633 ED visits followed 7,617 bariatric surgeries for a rate of 8.3%. According to Ms. Stevens, this is consistent with the rates of 5%-11% reported previously. Based on clinically abstracted data and patient interviews conducted by trained nurses in a sample of patients involved in these ED visits, it was estimated that 62% were made without any attempt to first contact the surgical team, she reported at an annual meeting presented by the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and The Obesity Society.

In the interviews, a variety of reasons were offered for not first contacting the surgical team, according to Ms. Stevens. Most commonly, patients reported that a sense of urgency drove them to the ED. In 18% of cases, the complaint occurred after office hours, leading the patient to believe that the ED was the only option. Another 16% of patients reported that calling the surgeon simply did not occur to them.

“When interviewed, many patients considered the visit necessary and unavoidable even after learning subsequently that the symptoms were not serious,” Ms. Stevens reported.

The primary reasons for the ED visit were nausea, vomiting, or abdominal pain, which accounted for 50% of the visits. The next most common reasons were chest pain (8%) and concerns regarding the incision (7%). Only 30% of the ED visits ultimately resulted in a hospital admission, but 60% of the visits resulted in administration of intravenous fluids. Thirty-eight percent of ED visits resulted in oral or intravenous therapy for pain.

Based on the interviews, most patients reported that they visited the ED because they wanted an immediate evaluation of their symptoms, according to Ms. Stevens. She said that the goal in most cases was simply obtaining reassurance. While better patient education about symptoms and recovery might have circumvented patient concerns about nonurgent complaints, Ms. Stevens also suggested that visits to a lower-acuity center, such as an urgent care facility, might provide a lower-cost alternative for reassurance or simple treatments.

As this study represents the first in a series to guide a quality improvement initiative, Ms. Stevens acknowledged that the best solution to reducing unnecessary ED visits is unclear, but she did suggest that multiple strategies might be needed. Based on this and previously published studies evaluating this issue “there is no silver bullet” for reducing ED visits, Ms. Stevens said.

In an animated discussion that followed presentation of these results, others recounting efforts to reduce ED visits following bariatric surgery emphasized the importance of follow-up phone calls or home visits within 2 or 3 days of surgery. According to several of those who commented, these steps allow early identification of problems while providing the type of reassurance that can prevent unnecessary ED visits.

The average cost of an ED visit following bariatric surgery is approximately $1,300, according to Ms. Stevens. For this and other reasons, strategies to reduce ED visits are needed, but Ms. Stevens cautioned that the solutions might not be simple. Based on data from this study, the key may be providing patients with a clear route to the reassurance they need to avoid seeking care for nonurgent issues.

Ms. Stevens reports no financial relationships relevant to this topic.

AT OBESITY WEEK 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In interviews after their ED visit, 91% of bariatric patients insisted the visit was needed, even when informed it was nonurgent.

Data source: Retrospective review and patient interview.

Disclosures: Ms. Stevens reports no financial relationships relevant to this topic.

Double Sequential Defibrillation for Refractory Ventricular Fibrillation and Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia

In 1930, Kouwenhoven, an electrical engineer, invented the first external cardiac defibrillator, and the first successful defibrillation performed on a human was reported in 1947.2Defibrillation devices have since evolved from the application of paddle electrodes to self-adhesive electrodes.

With the intent of producing a life-sustaining rhythm, a large dose of an electrical current from the defibrillator is used to depolarize the heart’s entire electrical conduction system. As medicine and technology advance, we continue to strive for better and more effective ways to improve the probability of survival for patients in cardiac arrest. One area of increasing interest in potentially improving survival rates is the use of double sequential defibrillation (DSD; double simultaneous defibrillation) in patients with V-fib and ventricular tachycardia (V-tach).

Double Sequential Defibrillation

Double sequential defibrillation, also known as double simultaneous defibrillation, is the use of two defibrillators simultaneously to deliver the maximum energy that may be necessary to treat refractory V-fib. In this review, we define refractory V-fib as V-fib/pulseless V-tach that does not revert to a life-sustaining rhythm after three or more shocks from a single defibrillator plus administration of at least a single dose of intravenous (IV) epinephrine and/or amiodarone.

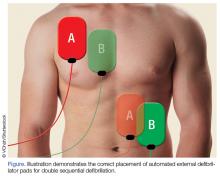

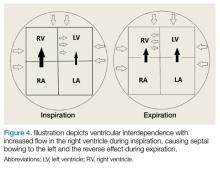

When utilizing DSD, one set of pads is placed in the anterior-posterior position and the other set of pads is placed in the anterior-lateral position as shown in the Figure.

In three retrospective cases, we describe our use of DSD for refractory V-fib in the ED, in the hopes of encouraging further exploration of this potentially life-saving treatment modality in the treatment of refractory V-fib.

Although studies to assess the benefit of DSD are still in their early stages, we believe this technique has the potential to improve the success rate in achieving return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) when compared to the standard method of defibrillation, described in the current advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) algorithms.

Cases

Case 1

A 39-year-old man with a medical history of type 1 diabetes mellitus arrived at our ED with a 6-hour history of nausea and vomiting. Upon arrival at the ED, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 109/52 mm Hg; heart rate, 120 beats/min; and respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min. Oxygen saturation was 94% on room air. Laboratory studies included a point-of-care blood glucose test, which revealed a glucose greater than 600 mg/dL.

The patient was initially resuscitated with 3 L Ringer’s lactate solution IV; and IV ondansetron for vomiting. One hour after his arrival, the patient developed monomorphic wide-complex tachycardia at 179 beats/min and began complaining of chest pain. An IV push of adenosine 6 mg was given with no effect on rhythm. The emergency physician (EP) then administered 300 mg of IV amiodarone followed by 100 mg of IV procainamide, without termination of the tachyarrhythmia.

The patient became hypotensive with a systolic blood pressure of 86 mm Hg, and an attempt was made to apply synchronized cardioversion at 100 J for his unstable V-tach. Shortly after cardioversion, the patient went into V-fib and became unconscious. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was initiated, and the patient was defibrillated at 200 J without success. He was then given 1 mg of IV epinephrine, 2 amp of IV sodium bicarbonate, and intubated.

The patient remained pulseless and in V-fib. A second unsuccessful defibrillation attempt at 200 J was made. Followed by CPR and a third unsuccessful attempt at defibrillation. The patient next received DSD with the two defibrillators each set at 200 J, and afterwards converted back to sinus rhythm.

After successful DSD, the patient was started on an insulin drip and was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). He survived to hospital discharge with a cerebral performance category (CPC) scale score of 1, defined as “good cerebral performance, neurologically intact, may lead a normal life”.3

Case 2

A 22-year-old woman with a known history of heroin abuse was brought to our ED by emergency medical services (EMS) following an unwitnessed cardiac arrest pulseless electrical activity (PEA). The patient’s parents stated that when they saw the patient approximately 5 hours earlier, she appeared normal physically and was behaving normally. Emergency medical technicians (EMTs) administered several milligrams of IV naloxone without success. The patient was intubated while en route to the hospital and CPR was performed for 35 minutes, after which ROSC was achieved.

However, en route to the hospital, the patient developed V-fib, for which she was unsuccessfully defibrillated three times at 200 J. Upon arrival at the ED, the patient was defibrillated twice more at 200 J but remained in V-fib. On the third pulse check DSD was performed, and the patient subsequently converted to a PEA rhythm; CPR was continued for two more cycles, after which the patient regained a weak pulse and an ETCO2 of 55 mm Hg. A central line was placed and the patient was started on IV epinephrine and dopamine. In the ICU she received targeted temperature management, but ultimately expired that evening.

Case 3

A 39-year-old woman with no known medical history was brought to the ED by EMS after she was discovered to be unconscious and pulseless by her husband in their home. Upon arrival, the EMTs found the patient in V-fib and performed endotracheal intubation and 30 minutes of CPR. The EMS report recorded that the patient had been defibrillated a total of five times at the scene before achieving ROSC. En route to the hospital, however, the patient’s rhythm reverted to V-fib; CPR was again initiated along with an unsuccessful attempt at defibrillation. The EMTs then administered 300 mg of IV amiodarone, 1 amp of sodium bicarbonate, and epinephrine IV every 3 to 5 minutes.

Upon arrival at the ED, the EP attempted defibrillation twice, unsuccessfully. The patient was then given IV magnesium, 1 amp of sodium bicarbonate IV, and three doses of IV epinephrine, but remained in V-fib. The EP then attempted DSD but with no success, but a second application of DSD resulted in conversion to a junctional bradycardia. After 1 hour of CPR, ROSC was achieved, and the patient was transferred to the ICU. Unfortunately, due to the burden of neurological damage from the cardiac arrest and poor predicted outcome, the patient’s family ultimately decided to have care withdrawn overnight. The patient expired shortly after being extubated.

Discussion

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest remains a leading cause of death today; of which cardiac arrests due to V-fib are associated with the highest survival rates.4 Our three cases suggest that application of DSD may be of benefit in the ED, in the treatment of refractory V-fib and refractory pulseless V-tach. All three of the patients we described achieved ROSC after DSD and unsuccessful prior attempts with standard defibrillation, though only one of the patients was discharged home with good neurological status.

One of the earliest known studies of the applications of DSD on human subjects was described in 1994 by Hoch et al.5 The study included 2,990 patients who underwent a total of 5,450 electrophysiological studies over a period of 3 years. The researchers induced V-fib/pulseless V-tach in approximately 30% of their study population. Five of these patients, who were all men with a mean age of 55 years, experienced refractory V-fib each of whom required seven to 20 unsuccessful attempts at defibrillation. The researchers ultimately found that when they applied DSD, only one attempt was needed for successful conversion to normal sinus rhythm in all five of the patients.5The authors acknowledged that there were many limitations to their study, which will likely continue to be factors in future studies as well.

DSD exists in the form of reviews, case reports, and retrospective studies in most of the recent literature. The reason for the paucity of research is probably due to the relative rarity and random nature of refractory V-fib (0.1% of V-fib arrests),6 making it nearly impossible for researchers to conduct large-scale studies in a controlled environment. Another limitation that hinders DSD research studies is the large number of variables that can determine a patient’s chance of survival after defibrillation. These variables include age, comorbidities, risk factors, timing of arrival at the ED, application and quality of prehospital CPR, laboratory abnormalities, and other patient-specific neurological or metabolic processes.

Several case series previously reported on the use of DSD, most of which describe patients in the out-of-hospital setting. The findings from these case series appear promising—at least to the extent in which patients were converted out of V-fib through DSD.

In 2014, Cabañas et al6 reported on a retrospective case series of 10 patients treated with DSD between 2008 and 2010, and found that 70% of the patients were successfully converted by DSD out of refractory V-fib. Unfortunately, none of the patients survived to hospital discharge.

Another recent retrospective study conducted by Cortez et al7 of 12 patients with refractory V-fib treated with DSD found that nine of the 12 patients (75%) converted out of V-fib, three of whom survived to hospital discharge, with two patients (16.7%) discharged with a CPC of 1.7 Lastly, Merlin et al8 reported on a retrospective case series in 2015 of EMTs delivering DSS in the field to a total of seven patients with refractory V-fib, five of whom (71%) were successfully converted out of V-fib, with four (57%) surviving to hospital admission.8

Pharmacological Agents Post-DSD

None of the patients in the study by Hoch et al5 received any pharmacological agents between initial unsuccessful attempts at defibrillation and the final application of DSD. As previously noted, all three of the patients in our cases had the full support of ED personnel, as well as the administration of appropriate pharmacological agents.

A randomized controlled trial published in 2006 by Hohnloser et al9 reported clinically significant results in studying the effects of antiarrhythmic agents, particularly amiodarone and sotalol, on defibrillation thresholds. They found that amiodarone increased the defibrillation threshold by 1.29 J, while sotalol decreased the defibrillation threshold by 0.89 J. However, despite their findings, Hohnloser et al9 believed that such differences were highly unlikely to influence patient outcomes.

Post-DSD Effects

The short- and long-term effects of DSD on the human body are unknown. Since the mechanism responsible for the efficacy of DSD is still unclear, many professionals and researchers are concerned that doubling the energy could cause myocardial damage. Although successful return of spontaneous circulation is an important first step in a successful resuscitation, the ultimate goal is to have a patient who is neurologically intact at the time of discharge home, with the capability of maintaining a favorable quality of life.

In 2016, Ross et al10 conducted a larger study comparing CPC scores of 279 patients in refractory V-fib, who received single shock (229 patients) vs DSD (50 patients). They found no statistically significant differences in neurologically intact survival rates between the two groups. This is an important finding that should be the goal for any future studies regarding DSD.10

Limitations to Future Research

For researchers to provide DSD results considered clinically significant, more cross-sectional, randomized-controlled studies need to be performed. Such studies will require a tremendous amount of time, effort, data collection, and a substantial sample size to prove that positive DSD results are not due to chance. As previously noted, the relatively rare incidence of true refractory V-fib makes it difficult for researchers to obtain large enough sample sizes to demonstrate clinically significant study results. Additionally, since medical institutions tend to adhere to different guidelines when running a code for cardiac arrest it would involve extraordinary measures to create and impose a single, standardized procedure/protocol for research purposes that each hospital would have to unanimously agree on.

Another limitation to producing large-scale, clinically significant research is that there is no universally accepted definition of refractory V-fib/pulseless V-tach. In all three of our cases, we defined it as V-fib/pulseless V-tach does not convert after three or more standard shocks, and at least one dose of either IV epinephrine and/or amiodarone. However, other clinicians and institutions define refractory V-fib as patients remaining in cardiac arrest for which the initial rhythm was either V-fib or V-tach, despite at least three defibrillation attempts, 3 mg of epinephrine, and 300 mg of amiodarone.11,12Importantly, DSD currently is neither endorsed as a standard of care nor recommended as part of the ACLS/American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines.

Conclusion

For every minute a patient remains in V-fib, the chance of survival decreases. Although the application of DSD has not been standardized at this time, we feel that it is a reasonable treatment option for patients in V-fib and pulseless V-tach, after all conventional interventions have failed. Though studies on DSD to date, as well as the three cases presented here, all involved relatively small sample sizes and isolated case reports, the results seem to suggest that DSD does improve chance of ROSC. We believe that DSD deserves further study and may be considered in cases of refractory V-fib and pulseless V-tach.

1. Efimov IR. Naum Lazarevich Gurvich (1905–1981) and his contribution to the history of defibrillation. Cardiol J. 2009;16(2):190-193.

2. Bocka JJ. Automatic External Defibrillator. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/780533-overview#a1. Published May 30, 2014. Accessed September 19, 2017.

3. Ajam K, Gold LS, Beck SS, et al. Reliability of cerebral performance category to classify neurological status among survivors of ventricular fibrillation arrest: a cohort study. Scand J Trauma Resus Emerg Med. 2011;19:38. doi:10.1186/1757-7241-19-38.

4. Daya MR, Schmicker RH, Zive DM, et al; Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium Investigators. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival improving over time: Results from the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium (ROC). Resuscitation. 2015;91:108-115. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.02.003.

5. Hoch DH, Batsford WP, Greenberg SM, et al. Double sequential external shocks for refractory ventricular fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23(5):1141-1145.

6. Cabañas JG, Myers JB, Williams JG, De Maio VJ, Bachman MW. Double sequential external defibrillation in out-of-hospital refractory ventricular fibrillation: a report of ten cases. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2015;19(1):126-130. doi:10.3109/10903127.2014.942476.

7. Cortez E, Krebs W, Davis J, Keseg DP, Panchal AR. Use of double sequential external defibrillation for refractory ventricular fibrillation during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2016;108:82-86. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.08.002.

8. Merlin MA, Tagore A, Bauter R, Arshad FH. A case series of double sequence defibrillation. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2016;20(4):550-553. doi:10.3109/10903127.2015.1128026.

9. Hohnloser SH, Dorian P, Roberts R, et al. Effect of amiodarone and sotalol on ventricular defibrillation threshold: the optimal pharmacological therapy in cardioverter defibrillator patients (OPTIC) trial. Circulation. 2006;114(2):104-109. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.618421.

10. Ross EM, Redman TT, Harper SA, Mapp JG, Wampler DA, Miramontes DA. Dual defibrillation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a retrospective cohort analysis. Resuscitation. 2016;106:14-17. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.06.011.11. Driver BE, Debaty G, Plummer DW, Smith SW. Use of esmolol after failure of standard cardiopulmonary resuscitation to treat patients with refractory ventricular fibrillation. Resuscitation. 2014;85(10):1337-1341. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.06.032.

12. Lee YH, Lee KJ, Min YH, et al. Refractory ventricular fibrillation treated with esmolol. Resuscitation. 2016;107:150-155. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.07.243.

In 1930, Kouwenhoven, an electrical engineer, invented the first external cardiac defibrillator, and the first successful defibrillation performed on a human was reported in 1947.2Defibrillation devices have since evolved from the application of paddle electrodes to self-adhesive electrodes.

With the intent of producing a life-sustaining rhythm, a large dose of an electrical current from the defibrillator is used to depolarize the heart’s entire electrical conduction system. As medicine and technology advance, we continue to strive for better and more effective ways to improve the probability of survival for patients in cardiac arrest. One area of increasing interest in potentially improving survival rates is the use of double sequential defibrillation (DSD; double simultaneous defibrillation) in patients with V-fib and ventricular tachycardia (V-tach).

Double Sequential Defibrillation

Double sequential defibrillation, also known as double simultaneous defibrillation, is the use of two defibrillators simultaneously to deliver the maximum energy that may be necessary to treat refractory V-fib. In this review, we define refractory V-fib as V-fib/pulseless V-tach that does not revert to a life-sustaining rhythm after three or more shocks from a single defibrillator plus administration of at least a single dose of intravenous (IV) epinephrine and/or amiodarone.

When utilizing DSD, one set of pads is placed in the anterior-posterior position and the other set of pads is placed in the anterior-lateral position as shown in the Figure.

In three retrospective cases, we describe our use of DSD for refractory V-fib in the ED, in the hopes of encouraging further exploration of this potentially life-saving treatment modality in the treatment of refractory V-fib.

Although studies to assess the benefit of DSD are still in their early stages, we believe this technique has the potential to improve the success rate in achieving return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) when compared to the standard method of defibrillation, described in the current advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) algorithms.

Cases

Case 1

A 39-year-old man with a medical history of type 1 diabetes mellitus arrived at our ED with a 6-hour history of nausea and vomiting. Upon arrival at the ED, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 109/52 mm Hg; heart rate, 120 beats/min; and respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min. Oxygen saturation was 94% on room air. Laboratory studies included a point-of-care blood glucose test, which revealed a glucose greater than 600 mg/dL.

The patient was initially resuscitated with 3 L Ringer’s lactate solution IV; and IV ondansetron for vomiting. One hour after his arrival, the patient developed monomorphic wide-complex tachycardia at 179 beats/min and began complaining of chest pain. An IV push of adenosine 6 mg was given with no effect on rhythm. The emergency physician (EP) then administered 300 mg of IV amiodarone followed by 100 mg of IV procainamide, without termination of the tachyarrhythmia.

The patient became hypotensive with a systolic blood pressure of 86 mm Hg, and an attempt was made to apply synchronized cardioversion at 100 J for his unstable V-tach. Shortly after cardioversion, the patient went into V-fib and became unconscious. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was initiated, and the patient was defibrillated at 200 J without success. He was then given 1 mg of IV epinephrine, 2 amp of IV sodium bicarbonate, and intubated.

The patient remained pulseless and in V-fib. A second unsuccessful defibrillation attempt at 200 J was made. Followed by CPR and a third unsuccessful attempt at defibrillation. The patient next received DSD with the two defibrillators each set at 200 J, and afterwards converted back to sinus rhythm.

After successful DSD, the patient was started on an insulin drip and was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). He survived to hospital discharge with a cerebral performance category (CPC) scale score of 1, defined as “good cerebral performance, neurologically intact, may lead a normal life”.3

Case 2

A 22-year-old woman with a known history of heroin abuse was brought to our ED by emergency medical services (EMS) following an unwitnessed cardiac arrest pulseless electrical activity (PEA). The patient’s parents stated that when they saw the patient approximately 5 hours earlier, she appeared normal physically and was behaving normally. Emergency medical technicians (EMTs) administered several milligrams of IV naloxone without success. The patient was intubated while en route to the hospital and CPR was performed for 35 minutes, after which ROSC was achieved.

However, en route to the hospital, the patient developed V-fib, for which she was unsuccessfully defibrillated three times at 200 J. Upon arrival at the ED, the patient was defibrillated twice more at 200 J but remained in V-fib. On the third pulse check DSD was performed, and the patient subsequently converted to a PEA rhythm; CPR was continued for two more cycles, after which the patient regained a weak pulse and an ETCO2 of 55 mm Hg. A central line was placed and the patient was started on IV epinephrine and dopamine. In the ICU she received targeted temperature management, but ultimately expired that evening.

Case 3

A 39-year-old woman with no known medical history was brought to the ED by EMS after she was discovered to be unconscious and pulseless by her husband in their home. Upon arrival, the EMTs found the patient in V-fib and performed endotracheal intubation and 30 minutes of CPR. The EMS report recorded that the patient had been defibrillated a total of five times at the scene before achieving ROSC. En route to the hospital, however, the patient’s rhythm reverted to V-fib; CPR was again initiated along with an unsuccessful attempt at defibrillation. The EMTs then administered 300 mg of IV amiodarone, 1 amp of sodium bicarbonate, and epinephrine IV every 3 to 5 minutes.

Upon arrival at the ED, the EP attempted defibrillation twice, unsuccessfully. The patient was then given IV magnesium, 1 amp of sodium bicarbonate IV, and three doses of IV epinephrine, but remained in V-fib. The EP then attempted DSD but with no success, but a second application of DSD resulted in conversion to a junctional bradycardia. After 1 hour of CPR, ROSC was achieved, and the patient was transferred to the ICU. Unfortunately, due to the burden of neurological damage from the cardiac arrest and poor predicted outcome, the patient’s family ultimately decided to have care withdrawn overnight. The patient expired shortly after being extubated.

Discussion

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest remains a leading cause of death today; of which cardiac arrests due to V-fib are associated with the highest survival rates.4 Our three cases suggest that application of DSD may be of benefit in the ED, in the treatment of refractory V-fib and refractory pulseless V-tach. All three of the patients we described achieved ROSC after DSD and unsuccessful prior attempts with standard defibrillation, though only one of the patients was discharged home with good neurological status.

One of the earliest known studies of the applications of DSD on human subjects was described in 1994 by Hoch et al.5 The study included 2,990 patients who underwent a total of 5,450 electrophysiological studies over a period of 3 years. The researchers induced V-fib/pulseless V-tach in approximately 30% of their study population. Five of these patients, who were all men with a mean age of 55 years, experienced refractory V-fib each of whom required seven to 20 unsuccessful attempts at defibrillation. The researchers ultimately found that when they applied DSD, only one attempt was needed for successful conversion to normal sinus rhythm in all five of the patients.5The authors acknowledged that there were many limitations to their study, which will likely continue to be factors in future studies as well.

DSD exists in the form of reviews, case reports, and retrospective studies in most of the recent literature. The reason for the paucity of research is probably due to the relative rarity and random nature of refractory V-fib (0.1% of V-fib arrests),6 making it nearly impossible for researchers to conduct large-scale studies in a controlled environment. Another limitation that hinders DSD research studies is the large number of variables that can determine a patient’s chance of survival after defibrillation. These variables include age, comorbidities, risk factors, timing of arrival at the ED, application and quality of prehospital CPR, laboratory abnormalities, and other patient-specific neurological or metabolic processes.

Several case series previously reported on the use of DSD, most of which describe patients in the out-of-hospital setting. The findings from these case series appear promising—at least to the extent in which patients were converted out of V-fib through DSD.

In 2014, Cabañas et al6 reported on a retrospective case series of 10 patients treated with DSD between 2008 and 2010, and found that 70% of the patients were successfully converted by DSD out of refractory V-fib. Unfortunately, none of the patients survived to hospital discharge.

Another recent retrospective study conducted by Cortez et al7 of 12 patients with refractory V-fib treated with DSD found that nine of the 12 patients (75%) converted out of V-fib, three of whom survived to hospital discharge, with two patients (16.7%) discharged with a CPC of 1.7 Lastly, Merlin et al8 reported on a retrospective case series in 2015 of EMTs delivering DSS in the field to a total of seven patients with refractory V-fib, five of whom (71%) were successfully converted out of V-fib, with four (57%) surviving to hospital admission.8

Pharmacological Agents Post-DSD

None of the patients in the study by Hoch et al5 received any pharmacological agents between initial unsuccessful attempts at defibrillation and the final application of DSD. As previously noted, all three of the patients in our cases had the full support of ED personnel, as well as the administration of appropriate pharmacological agents.

A randomized controlled trial published in 2006 by Hohnloser et al9 reported clinically significant results in studying the effects of antiarrhythmic agents, particularly amiodarone and sotalol, on defibrillation thresholds. They found that amiodarone increased the defibrillation threshold by 1.29 J, while sotalol decreased the defibrillation threshold by 0.89 J. However, despite their findings, Hohnloser et al9 believed that such differences were highly unlikely to influence patient outcomes.

Post-DSD Effects

The short- and long-term effects of DSD on the human body are unknown. Since the mechanism responsible for the efficacy of DSD is still unclear, many professionals and researchers are concerned that doubling the energy could cause myocardial damage. Although successful return of spontaneous circulation is an important first step in a successful resuscitation, the ultimate goal is to have a patient who is neurologically intact at the time of discharge home, with the capability of maintaining a favorable quality of life.

In 2016, Ross et al10 conducted a larger study comparing CPC scores of 279 patients in refractory V-fib, who received single shock (229 patients) vs DSD (50 patients). They found no statistically significant differences in neurologically intact survival rates between the two groups. This is an important finding that should be the goal for any future studies regarding DSD.10

Limitations to Future Research

For researchers to provide DSD results considered clinically significant, more cross-sectional, randomized-controlled studies need to be performed. Such studies will require a tremendous amount of time, effort, data collection, and a substantial sample size to prove that positive DSD results are not due to chance. As previously noted, the relatively rare incidence of true refractory V-fib makes it difficult for researchers to obtain large enough sample sizes to demonstrate clinically significant study results. Additionally, since medical institutions tend to adhere to different guidelines when running a code for cardiac arrest it would involve extraordinary measures to create and impose a single, standardized procedure/protocol for research purposes that each hospital would have to unanimously agree on.

Another limitation to producing large-scale, clinically significant research is that there is no universally accepted definition of refractory V-fib/pulseless V-tach. In all three of our cases, we defined it as V-fib/pulseless V-tach does not convert after three or more standard shocks, and at least one dose of either IV epinephrine and/or amiodarone. However, other clinicians and institutions define refractory V-fib as patients remaining in cardiac arrest for which the initial rhythm was either V-fib or V-tach, despite at least three defibrillation attempts, 3 mg of epinephrine, and 300 mg of amiodarone.11,12Importantly, DSD currently is neither endorsed as a standard of care nor recommended as part of the ACLS/American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines.

Conclusion

For every minute a patient remains in V-fib, the chance of survival decreases. Although the application of DSD has not been standardized at this time, we feel that it is a reasonable treatment option for patients in V-fib and pulseless V-tach, after all conventional interventions have failed. Though studies on DSD to date, as well as the three cases presented here, all involved relatively small sample sizes and isolated case reports, the results seem to suggest that DSD does improve chance of ROSC. We believe that DSD deserves further study and may be considered in cases of refractory V-fib and pulseless V-tach.