User login

Pseudo-Pedicle Heterotopic Ossification From Use of Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2 (rhBMP-2) in Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion Cages

ABSTRACT

We conducted a study to determine the common characteristics of patients who developed radiculopathy symptoms and corresponding heterotopic ossification (HO) from transforaminal lumbar interbody fusions (TLIF) using recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2 (rhBMP-2). HO can arise from a disk space with rhBMP-2 use in TLIF. Formation of bone around nerve roots or the thecal sac can cause a radiculopathy with a consistent pattern of symptoms.

We identified 38 patients (26 males, 12 females) with a mean (SD) age of 50.8 (7.5) years who developed radiculopathy symptoms and corresponding HO from TLIF with rhBMP-2 in the disk space between 2002 and 2015. To document this complication and improve its recognition, we recorded common patterns of symptom development and radiologic findings: specifically, time from implantation of rhBMP-2 to symptom development, consistency with side of TLIF placement, and radiologic findings.

Radicular pain generally developed a mean (SD) of 3.8 (1.0) months after TLIF with rhBMP-2. Development of radiculopathy symptoms corresponded to consistent “pseudo-pedicle”-like HO. In all 38 patients, HO arising from the annulotomy site showed a distinct pseudo-pedicle pattern encompassing nerve roots and the thecal sac. In addition, development of radiculopathy symptoms and corresponding HO appear to be independent of amount of rhBMP-2. HO resulting from TLIF with rhBMP-2 in the disk space is a pain generator and a recognizable complication that can be diagnosed by assessment of symptoms and computed tomography characteristics.

Continue to: Bone morphogenetic proteins...

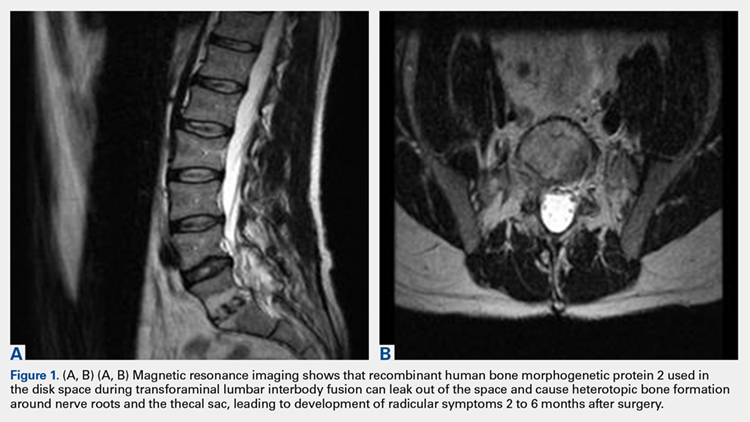

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), first isolated by Urist in 19641, are a family of growth factors that stimulate the cascade of bone formation. Recombinant human BMP (rhBMP), specifically rhBMP-2 and rhBMP-7 (also known as osteogenic protein 1 [OP-1]), was developed in the 1990s after the advent of gene splicing. Then, in 2002, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved use of rhBMP to stimulate fusion in the human spine. Specifically, rhBMP-2 (Medtronic) was approved for use in combination with a specific brand of interbody cage in 1-level anterior lumbar interbody fusion.2 Over the past decade, off-label use of rhBMP-2 to achieve osseous union has increased dramatically, particularly in spinal surgery: transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF), posterior lumbar interbody fusion, and posterolateral lumbar fusion.3-9 However, this widespread off-label use for posterior spinal fusion began despite FDA data indicating that specific complications were underreported in the peer-reviewed literature.10,11 Although rhBMP-2 is very effective in increasing osteoblast formation and improving osteogenesis and subsequent bone healing in spinal surgery,12,13 its use in TLIF resulted in significant adverse side effects, including radiculopathy with and without neuroforaminal heterotopic ossification (HO); 14-24 complications in the FDA studies; 14,22,25-27 and osteolysis causing intervertebral cage subsidence, inflammatory radiculitis, genitourinary complications, infections, possible systemic effects, and significant HO complications.10,28-30 Of these, HO complications involved rhBMP leakage through the annulotomy to the disk space that led to HO. Specifically, rhBMP leaked directly out of the disk space and formed a pillar of bone that encased the nerve roots and dura, which led to occlusion of the foramen and symptoms of radiculopathy.10,28-30

Despite this frequent finding of HO in the intervertebral space outside the target fusion area, use of rhBMP-2 with intervertebral cages increased so rapidly that rhBMP-2 was used more often than autologous bone.5,11,17,31 In this study, we reviewed the common characteristics of patients who developed HO and subsequent radiculopathy from TLIF with rhBMP.

METHODS

After this study received Institutional Review Board approval, we retrospectively reviewed cases of radiculopathy symptoms that developed after TLIF with rhBMP between January 2002 and January 2015. During this period, 38 patients (26 males, 12 females) with a mean (SD) age of 50.8 (7.5) years and radiculopathy symptoms arising from TLIF with rhBMP-2 were identified to determine commonalities and defining characteristics that will help facilitate diagnosis.

Inclusion criteria were computed tomography (CT)–documented HO arising from the TLIF annulotomy site in continuity with bone in the disk space or ectopic bone forming a distinctive shell with contouring around the thecal sac or nerve roots, as well as recurrence or initial occurrence of radiculopathy with signs and symptoms corresponding to the CT site of aberrant bone growth in terms of laterality and particular nerve root(s) involved. Exclusion criteria were malplacement of interbody cage or pedicle screws, disk herniation, systemic neuropathic disease, and new or unresolved radiculopathy immediately after index surgery.

To improve recognition of this complication, we also documented the amount of BMP used, common patterns of radiculopathy symptom development, and radiologic findings. Type and timing of radiculopathy symptom onset and consistency with side of TLIF placement were documented as well. Radiculopathy symptoms included shooting pain in the legs, incontinence, sexual dysfunction, and severe paralysis. Radiologic findings were specific to bone formation from the disk space (detected with CT).

Continue to: RESULTS

RESULTS

All 38 selected patients had radiculopathy symptoms from HO out of the intervertebral space. The Table lists the patients’ overall characteristics. The left side had the most radiculopathy symptoms (31/38 patients), followed by the right side (5/38) and both sides (2/38). Radiculopathy symptoms began a mean (SD) of 3.8 (1.0) months (range, 2-6 months) after index surgery. The 38 patients had 4 characteristics in common:

Table. Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion With Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2: Onset Time for Radiculopathy Symptoms, Surgery Level, Side of Pseudo-Pedicle Bone Formation, and Subsequent Complications

| Pt | Sympton Onset, mo | Surgery Level(s) | Side(s) | Complication(s) |

| 1 | 3 | L3-L5 (2) | Both | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, urine |

| 2 | 3 | L4-L5 (2) | R | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 3 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | R | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 4 | 5 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 5 | 4 | L4-S1 (2) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, subsidence |

| 6 | 5 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 7 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 8 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 9 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 10 | 2 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 11 | 2 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, subsidence, neurologic |

| 12 | 6 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 13 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, neurologic |

| 14 | 2 | L2-L3 (1) | R | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 15 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 16 | 3 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 17 | 3 | L2-L3, L4-L5 (2) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 18 | 3 | L4-L5, L2-L3 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, nonunion |

| 19 | 4 | L4-L5 (1) | R | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 20 | 5 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 21 | 5 | L5-S1 (1) | R | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 22 | 3 | L3-L4, L5-S1 (2) | Both | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 23 | 4 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 24 | 6 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 25 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 26 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, urine, bowel |

| 27 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 28 | 4 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 29 | 6 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 30 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 31 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 32 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 33 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 34 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 35 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 36 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 37 | 4 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 38 | 4 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

1. Bone growing out of the annulotomy site for TLIF cage placement was present and in continuity with the disk space in 33 (87%) of the 38 cases. In the other 5 cases (13%), HO was present around the neural tissue, but not necessarily in continuity with the disk space. This bone appeared ectopic and not osteophytic and facet-related, as it formed a shell around either the nerve root or the thecal sac, contouring to the structure.

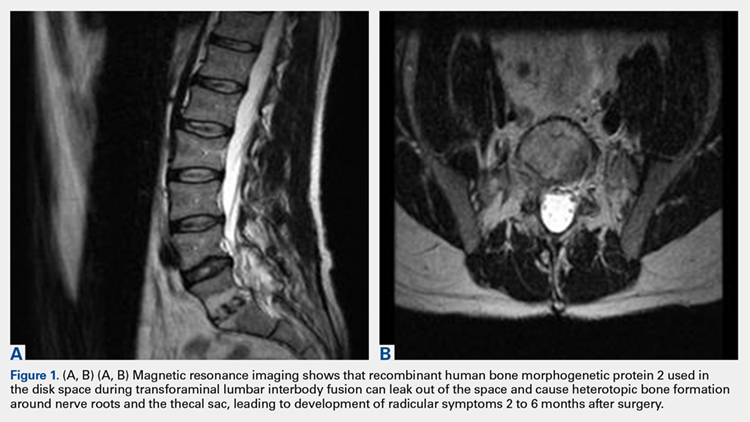

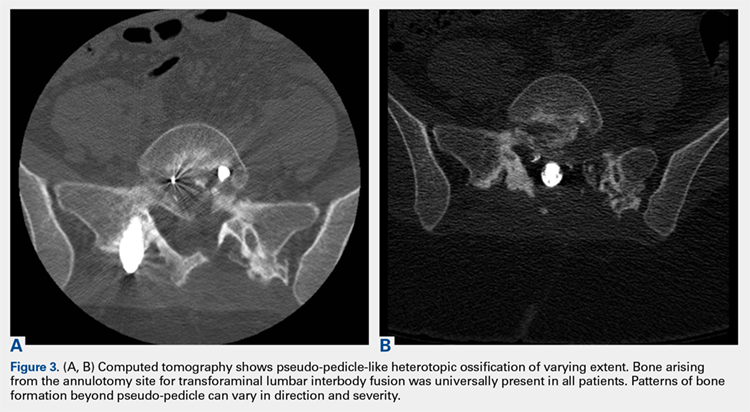

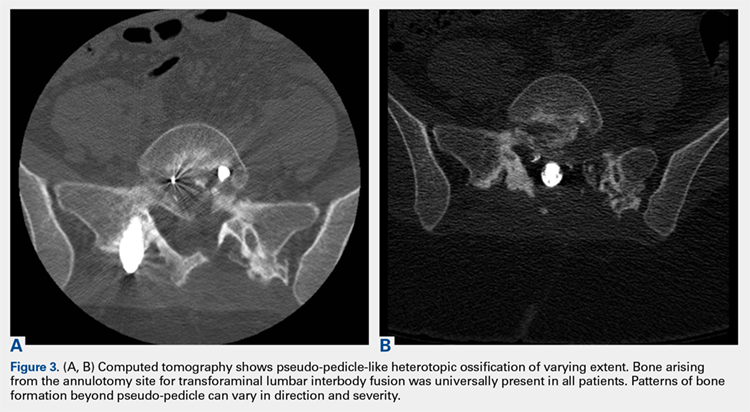

2. The common, novel finding on CT was a “pseudo-pedicle” (Figures 1A, 1B), which appeared as ectopic growth from the disk space—a solid piece of bone in the same direction as the anatomical pedicle. Confusing similarity to the anatomical pedicle is present on axial cuts and during surgery. The pseudo-pedicle varied in thickness and extent out of the disk space, but was always presented as a bar of bone arising from the annulotomy site. After arising from the disk space, the HO could disperse in any direction, further calcifying neural structures or the facet joints above or below. There was no apparent distinguishable repeating pattern, given the variable nature of arthritic facet changes, scoliotic deformities, size of annulotomies, amount of rhBMP used, and placement in cage and disk space or only in cage.

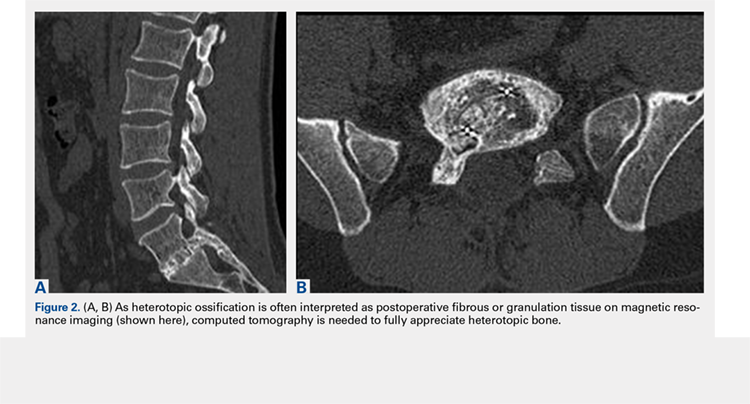

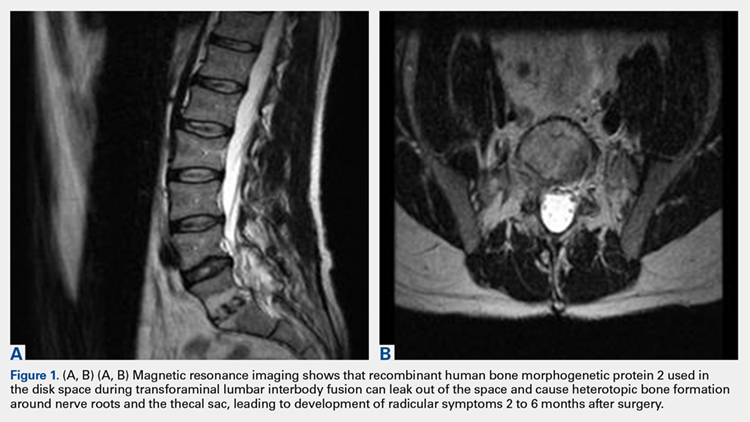

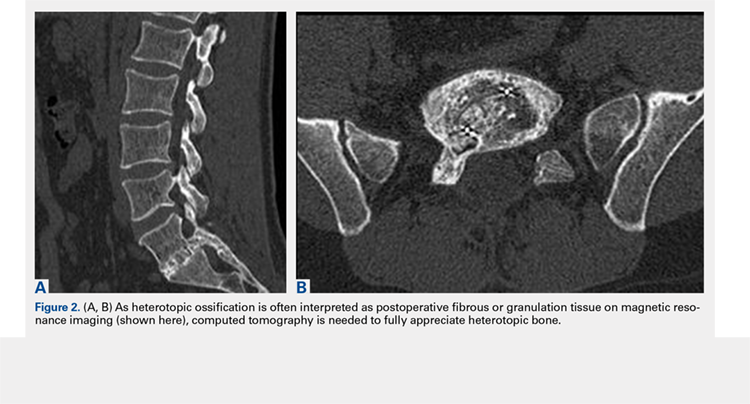

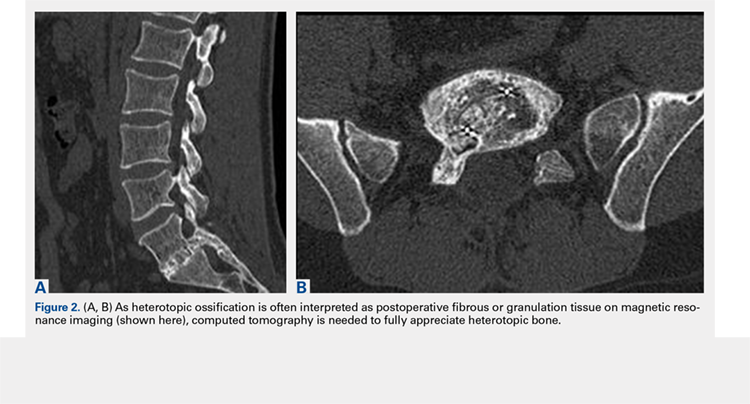

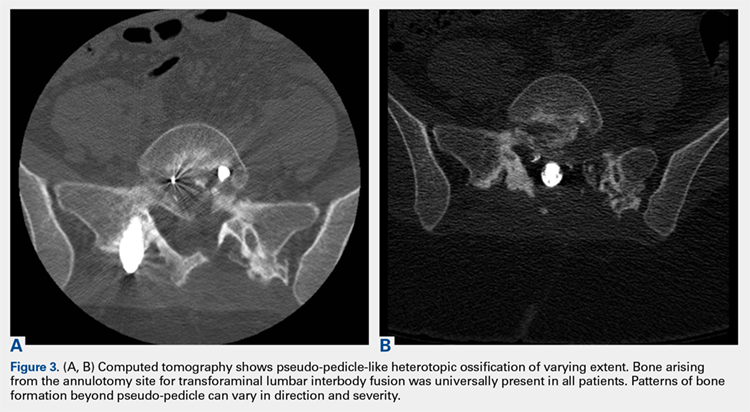

3. In 36 (95%) of the 38 cases, the initial interpretation of HO on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was of tissue other than bone, such as fibrous tissue, granulation tissue, recurrent disk herniation, or postoperative changes. However, this tissue was later determined to be bone from HO complications, which we confirmed with CT in all 38 cases. It is important to note that HO on MRI (Figures 2A, 2B) was initially interpreted by a radiologist as fibrous tissue, but same-level CT of the same case (Figures 3A, 3B) showed clear HO.

4. The radiculopathy symptoms caused by HO were independent of the amount of rhBMP-2 used in TLIF. Of the 38 patients, 19 had 1 rhBMP-2 sponge placed in the cage, 12 had a small kit sponge (1.05 mg), 5 had 1 sponge placed in the cage and 1 sponge placed directly in the disk space before cage placement (no notation of precise size or amount of rhBMP-2), and 2 had 1 sponge placed in the cage (no notation of rhBMP-2 amount). The data showed that HO can occur with even a small amount of rhBMP-2.

Continue to: Bone formation with rhBMP-2...

Bone formation with rhBMP-2 is robust and beneficial, but HO-related complications are significant, and identifiable on assessment of radiculopathy symptoms and CT characteristics.

DISCUSSION

We identified 38 patients with a recognizable and consistent pattern of complications of off-label use of rhBMP-2 in TLIF performed at our institution between 2002 and 2015. This pattern included consistent radiculopathy symptoms with corresponding HO at the annulotomy site in continuity with bone in the disk space or ectopic bone forming a distinctive shell around the thecal sac or nerve roots, as well as showing a distinct pseudo-pedicle pattern encompassing nerve roots and the thecal sac. Our finding differs from other findings of similar complication characteristics, but with much larger variations without consistency within the patient population.19,20,22,24 Specifically, previous studies found an association between off-label rhBMP-2 use in the posterior spine and radiculopathy with and without neuroforaminal HO. However, our study found consistent radiculopathy symptoms with pseudo-pedicle-like HO complications in all its 38 patients a mean (SD) of 3.8 (1.0) months after surgery.

In this study, consistent radiculopathy symptoms with pseudo-pedicle-like HO complications were independent of the amount of rhBMP-2 used, as some complications occurred with use of small pack rhBMP-2 with TLIF. It is well understood that high doses of rhBMP-2 may be required to improve fusion rates, but to our knowledge an optimal dosing strategy for TLIF has not been reported, particularly with respect to potential complications.8,20,31-33 For anterior lumbar interbody fusion surgery, the FDA-approved use of rhBMP-2 appears to have a significantly decreased risk of neuroforaminal HO complications. This may be attributable to the protective presence of the intact posterior annulus and longitudinal ligament for this procedure.20,33 For TLIF, it has been suggested that rhBMP-2 should be placed only along the anterior annulus with a posterior strut and morselized bone allograft barricade,33 and that fibrin glue should be used to limit BMP diffusion through the annulotomy site31 to prevent this complication.

Our study results suggest that radiculopathy symptoms with pseudo-pedicle-like HO complications appear to be caused by leakage of rhBMP-2 from the disk space through the annulotomy site. This was often initially interpreted incorrectly on MRI in the first year after surgery as being fibrous or granulation tissue, or even postoperative changes that the heterotopic tissue was bone was obvious only on CT. Even then the tissue may be incorrectly identified, as the encasing nerve roots in bone are similar to the scar tissue having no compressive effect. HO may compress, but it also has an inflammatory component that the scars lack. Additionally, the HO from the disk space, caused by leakage of the BMP placed in or around the fusion cage, can create a pseudo-pedicle of varying size and extent. This was present in all 38 of our cases.

This retrospective case series had its limitations. Its clinical and radiographic findings were not blinded. Confounding variables cannot be isolated for causal relationships, if any, to the complication in a case series such as this.

Bone formation with rhBMP-2 is robust and beneficial, but HO-related complications are significant, and identifiable on assessment of radiculopathy symptoms and CT characteristics.

1. Urist MR. Bone: formation by autoinduction. Science. 1965;150(3698):893-899.

2. Burkus JK, Gornet MF, Schuler TC, Kleeman TJ, Zdeblick TA. Six-year outcomes of anterior lumbar interbody arthrodesis with use of interbody fusion cages and recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(5):1181-1189.

3. Boden SD, Kang J, Sandhu H, Heller JG. Use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 to achieve posterolateral lumbar spine fusion in humans: a prospective, randomized clinical pilot trial: 2002 Volvo award in clinical studies. Spine. 2002;27(23):2662-2673.

4. Boden SD, Zdeblick TA, Sandhu HS, Heim SE. The use of rhBMP-2 in interbody fusion cages. Definitive evidence of osteoinduction in humans: a preliminary report. Spine. 2000;25(3):376-381.

5. Haid RW Jr, Branch CL Jr, Alexander JT, Burkus JK. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion using recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein type 2 with cylindrical interbody cages. Spine J. 2004;4(5):527-538.

6. Meisel HJ, Schnöring M, Hohaus C, et al. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion using rhBMP-2. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(12):1735-1744.

7. Mummaneni PV, Pan J, Haid RW, Rodts GE. Contribution of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 to the rapid creation of interbody fusion when used in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: a preliminary report. Invited submission from the Joint Section Meeting on Disorders of the Spine and Peripheral Nerves, March 2004. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;1(1):19-23.

8. Shimer AL, Oner FC, Vaccaro AR. Spinal reconstruction and bone morphogenetic proteins: open questions. Injury. 2009;40(suppl 3):S32-S38.

9. Slosar PJ, Josey R, Reynolds J. Accelerating lumbar fusions by combining rhBMP-2 with allograft bone: a prospective analysis of interbody fusion rates and clinical outcomes. Spine J. 2007;7(3):301-307.

10. Knox JB, Dai JM 3rd, Orchowski J. Osteolysis in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with bone morphogenetic protein-2. Spine. 2011;36(8):672-676.

11. Owens K, Glassman SD, Howard JM, Djurasovic M, Witten JL, Carreon LY. Perioperative complications with rhBMP-2 in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(4):612-617.

12. Mindea SA, Shih P, Song JK. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced radiculitis in elective minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusions: a series review. Spine. 2009;34(14):1480-1484.

13. Yoon ST, Park JS, Kim KS, et al. ISSLS prize winner: LMP-1 upregulates intervertebral disc cell production of proteoglycans and BMPs in vitro and in vivo. Spine. 2004;29(23):2603-2611.

14. Cahill KS, Chi JH, Day A, Claus EB. Prevalence, complications, and hospital charges associated with use of bone-morphogenetic proteins in spinal fusion procedures. JAMA. 2009;302(1):58-66.

15. Carragee EJ, Hurwitz EL, Weiner BK. A critical review of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 trials in spinal surgery: emerging safety concerns and lessons learned. Spine J. 2011;11(6):471-491.

16. Chen NF, Smith ZA, Stiner E, Armin S, Sheikh H, Khoo LT. Symptomatic ectopic bone formation after off-label use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;12(1):40-46.

17. Joseph V, Rampersaud YR. Heterotopic bone formation with the use of rhBMP2 in posterior minimal access interbody fusion: a CT analysis. Spine. 2007;32(25):2885-2890.

18. McClellan JW, Mulconrey DS, Forbes RJ, Fullmer N. Vertebral bone resorption after transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with bone morphogenetic protein (rhBMP-2). J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19(7):483-486.

19. Mroz TE, Wang JC, Hashimoto R, Norvell DC. Complications related to osteobiologics use in spine surgery: a systematic review. Spine. 2010;35(9 suppl):S86-S104.

20. Muchow RD, Hsu WK, Anderson PA. Histopathologic inflammatory response induced by recombinant bone morphogenetic protein-2 causing radiculopathy after transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Spine J. 2010;10(9):e1-e6.

21. Ong KL, Villarraga ML, Lau E, Carreon LY, Kurtz SM, Glassman SD. Off-label use of bone morphogenetic proteins in the United States using administrative data. Spine. 2010;35(19):1794-1800.

22. Rihn JA, Patel R, Makda J, et al. Complications associated with single-level transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Spine J. 2009;9(8):623-629.

23. Vaidya R, Sethi A, Bartol S, Jacobson M, Coe C, Craig JG. Complications in the use of rhBMP-2 in PEEK cages for interbody spinal fusions. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21(8):557-562.

24. Wong DA, Kumar A, Jatana S, Ghiselli G, Wong K. Neurologic impairment from ectopic bone in the lumbar canal: a potential complication of off-label PLIF/TLIF use of bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2). Spine J. 2008;8(6):1011-1018.

25. Delawi D, Dhert WJ, Rillardon L, et al. A prospective, randomized, controlled, multicenter study of osteogenic protein-1 in instrumented posterolateral fusions: report on safety and feasibility. Spine. 2010;35(12):1185-1191.

26. Vaccaro AR, Patel T, Fischgrund J, et al. A pilot study evaluating the safety and efficacy of OP-1 putty (rhBMP-7) as a replacement for iliac crest autograft in posterolateral lumbar arthrodesis for degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2004;29(17):1885-1892.

27. Vaidya R, Weir R, Sethi A, Meisterling S, Hakeos W, Wybo CD. Interbody fusion with allograft and rhBMP-2 leads to consistent fusion but early subsidence. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(3):342-345.

28. Glassman SD, Howard J, Dimar J, Sweet A, Wilson G, Carreon L. Complications with recombinant human bone morphogenic protein-2 in posterolateral spine fusion: a consecutive series of 1037 cases. Spine. 2011;36(22):1849-1854.

29. Helgeson MD, Lehman RA Jr, Patzkowski JC, Dmitriev AE, Rosner MK, Mack AW. Adjacent vertebral body osteolysis with bone morphogenetic protein use in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Spine J. 2011;11(6):507-510.

30. Hoffmann MF, Jones CB, Sietsema DL. Adjuncts in posterior lumbar spine fusion: comparison of complications and efficacy. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(8):1105-1110.

31. Villavicencio AT, Burneikiene S, Nelson EL, Bulsara KR, Favors M, Thramann J. Safety of transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion and intervertebral recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3(6):436-443.

32. Patel VV, Zhao L, Wong P, et al. Controlling bone morphogenetic protein diffusion and bone morphogenetic protein-stimulated bone growth using fibrin glue. Spine. 2006;31(11):1201-1206.

33. Zhang H, Sucato DJ, Welch RD. Recombinant human bone morphogenic protein-2-enhanced anterior spine fusion without bone encroachment into the spinal canal: a histomorphometric study in a thoracoscopically instrumented porcine model. Spine. 2005;30(5):512-518.

ABSTRACT

We conducted a study to determine the common characteristics of patients who developed radiculopathy symptoms and corresponding heterotopic ossification (HO) from transforaminal lumbar interbody fusions (TLIF) using recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2 (rhBMP-2). HO can arise from a disk space with rhBMP-2 use in TLIF. Formation of bone around nerve roots or the thecal sac can cause a radiculopathy with a consistent pattern of symptoms.

We identified 38 patients (26 males, 12 females) with a mean (SD) age of 50.8 (7.5) years who developed radiculopathy symptoms and corresponding HO from TLIF with rhBMP-2 in the disk space between 2002 and 2015. To document this complication and improve its recognition, we recorded common patterns of symptom development and radiologic findings: specifically, time from implantation of rhBMP-2 to symptom development, consistency with side of TLIF placement, and radiologic findings.

Radicular pain generally developed a mean (SD) of 3.8 (1.0) months after TLIF with rhBMP-2. Development of radiculopathy symptoms corresponded to consistent “pseudo-pedicle”-like HO. In all 38 patients, HO arising from the annulotomy site showed a distinct pseudo-pedicle pattern encompassing nerve roots and the thecal sac. In addition, development of radiculopathy symptoms and corresponding HO appear to be independent of amount of rhBMP-2. HO resulting from TLIF with rhBMP-2 in the disk space is a pain generator and a recognizable complication that can be diagnosed by assessment of symptoms and computed tomography characteristics.

Continue to: Bone morphogenetic proteins...

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), first isolated by Urist in 19641, are a family of growth factors that stimulate the cascade of bone formation. Recombinant human BMP (rhBMP), specifically rhBMP-2 and rhBMP-7 (also known as osteogenic protein 1 [OP-1]), was developed in the 1990s after the advent of gene splicing. Then, in 2002, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved use of rhBMP to stimulate fusion in the human spine. Specifically, rhBMP-2 (Medtronic) was approved for use in combination with a specific brand of interbody cage in 1-level anterior lumbar interbody fusion.2 Over the past decade, off-label use of rhBMP-2 to achieve osseous union has increased dramatically, particularly in spinal surgery: transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF), posterior lumbar interbody fusion, and posterolateral lumbar fusion.3-9 However, this widespread off-label use for posterior spinal fusion began despite FDA data indicating that specific complications were underreported in the peer-reviewed literature.10,11 Although rhBMP-2 is very effective in increasing osteoblast formation and improving osteogenesis and subsequent bone healing in spinal surgery,12,13 its use in TLIF resulted in significant adverse side effects, including radiculopathy with and without neuroforaminal heterotopic ossification (HO); 14-24 complications in the FDA studies; 14,22,25-27 and osteolysis causing intervertebral cage subsidence, inflammatory radiculitis, genitourinary complications, infections, possible systemic effects, and significant HO complications.10,28-30 Of these, HO complications involved rhBMP leakage through the annulotomy to the disk space that led to HO. Specifically, rhBMP leaked directly out of the disk space and formed a pillar of bone that encased the nerve roots and dura, which led to occlusion of the foramen and symptoms of radiculopathy.10,28-30

Despite this frequent finding of HO in the intervertebral space outside the target fusion area, use of rhBMP-2 with intervertebral cages increased so rapidly that rhBMP-2 was used more often than autologous bone.5,11,17,31 In this study, we reviewed the common characteristics of patients who developed HO and subsequent radiculopathy from TLIF with rhBMP.

METHODS

After this study received Institutional Review Board approval, we retrospectively reviewed cases of radiculopathy symptoms that developed after TLIF with rhBMP between January 2002 and January 2015. During this period, 38 patients (26 males, 12 females) with a mean (SD) age of 50.8 (7.5) years and radiculopathy symptoms arising from TLIF with rhBMP-2 were identified to determine commonalities and defining characteristics that will help facilitate diagnosis.

Inclusion criteria were computed tomography (CT)–documented HO arising from the TLIF annulotomy site in continuity with bone in the disk space or ectopic bone forming a distinctive shell with contouring around the thecal sac or nerve roots, as well as recurrence or initial occurrence of radiculopathy with signs and symptoms corresponding to the CT site of aberrant bone growth in terms of laterality and particular nerve root(s) involved. Exclusion criteria were malplacement of interbody cage or pedicle screws, disk herniation, systemic neuropathic disease, and new or unresolved radiculopathy immediately after index surgery.

To improve recognition of this complication, we also documented the amount of BMP used, common patterns of radiculopathy symptom development, and radiologic findings. Type and timing of radiculopathy symptom onset and consistency with side of TLIF placement were documented as well. Radiculopathy symptoms included shooting pain in the legs, incontinence, sexual dysfunction, and severe paralysis. Radiologic findings were specific to bone formation from the disk space (detected with CT).

Continue to: RESULTS

RESULTS

All 38 selected patients had radiculopathy symptoms from HO out of the intervertebral space. The Table lists the patients’ overall characteristics. The left side had the most radiculopathy symptoms (31/38 patients), followed by the right side (5/38) and both sides (2/38). Radiculopathy symptoms began a mean (SD) of 3.8 (1.0) months (range, 2-6 months) after index surgery. The 38 patients had 4 characteristics in common:

Table. Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion With Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2: Onset Time for Radiculopathy Symptoms, Surgery Level, Side of Pseudo-Pedicle Bone Formation, and Subsequent Complications

| Pt | Sympton Onset, mo | Surgery Level(s) | Side(s) | Complication(s) |

| 1 | 3 | L3-L5 (2) | Both | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, urine |

| 2 | 3 | L4-L5 (2) | R | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 3 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | R | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 4 | 5 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 5 | 4 | L4-S1 (2) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, subsidence |

| 6 | 5 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 7 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 8 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 9 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 10 | 2 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 11 | 2 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, subsidence, neurologic |

| 12 | 6 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 13 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, neurologic |

| 14 | 2 | L2-L3 (1) | R | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 15 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 16 | 3 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 17 | 3 | L2-L3, L4-L5 (2) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 18 | 3 | L4-L5, L2-L3 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, nonunion |

| 19 | 4 | L4-L5 (1) | R | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 20 | 5 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 21 | 5 | L5-S1 (1) | R | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 22 | 3 | L3-L4, L5-S1 (2) | Both | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 23 | 4 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 24 | 6 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 25 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 26 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, urine, bowel |

| 27 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 28 | 4 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 29 | 6 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 30 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 31 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 32 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 33 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 34 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 35 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 36 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 37 | 4 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 38 | 4 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

1. Bone growing out of the annulotomy site for TLIF cage placement was present and in continuity with the disk space in 33 (87%) of the 38 cases. In the other 5 cases (13%), HO was present around the neural tissue, but not necessarily in continuity with the disk space. This bone appeared ectopic and not osteophytic and facet-related, as it formed a shell around either the nerve root or the thecal sac, contouring to the structure.

2. The common, novel finding on CT was a “pseudo-pedicle” (Figures 1A, 1B), which appeared as ectopic growth from the disk space—a solid piece of bone in the same direction as the anatomical pedicle. Confusing similarity to the anatomical pedicle is present on axial cuts and during surgery. The pseudo-pedicle varied in thickness and extent out of the disk space, but was always presented as a bar of bone arising from the annulotomy site. After arising from the disk space, the HO could disperse in any direction, further calcifying neural structures or the facet joints above or below. There was no apparent distinguishable repeating pattern, given the variable nature of arthritic facet changes, scoliotic deformities, size of annulotomies, amount of rhBMP used, and placement in cage and disk space or only in cage.

3. In 36 (95%) of the 38 cases, the initial interpretation of HO on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was of tissue other than bone, such as fibrous tissue, granulation tissue, recurrent disk herniation, or postoperative changes. However, this tissue was later determined to be bone from HO complications, which we confirmed with CT in all 38 cases. It is important to note that HO on MRI (Figures 2A, 2B) was initially interpreted by a radiologist as fibrous tissue, but same-level CT of the same case (Figures 3A, 3B) showed clear HO.

4. The radiculopathy symptoms caused by HO were independent of the amount of rhBMP-2 used in TLIF. Of the 38 patients, 19 had 1 rhBMP-2 sponge placed in the cage, 12 had a small kit sponge (1.05 mg), 5 had 1 sponge placed in the cage and 1 sponge placed directly in the disk space before cage placement (no notation of precise size or amount of rhBMP-2), and 2 had 1 sponge placed in the cage (no notation of rhBMP-2 amount). The data showed that HO can occur with even a small amount of rhBMP-2.

Continue to: Bone formation with rhBMP-2...

Bone formation with rhBMP-2 is robust and beneficial, but HO-related complications are significant, and identifiable on assessment of radiculopathy symptoms and CT characteristics.

DISCUSSION

We identified 38 patients with a recognizable and consistent pattern of complications of off-label use of rhBMP-2 in TLIF performed at our institution between 2002 and 2015. This pattern included consistent radiculopathy symptoms with corresponding HO at the annulotomy site in continuity with bone in the disk space or ectopic bone forming a distinctive shell around the thecal sac or nerve roots, as well as showing a distinct pseudo-pedicle pattern encompassing nerve roots and the thecal sac. Our finding differs from other findings of similar complication characteristics, but with much larger variations without consistency within the patient population.19,20,22,24 Specifically, previous studies found an association between off-label rhBMP-2 use in the posterior spine and radiculopathy with and without neuroforaminal HO. However, our study found consistent radiculopathy symptoms with pseudo-pedicle-like HO complications in all its 38 patients a mean (SD) of 3.8 (1.0) months after surgery.

In this study, consistent radiculopathy symptoms with pseudo-pedicle-like HO complications were independent of the amount of rhBMP-2 used, as some complications occurred with use of small pack rhBMP-2 with TLIF. It is well understood that high doses of rhBMP-2 may be required to improve fusion rates, but to our knowledge an optimal dosing strategy for TLIF has not been reported, particularly with respect to potential complications.8,20,31-33 For anterior lumbar interbody fusion surgery, the FDA-approved use of rhBMP-2 appears to have a significantly decreased risk of neuroforaminal HO complications. This may be attributable to the protective presence of the intact posterior annulus and longitudinal ligament for this procedure.20,33 For TLIF, it has been suggested that rhBMP-2 should be placed only along the anterior annulus with a posterior strut and morselized bone allograft barricade,33 and that fibrin glue should be used to limit BMP diffusion through the annulotomy site31 to prevent this complication.

Our study results suggest that radiculopathy symptoms with pseudo-pedicle-like HO complications appear to be caused by leakage of rhBMP-2 from the disk space through the annulotomy site. This was often initially interpreted incorrectly on MRI in the first year after surgery as being fibrous or granulation tissue, or even postoperative changes that the heterotopic tissue was bone was obvious only on CT. Even then the tissue may be incorrectly identified, as the encasing nerve roots in bone are similar to the scar tissue having no compressive effect. HO may compress, but it also has an inflammatory component that the scars lack. Additionally, the HO from the disk space, caused by leakage of the BMP placed in or around the fusion cage, can create a pseudo-pedicle of varying size and extent. This was present in all 38 of our cases.

This retrospective case series had its limitations. Its clinical and radiographic findings were not blinded. Confounding variables cannot be isolated for causal relationships, if any, to the complication in a case series such as this.

Bone formation with rhBMP-2 is robust and beneficial, but HO-related complications are significant, and identifiable on assessment of radiculopathy symptoms and CT characteristics.

ABSTRACT

We conducted a study to determine the common characteristics of patients who developed radiculopathy symptoms and corresponding heterotopic ossification (HO) from transforaminal lumbar interbody fusions (TLIF) using recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2 (rhBMP-2). HO can arise from a disk space with rhBMP-2 use in TLIF. Formation of bone around nerve roots or the thecal sac can cause a radiculopathy with a consistent pattern of symptoms.

We identified 38 patients (26 males, 12 females) with a mean (SD) age of 50.8 (7.5) years who developed radiculopathy symptoms and corresponding HO from TLIF with rhBMP-2 in the disk space between 2002 and 2015. To document this complication and improve its recognition, we recorded common patterns of symptom development and radiologic findings: specifically, time from implantation of rhBMP-2 to symptom development, consistency with side of TLIF placement, and radiologic findings.

Radicular pain generally developed a mean (SD) of 3.8 (1.0) months after TLIF with rhBMP-2. Development of radiculopathy symptoms corresponded to consistent “pseudo-pedicle”-like HO. In all 38 patients, HO arising from the annulotomy site showed a distinct pseudo-pedicle pattern encompassing nerve roots and the thecal sac. In addition, development of radiculopathy symptoms and corresponding HO appear to be independent of amount of rhBMP-2. HO resulting from TLIF with rhBMP-2 in the disk space is a pain generator and a recognizable complication that can be diagnosed by assessment of symptoms and computed tomography characteristics.

Continue to: Bone morphogenetic proteins...

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), first isolated by Urist in 19641, are a family of growth factors that stimulate the cascade of bone formation. Recombinant human BMP (rhBMP), specifically rhBMP-2 and rhBMP-7 (also known as osteogenic protein 1 [OP-1]), was developed in the 1990s after the advent of gene splicing. Then, in 2002, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved use of rhBMP to stimulate fusion in the human spine. Specifically, rhBMP-2 (Medtronic) was approved for use in combination with a specific brand of interbody cage in 1-level anterior lumbar interbody fusion.2 Over the past decade, off-label use of rhBMP-2 to achieve osseous union has increased dramatically, particularly in spinal surgery: transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF), posterior lumbar interbody fusion, and posterolateral lumbar fusion.3-9 However, this widespread off-label use for posterior spinal fusion began despite FDA data indicating that specific complications were underreported in the peer-reviewed literature.10,11 Although rhBMP-2 is very effective in increasing osteoblast formation and improving osteogenesis and subsequent bone healing in spinal surgery,12,13 its use in TLIF resulted in significant adverse side effects, including radiculopathy with and without neuroforaminal heterotopic ossification (HO); 14-24 complications in the FDA studies; 14,22,25-27 and osteolysis causing intervertebral cage subsidence, inflammatory radiculitis, genitourinary complications, infections, possible systemic effects, and significant HO complications.10,28-30 Of these, HO complications involved rhBMP leakage through the annulotomy to the disk space that led to HO. Specifically, rhBMP leaked directly out of the disk space and formed a pillar of bone that encased the nerve roots and dura, which led to occlusion of the foramen and symptoms of radiculopathy.10,28-30

Despite this frequent finding of HO in the intervertebral space outside the target fusion area, use of rhBMP-2 with intervertebral cages increased so rapidly that rhBMP-2 was used more often than autologous bone.5,11,17,31 In this study, we reviewed the common characteristics of patients who developed HO and subsequent radiculopathy from TLIF with rhBMP.

METHODS

After this study received Institutional Review Board approval, we retrospectively reviewed cases of radiculopathy symptoms that developed after TLIF with rhBMP between January 2002 and January 2015. During this period, 38 patients (26 males, 12 females) with a mean (SD) age of 50.8 (7.5) years and radiculopathy symptoms arising from TLIF with rhBMP-2 were identified to determine commonalities and defining characteristics that will help facilitate diagnosis.

Inclusion criteria were computed tomography (CT)–documented HO arising from the TLIF annulotomy site in continuity with bone in the disk space or ectopic bone forming a distinctive shell with contouring around the thecal sac or nerve roots, as well as recurrence or initial occurrence of radiculopathy with signs and symptoms corresponding to the CT site of aberrant bone growth in terms of laterality and particular nerve root(s) involved. Exclusion criteria were malplacement of interbody cage or pedicle screws, disk herniation, systemic neuropathic disease, and new or unresolved radiculopathy immediately after index surgery.

To improve recognition of this complication, we also documented the amount of BMP used, common patterns of radiculopathy symptom development, and radiologic findings. Type and timing of radiculopathy symptom onset and consistency with side of TLIF placement were documented as well. Radiculopathy symptoms included shooting pain in the legs, incontinence, sexual dysfunction, and severe paralysis. Radiologic findings were specific to bone formation from the disk space (detected with CT).

Continue to: RESULTS

RESULTS

All 38 selected patients had radiculopathy symptoms from HO out of the intervertebral space. The Table lists the patients’ overall characteristics. The left side had the most radiculopathy symptoms (31/38 patients), followed by the right side (5/38) and both sides (2/38). Radiculopathy symptoms began a mean (SD) of 3.8 (1.0) months (range, 2-6 months) after index surgery. The 38 patients had 4 characteristics in common:

Table. Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion With Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2: Onset Time for Radiculopathy Symptoms, Surgery Level, Side of Pseudo-Pedicle Bone Formation, and Subsequent Complications

| Pt | Sympton Onset, mo | Surgery Level(s) | Side(s) | Complication(s) |

| 1 | 3 | L3-L5 (2) | Both | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, urine |

| 2 | 3 | L4-L5 (2) | R | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 3 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | R | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 4 | 5 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 5 | 4 | L4-S1 (2) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, subsidence |

| 6 | 5 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 7 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 8 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 9 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 10 | 2 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 11 | 2 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, subsidence, neurologic |

| 12 | 6 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 13 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, neurologic |

| 14 | 2 | L2-L3 (1) | R | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 15 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 16 | 3 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 17 | 3 | L2-L3, L4-L5 (2) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 18 | 3 | L4-L5, L2-L3 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, nonunion |

| 19 | 4 | L4-L5 (1) | R | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 20 | 5 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 21 | 5 | L5-S1 (1) | R | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 22 | 3 | L3-L4, L5-S1 (2) | Both | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 23 | 4 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 24 | 6 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 25 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 26 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle, urine, bowel |

| 27 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 28 | 4 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 29 | 6 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 30 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 31 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 32 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 33 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 34 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 35 | 4 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 36 | 3 | L5-S1 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 37 | 4 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

| 38 | 4 | L4-L5 (1) | L | Radiculopathy, pseudo-pedicle |

1. Bone growing out of the annulotomy site for TLIF cage placement was present and in continuity with the disk space in 33 (87%) of the 38 cases. In the other 5 cases (13%), HO was present around the neural tissue, but not necessarily in continuity with the disk space. This bone appeared ectopic and not osteophytic and facet-related, as it formed a shell around either the nerve root or the thecal sac, contouring to the structure.

2. The common, novel finding on CT was a “pseudo-pedicle” (Figures 1A, 1B), which appeared as ectopic growth from the disk space—a solid piece of bone in the same direction as the anatomical pedicle. Confusing similarity to the anatomical pedicle is present on axial cuts and during surgery. The pseudo-pedicle varied in thickness and extent out of the disk space, but was always presented as a bar of bone arising from the annulotomy site. After arising from the disk space, the HO could disperse in any direction, further calcifying neural structures or the facet joints above or below. There was no apparent distinguishable repeating pattern, given the variable nature of arthritic facet changes, scoliotic deformities, size of annulotomies, amount of rhBMP used, and placement in cage and disk space or only in cage.

3. In 36 (95%) of the 38 cases, the initial interpretation of HO on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was of tissue other than bone, such as fibrous tissue, granulation tissue, recurrent disk herniation, or postoperative changes. However, this tissue was later determined to be bone from HO complications, which we confirmed with CT in all 38 cases. It is important to note that HO on MRI (Figures 2A, 2B) was initially interpreted by a radiologist as fibrous tissue, but same-level CT of the same case (Figures 3A, 3B) showed clear HO.

4. The radiculopathy symptoms caused by HO were independent of the amount of rhBMP-2 used in TLIF. Of the 38 patients, 19 had 1 rhBMP-2 sponge placed in the cage, 12 had a small kit sponge (1.05 mg), 5 had 1 sponge placed in the cage and 1 sponge placed directly in the disk space before cage placement (no notation of precise size or amount of rhBMP-2), and 2 had 1 sponge placed in the cage (no notation of rhBMP-2 amount). The data showed that HO can occur with even a small amount of rhBMP-2.

Continue to: Bone formation with rhBMP-2...

Bone formation with rhBMP-2 is robust and beneficial, but HO-related complications are significant, and identifiable on assessment of radiculopathy symptoms and CT characteristics.

DISCUSSION

We identified 38 patients with a recognizable and consistent pattern of complications of off-label use of rhBMP-2 in TLIF performed at our institution between 2002 and 2015. This pattern included consistent radiculopathy symptoms with corresponding HO at the annulotomy site in continuity with bone in the disk space or ectopic bone forming a distinctive shell around the thecal sac or nerve roots, as well as showing a distinct pseudo-pedicle pattern encompassing nerve roots and the thecal sac. Our finding differs from other findings of similar complication characteristics, but with much larger variations without consistency within the patient population.19,20,22,24 Specifically, previous studies found an association between off-label rhBMP-2 use in the posterior spine and radiculopathy with and without neuroforaminal HO. However, our study found consistent radiculopathy symptoms with pseudo-pedicle-like HO complications in all its 38 patients a mean (SD) of 3.8 (1.0) months after surgery.

In this study, consistent radiculopathy symptoms with pseudo-pedicle-like HO complications were independent of the amount of rhBMP-2 used, as some complications occurred with use of small pack rhBMP-2 with TLIF. It is well understood that high doses of rhBMP-2 may be required to improve fusion rates, but to our knowledge an optimal dosing strategy for TLIF has not been reported, particularly with respect to potential complications.8,20,31-33 For anterior lumbar interbody fusion surgery, the FDA-approved use of rhBMP-2 appears to have a significantly decreased risk of neuroforaminal HO complications. This may be attributable to the protective presence of the intact posterior annulus and longitudinal ligament for this procedure.20,33 For TLIF, it has been suggested that rhBMP-2 should be placed only along the anterior annulus with a posterior strut and morselized bone allograft barricade,33 and that fibrin glue should be used to limit BMP diffusion through the annulotomy site31 to prevent this complication.

Our study results suggest that radiculopathy symptoms with pseudo-pedicle-like HO complications appear to be caused by leakage of rhBMP-2 from the disk space through the annulotomy site. This was often initially interpreted incorrectly on MRI in the first year after surgery as being fibrous or granulation tissue, or even postoperative changes that the heterotopic tissue was bone was obvious only on CT. Even then the tissue may be incorrectly identified, as the encasing nerve roots in bone are similar to the scar tissue having no compressive effect. HO may compress, but it also has an inflammatory component that the scars lack. Additionally, the HO from the disk space, caused by leakage of the BMP placed in or around the fusion cage, can create a pseudo-pedicle of varying size and extent. This was present in all 38 of our cases.

This retrospective case series had its limitations. Its clinical and radiographic findings were not blinded. Confounding variables cannot be isolated for causal relationships, if any, to the complication in a case series such as this.

Bone formation with rhBMP-2 is robust and beneficial, but HO-related complications are significant, and identifiable on assessment of radiculopathy symptoms and CT characteristics.

1. Urist MR. Bone: formation by autoinduction. Science. 1965;150(3698):893-899.

2. Burkus JK, Gornet MF, Schuler TC, Kleeman TJ, Zdeblick TA. Six-year outcomes of anterior lumbar interbody arthrodesis with use of interbody fusion cages and recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(5):1181-1189.

3. Boden SD, Kang J, Sandhu H, Heller JG. Use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 to achieve posterolateral lumbar spine fusion in humans: a prospective, randomized clinical pilot trial: 2002 Volvo award in clinical studies. Spine. 2002;27(23):2662-2673.

4. Boden SD, Zdeblick TA, Sandhu HS, Heim SE. The use of rhBMP-2 in interbody fusion cages. Definitive evidence of osteoinduction in humans: a preliminary report. Spine. 2000;25(3):376-381.

5. Haid RW Jr, Branch CL Jr, Alexander JT, Burkus JK. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion using recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein type 2 with cylindrical interbody cages. Spine J. 2004;4(5):527-538.

6. Meisel HJ, Schnöring M, Hohaus C, et al. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion using rhBMP-2. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(12):1735-1744.

7. Mummaneni PV, Pan J, Haid RW, Rodts GE. Contribution of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 to the rapid creation of interbody fusion when used in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: a preliminary report. Invited submission from the Joint Section Meeting on Disorders of the Spine and Peripheral Nerves, March 2004. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;1(1):19-23.

8. Shimer AL, Oner FC, Vaccaro AR. Spinal reconstruction and bone morphogenetic proteins: open questions. Injury. 2009;40(suppl 3):S32-S38.

9. Slosar PJ, Josey R, Reynolds J. Accelerating lumbar fusions by combining rhBMP-2 with allograft bone: a prospective analysis of interbody fusion rates and clinical outcomes. Spine J. 2007;7(3):301-307.

10. Knox JB, Dai JM 3rd, Orchowski J. Osteolysis in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with bone morphogenetic protein-2. Spine. 2011;36(8):672-676.

11. Owens K, Glassman SD, Howard JM, Djurasovic M, Witten JL, Carreon LY. Perioperative complications with rhBMP-2 in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(4):612-617.

12. Mindea SA, Shih P, Song JK. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced radiculitis in elective minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusions: a series review. Spine. 2009;34(14):1480-1484.

13. Yoon ST, Park JS, Kim KS, et al. ISSLS prize winner: LMP-1 upregulates intervertebral disc cell production of proteoglycans and BMPs in vitro and in vivo. Spine. 2004;29(23):2603-2611.

14. Cahill KS, Chi JH, Day A, Claus EB. Prevalence, complications, and hospital charges associated with use of bone-morphogenetic proteins in spinal fusion procedures. JAMA. 2009;302(1):58-66.

15. Carragee EJ, Hurwitz EL, Weiner BK. A critical review of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 trials in spinal surgery: emerging safety concerns and lessons learned. Spine J. 2011;11(6):471-491.

16. Chen NF, Smith ZA, Stiner E, Armin S, Sheikh H, Khoo LT. Symptomatic ectopic bone formation after off-label use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;12(1):40-46.

17. Joseph V, Rampersaud YR. Heterotopic bone formation with the use of rhBMP2 in posterior minimal access interbody fusion: a CT analysis. Spine. 2007;32(25):2885-2890.

18. McClellan JW, Mulconrey DS, Forbes RJ, Fullmer N. Vertebral bone resorption after transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with bone morphogenetic protein (rhBMP-2). J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19(7):483-486.

19. Mroz TE, Wang JC, Hashimoto R, Norvell DC. Complications related to osteobiologics use in spine surgery: a systematic review. Spine. 2010;35(9 suppl):S86-S104.

20. Muchow RD, Hsu WK, Anderson PA. Histopathologic inflammatory response induced by recombinant bone morphogenetic protein-2 causing radiculopathy after transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Spine J. 2010;10(9):e1-e6.

21. Ong KL, Villarraga ML, Lau E, Carreon LY, Kurtz SM, Glassman SD. Off-label use of bone morphogenetic proteins in the United States using administrative data. Spine. 2010;35(19):1794-1800.

22. Rihn JA, Patel R, Makda J, et al. Complications associated with single-level transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Spine J. 2009;9(8):623-629.

23. Vaidya R, Sethi A, Bartol S, Jacobson M, Coe C, Craig JG. Complications in the use of rhBMP-2 in PEEK cages for interbody spinal fusions. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21(8):557-562.

24. Wong DA, Kumar A, Jatana S, Ghiselli G, Wong K. Neurologic impairment from ectopic bone in the lumbar canal: a potential complication of off-label PLIF/TLIF use of bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2). Spine J. 2008;8(6):1011-1018.

25. Delawi D, Dhert WJ, Rillardon L, et al. A prospective, randomized, controlled, multicenter study of osteogenic protein-1 in instrumented posterolateral fusions: report on safety and feasibility. Spine. 2010;35(12):1185-1191.

26. Vaccaro AR, Patel T, Fischgrund J, et al. A pilot study evaluating the safety and efficacy of OP-1 putty (rhBMP-7) as a replacement for iliac crest autograft in posterolateral lumbar arthrodesis for degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2004;29(17):1885-1892.

27. Vaidya R, Weir R, Sethi A, Meisterling S, Hakeos W, Wybo CD. Interbody fusion with allograft and rhBMP-2 leads to consistent fusion but early subsidence. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(3):342-345.

28. Glassman SD, Howard J, Dimar J, Sweet A, Wilson G, Carreon L. Complications with recombinant human bone morphogenic protein-2 in posterolateral spine fusion: a consecutive series of 1037 cases. Spine. 2011;36(22):1849-1854.

29. Helgeson MD, Lehman RA Jr, Patzkowski JC, Dmitriev AE, Rosner MK, Mack AW. Adjacent vertebral body osteolysis with bone morphogenetic protein use in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Spine J. 2011;11(6):507-510.

30. Hoffmann MF, Jones CB, Sietsema DL. Adjuncts in posterior lumbar spine fusion: comparison of complications and efficacy. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(8):1105-1110.

31. Villavicencio AT, Burneikiene S, Nelson EL, Bulsara KR, Favors M, Thramann J. Safety of transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion and intervertebral recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3(6):436-443.

32. Patel VV, Zhao L, Wong P, et al. Controlling bone morphogenetic protein diffusion and bone morphogenetic protein-stimulated bone growth using fibrin glue. Spine. 2006;31(11):1201-1206.

33. Zhang H, Sucato DJ, Welch RD. Recombinant human bone morphogenic protein-2-enhanced anterior spine fusion without bone encroachment into the spinal canal: a histomorphometric study in a thoracoscopically instrumented porcine model. Spine. 2005;30(5):512-518.

1. Urist MR. Bone: formation by autoinduction. Science. 1965;150(3698):893-899.

2. Burkus JK, Gornet MF, Schuler TC, Kleeman TJ, Zdeblick TA. Six-year outcomes of anterior lumbar interbody arthrodesis with use of interbody fusion cages and recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(5):1181-1189.

3. Boden SD, Kang J, Sandhu H, Heller JG. Use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 to achieve posterolateral lumbar spine fusion in humans: a prospective, randomized clinical pilot trial: 2002 Volvo award in clinical studies. Spine. 2002;27(23):2662-2673.

4. Boden SD, Zdeblick TA, Sandhu HS, Heim SE. The use of rhBMP-2 in interbody fusion cages. Definitive evidence of osteoinduction in humans: a preliminary report. Spine. 2000;25(3):376-381.

5. Haid RW Jr, Branch CL Jr, Alexander JT, Burkus JK. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion using recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein type 2 with cylindrical interbody cages. Spine J. 2004;4(5):527-538.

6. Meisel HJ, Schnöring M, Hohaus C, et al. Posterior lumbar interbody fusion using rhBMP-2. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(12):1735-1744.

7. Mummaneni PV, Pan J, Haid RW, Rodts GE. Contribution of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 to the rapid creation of interbody fusion when used in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: a preliminary report. Invited submission from the Joint Section Meeting on Disorders of the Spine and Peripheral Nerves, March 2004. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;1(1):19-23.

8. Shimer AL, Oner FC, Vaccaro AR. Spinal reconstruction and bone morphogenetic proteins: open questions. Injury. 2009;40(suppl 3):S32-S38.

9. Slosar PJ, Josey R, Reynolds J. Accelerating lumbar fusions by combining rhBMP-2 with allograft bone: a prospective analysis of interbody fusion rates and clinical outcomes. Spine J. 2007;7(3):301-307.

10. Knox JB, Dai JM 3rd, Orchowski J. Osteolysis in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with bone morphogenetic protein-2. Spine. 2011;36(8):672-676.

11. Owens K, Glassman SD, Howard JM, Djurasovic M, Witten JL, Carreon LY. Perioperative complications with rhBMP-2 in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(4):612-617.

12. Mindea SA, Shih P, Song JK. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced radiculitis in elective minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusions: a series review. Spine. 2009;34(14):1480-1484.

13. Yoon ST, Park JS, Kim KS, et al. ISSLS prize winner: LMP-1 upregulates intervertebral disc cell production of proteoglycans and BMPs in vitro and in vivo. Spine. 2004;29(23):2603-2611.

14. Cahill KS, Chi JH, Day A, Claus EB. Prevalence, complications, and hospital charges associated with use of bone-morphogenetic proteins in spinal fusion procedures. JAMA. 2009;302(1):58-66.

15. Carragee EJ, Hurwitz EL, Weiner BK. A critical review of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 trials in spinal surgery: emerging safety concerns and lessons learned. Spine J. 2011;11(6):471-491.

16. Chen NF, Smith ZA, Stiner E, Armin S, Sheikh H, Khoo LT. Symptomatic ectopic bone formation after off-label use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;12(1):40-46.

17. Joseph V, Rampersaud YR. Heterotopic bone formation with the use of rhBMP2 in posterior minimal access interbody fusion: a CT analysis. Spine. 2007;32(25):2885-2890.

18. McClellan JW, Mulconrey DS, Forbes RJ, Fullmer N. Vertebral bone resorption after transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with bone morphogenetic protein (rhBMP-2). J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19(7):483-486.

19. Mroz TE, Wang JC, Hashimoto R, Norvell DC. Complications related to osteobiologics use in spine surgery: a systematic review. Spine. 2010;35(9 suppl):S86-S104.

20. Muchow RD, Hsu WK, Anderson PA. Histopathologic inflammatory response induced by recombinant bone morphogenetic protein-2 causing radiculopathy after transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Spine J. 2010;10(9):e1-e6.

21. Ong KL, Villarraga ML, Lau E, Carreon LY, Kurtz SM, Glassman SD. Off-label use of bone morphogenetic proteins in the United States using administrative data. Spine. 2010;35(19):1794-1800.

22. Rihn JA, Patel R, Makda J, et al. Complications associated with single-level transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Spine J. 2009;9(8):623-629.

23. Vaidya R, Sethi A, Bartol S, Jacobson M, Coe C, Craig JG. Complications in the use of rhBMP-2 in PEEK cages for interbody spinal fusions. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21(8):557-562.

24. Wong DA, Kumar A, Jatana S, Ghiselli G, Wong K. Neurologic impairment from ectopic bone in the lumbar canal: a potential complication of off-label PLIF/TLIF use of bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2). Spine J. 2008;8(6):1011-1018.

25. Delawi D, Dhert WJ, Rillardon L, et al. A prospective, randomized, controlled, multicenter study of osteogenic protein-1 in instrumented posterolateral fusions: report on safety and feasibility. Spine. 2010;35(12):1185-1191.

26. Vaccaro AR, Patel T, Fischgrund J, et al. A pilot study evaluating the safety and efficacy of OP-1 putty (rhBMP-7) as a replacement for iliac crest autograft in posterolateral lumbar arthrodesis for degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2004;29(17):1885-1892.

27. Vaidya R, Weir R, Sethi A, Meisterling S, Hakeos W, Wybo CD. Interbody fusion with allograft and rhBMP-2 leads to consistent fusion but early subsidence. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(3):342-345.

28. Glassman SD, Howard J, Dimar J, Sweet A, Wilson G, Carreon L. Complications with recombinant human bone morphogenic protein-2 in posterolateral spine fusion: a consecutive series of 1037 cases. Spine. 2011;36(22):1849-1854.

29. Helgeson MD, Lehman RA Jr, Patzkowski JC, Dmitriev AE, Rosner MK, Mack AW. Adjacent vertebral body osteolysis with bone morphogenetic protein use in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Spine J. 2011;11(6):507-510.

30. Hoffmann MF, Jones CB, Sietsema DL. Adjuncts in posterior lumbar spine fusion: comparison of complications and efficacy. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(8):1105-1110.

31. Villavicencio AT, Burneikiene S, Nelson EL, Bulsara KR, Favors M, Thramann J. Safety of transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion and intervertebral recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3(6):436-443.

32. Patel VV, Zhao L, Wong P, et al. Controlling bone morphogenetic protein diffusion and bone morphogenetic protein-stimulated bone growth using fibrin glue. Spine. 2006;31(11):1201-1206.

33. Zhang H, Sucato DJ, Welch RD. Recombinant human bone morphogenic protein-2-enhanced anterior spine fusion without bone encroachment into the spinal canal: a histomorphometric study in a thoracoscopically instrumented porcine model. Spine. 2005;30(5):512-518.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Use of rhBMP-2 in TLIF cages can result in HO out of the cage into the spinal canal.

- HO from rhBMP-2 in TLIF cages can result in a radiculopathy from compression or inflammatory reaction.

- HO out of the cage into the spinal canal resulting from use of rhBMP-2 in TLIF cages can be adequately diagnosed only with CT.

- HO can appear as a pedicle or pseudo-pedicle.

- Consider potential HO when using rhBMP-2 in TLIF cages.

Tough patient cases from 2017

AGA’s member-only online networking platform, the AGA Community, was the hub for clinical case scenarios in 2017. About 100 deidentified patient cases were submitted to the forum, generating over 475 private and public responses from your peers.

Here is a summary of the three cases that sparked the most discussion among AGA members. You can view all discussions in the forum at community.gastro.org/discussions.

#3 “Esophageal hyperkeratosis” (February 2017)

Patient scenario: Patient was having dysphagia. EGD showed circumferential thickening of esophageal lining in the lower half of the esophagus causing partial obstruction; lumen diameter was 7 mm (scope was able to pass with mild resistance). Human papillomavirus (HPV) stain was negative. Multiple biopsies were negative for malignancy, so the practice did not recommend esophagectomy and believed the symptoms were consistent with hyperkeratosis of esophagus. Endoscopic cryotherapy was being considered.

Question: Has anyone come across a case like this?

#2 Thickened stomach (May 2017)

Patient scenario: A 74-year-old male presented early satiety, anemia, and dyspepsia. EGD showed diffuse moderate erythema of the stomach sparing the antrum, and two small superficial duodenal ulcers. Biopsies showed mild chronic inflammation, duodenitis, and negative for H. pylori. The patient was started on a proton pump inhibitor (PPI).

One month later, patient reported early satiety, a 40-pound weight loss over last few months, nausea and vomiting, with minimal improvement while using the PPI. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed diffuse thickening of the stomach, but was otherwise unremarkable.

One month after that, a repeated EGD showed moderate erythema with enlarged gastric folds, cobblestone of mucosa, again all sparing the antrum. The colonoscopy results were unremarkable. Gastric biopsies showed mild chronic inflammation. Endoscopic ultrasound showed a thickened gastric wall to 14 mm (normal 5 mm) and fine needle aspiration showed normal gastric foveolar epithelium. The patient received a PEG-J tube to maintain nutrition, and then had a laparoscopic assisted full thickness gastric biopsy, which showed benign hypertrophic gastric smooth muscle tissue.

Serum protein electrophoresis and urine protein electrophoresis test results were normal, with total IgG and IgA normal, total IgM low at 31 (normal 60-265), albumin low, other proteins normal, and immunofixation negative. Prealbumin was low at 5 (normal 15-45). Albumin initially normal and over a couple of days low at 2.6 (normal 3.4-5.0). Total protein initially normal and over a couple of days was low at 6.3 (normal 6.8-8.8). Gastrin level was insignificant on the PPI, in the 400s. Zollinger Ellison gastrin not impressive, and the patient is HIV negative.

Question: With a negative biopsy and other test results, Menetrier’s, malignancy, sarcoidosis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, and amyloidosis can be ruled out. What could the diagnosis be?

#1 IBD and prior hep B (July 2017)

Patient scenario: A 53-year-old male diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC) at outside hospital after presenting with abdominal pain, perforation of sigmoid colon. He underwent total colectomy with ileostomy, which showed he has remnant rectum, and the path of colon showed UC with sigmoid stricture. There is no malignancy or dysplasia, and the terminal ileum included in the resection was normal. He had complicated post-op course with enterocutaneous fistula.

He underwent takedown of ileostomy, small bowel resection and ileostomy revision. Path showed segmental small bowel showing viable mucosa with acute serositis and serial adhesions. Ileal mucosa was normal. Rectum has inflammation, and he has symptoms of mucus, urgency, and blood. He had rectal burning and did not tolerate CANASA® suppository. He did not seem to improve with hydrocortisone suppository either.

In trying to decipher next treatment step, hepatitis panel was done, which showed positive hepatitis B core antibody (IgM). Hepatitis B viral load was undetectable. Hepatitis B surface antibody test (HBsAb) quantitative was 6 (not quite the range for immunity of greater than 10). Hepatitis B “e” antigen (HBeAg) negative and hepatitis B “e” antibody (HBeAb) positive. This patient’s hep B core total was positive and hep B surface antigen was negative.

Question: How would you treat this patient? Would you use Imuran?

Share your difficult patient case for the GI community to help you solve at community.gastro.org/quickpost.

AGA’s member-only online networking platform, the AGA Community, was the hub for clinical case scenarios in 2017. About 100 deidentified patient cases were submitted to the forum, generating over 475 private and public responses from your peers.

Here is a summary of the three cases that sparked the most discussion among AGA members. You can view all discussions in the forum at community.gastro.org/discussions.

#3 “Esophageal hyperkeratosis” (February 2017)

Patient scenario: Patient was having dysphagia. EGD showed circumferential thickening of esophageal lining in the lower half of the esophagus causing partial obstruction; lumen diameter was 7 mm (scope was able to pass with mild resistance). Human papillomavirus (HPV) stain was negative. Multiple biopsies were negative for malignancy, so the practice did not recommend esophagectomy and believed the symptoms were consistent with hyperkeratosis of esophagus. Endoscopic cryotherapy was being considered.

Question: Has anyone come across a case like this?

#2 Thickened stomach (May 2017)

Patient scenario: A 74-year-old male presented early satiety, anemia, and dyspepsia. EGD showed diffuse moderate erythema of the stomach sparing the antrum, and two small superficial duodenal ulcers. Biopsies showed mild chronic inflammation, duodenitis, and negative for H. pylori. The patient was started on a proton pump inhibitor (PPI).

One month later, patient reported early satiety, a 40-pound weight loss over last few months, nausea and vomiting, with minimal improvement while using the PPI. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed diffuse thickening of the stomach, but was otherwise unremarkable.

One month after that, a repeated EGD showed moderate erythema with enlarged gastric folds, cobblestone of mucosa, again all sparing the antrum. The colonoscopy results were unremarkable. Gastric biopsies showed mild chronic inflammation. Endoscopic ultrasound showed a thickened gastric wall to 14 mm (normal 5 mm) and fine needle aspiration showed normal gastric foveolar epithelium. The patient received a PEG-J tube to maintain nutrition, and then had a laparoscopic assisted full thickness gastric biopsy, which showed benign hypertrophic gastric smooth muscle tissue.

Serum protein electrophoresis and urine protein electrophoresis test results were normal, with total IgG and IgA normal, total IgM low at 31 (normal 60-265), albumin low, other proteins normal, and immunofixation negative. Prealbumin was low at 5 (normal 15-45). Albumin initially normal and over a couple of days low at 2.6 (normal 3.4-5.0). Total protein initially normal and over a couple of days was low at 6.3 (normal 6.8-8.8). Gastrin level was insignificant on the PPI, in the 400s. Zollinger Ellison gastrin not impressive, and the patient is HIV negative.

Question: With a negative biopsy and other test results, Menetrier’s, malignancy, sarcoidosis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, and amyloidosis can be ruled out. What could the diagnosis be?

#1 IBD and prior hep B (July 2017)

Patient scenario: A 53-year-old male diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC) at outside hospital after presenting with abdominal pain, perforation of sigmoid colon. He underwent total colectomy with ileostomy, which showed he has remnant rectum, and the path of colon showed UC with sigmoid stricture. There is no malignancy or dysplasia, and the terminal ileum included in the resection was normal. He had complicated post-op course with enterocutaneous fistula.

He underwent takedown of ileostomy, small bowel resection and ileostomy revision. Path showed segmental small bowel showing viable mucosa with acute serositis and serial adhesions. Ileal mucosa was normal. Rectum has inflammation, and he has symptoms of mucus, urgency, and blood. He had rectal burning and did not tolerate CANASA® suppository. He did not seem to improve with hydrocortisone suppository either.

In trying to decipher next treatment step, hepatitis panel was done, which showed positive hepatitis B core antibody (IgM). Hepatitis B viral load was undetectable. Hepatitis B surface antibody test (HBsAb) quantitative was 6 (not quite the range for immunity of greater than 10). Hepatitis B “e” antigen (HBeAg) negative and hepatitis B “e” antibody (HBeAb) positive. This patient’s hep B core total was positive and hep B surface antigen was negative.

Question: How would you treat this patient? Would you use Imuran?

Share your difficult patient case for the GI community to help you solve at community.gastro.org/quickpost.

AGA’s member-only online networking platform, the AGA Community, was the hub for clinical case scenarios in 2017. About 100 deidentified patient cases were submitted to the forum, generating over 475 private and public responses from your peers.

Here is a summary of the three cases that sparked the most discussion among AGA members. You can view all discussions in the forum at community.gastro.org/discussions.

#3 “Esophageal hyperkeratosis” (February 2017)

Patient scenario: Patient was having dysphagia. EGD showed circumferential thickening of esophageal lining in the lower half of the esophagus causing partial obstruction; lumen diameter was 7 mm (scope was able to pass with mild resistance). Human papillomavirus (HPV) stain was negative. Multiple biopsies were negative for malignancy, so the practice did not recommend esophagectomy and believed the symptoms were consistent with hyperkeratosis of esophagus. Endoscopic cryotherapy was being considered.

Question: Has anyone come across a case like this?

#2 Thickened stomach (May 2017)

Patient scenario: A 74-year-old male presented early satiety, anemia, and dyspepsia. EGD showed diffuse moderate erythema of the stomach sparing the antrum, and two small superficial duodenal ulcers. Biopsies showed mild chronic inflammation, duodenitis, and negative for H. pylori. The patient was started on a proton pump inhibitor (PPI).

One month later, patient reported early satiety, a 40-pound weight loss over last few months, nausea and vomiting, with minimal improvement while using the PPI. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed diffuse thickening of the stomach, but was otherwise unremarkable.

One month after that, a repeated EGD showed moderate erythema with enlarged gastric folds, cobblestone of mucosa, again all sparing the antrum. The colonoscopy results were unremarkable. Gastric biopsies showed mild chronic inflammation. Endoscopic ultrasound showed a thickened gastric wall to 14 mm (normal 5 mm) and fine needle aspiration showed normal gastric foveolar epithelium. The patient received a PEG-J tube to maintain nutrition, and then had a laparoscopic assisted full thickness gastric biopsy, which showed benign hypertrophic gastric smooth muscle tissue.

Serum protein electrophoresis and urine protein electrophoresis test results were normal, with total IgG and IgA normal, total IgM low at 31 (normal 60-265), albumin low, other proteins normal, and immunofixation negative. Prealbumin was low at 5 (normal 15-45). Albumin initially normal and over a couple of days low at 2.6 (normal 3.4-5.0). Total protein initially normal and over a couple of days was low at 6.3 (normal 6.8-8.8). Gastrin level was insignificant on the PPI, in the 400s. Zollinger Ellison gastrin not impressive, and the patient is HIV negative.

Question: With a negative biopsy and other test results, Menetrier’s, malignancy, sarcoidosis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, and amyloidosis can be ruled out. What could the diagnosis be?

#1 IBD and prior hep B (July 2017)

Patient scenario: A 53-year-old male diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC) at outside hospital after presenting with abdominal pain, perforation of sigmoid colon. He underwent total colectomy with ileostomy, which showed he has remnant rectum, and the path of colon showed UC with sigmoid stricture. There is no malignancy or dysplasia, and the terminal ileum included in the resection was normal. He had complicated post-op course with enterocutaneous fistula.

He underwent takedown of ileostomy, small bowel resection and ileostomy revision. Path showed segmental small bowel showing viable mucosa with acute serositis and serial adhesions. Ileal mucosa was normal. Rectum has inflammation, and he has symptoms of mucus, urgency, and blood. He had rectal burning and did not tolerate CANASA® suppository. He did not seem to improve with hydrocortisone suppository either.

In trying to decipher next treatment step, hepatitis panel was done, which showed positive hepatitis B core antibody (IgM). Hepatitis B viral load was undetectable. Hepatitis B surface antibody test (HBsAb) quantitative was 6 (not quite the range for immunity of greater than 10). Hepatitis B “e” antigen (HBeAg) negative and hepatitis B “e” antibody (HBeAb) positive. This patient’s hep B core total was positive and hep B surface antigen was negative.

Question: How would you treat this patient? Would you use Imuran?

Share your difficult patient case for the GI community to help you solve at community.gastro.org/quickpost.

Insurance barriers should not hinder step therapy treatment for IBD