User login

AGA Regional Practice Skills Workshops: New perspectives for young GI physicians

Medicine is an evolving field, and in this era of ever-changing medicine, physicians-in-training often lag behind in understanding the nuances of “real-world” medicine. From negotiating job contracts to understanding medical billing, coding systems, and performance metrics, physicians who are fresh out of training often feel ill prepared to deal with these issues that are rarely discussed during fellowship.

The American Gastroenterological Association’s Regional Practice Skills Workshops are designed to fill this void and provide the tools necessary to navigate the challenging transition from training into practice. Since the first pilot workshops were held in 2014, AGA’s Trainee and Early Career Committee has been diligently working to expand the number of workshop sites so that more trainees can benefit from them. This year, workshops will be held in Columbus, Ohio (Feb. 24), and in Philadelphia (April 11). An exciting development in 2017 was the opportunity to live stream the event held at the University of California, Los Angeles, to Stanford (Calif.) University and the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

This aforementioned workshop at UCLA was divided into two sessions. The first was focused on “Practice Options,” with talks geared toward highlighting the different practice models available in the GI market, including positions in academia, private practice, and mixed environments.

William Chey, MD, a professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, shared his experience as an academic gastroenterologist as well as his experience in managing a GI consulting firm. His advice to young gastroenterologists was to diversify. He suggested options such as working for pharmaceutical companies, being involved in drug trials, working in the innovation industry, and proactively seeking leadership positions in different organizations. V. Raman Muthusamy MD, AGAF, a clinical professor of medicine at UCLA, led the discussion with the million-dollar question: What is my net worth? He suggested doing some homework before negotiating one’s salary by visiting the Medical Group Management Association’s website. Having this information can provide a trainee with a head start in the negotiation process. Dr. Muthusamy recommended recalculating one’s net worth every 5 years and renegotiating your contract based on this information. In addition to possibly leading to a salary boost, such knowledge will render internal validation and boost self-confidence about one’s skill set. Keep in mind however, that checking this too often can be adversely distracting. Lynn S. Connolly, MD, also of UCLA brought to light the important fact that female gastroenterologists are often paid lower salaries than their male counterparts, even after adjusting for vacation time, practice type, and work hours. She urged female gastroenterologists not to undervalue themselves and avoid falling into this pitfall. Lin Chang, MD, a professor of medicine at UCLA, reinforced the need for young GI fellows to be passionate about the path they choose and to not make random choices or decisions based on convenience alone.

Gareth Dulai, MD, a gastroenterologist with Kaiser Permanente in Downey, CA, discussed the advantages of working in a big company, including salaries that are transparent and match the national average. One also does not have to worry about hiring staff and managing overhead costs. Martha Hierro, MD, who has been in private practice since fellowship, felt that a private group practice enables a higher salary potential and better flexibility with one’s schedule. Her group also has a pathology lab, research lab, and imaging center, which further augments the group’s earnings. The downsides to private practice, compared with bigger academic settings, include cumbersome negotiations with insurance companies and financial constraints when purchasing new technology. She advised young GI physicians to go through the partnership clause very carefully before joining any private practice. She recommended being prepared and fully informed before negotiating a contract, including speaking to other practicing gastroenterologists in the area about the earning potential in the practice. In the end, both speakers agreed that all types of practices have pros and cons and one can always move from one setting to another.

For young GI fellows who want to work as administrators, the common consensus among the panel members was that fellows should attend leadership courses at national meetings early in training and participate in the committees of national organizations like the AGA. Reaching out to educators and mentors is of key importance. Dr. Chey recommended that, when fellows are provided with an opportunity to work with a potential mentor, they should think it through before accepting the opportunity and, if they do accept it, make sure they finish the task in a timely manner.

The second session of the workshop was geared toward the interview process. James H. Tabibian, MD, PhD, of the University of California, Davis, shared some useful tips for job hunting. It is never too early to start the process of job hunting, and timing depends on the type of position one is seeking. For a competitive position, it may be best to start the process early. When looking for jobs, contact methods could include in-person encounters at national meetings, such as Digestive Disease Week, or through a mutual colleague or mentor. Emails to potential future employers should be succinct with an updated resume attached. Most importantly, make sure to follow up in a professional manner.

Dr. Connolly, who also spoke about interviewing, pointed out that one should always ask questions about the program and never offer any negative information about oneself. Discussing salary potential during an interview may not be perceived as a positive sign. One might ask the interviewer about what things the interviewer enjoys the most at work, what defines success in this position at the institution, what constitutes an ideal candidate for the program, and what is the growth plan for the program over the next 5-10 years. For subspecialty interviews, some questions that are good to ask include the volume of procedures done at the institute, what might a typical day for a fellow look like, where do fellows typically work after finishing, and how is the call schedule set up. In the end, look confident, be humble, and believe in yourself. You control how you are perceived.

Once you are offered a job, the next big task is contract negotiation. Negotiating a contract can be very time consuming and stressful. Some key concepts to keep in mind are: a) prepare ahead of time and know the institution well; b) the more offers you have, the more leverage you can get; c) take adequate time to evaluate the contract before signing; d) establish which clauses are nonnegotiable for you; e) try to get something back for everything you give up during negotiations; f) do not negotiate with yourself; g) keep calm and be flexible; and h) know what you want out of your job. Always keep in mind base salary and bonuses, student loan repayment, relocation expenses, medical and disability insurance, and malpractice insurance coverage. Always consider the possibility of buying into the practice. Be wary of indemnification and unreasonable noncompete clauses.

Overall, my colleagues and I found the workshop to be extremely informative. The live stream format was very well received, and as an audience, we felt engaged and encouraged to participate. We certainly appreciated the opportunity to ask questions in real time. This format allowed all our fellows to participate without needing to travel and to gain access to invaluable content that will surely help us in making important career decisions.

Dr. Ashat is a first-year gastroenterology fellow at The University of Iowa, Iowa City.

Medicine is an evolving field, and in this era of ever-changing medicine, physicians-in-training often lag behind in understanding the nuances of “real-world” medicine. From negotiating job contracts to understanding medical billing, coding systems, and performance metrics, physicians who are fresh out of training often feel ill prepared to deal with these issues that are rarely discussed during fellowship.

The American Gastroenterological Association’s Regional Practice Skills Workshops are designed to fill this void and provide the tools necessary to navigate the challenging transition from training into practice. Since the first pilot workshops were held in 2014, AGA’s Trainee and Early Career Committee has been diligently working to expand the number of workshop sites so that more trainees can benefit from them. This year, workshops will be held in Columbus, Ohio (Feb. 24), and in Philadelphia (April 11). An exciting development in 2017 was the opportunity to live stream the event held at the University of California, Los Angeles, to Stanford (Calif.) University and the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

This aforementioned workshop at UCLA was divided into two sessions. The first was focused on “Practice Options,” with talks geared toward highlighting the different practice models available in the GI market, including positions in academia, private practice, and mixed environments.

William Chey, MD, a professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, shared his experience as an academic gastroenterologist as well as his experience in managing a GI consulting firm. His advice to young gastroenterologists was to diversify. He suggested options such as working for pharmaceutical companies, being involved in drug trials, working in the innovation industry, and proactively seeking leadership positions in different organizations. V. Raman Muthusamy MD, AGAF, a clinical professor of medicine at UCLA, led the discussion with the million-dollar question: What is my net worth? He suggested doing some homework before negotiating one’s salary by visiting the Medical Group Management Association’s website. Having this information can provide a trainee with a head start in the negotiation process. Dr. Muthusamy recommended recalculating one’s net worth every 5 years and renegotiating your contract based on this information. In addition to possibly leading to a salary boost, such knowledge will render internal validation and boost self-confidence about one’s skill set. Keep in mind however, that checking this too often can be adversely distracting. Lynn S. Connolly, MD, also of UCLA brought to light the important fact that female gastroenterologists are often paid lower salaries than their male counterparts, even after adjusting for vacation time, practice type, and work hours. She urged female gastroenterologists not to undervalue themselves and avoid falling into this pitfall. Lin Chang, MD, a professor of medicine at UCLA, reinforced the need for young GI fellows to be passionate about the path they choose and to not make random choices or decisions based on convenience alone.

Gareth Dulai, MD, a gastroenterologist with Kaiser Permanente in Downey, CA, discussed the advantages of working in a big company, including salaries that are transparent and match the national average. One also does not have to worry about hiring staff and managing overhead costs. Martha Hierro, MD, who has been in private practice since fellowship, felt that a private group practice enables a higher salary potential and better flexibility with one’s schedule. Her group also has a pathology lab, research lab, and imaging center, which further augments the group’s earnings. The downsides to private practice, compared with bigger academic settings, include cumbersome negotiations with insurance companies and financial constraints when purchasing new technology. She advised young GI physicians to go through the partnership clause very carefully before joining any private practice. She recommended being prepared and fully informed before negotiating a contract, including speaking to other practicing gastroenterologists in the area about the earning potential in the practice. In the end, both speakers agreed that all types of practices have pros and cons and one can always move from one setting to another.

For young GI fellows who want to work as administrators, the common consensus among the panel members was that fellows should attend leadership courses at national meetings early in training and participate in the committees of national organizations like the AGA. Reaching out to educators and mentors is of key importance. Dr. Chey recommended that, when fellows are provided with an opportunity to work with a potential mentor, they should think it through before accepting the opportunity and, if they do accept it, make sure they finish the task in a timely manner.

The second session of the workshop was geared toward the interview process. James H. Tabibian, MD, PhD, of the University of California, Davis, shared some useful tips for job hunting. It is never too early to start the process of job hunting, and timing depends on the type of position one is seeking. For a competitive position, it may be best to start the process early. When looking for jobs, contact methods could include in-person encounters at national meetings, such as Digestive Disease Week, or through a mutual colleague or mentor. Emails to potential future employers should be succinct with an updated resume attached. Most importantly, make sure to follow up in a professional manner.

Dr. Connolly, who also spoke about interviewing, pointed out that one should always ask questions about the program and never offer any negative information about oneself. Discussing salary potential during an interview may not be perceived as a positive sign. One might ask the interviewer about what things the interviewer enjoys the most at work, what defines success in this position at the institution, what constitutes an ideal candidate for the program, and what is the growth plan for the program over the next 5-10 years. For subspecialty interviews, some questions that are good to ask include the volume of procedures done at the institute, what might a typical day for a fellow look like, where do fellows typically work after finishing, and how is the call schedule set up. In the end, look confident, be humble, and believe in yourself. You control how you are perceived.

Once you are offered a job, the next big task is contract negotiation. Negotiating a contract can be very time consuming and stressful. Some key concepts to keep in mind are: a) prepare ahead of time and know the institution well; b) the more offers you have, the more leverage you can get; c) take adequate time to evaluate the contract before signing; d) establish which clauses are nonnegotiable for you; e) try to get something back for everything you give up during negotiations; f) do not negotiate with yourself; g) keep calm and be flexible; and h) know what you want out of your job. Always keep in mind base salary and bonuses, student loan repayment, relocation expenses, medical and disability insurance, and malpractice insurance coverage. Always consider the possibility of buying into the practice. Be wary of indemnification and unreasonable noncompete clauses.

Overall, my colleagues and I found the workshop to be extremely informative. The live stream format was very well received, and as an audience, we felt engaged and encouraged to participate. We certainly appreciated the opportunity to ask questions in real time. This format allowed all our fellows to participate without needing to travel and to gain access to invaluable content that will surely help us in making important career decisions.

Dr. Ashat is a first-year gastroenterology fellow at The University of Iowa, Iowa City.

Medicine is an evolving field, and in this era of ever-changing medicine, physicians-in-training often lag behind in understanding the nuances of “real-world” medicine. From negotiating job contracts to understanding medical billing, coding systems, and performance metrics, physicians who are fresh out of training often feel ill prepared to deal with these issues that are rarely discussed during fellowship.

The American Gastroenterological Association’s Regional Practice Skills Workshops are designed to fill this void and provide the tools necessary to navigate the challenging transition from training into practice. Since the first pilot workshops were held in 2014, AGA’s Trainee and Early Career Committee has been diligently working to expand the number of workshop sites so that more trainees can benefit from them. This year, workshops will be held in Columbus, Ohio (Feb. 24), and in Philadelphia (April 11). An exciting development in 2017 was the opportunity to live stream the event held at the University of California, Los Angeles, to Stanford (Calif.) University and the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

This aforementioned workshop at UCLA was divided into two sessions. The first was focused on “Practice Options,” with talks geared toward highlighting the different practice models available in the GI market, including positions in academia, private practice, and mixed environments.

William Chey, MD, a professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, shared his experience as an academic gastroenterologist as well as his experience in managing a GI consulting firm. His advice to young gastroenterologists was to diversify. He suggested options such as working for pharmaceutical companies, being involved in drug trials, working in the innovation industry, and proactively seeking leadership positions in different organizations. V. Raman Muthusamy MD, AGAF, a clinical professor of medicine at UCLA, led the discussion with the million-dollar question: What is my net worth? He suggested doing some homework before negotiating one’s salary by visiting the Medical Group Management Association’s website. Having this information can provide a trainee with a head start in the negotiation process. Dr. Muthusamy recommended recalculating one’s net worth every 5 years and renegotiating your contract based on this information. In addition to possibly leading to a salary boost, such knowledge will render internal validation and boost self-confidence about one’s skill set. Keep in mind however, that checking this too often can be adversely distracting. Lynn S. Connolly, MD, also of UCLA brought to light the important fact that female gastroenterologists are often paid lower salaries than their male counterparts, even after adjusting for vacation time, practice type, and work hours. She urged female gastroenterologists not to undervalue themselves and avoid falling into this pitfall. Lin Chang, MD, a professor of medicine at UCLA, reinforced the need for young GI fellows to be passionate about the path they choose and to not make random choices or decisions based on convenience alone.

Gareth Dulai, MD, a gastroenterologist with Kaiser Permanente in Downey, CA, discussed the advantages of working in a big company, including salaries that are transparent and match the national average. One also does not have to worry about hiring staff and managing overhead costs. Martha Hierro, MD, who has been in private practice since fellowship, felt that a private group practice enables a higher salary potential and better flexibility with one’s schedule. Her group also has a pathology lab, research lab, and imaging center, which further augments the group’s earnings. The downsides to private practice, compared with bigger academic settings, include cumbersome negotiations with insurance companies and financial constraints when purchasing new technology. She advised young GI physicians to go through the partnership clause very carefully before joining any private practice. She recommended being prepared and fully informed before negotiating a contract, including speaking to other practicing gastroenterologists in the area about the earning potential in the practice. In the end, both speakers agreed that all types of practices have pros and cons and one can always move from one setting to another.

For young GI fellows who want to work as administrators, the common consensus among the panel members was that fellows should attend leadership courses at national meetings early in training and participate in the committees of national organizations like the AGA. Reaching out to educators and mentors is of key importance. Dr. Chey recommended that, when fellows are provided with an opportunity to work with a potential mentor, they should think it through before accepting the opportunity and, if they do accept it, make sure they finish the task in a timely manner.

The second session of the workshop was geared toward the interview process. James H. Tabibian, MD, PhD, of the University of California, Davis, shared some useful tips for job hunting. It is never too early to start the process of job hunting, and timing depends on the type of position one is seeking. For a competitive position, it may be best to start the process early. When looking for jobs, contact methods could include in-person encounters at national meetings, such as Digestive Disease Week, or through a mutual colleague or mentor. Emails to potential future employers should be succinct with an updated resume attached. Most importantly, make sure to follow up in a professional manner.

Dr. Connolly, who also spoke about interviewing, pointed out that one should always ask questions about the program and never offer any negative information about oneself. Discussing salary potential during an interview may not be perceived as a positive sign. One might ask the interviewer about what things the interviewer enjoys the most at work, what defines success in this position at the institution, what constitutes an ideal candidate for the program, and what is the growth plan for the program over the next 5-10 years. For subspecialty interviews, some questions that are good to ask include the volume of procedures done at the institute, what might a typical day for a fellow look like, where do fellows typically work after finishing, and how is the call schedule set up. In the end, look confident, be humble, and believe in yourself. You control how you are perceived.

Once you are offered a job, the next big task is contract negotiation. Negotiating a contract can be very time consuming and stressful. Some key concepts to keep in mind are: a) prepare ahead of time and know the institution well; b) the more offers you have, the more leverage you can get; c) take adequate time to evaluate the contract before signing; d) establish which clauses are nonnegotiable for you; e) try to get something back for everything you give up during negotiations; f) do not negotiate with yourself; g) keep calm and be flexible; and h) know what you want out of your job. Always keep in mind base salary and bonuses, student loan repayment, relocation expenses, medical and disability insurance, and malpractice insurance coverage. Always consider the possibility of buying into the practice. Be wary of indemnification and unreasonable noncompete clauses.

Overall, my colleagues and I found the workshop to be extremely informative. The live stream format was very well received, and as an audience, we felt engaged and encouraged to participate. We certainly appreciated the opportunity to ask questions in real time. This format allowed all our fellows to participate without needing to travel and to gain access to invaluable content that will surely help us in making important career decisions.

Dr. Ashat is a first-year gastroenterology fellow at The University of Iowa, Iowa City.

What Do You Want to Be When You Grow Up? Pearls for Postresidency Planning

Dermatology residency training can feel endless at the outset; an arduous intern year followed by 3 years of specialized training. However, I have realized that, within residency, time moves quickly. As I look ahead to postresidency life, I realize that residents are all facing the same question: What do you want to be when you grow up?

You may think you have answered that question already; however, there are many different careers within the field of dermatology and no amount of studying or reading will help you choose the right one. In an attempt to make sense of these choices, I have spoken to many recent dermatology graduates over the last several months to get a sense of how they made their postresidency decisions, and I want to share their pearls.

Pearl: Explore Fellowship Opportunities Early

The first decision is whether or not to pursue a fellowship after residency. There currently are 2 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–approved fellowships after dermatology residency: dermatopathology and micrographic surgery. Pediatric dermatology is another board-certified fellowship. A list of these training programs and the requirements can be found on the American Board of Dermatology website (www.abderm.org). There also are several nonaccredited fellowships including pediatrics, cosmetics, complex medical dermatology, cutaneous oncology, and rheumatology.

Even if you are not completely committed to pursuing a fellowship, it is beneficial to explore any fellowship options early in residency. Spend extra time in any field you are considering for fellowship and consider research in the field. If there is a fellowship position at your institution, try to rotate there early in residency. Rotations at other institutions can demonstrate your interest and enthusiasm while also helping you to network within your chosen subspecialty. Several of the dermatology interest groups even sponsor rotations at outside institutions, if extra funding is needed. If recent graduates from your program have matched in fellowship, it is always a good idea to reach out to them to get program-specific advice. It takes a lot of time, confidence, and persistence to organize the opportunities that will help you maximize your fellowship potential, but it is well worth the effort.

Fellowships can occur through an official “match,” similar to residency, or can be accepted on a rolling basis. For example, many dermatopathology fellowships can begin accepting applications as early as the summer between the first and second year of residency (www.abderm.org). It is important to get this information early so that you do not miss any application deadlines.

Pearl: Prioritize Where You Want to Practice

If you have decided that fellowship is not for you, then it is time to apply for your first job as a physician. There are several big factors that help narrow the search. It is best to start the search early to allow yourself time and different options. According to the 2016 American Academy of Dermatology database, there currently are approximately 3.4 dermatologists per 100,000 Americans; however, they are unevenly distributed throughout the country. In this study, the researchers found the highest density of dermatologists on the Upper East Side of Manhattan (41.8 per 100,000 dermatologists) compared to Swainsboro, Georgia (0.45 per 100,000 dermatologists).1

With more competition for jobs in areas with a higher concentration of dermatologists, compensation often is lower. There also are many personal factors that contribute to where you want to live and work, and if you prioritize them, it will lead to greater overall satisfaction in postresidency life.

Another large factor to consider is private practice versus academic dermatology. Academic dermatology can provide opportunities for research as well as the opportunity to work with students and residents. As part of a larger hospital system, there often is the opportunity for benefits, such as 401(k) matching, that might be less accessible in small practices.

Pearl: Get Recruiter Recommendations From Your Peers

There are many recruiting services that can help put you in touch with practices that are hiring. These services can be helpful but also can be overwhelming at times, with many emails and telephone calls. In my experience, recent graduates had mixed feelings about recruiting services. Those who had been the happiest with their recruiting experience had often gotten the name of a specific recruiter from someone else in their program who had a positive experience. Mentors at your training institution or beyond also can be a good source of information for job opportunities. It can be helpful to get involved early in the various dermatologic societies and network at academic conferences throughout your training.

Pearl: Talk to Partners and Nonpartners About the Practice’s Philosophy

When picking a private practice for your first job, make sure you get a sense of the philosophy of the practice, including the partners’ goals for the office, the patient population, and the dynamic of the office staff. If there is a cosmetic component, it is important to know what devices are available and which products are sold. It is important to talk to nonpartners at a practice and get a sense of their satisfaction. If you sign the employment contract, you will be in their shoes soon!

Pearl: Have an Attorney Review Your Contract

There are many important topics in your employment contract. After years of medical school loans and resident salary, it is easy to focus only on compensation. However, pay attention to the other aspects of reimbursement including bonuses, benefits, noncompete clauses, and call schedules. Also consider the termination policies. The general advice I have received is to have a lawyer look at your contract. Although it may be tempting to skip the lawyer’s fee and review it yourself, you may actually end up negotiating a contract that benefits you more in the long-run or avoid signing a contract that will limit you.

- Glazer AM, Farberg AS, Winkelmann RR, et al. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution and density of US dermatologists. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:322-325.

Dermatology residency training can feel endless at the outset; an arduous intern year followed by 3 years of specialized training. However, I have realized that, within residency, time moves quickly. As I look ahead to postresidency life, I realize that residents are all facing the same question: What do you want to be when you grow up?

You may think you have answered that question already; however, there are many different careers within the field of dermatology and no amount of studying or reading will help you choose the right one. In an attempt to make sense of these choices, I have spoken to many recent dermatology graduates over the last several months to get a sense of how they made their postresidency decisions, and I want to share their pearls.

Pearl: Explore Fellowship Opportunities Early

The first decision is whether or not to pursue a fellowship after residency. There currently are 2 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–approved fellowships after dermatology residency: dermatopathology and micrographic surgery. Pediatric dermatology is another board-certified fellowship. A list of these training programs and the requirements can be found on the American Board of Dermatology website (www.abderm.org). There also are several nonaccredited fellowships including pediatrics, cosmetics, complex medical dermatology, cutaneous oncology, and rheumatology.

Even if you are not completely committed to pursuing a fellowship, it is beneficial to explore any fellowship options early in residency. Spend extra time in any field you are considering for fellowship and consider research in the field. If there is a fellowship position at your institution, try to rotate there early in residency. Rotations at other institutions can demonstrate your interest and enthusiasm while also helping you to network within your chosen subspecialty. Several of the dermatology interest groups even sponsor rotations at outside institutions, if extra funding is needed. If recent graduates from your program have matched in fellowship, it is always a good idea to reach out to them to get program-specific advice. It takes a lot of time, confidence, and persistence to organize the opportunities that will help you maximize your fellowship potential, but it is well worth the effort.

Fellowships can occur through an official “match,” similar to residency, or can be accepted on a rolling basis. For example, many dermatopathology fellowships can begin accepting applications as early as the summer between the first and second year of residency (www.abderm.org). It is important to get this information early so that you do not miss any application deadlines.

Pearl: Prioritize Where You Want to Practice

If you have decided that fellowship is not for you, then it is time to apply for your first job as a physician. There are several big factors that help narrow the search. It is best to start the search early to allow yourself time and different options. According to the 2016 American Academy of Dermatology database, there currently are approximately 3.4 dermatologists per 100,000 Americans; however, they are unevenly distributed throughout the country. In this study, the researchers found the highest density of dermatologists on the Upper East Side of Manhattan (41.8 per 100,000 dermatologists) compared to Swainsboro, Georgia (0.45 per 100,000 dermatologists).1

With more competition for jobs in areas with a higher concentration of dermatologists, compensation often is lower. There also are many personal factors that contribute to where you want to live and work, and if you prioritize them, it will lead to greater overall satisfaction in postresidency life.

Another large factor to consider is private practice versus academic dermatology. Academic dermatology can provide opportunities for research as well as the opportunity to work with students and residents. As part of a larger hospital system, there often is the opportunity for benefits, such as 401(k) matching, that might be less accessible in small practices.

Pearl: Get Recruiter Recommendations From Your Peers

There are many recruiting services that can help put you in touch with practices that are hiring. These services can be helpful but also can be overwhelming at times, with many emails and telephone calls. In my experience, recent graduates had mixed feelings about recruiting services. Those who had been the happiest with their recruiting experience had often gotten the name of a specific recruiter from someone else in their program who had a positive experience. Mentors at your training institution or beyond also can be a good source of information for job opportunities. It can be helpful to get involved early in the various dermatologic societies and network at academic conferences throughout your training.

Pearl: Talk to Partners and Nonpartners About the Practice’s Philosophy

When picking a private practice for your first job, make sure you get a sense of the philosophy of the practice, including the partners’ goals for the office, the patient population, and the dynamic of the office staff. If there is a cosmetic component, it is important to know what devices are available and which products are sold. It is important to talk to nonpartners at a practice and get a sense of their satisfaction. If you sign the employment contract, you will be in their shoes soon!

Pearl: Have an Attorney Review Your Contract

There are many important topics in your employment contract. After years of medical school loans and resident salary, it is easy to focus only on compensation. However, pay attention to the other aspects of reimbursement including bonuses, benefits, noncompete clauses, and call schedules. Also consider the termination policies. The general advice I have received is to have a lawyer look at your contract. Although it may be tempting to skip the lawyer’s fee and review it yourself, you may actually end up negotiating a contract that benefits you more in the long-run or avoid signing a contract that will limit you.

Dermatology residency training can feel endless at the outset; an arduous intern year followed by 3 years of specialized training. However, I have realized that, within residency, time moves quickly. As I look ahead to postresidency life, I realize that residents are all facing the same question: What do you want to be when you grow up?

You may think you have answered that question already; however, there are many different careers within the field of dermatology and no amount of studying or reading will help you choose the right one. In an attempt to make sense of these choices, I have spoken to many recent dermatology graduates over the last several months to get a sense of how they made their postresidency decisions, and I want to share their pearls.

Pearl: Explore Fellowship Opportunities Early

The first decision is whether or not to pursue a fellowship after residency. There currently are 2 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–approved fellowships after dermatology residency: dermatopathology and micrographic surgery. Pediatric dermatology is another board-certified fellowship. A list of these training programs and the requirements can be found on the American Board of Dermatology website (www.abderm.org). There also are several nonaccredited fellowships including pediatrics, cosmetics, complex medical dermatology, cutaneous oncology, and rheumatology.

Even if you are not completely committed to pursuing a fellowship, it is beneficial to explore any fellowship options early in residency. Spend extra time in any field you are considering for fellowship and consider research in the field. If there is a fellowship position at your institution, try to rotate there early in residency. Rotations at other institutions can demonstrate your interest and enthusiasm while also helping you to network within your chosen subspecialty. Several of the dermatology interest groups even sponsor rotations at outside institutions, if extra funding is needed. If recent graduates from your program have matched in fellowship, it is always a good idea to reach out to them to get program-specific advice. It takes a lot of time, confidence, and persistence to organize the opportunities that will help you maximize your fellowship potential, but it is well worth the effort.

Fellowships can occur through an official “match,” similar to residency, or can be accepted on a rolling basis. For example, many dermatopathology fellowships can begin accepting applications as early as the summer between the first and second year of residency (www.abderm.org). It is important to get this information early so that you do not miss any application deadlines.

Pearl: Prioritize Where You Want to Practice

If you have decided that fellowship is not for you, then it is time to apply for your first job as a physician. There are several big factors that help narrow the search. It is best to start the search early to allow yourself time and different options. According to the 2016 American Academy of Dermatology database, there currently are approximately 3.4 dermatologists per 100,000 Americans; however, they are unevenly distributed throughout the country. In this study, the researchers found the highest density of dermatologists on the Upper East Side of Manhattan (41.8 per 100,000 dermatologists) compared to Swainsboro, Georgia (0.45 per 100,000 dermatologists).1

With more competition for jobs in areas with a higher concentration of dermatologists, compensation often is lower. There also are many personal factors that contribute to where you want to live and work, and if you prioritize them, it will lead to greater overall satisfaction in postresidency life.

Another large factor to consider is private practice versus academic dermatology. Academic dermatology can provide opportunities for research as well as the opportunity to work with students and residents. As part of a larger hospital system, there often is the opportunity for benefits, such as 401(k) matching, that might be less accessible in small practices.

Pearl: Get Recruiter Recommendations From Your Peers

There are many recruiting services that can help put you in touch with practices that are hiring. These services can be helpful but also can be overwhelming at times, with many emails and telephone calls. In my experience, recent graduates had mixed feelings about recruiting services. Those who had been the happiest with their recruiting experience had often gotten the name of a specific recruiter from someone else in their program who had a positive experience. Mentors at your training institution or beyond also can be a good source of information for job opportunities. It can be helpful to get involved early in the various dermatologic societies and network at academic conferences throughout your training.

Pearl: Talk to Partners and Nonpartners About the Practice’s Philosophy

When picking a private practice for your first job, make sure you get a sense of the philosophy of the practice, including the partners’ goals for the office, the patient population, and the dynamic of the office staff. If there is a cosmetic component, it is important to know what devices are available and which products are sold. It is important to talk to nonpartners at a practice and get a sense of their satisfaction. If you sign the employment contract, you will be in their shoes soon!

Pearl: Have an Attorney Review Your Contract

There are many important topics in your employment contract. After years of medical school loans and resident salary, it is easy to focus only on compensation. However, pay attention to the other aspects of reimbursement including bonuses, benefits, noncompete clauses, and call schedules. Also consider the termination policies. The general advice I have received is to have a lawyer look at your contract. Although it may be tempting to skip the lawyer’s fee and review it yourself, you may actually end up negotiating a contract that benefits you more in the long-run or avoid signing a contract that will limit you.

- Glazer AM, Farberg AS, Winkelmann RR, et al. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution and density of US dermatologists. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:322-325.

- Glazer AM, Farberg AS, Winkelmann RR, et al. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution and density of US dermatologists. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:322-325.

Multidisciplinary care improves surgical outcomes for elderly patients

and were able to leave the hospital after a shorter stay, according to findings from a case-control study of nearly 400 patients.

Data from previous studies suggest that preoperative assessment by geriatric experts can improve outcomes for the elderly, who are more likely than are younger patients to develop preventable postoperative complications, and “this evidence supports the formulation of a different approach to preoperative assessment and postoperative care for this population,” wrote Shelley R. McDonald, DO, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and colleagues.

The intervention, known as the Perioperative Optimization of Senior Health (POSH), was described as “a quality improvement initiative with prospective data collection.” Patients in a geriatrics clinic within an academic center were selected for the study if they were at high risk for complications linked to elective abdominal surgery. High risk was defined as older than 85 years of age, or older than 65 years of age with conditions including cognitive impairment, recent weight loss, multiple comorbidities, and polypharmacy (JAMA Surg. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513).

The POSH intervention patients received preoperative evaluation from a team including a geriatrician, geriatric resource nurse, social worker, program administrator, and nurse practitioner from the preoperative anesthesia testing clinic. Patients and families were advised on risk management and care optimization involving cognition, comorbidities, medications, mobility, functional status, nutrition, hydration, pain, and advanced care planning.

Patients in the POSH group were on average older, had more comorbidities, and were more likely to be smokers. But despite these disadvantaging characteristics, they still had better outcomes in several important variables than did those in the control group.

The POSH group had significantly shorter hospital stays, compared with controls (4 days vs. 6 days), and significantly lower all-cause readmission rates at both 7 days (2.8% vs. 9.9%) and 30 days (7.8% vs. 18.3%). The significance persisted whether the surgeries were laparoscopic or open.

The overall complication rate was lower in the POSH group, compared with the controls, but fell short of statistical significance (44.8% vs. 58.7%, P = .01). However, rates of specific complications were significantly lower in the POSH group, compared with controls, including postoperative cardiogenic or hypovolemic shock (2.2% vs. 8.4%), bleeding, either during or after surgery (6.1% vs. 15.4%), and postoperative ileus (4.9% vs. 20.3%).

“Delirium was identified in POSH patients at higher rates than in the control group, which is not unexpected because higher postoperative delirium rates are known to be identified with increased screening,” the researchers noted. “Collaborative care allows for increasing the recognition of geriatric syndromes like delirium, more focus on symptom management, and proactively anticipating complications,” they said.

The study results were limited by several factors including a long enrollment period for the POSH patients, and potential changes in surgical protocols, the researchers said. However, the findings support the need for further research and more refined analysis to identify the most beneficial aspects of care, and to support better clinical decision making about the timing of interventions and the type of patient who could benefit, they noted.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The John A. Hartford Foundation Center of Excellence National Program Award provided salary and database support.

SOURCE: McDonald S et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513.

and were able to leave the hospital after a shorter stay, according to findings from a case-control study of nearly 400 patients.

Data from previous studies suggest that preoperative assessment by geriatric experts can improve outcomes for the elderly, who are more likely than are younger patients to develop preventable postoperative complications, and “this evidence supports the formulation of a different approach to preoperative assessment and postoperative care for this population,” wrote Shelley R. McDonald, DO, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and colleagues.

The intervention, known as the Perioperative Optimization of Senior Health (POSH), was described as “a quality improvement initiative with prospective data collection.” Patients in a geriatrics clinic within an academic center were selected for the study if they were at high risk for complications linked to elective abdominal surgery. High risk was defined as older than 85 years of age, or older than 65 years of age with conditions including cognitive impairment, recent weight loss, multiple comorbidities, and polypharmacy (JAMA Surg. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513).

The POSH intervention patients received preoperative evaluation from a team including a geriatrician, geriatric resource nurse, social worker, program administrator, and nurse practitioner from the preoperative anesthesia testing clinic. Patients and families were advised on risk management and care optimization involving cognition, comorbidities, medications, mobility, functional status, nutrition, hydration, pain, and advanced care planning.

Patients in the POSH group were on average older, had more comorbidities, and were more likely to be smokers. But despite these disadvantaging characteristics, they still had better outcomes in several important variables than did those in the control group.

The POSH group had significantly shorter hospital stays, compared with controls (4 days vs. 6 days), and significantly lower all-cause readmission rates at both 7 days (2.8% vs. 9.9%) and 30 days (7.8% vs. 18.3%). The significance persisted whether the surgeries were laparoscopic or open.

The overall complication rate was lower in the POSH group, compared with the controls, but fell short of statistical significance (44.8% vs. 58.7%, P = .01). However, rates of specific complications were significantly lower in the POSH group, compared with controls, including postoperative cardiogenic or hypovolemic shock (2.2% vs. 8.4%), bleeding, either during or after surgery (6.1% vs. 15.4%), and postoperative ileus (4.9% vs. 20.3%).

“Delirium was identified in POSH patients at higher rates than in the control group, which is not unexpected because higher postoperative delirium rates are known to be identified with increased screening,” the researchers noted. “Collaborative care allows for increasing the recognition of geriatric syndromes like delirium, more focus on symptom management, and proactively anticipating complications,” they said.

The study results were limited by several factors including a long enrollment period for the POSH patients, and potential changes in surgical protocols, the researchers said. However, the findings support the need for further research and more refined analysis to identify the most beneficial aspects of care, and to support better clinical decision making about the timing of interventions and the type of patient who could benefit, they noted.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The John A. Hartford Foundation Center of Excellence National Program Award provided salary and database support.

SOURCE: McDonald S et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513.

and were able to leave the hospital after a shorter stay, according to findings from a case-control study of nearly 400 patients.

Data from previous studies suggest that preoperative assessment by geriatric experts can improve outcomes for the elderly, who are more likely than are younger patients to develop preventable postoperative complications, and “this evidence supports the formulation of a different approach to preoperative assessment and postoperative care for this population,” wrote Shelley R. McDonald, DO, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and colleagues.

The intervention, known as the Perioperative Optimization of Senior Health (POSH), was described as “a quality improvement initiative with prospective data collection.” Patients in a geriatrics clinic within an academic center were selected for the study if they were at high risk for complications linked to elective abdominal surgery. High risk was defined as older than 85 years of age, or older than 65 years of age with conditions including cognitive impairment, recent weight loss, multiple comorbidities, and polypharmacy (JAMA Surg. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513).

The POSH intervention patients received preoperative evaluation from a team including a geriatrician, geriatric resource nurse, social worker, program administrator, and nurse practitioner from the preoperative anesthesia testing clinic. Patients and families were advised on risk management and care optimization involving cognition, comorbidities, medications, mobility, functional status, nutrition, hydration, pain, and advanced care planning.

Patients in the POSH group were on average older, had more comorbidities, and were more likely to be smokers. But despite these disadvantaging characteristics, they still had better outcomes in several important variables than did those in the control group.

The POSH group had significantly shorter hospital stays, compared with controls (4 days vs. 6 days), and significantly lower all-cause readmission rates at both 7 days (2.8% vs. 9.9%) and 30 days (7.8% vs. 18.3%). The significance persisted whether the surgeries were laparoscopic or open.

The overall complication rate was lower in the POSH group, compared with the controls, but fell short of statistical significance (44.8% vs. 58.7%, P = .01). However, rates of specific complications were significantly lower in the POSH group, compared with controls, including postoperative cardiogenic or hypovolemic shock (2.2% vs. 8.4%), bleeding, either during or after surgery (6.1% vs. 15.4%), and postoperative ileus (4.9% vs. 20.3%).

“Delirium was identified in POSH patients at higher rates than in the control group, which is not unexpected because higher postoperative delirium rates are known to be identified with increased screening,” the researchers noted. “Collaborative care allows for increasing the recognition of geriatric syndromes like delirium, more focus on symptom management, and proactively anticipating complications,” they said.

The study results were limited by several factors including a long enrollment period for the POSH patients, and potential changes in surgical protocols, the researchers said. However, the findings support the need for further research and more refined analysis to identify the most beneficial aspects of care, and to support better clinical decision making about the timing of interventions and the type of patient who could benefit, they noted.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. The John A. Hartford Foundation Center of Excellence National Program Award provided salary and database support.

SOURCE: McDonald S et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: A preoperative surgical intervention improved outcomes and shortened hospital stays for seniors.

Major finding: The POSH group had significantly shorter hospital stays compared with controls (4 days vs. 6 days).

Study details: The data come from a study of 183 surgery patients and 143 controls.

Disclosures: The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: McDonald S JAMA Surg. 2018 Jan 3. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.5513

Shoulder Arthroplasty in Cases of Significant Bone Loss: An Overview

Over the past few decades, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of shoulder arthroplasties performed around the world. This increase is the result of an aging and increasingly more active population, better implant technology, and the advent of reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) for rotator cuff arthropathy. Additionally, as the indications for RSA have expanded to include pathologies such as rotator cuff insufficiency, chronic instabilities, trauma, and tumors, the number of arthroplasties will continue to increase. Although the results of most arthroplasties are good and predictable, any glenoid and/or humeral bone deficiencies can have detrimental effects on the clinical outcomes of these procedures. Bone loss becomes more of a problem in revision cases, and, as the number of primary arthroplasties increases, it follows that the number of revision procedures will also increase.

Many of the disease- or procedure-specific processes indicated for shoulder arthroplasty have predictable patterns of bone loss, especially on the glenoid side. Walch and colleagues1 and Bercik and colleagues2 made us aware that many patients with primary osteoarthritis have significant glenoid bone deformity. Similarly, there have been a number of first- and second-generation classification systems for delineating glenoid deformity in rotator cuff tear arthropathy and in revision settings. In revision settings, both glenoid and humeral bone deficiencies can occur as a result of implant removal, iatrogenic fracture, and even infection. Each of these bone loss patterns must be recognized and treated appropriately for the best surgical outcome.

The articles in this month of The American Journal of Orthopedics address the most up-to-date concepts and solutions regarding both humeral and glenoid bone loss in shoulder arthroplasty of all types.

HUMERAL BONE LOSS

Humeral bone loss is typically encountered in proximal humerus fractures, in revision surgery necessitating humeral component removal, and, less commonly, in tumors and infection.

In many displaced proximal humeral fractures indicated for shoulder arthroplasty, the bone is comminuted with displacement of the lesser and greater tuberosities. In these situations, failure of tuberosity healing may result in loss of rotator cuff function with loss of elevation, rotation, and even instability. Humeral shortening can also occur as a result of bone loss and can compromise deltoid function by loss of proper muscle tension, leading to instability, dysfunction, or both. In addition to possible instability, humeral shortening with metaphyseal bone loss can adversely affect long-term fixation of the humeral component, leading to stem loosening or failure. Cuff and colleagues3 showed significantly more rotational micromotion in cases lacking metaphyseal support, leading to aseptic loosening of the humeral stem.

Humeral bone loss can also result from humeral stem component removal in revision shoulder arthroplasty for infection, component failure or loosening, and even periprosthetic fracture resulting from surgery or trauma.

For the surgeon, humeral bone loss can create a complex set of circumstances related to rotator cuff attachment failure, soft-tissue balancing effects, and component fixation issues. Any such issue must be recognized and addressed for best outcomes. Best results can be obtained with preoperative imaging, planning, use of bone graft techniques, proximal humeral allografts, and, more recently, modular and patient-specific implants. All of these issues are discussed comprehensively in the articles this month.

Continue to: GLENOID BONE LOSS

GLENOID BONE LOSS

Proper glenoid component placement with durable fixation is crucial for success in anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty and RSA. Glenoid bone deformity and loss can result from intrinsic deformity characteristics seen in primary osteoarthritis, cuff tear arthropathy, or glenoid component removal in revision situations and infection. These bone deformity complications can be extremely difficult to treat and in some cases lead to catastrophic failure of the index arthroplasty.

We are now aware that one key to success in the face of moderate to severe deformity is proper recognition. Newer imaging techniques, including 2-dimensional (2-D) computed tomography (CT) and 3-dimensional (3-D) modeling and surgical planning software tools, which are outlined in an upcoming article, have given surgeons important new instruments that can help in treating these difficult cases.

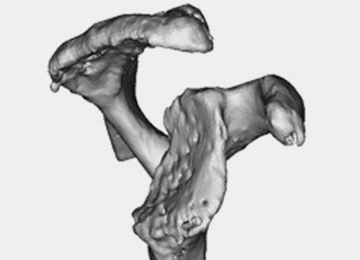

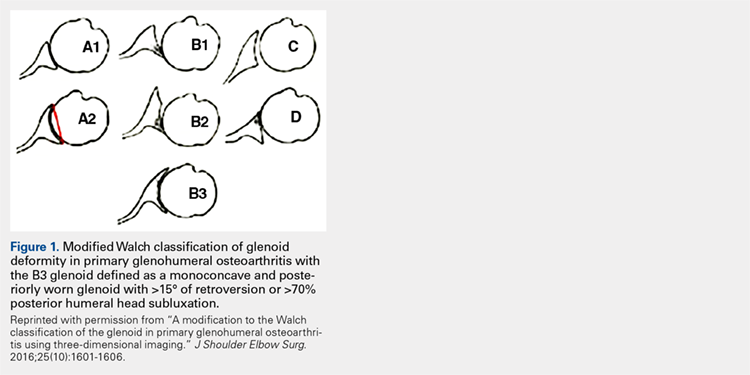

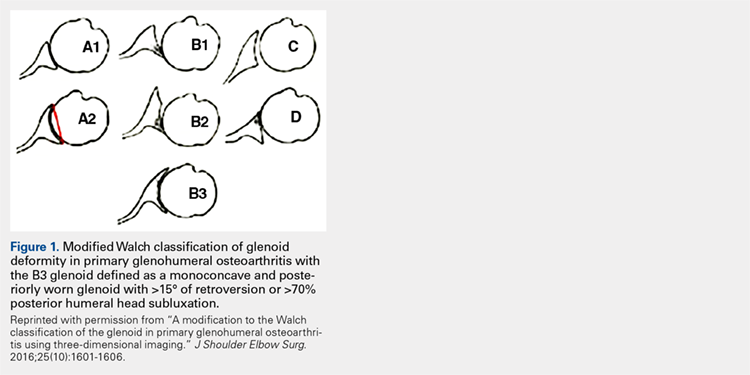

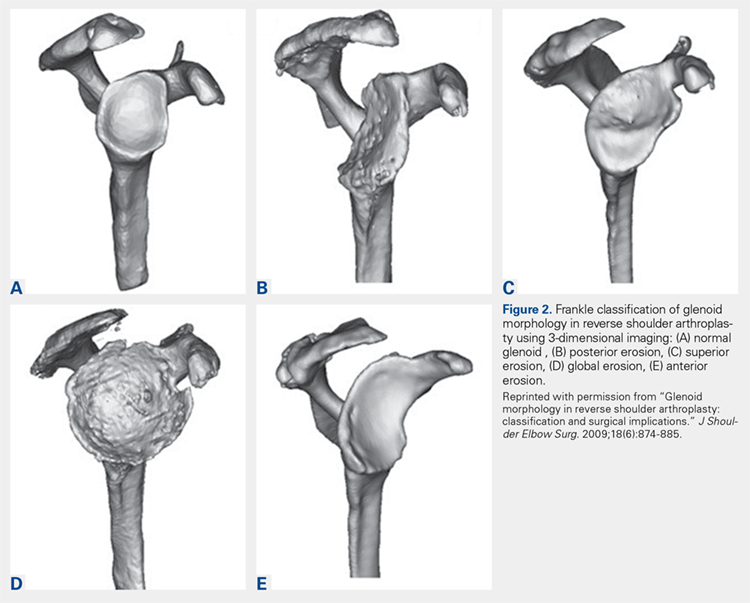

Glenoid bone deformity in primary osteoarthritis was well delineated in the 1999 seminal study of CT changes by Walch and colleagues.1 The Walch classification system, which characterized glenoid morphology based on 2-D CT findings, was recently upgraded, based on 3-D imaging technology, to include Walch B3 and D patterns (Figure 1).2 Recognition of certain primary deformities in osteoarthritis has led to increased use of RSA in some cases of Walch B2, B3, and C deformities with substantial glenoid retroversion and/or humeral head subluxation.4

In cases of rotator cuff tear arthropathy, glenoid bone deformities are well described with several classification systems based on degree and dimension of bone insufficiency. The Hamada classification system defines the degree of medial glenoid erosion and superior bone loss, as well as acetabularization of the acromion in 5 grades; 5 Rispoli and colleagues6 defined and graded the degree of medicalization of the glenohumeral joint based on degree of subchondral plate erosion; and Visotsky and colleagues7 based their classification system on wear patterns of bone loss, alignment, and concomitant soft-tissue insufficiencies leading to instability and rotation loss.

In severe glenoid bone deficiency after glenoid component removal, Antuna and colleagues8 described the classic findings related to medial bone loss, anterior and posterior wall failure, and combinations thereof.

Continue to: All these classification systems...

All these classification systems are based on the 2-D appearance of the glenoid and should be considered cautiously. The glenoid is a complex 3-D structure that can be affected by any number of disease processes, trauma, and surgical intervention. Using more modern CT techniques and 3-D imaging, we now know that many deformities previously classified as unidirectional are, instead, complex and multidirectional.

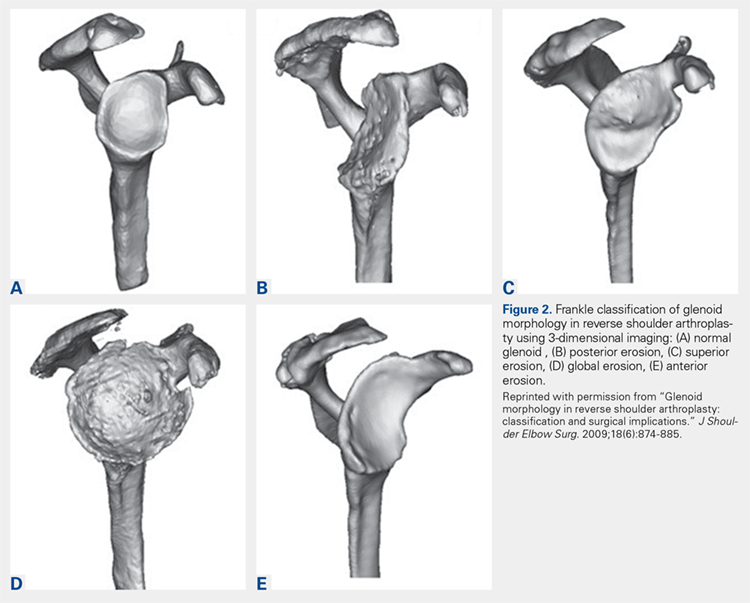

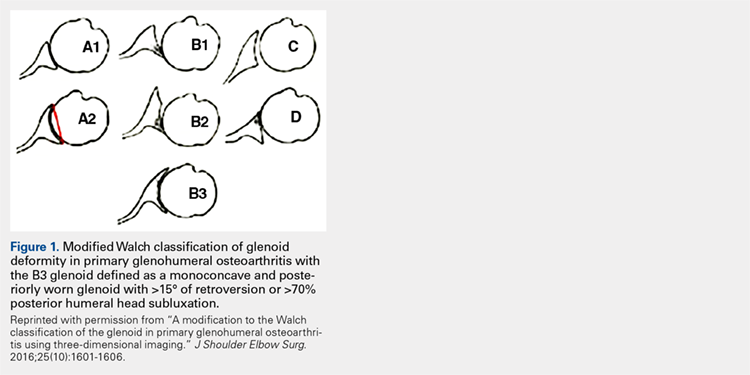

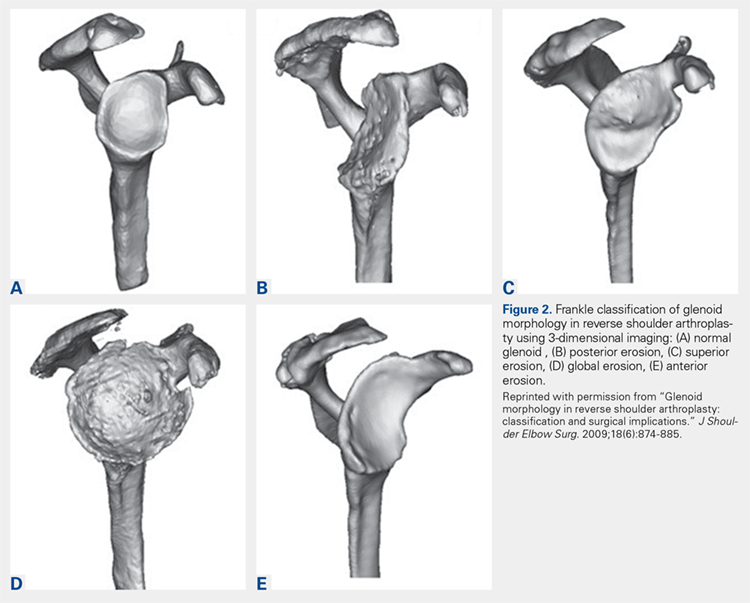

Frankle and colleagues9 developed a classification based more 3-D CT models which has further classified severe glenoid vault deformities in relation to direction and degree of bone loss (Figures 2A-2E). Using this system, they were better able to determine degree and direction of deformity than in previous 2-D evaluations, and they were able to determine the amount of glenoid vault bone available for baseplate fixation. Scalise and colleagues10 further defined the influence of such 3-D planning in total shoulder arthroplasty.

With knowledge of these classification systems and use of contemporary imaging systems, shoulder arthroplasty in cases of severe glenoid deficiency can be more successful. Potentially, we can improve outcomes even more in the more severe cases of bone loss with use of patient-specific planning tools, including the guides and patient-specific implants that are now readily available with many implant systems.11

Preoperative planning tools, bone-grafting techniques, augmented and specialized glenoid and humeral implants, and patient-specific implants are discussed this month to give our readers a comprehensive review of the latest concepts in shoulder arthroplasty in cases of significant bone loss or deformity.

This month of The American Journal of Orthopedics presents the most current and cutting-edge solutions for humeral and glenoid bone deformities and deficiencies in contemporary shoulder arthroplasties.

1. Walch G, Badet R, Boulahia A, Khoury A. Morphologic study of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(6):756-760.

2. Bercik MJ, Kruse K 2nd, Yalizis M, Gauci MO, Chaoui J, Walch G. A modification to the Walch classification of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis using three-dimensional imaging. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(10):1601-1606.

3. Cuff D, Levy JC, Gutiérrez S, Frankle M. Torsional stability of modular and non-modular reverse shoulder humeral components in a proximal humeral bone loss model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):646-651.

4. Denard PJ, Walch G. Current concepts in the surgical management of primary glenohumeral arthritis with a biconcave glenoid. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(11):1589-1598.

5. Hamada K, Fukuda H, Mikasa M, Kobayashi Y. Roentgenographic findings in massive rotator cuff tears. A long-term observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(254):92-96.

6. Rispoli D, Sperling JW, Athwal GS, Schleck CD, Cofield RH. Humeral head replacement for the treatment of osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(12):2637-2644.

7. Visotsky JL, Basamania C, Seebauer L, Rockwood CA, Jensen KL. Cuff tear arthropathy: pathogenesis, classification, and algorithm for treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(suppl 2):35-40.

8. Antuna SA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Glenoid revision surgery after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(3):217-224.

9. Frankle MA, Teramoto A, Luo ZP, Levy JC, Pupello D. Glenoid morphology in reverse shoulder arthroplasty: classification and surgical implications. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(6):874-885.

10. Scalise JJ, Codsi MJ, Bryan J, Brems JJ, Iannotti JP. The influence of three-dimensional computed tomography images of the shoulder in preoperative planning for total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(11):2438-2445.

11. Dines DM, Gulotta L, Craig EV, Dines JS. Novel solution for massive glenoid defects in shoulder arthroplasty: a patient-specific glenoid vault reconstruction system. Am J Orthop. 2017;46(2):104-108.

Over the past few decades, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of shoulder arthroplasties performed around the world. This increase is the result of an aging and increasingly more active population, better implant technology, and the advent of reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) for rotator cuff arthropathy. Additionally, as the indications for RSA have expanded to include pathologies such as rotator cuff insufficiency, chronic instabilities, trauma, and tumors, the number of arthroplasties will continue to increase. Although the results of most arthroplasties are good and predictable, any glenoid and/or humeral bone deficiencies can have detrimental effects on the clinical outcomes of these procedures. Bone loss becomes more of a problem in revision cases, and, as the number of primary arthroplasties increases, it follows that the number of revision procedures will also increase.

Many of the disease- or procedure-specific processes indicated for shoulder arthroplasty have predictable patterns of bone loss, especially on the glenoid side. Walch and colleagues1 and Bercik and colleagues2 made us aware that many patients with primary osteoarthritis have significant glenoid bone deformity. Similarly, there have been a number of first- and second-generation classification systems for delineating glenoid deformity in rotator cuff tear arthropathy and in revision settings. In revision settings, both glenoid and humeral bone deficiencies can occur as a result of implant removal, iatrogenic fracture, and even infection. Each of these bone loss patterns must be recognized and treated appropriately for the best surgical outcome.

The articles in this month of The American Journal of Orthopedics address the most up-to-date concepts and solutions regarding both humeral and glenoid bone loss in shoulder arthroplasty of all types.

HUMERAL BONE LOSS

Humeral bone loss is typically encountered in proximal humerus fractures, in revision surgery necessitating humeral component removal, and, less commonly, in tumors and infection.

In many displaced proximal humeral fractures indicated for shoulder arthroplasty, the bone is comminuted with displacement of the lesser and greater tuberosities. In these situations, failure of tuberosity healing may result in loss of rotator cuff function with loss of elevation, rotation, and even instability. Humeral shortening can also occur as a result of bone loss and can compromise deltoid function by loss of proper muscle tension, leading to instability, dysfunction, or both. In addition to possible instability, humeral shortening with metaphyseal bone loss can adversely affect long-term fixation of the humeral component, leading to stem loosening or failure. Cuff and colleagues3 showed significantly more rotational micromotion in cases lacking metaphyseal support, leading to aseptic loosening of the humeral stem.

Humeral bone loss can also result from humeral stem component removal in revision shoulder arthroplasty for infection, component failure or loosening, and even periprosthetic fracture resulting from surgery or trauma.

For the surgeon, humeral bone loss can create a complex set of circumstances related to rotator cuff attachment failure, soft-tissue balancing effects, and component fixation issues. Any such issue must be recognized and addressed for best outcomes. Best results can be obtained with preoperative imaging, planning, use of bone graft techniques, proximal humeral allografts, and, more recently, modular and patient-specific implants. All of these issues are discussed comprehensively in the articles this month.

Continue to: GLENOID BONE LOSS

GLENOID BONE LOSS

Proper glenoid component placement with durable fixation is crucial for success in anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty and RSA. Glenoid bone deformity and loss can result from intrinsic deformity characteristics seen in primary osteoarthritis, cuff tear arthropathy, or glenoid component removal in revision situations and infection. These bone deformity complications can be extremely difficult to treat and in some cases lead to catastrophic failure of the index arthroplasty.

We are now aware that one key to success in the face of moderate to severe deformity is proper recognition. Newer imaging techniques, including 2-dimensional (2-D) computed tomography (CT) and 3-dimensional (3-D) modeling and surgical planning software tools, which are outlined in an upcoming article, have given surgeons important new instruments that can help in treating these difficult cases.

Glenoid bone deformity in primary osteoarthritis was well delineated in the 1999 seminal study of CT changes by Walch and colleagues.1 The Walch classification system, which characterized glenoid morphology based on 2-D CT findings, was recently upgraded, based on 3-D imaging technology, to include Walch B3 and D patterns (Figure 1).2 Recognition of certain primary deformities in osteoarthritis has led to increased use of RSA in some cases of Walch B2, B3, and C deformities with substantial glenoid retroversion and/or humeral head subluxation.4

In cases of rotator cuff tear arthropathy, glenoid bone deformities are well described with several classification systems based on degree and dimension of bone insufficiency. The Hamada classification system defines the degree of medial glenoid erosion and superior bone loss, as well as acetabularization of the acromion in 5 grades; 5 Rispoli and colleagues6 defined and graded the degree of medicalization of the glenohumeral joint based on degree of subchondral plate erosion; and Visotsky and colleagues7 based their classification system on wear patterns of bone loss, alignment, and concomitant soft-tissue insufficiencies leading to instability and rotation loss.

In severe glenoid bone deficiency after glenoid component removal, Antuna and colleagues8 described the classic findings related to medial bone loss, anterior and posterior wall failure, and combinations thereof.

Continue to: All these classification systems...

All these classification systems are based on the 2-D appearance of the glenoid and should be considered cautiously. The glenoid is a complex 3-D structure that can be affected by any number of disease processes, trauma, and surgical intervention. Using more modern CT techniques and 3-D imaging, we now know that many deformities previously classified as unidirectional are, instead, complex and multidirectional.

Frankle and colleagues9 developed a classification based more 3-D CT models which has further classified severe glenoid vault deformities in relation to direction and degree of bone loss (Figures 2A-2E). Using this system, they were better able to determine degree and direction of deformity than in previous 2-D evaluations, and they were able to determine the amount of glenoid vault bone available for baseplate fixation. Scalise and colleagues10 further defined the influence of such 3-D planning in total shoulder arthroplasty.

With knowledge of these classification systems and use of contemporary imaging systems, shoulder arthroplasty in cases of severe glenoid deficiency can be more successful. Potentially, we can improve outcomes even more in the more severe cases of bone loss with use of patient-specific planning tools, including the guides and patient-specific implants that are now readily available with many implant systems.11

Preoperative planning tools, bone-grafting techniques, augmented and specialized glenoid and humeral implants, and patient-specific implants are discussed this month to give our readers a comprehensive review of the latest concepts in shoulder arthroplasty in cases of significant bone loss or deformity.

This month of The American Journal of Orthopedics presents the most current and cutting-edge solutions for humeral and glenoid bone deformities and deficiencies in contemporary shoulder arthroplasties.

Over the past few decades, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of shoulder arthroplasties performed around the world. This increase is the result of an aging and increasingly more active population, better implant technology, and the advent of reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) for rotator cuff arthropathy. Additionally, as the indications for RSA have expanded to include pathologies such as rotator cuff insufficiency, chronic instabilities, trauma, and tumors, the number of arthroplasties will continue to increase. Although the results of most arthroplasties are good and predictable, any glenoid and/or humeral bone deficiencies can have detrimental effects on the clinical outcomes of these procedures. Bone loss becomes more of a problem in revision cases, and, as the number of primary arthroplasties increases, it follows that the number of revision procedures will also increase.

Many of the disease- or procedure-specific processes indicated for shoulder arthroplasty have predictable patterns of bone loss, especially on the glenoid side. Walch and colleagues1 and Bercik and colleagues2 made us aware that many patients with primary osteoarthritis have significant glenoid bone deformity. Similarly, there have been a number of first- and second-generation classification systems for delineating glenoid deformity in rotator cuff tear arthropathy and in revision settings. In revision settings, both glenoid and humeral bone deficiencies can occur as a result of implant removal, iatrogenic fracture, and even infection. Each of these bone loss patterns must be recognized and treated appropriately for the best surgical outcome.

The articles in this month of The American Journal of Orthopedics address the most up-to-date concepts and solutions regarding both humeral and glenoid bone loss in shoulder arthroplasty of all types.

HUMERAL BONE LOSS

Humeral bone loss is typically encountered in proximal humerus fractures, in revision surgery necessitating humeral component removal, and, less commonly, in tumors and infection.

In many displaced proximal humeral fractures indicated for shoulder arthroplasty, the bone is comminuted with displacement of the lesser and greater tuberosities. In these situations, failure of tuberosity healing may result in loss of rotator cuff function with loss of elevation, rotation, and even instability. Humeral shortening can also occur as a result of bone loss and can compromise deltoid function by loss of proper muscle tension, leading to instability, dysfunction, or both. In addition to possible instability, humeral shortening with metaphyseal bone loss can adversely affect long-term fixation of the humeral component, leading to stem loosening or failure. Cuff and colleagues3 showed significantly more rotational micromotion in cases lacking metaphyseal support, leading to aseptic loosening of the humeral stem.

Humeral bone loss can also result from humeral stem component removal in revision shoulder arthroplasty for infection, component failure or loosening, and even periprosthetic fracture resulting from surgery or trauma.

For the surgeon, humeral bone loss can create a complex set of circumstances related to rotator cuff attachment failure, soft-tissue balancing effects, and component fixation issues. Any such issue must be recognized and addressed for best outcomes. Best results can be obtained with preoperative imaging, planning, use of bone graft techniques, proximal humeral allografts, and, more recently, modular and patient-specific implants. All of these issues are discussed comprehensively in the articles this month.

Continue to: GLENOID BONE LOSS

GLENOID BONE LOSS

Proper glenoid component placement with durable fixation is crucial for success in anatomical total shoulder arthroplasty and RSA. Glenoid bone deformity and loss can result from intrinsic deformity characteristics seen in primary osteoarthritis, cuff tear arthropathy, or glenoid component removal in revision situations and infection. These bone deformity complications can be extremely difficult to treat and in some cases lead to catastrophic failure of the index arthroplasty.

We are now aware that one key to success in the face of moderate to severe deformity is proper recognition. Newer imaging techniques, including 2-dimensional (2-D) computed tomography (CT) and 3-dimensional (3-D) modeling and surgical planning software tools, which are outlined in an upcoming article, have given surgeons important new instruments that can help in treating these difficult cases.

Glenoid bone deformity in primary osteoarthritis was well delineated in the 1999 seminal study of CT changes by Walch and colleagues.1 The Walch classification system, which characterized glenoid morphology based on 2-D CT findings, was recently upgraded, based on 3-D imaging technology, to include Walch B3 and D patterns (Figure 1).2 Recognition of certain primary deformities in osteoarthritis has led to increased use of RSA in some cases of Walch B2, B3, and C deformities with substantial glenoid retroversion and/or humeral head subluxation.4

In cases of rotator cuff tear arthropathy, glenoid bone deformities are well described with several classification systems based on degree and dimension of bone insufficiency. The Hamada classification system defines the degree of medial glenoid erosion and superior bone loss, as well as acetabularization of the acromion in 5 grades; 5 Rispoli and colleagues6 defined and graded the degree of medicalization of the glenohumeral joint based on degree of subchondral plate erosion; and Visotsky and colleagues7 based their classification system on wear patterns of bone loss, alignment, and concomitant soft-tissue insufficiencies leading to instability and rotation loss.

In severe glenoid bone deficiency after glenoid component removal, Antuna and colleagues8 described the classic findings related to medial bone loss, anterior and posterior wall failure, and combinations thereof.

Continue to: All these classification systems...

All these classification systems are based on the 2-D appearance of the glenoid and should be considered cautiously. The glenoid is a complex 3-D structure that can be affected by any number of disease processes, trauma, and surgical intervention. Using more modern CT techniques and 3-D imaging, we now know that many deformities previously classified as unidirectional are, instead, complex and multidirectional.