User login

Transitioning GI patients from pediatric to adult care

As pediatric patients with chronic gastrointestinal (GI) disorders mature into adulthood, they require a seamless transition of care into an adult practice. Health care transition is more than a simple transfer of care to an adult provider; it is a purposeful, planned movement of young adults with chronic medical conditions from a child-centered health care system to adult-oriented one.1 Many adolescents with chronic GI disorders are at increased risk of developmental and psychosocial delays and depressive disorders.2-6 A successful transition program can mitigate some of the psychosocial impacts of chronic disorders by improving self-efficacy and autonomy.7

Timing of transition

Unlike other nations where legislation often mandates the age of transition to adult care, the United States leaves decisions about the appropriate time to transition to the discretion of individual patients and pediatricians. While the actual transfer of care may not happen until later, it is prudent to start planning when the patient is in early adolescence. The pediatric gastroenterologist should initiate the discussion with patients and caregivers when the child is 13-15 years of age.12,13 Since health care transition is a complex and lengthy process, it should be approached within a framework that is appropriate for the developmental stage of the patient and at a time when their disease is in remission.14

During the initial discussions, the idea of transition should be introduced to the patient and his or her family by emphasizing the benefits of improved self-management skills, adherence to therapy, and normalization of development. The pediatrician should encourage a greater sense of independence and self-reliance by seeing the patient alone for at least a portion of the clinic visit and encourage future independent visits.

Developing a transition plan

Once the concept of transition of care has been introduced, it is prudent to devise a transition plan tailored to the specific needs and goals of the patient and family.24 Each plan should include who the adult provider will be, the tasks the adolescent must master before entering adult care, and how the care will be financed (because insurance coverage and options may change).25 A well-planned transition should enhance self-efficacy and self-management skills, increase knowledge of medical states, ensure adherence to therapy, and encourage independent decision making.12

Assessing transition readiness

Once the process of transitioning has been initiated, it is helpful to assess transition readiness at regular intervals. This will identify gaps in knowledge and inform appropriate interventions for individual patients. There are several questionnaires that can be administered at regular intervals and be made an integral part of routine clinic visits for adolescent patients. These assessments are now billable under CPT Code 99420 (administration and interpretation of health risk assessment). A standardized instrument should be used and the results recorded in the clinical encounter to ensure billing compliance.

The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (available online at www.GotTransition.org) is a validated tool that assesses an individual’s awareness of his or her medical needs, treatment plan, and ability to communicate effectively with his or her health care provider.26-28 While not specific to GI disorders, it has been validated in IBD patients and shown to correlate well with the IBD Self-Efficacy Scale for Adolescents.29,30 The University of North Carolina’s TRxANSITION Index, as well as the Social-Ecological Model of Adolescent and Young Adult Readiness for Transition, can be used for patients with various chronic diseases.31,32 Instruments specifically developed to assess transition readiness among patients with IBD include the “IBD-Yourself” questionnaire and MyHealth Passport for IBD.33,34 Additionally, Hait et al. provide a checklist of age-appropriate tasks for patients and their providers.14 The North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition has created the “Healthcare Provider Transition Checklist,” which is applicable to all chronic GI disorders.35

Transfer of care

The actual transfer of care is the culmination of the transition process. While the onus of initiating and monitoring a patient’s progress is driven by his or her pediatric provider, a responsive adult provider is integral, so it is vital to identify an adult gastroenterologist ahead of time. This can be especially difficult because most adult gastroenterologists feel uncomfortable about addressing adolescent developmental and mental health issues.36

Local chapters of societies such as the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, the American Liver Foundation, and statewide GI societies affiliated with the American College of Gastroenterology, as well as local or regional teaching institutions, are all good resources to identify adult providers interested in a coordinated transition of young adults into their practices. Depending on the availability of a local adult gastroenterologist, one approach to minimize the “growing pains” of transition can be to establish joint clinic visits with pediatric and adult providers; this strategy can help foster trust in the new physician and is generally well-received by patients.37,38 Other institutions may offer alternating visits with adult and pediatric providers during the first year of transition.

Regardless of the manner of the actual transfer of care, it is imperative the adult gastroenterologist be well versed with the natural history and disease complications of the pediatric onset of the specific GI disorder and also appreciate nutrition and concerns regarding growth and radiation. Moreover, they must recognize the convergence and divergence of traditional pediatric and adult care models, as well as the move from a family-centered to an individual-focused environment.39

At the time of the patient’s initial visit, the adult gastroenterologist needs a detailed history of the patient’s disease, a list of past and present medications, the details of any disease- or treatment-related complications or surgeries, and so on. The transfer of relevant medical records is an often overlooked, yet easily remediable, aspect of transfer of care.36 The overall process is best completed by eliciting posttransfer feedback from patients and families after they have established care with the adult provider.

Developing a transition model

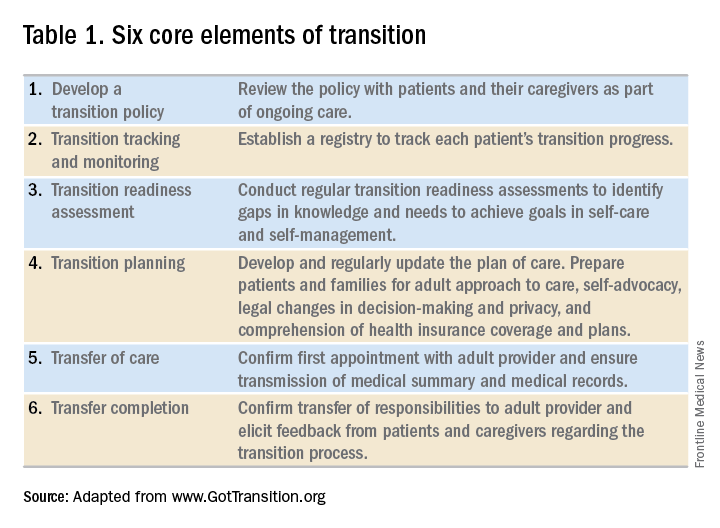

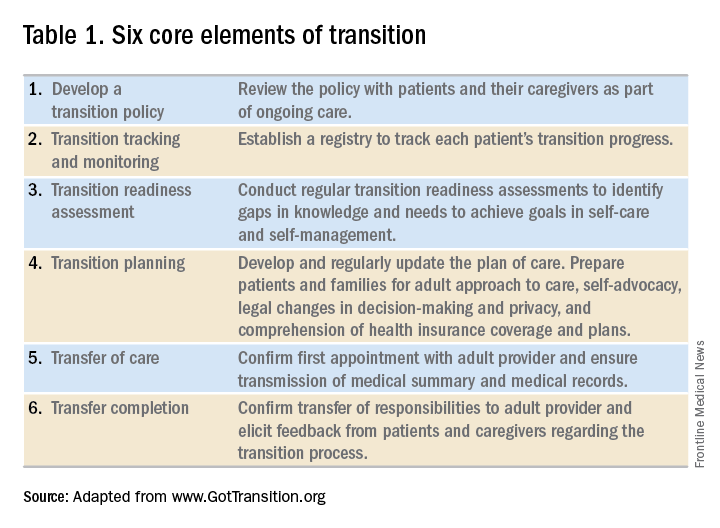

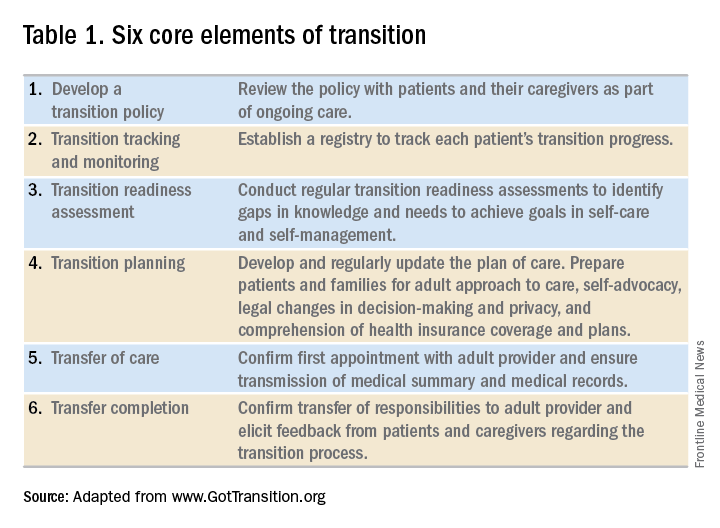

In the absence of standard, disease-specific models of transition, most institutions adapt available resources to develop their own protocols. In 2011, a joint task force of the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American College of Physicians published a clinical report on transition. Based on recommendations put forth by the Center for Health Care Transition Improvement – a joint endeavor of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau and the National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health – the aforementioned task force developed a “Got Transition” model that incorporates six core elements of health care transition (Table 1).

Within the realm of chronic GI disorders, IBD has the most reported data on various models of transition. These include joint adult and pediatric visits, coordinator-initiated transitions, and patient preparation using the assessment tools detailed above. There are no data comparing the efficacy and success of these models and, in the absence of a universally established model for transition in IBD, each institution needs to adopt an approach that best suits the needs of patients and utilizes available resources.

As is the case for patients with IBD, patients with celiac disease need to assume exclusive responsibility for their care as young adults. An important aspect of transition planning for patients with celiac disease is the need to incorporate dietician-led didactic sessions during the transition process. Since patients with celiac disease do not require medications to manage their disease, they are often lost to follow-up as young adults.40 In addition to dietary compliance, it is important to educate young adults about the long-term complications related to celiac disease and the need for regular clinical assessment and monitoring.

Transition of care for patients with EoE is relatively understudied. As EoE was first described only in the 1990s, the diagnosis is still relatively new, and transition programs are limited.41 The natural history and progression of EoE had led to disparate management strategies in adults and children. While the latter are managed with dietary modifications and steroids, adults with EoE often require frequent esophageal dilations because of the increased incidence of fibrosis. In a study of pediatric patients with EoE, most scored lower on transition readiness assessments than did patients with other chronic health conditions.42 Since a majority of patients with EoE require lifelong treatment, they need to be better prepared for transition to adult care.43

In summary, regardless of disease state, transition of care requires planning on the part of the pediatric provider and also close collaboration with patient coordinators, nurses, social workers, and adult providers. While transition is often a complex and lengthy process, it fosters self-reliance and independence among patients while improving their quality of life. Effective communication between pediatric and adult providers as well as patients and families is key to successful transition of care.

Dr. Kaur is the medical director at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center and an assistant professor in the section of gastroenterology and hepatology in the department of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; Dr. Wyatt is an assistant professor in the section of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition in the department of pediatrics at Baylor.

References

1. Blum RW et al. J Adolesc Health. 1993 Nov;14(7):570-6.

2. Greenley RN et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010 Sep;35(8):857-69.

3. Simsek S et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Sep;61(3):303-6.

4. Kanof ME et al. Gastroenterology. 1988 Dec;95(6):1523-7.

5. Mackner LM et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 Mar;12(3):239-44.

6. Hummel TZ et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013 Aug;57(2):219-24.

7. Rosen DS et al. J Adolesc Health. 2003 Oct;33(4):309-11.

8. Bollegala N et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2013 Mar;7(2):e55-60.

9. Reed-Knight B et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011 Apr;36(3):308-17.

10. Holmes-Walker DJ et al. Diabet Med. 2007 Jul;24(7):764-9.

11. Dabadie A et al. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008 May;32(5 Pt 1):451-9.

12. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002 Dec;110(6 Pt 2):1304-6.

13. Baldassano R et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002 Mar;34(3):245-8.

14. Hait E et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 Jan;12(1):70-3.

15. Gray WN et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 May;21(5):1125-31.

16. Whitfield EP et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Jan;60(1):36-41.

17. Rosen D et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 Mar;22(3):702-8.

18. Fishman LN et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014 Aug;59(2):221-4.

19. Huang JS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 Jun;10(6):626-32.

20. Habibi H et al. Clin Nurse Spec. 2017 Nov;31(6):329-34.

21. Yerushalmy-Feler A et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Jul;29(7):831-7.

22. Shanske S et al. Soc Work Health Care. 2012;51(4):279-95.

23. Fredericks EM et al. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2015 Sep;22(2-3):150-9.

24. Hardin AP et al. Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2151.

25. Leung Y et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 Oct;17(10):2169-73.

26. Wood DL et al. Acad Pediatr. 2014 Jul-Aug;14(4):415-22.

27. Sample Transition Readiness Assessment for Youth. Got Transition/Center for Health Care Transition Improvement, Jan 2014. Accessed Jan 4, 2017, at http://www.gottransition.org/resourceGet.cfm?id=224.

28. Sawicki GS et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011 Mar;36(2):160-71.

29. Izaguirre MR et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017 Nov;65(5):546-50.

30. Carlsen K et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017 Mar;23(3):341-6.

31. Ferris ME et al. Ren Fail. 2012;34(6):744-53.

32. Schwartz LA et al. Child Care Health Dev. 2011 Nov;37(6):883-95.

33. Zijlstra M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2013 Oct;7(9):e375-85.

34. Benchimol EI et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 May;17(5):1131-7.

35. Heath Care Provider Transitioning Checklist. NASPGHAN. Accessed Jan 4, 2018, at https://www.naspghan.org/files/documents/pdfs/medical-resources/ibd/Checklist_PatientandHealthcareProdiver_TransitionfromPedtoAdult.pdf.

36. Hait EJ et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009 Jan;48(1):61-5.

37. Escher JC. Dig Dis. 2009;27(3):382-6.

38. Crowley R et al. Arch Dis Child. 2011 Jun;96(6):548-53.

39. Trivedi I et al. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:260807.

40. O’Leary C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Dec;99(12):2437-41.

41. de Silva PSA et al. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2017 Jun;64(3):707-20.

42. Eluri S et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017 Jul;65(1):53-7.

43. Dellon ES et al. Dis Esophagus. 2013 Jan;26(1):7-13.

As pediatric patients with chronic gastrointestinal (GI) disorders mature into adulthood, they require a seamless transition of care into an adult practice. Health care transition is more than a simple transfer of care to an adult provider; it is a purposeful, planned movement of young adults with chronic medical conditions from a child-centered health care system to adult-oriented one.1 Many adolescents with chronic GI disorders are at increased risk of developmental and psychosocial delays and depressive disorders.2-6 A successful transition program can mitigate some of the psychosocial impacts of chronic disorders by improving self-efficacy and autonomy.7

Timing of transition

Unlike other nations where legislation often mandates the age of transition to adult care, the United States leaves decisions about the appropriate time to transition to the discretion of individual patients and pediatricians. While the actual transfer of care may not happen until later, it is prudent to start planning when the patient is in early adolescence. The pediatric gastroenterologist should initiate the discussion with patients and caregivers when the child is 13-15 years of age.12,13 Since health care transition is a complex and lengthy process, it should be approached within a framework that is appropriate for the developmental stage of the patient and at a time when their disease is in remission.14

During the initial discussions, the idea of transition should be introduced to the patient and his or her family by emphasizing the benefits of improved self-management skills, adherence to therapy, and normalization of development. The pediatrician should encourage a greater sense of independence and self-reliance by seeing the patient alone for at least a portion of the clinic visit and encourage future independent visits.

Developing a transition plan

Once the concept of transition of care has been introduced, it is prudent to devise a transition plan tailored to the specific needs and goals of the patient and family.24 Each plan should include who the adult provider will be, the tasks the adolescent must master before entering adult care, and how the care will be financed (because insurance coverage and options may change).25 A well-planned transition should enhance self-efficacy and self-management skills, increase knowledge of medical states, ensure adherence to therapy, and encourage independent decision making.12

Assessing transition readiness

Once the process of transitioning has been initiated, it is helpful to assess transition readiness at regular intervals. This will identify gaps in knowledge and inform appropriate interventions for individual patients. There are several questionnaires that can be administered at regular intervals and be made an integral part of routine clinic visits for adolescent patients. These assessments are now billable under CPT Code 99420 (administration and interpretation of health risk assessment). A standardized instrument should be used and the results recorded in the clinical encounter to ensure billing compliance.

The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (available online at www.GotTransition.org) is a validated tool that assesses an individual’s awareness of his or her medical needs, treatment plan, and ability to communicate effectively with his or her health care provider.26-28 While not specific to GI disorders, it has been validated in IBD patients and shown to correlate well with the IBD Self-Efficacy Scale for Adolescents.29,30 The University of North Carolina’s TRxANSITION Index, as well as the Social-Ecological Model of Adolescent and Young Adult Readiness for Transition, can be used for patients with various chronic diseases.31,32 Instruments specifically developed to assess transition readiness among patients with IBD include the “IBD-Yourself” questionnaire and MyHealth Passport for IBD.33,34 Additionally, Hait et al. provide a checklist of age-appropriate tasks for patients and their providers.14 The North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition has created the “Healthcare Provider Transition Checklist,” which is applicable to all chronic GI disorders.35

Transfer of care

The actual transfer of care is the culmination of the transition process. While the onus of initiating and monitoring a patient’s progress is driven by his or her pediatric provider, a responsive adult provider is integral, so it is vital to identify an adult gastroenterologist ahead of time. This can be especially difficult because most adult gastroenterologists feel uncomfortable about addressing adolescent developmental and mental health issues.36

Local chapters of societies such as the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, the American Liver Foundation, and statewide GI societies affiliated with the American College of Gastroenterology, as well as local or regional teaching institutions, are all good resources to identify adult providers interested in a coordinated transition of young adults into their practices. Depending on the availability of a local adult gastroenterologist, one approach to minimize the “growing pains” of transition can be to establish joint clinic visits with pediatric and adult providers; this strategy can help foster trust in the new physician and is generally well-received by patients.37,38 Other institutions may offer alternating visits with adult and pediatric providers during the first year of transition.

Regardless of the manner of the actual transfer of care, it is imperative the adult gastroenterologist be well versed with the natural history and disease complications of the pediatric onset of the specific GI disorder and also appreciate nutrition and concerns regarding growth and radiation. Moreover, they must recognize the convergence and divergence of traditional pediatric and adult care models, as well as the move from a family-centered to an individual-focused environment.39

At the time of the patient’s initial visit, the adult gastroenterologist needs a detailed history of the patient’s disease, a list of past and present medications, the details of any disease- or treatment-related complications or surgeries, and so on. The transfer of relevant medical records is an often overlooked, yet easily remediable, aspect of transfer of care.36 The overall process is best completed by eliciting posttransfer feedback from patients and families after they have established care with the adult provider.

Developing a transition model

In the absence of standard, disease-specific models of transition, most institutions adapt available resources to develop their own protocols. In 2011, a joint task force of the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American College of Physicians published a clinical report on transition. Based on recommendations put forth by the Center for Health Care Transition Improvement – a joint endeavor of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau and the National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health – the aforementioned task force developed a “Got Transition” model that incorporates six core elements of health care transition (Table 1).

Within the realm of chronic GI disorders, IBD has the most reported data on various models of transition. These include joint adult and pediatric visits, coordinator-initiated transitions, and patient preparation using the assessment tools detailed above. There are no data comparing the efficacy and success of these models and, in the absence of a universally established model for transition in IBD, each institution needs to adopt an approach that best suits the needs of patients and utilizes available resources.

As is the case for patients with IBD, patients with celiac disease need to assume exclusive responsibility for their care as young adults. An important aspect of transition planning for patients with celiac disease is the need to incorporate dietician-led didactic sessions during the transition process. Since patients with celiac disease do not require medications to manage their disease, they are often lost to follow-up as young adults.40 In addition to dietary compliance, it is important to educate young adults about the long-term complications related to celiac disease and the need for regular clinical assessment and monitoring.

Transition of care for patients with EoE is relatively understudied. As EoE was first described only in the 1990s, the diagnosis is still relatively new, and transition programs are limited.41 The natural history and progression of EoE had led to disparate management strategies in adults and children. While the latter are managed with dietary modifications and steroids, adults with EoE often require frequent esophageal dilations because of the increased incidence of fibrosis. In a study of pediatric patients with EoE, most scored lower on transition readiness assessments than did patients with other chronic health conditions.42 Since a majority of patients with EoE require lifelong treatment, they need to be better prepared for transition to adult care.43

In summary, regardless of disease state, transition of care requires planning on the part of the pediatric provider and also close collaboration with patient coordinators, nurses, social workers, and adult providers. While transition is often a complex and lengthy process, it fosters self-reliance and independence among patients while improving their quality of life. Effective communication between pediatric and adult providers as well as patients and families is key to successful transition of care.

Dr. Kaur is the medical director at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center and an assistant professor in the section of gastroenterology and hepatology in the department of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; Dr. Wyatt is an assistant professor in the section of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition in the department of pediatrics at Baylor.

References

1. Blum RW et al. J Adolesc Health. 1993 Nov;14(7):570-6.

2. Greenley RN et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010 Sep;35(8):857-69.

3. Simsek S et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Sep;61(3):303-6.

4. Kanof ME et al. Gastroenterology. 1988 Dec;95(6):1523-7.

5. Mackner LM et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 Mar;12(3):239-44.

6. Hummel TZ et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013 Aug;57(2):219-24.

7. Rosen DS et al. J Adolesc Health. 2003 Oct;33(4):309-11.

8. Bollegala N et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2013 Mar;7(2):e55-60.

9. Reed-Knight B et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011 Apr;36(3):308-17.

10. Holmes-Walker DJ et al. Diabet Med. 2007 Jul;24(7):764-9.

11. Dabadie A et al. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008 May;32(5 Pt 1):451-9.

12. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002 Dec;110(6 Pt 2):1304-6.

13. Baldassano R et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002 Mar;34(3):245-8.

14. Hait E et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 Jan;12(1):70-3.

15. Gray WN et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 May;21(5):1125-31.

16. Whitfield EP et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Jan;60(1):36-41.

17. Rosen D et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 Mar;22(3):702-8.

18. Fishman LN et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014 Aug;59(2):221-4.

19. Huang JS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 Jun;10(6):626-32.

20. Habibi H et al. Clin Nurse Spec. 2017 Nov;31(6):329-34.

21. Yerushalmy-Feler A et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Jul;29(7):831-7.

22. Shanske S et al. Soc Work Health Care. 2012;51(4):279-95.

23. Fredericks EM et al. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2015 Sep;22(2-3):150-9.

24. Hardin AP et al. Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2151.

25. Leung Y et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 Oct;17(10):2169-73.

26. Wood DL et al. Acad Pediatr. 2014 Jul-Aug;14(4):415-22.

27. Sample Transition Readiness Assessment for Youth. Got Transition/Center for Health Care Transition Improvement, Jan 2014. Accessed Jan 4, 2017, at http://www.gottransition.org/resourceGet.cfm?id=224.

28. Sawicki GS et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011 Mar;36(2):160-71.

29. Izaguirre MR et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017 Nov;65(5):546-50.

30. Carlsen K et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017 Mar;23(3):341-6.

31. Ferris ME et al. Ren Fail. 2012;34(6):744-53.

32. Schwartz LA et al. Child Care Health Dev. 2011 Nov;37(6):883-95.

33. Zijlstra M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2013 Oct;7(9):e375-85.

34. Benchimol EI et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 May;17(5):1131-7.

35. Heath Care Provider Transitioning Checklist. NASPGHAN. Accessed Jan 4, 2018, at https://www.naspghan.org/files/documents/pdfs/medical-resources/ibd/Checklist_PatientandHealthcareProdiver_TransitionfromPedtoAdult.pdf.

36. Hait EJ et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009 Jan;48(1):61-5.

37. Escher JC. Dig Dis. 2009;27(3):382-6.

38. Crowley R et al. Arch Dis Child. 2011 Jun;96(6):548-53.

39. Trivedi I et al. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:260807.

40. O’Leary C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Dec;99(12):2437-41.

41. de Silva PSA et al. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2017 Jun;64(3):707-20.

42. Eluri S et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017 Jul;65(1):53-7.

43. Dellon ES et al. Dis Esophagus. 2013 Jan;26(1):7-13.

As pediatric patients with chronic gastrointestinal (GI) disorders mature into adulthood, they require a seamless transition of care into an adult practice. Health care transition is more than a simple transfer of care to an adult provider; it is a purposeful, planned movement of young adults with chronic medical conditions from a child-centered health care system to adult-oriented one.1 Many adolescents with chronic GI disorders are at increased risk of developmental and psychosocial delays and depressive disorders.2-6 A successful transition program can mitigate some of the psychosocial impacts of chronic disorders by improving self-efficacy and autonomy.7

Timing of transition

Unlike other nations where legislation often mandates the age of transition to adult care, the United States leaves decisions about the appropriate time to transition to the discretion of individual patients and pediatricians. While the actual transfer of care may not happen until later, it is prudent to start planning when the patient is in early adolescence. The pediatric gastroenterologist should initiate the discussion with patients and caregivers when the child is 13-15 years of age.12,13 Since health care transition is a complex and lengthy process, it should be approached within a framework that is appropriate for the developmental stage of the patient and at a time when their disease is in remission.14

During the initial discussions, the idea of transition should be introduced to the patient and his or her family by emphasizing the benefits of improved self-management skills, adherence to therapy, and normalization of development. The pediatrician should encourage a greater sense of independence and self-reliance by seeing the patient alone for at least a portion of the clinic visit and encourage future independent visits.

Developing a transition plan

Once the concept of transition of care has been introduced, it is prudent to devise a transition plan tailored to the specific needs and goals of the patient and family.24 Each plan should include who the adult provider will be, the tasks the adolescent must master before entering adult care, and how the care will be financed (because insurance coverage and options may change).25 A well-planned transition should enhance self-efficacy and self-management skills, increase knowledge of medical states, ensure adherence to therapy, and encourage independent decision making.12

Assessing transition readiness

Once the process of transitioning has been initiated, it is helpful to assess transition readiness at regular intervals. This will identify gaps in knowledge and inform appropriate interventions for individual patients. There are several questionnaires that can be administered at regular intervals and be made an integral part of routine clinic visits for adolescent patients. These assessments are now billable under CPT Code 99420 (administration and interpretation of health risk assessment). A standardized instrument should be used and the results recorded in the clinical encounter to ensure billing compliance.

The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (available online at www.GotTransition.org) is a validated tool that assesses an individual’s awareness of his or her medical needs, treatment plan, and ability to communicate effectively with his or her health care provider.26-28 While not specific to GI disorders, it has been validated in IBD patients and shown to correlate well with the IBD Self-Efficacy Scale for Adolescents.29,30 The University of North Carolina’s TRxANSITION Index, as well as the Social-Ecological Model of Adolescent and Young Adult Readiness for Transition, can be used for patients with various chronic diseases.31,32 Instruments specifically developed to assess transition readiness among patients with IBD include the “IBD-Yourself” questionnaire and MyHealth Passport for IBD.33,34 Additionally, Hait et al. provide a checklist of age-appropriate tasks for patients and their providers.14 The North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition has created the “Healthcare Provider Transition Checklist,” which is applicable to all chronic GI disorders.35

Transfer of care

The actual transfer of care is the culmination of the transition process. While the onus of initiating and monitoring a patient’s progress is driven by his or her pediatric provider, a responsive adult provider is integral, so it is vital to identify an adult gastroenterologist ahead of time. This can be especially difficult because most adult gastroenterologists feel uncomfortable about addressing adolescent developmental and mental health issues.36

Local chapters of societies such as the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, the American Liver Foundation, and statewide GI societies affiliated with the American College of Gastroenterology, as well as local or regional teaching institutions, are all good resources to identify adult providers interested in a coordinated transition of young adults into their practices. Depending on the availability of a local adult gastroenterologist, one approach to minimize the “growing pains” of transition can be to establish joint clinic visits with pediatric and adult providers; this strategy can help foster trust in the new physician and is generally well-received by patients.37,38 Other institutions may offer alternating visits with adult and pediatric providers during the first year of transition.

Regardless of the manner of the actual transfer of care, it is imperative the adult gastroenterologist be well versed with the natural history and disease complications of the pediatric onset of the specific GI disorder and also appreciate nutrition and concerns regarding growth and radiation. Moreover, they must recognize the convergence and divergence of traditional pediatric and adult care models, as well as the move from a family-centered to an individual-focused environment.39

At the time of the patient’s initial visit, the adult gastroenterologist needs a detailed history of the patient’s disease, a list of past and present medications, the details of any disease- or treatment-related complications or surgeries, and so on. The transfer of relevant medical records is an often overlooked, yet easily remediable, aspect of transfer of care.36 The overall process is best completed by eliciting posttransfer feedback from patients and families after they have established care with the adult provider.

Developing a transition model

In the absence of standard, disease-specific models of transition, most institutions adapt available resources to develop their own protocols. In 2011, a joint task force of the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American College of Physicians published a clinical report on transition. Based on recommendations put forth by the Center for Health Care Transition Improvement – a joint endeavor of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau and the National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health – the aforementioned task force developed a “Got Transition” model that incorporates six core elements of health care transition (Table 1).

Within the realm of chronic GI disorders, IBD has the most reported data on various models of transition. These include joint adult and pediatric visits, coordinator-initiated transitions, and patient preparation using the assessment tools detailed above. There are no data comparing the efficacy and success of these models and, in the absence of a universally established model for transition in IBD, each institution needs to adopt an approach that best suits the needs of patients and utilizes available resources.

As is the case for patients with IBD, patients with celiac disease need to assume exclusive responsibility for their care as young adults. An important aspect of transition planning for patients with celiac disease is the need to incorporate dietician-led didactic sessions during the transition process. Since patients with celiac disease do not require medications to manage their disease, they are often lost to follow-up as young adults.40 In addition to dietary compliance, it is important to educate young adults about the long-term complications related to celiac disease and the need for regular clinical assessment and monitoring.

Transition of care for patients with EoE is relatively understudied. As EoE was first described only in the 1990s, the diagnosis is still relatively new, and transition programs are limited.41 The natural history and progression of EoE had led to disparate management strategies in adults and children. While the latter are managed with dietary modifications and steroids, adults with EoE often require frequent esophageal dilations because of the increased incidence of fibrosis. In a study of pediatric patients with EoE, most scored lower on transition readiness assessments than did patients with other chronic health conditions.42 Since a majority of patients with EoE require lifelong treatment, they need to be better prepared for transition to adult care.43

In summary, regardless of disease state, transition of care requires planning on the part of the pediatric provider and also close collaboration with patient coordinators, nurses, social workers, and adult providers. While transition is often a complex and lengthy process, it fosters self-reliance and independence among patients while improving their quality of life. Effective communication between pediatric and adult providers as well as patients and families is key to successful transition of care.

Dr. Kaur is the medical director at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center and an assistant professor in the section of gastroenterology and hepatology in the department of medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston; Dr. Wyatt is an assistant professor in the section of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition in the department of pediatrics at Baylor.

References

1. Blum RW et al. J Adolesc Health. 1993 Nov;14(7):570-6.

2. Greenley RN et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010 Sep;35(8):857-69.

3. Simsek S et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Sep;61(3):303-6.

4. Kanof ME et al. Gastroenterology. 1988 Dec;95(6):1523-7.

5. Mackner LM et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 Mar;12(3):239-44.

6. Hummel TZ et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013 Aug;57(2):219-24.

7. Rosen DS et al. J Adolesc Health. 2003 Oct;33(4):309-11.

8. Bollegala N et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2013 Mar;7(2):e55-60.

9. Reed-Knight B et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011 Apr;36(3):308-17.

10. Holmes-Walker DJ et al. Diabet Med. 2007 Jul;24(7):764-9.

11. Dabadie A et al. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008 May;32(5 Pt 1):451-9.

12. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002 Dec;110(6 Pt 2):1304-6.

13. Baldassano R et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002 Mar;34(3):245-8.

14. Hait E et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006 Jan;12(1):70-3.

15. Gray WN et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 May;21(5):1125-31.

16. Whitfield EP et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015 Jan;60(1):36-41.

17. Rosen D et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016 Mar;22(3):702-8.

18. Fishman LN et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014 Aug;59(2):221-4.

19. Huang JS et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012 Jun;10(6):626-32.

20. Habibi H et al. Clin Nurse Spec. 2017 Nov;31(6):329-34.

21. Yerushalmy-Feler A et al. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Jul;29(7):831-7.

22. Shanske S et al. Soc Work Health Care. 2012;51(4):279-95.

23. Fredericks EM et al. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2015 Sep;22(2-3):150-9.

24. Hardin AP et al. Pediatrics. 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2151.

25. Leung Y et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 Oct;17(10):2169-73.

26. Wood DL et al. Acad Pediatr. 2014 Jul-Aug;14(4):415-22.

27. Sample Transition Readiness Assessment for Youth. Got Transition/Center for Health Care Transition Improvement, Jan 2014. Accessed Jan 4, 2017, at http://www.gottransition.org/resourceGet.cfm?id=224.

28. Sawicki GS et al. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011 Mar;36(2):160-71.

29. Izaguirre MR et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017 Nov;65(5):546-50.

30. Carlsen K et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017 Mar;23(3):341-6.

31. Ferris ME et al. Ren Fail. 2012;34(6):744-53.

32. Schwartz LA et al. Child Care Health Dev. 2011 Nov;37(6):883-95.

33. Zijlstra M et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2013 Oct;7(9):e375-85.

34. Benchimol EI et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 May;17(5):1131-7.

35. Heath Care Provider Transitioning Checklist. NASPGHAN. Accessed Jan 4, 2018, at https://www.naspghan.org/files/documents/pdfs/medical-resources/ibd/Checklist_PatientandHealthcareProdiver_TransitionfromPedtoAdult.pdf.

36. Hait EJ et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009 Jan;48(1):61-5.

37. Escher JC. Dig Dis. 2009;27(3):382-6.

38. Crowley R et al. Arch Dis Child. 2011 Jun;96(6):548-53.

39. Trivedi I et al. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:260807.

40. O’Leary C et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Dec;99(12):2437-41.

41. de Silva PSA et al. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2017 Jun;64(3):707-20.

42. Eluri S et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017 Jul;65(1):53-7.

43. Dellon ES et al. Dis Esophagus. 2013 Jan;26(1):7-13.

Choosing a career in health care administration

Dr. Shah is chief medical officer, Mount Sinai Queens, director of quality and patient safety education, Mount Sinai Health System, associate professor of medicine/GI and geriatrics/palliative medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, N.Y.

How did your career pathway lead you into hospital administration?

My career pathway into hospital administration was not by design. Since college, I have always enjoyed building and managing programs. As chief resident, I was exposed to operational and managerial aspects of running an internal medicine residency program as well as an outpatient clinic. This program first exposed me to quality improvement and patient-safety functions within a hospital. I continued to build on this during my GI fellowship and in my first few years as faculty in our division. Patient safety and quality improvement involve the critical thinking and quantitative aspects of research applied to problems in the workplace. This interest and skill, along with my growing experience in management, led me to explore opportunities in hospital administration.

What are your responsibilities in a typical week?

As a chief medical officer at a smaller hospital, my scope of responsibilities includes overseeing health care quality and patient safety, building our outpatient practice and new clinical service lines, building a cohesive medical staff, handling disciplinary and professionalism issues, and overseeing six support departments. I work closely with our chief operating officer, chief nursing officer, executive director, and site chiefs.

What do you enjoy most about working in hospital administration?

I enjoy the work I do related to making care safer for our patients and for those who work in our hospital. I take each patient-safety event personally. The teamwork necessary to understand these events and develop creative solutions is extremely rewarding. I enjoy mentoring our faculty and hospital managers to achieve their own goals. Lastly, I have enjoyed working with professionals with backgrounds that differ from my own. I have learned an incredible amount about hospital operations, leadership, financing, as well as legal and labor-relations issues from our staff in other departments.

What do you find most challenging about working in hospital administration?

The scope of work in my role at my current hospital is very broad. It can be a challenge to focus on long-term goals given the number of “fires” that creep up during the week. I always try to keep patients and staff at the center of my decision making. However, a hospital is a complex organism and decisions also have a financial and operational impact. One challenge is to know and understand this impact and then work with other leaders to develop a solution that works for all.

The other challenge is managing conflict in a way that leads to creative solutions satisfying the needs of multiple stakeholders. We are constantly challenged by limited resources (including time). These challenges are inherent to any leadership position. I am fortunate to work within a leadership team that is collaborative; they are an invaluable resource when these issues arise.

What are the different hospital administration positions that are available to GIs?

More than ever, the options for administrative work in health care have expanded. There are hospital-based roles within a department (e.g., director of endoscopy, clinical chief, director of quality improvement/patient safety for GI) and larger roles in the hospital-at-large (e.g., chief operating officer, chief medical officer, chief quality officer). These roles require certain technical skills and knowledge as well as experience within patient care. Other opportunities include the medical board, credentials committee, or serving as a member of a hospital committee (e.g., pharmacy, perioperative, infection control, process improvement). Since hospitals and health systems have expanded into the outpatient setting, additional positions include medical director for a practice, director of population health, or a leadership role in clinical operations.

Physicians from many different specialties have entered these roles based on their local hospital needs. In addition to clinical experience, leadership and interpersonal skills are critical for success.

How would a fellow or early-career GI who is interested in hospital medicine pursue this career pathway?

My first suggestion is to get involved in local efforts based on your interest. For example, if you are interested in quality improvement, seek to be a member of your department or hospital quality improvement committee. In GI and hepatology, natural places to get involved are around the development of care pathways, readmission committees, and initiatives to increase screening and treatment of hepatitis C or colon cancer. If you are interested in operations, look to see if there is an endoscopy or clinic operations committee you can get involved in. Get to know your medical board and medical staff structure. I gained exposure to this world by observing some of these meetings and then being asked to join them. These are valuable groups that help to create policy, raise important issues, and work with administration in the management of the hospital.

I am also a big fan of informational interviewing. If there are leaders who do the type of work you are interested in, consider reaching out with a call or email and asking to meet with them to talk about their role and career path.

As a fellow, there is an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirement to incorporate residents and fellows onto hospital committees. This requirement has been a great way to have fellows incorporated into hospital work. You will find that those in hospital administration are eager to have interested and collegial partners in the work that is being done.

Are there any advanced training options available for those interested in hospital administration?

Depending on the position, there are numerous certificate and master’s programs that can provide formal education. CEOs and COOs may seek an MBA or master’s in Health Care Administration. There are programs that focus on Health Care Leadership or Quality and Patient Safety that are applicable to many leadership positions. These are offered in in-person and online formats. However, many physicians in these positions have a combination of informal and experiential learning programs that developed their skill set.

Some hospital systems offer an internal physician leadership training program to develop early and midcareer physician executives. There are professional organizations that offer courses for leadership development (e.g., American College of Physician Executives). Some business schools offer shorter-format programs that are geared toward health care leaders and focus on finance, operations, or quality.

I received some of my training through the Clinical Quality Fellowship Program, which is a 14-month experiential learning program in quality and patient safety that is run locally in New York City. In addition, I had some leadership training through the Association of American Medical Colleges and through the AGA Future Leaders Program (http://www.gastro.org/about/initiatives/aga-future-leaders-program).

Hospitals, outpatient practices, and health systems offer career paths including patient safety, quality improvement, or hospital management. I have enjoyed stretching my existing skill set in these roles while learning about how health facilities work, gaining knowledge of health care financing, and making care safer while ensuring high quality. These roles require teamwork across professions and specialties. As a gastroenterologist or hepatologist, we bring our own clinical and professional experience, which can be invaluable to the overall health care management team.

Dr. Shah is chief medical officer, Mount Sinai Queens, director of quality and patient safety education, Mount Sinai Health System, associate professor of medicine/GI and geriatrics/palliative medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, N.Y.

How did your career pathway lead you into hospital administration?

My career pathway into hospital administration was not by design. Since college, I have always enjoyed building and managing programs. As chief resident, I was exposed to operational and managerial aspects of running an internal medicine residency program as well as an outpatient clinic. This program first exposed me to quality improvement and patient-safety functions within a hospital. I continued to build on this during my GI fellowship and in my first few years as faculty in our division. Patient safety and quality improvement involve the critical thinking and quantitative aspects of research applied to problems in the workplace. This interest and skill, along with my growing experience in management, led me to explore opportunities in hospital administration.

What are your responsibilities in a typical week?

As a chief medical officer at a smaller hospital, my scope of responsibilities includes overseeing health care quality and patient safety, building our outpatient practice and new clinical service lines, building a cohesive medical staff, handling disciplinary and professionalism issues, and overseeing six support departments. I work closely with our chief operating officer, chief nursing officer, executive director, and site chiefs.

What do you enjoy most about working in hospital administration?

I enjoy the work I do related to making care safer for our patients and for those who work in our hospital. I take each patient-safety event personally. The teamwork necessary to understand these events and develop creative solutions is extremely rewarding. I enjoy mentoring our faculty and hospital managers to achieve their own goals. Lastly, I have enjoyed working with professionals with backgrounds that differ from my own. I have learned an incredible amount about hospital operations, leadership, financing, as well as legal and labor-relations issues from our staff in other departments.

What do you find most challenging about working in hospital administration?

The scope of work in my role at my current hospital is very broad. It can be a challenge to focus on long-term goals given the number of “fires” that creep up during the week. I always try to keep patients and staff at the center of my decision making. However, a hospital is a complex organism and decisions also have a financial and operational impact. One challenge is to know and understand this impact and then work with other leaders to develop a solution that works for all.

The other challenge is managing conflict in a way that leads to creative solutions satisfying the needs of multiple stakeholders. We are constantly challenged by limited resources (including time). These challenges are inherent to any leadership position. I am fortunate to work within a leadership team that is collaborative; they are an invaluable resource when these issues arise.

What are the different hospital administration positions that are available to GIs?

More than ever, the options for administrative work in health care have expanded. There are hospital-based roles within a department (e.g., director of endoscopy, clinical chief, director of quality improvement/patient safety for GI) and larger roles in the hospital-at-large (e.g., chief operating officer, chief medical officer, chief quality officer). These roles require certain technical skills and knowledge as well as experience within patient care. Other opportunities include the medical board, credentials committee, or serving as a member of a hospital committee (e.g., pharmacy, perioperative, infection control, process improvement). Since hospitals and health systems have expanded into the outpatient setting, additional positions include medical director for a practice, director of population health, or a leadership role in clinical operations.

Physicians from many different specialties have entered these roles based on their local hospital needs. In addition to clinical experience, leadership and interpersonal skills are critical for success.

How would a fellow or early-career GI who is interested in hospital medicine pursue this career pathway?

My first suggestion is to get involved in local efforts based on your interest. For example, if you are interested in quality improvement, seek to be a member of your department or hospital quality improvement committee. In GI and hepatology, natural places to get involved are around the development of care pathways, readmission committees, and initiatives to increase screening and treatment of hepatitis C or colon cancer. If you are interested in operations, look to see if there is an endoscopy or clinic operations committee you can get involved in. Get to know your medical board and medical staff structure. I gained exposure to this world by observing some of these meetings and then being asked to join them. These are valuable groups that help to create policy, raise important issues, and work with administration in the management of the hospital.

I am also a big fan of informational interviewing. If there are leaders who do the type of work you are interested in, consider reaching out with a call or email and asking to meet with them to talk about their role and career path.

As a fellow, there is an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirement to incorporate residents and fellows onto hospital committees. This requirement has been a great way to have fellows incorporated into hospital work. You will find that those in hospital administration are eager to have interested and collegial partners in the work that is being done.

Are there any advanced training options available for those interested in hospital administration?

Depending on the position, there are numerous certificate and master’s programs that can provide formal education. CEOs and COOs may seek an MBA or master’s in Health Care Administration. There are programs that focus on Health Care Leadership or Quality and Patient Safety that are applicable to many leadership positions. These are offered in in-person and online formats. However, many physicians in these positions have a combination of informal and experiential learning programs that developed their skill set.

Some hospital systems offer an internal physician leadership training program to develop early and midcareer physician executives. There are professional organizations that offer courses for leadership development (e.g., American College of Physician Executives). Some business schools offer shorter-format programs that are geared toward health care leaders and focus on finance, operations, or quality.

I received some of my training through the Clinical Quality Fellowship Program, which is a 14-month experiential learning program in quality and patient safety that is run locally in New York City. In addition, I had some leadership training through the Association of American Medical Colleges and through the AGA Future Leaders Program (http://www.gastro.org/about/initiatives/aga-future-leaders-program).

Hospitals, outpatient practices, and health systems offer career paths including patient safety, quality improvement, or hospital management. I have enjoyed stretching my existing skill set in these roles while learning about how health facilities work, gaining knowledge of health care financing, and making care safer while ensuring high quality. These roles require teamwork across professions and specialties. As a gastroenterologist or hepatologist, we bring our own clinical and professional experience, which can be invaluable to the overall health care management team.

Dr. Shah is chief medical officer, Mount Sinai Queens, director of quality and patient safety education, Mount Sinai Health System, associate professor of medicine/GI and geriatrics/palliative medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, N.Y.

How did your career pathway lead you into hospital administration?

My career pathway into hospital administration was not by design. Since college, I have always enjoyed building and managing programs. As chief resident, I was exposed to operational and managerial aspects of running an internal medicine residency program as well as an outpatient clinic. This program first exposed me to quality improvement and patient-safety functions within a hospital. I continued to build on this during my GI fellowship and in my first few years as faculty in our division. Patient safety and quality improvement involve the critical thinking and quantitative aspects of research applied to problems in the workplace. This interest and skill, along with my growing experience in management, led me to explore opportunities in hospital administration.

What are your responsibilities in a typical week?

As a chief medical officer at a smaller hospital, my scope of responsibilities includes overseeing health care quality and patient safety, building our outpatient practice and new clinical service lines, building a cohesive medical staff, handling disciplinary and professionalism issues, and overseeing six support departments. I work closely with our chief operating officer, chief nursing officer, executive director, and site chiefs.

What do you enjoy most about working in hospital administration?

I enjoy the work I do related to making care safer for our patients and for those who work in our hospital. I take each patient-safety event personally. The teamwork necessary to understand these events and develop creative solutions is extremely rewarding. I enjoy mentoring our faculty and hospital managers to achieve their own goals. Lastly, I have enjoyed working with professionals with backgrounds that differ from my own. I have learned an incredible amount about hospital operations, leadership, financing, as well as legal and labor-relations issues from our staff in other departments.

What do you find most challenging about working in hospital administration?

The scope of work in my role at my current hospital is very broad. It can be a challenge to focus on long-term goals given the number of “fires” that creep up during the week. I always try to keep patients and staff at the center of my decision making. However, a hospital is a complex organism and decisions also have a financial and operational impact. One challenge is to know and understand this impact and then work with other leaders to develop a solution that works for all.

The other challenge is managing conflict in a way that leads to creative solutions satisfying the needs of multiple stakeholders. We are constantly challenged by limited resources (including time). These challenges are inherent to any leadership position. I am fortunate to work within a leadership team that is collaborative; they are an invaluable resource when these issues arise.

What are the different hospital administration positions that are available to GIs?

More than ever, the options for administrative work in health care have expanded. There are hospital-based roles within a department (e.g., director of endoscopy, clinical chief, director of quality improvement/patient safety for GI) and larger roles in the hospital-at-large (e.g., chief operating officer, chief medical officer, chief quality officer). These roles require certain technical skills and knowledge as well as experience within patient care. Other opportunities include the medical board, credentials committee, or serving as a member of a hospital committee (e.g., pharmacy, perioperative, infection control, process improvement). Since hospitals and health systems have expanded into the outpatient setting, additional positions include medical director for a practice, director of population health, or a leadership role in clinical operations.

Physicians from many different specialties have entered these roles based on their local hospital needs. In addition to clinical experience, leadership and interpersonal skills are critical for success.

How would a fellow or early-career GI who is interested in hospital medicine pursue this career pathway?

My first suggestion is to get involved in local efforts based on your interest. For example, if you are interested in quality improvement, seek to be a member of your department or hospital quality improvement committee. In GI and hepatology, natural places to get involved are around the development of care pathways, readmission committees, and initiatives to increase screening and treatment of hepatitis C or colon cancer. If you are interested in operations, look to see if there is an endoscopy or clinic operations committee you can get involved in. Get to know your medical board and medical staff structure. I gained exposure to this world by observing some of these meetings and then being asked to join them. These are valuable groups that help to create policy, raise important issues, and work with administration in the management of the hospital.

I am also a big fan of informational interviewing. If there are leaders who do the type of work you are interested in, consider reaching out with a call or email and asking to meet with them to talk about their role and career path.

As a fellow, there is an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirement to incorporate residents and fellows onto hospital committees. This requirement has been a great way to have fellows incorporated into hospital work. You will find that those in hospital administration are eager to have interested and collegial partners in the work that is being done.

Are there any advanced training options available for those interested in hospital administration?

Depending on the position, there are numerous certificate and master’s programs that can provide formal education. CEOs and COOs may seek an MBA or master’s in Health Care Administration. There are programs that focus on Health Care Leadership or Quality and Patient Safety that are applicable to many leadership positions. These are offered in in-person and online formats. However, many physicians in these positions have a combination of informal and experiential learning programs that developed their skill set.

Some hospital systems offer an internal physician leadership training program to develop early and midcareer physician executives. There are professional organizations that offer courses for leadership development (e.g., American College of Physician Executives). Some business schools offer shorter-format programs that are geared toward health care leaders and focus on finance, operations, or quality.

I received some of my training through the Clinical Quality Fellowship Program, which is a 14-month experiential learning program in quality and patient safety that is run locally in New York City. In addition, I had some leadership training through the Association of American Medical Colleges and through the AGA Future Leaders Program (http://www.gastro.org/about/initiatives/aga-future-leaders-program).

Hospitals, outpatient practices, and health systems offer career paths including patient safety, quality improvement, or hospital management. I have enjoyed stretching my existing skill set in these roles while learning about how health facilities work, gaining knowledge of health care financing, and making care safer while ensuring high quality. These roles require teamwork across professions and specialties. As a gastroenterologist or hepatologist, we bring our own clinical and professional experience, which can be invaluable to the overall health care management team.

Gastroenterology debuts editorial fellowship program

The readership of Gastroenterology includes a broad distribution of stakeholders in digestive health, including those with vested interests in clinical practice, education, policy, clinical investigation, and basic research. One of our most critical constituencies, however, is trainees and early-career GIs. In an effort to support such individuals, our editorial team has developed a freshly minted 1-year editorial fellowship for Gastroenterology. The overarching purpose of this fellowship is to mentor an outstanding trainee for future editorial leadership roles in scientific publishing, as a means to promote the interests of trainee and early-career GI constituencies within the AGA and Gastroenterology. This fellowship is available to exceptional second- or third-year fellows through an application process. The intent of this training is to allow the selected applicant to become intimately involved with Gastroenterology’s entire editorial process, including peer review, editorial oversight, manuscript selection for publication, production, and postpublication activities. Our first fellow, Eric Shah, MD, MBA, was selected from a highly competitive pool of exceptional applicants, and began his fellowship on July 1, 2017.

This year, we have been delighted to work with Dr. Shah as our inaugural Gastroenterology fellow. Dr. Shah has a unique background, having pursued a joint MD and MBA (earning both concurrently), while also following venture-oriented interests in developing GI technology from academia. Dr. Shah began his research career under the mentorship of Mark Pimentel, MD, and Gil Melmed, MD, at Cedars-Sinai as part of a Research Honors Program. Since that time, he has focused on evaluating the comparative efficacy, durability, and harm associated with pharmacotherapy in functional bowel disorders. Dr. Shah was accepted into the GI fellowship training program at the University of Michigan and received a slot on the T32 training grant to study cost-effectiveness and qualitative research techniques to address gaps in the care of functional bowel disorders. His work under the mentorship of William Chey, MD, Ryan Stidham, MD, and Philip S. Schoenfeld, MD, has flourished and culminated in an oral presentation and several posters for DDW 2017, as well as several first-author manuscripts that have been submitted. Dr. Shah has fully embraced the Gastroenterology fellowship and has far surpassed our high expectations for this position.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

VIDEO SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

In addition to creating an editorial fellowship, our team has also developed other components within the journal that specifically target trainees and early-career GIs. The Mentoring, Education and Training section – initiated in 2011 through the vision and insight of Bishr Omary MD, PhD, and John Del Valle, MD, at the University of Michigan – has been extremely effective in highlighting critical issues relevant to trainees, young faculty, and early-career GIs. Topics have included mentoring advice not only for individuals in academic or private practice careers but also industry careers and midlevel providers. Other topics have included Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education milestones, career advancement for clinician-educators, sex and ethnic diversity, and maintenance of certification, as well as guidance regarding nontraditional funding mechanisms such as philanthropy. Potential future topics will include information about major new public and private funding initiatives, comments and input from National Institutes of Health officials, and reports of funding trends relevant to both physician scientists and clinicians. We are fortunate to have Prateek Sharma, MD, lead this section, and his depth of experience as an exceptional mentor has provided the requisite expertise.

Additionally, we offer a reduction in page charges to junior investigators (within 7 years of fellowship) who are the corresponding authors of exceedingly important original Gastroenterology manuscripts. These manuscripts from junior investigators will be highlighted in both print and online versions of Gastroenterology. We are using the journal to expand electronic access to educational offerings for new technologies, training, self-assessment, and practice improvement to establish the AGA as the ultimate resource for junior academicians and practicing physicians. We are also currently integrating Gastroenterology more closely into other AGA educational efforts that target young physicians, such as the AGA Education and Training Committee.

At Gastroenterology, we are acutely aware of the needs and obstacles facing trainees, young faculty, and early-career GIs. We have boldly adopted a multidimensional approach to provide guidance and opportunities to overcome these challenges, including the creation of the nascent Editorial Fellowship. We welcome applications for the next fellowship, which will be announced by the AGA in the spring of 2018!

Dr. Peek is the Mina Wallace Professor of Medicine, Cancer Biology, and Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, and director, division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. He has no conflicts of interest.

The readership of Gastroenterology includes a broad distribution of stakeholders in digestive health, including those with vested interests in clinical practice, education, policy, clinical investigation, and basic research. One of our most critical constituencies, however, is trainees and early-career GIs. In an effort to support such individuals, our editorial team has developed a freshly minted 1-year editorial fellowship for Gastroenterology. The overarching purpose of this fellowship is to mentor an outstanding trainee for future editorial leadership roles in scientific publishing, as a means to promote the interests of trainee and early-career GI constituencies within the AGA and Gastroenterology. This fellowship is available to exceptional second- or third-year fellows through an application process. The intent of this training is to allow the selected applicant to become intimately involved with Gastroenterology’s entire editorial process, including peer review, editorial oversight, manuscript selection for publication, production, and postpublication activities. Our first fellow, Eric Shah, MD, MBA, was selected from a highly competitive pool of exceptional applicants, and began his fellowship on July 1, 2017.

This year, we have been delighted to work with Dr. Shah as our inaugural Gastroenterology fellow. Dr. Shah has a unique background, having pursued a joint MD and MBA (earning both concurrently), while also following venture-oriented interests in developing GI technology from academia. Dr. Shah began his research career under the mentorship of Mark Pimentel, MD, and Gil Melmed, MD, at Cedars-Sinai as part of a Research Honors Program. Since that time, he has focused on evaluating the comparative efficacy, durability, and harm associated with pharmacotherapy in functional bowel disorders. Dr. Shah was accepted into the GI fellowship training program at the University of Michigan and received a slot on the T32 training grant to study cost-effectiveness and qualitative research techniques to address gaps in the care of functional bowel disorders. His work under the mentorship of William Chey, MD, Ryan Stidham, MD, and Philip S. Schoenfeld, MD, has flourished and culminated in an oral presentation and several posters for DDW 2017, as well as several first-author manuscripts that have been submitted. Dr. Shah has fully embraced the Gastroenterology fellowship and has far surpassed our high expectations for this position.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

VIDEO SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

In addition to creating an editorial fellowship, our team has also developed other components within the journal that specifically target trainees and early-career GIs. The Mentoring, Education and Training section – initiated in 2011 through the vision and insight of Bishr Omary MD, PhD, and John Del Valle, MD, at the University of Michigan – has been extremely effective in highlighting critical issues relevant to trainees, young faculty, and early-career GIs. Topics have included mentoring advice not only for individuals in academic or private practice careers but also industry careers and midlevel providers. Other topics have included Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education milestones, career advancement for clinician-educators, sex and ethnic diversity, and maintenance of certification, as well as guidance regarding nontraditional funding mechanisms such as philanthropy. Potential future topics will include information about major new public and private funding initiatives, comments and input from National Institutes of Health officials, and reports of funding trends relevant to both physician scientists and clinicians. We are fortunate to have Prateek Sharma, MD, lead this section, and his depth of experience as an exceptional mentor has provided the requisite expertise.

Additionally, we offer a reduction in page charges to junior investigators (within 7 years of fellowship) who are the corresponding authors of exceedingly important original Gastroenterology manuscripts. These manuscripts from junior investigators will be highlighted in both print and online versions of Gastroenterology. We are using the journal to expand electronic access to educational offerings for new technologies, training, self-assessment, and practice improvement to establish the AGA as the ultimate resource for junior academicians and practicing physicians. We are also currently integrating Gastroenterology more closely into other AGA educational efforts that target young physicians, such as the AGA Education and Training Committee.

At Gastroenterology, we are acutely aware of the needs and obstacles facing trainees, young faculty, and early-career GIs. We have boldly adopted a multidimensional approach to provide guidance and opportunities to overcome these challenges, including the creation of the nascent Editorial Fellowship. We welcome applications for the next fellowship, which will be announced by the AGA in the spring of 2018!

Dr. Peek is the Mina Wallace Professor of Medicine, Cancer Biology, and Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, and director, division of gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. He has no conflicts of interest.

The readership of Gastroenterology includes a broad distribution of stakeholders in digestive health, including those with vested interests in clinical practice, education, policy, clinical investigation, and basic research. One of our most critical constituencies, however, is trainees and early-career GIs. In an effort to support such individuals, our editorial team has developed a freshly minted 1-year editorial fellowship for Gastroenterology. The overarching purpose of this fellowship is to mentor an outstanding trainee for future editorial leadership roles in scientific publishing, as a means to promote the interests of trainee and early-career GI constituencies within the AGA and Gastroenterology. This fellowship is available to exceptional second- or third-year fellows through an application process. The intent of this training is to allow the selected applicant to become intimately involved with Gastroenterology’s entire editorial process, including peer review, editorial oversight, manuscript selection for publication, production, and postpublication activities. Our first fellow, Eric Shah, MD, MBA, was selected from a highly competitive pool of exceptional applicants, and began his fellowship on July 1, 2017.

This year, we have been delighted to work with Dr. Shah as our inaugural Gastroenterology fellow. Dr. Shah has a unique background, having pursued a joint MD and MBA (earning both concurrently), while also following venture-oriented interests in developing GI technology from academia. Dr. Shah began his research career under the mentorship of Mark Pimentel, MD, and Gil Melmed, MD, at Cedars-Sinai as part of a Research Honors Program. Since that time, he has focused on evaluating the comparative efficacy, durability, and harm associated with pharmacotherapy in functional bowel disorders. Dr. Shah was accepted into the GI fellowship training program at the University of Michigan and received a slot on the T32 training grant to study cost-effectiveness and qualitative research techniques to address gaps in the care of functional bowel disorders. His work under the mentorship of William Chey, MD, Ryan Stidham, MD, and Philip S. Schoenfeld, MD, has flourished and culminated in an oral presentation and several posters for DDW 2017, as well as several first-author manuscripts that have been submitted. Dr. Shah has fully embraced the Gastroenterology fellowship and has far surpassed our high expectations for this position.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

VIDEO SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

In addition to creating an editorial fellowship, our team has also developed other components within the journal that specifically target trainees and early-career GIs. The Mentoring, Education and Training section – initiated in 2011 through the vision and insight of Bishr Omary MD, PhD, and John Del Valle, MD, at the University of Michigan – has been extremely effective in highlighting critical issues relevant to trainees, young faculty, and early-career GIs. Topics have included mentoring advice not only for individuals in academic or private practice careers but also industry careers and midlevel providers. Other topics have included Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education milestones, career advancement for clinician-educators, sex and ethnic diversity, and maintenance of certification, as well as guidance regarding nontraditional funding mechanisms such as philanthropy. Potential future topics will include information about major new public and private funding initiatives, comments and input from National Institutes of Health officials, and reports of funding trends relevant to both physician scientists and clinicians. We are fortunate to have Prateek Sharma, MD, lead this section, and his depth of experience as an exceptional mentor has provided the requisite expertise.