User login

Pediatric Dermatology Consult - January 2018

Morphea, also known as localized scleroderma, is a rare fibrosing disorder of the skin and the underlying tissue that encompasses a variety of distinct subtypes classified by pattern and depth of lesion involvement. It may involve fat, fascia, muscle, and bone, and rarely, the central nervous system. Morphea is easily differentiated from systemic sclerosis by its primarily cutaneous involvement, although a minority of patients may have associated extracutaneous findings. Systemic sclerosis describes a well-defined disorder of skin sclerosis with a specific pattern of internal organ involvement.

Classification of the different subtypes of morphea are based on clinical presentation of the lesions. The most widely used system characterizes morphea into linear, circumscribed, generalized, pansclerotic, and mixed morphea subtypes.1 Mixed morphea describes the presence of two or more patterns of disease and affects 15% of patients. Morphea lesions initially present as erythematous to violaceous patches and plaques that eventually become white and sclerotic, with resulting destruction of the surrounding structures.

Linear scleroderma is the most common subtype of morphea in children and adolescents, affecting 42%-67% of children with morphea.1 It is characterized by linear plaques, often on the extremities, face, or scalp, that tend to follow Blaschko lines.4 These lesions may extend past the dermis to the subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and even bone, resulting in significant deformities. When on the scalp or face, particularly the forehead, the linear lesion may be referred to as the en coup de sabre variant. Ocular and CNS involvement should be of concern in these patients. When subcutaneous atrophy on the unilateral face is present with unaffected overlaying skin, this is known as the Parry-Romberg syndrome or progressive hemifacial atrophy. Involvement of the extremities is common, and unfortunately, may lead to muscle atrophy of the affected limb, contractures in areas overlying joint spaces, and occasionally limb length discrepancies.

Circumscribed morphea describes three or fewer discrete, oval, or round indurated plaques, with central whitening and a violaceous periphery. They generally are found on the trunk. When lesions have deeper involvement, delving past the dermis to involve the underlying fascia and muscle, the patient may experience a “bound down” sensation. Most lesions soften over 3-5 years.

Generalized morphea is used to describe the presence of at least four plaques, larger than 3 cm, that become confluent in at least two different locations on the body. Patients with generalized morphea have higher rates of systemic symptoms such as arthritis and fatigue.

Pansclerotic morphea, the most severe subtype, is characterized by significant body surface area involvement coupled with deep depth of involvement, often to the bone. The widespread blistering associated with pansclerotic morphea may lead to chronic ulceration and, later on, a higher risk of squamous cell carcinoma development. Despite its extensive distribution, pansclerotic morphea does not cause the severe organ and vascular fibrosis that is characteristically seen in systemic sclerosis. Raynaud’s phenomenon, abnormal nailfold capillaries, and sclerodactyly also will be absent in pansclerotic morphea.

Extracutaneous findings are present in up to 22% of patients with morphea.5 Arthritis is the most common associated finding, and often is correlated with a positive rheumatoid factor. Neurologic involvement most frequently is seen in patients with facial morphea and may present as seizures, as in this patient. MRI abnormalities such as calcifications and white matter changes may be seen. Other common extracutaneous features include fatigue, vascular abnormalities, and ocular findings, such as uveitis.

Morphea and systemic sclerosis appear similar on histology. In early morphea, lymphocytic perivascular infiltrates may be seen in the reticular dermis. In late morphea, the inflammatory cells are replaced by an abundance of collagen bundles infiltrating the dermis.

although the instigating factor activating this pathway is unknown. Multiple factors have been associated with the development of morphea, including autoimmunity, trauma, Borrelia and cytomegalovirus infections, radiation, and certain medications in case reports. Patients with morphea have higher rates of concomitant autoimmune diseases than that found in the general population6 and also have higher rates of autoantibody positivity. In a 750-patient, multicenter study of children with morphea, 42% of patients had positive antinuclear antibodies.7

Diagnosis

Morphea is diagnosed clinically, based on the characteristic appearance of the lesions. A biopsy may be helpful if the presentation is atypical. Although patients with morphea have higher rates of autoantibody positivity, there are no specific laboratory tests that consistently or reliably offer diagnostic value.8 Imaging modalities such as MRI may be utilized to view depth of involvement. Other noninvasive measures, such as thermography and ultrasonography, may be used to determine disease activity.9

Treatment

Treatment for morphea often is multidisciplinary and depends on the severity of involvement and extent to which it impedes functionality and quality of life. Localized plaques that do not restrict movement may be treated with topical corticosteroids, calcipotriene, and tacrolimus. However, topical corticosteroids should be discontinued if there are no signs of improvement in 2-3 months.

For patients with deforming or functionally significant disease, systemic treatment is advised. Methotrexate with or without systemic corticosteroids has been frequently studied, and is the most commonly recommended systemic therapy.11 Some experts have recommended treatment for at least 2-3 years, with at least 1 year of disease inactivity, before discontinuing treatment. Despite this duration of treatment, up to one-quarter of patients, especially those with linear morphea, will still experience recurrence of disease. Management of morphea may be aided by rheumatology and/or dermatology consultation.

Ms. Han is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and a professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Ms. Han and Dr. Eichenfield had no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

References

1. Fett N et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Feb;64(2):217-28.

2. Condie D et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Dec;66(12):3496-504.

3. Zulian F et al. J Pediatr. 2006 Aug;149(2):248-51.

4. Weibel L et al. Br J Dermatol. 2008 Jul;159(1):175-81.

5. Zulian F et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Sep;52(9):2873-81.

6. Leitenberger JJ et al. Arch Dermatol. 2009 May;145(5):545-50.

7. Zulian F et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006 May;45(5):614-20.

8. Dharamsi JW et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2013 Oct;149(10):1159-65.

9. Zulian F et al. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013 Sep;25(5):643-50.

10. Pope E et al. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014 Apr;61(2):309-19.

11. Strickland N et al. Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Apr; 72(4): 727-8.

12. Schoch JJ et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018. 35(1): 43-6.

Morphea, also known as localized scleroderma, is a rare fibrosing disorder of the skin and the underlying tissue that encompasses a variety of distinct subtypes classified by pattern and depth of lesion involvement. It may involve fat, fascia, muscle, and bone, and rarely, the central nervous system. Morphea is easily differentiated from systemic sclerosis by its primarily cutaneous involvement, although a minority of patients may have associated extracutaneous findings. Systemic sclerosis describes a well-defined disorder of skin sclerosis with a specific pattern of internal organ involvement.

Classification of the different subtypes of morphea are based on clinical presentation of the lesions. The most widely used system characterizes morphea into linear, circumscribed, generalized, pansclerotic, and mixed morphea subtypes.1 Mixed morphea describes the presence of two or more patterns of disease and affects 15% of patients. Morphea lesions initially present as erythematous to violaceous patches and plaques that eventually become white and sclerotic, with resulting destruction of the surrounding structures.

Linear scleroderma is the most common subtype of morphea in children and adolescents, affecting 42%-67% of children with morphea.1 It is characterized by linear plaques, often on the extremities, face, or scalp, that tend to follow Blaschko lines.4 These lesions may extend past the dermis to the subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and even bone, resulting in significant deformities. When on the scalp or face, particularly the forehead, the linear lesion may be referred to as the en coup de sabre variant. Ocular and CNS involvement should be of concern in these patients. When subcutaneous atrophy on the unilateral face is present with unaffected overlaying skin, this is known as the Parry-Romberg syndrome or progressive hemifacial atrophy. Involvement of the extremities is common, and unfortunately, may lead to muscle atrophy of the affected limb, contractures in areas overlying joint spaces, and occasionally limb length discrepancies.

Circumscribed morphea describes three or fewer discrete, oval, or round indurated plaques, with central whitening and a violaceous periphery. They generally are found on the trunk. When lesions have deeper involvement, delving past the dermis to involve the underlying fascia and muscle, the patient may experience a “bound down” sensation. Most lesions soften over 3-5 years.

Generalized morphea is used to describe the presence of at least four plaques, larger than 3 cm, that become confluent in at least two different locations on the body. Patients with generalized morphea have higher rates of systemic symptoms such as arthritis and fatigue.

Pansclerotic morphea, the most severe subtype, is characterized by significant body surface area involvement coupled with deep depth of involvement, often to the bone. The widespread blistering associated with pansclerotic morphea may lead to chronic ulceration and, later on, a higher risk of squamous cell carcinoma development. Despite its extensive distribution, pansclerotic morphea does not cause the severe organ and vascular fibrosis that is characteristically seen in systemic sclerosis. Raynaud’s phenomenon, abnormal nailfold capillaries, and sclerodactyly also will be absent in pansclerotic morphea.

Extracutaneous findings are present in up to 22% of patients with morphea.5 Arthritis is the most common associated finding, and often is correlated with a positive rheumatoid factor. Neurologic involvement most frequently is seen in patients with facial morphea and may present as seizures, as in this patient. MRI abnormalities such as calcifications and white matter changes may be seen. Other common extracutaneous features include fatigue, vascular abnormalities, and ocular findings, such as uveitis.

Morphea and systemic sclerosis appear similar on histology. In early morphea, lymphocytic perivascular infiltrates may be seen in the reticular dermis. In late morphea, the inflammatory cells are replaced by an abundance of collagen bundles infiltrating the dermis.

although the instigating factor activating this pathway is unknown. Multiple factors have been associated with the development of morphea, including autoimmunity, trauma, Borrelia and cytomegalovirus infections, radiation, and certain medications in case reports. Patients with morphea have higher rates of concomitant autoimmune diseases than that found in the general population6 and also have higher rates of autoantibody positivity. In a 750-patient, multicenter study of children with morphea, 42% of patients had positive antinuclear antibodies.7

Diagnosis

Morphea is diagnosed clinically, based on the characteristic appearance of the lesions. A biopsy may be helpful if the presentation is atypical. Although patients with morphea have higher rates of autoantibody positivity, there are no specific laboratory tests that consistently or reliably offer diagnostic value.8 Imaging modalities such as MRI may be utilized to view depth of involvement. Other noninvasive measures, such as thermography and ultrasonography, may be used to determine disease activity.9

Treatment

Treatment for morphea often is multidisciplinary and depends on the severity of involvement and extent to which it impedes functionality and quality of life. Localized plaques that do not restrict movement may be treated with topical corticosteroids, calcipotriene, and tacrolimus. However, topical corticosteroids should be discontinued if there are no signs of improvement in 2-3 months.

For patients with deforming or functionally significant disease, systemic treatment is advised. Methotrexate with or without systemic corticosteroids has been frequently studied, and is the most commonly recommended systemic therapy.11 Some experts have recommended treatment for at least 2-3 years, with at least 1 year of disease inactivity, before discontinuing treatment. Despite this duration of treatment, up to one-quarter of patients, especially those with linear morphea, will still experience recurrence of disease. Management of morphea may be aided by rheumatology and/or dermatology consultation.

Ms. Han is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and a professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Ms. Han and Dr. Eichenfield had no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

References

1. Fett N et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Feb;64(2):217-28.

2. Condie D et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Dec;66(12):3496-504.

3. Zulian F et al. J Pediatr. 2006 Aug;149(2):248-51.

4. Weibel L et al. Br J Dermatol. 2008 Jul;159(1):175-81.

5. Zulian F et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Sep;52(9):2873-81.

6. Leitenberger JJ et al. Arch Dermatol. 2009 May;145(5):545-50.

7. Zulian F et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006 May;45(5):614-20.

8. Dharamsi JW et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2013 Oct;149(10):1159-65.

9. Zulian F et al. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013 Sep;25(5):643-50.

10. Pope E et al. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014 Apr;61(2):309-19.

11. Strickland N et al. Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Apr; 72(4): 727-8.

12. Schoch JJ et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018. 35(1): 43-6.

Morphea, also known as localized scleroderma, is a rare fibrosing disorder of the skin and the underlying tissue that encompasses a variety of distinct subtypes classified by pattern and depth of lesion involvement. It may involve fat, fascia, muscle, and bone, and rarely, the central nervous system. Morphea is easily differentiated from systemic sclerosis by its primarily cutaneous involvement, although a minority of patients may have associated extracutaneous findings. Systemic sclerosis describes a well-defined disorder of skin sclerosis with a specific pattern of internal organ involvement.

Classification of the different subtypes of morphea are based on clinical presentation of the lesions. The most widely used system characterizes morphea into linear, circumscribed, generalized, pansclerotic, and mixed morphea subtypes.1 Mixed morphea describes the presence of two or more patterns of disease and affects 15% of patients. Morphea lesions initially present as erythematous to violaceous patches and plaques that eventually become white and sclerotic, with resulting destruction of the surrounding structures.

Linear scleroderma is the most common subtype of morphea in children and adolescents, affecting 42%-67% of children with morphea.1 It is characterized by linear plaques, often on the extremities, face, or scalp, that tend to follow Blaschko lines.4 These lesions may extend past the dermis to the subcutaneous tissue, muscle, and even bone, resulting in significant deformities. When on the scalp or face, particularly the forehead, the linear lesion may be referred to as the en coup de sabre variant. Ocular and CNS involvement should be of concern in these patients. When subcutaneous atrophy on the unilateral face is present with unaffected overlaying skin, this is known as the Parry-Romberg syndrome or progressive hemifacial atrophy. Involvement of the extremities is common, and unfortunately, may lead to muscle atrophy of the affected limb, contractures in areas overlying joint spaces, and occasionally limb length discrepancies.

Circumscribed morphea describes three or fewer discrete, oval, or round indurated plaques, with central whitening and a violaceous periphery. They generally are found on the trunk. When lesions have deeper involvement, delving past the dermis to involve the underlying fascia and muscle, the patient may experience a “bound down” sensation. Most lesions soften over 3-5 years.

Generalized morphea is used to describe the presence of at least four plaques, larger than 3 cm, that become confluent in at least two different locations on the body. Patients with generalized morphea have higher rates of systemic symptoms such as arthritis and fatigue.

Pansclerotic morphea, the most severe subtype, is characterized by significant body surface area involvement coupled with deep depth of involvement, often to the bone. The widespread blistering associated with pansclerotic morphea may lead to chronic ulceration and, later on, a higher risk of squamous cell carcinoma development. Despite its extensive distribution, pansclerotic morphea does not cause the severe organ and vascular fibrosis that is characteristically seen in systemic sclerosis. Raynaud’s phenomenon, abnormal nailfold capillaries, and sclerodactyly also will be absent in pansclerotic morphea.

Extracutaneous findings are present in up to 22% of patients with morphea.5 Arthritis is the most common associated finding, and often is correlated with a positive rheumatoid factor. Neurologic involvement most frequently is seen in patients with facial morphea and may present as seizures, as in this patient. MRI abnormalities such as calcifications and white matter changes may be seen. Other common extracutaneous features include fatigue, vascular abnormalities, and ocular findings, such as uveitis.

Morphea and systemic sclerosis appear similar on histology. In early morphea, lymphocytic perivascular infiltrates may be seen in the reticular dermis. In late morphea, the inflammatory cells are replaced by an abundance of collagen bundles infiltrating the dermis.

although the instigating factor activating this pathway is unknown. Multiple factors have been associated with the development of morphea, including autoimmunity, trauma, Borrelia and cytomegalovirus infections, radiation, and certain medications in case reports. Patients with morphea have higher rates of concomitant autoimmune diseases than that found in the general population6 and also have higher rates of autoantibody positivity. In a 750-patient, multicenter study of children with morphea, 42% of patients had positive antinuclear antibodies.7

Diagnosis

Morphea is diagnosed clinically, based on the characteristic appearance of the lesions. A biopsy may be helpful if the presentation is atypical. Although patients with morphea have higher rates of autoantibody positivity, there are no specific laboratory tests that consistently or reliably offer diagnostic value.8 Imaging modalities such as MRI may be utilized to view depth of involvement. Other noninvasive measures, such as thermography and ultrasonography, may be used to determine disease activity.9

Treatment

Treatment for morphea often is multidisciplinary and depends on the severity of involvement and extent to which it impedes functionality and quality of life. Localized plaques that do not restrict movement may be treated with topical corticosteroids, calcipotriene, and tacrolimus. However, topical corticosteroids should be discontinued if there are no signs of improvement in 2-3 months.

For patients with deforming or functionally significant disease, systemic treatment is advised. Methotrexate with or without systemic corticosteroids has been frequently studied, and is the most commonly recommended systemic therapy.11 Some experts have recommended treatment for at least 2-3 years, with at least 1 year of disease inactivity, before discontinuing treatment. Despite this duration of treatment, up to one-quarter of patients, especially those with linear morphea, will still experience recurrence of disease. Management of morphea may be aided by rheumatology and/or dermatology consultation.

Ms. Han is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and a professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Ms. Han and Dr. Eichenfield had no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

References

1. Fett N et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011 Feb;64(2):217-28.

2. Condie D et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Dec;66(12):3496-504.

3. Zulian F et al. J Pediatr. 2006 Aug;149(2):248-51.

4. Weibel L et al. Br J Dermatol. 2008 Jul;159(1):175-81.

5. Zulian F et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Sep;52(9):2873-81.

6. Leitenberger JJ et al. Arch Dermatol. 2009 May;145(5):545-50.

7. Zulian F et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006 May;45(5):614-20.

8. Dharamsi JW et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2013 Oct;149(10):1159-65.

9. Zulian F et al. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2013 Sep;25(5):643-50.

10. Pope E et al. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014 Apr;61(2):309-19.

11. Strickland N et al. Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Apr; 72(4): 727-8.

12. Schoch JJ et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018. 35(1): 43-6.

A 14-year-old patient presents to a dermatology clinic for a depression on his forehead, which has been there for about 2 years. A few years ago, he used to have a pruritic pink lesion on the forehead where the depression is now. He denies any symptoms.

Anxiety in teens

It seems that every week there is a new headline about the rising rates of anxiety in today’s adolescents. Schools often are asked to address high levels of stress and anxiety in their students, and the pediatrician’s office is often the first place worried parents will call. We will try to help you differentiate between what is normal – even healthy – adolescent stress, and what might represent treatable psychiatric problems. And we will review how to approach stress management with your patients and their parents. For all adolescents, even those with psychiatric diagnoses, learning to manage stress and anxiety is critical to their healthiest development into capable, confident, resilient adults.

Stress is the mental or emotional strain resulting from demanding or adverse circumstances. Anxiety is a feeling of unease about an imminent event with an uncertain outcome. An anxiety disorder is a psychiatric illness characterized by a state of excessive unease leading to functional impairment. These distinctions are critical, as both stress and anxiety are normal-but-uncomfortable parts of the adolescent experience. When all of a teenager’s stress and anxiety is medicalized, it promotes avoidance, which in turn may worsen your patient’s functional impairment rather than improving it.

This is not to suggest that there are not real (and common) psychiatric illnesses that can affect the levels of anxiety in your patients. Anxiety disorders start the earliest, with separation anxiety disorder, specific phobia, and social phobia all having a mean onset before puberty. Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent psychiatric disorders in youth (30% of youth psychiatric illness), and anxiety also may be related to substance use disorders (25%), disruptive behavior disorders (20%), and mood disorders (17%). Despite the excited news coverage, there is no evidence of a statistically significant increase in the incidence of anxiety or mood disorders in young people over the past decade.

It is not difficult to imagine that the challenges facing adolescents are considerable. Of course, adolescence is a time of major change starting with puberty, in which young people actively develop independence, identity, and a rich array of deep relationships beyond their families. Typically, this is a 5- to 10-year process of risk-taking, new experiences, setbacks, delight, heartbreak, and triumphs all alongside growing autonomy.

These forces may make their parents even more stressed than the adolescents themselves, but there is one dramatically different feature of adolescent life today: the constant presence of smartphones. While these devices can improve connectedness to school, family, and friends, use of smartphones also means that today’s teenagers often have little downtime cognitively or socially. Use of smartphones can facilitate both supportive affirmation from friends and relentless social pressures, and the feeling of being excluded or bullied. Smartphone use can interfere with restful sleep, and some virtual activities may compete with the genuine experimentation and exploration where teenagers discover their interests and abilities and develop meaningful confidence and independence.

Several factors might impair an adolescent’s ability to cope with challenge and stress. Those teenagers who have not had the opportunity to face and manage modest setbacks, difficulties, and discomforts during their elementary and middle school years may be overwhelmed by starting with the higher-stakes strains of adolescence. This can happen when young children have not explored many new activities, have been shielded from the consequences of failures, or have tried only activities that came easily to them. Certainly, teenagers who are managing a depressive or anxiety disorder as well as those with learning disabilities may have limited ability to cope with routine stress, although those who have a well-treated disorder often have robust coping skills.

Perhaps obvious, but still very important, chronic sleep deprivation can leave adolescents irritable, impatient, and distractible, all of which make coping with a challenge very difficult. Likewise, substance use can directly impair coping skills, and can create the habit of trying to escape stress rather than manage it.

So what does this mean for you? If your patient has an anxiety, depressive, or substance use disorder, refer for appropriate therapy. For both those who screen in and those who do not, your next task is to help them improve their coping skills. What specifically has them so stressed?

Are there family stressors or unrealistic expectations that can be addressed? Can they see their situation as a challenge and focus on what is within their control to do in response? Remind your patients that challenges are uncomfortable. Mastery comes with practice and, inevitably, some setbacks and failures. Have they identified personal goals or a transcendent purpose? This can improve motivation and keep a challenge in perspective. They might focus on learning about their coping style: Do they do better with a slow, steady, methodical approach or intense bursts of effort? Talk with them about self-care. Adequate sleep, regular exercise, putting effort into relaxation as well as work, and spending time with their actual (not just virtual) friends all are essential to keeping their batteries charged while doing the intense work of normal adolescence.

For those patients who do not meet criteria for depression or anxiety disorders, there are circumstances in which a referral for therapy can be helpful. If they are noticeably disconnected from their parents or their parents seem to be more reactive to the stress and pressures than they are, an outside therapist can be a meaningful support as they build skills. Those patients who are socially isolated and stressed, are using substances regularly, are withdrawing from other interests to manage their source of stress, or are having difficulty telling facts from feelings are at risk for failing to adequately manage their stress and for the development of psychiatric problems. Starting early, helping them to build autonomy as preadolescents, experiencing successes and failures, begins the cultivation of resilience and meaningful confidence they will need during adolescence. Your attention and guidance can help all of your adolescent patients improve their coping and lower both their stress and their anxiety.

It seems that every week there is a new headline about the rising rates of anxiety in today’s adolescents. Schools often are asked to address high levels of stress and anxiety in their students, and the pediatrician’s office is often the first place worried parents will call. We will try to help you differentiate between what is normal – even healthy – adolescent stress, and what might represent treatable psychiatric problems. And we will review how to approach stress management with your patients and their parents. For all adolescents, even those with psychiatric diagnoses, learning to manage stress and anxiety is critical to their healthiest development into capable, confident, resilient adults.

Stress is the mental or emotional strain resulting from demanding or adverse circumstances. Anxiety is a feeling of unease about an imminent event with an uncertain outcome. An anxiety disorder is a psychiatric illness characterized by a state of excessive unease leading to functional impairment. These distinctions are critical, as both stress and anxiety are normal-but-uncomfortable parts of the adolescent experience. When all of a teenager’s stress and anxiety is medicalized, it promotes avoidance, which in turn may worsen your patient’s functional impairment rather than improving it.

This is not to suggest that there are not real (and common) psychiatric illnesses that can affect the levels of anxiety in your patients. Anxiety disorders start the earliest, with separation anxiety disorder, specific phobia, and social phobia all having a mean onset before puberty. Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent psychiatric disorders in youth (30% of youth psychiatric illness), and anxiety also may be related to substance use disorders (25%), disruptive behavior disorders (20%), and mood disorders (17%). Despite the excited news coverage, there is no evidence of a statistically significant increase in the incidence of anxiety or mood disorders in young people over the past decade.

It is not difficult to imagine that the challenges facing adolescents are considerable. Of course, adolescence is a time of major change starting with puberty, in which young people actively develop independence, identity, and a rich array of deep relationships beyond their families. Typically, this is a 5- to 10-year process of risk-taking, new experiences, setbacks, delight, heartbreak, and triumphs all alongside growing autonomy.

These forces may make their parents even more stressed than the adolescents themselves, but there is one dramatically different feature of adolescent life today: the constant presence of smartphones. While these devices can improve connectedness to school, family, and friends, use of smartphones also means that today’s teenagers often have little downtime cognitively or socially. Use of smartphones can facilitate both supportive affirmation from friends and relentless social pressures, and the feeling of being excluded or bullied. Smartphone use can interfere with restful sleep, and some virtual activities may compete with the genuine experimentation and exploration where teenagers discover their interests and abilities and develop meaningful confidence and independence.

Several factors might impair an adolescent’s ability to cope with challenge and stress. Those teenagers who have not had the opportunity to face and manage modest setbacks, difficulties, and discomforts during their elementary and middle school years may be overwhelmed by starting with the higher-stakes strains of adolescence. This can happen when young children have not explored many new activities, have been shielded from the consequences of failures, or have tried only activities that came easily to them. Certainly, teenagers who are managing a depressive or anxiety disorder as well as those with learning disabilities may have limited ability to cope with routine stress, although those who have a well-treated disorder often have robust coping skills.

Perhaps obvious, but still very important, chronic sleep deprivation can leave adolescents irritable, impatient, and distractible, all of which make coping with a challenge very difficult. Likewise, substance use can directly impair coping skills, and can create the habit of trying to escape stress rather than manage it.

So what does this mean for you? If your patient has an anxiety, depressive, or substance use disorder, refer for appropriate therapy. For both those who screen in and those who do not, your next task is to help them improve their coping skills. What specifically has them so stressed?

Are there family stressors or unrealistic expectations that can be addressed? Can they see their situation as a challenge and focus on what is within their control to do in response? Remind your patients that challenges are uncomfortable. Mastery comes with practice and, inevitably, some setbacks and failures. Have they identified personal goals or a transcendent purpose? This can improve motivation and keep a challenge in perspective. They might focus on learning about their coping style: Do they do better with a slow, steady, methodical approach or intense bursts of effort? Talk with them about self-care. Adequate sleep, regular exercise, putting effort into relaxation as well as work, and spending time with their actual (not just virtual) friends all are essential to keeping their batteries charged while doing the intense work of normal adolescence.

For those patients who do not meet criteria for depression or anxiety disorders, there are circumstances in which a referral for therapy can be helpful. If they are noticeably disconnected from their parents or their parents seem to be more reactive to the stress and pressures than they are, an outside therapist can be a meaningful support as they build skills. Those patients who are socially isolated and stressed, are using substances regularly, are withdrawing from other interests to manage their source of stress, or are having difficulty telling facts from feelings are at risk for failing to adequately manage their stress and for the development of psychiatric problems. Starting early, helping them to build autonomy as preadolescents, experiencing successes and failures, begins the cultivation of resilience and meaningful confidence they will need during adolescence. Your attention and guidance can help all of your adolescent patients improve their coping and lower both their stress and their anxiety.

It seems that every week there is a new headline about the rising rates of anxiety in today’s adolescents. Schools often are asked to address high levels of stress and anxiety in their students, and the pediatrician’s office is often the first place worried parents will call. We will try to help you differentiate between what is normal – even healthy – adolescent stress, and what might represent treatable psychiatric problems. And we will review how to approach stress management with your patients and their parents. For all adolescents, even those with psychiatric diagnoses, learning to manage stress and anxiety is critical to their healthiest development into capable, confident, resilient adults.

Stress is the mental or emotional strain resulting from demanding or adverse circumstances. Anxiety is a feeling of unease about an imminent event with an uncertain outcome. An anxiety disorder is a psychiatric illness characterized by a state of excessive unease leading to functional impairment. These distinctions are critical, as both stress and anxiety are normal-but-uncomfortable parts of the adolescent experience. When all of a teenager’s stress and anxiety is medicalized, it promotes avoidance, which in turn may worsen your patient’s functional impairment rather than improving it.

This is not to suggest that there are not real (and common) psychiatric illnesses that can affect the levels of anxiety in your patients. Anxiety disorders start the earliest, with separation anxiety disorder, specific phobia, and social phobia all having a mean onset before puberty. Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent psychiatric disorders in youth (30% of youth psychiatric illness), and anxiety also may be related to substance use disorders (25%), disruptive behavior disorders (20%), and mood disorders (17%). Despite the excited news coverage, there is no evidence of a statistically significant increase in the incidence of anxiety or mood disorders in young people over the past decade.

It is not difficult to imagine that the challenges facing adolescents are considerable. Of course, adolescence is a time of major change starting with puberty, in which young people actively develop independence, identity, and a rich array of deep relationships beyond their families. Typically, this is a 5- to 10-year process of risk-taking, new experiences, setbacks, delight, heartbreak, and triumphs all alongside growing autonomy.

These forces may make their parents even more stressed than the adolescents themselves, but there is one dramatically different feature of adolescent life today: the constant presence of smartphones. While these devices can improve connectedness to school, family, and friends, use of smartphones also means that today’s teenagers often have little downtime cognitively or socially. Use of smartphones can facilitate both supportive affirmation from friends and relentless social pressures, and the feeling of being excluded or bullied. Smartphone use can interfere with restful sleep, and some virtual activities may compete with the genuine experimentation and exploration where teenagers discover their interests and abilities and develop meaningful confidence and independence.

Several factors might impair an adolescent’s ability to cope with challenge and stress. Those teenagers who have not had the opportunity to face and manage modest setbacks, difficulties, and discomforts during their elementary and middle school years may be overwhelmed by starting with the higher-stakes strains of adolescence. This can happen when young children have not explored many new activities, have been shielded from the consequences of failures, or have tried only activities that came easily to them. Certainly, teenagers who are managing a depressive or anxiety disorder as well as those with learning disabilities may have limited ability to cope with routine stress, although those who have a well-treated disorder often have robust coping skills.

Perhaps obvious, but still very important, chronic sleep deprivation can leave adolescents irritable, impatient, and distractible, all of which make coping with a challenge very difficult. Likewise, substance use can directly impair coping skills, and can create the habit of trying to escape stress rather than manage it.

So what does this mean for you? If your patient has an anxiety, depressive, or substance use disorder, refer for appropriate therapy. For both those who screen in and those who do not, your next task is to help them improve their coping skills. What specifically has them so stressed?

Are there family stressors or unrealistic expectations that can be addressed? Can they see their situation as a challenge and focus on what is within their control to do in response? Remind your patients that challenges are uncomfortable. Mastery comes with practice and, inevitably, some setbacks and failures. Have they identified personal goals or a transcendent purpose? This can improve motivation and keep a challenge in perspective. They might focus on learning about their coping style: Do they do better with a slow, steady, methodical approach or intense bursts of effort? Talk with them about self-care. Adequate sleep, regular exercise, putting effort into relaxation as well as work, and spending time with their actual (not just virtual) friends all are essential to keeping their batteries charged while doing the intense work of normal adolescence.

For those patients who do not meet criteria for depression or anxiety disorders, there are circumstances in which a referral for therapy can be helpful. If they are noticeably disconnected from their parents or their parents seem to be more reactive to the stress and pressures than they are, an outside therapist can be a meaningful support as they build skills. Those patients who are socially isolated and stressed, are using substances regularly, are withdrawing from other interests to manage their source of stress, or are having difficulty telling facts from feelings are at risk for failing to adequately manage their stress and for the development of psychiatric problems. Starting early, helping them to build autonomy as preadolescents, experiencing successes and failures, begins the cultivation of resilience and meaningful confidence they will need during adolescence. Your attention and guidance can help all of your adolescent patients improve their coping and lower both their stress and their anxiety.

Researcher’s talk will tackle aging and gut bacteria in MS

Germs, genes, and aging each play a role in the development of multiple sclerosis (MS), but researchers are still figuring out how they’re connected. Now, a speaker at a meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis will shed light on recent findings that offer new insight into a specific type of germ – gut bacteria.

Suhayl Dhib-Jalbut, MD, ACTRIMS’s former president, will highlight his team’s investigation into the links between aging and alterations in gut microbiota in MS during the Kenneth P. Johnson Memorial Lecture on Feb. 1 at the meeting in San Diego.

Dr. Dhib-Jalbut’s presentation will focus on findings of a study by his team that was published late last year in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A. (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Oct 31;114[44]:E9318-27).

As the study explains, Dr. Dhib-Jalbut and colleagues triggered spontaneous experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in transgenic mice by disrupting gut bacteria during adolescence and early young adulthood. But the process of aging in the mice past early young adulthood suppressed EAE onset by boosting immunologic tolerance.

The findings in this animal model offer insight into why the incidence of MS peaks at ages 20-40 years in humans, he said. “The implication is that one can perhaps manipulate gut bacteria with antibiotics or other treatments to impact the course of MS.”

Germs, genes, and aging each play a role in the development of multiple sclerosis (MS), but researchers are still figuring out how they’re connected. Now, a speaker at a meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis will shed light on recent findings that offer new insight into a specific type of germ – gut bacteria.

Suhayl Dhib-Jalbut, MD, ACTRIMS’s former president, will highlight his team’s investigation into the links between aging and alterations in gut microbiota in MS during the Kenneth P. Johnson Memorial Lecture on Feb. 1 at the meeting in San Diego.

Dr. Dhib-Jalbut’s presentation will focus on findings of a study by his team that was published late last year in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A. (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Oct 31;114[44]:E9318-27).

As the study explains, Dr. Dhib-Jalbut and colleagues triggered spontaneous experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in transgenic mice by disrupting gut bacteria during adolescence and early young adulthood. But the process of aging in the mice past early young adulthood suppressed EAE onset by boosting immunologic tolerance.

The findings in this animal model offer insight into why the incidence of MS peaks at ages 20-40 years in humans, he said. “The implication is that one can perhaps manipulate gut bacteria with antibiotics or other treatments to impact the course of MS.”

Germs, genes, and aging each play a role in the development of multiple sclerosis (MS), but researchers are still figuring out how they’re connected. Now, a speaker at a meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis will shed light on recent findings that offer new insight into a specific type of germ – gut bacteria.

Suhayl Dhib-Jalbut, MD, ACTRIMS’s former president, will highlight his team’s investigation into the links between aging and alterations in gut microbiota in MS during the Kenneth P. Johnson Memorial Lecture on Feb. 1 at the meeting in San Diego.

Dr. Dhib-Jalbut’s presentation will focus on findings of a study by his team that was published late last year in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A. (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Oct 31;114[44]:E9318-27).

As the study explains, Dr. Dhib-Jalbut and colleagues triggered spontaneous experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in transgenic mice by disrupting gut bacteria during adolescence and early young adulthood. But the process of aging in the mice past early young adulthood suppressed EAE onset by boosting immunologic tolerance.

The findings in this animal model offer insight into why the incidence of MS peaks at ages 20-40 years in humans, he said. “The implication is that one can perhaps manipulate gut bacteria with antibiotics or other treatments to impact the course of MS.”

REPORTING FROM ACTRIMS FORUM 2018

Literature review: Cryolipolysis safe, effective for reducing submental fat

Cryolipolysis is a safe and effective noninvasive treatment for reducing submental fat, according to a review of several published studies.

In a review of four clinical trials and one case series, which involved a total of 101 patients, , reported Shari R. Lipner, MD, of the department of dermatology at Cornell University, New York.

In 2015, the Food and Drug Administration cleared a cryolipolysis device for use in the submental area.

The literature review was performed in May 2017 using Pubmed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and CINAHL databases, searching for the terms cryolipolysis, submental, and paradoxical adipose hyperplasia. Non-English studies were excluded.

The studies included an open-label prospective multicenter trial of 60 patients who underwent cryolipolysis for submental fat reduction once or twice at –10°C for 60 minutes, which found that in 58 evaluable patients, blinded independent reviewers correctly identified baseline photos in 91.4% of cases (P less than .0001). Ultrasound, used to evaluate 57 patients, determined the mean fat layer reduction was 2.0 mm or 20% (ranging from an increase of 2.0 mm to a reduction of –5.9 mm; P less than .0001). Side effects included erythema, edema, bruising, and numbness, which resolved by week 12. Additionally, 83% of the 60 patients were satisfied with the results.

In another study, a prospective nonrandomized study that evaluated overlapping cryolipolysis applications on different visits in 14 patients, pretreatment and post-treatment photographs were correctly identified by blinded independent reviewers 81% of the time (95% confidence interval, 65.9%-91.4%; P = .02). In addition, the mean fat layer reduction, as measured with skin-fold calipers, was 2.3 mm (95% CI, 1.9-2.7 mm; P less than .001), and 93% of the patients were satisfied with the results.

A prospective nonrandomized single-center open-label study of 15 Hispanic patients evaluated cryolipolysis applied to the submental area at two different temperatures (–12°C for 45 minutes and –15°C for 30 minutes) with treatments given 10 weeks apart. The mean reduction in submental fat, as measured by calipers, was 33%, with no significant difference between the two. Blinded physicians correctly identified pre- and post- treatment photos in 60% of cases, and 80% of the patients said they “were satisfied or very satisfied” with the results, according to Dr. Lipner’s review, published online in the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology.

All studies reported adverse side effects, most commonly erythema, which resolved within weeks of treatment, she wrote. To date, she noted, no cases of mandibular nerve injury or paradoxical adipose hyperplasia have been reported after cryolipolysis for submental fat.

Dr. Lipner referred to early trials in humans found that cryolipolysis was safe and effective for treatment of the back, arms, and chest. Additional trials found no significant changes in lipids or liver function at 1, 4, and 12 weeks’ follow-up when patients were treated for fat in the flanks and lower abdomen.

The results of the literature review suggest that cryolipolysis is safe and effective for submental fat, Dr. Lipner wrote. Appropriate patient selection is important and “patients should be counseled on clinical improvement in the submental contour, number of sessions necessary, side effects, downtime, and cost,” she noted. Liposuction is still the gold standard for removal of large fat deposits, and although cryolipolysis can reduce submental fat, “it may also worsen the appearance on the neck by making platysmal banding or skin imperfections more obvious,” she added.

Dr. Lipner did not report any relevant disclosures. No funding source was provided.

SOURCE: J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018 Jan 17. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12495.

Cryolipolysis is a safe and effective noninvasive treatment for reducing submental fat, according to a review of several published studies.

In a review of four clinical trials and one case series, which involved a total of 101 patients, , reported Shari R. Lipner, MD, of the department of dermatology at Cornell University, New York.

In 2015, the Food and Drug Administration cleared a cryolipolysis device for use in the submental area.

The literature review was performed in May 2017 using Pubmed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and CINAHL databases, searching for the terms cryolipolysis, submental, and paradoxical adipose hyperplasia. Non-English studies were excluded.

The studies included an open-label prospective multicenter trial of 60 patients who underwent cryolipolysis for submental fat reduction once or twice at –10°C for 60 minutes, which found that in 58 evaluable patients, blinded independent reviewers correctly identified baseline photos in 91.4% of cases (P less than .0001). Ultrasound, used to evaluate 57 patients, determined the mean fat layer reduction was 2.0 mm or 20% (ranging from an increase of 2.0 mm to a reduction of –5.9 mm; P less than .0001). Side effects included erythema, edema, bruising, and numbness, which resolved by week 12. Additionally, 83% of the 60 patients were satisfied with the results.

In another study, a prospective nonrandomized study that evaluated overlapping cryolipolysis applications on different visits in 14 patients, pretreatment and post-treatment photographs were correctly identified by blinded independent reviewers 81% of the time (95% confidence interval, 65.9%-91.4%; P = .02). In addition, the mean fat layer reduction, as measured with skin-fold calipers, was 2.3 mm (95% CI, 1.9-2.7 mm; P less than .001), and 93% of the patients were satisfied with the results.

A prospective nonrandomized single-center open-label study of 15 Hispanic patients evaluated cryolipolysis applied to the submental area at two different temperatures (–12°C for 45 minutes and –15°C for 30 minutes) with treatments given 10 weeks apart. The mean reduction in submental fat, as measured by calipers, was 33%, with no significant difference between the two. Blinded physicians correctly identified pre- and post- treatment photos in 60% of cases, and 80% of the patients said they “were satisfied or very satisfied” with the results, according to Dr. Lipner’s review, published online in the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology.

All studies reported adverse side effects, most commonly erythema, which resolved within weeks of treatment, she wrote. To date, she noted, no cases of mandibular nerve injury or paradoxical adipose hyperplasia have been reported after cryolipolysis for submental fat.

Dr. Lipner referred to early trials in humans found that cryolipolysis was safe and effective for treatment of the back, arms, and chest. Additional trials found no significant changes in lipids or liver function at 1, 4, and 12 weeks’ follow-up when patients were treated for fat in the flanks and lower abdomen.

The results of the literature review suggest that cryolipolysis is safe and effective for submental fat, Dr. Lipner wrote. Appropriate patient selection is important and “patients should be counseled on clinical improvement in the submental contour, number of sessions necessary, side effects, downtime, and cost,” she noted. Liposuction is still the gold standard for removal of large fat deposits, and although cryolipolysis can reduce submental fat, “it may also worsen the appearance on the neck by making platysmal banding or skin imperfections more obvious,” she added.

Dr. Lipner did not report any relevant disclosures. No funding source was provided.

SOURCE: J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018 Jan 17. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12495.

Cryolipolysis is a safe and effective noninvasive treatment for reducing submental fat, according to a review of several published studies.

In a review of four clinical trials and one case series, which involved a total of 101 patients, , reported Shari R. Lipner, MD, of the department of dermatology at Cornell University, New York.

In 2015, the Food and Drug Administration cleared a cryolipolysis device for use in the submental area.

The literature review was performed in May 2017 using Pubmed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and CINAHL databases, searching for the terms cryolipolysis, submental, and paradoxical adipose hyperplasia. Non-English studies were excluded.

The studies included an open-label prospective multicenter trial of 60 patients who underwent cryolipolysis for submental fat reduction once or twice at –10°C for 60 minutes, which found that in 58 evaluable patients, blinded independent reviewers correctly identified baseline photos in 91.4% of cases (P less than .0001). Ultrasound, used to evaluate 57 patients, determined the mean fat layer reduction was 2.0 mm or 20% (ranging from an increase of 2.0 mm to a reduction of –5.9 mm; P less than .0001). Side effects included erythema, edema, bruising, and numbness, which resolved by week 12. Additionally, 83% of the 60 patients were satisfied with the results.

In another study, a prospective nonrandomized study that evaluated overlapping cryolipolysis applications on different visits in 14 patients, pretreatment and post-treatment photographs were correctly identified by blinded independent reviewers 81% of the time (95% confidence interval, 65.9%-91.4%; P = .02). In addition, the mean fat layer reduction, as measured with skin-fold calipers, was 2.3 mm (95% CI, 1.9-2.7 mm; P less than .001), and 93% of the patients were satisfied with the results.

A prospective nonrandomized single-center open-label study of 15 Hispanic patients evaluated cryolipolysis applied to the submental area at two different temperatures (–12°C for 45 minutes and –15°C for 30 minutes) with treatments given 10 weeks apart. The mean reduction in submental fat, as measured by calipers, was 33%, with no significant difference between the two. Blinded physicians correctly identified pre- and post- treatment photos in 60% of cases, and 80% of the patients said they “were satisfied or very satisfied” with the results, according to Dr. Lipner’s review, published online in the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology.

All studies reported adverse side effects, most commonly erythema, which resolved within weeks of treatment, she wrote. To date, she noted, no cases of mandibular nerve injury or paradoxical adipose hyperplasia have been reported after cryolipolysis for submental fat.

Dr. Lipner referred to early trials in humans found that cryolipolysis was safe and effective for treatment of the back, arms, and chest. Additional trials found no significant changes in lipids or liver function at 1, 4, and 12 weeks’ follow-up when patients were treated for fat in the flanks and lower abdomen.

The results of the literature review suggest that cryolipolysis is safe and effective for submental fat, Dr. Lipner wrote. Appropriate patient selection is important and “patients should be counseled on clinical improvement in the submental contour, number of sessions necessary, side effects, downtime, and cost,” she noted. Liposuction is still the gold standard for removal of large fat deposits, and although cryolipolysis can reduce submental fat, “it may also worsen the appearance on the neck by making platysmal banding or skin imperfections more obvious,” she added.

Dr. Lipner did not report any relevant disclosures. No funding source was provided.

SOURCE: J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018 Jan 17. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12495.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF COSMETIC DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Cryolipolysis appears to be a safe, effective noninvasive treatment for submental fat.

Major finding: Endpoints evaluating the effects of the cooling technique on submental fat included evaluations of blinded patient photos by blinded reviewers, who, in one study, correctly identified baseline photos in 91.4% of cases (P less than .0001).

Data source: A literature review of four clinical trials and one case series of a total of 101 patients who underwent cryolipolysis for reducing submental fat.

Disclosures: The author did not report any relevant disclosures. No funding source was provided.

Source: Cosmet Dermatol. 2018 Jan 17. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12495.

Arthroscopic Anterior Ankle Decompression Is Successful in National Football League Players

ABSTRACT

Anterior ankle impingement is a frequent cause of pain and disability in athletes with impingement of soft-tissue or osseous structures along the anterior margin of the tibiotalar joint during dorsiflexion.

In this study, we hypothesized that arthroscopic decompression of anterior ankle impingement would result in significant, reliable, and durable improvement in pain and range of motion (ROM), and would allow National Football League (NFL) players to return to their preoperative level of play.

We reviewed 29 arthroscopic ankle débridements performed by a single surgeon. Each NFL player underwent arthroscopic débridement of pathologic soft tissue and of tibial and talar osteophytes in the anterior ankle. Preoperative and postoperative visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores, American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) hindfoot scores, and ankle ROM were compared; time to return to play (RTP), events missed secondary to surgery, and complications were recorded.

All athletes returned to the same level of NFL play at a mean (SD) of 8.4 (4.1) weeks after surgery and continued playing for a mean (SD) of 3.43 (2.57) years after surgery. Mean (SD) VAS pain scores decreased significantly (P < .001), to 0.38 (0.89) from 4.21 (1.52). Mean (SD) active ankle dorsiflexion increased significantly (P < .001), to 18.86° (2.62°) from 8.28° (4.14°). Mean (SD) AOFAS hindfoot scores increased significantly (P < .001), to 97.45 (4.72) from 70.62 (10.39). Degree of arthritis (r = 0.305) and age (r = 0.106) were poorly correlated to time to RTP.

In all cases, arthroscopic débridement of anterior ankle impingement resulted in RTP at the same level at a mean of 2 months after surgery. There were significant improvements in VAS pain scores, AOFAS hindfoot scores, and ROM.

Arthroscopic débridement of anterior ankle impingement relieves pain, restores ROM and function, and results in reliable RTP in professional football players.

Continue to: Anterior ankle impingement...

Anterior ankle impingement is a frequent cause of disability in athletes.1 This condition results from repetitive trauma over time, which leads to osseous and soft-tissue impingement, pain, and decreased ankle range of motion (ROM).

First termed footballer’s ankle, this condition is linked to repeated, forceful plantarflexion,2 though later studies attributed the phenomenon to repeated dorsiflexion resulting in periosteal hemorrhage.3 Both osseous and soft-tissue structures can cause impingement at the tibiotalar joint, often with osteophytes anteromedially at the tibial talar joint. Soft-tissue structures, including hypertrophic synovium, meniscoid lesions, and a thickened anterior talofibular ligament, more often cause anterolateral impingement.4-6 This process results in pain in extreme dorsiflexion, which comes into play in almost all football maneuvers, including sprinting, back-peddling, and offensive and defensive stances. Therefore, maintenance of pain-free dorsiflexion is required for high-level football. Decreased ROM can lead to decreased ability to perform these high-level athletic functions and can limit performance.

Arthroscopic débridement improves functional outcomes and functional motion in both athletes and nonathletes.7,8 In addition, findings of a recent systematic review provide support for arthroscopic treatment of ankle impingement.9 Although arthroscopic treatment is effective in nonathletes and recreational athletes,10 there is a paucity of data on the efficacy of this procedure and on time to return to play (RTP) in professional football players.

We conducted a study to evaluate the outcomes (pain, ROM, RTP) of arthroscopic débridement for anterior ankle impingement in National Football League (NFL) players. We hypothesized that arthroscopic decompression of anterior ankle impingement would result in significant, reliable, and durable improvement in pain and ROM, and would allow NFL players to return to their preoperative level of play.

METHODS

After this study was granted Institutional Review Board approval, we retrospectively reviewed a consecutive series of arthroscopically treated anterior ankle impingement athletes by a single surgeon (JPB). Indications for surgery were anterior ankle impingement resulting in ankle pain and decreased ROM that interfered with sport. Active NFL players who underwent ankle arthroscopy for symptomatic anterior ankle impingement were included. Excluded were players who underwent surgery after retirement or who retired before returning to play for reasons unrelated to the ankle. Medical records, operative reports, and rehabilitation reports were reviewed.

Continue to: Preoperative and postoperative...

Preoperative and postoperative visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores, American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) hindfoot scores, and ankle ROM were compared; time to RTP, events missed secondary to surgery, and complications were recorded. These preoperative and postoperative variables were compared with paired Student 2-way t tests for continuous variables. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated.

PROCEDURE

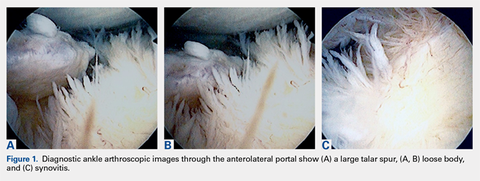

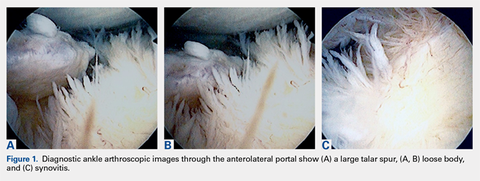

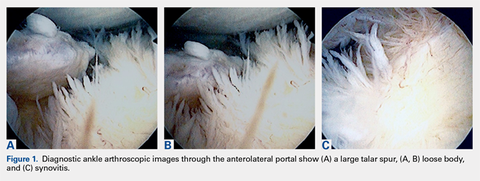

Ankle arthroscopy was performed with the patient supine after spinal or general anesthesia was induced. Prophylactic antibiotics were given in each case. Arthroscopy was performed with standard anterolateral and anteromedial portals. First, an incision was made through skin only, followed by blunt subcutaneous dissection down to the ankle capsule. A capsulotomy was then made bluntly. Care was taken to avoid all neurovascular structures. Posterior portals were not used. A 2.7-mm arthroscope was inserted and alternated between the anteromedial and anterolateral portals to maximally visualize the ankle joint. Diagnostic arthroscopy was performed to document synovitis, chondral injury, osseous, and soft-tissue impingement and any other noted pathology (Figures 1A-1C).

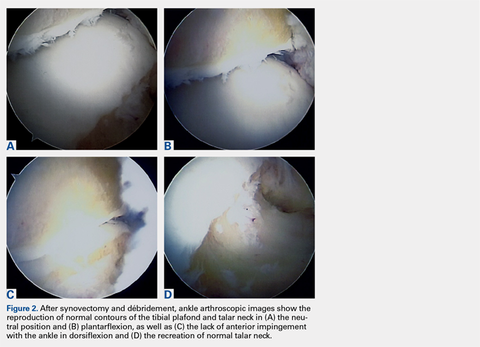

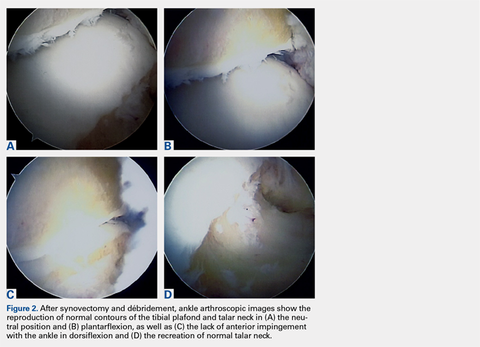

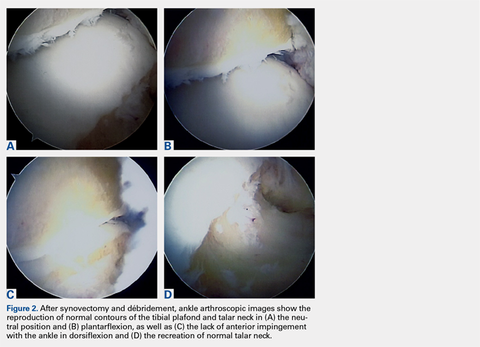

A full radius resector was then used to perform a synovectomy and débridement of impinging soft tissue from the anterior talofibular ligament or anterior inferior talofibular ligament. All patients underwent arthroscopic débridement of pathologic soft tissue and of tibial and talar osteophytes in the anterior ankle. A small burr was used to débride and remove the osteophytes on the talus and/or tibia. Soft-tissue and osseous structures were resected until the contours of the talus and tibia were normal. Any unstable articular defects were débrided and loose bodies were removed. Ankle ROM was checked to confirm complete resolution of impingement (Figures 2A-2D). Patients were not immobilized and were allowed progressive weight-bearing as tolerated. Crutches were used for assisted ambulation the first 3 to 5 postoperative days.

Physical therapy progressed through 3 phases: (1) inflammation control and ROM restoration, (2) initiation of ankle strengthening, including eversion and inversion, and (3) agility, proprioception, and functional rehabilitation.

RESULTS

Twenty-five NFL players (29 surgeries) were included in the study. Two players were excluded because they had retired at the end of the season before the surgery for reasons unrelated to the operative ankle. Mean (SD) age was 28.1 (2.9) years. Six included players had a history of ankle sprains, 1 had a history of ipsilateral ankle fracture, and 1 had a history of ipsilateral ankle dislocation. Table 1 lists the positions of players who underwent ankle arthroscopic decompression.

Table 1. Positions of National Football League Players Who Underwent Ankle Arthroscopic Decompression for Anterior Ankle Impingement

Position | Surgeries, n |

| Offensive line | 8 |

| Defensive line | 8 |

| Wide receiver | 4 |

| Running back | 4 |

| Linebacker | 3 |

| Quarterback | 1 |

| Defensive back | 1 |

Continue to: During diagnostic arthroscopy...

During diagnostic arthroscopy, changes to the articular cartilage were noted: grade 0 in 38% of patients, grade 1 in 17%, grade 2 in 21%, grade 3 in 21%, and grade 4 in 3%. Four patients had an osteochondral lesion (<1 cm in each case), which was treated with chondroplasty without microfracture.

Each included patient returned to NFL play. Mean (SD) time to RTP without restrictions was 8.4 (4.1) weeks after surgery (range, 2-20 weeks). There was a poor correlation between degree of chondrosis and time to RTP (r = 0.305). In addition, there was a poor correlation between age and time to RTP (r = 0.106).

Dorsiflexion improved significantly (P < .001), patients had significantly less pain after surgery (P < .001), and AOFAS hindfoot scores improved significantly (P < .001) (Table 2).

Table 2. Preoperative and Postoperative Dorsiflexion, Pain, and AOFAS Score Before and After Arthroscopic Débridement of Anterior Ankle Impingementa

| Mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | Postoperative | |

| Dorsiflexion | 8.28º (4.14º) | 18.86° (2.62°) |

| VAS pain score | 4.21 (1.52) | 0.38 (0.89) |

| AOFAS score | 70.62 (10.39) | 97.45 (4.72) |

aAll values were significantly improved after surgery (P < .001).

Abbreviations: AOFAS, American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society; VAS, visual analog scale.

The athletes played in the NFL for a mean (SD) of 3.43 (2.57) years after surgery (range, 1-10 seasons). These players included 6 who were still active at time of publication. No patient required revision surgery or additional surgery on the ipsilateral ankle. The one patient who was treated for superficial thrombophlebitis after surgery reported symptoms before surgery as well.

DISCUSSION

Arthroscopic decompression of anterior ankle impingement is safe and significantly improves pain and ROM in professional American football players. The procedure results in reliable RTP at an elite level, with durable results over the time remaining in their NFL careers.

Continue to: before the 1988 study by Hawkins...

Before the 1988 study by Hawkins,11 ankle spurs were removed with open procedures. Hawkins11 used arthroscopy for better and safer visualization of the ankle joint and used a burr for less painful removal of spurs from the tibia and the talus. In 2002, a series of 105 patients (median age, 35 years) had reduced pain and improved function a minimum of 2 years after arthroscopic débridement.12 These patients had a mix of pathology, including soft-tissue impingement, bony impingement, chondral lesions, loose bodies, and osteoarthritis.

For many elite athletes, anterior ankle impingement can cause significant limitation. Reduced ankle dorsiflexion can alter all limb mechanics and predispose athletes to injury.13 In addition, because NFL players’ ankle ROM often approaches or exceeds normal physiologic limits,14 an ankle ROM limitation will often hinder their performance.

Miyamoto and colleagues15 studied a series of 9 professional athletes (6 soccer players, 1 baseball pitcher, 1 mixed martial artist, 1 golfer) who underwent decompression of both anterior and posterior impingement. With regard to anterior impingement, they found anterior osteophytes in all the ankles, as was seen in the present study. Furthermore, they noted that mean dorsiflexion improved from 10° before surgery to 15° after surgery and that their athletes returned to play 12 to 15 weeks after surgery. Their results are similar to ours, though we noted more improvement in dorsiflexion, from 8.28° before surgery to 18.86° after surgery.

One of the most important metrics in evaluating treatment options for professional athletes is time from surgery to RTP without restrictions. Mean time to full RTP was shorter in our study (8.4 weeks) than in the study by Miyamoto and colleagues15 (up to 20 weeks). However, many of their procedures were performed during the off-season, when there was no need to expeditiously clear patients for full sports participation. In addition, the patients in their study had both anterior and posterior pathology.

Faster return to high-level athletics was supported in a study of 11 elite ballet dancers,16 whose pain and dance performance improved after arthroscopic débridement. Of the 11 patients, 9 returned to dance at a mean of 7 weeks after surgery; the other 2 required reoperation. Although the pathology differed in their study of elite professional soccer players, Calder and colleagues17 found that mean time to RTP after ankle arthroscopy for posterior impingement was 5 weeks.

Continue to: For the NFL players in our study...

For the NFL players in our study, RTP at their elite level was 100% after arthroscopic débridement of anterior ankle impingement. In the literature, time to RTP varies. Table 3 lists RTP rates for recreational athletes in published studies.18-27 In their recent systematic literature review, Zwiers and colleagues10 noted that 24% to 96.4% of recreational athletes returned to play after arthroscopic treatment for anterior ankle impingement. The percentage was significantly higher for the professional athletes in our study. Historical comparison supports an evolution in the indications and techniques for this procedure, with more recent literature suggesting a RTP rate much higher than earlier rates. In addition, compared with recreational athletes, professional athletes have strong financial incentives to return to their sports. Furthermore, our professional cohort was significantly younger than the recreational cohorts in those studies.

Table 3. Frequency of Recreational Athletes’ Return to Play After Arthroscopic Débridement of Anterior Ankle Impingement, as Reported in the Literature

| Study | Year | Journal | Return to Play | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N | % | |||

| Akseki et al18 | 1999 | Acta Orthop Scand | 10/11 | 91 |

| Baums et al19 | 2006 | Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc | 25/26 | 96 |

| Branca et al20 | 1997 | Foot Ankle Int | 13/27 | 48 |

| Di Palma et al21 | 1999 | J Sports Traumatol Relat Res | 21/32 | 66 |

| Ferkel et al22 | 1991 | Am J Sports Med | 27/31 | 87.1 |

| Hassan23 | 2007 | Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc | 9/11 | 82 |

| Jerosch et al24 | 1994 | Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc | 9/38 | 24 |

| Murawski & Kennedy25 | 2010 | Am J Sports Med | 27/28 | 96.4 |

| Ogilvie-Harris et al26 | 1993 | J Bone Joint Surg Br | 21/28 | 75 |

| Rouvillain et al27 | 2014 | Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol | 10/11 | 90 |

Total | 172/243 | 70 | ||

Current recommendations for recreational athletes include initial conservative treatment with rest, ankle bracing, and avoidance of jumping and other repetitive dorsiflexing activities. Physical therapy should include joint mobilization and work along the entire kinetic chain. Night splints or a removable walking boot can be used temporarily, as can a single intra-articular corticosteroid injection to reduce inflammation and evaluate improvement in more refractory cases.28 Commonly, conservative treatments fail if patients remain active, and soft tissue and/or osteophytes can be resected, though resection typically is reserved for recreational athletes for whom nonoperative treatments have been exhausted.29,30

This study had several limitations, including its retrospective nature and lack of control group. In addition, follow-up was relatively short, and we did not use more recently described outcome measures, such as the Sports subscale of the Foot and Ankle Ability Measure, which may be more sensitive in describing function in elite athletes. However, many of the cases in our study predated these measures, but the rate of RTP at the NFL level requires a very high degree of postoperative ankle function, making this outcome the most meaningful. In the context of professional athletes, specifically the length of their careers, our study results provide valuable information regarding expectations about RTP and the durability of arthroscopic débridement of anterior ankle impingement in a high-demand setting.

CONCLUSION

For all the NFL players in this study, arthroscopic débridement of anterior ankle impingement resulted in return to preoperative level of play at a mean of 2 months after surgery. There were significant improvements in VAS pain scores, AOFAS hindfoot scores, and ROM. Arthroscopic débridement of anterior ankle impingement relieves pain, restores ROM and function, and results in reliable RTP in professional football players.

1. Lubowitz JH. Editorial commentary: ankle anterior impingement is common in athletes and could be under-recognized. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(8):1597.

2. Mcdougall A. Footballer’s ankle. Lancet. 1955;269(6902):1219-1220.

3. Kleiger B. Anterior tibiotalar impingement syndromes in dancers. Foot Ankle. 1982;3(2):69-73.

4. Bassett FH 3rd, Gates HS 3rd, Billys JB, Morris HB, Nikolaou PK. Talar impingement by the anteroinferior tibiofibular ligament. A cause of chronic pain in the ankle after inversion sprain. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72(1):55-59.

5. Liu SH, Raskin A, Osti L, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of anterolateral ankle impingement. Arthroscopy. 1994;10(2):215-218.

6. Thein R, Eichenblat M. Arthroscopic treatment of sports-related synovitis of the ankle. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20(5):496-498.

7. Arnold H. Posttraumatic impingement syndrome of the ankle—indication and results of arthroscopic therapy. Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;17(2):85-88.

8. Walsh SJ, Twaddle BC, Rosenfeldt MP, Boyle MJ. Arthroscopic treatment of anterior ankle impingement: a prospective study of 46 patients with 5-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(11):2722-2726.

9. Glazebrook MA, Ganapathy V, Bridge MA, Stone JW, Allard JP. Evidence-based indications for ankle arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(12):1478-1490.

10. Zwiers R, Wiegerinck JI, Murawski CD, Fraser EJ, Kennedy JG, van Dijk CN. Arthroscopic treatment for anterior ankle impingement: a systematic review of the current literature. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(8):1585-1596.

11. Hawkins RB. Arthroscopic treatment of sports-related anterior osteophytes in the ankle. Foot Ankle. 1988;9(2):87-90.

12. Rasmussen S, Hjorth Jensen C. Arthroscopic treatment of impingement of the ankle reduces pain and enhances function. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2002;12(2):69-72.

13. Mason-Mackay AR, Whatman C, Reid D. The effect of reduced ankle dorsiflexion on lower extremity mechanics during landing: a systematic review. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20(5):451-458.

14. Riley PO, Kent RW, Dierks TA, Lievers WB, Frimenko RE, Crandall JR. Foot kinematics and loading of professional athletes in American football-specific tasks. Gait Posture. 2013;38(4):563-569.

15. Miyamoto W, Takao M, Matsui K, Matsushita T. Simultaneous ankle arthroscopy and hindfoot endoscopy for combined anterior and posterior ankle impingement syndrome in professional athletes. J Orthop Sci. 2015;20(4):642-648.

16. Nihal A, Rose DJ, Trepman E. Arthroscopic treatment of anterior ankle impingement syndrome in dancers. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26(11):908-912.

17. Calder JD, Sexton SA, Pearce CJ. Return to training and playing after posterior ankle arthroscopy for posterior impingement in elite professional soccer. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(1):120-124.

18. Akseki D, Pinar H, Bozkurt M, Yaldiz K, Arag S. The distal fascicle of the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament as a cause of anterolateral ankle impingement: results of arthroscopic resection. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70(5):478-482.

19. Baums MH, Kahl E, Schultz W, Klinger HM. Clinical outcome of the arthroscopic management of sports-related “anterior ankle pain”: a prospective study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(5):482-486.

20. Branca A, Di Palma L, Bucca C, Visconti CS, Di Mille M. Arthroscopic treatment of anterior ankle impingement. Foot Ankle Int. 1997;18(7):418-423.

21. Di Palma L, Bucca C, Di Mille M, Branca A. Diagnosis and arthroscopic treatment of fibrous impingement of the ankle. J Sports Traumatol Relat Res. 1999;21:170-177.

22. Ferkel RD, Karzel RP, Del Pizzo W, Friedman MJ, Fischer SP. Arthroscopic treatment of anterolateral impingement of the ankle. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(5):440-446.