User login

Register early for the AGA Postgraduate Course

We held a contest in the AGA Community forum asking members to share a piece of advice they learned or heard in the past year for a chance to win free registration to this year’s AGA Postgraduate Course in Washington, D.C., on June 2 and 3.

Here are some of our favorite responses from early career members, including our winner, Hüseyin Bozkurt from Medical Park Private Tarsus Hospital, Turkey:

- “We can provide healthy gut microbiome, don’t lose your hope. The future is changeable.” Hüseyin Bozkurt Sr., MD, contest winner.

- “Ambulatory reflux monitoring modalities can help phenotype GERD and guide optimal management.” Amit Patel, MD, 2018 AGA Postgraduate Course faculty.

- “One tip I heard from an attending in the first year of fellowship, which is particularly useful for IBS patients, is to set realistic expectations from the outset, for e.g. – when diagnosing patients with IBS and giving them advice, telling them ‘We are not looking to cure your GI symptoms, but to control them – you will have GI symptoms off and on despite treatment, my goal is to make sure you have more good days, than bad.’” Aakash Aggarwal, MD

Registration for the popular 1.5-day course is now open. Learn more at pgcourse.gastro.org and save $75 by registering before April 18.

The AGA Postgraduate Course takes place during AGA’s annual meeting Digestive Disease Week®, which is cosponsored by AASLD, ASGE, and SSAT. Learn more and register at www.ddw.org.

We held a contest in the AGA Community forum asking members to share a piece of advice they learned or heard in the past year for a chance to win free registration to this year’s AGA Postgraduate Course in Washington, D.C., on June 2 and 3.

Here are some of our favorite responses from early career members, including our winner, Hüseyin Bozkurt from Medical Park Private Tarsus Hospital, Turkey:

- “We can provide healthy gut microbiome, don’t lose your hope. The future is changeable.” Hüseyin Bozkurt Sr., MD, contest winner.

- “Ambulatory reflux monitoring modalities can help phenotype GERD and guide optimal management.” Amit Patel, MD, 2018 AGA Postgraduate Course faculty.

- “One tip I heard from an attending in the first year of fellowship, which is particularly useful for IBS patients, is to set realistic expectations from the outset, for e.g. – when diagnosing patients with IBS and giving them advice, telling them ‘We are not looking to cure your GI symptoms, but to control them – you will have GI symptoms off and on despite treatment, my goal is to make sure you have more good days, than bad.’” Aakash Aggarwal, MD

Registration for the popular 1.5-day course is now open. Learn more at pgcourse.gastro.org and save $75 by registering before April 18.

The AGA Postgraduate Course takes place during AGA’s annual meeting Digestive Disease Week®, which is cosponsored by AASLD, ASGE, and SSAT. Learn more and register at www.ddw.org.

We held a contest in the AGA Community forum asking members to share a piece of advice they learned or heard in the past year for a chance to win free registration to this year’s AGA Postgraduate Course in Washington, D.C., on June 2 and 3.

Here are some of our favorite responses from early career members, including our winner, Hüseyin Bozkurt from Medical Park Private Tarsus Hospital, Turkey:

- “We can provide healthy gut microbiome, don’t lose your hope. The future is changeable.” Hüseyin Bozkurt Sr., MD, contest winner.

- “Ambulatory reflux monitoring modalities can help phenotype GERD and guide optimal management.” Amit Patel, MD, 2018 AGA Postgraduate Course faculty.

- “One tip I heard from an attending in the first year of fellowship, which is particularly useful for IBS patients, is to set realistic expectations from the outset, for e.g. – when diagnosing patients with IBS and giving them advice, telling them ‘We are not looking to cure your GI symptoms, but to control them – you will have GI symptoms off and on despite treatment, my goal is to make sure you have more good days, than bad.’” Aakash Aggarwal, MD

Registration for the popular 1.5-day course is now open. Learn more at pgcourse.gastro.org and save $75 by registering before April 18.

The AGA Postgraduate Course takes place during AGA’s annual meeting Digestive Disease Week®, which is cosponsored by AASLD, ASGE, and SSAT. Learn more and register at www.ddw.org.

Five reasons to pursue a career in IBD research or patient care

A career in inflammatory bowel disease promises to be challenging, exciting, at times frustrating, and always educational. We asked our expert faculty at the inaugural Crohn’s & Colitis Congress, which took place Jan. 18-20 in Las Vegas, to reflect on why a career in IBD is an excellent path to take.

Why pursue a career in IBD

1. “IBD is the fastest moving area of GI to integrate science (genomics, microbiome, immunology) into care that will change the natural history of disease. The physicians and scientists have an unusually collegial culture, and the patients really care.” – Jonathan G. Braun, MD, PhD

2. “Managing patients with IBD is becoming ever more complex. When patients move beyond having mild disease, complex decisions need to be made. Choosing the right medication at the right time for the right patient will lead to the best outcomes for patients with IBD. I have every reason to believe that specializing in the clinical care of patients with IBD will be intellectually challenging while offering great personal satisfaction in taking care of these ill patients.” – Francis A. Farraye, MD, MSc

3. “IBD research findings and the implications for patient care are evolving rapidly. Many recommendations that we made 5-10 years ago have changed as we are learning more about IBD every day. There are so many opportunities to participate in the expansion of that knowledge base and help us reach our goal of a cure for IBD in the lifetime of many of our patients. Take the challenge.” – Teri Lynn Jackson, MSN, ARNP

4. “IBD is an outstanding field led by great people who want to see fellows and junior faculty succeed. Identify a mentor and listen to them, meet and engage with new people, be curious, think big, and work hard!” – Michael J. Rosen, MD, MSCI

5. “The best career in the world! Such variety. A home for everyone with any interest. It won’t always be smooth, but it will be incredibly rewarding with hardly a dull moment.” – Dermot McGovern, MD, PhD, FRCP

For additional tips and advice, visit the AGA Community.

A career in inflammatory bowel disease promises to be challenging, exciting, at times frustrating, and always educational. We asked our expert faculty at the inaugural Crohn’s & Colitis Congress, which took place Jan. 18-20 in Las Vegas, to reflect on why a career in IBD is an excellent path to take.

Why pursue a career in IBD

1. “IBD is the fastest moving area of GI to integrate science (genomics, microbiome, immunology) into care that will change the natural history of disease. The physicians and scientists have an unusually collegial culture, and the patients really care.” – Jonathan G. Braun, MD, PhD

2. “Managing patients with IBD is becoming ever more complex. When patients move beyond having mild disease, complex decisions need to be made. Choosing the right medication at the right time for the right patient will lead to the best outcomes for patients with IBD. I have every reason to believe that specializing in the clinical care of patients with IBD will be intellectually challenging while offering great personal satisfaction in taking care of these ill patients.” – Francis A. Farraye, MD, MSc

3. “IBD research findings and the implications for patient care are evolving rapidly. Many recommendations that we made 5-10 years ago have changed as we are learning more about IBD every day. There are so many opportunities to participate in the expansion of that knowledge base and help us reach our goal of a cure for IBD in the lifetime of many of our patients. Take the challenge.” – Teri Lynn Jackson, MSN, ARNP

4. “IBD is an outstanding field led by great people who want to see fellows and junior faculty succeed. Identify a mentor and listen to them, meet and engage with new people, be curious, think big, and work hard!” – Michael J. Rosen, MD, MSCI

5. “The best career in the world! Such variety. A home for everyone with any interest. It won’t always be smooth, but it will be incredibly rewarding with hardly a dull moment.” – Dermot McGovern, MD, PhD, FRCP

For additional tips and advice, visit the AGA Community.

A career in inflammatory bowel disease promises to be challenging, exciting, at times frustrating, and always educational. We asked our expert faculty at the inaugural Crohn’s & Colitis Congress, which took place Jan. 18-20 in Las Vegas, to reflect on why a career in IBD is an excellent path to take.

Why pursue a career in IBD

1. “IBD is the fastest moving area of GI to integrate science (genomics, microbiome, immunology) into care that will change the natural history of disease. The physicians and scientists have an unusually collegial culture, and the patients really care.” – Jonathan G. Braun, MD, PhD

2. “Managing patients with IBD is becoming ever more complex. When patients move beyond having mild disease, complex decisions need to be made. Choosing the right medication at the right time for the right patient will lead to the best outcomes for patients with IBD. I have every reason to believe that specializing in the clinical care of patients with IBD will be intellectually challenging while offering great personal satisfaction in taking care of these ill patients.” – Francis A. Farraye, MD, MSc

3. “IBD research findings and the implications for patient care are evolving rapidly. Many recommendations that we made 5-10 years ago have changed as we are learning more about IBD every day. There are so many opportunities to participate in the expansion of that knowledge base and help us reach our goal of a cure for IBD in the lifetime of many of our patients. Take the challenge.” – Teri Lynn Jackson, MSN, ARNP

4. “IBD is an outstanding field led by great people who want to see fellows and junior faculty succeed. Identify a mentor and listen to them, meet and engage with new people, be curious, think big, and work hard!” – Michael J. Rosen, MD, MSCI

5. “The best career in the world! Such variety. A home for everyone with any interest. It won’t always be smooth, but it will be incredibly rewarding with hardly a dull moment.” – Dermot McGovern, MD, PhD, FRCP

For additional tips and advice, visit the AGA Community.

How to help children process, overcome horrific traumas

Unfathomable. Unspeakable.

These are among the terms used to describe children’s extreme traumatic experiences such as severe abuse and neglect. It is often most shocking when these acts are perpetrated by the children’s parents – the very ones that children should be able to depend on for their protection and safety.

Many believe that, in addition to the cumulative and serious nature of repetitive interpersonal traumas themselves, this betrayal of trust will result in irreparable psychological damage. Fortunately, this does not have to be the case. Children are more resilient than we realize; with safety, support, and effective treatment, they can recover from even the most extreme traumas and live healthy, productive lives.

and allow them to live in safe, stable, supportive settings while minimizing traumatic separation from siblings or further disruptions in their living situation. Acute medical problems need to be stabilized, and a thorough mental health assessment should be conducted.

Evidence-based trauma-focused psychotherapy is the first-line treatment for addressing pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Apr;49[4]:414-30). Several treatments are currently available. A few examples are trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy, or TF-CBT, for children aged 3-18 years; child-parent psychotherapy (CPP) for children aged 0-6 years; a group school-based model, cognitive behavioral interventions for trauma in schools (CBITS); and Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education and Therapy for teens (TARGET).

Common elements of evidence-based trauma-focused treatments are: 1) nonperpetrating caregivers are included in therapy to enhance support and understanding of the child’s trauma responses, and to address trauma-related behavioral problems; 2) skills are provided to the youth and caregiver for coping with negative trauma-related thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; and 3) children are supported to directly talk about and make meaning of their trauma experiences.

Through trauma-focused treatment, children become able to cope with their traumatic experiences and memories – make sense out of them. These traumas are no longer “unfathomable or “unspeakable,” but rather, manageable memories of bad experiences that the children have had the courage to face and master.

Children can recover from even extreme trauma experiences when they receive effective trauma-focused treatment in the context of a supportive environment. More information about evidence-based treatments is available from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network at www.nctsn.org/resources/topics/treatments-that-work/promising-practices.

Unfathomable. Unspeakable.

These are among the terms used to describe children’s extreme traumatic experiences such as severe abuse and neglect. It is often most shocking when these acts are perpetrated by the children’s parents – the very ones that children should be able to depend on for their protection and safety.

Many believe that, in addition to the cumulative and serious nature of repetitive interpersonal traumas themselves, this betrayal of trust will result in irreparable psychological damage. Fortunately, this does not have to be the case. Children are more resilient than we realize; with safety, support, and effective treatment, they can recover from even the most extreme traumas and live healthy, productive lives.

and allow them to live in safe, stable, supportive settings while minimizing traumatic separation from siblings or further disruptions in their living situation. Acute medical problems need to be stabilized, and a thorough mental health assessment should be conducted.

Evidence-based trauma-focused psychotherapy is the first-line treatment for addressing pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Apr;49[4]:414-30). Several treatments are currently available. A few examples are trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy, or TF-CBT, for children aged 3-18 years; child-parent psychotherapy (CPP) for children aged 0-6 years; a group school-based model, cognitive behavioral interventions for trauma in schools (CBITS); and Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education and Therapy for teens (TARGET).

Common elements of evidence-based trauma-focused treatments are: 1) nonperpetrating caregivers are included in therapy to enhance support and understanding of the child’s trauma responses, and to address trauma-related behavioral problems; 2) skills are provided to the youth and caregiver for coping with negative trauma-related thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; and 3) children are supported to directly talk about and make meaning of their trauma experiences.

Through trauma-focused treatment, children become able to cope with their traumatic experiences and memories – make sense out of them. These traumas are no longer “unfathomable or “unspeakable,” but rather, manageable memories of bad experiences that the children have had the courage to face and master.

Children can recover from even extreme trauma experiences when they receive effective trauma-focused treatment in the context of a supportive environment. More information about evidence-based treatments is available from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network at www.nctsn.org/resources/topics/treatments-that-work/promising-practices.

Unfathomable. Unspeakable.

These are among the terms used to describe children’s extreme traumatic experiences such as severe abuse and neglect. It is often most shocking when these acts are perpetrated by the children’s parents – the very ones that children should be able to depend on for their protection and safety.

Many believe that, in addition to the cumulative and serious nature of repetitive interpersonal traumas themselves, this betrayal of trust will result in irreparable psychological damage. Fortunately, this does not have to be the case. Children are more resilient than we realize; with safety, support, and effective treatment, they can recover from even the most extreme traumas and live healthy, productive lives.

and allow them to live in safe, stable, supportive settings while minimizing traumatic separation from siblings or further disruptions in their living situation. Acute medical problems need to be stabilized, and a thorough mental health assessment should be conducted.

Evidence-based trauma-focused psychotherapy is the first-line treatment for addressing pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010 Apr;49[4]:414-30). Several treatments are currently available. A few examples are trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy, or TF-CBT, for children aged 3-18 years; child-parent psychotherapy (CPP) for children aged 0-6 years; a group school-based model, cognitive behavioral interventions for trauma in schools (CBITS); and Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education and Therapy for teens (TARGET).

Common elements of evidence-based trauma-focused treatments are: 1) nonperpetrating caregivers are included in therapy to enhance support and understanding of the child’s trauma responses, and to address trauma-related behavioral problems; 2) skills are provided to the youth and caregiver for coping with negative trauma-related thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; and 3) children are supported to directly talk about and make meaning of their trauma experiences.

Through trauma-focused treatment, children become able to cope with their traumatic experiences and memories – make sense out of them. These traumas are no longer “unfathomable or “unspeakable,” but rather, manageable memories of bad experiences that the children have had the courage to face and master.

Children can recover from even extreme trauma experiences when they receive effective trauma-focused treatment in the context of a supportive environment. More information about evidence-based treatments is available from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network at www.nctsn.org/resources/topics/treatments-that-work/promising-practices.

Analysis of Twitter lung cancer content reveals opportunity for clinicians

Social media communication around lung cancer is focused primarily on cancer treatment and use of pharmaceutical and research interventions, followed closely by awareness, prevention, and risk topics, according to an analysis of Twitter conversation over a 10-day period.

Although awareness and risk prevention tweets were likely to contain cues toward action, “messages focused on treatment, end of life ... were significantly less likely to integrate cues for personal activity,” the investigators wrote. The report was published in Journal of the American College of Radiology.

The investigators collected 1.3 million unique Twitter messages between Sept. 30 and Oct. 9, 2016, that contained at least one of six keywords commonly used to describe cancer: cancer, chemo, tumor, malignant, biopsy, and metastasis. They then drew a random, proportional stratified sample of 3,000 messages (12.5%) for manual coding from the 23,926 messages posted that included keywords related to lung cancer. Tweets were examined by user type (individuals, media, and organizations) to identify content and structural message features.

Message content was most frequently related to treatment (32.1%), followed by awareness (22.9%), end of life (15.5%), prevention and risk information (13.3%), active cancer-unknown phase (7.6%), diagnosis (6.1%), early detection (2.7%), and survivorship (1%), Dr. Sutton and her colleagues reported.

“The large volume of messages containing content about pharmaceuticals suggests that Twitter is also a forum for sharing information and discussing emerging treatments. Importantly, treatment messages were shared primarily by individuals, suggesting that this online user community jointly includes members of the public as well as medical practitioners and companies who have an awareness of emerging treatment approaches, suggesting an opportunity for online engagement between these various groups (e.g., Lung Cancer Social Media #LCSM community and related chats),” the investigators wrote.

The National Science Foundation supported parts of this research. None of the authors reported any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sutton J. et al., J Am Coll Radiol. 2018 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.09.043

Social media communication around lung cancer is focused primarily on cancer treatment and use of pharmaceutical and research interventions, followed closely by awareness, prevention, and risk topics, according to an analysis of Twitter conversation over a 10-day period.

Although awareness and risk prevention tweets were likely to contain cues toward action, “messages focused on treatment, end of life ... were significantly less likely to integrate cues for personal activity,” the investigators wrote. The report was published in Journal of the American College of Radiology.

The investigators collected 1.3 million unique Twitter messages between Sept. 30 and Oct. 9, 2016, that contained at least one of six keywords commonly used to describe cancer: cancer, chemo, tumor, malignant, biopsy, and metastasis. They then drew a random, proportional stratified sample of 3,000 messages (12.5%) for manual coding from the 23,926 messages posted that included keywords related to lung cancer. Tweets were examined by user type (individuals, media, and organizations) to identify content and structural message features.

Message content was most frequently related to treatment (32.1%), followed by awareness (22.9%), end of life (15.5%), prevention and risk information (13.3%), active cancer-unknown phase (7.6%), diagnosis (6.1%), early detection (2.7%), and survivorship (1%), Dr. Sutton and her colleagues reported.

“The large volume of messages containing content about pharmaceuticals suggests that Twitter is also a forum for sharing information and discussing emerging treatments. Importantly, treatment messages were shared primarily by individuals, suggesting that this online user community jointly includes members of the public as well as medical practitioners and companies who have an awareness of emerging treatment approaches, suggesting an opportunity for online engagement between these various groups (e.g., Lung Cancer Social Media #LCSM community and related chats),” the investigators wrote.

The National Science Foundation supported parts of this research. None of the authors reported any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sutton J. et al., J Am Coll Radiol. 2018 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.09.043

Social media communication around lung cancer is focused primarily on cancer treatment and use of pharmaceutical and research interventions, followed closely by awareness, prevention, and risk topics, according to an analysis of Twitter conversation over a 10-day period.

Although awareness and risk prevention tweets were likely to contain cues toward action, “messages focused on treatment, end of life ... were significantly less likely to integrate cues for personal activity,” the investigators wrote. The report was published in Journal of the American College of Radiology.

The investigators collected 1.3 million unique Twitter messages between Sept. 30 and Oct. 9, 2016, that contained at least one of six keywords commonly used to describe cancer: cancer, chemo, tumor, malignant, biopsy, and metastasis. They then drew a random, proportional stratified sample of 3,000 messages (12.5%) for manual coding from the 23,926 messages posted that included keywords related to lung cancer. Tweets were examined by user type (individuals, media, and organizations) to identify content and structural message features.

Message content was most frequently related to treatment (32.1%), followed by awareness (22.9%), end of life (15.5%), prevention and risk information (13.3%), active cancer-unknown phase (7.6%), diagnosis (6.1%), early detection (2.7%), and survivorship (1%), Dr. Sutton and her colleagues reported.

“The large volume of messages containing content about pharmaceuticals suggests that Twitter is also a forum for sharing information and discussing emerging treatments. Importantly, treatment messages were shared primarily by individuals, suggesting that this online user community jointly includes members of the public as well as medical practitioners and companies who have an awareness of emerging treatment approaches, suggesting an opportunity for online engagement between these various groups (e.g., Lung Cancer Social Media #LCSM community and related chats),” the investigators wrote.

The National Science Foundation supported parts of this research. None of the authors reported any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Sutton J. et al., J Am Coll Radiol. 2018 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.09.043

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RADIOLOGY

Key clinical point: In a random sample of Twitter conversation related to lung cancer, message content was most frequently related to treatment.

Major finding: Majority of tweets evaluated focused on lung cancer treatment and the use of pharmaceutical and research interventions, followed by awareness, prevention, and risk topics.

Study details: Random sample of 3,000 tweets posted in a 10-day period between Sept. 30 and Oct. 9, 2016. Lung cancer–specific tweets by user type (individuals, media, and organizations) were examined to identify content and structural message features.

Disclosures: The National Science Foundation supported parts of this research. None of the authors reported any conflicts of interest.

Source: Sutton J. et al., J Am Coll Radiol. 2018 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.09.043.

VIDEO: New stroke guideline embraces imaging-guided thrombectomy

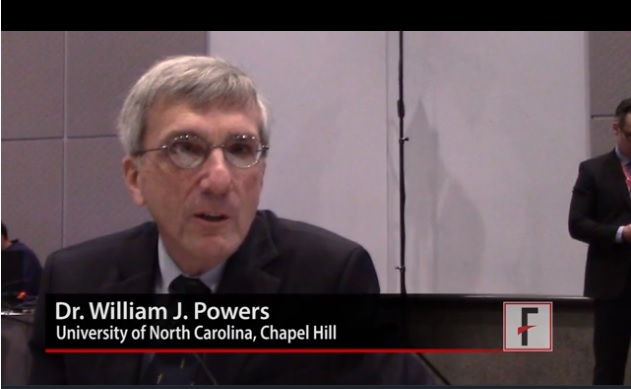

LOS ANGELES – When a panel organized by the American Heart Association’s Stroke Council recently revised the group’s guideline for early management of acute ischemic stroke, they were clear on the overarching change they had to make: Incorporate recent evidence collected in two trials that established brain imaging as the way to identify patients eligible for clot removal treatment by thrombectomy, a change in practice that has made this outcome-altering intervention available to more patients.

“The major take-home message [of the new guideline] is the extension of the time window for treating acute ischemic stroke,” said William J. Powers, MD, chair of the guideline group (Stroke. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158).

Based on recently reported results from the DAWN (N Engl J Med. 2018;378[1]:11-21) and DEFUSE 3 (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713973) trials “we know that there are patients out to 24 hours from their stroke onset who may benefit” from thrombectomy. “This is a major, major change in how we view care for patients with stroke,” Dr. Powers said in a video interview. “Now there’s much more time. Ideally, we’ll see smaller hospitals develop the ability to do the imaging” that makes it possible to select acute ischemic stroke patients eligible for thrombectomy despite a delay of up to 24 hours from their stroke onset to the time of thrombectomy, said Dr. Powers, professor and chair of neurology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

The big priority for the stroke community now that this major change in patient selection was incorporated into a U.S. practice guideline will be acting quickly to implement the steps needed to make this change happen, Dr. Powers and others said.

The new guideline will mean “changes in process and systems of care,” agreed Jeffrey L. Saver, MD, professor of neurology and director of the stroke unit at the University of California, Los Angeles. The imaging called for “will be practical at some primary stroke centers but not others,” he said, although most hospitals certified to provide stroke care as primary stroke centers or acute stroke–ready hospitals have a CT scanner that could provide the basic imaging needed to assess many patients. (CT angiography and perfusion CT are more informative for determining thrombectomy eligibility.) But interpretation of the brain images to distinguish patients eligible for thrombectomy from those who aren’t will likely happen at comprehensive stroke centers that perform thrombectomy or by experts using remote image reading.

Dr. Saver expects that the new guideline will translate most quickly into changes in the imaging and transfer protocols that the Joint Commission may now require from hospitals certified as primary stroke centers or acute stroke-ready hospitals, changes that could be in place sometime later in 2018, he predicted. These are steps “that would really help drive system change.”

Dr. Powers and Dr. Furie had no disclosures. Dr. Saver has received research support and personal fees from Medtronic-Abbott and Neuravia.

LOS ANGELES – When a panel organized by the American Heart Association’s Stroke Council recently revised the group’s guideline for early management of acute ischemic stroke, they were clear on the overarching change they had to make: Incorporate recent evidence collected in two trials that established brain imaging as the way to identify patients eligible for clot removal treatment by thrombectomy, a change in practice that has made this outcome-altering intervention available to more patients.

“The major take-home message [of the new guideline] is the extension of the time window for treating acute ischemic stroke,” said William J. Powers, MD, chair of the guideline group (Stroke. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158).

Based on recently reported results from the DAWN (N Engl J Med. 2018;378[1]:11-21) and DEFUSE 3 (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713973) trials “we know that there are patients out to 24 hours from their stroke onset who may benefit” from thrombectomy. “This is a major, major change in how we view care for patients with stroke,” Dr. Powers said in a video interview. “Now there’s much more time. Ideally, we’ll see smaller hospitals develop the ability to do the imaging” that makes it possible to select acute ischemic stroke patients eligible for thrombectomy despite a delay of up to 24 hours from their stroke onset to the time of thrombectomy, said Dr. Powers, professor and chair of neurology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

The big priority for the stroke community now that this major change in patient selection was incorporated into a U.S. practice guideline will be acting quickly to implement the steps needed to make this change happen, Dr. Powers and others said.

The new guideline will mean “changes in process and systems of care,” agreed Jeffrey L. Saver, MD, professor of neurology and director of the stroke unit at the University of California, Los Angeles. The imaging called for “will be practical at some primary stroke centers but not others,” he said, although most hospitals certified to provide stroke care as primary stroke centers or acute stroke–ready hospitals have a CT scanner that could provide the basic imaging needed to assess many patients. (CT angiography and perfusion CT are more informative for determining thrombectomy eligibility.) But interpretation of the brain images to distinguish patients eligible for thrombectomy from those who aren’t will likely happen at comprehensive stroke centers that perform thrombectomy or by experts using remote image reading.

Dr. Saver expects that the new guideline will translate most quickly into changes in the imaging and transfer protocols that the Joint Commission may now require from hospitals certified as primary stroke centers or acute stroke-ready hospitals, changes that could be in place sometime later in 2018, he predicted. These are steps “that would really help drive system change.”

Dr. Powers and Dr. Furie had no disclosures. Dr. Saver has received research support and personal fees from Medtronic-Abbott and Neuravia.

LOS ANGELES – When a panel organized by the American Heart Association’s Stroke Council recently revised the group’s guideline for early management of acute ischemic stroke, they were clear on the overarching change they had to make: Incorporate recent evidence collected in two trials that established brain imaging as the way to identify patients eligible for clot removal treatment by thrombectomy, a change in practice that has made this outcome-altering intervention available to more patients.

“The major take-home message [of the new guideline] is the extension of the time window for treating acute ischemic stroke,” said William J. Powers, MD, chair of the guideline group (Stroke. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158).

Based on recently reported results from the DAWN (N Engl J Med. 2018;378[1]:11-21) and DEFUSE 3 (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713973) trials “we know that there are patients out to 24 hours from their stroke onset who may benefit” from thrombectomy. “This is a major, major change in how we view care for patients with stroke,” Dr. Powers said in a video interview. “Now there’s much more time. Ideally, we’ll see smaller hospitals develop the ability to do the imaging” that makes it possible to select acute ischemic stroke patients eligible for thrombectomy despite a delay of up to 24 hours from their stroke onset to the time of thrombectomy, said Dr. Powers, professor and chair of neurology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

The big priority for the stroke community now that this major change in patient selection was incorporated into a U.S. practice guideline will be acting quickly to implement the steps needed to make this change happen, Dr. Powers and others said.

The new guideline will mean “changes in process and systems of care,” agreed Jeffrey L. Saver, MD, professor of neurology and director of the stroke unit at the University of California, Los Angeles. The imaging called for “will be practical at some primary stroke centers but not others,” he said, although most hospitals certified to provide stroke care as primary stroke centers or acute stroke–ready hospitals have a CT scanner that could provide the basic imaging needed to assess many patients. (CT angiography and perfusion CT are more informative for determining thrombectomy eligibility.) But interpretation of the brain images to distinguish patients eligible for thrombectomy from those who aren’t will likely happen at comprehensive stroke centers that perform thrombectomy or by experts using remote image reading.

Dr. Saver expects that the new guideline will translate most quickly into changes in the imaging and transfer protocols that the Joint Commission may now require from hospitals certified as primary stroke centers or acute stroke-ready hospitals, changes that could be in place sometime later in 2018, he predicted. These are steps “that would really help drive system change.”

Dr. Powers and Dr. Furie had no disclosures. Dr. Saver has received research support and personal fees from Medtronic-Abbott and Neuravia.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ISC 2018

Zika-linked birth defects climbing in U.S. hot spots

The prevalence of birth defects strongly linked with congenital Zika virus infection increased 21% from the first to the second half of 2016 in areas of the United States with local, endemic transmission: Puerto Rico, south Florida, and southern Texas, according to a report in the Jan. 26 edition of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In those areas, complications strongly associated with Zika – including microcephaly; brain and eye abnormalities; and neurogenic hip dislocation, clubfoot, hearing loss, and arthrogryposis – jumped from 2.0 to 2.4 cases per 1,000 live births, with 140 cases in the first half of the year and 169 cases in the second (P = .009). Microcephaly and brain abnormalities were the most common problems.

In places with less than one confirmed Zika case from travel per 100,000 residents, such as Hawaii and Utah, the prevalence of birth defects strongly linked to Zika actually dropped from 2.8 cases per 1,000 live births to 2.4 in 2016.

The 15 U.S. jurisdictions in the study included nearly 1 million live births, representing approximately one fourth of the total live births in the United States in 2016. The live birth rate was 92% among the 2,962 infants and fetuses with Zika-associated birth defects.

All the jurisdictions had existing birth defects surveillance systems that quickly adapted to monitor for potential Zika defects. However, although strongly associated with Zika, there’s no guarantee that the birth defects in the study were actually caused by the virus, the researchers noted.

“These data will help communities plan for needed resources to care for affected patients and families and can serve as a foundation for linking and evaluating health and developmental outcomes of affected children,” said the investigators, led by Augustina Delaney, PhD, of the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta.

The work was the first population-based birth defect surveillance report for Zika. The CDC follows confirmed Zika cases in pregnant women and their offspring closely, but only a small portion of women are actually tested, so there’s likely far more cases of congenital Zika infection than show up in registries. Despite its limits, birth defect surveillance likely provides a more accurate picture of the actual extent of the problem.

It’s not known why Zika-linked birth defects dropped off in areas with low or no travel-associated cases. “However ... further case ascertainment from the final quarter of 2016 is anticipated in all jurisdictions,” so the numbers could change, the authors said.

They had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Delaney A, et. al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018 Jan 26;67(3):91-6

Although these birth defects are not specific to congenital Zika virus infection, only those defects found previously to be most closely aligned with congenital Zika infection had increased prevalence.

It is critical that public health surveillance programs continue reporting the occurrence of these birth defects to monitor for trends following the Zika virus outbreak.

Brenda Fitzgerald , MD, is the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. Coleen A. Boyle , PhD, is the director of the CDC National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, and Margaret Honein , PhD, is chief of the agency’s Birth Defects Branch. They made their comments Jan. 25 in JAMA, and had no conflicts of interest (Jama. 2018 Jan 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0126).

Although these birth defects are not specific to congenital Zika virus infection, only those defects found previously to be most closely aligned with congenital Zika infection had increased prevalence.

It is critical that public health surveillance programs continue reporting the occurrence of these birth defects to monitor for trends following the Zika virus outbreak.

Brenda Fitzgerald , MD, is the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. Coleen A. Boyle , PhD, is the director of the CDC National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, and Margaret Honein , PhD, is chief of the agency’s Birth Defects Branch. They made their comments Jan. 25 in JAMA, and had no conflicts of interest (Jama. 2018 Jan 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0126).

Although these birth defects are not specific to congenital Zika virus infection, only those defects found previously to be most closely aligned with congenital Zika infection had increased prevalence.

It is critical that public health surveillance programs continue reporting the occurrence of these birth defects to monitor for trends following the Zika virus outbreak.

Brenda Fitzgerald , MD, is the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. Coleen A. Boyle , PhD, is the director of the CDC National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, and Margaret Honein , PhD, is chief of the agency’s Birth Defects Branch. They made their comments Jan. 25 in JAMA, and had no conflicts of interest (Jama. 2018 Jan 25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0126).

The prevalence of birth defects strongly linked with congenital Zika virus infection increased 21% from the first to the second half of 2016 in areas of the United States with local, endemic transmission: Puerto Rico, south Florida, and southern Texas, according to a report in the Jan. 26 edition of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In those areas, complications strongly associated with Zika – including microcephaly; brain and eye abnormalities; and neurogenic hip dislocation, clubfoot, hearing loss, and arthrogryposis – jumped from 2.0 to 2.4 cases per 1,000 live births, with 140 cases in the first half of the year and 169 cases in the second (P = .009). Microcephaly and brain abnormalities were the most common problems.

In places with less than one confirmed Zika case from travel per 100,000 residents, such as Hawaii and Utah, the prevalence of birth defects strongly linked to Zika actually dropped from 2.8 cases per 1,000 live births to 2.4 in 2016.

The 15 U.S. jurisdictions in the study included nearly 1 million live births, representing approximately one fourth of the total live births in the United States in 2016. The live birth rate was 92% among the 2,962 infants and fetuses with Zika-associated birth defects.

All the jurisdictions had existing birth defects surveillance systems that quickly adapted to monitor for potential Zika defects. However, although strongly associated with Zika, there’s no guarantee that the birth defects in the study were actually caused by the virus, the researchers noted.

“These data will help communities plan for needed resources to care for affected patients and families and can serve as a foundation for linking and evaluating health and developmental outcomes of affected children,” said the investigators, led by Augustina Delaney, PhD, of the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta.

The work was the first population-based birth defect surveillance report for Zika. The CDC follows confirmed Zika cases in pregnant women and their offspring closely, but only a small portion of women are actually tested, so there’s likely far more cases of congenital Zika infection than show up in registries. Despite its limits, birth defect surveillance likely provides a more accurate picture of the actual extent of the problem.

It’s not known why Zika-linked birth defects dropped off in areas with low or no travel-associated cases. “However ... further case ascertainment from the final quarter of 2016 is anticipated in all jurisdictions,” so the numbers could change, the authors said.

They had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Delaney A, et. al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018 Jan 26;67(3):91-6

The prevalence of birth defects strongly linked with congenital Zika virus infection increased 21% from the first to the second half of 2016 in areas of the United States with local, endemic transmission: Puerto Rico, south Florida, and southern Texas, according to a report in the Jan. 26 edition of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

In those areas, complications strongly associated with Zika – including microcephaly; brain and eye abnormalities; and neurogenic hip dislocation, clubfoot, hearing loss, and arthrogryposis – jumped from 2.0 to 2.4 cases per 1,000 live births, with 140 cases in the first half of the year and 169 cases in the second (P = .009). Microcephaly and brain abnormalities were the most common problems.

In places with less than one confirmed Zika case from travel per 100,000 residents, such as Hawaii and Utah, the prevalence of birth defects strongly linked to Zika actually dropped from 2.8 cases per 1,000 live births to 2.4 in 2016.

The 15 U.S. jurisdictions in the study included nearly 1 million live births, representing approximately one fourth of the total live births in the United States in 2016. The live birth rate was 92% among the 2,962 infants and fetuses with Zika-associated birth defects.

All the jurisdictions had existing birth defects surveillance systems that quickly adapted to monitor for potential Zika defects. However, although strongly associated with Zika, there’s no guarantee that the birth defects in the study were actually caused by the virus, the researchers noted.

“These data will help communities plan for needed resources to care for affected patients and families and can serve as a foundation for linking and evaluating health and developmental outcomes of affected children,” said the investigators, led by Augustina Delaney, PhD, of the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta.

The work was the first population-based birth defect surveillance report for Zika. The CDC follows confirmed Zika cases in pregnant women and their offspring closely, but only a small portion of women are actually tested, so there’s likely far more cases of congenital Zika infection than show up in registries. Despite its limits, birth defect surveillance likely provides a more accurate picture of the actual extent of the problem.

It’s not known why Zika-linked birth defects dropped off in areas with low or no travel-associated cases. “However ... further case ascertainment from the final quarter of 2016 is anticipated in all jurisdictions,” so the numbers could change, the authors said.

They had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Delaney A, et. al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018 Jan 26;67(3):91-6

FROM MMWR

Key clinical point: Although microcephaly and other birth defects strongly associated with Zika virus are holding steady or even decreasing elsewhere in the United States, there was an uptick in 2016 in areas with endemic transmission.

Major finding: The prevalence of birth defects strongly related to congenital Zika virus infection increased 21% from the first to the second half of 2016 in southern Texas, south Florida, and Puerto Rico.

Study details: Birth defects surveillance in about a quarter of the infants born in the United States in 2016.

Disclosures: The investigators had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Delaney A, et. al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018 Jan 26;67(3):91-6

Full report confirms solanezumab’s failure to rescue cognition in mild Alzheimer’s

More than a year after the release of EXPEDITION 3’s negative data, a new report is reminding the world once more that antiamyloid antibodies have yet to live up to their promise.

Solanezumab, an antibody that targets soluble amyloid-beta (AB) did nothing to improve cognition in the phase 3, placebo-controlled trial of 2,129 patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease, Lawrence Honig, MD, and his colleagues reported in the Jan. 24 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. Eli Lilly initially released the disappointing topline data in November 2016. The next month, Lilly detailed the numbers at the Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) meeting in San Diego.

Dr. Honig of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, presented the data at the San Diego meeting, as well as being primary author of the journal paper. In a nutshell, solanezumab was no better than placebo on any of the primary or secondary endpoints of cognition or function, he and his coinvestigators wrote.

At 80 weeks, scores on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale were similar in both treatment arms, with a change of 6.6 points in the solanezumab group and 7.4 in the placebo group. The secondary endpoints were considered descriptive only, but treated patients worsened on all of them: the Mini Mental State Exam, Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living Inventory, Functional Activities Questionnaire, and the Integrated Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale.

Adverse events were common among both groups, occurring in 84.5% of the active group and 83.4% of the placebo group. However, four categories of events occurred significantly more often among those taking solanezumab: vitamin D deficiency, nasal congestion, spinal osteoarthritis, and dysuria. The placebo group was more likely to experience gait disturbance and somnolence.

Adverse events led to study discontinuation in 4.5% of the solanezumab group and 3.6% of the placebo group. One patient taking solanezumab and two taking placebo developed amyloid-related imaging abnormalities of edema/effusions. These were asymptomatic.

The authors provided several explanations for the negative results. Solanezumab does not attack consolidated amyloid plaques but rather binds to soluble AB. Biomarker studies did indicate that the antibody was hitting this target, but, the team said, “the observed peripheral reductions in soluble-free AB concentrations may not have been sufficient to reduce deposited cerebral amyloid, neuronal atrophy, or the pathobiologic events that lead to clinical decline.”

This observation renders null the peripheral sink hypothesis, which proposes that reducing free AB in plasma should lead to AB clearance from the brain. Despite reducing plasma concentrations of AB by about 90%, there was no obvious clinical impact on cognition, and no evidence of change in existing brain plaques. “Thus, a reduction in peripheral-free AB alone is unlikely to lead to clinically meaningful cognitive benefits,” they noted.

The investigators also suggested that the 400-mg monthly dose was probably much too small. Only about 3% of the antibody crossed the blood-brain barrier – too little to have a clinically meaningful effect, they posited.

Indeed, this idea of ineffective dosing has saved solanezumab from the ever-growing scrap heap of a decade’s worth of failed antiamyloid drugs. Solanezumab is also being investigated in the ongoing Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease (A4) prevention study and the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network Trial (DIAN-TU).

Based on a rethinking of the failed EXPEDITION 3 and its likewise negative predecessors (EXPEDITION and EXPEDITION 2), researchers announced at CTAD 2017 that they will quadruple the dose of solanezumab in A4. Patients already enrolled will be titrated up from 400-mg to 1,600-mg infusions every month, principal investigator Reisa A. Sperling, MD, said at the meeting. DIAN-TU follows a dose-escalation pattern with no stated upward limit.

Timing – every AD researcher’s nightmare – also may have been a factor in EXPEDITION 3’s failure, Dr. Honig and his coauthors said. Even though it enrolled only patients with mild AD, they already may have been beyond the critical tipping point of potentially successful cognitive rescue.

“Some data from mouse models suggest that neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease may reach a point at which it becomes self-propagating and not susceptible to intervention,” the team wrote.

At CTAD 2017, Dr. Sperling, director of the Center for Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, echoed this comment, saying the fear of treating too late “keeps me up at night.” But recent advances in imaging confirm that amyloid pathology begins years, or even decades, before any cognitive changes occur. This gives researchers hope that backing up the treatment timeline even further may interrupt, or at least slow, the pathology that leads to memory loss.

“One of the greatest advances in this field over the past 10 years is the recognition that Alzheimer’s disease is a continuum that likely begins well before the stage we recognize as dementia, and even before the stages of mild cognitive impairment and prodromal Alzheimer’s,” Dr. Sperling said at the meeting. “Treating in the presymptomatic phase may be the best opportunity to bend this curve back toward the trajectory of normal aging.”

Studies of cognitively healthy elderly who are amyloid positive, like A4, and of healthy younger subjects with high genetic risk factors, like DIAN-TU and the Colombian study of those with presenilin-1 mutations, should answer this question.

Finally, Dr. Honig and his colleagues wrote, the amyloid cascade hypothesis – the foundation of all antiamyloid therapies – may itself be flawed.

“Although the amyloid hypothesis is based on considerable genetic and biomarker data, if amyloid is not the cause of the disease, solanezumab would not be expected to slow disease progression. A single study ought not to be viewed as disproving a hypothesis; nevertheless, the amyloid hypothesis will need to be considered in the context of accruing results from this trial and other clinical trials of antiamyloid therapies.”

Eli Lilly sponsored EXPEDITION 3. Dr. Honig reported receiving financial remuneration from the company and financial ties with numerous other pharmaceutical manufacturers.

SOURCE: Honig LS et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:321-30.

Antiamyloid therapies may be facing the solemn ticking of time, Michael Paul Murphy, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 378;4;391-2).

It’s still possible that such a treatment might achieve success. The antiamyloid antibody aducanumab, which targets fibrillar amyloid-beta (AB), has shown some evidence of clinical benefit, with cognitive improvement tracking amyloid plaque clearance. While solanezumab was highly effective at clearing soluble AB, however, it did nothing to improve cognition.

“If clearing previously deposited amyloid from the brain is more important than preventing its production, this could also at least partially explain the lack of success with other strategies such as beta-secretase inhibitors that have, after initial promise, proved disappointing,” Dr. Murphy wrote.

Although perhaps too early to abandon AB immunotherapy, however, “it would be foolish to ignore the continued failures of antiamyloid approaches. In spite of the mountain of evidence supporting the primacy of AB in Alzheimer’s disease, many researchers are coming to the realization that our preclinical models of the disease may be missing the mark. Even if there is some future success in a primary prevention trial, there is still little headway being made in improving the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.”

A multipronged treatment approach that attacks several key players in the AD pathologic parade, including tau, might be more successful.

“There is some hope that a combination of therapeutic approaches might help, since there is evidence that the different pathologic aspects of Alzheimer’s disease are interactive,” Dr. Murphy wrote. But “whether a multifaceted strategy or something entirely unforeseen is the answer, the field is clearly in need of innovative ideas. We may very well be nearing the end of the amyloid hypothesis rope, at which point one or two more failures will cause us to loosen our grip and let go.”

Dr. Murphy is an associate professor of cellular and molecular biochemistry at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. He has no relevant financial disclosures.

Antiamyloid therapies may be facing the solemn ticking of time, Michael Paul Murphy, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 378;4;391-2).

It’s still possible that such a treatment might achieve success. The antiamyloid antibody aducanumab, which targets fibrillar amyloid-beta (AB), has shown some evidence of clinical benefit, with cognitive improvement tracking amyloid plaque clearance. While solanezumab was highly effective at clearing soluble AB, however, it did nothing to improve cognition.

“If clearing previously deposited amyloid from the brain is more important than preventing its production, this could also at least partially explain the lack of success with other strategies such as beta-secretase inhibitors that have, after initial promise, proved disappointing,” Dr. Murphy wrote.

Although perhaps too early to abandon AB immunotherapy, however, “it would be foolish to ignore the continued failures of antiamyloid approaches. In spite of the mountain of evidence supporting the primacy of AB in Alzheimer’s disease, many researchers are coming to the realization that our preclinical models of the disease may be missing the mark. Even if there is some future success in a primary prevention trial, there is still little headway being made in improving the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.”

A multipronged treatment approach that attacks several key players in the AD pathologic parade, including tau, might be more successful.

“There is some hope that a combination of therapeutic approaches might help, since there is evidence that the different pathologic aspects of Alzheimer’s disease are interactive,” Dr. Murphy wrote. But “whether a multifaceted strategy or something entirely unforeseen is the answer, the field is clearly in need of innovative ideas. We may very well be nearing the end of the amyloid hypothesis rope, at which point one or two more failures will cause us to loosen our grip and let go.”

Dr. Murphy is an associate professor of cellular and molecular biochemistry at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. He has no relevant financial disclosures.

Antiamyloid therapies may be facing the solemn ticking of time, Michael Paul Murphy, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 378;4;391-2).

It’s still possible that such a treatment might achieve success. The antiamyloid antibody aducanumab, which targets fibrillar amyloid-beta (AB), has shown some evidence of clinical benefit, with cognitive improvement tracking amyloid plaque clearance. While solanezumab was highly effective at clearing soluble AB, however, it did nothing to improve cognition.

“If clearing previously deposited amyloid from the brain is more important than preventing its production, this could also at least partially explain the lack of success with other strategies such as beta-secretase inhibitors that have, after initial promise, proved disappointing,” Dr. Murphy wrote.

Although perhaps too early to abandon AB immunotherapy, however, “it would be foolish to ignore the continued failures of antiamyloid approaches. In spite of the mountain of evidence supporting the primacy of AB in Alzheimer’s disease, many researchers are coming to the realization that our preclinical models of the disease may be missing the mark. Even if there is some future success in a primary prevention trial, there is still little headway being made in improving the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.”

A multipronged treatment approach that attacks several key players in the AD pathologic parade, including tau, might be more successful.

“There is some hope that a combination of therapeutic approaches might help, since there is evidence that the different pathologic aspects of Alzheimer’s disease are interactive,” Dr. Murphy wrote. But “whether a multifaceted strategy or something entirely unforeseen is the answer, the field is clearly in need of innovative ideas. We may very well be nearing the end of the amyloid hypothesis rope, at which point one or two more failures will cause us to loosen our grip and let go.”

Dr. Murphy is an associate professor of cellular and molecular biochemistry at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. He has no relevant financial disclosures.

More than a year after the release of EXPEDITION 3’s negative data, a new report is reminding the world once more that antiamyloid antibodies have yet to live up to their promise.

Solanezumab, an antibody that targets soluble amyloid-beta (AB) did nothing to improve cognition in the phase 3, placebo-controlled trial of 2,129 patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease, Lawrence Honig, MD, and his colleagues reported in the Jan. 24 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. Eli Lilly initially released the disappointing topline data in November 2016. The next month, Lilly detailed the numbers at the Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) meeting in San Diego.

Dr. Honig of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, presented the data at the San Diego meeting, as well as being primary author of the journal paper. In a nutshell, solanezumab was no better than placebo on any of the primary or secondary endpoints of cognition or function, he and his coinvestigators wrote.

At 80 weeks, scores on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale were similar in both treatment arms, with a change of 6.6 points in the solanezumab group and 7.4 in the placebo group. The secondary endpoints were considered descriptive only, but treated patients worsened on all of them: the Mini Mental State Exam, Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living Inventory, Functional Activities Questionnaire, and the Integrated Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale.

Adverse events were common among both groups, occurring in 84.5% of the active group and 83.4% of the placebo group. However, four categories of events occurred significantly more often among those taking solanezumab: vitamin D deficiency, nasal congestion, spinal osteoarthritis, and dysuria. The placebo group was more likely to experience gait disturbance and somnolence.

Adverse events led to study discontinuation in 4.5% of the solanezumab group and 3.6% of the placebo group. One patient taking solanezumab and two taking placebo developed amyloid-related imaging abnormalities of edema/effusions. These were asymptomatic.

The authors provided several explanations for the negative results. Solanezumab does not attack consolidated amyloid plaques but rather binds to soluble AB. Biomarker studies did indicate that the antibody was hitting this target, but, the team said, “the observed peripheral reductions in soluble-free AB concentrations may not have been sufficient to reduce deposited cerebral amyloid, neuronal atrophy, or the pathobiologic events that lead to clinical decline.”

This observation renders null the peripheral sink hypothesis, which proposes that reducing free AB in plasma should lead to AB clearance from the brain. Despite reducing plasma concentrations of AB by about 90%, there was no obvious clinical impact on cognition, and no evidence of change in existing brain plaques. “Thus, a reduction in peripheral-free AB alone is unlikely to lead to clinically meaningful cognitive benefits,” they noted.

The investigators also suggested that the 400-mg monthly dose was probably much too small. Only about 3% of the antibody crossed the blood-brain barrier – too little to have a clinically meaningful effect, they posited.

Indeed, this idea of ineffective dosing has saved solanezumab from the ever-growing scrap heap of a decade’s worth of failed antiamyloid drugs. Solanezumab is also being investigated in the ongoing Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease (A4) prevention study and the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network Trial (DIAN-TU).

Based on a rethinking of the failed EXPEDITION 3 and its likewise negative predecessors (EXPEDITION and EXPEDITION 2), researchers announced at CTAD 2017 that they will quadruple the dose of solanezumab in A4. Patients already enrolled will be titrated up from 400-mg to 1,600-mg infusions every month, principal investigator Reisa A. Sperling, MD, said at the meeting. DIAN-TU follows a dose-escalation pattern with no stated upward limit.

Timing – every AD researcher’s nightmare – also may have been a factor in EXPEDITION 3’s failure, Dr. Honig and his coauthors said. Even though it enrolled only patients with mild AD, they already may have been beyond the critical tipping point of potentially successful cognitive rescue.

“Some data from mouse models suggest that neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease may reach a point at which it becomes self-propagating and not susceptible to intervention,” the team wrote.

At CTAD 2017, Dr. Sperling, director of the Center for Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, echoed this comment, saying the fear of treating too late “keeps me up at night.” But recent advances in imaging confirm that amyloid pathology begins years, or even decades, before any cognitive changes occur. This gives researchers hope that backing up the treatment timeline even further may interrupt, or at least slow, the pathology that leads to memory loss.

“One of the greatest advances in this field over the past 10 years is the recognition that Alzheimer’s disease is a continuum that likely begins well before the stage we recognize as dementia, and even before the stages of mild cognitive impairment and prodromal Alzheimer’s,” Dr. Sperling said at the meeting. “Treating in the presymptomatic phase may be the best opportunity to bend this curve back toward the trajectory of normal aging.”

Studies of cognitively healthy elderly who are amyloid positive, like A4, and of healthy younger subjects with high genetic risk factors, like DIAN-TU and the Colombian study of those with presenilin-1 mutations, should answer this question.

Finally, Dr. Honig and his colleagues wrote, the amyloid cascade hypothesis – the foundation of all antiamyloid therapies – may itself be flawed.

“Although the amyloid hypothesis is based on considerable genetic and biomarker data, if amyloid is not the cause of the disease, solanezumab would not be expected to slow disease progression. A single study ought not to be viewed as disproving a hypothesis; nevertheless, the amyloid hypothesis will need to be considered in the context of accruing results from this trial and other clinical trials of antiamyloid therapies.”

Eli Lilly sponsored EXPEDITION 3. Dr. Honig reported receiving financial remuneration from the company and financial ties with numerous other pharmaceutical manufacturers.

SOURCE: Honig LS et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:321-30.

More than a year after the release of EXPEDITION 3’s negative data, a new report is reminding the world once more that antiamyloid antibodies have yet to live up to their promise.

Solanezumab, an antibody that targets soluble amyloid-beta (AB) did nothing to improve cognition in the phase 3, placebo-controlled trial of 2,129 patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease, Lawrence Honig, MD, and his colleagues reported in the Jan. 24 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. Eli Lilly initially released the disappointing topline data in November 2016. The next month, Lilly detailed the numbers at the Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) meeting in San Diego.

Dr. Honig of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, presented the data at the San Diego meeting, as well as being primary author of the journal paper. In a nutshell, solanezumab was no better than placebo on any of the primary or secondary endpoints of cognition or function, he and his coinvestigators wrote.

At 80 weeks, scores on the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale were similar in both treatment arms, with a change of 6.6 points in the solanezumab group and 7.4 in the placebo group. The secondary endpoints were considered descriptive only, but treated patients worsened on all of them: the Mini Mental State Exam, Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living Inventory, Functional Activities Questionnaire, and the Integrated Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale.

Adverse events were common among both groups, occurring in 84.5% of the active group and 83.4% of the placebo group. However, four categories of events occurred significantly more often among those taking solanezumab: vitamin D deficiency, nasal congestion, spinal osteoarthritis, and dysuria. The placebo group was more likely to experience gait disturbance and somnolence.

Adverse events led to study discontinuation in 4.5% of the solanezumab group and 3.6% of the placebo group. One patient taking solanezumab and two taking placebo developed amyloid-related imaging abnormalities of edema/effusions. These were asymptomatic.

The authors provided several explanations for the negative results. Solanezumab does not attack consolidated amyloid plaques but rather binds to soluble AB. Biomarker studies did indicate that the antibody was hitting this target, but, the team said, “the observed peripheral reductions in soluble-free AB concentrations may not have been sufficient to reduce deposited cerebral amyloid, neuronal atrophy, or the pathobiologic events that lead to clinical decline.”

This observation renders null the peripheral sink hypothesis, which proposes that reducing free AB in plasma should lead to AB clearance from the brain. Despite reducing plasma concentrations of AB by about 90%, there was no obvious clinical impact on cognition, and no evidence of change in existing brain plaques. “Thus, a reduction in peripheral-free AB alone is unlikely to lead to clinically meaningful cognitive benefits,” they noted.

The investigators also suggested that the 400-mg monthly dose was probably much too small. Only about 3% of the antibody crossed the blood-brain barrier – too little to have a clinically meaningful effect, they posited.

Indeed, this idea of ineffective dosing has saved solanezumab from the ever-growing scrap heap of a decade’s worth of failed antiamyloid drugs. Solanezumab is also being investigated in the ongoing Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease (A4) prevention study and the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network Trial (DIAN-TU).

Based on a rethinking of the failed EXPEDITION 3 and its likewise negative predecessors (EXPEDITION and EXPEDITION 2), researchers announced at CTAD 2017 that they will quadruple the dose of solanezumab in A4. Patients already enrolled will be titrated up from 400-mg to 1,600-mg infusions every month, principal investigator Reisa A. Sperling, MD, said at the meeting. DIAN-TU follows a dose-escalation pattern with no stated upward limit.

Timing – every AD researcher’s nightmare – also may have been a factor in EXPEDITION 3’s failure, Dr. Honig and his coauthors said. Even though it enrolled only patients with mild AD, they already may have been beyond the critical tipping point of potentially successful cognitive rescue.

“Some data from mouse models suggest that neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease may reach a point at which it becomes self-propagating and not susceptible to intervention,” the team wrote.

At CTAD 2017, Dr. Sperling, director of the Center for Alzheimer’s Research and Treatment at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, echoed this comment, saying the fear of treating too late “keeps me up at night.” But recent advances in imaging confirm that amyloid pathology begins years, or even decades, before any cognitive changes occur. This gives researchers hope that backing up the treatment timeline even further may interrupt, or at least slow, the pathology that leads to memory loss.

“One of the greatest advances in this field over the past 10 years is the recognition that Alzheimer’s disease is a continuum that likely begins well before the stage we recognize as dementia, and even before the stages of mild cognitive impairment and prodromal Alzheimer’s,” Dr. Sperling said at the meeting. “Treating in the presymptomatic phase may be the best opportunity to bend this curve back toward the trajectory of normal aging.”

Studies of cognitively healthy elderly who are amyloid positive, like A4, and of healthy younger subjects with high genetic risk factors, like DIAN-TU and the Colombian study of those with presenilin-1 mutations, should answer this question.

Finally, Dr. Honig and his colleagues wrote, the amyloid cascade hypothesis – the foundation of all antiamyloid therapies – may itself be flawed.

“Although the amyloid hypothesis is based on considerable genetic and biomarker data, if amyloid is not the cause of the disease, solanezumab would not be expected to slow disease progression. A single study ought not to be viewed as disproving a hypothesis; nevertheless, the amyloid hypothesis will need to be considered in the context of accruing results from this trial and other clinical trials of antiamyloid therapies.”

Eli Lilly sponsored EXPEDITION 3. Dr. Honig reported receiving financial remuneration from the company and financial ties with numerous other pharmaceutical manufacturers.

SOURCE: Honig LS et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:321-30.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: The antiamyloid antibody solanezumab did not improve cognition relative to placebo in patients with mild Alzheimer’s.

Major finding: Scores on the ADAS-Cog14 were similar in the solanezumab and placebo groups (delta, 6.6 vs. 7.4 points).

Study details: The phase 3, randomized placebo-controlled study comprised 2,129 patients.

Disclosures: Eli Lilly sponsored the study. Dr. Honig has served as a consultant for the company and reported financial ties with numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Honig LS et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:321-30.

Calendar

For more information about upcoming events and award deadlines, please visit http://www.gastro.org/education and http://www.gastro.org/research-funding.

UPCOMING EVENTS

Feb. 22, 2018; March 22, 2018

Reimbursement, Coding and Compliance for Gastroenterology

Improve the efficiency and performance of your practice by staying current on the latest reimbursement, coding, and compliance changes.

2/22 (Edison, NJ); 3/22 (St. Charles, MO)

AGA Regional Practice Skills Workshop – Ohio

During this free workshop, senior and junior GI leaders will guide you through various practice options and address topics rarely discussed during fellowship, such as employment models, partnerships, hospital politics, billing and coding, compliance, contracts and more. Find out more at http://www.gastro.org/in-person/aga-regional-practice-skills-workshop-ohio.

Columbus, OH

March 12, 2018; March 14, 2018

Advancing Collaborative Approaches in IBD Treatment Decision-Making

This is a unique opportunity for payers and providers to gather in the same room to discuss inflammatory bowel disease therapy selection, disease monitoring, treatment criteria, and access.

3/12 (Pittsburgh); 3/14 (Chicago)

March 21-23, 2018

2018 AGA Tech Summit: Connecting Stakeholders in GI Innovation

Join leaders in the physician, investor, regulatory, and medtech communities as they examine the issues surrounding the development and delivery of new GI medical technologies.

Boston, MA

April 11, 2018

AGA Regional Practice Skills Workshop – Pennsylvania

During this free workshop, senior and junior GI leaders will guide you through various practice options and address topics rarely discussed during fellowship, such as employment models, partnerships, hospital politics, billing and coding, compliance, contracts, and more. Find out more at http://www.gastro.org/in-person/regional-practice-skills-workshop-philadelphia.

Philadelphia

May 10-11, 2018

HIV and Hepatitis Management: THE NEW YORK COURSE

This advanced CME activity will provide participants with state-of-the-art information and practical guidance on progress in managing HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C and will enable practitioners to deliver the highest-quality care in all practice settings.

New York City

Jun. 2-5, 2018

DIGESTIVE DISEASE WEEK® (DDW) 2018 – WASHINGTON, DC

AGA Trainee and Early-Career GI Sessions

Join your colleagues at special sessions to meet the unique needs of physicians who are new to the field. Participants will learn about all aspects of starting a career in clinical practice or research, have the opportunity to network with mentors and peers, and review board material.

• June 2, 8:15 a.m.-5:30 p.m.; June 3, 8:30 a.m.-12:35 p.m.

AGA Postgraduate Course: From Abstract to Reality

Attend this multi-topic course to get practical, applicable information to push your practice to the next level. The 2018 course will provide a comprehensive look at the latest medical, surgical, and technological advances over the past 12 months that aim to keep you up to date in a rapidly changing field. Each presenter will turn abstract ideas into concrete action items that you can implement in your practice immediately. AGA member trainees and early-career GIs receive discounted pricing for this course.

• June 3, 4-5:30 p.m.

Difficult Conversations: Navigating People, Negotiations, Promotions, and Complications

During this session, attendees will obtain effective negotiation techniques and learn how to navigate difficult situations in clinical and research environments.

• June 4, 4-5:30 p.m.

Advancing Clinical Practice: Gastroenterology Fellow–Directed Quality-Improvement Projects

This trainee-focused session will showcase selected abstracts from GI fellows based on quality improvement with a state-of-the-art lecture. Attendees will be provided with information that defines practical approaches to quality improvement from start to finish. A limited supply of coffee and tea will be provided during the session.

• June 5, 1:30-5:30 p.m.

Board Review Course

This session, designed around content from DDSEP® 8, serves as a primer for third-year fellows preparing for the board exam as well as a review course for others wanting to test their knowledge. Session attendees will receive a $50 coupon to use at the AGA Store at DDW to purchase DDSEP 8.

• TBD

AGA Early-Career Networking Hour

Date, time, and location to be announced soon.

June 4-8, 2018

Exosomes/Microvesicles: Heterogeneity, Biogenesis, Function, and Therapeutic Developments (E2)