User login

Longer withdrawal time in right colon increases adenoma detection rate

PHILADELPHIA – There was a significantly higher adenoma detection rate when the withdrawal rate in the right colon was more than 3 minutes in patients undergoing colonoscopy, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

Although adenomas precede colon cancer in approximately 70% of cases, and detection of adenomas is associated with 5% risk of dying from colorectal cancer, miss rates of adenomas are high in both sides of the colon and ideal withdrawal times are not known, Fahad F. Mir, MD, MSc, from the University of Missouri-Kansas City, said.

“Miss rates are high, especially in the right side of the colon. A colonoscopy offers protection in up to 80% of the left side of the patients but only up to 40%-60% in the right side of patients,” Dr. Mir stated in his presentation. “The quality standard now [for withdrawal time] is 6 minutes, so we hypothesized that adenoma detection rate is not the same if the right colon withdrawal time is equal to or more than 3 minutes, compared to less than 3 minutes.”

The abstract received an ACG Governor’s Award for Excellence in Clinical Research.

Dr. Mir and his colleagues performed a prospective, randomized, case-controlled study of 226 patients undergoing colonoscopy at three endoscopy centers in St. Luke’s Health System, Kansas City, who were aged at least 50 years and had not undergone colonic resections, emergent procedures, or were unable to consent because of mental status or language barrier. Patients were randomized to a control group (113 patients) in whom right colon withdrawal time was under 3 minutes and an intervention group (113 patients) in whom withdrawal time was 3 minutes or more.

There was a 33% adenoma detection rate in the 3 minute or more group, compared with 14% in the less than 3 minutes group (odds ratio, 3.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.62-5.64; P less than .001). Polyp detection rates were 49% in the 3 minutes or more group and 14% in the less than 3 minutes group (OR 5.1; 95% CI, 2.84-9.32; P less than .001). The optimal cut-off point was 3 minutes and 1 second with optimal sensitivity and specificity with an area under the curve of 0.73 (95% CI, 0.65-0.81; P less than .001) for optimal cut-off time for withdrawal from the right colon.

“There was a difference in fellow involvement, where fellows were more likely to be involved when the withdrawal time was more than 3 minutes as opposed to less than 3 minutes; the ADR [adenoma detection rate] was not different based upon fellow involvement,” Dr. Mir said.

The researchers noted similar rates of retroflexion between both groups and said there were no adverse events related to the study in either group. Limitations of the study included its unblinded design, data collection from multiple centers, and a higher rate of previous polyps in patients in the withdrawal in more than 3 minutes group.

Dr. Mir report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mir FF et al. ACG 2018, Presentation 5.

PHILADELPHIA – There was a significantly higher adenoma detection rate when the withdrawal rate in the right colon was more than 3 minutes in patients undergoing colonoscopy, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

Although adenomas precede colon cancer in approximately 70% of cases, and detection of adenomas is associated with 5% risk of dying from colorectal cancer, miss rates of adenomas are high in both sides of the colon and ideal withdrawal times are not known, Fahad F. Mir, MD, MSc, from the University of Missouri-Kansas City, said.

“Miss rates are high, especially in the right side of the colon. A colonoscopy offers protection in up to 80% of the left side of the patients but only up to 40%-60% in the right side of patients,” Dr. Mir stated in his presentation. “The quality standard now [for withdrawal time] is 6 minutes, so we hypothesized that adenoma detection rate is not the same if the right colon withdrawal time is equal to or more than 3 minutes, compared to less than 3 minutes.”

The abstract received an ACG Governor’s Award for Excellence in Clinical Research.

Dr. Mir and his colleagues performed a prospective, randomized, case-controlled study of 226 patients undergoing colonoscopy at three endoscopy centers in St. Luke’s Health System, Kansas City, who were aged at least 50 years and had not undergone colonic resections, emergent procedures, or were unable to consent because of mental status or language barrier. Patients were randomized to a control group (113 patients) in whom right colon withdrawal time was under 3 minutes and an intervention group (113 patients) in whom withdrawal time was 3 minutes or more.

There was a 33% adenoma detection rate in the 3 minute or more group, compared with 14% in the less than 3 minutes group (odds ratio, 3.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.62-5.64; P less than .001). Polyp detection rates were 49% in the 3 minutes or more group and 14% in the less than 3 minutes group (OR 5.1; 95% CI, 2.84-9.32; P less than .001). The optimal cut-off point was 3 minutes and 1 second with optimal sensitivity and specificity with an area under the curve of 0.73 (95% CI, 0.65-0.81; P less than .001) for optimal cut-off time for withdrawal from the right colon.

“There was a difference in fellow involvement, where fellows were more likely to be involved when the withdrawal time was more than 3 minutes as opposed to less than 3 minutes; the ADR [adenoma detection rate] was not different based upon fellow involvement,” Dr. Mir said.

The researchers noted similar rates of retroflexion between both groups and said there were no adverse events related to the study in either group. Limitations of the study included its unblinded design, data collection from multiple centers, and a higher rate of previous polyps in patients in the withdrawal in more than 3 minutes group.

Dr. Mir report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mir FF et al. ACG 2018, Presentation 5.

PHILADELPHIA – There was a significantly higher adenoma detection rate when the withdrawal rate in the right colon was more than 3 minutes in patients undergoing colonoscopy, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

Although adenomas precede colon cancer in approximately 70% of cases, and detection of adenomas is associated with 5% risk of dying from colorectal cancer, miss rates of adenomas are high in both sides of the colon and ideal withdrawal times are not known, Fahad F. Mir, MD, MSc, from the University of Missouri-Kansas City, said.

“Miss rates are high, especially in the right side of the colon. A colonoscopy offers protection in up to 80% of the left side of the patients but only up to 40%-60% in the right side of patients,” Dr. Mir stated in his presentation. “The quality standard now [for withdrawal time] is 6 minutes, so we hypothesized that adenoma detection rate is not the same if the right colon withdrawal time is equal to or more than 3 minutes, compared to less than 3 minutes.”

The abstract received an ACG Governor’s Award for Excellence in Clinical Research.

Dr. Mir and his colleagues performed a prospective, randomized, case-controlled study of 226 patients undergoing colonoscopy at three endoscopy centers in St. Luke’s Health System, Kansas City, who were aged at least 50 years and had not undergone colonic resections, emergent procedures, or were unable to consent because of mental status or language barrier. Patients were randomized to a control group (113 patients) in whom right colon withdrawal time was under 3 minutes and an intervention group (113 patients) in whom withdrawal time was 3 minutes or more.

There was a 33% adenoma detection rate in the 3 minute or more group, compared with 14% in the less than 3 minutes group (odds ratio, 3.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.62-5.64; P less than .001). Polyp detection rates were 49% in the 3 minutes or more group and 14% in the less than 3 minutes group (OR 5.1; 95% CI, 2.84-9.32; P less than .001). The optimal cut-off point was 3 minutes and 1 second with optimal sensitivity and specificity with an area under the curve of 0.73 (95% CI, 0.65-0.81; P less than .001) for optimal cut-off time for withdrawal from the right colon.

“There was a difference in fellow involvement, where fellows were more likely to be involved when the withdrawal time was more than 3 minutes as opposed to less than 3 minutes; the ADR [adenoma detection rate] was not different based upon fellow involvement,” Dr. Mir said.

The researchers noted similar rates of retroflexion between both groups and said there were no adverse events related to the study in either group. Limitations of the study included its unblinded design, data collection from multiple centers, and a higher rate of previous polyps in patients in the withdrawal in more than 3 minutes group.

Dr. Mir report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mir FF et al. ACG 2018, Presentation 5.

REPORTING FROM ACG 2018

Key clinical point: Spending more than 3 minutes in the right colon during withdrawal was associated with a greater adenoma detection rate during colonoscopy.

Major finding: There was a 33% rate of adenoma detection in patients in whom withdrawal time was greater than 3 minutes compared with a 14% detection rate when withdrawal time was under 3 minutes.

Study details: A prospective, randomized, case-controlled study of 226 patients undergoing colonoscopy.

Disclosures: Dr. Mir reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Mir FF et al. ACG 2018. Presentation 5.

Antimalarial-induced cardiomyopathy in lupus may be underrecognized

Cardiomyopathy induced by antimalarial treatment for systematic lupus erythematosus may not be as rare as previously thought, according to the authors of a case series published Oct. 15 in The Journal of Rheumatology.

The paper describes eight patients attending a lupus clinic, who were diagnosed with definite or possible antimalarial-induced cardiomyopathy over the course of 2 years.

Konstantinos Tselios, MD, PhD, a clinical research fellow at the University of Toronto Lupus Clinic, and his coauthors wrote that antimalarial-induced cardiomyopathy was thought to be relatively rare, with only 47 previous isolated reports, but they suggested the complication may be significantly underrecognized.

“Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and heart failure, the most common clinical features of AM-induced cardiomyopathy (AMIC), may be falsely attributed to other causes, such as arterial hypertension or ischemic cardiomyopathy,” the authors wrote. “Consequently, nonspecific therapeutic approaches with diuretics and/or antihypertensives will exert minimum or even deleterious effects on such patients.”

All eight patients in this series were female, with a median age of 62.5 years, median disease duration of 35 years, and median antimalarial use of 22 years. They presented with conditions such as heart failure, exertional dyspnea, and pedal edema. Several patients were asymptomatic but had been found to have elevated heart biomarker levels that prompted further investigation.

All patients showed abnormal cardiac troponin I and brain natriuretic peptide levels, and seven of the eight also had chronically elevated creatine phosphokinase.

In three patients, endomyocardial biopsy showed cardiomyocyte vacuolation, intracytoplasmic myelinoid inclusions, and curvilinear bodies.

Four patients were diagnosed based on cardiac MRI, which showed features suggestive of antimalarial-induced cardiomyopathy, including ventricular hypertrophy with or without atrial enlargement and late gadolinium enhancement in a nonvascular pattern.

All patients had left ventricular hypertrophy, and four also had right ventricular hypertrophy. Only one patient showed impaired systolic function, compared with around half of patients in the literature with antimalarial-induced cardiomyopathy, but seven patients showed a restrictive filling pattern of the left ventricle.

“It seems possible that AMIC is a chronic process and systolic dysfunction will become apparent only in late stages,” the authors suggested.

One patient showed complete atrioventricular block, left ventricular and septal hypertrophy, and concomitant ocular toxicity.

After patients stopped antimalarials, the hypertrophy regressed and heart biomarkers decreased in seven patients, but one patient died from refractory heart failure.

Based on their findings, the authors proposed that heart-specific biomarkers be used as a regular screening tool for detecting myocardial injury, followed by more thorough investigations, such as cardiac MRI, in patients with positive biomarker findings.

“However, drug cessation should be prompt and probably upon suspicion of AMIC, because complete investigation may be delayed significantly.”

One author was supported by the Geoff Carr Fellowship from Lupus Ontario. The University of Toronto Lupus Research Program is supported by the University Health Network, Lou and Marissa Rocca, and the Lupus Foundation of Ontario.

SOURCE: Tselios K et al. J Rheumatol, 2018 Oct 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180124.

Cardiomyopathy induced by antimalarial treatment for systematic lupus erythematosus may not be as rare as previously thought, according to the authors of a case series published Oct. 15 in The Journal of Rheumatology.

The paper describes eight patients attending a lupus clinic, who were diagnosed with definite or possible antimalarial-induced cardiomyopathy over the course of 2 years.

Konstantinos Tselios, MD, PhD, a clinical research fellow at the University of Toronto Lupus Clinic, and his coauthors wrote that antimalarial-induced cardiomyopathy was thought to be relatively rare, with only 47 previous isolated reports, but they suggested the complication may be significantly underrecognized.

“Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and heart failure, the most common clinical features of AM-induced cardiomyopathy (AMIC), may be falsely attributed to other causes, such as arterial hypertension or ischemic cardiomyopathy,” the authors wrote. “Consequently, nonspecific therapeutic approaches with diuretics and/or antihypertensives will exert minimum or even deleterious effects on such patients.”

All eight patients in this series were female, with a median age of 62.5 years, median disease duration of 35 years, and median antimalarial use of 22 years. They presented with conditions such as heart failure, exertional dyspnea, and pedal edema. Several patients were asymptomatic but had been found to have elevated heart biomarker levels that prompted further investigation.

All patients showed abnormal cardiac troponin I and brain natriuretic peptide levels, and seven of the eight also had chronically elevated creatine phosphokinase.

In three patients, endomyocardial biopsy showed cardiomyocyte vacuolation, intracytoplasmic myelinoid inclusions, and curvilinear bodies.

Four patients were diagnosed based on cardiac MRI, which showed features suggestive of antimalarial-induced cardiomyopathy, including ventricular hypertrophy with or without atrial enlargement and late gadolinium enhancement in a nonvascular pattern.

All patients had left ventricular hypertrophy, and four also had right ventricular hypertrophy. Only one patient showed impaired systolic function, compared with around half of patients in the literature with antimalarial-induced cardiomyopathy, but seven patients showed a restrictive filling pattern of the left ventricle.

“It seems possible that AMIC is a chronic process and systolic dysfunction will become apparent only in late stages,” the authors suggested.

One patient showed complete atrioventricular block, left ventricular and septal hypertrophy, and concomitant ocular toxicity.

After patients stopped antimalarials, the hypertrophy regressed and heart biomarkers decreased in seven patients, but one patient died from refractory heart failure.

Based on their findings, the authors proposed that heart-specific biomarkers be used as a regular screening tool for detecting myocardial injury, followed by more thorough investigations, such as cardiac MRI, in patients with positive biomarker findings.

“However, drug cessation should be prompt and probably upon suspicion of AMIC, because complete investigation may be delayed significantly.”

One author was supported by the Geoff Carr Fellowship from Lupus Ontario. The University of Toronto Lupus Research Program is supported by the University Health Network, Lou and Marissa Rocca, and the Lupus Foundation of Ontario.

SOURCE: Tselios K et al. J Rheumatol, 2018 Oct 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180124.

Cardiomyopathy induced by antimalarial treatment for systematic lupus erythematosus may not be as rare as previously thought, according to the authors of a case series published Oct. 15 in The Journal of Rheumatology.

The paper describes eight patients attending a lupus clinic, who were diagnosed with definite or possible antimalarial-induced cardiomyopathy over the course of 2 years.

Konstantinos Tselios, MD, PhD, a clinical research fellow at the University of Toronto Lupus Clinic, and his coauthors wrote that antimalarial-induced cardiomyopathy was thought to be relatively rare, with only 47 previous isolated reports, but they suggested the complication may be significantly underrecognized.

“Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and heart failure, the most common clinical features of AM-induced cardiomyopathy (AMIC), may be falsely attributed to other causes, such as arterial hypertension or ischemic cardiomyopathy,” the authors wrote. “Consequently, nonspecific therapeutic approaches with diuretics and/or antihypertensives will exert minimum or even deleterious effects on such patients.”

All eight patients in this series were female, with a median age of 62.5 years, median disease duration of 35 years, and median antimalarial use of 22 years. They presented with conditions such as heart failure, exertional dyspnea, and pedal edema. Several patients were asymptomatic but had been found to have elevated heart biomarker levels that prompted further investigation.

All patients showed abnormal cardiac troponin I and brain natriuretic peptide levels, and seven of the eight also had chronically elevated creatine phosphokinase.

In three patients, endomyocardial biopsy showed cardiomyocyte vacuolation, intracytoplasmic myelinoid inclusions, and curvilinear bodies.

Four patients were diagnosed based on cardiac MRI, which showed features suggestive of antimalarial-induced cardiomyopathy, including ventricular hypertrophy with or without atrial enlargement and late gadolinium enhancement in a nonvascular pattern.

All patients had left ventricular hypertrophy, and four also had right ventricular hypertrophy. Only one patient showed impaired systolic function, compared with around half of patients in the literature with antimalarial-induced cardiomyopathy, but seven patients showed a restrictive filling pattern of the left ventricle.

“It seems possible that AMIC is a chronic process and systolic dysfunction will become apparent only in late stages,” the authors suggested.

One patient showed complete atrioventricular block, left ventricular and septal hypertrophy, and concomitant ocular toxicity.

After patients stopped antimalarials, the hypertrophy regressed and heart biomarkers decreased in seven patients, but one patient died from refractory heart failure.

Based on their findings, the authors proposed that heart-specific biomarkers be used as a regular screening tool for detecting myocardial injury, followed by more thorough investigations, such as cardiac MRI, in patients with positive biomarker findings.

“However, drug cessation should be prompt and probably upon suspicion of AMIC, because complete investigation may be delayed significantly.”

One author was supported by the Geoff Carr Fellowship from Lupus Ontario. The University of Toronto Lupus Research Program is supported by the University Health Network, Lou and Marissa Rocca, and the Lupus Foundation of Ontario.

SOURCE: Tselios K et al. J Rheumatol, 2018 Oct 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180124.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Elevated cardiac troponin I and brain natriuretic peptide, and abnormal cardiac MRI may indicate antimalarial-induced cardiomyopathy.

Study details: Case series of eight patients with antimalarial-induced cardiomyopathy.

Disclosures: One author was supported by the Geoff Carr Fellowship from Lupus Ontario. The University of Toronto Lupus Research Program is supported by the University Health Network, Lou and Marissa Rocca, and the Lupus Foundation of Ontario.

Source: Tselios K et al. J Rheumatol. 2018 Oct 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180124.

Clinically meaningful change determined for RAPID-3 in active RA

An improvement of nearly 4 points on a 30-point, patient-scored disease severity index appears to be clinically meaningful for adults with active RA, according to a recent clinical trial analysis.

A 3.8-point decrease represented the minimal clinically important improvement in the Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID-3) index, investigators reported in The Journal of Rheumatology.

“Clinicians may feel comfortable documenting and monitoring patient status, recognizing an improvement of 3.8 units in patients with active RA to be meaningful in routine patient care,” Michael M. Ward, MD, PhD, of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), and his coinvestigators wrote.

The RAPID-3 index consists of three patient self-report measures out of the seven-item RA Core Data Set: physical function, pain, and patient’s global assessment. The index was initially designed to be feasible in routine care, such that a patient could fill it out in the waiting area, Dr. Ward and his colleagues noted in their report.

Previous investigations have shown that RAPID-3 is highly correlated with the 28-joint count Disease Activity Score (DAS28) and the Clinical Disease Activity Index, and in one study, it was more likely than erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) to identify incomplete responses to methotrexate.

However, prior to the present study, there were no reported estimates of the minimal clinically important improvement for the RAPID-3 index.

Knowing whether or not a decrease in RAPID-3 is clinically meaningful to patients would help clinicians interpret those changes in response to treatment, Dr. Ward and his coauthors wrote.

In the current study, RAPID-3 was calculated before and after escalation of treatment in a prospective study involving 250 adults with active RA, including 195 women (78%). The mean age of the patients was 51 years, and the median duration of RA was more than 6 years.

At the patients’ baseline visit and evaluation, rheumatologists prescribed prednisone, a new disease-modifying treatment, a new biologic, or increased the dose of a current treatment. The follow-up visit occurred at 4 months for most patients, though follow-up was at 1 month for prednisone-treated patients because of an expected rapid response.

At baseline, the mean RAPID-3 score was 16.3, which improved to 11.1 at the follow-up visit, for a mean change of –5.2 points, according to the investigators. The standardized response mean was –0.79 (95% confidence interval, –0.71 to –0.88), which investigators said demonstrated good sensitivity to change.

They found that the minimal clinically important improvement was –3.8 in a statistical analysis that optimized sensitivity and specificity, and –3.5 and –4.1 by alternate statistical criteria.

However, Dr. Ward and his coauthors cautioned that these estimates should be applied only to patient groups that have high levels of RA activity, similar to this study, in which patients had a baseline mean DAS28-ESR of 6.16 and a mean Simplified Disease Activity Index of 38.6.

Patients with low RA activity are closer to an acceptable symptom state, making the minimal clinically important improvement less relevant. “The margin for symptom improvement becomes smaller and ultimately indiscernible as the level of activity decreases,” they explained in their report.

The study was supported in part through the NIAMS Intramural Research Program and a grant from the U.S. Public Health Service. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Ward MM et al. J Rheumatol. 2018 Oct 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180153.

An improvement of nearly 4 points on a 30-point, patient-scored disease severity index appears to be clinically meaningful for adults with active RA, according to a recent clinical trial analysis.

A 3.8-point decrease represented the minimal clinically important improvement in the Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID-3) index, investigators reported in The Journal of Rheumatology.

“Clinicians may feel comfortable documenting and monitoring patient status, recognizing an improvement of 3.8 units in patients with active RA to be meaningful in routine patient care,” Michael M. Ward, MD, PhD, of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), and his coinvestigators wrote.

The RAPID-3 index consists of three patient self-report measures out of the seven-item RA Core Data Set: physical function, pain, and patient’s global assessment. The index was initially designed to be feasible in routine care, such that a patient could fill it out in the waiting area, Dr. Ward and his colleagues noted in their report.

Previous investigations have shown that RAPID-3 is highly correlated with the 28-joint count Disease Activity Score (DAS28) and the Clinical Disease Activity Index, and in one study, it was more likely than erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) to identify incomplete responses to methotrexate.

However, prior to the present study, there were no reported estimates of the minimal clinically important improvement for the RAPID-3 index.

Knowing whether or not a decrease in RAPID-3 is clinically meaningful to patients would help clinicians interpret those changes in response to treatment, Dr. Ward and his coauthors wrote.

In the current study, RAPID-3 was calculated before and after escalation of treatment in a prospective study involving 250 adults with active RA, including 195 women (78%). The mean age of the patients was 51 years, and the median duration of RA was more than 6 years.

At the patients’ baseline visit and evaluation, rheumatologists prescribed prednisone, a new disease-modifying treatment, a new biologic, or increased the dose of a current treatment. The follow-up visit occurred at 4 months for most patients, though follow-up was at 1 month for prednisone-treated patients because of an expected rapid response.

At baseline, the mean RAPID-3 score was 16.3, which improved to 11.1 at the follow-up visit, for a mean change of –5.2 points, according to the investigators. The standardized response mean was –0.79 (95% confidence interval, –0.71 to –0.88), which investigators said demonstrated good sensitivity to change.

They found that the minimal clinically important improvement was –3.8 in a statistical analysis that optimized sensitivity and specificity, and –3.5 and –4.1 by alternate statistical criteria.

However, Dr. Ward and his coauthors cautioned that these estimates should be applied only to patient groups that have high levels of RA activity, similar to this study, in which patients had a baseline mean DAS28-ESR of 6.16 and a mean Simplified Disease Activity Index of 38.6.

Patients with low RA activity are closer to an acceptable symptom state, making the minimal clinically important improvement less relevant. “The margin for symptom improvement becomes smaller and ultimately indiscernible as the level of activity decreases,” they explained in their report.

The study was supported in part through the NIAMS Intramural Research Program and a grant from the U.S. Public Health Service. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Ward MM et al. J Rheumatol. 2018 Oct 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180153.

An improvement of nearly 4 points on a 30-point, patient-scored disease severity index appears to be clinically meaningful for adults with active RA, according to a recent clinical trial analysis.

A 3.8-point decrease represented the minimal clinically important improvement in the Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID-3) index, investigators reported in The Journal of Rheumatology.

“Clinicians may feel comfortable documenting and monitoring patient status, recognizing an improvement of 3.8 units in patients with active RA to be meaningful in routine patient care,” Michael M. Ward, MD, PhD, of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), and his coinvestigators wrote.

The RAPID-3 index consists of three patient self-report measures out of the seven-item RA Core Data Set: physical function, pain, and patient’s global assessment. The index was initially designed to be feasible in routine care, such that a patient could fill it out in the waiting area, Dr. Ward and his colleagues noted in their report.

Previous investigations have shown that RAPID-3 is highly correlated with the 28-joint count Disease Activity Score (DAS28) and the Clinical Disease Activity Index, and in one study, it was more likely than erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) to identify incomplete responses to methotrexate.

However, prior to the present study, there were no reported estimates of the minimal clinically important improvement for the RAPID-3 index.

Knowing whether or not a decrease in RAPID-3 is clinically meaningful to patients would help clinicians interpret those changes in response to treatment, Dr. Ward and his coauthors wrote.

In the current study, RAPID-3 was calculated before and after escalation of treatment in a prospective study involving 250 adults with active RA, including 195 women (78%). The mean age of the patients was 51 years, and the median duration of RA was more than 6 years.

At the patients’ baseline visit and evaluation, rheumatologists prescribed prednisone, a new disease-modifying treatment, a new biologic, or increased the dose of a current treatment. The follow-up visit occurred at 4 months for most patients, though follow-up was at 1 month for prednisone-treated patients because of an expected rapid response.

At baseline, the mean RAPID-3 score was 16.3, which improved to 11.1 at the follow-up visit, for a mean change of –5.2 points, according to the investigators. The standardized response mean was –0.79 (95% confidence interval, –0.71 to –0.88), which investigators said demonstrated good sensitivity to change.

They found that the minimal clinically important improvement was –3.8 in a statistical analysis that optimized sensitivity and specificity, and –3.5 and –4.1 by alternate statistical criteria.

However, Dr. Ward and his coauthors cautioned that these estimates should be applied only to patient groups that have high levels of RA activity, similar to this study, in which patients had a baseline mean DAS28-ESR of 6.16 and a mean Simplified Disease Activity Index of 38.6.

Patients with low RA activity are closer to an acceptable symptom state, making the minimal clinically important improvement less relevant. “The margin for symptom improvement becomes smaller and ultimately indiscernible as the level of activity decreases,” they explained in their report.

The study was supported in part through the NIAMS Intramural Research Program and a grant from the U.S. Public Health Service. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Ward MM et al. J Rheumatol. 2018 Oct 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180153.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF RHEUMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Minimal clinically important improvement was –3.8 in a statistical analysis that optimized sensitivity and specificity, and –3.5 and –4.1 by alternate statistical criteria.

Study details: A prospective study of patient-reported outcome measures in 250 adults with active RA.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part through the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Intramural Research Program and a grant from the U.S. Public Health Service. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Ward MM et al. J Rheumatol. 2018 Oct 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180153.

Sensory feedback modalities tackle gait, balance problems in PD

NEW YORK – Sending sensory feedback upstream to patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) may offer a low-risk, nonpharmaceutical method to retain and improve motor function. These interventions may be especially helpful in the subpopulation of patients who are intolerant to exercise, with a growing body of evidence showing sustained benefit for newer sensory stimulation techniques.

“In a healthy person, movement is the seamless integration of sensory and motor systems,” said Ben Weinstock, DPT, speaking at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, pointing out that movement stimulates the senses, and sensory stimulation improves movement.

By contrast, patients with PD experience more than just problems with motor function. Patients with PD and sensory or autonomic dysfunction may find these disturbances contributing to motor dysfunction, said Dr. Weinstock, who treats patients with PD and a variety of complex medical conditions in his private practice.

Some of the hallmark features of PD are movement related: the cogwheel rigidity, bradykinesia, and freezing all contribute to poor balance and a fear of falling. Commonly, PD patients also experience fatigue and alterations in cognition and mood.

However, afferent small-fiber neuropathies and centrally mediated mechanisms in PD can also disturb sensory input: Vestibular function, equilibrium, proprioception, and light and deep touch may all be affected, Dr. Weinstock said.

Autonomic dysfunction can be an underappreciated feature of PD, but such manifestations as orthostatic hypotension and poor thermal regulation can have significant negative impact on quality of life for an individual with PD.

Perhaps the gravest variant of autonomic dysregulation, however, is the cardiac denervation that frequently accompanies PD, said Dr. Weinstock. “Although there is a belief that intensive exercise helps people with PD, many individuals are actually exercise intolerant because of loss of cardiac norepinephrine,” he said (J Neurochem. 2014;131[2]:219-228). “A person with PD who is exercise intolerant is at risk” of syncope, falls, and even serious cardiac events during exercise, he noted.

Cardiovascular dysautonomia in PD has been documented in serial 18F-dopamine PET scans, showing progressive reduction in uptake over the course of several years in individual patients (Neurobiol Dis. 2012 June;46[3]:572-80). Similarly, studies have shown lower cardiac radiotracer uptake in patients with PD, compared with normal controls, he said (NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2017. doi: 10.1038/S41531-017-0017-1).

It’s not easy to determine what level of nonmotor dysfunction a given patient has at a particular point in disease progression, said Dr. Weinstock.

“There is no correlation between motor and nonmotor deterioration,” he said. “Somebody might be newly diagnosed with just a mild tremor and still have significant cardiac denervation.”

Weighing how to help an exercise-intolerant patient with PD means taking into consideration the known risks and side effect profile of PD medications, Dr. Weinstock pointed out. Increasing medications, or beginning a new drug therapy, can mean increased risk for unwanted psychiatric side effects and ototoxicity, among other potential ill effects.

Similarly, the decision to implant deep brain stimulation is not to be taken lightly, since depression can begin or worsen, and any surgical procedure carries risks.

For Dr. Weinstock, using strategies to improve sensory input are “a valid option for people with PD.” Such a strategy is safe, and even brief bouts of stimulation “can have significant, beneficial effects,” he said. “The overall goal is to avoid sedentary behavior,” with its accompanying ills, he said.

Dr. Weinstock noted that he uses different strategies to stimulate the various senses, including bright light therapy, which can help regulate circadian rhythms and promote appropriate melatonin secretion, improving sleep and upping daytime wakefulness.

Another visual strategy when working on gait is to use surface lines, a checkerboard pattern, or other targets that provide a visual goal for step length, which typically shortens with PD progression. Though more high-tech options exist, Dr. Weinstock suggested patients begin with just laying lines of masking tape along the floor to mark the target gait length. “Usually the cheap technique is a good test to see if it’s going to work,” he said.

An auditory strategy to improve the gait cycle is use of a metronome or other rhythmic auditory stimulation; music can be helpful in this regard and as a general cognitive and emotional stimulus, said Dr. Weinstock.

“Loss of smell is an early sign of Parkinson’s,” said Dr. Weinstock, and taste also can be dulled. Though offering tasty meals could help reduce risk of malnutrition in PD patients, “It remains to be seen if aromatherapy can lead to neural plasticity and reverse smell loss in PD.”

Vestibular rehabilitation techniques can help not just with balance, but also with helping to lift mood and improve functional activities, according to one study (Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2009;67[2-A]:219-23).

Other ways to provide proprioceptive feedback include the use of orthotics and textured insoles and the use of a weighted vest. Dr. Weinstock also gives consideration to skin taping, which may give patients useful feedback about their bodies’ position in space, he said.

Intriguing results have been seen with acupuncture, acupressure, and electroacupuncture for PD patients, said Dr. Weinstock. In particular, a technique called automated mechanical pressure stimulation uses a bootlike device to provide mechanical stimulation to points at the head of the great toe and on the ball of the foot at the head of the first metatarsal bone.

One functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study showed acutely increased resting state functional connectivity after such stimulation, in comparison with a sham procedure that also applied pressure, but over a broader area, he said.

After the stimulation procedure used in the study, the patients who received actual stimulation also saw improved ability to initiate voluntary movements, less tremor and rigidity, and less gait freezing (PLoS One. 2015 Oct 15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137977).

Other studies of the mechanical stimulation device showed similar results, with some showing that repeated sessions helped maintain these and other benefits, such as improved walking velocity, stride length, and Timed Up and Go results – an assessment of fall risk (Int J Rehabil Res. 2015 Sep;38[3]:238-45). Treatment with the device, dubbed Gondola, is most widely available in Italy, where clinical trials are ongoing.

Stimulation to an acupuncture point located on the proximal lateral leg, near the head of the fibula, showed improvements in gait parameters and in fMRI-assessed brain connectivity as well, noted Dr. Weinstock (CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012 Sep;18[9]:781-90).

“There’s a growing amount of evidence that various types of sensory stimulation can have significant benefits for people with Parkinson’s Disease, especially for those who are exercise intolerant,” said Dr. Weinstock.

Dr. Weinstock reported no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

NEW YORK – Sending sensory feedback upstream to patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) may offer a low-risk, nonpharmaceutical method to retain and improve motor function. These interventions may be especially helpful in the subpopulation of patients who are intolerant to exercise, with a growing body of evidence showing sustained benefit for newer sensory stimulation techniques.

“In a healthy person, movement is the seamless integration of sensory and motor systems,” said Ben Weinstock, DPT, speaking at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, pointing out that movement stimulates the senses, and sensory stimulation improves movement.

By contrast, patients with PD experience more than just problems with motor function. Patients with PD and sensory or autonomic dysfunction may find these disturbances contributing to motor dysfunction, said Dr. Weinstock, who treats patients with PD and a variety of complex medical conditions in his private practice.

Some of the hallmark features of PD are movement related: the cogwheel rigidity, bradykinesia, and freezing all contribute to poor balance and a fear of falling. Commonly, PD patients also experience fatigue and alterations in cognition and mood.

However, afferent small-fiber neuropathies and centrally mediated mechanisms in PD can also disturb sensory input: Vestibular function, equilibrium, proprioception, and light and deep touch may all be affected, Dr. Weinstock said.

Autonomic dysfunction can be an underappreciated feature of PD, but such manifestations as orthostatic hypotension and poor thermal regulation can have significant negative impact on quality of life for an individual with PD.

Perhaps the gravest variant of autonomic dysregulation, however, is the cardiac denervation that frequently accompanies PD, said Dr. Weinstock. “Although there is a belief that intensive exercise helps people with PD, many individuals are actually exercise intolerant because of loss of cardiac norepinephrine,” he said (J Neurochem. 2014;131[2]:219-228). “A person with PD who is exercise intolerant is at risk” of syncope, falls, and even serious cardiac events during exercise, he noted.

Cardiovascular dysautonomia in PD has been documented in serial 18F-dopamine PET scans, showing progressive reduction in uptake over the course of several years in individual patients (Neurobiol Dis. 2012 June;46[3]:572-80). Similarly, studies have shown lower cardiac radiotracer uptake in patients with PD, compared with normal controls, he said (NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2017. doi: 10.1038/S41531-017-0017-1).

It’s not easy to determine what level of nonmotor dysfunction a given patient has at a particular point in disease progression, said Dr. Weinstock.

“There is no correlation between motor and nonmotor deterioration,” he said. “Somebody might be newly diagnosed with just a mild tremor and still have significant cardiac denervation.”

Weighing how to help an exercise-intolerant patient with PD means taking into consideration the known risks and side effect profile of PD medications, Dr. Weinstock pointed out. Increasing medications, or beginning a new drug therapy, can mean increased risk for unwanted psychiatric side effects and ototoxicity, among other potential ill effects.

Similarly, the decision to implant deep brain stimulation is not to be taken lightly, since depression can begin or worsen, and any surgical procedure carries risks.

For Dr. Weinstock, using strategies to improve sensory input are “a valid option for people with PD.” Such a strategy is safe, and even brief bouts of stimulation “can have significant, beneficial effects,” he said. “The overall goal is to avoid sedentary behavior,” with its accompanying ills, he said.

Dr. Weinstock noted that he uses different strategies to stimulate the various senses, including bright light therapy, which can help regulate circadian rhythms and promote appropriate melatonin secretion, improving sleep and upping daytime wakefulness.

Another visual strategy when working on gait is to use surface lines, a checkerboard pattern, or other targets that provide a visual goal for step length, which typically shortens with PD progression. Though more high-tech options exist, Dr. Weinstock suggested patients begin with just laying lines of masking tape along the floor to mark the target gait length. “Usually the cheap technique is a good test to see if it’s going to work,” he said.

An auditory strategy to improve the gait cycle is use of a metronome or other rhythmic auditory stimulation; music can be helpful in this regard and as a general cognitive and emotional stimulus, said Dr. Weinstock.

“Loss of smell is an early sign of Parkinson’s,” said Dr. Weinstock, and taste also can be dulled. Though offering tasty meals could help reduce risk of malnutrition in PD patients, “It remains to be seen if aromatherapy can lead to neural plasticity and reverse smell loss in PD.”

Vestibular rehabilitation techniques can help not just with balance, but also with helping to lift mood and improve functional activities, according to one study (Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2009;67[2-A]:219-23).

Other ways to provide proprioceptive feedback include the use of orthotics and textured insoles and the use of a weighted vest. Dr. Weinstock also gives consideration to skin taping, which may give patients useful feedback about their bodies’ position in space, he said.

Intriguing results have been seen with acupuncture, acupressure, and electroacupuncture for PD patients, said Dr. Weinstock. In particular, a technique called automated mechanical pressure stimulation uses a bootlike device to provide mechanical stimulation to points at the head of the great toe and on the ball of the foot at the head of the first metatarsal bone.

One functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study showed acutely increased resting state functional connectivity after such stimulation, in comparison with a sham procedure that also applied pressure, but over a broader area, he said.

After the stimulation procedure used in the study, the patients who received actual stimulation also saw improved ability to initiate voluntary movements, less tremor and rigidity, and less gait freezing (PLoS One. 2015 Oct 15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137977).

Other studies of the mechanical stimulation device showed similar results, with some showing that repeated sessions helped maintain these and other benefits, such as improved walking velocity, stride length, and Timed Up and Go results – an assessment of fall risk (Int J Rehabil Res. 2015 Sep;38[3]:238-45). Treatment with the device, dubbed Gondola, is most widely available in Italy, where clinical trials are ongoing.

Stimulation to an acupuncture point located on the proximal lateral leg, near the head of the fibula, showed improvements in gait parameters and in fMRI-assessed brain connectivity as well, noted Dr. Weinstock (CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012 Sep;18[9]:781-90).

“There’s a growing amount of evidence that various types of sensory stimulation can have significant benefits for people with Parkinson’s Disease, especially for those who are exercise intolerant,” said Dr. Weinstock.

Dr. Weinstock reported no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

NEW YORK – Sending sensory feedback upstream to patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) may offer a low-risk, nonpharmaceutical method to retain and improve motor function. These interventions may be especially helpful in the subpopulation of patients who are intolerant to exercise, with a growing body of evidence showing sustained benefit for newer sensory stimulation techniques.

“In a healthy person, movement is the seamless integration of sensory and motor systems,” said Ben Weinstock, DPT, speaking at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, pointing out that movement stimulates the senses, and sensory stimulation improves movement.

By contrast, patients with PD experience more than just problems with motor function. Patients with PD and sensory or autonomic dysfunction may find these disturbances contributing to motor dysfunction, said Dr. Weinstock, who treats patients with PD and a variety of complex medical conditions in his private practice.

Some of the hallmark features of PD are movement related: the cogwheel rigidity, bradykinesia, and freezing all contribute to poor balance and a fear of falling. Commonly, PD patients also experience fatigue and alterations in cognition and mood.

However, afferent small-fiber neuropathies and centrally mediated mechanisms in PD can also disturb sensory input: Vestibular function, equilibrium, proprioception, and light and deep touch may all be affected, Dr. Weinstock said.

Autonomic dysfunction can be an underappreciated feature of PD, but such manifestations as orthostatic hypotension and poor thermal regulation can have significant negative impact on quality of life for an individual with PD.

Perhaps the gravest variant of autonomic dysregulation, however, is the cardiac denervation that frequently accompanies PD, said Dr. Weinstock. “Although there is a belief that intensive exercise helps people with PD, many individuals are actually exercise intolerant because of loss of cardiac norepinephrine,” he said (J Neurochem. 2014;131[2]:219-228). “A person with PD who is exercise intolerant is at risk” of syncope, falls, and even serious cardiac events during exercise, he noted.

Cardiovascular dysautonomia in PD has been documented in serial 18F-dopamine PET scans, showing progressive reduction in uptake over the course of several years in individual patients (Neurobiol Dis. 2012 June;46[3]:572-80). Similarly, studies have shown lower cardiac radiotracer uptake in patients with PD, compared with normal controls, he said (NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2017. doi: 10.1038/S41531-017-0017-1).

It’s not easy to determine what level of nonmotor dysfunction a given patient has at a particular point in disease progression, said Dr. Weinstock.

“There is no correlation between motor and nonmotor deterioration,” he said. “Somebody might be newly diagnosed with just a mild tremor and still have significant cardiac denervation.”

Weighing how to help an exercise-intolerant patient with PD means taking into consideration the known risks and side effect profile of PD medications, Dr. Weinstock pointed out. Increasing medications, or beginning a new drug therapy, can mean increased risk for unwanted psychiatric side effects and ototoxicity, among other potential ill effects.

Similarly, the decision to implant deep brain stimulation is not to be taken lightly, since depression can begin or worsen, and any surgical procedure carries risks.

For Dr. Weinstock, using strategies to improve sensory input are “a valid option for people with PD.” Such a strategy is safe, and even brief bouts of stimulation “can have significant, beneficial effects,” he said. “The overall goal is to avoid sedentary behavior,” with its accompanying ills, he said.

Dr. Weinstock noted that he uses different strategies to stimulate the various senses, including bright light therapy, which can help regulate circadian rhythms and promote appropriate melatonin secretion, improving sleep and upping daytime wakefulness.

Another visual strategy when working on gait is to use surface lines, a checkerboard pattern, or other targets that provide a visual goal for step length, which typically shortens with PD progression. Though more high-tech options exist, Dr. Weinstock suggested patients begin with just laying lines of masking tape along the floor to mark the target gait length. “Usually the cheap technique is a good test to see if it’s going to work,” he said.

An auditory strategy to improve the gait cycle is use of a metronome or other rhythmic auditory stimulation; music can be helpful in this regard and as a general cognitive and emotional stimulus, said Dr. Weinstock.

“Loss of smell is an early sign of Parkinson’s,” said Dr. Weinstock, and taste also can be dulled. Though offering tasty meals could help reduce risk of malnutrition in PD patients, “It remains to be seen if aromatherapy can lead to neural plasticity and reverse smell loss in PD.”

Vestibular rehabilitation techniques can help not just with balance, but also with helping to lift mood and improve functional activities, according to one study (Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2009;67[2-A]:219-23).

Other ways to provide proprioceptive feedback include the use of orthotics and textured insoles and the use of a weighted vest. Dr. Weinstock also gives consideration to skin taping, which may give patients useful feedback about their bodies’ position in space, he said.

Intriguing results have been seen with acupuncture, acupressure, and electroacupuncture for PD patients, said Dr. Weinstock. In particular, a technique called automated mechanical pressure stimulation uses a bootlike device to provide mechanical stimulation to points at the head of the great toe and on the ball of the foot at the head of the first metatarsal bone.

One functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study showed acutely increased resting state functional connectivity after such stimulation, in comparison with a sham procedure that also applied pressure, but over a broader area, he said.

After the stimulation procedure used in the study, the patients who received actual stimulation also saw improved ability to initiate voluntary movements, less tremor and rigidity, and less gait freezing (PLoS One. 2015 Oct 15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137977).

Other studies of the mechanical stimulation device showed similar results, with some showing that repeated sessions helped maintain these and other benefits, such as improved walking velocity, stride length, and Timed Up and Go results – an assessment of fall risk (Int J Rehabil Res. 2015 Sep;38[3]:238-45). Treatment with the device, dubbed Gondola, is most widely available in Italy, where clinical trials are ongoing.

Stimulation to an acupuncture point located on the proximal lateral leg, near the head of the fibula, showed improvements in gait parameters and in fMRI-assessed brain connectivity as well, noted Dr. Weinstock (CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012 Sep;18[9]:781-90).

“There’s a growing amount of evidence that various types of sensory stimulation can have significant benefits for people with Parkinson’s Disease, especially for those who are exercise intolerant,” said Dr. Weinstock.

Dr. Weinstock reported no relevant disclosures.

[email protected]

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ICPDMD 2018

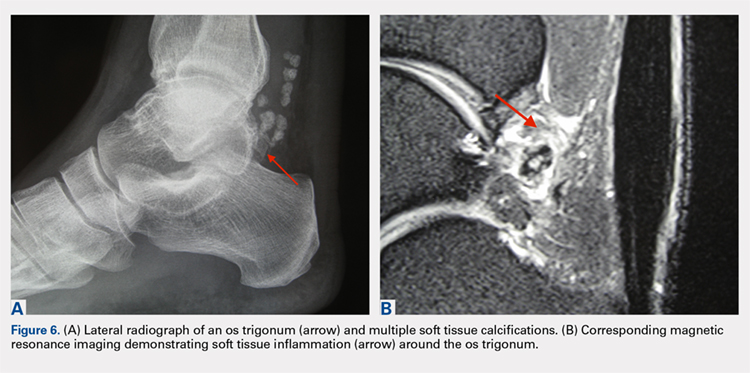

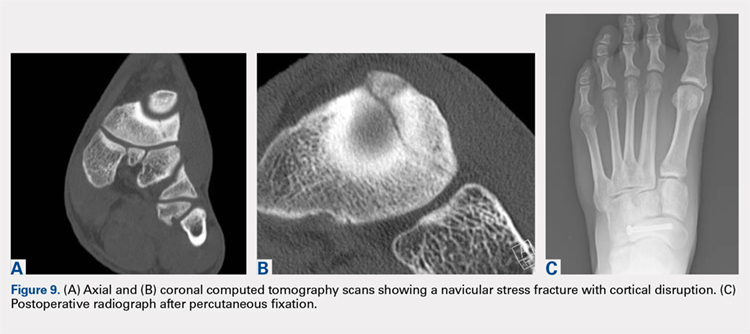

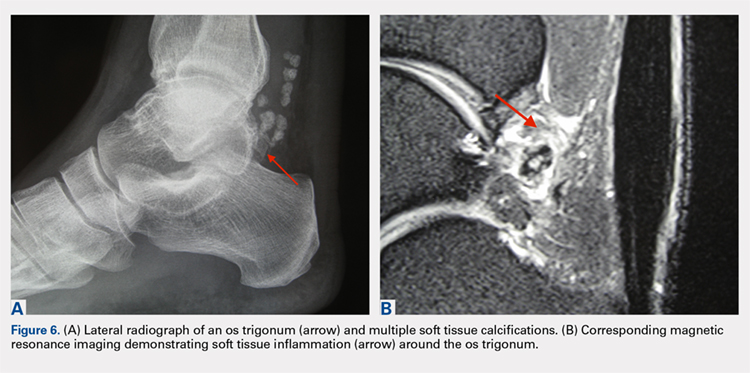

Foot and Ankle Injuries in Soccer

ABSTRACT

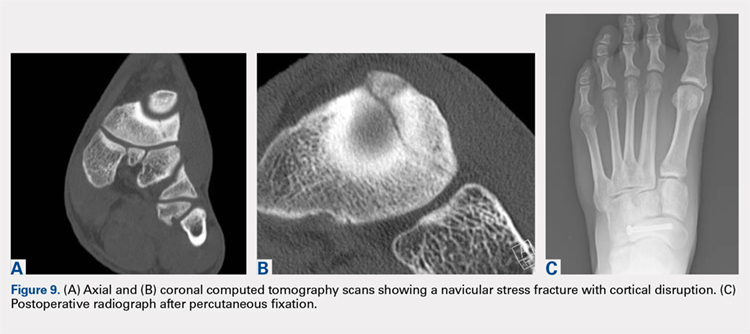

The ankle is one of the most commonly injured joints in soccer and represents a significant cost to the healthcare system. The ligaments that stabilize the ankle joint determine its biomechanics—alterations of which result from various soccer-related injuries. Acute sprains are among the most common injury in soccer players and are generally treated conservatively, with emphasis placed on secondary prevention to reduce the risk for future sprains and progression to chronic ankle instability. Repetitive ankle injuries in soccer players may cause chronic ankle instability, which includes both mechanical ligamentous laxity and functional changes. Chronic ankle pathology often requires surgery to repair ligamentous damage and remove soft-tissue or osseous impingement. Proper initial treatment, rehabilitation, and secondary prevention of ankle injuries can limit the amount of time lost from play and avoid negative long-term sequelae (eg, osteochondral lesions, arthritis). On the other hand, high ankle sprains portend a poorer prognosis and a longer recovery. These injuries will typically require surgical stabilization. Impingement-like syndromes of the ankle can undergo an initial trial of conservative treatment; when this fails, however, soccer players respond favorably to arthroscopic debridement of the lesions causing impingement. Finally, other pathologies (eg, stress fractures) are highly encouraged to be treated with surgical stabilization in elite soccer players.

Continue to: EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

With roughly 200,000 professional and around 240 million amateur soccer players, soccer has been recognized as the most popular sport worldwide. Nevertheless, given its rising popularity in society, one must also consider the increasing incidence of injuries as a result. Elite soccer players sustain between 10 and 35 injuries per 1000 competitive playing hours.1 Approximately 80% are traumatic, and 20% are overuse injuries.2 Soccer injuries are more frequent with increasing age of the participants, whereas the incidence of injuries in preadolescent players is low. The incidence of injuries has been found to be higher during competition when compared with practice/training sessions, with some studies showing that 59% of injuries occurred during games.2 Amateur or recreational soccer players sustain fewer injuries than professional soccer players, as one would expect, given both the higher intensity of training and match schedule in professionals.

The ankle is one of the most commonly injured joints in soccer, with some studies suggesting it comprises one-fifth of all injuries sustained during soccer, which is only second to those of the knee.2 Ankle sprains specifically are quite a common occurrence in soccer.3-9 A recent study of an English premier league club showed that over a 4-season period, 20% of injuries were of the foot and ankle with a mean return to sport time of 54 days.10 Of all foot and ankle related injuries, ankle sprains are the most common, followed by bruises/contusions, and tendon lesions. Fractures are very rare (1%) in soccer, but when they do occur they impart a much more extended recovery. During the 2010 Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) World Cup, ankle sprains were among the most common injuries and approximately half lead to players missing training or competitive matches.5

ANATOMY

Knowledge of the biomechanics of both the foot and ankle joints is essential to understand soccer injuries. The ankle joint (talocrural articulation) consists of the distal ends of the tibia and fibula, which form the mortise, and the superior aspect of the talar dome.11 As a hinge joint, the ankle provides 20° of dorsiflexion and 50° of plantar flexion,12 with stability provided by the lateral, medial, and superior ligamentous complexes. The superior articular surface of the talus is narrower posteriorly, which creates a looser fit within the mortise during plantar flexion.11 This decreased stability could help explain why the most common injury in soccer involves a plantar flexion mechanism.13,14 Inferiorly, the talus articulates with the calcaneus to form the subtalar joint. It is at this site that the majority of both foot inversion and eversion occurs. The transverse tarsal joints (Chopart’s joints) separate the hindfoot from the midfoot. Movement of this joint depends on the relative alignment of its 2 articulations: the talonavicular and calcaneocuboid joints. During foot eversion, these 2 joints are parallel to each other allowing supple motion and aiding in shock absorption during the heel strike phase of the gait cycle. With foot inversion, the joints become nonparallel and thus lock the transverse tarsal joints providing a rigid lever needed for push-off.11,12

LATERAL LIGAMENTS

The ankle joint is stabilized laterally by a ligament complex consisting of 3 individual ligaments, all originating from the lateral malleolus: the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), the posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL), and the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) (Figure 1).11,12,15 The ATFL is the primary restraint to inversion in plantar flexion, and it helps resist anterolateral translation of the talus in the mortise. However, it is the weakest and therefore the most frequently injured of the lateral ligaments. The PTFL plays only a supplementary role in ankle stability when the lateral ligament complex is intact. It is under the greatest strain in ankle dorsiflexion and acts to limit posterior talar displacement within the mortise as well as talar external rotation.13,16 The CFL is the primary restraint to inversion in the neutral or dorsiflexed position. It restrains subtalar inversion, thereby limiting talar tilt within the mortise.

DELTOID LIGAMENT

The deltoid ligament complex consists of 6 continuous adjacent superficial and deep ligaments that function synergistically to resist valgus and pronation forces, as well as external rotation of the talus in the mortise.11-13,17 The superficial layer crosses both ankle and subtalar joints. It originates from the anterior colliculus and fans out to insert into the navicular, neck of the talus, sustentaculum tali, and posteromedial talar tubercle. The tibiocalcaneal (sustentaculum tali) portion is the strongest component in the superficial layer and resists calcaneal eversion. The deep layer crosses the ankle joint only. It functions as the primary stabilizer of the medial ankle and prevents both lateral displacement and external rotation of the talus. It originates from the inferior and posterior aspects of the medial malleolus and inserts on the medial and posteromedial aspects of the talus.12,17,18

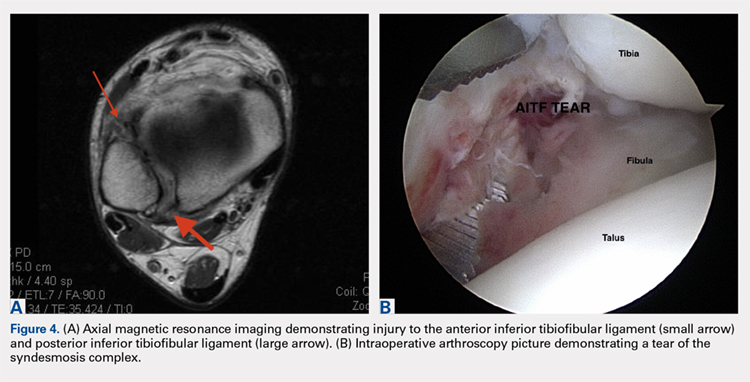

Continue to: SYNDESMOSIS

SYNDESMOSIS

The ankle syndesmosis, or inferior tibiofibular joint, is the distal articulation between the tibia and fibula. The syndesmosis contributes to ankle mortise integrity through its firm fixation of the lateral malleolus against the lateral surface of the talus. Ligaments comprising the ankle syndesmosis include the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (AITFL), the posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (PITFL), the inferior transverse ligament, and the interosseous ligament (IOL).12

ANKLE SPRAINS

Ankle sprains are the most common pathology encountered amongst soccer players, representing from one-half to two-thirds of all ankle related injuries. Most sprains occur outside of player contact.

LATERAL ANKLE SPRAINS AND INSTABILITY

Injury to the lateral ligaments of the ankle represents 77% to 91% of all ankle sprains in soccer.6,19 The greatest risk factor for an ankle sprain in a soccer player is a history of prior sprain.20 Other risk factors include increasing age, player-to-player contact, condition of the pitch, weight-bearing status of the injured limb at the time of injury, and joint instability or laxity.21,22

The evaluation of an ankle sprain to determine its severity is best done after the acute phase, approximately 4 to 7 days after the initial injury when both pain and swelling have subsided.23 The anterior drawer (ATFL instability) and talar tilt (CFL instability) tests are useful in evaluating ankle instability in the delayed or chronic setting; however, both have been shown to have limited sensitivity and significant variability amongst different examiners.24

Clinical examination will direct further diagnostic tests including X-rays, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT). The Ottawa ankle rules are generally helpful in determining whether plain X-rays are indicated in the acute setting.25,26 (Figure 2) According to these rules, ankle radiographs should be obtained if ankle pain is reported near the malleoli and 1 or more of the following is seen during examination: inability to bear weight immediately after injury and for 4 steps in the emergency department, and bony tenderness at the posterior edge or tip of the malleolus. Stress X-rays are generally not indicated in acute injuries but may be useful in chronic ankle instability cases.23

Continue to: Ankle sprains cover...

Ankle sprains cover a broad spectrum of injuries; therefore, a grading system was devised to aid in guiding treatment. Grade I (mild) sprains are those with minimal swelling and tenderness but have the ligaments still intact. Grade II (moderate) sprains occur when there are partial ligament tears associated with moderate pain, swelling, and tenderness. Finally, Grade III (severe) sprains are complete ligament tears with marked swelling, hemorrhage, tenderness, loss of function, and abnormal joint motion and instability.23, 24

Initial treatment for all ankle sprains is nonoperative and involves the RICE (rest, ice, compression, elevation) protocol with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) during the acute phase (first 4-5 days) with a short period (no >2 weeks) of immobilization.27 Most authors agree that early mobilization followed by phased rehabilitation is warranted to minimize time away from sports.28-31 Prolonged immobilization (>2 weeks) has detrimental effects and may lead to a longer return to play.28-31 The rehabilitation protocol is divided into stages: (1) pain and edema control, (2) range of motion (ROM) and strengthening exercises, (3) soccer specific functional training, and (4) prophylactic intervention with balance and proprioception exercises. Surgical intervention is rarely indicated for acute ankle sprains. There are exceptions, however, such as when ankle sprains are associated with other injuries that require acute intervention (eg, fracture, osteochondral lesion). Surgery is indicated in the setting of chronic, recurrent mechanical instability. Anatomical repairs (modified Brostrom) seem to produce better outcomes than non-anatomical reconstructions (eg, Chrisman-Snook). Surgical outcomes are good, and most athletes are able to return to their pre-injury level of function.32

In athletes, prevention of recurrent sprains is key. Braces may help prevent ankle sprains and bracing has been shown to be superior to taping, as tape loses its restrictive properties within 20 to 30 minutes of initiating activity.33,34 Application of an orthosis (lace-up ankle orthosis) has been shown to reduce the incidence of ankle re-injury in soccer players with previous ankle sprains. Several studies have found minimal, if any, effect of orthoses on athletic performance.20,35,36 Low-profile braces for soccer have been developed which allow for minimal disruption of the player’s boot and space proximally to insert the shin guard. Another essential component of prevention is prophylactic intervention with balance and proprioceptive exercises. A study looking at first division men’s league football (soccer) players in Iran showed a significant decrease in re-injury rates with proprioceptive training.37 In 2003, FIFA introduced a comprehensive warm-up program (FIFA 11+), which has since been shown in several studies to decrease the risk of injury in amateur soccer players.38-40

MEDIAL ANKLE SPRAINS AND INSTABILITY

Soccer places an unusually high demand on both the medial foot and ankle structures when compared with other sports. For instance, striking the ball requires the player to abduct and externally rotate the foot, which preloads medial structures.9 Hintermann18 looked at 54 cases of medial ankle instability and found that injury commonly occurred during landing on an uneven surface, which applies to soccer players when landing after heading the ball or jumping over a tackle. Pronation with eversion and extreme rotational injuries are well known to cause deltoid ligament injury. However, complete rupture of the deltoid ligament is rare and is more often associated with ankle fractures.41 Due to its close proximity and similarly shared function in medial plantar arch stabilization with the tibiospring and spring ligaments, posterior tibialis tendon dysfunction is also frequently seen in medial ankle instability.17 After an acute injury, patients can present with a medial ankle hematoma and pain along the deltoid ligament. Although chronic insufficiency is diagnosed based on the feeling of “giving way,” pain in the medial gutter of the ankle and a valgus and pronation deformity of the foot can be corrected by activating the peroneus tertius muscle. Arthroscopy is the most specific way to confirm clinically suspected instability of the medial ankle; however, MRI can demonstrate loss of organized medial fibers (Figures 3A, 3B).18 Primary surgical repair of deltoid ligament tears yield good to excellent results and should be considered in the soccer player to prevent problems associated with chronic non-repaired tears such as instability, osteoarthritis, and impingement syndromes.18 After surgical repair, players will undergo extensive physical therapy that progresses to sport-specific exercises with the ultimate goal of returning to competitive play around 4-6 months post-operatively.

HIGH ANKLE SPRAINS (SYNDESMOSIS)

High ankle sprains are much less common than low ankle sprains; however, when they do occur they portend a lengthier rehabilitation and a poorer prognosis, especially if undiagnosed. Lubberts and colleagues42 studied the epidemiology of isolated syndesmotic injuries in professional football players. They pooled data from 15 consecutive seasons of European professional football between 2001 and 2016. They examined a total of 3677 players from 61 teams across 17 countries. There were 1320 ankle ligament injuries registered during 15 seasons, of which 94 (7%) were isolated syndesmotic injuries. The incidence of these injuries increased annually between 2001 and 2016. Injuries were 74% contact-related, and isolated syndesmotic injuries were followed by a mean of a 39-day absence.42 Moreover, football players may have an increased risk of syndesmotic sprains due to foot planting and cutting action.41

Continue to: These injuriesa are typically...

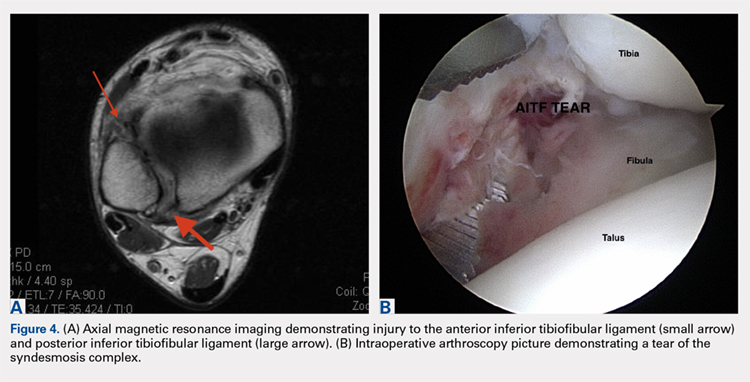

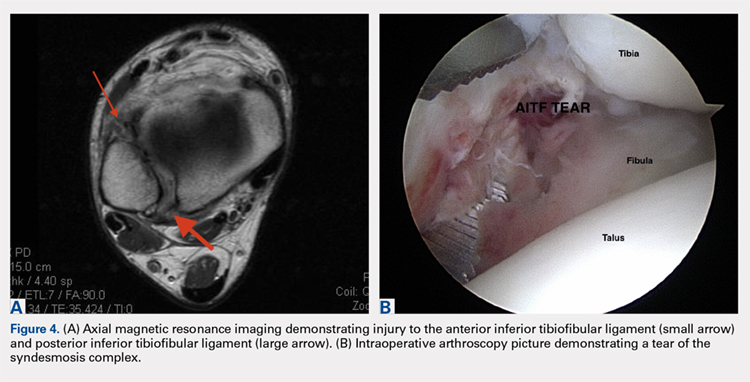

These injuries are typically identified with pain over the AITFL and interosseous membrane. Physical examination tests that help identify syndesmotic injuries include the squeeze test, external rotation test, and crossed-leg test.41 The diagnosis can be made on plain X-ray when there is clear diastasis between the distal tibia and fibula. Two critical measurements on plain films are made 1 cm above the tibial plafond and are used to evaluate the integrity of the syndesmosis: tibiofibular clear space >6 mm, and tibiofibular overlap <1 mm, which indicate disruption of the syndesmosis.43 More subtle injuries can be diagnosed with better sensitivity and specificity using MRI, which can also reveal secondary findings such as bone bruises, ATFL injury, osteochondral lesions, and tibiofibular incongruity.44,45 Arthroscopy is an invaluable diagnostic tool for syndesmotic injuries with a characteristic triad finding of PITFL scarring, disrupted interosseous ligament, and posterolateral tibial plafond chondral damage.46

Classification of the ligaments involved can aid in the selection of appropriate treatment. Grade I injuries involve AITFL tears. Grade IIa injuries involve AITFL and IOL tears. Grade IIb injuries include AITFL, PITFL, and IOL tears. Grade III injuries involve injury to all 3 ligaments, as well as a fibular fracture. Conservative treatment is recommended for Grades I and IIa, while surgical intervention is necessary for Grades IIb and III (Figures 4A, 4B). Compared with other ankle sprains, syndesmotic injuries typically require a more prolonged recovery/rehabilitation. Some studies suggest that these injuries require twice as long to heal.47 Hopkinson and colleagues48 reported a mean recovery time of 55 days following syndesmotic injuries in cadets at the United States Military Academy at West Point. Some surgeons advocate surgical intervention in professional athletes with mild sprains to expedite return to play.49

Surgery has been well established as necessary in more severe injuries where there is clear diastasis or instability of the syndesmosis. Traditionally, screws were used for surgical fixation; however, they often required a second surgery for subsequent removal. There is no general consensus on the optimal screw size, level of placement, or timing of removal.50,51 More recently, non-absorbable suture button fixation (eg, TightRope; Arthrex) has become more popular and provides certain advantages over screw fixation, such as avoiding the need for hardware removal. TightRope has been shown to provide more accurate stabilization of the syndesmosis as compared with screw fixation.52 Since malreduction is the most important indicator of poor long-term functional outcome, suture button fixation should be considered in the treatment of the football player.53 Finally, Colcuc and colleagues54 reported a lower complication rate and earlier return to sports in patients treated with knotless suture button devices compared with screw fixation.

OSTEOCHONDRAL LESIONS

Osteochondral lesions (OCLs) are cartilage-bone defects that are usually located in the talus. They can be caused by an acute traumatic event or repetitive microtrauma with no apparent history of trauma (eg, ankle instability). Acute OCLs can occur in soccer secondary to an ankle sprain or ankle fracture. Symptoms of OCLs include pain, swelling, and mechanical symptoms such as catching or locking, and on physical examination, one might see an effusion. The initial imaging modality of choice is radiographing; however, in ankle sprains with continued pain and swelling MRI may be indicated to rule out an underlying OCL. Missed acute lesions have a tendency not to heal and become chronic lesions, which can cause pain and playing disability. It is well established that chronic ankle instability is an important etiologic factor for OCLs. With the normal hydrostatic pressure within the ankle joint, synovial fluid gets pushed into cartilage/bone fissures, which can then lead to cystic degeneration of the subchondral bone.55-57

Surgical repair of an OCL is dependent on both the size and location of the lesion. Acute lesions can be managed by arthroscopic débridement, microfracture, or fixation of the lesion if enough bone remains attached to the chondral lesion. Return to play is based on development and maturation of fibrocartilage over the lesion (debridement/microfracture) or healing and incorporation of the new graft (chondral repair procedures). Meanwhile, chronic lesions can be managed in 1-stage (microfracture, osteochondral autograft transfer or 2-stage (autologous chondrocyte implantation [ACI]) procedures.56-57 Additional biologic healing augmentation with platelet-rich plasma has been described as well.58 Newer techniques in treating chronic talus OCLs, including ones that have failed to respond to bone marrow stimulation techniques, have been developed more recently such as the use of particulated juvenile articular cartilage allograft (DeNovo NT Natural Tissue Graft®; Zimmer Biomet).59 These newer techniques avoid the need for a 2-stage procedure, as is the case with ACI.

Continue to: Further studies are needed...

Further studies are needed to both investigate long-term outcomes and determine the superiority of the arthroscopic juvenile cartilage procedure compared with microfracture and other cartilage resurfacing procedures. When surgically treating OCLs, one must also restore normal ankle joint biomechanics for the lesion to heal. For instance, in the presence of ankle instability, ligament reconstruction must be performed. Also, one should also consider addressing any hindfoot malalignment with an osteotomy (calcaneus, supramalleolar). In a recent retrospective study, van Eekeren and colleagues60 showed that approximately 76% of patients were able to return to sports at long-term follow-up after arthroscopic débridement and bone marrow stimulation of talar OCLs. However, the activity level decreased at long-term follow-up and never attained the pre-injury level.60

ANKLE IMPINGEMENT

ANTERIOR ANKLE IMPINGEMENT (FOOTBALLER'S ANKLE)

Anterior ankle impingement is caused by anterior osteophytes on both the distal tibia and talar neck. It is thought to be related to repetitive microtrauma to the anteromedial aspect of the ankle from recurrent ball impact.61 It is very common amongst soccer players with some studies suggesting that 60% of soccer players have this syndrome. Ankle impingement is characterized by anterior pain with ankle dorsiflexion, decreased dorsiflexion, and swelling. It is primarily diagnosed with lateral ankle X-rays, which will show the osteophytes. An oblique anteromedial X-ray may increase detection of osteophytes (Figure 5). The early stages of anterior impingement can be treated successfully with injections and heel lifts. Treatment of lesions that fail to respond to conservative management involves arthroscopic or open excision of osteophytes. Most patients with no preexisting osteoarthritis treated arthroscopically will experience pain relief and return to full activity, though recurrent osteophyte formation has been noted at long-term follow-up.62

Anterior ankle impingement is most often caused by acute ankle sprains with an inversion type of mechanism.62 The subsequent reactive inflammation can cause fibrosis leading to distal fascicle enlargement of the AITFL. Impingement in the anterolateral gutter of this enlarged fascicle can also cause both chronic reactive synovitis and chondromalacia of the lateral talar dome.63 MRI can identify abnormal areas of pathology; however, 50% of cases are diagnosed based on clinical examination alone.63 Patients generally present with a history of anterolateral ankle pain and swelling with an occasional popping or snapping sensation.

Soccer players commonly develop anterior bony impingement due to repetitive loading of the anterior ankle from striking the ball. This repetition can lead to osteophyte formation of the anterior distal tibia and talar neck. After the osteophytes form, decreased dorsiflexion can occur due to a mechanical stop and inflammation of the interposed capsule.

The patient will exhibit tenderness to palpation along the anterolateral aspect of the ankle, with pain elicited at extreme passive dorsiflexion.62 Initially, an injection with local anesthetic and corticosteroid can serve both a diagnostic and therapeutic purpose; however, patients who fail conservative treatment can be treated with arthroscopy and resection of the involved scar tissue and osteophytes. The best results are seen in those patients with no concurrent intra-articular lesions or ankle osteoarthritis (Figure 5).62 When treated non-operatively, a player may return to play when pain resolves; however, if treated surgically with arthroscopic debridement/resection, a player must wait until his surgical scars have healed prior to attempting return to play.

Continue to: ANTEROMEDIAL ANKLE IMPINGEMENT

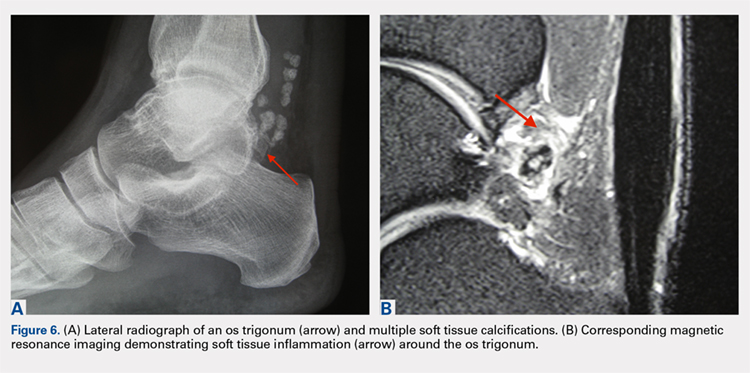

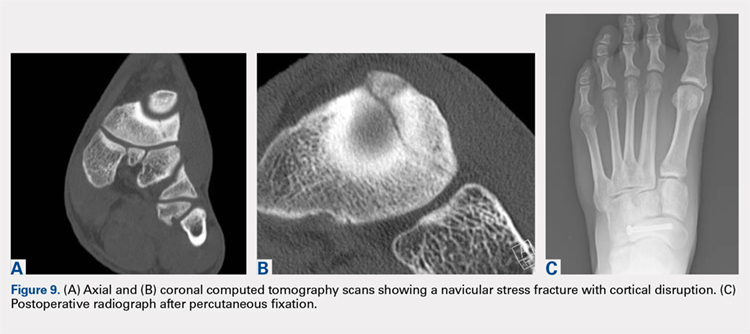

ANTEROMEDIAL ANKLE IMPINGEMENT