User login

Examining the Diagnostic Criteria for Migraine

The current diagnostic criteria for migraine outlined in the 3rd version of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) are far more sensitive and specific than the clinical criteria proposed in 1962. This is according to a recent review that examines how the diagnostic criteria for migraine have evolved during the past 45 years and evaluates the strengths and weaknesses of the current diagnostic criteria promulgated by the ICHD. In future iterations, dividing episodic and chronic migraine into subtypes based on frequency (ie, low frequency vs high frequency; near-daily vs daily) potentially could assist in guiding clinical management. In addition, a better understanding of aura, vestibular migraine, migrainous infarction, and hemiplegic migraine likely will lead to more refined diagnostic criteria for those entities. As the pathophysiology of migraine is more fully elucidated and more sophisticated diagnostic technologies are developed (eg, the identification of biomarkers), the current diagnostic criteria for migraine will likely be further refined. Furthermore, the ICHD has allowed for more precise research study design in the field of headache medicine.

Tinsley A. Rothrock JF. What are we missing in the diagnostic criteria for migraine? Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2018;22:84. doi:10.1007/s11916-018-0733-1.

The current diagnostic criteria for migraine outlined in the 3rd version of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) are far more sensitive and specific than the clinical criteria proposed in 1962. This is according to a recent review that examines how the diagnostic criteria for migraine have evolved during the past 45 years and evaluates the strengths and weaknesses of the current diagnostic criteria promulgated by the ICHD. In future iterations, dividing episodic and chronic migraine into subtypes based on frequency (ie, low frequency vs high frequency; near-daily vs daily) potentially could assist in guiding clinical management. In addition, a better understanding of aura, vestibular migraine, migrainous infarction, and hemiplegic migraine likely will lead to more refined diagnostic criteria for those entities. As the pathophysiology of migraine is more fully elucidated and more sophisticated diagnostic technologies are developed (eg, the identification of biomarkers), the current diagnostic criteria for migraine will likely be further refined. Furthermore, the ICHD has allowed for more precise research study design in the field of headache medicine.

Tinsley A. Rothrock JF. What are we missing in the diagnostic criteria for migraine? Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2018;22:84. doi:10.1007/s11916-018-0733-1.

The current diagnostic criteria for migraine outlined in the 3rd version of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) are far more sensitive and specific than the clinical criteria proposed in 1962. This is according to a recent review that examines how the diagnostic criteria for migraine have evolved during the past 45 years and evaluates the strengths and weaknesses of the current diagnostic criteria promulgated by the ICHD. In future iterations, dividing episodic and chronic migraine into subtypes based on frequency (ie, low frequency vs high frequency; near-daily vs daily) potentially could assist in guiding clinical management. In addition, a better understanding of aura, vestibular migraine, migrainous infarction, and hemiplegic migraine likely will lead to more refined diagnostic criteria for those entities. As the pathophysiology of migraine is more fully elucidated and more sophisticated diagnostic technologies are developed (eg, the identification of biomarkers), the current diagnostic criteria for migraine will likely be further refined. Furthermore, the ICHD has allowed for more precise research study design in the field of headache medicine.

Tinsley A. Rothrock JF. What are we missing in the diagnostic criteria for migraine? Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2018;22:84. doi:10.1007/s11916-018-0733-1.

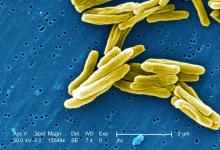

TB vaccine shows promise in previously infected

san francisco – A new The vaccine showed efficacy in young adults – an important finding because models suggest that inducing immunity in adolescents and young adults would be the fastest and most cost-effective approach to dealing with the global TB epidemic.

The study recruited adults who had previously been exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a population that receives no benefit from the long-standing bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. The overall efficacy of protection was 54%. “There isn’t any vaccine that’s been demonstrated to work in people who are already infected. It’s also the first vaccine to show this level of statistically significant protection in adults, and it’s adults who are the major transmitters of tuberculosis. The modeling has shown that even a vaccine that could protect infected adults at 20% vaccine efficacy would have a substantial impact on the epidemic and be cost effective,” said Ann Ginsberg, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at Aeras, which developed the vaccine and is now testing it in partnership with GlaxoSmithKline.

The results of the study were presented at ID Week 2018 and published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018 Sep 25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803484).

The results address a major weakness of the BCG vaccine, which is that some studies have shown it offers little benefit to subjects who are already infected with the disease, which is the case for about a quarter of the world’s population, according to Dr. Ginsberg. The probable explanation is that previous infection with M. tuberculosis or a related bacteria is common in some populations and that this exposure grants some protection against progression to active disease.

The researchers tested the M72/AS01E vaccine, which includes two M. tuberculosis antigens that were identified from patients who had controlled their infection and also the AS01 adjuvant, which contains two immunostimulating agents and is a component of a developmental malaria vaccine and the recombinant zoster vaccine Shingrix.

In Kenya, South Africa, and Zambia, the researchers randomized 3,330 participants (mean age, 28.9 years; 43% female) to receive two doses 1 month apart of either vaccine or placebo. After a mean follow-up of 2.3 years, the protocol efficacy analysis showed that the vaccine had an efficacy rate of 54.0% (P = .04) for pulmonary tuberculosis.

The vaccine had greater efficacy in men (75.2%; P = .03) than it did in women (27.4%; P = .52) and among individuals aged 25 years or younger (84.4%; P = .01) than it did among older subjects (10.2%, P = .82).

The frequency of serious adverse events was similar between the vaccine (1.6%) and the placebo group (1.8%). Unsolicited reports of adverse events were more common in the vaccine group than the placebo group (67.4% vs. 45.4%, respectively), driven largely by more reports of injection site reactions and flu-like symptoms. Solicited reports of adverse events were highlighted by a greater frequency of injection site pain in the vaccine group (81.8% vs. 34.4%). A total of 24.3% of the vaccine recipients reported grade 3 pain, compared with 3.3% in the placebo arm. Rates of fatigue, headache, malaise, or myalgia were also higher in the vaccine group, as was fever.

All of the subjects in the vaccine group had seroconversion at month 2, and 99% remained seroconverted at 12 months.

Next, the researchers plan to conduct studies in HIV-infected individuals and to proceed with phase III trials.

The trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals and Aeras. Dr. Ginsberg is an employee of Aeras.

SOURCE: Ginsberg A et al. IDWeek 2018, Abstract 120

san francisco – A new The vaccine showed efficacy in young adults – an important finding because models suggest that inducing immunity in adolescents and young adults would be the fastest and most cost-effective approach to dealing with the global TB epidemic.

The study recruited adults who had previously been exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a population that receives no benefit from the long-standing bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. The overall efficacy of protection was 54%. “There isn’t any vaccine that’s been demonstrated to work in people who are already infected. It’s also the first vaccine to show this level of statistically significant protection in adults, and it’s adults who are the major transmitters of tuberculosis. The modeling has shown that even a vaccine that could protect infected adults at 20% vaccine efficacy would have a substantial impact on the epidemic and be cost effective,” said Ann Ginsberg, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at Aeras, which developed the vaccine and is now testing it in partnership with GlaxoSmithKline.

The results of the study were presented at ID Week 2018 and published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018 Sep 25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803484).

The results address a major weakness of the BCG vaccine, which is that some studies have shown it offers little benefit to subjects who are already infected with the disease, which is the case for about a quarter of the world’s population, according to Dr. Ginsberg. The probable explanation is that previous infection with M. tuberculosis or a related bacteria is common in some populations and that this exposure grants some protection against progression to active disease.

The researchers tested the M72/AS01E vaccine, which includes two M. tuberculosis antigens that were identified from patients who had controlled their infection and also the AS01 adjuvant, which contains two immunostimulating agents and is a component of a developmental malaria vaccine and the recombinant zoster vaccine Shingrix.

In Kenya, South Africa, and Zambia, the researchers randomized 3,330 participants (mean age, 28.9 years; 43% female) to receive two doses 1 month apart of either vaccine or placebo. After a mean follow-up of 2.3 years, the protocol efficacy analysis showed that the vaccine had an efficacy rate of 54.0% (P = .04) for pulmonary tuberculosis.

The vaccine had greater efficacy in men (75.2%; P = .03) than it did in women (27.4%; P = .52) and among individuals aged 25 years or younger (84.4%; P = .01) than it did among older subjects (10.2%, P = .82).

The frequency of serious adverse events was similar between the vaccine (1.6%) and the placebo group (1.8%). Unsolicited reports of adverse events were more common in the vaccine group than the placebo group (67.4% vs. 45.4%, respectively), driven largely by more reports of injection site reactions and flu-like symptoms. Solicited reports of adverse events were highlighted by a greater frequency of injection site pain in the vaccine group (81.8% vs. 34.4%). A total of 24.3% of the vaccine recipients reported grade 3 pain, compared with 3.3% in the placebo arm. Rates of fatigue, headache, malaise, or myalgia were also higher in the vaccine group, as was fever.

All of the subjects in the vaccine group had seroconversion at month 2, and 99% remained seroconverted at 12 months.

Next, the researchers plan to conduct studies in HIV-infected individuals and to proceed with phase III trials.

The trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals and Aeras. Dr. Ginsberg is an employee of Aeras.

SOURCE: Ginsberg A et al. IDWeek 2018, Abstract 120

san francisco – A new The vaccine showed efficacy in young adults – an important finding because models suggest that inducing immunity in adolescents and young adults would be the fastest and most cost-effective approach to dealing with the global TB epidemic.

The study recruited adults who had previously been exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a population that receives no benefit from the long-standing bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. The overall efficacy of protection was 54%. “There isn’t any vaccine that’s been demonstrated to work in people who are already infected. It’s also the first vaccine to show this level of statistically significant protection in adults, and it’s adults who are the major transmitters of tuberculosis. The modeling has shown that even a vaccine that could protect infected adults at 20% vaccine efficacy would have a substantial impact on the epidemic and be cost effective,” said Ann Ginsberg, MD, PhD, chief medical officer at Aeras, which developed the vaccine and is now testing it in partnership with GlaxoSmithKline.

The results of the study were presented at ID Week 2018 and published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2018 Sep 25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803484).

The results address a major weakness of the BCG vaccine, which is that some studies have shown it offers little benefit to subjects who are already infected with the disease, which is the case for about a quarter of the world’s population, according to Dr. Ginsberg. The probable explanation is that previous infection with M. tuberculosis or a related bacteria is common in some populations and that this exposure grants some protection against progression to active disease.

The researchers tested the M72/AS01E vaccine, which includes two M. tuberculosis antigens that were identified from patients who had controlled their infection and also the AS01 adjuvant, which contains two immunostimulating agents and is a component of a developmental malaria vaccine and the recombinant zoster vaccine Shingrix.

In Kenya, South Africa, and Zambia, the researchers randomized 3,330 participants (mean age, 28.9 years; 43% female) to receive two doses 1 month apart of either vaccine or placebo. After a mean follow-up of 2.3 years, the protocol efficacy analysis showed that the vaccine had an efficacy rate of 54.0% (P = .04) for pulmonary tuberculosis.

The vaccine had greater efficacy in men (75.2%; P = .03) than it did in women (27.4%; P = .52) and among individuals aged 25 years or younger (84.4%; P = .01) than it did among older subjects (10.2%, P = .82).

The frequency of serious adverse events was similar between the vaccine (1.6%) and the placebo group (1.8%). Unsolicited reports of adverse events were more common in the vaccine group than the placebo group (67.4% vs. 45.4%, respectively), driven largely by more reports of injection site reactions and flu-like symptoms. Solicited reports of adverse events were highlighted by a greater frequency of injection site pain in the vaccine group (81.8% vs. 34.4%). A total of 24.3% of the vaccine recipients reported grade 3 pain, compared with 3.3% in the placebo arm. Rates of fatigue, headache, malaise, or myalgia were also higher in the vaccine group, as was fever.

All of the subjects in the vaccine group had seroconversion at month 2, and 99% remained seroconverted at 12 months.

Next, the researchers plan to conduct studies in HIV-infected individuals and to proceed with phase III trials.

The trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals and Aeras. Dr. Ginsberg is an employee of Aeras.

SOURCE: Ginsberg A et al. IDWeek 2018, Abstract 120

REPORTING FROM IDWEEK 2018

Key clinical point: The vaccine is the first to show efficacy in patients previously exposed to the TB bacterium.

Major finding: The vaccine had a protective efficacy of 54%.

Study details: Randomized, controlled trial with 3,330 participants.

Disclosures: The trial was funded by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals and Aeras. Dr. Ginsberg is an employee of Aeras.

Source: Ginsberg A et al. IDWeek 2018, Abstract 120.

Etrasimod improves clinical, endoscopic outcomes in patients with UC

PHILADELPHIA – Use of etrasimod was associated with improved clinical and endoscopic results, and was generally safe and well tolerated compared with placebo in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis, according to a recent award-winning presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

“Patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis receiving etrasimod 2 mg per day achieved statistically significant and clinically meaningful differences in all of the primary and secondary endpoints, and most exploratory endpoints were also significantly proved,” William J. Sandborn, MD, AGAF, FACG, professor of clinical medicine at the University of California, San Diego, stated in his presentation at the meeting. “A dose-response relationship was observed in virtually all of the measures of treatment efficacy.”

The abstract received the ACG Auxiliary Award (Member), which is given to ACG members each year with outstanding abstract submissions.

Dr. Sandborn and his colleagues enrolled 156 patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) into the OASIS study, a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, phase 2 study of etrasimod, an oral sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulator, compared with placebo. Patients were aged 18-80 years, with moderate to severe UC as defined by a three-component Mayo Clinic Score (MCS) comprising rectal bleeding, frequency of stool, and endoscopy.

Those patients who achieved an MCS score between 4 and 9 points with an endoscopic subscore of at least 2 and rectal bleeding (RB) subscore of at least 1 were included. Patients were divided into once-daily etrasimod 1 mg (52 patients), once-daily etrasimod 2 mg (50 patients) and placebo (54 patients) groups and treated over a 12-week period.

At 12 weeks, the least-squares mean difference for change in baseline in three-component MCS was 1.94 in the 1-mg etrasimod group and 2.49 in the 2-mg etrasimod group compared with placebo (1.50). Endoscopic improvement was greater in the 1-mg etrasimod (22.5%) and 2-mg (41.8%) groups compared with placebo (17.8%); endoscopic remission rates also improved in the 1-mg etrasimod (13.7%) and 2-mg (15.3%) groups compared with placebo (5.3%). Lymphocyte count circulation significantly decreased in the 1-mg etrasimod (37.2%) and 2-mg (57.3%) groups compared with the placebo group. With regard to rectal bleeding, the rectal bleeding subscore also decreased in the 1-mg etrasimod and 2-mg groups compared with placebo at 12 weeks from baseline.

The researchers noted no significant differences in adverse events among groups, with the placebo group showing a higher rate of major adverse events (11.1%) compared with the 1-mg etrasimod (5.8%) and 2-mg etrasimod (0%) groups.

“The OASIS trial results for etrasimod would support proceeding to a phase 3 program for this drug in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis,” Dr. Sandborn concluded.

Dr. Sandborn reports consultancies, speaker bureau memberships, and research support from AbbVie, Biogen, Celgene, Ferring, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Immune Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Lilly, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Salix, Theradiag, UCB Pharma, and Vascular Biogenics, among others.

SOURCE: Sandborn WJ et al. ACG 2018. Presentation 11.

PHILADELPHIA – Use of etrasimod was associated with improved clinical and endoscopic results, and was generally safe and well tolerated compared with placebo in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis, according to a recent award-winning presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

“Patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis receiving etrasimod 2 mg per day achieved statistically significant and clinically meaningful differences in all of the primary and secondary endpoints, and most exploratory endpoints were also significantly proved,” William J. Sandborn, MD, AGAF, FACG, professor of clinical medicine at the University of California, San Diego, stated in his presentation at the meeting. “A dose-response relationship was observed in virtually all of the measures of treatment efficacy.”

The abstract received the ACG Auxiliary Award (Member), which is given to ACG members each year with outstanding abstract submissions.

Dr. Sandborn and his colleagues enrolled 156 patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) into the OASIS study, a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, phase 2 study of etrasimod, an oral sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulator, compared with placebo. Patients were aged 18-80 years, with moderate to severe UC as defined by a three-component Mayo Clinic Score (MCS) comprising rectal bleeding, frequency of stool, and endoscopy.

Those patients who achieved an MCS score between 4 and 9 points with an endoscopic subscore of at least 2 and rectal bleeding (RB) subscore of at least 1 were included. Patients were divided into once-daily etrasimod 1 mg (52 patients), once-daily etrasimod 2 mg (50 patients) and placebo (54 patients) groups and treated over a 12-week period.

At 12 weeks, the least-squares mean difference for change in baseline in three-component MCS was 1.94 in the 1-mg etrasimod group and 2.49 in the 2-mg etrasimod group compared with placebo (1.50). Endoscopic improvement was greater in the 1-mg etrasimod (22.5%) and 2-mg (41.8%) groups compared with placebo (17.8%); endoscopic remission rates also improved in the 1-mg etrasimod (13.7%) and 2-mg (15.3%) groups compared with placebo (5.3%). Lymphocyte count circulation significantly decreased in the 1-mg etrasimod (37.2%) and 2-mg (57.3%) groups compared with the placebo group. With regard to rectal bleeding, the rectal bleeding subscore also decreased in the 1-mg etrasimod and 2-mg groups compared with placebo at 12 weeks from baseline.

The researchers noted no significant differences in adverse events among groups, with the placebo group showing a higher rate of major adverse events (11.1%) compared with the 1-mg etrasimod (5.8%) and 2-mg etrasimod (0%) groups.

“The OASIS trial results for etrasimod would support proceeding to a phase 3 program for this drug in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis,” Dr. Sandborn concluded.

Dr. Sandborn reports consultancies, speaker bureau memberships, and research support from AbbVie, Biogen, Celgene, Ferring, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Immune Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Lilly, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Salix, Theradiag, UCB Pharma, and Vascular Biogenics, among others.

SOURCE: Sandborn WJ et al. ACG 2018. Presentation 11.

PHILADELPHIA – Use of etrasimod was associated with improved clinical and endoscopic results, and was generally safe and well tolerated compared with placebo in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis, according to a recent award-winning presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

“Patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis receiving etrasimod 2 mg per day achieved statistically significant and clinically meaningful differences in all of the primary and secondary endpoints, and most exploratory endpoints were also significantly proved,” William J. Sandborn, MD, AGAF, FACG, professor of clinical medicine at the University of California, San Diego, stated in his presentation at the meeting. “A dose-response relationship was observed in virtually all of the measures of treatment efficacy.”

The abstract received the ACG Auxiliary Award (Member), which is given to ACG members each year with outstanding abstract submissions.

Dr. Sandborn and his colleagues enrolled 156 patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) into the OASIS study, a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, phase 2 study of etrasimod, an oral sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulator, compared with placebo. Patients were aged 18-80 years, with moderate to severe UC as defined by a three-component Mayo Clinic Score (MCS) comprising rectal bleeding, frequency of stool, and endoscopy.

Those patients who achieved an MCS score between 4 and 9 points with an endoscopic subscore of at least 2 and rectal bleeding (RB) subscore of at least 1 were included. Patients were divided into once-daily etrasimod 1 mg (52 patients), once-daily etrasimod 2 mg (50 patients) and placebo (54 patients) groups and treated over a 12-week period.

At 12 weeks, the least-squares mean difference for change in baseline in three-component MCS was 1.94 in the 1-mg etrasimod group and 2.49 in the 2-mg etrasimod group compared with placebo (1.50). Endoscopic improvement was greater in the 1-mg etrasimod (22.5%) and 2-mg (41.8%) groups compared with placebo (17.8%); endoscopic remission rates also improved in the 1-mg etrasimod (13.7%) and 2-mg (15.3%) groups compared with placebo (5.3%). Lymphocyte count circulation significantly decreased in the 1-mg etrasimod (37.2%) and 2-mg (57.3%) groups compared with the placebo group. With regard to rectal bleeding, the rectal bleeding subscore also decreased in the 1-mg etrasimod and 2-mg groups compared with placebo at 12 weeks from baseline.

The researchers noted no significant differences in adverse events among groups, with the placebo group showing a higher rate of major adverse events (11.1%) compared with the 1-mg etrasimod (5.8%) and 2-mg etrasimod (0%) groups.

“The OASIS trial results for etrasimod would support proceeding to a phase 3 program for this drug in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis,” Dr. Sandborn concluded.

Dr. Sandborn reports consultancies, speaker bureau memberships, and research support from AbbVie, Biogen, Celgene, Ferring, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Immune Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Lilly, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Salix, Theradiag, UCB Pharma, and Vascular Biogenics, among others.

SOURCE: Sandborn WJ et al. ACG 2018. Presentation 11.

REPORTING FROM ACG 2018

Key clinical point: Compared with placebo, etrasimod was associated with endoscopic and clinical improvement in patients with ulcerative colitis.

Major finding: Patients taking etrasimod 2 mg (41.8%) and etrasimod 1 mg (22.5%) saw greater endoscopic improvement compared with placebo (17.8%).

Study details: A randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, phase 2 study of 156 patients with ulcerative colitis receiving etrasimod or placebo.

Disclosures: Dr. Sandborn reports consultancies, speaker bureau memberships, and research support from AbbVie, Biogen, Celgene, Ferring, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Immune Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Lilly, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Ritter Pharmaceuticals, Salix, Theradiag, UCB Pharma, and Vascular Biogenics, among others.

Source: Sandborn WJ et al. ACG 2018. Presentation 11.

Smartphone device beat Holter for post-stroke AF detection

MONTREAL – A smartphone-based method for quick and inexpensive monitoring for atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized for a recent acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack identified three times more patients with the arrhythmia than did 24-hour Holter monitoring of the same patients after their hospital discharge.

This high level of atrial fibrillation (AF) detection using a relatively cheap and noninvasive device suggests that this method is a good “complement” to conventional monitoring by a 24-hour Holter recording or an implanted loop recorder in recent stroke patients, as called for in current guidelines of the world’s cardiology societies.

In the study, 294 of 1,079 patients hospitalized for an acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) underwent Holter monitoring, which identified 8 patients (3%) with AF, compared with 25 of these 294 patients (9%) identified with AF while they were hospitalized using serial, 30-second monitoring with the AliveCor device for smartphone assessment of ECG measurement, Bernard Yan, MD, said at the World Stroke Congress. Seven of the eight patients identified with AF by Holter monitoring were also found to have AF by the AliveCor device.

Dr. Yan, an interventional neurologist at the Comprehensive Stroke Center at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, attributed the higher pick-up rate for AF by monitoring during hospitalization to the timing of screening, which was within days of the stroke or TIA, rather than waiting to run a Holter sometime after the patient left the hospital.

“I suspect the difference in timing explains the difference” in detection, he said in an interview. “The difference may be because we monitored patients [with the AliveCor device] much earlier, during their ‘hot’ period, right after their stroke.”

The SPOT-AF trial ran at several centers in Australia, China, and Hong Kong, and enrolled 1,079 patients hospitalized for acute ischemic stroke or TIA who all underwent AliveCor monitoring during their median 4-day stay in the hospital. Patients performed a 30-second heart rhythm check every time a nurse saw them for a routine vital-sign examination, usually three or four times a day. The current analysis focused on the 294 patients (27% of the 1,079 patients) who also underwent 24-hour Holter monitoring following hospital discharge when ordered by their personal physician. This 27% incidence of postdischarge Holter monitoring despite guidelines that call for AF screening in all recent ischemic stroke and TIA patients was consistent with a 2016 review of more than 17,000 stroke or TIA patients in Canada that showed 31% underwent 24-hour Holter monitoring for AF during the 30 days following their index event (Stroke. 2016 Aug;47[8]:1982-9).

Although AF screening with a smartphone-based device is inexpensive and easy, Dr. Yan stopped short of suggesting that it is time for this approach to replace a Holter monitor or an implanted loop recorder because that is what current guidelines call for. “To change the guidelines, we need a different study that compares these approaches head to head.”

SPOT-AF received partial funding from Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Yan has been a speaker on behalf of Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and Stryker.

MONTREAL – A smartphone-based method for quick and inexpensive monitoring for atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized for a recent acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack identified three times more patients with the arrhythmia than did 24-hour Holter monitoring of the same patients after their hospital discharge.

This high level of atrial fibrillation (AF) detection using a relatively cheap and noninvasive device suggests that this method is a good “complement” to conventional monitoring by a 24-hour Holter recording or an implanted loop recorder in recent stroke patients, as called for in current guidelines of the world’s cardiology societies.

In the study, 294 of 1,079 patients hospitalized for an acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) underwent Holter monitoring, which identified 8 patients (3%) with AF, compared with 25 of these 294 patients (9%) identified with AF while they were hospitalized using serial, 30-second monitoring with the AliveCor device for smartphone assessment of ECG measurement, Bernard Yan, MD, said at the World Stroke Congress. Seven of the eight patients identified with AF by Holter monitoring were also found to have AF by the AliveCor device.

Dr. Yan, an interventional neurologist at the Comprehensive Stroke Center at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, attributed the higher pick-up rate for AF by monitoring during hospitalization to the timing of screening, which was within days of the stroke or TIA, rather than waiting to run a Holter sometime after the patient left the hospital.

“I suspect the difference in timing explains the difference” in detection, he said in an interview. “The difference may be because we monitored patients [with the AliveCor device] much earlier, during their ‘hot’ period, right after their stroke.”

The SPOT-AF trial ran at several centers in Australia, China, and Hong Kong, and enrolled 1,079 patients hospitalized for acute ischemic stroke or TIA who all underwent AliveCor monitoring during their median 4-day stay in the hospital. Patients performed a 30-second heart rhythm check every time a nurse saw them for a routine vital-sign examination, usually three or four times a day. The current analysis focused on the 294 patients (27% of the 1,079 patients) who also underwent 24-hour Holter monitoring following hospital discharge when ordered by their personal physician. This 27% incidence of postdischarge Holter monitoring despite guidelines that call for AF screening in all recent ischemic stroke and TIA patients was consistent with a 2016 review of more than 17,000 stroke or TIA patients in Canada that showed 31% underwent 24-hour Holter monitoring for AF during the 30 days following their index event (Stroke. 2016 Aug;47[8]:1982-9).

Although AF screening with a smartphone-based device is inexpensive and easy, Dr. Yan stopped short of suggesting that it is time for this approach to replace a Holter monitor or an implanted loop recorder because that is what current guidelines call for. “To change the guidelines, we need a different study that compares these approaches head to head.”

SPOT-AF received partial funding from Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Yan has been a speaker on behalf of Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and Stryker.

MONTREAL – A smartphone-based method for quick and inexpensive monitoring for atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized for a recent acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack identified three times more patients with the arrhythmia than did 24-hour Holter monitoring of the same patients after their hospital discharge.

This high level of atrial fibrillation (AF) detection using a relatively cheap and noninvasive device suggests that this method is a good “complement” to conventional monitoring by a 24-hour Holter recording or an implanted loop recorder in recent stroke patients, as called for in current guidelines of the world’s cardiology societies.

In the study, 294 of 1,079 patients hospitalized for an acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) underwent Holter monitoring, which identified 8 patients (3%) with AF, compared with 25 of these 294 patients (9%) identified with AF while they were hospitalized using serial, 30-second monitoring with the AliveCor device for smartphone assessment of ECG measurement, Bernard Yan, MD, said at the World Stroke Congress. Seven of the eight patients identified with AF by Holter monitoring were also found to have AF by the AliveCor device.

Dr. Yan, an interventional neurologist at the Comprehensive Stroke Center at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, attributed the higher pick-up rate for AF by monitoring during hospitalization to the timing of screening, which was within days of the stroke or TIA, rather than waiting to run a Holter sometime after the patient left the hospital.

“I suspect the difference in timing explains the difference” in detection, he said in an interview. “The difference may be because we monitored patients [with the AliveCor device] much earlier, during their ‘hot’ period, right after their stroke.”

The SPOT-AF trial ran at several centers in Australia, China, and Hong Kong, and enrolled 1,079 patients hospitalized for acute ischemic stroke or TIA who all underwent AliveCor monitoring during their median 4-day stay in the hospital. Patients performed a 30-second heart rhythm check every time a nurse saw them for a routine vital-sign examination, usually three or four times a day. The current analysis focused on the 294 patients (27% of the 1,079 patients) who also underwent 24-hour Holter monitoring following hospital discharge when ordered by their personal physician. This 27% incidence of postdischarge Holter monitoring despite guidelines that call for AF screening in all recent ischemic stroke and TIA patients was consistent with a 2016 review of more than 17,000 stroke or TIA patients in Canada that showed 31% underwent 24-hour Holter monitoring for AF during the 30 days following their index event (Stroke. 2016 Aug;47[8]:1982-9).

Although AF screening with a smartphone-based device is inexpensive and easy, Dr. Yan stopped short of suggesting that it is time for this approach to replace a Holter monitor or an implanted loop recorder because that is what current guidelines call for. “To change the guidelines, we need a different study that compares these approaches head to head.”

SPOT-AF received partial funding from Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Yan has been a speaker on behalf of Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and Stryker.

REPORTING FROM THE WORLD STROKE CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Holter monitoring detected atrial fibrillation in 8 of 294 patients, while smartphone monitoring identified 25 with the arrhythmia.

Study details: SPOT-AF, a multicenter study with 1,079 total patients, including 294 who underwent Holter monitoring.

Disclosures: SPOT-AF received partial funding from Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Yan has been a speaker on behalf of Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and Stryker.

Hypopigmentation

Hypopigmentation or depigmentation of the skin is very challenging to treat. The loss of melanin in the skin is often a frustrating problem, resulting from acne, burn scars, vitiligo, topically applied chemicals, or cryotherapy. To date, there is no universally accepted treatment that restores skin pigmentation. In our clinic, the induction of trauma to the skin via a series of microneedling or subcision treatments has shown promise in increasing the pigmentation of skin with localized hypo- or depigmented patches.

to improve the appearance of fine lines, acne scars, photoaging, stretch marks, enlarged pores, and other cosmetic issues characterized by loss of collagen or altered collagen remodeling. The skin-needling technique involves fine sterile needles 0.1 mm–2.5 mm in length that repeatedly pierce the stratum corneum producing microscopic “holes” in the dermis. These microscopic wounds lead to the release of growth factors stimulating the formation of new collagen, elastin, and neovascularization in the dermis. Similar to microneedling, subcision uses repeat trauma to the dermis and subcutis through the insertion and repeat movement of a needle.

In our practice, patients presenting with hypopigmentation of the skin from a variety of causes have been treated with a series of five subcision or microneedling procedures, resulting in rapid repigmentation of the skin with minimal to no side effects. Trauma to the skin causes regenerative mechanisms and wound healing. The release of cytokines that induce neoangiogenesis, neocollagenesis, and the deposition of hemosiderin from dermal bleeding induce the activation of melanocytes and stimulate skin pigmentation.

Subcision and microneedling are safe, effective, in-office procedures with vast indications that now can be applied to depigmented and hypopigmented skin. Patients have little to no downtime and results are permanent.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Dermatol Surg. 1995 Jun;21(6):543-9.

Aesthet Plast Surg. 1997 Jan-Feb;21(1):48-51.

Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2005 Feb;17(1):51-63.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Apr;121(4):1421-9.

Clin Dermatol. 2008 Mar-Apr;26(2):192-9.Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Nov;122(5):1553-63.

J Dermatolog Treat. 2012 Apr;23(2):144-52.

J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009 Jan;2(1):26-30.

J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009 Jul;2(2):110-1.

J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014 Sep;13(3):180-7.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov;75(5):e195-e197.

Hypopigmentation or depigmentation of the skin is very challenging to treat. The loss of melanin in the skin is often a frustrating problem, resulting from acne, burn scars, vitiligo, topically applied chemicals, or cryotherapy. To date, there is no universally accepted treatment that restores skin pigmentation. In our clinic, the induction of trauma to the skin via a series of microneedling or subcision treatments has shown promise in increasing the pigmentation of skin with localized hypo- or depigmented patches.

to improve the appearance of fine lines, acne scars, photoaging, stretch marks, enlarged pores, and other cosmetic issues characterized by loss of collagen or altered collagen remodeling. The skin-needling technique involves fine sterile needles 0.1 mm–2.5 mm in length that repeatedly pierce the stratum corneum producing microscopic “holes” in the dermis. These microscopic wounds lead to the release of growth factors stimulating the formation of new collagen, elastin, and neovascularization in the dermis. Similar to microneedling, subcision uses repeat trauma to the dermis and subcutis through the insertion and repeat movement of a needle.

In our practice, patients presenting with hypopigmentation of the skin from a variety of causes have been treated with a series of five subcision or microneedling procedures, resulting in rapid repigmentation of the skin with minimal to no side effects. Trauma to the skin causes regenerative mechanisms and wound healing. The release of cytokines that induce neoangiogenesis, neocollagenesis, and the deposition of hemosiderin from dermal bleeding induce the activation of melanocytes and stimulate skin pigmentation.

Subcision and microneedling are safe, effective, in-office procedures with vast indications that now can be applied to depigmented and hypopigmented skin. Patients have little to no downtime and results are permanent.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Dermatol Surg. 1995 Jun;21(6):543-9.

Aesthet Plast Surg. 1997 Jan-Feb;21(1):48-51.

Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2005 Feb;17(1):51-63.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Apr;121(4):1421-9.

Clin Dermatol. 2008 Mar-Apr;26(2):192-9.Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Nov;122(5):1553-63.

J Dermatolog Treat. 2012 Apr;23(2):144-52.

J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009 Jan;2(1):26-30.

J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009 Jul;2(2):110-1.

J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014 Sep;13(3):180-7.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov;75(5):e195-e197.

Hypopigmentation or depigmentation of the skin is very challenging to treat. The loss of melanin in the skin is often a frustrating problem, resulting from acne, burn scars, vitiligo, topically applied chemicals, or cryotherapy. To date, there is no universally accepted treatment that restores skin pigmentation. In our clinic, the induction of trauma to the skin via a series of microneedling or subcision treatments has shown promise in increasing the pigmentation of skin with localized hypo- or depigmented patches.

to improve the appearance of fine lines, acne scars, photoaging, stretch marks, enlarged pores, and other cosmetic issues characterized by loss of collagen or altered collagen remodeling. The skin-needling technique involves fine sterile needles 0.1 mm–2.5 mm in length that repeatedly pierce the stratum corneum producing microscopic “holes” in the dermis. These microscopic wounds lead to the release of growth factors stimulating the formation of new collagen, elastin, and neovascularization in the dermis. Similar to microneedling, subcision uses repeat trauma to the dermis and subcutis through the insertion and repeat movement of a needle.

In our practice, patients presenting with hypopigmentation of the skin from a variety of causes have been treated with a series of five subcision or microneedling procedures, resulting in rapid repigmentation of the skin with minimal to no side effects. Trauma to the skin causes regenerative mechanisms and wound healing. The release of cytokines that induce neoangiogenesis, neocollagenesis, and the deposition of hemosiderin from dermal bleeding induce the activation of melanocytes and stimulate skin pigmentation.

Subcision and microneedling are safe, effective, in-office procedures with vast indications that now can be applied to depigmented and hypopigmented skin. Patients have little to no downtime and results are permanent.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are co-contributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at [email protected]. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

Dermatol Surg. 1995 Jun;21(6):543-9.

Aesthet Plast Surg. 1997 Jan-Feb;21(1):48-51.

Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2005 Feb;17(1):51-63.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Apr;121(4):1421-9.

Clin Dermatol. 2008 Mar-Apr;26(2):192-9.Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Nov;122(5):1553-63.

J Dermatolog Treat. 2012 Apr;23(2):144-52.

J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009 Jan;2(1):26-30.

J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009 Jul;2(2):110-1.

J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014 Sep;13(3):180-7.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Nov;75(5):e195-e197.

Next-gen triple correctors look safe and effective for cystic fibrosis

Adding a next-generation corrector to dual corrector-potentiator therapy is safe and effective in cystic fibrosis patients with one or two Phe508del alleles, results of two randomized phase 2, proof-of-concept clinical trials suggest.

The were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Both triple combinations improved lung function for patients heterozygous for the Phe508del cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) mutation and a minimal function mutation (Phe508del-MF) who had not previously received CFTR modulators, according to the investigators, who reported results simultaneously at the North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference in Denver.

These therapies also were effective in patients homozygous for Phe508del CFTR mutation (Phe508del-Phe508del) who had previously been treated with tezacaftor-ivacaftor, the results show.

No dose-limiting side effects or toxic effects were observed in the phase 2 studies, which included 4-week treatment periods.

“These trials provide proof of the concept that targeting the Phe508del CFTR protein with a triple-combination corrector–potentiator regimen can restore CFTR function and has the potential to represent a clinical advance for patients with cystic fibrosis who harbor either one or two Phe508del alleles, approximately 9 of every 10 patients with the disease,” Steven M. Rowe, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and his coauthors said in the report on VX-659 phase 2 study.

In that report, 63 patients with the Phe508del-MF genotype were randomized to one of three VX-659 doses in combination with tezacaftor and ivacaftor versus triple placebo for 4 weeks, while 29 Phe508del-Phe508del patients underwent a 4-week tezacaftor-ivacaftor run-in phase before starting 4 weeks of the triple combination.

The primary efficacy endpoint of the study was the absolute increase in percentage of predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1).

In the Phe508del-MF patients, adding VX-659 improved that endpoint by up to 13.3 points versus baseline (P less than .001), whereas the absolute change was just 0.4 in the placebo group, the report shows. In the Phe508del-phe508del group, there was a 9.7-point increase over baseline.

Similarly, the companion study on VX-445, reported by Jennifer L. Taylor‑Cousar, MD, of National Jewish Health, Denver, and her colleagues, showed an increase in percentage of predicted FEV1 of up to 13.8 points for Phe508del-MF patients (P less than .001), and an increase of 11.0 points in the Phe508del-Phe508del group (P less than .001).

Those results suggest that targeting the Phe508del CFTR mutation with a combination of two correctors and a potentiator can produce effective CFTR function in patients who have these forms of cystic fibrosis, according to Dr. Taylor-Cousar and her colleagues.

“Lung function was improved by a magnitude similar to that achieved with the CFTR modulator ivacaftor in patients with gating mutations, in whom treatment has been disease modifying,” the researchers wrote in their report.

Sweat chloride concentrations were reduced and respiratory domain scores were improved in patients receiving triple therapy, investigators reported.

Triple therapy improved Phe508del CFTR protein processing and trafficking, and chloride transport more so than any two agents in combination, according in vitro results, also described in the studies.

Phase 3 trials of these compounds are now underway, they said.

Both studies were supported by Vertex Pharmaceuticals, which received funding from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation for the development of both VX-445 and VX-659. Dr. Rowe and Dr. Taylor-Cousar reported grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from Vertex while conducting the study. Study authors also reported disclosures related to AstraZeneca, Novartis, Bayer, Proteostasis, Gilead, Galapagos/AbbVie, and Celtaxsys, among other entities. Full disclosures for all authors were provided in the journal.

SOURCES: Keating D et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1807120; Davies JC et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1807119.

These recent investigations show that triple combination therapy improves lung function more than double combination therapy in patients with cystic fibrosis and Phe508del mutations, according to Fernando Holguin, MD, of the division of pulmonary sciences and critical care at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

“These reports represent a major breakthrough in cystic fibrosis therapeutics, with the potential for improving health and possibly survival in all patients who carry the most common cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator [CFTR] mutation,” Dr. Holguin said in an editorial.

Neither study reported dose-limiting side effects or toxicity, and only three patients in the VX-445 study stopped treatment due to adverse events, he remarked in his editorial.

However, it remains to be seen whether the lung function improvements will be maintained for longer treatment periods, he said. Patients in the phase 2 studies received a total of 4 weeks of the trial regimen, according to the reports. Also unknown is whether the new therapies will reduce exacerbation rates, or impact outcomes such as weight gain.

“These questions should soon be answered in the ongoing phase 3 trials of these regimens,” he added.

These comments are excerpted from an editorial by Dr. Holguin that accompanied the study (N Eng J Med. Oct 18; doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1811996). Dr. Holguin reported that he had no disclosures related to his editorial.

These recent investigations show that triple combination therapy improves lung function more than double combination therapy in patients with cystic fibrosis and Phe508del mutations, according to Fernando Holguin, MD, of the division of pulmonary sciences and critical care at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

“These reports represent a major breakthrough in cystic fibrosis therapeutics, with the potential for improving health and possibly survival in all patients who carry the most common cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator [CFTR] mutation,” Dr. Holguin said in an editorial.

Neither study reported dose-limiting side effects or toxicity, and only three patients in the VX-445 study stopped treatment due to adverse events, he remarked in his editorial.

However, it remains to be seen whether the lung function improvements will be maintained for longer treatment periods, he said. Patients in the phase 2 studies received a total of 4 weeks of the trial regimen, according to the reports. Also unknown is whether the new therapies will reduce exacerbation rates, or impact outcomes such as weight gain.

“These questions should soon be answered in the ongoing phase 3 trials of these regimens,” he added.

These comments are excerpted from an editorial by Dr. Holguin that accompanied the study (N Eng J Med. Oct 18; doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1811996). Dr. Holguin reported that he had no disclosures related to his editorial.

These recent investigations show that triple combination therapy improves lung function more than double combination therapy in patients with cystic fibrosis and Phe508del mutations, according to Fernando Holguin, MD, of the division of pulmonary sciences and critical care at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

“These reports represent a major breakthrough in cystic fibrosis therapeutics, with the potential for improving health and possibly survival in all patients who carry the most common cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator [CFTR] mutation,” Dr. Holguin said in an editorial.

Neither study reported dose-limiting side effects or toxicity, and only three patients in the VX-445 study stopped treatment due to adverse events, he remarked in his editorial.

However, it remains to be seen whether the lung function improvements will be maintained for longer treatment periods, he said. Patients in the phase 2 studies received a total of 4 weeks of the trial regimen, according to the reports. Also unknown is whether the new therapies will reduce exacerbation rates, or impact outcomes such as weight gain.

“These questions should soon be answered in the ongoing phase 3 trials of these regimens,” he added.

These comments are excerpted from an editorial by Dr. Holguin that accompanied the study (N Eng J Med. Oct 18; doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1811996). Dr. Holguin reported that he had no disclosures related to his editorial.

Adding a next-generation corrector to dual corrector-potentiator therapy is safe and effective in cystic fibrosis patients with one or two Phe508del alleles, results of two randomized phase 2, proof-of-concept clinical trials suggest.

The were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Both triple combinations improved lung function for patients heterozygous for the Phe508del cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) mutation and a minimal function mutation (Phe508del-MF) who had not previously received CFTR modulators, according to the investigators, who reported results simultaneously at the North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference in Denver.

These therapies also were effective in patients homozygous for Phe508del CFTR mutation (Phe508del-Phe508del) who had previously been treated with tezacaftor-ivacaftor, the results show.

No dose-limiting side effects or toxic effects were observed in the phase 2 studies, which included 4-week treatment periods.

“These trials provide proof of the concept that targeting the Phe508del CFTR protein with a triple-combination corrector–potentiator regimen can restore CFTR function and has the potential to represent a clinical advance for patients with cystic fibrosis who harbor either one or two Phe508del alleles, approximately 9 of every 10 patients with the disease,” Steven M. Rowe, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and his coauthors said in the report on VX-659 phase 2 study.

In that report, 63 patients with the Phe508del-MF genotype were randomized to one of three VX-659 doses in combination with tezacaftor and ivacaftor versus triple placebo for 4 weeks, while 29 Phe508del-Phe508del patients underwent a 4-week tezacaftor-ivacaftor run-in phase before starting 4 weeks of the triple combination.

The primary efficacy endpoint of the study was the absolute increase in percentage of predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1).

In the Phe508del-MF patients, adding VX-659 improved that endpoint by up to 13.3 points versus baseline (P less than .001), whereas the absolute change was just 0.4 in the placebo group, the report shows. In the Phe508del-phe508del group, there was a 9.7-point increase over baseline.

Similarly, the companion study on VX-445, reported by Jennifer L. Taylor‑Cousar, MD, of National Jewish Health, Denver, and her colleagues, showed an increase in percentage of predicted FEV1 of up to 13.8 points for Phe508del-MF patients (P less than .001), and an increase of 11.0 points in the Phe508del-Phe508del group (P less than .001).

Those results suggest that targeting the Phe508del CFTR mutation with a combination of two correctors and a potentiator can produce effective CFTR function in patients who have these forms of cystic fibrosis, according to Dr. Taylor-Cousar and her colleagues.

“Lung function was improved by a magnitude similar to that achieved with the CFTR modulator ivacaftor in patients with gating mutations, in whom treatment has been disease modifying,” the researchers wrote in their report.

Sweat chloride concentrations were reduced and respiratory domain scores were improved in patients receiving triple therapy, investigators reported.

Triple therapy improved Phe508del CFTR protein processing and trafficking, and chloride transport more so than any two agents in combination, according in vitro results, also described in the studies.

Phase 3 trials of these compounds are now underway, they said.

Both studies were supported by Vertex Pharmaceuticals, which received funding from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation for the development of both VX-445 and VX-659. Dr. Rowe and Dr. Taylor-Cousar reported grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from Vertex while conducting the study. Study authors also reported disclosures related to AstraZeneca, Novartis, Bayer, Proteostasis, Gilead, Galapagos/AbbVie, and Celtaxsys, among other entities. Full disclosures for all authors were provided in the journal.

SOURCES: Keating D et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1807120; Davies JC et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1807119.

Adding a next-generation corrector to dual corrector-potentiator therapy is safe and effective in cystic fibrosis patients with one or two Phe508del alleles, results of two randomized phase 2, proof-of-concept clinical trials suggest.

The were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Both triple combinations improved lung function for patients heterozygous for the Phe508del cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) mutation and a minimal function mutation (Phe508del-MF) who had not previously received CFTR modulators, according to the investigators, who reported results simultaneously at the North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference in Denver.

These therapies also were effective in patients homozygous for Phe508del CFTR mutation (Phe508del-Phe508del) who had previously been treated with tezacaftor-ivacaftor, the results show.

No dose-limiting side effects or toxic effects were observed in the phase 2 studies, which included 4-week treatment periods.

“These trials provide proof of the concept that targeting the Phe508del CFTR protein with a triple-combination corrector–potentiator regimen can restore CFTR function and has the potential to represent a clinical advance for patients with cystic fibrosis who harbor either one or two Phe508del alleles, approximately 9 of every 10 patients with the disease,” Steven M. Rowe, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and his coauthors said in the report on VX-659 phase 2 study.

In that report, 63 patients with the Phe508del-MF genotype were randomized to one of three VX-659 doses in combination with tezacaftor and ivacaftor versus triple placebo for 4 weeks, while 29 Phe508del-Phe508del patients underwent a 4-week tezacaftor-ivacaftor run-in phase before starting 4 weeks of the triple combination.

The primary efficacy endpoint of the study was the absolute increase in percentage of predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1).

In the Phe508del-MF patients, adding VX-659 improved that endpoint by up to 13.3 points versus baseline (P less than .001), whereas the absolute change was just 0.4 in the placebo group, the report shows. In the Phe508del-phe508del group, there was a 9.7-point increase over baseline.

Similarly, the companion study on VX-445, reported by Jennifer L. Taylor‑Cousar, MD, of National Jewish Health, Denver, and her colleagues, showed an increase in percentage of predicted FEV1 of up to 13.8 points for Phe508del-MF patients (P less than .001), and an increase of 11.0 points in the Phe508del-Phe508del group (P less than .001).

Those results suggest that targeting the Phe508del CFTR mutation with a combination of two correctors and a potentiator can produce effective CFTR function in patients who have these forms of cystic fibrosis, according to Dr. Taylor-Cousar and her colleagues.

“Lung function was improved by a magnitude similar to that achieved with the CFTR modulator ivacaftor in patients with gating mutations, in whom treatment has been disease modifying,” the researchers wrote in their report.

Sweat chloride concentrations were reduced and respiratory domain scores were improved in patients receiving triple therapy, investigators reported.

Triple therapy improved Phe508del CFTR protein processing and trafficking, and chloride transport more so than any two agents in combination, according in vitro results, also described in the studies.

Phase 3 trials of these compounds are now underway, they said.

Both studies were supported by Vertex Pharmaceuticals, which received funding from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation for the development of both VX-445 and VX-659. Dr. Rowe and Dr. Taylor-Cousar reported grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from Vertex while conducting the study. Study authors also reported disclosures related to AstraZeneca, Novartis, Bayer, Proteostasis, Gilead, Galapagos/AbbVie, and Celtaxsys, among other entities. Full disclosures for all authors were provided in the journal.

SOURCES: Keating D et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1807120; Davies JC et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1807119.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Adding the next-generation correctors VX-445 or VX-659 to tezacaftor-ivacaftor was safe and improved lung function in patients with one or two Phe508del alleles.

Major finding: Improvements of up to 13.8 points over baseline were noted in absolute increase in percentage of predicted FEV1, the primary efficacy endpoint of the investigations.

Study details: Companion phase 2, randomized proof-of-concept studies included a total of 117 and 123 patients with cystic fibrosis.

Disclosures: Both studies were supported by Vertex Pharmaceuticals. Lead investigators reported grants, personal fees, and nonfinancial support from Vertex during the study. Other disclosures reported were related to AstraZeneca, Novartis, Bayer, Gilead, and Galapagos/AbbVie, among others.

Sources: Keating D et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1807120; Davies JC et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1807119.

Flu vaccination lags among patients with psoriasis

Psoriasis patients are more vulnerable to systemic infections, including influenza-related pneumonia, but a new study shows that they are less likely to receive the influenza vaccine than patients with RA.

Vaccination rates were higher in psoriasis patients aged over 50 years, those who were female, and those with other chronic medical conditions, however.

Megan H. Noe, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her coauthors referred to recent evidence suggesting that psoriasis involves systemic inflammation that increase the risk of comorbidities and that hospitalization rates for serious infections, including lower respiratory tract infections and pneumonia, are higher among adults with psoriasis than those who do not have psoriasis.

drawing from administrative and commercial claims data from OptumInsight Clinformatics Data Mart. They examined all adult patients with psoriasis, RA, or chronic hypertension who required oral antihypertensive medication. The study population included individuals tracked during the 2010-2011 flu season and 24 months prior (September 2008 to March 2011). This year was chosen because it was labeled as a “typical” season by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The primary outcome was a claim for an influenza vaccine, and covariates included age, length of residency, gender, and a clinical history of a range of conditions known to be associated with greater risk of influenza complications.

The population included 17,078 patients with psoriasis, 21,832 with RA, and 496,972 with chronic hypertension. After controlling for sex and age, the probability of getting a flu vaccine was similar between psoriasis and hypertension patients, but RA patients were more likely to be vaccinated than patients with psoriasis (odds ratio, 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.13). But the likelihood varied with age: 30-year-old patients with RA were more likely than a 30-year-old psoriasis patient to get a flu shot (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.18-1.45), while a 70-year-old patient with RA was about as likely to get the flu vaccine as a 70-year-old patient with psoriasis.

Female psoriasis patients were more likely to get a flu shot than males (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.20-1.38). Among the psoriasis patients, having some medical comorbidities were linked to a greater likelihood of being vaccinated, including asthma (OR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.40-1.77), chronic liver disease (OR, 1.23; 95%, 1.03-1.47), diabetes (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.36-1.63), HIV (OR, 3.68; 95% CI, 2.06-6.57), history of malignancy (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.09-1.34), and psoriatic arthritis (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.25-1.58).

There was no association between the use of an oral systemic therapy or biologic treatment and vaccination rates.

The authors suggested that psoriasis patients, especially younger ones, may not get adequate counseling on the value of the flu vaccine from their physicians. Studies have shown that, among the American public, health care providers are the most influential source of information about the flu vaccine. Among younger patients, the dermatologist may be a psoriasis patient’s primary health care provider, so it is important for dermatologists to counsel patients about the recommended vaccines, the authors wrote.

“Further research understanding why adults with psoriasis do not receive recommended vaccinations will help to create targeted interventions to improve vaccination rates and decrease hospitalizations in adults with psoriasis,” they concluded.

The study relied on administrative claims, so the results may not be generalizable to patients with insurance types other than those in the database or who are uninsured, the authors noted.

This study was funded by the National Psoriasis Foundation, the Dermatology Foundation, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Noe and three other authors did not report any disclosures, the fifth author reported multiple disclosures related to various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Noe MH et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2018 Oct 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.09.012.

Psoriasis patients are more vulnerable to systemic infections, including influenza-related pneumonia, but a new study shows that they are less likely to receive the influenza vaccine than patients with RA.

Vaccination rates were higher in psoriasis patients aged over 50 years, those who were female, and those with other chronic medical conditions, however.

Megan H. Noe, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her coauthors referred to recent evidence suggesting that psoriasis involves systemic inflammation that increase the risk of comorbidities and that hospitalization rates for serious infections, including lower respiratory tract infections and pneumonia, are higher among adults with psoriasis than those who do not have psoriasis.

drawing from administrative and commercial claims data from OptumInsight Clinformatics Data Mart. They examined all adult patients with psoriasis, RA, or chronic hypertension who required oral antihypertensive medication. The study population included individuals tracked during the 2010-2011 flu season and 24 months prior (September 2008 to March 2011). This year was chosen because it was labeled as a “typical” season by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The primary outcome was a claim for an influenza vaccine, and covariates included age, length of residency, gender, and a clinical history of a range of conditions known to be associated with greater risk of influenza complications.

The population included 17,078 patients with psoriasis, 21,832 with RA, and 496,972 with chronic hypertension. After controlling for sex and age, the probability of getting a flu vaccine was similar between psoriasis and hypertension patients, but RA patients were more likely to be vaccinated than patients with psoriasis (odds ratio, 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.13). But the likelihood varied with age: 30-year-old patients with RA were more likely than a 30-year-old psoriasis patient to get a flu shot (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.18-1.45), while a 70-year-old patient with RA was about as likely to get the flu vaccine as a 70-year-old patient with psoriasis.

Female psoriasis patients were more likely to get a flu shot than males (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.20-1.38). Among the psoriasis patients, having some medical comorbidities were linked to a greater likelihood of being vaccinated, including asthma (OR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.40-1.77), chronic liver disease (OR, 1.23; 95%, 1.03-1.47), diabetes (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.36-1.63), HIV (OR, 3.68; 95% CI, 2.06-6.57), history of malignancy (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.09-1.34), and psoriatic arthritis (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.25-1.58).

There was no association between the use of an oral systemic therapy or biologic treatment and vaccination rates.

The authors suggested that psoriasis patients, especially younger ones, may not get adequate counseling on the value of the flu vaccine from their physicians. Studies have shown that, among the American public, health care providers are the most influential source of information about the flu vaccine. Among younger patients, the dermatologist may be a psoriasis patient’s primary health care provider, so it is important for dermatologists to counsel patients about the recommended vaccines, the authors wrote.

“Further research understanding why adults with psoriasis do not receive recommended vaccinations will help to create targeted interventions to improve vaccination rates and decrease hospitalizations in adults with psoriasis,” they concluded.

The study relied on administrative claims, so the results may not be generalizable to patients with insurance types other than those in the database or who are uninsured, the authors noted.

This study was funded by the National Psoriasis Foundation, the Dermatology Foundation, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Noe and three other authors did not report any disclosures, the fifth author reported multiple disclosures related to various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Noe MH et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2018 Oct 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.09.012.

Psoriasis patients are more vulnerable to systemic infections, including influenza-related pneumonia, but a new study shows that they are less likely to receive the influenza vaccine than patients with RA.

Vaccination rates were higher in psoriasis patients aged over 50 years, those who were female, and those with other chronic medical conditions, however.

Megan H. Noe, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her coauthors referred to recent evidence suggesting that psoriasis involves systemic inflammation that increase the risk of comorbidities and that hospitalization rates for serious infections, including lower respiratory tract infections and pneumonia, are higher among adults with psoriasis than those who do not have psoriasis.

drawing from administrative and commercial claims data from OptumInsight Clinformatics Data Mart. They examined all adult patients with psoriasis, RA, or chronic hypertension who required oral antihypertensive medication. The study population included individuals tracked during the 2010-2011 flu season and 24 months prior (September 2008 to March 2011). This year was chosen because it was labeled as a “typical” season by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The primary outcome was a claim for an influenza vaccine, and covariates included age, length of residency, gender, and a clinical history of a range of conditions known to be associated with greater risk of influenza complications.

The population included 17,078 patients with psoriasis, 21,832 with RA, and 496,972 with chronic hypertension. After controlling for sex and age, the probability of getting a flu vaccine was similar between psoriasis and hypertension patients, but RA patients were more likely to be vaccinated than patients with psoriasis (odds ratio, 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.13). But the likelihood varied with age: 30-year-old patients with RA were more likely than a 30-year-old psoriasis patient to get a flu shot (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.18-1.45), while a 70-year-old patient with RA was about as likely to get the flu vaccine as a 70-year-old patient with psoriasis.

Female psoriasis patients were more likely to get a flu shot than males (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.20-1.38). Among the psoriasis patients, having some medical comorbidities were linked to a greater likelihood of being vaccinated, including asthma (OR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.40-1.77), chronic liver disease (OR, 1.23; 95%, 1.03-1.47), diabetes (OR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.36-1.63), HIV (OR, 3.68; 95% CI, 2.06-6.57), history of malignancy (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.09-1.34), and psoriatic arthritis (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.25-1.58).

There was no association between the use of an oral systemic therapy or biologic treatment and vaccination rates.

The authors suggested that psoriasis patients, especially younger ones, may not get adequate counseling on the value of the flu vaccine from their physicians. Studies have shown that, among the American public, health care providers are the most influential source of information about the flu vaccine. Among younger patients, the dermatologist may be a psoriasis patient’s primary health care provider, so it is important for dermatologists to counsel patients about the recommended vaccines, the authors wrote.

“Further research understanding why adults with psoriasis do not receive recommended vaccinations will help to create targeted interventions to improve vaccination rates and decrease hospitalizations in adults with psoriasis,” they concluded.

The study relied on administrative claims, so the results may not be generalizable to patients with insurance types other than those in the database or who are uninsured, the authors noted.

This study was funded by the National Psoriasis Foundation, the Dermatology Foundation, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Noe and three other authors did not report any disclosures, the fifth author reported multiple disclosures related to various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Noe MH et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2018 Oct 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.09.012.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF INVESTIGATIVE DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Despite vulnerability to complications, fewer psoriasis patients received the vaccine, compared with RA patients.

Major finding: Patients with RA were 8% more likely to receive a flu vaccine than patients with psoriasis.

Study details: A retrospective cohort study of 535,882 subjects with psoriasis, RA, or hypertension.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Psoriasis Foundation, the Dermatology Foundation, and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Four authors did not report any disclosures; the fifth author reported multiple disclosures related to various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Noe MH et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2018 Oct 10. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.09.012.

November 2018

Desmoplastic trichilemmoma

that presents as a solitary, skin colored lesion on the midface. Lesions may appear smooth or verrucous. Lesions may occur alongside trichoepitheliomas. They may also occur on genital skin and resemble condyloma acuminata.

Histopathology reveals downward lobular growth of the epidermis. Keratinocytes are clear secondary to periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)–positive glycogen in the cells. In desmoplastic trichilemmoma, small clusters of cells are arranged in an infiltrative pattern that resembles invasive carcinoma. Often, the desmoplastic areas are surrounded by benign-appearing trichilemmomas, which helps to make the diagnosis. Desmoplastic trichilemmomas can also occur within nevus sebaceous. As trichilemmoma is a benign growth; no treatment is needed. However, if further removal is desired, electrodesiccation, cryotherapy, shave removal, or excision are treatment options. Rarely seen, the malignant counterpart to trichilemmomas is a trichilemmal carcinoma, which requires surgical excision or Mohs.

The appearance of multiple trichilemmomas is a marker for Cowden syndrome. Cowden syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant disorder in which there is a mutation in a tumor-suppressor gene called PTEN. Patients may have oral mucosal papillomas, sclerotic fibromas, acral keratotic papules, and are at risk for the development of adenocarcinoma of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, and thyroid.

Trichoepithelioma is a benign neoplasm derived from follicular germ cells that presents as a skin-colored papule on the midface, especially the nose. Multiple trichoepitheliomas are a marker for Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. A desmoplastic trichoepithelioma is a variant that has stromal sclerosis on pathology. It is a benign lesion, although may be difficult to differentiate from sclerosing basal cell or microcystic adnexal carcinoma.

Angiofibroma, or fibrous papule, is a commonly seen, benign, skin-colored papule also often occurring on the nose. They can be treated for cosmetic purposes. Multiple lesions are associated with tuberous sclerosis.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

Desmoplastic trichilemmoma