User login

Third ACR Plenary presentations set to make an impact in rheumatology

A new study that validates the use of the Lupus Low Disease Activity State as a treatment outcome in systemic lupus erythematosus clinical trials is one of the highly-rated abstracts that will be presented in the third Plenary Session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology on Tuesday, Oct. 23.

The prospective, multicenter validation study, to be presented by Vera Golder, MBBS, of Monash University in Melbourne, builds on the results of previously reported studies using the Lupus Low Disease Activity State as a treatment target at EULAR this year and at last year’s International Congress on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Among other presentations in the session will be the results of the PEXIVAS trial. Peter A. Merkel, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, will present findings from the randomized trial assessing oral glucocorticoid use and plasma exchange in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis. The results have been highly anticipated as being among several research efforts to support reduction of corticosteroids in these patients.

In addition, attendees will hear results of a phase 3 study of apremilast for the treatment of oral ulcers in patients with Behçet’s syndrome. In the study, presented by Gulen Hatemi, MD, of Cerrahpasa Medical School, Istanbul, benefits of the drug were sustained for 28 weeks. Findings from a phase 2 study were reported in 2015.

A new study that validates the use of the Lupus Low Disease Activity State as a treatment outcome in systemic lupus erythematosus clinical trials is one of the highly-rated abstracts that will be presented in the third Plenary Session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology on Tuesday, Oct. 23.

The prospective, multicenter validation study, to be presented by Vera Golder, MBBS, of Monash University in Melbourne, builds on the results of previously reported studies using the Lupus Low Disease Activity State as a treatment target at EULAR this year and at last year’s International Congress on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Among other presentations in the session will be the results of the PEXIVAS trial. Peter A. Merkel, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, will present findings from the randomized trial assessing oral glucocorticoid use and plasma exchange in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis. The results have been highly anticipated as being among several research efforts to support reduction of corticosteroids in these patients.

In addition, attendees will hear results of a phase 3 study of apremilast for the treatment of oral ulcers in patients with Behçet’s syndrome. In the study, presented by Gulen Hatemi, MD, of Cerrahpasa Medical School, Istanbul, benefits of the drug were sustained for 28 weeks. Findings from a phase 2 study were reported in 2015.

A new study that validates the use of the Lupus Low Disease Activity State as a treatment outcome in systemic lupus erythematosus clinical trials is one of the highly-rated abstracts that will be presented in the third Plenary Session at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology on Tuesday, Oct. 23.

The prospective, multicenter validation study, to be presented by Vera Golder, MBBS, of Monash University in Melbourne, builds on the results of previously reported studies using the Lupus Low Disease Activity State as a treatment target at EULAR this year and at last year’s International Congress on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

Among other presentations in the session will be the results of the PEXIVAS trial. Peter A. Merkel, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, will present findings from the randomized trial assessing oral glucocorticoid use and plasma exchange in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis. The results have been highly anticipated as being among several research efforts to support reduction of corticosteroids in these patients.

In addition, attendees will hear results of a phase 3 study of apremilast for the treatment of oral ulcers in patients with Behçet’s syndrome. In the study, presented by Gulen Hatemi, MD, of Cerrahpasa Medical School, Istanbul, benefits of the drug were sustained for 28 weeks. Findings from a phase 2 study were reported in 2015.

REPORTING FROM THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Pediatric Skin Care: Survey of the Cutis Editorial Board

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists from the Cutis Editorial Board answered 5 questions on pediatric skin care. Here’s what we found.

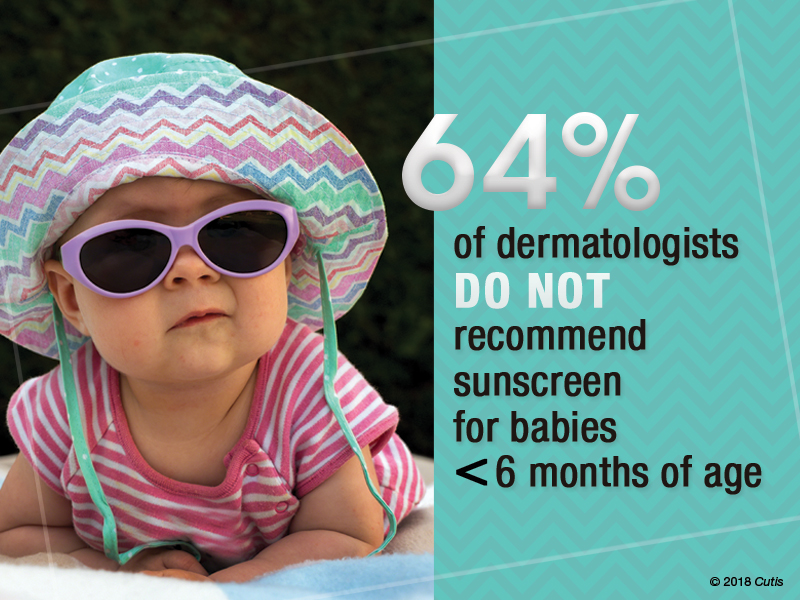

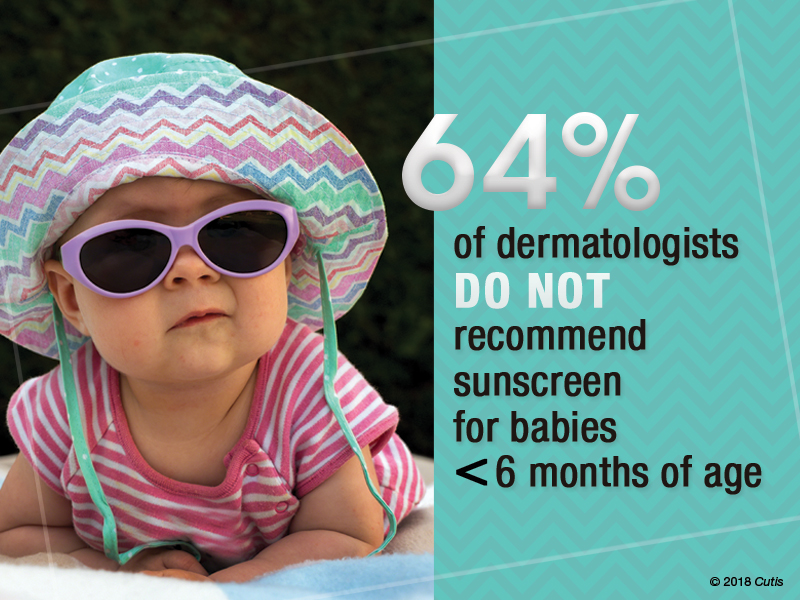

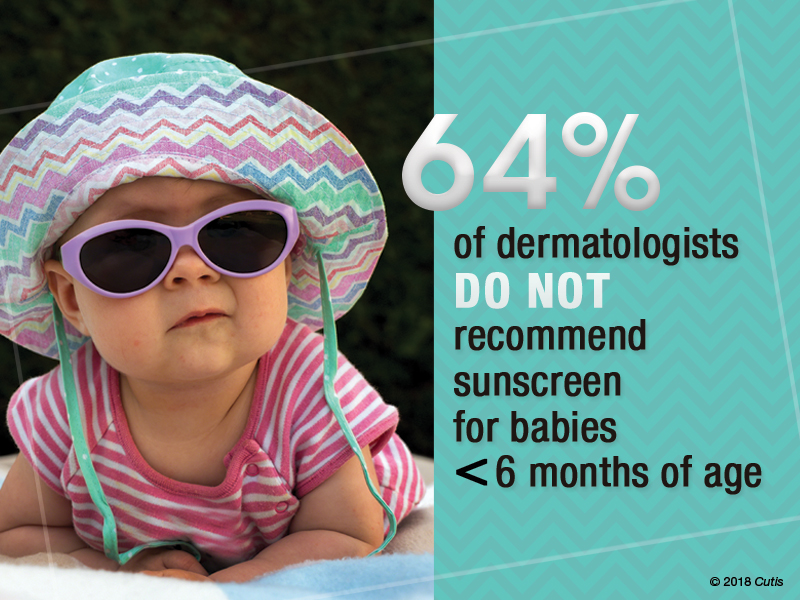

Do you recommend sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months?

More than half (64%) of dermatologists we surveyed do not recommend using sunscreens in babies younger than 6 months; they should stay out of the sun. They recommended sun-protective clothing, hats, and sunglasses in this age group.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Babies younger than 6 months are still developing barrier functionality and have a higher surface area to body weight ratio compared to older children and adults. There is decreased UV light barrier protection and increased risk for systemic drug absorption. Therefore, it is best to avoid sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months. Instead, I recommend avoiding sunlight during peak hours, keeping babies in the shade, and dressing them in sun-protective clothing and hats.

Next page: Bathing and eczema

What advice do you give parents/guardians on bathing for babies with eczema?

Two-thirds of dermatologists (68%) indicated that moisturizers should be applied after bathing babies with eczema. More than half (64%) suggested using fragrance-free cleansers. Results varied on the frequency of bathing; 32% said bathe once daily for short periods with warm water, and 41% suggested to reduce bathing to a few nights a week.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Dry skin is a characteristic feature of atopic dermatitis. We now know that skin barrier dysfunction, such as filaggrin deficiency, contributes to the pathophysiology in some patients. In addition, a paucity of stratum corneum and intercellular lipids increases transepidermal water loss. Therefore, emollients containing humectants to augment stratum corneum hydration and occludents to reduce evaporation are extremely helpful in maintenance treatment of atopic dermatitis.

Next page: Nonsteroidal agents

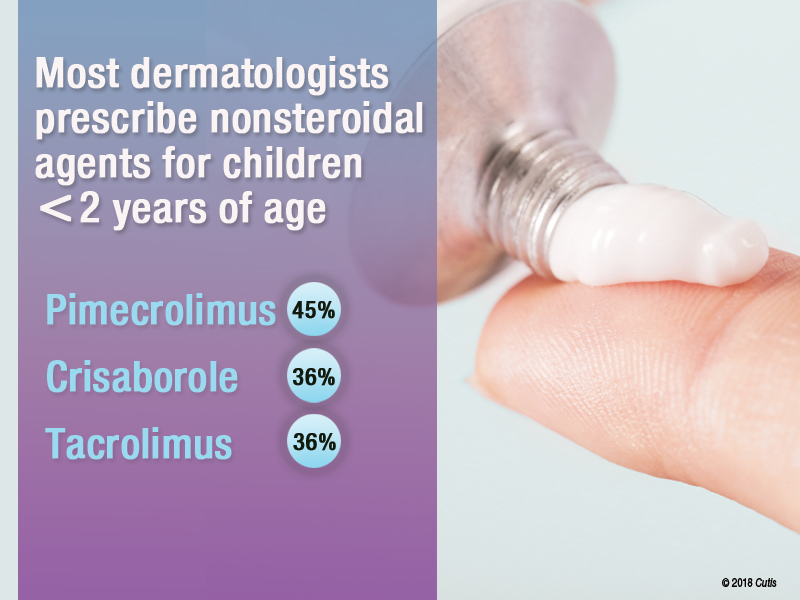

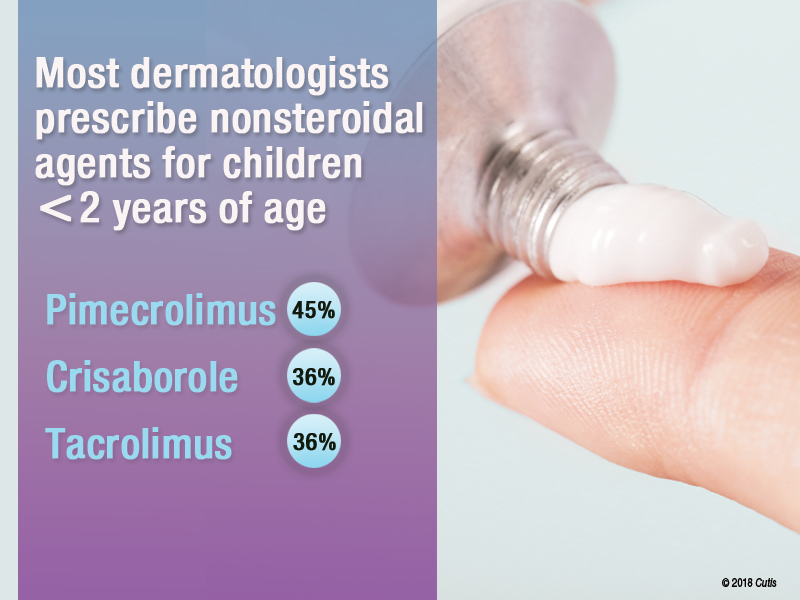

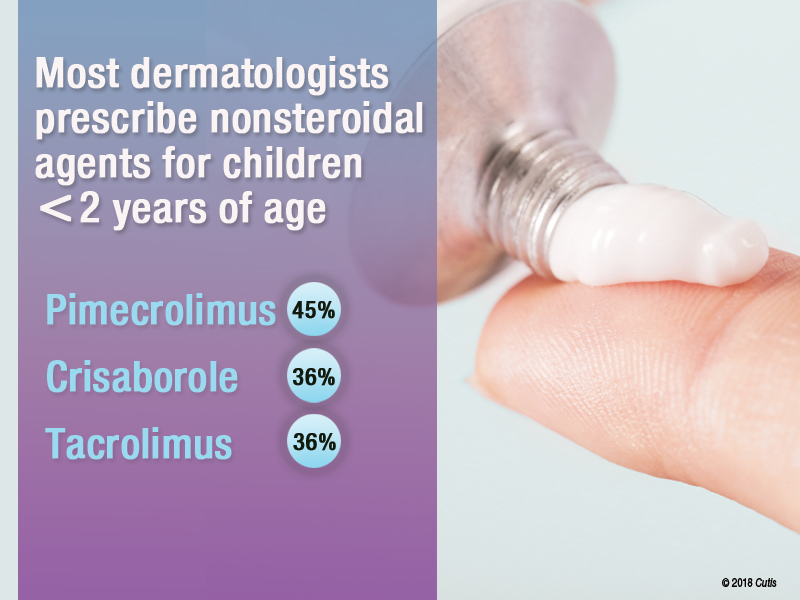

Do you prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years?

Almost two-thirds (64%) of dermatologists do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years.

If yes, which nonsteroidal agents do you prescribe for children?

Of those dermatologists who indicated that they do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years, almost half (45%) prescribe pimecrolimus, while 36% prescribe crisaborole or tacrolimus.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

We have limited options for US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies for atopic dermatitis in children younger than 2 years. The risks of adverse effects also are higher in younger children compared to older children and adults, particularly hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal suppression with corticosteroids. Pimecrolimus was the most common nonsteroidal prescribed in this group. It should be noted that pimecrolimus is not FDA approved for use in children younger than 2 years; however, 2 phase 3 studies were conducted with 436 infants aged 3 months to 23 months and they demonstrated safety and efficacy.

Next page: Procedures in adolescents

Which procedures do you perform on adolescents?

Forty-one percent of dermatologists surveyed indicated that they do not perform procedures on adolescents. Of those that do, 32% use laser hair removal or chemical peels in adolescents, while only 23% each use light therapy for acne or onabotulinumtoxinA for hyperhidrosis. Pulsed dye laser use was reported in only 18% of dermatologists.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

The results of this survey are a reflection of the relatively recent trends in dermatology training. Now that there is board certification in pediatric dermatology, many dermatologists now refer to pediatric dermatologists for children who need or want procedures.

Next page: More tips from derms

More Tips From Dermatologists

The dermatologists we polled had the following advice for their peers:

Keep the regimen as simple as possible and make sure your skin care advice is culturally relevant.—Craig Burkhart, MD (Chapel Hill, North Carolina)

Please, avoid direct sun exposure as much as possible by wearing protective garments and finding shades in the outside.—Jisun Cha, MD (New Brunswick, New Jersey)

Good habits start early. Teach children how to care for their skin and they will carry that practice with them over the course of their lifetime, and hopefully pass it on.—James Q. Del Rosso, DO (Las Vegas, Nevada)

About This Survey

The survey was fielded electronically to Cutis Editorial Board Members within the United States from September 13, 2018, to October 4, 2018. A total of 22 usable responses were received.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists from the Cutis Editorial Board answered 5 questions on pediatric skin care. Here’s what we found.

Do you recommend sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months?

More than half (64%) of dermatologists we surveyed do not recommend using sunscreens in babies younger than 6 months; they should stay out of the sun. They recommended sun-protective clothing, hats, and sunglasses in this age group.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Babies younger than 6 months are still developing barrier functionality and have a higher surface area to body weight ratio compared to older children and adults. There is decreased UV light barrier protection and increased risk for systemic drug absorption. Therefore, it is best to avoid sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months. Instead, I recommend avoiding sunlight during peak hours, keeping babies in the shade, and dressing them in sun-protective clothing and hats.

Next page: Bathing and eczema

What advice do you give parents/guardians on bathing for babies with eczema?

Two-thirds of dermatologists (68%) indicated that moisturizers should be applied after bathing babies with eczema. More than half (64%) suggested using fragrance-free cleansers. Results varied on the frequency of bathing; 32% said bathe once daily for short periods with warm water, and 41% suggested to reduce bathing to a few nights a week.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Dry skin is a characteristic feature of atopic dermatitis. We now know that skin barrier dysfunction, such as filaggrin deficiency, contributes to the pathophysiology in some patients. In addition, a paucity of stratum corneum and intercellular lipids increases transepidermal water loss. Therefore, emollients containing humectants to augment stratum corneum hydration and occludents to reduce evaporation are extremely helpful in maintenance treatment of atopic dermatitis.

Next page: Nonsteroidal agents

Do you prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years?

Almost two-thirds (64%) of dermatologists do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years.

If yes, which nonsteroidal agents do you prescribe for children?

Of those dermatologists who indicated that they do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years, almost half (45%) prescribe pimecrolimus, while 36% prescribe crisaborole or tacrolimus.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

We have limited options for US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies for atopic dermatitis in children younger than 2 years. The risks of adverse effects also are higher in younger children compared to older children and adults, particularly hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal suppression with corticosteroids. Pimecrolimus was the most common nonsteroidal prescribed in this group. It should be noted that pimecrolimus is not FDA approved for use in children younger than 2 years; however, 2 phase 3 studies were conducted with 436 infants aged 3 months to 23 months and they demonstrated safety and efficacy.

Next page: Procedures in adolescents

Which procedures do you perform on adolescents?

Forty-one percent of dermatologists surveyed indicated that they do not perform procedures on adolescents. Of those that do, 32% use laser hair removal or chemical peels in adolescents, while only 23% each use light therapy for acne or onabotulinumtoxinA for hyperhidrosis. Pulsed dye laser use was reported in only 18% of dermatologists.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

The results of this survey are a reflection of the relatively recent trends in dermatology training. Now that there is board certification in pediatric dermatology, many dermatologists now refer to pediatric dermatologists for children who need or want procedures.

Next page: More tips from derms

More Tips From Dermatologists

The dermatologists we polled had the following advice for their peers:

Keep the regimen as simple as possible and make sure your skin care advice is culturally relevant.—Craig Burkhart, MD (Chapel Hill, North Carolina)

Please, avoid direct sun exposure as much as possible by wearing protective garments and finding shades in the outside.—Jisun Cha, MD (New Brunswick, New Jersey)

Good habits start early. Teach children how to care for their skin and they will carry that practice with them over the course of their lifetime, and hopefully pass it on.—James Q. Del Rosso, DO (Las Vegas, Nevada)

About This Survey

The survey was fielded electronically to Cutis Editorial Board Members within the United States from September 13, 2018, to October 4, 2018. A total of 22 usable responses were received.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists from the Cutis Editorial Board answered 5 questions on pediatric skin care. Here’s what we found.

Do you recommend sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months?

More than half (64%) of dermatologists we surveyed do not recommend using sunscreens in babies younger than 6 months; they should stay out of the sun. They recommended sun-protective clothing, hats, and sunglasses in this age group.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Babies younger than 6 months are still developing barrier functionality and have a higher surface area to body weight ratio compared to older children and adults. There is decreased UV light barrier protection and increased risk for systemic drug absorption. Therefore, it is best to avoid sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months. Instead, I recommend avoiding sunlight during peak hours, keeping babies in the shade, and dressing them in sun-protective clothing and hats.

Next page: Bathing and eczema

What advice do you give parents/guardians on bathing for babies with eczema?

Two-thirds of dermatologists (68%) indicated that moisturizers should be applied after bathing babies with eczema. More than half (64%) suggested using fragrance-free cleansers. Results varied on the frequency of bathing; 32% said bathe once daily for short periods with warm water, and 41% suggested to reduce bathing to a few nights a week.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Dry skin is a characteristic feature of atopic dermatitis. We now know that skin barrier dysfunction, such as filaggrin deficiency, contributes to the pathophysiology in some patients. In addition, a paucity of stratum corneum and intercellular lipids increases transepidermal water loss. Therefore, emollients containing humectants to augment stratum corneum hydration and occludents to reduce evaporation are extremely helpful in maintenance treatment of atopic dermatitis.

Next page: Nonsteroidal agents

Do you prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years?

Almost two-thirds (64%) of dermatologists do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years.

If yes, which nonsteroidal agents do you prescribe for children?

Of those dermatologists who indicated that they do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years, almost half (45%) prescribe pimecrolimus, while 36% prescribe crisaborole or tacrolimus.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

We have limited options for US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies for atopic dermatitis in children younger than 2 years. The risks of adverse effects also are higher in younger children compared to older children and adults, particularly hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal suppression with corticosteroids. Pimecrolimus was the most common nonsteroidal prescribed in this group. It should be noted that pimecrolimus is not FDA approved for use in children younger than 2 years; however, 2 phase 3 studies were conducted with 436 infants aged 3 months to 23 months and they demonstrated safety and efficacy.

Next page: Procedures in adolescents

Which procedures do you perform on adolescents?

Forty-one percent of dermatologists surveyed indicated that they do not perform procedures on adolescents. Of those that do, 32% use laser hair removal or chemical peels in adolescents, while only 23% each use light therapy for acne or onabotulinumtoxinA for hyperhidrosis. Pulsed dye laser use was reported in only 18% of dermatologists.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

The results of this survey are a reflection of the relatively recent trends in dermatology training. Now that there is board certification in pediatric dermatology, many dermatologists now refer to pediatric dermatologists for children who need or want procedures.

Next page: More tips from derms

More Tips From Dermatologists

The dermatologists we polled had the following advice for their peers:

Keep the regimen as simple as possible and make sure your skin care advice is culturally relevant.—Craig Burkhart, MD (Chapel Hill, North Carolina)

Please, avoid direct sun exposure as much as possible by wearing protective garments and finding shades in the outside.—Jisun Cha, MD (New Brunswick, New Jersey)

Good habits start early. Teach children how to care for their skin and they will carry that practice with them over the course of their lifetime, and hopefully pass it on.—James Q. Del Rosso, DO (Las Vegas, Nevada)

About This Survey

The survey was fielded electronically to Cutis Editorial Board Members within the United States from September 13, 2018, to October 4, 2018. A total of 22 usable responses were received.

Book Review: DuPont’s approach to addiction is tough, yet compassionate

What do Queen Silvia of Sweden, Pope Francis, and the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) have in common? They all share a deep and sobering commitment to fighting the global disease of addiction.

Robert L. DuPont, MD, has written a beautiful and surprisingly spiritual guide into the American addiction epidemic. He is the author of “The Selfish Brain: Learning From Addiction” (Center City, Minn.: Hazelden, 2000) and with his newest publication, “Chemical Slavery: Understanding Addiction and Stopping the Drug Epidemic” (Institute for Behavior and Health, 2018), he writes a clear-eyed tome detailing the history of drug and alcohol use within the United States and the current state of America’s drug epidemic.

Dr. DuPont is well known within the American addiction community as NIDA’s first director and as the second drug czar, under two presidents, Richard M. Nixon and Gerald R. Ford. His breadth of experience, spanning 50-plus years, dates from his early career with the District of Columbia Department of Corrections, into his work in public policy on drugs and alcohol. This experience infuses his book with the hard science of addiction and the common-sense compassion required to shepherd people into recovery. One of us has worked with and been influenced by him since the 1970s. The other, also an addiction psychiatrist, finished this book both invigorated and compelled to say thank you to Dr. DuPont and his life’s work! He remains relevant, insightful, and always optimistic about the future of addiction treatment.

Harm reduction explored

The book begins with a cogent history of drug and alcohol use in America. Dr. DuPont details this as well as the public policies that have evolved to address them. He weaves into our national history reasoning behind why, as a “mass consumer” culture, we are more prone to addiction than ever before. The loss of cultural and societal pressures has a role to play in the rise along with genetics and environmental stress. The adolescent brain is prominently discussed throughout this first section as a highly vulnerable organ that can lead to lifelong addiction if primed early by addictive chemicals.

Dr. DuPont addresses the biology of addiction, delving into both the biological mechanisms within the brain, making those details accessible and understandable – to a practicing physician as well as a family member or patient struggling with addiction.

He also addresses harm reduction, a fairly new concept within the field. Harm reduction has taken on more prominence with localities across the country providing people with addictions with safe places and clean needles to continue their substance use without risks of serious or life-threatening diseases and crime. He challenges the idea that harm reduction is active recovery from substance addiction. Instead, he opines that harm reduction must be tethered to and must lead to real recovery work or it risks becoming an organizational enabling of the addict’s behavior.

Dr. DuPont pulls no punches with his language. He uses words such as “fatal,” “addict,” and “alcoholic.” He addresses the concerns by some in the field that those kinds of words are harsh, derogatory, and prejudicial by calling out addiction as a disease hallmarked primarily by loss of control and by dishonesty. To shun those words is to perpetuate the disease, delaying life-saving treatment.

Compassion is a theme throughout. He says we must stigmatize the addiction but not the addict. He advocates for real consequences to addictive behaviors as a key to getting addicted physicians and others with this disease into recovery. Treatment works, but we also have studied specific approaches that work and why.1 His writing conveys a genuine empathy for his patients and argues that treatment is delayed when serious and negative consequences for patients are removed.

Focus on prevention

A clear passion for prevention is evident within his chapters on youth addiction. For adolescents, Dr. DuPont presents a “One Choice approach,” which requires complete abstinence from alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana. He also presents science showing that patients younger than age 21 will have a greater risk of developing lifelong and debilitating addictions if they use these chemicals prior to this age. His emphasis for the One Choice approach carries ramifications throughout the primary care, pediatric, and family practice communities.

Dr. DuPont is nothing if not an optimist. Though he clearly defines addiction as an often-fatal disease, he remains positive about the future of addiction treatment, both with changes in public policy and with advancements in the medicine of addiction. He makes a compelling argument regarding Sweden’s approach to the drug problem, citing Queen Silvia’s lifelong commitment to prevent, control, and treat drug and alcohol addiction. Sweden’s model is, indeed, intriguing, and that country’s outcomes present a strong argument for the marriage of the criminal justice system with medical intervention – an approach that the United States has adopted only in a patchwork fashion.

The book describes controversies throughout, such as Dr. DuPont’s furtherance of our work on how best to treat dual disorders.2 He is not impressed with the self-medication hypothesis as well as the dive into the U.S. national medical marijuana experiment. We had looked at college students having new-onset memory or attention-deficit/hyperactivity problems, only to find that it was likely psychostimulant seeking to reverse marijuana effects.3 Physicians, families, and patients would be well served to review his arguments on the clear definition of “medicine” with regard to marijuana and the risks taken when we medicalize a known addictive chemical. He tackles the push for legalization as well, and the risks of increased societal acceptance and commercialization power that comes with this. He has led the field in thinking about the role of early drug exposure, brain training, and hijacking in the addictive process. This gateway hypothesis can occur whether the first teen drugs are cannabis or tobacco4 or alcohol.

Dr. DuPont finishes his work with a detailed biography, in which he addresses his family history of addiction, and his own overuse of alcohol in his late teens and early 20s as well as a confession of onetime use of marijuana during medical school. He always has led the field in trying to explain the disease of addiction, intervention, treatment, and recovery. But this self-reflection and brutal honesty is refreshing and in step with themes in his book, which promote the idea of recovery as an embrace of honesty, in mind, body, and spirit.

Dr. Jorandby trained in addiction psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and works as an addiction psychiatrist with Amen Clinics in Washington. Dr. Gold is the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University in St. Louis.

References

1. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009 Mar;36(2):159-71.

2. J Addict Dis. 2007;26 Suppl 1:13-23.

3. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Jun;164(6):973.

4. J Addict Dis. 2003;22(3):51-62.

What do Queen Silvia of Sweden, Pope Francis, and the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) have in common? They all share a deep and sobering commitment to fighting the global disease of addiction.

Robert L. DuPont, MD, has written a beautiful and surprisingly spiritual guide into the American addiction epidemic. He is the author of “The Selfish Brain: Learning From Addiction” (Center City, Minn.: Hazelden, 2000) and with his newest publication, “Chemical Slavery: Understanding Addiction and Stopping the Drug Epidemic” (Institute for Behavior and Health, 2018), he writes a clear-eyed tome detailing the history of drug and alcohol use within the United States and the current state of America’s drug epidemic.

Dr. DuPont is well known within the American addiction community as NIDA’s first director and as the second drug czar, under two presidents, Richard M. Nixon and Gerald R. Ford. His breadth of experience, spanning 50-plus years, dates from his early career with the District of Columbia Department of Corrections, into his work in public policy on drugs and alcohol. This experience infuses his book with the hard science of addiction and the common-sense compassion required to shepherd people into recovery. One of us has worked with and been influenced by him since the 1970s. The other, also an addiction psychiatrist, finished this book both invigorated and compelled to say thank you to Dr. DuPont and his life’s work! He remains relevant, insightful, and always optimistic about the future of addiction treatment.

Harm reduction explored

The book begins with a cogent history of drug and alcohol use in America. Dr. DuPont details this as well as the public policies that have evolved to address them. He weaves into our national history reasoning behind why, as a “mass consumer” culture, we are more prone to addiction than ever before. The loss of cultural and societal pressures has a role to play in the rise along with genetics and environmental stress. The adolescent brain is prominently discussed throughout this first section as a highly vulnerable organ that can lead to lifelong addiction if primed early by addictive chemicals.

Dr. DuPont addresses the biology of addiction, delving into both the biological mechanisms within the brain, making those details accessible and understandable – to a practicing physician as well as a family member or patient struggling with addiction.

He also addresses harm reduction, a fairly new concept within the field. Harm reduction has taken on more prominence with localities across the country providing people with addictions with safe places and clean needles to continue their substance use without risks of serious or life-threatening diseases and crime. He challenges the idea that harm reduction is active recovery from substance addiction. Instead, he opines that harm reduction must be tethered to and must lead to real recovery work or it risks becoming an organizational enabling of the addict’s behavior.

Dr. DuPont pulls no punches with his language. He uses words such as “fatal,” “addict,” and “alcoholic.” He addresses the concerns by some in the field that those kinds of words are harsh, derogatory, and prejudicial by calling out addiction as a disease hallmarked primarily by loss of control and by dishonesty. To shun those words is to perpetuate the disease, delaying life-saving treatment.

Compassion is a theme throughout. He says we must stigmatize the addiction but not the addict. He advocates for real consequences to addictive behaviors as a key to getting addicted physicians and others with this disease into recovery. Treatment works, but we also have studied specific approaches that work and why.1 His writing conveys a genuine empathy for his patients and argues that treatment is delayed when serious and negative consequences for patients are removed.

Focus on prevention

A clear passion for prevention is evident within his chapters on youth addiction. For adolescents, Dr. DuPont presents a “One Choice approach,” which requires complete abstinence from alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana. He also presents science showing that patients younger than age 21 will have a greater risk of developing lifelong and debilitating addictions if they use these chemicals prior to this age. His emphasis for the One Choice approach carries ramifications throughout the primary care, pediatric, and family practice communities.

Dr. DuPont is nothing if not an optimist. Though he clearly defines addiction as an often-fatal disease, he remains positive about the future of addiction treatment, both with changes in public policy and with advancements in the medicine of addiction. He makes a compelling argument regarding Sweden’s approach to the drug problem, citing Queen Silvia’s lifelong commitment to prevent, control, and treat drug and alcohol addiction. Sweden’s model is, indeed, intriguing, and that country’s outcomes present a strong argument for the marriage of the criminal justice system with medical intervention – an approach that the United States has adopted only in a patchwork fashion.

The book describes controversies throughout, such as Dr. DuPont’s furtherance of our work on how best to treat dual disorders.2 He is not impressed with the self-medication hypothesis as well as the dive into the U.S. national medical marijuana experiment. We had looked at college students having new-onset memory or attention-deficit/hyperactivity problems, only to find that it was likely psychostimulant seeking to reverse marijuana effects.3 Physicians, families, and patients would be well served to review his arguments on the clear definition of “medicine” with regard to marijuana and the risks taken when we medicalize a known addictive chemical. He tackles the push for legalization as well, and the risks of increased societal acceptance and commercialization power that comes with this. He has led the field in thinking about the role of early drug exposure, brain training, and hijacking in the addictive process. This gateway hypothesis can occur whether the first teen drugs are cannabis or tobacco4 or alcohol.

Dr. DuPont finishes his work with a detailed biography, in which he addresses his family history of addiction, and his own overuse of alcohol in his late teens and early 20s as well as a confession of onetime use of marijuana during medical school. He always has led the field in trying to explain the disease of addiction, intervention, treatment, and recovery. But this self-reflection and brutal honesty is refreshing and in step with themes in his book, which promote the idea of recovery as an embrace of honesty, in mind, body, and spirit.

Dr. Jorandby trained in addiction psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and works as an addiction psychiatrist with Amen Clinics in Washington. Dr. Gold is the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University in St. Louis.

References

1. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009 Mar;36(2):159-71.

2. J Addict Dis. 2007;26 Suppl 1:13-23.

3. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Jun;164(6):973.

4. J Addict Dis. 2003;22(3):51-62.

What do Queen Silvia of Sweden, Pope Francis, and the first director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) have in common? They all share a deep and sobering commitment to fighting the global disease of addiction.

Robert L. DuPont, MD, has written a beautiful and surprisingly spiritual guide into the American addiction epidemic. He is the author of “The Selfish Brain: Learning From Addiction” (Center City, Minn.: Hazelden, 2000) and with his newest publication, “Chemical Slavery: Understanding Addiction and Stopping the Drug Epidemic” (Institute for Behavior and Health, 2018), he writes a clear-eyed tome detailing the history of drug and alcohol use within the United States and the current state of America’s drug epidemic.

Dr. DuPont is well known within the American addiction community as NIDA’s first director and as the second drug czar, under two presidents, Richard M. Nixon and Gerald R. Ford. His breadth of experience, spanning 50-plus years, dates from his early career with the District of Columbia Department of Corrections, into his work in public policy on drugs and alcohol. This experience infuses his book with the hard science of addiction and the common-sense compassion required to shepherd people into recovery. One of us has worked with and been influenced by him since the 1970s. The other, also an addiction psychiatrist, finished this book both invigorated and compelled to say thank you to Dr. DuPont and his life’s work! He remains relevant, insightful, and always optimistic about the future of addiction treatment.

Harm reduction explored

The book begins with a cogent history of drug and alcohol use in America. Dr. DuPont details this as well as the public policies that have evolved to address them. He weaves into our national history reasoning behind why, as a “mass consumer” culture, we are more prone to addiction than ever before. The loss of cultural and societal pressures has a role to play in the rise along with genetics and environmental stress. The adolescent brain is prominently discussed throughout this first section as a highly vulnerable organ that can lead to lifelong addiction if primed early by addictive chemicals.

Dr. DuPont addresses the biology of addiction, delving into both the biological mechanisms within the brain, making those details accessible and understandable – to a practicing physician as well as a family member or patient struggling with addiction.

He also addresses harm reduction, a fairly new concept within the field. Harm reduction has taken on more prominence with localities across the country providing people with addictions with safe places and clean needles to continue their substance use without risks of serious or life-threatening diseases and crime. He challenges the idea that harm reduction is active recovery from substance addiction. Instead, he opines that harm reduction must be tethered to and must lead to real recovery work or it risks becoming an organizational enabling of the addict’s behavior.

Dr. DuPont pulls no punches with his language. He uses words such as “fatal,” “addict,” and “alcoholic.” He addresses the concerns by some in the field that those kinds of words are harsh, derogatory, and prejudicial by calling out addiction as a disease hallmarked primarily by loss of control and by dishonesty. To shun those words is to perpetuate the disease, delaying life-saving treatment.

Compassion is a theme throughout. He says we must stigmatize the addiction but not the addict. He advocates for real consequences to addictive behaviors as a key to getting addicted physicians and others with this disease into recovery. Treatment works, but we also have studied specific approaches that work and why.1 His writing conveys a genuine empathy for his patients and argues that treatment is delayed when serious and negative consequences for patients are removed.

Focus on prevention

A clear passion for prevention is evident within his chapters on youth addiction. For adolescents, Dr. DuPont presents a “One Choice approach,” which requires complete abstinence from alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana. He also presents science showing that patients younger than age 21 will have a greater risk of developing lifelong and debilitating addictions if they use these chemicals prior to this age. His emphasis for the One Choice approach carries ramifications throughout the primary care, pediatric, and family practice communities.

Dr. DuPont is nothing if not an optimist. Though he clearly defines addiction as an often-fatal disease, he remains positive about the future of addiction treatment, both with changes in public policy and with advancements in the medicine of addiction. He makes a compelling argument regarding Sweden’s approach to the drug problem, citing Queen Silvia’s lifelong commitment to prevent, control, and treat drug and alcohol addiction. Sweden’s model is, indeed, intriguing, and that country’s outcomes present a strong argument for the marriage of the criminal justice system with medical intervention – an approach that the United States has adopted only in a patchwork fashion.

The book describes controversies throughout, such as Dr. DuPont’s furtherance of our work on how best to treat dual disorders.2 He is not impressed with the self-medication hypothesis as well as the dive into the U.S. national medical marijuana experiment. We had looked at college students having new-onset memory or attention-deficit/hyperactivity problems, only to find that it was likely psychostimulant seeking to reverse marijuana effects.3 Physicians, families, and patients would be well served to review his arguments on the clear definition of “medicine” with regard to marijuana and the risks taken when we medicalize a known addictive chemical. He tackles the push for legalization as well, and the risks of increased societal acceptance and commercialization power that comes with this. He has led the field in thinking about the role of early drug exposure, brain training, and hijacking in the addictive process. This gateway hypothesis can occur whether the first teen drugs are cannabis or tobacco4 or alcohol.

Dr. DuPont finishes his work with a detailed biography, in which he addresses his family history of addiction, and his own overuse of alcohol in his late teens and early 20s as well as a confession of onetime use of marijuana during medical school. He always has led the field in trying to explain the disease of addiction, intervention, treatment, and recovery. But this self-reflection and brutal honesty is refreshing and in step with themes in his book, which promote the idea of recovery as an embrace of honesty, in mind, body, and spirit.

Dr. Jorandby trained in addiction psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and works as an addiction psychiatrist with Amen Clinics in Washington. Dr. Gold is the 17th Distinguished Alumni Professor at the University of Florida, Gainesville, and professor of psychiatry (adjunct) at Washington University in St. Louis.

References

1. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009 Mar;36(2):159-71.

2. J Addict Dis. 2007;26 Suppl 1:13-23.

3. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Jun;164(6):973.

4. J Addict Dis. 2003;22(3):51-62.

Gene-Replacement Therapy for SMA1 May Necessitate New Rating Measures to Capture Patients’ Motor Function Gains

CHOP-INTEND scores plateaued in a phase I trial of AVXS-101 even as patients reached new motor milestones.

CHICAGO—The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders (CHOP-INTEND) was designed to track motor function in patients with spinal muscular atrophy type 1 (SMA1), but the test may not be sensitive to advances in motor function made by patients who receive an investigational gene-replacement therapy, researchers said at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

AVXS-101 is an adeno-associated virus serotype 9 (AAV9)-based gene-replacement therapy that contains a copy of the SMN1 gene. AVXS-101 crosses the blood–brain barrier and is meant to treat the deletion or loss of function of the SMN1 gene in patients with SMA. The treatment may result in sustained SMN protein expression with a one-time dose.

Researchers conducted a phase I, open-label, dose-escalation study to study the treatment. Fifteen patients received AVXS-101 intravenously, and 12 participants received the proposed therapeutic dose.

“Patients treated with AVXS-101 achieved and maintained motor milestones unprecedented in the natural history of SMA1,” said Linda P. Lowes, PT, PhD, Principal Investigator for the Center for Gene Therapy at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, and Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Ohio State University, and colleagues. “CHOP-INTEND is a reliable tool for detecting early treatment impact, but appears insensitive to further motor function gains among AVXS-101–treated children as they age and develop.”

For example, the scale did not capture skills such as independent rolling and sitting that had not been seen in patients with SMA1, the researchers said.

CHOP-INTEND uses a 0–64-point scale where higher scores indicate better motor function. By six months, essentially no untreated patients with SMA1 achieve a score of 40 or greater points on the CHOP-INTEND, and scores may decrease between age 6 and 12 months. In the phase I trial of AVXS-101, CHOP-INTEND score increased from baseline by a mean of 9.8 points at one month postdose, 15.4 points at three months postdose, and 25.4 points at 24 months (n = 12 at all time points). Eleven of the 12 patients maintained a CHOP-INTEND score greater than 40 points for a mean of 19.5 months. Two children were able to crawl, pull to a stand, and stand and walk independently.

In the study, patients who achieved additional sitting milestones did not have accompanying increases on their CHOP-INTEND scores. For example, the 11 patients who sat for at least 5 seconds had a mean CHOP-INTEND plateau score of 56.9, while the 10 patients who sat for at least 10 seconds had a mean CHOP-INTEND plateau score of 57.0 and the nine patients who sat for at least 30 seconds had a mean CHOP-INTEND plateau score of 57.7.

The investigators suggested that the addition of scoring items such as supported sitting, head lifting, and walking could “mitigate the artificial ceiling effect” with the current scoring system. Other modifications to CHOP-INTEND, such as assessing one side of a patient instead of both sides, could reduce test administration time without affecting scores.

Furthermore, several CHOP-INTEND items may not perform well in assessing patients treated with AVXS-101 because they test primitive reflexes that fade as children live longer (eg, spinal incurvation) or children may become too heavy for the tests (eg, ventral suspension).

The study was sponsored by AveXis.

CHOP-INTEND scores plateaued in a phase I trial of AVXS-101 even as patients reached new motor milestones.

CHOP-INTEND scores plateaued in a phase I trial of AVXS-101 even as patients reached new motor milestones.

CHICAGO—The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders (CHOP-INTEND) was designed to track motor function in patients with spinal muscular atrophy type 1 (SMA1), but the test may not be sensitive to advances in motor function made by patients who receive an investigational gene-replacement therapy, researchers said at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

AVXS-101 is an adeno-associated virus serotype 9 (AAV9)-based gene-replacement therapy that contains a copy of the SMN1 gene. AVXS-101 crosses the blood–brain barrier and is meant to treat the deletion or loss of function of the SMN1 gene in patients with SMA. The treatment may result in sustained SMN protein expression with a one-time dose.

Researchers conducted a phase I, open-label, dose-escalation study to study the treatment. Fifteen patients received AVXS-101 intravenously, and 12 participants received the proposed therapeutic dose.

“Patients treated with AVXS-101 achieved and maintained motor milestones unprecedented in the natural history of SMA1,” said Linda P. Lowes, PT, PhD, Principal Investigator for the Center for Gene Therapy at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, and Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Ohio State University, and colleagues. “CHOP-INTEND is a reliable tool for detecting early treatment impact, but appears insensitive to further motor function gains among AVXS-101–treated children as they age and develop.”

For example, the scale did not capture skills such as independent rolling and sitting that had not been seen in patients with SMA1, the researchers said.

CHOP-INTEND uses a 0–64-point scale where higher scores indicate better motor function. By six months, essentially no untreated patients with SMA1 achieve a score of 40 or greater points on the CHOP-INTEND, and scores may decrease between age 6 and 12 months. In the phase I trial of AVXS-101, CHOP-INTEND score increased from baseline by a mean of 9.8 points at one month postdose, 15.4 points at three months postdose, and 25.4 points at 24 months (n = 12 at all time points). Eleven of the 12 patients maintained a CHOP-INTEND score greater than 40 points for a mean of 19.5 months. Two children were able to crawl, pull to a stand, and stand and walk independently.

In the study, patients who achieved additional sitting milestones did not have accompanying increases on their CHOP-INTEND scores. For example, the 11 patients who sat for at least 5 seconds had a mean CHOP-INTEND plateau score of 56.9, while the 10 patients who sat for at least 10 seconds had a mean CHOP-INTEND plateau score of 57.0 and the nine patients who sat for at least 30 seconds had a mean CHOP-INTEND plateau score of 57.7.

The investigators suggested that the addition of scoring items such as supported sitting, head lifting, and walking could “mitigate the artificial ceiling effect” with the current scoring system. Other modifications to CHOP-INTEND, such as assessing one side of a patient instead of both sides, could reduce test administration time without affecting scores.

Furthermore, several CHOP-INTEND items may not perform well in assessing patients treated with AVXS-101 because they test primitive reflexes that fade as children live longer (eg, spinal incurvation) or children may become too heavy for the tests (eg, ventral suspension).

The study was sponsored by AveXis.

CHICAGO—The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders (CHOP-INTEND) was designed to track motor function in patients with spinal muscular atrophy type 1 (SMA1), but the test may not be sensitive to advances in motor function made by patients who receive an investigational gene-replacement therapy, researchers said at the 47th Annual Meeting of the Child Neurology Society.

AVXS-101 is an adeno-associated virus serotype 9 (AAV9)-based gene-replacement therapy that contains a copy of the SMN1 gene. AVXS-101 crosses the blood–brain barrier and is meant to treat the deletion or loss of function of the SMN1 gene in patients with SMA. The treatment may result in sustained SMN protein expression with a one-time dose.

Researchers conducted a phase I, open-label, dose-escalation study to study the treatment. Fifteen patients received AVXS-101 intravenously, and 12 participants received the proposed therapeutic dose.

“Patients treated with AVXS-101 achieved and maintained motor milestones unprecedented in the natural history of SMA1,” said Linda P. Lowes, PT, PhD, Principal Investigator for the Center for Gene Therapy at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, and Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Ohio State University, and colleagues. “CHOP-INTEND is a reliable tool for detecting early treatment impact, but appears insensitive to further motor function gains among AVXS-101–treated children as they age and develop.”

For example, the scale did not capture skills such as independent rolling and sitting that had not been seen in patients with SMA1, the researchers said.

CHOP-INTEND uses a 0–64-point scale where higher scores indicate better motor function. By six months, essentially no untreated patients with SMA1 achieve a score of 40 or greater points on the CHOP-INTEND, and scores may decrease between age 6 and 12 months. In the phase I trial of AVXS-101, CHOP-INTEND score increased from baseline by a mean of 9.8 points at one month postdose, 15.4 points at three months postdose, and 25.4 points at 24 months (n = 12 at all time points). Eleven of the 12 patients maintained a CHOP-INTEND score greater than 40 points for a mean of 19.5 months. Two children were able to crawl, pull to a stand, and stand and walk independently.

In the study, patients who achieved additional sitting milestones did not have accompanying increases on their CHOP-INTEND scores. For example, the 11 patients who sat for at least 5 seconds had a mean CHOP-INTEND plateau score of 56.9, while the 10 patients who sat for at least 10 seconds had a mean CHOP-INTEND plateau score of 57.0 and the nine patients who sat for at least 30 seconds had a mean CHOP-INTEND plateau score of 57.7.

The investigators suggested that the addition of scoring items such as supported sitting, head lifting, and walking could “mitigate the artificial ceiling effect” with the current scoring system. Other modifications to CHOP-INTEND, such as assessing one side of a patient instead of both sides, could reduce test administration time without affecting scores.

Furthermore, several CHOP-INTEND items may not perform well in assessing patients treated with AVXS-101 because they test primitive reflexes that fade as children live longer (eg, spinal incurvation) or children may become too heavy for the tests (eg, ventral suspension).

The study was sponsored by AveXis.

Can ultrasound screening improve survival in ovarian cancer?

Annual ultrasound screening of asymptomatic women at risk of epithelial ovarian cancer can lead to lower staging of cancer at detection and improved survival, compared with no screening, according to a prospective clinical trial that followed more than 46,000 women over 2 decades.

“The findings of this study support the concept that a major predictor of ovarian cancer survival is stage at detection,” said John R. van Nagell Jr., MD, of the University of Kentucky–Markey Cancer Center, Lexington, and his coauthors. “The 10-year survival of women whose ovarian cancer was detected at an early stage (I or II) was 35% higher than that of women diagnosed with stage III cancer.” Study results were published in the November issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The study evaluated 46,101 women enrolled in the University of Kentucky Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial over 30.5 years. Trial participants, all of whom had annual ultrasound screening, were age 50 and older, or 25 and older with a family history of ovarian cancer. Overall, 23% and 44% of the women had a family history of either ovarian or breast cancer, respectively. Women in the study had an average of seven scans each. The unscreened comparator group was women with ovarian cancer referred to the UK Markey Cancer Center.

The study detected 71 cases of invasive epithelial ovarian cancers and 17 epithelial ovarian tumors of low malignant potential. None of the women with these tumors had a recurrence. Among the invasive cancers, the majority were either stage I (42%) or II (21%), and none were stage IV. The median age of these patients was 66 years. Of the low-malignancy tumors, 27% were stage I and 73% stage II, with none stage III or IV. A total of 699 women (1.5%) with persistent ovarian tumors had surgery.

Screened women also had improved survival compared to unscreened women: 86% vs. 45% at 5 years, 68% vs. 31% at 10 years (P less than .001).

However, the study also showed a high overall incidence rate for ovarian cancer, including false-positive and false-negative cases, compared with National Cancer Institute reports in the Kentucky state cancer profile: 271 per 100,000 vs. 10.4/100,000.

The study also looked at the economics of annual screening. “Ovarian screening reduced the 10-year mortality by 37% and produced 416 life years gained,” Dr. van Nagell and his coauthors said. Based on an estimated cost of $56 for each transvaginal ultrasound scan, that translates into a cost of $40,731 for each life year gained.

One concern of screening ultrasound is the high false-positive rate. “Although the sensitivity of transvaginal ultrasonography in detecting an ovarian abnormality is high, it has been unreliable in differentiating benign from malignant ovarian tumors,” they said. While they noted the accuracy of assessing malignancy has improved, the risk of complications in women who have surgery for benign tumors is an ongoing concern. “Additional research is necessary to identify high-risk populations who will benefit most from screening.”

Dr. van Nagell and his coauthors reported having no financial relationships. The study was supported by research grants from the Kentucky Department of Health and Human Services and the Telford Foundation.

SOURCE: Van Nagell JR Jr et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Nov;132[5]:1091-100. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002921.

Use a measure of caution when interpreting the results of the study by van Nagell et al., Sharon E. Robertson, MD, MPH, and Jeffery E. Peipert, MD, PhD, said in an invited commentary. First, they noted the “surprisingly high” rate of ovarian cancer (271 per 100,000) – although it may improve the predictive value of ultrasound screening, when one applies the test sensitivity and specificity the trial reported to the general population, “the positive predictive value falls to an unacceptable 0.7%.”

They also questioned the rationale for comparing the study population to an unscreened cohort of women with ovarian cancer referred to the University of Kentucky. “However, are we really comparing apples to apples?” they asked, noting “important key baseline differences” between the two groups, including that the screened cohort “could have contained an unbalanced proportion of genetically related ovarian cancers.” They also noted the risk profile of the unscreened cohort is unknown.

Addressing the differences in survival rates between screened and unscreened patients, Dr. Robertson and Dr. Peipert noted the study population had a higher rate of type I tumors than that seen in National Cancer Institute data for the general population (27% vs. 11%), along with the absence of genetic analysis. “For these reasons, we cannot confidently agree with the authors’ conclusion that the ultrasound screening reduced ovarian cancer mortality,” they stated.

They commended the Kentucky group for a “landmark study,” but added, “the evidence that screening for ovarian cancer improves survival remains elusive.” They called for more evidence before widespread screening programs are implemented.

Dr. Robertson and Dr. Peipert of Indiana University, Indianapolis, commented on the article by van Nagell et al. in Obstetrics and Gynecology (2018 Nov;132[5]:1089-90. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002962). Dr. Peipert disclosed relationships with Cooper Surgical/Teva, Merck, and Bayer. Dr. Robertson had no relevant financial relationships.

Use a measure of caution when interpreting the results of the study by van Nagell et al., Sharon E. Robertson, MD, MPH, and Jeffery E. Peipert, MD, PhD, said in an invited commentary. First, they noted the “surprisingly high” rate of ovarian cancer (271 per 100,000) – although it may improve the predictive value of ultrasound screening, when one applies the test sensitivity and specificity the trial reported to the general population, “the positive predictive value falls to an unacceptable 0.7%.”

They also questioned the rationale for comparing the study population to an unscreened cohort of women with ovarian cancer referred to the University of Kentucky. “However, are we really comparing apples to apples?” they asked, noting “important key baseline differences” between the two groups, including that the screened cohort “could have contained an unbalanced proportion of genetically related ovarian cancers.” They also noted the risk profile of the unscreened cohort is unknown.

Addressing the differences in survival rates between screened and unscreened patients, Dr. Robertson and Dr. Peipert noted the study population had a higher rate of type I tumors than that seen in National Cancer Institute data for the general population (27% vs. 11%), along with the absence of genetic analysis. “For these reasons, we cannot confidently agree with the authors’ conclusion that the ultrasound screening reduced ovarian cancer mortality,” they stated.

They commended the Kentucky group for a “landmark study,” but added, “the evidence that screening for ovarian cancer improves survival remains elusive.” They called for more evidence before widespread screening programs are implemented.

Dr. Robertson and Dr. Peipert of Indiana University, Indianapolis, commented on the article by van Nagell et al. in Obstetrics and Gynecology (2018 Nov;132[5]:1089-90. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002962). Dr. Peipert disclosed relationships with Cooper Surgical/Teva, Merck, and Bayer. Dr. Robertson had no relevant financial relationships.

Use a measure of caution when interpreting the results of the study by van Nagell et al., Sharon E. Robertson, MD, MPH, and Jeffery E. Peipert, MD, PhD, said in an invited commentary. First, they noted the “surprisingly high” rate of ovarian cancer (271 per 100,000) – although it may improve the predictive value of ultrasound screening, when one applies the test sensitivity and specificity the trial reported to the general population, “the positive predictive value falls to an unacceptable 0.7%.”

They also questioned the rationale for comparing the study population to an unscreened cohort of women with ovarian cancer referred to the University of Kentucky. “However, are we really comparing apples to apples?” they asked, noting “important key baseline differences” between the two groups, including that the screened cohort “could have contained an unbalanced proportion of genetically related ovarian cancers.” They also noted the risk profile of the unscreened cohort is unknown.

Addressing the differences in survival rates between screened and unscreened patients, Dr. Robertson and Dr. Peipert noted the study population had a higher rate of type I tumors than that seen in National Cancer Institute data for the general population (27% vs. 11%), along with the absence of genetic analysis. “For these reasons, we cannot confidently agree with the authors’ conclusion that the ultrasound screening reduced ovarian cancer mortality,” they stated.

They commended the Kentucky group for a “landmark study,” but added, “the evidence that screening for ovarian cancer improves survival remains elusive.” They called for more evidence before widespread screening programs are implemented.

Dr. Robertson and Dr. Peipert of Indiana University, Indianapolis, commented on the article by van Nagell et al. in Obstetrics and Gynecology (2018 Nov;132[5]:1089-90. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002962). Dr. Peipert disclosed relationships with Cooper Surgical/Teva, Merck, and Bayer. Dr. Robertson had no relevant financial relationships.

Annual ultrasound screening of asymptomatic women at risk of epithelial ovarian cancer can lead to lower staging of cancer at detection and improved survival, compared with no screening, according to a prospective clinical trial that followed more than 46,000 women over 2 decades.

“The findings of this study support the concept that a major predictor of ovarian cancer survival is stage at detection,” said John R. van Nagell Jr., MD, of the University of Kentucky–Markey Cancer Center, Lexington, and his coauthors. “The 10-year survival of women whose ovarian cancer was detected at an early stage (I or II) was 35% higher than that of women diagnosed with stage III cancer.” Study results were published in the November issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The study evaluated 46,101 women enrolled in the University of Kentucky Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial over 30.5 years. Trial participants, all of whom had annual ultrasound screening, were age 50 and older, or 25 and older with a family history of ovarian cancer. Overall, 23% and 44% of the women had a family history of either ovarian or breast cancer, respectively. Women in the study had an average of seven scans each. The unscreened comparator group was women with ovarian cancer referred to the UK Markey Cancer Center.

The study detected 71 cases of invasive epithelial ovarian cancers and 17 epithelial ovarian tumors of low malignant potential. None of the women with these tumors had a recurrence. Among the invasive cancers, the majority were either stage I (42%) or II (21%), and none were stage IV. The median age of these patients was 66 years. Of the low-malignancy tumors, 27% were stage I and 73% stage II, with none stage III or IV. A total of 699 women (1.5%) with persistent ovarian tumors had surgery.

Screened women also had improved survival compared to unscreened women: 86% vs. 45% at 5 years, 68% vs. 31% at 10 years (P less than .001).

However, the study also showed a high overall incidence rate for ovarian cancer, including false-positive and false-negative cases, compared with National Cancer Institute reports in the Kentucky state cancer profile: 271 per 100,000 vs. 10.4/100,000.

The study also looked at the economics of annual screening. “Ovarian screening reduced the 10-year mortality by 37% and produced 416 life years gained,” Dr. van Nagell and his coauthors said. Based on an estimated cost of $56 for each transvaginal ultrasound scan, that translates into a cost of $40,731 for each life year gained.

One concern of screening ultrasound is the high false-positive rate. “Although the sensitivity of transvaginal ultrasonography in detecting an ovarian abnormality is high, it has been unreliable in differentiating benign from malignant ovarian tumors,” they said. While they noted the accuracy of assessing malignancy has improved, the risk of complications in women who have surgery for benign tumors is an ongoing concern. “Additional research is necessary to identify high-risk populations who will benefit most from screening.”

Dr. van Nagell and his coauthors reported having no financial relationships. The study was supported by research grants from the Kentucky Department of Health and Human Services and the Telford Foundation.

SOURCE: Van Nagell JR Jr et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Nov;132[5]:1091-100. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002921.

Annual ultrasound screening of asymptomatic women at risk of epithelial ovarian cancer can lead to lower staging of cancer at detection and improved survival, compared with no screening, according to a prospective clinical trial that followed more than 46,000 women over 2 decades.

“The findings of this study support the concept that a major predictor of ovarian cancer survival is stage at detection,” said John R. van Nagell Jr., MD, of the University of Kentucky–Markey Cancer Center, Lexington, and his coauthors. “The 10-year survival of women whose ovarian cancer was detected at an early stage (I or II) was 35% higher than that of women diagnosed with stage III cancer.” Study results were published in the November issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The study evaluated 46,101 women enrolled in the University of Kentucky Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial over 30.5 years. Trial participants, all of whom had annual ultrasound screening, were age 50 and older, or 25 and older with a family history of ovarian cancer. Overall, 23% and 44% of the women had a family history of either ovarian or breast cancer, respectively. Women in the study had an average of seven scans each. The unscreened comparator group was women with ovarian cancer referred to the UK Markey Cancer Center.

The study detected 71 cases of invasive epithelial ovarian cancers and 17 epithelial ovarian tumors of low malignant potential. None of the women with these tumors had a recurrence. Among the invasive cancers, the majority were either stage I (42%) or II (21%), and none were stage IV. The median age of these patients was 66 years. Of the low-malignancy tumors, 27% were stage I and 73% stage II, with none stage III or IV. A total of 699 women (1.5%) with persistent ovarian tumors had surgery.

Screened women also had improved survival compared to unscreened women: 86% vs. 45% at 5 years, 68% vs. 31% at 10 years (P less than .001).

However, the study also showed a high overall incidence rate for ovarian cancer, including false-positive and false-negative cases, compared with National Cancer Institute reports in the Kentucky state cancer profile: 271 per 100,000 vs. 10.4/100,000.

The study also looked at the economics of annual screening. “Ovarian screening reduced the 10-year mortality by 37% and produced 416 life years gained,” Dr. van Nagell and his coauthors said. Based on an estimated cost of $56 for each transvaginal ultrasound scan, that translates into a cost of $40,731 for each life year gained.

One concern of screening ultrasound is the high false-positive rate. “Although the sensitivity of transvaginal ultrasonography in detecting an ovarian abnormality is high, it has been unreliable in differentiating benign from malignant ovarian tumors,” they said. While they noted the accuracy of assessing malignancy has improved, the risk of complications in women who have surgery for benign tumors is an ongoing concern. “Additional research is necessary to identify high-risk populations who will benefit most from screening.”

Dr. van Nagell and his coauthors reported having no financial relationships. The study was supported by research grants from the Kentucky Department of Health and Human Services and the Telford Foundation.

SOURCE: Van Nagell JR Jr et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Nov;132[5]:1091-100. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002921.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Annual ultrasound may improve outcomes for women at risk for epithelial ovarian cancer.

Major finding: Five-year survival was 86% for screened women vs. 45% for unscreened women (P less than .001).

Study details: Analysis of 46,101 at-risk women enrolled in the University of Kentucky Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial, a prospective cohort trial, from January 1987 to June 2017.

Disclosures: Dr. van Nagell and coauthors reported having no financial relationships. The study was supported by research grants from the Kentucky Department of Health and Human Services and the Telford Foundation.

Source: Van Nagell JR Jr et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Nov;132[5]:1091-100. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002921.

Expert Opinions: Considerations to Guide Conversion From Carbamazepine or Oxcarbazepine to Eslicarbazepine Acetate

Patients typically switch from carbamazepine (CBZ) or oxcarbazepine (OXC) to eslicarbazepine acetate (ESL) for at least 1 of 3 reasons: tolerability, simpler dosing, and/or efficacy. Since no evidence-based recommendations exist regarding the switching schedule, expert opinions may prove helpful for practitioners. In this supplement, expert epileptologists and clinical trialists share their experience about switching patients from CBZ or OXC to ESL.

Supplement

Click here or on the image below to read the supplement

Podcasts

Dr. Elinor Ben-Menachem discusses the case of a 28-year-old man with focal onset epilepsy who was switched from CBZ to ESL.

Dr. Toufic Fakhoury discusses the case of a 34-year-old female who became seizure-free after switching from OXC to ESL.

Dr. Mohamad Koubeissi discusses the case of a 22-year-old man with intractable epilepsy who was switched from OXC to ESL.

Dr. John Stern discusses the case of a 48-year-woman with tonic-clonic seizures who was switched from CBZ to ESL.

Dr. James Wheless discusses the case of an 8-year-old male who found relief having switched from OXC to ESL.

About the Faculty

Professor of Neurology

Director, Epilepsy Center

George Washington University

Washington, DC

Professor

Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology

Department of Clinical Neurosciences

The Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg

Department of Neurology

Sahlgrenska University Hospital

Gothenburg, Sweden

Saint Joseph Health System

Lexington, KY

Professor, Department of Neurology

Director, Epilepsy Clinical Program

Director, Epilepsy Residency Training Program

David Geffen School of Medicine

University of California, Los Angeles

Los Angeles, CA

Professor and Chief, Department of Pediatric Neurology

Chair, Division of Pediatric Neurology

Director, Le Bonheur Comprehensive Epilepsy Program

Director, Le Bonheur Neuroscience Center

University of Tennessee Health Science Center

Memphis, TN

Patients typically switch from carbamazepine (CBZ) or oxcarbazepine (OXC) to eslicarbazepine acetate (ESL) for at least 1 of 3 reasons: tolerability, simpler dosing, and/or efficacy. Since no evidence-based recommendations exist regarding the switching schedule, expert opinions may prove helpful for practitioners. In this supplement, expert epileptologists and clinical trialists share their experience about switching patients from CBZ or OXC to ESL.

Supplement

Click here or on the image below to read the supplement

Podcasts

Dr. Elinor Ben-Menachem discusses the case of a 28-year-old man with focal onset epilepsy who was switched from CBZ to ESL.

Dr. Toufic Fakhoury discusses the case of a 34-year-old female who became seizure-free after switching from OXC to ESL.

Dr. Mohamad Koubeissi discusses the case of a 22-year-old man with intractable epilepsy who was switched from OXC to ESL.

Dr. John Stern discusses the case of a 48-year-woman with tonic-clonic seizures who was switched from CBZ to ESL.

Dr. James Wheless discusses the case of an 8-year-old male who found relief having switched from OXC to ESL.

About the Faculty

Professor of Neurology

Director, Epilepsy Center

George Washington University

Washington, DC

Professor

Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology

Department of Clinical Neurosciences

The Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg

Department of Neurology

Sahlgrenska University Hospital

Gothenburg, Sweden

Saint Joseph Health System

Lexington, KY

Professor, Department of Neurology

Director, Epilepsy Clinical Program

Director, Epilepsy Residency Training Program

David Geffen School of Medicine

University of California, Los Angeles

Los Angeles, CA

Professor and Chief, Department of Pediatric Neurology

Chair, Division of Pediatric Neurology

Director, Le Bonheur Comprehensive Epilepsy Program

Director, Le Bonheur Neuroscience Center

University of Tennessee Health Science Center

Memphis, TN

Patients typically switch from carbamazepine (CBZ) or oxcarbazepine (OXC) to eslicarbazepine acetate (ESL) for at least 1 of 3 reasons: tolerability, simpler dosing, and/or efficacy. Since no evidence-based recommendations exist regarding the switching schedule, expert opinions may prove helpful for practitioners. In this supplement, expert epileptologists and clinical trialists share their experience about switching patients from CBZ or OXC to ESL.

Supplement

Click here or on the image below to read the supplement

Podcasts

Dr. Elinor Ben-Menachem discusses the case of a 28-year-old man with focal onset epilepsy who was switched from CBZ to ESL.

Dr. Toufic Fakhoury discusses the case of a 34-year-old female who became seizure-free after switching from OXC to ESL.

Dr. Mohamad Koubeissi discusses the case of a 22-year-old man with intractable epilepsy who was switched from OXC to ESL.

Dr. John Stern discusses the case of a 48-year-woman with tonic-clonic seizures who was switched from CBZ to ESL.

Dr. James Wheless discusses the case of an 8-year-old male who found relief having switched from OXC to ESL.

About the Faculty

Professor of Neurology

Director, Epilepsy Center

George Washington University

Washington, DC

Professor

Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology

Department of Clinical Neurosciences

The Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg

Department of Neurology

Sahlgrenska University Hospital

Gothenburg, Sweden

Saint Joseph Health System

Lexington, KY

Professor, Department of Neurology

Director, Epilepsy Clinical Program

Director, Epilepsy Residency Training Program

David Geffen School of Medicine

University of California, Los Angeles

Los Angeles, CA

Professor and Chief, Department of Pediatric Neurology

Chair, Division of Pediatric Neurology

Director, Le Bonheur Comprehensive Epilepsy Program

Director, Le Bonheur Neuroscience Center

University of Tennessee Health Science Center

Memphis, TN

Carl C. Bell: Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder Part II

Glycemic effects of lorcaserin

Also today, increased risk for suicide among adults who harm themselves, banning corporal punishment may reduce violence in youth, and a formula that scores the quality of a diet is validated.

Also today, increased risk for suicide among adults who harm themselves, banning corporal punishment may reduce violence in youth, and a formula that scores the quality of a diet is validated.

Also today, increased risk for suicide among adults who harm themselves, banning corporal punishment may reduce violence in youth, and a formula that scores the quality of a diet is validated.

Obesity Rates Are Up From 2016

In 2017, 7 states reported an adult obesity prevalence at or above 35%, up from 5 states in 2016. In 2012, obesity prevalence was lower than 35% in all states. The new data, from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, are detailed in the CDC’s 2017 Adult Obesity Prevalence Maps, www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html.

The highest levels were in Alabama, Arkansas, Iowa, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and West Virginia. The lowest prevalence was 22.6% in Colorado. Adults aged 45 to54 years were twice as likely as young adults to report obesity (36% vs 17%). Non-Hispanic blacks had the highest prevalence (39%), followed by Hispanics (32.4%), and non-Hispanic whites (29.3%). When education was factored in, adults without a high school degree had the highest prevalence at 35.6%; high school graduates, 32.9%; adults with some college, 31.9%; and college graduates, 22.7%.

Maps showing obesity levels overall, as well as by race and ethnicity, are also available for 2011 through 2016.

In 2017, 7 states reported an adult obesity prevalence at or above 35%, up from 5 states in 2016. In 2012, obesity prevalence was lower than 35% in all states. The new data, from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, are detailed in the CDC’s 2017 Adult Obesity Prevalence Maps, www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html.

The highest levels were in Alabama, Arkansas, Iowa, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and West Virginia. The lowest prevalence was 22.6% in Colorado. Adults aged 45 to54 years were twice as likely as young adults to report obesity (36% vs 17%). Non-Hispanic blacks had the highest prevalence (39%), followed by Hispanics (32.4%), and non-Hispanic whites (29.3%). When education was factored in, adults without a high school degree had the highest prevalence at 35.6%; high school graduates, 32.9%; adults with some college, 31.9%; and college graduates, 22.7%.

Maps showing obesity levels overall, as well as by race and ethnicity, are also available for 2011 through 2016.

In 2017, 7 states reported an adult obesity prevalence at or above 35%, up from 5 states in 2016. In 2012, obesity prevalence was lower than 35% in all states. The new data, from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, are detailed in the CDC’s 2017 Adult Obesity Prevalence Maps, www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html.

The highest levels were in Alabama, Arkansas, Iowa, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and West Virginia. The lowest prevalence was 22.6% in Colorado. Adults aged 45 to54 years were twice as likely as young adults to report obesity (36% vs 17%). Non-Hispanic blacks had the highest prevalence (39%), followed by Hispanics (32.4%), and non-Hispanic whites (29.3%). When education was factored in, adults without a high school degree had the highest prevalence at 35.6%; high school graduates, 32.9%; adults with some college, 31.9%; and college graduates, 22.7%.