User login

Screening for Prostate Cancer in Black Men

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Prostate cancer screening tools

- Ethic disparities

- Screening guidance

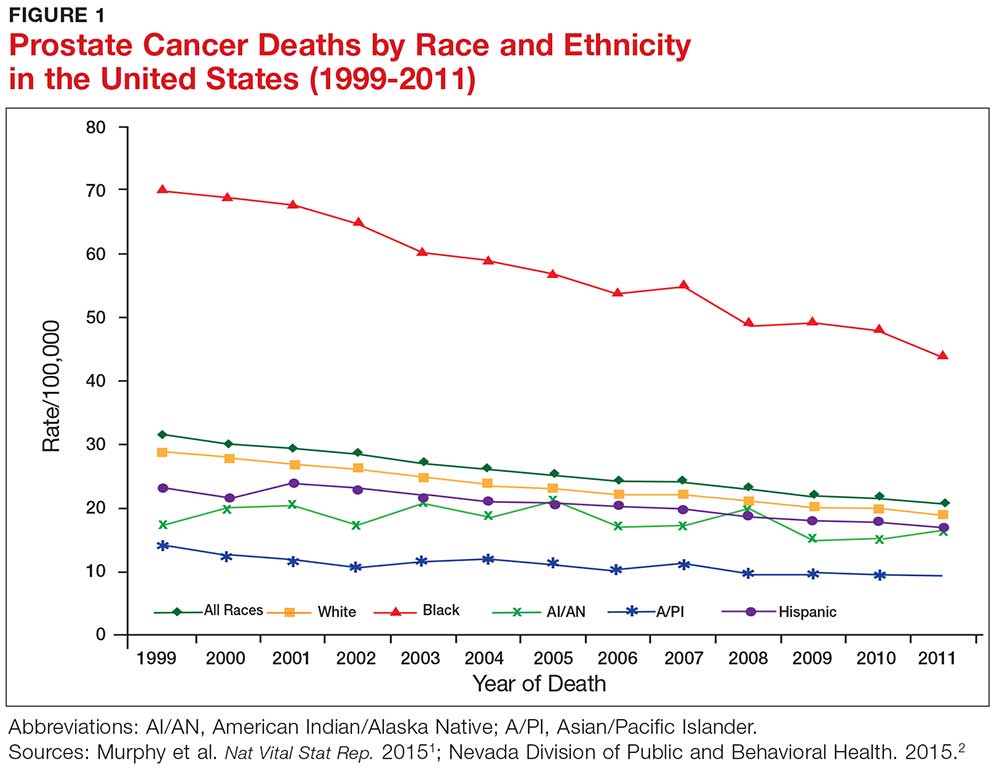

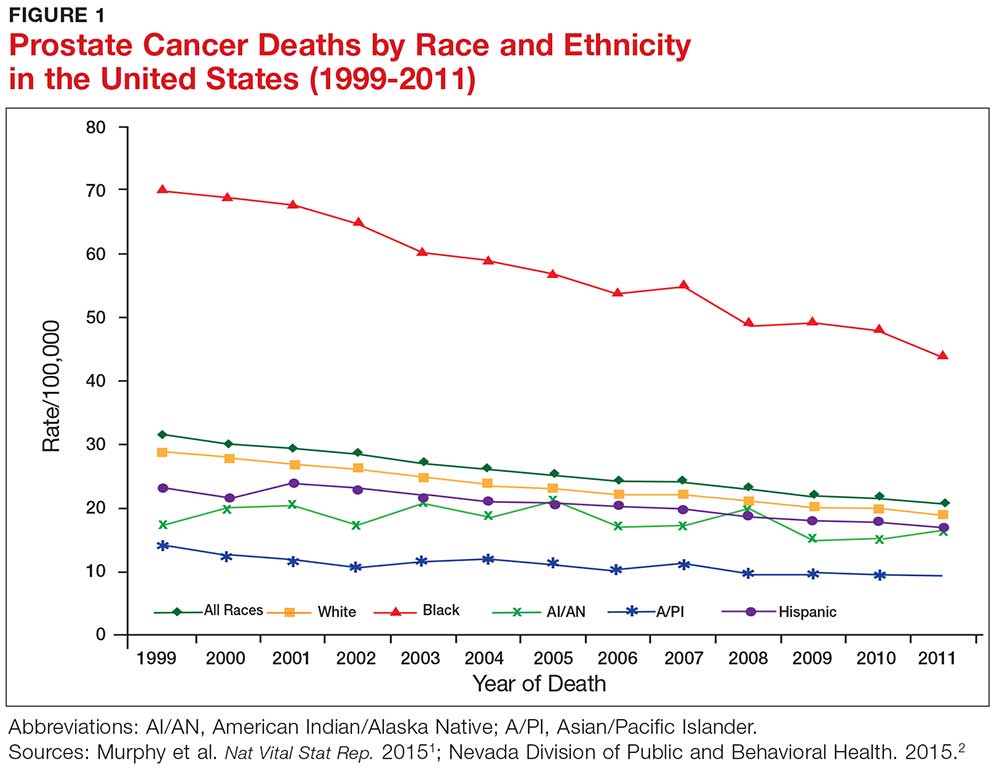

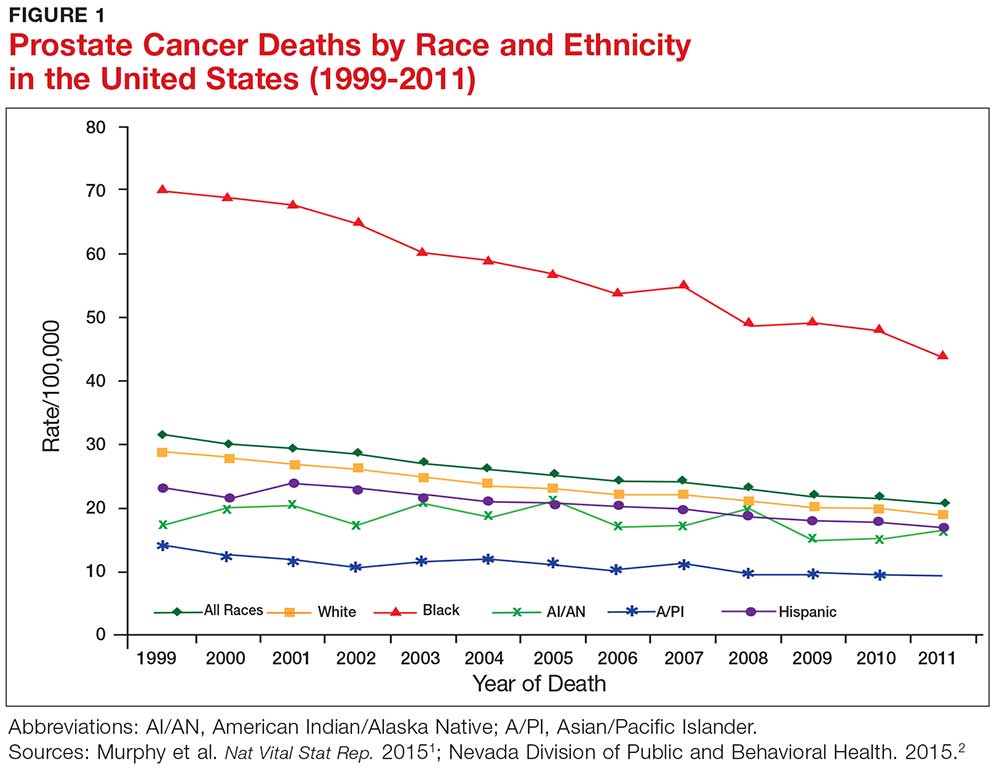

Prostate cancer, the second most common cancer to affect American men, is a slow-growing cancer that is curable when detected early. While the overall incidence has declined in the past 20 years (see Figure 1), prostate cancer remains a major concern among black men due to disproportionate incidence and mortality rates.1-3 A general understanding of the prostate and of prostate cancer lays the groundwork to acknowledge and address this divide.

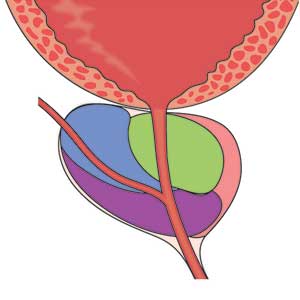

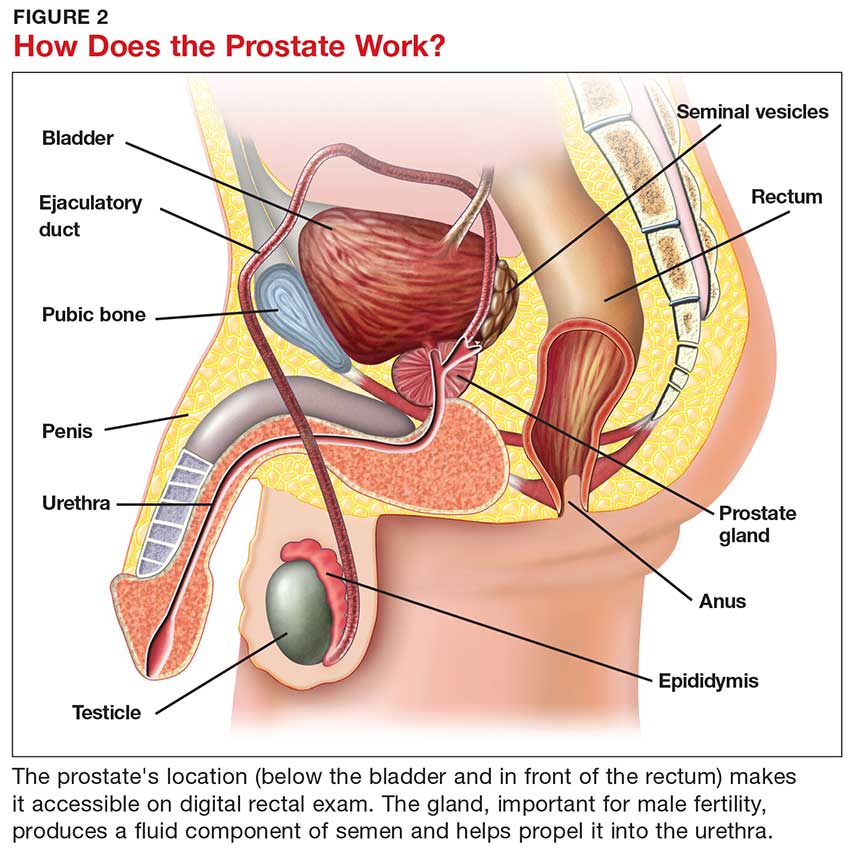

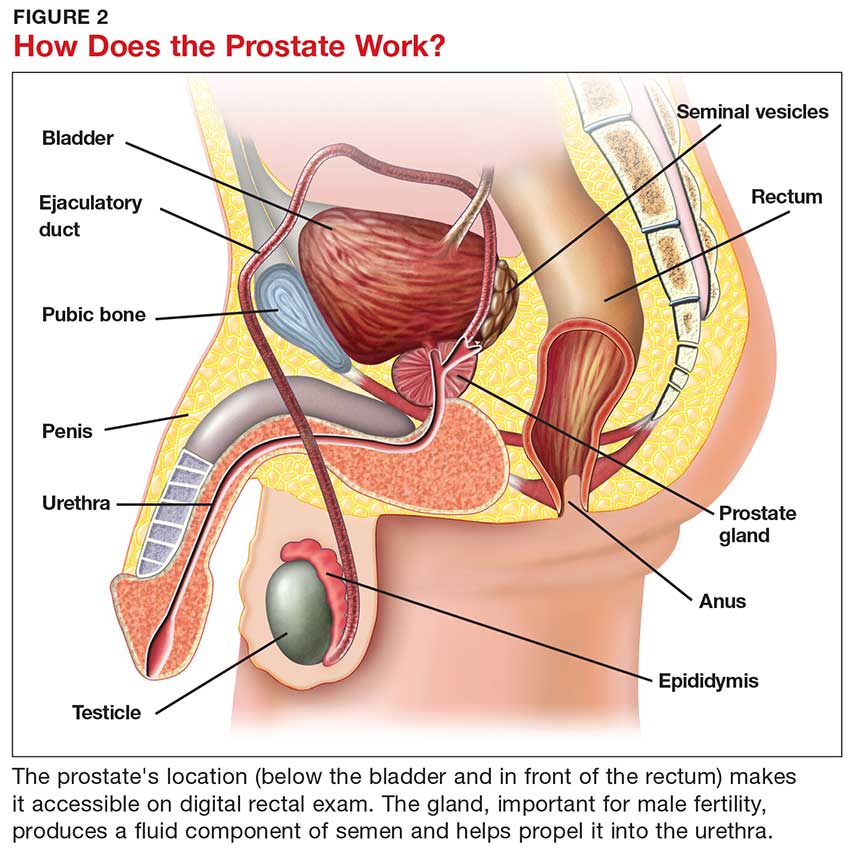

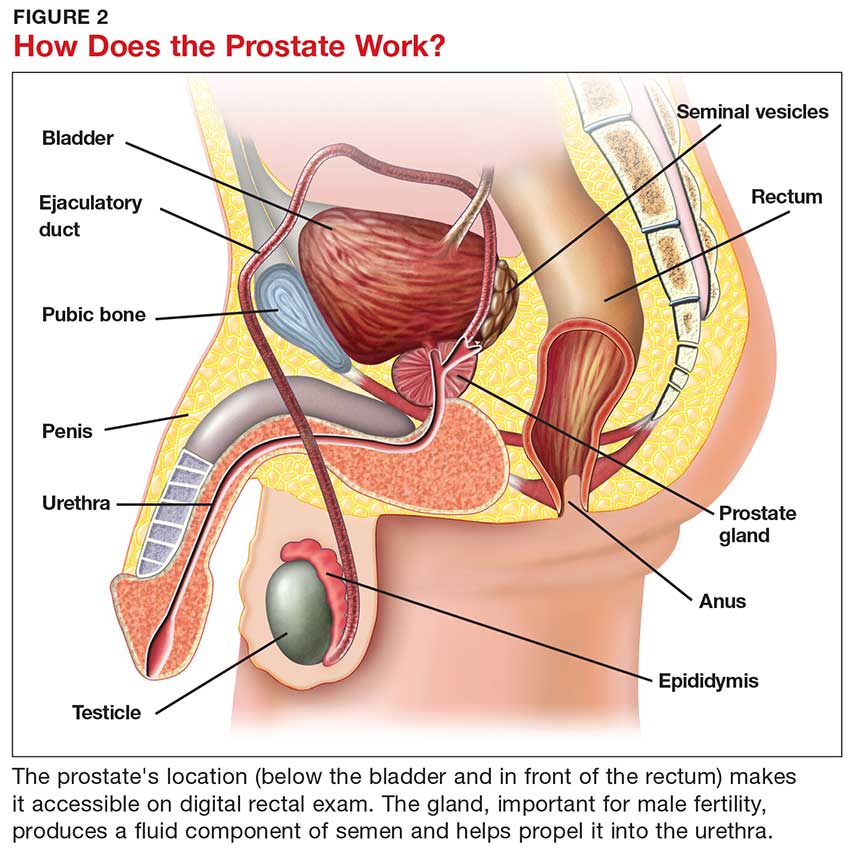

Although most men know where the prostate gland is located, many do not understand how it functions.4 The largest accessory gland of the male reproductive system, the prostate is located below the bladder and in front of the rectum (see Figure 2).5 The urethra passes through this gland; therefore, enlargement of the prostate can cause constriction of the urethra, which can affect the ability to eliminate urine from the body.5

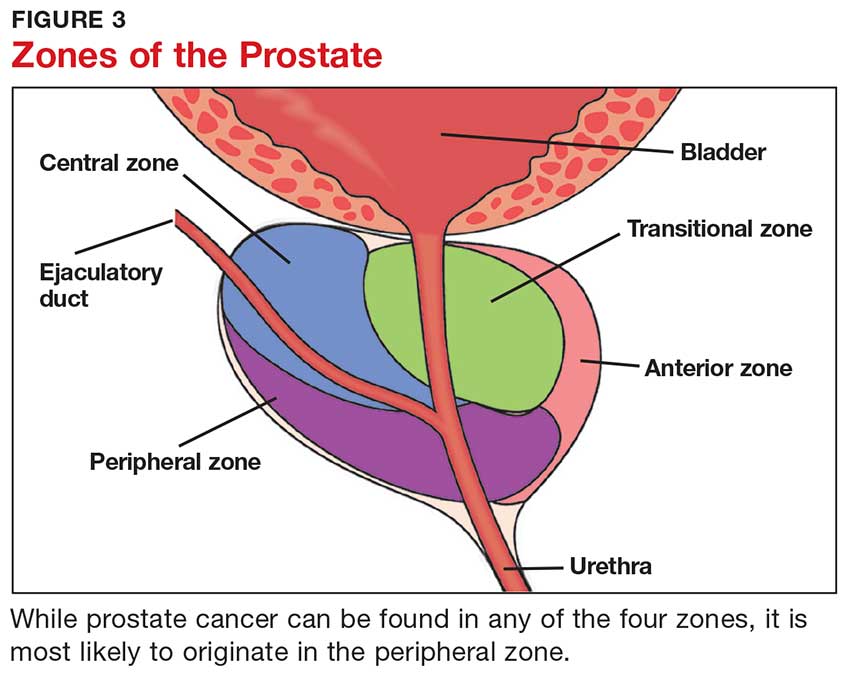

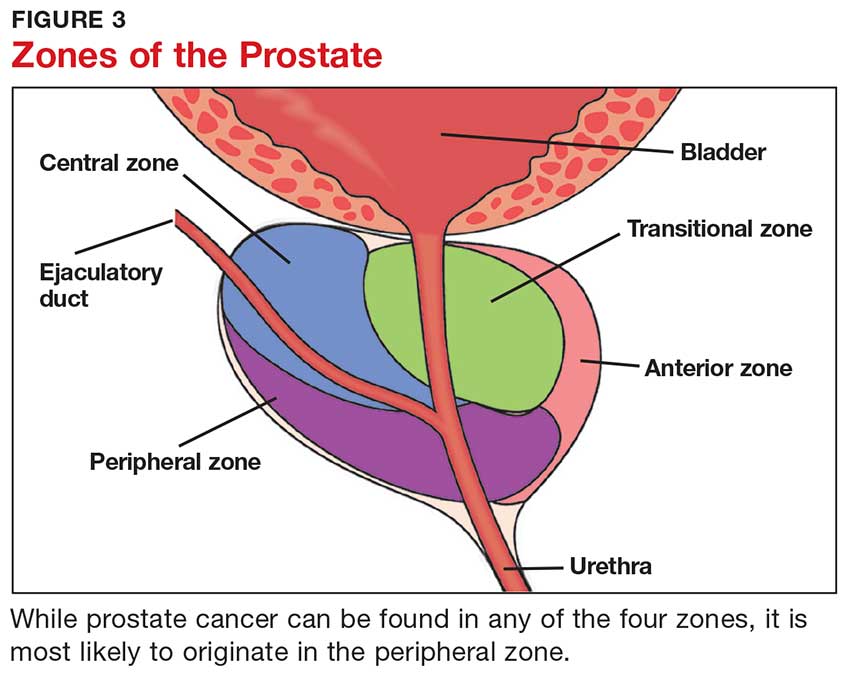

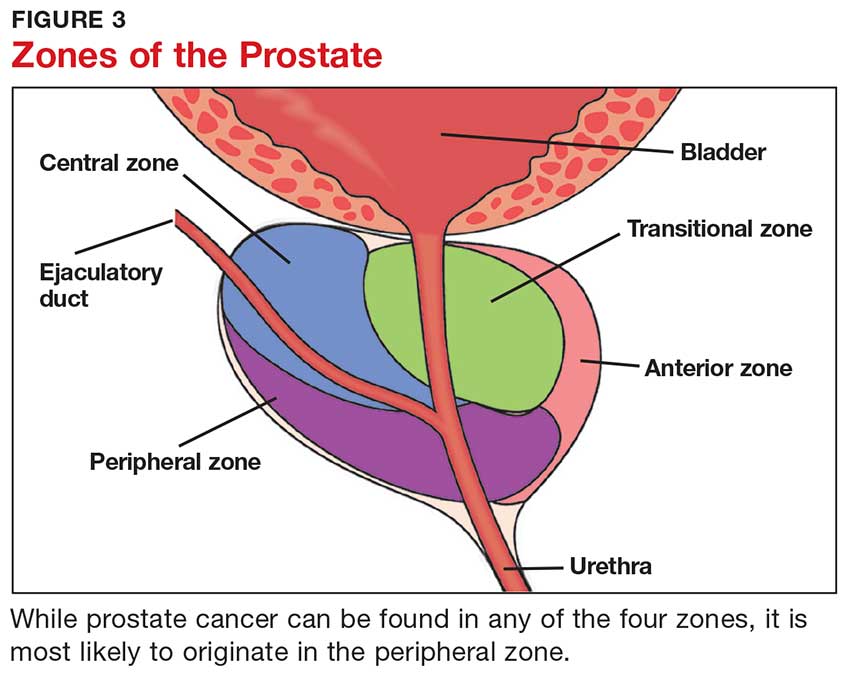

The prostate is broken down into four distinct regions (see Figure 3). Certain types of inflammation may occur more often in some regions of the prostate than others; as such, 75% of prostate cancer occurs in the peripheral zone (the region located closest to the rectal wall).5,6

DIAGNOSING PROSTATE CANCER

Signs and symptoms

According to the CDC, the signs and symptoms of prostate cancer include

- Difficulty starting urination

- Weak or interrupted flow of urine

- Frequent urination (especially at night)

- Difficulty emptying the bladder

- Pain or burning during urination

- Blood in the urine or semen

- Pain in the back, hips, or pelvis

- Painful ejaculation.

However, none of these signs and symptoms are unique to prostate cancer.7 For instance, difficulty starting urination, weak or interrupted flow of urine, and frequent urination can also be attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Further, in its early stages, prostate cancer may not exhibit any signs or symptoms, making accurate screening essential for detection and treatment.7

Screening tools

There are two primary tools for detection of prostate cancer: the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test and the digital rectal exam (DRE).8 The blood test for PSA is routinely used as a screening tool and is therefore considered a standard test for prostate cancer.9 A PSA level above 4.0 ng/mL is considered abnormal.10 Although measuring the PSA level can improve the odds of early prostate cancer detection, there is considerable debate over its dependability in this regard, as PSA can be elevated for benign reasons.

Sociocultural and genetic risk factors

While both black and white men are at an increased risk for prostate cancer if a first-degree relative (ie, father, brother, son) had the disease, one in five black men will develop prostate cancer in their lifetimes, compared with one in seven white men.3 And despite a five-year survival rate of nearly 100% for regional prostate cancer, black men are more than two times as likely as white men to die of the disease (1 in 23 and 1 in 38, respectively).8,11 From 2011 to 2015, the age-adjusted mortality rate of prostate cancer among black men was 40.8, versus 18.2 for non-Hispanic white men (per 100,000 population).12

Continue to: The disparity in prostate cancer mortality...

The disparity in prostate cancer mortality among black men has been attributed to multiple variables. Cultural differences can play a role in whether patients choose to undergo prostate cancer screening. Black men are, for example, less likely than other men to participate in preventive health care practices.13 Although an in-depth discussion is outside the scope of this article, researchers have identified some plausible factors for this, including economic limitations, lack of access to health care, distrust of the health care system, and an indifference to pain or discomfort.13,14 Decisions surrounding prostate screening can also be affected by a patient’s perceived risk for prostate cancer, the impact of a cancer diagnosis, and the availability of treatment.

Other factors that contribute to the higher incidence and mortality rate among black men include genetic predisposition, health beliefs, and knowledge about the prostate and cancer screenings.15 While most researchers have focused on men ages 40 and older, Ogunsanya et al suggested that educating black men about screening for prostate cancer at an earlier age may help them to make informed decisions later in life.15

PRACTICE POINTS

- Prostate cancer remains a major concern among black men due to disproportionate incidence and mortality.

- Developing prostate cancer screening recommendations for black men would help reduce mortality and morbidity in this population.

- Educating black men about screening for prostate cancer at an earlier age may help them to make informed decisions later in life.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

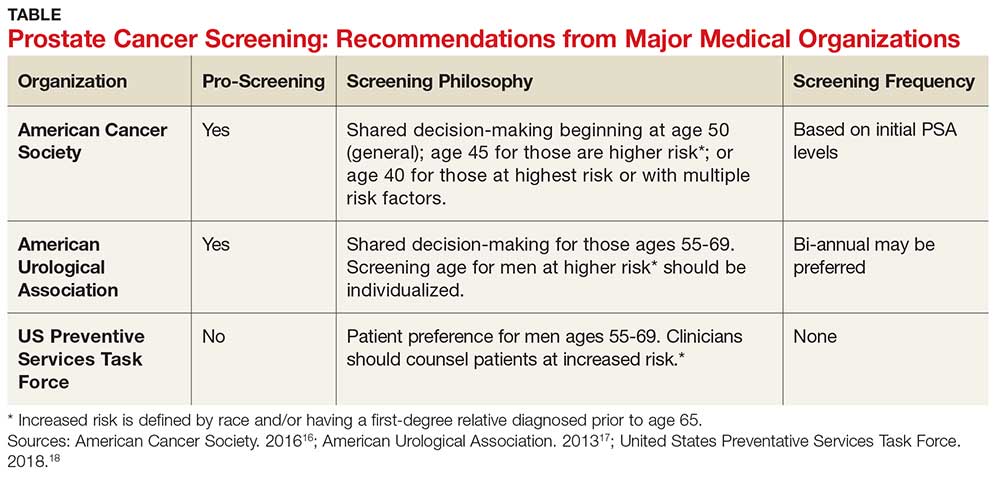

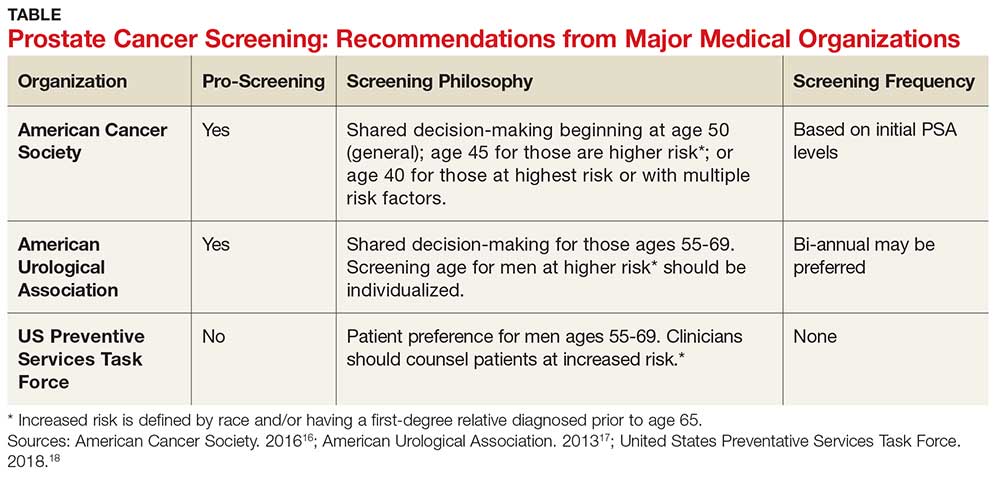

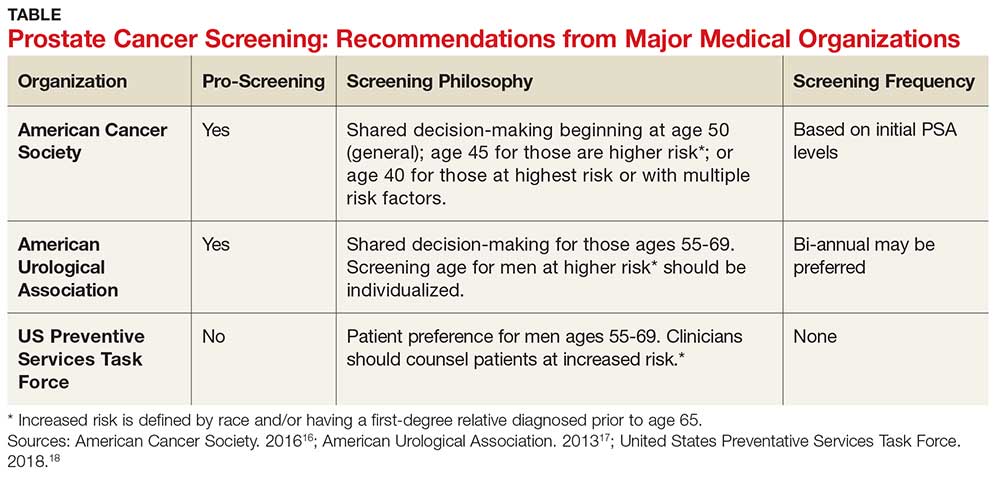

The age at which men should begin screening for prostate cancer has been a source of controversy due to the lack of consensus between the American Cancer Society, the American Urological Association, and the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines (see Table).16-18 The current USPSTF recommendations for prostate cancer screening do not take into account ethnic differences, despite the identified racial disparity.19 Ambiguity in public health policy creates a quandary in the decision-making process regarding testing and treatment.9,19,20

In addition, these guidelines recommend the use of both the DRE and PSA screening tests. Screening should be performed every two years for men who have a PSA level < 2.5 ng/mL, and every year for men who have a level > 2.5 ng/mL.

Continue to: TREATMENT

TREATMENT

Fortunately, there are several treatment options for men who are diagnosed with prostate cancer.22 These include watchful waiting, surgery, radiation, cryotherapy, hormone therapy, and chemotherapy. The type of treatment chosen depends on many factors, such as the tumor grade or cancer stage, the implications for quality of life, and the shared provider/patient decision-making process. Indeed, choosing the right treatment is a specialized approach that varies according to case and circumstance.22

CONCLUSION

There has been an increase in prostate cancer screening in recent years. However, black men still lag behind when it comes to having DRE and PSA tests. Many factors, including cultural perceptions of medical care among black men, often cause delays in seeking evaluation and treatment. Developing consistent and uniform prostate cancer screening recommendations for black men would be an important step in reducing mortality and morbidity in this population.

1. Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Xu J, Heron M. Deaths: final data for 2012. Nat Vital Stat Rep. 2015;63(9):37-80.

2. Nevada Division of Public and Behavioral Health. Comprehensive report: prostate cancer. September 2015. http://dpbh.nv.gov/Programs/Office_of_Public_Healh_Informatics_and_Epidemiology_(OPHIE)/. Accessed September 19, 2018.

3. Odedina FT, Dagne G, Pressey S, et al. Prostate cancer health and cultural beliefs of black men: the Florida prostate cancer disparity project. Infect Agent Cancer. 2011;6(2):1-7.

4. Winterich JA, Grzywacz JG, Quandt SA, et al. Men’s knowledge and beliefs about prostate cancer: education, race, and screening status. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(2):199-203.

5. Bhavsar A, Verma S. Anatomic imaging of the prostate. Biomed Res Int. 2014,1-9.

6. National Institutes of Health. Zones of the prostate. www.training.seer.cancer.gov/prostate/anatomy/zones.html. Accessed September 7, 2018.

7. CDC. Prostate cancer statistics. June 12, 2017. www.cdc.gov/cancer/prostate/statistics/. Accessed September 7, 2018.

8. American Cancer Society. Prostate cancer risk factors. www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/what-causes.html.

9. Mkanta W, Ndjakani Y, Bandiera F, et al. Prostate cancer screening and mortality in blacks and whites: a hospital-based case-control study. J Nat Med Assoc. 2015;107(2):32-38.

10. Hoffman R. Screening for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(21):2013-2019.

11. CDC. Who is at risk for prostate cancer? June 7, 2018. www.cdc.gov/cancer/prostate/basic_info/risk_factors.htm. Accessed September 7, 2018.

12. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2017. www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf. Accessed September 7, 2018.

13. Woods VD, Montgomery SB, Belliard JC, et al. Culture, black men, and prostate cancer: what is reality? Cancer Control. 2004;11(6):388-396.

14. Braithwaite RL. Health Issues in the Black Community. 2nd ed. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2001.

15. Ogunsanya ME, Brown CM, Odedina FT, et al. Beliefs regarding prostate cancer screening among black males aged 18 to 40 years. Am J Mens Health. 2017;11(1):41-53.

16. American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society Recommendations for Prostate Cancer Early Detection. April 14, 2016. www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/early-detection/acs-recommendations.html. Accessed September 7, 2018.

17. American Urological Association. Early detection of prostate cancer. 2013. www.auanet.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer-early-detection-(2013-reviewed-for-currency-2018). Accessed September 7, 2018.

18. United States Preventative Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement. Prostate cancer: screening. 2018. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prostate-cancer-screening1. Accessed September 7, 2018.

19. Shenoy D, Packianathan S, Chen AM, Vijayakumar S. Do African-American men need separate prostate cancer screening guidelines? BMC Urol. 2016;16(19):1-6.

20. Odedina FT, Campbell E, LaRose-Pierre M, et al. Personal factors affecting African-American men’s prostate cancer screening behavior. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(6):724-733.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Prostate cancer screening tools

- Ethic disparities

- Screening guidance

Prostate cancer, the second most common cancer to affect American men, is a slow-growing cancer that is curable when detected early. While the overall incidence has declined in the past 20 years (see Figure 1), prostate cancer remains a major concern among black men due to disproportionate incidence and mortality rates.1-3 A general understanding of the prostate and of prostate cancer lays the groundwork to acknowledge and address this divide.

Although most men know where the prostate gland is located, many do not understand how it functions.4 The largest accessory gland of the male reproductive system, the prostate is located below the bladder and in front of the rectum (see Figure 2).5 The urethra passes through this gland; therefore, enlargement of the prostate can cause constriction of the urethra, which can affect the ability to eliminate urine from the body.5

The prostate is broken down into four distinct regions (see Figure 3). Certain types of inflammation may occur more often in some regions of the prostate than others; as such, 75% of prostate cancer occurs in the peripheral zone (the region located closest to the rectal wall).5,6

DIAGNOSING PROSTATE CANCER

Signs and symptoms

According to the CDC, the signs and symptoms of prostate cancer include

- Difficulty starting urination

- Weak or interrupted flow of urine

- Frequent urination (especially at night)

- Difficulty emptying the bladder

- Pain or burning during urination

- Blood in the urine or semen

- Pain in the back, hips, or pelvis

- Painful ejaculation.

However, none of these signs and symptoms are unique to prostate cancer.7 For instance, difficulty starting urination, weak or interrupted flow of urine, and frequent urination can also be attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Further, in its early stages, prostate cancer may not exhibit any signs or symptoms, making accurate screening essential for detection and treatment.7

Screening tools

There are two primary tools for detection of prostate cancer: the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test and the digital rectal exam (DRE).8 The blood test for PSA is routinely used as a screening tool and is therefore considered a standard test for prostate cancer.9 A PSA level above 4.0 ng/mL is considered abnormal.10 Although measuring the PSA level can improve the odds of early prostate cancer detection, there is considerable debate over its dependability in this regard, as PSA can be elevated for benign reasons.

Sociocultural and genetic risk factors

While both black and white men are at an increased risk for prostate cancer if a first-degree relative (ie, father, brother, son) had the disease, one in five black men will develop prostate cancer in their lifetimes, compared with one in seven white men.3 And despite a five-year survival rate of nearly 100% for regional prostate cancer, black men are more than two times as likely as white men to die of the disease (1 in 23 and 1 in 38, respectively).8,11 From 2011 to 2015, the age-adjusted mortality rate of prostate cancer among black men was 40.8, versus 18.2 for non-Hispanic white men (per 100,000 population).12

Continue to: The disparity in prostate cancer mortality...

The disparity in prostate cancer mortality among black men has been attributed to multiple variables. Cultural differences can play a role in whether patients choose to undergo prostate cancer screening. Black men are, for example, less likely than other men to participate in preventive health care practices.13 Although an in-depth discussion is outside the scope of this article, researchers have identified some plausible factors for this, including economic limitations, lack of access to health care, distrust of the health care system, and an indifference to pain or discomfort.13,14 Decisions surrounding prostate screening can also be affected by a patient’s perceived risk for prostate cancer, the impact of a cancer diagnosis, and the availability of treatment.

Other factors that contribute to the higher incidence and mortality rate among black men include genetic predisposition, health beliefs, and knowledge about the prostate and cancer screenings.15 While most researchers have focused on men ages 40 and older, Ogunsanya et al suggested that educating black men about screening for prostate cancer at an earlier age may help them to make informed decisions later in life.15

PRACTICE POINTS

- Prostate cancer remains a major concern among black men due to disproportionate incidence and mortality.

- Developing prostate cancer screening recommendations for black men would help reduce mortality and morbidity in this population.

- Educating black men about screening for prostate cancer at an earlier age may help them to make informed decisions later in life.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

The age at which men should begin screening for prostate cancer has been a source of controversy due to the lack of consensus between the American Cancer Society, the American Urological Association, and the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines (see Table).16-18 The current USPSTF recommendations for prostate cancer screening do not take into account ethnic differences, despite the identified racial disparity.19 Ambiguity in public health policy creates a quandary in the decision-making process regarding testing and treatment.9,19,20

In addition, these guidelines recommend the use of both the DRE and PSA screening tests. Screening should be performed every two years for men who have a PSA level < 2.5 ng/mL, and every year for men who have a level > 2.5 ng/mL.

Continue to: TREATMENT

TREATMENT

Fortunately, there are several treatment options for men who are diagnosed with prostate cancer.22 These include watchful waiting, surgery, radiation, cryotherapy, hormone therapy, and chemotherapy. The type of treatment chosen depends on many factors, such as the tumor grade or cancer stage, the implications for quality of life, and the shared provider/patient decision-making process. Indeed, choosing the right treatment is a specialized approach that varies according to case and circumstance.22

CONCLUSION

There has been an increase in prostate cancer screening in recent years. However, black men still lag behind when it comes to having DRE and PSA tests. Many factors, including cultural perceptions of medical care among black men, often cause delays in seeking evaluation and treatment. Developing consistent and uniform prostate cancer screening recommendations for black men would be an important step in reducing mortality and morbidity in this population.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Prostate cancer screening tools

- Ethic disparities

- Screening guidance

Prostate cancer, the second most common cancer to affect American men, is a slow-growing cancer that is curable when detected early. While the overall incidence has declined in the past 20 years (see Figure 1), prostate cancer remains a major concern among black men due to disproportionate incidence and mortality rates.1-3 A general understanding of the prostate and of prostate cancer lays the groundwork to acknowledge and address this divide.

Although most men know where the prostate gland is located, many do not understand how it functions.4 The largest accessory gland of the male reproductive system, the prostate is located below the bladder and in front of the rectum (see Figure 2).5 The urethra passes through this gland; therefore, enlargement of the prostate can cause constriction of the urethra, which can affect the ability to eliminate urine from the body.5

The prostate is broken down into four distinct regions (see Figure 3). Certain types of inflammation may occur more often in some regions of the prostate than others; as such, 75% of prostate cancer occurs in the peripheral zone (the region located closest to the rectal wall).5,6

DIAGNOSING PROSTATE CANCER

Signs and symptoms

According to the CDC, the signs and symptoms of prostate cancer include

- Difficulty starting urination

- Weak or interrupted flow of urine

- Frequent urination (especially at night)

- Difficulty emptying the bladder

- Pain or burning during urination

- Blood in the urine or semen

- Pain in the back, hips, or pelvis

- Painful ejaculation.

However, none of these signs and symptoms are unique to prostate cancer.7 For instance, difficulty starting urination, weak or interrupted flow of urine, and frequent urination can also be attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Further, in its early stages, prostate cancer may not exhibit any signs or symptoms, making accurate screening essential for detection and treatment.7

Screening tools

There are two primary tools for detection of prostate cancer: the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test and the digital rectal exam (DRE).8 The blood test for PSA is routinely used as a screening tool and is therefore considered a standard test for prostate cancer.9 A PSA level above 4.0 ng/mL is considered abnormal.10 Although measuring the PSA level can improve the odds of early prostate cancer detection, there is considerable debate over its dependability in this regard, as PSA can be elevated for benign reasons.

Sociocultural and genetic risk factors

While both black and white men are at an increased risk for prostate cancer if a first-degree relative (ie, father, brother, son) had the disease, one in five black men will develop prostate cancer in their lifetimes, compared with one in seven white men.3 And despite a five-year survival rate of nearly 100% for regional prostate cancer, black men are more than two times as likely as white men to die of the disease (1 in 23 and 1 in 38, respectively).8,11 From 2011 to 2015, the age-adjusted mortality rate of prostate cancer among black men was 40.8, versus 18.2 for non-Hispanic white men (per 100,000 population).12

Continue to: The disparity in prostate cancer mortality...

The disparity in prostate cancer mortality among black men has been attributed to multiple variables. Cultural differences can play a role in whether patients choose to undergo prostate cancer screening. Black men are, for example, less likely than other men to participate in preventive health care practices.13 Although an in-depth discussion is outside the scope of this article, researchers have identified some plausible factors for this, including economic limitations, lack of access to health care, distrust of the health care system, and an indifference to pain or discomfort.13,14 Decisions surrounding prostate screening can also be affected by a patient’s perceived risk for prostate cancer, the impact of a cancer diagnosis, and the availability of treatment.

Other factors that contribute to the higher incidence and mortality rate among black men include genetic predisposition, health beliefs, and knowledge about the prostate and cancer screenings.15 While most researchers have focused on men ages 40 and older, Ogunsanya et al suggested that educating black men about screening for prostate cancer at an earlier age may help them to make informed decisions later in life.15

PRACTICE POINTS

- Prostate cancer remains a major concern among black men due to disproportionate incidence and mortality.

- Developing prostate cancer screening recommendations for black men would help reduce mortality and morbidity in this population.

- Educating black men about screening for prostate cancer at an earlier age may help them to make informed decisions later in life.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

The age at which men should begin screening for prostate cancer has been a source of controversy due to the lack of consensus between the American Cancer Society, the American Urological Association, and the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines (see Table).16-18 The current USPSTF recommendations for prostate cancer screening do not take into account ethnic differences, despite the identified racial disparity.19 Ambiguity in public health policy creates a quandary in the decision-making process regarding testing and treatment.9,19,20

In addition, these guidelines recommend the use of both the DRE and PSA screening tests. Screening should be performed every two years for men who have a PSA level < 2.5 ng/mL, and every year for men who have a level > 2.5 ng/mL.

Continue to: TREATMENT

TREATMENT

Fortunately, there are several treatment options for men who are diagnosed with prostate cancer.22 These include watchful waiting, surgery, radiation, cryotherapy, hormone therapy, and chemotherapy. The type of treatment chosen depends on many factors, such as the tumor grade or cancer stage, the implications for quality of life, and the shared provider/patient decision-making process. Indeed, choosing the right treatment is a specialized approach that varies according to case and circumstance.22

CONCLUSION

There has been an increase in prostate cancer screening in recent years. However, black men still lag behind when it comes to having DRE and PSA tests. Many factors, including cultural perceptions of medical care among black men, often cause delays in seeking evaluation and treatment. Developing consistent and uniform prostate cancer screening recommendations for black men would be an important step in reducing mortality and morbidity in this population.

1. Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Xu J, Heron M. Deaths: final data for 2012. Nat Vital Stat Rep. 2015;63(9):37-80.

2. Nevada Division of Public and Behavioral Health. Comprehensive report: prostate cancer. September 2015. http://dpbh.nv.gov/Programs/Office_of_Public_Healh_Informatics_and_Epidemiology_(OPHIE)/. Accessed September 19, 2018.

3. Odedina FT, Dagne G, Pressey S, et al. Prostate cancer health and cultural beliefs of black men: the Florida prostate cancer disparity project. Infect Agent Cancer. 2011;6(2):1-7.

4. Winterich JA, Grzywacz JG, Quandt SA, et al. Men’s knowledge and beliefs about prostate cancer: education, race, and screening status. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(2):199-203.

5. Bhavsar A, Verma S. Anatomic imaging of the prostate. Biomed Res Int. 2014,1-9.

6. National Institutes of Health. Zones of the prostate. www.training.seer.cancer.gov/prostate/anatomy/zones.html. Accessed September 7, 2018.

7. CDC. Prostate cancer statistics. June 12, 2017. www.cdc.gov/cancer/prostate/statistics/. Accessed September 7, 2018.

8. American Cancer Society. Prostate cancer risk factors. www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/what-causes.html.

9. Mkanta W, Ndjakani Y, Bandiera F, et al. Prostate cancer screening and mortality in blacks and whites: a hospital-based case-control study. J Nat Med Assoc. 2015;107(2):32-38.

10. Hoffman R. Screening for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(21):2013-2019.

11. CDC. Who is at risk for prostate cancer? June 7, 2018. www.cdc.gov/cancer/prostate/basic_info/risk_factors.htm. Accessed September 7, 2018.

12. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2017. www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf. Accessed September 7, 2018.

13. Woods VD, Montgomery SB, Belliard JC, et al. Culture, black men, and prostate cancer: what is reality? Cancer Control. 2004;11(6):388-396.

14. Braithwaite RL. Health Issues in the Black Community. 2nd ed. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2001.

15. Ogunsanya ME, Brown CM, Odedina FT, et al. Beliefs regarding prostate cancer screening among black males aged 18 to 40 years. Am J Mens Health. 2017;11(1):41-53.

16. American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society Recommendations for Prostate Cancer Early Detection. April 14, 2016. www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/early-detection/acs-recommendations.html. Accessed September 7, 2018.

17. American Urological Association. Early detection of prostate cancer. 2013. www.auanet.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer-early-detection-(2013-reviewed-for-currency-2018). Accessed September 7, 2018.

18. United States Preventative Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement. Prostate cancer: screening. 2018. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prostate-cancer-screening1. Accessed September 7, 2018.

19. Shenoy D, Packianathan S, Chen AM, Vijayakumar S. Do African-American men need separate prostate cancer screening guidelines? BMC Urol. 2016;16(19):1-6.

20. Odedina FT, Campbell E, LaRose-Pierre M, et al. Personal factors affecting African-American men’s prostate cancer screening behavior. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(6):724-733.

1. Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Xu J, Heron M. Deaths: final data for 2012. Nat Vital Stat Rep. 2015;63(9):37-80.

2. Nevada Division of Public and Behavioral Health. Comprehensive report: prostate cancer. September 2015. http://dpbh.nv.gov/Programs/Office_of_Public_Healh_Informatics_and_Epidemiology_(OPHIE)/. Accessed September 19, 2018.

3. Odedina FT, Dagne G, Pressey S, et al. Prostate cancer health and cultural beliefs of black men: the Florida prostate cancer disparity project. Infect Agent Cancer. 2011;6(2):1-7.

4. Winterich JA, Grzywacz JG, Quandt SA, et al. Men’s knowledge and beliefs about prostate cancer: education, race, and screening status. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(2):199-203.

5. Bhavsar A, Verma S. Anatomic imaging of the prostate. Biomed Res Int. 2014,1-9.

6. National Institutes of Health. Zones of the prostate. www.training.seer.cancer.gov/prostate/anatomy/zones.html. Accessed September 7, 2018.

7. CDC. Prostate cancer statistics. June 12, 2017. www.cdc.gov/cancer/prostate/statistics/. Accessed September 7, 2018.

8. American Cancer Society. Prostate cancer risk factors. www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/what-causes.html.

9. Mkanta W, Ndjakani Y, Bandiera F, et al. Prostate cancer screening and mortality in blacks and whites: a hospital-based case-control study. J Nat Med Assoc. 2015;107(2):32-38.

10. Hoffman R. Screening for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(21):2013-2019.

11. CDC. Who is at risk for prostate cancer? June 7, 2018. www.cdc.gov/cancer/prostate/basic_info/risk_factors.htm. Accessed September 7, 2018.

12. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2017. www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf. Accessed September 7, 2018.

13. Woods VD, Montgomery SB, Belliard JC, et al. Culture, black men, and prostate cancer: what is reality? Cancer Control. 2004;11(6):388-396.

14. Braithwaite RL. Health Issues in the Black Community. 2nd ed. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 2001.

15. Ogunsanya ME, Brown CM, Odedina FT, et al. Beliefs regarding prostate cancer screening among black males aged 18 to 40 years. Am J Mens Health. 2017;11(1):41-53.

16. American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society Recommendations for Prostate Cancer Early Detection. April 14, 2016. www.cancer.org/cancer/prostate-cancer/early-detection/acs-recommendations.html. Accessed September 7, 2018.

17. American Urological Association. Early detection of prostate cancer. 2013. www.auanet.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer-early-detection-(2013-reviewed-for-currency-2018). Accessed September 7, 2018.

18. United States Preventative Services Task Force. Final recommendation statement. Prostate cancer: screening. 2018. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/prostate-cancer-screening1. Accessed September 7, 2018.

19. Shenoy D, Packianathan S, Chen AM, Vijayakumar S. Do African-American men need separate prostate cancer screening guidelines? BMC Urol. 2016;16(19):1-6.

20. Odedina FT, Campbell E, LaRose-Pierre M, et al. Personal factors affecting African-American men’s prostate cancer screening behavior. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(6):724-733.

Corporal punishment bans may reduce youth violence

with males in those countries about 30% less likely to engage in fighting and females almost 60% less likely to do so, according to a study of school-based health surveys completed by 403,604 adolescents in 88 different countries published in BMJ Open.

“These findings add to a growing body of evidence on links between corporal punishment and adolescent health and safety. A growing number of countries have banned corporal punishment as an acceptable means of child discipline, and this is an important step that should be encouraged,” said Frank J. Elgar, PhD, of McGill University in Montreal and his colleagues. “Health providers are well positioned to offer practical and effective tools that support such approaches to child discipline. Cultural shifts from punitive to positive discipline happen slowly.”

The researchers placed countries into three categories: those that have banned corporate punishment in the home and at school; those that have banned it in school only (which include the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom); and those that have not banned corporal punishment in either setting.

Frequent fighting rates varied widely, Dr. Elgar and his colleagues noted, ranging from a low of less than 1% among females in Costa Rica, which bans all forms of corporal punishment, to a high of 35% among males in Samoa, which allows corporal punishment in both settings.

The 30 countries with full bans had rates of fighting 31% lower in males and 58% lower in females than the 20 countries with no ban. Thirty-eight countries with bans in schools but not in the home reported less fighting in females only – 44% lower than countries without bans.

The reasons for the gender difference in fighting rates among countries with partial bans is unclear, the authors said. “It could be that males, compared with females, experience more physical violence outside school settings or are affected differently by corporal punishment by teachers,” Dr. Elgar and his coauthors said. “Further investigation is needed.”

The study analyzed findings of two well-established surveys used internationally to measure fighting among adolescents: the World Health Organization Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) study and the Global School-based Health Survey (GSHS). The former is conducted among children ages 11, 13, and 15 in Canada, the United States, and most European countries every 4 years. The GSHS measures fighting among children aged 13-17 years in 55 low- and middle-income countries.

Among the limitations the study authors acknowledged was the inability to account for when the surveys were completed and when the bans were implemented, enforced, or modified, but they also pointed out the large and diverse sample of countries as a strength of the study.

Dr. Elgar and coauthors reported having no financial relationships. The work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, and the Canada Research Chairs programme.

SOURCE: Elgar FJ et al. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021616.

with males in those countries about 30% less likely to engage in fighting and females almost 60% less likely to do so, according to a study of school-based health surveys completed by 403,604 adolescents in 88 different countries published in BMJ Open.

“These findings add to a growing body of evidence on links between corporal punishment and adolescent health and safety. A growing number of countries have banned corporal punishment as an acceptable means of child discipline, and this is an important step that should be encouraged,” said Frank J. Elgar, PhD, of McGill University in Montreal and his colleagues. “Health providers are well positioned to offer practical and effective tools that support such approaches to child discipline. Cultural shifts from punitive to positive discipline happen slowly.”

The researchers placed countries into three categories: those that have banned corporate punishment in the home and at school; those that have banned it in school only (which include the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom); and those that have not banned corporal punishment in either setting.

Frequent fighting rates varied widely, Dr. Elgar and his colleagues noted, ranging from a low of less than 1% among females in Costa Rica, which bans all forms of corporal punishment, to a high of 35% among males in Samoa, which allows corporal punishment in both settings.

The 30 countries with full bans had rates of fighting 31% lower in males and 58% lower in females than the 20 countries with no ban. Thirty-eight countries with bans in schools but not in the home reported less fighting in females only – 44% lower than countries without bans.

The reasons for the gender difference in fighting rates among countries with partial bans is unclear, the authors said. “It could be that males, compared with females, experience more physical violence outside school settings or are affected differently by corporal punishment by teachers,” Dr. Elgar and his coauthors said. “Further investigation is needed.”

The study analyzed findings of two well-established surveys used internationally to measure fighting among adolescents: the World Health Organization Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) study and the Global School-based Health Survey (GSHS). The former is conducted among children ages 11, 13, and 15 in Canada, the United States, and most European countries every 4 years. The GSHS measures fighting among children aged 13-17 years in 55 low- and middle-income countries.

Among the limitations the study authors acknowledged was the inability to account for when the surveys were completed and when the bans were implemented, enforced, or modified, but they also pointed out the large and diverse sample of countries as a strength of the study.

Dr. Elgar and coauthors reported having no financial relationships. The work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, and the Canada Research Chairs programme.

SOURCE: Elgar FJ et al. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021616.

with males in those countries about 30% less likely to engage in fighting and females almost 60% less likely to do so, according to a study of school-based health surveys completed by 403,604 adolescents in 88 different countries published in BMJ Open.

“These findings add to a growing body of evidence on links between corporal punishment and adolescent health and safety. A growing number of countries have banned corporal punishment as an acceptable means of child discipline, and this is an important step that should be encouraged,” said Frank J. Elgar, PhD, of McGill University in Montreal and his colleagues. “Health providers are well positioned to offer practical and effective tools that support such approaches to child discipline. Cultural shifts from punitive to positive discipline happen slowly.”

The researchers placed countries into three categories: those that have banned corporate punishment in the home and at school; those that have banned it in school only (which include the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom); and those that have not banned corporal punishment in either setting.

Frequent fighting rates varied widely, Dr. Elgar and his colleagues noted, ranging from a low of less than 1% among females in Costa Rica, which bans all forms of corporal punishment, to a high of 35% among males in Samoa, which allows corporal punishment in both settings.

The 30 countries with full bans had rates of fighting 31% lower in males and 58% lower in females than the 20 countries with no ban. Thirty-eight countries with bans in schools but not in the home reported less fighting in females only – 44% lower than countries without bans.

The reasons for the gender difference in fighting rates among countries with partial bans is unclear, the authors said. “It could be that males, compared with females, experience more physical violence outside school settings or are affected differently by corporal punishment by teachers,” Dr. Elgar and his coauthors said. “Further investigation is needed.”

The study analyzed findings of two well-established surveys used internationally to measure fighting among adolescents: the World Health Organization Health Behavior in School-aged Children (HBSC) study and the Global School-based Health Survey (GSHS). The former is conducted among children ages 11, 13, and 15 in Canada, the United States, and most European countries every 4 years. The GSHS measures fighting among children aged 13-17 years in 55 low- and middle-income countries.

Among the limitations the study authors acknowledged was the inability to account for when the surveys were completed and when the bans were implemented, enforced, or modified, but they also pointed out the large and diverse sample of countries as a strength of the study.

Dr. Elgar and coauthors reported having no financial relationships. The work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, and the Canada Research Chairs programme.

SOURCE: Elgar FJ et al. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021616.

FROM BMJ OPEN

Key clinical point: Nations that ban corporal punishment of children have lower rates of youth violence.

Major finding: Countries with total bans on corporal punishment reported rates of fighting in males 31% lower than countries with no bans.

Study details: An ecological study evaluating school-based health surveys of 403,604 adolescents from 88 low- to high-income countries.

Disclosures: Dr. Elgar and coauthors reported having no financial relationships. The work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, and the Canada Research Chairs programme.

Source: Elgar FJ et al. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021616.

Older adults who self-harm face increased suicide risk

Adults aged 65 years and older with a self-harm history are more likely to die from unnatural causes – specifically suicide – than are those who do not self-harm, according to what researchers called the first study of self-harm that exclusively focused on older adults from the perspective of primary care.

“This work should alert policy makers and primary health care professionals to progress towards implementing preventive measures among older adults who consult with a GP,” lead author Catharine Morgan, PhD, and her coauthors, wrote in the Lancet Psychiatry.

The study, which reviewed the primary care records of 4,124 older adults in the United Kingdom with incidents of self-harm, found that , said Dr. Morgan, of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Greater Manchester (England) Patient Safety Translational Research Centre at the University of Manchester, and her coauthors. They also noted that, “compared with their peers who had not harmed themselves, adults in the self-harm cohort were an estimated 20 times more likely to die unnaturally during the first year after a self-harm episode and three or four times more likely to die unnaturally in subsequent years.”

The coauthors also found that, compared with a comparison cohort, the prevalence of a previous mental illness was twice as high among older adults who had engaged in self-harm (hazard ratio, 2.10; 95% confidence interval, 2.03-2.17). Older adults with a self-harm history also had a 20% higher prevalence of a physical illness (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.17-1.23), compared with those without such a history.

Dr. Morgan and her coauthors also uncovered differing likelihoods of referral to specialists, depending on socioeconomic status of the surrounding area. Older patients in “more socially deprived localities” were less likely to be referred to mental health services. Women also were more likely than men were to be referred, highlighting “an important target for improvement across the health care system.” They also recommended avoiding tricyclics for older patients and encouraged maintaining “frequent medication reviews after self-harm.”

The coauthors noted potential limitations in their study, including reliance on clinicians who entered the primary care records and reluctance of coroners to report suicide as the cause of death in certain scenarios. However, they strongly encouraged general practitioners to intervene early and consider alternative medications when treating older patients who exhibit risk factors.

“Health care professionals should take the opportunity to consider the risk of self-harm when an older person consults with other health problems, especially when major physical illnesses and psychopathology are both present, to reduce the risk of an escalation in self-harming behaviour and associated mortality,” they wrote.

The NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre funded the study. Dr. Morgan and three of her coauthors declared no conflicts of interest. Two authors reported grants from the NIHR, and one author reported grants from the Department of Health and Social Care and the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership.

SOURCE: Morgan C et al. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Oct 15. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30348-1.

The study by Morgan et al. and her colleagues reinforced both the risks of self-harm among older adults and the absence of follow-up, but more research needs to be done, according to Rebecca Mitchell, PhD, an associate professor at the Australian Institute of Health Innovation at Macquarie University in Sydney.

Just 11.7% of older adults who self-harmed were referred to a mental health specialist, even though the authors found that the older adult cohort had twice the prevalence of a previous mental illness, compared with a matched comparison cohort. Though we may not always know the factors that contributed to these incidents of self-harm, “Morgan and colleagues have provided evidence that the clinical management of older adults who self-harm needs to improve,” Dr. Mitchell wrote.

Next steps could include “qualitative studies that focus on life experiences, social connectedness, resilience, and experience of health care use,” she wrote, painting a fuller picture of the intentions behind those self-harm choices.

“Further research still needs to be done on self-harm among older adults, including the replication of Morgan and colleagues’ research in other countries, to increase our understanding of how primary care could present an early window of opportunity to prevent repeated self-harm attempts and unnatural deaths,” Dr. Mitchell added.

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Oct 15. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366[18]30358-4). Dr. Mitchell declared no conflicts of interest.

The study by Morgan et al. and her colleagues reinforced both the risks of self-harm among older adults and the absence of follow-up, but more research needs to be done, according to Rebecca Mitchell, PhD, an associate professor at the Australian Institute of Health Innovation at Macquarie University in Sydney.

Just 11.7% of older adults who self-harmed were referred to a mental health specialist, even though the authors found that the older adult cohort had twice the prevalence of a previous mental illness, compared with a matched comparison cohort. Though we may not always know the factors that contributed to these incidents of self-harm, “Morgan and colleagues have provided evidence that the clinical management of older adults who self-harm needs to improve,” Dr. Mitchell wrote.

Next steps could include “qualitative studies that focus on life experiences, social connectedness, resilience, and experience of health care use,” she wrote, painting a fuller picture of the intentions behind those self-harm choices.

“Further research still needs to be done on self-harm among older adults, including the replication of Morgan and colleagues’ research in other countries, to increase our understanding of how primary care could present an early window of opportunity to prevent repeated self-harm attempts and unnatural deaths,” Dr. Mitchell added.

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Oct 15. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366[18]30358-4). Dr. Mitchell declared no conflicts of interest.

The study by Morgan et al. and her colleagues reinforced both the risks of self-harm among older adults and the absence of follow-up, but more research needs to be done, according to Rebecca Mitchell, PhD, an associate professor at the Australian Institute of Health Innovation at Macquarie University in Sydney.

Just 11.7% of older adults who self-harmed were referred to a mental health specialist, even though the authors found that the older adult cohort had twice the prevalence of a previous mental illness, compared with a matched comparison cohort. Though we may not always know the factors that contributed to these incidents of self-harm, “Morgan and colleagues have provided evidence that the clinical management of older adults who self-harm needs to improve,” Dr. Mitchell wrote.

Next steps could include “qualitative studies that focus on life experiences, social connectedness, resilience, and experience of health care use,” she wrote, painting a fuller picture of the intentions behind those self-harm choices.

“Further research still needs to be done on self-harm among older adults, including the replication of Morgan and colleagues’ research in other countries, to increase our understanding of how primary care could present an early window of opportunity to prevent repeated self-harm attempts and unnatural deaths,” Dr. Mitchell added.

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Oct 15. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366[18]30358-4). Dr. Mitchell declared no conflicts of interest.

Adults aged 65 years and older with a self-harm history are more likely to die from unnatural causes – specifically suicide – than are those who do not self-harm, according to what researchers called the first study of self-harm that exclusively focused on older adults from the perspective of primary care.

“This work should alert policy makers and primary health care professionals to progress towards implementing preventive measures among older adults who consult with a GP,” lead author Catharine Morgan, PhD, and her coauthors, wrote in the Lancet Psychiatry.

The study, which reviewed the primary care records of 4,124 older adults in the United Kingdom with incidents of self-harm, found that , said Dr. Morgan, of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Greater Manchester (England) Patient Safety Translational Research Centre at the University of Manchester, and her coauthors. They also noted that, “compared with their peers who had not harmed themselves, adults in the self-harm cohort were an estimated 20 times more likely to die unnaturally during the first year after a self-harm episode and three or four times more likely to die unnaturally in subsequent years.”

The coauthors also found that, compared with a comparison cohort, the prevalence of a previous mental illness was twice as high among older adults who had engaged in self-harm (hazard ratio, 2.10; 95% confidence interval, 2.03-2.17). Older adults with a self-harm history also had a 20% higher prevalence of a physical illness (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.17-1.23), compared with those without such a history.

Dr. Morgan and her coauthors also uncovered differing likelihoods of referral to specialists, depending on socioeconomic status of the surrounding area. Older patients in “more socially deprived localities” were less likely to be referred to mental health services. Women also were more likely than men were to be referred, highlighting “an important target for improvement across the health care system.” They also recommended avoiding tricyclics for older patients and encouraged maintaining “frequent medication reviews after self-harm.”

The coauthors noted potential limitations in their study, including reliance on clinicians who entered the primary care records and reluctance of coroners to report suicide as the cause of death in certain scenarios. However, they strongly encouraged general practitioners to intervene early and consider alternative medications when treating older patients who exhibit risk factors.

“Health care professionals should take the opportunity to consider the risk of self-harm when an older person consults with other health problems, especially when major physical illnesses and psychopathology are both present, to reduce the risk of an escalation in self-harming behaviour and associated mortality,” they wrote.

The NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre funded the study. Dr. Morgan and three of her coauthors declared no conflicts of interest. Two authors reported grants from the NIHR, and one author reported grants from the Department of Health and Social Care and the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership.

SOURCE: Morgan C et al. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Oct 15. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30348-1.

Adults aged 65 years and older with a self-harm history are more likely to die from unnatural causes – specifically suicide – than are those who do not self-harm, according to what researchers called the first study of self-harm that exclusively focused on older adults from the perspective of primary care.

“This work should alert policy makers and primary health care professionals to progress towards implementing preventive measures among older adults who consult with a GP,” lead author Catharine Morgan, PhD, and her coauthors, wrote in the Lancet Psychiatry.

The study, which reviewed the primary care records of 4,124 older adults in the United Kingdom with incidents of self-harm, found that , said Dr. Morgan, of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Greater Manchester (England) Patient Safety Translational Research Centre at the University of Manchester, and her coauthors. They also noted that, “compared with their peers who had not harmed themselves, adults in the self-harm cohort were an estimated 20 times more likely to die unnaturally during the first year after a self-harm episode and three or four times more likely to die unnaturally in subsequent years.”

The coauthors also found that, compared with a comparison cohort, the prevalence of a previous mental illness was twice as high among older adults who had engaged in self-harm (hazard ratio, 2.10; 95% confidence interval, 2.03-2.17). Older adults with a self-harm history also had a 20% higher prevalence of a physical illness (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.17-1.23), compared with those without such a history.

Dr. Morgan and her coauthors also uncovered differing likelihoods of referral to specialists, depending on socioeconomic status of the surrounding area. Older patients in “more socially deprived localities” were less likely to be referred to mental health services. Women also were more likely than men were to be referred, highlighting “an important target for improvement across the health care system.” They also recommended avoiding tricyclics for older patients and encouraged maintaining “frequent medication reviews after self-harm.”

The coauthors noted potential limitations in their study, including reliance on clinicians who entered the primary care records and reluctance of coroners to report suicide as the cause of death in certain scenarios. However, they strongly encouraged general practitioners to intervene early and consider alternative medications when treating older patients who exhibit risk factors.

“Health care professionals should take the opportunity to consider the risk of self-harm when an older person consults with other health problems, especially when major physical illnesses and psychopathology are both present, to reduce the risk of an escalation in self-harming behaviour and associated mortality,” they wrote.

The NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre funded the study. Dr. Morgan and three of her coauthors declared no conflicts of interest. Two authors reported grants from the NIHR, and one author reported grants from the Department of Health and Social Care and the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership.

SOURCE: Morgan C et al. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Oct 15. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30348-1.

FROM THE LANCET PSYCHIATRY

Key clinical point: Consider medications other than tricyclics and frequent medication reviews for older adults who self-harm.

Major finding: “Adults in the self-harm cohort were an estimated 20 times more likely to die unnaturally during the first year after a self-harm episode and three or four times more likely to die unnaturally in subsequent years.”

Study details: A multiphase cohort study involving 4,124 adults in the United Kingdom, aged 65 years and older, with a self-harm episode recorded during 2001-2014.

Disclosures: The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre funded the study. Dr. Morgan and three of her coauthors declared no conflicts of interest. Two authors reported grants from the NIHR, and one reported grants from the Department of Health and Social Care and the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership.

Source: Morgan C et al. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Oct 15. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30348-1.

PURE Healthy Diet Score validated

MUNICH – A formula for scoring diet quality that during its development phase significantly correlated with overall survival received validation when tested using three independent, large data sets that together included almost 80,000 people.

With these new findings the PURE Healthy Diet Score had now shown consistent, significant correlations with overall survival and the incidence of MI and stroke in a total of about 218,000 people from 50 countries who had been followed in any of four separate studies. This new validation is especially notable because the optimal diet identified by the scoring system diverged from current American diet recommendations in two important ways: Optimal food consumption included three daily servings of full-fat dairy and 1.5 servings daily of unprocessed red meat Andrew Mente, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. He explained this finding as possibly related to the global scope of the study, which included many people from low- or middle-income countries where average diets are usually low in important nutrients.

The PURE Healthy Diet Score should now be “considered for broad, global dietary recommendations,” Dr. Mente said in a video interview. Testing a diet profile in a large, randomized trial would be ideal, but also difficult to run. Until then, the only alternative for defining an evidence-based optimal diet is observational data, as in the current study. The PURE Healthy Diet Score “is ready for routine use,” said Dr. Mente, a clinical epidemiologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada.

Dr. Mente and his associates developed the Pure Healthy Diet Score with data taken from 138,527 people enrolled in the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. They published a pair of reports in 2017 with their initial findings that also included some of their first steps toward developing the score (Lancet. 2017 Nov 4; 380[10107]:2037-49; 380[10107]:2050-62). The PURE analysis identified seven food groups for which daily intake levels significantly linked with survival: fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, dairy, red meat, and fish. Based on this, they devised a scoring formula that gives a person a rating of 1-5 for each of these seven food types, from the lowest quintile of consumption, which scores 1, to the highest quintile, which scores 5. The result is a score than can range from 7 to 35. They then divided the PURE participants into quintiles based on their intakes of all seven food types and found the highest survival rate among people in the quintile with the highest intake level for all of the food groups.

The best-outcome quintile consumed on average about eight servings of fruits and vegetables daily, 2.5 servings of legumes and nuts, three servings of full-fat daily, 1.5 servings of unprocessed red meat, and 0.3 servings of fish (or about two servings of fish weekly). Energy consumption in the best-outcome quintile received 54% of calories as carbohydrates, 28% as fat, and 18% as protein. In contrast, the worst-outcomes quintile received 69% of calories from carbohydrates, 19% from fat, and 12% from protein.

In a model that adjusted for all measured confounders the people in PURE with the best-outcome diet had a statistically significant, 25% reduced all-cause mortality, compared with people in the quintile with the worst diet.

To validate the formula the researchers used data collected from three other trials run by their group at McMaster University:

- The ONTARGET and TRANSCEND studies (N Engl J Med. 2008 Apr 10;358[15]:1547-58), which together included diet and outcomes data for 31,546 patients with vascular disease. Diet analysis and scoring showed that enrolled people in the quintile with the highest score had a statistically significant 24% relative reduction in mortality, compared with the quintile with the worst score after adjusting for measured confounders.

- The INTERHEART study (Lancet. 2004 Sep 11;364[9438]:937-52), which had data for 27,098 people and showed that the primary outcome of incident MI was a statistically significant 22% lower after adjustment in the quintile with the best diet score, compared with the quintile with the worst score.

- The INTERSTROKE study (Lancet. 2016 Aug 20;388[10046]:761-75), with data for 20,834 people, showed that the rate of stroke was a statistically significant 25% lower after adjustment in the quintile with the highest diet score, compared with those with the lowest score.

Dr. Mente had no financial disclosures.

Dr. Mente and his associates have validated the PURE Healthy Diet Score. However, it remains unclear whether the score captures all of the many facets of diet, and it’s also uncertain whether the score is sensitive to changes in diet.

Another issue with the quintile analysis that the researchers used to derive the formula was that the spread between the median scores of the bottom, worst-outcome quartile and the top, best-outcome quartile was only 7 points on a scale that ranged from 7 to 35. The small magnitude of the difference in scores between the bottom and top quintiles might limit the discriminatory power of this scoring system.

Eva Prescott, MD, is a cardiologist at Bispebjerg Hospital in Copenhagen. She has been an advisor to AstraZeneca, NovoNordisk, and Sanofi. She made these comments as designated discussant for the report.

Dr. Mente and his associates have validated the PURE Healthy Diet Score. However, it remains unclear whether the score captures all of the many facets of diet, and it’s also uncertain whether the score is sensitive to changes in diet.

Another issue with the quintile analysis that the researchers used to derive the formula was that the spread between the median scores of the bottom, worst-outcome quartile and the top, best-outcome quartile was only 7 points on a scale that ranged from 7 to 35. The small magnitude of the difference in scores between the bottom and top quintiles might limit the discriminatory power of this scoring system.

Eva Prescott, MD, is a cardiologist at Bispebjerg Hospital in Copenhagen. She has been an advisor to AstraZeneca, NovoNordisk, and Sanofi. She made these comments as designated discussant for the report.

Dr. Mente and his associates have validated the PURE Healthy Diet Score. However, it remains unclear whether the score captures all of the many facets of diet, and it’s also uncertain whether the score is sensitive to changes in diet.

Another issue with the quintile analysis that the researchers used to derive the formula was that the spread between the median scores of the bottom, worst-outcome quartile and the top, best-outcome quartile was only 7 points on a scale that ranged from 7 to 35. The small magnitude of the difference in scores between the bottom and top quintiles might limit the discriminatory power of this scoring system.

Eva Prescott, MD, is a cardiologist at Bispebjerg Hospital in Copenhagen. She has been an advisor to AstraZeneca, NovoNordisk, and Sanofi. She made these comments as designated discussant for the report.

MUNICH – A formula for scoring diet quality that during its development phase significantly correlated with overall survival received validation when tested using three independent, large data sets that together included almost 80,000 people.

With these new findings the PURE Healthy Diet Score had now shown consistent, significant correlations with overall survival and the incidence of MI and stroke in a total of about 218,000 people from 50 countries who had been followed in any of four separate studies. This new validation is especially notable because the optimal diet identified by the scoring system diverged from current American diet recommendations in two important ways: Optimal food consumption included three daily servings of full-fat dairy and 1.5 servings daily of unprocessed red meat Andrew Mente, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. He explained this finding as possibly related to the global scope of the study, which included many people from low- or middle-income countries where average diets are usually low in important nutrients.

The PURE Healthy Diet Score should now be “considered for broad, global dietary recommendations,” Dr. Mente said in a video interview. Testing a diet profile in a large, randomized trial would be ideal, but also difficult to run. Until then, the only alternative for defining an evidence-based optimal diet is observational data, as in the current study. The PURE Healthy Diet Score “is ready for routine use,” said Dr. Mente, a clinical epidemiologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada.

Dr. Mente and his associates developed the Pure Healthy Diet Score with data taken from 138,527 people enrolled in the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. They published a pair of reports in 2017 with their initial findings that also included some of their first steps toward developing the score (Lancet. 2017 Nov 4; 380[10107]:2037-49; 380[10107]:2050-62). The PURE analysis identified seven food groups for which daily intake levels significantly linked with survival: fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, dairy, red meat, and fish. Based on this, they devised a scoring formula that gives a person a rating of 1-5 for each of these seven food types, from the lowest quintile of consumption, which scores 1, to the highest quintile, which scores 5. The result is a score than can range from 7 to 35. They then divided the PURE participants into quintiles based on their intakes of all seven food types and found the highest survival rate among people in the quintile with the highest intake level for all of the food groups.

The best-outcome quintile consumed on average about eight servings of fruits and vegetables daily, 2.5 servings of legumes and nuts, three servings of full-fat daily, 1.5 servings of unprocessed red meat, and 0.3 servings of fish (or about two servings of fish weekly). Energy consumption in the best-outcome quintile received 54% of calories as carbohydrates, 28% as fat, and 18% as protein. In contrast, the worst-outcomes quintile received 69% of calories from carbohydrates, 19% from fat, and 12% from protein.

In a model that adjusted for all measured confounders the people in PURE with the best-outcome diet had a statistically significant, 25% reduced all-cause mortality, compared with people in the quintile with the worst diet.

To validate the formula the researchers used data collected from three other trials run by their group at McMaster University:

- The ONTARGET and TRANSCEND studies (N Engl J Med. 2008 Apr 10;358[15]:1547-58), which together included diet and outcomes data for 31,546 patients with vascular disease. Diet analysis and scoring showed that enrolled people in the quintile with the highest score had a statistically significant 24% relative reduction in mortality, compared with the quintile with the worst score after adjusting for measured confounders.

- The INTERHEART study (Lancet. 2004 Sep 11;364[9438]:937-52), which had data for 27,098 people and showed that the primary outcome of incident MI was a statistically significant 22% lower after adjustment in the quintile with the best diet score, compared with the quintile with the worst score.

- The INTERSTROKE study (Lancet. 2016 Aug 20;388[10046]:761-75), with data for 20,834 people, showed that the rate of stroke was a statistically significant 25% lower after adjustment in the quintile with the highest diet score, compared with those with the lowest score.

Dr. Mente had no financial disclosures.

MUNICH – A formula for scoring diet quality that during its development phase significantly correlated with overall survival received validation when tested using three independent, large data sets that together included almost 80,000 people.

With these new findings the PURE Healthy Diet Score had now shown consistent, significant correlations with overall survival and the incidence of MI and stroke in a total of about 218,000 people from 50 countries who had been followed in any of four separate studies. This new validation is especially notable because the optimal diet identified by the scoring system diverged from current American diet recommendations in two important ways: Optimal food consumption included three daily servings of full-fat dairy and 1.5 servings daily of unprocessed red meat Andrew Mente, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. He explained this finding as possibly related to the global scope of the study, which included many people from low- or middle-income countries where average diets are usually low in important nutrients.

The PURE Healthy Diet Score should now be “considered for broad, global dietary recommendations,” Dr. Mente said in a video interview. Testing a diet profile in a large, randomized trial would be ideal, but also difficult to run. Until then, the only alternative for defining an evidence-based optimal diet is observational data, as in the current study. The PURE Healthy Diet Score “is ready for routine use,” said Dr. Mente, a clinical epidemiologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada.

Dr. Mente and his associates developed the Pure Healthy Diet Score with data taken from 138,527 people enrolled in the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. They published a pair of reports in 2017 with their initial findings that also included some of their first steps toward developing the score (Lancet. 2017 Nov 4; 380[10107]:2037-49; 380[10107]:2050-62). The PURE analysis identified seven food groups for which daily intake levels significantly linked with survival: fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, dairy, red meat, and fish. Based on this, they devised a scoring formula that gives a person a rating of 1-5 for each of these seven food types, from the lowest quintile of consumption, which scores 1, to the highest quintile, which scores 5. The result is a score than can range from 7 to 35. They then divided the PURE participants into quintiles based on their intakes of all seven food types and found the highest survival rate among people in the quintile with the highest intake level for all of the food groups.

The best-outcome quintile consumed on average about eight servings of fruits and vegetables daily, 2.5 servings of legumes and nuts, three servings of full-fat daily, 1.5 servings of unprocessed red meat, and 0.3 servings of fish (or about two servings of fish weekly). Energy consumption in the best-outcome quintile received 54% of calories as carbohydrates, 28% as fat, and 18% as protein. In contrast, the worst-outcomes quintile received 69% of calories from carbohydrates, 19% from fat, and 12% from protein.

In a model that adjusted for all measured confounders the people in PURE with the best-outcome diet had a statistically significant, 25% reduced all-cause mortality, compared with people in the quintile with the worst diet.

To validate the formula the researchers used data collected from three other trials run by their group at McMaster University:

- The ONTARGET and TRANSCEND studies (N Engl J Med. 2008 Apr 10;358[15]:1547-58), which together included diet and outcomes data for 31,546 patients with vascular disease. Diet analysis and scoring showed that enrolled people in the quintile with the highest score had a statistically significant 24% relative reduction in mortality, compared with the quintile with the worst score after adjusting for measured confounders.

- The INTERHEART study (Lancet. 2004 Sep 11;364[9438]:937-52), which had data for 27,098 people and showed that the primary outcome of incident MI was a statistically significant 22% lower after adjustment in the quintile with the best diet score, compared with the quintile with the worst score.

- The INTERSTROKE study (Lancet. 2016 Aug 20;388[10046]:761-75), with data for 20,834 people, showed that the rate of stroke was a statistically significant 25% lower after adjustment in the quintile with the highest diet score, compared with those with the lowest score.

Dr. Mente had no financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The highest-scoring quintiles had about 25% fewer deaths, MIs, and strokes, compared with the lowest-scoring quintiles.

Study details: The PURE Healthy Diet Score underwent validation using three independent data sets with a total of 79,478 people.

Disclosures: Dr. Mente had no financial disclosures.

Optimizing use of TKIs in chronic leukemia

DUBROVNIK, CROATIA – Long-term efficacy and toxicity should inform decisions about tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), according to one expert.

Studies have indicated that long-term survival rates are similar whether CML patients receive frontline treatment with imatinib or second-generation TKIs. But the newer TKIs pose a higher risk of uncommon toxicities, Hagop M. Kantarjian, MD, said during the keynote presentation at Leukemia and Lymphoma, a meeting jointly sponsored by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and the School of Medicine at the University of Zagreb, Croatia.

Dr. Kantarjian, a professor at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, said most CML patients should receive daily treatment with TKIs – even if they are in complete cytogenetic response or 100% Philadelphia chromosome positive – because they will live longer.

Frontline treatment options for CML that are approved by the Food and Drug Administration include imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib, and bosutinib.

Dr. Kantarjian noted that dasatinib and nilotinib bested imatinib in early analyses from clinical trials, but all three TKIs produced similar rates of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) at extended follow-up.

Dasatinib and imatinib produced similar rates of 5-year OS and PFS in the DASISION trial (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jul 10;34[20]:2333-40).

In ENESTnd, 5-year OS and PFS rates were similar with nilotinib and imatinib (Leukemia. 2016 May;30[5]:1044-54).

However, the higher incidence of uncommon toxicities with the newer TKIs must be taken into account, Dr. Kantarjian said.

Choosing a TKI

Dr. Kantarjian recommends frontline imatinib for older patients (aged 65-70) and those who are low risk based on their Sokal score.

Second-generation TKIs should be given up front to patients who are at higher risk by Sokal and for “very young patients in whom early treatment discontinuation is important,” he said.

“In accelerated or blast phase, I always use the second-generation TKIs,” he said. “If there’s no binding mutation, I prefer dasatinib. I think it’s the most potent of them. If there are toxicities with dasatinib, bosutinib is equivalent in efficacy, so they are interchangeable.”

A TKI should not be discarded unless there is loss of complete cytogenetic response – not major molecular response – at the maximum tolerated adjusted dose that does not cause grade 3-4 toxicities or chronic grade 2 toxicities, Dr. Kantarjian added.

“We have to remember that we can go down on the dosages of, for example, imatinib, down to 200 mg a day, dasatinib as low as 20 mg a day, nilotinib as low as 150 mg twice a day or even 200 mg daily, and bosutinib down to 200 mg daily,” he said. “So if we have a patient who’s responding with side effects, we should not abandon the particular TKI, we should try to manipulate the dose schedule if they are having a good response.”

Dr. Kantarjian noted that pleural effusion is a toxicity of particular concern with dasatinib, but lowering the dose to 50 mg daily results in similar efficacy and significantly less toxicity than 100 mg daily. For patients over the age of 70, a 20-mg dose can be used.

Vaso-occlusive and vasospastic reactions are increasingly observed in patients treated with nilotinib. For that reason, Dr. Kantarjian said he prefers to forgo up-front nilotinib, particularly in patients who have cardiovascular or neurotoxic problems.

“The incidence of vaso-occlusive and vasospastic reactions is now close to 10%-15% at about 10 years with nilotinib,” Dr. Kantarjian said. “So it is not a trivial toxicity.”

For patients with vaso-occlusive/vasospastic reactions, “bosutinib is probably the safest drug,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

For second- or third-line therapy, patients can receive ponatinib or a second-generation TKI (dasatinib, nilotinib, or bosutinib), as well as omacetaxine or allogeneic stem cell transplant.

“If you disregard toxicities, I think ponatinib is the most powerful TKI, and I think that’s because we are using it at a higher dose that produces so many toxicities,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

Ponatinib is not used up front because of these toxicities, particularly pancreatitis, skin rashes, vaso-occlusive disorders, and hypertension, he added.

Dr. Kantarjian suggests giving ponatinib at 30 mg daily in patients with T315I mutation and those without guiding mutations who are resistant to second-generation TKIs.

Discontinuing a TKI

Dr. Kantarjian said patients can discontinue TKI therapy if they:

- Are low- or intermediate-risk by Sokal.

- Have quantifiable BCR-ABL transcripts.

- Are in chronic phase.

- Achieved an optimal response to their first TKI.

- Have been on TKI therapy for more than 8 years.

- Achieved a complete molecular response.

- Have had a molecular response for more than 2-3 years.

- Are available for monitoring every other month for the first 2 years.

Dr. Kantarjian did not report any conflicts of interest at the meeting. However, he has previously reported relationships with Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Ariad Pharmaceuticals.

The Leukemia and Lymphoma meeting is organized by Jonathan Wood & Association, which is owned by the parent company of this news organization.

DUBROVNIK, CROATIA – Long-term efficacy and toxicity should inform decisions about tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), according to one expert.

Studies have indicated that long-term survival rates are similar whether CML patients receive frontline treatment with imatinib or second-generation TKIs. But the newer TKIs pose a higher risk of uncommon toxicities, Hagop M. Kantarjian, MD, said during the keynote presentation at Leukemia and Lymphoma, a meeting jointly sponsored by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and the School of Medicine at the University of Zagreb, Croatia.