User login

Stepdown to oral ciprofloxacin looks safe in gram-negative bloodstream infections

SAN FRANCISCO – In gram-negative bloodstream infections, in patients who are stable at 48 hours, are no longer feverish, and whose infections aren’t invasive, it may be safe to step down from IV antibiotics to oral ciprofloxacin (PO). That is the tentative conclusion from a new single-center, retrospective chart review.

The study adds to growing suspicion among practitioners that stepping down may be safe in gram-negative patients, as well as mounting evidence that shorter treatment durations may also be safe, according to Gregory Cook, PharmD, who presented the study at a poster session at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. “We’re getting more aggressive” in backing off IV treatment, he said in an interview.

Oral medications are associated with shorter hospital stays and decreased costs.

Froedtert & the Medical College of Wisconsin, where the study was performed, switched some years ago from levofloxacin to ciprofloxacin for cost reasons. But ciprofloxacin has a lower bioavailability, and a recent study showed levofloxacin had less treatment failure at 90 days than ciprofloxacin. Levofloxacin is restricted at the institution and requires antibiotic stewardship approval for use, whereas ciprofloxacin can be used without approval.

But the researchers were concerned about bioavailability. “We like to think of ciprofloxacin as having excellent bioavailability, and it does, it has 80% bioavailability, but it’s still not exactly the same as levofloxacin. We wanted to look into this and see if we were doing our patients a disservice or not (by stepping down to ciprofloxacin),” said Dr. Cook, who is now the antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist at Children’s Hospital New Orleans. The results were reassuring. “Ultimately we were trying to see how our patients were doing on oral ciprofloxacin, and after 2-3 days of IV therapy, most of them did extremely well,” he said.

The researchers analyzed the records of 198 patients who presented with a monomicrobial, gram-negative bloodstream infection between January 2015 and January 2018, and who survived at least 5 days past blood culture collection. One hundred and three switched to PO within 5 days, while 95 remained on intravenous antibiotics for longer than 5 days. On average, patients in the PO group received IV antibiotics for 2 days, while the IV group averaged 15 days. Oral ciprofloxacin treatment length averaged 12 days.

The primary endpoint of treatment failure at 90 days, defined as recurrent infection or all-cause mortality, favored the PO group (1.9% versus 16.8%, P less than .01). This was likely because of patient selection, as those in the IV group tended to be more ill, according to Dr. Cook. More were immunosuppressed (41% IV versus 22% in PO group, P less than .01). There were more nonurinary sources of infection (41% in IV group, P less than .01; 65% urinary source in PO group). Thirty-four percent of the PO group had an infectious disease consult, compared with 60% of the IV group.

SOURCE: Gregory Cook et al. ID Week 2018. Abstract 39.

SAN FRANCISCO – In gram-negative bloodstream infections, in patients who are stable at 48 hours, are no longer feverish, and whose infections aren’t invasive, it may be safe to step down from IV antibiotics to oral ciprofloxacin (PO). That is the tentative conclusion from a new single-center, retrospective chart review.

The study adds to growing suspicion among practitioners that stepping down may be safe in gram-negative patients, as well as mounting evidence that shorter treatment durations may also be safe, according to Gregory Cook, PharmD, who presented the study at a poster session at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. “We’re getting more aggressive” in backing off IV treatment, he said in an interview.

Oral medications are associated with shorter hospital stays and decreased costs.

Froedtert & the Medical College of Wisconsin, where the study was performed, switched some years ago from levofloxacin to ciprofloxacin for cost reasons. But ciprofloxacin has a lower bioavailability, and a recent study showed levofloxacin had less treatment failure at 90 days than ciprofloxacin. Levofloxacin is restricted at the institution and requires antibiotic stewardship approval for use, whereas ciprofloxacin can be used without approval.

But the researchers were concerned about bioavailability. “We like to think of ciprofloxacin as having excellent bioavailability, and it does, it has 80% bioavailability, but it’s still not exactly the same as levofloxacin. We wanted to look into this and see if we were doing our patients a disservice or not (by stepping down to ciprofloxacin),” said Dr. Cook, who is now the antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist at Children’s Hospital New Orleans. The results were reassuring. “Ultimately we were trying to see how our patients were doing on oral ciprofloxacin, and after 2-3 days of IV therapy, most of them did extremely well,” he said.

The researchers analyzed the records of 198 patients who presented with a monomicrobial, gram-negative bloodstream infection between January 2015 and January 2018, and who survived at least 5 days past blood culture collection. One hundred and three switched to PO within 5 days, while 95 remained on intravenous antibiotics for longer than 5 days. On average, patients in the PO group received IV antibiotics for 2 days, while the IV group averaged 15 days. Oral ciprofloxacin treatment length averaged 12 days.

The primary endpoint of treatment failure at 90 days, defined as recurrent infection or all-cause mortality, favored the PO group (1.9% versus 16.8%, P less than .01). This was likely because of patient selection, as those in the IV group tended to be more ill, according to Dr. Cook. More were immunosuppressed (41% IV versus 22% in PO group, P less than .01). There were more nonurinary sources of infection (41% in IV group, P less than .01; 65% urinary source in PO group). Thirty-four percent of the PO group had an infectious disease consult, compared with 60% of the IV group.

SOURCE: Gregory Cook et al. ID Week 2018. Abstract 39.

SAN FRANCISCO – In gram-negative bloodstream infections, in patients who are stable at 48 hours, are no longer feverish, and whose infections aren’t invasive, it may be safe to step down from IV antibiotics to oral ciprofloxacin (PO). That is the tentative conclusion from a new single-center, retrospective chart review.

The study adds to growing suspicion among practitioners that stepping down may be safe in gram-negative patients, as well as mounting evidence that shorter treatment durations may also be safe, according to Gregory Cook, PharmD, who presented the study at a poster session at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases. “We’re getting more aggressive” in backing off IV treatment, he said in an interview.

Oral medications are associated with shorter hospital stays and decreased costs.

Froedtert & the Medical College of Wisconsin, where the study was performed, switched some years ago from levofloxacin to ciprofloxacin for cost reasons. But ciprofloxacin has a lower bioavailability, and a recent study showed levofloxacin had less treatment failure at 90 days than ciprofloxacin. Levofloxacin is restricted at the institution and requires antibiotic stewardship approval for use, whereas ciprofloxacin can be used without approval.

But the researchers were concerned about bioavailability. “We like to think of ciprofloxacin as having excellent bioavailability, and it does, it has 80% bioavailability, but it’s still not exactly the same as levofloxacin. We wanted to look into this and see if we were doing our patients a disservice or not (by stepping down to ciprofloxacin),” said Dr. Cook, who is now the antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist at Children’s Hospital New Orleans. The results were reassuring. “Ultimately we were trying to see how our patients were doing on oral ciprofloxacin, and after 2-3 days of IV therapy, most of them did extremely well,” he said.

The researchers analyzed the records of 198 patients who presented with a monomicrobial, gram-negative bloodstream infection between January 2015 and January 2018, and who survived at least 5 days past blood culture collection. One hundred and three switched to PO within 5 days, while 95 remained on intravenous antibiotics for longer than 5 days. On average, patients in the PO group received IV antibiotics for 2 days, while the IV group averaged 15 days. Oral ciprofloxacin treatment length averaged 12 days.

The primary endpoint of treatment failure at 90 days, defined as recurrent infection or all-cause mortality, favored the PO group (1.9% versus 16.8%, P less than .01). This was likely because of patient selection, as those in the IV group tended to be more ill, according to Dr. Cook. More were immunosuppressed (41% IV versus 22% in PO group, P less than .01). There were more nonurinary sources of infection (41% in IV group, P less than .01; 65% urinary source in PO group). Thirty-four percent of the PO group had an infectious disease consult, compared with 60% of the IV group.

SOURCE: Gregory Cook et al. ID Week 2018. Abstract 39.

REPORTING FROM IDWEEK 2018

Key clinical point: Stepping down to oral ciprofloxacin at 48 hours is likely safe in stable patients.

Major finding: The 90-day treatment failure rate was 1.9% in patients switched to oral ciprofloxacin.

Study details: Retrospective analysis of 193 cases.

Disclosures: The study was not funded. Dr. Cook declared no financial conflicts of interest.

Source: ID Week 2018. Abstract 39.

Benzodiazepines double risk of suicide among COPD patients

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who are taking benzodiazepines have more than double the risk of suicide compared with patients who are not on those medications. Also today, the feds say that the ACA’s silver plan premiums will drop in 2019, bias in the clinical setting can impact patient care, and managing asthma in children mean that pets do not always have to go.

The Postcall Podcast is available here: https://www.mdedge.com/podcasts

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who are taking benzodiazepines have more than double the risk of suicide compared with patients who are not on those medications. Also today, the feds say that the ACA’s silver plan premiums will drop in 2019, bias in the clinical setting can impact patient care, and managing asthma in children mean that pets do not always have to go.

The Postcall Podcast is available here: https://www.mdedge.com/podcasts

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who are taking benzodiazepines have more than double the risk of suicide compared with patients who are not on those medications. Also today, the feds say that the ACA’s silver plan premiums will drop in 2019, bias in the clinical setting can impact patient care, and managing asthma in children mean that pets do not always have to go.

The Postcall Podcast is available here: https://www.mdedge.com/podcasts

Which Patients Have the Best Chance With Checkpoint Inhibitors?

Checkpoint inhibitors are so new that not enough patients have received them to allow clinicians to predict who will benefit most. But researchers from the National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Institute; Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts; University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia; and University of Maryland in College Park may have found a clue: A gene expression predictor.

They began by looking at neuroblastoma cases where the immune system seemed to mount “an unprompted, successful immune response” to cancer, causing spontaneous tumor regression. The researchers were able to define gene expression features that separated regressing from nonregressing disease.

The researchers then computed Immuno-PREdictive Scores (IMPRES) for each patient sample. The higher the score, the more likely was spontaneous regression. Analyzing 297 samples from several studies, they found the predictor identified nearly all patients who responded to the inhibitors and more than half of those who did not. “Importantly,” the researchers say, their predictor was accurate across many different melanoma patient datasets.

Checkpoint inhibitors are so new that not enough patients have received them to allow clinicians to predict who will benefit most. But researchers from the National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Institute; Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts; University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia; and University of Maryland in College Park may have found a clue: A gene expression predictor.

They began by looking at neuroblastoma cases where the immune system seemed to mount “an unprompted, successful immune response” to cancer, causing spontaneous tumor regression. The researchers were able to define gene expression features that separated regressing from nonregressing disease.

The researchers then computed Immuno-PREdictive Scores (IMPRES) for each patient sample. The higher the score, the more likely was spontaneous regression. Analyzing 297 samples from several studies, they found the predictor identified nearly all patients who responded to the inhibitors and more than half of those who did not. “Importantly,” the researchers say, their predictor was accurate across many different melanoma patient datasets.

Checkpoint inhibitors are so new that not enough patients have received them to allow clinicians to predict who will benefit most. But researchers from the National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Institute; Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts; University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia; and University of Maryland in College Park may have found a clue: A gene expression predictor.

They began by looking at neuroblastoma cases where the immune system seemed to mount “an unprompted, successful immune response” to cancer, causing spontaneous tumor regression. The researchers were able to define gene expression features that separated regressing from nonregressing disease.

The researchers then computed Immuno-PREdictive Scores (IMPRES) for each patient sample. The higher the score, the more likely was spontaneous regression. Analyzing 297 samples from several studies, they found the predictor identified nearly all patients who responded to the inhibitors and more than half of those who did not. “Importantly,” the researchers say, their predictor was accurate across many different melanoma patient datasets.

Drones can deliver blood products, but hurdles remain

BOSTON—Drone-delivered blood products may be coming soon to a hospital near you, experts said at AABB 2018.

Using a system of completely autonomous delivery drones launched from a central location, U.S.-based Zipline International delivers blood products to treat postpartum hemorrhage, trauma, malaria, and other life-threatening conditions to patients in rural Rwanda, according to company spokesman Chris Kenney.

“In less than 2 years in Rwanda, we’ve made almost 10,000 deliveries,” Kenney said. “That’s almost 20,000 units of blood.”

One-third of all deliveries are needed for urgent, life-saving interventions, he added.

The system, which delivers 30% of all blood products used in Rwanda outside the capital Kigali, has resulted in 100% availability of blood products when needed, a 98% reduction in waste (i.e., when unused blood products are discarded because of age), and a 175% increase in the use of platelets and fresh frozen plasma, according to Kenney.

How it works

Kenney described the case of a 24-year-old Rwandan woman who had uncontrolled bleeding from complications following a cesarean section.

The clinicians treating her opted to give her an immediate red blood cell transfusion, but she continued to bleed, and the hospital ran out of red blood cells in about 15 minutes.

They placed an order for more blood products, which can be done by text message or via WhatsApp, a free messaging and voiceover IP calling service.

After the order was placed, Zipline was able to deliver blood products using multiple drone launches over the course of 90 minutes. The deliveries consisted of 7 units of red blood cells, 4 units of plasma, and 2 units of platelets, all of which were transfused into the patient and allowed her condition to stabilize.

Deliveries that would take a minimum of 3 hours by road can be accomplished in about 15 to 25 minutes by air, Kenney said.

The drones—more formally known as “unmanned aerial vehicles”—fly a loop starting at the distribution center, find their target, descend to a height of about 10 meters, and drop the package, which has a parachute attached.

Packages can be delivered within a drop zone the size of two parking spaces, even in gale-force winds, Kenney said.

“The whole process is 100% autonomous,” he noted. “The aircraft knows where it’s going, it knows what conditions [are], it knows what its payload characteristics are and flies to the delivery point and drops its package.”

As drones return to the distribution center, they are snared from the air with a wire that catches a small tail hook on the fuselage.

Airborne deliveries are significantly cheaper than ground-based services for local delivery, according to Paul Eastvold, MD, chief medical officer at Vitalant, a nonprofit network of community blood banks headquartered in Spokane, Wash.

Dr. Eastvold cited statistics suggesting the cost of ground shipping from a local warehouse by carriers such as UPS or FedEx could be $6 or more. However, drone delivery could be as cheap as 5 cents per mile.

Barriers to drone delivery

Setting up an airborne delivery network in the largely unregulated and uncrowded Rwandan airspace was a relatively simple process, compared with the myriad challenges of establishing a similar system for deliveries to urban medical centers in Boston, Chicago, New York, or Los Angeles, according to Dr. Eastvold.

He described the hurdles that will need to be surmounted before blood-delivery drones are as common a sight as traffic helicopters in the United States.

Dr. Eastvold said the barriers to adoption of drone-based delivery systems include differences in state laws about when, where, and how drones can be used and who can operate them as well as Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) airspace restrictions and regulations.

For example, the FAA currently requires “line-of-sight” operation for most drone operators, meaning the operator must have visual contact with the drone at all times. The FAA will, however, grant waivers to individual operators for specified flying conditions on a case-by-case basis, if compelling need or extenuating circumstances can be satisfactorily explained.

In addition, federal regulations require commercial drone pilots to be 16 or older, be fluent in English, be in a physical and mental condition that would not interfere with safe operation of a drone, pass an aeronautical knowledge exam at an FAA-approved testing center, and undergo a Transportation Safety Administration background security screening.

Despite these challenges, at least one U.S. medical center, Johns Hopkins University, is testing the use of drones for blood delivery.

In 2015, Johns Hopkins researchers reported that transporting blood samples on hobby-sized drones did not affect the results of common and routine blood tests.

In 2016, the researchers showed that large bags of blood products can maintain temperature and cellular integrity when transported by drones.

In 2017, the researchers demonstrated that a drone could deliver blood samples in temperature-controlled conditions across 161 miles of Arizona desert, in a flight lasting 3 hours.

Kenney said his company is developing a second distribution center in Rwanda that will expand coverage to the entire country and is also working with the FAA, federal regulators, and the state of North Carolina to develop a drone-based blood delivery system in the United States.

BOSTON—Drone-delivered blood products may be coming soon to a hospital near you, experts said at AABB 2018.

Using a system of completely autonomous delivery drones launched from a central location, U.S.-based Zipline International delivers blood products to treat postpartum hemorrhage, trauma, malaria, and other life-threatening conditions to patients in rural Rwanda, according to company spokesman Chris Kenney.

“In less than 2 years in Rwanda, we’ve made almost 10,000 deliveries,” Kenney said. “That’s almost 20,000 units of blood.”

One-third of all deliveries are needed for urgent, life-saving interventions, he added.

The system, which delivers 30% of all blood products used in Rwanda outside the capital Kigali, has resulted in 100% availability of blood products when needed, a 98% reduction in waste (i.e., when unused blood products are discarded because of age), and a 175% increase in the use of platelets and fresh frozen plasma, according to Kenney.

How it works

Kenney described the case of a 24-year-old Rwandan woman who had uncontrolled bleeding from complications following a cesarean section.

The clinicians treating her opted to give her an immediate red blood cell transfusion, but she continued to bleed, and the hospital ran out of red blood cells in about 15 minutes.

They placed an order for more blood products, which can be done by text message or via WhatsApp, a free messaging and voiceover IP calling service.

After the order was placed, Zipline was able to deliver blood products using multiple drone launches over the course of 90 minutes. The deliveries consisted of 7 units of red blood cells, 4 units of plasma, and 2 units of platelets, all of which were transfused into the patient and allowed her condition to stabilize.

Deliveries that would take a minimum of 3 hours by road can be accomplished in about 15 to 25 minutes by air, Kenney said.

The drones—more formally known as “unmanned aerial vehicles”—fly a loop starting at the distribution center, find their target, descend to a height of about 10 meters, and drop the package, which has a parachute attached.

Packages can be delivered within a drop zone the size of two parking spaces, even in gale-force winds, Kenney said.

“The whole process is 100% autonomous,” he noted. “The aircraft knows where it’s going, it knows what conditions [are], it knows what its payload characteristics are and flies to the delivery point and drops its package.”

As drones return to the distribution center, they are snared from the air with a wire that catches a small tail hook on the fuselage.

Airborne deliveries are significantly cheaper than ground-based services for local delivery, according to Paul Eastvold, MD, chief medical officer at Vitalant, a nonprofit network of community blood banks headquartered in Spokane, Wash.

Dr. Eastvold cited statistics suggesting the cost of ground shipping from a local warehouse by carriers such as UPS or FedEx could be $6 or more. However, drone delivery could be as cheap as 5 cents per mile.

Barriers to drone delivery

Setting up an airborne delivery network in the largely unregulated and uncrowded Rwandan airspace was a relatively simple process, compared with the myriad challenges of establishing a similar system for deliveries to urban medical centers in Boston, Chicago, New York, or Los Angeles, according to Dr. Eastvold.

He described the hurdles that will need to be surmounted before blood-delivery drones are as common a sight as traffic helicopters in the United States.

Dr. Eastvold said the barriers to adoption of drone-based delivery systems include differences in state laws about when, where, and how drones can be used and who can operate them as well as Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) airspace restrictions and regulations.

For example, the FAA currently requires “line-of-sight” operation for most drone operators, meaning the operator must have visual contact with the drone at all times. The FAA will, however, grant waivers to individual operators for specified flying conditions on a case-by-case basis, if compelling need or extenuating circumstances can be satisfactorily explained.

In addition, federal regulations require commercial drone pilots to be 16 or older, be fluent in English, be in a physical and mental condition that would not interfere with safe operation of a drone, pass an aeronautical knowledge exam at an FAA-approved testing center, and undergo a Transportation Safety Administration background security screening.

Despite these challenges, at least one U.S. medical center, Johns Hopkins University, is testing the use of drones for blood delivery.

In 2015, Johns Hopkins researchers reported that transporting blood samples on hobby-sized drones did not affect the results of common and routine blood tests.

In 2016, the researchers showed that large bags of blood products can maintain temperature and cellular integrity when transported by drones.

In 2017, the researchers demonstrated that a drone could deliver blood samples in temperature-controlled conditions across 161 miles of Arizona desert, in a flight lasting 3 hours.

Kenney said his company is developing a second distribution center in Rwanda that will expand coverage to the entire country and is also working with the FAA, federal regulators, and the state of North Carolina to develop a drone-based blood delivery system in the United States.

BOSTON—Drone-delivered blood products may be coming soon to a hospital near you, experts said at AABB 2018.

Using a system of completely autonomous delivery drones launched from a central location, U.S.-based Zipline International delivers blood products to treat postpartum hemorrhage, trauma, malaria, and other life-threatening conditions to patients in rural Rwanda, according to company spokesman Chris Kenney.

“In less than 2 years in Rwanda, we’ve made almost 10,000 deliveries,” Kenney said. “That’s almost 20,000 units of blood.”

One-third of all deliveries are needed for urgent, life-saving interventions, he added.

The system, which delivers 30% of all blood products used in Rwanda outside the capital Kigali, has resulted in 100% availability of blood products when needed, a 98% reduction in waste (i.e., when unused blood products are discarded because of age), and a 175% increase in the use of platelets and fresh frozen plasma, according to Kenney.

How it works

Kenney described the case of a 24-year-old Rwandan woman who had uncontrolled bleeding from complications following a cesarean section.

The clinicians treating her opted to give her an immediate red blood cell transfusion, but she continued to bleed, and the hospital ran out of red blood cells in about 15 minutes.

They placed an order for more blood products, which can be done by text message or via WhatsApp, a free messaging and voiceover IP calling service.

After the order was placed, Zipline was able to deliver blood products using multiple drone launches over the course of 90 minutes. The deliveries consisted of 7 units of red blood cells, 4 units of plasma, and 2 units of platelets, all of which were transfused into the patient and allowed her condition to stabilize.

Deliveries that would take a minimum of 3 hours by road can be accomplished in about 15 to 25 minutes by air, Kenney said.

The drones—more formally known as “unmanned aerial vehicles”—fly a loop starting at the distribution center, find their target, descend to a height of about 10 meters, and drop the package, which has a parachute attached.

Packages can be delivered within a drop zone the size of two parking spaces, even in gale-force winds, Kenney said.

“The whole process is 100% autonomous,” he noted. “The aircraft knows where it’s going, it knows what conditions [are], it knows what its payload characteristics are and flies to the delivery point and drops its package.”

As drones return to the distribution center, they are snared from the air with a wire that catches a small tail hook on the fuselage.

Airborne deliveries are significantly cheaper than ground-based services for local delivery, according to Paul Eastvold, MD, chief medical officer at Vitalant, a nonprofit network of community blood banks headquartered in Spokane, Wash.

Dr. Eastvold cited statistics suggesting the cost of ground shipping from a local warehouse by carriers such as UPS or FedEx could be $6 or more. However, drone delivery could be as cheap as 5 cents per mile.

Barriers to drone delivery

Setting up an airborne delivery network in the largely unregulated and uncrowded Rwandan airspace was a relatively simple process, compared with the myriad challenges of establishing a similar system for deliveries to urban medical centers in Boston, Chicago, New York, or Los Angeles, according to Dr. Eastvold.

He described the hurdles that will need to be surmounted before blood-delivery drones are as common a sight as traffic helicopters in the United States.

Dr. Eastvold said the barriers to adoption of drone-based delivery systems include differences in state laws about when, where, and how drones can be used and who can operate them as well as Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) airspace restrictions and regulations.

For example, the FAA currently requires “line-of-sight” operation for most drone operators, meaning the operator must have visual contact with the drone at all times. The FAA will, however, grant waivers to individual operators for specified flying conditions on a case-by-case basis, if compelling need or extenuating circumstances can be satisfactorily explained.

In addition, federal regulations require commercial drone pilots to be 16 or older, be fluent in English, be in a physical and mental condition that would not interfere with safe operation of a drone, pass an aeronautical knowledge exam at an FAA-approved testing center, and undergo a Transportation Safety Administration background security screening.

Despite these challenges, at least one U.S. medical center, Johns Hopkins University, is testing the use of drones for blood delivery.

In 2015, Johns Hopkins researchers reported that transporting blood samples on hobby-sized drones did not affect the results of common and routine blood tests.

In 2016, the researchers showed that large bags of blood products can maintain temperature and cellular integrity when transported by drones.

In 2017, the researchers demonstrated that a drone could deliver blood samples in temperature-controlled conditions across 161 miles of Arizona desert, in a flight lasting 3 hours.

Kenney said his company is developing a second distribution center in Rwanda that will expand coverage to the entire country and is also working with the FAA, federal regulators, and the state of North Carolina to develop a drone-based blood delivery system in the United States.

Obese PE patients have lower risk of death

SAN ANTONIO—Patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) have a lower mortality risk if they are obese, according to a retrospective analysis of nearly 2 million PE discharges.

The obese patients had a lower mortality risk despite receiving more thrombolytics and mechanical intubation, said study investigator Zubair Khan, MD, of the University of Toledo Medical Center in Ohio.

“Surprisingly, the mortality of PE was significantly less in obese patients,” Dr. Khan said. “When we initiated the study, we did not expect this result.”

Dr. Khan discussed this result in a presentation at CHEST 2018.

Dr. Khan noted that the association between obesity and lower mortality, sometimes called the “obesity paradox,” has been observed in studies of other chronic health conditions, including stable heart failure, coronary artery disease, unstable angina, myocardial infarction, and also in some PE studies.

His team’s study, conducted using the National Inpatient Sample database, included adults with a primary discharge diagnosis of PE between 2002 and 2014. The researchers included 1,959,018 PE discharges, of which 312,770 (16%) had an underlying obesity diagnosis.

Obese PE patients had more risk factors and more severe disease but an overall mortality of 2.2%, compared with 3.7% in PE patients without obesity (P<0.001), Dr. Khan reported.

Hypertension was significantly more prevalent in the obese PE patients (65% vs. 50.5%; P<0.001), as was chronic lung disease and chronic liver disease.

Obese patients more often received thrombolytics (3.6% vs. 1.9%; P<0.001) and mechanical ventilation (5.8% vs. 4%; P<0.001), and they more frequently had cardiogenic shock (0.65% vs. 0.45%; P<0.001).

The obese PE patients were more often female, black, and younger than 65 years of age.

Notably, the prevalence of obesity in PE patients more than doubled over the course of the study period, from 10.2% in 2002 to 22.6% in 2014.

The lower mortality in obese patients might be explained by increased levels of endocannabinoids, which have shown protective effects in rat and mouse studies, Dr. Khan said.

“I think it’s a rich area for more and further research, especially in basic science,” he added.

Dr. Khan and his coauthors said they had no relationships relevant to the study.

SAN ANTONIO—Patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) have a lower mortality risk if they are obese, according to a retrospective analysis of nearly 2 million PE discharges.

The obese patients had a lower mortality risk despite receiving more thrombolytics and mechanical intubation, said study investigator Zubair Khan, MD, of the University of Toledo Medical Center in Ohio.

“Surprisingly, the mortality of PE was significantly less in obese patients,” Dr. Khan said. “When we initiated the study, we did not expect this result.”

Dr. Khan discussed this result in a presentation at CHEST 2018.

Dr. Khan noted that the association between obesity and lower mortality, sometimes called the “obesity paradox,” has been observed in studies of other chronic health conditions, including stable heart failure, coronary artery disease, unstable angina, myocardial infarction, and also in some PE studies.

His team’s study, conducted using the National Inpatient Sample database, included adults with a primary discharge diagnosis of PE between 2002 and 2014. The researchers included 1,959,018 PE discharges, of which 312,770 (16%) had an underlying obesity diagnosis.

Obese PE patients had more risk factors and more severe disease but an overall mortality of 2.2%, compared with 3.7% in PE patients without obesity (P<0.001), Dr. Khan reported.

Hypertension was significantly more prevalent in the obese PE patients (65% vs. 50.5%; P<0.001), as was chronic lung disease and chronic liver disease.

Obese patients more often received thrombolytics (3.6% vs. 1.9%; P<0.001) and mechanical ventilation (5.8% vs. 4%; P<0.001), and they more frequently had cardiogenic shock (0.65% vs. 0.45%; P<0.001).

The obese PE patients were more often female, black, and younger than 65 years of age.

Notably, the prevalence of obesity in PE patients more than doubled over the course of the study period, from 10.2% in 2002 to 22.6% in 2014.

The lower mortality in obese patients might be explained by increased levels of endocannabinoids, which have shown protective effects in rat and mouse studies, Dr. Khan said.

“I think it’s a rich area for more and further research, especially in basic science,” he added.

Dr. Khan and his coauthors said they had no relationships relevant to the study.

SAN ANTONIO—Patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) have a lower mortality risk if they are obese, according to a retrospective analysis of nearly 2 million PE discharges.

The obese patients had a lower mortality risk despite receiving more thrombolytics and mechanical intubation, said study investigator Zubair Khan, MD, of the University of Toledo Medical Center in Ohio.

“Surprisingly, the mortality of PE was significantly less in obese patients,” Dr. Khan said. “When we initiated the study, we did not expect this result.”

Dr. Khan discussed this result in a presentation at CHEST 2018.

Dr. Khan noted that the association between obesity and lower mortality, sometimes called the “obesity paradox,” has been observed in studies of other chronic health conditions, including stable heart failure, coronary artery disease, unstable angina, myocardial infarction, and also in some PE studies.

His team’s study, conducted using the National Inpatient Sample database, included adults with a primary discharge diagnosis of PE between 2002 and 2014. The researchers included 1,959,018 PE discharges, of which 312,770 (16%) had an underlying obesity diagnosis.

Obese PE patients had more risk factors and more severe disease but an overall mortality of 2.2%, compared with 3.7% in PE patients without obesity (P<0.001), Dr. Khan reported.

Hypertension was significantly more prevalent in the obese PE patients (65% vs. 50.5%; P<0.001), as was chronic lung disease and chronic liver disease.

Obese patients more often received thrombolytics (3.6% vs. 1.9%; P<0.001) and mechanical ventilation (5.8% vs. 4%; P<0.001), and they more frequently had cardiogenic shock (0.65% vs. 0.45%; P<0.001).

The obese PE patients were more often female, black, and younger than 65 years of age.

Notably, the prevalence of obesity in PE patients more than doubled over the course of the study period, from 10.2% in 2002 to 22.6% in 2014.

The lower mortality in obese patients might be explained by increased levels of endocannabinoids, which have shown protective effects in rat and mouse studies, Dr. Khan said.

“I think it’s a rich area for more and further research, especially in basic science,” he added.

Dr. Khan and his coauthors said they had no relationships relevant to the study.

Time to Stop Glucosamine and Chondroitin for Knee OA?

A 65-year-old man with moderately severe osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee presents to your office for his annual exam. During the medication review, the patient mentions he is using glucosamine and chondroitin for his knee pain, which was recommended by a family member. Should you tell the patient to continue taking the medication?

Knee OA is a common condition in the United States, affecting an estimated 12% of adults ages 60 and older and 16% of those ages 70 and older.2 The primary goals of OA therapy are to minimize pain and improve function. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) agree that firstline treatment recommendations include aerobic exercise, resistance training, and weight loss.

Initial pharmacologic therapies include full-strength acetaminophen or oral/topical NSAIDs; the latter are also used if pain is unresponsive to acetaminophen.3,4 If initial therapy is inadequate to control pain, tramadol, other opioids, duloxetine, or intra-articular injections with corticosteroids or hyaluronate are alternatives.3,4 Total knee replacement may be indicated in moderate or severe knee OA with radiographic evidence.5 Vitamin D, lateral wedge insoles, and antioxidants are not currently recommended.6

Prior studies evaluating glucosamine and/or chondroitin have provided conflicting results regarding evidence on pain reduction, function, and quality of life. Therefore, guidelines on OA management do not recommend their use (AAOS, strong; ACR, conditional).3,4 However, consumption remains high, with 6.5 million US adults reporting use of glucosamine and/or chondroitin in the prior 30 days.7

A 2015 systematic review of 43 randomized trials evaluating oral chondroitin sulfate for OA of varying severity suggested there may be a significant decrease in short-term and long-term pain with doses ≥ 800 mg/d compared with placebo (level of evidence, low; risk for bias, high).8 However, no significant difference was noted in short- or long-term function, and the trials were highly heterogeneous.

Studies included in the 2015 systematic review found that glucosamine plus chondroitin did not have a significant effect on short- or long-term pain or physical function compared with placebo. Although glucosamine plus chondroitin led to significantly decreased pain compared with other medication, sensitivity analyses conducted for larger studies (N > 200) with adequate methods of blinding and allocation concealment found no difference in pain.8 There was no statistically significant difference in adverse events for glucosamine plus chondroitin vs placebo, based on data from three studies included in the review.8

This RCT from Roman-Blas et al evaluated chondroitin and glucosamine vs placebo in patients with more severe OA. The study was supported by Tedec-Meiji Farma (Madrid), maker of the combination of chondroitin plus glucosamine used in the study.1

Continue to: STUDY SUMMARY

STUDY SUMMARY

Chondroitin + glucosamine not better than placebo

This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in nine rheumatology referral centers and one orthopedic center in Spain. The trial evaluated the efficacy of chondroitin sulfate (1,200 mg) plus glucosamine sulfate (1,500 mg) (CS/GS) compared with placebo in 164 patients with Grade 2 or 3 knee OA and moderate-to-severe knee pain. OA grade was ascertained using the Kellgren-Lawrence scale, corresponding to osteophytes and either possible (Grade 2) or definite (Grade 3) joint space narrowing. Knee pain severity was defined by a self-reported global pain score of 40 to 80 mm on a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS).

No significant difference was noted in group characteristics; average age in the CS/GS group was 67 and in the placebo group, 65. Exclusion criteria included BMI ≥ 35, concurrent arthritic conditions, and any coexisting chronic disease that would prevent successful completion of the trial.1

The primary endpoint was mean reduction in global pain score on a 0- to 100-mm VAS at six months. Secondary outcomes included mean reduction in total and subscale scores in pain and function on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) index (0–100-mm VAS for each) and the use of rescue medication.

Baseline global pain scores were 62 mm in both groups. Acetaminophen, up to 3 g/d, was the only allowed rescue medication. Clinic visits occurred at 4, 12, and 24 weeks. A statistically significant difference between groups was defined as P < .03.1

Results. In the intention-to-treat analysis at six months, patients in the placebo group had a greater reduction in pain than the CS/GC group (–20 mm vs –12 mm; P = .029). No other difference was noted between the placebo and CS/GS groups in the total or subscales of the WOMAC index, and no difference was noted in use of acetaminophen. More patients in the placebo group had at least a 50% improvement in pain or function compared with the CS/GS group (47.4% vs 27.5%; P = .01).

Continue to: In the CS/GS group...

In the CS/GS group, 31% did not complete the six-month treatment period, compared with 18% in the placebo group. More patients dropped out because of adverse effects (diarrhea, upper abdominal pain, and constipation) in the CS/GS group than the placebo group (33 vs 19; P = .018).1

WHAT’S NEW

Pharma-sponsored study finds treatment ineffective

The effectiveness of CS/GS for the treatment of knee OA has been in question for years, but this RCT is the first trial sponsored by a pharmaceutical company to evaluate CS/GS efficacy. This trial found evidence of a lack of efficacy. In patients with more severe OA of the knee, placebo was more effective than CS/GS, and CS/GS had significantly more adverse events. Therefore, it may be time to advise patients to stop taking their CS/GS supplement.

CAVEATS

Cannot generalize findings

The study compared only one medication dosing regimen using a combination of CS and GS. Whether either agent alone, or different dosing, would lead to the same outcome is unknown.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2018. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2018; 67[9]:566-568).

1. Roman-Blas JA, Castañeda S, Sánchez-Pernaute O, et al. Combined treatment with chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine sulfate shows no superiority over placebo for reduction of joint pain and functional impairment in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a six-month multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:77-85.

2. Dillon CF, Rasch EK, Gu Q, et al. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States: arthritis data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1991-94. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2271-2279.

3. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:465-474.

4. Brown GA. AAOS clinical practice guideline: treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd ed. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:577-579.

5. Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1145-1155.

6. Ebell MH. Osteoarthritis: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:523-526.

7. Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, et al. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002-2012. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2015;(79):1-16.

8. Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, MacDonald R, et al. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD005614.

A 65-year-old man with moderately severe osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee presents to your office for his annual exam. During the medication review, the patient mentions he is using glucosamine and chondroitin for his knee pain, which was recommended by a family member. Should you tell the patient to continue taking the medication?

Knee OA is a common condition in the United States, affecting an estimated 12% of adults ages 60 and older and 16% of those ages 70 and older.2 The primary goals of OA therapy are to minimize pain and improve function. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) agree that firstline treatment recommendations include aerobic exercise, resistance training, and weight loss.

Initial pharmacologic therapies include full-strength acetaminophen or oral/topical NSAIDs; the latter are also used if pain is unresponsive to acetaminophen.3,4 If initial therapy is inadequate to control pain, tramadol, other opioids, duloxetine, or intra-articular injections with corticosteroids or hyaluronate are alternatives.3,4 Total knee replacement may be indicated in moderate or severe knee OA with radiographic evidence.5 Vitamin D, lateral wedge insoles, and antioxidants are not currently recommended.6

Prior studies evaluating glucosamine and/or chondroitin have provided conflicting results regarding evidence on pain reduction, function, and quality of life. Therefore, guidelines on OA management do not recommend their use (AAOS, strong; ACR, conditional).3,4 However, consumption remains high, with 6.5 million US adults reporting use of glucosamine and/or chondroitin in the prior 30 days.7

A 2015 systematic review of 43 randomized trials evaluating oral chondroitin sulfate for OA of varying severity suggested there may be a significant decrease in short-term and long-term pain with doses ≥ 800 mg/d compared with placebo (level of evidence, low; risk for bias, high).8 However, no significant difference was noted in short- or long-term function, and the trials were highly heterogeneous.

Studies included in the 2015 systematic review found that glucosamine plus chondroitin did not have a significant effect on short- or long-term pain or physical function compared with placebo. Although glucosamine plus chondroitin led to significantly decreased pain compared with other medication, sensitivity analyses conducted for larger studies (N > 200) with adequate methods of blinding and allocation concealment found no difference in pain.8 There was no statistically significant difference in adverse events for glucosamine plus chondroitin vs placebo, based on data from three studies included in the review.8

This RCT from Roman-Blas et al evaluated chondroitin and glucosamine vs placebo in patients with more severe OA. The study was supported by Tedec-Meiji Farma (Madrid), maker of the combination of chondroitin plus glucosamine used in the study.1

Continue to: STUDY SUMMARY

STUDY SUMMARY

Chondroitin + glucosamine not better than placebo

This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in nine rheumatology referral centers and one orthopedic center in Spain. The trial evaluated the efficacy of chondroitin sulfate (1,200 mg) plus glucosamine sulfate (1,500 mg) (CS/GS) compared with placebo in 164 patients with Grade 2 or 3 knee OA and moderate-to-severe knee pain. OA grade was ascertained using the Kellgren-Lawrence scale, corresponding to osteophytes and either possible (Grade 2) or definite (Grade 3) joint space narrowing. Knee pain severity was defined by a self-reported global pain score of 40 to 80 mm on a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS).

No significant difference was noted in group characteristics; average age in the CS/GS group was 67 and in the placebo group, 65. Exclusion criteria included BMI ≥ 35, concurrent arthritic conditions, and any coexisting chronic disease that would prevent successful completion of the trial.1

The primary endpoint was mean reduction in global pain score on a 0- to 100-mm VAS at six months. Secondary outcomes included mean reduction in total and subscale scores in pain and function on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) index (0–100-mm VAS for each) and the use of rescue medication.

Baseline global pain scores were 62 mm in both groups. Acetaminophen, up to 3 g/d, was the only allowed rescue medication. Clinic visits occurred at 4, 12, and 24 weeks. A statistically significant difference between groups was defined as P < .03.1

Results. In the intention-to-treat analysis at six months, patients in the placebo group had a greater reduction in pain than the CS/GC group (–20 mm vs –12 mm; P = .029). No other difference was noted between the placebo and CS/GS groups in the total or subscales of the WOMAC index, and no difference was noted in use of acetaminophen. More patients in the placebo group had at least a 50% improvement in pain or function compared with the CS/GS group (47.4% vs 27.5%; P = .01).

Continue to: In the CS/GS group...

In the CS/GS group, 31% did not complete the six-month treatment period, compared with 18% in the placebo group. More patients dropped out because of adverse effects (diarrhea, upper abdominal pain, and constipation) in the CS/GS group than the placebo group (33 vs 19; P = .018).1

WHAT’S NEW

Pharma-sponsored study finds treatment ineffective

The effectiveness of CS/GS for the treatment of knee OA has been in question for years, but this RCT is the first trial sponsored by a pharmaceutical company to evaluate CS/GS efficacy. This trial found evidence of a lack of efficacy. In patients with more severe OA of the knee, placebo was more effective than CS/GS, and CS/GS had significantly more adverse events. Therefore, it may be time to advise patients to stop taking their CS/GS supplement.

CAVEATS

Cannot generalize findings

The study compared only one medication dosing regimen using a combination of CS and GS. Whether either agent alone, or different dosing, would lead to the same outcome is unknown.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2018. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2018; 67[9]:566-568).

A 65-year-old man with moderately severe osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee presents to your office for his annual exam. During the medication review, the patient mentions he is using glucosamine and chondroitin for his knee pain, which was recommended by a family member. Should you tell the patient to continue taking the medication?

Knee OA is a common condition in the United States, affecting an estimated 12% of adults ages 60 and older and 16% of those ages 70 and older.2 The primary goals of OA therapy are to minimize pain and improve function. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) agree that firstline treatment recommendations include aerobic exercise, resistance training, and weight loss.

Initial pharmacologic therapies include full-strength acetaminophen or oral/topical NSAIDs; the latter are also used if pain is unresponsive to acetaminophen.3,4 If initial therapy is inadequate to control pain, tramadol, other opioids, duloxetine, or intra-articular injections with corticosteroids or hyaluronate are alternatives.3,4 Total knee replacement may be indicated in moderate or severe knee OA with radiographic evidence.5 Vitamin D, lateral wedge insoles, and antioxidants are not currently recommended.6

Prior studies evaluating glucosamine and/or chondroitin have provided conflicting results regarding evidence on pain reduction, function, and quality of life. Therefore, guidelines on OA management do not recommend their use (AAOS, strong; ACR, conditional).3,4 However, consumption remains high, with 6.5 million US adults reporting use of glucosamine and/or chondroitin in the prior 30 days.7

A 2015 systematic review of 43 randomized trials evaluating oral chondroitin sulfate for OA of varying severity suggested there may be a significant decrease in short-term and long-term pain with doses ≥ 800 mg/d compared with placebo (level of evidence, low; risk for bias, high).8 However, no significant difference was noted in short- or long-term function, and the trials were highly heterogeneous.

Studies included in the 2015 systematic review found that glucosamine plus chondroitin did not have a significant effect on short- or long-term pain or physical function compared with placebo. Although glucosamine plus chondroitin led to significantly decreased pain compared with other medication, sensitivity analyses conducted for larger studies (N > 200) with adequate methods of blinding and allocation concealment found no difference in pain.8 There was no statistically significant difference in adverse events for glucosamine plus chondroitin vs placebo, based on data from three studies included in the review.8

This RCT from Roman-Blas et al evaluated chondroitin and glucosamine vs placebo in patients with more severe OA. The study was supported by Tedec-Meiji Farma (Madrid), maker of the combination of chondroitin plus glucosamine used in the study.1

Continue to: STUDY SUMMARY

STUDY SUMMARY

Chondroitin + glucosamine not better than placebo

This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in nine rheumatology referral centers and one orthopedic center in Spain. The trial evaluated the efficacy of chondroitin sulfate (1,200 mg) plus glucosamine sulfate (1,500 mg) (CS/GS) compared with placebo in 164 patients with Grade 2 or 3 knee OA and moderate-to-severe knee pain. OA grade was ascertained using the Kellgren-Lawrence scale, corresponding to osteophytes and either possible (Grade 2) or definite (Grade 3) joint space narrowing. Knee pain severity was defined by a self-reported global pain score of 40 to 80 mm on a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS).

No significant difference was noted in group characteristics; average age in the CS/GS group was 67 and in the placebo group, 65. Exclusion criteria included BMI ≥ 35, concurrent arthritic conditions, and any coexisting chronic disease that would prevent successful completion of the trial.1

The primary endpoint was mean reduction in global pain score on a 0- to 100-mm VAS at six months. Secondary outcomes included mean reduction in total and subscale scores in pain and function on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) index (0–100-mm VAS for each) and the use of rescue medication.

Baseline global pain scores were 62 mm in both groups. Acetaminophen, up to 3 g/d, was the only allowed rescue medication. Clinic visits occurred at 4, 12, and 24 weeks. A statistically significant difference between groups was defined as P < .03.1

Results. In the intention-to-treat analysis at six months, patients in the placebo group had a greater reduction in pain than the CS/GC group (–20 mm vs –12 mm; P = .029). No other difference was noted between the placebo and CS/GS groups in the total or subscales of the WOMAC index, and no difference was noted in use of acetaminophen. More patients in the placebo group had at least a 50% improvement in pain or function compared with the CS/GS group (47.4% vs 27.5%; P = .01).

Continue to: In the CS/GS group...

In the CS/GS group, 31% did not complete the six-month treatment period, compared with 18% in the placebo group. More patients dropped out because of adverse effects (diarrhea, upper abdominal pain, and constipation) in the CS/GS group than the placebo group (33 vs 19; P = .018).1

WHAT’S NEW

Pharma-sponsored study finds treatment ineffective

The effectiveness of CS/GS for the treatment of knee OA has been in question for years, but this RCT is the first trial sponsored by a pharmaceutical company to evaluate CS/GS efficacy. This trial found evidence of a lack of efficacy. In patients with more severe OA of the knee, placebo was more effective than CS/GS, and CS/GS had significantly more adverse events. Therefore, it may be time to advise patients to stop taking their CS/GS supplement.

CAVEATS

Cannot generalize findings

The study compared only one medication dosing regimen using a combination of CS and GS. Whether either agent alone, or different dosing, would lead to the same outcome is unknown.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2018. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2018; 67[9]:566-568).

1. Roman-Blas JA, Castañeda S, Sánchez-Pernaute O, et al. Combined treatment with chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine sulfate shows no superiority over placebo for reduction of joint pain and functional impairment in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a six-month multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:77-85.

2. Dillon CF, Rasch EK, Gu Q, et al. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States: arthritis data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1991-94. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2271-2279.

3. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:465-474.

4. Brown GA. AAOS clinical practice guideline: treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd ed. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:577-579.

5. Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1145-1155.

6. Ebell MH. Osteoarthritis: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:523-526.

7. Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, et al. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002-2012. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2015;(79):1-16.

8. Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, MacDonald R, et al. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD005614.

1. Roman-Blas JA, Castañeda S, Sánchez-Pernaute O, et al. Combined treatment with chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine sulfate shows no superiority over placebo for reduction of joint pain and functional impairment in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a six-month multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:77-85.

2. Dillon CF, Rasch EK, Gu Q, et al. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States: arthritis data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1991-94. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2271-2279.

3. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:465-474.

4. Brown GA. AAOS clinical practice guideline: treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd ed. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:577-579.

5. Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1145-1155.

6. Ebell MH. Osteoarthritis: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:523-526.

7. Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, et al. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002-2012. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2015;(79):1-16.

8. Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, MacDonald R, et al. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD005614.

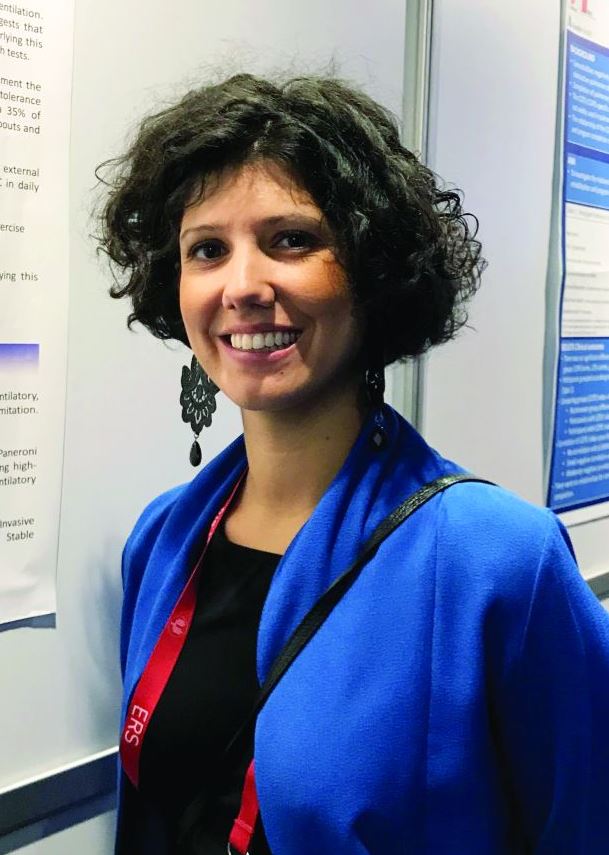

Nasal cannula device may be an option for severe COPD

PARIS – As an alternative to noninvasive ventilator devices (NIV), a battery-powered high-flow nasal cannula delivering heated air improves exercise tolerance as measured with the 6-minute walking distance (6MWD), according to a crossover trial presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Not least important, these preliminary results show treatment with the device to be well tolerated, a potential advantage over NIV, according to Ms. Rossi, who cited published studies suggesting up to 35% of patients are intolerant to ambulatory NIV therapy.

In the study, 12 clinically stable COPD patients with a 6MWD of less than 300 m and dyspnea at a low level of exertion were enrolled. In random order on 2 consecutive days, patients were evaluated with the 6MWD test while fitted with the high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) or while breathing room air.

The HFNC device delivers heated and humidified oxygen, which has been previously shown by the same group to improve oxygen saturation (Respir Med. 2016;118:128-32). In this study, the oxygen fraction (FiO2) of the air delivered by the proprietary HFNC device, marketed under the name AIRVO2 (Fisher & Paykel), was the same as the room air during the control exam.

In both tests, the patients performed the 6MWD while pushing a cart holding the device and the battery power source.

The mean 6MWD was 306 m using HFNC versus 267 m during the control test (P less than .05), even though the mean and nadir blood oxygenation (SpO2) levels were the same. However, the postexertion respiratory rate was significantly lower (P less than .05) when HFNC was used, Ms. Rossi reported. The inspiratory capacity was unchanged.

The improved levels of oxygen saturation (SaO2) demonstrated previously with high flows of humidified oxygen provided the basis for this preliminary crossover study, but a larger multicenter randomized trial was initiated last year. In that study with a planned enrollment of 160 COPD patients, the comparison will be between HFNC and usual oxygen delivered by a venturi mask. The primary outcome of the study, which will be completed early in 2019, is endurance improvement.

“COPD patients with severe dyspnea are frequently unable to achieve a workload that leads to improved exercise tolerance, with a result of reduced daily physical activities,” Ms. Rossi explained. She indicated that the HFNC, which is now being evaluated at several institutions, might be an important alternative to NIV in permitting patients to achieve adequate mobility.

The device is likely to be improved with technological advances, according to Ms. Rossi. She acknowledged that the current battery is heavy and the duration of the charge is relatively short, but she characterized this device as “good fit” for patients with very severe COPD. Only 8% of patients failed to complete this study.

Dr. Rossi reports no financial relationships relevant to this study.

PARIS – As an alternative to noninvasive ventilator devices (NIV), a battery-powered high-flow nasal cannula delivering heated air improves exercise tolerance as measured with the 6-minute walking distance (6MWD), according to a crossover trial presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Not least important, these preliminary results show treatment with the device to be well tolerated, a potential advantage over NIV, according to Ms. Rossi, who cited published studies suggesting up to 35% of patients are intolerant to ambulatory NIV therapy.

In the study, 12 clinically stable COPD patients with a 6MWD of less than 300 m and dyspnea at a low level of exertion were enrolled. In random order on 2 consecutive days, patients were evaluated with the 6MWD test while fitted with the high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) or while breathing room air.

The HFNC device delivers heated and humidified oxygen, which has been previously shown by the same group to improve oxygen saturation (Respir Med. 2016;118:128-32). In this study, the oxygen fraction (FiO2) of the air delivered by the proprietary HFNC device, marketed under the name AIRVO2 (Fisher & Paykel), was the same as the room air during the control exam.

In both tests, the patients performed the 6MWD while pushing a cart holding the device and the battery power source.

The mean 6MWD was 306 m using HFNC versus 267 m during the control test (P less than .05), even though the mean and nadir blood oxygenation (SpO2) levels were the same. However, the postexertion respiratory rate was significantly lower (P less than .05) when HFNC was used, Ms. Rossi reported. The inspiratory capacity was unchanged.

The improved levels of oxygen saturation (SaO2) demonstrated previously with high flows of humidified oxygen provided the basis for this preliminary crossover study, but a larger multicenter randomized trial was initiated last year. In that study with a planned enrollment of 160 COPD patients, the comparison will be between HFNC and usual oxygen delivered by a venturi mask. The primary outcome of the study, which will be completed early in 2019, is endurance improvement.

“COPD patients with severe dyspnea are frequently unable to achieve a workload that leads to improved exercise tolerance, with a result of reduced daily physical activities,” Ms. Rossi explained. She indicated that the HFNC, which is now being evaluated at several institutions, might be an important alternative to NIV in permitting patients to achieve adequate mobility.

The device is likely to be improved with technological advances, according to Ms. Rossi. She acknowledged that the current battery is heavy and the duration of the charge is relatively short, but she characterized this device as “good fit” for patients with very severe COPD. Only 8% of patients failed to complete this study.

Dr. Rossi reports no financial relationships relevant to this study.

PARIS – As an alternative to noninvasive ventilator devices (NIV), a battery-powered high-flow nasal cannula delivering heated air improves exercise tolerance as measured with the 6-minute walking distance (6MWD), according to a crossover trial presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Not least important, these preliminary results show treatment with the device to be well tolerated, a potential advantage over NIV, according to Ms. Rossi, who cited published studies suggesting up to 35% of patients are intolerant to ambulatory NIV therapy.

In the study, 12 clinically stable COPD patients with a 6MWD of less than 300 m and dyspnea at a low level of exertion were enrolled. In random order on 2 consecutive days, patients were evaluated with the 6MWD test while fitted with the high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) or while breathing room air.

The HFNC device delivers heated and humidified oxygen, which has been previously shown by the same group to improve oxygen saturation (Respir Med. 2016;118:128-32). In this study, the oxygen fraction (FiO2) of the air delivered by the proprietary HFNC device, marketed under the name AIRVO2 (Fisher & Paykel), was the same as the room air during the control exam.

In both tests, the patients performed the 6MWD while pushing a cart holding the device and the battery power source.

The mean 6MWD was 306 m using HFNC versus 267 m during the control test (P less than .05), even though the mean and nadir blood oxygenation (SpO2) levels were the same. However, the postexertion respiratory rate was significantly lower (P less than .05) when HFNC was used, Ms. Rossi reported. The inspiratory capacity was unchanged.

The improved levels of oxygen saturation (SaO2) demonstrated previously with high flows of humidified oxygen provided the basis for this preliminary crossover study, but a larger multicenter randomized trial was initiated last year. In that study with a planned enrollment of 160 COPD patients, the comparison will be between HFNC and usual oxygen delivered by a venturi mask. The primary outcome of the study, which will be completed early in 2019, is endurance improvement.

“COPD patients with severe dyspnea are frequently unable to achieve a workload that leads to improved exercise tolerance, with a result of reduced daily physical activities,” Ms. Rossi explained. She indicated that the HFNC, which is now being evaluated at several institutions, might be an important alternative to NIV in permitting patients to achieve adequate mobility.

The device is likely to be improved with technological advances, according to Ms. Rossi. She acknowledged that the current battery is heavy and the duration of the charge is relatively short, but she characterized this device as “good fit” for patients with very severe COPD. Only 8% of patients failed to complete this study.

Dr. Rossi reports no financial relationships relevant to this study.

REPORTNG FROM THE ERS CONGRESS 2018

Key clinical point: A battery-powered high-flow nasal cannula device improved the exercise capacity of patients with severe COPD.

Major finding: In a crossover study, the high-flow nasal cannula relative to no device increased mean 6-minute walking distance 39 m (15%).

Study details: Prospective crossover study.

Disclosures: Dr. Rossi reports no financial relationships relevant to this study.

In C. difficile, metronidazole may not benefit ICU patients on vancomycin

SAN FRANCISCO – , according to a review of 101 cases at the University of Maryland.

Adding metronidazole is a common move in ICUs when patients start circling the drain with C. difficile, in part because delivery to the gut doesn’t depend on gut motility. “At that point, you are throwing the kitchen sink at them, but it’s” based, like much in C. difficile management, on expert opinion, not evidence, said study lead Ana Vega, PharmD, a former resident at the university’s school of pharmacy in Baltimore, and now an infectious disease pharmacist at Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami. The investigators wanted to plug the evidence gap. Forty-seven of the 101 patients in their review – all with signs of C. difficile sepsis – had IV metronidazole added to their vancomycin regimens. Thirty-day mortality was 14.9% in the combination group versus 7.4% in the monotherapy arm, and not significantly different (P = .338). There were also no significant differences in resolution rates or normalization of white blood cell counts and temperature.

“Our data question the utility of” of adding IV metronidazole to oral vancomycin in patients with severe disease. “It’s definitely something to think twice about because metronidazole isn’t benign. It makes people feel crummy; you can induce resistance; and it increases the risk of vancomycin-resistant Enterococci colonization,” already a risk with vancomycin, Dr. Vega said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“When you get to the point that you are trying combination therapy based on expert opinion, I think fecal transplants are something to consider” because the success rates are so high. “That would be my suggestion,” she said, even though “it’s much easier to write an order for a drug than to get a fecal transplant.”

The issue is far from resolved, and debate will continue. A similar review of ICU patients at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, N.C., did find a significant mortality benefit with combination therapy, regardless of C. difficile severity (Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Sep 15. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ409).

The Maryland investigators excluded patients with toxic megacolon and other life-threatening intra-abdominal complications requiring surgery, because combination therapy is more strongly recommended in fulminant disease. They were interested in people who were not quite ready for the operating room, when what to do is more in doubt.

Subjects were admitted to the ICU from April 2016 to April 2018 with positive C. difficile nucleic acid testing and an order for oral vancomycin. The only statistically significant baseline differences were that patients who got IV metronidazole had higher median white blood cell counts (18,400 versus 13,900 cells/mL; P = .035) and were more likely to receive higher than 500-mg doses of vancomycin (36.2% versus 7.4%; P less than .0001).

The Mean Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score in the combination group was 23 versus 19 in the monotherapy arm (P = .247). There was no difference in the probability of receiving metronidazole based on the score.

The study again found no significant 30-day mortality differences among 76 patients matched by their APACHE II scores (15.8% in the combination arm versus 9.7%; P = .480).

Severe C. difficile infection was defined as either a white cell count above 15,000 or below 4,000 cells/mL, or a serum creatinine at least 1.5 times above baseline, plus at least one other sign of severe sepsis, such as a mean arterial pressure at or below 60 mm Hg. Metronidazole was started within 72 hours of the first vancomycin dose, and subjects on combination therapy were on both for at least 72 hours.

The mean age in the study was about 60 years old, and just over half of the subjects were men.

Dr. Vega said the investigators hope to expand their sample size and see if patients with more virulent strains of C. difficile do better on combination therapy.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators didn’t have any relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Vega AD et al. ID Week 2018, Abstract 488.

SAN FRANCISCO – , according to a review of 101 cases at the University of Maryland.

Adding metronidazole is a common move in ICUs when patients start circling the drain with C. difficile, in part because delivery to the gut doesn’t depend on gut motility. “At that point, you are throwing the kitchen sink at them, but it’s” based, like much in C. difficile management, on expert opinion, not evidence, said study lead Ana Vega, PharmD, a former resident at the university’s school of pharmacy in Baltimore, and now an infectious disease pharmacist at Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami. The investigators wanted to plug the evidence gap. Forty-seven of the 101 patients in their review – all with signs of C. difficile sepsis – had IV metronidazole added to their vancomycin regimens. Thirty-day mortality was 14.9% in the combination group versus 7.4% in the monotherapy arm, and not significantly different (P = .338). There were also no significant differences in resolution rates or normalization of white blood cell counts and temperature.

“Our data question the utility of” of adding IV metronidazole to oral vancomycin in patients with severe disease. “It’s definitely something to think twice about because metronidazole isn’t benign. It makes people feel crummy; you can induce resistance; and it increases the risk of vancomycin-resistant Enterococci colonization,” already a risk with vancomycin, Dr. Vega said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.