User login

Does the preterm birth racial disparity persist among black and white IVF users?

Investigators from the National Institutes of Health and Shady Grove Fertility found that among women having a singleton live birth resulting from in vitro fertilization (IVF) that black women are at higher risk for lower gestational age and preterm delivery than white women.1 The study results were presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6 to 10, Denver, Colorado).

Kate Devine, MD, coinvestigator of the retrospective cohort study said in an interview with OBG Management that “It’s been well documented that African Americans have a higher preterm birth rate in the United States compared to Caucasians and the overall population. While the exact mechanism of preterm birth is unknown and likely varied, and while the mechanism for the preterm birth rate being higher in African Americans is not well understood, it has been hypothesized that socioeconomic factors are responsible at least in part.”2 She added that the investigators used a population of women receiving IVF for the study because “access to reproductive care and IVF is in some way a leveling factor in terms of socioeconomics.”

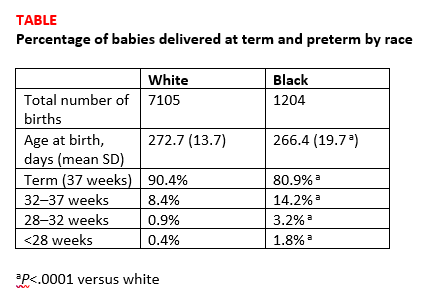

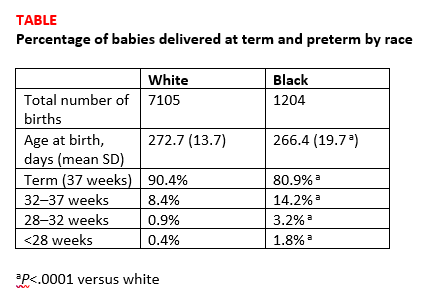

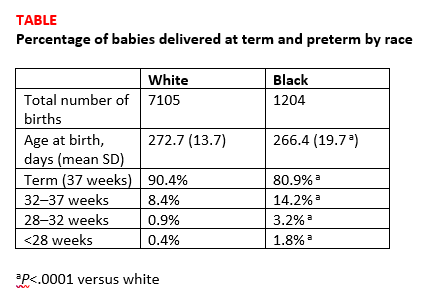

Details of the study. The investigators reviewed all singleton IVF pregnancies ending in live birth among women self-identifying as white, black, Asian, or Hispanic from 2004 to 2016 at a private IVF practice (N=10,371). The primary outcome was gestational age at birth, calculated as the number of days from oocyte retrieval to birth, plus 14, among white, black, Asian, and Hispanic women receiving IVF.

Births among black women occurred more than 6 days earlier than births among white women. The researchers noted that some of the shorter gestations among the black women could be explained by the higher average body mass index of the group (P<.0001). Dr. Devine explained that another contributing factor was the higher incidence of fibroid uterus among the black women (P<.0001). But after adjusting for these and other demographic variables, the black women still delivered 5.5 days earlier than the white women, and they were more than 3 times as likely to have either very preterm or extremely preterm deliveries (TABLE).1

Research implications. Dr. Devine said that black pregnant patients “perhaps should be monitored more closely” for signs or symptoms suggestive of preterm labor and would like to see more research into understanding the mechanisms of preterm birth that are resulting in greater rates of preterm birth among black women. She mentioned that research into how fibroids impact obstetric outcomes is also important.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letters to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Bishop LA, Devine K, Sasson I, et al. Lower gestational age and increased risk of preterm birth associated with singleton live birth resulting from in vitro fertilization (IVF) among African American versus comparable Caucasian women. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e7.

Investigators from the National Institutes of Health and Shady Grove Fertility found that among women having a singleton live birth resulting from in vitro fertilization (IVF) that black women are at higher risk for lower gestational age and preterm delivery than white women.1 The study results were presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6 to 10, Denver, Colorado).

Kate Devine, MD, coinvestigator of the retrospective cohort study said in an interview with OBG Management that “It’s been well documented that African Americans have a higher preterm birth rate in the United States compared to Caucasians and the overall population. While the exact mechanism of preterm birth is unknown and likely varied, and while the mechanism for the preterm birth rate being higher in African Americans is not well understood, it has been hypothesized that socioeconomic factors are responsible at least in part.”2 She added that the investigators used a population of women receiving IVF for the study because “access to reproductive care and IVF is in some way a leveling factor in terms of socioeconomics.”

Details of the study. The investigators reviewed all singleton IVF pregnancies ending in live birth among women self-identifying as white, black, Asian, or Hispanic from 2004 to 2016 at a private IVF practice (N=10,371). The primary outcome was gestational age at birth, calculated as the number of days from oocyte retrieval to birth, plus 14, among white, black, Asian, and Hispanic women receiving IVF.

Births among black women occurred more than 6 days earlier than births among white women. The researchers noted that some of the shorter gestations among the black women could be explained by the higher average body mass index of the group (P<.0001). Dr. Devine explained that another contributing factor was the higher incidence of fibroid uterus among the black women (P<.0001). But after adjusting for these and other demographic variables, the black women still delivered 5.5 days earlier than the white women, and they were more than 3 times as likely to have either very preterm or extremely preterm deliveries (TABLE).1

Research implications. Dr. Devine said that black pregnant patients “perhaps should be monitored more closely” for signs or symptoms suggestive of preterm labor and would like to see more research into understanding the mechanisms of preterm birth that are resulting in greater rates of preterm birth among black women. She mentioned that research into how fibroids impact obstetric outcomes is also important.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letters to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Investigators from the National Institutes of Health and Shady Grove Fertility found that among women having a singleton live birth resulting from in vitro fertilization (IVF) that black women are at higher risk for lower gestational age and preterm delivery than white women.1 The study results were presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6 to 10, Denver, Colorado).

Kate Devine, MD, coinvestigator of the retrospective cohort study said in an interview with OBG Management that “It’s been well documented that African Americans have a higher preterm birth rate in the United States compared to Caucasians and the overall population. While the exact mechanism of preterm birth is unknown and likely varied, and while the mechanism for the preterm birth rate being higher in African Americans is not well understood, it has been hypothesized that socioeconomic factors are responsible at least in part.”2 She added that the investigators used a population of women receiving IVF for the study because “access to reproductive care and IVF is in some way a leveling factor in terms of socioeconomics.”

Details of the study. The investigators reviewed all singleton IVF pregnancies ending in live birth among women self-identifying as white, black, Asian, or Hispanic from 2004 to 2016 at a private IVF practice (N=10,371). The primary outcome was gestational age at birth, calculated as the number of days from oocyte retrieval to birth, plus 14, among white, black, Asian, and Hispanic women receiving IVF.

Births among black women occurred more than 6 days earlier than births among white women. The researchers noted that some of the shorter gestations among the black women could be explained by the higher average body mass index of the group (P<.0001). Dr. Devine explained that another contributing factor was the higher incidence of fibroid uterus among the black women (P<.0001). But after adjusting for these and other demographic variables, the black women still delivered 5.5 days earlier than the white women, and they were more than 3 times as likely to have either very preterm or extremely preterm deliveries (TABLE).1

Research implications. Dr. Devine said that black pregnant patients “perhaps should be monitored more closely” for signs or symptoms suggestive of preterm labor and would like to see more research into understanding the mechanisms of preterm birth that are resulting in greater rates of preterm birth among black women. She mentioned that research into how fibroids impact obstetric outcomes is also important.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letters to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Bishop LA, Devine K, Sasson I, et al. Lower gestational age and increased risk of preterm birth associated with singleton live birth resulting from in vitro fertilization (IVF) among African American versus comparable Caucasian women. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e7.

- Bishop LA, Devine K, Sasson I, et al. Lower gestational age and increased risk of preterm birth associated with singleton live birth resulting from in vitro fertilization (IVF) among African American versus comparable Caucasian women. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e7.

Aspirin cuts risk of ovarian and liver cancer

Regular long-term aspirin use may lower the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and ovarian cancer, adding to the growing evidence that aspirin may play a role as a chemopreventive agent, according to two new studies published in JAMA Oncology.

In the first study, led by Tracey G. Simon, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, the authors evaluated the associations between aspirin dose and duration of use and the risk of developing HCC. They conducted a population-based study, with a pooled analysis of two large prospective U.S. cohort studies: the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. The cohort included a total of 133,371 health care professionals who reported long-term data on aspirin use, frequency, dosage, and duration of use.

For the 87,507 female participants, reporting began in 1980, and for the 45,864 men, reporting began in 1986. The mean age for women was 62 years and was 64 years for men at the midpoint of follow-up (1996). Compared with nonaspirin users, those who used aspirin regularly tended to be older, former smokers, and regularly used statins and multivitamins. During the follow-up period, which was more than 26 years, there were 108 incident cases of HCC (65 women, 43 men; 47 with noncirrhotic HCC).

The investigators found that regular aspirin use was associated with a significantly lower HCC risk versus nonregular use (multivariable hazard ratio, 0.51; 95% confidence interval, 0.34-0.77), and estimates were similar for both sexes. Adjustments for regular NSAID use (for example, at least two tablets per week) did not change the data, and results were similar after further adjustment for coffee consumption and adherence to a healthy diet. The benefit also appeared to be dose related, as compared with nonuse, the multivariable-adjusted HR for HCC was 0.87 (95% CI, 0.51-1.48) for up to 1.5 tablets of standard-dose aspirin per week and 0.51 (95% CI, 0.30-0.86) for 1.5-5 tablets per week. The most benefit was for at least five tablets per week (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.28-0.96; P = .006).

“Our findings add to the growing literature suggesting that the chemopreventive effects of aspirin may extend beyond colorectal cancer,” they wrote.

In the second study, Mollie E. Barnard, ScD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, and her colleagues looked at whether regular aspirin or NSAID use, as well as the patterns of use, were associated with a lower risk of ovarian cancer.

The data used were obtained from 93,664 women in the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), who were followed up from 1980 to 2014, and 111,834 people in the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII), who were followed up from 1989 to 2015. For each type of agent, including aspirin, low-dose aspirin, nonaspirin NSAIDs, and acetaminophen, they evaluated the timing, duration, frequency, and number of tablets that were used. The mean age of participants in the NHS at baseline was 45.9 years and 34.2 years in the NHSII.

There were 1,054 incident cases of epithelial ovarian cancer identified during the study period. The authors did not detect any significant associations between aspirin and ovarian cancer risk when current users and nonusers were compared, regardless of dose (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.83-1.19). But when low-dose (less than or equal to 100 mg) and standard-dose (325 mg) aspirin were analyzed separately, an inverse association for low-dose aspirin (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.61-0.96) was observed. However, there was no association for standard-dose aspirin (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.92-1.49).

In contrast, use of nonaspirin NSAIDs was positively associated with a higher risk of ovarian cancer when compared with nonuse (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.00-1.41), and there were significant positive trends for duration of use (P = .02) and cumulative average tablets per week (P = .03). No clear associations were identified for acetaminophen use.

“Our results also suggest an increased risk of ovarian cancer among long-term, high-quantity users of nonaspirin analgesics, although this finding may reflect unmeasured confounding,” wrote Dr. Barnard and her coauthors. “Further exploration is warranted to evaluate the mechanisms by which heavy use of aspirin, nonaspirin NSAIDs, and acetaminophen may contribute to the development of ovarian cancer and to replicate our findings.”

The ovarian cancer study was supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Barnard was supported by awards from the National Cancer Institute, and her coauthors had no disclosures to report. The HCC study was funded by an infrastructure grant from the Nurses’ Health Study, an infrastructure grant from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, and NIH grants to several of the authors. Dr. Chan has previously served as a consultant for Bayer on work unrelated to this article. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCES: Barnard ME et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 4. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4149; Simon TG et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 4. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4154.

In an accompanying editorial published in JAMA Oncology, Victoria L. Seewaldt, MD, of the City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center in Duarte, Calif., asked if we “have arrived,” as these two studies are a critical step in realizing the potential of aspirin for cancer chemoprevention beyond colorectal cancer.

Aspirin use is very common in the United States, with almost half of adults aged between 45 and 75 years taking it regularly. Many regular users also believe that aspirin has potential to protect against cancer, and in a 2015 study – which was conducted prior to any formal cancer prevention guidelines – 18% of those taking aspirin on a regular basis reported doing so to prevent cancer.

Based on the strength of the association between aspirin use and colorectal cancer risk reduction, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended in 2015 that, among individuals aged between 50 and 69 years who have specific cardiovascular risk profiles, colorectal cancer prevention be included as part of the rationale for regular aspirin prophylaxis, Dr. Seewaldt noted. Aspirin became the first drug to be included in USPSTF recommendations for cancer chemoprevention in a “population not characterized as having a high risk of developing cancer.”

But it now appears aspirin may be able to go beyond colorectal cancer for chemoprevention. Ovarian cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma are in need of new prevention strategies and these findings provide important information that can help guide chemoprevention with aspirin.

These two studies “have the power to start to change clinical practice,” Dr. Seewaldt wrote, but more research is needed to better understand the underlying mechanism behind the appropriate dose and duration of use. Importantly, the authors of both studies cautioned that the potential benefits of aspirin must be weighed against the risk of bleeding, which is particularly important in patients with chronic liver disease.

“To reach the full promise of aspirin’s ability to prevent cancer, there needs to be better understanding of dose, duration, and mechanism,” she emphasized.

Dr. Seewaldt reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute and is supported by the Prevent Cancer Foundation.

In an accompanying editorial published in JAMA Oncology, Victoria L. Seewaldt, MD, of the City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center in Duarte, Calif., asked if we “have arrived,” as these two studies are a critical step in realizing the potential of aspirin for cancer chemoprevention beyond colorectal cancer.

Aspirin use is very common in the United States, with almost half of adults aged between 45 and 75 years taking it regularly. Many regular users also believe that aspirin has potential to protect against cancer, and in a 2015 study – which was conducted prior to any formal cancer prevention guidelines – 18% of those taking aspirin on a regular basis reported doing so to prevent cancer.

Based on the strength of the association between aspirin use and colorectal cancer risk reduction, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended in 2015 that, among individuals aged between 50 and 69 years who have specific cardiovascular risk profiles, colorectal cancer prevention be included as part of the rationale for regular aspirin prophylaxis, Dr. Seewaldt noted. Aspirin became the first drug to be included in USPSTF recommendations for cancer chemoprevention in a “population not characterized as having a high risk of developing cancer.”

But it now appears aspirin may be able to go beyond colorectal cancer for chemoprevention. Ovarian cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma are in need of new prevention strategies and these findings provide important information that can help guide chemoprevention with aspirin.

These two studies “have the power to start to change clinical practice,” Dr. Seewaldt wrote, but more research is needed to better understand the underlying mechanism behind the appropriate dose and duration of use. Importantly, the authors of both studies cautioned that the potential benefits of aspirin must be weighed against the risk of bleeding, which is particularly important in patients with chronic liver disease.

“To reach the full promise of aspirin’s ability to prevent cancer, there needs to be better understanding of dose, duration, and mechanism,” she emphasized.

Dr. Seewaldt reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute and is supported by the Prevent Cancer Foundation.

In an accompanying editorial published in JAMA Oncology, Victoria L. Seewaldt, MD, of the City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center in Duarte, Calif., asked if we “have arrived,” as these two studies are a critical step in realizing the potential of aspirin for cancer chemoprevention beyond colorectal cancer.

Aspirin use is very common in the United States, with almost half of adults aged between 45 and 75 years taking it regularly. Many regular users also believe that aspirin has potential to protect against cancer, and in a 2015 study – which was conducted prior to any formal cancer prevention guidelines – 18% of those taking aspirin on a regular basis reported doing so to prevent cancer.

Based on the strength of the association between aspirin use and colorectal cancer risk reduction, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended in 2015 that, among individuals aged between 50 and 69 years who have specific cardiovascular risk profiles, colorectal cancer prevention be included as part of the rationale for regular aspirin prophylaxis, Dr. Seewaldt noted. Aspirin became the first drug to be included in USPSTF recommendations for cancer chemoprevention in a “population not characterized as having a high risk of developing cancer.”

But it now appears aspirin may be able to go beyond colorectal cancer for chemoprevention. Ovarian cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma are in need of new prevention strategies and these findings provide important information that can help guide chemoprevention with aspirin.

These two studies “have the power to start to change clinical practice,” Dr. Seewaldt wrote, but more research is needed to better understand the underlying mechanism behind the appropriate dose and duration of use. Importantly, the authors of both studies cautioned that the potential benefits of aspirin must be weighed against the risk of bleeding, which is particularly important in patients with chronic liver disease.

“To reach the full promise of aspirin’s ability to prevent cancer, there needs to be better understanding of dose, duration, and mechanism,” she emphasized.

Dr. Seewaldt reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute and is supported by the Prevent Cancer Foundation.

Regular long-term aspirin use may lower the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and ovarian cancer, adding to the growing evidence that aspirin may play a role as a chemopreventive agent, according to two new studies published in JAMA Oncology.

In the first study, led by Tracey G. Simon, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, the authors evaluated the associations between aspirin dose and duration of use and the risk of developing HCC. They conducted a population-based study, with a pooled analysis of two large prospective U.S. cohort studies: the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. The cohort included a total of 133,371 health care professionals who reported long-term data on aspirin use, frequency, dosage, and duration of use.

For the 87,507 female participants, reporting began in 1980, and for the 45,864 men, reporting began in 1986. The mean age for women was 62 years and was 64 years for men at the midpoint of follow-up (1996). Compared with nonaspirin users, those who used aspirin regularly tended to be older, former smokers, and regularly used statins and multivitamins. During the follow-up period, which was more than 26 years, there were 108 incident cases of HCC (65 women, 43 men; 47 with noncirrhotic HCC).

The investigators found that regular aspirin use was associated with a significantly lower HCC risk versus nonregular use (multivariable hazard ratio, 0.51; 95% confidence interval, 0.34-0.77), and estimates were similar for both sexes. Adjustments for regular NSAID use (for example, at least two tablets per week) did not change the data, and results were similar after further adjustment for coffee consumption and adherence to a healthy diet. The benefit also appeared to be dose related, as compared with nonuse, the multivariable-adjusted HR for HCC was 0.87 (95% CI, 0.51-1.48) for up to 1.5 tablets of standard-dose aspirin per week and 0.51 (95% CI, 0.30-0.86) for 1.5-5 tablets per week. The most benefit was for at least five tablets per week (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.28-0.96; P = .006).

“Our findings add to the growing literature suggesting that the chemopreventive effects of aspirin may extend beyond colorectal cancer,” they wrote.

In the second study, Mollie E. Barnard, ScD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, and her colleagues looked at whether regular aspirin or NSAID use, as well as the patterns of use, were associated with a lower risk of ovarian cancer.

The data used were obtained from 93,664 women in the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), who were followed up from 1980 to 2014, and 111,834 people in the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII), who were followed up from 1989 to 2015. For each type of agent, including aspirin, low-dose aspirin, nonaspirin NSAIDs, and acetaminophen, they evaluated the timing, duration, frequency, and number of tablets that were used. The mean age of participants in the NHS at baseline was 45.9 years and 34.2 years in the NHSII.

There were 1,054 incident cases of epithelial ovarian cancer identified during the study period. The authors did not detect any significant associations between aspirin and ovarian cancer risk when current users and nonusers were compared, regardless of dose (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.83-1.19). But when low-dose (less than or equal to 100 mg) and standard-dose (325 mg) aspirin were analyzed separately, an inverse association for low-dose aspirin (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.61-0.96) was observed. However, there was no association for standard-dose aspirin (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.92-1.49).

In contrast, use of nonaspirin NSAIDs was positively associated with a higher risk of ovarian cancer when compared with nonuse (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.00-1.41), and there were significant positive trends for duration of use (P = .02) and cumulative average tablets per week (P = .03). No clear associations were identified for acetaminophen use.

“Our results also suggest an increased risk of ovarian cancer among long-term, high-quantity users of nonaspirin analgesics, although this finding may reflect unmeasured confounding,” wrote Dr. Barnard and her coauthors. “Further exploration is warranted to evaluate the mechanisms by which heavy use of aspirin, nonaspirin NSAIDs, and acetaminophen may contribute to the development of ovarian cancer and to replicate our findings.”

The ovarian cancer study was supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Barnard was supported by awards from the National Cancer Institute, and her coauthors had no disclosures to report. The HCC study was funded by an infrastructure grant from the Nurses’ Health Study, an infrastructure grant from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, and NIH grants to several of the authors. Dr. Chan has previously served as a consultant for Bayer on work unrelated to this article. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCES: Barnard ME et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 4. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4149; Simon TG et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 4. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4154.

Regular long-term aspirin use may lower the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and ovarian cancer, adding to the growing evidence that aspirin may play a role as a chemopreventive agent, according to two new studies published in JAMA Oncology.

In the first study, led by Tracey G. Simon, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, the authors evaluated the associations between aspirin dose and duration of use and the risk of developing HCC. They conducted a population-based study, with a pooled analysis of two large prospective U.S. cohort studies: the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. The cohort included a total of 133,371 health care professionals who reported long-term data on aspirin use, frequency, dosage, and duration of use.

For the 87,507 female participants, reporting began in 1980, and for the 45,864 men, reporting began in 1986. The mean age for women was 62 years and was 64 years for men at the midpoint of follow-up (1996). Compared with nonaspirin users, those who used aspirin regularly tended to be older, former smokers, and regularly used statins and multivitamins. During the follow-up period, which was more than 26 years, there were 108 incident cases of HCC (65 women, 43 men; 47 with noncirrhotic HCC).

The investigators found that regular aspirin use was associated with a significantly lower HCC risk versus nonregular use (multivariable hazard ratio, 0.51; 95% confidence interval, 0.34-0.77), and estimates were similar for both sexes. Adjustments for regular NSAID use (for example, at least two tablets per week) did not change the data, and results were similar after further adjustment for coffee consumption and adherence to a healthy diet. The benefit also appeared to be dose related, as compared with nonuse, the multivariable-adjusted HR for HCC was 0.87 (95% CI, 0.51-1.48) for up to 1.5 tablets of standard-dose aspirin per week and 0.51 (95% CI, 0.30-0.86) for 1.5-5 tablets per week. The most benefit was for at least five tablets per week (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.28-0.96; P = .006).

“Our findings add to the growing literature suggesting that the chemopreventive effects of aspirin may extend beyond colorectal cancer,” they wrote.

In the second study, Mollie E. Barnard, ScD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, and her colleagues looked at whether regular aspirin or NSAID use, as well as the patterns of use, were associated with a lower risk of ovarian cancer.

The data used were obtained from 93,664 women in the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), who were followed up from 1980 to 2014, and 111,834 people in the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII), who were followed up from 1989 to 2015. For each type of agent, including aspirin, low-dose aspirin, nonaspirin NSAIDs, and acetaminophen, they evaluated the timing, duration, frequency, and number of tablets that were used. The mean age of participants in the NHS at baseline was 45.9 years and 34.2 years in the NHSII.

There were 1,054 incident cases of epithelial ovarian cancer identified during the study period. The authors did not detect any significant associations between aspirin and ovarian cancer risk when current users and nonusers were compared, regardless of dose (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.83-1.19). But when low-dose (less than or equal to 100 mg) and standard-dose (325 mg) aspirin were analyzed separately, an inverse association for low-dose aspirin (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.61-0.96) was observed. However, there was no association for standard-dose aspirin (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.92-1.49).

In contrast, use of nonaspirin NSAIDs was positively associated with a higher risk of ovarian cancer when compared with nonuse (HR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.00-1.41), and there were significant positive trends for duration of use (P = .02) and cumulative average tablets per week (P = .03). No clear associations were identified for acetaminophen use.

“Our results also suggest an increased risk of ovarian cancer among long-term, high-quantity users of nonaspirin analgesics, although this finding may reflect unmeasured confounding,” wrote Dr. Barnard and her coauthors. “Further exploration is warranted to evaluate the mechanisms by which heavy use of aspirin, nonaspirin NSAIDs, and acetaminophen may contribute to the development of ovarian cancer and to replicate our findings.”

The ovarian cancer study was supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Barnard was supported by awards from the National Cancer Institute, and her coauthors had no disclosures to report. The HCC study was funded by an infrastructure grant from the Nurses’ Health Study, an infrastructure grant from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, and NIH grants to several of the authors. Dr. Chan has previously served as a consultant for Bayer on work unrelated to this article. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCES: Barnard ME et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 4. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4149; Simon TG et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 4. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4154.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Regular aspirin use was associated with a decreased risk of ovarian cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Major finding: Low-dose aspirin was associated with a 23% lower risk of ovarian cancer and a 49% reduced risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma.

Study details: The hepatocellular carcinoma study was a population-based study of two nationwide, prospective cohorts of 87,507 men and 45,864 women; the ovarian cancer study was a cohort study using data from two prospective cohorts, with 93,664 people in one and 111,834 in the other.

Disclosures: The ovarian cancer study was supported by awards from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Barnard was supported by awards from the National Cancer Institute, and her coauthors had no disclosures to report. The hepatocellular carcinoma study was funded by an infrastructure grant from the Nurses’ Health Study, an infrastructure grant from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, and NIH grants to several of the authors. Dr. Chan has previously served as a consultant for Bayer on work unrelated to this article. No other disclosures were reported.

Sources: Barnard ME et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 4. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4149; Simon TG et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 4. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4154.

Two-thirds of COPD patients not using inhalers correctly

SAN ANTONIO – Two-thirds of U.S. adults with (MDIs), according to new research. About half of patients failed to inhale slowly and deeply to ensure they received the appropriate dose, and about 40% of patients failed to hold their breath for 5-10 seconds afterward so that the medication made its way to their lungs, the findings show.

“There’s a need to educate patients on proper inhalation technique to optimize the appropriate delivery of medication,” Maryam Navaie, DrPH, of Advance Health Solutions in New York told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. She also urged practitioners to think more carefully about what devices to prescribe to patients based on their own personal attributes.

“Nebulizer devices may be a better consideration for patients who have difficulty performing the necessary steps required by handheld inhalers,” Dr. Navaie said.

She and fellow researchers conducted a systematic review to gain more insights into the errors and difficulties experienced by U.S. adults using MDIs for COPD or asthma. They combed through PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Cochrane, and Google Scholar databases for English language studies about MDI-related errors in U.S. adult COPD or asthma patients published between January 2003 and February 2017.

The researchers included only randomized controlled trials and cross-sectional and observational studies, and they excluded studies with combined error rates across multiple devices so they could better parse out the data. They also used baseline rates only in studies that involved an intervention to reduce errors.

The researchers defined the proportion of overall MDI errors as “the percentage of patients who made errors in equal to or greater than 20% of inhalation steps.” They computed pooled estimates and created forest plots for both overall errors and for errors according to each step in using an MDI.

The eight studies they identified involved 1,221 patients, with ages ranging from a mean 48 to 82 years, 53% of whom were female. Nearly two-thirds of the patients had COPD (63.6%) while 36.4% had asthma. Most of the devices studied were MDIs alone (68.8%), while 31.2% included a spacer.

The pooled weighted average revealed a 66.5% error rate, that is, two-thirds of all the patients were making at least two errors during the 10 steps involved in using their device. The researchers then used individual error rates data in five studies to calculate the overall error rate for each step in using MDIs. The most common error, made by 73.8% of people in those five studies, was failing to attach the inhaler to the spacer. In addition, 68.7% of patients were failing to exhale fully and away from the inhaler before inhaling, and 47.8% were inhaling too fast instead of inhaling deeply.

“So these [findings] actually give you [some specific] ideas of how we could help improve patients’ ability to use the device properly,” Dr. Navaie told attendees, adding that these data can inform patient education needs and interventions.

Based on the data from those five studies, the error rates for all 10 steps to using an MDI were as follows:

- Failed to shake inhaler before use (37.9%).

- Failed to attach inhaler to spacer (73.8%).

- Failed to exhale fully and away from inhaler before inhalation (68.7%).

- Failed to place mouthpiece between teeth and sealed lips (7.4%).

- Failed to actuate once during inhalation (24.4%).

- Inhalation too fast, not deep (47.8%).

- Failed to hold breath for 5-10 seconds (40.1%).

- Failed to remove the inhaler/spacer from mouth (11.3%).

- Failed to exhale after inhalation (33.2%).

- Failed to repeat steps for second puff (36.7%).

Dr. Navaie also noted the investigators were surprised to learn that physicians themselves sometimes make several of these errors in explaining to patients how to use their devices.

“I think for the reps and other people who go out and visit doctors, it’s important to think about making sure the clinicians are using the devices properly,” Dr. Navaie said. She pointed out the potential for patients to forget steps between visits.

“One of the things a lot of our clinicians and key opinion leaders told us during the course of this study is that you shouldn’t just educate the patient at the time you are scripting the device but repeatedly because patients forget,” she said. She recommended having patients demonstrate their use of the device at each visit. If patients continue to struggle, it may be worth considering other therapies, such as a nebulizer, for patients unable to regularly use their devices correctly.

The meta-analysis was limited by the sparse research available in general on MDI errors in the U.S. adult population, so the data on error rates for each individual step may not be broadly generalizable. The studies also did not distinguish between rates among users with asthma vs. users with COPD. Further, too few data exist on associations between MDI errors and health outcomes to have a clear picture of the clinical implications of regularly making multiple errors in MDI use.

Dr. Navaie is employed by Advance Health Solutions, which received Sunovion Pharmaceuticals funding for the study.

SOURCE: Navaie M et al. CHEST 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.705.

SAN ANTONIO – Two-thirds of U.S. adults with (MDIs), according to new research. About half of patients failed to inhale slowly and deeply to ensure they received the appropriate dose, and about 40% of patients failed to hold their breath for 5-10 seconds afterward so that the medication made its way to their lungs, the findings show.

“There’s a need to educate patients on proper inhalation technique to optimize the appropriate delivery of medication,” Maryam Navaie, DrPH, of Advance Health Solutions in New York told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. She also urged practitioners to think more carefully about what devices to prescribe to patients based on their own personal attributes.

“Nebulizer devices may be a better consideration for patients who have difficulty performing the necessary steps required by handheld inhalers,” Dr. Navaie said.

She and fellow researchers conducted a systematic review to gain more insights into the errors and difficulties experienced by U.S. adults using MDIs for COPD or asthma. They combed through PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Cochrane, and Google Scholar databases for English language studies about MDI-related errors in U.S. adult COPD or asthma patients published between January 2003 and February 2017.

The researchers included only randomized controlled trials and cross-sectional and observational studies, and they excluded studies with combined error rates across multiple devices so they could better parse out the data. They also used baseline rates only in studies that involved an intervention to reduce errors.

The researchers defined the proportion of overall MDI errors as “the percentage of patients who made errors in equal to or greater than 20% of inhalation steps.” They computed pooled estimates and created forest plots for both overall errors and for errors according to each step in using an MDI.

The eight studies they identified involved 1,221 patients, with ages ranging from a mean 48 to 82 years, 53% of whom were female. Nearly two-thirds of the patients had COPD (63.6%) while 36.4% had asthma. Most of the devices studied were MDIs alone (68.8%), while 31.2% included a spacer.

The pooled weighted average revealed a 66.5% error rate, that is, two-thirds of all the patients were making at least two errors during the 10 steps involved in using their device. The researchers then used individual error rates data in five studies to calculate the overall error rate for each step in using MDIs. The most common error, made by 73.8% of people in those five studies, was failing to attach the inhaler to the spacer. In addition, 68.7% of patients were failing to exhale fully and away from the inhaler before inhaling, and 47.8% were inhaling too fast instead of inhaling deeply.

“So these [findings] actually give you [some specific] ideas of how we could help improve patients’ ability to use the device properly,” Dr. Navaie told attendees, adding that these data can inform patient education needs and interventions.

Based on the data from those five studies, the error rates for all 10 steps to using an MDI were as follows:

- Failed to shake inhaler before use (37.9%).

- Failed to attach inhaler to spacer (73.8%).

- Failed to exhale fully and away from inhaler before inhalation (68.7%).

- Failed to place mouthpiece between teeth and sealed lips (7.4%).

- Failed to actuate once during inhalation (24.4%).

- Inhalation too fast, not deep (47.8%).

- Failed to hold breath for 5-10 seconds (40.1%).

- Failed to remove the inhaler/spacer from mouth (11.3%).

- Failed to exhale after inhalation (33.2%).

- Failed to repeat steps for second puff (36.7%).

Dr. Navaie also noted the investigators were surprised to learn that physicians themselves sometimes make several of these errors in explaining to patients how to use their devices.

“I think for the reps and other people who go out and visit doctors, it’s important to think about making sure the clinicians are using the devices properly,” Dr. Navaie said. She pointed out the potential for patients to forget steps between visits.

“One of the things a lot of our clinicians and key opinion leaders told us during the course of this study is that you shouldn’t just educate the patient at the time you are scripting the device but repeatedly because patients forget,” she said. She recommended having patients demonstrate their use of the device at each visit. If patients continue to struggle, it may be worth considering other therapies, such as a nebulizer, for patients unable to regularly use their devices correctly.

The meta-analysis was limited by the sparse research available in general on MDI errors in the U.S. adult population, so the data on error rates for each individual step may not be broadly generalizable. The studies also did not distinguish between rates among users with asthma vs. users with COPD. Further, too few data exist on associations between MDI errors and health outcomes to have a clear picture of the clinical implications of regularly making multiple errors in MDI use.

Dr. Navaie is employed by Advance Health Solutions, which received Sunovion Pharmaceuticals funding for the study.

SOURCE: Navaie M et al. CHEST 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.705.

SAN ANTONIO – Two-thirds of U.S. adults with (MDIs), according to new research. About half of patients failed to inhale slowly and deeply to ensure they received the appropriate dose, and about 40% of patients failed to hold their breath for 5-10 seconds afterward so that the medication made its way to their lungs, the findings show.

“There’s a need to educate patients on proper inhalation technique to optimize the appropriate delivery of medication,” Maryam Navaie, DrPH, of Advance Health Solutions in New York told attendees at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians. She also urged practitioners to think more carefully about what devices to prescribe to patients based on their own personal attributes.

“Nebulizer devices may be a better consideration for patients who have difficulty performing the necessary steps required by handheld inhalers,” Dr. Navaie said.

She and fellow researchers conducted a systematic review to gain more insights into the errors and difficulties experienced by U.S. adults using MDIs for COPD or asthma. They combed through PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Cochrane, and Google Scholar databases for English language studies about MDI-related errors in U.S. adult COPD or asthma patients published between January 2003 and February 2017.

The researchers included only randomized controlled trials and cross-sectional and observational studies, and they excluded studies with combined error rates across multiple devices so they could better parse out the data. They also used baseline rates only in studies that involved an intervention to reduce errors.

The researchers defined the proportion of overall MDI errors as “the percentage of patients who made errors in equal to or greater than 20% of inhalation steps.” They computed pooled estimates and created forest plots for both overall errors and for errors according to each step in using an MDI.

The eight studies they identified involved 1,221 patients, with ages ranging from a mean 48 to 82 years, 53% of whom were female. Nearly two-thirds of the patients had COPD (63.6%) while 36.4% had asthma. Most of the devices studied were MDIs alone (68.8%), while 31.2% included a spacer.

The pooled weighted average revealed a 66.5% error rate, that is, two-thirds of all the patients were making at least two errors during the 10 steps involved in using their device. The researchers then used individual error rates data in five studies to calculate the overall error rate for each step in using MDIs. The most common error, made by 73.8% of people in those five studies, was failing to attach the inhaler to the spacer. In addition, 68.7% of patients were failing to exhale fully and away from the inhaler before inhaling, and 47.8% were inhaling too fast instead of inhaling deeply.

“So these [findings] actually give you [some specific] ideas of how we could help improve patients’ ability to use the device properly,” Dr. Navaie told attendees, adding that these data can inform patient education needs and interventions.

Based on the data from those five studies, the error rates for all 10 steps to using an MDI were as follows:

- Failed to shake inhaler before use (37.9%).

- Failed to attach inhaler to spacer (73.8%).

- Failed to exhale fully and away from inhaler before inhalation (68.7%).

- Failed to place mouthpiece between teeth and sealed lips (7.4%).

- Failed to actuate once during inhalation (24.4%).

- Inhalation too fast, not deep (47.8%).

- Failed to hold breath for 5-10 seconds (40.1%).

- Failed to remove the inhaler/spacer from mouth (11.3%).

- Failed to exhale after inhalation (33.2%).

- Failed to repeat steps for second puff (36.7%).

Dr. Navaie also noted the investigators were surprised to learn that physicians themselves sometimes make several of these errors in explaining to patients how to use their devices.

“I think for the reps and other people who go out and visit doctors, it’s important to think about making sure the clinicians are using the devices properly,” Dr. Navaie said. She pointed out the potential for patients to forget steps between visits.

“One of the things a lot of our clinicians and key opinion leaders told us during the course of this study is that you shouldn’t just educate the patient at the time you are scripting the device but repeatedly because patients forget,” she said. She recommended having patients demonstrate their use of the device at each visit. If patients continue to struggle, it may be worth considering other therapies, such as a nebulizer, for patients unable to regularly use their devices correctly.

The meta-analysis was limited by the sparse research available in general on MDI errors in the U.S. adult population, so the data on error rates for each individual step may not be broadly generalizable. The studies also did not distinguish between rates among users with asthma vs. users with COPD. Further, too few data exist on associations between MDI errors and health outcomes to have a clear picture of the clinical implications of regularly making multiple errors in MDI use.

Dr. Navaie is employed by Advance Health Solutions, which received Sunovion Pharmaceuticals funding for the study.

SOURCE: Navaie M et al. CHEST 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.705.

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2018

Key clinical point: 67% of US adult patients with COPD or asthma report making errors in using metered-dose inhalers.

Major finding: 69% of patients do not exhale fully and away from the inhaler before inhalation; 50% do not inhale slowly and deeply.

Study details: Meta-analysis of eight studies involving 1,221 U.S. adult patients with COPD or asthma who use metered-dose inhalers.

Disclosures: Dr. Navaie is employed by Advance Health Solutions, which received Sunovion Pharmaceuticals funding for the study.

Source: Navaie M et al. CHEST 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.705.

No ADT-dementia link in large VA prostate cancer cohort study

In contrast to other recent studies, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) had no link to dementia in a observational cohort study of more than 45,000 men with prostate cancer who received definitive radiotherapy, investigators have reported.

No significant associations were found between ADT and Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia, or between shorter or longer courses of ADT and any dementia studied, according to Rishi Deka, PhD, of Veterans Affairs San Diego Health Care System, La Jolla, Calif., and coinvestigators.

“These results may mitigate concerns regarding the long-term risks of ADT on cognitive health in the treatment of prostate cancer,” Dr. Deka and colleagues wrote in JAMA Oncology.

Two other recent studies showed strong, statistically significant associations between ADT and dementia in prostate cancer. However, those studies combined patients with local and metastatic disease, receiving ADT in the upfront or recurrent settings, while the present study looked specifically at men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer who received radiotherapy.

“Different treatment modalities and disease stages are associated with substantial selection bias that may predispose results to false associations,” noted Dr. Deka and coauthors.

Their observational cohort study comprised 45,218 men diagnosed with nonmetastatic prostate cancer at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs who underwent radiotherapy with or without ADT. The investigators excluded men who had a diagnosis of dementia within 1 year of the prostate cancer diagnosis or who had prior diagnoses of dementia, stroke, or cognitive impairment.

A total of 1,497 patients were diagnosed with dementia over a median of 6.8 years of follow-up: 404 with Alzheimer disease, 335 with vascular dementia, and 758 with other types or unclassified dementias.

The investigators found no significant association between use of ADT and development of any dementia, the primary outcome of the analysis (subdistribution hazard ratio [SHR], 1.04; 95% confidence interval, 0.94-1.16; P = .43).

Likewise, there was no association between ADT and vascular dementia, specifically, with an SHR of 1.20 (95% CI, 0.97-1.50; P = .10) or Alzheimer’s disease, with an SHR of 1.11 (95% CI, 0.91-1.36; P = .29).

Duration of ADT longer than 1 year was not significantly associated with dementia, nor was duration shorter than 1 year, with SHRs, of 1.08 and 1.01 respectively, the analysis shows.

The SHRs in these and other analysis reported ranged from 1.00 to 1.21. That is substantially lower than hazard ratios of 1.66 to 2.32 in one previous study linking ADT to dementia, according to the investigators, suggesting that the results of the current analysis were not due to inadequate power to detect differences.

Nevertheless, the findings may not be generalizable to some other populations, they cautioned, since it was focused demographically on veterans, and was limited to radiotherapy-treated patients.

Dr. Deka and coauthors reported no conflict of interest. Their study was funded by grants from the University of California San Diego Center for Precision Radiation Medicine.

SOURCE: Deka R et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 11. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4423.

In contrast to other recent studies, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) had no link to dementia in a observational cohort study of more than 45,000 men with prostate cancer who received definitive radiotherapy, investigators have reported.

No significant associations were found between ADT and Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia, or between shorter or longer courses of ADT and any dementia studied, according to Rishi Deka, PhD, of Veterans Affairs San Diego Health Care System, La Jolla, Calif., and coinvestigators.

“These results may mitigate concerns regarding the long-term risks of ADT on cognitive health in the treatment of prostate cancer,” Dr. Deka and colleagues wrote in JAMA Oncology.

Two other recent studies showed strong, statistically significant associations between ADT and dementia in prostate cancer. However, those studies combined patients with local and metastatic disease, receiving ADT in the upfront or recurrent settings, while the present study looked specifically at men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer who received radiotherapy.

“Different treatment modalities and disease stages are associated with substantial selection bias that may predispose results to false associations,” noted Dr. Deka and coauthors.

Their observational cohort study comprised 45,218 men diagnosed with nonmetastatic prostate cancer at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs who underwent radiotherapy with or without ADT. The investigators excluded men who had a diagnosis of dementia within 1 year of the prostate cancer diagnosis or who had prior diagnoses of dementia, stroke, or cognitive impairment.

A total of 1,497 patients were diagnosed with dementia over a median of 6.8 years of follow-up: 404 with Alzheimer disease, 335 with vascular dementia, and 758 with other types or unclassified dementias.

The investigators found no significant association between use of ADT and development of any dementia, the primary outcome of the analysis (subdistribution hazard ratio [SHR], 1.04; 95% confidence interval, 0.94-1.16; P = .43).

Likewise, there was no association between ADT and vascular dementia, specifically, with an SHR of 1.20 (95% CI, 0.97-1.50; P = .10) or Alzheimer’s disease, with an SHR of 1.11 (95% CI, 0.91-1.36; P = .29).

Duration of ADT longer than 1 year was not significantly associated with dementia, nor was duration shorter than 1 year, with SHRs, of 1.08 and 1.01 respectively, the analysis shows.

The SHRs in these and other analysis reported ranged from 1.00 to 1.21. That is substantially lower than hazard ratios of 1.66 to 2.32 in one previous study linking ADT to dementia, according to the investigators, suggesting that the results of the current analysis were not due to inadequate power to detect differences.

Nevertheless, the findings may not be generalizable to some other populations, they cautioned, since it was focused demographically on veterans, and was limited to radiotherapy-treated patients.

Dr. Deka and coauthors reported no conflict of interest. Their study was funded by grants from the University of California San Diego Center for Precision Radiation Medicine.

SOURCE: Deka R et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 11. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4423.

In contrast to other recent studies, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) had no link to dementia in a observational cohort study of more than 45,000 men with prostate cancer who received definitive radiotherapy, investigators have reported.

No significant associations were found between ADT and Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia, or between shorter or longer courses of ADT and any dementia studied, according to Rishi Deka, PhD, of Veterans Affairs San Diego Health Care System, La Jolla, Calif., and coinvestigators.

“These results may mitigate concerns regarding the long-term risks of ADT on cognitive health in the treatment of prostate cancer,” Dr. Deka and colleagues wrote in JAMA Oncology.

Two other recent studies showed strong, statistically significant associations between ADT and dementia in prostate cancer. However, those studies combined patients with local and metastatic disease, receiving ADT in the upfront or recurrent settings, while the present study looked specifically at men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer who received radiotherapy.

“Different treatment modalities and disease stages are associated with substantial selection bias that may predispose results to false associations,” noted Dr. Deka and coauthors.

Their observational cohort study comprised 45,218 men diagnosed with nonmetastatic prostate cancer at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs who underwent radiotherapy with or without ADT. The investigators excluded men who had a diagnosis of dementia within 1 year of the prostate cancer diagnosis or who had prior diagnoses of dementia, stroke, or cognitive impairment.

A total of 1,497 patients were diagnosed with dementia over a median of 6.8 years of follow-up: 404 with Alzheimer disease, 335 with vascular dementia, and 758 with other types or unclassified dementias.

The investigators found no significant association between use of ADT and development of any dementia, the primary outcome of the analysis (subdistribution hazard ratio [SHR], 1.04; 95% confidence interval, 0.94-1.16; P = .43).

Likewise, there was no association between ADT and vascular dementia, specifically, with an SHR of 1.20 (95% CI, 0.97-1.50; P = .10) or Alzheimer’s disease, with an SHR of 1.11 (95% CI, 0.91-1.36; P = .29).

Duration of ADT longer than 1 year was not significantly associated with dementia, nor was duration shorter than 1 year, with SHRs, of 1.08 and 1.01 respectively, the analysis shows.

The SHRs in these and other analysis reported ranged from 1.00 to 1.21. That is substantially lower than hazard ratios of 1.66 to 2.32 in one previous study linking ADT to dementia, according to the investigators, suggesting that the results of the current analysis were not due to inadequate power to detect differences.

Nevertheless, the findings may not be generalizable to some other populations, they cautioned, since it was focused demographically on veterans, and was limited to radiotherapy-treated patients.

Dr. Deka and coauthors reported no conflict of interest. Their study was funded by grants from the University of California San Diego Center for Precision Radiation Medicine.

SOURCE: Deka R et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 11. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4423.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: In contrast with other recent investigations in prostate cancer, researchers found no link between androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and development of dementia.

Major finding: No significant association was found between use of ADT and development of any dementia (subdistribution hazard ratio [SHR], 1.04; 95% CI, 0.94-1.16; P = .43).

Study details: Observational cohort study of more than 45,000 veterans with nonmetastatic prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy with or without ADT.

Disclosures: This study was funded by grants from the University of California San Diego Center for Precision Radiation Medicine. Dr. Deka and coauthors reported no conflict of interest disclosures related to the work.

Source: Deka R et al. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Oct 11. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4423.

Prior fertility treatment is associated with higher maternal morbidity during delivery

Investigators from the Stanford Hospital and Clinics in California found that while absolute risk is low, women who have received an infertility diagnosis or who have received fertility treatment are at higher risk of several markers of severe maternal morbidity than women who never received an infertility diagnosis or fertility treatment.1 The study results were presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6 to 10, Denver, Colorado).

Gaya Murugappan, MD, lead investigator on the study, explained in an interview with OBG Management, “We know that in the last decade or so the rate of maternal morbidity has been rising gradually in the US, and we know that the utilization of fertility technology and the incidence of infertility are also rising.” The retrospective analysis set out to determine if a connection exists.

Methods. The investigators used a large insurance claims database to look at data from 2003 to 2016. They identified a group of infertile women who later conceived without fertility treatment (n=1822 deliveries) and a group of women who received fertility treatment (n=782 deliveries) and compared them with a control group of women who never received an infertility diagnosis or fertility treatment (n=37,944 deliveries). Women who currently or previously had cancer were excluded from the study.

The primary outcome was the number of indicators of severe maternal morbidity that occurred during the 6 months prior to or following delivery.

Findings. Compared with the control group, the women diagnosed with infertility were almost 4 times as likely to experience severe anesthesia complications (0.38% vs 0.11%; odds ratio [OR], 3.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.69–8.70), about twice as likely to experience intraoperative heart failure (0.71% vs 0.31%; OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.05–3.34), and more than 3 times as likely to receive a hysterectomy (1.04% vs 0.28%; OR, 3.30; 95% CI, 2.02–5.40).

Similarly, compared with controls, women who had received fertility treatment had an OR of 2.66 for disseminated intravascular coagulation (2.81% vs 0.91%; 95% CI, 1.66–4.24), an OR of 5.17 for shock (0.90% vs 0.15%; 95% CI, 2.21–12.06), an OR of 1.61 for blood transfusions (3.71% vs 1.64%; 95% CI, 1.07–2.42), and an OR of 1.43 for cardiac monitoring (13.17% vs 8.14%; 95% CI, 1.14–1.79).

More research is needed. Dr. Murugappan noted, “I hope that these data help us identify high-risk populations of women so that we can minimize the occurrence of these potentially devastating health outcomes. Women need to be telling their ObGyns that they have a history of infertility and/or fertility treatment. Some women may not want to say that they conceived with donor egg, for example, but that could be a critical element of a patient’s history that an ObGyn should be aware of.”

More study is necessary, she added. For instance, “a study in the future looking at risk of maternal morbidity in patients who are infertile but then who go on to conceive spontaneously. Then we can tease out what is the effect of infertility versus the effect of fertility treatment.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Murugappan G, Li S, Lathi RB, Baker VL, Eisenberg ML. Increased risk of maternal morbidity in infertile women: analysis of US claims data. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e9.

Investigators from the Stanford Hospital and Clinics in California found that while absolute risk is low, women who have received an infertility diagnosis or who have received fertility treatment are at higher risk of several markers of severe maternal morbidity than women who never received an infertility diagnosis or fertility treatment.1 The study results were presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6 to 10, Denver, Colorado).

Gaya Murugappan, MD, lead investigator on the study, explained in an interview with OBG Management, “We know that in the last decade or so the rate of maternal morbidity has been rising gradually in the US, and we know that the utilization of fertility technology and the incidence of infertility are also rising.” The retrospective analysis set out to determine if a connection exists.

Methods. The investigators used a large insurance claims database to look at data from 2003 to 2016. They identified a group of infertile women who later conceived without fertility treatment (n=1822 deliveries) and a group of women who received fertility treatment (n=782 deliveries) and compared them with a control group of women who never received an infertility diagnosis or fertility treatment (n=37,944 deliveries). Women who currently or previously had cancer were excluded from the study.

The primary outcome was the number of indicators of severe maternal morbidity that occurred during the 6 months prior to or following delivery.

Findings. Compared with the control group, the women diagnosed with infertility were almost 4 times as likely to experience severe anesthesia complications (0.38% vs 0.11%; odds ratio [OR], 3.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.69–8.70), about twice as likely to experience intraoperative heart failure (0.71% vs 0.31%; OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.05–3.34), and more than 3 times as likely to receive a hysterectomy (1.04% vs 0.28%; OR, 3.30; 95% CI, 2.02–5.40).

Similarly, compared with controls, women who had received fertility treatment had an OR of 2.66 for disseminated intravascular coagulation (2.81% vs 0.91%; 95% CI, 1.66–4.24), an OR of 5.17 for shock (0.90% vs 0.15%; 95% CI, 2.21–12.06), an OR of 1.61 for blood transfusions (3.71% vs 1.64%; 95% CI, 1.07–2.42), and an OR of 1.43 for cardiac monitoring (13.17% vs 8.14%; 95% CI, 1.14–1.79).

More research is needed. Dr. Murugappan noted, “I hope that these data help us identify high-risk populations of women so that we can minimize the occurrence of these potentially devastating health outcomes. Women need to be telling their ObGyns that they have a history of infertility and/or fertility treatment. Some women may not want to say that they conceived with donor egg, for example, but that could be a critical element of a patient’s history that an ObGyn should be aware of.”

More study is necessary, she added. For instance, “a study in the future looking at risk of maternal morbidity in patients who are infertile but then who go on to conceive spontaneously. Then we can tease out what is the effect of infertility versus the effect of fertility treatment.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Investigators from the Stanford Hospital and Clinics in California found that while absolute risk is low, women who have received an infertility diagnosis or who have received fertility treatment are at higher risk of several markers of severe maternal morbidity than women who never received an infertility diagnosis or fertility treatment.1 The study results were presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) 2018 annual meeting (October 6 to 10, Denver, Colorado).

Gaya Murugappan, MD, lead investigator on the study, explained in an interview with OBG Management, “We know that in the last decade or so the rate of maternal morbidity has been rising gradually in the US, and we know that the utilization of fertility technology and the incidence of infertility are also rising.” The retrospective analysis set out to determine if a connection exists.

Methods. The investigators used a large insurance claims database to look at data from 2003 to 2016. They identified a group of infertile women who later conceived without fertility treatment (n=1822 deliveries) and a group of women who received fertility treatment (n=782 deliveries) and compared them with a control group of women who never received an infertility diagnosis or fertility treatment (n=37,944 deliveries). Women who currently or previously had cancer were excluded from the study.

The primary outcome was the number of indicators of severe maternal morbidity that occurred during the 6 months prior to or following delivery.

Findings. Compared with the control group, the women diagnosed with infertility were almost 4 times as likely to experience severe anesthesia complications (0.38% vs 0.11%; odds ratio [OR], 3.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.69–8.70), about twice as likely to experience intraoperative heart failure (0.71% vs 0.31%; OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.05–3.34), and more than 3 times as likely to receive a hysterectomy (1.04% vs 0.28%; OR, 3.30; 95% CI, 2.02–5.40).

Similarly, compared with controls, women who had received fertility treatment had an OR of 2.66 for disseminated intravascular coagulation (2.81% vs 0.91%; 95% CI, 1.66–4.24), an OR of 5.17 for shock (0.90% vs 0.15%; 95% CI, 2.21–12.06), an OR of 1.61 for blood transfusions (3.71% vs 1.64%; 95% CI, 1.07–2.42), and an OR of 1.43 for cardiac monitoring (13.17% vs 8.14%; 95% CI, 1.14–1.79).

More research is needed. Dr. Murugappan noted, “I hope that these data help us identify high-risk populations of women so that we can minimize the occurrence of these potentially devastating health outcomes. Women need to be telling their ObGyns that they have a history of infertility and/or fertility treatment. Some women may not want to say that they conceived with donor egg, for example, but that could be a critical element of a patient’s history that an ObGyn should be aware of.”

More study is necessary, she added. For instance, “a study in the future looking at risk of maternal morbidity in patients who are infertile but then who go on to conceive spontaneously. Then we can tease out what is the effect of infertility versus the effect of fertility treatment.”

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Murugappan G, Li S, Lathi RB, Baker VL, Eisenberg ML. Increased risk of maternal morbidity in infertile women: analysis of US claims data. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e9.

- Murugappan G, Li S, Lathi RB, Baker VL, Eisenberg ML. Increased risk of maternal morbidity in infertile women: analysis of US claims data. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(45 suppl):e9.

Rock Steady Boxing could prove beneficial for Parkinson’s patients

Exercise classes that focus on boxing movements such as punching a bag may help to improve motor learning patterns in patients with Parkinson’s disease, according to a new pilot study.

When presented with a computerized test in which study participants with Parkinson’s disease had to press buttons corresponding to patterns appearing on a screen, those who had been taking Rock Steady Boxing classes for at least 6 months demonstrated faster reaction time than did those who had never taken the classes, according to Christopher K. McLeod, a second-year medical student at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine in Old Westbury, N.Y. Mr. McLeod, who worked with Adena Leder, DO, director of the Parkinson’s Disease Treatment Center at the college, will present his research findings Oct. 20 at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders in New York.

While the results were not statistically significant, and the number of participants (n = 28) was relatively small, said Mr. McLeod, “We think this is a good pilot study for research going forward, since there really isn’t anything in the literature right now about how procedural memory and learning could be addressed from a therapeutic standpoint in Parkinson’s disease patients.” Procedural learning is a means of acquiring a new skill through repeating the task, like learning to drive a stick shift by doing it.

The investigators used a serial reaction time test to assess procedural memory in 14 patients diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease who had been regularly attending Rock Steady Boxing classes and in 14 patients who did not go to the classes. The test featured a computer screen with four squares that would light up and a box with four corresponding buttons to push as each square lit up. There were seven time blocks in which patients were presented with a series of 10 stimuli. The first pattern was random to get participants accustomed to the task. The second, third, fourth, and fifth blocks had the same sequence, to assess participants’ ability to learn the pattern and respond more quickly. The sixth block again had a random pattern to see if participants slowed down to learn the new pattern, and the seventh block repeated the familiar sequence from the second to fifth blocks.

Experienced boxers generally demonstrated faster reaction time than did nonboxers, the researchers found. Statistical analysis of the four learning blocks (blocks 2-5) revealed a moderate effect (P = .19), indicating that experienced boxers tended to react faster than nonboxers.

Diminished reaction time is a hallmark symptom of Parkinson’s disease, often resulting in patients having to give up the ability drive as the disease progresses, Mr. McLeod said: “Reaction time is something that could eventually lead to falling or not being able to drive, which are huge lifestyle changes that affect these patients emotionally and impact their quality of life.”

The researchers also observed a visible difference in how the two groups tended to respond to the random sequence following the repetitive blocks. Experienced boxers slowed slightly, with a 27.3-ms increase in reaction time, while nonboxers got faster, with a 93.5-ms decrease in reaction time. One possible explanation is that nonboxers simply got better at reacting to the stimuli over time without actually learning the repeated sequence, Mr. McLeod said.

Rock Steady Boxing was founded in Indianapolis by Scott Newman, a former county prosecutor who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease at age 40 and experienced significant improvement in his health and agility by engaging in rigorous workouts, such as boxing. Dr. Leder became certified in Rock Steady Boxing and opened a chapter at the New York college in May 2016. The classes include group activities, games, and boxing exercises designed to improve patients’ physical and mental stamina.

Mr. McLeod and Dr. Leder reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Exercise classes that focus on boxing movements such as punching a bag may help to improve motor learning patterns in patients with Parkinson’s disease, according to a new pilot study.

When presented with a computerized test in which study participants with Parkinson’s disease had to press buttons corresponding to patterns appearing on a screen, those who had been taking Rock Steady Boxing classes for at least 6 months demonstrated faster reaction time than did those who had never taken the classes, according to Christopher K. McLeod, a second-year medical student at the New York Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine in Old Westbury, N.Y. Mr. McLeod, who worked with Adena Leder, DO, director of the Parkinson’s Disease Treatment Center at the college, will present his research findings Oct. 20 at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders in New York.

While the results were not statistically significant, and the number of participants (n = 28) was relatively small, said Mr. McLeod, “We think this is a good pilot study for research going forward, since there really isn’t anything in the literature right now about how procedural memory and learning could be addressed from a therapeutic standpoint in Parkinson’s disease patients.” Procedural learning is a means of acquiring a new skill through repeating the task, like learning to drive a stick shift by doing it.

The investigators used a serial reaction time test to assess procedural memory in 14 patients diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease who had been regularly attending Rock Steady Boxing classes and in 14 patients who did not go to the classes. The test featured a computer screen with four squares that would light up and a box with four corresponding buttons to push as each square lit up. There were seven time blocks in which patients were presented with a series of 10 stimuli. The first pattern was random to get participants accustomed to the task. The second, third, fourth, and fifth blocks had the same sequence, to assess participants’ ability to learn the pattern and respond more quickly. The sixth block again had a random pattern to see if participants slowed down to learn the new pattern, and the seventh block repeated the familiar sequence from the second to fifth blocks.

Experienced boxers generally demonstrated faster reaction time than did nonboxers, the researchers found. Statistical analysis of the four learning blocks (blocks 2-5) revealed a moderate effect (P = .19), indicating that experienced boxers tended to react faster than nonboxers.

Diminished reaction time is a hallmark symptom of Parkinson’s disease, often resulting in patients having to give up the ability drive as the disease progresses, Mr. McLeod said: “Reaction time is something that could eventually lead to falling or not being able to drive, which are huge lifestyle changes that affect these patients emotionally and impact their quality of life.”

The researchers also observed a visible difference in how the two groups tended to respond to the random sequence following the repetitive blocks. Experienced boxers slowed slightly, with a 27.3-ms increase in reaction time, while nonboxers got faster, with a 93.5-ms decrease in reaction time. One possible explanation is that nonboxers simply got better at reacting to the stimuli over time without actually learning the repeated sequence, Mr. McLeod said.

Rock Steady Boxing was founded in Indianapolis by Scott Newman, a former county prosecutor who was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease at age 40 and experienced significant improvement in his health and agility by engaging in rigorous workouts, such as boxing. Dr. Leder became certified in Rock Steady Boxing and opened a chapter at the New York college in May 2016. The classes include group activities, games, and boxing exercises designed to improve patients’ physical and mental stamina.

Mr. McLeod and Dr. Leder reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Exercise classes that focus on boxing movements such as punching a bag may help to improve motor learning patterns in patients with Parkinson’s disease, according to a new pilot study.