User login

Understanding the role of HSCT in PTCL

DUBROVNIK, CROATIA—Hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) can be hit-or-miss in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs), according to a speaker at Leukemia and Lymphoma: Europe and the USA, Linking Knowledge and Practice.

Ali Bazarbachi, MD, PhD, of the American University of Beirut in Lebanon, noted that the success of HSCT varies according to the subtype of PTCL and the type of transplant.

For example, autologous (auto) HSCT given as frontline consolidation can be considered the standard of care for PTCL-not otherwise specified (NOS), angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), and certain patients with anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL), according to Dr. Bazarbachi.

On the other hand, auto-HSCT should never be used in patients with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL).

Both auto-HSCT and allogeneic (allo) HSCT are options for patients with non-localized, extranodal natural killer T-cell lymphoma (ENKTL), nasal type, but only at certain times.

State of PTCL treatment

Dr. Bazarbachi began his presentation by pointing out that patients with newly diagnosed PTCL are no longer treated like patients with B-cell lymphoma, but treatment outcomes in PTCL still leave a lot to be desired.

He noted that, with any of the chemotherapy regimens used, typically, about a third of patients are primary refractory, a third relapse, and a quarter are cured. Only two forms of PTCL are frequently curable—localized ENKTL and ALK-positive ALCL.

Current treatment strategies for PTCL do include HSCT, but recommendations vary. Dr. Bazarbachi made the following recommendations, supported by evidence from clinical trials.

HSCT in PTCL-NOS, AITL, and ALCL

For patients with PTCL-NOS, AITL, or ALK-negative, non-DUSP22 ALCL, auto-HSCT as frontline consolidation can be considered the standard of care in patients who responded to induction, Dr. Bazarbachi said.

In a study published in 20121, high-dose chemotherapy and auto-HSCT as consolidation improved 5-year overall survival—compared to previous results with CHOP2—in patients with ALK-negative ALCL, AITL, PTCL-NOS, and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma.

Allo-HSCT may also be an option for frontline consolidation in patients with PTCL-NOS, AITL, or ALK-negative, non-DUSP22 ALCL, according to Dr. Bazarbachi.

“Allo-transplant is not dead in this indication,” he said. “But it should be either part of a clinical trial or [given] to some selected patients—those with persistent bone marrow involvement, very young patients, or patients with primary refractory disease.”

Results from the COMPLETE study3 showed improved survival in patients who received consolidation with auto- or allo-HSCT, as compared to patients who did not receive a transplant.

COMPLETE patients with AITL or PTCL-NOS had improvements in progression-free and overall survival with HSCT. The survival advantage was “less evident” in patients with ALCL, the researchers said, but this trial included both ALK-negative and ALK-positive patients.

Dr. Bazarbachi noted that allo- and auto-HSCT can be options after relapse in patients with PTCL-NOS, AITL, or ALK-negative, non-DUSP22 ALCL.

However, chemosensitive patients who have relapsed should only receive auto-HSCT if they did not receive it frontline. Patients who have already undergone auto-HSCT can receive allo-HSCT, Dr. Bazarbachi said.

He added that refractory patients should not undergo auto-HSCT and should receive allo-HSCT only within the context of a clinical trial.

HSCT in ATLL

Dr. Bazarbachi noted that ATLL has a dismal prognosis, but allo-HSCT as frontline consolidation is potentially curative.4,5 It is most effective in patients who have achieved a complete or partial response to induction.

However, allo-HSCT should not be given as consolidation to ATLL patients who have received prior mogamulizumab. These patients have an increased risk of morbidity and mortality if they undergo allo-HSCT.

Allo-HSCT should not be given to refractory ATLL patients, although it may be an option for relapsed patients.

Dr. Bazarbachi stressed that ATLL patients should not receive auto-HSCT at any time—as frontline consolidation, after relapse, or if they have refractory disease.

Auto-HSCT “does not work in this disease,” he said. In a study published in 20145, all four ATLL patients who underwent auto-HSCT “rapidly” died.

HSCT in ENKTL

Dr. Bazarbachi said frontline consolidation with auto-HSCT should be considered the standard of care for patients with non-localized ENKTL, nasal type.

Auto-HSCT has been shown to improve survival in these patients6, and it is most effective when patients have achieved a complete response to induction.

Allo-HSCT is also an option for frontline consolidation in patients with non-localized ENKTL, nasal type, Dr. Bazarbachi said.

He added that chemosensitive patients who have relapsed can receive allo-HSCT, but they should only receive auto-HSCT if they did not receive it in the frontline setting. Both types of transplant should take place when patients are in complete remission.

Patients with refractory, non-localized ENKTL, nasal type should not receive auto-HSCT, but allo-HSCT is an option, Dr. Bazarbachi said.

He did not declare any conflicts of interest.

1. d’Amore F et al. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Sep 1;30(25):3093-9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.2719

2. AbouYabis AN et al. ISRN Hematol. 2011 Jun 16. doi: 10.5402/2011/623924

3. Park SI et al. Blood 2017 130:342

4. Ishida T et al. Blood 2012 Aug 23;120(8):1734-41. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-414490

5. Bazarbachi A et al. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014 Oct;49(10):1266-8. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.143

6. Lee J et al. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008 Dec;14(12):1356-64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.09.014

DUBROVNIK, CROATIA—Hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) can be hit-or-miss in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs), according to a speaker at Leukemia and Lymphoma: Europe and the USA, Linking Knowledge and Practice.

Ali Bazarbachi, MD, PhD, of the American University of Beirut in Lebanon, noted that the success of HSCT varies according to the subtype of PTCL and the type of transplant.

For example, autologous (auto) HSCT given as frontline consolidation can be considered the standard of care for PTCL-not otherwise specified (NOS), angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), and certain patients with anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL), according to Dr. Bazarbachi.

On the other hand, auto-HSCT should never be used in patients with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL).

Both auto-HSCT and allogeneic (allo) HSCT are options for patients with non-localized, extranodal natural killer T-cell lymphoma (ENKTL), nasal type, but only at certain times.

State of PTCL treatment

Dr. Bazarbachi began his presentation by pointing out that patients with newly diagnosed PTCL are no longer treated like patients with B-cell lymphoma, but treatment outcomes in PTCL still leave a lot to be desired.

He noted that, with any of the chemotherapy regimens used, typically, about a third of patients are primary refractory, a third relapse, and a quarter are cured. Only two forms of PTCL are frequently curable—localized ENKTL and ALK-positive ALCL.

Current treatment strategies for PTCL do include HSCT, but recommendations vary. Dr. Bazarbachi made the following recommendations, supported by evidence from clinical trials.

HSCT in PTCL-NOS, AITL, and ALCL

For patients with PTCL-NOS, AITL, or ALK-negative, non-DUSP22 ALCL, auto-HSCT as frontline consolidation can be considered the standard of care in patients who responded to induction, Dr. Bazarbachi said.

In a study published in 20121, high-dose chemotherapy and auto-HSCT as consolidation improved 5-year overall survival—compared to previous results with CHOP2—in patients with ALK-negative ALCL, AITL, PTCL-NOS, and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma.

Allo-HSCT may also be an option for frontline consolidation in patients with PTCL-NOS, AITL, or ALK-negative, non-DUSP22 ALCL, according to Dr. Bazarbachi.

“Allo-transplant is not dead in this indication,” he said. “But it should be either part of a clinical trial or [given] to some selected patients—those with persistent bone marrow involvement, very young patients, or patients with primary refractory disease.”

Results from the COMPLETE study3 showed improved survival in patients who received consolidation with auto- or allo-HSCT, as compared to patients who did not receive a transplant.

COMPLETE patients with AITL or PTCL-NOS had improvements in progression-free and overall survival with HSCT. The survival advantage was “less evident” in patients with ALCL, the researchers said, but this trial included both ALK-negative and ALK-positive patients.

Dr. Bazarbachi noted that allo- and auto-HSCT can be options after relapse in patients with PTCL-NOS, AITL, or ALK-negative, non-DUSP22 ALCL.

However, chemosensitive patients who have relapsed should only receive auto-HSCT if they did not receive it frontline. Patients who have already undergone auto-HSCT can receive allo-HSCT, Dr. Bazarbachi said.

He added that refractory patients should not undergo auto-HSCT and should receive allo-HSCT only within the context of a clinical trial.

HSCT in ATLL

Dr. Bazarbachi noted that ATLL has a dismal prognosis, but allo-HSCT as frontline consolidation is potentially curative.4,5 It is most effective in patients who have achieved a complete or partial response to induction.

However, allo-HSCT should not be given as consolidation to ATLL patients who have received prior mogamulizumab. These patients have an increased risk of morbidity and mortality if they undergo allo-HSCT.

Allo-HSCT should not be given to refractory ATLL patients, although it may be an option for relapsed patients.

Dr. Bazarbachi stressed that ATLL patients should not receive auto-HSCT at any time—as frontline consolidation, after relapse, or if they have refractory disease.

Auto-HSCT “does not work in this disease,” he said. In a study published in 20145, all four ATLL patients who underwent auto-HSCT “rapidly” died.

HSCT in ENKTL

Dr. Bazarbachi said frontline consolidation with auto-HSCT should be considered the standard of care for patients with non-localized ENKTL, nasal type.

Auto-HSCT has been shown to improve survival in these patients6, and it is most effective when patients have achieved a complete response to induction.

Allo-HSCT is also an option for frontline consolidation in patients with non-localized ENKTL, nasal type, Dr. Bazarbachi said.

He added that chemosensitive patients who have relapsed can receive allo-HSCT, but they should only receive auto-HSCT if they did not receive it in the frontline setting. Both types of transplant should take place when patients are in complete remission.

Patients with refractory, non-localized ENKTL, nasal type should not receive auto-HSCT, but allo-HSCT is an option, Dr. Bazarbachi said.

He did not declare any conflicts of interest.

1. d’Amore F et al. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Sep 1;30(25):3093-9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.2719

2. AbouYabis AN et al. ISRN Hematol. 2011 Jun 16. doi: 10.5402/2011/623924

3. Park SI et al. Blood 2017 130:342

4. Ishida T et al. Blood 2012 Aug 23;120(8):1734-41. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-414490

5. Bazarbachi A et al. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014 Oct;49(10):1266-8. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.143

6. Lee J et al. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008 Dec;14(12):1356-64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.09.014

DUBROVNIK, CROATIA—Hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) can be hit-or-miss in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs), according to a speaker at Leukemia and Lymphoma: Europe and the USA, Linking Knowledge and Practice.

Ali Bazarbachi, MD, PhD, of the American University of Beirut in Lebanon, noted that the success of HSCT varies according to the subtype of PTCL and the type of transplant.

For example, autologous (auto) HSCT given as frontline consolidation can be considered the standard of care for PTCL-not otherwise specified (NOS), angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), and certain patients with anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL), according to Dr. Bazarbachi.

On the other hand, auto-HSCT should never be used in patients with adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL).

Both auto-HSCT and allogeneic (allo) HSCT are options for patients with non-localized, extranodal natural killer T-cell lymphoma (ENKTL), nasal type, but only at certain times.

State of PTCL treatment

Dr. Bazarbachi began his presentation by pointing out that patients with newly diagnosed PTCL are no longer treated like patients with B-cell lymphoma, but treatment outcomes in PTCL still leave a lot to be desired.

He noted that, with any of the chemotherapy regimens used, typically, about a third of patients are primary refractory, a third relapse, and a quarter are cured. Only two forms of PTCL are frequently curable—localized ENKTL and ALK-positive ALCL.

Current treatment strategies for PTCL do include HSCT, but recommendations vary. Dr. Bazarbachi made the following recommendations, supported by evidence from clinical trials.

HSCT in PTCL-NOS, AITL, and ALCL

For patients with PTCL-NOS, AITL, or ALK-negative, non-DUSP22 ALCL, auto-HSCT as frontline consolidation can be considered the standard of care in patients who responded to induction, Dr. Bazarbachi said.

In a study published in 20121, high-dose chemotherapy and auto-HSCT as consolidation improved 5-year overall survival—compared to previous results with CHOP2—in patients with ALK-negative ALCL, AITL, PTCL-NOS, and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma.

Allo-HSCT may also be an option for frontline consolidation in patients with PTCL-NOS, AITL, or ALK-negative, non-DUSP22 ALCL, according to Dr. Bazarbachi.

“Allo-transplant is not dead in this indication,” he said. “But it should be either part of a clinical trial or [given] to some selected patients—those with persistent bone marrow involvement, very young patients, or patients with primary refractory disease.”

Results from the COMPLETE study3 showed improved survival in patients who received consolidation with auto- or allo-HSCT, as compared to patients who did not receive a transplant.

COMPLETE patients with AITL or PTCL-NOS had improvements in progression-free and overall survival with HSCT. The survival advantage was “less evident” in patients with ALCL, the researchers said, but this trial included both ALK-negative and ALK-positive patients.

Dr. Bazarbachi noted that allo- and auto-HSCT can be options after relapse in patients with PTCL-NOS, AITL, or ALK-negative, non-DUSP22 ALCL.

However, chemosensitive patients who have relapsed should only receive auto-HSCT if they did not receive it frontline. Patients who have already undergone auto-HSCT can receive allo-HSCT, Dr. Bazarbachi said.

He added that refractory patients should not undergo auto-HSCT and should receive allo-HSCT only within the context of a clinical trial.

HSCT in ATLL

Dr. Bazarbachi noted that ATLL has a dismal prognosis, but allo-HSCT as frontline consolidation is potentially curative.4,5 It is most effective in patients who have achieved a complete or partial response to induction.

However, allo-HSCT should not be given as consolidation to ATLL patients who have received prior mogamulizumab. These patients have an increased risk of morbidity and mortality if they undergo allo-HSCT.

Allo-HSCT should not be given to refractory ATLL patients, although it may be an option for relapsed patients.

Dr. Bazarbachi stressed that ATLL patients should not receive auto-HSCT at any time—as frontline consolidation, after relapse, or if they have refractory disease.

Auto-HSCT “does not work in this disease,” he said. In a study published in 20145, all four ATLL patients who underwent auto-HSCT “rapidly” died.

HSCT in ENKTL

Dr. Bazarbachi said frontline consolidation with auto-HSCT should be considered the standard of care for patients with non-localized ENKTL, nasal type.

Auto-HSCT has been shown to improve survival in these patients6, and it is most effective when patients have achieved a complete response to induction.

Allo-HSCT is also an option for frontline consolidation in patients with non-localized ENKTL, nasal type, Dr. Bazarbachi said.

He added that chemosensitive patients who have relapsed can receive allo-HSCT, but they should only receive auto-HSCT if they did not receive it in the frontline setting. Both types of transplant should take place when patients are in complete remission.

Patients with refractory, non-localized ENKTL, nasal type should not receive auto-HSCT, but allo-HSCT is an option, Dr. Bazarbachi said.

He did not declare any conflicts of interest.

1. d’Amore F et al. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Sep 1;30(25):3093-9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.2719

2. AbouYabis AN et al. ISRN Hematol. 2011 Jun 16. doi: 10.5402/2011/623924

3. Park SI et al. Blood 2017 130:342

4. Ishida T et al. Blood 2012 Aug 23;120(8):1734-41. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-414490

5. Bazarbachi A et al. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014 Oct;49(10):1266-8. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.143

6. Lee J et al. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008 Dec;14(12):1356-64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.09.014

How Do I Use the New Cholesterol Guidelines?

Q) I’m still confused by the change in approach to use of statin therapy for cardiovascular disease. How do I determine which patients need statins?

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is the leading cause of death in adults in the United States.1 Statins have long been recommended in the management of individuals with ASCVD.

Historically, statin use was guided by an LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) target, per the Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III) guidelines. Therapy was intensified based on whether patients met these targets. Newer guidelines from the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) base statin therapy not on an LDL-C number but rather on risk stratification that considers several factors.1-3

Continue to: The AHA/ACC guidelines classify statins as...

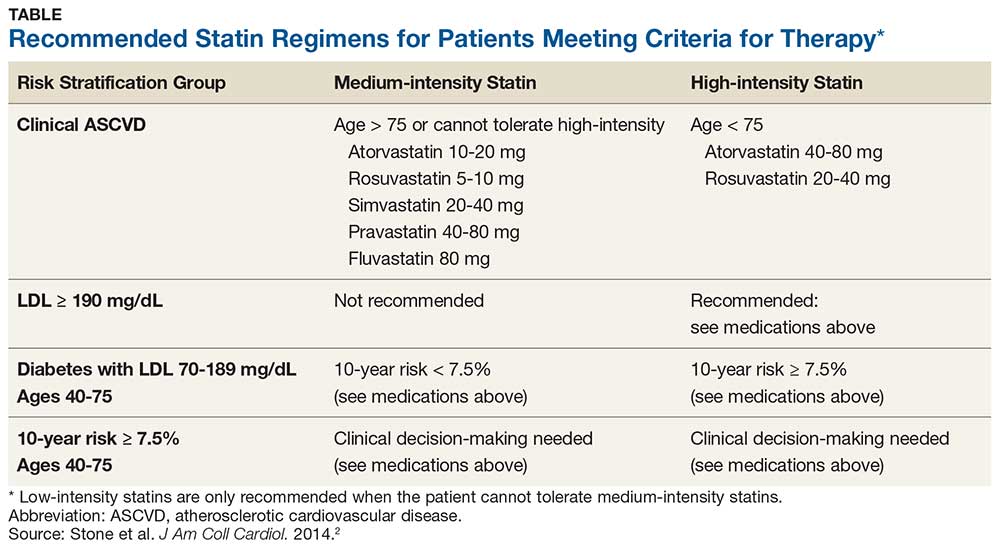

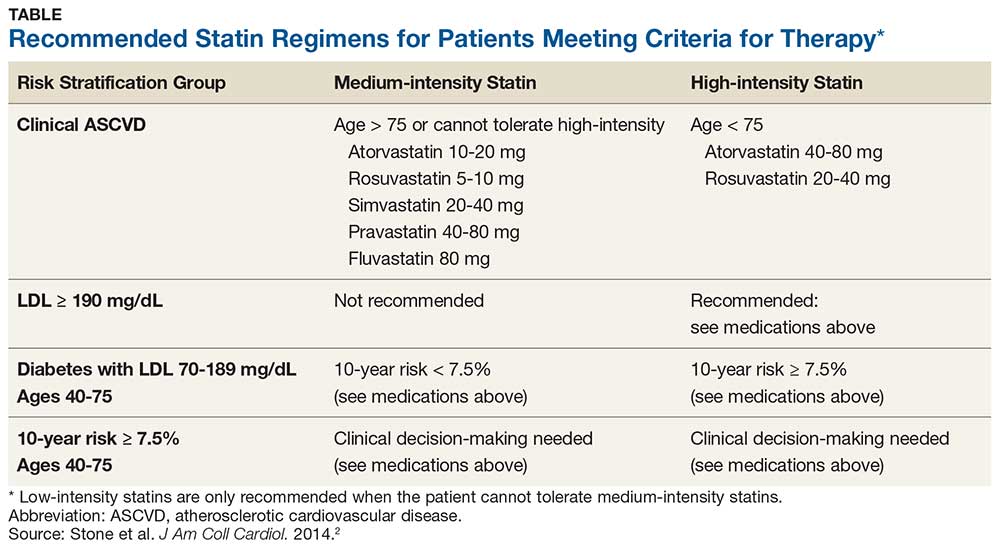

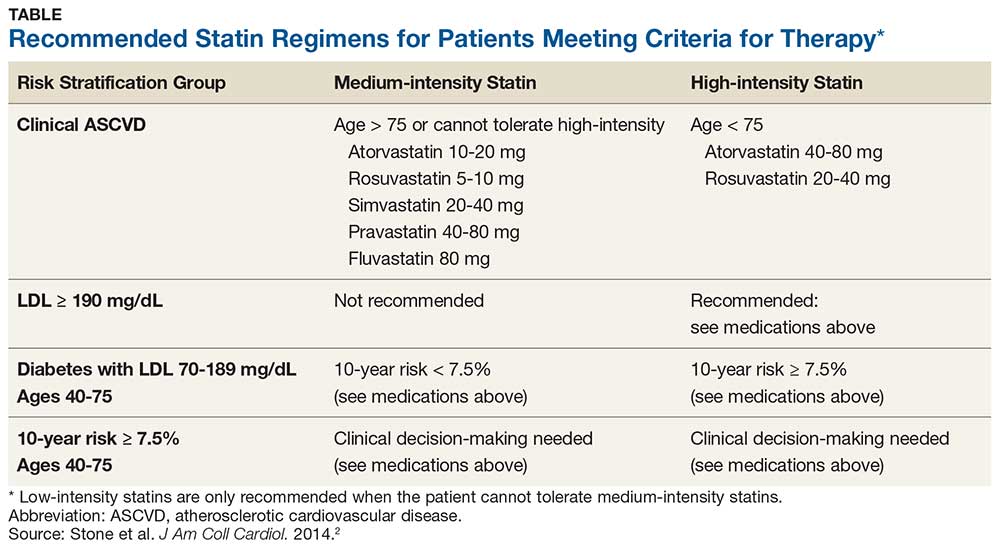

The AHA/ACC guidelines classify statins as high-, moderate-, or low-intensity.2 They also identify four major groups in whom the benefits of statin therapy for reducing ASCVD risk outweigh the risks of therapy. These include patients with

- Clinical ASCVD (eg, coronary heart disease, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease)

- Primary elevated LDL-C ≥ 190 mg/dL

- Diabetes (specifically, in those ages 40-75 with an LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL)

- An estimated 10-year ASCVD risk ≥ 7.5%.2,3 (A risk calculator can be found at www.cvriskcalculator.com).

Recommended statin regimens for patients meeting these criteria are outlined in the Table.

These new guidelines significantly increase the number of adults who are eligible for statin therapy. The number of adults ages 60 to 75 without cardiovascular disease who now qualify for statin therapy has substantially increased (from 30% to 87% in men and from 21% to 54% among women).4 The bulk of this increase is in adults needing primary prevention based on their 10-year cardiovascular risk.4 Evidence as to whether expanded use of statins will improve clinical outcomes is still pending. —AF

Ashley Fort

PA Program at Louisiana State University Health Science Center

1. Gencer B, Auer R, Nanchen D, et al. Expected impact of applying new 2013 AHA/ACC cholesterol guidelines criteria on the recommended lipid target achievement after acute coronary syndromes. Atherosclerosis. 2015; 239(1):118-124.

2. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25):2889-2934.

3. Adhyaru B, Jacobson T. New cholesterol guidelines for the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: a comparison of the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guidelines with the 2014 National Lipid Association recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia. Cardiol Clin. 2015;33(15):181-196.

4. Pencina MJ, Navar-Boggan AM, D’Agostino RB Sr, et al. Application of new cholesterol guidelines to a population-based sample. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(15):1422-1431.

Q) I’m still confused by the change in approach to use of statin therapy for cardiovascular disease. How do I determine which patients need statins?

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is the leading cause of death in adults in the United States.1 Statins have long been recommended in the management of individuals with ASCVD.

Historically, statin use was guided by an LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) target, per the Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III) guidelines. Therapy was intensified based on whether patients met these targets. Newer guidelines from the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) base statin therapy not on an LDL-C number but rather on risk stratification that considers several factors.1-3

Continue to: The AHA/ACC guidelines classify statins as...

The AHA/ACC guidelines classify statins as high-, moderate-, or low-intensity.2 They also identify four major groups in whom the benefits of statin therapy for reducing ASCVD risk outweigh the risks of therapy. These include patients with

- Clinical ASCVD (eg, coronary heart disease, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease)

- Primary elevated LDL-C ≥ 190 mg/dL

- Diabetes (specifically, in those ages 40-75 with an LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL)

- An estimated 10-year ASCVD risk ≥ 7.5%.2,3 (A risk calculator can be found at www.cvriskcalculator.com).

Recommended statin regimens for patients meeting these criteria are outlined in the Table.

These new guidelines significantly increase the number of adults who are eligible for statin therapy. The number of adults ages 60 to 75 without cardiovascular disease who now qualify for statin therapy has substantially increased (from 30% to 87% in men and from 21% to 54% among women).4 The bulk of this increase is in adults needing primary prevention based on their 10-year cardiovascular risk.4 Evidence as to whether expanded use of statins will improve clinical outcomes is still pending. —AF

Ashley Fort

PA Program at Louisiana State University Health Science Center

Q) I’m still confused by the change in approach to use of statin therapy for cardiovascular disease. How do I determine which patients need statins?

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is the leading cause of death in adults in the United States.1 Statins have long been recommended in the management of individuals with ASCVD.

Historically, statin use was guided by an LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) target, per the Adult Treatment Panel (ATP III) guidelines. Therapy was intensified based on whether patients met these targets. Newer guidelines from the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) base statin therapy not on an LDL-C number but rather on risk stratification that considers several factors.1-3

Continue to: The AHA/ACC guidelines classify statins as...

The AHA/ACC guidelines classify statins as high-, moderate-, or low-intensity.2 They also identify four major groups in whom the benefits of statin therapy for reducing ASCVD risk outweigh the risks of therapy. These include patients with

- Clinical ASCVD (eg, coronary heart disease, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease)

- Primary elevated LDL-C ≥ 190 mg/dL

- Diabetes (specifically, in those ages 40-75 with an LDL-C of 70-189 mg/dL)

- An estimated 10-year ASCVD risk ≥ 7.5%.2,3 (A risk calculator can be found at www.cvriskcalculator.com).

Recommended statin regimens for patients meeting these criteria are outlined in the Table.

These new guidelines significantly increase the number of adults who are eligible for statin therapy. The number of adults ages 60 to 75 without cardiovascular disease who now qualify for statin therapy has substantially increased (from 30% to 87% in men and from 21% to 54% among women).4 The bulk of this increase is in adults needing primary prevention based on their 10-year cardiovascular risk.4 Evidence as to whether expanded use of statins will improve clinical outcomes is still pending. —AF

Ashley Fort

PA Program at Louisiana State University Health Science Center

1. Gencer B, Auer R, Nanchen D, et al. Expected impact of applying new 2013 AHA/ACC cholesterol guidelines criteria on the recommended lipid target achievement after acute coronary syndromes. Atherosclerosis. 2015; 239(1):118-124.

2. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25):2889-2934.

3. Adhyaru B, Jacobson T. New cholesterol guidelines for the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: a comparison of the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guidelines with the 2014 National Lipid Association recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia. Cardiol Clin. 2015;33(15):181-196.

4. Pencina MJ, Navar-Boggan AM, D’Agostino RB Sr, et al. Application of new cholesterol guidelines to a population-based sample. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(15):1422-1431.

1. Gencer B, Auer R, Nanchen D, et al. Expected impact of applying new 2013 AHA/ACC cholesterol guidelines criteria on the recommended lipid target achievement after acute coronary syndromes. Atherosclerosis. 2015; 239(1):118-124.

2. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25):2889-2934.

3. Adhyaru B, Jacobson T. New cholesterol guidelines for the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: a comparison of the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guidelines with the 2014 National Lipid Association recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia. Cardiol Clin. 2015;33(15):181-196.

4. Pencina MJ, Navar-Boggan AM, D’Agostino RB Sr, et al. Application of new cholesterol guidelines to a population-based sample. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(15):1422-1431.

Long-term follow-up results of ongoing trials highlighted at ACR 2018

A 5-year follow-up study comparing methods of meniscal tear management in patients with osteoarthritis kicks off the second Plenary Session on Monday, Oct. 22, at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Jeffrey N. Katz, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues conducted a long-term follow-up of patients from the METEOR study, the early results of which were presented at OARSI in 2017. Dr. Katz and his colleagues randomized patients with knee pain, meniscal tears, and OA changes on x-ray or MRI to physical therapy vs. physical therapy plus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. After 5 years, pain relief was similar across treatment groups, supporting the short-term conclusion that these patients experience relief over time, irrespective of initial treatment. Overall, 25% of the patients had total knee replacement surgery during the follow-up period.

The session also includes a new presentation by Kenneth G. Saag, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham of 2-year outcomes from a phase 3 trial of denosumab versus risedronate for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis that was first presented at EULAR this year.

At 2 years, denosumab proved superior for increasing spine and hip bone mineral density in osteoporosis patients, compared with risedronate, and demonstrated a similar safety profile.

In addition, attendees will hear updated long-term results from the SCOT trial of myeloablative autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for scleroderma patients. Keith M. Sullivan, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and his colleagues found that the benefits of the treatment endured after 6-11 years, supporting results presented at ACR 2016.

A 5-year follow-up study comparing methods of meniscal tear management in patients with osteoarthritis kicks off the second Plenary Session on Monday, Oct. 22, at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Jeffrey N. Katz, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues conducted a long-term follow-up of patients from the METEOR study, the early results of which were presented at OARSI in 2017. Dr. Katz and his colleagues randomized patients with knee pain, meniscal tears, and OA changes on x-ray or MRI to physical therapy vs. physical therapy plus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. After 5 years, pain relief was similar across treatment groups, supporting the short-term conclusion that these patients experience relief over time, irrespective of initial treatment. Overall, 25% of the patients had total knee replacement surgery during the follow-up period.

The session also includes a new presentation by Kenneth G. Saag, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham of 2-year outcomes from a phase 3 trial of denosumab versus risedronate for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis that was first presented at EULAR this year.

At 2 years, denosumab proved superior for increasing spine and hip bone mineral density in osteoporosis patients, compared with risedronate, and demonstrated a similar safety profile.

In addition, attendees will hear updated long-term results from the SCOT trial of myeloablative autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for scleroderma patients. Keith M. Sullivan, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and his colleagues found that the benefits of the treatment endured after 6-11 years, supporting results presented at ACR 2016.

A 5-year follow-up study comparing methods of meniscal tear management in patients with osteoarthritis kicks off the second Plenary Session on Monday, Oct. 22, at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Jeffrey N. Katz, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues conducted a long-term follow-up of patients from the METEOR study, the early results of which were presented at OARSI in 2017. Dr. Katz and his colleagues randomized patients with knee pain, meniscal tears, and OA changes on x-ray or MRI to physical therapy vs. physical therapy plus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. After 5 years, pain relief was similar across treatment groups, supporting the short-term conclusion that these patients experience relief over time, irrespective of initial treatment. Overall, 25% of the patients had total knee replacement surgery during the follow-up period.

The session also includes a new presentation by Kenneth G. Saag, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham of 2-year outcomes from a phase 3 trial of denosumab versus risedronate for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis that was first presented at EULAR this year.

At 2 years, denosumab proved superior for increasing spine and hip bone mineral density in osteoporosis patients, compared with risedronate, and demonstrated a similar safety profile.

In addition, attendees will hear updated long-term results from the SCOT trial of myeloablative autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for scleroderma patients. Keith M. Sullivan, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and his colleagues found that the benefits of the treatment endured after 6-11 years, supporting results presented at ACR 2016.

REPORTING FROM THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

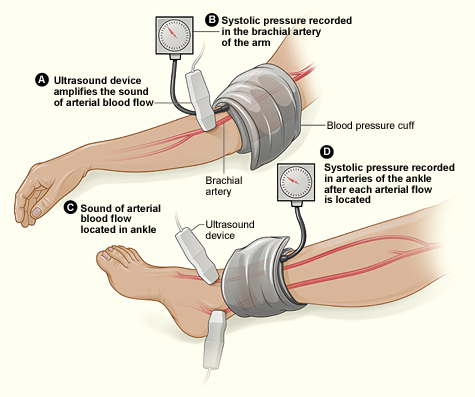

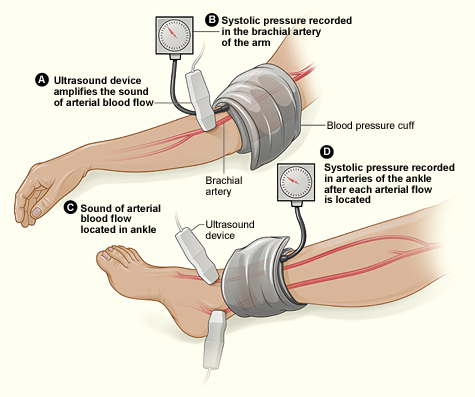

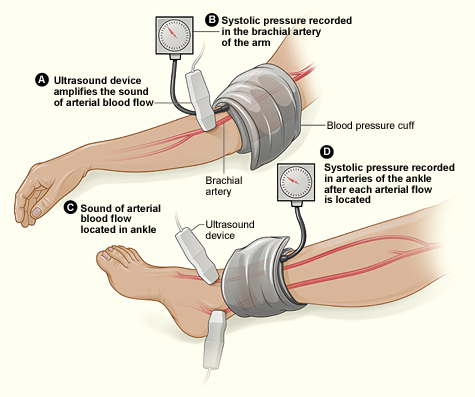

Six PAD diagnostic tests vary widely in patients with diabetes

Six different clinical tests used to identify peripheral arterial disease (PAD) were found to be significantly different in their ability to detect PAD in a population of 50 patients with diabetes, according to a report published online in Primary Care Diabetes.

This study assessed the same group of participants with each of the following six tests: Doppler Waveform, toe-brachial pressure index (TBPI), ankle-brachial pressure index (ABPI), posterior tibial artery pulse (ATP), transcutaneous oxygen pressure (TCPO), and pulse palpation. The right and left foot were assessed in each participant, yeilding100 limbs for analysis, according to Yvonne Midolo Azzopardi, MD, of the University of Malta in Msida and her colleagues.

The highest percent of participants who were found to have PAD was 93%, as detected by Doppler Waveform, followed by TBPI (72%), ABPI (57%), ATP (35%), TCPO (30%), and pulse palpation (23%). The difference between these percentages was significant at P less than .0005.

“The reported observations suggest that use of only one screening tool in isolation could yield high false results since it is clear that these tests do not concur with each other to a large extent,” the authors stated.

Dr. Azzopardi and her colleagues pointed out that the use of more specialized tools, such as duplex scanning, could be compared with these six modalities to detect PAD but that such methods were unlikely to be routinely available to primary care physicians who are at the front lines of making the determination of PAD in patients with diabetes.

“The authors advocate for urgent, more robust studies utilizing a gold standard modality for the diagnosis of PAD in order to provide evidence regarding which noninvasive screening modalities would yield the most valid results. This would significantly reduce the proportion of patients with diabetes who would be falsely identified as having no PAD and subsequently denied beneficial and effective secondary risk factor control,” Dr. Azzopardi and her colleagues concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Azzopardi YM et al. 2018. Prim Care Diabetes.. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2018.08.005.

Six different clinical tests used to identify peripheral arterial disease (PAD) were found to be significantly different in their ability to detect PAD in a population of 50 patients with diabetes, according to a report published online in Primary Care Diabetes.

This study assessed the same group of participants with each of the following six tests: Doppler Waveform, toe-brachial pressure index (TBPI), ankle-brachial pressure index (ABPI), posterior tibial artery pulse (ATP), transcutaneous oxygen pressure (TCPO), and pulse palpation. The right and left foot were assessed in each participant, yeilding100 limbs for analysis, according to Yvonne Midolo Azzopardi, MD, of the University of Malta in Msida and her colleagues.

The highest percent of participants who were found to have PAD was 93%, as detected by Doppler Waveform, followed by TBPI (72%), ABPI (57%), ATP (35%), TCPO (30%), and pulse palpation (23%). The difference between these percentages was significant at P less than .0005.

“The reported observations suggest that use of only one screening tool in isolation could yield high false results since it is clear that these tests do not concur with each other to a large extent,” the authors stated.

Dr. Azzopardi and her colleagues pointed out that the use of more specialized tools, such as duplex scanning, could be compared with these six modalities to detect PAD but that such methods were unlikely to be routinely available to primary care physicians who are at the front lines of making the determination of PAD in patients with diabetes.

“The authors advocate for urgent, more robust studies utilizing a gold standard modality for the diagnosis of PAD in order to provide evidence regarding which noninvasive screening modalities would yield the most valid results. This would significantly reduce the proportion of patients with diabetes who would be falsely identified as having no PAD and subsequently denied beneficial and effective secondary risk factor control,” Dr. Azzopardi and her colleagues concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Azzopardi YM et al. 2018. Prim Care Diabetes.. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2018.08.005.

Six different clinical tests used to identify peripheral arterial disease (PAD) were found to be significantly different in their ability to detect PAD in a population of 50 patients with diabetes, according to a report published online in Primary Care Diabetes.

This study assessed the same group of participants with each of the following six tests: Doppler Waveform, toe-brachial pressure index (TBPI), ankle-brachial pressure index (ABPI), posterior tibial artery pulse (ATP), transcutaneous oxygen pressure (TCPO), and pulse palpation. The right and left foot were assessed in each participant, yeilding100 limbs for analysis, according to Yvonne Midolo Azzopardi, MD, of the University of Malta in Msida and her colleagues.

The highest percent of participants who were found to have PAD was 93%, as detected by Doppler Waveform, followed by TBPI (72%), ABPI (57%), ATP (35%), TCPO (30%), and pulse palpation (23%). The difference between these percentages was significant at P less than .0005.

“The reported observations suggest that use of only one screening tool in isolation could yield high false results since it is clear that these tests do not concur with each other to a large extent,” the authors stated.

Dr. Azzopardi and her colleagues pointed out that the use of more specialized tools, such as duplex scanning, could be compared with these six modalities to detect PAD but that such methods were unlikely to be routinely available to primary care physicians who are at the front lines of making the determination of PAD in patients with diabetes.

“The authors advocate for urgent, more robust studies utilizing a gold standard modality for the diagnosis of PAD in order to provide evidence regarding which noninvasive screening modalities would yield the most valid results. This would significantly reduce the proportion of patients with diabetes who would be falsely identified as having no PAD and subsequently denied beneficial and effective secondary risk factor control,” Dr. Azzopardi and her colleagues concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Azzopardi YM et al. 2018. Prim Care Diabetes.. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2018.08.005.

FROM PRIMARY CARE DIABETES

Key clinical point: Six different tests used to identify PAD differed significantly in their ability to detect the disease.

Major finding: Detection ranged from 93% to 23% in the same group of patients.

Study details: Both legs of 50 patients with diabetes were assessed for PAD using six screening modalities.

Disclosures: The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

Source: Azzopardi YM et al. 2018. Prim Care Diabetes. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2018.08.005.

Get your MACRA updates here at ACR 2018

MACRA! MIPS! APMs! Confused? You won’t be after a Sunday morning session at this year’s annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Zachary S. Wallace, MD, of Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, moderates a panel that will answer your questions about the state of the Quality Payment Program (QPP).

The session will review the updates made to the QPP for 2019 and let attendees know what tools are available to help them maximize payments under each of the tracks. The session also will provide an update on the physician-focused alternative payment model (APM) for rheumatoid arthritis that has been developed by the ACR and submitted to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee for review. Read in depth here about the details of the ACR’s physician-focused APM as it was presented at last year’s annual meeting.

And if you don’t like what you hear about these programs, attendees will provide information on how to provide feedback to the agency to let your voice be heard when the QPP comes up for its annual update.

Sustain Your Practice: 2018 Medicare Update on MACRA and APMs

Sunday, Oct. 21, 9:00 a.m.–10:00 a.m.

MACRA! MIPS! APMs! Confused? You won’t be after a Sunday morning session at this year’s annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Zachary S. Wallace, MD, of Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, moderates a panel that will answer your questions about the state of the Quality Payment Program (QPP).

The session will review the updates made to the QPP for 2019 and let attendees know what tools are available to help them maximize payments under each of the tracks. The session also will provide an update on the physician-focused alternative payment model (APM) for rheumatoid arthritis that has been developed by the ACR and submitted to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee for review. Read in depth here about the details of the ACR’s physician-focused APM as it was presented at last year’s annual meeting.

And if you don’t like what you hear about these programs, attendees will provide information on how to provide feedback to the agency to let your voice be heard when the QPP comes up for its annual update.

Sustain Your Practice: 2018 Medicare Update on MACRA and APMs

Sunday, Oct. 21, 9:00 a.m.–10:00 a.m.

MACRA! MIPS! APMs! Confused? You won’t be after a Sunday morning session at this year’s annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Zachary S. Wallace, MD, of Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, moderates a panel that will answer your questions about the state of the Quality Payment Program (QPP).

The session will review the updates made to the QPP for 2019 and let attendees know what tools are available to help them maximize payments under each of the tracks. The session also will provide an update on the physician-focused alternative payment model (APM) for rheumatoid arthritis that has been developed by the ACR and submitted to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee for review. Read in depth here about the details of the ACR’s physician-focused APM as it was presented at last year’s annual meeting.

And if you don’t like what you hear about these programs, attendees will provide information on how to provide feedback to the agency to let your voice be heard when the QPP comes up for its annual update.

Sustain Your Practice: 2018 Medicare Update on MACRA and APMs

Sunday, Oct. 21, 9:00 a.m.–10:00 a.m.

REPORTING FROM THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Obesity tied to improved inpatient survival of patients with PAD

The obesity paradox appears alive and well in the treatment of peripheral arterial disease (PAD), according to the results of a 10-year, 5.6-million patient database study.

The researchers found that coding for obesity is associated with lower in-hospital mortality in PAD patients relative to those who were normal weight or overweight. This obesity survival paradox was independent of age, sex, and comorbidities and was seen in all obesity classes, according to Karsten Keller, MD, of the University Medical Center Mainz (Germany), and his colleagues.

In total, 5,611,827 inpatients aged 18 years or older with PAD were treated between 2005 and 2015 in Germany, 5,611,484 of whom (64.8% men) were eligible for analysis. Among these, 500,027 (8.9%) were coded with obesity and 16,620 (0.3%) were coded as underweight; 5,094,837 (90.8%) were in neither classification (considered healthy/overweight) and served as the reference group for comparison, according to Dr. Keller and his colleagues.

Obese PAD patients were younger, more frequently women, and had less cancer but were diagnosed more often with cardiovascular disease risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension, compared with the reference group. In addition, there were higher levels of coronary artery disease, heart failure, renal insufficiency, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in obese patients.

Obese patients had lower mortality (3.2% vs. 5.1%; P less than .001), compared with the reference group, and showed a reduced risk of in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 0.617; P less than .001). Univariate logistic regression analyses showed the association of obesity and reduced in-hospital mortality was consistent and significant, even with adjustment for age, sex, and comorbidities.

In contrast, underweight patients were significantly more likely to die than those in the reference group (6% vs. 5.1%; P less than .001), according to the researchers. Underweight was associated with an increased risk for in-hospital mortality (OR, 1.18; P less than .001), and this was consistent throughout univariate analysis.

Underweight PAD patients also had significantly higher frequencies of cancer and COPD, but lower rates of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and heart failure, compared with the reference group. Both obese and underweight PAD patients stayed longer in the hospital than the PAD patients who were not coded as underweight or obese.

Obese PAD patients had slight but significantly higher rates of MI (3.9% vs. 3.4%; P less than .001) and venous thromboembolic events, and more often had to undergo amputation surgery (8.3% vs. 8.1%; P less than .001), including a higher relative number of minor amputations (6.3% vs. 5.5%; P less than .001). However, major amputation rates were significantly lower in obese patients (2.6% vs. 3.2%; P less than .001), with univariate analysis showing a significant association between obesity and a lower risk of major amputation (OR, 0.82; P less than .001), which remained stable after multivariate adjustment.

Limitations of the study reported by the researchers included a lower than expected percent obesity in the 10-year database, compared with current rates, and the inability to follow tobacco use or to determine the socioeconomic status of the patients.

“Obesity is associated with lower in-hospital mortality in PAD patients relative to those with normal weight/overweight. ... Therefore, greater concern should be directed to the thinner patients with PAD who are particularly at increased risk of mortality,” the researchers concluded.

This study was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; the authors reported that they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Keller K et al. Clin Nutr. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.09.031.

The obesity paradox appears alive and well in the treatment of peripheral arterial disease (PAD), according to the results of a 10-year, 5.6-million patient database study.

The researchers found that coding for obesity is associated with lower in-hospital mortality in PAD patients relative to those who were normal weight or overweight. This obesity survival paradox was independent of age, sex, and comorbidities and was seen in all obesity classes, according to Karsten Keller, MD, of the University Medical Center Mainz (Germany), and his colleagues.

In total, 5,611,827 inpatients aged 18 years or older with PAD were treated between 2005 and 2015 in Germany, 5,611,484 of whom (64.8% men) were eligible for analysis. Among these, 500,027 (8.9%) were coded with obesity and 16,620 (0.3%) were coded as underweight; 5,094,837 (90.8%) were in neither classification (considered healthy/overweight) and served as the reference group for comparison, according to Dr. Keller and his colleagues.

Obese PAD patients were younger, more frequently women, and had less cancer but were diagnosed more often with cardiovascular disease risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension, compared with the reference group. In addition, there were higher levels of coronary artery disease, heart failure, renal insufficiency, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in obese patients.

Obese patients had lower mortality (3.2% vs. 5.1%; P less than .001), compared with the reference group, and showed a reduced risk of in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 0.617; P less than .001). Univariate logistic regression analyses showed the association of obesity and reduced in-hospital mortality was consistent and significant, even with adjustment for age, sex, and comorbidities.

In contrast, underweight patients were significantly more likely to die than those in the reference group (6% vs. 5.1%; P less than .001), according to the researchers. Underweight was associated with an increased risk for in-hospital mortality (OR, 1.18; P less than .001), and this was consistent throughout univariate analysis.

Underweight PAD patients also had significantly higher frequencies of cancer and COPD, but lower rates of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and heart failure, compared with the reference group. Both obese and underweight PAD patients stayed longer in the hospital than the PAD patients who were not coded as underweight or obese.

Obese PAD patients had slight but significantly higher rates of MI (3.9% vs. 3.4%; P less than .001) and venous thromboembolic events, and more often had to undergo amputation surgery (8.3% vs. 8.1%; P less than .001), including a higher relative number of minor amputations (6.3% vs. 5.5%; P less than .001). However, major amputation rates were significantly lower in obese patients (2.6% vs. 3.2%; P less than .001), with univariate analysis showing a significant association between obesity and a lower risk of major amputation (OR, 0.82; P less than .001), which remained stable after multivariate adjustment.

Limitations of the study reported by the researchers included a lower than expected percent obesity in the 10-year database, compared with current rates, and the inability to follow tobacco use or to determine the socioeconomic status of the patients.

“Obesity is associated with lower in-hospital mortality in PAD patients relative to those with normal weight/overweight. ... Therefore, greater concern should be directed to the thinner patients with PAD who are particularly at increased risk of mortality,” the researchers concluded.

This study was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; the authors reported that they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Keller K et al. Clin Nutr. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.09.031.

The obesity paradox appears alive and well in the treatment of peripheral arterial disease (PAD), according to the results of a 10-year, 5.6-million patient database study.

The researchers found that coding for obesity is associated with lower in-hospital mortality in PAD patients relative to those who were normal weight or overweight. This obesity survival paradox was independent of age, sex, and comorbidities and was seen in all obesity classes, according to Karsten Keller, MD, of the University Medical Center Mainz (Germany), and his colleagues.

In total, 5,611,827 inpatients aged 18 years or older with PAD were treated between 2005 and 2015 in Germany, 5,611,484 of whom (64.8% men) were eligible for analysis. Among these, 500,027 (8.9%) were coded with obesity and 16,620 (0.3%) were coded as underweight; 5,094,837 (90.8%) were in neither classification (considered healthy/overweight) and served as the reference group for comparison, according to Dr. Keller and his colleagues.

Obese PAD patients were younger, more frequently women, and had less cancer but were diagnosed more often with cardiovascular disease risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension, compared with the reference group. In addition, there were higher levels of coronary artery disease, heart failure, renal insufficiency, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in obese patients.

Obese patients had lower mortality (3.2% vs. 5.1%; P less than .001), compared with the reference group, and showed a reduced risk of in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 0.617; P less than .001). Univariate logistic regression analyses showed the association of obesity and reduced in-hospital mortality was consistent and significant, even with adjustment for age, sex, and comorbidities.

In contrast, underweight patients were significantly more likely to die than those in the reference group (6% vs. 5.1%; P less than .001), according to the researchers. Underweight was associated with an increased risk for in-hospital mortality (OR, 1.18; P less than .001), and this was consistent throughout univariate analysis.

Underweight PAD patients also had significantly higher frequencies of cancer and COPD, but lower rates of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and heart failure, compared with the reference group. Both obese and underweight PAD patients stayed longer in the hospital than the PAD patients who were not coded as underweight or obese.

Obese PAD patients had slight but significantly higher rates of MI (3.9% vs. 3.4%; P less than .001) and venous thromboembolic events, and more often had to undergo amputation surgery (8.3% vs. 8.1%; P less than .001), including a higher relative number of minor amputations (6.3% vs. 5.5%; P less than .001). However, major amputation rates were significantly lower in obese patients (2.6% vs. 3.2%; P less than .001), with univariate analysis showing a significant association between obesity and a lower risk of major amputation (OR, 0.82; P less than .001), which remained stable after multivariate adjustment.

Limitations of the study reported by the researchers included a lower than expected percent obesity in the 10-year database, compared with current rates, and the inability to follow tobacco use or to determine the socioeconomic status of the patients.

“Obesity is associated with lower in-hospital mortality in PAD patients relative to those with normal weight/overweight. ... Therefore, greater concern should be directed to the thinner patients with PAD who are particularly at increased risk of mortality,” the researchers concluded.

This study was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; the authors reported that they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Keller K et al. Clin Nutr. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.09.031.

FROM CLINICAL NUTRITION

Key clinical point: Obesity is associated with lower in-hospital mortality in patients with peripheral arterial disease relative to those who were healthy weight or overweight.

Major finding: Obese patients had a lower mortality (3.2% vs. 5.1%; P less than .001), compared with the reference group.

Study details: A database study of 5,611,484 inpatients diagnosed with peripheral arterial disease.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; the authors reported that they had no disclosures.

Source: Keller K et al. Clin Nutr. 2018 Oct 3. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.09.031.

Superheroes

Who’s your favorite superhero? I realize this might be impossible to answer – Marvel and DC Comics alone have thousands of heroes from which to choose. I recently visited the Seattle Museum of Pop Culture, known as MoPOP, where they have an awesome exhibit on the history of Marvel. I left understanding why superheroes are perennially popular and why we need them. I also felt a little more powerful myself.

The Avengers might seem like just a marketing scheme created to take your movie money. They’re more than that. Superheroes like Thor and Black Widow appear in all cultures and throughout time. There are short and tall, black and white, young and old, gay and straight, Muslim and Jewish, European, Asian, and African superheroes. The characters in The Iliad were superheroes to the ancients. In India today, you can buy comics featuring Lord Shiva.

Superheroes change with time, often reflecting our struggles and values. Captain America was created in 1941 to allay our fear of the then-metastasizing Nazis. The most popular Marvel hero at the MoPOP right now is Black Panther. Next year Captain Marvel will be released. Also known as Carol Danvers, Captain Marvel is one of Marvel Comics’ strongest women, a female Air Force officer with superhuman strength and speed.

Heroes change with the times and are metaphors for the real-life challenges we face and our abilities to overcome them. Superhero stories are our own stories.

When I was a kid, Spider-Man was my favorite. I watched him every afternoon at 3 o’clock when I got home from school. Spidey is a nerdy, little kid who can perform amazing feats to keep people safe and to right societal wrongs. Being a little kid who similarly loved science, he seemed like a good role model at the time. Interestingly, Spidey might have helped me. A couple of studies have shown that kids who pretend to be superheroes, like Batman for example, perform better on tasks, compared with those who aren’t pretending. In some ways, this strategy of imagining to have superpowers is an antidote to the impostor syndrome, a common experience of feeling powerless and undeserving of your position or role. By imagining that they have superpowers, children behave commensurately with these beliefs, which can help them develop self-efficacy at a critical period of development.

This strategy can work for adults too. Military men and women will adopt heroes like Punisher for their battalions, surgeons will don Superman scrub caps, and athletes will take nicknames like Batman for their professional personas. It is a strategy our ancient ancestors deployed, imagining they had the power of Hercules going into battle. No doubt, the energizing, empowering emotion we feel when we think of superheroes is why they are still so popular today. It is why you walk with a bit more swagger when you exit the theater of a good hero flick.

So indulge in a little Wonder Woman and Daredevil and Jessica Jones, even after Halloween has passed. When you do, remember they are here because they are us. and one that we need.

Nowadays, I probably relate most to Captain America: Lead a team, help make each team member better. And, yet, looking at Chris Evans, the actor who plays Captain America, it’s clear I need a lot more time at the gym. Or maybe I could just try to get bitten by a spider.

“Can he swing from a thread? Take a look overhead. Hey, there, there goes the Spider-Man!”

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Who’s your favorite superhero? I realize this might be impossible to answer – Marvel and DC Comics alone have thousands of heroes from which to choose. I recently visited the Seattle Museum of Pop Culture, known as MoPOP, where they have an awesome exhibit on the history of Marvel. I left understanding why superheroes are perennially popular and why we need them. I also felt a little more powerful myself.

The Avengers might seem like just a marketing scheme created to take your movie money. They’re more than that. Superheroes like Thor and Black Widow appear in all cultures and throughout time. There are short and tall, black and white, young and old, gay and straight, Muslim and Jewish, European, Asian, and African superheroes. The characters in The Iliad were superheroes to the ancients. In India today, you can buy comics featuring Lord Shiva.

Superheroes change with time, often reflecting our struggles and values. Captain America was created in 1941 to allay our fear of the then-metastasizing Nazis. The most popular Marvel hero at the MoPOP right now is Black Panther. Next year Captain Marvel will be released. Also known as Carol Danvers, Captain Marvel is one of Marvel Comics’ strongest women, a female Air Force officer with superhuman strength and speed.

Heroes change with the times and are metaphors for the real-life challenges we face and our abilities to overcome them. Superhero stories are our own stories.

When I was a kid, Spider-Man was my favorite. I watched him every afternoon at 3 o’clock when I got home from school. Spidey is a nerdy, little kid who can perform amazing feats to keep people safe and to right societal wrongs. Being a little kid who similarly loved science, he seemed like a good role model at the time. Interestingly, Spidey might have helped me. A couple of studies have shown that kids who pretend to be superheroes, like Batman for example, perform better on tasks, compared with those who aren’t pretending. In some ways, this strategy of imagining to have superpowers is an antidote to the impostor syndrome, a common experience of feeling powerless and undeserving of your position or role. By imagining that they have superpowers, children behave commensurately with these beliefs, which can help them develop self-efficacy at a critical period of development.

This strategy can work for adults too. Military men and women will adopt heroes like Punisher for their battalions, surgeons will don Superman scrub caps, and athletes will take nicknames like Batman for their professional personas. It is a strategy our ancient ancestors deployed, imagining they had the power of Hercules going into battle. No doubt, the energizing, empowering emotion we feel when we think of superheroes is why they are still so popular today. It is why you walk with a bit more swagger when you exit the theater of a good hero flick.

So indulge in a little Wonder Woman and Daredevil and Jessica Jones, even after Halloween has passed. When you do, remember they are here because they are us. and one that we need.

Nowadays, I probably relate most to Captain America: Lead a team, help make each team member better. And, yet, looking at Chris Evans, the actor who plays Captain America, it’s clear I need a lot more time at the gym. Or maybe I could just try to get bitten by a spider.

“Can he swing from a thread? Take a look overhead. Hey, there, there goes the Spider-Man!”

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

Who’s your favorite superhero? I realize this might be impossible to answer – Marvel and DC Comics alone have thousands of heroes from which to choose. I recently visited the Seattle Museum of Pop Culture, known as MoPOP, where they have an awesome exhibit on the history of Marvel. I left understanding why superheroes are perennially popular and why we need them. I also felt a little more powerful myself.

The Avengers might seem like just a marketing scheme created to take your movie money. They’re more than that. Superheroes like Thor and Black Widow appear in all cultures and throughout time. There are short and tall, black and white, young and old, gay and straight, Muslim and Jewish, European, Asian, and African superheroes. The characters in The Iliad were superheroes to the ancients. In India today, you can buy comics featuring Lord Shiva.

Superheroes change with time, often reflecting our struggles and values. Captain America was created in 1941 to allay our fear of the then-metastasizing Nazis. The most popular Marvel hero at the MoPOP right now is Black Panther. Next year Captain Marvel will be released. Also known as Carol Danvers, Captain Marvel is one of Marvel Comics’ strongest women, a female Air Force officer with superhuman strength and speed.

Heroes change with the times and are metaphors for the real-life challenges we face and our abilities to overcome them. Superhero stories are our own stories.

When I was a kid, Spider-Man was my favorite. I watched him every afternoon at 3 o’clock when I got home from school. Spidey is a nerdy, little kid who can perform amazing feats to keep people safe and to right societal wrongs. Being a little kid who similarly loved science, he seemed like a good role model at the time. Interestingly, Spidey might have helped me. A couple of studies have shown that kids who pretend to be superheroes, like Batman for example, perform better on tasks, compared with those who aren’t pretending. In some ways, this strategy of imagining to have superpowers is an antidote to the impostor syndrome, a common experience of feeling powerless and undeserving of your position or role. By imagining that they have superpowers, children behave commensurately with these beliefs, which can help them develop self-efficacy at a critical period of development.

This strategy can work for adults too. Military men and women will adopt heroes like Punisher for their battalions, surgeons will don Superman scrub caps, and athletes will take nicknames like Batman for their professional personas. It is a strategy our ancient ancestors deployed, imagining they had the power of Hercules going into battle. No doubt, the energizing, empowering emotion we feel when we think of superheroes is why they are still so popular today. It is why you walk with a bit more swagger when you exit the theater of a good hero flick.

So indulge in a little Wonder Woman and Daredevil and Jessica Jones, even after Halloween has passed. When you do, remember they are here because they are us. and one that we need.

Nowadays, I probably relate most to Captain America: Lead a team, help make each team member better. And, yet, looking at Chris Evans, the actor who plays Captain America, it’s clear I need a lot more time at the gym. Or maybe I could just try to get bitten by a spider.

“Can he swing from a thread? Take a look overhead. Hey, there, there goes the Spider-Man!”

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

How much more proof do you need?

One piece of wisdom I was given in medical school was to never be the first nor the last to adopt a new treatment. The history of medicine is full of new discoveries that don’t work out as well as the first report. It also is full of long standing dogmas that later were proven false. This balancing act is part of being a professional and being an advocate for your patient. There is science behind this art. Everett Rogers identified innovators, early adopters, and laggards as new ideas are diffused into practice.1

A 2007 French study2 that investigated oral amoxicillin for early-onset group B streptococcal (GBS) disease is one of the few times in the past 3 decades in which I changed my practice based on a single article. It was a large, conclusive study with 222 patients, so it doesn’t need a meta-analysis like American research often requires. The research showed that most of what I had been taught about oral amoxicillin was false. Amoxicillin is absorbed well even at doses above 50 mg/kg per day. It is absorbed reliably by full term neonates, even mildly sick ones. It does adequately cross the blood-brain barrier. The French researchers measured serum levels and proved all this using both scientific principles and through a clinical trial.

I have used this oral protocol (10 days total after 2-3 days IV therapy) on two occasions to treat GBS sepsis when I had informed consent of the parents and buy-in from the primary care pediatrician to be early adopters. I expected the Red Book would update its recommendations. That didn’t happen.

Meanwhile, I have seen other babies kept for 10 days in the hospital for IV therapy with resultant wasted costs (about $20 million/year in the United States) and income loss for the parents. I’ve treated complications and readmissions caused by peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line issues. One baby at home got a syringe of gentamicin given as an IV push instead of a normal saline flush. Mistakes happen at home and in the hospital.

Because late-onset GBS can be acquired environmentally, there always will be recurrences. Unless you are practicing defensive medicine, the issue isn’t the rate of recurrence; it is whether the more invasive intervention of prolonged IV therapy reduces that rate. Then balance any measured reduction (which apparently is zero) against the adverse effects of the invasive intervention, such as PICC line infections. This Bayesian decision making is hard for some risk-averse humans to assimilate. (I’m part Borg.)

Coon et al.3 have confirmed, using big data, that prolonged IV therapy of uncomplicated, late-onset GBS bacteremia does not generate a clinically significant benefit. It certainly is possible to sow doubt by asking for proof in a variety of subpopulations. Even in the era of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, which has halved the incidence of GBS disease, GBS disease occurs in about 2,000 babies per year in the United States. However, most are treated in community hospitals and are not included in the database used in this new report. With fewer than 2-3 cases of GBS bacteremia per year per hospital, a multicenter, randomized controlled trial would be an unprecedented undertaking, is ethically problematic, and is not realistically happening soon. So these observational data, skillfully acquired and analyzed, are and will remain the best available data.

This new article is in the context of multiple articles over the past decade that have disproven the myth of the superiority of IV therapy. Given the known risks and costs of PICC lines and prolonged IV therapy, the default should be, absent a credible rationale to the contrary, that oral therapy at home is better.

Coon et al. show that, by 2015, 5 of 49 children’s hospitals (10%) were early adopters and had already made the switch to mostly using short treatment courses for uncomplicated GBS bacteremia; 14 of 49 (29%) hadn’t changed at all from the obsolete Red Book recommendation. Given this new analysis, what are you laggards4 waiting for?

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. “Diffusion of Innovations,” 5th ed. (New York: Free Press, 2003).

2. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007 Jul;63(7):657-62.

3. Pediatrics. 2018;142(5):e20180345.

4. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diffusion_of_innovations.

One piece of wisdom I was given in medical school was to never be the first nor the last to adopt a new treatment. The history of medicine is full of new discoveries that don’t work out as well as the first report. It also is full of long standing dogmas that later were proven false. This balancing act is part of being a professional and being an advocate for your patient. There is science behind this art. Everett Rogers identified innovators, early adopters, and laggards as new ideas are diffused into practice.1

A 2007 French study2 that investigated oral amoxicillin for early-onset group B streptococcal (GBS) disease is one of the few times in the past 3 decades in which I changed my practice based on a single article. It was a large, conclusive study with 222 patients, so it doesn’t need a meta-analysis like American research often requires. The research showed that most of what I had been taught about oral amoxicillin was false. Amoxicillin is absorbed well even at doses above 50 mg/kg per day. It is absorbed reliably by full term neonates, even mildly sick ones. It does adequately cross the blood-brain barrier. The French researchers measured serum levels and proved all this using both scientific principles and through a clinical trial.

I have used this oral protocol (10 days total after 2-3 days IV therapy) on two occasions to treat GBS sepsis when I had informed consent of the parents and buy-in from the primary care pediatrician to be early adopters. I expected the Red Book would update its recommendations. That didn’t happen.

Meanwhile, I have seen other babies kept for 10 days in the hospital for IV therapy with resultant wasted costs (about $20 million/year in the United States) and income loss for the parents. I’ve treated complications and readmissions caused by peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line issues. One baby at home got a syringe of gentamicin given as an IV push instead of a normal saline flush. Mistakes happen at home and in the hospital.

Because late-onset GBS can be acquired environmentally, there always will be recurrences. Unless you are practicing defensive medicine, the issue isn’t the rate of recurrence; it is whether the more invasive intervention of prolonged IV therapy reduces that rate. Then balance any measured reduction (which apparently is zero) against the adverse effects of the invasive intervention, such as PICC line infections. This Bayesian decision making is hard for some risk-averse humans to assimilate. (I’m part Borg.)

Coon et al.3 have confirmed, using big data, that prolonged IV therapy of uncomplicated, late-onset GBS bacteremia does not generate a clinically significant benefit. It certainly is possible to sow doubt by asking for proof in a variety of subpopulations. Even in the era of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, which has halved the incidence of GBS disease, GBS disease occurs in about 2,000 babies per year in the United States. However, most are treated in community hospitals and are not included in the database used in this new report. With fewer than 2-3 cases of GBS bacteremia per year per hospital, a multicenter, randomized controlled trial would be an unprecedented undertaking, is ethically problematic, and is not realistically happening soon. So these observational data, skillfully acquired and analyzed, are and will remain the best available data.

This new article is in the context of multiple articles over the past decade that have disproven the myth of the superiority of IV therapy. Given the known risks and costs of PICC lines and prolonged IV therapy, the default should be, absent a credible rationale to the contrary, that oral therapy at home is better.

Coon et al. show that, by 2015, 5 of 49 children’s hospitals (10%) were early adopters and had already made the switch to mostly using short treatment courses for uncomplicated GBS bacteremia; 14 of 49 (29%) hadn’t changed at all from the obsolete Red Book recommendation. Given this new analysis, what are you laggards4 waiting for?

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. “Diffusion of Innovations,” 5th ed. (New York: Free Press, 2003).

2. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007 Jul;63(7):657-62.

3. Pediatrics. 2018;142(5):e20180345.

4. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diffusion_of_innovations.

One piece of wisdom I was given in medical school was to never be the first nor the last to adopt a new treatment. The history of medicine is full of new discoveries that don’t work out as well as the first report. It also is full of long standing dogmas that later were proven false. This balancing act is part of being a professional and being an advocate for your patient. There is science behind this art. Everett Rogers identified innovators, early adopters, and laggards as new ideas are diffused into practice.1

A 2007 French study2 that investigated oral amoxicillin for early-onset group B streptococcal (GBS) disease is one of the few times in the past 3 decades in which I changed my practice based on a single article. It was a large, conclusive study with 222 patients, so it doesn’t need a meta-analysis like American research often requires. The research showed that most of what I had been taught about oral amoxicillin was false. Amoxicillin is absorbed well even at doses above 50 mg/kg per day. It is absorbed reliably by full term neonates, even mildly sick ones. It does adequately cross the blood-brain barrier. The French researchers measured serum levels and proved all this using both scientific principles and through a clinical trial.

I have used this oral protocol (10 days total after 2-3 days IV therapy) on two occasions to treat GBS sepsis when I had informed consent of the parents and buy-in from the primary care pediatrician to be early adopters. I expected the Red Book would update its recommendations. That didn’t happen.

Meanwhile, I have seen other babies kept for 10 days in the hospital for IV therapy with resultant wasted costs (about $20 million/year in the United States) and income loss for the parents. I’ve treated complications and readmissions caused by peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line issues. One baby at home got a syringe of gentamicin given as an IV push instead of a normal saline flush. Mistakes happen at home and in the hospital.

Because late-onset GBS can be acquired environmentally, there always will be recurrences. Unless you are practicing defensive medicine, the issue isn’t the rate of recurrence; it is whether the more invasive intervention of prolonged IV therapy reduces that rate. Then balance any measured reduction (which apparently is zero) against the adverse effects of the invasive intervention, such as PICC line infections. This Bayesian decision making is hard for some risk-averse humans to assimilate. (I’m part Borg.)