User login

Time reveals benefit of CABG over PCI for left main disease

SAN DIEGO – In the long run, patients with left main coronary artery disease fare better if they undergo coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) instead of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with drug-eluting stents, suggest 10-year results of the MAIN-COMPARE trial. Findings were reported at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting.

Although CABG is the standard choice for revascularization in this patient population, PCI has been making inroads thanks to advances in stents, antithrombotic drugs, periprocedural management, and operator expertise, noted senior author Seung-Jung Park, MD, PhD, chairman of the Heart Institute at Asan Medical Center in Seoul and professor of medicine at University of Ulsan, South Korea. “Indeed, many studies showed that PCI using drug-eluting stents might be a good alternative for selected patients with left main coronary artery disease.”

Two large, randomized, controlled trials, EXCEL and NOBLE, have compared these treatment strategies and helped clarify outcomes at intermediate follow-up periods of 3-5 years. But long-term data, increasingly important as survival improves, are lacking.

Dr. Park reported the 10-year update of a prospective, observational cohort study that analyzed data from more than 2,000 patients with unprotected left main coronary artery disease in the MAIN-COMPARE registry, which captures revascularization procedures performed at 12 Korean cardiac centers.

In the entire cohort, about a fifth of the patients died, and roughly a fourth experienced a composite adverse outcome of death and cardiovascular events regardless of whether they received PCI or CABG, but the former yielded a rate of target vessel revascularization that was more than three times higher, according to results reported at the meeting and simultaneously published (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.012). Among the subset of patients treated in the more recent drug-eluting stent era, those who underwent PCI were more likely to die and to experience the composite outcome starting at the 5-year mark.

“Drug-eluting stents were associated with higher risks of death and serious composite outcomes compared to CABG after 5 years. The treatment benefit of CABG has diverged over time during continued follow-up,” Dr. Park noted. “The rate of target-vessel failure was consistently higher in the PCI group.”

“We used mainly first-generation drug-eluting stents,” he acknowledged. “However, many studies have demonstrated there is not too much difference between the first- and second-generation stents.”

Data worth the wait

In the same session, investigators reported the 10-year update of the European and U.S. randomized SYNTAX Extended Survival trial, called SYNTAXES. SYNTAX enrolled patients with three-vessel or left main coronary disease. That trial found no significant difference in survival between PCI with drug-eluting stents and CABG overall. In stratified analysis, mortality was higher with PCI among patients with three-vessel disease, but not among patients with left main disease.

Taken together, these trials help clarify the long-term comparative efficacy of PCI and begin to inform patient selection, according to press conference panelist Morton J. Kern, MD, a professor at the University of California, Irvine Medical Center.

“The fine subgroup analysis of who the best candidates are is still in question,” he elaborated. “The SYNTAXES study told us that surgery for left mains is still pretty good, and even though you can get good results with PCI, the event rates are higher in that three-vessel, high-SYNTAX score group, so we should be careful. Interventionalists need to know their limitations. I think that’s what both studies tell us, actually.”

Study details

The MAIN-COMPARE analyses were based on 2,240 patients with unprotected left main coronary artery disease (stenosis of more than 50% and no coronary artery bypass grafts to the left anterior descending or the left circumflex artery) treated during 2000-2006.

A total of 1,102 patients underwent PCI with stenting: 318 in the era of bare-metal stents and 784 in the era of drug-eluting stents, predominantly sirolimus-eluting stents. A total of 1,138 patients underwent CABG. The minimum follow-up was 10 years in all patients, with a median of 12 years.

In the entire study cohort, PCI and CABG yielded similar rates of death (21.1% vs. 23.2%) and the composite of death, Q-wave myocardial infarction, or stroke (23.8% vs. 26.3%), but the PCI patients had a significantly higher rate of target vessel revascularization (21.1% vs. 5.8%), according to data reported at the meeting, which was sponsored by the New York–based Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

In analyses using a propensity score weighting technique, results for the entire cohort were much the same. But on stratification, PCI with drug-eluting stents versus CABG yielded higher risks of death (hazard ratio, 1.35; P = .05) and the composite adverse outcome (HR, 1.46; P = .009) from 5 years onward, as well as a sharply higher risk of target vessel revascularization for the full duration of follow-up (HR, 5.82; P less than .001).

Dr. Park disclosed that he had no conflicts of interest. The study was supported by the Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology and the CardioVascular Research Foundation of South Korea.

SOURCE: Park SJ et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.012).

SAN DIEGO – In the long run, patients with left main coronary artery disease fare better if they undergo coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) instead of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with drug-eluting stents, suggest 10-year results of the MAIN-COMPARE trial. Findings were reported at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting.

Although CABG is the standard choice for revascularization in this patient population, PCI has been making inroads thanks to advances in stents, antithrombotic drugs, periprocedural management, and operator expertise, noted senior author Seung-Jung Park, MD, PhD, chairman of the Heart Institute at Asan Medical Center in Seoul and professor of medicine at University of Ulsan, South Korea. “Indeed, many studies showed that PCI using drug-eluting stents might be a good alternative for selected patients with left main coronary artery disease.”

Two large, randomized, controlled trials, EXCEL and NOBLE, have compared these treatment strategies and helped clarify outcomes at intermediate follow-up periods of 3-5 years. But long-term data, increasingly important as survival improves, are lacking.

Dr. Park reported the 10-year update of a prospective, observational cohort study that analyzed data from more than 2,000 patients with unprotected left main coronary artery disease in the MAIN-COMPARE registry, which captures revascularization procedures performed at 12 Korean cardiac centers.

In the entire cohort, about a fifth of the patients died, and roughly a fourth experienced a composite adverse outcome of death and cardiovascular events regardless of whether they received PCI or CABG, but the former yielded a rate of target vessel revascularization that was more than three times higher, according to results reported at the meeting and simultaneously published (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.012). Among the subset of patients treated in the more recent drug-eluting stent era, those who underwent PCI were more likely to die and to experience the composite outcome starting at the 5-year mark.

“Drug-eluting stents were associated with higher risks of death and serious composite outcomes compared to CABG after 5 years. The treatment benefit of CABG has diverged over time during continued follow-up,” Dr. Park noted. “The rate of target-vessel failure was consistently higher in the PCI group.”

“We used mainly first-generation drug-eluting stents,” he acknowledged. “However, many studies have demonstrated there is not too much difference between the first- and second-generation stents.”

Data worth the wait

In the same session, investigators reported the 10-year update of the European and U.S. randomized SYNTAX Extended Survival trial, called SYNTAXES. SYNTAX enrolled patients with three-vessel or left main coronary disease. That trial found no significant difference in survival between PCI with drug-eluting stents and CABG overall. In stratified analysis, mortality was higher with PCI among patients with three-vessel disease, but not among patients with left main disease.

Taken together, these trials help clarify the long-term comparative efficacy of PCI and begin to inform patient selection, according to press conference panelist Morton J. Kern, MD, a professor at the University of California, Irvine Medical Center.

“The fine subgroup analysis of who the best candidates are is still in question,” he elaborated. “The SYNTAXES study told us that surgery for left mains is still pretty good, and even though you can get good results with PCI, the event rates are higher in that three-vessel, high-SYNTAX score group, so we should be careful. Interventionalists need to know their limitations. I think that’s what both studies tell us, actually.”

Study details

The MAIN-COMPARE analyses were based on 2,240 patients with unprotected left main coronary artery disease (stenosis of more than 50% and no coronary artery bypass grafts to the left anterior descending or the left circumflex artery) treated during 2000-2006.

A total of 1,102 patients underwent PCI with stenting: 318 in the era of bare-metal stents and 784 in the era of drug-eluting stents, predominantly sirolimus-eluting stents. A total of 1,138 patients underwent CABG. The minimum follow-up was 10 years in all patients, with a median of 12 years.

In the entire study cohort, PCI and CABG yielded similar rates of death (21.1% vs. 23.2%) and the composite of death, Q-wave myocardial infarction, or stroke (23.8% vs. 26.3%), but the PCI patients had a significantly higher rate of target vessel revascularization (21.1% vs. 5.8%), according to data reported at the meeting, which was sponsored by the New York–based Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

In analyses using a propensity score weighting technique, results for the entire cohort were much the same. But on stratification, PCI with drug-eluting stents versus CABG yielded higher risks of death (hazard ratio, 1.35; P = .05) and the composite adverse outcome (HR, 1.46; P = .009) from 5 years onward, as well as a sharply higher risk of target vessel revascularization for the full duration of follow-up (HR, 5.82; P less than .001).

Dr. Park disclosed that he had no conflicts of interest. The study was supported by the Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology and the CardioVascular Research Foundation of South Korea.

SOURCE: Park SJ et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.012).

SAN DIEGO – In the long run, patients with left main coronary artery disease fare better if they undergo coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) instead of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with drug-eluting stents, suggest 10-year results of the MAIN-COMPARE trial. Findings were reported at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting.

Although CABG is the standard choice for revascularization in this patient population, PCI has been making inroads thanks to advances in stents, antithrombotic drugs, periprocedural management, and operator expertise, noted senior author Seung-Jung Park, MD, PhD, chairman of the Heart Institute at Asan Medical Center in Seoul and professor of medicine at University of Ulsan, South Korea. “Indeed, many studies showed that PCI using drug-eluting stents might be a good alternative for selected patients with left main coronary artery disease.”

Two large, randomized, controlled trials, EXCEL and NOBLE, have compared these treatment strategies and helped clarify outcomes at intermediate follow-up periods of 3-5 years. But long-term data, increasingly important as survival improves, are lacking.

Dr. Park reported the 10-year update of a prospective, observational cohort study that analyzed data from more than 2,000 patients with unprotected left main coronary artery disease in the MAIN-COMPARE registry, which captures revascularization procedures performed at 12 Korean cardiac centers.

In the entire cohort, about a fifth of the patients died, and roughly a fourth experienced a composite adverse outcome of death and cardiovascular events regardless of whether they received PCI or CABG, but the former yielded a rate of target vessel revascularization that was more than three times higher, according to results reported at the meeting and simultaneously published (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.012). Among the subset of patients treated in the more recent drug-eluting stent era, those who underwent PCI were more likely to die and to experience the composite outcome starting at the 5-year mark.

“Drug-eluting stents were associated with higher risks of death and serious composite outcomes compared to CABG after 5 years. The treatment benefit of CABG has diverged over time during continued follow-up,” Dr. Park noted. “The rate of target-vessel failure was consistently higher in the PCI group.”

“We used mainly first-generation drug-eluting stents,” he acknowledged. “However, many studies have demonstrated there is not too much difference between the first- and second-generation stents.”

Data worth the wait

In the same session, investigators reported the 10-year update of the European and U.S. randomized SYNTAX Extended Survival trial, called SYNTAXES. SYNTAX enrolled patients with three-vessel or left main coronary disease. That trial found no significant difference in survival between PCI with drug-eluting stents and CABG overall. In stratified analysis, mortality was higher with PCI among patients with three-vessel disease, but not among patients with left main disease.

Taken together, these trials help clarify the long-term comparative efficacy of PCI and begin to inform patient selection, according to press conference panelist Morton J. Kern, MD, a professor at the University of California, Irvine Medical Center.

“The fine subgroup analysis of who the best candidates are is still in question,” he elaborated. “The SYNTAXES study told us that surgery for left mains is still pretty good, and even though you can get good results with PCI, the event rates are higher in that three-vessel, high-SYNTAX score group, so we should be careful. Interventionalists need to know their limitations. I think that’s what both studies tell us, actually.”

Study details

The MAIN-COMPARE analyses were based on 2,240 patients with unprotected left main coronary artery disease (stenosis of more than 50% and no coronary artery bypass grafts to the left anterior descending or the left circumflex artery) treated during 2000-2006.

A total of 1,102 patients underwent PCI with stenting: 318 in the era of bare-metal stents and 784 in the era of drug-eluting stents, predominantly sirolimus-eluting stents. A total of 1,138 patients underwent CABG. The minimum follow-up was 10 years in all patients, with a median of 12 years.

In the entire study cohort, PCI and CABG yielded similar rates of death (21.1% vs. 23.2%) and the composite of death, Q-wave myocardial infarction, or stroke (23.8% vs. 26.3%), but the PCI patients had a significantly higher rate of target vessel revascularization (21.1% vs. 5.8%), according to data reported at the meeting, which was sponsored by the New York–based Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

In analyses using a propensity score weighting technique, results for the entire cohort were much the same. But on stratification, PCI with drug-eluting stents versus CABG yielded higher risks of death (hazard ratio, 1.35; P = .05) and the composite adverse outcome (HR, 1.46; P = .009) from 5 years onward, as well as a sharply higher risk of target vessel revascularization for the full duration of follow-up (HR, 5.82; P less than .001).

Dr. Park disclosed that he had no conflicts of interest. The study was supported by the Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology and the CardioVascular Research Foundation of South Korea.

SOURCE: Park SJ et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.012).

REPORTING FROM TCT 2018

Key clinical point: CABG had an edge over PCI with drug-eluting stents in patients with left main disease that became evident with longer follow-up.

Major finding: Compared with CABG, PCI with drug-eluting stents carried higher risks of death (hazard ratio, 1.35; P = .05) and a composite adverse outcome (HR, 1.46; P = .009) from 5 years onward.

Study details: Ten-year follow-up of a multicenter prospective cohort study of 2,240 patients with unprotected left main coronary artery disease who underwent either PCI with stenting or CABG (MAIN-COMPARE study).

Disclosures: Dr. Park disclosed that he had no conflicts of interest. The study was supported by the Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology and the CardioVascular Research Foundation of South Korea.

Source: Park S-J et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.012.

What Would I Tell My Intern-Year Self?

The training path to dermatology can seem interminable. From getting good grades in college to seeking out the “right” extracurricular activities and cramming for the MCAT, just getting into medical school was a huge challenge. In medical school, you may recognize the same chaos as you begin to prepare for US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1, try to volunteer, and publish original research. Dermatology is undeniably a competitive specialty. The 2018 data released by the National Resident Match Program (also called The Match) showed that only 83% of 412 US seniors who applied were matched to dermatology.1 The average Step 1 score for those who matched was 249 versus 241 for those who did not match. In addition, they had an average of 5.2 research experiences, 9.1 volunteer experiences, and 49.1 were members of Alpha Omega Alpha.1

After studying and working to meet these targets, it is not surprising that the transition to residency is a big change. As a dermatology preliminary intern, or“prelim,” our experience differs compared to other specialties, as other interns are jumping into their area of practice right away.

During my intern year, I had a tremendous amount of anxiety about 2 things: (1) being a subpar medical intern and (2) being unprepared for the beginning of my dermatology residency. This anxiety drove me to read a tremendous amount of medical and dermatological literature in an effort to do everything. Although hindsight is always 20/20, I will share some thoughts of my own as well as some from friends and colleagues.

First, enjoy intern year. I know that may sound ridiculous, but there were many aspects of intern year that I loved! When your pager beeps, it’s for YOU! You are no longer a subintern, running every decision past your intern or explaining your student status to the patients! Proudly introduce yourself as Dr. So-and-So. You earned it! I loved the camaraderie of working with my co-interns and senior residents. Going through the challenges of intern year together is a deep bonding experience, and I absolutely made lifelong friendships. It also does not hurt that I met my boyfriend (now husband), which has changed my life in a big way.

When it comes to learning internal medicine, pediatrics, or surgery (depending on your intern year), prepare for rounds, read about your patients, and pay attention in Grand Rounds. You can even consider taking the dermatologic cases that may be on your team, just for fun. I am always grateful for my internal medicine knowledge when managing complex medical dermatology patients and rounding on our consultation service on the wards. However, do not burden yourself with excessive studying. Enjoy your time off: spend it with family and friends or rediscover a hobby that has been neglected while you have been working toward your achievements.

When it comes to learning dermatology, do not rush it! You have 3 years and a ton of studying ahead of you! You will learn all of it. When July 1 of your first year of dermatology finally starts, immerse yourself in this new world:

- Attend conferences. Even if they are on topics you might not be interested in—from cosmetics to psoriasis—they provide a real-world perspective and often have great lecturers sharing their knowledge.

- Get involved. There are many dermatologic societies to take part in, and dues are waived or reduced when you sign up as a resident. Many of them provide great resources from study materials to journals, and they are always a great way to network when there are events.

- Volunteer. Many of the dermatologic societies sponsor volunteer events such as skin cancer screenings. It can be a fun way to network while also giving back to the community.

- Spend time figuring out what you really enjoy. This step may seem self-evident, but after many years of fulfilling the necessary criteria to get into medical school and residency, it can be habitual to start fulfilling the same criteria all over again. Explore all aspects of dermatology and see what truly interests you. Consider how you expect your life after residency to be and think what learning opportunities might be helpful down the road. Reach out to attendings you would like to work with, both in dermatology and in other specialties. I personally enjoyed working in wound and oncology clinics, learning how other specialties approach clinical dilemmas that we see in dermatology.

As I embark on my final year of dermatology residency, I am truly grateful for the wisdom that has been shared with me on this journey. Many people have provided key pieces of information that have helped shape my training and my plans for the future, and I hope that sharing it will help others!

- National Resident Matching Program, Charting Outcomes in the Match: U.S. Allopathic Seniors, 2018. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018-Seniors.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2018.

The training path to dermatology can seem interminable. From getting good grades in college to seeking out the “right” extracurricular activities and cramming for the MCAT, just getting into medical school was a huge challenge. In medical school, you may recognize the same chaos as you begin to prepare for US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1, try to volunteer, and publish original research. Dermatology is undeniably a competitive specialty. The 2018 data released by the National Resident Match Program (also called The Match) showed that only 83% of 412 US seniors who applied were matched to dermatology.1 The average Step 1 score for those who matched was 249 versus 241 for those who did not match. In addition, they had an average of 5.2 research experiences, 9.1 volunteer experiences, and 49.1 were members of Alpha Omega Alpha.1

After studying and working to meet these targets, it is not surprising that the transition to residency is a big change. As a dermatology preliminary intern, or“prelim,” our experience differs compared to other specialties, as other interns are jumping into their area of practice right away.

During my intern year, I had a tremendous amount of anxiety about 2 things: (1) being a subpar medical intern and (2) being unprepared for the beginning of my dermatology residency. This anxiety drove me to read a tremendous amount of medical and dermatological literature in an effort to do everything. Although hindsight is always 20/20, I will share some thoughts of my own as well as some from friends and colleagues.

First, enjoy intern year. I know that may sound ridiculous, but there were many aspects of intern year that I loved! When your pager beeps, it’s for YOU! You are no longer a subintern, running every decision past your intern or explaining your student status to the patients! Proudly introduce yourself as Dr. So-and-So. You earned it! I loved the camaraderie of working with my co-interns and senior residents. Going through the challenges of intern year together is a deep bonding experience, and I absolutely made lifelong friendships. It also does not hurt that I met my boyfriend (now husband), which has changed my life in a big way.

When it comes to learning internal medicine, pediatrics, or surgery (depending on your intern year), prepare for rounds, read about your patients, and pay attention in Grand Rounds. You can even consider taking the dermatologic cases that may be on your team, just for fun. I am always grateful for my internal medicine knowledge when managing complex medical dermatology patients and rounding on our consultation service on the wards. However, do not burden yourself with excessive studying. Enjoy your time off: spend it with family and friends or rediscover a hobby that has been neglected while you have been working toward your achievements.

When it comes to learning dermatology, do not rush it! You have 3 years and a ton of studying ahead of you! You will learn all of it. When July 1 of your first year of dermatology finally starts, immerse yourself in this new world:

- Attend conferences. Even if they are on topics you might not be interested in—from cosmetics to psoriasis—they provide a real-world perspective and often have great lecturers sharing their knowledge.

- Get involved. There are many dermatologic societies to take part in, and dues are waived or reduced when you sign up as a resident. Many of them provide great resources from study materials to journals, and they are always a great way to network when there are events.

- Volunteer. Many of the dermatologic societies sponsor volunteer events such as skin cancer screenings. It can be a fun way to network while also giving back to the community.

- Spend time figuring out what you really enjoy. This step may seem self-evident, but after many years of fulfilling the necessary criteria to get into medical school and residency, it can be habitual to start fulfilling the same criteria all over again. Explore all aspects of dermatology and see what truly interests you. Consider how you expect your life after residency to be and think what learning opportunities might be helpful down the road. Reach out to attendings you would like to work with, both in dermatology and in other specialties. I personally enjoyed working in wound and oncology clinics, learning how other specialties approach clinical dilemmas that we see in dermatology.

As I embark on my final year of dermatology residency, I am truly grateful for the wisdom that has been shared with me on this journey. Many people have provided key pieces of information that have helped shape my training and my plans for the future, and I hope that sharing it will help others!

The training path to dermatology can seem interminable. From getting good grades in college to seeking out the “right” extracurricular activities and cramming for the MCAT, just getting into medical school was a huge challenge. In medical school, you may recognize the same chaos as you begin to prepare for US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1, try to volunteer, and publish original research. Dermatology is undeniably a competitive specialty. The 2018 data released by the National Resident Match Program (also called The Match) showed that only 83% of 412 US seniors who applied were matched to dermatology.1 The average Step 1 score for those who matched was 249 versus 241 for those who did not match. In addition, they had an average of 5.2 research experiences, 9.1 volunteer experiences, and 49.1 were members of Alpha Omega Alpha.1

After studying and working to meet these targets, it is not surprising that the transition to residency is a big change. As a dermatology preliminary intern, or“prelim,” our experience differs compared to other specialties, as other interns are jumping into their area of practice right away.

During my intern year, I had a tremendous amount of anxiety about 2 things: (1) being a subpar medical intern and (2) being unprepared for the beginning of my dermatology residency. This anxiety drove me to read a tremendous amount of medical and dermatological literature in an effort to do everything. Although hindsight is always 20/20, I will share some thoughts of my own as well as some from friends and colleagues.

First, enjoy intern year. I know that may sound ridiculous, but there were many aspects of intern year that I loved! When your pager beeps, it’s for YOU! You are no longer a subintern, running every decision past your intern or explaining your student status to the patients! Proudly introduce yourself as Dr. So-and-So. You earned it! I loved the camaraderie of working with my co-interns and senior residents. Going through the challenges of intern year together is a deep bonding experience, and I absolutely made lifelong friendships. It also does not hurt that I met my boyfriend (now husband), which has changed my life in a big way.

When it comes to learning internal medicine, pediatrics, or surgery (depending on your intern year), prepare for rounds, read about your patients, and pay attention in Grand Rounds. You can even consider taking the dermatologic cases that may be on your team, just for fun. I am always grateful for my internal medicine knowledge when managing complex medical dermatology patients and rounding on our consultation service on the wards. However, do not burden yourself with excessive studying. Enjoy your time off: spend it with family and friends or rediscover a hobby that has been neglected while you have been working toward your achievements.

When it comes to learning dermatology, do not rush it! You have 3 years and a ton of studying ahead of you! You will learn all of it. When July 1 of your first year of dermatology finally starts, immerse yourself in this new world:

- Attend conferences. Even if they are on topics you might not be interested in—from cosmetics to psoriasis—they provide a real-world perspective and often have great lecturers sharing their knowledge.

- Get involved. There are many dermatologic societies to take part in, and dues are waived or reduced when you sign up as a resident. Many of them provide great resources from study materials to journals, and they are always a great way to network when there are events.

- Volunteer. Many of the dermatologic societies sponsor volunteer events such as skin cancer screenings. It can be a fun way to network while also giving back to the community.

- Spend time figuring out what you really enjoy. This step may seem self-evident, but after many years of fulfilling the necessary criteria to get into medical school and residency, it can be habitual to start fulfilling the same criteria all over again. Explore all aspects of dermatology and see what truly interests you. Consider how you expect your life after residency to be and think what learning opportunities might be helpful down the road. Reach out to attendings you would like to work with, both in dermatology and in other specialties. I personally enjoyed working in wound and oncology clinics, learning how other specialties approach clinical dilemmas that we see in dermatology.

As I embark on my final year of dermatology residency, I am truly grateful for the wisdom that has been shared with me on this journey. Many people have provided key pieces of information that have helped shape my training and my plans for the future, and I hope that sharing it will help others!

- National Resident Matching Program, Charting Outcomes in the Match: U.S. Allopathic Seniors, 2018. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018-Seniors.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2018.

- National Resident Matching Program, Charting Outcomes in the Match: U.S. Allopathic Seniors, 2018. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018-Seniors.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2018.

Weight-loss drug lorcaserin’s glycemic effects revealed

BERLIN – Lower rates of incident type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and improved glycemic control were two of the metabolic effects seen with the appetite-suppressant drug lorcaserin versus placebo on top of existing lifestyle management measures in a large-scale trial of more than 12,000 overweight or obese individuals with established cardiovascular disease or T2DM and other cardiovascular risk factors.

In the CAMELLIA-TIMI 61 trial, treatment with a twice-daily, 10-mg dose of lorcaserin for a median of 3.3 years was associated with a significant 19% reduction in the risk of incident T2DM in participants with prediabetes, compared with placebo (8.5% vs. 10.3%; hazard ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.99; P = .038). The reduction in the risk of incident T2DM was even greater (23%) in people without diabetes at baseline (6.7% lorcaserin vs. 8.4% placebo; HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.63-0.94; P = .012).

Furthermore, in patients with T2DM who had a mean baseline glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) of 7%, an absolute 0.33% reduction was seen at 1 year between the lorcaserin and placebo groups, with more modest but still significant between-group reductions (–0.09% and –0.08%) in individuals with prediabetes or normoglycemia (all P less than .0001). When baseline HbA1c levels were higher in patients with T2DM (8%), greater net reductions (0.52%) versus placebo were seen (P less than .0001).

These were some of the metabolic findings, published online in the Lancet to coincide with their presentation at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, that add to those already released from the CAMELLIA-TIMI 61 trial on cardiovascular safety, lead author and TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) group investigator Erin A. Bohula May, MD, observed during a press conference.

The cardiovascular safety data were presented at the 2018 annual congress of the European Society for Cardiology in August and published in the New England Journal of Medicine. These showed no increase with lorcaserin versus placebo in the risk of achieving a major cardiovascular endpoint (MACE) of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.85-1.14; P less than .001 for noninferiority). There was also no difference between groups in the cumulative incidence of MACE+, which included heart failure, hospitalization for unstable angina, and the need for coronary revascularization (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.87-1.07; P = .55 for superiority).

“We know that weight loss can improve cardiovascular and glycemic risk factors, but it’s difficult to achieve and maintain, and weight-loss agents are guideline-recommended adjuncts to lifestyle modification,” said Dr. Bohula May, who is a cardiovascular medicine and critical care specialist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“However, prior to this study no agent had convincingly demonstrated cardiovascular safety in a rigorous clinical outcomes study,” she said, noting that several agents, such as the now-withdrawn rimonabant (Acomplia/Zimulti) and sibutramine (Meridia), had been shown to precipitate cardiovascular or psychiatric events, which led the Food and Drug Administration to mandate that all weight-loss drugs be assessed for cardiovascular safety. Lorcaserin (Belviq) is a centrally acting 5-HT2C agonist that works by decreasing appetite and was approved by the FDA in 2012 but is not currently available in Europe.

Long-term data on the effects of weight-loss agents on glycemic parameters were limited, hence the remit of the CAMELLIA-TIMI 61 trial was to assess both the cardiovascular and metabolic safety of lorcaserin. The drug was used on a background of lifestyle modification in 6,000 obese or overweight individuals at high risk of cardiovascular events. A further 6,000 individuals received placebo.

“Lorcaserin induced and maintained weight loss across the glycemic categories,” said coauthor and TIMI group investigator Benjamin Scirica, MD, also of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who presented the metabolic data during a scientific session at the EASD meeting. Specifically, there was a net weight loss beyond that seen with placebo of 2.6 kg, 2.8 kg, and 3.3 kg in individuals with T2DM, prediabetes, and normoglycemia, respectively.

“Roughly 40% of patients with lorcaserin achieved a 5% weight loss, and about 14%-18% achieved a 10% weight loss across the glycemic categories,” Dr. Scirica reported. The corresponding values for the placebo-treated patients were 17%-18% and 4%-7%.

Naveed Sattar, MD, the independent commentator for the trial, noted the weight-loss reduction seen “was modest in the context of this trial, but I think the important point was that it was sustained. Sustained weight loss is difficult, and it was sustained on top of lifestyle and on top of the other drugs, and that is important.”

However, Dr. Sattar, who is professor and honorary consultant in cardiovascular and medical sciences at the University of Glasgow (Scotland), also observed that “as night follows day, glycemic improvements follow weight loss.” So, did the glycemic parameters improve purely because of the weight loss? While there is some preclinical evidence that lorcaserin may have an effect outside of its weight-lowering effects, Dr. Sattar felt this was unlikely to be clinically significant in itself.

“Obesity is probably the biggest challenge we have in the medical profession. We’ve got excellent cholesterol-lowering, blood pressure–lowering, and diabetes drugs. Yet obesity and complications are rising worldwide” and “safe weight-loss drugs remain sparse,” Dr. Sattar said.

He suggested that lorcaserin may well have an adjunctive place in the current treatment paradigm, but that place is probably “down the line” after other measures with greater weight-reducing effects or proven cardiovascular benefits were used. Not only are lifestyle modification approaches improving, Dr. Sattar said, but there are also over-the-counter options such as orlistat (Xenical), metformin, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, glucagonlike peptide receptor–1 agonists, and bariatric surgery that are likely to be used first.

“This is a fantastically well done trial, we needed it,” Dr. Sattar said. However, because there was modest weight loss and no real cardiovascular benefit (but also no cardiovascular safety concern) he called the results “a bust” saying that “we have to take them at face value for what they are.”

Dr. Sattar noted that his “gut feeling at the moment is that the clinical role for lorcaserin is probably, at best, a down-the-line adjunct in those who are still obese for additional weight reduction on top of other drugs and lifestyle modifications, particularly in those who are ‘super responders.’ ” This is so long as the safety signals remain strong and there are quality of life benefits, he added.

The study was designed by the TIMI Study Group in conjunction with the executive committee and the trial sponsor, Eisai. Dr. Bohula May and Dr. Scirica reported receiving grants from Eisai, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Sattar reported grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim, and being part of an advisory board or speaker’s bureau for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi.

SOURCES: Bohula May EA et al. Lancet. 2018 Oct 4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32328-6; Bohula May EA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:1107-17; Sattar N. EASD 2018, Session S33.

BERLIN – Lower rates of incident type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and improved glycemic control were two of the metabolic effects seen with the appetite-suppressant drug lorcaserin versus placebo on top of existing lifestyle management measures in a large-scale trial of more than 12,000 overweight or obese individuals with established cardiovascular disease or T2DM and other cardiovascular risk factors.

In the CAMELLIA-TIMI 61 trial, treatment with a twice-daily, 10-mg dose of lorcaserin for a median of 3.3 years was associated with a significant 19% reduction in the risk of incident T2DM in participants with prediabetes, compared with placebo (8.5% vs. 10.3%; hazard ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.99; P = .038). The reduction in the risk of incident T2DM was even greater (23%) in people without diabetes at baseline (6.7% lorcaserin vs. 8.4% placebo; HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.63-0.94; P = .012).

Furthermore, in patients with T2DM who had a mean baseline glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) of 7%, an absolute 0.33% reduction was seen at 1 year between the lorcaserin and placebo groups, with more modest but still significant between-group reductions (–0.09% and –0.08%) in individuals with prediabetes or normoglycemia (all P less than .0001). When baseline HbA1c levels were higher in patients with T2DM (8%), greater net reductions (0.52%) versus placebo were seen (P less than .0001).

These were some of the metabolic findings, published online in the Lancet to coincide with their presentation at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, that add to those already released from the CAMELLIA-TIMI 61 trial on cardiovascular safety, lead author and TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) group investigator Erin A. Bohula May, MD, observed during a press conference.

The cardiovascular safety data were presented at the 2018 annual congress of the European Society for Cardiology in August and published in the New England Journal of Medicine. These showed no increase with lorcaserin versus placebo in the risk of achieving a major cardiovascular endpoint (MACE) of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.85-1.14; P less than .001 for noninferiority). There was also no difference between groups in the cumulative incidence of MACE+, which included heart failure, hospitalization for unstable angina, and the need for coronary revascularization (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.87-1.07; P = .55 for superiority).

“We know that weight loss can improve cardiovascular and glycemic risk factors, but it’s difficult to achieve and maintain, and weight-loss agents are guideline-recommended adjuncts to lifestyle modification,” said Dr. Bohula May, who is a cardiovascular medicine and critical care specialist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“However, prior to this study no agent had convincingly demonstrated cardiovascular safety in a rigorous clinical outcomes study,” she said, noting that several agents, such as the now-withdrawn rimonabant (Acomplia/Zimulti) and sibutramine (Meridia), had been shown to precipitate cardiovascular or psychiatric events, which led the Food and Drug Administration to mandate that all weight-loss drugs be assessed for cardiovascular safety. Lorcaserin (Belviq) is a centrally acting 5-HT2C agonist that works by decreasing appetite and was approved by the FDA in 2012 but is not currently available in Europe.

Long-term data on the effects of weight-loss agents on glycemic parameters were limited, hence the remit of the CAMELLIA-TIMI 61 trial was to assess both the cardiovascular and metabolic safety of lorcaserin. The drug was used on a background of lifestyle modification in 6,000 obese or overweight individuals at high risk of cardiovascular events. A further 6,000 individuals received placebo.

“Lorcaserin induced and maintained weight loss across the glycemic categories,” said coauthor and TIMI group investigator Benjamin Scirica, MD, also of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who presented the metabolic data during a scientific session at the EASD meeting. Specifically, there was a net weight loss beyond that seen with placebo of 2.6 kg, 2.8 kg, and 3.3 kg in individuals with T2DM, prediabetes, and normoglycemia, respectively.

“Roughly 40% of patients with lorcaserin achieved a 5% weight loss, and about 14%-18% achieved a 10% weight loss across the glycemic categories,” Dr. Scirica reported. The corresponding values for the placebo-treated patients were 17%-18% and 4%-7%.

Naveed Sattar, MD, the independent commentator for the trial, noted the weight-loss reduction seen “was modest in the context of this trial, but I think the important point was that it was sustained. Sustained weight loss is difficult, and it was sustained on top of lifestyle and on top of the other drugs, and that is important.”

However, Dr. Sattar, who is professor and honorary consultant in cardiovascular and medical sciences at the University of Glasgow (Scotland), also observed that “as night follows day, glycemic improvements follow weight loss.” So, did the glycemic parameters improve purely because of the weight loss? While there is some preclinical evidence that lorcaserin may have an effect outside of its weight-lowering effects, Dr. Sattar felt this was unlikely to be clinically significant in itself.

“Obesity is probably the biggest challenge we have in the medical profession. We’ve got excellent cholesterol-lowering, blood pressure–lowering, and diabetes drugs. Yet obesity and complications are rising worldwide” and “safe weight-loss drugs remain sparse,” Dr. Sattar said.

He suggested that lorcaserin may well have an adjunctive place in the current treatment paradigm, but that place is probably “down the line” after other measures with greater weight-reducing effects or proven cardiovascular benefits were used. Not only are lifestyle modification approaches improving, Dr. Sattar said, but there are also over-the-counter options such as orlistat (Xenical), metformin, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, glucagonlike peptide receptor–1 agonists, and bariatric surgery that are likely to be used first.

“This is a fantastically well done trial, we needed it,” Dr. Sattar said. However, because there was modest weight loss and no real cardiovascular benefit (but also no cardiovascular safety concern) he called the results “a bust” saying that “we have to take them at face value for what they are.”

Dr. Sattar noted that his “gut feeling at the moment is that the clinical role for lorcaserin is probably, at best, a down-the-line adjunct in those who are still obese for additional weight reduction on top of other drugs and lifestyle modifications, particularly in those who are ‘super responders.’ ” This is so long as the safety signals remain strong and there are quality of life benefits, he added.

The study was designed by the TIMI Study Group in conjunction with the executive committee and the trial sponsor, Eisai. Dr. Bohula May and Dr. Scirica reported receiving grants from Eisai, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Sattar reported grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim, and being part of an advisory board or speaker’s bureau for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi.

SOURCES: Bohula May EA et al. Lancet. 2018 Oct 4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32328-6; Bohula May EA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:1107-17; Sattar N. EASD 2018, Session S33.

BERLIN – Lower rates of incident type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and improved glycemic control were two of the metabolic effects seen with the appetite-suppressant drug lorcaserin versus placebo on top of existing lifestyle management measures in a large-scale trial of more than 12,000 overweight or obese individuals with established cardiovascular disease or T2DM and other cardiovascular risk factors.

In the CAMELLIA-TIMI 61 trial, treatment with a twice-daily, 10-mg dose of lorcaserin for a median of 3.3 years was associated with a significant 19% reduction in the risk of incident T2DM in participants with prediabetes, compared with placebo (8.5% vs. 10.3%; hazard ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.99; P = .038). The reduction in the risk of incident T2DM was even greater (23%) in people without diabetes at baseline (6.7% lorcaserin vs. 8.4% placebo; HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.63-0.94; P = .012).

Furthermore, in patients with T2DM who had a mean baseline glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) of 7%, an absolute 0.33% reduction was seen at 1 year between the lorcaserin and placebo groups, with more modest but still significant between-group reductions (–0.09% and –0.08%) in individuals with prediabetes or normoglycemia (all P less than .0001). When baseline HbA1c levels were higher in patients with T2DM (8%), greater net reductions (0.52%) versus placebo were seen (P less than .0001).

These were some of the metabolic findings, published online in the Lancet to coincide with their presentation at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, that add to those already released from the CAMELLIA-TIMI 61 trial on cardiovascular safety, lead author and TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) group investigator Erin A. Bohula May, MD, observed during a press conference.

The cardiovascular safety data were presented at the 2018 annual congress of the European Society for Cardiology in August and published in the New England Journal of Medicine. These showed no increase with lorcaserin versus placebo in the risk of achieving a major cardiovascular endpoint (MACE) of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.85-1.14; P less than .001 for noninferiority). There was also no difference between groups in the cumulative incidence of MACE+, which included heart failure, hospitalization for unstable angina, and the need for coronary revascularization (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.87-1.07; P = .55 for superiority).

“We know that weight loss can improve cardiovascular and glycemic risk factors, but it’s difficult to achieve and maintain, and weight-loss agents are guideline-recommended adjuncts to lifestyle modification,” said Dr. Bohula May, who is a cardiovascular medicine and critical care specialist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“However, prior to this study no agent had convincingly demonstrated cardiovascular safety in a rigorous clinical outcomes study,” she said, noting that several agents, such as the now-withdrawn rimonabant (Acomplia/Zimulti) and sibutramine (Meridia), had been shown to precipitate cardiovascular or psychiatric events, which led the Food and Drug Administration to mandate that all weight-loss drugs be assessed for cardiovascular safety. Lorcaserin (Belviq) is a centrally acting 5-HT2C agonist that works by decreasing appetite and was approved by the FDA in 2012 but is not currently available in Europe.

Long-term data on the effects of weight-loss agents on glycemic parameters were limited, hence the remit of the CAMELLIA-TIMI 61 trial was to assess both the cardiovascular and metabolic safety of lorcaserin. The drug was used on a background of lifestyle modification in 6,000 obese or overweight individuals at high risk of cardiovascular events. A further 6,000 individuals received placebo.

“Lorcaserin induced and maintained weight loss across the glycemic categories,” said coauthor and TIMI group investigator Benjamin Scirica, MD, also of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, who presented the metabolic data during a scientific session at the EASD meeting. Specifically, there was a net weight loss beyond that seen with placebo of 2.6 kg, 2.8 kg, and 3.3 kg in individuals with T2DM, prediabetes, and normoglycemia, respectively.

“Roughly 40% of patients with lorcaserin achieved a 5% weight loss, and about 14%-18% achieved a 10% weight loss across the glycemic categories,” Dr. Scirica reported. The corresponding values for the placebo-treated patients were 17%-18% and 4%-7%.

Naveed Sattar, MD, the independent commentator for the trial, noted the weight-loss reduction seen “was modest in the context of this trial, but I think the important point was that it was sustained. Sustained weight loss is difficult, and it was sustained on top of lifestyle and on top of the other drugs, and that is important.”

However, Dr. Sattar, who is professor and honorary consultant in cardiovascular and medical sciences at the University of Glasgow (Scotland), also observed that “as night follows day, glycemic improvements follow weight loss.” So, did the glycemic parameters improve purely because of the weight loss? While there is some preclinical evidence that lorcaserin may have an effect outside of its weight-lowering effects, Dr. Sattar felt this was unlikely to be clinically significant in itself.

“Obesity is probably the biggest challenge we have in the medical profession. We’ve got excellent cholesterol-lowering, blood pressure–lowering, and diabetes drugs. Yet obesity and complications are rising worldwide” and “safe weight-loss drugs remain sparse,” Dr. Sattar said.

He suggested that lorcaserin may well have an adjunctive place in the current treatment paradigm, but that place is probably “down the line” after other measures with greater weight-reducing effects or proven cardiovascular benefits were used. Not only are lifestyle modification approaches improving, Dr. Sattar said, but there are also over-the-counter options such as orlistat (Xenical), metformin, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, glucagonlike peptide receptor–1 agonists, and bariatric surgery that are likely to be used first.

“This is a fantastically well done trial, we needed it,” Dr. Sattar said. However, because there was modest weight loss and no real cardiovascular benefit (but also no cardiovascular safety concern) he called the results “a bust” saying that “we have to take them at face value for what they are.”

Dr. Sattar noted that his “gut feeling at the moment is that the clinical role for lorcaserin is probably, at best, a down-the-line adjunct in those who are still obese for additional weight reduction on top of other drugs and lifestyle modifications, particularly in those who are ‘super responders.’ ” This is so long as the safety signals remain strong and there are quality of life benefits, he added.

The study was designed by the TIMI Study Group in conjunction with the executive committee and the trial sponsor, Eisai. Dr. Bohula May and Dr. Scirica reported receiving grants from Eisai, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Sattar reported grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim, and being part of an advisory board or speaker’s bureau for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi.

SOURCES: Bohula May EA et al. Lancet. 2018 Oct 4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32328-6; Bohula May EA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018; 379:1107-17; Sattar N. EASD 2018, Session S33.

REPORTING FROM EASD 2018

Key clinical point: Lorcaserin is an adjunctive treatment to lifestyle modification for chronic weight management that may improve metabolic health.

Major finding: A total of 8.5% of lorcaserin-treated individuals with prediabetes versus 10.3% of placebo-treated individuals developed incident type 2 diabetes mellitus at 1 year (hazard ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.99; P = .038).

Study details: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 12,000 overweight or obese individuals with established cardiovascular disease, established or no type 2 diabetes mellitus, and other cardiovascular risk factors.

Disclosures: The study was designed by the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction Study Group in conjunction with the executive committee and the trial sponsor, Eisai. Dr. Bohula May and Dr. Scirica reported receiving grants from Eisai, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Sattar reported grant support from Boehringer Ingelheim and being part of an advisory board or speaker’s bureau for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi.

Sources: Bohula May EA et al. Lancet. 2018. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32328-6; Bohula May EA et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1107-17; Sattar N. EASD 2018, Session S33.

For most veterans with PTSD, helping others is a lifeline

I am a former military psychiatrist who has published extensively about posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychological effects of war. Thus, I got sent the news clips many times about a potential candidate for mayor of Kansas City leaving the race to care for himself, his depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms.

Like many of our readers who are physicians, I have a very mixed response to the former candidate’s news.

On the one hand, kudos to him that he has decided to 1) get the help he says he needs, and 2) go public. On the other hand, I really wish that he did not have to drop out of the race to do so.

There are some parallels with leaving for severe physical illness, such as getting chemotherapy for cancer. However, for example, when Gov. Larry Hogan of Maryland received treatment for his cancer, he stayed in office.

Why can you stay in a race or office with cancer or heart disease but not with the very common psychiatric and treatable condition of PTSD?

I certainly do not know all the reasons the candidate for Kansas City mayor made this decision. He said he is encouraging other veterans to follow his example and get treatment for PTSD. He also alluded to suicidal ideation.

This got me thinking about the concept of needing to leave work to take care of yourself – a decision that is often lauded as both noble and wise. I will not opine much on nobility, other than saying it is always noble to help fellow veterans. Maybe his decision to go public will help other veterans. Hard to say. But I can on opine on wisdom, based on many years of working with veterans with PTSD. I almost always advise them to keep their jobs, if at all possible.

Taking time off from a job you care for actually might increase suicidal thoughts. That is due to less structure in the day, less socialization, and fewer feelings of self-worth. A consequent lack of funds might not help. I have long called holding a good job one of the best mental health interventions, superior to medicine and therapy alone (OK – I am being doctrinaire; there are no placebo-controlled, double blind trials on the topic. But I am also serious.)

In general, Why is it work or saving oneself? In my opinion, work helps to save oneself. Helping others, for most veterans, is a lifeline.

I wonder why he should have to drop out of work to receive treatment. Perhaps he was placed in a residential Veterans Affairs program, which often are 30-60 days long. It is notoriously hard to maintain a job during such treatment.

I believe that we should structure our PTSD therapy so that one can both work and receive appropriate treatment. We need war veterans, with or without PTSD, to run for office. And win.

Dr. Ritchie is chief of psychiatry at MedStar Washington Hospital Center.

I am a former military psychiatrist who has published extensively about posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychological effects of war. Thus, I got sent the news clips many times about a potential candidate for mayor of Kansas City leaving the race to care for himself, his depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms.

Like many of our readers who are physicians, I have a very mixed response to the former candidate’s news.

On the one hand, kudos to him that he has decided to 1) get the help he says he needs, and 2) go public. On the other hand, I really wish that he did not have to drop out of the race to do so.

There are some parallels with leaving for severe physical illness, such as getting chemotherapy for cancer. However, for example, when Gov. Larry Hogan of Maryland received treatment for his cancer, he stayed in office.

Why can you stay in a race or office with cancer or heart disease but not with the very common psychiatric and treatable condition of PTSD?

I certainly do not know all the reasons the candidate for Kansas City mayor made this decision. He said he is encouraging other veterans to follow his example and get treatment for PTSD. He also alluded to suicidal ideation.

This got me thinking about the concept of needing to leave work to take care of yourself – a decision that is often lauded as both noble and wise. I will not opine much on nobility, other than saying it is always noble to help fellow veterans. Maybe his decision to go public will help other veterans. Hard to say. But I can on opine on wisdom, based on many years of working with veterans with PTSD. I almost always advise them to keep their jobs, if at all possible.

Taking time off from a job you care for actually might increase suicidal thoughts. That is due to less structure in the day, less socialization, and fewer feelings of self-worth. A consequent lack of funds might not help. I have long called holding a good job one of the best mental health interventions, superior to medicine and therapy alone (OK – I am being doctrinaire; there are no placebo-controlled, double blind trials on the topic. But I am also serious.)

In general, Why is it work or saving oneself? In my opinion, work helps to save oneself. Helping others, for most veterans, is a lifeline.

I wonder why he should have to drop out of work to receive treatment. Perhaps he was placed in a residential Veterans Affairs program, which often are 30-60 days long. It is notoriously hard to maintain a job during such treatment.

I believe that we should structure our PTSD therapy so that one can both work and receive appropriate treatment. We need war veterans, with or without PTSD, to run for office. And win.

Dr. Ritchie is chief of psychiatry at MedStar Washington Hospital Center.

I am a former military psychiatrist who has published extensively about posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychological effects of war. Thus, I got sent the news clips many times about a potential candidate for mayor of Kansas City leaving the race to care for himself, his depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms.

Like many of our readers who are physicians, I have a very mixed response to the former candidate’s news.

On the one hand, kudos to him that he has decided to 1) get the help he says he needs, and 2) go public. On the other hand, I really wish that he did not have to drop out of the race to do so.

There are some parallels with leaving for severe physical illness, such as getting chemotherapy for cancer. However, for example, when Gov. Larry Hogan of Maryland received treatment for his cancer, he stayed in office.

Why can you stay in a race or office with cancer or heart disease but not with the very common psychiatric and treatable condition of PTSD?

I certainly do not know all the reasons the candidate for Kansas City mayor made this decision. He said he is encouraging other veterans to follow his example and get treatment for PTSD. He also alluded to suicidal ideation.

This got me thinking about the concept of needing to leave work to take care of yourself – a decision that is often lauded as both noble and wise. I will not opine much on nobility, other than saying it is always noble to help fellow veterans. Maybe his decision to go public will help other veterans. Hard to say. But I can on opine on wisdom, based on many years of working with veterans with PTSD. I almost always advise them to keep their jobs, if at all possible.

Taking time off from a job you care for actually might increase suicidal thoughts. That is due to less structure in the day, less socialization, and fewer feelings of self-worth. A consequent lack of funds might not help. I have long called holding a good job one of the best mental health interventions, superior to medicine and therapy alone (OK – I am being doctrinaire; there are no placebo-controlled, double blind trials on the topic. But I am also serious.)

In general, Why is it work or saving oneself? In my opinion, work helps to save oneself. Helping others, for most veterans, is a lifeline.

I wonder why he should have to drop out of work to receive treatment. Perhaps he was placed in a residential Veterans Affairs program, which often are 30-60 days long. It is notoriously hard to maintain a job during such treatment.

I believe that we should structure our PTSD therapy so that one can both work and receive appropriate treatment. We need war veterans, with or without PTSD, to run for office. And win.

Dr. Ritchie is chief of psychiatry at MedStar Washington Hospital Center.

A change in ‘incident to’ billing

Also today, stepping down to oral ciprofloxacin looks safe in gram-negative bloodstream infections, a nasal cannula device may be an option for severe COPD, and brexanolone injection quickly improves postpartum depression.

Also today, stepping down to oral ciprofloxacin looks safe in gram-negative bloodstream infections, a nasal cannula device may be an option for severe COPD, and brexanolone injection quickly improves postpartum depression.

Also today, stepping down to oral ciprofloxacin looks safe in gram-negative bloodstream infections, a nasal cannula device may be an option for severe COPD, and brexanolone injection quickly improves postpartum depression.

Improving Team-Based Care Coordination Delivery and Documentation in the Health Record

Chronic diseases affect a substantial proportion of the US population, with 25% of adults diagnosed with 2 or more chronic health conditions.1 In 2010, 2 chronic diseases, heart disease and cancer, accounted for nearly 48% of deaths.2 Due to the significant public heath burden, strategies to improve chronic disease management have attracted a great deal of focus.3,4 Within increasingly complex health care delivery systems, policy makers are promoting care coordination (CC) as a tool to reduce fragmented care for patients with multiple comorbidities, improve patient experience and quality of care, and decrease costs and risks for error.3-8

Background

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) defines care coordination as “deliberately organizing patient care activities and sharing information among all of the participants concerned with a patient’s care to achieve safer and more effective care.”5 Nationally, large scale investments have expanded health care models that provide team-based CC, such as patient-centered medical homes, known as patient-aligned care teams (PACTs) within the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), accountable care organizations, and other complex care management programs.9-12 Additionally, incentives that reimburse for CC, such as Medicare’s chronic care management and transition care management billing codes, also are emerging.13,14

While there is significant interest and investment in promoting CC, little data about the specific activities and time required to provide necessary CC exist, which limits the ability of health care teams to optimize CC delivery.6 Understanding the components of CC has implications for human resource allocation, labor mapping, reimbursement, staff training, and optimizing collaborative networks for health care systems, which may improve the quality of CC and health outcomes for patients. To date, few tools exist that can be used to identify and track the CC services delivered by interdisciplinary teams within and outside of the health care setting.

This article describes the development and preliminary results of the implementation of a CC Template that was created in the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) to identify and track the components of CC services, delivered by a multidisciplinary team, as part of a quality improvement (QI) pilot project. Through use of the template, the team sought a formative understanding of the following questions: (1) Is it feasible to use the CC Template during routine workflow? (2) What specific types of CC services are provided by the team? (3) How much time does it take to perform these activities? (4) Who is the team collaborating with inside and outside of the health care setting and how are they communicating? (5) Given new reimbursement incentives, can the provision of CC be standardized and documented for broad applicability?

In complex systems, where coordination is needed among primary, specialty, hospital, emergency, and nonclinical care settings, a tool such as the CC Template offers a sustainable and replicable way to standardize documentation and knowledge about CC components. This foundational information can be used to optimize team structure, training, and resource allocation, to improve the quality of CC and to link elements of CC with clinical and operational outcomes.

Pact Intensive Management

Despite the implementation of PACT within VA, patients with complex medical conditions combined with socioeconomic stressors, mental health comorbidities, and low health literacy are at high risk for preventable hospitalizations and acute care utilization.17,18 Due to unmet needs that are beyond what PACTs are able to deliver, these high-risk patients may benefit from additional services to coordinate care within and outside the VA health care system, as suggest by the Extended Chronic Care Model.19-21

In 2014, the Office of Primary Care Services sponsored a QI initiative at 5 VA demonstration sites to develop PACT Intensive Management (PIM) interventions targeting patients at high risk for hospitalization and acute care utilization within VA. The PIM program design is based on work described previously, with patients identified for enrollment based on 90-day hospitalization risk ≥ 90th percentile, based on a VA risk modeling tool, and an acute care episode in the previous 6 months. 19 A common component of all PIM programs is the provision of intensive care management and CC by an interdisciplinary team working in conjunction with PACT. The CC Template was developed to assist in documenting and rigorously understanding the implementation of CC by the PIM team.

Local Setting

The Atlanta VA Medical Center (AVAMC) was chosen as one of the PIM demonstration sites. The Atlanta PIM team identified and enrolled a random sample of eligible, high-risk patients from 1 community-based outpatient clinic (CBOC) in an urban location with 7,524 unique patients. Between September 2014 and September 2016, 300 patients were identified, and 86 patients agreed to participate in the PIM program.

In the CC Template pilot, the Atlanta PIM team included 2 nurse practitioners (NP), 2 social workers (SW), and 1 telehealth registered nurse (RN). Upon enrollment, members of the PIM team conducted comprehensive home assessments and offered intensive care management for medical, social, and behavioral needs. The main pillars of care management offered to high-risk patients were based on previous work done both inside and outside VA and included home visits, telephone-based disease management, co-attending appointments with patients, transition care management, and interdisciplinary team meetings with a focus on care coordination between PACT and all services required by patients.11,19

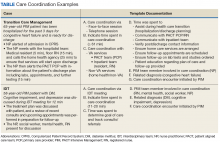

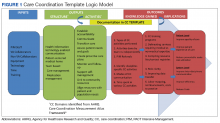

The Atlanta PIM team performed a variety of tasks to coordinate care for enrolled patients that included simple, 1-step tasks, such as chart reviews, and multistep, complex tasks that required the expertise of multiple team members (Figure 1).

Additionally, inconsistency in delivery of CC between PIM team members was noted. For example, there was significant variability in CC services provided by different team members in the provision of transition care management (TCM) and coordinating care from hospitalization back to home. Some PIM staff coordinated care and communicated with the patient, hospital team, home-care service, and primary-care team, while other staff only reviewed the chart and placed orders in CPRS. Additionally, much of the CC work was documented in administrative notes that did not trigger workload credit. This made it difficult to show how to appropriately labor map PIM staff or how staff were spending their time caring for patients.

In order to standardize documentation of the interdisciplinary CC activities performed by the PIM team and account for staff time, the Atlanta PIM team decided to develop a CPRS CC Template. The objective of the CC Template was to facilitate documentation of CC activities in the EHR, describe the types of CC activities performed by PIM team members, and track the time to perform these activities for patients with various chronic diseases.

Template Design and Implementation

The original design of the template was informed by the Atlanta PIM team after several informal focus groups and process mapping of CC pathways in the fall of 2015. The participants were all members of the Atlanta PIM team, 2 primary care physicians working with PIM, an AVAMC documentation specialist and a clinical applications coordinator (CAC) assigned to work with PIM. The major themes that arose during the brainstorming discussion were that the template should: (1) be feasible to use during their daily clinic workflow; (2) improve documentation of CC; and (3) have value for spread to other VA sites. Discussion centered on creating a CC Template versatile enough to:

- Decrease the number of steps for documenting CC;

- Consist only of check boxes, with very little need for free text, with the option to enter narrative free text after template completion;

- Document time spent in aggregate for completing complex CC encounters;

- Document various types of CC work and modes of communication;

- Allow for use by all PIM staff;

- Identify all team members that participated in the CC encounter to reduce redundant documentation by multiple staff;

- Adapt to different clinic sites based on the varied disciplines participating in other locations;

- Use evidence-based checklists to help standardize delivery of CC for certain activities such as TCM; and

- Extract data without extensive chart reviews to inform current CC and future QI work.

Following the brainstorming sessions, the authors performed a literature review to identify and integrate CC best practices. The AHRQ Care Coordination Atlas served as the main resource in the design of the logic model that depicted the delivery and subsequent documentation of high-quality, evidence-based CC in the CC Template (Figure 2).6

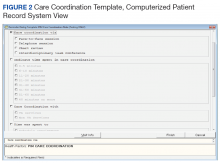

After reaching consensus about the key components of the CC Template, the CAC created a pilot version (Figure 3). All of the elements within the CC Template allowed for data abstraction from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) via discrete data elements known as health factors.

Over the course of implementation, the team became more enthusiastic about using the CC template to document previously unrecognized CC workload. Because the CC Template only was used to document CC workload and excluded encounters for clinical evaluation and management, specific notes were created and linked with the CC Template for optimal capture of encounters.

All components of the template were mandatory to eliminate the possibility of missing data. The Atlanta PIM site principal investigator developed a multicomponent training designed to increase support for the template by describing its value and to mitigate the potential for variability in how data are captured. Training included a face-to-face session with the team to review the template and work through sample CC cases. Additionally, a training manual with clear operational definitions and examples of how to complete each element of the CC Template was disseminated. The training was subsequently conducted with the San Francisco VA Medical Center PIM team, a spread site, via video conference. The spread site offered significant feedback on clarifying the training documents and adapting the CC template for their distinct care team structure. This feedback was incorporated into the final CC Template design to increase adaptability.

Implementation Evaluation

The RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance)framework served as the basis for evaluation of CC Template implementation. The RE-AIM framework is well established and able to evaluate the implementation and potential successful spread of new programs.23,24 Using RE-AIM, the authors planned to analyze data to explore the reach effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance of the CC Template use while providing complex care management for high-risk patients.

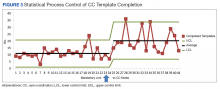

All data for the evaluation was extracted from the CDW by a data analyst and stored on a secure server. A statistical process control (SPC) chart was used to analyze the implementation process to assess variation in template use.

Results

After implementation, 35 weeks of CC Template pilot data were analyzed from June 1, 2015 to January 5, 2016. The PIM team completed 393 CC Templates over this collection period. After week 23, the CC template was linked to specific CC notes automatically. From weeks 23 to 35 an average of 20.3 CC Templates were completed per week by the team. The RE-AIM was used to assess the implementation of the CC Template.

Reach was determined by the number of patients enrolled in PIM with CC Template documentation. Of patients enrolled in Atlanta PIM, 90.1% had ≥ 1 CC encounter documented by the CC Template; 74.4% of Atlanta PIM patients had ≥ 1 CC encounter documented; 15.5% of patients had > 10 CC encounters documented; and 1 patient had > 25 CC encounters documented by the CC template.

Effectiveness for describing CC activities was captured through data from CC Template. The CC Template documentation by the PIM team showed that 79.4% of CC encounters were < 20 minutes, and 9.9% of encounters were > 61 minutes. Telephone communication was involved in 50.4% of CC encounters, and 24% required multiple modes of communication such as face-to-face, instant messenger, chart-based communication. Care coordination during hospitalization and discharge accounted for 5.9% of template use. Of the CC encounters documenting hospital transitions, 94.4% documented communication with the inpatient team, 58.3% documented coordination with social support, and only 11.1% documented communication with primary care teams. Improving communication with PACT teams after hospital discharge was identified as a future QI project based on these data. The PIM team initiated 83.2% of CC encounters.

Adoption was determined by the use of the CC Template by the team. All 5 team members used the CC template to document at least 1 CC encounter.