User login

When Is the Optimal Time to Start Treatment in Patients With Relapsing-Remitting MS?

Real-world data identify when therapy initiation has the best chance of reducing long-term disability.

BERLIN—Data from the Big Multiple Sclerosis Data (BMSD) Network indicate that the optimal time to start disease-modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) to prevent the long-term accumulation of disability is within six months of disease onset. This finding was presented by Pietro Iaffaldano, MD, and colleagues at ECTRIMS 2018. Dr. Iaffaldano is Assistant Professor of Neurology at the University of Bari, Italy.

Many randomized clinical trials support the early start of disease-modifying therapies in MS. However, there is still an ongoing discussion on the optimal timing of treatment. For insight into this and other questions, the Danish, Italian, and Swedish national MS registries, MSBase, and the OFSEP of France pooled data for specific research projects in the BMSD Network. One question they sought to answer with this large, real-world data set was the optimal time to start disease-modifying therapy to prevent long-term disability accumulation in MS.

A cohort of patients with relapsing-remitting MS who had 10 or more years of follow-up, three or more years of cumulative disease-modifying therapy exposure, and three or more Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score evaluations was selected from the pooled cohort of the BMSD Network. The researchers conducted a set of pairwise (1:1) propensity score matching analyses with 10 different cut-offs for early versus delayed treatment (> 0.5 year up to > 5.0 years, using 0.5-year intervals) to allow an unbiased comparison between groups. The logistic model to predict propensity score included the following covariates: age at onset of the disease, sex, baseline EDSS, number of relapses in the two years before disease-modifying therapy start, number of EDSS evaluations, decade of birth, and registry source. To estimate the risk of reaching 12 months-confirmed EDSS progression (EDSSpr), a set of Cox models, adjusted for disease duration and relapses after disease-modifying therapy start as time-dependent covariates, was calculated.

A cohort of 11,871 patients with relapsing-remitting MS (71.0% female) was retrieved from the pooled BMSD Network database. The median (interquartile range) age at onset was 27.7 (22.3–34.6), median follow-up was 13.2 (11.4–15.4) years, and median time to the first disease-modifying therapy start was 3.8 (1.5–8.5) years. During the follow-up, an EDSSpr was reached by 4,138 (34.9%) patients. The lowest hazard ratio (HR) with relative 95% confidence interval (CI) for the propensity score matched models was obtained by a cutoff of treatment start within six months from disease onset (n = 873 per group). Early treatment significantly reduced the risk of reaching an EDSSpr (HR, 0.72 ). All subsequent comparisons between early and delayed treatment were not statistically significant.

This project was supported by Biogen International (Zug, Switzerland) on the basis of a sponsored research agreement with the BMSD Network.

Real-world data identify when therapy initiation has the best chance of reducing long-term disability.

Real-world data identify when therapy initiation has the best chance of reducing long-term disability.

BERLIN—Data from the Big Multiple Sclerosis Data (BMSD) Network indicate that the optimal time to start disease-modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) to prevent the long-term accumulation of disability is within six months of disease onset. This finding was presented by Pietro Iaffaldano, MD, and colleagues at ECTRIMS 2018. Dr. Iaffaldano is Assistant Professor of Neurology at the University of Bari, Italy.

Many randomized clinical trials support the early start of disease-modifying therapies in MS. However, there is still an ongoing discussion on the optimal timing of treatment. For insight into this and other questions, the Danish, Italian, and Swedish national MS registries, MSBase, and the OFSEP of France pooled data for specific research projects in the BMSD Network. One question they sought to answer with this large, real-world data set was the optimal time to start disease-modifying therapy to prevent long-term disability accumulation in MS.

A cohort of patients with relapsing-remitting MS who had 10 or more years of follow-up, three or more years of cumulative disease-modifying therapy exposure, and three or more Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score evaluations was selected from the pooled cohort of the BMSD Network. The researchers conducted a set of pairwise (1:1) propensity score matching analyses with 10 different cut-offs for early versus delayed treatment (> 0.5 year up to > 5.0 years, using 0.5-year intervals) to allow an unbiased comparison between groups. The logistic model to predict propensity score included the following covariates: age at onset of the disease, sex, baseline EDSS, number of relapses in the two years before disease-modifying therapy start, number of EDSS evaluations, decade of birth, and registry source. To estimate the risk of reaching 12 months-confirmed EDSS progression (EDSSpr), a set of Cox models, adjusted for disease duration and relapses after disease-modifying therapy start as time-dependent covariates, was calculated.

A cohort of 11,871 patients with relapsing-remitting MS (71.0% female) was retrieved from the pooled BMSD Network database. The median (interquartile range) age at onset was 27.7 (22.3–34.6), median follow-up was 13.2 (11.4–15.4) years, and median time to the first disease-modifying therapy start was 3.8 (1.5–8.5) years. During the follow-up, an EDSSpr was reached by 4,138 (34.9%) patients. The lowest hazard ratio (HR) with relative 95% confidence interval (CI) for the propensity score matched models was obtained by a cutoff of treatment start within six months from disease onset (n = 873 per group). Early treatment significantly reduced the risk of reaching an EDSSpr (HR, 0.72 ). All subsequent comparisons between early and delayed treatment were not statistically significant.

This project was supported by Biogen International (Zug, Switzerland) on the basis of a sponsored research agreement with the BMSD Network.

BERLIN—Data from the Big Multiple Sclerosis Data (BMSD) Network indicate that the optimal time to start disease-modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) to prevent the long-term accumulation of disability is within six months of disease onset. This finding was presented by Pietro Iaffaldano, MD, and colleagues at ECTRIMS 2018. Dr. Iaffaldano is Assistant Professor of Neurology at the University of Bari, Italy.

Many randomized clinical trials support the early start of disease-modifying therapies in MS. However, there is still an ongoing discussion on the optimal timing of treatment. For insight into this and other questions, the Danish, Italian, and Swedish national MS registries, MSBase, and the OFSEP of France pooled data for specific research projects in the BMSD Network. One question they sought to answer with this large, real-world data set was the optimal time to start disease-modifying therapy to prevent long-term disability accumulation in MS.

A cohort of patients with relapsing-remitting MS who had 10 or more years of follow-up, three or more years of cumulative disease-modifying therapy exposure, and three or more Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score evaluations was selected from the pooled cohort of the BMSD Network. The researchers conducted a set of pairwise (1:1) propensity score matching analyses with 10 different cut-offs for early versus delayed treatment (> 0.5 year up to > 5.0 years, using 0.5-year intervals) to allow an unbiased comparison between groups. The logistic model to predict propensity score included the following covariates: age at onset of the disease, sex, baseline EDSS, number of relapses in the two years before disease-modifying therapy start, number of EDSS evaluations, decade of birth, and registry source. To estimate the risk of reaching 12 months-confirmed EDSS progression (EDSSpr), a set of Cox models, adjusted for disease duration and relapses after disease-modifying therapy start as time-dependent covariates, was calculated.

A cohort of 11,871 patients with relapsing-remitting MS (71.0% female) was retrieved from the pooled BMSD Network database. The median (interquartile range) age at onset was 27.7 (22.3–34.6), median follow-up was 13.2 (11.4–15.4) years, and median time to the first disease-modifying therapy start was 3.8 (1.5–8.5) years. During the follow-up, an EDSSpr was reached by 4,138 (34.9%) patients. The lowest hazard ratio (HR) with relative 95% confidence interval (CI) for the propensity score matched models was obtained by a cutoff of treatment start within six months from disease onset (n = 873 per group). Early treatment significantly reduced the risk of reaching an EDSSpr (HR, 0.72 ). All subsequent comparisons between early and delayed treatment were not statistically significant.

This project was supported by Biogen International (Zug, Switzerland) on the basis of a sponsored research agreement with the BMSD Network.

Rivaroxaban gains indication for prevention of major cardiovascular events in CAD/PAD

when taken with aspirin, Janssen Pharmaceuticals announced on October 11.

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval was based on a review of the 27,000-patient COMPASS trial, which showed last year that a low dosage of rivaroxaban (Xarelto) plus aspirin reduced the combined rate of cardiovascular disease events by 24% in patients with coronary artery disease and by 28% in participants with peripheral artery disease, compared with aspirin alone. (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 5;377[14]:1319-30)

The flip side to the reduction in COMPASS’s combined primary endpoint was a 51% increase in major bleeding. However, that bump did not translate to increases in fatal bleeds, intracerebral bleeds, or bleeding in other critical organs.

COMPASS (Cardiovascular Outcomes for People Using Anticoagulation Strategies) studied two dosages of rivaroxaban, 2.5 mg and 5 mg twice daily, and it was the lower dosage that did the trick. Until this approval, that formulation wasn’t available; Janssen announced the coming of the 2.5-mg pill in its release.

The new prescribing information states specifically that Xarelto 2.5 mg is indicated, in combination with aspirin, to reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events, cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke in patients with chronic coronary artery disease or peripheral artery disease.

This is the sixth indication for rivaroxaban, a factor Xa inhibitor that was first approved in 2011. It is also the first indication for cardiovascular prevention for any factor Xa inhibitor. Others on the U.S. market are apixaban (Eliquis), edoxaban (Savaysa), and betrixaban (Bevyxxa).

COMPASS was presented at the 2017 annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. At that time, Eugene Braunwald, MD, of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, commented that the trial produced “unambiguous results that should change guidelines and the management of stable coronary artery disease.” He added that the results are “an important step for thrombocardiology.”

when taken with aspirin, Janssen Pharmaceuticals announced on October 11.

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval was based on a review of the 27,000-patient COMPASS trial, which showed last year that a low dosage of rivaroxaban (Xarelto) plus aspirin reduced the combined rate of cardiovascular disease events by 24% in patients with coronary artery disease and by 28% in participants with peripheral artery disease, compared with aspirin alone. (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 5;377[14]:1319-30)

The flip side to the reduction in COMPASS’s combined primary endpoint was a 51% increase in major bleeding. However, that bump did not translate to increases in fatal bleeds, intracerebral bleeds, or bleeding in other critical organs.

COMPASS (Cardiovascular Outcomes for People Using Anticoagulation Strategies) studied two dosages of rivaroxaban, 2.5 mg and 5 mg twice daily, and it was the lower dosage that did the trick. Until this approval, that formulation wasn’t available; Janssen announced the coming of the 2.5-mg pill in its release.

The new prescribing information states specifically that Xarelto 2.5 mg is indicated, in combination with aspirin, to reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events, cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke in patients with chronic coronary artery disease or peripheral artery disease.

This is the sixth indication for rivaroxaban, a factor Xa inhibitor that was first approved in 2011. It is also the first indication for cardiovascular prevention for any factor Xa inhibitor. Others on the U.S. market are apixaban (Eliquis), edoxaban (Savaysa), and betrixaban (Bevyxxa).

COMPASS was presented at the 2017 annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. At that time, Eugene Braunwald, MD, of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, commented that the trial produced “unambiguous results that should change guidelines and the management of stable coronary artery disease.” He added that the results are “an important step for thrombocardiology.”

when taken with aspirin, Janssen Pharmaceuticals announced on October 11.

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval was based on a review of the 27,000-patient COMPASS trial, which showed last year that a low dosage of rivaroxaban (Xarelto) plus aspirin reduced the combined rate of cardiovascular disease events by 24% in patients with coronary artery disease and by 28% in participants with peripheral artery disease, compared with aspirin alone. (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 5;377[14]:1319-30)

The flip side to the reduction in COMPASS’s combined primary endpoint was a 51% increase in major bleeding. However, that bump did not translate to increases in fatal bleeds, intracerebral bleeds, or bleeding in other critical organs.

COMPASS (Cardiovascular Outcomes for People Using Anticoagulation Strategies) studied two dosages of rivaroxaban, 2.5 mg and 5 mg twice daily, and it was the lower dosage that did the trick. Until this approval, that formulation wasn’t available; Janssen announced the coming of the 2.5-mg pill in its release.

The new prescribing information states specifically that Xarelto 2.5 mg is indicated, in combination with aspirin, to reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events, cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke in patients with chronic coronary artery disease or peripheral artery disease.

This is the sixth indication for rivaroxaban, a factor Xa inhibitor that was first approved in 2011. It is also the first indication for cardiovascular prevention for any factor Xa inhibitor. Others on the U.S. market are apixaban (Eliquis), edoxaban (Savaysa), and betrixaban (Bevyxxa).

COMPASS was presented at the 2017 annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. At that time, Eugene Braunwald, MD, of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, commented that the trial produced “unambiguous results that should change guidelines and the management of stable coronary artery disease.” He added that the results are “an important step for thrombocardiology.”

Bias in the clinical setting can impact patient care

SAN ANTONIO – Physicians and other health care providers may harbor implicit, or unconscious, biases that contribute to health care disparities, patient communication researcher Stacey Passalacqua, PhD, said here at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Implicit biases are beliefs or attitudes, for example, about certain social groups, that exist outside of a health care provider’s conscious awareness, said Dr. Passalacqua of the department of communication at the University of Texas, San Antonio. If bias is implicit, it can be difficult self-assess.

among other social, ethnic, and racial groups, Dr. Passalacqua told attendees in workshops at the meeting.

“If a health care provider has negative biases toward a particular patient – maybe they think that these patients doesn’t care that much about their health or that they really have no interest in participating – then obviously that health care provider is far less likely to engage that patient in shared decision making,” she said in a video interview.

Diagnosis and treatment are subject to influence by the bias that physicians have toward certain patient groups, according to Dr. Passalacqua. For example, she said women with heart disease are less likely to be accurately diagnosed.

The bias in the medical setting might be mitigated by the presence of more individuals from the at-risk groups in the health care workforce, she added. In one recent retrospective study, investigators found that after an MI, a woman treated by a male physician was associated with higher mortality, while women and men had similar outcomes when treated by female physicians.

“That is one of the reasons why it is so important to have a diverse workforce, to have health care providers of different ethnicities, of different genders, or different backgrounds, because they are less subject to some of these implicit biases that we know are highly problematic in health care,” she said in the interview.

Dr. Passalacqua had no disclosures related to her presentation.

SAN ANTONIO – Physicians and other health care providers may harbor implicit, or unconscious, biases that contribute to health care disparities, patient communication researcher Stacey Passalacqua, PhD, said here at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Implicit biases are beliefs or attitudes, for example, about certain social groups, that exist outside of a health care provider’s conscious awareness, said Dr. Passalacqua of the department of communication at the University of Texas, San Antonio. If bias is implicit, it can be difficult self-assess.

among other social, ethnic, and racial groups, Dr. Passalacqua told attendees in workshops at the meeting.

“If a health care provider has negative biases toward a particular patient – maybe they think that these patients doesn’t care that much about their health or that they really have no interest in participating – then obviously that health care provider is far less likely to engage that patient in shared decision making,” she said in a video interview.

Diagnosis and treatment are subject to influence by the bias that physicians have toward certain patient groups, according to Dr. Passalacqua. For example, she said women with heart disease are less likely to be accurately diagnosed.

The bias in the medical setting might be mitigated by the presence of more individuals from the at-risk groups in the health care workforce, she added. In one recent retrospective study, investigators found that after an MI, a woman treated by a male physician was associated with higher mortality, while women and men had similar outcomes when treated by female physicians.

“That is one of the reasons why it is so important to have a diverse workforce, to have health care providers of different ethnicities, of different genders, or different backgrounds, because they are less subject to some of these implicit biases that we know are highly problematic in health care,” she said in the interview.

Dr. Passalacqua had no disclosures related to her presentation.

SAN ANTONIO – Physicians and other health care providers may harbor implicit, or unconscious, biases that contribute to health care disparities, patient communication researcher Stacey Passalacqua, PhD, said here at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Implicit biases are beliefs or attitudes, for example, about certain social groups, that exist outside of a health care provider’s conscious awareness, said Dr. Passalacqua of the department of communication at the University of Texas, San Antonio. If bias is implicit, it can be difficult self-assess.

among other social, ethnic, and racial groups, Dr. Passalacqua told attendees in workshops at the meeting.

“If a health care provider has negative biases toward a particular patient – maybe they think that these patients doesn’t care that much about their health or that they really have no interest in participating – then obviously that health care provider is far less likely to engage that patient in shared decision making,” she said in a video interview.

Diagnosis and treatment are subject to influence by the bias that physicians have toward certain patient groups, according to Dr. Passalacqua. For example, she said women with heart disease are less likely to be accurately diagnosed.

The bias in the medical setting might be mitigated by the presence of more individuals from the at-risk groups in the health care workforce, she added. In one recent retrospective study, investigators found that after an MI, a woman treated by a male physician was associated with higher mortality, while women and men had similar outcomes when treated by female physicians.

“That is one of the reasons why it is so important to have a diverse workforce, to have health care providers of different ethnicities, of different genders, or different backgrounds, because they are less subject to some of these implicit biases that we know are highly problematic in health care,” she said in the interview.

Dr. Passalacqua had no disclosures related to her presentation.

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2018

Diffuse Nonscarring Alopecia

The Diagnosis: Trichotillomania

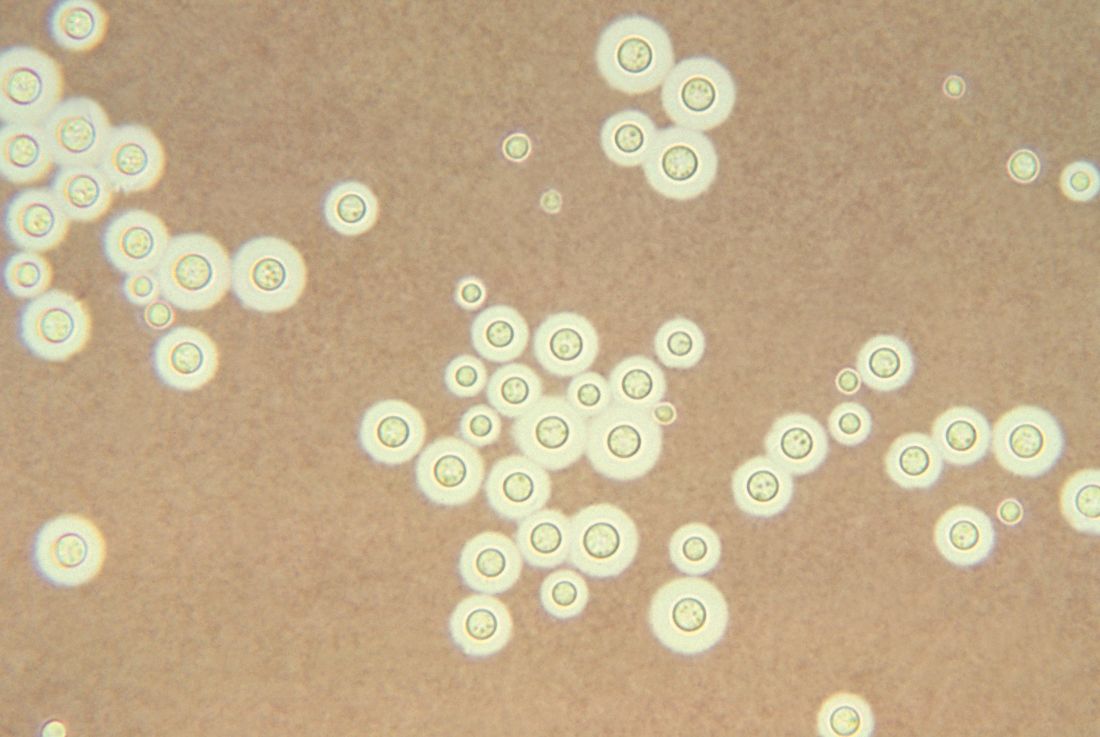

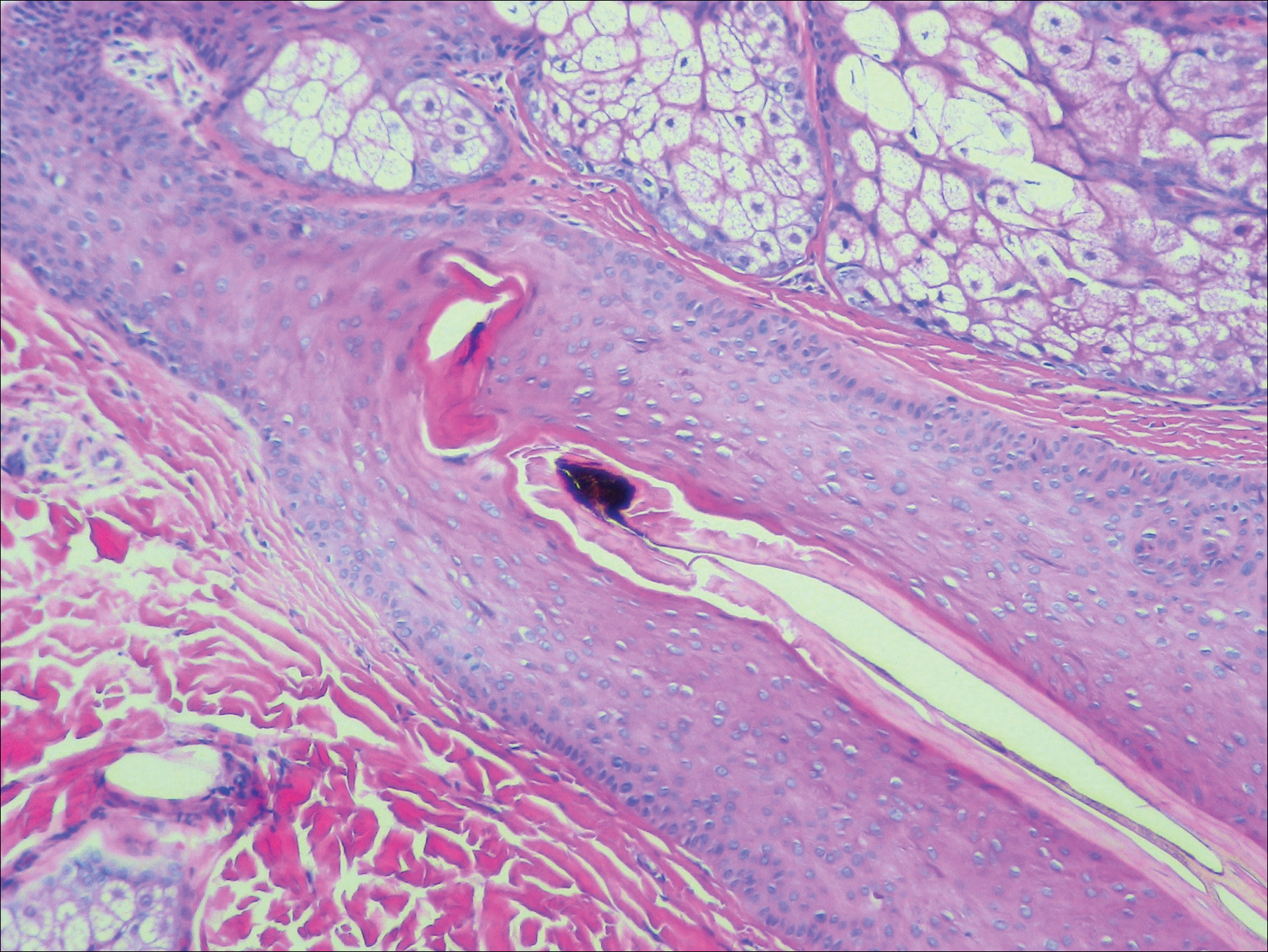

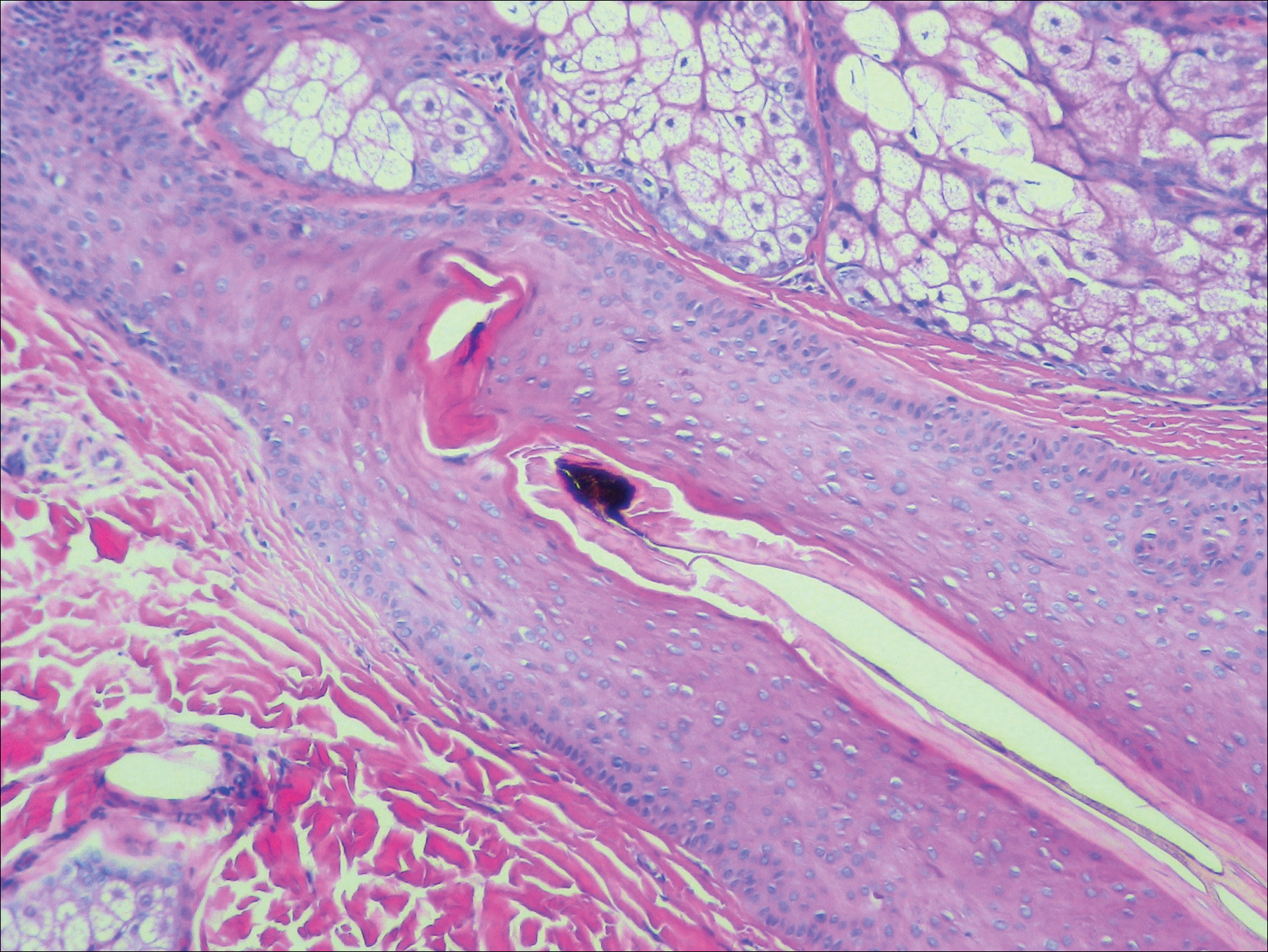

A scalp punch biopsy revealed pigmented hair casts, an increase in catagen and telogen follicles, and a lack of perifollicular inflammation (Figure). Based on the clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of trichotillomania (TTM) was established.

Trichotillomania is a hairpulling disorder with notable dermatologic and psychiatric overlap. Although previously considered an impulse control disorder, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) reclassified it within obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, which also include body dysmorphic disorder and excoriation (skin-picking) disorder. Diagnostic criteria for TTM include the following: the patient must have recurrent pulling out of his/her hair resulting in hair loss despite repeated attempts to stop; underlying medical conditions and other psychiatric diagnoses must be excluded; and the patient must experience distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of functioning from the hairpulling.1 Trichotillomania mainly occurs in children and young adults, with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 1% to 2%.2 The coexistence of a mood or anxiety disorder is common, as seen in our patient.

The diagnosis of TTM requires strong clinical suspicion because patients and their parents/guardians usually deny hairpulling. The main clinical differential diagnosis often is alopecia areata (AA) because both conditions can present as well-defined patches of nonscarring hair loss. Trichoscopy provides an invaluable noninvasive diagnostic tool that can be particularly useful in pediatric patients who may be reluctant to have a scalp biopsy. There are many overlapping trichoscopic findings of TTM and AA, including yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, coiled hairs, and exclamation mark hairs.3 More specific trichoscopy findings for TTM include flame hairs (wavy proximal hair residue), V-sign (2 shafts within 1 follicle broken at the same length), and tulip hairs (dark, tulip-shaped ends of broken hairs).4 Hair breakage of varying lengths and trichoptilosis (split ends) can be better visualized using trichoscopy and support a diagnosis of TTM over AA.

Androgenetic alopecia (female pattern hair loss) presents with gradual thinning around the part line of the frontal and parietal scalp with trichoscopy showing miniaturization of hairs and decreased follicle density. The moth-eaten-like appearance of alopecia due to secondary syphilis may mimic alopecia areata clinically, but serologic testing can confirm the diagnosis of syphilis. Telogen effluvium does not have the trichoscopic features that are seen in TTM and is clinically distinguished by hair shedding and a positive hair pull test.

Biopsy can provide objective yet nonspecific support for the diagnosis, demonstrating trichomalacia, pigmented hair casts, empty follicles, and an increase in catagen hairs with a lack of inflammation. Normal and damaged hair follicles may be seen in close proximity, and hemorrhage may be seen secondary to trauma. Pigmented hair casts are not specific to TTM and are present in other traumatic hair disorders, such as traction alopecia; therefore, clinical correlation is essential for diagnosis.

Habit reversal training is the most effective treatment of TTM and involves 3 major components: awareness training with self-monitoring, stimulus control, and competing response procedures.5 Although numerous pharmacotherapies have been reported as effective treatments for TTM, a 2013 Cochrane review of 8 randomized controlled trials concluded that no medication has demonstrated reliable efficacy. Reported therapies included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, naltrexone, olanzapine, N-acetylcysteine, and clomipramine.6

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Schumer MC, Panza KE, Mulqueen JM, et al. Long-term outcome in pediatric trichotillomania. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:737-743.

- Lencastre A, Tosti A. Role of trichoscopy on children's scalp and hair disorders. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:674-682.

- Rakowska A, Slowinska M, Olszewska M, et al. New trichoscopy findings in trichotillomania: flame hairs, V-sign, hook hairs, hair powder, tulip hairs. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:303-306.

- Morris S, Zickgraf H, Dingfelder H, et al. Habit reversal training in trichotillomania: guide for the clinician. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13:1069-1177.

- Rothbart R, Amos T, Siegfried N, et al. Pharmacotherapy for trichotillomania. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD007662.

The Diagnosis: Trichotillomania

A scalp punch biopsy revealed pigmented hair casts, an increase in catagen and telogen follicles, and a lack of perifollicular inflammation (Figure). Based on the clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of trichotillomania (TTM) was established.

Trichotillomania is a hairpulling disorder with notable dermatologic and psychiatric overlap. Although previously considered an impulse control disorder, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) reclassified it within obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, which also include body dysmorphic disorder and excoriation (skin-picking) disorder. Diagnostic criteria for TTM include the following: the patient must have recurrent pulling out of his/her hair resulting in hair loss despite repeated attempts to stop; underlying medical conditions and other psychiatric diagnoses must be excluded; and the patient must experience distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of functioning from the hairpulling.1 Trichotillomania mainly occurs in children and young adults, with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 1% to 2%.2 The coexistence of a mood or anxiety disorder is common, as seen in our patient.

The diagnosis of TTM requires strong clinical suspicion because patients and their parents/guardians usually deny hairpulling. The main clinical differential diagnosis often is alopecia areata (AA) because both conditions can present as well-defined patches of nonscarring hair loss. Trichoscopy provides an invaluable noninvasive diagnostic tool that can be particularly useful in pediatric patients who may be reluctant to have a scalp biopsy. There are many overlapping trichoscopic findings of TTM and AA, including yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, coiled hairs, and exclamation mark hairs.3 More specific trichoscopy findings for TTM include flame hairs (wavy proximal hair residue), V-sign (2 shafts within 1 follicle broken at the same length), and tulip hairs (dark, tulip-shaped ends of broken hairs).4 Hair breakage of varying lengths and trichoptilosis (split ends) can be better visualized using trichoscopy and support a diagnosis of TTM over AA.

Androgenetic alopecia (female pattern hair loss) presents with gradual thinning around the part line of the frontal and parietal scalp with trichoscopy showing miniaturization of hairs and decreased follicle density. The moth-eaten-like appearance of alopecia due to secondary syphilis may mimic alopecia areata clinically, but serologic testing can confirm the diagnosis of syphilis. Telogen effluvium does not have the trichoscopic features that are seen in TTM and is clinically distinguished by hair shedding and a positive hair pull test.

Biopsy can provide objective yet nonspecific support for the diagnosis, demonstrating trichomalacia, pigmented hair casts, empty follicles, and an increase in catagen hairs with a lack of inflammation. Normal and damaged hair follicles may be seen in close proximity, and hemorrhage may be seen secondary to trauma. Pigmented hair casts are not specific to TTM and are present in other traumatic hair disorders, such as traction alopecia; therefore, clinical correlation is essential for diagnosis.

Habit reversal training is the most effective treatment of TTM and involves 3 major components: awareness training with self-monitoring, stimulus control, and competing response procedures.5 Although numerous pharmacotherapies have been reported as effective treatments for TTM, a 2013 Cochrane review of 8 randomized controlled trials concluded that no medication has demonstrated reliable efficacy. Reported therapies included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, naltrexone, olanzapine, N-acetylcysteine, and clomipramine.6

The Diagnosis: Trichotillomania

A scalp punch biopsy revealed pigmented hair casts, an increase in catagen and telogen follicles, and a lack of perifollicular inflammation (Figure). Based on the clinical and histopathological findings, a diagnosis of trichotillomania (TTM) was established.

Trichotillomania is a hairpulling disorder with notable dermatologic and psychiatric overlap. Although previously considered an impulse control disorder, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) reclassified it within obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, which also include body dysmorphic disorder and excoriation (skin-picking) disorder. Diagnostic criteria for TTM include the following: the patient must have recurrent pulling out of his/her hair resulting in hair loss despite repeated attempts to stop; underlying medical conditions and other psychiatric diagnoses must be excluded; and the patient must experience distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of functioning from the hairpulling.1 Trichotillomania mainly occurs in children and young adults, with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 1% to 2%.2 The coexistence of a mood or anxiety disorder is common, as seen in our patient.

The diagnosis of TTM requires strong clinical suspicion because patients and their parents/guardians usually deny hairpulling. The main clinical differential diagnosis often is alopecia areata (AA) because both conditions can present as well-defined patches of nonscarring hair loss. Trichoscopy provides an invaluable noninvasive diagnostic tool that can be particularly useful in pediatric patients who may be reluctant to have a scalp biopsy. There are many overlapping trichoscopic findings of TTM and AA, including yellow dots, black dots, broken hairs, coiled hairs, and exclamation mark hairs.3 More specific trichoscopy findings for TTM include flame hairs (wavy proximal hair residue), V-sign (2 shafts within 1 follicle broken at the same length), and tulip hairs (dark, tulip-shaped ends of broken hairs).4 Hair breakage of varying lengths and trichoptilosis (split ends) can be better visualized using trichoscopy and support a diagnosis of TTM over AA.

Androgenetic alopecia (female pattern hair loss) presents with gradual thinning around the part line of the frontal and parietal scalp with trichoscopy showing miniaturization of hairs and decreased follicle density. The moth-eaten-like appearance of alopecia due to secondary syphilis may mimic alopecia areata clinically, but serologic testing can confirm the diagnosis of syphilis. Telogen effluvium does not have the trichoscopic features that are seen in TTM and is clinically distinguished by hair shedding and a positive hair pull test.

Biopsy can provide objective yet nonspecific support for the diagnosis, demonstrating trichomalacia, pigmented hair casts, empty follicles, and an increase in catagen hairs with a lack of inflammation. Normal and damaged hair follicles may be seen in close proximity, and hemorrhage may be seen secondary to trauma. Pigmented hair casts are not specific to TTM and are present in other traumatic hair disorders, such as traction alopecia; therefore, clinical correlation is essential for diagnosis.

Habit reversal training is the most effective treatment of TTM and involves 3 major components: awareness training with self-monitoring, stimulus control, and competing response procedures.5 Although numerous pharmacotherapies have been reported as effective treatments for TTM, a 2013 Cochrane review of 8 randomized controlled trials concluded that no medication has demonstrated reliable efficacy. Reported therapies included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, naltrexone, olanzapine, N-acetylcysteine, and clomipramine.6

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Schumer MC, Panza KE, Mulqueen JM, et al. Long-term outcome in pediatric trichotillomania. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:737-743.

- Lencastre A, Tosti A. Role of trichoscopy on children's scalp and hair disorders. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:674-682.

- Rakowska A, Slowinska M, Olszewska M, et al. New trichoscopy findings in trichotillomania: flame hairs, V-sign, hook hairs, hair powder, tulip hairs. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:303-306.

- Morris S, Zickgraf H, Dingfelder H, et al. Habit reversal training in trichotillomania: guide for the clinician. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13:1069-1177.

- Rothbart R, Amos T, Siegfried N, et al. Pharmacotherapy for trichotillomania. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD007662.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Schumer MC, Panza KE, Mulqueen JM, et al. Long-term outcome in pediatric trichotillomania. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32:737-743.

- Lencastre A, Tosti A. Role of trichoscopy on children's scalp and hair disorders. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:674-682.

- Rakowska A, Slowinska M, Olszewska M, et al. New trichoscopy findings in trichotillomania: flame hairs, V-sign, hook hairs, hair powder, tulip hairs. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:303-306.

- Morris S, Zickgraf H, Dingfelder H, et al. Habit reversal training in trichotillomania: guide for the clinician. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13:1069-1177.

- Rothbart R, Amos T, Siegfried N, et al. Pharmacotherapy for trichotillomania. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD007662.

A 19-year-old woman with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and an anxiety disorder presented with hair loss of 2 years' duration. She initially had small circular bald areas throughout the scalp that had progressed to diffuse hair loss of the entire scalp. She denied recent hairpulling but admitted to a remote prior history of eyelash and eyebrow pulling. She denied any voice changes, acne, or menstrual irregularities. Physical examination revealed short hairs of varying lengths throughout the scalp with no loss of follicles, erythema, scale, or exclamation point hairs. Eyebrows and eyelashes were normal. A hair-pull test was negative. Trichoscopy illuminated variation in hair shaft diameters, as well as short, irregularly broken hairs of different lengths (inset).

Introducing the Postcall Podcast

At MDedge, we know that medicine can be a bit of an awakening at every step of your career. So, we launched the Postcall Podcast as a way to share your stories: what you love about medicine and what you love outside of your career. This podcast is meant to be a place for you to find your truth.

In the first episode, Nick Andrews welcomes the Editor-In-Chief of MDedge Psychiatry and the host of the MDedge Psychcast, Dr. Lorenzo Norris.

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

At MDedge, we know that medicine can be a bit of an awakening at every step of your career. So, we launched the Postcall Podcast as a way to share your stories: what you love about medicine and what you love outside of your career. This podcast is meant to be a place for you to find your truth.

In the first episode, Nick Andrews welcomes the Editor-In-Chief of MDedge Psychiatry and the host of the MDedge Psychcast, Dr. Lorenzo Norris.

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

At MDedge, we know that medicine can be a bit of an awakening at every step of your career. So, we launched the Postcall Podcast as a way to share your stories: what you love about medicine and what you love outside of your career. This podcast is meant to be a place for you to find your truth.

In the first episode, Nick Andrews welcomes the Editor-In-Chief of MDedge Psychiatry and the host of the MDedge Psychcast, Dr. Lorenzo Norris.

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Dupilumab offers extra benefits to asthmatic teens

SAN ANTONIO – For adolescents with asthma, treatment with the biologic agent dupilumab provided benefits that were at least comparable with what was seen in adults, results from a retrospective analysis of a randomized, phase 3 study suggest.

Adolescents had reduced asthma exacerbations in line with what was seen in adults and had improvements in lung function that were at a greater magnitude than adults, according to study coauthor Neil M.H. Graham, MD, of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Tarrytown, N.Y.

“We think, overall, it’s a very good treatment response from this drug in this high-risk population, and it is generally well tolerated, as we’ve seen in other studies,” Dr. Graham said in a podium presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Dr. Graham presented results of an analysis of the 1,902-patient, phase 3 Liberty Asthma QUEST trial, published in May 2018 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Top-line results of QUEST showed that treatment with dupilumab, a fully human anti–IL-4Ra monoclonal antibody, resulted in significantly lower rates of severe asthma exacerbation, along with improved lung function, in patients aged 12 years and older with moderate to severe asthma.

Now, this retrospective analysis shows that, in adolescents, improvements from baseline to week 12 in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) were significant and at a greater magnitude than in adults, according to Dr. Graham and his coinvestigators.

The improvement over 12 weeks in FEV1 for adolescents was 0.36 L and 0.27 L, respectively, for the 200- and 300-mg doses of dupilumab (P less than .05 vs. placebo for both), Dr. Graham and his coinvestigators reported. In adults, the improvement was 0.12 L.

The annualized exacerbation rate dropped by 46.4% for those adolescents who received 200 mg dupilumab, though there was no treatment effect versus placebo for dupilumab 300 mg; the investigators said the lack of effect in this retrospective analysis could have been caused by imbalances in prior event rates or the small sample size.

A total of 107 out of 1,902 patients in QUEST were adolescents, and of those, 68 were randomly assigned to dupilumab, according to the report. Injection site reaction was the most common adverse event in adolescents in both dosing groups.

Dr. Graham reported disclosures related to his employment with Regeneron. Study coauthors reported disclosures related to Regeneron, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Teva Pharmaceutical, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Genentech, and others.

SOURCE: Graham NMH et al. CHEST. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.022.

SAN ANTONIO – For adolescents with asthma, treatment with the biologic agent dupilumab provided benefits that were at least comparable with what was seen in adults, results from a retrospective analysis of a randomized, phase 3 study suggest.

Adolescents had reduced asthma exacerbations in line with what was seen in adults and had improvements in lung function that were at a greater magnitude than adults, according to study coauthor Neil M.H. Graham, MD, of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Tarrytown, N.Y.

“We think, overall, it’s a very good treatment response from this drug in this high-risk population, and it is generally well tolerated, as we’ve seen in other studies,” Dr. Graham said in a podium presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Dr. Graham presented results of an analysis of the 1,902-patient, phase 3 Liberty Asthma QUEST trial, published in May 2018 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Top-line results of QUEST showed that treatment with dupilumab, a fully human anti–IL-4Ra monoclonal antibody, resulted in significantly lower rates of severe asthma exacerbation, along with improved lung function, in patients aged 12 years and older with moderate to severe asthma.

Now, this retrospective analysis shows that, in adolescents, improvements from baseline to week 12 in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) were significant and at a greater magnitude than in adults, according to Dr. Graham and his coinvestigators.

The improvement over 12 weeks in FEV1 for adolescents was 0.36 L and 0.27 L, respectively, for the 200- and 300-mg doses of dupilumab (P less than .05 vs. placebo for both), Dr. Graham and his coinvestigators reported. In adults, the improvement was 0.12 L.

The annualized exacerbation rate dropped by 46.4% for those adolescents who received 200 mg dupilumab, though there was no treatment effect versus placebo for dupilumab 300 mg; the investigators said the lack of effect in this retrospective analysis could have been caused by imbalances in prior event rates or the small sample size.

A total of 107 out of 1,902 patients in QUEST were adolescents, and of those, 68 were randomly assigned to dupilumab, according to the report. Injection site reaction was the most common adverse event in adolescents in both dosing groups.

Dr. Graham reported disclosures related to his employment with Regeneron. Study coauthors reported disclosures related to Regeneron, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Teva Pharmaceutical, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Genentech, and others.

SOURCE: Graham NMH et al. CHEST. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.022.

SAN ANTONIO – For adolescents with asthma, treatment with the biologic agent dupilumab provided benefits that were at least comparable with what was seen in adults, results from a retrospective analysis of a randomized, phase 3 study suggest.

Adolescents had reduced asthma exacerbations in line with what was seen in adults and had improvements in lung function that were at a greater magnitude than adults, according to study coauthor Neil M.H. Graham, MD, of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Tarrytown, N.Y.

“We think, overall, it’s a very good treatment response from this drug in this high-risk population, and it is generally well tolerated, as we’ve seen in other studies,” Dr. Graham said in a podium presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Dr. Graham presented results of an analysis of the 1,902-patient, phase 3 Liberty Asthma QUEST trial, published in May 2018 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Top-line results of QUEST showed that treatment with dupilumab, a fully human anti–IL-4Ra monoclonal antibody, resulted in significantly lower rates of severe asthma exacerbation, along with improved lung function, in patients aged 12 years and older with moderate to severe asthma.

Now, this retrospective analysis shows that, in adolescents, improvements from baseline to week 12 in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) were significant and at a greater magnitude than in adults, according to Dr. Graham and his coinvestigators.

The improvement over 12 weeks in FEV1 for adolescents was 0.36 L and 0.27 L, respectively, for the 200- and 300-mg doses of dupilumab (P less than .05 vs. placebo for both), Dr. Graham and his coinvestigators reported. In adults, the improvement was 0.12 L.

The annualized exacerbation rate dropped by 46.4% for those adolescents who received 200 mg dupilumab, though there was no treatment effect versus placebo for dupilumab 300 mg; the investigators said the lack of effect in this retrospective analysis could have been caused by imbalances in prior event rates or the small sample size.

A total of 107 out of 1,902 patients in QUEST were adolescents, and of those, 68 were randomly assigned to dupilumab, according to the report. Injection site reaction was the most common adverse event in adolescents in both dosing groups.

Dr. Graham reported disclosures related to his employment with Regeneron. Study coauthors reported disclosures related to Regeneron, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Teva Pharmaceutical, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Genentech, and others.

SOURCE: Graham NMH et al. CHEST. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.022.

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2018

Key clinical point: Dupilumab’s benefits in adolescents with moderate to severe asthma are at least comparable with what has been reported in adults.

Major finding: The improvement over 12 weeks in forced expiratory volume in 1 second for adolescents was 0.36 L and 0.27 L, respectively, for the 200- and 300-mg doses of dupilumab versus 0.12 L for adults.

Study details: A retrospective analysis of 1,902 patients (including 107 adolescents) in Liberty Asthma QUEST, a recently reported randomized, phase 3 trial.

Disclosures: Several study coauthors reported employment with Regeneron. Dr. Graham reported disclosures related to his employment with Regeneron. Other reported disclosures were related to AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Teva Pharmaceutical, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, and Genentech, among other entities.

Source: Graham NMH et al. CHEST. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j/chest.2018.08.002.

Lithium/cancer link debunked

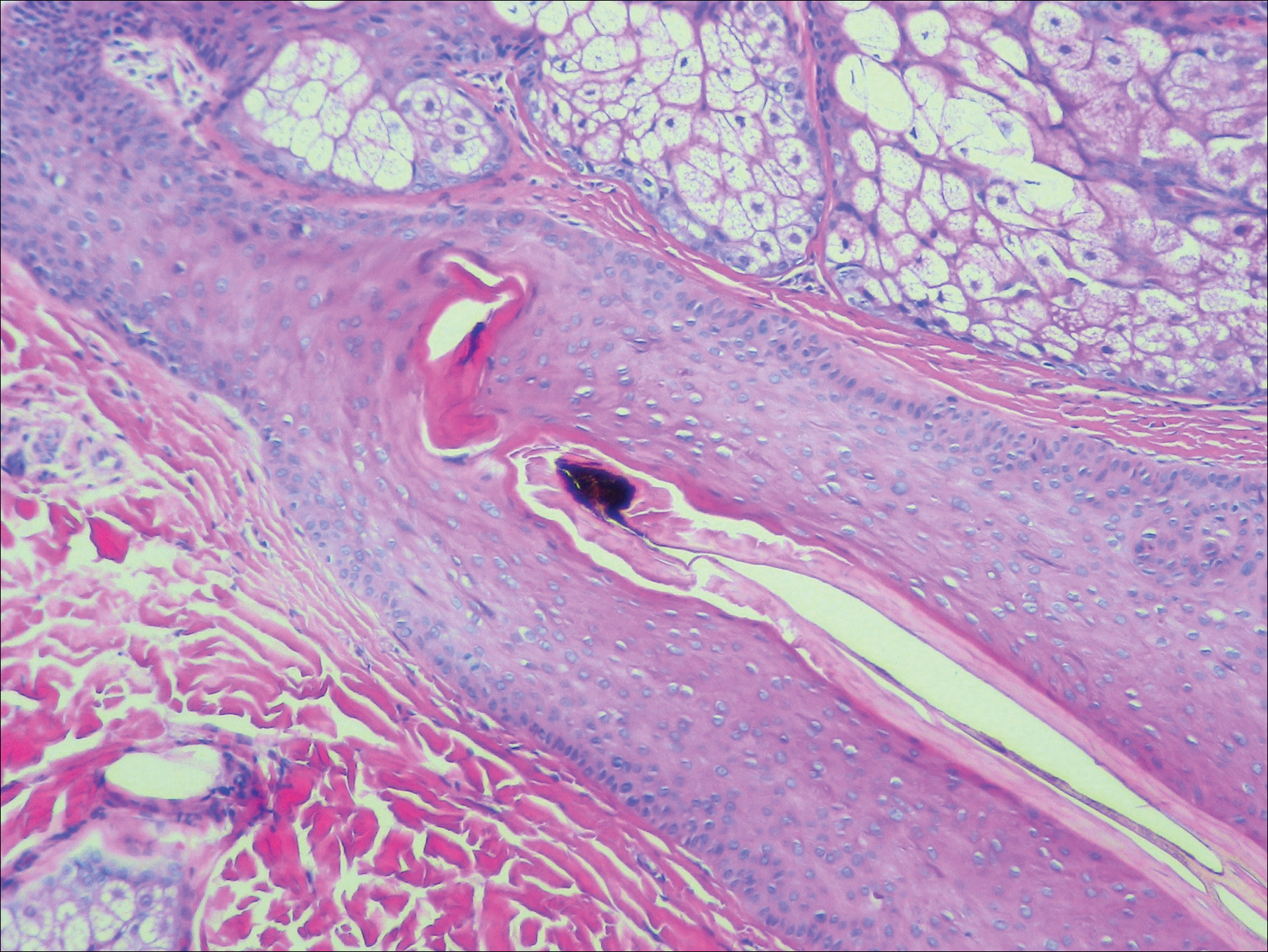

BARCELONA – A large Swedish national registry study has found no hint of increased cancer risk in bipolar patients on long-term lithium therapy.

“This is a very important null result. There is no increased risk for cancer for bipolar patients on lithium. It’s a bad rumor. It’s important to tell patients we’re very confident this is true. We studied every single type of cancer. We would have seen something here if there was something to see,” Lina Martinsson, MD, PhD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Using comprehensive registry data on nearly 2.6 million Swedes aged 50-84 years with 4 years of follow-up, including 2,393 patients with bipolar disorder on long-term lithium and 3,049 patients not on lithium, the overall cancer incidence rate was 5.9% in the group on lithium and 6.0% in those not taking the drug. Those rates were not different from the general Swedish population, reported Dr. Martinsson, a senior psychiatrist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.

Such patients had a 72% greater risk of lung cancer and other cancers of the respiratory system than the general population, a 47% increased risk of GI cancers, and a 150% greater risk of endocrine organ cancers.

“The increase in respiratory and digestive organ cancers might depend upon bipolar patients’ tendency for smoking and other types of hard living. We can’t explain the increase in endocrine cancers,” she said.

In contrast, the rates of these types of cancer were no different from the general population in bipolar patients taking lithium, hinting at a possible protective effect of the drug, although this remains speculative, the psychiatrist added.

The question of whether lithium is associated with increased cancer risk has been controversial. In particular, several groups have reported a possible increased risk of renal cancer on the basis of what Dr. Martinsson considers weak evidence. She felt a responsibility to undertake this definitive Swedish national study examining the issue because the cancer speculation arose following her earlier study demonstrating that bipolar patients on lithium had much longer telomeres than those not on the drug, and that the ones who responded well to lithium had longer telomeres than those who did not (Transl Psychiatry. 2013 May 21. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.37).

“If longer telomere length gives longer life to the wrong cells, it might enhance the risk of cancer,” she noted.

But this theoretical concern did not hold up under close Swedish scrutiny. “Warnings for cancer in patients with long-term lithium treatment are unnecessary and ought to be omitted from the current policies,” Dr. Martinsson said.

She reported no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was funded by the Swedish Research Council.

BARCELONA – A large Swedish national registry study has found no hint of increased cancer risk in bipolar patients on long-term lithium therapy.

“This is a very important null result. There is no increased risk for cancer for bipolar patients on lithium. It’s a bad rumor. It’s important to tell patients we’re very confident this is true. We studied every single type of cancer. We would have seen something here if there was something to see,” Lina Martinsson, MD, PhD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Using comprehensive registry data on nearly 2.6 million Swedes aged 50-84 years with 4 years of follow-up, including 2,393 patients with bipolar disorder on long-term lithium and 3,049 patients not on lithium, the overall cancer incidence rate was 5.9% in the group on lithium and 6.0% in those not taking the drug. Those rates were not different from the general Swedish population, reported Dr. Martinsson, a senior psychiatrist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.

Such patients had a 72% greater risk of lung cancer and other cancers of the respiratory system than the general population, a 47% increased risk of GI cancers, and a 150% greater risk of endocrine organ cancers.

“The increase in respiratory and digestive organ cancers might depend upon bipolar patients’ tendency for smoking and other types of hard living. We can’t explain the increase in endocrine cancers,” she said.

In contrast, the rates of these types of cancer were no different from the general population in bipolar patients taking lithium, hinting at a possible protective effect of the drug, although this remains speculative, the psychiatrist added.

The question of whether lithium is associated with increased cancer risk has been controversial. In particular, several groups have reported a possible increased risk of renal cancer on the basis of what Dr. Martinsson considers weak evidence. She felt a responsibility to undertake this definitive Swedish national study examining the issue because the cancer speculation arose following her earlier study demonstrating that bipolar patients on lithium had much longer telomeres than those not on the drug, and that the ones who responded well to lithium had longer telomeres than those who did not (Transl Psychiatry. 2013 May 21. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.37).

“If longer telomere length gives longer life to the wrong cells, it might enhance the risk of cancer,” she noted.

But this theoretical concern did not hold up under close Swedish scrutiny. “Warnings for cancer in patients with long-term lithium treatment are unnecessary and ought to be omitted from the current policies,” Dr. Martinsson said.

She reported no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was funded by the Swedish Research Council.

BARCELONA – A large Swedish national registry study has found no hint of increased cancer risk in bipolar patients on long-term lithium therapy.

“This is a very important null result. There is no increased risk for cancer for bipolar patients on lithium. It’s a bad rumor. It’s important to tell patients we’re very confident this is true. We studied every single type of cancer. We would have seen something here if there was something to see,” Lina Martinsson, MD, PhD, said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Using comprehensive registry data on nearly 2.6 million Swedes aged 50-84 years with 4 years of follow-up, including 2,393 patients with bipolar disorder on long-term lithium and 3,049 patients not on lithium, the overall cancer incidence rate was 5.9% in the group on lithium and 6.0% in those not taking the drug. Those rates were not different from the general Swedish population, reported Dr. Martinsson, a senior psychiatrist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.

Such patients had a 72% greater risk of lung cancer and other cancers of the respiratory system than the general population, a 47% increased risk of GI cancers, and a 150% greater risk of endocrine organ cancers.

“The increase in respiratory and digestive organ cancers might depend upon bipolar patients’ tendency for smoking and other types of hard living. We can’t explain the increase in endocrine cancers,” she said.

In contrast, the rates of these types of cancer were no different from the general population in bipolar patients taking lithium, hinting at a possible protective effect of the drug, although this remains speculative, the psychiatrist added.

The question of whether lithium is associated with increased cancer risk has been controversial. In particular, several groups have reported a possible increased risk of renal cancer on the basis of what Dr. Martinsson considers weak evidence. She felt a responsibility to undertake this definitive Swedish national study examining the issue because the cancer speculation arose following her earlier study demonstrating that bipolar patients on lithium had much longer telomeres than those not on the drug, and that the ones who responded well to lithium had longer telomeres than those who did not (Transl Psychiatry. 2013 May 21. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.37).

“If longer telomere length gives longer life to the wrong cells, it might enhance the risk of cancer,” she noted.

But this theoretical concern did not hold up under close Swedish scrutiny. “Warnings for cancer in patients with long-term lithium treatment are unnecessary and ought to be omitted from the current policies,” Dr. Martinsson said.

She reported no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was funded by the Swedish Research Council.

REPORTING FROM THE ECNP CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Long-term lithium therapy does not increase cancer risk.

Major finding: The overall incidence of cancer during 4 years of follow-up was 5.9% in bipolar patients on long-term lithium and 6.0% in those who were not.

Study details: This Swedish national registry study compared cancer incidence rates in more than 5,400 patients with bipolar disorder and nearly 2.6 million controls.

Disclosures: The presenter reported no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was supported by the Swedish Research Council.

DOACs cut mortality

Results from the GARFIELD-AF study show that patients who are newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation using a direct action anticoagulant led to benefits that tracked previously seen in randomized trials. Also today, the obesity paradox extends to PE patients, adjuvant flu vaccine reduces hospitalization in the oldest patients, and Tdap vaccination early in the third trimester of pregnancy raises antibodies in newborns.

Check out the MDedge Postcall podcast here:

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Results from the GARFIELD-AF study show that patients who are newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation using a direct action anticoagulant led to benefits that tracked previously seen in randomized trials. Also today, the obesity paradox extends to PE patients, adjuvant flu vaccine reduces hospitalization in the oldest patients, and Tdap vaccination early in the third trimester of pregnancy raises antibodies in newborns.

Check out the MDedge Postcall podcast here:

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Results from the GARFIELD-AF study show that patients who are newly diagnosed with atrial fibrillation using a direct action anticoagulant led to benefits that tracked previously seen in randomized trials. Also today, the obesity paradox extends to PE patients, adjuvant flu vaccine reduces hospitalization in the oldest patients, and Tdap vaccination early in the third trimester of pregnancy raises antibodies in newborns.

Check out the MDedge Postcall podcast here:

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

CT for evaluating pulmonary embolism overused

SAN ANTONIO – The recommended approach to evaluating suspected pulmonary embolism is “greatly underutilized” in the Veterans Health Administration system, Nancy Hsu, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Most Veterans Affairs sites did not require incorporation of a clinical decision rule (CDR) and highly sensitive D-dimer prior to ordering CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) for suspected pulmonary embolism (PE), according to results of a survey by Dr. Hsu and her coinvestigator, Guy Soo Hoo, MD.

While CTPA has become the imaging modality of choice for evaluating suspected PE, it is overused and potentially avoidable in one-third of cases, said Dr. Hsu, who is with the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System.

“In the 10 years following the advent of CTPA use, there was a 14-fold increase in usage, but there was no change in mortality,” Dr. Hsu said. “This is consistent with overdiagnosis.”

Dr. Hsu said.

Dr. Hsu and Dr. Soo Hoo surveyed 606 individuals at 18 Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) and 143 medical centers. A total of 120 fully completed questionnaires were analyzed.

Most respondents (63%) were chiefs, and 80% had 11+ years of experience, Dr. Hsu reported.

Almost all respondents (85%) said CDR with or without D-dimer was not required before ordering a CTPA, survey results show, while only about 7% required both.

“A very small minority of [Veterans Integrated Service Networks], or geographic regions, contained even one hospital that adhered to the guidelines,” Dr. Hsu added.

Though further analysis was limited by sample size, the average CTPA yield for PE appeared to be higher when both components were used in the evaluation, according to Dr. Hsu, who noted an 11.9% yield for CDR plus D-dimer.

Use of CTPA appeared lower at sites with CDR and D-dimer testing, Dr. Hsu added.

These results suggest a need for further research to compare CTPA use and yield in sites that have the algorithm in place, Dr. Hsu told attendees at the meeting.

Adherence to the CDR plus D-dimer diagnostic strategy is “modest at best” despite being a Top 5 Choosing Wisely recommendation in pulmonary medicine, Dr. Hsu told attendees.

The biggest barrier to optimal practice may be the fear of having a patient who “falls through the cracks” based on false-negative CDR and D-dimer data, according to Dr. Hsu.

On the other hand, judicious use of CTPA likely avoids negative sequelae related to radiation, contrast exposure, and treatment-related bleeding, Dr. Hsu said.

“It’s all about balancing risks and benefits,” she said from the podium in a discussion of the study results.

Dr. Hsu and Dr. Soo Hoo disclosed that they had no relationships relevant to their research.

SOURCE: Hsu N et al. CHEST. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.937

SAN ANTONIO – The recommended approach to evaluating suspected pulmonary embolism is “greatly underutilized” in the Veterans Health Administration system, Nancy Hsu, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Most Veterans Affairs sites did not require incorporation of a clinical decision rule (CDR) and highly sensitive D-dimer prior to ordering CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) for suspected pulmonary embolism (PE), according to results of a survey by Dr. Hsu and her coinvestigator, Guy Soo Hoo, MD.

While CTPA has become the imaging modality of choice for evaluating suspected PE, it is overused and potentially avoidable in one-third of cases, said Dr. Hsu, who is with the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System.

“In the 10 years following the advent of CTPA use, there was a 14-fold increase in usage, but there was no change in mortality,” Dr. Hsu said. “This is consistent with overdiagnosis.”

Dr. Hsu said.

Dr. Hsu and Dr. Soo Hoo surveyed 606 individuals at 18 Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) and 143 medical centers. A total of 120 fully completed questionnaires were analyzed.

Most respondents (63%) were chiefs, and 80% had 11+ years of experience, Dr. Hsu reported.

Almost all respondents (85%) said CDR with or without D-dimer was not required before ordering a CTPA, survey results show, while only about 7% required both.

“A very small minority of [Veterans Integrated Service Networks], or geographic regions, contained even one hospital that adhered to the guidelines,” Dr. Hsu added.

Though further analysis was limited by sample size, the average CTPA yield for PE appeared to be higher when both components were used in the evaluation, according to Dr. Hsu, who noted an 11.9% yield for CDR plus D-dimer.

Use of CTPA appeared lower at sites with CDR and D-dimer testing, Dr. Hsu added.

These results suggest a need for further research to compare CTPA use and yield in sites that have the algorithm in place, Dr. Hsu told attendees at the meeting.

Adherence to the CDR plus D-dimer diagnostic strategy is “modest at best” despite being a Top 5 Choosing Wisely recommendation in pulmonary medicine, Dr. Hsu told attendees.

The biggest barrier to optimal practice may be the fear of having a patient who “falls through the cracks” based on false-negative CDR and D-dimer data, according to Dr. Hsu.

On the other hand, judicious use of CTPA likely avoids negative sequelae related to radiation, contrast exposure, and treatment-related bleeding, Dr. Hsu said.

“It’s all about balancing risks and benefits,” she said from the podium in a discussion of the study results.

Dr. Hsu and Dr. Soo Hoo disclosed that they had no relationships relevant to their research.

SOURCE: Hsu N et al. CHEST. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.937

SAN ANTONIO – The recommended approach to evaluating suspected pulmonary embolism is “greatly underutilized” in the Veterans Health Administration system, Nancy Hsu, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Most Veterans Affairs sites did not require incorporation of a clinical decision rule (CDR) and highly sensitive D-dimer prior to ordering CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) for suspected pulmonary embolism (PE), according to results of a survey by Dr. Hsu and her coinvestigator, Guy Soo Hoo, MD.

While CTPA has become the imaging modality of choice for evaluating suspected PE, it is overused and potentially avoidable in one-third of cases, said Dr. Hsu, who is with the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System.

“In the 10 years following the advent of CTPA use, there was a 14-fold increase in usage, but there was no change in mortality,” Dr. Hsu said. “This is consistent with overdiagnosis.”

Dr. Hsu said.

Dr. Hsu and Dr. Soo Hoo surveyed 606 individuals at 18 Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) and 143 medical centers. A total of 120 fully completed questionnaires were analyzed.

Most respondents (63%) were chiefs, and 80% had 11+ years of experience, Dr. Hsu reported.

Almost all respondents (85%) said CDR with or without D-dimer was not required before ordering a CTPA, survey results show, while only about 7% required both.

“A very small minority of [Veterans Integrated Service Networks], or geographic regions, contained even one hospital that adhered to the guidelines,” Dr. Hsu added.

Though further analysis was limited by sample size, the average CTPA yield for PE appeared to be higher when both components were used in the evaluation, according to Dr. Hsu, who noted an 11.9% yield for CDR plus D-dimer.

Use of CTPA appeared lower at sites with CDR and D-dimer testing, Dr. Hsu added.

These results suggest a need for further research to compare CTPA use and yield in sites that have the algorithm in place, Dr. Hsu told attendees at the meeting.

Adherence to the CDR plus D-dimer diagnostic strategy is “modest at best” despite being a Top 5 Choosing Wisely recommendation in pulmonary medicine, Dr. Hsu told attendees.

The biggest barrier to optimal practice may be the fear of having a patient who “falls through the cracks” based on false-negative CDR and D-dimer data, according to Dr. Hsu.

On the other hand, judicious use of CTPA likely avoids negative sequelae related to radiation, contrast exposure, and treatment-related bleeding, Dr. Hsu said.

“It’s all about balancing risks and benefits,” she said from the podium in a discussion of the study results.

Dr. Hsu and Dr. Soo Hoo disclosed that they had no relationships relevant to their research.

SOURCE: Hsu N et al. CHEST. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.08.937

REPORTING FROM CHEST 2018

Key clinical point: The recommended approach to evaluating suspected pulmonary embolism was underutilized in VA facilities.

Major finding: 85% of respondents said incorporation of a clinical decision rule plus highly sensitive D-dimer was not required prior to CTPA.

Study details: Analysis of 120 survey questionnaires completed by individuals working in Veterans Integrated Service Networks and medical centers.

Disclosures: Study authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Hsu N et al. CHEST 2018 Oct. doi: 10/1016/j.chest.2018.08.937.

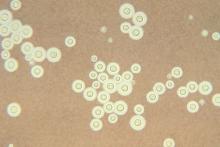

Treating cryptococcal meningitis in patients with HIV

One-week treatment with amphotericin B deoxycholate (AmBd)– and flucytosine (5FC)–based therapy, followed by fluconazole (FLU) on days 8 through 14, is probably superior to other regimens for treatment of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis, according to the authors of a review of the available literature in the Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews.

The review is an update of one previous previously published in 2011. The authors found 13 eligible studies that enrolled 2,426 participants and compared 21 interventions. They performed a network meta-analysis using multivariate meta-regression, modeled treatment differences (RR and 95% confidence interval), and determined treatment rankings for 2-week and 10-week mortality outcomes using surface under the cumulative ranking curve, which represents the probability that a treatment will present the best outcome with no uncertainty and was used to develop a hierarchy of treatments for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis.

In addition, certainty of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach, according to Mark W. Tenforde, MD, of the University of Washington School of Public Health, Seattle, and his colleagues.

They found “reduced 10-week mortality with shortened [AmBd and 5FC] induction therapy, compared to the current gold standard of 2 weeks of AmBd and 5FC, based on moderate-certainty evidence.” They also found no mortality benefit of combination 2 weeks AmBd and FLU, compared with AmBd alone.

“In resource-limited settings, 1-week AmBd- and 5FC-based therapy is probably superior to other regimens for treatment of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis,” they wrote. “An all-oral regimen of 2 weeks 5FC and FLU may be an alternative in settings where AmBd is unavailable or intravenous therapy cannot be safely administered.” These results indicated the need to expand access to 5FC in resource-limited settings in which HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis is most common.

They also reported finding no mortality benefit of 2 weeks of combination AmBd and FLU, compared with AmBd alone.

“Given the absence of data from studies in children, and limited data from high-income countries, our findings provide limited guidance for treatment in these patients and settings,” Dr. Tenforde and his colleagues stated.

The authors reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tenforde MW et al. Treatment for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Jul 25;7:CD005647. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005647.

One-week treatment with amphotericin B deoxycholate (AmBd)– and flucytosine (5FC)–based therapy, followed by fluconazole (FLU) on days 8 through 14, is probably superior to other regimens for treatment of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis, according to the authors of a review of the available literature in the Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews.

The review is an update of one previous previously published in 2011. The authors found 13 eligible studies that enrolled 2,426 participants and compared 21 interventions. They performed a network meta-analysis using multivariate meta-regression, modeled treatment differences (RR and 95% confidence interval), and determined treatment rankings for 2-week and 10-week mortality outcomes using surface under the cumulative ranking curve, which represents the probability that a treatment will present the best outcome with no uncertainty and was used to develop a hierarchy of treatments for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis.

In addition, certainty of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach, according to Mark W. Tenforde, MD, of the University of Washington School of Public Health, Seattle, and his colleagues.

They found “reduced 10-week mortality with shortened [AmBd and 5FC] induction therapy, compared to the current gold standard of 2 weeks of AmBd and 5FC, based on moderate-certainty evidence.” They also found no mortality benefit of combination 2 weeks AmBd and FLU, compared with AmBd alone.

“In resource-limited settings, 1-week AmBd- and 5FC-based therapy is probably superior to other regimens for treatment of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis,” they wrote. “An all-oral regimen of 2 weeks 5FC and FLU may be an alternative in settings where AmBd is unavailable or intravenous therapy cannot be safely administered.” These results indicated the need to expand access to 5FC in resource-limited settings in which HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis is most common.

They also reported finding no mortality benefit of 2 weeks of combination AmBd and FLU, compared with AmBd alone.

“Given the absence of data from studies in children, and limited data from high-income countries, our findings provide limited guidance for treatment in these patients and settings,” Dr. Tenforde and his colleagues stated.

The authors reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tenforde MW et al. Treatment for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Jul 25;7:CD005647. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005647.

One-week treatment with amphotericin B deoxycholate (AmBd)– and flucytosine (5FC)–based therapy, followed by fluconazole (FLU) on days 8 through 14, is probably superior to other regimens for treatment of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis, according to the authors of a review of the available literature in the Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews.

The review is an update of one previous previously published in 2011. The authors found 13 eligible studies that enrolled 2,426 participants and compared 21 interventions. They performed a network meta-analysis using multivariate meta-regression, modeled treatment differences (RR and 95% confidence interval), and determined treatment rankings for 2-week and 10-week mortality outcomes using surface under the cumulative ranking curve, which represents the probability that a treatment will present the best outcome with no uncertainty and was used to develop a hierarchy of treatments for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis.

In addition, certainty of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach, according to Mark W. Tenforde, MD, of the University of Washington School of Public Health, Seattle, and his colleagues.

They found “reduced 10-week mortality with shortened [AmBd and 5FC] induction therapy, compared to the current gold standard of 2 weeks of AmBd and 5FC, based on moderate-certainty evidence.” They also found no mortality benefit of combination 2 weeks AmBd and FLU, compared with AmBd alone.

“In resource-limited settings, 1-week AmBd- and 5FC-based therapy is probably superior to other regimens for treatment of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis,” they wrote. “An all-oral regimen of 2 weeks 5FC and FLU may be an alternative in settings where AmBd is unavailable or intravenous therapy cannot be safely administered.” These results indicated the need to expand access to 5FC in resource-limited settings in which HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis is most common.

They also reported finding no mortality benefit of 2 weeks of combination AmBd and FLU, compared with AmBd alone.

“Given the absence of data from studies in children, and limited data from high-income countries, our findings provide limited guidance for treatment in these patients and settings,” Dr. Tenforde and his colleagues stated.

The authors reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Tenforde MW et al. Treatment for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Jul 25;7:CD005647. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005647.

FROM COCHRANE DATABASE OF SYSTEMIC REVIEWS

Key clinical point: Shorter drug treatment beat the gold standard for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis according to a literature review.

Major finding:

Study details: Updated review of articles, registries, and clinical trials during Jan. 1, 1980–July 9, 2018.

Disclosures: The authors reported that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Tenforde MW et al. Treatment for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Jul 25;7:CD005647. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005647.