User login

Study explores link between GERD and poor sleep quality

ATLANTA – results from an ongoing longitudinal analysis demonstrated.

“We have little longitudinal information on GERD in the general population; the last published article on GERD incidence was 20 years ago,” lead study author Maurice M. Ohayon, MD, DSc, PhD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “As a sleep specialist, I am always interested to see how a specific medical condition may affect the sleep quality of the individuals with that condition. How we live our day has an impact on our night; it works together.”

In an effort to examine the long-term effects of GERD on sleep disturbances, Dr. Ohayon, director of the Stanford (Calif.) Sleep Epidemiology Research Center, and his colleagues used U.S. Census data to identify a random sample of adults in Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Texas. The researchers conducted two waves of phone interviews with the subjects 3 years apart, beginning in 2004. They limited their analysis to 10,930 subjects with a mean age of 43 years who participated in both interviews.

Between wave 1 and wave 2 of phone interviews, the proportion of adults who reported having GERD rose from 10.6% to 12.4% and the prevalence of new GERD cases was 8.5% per year, while the incidence was 3.2% per year. Chronic GERD, defined as that present during both interview periods, was observed in 3.9% of the sample.

The researchers found that 77.3% of GERD subjects were taking a treatment to alleviate their symptoms, mostly proton-pump inhibitors. Those with chronic GERD were more likely to report being dissatisfied with their sleep during wave 2 of the study, compared with wave 1 (24.2% vs. 13.5%; P less than .001). In addition, compared with their non-GERD counterparts, those with chronic GERD were more likely to wake up at night (33.9% vs. 28.3%; P less than .001) and to have nonrestorative sleep (15.6% vs. 10.5%; P less than .001).

“Discomfort related to GERD may happen while you are sleeping,” said Dr. Ohayon, who is also a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University. “It may wake you up and, if not, it may make you feel unrested when you wake up. We observed both of these symptoms in our GERD participants. Insomnia disorders were also rampant in the chronic GERD group (24.5%, compared with 14.4% in non-GERD participants). An insomnia disorder is more than just having difficulty falling asleep or waking up at night, it means that your daytime functioning is affected by the poor quality of your night.”

Dr. Ohayon said other findings from the study were “rather alarming.” For example, individuals with GERD, especially those with the chronic form, weighed much more than those with no GERD did. “Over a 3-year period, the chronic GERD individuals gained one point in the body mass index, which for a 6-foot tall man translates into a weight gain of 30 pounds,” he said. “Of course, with that follows high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, chronic pain, and heart disease.”

He concluded that GERD has its main manifestations when affected individuals are sleeping on their backs. “The impact of GERD on the quality of sleep is major,” he said. “Sleepiness and fatigue during the day are the consequences impacting work, family, and quality of life.”

Dr. Ohayon acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that GERD was based on self-report. The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from Takeda.

Source: Oyahon et al. ANA 2018, Abstract 625.

ATLANTA – results from an ongoing longitudinal analysis demonstrated.

“We have little longitudinal information on GERD in the general population; the last published article on GERD incidence was 20 years ago,” lead study author Maurice M. Ohayon, MD, DSc, PhD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “As a sleep specialist, I am always interested to see how a specific medical condition may affect the sleep quality of the individuals with that condition. How we live our day has an impact on our night; it works together.”

In an effort to examine the long-term effects of GERD on sleep disturbances, Dr. Ohayon, director of the Stanford (Calif.) Sleep Epidemiology Research Center, and his colleagues used U.S. Census data to identify a random sample of adults in Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Texas. The researchers conducted two waves of phone interviews with the subjects 3 years apart, beginning in 2004. They limited their analysis to 10,930 subjects with a mean age of 43 years who participated in both interviews.

Between wave 1 and wave 2 of phone interviews, the proportion of adults who reported having GERD rose from 10.6% to 12.4% and the prevalence of new GERD cases was 8.5% per year, while the incidence was 3.2% per year. Chronic GERD, defined as that present during both interview periods, was observed in 3.9% of the sample.

The researchers found that 77.3% of GERD subjects were taking a treatment to alleviate their symptoms, mostly proton-pump inhibitors. Those with chronic GERD were more likely to report being dissatisfied with their sleep during wave 2 of the study, compared with wave 1 (24.2% vs. 13.5%; P less than .001). In addition, compared with their non-GERD counterparts, those with chronic GERD were more likely to wake up at night (33.9% vs. 28.3%; P less than .001) and to have nonrestorative sleep (15.6% vs. 10.5%; P less than .001).

“Discomfort related to GERD may happen while you are sleeping,” said Dr. Ohayon, who is also a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University. “It may wake you up and, if not, it may make you feel unrested when you wake up. We observed both of these symptoms in our GERD participants. Insomnia disorders were also rampant in the chronic GERD group (24.5%, compared with 14.4% in non-GERD participants). An insomnia disorder is more than just having difficulty falling asleep or waking up at night, it means that your daytime functioning is affected by the poor quality of your night.”

Dr. Ohayon said other findings from the study were “rather alarming.” For example, individuals with GERD, especially those with the chronic form, weighed much more than those with no GERD did. “Over a 3-year period, the chronic GERD individuals gained one point in the body mass index, which for a 6-foot tall man translates into a weight gain of 30 pounds,” he said. “Of course, with that follows high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, chronic pain, and heart disease.”

He concluded that GERD has its main manifestations when affected individuals are sleeping on their backs. “The impact of GERD on the quality of sleep is major,” he said. “Sleepiness and fatigue during the day are the consequences impacting work, family, and quality of life.”

Dr. Ohayon acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that GERD was based on self-report. The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from Takeda.

Source: Oyahon et al. ANA 2018, Abstract 625.

ATLANTA – results from an ongoing longitudinal analysis demonstrated.

“We have little longitudinal information on GERD in the general population; the last published article on GERD incidence was 20 years ago,” lead study author Maurice M. Ohayon, MD, DSc, PhD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “As a sleep specialist, I am always interested to see how a specific medical condition may affect the sleep quality of the individuals with that condition. How we live our day has an impact on our night; it works together.”

In an effort to examine the long-term effects of GERD on sleep disturbances, Dr. Ohayon, director of the Stanford (Calif.) Sleep Epidemiology Research Center, and his colleagues used U.S. Census data to identify a random sample of adults in Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Texas. The researchers conducted two waves of phone interviews with the subjects 3 years apart, beginning in 2004. They limited their analysis to 10,930 subjects with a mean age of 43 years who participated in both interviews.

Between wave 1 and wave 2 of phone interviews, the proportion of adults who reported having GERD rose from 10.6% to 12.4% and the prevalence of new GERD cases was 8.5% per year, while the incidence was 3.2% per year. Chronic GERD, defined as that present during both interview periods, was observed in 3.9% of the sample.

The researchers found that 77.3% of GERD subjects were taking a treatment to alleviate their symptoms, mostly proton-pump inhibitors. Those with chronic GERD were more likely to report being dissatisfied with their sleep during wave 2 of the study, compared with wave 1 (24.2% vs. 13.5%; P less than .001). In addition, compared with their non-GERD counterparts, those with chronic GERD were more likely to wake up at night (33.9% vs. 28.3%; P less than .001) and to have nonrestorative sleep (15.6% vs. 10.5%; P less than .001).

“Discomfort related to GERD may happen while you are sleeping,” said Dr. Ohayon, who is also a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University. “It may wake you up and, if not, it may make you feel unrested when you wake up. We observed both of these symptoms in our GERD participants. Insomnia disorders were also rampant in the chronic GERD group (24.5%, compared with 14.4% in non-GERD participants). An insomnia disorder is more than just having difficulty falling asleep or waking up at night, it means that your daytime functioning is affected by the poor quality of your night.”

Dr. Ohayon said other findings from the study were “rather alarming.” For example, individuals with GERD, especially those with the chronic form, weighed much more than those with no GERD did. “Over a 3-year period, the chronic GERD individuals gained one point in the body mass index, which for a 6-foot tall man translates into a weight gain of 30 pounds,” he said. “Of course, with that follows high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, chronic pain, and heart disease.”

He concluded that GERD has its main manifestations when affected individuals are sleeping on their backs. “The impact of GERD on the quality of sleep is major,” he said. “Sleepiness and fatigue during the day are the consequences impacting work, family, and quality of life.”

Dr. Ohayon acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that GERD was based on self-report. The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from Takeda.

Source: Oyahon et al. ANA 2018, Abstract 625.

REPORTING FROM ANA 2018

Key clinical point: GERD has a major impact on quality of sleep.

Major finding: Study participants with chronic GERD were more likely to report being dissatisfied with their sleep during wave 2 of the study, compared with wave 1 (24.2% vs. 13.5%; P less than .001).

Study details: A telephone-based survey of 10,930 U.S. adults who were interviewed during two waves 3 years apart.

Disclosures: The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from Takeda.

Source: Oyahon et al. ANA 2018, Abstract 625.

Finally, immunotherapy shows benefit in TNBC

MUNICH – For the first time, a combination of an immune checkpoint inhibitor and a taxane has shown significant clinical benefit in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer in a phase 3 trial, but the benefit was seen only in patients positive for programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), investigators reported.

Among 902 patients with untreated metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC) randomly assigned to receive the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab (Tecentriq) plus nanoparticle albumin-bound (nab)-paclitaxel or placebo plus nab-paclitaxel, atezolizumab was associated with a 38% improvement in median overall survival among patients with PD-L1–positive disease in an interim analysis of the IMpassion 130 trial.

However, although there was a significant progression-free survival (PFS) benefit with atezolizumab in an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis that included patients with PD-L1 negative tumors, there was no significant difference in median overall survival (OS) when all patients were considered together, said Peter Schmid, MD, PhD, Barts Cancer Institute, Queen Mary University of London.

“For patients with PD-L1–positive tumors, these data establish atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel as a new standard of care,” he said at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

The results were published online in the New England Journal of Medicine to coincide with the presentation of the data.

At a briefing prior to presentation of the data in a symposium, discussant Nadia Harbeck, MD, of the University of Munich Medical Center, a breast cancer specialist, confessed to being of envious of her colleagues in other oncology specialties in which immunotherapy has made great inroads.

“We have a lot of patients out there right now in clinical trials with immune therapy, but so far in breast cancer, we have not seen the tremendous effects we have seen in melanoma or lung cancer, so this is the first time we have a phase 3 trial proving that immune therapy in triple-negative breast cancer improves survival, and I think this is something that will change the way we practice in triple-negative breast cancer,” she said.

The rationale for using a PD-L1 inhibitor comes from the discovery that PD-L1 expression occurs primarily on tumor-infiltrating cells in TNBC rather than on tumor cells, which can inhibit immune responses directed against tumors.

The investigators enrolled 902 patients with previously untreated mTNBC and randomly assigned them to receive nab-paclitaxel 100 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle, plus either atezolizumab 804 mg intravenously or placebo on days 1 and 15 of each cycle.

Patients were stratified according to whether they received neoadjuvant or adjuvant taxane therapy, the presence of liver metastases at baseline, and PD-L1 expression at baseline.

Treatment was continued until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The primary endpoints were PFS and OS in both the ITT and PD-L1–positive population.

In the ITT analysis, 1-year PFS rate was significantly improved in the atezolizumab arm, at 24% vs. 18% in the placebo arm. This translated into a stratified hazard ratio of 0.80 (P = .0025).

In the analysis restricted to the PD-L1-positive population (369 patients), the 1-year PFS rates were 29% for atezolizumab vs. 16% for placebo, translating into to an HR of 0.62 (P less than .0001).

As noted before, the interim OS analysis in the PD-L1 population showed a clinical benefit with atezolizumab, with a 2-year OS rate of 54% vs. 37%, respectively. The median OS in this analysis was 25 months with atezolizumab, vs. 15.5 months with placebo. The stratified HR favoring the PD-L1 inhibitor was 0.62, but because of the hierarchical statistical analysis design of the trial, formal testing of OS was not performed for the interim analysis.

Adverse events of any kind occurred in 99.3% of patients assigned to atezolizumab/nab-paclitaxel and 97.9% of those assigned to placebo/nab-paclitaxel.

Grade 1 or 2 immune-related hypothyroidism occurred more frequently with atezolizumab (17.3% vs. 4.3%), but none led to discontinuation of the drug regimen.

Six patients assigned to atezolizumab and three assigned to placebo died. Four of the deaths were deemed by investigators to be related to the trial regimen, include three deaths in the atezolizumab arm (from autoimmune hepatitis, mucosal inflammation, and septic shock), and one death in the placebo arm (from hepatic failure).

“A benefit with atezolizumab/nab-paclitaxel in patients with PD-L1–positive tumors that was shown in our trial provides evidence of the efficacy of immunotherapy in at least a subset of patients. It is important for patients’ PD-L1 expression status on tumor-infiltrating immune cells to be taken into consideration to inform treatment choices for patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer,” Dr. Schmid and his colleagues wrote in the study’s conclusion.

“I really do think that these results are going to make a very big difference,” said coinvestigator Hope S. Rugo, MD, a clinical professor of medicine and director of the Breast Oncology Clinical Trials Program at the University of California, San Francisco, Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“We believed from the phase 1 data and the less-than-exciting phase 2 data that there was clearly some role for immunotherapy in breast cancer but were really struggling as to what that role was. We knew for example that if they had a response, patients lived longer and really dramatically longer,” she said in an interview.

But unlike the clinical revolution brought about by the introduction of trastuzumab, in which clinicians had a biomarker and a large number of patients benefited, “here we have no biomarker and a small number of patients benefited, but the benefit is huge,” she said.

Giuseppe Curigliano, MD, PhD, from the University of Milan and European Cancer Institute, Italy, the invited discussant at the symposium, agreed that the study “brings breast cancer into the immunotherapy era.”

Dr. Curigliano added, however, that the study was missing an arm – atezolizumab alone, which might be a good option for a subset of patients.

He also questioned whether nab-paclitaxel was the best partner for atezolizumab, vs. other drugs with known immunogenic effects, such as doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, other taxanes, gemcitabine, or platinum salts.

The study was supported by F. Hoffmann–La Roche/Genentech. Dr. Schmid reported grant and nonfinancial support from Roche. Multiple coauthors reported financial relationships with Roche/Genentech and others. Dr. Harbeck has disclosed honoraria from and serving as a consultant for Roche and others. Dr. Rugo disclosed grants and nonfinancial support from F. Hoffmann–La Roche. Dr. Curigliano disclosed consulting/advising, speakers bureau participation, and travel/accommodations from Roche/Genentech.

SOURCE: Schmid P et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809615.

MUNICH – For the first time, a combination of an immune checkpoint inhibitor and a taxane has shown significant clinical benefit in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer in a phase 3 trial, but the benefit was seen only in patients positive for programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), investigators reported.

Among 902 patients with untreated metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC) randomly assigned to receive the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab (Tecentriq) plus nanoparticle albumin-bound (nab)-paclitaxel or placebo plus nab-paclitaxel, atezolizumab was associated with a 38% improvement in median overall survival among patients with PD-L1–positive disease in an interim analysis of the IMpassion 130 trial.

However, although there was a significant progression-free survival (PFS) benefit with atezolizumab in an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis that included patients with PD-L1 negative tumors, there was no significant difference in median overall survival (OS) when all patients were considered together, said Peter Schmid, MD, PhD, Barts Cancer Institute, Queen Mary University of London.

“For patients with PD-L1–positive tumors, these data establish atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel as a new standard of care,” he said at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

The results were published online in the New England Journal of Medicine to coincide with the presentation of the data.

At a briefing prior to presentation of the data in a symposium, discussant Nadia Harbeck, MD, of the University of Munich Medical Center, a breast cancer specialist, confessed to being of envious of her colleagues in other oncology specialties in which immunotherapy has made great inroads.

“We have a lot of patients out there right now in clinical trials with immune therapy, but so far in breast cancer, we have not seen the tremendous effects we have seen in melanoma or lung cancer, so this is the first time we have a phase 3 trial proving that immune therapy in triple-negative breast cancer improves survival, and I think this is something that will change the way we practice in triple-negative breast cancer,” she said.

The rationale for using a PD-L1 inhibitor comes from the discovery that PD-L1 expression occurs primarily on tumor-infiltrating cells in TNBC rather than on tumor cells, which can inhibit immune responses directed against tumors.

The investigators enrolled 902 patients with previously untreated mTNBC and randomly assigned them to receive nab-paclitaxel 100 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle, plus either atezolizumab 804 mg intravenously or placebo on days 1 and 15 of each cycle.

Patients were stratified according to whether they received neoadjuvant or adjuvant taxane therapy, the presence of liver metastases at baseline, and PD-L1 expression at baseline.

Treatment was continued until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The primary endpoints were PFS and OS in both the ITT and PD-L1–positive population.

In the ITT analysis, 1-year PFS rate was significantly improved in the atezolizumab arm, at 24% vs. 18% in the placebo arm. This translated into a stratified hazard ratio of 0.80 (P = .0025).

In the analysis restricted to the PD-L1-positive population (369 patients), the 1-year PFS rates were 29% for atezolizumab vs. 16% for placebo, translating into to an HR of 0.62 (P less than .0001).

As noted before, the interim OS analysis in the PD-L1 population showed a clinical benefit with atezolizumab, with a 2-year OS rate of 54% vs. 37%, respectively. The median OS in this analysis was 25 months with atezolizumab, vs. 15.5 months with placebo. The stratified HR favoring the PD-L1 inhibitor was 0.62, but because of the hierarchical statistical analysis design of the trial, formal testing of OS was not performed for the interim analysis.

Adverse events of any kind occurred in 99.3% of patients assigned to atezolizumab/nab-paclitaxel and 97.9% of those assigned to placebo/nab-paclitaxel.

Grade 1 or 2 immune-related hypothyroidism occurred more frequently with atezolizumab (17.3% vs. 4.3%), but none led to discontinuation of the drug regimen.

Six patients assigned to atezolizumab and three assigned to placebo died. Four of the deaths were deemed by investigators to be related to the trial regimen, include three deaths in the atezolizumab arm (from autoimmune hepatitis, mucosal inflammation, and septic shock), and one death in the placebo arm (from hepatic failure).

“A benefit with atezolizumab/nab-paclitaxel in patients with PD-L1–positive tumors that was shown in our trial provides evidence of the efficacy of immunotherapy in at least a subset of patients. It is important for patients’ PD-L1 expression status on tumor-infiltrating immune cells to be taken into consideration to inform treatment choices for patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer,” Dr. Schmid and his colleagues wrote in the study’s conclusion.

“I really do think that these results are going to make a very big difference,” said coinvestigator Hope S. Rugo, MD, a clinical professor of medicine and director of the Breast Oncology Clinical Trials Program at the University of California, San Francisco, Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“We believed from the phase 1 data and the less-than-exciting phase 2 data that there was clearly some role for immunotherapy in breast cancer but were really struggling as to what that role was. We knew for example that if they had a response, patients lived longer and really dramatically longer,” she said in an interview.

But unlike the clinical revolution brought about by the introduction of trastuzumab, in which clinicians had a biomarker and a large number of patients benefited, “here we have no biomarker and a small number of patients benefited, but the benefit is huge,” she said.

Giuseppe Curigliano, MD, PhD, from the University of Milan and European Cancer Institute, Italy, the invited discussant at the symposium, agreed that the study “brings breast cancer into the immunotherapy era.”

Dr. Curigliano added, however, that the study was missing an arm – atezolizumab alone, which might be a good option for a subset of patients.

He also questioned whether nab-paclitaxel was the best partner for atezolizumab, vs. other drugs with known immunogenic effects, such as doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, other taxanes, gemcitabine, or platinum salts.

The study was supported by F. Hoffmann–La Roche/Genentech. Dr. Schmid reported grant and nonfinancial support from Roche. Multiple coauthors reported financial relationships with Roche/Genentech and others. Dr. Harbeck has disclosed honoraria from and serving as a consultant for Roche and others. Dr. Rugo disclosed grants and nonfinancial support from F. Hoffmann–La Roche. Dr. Curigliano disclosed consulting/advising, speakers bureau participation, and travel/accommodations from Roche/Genentech.

SOURCE: Schmid P et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809615.

MUNICH – For the first time, a combination of an immune checkpoint inhibitor and a taxane has shown significant clinical benefit in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer in a phase 3 trial, but the benefit was seen only in patients positive for programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), investigators reported.

Among 902 patients with untreated metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC) randomly assigned to receive the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab (Tecentriq) plus nanoparticle albumin-bound (nab)-paclitaxel or placebo plus nab-paclitaxel, atezolizumab was associated with a 38% improvement in median overall survival among patients with PD-L1–positive disease in an interim analysis of the IMpassion 130 trial.

However, although there was a significant progression-free survival (PFS) benefit with atezolizumab in an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis that included patients with PD-L1 negative tumors, there was no significant difference in median overall survival (OS) when all patients were considered together, said Peter Schmid, MD, PhD, Barts Cancer Institute, Queen Mary University of London.

“For patients with PD-L1–positive tumors, these data establish atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel as a new standard of care,” he said at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

The results were published online in the New England Journal of Medicine to coincide with the presentation of the data.

At a briefing prior to presentation of the data in a symposium, discussant Nadia Harbeck, MD, of the University of Munich Medical Center, a breast cancer specialist, confessed to being of envious of her colleagues in other oncology specialties in which immunotherapy has made great inroads.

“We have a lot of patients out there right now in clinical trials with immune therapy, but so far in breast cancer, we have not seen the tremendous effects we have seen in melanoma or lung cancer, so this is the first time we have a phase 3 trial proving that immune therapy in triple-negative breast cancer improves survival, and I think this is something that will change the way we practice in triple-negative breast cancer,” she said.

The rationale for using a PD-L1 inhibitor comes from the discovery that PD-L1 expression occurs primarily on tumor-infiltrating cells in TNBC rather than on tumor cells, which can inhibit immune responses directed against tumors.

The investigators enrolled 902 patients with previously untreated mTNBC and randomly assigned them to receive nab-paclitaxel 100 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle, plus either atezolizumab 804 mg intravenously or placebo on days 1 and 15 of each cycle.

Patients were stratified according to whether they received neoadjuvant or adjuvant taxane therapy, the presence of liver metastases at baseline, and PD-L1 expression at baseline.

Treatment was continued until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The primary endpoints were PFS and OS in both the ITT and PD-L1–positive population.

In the ITT analysis, 1-year PFS rate was significantly improved in the atezolizumab arm, at 24% vs. 18% in the placebo arm. This translated into a stratified hazard ratio of 0.80 (P = .0025).

In the analysis restricted to the PD-L1-positive population (369 patients), the 1-year PFS rates were 29% for atezolizumab vs. 16% for placebo, translating into to an HR of 0.62 (P less than .0001).

As noted before, the interim OS analysis in the PD-L1 population showed a clinical benefit with atezolizumab, with a 2-year OS rate of 54% vs. 37%, respectively. The median OS in this analysis was 25 months with atezolizumab, vs. 15.5 months with placebo. The stratified HR favoring the PD-L1 inhibitor was 0.62, but because of the hierarchical statistical analysis design of the trial, formal testing of OS was not performed for the interim analysis.

Adverse events of any kind occurred in 99.3% of patients assigned to atezolizumab/nab-paclitaxel and 97.9% of those assigned to placebo/nab-paclitaxel.

Grade 1 or 2 immune-related hypothyroidism occurred more frequently with atezolizumab (17.3% vs. 4.3%), but none led to discontinuation of the drug regimen.

Six patients assigned to atezolizumab and three assigned to placebo died. Four of the deaths were deemed by investigators to be related to the trial regimen, include three deaths in the atezolizumab arm (from autoimmune hepatitis, mucosal inflammation, and septic shock), and one death in the placebo arm (from hepatic failure).

“A benefit with atezolizumab/nab-paclitaxel in patients with PD-L1–positive tumors that was shown in our trial provides evidence of the efficacy of immunotherapy in at least a subset of patients. It is important for patients’ PD-L1 expression status on tumor-infiltrating immune cells to be taken into consideration to inform treatment choices for patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer,” Dr. Schmid and his colleagues wrote in the study’s conclusion.

“I really do think that these results are going to make a very big difference,” said coinvestigator Hope S. Rugo, MD, a clinical professor of medicine and director of the Breast Oncology Clinical Trials Program at the University of California, San Francisco, Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“We believed from the phase 1 data and the less-than-exciting phase 2 data that there was clearly some role for immunotherapy in breast cancer but were really struggling as to what that role was. We knew for example that if they had a response, patients lived longer and really dramatically longer,” she said in an interview.

But unlike the clinical revolution brought about by the introduction of trastuzumab, in which clinicians had a biomarker and a large number of patients benefited, “here we have no biomarker and a small number of patients benefited, but the benefit is huge,” she said.

Giuseppe Curigliano, MD, PhD, from the University of Milan and European Cancer Institute, Italy, the invited discussant at the symposium, agreed that the study “brings breast cancer into the immunotherapy era.”

Dr. Curigliano added, however, that the study was missing an arm – atezolizumab alone, which might be a good option for a subset of patients.

He also questioned whether nab-paclitaxel was the best partner for atezolizumab, vs. other drugs with known immunogenic effects, such as doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, other taxanes, gemcitabine, or platinum salts.

The study was supported by F. Hoffmann–La Roche/Genentech. Dr. Schmid reported grant and nonfinancial support from Roche. Multiple coauthors reported financial relationships with Roche/Genentech and others. Dr. Harbeck has disclosed honoraria from and serving as a consultant for Roche and others. Dr. Rugo disclosed grants and nonfinancial support from F. Hoffmann–La Roche. Dr. Curigliano disclosed consulting/advising, speakers bureau participation, and travel/accommodations from Roche/Genentech.

SOURCE: Schmid P et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809615.

AT ESMO 2018

Key clinical point: IMpassion 130 is the first phase 3 trial to show a benefit of immunotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer.

Major finding: Progression-free and overall survival were significantly improved with atezolizumab in the PD-L1–positive population.

Study details: Randomized phase 3 trial in 902 patients with triple-negative breast cancer.

Disclosures: The study was supported by F. Hoffmann–La Roche/Genentech. Dr. Schmid reported grant and nonfinancial support from Roche. Multiple coauthors reported financial relationships with Roche/Genentech and others. Dr. Harbeck has disclosed honoraria from and serving as a consultant for Roche and others. Dr. Rugo disclosed grants and nonfinancial support from F. Hoffmann–La Roche. Dr. Curigliano disclosed consulting/advising, speakers bureau participation, and travel/accommodations from Roche/Genentech.

Source: Schmid P et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Oct 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809615.

Computer program credited with cognitive stability in Alzheimer’s

NEW YORK – As part of a comprehensive support program, a computer program administered to patients with cognitive impairment, including those with Alzheimer’s disease, has been associated with preserved cognitive function.

“Based on this series of cases, we believe that the brain in patients with dementia can maintain cognitive function for up to 8 years when an integrative rehabilitation program is employed,” reported Valentin I. Bragin, MD, PhD, of the Stress and Pain Relief Memory Training Center, New York.

While the integrative program involves other types of supportive care, including physical exercises and pharmacologic treatments, the focus of this case series was on the contribution of a computer program for cognitive training. As described by Dr. Bragin, it consists of tasks aimed at training working memory, selective attention, visual field expansion, and eye-hand coordination.

The computer program is designed to improve or maintain motor speed and reaction time. The aim is a rehabilitation process to activate the brain via sensory motor and other bodily systems to prevent patients with Alzheimer’s disease from decline, according to Dr. Bragin. He explained that the computer program is augmented with pen and paper tasks, such as clock drawing, that also stimulate cognitive function.

“The theory behind this treatment is the notion that increased cerebral blood flow is a highly modifiable factor in the risk of cognitive decline,” Dr. Bragin explained at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders. This premise is supported by a case series of four patients. The shortest duration of treatment was 4 years, but two patients were treated for 7 years and one for 8 years. In this series, motor speed has remained stable in all four patients throughout follow-up. Reaction time remained stable over the period of study in three of four patients, while working memory remained stable in two of the four. Although there was no control group, this persistence of cognitive function is longer than that expected in patients with progressive dementia, according to Dr. Bragin.

“Previously, we demonstrated an improvement and stabilization of cognitive functions in people with mild dementia and depression for periods of up to 6 years by using pen and paper tests,” Dr. Bragin reported. He explained that the computer program expands on this approach.

“We believe that cerebral blood flow is a highly modifiable factor that is a crucial element for reducing hypoxia, improving energy production, and increasing protein synthesis to prevent dementia,” Dr. Bragin said.

Although Dr. Bragin acknowledged that the findings from this case series are preliminary and need to be replicated in a large and controlled trial, he considers it a reasonable empirical strategy, particularly when employed as part of an integrative rehabilitation program like the one now in place at his center.

“This could be a feasible treatment option for dementia patients to stabilize their cognition and improve their quality of life until newer effective approaches become available,” Dr. Bragin said. He noted in the absence of a clear understanding of the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease and other progressive disorders involving cognitive decline, “the most successful treatment model is integrative care.”

NEW YORK – As part of a comprehensive support program, a computer program administered to patients with cognitive impairment, including those with Alzheimer’s disease, has been associated with preserved cognitive function.

“Based on this series of cases, we believe that the brain in patients with dementia can maintain cognitive function for up to 8 years when an integrative rehabilitation program is employed,” reported Valentin I. Bragin, MD, PhD, of the Stress and Pain Relief Memory Training Center, New York.

While the integrative program involves other types of supportive care, including physical exercises and pharmacologic treatments, the focus of this case series was on the contribution of a computer program for cognitive training. As described by Dr. Bragin, it consists of tasks aimed at training working memory, selective attention, visual field expansion, and eye-hand coordination.

The computer program is designed to improve or maintain motor speed and reaction time. The aim is a rehabilitation process to activate the brain via sensory motor and other bodily systems to prevent patients with Alzheimer’s disease from decline, according to Dr. Bragin. He explained that the computer program is augmented with pen and paper tasks, such as clock drawing, that also stimulate cognitive function.

“The theory behind this treatment is the notion that increased cerebral blood flow is a highly modifiable factor in the risk of cognitive decline,” Dr. Bragin explained at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders. This premise is supported by a case series of four patients. The shortest duration of treatment was 4 years, but two patients were treated for 7 years and one for 8 years. In this series, motor speed has remained stable in all four patients throughout follow-up. Reaction time remained stable over the period of study in three of four patients, while working memory remained stable in two of the four. Although there was no control group, this persistence of cognitive function is longer than that expected in patients with progressive dementia, according to Dr. Bragin.

“Previously, we demonstrated an improvement and stabilization of cognitive functions in people with mild dementia and depression for periods of up to 6 years by using pen and paper tests,” Dr. Bragin reported. He explained that the computer program expands on this approach.

“We believe that cerebral blood flow is a highly modifiable factor that is a crucial element for reducing hypoxia, improving energy production, and increasing protein synthesis to prevent dementia,” Dr. Bragin said.

Although Dr. Bragin acknowledged that the findings from this case series are preliminary and need to be replicated in a large and controlled trial, he considers it a reasonable empirical strategy, particularly when employed as part of an integrative rehabilitation program like the one now in place at his center.

“This could be a feasible treatment option for dementia patients to stabilize their cognition and improve their quality of life until newer effective approaches become available,” Dr. Bragin said. He noted in the absence of a clear understanding of the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease and other progressive disorders involving cognitive decline, “the most successful treatment model is integrative care.”

NEW YORK – As part of a comprehensive support program, a computer program administered to patients with cognitive impairment, including those with Alzheimer’s disease, has been associated with preserved cognitive function.

“Based on this series of cases, we believe that the brain in patients with dementia can maintain cognitive function for up to 8 years when an integrative rehabilitation program is employed,” reported Valentin I. Bragin, MD, PhD, of the Stress and Pain Relief Memory Training Center, New York.

While the integrative program involves other types of supportive care, including physical exercises and pharmacologic treatments, the focus of this case series was on the contribution of a computer program for cognitive training. As described by Dr. Bragin, it consists of tasks aimed at training working memory, selective attention, visual field expansion, and eye-hand coordination.

The computer program is designed to improve or maintain motor speed and reaction time. The aim is a rehabilitation process to activate the brain via sensory motor and other bodily systems to prevent patients with Alzheimer’s disease from decline, according to Dr. Bragin. He explained that the computer program is augmented with pen and paper tasks, such as clock drawing, that also stimulate cognitive function.

“The theory behind this treatment is the notion that increased cerebral blood flow is a highly modifiable factor in the risk of cognitive decline,” Dr. Bragin explained at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders. This premise is supported by a case series of four patients. The shortest duration of treatment was 4 years, but two patients were treated for 7 years and one for 8 years. In this series, motor speed has remained stable in all four patients throughout follow-up. Reaction time remained stable over the period of study in three of four patients, while working memory remained stable in two of the four. Although there was no control group, this persistence of cognitive function is longer than that expected in patients with progressive dementia, according to Dr. Bragin.

“Previously, we demonstrated an improvement and stabilization of cognitive functions in people with mild dementia and depression for periods of up to 6 years by using pen and paper tests,” Dr. Bragin reported. He explained that the computer program expands on this approach.

“We believe that cerebral blood flow is a highly modifiable factor that is a crucial element for reducing hypoxia, improving energy production, and increasing protein synthesis to prevent dementia,” Dr. Bragin said.

Although Dr. Bragin acknowledged that the findings from this case series are preliminary and need to be replicated in a large and controlled trial, he considers it a reasonable empirical strategy, particularly when employed as part of an integrative rehabilitation program like the one now in place at his center.

“This could be a feasible treatment option for dementia patients to stabilize their cognition and improve their quality of life until newer effective approaches become available,” Dr. Bragin said. He noted in the absence of a clear understanding of the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease and other progressive disorders involving cognitive decline, “the most successful treatment model is integrative care.”

REPORTING FROM ICPDMD 2018

Key clinical point: Patients with cognitive impairment can prevent loss with a computerized program with cognitive tasks.

Major finding: In all but one patient in a small series, reaction time remains stable throughout at least four years of follow-up.

Study details: Case series.

Disclosures: Dr. Bragin reported no financial relationships relevant to this study.

Objective studies help identify Parkinson’s patients at risk for falls

NEW YORK – There are numerous clinical factors and objective tools for identifying patients with Parkinson’s disease who have an increased risk of falls, according to data from a prospective study and an overview of this topic that was presented at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders

“Identifying risk of falls, which can produce complications beyond the acute injury, is one of the most important unmet needs in Parkinson’s disease,” reported A.V. Srinivasan, MD, PhD, DSc, of the Tamil Nadu Dr. MGR Medial University, Chennai, India.

Falls pose a risk of complications beyond acute injury because of the potential domino effect, according to Dr. Srinivasan. He maintained that when aging Parkinson’s disease patients are confined to bed for an extended period of recovery, a host of adverse health consequences can follow, including such life-threatening events as aspiration pneumonia.

“A serious fall can be the start of a downward clinical slope,” according to Dr. Srinivasan, who cited data suggesting that 40%-70% of Parkinson’s disease patients will have a serious fall at advanced stages of disease.

To identify those at greatest risk, a number of objective studies were shown to be useful in a study undertaken at the Institute of Neurology of Madras (India) Medical College, according to Dr. Srinivasan, where he was a professor when the study was conducted. In this study, 112 patients were evaluated with more than 15 months of follow-up. The 57 (51%) who experienced a fall were compared with the 55 who did not.

Between these groups, there was no difference in mean age (approximately 57 years in both) or in gender (approximately 70% male in both), according to Dr. Srinivasan. However, those who fell were significantly more likely to be obese (P = .009), to be on two or more anti-Parkinson’s medication (P = .01), and to be hypertensive (P = .018). Disease duration was significantly longer and disease severity significantly greater in those who fell relative to those who did not, according to Dr. Srinivasan.

However, Dr. Srinivasan placed particular emphasis on the objective studies that predicted risk of falls.

“When we compared baseline characteristics, Tinetti balance score, episodes of freezing gait, and the Get-Up-And-Go Test [GAGT], were all significant predictors of falls [all P less than .001],” Dr. Srinivasan said.

Of clinical studies, he suggested that GAGT is particularly simple and helpful. In GAGT, the time for a patient to rise from a chair, walk 10 feet, and return to their original sitting position, is timed. According to Dr. Srinivasan, an interval of 12 seconds or greater is a measure of impaired mobility and a signal for increased risk of falls.

Other patient characteristics or disease features that predicted increased risk of falls included the presence of dyskinesias and treatment with relatively high doses of levodopa. All of these factors should be considered when conducting a comprehensive risk assessment.

“A formal evaluation should be conducted routinely in all patients because there are a number of simple and effective strategies to reduce falls in patients at high risk,” Dr. Srinivasan said. These include teaching patients to avoid abrupt movements and modifying therapies to avoid gait freezing and other symptoms associated with falls. He cited a 2014 review article by Canning et al. (Neurodegen Dis Manag. 2014;4:203-21) as one source of clinically useful approaches.

“Early prevention is important. One of the most significant risks of falls is a previous fall. Control of disease symptoms lowers risk, but motor symptoms are not the only concern,” Dr. Srinivasan said. He suggested nonmotor issues, including inadequate sleep, impaired cognitive function, and attention deficits, can all be addressed in order to prevent falls and the risks they pose to quality of life and outcome.

NEW YORK – There are numerous clinical factors and objective tools for identifying patients with Parkinson’s disease who have an increased risk of falls, according to data from a prospective study and an overview of this topic that was presented at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders

“Identifying risk of falls, which can produce complications beyond the acute injury, is one of the most important unmet needs in Parkinson’s disease,” reported A.V. Srinivasan, MD, PhD, DSc, of the Tamil Nadu Dr. MGR Medial University, Chennai, India.

Falls pose a risk of complications beyond acute injury because of the potential domino effect, according to Dr. Srinivasan. He maintained that when aging Parkinson’s disease patients are confined to bed for an extended period of recovery, a host of adverse health consequences can follow, including such life-threatening events as aspiration pneumonia.

“A serious fall can be the start of a downward clinical slope,” according to Dr. Srinivasan, who cited data suggesting that 40%-70% of Parkinson’s disease patients will have a serious fall at advanced stages of disease.

To identify those at greatest risk, a number of objective studies were shown to be useful in a study undertaken at the Institute of Neurology of Madras (India) Medical College, according to Dr. Srinivasan, where he was a professor when the study was conducted. In this study, 112 patients were evaluated with more than 15 months of follow-up. The 57 (51%) who experienced a fall were compared with the 55 who did not.

Between these groups, there was no difference in mean age (approximately 57 years in both) or in gender (approximately 70% male in both), according to Dr. Srinivasan. However, those who fell were significantly more likely to be obese (P = .009), to be on two or more anti-Parkinson’s medication (P = .01), and to be hypertensive (P = .018). Disease duration was significantly longer and disease severity significantly greater in those who fell relative to those who did not, according to Dr. Srinivasan.

However, Dr. Srinivasan placed particular emphasis on the objective studies that predicted risk of falls.

“When we compared baseline characteristics, Tinetti balance score, episodes of freezing gait, and the Get-Up-And-Go Test [GAGT], were all significant predictors of falls [all P less than .001],” Dr. Srinivasan said.

Of clinical studies, he suggested that GAGT is particularly simple and helpful. In GAGT, the time for a patient to rise from a chair, walk 10 feet, and return to their original sitting position, is timed. According to Dr. Srinivasan, an interval of 12 seconds or greater is a measure of impaired mobility and a signal for increased risk of falls.

Other patient characteristics or disease features that predicted increased risk of falls included the presence of dyskinesias and treatment with relatively high doses of levodopa. All of these factors should be considered when conducting a comprehensive risk assessment.

“A formal evaluation should be conducted routinely in all patients because there are a number of simple and effective strategies to reduce falls in patients at high risk,” Dr. Srinivasan said. These include teaching patients to avoid abrupt movements and modifying therapies to avoid gait freezing and other symptoms associated with falls. He cited a 2014 review article by Canning et al. (Neurodegen Dis Manag. 2014;4:203-21) as one source of clinically useful approaches.

“Early prevention is important. One of the most significant risks of falls is a previous fall. Control of disease symptoms lowers risk, but motor symptoms are not the only concern,” Dr. Srinivasan said. He suggested nonmotor issues, including inadequate sleep, impaired cognitive function, and attention deficits, can all be addressed in order to prevent falls and the risks they pose to quality of life and outcome.

NEW YORK – There are numerous clinical factors and objective tools for identifying patients with Parkinson’s disease who have an increased risk of falls, according to data from a prospective study and an overview of this topic that was presented at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders

“Identifying risk of falls, which can produce complications beyond the acute injury, is one of the most important unmet needs in Parkinson’s disease,” reported A.V. Srinivasan, MD, PhD, DSc, of the Tamil Nadu Dr. MGR Medial University, Chennai, India.

Falls pose a risk of complications beyond acute injury because of the potential domino effect, according to Dr. Srinivasan. He maintained that when aging Parkinson’s disease patients are confined to bed for an extended period of recovery, a host of adverse health consequences can follow, including such life-threatening events as aspiration pneumonia.

“A serious fall can be the start of a downward clinical slope,” according to Dr. Srinivasan, who cited data suggesting that 40%-70% of Parkinson’s disease patients will have a serious fall at advanced stages of disease.

To identify those at greatest risk, a number of objective studies were shown to be useful in a study undertaken at the Institute of Neurology of Madras (India) Medical College, according to Dr. Srinivasan, where he was a professor when the study was conducted. In this study, 112 patients were evaluated with more than 15 months of follow-up. The 57 (51%) who experienced a fall were compared with the 55 who did not.

Between these groups, there was no difference in mean age (approximately 57 years in both) or in gender (approximately 70% male in both), according to Dr. Srinivasan. However, those who fell were significantly more likely to be obese (P = .009), to be on two or more anti-Parkinson’s medication (P = .01), and to be hypertensive (P = .018). Disease duration was significantly longer and disease severity significantly greater in those who fell relative to those who did not, according to Dr. Srinivasan.

However, Dr. Srinivasan placed particular emphasis on the objective studies that predicted risk of falls.

“When we compared baseline characteristics, Tinetti balance score, episodes of freezing gait, and the Get-Up-And-Go Test [GAGT], were all significant predictors of falls [all P less than .001],” Dr. Srinivasan said.

Of clinical studies, he suggested that GAGT is particularly simple and helpful. In GAGT, the time for a patient to rise from a chair, walk 10 feet, and return to their original sitting position, is timed. According to Dr. Srinivasan, an interval of 12 seconds or greater is a measure of impaired mobility and a signal for increased risk of falls.

Other patient characteristics or disease features that predicted increased risk of falls included the presence of dyskinesias and treatment with relatively high doses of levodopa. All of these factors should be considered when conducting a comprehensive risk assessment.

“A formal evaluation should be conducted routinely in all patients because there are a number of simple and effective strategies to reduce falls in patients at high risk,” Dr. Srinivasan said. These include teaching patients to avoid abrupt movements and modifying therapies to avoid gait freezing and other symptoms associated with falls. He cited a 2014 review article by Canning et al. (Neurodegen Dis Manag. 2014;4:203-21) as one source of clinically useful approaches.

“Early prevention is important. One of the most significant risks of falls is a previous fall. Control of disease symptoms lowers risk, but motor symptoms are not the only concern,” Dr. Srinivasan said. He suggested nonmotor issues, including inadequate sleep, impaired cognitive function, and attention deficits, can all be addressed in order to prevent falls and the risks they pose to quality of life and outcome.

REPORTING FROM ICPDMD 2018

Key clinical point: Patients with Parkinson’s disease at high risk for falls can be identified in order to initiate preventive strategies.

Major finding: For predicting falls, the Tinetti balance score and the Get-Up-And-Go test are both highly significant predictors (both P less than .001).

Study details: Observational study.

Disclosures: Dr. Srinivasan reports no financial relationships relevant to this study.

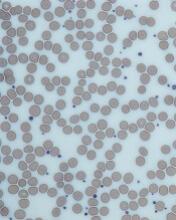

Inhibitor receives orphan designation for ITP

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to PRN1008 for the treatment of patients with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

PRN1008 is an oral, reversible, covalent Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor being developed by Principia Biopharma, Inc.

Principia is conducting a phase 1/2 trial (NCT03395210) to evaluate the safety and efficacy of PRN1008 in patients with ITP.

Results of preclinical research with PRN1008 in ITP were presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting.

There, researchers reported that PRN1008 significantly reduced platelet loss in a mouse model of ITP.

The team found the BTK inhibitor could diminish platelet loss in two ways:

- By reducing platelet destruction via inhibition of autoantibody/FcγR signaling in splenic macrophages

- By reducing autoantibody generation through inhibition of B-cell activation and maturation.

The researchers also assessed the effects of PRN1008 and ibrutinib on platelet function in samples from healthy volunteers and ITP patients.

Samples were treated with one of the two BTK inhibitors, and platelet aggregation was induced by platelet agonists.

Unlike ibrutinib, PRN1008 did not impact platelet aggregation in healthy volunteer or ITP patient samples.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the United States.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

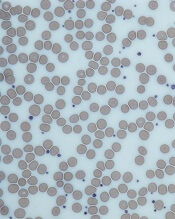

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to PRN1008 for the treatment of patients with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

PRN1008 is an oral, reversible, covalent Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor being developed by Principia Biopharma, Inc.

Principia is conducting a phase 1/2 trial (NCT03395210) to evaluate the safety and efficacy of PRN1008 in patients with ITP.

Results of preclinical research with PRN1008 in ITP were presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting.

There, researchers reported that PRN1008 significantly reduced platelet loss in a mouse model of ITP.

The team found the BTK inhibitor could diminish platelet loss in two ways:

- By reducing platelet destruction via inhibition of autoantibody/FcγR signaling in splenic macrophages

- By reducing autoantibody generation through inhibition of B-cell activation and maturation.

The researchers also assessed the effects of PRN1008 and ibrutinib on platelet function in samples from healthy volunteers and ITP patients.

Samples were treated with one of the two BTK inhibitors, and platelet aggregation was induced by platelet agonists.

Unlike ibrutinib, PRN1008 did not impact platelet aggregation in healthy volunteer or ITP patient samples.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the United States.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to PRN1008 for the treatment of patients with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

PRN1008 is an oral, reversible, covalent Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor being developed by Principia Biopharma, Inc.

Principia is conducting a phase 1/2 trial (NCT03395210) to evaluate the safety and efficacy of PRN1008 in patients with ITP.

Results of preclinical research with PRN1008 in ITP were presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting.

There, researchers reported that PRN1008 significantly reduced platelet loss in a mouse model of ITP.

The team found the BTK inhibitor could diminish platelet loss in two ways:

- By reducing platelet destruction via inhibition of autoantibody/FcγR signaling in splenic macrophages

- By reducing autoantibody generation through inhibition of B-cell activation and maturation.

The researchers also assessed the effects of PRN1008 and ibrutinib on platelet function in samples from healthy volunteers and ITP patients.

Samples were treated with one of the two BTK inhibitors, and platelet aggregation was induced by platelet agonists.

Unlike ibrutinib, PRN1008 did not impact platelet aggregation in healthy volunteer or ITP patient samples.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the United States.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

Investigational BTK inhibitor for relapsing MS advances on positive phase 2 data

BERLIN – Evobrutinib, an investigational inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK), significantly reduced the number of new T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions at 24 weeks compared with placebo in patients with relapsing multiples sclerosis (MS).

However, the molecule was also associated with grade 3 and 4 elevations in alanine aminotransferase – a troubling finding, Xavier Montalban, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

“Fortunately, all patients were asymptomatic, and the elevations were completely reversible. The results of this trial do support further development of this molecule,” said Dr. Montalban, director of the Multiple Sclerosis Centre of Catalonia at the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital in Barcelona.

Evobrutinib exerts a dual action in MS, Dr. Montalban said. By inhibiting BTK, the drug blocks B-cell activation and interaction between B and T cells. It also inhibits macrophage survival and dampens cytokine release, he said.

The study randomized 213 patients with relapsing MS to placebo or to evobrutinib in three daily doses: 25 mg, 75 mg, or 150 mg. A control arm of 54 additional patients received treatment with dimethyl fumarate. After 24 weeks of randomized treatment, patients who got placebo switched to 25 mg per day; everyone else continued in their assigned groups for another 24 weeks. The study concluded with an open-label extension phase during which everyone took 75 mg daily.

Dr. Montalban reported the primary 24-week analysis. The remainder of the data has not been analyzed yet, he said. The primary endpoint was the total number of T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions at weeks 12, 16, 20, and 24. Secondary endpoints included the 24-week annualized relapse rate and safety signals. Patients were a mean of 41 years old, with a mean disease duration of 10 years. They had experienced a mean of two relapses in the prior 2 years. About 20% had gadolinium-enhancing lesions at baseline.

Compared with placebo and with the 25-mg dose, evobrutinib 75 mg and 150 mg significantly reduced the number of new enhancing lesions at 24 weeks. There was evidence of a dose-response effect, Dr. Montalban said. Patients taking placebo developed a mean of 3.8 new lesions, while those on 75 mg developed a mean of 1.69 and those taking 150 mg, a mean of 1.15. Patients in the 25-mg group developed a mean of four new lesions – not significantly different than placebo.

Both the 75-mg and 150-mg doses decreased the annualized relapse rate, compared with placebo but missed statistical significance, with P values of 0.90 and 0.63, respectively.

These two doses also conferred significant benefit on two other secondary endpoints, significantly reducing the number of new or enlarging T2 lesions and reducing the total T2 lesion volume, compared with placebo.

The safety profile was relatively benign, with no infections, including no opportunistic infections, and no neoplasms. About 7% of the highest-dose group experienced nausea, and the same number, arthralgia. Seven patients taking evobrutinib experienced grade 1 lymphopenia, compared with three patients taking placebo; grade 2 lymphopenia developed in one patient in the highest-dose group.

ALT elevation was the most concerning adverse event, Dr. Montalban said. Grade 1 elevations developed in 17% of the low-dose group and about 22% of the other two active groups (11 patients each), compared with 7% of the placebo group. Grade 2 elevations developed in three placebo patients and in two taking the highest dose of evobrutinib. There was one grade 3 elevation, which occurred in a patient in the highest-dose group. These were asymptomatic and resolved after discontinuing the medication. Lipase and aspartate transaminase elevations were also associated with evobrutinib, but Dr. Montalban did not provide these details.

He has been a paid consultant for Merck Serono, which is developing evobrutinib.

SOURCE: Montalban X et al. ECTRIMS 2018. Abstract 322.

BERLIN – Evobrutinib, an investigational inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK), significantly reduced the number of new T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions at 24 weeks compared with placebo in patients with relapsing multiples sclerosis (MS).

However, the molecule was also associated with grade 3 and 4 elevations in alanine aminotransferase – a troubling finding, Xavier Montalban, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

“Fortunately, all patients were asymptomatic, and the elevations were completely reversible. The results of this trial do support further development of this molecule,” said Dr. Montalban, director of the Multiple Sclerosis Centre of Catalonia at the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital in Barcelona.

Evobrutinib exerts a dual action in MS, Dr. Montalban said. By inhibiting BTK, the drug blocks B-cell activation and interaction between B and T cells. It also inhibits macrophage survival and dampens cytokine release, he said.

The study randomized 213 patients with relapsing MS to placebo or to evobrutinib in three daily doses: 25 mg, 75 mg, or 150 mg. A control arm of 54 additional patients received treatment with dimethyl fumarate. After 24 weeks of randomized treatment, patients who got placebo switched to 25 mg per day; everyone else continued in their assigned groups for another 24 weeks. The study concluded with an open-label extension phase during which everyone took 75 mg daily.

Dr. Montalban reported the primary 24-week analysis. The remainder of the data has not been analyzed yet, he said. The primary endpoint was the total number of T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions at weeks 12, 16, 20, and 24. Secondary endpoints included the 24-week annualized relapse rate and safety signals. Patients were a mean of 41 years old, with a mean disease duration of 10 years. They had experienced a mean of two relapses in the prior 2 years. About 20% had gadolinium-enhancing lesions at baseline.

Compared with placebo and with the 25-mg dose, evobrutinib 75 mg and 150 mg significantly reduced the number of new enhancing lesions at 24 weeks. There was evidence of a dose-response effect, Dr. Montalban said. Patients taking placebo developed a mean of 3.8 new lesions, while those on 75 mg developed a mean of 1.69 and those taking 150 mg, a mean of 1.15. Patients in the 25-mg group developed a mean of four new lesions – not significantly different than placebo.

Both the 75-mg and 150-mg doses decreased the annualized relapse rate, compared with placebo but missed statistical significance, with P values of 0.90 and 0.63, respectively.

These two doses also conferred significant benefit on two other secondary endpoints, significantly reducing the number of new or enlarging T2 lesions and reducing the total T2 lesion volume, compared with placebo.

The safety profile was relatively benign, with no infections, including no opportunistic infections, and no neoplasms. About 7% of the highest-dose group experienced nausea, and the same number, arthralgia. Seven patients taking evobrutinib experienced grade 1 lymphopenia, compared with three patients taking placebo; grade 2 lymphopenia developed in one patient in the highest-dose group.

ALT elevation was the most concerning adverse event, Dr. Montalban said. Grade 1 elevations developed in 17% of the low-dose group and about 22% of the other two active groups (11 patients each), compared with 7% of the placebo group. Grade 2 elevations developed in three placebo patients and in two taking the highest dose of evobrutinib. There was one grade 3 elevation, which occurred in a patient in the highest-dose group. These were asymptomatic and resolved after discontinuing the medication. Lipase and aspartate transaminase elevations were also associated with evobrutinib, but Dr. Montalban did not provide these details.

He has been a paid consultant for Merck Serono, which is developing evobrutinib.

SOURCE: Montalban X et al. ECTRIMS 2018. Abstract 322.

BERLIN – Evobrutinib, an investigational inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK), significantly reduced the number of new T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions at 24 weeks compared with placebo in patients with relapsing multiples sclerosis (MS).

However, the molecule was also associated with grade 3 and 4 elevations in alanine aminotransferase – a troubling finding, Xavier Montalban, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

“Fortunately, all patients were asymptomatic, and the elevations were completely reversible. The results of this trial do support further development of this molecule,” said Dr. Montalban, director of the Multiple Sclerosis Centre of Catalonia at the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital in Barcelona.

Evobrutinib exerts a dual action in MS, Dr. Montalban said. By inhibiting BTK, the drug blocks B-cell activation and interaction between B and T cells. It also inhibits macrophage survival and dampens cytokine release, he said.

The study randomized 213 patients with relapsing MS to placebo or to evobrutinib in three daily doses: 25 mg, 75 mg, or 150 mg. A control arm of 54 additional patients received treatment with dimethyl fumarate. After 24 weeks of randomized treatment, patients who got placebo switched to 25 mg per day; everyone else continued in their assigned groups for another 24 weeks. The study concluded with an open-label extension phase during which everyone took 75 mg daily.

Dr. Montalban reported the primary 24-week analysis. The remainder of the data has not been analyzed yet, he said. The primary endpoint was the total number of T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions at weeks 12, 16, 20, and 24. Secondary endpoints included the 24-week annualized relapse rate and safety signals. Patients were a mean of 41 years old, with a mean disease duration of 10 years. They had experienced a mean of two relapses in the prior 2 years. About 20% had gadolinium-enhancing lesions at baseline.

Compared with placebo and with the 25-mg dose, evobrutinib 75 mg and 150 mg significantly reduced the number of new enhancing lesions at 24 weeks. There was evidence of a dose-response effect, Dr. Montalban said. Patients taking placebo developed a mean of 3.8 new lesions, while those on 75 mg developed a mean of 1.69 and those taking 150 mg, a mean of 1.15. Patients in the 25-mg group developed a mean of four new lesions – not significantly different than placebo.

Both the 75-mg and 150-mg doses decreased the annualized relapse rate, compared with placebo but missed statistical significance, with P values of 0.90 and 0.63, respectively.

These two doses also conferred significant benefit on two other secondary endpoints, significantly reducing the number of new or enlarging T2 lesions and reducing the total T2 lesion volume, compared with placebo.

The safety profile was relatively benign, with no infections, including no opportunistic infections, and no neoplasms. About 7% of the highest-dose group experienced nausea, and the same number, arthralgia. Seven patients taking evobrutinib experienced grade 1 lymphopenia, compared with three patients taking placebo; grade 2 lymphopenia developed in one patient in the highest-dose group.

ALT elevation was the most concerning adverse event, Dr. Montalban said. Grade 1 elevations developed in 17% of the low-dose group and about 22% of the other two active groups (11 patients each), compared with 7% of the placebo group. Grade 2 elevations developed in three placebo patients and in two taking the highest dose of evobrutinib. There was one grade 3 elevation, which occurred in a patient in the highest-dose group. These were asymptomatic and resolved after discontinuing the medication. Lipase and aspartate transaminase elevations were also associated with evobrutinib, but Dr. Montalban did not provide these details.

He has been a paid consultant for Merck Serono, which is developing evobrutinib.

SOURCE: Montalban X et al. ECTRIMS 2018. Abstract 322.

REPORTING FROM ECTRIMS 2018

Key clinical point: Evobrutinib reduced the number of new T1 gadolinium-enhancing lesions.

Major finding: At 24 weeks, the 150-mg group had a mean of 1.15 new lesions vs. 3.8 in the placebo group.

Study details: The phase 2 study randomized 213 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Montalban has been a paid consultant for Merck Serono, which is developing the molecule.

Source: Montalban X et al. ECTRIMS 2018.Abstract 322.

Physiologically functional organoid offers promise for rapid, realistic in vitro drug discovery

NEW YORK – A self-assembling model brain neurovascular unit showed that it emulated in vivo behavior of the human blood-brain barrier under a variety of conditions, including hypoxia and histamine exposure.

Goodwell Nzou, a doctoral student at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., discussed findings published earlier this year in Scientific Reports showing that the three-dimensional brain organoid has promise for rapid in vitro testing of central nervous system drugs.

The model contains all the primary cell types in the human brain cortex, said Mr. Nzou, speaking at the International Conference for Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders. These include human brain microvascular endothelial cells, pericytes, astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes, and neurons. Human endothelial cells enclose the parenchymal cells in the model.

The human neurovascular unit (NVU) organoid model was developed using induced pluripotent stem cells for the microglial, oligodendrocyte, and neuron cell components. Human primary cells were used for the remaining components.

First, Mr. Nzou and his collaborators constructed a four-cell model. By placing the cells in a hanging drop culture environment and culturing for 96 hours, the investigators were able to induce assembly of the organoids. Since the cells had been pretreated with a durable labeling dye, the investigators could confirm anatomically appropriate self-assembly using confocal microscopy. Blood-brain barrier (BBB) tight junctions were confirmed by testing for the tight junction protein ZO-1 via immunofluorescent labeling, said Mr. Nzou.

From this experience, they were able to conduct a staged assembly using all six cell types, yielding a neurovascular unit that was durable, maintaining “very high cell viability for up to 21 days in vitro,” Mr. Nzou said, with both core and outer cells showing good viability.

Mr. Nzou and his colleagues at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine tested the model’s function against several emulated physical states: In one, they flooded the field with histamine, finding that the junctions lost integrity, accurately mimicking the “leaky” tissue state that occurs in vivo with histamine release.

The histamine-treated organoids allowed IgG permeability that was largely absent in the control organoids. “In the control system we did not see much of the IgG going in. We did see a lot more going in after we treated the organoids with histamine,” said Mr. Nzou.

However, IgG is a large molecule, and much CNS drug discovery right now is focused on small molecules, so Mr. Nzou and his colleagues also wanted to see whether the NVU’s BBB integrity would hold up against a small molecule.

Using exposure to a molecule called MPTP, Mr. Nzou and his collaborators compared how much MPTP entered two different types of organoids: One was the six-cell organoid, and the other was made up of neurons only.

The neuron-only organoid would not be expected to prevent influx of MPTP since it lacked the BBB-like composition of the full organoid, explained Mr. Nzou. Once past the BBB, MPTP is converted to an active substance that interferes with adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production . The investigators did see a significant drop in APT production with MPTP exposure in the neuron-only, but not the full, organoid, said Mr. Nzou.

In another trial, they exposed the model to an atmosphere with lowered oxygen tension and saw resultant changes consistent with ischemia. The model “showed normal physiologic responses under hypoxic conditions,” they said. These included increased proinflammatory cytokine production and decreased integrity of the BBB.

The in vitro hypoxia was profound – oxygen exposure was dropped to 1% from normal atmospheric composition of 21%. Still, the organoids maintained good viability despite the hypoxia-induced changes in physiology, making them appropriate candidates for testing such hypoxic conditions as ischemic stroke and conditions that elevate intracranial pressure, Mr. Nzou said.