User login

Cardiomyopathy could be under recognized in lupus

Also today, low bone mineral density and spinal syndesmophytes predict radiographic progression in axial spondyloarthritis, sensory feedback modalities tackle gait and balance problems in Parkinson’s disease, and clinically meaningful change is determined for RAPID-3 in active RA.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, low bone mineral density and spinal syndesmophytes predict radiographic progression in axial spondyloarthritis, sensory feedback modalities tackle gait and balance problems in Parkinson’s disease, and clinically meaningful change is determined for RAPID-3 in active RA.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, low bone mineral density and spinal syndesmophytes predict radiographic progression in axial spondyloarthritis, sensory feedback modalities tackle gait and balance problems in Parkinson’s disease, and clinically meaningful change is determined for RAPID-3 in active RA.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Spotify

An Overview of Pharmacotherapy Options for Alcohol Use Disorder

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a relatively common condition characterized by a pattern of problematic alcohol consumption. According to the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) approximately 14.6 million Americans aged > 18 years had a diagnosis of AUD.1 This same survey also found that 26.2% of individuals over the age of 18 years reported engaging in binge drinking, which is ≥ 5 drinks in males or ≥ 4 drinks in females on the same occasion in the past month. Of those surveyed, 6.6% reported engaging in heavy drinking (binge drinking on 5 or more days in the past month).1

Military and veteran populations have a higher prevalence of alcohol misuse compared with that of the general population.2 Two out of 5 US veterans screen positive for lifetime AUD, which is higher than the prevalence of AUD in the general population.3 A number of studies have found that excessive alcohol use is common among military personnel.2,4,5 One study suggested that the average active-duty military member engages in approximately 30 binge drinking episodes per person per year.4 Military veterans may continue with a similar drinking pattern when transitioning to civilian life, explaining the high prevalence of AUD in the veteran population.6 Furthermore, since alcohol use provides temporary relief of posttraumatic stress disorder(PTSD) symptoms, a diagnosis of PTSD may also contribute to hazardous drinking in this population.7

Excessive alcohol consumption is associated with a number of negative outcomes, including increased motor-vehicle accidents, decreased medication adherence, and therefore, decreased efficacy, increased health care costs, and increased morbidity and mortality.8-13 Additionally, alcohol use is associated with a number of medical and psychiatric comorbidities.14,15 Compared with veterans without AUD, those with a diagnosis of AUD were 2.6 times more likely to have current depression and 2.8 times more likely to have generalized anxiety.3 Veterans with AUD also are 2.1 times more likely to have current suicidal ideation and 4.1 times more likely to have had a suicide attempt compared with veterans without AUD.3

Given the high prevalence and the associated risks, alcohol misuse should be properly addressed and treated. Pharmacotherapy for AUD has demonstrated efficacy in decreasing heavy drinking and prolonging periods of abstinence.16 Despite the proven benefits of available pharmacotherapy, these medications still are drastically underutilized in both the nonveteran and veteran populations. In fiscal year 2012, there were 444,000 veterans with a documented diagnosis of AUD; however, only 5.8% received evidence-based pharmacotherapy.17 The potential barriers for the utilization of AUD pharmacotherapy includes perceived low patient demand, lack of skill or knowledge about addiction, and lack of health care provider (HCP) confidence in efficacy.18 This article will provide a thorough overview of the pharmacotherapy options for the treatment of AUD and the evidence that supports the use of pharmacotherapy. We will then conclude with the recommended treatment approach for specialized patient populations.

FDA-Approved Pharmacotherapies

Naltrexone

Naltrexone was the second FDA-approved medication for the treatment of AUD and is considered a first-line agent by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).19,20 Unlike its predecessor, disulfiram, naltrexone significantly reduces cravings.21 During alcohol consumption endogenous opioid activity is greatly enhanced, leading to the rewarding effects of alcohol. By antagonizing the µ-opioid receptor, naltrexone mediates endorphin release during alcohol consumption, explaining the efficacy of naltrexone in AUD.21-28 Since cravings are reduced, patients are able to abstain from drinking for longer periods of time, and since pleasure is reduced, heavy drinking is also reduced.21,25

When compared with other pharmacotherapy options for AUD, naltrexone is less effective for abstinence and more effective for decreasing the time and frequency of heavy drinking days and average number of drinks consumed.29 A meta-analysis of 19 clinical trials found that naltrexone significantly reduced relapse rates in patients with AUD compared with those of placebo.30 This analysis also found that naltrexone reduced both the number of alcoholic beverages consumed and the risk of relapse to heavy drinking while increasing the total number of days of abstinence.30 The COMBINE study also found that patients receiving oral naltrexone in combination with medical treatment had a 28% reduced risk of having a heavy-drinking day.31

Dosing and Formulations

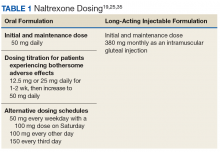

Naltrexone is available as a tablet or a long-acting injectable. The tablet is often dosed as 50 mg daily; although some studies suggest that daily doses up to 150 mg are safe and efficacious.21,25,32 The initial and maintenance dose for most patients is 50 mg daily.

Nonadherence to the oral formulation of naltrexone is a significant barrier to the treatment of AUD. The long-acting injectable formulation is an option for patients who may have difficulty with adhering to oral naltrexone. As with the oral formulation, the long-acting naltrexone injection significantly reduces drinking days and increases abstinence.33 It was also found to be superior to oral naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram in preventing discontinuation of AUD treatment.34 The long-acting injectable should be administered as an intramuscular gluteal injection at a dose of 380 mg monthly.35

Ideally, naltrexone should be initiated following the cessation of alcohol withdrawal symptoms. However, naltrexone can be safely administered in patients who are actively withdrawing from alcohol or in patients who continue to consume alcohol.25

Warnings, Precautions, and AEs

Naltrexone carries a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) boxed warning for reversible hepatotoxicity. The risk of hepatotoxicity is increased in patients who receive higher doses (100-300 mg daily).21 A safety study demonstrated that the administration of 50 mg daily or less is not associated with significant hepatotoxicity.21,31 It is contraindicated in patients with acute hepatitis or liver failure and should be avoided in patients with liver function tests > 5 times the upper limit of normal.

Since naltrexone is a µ-opioid receptor antagonist, it is contraindicated in patients who are actively taking opioids or patients who have used opioids within the past 7 days. Co-administration with an opioid can lead to precipitated opioid withdrawal.21 Therefore, opioids should not be administered within 7 to 10 days of initiating naltrexone and 2 to 3 days after discontinuation of oral naltrexone.21 For patients receiving the long-acting injectable form of naltrexone, opioids should be avoided at least 1 month after the injection.25

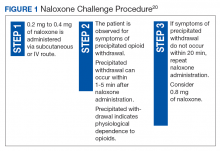

To ensure that a patient is opioid free, HCPs can perform a toxicology screening prior to the initiation of naltrexone. Some HCPs may also perform a naloxone challenge to test whether a patient is at risk for precipitated opioid withdrawal prior to prescribing naltrexone.

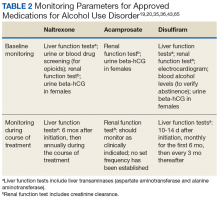

The adverse effects (AEs) of naltrexone are transient and include nausea, vomiting, anorexia, dizziness, and fatigue.19,35 Injection site reactions can be experienced with the long-acting naltrexone injection. Liver transaminases, such as the alanine aminotransferase and aspartate transaminase, should be monitored at baseline, 6 months after initiation, and annually during the course of treatment (Table 2).

Acamprosate

The FDA approved acamprosate for the treatment of AUD in 2004, and it is also considered a first-line agent for AUD by the VA.20 It is approved for the maintenance of abstinence from alcohol use and is most efficacious when initiated in patients who are abstinent prior to treatment.29,36 Patients with AUD typically have a disruption in the balance between the inhibitory neurotransmitter, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and the excitatory neurotransmitter, glutamate. While its mechanism of action remains unknown, acamprosate is thought to increase the activity of GABA and to decrease the activity of glutamate at the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in the central nervous system. In essence, it is thought to restores the balance between GABA and glutamate in patients with AUD.36

Acamprosate has been found to effectively prevent relapse. Three randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled European clinical trials evaluated the efficacy of acamprosate in combination with psychotherapy. The results demonstrated that patients taking acamprosate had longer durations of abstinence compared with that of placebo, improved rates of complete abstinence, and a prolonged time to first drink.37-39 A meta-analysis evaluated the use of acamprosate in AUD showed that acamprosate was more effective at maintaining abstinence in patients who had been abstinent prior to the initiation of therapy.29 These patients also had better abstinence rates if they had been abstinent for a longer duration prior to treatment initiation.30 Studies also showed that acamprosate significantly assisted with maintaining abstinence, improved rates of abstinence, and led to more days of abstinence.40,41 Of note, there also have been studies that have shown no significant benefit with acamprosate compared with placebo in the treatment of AUD.42

Dosing and Formulations

Acamprosate is available as a 333 mg delayed-release tablet. The recommended dose is 666 mg 3 times daily.36 The dose can be decreased to 333 mg 3 times a day in patients with moderate renal impairment (CrCl-30-50 mL/min).

Since acamprosate has been proven more effective in patients who are abstinent prior to initiation, acamprosate is typically initiated 5 days following alcohol cessation.25 However, it may be safely administered with alcohol and can continue to be administered in the event of a relapse.36

Warnings, Precautions, and AEs

Acamprosate is safe to use in patients with hepatic and mild-to-moderate renal impairment; however, it is contraindicated in patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance [CrCl] ≤ 30 mL/min).36 Serum creatinine levels should be monitored at baseline and during treatment.

Acamprosate has a number of related AEs. The most common is diarrhea. Less common AEs include insomnia, anxiety, and depression. Due to its possible potential to increase suicidality, HCPs should monitor for the emergence of mood changes.36

Disulfiram

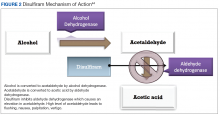

Disulfiram is an aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitor that is FDA approved for the management of AUD.43 When ingested, ethanol is typically metabolized to acetaldehyde, which is further metabolized to acetic acid by aldehyde dehydrogenase.44 Disulfiram inhibits aldehyde dehydrogenase, leading to a rapid accumulation of acetaldehyde within the plasma (outlined in Figure 2).

There are limited studies that prove the efficacy of disulfiram. In a randomized trial comparing disulfiram, acamprosate, and naltrexone, patients treated with disulfiram had fewer heavy drinking days, lower rates of weekly alcohol consumption, and a longer period of abstinence compared to other medications.45 Additionally, a 2014 meta-analysis showed that in open-label studies, disulfiram was more beneficial in preventing alcohol consumption when compared with acamprosate, naltrexone, and placebo. This result was not seen in blinded studies.46 Disulfiram does not reduce alcohol cravings, and adherence is a significant issue. It is most effective between 2 and 12 months, when taken under supervised administration.47

Dosing and Formulations

Disulfiram is only available as a tablet. The recommended starting dose is up to 500 mg for the first 2 weeks. However, the maintenance dose can range from 125 to 500 mg daily.43 Patients must be abstinent from alcohol at least 12 to 24 hours prior to the initiation of disulfiram.25 A blood alcohol level can be obtained in order to confirm abstinence.25

Warnings, Precautions, and AEs

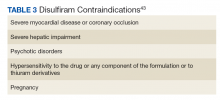

Disulfiram is contraindicated in patients with severe myocardial disease or coronary occlusion and severe hepatic impairment.43 Other contraindications are outlined in Table 3.

Common AEs include somnolence, a metallic after-taste, and peripheral neuropathy.43 Patients should be informed that they could experience a disulfiram reaction with even small amounts of alcohol; all foods, drinks, and medications containing alcohol should be avoided. Due to the potential of disulfiram potential to cause hepatotoxicity, liver transaminases should be monitored at baseline, 2 weeks after initiation, and monthly for the first 6 months of therapy, and every 3 months thereafter (Table 2).25

Off-Label Pharmacotherapies

Topiramate

Although not approved for AUD, topiramate has been used off-label for this indication as it has proven efficacy in clinical trials.48-56 While its mechanism of action for AUD is unclear, it has been theorized that topiramate antagonizes glutamate receptors, thereby reducing dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens upon alcohol consumption, and potentiates the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA.50,51,57-60

In clinical trials, topiramate has demonstrated significant efficacy in reducing cravings, the risk of relapse, and the number of drinks consumed daily, while increasing abstinence.51,53,60 Batki and colleagues report that the administration of topiramate in veterans with co-occurring AUD and PTSD reduced alcohol consumption, cravings, and the severity of their PTSD symptoms.61

Dosing and Formulations

Topiramate is available in a number of formulations; however, only the immediate-release formulation is recommended for the treatment of AUD. The extended-release formulation is contraindicated in the setting of alcohol consumption and is therefore not used for the treatment of AUD.62 Doses should be initiated at 25 mg daily and can be titrated in 25 to 50 mg weekly increments. To minimize AEs and to reduce the risk of patients discontinuing therapy, the dose may be slowly titrated over 8 weeks.53,59 An effective dose can range from 75 to 300 mg in divided doses; however, AEs often limit the tolerability of increased doses.48,50,63,64 The VA/DoD Practice Guideline for the Management of Substance Use Disorders recommends titrating topiramate to a target dose of 100 mg twice daily.65

Warnings, Precautions, and AEs

Common AEs include memory impairment, anorexia, fatigue, paresthesias, and somnolence.62 There is an increased risk of nephrolithiasis with topiramate administration; therefore, adequate hydration is crucial.49,59 Titration of topiramate to the target dose is suggested to limit AEs.35

Prior to initiating topiramate, the patient’s renal function should be assessed. In those with a CrCl < 70 mL/min the dose should be decreased by 50% and titrated more slowly.62

Gabapentin

Gabapentin is prescribed for the treatment of partial seizures and postherpetic neuralgia. In recent years, it has shown efficacy for treating other conditions, such as AUD. While its mechanism for this indication remains unclear, the inhibition of excitatory alpha-2-delta calcium channels and stimulation of inhibitory GABAA receptors by gabapentin is believed to decrease alcohol cravings, reduce anxiety, and increase abstinence.66

A 12-week, double-blind, randomized controlled trial demonstrated that oral gabapentin was more efficacious than was placebo for improving rates of abstinence, decreasing heavy drinking, and reducing alcohol cravings.67 Gabapentin may also serve as a good adjunctive option to naltrexone therapy either when naltrexone monotherapy fails or if a patient is complaining of sleep and mood disturbances with abstinence.67,68

Dosing and Formulations

Gabapentin should be titrated slowly to minimize AEs. It can be initiated at 300 mgon day 1 and increase by 300-mg increments. Doses of 900 to 1,800 mg per day have proven to be efficacious for the treatment of AUD.66,67 These proposed doses can be safely administered to most patients, but caution should be observed in elderly and patients with renal impairment.69,70

Warnings, Precautions, and AEs

The most common AEs for gabapentin include drowsiness, dizziness, and fatigue.69 Since it is renally cleared, renal function should be monitored at baseline and periodically during treatment. Gabapentin is not metabolized by liver enzymes and does not significantly interact with drugs that require hepatic metabolism.

Baclofen

Baclofen has generated attention as an unconventional treatment option for alcohol dependence. Its unique mechanism of action, which involves the activation of GABAB receptors and the subsequent inhibition of dopaminergic neurons, makes it useful for the treatment of AUD.71

A 12-week study evaluating the effectiveness and safety of baclofen for the maintenance of alcohol abstinence demonstrated that baclofen was more efficacious than placebo for increasing abstinence in patients with liver cirrhosis. In addition, there were more cumulative days of abstinence with baclofen use (62.8 days) vs placebo (30.8 days) in cirrhotic patients.72

Dosing and Formulations

There has been a range of doses studied for baclofen in the treatment of AUD. Studies indicate that initiating baclofen at 30 mg daily and increasing doses based on the patient’s clinical response is most effective.72 As a result, doses as high as 275 mg per day have been used for some patients.73 Baclofen is renally cleared; therefore, the dose should be adjusted in patients with renal impairment.74

Warnings, Precautions, and AEs

Some of the common AEs of baclofen include drowsiness, confusion, headache, and nausea. Due to its CNS depressant effects, baclofen should be used with caution in the elderly. Also, due to its potential to cause withdrawal symptoms, baclofen should not be discontinued abruptly.74,75 Baclofen is a safe option for patients with severe liver disease, due to its minimal hepatic metabolism.76

Ondansetron

Ondansetron is approved for both prophylactic and therapeutic use as an antiemetic agent for chemotherapy and anesthesia-induced nausea and vomiting.77As a highly selective and competitive 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, ondansetron has demonstrated efficacy in reducing serotonin-mediated dopaminergic effects in AUD.78,79 The lowering of these dopaminergic effects is associated with a reduction in alcohol-induced gratification and consumption.

In a 12-week, randomized controlled trial, 271 patients diagnosed with AUD received ondansetron twice daily or placebo, combined with weekly cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). There was a statistically significant decrease in alcohol consumption in patients treated with ondansetron compared with those who received placebo. Additionally, ondansetron was superior to placebo for increasing the percentage and total amount of days abstinent.80 These results were primarily observed in participants diagnosed with early-onset AUD (defined as onset at 25 years or younger), which may suggest the presence of genetically predisposed serotonin dysfunctions.80,81 In contrast, there were no significant differences observed in participants with late-onset AUD (onset after age 25 years) in either study group.80

Dosing and Formulations

Given its modest efficacy for the treatment of AUD, ondansetron has demonstrated clinical benefits at doses of 0.001 to 0.016 mg/kg twice daily. Additionally, 1 study reported that low-dose ondansetron (0.25 mg twice daily) was effective in reducing alcohol consumption when compared with placebo or high-dose ondansetron, which was considered 2 mg twice daily.82

Warnings, Precautions, and AEs

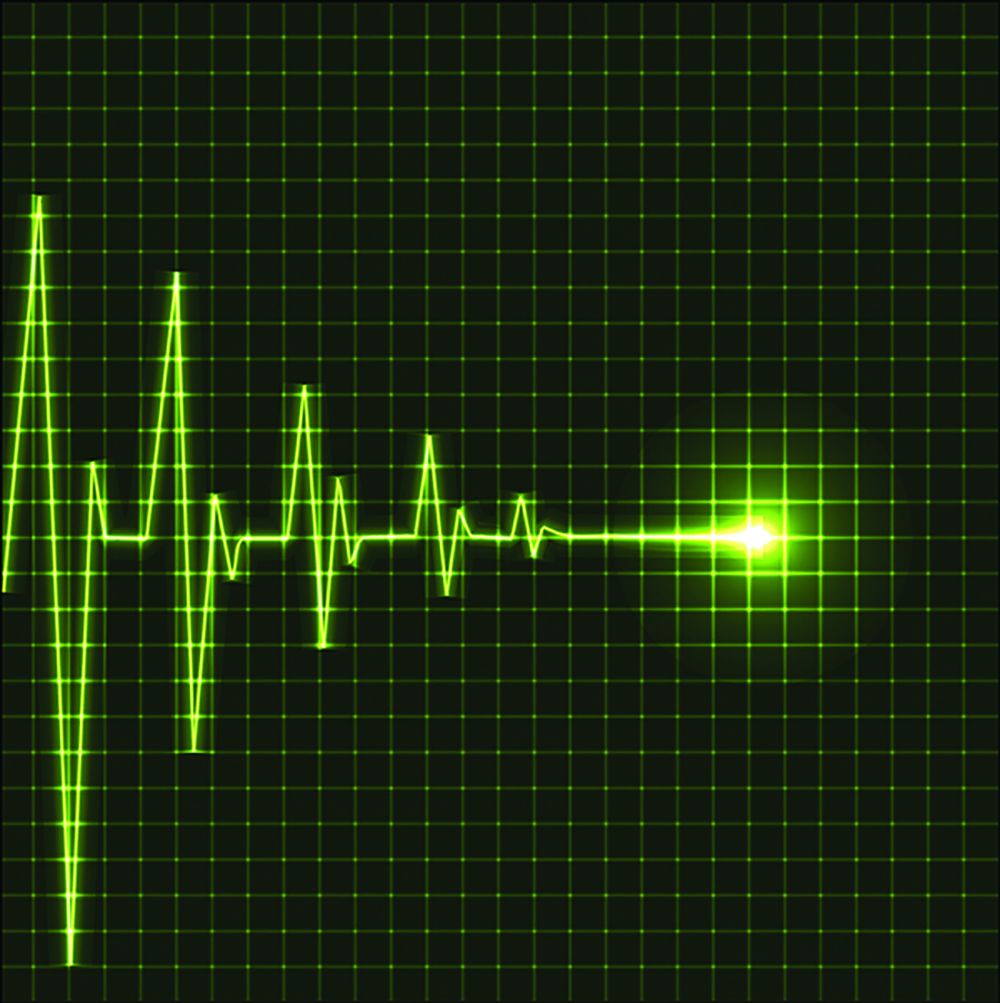

The most commonly reported AEs with ondansetron include fatigue, headache, anxiety, and serotonin syndrome when used concomitantly with other serotonergic agents.77 Also, serious cardiovascular complications, such as QTc prolongation, angina pectoris, atrial fibrillation, and arrhythmias have been observed with IV administration.77,81,83 Consequently, patients with electrolyte imbalances (eg, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia), a history of congestive heart failure, or concomitant medications associated with QTc prolongation, should be monitored with an electrocardiogram (ECG) or switched to another agent.77

Treatment Approach with AUD Pharmacotherapy

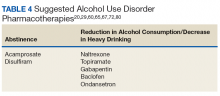

There is insufficient evidence to support the use of 1 medication for AUD over the others.16,46,84 Instead, the choice of therapy largely depends on the patient’s comorbidities, renal and hepatic function, and on the patient’s established goals, whether abstinence or reduction in alcohol consumption (Table 4).

There is much debate over the appropriate duration of treatment for AUD pharmacotherapy. It is recommended that patients remain on these medications for at least 3 months. Pharmacotherapy can be continued for 6 to 12 months as the risk for relapse is highest during this time frame.85,86 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines recommend discontinuing AUD pharmacotherapy if alcohol consumption persists 4 to 6 weeks after initiation.86

Comorbid Liver Disease

Due to the negative effects of heavy alcohol consumption on the liver, patients with AUD may develop liver disease. Health care providers should be aware of the appropriate pharmacotherapy options for patients with comorbid liver disease. Acamprosate is mostly excreted unchanged by the kidneys, therefore is an option for patients with liver disease whose goal is complete abstinence. Topiramate is another option for use in patients with liver impairment. Unlike acamprosate, topiramate would be a better option in patients who may not completely abstain from alcohol consumption but would like to decrease the amount of heavy drinking days.87

Gabapentin, baclofen, and ondansetron are also options for those with liver disease. Baclofen in particular has been studied in those with advanced liver disease, and it was found to be safe and effective.88,89

Comorbid Renal Disease

Naltrexone is an option for patients with mild renal impairment. Naltrexone and its major metabolite, 6-ß-naltrexol, are renally excreted; however, urinary excretion of unchanged naltrexone accounts for < 2% of the oral dose.19 Even with its low potential for accumulation, HCPs should carefully monitor for AEs in patients with moderate-to-severe renal impairment. Disulfiram is another pharmacotherapy option, since it is mostly metabolized by the liver.

Gabapentin, baclofen, and ondansetron are also possible options; however, their doses should be renally adjusted. Overall, there are limited studies on the use of these medications treating AUD in patients with renal impairment.

Pregnancy

Alcohol consumption during pregnancy can result in a wide range of birth defects to the unborn fetus. Due to the negative effects of alcohol consumption on the fetus, pregnant females should be referred to a professional alcohol treatment program. Although AUD pharmacotherapy may be considered in pregnant females, there have been no human studies that have examined the efficacy and safety in this patient population. All evidence comes from animal studies, case reports, and case series.90

Naltrexone is the most widely used medication for AUD in pregnancy. It is considered pregnancy category C and 1 study in particular did not detect any gross abnormalities in fetal development in pregnancy.19, 90 Disulfiram, acamprosate, and topiramate have all been shown to cause harm to either animal or human fetuses and are generally not recommended.36,44,63 Similar to naltrexone, gabapentin and baclofen are also pregnancy category C.69,77 Ondansetron is pregnancy category B, but it should still be used with caution since its use in pregnancy for the treatment of AUD has not been studied.77,90

Psychosocial Interventions

It is recommended that AUD pharmacotherapy be used in conjunction with a psychosocial intervention, such as CBT or medical management. Many of the studies evaluating the efficacy of AUD pharmacotherapy combined psychosocial interventions with medications. The literature suggests that when combined with CBT or medical management therapy, pharmacotherapy used for AUD results in better alcohol consumption outcomes.31,91 It has also been suggested that psychosocial interventions may improve patient adherence to AUD pharmacotherapy.25

Barriers

Inadequate HCP training on the use of AUD pharmacotherapy has been found to be a major barrier to the utilization of AUD pharmacotherapy, along with a lack of confidence in the effectiveness of these medications.18 Increasing HCP education on the use and benefits of these agents may increase the overall confidence of HCPs in prescribing pharmacotherapy for the treatment of AUD, especially in the primary care setting. One aspect that has been found to improve education and the prescribing of pharmacotherapy for AUD within the Veterans Health Administration has been the use of academic detailing programs.92 Academic detailing is a multifaceted educational outreach program that is used to assist with HCP education. Additionally, clinical pharmacists can be consulted to help develop a safe and effective AUD pharmacotherapy treatment regimen.

Conclusion

There is a major disparity in the prevalence of AUD between the general population and the military and veteran populations. Many clinical trials have found a number of pharmacotherapy options to be effective for the treatment of AUD. Despite the need and the proven benefits, the utilization of AUD pharmacotherapy still remains low in both the general and veteran populations. Increasing provider education and addressing other potential barriers for the use of pharmacotherapy for AUD can have a positive impact on prescribing patterns, which can ultimately improve alcohol consumption outcomes in patients with a diagnosis of AUD.

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: detailed tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2016/NSDUH-DetTabs-2016.pdf. Published September 7, 2017. Accessed September 13, 2018.

2. Jones E, Fear NT. Alcohol use and misuse within the military: a review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2011;23(2):166-172.

3. Fuehrlein BS, Mota N, Arias AJ, et al. The burden of alcohol use disorders in US military veterans: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Addiction. 2016;111(10):1786-1794.

4. Stahre MA, Brewer RD, Fonseca VP, Naimi TS. Binge drinking among US active-duty military personnel. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(3):208-217.

5. Institute of Medicine. Substance use disorders in the U.S. armed forces. https://www.nap.edu/resource/13441/SUD_rb.pdf. Published September 2012. Accessed September 12, 2018.

6. McDevitt-Murphy ME, Murphy JG, Williams JL, Monahan CJ, Bracken-Minor KL. Brief intervention to reduce hazardous drinking and enhance coping among OEF/OIF/OND veterans. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2015;46(2):83-89.

7. Jacobson IG, Ryan MA, Hooper TI, et al. Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems before and after military combat deployment. JAMA. 2008;300(6):663-675.

8. Chou SP, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, et al. The prevalence of drinking and driving in the United States, 2001-2002: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83(2):137-146.

9. Bazargan-Hejazi S, Bazargan M, Hardin E, Bing EG. Alcohol use and adherence to prescribed therapy among under-served Latino and African-American patients using emergency department services. Ethn Dis. 2005;15(2):267-275.

10. Kamali M, Kelly BD, Clarke M, et al. A prospective evaluation of adherence to medication in first episode of schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2006;21(1):29-33.

11. Tucker JS, Burnam MA, Sherbourne CD, Kung FY, Gifford AL. Substance abuse and mental health correlates of nonadherence to antiretroviral medications in a sample of patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Med. 2003;114(7):573-580.

12. Rehm J, Room R, Graham K, Monteiro M, Gmel G, Sempos CT. The relationship of average volume of alcohol consumption and patterns of drinking to burden of disease: an overview. Addiction. 2003;98(9):1209-1228.

13. Kendler KS, Ohlsson H, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Alcohol use disorder and mortality across the lifespan: a longitudinal cohort and co-relative analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(6):575-581.

14. Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830-842.

15. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807-816.

16. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1889-1900.

17. Del Re AC, Gordon AJ, Lembke A, Harris AH. Prescription of topiramate to treat alcohol use disorders in the Veterans Health Administration. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2013;8:12.

18. Harris AH, Ellerbe L, Reeder RN, et al. Pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence: perceived treatment barriers and action strategies among Veterans Health Administration service providers. Psychol Serv. 2013;10(4):410-419.

19. ReVia [package insert]. Pomona, NY: Duramed Pharmaceuticals; 2013.

20. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, and VISN Pharmacist Executives. Alcohol use disorder pharmacotherapy: naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram recommendations for use. https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/clinicalguidance/clinicalrecommendations/Alcohol_Use_Disorder_Pharmacotherapy_Acamprosate_Naltrexone_Disulfiram_Recommendations_for_Use.docx. Published December 2013. Accessed September 17, 2018.

21. Anton RF. Naltrexone for the management of alcohol dependence. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(7):715-721.

22. O’Malley SS, Rounsaville BJ, Farren C, et al. Initial and maintenance naltrexone treatment for alcohol dependence using primary care vs specialty care: a nested sequence of 3 randomized trials. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(14):1695-1704.

23. O’Brien CP. A range of research-based pharmacotherapies for addiction. Science. 1997;278(5335):66-70.

24. Swift RM. Effect of naltrexone on human alcohol consumption. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56 (suppl 7):24-29.

25. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Incorporating Alcohol Pharmacotherapies into Medical Practice. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 49. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2009.

26. Spanagel R, Zieglgänsberger W. Anti-craving compounds for ethanol: new pharmacological tools to study addictive processes. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18(2):54-59.

27. Herz A. Endogenous opioid systems and alcohol addiction. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1997;129(2):99-111.

28. Miller NS. The integration of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments in drug/alcohol addiction. J Addict Dis. 1997;16(4):1-5.

29. Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Wilbourne PL, Humphreys K, Finney JW. Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: when are these medications most helpful? Addiction. 2013;108(2):275-293.

29. Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Wilbourne PL, Humphreys K, Finney JW. Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: when are these medications most helpful? Addiction. 2013;108(2):275-293.

30. Bouza C, Angeles M, Muñoz A, Amate JM. Efficacy and safety of naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review. Addiction. 2004;99(7):811-828.

31. Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al; COMBINE Study Research Group. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2003-2017.

32. Oslin DW, Pettinati HM, Volpicelli JR, Wolf AL, Kampman KM, O’Brien CP. The effects of naltrexone on alcohol and cocaine use in dually addicted patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1999;16(2):163-167.

33. Kranzler HR, Wesson DR, Billot L; DrugAbuse Sciences Naltrexone Depot Study Group. Naltrexone depot for treatment of alcohol dependence: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(7):1051-1059.

34. Bryson WC, McConnell J, Korthuis PT, McCarty D. Extended-release naltrexone for alcohol dependence: persistence and healthcare costs and utilization. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17 (suppl 8):S222-S234.

35. Vivitrol [package insert]. Waltham, MA: Alkermes, Inc.; 2010.

36. Campral [package insert]. St. Louis, MO: Forest Laboratories Inc; 2012.

37. Paille F, Guelfi J, Perkins AC, Royer RJ, Steru L, Parot P. Double-blind randomized multicentre trial of acamprosate in maintaining abstinence from alcohol. Alcohol. 1995;30(2):239-247.

38. Pelc I, Verbanck P, Le Bon O, Gavrilovic M, Lion K, Lehert P. Efficacy and safety of acamprosate in the treatment of detoxified alcohol-dependent patients. A 90-day placebo-controlled dose-finding study. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:73-77.

39. Sass H, Soyka M, Mann K, Zieglgänsberger W. Relapse prevention by acamprosate. Results from a placebo-controlled study on alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(8):673-680.

40. Mann K, Lehert P, Morgan MY. The efficacy of acamprosate in the maintenance of abstinence in alcohol-dependent individuals: results of a meta-analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(1):51-63.

41. Mason BJ, Lehert P. Acamprosate for alcohol dependence: a sex-specific meta-analysis based on individual patient data. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(3):497-508.

42. Richardson K, Baillie A, Reid S, et al. Do acamprosate or naltrexone have an effect on daily drinking by reducing craving for alcohol? Addiction. 2008;103(6):953-959.

43. Antabuse [package insert]. North Wales, PA: Teva Pharmaceuticals; 2015.

44. Ait-Daoud N, Johnson BA. Medications for the treatment of alcoholism. In: Johnson BA, Ruiz P, Galanter M, eds. Handbook of Clinical Alcoholism Treatment. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore; 2003

45. Laaksonen E, Koski-Jännes A, Salaspuro M, Ahtinen H, Alho H. A randomized, multicentre, open-label, comparative trial of disulfiram, naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43(1):53-61.

46. Skinner MD, Lahmek P, Pham H, Aubin HJ. Disulfiram efficacy in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87366.

47. Jørgensen CH, Pedersen B, Tønnesen H. The efficacy of disulfiram for the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35(10):1749-1758.

48. Arbaizar B, Diersen-Sotos T, Gómez-Acebo I, Llorca J. Topiramate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a meta-analysis. [Article in English, Spanish] Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2010;38(1):8-12.

49. Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N. Topiramate in the new generation of drugs: efficacy in the treatment of alcoholic patients. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(19):2103-2112.

50. Paparrigopoulos T, Tzavellas E, Karaiskos D, Kourlaba G, Liappas I. Treatment of alcohol dependence with low-dose topiramate: an open-label controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:41.

51. Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Bowden CL, et al. Oral topiramate for treatment of alcohol dependence: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9370):1677-1685.

52. Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Akhtar FZ, Ma JZ. Oral topiramate reduces the consequences of drinking and improves the quality of life of alcohol-dependent individuals: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(9):905-912.

53. Johnson BA, Rosenthal N, Capece JA, et al; Topiramate for Alcoholism Advisory Board; Topiramate for Alcoholism Study Group. Topiramate for treating alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(14):1641-1651.

54. Flórez G, García-Portilla P, Alvarez S, Saiz PA, Nogueiras L, Bobes J. Using topiramate or naltrexone for the treatment of alcohol-dependent patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(7):1251-1259.

55. Flórez G, Saiz PA, Garcia-Portilla P, Alvarez S, Nogueiras L, Bobes J. Topiramate for the treatment of alcohol dependence: comparison with naltrexone. Eur Addict Res. 2011;17(1):29-36.

56. Baltieri DA, Daró FR, Ribeiro PL, de Andrade AG. Comparing topiramate with naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2008;103(12):2035-2044.

57. White HS, Brown SD, Woodhead JH, Skeen GA, Wolf HH. Topiramate modulates GABA-evoked currents in murine cortical neurons by a nonbenzodiazepine mechanism. Epilepsia. 2000;41(suppl 1):S17-S20.

58. White HS, Brown SD, Woodhead JH, Skeen GA, Wolf HH. Topiramate enhances GABA-mediated chloride flux and GABA-evoked chloride currents in murine brain neurons and increases seizure threshold. Epilepsy Res. 1997;28(3):167-179.

59. Guglielmo R, Martinotti G, Quatrale M, et al. Topiramate in alcohol use disorders: review and update. CNS Drugs. 2015;29(5):383-395.

60. Kranzler HR, Covault J, Feinn R, et al. Topiramate treatment for heavy drinkers: moderation by a GRIK1 polymorphism. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(4):445-452.

61. Batki SL, Pennington DL, Lasher B, et al. Topiramate treatment of alcohol use disorder in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(8):2169-2177.

62. Topamax [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc; 2017.

63. Meador KJ. Cognitive effects of levetiracetam versus topiramate. Epilepsy Curr. 2008;8(3):64-65.

64. Luykx JJ, Carpay JA. Nervous system adverse responses to topiramate in the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2010;9(4):623-631.

65. The Management of Substance Use Disorder Work Group; US Department of Veteran Affairs, US Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of substance use disorders. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/sud/VADODSUDCPGRevised22216.pdf. Published December 2015. Accessed September 12, 2018.

66. Sills GJ. The mechanism of action of gabapentin and pregabalin. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6(1):108-113.

67. Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V, Shandan F, Kyle M, Begovic A. Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):70-77.

68. Anton RF, Myrick H, Wright TM, et al. Gabapentin combined with naltrexone for the treatment of alcohol dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(7):709-717.

69. Neurontin [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2017.

70. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

71. Addolorato G, Leggio L. Safety and efficacy of baclofen in the treatment of alcohol-dependent patients. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(19):2113-2117.

72. Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of baclofen for maintenance of alcohol abstinence in alcohol-dependent patients with liver cirrhosis: a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Lancet. 2007;370(9603):1915-1922.

73. Dore GM, Lo K, Juckes L, Bezyan S, Latt N. Clinical experience with baclofen in the management of alcohol-dependent patients with psychiatric comorbidity: a selected cases series. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46(6):714-720.

74. Baclofen tablet [package insert]. Pulaski, TN: AvKare Inc; 2018.

75. Hansel DE, Hansel CR, Shindle MK, et al. Oral baclofen in cerebral palsy: possible seizure potentiation? Pediatr Neurol. 2003;29(3):203-206.

76. Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Zambon A, et al. Baclofen promotes alcohol abstinence in alcohol dependent cirrhotic patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Addict Behav. 2012;37(4):561-564.

77. Zofran [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Norvartis Pharmaceuticals; 2017.

78. Barnes NM, Sharp T. A review of central 5-HT receptors and their function. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38(8):1083-1152.

79. Johnson BA, Campling GM, Griffiths P, Cowen PJ. Attenuation of some alcohol-induced mood changes and the desire to drink by 5-HT3 receptor blockade: a preliminary study in health male volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1993;112(1):142-144.

80. Johnson B, Roache J, Javors M, et al. Ondansetron for reduction of drinking among biologically predisposed alcoholic patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;284(8):963-971.

81. Kasinath NS, Malak O, Tetzlaff J. Atrial fibrillation after ondansetron for the prevention and treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a case report. Can J Anaesth. 2003;50(3):229-231.

82. Sellers EM, Toneatto T, Romach MK, Somer GR, Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Clinical efficacy of the 5-HT3 antagonist ondansetron in alcohol abuse and dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18(4):879-885.

83. Havrilla PL, Kane-Gill SL, Verrico MM, Seybert AL, Reis SE. Coronary vasospasm and atrial fibrillation associated with ondansetron therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(3):532-536.

84. Donoghue K, Elzerbi C, Saunders R, Whittington C, Pilling S, Drummond C. The efficacy of acamprosate and naltrexone in the treatment alcohol dependence, Europe versus the rest of the world: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2015;110(6):920-930.

85. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Alcohol-use disorder: diagnosis, assessment and management of harmful drinking and alcohol dependence. Clinical guideline [CG115]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg115. Published February 2011. Accessed September 12, 2018.

86. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much a clinician’s guide. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/guide. Accessed September 12, 2018.

87. Blodgett JC, Del Re AC, Maisel NC, Finney JW. A meta-analysis of topiramate’s effects for individuals with alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(6):1481-1488.

88. Müller CA, Geisel O, Pelz P, et al. High-dose baclofen for the treatment of alcohol dependence (BACLAD study): a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25(8):1167-1177.

89. Beraha EM, Salemink E, Goudriaan AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of high-dose baclofen for the treatment of alcohol dependence: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26(12):1950-1959.

90. DeVido J, Bogunovic O, Weiss RD. Alcohol use disorders in pregnancy. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23(2)112-121.

91. Anton RF, Moak DH, Latham P, et al. Naltrexone combined with either cognitive behavioral or motivational enhancement therapy for alcohol dependence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25(4):349-357.

92. Harris AHS, Bowe T, Hagedorn H, et al. Multifaceted academic detailing program to increase pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder: interrupted time series evaluation of effectiveness. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2016;11(1):15.

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a relatively common condition characterized by a pattern of problematic alcohol consumption. According to the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) approximately 14.6 million Americans aged > 18 years had a diagnosis of AUD.1 This same survey also found that 26.2% of individuals over the age of 18 years reported engaging in binge drinking, which is ≥ 5 drinks in males or ≥ 4 drinks in females on the same occasion in the past month. Of those surveyed, 6.6% reported engaging in heavy drinking (binge drinking on 5 or more days in the past month).1

Military and veteran populations have a higher prevalence of alcohol misuse compared with that of the general population.2 Two out of 5 US veterans screen positive for lifetime AUD, which is higher than the prevalence of AUD in the general population.3 A number of studies have found that excessive alcohol use is common among military personnel.2,4,5 One study suggested that the average active-duty military member engages in approximately 30 binge drinking episodes per person per year.4 Military veterans may continue with a similar drinking pattern when transitioning to civilian life, explaining the high prevalence of AUD in the veteran population.6 Furthermore, since alcohol use provides temporary relief of posttraumatic stress disorder(PTSD) symptoms, a diagnosis of PTSD may also contribute to hazardous drinking in this population.7

Excessive alcohol consumption is associated with a number of negative outcomes, including increased motor-vehicle accidents, decreased medication adherence, and therefore, decreased efficacy, increased health care costs, and increased morbidity and mortality.8-13 Additionally, alcohol use is associated with a number of medical and psychiatric comorbidities.14,15 Compared with veterans without AUD, those with a diagnosis of AUD were 2.6 times more likely to have current depression and 2.8 times more likely to have generalized anxiety.3 Veterans with AUD also are 2.1 times more likely to have current suicidal ideation and 4.1 times more likely to have had a suicide attempt compared with veterans without AUD.3

Given the high prevalence and the associated risks, alcohol misuse should be properly addressed and treated. Pharmacotherapy for AUD has demonstrated efficacy in decreasing heavy drinking and prolonging periods of abstinence.16 Despite the proven benefits of available pharmacotherapy, these medications still are drastically underutilized in both the nonveteran and veteran populations. In fiscal year 2012, there were 444,000 veterans with a documented diagnosis of AUD; however, only 5.8% received evidence-based pharmacotherapy.17 The potential barriers for the utilization of AUD pharmacotherapy includes perceived low patient demand, lack of skill or knowledge about addiction, and lack of health care provider (HCP) confidence in efficacy.18 This article will provide a thorough overview of the pharmacotherapy options for the treatment of AUD and the evidence that supports the use of pharmacotherapy. We will then conclude with the recommended treatment approach for specialized patient populations.

FDA-Approved Pharmacotherapies

Naltrexone

Naltrexone was the second FDA-approved medication for the treatment of AUD and is considered a first-line agent by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).19,20 Unlike its predecessor, disulfiram, naltrexone significantly reduces cravings.21 During alcohol consumption endogenous opioid activity is greatly enhanced, leading to the rewarding effects of alcohol. By antagonizing the µ-opioid receptor, naltrexone mediates endorphin release during alcohol consumption, explaining the efficacy of naltrexone in AUD.21-28 Since cravings are reduced, patients are able to abstain from drinking for longer periods of time, and since pleasure is reduced, heavy drinking is also reduced.21,25

When compared with other pharmacotherapy options for AUD, naltrexone is less effective for abstinence and more effective for decreasing the time and frequency of heavy drinking days and average number of drinks consumed.29 A meta-analysis of 19 clinical trials found that naltrexone significantly reduced relapse rates in patients with AUD compared with those of placebo.30 This analysis also found that naltrexone reduced both the number of alcoholic beverages consumed and the risk of relapse to heavy drinking while increasing the total number of days of abstinence.30 The COMBINE study also found that patients receiving oral naltrexone in combination with medical treatment had a 28% reduced risk of having a heavy-drinking day.31

Dosing and Formulations

Naltrexone is available as a tablet or a long-acting injectable. The tablet is often dosed as 50 mg daily; although some studies suggest that daily doses up to 150 mg are safe and efficacious.21,25,32 The initial and maintenance dose for most patients is 50 mg daily.

Nonadherence to the oral formulation of naltrexone is a significant barrier to the treatment of AUD. The long-acting injectable formulation is an option for patients who may have difficulty with adhering to oral naltrexone. As with the oral formulation, the long-acting naltrexone injection significantly reduces drinking days and increases abstinence.33 It was also found to be superior to oral naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram in preventing discontinuation of AUD treatment.34 The long-acting injectable should be administered as an intramuscular gluteal injection at a dose of 380 mg monthly.35

Ideally, naltrexone should be initiated following the cessation of alcohol withdrawal symptoms. However, naltrexone can be safely administered in patients who are actively withdrawing from alcohol or in patients who continue to consume alcohol.25

Warnings, Precautions, and AEs

Naltrexone carries a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) boxed warning for reversible hepatotoxicity. The risk of hepatotoxicity is increased in patients who receive higher doses (100-300 mg daily).21 A safety study demonstrated that the administration of 50 mg daily or less is not associated with significant hepatotoxicity.21,31 It is contraindicated in patients with acute hepatitis or liver failure and should be avoided in patients with liver function tests > 5 times the upper limit of normal.

Since naltrexone is a µ-opioid receptor antagonist, it is contraindicated in patients who are actively taking opioids or patients who have used opioids within the past 7 days. Co-administration with an opioid can lead to precipitated opioid withdrawal.21 Therefore, opioids should not be administered within 7 to 10 days of initiating naltrexone and 2 to 3 days after discontinuation of oral naltrexone.21 For patients receiving the long-acting injectable form of naltrexone, opioids should be avoided at least 1 month after the injection.25

To ensure that a patient is opioid free, HCPs can perform a toxicology screening prior to the initiation of naltrexone. Some HCPs may also perform a naloxone challenge to test whether a patient is at risk for precipitated opioid withdrawal prior to prescribing naltrexone.

The adverse effects (AEs) of naltrexone are transient and include nausea, vomiting, anorexia, dizziness, and fatigue.19,35 Injection site reactions can be experienced with the long-acting naltrexone injection. Liver transaminases, such as the alanine aminotransferase and aspartate transaminase, should be monitored at baseline, 6 months after initiation, and annually during the course of treatment (Table 2).

Acamprosate

The FDA approved acamprosate for the treatment of AUD in 2004, and it is also considered a first-line agent for AUD by the VA.20 It is approved for the maintenance of abstinence from alcohol use and is most efficacious when initiated in patients who are abstinent prior to treatment.29,36 Patients with AUD typically have a disruption in the balance between the inhibitory neurotransmitter, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and the excitatory neurotransmitter, glutamate. While its mechanism of action remains unknown, acamprosate is thought to increase the activity of GABA and to decrease the activity of glutamate at the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in the central nervous system. In essence, it is thought to restores the balance between GABA and glutamate in patients with AUD.36

Acamprosate has been found to effectively prevent relapse. Three randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled European clinical trials evaluated the efficacy of acamprosate in combination with psychotherapy. The results demonstrated that patients taking acamprosate had longer durations of abstinence compared with that of placebo, improved rates of complete abstinence, and a prolonged time to first drink.37-39 A meta-analysis evaluated the use of acamprosate in AUD showed that acamprosate was more effective at maintaining abstinence in patients who had been abstinent prior to the initiation of therapy.29 These patients also had better abstinence rates if they had been abstinent for a longer duration prior to treatment initiation.30 Studies also showed that acamprosate significantly assisted with maintaining abstinence, improved rates of abstinence, and led to more days of abstinence.40,41 Of note, there also have been studies that have shown no significant benefit with acamprosate compared with placebo in the treatment of AUD.42

Dosing and Formulations

Acamprosate is available as a 333 mg delayed-release tablet. The recommended dose is 666 mg 3 times daily.36 The dose can be decreased to 333 mg 3 times a day in patients with moderate renal impairment (CrCl-30-50 mL/min).

Since acamprosate has been proven more effective in patients who are abstinent prior to initiation, acamprosate is typically initiated 5 days following alcohol cessation.25 However, it may be safely administered with alcohol and can continue to be administered in the event of a relapse.36

Warnings, Precautions, and AEs

Acamprosate is safe to use in patients with hepatic and mild-to-moderate renal impairment; however, it is contraindicated in patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance [CrCl] ≤ 30 mL/min).36 Serum creatinine levels should be monitored at baseline and during treatment.

Acamprosate has a number of related AEs. The most common is diarrhea. Less common AEs include insomnia, anxiety, and depression. Due to its possible potential to increase suicidality, HCPs should monitor for the emergence of mood changes.36

Disulfiram

Disulfiram is an aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitor that is FDA approved for the management of AUD.43 When ingested, ethanol is typically metabolized to acetaldehyde, which is further metabolized to acetic acid by aldehyde dehydrogenase.44 Disulfiram inhibits aldehyde dehydrogenase, leading to a rapid accumulation of acetaldehyde within the plasma (outlined in Figure 2).

There are limited studies that prove the efficacy of disulfiram. In a randomized trial comparing disulfiram, acamprosate, and naltrexone, patients treated with disulfiram had fewer heavy drinking days, lower rates of weekly alcohol consumption, and a longer period of abstinence compared to other medications.45 Additionally, a 2014 meta-analysis showed that in open-label studies, disulfiram was more beneficial in preventing alcohol consumption when compared with acamprosate, naltrexone, and placebo. This result was not seen in blinded studies.46 Disulfiram does not reduce alcohol cravings, and adherence is a significant issue. It is most effective between 2 and 12 months, when taken under supervised administration.47

Dosing and Formulations

Disulfiram is only available as a tablet. The recommended starting dose is up to 500 mg for the first 2 weeks. However, the maintenance dose can range from 125 to 500 mg daily.43 Patients must be abstinent from alcohol at least 12 to 24 hours prior to the initiation of disulfiram.25 A blood alcohol level can be obtained in order to confirm abstinence.25

Warnings, Precautions, and AEs

Disulfiram is contraindicated in patients with severe myocardial disease or coronary occlusion and severe hepatic impairment.43 Other contraindications are outlined in Table 3.

Common AEs include somnolence, a metallic after-taste, and peripheral neuropathy.43 Patients should be informed that they could experience a disulfiram reaction with even small amounts of alcohol; all foods, drinks, and medications containing alcohol should be avoided. Due to the potential of disulfiram potential to cause hepatotoxicity, liver transaminases should be monitored at baseline, 2 weeks after initiation, and monthly for the first 6 months of therapy, and every 3 months thereafter (Table 2).25

Off-Label Pharmacotherapies

Topiramate

Although not approved for AUD, topiramate has been used off-label for this indication as it has proven efficacy in clinical trials.48-56 While its mechanism of action for AUD is unclear, it has been theorized that topiramate antagonizes glutamate receptors, thereby reducing dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens upon alcohol consumption, and potentiates the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA.50,51,57-60

In clinical trials, topiramate has demonstrated significant efficacy in reducing cravings, the risk of relapse, and the number of drinks consumed daily, while increasing abstinence.51,53,60 Batki and colleagues report that the administration of topiramate in veterans with co-occurring AUD and PTSD reduced alcohol consumption, cravings, and the severity of their PTSD symptoms.61

Dosing and Formulations

Topiramate is available in a number of formulations; however, only the immediate-release formulation is recommended for the treatment of AUD. The extended-release formulation is contraindicated in the setting of alcohol consumption and is therefore not used for the treatment of AUD.62 Doses should be initiated at 25 mg daily and can be titrated in 25 to 50 mg weekly increments. To minimize AEs and to reduce the risk of patients discontinuing therapy, the dose may be slowly titrated over 8 weeks.53,59 An effective dose can range from 75 to 300 mg in divided doses; however, AEs often limit the tolerability of increased doses.48,50,63,64 The VA/DoD Practice Guideline for the Management of Substance Use Disorders recommends titrating topiramate to a target dose of 100 mg twice daily.65

Warnings, Precautions, and AEs

Common AEs include memory impairment, anorexia, fatigue, paresthesias, and somnolence.62 There is an increased risk of nephrolithiasis with topiramate administration; therefore, adequate hydration is crucial.49,59 Titration of topiramate to the target dose is suggested to limit AEs.35

Prior to initiating topiramate, the patient’s renal function should be assessed. In those with a CrCl < 70 mL/min the dose should be decreased by 50% and titrated more slowly.62

Gabapentin

Gabapentin is prescribed for the treatment of partial seizures and postherpetic neuralgia. In recent years, it has shown efficacy for treating other conditions, such as AUD. While its mechanism for this indication remains unclear, the inhibition of excitatory alpha-2-delta calcium channels and stimulation of inhibitory GABAA receptors by gabapentin is believed to decrease alcohol cravings, reduce anxiety, and increase abstinence.66

A 12-week, double-blind, randomized controlled trial demonstrated that oral gabapentin was more efficacious than was placebo for improving rates of abstinence, decreasing heavy drinking, and reducing alcohol cravings.67 Gabapentin may also serve as a good adjunctive option to naltrexone therapy either when naltrexone monotherapy fails or if a patient is complaining of sleep and mood disturbances with abstinence.67,68

Dosing and Formulations

Gabapentin should be titrated slowly to minimize AEs. It can be initiated at 300 mgon day 1 and increase by 300-mg increments. Doses of 900 to 1,800 mg per day have proven to be efficacious for the treatment of AUD.66,67 These proposed doses can be safely administered to most patients, but caution should be observed in elderly and patients with renal impairment.69,70

Warnings, Precautions, and AEs

The most common AEs for gabapentin include drowsiness, dizziness, and fatigue.69 Since it is renally cleared, renal function should be monitored at baseline and periodically during treatment. Gabapentin is not metabolized by liver enzymes and does not significantly interact with drugs that require hepatic metabolism.

Baclofen

Baclofen has generated attention as an unconventional treatment option for alcohol dependence. Its unique mechanism of action, which involves the activation of GABAB receptors and the subsequent inhibition of dopaminergic neurons, makes it useful for the treatment of AUD.71

A 12-week study evaluating the effectiveness and safety of baclofen for the maintenance of alcohol abstinence demonstrated that baclofen was more efficacious than placebo for increasing abstinence in patients with liver cirrhosis. In addition, there were more cumulative days of abstinence with baclofen use (62.8 days) vs placebo (30.8 days) in cirrhotic patients.72

Dosing and Formulations

There has been a range of doses studied for baclofen in the treatment of AUD. Studies indicate that initiating baclofen at 30 mg daily and increasing doses based on the patient’s clinical response is most effective.72 As a result, doses as high as 275 mg per day have been used for some patients.73 Baclofen is renally cleared; therefore, the dose should be adjusted in patients with renal impairment.74

Warnings, Precautions, and AEs

Some of the common AEs of baclofen include drowsiness, confusion, headache, and nausea. Due to its CNS depressant effects, baclofen should be used with caution in the elderly. Also, due to its potential to cause withdrawal symptoms, baclofen should not be discontinued abruptly.74,75 Baclofen is a safe option for patients with severe liver disease, due to its minimal hepatic metabolism.76

Ondansetron

Ondansetron is approved for both prophylactic and therapeutic use as an antiemetic agent for chemotherapy and anesthesia-induced nausea and vomiting.77As a highly selective and competitive 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, ondansetron has demonstrated efficacy in reducing serotonin-mediated dopaminergic effects in AUD.78,79 The lowering of these dopaminergic effects is associated with a reduction in alcohol-induced gratification and consumption.

In a 12-week, randomized controlled trial, 271 patients diagnosed with AUD received ondansetron twice daily or placebo, combined with weekly cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). There was a statistically significant decrease in alcohol consumption in patients treated with ondansetron compared with those who received placebo. Additionally, ondansetron was superior to placebo for increasing the percentage and total amount of days abstinent.80 These results were primarily observed in participants diagnosed with early-onset AUD (defined as onset at 25 years or younger), which may suggest the presence of genetically predisposed serotonin dysfunctions.80,81 In contrast, there were no significant differences observed in participants with late-onset AUD (onset after age 25 years) in either study group.80

Dosing and Formulations

Given its modest efficacy for the treatment of AUD, ondansetron has demonstrated clinical benefits at doses of 0.001 to 0.016 mg/kg twice daily. Additionally, 1 study reported that low-dose ondansetron (0.25 mg twice daily) was effective in reducing alcohol consumption when compared with placebo or high-dose ondansetron, which was considered 2 mg twice daily.82

Warnings, Precautions, and AEs

The most commonly reported AEs with ondansetron include fatigue, headache, anxiety, and serotonin syndrome when used concomitantly with other serotonergic agents.77 Also, serious cardiovascular complications, such as QTc prolongation, angina pectoris, atrial fibrillation, and arrhythmias have been observed with IV administration.77,81,83 Consequently, patients with electrolyte imbalances (eg, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia), a history of congestive heart failure, or concomitant medications associated with QTc prolongation, should be monitored with an electrocardiogram (ECG) or switched to another agent.77

Treatment Approach with AUD Pharmacotherapy

There is insufficient evidence to support the use of 1 medication for AUD over the others.16,46,84 Instead, the choice of therapy largely depends on the patient’s comorbidities, renal and hepatic function, and on the patient’s established goals, whether abstinence or reduction in alcohol consumption (Table 4).

There is much debate over the appropriate duration of treatment for AUD pharmacotherapy. It is recommended that patients remain on these medications for at least 3 months. Pharmacotherapy can be continued for 6 to 12 months as the risk for relapse is highest during this time frame.85,86 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines recommend discontinuing AUD pharmacotherapy if alcohol consumption persists 4 to 6 weeks after initiation.86

Comorbid Liver Disease

Due to the negative effects of heavy alcohol consumption on the liver, patients with AUD may develop liver disease. Health care providers should be aware of the appropriate pharmacotherapy options for patients with comorbid liver disease. Acamprosate is mostly excreted unchanged by the kidneys, therefore is an option for patients with liver disease whose goal is complete abstinence. Topiramate is another option for use in patients with liver impairment. Unlike acamprosate, topiramate would be a better option in patients who may not completely abstain from alcohol consumption but would like to decrease the amount of heavy drinking days.87

Gabapentin, baclofen, and ondansetron are also options for those with liver disease. Baclofen in particular has been studied in those with advanced liver disease, and it was found to be safe and effective.88,89

Comorbid Renal Disease

Naltrexone is an option for patients with mild renal impairment. Naltrexone and its major metabolite, 6-ß-naltrexol, are renally excreted; however, urinary excretion of unchanged naltrexone accounts for < 2% of the oral dose.19 Even with its low potential for accumulation, HCPs should carefully monitor for AEs in patients with moderate-to-severe renal impairment. Disulfiram is another pharmacotherapy option, since it is mostly metabolized by the liver.

Gabapentin, baclofen, and ondansetron are also possible options; however, their doses should be renally adjusted. Overall, there are limited studies on the use of these medications treating AUD in patients with renal impairment.

Pregnancy

Alcohol consumption during pregnancy can result in a wide range of birth defects to the unborn fetus. Due to the negative effects of alcohol consumption on the fetus, pregnant females should be referred to a professional alcohol treatment program. Although AUD pharmacotherapy may be considered in pregnant females, there have been no human studies that have examined the efficacy and safety in this patient population. All evidence comes from animal studies, case reports, and case series.90

Naltrexone is the most widely used medication for AUD in pregnancy. It is considered pregnancy category C and 1 study in particular did not detect any gross abnormalities in fetal development in pregnancy.19, 90 Disulfiram, acamprosate, and topiramate have all been shown to cause harm to either animal or human fetuses and are generally not recommended.36,44,63 Similar to naltrexone, gabapentin and baclofen are also pregnancy category C.69,77 Ondansetron is pregnancy category B, but it should still be used with caution since its use in pregnancy for the treatment of AUD has not been studied.77,90

Psychosocial Interventions

It is recommended that AUD pharmacotherapy be used in conjunction with a psychosocial intervention, such as CBT or medical management. Many of the studies evaluating the efficacy of AUD pharmacotherapy combined psychosocial interventions with medications. The literature suggests that when combined with CBT or medical management therapy, pharmacotherapy used for AUD results in better alcohol consumption outcomes.31,91 It has also been suggested that psychosocial interventions may improve patient adherence to AUD pharmacotherapy.25

Barriers

Inadequate HCP training on the use of AUD pharmacotherapy has been found to be a major barrier to the utilization of AUD pharmacotherapy, along with a lack of confidence in the effectiveness of these medications.18 Increasing HCP education on the use and benefits of these agents may increase the overall confidence of HCPs in prescribing pharmacotherapy for the treatment of AUD, especially in the primary care setting. One aspect that has been found to improve education and the prescribing of pharmacotherapy for AUD within the Veterans Health Administration has been the use of academic detailing programs.92 Academic detailing is a multifaceted educational outreach program that is used to assist with HCP education. Additionally, clinical pharmacists can be consulted to help develop a safe and effective AUD pharmacotherapy treatment regimen.

Conclusion

There is a major disparity in the prevalence of AUD between the general population and the military and veteran populations. Many clinical trials have found a number of pharmacotherapy options to be effective for the treatment of AUD. Despite the need and the proven benefits, the utilization of AUD pharmacotherapy still remains low in both the general and veteran populations. Increasing provider education and addressing other potential barriers for the use of pharmacotherapy for AUD can have a positive impact on prescribing patterns, which can ultimately improve alcohol consumption outcomes in patients with a diagnosis of AUD.

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a relatively common condition characterized by a pattern of problematic alcohol consumption. According to the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) approximately 14.6 million Americans aged > 18 years had a diagnosis of AUD.1 This same survey also found that 26.2% of individuals over the age of 18 years reported engaging in binge drinking, which is ≥ 5 drinks in males or ≥ 4 drinks in females on the same occasion in the past month. Of those surveyed, 6.6% reported engaging in heavy drinking (binge drinking on 5 or more days in the past month).1

Military and veteran populations have a higher prevalence of alcohol misuse compared with that of the general population.2 Two out of 5 US veterans screen positive for lifetime AUD, which is higher than the prevalence of AUD in the general population.3 A number of studies have found that excessive alcohol use is common among military personnel.2,4,5 One study suggested that the average active-duty military member engages in approximately 30 binge drinking episodes per person per year.4 Military veterans may continue with a similar drinking pattern when transitioning to civilian life, explaining the high prevalence of AUD in the veteran population.6 Furthermore, since alcohol use provides temporary relief of posttraumatic stress disorder(PTSD) symptoms, a diagnosis of PTSD may also contribute to hazardous drinking in this population.7

Excessive alcohol consumption is associated with a number of negative outcomes, including increased motor-vehicle accidents, decreased medication adherence, and therefore, decreased efficacy, increased health care costs, and increased morbidity and mortality.8-13 Additionally, alcohol use is associated with a number of medical and psychiatric comorbidities.14,15 Compared with veterans without AUD, those with a diagnosis of AUD were 2.6 times more likely to have current depression and 2.8 times more likely to have generalized anxiety.3 Veterans with AUD also are 2.1 times more likely to have current suicidal ideation and 4.1 times more likely to have had a suicide attempt compared with veterans without AUD.3

Given the high prevalence and the associated risks, alcohol misuse should be properly addressed and treated. Pharmacotherapy for AUD has demonstrated efficacy in decreasing heavy drinking and prolonging periods of abstinence.16 Despite the proven benefits of available pharmacotherapy, these medications still are drastically underutilized in both the nonveteran and veteran populations. In fiscal year 2012, there were 444,000 veterans with a documented diagnosis of AUD; however, only 5.8% received evidence-based pharmacotherapy.17 The potential barriers for the utilization of AUD pharmacotherapy includes perceived low patient demand, lack of skill or knowledge about addiction, and lack of health care provider (HCP) confidence in efficacy.18 This article will provide a thorough overview of the pharmacotherapy options for the treatment of AUD and the evidence that supports the use of pharmacotherapy. We will then conclude with the recommended treatment approach for specialized patient populations.

FDA-Approved Pharmacotherapies

Naltrexone

Naltrexone was the second FDA-approved medication for the treatment of AUD and is considered a first-line agent by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).19,20 Unlike its predecessor, disulfiram, naltrexone significantly reduces cravings.21 During alcohol consumption endogenous opioid activity is greatly enhanced, leading to the rewarding effects of alcohol. By antagonizing the µ-opioid receptor, naltrexone mediates endorphin release during alcohol consumption, explaining the efficacy of naltrexone in AUD.21-28 Since cravings are reduced, patients are able to abstain from drinking for longer periods of time, and since pleasure is reduced, heavy drinking is also reduced.21,25

When compared with other pharmacotherapy options for AUD, naltrexone is less effective for abstinence and more effective for decreasing the time and frequency of heavy drinking days and average number of drinks consumed.29 A meta-analysis of 19 clinical trials found that naltrexone significantly reduced relapse rates in patients with AUD compared with those of placebo.30 This analysis also found that naltrexone reduced both the number of alcoholic beverages consumed and the risk of relapse to heavy drinking while increasing the total number of days of abstinence.30 The COMBINE study also found that patients receiving oral naltrexone in combination with medical treatment had a 28% reduced risk of having a heavy-drinking day.31

Dosing and Formulations

Naltrexone is available as a tablet or a long-acting injectable. The tablet is often dosed as 50 mg daily; although some studies suggest that daily doses up to 150 mg are safe and efficacious.21,25,32 The initial and maintenance dose for most patients is 50 mg daily.

Nonadherence to the oral formulation of naltrexone is a significant barrier to the treatment of AUD. The long-acting injectable formulation is an option for patients who may have difficulty with adhering to oral naltrexone. As with the oral formulation, the long-acting naltrexone injection significantly reduces drinking days and increases abstinence.33 It was also found to be superior to oral naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram in preventing discontinuation of AUD treatment.34 The long-acting injectable should be administered as an intramuscular gluteal injection at a dose of 380 mg monthly.35

Ideally, naltrexone should be initiated following the cessation of alcohol withdrawal symptoms. However, naltrexone can be safely administered in patients who are actively withdrawing from alcohol or in patients who continue to consume alcohol.25

Warnings, Precautions, and AEs

Naltrexone carries a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) boxed warning for reversible hepatotoxicity. The risk of hepatotoxicity is increased in patients who receive higher doses (100-300 mg daily).21 A safety study demonstrated that the administration of 50 mg daily or less is not associated with significant hepatotoxicity.21,31 It is contraindicated in patients with acute hepatitis or liver failure and should be avoided in patients with liver function tests > 5 times the upper limit of normal.

Since naltrexone is a µ-opioid receptor antagonist, it is contraindicated in patients who are actively taking opioids or patients who have used opioids within the past 7 days. Co-administration with an opioid can lead to precipitated opioid withdrawal.21 Therefore, opioids should not be administered within 7 to 10 days of initiating naltrexone and 2 to 3 days after discontinuation of oral naltrexone.21 For patients receiving the long-acting injectable form of naltrexone, opioids should be avoided at least 1 month after the injection.25

To ensure that a patient is opioid free, HCPs can perform a toxicology screening prior to the initiation of naltrexone. Some HCPs may also perform a naloxone challenge to test whether a patient is at risk for precipitated opioid withdrawal prior to prescribing naltrexone.

The adverse effects (AEs) of naltrexone are transient and include nausea, vomiting, anorexia, dizziness, and fatigue.19,35 Injection site reactions can be experienced with the long-acting naltrexone injection. Liver transaminases, such as the alanine aminotransferase and aspartate transaminase, should be monitored at baseline, 6 months after initiation, and annually during the course of treatment (Table 2).

Acamprosate