User login

Specificity is essential in documentation and coding

Throughout medical training, you learn to write complete and detailed notes to communicate with other physicians. As a student and resident, you are praised when you succinctly analyze and address all patient problems while justifying your orders for the day. But notes do not exist just to document patient care; they are the template by which our actual quality of care is judged and our patients’ severity of illness is captured.

Like it or not, ICD-10 coding, documentation, denials, calls, and emails from administrators are integral parts of a hospitalist’s day-to-day job. Why? The specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses affect such metrics as hospital length of stay, mortality, and Case Mix Index documentation.

Good documentation can lead to better severity of illness (SOI) and risk of mortality (ROM) scores, better patient safety indicator (PSI) scores, better Healthgrades scores, better University Hospital Consortium (UHC) scores, and decreased Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) denials as well as appropriate reimbursement. Good documentation can even lead to improved patient care and better perceived treatment outcomes.

It is no surprise that many hospital administrators invest time and money in staff to support the proper usage of language in your notes. Of course, sometimes these well-meaning “queries” can throw you into emotional turmoil as you try to understand what was not clear in your excellent note about your patient’s heart failure exacerbation. In this article, we will try to help you take your specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses to the next level.

Basics of billing

Physicians do not need to become coders but it is helpful to have some understanding of what happens behind the scenes. Not everyone realizes that physician billing is completely different from hospital billing. Physician billing pertains to the care provided by the clinician, whereas hospital billing pertains to the overall care the patient received.

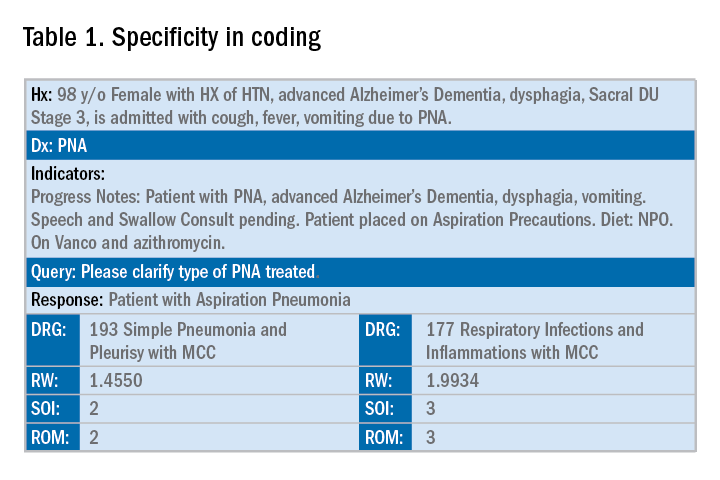

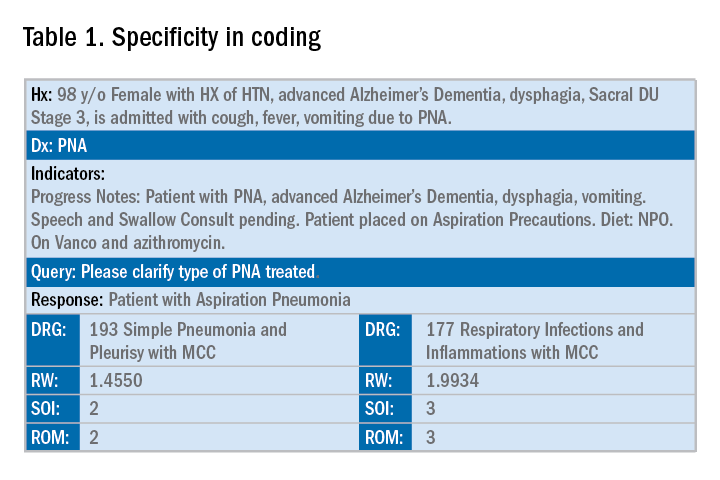

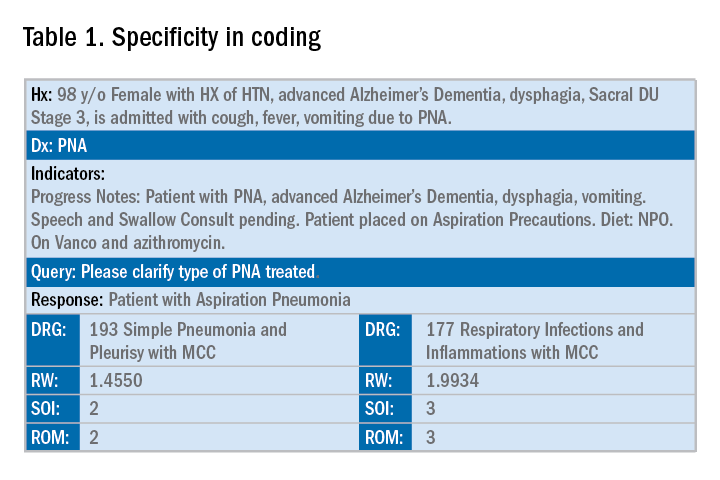

Below is an example of a case of pneumonia, (see Table 1) which shows the importance of specificity. Just by specifying ‘Aspiration’ for the type of pneumonia, we increased the SOI and the expected ROM appropriately. Also see a change in relative weight (RW): Each diagnosis-related group (DRG) is assigned a relative weight = estimated use of resources, and payment per case is based on estimated resource consumption = relative weight x “blended rate for each hospital.”

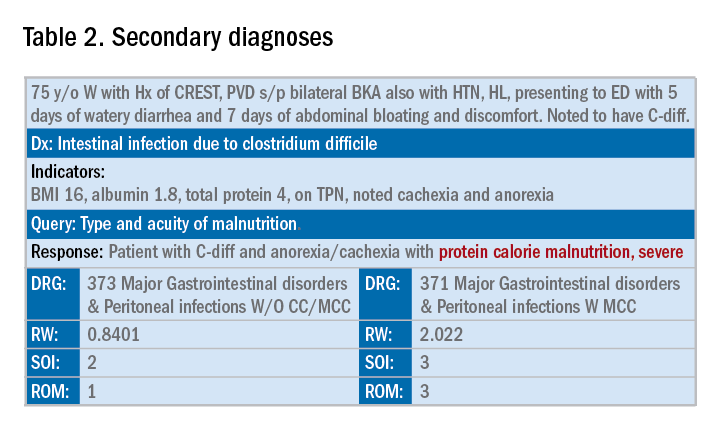

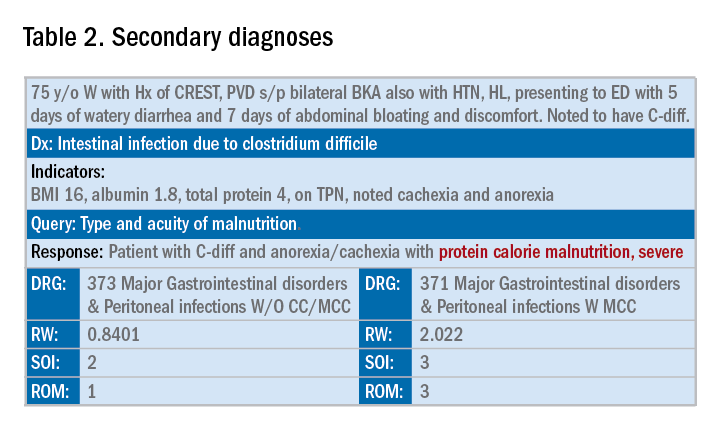

In addition to specificity, it is important to include all secondary diagnosis (know as cc/MCC – complication or comorbidity or a major complication or comorbidity – in the coding world). Table 2 is an example of using the correct terms and documenting secondary diagnosis. By documenting the type and severity of malnutrition we again increase the expected risk of mortality and the severity of illness.

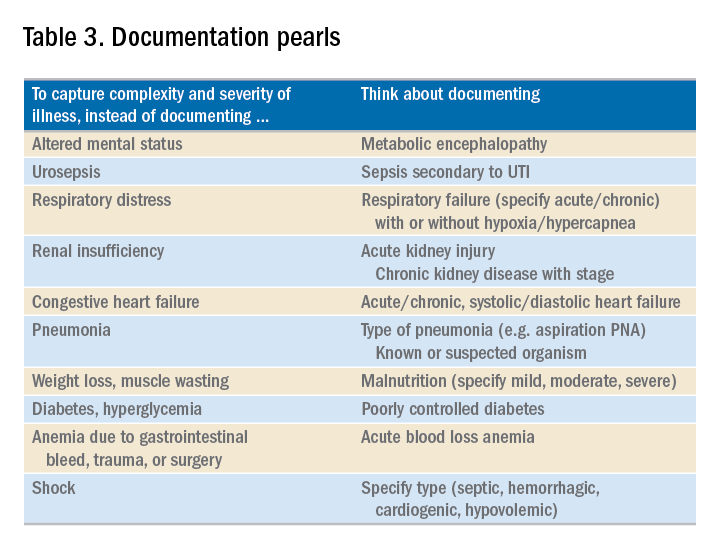

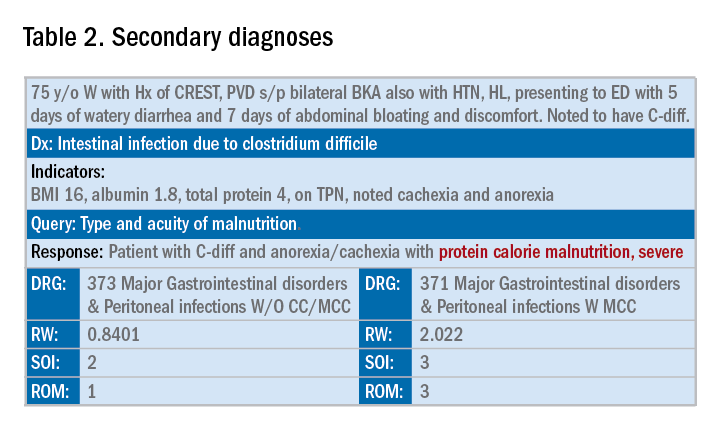

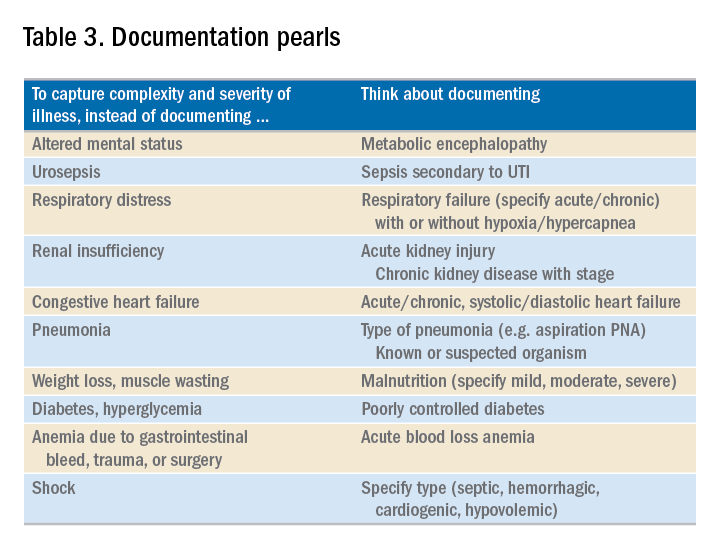

Physicians often do a lot more than what we record in the chart. Learning to document accurately to show the true clinical picture is an important skill set. Here are some tips to help understand and even avoid calls for better documentation.

- Use the terms “probable,” “possible,” “suspected,” or “likely” in documenting uncertain diagnoses (i.e., conditions for which physicians find clinical evidence that leads to a suspicion but not a definitive diagnosis). If conditions are ruled out or confirmed, clearly state so. If it remains uncertain, remember to carry this “possible” or “probable” diagnosis all the way through to the discharge summary or final progress note.

- Use linking of diagnoses when appropriate. For example, if the patient’s neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy are related to their uncontrolled insulin dependent diabetes, state “uncontrolled insulin-dependent DMII with A1c of 11 complicated with nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy.” The coders cannot link these diagnoses, and when you link them, you show a higher complexity of your patient. Remember to link the diagnoses only when they are truly related – this is where your medical knowledge and expertise come into play.

- Use the highest specificity of evidence that supports your medical decision making. You don’t need to be too verbose, all you need is evidence supporting your medical decision making and treatment plan. Think of it as demonstrating the logic of your diagnosis to another physician.

- Use Acuity (acute, chronic, acute on chronic, mild, moderate, severe, etc.) per diagnosis. For example, if you say heart failure exacerbation, it makes perfect sense to your medical colleagues, but in the coding world, it means nothing. Specify if it is acute, or acute on chronic, heart failure.

- Use status of each diagnosis. Is the condition improving, worsening, or resolved? Status does not have to be mentioned in all progress notes. Try to include this descriptor in the discharge summary and the day of the event.

- Always document the clinical significance of any abnormal laboratory, radiology reports, or pathology finding. Coders cannot use test results as a basis for coding unless a clinician has reviewed, interpreted, and documented the significance of the results in the progress note. Simply copying and pasting a report in the notes is not considered clinical acknowledgment. Shorthand notes like “Na=150, start hydration with 0.45% saline” is not acceptable. The actual diagnosis has to be written (i.e. “hypernatremia”). In addition, coders cannot code from nursing, dietitian, respiratory, and physical therapy notes. For example, if nursing documents that a patient has a pressure ulcer the clinician must still document the diagnosis of pressure ulcer, location, and stage. Although dietitian notes may state a body mass index greater than 40, coders cannot assume that patient is morbidly obese. Physician documentation is needed to support the obesity code assignment.

- Document all conditions that affect the patient’s stay, including complications and chronic conditions for which medications have been ordered. These secondary diagnoses paint the most accurate clinical picture and provide information needed to calculate important data, such as complexity and severity of patient illness and mortality risk. A patient with community-acquired pneumonia without other comorbidities requires fewer resources and has a greater chance of a good outcome than does the same patient with complications, such as acute heart failure.

- Downcoding brings losses, upcoding brings fines. Exaggerating the severity of patient conditions can lead to payer audits, reimbursement take backs, and charges of abuse and fraudulent billing. Never stretch the truth. Make sure you can support every diagnosis in the patient’s chart using clinical criteria.

You may be frustrated by the need to choose specific words about diagnoses that seem obvious to you without these descriptors. But accurate documentation can make a huge difference in your hospital’s bottom line and published metrics. Understanding the relative impact of changing your terminology can help you make these changes, until the language becomes second nature. Your hospital administrators will be grateful – and you just might cut down your queries!

Dr. Rajda is medical director of clinical documentation and quality improvement for Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and medical director for DRG appeals for the Mount Sinai Health System. She serves as assistant professor of medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Fatemi is an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. She is director of documentation, coding, and billing for the division of hospital medicine at UNM. Dr. Reyna is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine and medical director for clinical documentation and quality improvement at Mount Sinai Medical Center.

Specificity is essential in documentation and coding

Specificity is essential in documentation and coding

Throughout medical training, you learn to write complete and detailed notes to communicate with other physicians. As a student and resident, you are praised when you succinctly analyze and address all patient problems while justifying your orders for the day. But notes do not exist just to document patient care; they are the template by which our actual quality of care is judged and our patients’ severity of illness is captured.

Like it or not, ICD-10 coding, documentation, denials, calls, and emails from administrators are integral parts of a hospitalist’s day-to-day job. Why? The specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses affect such metrics as hospital length of stay, mortality, and Case Mix Index documentation.

Good documentation can lead to better severity of illness (SOI) and risk of mortality (ROM) scores, better patient safety indicator (PSI) scores, better Healthgrades scores, better University Hospital Consortium (UHC) scores, and decreased Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) denials as well as appropriate reimbursement. Good documentation can even lead to improved patient care and better perceived treatment outcomes.

It is no surprise that many hospital administrators invest time and money in staff to support the proper usage of language in your notes. Of course, sometimes these well-meaning “queries” can throw you into emotional turmoil as you try to understand what was not clear in your excellent note about your patient’s heart failure exacerbation. In this article, we will try to help you take your specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses to the next level.

Basics of billing

Physicians do not need to become coders but it is helpful to have some understanding of what happens behind the scenes. Not everyone realizes that physician billing is completely different from hospital billing. Physician billing pertains to the care provided by the clinician, whereas hospital billing pertains to the overall care the patient received.

Below is an example of a case of pneumonia, (see Table 1) which shows the importance of specificity. Just by specifying ‘Aspiration’ for the type of pneumonia, we increased the SOI and the expected ROM appropriately. Also see a change in relative weight (RW): Each diagnosis-related group (DRG) is assigned a relative weight = estimated use of resources, and payment per case is based on estimated resource consumption = relative weight x “blended rate for each hospital.”

In addition to specificity, it is important to include all secondary diagnosis (know as cc/MCC – complication or comorbidity or a major complication or comorbidity – in the coding world). Table 2 is an example of using the correct terms and documenting secondary diagnosis. By documenting the type and severity of malnutrition we again increase the expected risk of mortality and the severity of illness.

Physicians often do a lot more than what we record in the chart. Learning to document accurately to show the true clinical picture is an important skill set. Here are some tips to help understand and even avoid calls for better documentation.

- Use the terms “probable,” “possible,” “suspected,” or “likely” in documenting uncertain diagnoses (i.e., conditions for which physicians find clinical evidence that leads to a suspicion but not a definitive diagnosis). If conditions are ruled out or confirmed, clearly state so. If it remains uncertain, remember to carry this “possible” or “probable” diagnosis all the way through to the discharge summary or final progress note.

- Use linking of diagnoses when appropriate. For example, if the patient’s neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy are related to their uncontrolled insulin dependent diabetes, state “uncontrolled insulin-dependent DMII with A1c of 11 complicated with nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy.” The coders cannot link these diagnoses, and when you link them, you show a higher complexity of your patient. Remember to link the diagnoses only when they are truly related – this is where your medical knowledge and expertise come into play.

- Use the highest specificity of evidence that supports your medical decision making. You don’t need to be too verbose, all you need is evidence supporting your medical decision making and treatment plan. Think of it as demonstrating the logic of your diagnosis to another physician.

- Use Acuity (acute, chronic, acute on chronic, mild, moderate, severe, etc.) per diagnosis. For example, if you say heart failure exacerbation, it makes perfect sense to your medical colleagues, but in the coding world, it means nothing. Specify if it is acute, or acute on chronic, heart failure.

- Use status of each diagnosis. Is the condition improving, worsening, or resolved? Status does not have to be mentioned in all progress notes. Try to include this descriptor in the discharge summary and the day of the event.

- Always document the clinical significance of any abnormal laboratory, radiology reports, or pathology finding. Coders cannot use test results as a basis for coding unless a clinician has reviewed, interpreted, and documented the significance of the results in the progress note. Simply copying and pasting a report in the notes is not considered clinical acknowledgment. Shorthand notes like “Na=150, start hydration with 0.45% saline” is not acceptable. The actual diagnosis has to be written (i.e. “hypernatremia”). In addition, coders cannot code from nursing, dietitian, respiratory, and physical therapy notes. For example, if nursing documents that a patient has a pressure ulcer the clinician must still document the diagnosis of pressure ulcer, location, and stage. Although dietitian notes may state a body mass index greater than 40, coders cannot assume that patient is morbidly obese. Physician documentation is needed to support the obesity code assignment.

- Document all conditions that affect the patient’s stay, including complications and chronic conditions for which medications have been ordered. These secondary diagnoses paint the most accurate clinical picture and provide information needed to calculate important data, such as complexity and severity of patient illness and mortality risk. A patient with community-acquired pneumonia without other comorbidities requires fewer resources and has a greater chance of a good outcome than does the same patient with complications, such as acute heart failure.

- Downcoding brings losses, upcoding brings fines. Exaggerating the severity of patient conditions can lead to payer audits, reimbursement take backs, and charges of abuse and fraudulent billing. Never stretch the truth. Make sure you can support every diagnosis in the patient’s chart using clinical criteria.

You may be frustrated by the need to choose specific words about diagnoses that seem obvious to you without these descriptors. But accurate documentation can make a huge difference in your hospital’s bottom line and published metrics. Understanding the relative impact of changing your terminology can help you make these changes, until the language becomes second nature. Your hospital administrators will be grateful – and you just might cut down your queries!

Dr. Rajda is medical director of clinical documentation and quality improvement for Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and medical director for DRG appeals for the Mount Sinai Health System. She serves as assistant professor of medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Fatemi is an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. She is director of documentation, coding, and billing for the division of hospital medicine at UNM. Dr. Reyna is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine and medical director for clinical documentation and quality improvement at Mount Sinai Medical Center.

Throughout medical training, you learn to write complete and detailed notes to communicate with other physicians. As a student and resident, you are praised when you succinctly analyze and address all patient problems while justifying your orders for the day. But notes do not exist just to document patient care; they are the template by which our actual quality of care is judged and our patients’ severity of illness is captured.

Like it or not, ICD-10 coding, documentation, denials, calls, and emails from administrators are integral parts of a hospitalist’s day-to-day job. Why? The specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses affect such metrics as hospital length of stay, mortality, and Case Mix Index documentation.

Good documentation can lead to better severity of illness (SOI) and risk of mortality (ROM) scores, better patient safety indicator (PSI) scores, better Healthgrades scores, better University Hospital Consortium (UHC) scores, and decreased Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) denials as well as appropriate reimbursement. Good documentation can even lead to improved patient care and better perceived treatment outcomes.

It is no surprise that many hospital administrators invest time and money in staff to support the proper usage of language in your notes. Of course, sometimes these well-meaning “queries” can throw you into emotional turmoil as you try to understand what was not clear in your excellent note about your patient’s heart failure exacerbation. In this article, we will try to help you take your specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses to the next level.

Basics of billing

Physicians do not need to become coders but it is helpful to have some understanding of what happens behind the scenes. Not everyone realizes that physician billing is completely different from hospital billing. Physician billing pertains to the care provided by the clinician, whereas hospital billing pertains to the overall care the patient received.

Below is an example of a case of pneumonia, (see Table 1) which shows the importance of specificity. Just by specifying ‘Aspiration’ for the type of pneumonia, we increased the SOI and the expected ROM appropriately. Also see a change in relative weight (RW): Each diagnosis-related group (DRG) is assigned a relative weight = estimated use of resources, and payment per case is based on estimated resource consumption = relative weight x “blended rate for each hospital.”

In addition to specificity, it is important to include all secondary diagnosis (know as cc/MCC – complication or comorbidity or a major complication or comorbidity – in the coding world). Table 2 is an example of using the correct terms and documenting secondary diagnosis. By documenting the type and severity of malnutrition we again increase the expected risk of mortality and the severity of illness.

Physicians often do a lot more than what we record in the chart. Learning to document accurately to show the true clinical picture is an important skill set. Here are some tips to help understand and even avoid calls for better documentation.

- Use the terms “probable,” “possible,” “suspected,” or “likely” in documenting uncertain diagnoses (i.e., conditions for which physicians find clinical evidence that leads to a suspicion but not a definitive diagnosis). If conditions are ruled out or confirmed, clearly state so. If it remains uncertain, remember to carry this “possible” or “probable” diagnosis all the way through to the discharge summary or final progress note.

- Use linking of diagnoses when appropriate. For example, if the patient’s neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy are related to their uncontrolled insulin dependent diabetes, state “uncontrolled insulin-dependent DMII with A1c of 11 complicated with nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy.” The coders cannot link these diagnoses, and when you link them, you show a higher complexity of your patient. Remember to link the diagnoses only when they are truly related – this is where your medical knowledge and expertise come into play.

- Use the highest specificity of evidence that supports your medical decision making. You don’t need to be too verbose, all you need is evidence supporting your medical decision making and treatment plan. Think of it as demonstrating the logic of your diagnosis to another physician.

- Use Acuity (acute, chronic, acute on chronic, mild, moderate, severe, etc.) per diagnosis. For example, if you say heart failure exacerbation, it makes perfect sense to your medical colleagues, but in the coding world, it means nothing. Specify if it is acute, or acute on chronic, heart failure.

- Use status of each diagnosis. Is the condition improving, worsening, or resolved? Status does not have to be mentioned in all progress notes. Try to include this descriptor in the discharge summary and the day of the event.

- Always document the clinical significance of any abnormal laboratory, radiology reports, or pathology finding. Coders cannot use test results as a basis for coding unless a clinician has reviewed, interpreted, and documented the significance of the results in the progress note. Simply copying and pasting a report in the notes is not considered clinical acknowledgment. Shorthand notes like “Na=150, start hydration with 0.45% saline” is not acceptable. The actual diagnosis has to be written (i.e. “hypernatremia”). In addition, coders cannot code from nursing, dietitian, respiratory, and physical therapy notes. For example, if nursing documents that a patient has a pressure ulcer the clinician must still document the diagnosis of pressure ulcer, location, and stage. Although dietitian notes may state a body mass index greater than 40, coders cannot assume that patient is morbidly obese. Physician documentation is needed to support the obesity code assignment.

- Document all conditions that affect the patient’s stay, including complications and chronic conditions for which medications have been ordered. These secondary diagnoses paint the most accurate clinical picture and provide information needed to calculate important data, such as complexity and severity of patient illness and mortality risk. A patient with community-acquired pneumonia without other comorbidities requires fewer resources and has a greater chance of a good outcome than does the same patient with complications, such as acute heart failure.

- Downcoding brings losses, upcoding brings fines. Exaggerating the severity of patient conditions can lead to payer audits, reimbursement take backs, and charges of abuse and fraudulent billing. Never stretch the truth. Make sure you can support every diagnosis in the patient’s chart using clinical criteria.

You may be frustrated by the need to choose specific words about diagnoses that seem obvious to you without these descriptors. But accurate documentation can make a huge difference in your hospital’s bottom line and published metrics. Understanding the relative impact of changing your terminology can help you make these changes, until the language becomes second nature. Your hospital administrators will be grateful – and you just might cut down your queries!

Dr. Rajda is medical director of clinical documentation and quality improvement for Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and medical director for DRG appeals for the Mount Sinai Health System. She serves as assistant professor of medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Fatemi is an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. She is director of documentation, coding, and billing for the division of hospital medicine at UNM. Dr. Reyna is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine and medical director for clinical documentation and quality improvement at Mount Sinai Medical Center.