User login

FDA expands use of Vraylar to treatment of bipolar-associated depressive episodes

The Food and Drug Administration on May 28 approved a supplemental New Drug Application for cariprazine (Vraylar) for the treatment of depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder.

Approval for the expanded label was based on results of the RGH-MD-53, RGH-MD-54, and RGH-MD-56 clinical trials, in which cariprazine was compared with placebo over a 6-week period in patients with bipolar I disorder. In all three trials, patients receiving 1.5 mg cariprazine had significantly greater improvement in their Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating scale after 6 weeks, compared with patients receiving placebo.

Cariprazine previously was indicated for the treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder in adults. The most common adverse reactions reported in the clinical trials were nausea, akathisia, restlessness, and extrapyramidal symptoms; these symptoms are similar to those on the Vraylar label.

“Treating bipolar disorder can be very difficult, because people living with the illness experience a range of depressive and manic symptoms, sometimes both at the same time, and , specifically manic, mixed, and depressive episodes, with just one medication,” Stephen M. Stahl, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Allergan website.

The Food and Drug Administration on May 28 approved a supplemental New Drug Application for cariprazine (Vraylar) for the treatment of depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder.

Approval for the expanded label was based on results of the RGH-MD-53, RGH-MD-54, and RGH-MD-56 clinical trials, in which cariprazine was compared with placebo over a 6-week period in patients with bipolar I disorder. In all three trials, patients receiving 1.5 mg cariprazine had significantly greater improvement in their Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating scale after 6 weeks, compared with patients receiving placebo.

Cariprazine previously was indicated for the treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder in adults. The most common adverse reactions reported in the clinical trials were nausea, akathisia, restlessness, and extrapyramidal symptoms; these symptoms are similar to those on the Vraylar label.

“Treating bipolar disorder can be very difficult, because people living with the illness experience a range of depressive and manic symptoms, sometimes both at the same time, and , specifically manic, mixed, and depressive episodes, with just one medication,” Stephen M. Stahl, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Allergan website.

The Food and Drug Administration on May 28 approved a supplemental New Drug Application for cariprazine (Vraylar) for the treatment of depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder.

Approval for the expanded label was based on results of the RGH-MD-53, RGH-MD-54, and RGH-MD-56 clinical trials, in which cariprazine was compared with placebo over a 6-week period in patients with bipolar I disorder. In all three trials, patients receiving 1.5 mg cariprazine had significantly greater improvement in their Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating scale after 6 weeks, compared with patients receiving placebo.

Cariprazine previously was indicated for the treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder in adults. The most common adverse reactions reported in the clinical trials were nausea, akathisia, restlessness, and extrapyramidal symptoms; these symptoms are similar to those on the Vraylar label.

“Treating bipolar disorder can be very difficult, because people living with the illness experience a range of depressive and manic symptoms, sometimes both at the same time, and , specifically manic, mixed, and depressive episodes, with just one medication,” Stephen M. Stahl, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, said in the press release.

Find the full press release on the Allergan website.

Building better flu vaccines is daunting

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Don’t hold your breath waiting for a substantially better, more reliably effective influenza vaccine.

That was a key cautionary message provided by vaccine expert Edward A. Belongia, MD, at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccine varies from 10% to 60% year by year, leaving enormous room for improvement. But many obstacles exist to developing a more consistent and reliably effective version of the seasonal influenza vaccine. And the lofty goal of creating a universal vaccine is even more ambitious, although the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has declared it to be a top priority and mapped out a strategic plan for getting there (J Infect Dis. 2018 Jul 2;218[3]:347-54).

“Ultimately the Holy Grail is a universal flu vaccine that would provide pan-A and pan-B protection that would last for more than 1 year, with protection against avian and pandemic viruses, and would work for both children and adults. We are nowhere near that. Every 5 years someone says we’re 5 years away, and then 5 years go by and we’re still 5 years away. So I’m not making any predictions on that,” said Dr. Belongia, director of the Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Population Health at the Marshfield (Wisc.) Clinic Research Institute, which is part of the U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network.

One of the big problems in creating a more effective flu vaccine, particularly for children, is the H3N2 virus subtype. Dr. Belongia was first author of a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of more than a dozen recent flu seasons showing that although vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 varied widely from year to year, it was consistently lower than against influenza type B and H1N1 (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Aug;16[8]:942-51).

And that’s especially true in children and adolescents. Notably, in the 2014-2015 U.S. flu season, vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 in children aged 6 months to 8 years was low at 23%, but shockingly lower at a mere 7% in the 9- to 17-year-olds. Whereas in the 2017-2018 season, vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 in the 9- to 17-year-olds jumped to 46% while remaining low but consistent at 22% in the younger children.

“We see a very different age pattern here for the older children compared to the younger children, and quite frankly we don’t really understand what’s doing this,” said Dr. Belongia.

What is well understood, however, is that the problematic performance of influenza vaccines when it comes to protecting against H3N2 is a complicated matter stemming from three sources: the virus itself; the current egg-based vaccine manufacturing methodology, which is now 7 decades old; and host factors.

That troublesome H3N2 virus

Antigenic evolution of the H3N2 virus occurs at a 5- to 6-fold higher rate than for influenza B virus and roughly 17-fold faster than for H1N1. That high mutation rate makes for a moving target that’s a real problem when trying to keep a vaccine current. Also, the globular head of the virus is prone to glycosylation, which enables the virus to evade immune detection.

Vaccine-related factors

It’s likely that the availability of the flu vaccine for the upcoming 2019-2020 season is going to be delayed because of late selection of the strains for inclusion. The World Health Organization ordinarily selects strains for vaccines for the Northern Hemisphere in February, giving vaccine manufacturers 6-8 months to produce their vaccines and ship them in time for administration from September through November. This year, however, the WHO delayed selection of the H3N2 component until March because of the high level of antigenic and genetic diversity of circulating strains.

“This hasn’t happened since 2003 – it’s a very rare occurrence – but it does increase the potential that there’s going to be a delay in the availability of the vaccine in the fall,” he explained.

Eventually, the WHO selected a new clade 3C.3a virus called A/Kansas/14/2017 for the 2019-2020 vaccine. It should cover the circulating strains of H3N2 “reasonably well,” according to the physician.

Another issue: H3N2 has become adapted to the mammalian environment, so growing the virus in eggs introduces strong selection pressure for mutations leading to reduced vaccine effectiveness. Yet only two flu vaccines licensed in the United States are manufactured without eggs: Flucelvax, marketed by Seqirus for patients aged 4 years and up, and Sanofi’s Flublok, which is licensed for individuals who are 18 years of age or older. Studies are underway looking at the relative effectiveness of egg-based versus cell culture-manufactured flu vaccines in real-world settings.

Host factors

Hemagglutinin imprinting, sometimes referred to as “original antigenic sin,” is a decades-old concept whereby early childhood exposure to influenza viruses shapes future vaccine response.

“It suggests there could be some birth cohort effects in vaccine responsiveness, depending on what was circulating in the first 2-3 years after birth. It would complicate vaccine strategy quite a bit if you had to have different strategies for different birth cohorts,” Dr. Belongia observed.

Another host factor issue is the controversial topic of negative interference stemming from repeated vaccinations. It’s unclear how important this is in the real world, because studies have been inconsistent. Reassuringly, Dr. Belongia and coworkers found no association between prior-season influenza vaccination and diminished vaccine effectiveness in 3,369 U.S. children aged 2-17 years studied during the 2013-14 through 2015-16 flu seasons (JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Oct 5;1[6]:e183742. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3742).

“We found no suggestion at all of a problem with being vaccinated two seasons in a row,” according to Dr. Belongia.

How to build a better influenza vaccine for children

“I would say that even before we get to a universal vaccine, the next generation of flu vaccines that are more effective are not going to be manufactured using eggs, although we’re not real close to that. But I think that’s eventually where we’re going,” he said.

“I think it’s going to take a systems biology approach in order to really understand the adaptive immune response to infection and vaccination in early life. That means a much more detailed understanding of what is underlying the imprinting mechanisms and what is the adaptive response to repeated vaccination and infection. I think this is going to take prospective infant cohort studies; the National Institutes of Health is funding some that will begin within the next year,” Dr. Belongia added.

Many investigational approaches to improving influenza virus subtype-level protection are being explored. These include novel adjuvants, nanoparticle vaccines, computationally optimized broadly reactive antigens, and standardization of neuraminidase content.

And as for the much-desired universal flu vaccine?

“I will say that if a universal vaccine is going to work it’s probably going to work first in children. They have a much shorter immune history and their antibody landscape is a lot smaller, so you have a much better opportunity, I think, to generate a broad response to a universal vaccine compared to adults, who have much more complex immune landscapes,” he said.

Dr. Belongia reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Don’t hold your breath waiting for a substantially better, more reliably effective influenza vaccine.

That was a key cautionary message provided by vaccine expert Edward A. Belongia, MD, at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccine varies from 10% to 60% year by year, leaving enormous room for improvement. But many obstacles exist to developing a more consistent and reliably effective version of the seasonal influenza vaccine. And the lofty goal of creating a universal vaccine is even more ambitious, although the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has declared it to be a top priority and mapped out a strategic plan for getting there (J Infect Dis. 2018 Jul 2;218[3]:347-54).

“Ultimately the Holy Grail is a universal flu vaccine that would provide pan-A and pan-B protection that would last for more than 1 year, with protection against avian and pandemic viruses, and would work for both children and adults. We are nowhere near that. Every 5 years someone says we’re 5 years away, and then 5 years go by and we’re still 5 years away. So I’m not making any predictions on that,” said Dr. Belongia, director of the Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Population Health at the Marshfield (Wisc.) Clinic Research Institute, which is part of the U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network.

One of the big problems in creating a more effective flu vaccine, particularly for children, is the H3N2 virus subtype. Dr. Belongia was first author of a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of more than a dozen recent flu seasons showing that although vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 varied widely from year to year, it was consistently lower than against influenza type B and H1N1 (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Aug;16[8]:942-51).

And that’s especially true in children and adolescents. Notably, in the 2014-2015 U.S. flu season, vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 in children aged 6 months to 8 years was low at 23%, but shockingly lower at a mere 7% in the 9- to 17-year-olds. Whereas in the 2017-2018 season, vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 in the 9- to 17-year-olds jumped to 46% while remaining low but consistent at 22% in the younger children.

“We see a very different age pattern here for the older children compared to the younger children, and quite frankly we don’t really understand what’s doing this,” said Dr. Belongia.

What is well understood, however, is that the problematic performance of influenza vaccines when it comes to protecting against H3N2 is a complicated matter stemming from three sources: the virus itself; the current egg-based vaccine manufacturing methodology, which is now 7 decades old; and host factors.

That troublesome H3N2 virus

Antigenic evolution of the H3N2 virus occurs at a 5- to 6-fold higher rate than for influenza B virus and roughly 17-fold faster than for H1N1. That high mutation rate makes for a moving target that’s a real problem when trying to keep a vaccine current. Also, the globular head of the virus is prone to glycosylation, which enables the virus to evade immune detection.

Vaccine-related factors

It’s likely that the availability of the flu vaccine for the upcoming 2019-2020 season is going to be delayed because of late selection of the strains for inclusion. The World Health Organization ordinarily selects strains for vaccines for the Northern Hemisphere in February, giving vaccine manufacturers 6-8 months to produce their vaccines and ship them in time for administration from September through November. This year, however, the WHO delayed selection of the H3N2 component until March because of the high level of antigenic and genetic diversity of circulating strains.

“This hasn’t happened since 2003 – it’s a very rare occurrence – but it does increase the potential that there’s going to be a delay in the availability of the vaccine in the fall,” he explained.

Eventually, the WHO selected a new clade 3C.3a virus called A/Kansas/14/2017 for the 2019-2020 vaccine. It should cover the circulating strains of H3N2 “reasonably well,” according to the physician.

Another issue: H3N2 has become adapted to the mammalian environment, so growing the virus in eggs introduces strong selection pressure for mutations leading to reduced vaccine effectiveness. Yet only two flu vaccines licensed in the United States are manufactured without eggs: Flucelvax, marketed by Seqirus for patients aged 4 years and up, and Sanofi’s Flublok, which is licensed for individuals who are 18 years of age or older. Studies are underway looking at the relative effectiveness of egg-based versus cell culture-manufactured flu vaccines in real-world settings.

Host factors

Hemagglutinin imprinting, sometimes referred to as “original antigenic sin,” is a decades-old concept whereby early childhood exposure to influenza viruses shapes future vaccine response.

“It suggests there could be some birth cohort effects in vaccine responsiveness, depending on what was circulating in the first 2-3 years after birth. It would complicate vaccine strategy quite a bit if you had to have different strategies for different birth cohorts,” Dr. Belongia observed.

Another host factor issue is the controversial topic of negative interference stemming from repeated vaccinations. It’s unclear how important this is in the real world, because studies have been inconsistent. Reassuringly, Dr. Belongia and coworkers found no association between prior-season influenza vaccination and diminished vaccine effectiveness in 3,369 U.S. children aged 2-17 years studied during the 2013-14 through 2015-16 flu seasons (JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Oct 5;1[6]:e183742. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3742).

“We found no suggestion at all of a problem with being vaccinated two seasons in a row,” according to Dr. Belongia.

How to build a better influenza vaccine for children

“I would say that even before we get to a universal vaccine, the next generation of flu vaccines that are more effective are not going to be manufactured using eggs, although we’re not real close to that. But I think that’s eventually where we’re going,” he said.

“I think it’s going to take a systems biology approach in order to really understand the adaptive immune response to infection and vaccination in early life. That means a much more detailed understanding of what is underlying the imprinting mechanisms and what is the adaptive response to repeated vaccination and infection. I think this is going to take prospective infant cohort studies; the National Institutes of Health is funding some that will begin within the next year,” Dr. Belongia added.

Many investigational approaches to improving influenza virus subtype-level protection are being explored. These include novel adjuvants, nanoparticle vaccines, computationally optimized broadly reactive antigens, and standardization of neuraminidase content.

And as for the much-desired universal flu vaccine?

“I will say that if a universal vaccine is going to work it’s probably going to work first in children. They have a much shorter immune history and their antibody landscape is a lot smaller, so you have a much better opportunity, I think, to generate a broad response to a universal vaccine compared to adults, who have much more complex immune landscapes,” he said.

Dr. Belongia reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Don’t hold your breath waiting for a substantially better, more reliably effective influenza vaccine.

That was a key cautionary message provided by vaccine expert Edward A. Belongia, MD, at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccine varies from 10% to 60% year by year, leaving enormous room for improvement. But many obstacles exist to developing a more consistent and reliably effective version of the seasonal influenza vaccine. And the lofty goal of creating a universal vaccine is even more ambitious, although the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has declared it to be a top priority and mapped out a strategic plan for getting there (J Infect Dis. 2018 Jul 2;218[3]:347-54).

“Ultimately the Holy Grail is a universal flu vaccine that would provide pan-A and pan-B protection that would last for more than 1 year, with protection against avian and pandemic viruses, and would work for both children and adults. We are nowhere near that. Every 5 years someone says we’re 5 years away, and then 5 years go by and we’re still 5 years away. So I’m not making any predictions on that,” said Dr. Belongia, director of the Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Population Health at the Marshfield (Wisc.) Clinic Research Institute, which is part of the U.S. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network.

One of the big problems in creating a more effective flu vaccine, particularly for children, is the H3N2 virus subtype. Dr. Belongia was first author of a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of more than a dozen recent flu seasons showing that although vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 varied widely from year to year, it was consistently lower than against influenza type B and H1N1 (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Aug;16[8]:942-51).

And that’s especially true in children and adolescents. Notably, in the 2014-2015 U.S. flu season, vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 in children aged 6 months to 8 years was low at 23%, but shockingly lower at a mere 7% in the 9- to 17-year-olds. Whereas in the 2017-2018 season, vaccine effectiveness against H3N2 in the 9- to 17-year-olds jumped to 46% while remaining low but consistent at 22% in the younger children.

“We see a very different age pattern here for the older children compared to the younger children, and quite frankly we don’t really understand what’s doing this,” said Dr. Belongia.

What is well understood, however, is that the problematic performance of influenza vaccines when it comes to protecting against H3N2 is a complicated matter stemming from three sources: the virus itself; the current egg-based vaccine manufacturing methodology, which is now 7 decades old; and host factors.

That troublesome H3N2 virus

Antigenic evolution of the H3N2 virus occurs at a 5- to 6-fold higher rate than for influenza B virus and roughly 17-fold faster than for H1N1. That high mutation rate makes for a moving target that’s a real problem when trying to keep a vaccine current. Also, the globular head of the virus is prone to glycosylation, which enables the virus to evade immune detection.

Vaccine-related factors

It’s likely that the availability of the flu vaccine for the upcoming 2019-2020 season is going to be delayed because of late selection of the strains for inclusion. The World Health Organization ordinarily selects strains for vaccines for the Northern Hemisphere in February, giving vaccine manufacturers 6-8 months to produce their vaccines and ship them in time for administration from September through November. This year, however, the WHO delayed selection of the H3N2 component until March because of the high level of antigenic and genetic diversity of circulating strains.

“This hasn’t happened since 2003 – it’s a very rare occurrence – but it does increase the potential that there’s going to be a delay in the availability of the vaccine in the fall,” he explained.

Eventually, the WHO selected a new clade 3C.3a virus called A/Kansas/14/2017 for the 2019-2020 vaccine. It should cover the circulating strains of H3N2 “reasonably well,” according to the physician.

Another issue: H3N2 has become adapted to the mammalian environment, so growing the virus in eggs introduces strong selection pressure for mutations leading to reduced vaccine effectiveness. Yet only two flu vaccines licensed in the United States are manufactured without eggs: Flucelvax, marketed by Seqirus for patients aged 4 years and up, and Sanofi’s Flublok, which is licensed for individuals who are 18 years of age or older. Studies are underway looking at the relative effectiveness of egg-based versus cell culture-manufactured flu vaccines in real-world settings.

Host factors

Hemagglutinin imprinting, sometimes referred to as “original antigenic sin,” is a decades-old concept whereby early childhood exposure to influenza viruses shapes future vaccine response.

“It suggests there could be some birth cohort effects in vaccine responsiveness, depending on what was circulating in the first 2-3 years after birth. It would complicate vaccine strategy quite a bit if you had to have different strategies for different birth cohorts,” Dr. Belongia observed.

Another host factor issue is the controversial topic of negative interference stemming from repeated vaccinations. It’s unclear how important this is in the real world, because studies have been inconsistent. Reassuringly, Dr. Belongia and coworkers found no association between prior-season influenza vaccination and diminished vaccine effectiveness in 3,369 U.S. children aged 2-17 years studied during the 2013-14 through 2015-16 flu seasons (JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Oct 5;1[6]:e183742. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3742).

“We found no suggestion at all of a problem with being vaccinated two seasons in a row,” according to Dr. Belongia.

How to build a better influenza vaccine for children

“I would say that even before we get to a universal vaccine, the next generation of flu vaccines that are more effective are not going to be manufactured using eggs, although we’re not real close to that. But I think that’s eventually where we’re going,” he said.

“I think it’s going to take a systems biology approach in order to really understand the adaptive immune response to infection and vaccination in early life. That means a much more detailed understanding of what is underlying the imprinting mechanisms and what is the adaptive response to repeated vaccination and infection. I think this is going to take prospective infant cohort studies; the National Institutes of Health is funding some that will begin within the next year,” Dr. Belongia added.

Many investigational approaches to improving influenza virus subtype-level protection are being explored. These include novel adjuvants, nanoparticle vaccines, computationally optimized broadly reactive antigens, and standardization of neuraminidase content.

And as for the much-desired universal flu vaccine?

“I will say that if a universal vaccine is going to work it’s probably going to work first in children. They have a much shorter immune history and their antibody landscape is a lot smaller, so you have a much better opportunity, I think, to generate a broad response to a universal vaccine compared to adults, who have much more complex immune landscapes,” he said.

Dr. Belongia reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2019

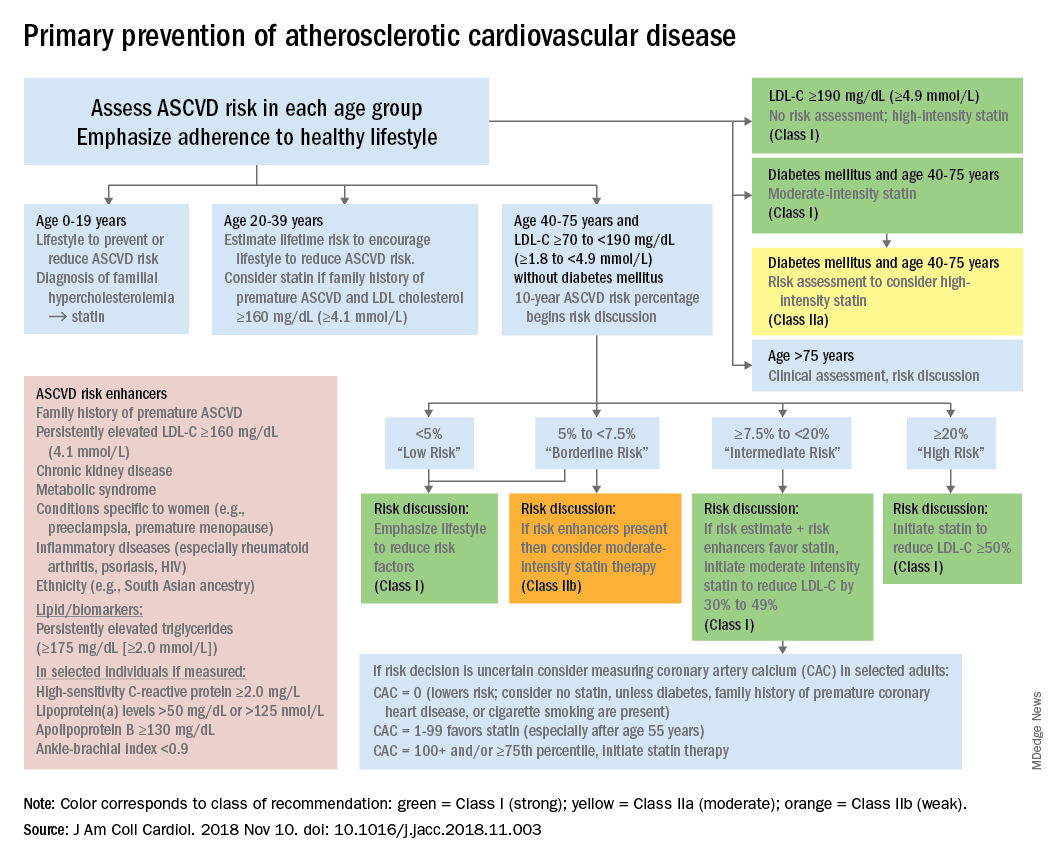

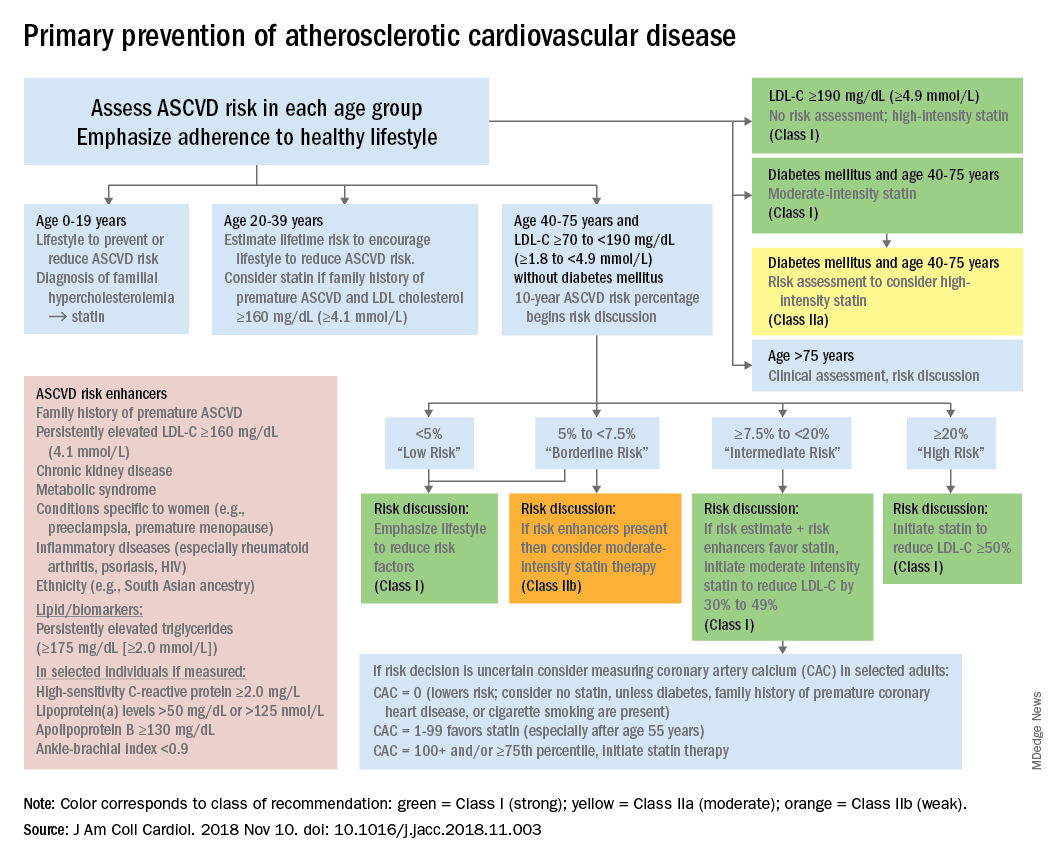

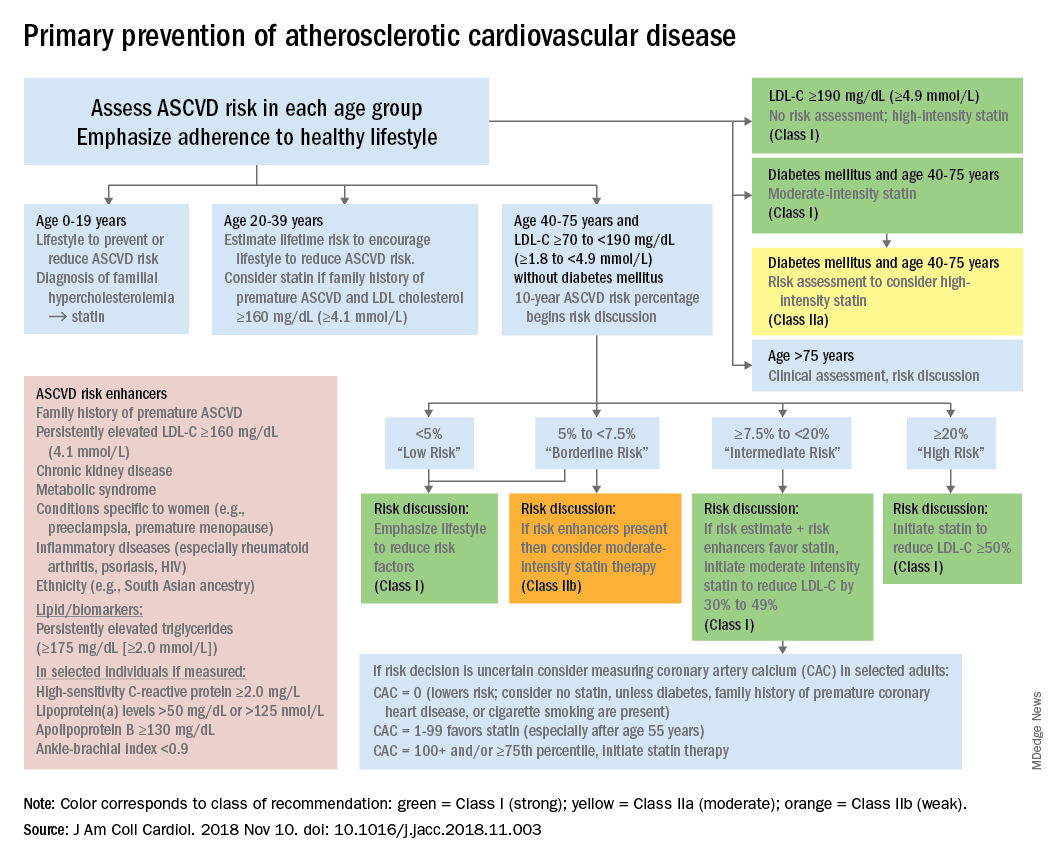

Cholesterol guideline: Risk assessment gets personal

according to the 2018 update to U.S. guidelines for cholesterol management from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology.

The guideline also emphasizes “careful adherence to lifestyle recommendations at an early age [to] reduce risk factor burden over the lifespan and decrease the need for preventive drug therapies later in life,” Scott M. Grundy, MD, PhD, and Neil J. Stone, MD, said in a synopsis of the document in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

For primary prevention in patients aged 40-75 years, estimation of 10-year ASCVD risk – introduced in the 2013 guidelines – and stratification into one of four categories should set the stage for clinician-patient discussion. A score of less than 5% indicates low risk and should prompt a risk discussion that emphasizes lifestyle recommendations. “Statins are clinically efficacious in the latter three categories, but the higher the risk, the stronger the statin indication,” said Dr. Grundy of the University of Texas, Dallas, and Dr. Stone of Northwestern University, Chicago.

When risk status is uncertain, measurement of coronary artery calcium should be considered in patients aged 40-75 years with LDL cholesterol levels of 70-189 mg/dL who do no not have diabetes, they noted.

The guideline emphasizes secondary prevention with “maximally tolerated doses of statins” and the use of nonstatin drugs such as ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors for patients with very high ASCVD risk – defined as a history of multiple major events or one event and other high-risk conditions, Dr. Grundy and Dr. Stone wrote.

Financial support for the Guideline Writing Committee for the 2018 Cholesterol Guidelines came from the AHA and the ACC. Dr. Grundy and Dr. Stone said that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Grundy SM and Stone NJ. Ann Intern Med. 2019 May 28. doi: 10.7326/M19-0365.

according to the 2018 update to U.S. guidelines for cholesterol management from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology.

The guideline also emphasizes “careful adherence to lifestyle recommendations at an early age [to] reduce risk factor burden over the lifespan and decrease the need for preventive drug therapies later in life,” Scott M. Grundy, MD, PhD, and Neil J. Stone, MD, said in a synopsis of the document in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

For primary prevention in patients aged 40-75 years, estimation of 10-year ASCVD risk – introduced in the 2013 guidelines – and stratification into one of four categories should set the stage for clinician-patient discussion. A score of less than 5% indicates low risk and should prompt a risk discussion that emphasizes lifestyle recommendations. “Statins are clinically efficacious in the latter three categories, but the higher the risk, the stronger the statin indication,” said Dr. Grundy of the University of Texas, Dallas, and Dr. Stone of Northwestern University, Chicago.

When risk status is uncertain, measurement of coronary artery calcium should be considered in patients aged 40-75 years with LDL cholesterol levels of 70-189 mg/dL who do no not have diabetes, they noted.

The guideline emphasizes secondary prevention with “maximally tolerated doses of statins” and the use of nonstatin drugs such as ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors for patients with very high ASCVD risk – defined as a history of multiple major events or one event and other high-risk conditions, Dr. Grundy and Dr. Stone wrote.

Financial support for the Guideline Writing Committee for the 2018 Cholesterol Guidelines came from the AHA and the ACC. Dr. Grundy and Dr. Stone said that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Grundy SM and Stone NJ. Ann Intern Med. 2019 May 28. doi: 10.7326/M19-0365.

according to the 2018 update to U.S. guidelines for cholesterol management from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology.

The guideline also emphasizes “careful adherence to lifestyle recommendations at an early age [to] reduce risk factor burden over the lifespan and decrease the need for preventive drug therapies later in life,” Scott M. Grundy, MD, PhD, and Neil J. Stone, MD, said in a synopsis of the document in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

For primary prevention in patients aged 40-75 years, estimation of 10-year ASCVD risk – introduced in the 2013 guidelines – and stratification into one of four categories should set the stage for clinician-patient discussion. A score of less than 5% indicates low risk and should prompt a risk discussion that emphasizes lifestyle recommendations. “Statins are clinically efficacious in the latter three categories, but the higher the risk, the stronger the statin indication,” said Dr. Grundy of the University of Texas, Dallas, and Dr. Stone of Northwestern University, Chicago.

When risk status is uncertain, measurement of coronary artery calcium should be considered in patients aged 40-75 years with LDL cholesterol levels of 70-189 mg/dL who do no not have diabetes, they noted.

The guideline emphasizes secondary prevention with “maximally tolerated doses of statins” and the use of nonstatin drugs such as ezetimibe and PCSK9 inhibitors for patients with very high ASCVD risk – defined as a history of multiple major events or one event and other high-risk conditions, Dr. Grundy and Dr. Stone wrote.

Financial support for the Guideline Writing Committee for the 2018 Cholesterol Guidelines came from the AHA and the ACC. Dr. Grundy and Dr. Stone said that they had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Grundy SM and Stone NJ. Ann Intern Med. 2019 May 28. doi: 10.7326/M19-0365.

FROM THE ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

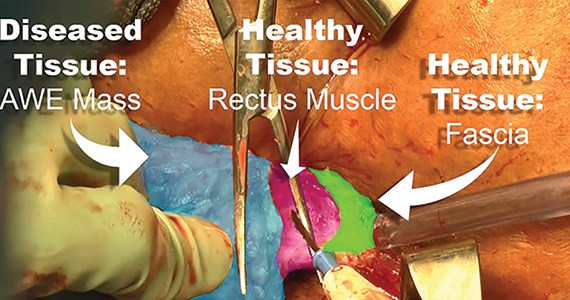

Excision of abdominal wall endometriosis

Endometriosis, defined by the ectopic growth of functioning endometrial glands and stroma,1,2 usually affects the peritoneal cavity. However, endometriosis has been identified in the pneumothorax, brain, and within the extraperitoneum, such as the abdominal wall.1-3 Incidence of abdominal wall endometriosis can be up to 12%.3-5 If patients report symptoms, they can include abdominal pain, a palpable mass, pelvic pain consistent with endometriosis, and bleeding from involvement of the overlying skin. Abdominal wall endometriosis can be surgically resected, with complete resolution and a low rate of recurrence.

In the following video, we review the diagnosis of abdominal wall endometriosis, including our imaging of choice, and treatment options. In addition, we illustrate a surgical technique for the excision of abdominal wall endometriosis in a 38-year-old patient with symptomatic disease. We conclude with a review of key surgical steps.

We hope that you find this video useful to your clinical practice.

>> Dr. Arnold P. Advincula, and colleagues

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:511-519.

- Ecker AM, Donnellan NM, Shepherd JP, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: 12 years of experience at a large academic institution. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:363.e1-e5.

- Horton JD, Dezee KJ, Ahnfeldt EP, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: a surgeon’s perspective and review of 445 cases. Am J Surg. 2008;196:207-212.

- Ding Y, Zhu J. A retrospective review of abdominal wall endometriosis in Shanghai, China. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;121:41-44.

- Chang Y, Tsai EM, Long CY, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis. J Reproductive Med. 2009;54:155-159.

Endometriosis, defined by the ectopic growth of functioning endometrial glands and stroma,1,2 usually affects the peritoneal cavity. However, endometriosis has been identified in the pneumothorax, brain, and within the extraperitoneum, such as the abdominal wall.1-3 Incidence of abdominal wall endometriosis can be up to 12%.3-5 If patients report symptoms, they can include abdominal pain, a palpable mass, pelvic pain consistent with endometriosis, and bleeding from involvement of the overlying skin. Abdominal wall endometriosis can be surgically resected, with complete resolution and a low rate of recurrence.

In the following video, we review the diagnosis of abdominal wall endometriosis, including our imaging of choice, and treatment options. In addition, we illustrate a surgical technique for the excision of abdominal wall endometriosis in a 38-year-old patient with symptomatic disease. We conclude with a review of key surgical steps.

We hope that you find this video useful to your clinical practice.

>> Dr. Arnold P. Advincula, and colleagues

Endometriosis, defined by the ectopic growth of functioning endometrial glands and stroma,1,2 usually affects the peritoneal cavity. However, endometriosis has been identified in the pneumothorax, brain, and within the extraperitoneum, such as the abdominal wall.1-3 Incidence of abdominal wall endometriosis can be up to 12%.3-5 If patients report symptoms, they can include abdominal pain, a palpable mass, pelvic pain consistent with endometriosis, and bleeding from involvement of the overlying skin. Abdominal wall endometriosis can be surgically resected, with complete resolution and a low rate of recurrence.

In the following video, we review the diagnosis of abdominal wall endometriosis, including our imaging of choice, and treatment options. In addition, we illustrate a surgical technique for the excision of abdominal wall endometriosis in a 38-year-old patient with symptomatic disease. We conclude with a review of key surgical steps.

We hope that you find this video useful to your clinical practice.

>> Dr. Arnold P. Advincula, and colleagues

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:511-519.

- Ecker AM, Donnellan NM, Shepherd JP, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: 12 years of experience at a large academic institution. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:363.e1-e5.

- Horton JD, Dezee KJ, Ahnfeldt EP, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: a surgeon’s perspective and review of 445 cases. Am J Surg. 2008;196:207-212.

- Ding Y, Zhu J. A retrospective review of abdominal wall endometriosis in Shanghai, China. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;121:41-44.

- Chang Y, Tsai EM, Long CY, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis. J Reproductive Med. 2009;54:155-159.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC. Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:511-519.

- Ecker AM, Donnellan NM, Shepherd JP, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: 12 years of experience at a large academic institution. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:363.e1-e5.

- Horton JD, Dezee KJ, Ahnfeldt EP, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: a surgeon’s perspective and review of 445 cases. Am J Surg. 2008;196:207-212.

- Ding Y, Zhu J. A retrospective review of abdominal wall endometriosis in Shanghai, China. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;121:41-44.

- Chang Y, Tsai EM, Long CY, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis. J Reproductive Med. 2009;54:155-159.

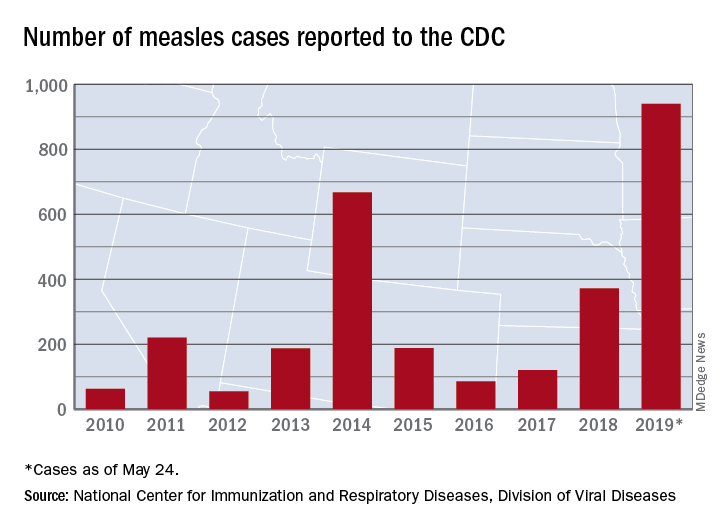

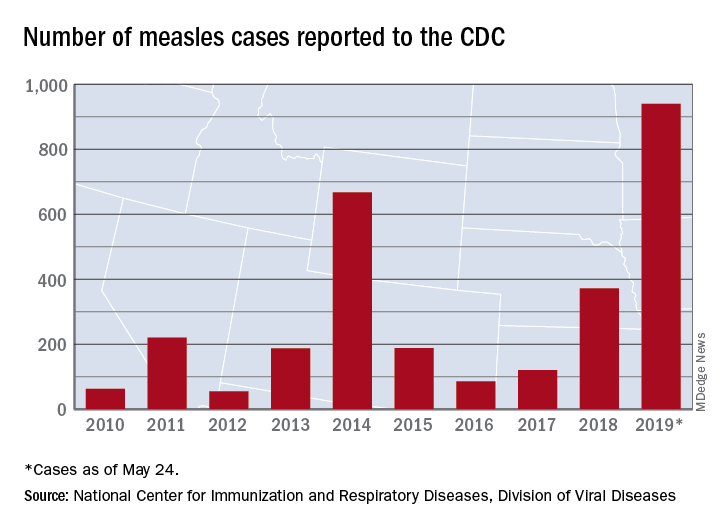

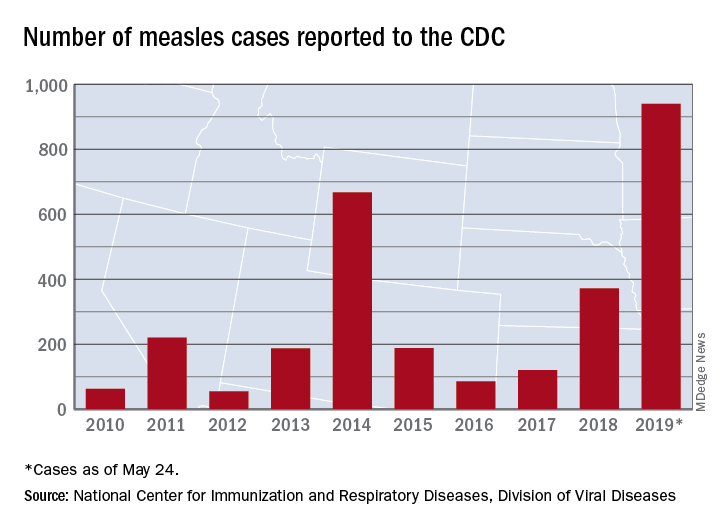

Measles count for 2019 now over 900 cases

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC received reports of 60 new measles cases last week – up from 41 the previous week – bringing the U.S. total to 940 for the year as of May 24. The CDC is currently tracking 10 outbreaks in seven states: California (3), Georgia, Maryland, Michigan, New York (2), Pennsylvania, and Washington.

The Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the state’s first case on May 20. The school-aged child from Somerset County had been vaccinated and is fully recovered from the disease. It’s not yet known where the child was exposed to measles, but sporadic cases are not unexpected, the Maine CDC said.

New Mexico’s first measles case of the year, a 1-year-old in Sierra County, has at least one state lawmaker considering changes to the state’s immunization exemption laws, the Farmington Daily Times reported.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC received reports of 60 new measles cases last week – up from 41 the previous week – bringing the U.S. total to 940 for the year as of May 24. The CDC is currently tracking 10 outbreaks in seven states: California (3), Georgia, Maryland, Michigan, New York (2), Pennsylvania, and Washington.

The Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the state’s first case on May 20. The school-aged child from Somerset County had been vaccinated and is fully recovered from the disease. It’s not yet known where the child was exposed to measles, but sporadic cases are not unexpected, the Maine CDC said.

New Mexico’s first measles case of the year, a 1-year-old in Sierra County, has at least one state lawmaker considering changes to the state’s immunization exemption laws, the Farmington Daily Times reported.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC received reports of 60 new measles cases last week – up from 41 the previous week – bringing the U.S. total to 940 for the year as of May 24. The CDC is currently tracking 10 outbreaks in seven states: California (3), Georgia, Maryland, Michigan, New York (2), Pennsylvania, and Washington.

The Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the state’s first case on May 20. The school-aged child from Somerset County had been vaccinated and is fully recovered from the disease. It’s not yet known where the child was exposed to measles, but sporadic cases are not unexpected, the Maine CDC said.

New Mexico’s first measles case of the year, a 1-year-old in Sierra County, has at least one state lawmaker considering changes to the state’s immunization exemption laws, the Farmington Daily Times reported.

Scandinavian studies shed light on OA inheritance

TORONTO – Patients with osteoarthritis often want to know if their debilitating disease is likely to be passed on to their children. Karin Magnusson, PhD, believes she can answer that question based upon an analysis of two large Nordic studies.

“OA in the mother, but not in the father, increases the risk of surgical and clinically defined hip, knee, and hand OA in the offspring, and particularly in daughters,” she reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

Dr. Magnusson, an epidemiologist at Lund (Sweden) University, and her coinvestigators, turned to the Musculoskeletal Pain in Ullensaker Study (MUST) of 630 individuals aged 40-79 with rheumatologist-diagnosed hand, hip, or knee OA by American College of Rheumatology clinical criteria and their offspring, as well as the Nor-Twin OA Study of 7,184 twins, aged 30-75, and their children. Linkage with a national registry that records virtually all joint arthroplasties performed in Norway enabled the investigators to identify which subjects in the two studies had joint surgery for OA, she explained at the meeting, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The main outcome in this analysis was the relative risk of hip, knee, or hand OA in the sons and daughters of families in which a parent had OA at those sites, compared with the rate when neither parent had OA. The key finding: If the mother had OA, her daughters had a 13% increased risk of OA in MUST and a 44% increased risk in the Nor-Twin OA Study when compared with daughters of women without OA. In contrast, the sons of a mother with OA had no significant increase in risk of OA. And when OA was present in the father, there was no increased risk of OA at any site in his daughters or sons.

“The implication is the heredity of OA is linked to maternal genes and/or maternal-specific factors, such as the fetal environment,” according to Dr. Magnusson.

And for clinical practice, the implication is that it’s important to ask about family history of OA, and in which parent, to better predict future risk of disease transmission to the children, she added.

These Norwegian study results open the door to exploration of the possible role of mitochondrial DNA in familial clustering of OA, since mitochondrial DNA is inherited only from the mother, Dr. Magnusson noted.

David T. Felson, MD, rose from the audience to say, “I’m a little bit worried” about the fact that when he and other Framingham Heart Study investigators looked specifically for possible mother/daughter, mother/son, father/daughter, and father/son associations for knee and hip OA, “we really didn’t find any.

“You can go through all of the explanations that you want about maternal inheritance, but I’m not sure that’s the best explanation. It might just be that what’s going on here is you’re seeing guys who are relatively young and who got their OA through injury or sports, which is fairly common in young men, and not through inheritance,” said Dr. Felson, professor of medicine and epidemiology at Boston University.

So a third observational study in an independent cohort might be needed as a tie breaker regarding the issue of OA inheritance.

Dr. Magnusson reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, conducted free of commercial support.

SOURCE: Magnusson K et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S47, Abstract 33

TORONTO – Patients with osteoarthritis often want to know if their debilitating disease is likely to be passed on to their children. Karin Magnusson, PhD, believes she can answer that question based upon an analysis of two large Nordic studies.

“OA in the mother, but not in the father, increases the risk of surgical and clinically defined hip, knee, and hand OA in the offspring, and particularly in daughters,” she reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

Dr. Magnusson, an epidemiologist at Lund (Sweden) University, and her coinvestigators, turned to the Musculoskeletal Pain in Ullensaker Study (MUST) of 630 individuals aged 40-79 with rheumatologist-diagnosed hand, hip, or knee OA by American College of Rheumatology clinical criteria and their offspring, as well as the Nor-Twin OA Study of 7,184 twins, aged 30-75, and their children. Linkage with a national registry that records virtually all joint arthroplasties performed in Norway enabled the investigators to identify which subjects in the two studies had joint surgery for OA, she explained at the meeting, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The main outcome in this analysis was the relative risk of hip, knee, or hand OA in the sons and daughters of families in which a parent had OA at those sites, compared with the rate when neither parent had OA. The key finding: If the mother had OA, her daughters had a 13% increased risk of OA in MUST and a 44% increased risk in the Nor-Twin OA Study when compared with daughters of women without OA. In contrast, the sons of a mother with OA had no significant increase in risk of OA. And when OA was present in the father, there was no increased risk of OA at any site in his daughters or sons.

“The implication is the heredity of OA is linked to maternal genes and/or maternal-specific factors, such as the fetal environment,” according to Dr. Magnusson.

And for clinical practice, the implication is that it’s important to ask about family history of OA, and in which parent, to better predict future risk of disease transmission to the children, she added.

These Norwegian study results open the door to exploration of the possible role of mitochondrial DNA in familial clustering of OA, since mitochondrial DNA is inherited only from the mother, Dr. Magnusson noted.

David T. Felson, MD, rose from the audience to say, “I’m a little bit worried” about the fact that when he and other Framingham Heart Study investigators looked specifically for possible mother/daughter, mother/son, father/daughter, and father/son associations for knee and hip OA, “we really didn’t find any.

“You can go through all of the explanations that you want about maternal inheritance, but I’m not sure that’s the best explanation. It might just be that what’s going on here is you’re seeing guys who are relatively young and who got their OA through injury or sports, which is fairly common in young men, and not through inheritance,” said Dr. Felson, professor of medicine and epidemiology at Boston University.

So a third observational study in an independent cohort might be needed as a tie breaker regarding the issue of OA inheritance.

Dr. Magnusson reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, conducted free of commercial support.

SOURCE: Magnusson K et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S47, Abstract 33

TORONTO – Patients with osteoarthritis often want to know if their debilitating disease is likely to be passed on to their children. Karin Magnusson, PhD, believes she can answer that question based upon an analysis of two large Nordic studies.

“OA in the mother, but not in the father, increases the risk of surgical and clinically defined hip, knee, and hand OA in the offspring, and particularly in daughters,” she reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

Dr. Magnusson, an epidemiologist at Lund (Sweden) University, and her coinvestigators, turned to the Musculoskeletal Pain in Ullensaker Study (MUST) of 630 individuals aged 40-79 with rheumatologist-diagnosed hand, hip, or knee OA by American College of Rheumatology clinical criteria and their offspring, as well as the Nor-Twin OA Study of 7,184 twins, aged 30-75, and their children. Linkage with a national registry that records virtually all joint arthroplasties performed in Norway enabled the investigators to identify which subjects in the two studies had joint surgery for OA, she explained at the meeting, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

The main outcome in this analysis was the relative risk of hip, knee, or hand OA in the sons and daughters of families in which a parent had OA at those sites, compared with the rate when neither parent had OA. The key finding: If the mother had OA, her daughters had a 13% increased risk of OA in MUST and a 44% increased risk in the Nor-Twin OA Study when compared with daughters of women without OA. In contrast, the sons of a mother with OA had no significant increase in risk of OA. And when OA was present in the father, there was no increased risk of OA at any site in his daughters or sons.

“The implication is the heredity of OA is linked to maternal genes and/or maternal-specific factors, such as the fetal environment,” according to Dr. Magnusson.

And for clinical practice, the implication is that it’s important to ask about family history of OA, and in which parent, to better predict future risk of disease transmission to the children, she added.

These Norwegian study results open the door to exploration of the possible role of mitochondrial DNA in familial clustering of OA, since mitochondrial DNA is inherited only from the mother, Dr. Magnusson noted.

David T. Felson, MD, rose from the audience to say, “I’m a little bit worried” about the fact that when he and other Framingham Heart Study investigators looked specifically for possible mother/daughter, mother/son, father/daughter, and father/son associations for knee and hip OA, “we really didn’t find any.

“You can go through all of the explanations that you want about maternal inheritance, but I’m not sure that’s the best explanation. It might just be that what’s going on here is you’re seeing guys who are relatively young and who got their OA through injury or sports, which is fairly common in young men, and not through inheritance,” said Dr. Felson, professor of medicine and epidemiology at Boston University.

So a third observational study in an independent cohort might be needed as a tie breaker regarding the issue of OA inheritance.

Dr. Magnusson reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, conducted free of commercial support.

SOURCE: Magnusson K et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S47, Abstract 33

REPORTING FROM OARSI 2019

Alemtuzumab provides greater reductions in serum NfL than interferon beta-1a

Seattle – (MS), according to an analysis presented at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. This finding is consistent with the superior clinical efficacy of alemtuzumab, compared with interferon beta-1a, seen in clinical trials, said the researchers. The clinical implications of alemtuzumab’s reduction of NfL levels remain to be clarified.

The CARE-MS I trial indicated that alemtuzumab significantly improved clinical and MRI outcomes vs. subcutaneous interferon beta-1a over 2 years in treatment-naive patients with relapsing-remitting MS. Serum NfL level may indicate response to disease-modifying therapy.

Evis Havari, MSc, laboratory head of neuroimmunology immunomodulation at Sanofi in Framingham, Mass., and colleagues analyzed CARE-MS I data to determine the effect of alemtuzumab and subcutaneous interferon beta-1a on serum NfL over 2 years. The investigators also sought to compare participants’ serum NfL levels with the age-dependent median serum NfL levels in healthy controls, based on the approach described by Disanto et al. (Ann Neurol. 2017;81[6]:857-70).

In CARE-MS I, the investigators measured serum NfL with a single-molecule array. They used Generalized Additive Models of Location, Scale, and Shape to model serum NfL distribution in healthy controls and its association with age. They also derived age-dependent percentiles of serum NfL. CARE-MS I patients received 44 mcg of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a 3 times per week or 12 mg/day of alemtuzumab (a 5-day course at baseline and a 3-day course at 1 year). To obtain an age-independent measure of serum NfL, the researchers dichotomized samples into levels above or below the median. They used repeated logistic regression to estimate odds ratios (ORs).

The age range of participants in CARE-MS I was 18-53 years. Mean Expanded Disability Status Scale score was 2.0. In all, 354 participants received alemtuzumab, and 157 received interferon beta-1a.

Median serum NfL levels for healthy controls ranged from 12.0 pg/mL at 18 years of age to 27.1 pg/mL at 53 years. Median serum NfL levels were similar between the alemtuzumab and interferon beta-1a groups at baseline (31.7 pg/mL vs. 31.4 pg/mL). At 6 months after treatment, median serum NfL levels were significantly lower with alemtuzumab than with interferon beta-1a (17.2 pg/mL vs. 21.4 pg/mL). These levels remained significantly lower at month 24 in the alemtuzumab group (13.2 pg/mL vs. 18.7 pg/mL).

Significantly fewer patients in the alemtuzumab group had serum NfL levels higher than the age-dependent median in healthy controls at each post baseline time point, compared with the interferon beta-1a group (month 6: 46% vs. 65%; month 12: 38% vs. 53%; month 18: 31% vs. 44%; month 24: 28% vs. 53%). The odds for achieving serum NfL levels less than or equal to median levels for healthy controls were significantly greater for alemtuzumab than interferon beta-1a at month 6 (OR, 2.34), month 12 (OR, 1.81), month 18 (OR, 1.72), and month 24 (OR, 2.85).

Sanofi and Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals supported the study. Several of the investigators are employees of Sanofi.

SOURCE: Havari E et al. CMSC 2019. Abstract NIB01.

Seattle – (MS), according to an analysis presented at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. This finding is consistent with the superior clinical efficacy of alemtuzumab, compared with interferon beta-1a, seen in clinical trials, said the researchers. The clinical implications of alemtuzumab’s reduction of NfL levels remain to be clarified.

The CARE-MS I trial indicated that alemtuzumab significantly improved clinical and MRI outcomes vs. subcutaneous interferon beta-1a over 2 years in treatment-naive patients with relapsing-remitting MS. Serum NfL level may indicate response to disease-modifying therapy.

Evis Havari, MSc, laboratory head of neuroimmunology immunomodulation at Sanofi in Framingham, Mass., and colleagues analyzed CARE-MS I data to determine the effect of alemtuzumab and subcutaneous interferon beta-1a on serum NfL over 2 years. The investigators also sought to compare participants’ serum NfL levels with the age-dependent median serum NfL levels in healthy controls, based on the approach described by Disanto et al. (Ann Neurol. 2017;81[6]:857-70).

In CARE-MS I, the investigators measured serum NfL with a single-molecule array. They used Generalized Additive Models of Location, Scale, and Shape to model serum NfL distribution in healthy controls and its association with age. They also derived age-dependent percentiles of serum NfL. CARE-MS I patients received 44 mcg of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a 3 times per week or 12 mg/day of alemtuzumab (a 5-day course at baseline and a 3-day course at 1 year). To obtain an age-independent measure of serum NfL, the researchers dichotomized samples into levels above or below the median. They used repeated logistic regression to estimate odds ratios (ORs).

The age range of participants in CARE-MS I was 18-53 years. Mean Expanded Disability Status Scale score was 2.0. In all, 354 participants received alemtuzumab, and 157 received interferon beta-1a.

Median serum NfL levels for healthy controls ranged from 12.0 pg/mL at 18 years of age to 27.1 pg/mL at 53 years. Median serum NfL levels were similar between the alemtuzumab and interferon beta-1a groups at baseline (31.7 pg/mL vs. 31.4 pg/mL). At 6 months after treatment, median serum NfL levels were significantly lower with alemtuzumab than with interferon beta-1a (17.2 pg/mL vs. 21.4 pg/mL). These levels remained significantly lower at month 24 in the alemtuzumab group (13.2 pg/mL vs. 18.7 pg/mL).

Significantly fewer patients in the alemtuzumab group had serum NfL levels higher than the age-dependent median in healthy controls at each post baseline time point, compared with the interferon beta-1a group (month 6: 46% vs. 65%; month 12: 38% vs. 53%; month 18: 31% vs. 44%; month 24: 28% vs. 53%). The odds for achieving serum NfL levels less than or equal to median levels for healthy controls were significantly greater for alemtuzumab than interferon beta-1a at month 6 (OR, 2.34), month 12 (OR, 1.81), month 18 (OR, 1.72), and month 24 (OR, 2.85).

Sanofi and Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals supported the study. Several of the investigators are employees of Sanofi.

SOURCE: Havari E et al. CMSC 2019. Abstract NIB01.

Seattle – (MS), according to an analysis presented at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. This finding is consistent with the superior clinical efficacy of alemtuzumab, compared with interferon beta-1a, seen in clinical trials, said the researchers. The clinical implications of alemtuzumab’s reduction of NfL levels remain to be clarified.

The CARE-MS I trial indicated that alemtuzumab significantly improved clinical and MRI outcomes vs. subcutaneous interferon beta-1a over 2 years in treatment-naive patients with relapsing-remitting MS. Serum NfL level may indicate response to disease-modifying therapy.

Evis Havari, MSc, laboratory head of neuroimmunology immunomodulation at Sanofi in Framingham, Mass., and colleagues analyzed CARE-MS I data to determine the effect of alemtuzumab and subcutaneous interferon beta-1a on serum NfL over 2 years. The investigators also sought to compare participants’ serum NfL levels with the age-dependent median serum NfL levels in healthy controls, based on the approach described by Disanto et al. (Ann Neurol. 2017;81[6]:857-70).

In CARE-MS I, the investigators measured serum NfL with a single-molecule array. They used Generalized Additive Models of Location, Scale, and Shape to model serum NfL distribution in healthy controls and its association with age. They also derived age-dependent percentiles of serum NfL. CARE-MS I patients received 44 mcg of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a 3 times per week or 12 mg/day of alemtuzumab (a 5-day course at baseline and a 3-day course at 1 year). To obtain an age-independent measure of serum NfL, the researchers dichotomized samples into levels above or below the median. They used repeated logistic regression to estimate odds ratios (ORs).

The age range of participants in CARE-MS I was 18-53 years. Mean Expanded Disability Status Scale score was 2.0. In all, 354 participants received alemtuzumab, and 157 received interferon beta-1a.

Median serum NfL levels for healthy controls ranged from 12.0 pg/mL at 18 years of age to 27.1 pg/mL at 53 years. Median serum NfL levels were similar between the alemtuzumab and interferon beta-1a groups at baseline (31.7 pg/mL vs. 31.4 pg/mL). At 6 months after treatment, median serum NfL levels were significantly lower with alemtuzumab than with interferon beta-1a (17.2 pg/mL vs. 21.4 pg/mL). These levels remained significantly lower at month 24 in the alemtuzumab group (13.2 pg/mL vs. 18.7 pg/mL).

Significantly fewer patients in the alemtuzumab group had serum NfL levels higher than the age-dependent median in healthy controls at each post baseline time point, compared with the interferon beta-1a group (month 6: 46% vs. 65%; month 12: 38% vs. 53%; month 18: 31% vs. 44%; month 24: 28% vs. 53%). The odds for achieving serum NfL levels less than or equal to median levels for healthy controls were significantly greater for alemtuzumab than interferon beta-1a at month 6 (OR, 2.34), month 12 (OR, 1.81), month 18 (OR, 1.72), and month 24 (OR, 2.85).

Sanofi and Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals supported the study. Several of the investigators are employees of Sanofi.

SOURCE: Havari E et al. CMSC 2019. Abstract NIB01.

REPORTING FROM CMSC 2019

Key clinical point: Compared with interferon beta-1a, alemtuzumab provides greater reduction of serum NfL level.

Major finding: At month 24, median serum NfL level was 13.2 pg/mL in the alemtuzumab group and 18.7 pg/mL in the interferon group.

Study details: A prospective, randomized study of 511 patients with relapsing-remitting MS.

Disclosures: Sanofi and Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals supported the study. Several of the investigators are employees of Sanofi.

Source: Havari E et al. CMSC 2019. Abstract NIB01.

Association between cytomegalovirus and MS varies by region

SEATTLE – presented at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. In the United States, the association between CMV seropositivity and MS is not statistically significant, whereas combined data from all regions show a significant positive association, researchers said.

“To our knowledge, this is the largest meta-analysis evaluation of the association between CMV seropositivity and MS,” said Smathorn Thakolwiboon, MD, a neurology resident at Texas Tech University, Lubbock, and colleagues. Understanding the reasons for the geographic heterogeneity will require further research, they said.

Researchers have hypothesized that increased incidence of autoimmune conditions may be linked to the prevention or delay of common infections, but studies have been inconclusive (Neurology. 2017 Sep 26;89[13]:1330-7.).

To evaluate the association between CMV seropositivity and MS, Dr. Thakolwiboon and colleagues searched databases, including PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science, from inception through Dec. 2018. They included in their analysis observational studies that evaluated the seroprevalence of CMV immunoglobulin G (IgG) in adults with MS and healthy controls. They estimated the odds ratio (OR) for CMV seropositivity and MS.

An initial search yielded 982 articles, 56 of which underwent full review. The researchers ultimately included 13 articles in their quantitative analysis. The studies included data from 3,049 patients with MS and 3,604 controls.

Overall, CMV seropositivity was significantly associated with MS (OR, 1.58; 95% confidence interval, 1.04-2.39; P = .031), but the relationship varied by region. In five U.S. studies, the association was not statistically significant (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 0.83-2.99; P = .168). CMV seropositivity was negatively associated with MS in Europe (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.68-0.96; P less than .001), but positively associated with MS in the Middle East (OR, 5.42; 95% CI, 1.06-27.89; P less than .001). “The meta-analysis showed a heterogeneity of the association between CMV seropositivity and MS,” the researchers concluded. “More genetic and environmental studies are needed for better understanding this geographic heterogeneity.”

Dr. Thakolwiboon had no disclosures. A coauthor disclosed speaking and advisory board roles with EMD Serono, Genzyme, Novartis, and Teva.

SOURCE: Thakolwiboon S et al. CMSC 2019. Abstract EPI01.

SEATTLE – presented at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. In the United States, the association between CMV seropositivity and MS is not statistically significant, whereas combined data from all regions show a significant positive association, researchers said.

“To our knowledge, this is the largest meta-analysis evaluation of the association between CMV seropositivity and MS,” said Smathorn Thakolwiboon, MD, a neurology resident at Texas Tech University, Lubbock, and colleagues. Understanding the reasons for the geographic heterogeneity will require further research, they said.

Researchers have hypothesized that increased incidence of autoimmune conditions may be linked to the prevention or delay of common infections, but studies have been inconclusive (Neurology. 2017 Sep 26;89[13]:1330-7.).

To evaluate the association between CMV seropositivity and MS, Dr. Thakolwiboon and colleagues searched databases, including PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science, from inception through Dec. 2018. They included in their analysis observational studies that evaluated the seroprevalence of CMV immunoglobulin G (IgG) in adults with MS and healthy controls. They estimated the odds ratio (OR) for CMV seropositivity and MS.

An initial search yielded 982 articles, 56 of which underwent full review. The researchers ultimately included 13 articles in their quantitative analysis. The studies included data from 3,049 patients with MS and 3,604 controls.

Overall, CMV seropositivity was significantly associated with MS (OR, 1.58; 95% confidence interval, 1.04-2.39; P = .031), but the relationship varied by region. In five U.S. studies, the association was not statistically significant (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 0.83-2.99; P = .168). CMV seropositivity was negatively associated with MS in Europe (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.68-0.96; P less than .001), but positively associated with MS in the Middle East (OR, 5.42; 95% CI, 1.06-27.89; P less than .001). “The meta-analysis showed a heterogeneity of the association between CMV seropositivity and MS,” the researchers concluded. “More genetic and environmental studies are needed for better understanding this geographic heterogeneity.”

Dr. Thakolwiboon had no disclosures. A coauthor disclosed speaking and advisory board roles with EMD Serono, Genzyme, Novartis, and Teva.

SOURCE: Thakolwiboon S et al. CMSC 2019. Abstract EPI01.

SEATTLE – presented at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. In the United States, the association between CMV seropositivity and MS is not statistically significant, whereas combined data from all regions show a significant positive association, researchers said.

“To our knowledge, this is the largest meta-analysis evaluation of the association between CMV seropositivity and MS,” said Smathorn Thakolwiboon, MD, a neurology resident at Texas Tech University, Lubbock, and colleagues. Understanding the reasons for the geographic heterogeneity will require further research, they said.

Researchers have hypothesized that increased incidence of autoimmune conditions may be linked to the prevention or delay of common infections, but studies have been inconclusive (Neurology. 2017 Sep 26;89[13]:1330-7.).

To evaluate the association between CMV seropositivity and MS, Dr. Thakolwiboon and colleagues searched databases, including PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science, from inception through Dec. 2018. They included in their analysis observational studies that evaluated the seroprevalence of CMV immunoglobulin G (IgG) in adults with MS and healthy controls. They estimated the odds ratio (OR) for CMV seropositivity and MS.

An initial search yielded 982 articles, 56 of which underwent full review. The researchers ultimately included 13 articles in their quantitative analysis. The studies included data from 3,049 patients with MS and 3,604 controls.

Overall, CMV seropositivity was significantly associated with MS (OR, 1.58; 95% confidence interval, 1.04-2.39; P = .031), but the relationship varied by region. In five U.S. studies, the association was not statistically significant (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 0.83-2.99; P = .168). CMV seropositivity was negatively associated with MS in Europe (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.68-0.96; P less than .001), but positively associated with MS in the Middle East (OR, 5.42; 95% CI, 1.06-27.89; P less than .001). “The meta-analysis showed a heterogeneity of the association between CMV seropositivity and MS,” the researchers concluded. “More genetic and environmental studies are needed for better understanding this geographic heterogeneity.”

Dr. Thakolwiboon had no disclosures. A coauthor disclosed speaking and advisory board roles with EMD Serono, Genzyme, Novartis, and Teva.

SOURCE: Thakolwiboon S et al. CMSC 2019. Abstract EPI01.

REPORTING FROM CMSC 2019

Key clinical point: Cytomegalovirus seropositivity may be associated with increased likelihood of multiple sclerosis in the Middle East and decreased likelihood in Europe.

Major finding: Overall, cytomegalovirus seropositivity was significantly associated with multiple sclerosis (OR, 1.58), but the relationship varied by region.

Study details: A meta-analysis of 13 studies that included data from 3,049 patients with MS and 3,604 controls.

Disclosures: Dr. Thakolwiboon had no disclosures. A coauthor disclosed speaking and advisory board roles with EMD Serono, Genzyme, Novartis, and Teva.

Source: Thakolwiboon S et al. CMSC 2019. Abstract EPI01.

Periodic limb movements during sleep are common in patients with MS and fatigue

Seattle – , according to a retrospective analysis described at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

“PLMS may contribute to daytime sleepiness and should be recognized and potentially treated. The etiology of fatigue related to sleep problems in people with MS is multifactorial and not just due to obstructive sleep apnea,” said lead author Jared Srinivasan, clinical research coordinator at South Shore Neurologic Associates in East Northport, New York, and colleagues.

Fatigue is common in patients with MS and can be disabling. For many patients with MS, sleep apnea is the underlying cause of fatigue. PLMS – leg movements that usually occur at 20- to 40-second intervals during sleep – are not commonly reported in MS. These movements cause sleep fragmentation, increase the energy cost of sleep, and contribute to daytime somnolence. Patients with PLMS often are unaware that they have them and do not report related symptoms unless they are specifically questioned about them. Polysomnography (PSG) is an effective, objective method of evaluating a patient for PLMS, but previous studies of PLMS in patients with MS have been small.

Mr. Srinivasan and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis to investigate the incidence and degree of PLMS in people with MS who had reported fatigue, had not previously been diagnosed as having sleep apnea or PLMS, and agreed to undergo overnight PSG.

The investigators included 292 participants in their study. The population’s average age was 47.3 years. Approximately 81% of patients were female. About 41% of the population had a PLMS index (PLMS per hour) greater than 0. Of participants with PSG-identified PLMS, 10% had a PLMS index of 5-10, 5% had a PLMS index of 11-21, and 12% had a PLMS index greater than 21. About 38% of the population experienced arousal because of PLMS. Of patients with arousal, 34% had a PLMS arousal index (number of arousals per hour) between 0 and 5, 31% had PLMS arousal index of 5-20, 14% had a PLMS arousal index of 20-50, and 21% had a PLMS arousal index greater than 50.

The investigators did not receive financial support for this study and did not report disclosures.

SOURCE: Srinivasan J et al. CMSC 2019. Abstract QOL29.

Seattle – , according to a retrospective analysis described at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

“PLMS may contribute to daytime sleepiness and should be recognized and potentially treated. The etiology of fatigue related to sleep problems in people with MS is multifactorial and not just due to obstructive sleep apnea,” said lead author Jared Srinivasan, clinical research coordinator at South Shore Neurologic Associates in East Northport, New York, and colleagues.

Fatigue is common in patients with MS and can be disabling. For many patients with MS, sleep apnea is the underlying cause of fatigue. PLMS – leg movements that usually occur at 20- to 40-second intervals during sleep – are not commonly reported in MS. These movements cause sleep fragmentation, increase the energy cost of sleep, and contribute to daytime somnolence. Patients with PLMS often are unaware that they have them and do not report related symptoms unless they are specifically questioned about them. Polysomnography (PSG) is an effective, objective method of evaluating a patient for PLMS, but previous studies of PLMS in patients with MS have been small.

Mr. Srinivasan and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis to investigate the incidence and degree of PLMS in people with MS who had reported fatigue, had not previously been diagnosed as having sleep apnea or PLMS, and agreed to undergo overnight PSG.

The investigators included 292 participants in their study. The population’s average age was 47.3 years. Approximately 81% of patients were female. About 41% of the population had a PLMS index (PLMS per hour) greater than 0. Of participants with PSG-identified PLMS, 10% had a PLMS index of 5-10, 5% had a PLMS index of 11-21, and 12% had a PLMS index greater than 21. About 38% of the population experienced arousal because of PLMS. Of patients with arousal, 34% had a PLMS arousal index (number of arousals per hour) between 0 and 5, 31% had PLMS arousal index of 5-20, 14% had a PLMS arousal index of 20-50, and 21% had a PLMS arousal index greater than 50.

The investigators did not receive financial support for this study and did not report disclosures.

SOURCE: Srinivasan J et al. CMSC 2019. Abstract QOL29.

Seattle – , according to a retrospective analysis described at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

“PLMS may contribute to daytime sleepiness and should be recognized and potentially treated. The etiology of fatigue related to sleep problems in people with MS is multifactorial and not just due to obstructive sleep apnea,” said lead author Jared Srinivasan, clinical research coordinator at South Shore Neurologic Associates in East Northport, New York, and colleagues.

Fatigue is common in patients with MS and can be disabling. For many patients with MS, sleep apnea is the underlying cause of fatigue. PLMS – leg movements that usually occur at 20- to 40-second intervals during sleep – are not commonly reported in MS. These movements cause sleep fragmentation, increase the energy cost of sleep, and contribute to daytime somnolence. Patients with PLMS often are unaware that they have them and do not report related symptoms unless they are specifically questioned about them. Polysomnography (PSG) is an effective, objective method of evaluating a patient for PLMS, but previous studies of PLMS in patients with MS have been small.

Mr. Srinivasan and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis to investigate the incidence and degree of PLMS in people with MS who had reported fatigue, had not previously been diagnosed as having sleep apnea or PLMS, and agreed to undergo overnight PSG.

The investigators included 292 participants in their study. The population’s average age was 47.3 years. Approximately 81% of patients were female. About 41% of the population had a PLMS index (PLMS per hour) greater than 0. Of participants with PSG-identified PLMS, 10% had a PLMS index of 5-10, 5% had a PLMS index of 11-21, and 12% had a PLMS index greater than 21. About 38% of the population experienced arousal because of PLMS. Of patients with arousal, 34% had a PLMS arousal index (number of arousals per hour) between 0 and 5, 31% had PLMS arousal index of 5-20, 14% had a PLMS arousal index of 20-50, and 21% had a PLMS arousal index greater than 50.

The investigators did not receive financial support for this study and did not report disclosures.

SOURCE: Srinivasan J et al. CMSC 2019. Abstract QOL29.

REPORTING FROM CMSC 2019

Key clinical point: Periodic limb movements during sleep are common in patients with multiple sclerosis who report fatigue.

Major finding: Approximately 41% of patients with multiple sclerosis and fatigue had periodic limb movements during sleep.

Study details: A retrospective study of 292 patients with MS and fatigue who underwent polysomnography.

Disclosures: The investigators did not receive financial support for this study and did not report disclosures.

Source: Srinivasan J et al. CMSC 2019. Abstract QOL29.

General neurologists lag on prescribing high-efficacy MS drugs

SEATTLE – It is not clear if the greater reluctance among general neurologists to prescribe the drugs is hurting the health of patients, and the study does not examine whether general neurologists are referring their toughest patients to their subspecialist colleagues.

Still, the findings raise questions because “starting highly effective drugs early can prevent long-term disability,” said study lead author and neurologist Casey V. Farin, MD, a clinical fellow in the department of neurology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., who spoke in an interview prior to the presentation of the study findings at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. “A lot of our general neurologists are prescribing the traditional platform therapies that have fallen a bit out of favor in the MS community,” she said.

Dr. Farin and colleagues launched their study to better understand whether “therapeutic inertia” is affecting how general neurologists treat MS. The term refers to “staying with one drug just because it is easier not to rock the boat,” she said. For the purposes of their study, the term encompasses reluctance of neurologists to escalate therapy or prescribe high-efficacy drugs.

“There have been small studies comparing subspecialists and general neurologists using surveys of theoretical cases,” she said. “No studies have looked at how people are prescribing disease-modifying therapy.”

In the new age of high-efficacy treatment, guidelines about early MS treatment are lacking. As the study abstract notes, “in the absence of robust head-to-head clinical data, neurologists do not have an accepted algorithm for initiation and escalation of therapy, although recent research indicates a benefit in initiating highly effective therapies early in the disease course.”

For the study, researchers tracked 4,753 patients with MS who were treated at the Duke University Health System from 2016 to 2018.