User login

When adolescents visit the ED, 10% leave with an opioid

although there was a small but significant decrease in prescriptions over that time, according to an analysis of two nationwide ambulatory care surveys.

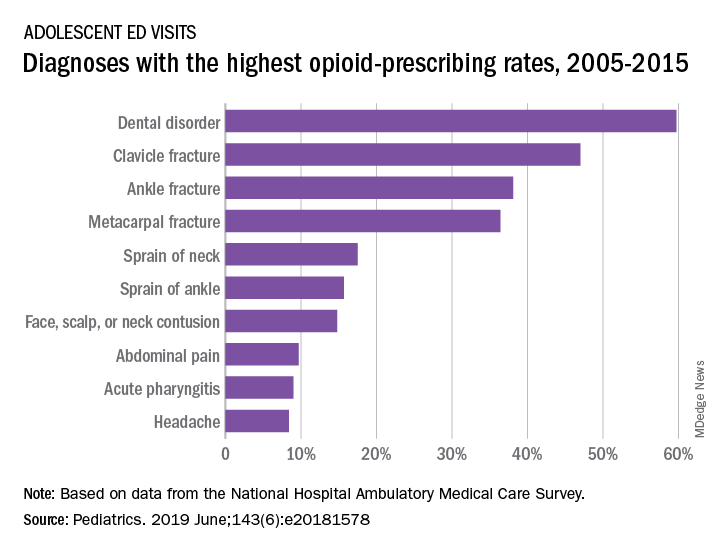

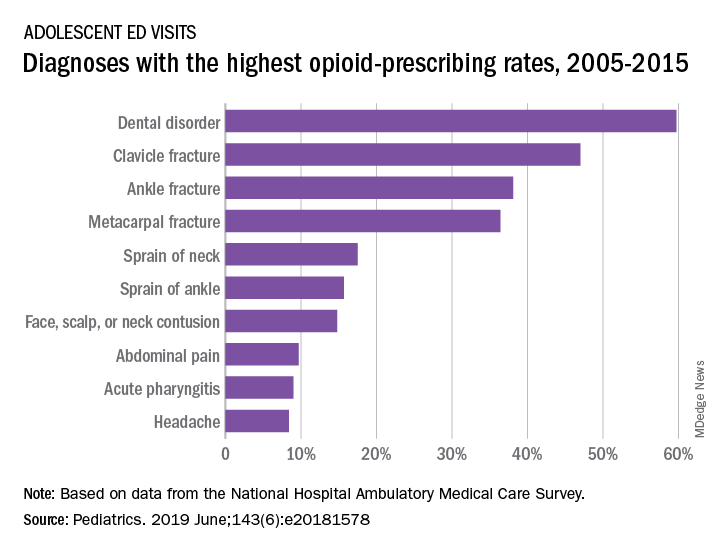

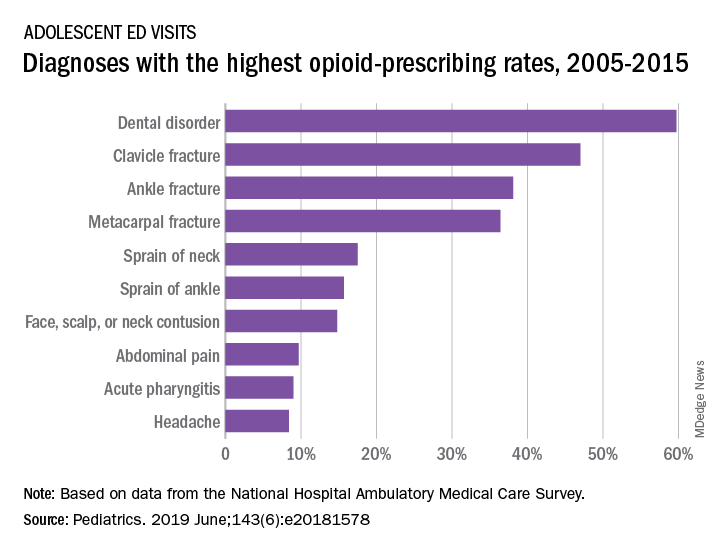

For adolescents aged 13-17 years, 10.4% of ED visits were associated with a prescription for an opioid versus 1.6% among outpatient visits. There was a slight but significant decrease in the rate of opioid prescriptions in the ED setting over the study period, with an odds ratio of 0.95 (95% confidence interval, 0.92-0.97), but there was no significant change in the trend over time in the outpatient setting (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.99-1.09), Joel D. Hudgins, MD, and associates reported in Pediatrics.

“Opioid prescribing in ambulatory care visits is particularly high in the ED setting and … certain diagnoses appear to be routinely treated with an opioid,” said Dr. Hudgins and associates from Boston Children’s Hospital.

The highest rates of opioid prescribing among adolescents visiting the ED involved dental disorders (60%) and acute injuries such as fractures of the clavicle (47%), ankle (38%), and metacarpals (36%). “However, when considering the total volume of opioid prescriptions dispensed [over 7.8 million during 2005-2015], certain common conditions, including abdominal pain, acute pharyngitis, urinary tract infection, and headache, contributed large numbers of prescriptions as well,” they added.

The study involved data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (hospital-based EDs) and the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (office-based practices), which both are conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics.

The senior investigator is supported by an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund by the Harvard-MIT Center for Regulatory Science. The authors said that they have no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Hudgins JD et al. Pediatrics. 2019 June. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1578.

although there was a small but significant decrease in prescriptions over that time, according to an analysis of two nationwide ambulatory care surveys.

For adolescents aged 13-17 years, 10.4% of ED visits were associated with a prescription for an opioid versus 1.6% among outpatient visits. There was a slight but significant decrease in the rate of opioid prescriptions in the ED setting over the study period, with an odds ratio of 0.95 (95% confidence interval, 0.92-0.97), but there was no significant change in the trend over time in the outpatient setting (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.99-1.09), Joel D. Hudgins, MD, and associates reported in Pediatrics.

“Opioid prescribing in ambulatory care visits is particularly high in the ED setting and … certain diagnoses appear to be routinely treated with an opioid,” said Dr. Hudgins and associates from Boston Children’s Hospital.

The highest rates of opioid prescribing among adolescents visiting the ED involved dental disorders (60%) and acute injuries such as fractures of the clavicle (47%), ankle (38%), and metacarpals (36%). “However, when considering the total volume of opioid prescriptions dispensed [over 7.8 million during 2005-2015], certain common conditions, including abdominal pain, acute pharyngitis, urinary tract infection, and headache, contributed large numbers of prescriptions as well,” they added.

The study involved data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (hospital-based EDs) and the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (office-based practices), which both are conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics.

The senior investigator is supported by an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund by the Harvard-MIT Center for Regulatory Science. The authors said that they have no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Hudgins JD et al. Pediatrics. 2019 June. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1578.

although there was a small but significant decrease in prescriptions over that time, according to an analysis of two nationwide ambulatory care surveys.

For adolescents aged 13-17 years, 10.4% of ED visits were associated with a prescription for an opioid versus 1.6% among outpatient visits. There was a slight but significant decrease in the rate of opioid prescriptions in the ED setting over the study period, with an odds ratio of 0.95 (95% confidence interval, 0.92-0.97), but there was no significant change in the trend over time in the outpatient setting (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.99-1.09), Joel D. Hudgins, MD, and associates reported in Pediatrics.

“Opioid prescribing in ambulatory care visits is particularly high in the ED setting and … certain diagnoses appear to be routinely treated with an opioid,” said Dr. Hudgins and associates from Boston Children’s Hospital.

The highest rates of opioid prescribing among adolescents visiting the ED involved dental disorders (60%) and acute injuries such as fractures of the clavicle (47%), ankle (38%), and metacarpals (36%). “However, when considering the total volume of opioid prescriptions dispensed [over 7.8 million during 2005-2015], certain common conditions, including abdominal pain, acute pharyngitis, urinary tract infection, and headache, contributed large numbers of prescriptions as well,” they added.

The study involved data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (hospital-based EDs) and the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (office-based practices), which both are conducted annually by the National Center for Health Statistics.

The senior investigator is supported by an award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund by the Harvard-MIT Center for Regulatory Science. The authors said that they have no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Hudgins JD et al. Pediatrics. 2019 June. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1578.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Social Media and Suicide

The potential harms of excessive Internet use are serious enough for the medical community to debate whether it should be included as a disorder associated with addiction. One question is Where do you draw the line between excessive use—considered nonpathologic behavior—and addiction?

Researchers surveyed 374 university students about social network habits, testing for obsession, lack of personal control, and excessive use. The questionnaire included questions such as “I feel a great need to stay connected to social media” and “I feel anxious when I cannot connect to social media.” The researchers also used a questionnaire about suicidal ideation.

More than half the students reported that WhatsApp is their most important social network, followed by Facebook. The respondents used social media for an average of nearly 7 hours a day. They used social media mainly for contact with friends, entertainment, conversing with a partner, maintaining contact with colleagues for academic matters, and contact with family.

The researchers divided the participants into 3 groups, based on their risk of addiction. The majority were considered “moderate risk.” Approximately 10% were considered “high risk.” The high-risk students spent roughly 11 hours a day on social media compared with the low-risk students who spent about 4 hours. Greater risk also implied more depressive symptoms, more mobile use, and less positive suicidal ideation.

Almost 4 in 10 students had thoughts and wishes about their death at least once in the 2 weeks before the survey. Interestingly, however, the researchers found no relationship between suicidal ideation and addictive behavior. But adding depression did make a difference. Unlike excessive use, addictive behavior was significantly related to depression and suicidal ideation.

The researchers cite other studies that have found addiction to social networks predicts depression and can worsen symptoms. But they also say their findings confirm other research that suggests social media communication can be protective for people who have suicidal thoughts. What looks like addiction may be “an act of escape” from unpleasant thoughts and feelings. Social media, they say, can be a “refuge.”

The potential harms of excessive Internet use are serious enough for the medical community to debate whether it should be included as a disorder associated with addiction. One question is Where do you draw the line between excessive use—considered nonpathologic behavior—and addiction?

Researchers surveyed 374 university students about social network habits, testing for obsession, lack of personal control, and excessive use. The questionnaire included questions such as “I feel a great need to stay connected to social media” and “I feel anxious when I cannot connect to social media.” The researchers also used a questionnaire about suicidal ideation.

More than half the students reported that WhatsApp is their most important social network, followed by Facebook. The respondents used social media for an average of nearly 7 hours a day. They used social media mainly for contact with friends, entertainment, conversing with a partner, maintaining contact with colleagues for academic matters, and contact with family.

The researchers divided the participants into 3 groups, based on their risk of addiction. The majority were considered “moderate risk.” Approximately 10% were considered “high risk.” The high-risk students spent roughly 11 hours a day on social media compared with the low-risk students who spent about 4 hours. Greater risk also implied more depressive symptoms, more mobile use, and less positive suicidal ideation.

Almost 4 in 10 students had thoughts and wishes about their death at least once in the 2 weeks before the survey. Interestingly, however, the researchers found no relationship between suicidal ideation and addictive behavior. But adding depression did make a difference. Unlike excessive use, addictive behavior was significantly related to depression and suicidal ideation.

The researchers cite other studies that have found addiction to social networks predicts depression and can worsen symptoms. But they also say their findings confirm other research that suggests social media communication can be protective for people who have suicidal thoughts. What looks like addiction may be “an act of escape” from unpleasant thoughts and feelings. Social media, they say, can be a “refuge.”

The potential harms of excessive Internet use are serious enough for the medical community to debate whether it should be included as a disorder associated with addiction. One question is Where do you draw the line between excessive use—considered nonpathologic behavior—and addiction?

Researchers surveyed 374 university students about social network habits, testing for obsession, lack of personal control, and excessive use. The questionnaire included questions such as “I feel a great need to stay connected to social media” and “I feel anxious when I cannot connect to social media.” The researchers also used a questionnaire about suicidal ideation.

More than half the students reported that WhatsApp is their most important social network, followed by Facebook. The respondents used social media for an average of nearly 7 hours a day. They used social media mainly for contact with friends, entertainment, conversing with a partner, maintaining contact with colleagues for academic matters, and contact with family.

The researchers divided the participants into 3 groups, based on their risk of addiction. The majority were considered “moderate risk.” Approximately 10% were considered “high risk.” The high-risk students spent roughly 11 hours a day on social media compared with the low-risk students who spent about 4 hours. Greater risk also implied more depressive symptoms, more mobile use, and less positive suicidal ideation.

Almost 4 in 10 students had thoughts and wishes about their death at least once in the 2 weeks before the survey. Interestingly, however, the researchers found no relationship between suicidal ideation and addictive behavior. But adding depression did make a difference. Unlike excessive use, addictive behavior was significantly related to depression and suicidal ideation.

The researchers cite other studies that have found addiction to social networks predicts depression and can worsen symptoms. But they also say their findings confirm other research that suggests social media communication can be protective for people who have suicidal thoughts. What looks like addiction may be “an act of escape” from unpleasant thoughts and feelings. Social media, they say, can be a “refuge.”

Do You Know Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever When You See It?

In 2017, the number of cases of tickborne spotted fever rickettsiosis (SFR) reported to the CDC jumped 46%—from 4,269 in 2016 to a “record” 6,248 cases. The New England, East North Central, and Mid-Atlantic regions in 2017 alone experienced a 215%, 78%, and 65% increase, respectively, although they typically report only a handful of cases each year.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is the most severe of the SFR. It begins with nonspecific symptoms such as fever and headache, and sometimes rash, but when left untreated, the disease can have serious consequences, including amputation. Roughly 1 in 5 untreated cases is fatal; half of those deaths occur within the first 8 days of illness.

However, RMSF is treatable with doxycycline, which can prevent disability and death if prescribed within the first 5 days of illness, meaning that early recognition and treatment can save lives. Yet cases “often go unrecognized because the signs and symptoms are similar to those of many other diseases,” says CDC Director Robert Redfield, MD. Less than 1% of the reported SFR cases in 2017 had sufficient laboratory evidence to be confirmed. And although the annual incidence of SFR in the US increased from 6.4 to 19.2 cases per million persons between years 2010 and 2017, the proportion of confirmed cases went down.

Citing the need to train health care providers (HCPs) on the best methods to diagnose tickborne diseases, the CDC has created a “first of its kind” clinical education tool that uses scenarios based on real cases to help clinicians recognize and differentiate among the various possibilities. The module is self-directed with knowledge checks, reference materials, and an interactive rash identification tool that allows HCPs to compare the rash seen in RMSF with that of other illnesses.

Continuing education credit is available for physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, veterinarians, nurses, epidemiologists, public health professionals, educators, and health communicators. To access the module, go to https://www.cdc.gov/rmsf/resources/module.html

In 2017, the number of cases of tickborne spotted fever rickettsiosis (SFR) reported to the CDC jumped 46%—from 4,269 in 2016 to a “record” 6,248 cases. The New England, East North Central, and Mid-Atlantic regions in 2017 alone experienced a 215%, 78%, and 65% increase, respectively, although they typically report only a handful of cases each year.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is the most severe of the SFR. It begins with nonspecific symptoms such as fever and headache, and sometimes rash, but when left untreated, the disease can have serious consequences, including amputation. Roughly 1 in 5 untreated cases is fatal; half of those deaths occur within the first 8 days of illness.

However, RMSF is treatable with doxycycline, which can prevent disability and death if prescribed within the first 5 days of illness, meaning that early recognition and treatment can save lives. Yet cases “often go unrecognized because the signs and symptoms are similar to those of many other diseases,” says CDC Director Robert Redfield, MD. Less than 1% of the reported SFR cases in 2017 had sufficient laboratory evidence to be confirmed. And although the annual incidence of SFR in the US increased from 6.4 to 19.2 cases per million persons between years 2010 and 2017, the proportion of confirmed cases went down.

Citing the need to train health care providers (HCPs) on the best methods to diagnose tickborne diseases, the CDC has created a “first of its kind” clinical education tool that uses scenarios based on real cases to help clinicians recognize and differentiate among the various possibilities. The module is self-directed with knowledge checks, reference materials, and an interactive rash identification tool that allows HCPs to compare the rash seen in RMSF with that of other illnesses.

Continuing education credit is available for physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, veterinarians, nurses, epidemiologists, public health professionals, educators, and health communicators. To access the module, go to https://www.cdc.gov/rmsf/resources/module.html

In 2017, the number of cases of tickborne spotted fever rickettsiosis (SFR) reported to the CDC jumped 46%—from 4,269 in 2016 to a “record” 6,248 cases. The New England, East North Central, and Mid-Atlantic regions in 2017 alone experienced a 215%, 78%, and 65% increase, respectively, although they typically report only a handful of cases each year.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) is the most severe of the SFR. It begins with nonspecific symptoms such as fever and headache, and sometimes rash, but when left untreated, the disease can have serious consequences, including amputation. Roughly 1 in 5 untreated cases is fatal; half of those deaths occur within the first 8 days of illness.

However, RMSF is treatable with doxycycline, which can prevent disability and death if prescribed within the first 5 days of illness, meaning that early recognition and treatment can save lives. Yet cases “often go unrecognized because the signs and symptoms are similar to those of many other diseases,” says CDC Director Robert Redfield, MD. Less than 1% of the reported SFR cases in 2017 had sufficient laboratory evidence to be confirmed. And although the annual incidence of SFR in the US increased from 6.4 to 19.2 cases per million persons between years 2010 and 2017, the proportion of confirmed cases went down.

Citing the need to train health care providers (HCPs) on the best methods to diagnose tickborne diseases, the CDC has created a “first of its kind” clinical education tool that uses scenarios based on real cases to help clinicians recognize and differentiate among the various possibilities. The module is self-directed with knowledge checks, reference materials, and an interactive rash identification tool that allows HCPs to compare the rash seen in RMSF with that of other illnesses.

Continuing education credit is available for physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, veterinarians, nurses, epidemiologists, public health professionals, educators, and health communicators. To access the module, go to https://www.cdc.gov/rmsf/resources/module.html

How Meth Abuse May Affect Visuospatial Processing

Methamphetamine (MA) abuse has been linked to psychological problems, such as depression, anxiety, and psychosis. It also has been linked to problems in everyday functioning (eg, impulsivity), and neurocognitive deficits in attention, memory, learning, executive function, and fine motor speed. But researchers from Capital Medical University in Beijing and Fujian Medical University in Fuzhou, both in China, say current understanding is limited about the impact of MA abuse in spatial processing, which affects, among other things, alertness.

The researchers conducted a study with 40 MA abusers and 40 nonusers. Participants performed 3 tasks randomly. During the Simple Reaction Task, they pressed a mouse key as quickly and accurately as possible, discriminating between hand and foot pictures. The Spatial Orientation Task asked them to gauge the direction of fingers or toes shown in pictures. The Mental Rotation Task randomly showed hands and feet in 2 different views (dorsum, palm/plantar) and oriented in 1 of 6 clockwise angles. It also assessed 2 different mental rotation strategies: object based and egocentric based, or the ability to judge which side a body part belongs to in the picture and in the participant’s own body. In this test, the researchers say, the transformation of visuospatial mental image is crucial to action, navigation, and reasoning.

The researchers found no significant difference in either accuracy or reaction time between the 2 groups in the first task. In the second, MA users performed less well on reaction time but not accuracy. The results of that task suggested that MA abuse may induce a deficit in spatial orientation ability, mainly on horizontal surface.

On the third task, however, MA abusers performed worse and committed more errors than did the nonusers. They had worse results at every orientation angle and took longer to judge the orientation of leftward but not rightward foot pictures. Such phenomena likely relate to MA damage to cortical gray and white matter, the researchers say. They note that MA users also have shown less activation in the right hemisphere when performing a facial-affect matching task. MA abuse may mainly target the right hemisphere, the researchers add, but the findings may support other research that has found poor decision-making performance in MA abusers that is related to inadequate activation of many brain areas.

The study confirmed “considerably poor visuospatial ability” in MA users. The Mental Rotation Task findings also showed MA abuse of longer duration had more negative effect on spatial process speed. Because both cognitive speed and accuracy were affected on the Mental Rotation Task, but only cognitive speed on Spatial Orientation, MA abuse may affect visuospatial ability more seriously than spatial orientation ability, the researchers say.

Methamphetamine (MA) abuse has been linked to psychological problems, such as depression, anxiety, and psychosis. It also has been linked to problems in everyday functioning (eg, impulsivity), and neurocognitive deficits in attention, memory, learning, executive function, and fine motor speed. But researchers from Capital Medical University in Beijing and Fujian Medical University in Fuzhou, both in China, say current understanding is limited about the impact of MA abuse in spatial processing, which affects, among other things, alertness.

The researchers conducted a study with 40 MA abusers and 40 nonusers. Participants performed 3 tasks randomly. During the Simple Reaction Task, they pressed a mouse key as quickly and accurately as possible, discriminating between hand and foot pictures. The Spatial Orientation Task asked them to gauge the direction of fingers or toes shown in pictures. The Mental Rotation Task randomly showed hands and feet in 2 different views (dorsum, palm/plantar) and oriented in 1 of 6 clockwise angles. It also assessed 2 different mental rotation strategies: object based and egocentric based, or the ability to judge which side a body part belongs to in the picture and in the participant’s own body. In this test, the researchers say, the transformation of visuospatial mental image is crucial to action, navigation, and reasoning.

The researchers found no significant difference in either accuracy or reaction time between the 2 groups in the first task. In the second, MA users performed less well on reaction time but not accuracy. The results of that task suggested that MA abuse may induce a deficit in spatial orientation ability, mainly on horizontal surface.

On the third task, however, MA abusers performed worse and committed more errors than did the nonusers. They had worse results at every orientation angle and took longer to judge the orientation of leftward but not rightward foot pictures. Such phenomena likely relate to MA damage to cortical gray and white matter, the researchers say. They note that MA users also have shown less activation in the right hemisphere when performing a facial-affect matching task. MA abuse may mainly target the right hemisphere, the researchers add, but the findings may support other research that has found poor decision-making performance in MA abusers that is related to inadequate activation of many brain areas.

The study confirmed “considerably poor visuospatial ability” in MA users. The Mental Rotation Task findings also showed MA abuse of longer duration had more negative effect on spatial process speed. Because both cognitive speed and accuracy were affected on the Mental Rotation Task, but only cognitive speed on Spatial Orientation, MA abuse may affect visuospatial ability more seriously than spatial orientation ability, the researchers say.

Methamphetamine (MA) abuse has been linked to psychological problems, such as depression, anxiety, and psychosis. It also has been linked to problems in everyday functioning (eg, impulsivity), and neurocognitive deficits in attention, memory, learning, executive function, and fine motor speed. But researchers from Capital Medical University in Beijing and Fujian Medical University in Fuzhou, both in China, say current understanding is limited about the impact of MA abuse in spatial processing, which affects, among other things, alertness.

The researchers conducted a study with 40 MA abusers and 40 nonusers. Participants performed 3 tasks randomly. During the Simple Reaction Task, they pressed a mouse key as quickly and accurately as possible, discriminating between hand and foot pictures. The Spatial Orientation Task asked them to gauge the direction of fingers or toes shown in pictures. The Mental Rotation Task randomly showed hands and feet in 2 different views (dorsum, palm/plantar) and oriented in 1 of 6 clockwise angles. It also assessed 2 different mental rotation strategies: object based and egocentric based, or the ability to judge which side a body part belongs to in the picture and in the participant’s own body. In this test, the researchers say, the transformation of visuospatial mental image is crucial to action, navigation, and reasoning.

The researchers found no significant difference in either accuracy or reaction time between the 2 groups in the first task. In the second, MA users performed less well on reaction time but not accuracy. The results of that task suggested that MA abuse may induce a deficit in spatial orientation ability, mainly on horizontal surface.

On the third task, however, MA abusers performed worse and committed more errors than did the nonusers. They had worse results at every orientation angle and took longer to judge the orientation of leftward but not rightward foot pictures. Such phenomena likely relate to MA damage to cortical gray and white matter, the researchers say. They note that MA users also have shown less activation in the right hemisphere when performing a facial-affect matching task. MA abuse may mainly target the right hemisphere, the researchers add, but the findings may support other research that has found poor decision-making performance in MA abusers that is related to inadequate activation of many brain areas.

The study confirmed “considerably poor visuospatial ability” in MA users. The Mental Rotation Task findings also showed MA abuse of longer duration had more negative effect on spatial process speed. Because both cognitive speed and accuracy were affected on the Mental Rotation Task, but only cognitive speed on Spatial Orientation, MA abuse may affect visuospatial ability more seriously than spatial orientation ability, the researchers say.

Tanezumab acts fast for OA pain relief

TORONTO – , according to a secondary analysis of a phase 3 randomized trial.

“The onset is relatively quick. It’s a monoclonal antibody, so it doesn’t work overnight, but by 3-5 days you see a significant difference,” Thomas J. Schnitzer, MD, PhD, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

He had previously presented the primary outcomes of this 696-patient, phase 3, randomized trial at the 2018 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. At OARSI 2019, the rheumatologist presented new data focusing on the speed and durability of the pain relief provided by tanezumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody designed to help keep pain signals produced in the periphery from reaching the CNS.

The double-blind trial included U.S. patients with an average 9.3-year disease duration who were randomized to either two 2.5-mg subcutaneous injections of the nerve growth factor inhibitor 8 weeks apart, a 2.5-mg dose followed 8 weeks later by a 5-mg dose, or two placebo injections. Eighty-five percent of subjects had knee OA, and the rest had hip OA. The patients had fairly severe pain, with average baseline Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain scores of 7.1-7.4. Notably, all study participants had to have a documented history of previous failure to respond to at least three pain relievers: acetaminophen, oral NSAIDs, and tramadol or opioids, according to Dr. Schnitzer, a rheumatologist who is professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation, anesthesiology, and medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

As previously reported, the co–primary endpoint of change from baseline to week 16 in WOMAC pain was –3.22 points with the 2.5-mg tanezumab regimen and –3.45 with the 2.5/5–mg strategy, both significantly better than the 2.56-point improvement with placebo. Improvement in WOMAC physical function followed suit, he said at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

Assessments were made at office visits every 2 weeks during the study. By the first visit at week 2, tanezumab was significantly better than placebo on both WOMAC measures, an advantage maintained for the rest of the 16 weeks. Pain relief in the tanezumab-treated groups was maximum at weeks 4 and 12; that is, 4 weeks following the first and second injections.

“This suggests that there’s an immediate effect of the antibody, which then tends to wane as the antibody begins to get cleared,” Dr. Schnitzer observed.

Study participants kept a structured daily pain diary, which enabled investigators to zero in on the timing of pain relief. Statistically significant separation from placebo was documented by day 3 in one group on tanezumab and by day 5 in the other.

An increased rate of rapidly progressive OA was a concern years ago in earlier studies of a now-abandoned intravenous formulation of tanezumab. However, in the phase 3 trial of the subcutaneous humanized monoclonal antibody, rapidly progressive OA occurred in only six patients, or 1.3%, during the 24-week safety follow-up period. Interestingly, the phenomenon was not dose related, as five of the six cases occurred in patients on the twin 2.5-mg regimen, and only one in the 2.5/5-mg group. No cases of osteonecrosis occurred in the trial.

One audience member rose to say she and her fellow rheumatologists are very excited about the prospect of possible access to a novel and more effective OA therapy. But she took issue with the trial’s reliance on WOMAC pain and physical function scores as primary endpoints, noting that OARSI experts have developed and validated several more comprehensive and globally informative assessment tools. Dr. Schnitzer readily agreed. The investigators utilized WOMAC pain and physical function because that’s what the U.S. and European regulatory agencies insist upon, he explained.

Clinicians should stay tuned because the results of much larger, longer-term phase 3 trials of tanezumab are due to be presented soon, he added.

Dr. Schnitzer reported serving as a consultant to Pfizer and Eli Lilly, which are jointly developing tanezumab and sponsored the trial, as well as to a handful of other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Bessette L et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S85-6, Abstract 88.

TORONTO – , according to a secondary analysis of a phase 3 randomized trial.

“The onset is relatively quick. It’s a monoclonal antibody, so it doesn’t work overnight, but by 3-5 days you see a significant difference,” Thomas J. Schnitzer, MD, PhD, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

He had previously presented the primary outcomes of this 696-patient, phase 3, randomized trial at the 2018 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. At OARSI 2019, the rheumatologist presented new data focusing on the speed and durability of the pain relief provided by tanezumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody designed to help keep pain signals produced in the periphery from reaching the CNS.

The double-blind trial included U.S. patients with an average 9.3-year disease duration who were randomized to either two 2.5-mg subcutaneous injections of the nerve growth factor inhibitor 8 weeks apart, a 2.5-mg dose followed 8 weeks later by a 5-mg dose, or two placebo injections. Eighty-five percent of subjects had knee OA, and the rest had hip OA. The patients had fairly severe pain, with average baseline Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain scores of 7.1-7.4. Notably, all study participants had to have a documented history of previous failure to respond to at least three pain relievers: acetaminophen, oral NSAIDs, and tramadol or opioids, according to Dr. Schnitzer, a rheumatologist who is professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation, anesthesiology, and medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

As previously reported, the co–primary endpoint of change from baseline to week 16 in WOMAC pain was –3.22 points with the 2.5-mg tanezumab regimen and –3.45 with the 2.5/5–mg strategy, both significantly better than the 2.56-point improvement with placebo. Improvement in WOMAC physical function followed suit, he said at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

Assessments were made at office visits every 2 weeks during the study. By the first visit at week 2, tanezumab was significantly better than placebo on both WOMAC measures, an advantage maintained for the rest of the 16 weeks. Pain relief in the tanezumab-treated groups was maximum at weeks 4 and 12; that is, 4 weeks following the first and second injections.

“This suggests that there’s an immediate effect of the antibody, which then tends to wane as the antibody begins to get cleared,” Dr. Schnitzer observed.

Study participants kept a structured daily pain diary, which enabled investigators to zero in on the timing of pain relief. Statistically significant separation from placebo was documented by day 3 in one group on tanezumab and by day 5 in the other.

An increased rate of rapidly progressive OA was a concern years ago in earlier studies of a now-abandoned intravenous formulation of tanezumab. However, in the phase 3 trial of the subcutaneous humanized monoclonal antibody, rapidly progressive OA occurred in only six patients, or 1.3%, during the 24-week safety follow-up period. Interestingly, the phenomenon was not dose related, as five of the six cases occurred in patients on the twin 2.5-mg regimen, and only one in the 2.5/5-mg group. No cases of osteonecrosis occurred in the trial.

One audience member rose to say she and her fellow rheumatologists are very excited about the prospect of possible access to a novel and more effective OA therapy. But she took issue with the trial’s reliance on WOMAC pain and physical function scores as primary endpoints, noting that OARSI experts have developed and validated several more comprehensive and globally informative assessment tools. Dr. Schnitzer readily agreed. The investigators utilized WOMAC pain and physical function because that’s what the U.S. and European regulatory agencies insist upon, he explained.

Clinicians should stay tuned because the results of much larger, longer-term phase 3 trials of tanezumab are due to be presented soon, he added.

Dr. Schnitzer reported serving as a consultant to Pfizer and Eli Lilly, which are jointly developing tanezumab and sponsored the trial, as well as to a handful of other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Bessette L et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S85-6, Abstract 88.

TORONTO – , according to a secondary analysis of a phase 3 randomized trial.

“The onset is relatively quick. It’s a monoclonal antibody, so it doesn’t work overnight, but by 3-5 days you see a significant difference,” Thomas J. Schnitzer, MD, PhD, reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

He had previously presented the primary outcomes of this 696-patient, phase 3, randomized trial at the 2018 annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. At OARSI 2019, the rheumatologist presented new data focusing on the speed and durability of the pain relief provided by tanezumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody designed to help keep pain signals produced in the periphery from reaching the CNS.

The double-blind trial included U.S. patients with an average 9.3-year disease duration who were randomized to either two 2.5-mg subcutaneous injections of the nerve growth factor inhibitor 8 weeks apart, a 2.5-mg dose followed 8 weeks later by a 5-mg dose, or two placebo injections. Eighty-five percent of subjects had knee OA, and the rest had hip OA. The patients had fairly severe pain, with average baseline Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain scores of 7.1-7.4. Notably, all study participants had to have a documented history of previous failure to respond to at least three pain relievers: acetaminophen, oral NSAIDs, and tramadol or opioids, according to Dr. Schnitzer, a rheumatologist who is professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation, anesthesiology, and medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

As previously reported, the co–primary endpoint of change from baseline to week 16 in WOMAC pain was –3.22 points with the 2.5-mg tanezumab regimen and –3.45 with the 2.5/5–mg strategy, both significantly better than the 2.56-point improvement with placebo. Improvement in WOMAC physical function followed suit, he said at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

Assessments were made at office visits every 2 weeks during the study. By the first visit at week 2, tanezumab was significantly better than placebo on both WOMAC measures, an advantage maintained for the rest of the 16 weeks. Pain relief in the tanezumab-treated groups was maximum at weeks 4 and 12; that is, 4 weeks following the first and second injections.

“This suggests that there’s an immediate effect of the antibody, which then tends to wane as the antibody begins to get cleared,” Dr. Schnitzer observed.

Study participants kept a structured daily pain diary, which enabled investigators to zero in on the timing of pain relief. Statistically significant separation from placebo was documented by day 3 in one group on tanezumab and by day 5 in the other.

An increased rate of rapidly progressive OA was a concern years ago in earlier studies of a now-abandoned intravenous formulation of tanezumab. However, in the phase 3 trial of the subcutaneous humanized monoclonal antibody, rapidly progressive OA occurred in only six patients, or 1.3%, during the 24-week safety follow-up period. Interestingly, the phenomenon was not dose related, as five of the six cases occurred in patients on the twin 2.5-mg regimen, and only one in the 2.5/5-mg group. No cases of osteonecrosis occurred in the trial.

One audience member rose to say she and her fellow rheumatologists are very excited about the prospect of possible access to a novel and more effective OA therapy. But she took issue with the trial’s reliance on WOMAC pain and physical function scores as primary endpoints, noting that OARSI experts have developed and validated several more comprehensive and globally informative assessment tools. Dr. Schnitzer readily agreed. The investigators utilized WOMAC pain and physical function because that’s what the U.S. and European regulatory agencies insist upon, he explained.

Clinicians should stay tuned because the results of much larger, longer-term phase 3 trials of tanezumab are due to be presented soon, he added.

Dr. Schnitzer reported serving as a consultant to Pfizer and Eli Lilly, which are jointly developing tanezumab and sponsored the trial, as well as to a handful of other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Bessette L et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S85-6, Abstract 88.

REPORTING FROM OARSI 2019

Key clinical point: The nerve growth factor inhibitor tanezumab brings rapid improvement in pain.

Major finding: Tanezumab-treated patients experienced significant pain reduction within 3-5 days after their first dose.

Study details: This was a phase 3, prospective, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 696 patients with refractory pain attributable to knee or hip OA.

Disclosures: The presenter reported serving as a consultant to Pfizer and Eli Lilly, which cosponsored the phase 3 trial.

Source: Bessette L et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019 Apr;27[suppl 1]:S85-6, Abstract 88.

Trump administration plans to repeal transgender health care protections

In a proposed rule issued May 24, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services outlined its plan to repeal an Obama-era policy that banned health care providers from discriminating against transgender patients. As part of the Affordable Care Act, Congress had directed HHS to apply existing civil rights and health care regulations to the health law exchanges, including rules that were consistent with Title IX, the federal law that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in federally funded programs. The Obama administration’s interpretation of this directive barred health care providers from denying care to transgender patients based on gender identify, defined as a patient’s “internal sense of being male, female, neither, or a combination of male and female.”

Repealing the transgender protections in the antidiscrimination policy will make the regulation more consistent with Title IX, according to HHS. In addition, revoking other provisions in the Obama-era policy associated with non–English speaking patients will reduce regulatory costs for unnecessary paperwork by $3.2 billion, according to a statement from the HHS.

“When Congress prohibited sex discrimination, it did so according to the plain meaning of the term, and we are making our regulations conform,” said Roger Severino, director of the HHS’s Office for Civil Rights, in the statement. “The American people want vigorous protection of civil rights and faithfulness to the text of the laws passed by their representatives. The proposed rule would accomplish both goals.”

In addressing the reasoning for the proposal, Mr. Severino noted two court decisions that have found the Obama-era policy unlawful. In 2016, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas temporarily barred the protections from being enacted, ruling that HHS had adopted an erroneous interpretation of “sex” under Title IX, and that the regulation was arbitrary and capricious for failing to incorporate Title IX’s religious and abortion exemptions. The U.S. District Court for the District of North Dakota agreed in a subsequent decision. Since the preliminary bans against the provisions, HHS has not enforced the protections. Removal of the discrimination protections for transgender patients would conform with the courts’ plain understanding of federal sex discrimination laws, according to HHS.

HHS emphasized that the proposed rule is not intended to remove any protections provided by Congress or to restrict states’ ability to enact health care discrimination protections that exceed Title IX requirements. Rather, the proposed rule would ensure that Title IX and corresponding regulations “follow the will of Congress with respect to the states by not expanding Title IX’s definition of ‘sex’ beyond the statutory bounds,” according to the proposed rule.

In addition to removing the transgender protections, the HHS also proposed to eliminate provisions under the Obama-era policy that required health care literature to be translated into 15 languages. The proposed revisions would eliminate $3.2 billion in unneeded paperwork burdens imposed by the translations, according to the agency. Mr. Severino indicated that the money saved could be used to more effectively address individual needs of non–English speakers such as by providing increased access to translators and interpreters.

The American College of Physicians expressed concern about the agency’s move to rewrite the discrimination rule.

“ACP believes that discrimination against patients, including those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT), creates social stigma that has been linked to negative physical and mental health outcomes, including anxiety, suicide, and substance or alcohol abuse,” ACP President Robert McLean, MD, said in a statement. “ACP strongly urges the administration to withdraw their proposal, and instead, make meaningful policy changes that will ensure nondiscrimination in health care against all patients, regardless of their sexual orientation, gender or gender identity, disability, or proficiency in the English language.”

In a proposed rule issued May 24, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services outlined its plan to repeal an Obama-era policy that banned health care providers from discriminating against transgender patients. As part of the Affordable Care Act, Congress had directed HHS to apply existing civil rights and health care regulations to the health law exchanges, including rules that were consistent with Title IX, the federal law that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in federally funded programs. The Obama administration’s interpretation of this directive barred health care providers from denying care to transgender patients based on gender identify, defined as a patient’s “internal sense of being male, female, neither, or a combination of male and female.”

Repealing the transgender protections in the antidiscrimination policy will make the regulation more consistent with Title IX, according to HHS. In addition, revoking other provisions in the Obama-era policy associated with non–English speaking patients will reduce regulatory costs for unnecessary paperwork by $3.2 billion, according to a statement from the HHS.

“When Congress prohibited sex discrimination, it did so according to the plain meaning of the term, and we are making our regulations conform,” said Roger Severino, director of the HHS’s Office for Civil Rights, in the statement. “The American people want vigorous protection of civil rights and faithfulness to the text of the laws passed by their representatives. The proposed rule would accomplish both goals.”

In addressing the reasoning for the proposal, Mr. Severino noted two court decisions that have found the Obama-era policy unlawful. In 2016, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas temporarily barred the protections from being enacted, ruling that HHS had adopted an erroneous interpretation of “sex” under Title IX, and that the regulation was arbitrary and capricious for failing to incorporate Title IX’s religious and abortion exemptions. The U.S. District Court for the District of North Dakota agreed in a subsequent decision. Since the preliminary bans against the provisions, HHS has not enforced the protections. Removal of the discrimination protections for transgender patients would conform with the courts’ plain understanding of federal sex discrimination laws, according to HHS.

HHS emphasized that the proposed rule is not intended to remove any protections provided by Congress or to restrict states’ ability to enact health care discrimination protections that exceed Title IX requirements. Rather, the proposed rule would ensure that Title IX and corresponding regulations “follow the will of Congress with respect to the states by not expanding Title IX’s definition of ‘sex’ beyond the statutory bounds,” according to the proposed rule.

In addition to removing the transgender protections, the HHS also proposed to eliminate provisions under the Obama-era policy that required health care literature to be translated into 15 languages. The proposed revisions would eliminate $3.2 billion in unneeded paperwork burdens imposed by the translations, according to the agency. Mr. Severino indicated that the money saved could be used to more effectively address individual needs of non–English speakers such as by providing increased access to translators and interpreters.

The American College of Physicians expressed concern about the agency’s move to rewrite the discrimination rule.

“ACP believes that discrimination against patients, including those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT), creates social stigma that has been linked to negative physical and mental health outcomes, including anxiety, suicide, and substance or alcohol abuse,” ACP President Robert McLean, MD, said in a statement. “ACP strongly urges the administration to withdraw their proposal, and instead, make meaningful policy changes that will ensure nondiscrimination in health care against all patients, regardless of their sexual orientation, gender or gender identity, disability, or proficiency in the English language.”

In a proposed rule issued May 24, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services outlined its plan to repeal an Obama-era policy that banned health care providers from discriminating against transgender patients. As part of the Affordable Care Act, Congress had directed HHS to apply existing civil rights and health care regulations to the health law exchanges, including rules that were consistent with Title IX, the federal law that prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in federally funded programs. The Obama administration’s interpretation of this directive barred health care providers from denying care to transgender patients based on gender identify, defined as a patient’s “internal sense of being male, female, neither, or a combination of male and female.”

Repealing the transgender protections in the antidiscrimination policy will make the regulation more consistent with Title IX, according to HHS. In addition, revoking other provisions in the Obama-era policy associated with non–English speaking patients will reduce regulatory costs for unnecessary paperwork by $3.2 billion, according to a statement from the HHS.

“When Congress prohibited sex discrimination, it did so according to the plain meaning of the term, and we are making our regulations conform,” said Roger Severino, director of the HHS’s Office for Civil Rights, in the statement. “The American people want vigorous protection of civil rights and faithfulness to the text of the laws passed by their representatives. The proposed rule would accomplish both goals.”

In addressing the reasoning for the proposal, Mr. Severino noted two court decisions that have found the Obama-era policy unlawful. In 2016, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas temporarily barred the protections from being enacted, ruling that HHS had adopted an erroneous interpretation of “sex” under Title IX, and that the regulation was arbitrary and capricious for failing to incorporate Title IX’s religious and abortion exemptions. The U.S. District Court for the District of North Dakota agreed in a subsequent decision. Since the preliminary bans against the provisions, HHS has not enforced the protections. Removal of the discrimination protections for transgender patients would conform with the courts’ plain understanding of federal sex discrimination laws, according to HHS.

HHS emphasized that the proposed rule is not intended to remove any protections provided by Congress or to restrict states’ ability to enact health care discrimination protections that exceed Title IX requirements. Rather, the proposed rule would ensure that Title IX and corresponding regulations “follow the will of Congress with respect to the states by not expanding Title IX’s definition of ‘sex’ beyond the statutory bounds,” according to the proposed rule.

In addition to removing the transgender protections, the HHS also proposed to eliminate provisions under the Obama-era policy that required health care literature to be translated into 15 languages. The proposed revisions would eliminate $3.2 billion in unneeded paperwork burdens imposed by the translations, according to the agency. Mr. Severino indicated that the money saved could be used to more effectively address individual needs of non–English speakers such as by providing increased access to translators and interpreters.

The American College of Physicians expressed concern about the agency’s move to rewrite the discrimination rule.

“ACP believes that discrimination against patients, including those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT), creates social stigma that has been linked to negative physical and mental health outcomes, including anxiety, suicide, and substance or alcohol abuse,” ACP President Robert McLean, MD, said in a statement. “ACP strongly urges the administration to withdraw their proposal, and instead, make meaningful policy changes that will ensure nondiscrimination in health care against all patients, regardless of their sexual orientation, gender or gender identity, disability, or proficiency in the English language.”

Babesiosis HIV

According to the CDC, the number of reported tickborne diseases more than doubled between 2004-2016 and accounted for > 60% of all reported mosquito-borne, tickborne, and fleaborne disease cases. Which is why it is important to keep an eye out for anyone who has a history of being in a tick-promoting environment. Clinicians from Lehigh Valley Health Network Pocono and Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine, both in East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, report on a patient whose diagnosis turned on that fact.

The patient, a 71-year-old man, had fever, weakness, headaches, near syncope, and nausea for 4 days. He also had not been eating well.

A complete blood count showed pancytopenia with an excess of band cells, an indicator of inflammation and infection. The patient’s aspartate transaminase levels were elevated. The diagnostic dilemma centered on these findings: Serology tests for HIV 1 and 2 were positive, and a peripheral blood smear showed 0.5% parasitemia consistent with Babesia microti. Both babesiosis and HIV were among the possible diagnoses. Two important factors the clinicians had to consider: The patient had recently been bitten by ticks and was homosexual.

The clinicians note that a variety of infections can lead to false-positive HIV serology, such as malaria, Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Rickettsia species, influenza and hepatitis B vaccinations. Moreover, the Ixodes tick, the same vector that transmits Borrelia burgdorferi, which causes Lyme disease, also transmits B microti. Conversely, HIV infection can exacerbate Lyme disease or babesiosis.

The tests showing B microti were the clincher for the clinicians, who started treatment with fluids, atovaquone, and azithromycin. The patient recovered completely. Repeat HIV serology was negative.

The authors of the report note that babesiosis can be a life-threatening infection in patients with reduced immunity. It is possible that, like malaria and HIV serologies, Babesia and HIV serologies cross-react, the clinicians say. Thus, it is important to screen for both in both infections.

This is the first case, to the clinician’s knowledge, of HIV associated with active babesiosis

According to the CDC, the number of reported tickborne diseases more than doubled between 2004-2016 and accounted for > 60% of all reported mosquito-borne, tickborne, and fleaborne disease cases. Which is why it is important to keep an eye out for anyone who has a history of being in a tick-promoting environment. Clinicians from Lehigh Valley Health Network Pocono and Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine, both in East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, report on a patient whose diagnosis turned on that fact.

The patient, a 71-year-old man, had fever, weakness, headaches, near syncope, and nausea for 4 days. He also had not been eating well.

A complete blood count showed pancytopenia with an excess of band cells, an indicator of inflammation and infection. The patient’s aspartate transaminase levels were elevated. The diagnostic dilemma centered on these findings: Serology tests for HIV 1 and 2 were positive, and a peripheral blood smear showed 0.5% parasitemia consistent with Babesia microti. Both babesiosis and HIV were among the possible diagnoses. Two important factors the clinicians had to consider: The patient had recently been bitten by ticks and was homosexual.

The clinicians note that a variety of infections can lead to false-positive HIV serology, such as malaria, Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Rickettsia species, influenza and hepatitis B vaccinations. Moreover, the Ixodes tick, the same vector that transmits Borrelia burgdorferi, which causes Lyme disease, also transmits B microti. Conversely, HIV infection can exacerbate Lyme disease or babesiosis.

The tests showing B microti were the clincher for the clinicians, who started treatment with fluids, atovaquone, and azithromycin. The patient recovered completely. Repeat HIV serology was negative.

The authors of the report note that babesiosis can be a life-threatening infection in patients with reduced immunity. It is possible that, like malaria and HIV serologies, Babesia and HIV serologies cross-react, the clinicians say. Thus, it is important to screen for both in both infections.

This is the first case, to the clinician’s knowledge, of HIV associated with active babesiosis

According to the CDC, the number of reported tickborne diseases more than doubled between 2004-2016 and accounted for > 60% of all reported mosquito-borne, tickborne, and fleaborne disease cases. Which is why it is important to keep an eye out for anyone who has a history of being in a tick-promoting environment. Clinicians from Lehigh Valley Health Network Pocono and Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine, both in East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, report on a patient whose diagnosis turned on that fact.

The patient, a 71-year-old man, had fever, weakness, headaches, near syncope, and nausea for 4 days. He also had not been eating well.

A complete blood count showed pancytopenia with an excess of band cells, an indicator of inflammation and infection. The patient’s aspartate transaminase levels were elevated. The diagnostic dilemma centered on these findings: Serology tests for HIV 1 and 2 were positive, and a peripheral blood smear showed 0.5% parasitemia consistent with Babesia microti. Both babesiosis and HIV were among the possible diagnoses. Two important factors the clinicians had to consider: The patient had recently been bitten by ticks and was homosexual.

The clinicians note that a variety of infections can lead to false-positive HIV serology, such as malaria, Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Rickettsia species, influenza and hepatitis B vaccinations. Moreover, the Ixodes tick, the same vector that transmits Borrelia burgdorferi, which causes Lyme disease, also transmits B microti. Conversely, HIV infection can exacerbate Lyme disease or babesiosis.

The tests showing B microti were the clincher for the clinicians, who started treatment with fluids, atovaquone, and azithromycin. The patient recovered completely. Repeat HIV serology was negative.

The authors of the report note that babesiosis can be a life-threatening infection in patients with reduced immunity. It is possible that, like malaria and HIV serologies, Babesia and HIV serologies cross-react, the clinicians say. Thus, it is important to screen for both in both infections.

This is the first case, to the clinician’s knowledge, of HIV associated with active babesiosis

FDA approves PI3K inhibitor alpelisib for breast cancer

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first PI3K inhibitor for the treatment of breast cancer.

The drug, alpelisib (Piqray), was approved for use in combination with fulvestrant for men and postmenopausal women who have hormone receptor (HR)–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–negative, PIK3CA-mutated, advanced or metastatic breast cancer after progression on, or after, an endocrine-based regimen. The approval was announced by the FDA in a statement.

The agency also approved a diagnostic test – the therascreen PIK3CA RGQ PCR Kit – for detecting the PIK3CA mutation. The approval is based on results from the SOLAR-1 trial. In 572 HR-positive, HER2-negative patients with advanced or metastatic breast cancer who progressed after, or during, treatment with an aromatase inhibitor, the addition of alpelisib to fulvestrant significantly improved progression-free survival in patients with PIK3CA mutated tumors.

Median progression-free survival was 5.7 months on fulvestrant plus placebo, versus 11 months with fulvestrant plus alpelisib (hazard ratio for progression or death, 0.65; 95% confidence interval, 0.50-0.85; P less than .001). The results of the trial were recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 May 16;380[20]:1929-40).

In the FDA statement, Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, noted that alpelisib is the “first PI3K inhibitor to demonstrate a clinically meaningful benefit in treating patients with this type of breast cancer.”

The drug’s application was approved under the Real-Time Oncology Review pilot program, which allows the FDA to begin analyzing efficacy and safety databases before a new drug application is even submitted.

The FDA noted that patients should not start treatment on alpelisib if they have a history of severe skin reactions, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, or toxic epidermal necrolysis.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first PI3K inhibitor for the treatment of breast cancer.

The drug, alpelisib (Piqray), was approved for use in combination with fulvestrant for men and postmenopausal women who have hormone receptor (HR)–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–negative, PIK3CA-mutated, advanced or metastatic breast cancer after progression on, or after, an endocrine-based regimen. The approval was announced by the FDA in a statement.

The agency also approved a diagnostic test – the therascreen PIK3CA RGQ PCR Kit – for detecting the PIK3CA mutation. The approval is based on results from the SOLAR-1 trial. In 572 HR-positive, HER2-negative patients with advanced or metastatic breast cancer who progressed after, or during, treatment with an aromatase inhibitor, the addition of alpelisib to fulvestrant significantly improved progression-free survival in patients with PIK3CA mutated tumors.

Median progression-free survival was 5.7 months on fulvestrant plus placebo, versus 11 months with fulvestrant plus alpelisib (hazard ratio for progression or death, 0.65; 95% confidence interval, 0.50-0.85; P less than .001). The results of the trial were recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 May 16;380[20]:1929-40).

In the FDA statement, Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, noted that alpelisib is the “first PI3K inhibitor to demonstrate a clinically meaningful benefit in treating patients with this type of breast cancer.”

The drug’s application was approved under the Real-Time Oncology Review pilot program, which allows the FDA to begin analyzing efficacy and safety databases before a new drug application is even submitted.

The FDA noted that patients should not start treatment on alpelisib if they have a history of severe skin reactions, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, or toxic epidermal necrolysis.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first PI3K inhibitor for the treatment of breast cancer.

The drug, alpelisib (Piqray), was approved for use in combination with fulvestrant for men and postmenopausal women who have hormone receptor (HR)–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–negative, PIK3CA-mutated, advanced or metastatic breast cancer after progression on, or after, an endocrine-based regimen. The approval was announced by the FDA in a statement.

The agency also approved a diagnostic test – the therascreen PIK3CA RGQ PCR Kit – for detecting the PIK3CA mutation. The approval is based on results from the SOLAR-1 trial. In 572 HR-positive, HER2-negative patients with advanced or metastatic breast cancer who progressed after, or during, treatment with an aromatase inhibitor, the addition of alpelisib to fulvestrant significantly improved progression-free survival in patients with PIK3CA mutated tumors.

Median progression-free survival was 5.7 months on fulvestrant plus placebo, versus 11 months with fulvestrant plus alpelisib (hazard ratio for progression or death, 0.65; 95% confidence interval, 0.50-0.85; P less than .001). The results of the trial were recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2019 May 16;380[20]:1929-40).

In the FDA statement, Richard Pazdur, MD, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, noted that alpelisib is the “first PI3K inhibitor to demonstrate a clinically meaningful benefit in treating patients with this type of breast cancer.”

The drug’s application was approved under the Real-Time Oncology Review pilot program, which allows the FDA to begin analyzing efficacy and safety databases before a new drug application is even submitted.

The FDA noted that patients should not start treatment on alpelisib if they have a history of severe skin reactions, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, or toxic epidermal necrolysis.

FDA announces clearance of modified endoscope connector

which was designed to reduce the risk of cross-contamination previously identified by the FDA.

In a letter published April 18, the FDA had written that the original version of the product, the Erbe USA ERBEFLO port connector, was the only one of its type on the market that did not feature a method of backflow prevention, as recommended by new FDA guidelines. As such, the original ERBEFLO device did not adequately reduce the risk of cross-contamination; blood, stool, or other fluids from previous patients could travel through the endoscopy channels, contaminating the connector, tubing, and water bottle.

The FDA approval of the modified ERBEFLO port connector is based on a review of the functional and simulated use testing of the modified device design. The effectiveness of the device at reducing the risk of backflow and contamination is also supported by simulated testing.

Revised labeling included with the product identifies compatible endoscopes and accessories and provides warnings to ensure proper usage.

“The clearance of the modified ERBEFLO 24-hour use port connector provides another option for health care facilities whose staff understand and can fully implement the instructions for use to reduce the risk of cross-contamination and infection,” the FDA said in the May 23 update letter.

which was designed to reduce the risk of cross-contamination previously identified by the FDA.

In a letter published April 18, the FDA had written that the original version of the product, the Erbe USA ERBEFLO port connector, was the only one of its type on the market that did not feature a method of backflow prevention, as recommended by new FDA guidelines. As such, the original ERBEFLO device did not adequately reduce the risk of cross-contamination; blood, stool, or other fluids from previous patients could travel through the endoscopy channels, contaminating the connector, tubing, and water bottle.

The FDA approval of the modified ERBEFLO port connector is based on a review of the functional and simulated use testing of the modified device design. The effectiveness of the device at reducing the risk of backflow and contamination is also supported by simulated testing.

Revised labeling included with the product identifies compatible endoscopes and accessories and provides warnings to ensure proper usage.

“The clearance of the modified ERBEFLO 24-hour use port connector provides another option for health care facilities whose staff understand and can fully implement the instructions for use to reduce the risk of cross-contamination and infection,” the FDA said in the May 23 update letter.

which was designed to reduce the risk of cross-contamination previously identified by the FDA.

In a letter published April 18, the FDA had written that the original version of the product, the Erbe USA ERBEFLO port connector, was the only one of its type on the market that did not feature a method of backflow prevention, as recommended by new FDA guidelines. As such, the original ERBEFLO device did not adequately reduce the risk of cross-contamination; blood, stool, or other fluids from previous patients could travel through the endoscopy channels, contaminating the connector, tubing, and water bottle.

The FDA approval of the modified ERBEFLO port connector is based on a review of the functional and simulated use testing of the modified device design. The effectiveness of the device at reducing the risk of backflow and contamination is also supported by simulated testing.

Revised labeling included with the product identifies compatible endoscopes and accessories and provides warnings to ensure proper usage.

“The clearance of the modified ERBEFLO 24-hour use port connector provides another option for health care facilities whose staff understand and can fully implement the instructions for use to reduce the risk of cross-contamination and infection,” the FDA said in the May 23 update letter.

FDA approves NovoTTF-100L System for advanced mesothelioma

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the NovoTTF-100L System in combination with pemetrexed plus platinum-based chemotherapy for the first-line treatment of unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic, malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM).

The NovoTTF-100L System uses electric fields tuned to specific frequencies to disrupt solid tumor cancer cell division, Novocure, makers of NovoTTF-100L, said in a press release.

FDA approval was based on the single-arm STELLAR registration trial, which included 80 patients with unresectable and previously untreated MPM who were candidates for treatment with pemetrexed and cisplatin or carboplatin.

Median overall survival among all patients treated with NovoTTF-100L plus chemotherapy was 18.2 months (95% confidence interval, 12.1-25.8). The disease control rate in the 72 patients with at least one follow-up CT scan performed was 97%; 40% of patients had a partial response, 57% had stable disease, and 3% had progressive disease. The median progression free survival was 7.6 months.

The most common adverse events observed with the NovoTTF-100L System in combination with chemotherapy in patients with MPM were anemia, constipation, nausea, asthenia, chest pain, fatigue, device skin reaction, pruritus, and cough.

Other potential adverse effects associated with the use of the NovoTTF-100L System include: treatment related skin toxicity, allergic reaction to the plaster or to the gel, electrode overheating leading to pain and/or local skin burns, infections at sites of electrode contact with the skin, local warmth and tingling sensation beneath the electrodes, muscle twitching, medical site reaction, and skin breakdown/skin ulcer.

The NovoTTF-100L System can be prescribed only by a health care provider who has completed the required certification training provided by Novocure, the company said in the press release.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the NovoTTF-100L System in combination with pemetrexed plus platinum-based chemotherapy for the first-line treatment of unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic, malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM).

The NovoTTF-100L System uses electric fields tuned to specific frequencies to disrupt solid tumor cancer cell division, Novocure, makers of NovoTTF-100L, said in a press release.

FDA approval was based on the single-arm STELLAR registration trial, which included 80 patients with unresectable and previously untreated MPM who were candidates for treatment with pemetrexed and cisplatin or carboplatin.

Median overall survival among all patients treated with NovoTTF-100L plus chemotherapy was 18.2 months (95% confidence interval, 12.1-25.8). The disease control rate in the 72 patients with at least one follow-up CT scan performed was 97%; 40% of patients had a partial response, 57% had stable disease, and 3% had progressive disease. The median progression free survival was 7.6 months.

The most common adverse events observed with the NovoTTF-100L System in combination with chemotherapy in patients with MPM were anemia, constipation, nausea, asthenia, chest pain, fatigue, device skin reaction, pruritus, and cough.

Other potential adverse effects associated with the use of the NovoTTF-100L System include: treatment related skin toxicity, allergic reaction to the plaster or to the gel, electrode overheating leading to pain and/or local skin burns, infections at sites of electrode contact with the skin, local warmth and tingling sensation beneath the electrodes, muscle twitching, medical site reaction, and skin breakdown/skin ulcer.

The NovoTTF-100L System can be prescribed only by a health care provider who has completed the required certification training provided by Novocure, the company said in the press release.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the NovoTTF-100L System in combination with pemetrexed plus platinum-based chemotherapy for the first-line treatment of unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic, malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM).

The NovoTTF-100L System uses electric fields tuned to specific frequencies to disrupt solid tumor cancer cell division, Novocure, makers of NovoTTF-100L, said in a press release.

FDA approval was based on the single-arm STELLAR registration trial, which included 80 patients with unresectable and previously untreated MPM who were candidates for treatment with pemetrexed and cisplatin or carboplatin.

Median overall survival among all patients treated with NovoTTF-100L plus chemotherapy was 18.2 months (95% confidence interval, 12.1-25.8). The disease control rate in the 72 patients with at least one follow-up CT scan performed was 97%; 40% of patients had a partial response, 57% had stable disease, and 3% had progressive disease. The median progression free survival was 7.6 months.

The most common adverse events observed with the NovoTTF-100L System in combination with chemotherapy in patients with MPM were anemia, constipation, nausea, asthenia, chest pain, fatigue, device skin reaction, pruritus, and cough.

Other potential adverse effects associated with the use of the NovoTTF-100L System include: treatment related skin toxicity, allergic reaction to the plaster or to the gel, electrode overheating leading to pain and/or local skin burns, infections at sites of electrode contact with the skin, local warmth and tingling sensation beneath the electrodes, muscle twitching, medical site reaction, and skin breakdown/skin ulcer.

The NovoTTF-100L System can be prescribed only by a health care provider who has completed the required certification training provided by Novocure, the company said in the press release.