User login

Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome and Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an aggressive neuroendocrine malignancy of the skin that is thought to arise from neural crest cells. It has an estimated annual incidence of 0.6 per 100,000 individuals, typically occurs in the elderly population, and is most common in white males.1 The tumor presents as a rapidly growing, violaceous nodule in sun-exposed areas of the skin; early in the course, it can be mistaken for a benign entity such as an epidermal cyst.2 Merkel cell carcinoma has a propensity to spread to regional lymph nodes, and in some cases, it occurs in the absence of skin findings.3 Histologically, MCC is nearly indistinguishable from small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC).4 The overall prognosis for patients with MCC is poor and largely dependent on the stage at diagnosis. Patients with regional and distant metastases have a 5-year survival rate of 26% to 42% and 18%, respectively.3

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) is a paraneoplastic or autoimmune disorder of the neuromuscular junction that is found in 3% of cases of SCLC.4 Reported cases of LEMS in patients with MCC are exceedingly rare.5-8 We provide a full report and longitudinal clinical follow-up of a case that was briefly discussed by Simmons et al,8 and we review the literature regarding paraneoplastic syndromes associated with MCC and other extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas (EPSCCs).

Case Report

A 63-year-old man was evaluated in the neurology clinic due to difficulty walking, climbing stairs, and performing push-ups over the last month. Prior to the onset of symptoms, he was otherwise healthy, walking 3 miles daily; however, at presentation he required use of a cane. Leg weakness worsened as the day progressed. In addition, he reported constipation, urinary urgency, dry mouth, mild dysphagia, reduced sensation below the knees, and a nasal quality in his speech. He had no ptosis, diplopia, dysarthria, muscle cramps, myalgia, or facial weakness. He denied fevers, chills, and night sweats but did admit to an unintentional 10- to 15-lb weight loss over the preceding few months.

The neurologic examination revealed mild proximal upper extremity weakness in the bilateral shoulder abductors, infraspinatus, hip extensors, and hip flexors (Medical Research Council muscle scale grade 4). All deep tendon reflexes, except the Achilles reflex, were present. Despite subjective sensory concerns, objective examination of all sensory modalities was normal. Cranial nerve examination was normal, except for a slight nasal quality to his voice.

A qualitative assay was positive for the presence of P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channel (VGCC) antibodies. Other laboratory studies were within reference range, including acetylcholine-receptor antibodies (blocking, binding, and modulating) and muscle-specific kinase antibodies.

Lumbar and cervical spine magnetic resonance imaging revealed multilevel neuroforaminal stenosis without spinal canal stenosis or myelopathy. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest was notable for 2 pathologically enlarged lymph nodes in the left axilla and no evidence of primary pulmonary malignancy. Nerve-conduction studies (NCSs) in conjunction with other clinical findings were consistent with the diagnosis of LEMS.

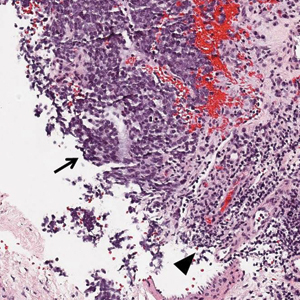

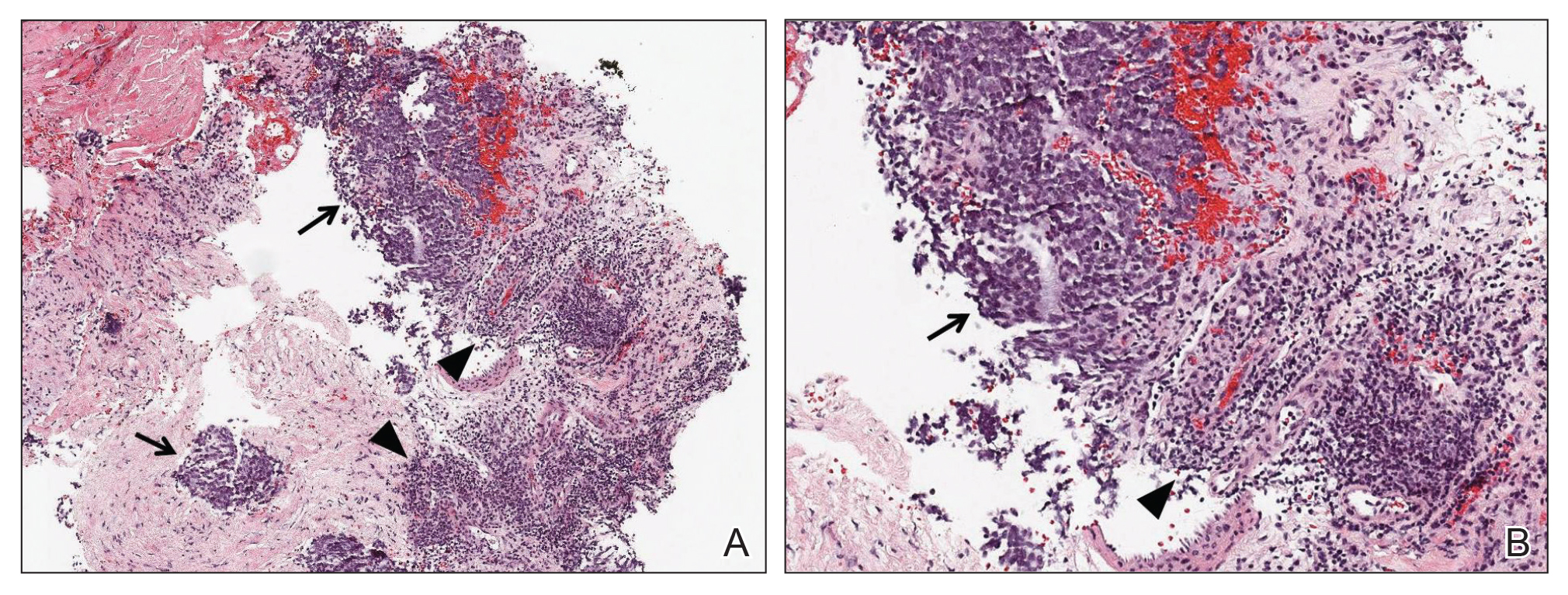

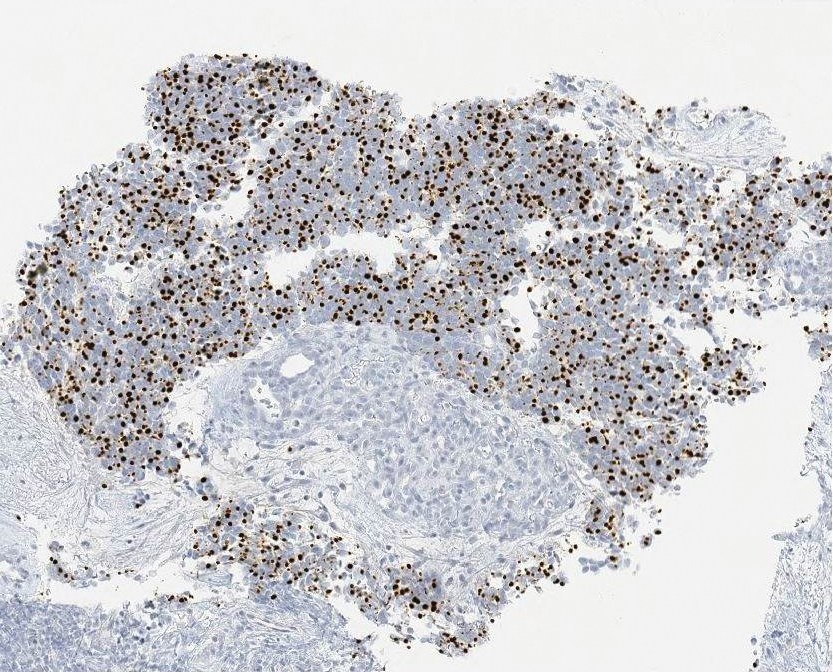

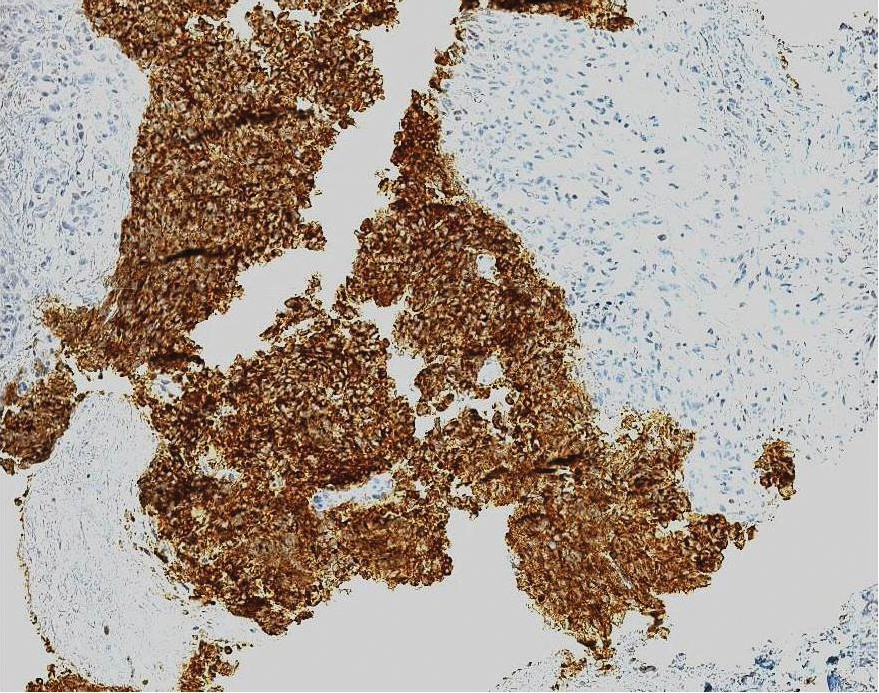

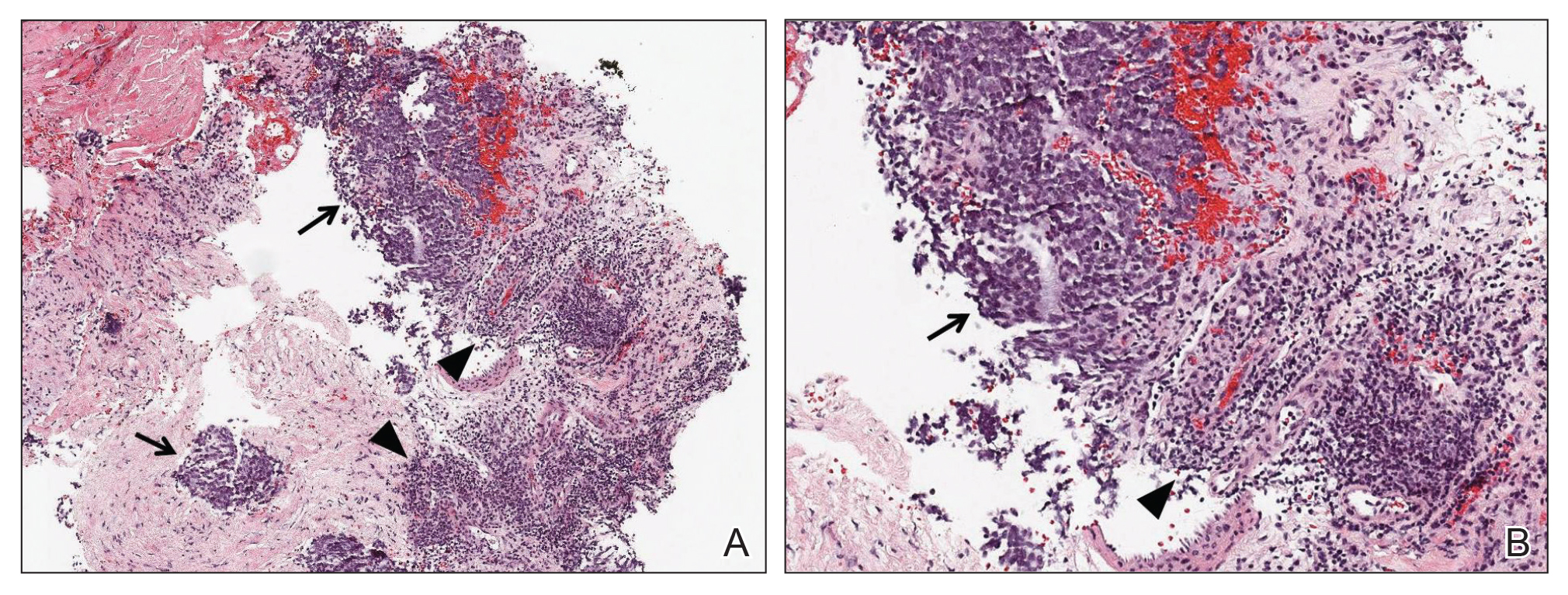

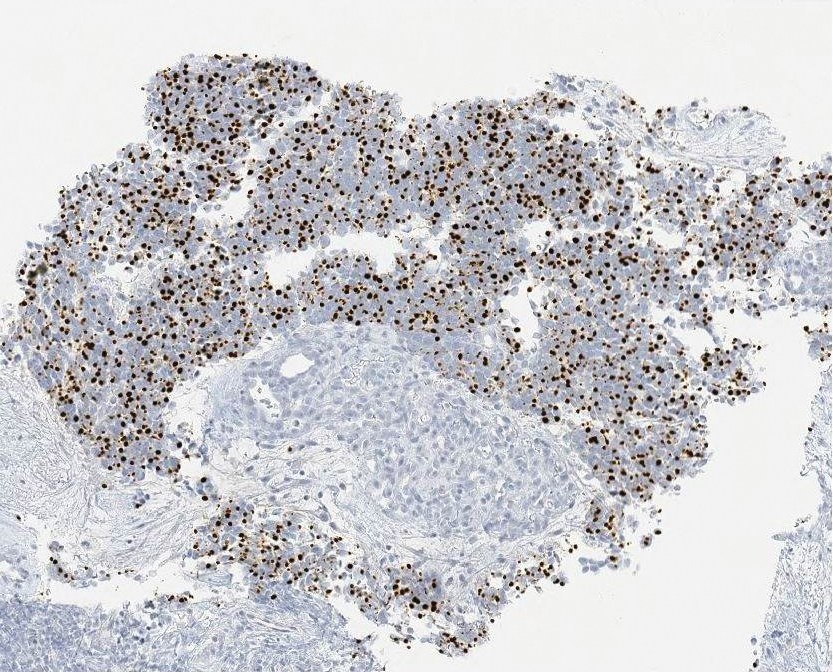

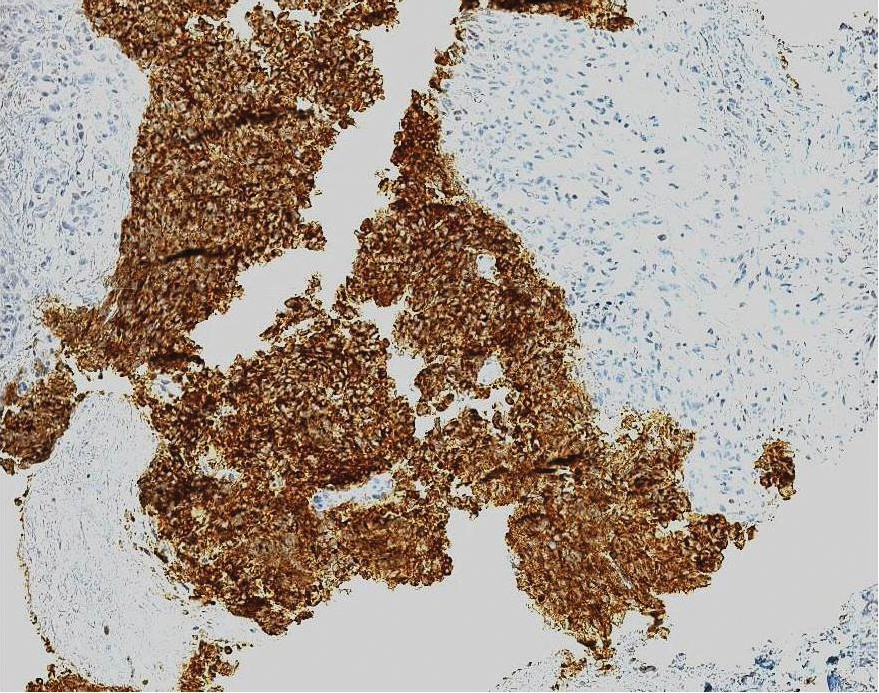

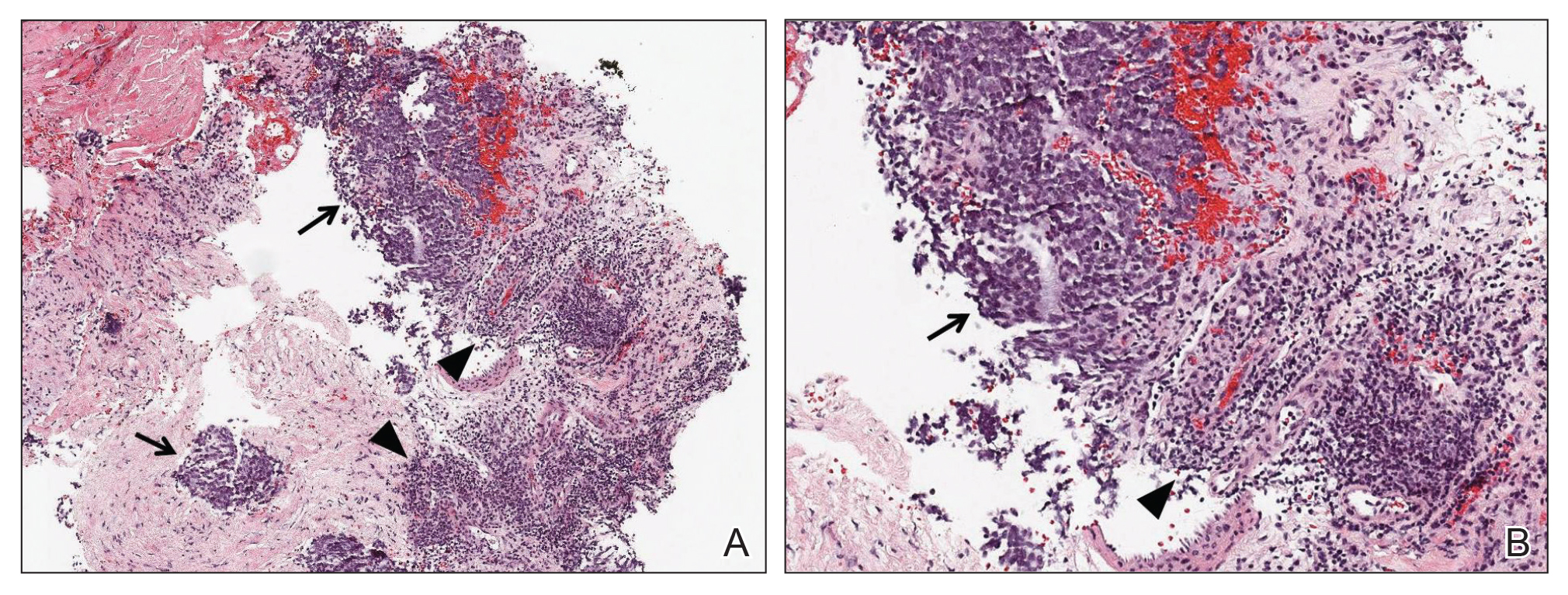

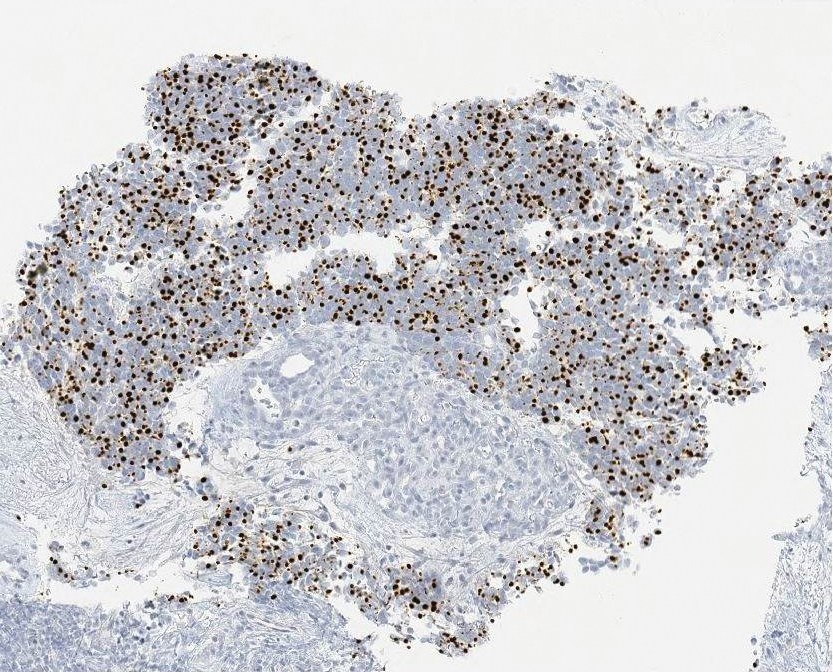

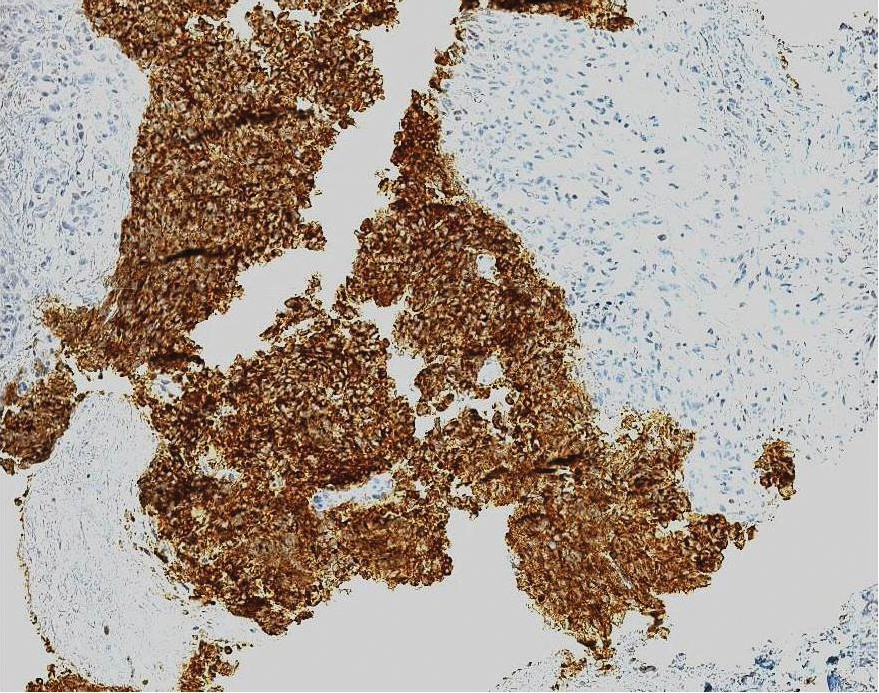

Ultrasound-guided biopsy of the enlarged axillary lymph nodes demonstrated sheets and nests of small round blue tumor cells with minimal cytoplasm, high mitotic rate, and foci of necrosis (Figure 1). The tumor cells were positive for pancytokeratin (Lu-5) and cytokeratin (CK) 20 in a perinuclear dotlike pattern (Figure 2), as well as for the neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin (Figure 3), chromogranin A, and CD56. The tumor cells showed no immunoreactivity for CK7, thyroid transcription factor 1, CD3, CD5, or CD20. Flow cytometry demonstrated low cellularity, low specimen viability, and no evidence of an abnormal B-cell population. These findings were consistent with the diagnosis of MCC.

The patient underwent surgical excision of the involved lymph nodes. Four weeks after surgery, he reported dramatic improvement in strength, with complete resolution of the nasal speech, dysphagia, dry mouth, urinary retention, and constipation. Two months after surgery, his strength had normalized, except for slight persistent weakness in the bilateral shoulder abductors, trace weakness in the hip flexors, and a slight Trendelenburg gait. He was able to rise from a chair without using his arms and no longer required a cane for ambulation.

The patient underwent adjuvant radiation therapy after 2-month surgical follow-up with 5000-cGy radiation treatment to the left axillary region. Six months following primary definitive surgery and 4 months following adjuvant radiation therapy, he reported a 95% subjective return of physical strength. The patient was able to return to near-baseline physical activity. He continued to deny symptoms of dry mouth, incontinence, or constipation. Objectively, he had no focal neurologic deficits or weakness; no evidence of new skin lesions or lymphadenopathy was noted.

Comment

MCC vs SCLC

Merkel cell carcinoma is classified as a type of EPSCC. The histologic appearance of MCC is indistinguishable from SCLC. Both tumors are composed of uniform sheets of small round cells with a high nucleus to cytoplasm ratio, and both can express neuroendocrine markers, such as neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin A, and synaptophysin.9 Immunohistochemical positivity for CK20 and neurofilaments in combination with negative staining for thyroid transcription factor 1 and CK7 effectively differentiate MCC from SCLC.9 In addition, MCC often displays CK20 positivity in a perinuclear dotlike or punctate pattern, which is characteristic of this tumor.3,9,10 Negative immunohistochemical markers for B cells (CD20) and T cells (CD3) are important in excluding lymphoma.

LEMS Diagnosis

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome is a paraneoplastic or autoimmune disorder involving the neuromuscular junction. Autoantibodies to VGCC impair calcium influx into the presynaptic terminal, resulting in marked reduction of acetylcholine release into the synaptic cleft. The reduction in acetylcholine activity impairs production of muscle fiber action potentials, resulting in clinical weakness. The diagnosis of LEMS rests on clinical presentation, positive serology, and confirmatory neurophysiologic testing by NCS. Clinically, patients present with proximal weakness, hyporeflexia or areflexia, and autonomic dysfunction. Antibodies to P/Q-type VGCCs are found in 85% to 90% of cases of LEMS and are thought to play a direct causative role in the development of weakness.11 The finding of postexercise facilitation on motor NCS is the neurophysiologic hallmark and is highly specific for the diagnosis.

Approximately 50% to 60% of patients who present with LEMS have an underlying tumor, the vast majority of which are SCLC.11 There are a few reports of LEMS associated with other malignancies, including lymphoma; thymoma; neuroblastoma; and carcinoma of the breast, stomach, prostate, bladder, kidney, and gallbladder.12 Patients with nontumor or autoimmune LEMS tend to be younger, and there is no male predominance, as there is in paraneoplastic LEMS.13 Given the risk of underlying malignancy in LEMS, Titulaer et al14 proposed a screening protocol for patients presenting with LEMS, recommending initial primary screening using CT of the chest. If the CT scan is negative, total-body fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography should be performed to assess for fludeoxyglucose avid lesions. If both initial studies are negative, routine follow-up with CT of the chest at 6-month intervals for a minimum of 2 to 4 years after the initial diagnosis of LEMS was recommended. An exception to this protocol was suggested to allow consideration to stop screening after the first 6-month follow-up chest CT for patients younger than 45 years who have never smoked and who have an HLA 8.1 haplotype for which nontumor LEMS would be a more probable diagnosis.14

In addition to a screening protocol, a validated prediction tool, the Dutch-English LEMS Tumor Association prediction score, was developed. It uses common signs and symptoms of LEMS and risk factors for SCLC to help guide the need for further screening.15

Paraneoplastic Syndromes Associated With MCC

Other paraneoplastic syndromes have been reported in association with MCC. A patient with brainstem encephalitis associated with MCC was reported in a trial of a novel immunotherapy for paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes.16,17 A syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) secretion was reported in a patient with N-type calcium channel antibodies.18 Two cases of paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration have been reported; the first was associated with a novel 70-kD antibody,19 and the second was associated with the P/Q-type VGCC antibody.20 Anti-Hu antibodies have been found in a handful of reports of neurologic deterioration in patients with MCC. Hocar et al21 reported a severe necrotizing myopathy; Greenlee et al22 described a syndrome of progressive sensorimotor and autonomic neuropathy with encephalopathy; and Lopez et al23 described a constellation of vision changes, gait imbalance, and proximal weakness. Support for a pathophysiologic connection among these 3 cases is suggested by the finding of Hu antigen expression by MCC in 2 studies.24,25 Because MCC can present with occult lymph node involvement in the absence of primary cutaneous findings,3 there are more cases of paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes that were not recognized.

Extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas such as MCC are morphologically indistinguishable from their pulmonary counterparts and have been reported in most anatomic regions of the body, including gynecologic organs (eg, ovaries, cervix), genitourinary organs (eg, bladder, prostate), the gastrointestinal tract (eg, esophagus), skin (eg, MCC), and the head and neck region. Extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma is a rare entity, with the most common form found in the gynecologic tract, representing only 2% of gynecologic malignancies.26

Paraneoplastic syndromes of EPSCC are rare given the paucity of the malignancy. Several case reports discuss findings of SIADH in EPSCC of the cervix, as well as hypercalcemia, polyneuropathy, Cushing syndrome, limbic encephalitis, and peripheral neuropathy in EPSCC of the prostate.27,28 In contrast, SCLC has long been associated with paraneoplastic syndromes. Numerous case reports have been published describing SCLC-associated paraneoplastic syndromes to include hypercalcemia, Cushing syndrome, SIADH, vasoactive peptide production, cerebellar degeneration, limbic encephalitis, visceral plexopathy, autonomic dysfunction, and LEMS.29 As more cases of EPSCC with paraneoplastic syndromes are identified and reported, we might gain a better understanding of this interesting phenomenon.

Conclusion

Merkel cell carcinoma is an aggressive neuroendocrine malignancy associated with paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes, including LEMS. A thorough search for an underlying malignancy is highly recommended in patients with diagnosed LEMS without clear cause. Early identification and treatment of the primary tumor can lead to improvement of neurologic symptoms.

We present a case of LEMS with no clearly identifiable cause on presentation with later diagnosis of metastatic MCC of unknown primary origin. After surgical excision of affected lymph nodes and adjuvant radiation therapy, the patient had near-complete resolution of LEMS symptoms at 6-month follow-up, without additional findings of lymphadenopathy or skin lesions. Although this patient is not undergoing routine surveillance imaging to monitor for recurrence of MCC, a chest CT or positron emission tomography–CT for secondary screening would be considered if the patient experienced clinical symptoms consistent with LEMS.

In cases of LEMS without pulmonary malignancy, we recommend considering MCC in the differential diagnosis during the workup of an underlying malignancy

- Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population based study. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:20-27.

- Senchenkov A, Moran SL. Merkel cell carcinoma: diagnosis, management, and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:E771-E778.

- Han SY, North JP, Canavan T, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 2012;26:1351-1374.

- Vernino S. Paraneoplastic disorders affecting the neuromuscular junction or anterior horn cell. CONTINUUM Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 2009;15:132-146.

- Eggers SD, Salomao DR, Dinapoli RP, et al. Paraneoplastic and metastatic neurologic complications of Merkel cell carcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:327-330.

- Siau RT, Morris A, Karoo RO. Surgery results in complete cure of Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome in a patient with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:e162-e164.

- Bombelli F, Lispi L, Calabrò F, et al. Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome associated to Merkel cell carcinoma: report of a case. Neurol Sci. 2015;36:1491-1492.

- Simmons DB, Duginski TM, McClean JC, et al. Lambert-eaton myasthenic syndrome and merkel cell carcinoma. Muscle Nerve. 2015;53:325-326.

- Bobos M, Hytiroglou P, Kostopoulos I, et al. Immunohistochemical distinction between Merkel cell carcinoma and small cell carcinoma of the lung. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:99-104.

- Jensen K, Kohler S, Rouse RV. Cytokeratin staining in Merkel cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study of cytokeratins 5/6, 7, 17, and 20. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2000;8:310-315.

- Titulaer MJ, Lang B, Verschuuren JJ. Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome: from clinical characteristics to therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:1098-1107.

- Sanders DB. Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome. In: Daroff R, Aminoff MJ, eds. Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences. Vol 2. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2009:819-822.

- Wirtz PW, Smallegange TM, Wintzen AR, et al. Differences in clinical features between the Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome with and without cancer: an analysis of 227 published cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2002;104:359-363.

- Titulaer MJ, Wirtz PW, Willems LN, et al. Screening for small-cell lung cancer: a follow-up study of patients with Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4276-4281.

- Titulaer MJ, Maddison P, Sont JK, et al. Clinical Dutch-English Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome (LEMS) Tumor Association prediction score accurately predicts small-cell lung cancer in the LEMS. J Clin Oncol. 2011;7:902-908.

- Cher LM, Hochberg FH, Teruya J, et al. Therapy for paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes in six patients with protein A column immunoadsorption. Cancer. 1995;75:1678-1683.

- Batchelor TT, Platten M, Hochberg FH. Immunoadsorption therapy for paraneoplastic syndromes. J Neurooncol. 1998;40:131-136.

- Blondin NA, Vortmeyer AO, Harel NY. Paraneoplastic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone mimicking limbic encephalitis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1591-1594.

- Balegno S, Ceroni M, Corato M, et al. Antibodies to cerebellar nerve fibres in two patients with paraneoplastic cerebellar ataxia. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:3211-3214.

- Zhang C, Emery L, Lancaster E. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration associated with noncutaneous Merkel cell carcinoma. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2014;1:e17.

- Hocar O, Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Faye O, et al. Severe necrotizing myopathy subsequent to Merkel cell carcinoma. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2011;138:130-134.

- Greenlee JE, Steffens JD, Clawson SA, et al. Anti-Hu antibodies in Merkel cell carcinoma. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:111-115.

- Lopez MC, Pericay C, Agustí M, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma associated with a paraneoplastic neurologic syndrome. Histopathology. 2004;44:628-629.

- Dalmau J, Furneaux HM, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. The expression of the Hu (paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis/sensory neuronopathy) antigen in human normal and tumor tissues. Am J Pathol. 1992;141:881-886.

- Gultekin SH, Rosai J, Demopoulos A, et al. Hu immunolabeling as a marker of neural and neuroendocrine differentiation in normal and neoplastic human tissues: assessment using a recombinant anti-Hu Fab fragment. Int J Surg Pathol. 2000;8:109-117.

- Zheng X, Liu D, Fallon JT, et al. Distinct genetic alterations in small cell carcinoma from different anatomic sites. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2015;4:2.

- Kim D, Yun H, Lee Y, et al. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix presenting with syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013;56:420-425.

- Venkatesh PK, Motwani B, Sherman N, et al. Metastatic pure small-cell carcinoma of prostate. Am J Med Sci. 2004;328:286-289.

- Kaltsas G, Androulakis II, de Herder WW, et al. Paraneoplastic syndromes secondary to neuroendocrine tumours. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:R173-R193.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an aggressive neuroendocrine malignancy of the skin that is thought to arise from neural crest cells. It has an estimated annual incidence of 0.6 per 100,000 individuals, typically occurs in the elderly population, and is most common in white males.1 The tumor presents as a rapidly growing, violaceous nodule in sun-exposed areas of the skin; early in the course, it can be mistaken for a benign entity such as an epidermal cyst.2 Merkel cell carcinoma has a propensity to spread to regional lymph nodes, and in some cases, it occurs in the absence of skin findings.3 Histologically, MCC is nearly indistinguishable from small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC).4 The overall prognosis for patients with MCC is poor and largely dependent on the stage at diagnosis. Patients with regional and distant metastases have a 5-year survival rate of 26% to 42% and 18%, respectively.3

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) is a paraneoplastic or autoimmune disorder of the neuromuscular junction that is found in 3% of cases of SCLC.4 Reported cases of LEMS in patients with MCC are exceedingly rare.5-8 We provide a full report and longitudinal clinical follow-up of a case that was briefly discussed by Simmons et al,8 and we review the literature regarding paraneoplastic syndromes associated with MCC and other extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas (EPSCCs).

Case Report

A 63-year-old man was evaluated in the neurology clinic due to difficulty walking, climbing stairs, and performing push-ups over the last month. Prior to the onset of symptoms, he was otherwise healthy, walking 3 miles daily; however, at presentation he required use of a cane. Leg weakness worsened as the day progressed. In addition, he reported constipation, urinary urgency, dry mouth, mild dysphagia, reduced sensation below the knees, and a nasal quality in his speech. He had no ptosis, diplopia, dysarthria, muscle cramps, myalgia, or facial weakness. He denied fevers, chills, and night sweats but did admit to an unintentional 10- to 15-lb weight loss over the preceding few months.

The neurologic examination revealed mild proximal upper extremity weakness in the bilateral shoulder abductors, infraspinatus, hip extensors, and hip flexors (Medical Research Council muscle scale grade 4). All deep tendon reflexes, except the Achilles reflex, were present. Despite subjective sensory concerns, objective examination of all sensory modalities was normal. Cranial nerve examination was normal, except for a slight nasal quality to his voice.

A qualitative assay was positive for the presence of P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channel (VGCC) antibodies. Other laboratory studies were within reference range, including acetylcholine-receptor antibodies (blocking, binding, and modulating) and muscle-specific kinase antibodies.

Lumbar and cervical spine magnetic resonance imaging revealed multilevel neuroforaminal stenosis without spinal canal stenosis or myelopathy. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest was notable for 2 pathologically enlarged lymph nodes in the left axilla and no evidence of primary pulmonary malignancy. Nerve-conduction studies (NCSs) in conjunction with other clinical findings were consistent with the diagnosis of LEMS.

Ultrasound-guided biopsy of the enlarged axillary lymph nodes demonstrated sheets and nests of small round blue tumor cells with minimal cytoplasm, high mitotic rate, and foci of necrosis (Figure 1). The tumor cells were positive for pancytokeratin (Lu-5) and cytokeratin (CK) 20 in a perinuclear dotlike pattern (Figure 2), as well as for the neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin (Figure 3), chromogranin A, and CD56. The tumor cells showed no immunoreactivity for CK7, thyroid transcription factor 1, CD3, CD5, or CD20. Flow cytometry demonstrated low cellularity, low specimen viability, and no evidence of an abnormal B-cell population. These findings were consistent with the diagnosis of MCC.

The patient underwent surgical excision of the involved lymph nodes. Four weeks after surgery, he reported dramatic improvement in strength, with complete resolution of the nasal speech, dysphagia, dry mouth, urinary retention, and constipation. Two months after surgery, his strength had normalized, except for slight persistent weakness in the bilateral shoulder abductors, trace weakness in the hip flexors, and a slight Trendelenburg gait. He was able to rise from a chair without using his arms and no longer required a cane for ambulation.

The patient underwent adjuvant radiation therapy after 2-month surgical follow-up with 5000-cGy radiation treatment to the left axillary region. Six months following primary definitive surgery and 4 months following adjuvant radiation therapy, he reported a 95% subjective return of physical strength. The patient was able to return to near-baseline physical activity. He continued to deny symptoms of dry mouth, incontinence, or constipation. Objectively, he had no focal neurologic deficits or weakness; no evidence of new skin lesions or lymphadenopathy was noted.

Comment

MCC vs SCLC

Merkel cell carcinoma is classified as a type of EPSCC. The histologic appearance of MCC is indistinguishable from SCLC. Both tumors are composed of uniform sheets of small round cells with a high nucleus to cytoplasm ratio, and both can express neuroendocrine markers, such as neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin A, and synaptophysin.9 Immunohistochemical positivity for CK20 and neurofilaments in combination with negative staining for thyroid transcription factor 1 and CK7 effectively differentiate MCC from SCLC.9 In addition, MCC often displays CK20 positivity in a perinuclear dotlike or punctate pattern, which is characteristic of this tumor.3,9,10 Negative immunohistochemical markers for B cells (CD20) and T cells (CD3) are important in excluding lymphoma.

LEMS Diagnosis

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome is a paraneoplastic or autoimmune disorder involving the neuromuscular junction. Autoantibodies to VGCC impair calcium influx into the presynaptic terminal, resulting in marked reduction of acetylcholine release into the synaptic cleft. The reduction in acetylcholine activity impairs production of muscle fiber action potentials, resulting in clinical weakness. The diagnosis of LEMS rests on clinical presentation, positive serology, and confirmatory neurophysiologic testing by NCS. Clinically, patients present with proximal weakness, hyporeflexia or areflexia, and autonomic dysfunction. Antibodies to P/Q-type VGCCs are found in 85% to 90% of cases of LEMS and are thought to play a direct causative role in the development of weakness.11 The finding of postexercise facilitation on motor NCS is the neurophysiologic hallmark and is highly specific for the diagnosis.

Approximately 50% to 60% of patients who present with LEMS have an underlying tumor, the vast majority of which are SCLC.11 There are a few reports of LEMS associated with other malignancies, including lymphoma; thymoma; neuroblastoma; and carcinoma of the breast, stomach, prostate, bladder, kidney, and gallbladder.12 Patients with nontumor or autoimmune LEMS tend to be younger, and there is no male predominance, as there is in paraneoplastic LEMS.13 Given the risk of underlying malignancy in LEMS, Titulaer et al14 proposed a screening protocol for patients presenting with LEMS, recommending initial primary screening using CT of the chest. If the CT scan is negative, total-body fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography should be performed to assess for fludeoxyglucose avid lesions. If both initial studies are negative, routine follow-up with CT of the chest at 6-month intervals for a minimum of 2 to 4 years after the initial diagnosis of LEMS was recommended. An exception to this protocol was suggested to allow consideration to stop screening after the first 6-month follow-up chest CT for patients younger than 45 years who have never smoked and who have an HLA 8.1 haplotype for which nontumor LEMS would be a more probable diagnosis.14

In addition to a screening protocol, a validated prediction tool, the Dutch-English LEMS Tumor Association prediction score, was developed. It uses common signs and symptoms of LEMS and risk factors for SCLC to help guide the need for further screening.15

Paraneoplastic Syndromes Associated With MCC

Other paraneoplastic syndromes have been reported in association with MCC. A patient with brainstem encephalitis associated with MCC was reported in a trial of a novel immunotherapy for paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes.16,17 A syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) secretion was reported in a patient with N-type calcium channel antibodies.18 Two cases of paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration have been reported; the first was associated with a novel 70-kD antibody,19 and the second was associated with the P/Q-type VGCC antibody.20 Anti-Hu antibodies have been found in a handful of reports of neurologic deterioration in patients with MCC. Hocar et al21 reported a severe necrotizing myopathy; Greenlee et al22 described a syndrome of progressive sensorimotor and autonomic neuropathy with encephalopathy; and Lopez et al23 described a constellation of vision changes, gait imbalance, and proximal weakness. Support for a pathophysiologic connection among these 3 cases is suggested by the finding of Hu antigen expression by MCC in 2 studies.24,25 Because MCC can present with occult lymph node involvement in the absence of primary cutaneous findings,3 there are more cases of paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes that were not recognized.

Extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas such as MCC are morphologically indistinguishable from their pulmonary counterparts and have been reported in most anatomic regions of the body, including gynecologic organs (eg, ovaries, cervix), genitourinary organs (eg, bladder, prostate), the gastrointestinal tract (eg, esophagus), skin (eg, MCC), and the head and neck region. Extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma is a rare entity, with the most common form found in the gynecologic tract, representing only 2% of gynecologic malignancies.26

Paraneoplastic syndromes of EPSCC are rare given the paucity of the malignancy. Several case reports discuss findings of SIADH in EPSCC of the cervix, as well as hypercalcemia, polyneuropathy, Cushing syndrome, limbic encephalitis, and peripheral neuropathy in EPSCC of the prostate.27,28 In contrast, SCLC has long been associated with paraneoplastic syndromes. Numerous case reports have been published describing SCLC-associated paraneoplastic syndromes to include hypercalcemia, Cushing syndrome, SIADH, vasoactive peptide production, cerebellar degeneration, limbic encephalitis, visceral plexopathy, autonomic dysfunction, and LEMS.29 As more cases of EPSCC with paraneoplastic syndromes are identified and reported, we might gain a better understanding of this interesting phenomenon.

Conclusion

Merkel cell carcinoma is an aggressive neuroendocrine malignancy associated with paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes, including LEMS. A thorough search for an underlying malignancy is highly recommended in patients with diagnosed LEMS without clear cause. Early identification and treatment of the primary tumor can lead to improvement of neurologic symptoms.

We present a case of LEMS with no clearly identifiable cause on presentation with later diagnosis of metastatic MCC of unknown primary origin. After surgical excision of affected lymph nodes and adjuvant radiation therapy, the patient had near-complete resolution of LEMS symptoms at 6-month follow-up, without additional findings of lymphadenopathy or skin lesions. Although this patient is not undergoing routine surveillance imaging to monitor for recurrence of MCC, a chest CT or positron emission tomography–CT for secondary screening would be considered if the patient experienced clinical symptoms consistent with LEMS.

In cases of LEMS without pulmonary malignancy, we recommend considering MCC in the differential diagnosis during the workup of an underlying malignancy

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an aggressive neuroendocrine malignancy of the skin that is thought to arise from neural crest cells. It has an estimated annual incidence of 0.6 per 100,000 individuals, typically occurs in the elderly population, and is most common in white males.1 The tumor presents as a rapidly growing, violaceous nodule in sun-exposed areas of the skin; early in the course, it can be mistaken for a benign entity such as an epidermal cyst.2 Merkel cell carcinoma has a propensity to spread to regional lymph nodes, and in some cases, it occurs in the absence of skin findings.3 Histologically, MCC is nearly indistinguishable from small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC).4 The overall prognosis for patients with MCC is poor and largely dependent on the stage at diagnosis. Patients with regional and distant metastases have a 5-year survival rate of 26% to 42% and 18%, respectively.3

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) is a paraneoplastic or autoimmune disorder of the neuromuscular junction that is found in 3% of cases of SCLC.4 Reported cases of LEMS in patients with MCC are exceedingly rare.5-8 We provide a full report and longitudinal clinical follow-up of a case that was briefly discussed by Simmons et al,8 and we review the literature regarding paraneoplastic syndromes associated with MCC and other extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas (EPSCCs).

Case Report

A 63-year-old man was evaluated in the neurology clinic due to difficulty walking, climbing stairs, and performing push-ups over the last month. Prior to the onset of symptoms, he was otherwise healthy, walking 3 miles daily; however, at presentation he required use of a cane. Leg weakness worsened as the day progressed. In addition, he reported constipation, urinary urgency, dry mouth, mild dysphagia, reduced sensation below the knees, and a nasal quality in his speech. He had no ptosis, diplopia, dysarthria, muscle cramps, myalgia, or facial weakness. He denied fevers, chills, and night sweats but did admit to an unintentional 10- to 15-lb weight loss over the preceding few months.

The neurologic examination revealed mild proximal upper extremity weakness in the bilateral shoulder abductors, infraspinatus, hip extensors, and hip flexors (Medical Research Council muscle scale grade 4). All deep tendon reflexes, except the Achilles reflex, were present. Despite subjective sensory concerns, objective examination of all sensory modalities was normal. Cranial nerve examination was normal, except for a slight nasal quality to his voice.

A qualitative assay was positive for the presence of P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channel (VGCC) antibodies. Other laboratory studies were within reference range, including acetylcholine-receptor antibodies (blocking, binding, and modulating) and muscle-specific kinase antibodies.

Lumbar and cervical spine magnetic resonance imaging revealed multilevel neuroforaminal stenosis without spinal canal stenosis or myelopathy. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest was notable for 2 pathologically enlarged lymph nodes in the left axilla and no evidence of primary pulmonary malignancy. Nerve-conduction studies (NCSs) in conjunction with other clinical findings were consistent with the diagnosis of LEMS.

Ultrasound-guided biopsy of the enlarged axillary lymph nodes demonstrated sheets and nests of small round blue tumor cells with minimal cytoplasm, high mitotic rate, and foci of necrosis (Figure 1). The tumor cells were positive for pancytokeratin (Lu-5) and cytokeratin (CK) 20 in a perinuclear dotlike pattern (Figure 2), as well as for the neuroendocrine markers synaptophysin (Figure 3), chromogranin A, and CD56. The tumor cells showed no immunoreactivity for CK7, thyroid transcription factor 1, CD3, CD5, or CD20. Flow cytometry demonstrated low cellularity, low specimen viability, and no evidence of an abnormal B-cell population. These findings were consistent with the diagnosis of MCC.

The patient underwent surgical excision of the involved lymph nodes. Four weeks after surgery, he reported dramatic improvement in strength, with complete resolution of the nasal speech, dysphagia, dry mouth, urinary retention, and constipation. Two months after surgery, his strength had normalized, except for slight persistent weakness in the bilateral shoulder abductors, trace weakness in the hip flexors, and a slight Trendelenburg gait. He was able to rise from a chair without using his arms and no longer required a cane for ambulation.

The patient underwent adjuvant radiation therapy after 2-month surgical follow-up with 5000-cGy radiation treatment to the left axillary region. Six months following primary definitive surgery and 4 months following adjuvant radiation therapy, he reported a 95% subjective return of physical strength. The patient was able to return to near-baseline physical activity. He continued to deny symptoms of dry mouth, incontinence, or constipation. Objectively, he had no focal neurologic deficits or weakness; no evidence of new skin lesions or lymphadenopathy was noted.

Comment

MCC vs SCLC

Merkel cell carcinoma is classified as a type of EPSCC. The histologic appearance of MCC is indistinguishable from SCLC. Both tumors are composed of uniform sheets of small round cells with a high nucleus to cytoplasm ratio, and both can express neuroendocrine markers, such as neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin A, and synaptophysin.9 Immunohistochemical positivity for CK20 and neurofilaments in combination with negative staining for thyroid transcription factor 1 and CK7 effectively differentiate MCC from SCLC.9 In addition, MCC often displays CK20 positivity in a perinuclear dotlike or punctate pattern, which is characteristic of this tumor.3,9,10 Negative immunohistochemical markers for B cells (CD20) and T cells (CD3) are important in excluding lymphoma.

LEMS Diagnosis

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome is a paraneoplastic or autoimmune disorder involving the neuromuscular junction. Autoantibodies to VGCC impair calcium influx into the presynaptic terminal, resulting in marked reduction of acetylcholine release into the synaptic cleft. The reduction in acetylcholine activity impairs production of muscle fiber action potentials, resulting in clinical weakness. The diagnosis of LEMS rests on clinical presentation, positive serology, and confirmatory neurophysiologic testing by NCS. Clinically, patients present with proximal weakness, hyporeflexia or areflexia, and autonomic dysfunction. Antibodies to P/Q-type VGCCs are found in 85% to 90% of cases of LEMS and are thought to play a direct causative role in the development of weakness.11 The finding of postexercise facilitation on motor NCS is the neurophysiologic hallmark and is highly specific for the diagnosis.

Approximately 50% to 60% of patients who present with LEMS have an underlying tumor, the vast majority of which are SCLC.11 There are a few reports of LEMS associated with other malignancies, including lymphoma; thymoma; neuroblastoma; and carcinoma of the breast, stomach, prostate, bladder, kidney, and gallbladder.12 Patients with nontumor or autoimmune LEMS tend to be younger, and there is no male predominance, as there is in paraneoplastic LEMS.13 Given the risk of underlying malignancy in LEMS, Titulaer et al14 proposed a screening protocol for patients presenting with LEMS, recommending initial primary screening using CT of the chest. If the CT scan is negative, total-body fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography should be performed to assess for fludeoxyglucose avid lesions. If both initial studies are negative, routine follow-up with CT of the chest at 6-month intervals for a minimum of 2 to 4 years after the initial diagnosis of LEMS was recommended. An exception to this protocol was suggested to allow consideration to stop screening after the first 6-month follow-up chest CT for patients younger than 45 years who have never smoked and who have an HLA 8.1 haplotype for which nontumor LEMS would be a more probable diagnosis.14

In addition to a screening protocol, a validated prediction tool, the Dutch-English LEMS Tumor Association prediction score, was developed. It uses common signs and symptoms of LEMS and risk factors for SCLC to help guide the need for further screening.15

Paraneoplastic Syndromes Associated With MCC

Other paraneoplastic syndromes have been reported in association with MCC. A patient with brainstem encephalitis associated with MCC was reported in a trial of a novel immunotherapy for paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes.16,17 A syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) secretion was reported in a patient with N-type calcium channel antibodies.18 Two cases of paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration have been reported; the first was associated with a novel 70-kD antibody,19 and the second was associated with the P/Q-type VGCC antibody.20 Anti-Hu antibodies have been found in a handful of reports of neurologic deterioration in patients with MCC. Hocar et al21 reported a severe necrotizing myopathy; Greenlee et al22 described a syndrome of progressive sensorimotor and autonomic neuropathy with encephalopathy; and Lopez et al23 described a constellation of vision changes, gait imbalance, and proximal weakness. Support for a pathophysiologic connection among these 3 cases is suggested by the finding of Hu antigen expression by MCC in 2 studies.24,25 Because MCC can present with occult lymph node involvement in the absence of primary cutaneous findings,3 there are more cases of paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes that were not recognized.

Extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas such as MCC are morphologically indistinguishable from their pulmonary counterparts and have been reported in most anatomic regions of the body, including gynecologic organs (eg, ovaries, cervix), genitourinary organs (eg, bladder, prostate), the gastrointestinal tract (eg, esophagus), skin (eg, MCC), and the head and neck region. Extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma is a rare entity, with the most common form found in the gynecologic tract, representing only 2% of gynecologic malignancies.26

Paraneoplastic syndromes of EPSCC are rare given the paucity of the malignancy. Several case reports discuss findings of SIADH in EPSCC of the cervix, as well as hypercalcemia, polyneuropathy, Cushing syndrome, limbic encephalitis, and peripheral neuropathy in EPSCC of the prostate.27,28 In contrast, SCLC has long been associated with paraneoplastic syndromes. Numerous case reports have been published describing SCLC-associated paraneoplastic syndromes to include hypercalcemia, Cushing syndrome, SIADH, vasoactive peptide production, cerebellar degeneration, limbic encephalitis, visceral plexopathy, autonomic dysfunction, and LEMS.29 As more cases of EPSCC with paraneoplastic syndromes are identified and reported, we might gain a better understanding of this interesting phenomenon.

Conclusion

Merkel cell carcinoma is an aggressive neuroendocrine malignancy associated with paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes, including LEMS. A thorough search for an underlying malignancy is highly recommended in patients with diagnosed LEMS without clear cause. Early identification and treatment of the primary tumor can lead to improvement of neurologic symptoms.

We present a case of LEMS with no clearly identifiable cause on presentation with later diagnosis of metastatic MCC of unknown primary origin. After surgical excision of affected lymph nodes and adjuvant radiation therapy, the patient had near-complete resolution of LEMS symptoms at 6-month follow-up, without additional findings of lymphadenopathy or skin lesions. Although this patient is not undergoing routine surveillance imaging to monitor for recurrence of MCC, a chest CT or positron emission tomography–CT for secondary screening would be considered if the patient experienced clinical symptoms consistent with LEMS.

In cases of LEMS without pulmonary malignancy, we recommend considering MCC in the differential diagnosis during the workup of an underlying malignancy

- Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population based study. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:20-27.

- Senchenkov A, Moran SL. Merkel cell carcinoma: diagnosis, management, and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:E771-E778.

- Han SY, North JP, Canavan T, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 2012;26:1351-1374.

- Vernino S. Paraneoplastic disorders affecting the neuromuscular junction or anterior horn cell. CONTINUUM Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 2009;15:132-146.

- Eggers SD, Salomao DR, Dinapoli RP, et al. Paraneoplastic and metastatic neurologic complications of Merkel cell carcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:327-330.

- Siau RT, Morris A, Karoo RO. Surgery results in complete cure of Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome in a patient with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:e162-e164.

- Bombelli F, Lispi L, Calabrò F, et al. Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome associated to Merkel cell carcinoma: report of a case. Neurol Sci. 2015;36:1491-1492.

- Simmons DB, Duginski TM, McClean JC, et al. Lambert-eaton myasthenic syndrome and merkel cell carcinoma. Muscle Nerve. 2015;53:325-326.

- Bobos M, Hytiroglou P, Kostopoulos I, et al. Immunohistochemical distinction between Merkel cell carcinoma and small cell carcinoma of the lung. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:99-104.

- Jensen K, Kohler S, Rouse RV. Cytokeratin staining in Merkel cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study of cytokeratins 5/6, 7, 17, and 20. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2000;8:310-315.

- Titulaer MJ, Lang B, Verschuuren JJ. Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome: from clinical characteristics to therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:1098-1107.

- Sanders DB. Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome. In: Daroff R, Aminoff MJ, eds. Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences. Vol 2. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2009:819-822.

- Wirtz PW, Smallegange TM, Wintzen AR, et al. Differences in clinical features between the Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome with and without cancer: an analysis of 227 published cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2002;104:359-363.

- Titulaer MJ, Wirtz PW, Willems LN, et al. Screening for small-cell lung cancer: a follow-up study of patients with Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4276-4281.

- Titulaer MJ, Maddison P, Sont JK, et al. Clinical Dutch-English Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome (LEMS) Tumor Association prediction score accurately predicts small-cell lung cancer in the LEMS. J Clin Oncol. 2011;7:902-908.

- Cher LM, Hochberg FH, Teruya J, et al. Therapy for paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes in six patients with protein A column immunoadsorption. Cancer. 1995;75:1678-1683.

- Batchelor TT, Platten M, Hochberg FH. Immunoadsorption therapy for paraneoplastic syndromes. J Neurooncol. 1998;40:131-136.

- Blondin NA, Vortmeyer AO, Harel NY. Paraneoplastic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone mimicking limbic encephalitis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1591-1594.

- Balegno S, Ceroni M, Corato M, et al. Antibodies to cerebellar nerve fibres in two patients with paraneoplastic cerebellar ataxia. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:3211-3214.

- Zhang C, Emery L, Lancaster E. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration associated with noncutaneous Merkel cell carcinoma. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2014;1:e17.

- Hocar O, Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Faye O, et al. Severe necrotizing myopathy subsequent to Merkel cell carcinoma. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2011;138:130-134.

- Greenlee JE, Steffens JD, Clawson SA, et al. Anti-Hu antibodies in Merkel cell carcinoma. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:111-115.

- Lopez MC, Pericay C, Agustí M, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma associated with a paraneoplastic neurologic syndrome. Histopathology. 2004;44:628-629.

- Dalmau J, Furneaux HM, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. The expression of the Hu (paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis/sensory neuronopathy) antigen in human normal and tumor tissues. Am J Pathol. 1992;141:881-886.

- Gultekin SH, Rosai J, Demopoulos A, et al. Hu immunolabeling as a marker of neural and neuroendocrine differentiation in normal and neoplastic human tissues: assessment using a recombinant anti-Hu Fab fragment. Int J Surg Pathol. 2000;8:109-117.

- Zheng X, Liu D, Fallon JT, et al. Distinct genetic alterations in small cell carcinoma from different anatomic sites. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2015;4:2.

- Kim D, Yun H, Lee Y, et al. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix presenting with syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013;56:420-425.

- Venkatesh PK, Motwani B, Sherman N, et al. Metastatic pure small-cell carcinoma of prostate. Am J Med Sci. 2004;328:286-289.

- Kaltsas G, Androulakis II, de Herder WW, et al. Paraneoplastic syndromes secondary to neuroendocrine tumours. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:R173-R193.

- Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population based study. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:20-27.

- Senchenkov A, Moran SL. Merkel cell carcinoma: diagnosis, management, and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:E771-E778.

- Han SY, North JP, Canavan T, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 2012;26:1351-1374.

- Vernino S. Paraneoplastic disorders affecting the neuromuscular junction or anterior horn cell. CONTINUUM Lifelong Learning in Neurology. 2009;15:132-146.

- Eggers SD, Salomao DR, Dinapoli RP, et al. Paraneoplastic and metastatic neurologic complications of Merkel cell carcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:327-330.

- Siau RT, Morris A, Karoo RO. Surgery results in complete cure of Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome in a patient with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:e162-e164.

- Bombelli F, Lispi L, Calabrò F, et al. Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome associated to Merkel cell carcinoma: report of a case. Neurol Sci. 2015;36:1491-1492.

- Simmons DB, Duginski TM, McClean JC, et al. Lambert-eaton myasthenic syndrome and merkel cell carcinoma. Muscle Nerve. 2015;53:325-326.

- Bobos M, Hytiroglou P, Kostopoulos I, et al. Immunohistochemical distinction between Merkel cell carcinoma and small cell carcinoma of the lung. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:99-104.

- Jensen K, Kohler S, Rouse RV. Cytokeratin staining in Merkel cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study of cytokeratins 5/6, 7, 17, and 20. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2000;8:310-315.

- Titulaer MJ, Lang B, Verschuuren JJ. Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome: from clinical characteristics to therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:1098-1107.

- Sanders DB. Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome. In: Daroff R, Aminoff MJ, eds. Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences. Vol 2. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2009:819-822.

- Wirtz PW, Smallegange TM, Wintzen AR, et al. Differences in clinical features between the Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome with and without cancer: an analysis of 227 published cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2002;104:359-363.

- Titulaer MJ, Wirtz PW, Willems LN, et al. Screening for small-cell lung cancer: a follow-up study of patients with Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4276-4281.

- Titulaer MJ, Maddison P, Sont JK, et al. Clinical Dutch-English Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome (LEMS) Tumor Association prediction score accurately predicts small-cell lung cancer in the LEMS. J Clin Oncol. 2011;7:902-908.

- Cher LM, Hochberg FH, Teruya J, et al. Therapy for paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes in six patients with protein A column immunoadsorption. Cancer. 1995;75:1678-1683.

- Batchelor TT, Platten M, Hochberg FH. Immunoadsorption therapy for paraneoplastic syndromes. J Neurooncol. 1998;40:131-136.

- Blondin NA, Vortmeyer AO, Harel NY. Paraneoplastic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone mimicking limbic encephalitis. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1591-1594.

- Balegno S, Ceroni M, Corato M, et al. Antibodies to cerebellar nerve fibres in two patients with paraneoplastic cerebellar ataxia. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:3211-3214.

- Zhang C, Emery L, Lancaster E. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration associated with noncutaneous Merkel cell carcinoma. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2014;1:e17.

- Hocar O, Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Faye O, et al. Severe necrotizing myopathy subsequent to Merkel cell carcinoma. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2011;138:130-134.

- Greenlee JE, Steffens JD, Clawson SA, et al. Anti-Hu antibodies in Merkel cell carcinoma. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:111-115.

- Lopez MC, Pericay C, Agustí M, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma associated with a paraneoplastic neurologic syndrome. Histopathology. 2004;44:628-629.

- Dalmau J, Furneaux HM, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. The expression of the Hu (paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis/sensory neuronopathy) antigen in human normal and tumor tissues. Am J Pathol. 1992;141:881-886.

- Gultekin SH, Rosai J, Demopoulos A, et al. Hu immunolabeling as a marker of neural and neuroendocrine differentiation in normal and neoplastic human tissues: assessment using a recombinant anti-Hu Fab fragment. Int J Surg Pathol. 2000;8:109-117.

- Zheng X, Liu D, Fallon JT, et al. Distinct genetic alterations in small cell carcinoma from different anatomic sites. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2015;4:2.

- Kim D, Yun H, Lee Y, et al. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix presenting with syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013;56:420-425.

- Venkatesh PK, Motwani B, Sherman N, et al. Metastatic pure small-cell carcinoma of prostate. Am J Med Sci. 2004;328:286-289.

- Kaltsas G, Androulakis II, de Herder WW, et al. Paraneoplastic syndromes secondary to neuroendocrine tumours. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:R173-R193.

Practice Points

- Approximately 50% to 60% of patients with Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) have an underlying tumor, most commonly small cell lung carcinoma.

- A thorough search for an underlying malignancy is highly recommended in patients with diagnosed LEMS without clear cause; to this end, a screening protocol comprising computed tomography and total-body fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography has been established.

- Because Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) can present as occult lymph node involvement with primary cutaneous findings absent, it is recommended that MCC be considered in the differential diagnosis of an underlying malignancy in a LEMS patient.

- Early identification and treatment of the primary tumor can lead to improvement of neurologic symptoms.

FDA permits marketing of Zika diagnostic test

A Zika virus test initially authorized only for emergency use has now been approved for use in nonemergency situations, according to a statement from the Food and Drug Administration.

The ZIKV Detect 2.0 IgM Capture ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) is now authorized for use in patients with clinical signs and symptoms consistent with Zika virus infection, as well as those who meet the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention epidemiologic criteria, including residence in or travel to a region deemed high risk because of active Zika transmission.

The test is designed to identify Zika antibodies in the blood, and the FDA cited a review of clinical trial data and analytic data to support the test’s safety and effectiveness.

“Results of this test are intended to be used in conjunction with clinical observations, patient history, epidemiological information, and other laboratory evidence to make patient management decisions,” the FDA stated.

The ZIKV Detect 2.0 IgM Capture ELISA, initially approved in 2016, had been authorized by the FDA only for emergency use, along with other tests for detecting Zika virus, under the under the FDA’s Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) authority.

The FDA granted marketing authorization to test manufacturer InBios International.

The FDA is communicating with four EUA holders to gather information to evaluate whether the FDA should revoke the EUAs for these specific tests. The marketing authorization of ZIKV Detect 2.0 IgM Capture ELISA does not impact the availability of the other 14 Zika nucleic acid diagnostics available under EUAs.

The Zika virus, typically transmitted by an infected mosquito, is especially a risk for pregnant women as the fetus may experience neurologic complications and microcephaly as a result of infection.

A Zika virus test initially authorized only for emergency use has now been approved for use in nonemergency situations, according to a statement from the Food and Drug Administration.

The ZIKV Detect 2.0 IgM Capture ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) is now authorized for use in patients with clinical signs and symptoms consistent with Zika virus infection, as well as those who meet the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention epidemiologic criteria, including residence in or travel to a region deemed high risk because of active Zika transmission.

The test is designed to identify Zika antibodies in the blood, and the FDA cited a review of clinical trial data and analytic data to support the test’s safety and effectiveness.

“Results of this test are intended to be used in conjunction with clinical observations, patient history, epidemiological information, and other laboratory evidence to make patient management decisions,” the FDA stated.

The ZIKV Detect 2.0 IgM Capture ELISA, initially approved in 2016, had been authorized by the FDA only for emergency use, along with other tests for detecting Zika virus, under the under the FDA’s Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) authority.

The FDA granted marketing authorization to test manufacturer InBios International.

The FDA is communicating with four EUA holders to gather information to evaluate whether the FDA should revoke the EUAs for these specific tests. The marketing authorization of ZIKV Detect 2.0 IgM Capture ELISA does not impact the availability of the other 14 Zika nucleic acid diagnostics available under EUAs.

The Zika virus, typically transmitted by an infected mosquito, is especially a risk for pregnant women as the fetus may experience neurologic complications and microcephaly as a result of infection.

A Zika virus test initially authorized only for emergency use has now been approved for use in nonemergency situations, according to a statement from the Food and Drug Administration.

The ZIKV Detect 2.0 IgM Capture ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) is now authorized for use in patients with clinical signs and symptoms consistent with Zika virus infection, as well as those who meet the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention epidemiologic criteria, including residence in or travel to a region deemed high risk because of active Zika transmission.

The test is designed to identify Zika antibodies in the blood, and the FDA cited a review of clinical trial data and analytic data to support the test’s safety and effectiveness.

“Results of this test are intended to be used in conjunction with clinical observations, patient history, epidemiological information, and other laboratory evidence to make patient management decisions,” the FDA stated.

The ZIKV Detect 2.0 IgM Capture ELISA, initially approved in 2016, had been authorized by the FDA only for emergency use, along with other tests for detecting Zika virus, under the under the FDA’s Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) authority.

The FDA granted marketing authorization to test manufacturer InBios International.

The FDA is communicating with four EUA holders to gather information to evaluate whether the FDA should revoke the EUAs for these specific tests. The marketing authorization of ZIKV Detect 2.0 IgM Capture ELISA does not impact the availability of the other 14 Zika nucleic acid diagnostics available under EUAs.

The Zika virus, typically transmitted by an infected mosquito, is especially a risk for pregnant women as the fetus may experience neurologic complications and microcephaly as a result of infection.

Equal access to care for black men lowers risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality

Black men with newly diagnosed nonmetastatic prostate cancer had no significant difference in prostate cancer–specific mortality compared with white men when treated with a standardized approach and follow-up or at a health care system with standardized access, according to recent research published in JAMA Oncology.

Robert T. Dess, MD, from the department of radiation oncology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues examined data from 296,273 patients in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cohort, 3,972 patients from the Veterans Affairs (VA) health system, and 5,854 patients in four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) from the National Cancer Institute–sponsored Radiation Therapy Oncology Group between January 1992 and December 2013. Of these, 52,840 patients (17.8%) in the SEER cohort, 1,513 patients (38.1%) in the VA cohort, and 1,129 (19.3%) in the RCT cohort were black men. The mean age across all cohorts was 64.9 years, and the median follow-up was 75 months in the SEER cohort, 97 months in the VA cohort, and 104 months in the RCT cohort.

After adjustment for age in the SEER cohort, black men had a 30% increased risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality (PCSM) compared with white men (subdistribution hazard ratio, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.23-1.37; P less than .001). However, after the researchers performed inverse probability weighting (IPW) to adjust for race-based imbalances such as access to care and standardized treatment, there was a 0.5% increased risk over 10 years (sHR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.04-1.15; P less than .001) after diagnosis.

In the VA cohort, IPW yielded no significant differences between black men and white men (sHR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.56-1.30; P = .46), and there was a significantly lower risk for black men in the RCT cohort after IPW (sHR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.66-0.99; P = .04). With regard to other outcomes, other-cause mortality was significantly higher for black men in the SEER cohort (sHR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.27-1.34; P less than .001) and in the RCT cohort (sHR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.06-1.29; P = .002) after IPW.

“Black race remains associated with many factors that negatively affect outcomes, and disparities persist at the population level,” Dr. Dess and colleagues wrote in their study. “Continued efforts are needed to address this clear racial health inequity driven by modifiable nonbiological risk factors.”

The researchers said some residual confounding may exist, but noted the strengths of the study included a diverse cohort with a large range of treatment approaches.

This study was funded in part by the Prostate Cancer Foundation, a grant from the Prostate Cancer National Institutes of Health Specialized Programs of Research Excellence, two grants from the Department of Defense, a grant from NIH, and a grant from the NIH Cancer Center. One or more of the authors reported relationships in the form of grants, personal fees, and consulting fees with numerous companies. The other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dess RT et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 May 23. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0826.

The results by Dess et al. show that inequality in prostate cancer mortality is the result of socioeconomic barriers that reduce access to care rather than a biological predisposition, Channing J. Paller, MD; Lin Wang, MSc, MMed; and Otis W. Brawley, MD, wrote in an editorial (JAMA Oncol 2019 May 23. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0812).

As registries collect more socioeconomic data from patients, including information on insurance status and health care system where treatment occurred, adjusting for confounders to study the effects of prevention, diagnostic and treatment strategies in addition to “open-minded analyses will help to mitigate some of the prevailing biases” about racial differences in medicine, they said.

While profiling by population can be a useful tool, tracking by geographical location may be a better way to categorize patients, such as glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency that came about as protection from malaria in the case of Mediterranean, African, and Asian populations.

“Although it is still true that men of African origin have a higher incidence of prostate cancer and higher mortality rates, the causes of these differences are complex and may involve exposure to prostate cancer risk factors, genomic differences, and other biology-based factors,” the authors wrote. “Research to determine the relative contributions of these factors should continue; but in the meantime, we as health care professionals are likely to have the greatest effect on improved outcomes for African American patients with prostate cancer by ensuring that they get the same care as white patients, not just in clinical trials but throughout the national health care system.”

In addition, comorbid disease associated with prostate cancer is a significant cause of mortality among African American and white patients, and efforts to treat cancer should also consider cardiovascular disease, diabetes and other comorbidities.

“It is an unsettling fact that there is not equal treatment in the United States. African Americans, other minorities, and the poor in general often experience disparate quality of care or no care at all,” they said. “Although race does not matter biologically, race still matters.”

Dr. Paller and Dr. Brawley are from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; Lin Wang and Dr. Brawley are from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore. These comments summarize their editorial in response to Dess et al. Dr. Brawley reports receiving grants from the National Cancer Institute and Bloomberg Philanthropies. The other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

The results by Dess et al. show that inequality in prostate cancer mortality is the result of socioeconomic barriers that reduce access to care rather than a biological predisposition, Channing J. Paller, MD; Lin Wang, MSc, MMed; and Otis W. Brawley, MD, wrote in an editorial (JAMA Oncol 2019 May 23. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0812).

As registries collect more socioeconomic data from patients, including information on insurance status and health care system where treatment occurred, adjusting for confounders to study the effects of prevention, diagnostic and treatment strategies in addition to “open-minded analyses will help to mitigate some of the prevailing biases” about racial differences in medicine, they said.

While profiling by population can be a useful tool, tracking by geographical location may be a better way to categorize patients, such as glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency that came about as protection from malaria in the case of Mediterranean, African, and Asian populations.

“Although it is still true that men of African origin have a higher incidence of prostate cancer and higher mortality rates, the causes of these differences are complex and may involve exposure to prostate cancer risk factors, genomic differences, and other biology-based factors,” the authors wrote. “Research to determine the relative contributions of these factors should continue; but in the meantime, we as health care professionals are likely to have the greatest effect on improved outcomes for African American patients with prostate cancer by ensuring that they get the same care as white patients, not just in clinical trials but throughout the national health care system.”

In addition, comorbid disease associated with prostate cancer is a significant cause of mortality among African American and white patients, and efforts to treat cancer should also consider cardiovascular disease, diabetes and other comorbidities.

“It is an unsettling fact that there is not equal treatment in the United States. African Americans, other minorities, and the poor in general often experience disparate quality of care or no care at all,” they said. “Although race does not matter biologically, race still matters.”

Dr. Paller and Dr. Brawley are from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; Lin Wang and Dr. Brawley are from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore. These comments summarize their editorial in response to Dess et al. Dr. Brawley reports receiving grants from the National Cancer Institute and Bloomberg Philanthropies. The other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

The results by Dess et al. show that inequality in prostate cancer mortality is the result of socioeconomic barriers that reduce access to care rather than a biological predisposition, Channing J. Paller, MD; Lin Wang, MSc, MMed; and Otis W. Brawley, MD, wrote in an editorial (JAMA Oncol 2019 May 23. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0812).

As registries collect more socioeconomic data from patients, including information on insurance status and health care system where treatment occurred, adjusting for confounders to study the effects of prevention, diagnostic and treatment strategies in addition to “open-minded analyses will help to mitigate some of the prevailing biases” about racial differences in medicine, they said.

While profiling by population can be a useful tool, tracking by geographical location may be a better way to categorize patients, such as glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency that came about as protection from malaria in the case of Mediterranean, African, and Asian populations.

“Although it is still true that men of African origin have a higher incidence of prostate cancer and higher mortality rates, the causes of these differences are complex and may involve exposure to prostate cancer risk factors, genomic differences, and other biology-based factors,” the authors wrote. “Research to determine the relative contributions of these factors should continue; but in the meantime, we as health care professionals are likely to have the greatest effect on improved outcomes for African American patients with prostate cancer by ensuring that they get the same care as white patients, not just in clinical trials but throughout the national health care system.”

In addition, comorbid disease associated with prostate cancer is a significant cause of mortality among African American and white patients, and efforts to treat cancer should also consider cardiovascular disease, diabetes and other comorbidities.

“It is an unsettling fact that there is not equal treatment in the United States. African Americans, other minorities, and the poor in general often experience disparate quality of care or no care at all,” they said. “Although race does not matter biologically, race still matters.”

Dr. Paller and Dr. Brawley are from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; Lin Wang and Dr. Brawley are from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore. These comments summarize their editorial in response to Dess et al. Dr. Brawley reports receiving grants from the National Cancer Institute and Bloomberg Philanthropies. The other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Black men with newly diagnosed nonmetastatic prostate cancer had no significant difference in prostate cancer–specific mortality compared with white men when treated with a standardized approach and follow-up or at a health care system with standardized access, according to recent research published in JAMA Oncology.

Robert T. Dess, MD, from the department of radiation oncology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues examined data from 296,273 patients in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cohort, 3,972 patients from the Veterans Affairs (VA) health system, and 5,854 patients in four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) from the National Cancer Institute–sponsored Radiation Therapy Oncology Group between January 1992 and December 2013. Of these, 52,840 patients (17.8%) in the SEER cohort, 1,513 patients (38.1%) in the VA cohort, and 1,129 (19.3%) in the RCT cohort were black men. The mean age across all cohorts was 64.9 years, and the median follow-up was 75 months in the SEER cohort, 97 months in the VA cohort, and 104 months in the RCT cohort.

After adjustment for age in the SEER cohort, black men had a 30% increased risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality (PCSM) compared with white men (subdistribution hazard ratio, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.23-1.37; P less than .001). However, after the researchers performed inverse probability weighting (IPW) to adjust for race-based imbalances such as access to care and standardized treatment, there was a 0.5% increased risk over 10 years (sHR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.04-1.15; P less than .001) after diagnosis.

In the VA cohort, IPW yielded no significant differences between black men and white men (sHR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.56-1.30; P = .46), and there was a significantly lower risk for black men in the RCT cohort after IPW (sHR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.66-0.99; P = .04). With regard to other outcomes, other-cause mortality was significantly higher for black men in the SEER cohort (sHR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.27-1.34; P less than .001) and in the RCT cohort (sHR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.06-1.29; P = .002) after IPW.

“Black race remains associated with many factors that negatively affect outcomes, and disparities persist at the population level,” Dr. Dess and colleagues wrote in their study. “Continued efforts are needed to address this clear racial health inequity driven by modifiable nonbiological risk factors.”

The researchers said some residual confounding may exist, but noted the strengths of the study included a diverse cohort with a large range of treatment approaches.

This study was funded in part by the Prostate Cancer Foundation, a grant from the Prostate Cancer National Institutes of Health Specialized Programs of Research Excellence, two grants from the Department of Defense, a grant from NIH, and a grant from the NIH Cancer Center. One or more of the authors reported relationships in the form of grants, personal fees, and consulting fees with numerous companies. The other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dess RT et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 May 23. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0826.

Black men with newly diagnosed nonmetastatic prostate cancer had no significant difference in prostate cancer–specific mortality compared with white men when treated with a standardized approach and follow-up or at a health care system with standardized access, according to recent research published in JAMA Oncology.

Robert T. Dess, MD, from the department of radiation oncology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues examined data from 296,273 patients in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cohort, 3,972 patients from the Veterans Affairs (VA) health system, and 5,854 patients in four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) from the National Cancer Institute–sponsored Radiation Therapy Oncology Group between January 1992 and December 2013. Of these, 52,840 patients (17.8%) in the SEER cohort, 1,513 patients (38.1%) in the VA cohort, and 1,129 (19.3%) in the RCT cohort were black men. The mean age across all cohorts was 64.9 years, and the median follow-up was 75 months in the SEER cohort, 97 months in the VA cohort, and 104 months in the RCT cohort.

After adjustment for age in the SEER cohort, black men had a 30% increased risk of prostate cancer–specific mortality (PCSM) compared with white men (subdistribution hazard ratio, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.23-1.37; P less than .001). However, after the researchers performed inverse probability weighting (IPW) to adjust for race-based imbalances such as access to care and standardized treatment, there was a 0.5% increased risk over 10 years (sHR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.04-1.15; P less than .001) after diagnosis.

In the VA cohort, IPW yielded no significant differences between black men and white men (sHR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.56-1.30; P = .46), and there was a significantly lower risk for black men in the RCT cohort after IPW (sHR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.66-0.99; P = .04). With regard to other outcomes, other-cause mortality was significantly higher for black men in the SEER cohort (sHR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.27-1.34; P less than .001) and in the RCT cohort (sHR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.06-1.29; P = .002) after IPW.

“Black race remains associated with many factors that negatively affect outcomes, and disparities persist at the population level,” Dr. Dess and colleagues wrote in their study. “Continued efforts are needed to address this clear racial health inequity driven by modifiable nonbiological risk factors.”

The researchers said some residual confounding may exist, but noted the strengths of the study included a diverse cohort with a large range of treatment approaches.

This study was funded in part by the Prostate Cancer Foundation, a grant from the Prostate Cancer National Institutes of Health Specialized Programs of Research Excellence, two grants from the Department of Defense, a grant from NIH, and a grant from the NIH Cancer Center. One or more of the authors reported relationships in the form of grants, personal fees, and consulting fees with numerous companies. The other authors report no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Dess RT et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 May 23. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0826.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Warfarin boosts OA risk in Rotterdam Study

TORONTO – The use of warfarin or related vitamin K antagonists was associated with a more than 100% increased risk of incident or progressive knee or hip osteoarthritis in the Rotterdam Study, Cindy G. Boer reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

A biologically plausible mechanism exists for this relationship, added Ms. Boer, a PhD student with a special interest in the molecular genetics of OA at Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

In a previous genetic study, she and her coinvestigators identified two genetic variants that result in loss of function of matrix Gla protein (MGP), a key inhibitor of cartilage calcification. They showed that the presence of these alleles was associated with a significantly increased risk of hand OA, which makes sense because increased calcification within a vulnerable joint promotes OA.

“The interesting thing here is that, in order for MGP to inhibit calcification, it needs to be gamma-carboxylated by vitamin K. If it’s not gamma-carboxylated it cannot inhibit calcification,” Ms. Boer said at the meeting sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

This observation led her to hypothesize that patients on warfarin or other vitamin K antagonists might have an increased risk of developing new-onset OA or, if they already had OA, of experiencing disease progression, since their medication inhibits MGP. To test this hypothesis, she and her coinvestigators turned to the landmark Rotterdam Study, a prospective, population-based cohort study of 15,000 participants, ongoing since 1990. Two large cohorts within the study had data available on the incidence and progression of radiographic knee and hip OA, one group over the course of 5 years of follow-up, the other with 10 years.

Serial x-rays of 8,845 knee joints were available, including 657 of warfarin users. Their rate of incident or progressive knee OA was 13%, compared with 5.9% in the nonusers in an analysis adjusted for age, sex, BMI, baseline OA status, and time between study visits.

In a similar vein, the rate of incident or progressive hip OA was 12% in the warfarin users, compared with 3.1% in nonusers.

About 80% of the OA endpoints in this analysis involved incident OA, defined radiographically as Kellgren-Lawrence grade 2. Progressive OA was defined as going from grade 2 at baseline to grade 3-4 during follow-up.

There was a signal of a treatment duration-related effect, with OA rates trending highest in individuals on warfarin for longer than 365 days, followed by those on the oral anticoagulant for more than 100 days, who in turn had higher rates than those on warfarin for less time.

Ms. Boer said an important next step in this research is to replicate the warfarin/OA association in an independent cohort. Also, she and her coworkers are now gathering OA incidence and progression data in patients on direct oral anticoagulants rather than warfarin to test the hypothesis that they will not have an increased rate of OA, compared with nonusers, since these newer agents don’t affect vitamin K. Of course, if they do turn out to have an elevated risk, it would point to one or more of the conditions for which oral anticoagulants are commonly prescribed as the explanation.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, sponsored by Erasmus University and the Dutch government.

TORONTO – The use of warfarin or related vitamin K antagonists was associated with a more than 100% increased risk of incident or progressive knee or hip osteoarthritis in the Rotterdam Study, Cindy G. Boer reported at the OARSI 2019 World Congress.

A biologically plausible mechanism exists for this relationship, added Ms. Boer, a PhD student with a special interest in the molecular genetics of OA at Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands.