User login

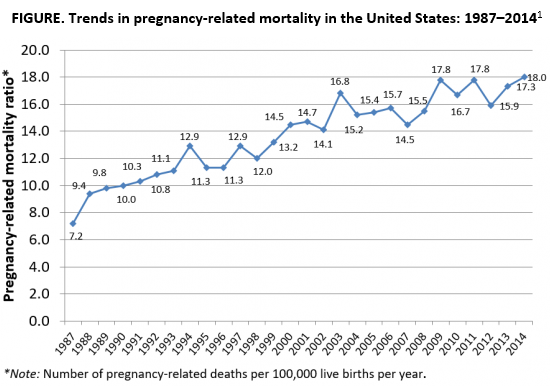

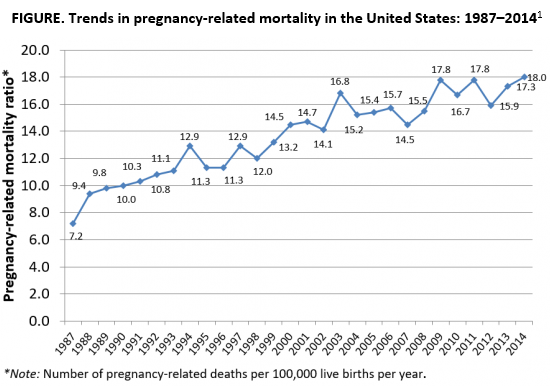

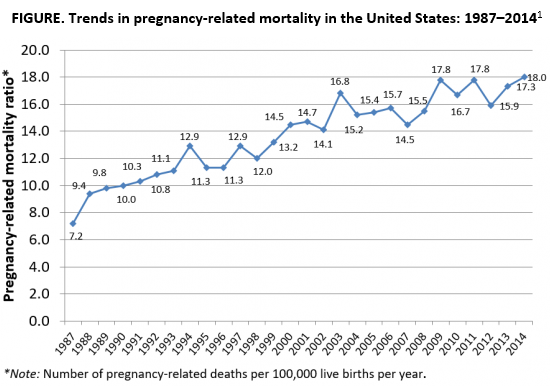

Pregnancy-Related Deaths: A “Web of Missed Opportunities”

The causes of death differ throughout pregnancy and postpartum. Overall, heart disease and stroke cause > 1 in 3 deaths. At delivery, most deaths are due to obstetric emergencies, such as severe bleeding and amniotic fluid embolism. In the week after delivery, severe bleeding, high blood pressure, and infection are most common. But one-third of the deaths happen 1 week to 1 year after delivery, most often caused by cardiomyopathy.

The findings also confirm racial disparities, the CDC says. Black and Native American women were about 3 times as likely as white women to die of a pregnancy-related cause.

The researchers analyzed 2011-2015 national data on pregnancy mortality and 2013-2017 data from 13 state maternal mortality review committees. Their analysis revealed that most pregnancy-related deaths were preventable regardless of race or ethnicity. Each death represents a “web of missed opportunities,” the CDC says. The mortality review committees determined that each death was associated with several contributing factors, including lack of access to appropriate care, missed or delayed diagnoses, and lack of knowledge among patients and providers about warning signs.

The CDC offers advice on how to help keep patients safe during and after pregnancy. For example:

- Help patients manage their chronic conditions;

- Teach patients about warning signs; and

- Use tools to flag warning signs early so women can receive timely treatment

Hospitals also can standardize patient care, the CDC advises, including delivering high-risk women at hospitals with specialized providers and equipment. They can train nonobstetric providers to consider the patient’s recent pregnancy history. Importantly, health care practitioners should continue to provide high-quality care for mothers up to at least 1 year after birth.

The causes of death differ throughout pregnancy and postpartum. Overall, heart disease and stroke cause > 1 in 3 deaths. At delivery, most deaths are due to obstetric emergencies, such as severe bleeding and amniotic fluid embolism. In the week after delivery, severe bleeding, high blood pressure, and infection are most common. But one-third of the deaths happen 1 week to 1 year after delivery, most often caused by cardiomyopathy.

The findings also confirm racial disparities, the CDC says. Black and Native American women were about 3 times as likely as white women to die of a pregnancy-related cause.

The researchers analyzed 2011-2015 national data on pregnancy mortality and 2013-2017 data from 13 state maternal mortality review committees. Their analysis revealed that most pregnancy-related deaths were preventable regardless of race or ethnicity. Each death represents a “web of missed opportunities,” the CDC says. The mortality review committees determined that each death was associated with several contributing factors, including lack of access to appropriate care, missed or delayed diagnoses, and lack of knowledge among patients and providers about warning signs.

The CDC offers advice on how to help keep patients safe during and after pregnancy. For example:

- Help patients manage their chronic conditions;

- Teach patients about warning signs; and

- Use tools to flag warning signs early so women can receive timely treatment

Hospitals also can standardize patient care, the CDC advises, including delivering high-risk women at hospitals with specialized providers and equipment. They can train nonobstetric providers to consider the patient’s recent pregnancy history. Importantly, health care practitioners should continue to provide high-quality care for mothers up to at least 1 year after birth.

The causes of death differ throughout pregnancy and postpartum. Overall, heart disease and stroke cause > 1 in 3 deaths. At delivery, most deaths are due to obstetric emergencies, such as severe bleeding and amniotic fluid embolism. In the week after delivery, severe bleeding, high blood pressure, and infection are most common. But one-third of the deaths happen 1 week to 1 year after delivery, most often caused by cardiomyopathy.

The findings also confirm racial disparities, the CDC says. Black and Native American women were about 3 times as likely as white women to die of a pregnancy-related cause.

The researchers analyzed 2011-2015 national data on pregnancy mortality and 2013-2017 data from 13 state maternal mortality review committees. Their analysis revealed that most pregnancy-related deaths were preventable regardless of race or ethnicity. Each death represents a “web of missed opportunities,” the CDC says. The mortality review committees determined that each death was associated with several contributing factors, including lack of access to appropriate care, missed or delayed diagnoses, and lack of knowledge among patients and providers about warning signs.

The CDC offers advice on how to help keep patients safe during and after pregnancy. For example:

- Help patients manage their chronic conditions;

- Teach patients about warning signs; and

- Use tools to flag warning signs early so women can receive timely treatment

Hospitals also can standardize patient care, the CDC advises, including delivering high-risk women at hospitals with specialized providers and equipment. They can train nonobstetric providers to consider the patient’s recent pregnancy history. Importantly, health care practitioners should continue to provide high-quality care for mothers up to at least 1 year after birth.

Generalized rash following ankle ulceration

At the hospital, the physicians noted that there were no lesions on the mucous membranes of the patient’s eyes, ears, nose, mouth or anus and his vital signs were within normal limits. He was empirically treated with 1 dose of methylprednisolone (125 mg intravenous [IV]) and started on IV piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin. The patient subsequently revealed that he’d had a similar experience a year earlier after being treated with TMP-SMX for cellulitis. During the previous episode, he said the lesions were located on the exact same areas of his glans penis and chin. Based on the morphologic characteristics of the eruption and the history of similar lesions that appeared following previous treatment with TMP-SMX, the physician diagnosed disseminated fixed-drug eruption in this patient.

A fixed-drug eruption is an adverse cutaneous reaction to a drug that is defined by a dusky red or violaceous macule, which evolves into a patch, and eventually, an edematous plaque. Fixed-drug eruptions are typically solitary, but may be generalized (as was the case with this patient). The pathophysiology of the disease involves resident intra-epidermal CD8+ T-cells resembling effector memory T-cells. These T-cells are increased in number at the dermoepidermal junction of normal appearing skin; their aberrant activation leads to an inflammatory response, stimulating tissue destruction and formation of the classic fixed-drug lesion.

This diagnosis usually is made based on a history of similar lesions recurring at the same location in response to a specific drug and the classic physical exam findings of well-demarcated, edematous, and violaceous plaques. A skin biopsy may be performed to confirm a fixed-drug eruption in the case of clinical equipoise.

Fixed-drug eruptions occasionally exhibit bullae and erosions and must be differentiated from more serious generalized bullous diseases, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). The differential diagnosis also includes erythema multiforme, early bullous drug eruption, and bullous arthropod assault, which may leave similar hyperpigmented patches.

Management of a disseminated fixed-drug eruption requires a thorough history to identify the causative agent (including over-the-counter drugs, herbals, topicals, and eye drops). Most patients are asymptomatic, but some (like this patient) are symptomatic and experience generalized pruritus, cutaneous burning, and/or pain. Symptomatic therapy includes oral antihistamines and potent topical glucocorticoid ointment for non-eroded lesions. Additionally, if not medically contraindicated, oral steroids may be used for generalized or extremely painful mucosal lesions at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg daily for 3 to 5 days.

Local wound care of eroded lesions includes keeping the site moist with a bland emollient and bandaging. The inciting agent must be added to the patient’s allergy list and avoided in the future. In equivocal cases, it is prudent to admit the patient for observation to ensure that the eruption is not a nascent SJS or TEN eruption.

In this case, the patient was admitted to the observation unit overnight to monitor for the appearance of systemic symptoms and to assess the evolution of the rash for further mucosal involvement that could have indicated SJS. Upon reassessment the next day, his older lesions had evolved into vesiculated and necrotic areas as per the natural history of severe fixed-drug eruption. He was prescribed prednisone 40 mg/d for 3 days to help with local inflammation, pain, and itching. TMP-SMX was added to his allergy list and he was given local wound care instructions. He was told to return if he developed any systemic symptoms.

This case was adapted from: Bucher J, Rahnama-Moghadam S, Osswald S. Generalized rash follows ankle ulceration. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:489-491.

At the hospital, the physicians noted that there were no lesions on the mucous membranes of the patient’s eyes, ears, nose, mouth or anus and his vital signs were within normal limits. He was empirically treated with 1 dose of methylprednisolone (125 mg intravenous [IV]) and started on IV piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin. The patient subsequently revealed that he’d had a similar experience a year earlier after being treated with TMP-SMX for cellulitis. During the previous episode, he said the lesions were located on the exact same areas of his glans penis and chin. Based on the morphologic characteristics of the eruption and the history of similar lesions that appeared following previous treatment with TMP-SMX, the physician diagnosed disseminated fixed-drug eruption in this patient.

A fixed-drug eruption is an adverse cutaneous reaction to a drug that is defined by a dusky red or violaceous macule, which evolves into a patch, and eventually, an edematous plaque. Fixed-drug eruptions are typically solitary, but may be generalized (as was the case with this patient). The pathophysiology of the disease involves resident intra-epidermal CD8+ T-cells resembling effector memory T-cells. These T-cells are increased in number at the dermoepidermal junction of normal appearing skin; their aberrant activation leads to an inflammatory response, stimulating tissue destruction and formation of the classic fixed-drug lesion.

This diagnosis usually is made based on a history of similar lesions recurring at the same location in response to a specific drug and the classic physical exam findings of well-demarcated, edematous, and violaceous plaques. A skin biopsy may be performed to confirm a fixed-drug eruption in the case of clinical equipoise.

Fixed-drug eruptions occasionally exhibit bullae and erosions and must be differentiated from more serious generalized bullous diseases, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). The differential diagnosis also includes erythema multiforme, early bullous drug eruption, and bullous arthropod assault, which may leave similar hyperpigmented patches.

Management of a disseminated fixed-drug eruption requires a thorough history to identify the causative agent (including over-the-counter drugs, herbals, topicals, and eye drops). Most patients are asymptomatic, but some (like this patient) are symptomatic and experience generalized pruritus, cutaneous burning, and/or pain. Symptomatic therapy includes oral antihistamines and potent topical glucocorticoid ointment for non-eroded lesions. Additionally, if not medically contraindicated, oral steroids may be used for generalized or extremely painful mucosal lesions at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg daily for 3 to 5 days.

Local wound care of eroded lesions includes keeping the site moist with a bland emollient and bandaging. The inciting agent must be added to the patient’s allergy list and avoided in the future. In equivocal cases, it is prudent to admit the patient for observation to ensure that the eruption is not a nascent SJS or TEN eruption.

In this case, the patient was admitted to the observation unit overnight to monitor for the appearance of systemic symptoms and to assess the evolution of the rash for further mucosal involvement that could have indicated SJS. Upon reassessment the next day, his older lesions had evolved into vesiculated and necrotic areas as per the natural history of severe fixed-drug eruption. He was prescribed prednisone 40 mg/d for 3 days to help with local inflammation, pain, and itching. TMP-SMX was added to his allergy list and he was given local wound care instructions. He was told to return if he developed any systemic symptoms.

This case was adapted from: Bucher J, Rahnama-Moghadam S, Osswald S. Generalized rash follows ankle ulceration. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:489-491.

At the hospital, the physicians noted that there were no lesions on the mucous membranes of the patient’s eyes, ears, nose, mouth or anus and his vital signs were within normal limits. He was empirically treated with 1 dose of methylprednisolone (125 mg intravenous [IV]) and started on IV piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin. The patient subsequently revealed that he’d had a similar experience a year earlier after being treated with TMP-SMX for cellulitis. During the previous episode, he said the lesions were located on the exact same areas of his glans penis and chin. Based on the morphologic characteristics of the eruption and the history of similar lesions that appeared following previous treatment with TMP-SMX, the physician diagnosed disseminated fixed-drug eruption in this patient.

A fixed-drug eruption is an adverse cutaneous reaction to a drug that is defined by a dusky red or violaceous macule, which evolves into a patch, and eventually, an edematous plaque. Fixed-drug eruptions are typically solitary, but may be generalized (as was the case with this patient). The pathophysiology of the disease involves resident intra-epidermal CD8+ T-cells resembling effector memory T-cells. These T-cells are increased in number at the dermoepidermal junction of normal appearing skin; their aberrant activation leads to an inflammatory response, stimulating tissue destruction and formation of the classic fixed-drug lesion.

This diagnosis usually is made based on a history of similar lesions recurring at the same location in response to a specific drug and the classic physical exam findings of well-demarcated, edematous, and violaceous plaques. A skin biopsy may be performed to confirm a fixed-drug eruption in the case of clinical equipoise.

Fixed-drug eruptions occasionally exhibit bullae and erosions and must be differentiated from more serious generalized bullous diseases, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). The differential diagnosis also includes erythema multiforme, early bullous drug eruption, and bullous arthropod assault, which may leave similar hyperpigmented patches.

Management of a disseminated fixed-drug eruption requires a thorough history to identify the causative agent (including over-the-counter drugs, herbals, topicals, and eye drops). Most patients are asymptomatic, but some (like this patient) are symptomatic and experience generalized pruritus, cutaneous burning, and/or pain. Symptomatic therapy includes oral antihistamines and potent topical glucocorticoid ointment for non-eroded lesions. Additionally, if not medically contraindicated, oral steroids may be used for generalized or extremely painful mucosal lesions at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg daily for 3 to 5 days.

Local wound care of eroded lesions includes keeping the site moist with a bland emollient and bandaging. The inciting agent must be added to the patient’s allergy list and avoided in the future. In equivocal cases, it is prudent to admit the patient for observation to ensure that the eruption is not a nascent SJS or TEN eruption.

In this case, the patient was admitted to the observation unit overnight to monitor for the appearance of systemic symptoms and to assess the evolution of the rash for further mucosal involvement that could have indicated SJS. Upon reassessment the next day, his older lesions had evolved into vesiculated and necrotic areas as per the natural history of severe fixed-drug eruption. He was prescribed prednisone 40 mg/d for 3 days to help with local inflammation, pain, and itching. TMP-SMX was added to his allergy list and he was given local wound care instructions. He was told to return if he developed any systemic symptoms.

This case was adapted from: Bucher J, Rahnama-Moghadam S, Osswald S. Generalized rash follows ankle ulceration. J Fam Pract. 2016;65:489-491.

Children’s book effectively assesses literary skills during well-child visits

reported John S. Hutton, MS, MD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and his associates.

The Reading House (TRH) is a 14-page, full-color, board book with a simple, rhyming narrative and illustrated content showing children of various ethnicities and sexes going about their day. For the study, published in Pediatrics, 278 children aged 36-52 months (mean age, 43.1 months) were recruited from seven pediatric primary care clinics, two of which were affiliated with an academic children’s hospital primarily serving families of lower socioeconomic status. The children’s reading comprehension was measured by way of a 9-item TRH assessment, as well as the 25-item Get Ready to Read! (GRTR) validated measure; parent, child, and provider impressions of TRH also were collected.

The mean TRH assessment score was 4.2, and the mean GRTR score was 11.1. The TRH score was positively associated with GRTR score, female sex, private practice, and child age (Pediatrics 2019 May 30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3843).

Of the 72 clinical providers surveyed on the effectiveness of the TRH assessment, most reported that the assessment was not invasive in patient flow (93% not at all, 6% somewhat, 1% very much), that TRH would be feasible to administer (49% yes, 43% not sure, 8% no), would be clinically useful (67% yes, 31% not sure, 2% no), and would be useful for families (85% yes, 14% not sure, 1% no). Similar results on the effectiveness and enjoyability of TRH were reported by parents and children.

“Although psychometric properties are critical, effective screening should be perceived as useful and not burdensome or invasive. Responses to parent, child, and provider surveys were favorable, which suggests that TRH screening may be an enjoyable and valuable addition to well-child visits,” the investigators wrote.

Dr. Hutton conceived, wrote, and edited the children’s book used in the study, and is the founder of the company that published the book, although he receives no salary or compensation for this role. The book’s intended use is as a screening tool, distributed at low cost to clinical practices and organizations. The other study authors did not report any conflicts of interest.

reported John S. Hutton, MS, MD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and his associates.

The Reading House (TRH) is a 14-page, full-color, board book with a simple, rhyming narrative and illustrated content showing children of various ethnicities and sexes going about their day. For the study, published in Pediatrics, 278 children aged 36-52 months (mean age, 43.1 months) were recruited from seven pediatric primary care clinics, two of which were affiliated with an academic children’s hospital primarily serving families of lower socioeconomic status. The children’s reading comprehension was measured by way of a 9-item TRH assessment, as well as the 25-item Get Ready to Read! (GRTR) validated measure; parent, child, and provider impressions of TRH also were collected.

The mean TRH assessment score was 4.2, and the mean GRTR score was 11.1. The TRH score was positively associated with GRTR score, female sex, private practice, and child age (Pediatrics 2019 May 30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3843).

Of the 72 clinical providers surveyed on the effectiveness of the TRH assessment, most reported that the assessment was not invasive in patient flow (93% not at all, 6% somewhat, 1% very much), that TRH would be feasible to administer (49% yes, 43% not sure, 8% no), would be clinically useful (67% yes, 31% not sure, 2% no), and would be useful for families (85% yes, 14% not sure, 1% no). Similar results on the effectiveness and enjoyability of TRH were reported by parents and children.

“Although psychometric properties are critical, effective screening should be perceived as useful and not burdensome or invasive. Responses to parent, child, and provider surveys were favorable, which suggests that TRH screening may be an enjoyable and valuable addition to well-child visits,” the investigators wrote.

Dr. Hutton conceived, wrote, and edited the children’s book used in the study, and is the founder of the company that published the book, although he receives no salary or compensation for this role. The book’s intended use is as a screening tool, distributed at low cost to clinical practices and organizations. The other study authors did not report any conflicts of interest.

reported John S. Hutton, MS, MD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and his associates.

The Reading House (TRH) is a 14-page, full-color, board book with a simple, rhyming narrative and illustrated content showing children of various ethnicities and sexes going about their day. For the study, published in Pediatrics, 278 children aged 36-52 months (mean age, 43.1 months) were recruited from seven pediatric primary care clinics, two of which were affiliated with an academic children’s hospital primarily serving families of lower socioeconomic status. The children’s reading comprehension was measured by way of a 9-item TRH assessment, as well as the 25-item Get Ready to Read! (GRTR) validated measure; parent, child, and provider impressions of TRH also were collected.

The mean TRH assessment score was 4.2, and the mean GRTR score was 11.1. The TRH score was positively associated with GRTR score, female sex, private practice, and child age (Pediatrics 2019 May 30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3843).

Of the 72 clinical providers surveyed on the effectiveness of the TRH assessment, most reported that the assessment was not invasive in patient flow (93% not at all, 6% somewhat, 1% very much), that TRH would be feasible to administer (49% yes, 43% not sure, 8% no), would be clinically useful (67% yes, 31% not sure, 2% no), and would be useful for families (85% yes, 14% not sure, 1% no). Similar results on the effectiveness and enjoyability of TRH were reported by parents and children.

“Although psychometric properties are critical, effective screening should be perceived as useful and not burdensome or invasive. Responses to parent, child, and provider surveys were favorable, which suggests that TRH screening may be an enjoyable and valuable addition to well-child visits,” the investigators wrote.

Dr. Hutton conceived, wrote, and edited the children’s book used in the study, and is the founder of the company that published the book, although he receives no salary or compensation for this role. The book’s intended use is as a screening tool, distributed at low cost to clinical practices and organizations. The other study authors did not report any conflicts of interest.

FROM PEDIATRICS

AAD’s augmented intelligence position statement provides look to the future

A blueprint for the future of into clinical settings, and postmarketing surveillance – is the focus of a newly published American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) position statement.

The statement describes AuI as “a concept that focuses on artificial intelligence’s (AI) assistive role,” emphasizing that AuI is “designed to enhance human intelligence and the physician/patient relationship,” not to replace that relationship. The statement, available on the AAD website, also emphasizes the importance of the human-centered nature of this concept as dermatologists integrate AuI into their practice, noting that “patients should feel well cared for even when interacting with software.”

“We are at the precipice of seeing the beginnings of augmented intelligence tools influence our practice,” statement coauthor Justin M. Ko, MD, MBA, said in an interview. “At the outset, it will likely be systems and tools that are working on practice management processes, insights, and analytics. However, I don’t believe we’re far from seeing the mainstream integration say, of triage, point of care diagnostic support, or chronic disease management capabilities that rely in some part on augmented intelligence models.”

“The key is that we recognize that this is on the horizon, and that we actively work to shape the development and deployment of these tools in a responsible way that enhances patient care and ensures that patient safety is held paramount,” added Dr. Ko, director and chief of medical dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

“We want patients and clinicians to recognize the potential of such tools to augment the core care relationship and improve the delivery of such care,” he explained. “At the same time, we know that, from the technology that exists all around us in all aspects of our lives, that despite the best intentions, there [may be] unintended consequences in the medical realm. We must be cognizant of possibilities, for example, of amplifying bias and increasing health inequity, and take an active approach to mitigating these risks.”

The AAD position statement notes that high-quality AuI will be “designed and evaluated in a manner that enables the delivery of high-quality care to patients.” During development and clinical deployment, the statement highlighted the importance of collaboration with practitioners, and that “AuI must integrate into physician and provider workflows.” The statement advises that AuI tools should be regulated appropriately, and that postmarketing surveillance will be necessary after clinical launch of these tools, measuring outcomes such as “quality, cost, and/or efficiency of care delivery.”

While the first half of the statement provides a roadmap for AuI development and implementation, the second half further emphasizes collaboration and communication with a number of stakeholders. “Effective and ethical development and implementation of AuI will require continuous engagement, education, exploration of privacy and medical-legal issues, and advocacy,” the statement says. “Although the promise of AuI to improve health and wellness holds significant potential,” the statement says, “issues related to privacy and medical-legal complications are amplified by technology that requires transmission of data beyond the confines of a providers’ institution. Protected Health Information must be managed with effective safeguards to prevent inadvertent exposure.”

The conclusion of the statement revisits the game-changing nature of AuI while asserting the AAD’s commitment to guiding integration with dermatology practice. “AuI has the potential to transform our collective and personal experience of health, health care, and wellness,” the AAD wrote. “To achieve this potential, deliberate and diligent efforts must be taken to engage and collaborate with stakeholders and policy makers. The Academy hopes to work with administrative and legislative colleagues to create policies that promote AuI that is high quality, inclusive, equitable, and accessible. Through collaboration and research, the Academy strives to guide the design, implementation, and regulation of these technologies and augment care for all.”

The statement also includes a glossary of terms used in this area. The AAD’s Ad Hoc Taskforce on Augmented Intelligence wrote the position statement; Dr. Ko is on the task force and serves as its chairman.

A blueprint for the future of into clinical settings, and postmarketing surveillance – is the focus of a newly published American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) position statement.

The statement describes AuI as “a concept that focuses on artificial intelligence’s (AI) assistive role,” emphasizing that AuI is “designed to enhance human intelligence and the physician/patient relationship,” not to replace that relationship. The statement, available on the AAD website, also emphasizes the importance of the human-centered nature of this concept as dermatologists integrate AuI into their practice, noting that “patients should feel well cared for even when interacting with software.”

“We are at the precipice of seeing the beginnings of augmented intelligence tools influence our practice,” statement coauthor Justin M. Ko, MD, MBA, said in an interview. “At the outset, it will likely be systems and tools that are working on practice management processes, insights, and analytics. However, I don’t believe we’re far from seeing the mainstream integration say, of triage, point of care diagnostic support, or chronic disease management capabilities that rely in some part on augmented intelligence models.”

“The key is that we recognize that this is on the horizon, and that we actively work to shape the development and deployment of these tools in a responsible way that enhances patient care and ensures that patient safety is held paramount,” added Dr. Ko, director and chief of medical dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

“We want patients and clinicians to recognize the potential of such tools to augment the core care relationship and improve the delivery of such care,” he explained. “At the same time, we know that, from the technology that exists all around us in all aspects of our lives, that despite the best intentions, there [may be] unintended consequences in the medical realm. We must be cognizant of possibilities, for example, of amplifying bias and increasing health inequity, and take an active approach to mitigating these risks.”

The AAD position statement notes that high-quality AuI will be “designed and evaluated in a manner that enables the delivery of high-quality care to patients.” During development and clinical deployment, the statement highlighted the importance of collaboration with practitioners, and that “AuI must integrate into physician and provider workflows.” The statement advises that AuI tools should be regulated appropriately, and that postmarketing surveillance will be necessary after clinical launch of these tools, measuring outcomes such as “quality, cost, and/or efficiency of care delivery.”

While the first half of the statement provides a roadmap for AuI development and implementation, the second half further emphasizes collaboration and communication with a number of stakeholders. “Effective and ethical development and implementation of AuI will require continuous engagement, education, exploration of privacy and medical-legal issues, and advocacy,” the statement says. “Although the promise of AuI to improve health and wellness holds significant potential,” the statement says, “issues related to privacy and medical-legal complications are amplified by technology that requires transmission of data beyond the confines of a providers’ institution. Protected Health Information must be managed with effective safeguards to prevent inadvertent exposure.”

The conclusion of the statement revisits the game-changing nature of AuI while asserting the AAD’s commitment to guiding integration with dermatology practice. “AuI has the potential to transform our collective and personal experience of health, health care, and wellness,” the AAD wrote. “To achieve this potential, deliberate and diligent efforts must be taken to engage and collaborate with stakeholders and policy makers. The Academy hopes to work with administrative and legislative colleagues to create policies that promote AuI that is high quality, inclusive, equitable, and accessible. Through collaboration and research, the Academy strives to guide the design, implementation, and regulation of these technologies and augment care for all.”

The statement also includes a glossary of terms used in this area. The AAD’s Ad Hoc Taskforce on Augmented Intelligence wrote the position statement; Dr. Ko is on the task force and serves as its chairman.

A blueprint for the future of into clinical settings, and postmarketing surveillance – is the focus of a newly published American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) position statement.

The statement describes AuI as “a concept that focuses on artificial intelligence’s (AI) assistive role,” emphasizing that AuI is “designed to enhance human intelligence and the physician/patient relationship,” not to replace that relationship. The statement, available on the AAD website, also emphasizes the importance of the human-centered nature of this concept as dermatologists integrate AuI into their practice, noting that “patients should feel well cared for even when interacting with software.”

“We are at the precipice of seeing the beginnings of augmented intelligence tools influence our practice,” statement coauthor Justin M. Ko, MD, MBA, said in an interview. “At the outset, it will likely be systems and tools that are working on practice management processes, insights, and analytics. However, I don’t believe we’re far from seeing the mainstream integration say, of triage, point of care diagnostic support, or chronic disease management capabilities that rely in some part on augmented intelligence models.”

“The key is that we recognize that this is on the horizon, and that we actively work to shape the development and deployment of these tools in a responsible way that enhances patient care and ensures that patient safety is held paramount,” added Dr. Ko, director and chief of medical dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

“We want patients and clinicians to recognize the potential of such tools to augment the core care relationship and improve the delivery of such care,” he explained. “At the same time, we know that, from the technology that exists all around us in all aspects of our lives, that despite the best intentions, there [may be] unintended consequences in the medical realm. We must be cognizant of possibilities, for example, of amplifying bias and increasing health inequity, and take an active approach to mitigating these risks.”

The AAD position statement notes that high-quality AuI will be “designed and evaluated in a manner that enables the delivery of high-quality care to patients.” During development and clinical deployment, the statement highlighted the importance of collaboration with practitioners, and that “AuI must integrate into physician and provider workflows.” The statement advises that AuI tools should be regulated appropriately, and that postmarketing surveillance will be necessary after clinical launch of these tools, measuring outcomes such as “quality, cost, and/or efficiency of care delivery.”

While the first half of the statement provides a roadmap for AuI development and implementation, the second half further emphasizes collaboration and communication with a number of stakeholders. “Effective and ethical development and implementation of AuI will require continuous engagement, education, exploration of privacy and medical-legal issues, and advocacy,” the statement says. “Although the promise of AuI to improve health and wellness holds significant potential,” the statement says, “issues related to privacy and medical-legal complications are amplified by technology that requires transmission of data beyond the confines of a providers’ institution. Protected Health Information must be managed with effective safeguards to prevent inadvertent exposure.”

The conclusion of the statement revisits the game-changing nature of AuI while asserting the AAD’s commitment to guiding integration with dermatology practice. “AuI has the potential to transform our collective and personal experience of health, health care, and wellness,” the AAD wrote. “To achieve this potential, deliberate and diligent efforts must be taken to engage and collaborate with stakeholders and policy makers. The Academy hopes to work with administrative and legislative colleagues to create policies that promote AuI that is high quality, inclusive, equitable, and accessible. Through collaboration and research, the Academy strives to guide the design, implementation, and regulation of these technologies and augment care for all.”

The statement also includes a glossary of terms used in this area. The AAD’s Ad Hoc Taskforce on Augmented Intelligence wrote the position statement; Dr. Ko is on the task force and serves as its chairman.

New tickborne virus emerges in China

A new virus has been associated with febrile illness in China in patients with histories of tick bites. The data on the discovery, isolation, and characterization of the virus were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The segmented RNA virus now known as Alongshan virus (ALSV) “belongs to the unclassified jingmenvirus group in the family Flaviviridae, which includes the genera flavivirus, pestivirus, hepacivirus, and pegivirus,” wrote Ze-Dong Wang, PhD, of Foshan (China) University, and colleagues.

The index patient with ALSV was a 42-year-old female farmer from the town of Alongshan, China, who presented to a regional hospital in April 2017 with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites. The initial clinical features were similar to those seen in tickborne diseases, but a blood sample showed no RNA or antibodies for tickborne encephalitis virus. Investigators obtained a blood specimen from the index patient 4 days after the onset of illness. After culturing the sample, the investigators extracted the viral RNA genome and sequenced it.

Sequence analysis found that the new pathogen was related to segmented viruses in the jingmenvirus group of the family Flaviviridae; however, “comparison of the amino acids further confirmed that ALSV is genetically distinct from other jingmenviruses,” the investigators said.

The investigators identified 374 patients who presented to the hospital with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites during May 2017–September 2017; 86 patients had confirmed ALSV infections via nested reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction testing. Of these, 63 were men and 84 were farmers or forestry workers. Although ticks were common in the patients’ environments, no other evidence of tickborne diseases was noted. The patients ranged in age from 24 to 77 years, and the average duration of the infection was 3-7 days.

Symptoms were nonspecific and included fever, headache, fatigue, nausea, cough, and sore throat. All 86 patients were treated with intravenous ribavirin (0.5 g/day), and intramuscular benzylpenicillin sodium (2 million U/day) for 3-5 days. The median hospital stay was 11 days, and no deaths or long-term clinical complications occurred in the confirmed ALSV patients.

ALSV is similar to other jingmenviruses, but is distinct from other infections in part because of the absence of a rash or jaundice, the investigators said.

Although the investigators said they suspected the disease was carried by ticks, they would not rule out mosquitoes as a possible carrier because ALSV RNA was found in mosquitoes in a Northeastern province of China, and the RNA from those mosquitoes was found to be genetically related to the RNA assessed in this study.

Overall, “our findings suggest that ALSV may be the cause of a previously unknown febrile disease, and more studies should be conducted to determine the geographic distribution of this disease outside its current areas of identification,” they said.

The research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

SOURCE: Wang Z et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805068.

New technology and genomic surveys will continue to help identify emerging pathogens, however, “they may provide limited value in understanding the mechanisms of disease emergence,” wrote Nikos Vasilakis, PhD, and David H. Walker, MD, in an accompanying editorial. An active surveillance program allowed the investigators of the previously unknown tickborne pathogen in China to identify a group of patients with similar history. The new pathogen was classified as one of the jingmenviruses, which “reveal that RNA virus segmentation is an evolutionary process that has occurred in previously unanticipated circumstances.” This study by Wang et al. shows that these viruses are not limited to arthropod hosts but can be dangerous to humans.

The new pathogen had likely been evolving for some time before it was discovered, the editorialists said. “The key to making such discoveries is the study of ill persons, isolation of the etiologic agent, use of tools that will reveal the nature of the agent (e.g., electron microscopy), and application of the appropriate tools for definitive characterization (e.g., sequencing of the RNA genome),” they emphasized. However, to mitigate outbreaks, “proactive, real-time surveillance” may be more cost effective than extensive genomic surveys, they noted (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1901212).

Dr. Vasilakis and Dr. Walker are affiliated with the department of pathology, Center for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases, Center for Tropical Diseases, and the Institute for Human Infections and Immunity, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. They had no financial conflicts to disclose.

New technology and genomic surveys will continue to help identify emerging pathogens, however, “they may provide limited value in understanding the mechanisms of disease emergence,” wrote Nikos Vasilakis, PhD, and David H. Walker, MD, in an accompanying editorial. An active surveillance program allowed the investigators of the previously unknown tickborne pathogen in China to identify a group of patients with similar history. The new pathogen was classified as one of the jingmenviruses, which “reveal that RNA virus segmentation is an evolutionary process that has occurred in previously unanticipated circumstances.” This study by Wang et al. shows that these viruses are not limited to arthropod hosts but can be dangerous to humans.

The new pathogen had likely been evolving for some time before it was discovered, the editorialists said. “The key to making such discoveries is the study of ill persons, isolation of the etiologic agent, use of tools that will reveal the nature of the agent (e.g., electron microscopy), and application of the appropriate tools for definitive characterization (e.g., sequencing of the RNA genome),” they emphasized. However, to mitigate outbreaks, “proactive, real-time surveillance” may be more cost effective than extensive genomic surveys, they noted (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1901212).

Dr. Vasilakis and Dr. Walker are affiliated with the department of pathology, Center for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases, Center for Tropical Diseases, and the Institute for Human Infections and Immunity, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. They had no financial conflicts to disclose.

New technology and genomic surveys will continue to help identify emerging pathogens, however, “they may provide limited value in understanding the mechanisms of disease emergence,” wrote Nikos Vasilakis, PhD, and David H. Walker, MD, in an accompanying editorial. An active surveillance program allowed the investigators of the previously unknown tickborne pathogen in China to identify a group of patients with similar history. The new pathogen was classified as one of the jingmenviruses, which “reveal that RNA virus segmentation is an evolutionary process that has occurred in previously unanticipated circumstances.” This study by Wang et al. shows that these viruses are not limited to arthropod hosts but can be dangerous to humans.

The new pathogen had likely been evolving for some time before it was discovered, the editorialists said. “The key to making such discoveries is the study of ill persons, isolation of the etiologic agent, use of tools that will reveal the nature of the agent (e.g., electron microscopy), and application of the appropriate tools for definitive characterization (e.g., sequencing of the RNA genome),” they emphasized. However, to mitigate outbreaks, “proactive, real-time surveillance” may be more cost effective than extensive genomic surveys, they noted (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1901212).

Dr. Vasilakis and Dr. Walker are affiliated with the department of pathology, Center for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases, Center for Tropical Diseases, and the Institute for Human Infections and Immunity, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston. They had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A new virus has been associated with febrile illness in China in patients with histories of tick bites. The data on the discovery, isolation, and characterization of the virus were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The segmented RNA virus now known as Alongshan virus (ALSV) “belongs to the unclassified jingmenvirus group in the family Flaviviridae, which includes the genera flavivirus, pestivirus, hepacivirus, and pegivirus,” wrote Ze-Dong Wang, PhD, of Foshan (China) University, and colleagues.

The index patient with ALSV was a 42-year-old female farmer from the town of Alongshan, China, who presented to a regional hospital in April 2017 with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites. The initial clinical features were similar to those seen in tickborne diseases, but a blood sample showed no RNA or antibodies for tickborne encephalitis virus. Investigators obtained a blood specimen from the index patient 4 days after the onset of illness. After culturing the sample, the investigators extracted the viral RNA genome and sequenced it.

Sequence analysis found that the new pathogen was related to segmented viruses in the jingmenvirus group of the family Flaviviridae; however, “comparison of the amino acids further confirmed that ALSV is genetically distinct from other jingmenviruses,” the investigators said.

The investigators identified 374 patients who presented to the hospital with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites during May 2017–September 2017; 86 patients had confirmed ALSV infections via nested reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction testing. Of these, 63 were men and 84 were farmers or forestry workers. Although ticks were common in the patients’ environments, no other evidence of tickborne diseases was noted. The patients ranged in age from 24 to 77 years, and the average duration of the infection was 3-7 days.

Symptoms were nonspecific and included fever, headache, fatigue, nausea, cough, and sore throat. All 86 patients were treated with intravenous ribavirin (0.5 g/day), and intramuscular benzylpenicillin sodium (2 million U/day) for 3-5 days. The median hospital stay was 11 days, and no deaths or long-term clinical complications occurred in the confirmed ALSV patients.

ALSV is similar to other jingmenviruses, but is distinct from other infections in part because of the absence of a rash or jaundice, the investigators said.

Although the investigators said they suspected the disease was carried by ticks, they would not rule out mosquitoes as a possible carrier because ALSV RNA was found in mosquitoes in a Northeastern province of China, and the RNA from those mosquitoes was found to be genetically related to the RNA assessed in this study.

Overall, “our findings suggest that ALSV may be the cause of a previously unknown febrile disease, and more studies should be conducted to determine the geographic distribution of this disease outside its current areas of identification,” they said.

The research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

SOURCE: Wang Z et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805068.

A new virus has been associated with febrile illness in China in patients with histories of tick bites. The data on the discovery, isolation, and characterization of the virus were reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The segmented RNA virus now known as Alongshan virus (ALSV) “belongs to the unclassified jingmenvirus group in the family Flaviviridae, which includes the genera flavivirus, pestivirus, hepacivirus, and pegivirus,” wrote Ze-Dong Wang, PhD, of Foshan (China) University, and colleagues.

The index patient with ALSV was a 42-year-old female farmer from the town of Alongshan, China, who presented to a regional hospital in April 2017 with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites. The initial clinical features were similar to those seen in tickborne diseases, but a blood sample showed no RNA or antibodies for tickborne encephalitis virus. Investigators obtained a blood specimen from the index patient 4 days after the onset of illness. After culturing the sample, the investigators extracted the viral RNA genome and sequenced it.

Sequence analysis found that the new pathogen was related to segmented viruses in the jingmenvirus group of the family Flaviviridae; however, “comparison of the amino acids further confirmed that ALSV is genetically distinct from other jingmenviruses,” the investigators said.

The investigators identified 374 patients who presented to the hospital with fever, headache, and a history of tick bites during May 2017–September 2017; 86 patients had confirmed ALSV infections via nested reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction testing. Of these, 63 were men and 84 were farmers or forestry workers. Although ticks were common in the patients’ environments, no other evidence of tickborne diseases was noted. The patients ranged in age from 24 to 77 years, and the average duration of the infection was 3-7 days.

Symptoms were nonspecific and included fever, headache, fatigue, nausea, cough, and sore throat. All 86 patients were treated with intravenous ribavirin (0.5 g/day), and intramuscular benzylpenicillin sodium (2 million U/day) for 3-5 days. The median hospital stay was 11 days, and no deaths or long-term clinical complications occurred in the confirmed ALSV patients.

ALSV is similar to other jingmenviruses, but is distinct from other infections in part because of the absence of a rash or jaundice, the investigators said.

Although the investigators said they suspected the disease was carried by ticks, they would not rule out mosquitoes as a possible carrier because ALSV RNA was found in mosquitoes in a Northeastern province of China, and the RNA from those mosquitoes was found to be genetically related to the RNA assessed in this study.

Overall, “our findings suggest that ALSV may be the cause of a previously unknown febrile disease, and more studies should be conducted to determine the geographic distribution of this disease outside its current areas of identification,” they said.

The research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

SOURCE: Wang Z et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805068.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

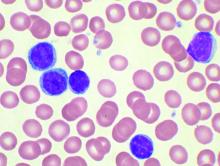

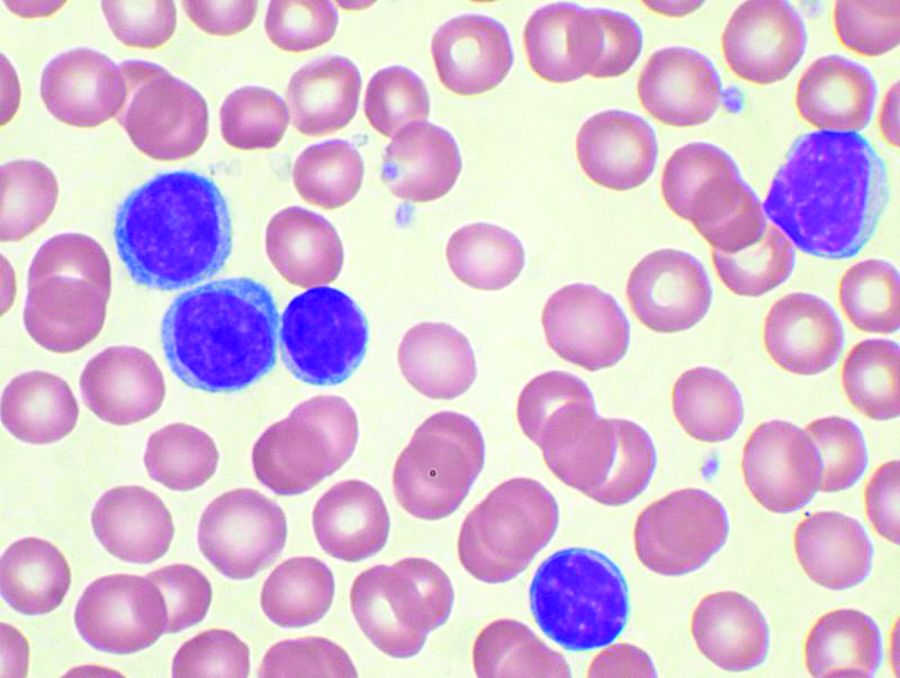

Venetoclax plus ibrutinib appears to suit elderly and high-risk patients with CLL

A combination of venetoclax and ibrutinib may be a safe and effective treatment option for previously untreated elderly and high-risk patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), according to investigators of a phase 2 trial of the combination.

About 88% of patients achieved complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery after 12 cycles of treatment, reported lead author Nitin Jain, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and colleagues.

There were no new safety signals for the combination of ibrutinib, an irreversible inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, and venetoclax, a B-cell lymphoma 2 protein inhibitor, the investigators noted.

“This combination was reported to be safe and active in patients with mantle cell lymphoma,” they wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine. “Given the clinically complementary activity, preclinical synergism, and nonoverlapping toxic effects, we examined the safety and efficacy of combined ibrutinib and venetoclax treatment in previously untreated patients with CLL.”

In particular, the investigators recruited older patients, as this is a common population that can be challenging to treat. “Because CLL typically occurs in older adults, the majority of patients who need treatment are older than 65 years of age,” the investigators wrote. “This group of patients often has unacceptable side effects and has a lower rate of complete remission and undetectable minimal residual disease with chemoimmunotherapy than younger patients.”

The open-label, phase 2 trial enrolled 80 elderly and high-risk patients with previously untreated CLL. Eligibility required an age of at least 65 years or presence of at least one high-risk genetic feature; namely, mutated TP53, unmutated IgVH, or chromosome 11q deletion.

In order to reduce the risk of tumor lysis syndrome, ibrutinib (420 mg once daily) was given as monotherapy for three 28-day cycles. From the fourth cycle onward, venetoclax was also given, with weekly dose escalations to a target dose of 400 mg once daily. The combination was given for 24 cycles, with treatment continuation offered to patients who were still positive for minimal residual disease.

The median patient age was 65 years, with 30% of the population aged 70 years or older. A large majority (92%) had at least one high-risk genetic feature.

Following initiation with three cycles of ibrutinib, most patients had partial responses, the investigators wrote; however, with the addition of venetoclax, responses improved over time. Of all 80 patients, 59 (74%) had a best response of complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery.

After six cycles, 51 out of 70 patients (73%) achieved this marker. After 12 cycles, 29 of 33 patients (88%) had this response, with 61% of the same group demonstrating undetectable minimal residual disease in bone marrow.

After 18 cycles, 25 of 26 patients (96%) had complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery, 18 of which (69%) were negative for minimal residual disease. Three patients completed 24 cycles of combined therapy, all of whom achieved complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery and undetectable minimal residual disease.

Focusing on patients aged 65 years or older, 74% had complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery after six cycles of therapy and nearly half (44%) had undetectable minimal residual disease. After 12 cycles, these rates increased to 94% and 76%, respectively. Responses were also seen across genetically high-risk subgroups.

One patient died from a cryptococcal infection of the central nervous system; this was deemed unrelated to treatment, as symptoms began prior to initiation of treatment and only one dose of ibrutinib was given.

The estimated 1-year progression-free survival rate was 98% and the estimated overall survival rate was 99%. At the time of publication, no patients had disease progression.

Among all patients, 60% experienced grade 3 or higher adverse events, the most common being neutropenia (48%).

Almost half of the patient population (44%) required dose reductions of ibrutinib, most commonly because of atrial fibrillation, and 24% required dose reductions of venetoclax, most often because of neutropenia.

“Our data showed that combination therapy with ibrutinib and venetoclax was effective in patients with CLL, with no new toxic effects from the combination that were not reported previously for the individual agents,” the investigators wrote, adding that the efficacy findings were also “substantially better” than what has been reported with monotherapy for each of the agents in patients with CLL.

The study was funded by AbbVie, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Moon Shot program, the Andrew Sabin Family Foundation, and the CLL Global Research Foundation. The investigators reported relationships with AbbVie, Incyte, Celgene, and other companies.

SOURCE: Jain N et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2095-103.

In addition to noting the “impressive” results from combining venetoclax and ibrutinib as frontline CLL therapy, Adrian Wiestner, MD, PhD, highlighted the lack of a Kaplan-Meier curve in the paper published by Jain et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Here, assessment of minimal residual disease has replaced the progression-free survival curve of old, indicating a possible shift in focus away from traditional clinical trial endpoints and toward even more stringent measures of clinical efficacy that may be central to regulatory decisions,” Dr. Wiestner wrote.

Dr. Wiestner of the National Institutes of Health made his remarks in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1904362). He reported grants from with Merck, Pharmacyclics (an AbbVie company), and Acerta Pharma.

In addition to noting the “impressive” results from combining venetoclax and ibrutinib as frontline CLL therapy, Adrian Wiestner, MD, PhD, highlighted the lack of a Kaplan-Meier curve in the paper published by Jain et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Here, assessment of minimal residual disease has replaced the progression-free survival curve of old, indicating a possible shift in focus away from traditional clinical trial endpoints and toward even more stringent measures of clinical efficacy that may be central to regulatory decisions,” Dr. Wiestner wrote.

Dr. Wiestner of the National Institutes of Health made his remarks in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1904362). He reported grants from with Merck, Pharmacyclics (an AbbVie company), and Acerta Pharma.

In addition to noting the “impressive” results from combining venetoclax and ibrutinib as frontline CLL therapy, Adrian Wiestner, MD, PhD, highlighted the lack of a Kaplan-Meier curve in the paper published by Jain et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“Here, assessment of minimal residual disease has replaced the progression-free survival curve of old, indicating a possible shift in focus away from traditional clinical trial endpoints and toward even more stringent measures of clinical efficacy that may be central to regulatory decisions,” Dr. Wiestner wrote.

Dr. Wiestner of the National Institutes of Health made his remarks in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1904362). He reported grants from with Merck, Pharmacyclics (an AbbVie company), and Acerta Pharma.

A combination of venetoclax and ibrutinib may be a safe and effective treatment option for previously untreated elderly and high-risk patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), according to investigators of a phase 2 trial of the combination.

About 88% of patients achieved complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery after 12 cycles of treatment, reported lead author Nitin Jain, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and colleagues.

There were no new safety signals for the combination of ibrutinib, an irreversible inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, and venetoclax, a B-cell lymphoma 2 protein inhibitor, the investigators noted.

“This combination was reported to be safe and active in patients with mantle cell lymphoma,” they wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine. “Given the clinically complementary activity, preclinical synergism, and nonoverlapping toxic effects, we examined the safety and efficacy of combined ibrutinib and venetoclax treatment in previously untreated patients with CLL.”

In particular, the investigators recruited older patients, as this is a common population that can be challenging to treat. “Because CLL typically occurs in older adults, the majority of patients who need treatment are older than 65 years of age,” the investigators wrote. “This group of patients often has unacceptable side effects and has a lower rate of complete remission and undetectable minimal residual disease with chemoimmunotherapy than younger patients.”

The open-label, phase 2 trial enrolled 80 elderly and high-risk patients with previously untreated CLL. Eligibility required an age of at least 65 years or presence of at least one high-risk genetic feature; namely, mutated TP53, unmutated IgVH, or chromosome 11q deletion.

In order to reduce the risk of tumor lysis syndrome, ibrutinib (420 mg once daily) was given as monotherapy for three 28-day cycles. From the fourth cycle onward, venetoclax was also given, with weekly dose escalations to a target dose of 400 mg once daily. The combination was given for 24 cycles, with treatment continuation offered to patients who were still positive for minimal residual disease.

The median patient age was 65 years, with 30% of the population aged 70 years or older. A large majority (92%) had at least one high-risk genetic feature.

Following initiation with three cycles of ibrutinib, most patients had partial responses, the investigators wrote; however, with the addition of venetoclax, responses improved over time. Of all 80 patients, 59 (74%) had a best response of complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery.

After six cycles, 51 out of 70 patients (73%) achieved this marker. After 12 cycles, 29 of 33 patients (88%) had this response, with 61% of the same group demonstrating undetectable minimal residual disease in bone marrow.

After 18 cycles, 25 of 26 patients (96%) had complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery, 18 of which (69%) were negative for minimal residual disease. Three patients completed 24 cycles of combined therapy, all of whom achieved complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery and undetectable minimal residual disease.

Focusing on patients aged 65 years or older, 74% had complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery after six cycles of therapy and nearly half (44%) had undetectable minimal residual disease. After 12 cycles, these rates increased to 94% and 76%, respectively. Responses were also seen across genetically high-risk subgroups.

One patient died from a cryptococcal infection of the central nervous system; this was deemed unrelated to treatment, as symptoms began prior to initiation of treatment and only one dose of ibrutinib was given.

The estimated 1-year progression-free survival rate was 98% and the estimated overall survival rate was 99%. At the time of publication, no patients had disease progression.

Among all patients, 60% experienced grade 3 or higher adverse events, the most common being neutropenia (48%).

Almost half of the patient population (44%) required dose reductions of ibrutinib, most commonly because of atrial fibrillation, and 24% required dose reductions of venetoclax, most often because of neutropenia.

“Our data showed that combination therapy with ibrutinib and venetoclax was effective in patients with CLL, with no new toxic effects from the combination that were not reported previously for the individual agents,” the investigators wrote, adding that the efficacy findings were also “substantially better” than what has been reported with monotherapy for each of the agents in patients with CLL.

The study was funded by AbbVie, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Moon Shot program, the Andrew Sabin Family Foundation, and the CLL Global Research Foundation. The investigators reported relationships with AbbVie, Incyte, Celgene, and other companies.

SOURCE: Jain N et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2095-103.

A combination of venetoclax and ibrutinib may be a safe and effective treatment option for previously untreated elderly and high-risk patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), according to investigators of a phase 2 trial of the combination.

About 88% of patients achieved complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery after 12 cycles of treatment, reported lead author Nitin Jain, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and colleagues.

There were no new safety signals for the combination of ibrutinib, an irreversible inhibitor of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, and venetoclax, a B-cell lymphoma 2 protein inhibitor, the investigators noted.

“This combination was reported to be safe and active in patients with mantle cell lymphoma,” they wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine. “Given the clinically complementary activity, preclinical synergism, and nonoverlapping toxic effects, we examined the safety and efficacy of combined ibrutinib and venetoclax treatment in previously untreated patients with CLL.”

In particular, the investigators recruited older patients, as this is a common population that can be challenging to treat. “Because CLL typically occurs in older adults, the majority of patients who need treatment are older than 65 years of age,” the investigators wrote. “This group of patients often has unacceptable side effects and has a lower rate of complete remission and undetectable minimal residual disease with chemoimmunotherapy than younger patients.”

The open-label, phase 2 trial enrolled 80 elderly and high-risk patients with previously untreated CLL. Eligibility required an age of at least 65 years or presence of at least one high-risk genetic feature; namely, mutated TP53, unmutated IgVH, or chromosome 11q deletion.

In order to reduce the risk of tumor lysis syndrome, ibrutinib (420 mg once daily) was given as monotherapy for three 28-day cycles. From the fourth cycle onward, venetoclax was also given, with weekly dose escalations to a target dose of 400 mg once daily. The combination was given for 24 cycles, with treatment continuation offered to patients who were still positive for minimal residual disease.

The median patient age was 65 years, with 30% of the population aged 70 years or older. A large majority (92%) had at least one high-risk genetic feature.

Following initiation with three cycles of ibrutinib, most patients had partial responses, the investigators wrote; however, with the addition of venetoclax, responses improved over time. Of all 80 patients, 59 (74%) had a best response of complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery.

After six cycles, 51 out of 70 patients (73%) achieved this marker. After 12 cycles, 29 of 33 patients (88%) had this response, with 61% of the same group demonstrating undetectable minimal residual disease in bone marrow.

After 18 cycles, 25 of 26 patients (96%) had complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery, 18 of which (69%) were negative for minimal residual disease. Three patients completed 24 cycles of combined therapy, all of whom achieved complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery and undetectable minimal residual disease.

Focusing on patients aged 65 years or older, 74% had complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery after six cycles of therapy and nearly half (44%) had undetectable minimal residual disease. After 12 cycles, these rates increased to 94% and 76%, respectively. Responses were also seen across genetically high-risk subgroups.

One patient died from a cryptococcal infection of the central nervous system; this was deemed unrelated to treatment, as symptoms began prior to initiation of treatment and only one dose of ibrutinib was given.

The estimated 1-year progression-free survival rate was 98% and the estimated overall survival rate was 99%. At the time of publication, no patients had disease progression.

Among all patients, 60% experienced grade 3 or higher adverse events, the most common being neutropenia (48%).

Almost half of the patient population (44%) required dose reductions of ibrutinib, most commonly because of atrial fibrillation, and 24% required dose reductions of venetoclax, most often because of neutropenia.

“Our data showed that combination therapy with ibrutinib and venetoclax was effective in patients with CLL, with no new toxic effects from the combination that were not reported previously for the individual agents,” the investigators wrote, adding that the efficacy findings were also “substantially better” than what has been reported with monotherapy for each of the agents in patients with CLL.

The study was funded by AbbVie, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Moon Shot program, the Andrew Sabin Family Foundation, and the CLL Global Research Foundation. The investigators reported relationships with AbbVie, Incyte, Celgene, and other companies.

SOURCE: Jain N et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2095-103.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: After 12 cycles of treatment with venetoclax and ibrutinib, 88% of patients had complete remission or complete remission with incomplete count recovery.

Study details: A randomized, open-label, phase 2 study involving 80 elderly and high-risk patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Disclosures: The study was funded by AbbVie, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Moon Shot program, the Andrew Sabin Family Foundation, and the CLL Global Research Foundation. The investigators reported relationships with AbbVie, Incyte, Celgene, and other companies.

Source: Jain N et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2095-103.

Daratumumab regimen shows benefit in transplant-ineligible myeloma

For patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who are ineligible for autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), adding daratumumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone provides better outcomes than standard therapy alone, based on an interim analysis from the phase 3 MAIA trial.

A greater proportion of patients in the daratumumab group had complete responses and were alive without disease progression after a median follow-up of 28 months, reported lead author Thierry Facon, MD, of the University of Lille (France) and colleagues, who also noted that daratumumab was associated with higher rates of grade 3 or 4 pneumonia, neutropenia, and lymphopenia.

“For patients who are ineligible for stem-cell transplantation, multiagent regimens, including alkylating agents, glucocorticoids, immunomodulatory drugs, proteasome inhibitors, and new agents, are the standard of care,” the investigators wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The findings from MAIA add clarity to the efficacy and safety of daratumumab in this setting, building on previous phase 3 myeloma trials in the same area, such as ALCYONE, CASTOR, and POLLUX, the investigators noted.

MAIA was an open-label, international trial involving 737 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who were ineligible for ASCT. Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (daratumumab group; n = 368) or lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone (control group; n = 369).

On a 28-day cycle, all patients received oral lenalidomide 25 mg on days 1-21 and oral dexamethasone 40 mg on days 1, 8, 15, and 22. Patients in the daratumumab group received intravenous daratumumab dosed at 16 mg/kg once a week for cycles 1 and 2, every 2 weeks for cycles 3-6, and then every 4 weeks thereafter. Treatment was continued until unacceptable toxic effects or disease progression occurred.

The primary end point was progression-free survival (PFS). Various secondary end points were also evaluated, including time to progression, complete responses, overall survival, and others.

Among the 737 randomized patients, 729 ultimately underwent treatment. The median patient age was 73 years.

Generally, efficacy measures favored adding daratumumab. After a median follow-up of 28.0 months, disease progression or death had occurred in 26.4% of patients in the daratumumab group, compared with 38.8% in the control group.

The median PFS was not reached in the daratumumab group, compared with 31.9 months in the control group. There was a 44% lower risk of disease progression or death among patients who received daratumumab, compared with the control group (hazard ratio, 0.56, P less than .001).

This PFS trend was consistent across most subgroups, including those for sex, age, and race, with the exception of patients with baseline hepatic impairment.

Additional efficacy measures added weight to the apparent benefit of adding daratumumab. For instance, more patients in the daratumumab group achieved a complete response or better (47.6% vs. 24.9%) and were negative for minimum residual disease (24.2% vs. 7.3%).

In terms of safety, more patients in the daratumumab group than the control group developed grade 3 or higher neutropenia (50% vs. 35.3%), lymphopenia (15.1% vs. 10.7%), infections (32.1% vs. 23.3%) or pneumonia (13.7% vs. 7.9%).

In contrast, grade 3 or 4 anemia was less common in the daratumumab group than the control group (11.8% vs. 19.7%). Overall, the rate of serious adverse events was similar for both groups (approximately 63%), as was the rate of adverse events resulting in death (approximately 6%-7%).

“In this trial involving patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who were ineligible for stem-cell transplantation, the addition of daratumumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone resulted in significantly longer progression-free survival, a higher response rate, an increased depth of response, and a longer duration of response than lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone,” the investigators concluded.

The study was funded by Janssen Research and Development. The investigators reported relationships with Janssen, Celgene, Takeda, Sanofi, and other companies.

SOURCE: Facon T et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2104-15.

The findings from the phase 3 MAIA trial highlight the “superior efficacy” of adding daratumumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who are ineligible for stem cell transplantation, Jacob Laubach, MD, commented in an accompanying editorial.

Dr. Laubach noted several important clinical implications of the study findings, including that the use of CD38-targeting monoclonal antibody therapy was associated with a significant improvement in the number of patients who had a complete response to therapy and who were negative for minimal residual disease.

However, with daratumumab as a component of induction and maintenance therapy for patients with multiple myeloma who are ineligible for transplantation, it is important to consider the feasibility of retreatment with CD38-targeting therapy in patients who become resistant to daratumumab-containing regimens.

Jacob Laubach, MD, is at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. He reported having no financial disclosures. He made his remarks in an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine (2019;380:2172-3).

The findings from the phase 3 MAIA trial highlight the “superior efficacy” of adding daratumumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who are ineligible for stem cell transplantation, Jacob Laubach, MD, commented in an accompanying editorial.

Dr. Laubach noted several important clinical implications of the study findings, including that the use of CD38-targeting monoclonal antibody therapy was associated with a significant improvement in the number of patients who had a complete response to therapy and who were negative for minimal residual disease.

However, with daratumumab as a component of induction and maintenance therapy for patients with multiple myeloma who are ineligible for transplantation, it is important to consider the feasibility of retreatment with CD38-targeting therapy in patients who become resistant to daratumumab-containing regimens.

Jacob Laubach, MD, is at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. He reported having no financial disclosures. He made his remarks in an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine (2019;380:2172-3).

The findings from the phase 3 MAIA trial highlight the “superior efficacy” of adding daratumumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who are ineligible for stem cell transplantation, Jacob Laubach, MD, commented in an accompanying editorial.

Dr. Laubach noted several important clinical implications of the study findings, including that the use of CD38-targeting monoclonal antibody therapy was associated with a significant improvement in the number of patients who had a complete response to therapy and who were negative for minimal residual disease.

However, with daratumumab as a component of induction and maintenance therapy for patients with multiple myeloma who are ineligible for transplantation, it is important to consider the feasibility of retreatment with CD38-targeting therapy in patients who become resistant to daratumumab-containing regimens.

Jacob Laubach, MD, is at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. He reported having no financial disclosures. He made his remarks in an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine (2019;380:2172-3).

For patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who are ineligible for autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), adding daratumumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone provides better outcomes than standard therapy alone, based on an interim analysis from the phase 3 MAIA trial.