User login

Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC) and Its Importance in Clinical Practice

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a rare, chronic, and progressive cholestatic liver disorder.1 Commonly associated with pruritus, an intense itch that significantly impacts patients’ lives, PSC is characterized by inflammation, fibrosis, and stricturing of the intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic bile ducts.1,2 The natural history of PSC is highly variable, but disease progression frequently leads to end-stage liver disease, with liver transplantation as the only currently available treatment option.1,2 PSC has a close association with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), with approximately 60% to 80% of patients with PSC having a diagnosis of either ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease.1,3 Although the exact pathogenesis of PSC is still under investigation, evidence suggests a complex interplay of genetic susceptibility, immune dysregulation, and environmental factors may be responsible.4

PSC is considered a rare disease, with an estimated global median incidence of 0.7 to 0.8 per 100,000 and estimated prevalence of 10 cases per 100,000.5 PSC is more common in men (60% to 70%), with men having a 2-fold higher risk of developing PSC than women.2,6,7 The majority of patients are diagnosed between the ages of 30 to 40 years, with a median survival time after diagnosis without a liver transplant of 10 to 20 years.2,7-9

Signs and Symptoms of PSC

Approximately 50% of patients with PSC are asymptomatic when persistently abnormal liver function tests trigger further evaluation.1,2,10 Patients may complain of pruritus, which may be episodic; right upper quadrant pain; fatigue; and jaundice.2,7 Fevers, chills, and night sweats may also be present at the time of diagnosis.2

Pruritus and fatigue are common symptoms of PSC and can have a significant impact on the lives of patients.5 The pathogenesis of pruritus is complex and not completely understood but is believed to be caused by a toxic buildup of bile acids due to a decrease in bile flow related to inflammation, fibrosis, and stricturing resulting from PSC.11,12

Pruritus has been shown to have a substantial impact on patients’ health-related quality of life (QoL), with greater impairment seen with increased severity of pruritus.13 Specifically, patients with pruritus report physical limitations on QoL-specific questionnaires, as well as an impact on emotional, bodily pain, vitality, energy, and physical mobility measures.14

From a multinational survey on the impact of pruritus in PSC patients, 96% of respondents indicated that their itch was worst in the evening, with 58% indicating mood changes, including anxiety, irritability, and feelings of hopelessness due to their itch. Further, respondents reported that their pruritus disrupted their day-to-day responsibilities and that this disruption lasted 1 month or more.15

The psychological impact of living with PSC has not been well studied, although it has been found that individuals living with the disease demonstrated a greater number of depressive symptoms and poorer well-being, often coinciding with their stage of liver disease and comorbidity with IBD.16

In those living with PSC, mental health-related QoL has been shown to be influenced by liver disease, pruritus, social isolation, and depression. In one study, nearly 75% of patients expressed existential anxiety regarding disease progression and shortened life expectancy, with 25% disclosing social isolation.13

Diagnosing PSC

PSC should be considered in patients with a cholestatic pattern of liver test abnormalities, especially in those with underlying IBD. Abnormalities that may be detected on physical examination include jaundice, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and excoriations from scratching.3,5 PSC and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) may coexist, particularly in younger patients, with serum biochemical tests and autoantibodies suggestive of AIH.2 Most patients demonstrate elevated serum alkaline phosphatase levels, as well as modest elevation of transaminases.2 Bilirubin and albumin levels may be normal at the time of diagnosis, although they may become increasingly abnormal as the disease progresses.2 A subset of patients (10%) may have elevated levels of immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) and tend to progress more rapidly in the absence of treatment.2 Autoantibodies, which are characteristic of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC)—another rare, chronic, and progressive liver disease—are usually absent in PSC. When present, autoantibodies are of unknown clinical significance.2,17

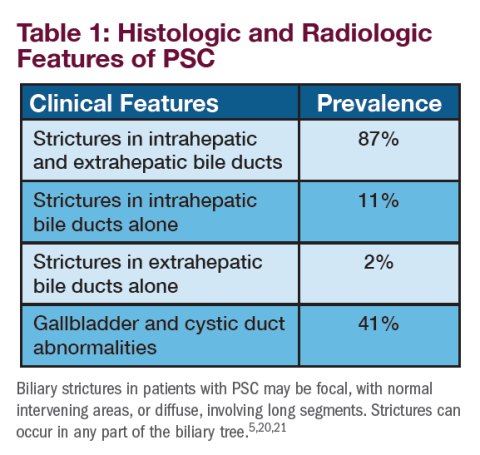

Imaging, including cross-sectional imaging, particularly magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, is often used to the biliary tree in patients with persistently abnormal cholestatic tests.2 A diagnosis of PSC is typically established by the demonstration of characteristic multifocal stricturing and dilation of intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic bile ducts on cholangiography.5 The diagnosis of PSC is occasionally made on liver biopsy, which may reveal characteristic features of “onion skin fibrosis” and fibro-obliterative cholangitis when cholangiography is normal. In this circumstance, it is classified as “small-duct PSC.”5,18

Treatment and Management of PSC

Despite advances in our understanding of PSC, there are currently no approved drug therapies for PSC and no approved treatments for PSC-associated pruritus. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) published the most recent practice guidance for the treatment and management of PSC in 2022.7

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) has been widely studied as a potential PSC treatment. While UDCA demonstrates improvements in biochemical measures, there has been a lack of evidence demonstrating clinical improvement.19

The role of UDCA in the treatment of PSC is unclear and, at this time, is not supported by the American College of Gastroenterology or AASLD.2,7 Additional treatments, including immunosuppressive medications (methotrexate, tacrolimus), corticosteroids (prednisolone), and antibiotics (minocycline, vancomycin) have been explored but have not shown definitive clinical benefit.2

UDCA, if used, should not be prescribed at doses in excess of 20 mg/kg/day since high-dose UDCA (28-30 mg/kg) was associated with adverse liver outcomes.2

Although there are no therapies approved specifically to manage PSC-associated pruritus, cholestyramine and rifampin have been shown to be beneficial in relieving itch in some patients.22 In a survey of PSC patients, one in three reported suffering from pruritus during the previous week. It is possible that the prevalence and severity of pruritus in PSC may be under-recognized compared with PBC, given that patients and physicians may be focused on the many other medical issues that are often prioritized over symptoms, such as concern about cancer risk and need for frequent surveillance procedures.15,23 Discussions between patients and physicians are important to deepen our understanding of the prevalence of pruritus and its burden on the lives of patients.

Novel therapies for PSC and PSC-associated pruritus, including a selective inhibitor of the ileal bile acid transporter (IBAT), are currently being explored in clinical trials. Research suggests that the inhibition of IBAT blocks the recycling of bile acids, which reduces bile acids systemically and in the liver. Early clinical studies demonstrated on-target fecal bile acid excretion, a pharmacodynamic marker of IBAT inhibition, in addition to decreases in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and increases in 7αC4, which are markers of bile acid synthesis.24

To learn more about ongoing clinical trials, please visit https://www.mirumclinicaltrials.com.

References

1. Karlsen TH, Folseraas T, Thorburn D, Vesterhus M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis – a comprehensive review. J Hepatol. 2017;67(6):1298-1323. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.07.022

2. Lindor KD, Kowdley KV, Harrison EM. ACG clinical guideline: primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 110, 646–659 (2015).

3. Chapman R, Fevery J, Kalloo A, et al; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2010;51(2):660-678. doi:10.1002/hep.23294

4. Jiang X, Karlsen TH. Genetics of primary sclerosing cholangitis and pathophysiological implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(5):279-295. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2016.154

5. Sohal A, Kayani S, Kowdley KV. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and presentation. Clin Liver Dis. 2024;28(1):129-141. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2023.07.005

6. Molodecky NA, Kareemi H, Parab R, et al. Incidence of primary sclerosing cholangitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2011;53(5):1590-1599. doi:10.1002/hep.24247

7. Bowlus CL, Arrivé L, Bergquist A, et al. AASLD practice guidance on primary sclerosing cholangitis and cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2023;77(2):659-702. doi:10.1002/hep.32771

8. Hirschfield GM, Karlsen TH, Lindor KD, Adams DH. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1587-1599.

9. Trivedi PJ, Bowlus CL, Yimam KK, Razavi H, Estes C. Epidemiology, natural history, and outcomes of primary sclerosing cholangitis: a systematic review of population-based studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(8):1687-1700.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2021.08.039

10. Tischendorf JJ, Hecker H, Krüger M, Manns MP, Meier PN. Characterization, outcome, and prognosis in 273 patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a single center study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(1):107-114. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00872.x

11. Sanjel B, Shim WS. Recent advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms of cholestatic pruritus: a review. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866(12):165958. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.16595

12. Patel SP, Vasavda C, Ho B, Meixiong J, Dong X, Kwatra SG. Cholestatic pruritus: emerging mechanisms and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(6):1371-1378. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.035

13. Cheung AC, Patel H, Meza-Cardona J, Cino M, Sockalingam S, Hirschfield GM. Factors that influence health-related quality of life in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(6):1692-9. doi:10.1007/s10620-015-4013-1

14. Jin XY, Khan TM. Quality of life among patients suffering from cholestatic liver disease-induced pruritus: a systematic review. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016;115(9):689-702. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2016.05.006

15. Kowdley K, et al. Impact of pruritus in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC): a multinational survey. J. Hepatol. 2022;(1)77:S312-S313.

16. Ranieri V, Kennedy E, Walmsley M, Thorburn D, McKay K. The Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC) Wellbeing Study: understanding psychological distress in those living with PSC and those who support them. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0234624.:10.1371/journal.pone.0234624

17. Hov JR, Boberg KM, Karlsen TH. Autoantibodies in primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(24):3781-91. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.3781

18. Cazzagon N, Sarcognato S, Catanzaro E, Bonaiuto E, Peviani M, Pezzato F, Motta R. Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis: Diagnostic Criteria. Tomography. 2024;10(1):47-65. doi:10.3390/tomography10010005

19. Lindor KD. Ursodiol for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Mayo Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis-Ursodeoxycholic Acid Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(10):691-695. doi:10.1056/NEJM199703063361003

20. Lee YM, Kaplan MM. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(14):924-33. doi:10.1056/NEJM199504063321406

21. Said K, Glaumann H, Bergquist A. Gallbladder disease in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2008;48(4):598-605. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.01

22. Basic PSC facts: basic facts. PSC Partners Seeking a Cure. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://pscpartners.org/about/the-disease/basic-facts.html

23. PSC support: patient insights report. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://pscsupport.org.uk/surveys/insights-living-with-psc/

24. Key C, McKibben A, Chien E. A phase 1 dose-ranging study assessing fecal bile acid excretion by volixibat, an apical sodium‑dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor, and coadministration with loperamide. Poster presented at The Liver Meeting Digital Experience™ (TLMdX), American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD); November 13-16, 2020.

US-DS-2400079 December 2024

Neither of the editors of GI & Hepatology News® nor the Editorial Advisory Board nor the reporting staff contributed to this content.

Faculty Disclosure: Dr. Kowdley has been paid consulting fees by Mirum.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a rare, chronic, and progressive cholestatic liver disorder.1 Commonly associated with pruritus, an intense itch that significantly impacts patients’ lives, PSC is characterized by inflammation, fibrosis, and stricturing of the intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic bile ducts.1,2 The natural history of PSC is highly variable, but disease progression frequently leads to end-stage liver disease, with liver transplantation as the only currently available treatment option.1,2 PSC has a close association with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), with approximately 60% to 80% of patients with PSC having a diagnosis of either ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease.1,3 Although the exact pathogenesis of PSC is still under investigation, evidence suggests a complex interplay of genetic susceptibility, immune dysregulation, and environmental factors may be responsible.4

PSC is considered a rare disease, with an estimated global median incidence of 0.7 to 0.8 per 100,000 and estimated prevalence of 10 cases per 100,000.5 PSC is more common in men (60% to 70%), with men having a 2-fold higher risk of developing PSC than women.2,6,7 The majority of patients are diagnosed between the ages of 30 to 40 years, with a median survival time after diagnosis without a liver transplant of 10 to 20 years.2,7-9

Signs and Symptoms of PSC

Approximately 50% of patients with PSC are asymptomatic when persistently abnormal liver function tests trigger further evaluation.1,2,10 Patients may complain of pruritus, which may be episodic; right upper quadrant pain; fatigue; and jaundice.2,7 Fevers, chills, and night sweats may also be present at the time of diagnosis.2

Pruritus and fatigue are common symptoms of PSC and can have a significant impact on the lives of patients.5 The pathogenesis of pruritus is complex and not completely understood but is believed to be caused by a toxic buildup of bile acids due to a decrease in bile flow related to inflammation, fibrosis, and stricturing resulting from PSC.11,12

Pruritus has been shown to have a substantial impact on patients’ health-related quality of life (QoL), with greater impairment seen with increased severity of pruritus.13 Specifically, patients with pruritus report physical limitations on QoL-specific questionnaires, as well as an impact on emotional, bodily pain, vitality, energy, and physical mobility measures.14

From a multinational survey on the impact of pruritus in PSC patients, 96% of respondents indicated that their itch was worst in the evening, with 58% indicating mood changes, including anxiety, irritability, and feelings of hopelessness due to their itch. Further, respondents reported that their pruritus disrupted their day-to-day responsibilities and that this disruption lasted 1 month or more.15

The psychological impact of living with PSC has not been well studied, although it has been found that individuals living with the disease demonstrated a greater number of depressive symptoms and poorer well-being, often coinciding with their stage of liver disease and comorbidity with IBD.16

In those living with PSC, mental health-related QoL has been shown to be influenced by liver disease, pruritus, social isolation, and depression. In one study, nearly 75% of patients expressed existential anxiety regarding disease progression and shortened life expectancy, with 25% disclosing social isolation.13

Diagnosing PSC

PSC should be considered in patients with a cholestatic pattern of liver test abnormalities, especially in those with underlying IBD. Abnormalities that may be detected on physical examination include jaundice, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and excoriations from scratching.3,5 PSC and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) may coexist, particularly in younger patients, with serum biochemical tests and autoantibodies suggestive of AIH.2 Most patients demonstrate elevated serum alkaline phosphatase levels, as well as modest elevation of transaminases.2 Bilirubin and albumin levels may be normal at the time of diagnosis, although they may become increasingly abnormal as the disease progresses.2 A subset of patients (10%) may have elevated levels of immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) and tend to progress more rapidly in the absence of treatment.2 Autoantibodies, which are characteristic of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC)—another rare, chronic, and progressive liver disease—are usually absent in PSC. When present, autoantibodies are of unknown clinical significance.2,17

Imaging, including cross-sectional imaging, particularly magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, is often used to the biliary tree in patients with persistently abnormal cholestatic tests.2 A diagnosis of PSC is typically established by the demonstration of characteristic multifocal stricturing and dilation of intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic bile ducts on cholangiography.5 The diagnosis of PSC is occasionally made on liver biopsy, which may reveal characteristic features of “onion skin fibrosis” and fibro-obliterative cholangitis when cholangiography is normal. In this circumstance, it is classified as “small-duct PSC.”5,18

Treatment and Management of PSC

Despite advances in our understanding of PSC, there are currently no approved drug therapies for PSC and no approved treatments for PSC-associated pruritus. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) published the most recent practice guidance for the treatment and management of PSC in 2022.7

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) has been widely studied as a potential PSC treatment. While UDCA demonstrates improvements in biochemical measures, there has been a lack of evidence demonstrating clinical improvement.19

The role of UDCA in the treatment of PSC is unclear and, at this time, is not supported by the American College of Gastroenterology or AASLD.2,7 Additional treatments, including immunosuppressive medications (methotrexate, tacrolimus), corticosteroids (prednisolone), and antibiotics (minocycline, vancomycin) have been explored but have not shown definitive clinical benefit.2

UDCA, if used, should not be prescribed at doses in excess of 20 mg/kg/day since high-dose UDCA (28-30 mg/kg) was associated with adverse liver outcomes.2

Although there are no therapies approved specifically to manage PSC-associated pruritus, cholestyramine and rifampin have been shown to be beneficial in relieving itch in some patients.22 In a survey of PSC patients, one in three reported suffering from pruritus during the previous week. It is possible that the prevalence and severity of pruritus in PSC may be under-recognized compared with PBC, given that patients and physicians may be focused on the many other medical issues that are often prioritized over symptoms, such as concern about cancer risk and need for frequent surveillance procedures.15,23 Discussions between patients and physicians are important to deepen our understanding of the prevalence of pruritus and its burden on the lives of patients.

Novel therapies for PSC and PSC-associated pruritus, including a selective inhibitor of the ileal bile acid transporter (IBAT), are currently being explored in clinical trials. Research suggests that the inhibition of IBAT blocks the recycling of bile acids, which reduces bile acids systemically and in the liver. Early clinical studies demonstrated on-target fecal bile acid excretion, a pharmacodynamic marker of IBAT inhibition, in addition to decreases in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and increases in 7αC4, which are markers of bile acid synthesis.24

To learn more about ongoing clinical trials, please visit https://www.mirumclinicaltrials.com.

References

1. Karlsen TH, Folseraas T, Thorburn D, Vesterhus M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis – a comprehensive review. J Hepatol. 2017;67(6):1298-1323. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.07.022

2. Lindor KD, Kowdley KV, Harrison EM. ACG clinical guideline: primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 110, 646–659 (2015).

3. Chapman R, Fevery J, Kalloo A, et al; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2010;51(2):660-678. doi:10.1002/hep.23294

4. Jiang X, Karlsen TH. Genetics of primary sclerosing cholangitis and pathophysiological implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(5):279-295. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2016.154

5. Sohal A, Kayani S, Kowdley KV. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and presentation. Clin Liver Dis. 2024;28(1):129-141. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2023.07.005

6. Molodecky NA, Kareemi H, Parab R, et al. Incidence of primary sclerosing cholangitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2011;53(5):1590-1599. doi:10.1002/hep.24247

7. Bowlus CL, Arrivé L, Bergquist A, et al. AASLD practice guidance on primary sclerosing cholangitis and cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2023;77(2):659-702. doi:10.1002/hep.32771

8. Hirschfield GM, Karlsen TH, Lindor KD, Adams DH. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1587-1599.

9. Trivedi PJ, Bowlus CL, Yimam KK, Razavi H, Estes C. Epidemiology, natural history, and outcomes of primary sclerosing cholangitis: a systematic review of population-based studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(8):1687-1700.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2021.08.039

10. Tischendorf JJ, Hecker H, Krüger M, Manns MP, Meier PN. Characterization, outcome, and prognosis in 273 patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a single center study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(1):107-114. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00872.x

11. Sanjel B, Shim WS. Recent advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms of cholestatic pruritus: a review. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866(12):165958. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.16595

12. Patel SP, Vasavda C, Ho B, Meixiong J, Dong X, Kwatra SG. Cholestatic pruritus: emerging mechanisms and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(6):1371-1378. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.035

13. Cheung AC, Patel H, Meza-Cardona J, Cino M, Sockalingam S, Hirschfield GM. Factors that influence health-related quality of life in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(6):1692-9. doi:10.1007/s10620-015-4013-1

14. Jin XY, Khan TM. Quality of life among patients suffering from cholestatic liver disease-induced pruritus: a systematic review. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016;115(9):689-702. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2016.05.006

15. Kowdley K, et al. Impact of pruritus in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC): a multinational survey. J. Hepatol. 2022;(1)77:S312-S313.

16. Ranieri V, Kennedy E, Walmsley M, Thorburn D, McKay K. The Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC) Wellbeing Study: understanding psychological distress in those living with PSC and those who support them. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0234624.:10.1371/journal.pone.0234624

17. Hov JR, Boberg KM, Karlsen TH. Autoantibodies in primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(24):3781-91. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.3781

18. Cazzagon N, Sarcognato S, Catanzaro E, Bonaiuto E, Peviani M, Pezzato F, Motta R. Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis: Diagnostic Criteria. Tomography. 2024;10(1):47-65. doi:10.3390/tomography10010005

19. Lindor KD. Ursodiol for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Mayo Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis-Ursodeoxycholic Acid Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(10):691-695. doi:10.1056/NEJM199703063361003

20. Lee YM, Kaplan MM. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(14):924-33. doi:10.1056/NEJM199504063321406

21. Said K, Glaumann H, Bergquist A. Gallbladder disease in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2008;48(4):598-605. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.01

22. Basic PSC facts: basic facts. PSC Partners Seeking a Cure. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://pscpartners.org/about/the-disease/basic-facts.html

23. PSC support: patient insights report. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://pscsupport.org.uk/surveys/insights-living-with-psc/

24. Key C, McKibben A, Chien E. A phase 1 dose-ranging study assessing fecal bile acid excretion by volixibat, an apical sodium‑dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor, and coadministration with loperamide. Poster presented at The Liver Meeting Digital Experience™ (TLMdX), American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD); November 13-16, 2020.

US-DS-2400079 December 2024

Neither of the editors of GI & Hepatology News® nor the Editorial Advisory Board nor the reporting staff contributed to this content.

Faculty Disclosure: Dr. Kowdley has been paid consulting fees by Mirum.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a rare, chronic, and progressive cholestatic liver disorder.1 Commonly associated with pruritus, an intense itch that significantly impacts patients’ lives, PSC is characterized by inflammation, fibrosis, and stricturing of the intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic bile ducts.1,2 The natural history of PSC is highly variable, but disease progression frequently leads to end-stage liver disease, with liver transplantation as the only currently available treatment option.1,2 PSC has a close association with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), with approximately 60% to 80% of patients with PSC having a diagnosis of either ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease.1,3 Although the exact pathogenesis of PSC is still under investigation, evidence suggests a complex interplay of genetic susceptibility, immune dysregulation, and environmental factors may be responsible.4

PSC is considered a rare disease, with an estimated global median incidence of 0.7 to 0.8 per 100,000 and estimated prevalence of 10 cases per 100,000.5 PSC is more common in men (60% to 70%), with men having a 2-fold higher risk of developing PSC than women.2,6,7 The majority of patients are diagnosed between the ages of 30 to 40 years, with a median survival time after diagnosis without a liver transplant of 10 to 20 years.2,7-9

Signs and Symptoms of PSC

Approximately 50% of patients with PSC are asymptomatic when persistently abnormal liver function tests trigger further evaluation.1,2,10 Patients may complain of pruritus, which may be episodic; right upper quadrant pain; fatigue; and jaundice.2,7 Fevers, chills, and night sweats may also be present at the time of diagnosis.2

Pruritus and fatigue are common symptoms of PSC and can have a significant impact on the lives of patients.5 The pathogenesis of pruritus is complex and not completely understood but is believed to be caused by a toxic buildup of bile acids due to a decrease in bile flow related to inflammation, fibrosis, and stricturing resulting from PSC.11,12

Pruritus has been shown to have a substantial impact on patients’ health-related quality of life (QoL), with greater impairment seen with increased severity of pruritus.13 Specifically, patients with pruritus report physical limitations on QoL-specific questionnaires, as well as an impact on emotional, bodily pain, vitality, energy, and physical mobility measures.14

From a multinational survey on the impact of pruritus in PSC patients, 96% of respondents indicated that their itch was worst in the evening, with 58% indicating mood changes, including anxiety, irritability, and feelings of hopelessness due to their itch. Further, respondents reported that their pruritus disrupted their day-to-day responsibilities and that this disruption lasted 1 month or more.15

The psychological impact of living with PSC has not been well studied, although it has been found that individuals living with the disease demonstrated a greater number of depressive symptoms and poorer well-being, often coinciding with their stage of liver disease and comorbidity with IBD.16

In those living with PSC, mental health-related QoL has been shown to be influenced by liver disease, pruritus, social isolation, and depression. In one study, nearly 75% of patients expressed existential anxiety regarding disease progression and shortened life expectancy, with 25% disclosing social isolation.13

Diagnosing PSC

PSC should be considered in patients with a cholestatic pattern of liver test abnormalities, especially in those with underlying IBD. Abnormalities that may be detected on physical examination include jaundice, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and excoriations from scratching.3,5 PSC and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) may coexist, particularly in younger patients, with serum biochemical tests and autoantibodies suggestive of AIH.2 Most patients demonstrate elevated serum alkaline phosphatase levels, as well as modest elevation of transaminases.2 Bilirubin and albumin levels may be normal at the time of diagnosis, although they may become increasingly abnormal as the disease progresses.2 A subset of patients (10%) may have elevated levels of immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) and tend to progress more rapidly in the absence of treatment.2 Autoantibodies, which are characteristic of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC)—another rare, chronic, and progressive liver disease—are usually absent in PSC. When present, autoantibodies are of unknown clinical significance.2,17

Imaging, including cross-sectional imaging, particularly magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, is often used to the biliary tree in patients with persistently abnormal cholestatic tests.2 A diagnosis of PSC is typically established by the demonstration of characteristic multifocal stricturing and dilation of intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic bile ducts on cholangiography.5 The diagnosis of PSC is occasionally made on liver biopsy, which may reveal characteristic features of “onion skin fibrosis” and fibro-obliterative cholangitis when cholangiography is normal. In this circumstance, it is classified as “small-duct PSC.”5,18

Treatment and Management of PSC

Despite advances in our understanding of PSC, there are currently no approved drug therapies for PSC and no approved treatments for PSC-associated pruritus. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) published the most recent practice guidance for the treatment and management of PSC in 2022.7

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) has been widely studied as a potential PSC treatment. While UDCA demonstrates improvements in biochemical measures, there has been a lack of evidence demonstrating clinical improvement.19

The role of UDCA in the treatment of PSC is unclear and, at this time, is not supported by the American College of Gastroenterology or AASLD.2,7 Additional treatments, including immunosuppressive medications (methotrexate, tacrolimus), corticosteroids (prednisolone), and antibiotics (minocycline, vancomycin) have been explored but have not shown definitive clinical benefit.2

UDCA, if used, should not be prescribed at doses in excess of 20 mg/kg/day since high-dose UDCA (28-30 mg/kg) was associated with adverse liver outcomes.2

Although there are no therapies approved specifically to manage PSC-associated pruritus, cholestyramine and rifampin have been shown to be beneficial in relieving itch in some patients.22 In a survey of PSC patients, one in three reported suffering from pruritus during the previous week. It is possible that the prevalence and severity of pruritus in PSC may be under-recognized compared with PBC, given that patients and physicians may be focused on the many other medical issues that are often prioritized over symptoms, such as concern about cancer risk and need for frequent surveillance procedures.15,23 Discussions between patients and physicians are important to deepen our understanding of the prevalence of pruritus and its burden on the lives of patients.

Novel therapies for PSC and PSC-associated pruritus, including a selective inhibitor of the ileal bile acid transporter (IBAT), are currently being explored in clinical trials. Research suggests that the inhibition of IBAT blocks the recycling of bile acids, which reduces bile acids systemically and in the liver. Early clinical studies demonstrated on-target fecal bile acid excretion, a pharmacodynamic marker of IBAT inhibition, in addition to decreases in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and increases in 7αC4, which are markers of bile acid synthesis.24

To learn more about ongoing clinical trials, please visit https://www.mirumclinicaltrials.com.

References

1. Karlsen TH, Folseraas T, Thorburn D, Vesterhus M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis – a comprehensive review. J Hepatol. 2017;67(6):1298-1323. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.07.022

2. Lindor KD, Kowdley KV, Harrison EM. ACG clinical guideline: primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 110, 646–659 (2015).

3. Chapman R, Fevery J, Kalloo A, et al; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2010;51(2):660-678. doi:10.1002/hep.23294

4. Jiang X, Karlsen TH. Genetics of primary sclerosing cholangitis and pathophysiological implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(5):279-295. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2016.154

5. Sohal A, Kayani S, Kowdley KV. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and presentation. Clin Liver Dis. 2024;28(1):129-141. doi:10.1016/j.cld.2023.07.005

6. Molodecky NA, Kareemi H, Parab R, et al. Incidence of primary sclerosing cholangitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2011;53(5):1590-1599. doi:10.1002/hep.24247

7. Bowlus CL, Arrivé L, Bergquist A, et al. AASLD practice guidance on primary sclerosing cholangitis and cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2023;77(2):659-702. doi:10.1002/hep.32771

8. Hirschfield GM, Karlsen TH, Lindor KD, Adams DH. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1587-1599.

9. Trivedi PJ, Bowlus CL, Yimam KK, Razavi H, Estes C. Epidemiology, natural history, and outcomes of primary sclerosing cholangitis: a systematic review of population-based studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(8):1687-1700.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2021.08.039

10. Tischendorf JJ, Hecker H, Krüger M, Manns MP, Meier PN. Characterization, outcome, and prognosis in 273 patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a single center study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(1):107-114. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00872.x

11. Sanjel B, Shim WS. Recent advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms of cholestatic pruritus: a review. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866(12):165958. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.16595

12. Patel SP, Vasavda C, Ho B, Meixiong J, Dong X, Kwatra SG. Cholestatic pruritus: emerging mechanisms and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(6):1371-1378. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.035

13. Cheung AC, Patel H, Meza-Cardona J, Cino M, Sockalingam S, Hirschfield GM. Factors that influence health-related quality of life in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(6):1692-9. doi:10.1007/s10620-015-4013-1

14. Jin XY, Khan TM. Quality of life among patients suffering from cholestatic liver disease-induced pruritus: a systematic review. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016;115(9):689-702. doi:10.1016/j.jfma.2016.05.006

15. Kowdley K, et al. Impact of pruritus in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC): a multinational survey. J. Hepatol. 2022;(1)77:S312-S313.

16. Ranieri V, Kennedy E, Walmsley M, Thorburn D, McKay K. The Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis (PSC) Wellbeing Study: understanding psychological distress in those living with PSC and those who support them. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0234624.:10.1371/journal.pone.0234624

17. Hov JR, Boberg KM, Karlsen TH. Autoantibodies in primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(24):3781-91. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.3781

18. Cazzagon N, Sarcognato S, Catanzaro E, Bonaiuto E, Peviani M, Pezzato F, Motta R. Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis: Diagnostic Criteria. Tomography. 2024;10(1):47-65. doi:10.3390/tomography10010005

19. Lindor KD. Ursodiol for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Mayo Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis-Ursodeoxycholic Acid Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(10):691-695. doi:10.1056/NEJM199703063361003

20. Lee YM, Kaplan MM. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(14):924-33. doi:10.1056/NEJM199504063321406

21. Said K, Glaumann H, Bergquist A. Gallbladder disease in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2008;48(4):598-605. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.01

22. Basic PSC facts: basic facts. PSC Partners Seeking a Cure. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://pscpartners.org/about/the-disease/basic-facts.html

23. PSC support: patient insights report. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://pscsupport.org.uk/surveys/insights-living-with-psc/

24. Key C, McKibben A, Chien E. A phase 1 dose-ranging study assessing fecal bile acid excretion by volixibat, an apical sodium‑dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor, and coadministration with loperamide. Poster presented at The Liver Meeting Digital Experience™ (TLMdX), American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD); November 13-16, 2020.

US-DS-2400079 December 2024

Neither of the editors of GI & Hepatology News® nor the Editorial Advisory Board nor the reporting staff contributed to this content.

Faculty Disclosure: Dr. Kowdley has been paid consulting fees by Mirum.

Practical advice for colorectal cancer screening

Douglas K. Rex, MD, AGAF, MACP, MACG, FASGE; offers advice and insight for colorectal cancer screening, highlighting:

- Clinically relevant facts about the spectrum of precancerous lesions that can be targeted during screening;

- Key practical aspects of the 3 screening tests that receive significant use in the United States.

- Why some tests are used more than others

Click HERE to read the supplement

Douglas K. Rex, MD, AGAF, MACP, MACG, FASGE; offers advice and insight for colorectal cancer screening, highlighting:

- Clinically relevant facts about the spectrum of precancerous lesions that can be targeted during screening;

- Key practical aspects of the 3 screening tests that receive significant use in the United States.

- Why some tests are used more than others

Click HERE to read the supplement

Douglas K. Rex, MD, AGAF, MACP, MACG, FASGE; offers advice and insight for colorectal cancer screening, highlighting:

- Clinically relevant facts about the spectrum of precancerous lesions that can be targeted during screening;

- Key practical aspects of the 3 screening tests that receive significant use in the United States.

- Why some tests are used more than others

Click HERE to read the supplement

Letter from the Editor: Value-based reimbursement is here to stay

For years, we advocated to repeal the sustainable growth rate (SGR) payment formula. Congress, by passing the MACRA legislation, eliminated SGR but created a new process that links provider reimbursement to value (quality and cost). Value-based reimbursement is here to stay. We now must help CMS devise reasonable linkages that will truly improve patient care, yet keep us in business. MACRA’s final rule is an improvement over the preliminary rule published earlier this spring. Gastroenterologists that plan to practice (and accept Medicare reimbursement) must educate themselves about both the incentive portion (MIPS) and alternative payment models.

MACRA intends to move independent practices into health systems (whether employed or contracted) that will assume financial and clinical risk. Gastroenterologists must lead clinical service lines for colon cancer prevention and integrated care for patients with IBD or cirrhosis. These care models must demonstrate good outcomes and substantive cost savings.

There are many sources of information about MACRA (see AGA resources at www.gastro.org/MACRA). I have listed four key websites:

https://qpp.cms.gov/docs/QPP_Executive_Summary_of_Final_Rule.pdf

http://healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief_pdfs/healthpolicybrief_156.pdf

https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Transforming-Clinical-Practices/

I hope you will take it to heart that we are moving into a new world of care delivery and payment. We need physician leaders and innovators to make sure this works well for our patients and our profession.

John I. Allen MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

For years, we advocated to repeal the sustainable growth rate (SGR) payment formula. Congress, by passing the MACRA legislation, eliminated SGR but created a new process that links provider reimbursement to value (quality and cost). Value-based reimbursement is here to stay. We now must help CMS devise reasonable linkages that will truly improve patient care, yet keep us in business. MACRA’s final rule is an improvement over the preliminary rule published earlier this spring. Gastroenterologists that plan to practice (and accept Medicare reimbursement) must educate themselves about both the incentive portion (MIPS) and alternative payment models.

MACRA intends to move independent practices into health systems (whether employed or contracted) that will assume financial and clinical risk. Gastroenterologists must lead clinical service lines for colon cancer prevention and integrated care for patients with IBD or cirrhosis. These care models must demonstrate good outcomes and substantive cost savings.

There are many sources of information about MACRA (see AGA resources at www.gastro.org/MACRA). I have listed four key websites:

https://qpp.cms.gov/docs/QPP_Executive_Summary_of_Final_Rule.pdf

http://healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief_pdfs/healthpolicybrief_156.pdf

https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Transforming-Clinical-Practices/

I hope you will take it to heart that we are moving into a new world of care delivery and payment. We need physician leaders and innovators to make sure this works well for our patients and our profession.

John I. Allen MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

For years, we advocated to repeal the sustainable growth rate (SGR) payment formula. Congress, by passing the MACRA legislation, eliminated SGR but created a new process that links provider reimbursement to value (quality and cost). Value-based reimbursement is here to stay. We now must help CMS devise reasonable linkages that will truly improve patient care, yet keep us in business. MACRA’s final rule is an improvement over the preliminary rule published earlier this spring. Gastroenterologists that plan to practice (and accept Medicare reimbursement) must educate themselves about both the incentive portion (MIPS) and alternative payment models.

MACRA intends to move independent practices into health systems (whether employed or contracted) that will assume financial and clinical risk. Gastroenterologists must lead clinical service lines for colon cancer prevention and integrated care for patients with IBD or cirrhosis. These care models must demonstrate good outcomes and substantive cost savings.

There are many sources of information about MACRA (see AGA resources at www.gastro.org/MACRA). I have listed four key websites:

https://qpp.cms.gov/docs/QPP_Executive_Summary_of_Final_Rule.pdf

http://healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief_pdfs/healthpolicybrief_156.pdf

https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Transforming-Clinical-Practices/

I hope you will take it to heart that we are moving into a new world of care delivery and payment. We need physician leaders and innovators to make sure this works well for our patients and our profession.

John I. Allen MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief