User login

In memory of Dr. Carl Compton Bell

It was a simple message in the body of an email: “A strong voice in and for psychiatry is now silent.”

That is how I shared the news of the passing of Carl Compton Bell, MD, with the leadership of the American Psychiatric Association and what I think Carl would have approved be shared. Although he was a member of APA, he was never interested in the trappings of leadership there or any other organizations of which he was a longtime member, really. He preferred to “do the work” and was known to not suffer fools who were in it to promote themselves. He was always ready, willing, and able to offer guidance or assistance in your work and never failed to have an opinion on what else you needed to do. Some of my favorite memories of Carl are the talks he initiated at the drop of a hat where he “dropped some knowledge” about what he was doing or what you should be doing.

Upon hearing of his death, I described him to someone as fearless, unapologetic, smart, and ready to advocate for black people at the drop of one of the many hats he wore over the years. In fact, his decades of wardrobes is one the other things many of us will remember – the CMHC baseball cap with the “Stop Black on Black” crime T-shirt, the Obama cap paired with an assortment of message T-shirts (depending on what issue he was focused on at the time), and, most recently, the longer hair sticking out from under the wide brim leather cowboy hat with the highway patrol polarized sunglasses.

And whether it was the Surgeon General or an audience at the Carter Center, the message was consistent and powerful. An international researcher, clinician, teacher, and author of more than 500 books, chapters, and articles, he spent most of his career directly addressing issues of violence and HIV prevention, misdiagnosis of psychiatric disorders in African Americans, and the psychological effects on children exposed to violence.

Honoring the legacy of Carl Bell is about more than how we can all follow in his footsteps and more about being like him – unapologetically fearless and focused on improving the health, mental health, and overall well-being of black people. He was very clear that his talents, his skills, his focus – whether it was clinical care, training, or research – would be on black people, and he was often amused at the response, mostly from white people, when he stated clearly that this was his focus. He was often challenged by them, and his response as I frequently heard him say was: “I care about black people; I want to help black people.” I think he basically felt that, if it was good for black people, it would also benefit everyone else.

So, there’s a lesson for us as we heap on the well-deserved accolades on him and his life’s work, and reminisce about our personal encounters and experiences with him over the decades. As we reflect on what he meant to each of us as a friend, a colleague, and a history maker, I think the lesson is that if Carl were here today, he’d say: “OK, that’s all good, thank you for the nice words but what are you doing for black people today? What are you doing to improve their health and life condition today?” I think if we really want to honor his legacy and continue his work, we must be as fearless and focused as he was as we follow his lead and carry on with the work that promotes mental health in the black community. And when we are challenged for wanting to do this work, we must be just as unapologetic and thoughtful as he was, even channeling our own “Carl Bell” moment if needed. As a lifelong martial arts practitioner, I will end with this: “The bamboo which bends in the wind is stronger than the mighty oak which breaks in a storm.” Carl was the bamboo, and he’s with the Ancestors now, encouraging us to do the work and bend not break. Rest, my brother; job well done!

Dr. Stewart is immediate past president of the American Psychiatric Association.

It was a simple message in the body of an email: “A strong voice in and for psychiatry is now silent.”

That is how I shared the news of the passing of Carl Compton Bell, MD, with the leadership of the American Psychiatric Association and what I think Carl would have approved be shared. Although he was a member of APA, he was never interested in the trappings of leadership there or any other organizations of which he was a longtime member, really. He preferred to “do the work” and was known to not suffer fools who were in it to promote themselves. He was always ready, willing, and able to offer guidance or assistance in your work and never failed to have an opinion on what else you needed to do. Some of my favorite memories of Carl are the talks he initiated at the drop of a hat where he “dropped some knowledge” about what he was doing or what you should be doing.

Upon hearing of his death, I described him to someone as fearless, unapologetic, smart, and ready to advocate for black people at the drop of one of the many hats he wore over the years. In fact, his decades of wardrobes is one the other things many of us will remember – the CMHC baseball cap with the “Stop Black on Black” crime T-shirt, the Obama cap paired with an assortment of message T-shirts (depending on what issue he was focused on at the time), and, most recently, the longer hair sticking out from under the wide brim leather cowboy hat with the highway patrol polarized sunglasses.

And whether it was the Surgeon General or an audience at the Carter Center, the message was consistent and powerful. An international researcher, clinician, teacher, and author of more than 500 books, chapters, and articles, he spent most of his career directly addressing issues of violence and HIV prevention, misdiagnosis of psychiatric disorders in African Americans, and the psychological effects on children exposed to violence.

Honoring the legacy of Carl Bell is about more than how we can all follow in his footsteps and more about being like him – unapologetically fearless and focused on improving the health, mental health, and overall well-being of black people. He was very clear that his talents, his skills, his focus – whether it was clinical care, training, or research – would be on black people, and he was often amused at the response, mostly from white people, when he stated clearly that this was his focus. He was often challenged by them, and his response as I frequently heard him say was: “I care about black people; I want to help black people.” I think he basically felt that, if it was good for black people, it would also benefit everyone else.

So, there’s a lesson for us as we heap on the well-deserved accolades on him and his life’s work, and reminisce about our personal encounters and experiences with him over the decades. As we reflect on what he meant to each of us as a friend, a colleague, and a history maker, I think the lesson is that if Carl were here today, he’d say: “OK, that’s all good, thank you for the nice words but what are you doing for black people today? What are you doing to improve their health and life condition today?” I think if we really want to honor his legacy and continue his work, we must be as fearless and focused as he was as we follow his lead and carry on with the work that promotes mental health in the black community. And when we are challenged for wanting to do this work, we must be just as unapologetic and thoughtful as he was, even channeling our own “Carl Bell” moment if needed. As a lifelong martial arts practitioner, I will end with this: “The bamboo which bends in the wind is stronger than the mighty oak which breaks in a storm.” Carl was the bamboo, and he’s with the Ancestors now, encouraging us to do the work and bend not break. Rest, my brother; job well done!

Dr. Stewart is immediate past president of the American Psychiatric Association.

It was a simple message in the body of an email: “A strong voice in and for psychiatry is now silent.”

That is how I shared the news of the passing of Carl Compton Bell, MD, with the leadership of the American Psychiatric Association and what I think Carl would have approved be shared. Although he was a member of APA, he was never interested in the trappings of leadership there or any other organizations of which he was a longtime member, really. He preferred to “do the work” and was known to not suffer fools who were in it to promote themselves. He was always ready, willing, and able to offer guidance or assistance in your work and never failed to have an opinion on what else you needed to do. Some of my favorite memories of Carl are the talks he initiated at the drop of a hat where he “dropped some knowledge” about what he was doing or what you should be doing.

Upon hearing of his death, I described him to someone as fearless, unapologetic, smart, and ready to advocate for black people at the drop of one of the many hats he wore over the years. In fact, his decades of wardrobes is one the other things many of us will remember – the CMHC baseball cap with the “Stop Black on Black” crime T-shirt, the Obama cap paired with an assortment of message T-shirts (depending on what issue he was focused on at the time), and, most recently, the longer hair sticking out from under the wide brim leather cowboy hat with the highway patrol polarized sunglasses.

And whether it was the Surgeon General or an audience at the Carter Center, the message was consistent and powerful. An international researcher, clinician, teacher, and author of more than 500 books, chapters, and articles, he spent most of his career directly addressing issues of violence and HIV prevention, misdiagnosis of psychiatric disorders in African Americans, and the psychological effects on children exposed to violence.

Honoring the legacy of Carl Bell is about more than how we can all follow in his footsteps and more about being like him – unapologetically fearless and focused on improving the health, mental health, and overall well-being of black people. He was very clear that his talents, his skills, his focus – whether it was clinical care, training, or research – would be on black people, and he was often amused at the response, mostly from white people, when he stated clearly that this was his focus. He was often challenged by them, and his response as I frequently heard him say was: “I care about black people; I want to help black people.” I think he basically felt that, if it was good for black people, it would also benefit everyone else.

So, there’s a lesson for us as we heap on the well-deserved accolades on him and his life’s work, and reminisce about our personal encounters and experiences with him over the decades. As we reflect on what he meant to each of us as a friend, a colleague, and a history maker, I think the lesson is that if Carl were here today, he’d say: “OK, that’s all good, thank you for the nice words but what are you doing for black people today? What are you doing to improve their health and life condition today?” I think if we really want to honor his legacy and continue his work, we must be as fearless and focused as he was as we follow his lead and carry on with the work that promotes mental health in the black community. And when we are challenged for wanting to do this work, we must be just as unapologetic and thoughtful as he was, even channeling our own “Carl Bell” moment if needed. As a lifelong martial arts practitioner, I will end with this: “The bamboo which bends in the wind is stronger than the mighty oak which breaks in a storm.” Carl was the bamboo, and he’s with the Ancestors now, encouraging us to do the work and bend not break. Rest, my brother; job well done!

Dr. Stewart is immediate past president of the American Psychiatric Association.

Hormone therapy and cognition: What is best for the midlife brain?

CASE HT for vasomotor symptoms in perimenopausal woman with cognitive concerns

Jackie is a 49-year-old woman. Her body mass index is 33 kg/m2, and she has mild hypertension that is effectively controlled with antihypertensive medications. Otherwise, she is in good health.During her annual gynecologic exam, she reports that for the past 9 months her menstrual cycles have not been as regular as they used to be and that 3 months ago she skipped a cycle. She is having bothersome vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and is concerned about her memory. She says she is forgetful at work and in social situations. During a recent presentation, she could not remember the name of one of her former clients. At a work happy hour, she forgot the name of her coworker’s husband, although she did remember it later after returning home.

Her mother has Alzheimer disease (AD), and Jackie worries about whether she, too, might be developing dementia and whether her memory will fail her in social situations.

She is concerned about using hormone therapy (HT) for her vasomotor symptoms because she has heard that it can lead to breast cancer and/or AD.

How would you advise her?

HT remains the most effective treatment for bothersome VMS, but concerns about its cognitive safety persist. Such concerns, and indeed a black-box warning about the risk of dementia with HT use, initially arose following the 2003 publication of the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS), a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of HT for the primary prevention of dementia in women aged 65 years and older at baseline.1 The study found that combination estrogen/progestin therapy was associated with a 2-fold increase in dementia when compared with placebo.

One of the critical questions arising even before WHIMS was whether the cognitive risks associated with HT that were seen in WHIMS apply to younger women. Attempting to answer the question and adding fuel to the fire are the results of a recent case-control study from Finland.2 This study compared HT use in Finnish women with and without AD and found that HT use was higher among Finnish women with AD compared with those without AD, regardless of age. The authors concluded, “Our data must be implemented into information for the present and future users of HT, even though the absolute risk increase is small.”

However, given the limitations inherent to observational and registry studies, and the contrasting findings of 3 high-quality, randomized controlled trials (RCTs; more details below), providers actually can reassure younger peri- and postmenopausal women about the cognitive safety of HT.3 They also can explain to patients that cognitive symptoms like the ones described in the case example are normal and provide general guidance to midlife women on how to optimize brain health.

Continue to: Closer look at WHI and RCT research pinpoints cognitively neutral HT...

Closer look at WHI and RCT research pinpoints cognitively neutral HT

In WHIMS, the combination of conjugated equine estrogen (CEE; 0.625 mg/d) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA; 2.5 mg/d) led to a doubling of the risk of all-cause dementia compared with placebo in a sample of 4,532 women aged 65 years and older at baseline.1 CEE alone (0.625 mg) did not lead to an increased risk of all-cause dementia.4

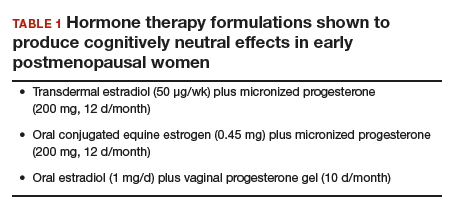

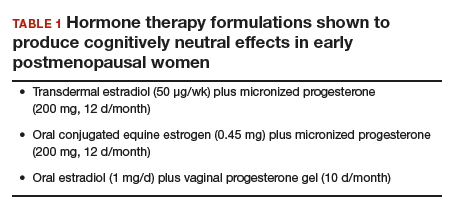

Whether those formulations led to cognitive impairment in younger postmenopausal women was the focus of WHIMS-Younger (WHIMS-Y), which involved WHI participants aged 50 to 55 years at baseline.5 Results revealed neutral cognitive effects (ie, no differences in cognitive performance in women randomly assigned to HT or placebo) in women tested 7.2 years after the end of the WHI trial. WHIMS-Y findings indicated that there were no sustained cognitive risks of CEE or CEE/MPA therapy. Two randomized, placebo-controlled trials involving younger postmenopausal women yielded similar findings.6,7 HT shown to produce cognitively neutral effects during active treatment included transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone,6 CEE plus progesterone,6 and oral estradiol plus vaginal progesterone gel.7 The findings of these randomized trials are critical for guiding decisions regarding the cognitive risks of HT in early postmenopausal women (TABLE 1).

What about women with VMS?

A key gap in knowledge about the cognitive effects of HT is whether HT confers cognitive advantages to women with bothersome VMS. This is a striking absence given that the key indication for HT is the treatment of VMS. While some symptomatic women were included in the trials of HT in younger postmenopausal women described above, no large trial to date has selectively enrolled women with moderate-to-severe VMS to determine if HT is cognitively neutral, beneficial, or detrimental in that group. Some studies involving midlife women have found associations between VMS (as measured with ambulatory skin conductance monitors) and multiple measures of brain health, including memory performance,8 small ischemic lesions on structural brain scans,9 and altered brain function.10 In a small trial of a nonhormonal intervention for VMS, improvement in VMS following the intervention was directly related to improvement in memory performance.11 The reliability of these findings continues to be evaluated but raises the hypothesis that VMS treatments might improve memory in midlife women.

Memory complaints common among midlife women

About 60% of women report an undesirable change in memory performance at midlife as compared with earlier in their lives.12,13 Complaints of forgetfulness are higher in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women compared with premenopausal women, even when those women are similar in age.14 Two large prospective studies found that memory performance decreases during the perimenopause and then rebounds, suggesting a transient decrease in memory.15,16 Although cognitive complaints are common among women in their 40s and 50s, AD is rare in that age group. The risk is largely limited to those women with a parent who developed dementia before age 65, as such cases suggest a familial form of AD.

Continue to: What causes cognitive difficulties during midlife?

What causes cognitive difficulties during midlife?

First, some cognitive decline is expected at midlife based on increasing age. Second, above and beyond the role of chronologic aging (ie, getting one year older each year), ovarian aging plays a role. A role of estrogen was verified in clinical trials showing that memory decreased following oophorectomy in premenopausal women in their 40s but returned to presurgical levels following treatment with estrogen therapy (ET).17 Cohort studies indicate that women who undergo oophorectomy before the typical age of menopause are at increased risk for cognitive impairment or dementia, but those who take ET after oophorectomy until the typical age of menopause do not show that risk.18

Third, cognitive problems are linked not only to VMS but also to sleep disturbance, depressed mood, and increased anxiety—all of which are common in midlife women.15,19 Lastly, health factors play a role. Hypertension, obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, and smoking are associated with adverse brain changes at midlife.20

Giving advice to your patients

First, normalize the cognitive complaints, noting that some cognitive changes are an expected part of aging for all people regardless of whether they are male or female. Advise that while the best studies indicate that these cognitive lapses are especially common in perimenopausal women, they appear to be temporary; women are likely to resume normal cognitive function once the hormonal changes associated with menopause subside.15,16 Note that the one unknown is the role that VMS play in memory problems and that some studies indicate a link between VMS and cognitive problems. Women may experience some cognitive improvement if VMS are effectively treated.

Advise patients that the Endocrine Society, the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), and the International Menopause Society all have published guidelines saying that the benefits of HT outweigh the risks for most women aged 50 to 60 years.21 For concerns about the cognitive adverse effects of HT, discuss the best quality evidence—that which comes from randomized trials—which shows no harmful effects of HT in midlife women.5-7 Especially reassuring is that one of these high-quality studies was conducted by the same researchers who found that HT can be risky in older women (ie, the WHI Investigators).5

Going one step further: Protecting brain health

As primary care providers to midlife women, ObGyns can go one step further and advise patients on how to proactively nurture their brain health. Great evidence-based resources for information on maintaining brain health include the Alzheimer’s Association (https://www.alz.org) and the Women’s Brain Health Initiative (https://womensbrainhealth.org). Primary prevention of AD begins decades before the typical age of an AD diagnosis, and many risk factors for AD are modifiable.22 Patients can keep their brains healthy through myriad approaches including treating hypertension, reducing body mass index, engaging in regular aerobic exercise (brisk walking is fine), eating a Mediterranean diet, maintaining an active social life, and engaging in novel challenging activities like learning a new language or a new skill like dancing.20

Also important is the overlap between cognitive issues, mood, and alcohol use. In the opening case, Jackie mentions alcohol use and social withdrawal. According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), low-risk drinking for women is defined as no more than 3 drinks on any single day and no more than 7 drinks per week.23 Heavy alcohol use not only affects brain function but also mood, and depressed mood can lead women to drink excessively.24

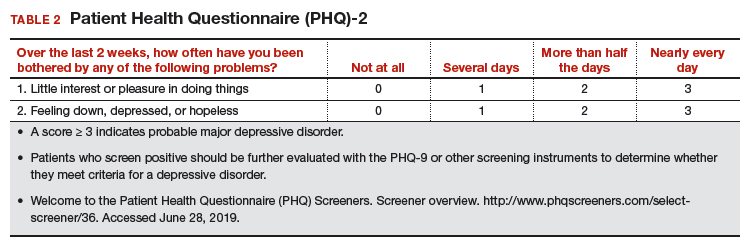

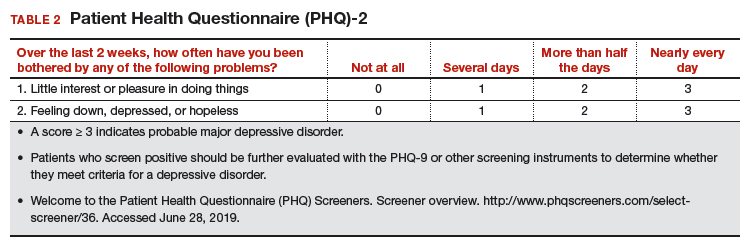

In addition, Jackie’s mother has AD, and that stressor can contribute to depressed feelings, especially if Jackie is involved in caregiving. A quick screen for depression with an instrument like the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2; TABLE 2)25 can rule out a more serious mood disorder—an approach that is particularly important for patients with a history of major depression, as 58% of those patients experience a major depressive episode during the menopausal transition.26 For this reason, it is important to ask patients like Jackie if they have a history of depression; if they do and were treated medically, consider prescribing the antidepressant that worked in the past. For information on menopause and mood-related issues, providers can access new guidelines from NAMS and the National Network of Depression Centers (NNDC).27 There is also a handy patient information sheet to accompany those guidelines on the NAMS website (https://www.menopause.org/).

Continue to: CASE Resolved...

CASE Resolved

When approaching Jackie, most importantly, I would normalize her experience and tell her that memory problems are common in the menopausal transition, especially for women with bothersome VMS. Research suggests that the memory problems she is experiencing are related to hormonal changes and not to AD, and that her memory will likely improve once she has transitioned through the menopause. I would tell her that AD is rare at midlife unless there is a family history of early onset of AD (before age 65), and I would verify the age at which her mother was diagnosed to confirm that it was late-onset AD.

For now, I would recommend that she be prescribed HT for her bothersome hot flashes using one of the “safe” formulations in the Table on page 24. I also would tell her that there is much she can do to lower her risk of AD and that it is best to start now as she enters her 50s because that is when AD changes typically start in the brain, and she can start to prevent those changes now.

I would tell her that experts in the field of AD agree that these lifestyle interventions are currently the best way to prevent AD and that the more of them she engages in, the more her brain will benefit. I would advise her to continue to manage her hypertension and to consider ways of lowering her BMI to enhance her brain health. Engaging in regular brisk walking or other aerobic exercise, as well as incorporating more of the Mediterranean diet into her daily food intake would also benefit her brain. As a working woman, she is exercising her brain, and she should consider other cognitively challenging activities to keep her brain in good shape.

I would follow up with her in a few months to see if her memory functioning is better. If it is not, and if her VMS continue to be bothersome, I would increase her dose of HT. Only if her VMS are treated but her memory problems are getting worse would I screen her with a Mini-Mental State Exam and refer her to a neurologist for an evaluation.

- Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2651-2662.

- Savolainen-Peltonen H, Rahkola-Soisalo P, Hoti F, et al. Use of postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of Alzheimer’s disease in Finland: nationwide case-control study. BMJ. 2019;364:1665.

- Maki PM, Girard LM, Manson JE. Menopausal hormone therapy and cognition. BMJ. 2019;364:1877.

- Shumaker SA, Legault C, Kuller L, et al. Conjugated equine estrogens and incidence of probable dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA. 2004;291:2947-2958.

- Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, Leng I, et al. Long-term effects on cognitive function of postmenopausal hormone therapy prescribed to women aged 50 to 55 years. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1429-1436.

- Gleason CE, Dowling NM, Wharton W, et al. Effects of hormone therapy on cognition and mood in recently postmenopausal women: findings from the randomized, controlled KEEPS-cognitive and affective study. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001833.

- Henderson VW, St. John JA, Hodis HN, et al. Cognitive effects of estradiol after menopause: a randomized trial of the timing hypothesis. Neurology. 2016;87:699-708.

- Maki PM, Drogos LL, Rubin LH, et al. Objective hot flashes are negatively related to verbal memory performance in midlife women. Menopause. 2008;15:848-856.

- Thurston RC, Aizenstein HJ, Derby CA, et al. Menopausal hot flashes and white matter hyperintensities. Menopause. 2016;23:27-32.

- Thurston RC, Maki PM, Derby CA, et al. Menopausal hot flashes and the default mode network. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:1572-1578.e1.

- Maki PM, Rubin LH, Savarese A, et al. Stellate ganglion blockade and verbal memory in midlife women: evidence from a randomized trial. Maturitas. 2016;92:123-129.

- Woods NF, Mitchell ES, Adams C. Memory functioning among midlife women: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. Menopause. 2000;7:257-265.

- Sullivan Mitchell E, Fugate Woods N. Midlife women’s attributions about perceived memory changes: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:351-362.

- Gold EB, Sternfeld B, Kelsey JL, et al. Relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multi-racial/ethnic population of women 40-55 years of age. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:463-473.

CASE HT for vasomotor symptoms in perimenopausal woman with cognitive concerns

Jackie is a 49-year-old woman. Her body mass index is 33 kg/m2, and she has mild hypertension that is effectively controlled with antihypertensive medications. Otherwise, she is in good health.During her annual gynecologic exam, she reports that for the past 9 months her menstrual cycles have not been as regular as they used to be and that 3 months ago she skipped a cycle. She is having bothersome vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and is concerned about her memory. She says she is forgetful at work and in social situations. During a recent presentation, she could not remember the name of one of her former clients. At a work happy hour, she forgot the name of her coworker’s husband, although she did remember it later after returning home.

Her mother has Alzheimer disease (AD), and Jackie worries about whether she, too, might be developing dementia and whether her memory will fail her in social situations.

She is concerned about using hormone therapy (HT) for her vasomotor symptoms because she has heard that it can lead to breast cancer and/or AD.

How would you advise her?

HT remains the most effective treatment for bothersome VMS, but concerns about its cognitive safety persist. Such concerns, and indeed a black-box warning about the risk of dementia with HT use, initially arose following the 2003 publication of the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS), a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of HT for the primary prevention of dementia in women aged 65 years and older at baseline.1 The study found that combination estrogen/progestin therapy was associated with a 2-fold increase in dementia when compared with placebo.

One of the critical questions arising even before WHIMS was whether the cognitive risks associated with HT that were seen in WHIMS apply to younger women. Attempting to answer the question and adding fuel to the fire are the results of a recent case-control study from Finland.2 This study compared HT use in Finnish women with and without AD and found that HT use was higher among Finnish women with AD compared with those without AD, regardless of age. The authors concluded, “Our data must be implemented into information for the present and future users of HT, even though the absolute risk increase is small.”

However, given the limitations inherent to observational and registry studies, and the contrasting findings of 3 high-quality, randomized controlled trials (RCTs; more details below), providers actually can reassure younger peri- and postmenopausal women about the cognitive safety of HT.3 They also can explain to patients that cognitive symptoms like the ones described in the case example are normal and provide general guidance to midlife women on how to optimize brain health.

Continue to: Closer look at WHI and RCT research pinpoints cognitively neutral HT...

Closer look at WHI and RCT research pinpoints cognitively neutral HT

In WHIMS, the combination of conjugated equine estrogen (CEE; 0.625 mg/d) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA; 2.5 mg/d) led to a doubling of the risk of all-cause dementia compared with placebo in a sample of 4,532 women aged 65 years and older at baseline.1 CEE alone (0.625 mg) did not lead to an increased risk of all-cause dementia.4

Whether those formulations led to cognitive impairment in younger postmenopausal women was the focus of WHIMS-Younger (WHIMS-Y), which involved WHI participants aged 50 to 55 years at baseline.5 Results revealed neutral cognitive effects (ie, no differences in cognitive performance in women randomly assigned to HT or placebo) in women tested 7.2 years after the end of the WHI trial. WHIMS-Y findings indicated that there were no sustained cognitive risks of CEE or CEE/MPA therapy. Two randomized, placebo-controlled trials involving younger postmenopausal women yielded similar findings.6,7 HT shown to produce cognitively neutral effects during active treatment included transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone,6 CEE plus progesterone,6 and oral estradiol plus vaginal progesterone gel.7 The findings of these randomized trials are critical for guiding decisions regarding the cognitive risks of HT in early postmenopausal women (TABLE 1).

What about women with VMS?

A key gap in knowledge about the cognitive effects of HT is whether HT confers cognitive advantages to women with bothersome VMS. This is a striking absence given that the key indication for HT is the treatment of VMS. While some symptomatic women were included in the trials of HT in younger postmenopausal women described above, no large trial to date has selectively enrolled women with moderate-to-severe VMS to determine if HT is cognitively neutral, beneficial, or detrimental in that group. Some studies involving midlife women have found associations between VMS (as measured with ambulatory skin conductance monitors) and multiple measures of brain health, including memory performance,8 small ischemic lesions on structural brain scans,9 and altered brain function.10 In a small trial of a nonhormonal intervention for VMS, improvement in VMS following the intervention was directly related to improvement in memory performance.11 The reliability of these findings continues to be evaluated but raises the hypothesis that VMS treatments might improve memory in midlife women.

Memory complaints common among midlife women

About 60% of women report an undesirable change in memory performance at midlife as compared with earlier in their lives.12,13 Complaints of forgetfulness are higher in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women compared with premenopausal women, even when those women are similar in age.14 Two large prospective studies found that memory performance decreases during the perimenopause and then rebounds, suggesting a transient decrease in memory.15,16 Although cognitive complaints are common among women in their 40s and 50s, AD is rare in that age group. The risk is largely limited to those women with a parent who developed dementia before age 65, as such cases suggest a familial form of AD.

Continue to: What causes cognitive difficulties during midlife?

What causes cognitive difficulties during midlife?

First, some cognitive decline is expected at midlife based on increasing age. Second, above and beyond the role of chronologic aging (ie, getting one year older each year), ovarian aging plays a role. A role of estrogen was verified in clinical trials showing that memory decreased following oophorectomy in premenopausal women in their 40s but returned to presurgical levels following treatment with estrogen therapy (ET).17 Cohort studies indicate that women who undergo oophorectomy before the typical age of menopause are at increased risk for cognitive impairment or dementia, but those who take ET after oophorectomy until the typical age of menopause do not show that risk.18

Third, cognitive problems are linked not only to VMS but also to sleep disturbance, depressed mood, and increased anxiety—all of which are common in midlife women.15,19 Lastly, health factors play a role. Hypertension, obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, and smoking are associated with adverse brain changes at midlife.20

Giving advice to your patients

First, normalize the cognitive complaints, noting that some cognitive changes are an expected part of aging for all people regardless of whether they are male or female. Advise that while the best studies indicate that these cognitive lapses are especially common in perimenopausal women, they appear to be temporary; women are likely to resume normal cognitive function once the hormonal changes associated with menopause subside.15,16 Note that the one unknown is the role that VMS play in memory problems and that some studies indicate a link between VMS and cognitive problems. Women may experience some cognitive improvement if VMS are effectively treated.

Advise patients that the Endocrine Society, the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), and the International Menopause Society all have published guidelines saying that the benefits of HT outweigh the risks for most women aged 50 to 60 years.21 For concerns about the cognitive adverse effects of HT, discuss the best quality evidence—that which comes from randomized trials—which shows no harmful effects of HT in midlife women.5-7 Especially reassuring is that one of these high-quality studies was conducted by the same researchers who found that HT can be risky in older women (ie, the WHI Investigators).5

Going one step further: Protecting brain health

As primary care providers to midlife women, ObGyns can go one step further and advise patients on how to proactively nurture their brain health. Great evidence-based resources for information on maintaining brain health include the Alzheimer’s Association (https://www.alz.org) and the Women’s Brain Health Initiative (https://womensbrainhealth.org). Primary prevention of AD begins decades before the typical age of an AD diagnosis, and many risk factors for AD are modifiable.22 Patients can keep their brains healthy through myriad approaches including treating hypertension, reducing body mass index, engaging in regular aerobic exercise (brisk walking is fine), eating a Mediterranean diet, maintaining an active social life, and engaging in novel challenging activities like learning a new language or a new skill like dancing.20

Also important is the overlap between cognitive issues, mood, and alcohol use. In the opening case, Jackie mentions alcohol use and social withdrawal. According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), low-risk drinking for women is defined as no more than 3 drinks on any single day and no more than 7 drinks per week.23 Heavy alcohol use not only affects brain function but also mood, and depressed mood can lead women to drink excessively.24

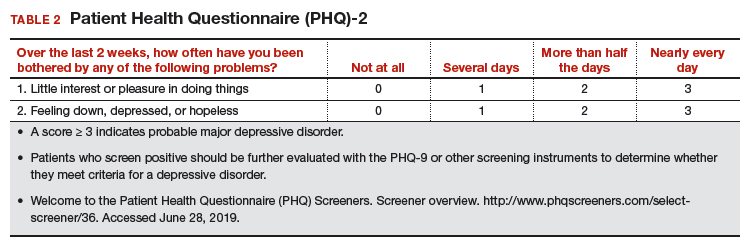

In addition, Jackie’s mother has AD, and that stressor can contribute to depressed feelings, especially if Jackie is involved in caregiving. A quick screen for depression with an instrument like the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2; TABLE 2)25 can rule out a more serious mood disorder—an approach that is particularly important for patients with a history of major depression, as 58% of those patients experience a major depressive episode during the menopausal transition.26 For this reason, it is important to ask patients like Jackie if they have a history of depression; if they do and were treated medically, consider prescribing the antidepressant that worked in the past. For information on menopause and mood-related issues, providers can access new guidelines from NAMS and the National Network of Depression Centers (NNDC).27 There is also a handy patient information sheet to accompany those guidelines on the NAMS website (https://www.menopause.org/).

Continue to: CASE Resolved...

CASE Resolved

When approaching Jackie, most importantly, I would normalize her experience and tell her that memory problems are common in the menopausal transition, especially for women with bothersome VMS. Research suggests that the memory problems she is experiencing are related to hormonal changes and not to AD, and that her memory will likely improve once she has transitioned through the menopause. I would tell her that AD is rare at midlife unless there is a family history of early onset of AD (before age 65), and I would verify the age at which her mother was diagnosed to confirm that it was late-onset AD.

For now, I would recommend that she be prescribed HT for her bothersome hot flashes using one of the “safe” formulations in the Table on page 24. I also would tell her that there is much she can do to lower her risk of AD and that it is best to start now as she enters her 50s because that is when AD changes typically start in the brain, and she can start to prevent those changes now.

I would tell her that experts in the field of AD agree that these lifestyle interventions are currently the best way to prevent AD and that the more of them she engages in, the more her brain will benefit. I would advise her to continue to manage her hypertension and to consider ways of lowering her BMI to enhance her brain health. Engaging in regular brisk walking or other aerobic exercise, as well as incorporating more of the Mediterranean diet into her daily food intake would also benefit her brain. As a working woman, she is exercising her brain, and she should consider other cognitively challenging activities to keep her brain in good shape.

I would follow up with her in a few months to see if her memory functioning is better. If it is not, and if her VMS continue to be bothersome, I would increase her dose of HT. Only if her VMS are treated but her memory problems are getting worse would I screen her with a Mini-Mental State Exam and refer her to a neurologist for an evaluation.

CASE HT for vasomotor symptoms in perimenopausal woman with cognitive concerns

Jackie is a 49-year-old woman. Her body mass index is 33 kg/m2, and she has mild hypertension that is effectively controlled with antihypertensive medications. Otherwise, she is in good health.During her annual gynecologic exam, she reports that for the past 9 months her menstrual cycles have not been as regular as they used to be and that 3 months ago she skipped a cycle. She is having bothersome vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and is concerned about her memory. She says she is forgetful at work and in social situations. During a recent presentation, she could not remember the name of one of her former clients. At a work happy hour, she forgot the name of her coworker’s husband, although she did remember it later after returning home.

Her mother has Alzheimer disease (AD), and Jackie worries about whether she, too, might be developing dementia and whether her memory will fail her in social situations.

She is concerned about using hormone therapy (HT) for her vasomotor symptoms because she has heard that it can lead to breast cancer and/or AD.

How would you advise her?

HT remains the most effective treatment for bothersome VMS, but concerns about its cognitive safety persist. Such concerns, and indeed a black-box warning about the risk of dementia with HT use, initially arose following the 2003 publication of the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS), a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of HT for the primary prevention of dementia in women aged 65 years and older at baseline.1 The study found that combination estrogen/progestin therapy was associated with a 2-fold increase in dementia when compared with placebo.

One of the critical questions arising even before WHIMS was whether the cognitive risks associated with HT that were seen in WHIMS apply to younger women. Attempting to answer the question and adding fuel to the fire are the results of a recent case-control study from Finland.2 This study compared HT use in Finnish women with and without AD and found that HT use was higher among Finnish women with AD compared with those without AD, regardless of age. The authors concluded, “Our data must be implemented into information for the present and future users of HT, even though the absolute risk increase is small.”

However, given the limitations inherent to observational and registry studies, and the contrasting findings of 3 high-quality, randomized controlled trials (RCTs; more details below), providers actually can reassure younger peri- and postmenopausal women about the cognitive safety of HT.3 They also can explain to patients that cognitive symptoms like the ones described in the case example are normal and provide general guidance to midlife women on how to optimize brain health.

Continue to: Closer look at WHI and RCT research pinpoints cognitively neutral HT...

Closer look at WHI and RCT research pinpoints cognitively neutral HT

In WHIMS, the combination of conjugated equine estrogen (CEE; 0.625 mg/d) plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA; 2.5 mg/d) led to a doubling of the risk of all-cause dementia compared with placebo in a sample of 4,532 women aged 65 years and older at baseline.1 CEE alone (0.625 mg) did not lead to an increased risk of all-cause dementia.4

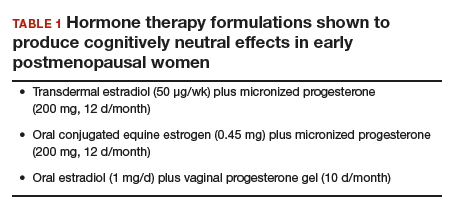

Whether those formulations led to cognitive impairment in younger postmenopausal women was the focus of WHIMS-Younger (WHIMS-Y), which involved WHI participants aged 50 to 55 years at baseline.5 Results revealed neutral cognitive effects (ie, no differences in cognitive performance in women randomly assigned to HT or placebo) in women tested 7.2 years after the end of the WHI trial. WHIMS-Y findings indicated that there were no sustained cognitive risks of CEE or CEE/MPA therapy. Two randomized, placebo-controlled trials involving younger postmenopausal women yielded similar findings.6,7 HT shown to produce cognitively neutral effects during active treatment included transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone,6 CEE plus progesterone,6 and oral estradiol plus vaginal progesterone gel.7 The findings of these randomized trials are critical for guiding decisions regarding the cognitive risks of HT in early postmenopausal women (TABLE 1).

What about women with VMS?

A key gap in knowledge about the cognitive effects of HT is whether HT confers cognitive advantages to women with bothersome VMS. This is a striking absence given that the key indication for HT is the treatment of VMS. While some symptomatic women were included in the trials of HT in younger postmenopausal women described above, no large trial to date has selectively enrolled women with moderate-to-severe VMS to determine if HT is cognitively neutral, beneficial, or detrimental in that group. Some studies involving midlife women have found associations between VMS (as measured with ambulatory skin conductance monitors) and multiple measures of brain health, including memory performance,8 small ischemic lesions on structural brain scans,9 and altered brain function.10 In a small trial of a nonhormonal intervention for VMS, improvement in VMS following the intervention was directly related to improvement in memory performance.11 The reliability of these findings continues to be evaluated but raises the hypothesis that VMS treatments might improve memory in midlife women.

Memory complaints common among midlife women

About 60% of women report an undesirable change in memory performance at midlife as compared with earlier in their lives.12,13 Complaints of forgetfulness are higher in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women compared with premenopausal women, even when those women are similar in age.14 Two large prospective studies found that memory performance decreases during the perimenopause and then rebounds, suggesting a transient decrease in memory.15,16 Although cognitive complaints are common among women in their 40s and 50s, AD is rare in that age group. The risk is largely limited to those women with a parent who developed dementia before age 65, as such cases suggest a familial form of AD.

Continue to: What causes cognitive difficulties during midlife?

What causes cognitive difficulties during midlife?

First, some cognitive decline is expected at midlife based on increasing age. Second, above and beyond the role of chronologic aging (ie, getting one year older each year), ovarian aging plays a role. A role of estrogen was verified in clinical trials showing that memory decreased following oophorectomy in premenopausal women in their 40s but returned to presurgical levels following treatment with estrogen therapy (ET).17 Cohort studies indicate that women who undergo oophorectomy before the typical age of menopause are at increased risk for cognitive impairment or dementia, but those who take ET after oophorectomy until the typical age of menopause do not show that risk.18

Third, cognitive problems are linked not only to VMS but also to sleep disturbance, depressed mood, and increased anxiety—all of which are common in midlife women.15,19 Lastly, health factors play a role. Hypertension, obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, and smoking are associated with adverse brain changes at midlife.20

Giving advice to your patients

First, normalize the cognitive complaints, noting that some cognitive changes are an expected part of aging for all people regardless of whether they are male or female. Advise that while the best studies indicate that these cognitive lapses are especially common in perimenopausal women, they appear to be temporary; women are likely to resume normal cognitive function once the hormonal changes associated with menopause subside.15,16 Note that the one unknown is the role that VMS play in memory problems and that some studies indicate a link between VMS and cognitive problems. Women may experience some cognitive improvement if VMS are effectively treated.

Advise patients that the Endocrine Society, the North American Menopause Society (NAMS), and the International Menopause Society all have published guidelines saying that the benefits of HT outweigh the risks for most women aged 50 to 60 years.21 For concerns about the cognitive adverse effects of HT, discuss the best quality evidence—that which comes from randomized trials—which shows no harmful effects of HT in midlife women.5-7 Especially reassuring is that one of these high-quality studies was conducted by the same researchers who found that HT can be risky in older women (ie, the WHI Investigators).5

Going one step further: Protecting brain health

As primary care providers to midlife women, ObGyns can go one step further and advise patients on how to proactively nurture their brain health. Great evidence-based resources for information on maintaining brain health include the Alzheimer’s Association (https://www.alz.org) and the Women’s Brain Health Initiative (https://womensbrainhealth.org). Primary prevention of AD begins decades before the typical age of an AD diagnosis, and many risk factors for AD are modifiable.22 Patients can keep their brains healthy through myriad approaches including treating hypertension, reducing body mass index, engaging in regular aerobic exercise (brisk walking is fine), eating a Mediterranean diet, maintaining an active social life, and engaging in novel challenging activities like learning a new language or a new skill like dancing.20

Also important is the overlap between cognitive issues, mood, and alcohol use. In the opening case, Jackie mentions alcohol use and social withdrawal. According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), low-risk drinking for women is defined as no more than 3 drinks on any single day and no more than 7 drinks per week.23 Heavy alcohol use not only affects brain function but also mood, and depressed mood can lead women to drink excessively.24

In addition, Jackie’s mother has AD, and that stressor can contribute to depressed feelings, especially if Jackie is involved in caregiving. A quick screen for depression with an instrument like the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2; TABLE 2)25 can rule out a more serious mood disorder—an approach that is particularly important for patients with a history of major depression, as 58% of those patients experience a major depressive episode during the menopausal transition.26 For this reason, it is important to ask patients like Jackie if they have a history of depression; if they do and were treated medically, consider prescribing the antidepressant that worked in the past. For information on menopause and mood-related issues, providers can access new guidelines from NAMS and the National Network of Depression Centers (NNDC).27 There is also a handy patient information sheet to accompany those guidelines on the NAMS website (https://www.menopause.org/).

Continue to: CASE Resolved...

CASE Resolved

When approaching Jackie, most importantly, I would normalize her experience and tell her that memory problems are common in the menopausal transition, especially for women with bothersome VMS. Research suggests that the memory problems she is experiencing are related to hormonal changes and not to AD, and that her memory will likely improve once she has transitioned through the menopause. I would tell her that AD is rare at midlife unless there is a family history of early onset of AD (before age 65), and I would verify the age at which her mother was diagnosed to confirm that it was late-onset AD.

For now, I would recommend that she be prescribed HT for her bothersome hot flashes using one of the “safe” formulations in the Table on page 24. I also would tell her that there is much she can do to lower her risk of AD and that it is best to start now as she enters her 50s because that is when AD changes typically start in the brain, and she can start to prevent those changes now.

I would tell her that experts in the field of AD agree that these lifestyle interventions are currently the best way to prevent AD and that the more of them she engages in, the more her brain will benefit. I would advise her to continue to manage her hypertension and to consider ways of lowering her BMI to enhance her brain health. Engaging in regular brisk walking or other aerobic exercise, as well as incorporating more of the Mediterranean diet into her daily food intake would also benefit her brain. As a working woman, she is exercising her brain, and she should consider other cognitively challenging activities to keep her brain in good shape.

I would follow up with her in a few months to see if her memory functioning is better. If it is not, and if her VMS continue to be bothersome, I would increase her dose of HT. Only if her VMS are treated but her memory problems are getting worse would I screen her with a Mini-Mental State Exam and refer her to a neurologist for an evaluation.

- Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2651-2662.

- Savolainen-Peltonen H, Rahkola-Soisalo P, Hoti F, et al. Use of postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of Alzheimer’s disease in Finland: nationwide case-control study. BMJ. 2019;364:1665.

- Maki PM, Girard LM, Manson JE. Menopausal hormone therapy and cognition. BMJ. 2019;364:1877.

- Shumaker SA, Legault C, Kuller L, et al. Conjugated equine estrogens and incidence of probable dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA. 2004;291:2947-2958.

- Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, Leng I, et al. Long-term effects on cognitive function of postmenopausal hormone therapy prescribed to women aged 50 to 55 years. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1429-1436.

- Gleason CE, Dowling NM, Wharton W, et al. Effects of hormone therapy on cognition and mood in recently postmenopausal women: findings from the randomized, controlled KEEPS-cognitive and affective study. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001833.

- Henderson VW, St. John JA, Hodis HN, et al. Cognitive effects of estradiol after menopause: a randomized trial of the timing hypothesis. Neurology. 2016;87:699-708.

- Maki PM, Drogos LL, Rubin LH, et al. Objective hot flashes are negatively related to verbal memory performance in midlife women. Menopause. 2008;15:848-856.

- Thurston RC, Aizenstein HJ, Derby CA, et al. Menopausal hot flashes and white matter hyperintensities. Menopause. 2016;23:27-32.

- Thurston RC, Maki PM, Derby CA, et al. Menopausal hot flashes and the default mode network. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:1572-1578.e1.

- Maki PM, Rubin LH, Savarese A, et al. Stellate ganglion blockade and verbal memory in midlife women: evidence from a randomized trial. Maturitas. 2016;92:123-129.

- Woods NF, Mitchell ES, Adams C. Memory functioning among midlife women: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. Menopause. 2000;7:257-265.

- Sullivan Mitchell E, Fugate Woods N. Midlife women’s attributions about perceived memory changes: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:351-362.

- Gold EB, Sternfeld B, Kelsey JL, et al. Relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multi-racial/ethnic population of women 40-55 years of age. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:463-473.

- Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2651-2662.

- Savolainen-Peltonen H, Rahkola-Soisalo P, Hoti F, et al. Use of postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of Alzheimer’s disease in Finland: nationwide case-control study. BMJ. 2019;364:1665.

- Maki PM, Girard LM, Manson JE. Menopausal hormone therapy and cognition. BMJ. 2019;364:1877.

- Shumaker SA, Legault C, Kuller L, et al. Conjugated equine estrogens and incidence of probable dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. JAMA. 2004;291:2947-2958.

- Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, Leng I, et al. Long-term effects on cognitive function of postmenopausal hormone therapy prescribed to women aged 50 to 55 years. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1429-1436.

- Gleason CE, Dowling NM, Wharton W, et al. Effects of hormone therapy on cognition and mood in recently postmenopausal women: findings from the randomized, controlled KEEPS-cognitive and affective study. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001833.

- Henderson VW, St. John JA, Hodis HN, et al. Cognitive effects of estradiol after menopause: a randomized trial of the timing hypothesis. Neurology. 2016;87:699-708.

- Maki PM, Drogos LL, Rubin LH, et al. Objective hot flashes are negatively related to verbal memory performance in midlife women. Menopause. 2008;15:848-856.

- Thurston RC, Aizenstein HJ, Derby CA, et al. Menopausal hot flashes and white matter hyperintensities. Menopause. 2016;23:27-32.

- Thurston RC, Maki PM, Derby CA, et al. Menopausal hot flashes and the default mode network. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:1572-1578.e1.

- Maki PM, Rubin LH, Savarese A, et al. Stellate ganglion blockade and verbal memory in midlife women: evidence from a randomized trial. Maturitas. 2016;92:123-129.

- Woods NF, Mitchell ES, Adams C. Memory functioning among midlife women: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. Menopause. 2000;7:257-265.

- Sullivan Mitchell E, Fugate Woods N. Midlife women’s attributions about perceived memory changes: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women’s Health Study. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:351-362.

- Gold EB, Sternfeld B, Kelsey JL, et al. Relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multi-racial/ethnic population of women 40-55 years of age. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:463-473.

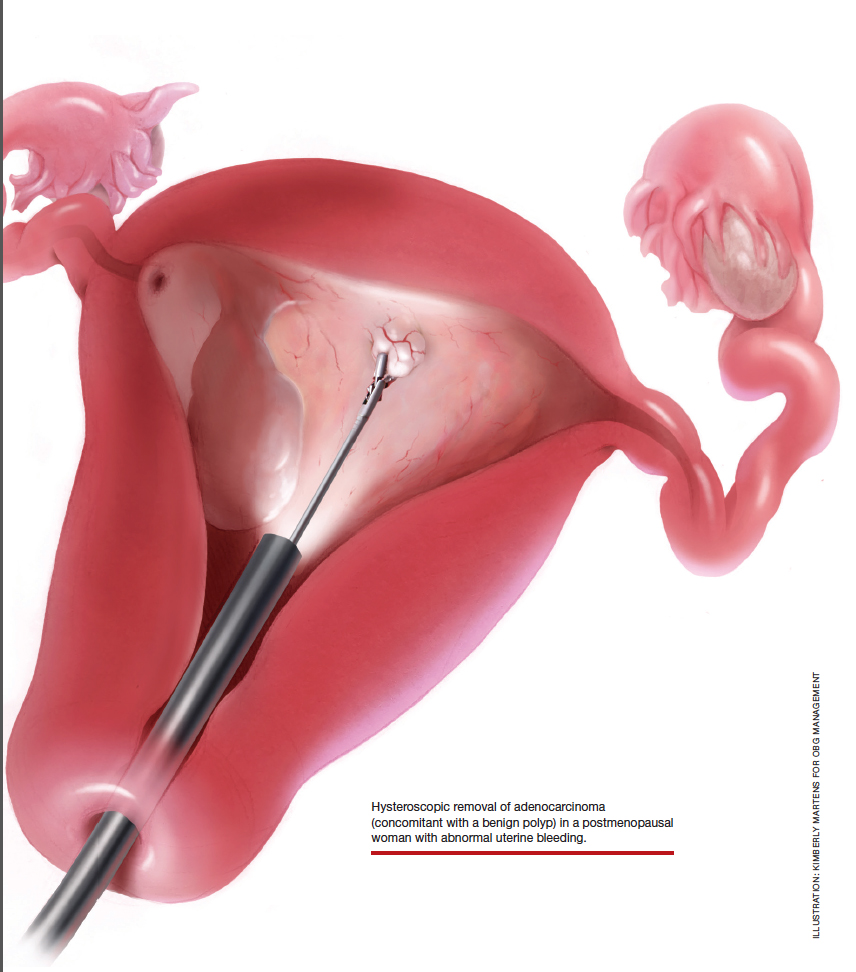

Office hysteroscopic evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding

Postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is the presenting sign in most cases of endometrial carcinoma. Prompt evaluation of PMB can exclude, or diagnose, endometrial carcinoma.1 Although no general consensus exists for PMB evaluation, it involves endometrial assessment with transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) and subsequent endometrial biopsy when a thickened endometrium is found. When biopsy results reveal insufficient or scant tissue, further investigation into the etiology of PMB should include office hysteroscopy with possible directed biopsy. In this article I discuss the prevalence of PMB and steps for evaluation, providing clinical takeaways.

Postmenopausal bleeding: Its risk for cancer

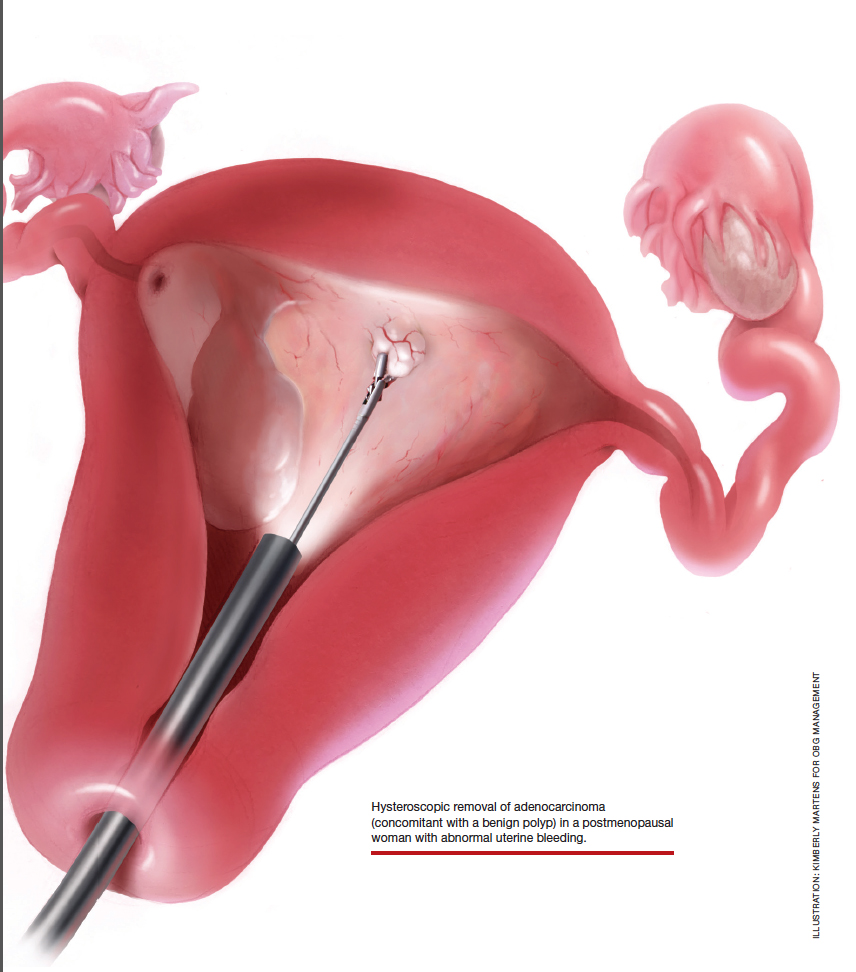

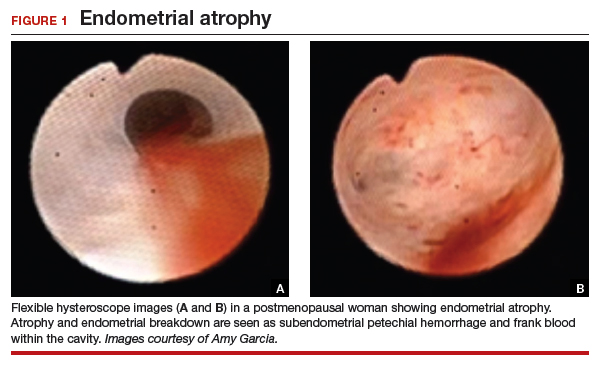

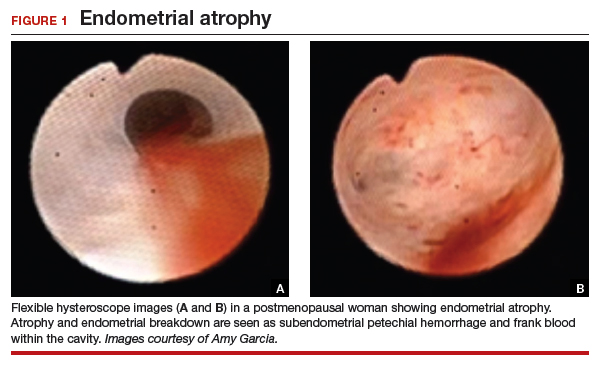

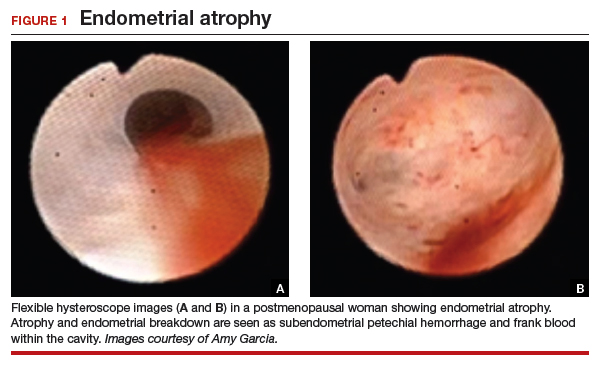

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) in a postmenopausal woman is of particular concern to the gynecologist and the patient because of the increased possibility of endometrial carcinoma in this age group. AUB is present in more than 90% of postmenopausal women with endometrial carcinoma, which leads to diagnosis in the early stages of the disease. Approximately 3% to 7% of postmenopausal women with PMB will have endometrial carcinoma.2 Most women with PMB, however, experience bleeding secondary to atrophic changes of the vagina or endometrium and not to endometrial carcinoma. (FIGURE 1, VIDEO 1) In addition, women who take gonadal steroids for hormone replacement therapy (HRT) may experience breakthrough bleeding that leads to initial investigation with TVUS.

Video 1

The risk of malignancy in polyps in postmenopausal women over the age of 59 who present with PMB is approximately 12%, and hysteroscopic resection should routinely be performed. For asymptomatic patients, the risk of a malignant lesion is low—approximately 3%—and for these women intervention should be assessed individually for the risks of carcinoma and benefits of hysteroscopic removal.3

Clinical takeaway. The high possibility of endometrial carcinoma in postmenopausal women warrants that any patient who is symptomatic with PMB should be presumed to have endometrial cancer until the diagnostic evaluation process proves she does not.

Evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding

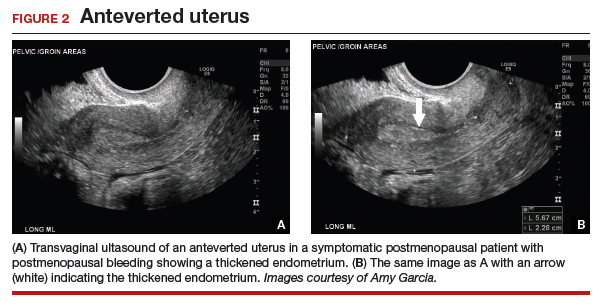

Transvaginal ultrasound

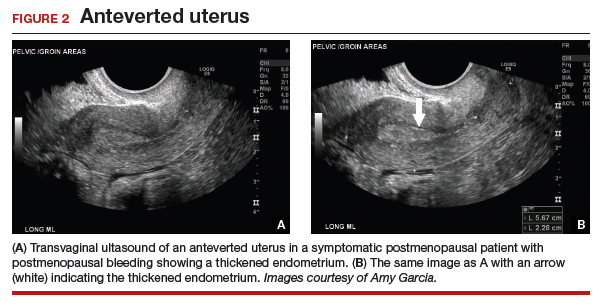

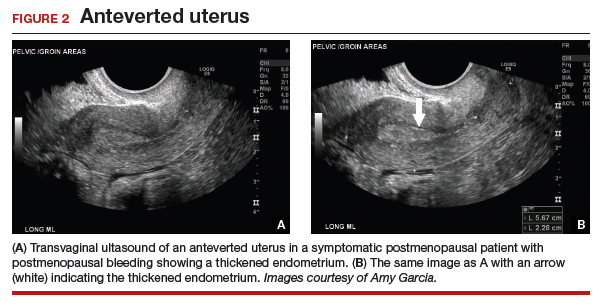

As mentioned, no general consensus exists for the evaluation of PMB; however, initial evaluation by TVUS is recommended. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) concluded that when the endometrium measures ≤4 mm with TVUS, the likelihood that bleeding is secondary to endometrial carcinoma is less than 1% (negative predictive value 99%), and endometrial biopsy is not recommended.3 Endometrial sampling in this clinical scenario likely will result in insufficient tissue for evaluation, and it is reasonable to consider initial management for atrophy. A thickened endometrium on TVUS (>4 mm in a postmenopausal woman with PMB) warrants additional evaluation with endometrial sampling (FIGURE 2).

Clinical takeaway. A thickened endometrium on TVUS ≥4 mm in a postmenopausal woman with PMB warrants additional evaluation with endometrial sampling.

Endometrial biopsy

An endometrial biopsy is performed to determine whether endometrial cancer or precancer is present in women with AUB. ACOG recommends that endometrial biopsy be performed for women older than age 45. It is also appropriate in women younger than 45 years if they have risk factors for developing endometrial cancer, including unopposed estrogen exposure (obesity, ovulatory dysfunction), failed medical management of AUB, or persistence of AUB.4

Continue to: Endometrial biopsy has some...

Endometrial biopsy has some diagnostic shortcomings, however. In 2016 a systematic review and meta-analysis found that, in women with PMB, the specificity of endometrial biopsy was 98% to 100% (accurate diagnosis with a positive result). The sensitivity (ability to make an accurate diagnosis) of endometrial biopsy to identify endometrial pathology (carcinoma, atypical hyperplasia, and polyps) is lower than typically thought. These investigators found an endometrial biopsy failure rate of 11% (range, 1% to 53%) and rate of insufficient samples of 31% (range, 7% to 76%). In women with insufficient or failed samples, endometrial cancer or precancer was found in 7% (range, 0% to 18%).5 Therefore, a negative tissue biopsy result in women with PMB is not considered to be an endpoint, and further evaluation with hysteroscopy to evaluate for focal disease is imperative. The results of endometrial biopsy are only an endpoint to the evaluation of PMB when atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer is identified.

Clinical takeaway. A negative tissue biopsy result in women with PMB is not considered to be an endpoint, and further evaluation with hysteroscopy to evaluate for focal disease is imperative.

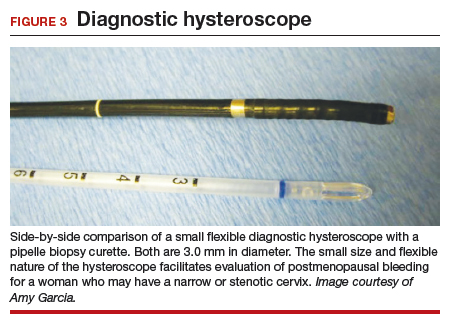

Hysteroscopy

Hysteroscopy is the gold standard for evaluating the uterine cavity, diagnosing intrauterine pathology, and operative intervention for some causes of AUB. It also is easily performed in the office. This makes the hysteroscope an essential instrument for the gynecologist. Dr. Linda Bradley, a preeminent leader in hysteroscopic surgical education, has coined the phrase, “My hysteroscope is my stethoscope.”6 As gynecologists, we should be as adept at using a hysteroscope in the office as the cardiologist is at using a stethoscope.

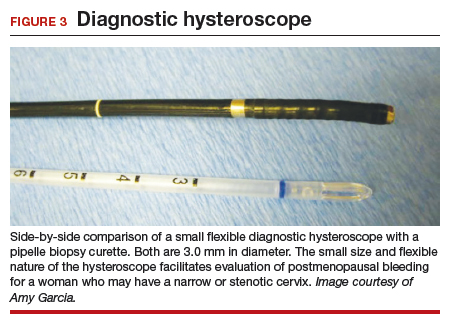

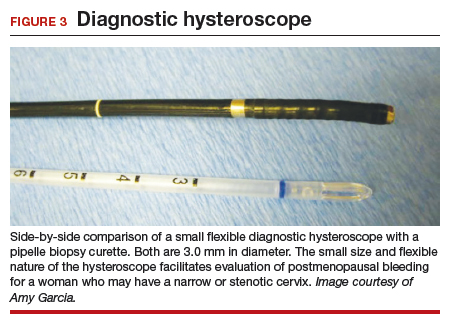

It has been known for some time that hysteroscopy improves our diagnostic capabilities over blinded procedures such as endometrial biopsy and dilation and curettage (D&C). As far back as 1989, Dr. Frank Loffer reported the increased sensitivity (ability to make an accurate diagnosis) of hysteroscopy with directed biopsy over blinded D&C (98% vs 65%) in the evaluation of AUB.7 Evaluation of the endometrium with D&C is no longer recommended; yet today, few gynecologists perform hysteroscopic-directed biopsy for AUB evaluation instead of blinded tissue sampling despite the clinical superiority and in-office capabilities (FIGURE 3).

Continue to: Hysteroscopy and endometrial carcinoma...

Hysteroscopy and endometrial carcinoma

The most common type of gynecologic cancer in the United States is endometrial adenocarcinoma (type 1 endometrial cancer). There is some concern about the effect of hysteroscopy on endometrial cancer prognosis and the spread of cells to the peritoneum at the time of hysteroscopy. A large meta-analysis found that hysteroscopy performed in the presence of type 1 endometrial cancer statistically significantly increased the likelihood of positive intraperitoneal cytology; however, it did not alter the clinical outcome. It was recommended that hysteroscopy not be avoided for this reason and is helpful in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer, especially in the early stages of disease.8

For endometrial cancer type 2 (serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and carcinosarcoma), Chen and colleagues reported a statistically significant increase in positive peritoneal cytology for cancers evaluated by hysteroscopy versus D&C. The disease-specific survival for the hysteroscopy group was 60 months, compared with 71 months for the D&C group. While this finding was not statistically significant, it was clinically relevant, and the effect of hysteroscopy on prognosis with type 2 endometrial cancer is unclear.9

A common occurrence in the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is an initial TVUS finding of an enlarged endometrium and an endometrial biopsy that is negative or reveals scant or insufficient tissue. Unfortunately, the diagnostic evaluation process often stops here, and a diagnosis for the PMB is never actually identified. Here are several clinical scenarios that highlight the need for hysteroscopy in the initial evaluation of PMB, especially when there is a discordance between transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) and endometrial biopsy findings.

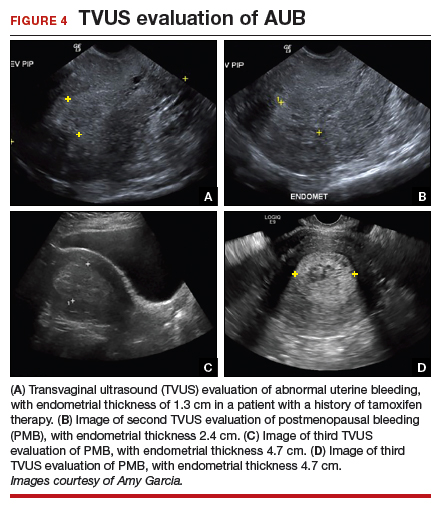

Patient 1: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with benign findings

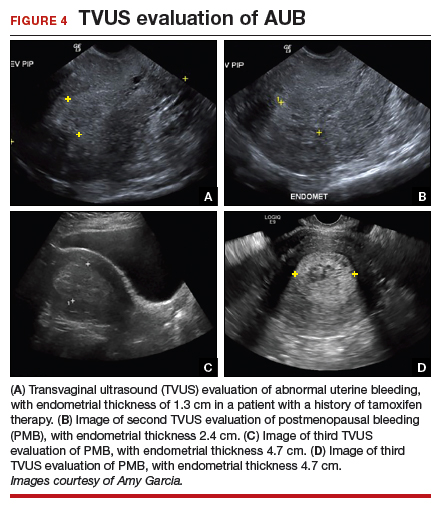

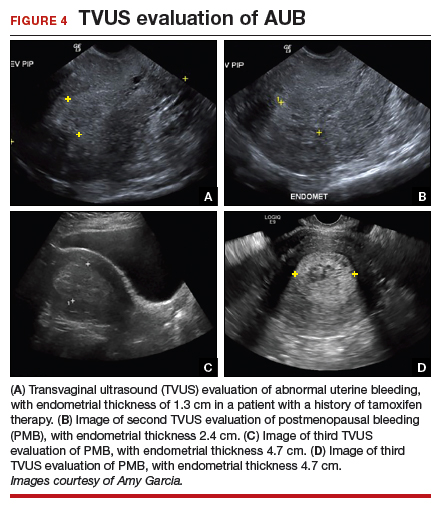

The patient is a 52-year-old woman who presented to her gynecologist reporting abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). She has a history of breast cancer, and she completed tamoxifen treatment. Pelvic ultrasonography was performed; an enlarged endometrial stripe of 1.3 cm was found (FIGURE 4A). Endometrial biopsy was performed, showing adequate tissue but with a negative result. The patient is told that she is likely perimenopausal, which is the reason for her bleeding.

At the time of referral, the patient is evaluated with in-office hysteroscopy. Diagnosis of a 5 cm x 7 cm benign endometrial polyp is made. An uneventful hysteroscopic polypectomy is performed (VIDEO 2).

Video 2

This scenario illustrates the shortcoming of initial evaluation by not performing a hysteroscopy, especially in a woman with a thickened endometrium with previous tamoxifen therapy. Subsequent visits failed to correlate bleeding etiology with discordant TVUS and endometrial biopsy results with hysteroscopy, and no hysteroscopy was performed in the operating room at the time of D&C.

Patient 2: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with premalignant findings

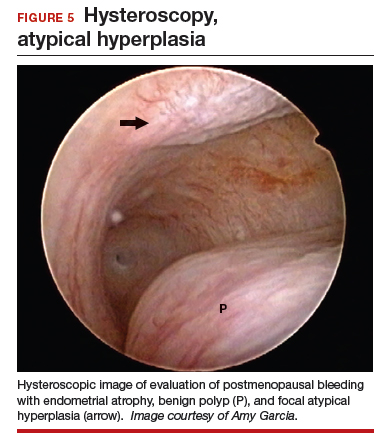

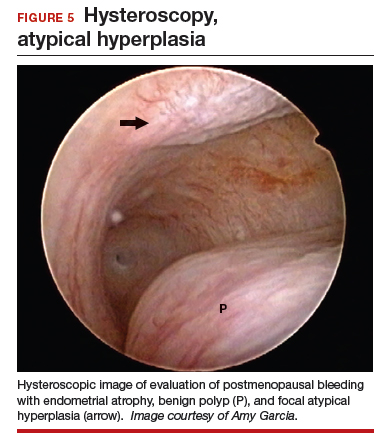

The patient is a 62-year-old woman who had incidental findings of a thickened endometrium on computed tomography scan of the pelvis. TVUS confirmed a thickened endometrium measuring 17 mm, and an endometrial biopsy showed scant tissue.

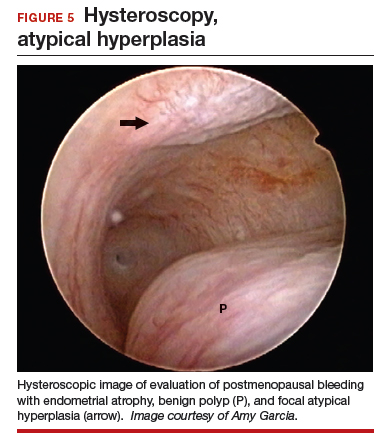

At the time of referral, a diagnostic hysteroscopy was performed in the office. Endometrial atrophy, a large benign appearing polyp, and focal abnormal appearing tissue were seen (FIGURE 5). A decision for polypectomy and directed biopsy was made. Histology findings confirmed benign polyp and atypical hyperplasia (VIDEO 3).

Video 3

This scenario illustrates that while the patient was asymptomatic, there was discordance between the TVUS and endometrial biopsy. Hysteroscopy identified a benign endometrial polyp, which is common in asymptomatic postmenopausal patients with a thickened endometrium and endometrial biopsy showing scant tissue. However, addition of the diagnostic hysteroscopy identified focal precancerous tissue, removed under directed biopsy.

Patient 3: Discordant TVUS and biopsy, with malignant findings

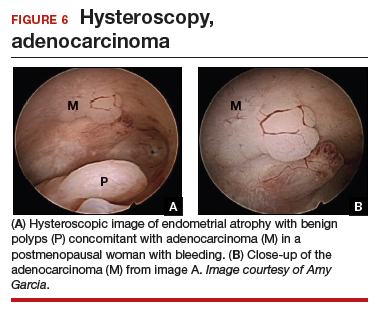

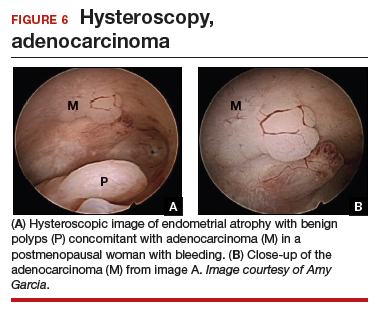

The patient is a 68-year-old woman with PMB. TVUS showed a thickened endometrium measuring 14 mm. An endometrial biopsy was negative, showing scant tissue. No additional diagnostic evaluation or management was offered.

Video 4A

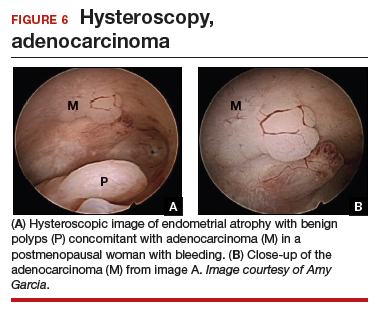

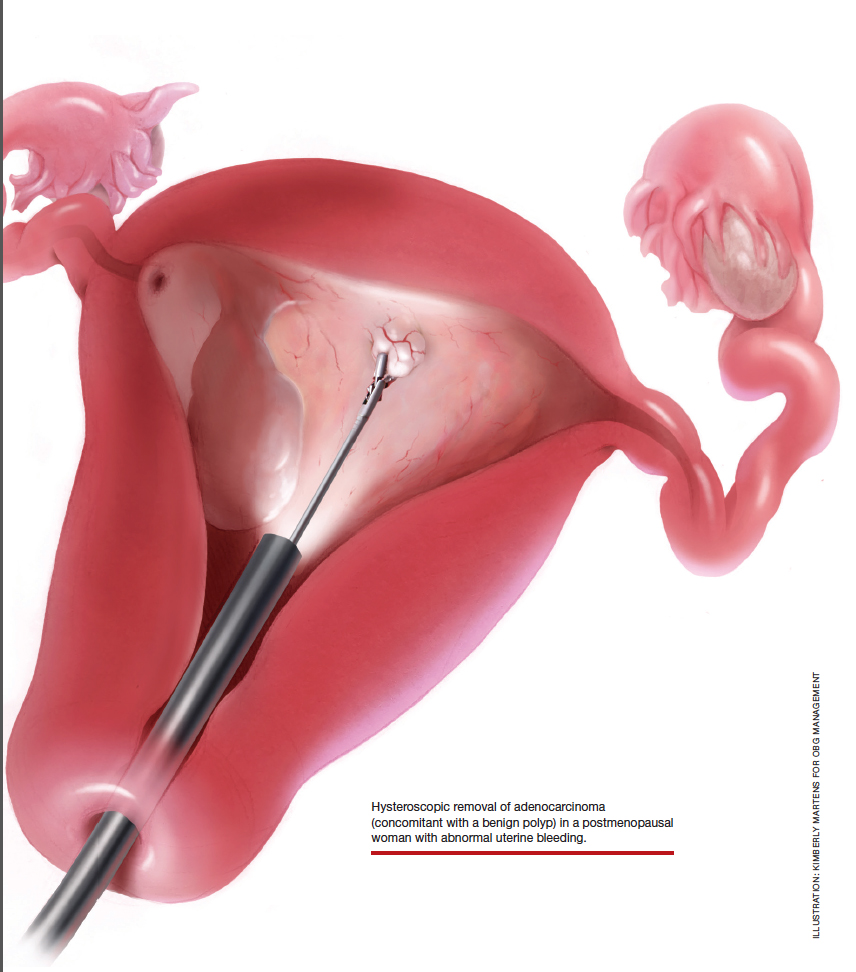

At the time of referral, the patient was evaluated with in-office diagnostic hysteroscopy, and the patient was found to have endometrial atrophy, benign appearing polyps, and focal abnormal tissue (FIGURE 6). A decision for polypectomy and directed biopsy was made. Histology confirmed benign polyps and grade 1 adenocarcinoma (VIDEOS 4A, 4B, 4C).

Video 4B

This scenario illustrates the possibility of having multiple endometrial pathologies present at the time of discordant TVUS and endometrial biopsy. Hysteroscopy plays a critical role in additional evaluation and diagnosis of endometrial carcinoma with directed biopsy, especially in a symptomatic woman with PMB.

Video 4C

Conclusion

Evaluation of PMB begins with a screening TVUS. Findings of an endometrium of ≤4 mm indicate a very low likelihood of the presence of endometrial cancer, and treatment for atrophy or changes to hormone replacement therapy regimen is reasonable first-line management; endometrial biopsy is not recommended. For patients with persistent PMB or thickened endometrium ≥4 mm on TVUS, biopsy sampling of the endometrium should be performed. If the endometrial biopsy does not explain the etiology of the PMB with atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer, then hysteroscopy should be performed to evaluate for focal endometrial disease and possible directed biopsy.

- ACOG Committee Opinion no. 734: the role of transvaginal ultrasonography in evaluating the endometrium of women with postmenopausal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e124-e129.

- Goldstein SR. Appropriate evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding. Menopause. 2018;25:1476-1478.

- Bel S, Billard C, Godet J, et al. Risk of malignancy on suspicion of polyps in menopausal women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;216:138-142.

- Practice bulletin no. 128: diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:197-206.

- van Hanegem N, Prins MM, Bongers MY. The accuracy of endometrial sampling in women with postmenopausal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;197:147-155.

- Embracing hysteroscopy. September 6, 2017. https://consultqd.clevelandclinic.org/embracing-hysteroscopy/. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D&C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:16-20.

- Chang YN, Zhang Y, Wang LP, et al. Effect of hysteroscopy on the peritoneal dissemination of endometrial cancer cells: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:957-961.

- Chen J, Clark LH, Kong WM, et al. Does hysteroscopy worsen prognosis in women with type II endometrial carcinoma? PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174226.

Postmenopausal bleeding (PMB) is the presenting sign in most cases of endometrial carcinoma. Prompt evaluation of PMB can exclude, or diagnose, endometrial carcinoma.1 Although no general consensus exists for PMB evaluation, it involves endometrial assessment with transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) and subsequent endometrial biopsy when a thickened endometrium is found. When biopsy results reveal insufficient or scant tissue, further investigation into the etiology of PMB should include office hysteroscopy with possible directed biopsy. In this article I discuss the prevalence of PMB and steps for evaluation, providing clinical takeaways.

Postmenopausal bleeding: Its risk for cancer

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) in a postmenopausal woman is of particular concern to the gynecologist and the patient because of the increased possibility of endometrial carcinoma in this age group. AUB is present in more than 90% of postmenopausal women with endometrial carcinoma, which leads to diagnosis in the early stages of the disease. Approximately 3% to 7% of postmenopausal women with PMB will have endometrial carcinoma.2 Most women with PMB, however, experience bleeding secondary to atrophic changes of the vagina or endometrium and not to endometrial carcinoma. (FIGURE 1, VIDEO 1) In addition, women who take gonadal steroids for hormone replacement therapy (HRT) may experience breakthrough bleeding that leads to initial investigation with TVUS.

Video 1

The risk of malignancy in polyps in postmenopausal women over the age of 59 who present with PMB is approximately 12%, and hysteroscopic resection should routinely be performed. For asymptomatic patients, the risk of a malignant lesion is low—approximately 3%—and for these women intervention should be assessed individually for the risks of carcinoma and benefits of hysteroscopic removal.3

Clinical takeaway. The high possibility of endometrial carcinoma in postmenopausal women warrants that any patient who is symptomatic with PMB should be presumed to have endometrial cancer until the diagnostic evaluation process proves she does not.

Evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding

Transvaginal ultrasound

As mentioned, no general consensus exists for the evaluation of PMB; however, initial evaluation by TVUS is recommended. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) concluded that when the endometrium measures ≤4 mm with TVUS, the likelihood that bleeding is secondary to endometrial carcinoma is less than 1% (negative predictive value 99%), and endometrial biopsy is not recommended.3 Endometrial sampling in this clinical scenario likely will result in insufficient tissue for evaluation, and it is reasonable to consider initial management for atrophy. A thickened endometrium on TVUS (>4 mm in a postmenopausal woman with PMB) warrants additional evaluation with endometrial sampling (FIGURE 2).

Clinical takeaway. A thickened endometrium on TVUS ≥4 mm in a postmenopausal woman with PMB warrants additional evaluation with endometrial sampling.

Endometrial biopsy

An endometrial biopsy is performed to determine whether endometrial cancer or precancer is present in women with AUB. ACOG recommends that endometrial biopsy be performed for women older than age 45. It is also appropriate in women younger than 45 years if they have risk factors for developing endometrial cancer, including unopposed estrogen exposure (obesity, ovulatory dysfunction), failed medical management of AUB, or persistence of AUB.4

Continue to: Endometrial biopsy has some...

Endometrial biopsy has some diagnostic shortcomings, however. In 2016 a systematic review and meta-analysis found that, in women with PMB, the specificity of endometrial biopsy was 98% to 100% (accurate diagnosis with a positive result). The sensitivity (ability to make an accurate diagnosis) of endometrial biopsy to identify endometrial pathology (carcinoma, atypical hyperplasia, and polyps) is lower than typically thought. These investigators found an endometrial biopsy failure rate of 11% (range, 1% to 53%) and rate of insufficient samples of 31% (range, 7% to 76%). In women with insufficient or failed samples, endometrial cancer or precancer was found in 7% (range, 0% to 18%).5 Therefore, a negative tissue biopsy result in women with PMB is not considered to be an endpoint, and further evaluation with hysteroscopy to evaluate for focal disease is imperative. The results of endometrial biopsy are only an endpoint to the evaluation of PMB when atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer is identified.

Clinical takeaway. A negative tissue biopsy result in women with PMB is not considered to be an endpoint, and further evaluation with hysteroscopy to evaluate for focal disease is imperative.

Hysteroscopy

Hysteroscopy is the gold standard for evaluating the uterine cavity, diagnosing intrauterine pathology, and operative intervention for some causes of AUB. It also is easily performed in the office. This makes the hysteroscope an essential instrument for the gynecologist. Dr. Linda Bradley, a preeminent leader in hysteroscopic surgical education, has coined the phrase, “My hysteroscope is my stethoscope.”6 As gynecologists, we should be as adept at using a hysteroscope in the office as the cardiologist is at using a stethoscope.

It has been known for some time that hysteroscopy improves our diagnostic capabilities over blinded procedures such as endometrial biopsy and dilation and curettage (D&C). As far back as 1989, Dr. Frank Loffer reported the increased sensitivity (ability to make an accurate diagnosis) of hysteroscopy with directed biopsy over blinded D&C (98% vs 65%) in the evaluation of AUB.7 Evaluation of the endometrium with D&C is no longer recommended; yet today, few gynecologists perform hysteroscopic-directed biopsy for AUB evaluation instead of blinded tissue sampling despite the clinical superiority and in-office capabilities (FIGURE 3).

Continue to: Hysteroscopy and endometrial carcinoma...

Hysteroscopy and endometrial carcinoma

The most common type of gynecologic cancer in the United States is endometrial adenocarcinoma (type 1 endometrial cancer). There is some concern about the effect of hysteroscopy on endometrial cancer prognosis and the spread of cells to the peritoneum at the time of hysteroscopy. A large meta-analysis found that hysteroscopy performed in the presence of type 1 endometrial cancer statistically significantly increased the likelihood of positive intraperitoneal cytology; however, it did not alter the clinical outcome. It was recommended that hysteroscopy not be avoided for this reason and is helpful in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer, especially in the early stages of disease.8

For endometrial cancer type 2 (serous carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and carcinosarcoma), Chen and colleagues reported a statistically significant increase in positive peritoneal cytology for cancers evaluated by hysteroscopy versus D&C. The disease-specific survival for the hysteroscopy group was 60 months, compared with 71 months for the D&C group. While this finding was not statistically significant, it was clinically relevant, and the effect of hysteroscopy on prognosis with type 2 endometrial cancer is unclear.9