User login

Review of Radiologic Considerations in an Immunocompetent Patient With Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma (FULL)

Central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma can be classified into 2 categories: primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL), which includes disease limited to brain, eyes, spinal cord; and leptomeninges without coexisting or previous systemic lymphoma. Secondary CNS lymphoma (SCNSL) is essentially metastatic disease from a systemic primary site.1 The focus of this case presentation is PCNSL, with an emphasis on imaging characteristics and differential diagnosis.

The median age at diagnosis for PCNSL is 65 years, and the overall incidence has been decreasing since the mid-1990s, likely related to the increased use of highly-active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in patients with AIDS.2,3 Although overall incidence has decreased, incidence in the elderly population has increased.4 Historically, PCNSL has been considered an AIDS-defining illness.5 These patients, among other immunocompromised patients, such as those on chronic immunosuppressive therapy, are at a higher risk for developing the malignancy.6

Clinical presentation varies because of the location of CNS involvement and may present with headache, mood or personality disturbances, or focal neurologic deficits. Seizures are less likely due to the tendency of PCNSL to spare gray matter. Initial workup generally includes a head computed tomography (CT) scan, as well as a contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance image (MRI), which may help direct clinicians to the appropriate diagnosis. However, there is significant overlap between the imaging characteristics of PCNSL and numerous other disease processes, including glioblastoma and demyelination. The imaging characteristics of PCNSL are considerably different depending on the patient’s immune status.7

This case illustrates a rare presentation of PCNSL in an immunocompetent patient whose MRI characteristics were seemingly more consistent with those seen in patients with immunodeficiency. The main differential diagnoses and key imaging characteristics, which may help obtain accurate diagnosis, will be discussed.

Case Presentation

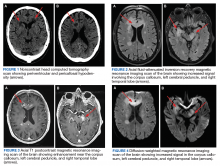

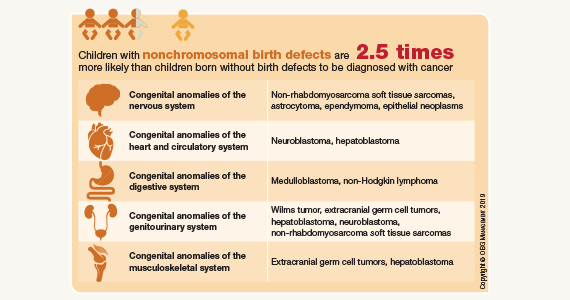

A 72-year-old male veteran presented with a 2-month history of subjective weakness in his upper and lower extremities progressing to multiple falls at home. He had no significant medical history other than a thymectomy at age 15 for an enlarged thymus, which per patient report, was benign. An initial laboratory test that included vitamin B12, folate, thyroid-stimulating hormone, complete blood cell count, and comprehensive metabolic panel, were unremarkable, with a white blood cell count of 8.5 K/uL. The initial neurologic evaluation did not show any focal neurologic deficits; however, during the initial hospital stay, the patient developed increasing lower extremity weakness on examination. A noncontrast CT head scan showed extensive nonspecific hypodensities within the periventricular white matter (Figure 1). A contrast-enhanced MRI showed enhancing lesions involving the corpus callosum, left cerebral peduncle, and right temporal lobe (Figures 2, 3, and 4). These lesions also exhibited significant restricted diffusion and a mild amount of surrounding vasogenic edema. The working diagnosis after the MRI included primary CNS lymphoma, multifocal glioblastoma, and tumefactive demyelinating disease. The patient was started on IV steroids and transferred for neurosurgical evaluation and biopsy at an outside hospital. The frontal lesion was biopsied, and the initial frozen section was consistent with lymphoma; a bone marrow biopsy was negative. The workup for immunodeficiency was unremarkable. Pathology revealed high-grade B-cell lymphoma, and the patient began a chemotherapy regimen.

Discussion

The workup of altered mental status, focal neurologic deficits, headaches, or other neurologic conditions often begins with a noncontrast CT scan. On CT, PCNSL generally appears isodense to hyperdense to gray matter, but appearance is variable. The often hyperdense appearance is attributable to the hypercellular nature of lymphoma. Many times, as in this case, CT may show only vague hypodensities, some of which may be associated with surrounding edema. This presentation is nonspecific and may be seen with advancing age due to changes of chronic microvascular ischemia as well as demyelination, other malignancies, and several other disease processes, both benign and malignant. After the initial CT scan, further workup requires evaluation with MRI. PCNSL exhibits restricted diffusion and variable signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging.

PCNSL is frequently centrally located within the periventricular white matter, often within the frontal lobe but can involve other lobes, the basal ganglia, brainstem, cerebellum, or less likely, the spinal canal.7 Contrary to primary CNS disease, secondary lymphoma within the CNS has been described classically as affecting a leptomeningeal (pia and arachnoid mater) distribution two-thirds of the time, with parenchymal involvement occurring in the other one-third of patients. A recent study by Malikova and colleagues found parenchymal involvement may be much more common than previously thought.1 Leptomeningeal spread of disease often involves the cranial nerves, subependymal regions, spinal cord, or spinal nerve roots. Dural involvement in primary or secondary lymphoma is rare.

PCNSL nearly always shows enhancement. Linear enhancement along perivascular spaces is highly characteristic of PCNSL. The typical appearance of PCNSL associated with immunodeficiency varies from that seen in an otherwise immunocompetent patient. Patients with immunodeficiency usually have multifocal involvement, central necrosis leading to a ring enhancement appearance, and have more propensity for spontaneous hemorrhage.7 Immunocompetent patients are less likely to present with multifocal disease and rarely show ring enhancement. Also, spontaneous hemorrhage is rare in immunocompetent patients. In our case, extensive multifocal involvement was present, whereas typically immunocompetent patients will present with a solitary homogeneously enhancing parenchymal mass.

The primary differential for PCNSL includes malignant glioma, tumefactive multiple sclerosis, metastatic disease, and in an immunocompromised patient, toxoplasmosis. The degree of associated vasogenic edema and mass effect is generally lower in PCNSL than that of malignant gliomas and metastasis. Also, PCNSL tends to spare the cerebral cortex.8

Classically, PCNSL, malignant gliomas, and demyelinating disease have been considered the main differential for lesions that cross midline and involve both cerebral hemispheres. Lymphoma generally exhibits more restricted diffusion than malignant gliomas and metastasis, attributable to the highly cellular nature of lymphoma.7 Tumefactive multiple sclerosis is associated with relatively minimal mass effect for lesion size and exhibits less restricted diffusion values when compared to high grade gliomas and PCNSL. One fairly specific finding for tumefactive demyelinating lesions is incomplete rim enhancement.9 Unfortunately, an MRI is not reliable in differentiating these entities, and biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. Many advancing imaging modalities may help provide the correct diagnosis of PCNSL, including diffusion-weighted and apparent diffusion coefficient imaging, diffusion tensor imaging, MR spectroscopy and PET imaging.7

Conclusion

With the increasing use of HAART, the paradigm of PCNSL is shifting toward one predominantly affecting immunocompetent patients. PCNSL should be considered in any patient with multiple enhancing CNS lesions, regardless of immune status. Several key imaging characteristics may help differentiate PCNSL and other disease processes; however, at this time, biopsy is recommended for definitive diagnosis.

1. Malikova H, Burghardtova M, Koubska E, Mandys V, Kozak T, Weichet J. Secondary central nervous system lymphoma: spectrum of morphological MRI appearances. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;4:733-740.

2. Dolecek TA, Propp JM, Stroup NE, Kruchko C. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2005-2009. Neuro-Oncol. 2012;14(suppl 5):v1-v49.

3. Diamond C, Taylor TH, Aboumrad T, Anton-Culver H. Changes in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: incidence, presentation, treatment, and survival. Cancer. 2006;106(1):128-135.

4. O’Neill BP, Decker PA, Tieu C, Cerhan JR. The changing incidence of primary central nervous system lymphoma is driven primarily by the changing incidence in young and middle-aged men and differs from time trends in systemic diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkins lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(12):997-1000.

5. [no authors listed]. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1992;41(rr-17):1-19.

6. Maiuri F. Central nervous system lymphomas and immunodeficiency. Neurological Research. 1989;11(1):2-5.

7. Haldorsen IS, Espeland A, Larsson EM. Central nervous system lymphoma: characteristic findings on traditional and advanced imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;32(6):984-992.

8. Gómez Roselló E, Quiles Granado AM, Laguillo Sala G, Gutiérrez S. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: spectrum of findings and differential characteristics. Radiología. 2018;60(4):280-289.

9. Mabray MC, Cohen BA, Villanueva-Meyer JE, et al. Performance of Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Values and Conventional MRI Features in Differentiating Tumefactive Demyelinating Lesions From Primary Brain Neoplasms. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2015;205(5):1075-1085.

Central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma can be classified into 2 categories: primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL), which includes disease limited to brain, eyes, spinal cord; and leptomeninges without coexisting or previous systemic lymphoma. Secondary CNS lymphoma (SCNSL) is essentially metastatic disease from a systemic primary site.1 The focus of this case presentation is PCNSL, with an emphasis on imaging characteristics and differential diagnosis.

The median age at diagnosis for PCNSL is 65 years, and the overall incidence has been decreasing since the mid-1990s, likely related to the increased use of highly-active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in patients with AIDS.2,3 Although overall incidence has decreased, incidence in the elderly population has increased.4 Historically, PCNSL has been considered an AIDS-defining illness.5 These patients, among other immunocompromised patients, such as those on chronic immunosuppressive therapy, are at a higher risk for developing the malignancy.6

Clinical presentation varies because of the location of CNS involvement and may present with headache, mood or personality disturbances, or focal neurologic deficits. Seizures are less likely due to the tendency of PCNSL to spare gray matter. Initial workup generally includes a head computed tomography (CT) scan, as well as a contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance image (MRI), which may help direct clinicians to the appropriate diagnosis. However, there is significant overlap between the imaging characteristics of PCNSL and numerous other disease processes, including glioblastoma and demyelination. The imaging characteristics of PCNSL are considerably different depending on the patient’s immune status.7

This case illustrates a rare presentation of PCNSL in an immunocompetent patient whose MRI characteristics were seemingly more consistent with those seen in patients with immunodeficiency. The main differential diagnoses and key imaging characteristics, which may help obtain accurate diagnosis, will be discussed.

Case Presentation

A 72-year-old male veteran presented with a 2-month history of subjective weakness in his upper and lower extremities progressing to multiple falls at home. He had no significant medical history other than a thymectomy at age 15 for an enlarged thymus, which per patient report, was benign. An initial laboratory test that included vitamin B12, folate, thyroid-stimulating hormone, complete blood cell count, and comprehensive metabolic panel, were unremarkable, with a white blood cell count of 8.5 K/uL. The initial neurologic evaluation did not show any focal neurologic deficits; however, during the initial hospital stay, the patient developed increasing lower extremity weakness on examination. A noncontrast CT head scan showed extensive nonspecific hypodensities within the periventricular white matter (Figure 1). A contrast-enhanced MRI showed enhancing lesions involving the corpus callosum, left cerebral peduncle, and right temporal lobe (Figures 2, 3, and 4). These lesions also exhibited significant restricted diffusion and a mild amount of surrounding vasogenic edema. The working diagnosis after the MRI included primary CNS lymphoma, multifocal glioblastoma, and tumefactive demyelinating disease. The patient was started on IV steroids and transferred for neurosurgical evaluation and biopsy at an outside hospital. The frontal lesion was biopsied, and the initial frozen section was consistent with lymphoma; a bone marrow biopsy was negative. The workup for immunodeficiency was unremarkable. Pathology revealed high-grade B-cell lymphoma, and the patient began a chemotherapy regimen.

Discussion

The workup of altered mental status, focal neurologic deficits, headaches, or other neurologic conditions often begins with a noncontrast CT scan. On CT, PCNSL generally appears isodense to hyperdense to gray matter, but appearance is variable. The often hyperdense appearance is attributable to the hypercellular nature of lymphoma. Many times, as in this case, CT may show only vague hypodensities, some of which may be associated with surrounding edema. This presentation is nonspecific and may be seen with advancing age due to changes of chronic microvascular ischemia as well as demyelination, other malignancies, and several other disease processes, both benign and malignant. After the initial CT scan, further workup requires evaluation with MRI. PCNSL exhibits restricted diffusion and variable signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging.

PCNSL is frequently centrally located within the periventricular white matter, often within the frontal lobe but can involve other lobes, the basal ganglia, brainstem, cerebellum, or less likely, the spinal canal.7 Contrary to primary CNS disease, secondary lymphoma within the CNS has been described classically as affecting a leptomeningeal (pia and arachnoid mater) distribution two-thirds of the time, with parenchymal involvement occurring in the other one-third of patients. A recent study by Malikova and colleagues found parenchymal involvement may be much more common than previously thought.1 Leptomeningeal spread of disease often involves the cranial nerves, subependymal regions, spinal cord, or spinal nerve roots. Dural involvement in primary or secondary lymphoma is rare.

PCNSL nearly always shows enhancement. Linear enhancement along perivascular spaces is highly characteristic of PCNSL. The typical appearance of PCNSL associated with immunodeficiency varies from that seen in an otherwise immunocompetent patient. Patients with immunodeficiency usually have multifocal involvement, central necrosis leading to a ring enhancement appearance, and have more propensity for spontaneous hemorrhage.7 Immunocompetent patients are less likely to present with multifocal disease and rarely show ring enhancement. Also, spontaneous hemorrhage is rare in immunocompetent patients. In our case, extensive multifocal involvement was present, whereas typically immunocompetent patients will present with a solitary homogeneously enhancing parenchymal mass.

The primary differential for PCNSL includes malignant glioma, tumefactive multiple sclerosis, metastatic disease, and in an immunocompromised patient, toxoplasmosis. The degree of associated vasogenic edema and mass effect is generally lower in PCNSL than that of malignant gliomas and metastasis. Also, PCNSL tends to spare the cerebral cortex.8

Classically, PCNSL, malignant gliomas, and demyelinating disease have been considered the main differential for lesions that cross midline and involve both cerebral hemispheres. Lymphoma generally exhibits more restricted diffusion than malignant gliomas and metastasis, attributable to the highly cellular nature of lymphoma.7 Tumefactive multiple sclerosis is associated with relatively minimal mass effect for lesion size and exhibits less restricted diffusion values when compared to high grade gliomas and PCNSL. One fairly specific finding for tumefactive demyelinating lesions is incomplete rim enhancement.9 Unfortunately, an MRI is not reliable in differentiating these entities, and biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. Many advancing imaging modalities may help provide the correct diagnosis of PCNSL, including diffusion-weighted and apparent diffusion coefficient imaging, diffusion tensor imaging, MR spectroscopy and PET imaging.7

Conclusion

With the increasing use of HAART, the paradigm of PCNSL is shifting toward one predominantly affecting immunocompetent patients. PCNSL should be considered in any patient with multiple enhancing CNS lesions, regardless of immune status. Several key imaging characteristics may help differentiate PCNSL and other disease processes; however, at this time, biopsy is recommended for definitive diagnosis.

Central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma can be classified into 2 categories: primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL), which includes disease limited to brain, eyes, spinal cord; and leptomeninges without coexisting or previous systemic lymphoma. Secondary CNS lymphoma (SCNSL) is essentially metastatic disease from a systemic primary site.1 The focus of this case presentation is PCNSL, with an emphasis on imaging characteristics and differential diagnosis.

The median age at diagnosis for PCNSL is 65 years, and the overall incidence has been decreasing since the mid-1990s, likely related to the increased use of highly-active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in patients with AIDS.2,3 Although overall incidence has decreased, incidence in the elderly population has increased.4 Historically, PCNSL has been considered an AIDS-defining illness.5 These patients, among other immunocompromised patients, such as those on chronic immunosuppressive therapy, are at a higher risk for developing the malignancy.6

Clinical presentation varies because of the location of CNS involvement and may present with headache, mood or personality disturbances, or focal neurologic deficits. Seizures are less likely due to the tendency of PCNSL to spare gray matter. Initial workup generally includes a head computed tomography (CT) scan, as well as a contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance image (MRI), which may help direct clinicians to the appropriate diagnosis. However, there is significant overlap between the imaging characteristics of PCNSL and numerous other disease processes, including glioblastoma and demyelination. The imaging characteristics of PCNSL are considerably different depending on the patient’s immune status.7

This case illustrates a rare presentation of PCNSL in an immunocompetent patient whose MRI characteristics were seemingly more consistent with those seen in patients with immunodeficiency. The main differential diagnoses and key imaging characteristics, which may help obtain accurate diagnosis, will be discussed.

Case Presentation

A 72-year-old male veteran presented with a 2-month history of subjective weakness in his upper and lower extremities progressing to multiple falls at home. He had no significant medical history other than a thymectomy at age 15 for an enlarged thymus, which per patient report, was benign. An initial laboratory test that included vitamin B12, folate, thyroid-stimulating hormone, complete blood cell count, and comprehensive metabolic panel, were unremarkable, with a white blood cell count of 8.5 K/uL. The initial neurologic evaluation did not show any focal neurologic deficits; however, during the initial hospital stay, the patient developed increasing lower extremity weakness on examination. A noncontrast CT head scan showed extensive nonspecific hypodensities within the periventricular white matter (Figure 1). A contrast-enhanced MRI showed enhancing lesions involving the corpus callosum, left cerebral peduncle, and right temporal lobe (Figures 2, 3, and 4). These lesions also exhibited significant restricted diffusion and a mild amount of surrounding vasogenic edema. The working diagnosis after the MRI included primary CNS lymphoma, multifocal glioblastoma, and tumefactive demyelinating disease. The patient was started on IV steroids and transferred for neurosurgical evaluation and biopsy at an outside hospital. The frontal lesion was biopsied, and the initial frozen section was consistent with lymphoma; a bone marrow biopsy was negative. The workup for immunodeficiency was unremarkable. Pathology revealed high-grade B-cell lymphoma, and the patient began a chemotherapy regimen.

Discussion

The workup of altered mental status, focal neurologic deficits, headaches, or other neurologic conditions often begins with a noncontrast CT scan. On CT, PCNSL generally appears isodense to hyperdense to gray matter, but appearance is variable. The often hyperdense appearance is attributable to the hypercellular nature of lymphoma. Many times, as in this case, CT may show only vague hypodensities, some of which may be associated with surrounding edema. This presentation is nonspecific and may be seen with advancing age due to changes of chronic microvascular ischemia as well as demyelination, other malignancies, and several other disease processes, both benign and malignant. After the initial CT scan, further workup requires evaluation with MRI. PCNSL exhibits restricted diffusion and variable signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging.

PCNSL is frequently centrally located within the periventricular white matter, often within the frontal lobe but can involve other lobes, the basal ganglia, brainstem, cerebellum, or less likely, the spinal canal.7 Contrary to primary CNS disease, secondary lymphoma within the CNS has been described classically as affecting a leptomeningeal (pia and arachnoid mater) distribution two-thirds of the time, with parenchymal involvement occurring in the other one-third of patients. A recent study by Malikova and colleagues found parenchymal involvement may be much more common than previously thought.1 Leptomeningeal spread of disease often involves the cranial nerves, subependymal regions, spinal cord, or spinal nerve roots. Dural involvement in primary or secondary lymphoma is rare.

PCNSL nearly always shows enhancement. Linear enhancement along perivascular spaces is highly characteristic of PCNSL. The typical appearance of PCNSL associated with immunodeficiency varies from that seen in an otherwise immunocompetent patient. Patients with immunodeficiency usually have multifocal involvement, central necrosis leading to a ring enhancement appearance, and have more propensity for spontaneous hemorrhage.7 Immunocompetent patients are less likely to present with multifocal disease and rarely show ring enhancement. Also, spontaneous hemorrhage is rare in immunocompetent patients. In our case, extensive multifocal involvement was present, whereas typically immunocompetent patients will present with a solitary homogeneously enhancing parenchymal mass.

The primary differential for PCNSL includes malignant glioma, tumefactive multiple sclerosis, metastatic disease, and in an immunocompromised patient, toxoplasmosis. The degree of associated vasogenic edema and mass effect is generally lower in PCNSL than that of malignant gliomas and metastasis. Also, PCNSL tends to spare the cerebral cortex.8

Classically, PCNSL, malignant gliomas, and demyelinating disease have been considered the main differential for lesions that cross midline and involve both cerebral hemispheres. Lymphoma generally exhibits more restricted diffusion than malignant gliomas and metastasis, attributable to the highly cellular nature of lymphoma.7 Tumefactive multiple sclerosis is associated with relatively minimal mass effect for lesion size and exhibits less restricted diffusion values when compared to high grade gliomas and PCNSL. One fairly specific finding for tumefactive demyelinating lesions is incomplete rim enhancement.9 Unfortunately, an MRI is not reliable in differentiating these entities, and biopsy is required for definitive diagnosis. Many advancing imaging modalities may help provide the correct diagnosis of PCNSL, including diffusion-weighted and apparent diffusion coefficient imaging, diffusion tensor imaging, MR spectroscopy and PET imaging.7

Conclusion

With the increasing use of HAART, the paradigm of PCNSL is shifting toward one predominantly affecting immunocompetent patients. PCNSL should be considered in any patient with multiple enhancing CNS lesions, regardless of immune status. Several key imaging characteristics may help differentiate PCNSL and other disease processes; however, at this time, biopsy is recommended for definitive diagnosis.

1. Malikova H, Burghardtova M, Koubska E, Mandys V, Kozak T, Weichet J. Secondary central nervous system lymphoma: spectrum of morphological MRI appearances. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;4:733-740.

2. Dolecek TA, Propp JM, Stroup NE, Kruchko C. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2005-2009. Neuro-Oncol. 2012;14(suppl 5):v1-v49.

3. Diamond C, Taylor TH, Aboumrad T, Anton-Culver H. Changes in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: incidence, presentation, treatment, and survival. Cancer. 2006;106(1):128-135.

4. O’Neill BP, Decker PA, Tieu C, Cerhan JR. The changing incidence of primary central nervous system lymphoma is driven primarily by the changing incidence in young and middle-aged men and differs from time trends in systemic diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkins lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(12):997-1000.

5. [no authors listed]. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1992;41(rr-17):1-19.

6. Maiuri F. Central nervous system lymphomas and immunodeficiency. Neurological Research. 1989;11(1):2-5.

7. Haldorsen IS, Espeland A, Larsson EM. Central nervous system lymphoma: characteristic findings on traditional and advanced imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;32(6):984-992.

8. Gómez Roselló E, Quiles Granado AM, Laguillo Sala G, Gutiérrez S. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: spectrum of findings and differential characteristics. Radiología. 2018;60(4):280-289.

9. Mabray MC, Cohen BA, Villanueva-Meyer JE, et al. Performance of Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Values and Conventional MRI Features in Differentiating Tumefactive Demyelinating Lesions From Primary Brain Neoplasms. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2015;205(5):1075-1085.

1. Malikova H, Burghardtova M, Koubska E, Mandys V, Kozak T, Weichet J. Secondary central nervous system lymphoma: spectrum of morphological MRI appearances. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;4:733-740.

2. Dolecek TA, Propp JM, Stroup NE, Kruchko C. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2005-2009. Neuro-Oncol. 2012;14(suppl 5):v1-v49.

3. Diamond C, Taylor TH, Aboumrad T, Anton-Culver H. Changes in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: incidence, presentation, treatment, and survival. Cancer. 2006;106(1):128-135.

4. O’Neill BP, Decker PA, Tieu C, Cerhan JR. The changing incidence of primary central nervous system lymphoma is driven primarily by the changing incidence in young and middle-aged men and differs from time trends in systemic diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkins lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(12):997-1000.

5. [no authors listed]. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1992;41(rr-17):1-19.

6. Maiuri F. Central nervous system lymphomas and immunodeficiency. Neurological Research. 1989;11(1):2-5.

7. Haldorsen IS, Espeland A, Larsson EM. Central nervous system lymphoma: characteristic findings on traditional and advanced imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;32(6):984-992.

8. Gómez Roselló E, Quiles Granado AM, Laguillo Sala G, Gutiérrez S. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: spectrum of findings and differential characteristics. Radiología. 2018;60(4):280-289.

9. Mabray MC, Cohen BA, Villanueva-Meyer JE, et al. Performance of Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Values and Conventional MRI Features in Differentiating Tumefactive Demyelinating Lesions From Primary Brain Neoplasms. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2015;205(5):1075-1085.

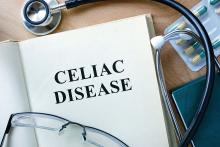

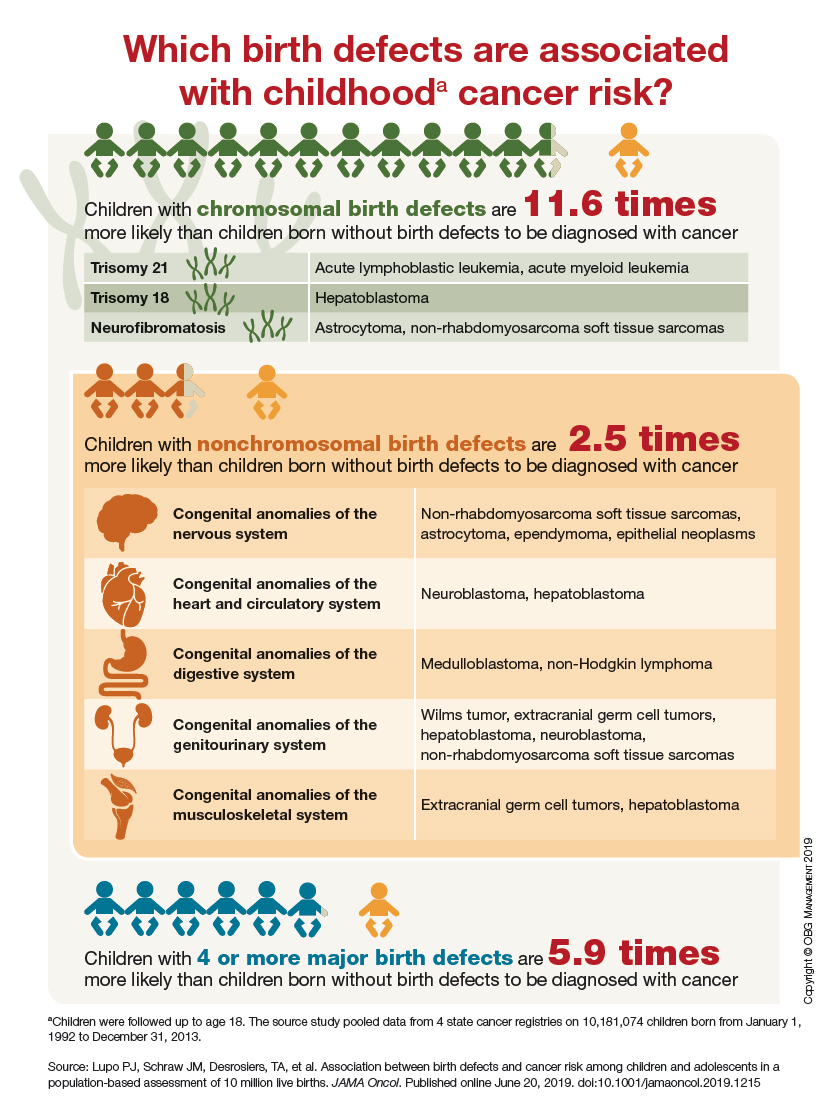

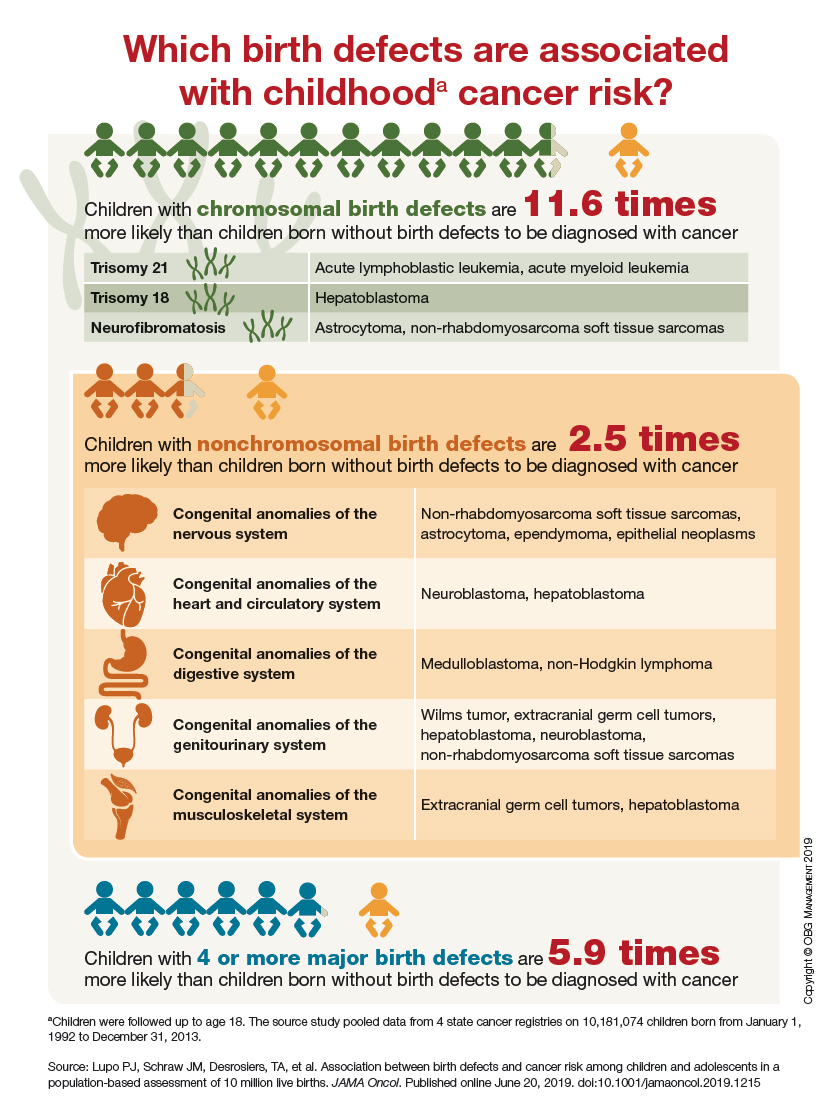

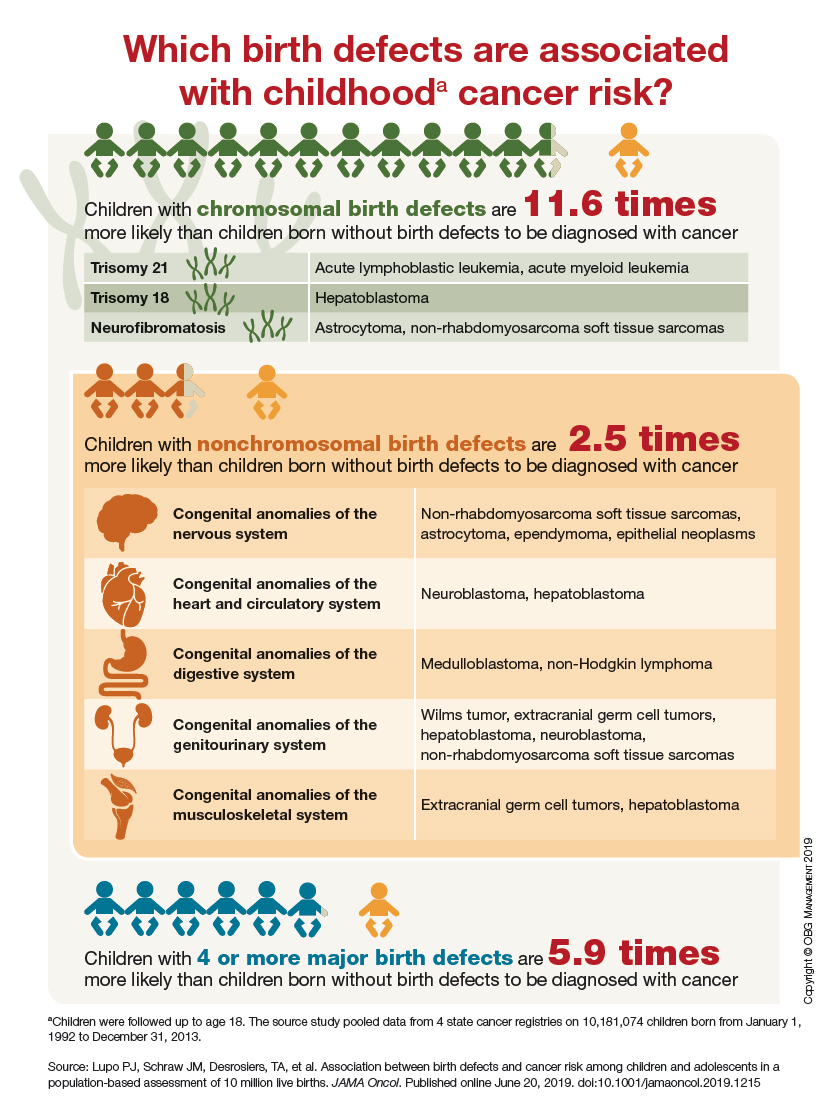

Which birth defects are associated with childhood cancer risk?

Accuracy of Endoscopic Ultrasound in Staging of Early Rectal Cancer (FULL)

Endoscopic ultrasound can be highly accurate for the staging of neoplasms in early rectal cancer.

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death in the US, with one-third of all colorectal cancers occurring within the rectum. Each year, an estimated 40000 Americans are diagnosed with rectal cancer (RC).1,2 The prognosis and treatment of RC depends on both T and N stage at the time of diagnosis.3-5 According to the most recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines from May 2019, patients with T1 to T2N0 tumors should undergo transanal or transabdominal surgery upfront, whereas patients with T3 to T4N0 or any TN1 to 2 should start with neoadjuvant therapy for better locoregional control, followed by surgery.6 Therefore, the appropriate management of RC requires adequate staging.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT) are the imaging techniques currently used to stage RC. In a meta-analysis of 90 articles published between 1985 and 2002 that compared the 3 radiologic modalities, Bipat and colleagues found that MRI and EUS had a similar sensitivity of 94%, whereas the specificity of EUS (86%) was significantly higher than that of MRI (69%) for muscularis propria invasion.7 CT was performed only in a limited number of trials because CT was considered inadequate to assess early T stage. For perirectal tissue invasion, the sensitivity of EUS was statistically higher than that of CT and MRI imaging: 90% compared with 79% and 82%, respectively. The specificity estimates for EUS, CT, and MRI were comparable: 75%, 78%, and 76%, respectively. The respective sensitivity and specificity of the 3 imaging modalities to evaluate lymph nodes were also comparable: EUS, 67% and 78%; CT, 55% and 74%; and MRI, 66% and 76%.

The role of EUS in the diagnosis and treatment of RC has long been validated.1,2-5 A meta-analysis of 42 studies involving 5039 patients found EUS to be highly accurate for differentiating various T stages.8 However, EUS cannot assess iliac and mesenteric lymph nodes or posterior tumor extension beyond endopelvic fascia in advanced RC. Notable heterogeneity was found among the studies in the meta-analyses with regard to the type of equipment used for staging, as well as the criteria used to assess the depth of penetration and nodal status. The recent introduction of phased-array coils and the development of T2-weighted fast spin sequences have improved the resolution of MRI. The MERCURY trial showed that extension of tumor to within 1 mm of the circumferential margin on high-resolution MRI correctly predicted margin involvement at the time of surgery in 92% of the patients.9 In the retrospective study by Balyasnikova and colleagues, MRI was found to correctly identify partial submucosal invasion and suitability for local excision in 89% of the cases.10

Therefore, both EUS and MRI are useful, more so than CT, in assessment of the depth of tumor invasion, nodal staging, and predicting the circumferential resection margin. The use of EUS, however, does not preclude the use of MRI, or vice versa. Rather, the 2 modalities can complement each other in staging and proper patient selection for treatment.11

Despite data supporting the value of EUS in staging RC, its use is limited by a high degree of operator dependence and a substantial learning curve,12-17 which may explain the low EUS accuracy observed in some reports.7,13,15 Given the presence of recognized alternatives such as MRI, we decided to reevaluate EUS accuracy for the staging of RC outside high-volume specialized centers and prospective clinical trials.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed that included all consecutive patients undergoing rectal ultrasound from January 2011 to August 2015 at the US Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Memphis, Tennessee. Sixty-five patients with short-stocked or sessile lesions < 15 cm from anal margin staged T2N0M0 or lower by endorectal ultrasound (ERUS) were included. The patients with neoplasms staged in excess of T2 or N0 were excluded from the study because treatment protocol dictates immediate neoadjuvant treatment, the administration of which would affect subsequent histopathology.

For the 37 patients included in the final analysis, ERUS results were compared with surgical pathology to ascertain accuracy. The resections were performed endoscopically or surgically with a goal of obtaining clear margins. The choice of procedure depended on size, shape, location, and depth of invasion. All patients underwent clinical and endoscopic surveillance with flexible sigmoidoscopy/EUS every 3 to 6 months for the first 2 years. We used 2 different gold standards for surveillance depending on the type of procedure performed to remove the lesion. A pathology report was the gold standard used for patients who underwent surgery. In patients who underwent endoscopic resection, we used the lack of recurrent disease, determined by normal endoscopic and endoscopic ultrasound examination, to signify complete endoscopic resection and therefore adequate staging as an early neoplasm.

Results

From January 2011 to August 2015, 65 rectal ultrasounds were performed. All EUS procedures were performed by 1 physician (C Ruben Tombazzi). All patients had previous endoscopic evaluation and tissue diagnoses. Twenty-eight patients were excluded: 18 had T3 or N1 disease, 2 had T2N0 but refused surgery, 2 had anal cancer, 3 patients with suspected cancer had benign nonneoplastic disease (2 radiation proctitis, 1 normal rectal wall), and 3 underwent EUS for benign tumors (1 ganglioneuroma and 2 lipomas).

Thirty-seven patients were included in the study, 3 of whom were staged as T2N0 and 34 as T1N0 or lower by EUS. All patients were men ranging in age from 43 to 73 years (mean, 59 years). All 37 patients underwent endoscopic or surgical resection of their early rectal neoplasm. The final pathologic evaluation of the specimens demonstrated 14 carcinoid tumors, 11 adenocarcinomas, 6 tubular adenomas with high-grade dysplasia, and 6 benign adenomas. The preoperative EUS staging was confirmed for all patients, with 100% sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. None of the patients who underwent endoscopic or surgical transanal resection had recurrence, determined by normal endoscopic and endoscopic ultrasound appearance, during a mean of 32.6 months surveillance.

Discussion

EUS has long been a recognized method for T and N staging of RC.1,3-5,7,8 Our data confirm that, in experienced hands, EUS is highly accurate in the staging of early rectal cancers.

The impact of EUS on the management of RC was demonstrated in a Mayo Clinic prospective blinded study.1 In that cohort of 80 consecutive patients who had previously had a CT for staging, EUS altered patient management in about 30% of cases. The most common change precipatated by EUS was the indication for additional neoadjuvant treatment.

However, the results have not been as encouraging when ERUS is performed outside of strict research protocol. A multicenter, prospective, country-wide quality assurance study from > 300 German hospitals was designed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of EUS in RC.13 Of 29206 patients, 7096 underwent surgery, without neoadjuvant treatment, and were included in the final analysis. The correspondence of tumor invasion with histopathology was 64.7%, with understaging of 18% and overstaging of 17.3%.13 These numbers were better in hospitals with greater experience performing ERUS: 73% accuracy in the centers with a case load of > 30 cases per year compared with 63.2% accuracy for the centers with < 10 cases a year. Marusch and colleagues had previously demonstrated an EUS accuracy of 63.3% in a study of 1463 patients with RC in Germany.14 Another study based out of the UK had similar findings. Ashraf and colleagues performed a database analyses from 20 UK centers and identified 165 patients with RC who underwent ERUS and endoscopic microsurgery.15 Compared with histopathology, EUS had 57.1% sensitivity, 73% specificity, and 42.9% accuracy for T1 cancers; EUS accuracy was 50% for T2 and 58% for T3 tumors. The authors concluded that the general accuracy of EUS in determining stage was around 50%, the statistical equivalent of flipping a coin.

The low accuracy of EUS observed by German and British multicenter studies13-15 was attributed to the difference that may exist in clinical trials at specialized centers compared with wider use of EUS in a community setting. As seen by our data, the Memphis VAMC is not a high-volume center for the treatment of RC. However, all our EUS procedures were performed and interpreted by a single operator (C. Ruben Tombazzi) with 18 years of EUS experience. We cannot conclude that no patient was overstaged, as patients receiving a stage of T3N0 or T > N0 received neoadjuvant treatment and were not included. However, we can conclude that no patient was understaged. All patients deemed to be T1 to T2N0 included in our study received accurate staging. Our results are consistent with the high accuracy of EUS reported from other centers with experience in diagnosis and treatment of RC.1,3-5,17,18

Although EUS is accurate in differentiating T1 from T2 tumors, it cannot reliably differentiate T1 from T0 lesions. In one study, 57.6% of adenomas and 30.7% of carcinomas in situ were staged as T1 on EUS, while almost half of T1 cancers were interpreted as T0.17 This drawback is a well-known limitation of EUS; although, the misinterpretation does not affect treatment, as both T0 and T1 lesions can be treated successfully by local excision alone, which was the algorithm used for our patients. The choice of the specific procedure for local excision was left to the clinicians and included transanal endoscopic or surgical resections. At a mean follow-up of 32.6 months, none of the 37 patients who underwent endoscopic or surgical transanal resection had evidence of recurrent disease.

A limitation of EUS, or any other imaging modality, is differentiating tumor invasion from peritumoral inflammation. The inflammation can render images of tumor borders ill-defined and irregular, which hinders precise staging. However, the accurate identification of tumors with deep involvement of the submucosa (T1sm3) is of importance, because these tumors are more advanced than the superficial and intermediate T1 lesions (T1sm1 and T1sm2, respectively).

Patients with RC whose lesions are considered T1sm3 are at higher risk of harboring lymph node metastases.18 Nascimbeni and colleagues had shown that the invasion into the lower third of the submucosa (sm3) was an independent risk factor for lower cancer-free survival among patients with T1 RC.19

Unlike rectal adenocarcinomas, the prognosis for carcinoid tumors correlates not only with the depth of invasion but also with the size of the tumor. The other adverse prognostic features include poor differentiation, high mitosis index, and lymphovascular invasion.20

EUS had been shown to be highly accurate in determining the precise carcinoid tumor size, depth of invasion, and lymph node metastases.20,21 In a study of 66 resected rectal carcinoid tumors by Ishii and colleagues, 57 lesions had a diameter of ≤ 10 mm and 9 lesions had a diameter of > 10 mm.21 All of the 57 carcinoid tumors with a diameter of ≤ 10 mm were confined to the submucosa. In contrast, 5 of the 9 lesions > 10 mm invaded the muscularis propria, 6 had a lymphovascular invasion, 4 were lymph node metastases, and 1 was a liver metastasis.

In our series, 4 of the 14 carcinoid tumors were > 10 mm but none were > 20 mm. None of the carcinoids with a diameter ≤ 10 mm invaded the muscularis propria. Of the 4 carcinoids > 10 mm, 1 was T2N0 and 3 were T1N0. All carcinoid tumors in our series were low grade and with low proliferation indexes, and all were treated successfully by local excision.

Conclusion

We believe our study shows that EUS can be highly accurate in staging rectal lesions, specifically lesions that are T1-T2N0, be they adenocarcinoma or carcinoid. Although we could not assess overstaging for lesions that were staged > T2 or > N0, we w

1. Harewood GC, Wiersema MJ, Nelson H, et al. A prospective, blinded assessment of the impact of preoperative staging on the management of rectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(1):24-32.

2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5-29.

3. Ahuja NK, Sauer BG, Wang AY, et al. Performance of endoscopic ultrasound in staging rectal adenocarcinoma appropriate for primary surgical resection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:339-44.

4. Doornebosch PG, Bronkhorst PJ, Hop WC, Bode WA, Sing AK, de Graaf EJ. The role of endorectal ultrasound in therapeutic decision-making for local vs. transabdominal resection of rectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(1):38-42.

5. Santoro GA, Gizzi G, Pellegrini L, Battistella G, Di Falco G. The value of high-resolution three-dimensional endorectal ultrasonography in the management of submucosal invasive rectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(11):1837-1843.

6. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: rectal cancer, version 2.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/rectal.pdf. Published May 15, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019.

7. Bipat S, Glas AS, Slors FJ, Zwinderman AH, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J. Rectal cancer: local staging and assessment of lymph node involvement with endoluminal US, CT, and MR imaging—a meta-analysis. Radiology. 2004;232(3):773-783.

8. Puli SR, Bechtold ML, Reddy JB, Choudhary A, Antillon MR, Brugge WR. How good is endoscopic ultrasound in differentiating various T stages of rectal cancer? Meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(2):254-265.

9. MERCURY Study Group. Diagnostic accuracy of preoperative magnetic resonance imaging in predicting curative resection of rectal cancer: prospective observational study. BMJ. 2006;333(7572):779.

10. Balyasnikova S, Read J, Wotherspoon A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of high-resolution MRI as a method to predict potentially safe endoscopic and surgical planes in patient with early rectal cancer. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2017;4(1):e000151.

11. Frasson M, Garcia-Granero E, Roda D, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation may not always be needed for patients with T3 and T2N+ rectal cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(14):3118-3125.

12. Rafaelsen SR, Sørensen T, Jakobsen A, Bisgaard C, Lindebjerg J. Transrectal ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the staging of rectal cancer. Effect of experience. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(4):440-446.

13. Marusch F, Ptok H, Sahm M, et al. Endorectal ultrasound in rectal carcinoma – do the literature results really correspond to the realities of routine clinical care? Endoscopy. 2011;43(5):425-431.

14. Marusch F, Koch A, Schmidt U, et al. Routine use of transrectal ultrasound in rectal carcinoma: results of a prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2002;34(5):385-390.

15. Ashraf S, Hompes R, Slater A, et al; Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery (TEM) Collaboration. A critical appraisal of endorectal ultrasound and transanal endoscopic microsurgery and decision-making in early rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(7):821-826.

16. Harewood GC. Assessment of clinical impact of endoscopic ultrasound on rectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(4):623-627.

17. Zorcolo L, Fantola G, Cabras F, Marongiu L, D’Alia G, Casula G. Preoperative staging of patients with rectal tumors suitable for transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM): comparison of endorectal ultrasound and histopathologic findings. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(6):1384-1389.

18. Akasu T, Kondo H, Moriya Y, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography and treatment of early stage rectal cancer. World J Surg. 2000;24(9):1061-1068.

19. Nascimbeni R, Nivatvongs S, Larson DR, Burgart LJ. Long-term survival after local excision for T1 carcinoma of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(11):1773-1779.

20. Park CH, Cheon JH, Kim JO, et al. Criteria for decision making after endoscopic resection of well-differentiated rectal carcinoids with regard to potential lymphatic spread. Endoscopy. 2011;43(9):790-795.

21. Ishii N, Horiki N, Itoh T, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection and preoperative assessment with endoscopic ultrasonography for the treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(6):1413-1419.

Endoscopic ultrasound can be highly accurate for the staging of neoplasms in early rectal cancer.

Endoscopic ultrasound can be highly accurate for the staging of neoplasms in early rectal cancer.

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death in the US, with one-third of all colorectal cancers occurring within the rectum. Each year, an estimated 40000 Americans are diagnosed with rectal cancer (RC).1,2 The prognosis and treatment of RC depends on both T and N stage at the time of diagnosis.3-5 According to the most recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines from May 2019, patients with T1 to T2N0 tumors should undergo transanal or transabdominal surgery upfront, whereas patients with T3 to T4N0 or any TN1 to 2 should start with neoadjuvant therapy for better locoregional control, followed by surgery.6 Therefore, the appropriate management of RC requires adequate staging.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT) are the imaging techniques currently used to stage RC. In a meta-analysis of 90 articles published between 1985 and 2002 that compared the 3 radiologic modalities, Bipat and colleagues found that MRI and EUS had a similar sensitivity of 94%, whereas the specificity of EUS (86%) was significantly higher than that of MRI (69%) for muscularis propria invasion.7 CT was performed only in a limited number of trials because CT was considered inadequate to assess early T stage. For perirectal tissue invasion, the sensitivity of EUS was statistically higher than that of CT and MRI imaging: 90% compared with 79% and 82%, respectively. The specificity estimates for EUS, CT, and MRI were comparable: 75%, 78%, and 76%, respectively. The respective sensitivity and specificity of the 3 imaging modalities to evaluate lymph nodes were also comparable: EUS, 67% and 78%; CT, 55% and 74%; and MRI, 66% and 76%.

The role of EUS in the diagnosis and treatment of RC has long been validated.1,2-5 A meta-analysis of 42 studies involving 5039 patients found EUS to be highly accurate for differentiating various T stages.8 However, EUS cannot assess iliac and mesenteric lymph nodes or posterior tumor extension beyond endopelvic fascia in advanced RC. Notable heterogeneity was found among the studies in the meta-analyses with regard to the type of equipment used for staging, as well as the criteria used to assess the depth of penetration and nodal status. The recent introduction of phased-array coils and the development of T2-weighted fast spin sequences have improved the resolution of MRI. The MERCURY trial showed that extension of tumor to within 1 mm of the circumferential margin on high-resolution MRI correctly predicted margin involvement at the time of surgery in 92% of the patients.9 In the retrospective study by Balyasnikova and colleagues, MRI was found to correctly identify partial submucosal invasion and suitability for local excision in 89% of the cases.10

Therefore, both EUS and MRI are useful, more so than CT, in assessment of the depth of tumor invasion, nodal staging, and predicting the circumferential resection margin. The use of EUS, however, does not preclude the use of MRI, or vice versa. Rather, the 2 modalities can complement each other in staging and proper patient selection for treatment.11

Despite data supporting the value of EUS in staging RC, its use is limited by a high degree of operator dependence and a substantial learning curve,12-17 which may explain the low EUS accuracy observed in some reports.7,13,15 Given the presence of recognized alternatives such as MRI, we decided to reevaluate EUS accuracy for the staging of RC outside high-volume specialized centers and prospective clinical trials.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed that included all consecutive patients undergoing rectal ultrasound from January 2011 to August 2015 at the US Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Memphis, Tennessee. Sixty-five patients with short-stocked or sessile lesions < 15 cm from anal margin staged T2N0M0 or lower by endorectal ultrasound (ERUS) were included. The patients with neoplasms staged in excess of T2 or N0 were excluded from the study because treatment protocol dictates immediate neoadjuvant treatment, the administration of which would affect subsequent histopathology.

For the 37 patients included in the final analysis, ERUS results were compared with surgical pathology to ascertain accuracy. The resections were performed endoscopically or surgically with a goal of obtaining clear margins. The choice of procedure depended on size, shape, location, and depth of invasion. All patients underwent clinical and endoscopic surveillance with flexible sigmoidoscopy/EUS every 3 to 6 months for the first 2 years. We used 2 different gold standards for surveillance depending on the type of procedure performed to remove the lesion. A pathology report was the gold standard used for patients who underwent surgery. In patients who underwent endoscopic resection, we used the lack of recurrent disease, determined by normal endoscopic and endoscopic ultrasound examination, to signify complete endoscopic resection and therefore adequate staging as an early neoplasm.

Results

From January 2011 to August 2015, 65 rectal ultrasounds were performed. All EUS procedures were performed by 1 physician (C Ruben Tombazzi). All patients had previous endoscopic evaluation and tissue diagnoses. Twenty-eight patients were excluded: 18 had T3 or N1 disease, 2 had T2N0 but refused surgery, 2 had anal cancer, 3 patients with suspected cancer had benign nonneoplastic disease (2 radiation proctitis, 1 normal rectal wall), and 3 underwent EUS for benign tumors (1 ganglioneuroma and 2 lipomas).

Thirty-seven patients were included in the study, 3 of whom were staged as T2N0 and 34 as T1N0 or lower by EUS. All patients were men ranging in age from 43 to 73 years (mean, 59 years). All 37 patients underwent endoscopic or surgical resection of their early rectal neoplasm. The final pathologic evaluation of the specimens demonstrated 14 carcinoid tumors, 11 adenocarcinomas, 6 tubular adenomas with high-grade dysplasia, and 6 benign adenomas. The preoperative EUS staging was confirmed for all patients, with 100% sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. None of the patients who underwent endoscopic or surgical transanal resection had recurrence, determined by normal endoscopic and endoscopic ultrasound appearance, during a mean of 32.6 months surveillance.

Discussion

EUS has long been a recognized method for T and N staging of RC.1,3-5,7,8 Our data confirm that, in experienced hands, EUS is highly accurate in the staging of early rectal cancers.

The impact of EUS on the management of RC was demonstrated in a Mayo Clinic prospective blinded study.1 In that cohort of 80 consecutive patients who had previously had a CT for staging, EUS altered patient management in about 30% of cases. The most common change precipatated by EUS was the indication for additional neoadjuvant treatment.

However, the results have not been as encouraging when ERUS is performed outside of strict research protocol. A multicenter, prospective, country-wide quality assurance study from > 300 German hospitals was designed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of EUS in RC.13 Of 29206 patients, 7096 underwent surgery, without neoadjuvant treatment, and were included in the final analysis. The correspondence of tumor invasion with histopathology was 64.7%, with understaging of 18% and overstaging of 17.3%.13 These numbers were better in hospitals with greater experience performing ERUS: 73% accuracy in the centers with a case load of > 30 cases per year compared with 63.2% accuracy for the centers with < 10 cases a year. Marusch and colleagues had previously demonstrated an EUS accuracy of 63.3% in a study of 1463 patients with RC in Germany.14 Another study based out of the UK had similar findings. Ashraf and colleagues performed a database analyses from 20 UK centers and identified 165 patients with RC who underwent ERUS and endoscopic microsurgery.15 Compared with histopathology, EUS had 57.1% sensitivity, 73% specificity, and 42.9% accuracy for T1 cancers; EUS accuracy was 50% for T2 and 58% for T3 tumors. The authors concluded that the general accuracy of EUS in determining stage was around 50%, the statistical equivalent of flipping a coin.

The low accuracy of EUS observed by German and British multicenter studies13-15 was attributed to the difference that may exist in clinical trials at specialized centers compared with wider use of EUS in a community setting. As seen by our data, the Memphis VAMC is not a high-volume center for the treatment of RC. However, all our EUS procedures were performed and interpreted by a single operator (C. Ruben Tombazzi) with 18 years of EUS experience. We cannot conclude that no patient was overstaged, as patients receiving a stage of T3N0 or T > N0 received neoadjuvant treatment and were not included. However, we can conclude that no patient was understaged. All patients deemed to be T1 to T2N0 included in our study received accurate staging. Our results are consistent with the high accuracy of EUS reported from other centers with experience in diagnosis and treatment of RC.1,3-5,17,18

Although EUS is accurate in differentiating T1 from T2 tumors, it cannot reliably differentiate T1 from T0 lesions. In one study, 57.6% of adenomas and 30.7% of carcinomas in situ were staged as T1 on EUS, while almost half of T1 cancers were interpreted as T0.17 This drawback is a well-known limitation of EUS; although, the misinterpretation does not affect treatment, as both T0 and T1 lesions can be treated successfully by local excision alone, which was the algorithm used for our patients. The choice of the specific procedure for local excision was left to the clinicians and included transanal endoscopic or surgical resections. At a mean follow-up of 32.6 months, none of the 37 patients who underwent endoscopic or surgical transanal resection had evidence of recurrent disease.

A limitation of EUS, or any other imaging modality, is differentiating tumor invasion from peritumoral inflammation. The inflammation can render images of tumor borders ill-defined and irregular, which hinders precise staging. However, the accurate identification of tumors with deep involvement of the submucosa (T1sm3) is of importance, because these tumors are more advanced than the superficial and intermediate T1 lesions (T1sm1 and T1sm2, respectively).

Patients with RC whose lesions are considered T1sm3 are at higher risk of harboring lymph node metastases.18 Nascimbeni and colleagues had shown that the invasion into the lower third of the submucosa (sm3) was an independent risk factor for lower cancer-free survival among patients with T1 RC.19

Unlike rectal adenocarcinomas, the prognosis for carcinoid tumors correlates not only with the depth of invasion but also with the size of the tumor. The other adverse prognostic features include poor differentiation, high mitosis index, and lymphovascular invasion.20

EUS had been shown to be highly accurate in determining the precise carcinoid tumor size, depth of invasion, and lymph node metastases.20,21 In a study of 66 resected rectal carcinoid tumors by Ishii and colleagues, 57 lesions had a diameter of ≤ 10 mm and 9 lesions had a diameter of > 10 mm.21 All of the 57 carcinoid tumors with a diameter of ≤ 10 mm were confined to the submucosa. In contrast, 5 of the 9 lesions > 10 mm invaded the muscularis propria, 6 had a lymphovascular invasion, 4 were lymph node metastases, and 1 was a liver metastasis.

In our series, 4 of the 14 carcinoid tumors were > 10 mm but none were > 20 mm. None of the carcinoids with a diameter ≤ 10 mm invaded the muscularis propria. Of the 4 carcinoids > 10 mm, 1 was T2N0 and 3 were T1N0. All carcinoid tumors in our series were low grade and with low proliferation indexes, and all were treated successfully by local excision.

Conclusion

We believe our study shows that EUS can be highly accurate in staging rectal lesions, specifically lesions that are T1-T2N0, be they adenocarcinoma or carcinoid. Although we could not assess overstaging for lesions that were staged > T2 or > N0, we w

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death in the US, with one-third of all colorectal cancers occurring within the rectum. Each year, an estimated 40000 Americans are diagnosed with rectal cancer (RC).1,2 The prognosis and treatment of RC depends on both T and N stage at the time of diagnosis.3-5 According to the most recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines from May 2019, patients with T1 to T2N0 tumors should undergo transanal or transabdominal surgery upfront, whereas patients with T3 to T4N0 or any TN1 to 2 should start with neoadjuvant therapy for better locoregional control, followed by surgery.6 Therefore, the appropriate management of RC requires adequate staging.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT) are the imaging techniques currently used to stage RC. In a meta-analysis of 90 articles published between 1985 and 2002 that compared the 3 radiologic modalities, Bipat and colleagues found that MRI and EUS had a similar sensitivity of 94%, whereas the specificity of EUS (86%) was significantly higher than that of MRI (69%) for muscularis propria invasion.7 CT was performed only in a limited number of trials because CT was considered inadequate to assess early T stage. For perirectal tissue invasion, the sensitivity of EUS was statistically higher than that of CT and MRI imaging: 90% compared with 79% and 82%, respectively. The specificity estimates for EUS, CT, and MRI were comparable: 75%, 78%, and 76%, respectively. The respective sensitivity and specificity of the 3 imaging modalities to evaluate lymph nodes were also comparable: EUS, 67% and 78%; CT, 55% and 74%; and MRI, 66% and 76%.

The role of EUS in the diagnosis and treatment of RC has long been validated.1,2-5 A meta-analysis of 42 studies involving 5039 patients found EUS to be highly accurate for differentiating various T stages.8 However, EUS cannot assess iliac and mesenteric lymph nodes or posterior tumor extension beyond endopelvic fascia in advanced RC. Notable heterogeneity was found among the studies in the meta-analyses with regard to the type of equipment used for staging, as well as the criteria used to assess the depth of penetration and nodal status. The recent introduction of phased-array coils and the development of T2-weighted fast spin sequences have improved the resolution of MRI. The MERCURY trial showed that extension of tumor to within 1 mm of the circumferential margin on high-resolution MRI correctly predicted margin involvement at the time of surgery in 92% of the patients.9 In the retrospective study by Balyasnikova and colleagues, MRI was found to correctly identify partial submucosal invasion and suitability for local excision in 89% of the cases.10

Therefore, both EUS and MRI are useful, more so than CT, in assessment of the depth of tumor invasion, nodal staging, and predicting the circumferential resection margin. The use of EUS, however, does not preclude the use of MRI, or vice versa. Rather, the 2 modalities can complement each other in staging and proper patient selection for treatment.11

Despite data supporting the value of EUS in staging RC, its use is limited by a high degree of operator dependence and a substantial learning curve,12-17 which may explain the low EUS accuracy observed in some reports.7,13,15 Given the presence of recognized alternatives such as MRI, we decided to reevaluate EUS accuracy for the staging of RC outside high-volume specialized centers and prospective clinical trials.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was performed that included all consecutive patients undergoing rectal ultrasound from January 2011 to August 2015 at the US Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Memphis, Tennessee. Sixty-five patients with short-stocked or sessile lesions < 15 cm from anal margin staged T2N0M0 or lower by endorectal ultrasound (ERUS) were included. The patients with neoplasms staged in excess of T2 or N0 were excluded from the study because treatment protocol dictates immediate neoadjuvant treatment, the administration of which would affect subsequent histopathology.

For the 37 patients included in the final analysis, ERUS results were compared with surgical pathology to ascertain accuracy. The resections were performed endoscopically or surgically with a goal of obtaining clear margins. The choice of procedure depended on size, shape, location, and depth of invasion. All patients underwent clinical and endoscopic surveillance with flexible sigmoidoscopy/EUS every 3 to 6 months for the first 2 years. We used 2 different gold standards for surveillance depending on the type of procedure performed to remove the lesion. A pathology report was the gold standard used for patients who underwent surgery. In patients who underwent endoscopic resection, we used the lack of recurrent disease, determined by normal endoscopic and endoscopic ultrasound examination, to signify complete endoscopic resection and therefore adequate staging as an early neoplasm.

Results

From January 2011 to August 2015, 65 rectal ultrasounds were performed. All EUS procedures were performed by 1 physician (C Ruben Tombazzi). All patients had previous endoscopic evaluation and tissue diagnoses. Twenty-eight patients were excluded: 18 had T3 or N1 disease, 2 had T2N0 but refused surgery, 2 had anal cancer, 3 patients with suspected cancer had benign nonneoplastic disease (2 radiation proctitis, 1 normal rectal wall), and 3 underwent EUS for benign tumors (1 ganglioneuroma and 2 lipomas).

Thirty-seven patients were included in the study, 3 of whom were staged as T2N0 and 34 as T1N0 or lower by EUS. All patients were men ranging in age from 43 to 73 years (mean, 59 years). All 37 patients underwent endoscopic or surgical resection of their early rectal neoplasm. The final pathologic evaluation of the specimens demonstrated 14 carcinoid tumors, 11 adenocarcinomas, 6 tubular adenomas with high-grade dysplasia, and 6 benign adenomas. The preoperative EUS staging was confirmed for all patients, with 100% sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. None of the patients who underwent endoscopic or surgical transanal resection had recurrence, determined by normal endoscopic and endoscopic ultrasound appearance, during a mean of 32.6 months surveillance.

Discussion

EUS has long been a recognized method for T and N staging of RC.1,3-5,7,8 Our data confirm that, in experienced hands, EUS is highly accurate in the staging of early rectal cancers.

The impact of EUS on the management of RC was demonstrated in a Mayo Clinic prospective blinded study.1 In that cohort of 80 consecutive patients who had previously had a CT for staging, EUS altered patient management in about 30% of cases. The most common change precipatated by EUS was the indication for additional neoadjuvant treatment.

However, the results have not been as encouraging when ERUS is performed outside of strict research protocol. A multicenter, prospective, country-wide quality assurance study from > 300 German hospitals was designed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of EUS in RC.13 Of 29206 patients, 7096 underwent surgery, without neoadjuvant treatment, and were included in the final analysis. The correspondence of tumor invasion with histopathology was 64.7%, with understaging of 18% and overstaging of 17.3%.13 These numbers were better in hospitals with greater experience performing ERUS: 73% accuracy in the centers with a case load of > 30 cases per year compared with 63.2% accuracy for the centers with < 10 cases a year. Marusch and colleagues had previously demonstrated an EUS accuracy of 63.3% in a study of 1463 patients with RC in Germany.14 Another study based out of the UK had similar findings. Ashraf and colleagues performed a database analyses from 20 UK centers and identified 165 patients with RC who underwent ERUS and endoscopic microsurgery.15 Compared with histopathology, EUS had 57.1% sensitivity, 73% specificity, and 42.9% accuracy for T1 cancers; EUS accuracy was 50% for T2 and 58% for T3 tumors. The authors concluded that the general accuracy of EUS in determining stage was around 50%, the statistical equivalent of flipping a coin.

The low accuracy of EUS observed by German and British multicenter studies13-15 was attributed to the difference that may exist in clinical trials at specialized centers compared with wider use of EUS in a community setting. As seen by our data, the Memphis VAMC is not a high-volume center for the treatment of RC. However, all our EUS procedures were performed and interpreted by a single operator (C. Ruben Tombazzi) with 18 years of EUS experience. We cannot conclude that no patient was overstaged, as patients receiving a stage of T3N0 or T > N0 received neoadjuvant treatment and were not included. However, we can conclude that no patient was understaged. All patients deemed to be T1 to T2N0 included in our study received accurate staging. Our results are consistent with the high accuracy of EUS reported from other centers with experience in diagnosis and treatment of RC.1,3-5,17,18

Although EUS is accurate in differentiating T1 from T2 tumors, it cannot reliably differentiate T1 from T0 lesions. In one study, 57.6% of adenomas and 30.7% of carcinomas in situ were staged as T1 on EUS, while almost half of T1 cancers were interpreted as T0.17 This drawback is a well-known limitation of EUS; although, the misinterpretation does not affect treatment, as both T0 and T1 lesions can be treated successfully by local excision alone, which was the algorithm used for our patients. The choice of the specific procedure for local excision was left to the clinicians and included transanal endoscopic or surgical resections. At a mean follow-up of 32.6 months, none of the 37 patients who underwent endoscopic or surgical transanal resection had evidence of recurrent disease.

A limitation of EUS, or any other imaging modality, is differentiating tumor invasion from peritumoral inflammation. The inflammation can render images of tumor borders ill-defined and irregular, which hinders precise staging. However, the accurate identification of tumors with deep involvement of the submucosa (T1sm3) is of importance, because these tumors are more advanced than the superficial and intermediate T1 lesions (T1sm1 and T1sm2, respectively).

Patients with RC whose lesions are considered T1sm3 are at higher risk of harboring lymph node metastases.18 Nascimbeni and colleagues had shown that the invasion into the lower third of the submucosa (sm3) was an independent risk factor for lower cancer-free survival among patients with T1 RC.19

Unlike rectal adenocarcinomas, the prognosis for carcinoid tumors correlates not only with the depth of invasion but also with the size of the tumor. The other adverse prognostic features include poor differentiation, high mitosis index, and lymphovascular invasion.20

EUS had been shown to be highly accurate in determining the precise carcinoid tumor size, depth of invasion, and lymph node metastases.20,21 In a study of 66 resected rectal carcinoid tumors by Ishii and colleagues, 57 lesions had a diameter of ≤ 10 mm and 9 lesions had a diameter of > 10 mm.21 All of the 57 carcinoid tumors with a diameter of ≤ 10 mm were confined to the submucosa. In contrast, 5 of the 9 lesions > 10 mm invaded the muscularis propria, 6 had a lymphovascular invasion, 4 were lymph node metastases, and 1 was a liver metastasis.

In our series, 4 of the 14 carcinoid tumors were > 10 mm but none were > 20 mm. None of the carcinoids with a diameter ≤ 10 mm invaded the muscularis propria. Of the 4 carcinoids > 10 mm, 1 was T2N0 and 3 were T1N0. All carcinoid tumors in our series were low grade and with low proliferation indexes, and all were treated successfully by local excision.

Conclusion

We believe our study shows that EUS can be highly accurate in staging rectal lesions, specifically lesions that are T1-T2N0, be they adenocarcinoma or carcinoid. Although we could not assess overstaging for lesions that were staged > T2 or > N0, we w

1. Harewood GC, Wiersema MJ, Nelson H, et al. A prospective, blinded assessment of the impact of preoperative staging on the management of rectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(1):24-32.

2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5-29.

3. Ahuja NK, Sauer BG, Wang AY, et al. Performance of endoscopic ultrasound in staging rectal adenocarcinoma appropriate for primary surgical resection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:339-44.

4. Doornebosch PG, Bronkhorst PJ, Hop WC, Bode WA, Sing AK, de Graaf EJ. The role of endorectal ultrasound in therapeutic decision-making for local vs. transabdominal resection of rectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(1):38-42.

5. Santoro GA, Gizzi G, Pellegrini L, Battistella G, Di Falco G. The value of high-resolution three-dimensional endorectal ultrasonography in the management of submucosal invasive rectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(11):1837-1843.

6. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: rectal cancer, version 2.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/rectal.pdf. Published May 15, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019.

7. Bipat S, Glas AS, Slors FJ, Zwinderman AH, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J. Rectal cancer: local staging and assessment of lymph node involvement with endoluminal US, CT, and MR imaging—a meta-analysis. Radiology. 2004;232(3):773-783.

8. Puli SR, Bechtold ML, Reddy JB, Choudhary A, Antillon MR, Brugge WR. How good is endoscopic ultrasound in differentiating various T stages of rectal cancer? Meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(2):254-265.

9. MERCURY Study Group. Diagnostic accuracy of preoperative magnetic resonance imaging in predicting curative resection of rectal cancer: prospective observational study. BMJ. 2006;333(7572):779.

10. Balyasnikova S, Read J, Wotherspoon A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of high-resolution MRI as a method to predict potentially safe endoscopic and surgical planes in patient with early rectal cancer. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2017;4(1):e000151.

11. Frasson M, Garcia-Granero E, Roda D, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation may not always be needed for patients with T3 and T2N+ rectal cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(14):3118-3125.

12. Rafaelsen SR, Sørensen T, Jakobsen A, Bisgaard C, Lindebjerg J. Transrectal ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the staging of rectal cancer. Effect of experience. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(4):440-446.

13. Marusch F, Ptok H, Sahm M, et al. Endorectal ultrasound in rectal carcinoma – do the literature results really correspond to the realities of routine clinical care? Endoscopy. 2011;43(5):425-431.

14. Marusch F, Koch A, Schmidt U, et al. Routine use of transrectal ultrasound in rectal carcinoma: results of a prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2002;34(5):385-390.

15. Ashraf S, Hompes R, Slater A, et al; Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery (TEM) Collaboration. A critical appraisal of endorectal ultrasound and transanal endoscopic microsurgery and decision-making in early rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(7):821-826.

16. Harewood GC. Assessment of clinical impact of endoscopic ultrasound on rectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(4):623-627.

17. Zorcolo L, Fantola G, Cabras F, Marongiu L, D’Alia G, Casula G. Preoperative staging of patients with rectal tumors suitable for transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM): comparison of endorectal ultrasound and histopathologic findings. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(6):1384-1389.

18. Akasu T, Kondo H, Moriya Y, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography and treatment of early stage rectal cancer. World J Surg. 2000;24(9):1061-1068.

19. Nascimbeni R, Nivatvongs S, Larson DR, Burgart LJ. Long-term survival after local excision for T1 carcinoma of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(11):1773-1779.

20. Park CH, Cheon JH, Kim JO, et al. Criteria for decision making after endoscopic resection of well-differentiated rectal carcinoids with regard to potential lymphatic spread. Endoscopy. 2011;43(9):790-795.

21. Ishii N, Horiki N, Itoh T, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection and preoperative assessment with endoscopic ultrasonography for the treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(6):1413-1419.

1. Harewood GC, Wiersema MJ, Nelson H, et al. A prospective, blinded assessment of the impact of preoperative staging on the management of rectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(1):24-32.

2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5-29.

3. Ahuja NK, Sauer BG, Wang AY, et al. Performance of endoscopic ultrasound in staging rectal adenocarcinoma appropriate for primary surgical resection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:339-44.

4. Doornebosch PG, Bronkhorst PJ, Hop WC, Bode WA, Sing AK, de Graaf EJ. The role of endorectal ultrasound in therapeutic decision-making for local vs. transabdominal resection of rectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(1):38-42.

5. Santoro GA, Gizzi G, Pellegrini L, Battistella G, Di Falco G. The value of high-resolution three-dimensional endorectal ultrasonography in the management of submucosal invasive rectal tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(11):1837-1843.

6. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: rectal cancer, version 2.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/rectal.pdf. Published May 15, 2019. Accessed July 19, 2019.

7. Bipat S, Glas AS, Slors FJ, Zwinderman AH, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J. Rectal cancer: local staging and assessment of lymph node involvement with endoluminal US, CT, and MR imaging—a meta-analysis. Radiology. 2004;232(3):773-783.

8. Puli SR, Bechtold ML, Reddy JB, Choudhary A, Antillon MR, Brugge WR. How good is endoscopic ultrasound in differentiating various T stages of rectal cancer? Meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(2):254-265.

9. MERCURY Study Group. Diagnostic accuracy of preoperative magnetic resonance imaging in predicting curative resection of rectal cancer: prospective observational study. BMJ. 2006;333(7572):779.

10. Balyasnikova S, Read J, Wotherspoon A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of high-resolution MRI as a method to predict potentially safe endoscopic and surgical planes in patient with early rectal cancer. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2017;4(1):e000151.

11. Frasson M, Garcia-Granero E, Roda D, et al. Preoperative chemoradiation may not always be needed for patients with T3 and T2N+ rectal cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(14):3118-3125.

12. Rafaelsen SR, Sørensen T, Jakobsen A, Bisgaard C, Lindebjerg J. Transrectal ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the staging of rectal cancer. Effect of experience. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(4):440-446.

13. Marusch F, Ptok H, Sahm M, et al. Endorectal ultrasound in rectal carcinoma – do the literature results really correspond to the realities of routine clinical care? Endoscopy. 2011;43(5):425-431.

14. Marusch F, Koch A, Schmidt U, et al. Routine use of transrectal ultrasound in rectal carcinoma: results of a prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2002;34(5):385-390.

15. Ashraf S, Hompes R, Slater A, et al; Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery (TEM) Collaboration. A critical appraisal of endorectal ultrasound and transanal endoscopic microsurgery and decision-making in early rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(7):821-826.

16. Harewood GC. Assessment of clinical impact of endoscopic ultrasound on rectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(4):623-627.

17. Zorcolo L, Fantola G, Cabras F, Marongiu L, D’Alia G, Casula G. Preoperative staging of patients with rectal tumors suitable for transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM): comparison of endorectal ultrasound and histopathologic findings. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(6):1384-1389.

18. Akasu T, Kondo H, Moriya Y, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography and treatment of early stage rectal cancer. World J Surg. 2000;24(9):1061-1068.

19. Nascimbeni R, Nivatvongs S, Larson DR, Burgart LJ. Long-term survival after local excision for T1 carcinoma of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(11):1773-1779.