User login

Professional coaching keeps doctors in the game

Physicians who receive professional coaching are less emotionally exhausted and less vulnerable to burnout, according to the results of a pilot study.

“This intervention adds to the growing literature of evidence-based approaches to promote physician well-being and should be considered a complementary strategy to be deployed in combination with other organizational approaches to improve system-level drivers of work-related stressors,” wrote Liselotte N. Dyrbye, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and coauthors in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Dr. Dyrbye and colleagues conducted a randomized pilot study of 88 Mayo Clinic physicians in the departments of medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics. Half (n = 44) received 3.5 hours of sessions facilitated by a professional coach. The other half (n = 44) served as controls. Participants’ well-being – in regard to burnout, quality of life, resilience, job satisfaction, engagement, and meaning at work – was surveyed at baseline and the study’s completion.

Physicians in the coaching group participated in a 1-hour initial telephone session, designed to establish a relationship between the physician and coach, as well as to assess needs, set goals, identify values, and create an action plan. During follow-up sessions, coaches would check in, help plan and set goals, and suggest strategies/changes to incorporate into daily life. Physicians were permitted to ask for support on any issue, but also were expected to see as many patients as their colleagues outside of the study.

After 6 months, physicians in the coaching group saw a significant decrease in emotional exhaustion by a mean of 5.2 points, compared with an increase of 1.5 points in the control group. At 5 months, absolute rates of high emotional exhaustion decreased by 19.5% in the coaching group and increased by 9.8% in the control group and absolute rates of overall burnout decreased by 17.1% in the coaching group and increased by 4.9% in the control group. Quality of life and resilience scores also improved, though there were no notable differences between groups in measures of job satisfaction, engagement, and meaning at work.

The authors noted their study’s limitations, which included a modest sample size and a volunteer group of participants.

In addition, the lower percentage of men in the study – 48 of 88 participants were women – may be a result of factors that deserve further investigation. Finally, burnout rates among volunteers were higher than those among other physicians, suggesting that “the study appealed to those in greatest need of the intervention.”

The study was funded by the Mayo Clinic department of medicine’s Program on Physician Well-Being and the Physician Foundation. Two of the authors – Dr. Dyrbye and Tait D. Shanafelt, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University – reported being the coinventors of, and receiving royalties for, the Physician Well-Being Index, Medical Student Well-Being Index, Nurse Well-Being Index, and the Well-Being Index.

SOURCE: Dyrbye LN et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2425.

Physicians who receive professional coaching are less emotionally exhausted and less vulnerable to burnout, according to the results of a pilot study.

“This intervention adds to the growing literature of evidence-based approaches to promote physician well-being and should be considered a complementary strategy to be deployed in combination with other organizational approaches to improve system-level drivers of work-related stressors,” wrote Liselotte N. Dyrbye, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and coauthors in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Dr. Dyrbye and colleagues conducted a randomized pilot study of 88 Mayo Clinic physicians in the departments of medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics. Half (n = 44) received 3.5 hours of sessions facilitated by a professional coach. The other half (n = 44) served as controls. Participants’ well-being – in regard to burnout, quality of life, resilience, job satisfaction, engagement, and meaning at work – was surveyed at baseline and the study’s completion.

Physicians in the coaching group participated in a 1-hour initial telephone session, designed to establish a relationship between the physician and coach, as well as to assess needs, set goals, identify values, and create an action plan. During follow-up sessions, coaches would check in, help plan and set goals, and suggest strategies/changes to incorporate into daily life. Physicians were permitted to ask for support on any issue, but also were expected to see as many patients as their colleagues outside of the study.

After 6 months, physicians in the coaching group saw a significant decrease in emotional exhaustion by a mean of 5.2 points, compared with an increase of 1.5 points in the control group. At 5 months, absolute rates of high emotional exhaustion decreased by 19.5% in the coaching group and increased by 9.8% in the control group and absolute rates of overall burnout decreased by 17.1% in the coaching group and increased by 4.9% in the control group. Quality of life and resilience scores also improved, though there were no notable differences between groups in measures of job satisfaction, engagement, and meaning at work.

The authors noted their study’s limitations, which included a modest sample size and a volunteer group of participants.

In addition, the lower percentage of men in the study – 48 of 88 participants were women – may be a result of factors that deserve further investigation. Finally, burnout rates among volunteers were higher than those among other physicians, suggesting that “the study appealed to those in greatest need of the intervention.”

The study was funded by the Mayo Clinic department of medicine’s Program on Physician Well-Being and the Physician Foundation. Two of the authors – Dr. Dyrbye and Tait D. Shanafelt, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University – reported being the coinventors of, and receiving royalties for, the Physician Well-Being Index, Medical Student Well-Being Index, Nurse Well-Being Index, and the Well-Being Index.

SOURCE: Dyrbye LN et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2425.

Physicians who receive professional coaching are less emotionally exhausted and less vulnerable to burnout, according to the results of a pilot study.

“This intervention adds to the growing literature of evidence-based approaches to promote physician well-being and should be considered a complementary strategy to be deployed in combination with other organizational approaches to improve system-level drivers of work-related stressors,” wrote Liselotte N. Dyrbye, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and coauthors in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Dr. Dyrbye and colleagues conducted a randomized pilot study of 88 Mayo Clinic physicians in the departments of medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics. Half (n = 44) received 3.5 hours of sessions facilitated by a professional coach. The other half (n = 44) served as controls. Participants’ well-being – in regard to burnout, quality of life, resilience, job satisfaction, engagement, and meaning at work – was surveyed at baseline and the study’s completion.

Physicians in the coaching group participated in a 1-hour initial telephone session, designed to establish a relationship between the physician and coach, as well as to assess needs, set goals, identify values, and create an action plan. During follow-up sessions, coaches would check in, help plan and set goals, and suggest strategies/changes to incorporate into daily life. Physicians were permitted to ask for support on any issue, but also were expected to see as many patients as their colleagues outside of the study.

After 6 months, physicians in the coaching group saw a significant decrease in emotional exhaustion by a mean of 5.2 points, compared with an increase of 1.5 points in the control group. At 5 months, absolute rates of high emotional exhaustion decreased by 19.5% in the coaching group and increased by 9.8% in the control group and absolute rates of overall burnout decreased by 17.1% in the coaching group and increased by 4.9% in the control group. Quality of life and resilience scores also improved, though there were no notable differences between groups in measures of job satisfaction, engagement, and meaning at work.

The authors noted their study’s limitations, which included a modest sample size and a volunteer group of participants.

In addition, the lower percentage of men in the study – 48 of 88 participants were women – may be a result of factors that deserve further investigation. Finally, burnout rates among volunteers were higher than those among other physicians, suggesting that “the study appealed to those in greatest need of the intervention.”

The study was funded by the Mayo Clinic department of medicine’s Program on Physician Well-Being and the Physician Foundation. Two of the authors – Dr. Dyrbye and Tait D. Shanafelt, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University – reported being the coinventors of, and receiving royalties for, the Physician Well-Being Index, Medical Student Well-Being Index, Nurse Well-Being Index, and the Well-Being Index.

SOURCE: Dyrbye LN et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2425.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Antiepileptic drug outcomes have remained flat for 3 decades

BANGKOK – Since founding the Epilepsy Unit at Glasgow’s Western Infirmary 37 years ago, Martin J. Brodie, MD, has seen many changes in the field, including the introduction of more than a dozen new antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) in the past 2 decades.

And based upon this vast clinical experience coupled with his leadership of landmark studies, he has a message for his physician colleagues and their epilepsy patients. And it’s not pretty.

“Has the probability of achieving seizure freedom increased significantly in the last 3 decades? Regrettably, the answer is no,” he declared at the International Epilepsy Congress.

“Over all these years, in terms of seizure freedom there has been no real difference in outcome. There’s really quite a long way to go before we can say that we are doing all that well for people,” he said at the congress sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

In the year 2000, he and his coinvestigators published a prospective, longitudinal, observational cohort study of 470 newly diagnosed patients with epilepsy treated at the Western Infirmary during 1982-1997, all with a minimum of 2 years’ follow-up. Sixty-one percent achieved complete freedom from seizures for at least 1 year on monotherapy, and another 3% did so on polytherapy, for a total rate of 64% (N Engl J Med. 2000 Feb 3;342[5]:314-19).

But these were patients who by and large were treated with older AEDs such as carbamazepine, which has since fallen by the wayside because of toxicities. Scottish neurologists now generally turn to lamotrigine (Lamictal), levetiracetam (Spritam), and other, newer AEDs. So Dr. Brodie and his coworkers recently published a follow-up study, this one featuring 30 years of longitudinal follow-up of 1,795 patients newly treated for epilepsy with AEDs, new and old, during 1982-2012. The investigators demonstrated that the seizure-free survival curves over time were virtually superimposable. In the larger, more recent study, remission was achieved in 55% of patients with AED monotherapy and in another 9% with polytherapy, for a total rate of 64%, identical to the rate in the 2000 study, and as was the case in the earlier study, 36% of patients remained uncontrolled (JAMA Neurol. 2018 Mar 1;75[3]:279-86).

“Overall, the way this population behaves, there’s no difference in efficacy and no difference in tolerability whether you’re using old drugs used properly or new drugs used properly,” said Dr. Brodie, professor of neurology at the University of Glasgow (Scotland).

It’s noteworthy that Sir William R. Gowers, the Londoner who has been called the greatest neurologist of all time, reported a 70% seizure-free rate in 1881, while Dr. Brodie and workers achieved a 64% rate in their 30-year study. “It’s interesting that the numbers are so bad, really, I suppose,” Dr. Brodie commented.

How about outcomes in pediatric epilepsy?

Dr. Brodie and coworkers recently published a 30-year prospective cohort study of 332 adolescent epilepsy patients newly diagnosed and treated at the Western Infirmary during 1982-2012. At the end of the study, 67% were seizure-free for at least the past year, a feat accomplished via monotherapy in 83% of cases. The seizure-free rate was 72% in those with generalized epilepsy, significantly better than the 60% figure in those with focal epilepsy. The efficacy rate was 74% with newer AED monotherapy and similar at 77% with monotherapy older drugs. Adverse event rates ranged from a low of 12% with lamotrigine to 56% with topiramate (Topamax), according to the findings published in Epilepsia (2019 Jun;60[6]:1083-90).

Roughly similar outcomes have been reported from Norway in a study of 600 children with epilepsy, median age 7 years, with a median follow-up of 5.8 years that is considerably shorter than that in the Glasgow pediatric study. Overall, 59% of the Norwegian children remained seizure free for at least 1 year, 30% developed drug-resistant epilepsy, and 11% followed an intermediate remitting/relapsing course (Pediatrics. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4016).

Why the decades of flat pharmacologic outcomes?

The consistently suboptimal seizure-free outcomes obtained over the past 30 years shouldn’t really be surprising, according to Dr. Brodie.

“Although we think we have lots of mechanisms of action and lots of differences between the drugs, they’re arguably all antiseizure drugs and not antiepilepsy drugs. We don’t treat the whale; we treat the spout. We don’t treat what we cannot see; we treat what we can see, which is the seizures, but we’re not influencing the long-term outcome,” the neurologist explained.

The compelling case for early epilepsy surgery

Epilepsy surgery remains underutilized, according to Dr. Brodie and other experts.

The International League Against Epilepsy defines drug-resistant epilepsy as failure to achieve sustained seizure freedom after adequate trials of two tolerated and appropriately chosen and used AED schedules. Dr. Brodie’s work was influential in creating that definition because his data demonstrated the sharply diminishing returns of additional drug trials.

“When do we consider epilepsy surgery? Arguably, the earlier, the better. After two drugs have failed appropriately, I don’t think anybody in this room would argue about that, although people in some of the other rooms might,” he said at the congress.

Influential in his thinking on this score were the impressive results of an early study, the first-ever randomized trial of surgery for epilepsy. In 80 patients with a 21-year history of drug-refractory temporal lobe epilepsy who were randomized to surgery or 1 year of AED therapy, at 1 year of follow-up blinded epileptologists rated 58% of surgically treated patients as free from seizures that impair awareness of self and surroundings, compared with just 8% in the AED group (N Engl J Med. 2001 Aug 2;345[5]:311-8).

“That’s a big outcome, and I’m very keen to ensure that my data continue to drive the push for early surgery,” according to the neurologist.

A Cochrane review of 177 studies totaling more than 16,000 patients concluded that 65% of epilepsy patients had good outcomes following surgery. Prognostic factors associated with better surgical outcomes included complete surgical resection of the epileptogenic focus, the presence of mesial temporal sclerosis, concordance of MRI and EEG findings, and an absence of cortical dysplasia (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;6:CD010541. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010541.pub3).

In addition, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Canadian investigators found that 72% of adults with lesional epilepsy identified by MRI or histopathology were seizure-free after surgery, compared with 36% of those with nonlesional epilepsy. The disparity in outcomes was similar in pediatric epilepsy patients, with seizure freedom after surgery in 74% of those with lesional disease versus 45% with nonlesional epilepsy (Epilepsy Res. 2010 May;89[2-3]:310-8).

Whither are neurostimulatory device therapies headed?

Dr. Brodie was quick to admit that as a pharmacologic researcher, device modalities including vagus nerve stimulation, responsive neurostimulation, and deep brain stimulation are outside his area of expertise. But he’s been following developments in the field with interest.

“These device therapies have shown efficacy in short-term randomized trials, but very few patients attain long-term seizure freedom. I think these are largely palliative techniques. I gave up on these techniques a long time ago because I felt it was a very costly way of reducing seizures by a relatively small margin, and really we need to go a little bit further than that. But I know there’s a lot of work going on at the moment,” he said.

Dr. Brodie reported serving on the scientific advisory boards of more than a half dozen pharmaceutical companies.

BANGKOK – Since founding the Epilepsy Unit at Glasgow’s Western Infirmary 37 years ago, Martin J. Brodie, MD, has seen many changes in the field, including the introduction of more than a dozen new antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) in the past 2 decades.

And based upon this vast clinical experience coupled with his leadership of landmark studies, he has a message for his physician colleagues and their epilepsy patients. And it’s not pretty.

“Has the probability of achieving seizure freedom increased significantly in the last 3 decades? Regrettably, the answer is no,” he declared at the International Epilepsy Congress.

“Over all these years, in terms of seizure freedom there has been no real difference in outcome. There’s really quite a long way to go before we can say that we are doing all that well for people,” he said at the congress sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

In the year 2000, he and his coinvestigators published a prospective, longitudinal, observational cohort study of 470 newly diagnosed patients with epilepsy treated at the Western Infirmary during 1982-1997, all with a minimum of 2 years’ follow-up. Sixty-one percent achieved complete freedom from seizures for at least 1 year on monotherapy, and another 3% did so on polytherapy, for a total rate of 64% (N Engl J Med. 2000 Feb 3;342[5]:314-19).

But these were patients who by and large were treated with older AEDs such as carbamazepine, which has since fallen by the wayside because of toxicities. Scottish neurologists now generally turn to lamotrigine (Lamictal), levetiracetam (Spritam), and other, newer AEDs. So Dr. Brodie and his coworkers recently published a follow-up study, this one featuring 30 years of longitudinal follow-up of 1,795 patients newly treated for epilepsy with AEDs, new and old, during 1982-2012. The investigators demonstrated that the seizure-free survival curves over time were virtually superimposable. In the larger, more recent study, remission was achieved in 55% of patients with AED monotherapy and in another 9% with polytherapy, for a total rate of 64%, identical to the rate in the 2000 study, and as was the case in the earlier study, 36% of patients remained uncontrolled (JAMA Neurol. 2018 Mar 1;75[3]:279-86).

“Overall, the way this population behaves, there’s no difference in efficacy and no difference in tolerability whether you’re using old drugs used properly or new drugs used properly,” said Dr. Brodie, professor of neurology at the University of Glasgow (Scotland).

It’s noteworthy that Sir William R. Gowers, the Londoner who has been called the greatest neurologist of all time, reported a 70% seizure-free rate in 1881, while Dr. Brodie and workers achieved a 64% rate in their 30-year study. “It’s interesting that the numbers are so bad, really, I suppose,” Dr. Brodie commented.

How about outcomes in pediatric epilepsy?

Dr. Brodie and coworkers recently published a 30-year prospective cohort study of 332 adolescent epilepsy patients newly diagnosed and treated at the Western Infirmary during 1982-2012. At the end of the study, 67% were seizure-free for at least the past year, a feat accomplished via monotherapy in 83% of cases. The seizure-free rate was 72% in those with generalized epilepsy, significantly better than the 60% figure in those with focal epilepsy. The efficacy rate was 74% with newer AED monotherapy and similar at 77% with monotherapy older drugs. Adverse event rates ranged from a low of 12% with lamotrigine to 56% with topiramate (Topamax), according to the findings published in Epilepsia (2019 Jun;60[6]:1083-90).

Roughly similar outcomes have been reported from Norway in a study of 600 children with epilepsy, median age 7 years, with a median follow-up of 5.8 years that is considerably shorter than that in the Glasgow pediatric study. Overall, 59% of the Norwegian children remained seizure free for at least 1 year, 30% developed drug-resistant epilepsy, and 11% followed an intermediate remitting/relapsing course (Pediatrics. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4016).

Why the decades of flat pharmacologic outcomes?

The consistently suboptimal seizure-free outcomes obtained over the past 30 years shouldn’t really be surprising, according to Dr. Brodie.

“Although we think we have lots of mechanisms of action and lots of differences between the drugs, they’re arguably all antiseizure drugs and not antiepilepsy drugs. We don’t treat the whale; we treat the spout. We don’t treat what we cannot see; we treat what we can see, which is the seizures, but we’re not influencing the long-term outcome,” the neurologist explained.

The compelling case for early epilepsy surgery

Epilepsy surgery remains underutilized, according to Dr. Brodie and other experts.

The International League Against Epilepsy defines drug-resistant epilepsy as failure to achieve sustained seizure freedom after adequate trials of two tolerated and appropriately chosen and used AED schedules. Dr. Brodie’s work was influential in creating that definition because his data demonstrated the sharply diminishing returns of additional drug trials.

“When do we consider epilepsy surgery? Arguably, the earlier, the better. After two drugs have failed appropriately, I don’t think anybody in this room would argue about that, although people in some of the other rooms might,” he said at the congress.

Influential in his thinking on this score were the impressive results of an early study, the first-ever randomized trial of surgery for epilepsy. In 80 patients with a 21-year history of drug-refractory temporal lobe epilepsy who were randomized to surgery or 1 year of AED therapy, at 1 year of follow-up blinded epileptologists rated 58% of surgically treated patients as free from seizures that impair awareness of self and surroundings, compared with just 8% in the AED group (N Engl J Med. 2001 Aug 2;345[5]:311-8).

“That’s a big outcome, and I’m very keen to ensure that my data continue to drive the push for early surgery,” according to the neurologist.

A Cochrane review of 177 studies totaling more than 16,000 patients concluded that 65% of epilepsy patients had good outcomes following surgery. Prognostic factors associated with better surgical outcomes included complete surgical resection of the epileptogenic focus, the presence of mesial temporal sclerosis, concordance of MRI and EEG findings, and an absence of cortical dysplasia (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;6:CD010541. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010541.pub3).

In addition, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Canadian investigators found that 72% of adults with lesional epilepsy identified by MRI or histopathology were seizure-free after surgery, compared with 36% of those with nonlesional epilepsy. The disparity in outcomes was similar in pediatric epilepsy patients, with seizure freedom after surgery in 74% of those with lesional disease versus 45% with nonlesional epilepsy (Epilepsy Res. 2010 May;89[2-3]:310-8).

Whither are neurostimulatory device therapies headed?

Dr. Brodie was quick to admit that as a pharmacologic researcher, device modalities including vagus nerve stimulation, responsive neurostimulation, and deep brain stimulation are outside his area of expertise. But he’s been following developments in the field with interest.

“These device therapies have shown efficacy in short-term randomized trials, but very few patients attain long-term seizure freedom. I think these are largely palliative techniques. I gave up on these techniques a long time ago because I felt it was a very costly way of reducing seizures by a relatively small margin, and really we need to go a little bit further than that. But I know there’s a lot of work going on at the moment,” he said.

Dr. Brodie reported serving on the scientific advisory boards of more than a half dozen pharmaceutical companies.

BANGKOK – Since founding the Epilepsy Unit at Glasgow’s Western Infirmary 37 years ago, Martin J. Brodie, MD, has seen many changes in the field, including the introduction of more than a dozen new antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) in the past 2 decades.

And based upon this vast clinical experience coupled with his leadership of landmark studies, he has a message for his physician colleagues and their epilepsy patients. And it’s not pretty.

“Has the probability of achieving seizure freedom increased significantly in the last 3 decades? Regrettably, the answer is no,” he declared at the International Epilepsy Congress.

“Over all these years, in terms of seizure freedom there has been no real difference in outcome. There’s really quite a long way to go before we can say that we are doing all that well for people,” he said at the congress sponsored by the International League Against Epilepsy.

In the year 2000, he and his coinvestigators published a prospective, longitudinal, observational cohort study of 470 newly diagnosed patients with epilepsy treated at the Western Infirmary during 1982-1997, all with a minimum of 2 years’ follow-up. Sixty-one percent achieved complete freedom from seizures for at least 1 year on monotherapy, and another 3% did so on polytherapy, for a total rate of 64% (N Engl J Med. 2000 Feb 3;342[5]:314-19).

But these were patients who by and large were treated with older AEDs such as carbamazepine, which has since fallen by the wayside because of toxicities. Scottish neurologists now generally turn to lamotrigine (Lamictal), levetiracetam (Spritam), and other, newer AEDs. So Dr. Brodie and his coworkers recently published a follow-up study, this one featuring 30 years of longitudinal follow-up of 1,795 patients newly treated for epilepsy with AEDs, new and old, during 1982-2012. The investigators demonstrated that the seizure-free survival curves over time were virtually superimposable. In the larger, more recent study, remission was achieved in 55% of patients with AED monotherapy and in another 9% with polytherapy, for a total rate of 64%, identical to the rate in the 2000 study, and as was the case in the earlier study, 36% of patients remained uncontrolled (JAMA Neurol. 2018 Mar 1;75[3]:279-86).

“Overall, the way this population behaves, there’s no difference in efficacy and no difference in tolerability whether you’re using old drugs used properly or new drugs used properly,” said Dr. Brodie, professor of neurology at the University of Glasgow (Scotland).

It’s noteworthy that Sir William R. Gowers, the Londoner who has been called the greatest neurologist of all time, reported a 70% seizure-free rate in 1881, while Dr. Brodie and workers achieved a 64% rate in their 30-year study. “It’s interesting that the numbers are so bad, really, I suppose,” Dr. Brodie commented.

How about outcomes in pediatric epilepsy?

Dr. Brodie and coworkers recently published a 30-year prospective cohort study of 332 adolescent epilepsy patients newly diagnosed and treated at the Western Infirmary during 1982-2012. At the end of the study, 67% were seizure-free for at least the past year, a feat accomplished via monotherapy in 83% of cases. The seizure-free rate was 72% in those with generalized epilepsy, significantly better than the 60% figure in those with focal epilepsy. The efficacy rate was 74% with newer AED monotherapy and similar at 77% with monotherapy older drugs. Adverse event rates ranged from a low of 12% with lamotrigine to 56% with topiramate (Topamax), according to the findings published in Epilepsia (2019 Jun;60[6]:1083-90).

Roughly similar outcomes have been reported from Norway in a study of 600 children with epilepsy, median age 7 years, with a median follow-up of 5.8 years that is considerably shorter than that in the Glasgow pediatric study. Overall, 59% of the Norwegian children remained seizure free for at least 1 year, 30% developed drug-resistant epilepsy, and 11% followed an intermediate remitting/relapsing course (Pediatrics. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4016).

Why the decades of flat pharmacologic outcomes?

The consistently suboptimal seizure-free outcomes obtained over the past 30 years shouldn’t really be surprising, according to Dr. Brodie.

“Although we think we have lots of mechanisms of action and lots of differences between the drugs, they’re arguably all antiseizure drugs and not antiepilepsy drugs. We don’t treat the whale; we treat the spout. We don’t treat what we cannot see; we treat what we can see, which is the seizures, but we’re not influencing the long-term outcome,” the neurologist explained.

The compelling case for early epilepsy surgery

Epilepsy surgery remains underutilized, according to Dr. Brodie and other experts.

The International League Against Epilepsy defines drug-resistant epilepsy as failure to achieve sustained seizure freedom after adequate trials of two tolerated and appropriately chosen and used AED schedules. Dr. Brodie’s work was influential in creating that definition because his data demonstrated the sharply diminishing returns of additional drug trials.

“When do we consider epilepsy surgery? Arguably, the earlier, the better. After two drugs have failed appropriately, I don’t think anybody in this room would argue about that, although people in some of the other rooms might,” he said at the congress.

Influential in his thinking on this score were the impressive results of an early study, the first-ever randomized trial of surgery for epilepsy. In 80 patients with a 21-year history of drug-refractory temporal lobe epilepsy who were randomized to surgery or 1 year of AED therapy, at 1 year of follow-up blinded epileptologists rated 58% of surgically treated patients as free from seizures that impair awareness of self and surroundings, compared with just 8% in the AED group (N Engl J Med. 2001 Aug 2;345[5]:311-8).

“That’s a big outcome, and I’m very keen to ensure that my data continue to drive the push for early surgery,” according to the neurologist.

A Cochrane review of 177 studies totaling more than 16,000 patients concluded that 65% of epilepsy patients had good outcomes following surgery. Prognostic factors associated with better surgical outcomes included complete surgical resection of the epileptogenic focus, the presence of mesial temporal sclerosis, concordance of MRI and EEG findings, and an absence of cortical dysplasia (Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;6:CD010541. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010541.pub3).

In addition, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Canadian investigators found that 72% of adults with lesional epilepsy identified by MRI or histopathology were seizure-free after surgery, compared with 36% of those with nonlesional epilepsy. The disparity in outcomes was similar in pediatric epilepsy patients, with seizure freedom after surgery in 74% of those with lesional disease versus 45% with nonlesional epilepsy (Epilepsy Res. 2010 May;89[2-3]:310-8).

Whither are neurostimulatory device therapies headed?

Dr. Brodie was quick to admit that as a pharmacologic researcher, device modalities including vagus nerve stimulation, responsive neurostimulation, and deep brain stimulation are outside his area of expertise. But he’s been following developments in the field with interest.

“These device therapies have shown efficacy in short-term randomized trials, but very few patients attain long-term seizure freedom. I think these are largely palliative techniques. I gave up on these techniques a long time ago because I felt it was a very costly way of reducing seizures by a relatively small margin, and really we need to go a little bit further than that. But I know there’s a lot of work going on at the moment,” he said.

Dr. Brodie reported serving on the scientific advisory boards of more than a half dozen pharmaceutical companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM IEC 2019

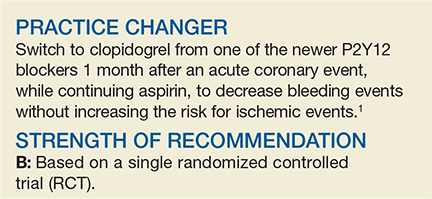

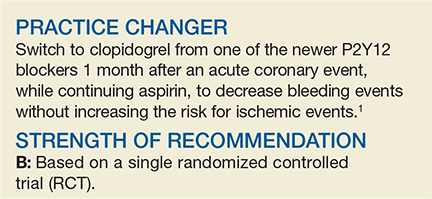

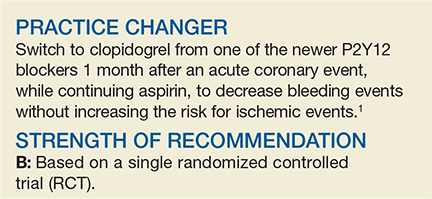

Should You Switch the DAPT Agent a Month After ACS?

A 60-year-old man visits your clinic 30 days after he was hospitalized for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) due to ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The patient underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with placement of a stent and received aspirin and a loading dose of ticagrelor for antiplatelet therapy. He was discharged on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) consisting of daily aspirin and ticagrelor. He asks about the risk for bleeding associated with these medications. Should you recommend any changes?

Platelet inhibition during and after ACS to prevent recurrent ischemic events is a cornerstone of treatment for patients after a myocardial infarction (MI).2 Current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend that patients with coronary artery disease who recently had an MI continue DAPT with aspirin and a P2Y12 blocker (clopidogrel, ticlopidine, ticagrelor, prasugrel, or cangrelor) for 12 months following ACS to reduce recurrent ischemia.2-4

Studies have shown that using the newer P2Y12 inhibitors (prasugrel and ticagrelor) after PCI leads to a significant reduction in recurrent ischemic events, compared with clopidogrel.5-7 These data prompted a guideline change recommending the use of the newer agents over clopidogrel for 12 months following PCI.2 Follow-up studies show strong evidence for the use of the newer P2Y12 agents in the first month following PCI, but they also demonstrate an increased bleeding risk in the maintenance phase (from 30 days to 12 months post-PCI).6,7 This increased risk is the basis for the study by Cuisset et al, which examined switching from a newer P2Y12 agent to clopidogrel after the initial 30-day period following PCI.

STUDY SUMMARY

Switched DAPT is superior

This open-label RCT (N = 646) evaluated changing DAPT from aspirin plus a newer P2Y12 blocker (prasugrel or ticagrelor) to a combination of aspirin and clopidogrel after the first month of DAPT post-ACS.1 Prior to PCI, patients received a loading dose of ticagrelor (180 mg) or prasugrel (60 mg). Subsequently, all patients took aspirin (75 mg/d) and either prasugrel (10 mg/d) or ticagrelor (90 mg bid) for 1 month. After 30 days, participants who had no adverse events were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to continue the aspirin and newer P2Y12 blocker regimen or switch to aspirin and clopidogrel (75 mg/d). In the following year, researchers examined the composite outcome of cardiovascular death, urgent revascularization, stroke, and major bleeding (defined by a Bleeding Academic Research Consortium [BARC] classification ≥ Type 2 at 1-year post-ACS).

Of the participants (average age, 60), 40% had a STEMI and 60% had a non-STEMI. Overall, 43% of patients were prescribed ticagrelor and 57% prasugrel. At 1 year, 86% of the switched-DAPT group and 75% of the unchanged-DAPT group were still taking their medication. The composite outcome at 1-year follow-up was lower in the switched group compared with the unchanged group (13.4% vs 26.3%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.48; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.34-0.68; number needed to treat [NNT], 8).

Bleeding events (ranging from minimal to fatal) were lower in the switched group (9.3% vs 23.5%; HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.27-0.57; NNT, 7) and events identified as BARC ≥ Type 2 (defined as needing medical treatment) were also lower in this group (4% vs 14.9%; HR, 0.30, 95% CI, 0.18-0.50; NNT, 9). There were no significant differences in reported recurrent cardiovascular ischemic events (9.3% vs 11.5%; HR, 0.80, 95% CI, 0.50-1.29).

WHAT’S NEW

Less bleeding, no increase in ischemic events

Cardiology guidelines recommend the newer P2Y12 blockers as part of DAPT after ACS, but this trial showed switching to clopidogrel for DAPT after 30 days of treatment lowers bleeding events with no difference in recurrent ischemic events.2-4

Continue to: CAVEATS

CAVEATS

Less-than-ideal study methods

In this open-label and unblinded study, the investigators adjudicating critical events were blinded to the treatment allocation. However, patients could self-report minor bleeding and medication discontinuation for which no consultation was sought. In addition, the investigators used opaque envelopes—a less-than-ideal method—to conceal allocation at enrollment.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

PCP may not change cardiologist’s prescription

Implementing this practice is facilitated by the comparatively lower cost of clopidogrel versus the newer P2Y12 blockers. However, after ACS and PCI treatment, cardiologists usually initiate antiplatelet therapy and may continue to manage patients after discharge. The primary care provider (PCP) may not be responsible for the DAPT switch initially; furthermore, ordering a switch may require coordination if the PCP is hesitant to change the cardiologist’s prescription. Lastly, guidelines currently recommend using the newer P2Y12 blockers for 12 months.2 CR

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2019. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2019;68[3]:162,164).

1. Cuisset T, Deharo P, Quilici J, et al. Benefit of switching dual antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome: the TOPIC (timing of platelet inhibition after acute coronary syndrome) randomized study. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(41):3070-3078.

2. Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(10):1082-1115.

3. Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, et al; Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(20):2569-2619.

4. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet J-P, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: task force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2015;37(3):267-315.

5. Antman EM, Wiviott SD, Murphy SA, et al. Early and late benefits of prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a TRITON-TIMI 38 (TRial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet InhibitioN with Prasugrel-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction) analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(21): 2028-2033.

6. Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(11):1045-1057.

7. Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al; TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(20):2001-2015.

A 60-year-old man visits your clinic 30 days after he was hospitalized for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) due to ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The patient underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with placement of a stent and received aspirin and a loading dose of ticagrelor for antiplatelet therapy. He was discharged on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) consisting of daily aspirin and ticagrelor. He asks about the risk for bleeding associated with these medications. Should you recommend any changes?

Platelet inhibition during and after ACS to prevent recurrent ischemic events is a cornerstone of treatment for patients after a myocardial infarction (MI).2 Current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend that patients with coronary artery disease who recently had an MI continue DAPT with aspirin and a P2Y12 blocker (clopidogrel, ticlopidine, ticagrelor, prasugrel, or cangrelor) for 12 months following ACS to reduce recurrent ischemia.2-4

Studies have shown that using the newer P2Y12 inhibitors (prasugrel and ticagrelor) after PCI leads to a significant reduction in recurrent ischemic events, compared with clopidogrel.5-7 These data prompted a guideline change recommending the use of the newer agents over clopidogrel for 12 months following PCI.2 Follow-up studies show strong evidence for the use of the newer P2Y12 agents in the first month following PCI, but they also demonstrate an increased bleeding risk in the maintenance phase (from 30 days to 12 months post-PCI).6,7 This increased risk is the basis for the study by Cuisset et al, which examined switching from a newer P2Y12 agent to clopidogrel after the initial 30-day period following PCI.

STUDY SUMMARY

Switched DAPT is superior

This open-label RCT (N = 646) evaluated changing DAPT from aspirin plus a newer P2Y12 blocker (prasugrel or ticagrelor) to a combination of aspirin and clopidogrel after the first month of DAPT post-ACS.1 Prior to PCI, patients received a loading dose of ticagrelor (180 mg) or prasugrel (60 mg). Subsequently, all patients took aspirin (75 mg/d) and either prasugrel (10 mg/d) or ticagrelor (90 mg bid) for 1 month. After 30 days, participants who had no adverse events were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to continue the aspirin and newer P2Y12 blocker regimen or switch to aspirin and clopidogrel (75 mg/d). In the following year, researchers examined the composite outcome of cardiovascular death, urgent revascularization, stroke, and major bleeding (defined by a Bleeding Academic Research Consortium [BARC] classification ≥ Type 2 at 1-year post-ACS).

Of the participants (average age, 60), 40% had a STEMI and 60% had a non-STEMI. Overall, 43% of patients were prescribed ticagrelor and 57% prasugrel. At 1 year, 86% of the switched-DAPT group and 75% of the unchanged-DAPT group were still taking their medication. The composite outcome at 1-year follow-up was lower in the switched group compared with the unchanged group (13.4% vs 26.3%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.48; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.34-0.68; number needed to treat [NNT], 8).

Bleeding events (ranging from minimal to fatal) were lower in the switched group (9.3% vs 23.5%; HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.27-0.57; NNT, 7) and events identified as BARC ≥ Type 2 (defined as needing medical treatment) were also lower in this group (4% vs 14.9%; HR, 0.30, 95% CI, 0.18-0.50; NNT, 9). There were no significant differences in reported recurrent cardiovascular ischemic events (9.3% vs 11.5%; HR, 0.80, 95% CI, 0.50-1.29).

WHAT’S NEW

Less bleeding, no increase in ischemic events

Cardiology guidelines recommend the newer P2Y12 blockers as part of DAPT after ACS, but this trial showed switching to clopidogrel for DAPT after 30 days of treatment lowers bleeding events with no difference in recurrent ischemic events.2-4

Continue to: CAVEATS

CAVEATS

Less-than-ideal study methods

In this open-label and unblinded study, the investigators adjudicating critical events were blinded to the treatment allocation. However, patients could self-report minor bleeding and medication discontinuation for which no consultation was sought. In addition, the investigators used opaque envelopes—a less-than-ideal method—to conceal allocation at enrollment.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

PCP may not change cardiologist’s prescription

Implementing this practice is facilitated by the comparatively lower cost of clopidogrel versus the newer P2Y12 blockers. However, after ACS and PCI treatment, cardiologists usually initiate antiplatelet therapy and may continue to manage patients after discharge. The primary care provider (PCP) may not be responsible for the DAPT switch initially; furthermore, ordering a switch may require coordination if the PCP is hesitant to change the cardiologist’s prescription. Lastly, guidelines currently recommend using the newer P2Y12 blockers for 12 months.2 CR

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2019. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2019;68[3]:162,164).

A 60-year-old man visits your clinic 30 days after he was hospitalized for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) due to ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The patient underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with placement of a stent and received aspirin and a loading dose of ticagrelor for antiplatelet therapy. He was discharged on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) consisting of daily aspirin and ticagrelor. He asks about the risk for bleeding associated with these medications. Should you recommend any changes?

Platelet inhibition during and after ACS to prevent recurrent ischemic events is a cornerstone of treatment for patients after a myocardial infarction (MI).2 Current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend that patients with coronary artery disease who recently had an MI continue DAPT with aspirin and a P2Y12 blocker (clopidogrel, ticlopidine, ticagrelor, prasugrel, or cangrelor) for 12 months following ACS to reduce recurrent ischemia.2-4

Studies have shown that using the newer P2Y12 inhibitors (prasugrel and ticagrelor) after PCI leads to a significant reduction in recurrent ischemic events, compared with clopidogrel.5-7 These data prompted a guideline change recommending the use of the newer agents over clopidogrel for 12 months following PCI.2 Follow-up studies show strong evidence for the use of the newer P2Y12 agents in the first month following PCI, but they also demonstrate an increased bleeding risk in the maintenance phase (from 30 days to 12 months post-PCI).6,7 This increased risk is the basis for the study by Cuisset et al, which examined switching from a newer P2Y12 agent to clopidogrel after the initial 30-day period following PCI.

STUDY SUMMARY

Switched DAPT is superior

This open-label RCT (N = 646) evaluated changing DAPT from aspirin plus a newer P2Y12 blocker (prasugrel or ticagrelor) to a combination of aspirin and clopidogrel after the first month of DAPT post-ACS.1 Prior to PCI, patients received a loading dose of ticagrelor (180 mg) or prasugrel (60 mg). Subsequently, all patients took aspirin (75 mg/d) and either prasugrel (10 mg/d) or ticagrelor (90 mg bid) for 1 month. After 30 days, participants who had no adverse events were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to continue the aspirin and newer P2Y12 blocker regimen or switch to aspirin and clopidogrel (75 mg/d). In the following year, researchers examined the composite outcome of cardiovascular death, urgent revascularization, stroke, and major bleeding (defined by a Bleeding Academic Research Consortium [BARC] classification ≥ Type 2 at 1-year post-ACS).

Of the participants (average age, 60), 40% had a STEMI and 60% had a non-STEMI. Overall, 43% of patients were prescribed ticagrelor and 57% prasugrel. At 1 year, 86% of the switched-DAPT group and 75% of the unchanged-DAPT group were still taking their medication. The composite outcome at 1-year follow-up was lower in the switched group compared with the unchanged group (13.4% vs 26.3%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.48; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.34-0.68; number needed to treat [NNT], 8).

Bleeding events (ranging from minimal to fatal) were lower in the switched group (9.3% vs 23.5%; HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.27-0.57; NNT, 7) and events identified as BARC ≥ Type 2 (defined as needing medical treatment) were also lower in this group (4% vs 14.9%; HR, 0.30, 95% CI, 0.18-0.50; NNT, 9). There were no significant differences in reported recurrent cardiovascular ischemic events (9.3% vs 11.5%; HR, 0.80, 95% CI, 0.50-1.29).

WHAT’S NEW

Less bleeding, no increase in ischemic events

Cardiology guidelines recommend the newer P2Y12 blockers as part of DAPT after ACS, but this trial showed switching to clopidogrel for DAPT after 30 days of treatment lowers bleeding events with no difference in recurrent ischemic events.2-4

Continue to: CAVEATS

CAVEATS

Less-than-ideal study methods

In this open-label and unblinded study, the investigators adjudicating critical events were blinded to the treatment allocation. However, patients could self-report minor bleeding and medication discontinuation for which no consultation was sought. In addition, the investigators used opaque envelopes—a less-than-ideal method—to conceal allocation at enrollment.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

PCP may not change cardiologist’s prescription

Implementing this practice is facilitated by the comparatively lower cost of clopidogrel versus the newer P2Y12 blockers. However, after ACS and PCI treatment, cardiologists usually initiate antiplatelet therapy and may continue to manage patients after discharge. The primary care provider (PCP) may not be responsible for the DAPT switch initially; furthermore, ordering a switch may require coordination if the PCP is hesitant to change the cardiologist’s prescription. Lastly, guidelines currently recommend using the newer P2Y12 blockers for 12 months.2 CR

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2019. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2019;68[3]:162,164).

1. Cuisset T, Deharo P, Quilici J, et al. Benefit of switching dual antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome: the TOPIC (timing of platelet inhibition after acute coronary syndrome) randomized study. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(41):3070-3078.

2. Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(10):1082-1115.

3. Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, et al; Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(20):2569-2619.

4. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet J-P, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: task force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2015;37(3):267-315.

5. Antman EM, Wiviott SD, Murphy SA, et al. Early and late benefits of prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a TRITON-TIMI 38 (TRial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet InhibitioN with Prasugrel-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction) analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(21): 2028-2033.

6. Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(11):1045-1057.

7. Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al; TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(20):2001-2015.

1. Cuisset T, Deharo P, Quilici J, et al. Benefit of switching dual antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome: the TOPIC (timing of platelet inhibition after acute coronary syndrome) randomized study. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(41):3070-3078.

2. Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(10):1082-1115.

3. Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, et al; Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(20):2569-2619.

4. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet J-P, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: task force for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2015;37(3):267-315.

5. Antman EM, Wiviott SD, Murphy SA, et al. Early and late benefits of prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a TRITON-TIMI 38 (TRial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet InhibitioN with Prasugrel-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction) analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(21): 2028-2033.

6. Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(11):1045-1057.

7. Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al; TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(20):2001-2015.

Benefit of chemo + RT for high-risk endometrial cancer increases with time

Benefits of adding chemotherapy to pelvic radiotherapy in localized high-risk endometrial cancer increase with follow-up, finds an updated analysis of the randomized PORTEC-3 trial.

The relative risk-benefit profile of chemoradiotherapy is uncertain, with some evidence suggesting it varies according to disease histology and stage, noted lead investigator Stephanie de Boer, MD, department of radiation oncology, Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, and coinvestigators.

PORTEC-3, a multicenter phase 3 trial, enrolled women who had undergone surgery for high-risk endometrial cancer: FIGO 2009 stage I, endometrioid grade 3 cancer with deep myometrial invasion, lymphovascular space invasion, or both; stage II or III disease; or stage I to III disease with serous or clear cell histology. In all, 660 women were evenly assigned to external-beam radiotherapy alone (48.6 Gy in 1.8-Gy fractions, on 5 days per week) or radiotherapy and chemotherapy (two cycles of cisplatin given during radiotherapy, followed by four cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel).

A previous analysis, at a median follow-up of 60.2 months (5.0 years), showed a significant 5-year failure-free survival benefit of chemoradiotherapy over radiotherapy (hazard ratio [HR], 0.71; P = .022) but only a trend toward an overall survival benefit (Lancet Oncol. 2018;19[3]:295-309).

The updated analysis, now at a median follow-up of 72.6 months (6.1 years), was reported in Lancet Oncology and showed that chemoradiotherapy was still significantly superior to radiotherapy alone in terms of 5-year failure-free survival (76.5% vs. 69.1%; adjusted HR, 0.70; P = .016) but was now also significantly superior in terms of 5-year overall survival (81.4% vs. 76.1%; adjusted HR, 0.70; P = .034)

The 5-year probability of distant metastasis was lower with chemoradiotherapy than with radiotherapy alone (21.4% vs. 29.1%; HR, 0.74; P = .047). The two groups did not differ significantly with respect to isolated vaginal recurrence as first site (0.3% in each group) or isolated pelvic recurrence as first site (0.9% in each group).

Only a single patient, in the chemoradiotherapy group, experienced a grade 4 adverse event (ileus or obstruction). The chemoradiotherapy and radiotherapy-only groups were similar on the rate of grade 3 adverse events (8% vs. 5%; P = .24), the most common of which was hypertension. However, the former had a higher rate of grade 2 or worse adverse events (38% vs. 23%; P = .002), such as persistent sensory neuropathy (6% vs. 0%). None of the patients died from treatment-related causes.

“Combined adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy should be discussed and recommended as a new standard of care, especially for women with stage III endometrial cancer or serous cancers, or both,” Dr. de Boer and coinvestigators maintained. “Shared decision making between doctors and their patients remains essential to weigh the costs and benefits for individual patients.

“Molecular analysis has the potential to improve risk stratification and should be used to identify subgroups that can derive the greatest benefit from chemotherapy and to select patients for targeted therapies; molecular studies on tissue samples donated by PORTEC-3 trial participants are ongoing,” they noted.

Dr. de Boer disclosed no competing interests in relation to the study. The study was supported in part by the Dutch Cancer Society, Cancer Research UK, National Health and Medical Research Council, Cancer Australia, the Italian Medicines Agency, and the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute.

SOURCE: de Boer SM et al. Lancet Oncol. 2019 July 22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30395-X.

Results of PORTEC-3 are potentially practice changing but generate several questions relevant to optimizing adjuvant therapy for high-risk endometrial cancer, Marcus Randall, MD, contends in a commentary (Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jul 22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045[19]30416-4).

One question is applicability of the findings across trial subgroups, which is still uncertain. “However, taking into account the statistical limitations of subgroup analyses, the therapeutic benefit of combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy (vs. radiotherapy alone) appeared to remain confined to patients with stage III disease and those with serous carcinomas of all stages,” he noted.

Another question is whether chemotherapy alone is sufficient. Here, results from trials conducted by the Gynecologic Oncology Group (now NRG Oncology) suggest that omitting pelvic radiotherapy increases the risk of locoregional failure, according to Dr. Randall.

A final question is whether there is a preferred approach for combining chemotherapy with radiotherapy. “Increasing evidence supports the use of upfront systemic therapy, when combined with radiotherapy, as a strategy to maximise both systemic and local control. ... Many clinicians often use this regimen as a preferred adjuvant approach in locally advanced endometrial cancer,” he noted.

“Based on outstanding work done by the PORTEC Study Group and others, we have made good progress in improving outcomes for women with high-risk and locally advanced endometrial cancers. However, we are not there yet,” Dr. Randall concludes.

Marcus Randall, MD, is with the department of radiation medicine, University of Kentucky, Lexington. He has no disclosures related to the commentary.

Results of PORTEC-3 are potentially practice changing but generate several questions relevant to optimizing adjuvant therapy for high-risk endometrial cancer, Marcus Randall, MD, contends in a commentary (Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jul 22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045[19]30416-4).

One question is applicability of the findings across trial subgroups, which is still uncertain. “However, taking into account the statistical limitations of subgroup analyses, the therapeutic benefit of combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy (vs. radiotherapy alone) appeared to remain confined to patients with stage III disease and those with serous carcinomas of all stages,” he noted.

Another question is whether chemotherapy alone is sufficient. Here, results from trials conducted by the Gynecologic Oncology Group (now NRG Oncology) suggest that omitting pelvic radiotherapy increases the risk of locoregional failure, according to Dr. Randall.

A final question is whether there is a preferred approach for combining chemotherapy with radiotherapy. “Increasing evidence supports the use of upfront systemic therapy, when combined with radiotherapy, as a strategy to maximise both systemic and local control. ... Many clinicians often use this regimen as a preferred adjuvant approach in locally advanced endometrial cancer,” he noted.

“Based on outstanding work done by the PORTEC Study Group and others, we have made good progress in improving outcomes for women with high-risk and locally advanced endometrial cancers. However, we are not there yet,” Dr. Randall concludes.

Marcus Randall, MD, is with the department of radiation medicine, University of Kentucky, Lexington. He has no disclosures related to the commentary.

Results of PORTEC-3 are potentially practice changing but generate several questions relevant to optimizing adjuvant therapy for high-risk endometrial cancer, Marcus Randall, MD, contends in a commentary (Lancet Oncol. 2019 Jul 22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045[19]30416-4).

One question is applicability of the findings across trial subgroups, which is still uncertain. “However, taking into account the statistical limitations of subgroup analyses, the therapeutic benefit of combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy (vs. radiotherapy alone) appeared to remain confined to patients with stage III disease and those with serous carcinomas of all stages,” he noted.

Another question is whether chemotherapy alone is sufficient. Here, results from trials conducted by the Gynecologic Oncology Group (now NRG Oncology) suggest that omitting pelvic radiotherapy increases the risk of locoregional failure, according to Dr. Randall.

A final question is whether there is a preferred approach for combining chemotherapy with radiotherapy. “Increasing evidence supports the use of upfront systemic therapy, when combined with radiotherapy, as a strategy to maximise both systemic and local control. ... Many clinicians often use this regimen as a preferred adjuvant approach in locally advanced endometrial cancer,” he noted.

“Based on outstanding work done by the PORTEC Study Group and others, we have made good progress in improving outcomes for women with high-risk and locally advanced endometrial cancers. However, we are not there yet,” Dr. Randall concludes.

Marcus Randall, MD, is with the department of radiation medicine, University of Kentucky, Lexington. He has no disclosures related to the commentary.

Benefits of adding chemotherapy to pelvic radiotherapy in localized high-risk endometrial cancer increase with follow-up, finds an updated analysis of the randomized PORTEC-3 trial.

The relative risk-benefit profile of chemoradiotherapy is uncertain, with some evidence suggesting it varies according to disease histology and stage, noted lead investigator Stephanie de Boer, MD, department of radiation oncology, Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, and coinvestigators.

PORTEC-3, a multicenter phase 3 trial, enrolled women who had undergone surgery for high-risk endometrial cancer: FIGO 2009 stage I, endometrioid grade 3 cancer with deep myometrial invasion, lymphovascular space invasion, or both; stage II or III disease; or stage I to III disease with serous or clear cell histology. In all, 660 women were evenly assigned to external-beam radiotherapy alone (48.6 Gy in 1.8-Gy fractions, on 5 days per week) or radiotherapy and chemotherapy (two cycles of cisplatin given during radiotherapy, followed by four cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel).

A previous analysis, at a median follow-up of 60.2 months (5.0 years), showed a significant 5-year failure-free survival benefit of chemoradiotherapy over radiotherapy (hazard ratio [HR], 0.71; P = .022) but only a trend toward an overall survival benefit (Lancet Oncol. 2018;19[3]:295-309).

The updated analysis, now at a median follow-up of 72.6 months (6.1 years), was reported in Lancet Oncology and showed that chemoradiotherapy was still significantly superior to radiotherapy alone in terms of 5-year failure-free survival (76.5% vs. 69.1%; adjusted HR, 0.70; P = .016) but was now also significantly superior in terms of 5-year overall survival (81.4% vs. 76.1%; adjusted HR, 0.70; P = .034)

The 5-year probability of distant metastasis was lower with chemoradiotherapy than with radiotherapy alone (21.4% vs. 29.1%; HR, 0.74; P = .047). The two groups did not differ significantly with respect to isolated vaginal recurrence as first site (0.3% in each group) or isolated pelvic recurrence as first site (0.9% in each group).

Only a single patient, in the chemoradiotherapy group, experienced a grade 4 adverse event (ileus or obstruction). The chemoradiotherapy and radiotherapy-only groups were similar on the rate of grade 3 adverse events (8% vs. 5%; P = .24), the most common of which was hypertension. However, the former had a higher rate of grade 2 or worse adverse events (38% vs. 23%; P = .002), such as persistent sensory neuropathy (6% vs. 0%). None of the patients died from treatment-related causes.

“Combined adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy should be discussed and recommended as a new standard of care, especially for women with stage III endometrial cancer or serous cancers, or both,” Dr. de Boer and coinvestigators maintained. “Shared decision making between doctors and their patients remains essential to weigh the costs and benefits for individual patients.

“Molecular analysis has the potential to improve risk stratification and should be used to identify subgroups that can derive the greatest benefit from chemotherapy and to select patients for targeted therapies; molecular studies on tissue samples donated by PORTEC-3 trial participants are ongoing,” they noted.

Dr. de Boer disclosed no competing interests in relation to the study. The study was supported in part by the Dutch Cancer Society, Cancer Research UK, National Health and Medical Research Council, Cancer Australia, the Italian Medicines Agency, and the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute.

SOURCE: de Boer SM et al. Lancet Oncol. 2019 July 22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30395-X.

Benefits of adding chemotherapy to pelvic radiotherapy in localized high-risk endometrial cancer increase with follow-up, finds an updated analysis of the randomized PORTEC-3 trial.

The relative risk-benefit profile of chemoradiotherapy is uncertain, with some evidence suggesting it varies according to disease histology and stage, noted lead investigator Stephanie de Boer, MD, department of radiation oncology, Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, and coinvestigators.

PORTEC-3, a multicenter phase 3 trial, enrolled women who had undergone surgery for high-risk endometrial cancer: FIGO 2009 stage I, endometrioid grade 3 cancer with deep myometrial invasion, lymphovascular space invasion, or both; stage II or III disease; or stage I to III disease with serous or clear cell histology. In all, 660 women were evenly assigned to external-beam radiotherapy alone (48.6 Gy in 1.8-Gy fractions, on 5 days per week) or radiotherapy and chemotherapy (two cycles of cisplatin given during radiotherapy, followed by four cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel).

A previous analysis, at a median follow-up of 60.2 months (5.0 years), showed a significant 5-year failure-free survival benefit of chemoradiotherapy over radiotherapy (hazard ratio [HR], 0.71; P = .022) but only a trend toward an overall survival benefit (Lancet Oncol. 2018;19[3]:295-309).

The updated analysis, now at a median follow-up of 72.6 months (6.1 years), was reported in Lancet Oncology and showed that chemoradiotherapy was still significantly superior to radiotherapy alone in terms of 5-year failure-free survival (76.5% vs. 69.1%; adjusted HR, 0.70; P = .016) but was now also significantly superior in terms of 5-year overall survival (81.4% vs. 76.1%; adjusted HR, 0.70; P = .034)

The 5-year probability of distant metastasis was lower with chemoradiotherapy than with radiotherapy alone (21.4% vs. 29.1%; HR, 0.74; P = .047). The two groups did not differ significantly with respect to isolated vaginal recurrence as first site (0.3% in each group) or isolated pelvic recurrence as first site (0.9% in each group).

Only a single patient, in the chemoradiotherapy group, experienced a grade 4 adverse event (ileus or obstruction). The chemoradiotherapy and radiotherapy-only groups were similar on the rate of grade 3 adverse events (8% vs. 5%; P = .24), the most common of which was hypertension. However, the former had a higher rate of grade 2 or worse adverse events (38% vs. 23%; P = .002), such as persistent sensory neuropathy (6% vs. 0%). None of the patients died from treatment-related causes.

“Combined adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy should be discussed and recommended as a new standard of care, especially for women with stage III endometrial cancer or serous cancers, or both,” Dr. de Boer and coinvestigators maintained. “Shared decision making between doctors and their patients remains essential to weigh the costs and benefits for individual patients.

“Molecular analysis has the potential to improve risk stratification and should be used to identify subgroups that can derive the greatest benefit from chemotherapy and to select patients for targeted therapies; molecular studies on tissue samples donated by PORTEC-3 trial participants are ongoing,” they noted.

Dr. de Boer disclosed no competing interests in relation to the study. The study was supported in part by the Dutch Cancer Society, Cancer Research UK, National Health and Medical Research Council, Cancer Australia, the Italian Medicines Agency, and the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute.

SOURCE: de Boer SM et al. Lancet Oncol. 2019 July 22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30395-X.

FROM LANCET ONCOLOGY

Commentary: Medical educators must do more to prevent physician suicides

while describing two exemplars at providing physicians with mental health support, in a recently published commentary.

“I want to call attention to the gap between what educators think and say is available, in terms of mental health support, and what trainees experience,” Dr. Poorman said in a statement on her piece in the Journal of Patient Safety and Risk Management. She shared the results of an anonymous depression survey of interns, which showed that 41.8% of participants screened positive for depression. Dr. Poorman also provided statistics on physician suicide, including that at least 66 residents killed themselves between 2000 and 2014, according to ACGME, and that another source estimated that 300-400 physician suicide deaths occur annually.

“When it comes to mental illness and suicide, we are all at risk, but we too often lacked compassion in the way we approach our colleagues. We have lacked the courage to fight the stigma that is killing us. We have not asked whether our unwillingness to reform medical training has eroded the empathy of generations of doctors. We have not done enough to fight medical boards that ask doctors about mental health diagnoses in the same way they ask if we have domestic violence charges,” wrote Dr. Poorman, who practices at a University of Washington neighborhood clinic in Kent.

“A focus on the occupational risks we face would shift us away from ‘wellness’ and ‘resilience,’ and place the onus on schools, training programs, and hospitals to do better for providers and patients,” continued Dr. Poorman, who serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

She commended Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and Stanford (Calif.) University’s divisions of general surgery for providing “rigorously confidential mental health support” through a wellness and suicide prevention program for residents and faculty, and a wellness program for residents “that emphasizes relationships, structural support, and psychological safety,” respectively. Dr. Poorman also applauded both for speaking openly about physician suicides.

SOURCE: Poorman E. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1177/2516043519866993.

This article was updated 8/5/19.

while describing two exemplars at providing physicians with mental health support, in a recently published commentary.

“I want to call attention to the gap between what educators think and say is available, in terms of mental health support, and what trainees experience,” Dr. Poorman said in a statement on her piece in the Journal of Patient Safety and Risk Management. She shared the results of an anonymous depression survey of interns, which showed that 41.8% of participants screened positive for depression. Dr. Poorman also provided statistics on physician suicide, including that at least 66 residents killed themselves between 2000 and 2014, according to ACGME, and that another source estimated that 300-400 physician suicide deaths occur annually.

“When it comes to mental illness and suicide, we are all at risk, but we too often lacked compassion in the way we approach our colleagues. We have lacked the courage to fight the stigma that is killing us. We have not asked whether our unwillingness to reform medical training has eroded the empathy of generations of doctors. We have not done enough to fight medical boards that ask doctors about mental health diagnoses in the same way they ask if we have domestic violence charges,” wrote Dr. Poorman, who practices at a University of Washington neighborhood clinic in Kent.

“A focus on the occupational risks we face would shift us away from ‘wellness’ and ‘resilience,’ and place the onus on schools, training programs, and hospitals to do better for providers and patients,” continued Dr. Poorman, who serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.

She commended Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and Stanford (Calif.) University’s divisions of general surgery for providing “rigorously confidential mental health support” through a wellness and suicide prevention program for residents and faculty, and a wellness program for residents “that emphasizes relationships, structural support, and psychological safety,” respectively. Dr. Poorman also applauded both for speaking openly about physician suicides.

SOURCE: Poorman E. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2019 Aug 5. doi: 10.1177/2516043519866993.

This article was updated 8/5/19.

while describing two exemplars at providing physicians with mental health support, in a recently published commentary.

“I want to call attention to the gap between what educators think and say is available, in terms of mental health support, and what trainees experience,” Dr. Poorman said in a statement on her piece in the Journal of Patient Safety and Risk Management. She shared the results of an anonymous depression survey of interns, which showed that 41.8% of participants screened positive for depression. Dr. Poorman also provided statistics on physician suicide, including that at least 66 residents killed themselves between 2000 and 2014, according to ACGME, and that another source estimated that 300-400 physician suicide deaths occur annually.

“When it comes to mental illness and suicide, we are all at risk, but we too often lacked compassion in the way we approach our colleagues. We have lacked the courage to fight the stigma that is killing us. We have not asked whether our unwillingness to reform medical training has eroded the empathy of generations of doctors. We have not done enough to fight medical boards that ask doctors about mental health diagnoses in the same way they ask if we have domestic violence charges,” wrote Dr. Poorman, who practices at a University of Washington neighborhood clinic in Kent.

“A focus on the occupational risks we face would shift us away from ‘wellness’ and ‘resilience,’ and place the onus on schools, training programs, and hospitals to do better for providers and patients,” continued Dr. Poorman, who serves on the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News.