User login

Why do so many women aged 65 years and older die of cervical cancer?

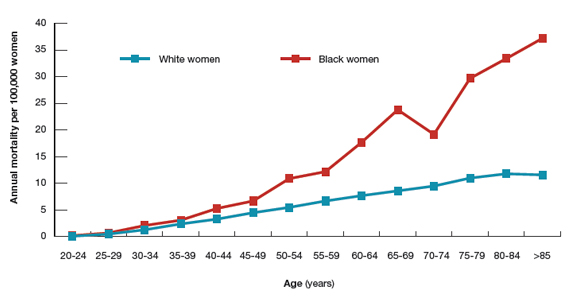

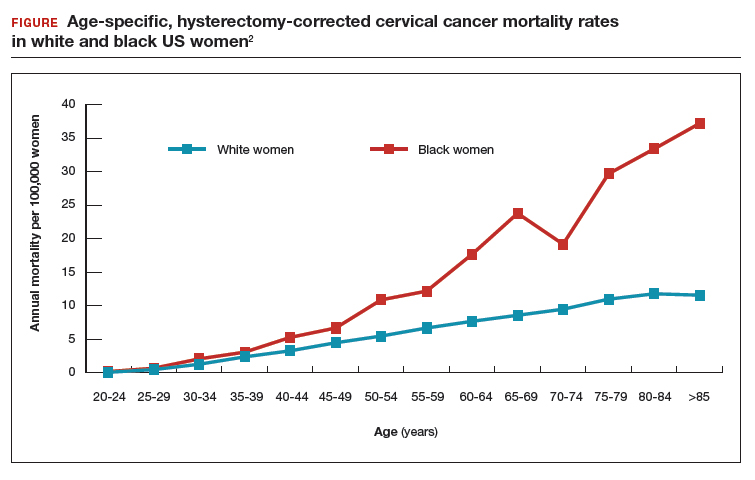

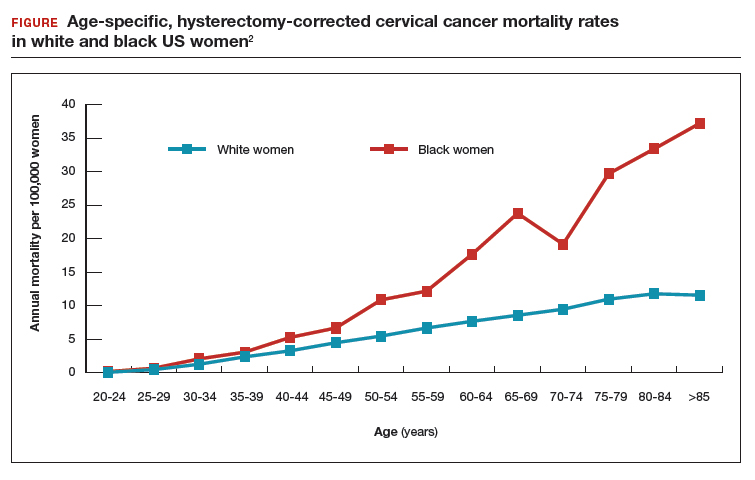

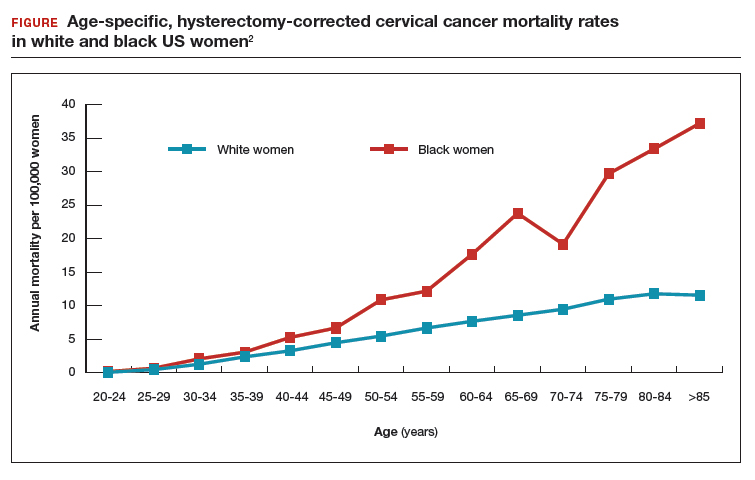

Surprisingly, the cervical cancer death rate is greater among women aged >65 years than among younger women1,2 (FIGURE). Paradoxically, most of our screening programs focus on women <65 years of age. A nationwide study from Denmark estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 3.8 and 9.0, respectively.1 In other words, the cervical cancer death rate at age 65 to 69 years was 2.36 times higher than at age 40 to 44 years.1

A study from the United States estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 white women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 3.3 and 8.6, respectively,2 very similar to the findings from Denmark. The same US study estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 black women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 5.3 and 23.8, highlighting the fact that, in the United States, cervical cancer disease burden is disproportionately greater among black than among white women.2 In addition, the cervical cancer death rate among black women at age 65 to 69 was 4.49 times higher than at age 40 to 44 years.2

Given the high death rate from cervical cancer in women >65 years of age, it is paradoxical that most professional society guidelines recommend discontinuing cervical cancer screening at 65 years of age, if previous cervical cancer screening is normal.3,4 Is the problem due to an inability to implement the current guidelines? Or is the problem that the guidelines are not optimally designed to reduce cervical cancer risk in women >65 years of age?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend against cervical cancer screening in women >65 years of age who have had adequate prior screening and are not otherwise at high risk for cervical cancer. However, ACOG and the USPSTF caution that there are many groups of women that may benefit from continued screening after 65 years of age, including women with HIV infection, a compromised immune system, or previous high-grade precancerous lesion or cervicalcancer; women with limited access to care; women from racial/ethnic minority groups; and migrant women.4 Many clinicians remember the guidance, “discontinue cervical cancer screening at 65 years” but do not recall all the clinical factors that might warrant continued screening past age 65. Of special concern is that black,2 Hispanic,5 and migrant women6 are at much higher risk for invasive cervical cancer than white or US-born women.

The optimal implementation of the ACOG and USPSTF guidelines are undermined by a fractured health care system, where key pieces of information may be unavailable to the clinician tasked with making a decision about discontinuing cervical cancer screening. Imagine the case in which a 65-year-old woman pre‑sents to her primary care physician for cervical cancer screening. The clinician performs a cervical cytology test and obtains a report of “no intraepithelial lesion or malignancy.” The clinician then recommends that the patient discontinue cervical cancer screening. Unbeknownst to the clinician, the patient had a positive HPV 16/18/45 test within the past 10 years in another health system. In this case, it would be inappropriate to terminate the patient from cervical cancer screening.

Continue to: Testing for hrHPV is superior to cervical cytology in women >65 years...

Testing for hrHPV is superior to cervical cytology in women >65 years

In Sweden, about 30% of cervical cancer cases occur in women aged >60 years.7 To assess the prevalence of oncogenic high-risk HPV (hrHPV), women at ages 60, 65, 70, and 75 years were invited to send sequential self-collected vaginal samples for nucleic acid testing for hrHPV. The prevalence of hrHPV was found to be 4.4%. Women with a second positive, self-collected, hrHPV test were invited for colposcopy, cervical biopsy, and cytology testing. Among the women with two positive hrHPV tests, cervical biopsy revealed 7 cases of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN2), 6 cases of CIN1, and 4 biopsies without CIN. In these women 94% of the cervical cytology samples returned, “no intraepithelial lesion or malignancy” and 6% revealed atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. This study suggests that, in women aged >65 years, cervical cytology may have a high rate of false-negative results, possibly due to epithelial atrophy. An evolving clinical pearl is that, when using the current cervical cancer screening guidelines, the final screen for cervical cancer must include a nucleic acid test for hrHPV.

In women 65 to 90 years, the prevalence of hrHPV is approximately 5%

In a study of 40,382 women aged 14 to 95 years, the prevalence of hrHPV was 46% in 20- to 23-year-old women and 5.7% in women older than 65 years of age.8 In a study of more than 108,000 women aged 69 to >89 years the prevalence of hrHPV was 4.3%, and similar prevalence rates were seen across all ages from 69 to >89 years.9 The carcinogenic role of persistent hrHPV infection in women >65 years is an important area for future research.

Latent HPV virus infection

Following a primary varicella-zoster infection (chickenpox), the virus may remain in a latent state in sensory ganglia, reactivating later in life to cause shingles. Thirty percent of people who have a primary chickenpox infection eventually will develop a case of shingles. Immunocompromised populations are at an increased risk of developing shingles because of reduced T-cell mediated immunity.

A recent hypothesis is that in immunocompromised and older women, latent HPV can reactivate and cause clinically significant infection.10 Following renal transplantation investigators have reported a significant increase in the prevalence of genital HPV, without a change in sexual behavior.11 In cervical tissue from women with no evidence of active HPV infection, highly sensitive PCR-based assays detected HPV16 virus in a latent state in some women, possibly due to disruption of the viral E2 gene.12 If latent HPV infection is a valid biological concept, it suggests that there is no “safe age” at which to discontinue screening for HPV infection because the virus cannot be detected in screening samples while it is latent.

Options for cervical cancer screening in women >65 years

Three options might reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with cervical cancer in women >65 years.

Option 1: Double-down on trying to effectively implement current guidelines. The high rate of cervical cancer mortality in women >65 years of age indicates that the current guidelines, as implemented in real clinical practice, are not working. A problem with the current screening guidelines is that clinicians are expected to be capable of finding all relevant cervical cancer test results and properly interpreting the results. Clinicians are over-taxed and fallible, and the current approach is not likely to be successful unless additional information technology solutions are implemented.

Continue to: Health systems could use information...

Health systems could use information technology to mitigate these problems. For example, health systems could deploy software to assemble every cervical screening result on each woman and pre‑sent those results to clinicians in a single integrated view in the electronic record. Additionally, once all lifetime screening results are consolidated in one view, artificial intelligence systems could be used to analyze the totality of results and identify women who would benefit by continued screening past age 65 and women who could safely discontinue screening.

Option 2: Adopt the Australian approach to cervical cancer screening. The current Australian approach to cervical cancer screening is built on 3 pillars: 1) school-based vaccination of all children against hrHPV, 2) screening all women from 25 to 74 years of age every 5 years using nucleic acid testing for hrHPV, and 3) providing a system for the testing of samples self-collected by women who are reluctant to visit a clinician for screening.13 Australia has one of the lowest cervical cancer death rates in the world.

Option 3: Continue screening most women past age 65. Women >65 years of age are known to be infected with hrHPV genotypes. hrHPV infection causes cervical cancer. Cervical cancer causes many deaths in women aged >65 years. There is no strong rationale for ignoring these three facts. hrHPV screening every 5 years as long as the woman is healthy and has a reasonable life expectancy is an option that could be evaluated in randomized studies.

Given the high rate of cervical cancer death in women >65 years of age, I plan to be very cautious about discontinuing cervical cancer screening until I can personally ensure that my patient has no evidence of hrHPV infection.

In 2008, Harald zur Hausen, MD, received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering that human papilloma virus (HPV) caused cervical cancer. In a recent study, 74% of cervical cancers were associated with HPV 16 or 18 infections. A total of 89% of the cancers were associated with one of the high-risk HPV genotypes, including HPV 16/18/31/33/45/52/58.1

Recently, HPV has been shown to be a major cause of oropharyngeal cancer. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calculated that in CY2015 in the United States there were 18,917 cases of HPV-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer and 11,788 cases of cervical cancer.2 Most cases of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer occur in men, and HPV vaccination of boys may help to prevent this cancer type. Oncogenic HPV produce two proteins (E6 and E7) that promote viral replication and squamous cell growth by inhibiting the function of p53 and retinoblastoma protein. The immortalized HeLa cell line, derived from Ms. Henrietta Lack's cervical cancer, contains integrated HPV18 nucleic acid sequences.3,4

The discovery that HPV causes cancer catalyzed the development of nucleic acid tests to identify high-risk oncogenic HPV and vaccines against high-risk oncogenic HPV genotypes that prevent cervical cancer. From a public health perspective, it is more effective to vaccinate the population against oncogenic HPV genotypes than to screen and treat cancer. In the United States, vaccination rates range from a high of 92% (District of Columbia) and 89% (Rhode Island) to a low of 47% (Wyoming) and 50% (Kentucky and Mississippi).5 To reduce HPV-associated cancer mortality, the gap in vaccination compliance must be closed.

References

- Kjaer SK, Munk C, Junge J, et al. Carcinogenic HPV prevalence and age-specific type distribution in 40,382 women with normal cervical cytology, ACSUC/LSIL, HSIL, or cervical cancer: what is the potential for prevention? Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:179-189.

- Van Dyne EA, Henley SJ, Saraiya M, et al. Trends in human papillomavirus-associated cancers - United States, 1999-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:918-924.

- Rosl F, Westphal EM, zur Hausen H. Chromatin structure and transcriptional regulation of human papillomavirus type 18 DNA in HeLa cells. Mol Carcinog. 1989;2:72-80.

- Adey A, Burton JN, Kitzman, et al. The haplotype-resolved genome and epigenome of the aneuploid HeLa cancer cell line. Nature. 2013;500:207-211.

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:874-882.

- Hammer A, Kahlert J, Gravitt PE, et al. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates in Denmark during 2002-2015: a registry-based cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98:1063-1069.

- Beavis AL, Gravitt PE, Rositch AF. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates reveal a larger racial disparity in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123:1044-1050.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins--Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 168: cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e111-30.

- Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

- Stang A, Hawk H, Knowlton R, et al. Hysterectomy-corrected incidence rates of cervical and uterine cancers in Massachusetts, 1995-2010. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24:849-854.

- Hallowell BD, Endeshaw M, McKenna MT, et al. Cervical cancer death rates among U.S.- and foreign-born women: U.S., 2005-2014. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56:869-874.

- Lindström AK, Hermansson RS, Gustavsson I, et al. Cervical dysplasia in elderly women performing repeated self-sampling for HPV testing. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207714.

- Kjaer SK, Munk C, Junge J, et al. Carcinogenic HPV prevalence and age-specific type distribution in 40,382 women with normal cervical cytology, ACSUC/LSIL, HSIL, or cervical cancer: what is the potential for prevention? Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:179-189.

- Andersen B, Christensen BS, Christensen J, et al. HPV-prevalence in elderly women in Denmark. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;154:118-123.

- Gravitt PE, Winer RL. Natural history of HPV infection across the lifespan: role of viral latency. Viruses. 2017;9:E267.

- Hinten F, Hilbrands LB, Meeuwis KAP, et al. Reactivation of latent HPV infections after renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:1563-1573.

- Leonard SM, Pereira M, Roberts S, et al. Evidence of disrupted high-risk human papillomavirus DNA in morphologically normal cervices of older women. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20847.

- Cervical cancer screening. Cancer Council website. https://www.cancer.org.au/about-cancer/early-detection/screening-programs/cervical-cancer-screening.html. Updated March 15, 2019. Accessed July 23, 2019.

Surprisingly, the cervical cancer death rate is greater among women aged >65 years than among younger women1,2 (FIGURE). Paradoxically, most of our screening programs focus on women <65 years of age. A nationwide study from Denmark estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 3.8 and 9.0, respectively.1 In other words, the cervical cancer death rate at age 65 to 69 years was 2.36 times higher than at age 40 to 44 years.1

A study from the United States estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 white women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 3.3 and 8.6, respectively,2 very similar to the findings from Denmark. The same US study estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 black women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 5.3 and 23.8, highlighting the fact that, in the United States, cervical cancer disease burden is disproportionately greater among black than among white women.2 In addition, the cervical cancer death rate among black women at age 65 to 69 was 4.49 times higher than at age 40 to 44 years.2

Given the high death rate from cervical cancer in women >65 years of age, it is paradoxical that most professional society guidelines recommend discontinuing cervical cancer screening at 65 years of age, if previous cervical cancer screening is normal.3,4 Is the problem due to an inability to implement the current guidelines? Or is the problem that the guidelines are not optimally designed to reduce cervical cancer risk in women >65 years of age?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend against cervical cancer screening in women >65 years of age who have had adequate prior screening and are not otherwise at high risk for cervical cancer. However, ACOG and the USPSTF caution that there are many groups of women that may benefit from continued screening after 65 years of age, including women with HIV infection, a compromised immune system, or previous high-grade precancerous lesion or cervicalcancer; women with limited access to care; women from racial/ethnic minority groups; and migrant women.4 Many clinicians remember the guidance, “discontinue cervical cancer screening at 65 years” but do not recall all the clinical factors that might warrant continued screening past age 65. Of special concern is that black,2 Hispanic,5 and migrant women6 are at much higher risk for invasive cervical cancer than white or US-born women.

The optimal implementation of the ACOG and USPSTF guidelines are undermined by a fractured health care system, where key pieces of information may be unavailable to the clinician tasked with making a decision about discontinuing cervical cancer screening. Imagine the case in which a 65-year-old woman pre‑sents to her primary care physician for cervical cancer screening. The clinician performs a cervical cytology test and obtains a report of “no intraepithelial lesion or malignancy.” The clinician then recommends that the patient discontinue cervical cancer screening. Unbeknownst to the clinician, the patient had a positive HPV 16/18/45 test within the past 10 years in another health system. In this case, it would be inappropriate to terminate the patient from cervical cancer screening.

Continue to: Testing for hrHPV is superior to cervical cytology in women >65 years...

Testing for hrHPV is superior to cervical cytology in women >65 years

In Sweden, about 30% of cervical cancer cases occur in women aged >60 years.7 To assess the prevalence of oncogenic high-risk HPV (hrHPV), women at ages 60, 65, 70, and 75 years were invited to send sequential self-collected vaginal samples for nucleic acid testing for hrHPV. The prevalence of hrHPV was found to be 4.4%. Women with a second positive, self-collected, hrHPV test were invited for colposcopy, cervical biopsy, and cytology testing. Among the women with two positive hrHPV tests, cervical biopsy revealed 7 cases of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN2), 6 cases of CIN1, and 4 biopsies without CIN. In these women 94% of the cervical cytology samples returned, “no intraepithelial lesion or malignancy” and 6% revealed atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. This study suggests that, in women aged >65 years, cervical cytology may have a high rate of false-negative results, possibly due to epithelial atrophy. An evolving clinical pearl is that, when using the current cervical cancer screening guidelines, the final screen for cervical cancer must include a nucleic acid test for hrHPV.

In women 65 to 90 years, the prevalence of hrHPV is approximately 5%

In a study of 40,382 women aged 14 to 95 years, the prevalence of hrHPV was 46% in 20- to 23-year-old women and 5.7% in women older than 65 years of age.8 In a study of more than 108,000 women aged 69 to >89 years the prevalence of hrHPV was 4.3%, and similar prevalence rates were seen across all ages from 69 to >89 years.9 The carcinogenic role of persistent hrHPV infection in women >65 years is an important area for future research.

Latent HPV virus infection

Following a primary varicella-zoster infection (chickenpox), the virus may remain in a latent state in sensory ganglia, reactivating later in life to cause shingles. Thirty percent of people who have a primary chickenpox infection eventually will develop a case of shingles. Immunocompromised populations are at an increased risk of developing shingles because of reduced T-cell mediated immunity.

A recent hypothesis is that in immunocompromised and older women, latent HPV can reactivate and cause clinically significant infection.10 Following renal transplantation investigators have reported a significant increase in the prevalence of genital HPV, without a change in sexual behavior.11 In cervical tissue from women with no evidence of active HPV infection, highly sensitive PCR-based assays detected HPV16 virus in a latent state in some women, possibly due to disruption of the viral E2 gene.12 If latent HPV infection is a valid biological concept, it suggests that there is no “safe age” at which to discontinue screening for HPV infection because the virus cannot be detected in screening samples while it is latent.

Options for cervical cancer screening in women >65 years

Three options might reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with cervical cancer in women >65 years.

Option 1: Double-down on trying to effectively implement current guidelines. The high rate of cervical cancer mortality in women >65 years of age indicates that the current guidelines, as implemented in real clinical practice, are not working. A problem with the current screening guidelines is that clinicians are expected to be capable of finding all relevant cervical cancer test results and properly interpreting the results. Clinicians are over-taxed and fallible, and the current approach is not likely to be successful unless additional information technology solutions are implemented.

Continue to: Health systems could use information...

Health systems could use information technology to mitigate these problems. For example, health systems could deploy software to assemble every cervical screening result on each woman and pre‑sent those results to clinicians in a single integrated view in the electronic record. Additionally, once all lifetime screening results are consolidated in one view, artificial intelligence systems could be used to analyze the totality of results and identify women who would benefit by continued screening past age 65 and women who could safely discontinue screening.

Option 2: Adopt the Australian approach to cervical cancer screening. The current Australian approach to cervical cancer screening is built on 3 pillars: 1) school-based vaccination of all children against hrHPV, 2) screening all women from 25 to 74 years of age every 5 years using nucleic acid testing for hrHPV, and 3) providing a system for the testing of samples self-collected by women who are reluctant to visit a clinician for screening.13 Australia has one of the lowest cervical cancer death rates in the world.

Option 3: Continue screening most women past age 65. Women >65 years of age are known to be infected with hrHPV genotypes. hrHPV infection causes cervical cancer. Cervical cancer causes many deaths in women aged >65 years. There is no strong rationale for ignoring these three facts. hrHPV screening every 5 years as long as the woman is healthy and has a reasonable life expectancy is an option that could be evaluated in randomized studies.

Given the high rate of cervical cancer death in women >65 years of age, I plan to be very cautious about discontinuing cervical cancer screening until I can personally ensure that my patient has no evidence of hrHPV infection.

In 2008, Harald zur Hausen, MD, received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering that human papilloma virus (HPV) caused cervical cancer. In a recent study, 74% of cervical cancers were associated with HPV 16 or 18 infections. A total of 89% of the cancers were associated with one of the high-risk HPV genotypes, including HPV 16/18/31/33/45/52/58.1

Recently, HPV has been shown to be a major cause of oropharyngeal cancer. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calculated that in CY2015 in the United States there were 18,917 cases of HPV-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer and 11,788 cases of cervical cancer.2 Most cases of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer occur in men, and HPV vaccination of boys may help to prevent this cancer type. Oncogenic HPV produce two proteins (E6 and E7) that promote viral replication and squamous cell growth by inhibiting the function of p53 and retinoblastoma protein. The immortalized HeLa cell line, derived from Ms. Henrietta Lack's cervical cancer, contains integrated HPV18 nucleic acid sequences.3,4

The discovery that HPV causes cancer catalyzed the development of nucleic acid tests to identify high-risk oncogenic HPV and vaccines against high-risk oncogenic HPV genotypes that prevent cervical cancer. From a public health perspective, it is more effective to vaccinate the population against oncogenic HPV genotypes than to screen and treat cancer. In the United States, vaccination rates range from a high of 92% (District of Columbia) and 89% (Rhode Island) to a low of 47% (Wyoming) and 50% (Kentucky and Mississippi).5 To reduce HPV-associated cancer mortality, the gap in vaccination compliance must be closed.

References

- Kjaer SK, Munk C, Junge J, et al. Carcinogenic HPV prevalence and age-specific type distribution in 40,382 women with normal cervical cytology, ACSUC/LSIL, HSIL, or cervical cancer: what is the potential for prevention? Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:179-189.

- Van Dyne EA, Henley SJ, Saraiya M, et al. Trends in human papillomavirus-associated cancers - United States, 1999-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:918-924.

- Rosl F, Westphal EM, zur Hausen H. Chromatin structure and transcriptional regulation of human papillomavirus type 18 DNA in HeLa cells. Mol Carcinog. 1989;2:72-80.

- Adey A, Burton JN, Kitzman, et al. The haplotype-resolved genome and epigenome of the aneuploid HeLa cancer cell line. Nature. 2013;500:207-211.

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:874-882.

Surprisingly, the cervical cancer death rate is greater among women aged >65 years than among younger women1,2 (FIGURE). Paradoxically, most of our screening programs focus on women <65 years of age. A nationwide study from Denmark estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 3.8 and 9.0, respectively.1 In other words, the cervical cancer death rate at age 65 to 69 years was 2.36 times higher than at age 40 to 44 years.1

A study from the United States estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 white women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 3.3 and 8.6, respectively,2 very similar to the findings from Denmark. The same US study estimated that the cervical cancer death rate per 100,000 black women at ages 40 to 44 and 65 to 69 was 5.3 and 23.8, highlighting the fact that, in the United States, cervical cancer disease burden is disproportionately greater among black than among white women.2 In addition, the cervical cancer death rate among black women at age 65 to 69 was 4.49 times higher than at age 40 to 44 years.2

Given the high death rate from cervical cancer in women >65 years of age, it is paradoxical that most professional society guidelines recommend discontinuing cervical cancer screening at 65 years of age, if previous cervical cancer screening is normal.3,4 Is the problem due to an inability to implement the current guidelines? Or is the problem that the guidelines are not optimally designed to reduce cervical cancer risk in women >65 years of age?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend against cervical cancer screening in women >65 years of age who have had adequate prior screening and are not otherwise at high risk for cervical cancer. However, ACOG and the USPSTF caution that there are many groups of women that may benefit from continued screening after 65 years of age, including women with HIV infection, a compromised immune system, or previous high-grade precancerous lesion or cervicalcancer; women with limited access to care; women from racial/ethnic minority groups; and migrant women.4 Many clinicians remember the guidance, “discontinue cervical cancer screening at 65 years” but do not recall all the clinical factors that might warrant continued screening past age 65. Of special concern is that black,2 Hispanic,5 and migrant women6 are at much higher risk for invasive cervical cancer than white or US-born women.

The optimal implementation of the ACOG and USPSTF guidelines are undermined by a fractured health care system, where key pieces of information may be unavailable to the clinician tasked with making a decision about discontinuing cervical cancer screening. Imagine the case in which a 65-year-old woman pre‑sents to her primary care physician for cervical cancer screening. The clinician performs a cervical cytology test and obtains a report of “no intraepithelial lesion or malignancy.” The clinician then recommends that the patient discontinue cervical cancer screening. Unbeknownst to the clinician, the patient had a positive HPV 16/18/45 test within the past 10 years in another health system. In this case, it would be inappropriate to terminate the patient from cervical cancer screening.

Continue to: Testing for hrHPV is superior to cervical cytology in women >65 years...

Testing for hrHPV is superior to cervical cytology in women >65 years

In Sweden, about 30% of cervical cancer cases occur in women aged >60 years.7 To assess the prevalence of oncogenic high-risk HPV (hrHPV), women at ages 60, 65, 70, and 75 years were invited to send sequential self-collected vaginal samples for nucleic acid testing for hrHPV. The prevalence of hrHPV was found to be 4.4%. Women with a second positive, self-collected, hrHPV test were invited for colposcopy, cervical biopsy, and cytology testing. Among the women with two positive hrHPV tests, cervical biopsy revealed 7 cases of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN2), 6 cases of CIN1, and 4 biopsies without CIN. In these women 94% of the cervical cytology samples returned, “no intraepithelial lesion or malignancy” and 6% revealed atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. This study suggests that, in women aged >65 years, cervical cytology may have a high rate of false-negative results, possibly due to epithelial atrophy. An evolving clinical pearl is that, when using the current cervical cancer screening guidelines, the final screen for cervical cancer must include a nucleic acid test for hrHPV.

In women 65 to 90 years, the prevalence of hrHPV is approximately 5%

In a study of 40,382 women aged 14 to 95 years, the prevalence of hrHPV was 46% in 20- to 23-year-old women and 5.7% in women older than 65 years of age.8 In a study of more than 108,000 women aged 69 to >89 years the prevalence of hrHPV was 4.3%, and similar prevalence rates were seen across all ages from 69 to >89 years.9 The carcinogenic role of persistent hrHPV infection in women >65 years is an important area for future research.

Latent HPV virus infection

Following a primary varicella-zoster infection (chickenpox), the virus may remain in a latent state in sensory ganglia, reactivating later in life to cause shingles. Thirty percent of people who have a primary chickenpox infection eventually will develop a case of shingles. Immunocompromised populations are at an increased risk of developing shingles because of reduced T-cell mediated immunity.

A recent hypothesis is that in immunocompromised and older women, latent HPV can reactivate and cause clinically significant infection.10 Following renal transplantation investigators have reported a significant increase in the prevalence of genital HPV, without a change in sexual behavior.11 In cervical tissue from women with no evidence of active HPV infection, highly sensitive PCR-based assays detected HPV16 virus in a latent state in some women, possibly due to disruption of the viral E2 gene.12 If latent HPV infection is a valid biological concept, it suggests that there is no “safe age” at which to discontinue screening for HPV infection because the virus cannot be detected in screening samples while it is latent.

Options for cervical cancer screening in women >65 years

Three options might reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with cervical cancer in women >65 years.

Option 1: Double-down on trying to effectively implement current guidelines. The high rate of cervical cancer mortality in women >65 years of age indicates that the current guidelines, as implemented in real clinical practice, are not working. A problem with the current screening guidelines is that clinicians are expected to be capable of finding all relevant cervical cancer test results and properly interpreting the results. Clinicians are over-taxed and fallible, and the current approach is not likely to be successful unless additional information technology solutions are implemented.

Continue to: Health systems could use information...

Health systems could use information technology to mitigate these problems. For example, health systems could deploy software to assemble every cervical screening result on each woman and pre‑sent those results to clinicians in a single integrated view in the electronic record. Additionally, once all lifetime screening results are consolidated in one view, artificial intelligence systems could be used to analyze the totality of results and identify women who would benefit by continued screening past age 65 and women who could safely discontinue screening.

Option 2: Adopt the Australian approach to cervical cancer screening. The current Australian approach to cervical cancer screening is built on 3 pillars: 1) school-based vaccination of all children against hrHPV, 2) screening all women from 25 to 74 years of age every 5 years using nucleic acid testing for hrHPV, and 3) providing a system for the testing of samples self-collected by women who are reluctant to visit a clinician for screening.13 Australia has one of the lowest cervical cancer death rates in the world.

Option 3: Continue screening most women past age 65. Women >65 years of age are known to be infected with hrHPV genotypes. hrHPV infection causes cervical cancer. Cervical cancer causes many deaths in women aged >65 years. There is no strong rationale for ignoring these three facts. hrHPV screening every 5 years as long as the woman is healthy and has a reasonable life expectancy is an option that could be evaluated in randomized studies.

Given the high rate of cervical cancer death in women >65 years of age, I plan to be very cautious about discontinuing cervical cancer screening until I can personally ensure that my patient has no evidence of hrHPV infection.

In 2008, Harald zur Hausen, MD, received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering that human papilloma virus (HPV) caused cervical cancer. In a recent study, 74% of cervical cancers were associated with HPV 16 or 18 infections. A total of 89% of the cancers were associated with one of the high-risk HPV genotypes, including HPV 16/18/31/33/45/52/58.1

Recently, HPV has been shown to be a major cause of oropharyngeal cancer. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calculated that in CY2015 in the United States there were 18,917 cases of HPV-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer and 11,788 cases of cervical cancer.2 Most cases of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer occur in men, and HPV vaccination of boys may help to prevent this cancer type. Oncogenic HPV produce two proteins (E6 and E7) that promote viral replication and squamous cell growth by inhibiting the function of p53 and retinoblastoma protein. The immortalized HeLa cell line, derived from Ms. Henrietta Lack's cervical cancer, contains integrated HPV18 nucleic acid sequences.3,4

The discovery that HPV causes cancer catalyzed the development of nucleic acid tests to identify high-risk oncogenic HPV and vaccines against high-risk oncogenic HPV genotypes that prevent cervical cancer. From a public health perspective, it is more effective to vaccinate the population against oncogenic HPV genotypes than to screen and treat cancer. In the United States, vaccination rates range from a high of 92% (District of Columbia) and 89% (Rhode Island) to a low of 47% (Wyoming) and 50% (Kentucky and Mississippi).5 To reduce HPV-associated cancer mortality, the gap in vaccination compliance must be closed.

References

- Kjaer SK, Munk C, Junge J, et al. Carcinogenic HPV prevalence and age-specific type distribution in 40,382 women with normal cervical cytology, ACSUC/LSIL, HSIL, or cervical cancer: what is the potential for prevention? Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:179-189.

- Van Dyne EA, Henley SJ, Saraiya M, et al. Trends in human papillomavirus-associated cancers - United States, 1999-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:918-924.

- Rosl F, Westphal EM, zur Hausen H. Chromatin structure and transcriptional regulation of human papillomavirus type 18 DNA in HeLa cells. Mol Carcinog. 1989;2:72-80.

- Adey A, Burton JN, Kitzman, et al. The haplotype-resolved genome and epigenome of the aneuploid HeLa cancer cell line. Nature. 2013;500:207-211.

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:874-882.

- Hammer A, Kahlert J, Gravitt PE, et al. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates in Denmark during 2002-2015: a registry-based cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98:1063-1069.

- Beavis AL, Gravitt PE, Rositch AF. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates reveal a larger racial disparity in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123:1044-1050.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins--Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 168: cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e111-30.

- Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

- Stang A, Hawk H, Knowlton R, et al. Hysterectomy-corrected incidence rates of cervical and uterine cancers in Massachusetts, 1995-2010. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24:849-854.

- Hallowell BD, Endeshaw M, McKenna MT, et al. Cervical cancer death rates among U.S.- and foreign-born women: U.S., 2005-2014. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56:869-874.

- Lindström AK, Hermansson RS, Gustavsson I, et al. Cervical dysplasia in elderly women performing repeated self-sampling for HPV testing. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207714.

- Kjaer SK, Munk C, Junge J, et al. Carcinogenic HPV prevalence and age-specific type distribution in 40,382 women with normal cervical cytology, ACSUC/LSIL, HSIL, or cervical cancer: what is the potential for prevention? Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:179-189.

- Andersen B, Christensen BS, Christensen J, et al. HPV-prevalence in elderly women in Denmark. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;154:118-123.

- Gravitt PE, Winer RL. Natural history of HPV infection across the lifespan: role of viral latency. Viruses. 2017;9:E267.

- Hinten F, Hilbrands LB, Meeuwis KAP, et al. Reactivation of latent HPV infections after renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:1563-1573.

- Leonard SM, Pereira M, Roberts S, et al. Evidence of disrupted high-risk human papillomavirus DNA in morphologically normal cervices of older women. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20847.

- Cervical cancer screening. Cancer Council website. https://www.cancer.org.au/about-cancer/early-detection/screening-programs/cervical-cancer-screening.html. Updated March 15, 2019. Accessed July 23, 2019.

- Hammer A, Kahlert J, Gravitt PE, et al. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates in Denmark during 2002-2015: a registry-based cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98:1063-1069.

- Beavis AL, Gravitt PE, Rositch AF. Hysterectomy-corrected cervical cancer mortality rates reveal a larger racial disparity in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123:1044-1050.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins--Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 168: cervical cancer screening and prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e111-30.

- Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

- Stang A, Hawk H, Knowlton R, et al. Hysterectomy-corrected incidence rates of cervical and uterine cancers in Massachusetts, 1995-2010. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24:849-854.

- Hallowell BD, Endeshaw M, McKenna MT, et al. Cervical cancer death rates among U.S.- and foreign-born women: U.S., 2005-2014. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56:869-874.

- Lindström AK, Hermansson RS, Gustavsson I, et al. Cervical dysplasia in elderly women performing repeated self-sampling for HPV testing. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207714.

- Kjaer SK, Munk C, Junge J, et al. Carcinogenic HPV prevalence and age-specific type distribution in 40,382 women with normal cervical cytology, ACSUC/LSIL, HSIL, or cervical cancer: what is the potential for prevention? Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:179-189.

- Andersen B, Christensen BS, Christensen J, et al. HPV-prevalence in elderly women in Denmark. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;154:118-123.

- Gravitt PE, Winer RL. Natural history of HPV infection across the lifespan: role of viral latency. Viruses. 2017;9:E267.

- Hinten F, Hilbrands LB, Meeuwis KAP, et al. Reactivation of latent HPV infections after renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:1563-1573.

- Leonard SM, Pereira M, Roberts S, et al. Evidence of disrupted high-risk human papillomavirus DNA in morphologically normal cervices of older women. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20847.

- Cervical cancer screening. Cancer Council website. https://www.cancer.org.au/about-cancer/early-detection/screening-programs/cervical-cancer-screening.html. Updated March 15, 2019. Accessed July 23, 2019.

August 2019 - Quick Quiz Question 2

Q2. Correct answer: E

Rationale:

Radiographic evaluation is commonly employed in the diagnosis and management of patients with lower GI bleeding. CT scans, tagged red blood cell scintigraphy, and angiography all have roles in the care of these patients. Though tagged red blood cell scintigraphy is the most sensitive modality at detecting active bleeding, requiring rates from 0.05-0.1 cc/min, it is relatively poor at localizing the bleeding, accurately predicting the location in only 60%-70% of cases. CT scans have the advantage of being quickly performed and are widely available. If extravasation is seen, its location is also accurately determined. It is not as sensitive as red blood cell scintigraphy, however, and requires bleeding rates of 0.3-0.5 cc/min to be positive. Angiography has the advantage of being both diagnostic and potentially therapeutic. It is best performed in sicker patients with hypotension and high transfusion demands as it is higher yield in these situations. Angiography is the least sensitive of these modalities, requiring bleeding rates between 0.5 and 1 cc/min to be positive.

Reference:

1. Strate LL, Naumann CR. The role of colonoscopy and radiological procedures in the management of acute lower intestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Apr;8(4):333-43.

Q2. Correct answer: E

Rationale:

Radiographic evaluation is commonly employed in the diagnosis and management of patients with lower GI bleeding. CT scans, tagged red blood cell scintigraphy, and angiography all have roles in the care of these patients. Though tagged red blood cell scintigraphy is the most sensitive modality at detecting active bleeding, requiring rates from 0.05-0.1 cc/min, it is relatively poor at localizing the bleeding, accurately predicting the location in only 60%-70% of cases. CT scans have the advantage of being quickly performed and are widely available. If extravasation is seen, its location is also accurately determined. It is not as sensitive as red blood cell scintigraphy, however, and requires bleeding rates of 0.3-0.5 cc/min to be positive. Angiography has the advantage of being both diagnostic and potentially therapeutic. It is best performed in sicker patients with hypotension and high transfusion demands as it is higher yield in these situations. Angiography is the least sensitive of these modalities, requiring bleeding rates between 0.5 and 1 cc/min to be positive.

Reference:

1. Strate LL, Naumann CR. The role of colonoscopy and radiological procedures in the management of acute lower intestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Apr;8(4):333-43.

Q2. Correct answer: E

Rationale:

Radiographic evaluation is commonly employed in the diagnosis and management of patients with lower GI bleeding. CT scans, tagged red blood cell scintigraphy, and angiography all have roles in the care of these patients. Though tagged red blood cell scintigraphy is the most sensitive modality at detecting active bleeding, requiring rates from 0.05-0.1 cc/min, it is relatively poor at localizing the bleeding, accurately predicting the location in only 60%-70% of cases. CT scans have the advantage of being quickly performed and are widely available. If extravasation is seen, its location is also accurately determined. It is not as sensitive as red blood cell scintigraphy, however, and requires bleeding rates of 0.3-0.5 cc/min to be positive. Angiography has the advantage of being both diagnostic and potentially therapeutic. It is best performed in sicker patients with hypotension and high transfusion demands as it is higher yield in these situations. Angiography is the least sensitive of these modalities, requiring bleeding rates between 0.5 and 1 cc/min to be positive.

Reference:

1. Strate LL, Naumann CR. The role of colonoscopy and radiological procedures in the management of acute lower intestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010 Apr;8(4):333-43.

Q2:

August 2019 - Question 1

Q1. Correct answer: C

Rationale:

The two standard treatment regimens for AIH include corticosteroids (prednisone or prednisolone) alone, or corticosteroids combined with azathioprine. The combination regimen allows for a lower dose of steroids and fewer side effects with the same therapeutic efficacy. This patient appears to have developed azathioprine-induced pancreatitis, which is a rare complication more often seen in patients with Crohn's disease treated with azathioprine. In patients who are intolerant of azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil and calcineurin inhibitors have been used with success.

There are data supporting the use of budesonide in place of prednisone, but this regimen is not as effective in patients with cirrhosis or advanced fibrosis, so it is reserved for patients with lesser degrees of liver fibrosis. The TNF-alpha inhibitors are not used to treat AIH, nor is the IL-1 inhibitor anakinra.

References:

1. Czaja AJ. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis: Current status and future directions. Gut Liver. 2016;10:177-203.

2. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune Hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015:63:971-1004.

3. Manns MP, et al. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:1-31.

Q1. Correct answer: C

Rationale:

The two standard treatment regimens for AIH include corticosteroids (prednisone or prednisolone) alone, or corticosteroids combined with azathioprine. The combination regimen allows for a lower dose of steroids and fewer side effects with the same therapeutic efficacy. This patient appears to have developed azathioprine-induced pancreatitis, which is a rare complication more often seen in patients with Crohn's disease treated with azathioprine. In patients who are intolerant of azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil and calcineurin inhibitors have been used with success.

There are data supporting the use of budesonide in place of prednisone, but this regimen is not as effective in patients with cirrhosis or advanced fibrosis, so it is reserved for patients with lesser degrees of liver fibrosis. The TNF-alpha inhibitors are not used to treat AIH, nor is the IL-1 inhibitor anakinra.

References:

1. Czaja AJ. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis: Current status and future directions. Gut Liver. 2016;10:177-203.

2. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune Hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015:63:971-1004.

3. Manns MP, et al. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:1-31.

Q1. Correct answer: C

Rationale:

The two standard treatment regimens for AIH include corticosteroids (prednisone or prednisolone) alone, or corticosteroids combined with azathioprine. The combination regimen allows for a lower dose of steroids and fewer side effects with the same therapeutic efficacy. This patient appears to have developed azathioprine-induced pancreatitis, which is a rare complication more often seen in patients with Crohn's disease treated with azathioprine. In patients who are intolerant of azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil and calcineurin inhibitors have been used with success.

There are data supporting the use of budesonide in place of prednisone, but this regimen is not as effective in patients with cirrhosis or advanced fibrosis, so it is reserved for patients with lesser degrees of liver fibrosis. The TNF-alpha inhibitors are not used to treat AIH, nor is the IL-1 inhibitor anakinra.

References:

1. Czaja AJ. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis: Current status and future directions. Gut Liver. 2016;10:177-203.

2. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune Hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015:63:971-1004.

3. Manns MP, et al. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:1-31.

A 21-year-old woman is diagnosed with autoimmune hepatitis and is started on prednisone and azathioprine. Within a week, she develops mid-abdominal pain, radiating to the back, and her lipase level is 537 U/L.

How do new BP guidelines affect identifying risk for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy?

Hauspurg A, Parry S, Mercer BM, et al. Blood pressure trajectory and category and risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019. pii: S0002-9378(19)30807-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.06.031.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Hauspurg and colleagues set out to determine whether redefined BP category (normal, < 120/80 mm Hg) and trajectory (a difference of ≥ 5 mm Hg systolic, diastolic, or mean arterial pressure between the first and second prenatal visit) helps to identify women at increased risk for developing hypertensive disorders of pregnancy or preeclampsia.

With respect to the former variable, such an association was demonstrated in the first National Institutes of Health–funded preeclampsia prevention trial published in 1993, which used low-dose aspirin.1 In that trial, low-dose aspirin was not found to be effective in preventing preeclampsia in young, healthy nulliparous women. Interestingly, the 2 factors most associated with developing preeclampsia were an initial systolic BP of 120 to 134 mm Hg and an initial weight of >60 kg. For most clinicians, these findings would not be helpful in trying to better identify a high-risk group.

Details of the study

The idea of BP “trajectory” is interesting in the Hauspurg and colleagues’ study. The authors analyzed data from the Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-Be (nuMoM2b), a prospective cohort study, and included a very large population of almost 9,000 women in the analysis. Participants were classified according to their BP measurement at the first study visit, with BP categories based on updated American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines. The primary outcome was the risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including gestational hypertension and preeclampsia.

The data analysis found that elevated BP was associated with an adjusted risk ratio (aRR) of 1.54 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.18–2.02). Stage 1 hypertension was associated with an aRR of 2.16 (95% CI, 1.31–3.57). Compared with women whose BP had a downward systolic trajectory, women with normal BP and an upward systolic trajectory had a 41% increased risk of any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (aRR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.20–1.65).

Study strengths and limitations

While the large study population is a strength of this study, there are a number of limitations, such as the use of BP measurements during pregnancy only, without having pre-pregnancy measurements available. Further, a single BP measurement during each visit is also a drawback, although the standardized measurement by study staff is a strength.

Anticlimactic conclusions. The conclusions of the study, however, are either not surprising, not clinically meaningful, or of little value to clinicians at present, at least with respect to patient management.

Continue to: Conclusions that were not surprising included...

Conclusions that were not surprising included a statistically lower chance of indicated preterm delivery in the normal BP group than in the elevated BP or stage 1 hypertension groups. Conclusions that were not meaningful included a statistically significant lower birthweight in the elevated BP group (3,269 g) and in the stage 1 hypertension group (3,258 g) compared with the normal BP group (3,279 g), but the clinical significance of these differences is arguable.

Lastly is the issue of what these data mean for clinical practice. The idea of identifying high-risk groups is attractive, provided that there are effective intervention strategies available. If one follows the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations for preeclampsia prevention,2 then virtually every nulliparous woman is a candidate for low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prophylaxis. Beyond that, the current data do not support any change in the standard clinical practice of managing these “now identified” high-risk women. Increasing prenatal visits, using biomarkers to further delineate risk, and using uterine artery Doppler studies are all strategies that have been or are being investigated, but as yet they are not supported by conclusive data documenting improved outcomes—a sentiment supported by both the USPSTF3 and the authors of the study.

Until further data are available, my advice to clinicians is to pay close attention to all risk factors for any of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Initial BP and BP trajectory are important but probably something that sound clinical judgment would identify anyway. My recommendation is to continue to use those methods of prophylaxis, fetal surveillance, and indications for delivery that are supported by current data and await the additional investigations that Hauspurg and colleagues suggest need to be done before altering your management of women at increased risk for any of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

JOHN T. REPKE, MD

- Sibai BM, Caritis SN, Thom E, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Prevention of preeclampsia with low-dose aspirin in healthy nulliparous pregnant women. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1213-1218.

- United States Preventive Services Task Force. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: preventive medication. September 2014. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication. Accessed July 30, 2019.

- United States Preventive Service Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for preeclampsia: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;387:1661-1667.

Hauspurg A, Parry S, Mercer BM, et al. Blood pressure trajectory and category and risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019. pii: S0002-9378(19)30807-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.06.031.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Hauspurg and colleagues set out to determine whether redefined BP category (normal, < 120/80 mm Hg) and trajectory (a difference of ≥ 5 mm Hg systolic, diastolic, or mean arterial pressure between the first and second prenatal visit) helps to identify women at increased risk for developing hypertensive disorders of pregnancy or preeclampsia.

With respect to the former variable, such an association was demonstrated in the first National Institutes of Health–funded preeclampsia prevention trial published in 1993, which used low-dose aspirin.1 In that trial, low-dose aspirin was not found to be effective in preventing preeclampsia in young, healthy nulliparous women. Interestingly, the 2 factors most associated with developing preeclampsia were an initial systolic BP of 120 to 134 mm Hg and an initial weight of >60 kg. For most clinicians, these findings would not be helpful in trying to better identify a high-risk group.

Details of the study

The idea of BP “trajectory” is interesting in the Hauspurg and colleagues’ study. The authors analyzed data from the Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-Be (nuMoM2b), a prospective cohort study, and included a very large population of almost 9,000 women in the analysis. Participants were classified according to their BP measurement at the first study visit, with BP categories based on updated American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines. The primary outcome was the risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including gestational hypertension and preeclampsia.

The data analysis found that elevated BP was associated with an adjusted risk ratio (aRR) of 1.54 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.18–2.02). Stage 1 hypertension was associated with an aRR of 2.16 (95% CI, 1.31–3.57). Compared with women whose BP had a downward systolic trajectory, women with normal BP and an upward systolic trajectory had a 41% increased risk of any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (aRR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.20–1.65).

Study strengths and limitations

While the large study population is a strength of this study, there are a number of limitations, such as the use of BP measurements during pregnancy only, without having pre-pregnancy measurements available. Further, a single BP measurement during each visit is also a drawback, although the standardized measurement by study staff is a strength.

Anticlimactic conclusions. The conclusions of the study, however, are either not surprising, not clinically meaningful, or of little value to clinicians at present, at least with respect to patient management.

Continue to: Conclusions that were not surprising included...

Conclusions that were not surprising included a statistically lower chance of indicated preterm delivery in the normal BP group than in the elevated BP or stage 1 hypertension groups. Conclusions that were not meaningful included a statistically significant lower birthweight in the elevated BP group (3,269 g) and in the stage 1 hypertension group (3,258 g) compared with the normal BP group (3,279 g), but the clinical significance of these differences is arguable.

Lastly is the issue of what these data mean for clinical practice. The idea of identifying high-risk groups is attractive, provided that there are effective intervention strategies available. If one follows the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations for preeclampsia prevention,2 then virtually every nulliparous woman is a candidate for low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prophylaxis. Beyond that, the current data do not support any change in the standard clinical practice of managing these “now identified” high-risk women. Increasing prenatal visits, using biomarkers to further delineate risk, and using uterine artery Doppler studies are all strategies that have been or are being investigated, but as yet they are not supported by conclusive data documenting improved outcomes—a sentiment supported by both the USPSTF3 and the authors of the study.

Until further data are available, my advice to clinicians is to pay close attention to all risk factors for any of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Initial BP and BP trajectory are important but probably something that sound clinical judgment would identify anyway. My recommendation is to continue to use those methods of prophylaxis, fetal surveillance, and indications for delivery that are supported by current data and await the additional investigations that Hauspurg and colleagues suggest need to be done before altering your management of women at increased risk for any of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

JOHN T. REPKE, MD

Hauspurg A, Parry S, Mercer BM, et al. Blood pressure trajectory and category and risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019. pii: S0002-9378(19)30807-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.06.031.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Hauspurg and colleagues set out to determine whether redefined BP category (normal, < 120/80 mm Hg) and trajectory (a difference of ≥ 5 mm Hg systolic, diastolic, or mean arterial pressure between the first and second prenatal visit) helps to identify women at increased risk for developing hypertensive disorders of pregnancy or preeclampsia.

With respect to the former variable, such an association was demonstrated in the first National Institutes of Health–funded preeclampsia prevention trial published in 1993, which used low-dose aspirin.1 In that trial, low-dose aspirin was not found to be effective in preventing preeclampsia in young, healthy nulliparous women. Interestingly, the 2 factors most associated with developing preeclampsia were an initial systolic BP of 120 to 134 mm Hg and an initial weight of >60 kg. For most clinicians, these findings would not be helpful in trying to better identify a high-risk group.

Details of the study

The idea of BP “trajectory” is interesting in the Hauspurg and colleagues’ study. The authors analyzed data from the Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-Be (nuMoM2b), a prospective cohort study, and included a very large population of almost 9,000 women in the analysis. Participants were classified according to their BP measurement at the first study visit, with BP categories based on updated American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines. The primary outcome was the risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including gestational hypertension and preeclampsia.

The data analysis found that elevated BP was associated with an adjusted risk ratio (aRR) of 1.54 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.18–2.02). Stage 1 hypertension was associated with an aRR of 2.16 (95% CI, 1.31–3.57). Compared with women whose BP had a downward systolic trajectory, women with normal BP and an upward systolic trajectory had a 41% increased risk of any hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (aRR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.20–1.65).

Study strengths and limitations

While the large study population is a strength of this study, there are a number of limitations, such as the use of BP measurements during pregnancy only, without having pre-pregnancy measurements available. Further, a single BP measurement during each visit is also a drawback, although the standardized measurement by study staff is a strength.

Anticlimactic conclusions. The conclusions of the study, however, are either not surprising, not clinically meaningful, or of little value to clinicians at present, at least with respect to patient management.

Continue to: Conclusions that were not surprising included...

Conclusions that were not surprising included a statistically lower chance of indicated preterm delivery in the normal BP group than in the elevated BP or stage 1 hypertension groups. Conclusions that were not meaningful included a statistically significant lower birthweight in the elevated BP group (3,269 g) and in the stage 1 hypertension group (3,258 g) compared with the normal BP group (3,279 g), but the clinical significance of these differences is arguable.

Lastly is the issue of what these data mean for clinical practice. The idea of identifying high-risk groups is attractive, provided that there are effective intervention strategies available. If one follows the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations for preeclampsia prevention,2 then virtually every nulliparous woman is a candidate for low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prophylaxis. Beyond that, the current data do not support any change in the standard clinical practice of managing these “now identified” high-risk women. Increasing prenatal visits, using biomarkers to further delineate risk, and using uterine artery Doppler studies are all strategies that have been or are being investigated, but as yet they are not supported by conclusive data documenting improved outcomes—a sentiment supported by both the USPSTF3 and the authors of the study.

Until further data are available, my advice to clinicians is to pay close attention to all risk factors for any of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Initial BP and BP trajectory are important but probably something that sound clinical judgment would identify anyway. My recommendation is to continue to use those methods of prophylaxis, fetal surveillance, and indications for delivery that are supported by current data and await the additional investigations that Hauspurg and colleagues suggest need to be done before altering your management of women at increased risk for any of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

JOHN T. REPKE, MD

- Sibai BM, Caritis SN, Thom E, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Prevention of preeclampsia with low-dose aspirin in healthy nulliparous pregnant women. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1213-1218.

- United States Preventive Services Task Force. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: preventive medication. September 2014. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication. Accessed July 30, 2019.

- United States Preventive Service Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for preeclampsia: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;387:1661-1667.

- Sibai BM, Caritis SN, Thom E, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Prevention of preeclampsia with low-dose aspirin in healthy nulliparous pregnant women. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1213-1218.

- United States Preventive Services Task Force. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: preventive medication. September 2014. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication. Accessed July 30, 2019.

- United States Preventive Service Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for preeclampsia: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2017;387:1661-1667.

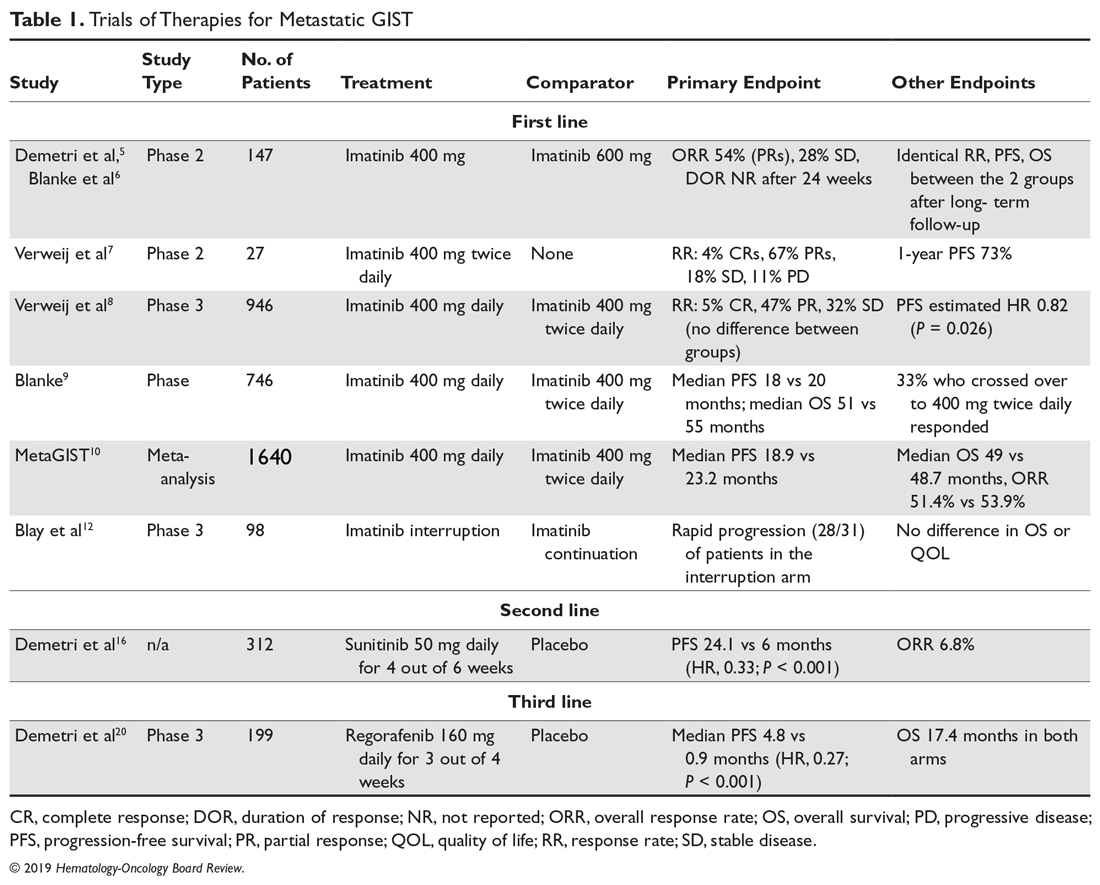

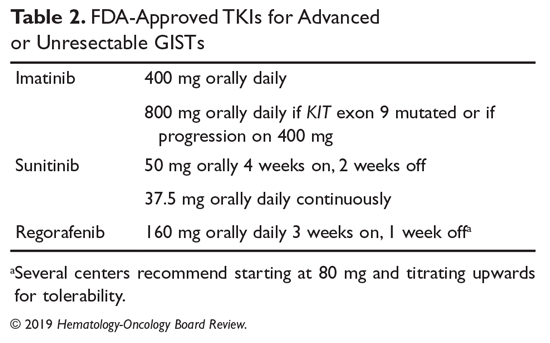

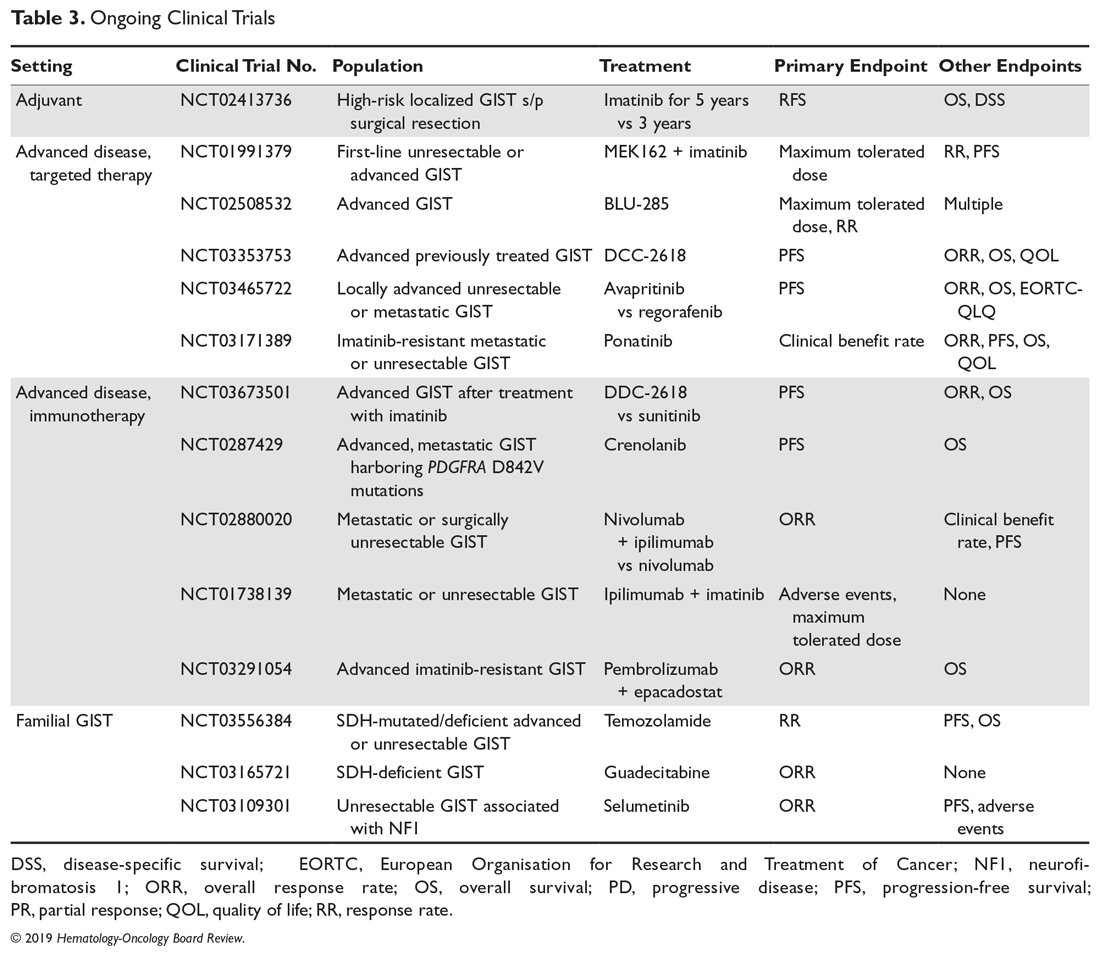

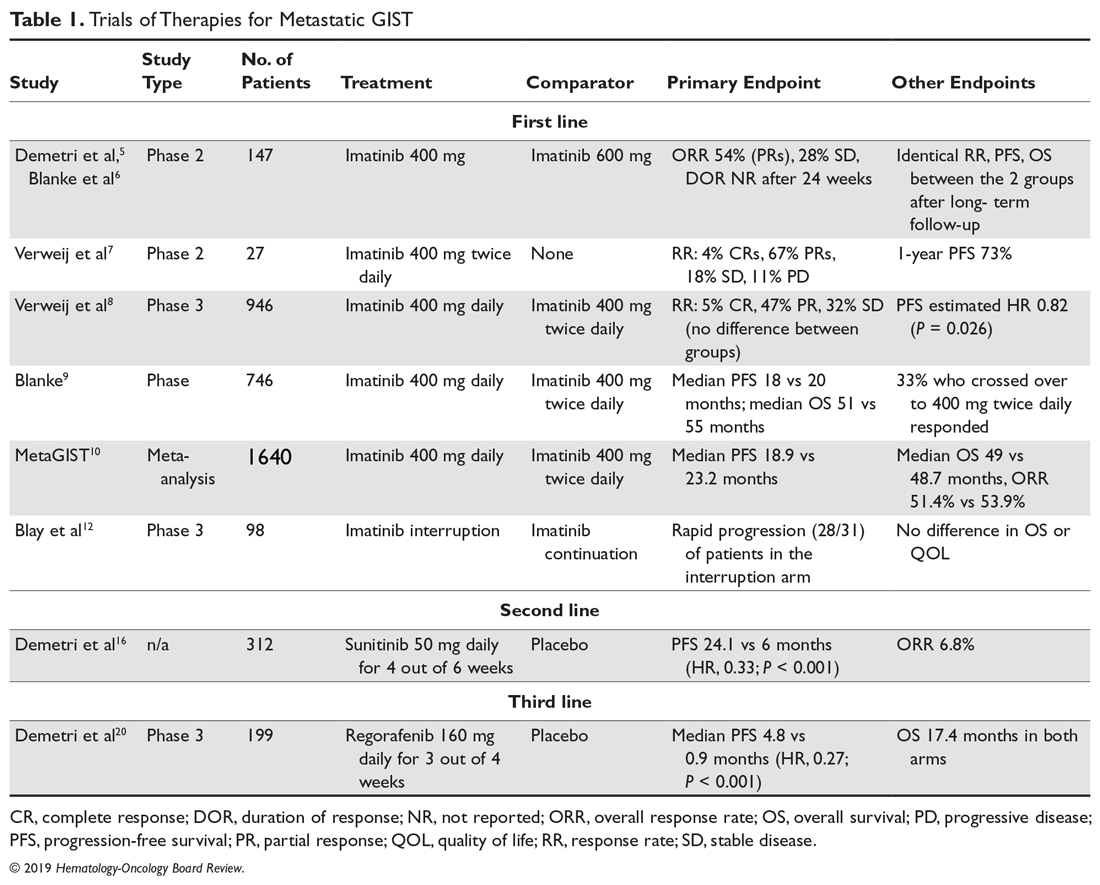

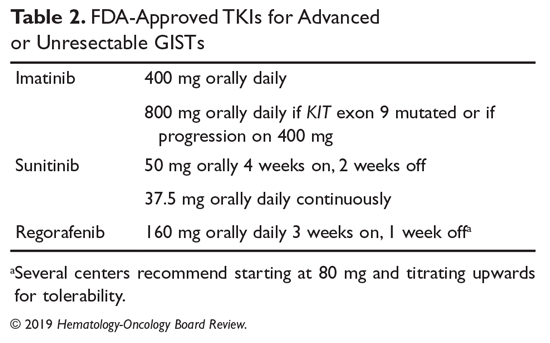

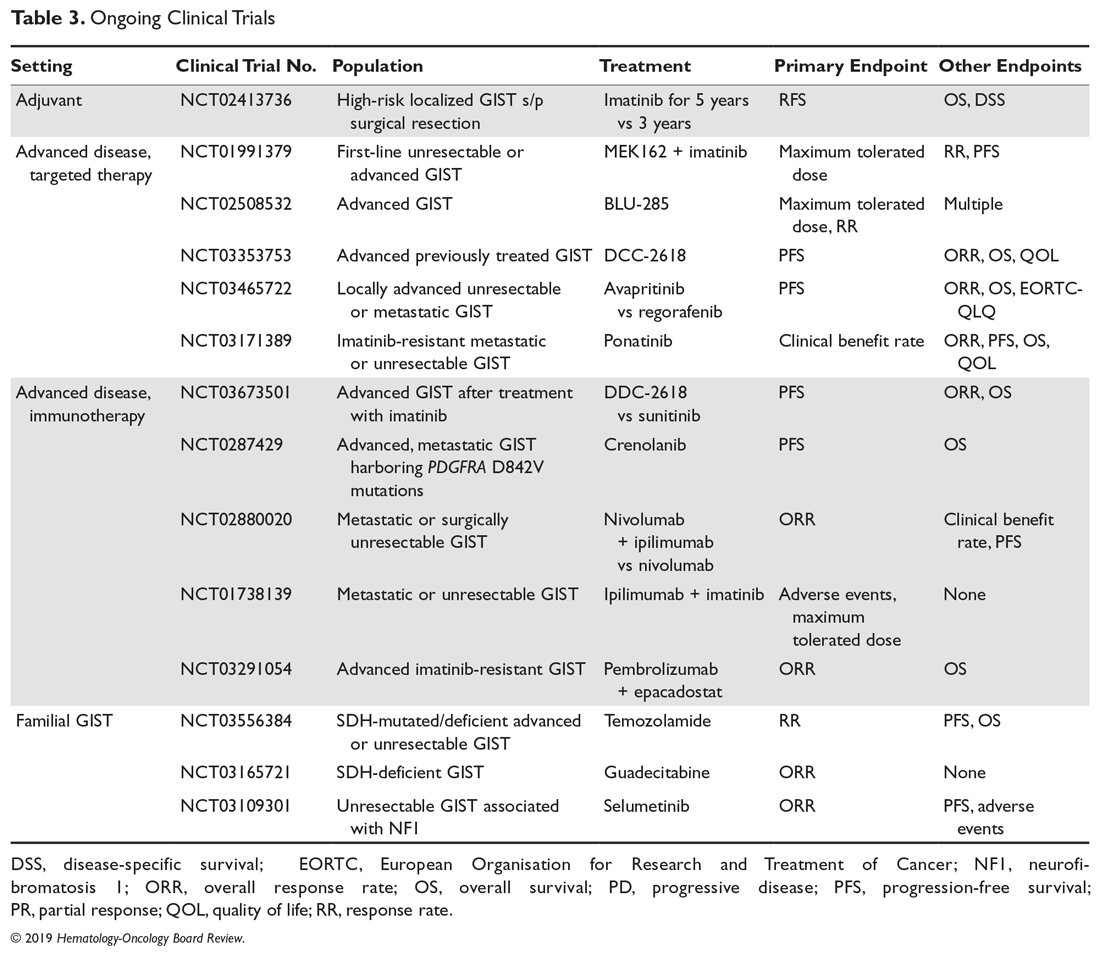

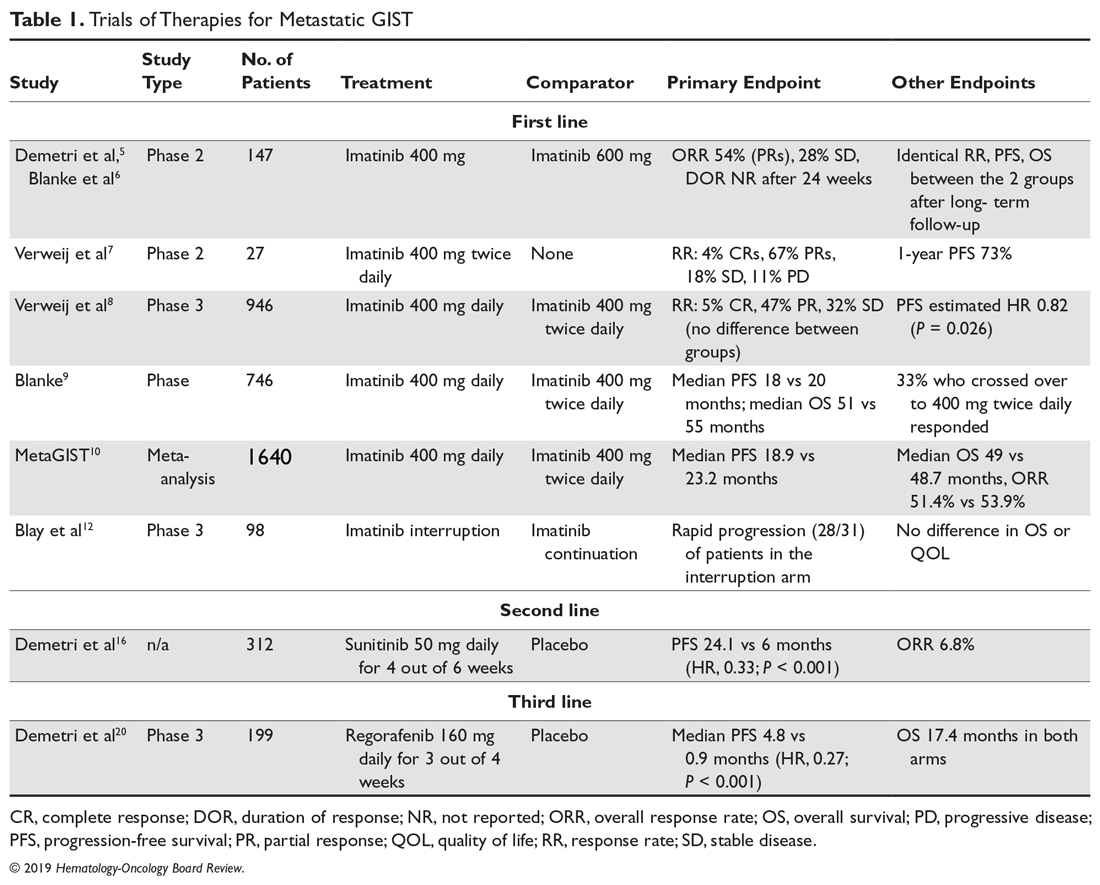

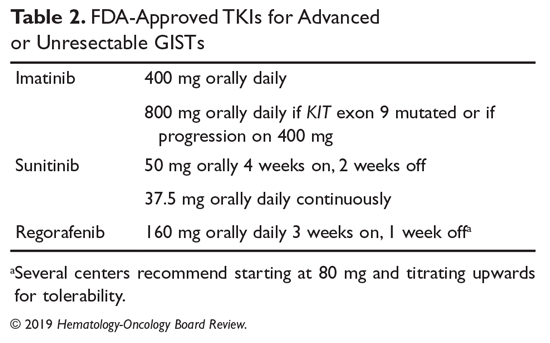

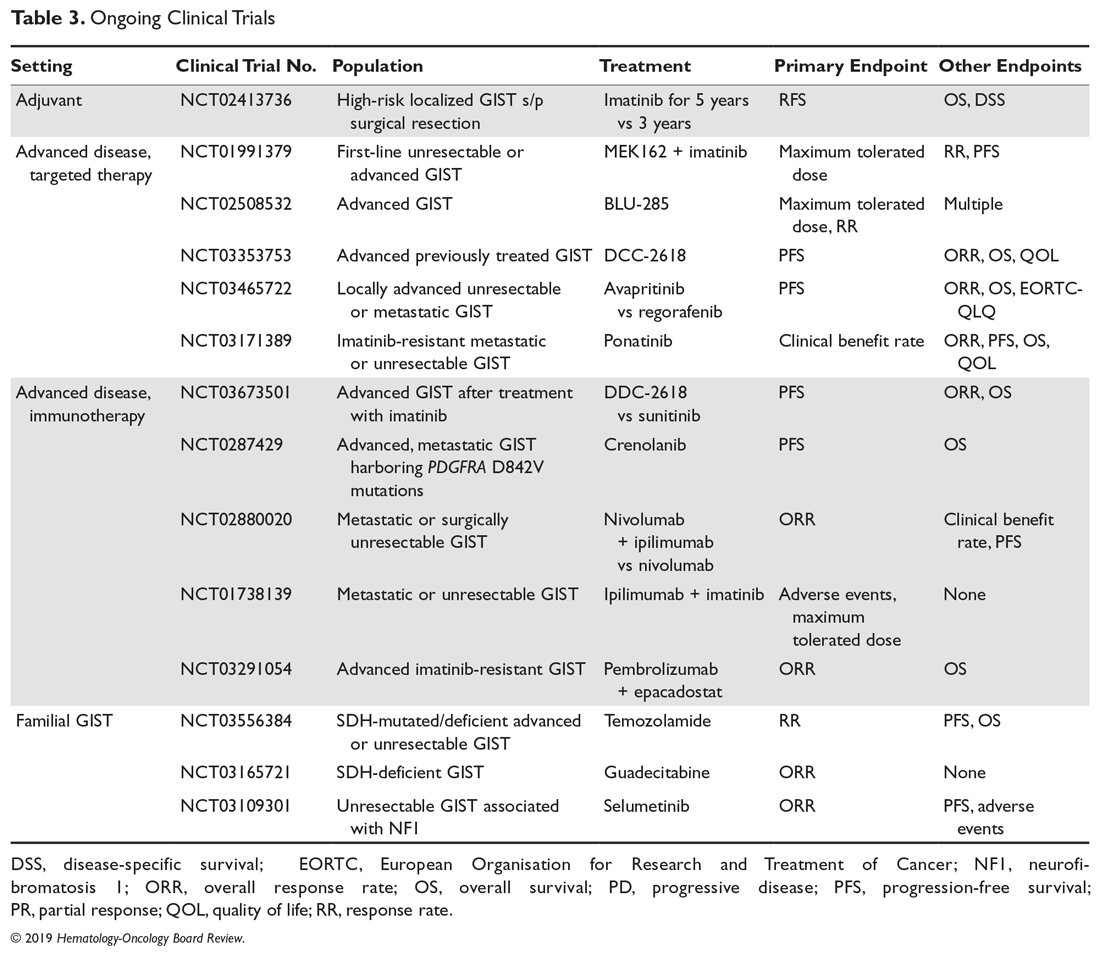

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors: Management of Localized Disease

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumor of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and arise from the interstitial cells of Cajal of the myenteric plexus. These tumors are rare, with about 1 case per 100,000 persons diagnosed in the United States annually, but may be incidentally discovered in up to 1 in 5 autopsy specimens of older adults.1,2 Epidemiologic risk factors include increasing age, with a peak incidence between age 60 and 65 years, male gender, black race, and non-Hispanic white ethnicity. Germline predisposition can also increase the risk of developing GISTs; molecular drivers of GIST include gain-of-function mutations in the KIT proto-oncogene and platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRA) gene, which both encode structurally similar tyrosine kinase receptors; germline mutations of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) subunit genes; and mutations associated with neurofibromatosis type 1.

GISTs most commonly involve the stomach, followed by the small intestine, but can arise anywhere within the GI tract (esophagus, colon, rectum, and anus). They can also develop outside the GI tract, arising from the mesentery, omentum, and retroperitoneum. The majority of cases are localized or locoregional, whereas about 20% are metastatic at presentation.1 GISTs can occur in children, adolescents, and young adults. Pediatric GISTs represent a distinct subset marked by female predominance and gastric origin, are often multifocal, can sometimes have lymph node involvement, and typically lack mutations in the KIT and PDGFRA genes.

This review is the first of 2 articles focusing on the diagnosis and management of GISTs. Here, we review the evaluation and diagnosis of GISTs along with management of localized disease. Management of advanced disease is reviewed in a separate article.

Case Presentation

A 64-year-old African American man with progressive iron deficiency and abdominal discomfort undergoes upper and lower endoscopy and is found to have a bulging mass within his abdominal cavity. He undergoes a computed tomography (CT) evaluation of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast, which reveals the presence of a 10-cm gastric mass, with no other lesions identified. He undergoes surgical resection of the mass and presents for review of his pathology and to discuss his treatment plan.

What histopathologic features are consistent with GIST?

What factors are used for risk stratification and to predict likelihood of recurrence?

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Most patients present with symptoms of overt or occult GI bleeding or abdominal discomfort, but a significant proportion of GISTs are discovered incidentally. Lymph node involvement is not typical, except for GISTs occurring in children and/or with rare syndromes. Most syndromic GISTs are multifocal and multicentric. After surgical resection, GISTs usually recur or metastasize within the abdominal cavity, including the omentum, peritoneum, or liver. These tumors rarely spread to the lungs, brain, or bones; when tumor spread does occur, it tends to be in heavily pre-treated patients with advanced disease who have been on multiple lines of therapy for a long duration of time.

The diagnosis usually can be made by histopathology. Specimens can be obtained by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)– or CT-guided methods, the latter of which carries a very small risk of contamination from percutaneous biopsy. In terms of morphology, GISTs can be spindle cell, epithelioid, or mixed neoplasms. Epithelioid tumors are more commonly seen in the stomach and are often PDGFRA-mutated or SDH-deficient. The differential diagnosis includes other soft-tissue GI wall tumors such as leiomyosarcomas/leiomyomas, germ cell tumors, lymphomas, fibromatosis, and neuroendocrine and neurogenic tumors. A unique feature of GISTs that differentiates them from leiomyomas is near universal expression of CD117 by immunohistochemistry (IHC); this characteristic has allowed pathologists and providers to accurately distinguish true GISTs from other GI mesenchymal tumors.3 Recently, DOG1 (discovered on GIST1) immunoreactivity has been found to be helpful in identifying patients with CD117-negative GISTs. Initially identified through gene expression analysis of GISTs, DOG1 IHC can identify the common mutant c-Kit-driven CD117-positive GISTs as well as the rare CD117-negative GISTs, which are often driven by mutated PDGFRA.4 Importantly, IHC for KIT and DOG1 are not surrogates for mutational status, nor are they predictive of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) sensitivity. If IHC of a tumor specimen is CD117- and DOG1-negative, the specimen can be sent for KIT and PDGFRA mutational analysis to confirm the diagnosis. If analysis reveals that these genes are wild-type, then IHC staining for SDH B (SDHB) should follow to assess for an SDH-deficient GIST (negative staining).

Risk Stratification for Recurrence

The clinical behavior of GISTs can be variable. Some are indolent, while others behave more aggressively, with a greater malignant potential and a higher propensity to recur and metastasize. Clinical and pathologic features can provide important prognostic information that allows providers to risk-stratify patients. Various institutions have assessed prognostic variables for GISTs. In 2001, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) held a GIST workshop that proposed an approach to estimating metastatic risk based on tumor size and mitotic index (NIH or Fletcher criteria).5 Joensuu et al later proposed a modification of the NIH risk classification to include tumor location and tumor rupture (modified NIH criteria or Joensuu criteria).6-8 Similarly, the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) identified tumor site as a prognostic factor, with gastric GISTs having the best prognosis (AFIP-Miettinen criteria).9-11 Tabular schemes were designed which stratified patients into discrete groups with ranges for mitotic rate and tumor size. Nomograms for ease of use were then constructed utilizing a bimodal mitotic rate and included tumor site and size.12 Finally, contour maps were developed, which have the advantage of evaluating mitotic rate and tumor size as continuous nonlinear variables and also include tumor site and rupture (associated with a high risk of peritoneal metastasis) separately, further improving risk assessment. These contour maps have been validated against pooled data from 10 series (2560 patients).13 High-risk features identified from these studies include tumor location, size, mitotic rate and tumor rupture and are now used for deciding on the use of adjuvant imatinib and as requirements to enter clinical trials assessing adjuvant therapy for resected GISTs.

Case Continued

The patient’s operative and pathology reports indicate that the tumor is a spindle cell neoplasm of the stomach that is positive for CD117, DOG1, and CD34 and negative for smooth muscle actin and S-100, consistent with a diagnosis of GIST. Resection margins are negative. There are 10 mitoses per 50 high-power fields (HPF). Per the operative report, there was no intraoperative or intraperitoneal tumor rupture. Thus, while his GIST was gastric, which generally has a more favorable prognosis, the tumor harbors high-risk features based on its size and mitotic index.

What further testing should be requested?

Molecular Alterations

It is recommended that a mutational analysis be performed as part of the diagnostic work-up of all GISTs.14 Mutational analysis can provide prognostic and predictive information for sensitivity to imatinib and should be considered standard of care. It may also be useful for confirming a GIST diagnosis, or, if negative, lead to further evaluation with an IHC stain for SDHB. The c-Kit receptor is a member of the tyrosine kinase family and, through direct interactions with stem cell factor (SCF), can upregulate the PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK, and JAK-STAT pathways, resulting in transcription and translation of genes that enhance cell growth and survival.15 The cell of origin of GISTs, the interstitial cells of Cajal, are dependent on the SCF–c-Kit interaction for development.16 Likewise, the large majority of GISTs (about 70%) are driven by upregulation and constitutive activation of c-Kit, which is normally autoinhibited. About 80% of KIT mutations involve exon 11; these GISTs are most often associated with a gastric location and are associated with a favorable recurrence-free survival (RFS) rate with surgery alone.17 KIT exon 9 mutations are much less common, encompassing only about 10% of GIST KIT mutations, and GISTs with these mutations are more likely to arise from the small bowel.17

About 8% of GISTs harbor gain-of-function PDGFRA driver mutations rendering constitutively active PDGFRA.18 PDGFRA mutations are mutually exclusive from KIT mutations, and PDGFRA-mutated tumors most often occur in the stomach. PDGFRA mutations generally are associated with a lower mitotic rate and gastric location. Identification of the PDGFRA D842V mutation on exon 18, which is the most common, is important, as it is associated with imatinib resistance, and these patients should not be offered imatinib.19

Several other mutations associated with GISTs outside of the KIT and PDGFRA spectrum have been identified. About 10% of GISTs are wildtype for KIT and PDGFRA, and not all KIT/PDGFRA-wildtype GISTs are imatinib-sensitive and/or respond to other TKIs.18 These tumors may harbor aberrations in SDH and NF1, or less commonly, BRAF V600E, FGFR, and NTRK.20,21 SDH subunits B, C and D play a role in the Krebs cycle and electron transport chain. Germline mutations in these SDH subunits can result in the Carney-Stratakis syndrome characterized by the dyad of multifocal GISTs and multicentric paragangliomas.22 This syndrome is most likely to manifest in the pediatric or young adult population. In contradistinction is the Carney triad, which is associated with acquired loss of function of the SDHC gene due to promoter hypermethylation. This syndrome classically occurs in young women and is characterized by an indolent-behaving triad of multicentric GISTs, non-adrenal paragangliomas, and pulmonary chondromas.23 Like PDGFRA D842V–mutated GISTs, SDH-deficient and NF1-associated GISTs are considered imatinib resistant, and these patients should not be offered imatinib therapy.14

Case Continued

The patient’s GIST is found to harbor a KIT exon 11 single codon deletion. He appears anxious and asks to have everything done to prevent his GIST from coming back and to improve his lifespan.

What are the next steps in the management of this patient?

Management

A multidisciplinary team approach to the management of all GISTs is essential and includes input from radiology, gastroenterology, pathology, medical and surgical oncology, nuclear medicine, and nursing.

Surgical Resection