User login

FDA approves pembrolizumab as second-line for advanced ESCC

The Food and Drug Administration has approved pembrolizumab (Keytruda) for patients with recurrent, locally advanced, or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) whose tumors express PD-L1, as determined by an FDA-approved test, with disease progression after one or more prior lines of systemic therapy.

FDA approval was based on results of two clinical trials: KEYNOTE-180 and KEYNOTE-181. KEYNOTE-181 was a randomized, open-label, active-controlled trial of 628 patients with recurrent, locally advanced, or metastatic esophageal cancer who progressed on or after one prior line of systemic treatment for advanced or metastatic disease. Patients who received pembrolizumab had a median overall survival of 10.3 months, compared with 6.7 months for patients who received control drugs.

In KEYNOTE-180, a single-arm, open-label trial of 121 patients with esophageal cancer who progressed after two prior lines of treatment, patients who had a PD-L1 combined positive score of at least 10 had an overall response rate of 20%, with response durations ranging from 4.2 to over 25.1 months, and with 71% of those patients having a response time over 6 months.

Adverse reactions reported in KEYNOTE-180 and –181 were similar to those in previous trials involving pembrolizumab in patients with melanoma and non–small cell lung cancer. The most common reactions were fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, decreased appetite, pruritus, diarrhea, nausea, rash, pyrexia, cough, dyspnea, constipation, pain, and abdominal pain.

The PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx kit was approved as the companion diagnostic device, the FDA said.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved pembrolizumab (Keytruda) for patients with recurrent, locally advanced, or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) whose tumors express PD-L1, as determined by an FDA-approved test, with disease progression after one or more prior lines of systemic therapy.

FDA approval was based on results of two clinical trials: KEYNOTE-180 and KEYNOTE-181. KEYNOTE-181 was a randomized, open-label, active-controlled trial of 628 patients with recurrent, locally advanced, or metastatic esophageal cancer who progressed on or after one prior line of systemic treatment for advanced or metastatic disease. Patients who received pembrolizumab had a median overall survival of 10.3 months, compared with 6.7 months for patients who received control drugs.

In KEYNOTE-180, a single-arm, open-label trial of 121 patients with esophageal cancer who progressed after two prior lines of treatment, patients who had a PD-L1 combined positive score of at least 10 had an overall response rate of 20%, with response durations ranging from 4.2 to over 25.1 months, and with 71% of those patients having a response time over 6 months.

Adverse reactions reported in KEYNOTE-180 and –181 were similar to those in previous trials involving pembrolizumab in patients with melanoma and non–small cell lung cancer. The most common reactions were fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, decreased appetite, pruritus, diarrhea, nausea, rash, pyrexia, cough, dyspnea, constipation, pain, and abdominal pain.

The PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx kit was approved as the companion diagnostic device, the FDA said.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved pembrolizumab (Keytruda) for patients with recurrent, locally advanced, or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) whose tumors express PD-L1, as determined by an FDA-approved test, with disease progression after one or more prior lines of systemic therapy.

FDA approval was based on results of two clinical trials: KEYNOTE-180 and KEYNOTE-181. KEYNOTE-181 was a randomized, open-label, active-controlled trial of 628 patients with recurrent, locally advanced, or metastatic esophageal cancer who progressed on or after one prior line of systemic treatment for advanced or metastatic disease. Patients who received pembrolizumab had a median overall survival of 10.3 months, compared with 6.7 months for patients who received control drugs.

In KEYNOTE-180, a single-arm, open-label trial of 121 patients with esophageal cancer who progressed after two prior lines of treatment, patients who had a PD-L1 combined positive score of at least 10 had an overall response rate of 20%, with response durations ranging from 4.2 to over 25.1 months, and with 71% of those patients having a response time over 6 months.

Adverse reactions reported in KEYNOTE-180 and –181 were similar to those in previous trials involving pembrolizumab in patients with melanoma and non–small cell lung cancer. The most common reactions were fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, decreased appetite, pruritus, diarrhea, nausea, rash, pyrexia, cough, dyspnea, constipation, pain, and abdominal pain.

The PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx kit was approved as the companion diagnostic device, the FDA said.

Find the full press release on the FDA website.

ctDNA may predict relapse risk in early breast cancer

Following therapy with curative intent for early-stage primary breast care, the presence of circulating tumor DNA may identify those patients at high risk for relapse, investigators reported.

Among 101 women treated for early-stage breast cancer and followed for a median of nearly 3 years, detection of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) during follow-up was associated with a 2,400% increased risk for relapse, and detection of ctDNA at diagnosis but before treatment was associated with a nearly 500% risk, wrote Isaac Garcia-Murillas, PhD, of the Institute of Cancer Research, London, and colleagues.

“Prospective clinical trials are now required to assess whether detection of ctDNA can improve outcomes in patients, and a phase 2 interventional trial in TNBC [triple-negative breast cancer] has been initiated. This trial may develop a new treatment paradigm for treating breast cancer, in which treatment is initiated at molecular relapse without waiting for symptomatic incurable metastatic disease to develop,” they wrote in JAMA Oncology.

The investigators conducted a prospective, multicenter validation study of samples collected from women with early-stage breast cancer irrespective of hormone-receptor or HER2 status. The patients were scheduled for neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery, or surgery followed by adjuvant therapy.

Of 170 women recruited, 101 had tumors with identified mutations and were included in the main cohort. The investigators also conducted secondary analyses with patients in this cohort plus an additional 43 women who had participated in a previous proof-of-principle study.

They first sequenced tumor DNA to identify somatic mutations in primary tumors that could then be tracked using a breast cancer driver gene panel. For each sample, a personalized digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR) assay was created to identify the mutations in plasma samples.

The plasma samples were collected every 3 months for the first year of follow-up, then every 6 months thereafter.

In the main cohort, the median age was 54 years, and the median follow-up was 35.5 months. The investigators found that, for the primary endpoint of relapse-free survival, ctDNA was associated with a hazard ratio for relapse of 25.2 (P less than .001). Detection of ctDNA in samples taken at the time of diagnosis was also associated with worse relapse-free survival, with an HR of 5.8 (P = .01).

In a secondary analysis, ctDNA detection preceded clinical relapse by a median of 10.7 months, and was associated with relapse in all breast cancer subtypes.

Of 29 patients who experienced a relapse, 22 of 23 with extracranial distant metastatic relapse had prior ctDNA detection.

The remaining six patients experienced relapse without ctDNA detection either before or at the time of relapse. Each of these six patients had a relapse at a single site: in the brain in three patients (with no extracranial relapses), in the ovaries in one patient, and solitary locoregional relapses in two patients.

The investigators acknowledged that the results “demonstrate clinical validity for ctDNA mutation tracking with dPCR but do not demonstrate clinical utility. Without evidence that mutation tracking can improve patient outcome, our results should not be recommended yet for routine clinical practice.”

The study was funded by Breast Cancer Now, Le Cure, and National Institute for Health Research funding to the Biomedical Research Centre at the Royal Marsden Hospital and the Institute of Cancer Research. Dr. Garcia-Murillas had no disclosures. Multiple coauthors reported grants and/or fees from various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Garcia-Murillias I et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Aug 1. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1838.

Although a strength of the study is the inclusion of all subtypes of breast cancer, Garcia-Murillas et al. found that the ability to detect circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) was likely influenced by biologic factors, including receptor subtypes. The study had a median follow-up of 36.3 months (in the combined cohorts); however, because the risk of relapse for luminal estrogen receptor–positive breast cancers is known to persist for decades, these data cannot be applied to late recurrences, which are largely derived from luminal estrogen receptor–positive disease. Longer-term follow-up with serial sampling of ctDNA will be required to demonstrate validation for this patient population.

As addressed by the authors, the clinical utility for ctDNA detection in early-stage breast cancer is still unknown. Proof of clinical utility can be accomplished through prospective, multi-institutional trials randomizing ctDNA-positive patients to therapy versus control and demonstrating reductions in disease-free and overall survival. The use of real-time testing and rapid turnaround time may prove to be challenging if we are to implement ctDNA testing as an integral biomarker for clinical decision making. However, the study by Garcia-Murillas et al. is a major step forward in reaching this goal because the results suggest the feasibility and clinical validation of ctDNA for patients with early-stage disease.

Remarks from Swathi Karthikeyan, MS, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and Ben Ho Park, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins and Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., are condensed and adapted from an editorial accompanying the study by Garcia-Murillas et al. Dr. Park reported royalties from Horizon Discovery, serving as a scientific advisory board member for Loxo Oncology, having an ownership interest in Loxo Oncology, serving as a recent paid consultant for Foundation Medicine, Jackson Laboratories, H3 Biomedicine, Casdin Capital, Roche, Eli Lilly, and Astra Zeneca, and having research contracts with Abbvie, Foundation Medicine, and Pfizer. No other disclosures were reported.

Although a strength of the study is the inclusion of all subtypes of breast cancer, Garcia-Murillas et al. found that the ability to detect circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) was likely influenced by biologic factors, including receptor subtypes. The study had a median follow-up of 36.3 months (in the combined cohorts); however, because the risk of relapse for luminal estrogen receptor–positive breast cancers is known to persist for decades, these data cannot be applied to late recurrences, which are largely derived from luminal estrogen receptor–positive disease. Longer-term follow-up with serial sampling of ctDNA will be required to demonstrate validation for this patient population.

As addressed by the authors, the clinical utility for ctDNA detection in early-stage breast cancer is still unknown. Proof of clinical utility can be accomplished through prospective, multi-institutional trials randomizing ctDNA-positive patients to therapy versus control and demonstrating reductions in disease-free and overall survival. The use of real-time testing and rapid turnaround time may prove to be challenging if we are to implement ctDNA testing as an integral biomarker for clinical decision making. However, the study by Garcia-Murillas et al. is a major step forward in reaching this goal because the results suggest the feasibility and clinical validation of ctDNA for patients with early-stage disease.

Remarks from Swathi Karthikeyan, MS, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and Ben Ho Park, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins and Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., are condensed and adapted from an editorial accompanying the study by Garcia-Murillas et al. Dr. Park reported royalties from Horizon Discovery, serving as a scientific advisory board member for Loxo Oncology, having an ownership interest in Loxo Oncology, serving as a recent paid consultant for Foundation Medicine, Jackson Laboratories, H3 Biomedicine, Casdin Capital, Roche, Eli Lilly, and Astra Zeneca, and having research contracts with Abbvie, Foundation Medicine, and Pfizer. No other disclosures were reported.

Although a strength of the study is the inclusion of all subtypes of breast cancer, Garcia-Murillas et al. found that the ability to detect circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) was likely influenced by biologic factors, including receptor subtypes. The study had a median follow-up of 36.3 months (in the combined cohorts); however, because the risk of relapse for luminal estrogen receptor–positive breast cancers is known to persist for decades, these data cannot be applied to late recurrences, which are largely derived from luminal estrogen receptor–positive disease. Longer-term follow-up with serial sampling of ctDNA will be required to demonstrate validation for this patient population.

As addressed by the authors, the clinical utility for ctDNA detection in early-stage breast cancer is still unknown. Proof of clinical utility can be accomplished through prospective, multi-institutional trials randomizing ctDNA-positive patients to therapy versus control and demonstrating reductions in disease-free and overall survival. The use of real-time testing and rapid turnaround time may prove to be challenging if we are to implement ctDNA testing as an integral biomarker for clinical decision making. However, the study by Garcia-Murillas et al. is a major step forward in reaching this goal because the results suggest the feasibility and clinical validation of ctDNA for patients with early-stage disease.

Remarks from Swathi Karthikeyan, MS, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and Ben Ho Park, MD, PhD, of Johns Hopkins and Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., are condensed and adapted from an editorial accompanying the study by Garcia-Murillas et al. Dr. Park reported royalties from Horizon Discovery, serving as a scientific advisory board member for Loxo Oncology, having an ownership interest in Loxo Oncology, serving as a recent paid consultant for Foundation Medicine, Jackson Laboratories, H3 Biomedicine, Casdin Capital, Roche, Eli Lilly, and Astra Zeneca, and having research contracts with Abbvie, Foundation Medicine, and Pfizer. No other disclosures were reported.

Following therapy with curative intent for early-stage primary breast care, the presence of circulating tumor DNA may identify those patients at high risk for relapse, investigators reported.

Among 101 women treated for early-stage breast cancer and followed for a median of nearly 3 years, detection of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) during follow-up was associated with a 2,400% increased risk for relapse, and detection of ctDNA at diagnosis but before treatment was associated with a nearly 500% risk, wrote Isaac Garcia-Murillas, PhD, of the Institute of Cancer Research, London, and colleagues.

“Prospective clinical trials are now required to assess whether detection of ctDNA can improve outcomes in patients, and a phase 2 interventional trial in TNBC [triple-negative breast cancer] has been initiated. This trial may develop a new treatment paradigm for treating breast cancer, in which treatment is initiated at molecular relapse without waiting for symptomatic incurable metastatic disease to develop,” they wrote in JAMA Oncology.

The investigators conducted a prospective, multicenter validation study of samples collected from women with early-stage breast cancer irrespective of hormone-receptor or HER2 status. The patients were scheduled for neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery, or surgery followed by adjuvant therapy.

Of 170 women recruited, 101 had tumors with identified mutations and were included in the main cohort. The investigators also conducted secondary analyses with patients in this cohort plus an additional 43 women who had participated in a previous proof-of-principle study.

They first sequenced tumor DNA to identify somatic mutations in primary tumors that could then be tracked using a breast cancer driver gene panel. For each sample, a personalized digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR) assay was created to identify the mutations in plasma samples.

The plasma samples were collected every 3 months for the first year of follow-up, then every 6 months thereafter.

In the main cohort, the median age was 54 years, and the median follow-up was 35.5 months. The investigators found that, for the primary endpoint of relapse-free survival, ctDNA was associated with a hazard ratio for relapse of 25.2 (P less than .001). Detection of ctDNA in samples taken at the time of diagnosis was also associated with worse relapse-free survival, with an HR of 5.8 (P = .01).

In a secondary analysis, ctDNA detection preceded clinical relapse by a median of 10.7 months, and was associated with relapse in all breast cancer subtypes.

Of 29 patients who experienced a relapse, 22 of 23 with extracranial distant metastatic relapse had prior ctDNA detection.

The remaining six patients experienced relapse without ctDNA detection either before or at the time of relapse. Each of these six patients had a relapse at a single site: in the brain in three patients (with no extracranial relapses), in the ovaries in one patient, and solitary locoregional relapses in two patients.

The investigators acknowledged that the results “demonstrate clinical validity for ctDNA mutation tracking with dPCR but do not demonstrate clinical utility. Without evidence that mutation tracking can improve patient outcome, our results should not be recommended yet for routine clinical practice.”

The study was funded by Breast Cancer Now, Le Cure, and National Institute for Health Research funding to the Biomedical Research Centre at the Royal Marsden Hospital and the Institute of Cancer Research. Dr. Garcia-Murillas had no disclosures. Multiple coauthors reported grants and/or fees from various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Garcia-Murillias I et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Aug 1. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1838.

Following therapy with curative intent for early-stage primary breast care, the presence of circulating tumor DNA may identify those patients at high risk for relapse, investigators reported.

Among 101 women treated for early-stage breast cancer and followed for a median of nearly 3 years, detection of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) during follow-up was associated with a 2,400% increased risk for relapse, and detection of ctDNA at diagnosis but before treatment was associated with a nearly 500% risk, wrote Isaac Garcia-Murillas, PhD, of the Institute of Cancer Research, London, and colleagues.

“Prospective clinical trials are now required to assess whether detection of ctDNA can improve outcomes in patients, and a phase 2 interventional trial in TNBC [triple-negative breast cancer] has been initiated. This trial may develop a new treatment paradigm for treating breast cancer, in which treatment is initiated at molecular relapse without waiting for symptomatic incurable metastatic disease to develop,” they wrote in JAMA Oncology.

The investigators conducted a prospective, multicenter validation study of samples collected from women with early-stage breast cancer irrespective of hormone-receptor or HER2 status. The patients were scheduled for neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery, or surgery followed by adjuvant therapy.

Of 170 women recruited, 101 had tumors with identified mutations and were included in the main cohort. The investigators also conducted secondary analyses with patients in this cohort plus an additional 43 women who had participated in a previous proof-of-principle study.

They first sequenced tumor DNA to identify somatic mutations in primary tumors that could then be tracked using a breast cancer driver gene panel. For each sample, a personalized digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR) assay was created to identify the mutations in plasma samples.

The plasma samples were collected every 3 months for the first year of follow-up, then every 6 months thereafter.

In the main cohort, the median age was 54 years, and the median follow-up was 35.5 months. The investigators found that, for the primary endpoint of relapse-free survival, ctDNA was associated with a hazard ratio for relapse of 25.2 (P less than .001). Detection of ctDNA in samples taken at the time of diagnosis was also associated with worse relapse-free survival, with an HR of 5.8 (P = .01).

In a secondary analysis, ctDNA detection preceded clinical relapse by a median of 10.7 months, and was associated with relapse in all breast cancer subtypes.

Of 29 patients who experienced a relapse, 22 of 23 with extracranial distant metastatic relapse had prior ctDNA detection.

The remaining six patients experienced relapse without ctDNA detection either before or at the time of relapse. Each of these six patients had a relapse at a single site: in the brain in three patients (with no extracranial relapses), in the ovaries in one patient, and solitary locoregional relapses in two patients.

The investigators acknowledged that the results “demonstrate clinical validity for ctDNA mutation tracking with dPCR but do not demonstrate clinical utility. Without evidence that mutation tracking can improve patient outcome, our results should not be recommended yet for routine clinical practice.”

The study was funded by Breast Cancer Now, Le Cure, and National Institute for Health Research funding to the Biomedical Research Centre at the Royal Marsden Hospital and the Institute of Cancer Research. Dr. Garcia-Murillas had no disclosures. Multiple coauthors reported grants and/or fees from various pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Garcia-Murillias I et al. JAMA Oncol. 2019 Aug 1. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1838.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

Functional GI Disorders Common in MS

Key clinical point: Managing comorbid psychiatric disorders in patients with MS could reduce the burden of functional GI disorders.

Major finding: Approximately 42% of patients with MS report functional GI disorders.

Study details: A survey of 6,312 participants in the North American Research Committee on MS Registry.

Disclosures: The study had no sponsor. Dr. Marrie had no disclosures, but other researchers had financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies, such as Merck, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and Teva.

Citation: Marrie RA et al. CMSC 2019, Abstract QOL13.

Key clinical point: Managing comorbid psychiatric disorders in patients with MS could reduce the burden of functional GI disorders.

Major finding: Approximately 42% of patients with MS report functional GI disorders.

Study details: A survey of 6,312 participants in the North American Research Committee on MS Registry.

Disclosures: The study had no sponsor. Dr. Marrie had no disclosures, but other researchers had financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies, such as Merck, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and Teva.

Citation: Marrie RA et al. CMSC 2019, Abstract QOL13.

Key clinical point: Managing comorbid psychiatric disorders in patients with MS could reduce the burden of functional GI disorders.

Major finding: Approximately 42% of patients with MS report functional GI disorders.

Study details: A survey of 6,312 participants in the North American Research Committee on MS Registry.

Disclosures: The study had no sponsor. Dr. Marrie had no disclosures, but other researchers had financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies, such as Merck, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, and Teva.

Citation: Marrie RA et al. CMSC 2019, Abstract QOL13.

Age Does Not Influence Cladribine’s Efficacy in MS

Key clinical point: Patients with relapsing-remitting MS gain comparable benefits from cladribine therapy, regardless of age.

Major finding: The annual rate of qualifying relapses was 0.14 for treated patients older than 45 years and 0.15 for treated patients aged 45 or younger.

Study details: A post hoc analysis of data from the CLARITY and CLARITY extension studies, which included 870 patients.

Disclosures: Merck KGaA, which manufactures and markets cladribine, supported the study. Several of the investigators have received speaker honoraria, consulting fees, or other funding from Merck KGaA.

Citation: REPORTING FROM CMSC 2019

Key clinical point: Patients with relapsing-remitting MS gain comparable benefits from cladribine therapy, regardless of age.

Major finding: The annual rate of qualifying relapses was 0.14 for treated patients older than 45 years and 0.15 for treated patients aged 45 or younger.

Study details: A post hoc analysis of data from the CLARITY and CLARITY extension studies, which included 870 patients.

Disclosures: Merck KGaA, which manufactures and markets cladribine, supported the study. Several of the investigators have received speaker honoraria, consulting fees, or other funding from Merck KGaA.

Citation: REPORTING FROM CMSC 2019

Key clinical point: Patients with relapsing-remitting MS gain comparable benefits from cladribine therapy, regardless of age.

Major finding: The annual rate of qualifying relapses was 0.14 for treated patients older than 45 years and 0.15 for treated patients aged 45 or younger.

Study details: A post hoc analysis of data from the CLARITY and CLARITY extension studies, which included 870 patients.

Disclosures: Merck KGaA, which manufactures and markets cladribine, supported the study. Several of the investigators have received speaker honoraria, consulting fees, or other funding from Merck KGaA.

Citation: REPORTING FROM CMSC 2019

Evobrutinib Demonstrates Efficacy, Safety in Relapsing MS

Key clinical point: Treatment with evobrutinib reduced the number of enhancing lesions versus placebo in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis, supporting further development of this Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor.

Major finding: The cumulative number of MRI-assessed T1 Gd+ lesions from weeks 12-24 was significantly reduced versus placebo; lesion rate ratios were 0.30 for the 75-mg daily arm, and 0.44 for the 75-mg twice-daily arm, with unadjusted P values of .002 and .031, respectively.

Study details: Forty-eight-week results of a randomized, phase 2, placebo-controlled study of 267 patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis.

Disclosures: Dr. Montalban provided disclosures related to Biogen, Merck Serono, Genentech, Genzyme, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Celgene, Actelion, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and Multiple Sclerosis International Federation.

Citation: Montalban X et al. AAN 2019. Abstract S56.004.

Key clinical point: Treatment with evobrutinib reduced the number of enhancing lesions versus placebo in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis, supporting further development of this Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor.

Major finding: The cumulative number of MRI-assessed T1 Gd+ lesions from weeks 12-24 was significantly reduced versus placebo; lesion rate ratios were 0.30 for the 75-mg daily arm, and 0.44 for the 75-mg twice-daily arm, with unadjusted P values of .002 and .031, respectively.

Study details: Forty-eight-week results of a randomized, phase 2, placebo-controlled study of 267 patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis.

Disclosures: Dr. Montalban provided disclosures related to Biogen, Merck Serono, Genentech, Genzyme, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Celgene, Actelion, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and Multiple Sclerosis International Federation.

Citation: Montalban X et al. AAN 2019. Abstract S56.004.

Key clinical point: Treatment with evobrutinib reduced the number of enhancing lesions versus placebo in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis, supporting further development of this Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor.

Major finding: The cumulative number of MRI-assessed T1 Gd+ lesions from weeks 12-24 was significantly reduced versus placebo; lesion rate ratios were 0.30 for the 75-mg daily arm, and 0.44 for the 75-mg twice-daily arm, with unadjusted P values of .002 and .031, respectively.

Study details: Forty-eight-week results of a randomized, phase 2, placebo-controlled study of 267 patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis.

Disclosures: Dr. Montalban provided disclosures related to Biogen, Merck Serono, Genentech, Genzyme, Novartis, Sanofi-Aventis, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Celgene, Actelion, National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and Multiple Sclerosis International Federation.

Citation: Montalban X et al. AAN 2019. Abstract S56.004.

Sinusitis treatment depends on classification, duration of symptoms

ORLANDO – according to a speaker at the Cardiovascular & Respiratory Summit by Global Academy for Medical Education.

The major signs and symptoms of sinusitis are pressure and pain on the anterior side of the face or in a localized headache, nasal obstruction, and pus observed at exam that is clouded or colored. Patients may also present with a feeling of facial congestion or fullness, nasal discharge, and fever, noted Brian Bizik, MS, PA-C, from Asthma & Allergy of Idaho and Nevada. The condition can present as acute (up to 4 weeks), subacute (4-12 weeks, with resolution of symptoms), chronic (12 weeks or more), and recurrent acute chronic sinusitis. Most cases of sinusitis are accompanied with contiguous nasal mucosa inflammation, and therefore the term rhinosinusitis is preferred.

To diagnose sinusitis, “you want patients to tell you where they’re hurting, and where their pressure is,” Mr. Bizik said, noting that he instructs patients to “point with one finger and tell me how you feel without using the word ‘sinus.’ ” Clinicians should ask whether a patient’s pain is continuous or cyclic, if they have bad breath even after brushing their teeth, if they have a chronic cough as opposed to postnasal drip, whether they have pain when they chew or walk, and if they feel like they are always tired.

According to guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America, if symptoms last longer than 10 days and patients have a fever above 39° C (102.2° F), it is more likely bacterial rather than viral. Another sign of bacterial infection is when patients get better after a few days before worsening again later, said Mr. Bizik. In patients where clinicians suspect bacterial infection, the IDSA recommends amoxicillin/clavulanate over amoxicillin alone because some acute bacterial rhinosinusitis could be Haemophilus influenzae, and up to 30% of these infections can produce beta-lactamase. Patients with an amoxicillin allergy should take doxycycline, which is the only currently recommended antibiotic for patients with acute bacterial rhinosinusitis.

In general, clinicians should treat acute bacterial rhinosinusitis based on whether the patient has the most severe disease, said Mr. Bizik. “Use those three criteria: fever, symptoms longer than 10 days, purulence, and feeling lousy. If you find these people are in the high-risk group, [the guidelines] recommend antibiotic treatment.”

In addition to antibiotics, patients can likely benefit from use of topical corticosteroids such as mometasone, fluticasone, flunisolide, and beclomethasone. “It comes down to simply what you like and what works well for you,” he said. With regard to oral steroids, patients with severe pain can benefit from medication like prednisone. Finally, decongestants and relief with sinus irrigation treatments like Neti pots can help relieve symptoms and promote healthy mucosal function.

On the other hand, sinusitis with a viral origin tends to have “light” flu symptoms that do not worsen over time and almost always resolve within 10 days. “If they fit the viral mold, we’re going to do everything the same [as bacterial sinusitis]; just skip the antibiotics,” he said.

In patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), the symptoms persist over a longer period of time. CRS has a large number of associated conditions, such as allergic rhinitis and gastroesophageal reflux, as well as environmental factors like cigarette smoke, viral illness, and rebound rhinitis. If a patient’s CRS is caused by allergies, treating the allergies aggressively will improve CRS symptoms. “If they have an allergic component, you really have to have a reason not to put them on montelukast. I would encourage you to do that,” said Mr. Bizik. “Cetirizine and montelukast at bedtime works very well. They’re cheap, effective, generic, and nonsteroidal.”

Other methods for treating symptoms of CRS include saline irrigation to increase mucociliary flow rates, high doses of mucolytics, and first- and second-generation antihistamines, which can take up to 10 days to see the full effect. “I have a 10-day reminder, and I call them on day 11,” said Mr. Bizik. “If they stick with it, they say it really did help. It’s a great way to avoid antibiotics.”

Intranasal corticosteroids are also effective first-line therapies for CRS. However, technique is important when using these medications. In his presentation, Mr. Bizik described the “opposite-hand” technique he teaches to patients to reduce some of the side effects patients experience when using intranasal corticosteroids, including nosebleeds.

“You insert it in the nose, you go in all the way until you just feel your fingers touching your nose, and you point it towards the earlobe so the left nostril goes to the left earlobe [and vice versa], and you just spray,” once or twice a day depending on indication, he said. “Using those consistently, when you do this, the flower smell is less, it doesn’t bother you, less goes down your throat, and it’s very effective.”

Dr. Bizik reports being a speaking and consultant for Grifols, Boehringer Ingelheim, Meda Pharmaceuticals, and an advisory board member for Circassia Pharmaceuticals.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

ORLANDO – according to a speaker at the Cardiovascular & Respiratory Summit by Global Academy for Medical Education.

The major signs and symptoms of sinusitis are pressure and pain on the anterior side of the face or in a localized headache, nasal obstruction, and pus observed at exam that is clouded or colored. Patients may also present with a feeling of facial congestion or fullness, nasal discharge, and fever, noted Brian Bizik, MS, PA-C, from Asthma & Allergy of Idaho and Nevada. The condition can present as acute (up to 4 weeks), subacute (4-12 weeks, with resolution of symptoms), chronic (12 weeks or more), and recurrent acute chronic sinusitis. Most cases of sinusitis are accompanied with contiguous nasal mucosa inflammation, and therefore the term rhinosinusitis is preferred.

To diagnose sinusitis, “you want patients to tell you where they’re hurting, and where their pressure is,” Mr. Bizik said, noting that he instructs patients to “point with one finger and tell me how you feel without using the word ‘sinus.’ ” Clinicians should ask whether a patient’s pain is continuous or cyclic, if they have bad breath even after brushing their teeth, if they have a chronic cough as opposed to postnasal drip, whether they have pain when they chew or walk, and if they feel like they are always tired.

According to guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America, if symptoms last longer than 10 days and patients have a fever above 39° C (102.2° F), it is more likely bacterial rather than viral. Another sign of bacterial infection is when patients get better after a few days before worsening again later, said Mr. Bizik. In patients where clinicians suspect bacterial infection, the IDSA recommends amoxicillin/clavulanate over amoxicillin alone because some acute bacterial rhinosinusitis could be Haemophilus influenzae, and up to 30% of these infections can produce beta-lactamase. Patients with an amoxicillin allergy should take doxycycline, which is the only currently recommended antibiotic for patients with acute bacterial rhinosinusitis.

In general, clinicians should treat acute bacterial rhinosinusitis based on whether the patient has the most severe disease, said Mr. Bizik. “Use those three criteria: fever, symptoms longer than 10 days, purulence, and feeling lousy. If you find these people are in the high-risk group, [the guidelines] recommend antibiotic treatment.”

In addition to antibiotics, patients can likely benefit from use of topical corticosteroids such as mometasone, fluticasone, flunisolide, and beclomethasone. “It comes down to simply what you like and what works well for you,” he said. With regard to oral steroids, patients with severe pain can benefit from medication like prednisone. Finally, decongestants and relief with sinus irrigation treatments like Neti pots can help relieve symptoms and promote healthy mucosal function.

On the other hand, sinusitis with a viral origin tends to have “light” flu symptoms that do not worsen over time and almost always resolve within 10 days. “If they fit the viral mold, we’re going to do everything the same [as bacterial sinusitis]; just skip the antibiotics,” he said.

In patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), the symptoms persist over a longer period of time. CRS has a large number of associated conditions, such as allergic rhinitis and gastroesophageal reflux, as well as environmental factors like cigarette smoke, viral illness, and rebound rhinitis. If a patient’s CRS is caused by allergies, treating the allergies aggressively will improve CRS symptoms. “If they have an allergic component, you really have to have a reason not to put them on montelukast. I would encourage you to do that,” said Mr. Bizik. “Cetirizine and montelukast at bedtime works very well. They’re cheap, effective, generic, and nonsteroidal.”

Other methods for treating symptoms of CRS include saline irrigation to increase mucociliary flow rates, high doses of mucolytics, and first- and second-generation antihistamines, which can take up to 10 days to see the full effect. “I have a 10-day reminder, and I call them on day 11,” said Mr. Bizik. “If they stick with it, they say it really did help. It’s a great way to avoid antibiotics.”

Intranasal corticosteroids are also effective first-line therapies for CRS. However, technique is important when using these medications. In his presentation, Mr. Bizik described the “opposite-hand” technique he teaches to patients to reduce some of the side effects patients experience when using intranasal corticosteroids, including nosebleeds.

“You insert it in the nose, you go in all the way until you just feel your fingers touching your nose, and you point it towards the earlobe so the left nostril goes to the left earlobe [and vice versa], and you just spray,” once or twice a day depending on indication, he said. “Using those consistently, when you do this, the flower smell is less, it doesn’t bother you, less goes down your throat, and it’s very effective.”

Dr. Bizik reports being a speaking and consultant for Grifols, Boehringer Ingelheim, Meda Pharmaceuticals, and an advisory board member for Circassia Pharmaceuticals.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

ORLANDO – according to a speaker at the Cardiovascular & Respiratory Summit by Global Academy for Medical Education.

The major signs and symptoms of sinusitis are pressure and pain on the anterior side of the face or in a localized headache, nasal obstruction, and pus observed at exam that is clouded or colored. Patients may also present with a feeling of facial congestion or fullness, nasal discharge, and fever, noted Brian Bizik, MS, PA-C, from Asthma & Allergy of Idaho and Nevada. The condition can present as acute (up to 4 weeks), subacute (4-12 weeks, with resolution of symptoms), chronic (12 weeks or more), and recurrent acute chronic sinusitis. Most cases of sinusitis are accompanied with contiguous nasal mucosa inflammation, and therefore the term rhinosinusitis is preferred.

To diagnose sinusitis, “you want patients to tell you where they’re hurting, and where their pressure is,” Mr. Bizik said, noting that he instructs patients to “point with one finger and tell me how you feel without using the word ‘sinus.’ ” Clinicians should ask whether a patient’s pain is continuous or cyclic, if they have bad breath even after brushing their teeth, if they have a chronic cough as opposed to postnasal drip, whether they have pain when they chew or walk, and if they feel like they are always tired.

According to guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America, if symptoms last longer than 10 days and patients have a fever above 39° C (102.2° F), it is more likely bacterial rather than viral. Another sign of bacterial infection is when patients get better after a few days before worsening again later, said Mr. Bizik. In patients where clinicians suspect bacterial infection, the IDSA recommends amoxicillin/clavulanate over amoxicillin alone because some acute bacterial rhinosinusitis could be Haemophilus influenzae, and up to 30% of these infections can produce beta-lactamase. Patients with an amoxicillin allergy should take doxycycline, which is the only currently recommended antibiotic for patients with acute bacterial rhinosinusitis.

In general, clinicians should treat acute bacterial rhinosinusitis based on whether the patient has the most severe disease, said Mr. Bizik. “Use those three criteria: fever, symptoms longer than 10 days, purulence, and feeling lousy. If you find these people are in the high-risk group, [the guidelines] recommend antibiotic treatment.”

In addition to antibiotics, patients can likely benefit from use of topical corticosteroids such as mometasone, fluticasone, flunisolide, and beclomethasone. “It comes down to simply what you like and what works well for you,” he said. With regard to oral steroids, patients with severe pain can benefit from medication like prednisone. Finally, decongestants and relief with sinus irrigation treatments like Neti pots can help relieve symptoms and promote healthy mucosal function.

On the other hand, sinusitis with a viral origin tends to have “light” flu symptoms that do not worsen over time and almost always resolve within 10 days. “If they fit the viral mold, we’re going to do everything the same [as bacterial sinusitis]; just skip the antibiotics,” he said.

In patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), the symptoms persist over a longer period of time. CRS has a large number of associated conditions, such as allergic rhinitis and gastroesophageal reflux, as well as environmental factors like cigarette smoke, viral illness, and rebound rhinitis. If a patient’s CRS is caused by allergies, treating the allergies aggressively will improve CRS symptoms. “If they have an allergic component, you really have to have a reason not to put them on montelukast. I would encourage you to do that,” said Mr. Bizik. “Cetirizine and montelukast at bedtime works very well. They’re cheap, effective, generic, and nonsteroidal.”

Other methods for treating symptoms of CRS include saline irrigation to increase mucociliary flow rates, high doses of mucolytics, and first- and second-generation antihistamines, which can take up to 10 days to see the full effect. “I have a 10-day reminder, and I call them on day 11,” said Mr. Bizik. “If they stick with it, they say it really did help. It’s a great way to avoid antibiotics.”

Intranasal corticosteroids are also effective first-line therapies for CRS. However, technique is important when using these medications. In his presentation, Mr. Bizik described the “opposite-hand” technique he teaches to patients to reduce some of the side effects patients experience when using intranasal corticosteroids, including nosebleeds.

“You insert it in the nose, you go in all the way until you just feel your fingers touching your nose, and you point it towards the earlobe so the left nostril goes to the left earlobe [and vice versa], and you just spray,” once or twice a day depending on indication, he said. “Using those consistently, when you do this, the flower smell is less, it doesn’t bother you, less goes down your throat, and it’s very effective.”

Dr. Bizik reports being a speaking and consultant for Grifols, Boehringer Ingelheim, Meda Pharmaceuticals, and an advisory board member for Circassia Pharmaceuticals.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CARPS 2019

Machine-learning model predicts anti-TNF nonresponse in RA patients

A machine-learning model that uses clinical profiles and genetic information has shown promise in predicting which rheumatoid arthritis patients respond to anti–tumor necrosis factor drugs in a patient population of European descent.

The model can “help up to 40% of European-descent anti–tumor necrosis factor [TNF] nonresponders avoid ineffective treatments” when compared with the usual “trial-and-error practice,” according to the authors led by Yuanfang Guan, PhD, of the department of computational medicine and bioinformatics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The ability to accurately predict rheumatoid arthritis patients’ response to treatments would provide valuable information for optimal drug selection and would help potential nonresponders avoid drug expenses and side effects, such as an increased risk of infections, Dr. Guan and coauthors noted in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

The investigators used a modeling technique called Gaussian process regression (GPR) to predict anti-TNF drug responses. “GPR is designed to predict the unknown dependent variable for any given independent variables based on known but noisy observations of the dependent and independent variables,” they explained.

The model they used won first place in the Dialogue on Reverse Engineering Assessment and Methods: Rheumatoid Arthritis Responder Challenge, which used a crowd-based competition framework to develop a validated molecular predictor of anti-TNF response in RA.

The model was developed and cross-validated using 1,892 patients randomly selected from a training data set of 2,706 individuals of European ancestry compiled from 13 patient cohorts. All patients met 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria for RA or were diagnosed by a board-certified rheumatologist. In addition, patients were required to have at least moderate disease activity at baseline, based on a 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) greater than 3.2.

The research team also evaluated the model using an independent dataset of 680 patients from the CERTAIN (Comparative Effectiveness Registry to study Therapies for Arthritis and Inflammatory Conditions) study.

The model combined demographic, clinical, and genetic markers to predict patients’ changes in DAS28 24 months after their baseline assessment, and identify nonresponders to anti-TNF treatments, the authors explained.

“Specifically, the [model] predicts the changes in [DAS28] of patients who have taken 12 months of anti-TNF treatments, and also classifies the patients’ responses based on the EULAR response metric,” they wrote.

Results showed that, in cross-validation tests, the model predicted changes in DAS28 with a correlation coefficient of 0.406, correctly classifying responses of 78% of subjects, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of about 0.66.

In the independent test, the method achieved a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.393 in predicting the change in DAS28.

Genetic SNP biomarkers provided a small additional contribution to the prediction on top of the clinical models, the authors noted.

“Compared to traditional trial-and-error practice, our model can help up to 40% of European-descent anti-TNF nonresponders avoid ineffective treatments. The model performance is even comparable to some published models utilizing additional biomarker data, whose AUROC ranges from 55% to 74% over various testing sets,” they wrote.

The GPR model has practical advantages in clinical application, unlike many sophisticated machine-learning algorithms, according to the authors. For example, GPR is a well-studied statistical model, its similarity-modeling approach is intuitive, and its results are easy to interpret.

“Our GPR model can predict subpopulations that do not respond to the treatment. This can help physicians tailor treatments for individual patients based on their conditions. ... The model can also estimate confidence intervals for its predictions, allowing physicians to judge how confident the predictions are,” the study authors wrote.

However, they cautioned that because the model was built using patients of European descent they did not expect it to achieve a similar performance in other populations. “Extension of the model over other populations requires new patient data and separate feature selection.”

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. Several of the researchers reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical or technology companies.

SOURCE: Guan Y et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Jul 24. doi: 10.1002/art.41056.

A machine-learning model that uses clinical profiles and genetic information has shown promise in predicting which rheumatoid arthritis patients respond to anti–tumor necrosis factor drugs in a patient population of European descent.

The model can “help up to 40% of European-descent anti–tumor necrosis factor [TNF] nonresponders avoid ineffective treatments” when compared with the usual “trial-and-error practice,” according to the authors led by Yuanfang Guan, PhD, of the department of computational medicine and bioinformatics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The ability to accurately predict rheumatoid arthritis patients’ response to treatments would provide valuable information for optimal drug selection and would help potential nonresponders avoid drug expenses and side effects, such as an increased risk of infections, Dr. Guan and coauthors noted in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

The investigators used a modeling technique called Gaussian process regression (GPR) to predict anti-TNF drug responses. “GPR is designed to predict the unknown dependent variable for any given independent variables based on known but noisy observations of the dependent and independent variables,” they explained.

The model they used won first place in the Dialogue on Reverse Engineering Assessment and Methods: Rheumatoid Arthritis Responder Challenge, which used a crowd-based competition framework to develop a validated molecular predictor of anti-TNF response in RA.

The model was developed and cross-validated using 1,892 patients randomly selected from a training data set of 2,706 individuals of European ancestry compiled from 13 patient cohorts. All patients met 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria for RA or were diagnosed by a board-certified rheumatologist. In addition, patients were required to have at least moderate disease activity at baseline, based on a 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) greater than 3.2.

The research team also evaluated the model using an independent dataset of 680 patients from the CERTAIN (Comparative Effectiveness Registry to study Therapies for Arthritis and Inflammatory Conditions) study.

The model combined demographic, clinical, and genetic markers to predict patients’ changes in DAS28 24 months after their baseline assessment, and identify nonresponders to anti-TNF treatments, the authors explained.

“Specifically, the [model] predicts the changes in [DAS28] of patients who have taken 12 months of anti-TNF treatments, and also classifies the patients’ responses based on the EULAR response metric,” they wrote.

Results showed that, in cross-validation tests, the model predicted changes in DAS28 with a correlation coefficient of 0.406, correctly classifying responses of 78% of subjects, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of about 0.66.

In the independent test, the method achieved a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.393 in predicting the change in DAS28.

Genetic SNP biomarkers provided a small additional contribution to the prediction on top of the clinical models, the authors noted.

“Compared to traditional trial-and-error practice, our model can help up to 40% of European-descent anti-TNF nonresponders avoid ineffective treatments. The model performance is even comparable to some published models utilizing additional biomarker data, whose AUROC ranges from 55% to 74% over various testing sets,” they wrote.

The GPR model has practical advantages in clinical application, unlike many sophisticated machine-learning algorithms, according to the authors. For example, GPR is a well-studied statistical model, its similarity-modeling approach is intuitive, and its results are easy to interpret.

“Our GPR model can predict subpopulations that do not respond to the treatment. This can help physicians tailor treatments for individual patients based on their conditions. ... The model can also estimate confidence intervals for its predictions, allowing physicians to judge how confident the predictions are,” the study authors wrote.

However, they cautioned that because the model was built using patients of European descent they did not expect it to achieve a similar performance in other populations. “Extension of the model over other populations requires new patient data and separate feature selection.”

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. Several of the researchers reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical or technology companies.

SOURCE: Guan Y et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Jul 24. doi: 10.1002/art.41056.

A machine-learning model that uses clinical profiles and genetic information has shown promise in predicting which rheumatoid arthritis patients respond to anti–tumor necrosis factor drugs in a patient population of European descent.

The model can “help up to 40% of European-descent anti–tumor necrosis factor [TNF] nonresponders avoid ineffective treatments” when compared with the usual “trial-and-error practice,” according to the authors led by Yuanfang Guan, PhD, of the department of computational medicine and bioinformatics at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The ability to accurately predict rheumatoid arthritis patients’ response to treatments would provide valuable information for optimal drug selection and would help potential nonresponders avoid drug expenses and side effects, such as an increased risk of infections, Dr. Guan and coauthors noted in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

The investigators used a modeling technique called Gaussian process regression (GPR) to predict anti-TNF drug responses. “GPR is designed to predict the unknown dependent variable for any given independent variables based on known but noisy observations of the dependent and independent variables,” they explained.

The model they used won first place in the Dialogue on Reverse Engineering Assessment and Methods: Rheumatoid Arthritis Responder Challenge, which used a crowd-based competition framework to develop a validated molecular predictor of anti-TNF response in RA.

The model was developed and cross-validated using 1,892 patients randomly selected from a training data set of 2,706 individuals of European ancestry compiled from 13 patient cohorts. All patients met 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria for RA or were diagnosed by a board-certified rheumatologist. In addition, patients were required to have at least moderate disease activity at baseline, based on a 28-joint Disease Activity Score (DAS28) greater than 3.2.

The research team also evaluated the model using an independent dataset of 680 patients from the CERTAIN (Comparative Effectiveness Registry to study Therapies for Arthritis and Inflammatory Conditions) study.

The model combined demographic, clinical, and genetic markers to predict patients’ changes in DAS28 24 months after their baseline assessment, and identify nonresponders to anti-TNF treatments, the authors explained.

“Specifically, the [model] predicts the changes in [DAS28] of patients who have taken 12 months of anti-TNF treatments, and also classifies the patients’ responses based on the EULAR response metric,” they wrote.

Results showed that, in cross-validation tests, the model predicted changes in DAS28 with a correlation coefficient of 0.406, correctly classifying responses of 78% of subjects, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of about 0.66.

In the independent test, the method achieved a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.393 in predicting the change in DAS28.

Genetic SNP biomarkers provided a small additional contribution to the prediction on top of the clinical models, the authors noted.

“Compared to traditional trial-and-error practice, our model can help up to 40% of European-descent anti-TNF nonresponders avoid ineffective treatments. The model performance is even comparable to some published models utilizing additional biomarker data, whose AUROC ranges from 55% to 74% over various testing sets,” they wrote.

The GPR model has practical advantages in clinical application, unlike many sophisticated machine-learning algorithms, according to the authors. For example, GPR is a well-studied statistical model, its similarity-modeling approach is intuitive, and its results are easy to interpret.

“Our GPR model can predict subpopulations that do not respond to the treatment. This can help physicians tailor treatments for individual patients based on their conditions. ... The model can also estimate confidence intervals for its predictions, allowing physicians to judge how confident the predictions are,” the study authors wrote.

However, they cautioned that because the model was built using patients of European descent they did not expect it to achieve a similar performance in other populations. “Extension of the model over other populations requires new patient data and separate feature selection.”

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. Several of the researchers reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical or technology companies.

SOURCE: Guan Y et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 Jul 24. doi: 10.1002/art.41056.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Did You Know? Psoriasis and cardiovascular disease

Infective endocarditis: Beyond the usual tests

Prompt diagnois of infective endocarditis is critical. Potential consequences of missed or delayed diagnosis, including heart failure, stroke, intracardiac abscess, conduction delays, prosthesis dysfunction, and cerebral emboli, are often catastrophic. Echocardiography is the test used most frequently to evaluate for infective endocarditis, but it misses the diagnosis in almost one-third of cases, and even more often if the patient has a prosthetic valve.

But now, several sophisticated imaging tests are available that complement echocardiography in diagnosing and assessing infective endocarditis; these include 4-dimensional computed tomography (4D CT), fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), and leukocyte scintigraphy. These tests have greatly improved our ability not only to diagnose infective endocarditis, but also to determine the extent and spread of infection, and they aid in perioperative assessment. Abnormal findings on these tests have been incorporated into the European Society of Cardiology’s 2015 modified diagnostic criteria for infective endocarditis.1

This article details the indications, advantages, and limitations of the various imaging tests for diagnosing and evaluating infective endocarditis (Table 1).

INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS IS DIFFICULT TO DIAGNOSE AND TREAT

Infective endocarditis is difficult to diagnose and treat. Clinical and imaging clues can be subtle, and the diagnosis requires a high level of suspicion and visualization of cardiac structures.

Further, the incidence of infective endocarditis is on the rise in the United States, particularly in women and young adults, likely due to intravenous drug use.2,3

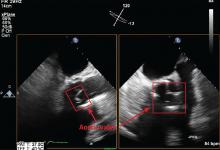

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY HAS AN IMPORTANT ROLE, BUT IS LIMITED

Echocardiography remains the most commonly performed study for diagnosing infective endocarditis, as it is fast, widely accessible, and less expensive than other imaging tests.

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is often the first choice for testing. However, its sensitivity is only about 70% for detecting vegetations on native valves and 50% for detecting vegetations on prosthetic valves.1 It is inherently constrained by the limited number of views by which a comprehensive external evaluation of the heart can be achieved. Using a 2-dimensional instrument to view a 3-dimensional object is difficult, and depending on several factors, it can be hard to see vegetations and abscesses that are associated with infective endocarditis. Further, TTE is impeded by obesity and by hyperinflated lungs from obstructive pulmonary disease or mechanical ventilation. It has poor sensitivity for detecting small vegetations and for detecting vegetations and paravalvular complications in patients who have a prosthetic valve or a cardiac implanted electronic device.

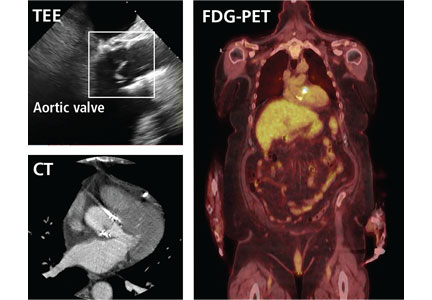

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is the recommended first-line imaging test for patients with prosthetic valves and no contraindications to the test. Otherwise, it should be done after TTE if the results of TTE are negative but clinical suspicion for infective endocarditis remains high (eg, because the patient uses intravenous drugs). But although TEE has a higher sensitivity than TTE (up to 96% for vegetations on native valves and 92% for those on prosthetic valves, if performed by an experienced sonographer), it can still miss infective endocarditis. Also, TEE does not provide a significant advantage over TTE in patients who have a cardiac implanted electronic device.1,4,5

Regardless of whether TTE or TEE is used, they are estimated to miss up to 30% of cases of infective endocarditis and its sequelae.4 False-negative findings are likelier in patients who have preexisting severe valvular lesions, prosthetic valves, cardiac implanted electronic devices, small vegetations, or abscesses, or if a vegetation has already broken free and embolized. Furthermore, distinguishing between vegetations and thrombi, cardiac tumors, and myxomatous changes using echocardiography is difficult.

CARDIAC CT

For patients who have inconclusive results on echocardiography, contraindications to TEE, or poor sonic windows, cardiac CT can be an excellent alternative. It is especially useful in the setting of a prosthetic valve.

Synchronized (“gated”) with the patient’s heart rate and rhythm, CT machines can acquire images during diastole, reducing motion artifact, and can create 3D images of the heart. In addition, newer machines can acquire several images at different points in the heart cycle to add a fourth dimension—time. The resulting 4D images play like short video loops of the beating heart and allow noninvasive assessment of cardiac anatomy with remarkable detail and resolution.

4D CT is increasingly being used in infective endocarditis, and growing evidence indicates that its accuracy is similar to that of TEE in the preoperative evaluation of patients with aortic prosthetic valve endocarditis.6 In a study of 28 patients, complementary use of CT angiography led to a change in treatment strategy in 7 (25%) compared with routine clinical workup.7 Several studies have found no difference between 4D CT and preoperative TEE in detecting pseudoaneurysm, abscess, or valve dehiscence. TEE and 4D CT also have similar sensitivities for detecting infective endocarditis in native and prosthetic valves.8,9

Coupled with CT angiography, 4D CT is also an excellent noninvasive way to perioperatively evaluate the coronary arteries without the risks associated with catheterization in those requiring nonemergency surgery (Figure 1A, B, and C).

4D CT performs well for detecting abscess and pseudoaneurysm but has slightly lower sensitivity for vegetations than TEE (91% vs 99%).9

Gated CT, PET, or both may be useful in cases of suspected prosthetic aortic valve endocarditis when TEE is negative. Pseudoaneurysms are not well visualized with TEE, and the atrial mitral curtain area is often thickened on TEE in cases of aortic prosthetic valve infective endocarditis that do not definitely involve abscesses. Gated CT and PET show this area better.8 This information is important in cases in which a surgeon may be unconvinced that the patient has prosthetic valve endocarditis.

Limitations of 4D cardiac CT

4D CT with or without angiography has limitations. It requires a wide-volume scanner and an experienced reader.

Patients with irregular heart rhythms or uncontrolled tachycardia pose technical problems for image acquisition. Cardiac CT is typically gated (ie, images are obtained within a defined time period) to acquire images during diastole. Ideally, images are acquired when the heart is in mid to late diastole, a time of minimal cardiac motion, so that motion artifact is minimized. To estimate the timing of image acquisition, the cardiac cycle must be predictable, and its duration should be as long as possible. Tachycardia or irregular rhythms such as frequent ectopic beats or atrial fibrillation make acquisition timing difficult, and thus make it nearly impossible to accurately obtain images when the heart is at minimum motion, limiting assessment of cardiac structures or the coronary tree.4,10

Extensive coronary calcification can hinder assessment of the coronary tree by CT coronary angiography.

Contrast exposure may limit the use of CT in some patients (eg, those with contrast allergies or renal dysfunction). However, modern scanners allow for much smaller contrast boluses without decreasing sensitivity.

4D CT involves radiation exposure, especially when done with angiography, although modern scanners have greatly reduced exposure. The average radiation dose in CT coronary angiography is 2.9 to 5.9 mSv11 compared with 7 mSv in diagnostic cardiac catheterization (without angioplasty or stenting) or 16 mSv in routine CT of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast.12,13 In view of the morbidity and mortality risks associated with infective endocarditis, especially if the diagnosis is delayed, this small radiation exposure may be justifiable.

Bottom line for cardiac CT

4D CT is an excellent alternative to echocardiography for select patients. Clinicians should strongly consider this study in the following situations:

- Patients with a prosthetic valve

- Patients who are strongly suspected of having infective endocarditis but who have a poor sonic window on TTE or TEE, as can occur with chronic obstructive lung disease, morbid obesity, or previous thoracic or cardiovascular surgery

- Patients who meet clinical indications for TEE, such as having a prosthetic valve or a high suspicion for native valve infective endocarditis with negative TTE, but who have contraindications to TEE

- As an alternative to TEE for preoperative evaluation in patients with known infective endocarditis.

Patients with tachycardia or irregular heart rhythms are not good candidates for this test.

FDG-PET AND LEUKOCYTE SCINTIGRAPHY

FDG-PET and leukocyte scintigraphy are other options for diagnosing infective endocarditis and determining the presence and extent of intra- and extracardiac infection. They are more sensitive than echocardiography for detecting infection of cardiac implanted electronic devices such as ventricular assist devices, pacemakers, implanted cardiac defibrillators, and cardiac resynchronization therapy devices.14–16

The utility of FDG-PET is founded on the uptake of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose by cells, with higher uptake taking place in cells with higher metabolic activity (such as in areas of inflammation). Similarly, leukocyte scintigraphy relies on the use of radiolabeled leukocytes (ie, leukocytes previously extracted from the patient, labelled, and re-introduced into the patient) to allow for localization of inflamed tissue.

The most significant contribution of FDG-PET may be the ability to detect infective endocarditis early, when echocardiography is initially negative. When abnormal FDG uptake was included in the modified Duke criteria, it increased the sensitivity to 97% for detecting infective endocarditis on admission, leading some to propose its incorporation as a major criterion.17 In patients with prosthetic valves and suspected infective endocarditis, FDG-PET was found in one study to have a sensitivity of up to 91% and a specificity of up to 95%.18

Both FDG-PET and leukocyte scintigraphy have a high sensitivity, specificity, and negative predictive value for cardiac implanted electronic device infection, and should be strongly considered in patients in whom it is suspected but who have negative or inconclusive findings on echocardiography.14,15

In addition, a common conundrum faced by clinicians with use of echocardiography is the difficulty of differentiating thrombus from infected vegetation on valves or device lead wires. Some evidence indicates that FDG-PET may help to discriminate between vegetation and thrombus, although more rigorous studies are needed before its use for that purpose can be recommended.19

Limitations of nuclear studies

Both FDG-PET and leukocyte scintigraphy perform poorly for detecting native-valve infective endocarditis. In a study in which 90% of the patients had native-valve infective endocarditis according to the Duke criteria, FDG-PET had a specificity of 93% but a sensitivity of only 39%.20

Both studies can be cumbersome, laborious, and time-consuming for patients. FDG-PET requires a fasting or glucose-restricted diet before testing, and the test itself can be complicated by development of hyperglycemia, although this is rare.

While FDG-PET is most effective in detecting infections of prosthetic valves and cardiac implanted electronic devices, the results can be falsely positive in patients with a history of recent cardiac surgery (due to ongoing tissue healing), as well as maladies other than infective endocarditis that lead to inflammation, such as vasculitis or malignancy. Similarly, for unclear reasons, leukocyte scintigraphy can yield false-negative results in patients with enterococcal or candidal infective endocarditis.21

FDG-PET and leukocyte scintigraphy are more expensive than TEE and cardiac CT22 and are not widely available.

Both tests entail radiation exposure, with the average dose ranging from 7 to 14 mSv. However, this is less than the average amount acquired during percutaneous coronary intervention (16 mSv), and overlaps with the amount in chest CT with contrast when assessing for pulmonary embolism (7 to 9 mSv). Lower doses are possible with optimized protocols.12,13,15,23

Bottom line for nuclear studies

FDG-PET and leukocyte scintigraphy are especially useful for patients with a prosthetic valve or cardiac implanted electronic device. However, limitations must be kept in mind.

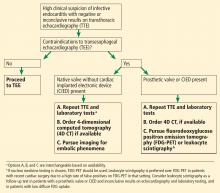

A suggested algorithm for testing with nuclear imaging is shown in Figure 2.1,4

CEREBRAL MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive than cerebral CT for detecting emboli in the brain. According to American Heart Association guidelines, cerebral MRI should be done in patients with known or suspected infective endocarditis and neurologic impairment, defined as headaches, meningeal symptoms, or neurologic deficits. It is also often used in neurologically asymptomatic patients with infective endocarditis who have indications for valve surgery to assess for mycotic aneurysms, which are associated with increased intracranial bleeding during surgery.

MRI use in other asymptomatic patients remains controversial.24 In cases with high clinical suspicion for infective endocarditis and no findings on echocardiography, cerebral MRI can increase the sensitivity of the Duke criteria by adding a minor criterion. Some have argued that, in patients with definite infective endocarditis, detecting silent cerebral complications can lead to management changes. However, more studies are needed to determine if there is indeed a group of neurologically asymptomatic infective endocarditis patients for whom cerebral MRI leads to improved outcomes.

Limitations of cerebral MRI

Cerebral MRI cannot be used in patients with non-MRI-compatible implanted hardware.

Gadolinium, the contrast agent typically used, can cause nephrogenic systemic fibrosis in patients who have poor renal function. This rare but serious adverse effect is characterized by irreversible systemic fibrosis affecting skin, muscles, and even visceral tissue such as lungs. The American College of Radiology allows for gadolinium use in patients without acute kidney injury and patients with stable chronic kidney disease with a glomerular filtration rate of at least 30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Its use should be avoided in patients with renal failure on replacement therapy, with advanced chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2), or with acute kidney injury, even if they do not need renal replacement therapy.25

Concerns have also been raised about gadolinium retention in the brain, even in patients with normal renal function.26–28 Thus far, no conclusive clinical adverse effects of retention have been found, although more study is warranted. Nevertheless, the US Food and Drug Administration now requires a black-box warning about this possibility and advises clinicians to counsel patients appropriately.

Bottom line on cerebral MRI

Cerebral MRI should be obtained when a patient presents with definite or possible infective endocarditis with neurologic impairment, such as new headaches, meningismus, or focal neurologic deficits. Routine brain MRI in patients with confirmed infective endocarditis without neurologic symptoms, or those without definite infective endocarditis, is discouraged.

CARDIAC MRI

Cardiac MRI, typically obtained with gadolinium contrast, allows for better 3D assessment of cardiac structures and morphology than echocardiography or CT, and can detect infiltrative cardiac disease, myopericarditis, and much more. It is increasingly used in the field of structural cardiology, but its role for evaluating infective endocarditis remains unclear.

Cardiac MRI does not appear to be better than echocardiography for diagnosing infective endocarditis. However, it may prove helpful in the evaluation of patients known to have infective endocarditis but who cannot be properly evaluated for disease extent because of poor image quality on echocardiography and contraindications to CT.1,29 Its role is limited in patients with cardiac implanted electronic devices, as most devices are incompatible with MRI use, although newer devices obviate this concern. But even for devices that are MRI-compatible, results are diminished due to an eclipsing effect, wherein the device parts can make it hard to see structures clearly because the “brightness” basically eclipses the surrounding area.4

Concerns regarding use of gadolinium as described above need also be considered.

The role of cardiac MRI in diagnosing and managing infective endocarditis may evolve, but at present, the 2017 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association appropriate-use criteria discourage its use for these purposes.16

Bottom line for cardiac MRI

Cardiac MRI to evaluate a patient for suspected infective endocarditis is not recommended due to lack of superiority compared with echocardiography or CT, and the risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis from gadolinium in patients with renal compromise.

- Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J 2015; 36(44):3075–3128. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319

- Durante-Mangoni E, Bradley S, Selton-Suty C, et al; International Collaboration on Endocarditis Prospective Cohort Study Group. Current features of infective endocarditis in elderly patients: results of the International Collaboration on Endocarditis Prospective Cohort Study. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168(19):2095–2103. doi:10.1001/archinte.168.19.2095

- Wurcel AG, Anderson JE, Chui KK, et al. Increasing infectious endocarditis admissions among young people who inject drugs. Open Forum Infect Dis 2016; 3(3):ofw157. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofw157

- Gomes A, Glaudemans AW, Touw DJ, et al. Diagnostic value of imaging in infective endocarditis: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17(1):e1–e14. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30141-4

- Cahill TJ, Baddour LM, Habib G, et al. Challenges in infective endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(3):325–344. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.066

- Fagman E, Perrotta S, Bech-Hanssen O, et al. ECG-gated computed tomography: a new role for patients with suspected aortic prosthetic valve endocarditis. Eur Radiol 2012; 22(11):2407–2414. doi:10.1007/s00330-012-2491-5