User login

Pandemic drives demand for self-managed abortions

Requests for self-managed abortion via a telemedicine service increased by 27% from March 20, 2020, to April 11, 2020, in the United States in the wake of widespread lockdowns and shelter-in-place directives because of the COVID-19 pandemic, based on data from a provider of such services.

Access to abortion care is challenging in many areas under ordinary circumstances, but the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic led to many states suspending or limiting in-clinic services, wrote Abigail R.A. Aiken, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas at Austin and colleagues.

“As a result, people may increasingly be seeking self-managed abortion outside the formal health care system,” they said.

In a research letter published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the investigators reviewed request data from Aid Access, a telemedicine service that provides medication for abortion at up to 10 weeks’ gestation for users who complete an online consultation form. They also collected data on the implementation and scope of COVID-19–related abortion restrictions by state.

The analysis included all 49,935 requests made between January 1, 2019, and April 11, 2020.

Overall, the rate of requests for self-managed medical abortions increased significantly, by 27%, during the period from March 20, 2020, to April 11, 2020, which reflected the average period after clinic restrictions or closures at the state level. A total of 11 states showed individually significant increases in requests for self-managed medical abortions, with the highest of 94% in Texas and the lowest of 22% in Ohio. In these 11 states, the median time spent at home was 5% higher than in states without significant increases in requests for self-managed medical abortions during the same period. These states also had “particularly high COVID-19 rates or more severe COVID-19–related restrictions on in-clinic abortion access,” the researchers noted.

Patients want alternatives to in-person care

“Our results may reflect two distinct phenomena,” Dr. Aiken and associates wrote. “First, more people may be seeking abortion through all channels, whether due to COVID-19 risks during pregnancy, reduced access to prenatal care, or the pandemic-related economic downturn. Second, there may be shift in demand from in-clinic to self-managed abortion during the pandemic, possibly owing to fear of infection during in-person care or inability to get to a clinic because of childcare and transit disruptions,” they explained.

The study findings were limited by the inability to measure all options for women to achieve self-managed abortions and a lack of power to detect changes in states with low request numbers or where restrictions were implemented at later dates, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that telemedicine services for medication abortion should be a policy priority because patients may continue to seek alternatives while in-clinic services remain restricted, they said.

In fact, “the World Health Organization recommends telemedicine and self-management abortion-care models during the pandemic, and the United Kingdom has temporarily implemented fully remote provision of abortion medications,” the researchers wrote. However, similar strategies in the United States “would depend on sustained changes to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy, which requires patients to collect mifepristone at a hospital or medical facility, as well as changes to state-specific laws that prohibit remote provider consultation,” Dr. Aiken and associates concluded.

Lift barriers to protect patients

Eve Espey, MD, of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, said in an interview.

“As background, state abortion restrictions have increased exponentially over the last decade, while research over the same time period has demonstrated the safety of telemedicine abortion – a form of self-managed abortion – with no in-person visit for appropriate candidates,” she said.

“Enter the coronavirus pandemic with safety concerns related to in-person medical visits and certain states leveraging the opportunity to enact even more stringent abortion restrictions. Unsurprisingly, the result, as documented in this excellent research report, is a significant increase in requests for telemedicine abortion in many states, particularly the most restrictive, from the single online service in the United States, Aid Access,” said Dr. Espey.

“Barriers to self-managed abortion include the [FDA] Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy for mifepristone, a set of unnecessary restrictions requiring that providers meet certain qualifications and dispense the medication only in a clinic, office, or hospital,” she said. “The REMS precludes the use of telemedicine abortion; Aid Access and the FDA are in legal proceedings,” she noted.

“Most recently, the [American Civil Liberties Union] sued the FDA on behalf of a coalition of medical experts led by [American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists] to suspend the REMS for mifepristone during the COVID public health emergency, to allow patients to receive the medications for early abortion without a visit to a health care provider,” Dr. Espey said. “Fortunately, a federal district court required the temporary suspension of the in-person dispensing restriction. Although this is a great step to improve abortion access during the pandemic, a permanent removal of the REMS would pave the way for ongoing safe, effective, and patient-centered early abortion care,” noted Dr. Espey, who was asked to comment on the research letter.

Dr. Aiken disclosed serving as a consultant for Agile Therapeutics, and a coauthor is the founder and director of Aid Access. Dr. Espey had no financial conflicts to disclose. She is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board.

SOURCE: Aiken ARA et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jul 21. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004081.

Requests for self-managed abortion via a telemedicine service increased by 27% from March 20, 2020, to April 11, 2020, in the United States in the wake of widespread lockdowns and shelter-in-place directives because of the COVID-19 pandemic, based on data from a provider of such services.

Access to abortion care is challenging in many areas under ordinary circumstances, but the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic led to many states suspending or limiting in-clinic services, wrote Abigail R.A. Aiken, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas at Austin and colleagues.

“As a result, people may increasingly be seeking self-managed abortion outside the formal health care system,” they said.

In a research letter published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the investigators reviewed request data from Aid Access, a telemedicine service that provides medication for abortion at up to 10 weeks’ gestation for users who complete an online consultation form. They also collected data on the implementation and scope of COVID-19–related abortion restrictions by state.

The analysis included all 49,935 requests made between January 1, 2019, and April 11, 2020.

Overall, the rate of requests for self-managed medical abortions increased significantly, by 27%, during the period from March 20, 2020, to April 11, 2020, which reflected the average period after clinic restrictions or closures at the state level. A total of 11 states showed individually significant increases in requests for self-managed medical abortions, with the highest of 94% in Texas and the lowest of 22% in Ohio. In these 11 states, the median time spent at home was 5% higher than in states without significant increases in requests for self-managed medical abortions during the same period. These states also had “particularly high COVID-19 rates or more severe COVID-19–related restrictions on in-clinic abortion access,” the researchers noted.

Patients want alternatives to in-person care

“Our results may reflect two distinct phenomena,” Dr. Aiken and associates wrote. “First, more people may be seeking abortion through all channels, whether due to COVID-19 risks during pregnancy, reduced access to prenatal care, or the pandemic-related economic downturn. Second, there may be shift in demand from in-clinic to self-managed abortion during the pandemic, possibly owing to fear of infection during in-person care or inability to get to a clinic because of childcare and transit disruptions,” they explained.

The study findings were limited by the inability to measure all options for women to achieve self-managed abortions and a lack of power to detect changes in states with low request numbers or where restrictions were implemented at later dates, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that telemedicine services for medication abortion should be a policy priority because patients may continue to seek alternatives while in-clinic services remain restricted, they said.

In fact, “the World Health Organization recommends telemedicine and self-management abortion-care models during the pandemic, and the United Kingdom has temporarily implemented fully remote provision of abortion medications,” the researchers wrote. However, similar strategies in the United States “would depend on sustained changes to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy, which requires patients to collect mifepristone at a hospital or medical facility, as well as changes to state-specific laws that prohibit remote provider consultation,” Dr. Aiken and associates concluded.

Lift barriers to protect patients

Eve Espey, MD, of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, said in an interview.

“As background, state abortion restrictions have increased exponentially over the last decade, while research over the same time period has demonstrated the safety of telemedicine abortion – a form of self-managed abortion – with no in-person visit for appropriate candidates,” she said.

“Enter the coronavirus pandemic with safety concerns related to in-person medical visits and certain states leveraging the opportunity to enact even more stringent abortion restrictions. Unsurprisingly, the result, as documented in this excellent research report, is a significant increase in requests for telemedicine abortion in many states, particularly the most restrictive, from the single online service in the United States, Aid Access,” said Dr. Espey.

“Barriers to self-managed abortion include the [FDA] Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy for mifepristone, a set of unnecessary restrictions requiring that providers meet certain qualifications and dispense the medication only in a clinic, office, or hospital,” she said. “The REMS precludes the use of telemedicine abortion; Aid Access and the FDA are in legal proceedings,” she noted.

“Most recently, the [American Civil Liberties Union] sued the FDA on behalf of a coalition of medical experts led by [American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists] to suspend the REMS for mifepristone during the COVID public health emergency, to allow patients to receive the medications for early abortion without a visit to a health care provider,” Dr. Espey said. “Fortunately, a federal district court required the temporary suspension of the in-person dispensing restriction. Although this is a great step to improve abortion access during the pandemic, a permanent removal of the REMS would pave the way for ongoing safe, effective, and patient-centered early abortion care,” noted Dr. Espey, who was asked to comment on the research letter.

Dr. Aiken disclosed serving as a consultant for Agile Therapeutics, and a coauthor is the founder and director of Aid Access. Dr. Espey had no financial conflicts to disclose. She is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board.

SOURCE: Aiken ARA et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jul 21. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004081.

Requests for self-managed abortion via a telemedicine service increased by 27% from March 20, 2020, to April 11, 2020, in the United States in the wake of widespread lockdowns and shelter-in-place directives because of the COVID-19 pandemic, based on data from a provider of such services.

Access to abortion care is challenging in many areas under ordinary circumstances, but the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic led to many states suspending or limiting in-clinic services, wrote Abigail R.A. Aiken, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas at Austin and colleagues.

“As a result, people may increasingly be seeking self-managed abortion outside the formal health care system,” they said.

In a research letter published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the investigators reviewed request data from Aid Access, a telemedicine service that provides medication for abortion at up to 10 weeks’ gestation for users who complete an online consultation form. They also collected data on the implementation and scope of COVID-19–related abortion restrictions by state.

The analysis included all 49,935 requests made between January 1, 2019, and April 11, 2020.

Overall, the rate of requests for self-managed medical abortions increased significantly, by 27%, during the period from March 20, 2020, to April 11, 2020, which reflected the average period after clinic restrictions or closures at the state level. A total of 11 states showed individually significant increases in requests for self-managed medical abortions, with the highest of 94% in Texas and the lowest of 22% in Ohio. In these 11 states, the median time spent at home was 5% higher than in states without significant increases in requests for self-managed medical abortions during the same period. These states also had “particularly high COVID-19 rates or more severe COVID-19–related restrictions on in-clinic abortion access,” the researchers noted.

Patients want alternatives to in-person care

“Our results may reflect two distinct phenomena,” Dr. Aiken and associates wrote. “First, more people may be seeking abortion through all channels, whether due to COVID-19 risks during pregnancy, reduced access to prenatal care, or the pandemic-related economic downturn. Second, there may be shift in demand from in-clinic to self-managed abortion during the pandemic, possibly owing to fear of infection during in-person care or inability to get to a clinic because of childcare and transit disruptions,” they explained.

The study findings were limited by the inability to measure all options for women to achieve self-managed abortions and a lack of power to detect changes in states with low request numbers or where restrictions were implemented at later dates, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that telemedicine services for medication abortion should be a policy priority because patients may continue to seek alternatives while in-clinic services remain restricted, they said.

In fact, “the World Health Organization recommends telemedicine and self-management abortion-care models during the pandemic, and the United Kingdom has temporarily implemented fully remote provision of abortion medications,” the researchers wrote. However, similar strategies in the United States “would depend on sustained changes to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy, which requires patients to collect mifepristone at a hospital or medical facility, as well as changes to state-specific laws that prohibit remote provider consultation,” Dr. Aiken and associates concluded.

Lift barriers to protect patients

Eve Espey, MD, of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, said in an interview.

“As background, state abortion restrictions have increased exponentially over the last decade, while research over the same time period has demonstrated the safety of telemedicine abortion – a form of self-managed abortion – with no in-person visit for appropriate candidates,” she said.

“Enter the coronavirus pandemic with safety concerns related to in-person medical visits and certain states leveraging the opportunity to enact even more stringent abortion restrictions. Unsurprisingly, the result, as documented in this excellent research report, is a significant increase in requests for telemedicine abortion in many states, particularly the most restrictive, from the single online service in the United States, Aid Access,” said Dr. Espey.

“Barriers to self-managed abortion include the [FDA] Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy for mifepristone, a set of unnecessary restrictions requiring that providers meet certain qualifications and dispense the medication only in a clinic, office, or hospital,” she said. “The REMS precludes the use of telemedicine abortion; Aid Access and the FDA are in legal proceedings,” she noted.

“Most recently, the [American Civil Liberties Union] sued the FDA on behalf of a coalition of medical experts led by [American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists] to suspend the REMS for mifepristone during the COVID public health emergency, to allow patients to receive the medications for early abortion without a visit to a health care provider,” Dr. Espey said. “Fortunately, a federal district court required the temporary suspension of the in-person dispensing restriction. Although this is a great step to improve abortion access during the pandemic, a permanent removal of the REMS would pave the way for ongoing safe, effective, and patient-centered early abortion care,” noted Dr. Espey, who was asked to comment on the research letter.

Dr. Aiken disclosed serving as a consultant for Agile Therapeutics, and a coauthor is the founder and director of Aid Access. Dr. Espey had no financial conflicts to disclose. She is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board.

SOURCE: Aiken ARA et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jul 21. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004081.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

MS Highlights from AAN & CMSC

- Initial high-efficacy MS therapy is associated with less disability later

- Serum NfL in early MS can help predict clinical course

- No benefit of three commonly used medications for MS fatigue

- Telerehabilitation may be effective in MS

- CMSC MRI guidelines evolve into international consensus protocol

- Newest oral DMTs haven’t yet made a big impact in the MS world

Read the supplement.

- Initial high-efficacy MS therapy is associated with less disability later

- Serum NfL in early MS can help predict clinical course

- No benefit of three commonly used medications for MS fatigue

- Telerehabilitation may be effective in MS

- CMSC MRI guidelines evolve into international consensus protocol

- Newest oral DMTs haven’t yet made a big impact in the MS world

Read the supplement.

- Initial high-efficacy MS therapy is associated with less disability later

- Serum NfL in early MS can help predict clinical course

- No benefit of three commonly used medications for MS fatigue

- Telerehabilitation may be effective in MS

- CMSC MRI guidelines evolve into international consensus protocol

- Newest oral DMTs haven’t yet made a big impact in the MS world

Read the supplement.

Pandemic poses new challenges for rural doctors

These include struggling with seeing patients virtually and treating patients who have politicized the virus. Additionally, the pandemic has exposed rural practices to greater financial difficulties.

Before the pandemic some rurally based primary care physicians were already working through big challenges, such as having few local medical colleagues to consult and working in small practices with lean budgets. In fact, data gathered by the National Rural Health Association showed that there are only 40 primary care physicians per 100,000 patients in rural regions, compared with 53 in urban areas – and the number of physicians overall is 13 per 10,000 in rural areas, compared with 31 in cities.

In the prepandemic world, for some doctors, the challenges were balanced by the benefits of practicing in these sparsely populated communities with scenic, low-traffic roads. Some perks of practicing in rural areas touted by doctors included having a fast commute, being able to swim in a lake near the office before work, having a low cost of living, and feeling like they are making a difference in their communities as they treat generations of the families they see around town.

But today, new hurdles to practicing medicine in rural America created by the COVID-19 pandemic have caused the hardships to feel heavier than the joys at times for some physicians interviewed by MDedge.

Many independent rural practices in need of assistance were not able to get much from the federal Provider Relief Funds, said John M. Westfall, MD, who is director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care, in an interview.

“Rural primary care doctors function independently or in smaller critical access hospitals and community health centers,” said Dr. Westfall, who previously practiced family medicine in a small town in Colorado. “Many of these have much less financial reserves so are at risk of cutbacks and closure.”

Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, an internist based in a tiny Georgia community along the highway between Atlanta and Augusta, said her small practice works on really thin margins and doesn’t have much cushion. At the beginning of the pandemic, all visits were down, and her practice operated at a loss. To help, Dr. Fincher and her colleagues applied for funding from the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) through the CARES Act.

“COVID-19 has had a tremendous impact especially on primary care practices. We live and die by volume. … Our volume in mid-March to mid-May really dropped dramatically,” explained Dr. Fincher, who is also president of the American College of Physicians. “The PPP sustained us for 2 months, enabling us to pay our staff and to remain open and get us up and running on telehealth.”

Starting up telemedicine

Experiencing spotty or no access to broadband Internet is nothing new to rural physicians, but having this problem interfere with their ability to provide care to patients is.

As much of the American health system rapidly embraced telehealth during the pandemic, obtaining access to high-speed Internet has been a major challenge for rural patients, noted Dr. Westfall.

“Some practices were able to quickly adopt some telehealth capacity with phone and video. Changes in payment for telehealth helped. But in some rural communities there was not adequate Internet bandwidth for quality video connections. And some patients did not have the means for high-speed video connections,” Dr. Westfall said.

Indeed, according to a 2019 Pew Research Center survey, 63% of rural Americans say they can access the Internet through a broadband connection at home, compared with 75% and 79% in suburban and urban areas, respectively.

In the Appalachian town of Zanesville, Ohio, for example, family physician Shelly L. Dunmyer, MD, and her colleagues discovered that many patients don’t have Internet access at home. Dr. Fincher has to go to the office to conduct telehealth visits because her own Internet access at home is unpredictable. As for patients, it may take 15 minutes for them to work out technical glitches and find good Internet reception, said Dr. Fincher. For internist Y. Ki Shin, MD, who practices in the coastal town of Montesano in Washington state, about 25% of his practice’s telehealth visits must be conducted by phone because of limitations on video, such as lack of high-speed access.

But telephone visits are often insufficient replacements for appointments via video, according to several rural physicians interviewed for this piece.

“Telehealth can be frustrating at times due to connectivity issues which can be difficult at times in the rural areas,” said Dr. Fincher. “In order for telehealth to be reasonably helpful to patients and physicians to care for people with chronic problems, the patients must have things like blood pressure monitors, glucometers, and scales to address problems like hypertension, diabetes myelitis, and congestive heart failure.”

“If you have the audio and video and the data from these devices, you’re good. If you don’t have these data, and/or don’t have the video you just can’t provide good care,” she explained.

Dr. Dunmyer and her colleagues at Medical Home Primary Care Center in Zanesville, Ohio, found a way to get around the problem of patients not being able to access Internet to participate in video visits from their homes. This involved having her patients drive into her practice’s parking lot to participate in modified telehealth visits. Staffers gave iPads to patients in their cars, and Dr. Dunmyer conducted visits from her office, about 50 yards away.

“We were even doing Medicare wellness visits: Instead of asking them to get up and move around the room, we would sit at the window and wave at them, ask them to get out, walk around the car. We were able to check mobility and all kinds of things that we’d normally do in the office,” Dr. Dunmyer explained in an interview.

The family physician noted that her practice is now conducting fewer parking lot visits since her office is allowing in-person appointments, but that they’re still an option for her patients.

Treating political adversaries

Some rural physicians have experienced strained relationships with patients for reasons other than technology – stark differences in opinion over the pandemic itself. Certain patients are following President Trump’s lead and questioning everything from the pandemic death toll to preventive measures recommended by scientists and medical experts, physicians interviewed by MDedge said.

Patients everywhere share these viewpoints, of course, but research and election results confirm that rural areas are more receptive to conservative viewpoints. In 2018, a Pew Research Center survey reported that rural and urban areas are “becoming more polarized politically,” and “rural areas tend to have a higher concentration of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents.” For example, 40% of rural respondents reported “very warm” or “somewhat warm” feelings toward Donald Trump, compared with just 19% in urban areas.

Dr. Shin has struggled to cope with patients who want to argue about pandemic safety precautions like wearing masks and seem to question whether systemic racism exists.

“We are seeing a lot more people who feel that this pandemic is not real, that it’s a political and not-true infection,” he said in an interview. “We’ve had patients who were angry at us because we made them wear masks, and some were demanding hydroxychloroquine and wanted to have an argument because we’re not going to prescribe it for them.”

In one situation, which he found especially disturbing, Dr. Shin had to leave the exam room because a patient wouldn’t stop challenging him regarding the pandemic. Things have gotten so bad that Dr. Shin has even questioned whether he wants to continue his long career in his small town because of local political attitudes such as opposition to mask-wearing and social distancing.

“Mr. Trump’s misinformation on this pandemic made my job much more difficult. As a minority, I feel less safe in my community than ever,” said Dr. Shin, who described himself as Asian American.

Despite these new stressors, Dr. Shin has experienced some joyful moments while practicing medicine in the pandemic.

He said a recent home visit to a patient who had been hospitalized for over 3 months and nearly died helped him put political disputes with his patients into perspective.

“He was discharged home but is bedbound. He had gangrene on his toes, and I could not fully examine him using video,” Dr. Shin recalled. “It was tricky to find the house, but a very large Trump sign was very helpful in locating it. It was a good visit: He was happy to see me, and I was happy to see that he was doing okay at home.”

“I need to remind myself that supporting Mr. Trump does not always mean that my patient supports Mr. Trump’s view on the pandemic and the race issues in our country,” Dr. Shin added.

The Washington-based internist said he also tells himself that, even if his patients refuse to follow his strong advice regarding pandemic precautions, it does not mean he has failed as a doctor.

“I need to continue to educate patients about the dangers of COVID infection but cannot be angry if they don’t choose to follow my recommendations,” he noted.

Dr. Fincher says her close connection with patients has allowed her to smooth over politically charged claims about the pandemic in the town of Thomson, Georgia, with a population 6,800.

“I have a sense that, even though we may differ in our understanding of some basic facts, they appreciate what I say since we have a long-term relationship built on trust,” she said. This kind of trust, Dr. Fincher suggested, may be more common than in urban areas where there’s a larger supply of physicians, and patients don’t see the same doctors for long periods of time.

“It’s more meaningful when it comes from me, rather than doctors who are [new to patients] every year when their employer changes their insurance,” she noted.

These include struggling with seeing patients virtually and treating patients who have politicized the virus. Additionally, the pandemic has exposed rural practices to greater financial difficulties.

Before the pandemic some rurally based primary care physicians were already working through big challenges, such as having few local medical colleagues to consult and working in small practices with lean budgets. In fact, data gathered by the National Rural Health Association showed that there are only 40 primary care physicians per 100,000 patients in rural regions, compared with 53 in urban areas – and the number of physicians overall is 13 per 10,000 in rural areas, compared with 31 in cities.

In the prepandemic world, for some doctors, the challenges were balanced by the benefits of practicing in these sparsely populated communities with scenic, low-traffic roads. Some perks of practicing in rural areas touted by doctors included having a fast commute, being able to swim in a lake near the office before work, having a low cost of living, and feeling like they are making a difference in their communities as they treat generations of the families they see around town.

But today, new hurdles to practicing medicine in rural America created by the COVID-19 pandemic have caused the hardships to feel heavier than the joys at times for some physicians interviewed by MDedge.

Many independent rural practices in need of assistance were not able to get much from the federal Provider Relief Funds, said John M. Westfall, MD, who is director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care, in an interview.

“Rural primary care doctors function independently or in smaller critical access hospitals and community health centers,” said Dr. Westfall, who previously practiced family medicine in a small town in Colorado. “Many of these have much less financial reserves so are at risk of cutbacks and closure.”

Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, an internist based in a tiny Georgia community along the highway between Atlanta and Augusta, said her small practice works on really thin margins and doesn’t have much cushion. At the beginning of the pandemic, all visits were down, and her practice operated at a loss. To help, Dr. Fincher and her colleagues applied for funding from the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) through the CARES Act.

“COVID-19 has had a tremendous impact especially on primary care practices. We live and die by volume. … Our volume in mid-March to mid-May really dropped dramatically,” explained Dr. Fincher, who is also president of the American College of Physicians. “The PPP sustained us for 2 months, enabling us to pay our staff and to remain open and get us up and running on telehealth.”

Starting up telemedicine

Experiencing spotty or no access to broadband Internet is nothing new to rural physicians, but having this problem interfere with their ability to provide care to patients is.

As much of the American health system rapidly embraced telehealth during the pandemic, obtaining access to high-speed Internet has been a major challenge for rural patients, noted Dr. Westfall.

“Some practices were able to quickly adopt some telehealth capacity with phone and video. Changes in payment for telehealth helped. But in some rural communities there was not adequate Internet bandwidth for quality video connections. And some patients did not have the means for high-speed video connections,” Dr. Westfall said.

Indeed, according to a 2019 Pew Research Center survey, 63% of rural Americans say they can access the Internet through a broadband connection at home, compared with 75% and 79% in suburban and urban areas, respectively.

In the Appalachian town of Zanesville, Ohio, for example, family physician Shelly L. Dunmyer, MD, and her colleagues discovered that many patients don’t have Internet access at home. Dr. Fincher has to go to the office to conduct telehealth visits because her own Internet access at home is unpredictable. As for patients, it may take 15 minutes for them to work out technical glitches and find good Internet reception, said Dr. Fincher. For internist Y. Ki Shin, MD, who practices in the coastal town of Montesano in Washington state, about 25% of his practice’s telehealth visits must be conducted by phone because of limitations on video, such as lack of high-speed access.

But telephone visits are often insufficient replacements for appointments via video, according to several rural physicians interviewed for this piece.

“Telehealth can be frustrating at times due to connectivity issues which can be difficult at times in the rural areas,” said Dr. Fincher. “In order for telehealth to be reasonably helpful to patients and physicians to care for people with chronic problems, the patients must have things like blood pressure monitors, glucometers, and scales to address problems like hypertension, diabetes myelitis, and congestive heart failure.”

“If you have the audio and video and the data from these devices, you’re good. If you don’t have these data, and/or don’t have the video you just can’t provide good care,” she explained.

Dr. Dunmyer and her colleagues at Medical Home Primary Care Center in Zanesville, Ohio, found a way to get around the problem of patients not being able to access Internet to participate in video visits from their homes. This involved having her patients drive into her practice’s parking lot to participate in modified telehealth visits. Staffers gave iPads to patients in their cars, and Dr. Dunmyer conducted visits from her office, about 50 yards away.

“We were even doing Medicare wellness visits: Instead of asking them to get up and move around the room, we would sit at the window and wave at them, ask them to get out, walk around the car. We were able to check mobility and all kinds of things that we’d normally do in the office,” Dr. Dunmyer explained in an interview.

The family physician noted that her practice is now conducting fewer parking lot visits since her office is allowing in-person appointments, but that they’re still an option for her patients.

Treating political adversaries

Some rural physicians have experienced strained relationships with patients for reasons other than technology – stark differences in opinion over the pandemic itself. Certain patients are following President Trump’s lead and questioning everything from the pandemic death toll to preventive measures recommended by scientists and medical experts, physicians interviewed by MDedge said.

Patients everywhere share these viewpoints, of course, but research and election results confirm that rural areas are more receptive to conservative viewpoints. In 2018, a Pew Research Center survey reported that rural and urban areas are “becoming more polarized politically,” and “rural areas tend to have a higher concentration of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents.” For example, 40% of rural respondents reported “very warm” or “somewhat warm” feelings toward Donald Trump, compared with just 19% in urban areas.

Dr. Shin has struggled to cope with patients who want to argue about pandemic safety precautions like wearing masks and seem to question whether systemic racism exists.

“We are seeing a lot more people who feel that this pandemic is not real, that it’s a political and not-true infection,” he said in an interview. “We’ve had patients who were angry at us because we made them wear masks, and some were demanding hydroxychloroquine and wanted to have an argument because we’re not going to prescribe it for them.”

In one situation, which he found especially disturbing, Dr. Shin had to leave the exam room because a patient wouldn’t stop challenging him regarding the pandemic. Things have gotten so bad that Dr. Shin has even questioned whether he wants to continue his long career in his small town because of local political attitudes such as opposition to mask-wearing and social distancing.

“Mr. Trump’s misinformation on this pandemic made my job much more difficult. As a minority, I feel less safe in my community than ever,” said Dr. Shin, who described himself as Asian American.

Despite these new stressors, Dr. Shin has experienced some joyful moments while practicing medicine in the pandemic.

He said a recent home visit to a patient who had been hospitalized for over 3 months and nearly died helped him put political disputes with his patients into perspective.

“He was discharged home but is bedbound. He had gangrene on his toes, and I could not fully examine him using video,” Dr. Shin recalled. “It was tricky to find the house, but a very large Trump sign was very helpful in locating it. It was a good visit: He was happy to see me, and I was happy to see that he was doing okay at home.”

“I need to remind myself that supporting Mr. Trump does not always mean that my patient supports Mr. Trump’s view on the pandemic and the race issues in our country,” Dr. Shin added.

The Washington-based internist said he also tells himself that, even if his patients refuse to follow his strong advice regarding pandemic precautions, it does not mean he has failed as a doctor.

“I need to continue to educate patients about the dangers of COVID infection but cannot be angry if they don’t choose to follow my recommendations,” he noted.

Dr. Fincher says her close connection with patients has allowed her to smooth over politically charged claims about the pandemic in the town of Thomson, Georgia, with a population 6,800.

“I have a sense that, even though we may differ in our understanding of some basic facts, they appreciate what I say since we have a long-term relationship built on trust,” she said. This kind of trust, Dr. Fincher suggested, may be more common than in urban areas where there’s a larger supply of physicians, and patients don’t see the same doctors for long periods of time.

“It’s more meaningful when it comes from me, rather than doctors who are [new to patients] every year when their employer changes their insurance,” she noted.

These include struggling with seeing patients virtually and treating patients who have politicized the virus. Additionally, the pandemic has exposed rural practices to greater financial difficulties.

Before the pandemic some rurally based primary care physicians were already working through big challenges, such as having few local medical colleagues to consult and working in small practices with lean budgets. In fact, data gathered by the National Rural Health Association showed that there are only 40 primary care physicians per 100,000 patients in rural regions, compared with 53 in urban areas – and the number of physicians overall is 13 per 10,000 in rural areas, compared with 31 in cities.

In the prepandemic world, for some doctors, the challenges were balanced by the benefits of practicing in these sparsely populated communities with scenic, low-traffic roads. Some perks of practicing in rural areas touted by doctors included having a fast commute, being able to swim in a lake near the office before work, having a low cost of living, and feeling like they are making a difference in their communities as they treat generations of the families they see around town.

But today, new hurdles to practicing medicine in rural America created by the COVID-19 pandemic have caused the hardships to feel heavier than the joys at times for some physicians interviewed by MDedge.

Many independent rural practices in need of assistance were not able to get much from the federal Provider Relief Funds, said John M. Westfall, MD, who is director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care, in an interview.

“Rural primary care doctors function independently or in smaller critical access hospitals and community health centers,” said Dr. Westfall, who previously practiced family medicine in a small town in Colorado. “Many of these have much less financial reserves so are at risk of cutbacks and closure.”

Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, an internist based in a tiny Georgia community along the highway between Atlanta and Augusta, said her small practice works on really thin margins and doesn’t have much cushion. At the beginning of the pandemic, all visits were down, and her practice operated at a loss. To help, Dr. Fincher and her colleagues applied for funding from the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) through the CARES Act.

“COVID-19 has had a tremendous impact especially on primary care practices. We live and die by volume. … Our volume in mid-March to mid-May really dropped dramatically,” explained Dr. Fincher, who is also president of the American College of Physicians. “The PPP sustained us for 2 months, enabling us to pay our staff and to remain open and get us up and running on telehealth.”

Starting up telemedicine

Experiencing spotty or no access to broadband Internet is nothing new to rural physicians, but having this problem interfere with their ability to provide care to patients is.

As much of the American health system rapidly embraced telehealth during the pandemic, obtaining access to high-speed Internet has been a major challenge for rural patients, noted Dr. Westfall.

“Some practices were able to quickly adopt some telehealth capacity with phone and video. Changes in payment for telehealth helped. But in some rural communities there was not adequate Internet bandwidth for quality video connections. And some patients did not have the means for high-speed video connections,” Dr. Westfall said.

Indeed, according to a 2019 Pew Research Center survey, 63% of rural Americans say they can access the Internet through a broadband connection at home, compared with 75% and 79% in suburban and urban areas, respectively.

In the Appalachian town of Zanesville, Ohio, for example, family physician Shelly L. Dunmyer, MD, and her colleagues discovered that many patients don’t have Internet access at home. Dr. Fincher has to go to the office to conduct telehealth visits because her own Internet access at home is unpredictable. As for patients, it may take 15 minutes for them to work out technical glitches and find good Internet reception, said Dr. Fincher. For internist Y. Ki Shin, MD, who practices in the coastal town of Montesano in Washington state, about 25% of his practice’s telehealth visits must be conducted by phone because of limitations on video, such as lack of high-speed access.

But telephone visits are often insufficient replacements for appointments via video, according to several rural physicians interviewed for this piece.

“Telehealth can be frustrating at times due to connectivity issues which can be difficult at times in the rural areas,” said Dr. Fincher. “In order for telehealth to be reasonably helpful to patients and physicians to care for people with chronic problems, the patients must have things like blood pressure monitors, glucometers, and scales to address problems like hypertension, diabetes myelitis, and congestive heart failure.”

“If you have the audio and video and the data from these devices, you’re good. If you don’t have these data, and/or don’t have the video you just can’t provide good care,” she explained.

Dr. Dunmyer and her colleagues at Medical Home Primary Care Center in Zanesville, Ohio, found a way to get around the problem of patients not being able to access Internet to participate in video visits from their homes. This involved having her patients drive into her practice’s parking lot to participate in modified telehealth visits. Staffers gave iPads to patients in their cars, and Dr. Dunmyer conducted visits from her office, about 50 yards away.

“We were even doing Medicare wellness visits: Instead of asking them to get up and move around the room, we would sit at the window and wave at them, ask them to get out, walk around the car. We were able to check mobility and all kinds of things that we’d normally do in the office,” Dr. Dunmyer explained in an interview.

The family physician noted that her practice is now conducting fewer parking lot visits since her office is allowing in-person appointments, but that they’re still an option for her patients.

Treating political adversaries

Some rural physicians have experienced strained relationships with patients for reasons other than technology – stark differences in opinion over the pandemic itself. Certain patients are following President Trump’s lead and questioning everything from the pandemic death toll to preventive measures recommended by scientists and medical experts, physicians interviewed by MDedge said.

Patients everywhere share these viewpoints, of course, but research and election results confirm that rural areas are more receptive to conservative viewpoints. In 2018, a Pew Research Center survey reported that rural and urban areas are “becoming more polarized politically,” and “rural areas tend to have a higher concentration of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents.” For example, 40% of rural respondents reported “very warm” or “somewhat warm” feelings toward Donald Trump, compared with just 19% in urban areas.

Dr. Shin has struggled to cope with patients who want to argue about pandemic safety precautions like wearing masks and seem to question whether systemic racism exists.

“We are seeing a lot more people who feel that this pandemic is not real, that it’s a political and not-true infection,” he said in an interview. “We’ve had patients who were angry at us because we made them wear masks, and some were demanding hydroxychloroquine and wanted to have an argument because we’re not going to prescribe it for them.”

In one situation, which he found especially disturbing, Dr. Shin had to leave the exam room because a patient wouldn’t stop challenging him regarding the pandemic. Things have gotten so bad that Dr. Shin has even questioned whether he wants to continue his long career in his small town because of local political attitudes such as opposition to mask-wearing and social distancing.

“Mr. Trump’s misinformation on this pandemic made my job much more difficult. As a minority, I feel less safe in my community than ever,” said Dr. Shin, who described himself as Asian American.

Despite these new stressors, Dr. Shin has experienced some joyful moments while practicing medicine in the pandemic.

He said a recent home visit to a patient who had been hospitalized for over 3 months and nearly died helped him put political disputes with his patients into perspective.

“He was discharged home but is bedbound. He had gangrene on his toes, and I could not fully examine him using video,” Dr. Shin recalled. “It was tricky to find the house, but a very large Trump sign was very helpful in locating it. It was a good visit: He was happy to see me, and I was happy to see that he was doing okay at home.”

“I need to remind myself that supporting Mr. Trump does not always mean that my patient supports Mr. Trump’s view on the pandemic and the race issues in our country,” Dr. Shin added.

The Washington-based internist said he also tells himself that, even if his patients refuse to follow his strong advice regarding pandemic precautions, it does not mean he has failed as a doctor.

“I need to continue to educate patients about the dangers of COVID infection but cannot be angry if they don’t choose to follow my recommendations,” he noted.

Dr. Fincher says her close connection with patients has allowed her to smooth over politically charged claims about the pandemic in the town of Thomson, Georgia, with a population 6,800.

“I have a sense that, even though we may differ in our understanding of some basic facts, they appreciate what I say since we have a long-term relationship built on trust,” she said. This kind of trust, Dr. Fincher suggested, may be more common than in urban areas where there’s a larger supply of physicians, and patients don’t see the same doctors for long periods of time.

“It’s more meaningful when it comes from me, rather than doctors who are [new to patients] every year when their employer changes their insurance,” she noted.

Congenital Defect of the Toenail

The Diagnosis: Onychodystrophy Secondary to Polydactyly

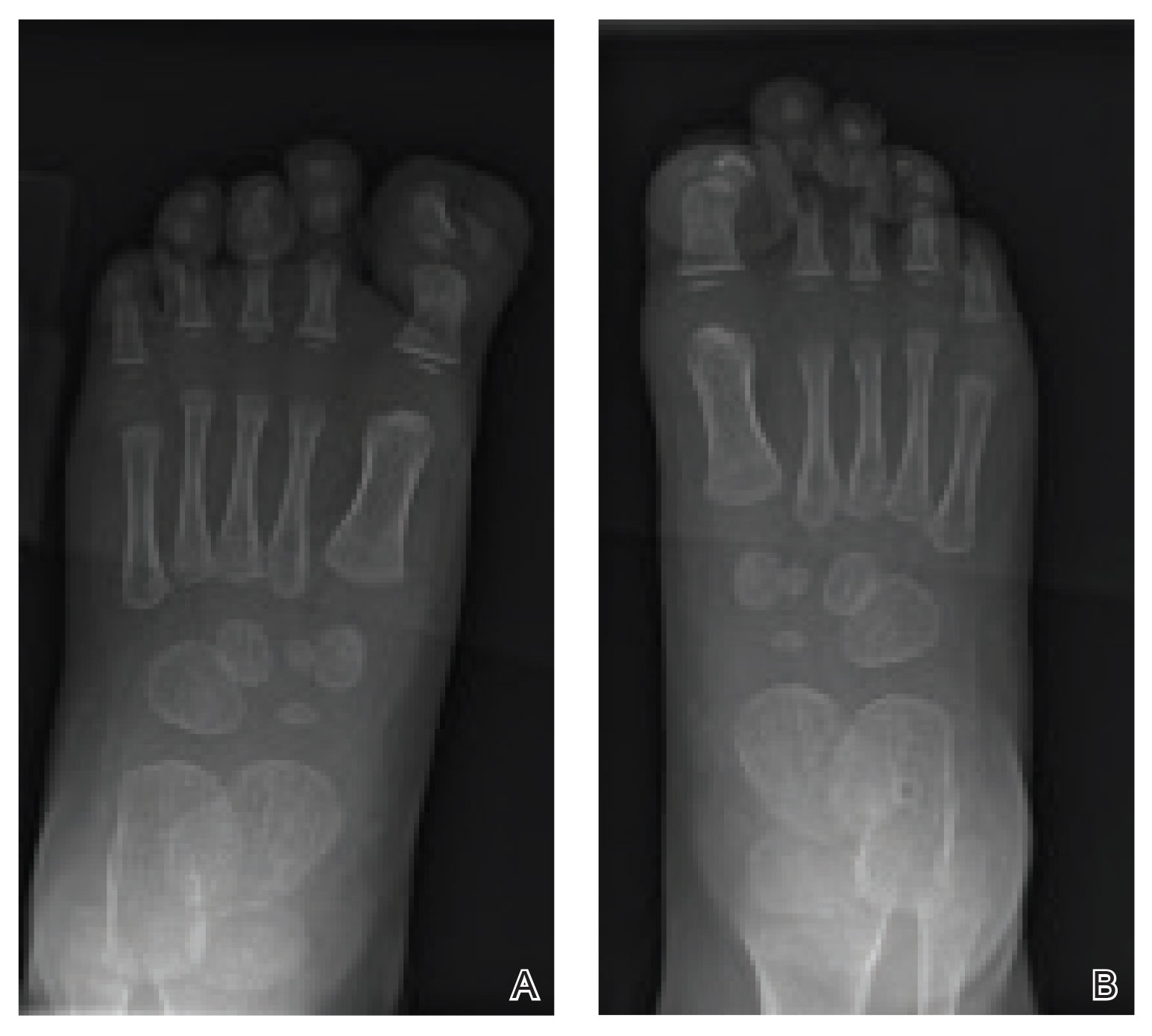

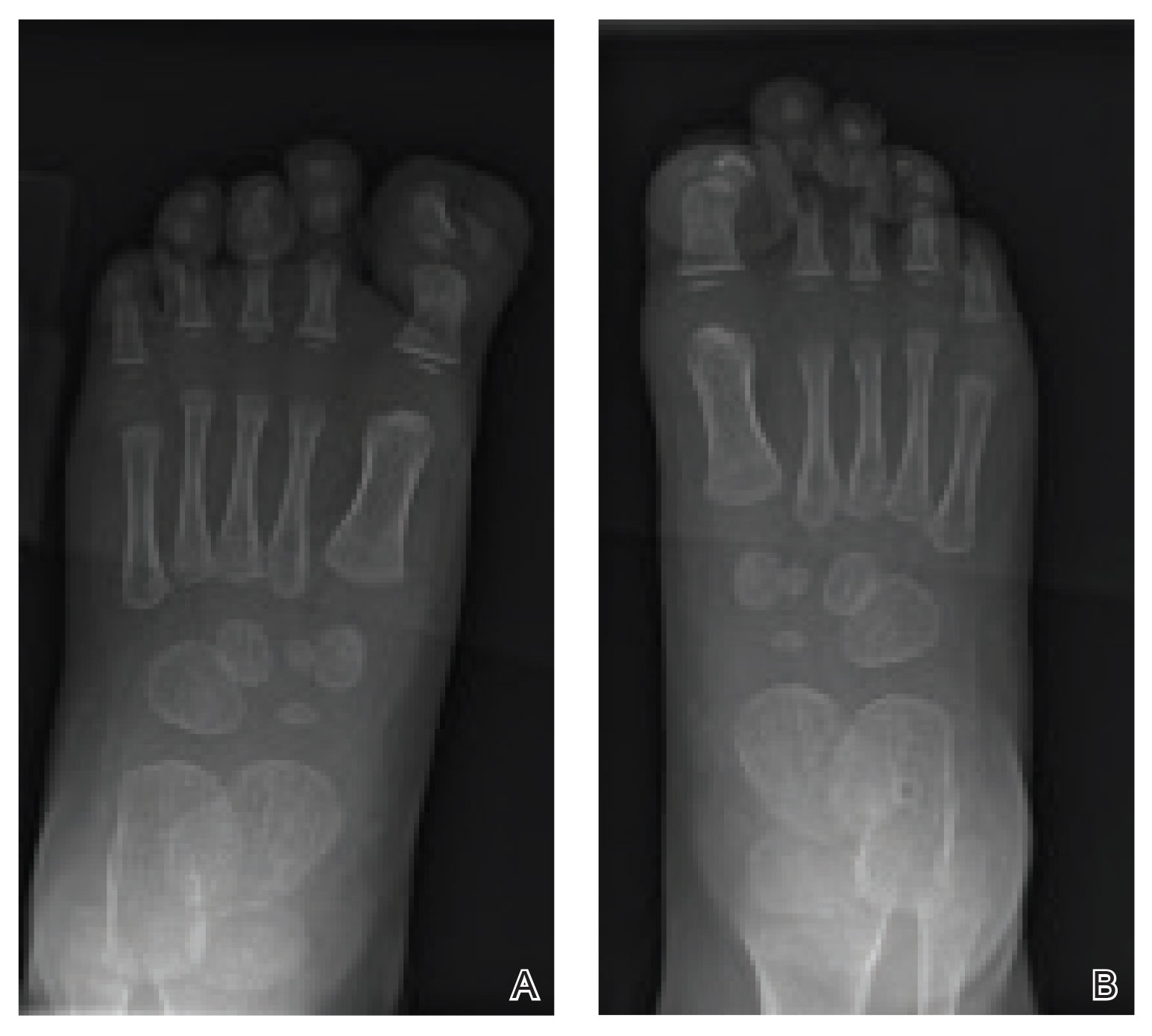

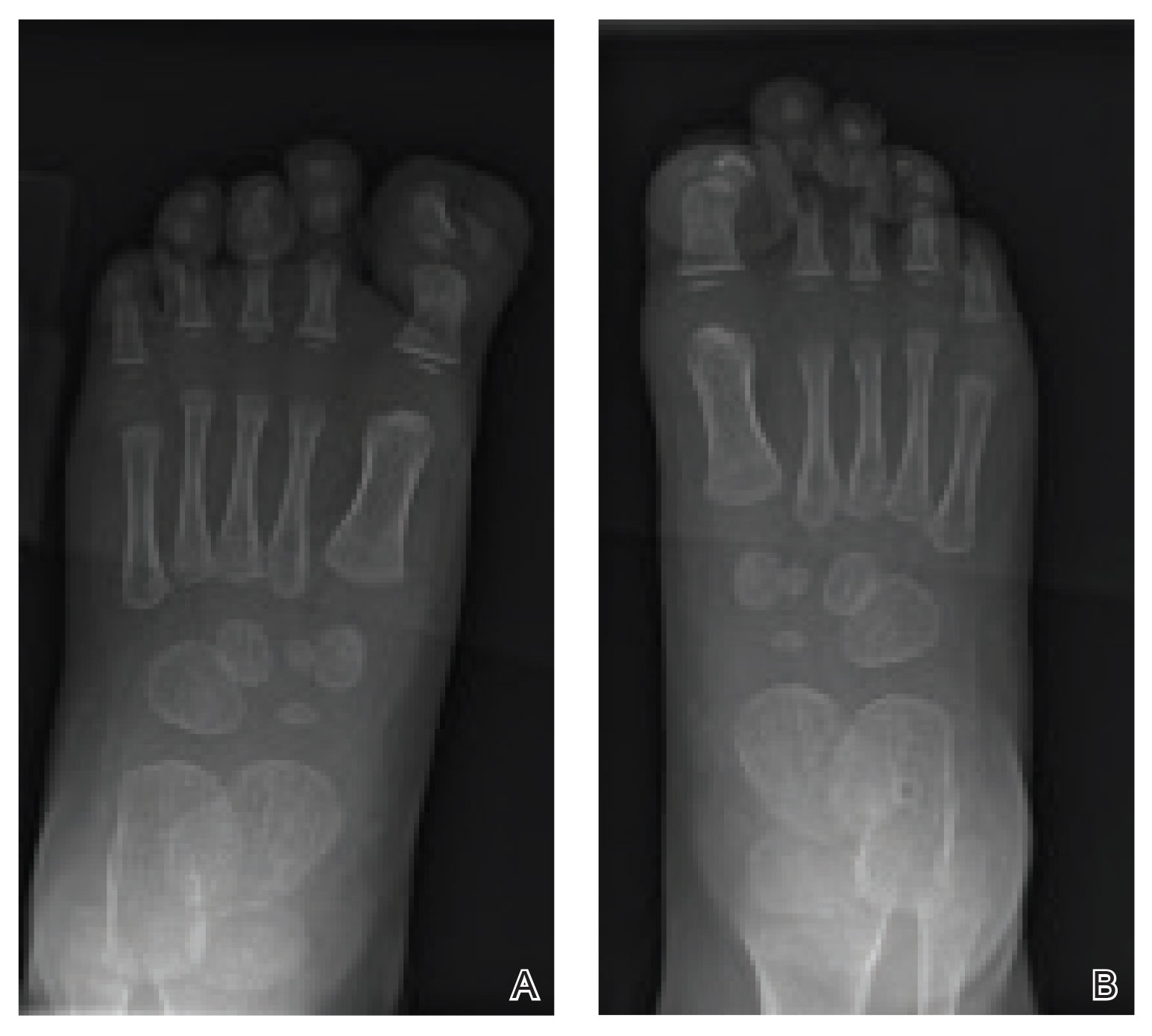

Radiographs of the feet demonstrated an accessory distal phalanx of the left great toe with a similar smaller accessory distal phalanx on the right great toe (Figure). The patient was referred to orthopedic surgery, and surgical intervention was recommended for only the left great toe given recurrent skin inflammation and nail complications. An excision of the left great toe polydactyly was performed. The patient healed well without complications.

Many clinically heterogeneous phenotypes exist for polydactyly and syndactyly, which both are common entities with incidences of 1 in 700 to 1000 births and 1 in 2000 to 3000 births, respectively.1 Both polydactyly and syndactyly can be an isolated variant in newborns or present with multiple concurrent malformations as part of a genetic syndrome, with more than 300 syndromic anomalies described. The genetic basis of these conditions is equally diverse, with homeobox genes, hedgehog pathways, fibroblast growth factors, and boneand cartilage-derived morphogenetic proteins implicated in their development.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient included congenital malalignment of the great toenails, nail-patella syndrome, onychodystrophy secondary to polydactyly, and congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail fold. Given the strong family history, polydactyly was suspected.

Congenital malalignment of the great toenails results in lateral deviation of the nail plates.2 It is an underdiagnosed condition with different etiologies hypothesized, such as genetic factors with possible autosomal-dominant transmission and extrinsic factors.3 One proposed mechanism of pathogenesis is desynchronization during growth of the nail and distal phalanx of the hallux, leading to larger nail plates that grow laterally.4 Typical features associated with this disease are nail discoloration, nail plate thickening, and transversal grooves or ridges, none of which were seen in our patient.2

Children with nail-patella syndrome have dysplastic nails and associated bony abnormalities, such as absent patellae.5 This syndrome results from an autosomaldominant mutation in the LIM homeobox transcription factor 1-beta gene, LMX1B, which is responsible for dorsal-ventral patterning of the limb, as well as patterning of the nails, patellae and long bones, and even the kidney tubule.6 As such, patients with nail-patella syndrome have associated renal abnormalities. The findings in our patient were limited to the feet, making an underlying syndrome unlikely to be the cause.

First described in 1968 by Meadow,7 fetal hydantoin syndrome is a well-documented sequela in women taking phenytoin throughout pregnancy. Multiple malformations are possible, including cardiac defects, cleft lip/palate, digit and nail hypoplasia, abnormal facial features, mental disability, and growth abnormalities.8 The teratogenicity behind phenytoin results from reactive oxygen species that alter embryonic DNA, proteins, and lipids.9 The mother of this child was not on any seizure prophylaxis, eliminating it from the differential.

Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail fold is a defect of the soft tissue of the hallux leading to hypertrophy of the nail fold, commonly presenting with inflammation and pain10 possibly due to dyssynchronous growth between the soft tissue and nail plate.11 With this defect, a lip covering the nail plate is common, which was not seen in our patient.

As demonstrated in our patient, family history can help guide the diagnosis. Seven of 9 nonsyndromic forms of syndactyly are inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion and range from mild presentations, as in our patient, to more severe deformations with underlying bone fusion and functional impairment.12 Polydactyly also often is expressed in an autosomal-dominant pattern, with up to 30% of patients having a positive family history. Polydactyly traditionally is classified by the location of the supernumerary digit as preaxial (radial), central, or postaxial (ulnar), and many further morphologic variations exist within these groups. Overall, preaxial polydactyly is relatively rare and represents 15% of polydactylies, with central and postaxial comprising the other 6% and 79%, respectively.13 Delineation of the underlying anatomy may reveal ray duplications (digit and corresponding metacarpal or metatarsal bone), metatarsal variants, and duplicated phalanges that may be hypoplastic or deformed. Patients may report difficulty finding comfortable footwear, cosmetic concerns, and nail-related complications. Although not always required, surgical intervention may provide definitive treatment but can leave residual deformities in the surrounding altered anatomy; thus, orthopedic or plastic surgery consultations are critical in appropriately counseling patients.

- Ahmed H, Akbari H, Emanmi A, et al. Genetic overview of syndactyly and polydactyly. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5:e1549.

- Catalfo P, Musumeci ML, Lacarrubba F, et al. Congenital malalignment of the great toenails: a review. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4:230-235.

- Kus S, Tahmaz E, Gurunluoglu R, et al. Congenital malalignment of the great toenails in dizygotic twins. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:434-435.

- Chaniotakis I, Bonitsis N, Stergiopoulou C, et al. Dizygotic twins with congenital malalignment of the great toenails: reappraisal of the pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:711-715.

- Witzgall R. Nail-patella syndrome. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469:927-936.

- Dreyer SD, Zhou G, Baldini A, et al, Mutations in LMX1B cause abnormal skeletal patterning and renal dysplasia in nail patella syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;19:47-50.

- Meadow SR. Anticonvulsant drugs and congenital abnormalities. Lancet. 1968;2:1296.

- Scheinfeld N. Phenytoin in cutaneous medicine: its uses, mechanisms and side effects. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:6.

- Winn LM, Wells PG. Phenytoin-initiated DNA oxidation in murine embryo culture, and embryo protection by the antioxidative enzymes superoxide dismutase and catalase: evidence for reactive oxygen species-mediated DNA oxidation in the molecular mechanism of phenytoin teratogenicity. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:112-120.

- Piraccini BM, Parente GL, Varotti E, et al. Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds of the hallux: clinical features and follow-up of seven cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:348-351.

- Martinet C, Pascal M, Civatte J, et al. Lateral nail-pad of the big toe in infants. apropos of 2 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1984;111:731-732.

- Malik S. Syndactyly: phenotypes, genetics and current classification. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:817-824.

- Belthur MV, Linton JL, Barnes DA. The spectrum of preaxial polydactyly of the foot. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31:435-447.

The Diagnosis: Onychodystrophy Secondary to Polydactyly

Radiographs of the feet demonstrated an accessory distal phalanx of the left great toe with a similar smaller accessory distal phalanx on the right great toe (Figure). The patient was referred to orthopedic surgery, and surgical intervention was recommended for only the left great toe given recurrent skin inflammation and nail complications. An excision of the left great toe polydactyly was performed. The patient healed well without complications.

Many clinically heterogeneous phenotypes exist for polydactyly and syndactyly, which both are common entities with incidences of 1 in 700 to 1000 births and 1 in 2000 to 3000 births, respectively.1 Both polydactyly and syndactyly can be an isolated variant in newborns or present with multiple concurrent malformations as part of a genetic syndrome, with more than 300 syndromic anomalies described. The genetic basis of these conditions is equally diverse, with homeobox genes, hedgehog pathways, fibroblast growth factors, and boneand cartilage-derived morphogenetic proteins implicated in their development.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient included congenital malalignment of the great toenails, nail-patella syndrome, onychodystrophy secondary to polydactyly, and congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail fold. Given the strong family history, polydactyly was suspected.

Congenital malalignment of the great toenails results in lateral deviation of the nail plates.2 It is an underdiagnosed condition with different etiologies hypothesized, such as genetic factors with possible autosomal-dominant transmission and extrinsic factors.3 One proposed mechanism of pathogenesis is desynchronization during growth of the nail and distal phalanx of the hallux, leading to larger nail plates that grow laterally.4 Typical features associated with this disease are nail discoloration, nail plate thickening, and transversal grooves or ridges, none of which were seen in our patient.2

Children with nail-patella syndrome have dysplastic nails and associated bony abnormalities, such as absent patellae.5 This syndrome results from an autosomaldominant mutation in the LIM homeobox transcription factor 1-beta gene, LMX1B, which is responsible for dorsal-ventral patterning of the limb, as well as patterning of the nails, patellae and long bones, and even the kidney tubule.6 As such, patients with nail-patella syndrome have associated renal abnormalities. The findings in our patient were limited to the feet, making an underlying syndrome unlikely to be the cause.

First described in 1968 by Meadow,7 fetal hydantoin syndrome is a well-documented sequela in women taking phenytoin throughout pregnancy. Multiple malformations are possible, including cardiac defects, cleft lip/palate, digit and nail hypoplasia, abnormal facial features, mental disability, and growth abnormalities.8 The teratogenicity behind phenytoin results from reactive oxygen species that alter embryonic DNA, proteins, and lipids.9 The mother of this child was not on any seizure prophylaxis, eliminating it from the differential.

Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail fold is a defect of the soft tissue of the hallux leading to hypertrophy of the nail fold, commonly presenting with inflammation and pain10 possibly due to dyssynchronous growth between the soft tissue and nail plate.11 With this defect, a lip covering the nail plate is common, which was not seen in our patient.

As demonstrated in our patient, family history can help guide the diagnosis. Seven of 9 nonsyndromic forms of syndactyly are inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion and range from mild presentations, as in our patient, to more severe deformations with underlying bone fusion and functional impairment.12 Polydactyly also often is expressed in an autosomal-dominant pattern, with up to 30% of patients having a positive family history. Polydactyly traditionally is classified by the location of the supernumerary digit as preaxial (radial), central, or postaxial (ulnar), and many further morphologic variations exist within these groups. Overall, preaxial polydactyly is relatively rare and represents 15% of polydactylies, with central and postaxial comprising the other 6% and 79%, respectively.13 Delineation of the underlying anatomy may reveal ray duplications (digit and corresponding metacarpal or metatarsal bone), metatarsal variants, and duplicated phalanges that may be hypoplastic or deformed. Patients may report difficulty finding comfortable footwear, cosmetic concerns, and nail-related complications. Although not always required, surgical intervention may provide definitive treatment but can leave residual deformities in the surrounding altered anatomy; thus, orthopedic or plastic surgery consultations are critical in appropriately counseling patients.

The Diagnosis: Onychodystrophy Secondary to Polydactyly

Radiographs of the feet demonstrated an accessory distal phalanx of the left great toe with a similar smaller accessory distal phalanx on the right great toe (Figure). The patient was referred to orthopedic surgery, and surgical intervention was recommended for only the left great toe given recurrent skin inflammation and nail complications. An excision of the left great toe polydactyly was performed. The patient healed well without complications.

Many clinically heterogeneous phenotypes exist for polydactyly and syndactyly, which both are common entities with incidences of 1 in 700 to 1000 births and 1 in 2000 to 3000 births, respectively.1 Both polydactyly and syndactyly can be an isolated variant in newborns or present with multiple concurrent malformations as part of a genetic syndrome, with more than 300 syndromic anomalies described. The genetic basis of these conditions is equally diverse, with homeobox genes, hedgehog pathways, fibroblast growth factors, and boneand cartilage-derived morphogenetic proteins implicated in their development.1

The differential diagnosis for our patient included congenital malalignment of the great toenails, nail-patella syndrome, onychodystrophy secondary to polydactyly, and congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail fold. Given the strong family history, polydactyly was suspected.

Congenital malalignment of the great toenails results in lateral deviation of the nail plates.2 It is an underdiagnosed condition with different etiologies hypothesized, such as genetic factors with possible autosomal-dominant transmission and extrinsic factors.3 One proposed mechanism of pathogenesis is desynchronization during growth of the nail and distal phalanx of the hallux, leading to larger nail plates that grow laterally.4 Typical features associated with this disease are nail discoloration, nail plate thickening, and transversal grooves or ridges, none of which were seen in our patient.2

Children with nail-patella syndrome have dysplastic nails and associated bony abnormalities, such as absent patellae.5 This syndrome results from an autosomaldominant mutation in the LIM homeobox transcription factor 1-beta gene, LMX1B, which is responsible for dorsal-ventral patterning of the limb, as well as patterning of the nails, patellae and long bones, and even the kidney tubule.6 As such, patients with nail-patella syndrome have associated renal abnormalities. The findings in our patient were limited to the feet, making an underlying syndrome unlikely to be the cause.

First described in 1968 by Meadow,7 fetal hydantoin syndrome is a well-documented sequela in women taking phenytoin throughout pregnancy. Multiple malformations are possible, including cardiac defects, cleft lip/palate, digit and nail hypoplasia, abnormal facial features, mental disability, and growth abnormalities.8 The teratogenicity behind phenytoin results from reactive oxygen species that alter embryonic DNA, proteins, and lipids.9 The mother of this child was not on any seizure prophylaxis, eliminating it from the differential.

Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail fold is a defect of the soft tissue of the hallux leading to hypertrophy of the nail fold, commonly presenting with inflammation and pain10 possibly due to dyssynchronous growth between the soft tissue and nail plate.11 With this defect, a lip covering the nail plate is common, which was not seen in our patient.

As demonstrated in our patient, family history can help guide the diagnosis. Seven of 9 nonsyndromic forms of syndactyly are inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion and range from mild presentations, as in our patient, to more severe deformations with underlying bone fusion and functional impairment.12 Polydactyly also often is expressed in an autosomal-dominant pattern, with up to 30% of patients having a positive family history. Polydactyly traditionally is classified by the location of the supernumerary digit as preaxial (radial), central, or postaxial (ulnar), and many further morphologic variations exist within these groups. Overall, preaxial polydactyly is relatively rare and represents 15% of polydactylies, with central and postaxial comprising the other 6% and 79%, respectively.13 Delineation of the underlying anatomy may reveal ray duplications (digit and corresponding metacarpal or metatarsal bone), metatarsal variants, and duplicated phalanges that may be hypoplastic or deformed. Patients may report difficulty finding comfortable footwear, cosmetic concerns, and nail-related complications. Although not always required, surgical intervention may provide definitive treatment but can leave residual deformities in the surrounding altered anatomy; thus, orthopedic or plastic surgery consultations are critical in appropriately counseling patients.

- Ahmed H, Akbari H, Emanmi A, et al. Genetic overview of syndactyly and polydactyly. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5:e1549.

- Catalfo P, Musumeci ML, Lacarrubba F, et al. Congenital malalignment of the great toenails: a review. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4:230-235.

- Kus S, Tahmaz E, Gurunluoglu R, et al. Congenital malalignment of the great toenails in dizygotic twins. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:434-435.

- Chaniotakis I, Bonitsis N, Stergiopoulou C, et al. Dizygotic twins with congenital malalignment of the great toenails: reappraisal of the pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:711-715.

- Witzgall R. Nail-patella syndrome. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469:927-936.

- Dreyer SD, Zhou G, Baldini A, et al, Mutations in LMX1B cause abnormal skeletal patterning and renal dysplasia in nail patella syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;19:47-50.

- Meadow SR. Anticonvulsant drugs and congenital abnormalities. Lancet. 1968;2:1296.

- Scheinfeld N. Phenytoin in cutaneous medicine: its uses, mechanisms and side effects. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:6.

- Winn LM, Wells PG. Phenytoin-initiated DNA oxidation in murine embryo culture, and embryo protection by the antioxidative enzymes superoxide dismutase and catalase: evidence for reactive oxygen species-mediated DNA oxidation in the molecular mechanism of phenytoin teratogenicity. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:112-120.

- Piraccini BM, Parente GL, Varotti E, et al. Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds of the hallux: clinical features and follow-up of seven cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:348-351.

- Martinet C, Pascal M, Civatte J, et al. Lateral nail-pad of the big toe in infants. apropos of 2 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1984;111:731-732.

- Malik S. Syndactyly: phenotypes, genetics and current classification. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:817-824.

- Belthur MV, Linton JL, Barnes DA. The spectrum of preaxial polydactyly of the foot. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31:435-447.

- Ahmed H, Akbari H, Emanmi A, et al. Genetic overview of syndactyly and polydactyly. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017;5:e1549.

- Catalfo P, Musumeci ML, Lacarrubba F, et al. Congenital malalignment of the great toenails: a review. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4:230-235.

- Kus S, Tahmaz E, Gurunluoglu R, et al. Congenital malalignment of the great toenails in dizygotic twins. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:434-435.

- Chaniotakis I, Bonitsis N, Stergiopoulou C, et al. Dizygotic twins with congenital malalignment of the great toenails: reappraisal of the pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:711-715.

- Witzgall R. Nail-patella syndrome. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469:927-936.

- Dreyer SD, Zhou G, Baldini A, et al, Mutations in LMX1B cause abnormal skeletal patterning and renal dysplasia in nail patella syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;19:47-50.

- Meadow SR. Anticonvulsant drugs and congenital abnormalities. Lancet. 1968;2:1296.

- Scheinfeld N. Phenytoin in cutaneous medicine: its uses, mechanisms and side effects. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:6.

- Winn LM, Wells PG. Phenytoin-initiated DNA oxidation in murine embryo culture, and embryo protection by the antioxidative enzymes superoxide dismutase and catalase: evidence for reactive oxygen species-mediated DNA oxidation in the molecular mechanism of phenytoin teratogenicity. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:112-120.

- Piraccini BM, Parente GL, Varotti E, et al. Congenital hypertrophy of the lateral nail folds of the hallux: clinical features and follow-up of seven cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:348-351.

- Martinet C, Pascal M, Civatte J, et al. Lateral nail-pad of the big toe in infants. apropos of 2 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1984;111:731-732.

- Malik S. Syndactyly: phenotypes, genetics and current classification. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:817-824.

- Belthur MV, Linton JL, Barnes DA. The spectrum of preaxial polydactyly of the foot. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;31:435-447.

An 18-month-old girl presented for evaluation of nail dystrophy. The patient’s parents stated that the left great toenail had been dystrophic since birth, leading to skin irritation and “snagging” of the toenail on socks and footwear. Additional history revealed that the patient also had webbed toes, and there was a paternal family history of polydactyly and syndactyly. Physical examination revealed webbing of the second and third toes to the distal interphalangeal joints on both feet, marked nail plate dystrophy on the left big toe, and an irregularly shaped nail plate on the right big toe. The patient had no similar findings on the hands.

Dr. Brian Mandell gives his take on ACR’s newest gout guideline

Guidance on the initiation and use of urate-lowering therapies was among the strong recommendations in the updated gout guideline recently issued by the American College of Rheumatology, said Brian F. Mandell, MD, PhD, in a virtual presentation at the annual Perspectives in Rheumatic Diseases held by Global Academy for Medical Education.

The 2020 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Management of Gout is “intended to provide guidance for particular patterns of practice and not to dictate the care of a particular patient,” said Dr. Mandell, chair of academic medicine at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio and cochair of the conference. However, “there was a hope that, with additional evidence since the previous guideline issued in 2012, the recommendations are more firmly based and will improve care,” he said.

Of 42 recommendations, 16 were strong, and these included guidance on several points: when to initiate urate-lowering therapy and using a treat-to-target strategy for lowering serum uric acid to less than 6 mg/dL; prophylaxis against attacks; the use of allopurinol as the first-choice drug and how to avoid hypersensitivity reactions; the use of pegloticase (Krystexxa); and treating flares.

Hyperuricemia does not automatically equal gout, Dr. Mandell said. A 2018 published analysis of data from several large cohorts including 18,889 adults who were gout-free at baseline showed that serum uric acid levels could not accurately predict an initial gout attack. Therefore, the guideline conditionally recommends against initiating any pharmacologic urate-lowering therapy in patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia. The guideline authors intentionally did not include the presence of comorbidities or deposits of uric acid in making their recommendation. But when advising an individual patient, these factors plus the patient’s age and family history should be considered, he said. “Individualize the decision to use ULT [urate-lowering therapy] to prevent possible future flares,” he advised, with consideration of age, the effects of the flare on the patient’s life, and challenges in treating flares.

For patients who are being treated with urate-lowering therapy, a published study indicated that if treatment is discontinued, “gout attacks will recur, depending on the new serum urate level,” Dr. Mandell said. “Maintenance of low SUA [serum uric acid] must be lifelong to stop attacks,” he emphasized, noting that this is counter to a management guideline published by the American College of Physicians in 2017.

“For patients starting any ULT, we strongly recommend allopurinol over all other urate-lowering therapies as the preferred first-line agent for all patients, including those with CKD [chronic kidney disease] stage 3 or higher,” according to the new guideline, which also recommends starting at a low dose followed by dose titration to target versus starting at a higher dose.

Two reasons in support of a slow up-titration of urate-lowering therapy are a lower frequency of mobilization flares and a possibly lower chance of allopurinol hypersensitivity reactions, Dr. Mandell said.

Although the guideline recommends allopurinol over probenecid, “probenecid works well as monotherapy and effectively as add-on therapy to a xanthine oxidase inhibitor, and it is cheap,” Dr. Mandell said.

Allopurinol can be associated with life-threatening hypersensitivity reactions, but most of these have been associated with a higher-than-recommended starting dose, according to the literature, he noted. The new guideline suggests checking for the HLA-B*5801 haplotype in high-risk demographic groups, and if it is present, to use an alternative to allopurinol if possible

The updated guideline also carries a strong recommendation for the use of pegloticase for patients with frequent gout flares and nonresolving subcutaneous tophi, but it strongly recommends against switching to pegloticase for patients with infrequent gout flares and no tophi.

However, Dr. Mandell said that he will consider off-label treatment of gout with pegloticase “in patients where a shorter time to response really matters,” which is consistent with his belief that, within these treatment principles, the management of gout must be individualized to the specific patient.

For treating acute gout flares, the guideline recommendations strongly supports the use of oral colchicine, NSAIDs, or glucocorticoids as an appropriate first-line therapy, based on patient factors and preferences, instead of using interleukin-1 inhibitors or adrenocorticotropic hormone. However, the interleukin-1 inhibitor anakinra has shown relatively rapid and successful response in treating patients hospitalized with acute gout, Dr. Mandell said. No large, randomized, trials have been conducted, but he cited his experience at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, where anakinra is the most common treatment for acute gout on inpatient consults, and he cited a representative small study of 26 patients in which 73% showed “significant response” within 5 days of treatment, which meant that they were able to move and bear weight without pain. In addition, a more recent study of 100 hospitalized patients in the Journal of Rheumatology, found that 75% showed a rapid response to anakinra and improvement or resolution of flares within 4 days, Dr. Mandell said.

Dr. Mandell disclosed relationships with companies including Horizon, Ardea/AstraZeneca/Ironwood, and Takeda. He served as coauthor on the 2012 American College of Rheumatology gout guideline.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Guidance on the initiation and use of urate-lowering therapies was among the strong recommendations in the updated gout guideline recently issued by the American College of Rheumatology, said Brian F. Mandell, MD, PhD, in a virtual presentation at the annual Perspectives in Rheumatic Diseases held by Global Academy for Medical Education.

The 2020 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Management of Gout is “intended to provide guidance for particular patterns of practice and not to dictate the care of a particular patient,” said Dr. Mandell, chair of academic medicine at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio and cochair of the conference. However, “there was a hope that, with additional evidence since the previous guideline issued in 2012, the recommendations are more firmly based and will improve care,” he said.

Of 42 recommendations, 16 were strong, and these included guidance on several points: when to initiate urate-lowering therapy and using a treat-to-target strategy for lowering serum uric acid to less than 6 mg/dL; prophylaxis against attacks; the use of allopurinol as the first-choice drug and how to avoid hypersensitivity reactions; the use of pegloticase (Krystexxa); and treating flares.

Hyperuricemia does not automatically equal gout, Dr. Mandell said. A 2018 published analysis of data from several large cohorts including 18,889 adults who were gout-free at baseline showed that serum uric acid levels could not accurately predict an initial gout attack. Therefore, the guideline conditionally recommends against initiating any pharmacologic urate-lowering therapy in patients with asymptomatic hyperuricemia. The guideline authors intentionally did not include the presence of comorbidities or deposits of uric acid in making their recommendation. But when advising an individual patient, these factors plus the patient’s age and family history should be considered, he said. “Individualize the decision to use ULT [urate-lowering therapy] to prevent possible future flares,” he advised, with consideration of age, the effects of the flare on the patient’s life, and challenges in treating flares.