User login

Long-Term Oxygen Therapy and Risk of Fire-Related Events

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has been the third leading cause of death in the US since 2008.1 Current management of COPD includes smoking cessation, adequate nutrition, medication therapy, pulmonary rehabilitation, and vaccines.2 Outside of pharmacologic management, oxygen therapy has become a staple treatment of chronic hypoxemic respiratory failure due to COPD. Landmark trials, including the Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial (NOTT) and Medical Research Council (MRC) study, demonstrated improved survival in patients with COPD and hypoxemia, particularly if these patients received oxygen for 18 hours per day.3,4 NOTT prospectively evaluated 203 patients at 6 centers who were randomly allocated to either continuous oxygen therapy or 12-hour nocturnal oxygen therapy. The overall mortality in the nocturnal oxygen therapy group was 1.94 times that in the continuous oxygen therapy group (P = .01).3 The MRC study included 87 patients who were randomized to oxygen therapy or no oxygen; risk of death was 12% per year in the treated group vs 29% per year in the control group (P = .04).4 The effectiveness of long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) in active smokers continues to be a source of debate; although 50% of patients in the NOTT trial were smokers, there was no subgroup analysis of whether smoking status had an impact on survival in those on continuous oxygen therapy.

Although many therapies are available for the treatment of COPD, the most effective treatment to prevent the progression of COPD is smoking cessation. Resources like smoking cessation programs, nicotine patches, and medications, such as bupropion and varenicline, are available to aid smoking cessation.5 However, many patients are unable to quit tobacco use despite their best efforts using available resources, and they continue to smoke even with progressive COPD. Long-time smokers also are likely to continue smoking while on LTOT, which increases their risk for fire-related injury.6-8

Traditional indications are being scrutinized after the LTOT trial found no benefit with respect to time to death or first hospitalization among patients with stable COPD and resting or exercise-induced moderate desaturation.9

Although oxygen accelerates combustion and is a potential fire hazard, LTOT has been prescribed even to active smokers as the 2 landmark trials did not exclude patients who were active smokers from receiving oxygen therapy.3,4 Therefore, LTOT has traditionally been prescribed to veterans who are actively smoking, despite the fire hazard. Attempts at mitigating hazards related to oxygen therapy in active smokers include counseling extensively about safety measures (which includes avoiding open flames such as candles, large fires, or sparks when on LTOT and providing Home Safety Agreements—a written contract between prescriber and patient wherein the patient agrees to abide by the terms of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to mitigate hazards related to LTOT in order to receive LTOT (eAppendix

Methods

With this practice in mind, we conducted an institutional review board approved retrospective chart review of all veterans with diagnosis of COPD within the Central Texas Veterans Health Care System (CTVHCS) who were prescribed new LTOT between October 1, 2010 and September 30, 2015. Given the retrospective nature of the chart review, patient consent was not obtained. Inclusion criteria were veterans aged > 18 years who had a confirmed diagnosis of COPD by spirometry and who met criteria for either continuous or ambulation- only oxygen therapy.

Criteria for exclusion included patients with hypoxemia not solely attributable to COPD or due to diseases other than COPD. We reviewed encounters in these patients’ charts, including follow-up in the clinic of the providers prescribing oxygen, to assess for fire-related incidents, defined as events wherein fire was visualized by the patient or by individuals living with the patient and with report provided to medical equipment company providing oxygen; the patient did not have to seek medical care to qualify for fire-related incident. Of the 158 patients who met the criteria for inclusion in the study, 152 were male.

Statistics

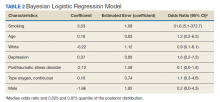

Bayesian logistic regression was used to model the outcome variable fire-related incident with the predictors smoking status, age, race, depression, PTSD, and type of oxygen used. Mental health disorders have significant effect on substance use disorders, such as alcohol use. Depression and PTSD were more common mental health diagnoses found in our patient population. Additionally, due to the small sample size, these psychiatric diagnoses were chosen to evaluate the impact of mental health disorders on firerelated events.

Although the sample size of events was small, weakly informative normal priors (0, 2.5) were used to shrink parameter estimates toward 0 and minimize overfitting. Weakly informative normal priors have also been suggested to deal with the problem of quasi-complete separation, where in our case, both smoking and no-PTSD perfectly predicted the 9 fire-related incidents.10 All input variables were centered and scaled as recommended. 9 The model fit well as assessed by posterior predictive checks, and Rhat was 1.00 for all parameters, indicating that all chains converged. Analysis was completed in R version 3.5.1 using the ‘brms’ package for Bayesian modeling.11

Results

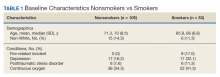

The mean age for the 158 included patients was 71.3 years in nonsmokers and 65.9 years in smokers. Fifty-three of the included patients were active smokers when LTOT was initiated. Nine veterans had fire-related incidents during the study period. All 9 patients were actively smoking (about 17%) at the time of the fire incidents. There were no deaths, and 5 patients required hospitalization due to facial burns resulting from the fire-related incidents. Our study focused on 5 baseline characteristics in our population (Table 1). After gathering data, our group inferred that these characteristics had a potential relationship to fire-related incidents compared with other variables that were studied. Future studies could look at other patient characteristics that may be linked to fire-related incidents in patients on LTOT. For example, not having PTSD also perfectly predicts fire-related incidents in our data (ie, none of the participants who had fire-related incidents had PTSD). Although this finding was not within the 95% confidence interval (CI) in the model, it does show that care must be taken when interpreting effects from small samples (Table 2). The modelestimated odds of a fire-related incident occurring in a smoker were 31.6 (5.1-372.7) times more likely than were the odds of a firerelated incident occurring in a nonsmoker, holding all other predictors at their reference level; 95% CI for the odds ratios for all other predictors in the model included a value of 1.

Discussion

This study showed evidence of increased odds of fire-related events in actively smoking patients receiving LTOT compared with patients who do not actively smoke while attempting to adjust for potential confounders. Of the 9 patients who had fire events, 5 required hospitalization for burns.

A similar retrospective cohort study by Sharma and colleagues in 2015 demonstrated an increased risk of burn-related injury when on LTOT but reiterated that the benefit of oxygen outweighs the risk of burn-related injury in patients requiring oxygen therapy.12 Interestingly, Sharma and colleagues were unable to identify smoking status for the patients studied but further identified factors associated with burn injury to include male sex, low socioeconomic status, oxygen therapy use, and ≥ 3 comorbidities. The study’s conclusion recommended continued education by health care professionals (HCPs) to their patients on LTOT regarding potential for burn injury. In the same vein, the VA National Center for Ethics in Health Care noted that “clinicians should familiarize themselves with the risks and benefits of LTOT; should inform their patients of the risks and benefits without exaggerating the risk associated with smoking; avoid undue coercion inherent in the clinician’s ability to withdraw LTOT; reduce the risk to the greatest degree possible; and consider termination of LTOT in very extreme cases and in consultation with a multidisciplinary committee.”13

This statement is in contrast to the guidelines and policies of other countries, such as Sweden, where smoking is a direct contraindication for prescription of oxygen therapy, or in Australia and New Zealand, where the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand oxygen therapy guidelines recommend against prescription of LTOT, citing “increased fire risk and the probability that the poorer prognosis conferred by smoking will offset treatment benefit.”6,14

The prevalence of oxygen therapy introduces the potential for fire-related incidents with subsequent injury requiring medical care. There are few studies regarding home oxygen fire in the US due to the lack of a uniform reporting system. One study by Wendling and Pelletier analyzed deaths in Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Oklahoma between 2000 and 2007 and found 38 deaths directly attributable to home oxygen fires as a result of smoking.15 Further, the Consumer Product Safety Commission’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System between 2003 and 2006 attributed 1,190 thermal burns related to home oxygen fires; the majority of which were ignited by tobacco smoking.15 The Swedish National Register of Respiratory Failure (Swedevox) published prospective population-based, consecutive cohort study that collected data over 17 years and evaluated the risk of fire-related incident in those on LTOT. Of the 12,497 patients sampled, 17 had a burn injury and 2 patients died. The low incidence of burn injury on LTOT was attributed to the strict guidelines instituted in Sweden for doctors to avoid prescribing LTOT to actively smoking patients.6 A follow-up study by Tanash and colleagues compared the risk of burn injury in each country, respectively. The results found an increased number of burn injuries in those on oxygen therapy in Denmark, a country with fewer restrictions on smoking compared with those of Sweden.7 Similarly, our results showed that the rate of fire and burn injuries was exclusively among veterans who were active smokers. All patients who were prescribed oxygen therapy at CTVHCS received counseling and signed Home Safety Agreements. Despite following the recommendations set forth by the VA on counseling, extensive harm reduction techniques, and close follow-up, we found there was still a high incidence of fires in veterans with COPD on LTOT who continue to smoke.

The findings from our study concur with those previously published regarding the risk of home oxygen fire and concomitant smoking, supporting the idea for more regulated and concrete guidelines for prescribing LTOT to those requiring it.8

Limitations

The major limitation was the small sample size of our study. Another limitation was that our study population is predominantly male as is common in veteran cohorts. In fiscal year 2016, the veteran population of Texas was 1,434,361 males and 168,967 females.16 According to Franklin and colleagues, HCPs noticed an increase use of long-term oxygen among women compared with that of men.17

Conclusions

Our study showed an increased odds of firerelated incidents of patients while on LTOT, strengthening the argument that even with extensive education, those who smoke and are on LTOT continue to put themselves at risk of a fire-related incident. This finding stresses the importance of continuing patient education on the importance of smoking cessation prior to administration of LTOT or avoiding fire hazards while on LTOT. Further research into LTOT and fire hazards could help in implementing a more structured approval process for patients who want to obtain LTOT. We propose further studies evaluating risk factors for the incidence of fire events among patients prescribed LTOT. A growing and aging population with a need for LTOT necessitates examination of oxygen safe prescribing.

1. Ni H, Xu J. COPD-related mortality by sex and race among adults aged 25 and over: United States 2000-2014. https:// www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db256.pdf. Published September 2016. Accessed September 10, 2020.

2. Itoh M, Tsuji T, Nemoto K, Nakamura H, Aoshiba K. Undernutrition in patients with COPD and its treatment. Nutrients. 2013;5(4):1316-1335. doi:10.3390/nu5041316

3. Continuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive lung disease: a clinical trial. Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial Group. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93(3):391. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-93-3-391

4. Long term domiciliary oxygen therapy in chronic hypoxic cor pulmonale complicating chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Report of the Medical Research Council Working Party. Lancet. 1981;1(8222):681-686. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(81)91970-X

5. Anthonisen NR, Skeans MA, Wise RA, Manfreda J, Kanner RE, Connett JE. The effects of a smoking cessation intervention on 14.5-year mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(4):233-239. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-4 -200502150-00005

6. Tanash HA, Huss F, Ekström M. The risk of burn injury during long-term oxygen therapy: a 17-year longitudinal national study in Sweden. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2479-2484. doi:10.2147/COPD.S91508

7. Tanash HA, Ringbaek T, Huss F, Ekström M. Burn injury during long-term oxygen therapy in Denmark and Sweden: the potential role of smoking. Int J Chronic Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:193-197. doi:10.2147/COPD.S119949

8. Kassis SA, Savetamal A, Assi R, et al. Characteristics of patients with injury secondary to smoking on home oxygen therapy transferred intubated to a burn center. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(6):1182-1186. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.055

9. Long-Term Oxygen Treatment Trial Research Group, Albert RK, Au DH, et al. A Randomized Trial of Long-Term Oxygen for COPD with Moderate Desaturation. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(17):1617-1627. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1604344

10. Ghosh J, Li Y, Mitra R. On the use of Cauchy prior distributions for Bayesian logistic regression. Bayesian Anal. 2018;13(2):359-383. doi:10.1214/17-ba1051

11. Bürkner P-C. brms: An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J Stat Software. 2017;80(1). doi:10.18637/jss.v080.i01

12. Sharma G, Meena R, Goodwin JS, Zhang W, Kuo Y-F, Duarte AG. Burn injury associated with home oxygen use in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(4):492-499. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.12.024

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Ethics Committee. Ethical considerations that arise when a home care patient on long term oxygen therapy continues to smoke. http://vaww.ethics.va.gov/docs/necrpts/NEC_Report_20100301_Smoking_while_on_LTOT.pdf. Published March 2010. [Nonpublic, source not verified.]

14. McDonald C F, Whyte K, Jenkins S, Serginson J. Frith P. Clinical practice guideline on adult domiciliary oxygen therapy: executive summary from the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand. Respirology. 2016;21(1):76-78. doi:10.1111/resp.12678

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Fatal fires associated with smoking during long-term oxygen therapy--Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Oklahoma, 2000-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(31):852-854.

16. US Department of Veteran Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Population tables: the state, age/gender, 2016. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_ Population.asp. Updated August 5, 2020. Accessed September 11, 2020.

17. Franklin KA, Gustafson T, Ranstam J, Ström K. Survival and future need of long-term oxygen therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease--gender differences. Respir Med. 2007;101(7):1506-1511. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2007.01.009

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has been the third leading cause of death in the US since 2008.1 Current management of COPD includes smoking cessation, adequate nutrition, medication therapy, pulmonary rehabilitation, and vaccines.2 Outside of pharmacologic management, oxygen therapy has become a staple treatment of chronic hypoxemic respiratory failure due to COPD. Landmark trials, including the Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial (NOTT) and Medical Research Council (MRC) study, demonstrated improved survival in patients with COPD and hypoxemia, particularly if these patients received oxygen for 18 hours per day.3,4 NOTT prospectively evaluated 203 patients at 6 centers who were randomly allocated to either continuous oxygen therapy or 12-hour nocturnal oxygen therapy. The overall mortality in the nocturnal oxygen therapy group was 1.94 times that in the continuous oxygen therapy group (P = .01).3 The MRC study included 87 patients who were randomized to oxygen therapy or no oxygen; risk of death was 12% per year in the treated group vs 29% per year in the control group (P = .04).4 The effectiveness of long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) in active smokers continues to be a source of debate; although 50% of patients in the NOTT trial were smokers, there was no subgroup analysis of whether smoking status had an impact on survival in those on continuous oxygen therapy.

Although many therapies are available for the treatment of COPD, the most effective treatment to prevent the progression of COPD is smoking cessation. Resources like smoking cessation programs, nicotine patches, and medications, such as bupropion and varenicline, are available to aid smoking cessation.5 However, many patients are unable to quit tobacco use despite their best efforts using available resources, and they continue to smoke even with progressive COPD. Long-time smokers also are likely to continue smoking while on LTOT, which increases their risk for fire-related injury.6-8

Traditional indications are being scrutinized after the LTOT trial found no benefit with respect to time to death or first hospitalization among patients with stable COPD and resting or exercise-induced moderate desaturation.9

Although oxygen accelerates combustion and is a potential fire hazard, LTOT has been prescribed even to active smokers as the 2 landmark trials did not exclude patients who were active smokers from receiving oxygen therapy.3,4 Therefore, LTOT has traditionally been prescribed to veterans who are actively smoking, despite the fire hazard. Attempts at mitigating hazards related to oxygen therapy in active smokers include counseling extensively about safety measures (which includes avoiding open flames such as candles, large fires, or sparks when on LTOT and providing Home Safety Agreements—a written contract between prescriber and patient wherein the patient agrees to abide by the terms of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to mitigate hazards related to LTOT in order to receive LTOT (eAppendix

Methods

With this practice in mind, we conducted an institutional review board approved retrospective chart review of all veterans with diagnosis of COPD within the Central Texas Veterans Health Care System (CTVHCS) who were prescribed new LTOT between October 1, 2010 and September 30, 2015. Given the retrospective nature of the chart review, patient consent was not obtained. Inclusion criteria were veterans aged > 18 years who had a confirmed diagnosis of COPD by spirometry and who met criteria for either continuous or ambulation- only oxygen therapy.

Criteria for exclusion included patients with hypoxemia not solely attributable to COPD or due to diseases other than COPD. We reviewed encounters in these patients’ charts, including follow-up in the clinic of the providers prescribing oxygen, to assess for fire-related incidents, defined as events wherein fire was visualized by the patient or by individuals living with the patient and with report provided to medical equipment company providing oxygen; the patient did not have to seek medical care to qualify for fire-related incident. Of the 158 patients who met the criteria for inclusion in the study, 152 were male.

Statistics

Bayesian logistic regression was used to model the outcome variable fire-related incident with the predictors smoking status, age, race, depression, PTSD, and type of oxygen used. Mental health disorders have significant effect on substance use disorders, such as alcohol use. Depression and PTSD were more common mental health diagnoses found in our patient population. Additionally, due to the small sample size, these psychiatric diagnoses were chosen to evaluate the impact of mental health disorders on firerelated events.

Although the sample size of events was small, weakly informative normal priors (0, 2.5) were used to shrink parameter estimates toward 0 and minimize overfitting. Weakly informative normal priors have also been suggested to deal with the problem of quasi-complete separation, where in our case, both smoking and no-PTSD perfectly predicted the 9 fire-related incidents.10 All input variables were centered and scaled as recommended. 9 The model fit well as assessed by posterior predictive checks, and Rhat was 1.00 for all parameters, indicating that all chains converged. Analysis was completed in R version 3.5.1 using the ‘brms’ package for Bayesian modeling.11

Results

The mean age for the 158 included patients was 71.3 years in nonsmokers and 65.9 years in smokers. Fifty-three of the included patients were active smokers when LTOT was initiated. Nine veterans had fire-related incidents during the study period. All 9 patients were actively smoking (about 17%) at the time of the fire incidents. There were no deaths, and 5 patients required hospitalization due to facial burns resulting from the fire-related incidents. Our study focused on 5 baseline characteristics in our population (Table 1). After gathering data, our group inferred that these characteristics had a potential relationship to fire-related incidents compared with other variables that were studied. Future studies could look at other patient characteristics that may be linked to fire-related incidents in patients on LTOT. For example, not having PTSD also perfectly predicts fire-related incidents in our data (ie, none of the participants who had fire-related incidents had PTSD). Although this finding was not within the 95% confidence interval (CI) in the model, it does show that care must be taken when interpreting effects from small samples (Table 2). The modelestimated odds of a fire-related incident occurring in a smoker were 31.6 (5.1-372.7) times more likely than were the odds of a firerelated incident occurring in a nonsmoker, holding all other predictors at their reference level; 95% CI for the odds ratios for all other predictors in the model included a value of 1.

Discussion

This study showed evidence of increased odds of fire-related events in actively smoking patients receiving LTOT compared with patients who do not actively smoke while attempting to adjust for potential confounders. Of the 9 patients who had fire events, 5 required hospitalization for burns.

A similar retrospective cohort study by Sharma and colleagues in 2015 demonstrated an increased risk of burn-related injury when on LTOT but reiterated that the benefit of oxygen outweighs the risk of burn-related injury in patients requiring oxygen therapy.12 Interestingly, Sharma and colleagues were unable to identify smoking status for the patients studied but further identified factors associated with burn injury to include male sex, low socioeconomic status, oxygen therapy use, and ≥ 3 comorbidities. The study’s conclusion recommended continued education by health care professionals (HCPs) to their patients on LTOT regarding potential for burn injury. In the same vein, the VA National Center for Ethics in Health Care noted that “clinicians should familiarize themselves with the risks and benefits of LTOT; should inform their patients of the risks and benefits without exaggerating the risk associated with smoking; avoid undue coercion inherent in the clinician’s ability to withdraw LTOT; reduce the risk to the greatest degree possible; and consider termination of LTOT in very extreme cases and in consultation with a multidisciplinary committee.”13

This statement is in contrast to the guidelines and policies of other countries, such as Sweden, where smoking is a direct contraindication for prescription of oxygen therapy, or in Australia and New Zealand, where the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand oxygen therapy guidelines recommend against prescription of LTOT, citing “increased fire risk and the probability that the poorer prognosis conferred by smoking will offset treatment benefit.”6,14

The prevalence of oxygen therapy introduces the potential for fire-related incidents with subsequent injury requiring medical care. There are few studies regarding home oxygen fire in the US due to the lack of a uniform reporting system. One study by Wendling and Pelletier analyzed deaths in Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Oklahoma between 2000 and 2007 and found 38 deaths directly attributable to home oxygen fires as a result of smoking.15 Further, the Consumer Product Safety Commission’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System between 2003 and 2006 attributed 1,190 thermal burns related to home oxygen fires; the majority of which were ignited by tobacco smoking.15 The Swedish National Register of Respiratory Failure (Swedevox) published prospective population-based, consecutive cohort study that collected data over 17 years and evaluated the risk of fire-related incident in those on LTOT. Of the 12,497 patients sampled, 17 had a burn injury and 2 patients died. The low incidence of burn injury on LTOT was attributed to the strict guidelines instituted in Sweden for doctors to avoid prescribing LTOT to actively smoking patients.6 A follow-up study by Tanash and colleagues compared the risk of burn injury in each country, respectively. The results found an increased number of burn injuries in those on oxygen therapy in Denmark, a country with fewer restrictions on smoking compared with those of Sweden.7 Similarly, our results showed that the rate of fire and burn injuries was exclusively among veterans who were active smokers. All patients who were prescribed oxygen therapy at CTVHCS received counseling and signed Home Safety Agreements. Despite following the recommendations set forth by the VA on counseling, extensive harm reduction techniques, and close follow-up, we found there was still a high incidence of fires in veterans with COPD on LTOT who continue to smoke.

The findings from our study concur with those previously published regarding the risk of home oxygen fire and concomitant smoking, supporting the idea for more regulated and concrete guidelines for prescribing LTOT to those requiring it.8

Limitations

The major limitation was the small sample size of our study. Another limitation was that our study population is predominantly male as is common in veteran cohorts. In fiscal year 2016, the veteran population of Texas was 1,434,361 males and 168,967 females.16 According to Franklin and colleagues, HCPs noticed an increase use of long-term oxygen among women compared with that of men.17

Conclusions

Our study showed an increased odds of firerelated incidents of patients while on LTOT, strengthening the argument that even with extensive education, those who smoke and are on LTOT continue to put themselves at risk of a fire-related incident. This finding stresses the importance of continuing patient education on the importance of smoking cessation prior to administration of LTOT or avoiding fire hazards while on LTOT. Further research into LTOT and fire hazards could help in implementing a more structured approval process for patients who want to obtain LTOT. We propose further studies evaluating risk factors for the incidence of fire events among patients prescribed LTOT. A growing and aging population with a need for LTOT necessitates examination of oxygen safe prescribing.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has been the third leading cause of death in the US since 2008.1 Current management of COPD includes smoking cessation, adequate nutrition, medication therapy, pulmonary rehabilitation, and vaccines.2 Outside of pharmacologic management, oxygen therapy has become a staple treatment of chronic hypoxemic respiratory failure due to COPD. Landmark trials, including the Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial (NOTT) and Medical Research Council (MRC) study, demonstrated improved survival in patients with COPD and hypoxemia, particularly if these patients received oxygen for 18 hours per day.3,4 NOTT prospectively evaluated 203 patients at 6 centers who were randomly allocated to either continuous oxygen therapy or 12-hour nocturnal oxygen therapy. The overall mortality in the nocturnal oxygen therapy group was 1.94 times that in the continuous oxygen therapy group (P = .01).3 The MRC study included 87 patients who were randomized to oxygen therapy or no oxygen; risk of death was 12% per year in the treated group vs 29% per year in the control group (P = .04).4 The effectiveness of long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) in active smokers continues to be a source of debate; although 50% of patients in the NOTT trial were smokers, there was no subgroup analysis of whether smoking status had an impact on survival in those on continuous oxygen therapy.

Although many therapies are available for the treatment of COPD, the most effective treatment to prevent the progression of COPD is smoking cessation. Resources like smoking cessation programs, nicotine patches, and medications, such as bupropion and varenicline, are available to aid smoking cessation.5 However, many patients are unable to quit tobacco use despite their best efforts using available resources, and they continue to smoke even with progressive COPD. Long-time smokers also are likely to continue smoking while on LTOT, which increases their risk for fire-related injury.6-8

Traditional indications are being scrutinized after the LTOT trial found no benefit with respect to time to death or first hospitalization among patients with stable COPD and resting or exercise-induced moderate desaturation.9

Although oxygen accelerates combustion and is a potential fire hazard, LTOT has been prescribed even to active smokers as the 2 landmark trials did not exclude patients who were active smokers from receiving oxygen therapy.3,4 Therefore, LTOT has traditionally been prescribed to veterans who are actively smoking, despite the fire hazard. Attempts at mitigating hazards related to oxygen therapy in active smokers include counseling extensively about safety measures (which includes avoiding open flames such as candles, large fires, or sparks when on LTOT and providing Home Safety Agreements—a written contract between prescriber and patient wherein the patient agrees to abide by the terms of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to mitigate hazards related to LTOT in order to receive LTOT (eAppendix

Methods

With this practice in mind, we conducted an institutional review board approved retrospective chart review of all veterans with diagnosis of COPD within the Central Texas Veterans Health Care System (CTVHCS) who were prescribed new LTOT between October 1, 2010 and September 30, 2015. Given the retrospective nature of the chart review, patient consent was not obtained. Inclusion criteria were veterans aged > 18 years who had a confirmed diagnosis of COPD by spirometry and who met criteria for either continuous or ambulation- only oxygen therapy.

Criteria for exclusion included patients with hypoxemia not solely attributable to COPD or due to diseases other than COPD. We reviewed encounters in these patients’ charts, including follow-up in the clinic of the providers prescribing oxygen, to assess for fire-related incidents, defined as events wherein fire was visualized by the patient or by individuals living with the patient and with report provided to medical equipment company providing oxygen; the patient did not have to seek medical care to qualify for fire-related incident. Of the 158 patients who met the criteria for inclusion in the study, 152 were male.

Statistics

Bayesian logistic regression was used to model the outcome variable fire-related incident with the predictors smoking status, age, race, depression, PTSD, and type of oxygen used. Mental health disorders have significant effect on substance use disorders, such as alcohol use. Depression and PTSD were more common mental health diagnoses found in our patient population. Additionally, due to the small sample size, these psychiatric diagnoses were chosen to evaluate the impact of mental health disorders on firerelated events.

Although the sample size of events was small, weakly informative normal priors (0, 2.5) were used to shrink parameter estimates toward 0 and minimize overfitting. Weakly informative normal priors have also been suggested to deal with the problem of quasi-complete separation, where in our case, both smoking and no-PTSD perfectly predicted the 9 fire-related incidents.10 All input variables were centered and scaled as recommended. 9 The model fit well as assessed by posterior predictive checks, and Rhat was 1.00 for all parameters, indicating that all chains converged. Analysis was completed in R version 3.5.1 using the ‘brms’ package for Bayesian modeling.11

Results

The mean age for the 158 included patients was 71.3 years in nonsmokers and 65.9 years in smokers. Fifty-three of the included patients were active smokers when LTOT was initiated. Nine veterans had fire-related incidents during the study period. All 9 patients were actively smoking (about 17%) at the time of the fire incidents. There were no deaths, and 5 patients required hospitalization due to facial burns resulting from the fire-related incidents. Our study focused on 5 baseline characteristics in our population (Table 1). After gathering data, our group inferred that these characteristics had a potential relationship to fire-related incidents compared with other variables that were studied. Future studies could look at other patient characteristics that may be linked to fire-related incidents in patients on LTOT. For example, not having PTSD also perfectly predicts fire-related incidents in our data (ie, none of the participants who had fire-related incidents had PTSD). Although this finding was not within the 95% confidence interval (CI) in the model, it does show that care must be taken when interpreting effects from small samples (Table 2). The modelestimated odds of a fire-related incident occurring in a smoker were 31.6 (5.1-372.7) times more likely than were the odds of a firerelated incident occurring in a nonsmoker, holding all other predictors at their reference level; 95% CI for the odds ratios for all other predictors in the model included a value of 1.

Discussion

This study showed evidence of increased odds of fire-related events in actively smoking patients receiving LTOT compared with patients who do not actively smoke while attempting to adjust for potential confounders. Of the 9 patients who had fire events, 5 required hospitalization for burns.

A similar retrospective cohort study by Sharma and colleagues in 2015 demonstrated an increased risk of burn-related injury when on LTOT but reiterated that the benefit of oxygen outweighs the risk of burn-related injury in patients requiring oxygen therapy.12 Interestingly, Sharma and colleagues were unable to identify smoking status for the patients studied but further identified factors associated with burn injury to include male sex, low socioeconomic status, oxygen therapy use, and ≥ 3 comorbidities. The study’s conclusion recommended continued education by health care professionals (HCPs) to their patients on LTOT regarding potential for burn injury. In the same vein, the VA National Center for Ethics in Health Care noted that “clinicians should familiarize themselves with the risks and benefits of LTOT; should inform their patients of the risks and benefits without exaggerating the risk associated with smoking; avoid undue coercion inherent in the clinician’s ability to withdraw LTOT; reduce the risk to the greatest degree possible; and consider termination of LTOT in very extreme cases and in consultation with a multidisciplinary committee.”13

This statement is in contrast to the guidelines and policies of other countries, such as Sweden, where smoking is a direct contraindication for prescription of oxygen therapy, or in Australia and New Zealand, where the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand oxygen therapy guidelines recommend against prescription of LTOT, citing “increased fire risk and the probability that the poorer prognosis conferred by smoking will offset treatment benefit.”6,14

The prevalence of oxygen therapy introduces the potential for fire-related incidents with subsequent injury requiring medical care. There are few studies regarding home oxygen fire in the US due to the lack of a uniform reporting system. One study by Wendling and Pelletier analyzed deaths in Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Oklahoma between 2000 and 2007 and found 38 deaths directly attributable to home oxygen fires as a result of smoking.15 Further, the Consumer Product Safety Commission’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System between 2003 and 2006 attributed 1,190 thermal burns related to home oxygen fires; the majority of which were ignited by tobacco smoking.15 The Swedish National Register of Respiratory Failure (Swedevox) published prospective population-based, consecutive cohort study that collected data over 17 years and evaluated the risk of fire-related incident in those on LTOT. Of the 12,497 patients sampled, 17 had a burn injury and 2 patients died. The low incidence of burn injury on LTOT was attributed to the strict guidelines instituted in Sweden for doctors to avoid prescribing LTOT to actively smoking patients.6 A follow-up study by Tanash and colleagues compared the risk of burn injury in each country, respectively. The results found an increased number of burn injuries in those on oxygen therapy in Denmark, a country with fewer restrictions on smoking compared with those of Sweden.7 Similarly, our results showed that the rate of fire and burn injuries was exclusively among veterans who were active smokers. All patients who were prescribed oxygen therapy at CTVHCS received counseling and signed Home Safety Agreements. Despite following the recommendations set forth by the VA on counseling, extensive harm reduction techniques, and close follow-up, we found there was still a high incidence of fires in veterans with COPD on LTOT who continue to smoke.

The findings from our study concur with those previously published regarding the risk of home oxygen fire and concomitant smoking, supporting the idea for more regulated and concrete guidelines for prescribing LTOT to those requiring it.8

Limitations

The major limitation was the small sample size of our study. Another limitation was that our study population is predominantly male as is common in veteran cohorts. In fiscal year 2016, the veteran population of Texas was 1,434,361 males and 168,967 females.16 According to Franklin and colleagues, HCPs noticed an increase use of long-term oxygen among women compared with that of men.17

Conclusions

Our study showed an increased odds of firerelated incidents of patients while on LTOT, strengthening the argument that even with extensive education, those who smoke and are on LTOT continue to put themselves at risk of a fire-related incident. This finding stresses the importance of continuing patient education on the importance of smoking cessation prior to administration of LTOT or avoiding fire hazards while on LTOT. Further research into LTOT and fire hazards could help in implementing a more structured approval process for patients who want to obtain LTOT. We propose further studies evaluating risk factors for the incidence of fire events among patients prescribed LTOT. A growing and aging population with a need for LTOT necessitates examination of oxygen safe prescribing.

1. Ni H, Xu J. COPD-related mortality by sex and race among adults aged 25 and over: United States 2000-2014. https:// www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db256.pdf. Published September 2016. Accessed September 10, 2020.

2. Itoh M, Tsuji T, Nemoto K, Nakamura H, Aoshiba K. Undernutrition in patients with COPD and its treatment. Nutrients. 2013;5(4):1316-1335. doi:10.3390/nu5041316

3. Continuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive lung disease: a clinical trial. Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial Group. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93(3):391. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-93-3-391

4. Long term domiciliary oxygen therapy in chronic hypoxic cor pulmonale complicating chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Report of the Medical Research Council Working Party. Lancet. 1981;1(8222):681-686. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(81)91970-X

5. Anthonisen NR, Skeans MA, Wise RA, Manfreda J, Kanner RE, Connett JE. The effects of a smoking cessation intervention on 14.5-year mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(4):233-239. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-4 -200502150-00005

6. Tanash HA, Huss F, Ekström M. The risk of burn injury during long-term oxygen therapy: a 17-year longitudinal national study in Sweden. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2479-2484. doi:10.2147/COPD.S91508

7. Tanash HA, Ringbaek T, Huss F, Ekström M. Burn injury during long-term oxygen therapy in Denmark and Sweden: the potential role of smoking. Int J Chronic Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:193-197. doi:10.2147/COPD.S119949

8. Kassis SA, Savetamal A, Assi R, et al. Characteristics of patients with injury secondary to smoking on home oxygen therapy transferred intubated to a burn center. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(6):1182-1186. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.055

9. Long-Term Oxygen Treatment Trial Research Group, Albert RK, Au DH, et al. A Randomized Trial of Long-Term Oxygen for COPD with Moderate Desaturation. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(17):1617-1627. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1604344

10. Ghosh J, Li Y, Mitra R. On the use of Cauchy prior distributions for Bayesian logistic regression. Bayesian Anal. 2018;13(2):359-383. doi:10.1214/17-ba1051

11. Bürkner P-C. brms: An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J Stat Software. 2017;80(1). doi:10.18637/jss.v080.i01

12. Sharma G, Meena R, Goodwin JS, Zhang W, Kuo Y-F, Duarte AG. Burn injury associated with home oxygen use in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(4):492-499. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.12.024

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Ethics Committee. Ethical considerations that arise when a home care patient on long term oxygen therapy continues to smoke. http://vaww.ethics.va.gov/docs/necrpts/NEC_Report_20100301_Smoking_while_on_LTOT.pdf. Published March 2010. [Nonpublic, source not verified.]

14. McDonald C F, Whyte K, Jenkins S, Serginson J. Frith P. Clinical practice guideline on adult domiciliary oxygen therapy: executive summary from the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand. Respirology. 2016;21(1):76-78. doi:10.1111/resp.12678

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Fatal fires associated with smoking during long-term oxygen therapy--Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Oklahoma, 2000-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(31):852-854.

16. US Department of Veteran Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Population tables: the state, age/gender, 2016. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_ Population.asp. Updated August 5, 2020. Accessed September 11, 2020.

17. Franklin KA, Gustafson T, Ranstam J, Ström K. Survival and future need of long-term oxygen therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease--gender differences. Respir Med. 2007;101(7):1506-1511. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2007.01.009

1. Ni H, Xu J. COPD-related mortality by sex and race among adults aged 25 and over: United States 2000-2014. https:// www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db256.pdf. Published September 2016. Accessed September 10, 2020.

2. Itoh M, Tsuji T, Nemoto K, Nakamura H, Aoshiba K. Undernutrition in patients with COPD and its treatment. Nutrients. 2013;5(4):1316-1335. doi:10.3390/nu5041316

3. Continuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive lung disease: a clinical trial. Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial Group. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93(3):391. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-93-3-391

4. Long term domiciliary oxygen therapy in chronic hypoxic cor pulmonale complicating chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Report of the Medical Research Council Working Party. Lancet. 1981;1(8222):681-686. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(81)91970-X

5. Anthonisen NR, Skeans MA, Wise RA, Manfreda J, Kanner RE, Connett JE. The effects of a smoking cessation intervention on 14.5-year mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(4):233-239. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-4 -200502150-00005

6. Tanash HA, Huss F, Ekström M. The risk of burn injury during long-term oxygen therapy: a 17-year longitudinal national study in Sweden. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2479-2484. doi:10.2147/COPD.S91508

7. Tanash HA, Ringbaek T, Huss F, Ekström M. Burn injury during long-term oxygen therapy in Denmark and Sweden: the potential role of smoking. Int J Chronic Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:193-197. doi:10.2147/COPD.S119949

8. Kassis SA, Savetamal A, Assi R, et al. Characteristics of patients with injury secondary to smoking on home oxygen therapy transferred intubated to a burn center. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(6):1182-1186. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.055

9. Long-Term Oxygen Treatment Trial Research Group, Albert RK, Au DH, et al. A Randomized Trial of Long-Term Oxygen for COPD with Moderate Desaturation. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(17):1617-1627. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1604344

10. Ghosh J, Li Y, Mitra R. On the use of Cauchy prior distributions for Bayesian logistic regression. Bayesian Anal. 2018;13(2):359-383. doi:10.1214/17-ba1051

11. Bürkner P-C. brms: An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J Stat Software. 2017;80(1). doi:10.18637/jss.v080.i01

12. Sharma G, Meena R, Goodwin JS, Zhang W, Kuo Y-F, Duarte AG. Burn injury associated with home oxygen use in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(4):492-499. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.12.024

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Ethics Committee. Ethical considerations that arise when a home care patient on long term oxygen therapy continues to smoke. http://vaww.ethics.va.gov/docs/necrpts/NEC_Report_20100301_Smoking_while_on_LTOT.pdf. Published March 2010. [Nonpublic, source not verified.]

14. McDonald C F, Whyte K, Jenkins S, Serginson J. Frith P. Clinical practice guideline on adult domiciliary oxygen therapy: executive summary from the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand. Respirology. 2016;21(1):76-78. doi:10.1111/resp.12678

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Fatal fires associated with smoking during long-term oxygen therapy--Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Oklahoma, 2000-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(31):852-854.

16. US Department of Veteran Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Population tables: the state, age/gender, 2016. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/Veteran_ Population.asp. Updated August 5, 2020. Accessed September 11, 2020.

17. Franklin KA, Gustafson T, Ranstam J, Ström K. Survival and future need of long-term oxygen therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease--gender differences. Respir Med. 2007;101(7):1506-1511. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2007.01.009

Restarting breast cancer screening after disruption not so simple

according to a modeling study reported at the 12th European Breast Cancer Conference.

Fallout of the pandemic has included reductions in cancer screening and diagnosis, said study investigator Lindy M. Kregting, a PhD student in the department of public health at Erasmus Medical Center, University Medical Center Rotterdam (the Netherlands).

In the Netherlands, new breast cancer diagnoses fell dramatically from historical levels starting in February. The number in April was less than half of that expected.

Ms. Kregting and colleagues used modeling to assess the impact of four strategies for restarting breast cancer screening in the Netherlands. The strategies differed regarding the population affected, the duration of the effects, and changes in stopping age. The usual situation, without any disruption, served as the comparator.

Results showed wide variation across strategies with respect to the increase in screening capacity needed during the latter half of this year – from 0% to 100% – and the excess breast cancer mortality occurring during 2020-2030 – from as many as 181 excess breast cancer deaths to as few as 14.

“The effects of the disruption are dependent on the chosen restart strategy,” Ms. Kregting summarized. “It would be preferred to immediately catch up because this minimizes the impact, but it also requires a very high capacity, so it may not always be possible. A proper alternative would be to increase the stopping age, so no screens are omitted, because this requires a rather normal capacity, and it will result in only small effects on incidence and mortality.”

As screening programs restart in some countries, there are still a lot of unknowns that could affect outcomes, including how many women will attend given that some may stay away out of fear, Ms. Kregting cautioned.

“We plan to do further model calculations when we know exactly what has happened. ... For now, we just assumed some reasonable disruption periods, and we assumed that capacity would be back to the original, before COVID-19, but I think we can say this is probably not the case,” she added.

Study details

Ms. Kregting and colleagues used Dutch breast cancer screening program parameters (biennial digital mammography for women aged 50-75 years) and a microsimulation screening analysis model to simulate four strategies for restarting breast cancer screening after a 6-month disruption:

- “Everyone delay,” a strategy in which all screening continues in the order planned with no change in the stopping age of 75 years (so that one in four women ultimately miss a screening during their lifetime)

- “First rounds no delay,” in which there is a delay in screening except for women having their first screening

- “Continue after stopping age,” in which there is a delay in screening but temporary increasing of the stopping age (to 76.5 years) to ensure all women get their final screen

- “Catch-up after stop,” in which capacity is increased to ensure full catch-up, with all delayed screens caught up in a 6-month period (the second half of 2020).

Results showed that 5,872 women would be screened in the latter half of 2020 if screening proceeded as usual without disruption. The necessary capacity was essentially the same with all of the restarting strategies, except for the catch-up-after-stop strategy, which would require a doubling of that number.

The temporal pattern of breast cancer incidence varied according to restart strategy early on, but incidence essentially returned to that expected with undisrupted screening by 2025 for all four strategies, with some small fluctuations thereafter.

The impact on breast cancer mortality differed considerably long term. It increased slightly and transiently above the expected level with the catch-up-after-stop strategy, but there were sizable, long-lasting increases with the other strategies, with excess deaths still seen in 2060 for the everyone-delay strategy.

In absolute terms, the excess number of breast cancer deaths during 2020-2030, compared with undisrupted screening, was 181 with the everyone-delay strategy, 155 with the first-rounds-no-delay strategy, 145 with the continue-after-stopping-age strategy, and just 14 with the catch-up-after-stop strategy. Ms. Kregting declined to provide numbers for other countries, given that the model is based on the Dutch population and screening program.

Results in context

“The unprecedented burden of COVID-19 on health systems worldwide has important implications for cancer care,” said invited discussant Alessandra Gennari, MD, PhD, of the University of Eastern Piedmont and Maggiore della Carità Hospital, both in Novara, Italy.

“There is a delay in diagnosis due to the fact that screening programs and diagnostic programs have been decreased or suspended in many Western countries where this is standard of care. Patients also are more reluctant to present to health care services, delaying their diagnosis,” Dr. Gennari said.

Findings of this new study add to those of similar studies undertaken in Italy (published in In Vivo) and the United Kingdom (published in The Lancet Oncology) showing the likely marked toll of the pandemic on cancer diagnosis and mortality, Dr. Gennari noted. Taken together, the findings underscore the urgent need for policy interventions to mitigate this impact.

“These interventions should focus on increasing routine diagnostic capacity, through which up to 40% of patients with cancer are diagnosed,” Dr. Gennari recommended. “Public health messaging is needed that accurately conveys the risk of severe illness from COVID-19 versus the risks of not seeking health care advice if patients are symptomatic. Finally, there is a need for provision of evidence-based data on which clinicians can adequately base their decision on how to manage the risks of cancer patients and the risks and benefits of procedures during the pandemic.”

The current study did not have any specific funding, and Ms. Kregting disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Gennari disclosed relationships with Roche, Eisai, Lilly, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Kregting L et al. EBCC-12 Virtual Conference, Abstract 24.

according to a modeling study reported at the 12th European Breast Cancer Conference.

Fallout of the pandemic has included reductions in cancer screening and diagnosis, said study investigator Lindy M. Kregting, a PhD student in the department of public health at Erasmus Medical Center, University Medical Center Rotterdam (the Netherlands).

In the Netherlands, new breast cancer diagnoses fell dramatically from historical levels starting in February. The number in April was less than half of that expected.

Ms. Kregting and colleagues used modeling to assess the impact of four strategies for restarting breast cancer screening in the Netherlands. The strategies differed regarding the population affected, the duration of the effects, and changes in stopping age. The usual situation, without any disruption, served as the comparator.

Results showed wide variation across strategies with respect to the increase in screening capacity needed during the latter half of this year – from 0% to 100% – and the excess breast cancer mortality occurring during 2020-2030 – from as many as 181 excess breast cancer deaths to as few as 14.

“The effects of the disruption are dependent on the chosen restart strategy,” Ms. Kregting summarized. “It would be preferred to immediately catch up because this minimizes the impact, but it also requires a very high capacity, so it may not always be possible. A proper alternative would be to increase the stopping age, so no screens are omitted, because this requires a rather normal capacity, and it will result in only small effects on incidence and mortality.”

As screening programs restart in some countries, there are still a lot of unknowns that could affect outcomes, including how many women will attend given that some may stay away out of fear, Ms. Kregting cautioned.

“We plan to do further model calculations when we know exactly what has happened. ... For now, we just assumed some reasonable disruption periods, and we assumed that capacity would be back to the original, before COVID-19, but I think we can say this is probably not the case,” she added.

Study details

Ms. Kregting and colleagues used Dutch breast cancer screening program parameters (biennial digital mammography for women aged 50-75 years) and a microsimulation screening analysis model to simulate four strategies for restarting breast cancer screening after a 6-month disruption:

- “Everyone delay,” a strategy in which all screening continues in the order planned with no change in the stopping age of 75 years (so that one in four women ultimately miss a screening during their lifetime)

- “First rounds no delay,” in which there is a delay in screening except for women having their first screening

- “Continue after stopping age,” in which there is a delay in screening but temporary increasing of the stopping age (to 76.5 years) to ensure all women get their final screen

- “Catch-up after stop,” in which capacity is increased to ensure full catch-up, with all delayed screens caught up in a 6-month period (the second half of 2020).

Results showed that 5,872 women would be screened in the latter half of 2020 if screening proceeded as usual without disruption. The necessary capacity was essentially the same with all of the restarting strategies, except for the catch-up-after-stop strategy, which would require a doubling of that number.

The temporal pattern of breast cancer incidence varied according to restart strategy early on, but incidence essentially returned to that expected with undisrupted screening by 2025 for all four strategies, with some small fluctuations thereafter.

The impact on breast cancer mortality differed considerably long term. It increased slightly and transiently above the expected level with the catch-up-after-stop strategy, but there were sizable, long-lasting increases with the other strategies, with excess deaths still seen in 2060 for the everyone-delay strategy.

In absolute terms, the excess number of breast cancer deaths during 2020-2030, compared with undisrupted screening, was 181 with the everyone-delay strategy, 155 with the first-rounds-no-delay strategy, 145 with the continue-after-stopping-age strategy, and just 14 with the catch-up-after-stop strategy. Ms. Kregting declined to provide numbers for other countries, given that the model is based on the Dutch population and screening program.

Results in context

“The unprecedented burden of COVID-19 on health systems worldwide has important implications for cancer care,” said invited discussant Alessandra Gennari, MD, PhD, of the University of Eastern Piedmont and Maggiore della Carità Hospital, both in Novara, Italy.

“There is a delay in diagnosis due to the fact that screening programs and diagnostic programs have been decreased or suspended in many Western countries where this is standard of care. Patients also are more reluctant to present to health care services, delaying their diagnosis,” Dr. Gennari said.

Findings of this new study add to those of similar studies undertaken in Italy (published in In Vivo) and the United Kingdom (published in The Lancet Oncology) showing the likely marked toll of the pandemic on cancer diagnosis and mortality, Dr. Gennari noted. Taken together, the findings underscore the urgent need for policy interventions to mitigate this impact.

“These interventions should focus on increasing routine diagnostic capacity, through which up to 40% of patients with cancer are diagnosed,” Dr. Gennari recommended. “Public health messaging is needed that accurately conveys the risk of severe illness from COVID-19 versus the risks of not seeking health care advice if patients are symptomatic. Finally, there is a need for provision of evidence-based data on which clinicians can adequately base their decision on how to manage the risks of cancer patients and the risks and benefits of procedures during the pandemic.”

The current study did not have any specific funding, and Ms. Kregting disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Gennari disclosed relationships with Roche, Eisai, Lilly, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Kregting L et al. EBCC-12 Virtual Conference, Abstract 24.

according to a modeling study reported at the 12th European Breast Cancer Conference.

Fallout of the pandemic has included reductions in cancer screening and diagnosis, said study investigator Lindy M. Kregting, a PhD student in the department of public health at Erasmus Medical Center, University Medical Center Rotterdam (the Netherlands).

In the Netherlands, new breast cancer diagnoses fell dramatically from historical levels starting in February. The number in April was less than half of that expected.

Ms. Kregting and colleagues used modeling to assess the impact of four strategies for restarting breast cancer screening in the Netherlands. The strategies differed regarding the population affected, the duration of the effects, and changes in stopping age. The usual situation, without any disruption, served as the comparator.

Results showed wide variation across strategies with respect to the increase in screening capacity needed during the latter half of this year – from 0% to 100% – and the excess breast cancer mortality occurring during 2020-2030 – from as many as 181 excess breast cancer deaths to as few as 14.

“The effects of the disruption are dependent on the chosen restart strategy,” Ms. Kregting summarized. “It would be preferred to immediately catch up because this minimizes the impact, but it also requires a very high capacity, so it may not always be possible. A proper alternative would be to increase the stopping age, so no screens are omitted, because this requires a rather normal capacity, and it will result in only small effects on incidence and mortality.”

As screening programs restart in some countries, there are still a lot of unknowns that could affect outcomes, including how many women will attend given that some may stay away out of fear, Ms. Kregting cautioned.

“We plan to do further model calculations when we know exactly what has happened. ... For now, we just assumed some reasonable disruption periods, and we assumed that capacity would be back to the original, before COVID-19, but I think we can say this is probably not the case,” she added.

Study details

Ms. Kregting and colleagues used Dutch breast cancer screening program parameters (biennial digital mammography for women aged 50-75 years) and a microsimulation screening analysis model to simulate four strategies for restarting breast cancer screening after a 6-month disruption:

- “Everyone delay,” a strategy in which all screening continues in the order planned with no change in the stopping age of 75 years (so that one in four women ultimately miss a screening during their lifetime)

- “First rounds no delay,” in which there is a delay in screening except for women having their first screening

- “Continue after stopping age,” in which there is a delay in screening but temporary increasing of the stopping age (to 76.5 years) to ensure all women get their final screen

- “Catch-up after stop,” in which capacity is increased to ensure full catch-up, with all delayed screens caught up in a 6-month period (the second half of 2020).

Results showed that 5,872 women would be screened in the latter half of 2020 if screening proceeded as usual without disruption. The necessary capacity was essentially the same with all of the restarting strategies, except for the catch-up-after-stop strategy, which would require a doubling of that number.

The temporal pattern of breast cancer incidence varied according to restart strategy early on, but incidence essentially returned to that expected with undisrupted screening by 2025 for all four strategies, with some small fluctuations thereafter.

The impact on breast cancer mortality differed considerably long term. It increased slightly and transiently above the expected level with the catch-up-after-stop strategy, but there were sizable, long-lasting increases with the other strategies, with excess deaths still seen in 2060 for the everyone-delay strategy.

In absolute terms, the excess number of breast cancer deaths during 2020-2030, compared with undisrupted screening, was 181 with the everyone-delay strategy, 155 with the first-rounds-no-delay strategy, 145 with the continue-after-stopping-age strategy, and just 14 with the catch-up-after-stop strategy. Ms. Kregting declined to provide numbers for other countries, given that the model is based on the Dutch population and screening program.

Results in context

“The unprecedented burden of COVID-19 on health systems worldwide has important implications for cancer care,” said invited discussant Alessandra Gennari, MD, PhD, of the University of Eastern Piedmont and Maggiore della Carità Hospital, both in Novara, Italy.

“There is a delay in diagnosis due to the fact that screening programs and diagnostic programs have been decreased or suspended in many Western countries where this is standard of care. Patients also are more reluctant to present to health care services, delaying their diagnosis,” Dr. Gennari said.

Findings of this new study add to those of similar studies undertaken in Italy (published in In Vivo) and the United Kingdom (published in The Lancet Oncology) showing the likely marked toll of the pandemic on cancer diagnosis and mortality, Dr. Gennari noted. Taken together, the findings underscore the urgent need for policy interventions to mitigate this impact.

“These interventions should focus on increasing routine diagnostic capacity, through which up to 40% of patients with cancer are diagnosed,” Dr. Gennari recommended. “Public health messaging is needed that accurately conveys the risk of severe illness from COVID-19 versus the risks of not seeking health care advice if patients are symptomatic. Finally, there is a need for provision of evidence-based data on which clinicians can adequately base their decision on how to manage the risks of cancer patients and the risks and benefits of procedures during the pandemic.”

The current study did not have any specific funding, and Ms. Kregting disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Gennari disclosed relationships with Roche, Eisai, Lilly, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Kregting L et al. EBCC-12 Virtual Conference, Abstract 24.

FROM EBCC-12 VIRTUAL CONFERENCE

Chronic, preventive care fell as telemedicine soared during COVID-19

As the COVID-19 pandemic drove down the number of primary care visits and altered the method – moving many to telehealth appointments instead of in-person visits – the content of those appointments also changed, researchers reported in JAMA Network Open.

For the study, G. Caleb Alexander, MD, from the Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues analyzed data from the IQVIA National Disease and Therapeutic Index, a nationally representative audit of outpatient care in the United States, from the first quarter of 2018 through the second quarter of 2020.

Most primary care visits in 2018 and 2019 were office based, the authors noted. In the second quarter (Q2, April-May) of 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the country, the total number of primary care encounters decreased by 21.4%, and the number of office visits dropped by 50.2%, compared with the average of visits during Q2 in 2018 and 2019.

At the same time, telemedicine visits increased from just 1.1% of total visits in Q2 of 2018 and 2019 to 4.1% of visits in the first quarter (January through March) of 2020 and to 35.3% of visits in Q2 of 2020.

The authors also found that the use of telemedicine in the first half of 2020 varied by geographical region and was not associated with the regional COVID-19 burden. In the Pacific region (Washington, Oregon, and California), 26.8% of encounters were virtual. By contrast, the proportion of telemedicine encounters accounted for only 15.1% of visits in the East North Central states (Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio).

Adults between the ages of 19 and 55 years were more likely to attend telemedicine visits than were those younger or older. Additionally, adults who were commercially insured were more likely to adopt telemedicine versus those with public or no insurance. The study did not find substantial differences in telemedicine use by payer type, nor evidence of a racial disparity between Black and White people in their use of telemedicine.

Drop-off in preventive and chronic care

During the second quarter of this year, the authors reported, the number of visits that included blood pressure assessments dropped by 50.1% and the number of visits in which cholesterol levels were assessed fell by 36.9%, compared with the Q2 of 2018 and 2019.

Visits in which providers prescribed new antihypertensive or cholesterol-lowering medications decreased by 26% in Q2 of 2020 versus the same periods in the previous 2 years. The number of visits in which such prescriptions were renewed dropped by 8.9%.

New treatments also decreased significantly in Q2 of 2020 for patients with chronic conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol, asthma, depression, and insomnia.

When the authors compared the content of telemedicine versus in-person visits in Q2 of 2020, they found a substantial difference. Blood pressure was assessed in 69.7% of office visits, compared with 9.6% of telemedicine. Similarly, cholesterol levels were evaluated in 21.6% of office visits versus 13.5% of telemedicine encounters. New medications were ordered in similar proportions of office-based and telemedicine visits.

The authors concluded that “the COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with changes in the structure of primary care delivery, with the content of telemedicine visits differing from that of office-based encounters.”

While limited in scope, the authors noted, their study is one of the first to evaluate the changes in the content of primary care visits during the pandemic. They attributed the decline in evaluations of cardiovascular risk factors such as blood pressure and cholesterol to “fewer total visits and less frequent assessments during telemedicine encounters.”

While pointing to the inherent limitations of telemedicine, the study did not mention the availability of digital home blood pressure cuffs or home cholesterol test kits. Both kinds of devices are available at consumer-friendly price points and can help people track their indicators, but they’re not considered a substitute for sphygmomanometers used in offices or conventional lab tests. It’s not known how many consumers with cardiovascular risk factors have this kind of home monitoring equipment or how many doctors look at this kind of data.

Dr. Alexander reported serving as a paid adviser to IQVIA; that he is a cofounding principal and equity holder in Monument Analytics, a health care consultancy whose clients include the life sciences industry as well as plaintiffs in opioid litigation; and that he is a member of OptumRx’s National P&T Committee. One coauthor reported serving as an unpaid adviser to IQVIA and receiving personal fees from the states of California, Washington, and Alaska outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

As the COVID-19 pandemic drove down the number of primary care visits and altered the method – moving many to telehealth appointments instead of in-person visits – the content of those appointments also changed, researchers reported in JAMA Network Open.

For the study, G. Caleb Alexander, MD, from the Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues analyzed data from the IQVIA National Disease and Therapeutic Index, a nationally representative audit of outpatient care in the United States, from the first quarter of 2018 through the second quarter of 2020.

Most primary care visits in 2018 and 2019 were office based, the authors noted. In the second quarter (Q2, April-May) of 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the country, the total number of primary care encounters decreased by 21.4%, and the number of office visits dropped by 50.2%, compared with the average of visits during Q2 in 2018 and 2019.

At the same time, telemedicine visits increased from just 1.1% of total visits in Q2 of 2018 and 2019 to 4.1% of visits in the first quarter (January through March) of 2020 and to 35.3% of visits in Q2 of 2020.

The authors also found that the use of telemedicine in the first half of 2020 varied by geographical region and was not associated with the regional COVID-19 burden. In the Pacific region (Washington, Oregon, and California), 26.8% of encounters were virtual. By contrast, the proportion of telemedicine encounters accounted for only 15.1% of visits in the East North Central states (Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio).

Adults between the ages of 19 and 55 years were more likely to attend telemedicine visits than were those younger or older. Additionally, adults who were commercially insured were more likely to adopt telemedicine versus those with public or no insurance. The study did not find substantial differences in telemedicine use by payer type, nor evidence of a racial disparity between Black and White people in their use of telemedicine.

Drop-off in preventive and chronic care

During the second quarter of this year, the authors reported, the number of visits that included blood pressure assessments dropped by 50.1% and the number of visits in which cholesterol levels were assessed fell by 36.9%, compared with the Q2 of 2018 and 2019.

Visits in which providers prescribed new antihypertensive or cholesterol-lowering medications decreased by 26% in Q2 of 2020 versus the same periods in the previous 2 years. The number of visits in which such prescriptions were renewed dropped by 8.9%.

New treatments also decreased significantly in Q2 of 2020 for patients with chronic conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol, asthma, depression, and insomnia.

When the authors compared the content of telemedicine versus in-person visits in Q2 of 2020, they found a substantial difference. Blood pressure was assessed in 69.7% of office visits, compared with 9.6% of telemedicine. Similarly, cholesterol levels were evaluated in 21.6% of office visits versus 13.5% of telemedicine encounters. New medications were ordered in similar proportions of office-based and telemedicine visits.

The authors concluded that “the COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with changes in the structure of primary care delivery, with the content of telemedicine visits differing from that of office-based encounters.”

While limited in scope, the authors noted, their study is one of the first to evaluate the changes in the content of primary care visits during the pandemic. They attributed the decline in evaluations of cardiovascular risk factors such as blood pressure and cholesterol to “fewer total visits and less frequent assessments during telemedicine encounters.”

While pointing to the inherent limitations of telemedicine, the study did not mention the availability of digital home blood pressure cuffs or home cholesterol test kits. Both kinds of devices are available at consumer-friendly price points and can help people track their indicators, but they’re not considered a substitute for sphygmomanometers used in offices or conventional lab tests. It’s not known how many consumers with cardiovascular risk factors have this kind of home monitoring equipment or how many doctors look at this kind of data.

Dr. Alexander reported serving as a paid adviser to IQVIA; that he is a cofounding principal and equity holder in Monument Analytics, a health care consultancy whose clients include the life sciences industry as well as plaintiffs in opioid litigation; and that he is a member of OptumRx’s National P&T Committee. One coauthor reported serving as an unpaid adviser to IQVIA and receiving personal fees from the states of California, Washington, and Alaska outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

As the COVID-19 pandemic drove down the number of primary care visits and altered the method – moving many to telehealth appointments instead of in-person visits – the content of those appointments also changed, researchers reported in JAMA Network Open.

For the study, G. Caleb Alexander, MD, from the Center for Drug Safety and Effectiveness, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues analyzed data from the IQVIA National Disease and Therapeutic Index, a nationally representative audit of outpatient care in the United States, from the first quarter of 2018 through the second quarter of 2020.

Most primary care visits in 2018 and 2019 were office based, the authors noted. In the second quarter (Q2, April-May) of 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the country, the total number of primary care encounters decreased by 21.4%, and the number of office visits dropped by 50.2%, compared with the average of visits during Q2 in 2018 and 2019.

At the same time, telemedicine visits increased from just 1.1% of total visits in Q2 of 2018 and 2019 to 4.1% of visits in the first quarter (January through March) of 2020 and to 35.3% of visits in Q2 of 2020.

The authors also found that the use of telemedicine in the first half of 2020 varied by geographical region and was not associated with the regional COVID-19 burden. In the Pacific region (Washington, Oregon, and California), 26.8% of encounters were virtual. By contrast, the proportion of telemedicine encounters accounted for only 15.1% of visits in the East North Central states (Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio).

Adults between the ages of 19 and 55 years were more likely to attend telemedicine visits than were those younger or older. Additionally, adults who were commercially insured were more likely to adopt telemedicine versus those with public or no insurance. The study did not find substantial differences in telemedicine use by payer type, nor evidence of a racial disparity between Black and White people in their use of telemedicine.

Drop-off in preventive and chronic care