User login

Hidradenitis suppurativa therapy options should be patient guided

of their most challenging symptoms, according to an expert summary presented at the Skin of Color Update 2020.

“If your patient is only focused on the appearance of the lesions or the presence of sinus tracts, they might not think your treatment is working,” said Ginette A. Okoye, MD, professor and chair, department of dermatology, Howard University, Washington.

Instead, she advised working with patients to define priorities, allowing them to measure and appreciate improvement. The most difficult symptoms for one patient, such as pain or persistent abscess drainage, might not be the same for another.

There is a large array of treatment options for HS. These were once typically employed in stepwise manner, moving from steroids to hormonal therapies, antibiotics, and on to biologics and lasers, but Dr. Okoye reported that she layers on treatments, guided by patient priorities and responses. “Most of my patients are not on just one treatment at a time,” she said.

In addition to patient goals, her treatment choices are also influenced by the presence of comorbidities such as metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). For example, she reported she is more likely to include metformin among treatment options in patients with central obesity or insulin resistance, whereas she moves more quickly to a biologic for those with another systemic inflammatory disease such as IBD.

Although multiple factors appear to contribute to the symptoms of HS, the pathophysiology remains incompletely understood, but follicular occlusion is often “a primary inciting event,” Dr. Okoye said.

For this reason, laser hair removal can provide substantial benefit, she noted. Not only does it eliminate the occlusion, but the heat generated by the laser eliminates some of the pathogens, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, associated with HS.

“Lasers work well for preventing new lesions from forming but also in making active lesions go away faster,” said Dr. Okoye, who relies on the Nd:YAG laser when treating this disease in darker skin. She has found lasers to be particularly effective in mild to moderate disease.

When using lasers, one challenge is third-party insurance, according to Dr. Okoye, who reported that she has tried repeatedly to convince payers that this treatment is medically indicated for HS, but claims have been routinely denied. As a result, she has had to significantly discount the cost of laser at her center in order to provide access to “a modality that actually works.”

Incision and drainage of inflamed painful lesions is a common intervention in HS, but Dr. Okoye discourages this approach. Because of the high recurrence rates, the benefits are temporary. Instead, she recommends an intralesional injection of triamcinolone acetonide diluted with equal amounts of lidocaine.

With this injection, “there is immediate pain relief followed by significant resolution of the inflammation,” she said. Because of the likelihood that patients seeking care in the emergency department for acutely inflamed lesions will receive surgical treatment, Dr. Okoye recommends offering patients urgent appointments for steroid injections when painful and inflamed lesions need immediate attention.

In contrast, marsupialization of abscesses or sinus tracts, often called deroofing, is associated with a relatively low risk of recurrence, can be done under local anesthesia in an office, and can lead to resolution of persistent nodules in patients with mild disease.

“This is an easy procedure that takes relatively little time,” advised Dr. Okoye, who provided CPT codes (10060 and 10061) that will provide reimbursement as long as procedural notes describe the rationale.

Metformin is an attractive adjunctive therapy for HS in patients with type 2 diabetes or features that suggest metabolic disturbances, such as central obesity, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, or hypertriglyceridemia. It should also be considered in patients with PCOS because metformin decreases ovarian androgen production, she said.

When prescribing metformin in HS, which is an off-label indication, “I prefer the extended release formulation. It has a better profile in regard to gastrointestinal side effects and it can be taken once-daily,” Dr. Okoye said.

Citing a study that suggests patients with HS have even worse quality of life scores than do patients with diabetes, Dr. Okoye also emphasized the importance of psychosocial support and lifestyle modification as part of a holistic approach. With multiple manifestations of varying severity, individualizing therapy to control symptoms that the patient finds most bothersome is essential for optimizing patient well being.

Tien Viet Nguyen, MD, who practices dermatology and conducts clinical research in Bellevue, Wash., agrees that a comprehensive treatment program is needed. First author of a recent review article on HS, Dr. Nguyen agreed that common comorbidities like IBD, PCOS, and diabetes are accompanied frequently by a host of mental health and behavioral issues that contribute to impaired quality of life, such as depression, low self-esteem, sexual dysfunction, impaired sleep, and substance use disorders.

“Therefore, addressing these important comorbidities and quality of life issues with other health care professionals as a team is the best approach to improving health outcomes,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Nguyen also recently authored a chapter on quality of life issues associated with HS in the soon-to-be-published Comprehensive Guide to Hidradenitis Suppurativa (1st Edition, Dermatology Clinics). He agreed that optimal outcomes are achieved by an interdisciplinary team of health care providers who can address the sometimes independent but often interrelated comorbidities associated with this disorder.

Dr. Okoye has financial relationships with Pfizer and Unilver, but neither is relevant to this topic.

of their most challenging symptoms, according to an expert summary presented at the Skin of Color Update 2020.

“If your patient is only focused on the appearance of the lesions or the presence of sinus tracts, they might not think your treatment is working,” said Ginette A. Okoye, MD, professor and chair, department of dermatology, Howard University, Washington.

Instead, she advised working with patients to define priorities, allowing them to measure and appreciate improvement. The most difficult symptoms for one patient, such as pain or persistent abscess drainage, might not be the same for another.

There is a large array of treatment options for HS. These were once typically employed in stepwise manner, moving from steroids to hormonal therapies, antibiotics, and on to biologics and lasers, but Dr. Okoye reported that she layers on treatments, guided by patient priorities and responses. “Most of my patients are not on just one treatment at a time,” she said.

In addition to patient goals, her treatment choices are also influenced by the presence of comorbidities such as metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). For example, she reported she is more likely to include metformin among treatment options in patients with central obesity or insulin resistance, whereas she moves more quickly to a biologic for those with another systemic inflammatory disease such as IBD.

Although multiple factors appear to contribute to the symptoms of HS, the pathophysiology remains incompletely understood, but follicular occlusion is often “a primary inciting event,” Dr. Okoye said.

For this reason, laser hair removal can provide substantial benefit, she noted. Not only does it eliminate the occlusion, but the heat generated by the laser eliminates some of the pathogens, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, associated with HS.

“Lasers work well for preventing new lesions from forming but also in making active lesions go away faster,” said Dr. Okoye, who relies on the Nd:YAG laser when treating this disease in darker skin. She has found lasers to be particularly effective in mild to moderate disease.

When using lasers, one challenge is third-party insurance, according to Dr. Okoye, who reported that she has tried repeatedly to convince payers that this treatment is medically indicated for HS, but claims have been routinely denied. As a result, she has had to significantly discount the cost of laser at her center in order to provide access to “a modality that actually works.”

Incision and drainage of inflamed painful lesions is a common intervention in HS, but Dr. Okoye discourages this approach. Because of the high recurrence rates, the benefits are temporary. Instead, she recommends an intralesional injection of triamcinolone acetonide diluted with equal amounts of lidocaine.

With this injection, “there is immediate pain relief followed by significant resolution of the inflammation,” she said. Because of the likelihood that patients seeking care in the emergency department for acutely inflamed lesions will receive surgical treatment, Dr. Okoye recommends offering patients urgent appointments for steroid injections when painful and inflamed lesions need immediate attention.

In contrast, marsupialization of abscesses or sinus tracts, often called deroofing, is associated with a relatively low risk of recurrence, can be done under local anesthesia in an office, and can lead to resolution of persistent nodules in patients with mild disease.

“This is an easy procedure that takes relatively little time,” advised Dr. Okoye, who provided CPT codes (10060 and 10061) that will provide reimbursement as long as procedural notes describe the rationale.

Metformin is an attractive adjunctive therapy for HS in patients with type 2 diabetes or features that suggest metabolic disturbances, such as central obesity, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, or hypertriglyceridemia. It should also be considered in patients with PCOS because metformin decreases ovarian androgen production, she said.

When prescribing metformin in HS, which is an off-label indication, “I prefer the extended release formulation. It has a better profile in regard to gastrointestinal side effects and it can be taken once-daily,” Dr. Okoye said.

Citing a study that suggests patients with HS have even worse quality of life scores than do patients with diabetes, Dr. Okoye also emphasized the importance of psychosocial support and lifestyle modification as part of a holistic approach. With multiple manifestations of varying severity, individualizing therapy to control symptoms that the patient finds most bothersome is essential for optimizing patient well being.

Tien Viet Nguyen, MD, who practices dermatology and conducts clinical research in Bellevue, Wash., agrees that a comprehensive treatment program is needed. First author of a recent review article on HS, Dr. Nguyen agreed that common comorbidities like IBD, PCOS, and diabetes are accompanied frequently by a host of mental health and behavioral issues that contribute to impaired quality of life, such as depression, low self-esteem, sexual dysfunction, impaired sleep, and substance use disorders.

“Therefore, addressing these important comorbidities and quality of life issues with other health care professionals as a team is the best approach to improving health outcomes,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Nguyen also recently authored a chapter on quality of life issues associated with HS in the soon-to-be-published Comprehensive Guide to Hidradenitis Suppurativa (1st Edition, Dermatology Clinics). He agreed that optimal outcomes are achieved by an interdisciplinary team of health care providers who can address the sometimes independent but often interrelated comorbidities associated with this disorder.

Dr. Okoye has financial relationships with Pfizer and Unilver, but neither is relevant to this topic.

of their most challenging symptoms, according to an expert summary presented at the Skin of Color Update 2020.

“If your patient is only focused on the appearance of the lesions or the presence of sinus tracts, they might not think your treatment is working,” said Ginette A. Okoye, MD, professor and chair, department of dermatology, Howard University, Washington.

Instead, she advised working with patients to define priorities, allowing them to measure and appreciate improvement. The most difficult symptoms for one patient, such as pain or persistent abscess drainage, might not be the same for another.

There is a large array of treatment options for HS. These were once typically employed in stepwise manner, moving from steroids to hormonal therapies, antibiotics, and on to biologics and lasers, but Dr. Okoye reported that she layers on treatments, guided by patient priorities and responses. “Most of my patients are not on just one treatment at a time,” she said.

In addition to patient goals, her treatment choices are also influenced by the presence of comorbidities such as metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). For example, she reported she is more likely to include metformin among treatment options in patients with central obesity or insulin resistance, whereas she moves more quickly to a biologic for those with another systemic inflammatory disease such as IBD.

Although multiple factors appear to contribute to the symptoms of HS, the pathophysiology remains incompletely understood, but follicular occlusion is often “a primary inciting event,” Dr. Okoye said.

For this reason, laser hair removal can provide substantial benefit, she noted. Not only does it eliminate the occlusion, but the heat generated by the laser eliminates some of the pathogens, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, associated with HS.

“Lasers work well for preventing new lesions from forming but also in making active lesions go away faster,” said Dr. Okoye, who relies on the Nd:YAG laser when treating this disease in darker skin. She has found lasers to be particularly effective in mild to moderate disease.

When using lasers, one challenge is third-party insurance, according to Dr. Okoye, who reported that she has tried repeatedly to convince payers that this treatment is medically indicated for HS, but claims have been routinely denied. As a result, she has had to significantly discount the cost of laser at her center in order to provide access to “a modality that actually works.”

Incision and drainage of inflamed painful lesions is a common intervention in HS, but Dr. Okoye discourages this approach. Because of the high recurrence rates, the benefits are temporary. Instead, she recommends an intralesional injection of triamcinolone acetonide diluted with equal amounts of lidocaine.

With this injection, “there is immediate pain relief followed by significant resolution of the inflammation,” she said. Because of the likelihood that patients seeking care in the emergency department for acutely inflamed lesions will receive surgical treatment, Dr. Okoye recommends offering patients urgent appointments for steroid injections when painful and inflamed lesions need immediate attention.

In contrast, marsupialization of abscesses or sinus tracts, often called deroofing, is associated with a relatively low risk of recurrence, can be done under local anesthesia in an office, and can lead to resolution of persistent nodules in patients with mild disease.

“This is an easy procedure that takes relatively little time,” advised Dr. Okoye, who provided CPT codes (10060 and 10061) that will provide reimbursement as long as procedural notes describe the rationale.

Metformin is an attractive adjunctive therapy for HS in patients with type 2 diabetes or features that suggest metabolic disturbances, such as central obesity, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, or hypertriglyceridemia. It should also be considered in patients with PCOS because metformin decreases ovarian androgen production, she said.

When prescribing metformin in HS, which is an off-label indication, “I prefer the extended release formulation. It has a better profile in regard to gastrointestinal side effects and it can be taken once-daily,” Dr. Okoye said.

Citing a study that suggests patients with HS have even worse quality of life scores than do patients with diabetes, Dr. Okoye also emphasized the importance of psychosocial support and lifestyle modification as part of a holistic approach. With multiple manifestations of varying severity, individualizing therapy to control symptoms that the patient finds most bothersome is essential for optimizing patient well being.

Tien Viet Nguyen, MD, who practices dermatology and conducts clinical research in Bellevue, Wash., agrees that a comprehensive treatment program is needed. First author of a recent review article on HS, Dr. Nguyen agreed that common comorbidities like IBD, PCOS, and diabetes are accompanied frequently by a host of mental health and behavioral issues that contribute to impaired quality of life, such as depression, low self-esteem, sexual dysfunction, impaired sleep, and substance use disorders.

“Therefore, addressing these important comorbidities and quality of life issues with other health care professionals as a team is the best approach to improving health outcomes,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Nguyen also recently authored a chapter on quality of life issues associated with HS in the soon-to-be-published Comprehensive Guide to Hidradenitis Suppurativa (1st Edition, Dermatology Clinics). He agreed that optimal outcomes are achieved by an interdisciplinary team of health care providers who can address the sometimes independent but often interrelated comorbidities associated with this disorder.

Dr. Okoye has financial relationships with Pfizer and Unilver, but neither is relevant to this topic.

FROM SOC 2020

Expert offers tips for combining lasers and injectables on the same day

While if it involves the same area.

“Swelling from the laser can potentially make the toxin migrate and cause ptosis,” Arisa E. Ortiz, MD, said at the virtual annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “Even though this is temporary, your patient’s not going to be very happy with you. I would separate these at least 1 day apart, and then you should be OK.”

When using a filler on the same day as a laser treatment, Dr. Ortiz, who is director of laser and cosmetic dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, performs the laser procedure after injecting the filler, “because you may get some swelling, which can distort your need for filler,” she said. “I like to do the filler first to make sure I can assess how much volume loss they have. Then I’ll do the laser procedure right after.”

Another general rule of thumb is that, when combining lasers on the same day, consider lowering the device settings, “because it’s going to be a more aggressive treatment when you’re combining various laser procedures,” she said. “Treat vascular lesions first to not exacerbate nonspecific erythema. Then treat pigment, then resurfacing, followed by liquid nitrogen if needed to treat seborrheic keratoses.”

For periorbital rejuvenation, Dr. Ortiz likes to use a neurotoxin 1 week before performing the laser-resurfacing or skin-tightening procedure, followed by injection of a filler. “This augments your results,” she said. “Studies have shown that, if you start with a neuromodulator, you can get more improvement with your resurfacing procedure,” she said. “That makes sense, because you’re not contracting the muscle while you’re healing from the laser, so you get more effective collagen remodeling.”

When using a neuromodulator for dynamic periorbital rhytides, place it superficially to avoid bruising and stay superior to the maxillary prominence to avoid the zygomaticus major “so you don’t get a droopy smile,” she said. “The approved dosing is 24 units, 12 on each side. Less may be required for younger patients and more for more severe rhytides.”

For static rhytides, fractional resurfacing procedures will provide a more modest result with less downtime, while fully ablative laser resurfacing procedures will provide more dramatic improvement with more downtime. “You’re really going to tailor your treatment to what the patient is looking for,” Dr. Ortiz said. “If you use a fractional device you may need multiple treatments. Using a corneal shield when you’re resurfacing within the periorbital rim is a must, so you need to know how to place these if you’re going to be resurfacing in that area.”

For anesthesia, Dr. Ortiz likes to use injectable lidocaine, “because if you use a topical it can creep into the eye, and then you get a chemical corneal abrasion. This resolves after a few days but it’s really painful and your patient won’t be very happy.”

For tear troughs, use a hyaluronic acid filler with a low G prime. “If you use a thicker filler it can look lumpy or too full,” she said. While some clinicians use a needle to administer the filler, Dr. Ortiz prefers to use a blunt-tipped cannula. “It’s less painful and there’s less risk of bruising or swelling,” she said. “There’s also less risk of cannulizing a vessel. This is not zero risk. It’s been shown that the 27-gauge can actually cannulize the vessel, so it shouldn’t give you a false sense of security, but there is less risk, compared with using a needle. You can use the cannula to thread. If you’re using a needle you can inject a bolus and then massage it in, or you can use the microdroplet technique.”

With the cannula technique, bruising or swelling can occur even in the most experienced hands, “so make sure your patients don’t have an important event coming up,” Dr. Ortiz said. “With filler, not only do you improve the volume loss, but sometimes you improve the dark circles. I tend to see this more in lighter-skinned patients. In darker-skinned patients, the dark circles can be caused by racial pigmentation. That’s hard to fix, so I never promise that we can improve dark circles, but sometimes it does improve.”

For dynamic perioral rhytides, Dr. Ortiz generally treats with a neuromodulator 1 week in advance of laser resurfacing, followed by a filler for any etched-in lines. Use of a neuromodulator in the perioral region of musicians or singers is contraindicated “because it can affect their phonation,” she said. “Also, older patients might complain that it’s difficult for them to pucker their lips when they’re putting on a lip liner or lipstick. There are four injection sites on the upper lip and two on the lower lip. I do 1 unit at each injection site, with a max of 6-8 units. Any more than that and they’ll have difficulty puckering.”

Two main options for treating submental fullness include cryolipolysis or deoxycholic acid. “If you have a lot of volume, you want to use cryolipolysis,” Dr. Ortiz said. “The general rule is, if it fits in the cup [of the applicator], hook them up.” Use deoxycholic acid for areas of smaller volume, or to fine-tune, she added.

For platysmal bands, Dr. Ortiz favors injecting 2 units of botulinum toxin at three to four sites along the band. She pulls away and injects superficially and limits the treatment dose to 40 units in one session “because excessive doses can cause dysphagia,” she said. “If they need additional units, I’ll have them come back in 2 weeks.”

The Nefertiti lift combines the treatment of the platysma with the insertion point of the platysma along the jawline. Treatment of the patient along the lateral jawline with 2 units of botulinum toxin every centimeter or so can actually improve the definition of the jawline, “because your platysma is pulling down on your lower face,” Dr. Ortiz explained. “So, if you relax that, it can help to define the jawline. By treating the platysma, you can also prevent or soften the horizontal bands that occur across the neck.”

For necklace creases, she likes to inject 1-2 units of a low-HA filler along the crease – evenly spaced all along. “I’ll dilute it even further with 0.5 cc of lidocaine with epinephrine,” she said. “Then you can do serial punctures or you can thread along that line.”

For treating static rhytides on the neck, laser-resurfacing procedures work best, but at low settings. “Because there are fewer adnexal structures, the neck is at increased risk for scarring,” Dr. Ortiz said. “You want to use a lower fluence because your neck skin is thin. Your fluence determines your depth with resurfacing. Most importantly, use a lower density for a more conservative setting”

Options for treating poikiloderma of Civatte include the vascular laser, an IPL [intense pulsed light device], or a 1927-nm thulium laser. To avoid footprinting, or a “chicken wire” appearance to the treated area, Dr. Ortiz recommends using a large spot size with the pulsed dye laser or the IPL.

She concluded her presentation by underscoring the importance of communicating realistic expectations with patients. “There is some delayed gratification here,” she said. “For procedures that take time to see results, consider adding another procedure that will give them immediate results.”

Dr. Ortiz disclosed having financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical and device companies. She is also cochair of the MOA.

While if it involves the same area.

“Swelling from the laser can potentially make the toxin migrate and cause ptosis,” Arisa E. Ortiz, MD, said at the virtual annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “Even though this is temporary, your patient’s not going to be very happy with you. I would separate these at least 1 day apart, and then you should be OK.”

When using a filler on the same day as a laser treatment, Dr. Ortiz, who is director of laser and cosmetic dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, performs the laser procedure after injecting the filler, “because you may get some swelling, which can distort your need for filler,” she said. “I like to do the filler first to make sure I can assess how much volume loss they have. Then I’ll do the laser procedure right after.”

Another general rule of thumb is that, when combining lasers on the same day, consider lowering the device settings, “because it’s going to be a more aggressive treatment when you’re combining various laser procedures,” she said. “Treat vascular lesions first to not exacerbate nonspecific erythema. Then treat pigment, then resurfacing, followed by liquid nitrogen if needed to treat seborrheic keratoses.”

For periorbital rejuvenation, Dr. Ortiz likes to use a neurotoxin 1 week before performing the laser-resurfacing or skin-tightening procedure, followed by injection of a filler. “This augments your results,” she said. “Studies have shown that, if you start with a neuromodulator, you can get more improvement with your resurfacing procedure,” she said. “That makes sense, because you’re not contracting the muscle while you’re healing from the laser, so you get more effective collagen remodeling.”

When using a neuromodulator for dynamic periorbital rhytides, place it superficially to avoid bruising and stay superior to the maxillary prominence to avoid the zygomaticus major “so you don’t get a droopy smile,” she said. “The approved dosing is 24 units, 12 on each side. Less may be required for younger patients and more for more severe rhytides.”

For static rhytides, fractional resurfacing procedures will provide a more modest result with less downtime, while fully ablative laser resurfacing procedures will provide more dramatic improvement with more downtime. “You’re really going to tailor your treatment to what the patient is looking for,” Dr. Ortiz said. “If you use a fractional device you may need multiple treatments. Using a corneal shield when you’re resurfacing within the periorbital rim is a must, so you need to know how to place these if you’re going to be resurfacing in that area.”

For anesthesia, Dr. Ortiz likes to use injectable lidocaine, “because if you use a topical it can creep into the eye, and then you get a chemical corneal abrasion. This resolves after a few days but it’s really painful and your patient won’t be very happy.”

For tear troughs, use a hyaluronic acid filler with a low G prime. “If you use a thicker filler it can look lumpy or too full,” she said. While some clinicians use a needle to administer the filler, Dr. Ortiz prefers to use a blunt-tipped cannula. “It’s less painful and there’s less risk of bruising or swelling,” she said. “There’s also less risk of cannulizing a vessel. This is not zero risk. It’s been shown that the 27-gauge can actually cannulize the vessel, so it shouldn’t give you a false sense of security, but there is less risk, compared with using a needle. You can use the cannula to thread. If you’re using a needle you can inject a bolus and then massage it in, or you can use the microdroplet technique.”

With the cannula technique, bruising or swelling can occur even in the most experienced hands, “so make sure your patients don’t have an important event coming up,” Dr. Ortiz said. “With filler, not only do you improve the volume loss, but sometimes you improve the dark circles. I tend to see this more in lighter-skinned patients. In darker-skinned patients, the dark circles can be caused by racial pigmentation. That’s hard to fix, so I never promise that we can improve dark circles, but sometimes it does improve.”

For dynamic perioral rhytides, Dr. Ortiz generally treats with a neuromodulator 1 week in advance of laser resurfacing, followed by a filler for any etched-in lines. Use of a neuromodulator in the perioral region of musicians or singers is contraindicated “because it can affect their phonation,” she said. “Also, older patients might complain that it’s difficult for them to pucker their lips when they’re putting on a lip liner or lipstick. There are four injection sites on the upper lip and two on the lower lip. I do 1 unit at each injection site, with a max of 6-8 units. Any more than that and they’ll have difficulty puckering.”

Two main options for treating submental fullness include cryolipolysis or deoxycholic acid. “If you have a lot of volume, you want to use cryolipolysis,” Dr. Ortiz said. “The general rule is, if it fits in the cup [of the applicator], hook them up.” Use deoxycholic acid for areas of smaller volume, or to fine-tune, she added.

For platysmal bands, Dr. Ortiz favors injecting 2 units of botulinum toxin at three to four sites along the band. She pulls away and injects superficially and limits the treatment dose to 40 units in one session “because excessive doses can cause dysphagia,” she said. “If they need additional units, I’ll have them come back in 2 weeks.”

The Nefertiti lift combines the treatment of the platysma with the insertion point of the platysma along the jawline. Treatment of the patient along the lateral jawline with 2 units of botulinum toxin every centimeter or so can actually improve the definition of the jawline, “because your platysma is pulling down on your lower face,” Dr. Ortiz explained. “So, if you relax that, it can help to define the jawline. By treating the platysma, you can also prevent or soften the horizontal bands that occur across the neck.”

For necklace creases, she likes to inject 1-2 units of a low-HA filler along the crease – evenly spaced all along. “I’ll dilute it even further with 0.5 cc of lidocaine with epinephrine,” she said. “Then you can do serial punctures or you can thread along that line.”

For treating static rhytides on the neck, laser-resurfacing procedures work best, but at low settings. “Because there are fewer adnexal structures, the neck is at increased risk for scarring,” Dr. Ortiz said. “You want to use a lower fluence because your neck skin is thin. Your fluence determines your depth with resurfacing. Most importantly, use a lower density for a more conservative setting”

Options for treating poikiloderma of Civatte include the vascular laser, an IPL [intense pulsed light device], or a 1927-nm thulium laser. To avoid footprinting, or a “chicken wire” appearance to the treated area, Dr. Ortiz recommends using a large spot size with the pulsed dye laser or the IPL.

She concluded her presentation by underscoring the importance of communicating realistic expectations with patients. “There is some delayed gratification here,” she said. “For procedures that take time to see results, consider adding another procedure that will give them immediate results.”

Dr. Ortiz disclosed having financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical and device companies. She is also cochair of the MOA.

While if it involves the same area.

“Swelling from the laser can potentially make the toxin migrate and cause ptosis,” Arisa E. Ortiz, MD, said at the virtual annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “Even though this is temporary, your patient’s not going to be very happy with you. I would separate these at least 1 day apart, and then you should be OK.”

When using a filler on the same day as a laser treatment, Dr. Ortiz, who is director of laser and cosmetic dermatology at the University of California, San Diego, performs the laser procedure after injecting the filler, “because you may get some swelling, which can distort your need for filler,” she said. “I like to do the filler first to make sure I can assess how much volume loss they have. Then I’ll do the laser procedure right after.”

Another general rule of thumb is that, when combining lasers on the same day, consider lowering the device settings, “because it’s going to be a more aggressive treatment when you’re combining various laser procedures,” she said. “Treat vascular lesions first to not exacerbate nonspecific erythema. Then treat pigment, then resurfacing, followed by liquid nitrogen if needed to treat seborrheic keratoses.”

For periorbital rejuvenation, Dr. Ortiz likes to use a neurotoxin 1 week before performing the laser-resurfacing or skin-tightening procedure, followed by injection of a filler. “This augments your results,” she said. “Studies have shown that, if you start with a neuromodulator, you can get more improvement with your resurfacing procedure,” she said. “That makes sense, because you’re not contracting the muscle while you’re healing from the laser, so you get more effective collagen remodeling.”

When using a neuromodulator for dynamic periorbital rhytides, place it superficially to avoid bruising and stay superior to the maxillary prominence to avoid the zygomaticus major “so you don’t get a droopy smile,” she said. “The approved dosing is 24 units, 12 on each side. Less may be required for younger patients and more for more severe rhytides.”

For static rhytides, fractional resurfacing procedures will provide a more modest result with less downtime, while fully ablative laser resurfacing procedures will provide more dramatic improvement with more downtime. “You’re really going to tailor your treatment to what the patient is looking for,” Dr. Ortiz said. “If you use a fractional device you may need multiple treatments. Using a corneal shield when you’re resurfacing within the periorbital rim is a must, so you need to know how to place these if you’re going to be resurfacing in that area.”

For anesthesia, Dr. Ortiz likes to use injectable lidocaine, “because if you use a topical it can creep into the eye, and then you get a chemical corneal abrasion. This resolves after a few days but it’s really painful and your patient won’t be very happy.”

For tear troughs, use a hyaluronic acid filler with a low G prime. “If you use a thicker filler it can look lumpy or too full,” she said. While some clinicians use a needle to administer the filler, Dr. Ortiz prefers to use a blunt-tipped cannula. “It’s less painful and there’s less risk of bruising or swelling,” she said. “There’s also less risk of cannulizing a vessel. This is not zero risk. It’s been shown that the 27-gauge can actually cannulize the vessel, so it shouldn’t give you a false sense of security, but there is less risk, compared with using a needle. You can use the cannula to thread. If you’re using a needle you can inject a bolus and then massage it in, or you can use the microdroplet technique.”

With the cannula technique, bruising or swelling can occur even in the most experienced hands, “so make sure your patients don’t have an important event coming up,” Dr. Ortiz said. “With filler, not only do you improve the volume loss, but sometimes you improve the dark circles. I tend to see this more in lighter-skinned patients. In darker-skinned patients, the dark circles can be caused by racial pigmentation. That’s hard to fix, so I never promise that we can improve dark circles, but sometimes it does improve.”

For dynamic perioral rhytides, Dr. Ortiz generally treats with a neuromodulator 1 week in advance of laser resurfacing, followed by a filler for any etched-in lines. Use of a neuromodulator in the perioral region of musicians or singers is contraindicated “because it can affect their phonation,” she said. “Also, older patients might complain that it’s difficult for them to pucker their lips when they’re putting on a lip liner or lipstick. There are four injection sites on the upper lip and two on the lower lip. I do 1 unit at each injection site, with a max of 6-8 units. Any more than that and they’ll have difficulty puckering.”

Two main options for treating submental fullness include cryolipolysis or deoxycholic acid. “If you have a lot of volume, you want to use cryolipolysis,” Dr. Ortiz said. “The general rule is, if it fits in the cup [of the applicator], hook them up.” Use deoxycholic acid for areas of smaller volume, or to fine-tune, she added.

For platysmal bands, Dr. Ortiz favors injecting 2 units of botulinum toxin at three to four sites along the band. She pulls away and injects superficially and limits the treatment dose to 40 units in one session “because excessive doses can cause dysphagia,” she said. “If they need additional units, I’ll have them come back in 2 weeks.”

The Nefertiti lift combines the treatment of the platysma with the insertion point of the platysma along the jawline. Treatment of the patient along the lateral jawline with 2 units of botulinum toxin every centimeter or so can actually improve the definition of the jawline, “because your platysma is pulling down on your lower face,” Dr. Ortiz explained. “So, if you relax that, it can help to define the jawline. By treating the platysma, you can also prevent or soften the horizontal bands that occur across the neck.”

For necklace creases, she likes to inject 1-2 units of a low-HA filler along the crease – evenly spaced all along. “I’ll dilute it even further with 0.5 cc of lidocaine with epinephrine,” she said. “Then you can do serial punctures or you can thread along that line.”

For treating static rhytides on the neck, laser-resurfacing procedures work best, but at low settings. “Because there are fewer adnexal structures, the neck is at increased risk for scarring,” Dr. Ortiz said. “You want to use a lower fluence because your neck skin is thin. Your fluence determines your depth with resurfacing. Most importantly, use a lower density for a more conservative setting”

Options for treating poikiloderma of Civatte include the vascular laser, an IPL [intense pulsed light device], or a 1927-nm thulium laser. To avoid footprinting, or a “chicken wire” appearance to the treated area, Dr. Ortiz recommends using a large spot size with the pulsed dye laser or the IPL.

She concluded her presentation by underscoring the importance of communicating realistic expectations with patients. “There is some delayed gratification here,” she said. “For procedures that take time to see results, consider adding another procedure that will give them immediate results.”

Dr. Ortiz disclosed having financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical and device companies. She is also cochair of the MOA.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM MOA 2020

Medical Communities Go Virtual

Throughout history, physicians have formed communities to aid in the dissemination of knowledge, skills, and professional norms. From local physician groups to international societies and conferences, this drive to connect with members of our profession across the globe is timeless. We do so to learn from each other and continue to move the field of medicine forward.

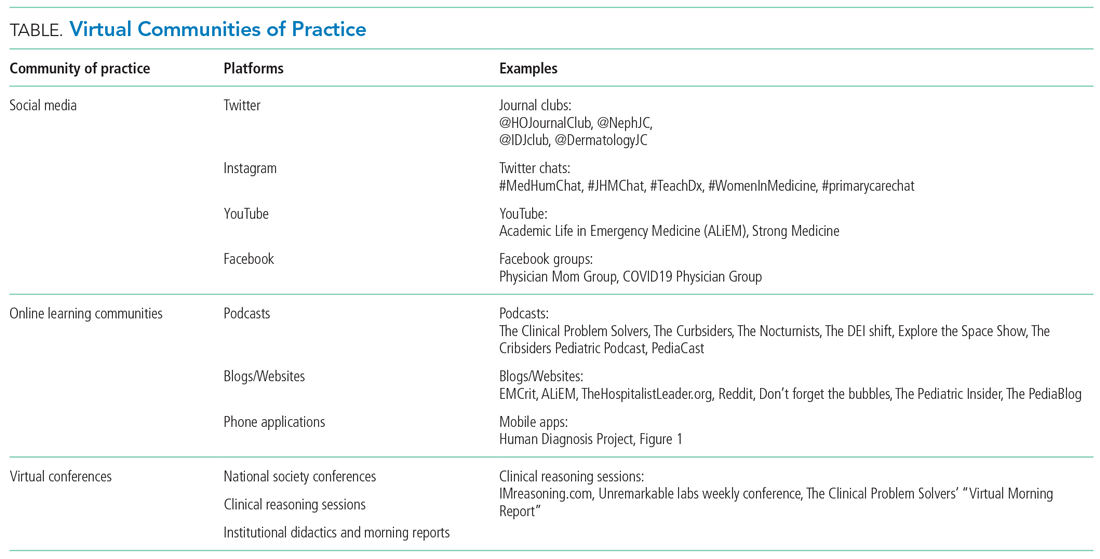

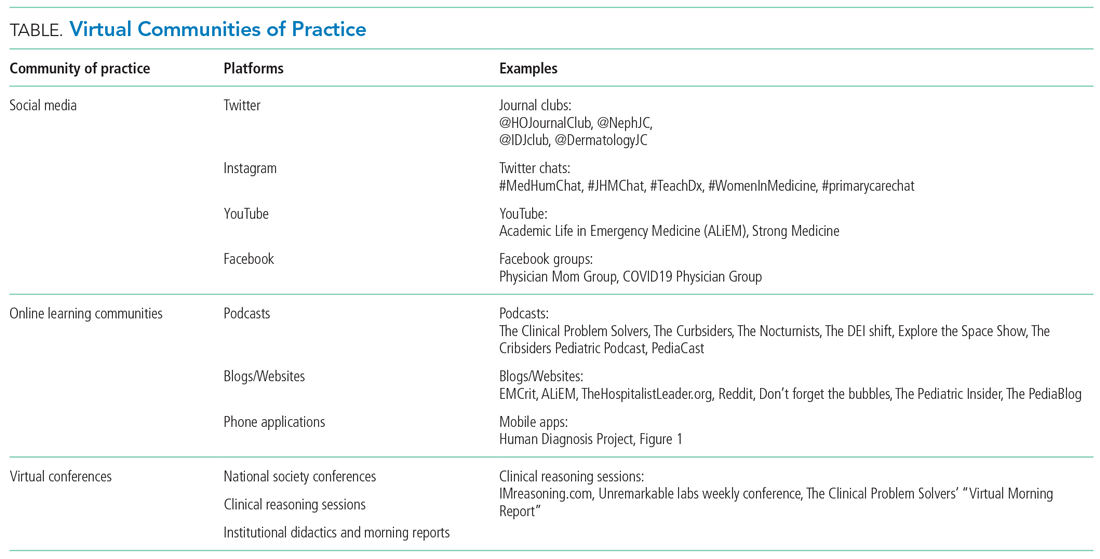

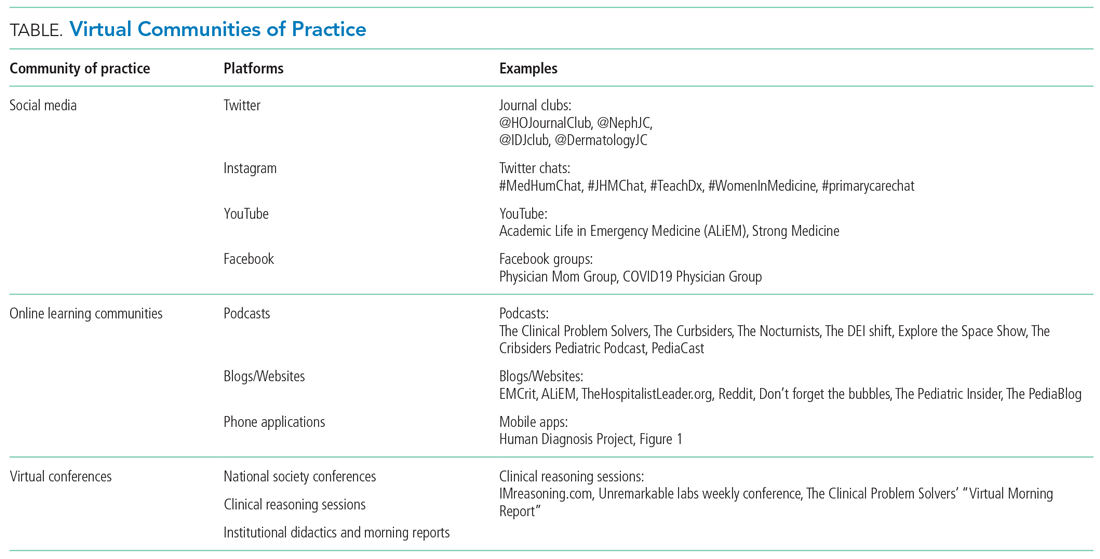

Yet, these communities are being strained by necessary physical distancing required during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many physicians accustomed to a sense of community are now finding themselves surprisingly isolated and alone. Into this distanced landscape, however, new digital groups—specifically social media (SoMe), online learning communities, and virtual conferences—have emerged. We are all active members in virtual communities; all of the authors are team members of The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast and one author of this paper, A.P., has previously served as the medical education lead for the Human Diagnosis Project. Both entities are described later in this article. Here, we provide an overview of these virtual communities and discuss how they have the potential to more equitably and effectively disseminate medical knowledge and education both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Table).

SOCIAL MEDIA

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, SoMe—especially Twitter—had become a virtual gathering place where digital colleagues exchange Twitter handles like business cards.1,2 They celebrate each other’s achievements and provide support during difficult times.

Importantly, the format of Twitter tends toward a flattened hierarchy. It is this egalitarian nature that has served SoMe well in its position as a modern learning community. Users from across the experience spectrum engage with and create novel educational content. This often occurs in the form of Tweetorials, or short lessons conveyed over a series of linked tweets. These have gained immense popularity on the platform and are becoming increasingly recognized forms of scholarship.3 Further, case-based lessons have become ubiquitous and are valuable opportunities for users to learn from other members of their digital communities. During the current pandemic, SoMe has become extremely important in the early dissemination and critique of the slew of research on the COVID-19 crisis.4

Beyond its role as an educational platform, SoMe functions as a virtual gathering place for members of the medical community to discuss topics relevant to the field. Subspecialists and researchers have gathered in digital journal clubs (eg, #NephJC, #IDJClub, #BloodandBone) and a number of journals have hosted live Twitter chats covering topics like controversies in clinical practice or professional development (eg, #JHMChat). More recently, social issues affecting the medical field, such as gender equity and the growing antiracism movement, have led to robust discussion on this medium.

Beyond Twitter, many medical professionals gather and exchange ideas on other platforms. Virtual networking and educational groups have arisen using Slack and Facebook.5-7 Trainees and faculty members alike consume and produce content on YouTube, which often serve to teach technical skills.8 Given widespread use of SoMe, we anticipate that the range of platforms utilized by medical professionals will continue to expand in the future.

ONLINE LEARNING COMMUNITIES

There have long existed multiple print and online forums dedicated to the development of clinical skills. These include clinical challenges in medical journals, interactive online cases, and more formal diagnostic education curricula at academic centers.9-11 With the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become more difficult to ensure that trainees have an in-person learning community to discuss and receive feedback. This has led to a wider adoption of application-based clinical exercises, educational podcasts, and curricular innovations to support these virtual efforts.

The Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) is a smart-phone application that provides a platform for individuals to submit clinical cases that can be rapidly peer-reviewed and disseminated to the larger user pool. Human Dx is notable for fostering a strong sense of community amongst its users.12,13 Case consumers and case creators are able to engage in further discussion after solving a case, and opportunities for feedback and growth are ample.

Medical education podcasts have taken on greater importance during the pandemic.14,15 Many educators have begun referring their learners towards certain podcasts as in-person learning communities have been put on hold. Medical professionals may appreciate the up-to-date and candid conversations held on many podcasts, which can provide both educationally useful and emotionally sympathetic connections to their distanced peers. Similarly, while academic clinicians previously benefitted from invited grand rounds speakers, they may now find that such expert discussants are most easily accessible through their appearances on podcasts.

As institutions suspended clerkships during the pandemic, many created virtual communities for trainees to engage in diagnostic reasoning and education. They built novel curricula that meld asynchronous learning with online community-based learning.14 Gamified learning tools and quizzes have also been incorporated into these hybrid curricula to help ensure participation of learners within their virtual communities.16,17

VIRTUAL CONFERENCES

Perhaps the most notable advance in digital communities catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic has been the increasing reliance on and comfort with video-based software. While many of our clinical, administrative, and social activities have migrated toward these virtual environments, they have also been used for a variety of activities related to education and professional development.

As institutions struggled to adapt to physical distancing, many medical schools and residency programs have moved their regular meetings and conferences to virtual platforms. Similar free and open-access conferences have also emerged, including the “Virtual Morning Report” (VMR) series from The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast, wherein a few individuals are invited to discuss a case on the video conference, with the remainder of the audience contributing via the chat feature.

Beyond the growing popularity of video conferencing for education, these virtual sessions have become their own community. On The Clinical Problem Solvers VMR, many participants, ranging from preclinical students to seasoned attendings, show up on a daily basis and interact with each other as close friends, as do members of more insular institutional sessions (eg, residency run reports). In these strangely isolating times, many of us have experienced comfort in seeing the faces of our friends and colleagues joining us to listen and discuss cases.

Separately, many professional societies have struggled with how to replace their large yearly in-person conferences, which would pose substantial infectious risks were they to be held in person. While many of those scheduled to occur during the early days of the pandemic were canceled or held limited online sessions, the trend towards virtual conference platforms seems to be accelerating. Organizers of the 2020 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (March 8-11, 2020) decided to convert from an in-person to entirely virtual conference 48 hours before it started. With the benefit of more forewarning, other conferences are planning and exploring best practices to promote networking and advancement of research goals at future academic meetings.18,19

BENEFITS OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITIES

The growing importance of these new digital communities could be viewed as a necessary evolution in the way that we gather and learn from each other. Traditional physician communities were inherently restricted by location, specialty, and hierarchy, thereby limiting the dissemination of knowledge and changes to professional norms. These restrictions could conceivably insulate and promote elite institutions in a fashion that perpetuates the inequalities within global medical systems. Unrestricted and open-access virtual communities, in contrast, have the potential to remove historical barriers and connect first-class mentors with trainees they would never have met otherwise.

Beyond promoting a more equitable distribution of knowledge and resources, these virtual communities are well suited to harness the benefits of group learning. The concept of communities of practice (CoP) refers to groupings of individuals involved in a personal or professional endeavor, with the community facilitating advancement of their own knowledge and skill set. Members of the CoP learn from each other, with more established members passing down essential knowledge and cultural norms. The three main components of CoP are maintaining a social network, a mutual enterprise (eg, a common goal), and a shared repertoire (eg, experiences, languages, etc).

Designing virtual learning spaces with these aspects in mind may allow these communities to function as CoPs. Some strategies include use of chat functions in videoconferences (to promote further dialogue) and development of dedicated sessions for specific subgroups or aims (eg, professional mentorship). The anticipated benefits of integrating virtual CoPs into medical education are notable, as a number of studies have already suggested that they are effective for disseminating knowledge, enhancing social learning, and aiding with professional development.7,20-23 These virtual CoPs continue to evolve, however, and further research is warranted to clarify how best to utilize them in medical education and professional societies.

CONCLUSION

Amidst the tragic loss of lives and financial calamity, the COVID-19 pandemic has also spurred innovation and change in the way health professionals learn and communicate. Going forward, the medical establishment should capitalize on these recent innovations and work to further build, recognize, and foster such digital gathering spaces in order to more equitably and effectively disseminate knowledge and educational resources.

Despite physical distancing, health professionals have grown closer during these past few months. Innovations spurred by the pandemic have made us stronger and more united. Our experience with social media, online learning communities, and virtual conferences suggests the opportunity to grow and evolve from this experience. As Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in March 2020, “...life is not going to be how it used to be [after the pandemic]…” Let’s hope he’s right.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Reza Manesh, MD, Rabih Geha, MD, and Jack Penner, MD, for their careful review of the manuscript.

1. Markham MJ, Gentile D, Graham DL. Social media for networking, professional development, and patient engagement. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:782-787. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_180077

2. Melvin L, Chan T. Using Twitter in clinical education and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):581-582. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00342.1

3. Breu AC. Why is a cow? Curiosity, Tweetorials, and the return to why. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1097-1098. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1906790

4. Chan AKM, Nickson CP, Rudolph JW, Lee A, Joynt GM. Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: early experience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020:10.1111/anae.15057. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15057

5. Pander T, Pinilla S, Dimitriadis K, Fischer MR. The use of Facebook in medical education--a literature review. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2014;31(3):Doc33. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma000925

6. Cree-Green M, Carreau AM, Davis SM, et al. Peer mentoring for professional and personal growth in academic medicine. J Investig Med. 2020;68(6):1128-1134. https://doi.org/10.1136/jim-2020-001391

7. Yarris LM, Chan TM, Gottlieb M, Juve AM. Finding your people in the digital age: virtual communities of practice to promote education scholarship. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(1):1-5. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-18-01093.1

8. Sterling M, Leung P, Wright D, Bishop TF. The use of social media in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):1043-1056. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001617

9. Manesh R, Dhaliwal G. Digital tools to enhance clinical reasoning. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(3):559-565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2017.12.015

10. Subramanian A, Connor DM, Berger G, et al. A curriculum for diagnostic reasoning: JGIM’s exercises in clinical reasoning. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(3):344-345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4689-y

11. Olson APJ, Singhal G, Dhaliwal G. Diagnosis education - an emerging field. Diagnosis (Berl). 2019;6(2):75-77. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0029

12. Chatterjee S, Desai S, Manesh R, Sun J, Nundy S, Wright SM. Assessment of a simulated case-based measurement of physician diagnostic performance. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e187006. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7006

13. Russell SW, Desai SV, O’Rourke P, et al. The genealogy of teaching clinical reasoning and diagnostic skill: the GEL Study. Diagnosis (Berl). 2020;7(3):197-203. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0107

14. Geha R, Dhaliwal G. Pilot virtual clerkship curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic: podcasts, peers, and problem-solving. Med Educ. 2020;54(9):855-856. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14246

15. AlGaeed M, Grewal M, Richardson PK, Leon Guerrero CR. COVID-19: Neurology residents’ perspective. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;78:452-453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.032

16. Moro C, Stromberga Z. Enhancing variety through gamified, interactive learning experiences. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14251

17. Morawo A, Sun C, Lowden M. Enhancing engagement during live virtual learning using interactive quizzes. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14253

18. Rubinger L, Gazendam A, Ekhtiari S, et al. Maximizing virtual meetings and conferences: a review of best practices. Int Orthop. 2020;44(8):1461-1466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04615-9

19. Woolston C. Learning to love virtual conferences in the coronavirus era. Nature. 2020;582(7810):135-136. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01489-0

20. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185-191. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826

21. McLoughlin C, Patel KD, O’Callaghan T, Reeves S. The use of virtual communities of practice to improve interprofessional collaboration and education: findings from an integrated review. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(2):136-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1377692

22. Barnett S, Jones SC, Caton T, Iverson D, Bennett S, Robinson L. Implementing a virtual community of practice for family physician training: a mixed-methods case study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e83. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3083

23. Healy MG, Traeger LN, Axelsson CGS, et al. NEJM Knowledge+ Question of the Week: a novel virtual learning community effectively utilizing an online discussion forum. Med Teach. 2019;41(11):1270-1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2019.1635685

Throughout history, physicians have formed communities to aid in the dissemination of knowledge, skills, and professional norms. From local physician groups to international societies and conferences, this drive to connect with members of our profession across the globe is timeless. We do so to learn from each other and continue to move the field of medicine forward.

Yet, these communities are being strained by necessary physical distancing required during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many physicians accustomed to a sense of community are now finding themselves surprisingly isolated and alone. Into this distanced landscape, however, new digital groups—specifically social media (SoMe), online learning communities, and virtual conferences—have emerged. We are all active members in virtual communities; all of the authors are team members of The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast and one author of this paper, A.P., has previously served as the medical education lead for the Human Diagnosis Project. Both entities are described later in this article. Here, we provide an overview of these virtual communities and discuss how they have the potential to more equitably and effectively disseminate medical knowledge and education both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Table).

SOCIAL MEDIA

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, SoMe—especially Twitter—had become a virtual gathering place where digital colleagues exchange Twitter handles like business cards.1,2 They celebrate each other’s achievements and provide support during difficult times.

Importantly, the format of Twitter tends toward a flattened hierarchy. It is this egalitarian nature that has served SoMe well in its position as a modern learning community. Users from across the experience spectrum engage with and create novel educational content. This often occurs in the form of Tweetorials, or short lessons conveyed over a series of linked tweets. These have gained immense popularity on the platform and are becoming increasingly recognized forms of scholarship.3 Further, case-based lessons have become ubiquitous and are valuable opportunities for users to learn from other members of their digital communities. During the current pandemic, SoMe has become extremely important in the early dissemination and critique of the slew of research on the COVID-19 crisis.4

Beyond its role as an educational platform, SoMe functions as a virtual gathering place for members of the medical community to discuss topics relevant to the field. Subspecialists and researchers have gathered in digital journal clubs (eg, #NephJC, #IDJClub, #BloodandBone) and a number of journals have hosted live Twitter chats covering topics like controversies in clinical practice or professional development (eg, #JHMChat). More recently, social issues affecting the medical field, such as gender equity and the growing antiracism movement, have led to robust discussion on this medium.

Beyond Twitter, many medical professionals gather and exchange ideas on other platforms. Virtual networking and educational groups have arisen using Slack and Facebook.5-7 Trainees and faculty members alike consume and produce content on YouTube, which often serve to teach technical skills.8 Given widespread use of SoMe, we anticipate that the range of platforms utilized by medical professionals will continue to expand in the future.

ONLINE LEARNING COMMUNITIES

There have long existed multiple print and online forums dedicated to the development of clinical skills. These include clinical challenges in medical journals, interactive online cases, and more formal diagnostic education curricula at academic centers.9-11 With the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become more difficult to ensure that trainees have an in-person learning community to discuss and receive feedback. This has led to a wider adoption of application-based clinical exercises, educational podcasts, and curricular innovations to support these virtual efforts.

The Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) is a smart-phone application that provides a platform for individuals to submit clinical cases that can be rapidly peer-reviewed and disseminated to the larger user pool. Human Dx is notable for fostering a strong sense of community amongst its users.12,13 Case consumers and case creators are able to engage in further discussion after solving a case, and opportunities for feedback and growth are ample.

Medical education podcasts have taken on greater importance during the pandemic.14,15 Many educators have begun referring their learners towards certain podcasts as in-person learning communities have been put on hold. Medical professionals may appreciate the up-to-date and candid conversations held on many podcasts, which can provide both educationally useful and emotionally sympathetic connections to their distanced peers. Similarly, while academic clinicians previously benefitted from invited grand rounds speakers, they may now find that such expert discussants are most easily accessible through their appearances on podcasts.

As institutions suspended clerkships during the pandemic, many created virtual communities for trainees to engage in diagnostic reasoning and education. They built novel curricula that meld asynchronous learning with online community-based learning.14 Gamified learning tools and quizzes have also been incorporated into these hybrid curricula to help ensure participation of learners within their virtual communities.16,17

VIRTUAL CONFERENCES

Perhaps the most notable advance in digital communities catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic has been the increasing reliance on and comfort with video-based software. While many of our clinical, administrative, and social activities have migrated toward these virtual environments, they have also been used for a variety of activities related to education and professional development.

As institutions struggled to adapt to physical distancing, many medical schools and residency programs have moved their regular meetings and conferences to virtual platforms. Similar free and open-access conferences have also emerged, including the “Virtual Morning Report” (VMR) series from The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast, wherein a few individuals are invited to discuss a case on the video conference, with the remainder of the audience contributing via the chat feature.

Beyond the growing popularity of video conferencing for education, these virtual sessions have become their own community. On The Clinical Problem Solvers VMR, many participants, ranging from preclinical students to seasoned attendings, show up on a daily basis and interact with each other as close friends, as do members of more insular institutional sessions (eg, residency run reports). In these strangely isolating times, many of us have experienced comfort in seeing the faces of our friends and colleagues joining us to listen and discuss cases.

Separately, many professional societies have struggled with how to replace their large yearly in-person conferences, which would pose substantial infectious risks were they to be held in person. While many of those scheduled to occur during the early days of the pandemic were canceled or held limited online sessions, the trend towards virtual conference platforms seems to be accelerating. Organizers of the 2020 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (March 8-11, 2020) decided to convert from an in-person to entirely virtual conference 48 hours before it started. With the benefit of more forewarning, other conferences are planning and exploring best practices to promote networking and advancement of research goals at future academic meetings.18,19

BENEFITS OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITIES

The growing importance of these new digital communities could be viewed as a necessary evolution in the way that we gather and learn from each other. Traditional physician communities were inherently restricted by location, specialty, and hierarchy, thereby limiting the dissemination of knowledge and changes to professional norms. These restrictions could conceivably insulate and promote elite institutions in a fashion that perpetuates the inequalities within global medical systems. Unrestricted and open-access virtual communities, in contrast, have the potential to remove historical barriers and connect first-class mentors with trainees they would never have met otherwise.

Beyond promoting a more equitable distribution of knowledge and resources, these virtual communities are well suited to harness the benefits of group learning. The concept of communities of practice (CoP) refers to groupings of individuals involved in a personal or professional endeavor, with the community facilitating advancement of their own knowledge and skill set. Members of the CoP learn from each other, with more established members passing down essential knowledge and cultural norms. The three main components of CoP are maintaining a social network, a mutual enterprise (eg, a common goal), and a shared repertoire (eg, experiences, languages, etc).

Designing virtual learning spaces with these aspects in mind may allow these communities to function as CoPs. Some strategies include use of chat functions in videoconferences (to promote further dialogue) and development of dedicated sessions for specific subgroups or aims (eg, professional mentorship). The anticipated benefits of integrating virtual CoPs into medical education are notable, as a number of studies have already suggested that they are effective for disseminating knowledge, enhancing social learning, and aiding with professional development.7,20-23 These virtual CoPs continue to evolve, however, and further research is warranted to clarify how best to utilize them in medical education and professional societies.

CONCLUSION

Amidst the tragic loss of lives and financial calamity, the COVID-19 pandemic has also spurred innovation and change in the way health professionals learn and communicate. Going forward, the medical establishment should capitalize on these recent innovations and work to further build, recognize, and foster such digital gathering spaces in order to more equitably and effectively disseminate knowledge and educational resources.

Despite physical distancing, health professionals have grown closer during these past few months. Innovations spurred by the pandemic have made us stronger and more united. Our experience with social media, online learning communities, and virtual conferences suggests the opportunity to grow and evolve from this experience. As Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in March 2020, “...life is not going to be how it used to be [after the pandemic]…” Let’s hope he’s right.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Reza Manesh, MD, Rabih Geha, MD, and Jack Penner, MD, for their careful review of the manuscript.

Throughout history, physicians have formed communities to aid in the dissemination of knowledge, skills, and professional norms. From local physician groups to international societies and conferences, this drive to connect with members of our profession across the globe is timeless. We do so to learn from each other and continue to move the field of medicine forward.

Yet, these communities are being strained by necessary physical distancing required during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many physicians accustomed to a sense of community are now finding themselves surprisingly isolated and alone. Into this distanced landscape, however, new digital groups—specifically social media (SoMe), online learning communities, and virtual conferences—have emerged. We are all active members in virtual communities; all of the authors are team members of The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast and one author of this paper, A.P., has previously served as the medical education lead for the Human Diagnosis Project. Both entities are described later in this article. Here, we provide an overview of these virtual communities and discuss how they have the potential to more equitably and effectively disseminate medical knowledge and education both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Table).

SOCIAL MEDIA

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, SoMe—especially Twitter—had become a virtual gathering place where digital colleagues exchange Twitter handles like business cards.1,2 They celebrate each other’s achievements and provide support during difficult times.

Importantly, the format of Twitter tends toward a flattened hierarchy. It is this egalitarian nature that has served SoMe well in its position as a modern learning community. Users from across the experience spectrum engage with and create novel educational content. This often occurs in the form of Tweetorials, or short lessons conveyed over a series of linked tweets. These have gained immense popularity on the platform and are becoming increasingly recognized forms of scholarship.3 Further, case-based lessons have become ubiquitous and are valuable opportunities for users to learn from other members of their digital communities. During the current pandemic, SoMe has become extremely important in the early dissemination and critique of the slew of research on the COVID-19 crisis.4

Beyond its role as an educational platform, SoMe functions as a virtual gathering place for members of the medical community to discuss topics relevant to the field. Subspecialists and researchers have gathered in digital journal clubs (eg, #NephJC, #IDJClub, #BloodandBone) and a number of journals have hosted live Twitter chats covering topics like controversies in clinical practice or professional development (eg, #JHMChat). More recently, social issues affecting the medical field, such as gender equity and the growing antiracism movement, have led to robust discussion on this medium.

Beyond Twitter, many medical professionals gather and exchange ideas on other platforms. Virtual networking and educational groups have arisen using Slack and Facebook.5-7 Trainees and faculty members alike consume and produce content on YouTube, which often serve to teach technical skills.8 Given widespread use of SoMe, we anticipate that the range of platforms utilized by medical professionals will continue to expand in the future.

ONLINE LEARNING COMMUNITIES

There have long existed multiple print and online forums dedicated to the development of clinical skills. These include clinical challenges in medical journals, interactive online cases, and more formal diagnostic education curricula at academic centers.9-11 With the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become more difficult to ensure that trainees have an in-person learning community to discuss and receive feedback. This has led to a wider adoption of application-based clinical exercises, educational podcasts, and curricular innovations to support these virtual efforts.

The Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) is a smart-phone application that provides a platform for individuals to submit clinical cases that can be rapidly peer-reviewed and disseminated to the larger user pool. Human Dx is notable for fostering a strong sense of community amongst its users.12,13 Case consumers and case creators are able to engage in further discussion after solving a case, and opportunities for feedback and growth are ample.

Medical education podcasts have taken on greater importance during the pandemic.14,15 Many educators have begun referring their learners towards certain podcasts as in-person learning communities have been put on hold. Medical professionals may appreciate the up-to-date and candid conversations held on many podcasts, which can provide both educationally useful and emotionally sympathetic connections to their distanced peers. Similarly, while academic clinicians previously benefitted from invited grand rounds speakers, they may now find that such expert discussants are most easily accessible through their appearances on podcasts.

As institutions suspended clerkships during the pandemic, many created virtual communities for trainees to engage in diagnostic reasoning and education. They built novel curricula that meld asynchronous learning with online community-based learning.14 Gamified learning tools and quizzes have also been incorporated into these hybrid curricula to help ensure participation of learners within their virtual communities.16,17

VIRTUAL CONFERENCES

Perhaps the most notable advance in digital communities catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic has been the increasing reliance on and comfort with video-based software. While many of our clinical, administrative, and social activities have migrated toward these virtual environments, they have also been used for a variety of activities related to education and professional development.

As institutions struggled to adapt to physical distancing, many medical schools and residency programs have moved their regular meetings and conferences to virtual platforms. Similar free and open-access conferences have also emerged, including the “Virtual Morning Report” (VMR) series from The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast, wherein a few individuals are invited to discuss a case on the video conference, with the remainder of the audience contributing via the chat feature.

Beyond the growing popularity of video conferencing for education, these virtual sessions have become their own community. On The Clinical Problem Solvers VMR, many participants, ranging from preclinical students to seasoned attendings, show up on a daily basis and interact with each other as close friends, as do members of more insular institutional sessions (eg, residency run reports). In these strangely isolating times, many of us have experienced comfort in seeing the faces of our friends and colleagues joining us to listen and discuss cases.

Separately, many professional societies have struggled with how to replace their large yearly in-person conferences, which would pose substantial infectious risks were they to be held in person. While many of those scheduled to occur during the early days of the pandemic were canceled or held limited online sessions, the trend towards virtual conference platforms seems to be accelerating. Organizers of the 2020 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (March 8-11, 2020) decided to convert from an in-person to entirely virtual conference 48 hours before it started. With the benefit of more forewarning, other conferences are planning and exploring best practices to promote networking and advancement of research goals at future academic meetings.18,19

BENEFITS OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITIES

The growing importance of these new digital communities could be viewed as a necessary evolution in the way that we gather and learn from each other. Traditional physician communities were inherently restricted by location, specialty, and hierarchy, thereby limiting the dissemination of knowledge and changes to professional norms. These restrictions could conceivably insulate and promote elite institutions in a fashion that perpetuates the inequalities within global medical systems. Unrestricted and open-access virtual communities, in contrast, have the potential to remove historical barriers and connect first-class mentors with trainees they would never have met otherwise.

Beyond promoting a more equitable distribution of knowledge and resources, these virtual communities are well suited to harness the benefits of group learning. The concept of communities of practice (CoP) refers to groupings of individuals involved in a personal or professional endeavor, with the community facilitating advancement of their own knowledge and skill set. Members of the CoP learn from each other, with more established members passing down essential knowledge and cultural norms. The three main components of CoP are maintaining a social network, a mutual enterprise (eg, a common goal), and a shared repertoire (eg, experiences, languages, etc).

Designing virtual learning spaces with these aspects in mind may allow these communities to function as CoPs. Some strategies include use of chat functions in videoconferences (to promote further dialogue) and development of dedicated sessions for specific subgroups or aims (eg, professional mentorship). The anticipated benefits of integrating virtual CoPs into medical education are notable, as a number of studies have already suggested that they are effective for disseminating knowledge, enhancing social learning, and aiding with professional development.7,20-23 These virtual CoPs continue to evolve, however, and further research is warranted to clarify how best to utilize them in medical education and professional societies.

CONCLUSION

Amidst the tragic loss of lives and financial calamity, the COVID-19 pandemic has also spurred innovation and change in the way health professionals learn and communicate. Going forward, the medical establishment should capitalize on these recent innovations and work to further build, recognize, and foster such digital gathering spaces in order to more equitably and effectively disseminate knowledge and educational resources.

Despite physical distancing, health professionals have grown closer during these past few months. Innovations spurred by the pandemic have made us stronger and more united. Our experience with social media, online learning communities, and virtual conferences suggests the opportunity to grow and evolve from this experience. As Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in March 2020, “...life is not going to be how it used to be [after the pandemic]…” Let’s hope he’s right.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Reza Manesh, MD, Rabih Geha, MD, and Jack Penner, MD, for their careful review of the manuscript.

1. Markham MJ, Gentile D, Graham DL. Social media for networking, professional development, and patient engagement. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:782-787. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_180077

2. Melvin L, Chan T. Using Twitter in clinical education and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):581-582. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00342.1

3. Breu AC. Why is a cow? Curiosity, Tweetorials, and the return to why. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1097-1098. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1906790

4. Chan AKM, Nickson CP, Rudolph JW, Lee A, Joynt GM. Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: early experience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020:10.1111/anae.15057. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15057

5. Pander T, Pinilla S, Dimitriadis K, Fischer MR. The use of Facebook in medical education--a literature review. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2014;31(3):Doc33. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma000925

6. Cree-Green M, Carreau AM, Davis SM, et al. Peer mentoring for professional and personal growth in academic medicine. J Investig Med. 2020;68(6):1128-1134. https://doi.org/10.1136/jim-2020-001391

7. Yarris LM, Chan TM, Gottlieb M, Juve AM. Finding your people in the digital age: virtual communities of practice to promote education scholarship. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(1):1-5. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-18-01093.1