User login

MI recurrences drop, but women underestimate disease risk

The number of heart attack survivors in the United States who experienced repeat attacks within a year decreased between 2008 and 2017, especially among women, yet women’s awareness of their risk of death from heart disease also decreased, according to data from a pair of studies published in Circulation.

Recurrent MI rates drop, but not enough

Although the overall morbidity and mortality from coronary heart disease (CHD) in the United States has been on the decline for decades, CHD remains the leading cause of death and disability in both sexes, wrote Sanne A.E. Peters, PhD, of Imperial College London, and colleagues.

To better assess the rates of recurrent CHD by sex, the researchers reviewed data from 770,408 women and 700,477 men younger than 65 years with commercial health insurance or aged 66 years and older with Medicare who were hospitalized for myocardial infarction between 2008 and 2017. The patients were followed for 1 year for recurrent MIs, recurrent CHD events, heart failure hospitalization, and all-cause mortality.

In the study of recurrent heart disease, the rate of recurrent heart attacks per 1,000 person-years declined from 89.2 to 72.3 in women and from 94.2 to 81.3 in men. In addition, the rate of recurrent heart disease events (defined as either an MI or an artery-opening procedure), dropped per 1,000 person-years from 166.3 to 133.3 in women and from 198.1 to 176.8 in men. The reduction was significantly greater among women compared with men (P < .001 for both recurrent MIs and recurrent CHD events) and the differences by sex were consistent throughout the study period.

However, no significant difference occurred in recurrent MI rates among younger women (aged 21-54 years), or men aged 55-79 years, the researchers noted.

Heart failure rates per 1,000 person-years decreased from 177.4 to 158.1 in women and from 162.9 to 156.1 in men during the study period, and all-cause mortality decreased per 1,000 person-years from 403.2 to 389.5 for women and from 436.1 to 417.9 in men.

Potential contributing factors to the reductions in rates of recurrent events after a heart attack may include improved acute cardiac procedures, in-hospital therapy, and secondary prevention, the researchers noted. In addition, “changes in the type and definition of MI may also have contributed to the decline in recurrent events,” they said. “Also, the introduction and increasing sensitivity of cardiac biomarkers assays, especially cardiac troponin, may have contributed to an increased detection of less severe MIs over time, which, in turn, could have resulted in artifactual reductions in the consequences of MI,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of claims data, lack of information on the severity of heart attacks, and inability to analyze population subgroups, but the results were strengthened by the use of a large, multicultural database.

Despite the decline seen in this study, overall rates of recurrent MI, recurrent CHD events, heart failure hospitalization, and mortality remain high, the researchers said, and the results “highlight the need for interventions to ensure men and women receive guideline recommended treatment to lower the risk for recurrent MI, recurrent CHD, heart failure, and mortality after hospital discharge for MI,” they concluded.

Many women don’t recognize heart disease risk

Although women showed a greater reduction in recurrent MI and recurrent CHD events compared with men, the awareness of heart disease as the No. 1 killer of women has declined, according to a special report from the American Heart Association.

Based on survey data from 2009, 65% of women were aware that heart disease was their leading cause of death (LCOD); by 2019 the number dropped to 44%. The 10-year decline occurred across all races and ethnicities, as well as ages, with the exception of women aged 65 years and older.

The American Heart Association has conducted national surveys since 1997 to monitor awareness of cardiovascular disease among U.S. women. Data from earlier surveys showed increased awareness of heart disease as LCOD and increased awareness of heart attack symptoms between 1997 and 2012, wrote Mary Cushman, MD, of the University of Vermont, Burlington, chair of the writing group for the statement, and colleagues.

However, overall awareness and knowledge of heart disease among women remains poor, they wrote.

“Awareness programs designed to educate the public about CVD among women in the United States include Go Red for Women by the American Heart Association; The Heart Truth by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and Make the Call, Don’t Miss a Beat by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,” the researchers noted. To determine the change in awareness of heart disease as the LCOD among women, the researchers conducted a multivariate analysis of 1,158 women who completed the 2009 survey and 1,345 who completed the 2019 survey. The average age was 50 years; roughly 70% of the participants in the 2009 survey and 62% in the 2019 survey were non-Hispanic White.

The greatest declines in awareness of heart disease as LCOD occurred among Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks and among all respondents aged 25-34 years.

Awareness of heart disease as LCOD was 30% lower among women with high blood pressure compared with women overall, the researchers noted.

“In both surveys, higher educational attainment was strongly related to awareness that heart disease is the LCOD,” the researchers said. However, the results highlight the need for renewed efforts to educate younger women, Hispanic women, and non-Hispanic Black women, they emphasized. Unpublished data from the AHA survey showed that “younger women were less likely to report leading a heart-healthy lifestyle and were more likely to identify multiple barriers to leading a heart-healthy lifestyle, including lack of time, stress, and lack of confidence,” they wrote.

In addition, awareness of heart attack warning signs declined overall and within each ethnic group between 2009 and 2019.

The survey results were limited by several factors including the use of an online-only model that might limit generalizability to populations without online access, and was conducted only in English, the researchers wrote.

Heart disease needs new PR plan

The study of heart disease risk awareness among women was an important update to understand how well the message about women’s risk is getting out, said Martha Gulati, MD, president-elect of the American Society of Preventive Cardiology, in an interview.

The issue remains that heart disease is the No. 1 killer of women, and the decrease in awareness “means we need to amplify our message,” she said.

“I also question whether the symbol of the red dress [for women’s heart disease] is working, and it seems that now is the time to change this symbol,” she emphasized. “I wear a red dress pin on my lab coat and every day someone asks what it means, and no one recognizes it,” she said. “I think ‘Go Red for Women’ is great and part of our outward campaign, but our symbol needs to change to increase the connection and awareness in women,” she said.

What might be a better symbol? Simply, a heart, said Dr. Gulati. But “we need to study whatever is next to really connect with women and make them understand their risk for heart disease,” she added.

“Additionally, we really need to get to minority women,” she said. “We are lagging there, and the survey was conducted in English so it missed many people,” she noted.

Dr. Gulati said she was shocked at how much awareness of heart disease risk has fallen among women, even in those with risk factors such as hypertension, who were 30% less likely to be aware that heart disease remains their leading cause of death. “Younger women as well as very unaware; what this means to me is that our public education efforts need to be amplified,” Dr. Gulati said.

Barriers to educating women about heart disease risk include language and access to affordable screening, Dr. Gulati emphasized. “We need to ensure screening for heart disease is always included as a covered cost for a preventive service,” she said.

“Research needs to be done to identify what works toward educating women about cardiac risk. We need to identify a marketing tool to increase awareness in women. It might be something different for one race versus another,” Dr. Gulati said. “Our messaging needs to improve, but how we improve it needs more than just health care professionals,” she said.

Focus on prevention to reduce MI recurrence

“The study regarding recurrent events after MI is important because we really don’t know much about recurrent coronary heart disease after a MI over time,” said Dr. Gulati. These data can be helpful in managing surviving patients and understanding future risk, she said. “But I was surprised to see fewer recurrent events in women, as women still have more heart failure than men even if it has declined with time,” she noted.

Dr. Gulati questioned several aspects of the study and highlighted some of the limitations. “These are claims data, so do they accurately reflect the U.S. population?” she asked. “Remember, this is a study of people who survived a heart attack; those who didn’t survive aren’t included, and that group is more likely to be women, especially women younger than 55 years,” she said.

In addition, Dr. Gulati noted the lack of data on type of heart attack and on treatment adherence or referral to cardiac rehab, as well as lack of data on long-term medication adherence or follow-up care.

Prevention is the key take-home message from both studies, “whether we are talking primary prevention for the heart disease awareness study or secondary prevention for the recurrent heart attack study,” Dr. Gulati said.

The recurrent heart disease study was supported in part by Amgen and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Lead author Dr. Peters disclosed support from a UK Medical Research Council Skills Development Fellowship with no financial conflicts. Dr. Cushman had no financial conflicts to disclose; several coauthors on the writing committee disclosed relationships with companies including Amarin and Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Gulati had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Peters SAE et al. Circulation. 2020 Sep 21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047065; Cushman M et al. Circulation. 2020 Sep 21. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000907.

The number of heart attack survivors in the United States who experienced repeat attacks within a year decreased between 2008 and 2017, especially among women, yet women’s awareness of their risk of death from heart disease also decreased, according to data from a pair of studies published in Circulation.

Recurrent MI rates drop, but not enough

Although the overall morbidity and mortality from coronary heart disease (CHD) in the United States has been on the decline for decades, CHD remains the leading cause of death and disability in both sexes, wrote Sanne A.E. Peters, PhD, of Imperial College London, and colleagues.

To better assess the rates of recurrent CHD by sex, the researchers reviewed data from 770,408 women and 700,477 men younger than 65 years with commercial health insurance or aged 66 years and older with Medicare who were hospitalized for myocardial infarction between 2008 and 2017. The patients were followed for 1 year for recurrent MIs, recurrent CHD events, heart failure hospitalization, and all-cause mortality.

In the study of recurrent heart disease, the rate of recurrent heart attacks per 1,000 person-years declined from 89.2 to 72.3 in women and from 94.2 to 81.3 in men. In addition, the rate of recurrent heart disease events (defined as either an MI or an artery-opening procedure), dropped per 1,000 person-years from 166.3 to 133.3 in women and from 198.1 to 176.8 in men. The reduction was significantly greater among women compared with men (P < .001 for both recurrent MIs and recurrent CHD events) and the differences by sex were consistent throughout the study period.

However, no significant difference occurred in recurrent MI rates among younger women (aged 21-54 years), or men aged 55-79 years, the researchers noted.

Heart failure rates per 1,000 person-years decreased from 177.4 to 158.1 in women and from 162.9 to 156.1 in men during the study period, and all-cause mortality decreased per 1,000 person-years from 403.2 to 389.5 for women and from 436.1 to 417.9 in men.

Potential contributing factors to the reductions in rates of recurrent events after a heart attack may include improved acute cardiac procedures, in-hospital therapy, and secondary prevention, the researchers noted. In addition, “changes in the type and definition of MI may also have contributed to the decline in recurrent events,” they said. “Also, the introduction and increasing sensitivity of cardiac biomarkers assays, especially cardiac troponin, may have contributed to an increased detection of less severe MIs over time, which, in turn, could have resulted in artifactual reductions in the consequences of MI,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of claims data, lack of information on the severity of heart attacks, and inability to analyze population subgroups, but the results were strengthened by the use of a large, multicultural database.

Despite the decline seen in this study, overall rates of recurrent MI, recurrent CHD events, heart failure hospitalization, and mortality remain high, the researchers said, and the results “highlight the need for interventions to ensure men and women receive guideline recommended treatment to lower the risk for recurrent MI, recurrent CHD, heart failure, and mortality after hospital discharge for MI,” they concluded.

Many women don’t recognize heart disease risk

Although women showed a greater reduction in recurrent MI and recurrent CHD events compared with men, the awareness of heart disease as the No. 1 killer of women has declined, according to a special report from the American Heart Association.

Based on survey data from 2009, 65% of women were aware that heart disease was their leading cause of death (LCOD); by 2019 the number dropped to 44%. The 10-year decline occurred across all races and ethnicities, as well as ages, with the exception of women aged 65 years and older.

The American Heart Association has conducted national surveys since 1997 to monitor awareness of cardiovascular disease among U.S. women. Data from earlier surveys showed increased awareness of heart disease as LCOD and increased awareness of heart attack symptoms between 1997 and 2012, wrote Mary Cushman, MD, of the University of Vermont, Burlington, chair of the writing group for the statement, and colleagues.

However, overall awareness and knowledge of heart disease among women remains poor, they wrote.

“Awareness programs designed to educate the public about CVD among women in the United States include Go Red for Women by the American Heart Association; The Heart Truth by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and Make the Call, Don’t Miss a Beat by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,” the researchers noted. To determine the change in awareness of heart disease as the LCOD among women, the researchers conducted a multivariate analysis of 1,158 women who completed the 2009 survey and 1,345 who completed the 2019 survey. The average age was 50 years; roughly 70% of the participants in the 2009 survey and 62% in the 2019 survey were non-Hispanic White.

The greatest declines in awareness of heart disease as LCOD occurred among Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks and among all respondents aged 25-34 years.

Awareness of heart disease as LCOD was 30% lower among women with high blood pressure compared with women overall, the researchers noted.

“In both surveys, higher educational attainment was strongly related to awareness that heart disease is the LCOD,” the researchers said. However, the results highlight the need for renewed efforts to educate younger women, Hispanic women, and non-Hispanic Black women, they emphasized. Unpublished data from the AHA survey showed that “younger women were less likely to report leading a heart-healthy lifestyle and were more likely to identify multiple barriers to leading a heart-healthy lifestyle, including lack of time, stress, and lack of confidence,” they wrote.

In addition, awareness of heart attack warning signs declined overall and within each ethnic group between 2009 and 2019.

The survey results were limited by several factors including the use of an online-only model that might limit generalizability to populations without online access, and was conducted only in English, the researchers wrote.

Heart disease needs new PR plan

The study of heart disease risk awareness among women was an important update to understand how well the message about women’s risk is getting out, said Martha Gulati, MD, president-elect of the American Society of Preventive Cardiology, in an interview.

The issue remains that heart disease is the No. 1 killer of women, and the decrease in awareness “means we need to amplify our message,” she said.

“I also question whether the symbol of the red dress [for women’s heart disease] is working, and it seems that now is the time to change this symbol,” she emphasized. “I wear a red dress pin on my lab coat and every day someone asks what it means, and no one recognizes it,” she said. “I think ‘Go Red for Women’ is great and part of our outward campaign, but our symbol needs to change to increase the connection and awareness in women,” she said.

What might be a better symbol? Simply, a heart, said Dr. Gulati. But “we need to study whatever is next to really connect with women and make them understand their risk for heart disease,” she added.

“Additionally, we really need to get to minority women,” she said. “We are lagging there, and the survey was conducted in English so it missed many people,” she noted.

Dr. Gulati said she was shocked at how much awareness of heart disease risk has fallen among women, even in those with risk factors such as hypertension, who were 30% less likely to be aware that heart disease remains their leading cause of death. “Younger women as well as very unaware; what this means to me is that our public education efforts need to be amplified,” Dr. Gulati said.

Barriers to educating women about heart disease risk include language and access to affordable screening, Dr. Gulati emphasized. “We need to ensure screening for heart disease is always included as a covered cost for a preventive service,” she said.

“Research needs to be done to identify what works toward educating women about cardiac risk. We need to identify a marketing tool to increase awareness in women. It might be something different for one race versus another,” Dr. Gulati said. “Our messaging needs to improve, but how we improve it needs more than just health care professionals,” she said.

Focus on prevention to reduce MI recurrence

“The study regarding recurrent events after MI is important because we really don’t know much about recurrent coronary heart disease after a MI over time,” said Dr. Gulati. These data can be helpful in managing surviving patients and understanding future risk, she said. “But I was surprised to see fewer recurrent events in women, as women still have more heart failure than men even if it has declined with time,” she noted.

Dr. Gulati questioned several aspects of the study and highlighted some of the limitations. “These are claims data, so do they accurately reflect the U.S. population?” she asked. “Remember, this is a study of people who survived a heart attack; those who didn’t survive aren’t included, and that group is more likely to be women, especially women younger than 55 years,” she said.

In addition, Dr. Gulati noted the lack of data on type of heart attack and on treatment adherence or referral to cardiac rehab, as well as lack of data on long-term medication adherence or follow-up care.

Prevention is the key take-home message from both studies, “whether we are talking primary prevention for the heart disease awareness study or secondary prevention for the recurrent heart attack study,” Dr. Gulati said.

The recurrent heart disease study was supported in part by Amgen and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Lead author Dr. Peters disclosed support from a UK Medical Research Council Skills Development Fellowship with no financial conflicts. Dr. Cushman had no financial conflicts to disclose; several coauthors on the writing committee disclosed relationships with companies including Amarin and Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Gulati had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Peters SAE et al. Circulation. 2020 Sep 21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047065; Cushman M et al. Circulation. 2020 Sep 21. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000907.

The number of heart attack survivors in the United States who experienced repeat attacks within a year decreased between 2008 and 2017, especially among women, yet women’s awareness of their risk of death from heart disease also decreased, according to data from a pair of studies published in Circulation.

Recurrent MI rates drop, but not enough

Although the overall morbidity and mortality from coronary heart disease (CHD) in the United States has been on the decline for decades, CHD remains the leading cause of death and disability in both sexes, wrote Sanne A.E. Peters, PhD, of Imperial College London, and colleagues.

To better assess the rates of recurrent CHD by sex, the researchers reviewed data from 770,408 women and 700,477 men younger than 65 years with commercial health insurance or aged 66 years and older with Medicare who were hospitalized for myocardial infarction between 2008 and 2017. The patients were followed for 1 year for recurrent MIs, recurrent CHD events, heart failure hospitalization, and all-cause mortality.

In the study of recurrent heart disease, the rate of recurrent heart attacks per 1,000 person-years declined from 89.2 to 72.3 in women and from 94.2 to 81.3 in men. In addition, the rate of recurrent heart disease events (defined as either an MI or an artery-opening procedure), dropped per 1,000 person-years from 166.3 to 133.3 in women and from 198.1 to 176.8 in men. The reduction was significantly greater among women compared with men (P < .001 for both recurrent MIs and recurrent CHD events) and the differences by sex were consistent throughout the study period.

However, no significant difference occurred in recurrent MI rates among younger women (aged 21-54 years), or men aged 55-79 years, the researchers noted.

Heart failure rates per 1,000 person-years decreased from 177.4 to 158.1 in women and from 162.9 to 156.1 in men during the study period, and all-cause mortality decreased per 1,000 person-years from 403.2 to 389.5 for women and from 436.1 to 417.9 in men.

Potential contributing factors to the reductions in rates of recurrent events after a heart attack may include improved acute cardiac procedures, in-hospital therapy, and secondary prevention, the researchers noted. In addition, “changes in the type and definition of MI may also have contributed to the decline in recurrent events,” they said. “Also, the introduction and increasing sensitivity of cardiac biomarkers assays, especially cardiac troponin, may have contributed to an increased detection of less severe MIs over time, which, in turn, could have resulted in artifactual reductions in the consequences of MI,” they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of claims data, lack of information on the severity of heart attacks, and inability to analyze population subgroups, but the results were strengthened by the use of a large, multicultural database.

Despite the decline seen in this study, overall rates of recurrent MI, recurrent CHD events, heart failure hospitalization, and mortality remain high, the researchers said, and the results “highlight the need for interventions to ensure men and women receive guideline recommended treatment to lower the risk for recurrent MI, recurrent CHD, heart failure, and mortality after hospital discharge for MI,” they concluded.

Many women don’t recognize heart disease risk

Although women showed a greater reduction in recurrent MI and recurrent CHD events compared with men, the awareness of heart disease as the No. 1 killer of women has declined, according to a special report from the American Heart Association.

Based on survey data from 2009, 65% of women were aware that heart disease was their leading cause of death (LCOD); by 2019 the number dropped to 44%. The 10-year decline occurred across all races and ethnicities, as well as ages, with the exception of women aged 65 years and older.

The American Heart Association has conducted national surveys since 1997 to monitor awareness of cardiovascular disease among U.S. women. Data from earlier surveys showed increased awareness of heart disease as LCOD and increased awareness of heart attack symptoms between 1997 and 2012, wrote Mary Cushman, MD, of the University of Vermont, Burlington, chair of the writing group for the statement, and colleagues.

However, overall awareness and knowledge of heart disease among women remains poor, they wrote.

“Awareness programs designed to educate the public about CVD among women in the United States include Go Red for Women by the American Heart Association; The Heart Truth by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and Make the Call, Don’t Miss a Beat by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,” the researchers noted. To determine the change in awareness of heart disease as the LCOD among women, the researchers conducted a multivariate analysis of 1,158 women who completed the 2009 survey and 1,345 who completed the 2019 survey. The average age was 50 years; roughly 70% of the participants in the 2009 survey and 62% in the 2019 survey were non-Hispanic White.

The greatest declines in awareness of heart disease as LCOD occurred among Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks and among all respondents aged 25-34 years.

Awareness of heart disease as LCOD was 30% lower among women with high blood pressure compared with women overall, the researchers noted.

“In both surveys, higher educational attainment was strongly related to awareness that heart disease is the LCOD,” the researchers said. However, the results highlight the need for renewed efforts to educate younger women, Hispanic women, and non-Hispanic Black women, they emphasized. Unpublished data from the AHA survey showed that “younger women were less likely to report leading a heart-healthy lifestyle and were more likely to identify multiple barriers to leading a heart-healthy lifestyle, including lack of time, stress, and lack of confidence,” they wrote.

In addition, awareness of heart attack warning signs declined overall and within each ethnic group between 2009 and 2019.

The survey results were limited by several factors including the use of an online-only model that might limit generalizability to populations without online access, and was conducted only in English, the researchers wrote.

Heart disease needs new PR plan

The study of heart disease risk awareness among women was an important update to understand how well the message about women’s risk is getting out, said Martha Gulati, MD, president-elect of the American Society of Preventive Cardiology, in an interview.

The issue remains that heart disease is the No. 1 killer of women, and the decrease in awareness “means we need to amplify our message,” she said.

“I also question whether the symbol of the red dress [for women’s heart disease] is working, and it seems that now is the time to change this symbol,” she emphasized. “I wear a red dress pin on my lab coat and every day someone asks what it means, and no one recognizes it,” she said. “I think ‘Go Red for Women’ is great and part of our outward campaign, but our symbol needs to change to increase the connection and awareness in women,” she said.

What might be a better symbol? Simply, a heart, said Dr. Gulati. But “we need to study whatever is next to really connect with women and make them understand their risk for heart disease,” she added.

“Additionally, we really need to get to minority women,” she said. “We are lagging there, and the survey was conducted in English so it missed many people,” she noted.

Dr. Gulati said she was shocked at how much awareness of heart disease risk has fallen among women, even in those with risk factors such as hypertension, who were 30% less likely to be aware that heart disease remains their leading cause of death. “Younger women as well as very unaware; what this means to me is that our public education efforts need to be amplified,” Dr. Gulati said.

Barriers to educating women about heart disease risk include language and access to affordable screening, Dr. Gulati emphasized. “We need to ensure screening for heart disease is always included as a covered cost for a preventive service,” she said.

“Research needs to be done to identify what works toward educating women about cardiac risk. We need to identify a marketing tool to increase awareness in women. It might be something different for one race versus another,” Dr. Gulati said. “Our messaging needs to improve, but how we improve it needs more than just health care professionals,” she said.

Focus on prevention to reduce MI recurrence

“The study regarding recurrent events after MI is important because we really don’t know much about recurrent coronary heart disease after a MI over time,” said Dr. Gulati. These data can be helpful in managing surviving patients and understanding future risk, she said. “But I was surprised to see fewer recurrent events in women, as women still have more heart failure than men even if it has declined with time,” she noted.

Dr. Gulati questioned several aspects of the study and highlighted some of the limitations. “These are claims data, so do they accurately reflect the U.S. population?” she asked. “Remember, this is a study of people who survived a heart attack; those who didn’t survive aren’t included, and that group is more likely to be women, especially women younger than 55 years,” she said.

In addition, Dr. Gulati noted the lack of data on type of heart attack and on treatment adherence or referral to cardiac rehab, as well as lack of data on long-term medication adherence or follow-up care.

Prevention is the key take-home message from both studies, “whether we are talking primary prevention for the heart disease awareness study or secondary prevention for the recurrent heart attack study,” Dr. Gulati said.

The recurrent heart disease study was supported in part by Amgen and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Lead author Dr. Peters disclosed support from a UK Medical Research Council Skills Development Fellowship with no financial conflicts. Dr. Cushman had no financial conflicts to disclose; several coauthors on the writing committee disclosed relationships with companies including Amarin and Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Gulati had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Peters SAE et al. Circulation. 2020 Sep 21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047065; Cushman M et al. Circulation. 2020 Sep 21. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000907.

FROM CIRCULATION

2020 has been quite a year

I remember New Year’s Day 2020, full of hope and wonderment of what the year would bring. I was coming into the Society of Hospital Medicine as the incoming President, taking the 2020 reins in the organization’s 20th year. It would be a year of transitioning to a new CEO, reinvigorating our membership engagement efforts, and renewing a strategic plan for forward progress into the next decade. It would be a year chock full of travel, speaking engagements, and meetings with thousands of hospitalists around the globe.

What I didn’t know is that we would soon face the grim reality that the long-voiced concern of infectious disease experts and epidemiologists would come true. That our colleagues and friends and families would be infected, hospitalized, and die from this new disease, for which there were no good, effective treatments. That our ability to come together as a nation to implement basic infection control and epidemiologic practices would be fractured, uncoordinated, and ineffective. That within 6 months of the first case on U.S. soil, we would witness 5,270,000 people being infected from the disease, and 167,000 dying from it. And that the stunning toll of the disease would ripple into every nook and cranny of our society, from the economy to the fabric of our families and to the mental and physical health of all of our citizens.

However, what I couldn’t have known on this past New Year’s Day is how incredibly resilient and innovative our hospital medicine society and community would be to not only endure this new way of working and living, but also to find ways to improve upon how we care for all patients, despite COVID-19. What I couldn’t have known is how hospitalists would pivot to new arenas of care settings, including the EDs, ICUs, “COVID units,” and telehealth – flawlessly and seamlessly filling care gaps that would otherwise be catastrophically unfilled.

What I couldn’t have known is how we would be willing to come back into work, day after day, to care for our patients, despite the risks to ourselves and our families. What I couldn’t have known is how hospitalists would come together as a community to network and share knowledge in unprecedented ways, both humbly and proactively – knowing that we would not have all the answers but that we probably had better answers than most. What I couldn’t have known is that the SHM staff would pivot our entire SHM team away from previous “staple” offerings (e.g., live meetings) to virtual learning and network opportunities, which would be attended at rates higher than ever seen before, including live webinars, HMX exchanges, and e-learnings. What I couldn’t have known is that we would figure out, in a matter of weeks, what treatments were and were not effective for our patients and get those treatments to them despite the difficulties. And what I couldn’t have known is how much prouder I would be, more than ever before, to tell people: “I am a hospitalist.”

I took my son to the dentist recently, and when we were just about to leave, the dentist asked: “What do you do for a living?” and I stated: “I am a hospitalist.” He slowly breathed in and replied: “Oh … wow … you have really seen things …” Yes, we have.

So, is 2020 shaping up as expected? Absolutely not! But I am more inspired, humbled, and motivated than ever to proudly serve SHM with more energy and enthusiasm than I would have dreamed on New Year’s Day. And even if we can’t see each other in person (as we so naively planned), through virtual meetings (national, regional, and chapter), webinars, social media, and other listening modes, we will still be able to connect as a community and share ideas and issues as we muddle through the remainder of 2020 and beyond. We need each other more than ever before, and I am so proud to be a part of this SHM family.

Dr. Scheurer is chief quality officer and professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is president of SHM.

I remember New Year’s Day 2020, full of hope and wonderment of what the year would bring. I was coming into the Society of Hospital Medicine as the incoming President, taking the 2020 reins in the organization’s 20th year. It would be a year of transitioning to a new CEO, reinvigorating our membership engagement efforts, and renewing a strategic plan for forward progress into the next decade. It would be a year chock full of travel, speaking engagements, and meetings with thousands of hospitalists around the globe.

What I didn’t know is that we would soon face the grim reality that the long-voiced concern of infectious disease experts and epidemiologists would come true. That our colleagues and friends and families would be infected, hospitalized, and die from this new disease, for which there were no good, effective treatments. That our ability to come together as a nation to implement basic infection control and epidemiologic practices would be fractured, uncoordinated, and ineffective. That within 6 months of the first case on U.S. soil, we would witness 5,270,000 people being infected from the disease, and 167,000 dying from it. And that the stunning toll of the disease would ripple into every nook and cranny of our society, from the economy to the fabric of our families and to the mental and physical health of all of our citizens.

However, what I couldn’t have known on this past New Year’s Day is how incredibly resilient and innovative our hospital medicine society and community would be to not only endure this new way of working and living, but also to find ways to improve upon how we care for all patients, despite COVID-19. What I couldn’t have known is how hospitalists would pivot to new arenas of care settings, including the EDs, ICUs, “COVID units,” and telehealth – flawlessly and seamlessly filling care gaps that would otherwise be catastrophically unfilled.

What I couldn’t have known is how we would be willing to come back into work, day after day, to care for our patients, despite the risks to ourselves and our families. What I couldn’t have known is how hospitalists would come together as a community to network and share knowledge in unprecedented ways, both humbly and proactively – knowing that we would not have all the answers but that we probably had better answers than most. What I couldn’t have known is that the SHM staff would pivot our entire SHM team away from previous “staple” offerings (e.g., live meetings) to virtual learning and network opportunities, which would be attended at rates higher than ever seen before, including live webinars, HMX exchanges, and e-learnings. What I couldn’t have known is that we would figure out, in a matter of weeks, what treatments were and were not effective for our patients and get those treatments to them despite the difficulties. And what I couldn’t have known is how much prouder I would be, more than ever before, to tell people: “I am a hospitalist.”

I took my son to the dentist recently, and when we were just about to leave, the dentist asked: “What do you do for a living?” and I stated: “I am a hospitalist.” He slowly breathed in and replied: “Oh … wow … you have really seen things …” Yes, we have.

So, is 2020 shaping up as expected? Absolutely not! But I am more inspired, humbled, and motivated than ever to proudly serve SHM with more energy and enthusiasm than I would have dreamed on New Year’s Day. And even if we can’t see each other in person (as we so naively planned), through virtual meetings (national, regional, and chapter), webinars, social media, and other listening modes, we will still be able to connect as a community and share ideas and issues as we muddle through the remainder of 2020 and beyond. We need each other more than ever before, and I am so proud to be a part of this SHM family.

Dr. Scheurer is chief quality officer and professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is president of SHM.

I remember New Year’s Day 2020, full of hope and wonderment of what the year would bring. I was coming into the Society of Hospital Medicine as the incoming President, taking the 2020 reins in the organization’s 20th year. It would be a year of transitioning to a new CEO, reinvigorating our membership engagement efforts, and renewing a strategic plan for forward progress into the next decade. It would be a year chock full of travel, speaking engagements, and meetings with thousands of hospitalists around the globe.

What I didn’t know is that we would soon face the grim reality that the long-voiced concern of infectious disease experts and epidemiologists would come true. That our colleagues and friends and families would be infected, hospitalized, and die from this new disease, for which there were no good, effective treatments. That our ability to come together as a nation to implement basic infection control and epidemiologic practices would be fractured, uncoordinated, and ineffective. That within 6 months of the first case on U.S. soil, we would witness 5,270,000 people being infected from the disease, and 167,000 dying from it. And that the stunning toll of the disease would ripple into every nook and cranny of our society, from the economy to the fabric of our families and to the mental and physical health of all of our citizens.

However, what I couldn’t have known on this past New Year’s Day is how incredibly resilient and innovative our hospital medicine society and community would be to not only endure this new way of working and living, but also to find ways to improve upon how we care for all patients, despite COVID-19. What I couldn’t have known is how hospitalists would pivot to new arenas of care settings, including the EDs, ICUs, “COVID units,” and telehealth – flawlessly and seamlessly filling care gaps that would otherwise be catastrophically unfilled.

What I couldn’t have known is how we would be willing to come back into work, day after day, to care for our patients, despite the risks to ourselves and our families. What I couldn’t have known is how hospitalists would come together as a community to network and share knowledge in unprecedented ways, both humbly and proactively – knowing that we would not have all the answers but that we probably had better answers than most. What I couldn’t have known is that the SHM staff would pivot our entire SHM team away from previous “staple” offerings (e.g., live meetings) to virtual learning and network opportunities, which would be attended at rates higher than ever seen before, including live webinars, HMX exchanges, and e-learnings. What I couldn’t have known is that we would figure out, in a matter of weeks, what treatments were and were not effective for our patients and get those treatments to them despite the difficulties. And what I couldn’t have known is how much prouder I would be, more than ever before, to tell people: “I am a hospitalist.”

I took my son to the dentist recently, and when we were just about to leave, the dentist asked: “What do you do for a living?” and I stated: “I am a hospitalist.” He slowly breathed in and replied: “Oh … wow … you have really seen things …” Yes, we have.

So, is 2020 shaping up as expected? Absolutely not! But I am more inspired, humbled, and motivated than ever to proudly serve SHM with more energy and enthusiasm than I would have dreamed on New Year’s Day. And even if we can’t see each other in person (as we so naively planned), through virtual meetings (national, regional, and chapter), webinars, social media, and other listening modes, we will still be able to connect as a community and share ideas and issues as we muddle through the remainder of 2020 and beyond. We need each other more than ever before, and I am so proud to be a part of this SHM family.

Dr. Scheurer is chief quality officer and professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is president of SHM.

Expert spotlights recent advances in the medical treatment of acne

During the virtual annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium, he highlighted the following new acne treatment options:

- Trifarotene cream 0.005% (Aklief). This marks the first new retinoid indicated for acne in several decades. It is indicated for the topical treatment of acne vulgaris in patients 9 years of age and older and has been studied in acne of the face, chest, and back. “It’s nice to have in our armamentarium,” he said.

- Tazarotene lotion 0.045% (Arazlo). The 0.1% formulation of tazarotene is commonly used for acne, but it can cause skin irritation, dryness, and erythema. The new 0.045% formulation was developed in a three-dimensional mesh matrix, with ingredients from an oil-in-water emulsion. “This allows for graduated dosing on the skin without as much irritation,” said Dr. Eichenfield, who is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego.

- Minocycline 4% topical foam (Amzeeq). This marks the first and only topical minocycline prescription treatment for acne. “Its hydrophobic composition allows for stable and efficient delivery of inherently unstable pharmaceutical ingredients,” he said. “There is no evidence of photosensitivity as you’d expect from a minocycline-based product, and there are low systemic levels compared with oral minocycline.”

- Clascoterone cream 1% (Winlevi). This first-in-class topical androgen receptor inhibitor has been approved for the treatment of acne in patients 12 years and older. It competes with dihydrotestosterone and selectively targets androgen receptors in sebocytes and hair papilla cells. “It has been studied on the face and trunk and has been shown to inhibit sebum production, reduce secretion of inflammatory cytokines, and inhibit inflammatory pathways,” said Dr. Eichenfield, who is also professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego.

- From a systemic standpoint, sarecycline, a new tetracycline class antibiotic, has been approved for the treatment of inflammatory lesions of nonnodular moderate to severe acne vulgaris in patients 9 years and older. The once-daily drug can be taken with or without food in a weight-based dose. “This medicine appears to have a narrow spectrum of antibacterial activity compared with other tetracyclines,” he said. “It may have less of a negative effect on gut microbiome than traditional oral antibiotics.”

As for integrating these new options into existing clinical practice, Dr. Eichenfield predicts that the general approach to acne treatment will remain the same. “We’ll have to wait to see where the topical androgens fit into the treatment algorithms,” he said. “Our goal is to minimize scarring, minimize disease, and to modulate the disease course.”

Dr. Eichenfield disclosed that he has been an investigator and/or consultant for Almirall, Cassiopea, Dermata, Foamix, Galderma, L’Oreal, and Ortho Dermatologics.

During the virtual annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium, he highlighted the following new acne treatment options:

- Trifarotene cream 0.005% (Aklief). This marks the first new retinoid indicated for acne in several decades. It is indicated for the topical treatment of acne vulgaris in patients 9 years of age and older and has been studied in acne of the face, chest, and back. “It’s nice to have in our armamentarium,” he said.

- Tazarotene lotion 0.045% (Arazlo). The 0.1% formulation of tazarotene is commonly used for acne, but it can cause skin irritation, dryness, and erythema. The new 0.045% formulation was developed in a three-dimensional mesh matrix, with ingredients from an oil-in-water emulsion. “This allows for graduated dosing on the skin without as much irritation,” said Dr. Eichenfield, who is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego.

- Minocycline 4% topical foam (Amzeeq). This marks the first and only topical minocycline prescription treatment for acne. “Its hydrophobic composition allows for stable and efficient delivery of inherently unstable pharmaceutical ingredients,” he said. “There is no evidence of photosensitivity as you’d expect from a minocycline-based product, and there are low systemic levels compared with oral minocycline.”

- Clascoterone cream 1% (Winlevi). This first-in-class topical androgen receptor inhibitor has been approved for the treatment of acne in patients 12 years and older. It competes with dihydrotestosterone and selectively targets androgen receptors in sebocytes and hair papilla cells. “It has been studied on the face and trunk and has been shown to inhibit sebum production, reduce secretion of inflammatory cytokines, and inhibit inflammatory pathways,” said Dr. Eichenfield, who is also professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego.

- From a systemic standpoint, sarecycline, a new tetracycline class antibiotic, has been approved for the treatment of inflammatory lesions of nonnodular moderate to severe acne vulgaris in patients 9 years and older. The once-daily drug can be taken with or without food in a weight-based dose. “This medicine appears to have a narrow spectrum of antibacterial activity compared with other tetracyclines,” he said. “It may have less of a negative effect on gut microbiome than traditional oral antibiotics.”

As for integrating these new options into existing clinical practice, Dr. Eichenfield predicts that the general approach to acne treatment will remain the same. “We’ll have to wait to see where the topical androgens fit into the treatment algorithms,” he said. “Our goal is to minimize scarring, minimize disease, and to modulate the disease course.”

Dr. Eichenfield disclosed that he has been an investigator and/or consultant for Almirall, Cassiopea, Dermata, Foamix, Galderma, L’Oreal, and Ortho Dermatologics.

During the virtual annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium, he highlighted the following new acne treatment options:

- Trifarotene cream 0.005% (Aklief). This marks the first new retinoid indicated for acne in several decades. It is indicated for the topical treatment of acne vulgaris in patients 9 years of age and older and has been studied in acne of the face, chest, and back. “It’s nice to have in our armamentarium,” he said.

- Tazarotene lotion 0.045% (Arazlo). The 0.1% formulation of tazarotene is commonly used for acne, but it can cause skin irritation, dryness, and erythema. The new 0.045% formulation was developed in a three-dimensional mesh matrix, with ingredients from an oil-in-water emulsion. “This allows for graduated dosing on the skin without as much irritation,” said Dr. Eichenfield, who is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego.

- Minocycline 4% topical foam (Amzeeq). This marks the first and only topical minocycline prescription treatment for acne. “Its hydrophobic composition allows for stable and efficient delivery of inherently unstable pharmaceutical ingredients,” he said. “There is no evidence of photosensitivity as you’d expect from a minocycline-based product, and there are low systemic levels compared with oral minocycline.”

- Clascoterone cream 1% (Winlevi). This first-in-class topical androgen receptor inhibitor has been approved for the treatment of acne in patients 12 years and older. It competes with dihydrotestosterone and selectively targets androgen receptors in sebocytes and hair papilla cells. “It has been studied on the face and trunk and has been shown to inhibit sebum production, reduce secretion of inflammatory cytokines, and inhibit inflammatory pathways,” said Dr. Eichenfield, who is also professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego.

- From a systemic standpoint, sarecycline, a new tetracycline class antibiotic, has been approved for the treatment of inflammatory lesions of nonnodular moderate to severe acne vulgaris in patients 9 years and older. The once-daily drug can be taken with or without food in a weight-based dose. “This medicine appears to have a narrow spectrum of antibacterial activity compared with other tetracyclines,” he said. “It may have less of a negative effect on gut microbiome than traditional oral antibiotics.”

As for integrating these new options into existing clinical practice, Dr. Eichenfield predicts that the general approach to acne treatment will remain the same. “We’ll have to wait to see where the topical androgens fit into the treatment algorithms,” he said. “Our goal is to minimize scarring, minimize disease, and to modulate the disease course.”

Dr. Eichenfield disclosed that he has been an investigator and/or consultant for Almirall, Cassiopea, Dermata, Foamix, Galderma, L’Oreal, and Ortho Dermatologics.

FROM MOA 2020

Evaluation of Glycemic Control and Cost Savings Associated With Liraglutide Dose Reduction at a Veterans Affairs Hospital

Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) are injectable incretin hormones approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). They are highly efficacious agents with hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) reduction potential of approximately 0.8 to 1.6% and mechanisms of action that result in an average weight loss of 1 to 3 kg.1,2 Published in 2016, The LEADER (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results) trial established cardiovascular benefits associated with liraglutide, making it a preferred GLP-1 RA.3

In addition to HbA1c reduction, weight loss, and cardiovascular benefits, liraglutide also has shown insulin-sparing effects when used in combination with insulin. A trial by Lane and colleagues revealed a 34% decrease in total daily insulin dose 6 months after the addition of liraglutide to insulin in patients with T2DM receiving > 100 units of insulin daily.4 When used in combination with basal insulin analogues (glargine or detemir) similar findings also were shown.5

The Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, selected liraglutide as its preferred GLP-1 RA because of its favorable glycemic and cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, as part of a cost-savings initiative for fiscal year 2018, liraglutide 6 mg/mL injection 2-count pen packs was selected as the preferred liraglutide product. Before the availability of the 2-count pen packs, veterans previously received 3-count pen packs, which allowed for up to a 30-day supply of liraglutide 1.8 mg daily dosing. However, the cost-efficient 2-count pen packs allow for up to 1.2 mg daily dose of liraglutide for a 30-day supply. Due to these changes, veterans at MEDVAMC were converted from liraglutide 1.8 mg daily to 1.2 mg daily between May 2018 and August 2018.

The primary objective of this study was to assess sustained glycemic control and cost savings that resulted from this change. The secondary objectives were to assess sustained weight loss and adverse effects (AEs).

Methods

This study was approved by the MEDVAMC Quality Assurance and Regulatory Affairs committee. In this single-center study, a retrospective chart review was conducted on veterans with T2DM who underwent a liraglutide dose reduction from 1.8 mg daily to 1.2 mg daily between May 2018 and August 2018. Patients were included if they were aged ≥ 18 years with an active prescription for liraglutide 1.8 mg daily and insulin (with or without other antihyperglycemic agents) at the time of conversion. In addition, patients must have had ≥ 1 HbA1c reading within 3 months of the dose conversion and a follow-up HbA1c within 6 months after the dose conversion. To assess the primary objective of glycemic control that resulted from the liraglutide dose reduction, mean change of HbA1c at time of dose conversion was compared with mean HbA1c 6 months postconversion. To assess savings, cost information was obtained from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Drug Price Database and monthly and annual costs of liraglutide 6 mg/mL injection 2-count pen pack were compared with that of the 3-count pen pack. A chart review of patients’ electronic health records assessed secondary outcomes. The VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) was used to collect patient data.

Patients and Characteristics

The following patient information was obtained from patients’ records: age, sex, race/ethnicity, diabetic medications (at time of conversion and 6 months after conversion), cardiovascular history and risk factors (hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, arrhythmias, peripheral artery disease, obesity, etc), prescriber type (physician, nurse practitioner/physician assistant, pharmacist, etc), weight (at baseline, at time of conversion, and 6 months after conversion), HbA1c (at baseline, at time of conversion, and 6 months after conversion), average blood glucose (at baseline, at time of conversion, and 6 months after conversion), insulin dose (at time of conversion and 6 months after conversion), and reported AEs.

Statistical Analysis

The 2-tailed, paired t test was used to assess changes in HbA1c, average blood glucose, and body weight. Demographic data and other outcomes were assessed using descriptive statistics.

Results

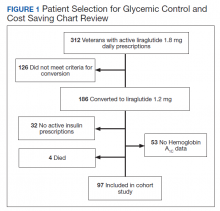

Prior to the dose reduction, 312 veterans had active prescriptions for liraglutide 1.8 mg daily. Due to lack of glycemic control benefit (failing to achieve a HbA1c reduction of at least 0.5% after at least 3 to 6 months following initiation of therapy) or nonadherence (assessed by medication refill history), 126 veterans did not meet the criteria for the dose conversion. As a result, liraglutide was discontinued, and veterans were sent patient letter notifications and health care providers were notified via medication review notes in the patient electronic health record “to make medication adjustments if warranted. A total of 186 veterans underwent a liraglutide dose reduction between May and August 2018. Thirty-two veterans were without active insulin prescriptions, 53 were without HbA1c results, and 4 veterans died; resulting in 97 veterans who were included in the study (Figure 1).

Most of the patients included in the study were male (90.7%) and White (63.9%) with an average (SD) age of 65.9 years (7.9) and a mean (SD) HbA1c at baseline of 8.4% (1.2). About 56.7% received concurrent T2DM treatment with metformin, and 8.3% received concurrent treatment with empagliflozin. The most common cardiovascular disease/risk factors included hypertension (93.8%), hyperlipidemia (85.6%), and obesity (85.6%) (Table 1).

Glycemic Control and Weight Loss

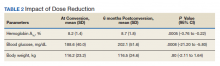

At the time of conversion, the average (SD) HbA1c was 8.2% (1.4) and increased to an average (SD) of 8.7% (1.8) (P =.0005) 6 months after the dose reduction (Table 2). The average (SD) body weight was 116.2 kg (23.2) at time of conversion and increased to 116.5 (24.6) 6 months following the dose reduction; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P = .8).

As a result of the HbA1c change, 41.2% of veterans underwent an insulin dose increase with dose increase of 5 to 200 units of total daily insulin during the 6-month period. Antihyperglycemic regimen remained unchanged for 40.2% of veterans, while additional glucose lowering agents were initiated in 6 veterans. Medications initiated included empagliflozin in 4 veterans and saxagliptin in 2 veterans.

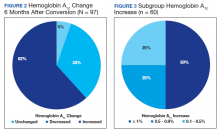

HbA1c reduction was noted in 33% of veterans (Figure 2) mostly due to improved diet and exercise habits. A majority of veterans, 62%, experienced an increase in HbA1c, whereas 5.2% of veterans maintained the same HbA1c. Of 60 veterans with HbA1c increases, 15 had an increase between 0.1% and 0.5%, another 15 with an increase between 0.5 to 0.9%, and half had HbA1c increases of at least 1% with a maximum increase of 5.1% (Figure 3).

Cost Savings

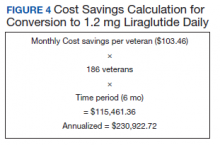

Cost information was obtained from the VA Drug Price Database. The estimated monthly cost savings per patient associated with the conversion from 3-count to 2-count injection pen packs of liraglutide 6 mg/mL was $103.46. With 186 veterans converted to the 2-count pen packs, MEDVAMC saved $115,461.36 in a 6-month period. The estimated annualized cost savings was estimated to be about $231,000 (Figure 4).

Adverse Effects During the 6-month period following the dose conversion, no major AEs associated with liraglutide were documented. Documented AEs included 3 cases of diarrhea, resulting in the discontinuation of metformin. Metformin also was discontinued in a veteran with worsened renal function and eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Discussion

According to previous clinical trials, when used in combination with insulin, 1.2 mg and 1.8 mg daily liraglutide showed significant improvement in glycemic control and body weight and was associated with decreased insulin requirements.4-6 However, subgroup analyses were not performed to show differences in benefit between the liraglutide 1.8 mg and 1.2 mg groups.4-6 Similarly, cardiovascular benefit was observed in patients receiving liraglutide 1.2 mg daily and liraglutide 1.8 mg daily in the LEADER trial with no subgroup analysis or distinction between treatment doses.3 With this information and approval by the Veterans Integrated Services Network, the pharmacoeconomics team at MEDVAMC made the decision to select a more cost-efficient preparation and, hence, lower dose of liraglutide.

To ensure that patients only taking liraglutide for glycemic control were captured, patients without insulin therapies at baseline were excluded. Due to concerns of potential off-label use of liraglutide for weight loss, patients without active prescriptions for insulin at baseline were excluded.

A mean HbA1c increase of 0.5% was observed over the 6-month period, supporting findings of a dose-dependent HbA1c decrease observed in clinical trials. In the LEAD-3 MONO trial when used as monotherapy, liraglutide 1.8 mg was associated with significantly greater HbA1c reduction than liraglutide 1.2 mg (–0·29%; –0·50 to –0.09, P = .005) after 52 weeks of treatment.7 Liraglutide 1.8 mg was also associated with higher rates of AEs; particularly gastrointestinal. 7 To minimize these AEs, it is recommended to initiate liraglutide at 0.6 mg daily for a week then increase to 1.2 mg daily. If tolerated, liraglutide can be further titrated to 1.8 mg daily to optimize glycemic control.8 Unsurprisingly, no major AEs were noted in this study, as AEs are typically noted with increased doses.

Despite the observed trend of increased HbA1c, no changes were made to glucoselowering agents in 39 veterans. This group of veterans consisted primarily of those whose HbA1c remained unchanged during the 6-month period, those whose HbA1c improved (with no documented hypoglycemia), and older veterans with less stringent HbA1c goals. As a result, doses of glucose lowering agents were maintained as appropriate.

No significant difference was noted in body weight during the 6-month period. The slight weight gain observed may have been due to several factors. Lack of exercise and dietary changes may have contributed to weight gain. In addition, insulin doses were increased in 40 veterans, which may have contributed to the observed weight gain.

As expected, significant cost savings were achieved as a result of the liraglutide dose reduction. Of note, liraglutide was discontinued in 126 veterans (prior to the dose reduction) due to nonadherence or inadequate response to therapy, which also resulted in additional savings. Although cost savings was achieved, the long-term benefit of this initiative still remains unknown. The worsened glycemic control that was detected may increase the risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications, thereby negating cost savings achieved. To assess this effect, longterm prospective studies are warranted.

Limitations

A number of issues limit these finding, including its retrospective data review, small sample size, additional factors contributing to HbA1c increase, and missing documentation in some patient records. Only 97 patients were included in the study, reflecting less than half of the charts reviewed (52% exclusion rate). In addition, several confounding factors may have contributed to the increased HbA1c observed. Medication changes and lifestyle factors may have contributed to the observed change in HbA1c levels. Exclusion of patients without active prescriptions for insulin may have contributed to a selection bias, as most patients included in the study were veterans with uncontrolled T2DM requiring insulin. Finally, as a retrospective study involving patient records, investigators relied heavily on information provided in patients’ charts (HbA1c, body weight, insulin doses, adverse effects, etc), which may not entirely be accurate and may have been missing other pertinent information.

Conclusions

The daily dose reduction of liraglutide from 1.8 mg to 1.2 mg due to a cost-savings initiative resulted in a HbA1c increase of 0.5% in a 6-month period. Due to HbA1c increases, 41.2% of veterans underwent an insulin dose increase, negating the insulin-sparing role of liraglutide. Although this study further confirms the dose-dependent HbA1c reduction with liraglutide that has been noted in previous trials, long-term prospective studies and cost-effectiveness analyses are warranted to assess the overall clinical significance and other benefits of the change, including its effects on cardiovascular outcomes.

1. American Diabetes Association. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(suppl 1):S90-S102. doi:10.2337/dc19-S009

2. Hinnen D. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2017;30(3):202-210. doi:10.2337/ds16-0026

3. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311-322. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1603827

4. Lane W, Weinrib S, Rappaport J, Hale C. The effect of addition of liraglutide to high-dose intensive insulin therapy: a randomized prospective trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(9):827-832. doi:10.1111/dom.12286

5. Ahmann A, Rodbard HW, Rosenstock J, et al. Efficacy and safety of liraglutide versus placebo added to basal insulin analogues (with or without metformin) in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(11):1056-1064. doi:10.1111/dom.12539

6. Lane W, Weinrib S, Rappaport J. The effect of liraglutide added to U-500 insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes and high insulin requirements. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2011;13(5):592-595. doi:10.1089/dia.2010.0221

7. Garber A, Henry R, Ratner R, et al. Liraglutide versus glimepiride monotherapy for type 2 diabetes (LEAD-3 Mono): a randomised, 52-week, phase III, double-blind, parallel-treatment trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):473-481. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61246-5.

8. Victoza [package insert]. Princeton: Novo Nordisk Inc; 2020.

Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) are injectable incretin hormones approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). They are highly efficacious agents with hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) reduction potential of approximately 0.8 to 1.6% and mechanisms of action that result in an average weight loss of 1 to 3 kg.1,2 Published in 2016, The LEADER (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results) trial established cardiovascular benefits associated with liraglutide, making it a preferred GLP-1 RA.3

In addition to HbA1c reduction, weight loss, and cardiovascular benefits, liraglutide also has shown insulin-sparing effects when used in combination with insulin. A trial by Lane and colleagues revealed a 34% decrease in total daily insulin dose 6 months after the addition of liraglutide to insulin in patients with T2DM receiving > 100 units of insulin daily.4 When used in combination with basal insulin analogues (glargine or detemir) similar findings also were shown.5

The Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, selected liraglutide as its preferred GLP-1 RA because of its favorable glycemic and cardiovascular outcomes. In addition, as part of a cost-savings initiative for fiscal year 2018, liraglutide 6 mg/mL injection 2-count pen packs was selected as the preferred liraglutide product. Before the availability of the 2-count pen packs, veterans previously received 3-count pen packs, which allowed for up to a 30-day supply of liraglutide 1.8 mg daily dosing. However, the cost-efficient 2-count pen packs allow for up to 1.2 mg daily dose of liraglutide for a 30-day supply. Due to these changes, veterans at MEDVAMC were converted from liraglutide 1.8 mg daily to 1.2 mg daily between May 2018 and August 2018.

The primary objective of this study was to assess sustained glycemic control and cost savings that resulted from this change. The secondary objectives were to assess sustained weight loss and adverse effects (AEs).

Methods

This study was approved by the MEDVAMC Quality Assurance and Regulatory Affairs committee. In this single-center study, a retrospective chart review was conducted on veterans with T2DM who underwent a liraglutide dose reduction from 1.8 mg daily to 1.2 mg daily between May 2018 and August 2018. Patients were included if they were aged ≥ 18 years with an active prescription for liraglutide 1.8 mg daily and insulin (with or without other antihyperglycemic agents) at the time of conversion. In addition, patients must have had ≥ 1 HbA1c reading within 3 months of the dose conversion and a follow-up HbA1c within 6 months after the dose conversion. To assess the primary objective of glycemic control that resulted from the liraglutide dose reduction, mean change of HbA1c at time of dose conversion was compared with mean HbA1c 6 months postconversion. To assess savings, cost information was obtained from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Drug Price Database and monthly and annual costs of liraglutide 6 mg/mL injection 2-count pen pack were compared with that of the 3-count pen pack. A chart review of patients’ electronic health records assessed secondary outcomes. The VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) was used to collect patient data.

Patients and Characteristics

The following patient information was obtained from patients’ records: age, sex, race/ethnicity, diabetic medications (at time of conversion and 6 months after conversion), cardiovascular history and risk factors (hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, arrhythmias, peripheral artery disease, obesity, etc), prescriber type (physician, nurse practitioner/physician assistant, pharmacist, etc), weight (at baseline, at time of conversion, and 6 months after conversion), HbA1c (at baseline, at time of conversion, and 6 months after conversion), average blood glucose (at baseline, at time of conversion, and 6 months after conversion), insulin dose (at time of conversion and 6 months after conversion), and reported AEs.

Statistical Analysis

The 2-tailed, paired t test was used to assess changes in HbA1c, average blood glucose, and body weight. Demographic data and other outcomes were assessed using descriptive statistics.

Results

Prior to the dose reduction, 312 veterans had active prescriptions for liraglutide 1.8 mg daily. Due to lack of glycemic control benefit (failing to achieve a HbA1c reduction of at least 0.5% after at least 3 to 6 months following initiation of therapy) or nonadherence (assessed by medication refill history), 126 veterans did not meet the criteria for the dose conversion. As a result, liraglutide was discontinued, and veterans were sent patient letter notifications and health care providers were notified via medication review notes in the patient electronic health record “to make medication adjustments if warranted. A total of 186 veterans underwent a liraglutide dose reduction between May and August 2018. Thirty-two veterans were without active insulin prescriptions, 53 were without HbA1c results, and 4 veterans died; resulting in 97 veterans who were included in the study (Figure 1).

Most of the patients included in the study were male (90.7%) and White (63.9%) with an average (SD) age of 65.9 years (7.9) and a mean (SD) HbA1c at baseline of 8.4% (1.2). About 56.7% received concurrent T2DM treatment with metformin, and 8.3% received concurrent treatment with empagliflozin. The most common cardiovascular disease/risk factors included hypertension (93.8%), hyperlipidemia (85.6%), and obesity (85.6%) (Table 1).

Glycemic Control and Weight Loss

At the time of conversion, the average (SD) HbA1c was 8.2% (1.4) and increased to an average (SD) of 8.7% (1.8) (P =.0005) 6 months after the dose reduction (Table 2). The average (SD) body weight was 116.2 kg (23.2) at time of conversion and increased to 116.5 (24.6) 6 months following the dose reduction; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P = .8).

As a result of the HbA1c change, 41.2% of veterans underwent an insulin dose increase with dose increase of 5 to 200 units of total daily insulin during the 6-month period. Antihyperglycemic regimen remained unchanged for 40.2% of veterans, while additional glucose lowering agents were initiated in 6 veterans. Medications initiated included empagliflozin in 4 veterans and saxagliptin in 2 veterans.

HbA1c reduction was noted in 33% of veterans (Figure 2) mostly due to improved diet and exercise habits. A majority of veterans, 62%, experienced an increase in HbA1c, whereas 5.2% of veterans maintained the same HbA1c. Of 60 veterans with HbA1c increases, 15 had an increase between 0.1% and 0.5%, another 15 with an increase between 0.5 to 0.9%, and half had HbA1c increases of at least 1% with a maximum increase of 5.1% (Figure 3).

Cost Savings

Cost information was obtained from the VA Drug Price Database. The estimated monthly cost savings per patient associated with the conversion from 3-count to 2-count injection pen packs of liraglutide 6 mg/mL was $103.46. With 186 veterans converted to the 2-count pen packs, MEDVAMC saved $115,461.36 in a 6-month period. The estimated annualized cost savings was estimated to be about $231,000 (Figure 4).

Adverse Effects During the 6-month period following the dose conversion, no major AEs associated with liraglutide were documented. Documented AEs included 3 cases of diarrhea, resulting in the discontinuation of metformin. Metformin also was discontinued in a veteran with worsened renal function and eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Discussion

According to previous clinical trials, when used in combination with insulin, 1.2 mg and 1.8 mg daily liraglutide showed significant improvement in glycemic control and body weight and was associated with decreased insulin requirements.4-6 However, subgroup analyses were not performed to show differences in benefit between the liraglutide 1.8 mg and 1.2 mg groups.4-6 Similarly, cardiovascular benefit was observed in patients receiving liraglutide 1.2 mg daily and liraglutide 1.8 mg daily in the LEADER trial with no subgroup analysis or distinction between treatment doses.3 With this information and approval by the Veterans Integrated Services Network, the pharmacoeconomics team at MEDVAMC made the decision to select a more cost-efficient preparation and, hence, lower dose of liraglutide.

To ensure that patients only taking liraglutide for glycemic control were captured, patients without insulin therapies at baseline were excluded. Due to concerns of potential off-label use of liraglutide for weight loss, patients without active prescriptions for insulin at baseline were excluded.

A mean HbA1c increase of 0.5% was observed over the 6-month period, supporting findings of a dose-dependent HbA1c decrease observed in clinical trials. In the LEAD-3 MONO trial when used as monotherapy, liraglutide 1.8 mg was associated with significantly greater HbA1c reduction than liraglutide 1.2 mg (–0·29%; –0·50 to –0.09, P = .005) after 52 weeks of treatment.7 Liraglutide 1.8 mg was also associated with higher rates of AEs; particularly gastrointestinal. 7 To minimize these AEs, it is recommended to initiate liraglutide at 0.6 mg daily for a week then increase to 1.2 mg daily. If tolerated, liraglutide can be further titrated to 1.8 mg daily to optimize glycemic control.8 Unsurprisingly, no major AEs were noted in this study, as AEs are typically noted with increased doses.

Despite the observed trend of increased HbA1c, no changes were made to glucoselowering agents in 39 veterans. This group of veterans consisted primarily of those whose HbA1c remained unchanged during the 6-month period, those whose HbA1c improved (with no documented hypoglycemia), and older veterans with less stringent HbA1c goals. As a result, doses of glucose lowering agents were maintained as appropriate.

No significant difference was noted in body weight during the 6-month period. The slight weight gain observed may have been due to several factors. Lack of exercise and dietary changes may have contributed to weight gain. In addition, insulin doses were increased in 40 veterans, which may have contributed to the observed weight gain.

As expected, significant cost savings were achieved as a result of the liraglutide dose reduction. Of note, liraglutide was discontinued in 126 veterans (prior to the dose reduction) due to nonadherence or inadequate response to therapy, which also resulted in additional savings. Although cost savings was achieved, the long-term benefit of this initiative still remains unknown. The worsened glycemic control that was detected may increase the risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications, thereby negating cost savings achieved. To assess this effect, longterm prospective studies are warranted.

Limitations

A number of issues limit these finding, including its retrospective data review, small sample size, additional factors contributing to HbA1c increase, and missing documentation in some patient records. Only 97 patients were included in the study, reflecting less than half of the charts reviewed (52% exclusion rate). In addition, several confounding factors may have contributed to the increased HbA1c observed. Medication changes and lifestyle factors may have contributed to the observed change in HbA1c levels. Exclusion of patients without active prescriptions for insulin may have contributed to a selection bias, as most patients included in the study were veterans with uncontrolled T2DM requiring insulin. Finally, as a retrospective study involving patient records, investigators relied heavily on information provided in patients’ charts (HbA1c, body weight, insulin doses, adverse effects, etc), which may not entirely be accurate and may have been missing other pertinent information.

Conclusions