User login

Retrospective Review on the Safety and Efficacy of Direct Oral Anticoagulants Compared With Warfarin in Patients With Cirrhosis

Coagulation in patients with cirrhosis is a complicated area of evolving research. Patients with cirrhosis were originally thought to be naturally anticoagulated due to the decreased production of clotting factors and platelets, combined with an increased international normalized ratio (INR).1 New data have shown that patients with cirrhosis are at a concomitant risk of bleeding and thrombosis due to increased platelet aggregation, decreased fibrinolysis, and decreased production of natural anticoagulants such as protein C and antithrombin.1 Traditionally, patients with cirrhosis needing anticoagulation therapy for comorbid conditions, such as nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) or venous thromboembolism (VTE) were placed on warfarin therapy. Managing warfarin in patients with cirrhosis poses a challenge to clinicians due to the many food and drug interactions, narrow therapeutic index, and complications with maintaining a therapeutic INR.1

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have several benefits over warfarin therapy, including convenience, decreased monitoring, decreased drug and dietary restrictions, and faster onset of action.2 Conversely, DOACs undergo extensive hepatic metabolism giving rise to concerns about supratherapeutic drug levels and increased bleeding rates in patients with liver dysfunction.1 Consequently, patients with cirrhosis were excluded from the pivotal trials establishing DOACs for NVAF and VTE treatment. Exclusion of these patients in major clinical trials alongside the challenges of managing warfarin warrant an evaluation of the efficacy and safety of DOACs in patients with cirrhosis.

Recent retrospective studies have examined the use of DOACs in patients with cirrhosis and found favorable results. A retrospective chart review by Intagliata and colleagues consisting of 39 patients with cirrhosis using either a DOAC or warfarin found similar rates of all-cause bleeding and major bleeding between the 2 groups.3 A retrospective cohort study by Hum and colleagues consisting of 45 patients with cirrhosis compared the use of DOACs with warfarin or low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH).4 Hum and colleagues found patients prescribed a DOAC had significantly fewer major bleeding events than did patients using warfarin or LMWH.4 The largest retrospective cohort study consisted of 233 patients with chronic liver disease and found no differences among all-cause bleeding and major bleeding rates between patients using DOACs compared with those of patients using warfarin.5

The purpose of this research is to evaluate the safety and efficacy of DOACs in veteran patients with cirrhosis compared with patients using warfarin.

Methods

A retrospective single-center chart review was conducted at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, between October 31, 2014 and October 31, 2018. Patients included in the study were adults aged ≥ 18 years with a diagnosis of cirrhosis and prescribed any of the following oral anticoagulants: apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, rivaroxaban, or warfarin. Patients prescribed apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban were collectively grouped into the DOAC group, while patients prescribed warfarin were classified as the standard of care comparator group.

A diagnosis of cirrhosis was confirmed using a combination of the codes from the ninth and tenth editions of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) for cirrhosis, documentation of diagnostic confirmation by clinicians from the gastroenterology or hepatology services, and positive liver biopsy result. Liver function tests, liver ultrasound results, and FibroSure biomarker assays were used to aid in confirming the diagnosis of cirrhosis but were not considered definitive. Patients were excluded from the trial if they had indications for anticoagulation other than NVAF and VTE and/or were prescribed triple antithrombotic therapy (dual antiplatelet therapy plus an anticoagulant). Patients who switched anticoagulant therapy during the trial period (ie, switched from warfarin to a DOAC) were also excluded from the analysis.

Patient demographic characteristics that were collected included weight; body mass index (BMI); etiology of cirrhosis; Child-Turcotte-Pugh, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), and CHA2DS2-VASc score; concomitant antiplatelet, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), proton pump inhibitor (PPI), and histamine-2 receptor antagonist

Two patient lists were used to identify patients for inclusion in the warfarin arm. The first patient list was generated using the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Cirrhosis Tracker, which identified patients with an ICD-9/10 code for cirrhosis and an INR laboratory value. Patients generated from the VA Cirrhosis Tracker with an INR > 1.5 were screened for a warfarin prescription and then evaluated for full study inclusion. The second patient list was generated using the VA Advanced Liver Disease Dashboard which identified patients with ICD-9/10 codes for advanced liver disease and an active warfarin prescription. Patients with an active warfarin prescription were then evaluated for full study inclusion. A single patient list was generated to identify patients for inclusion in the DOAC arm. This patient list was generated using the VA DOAC dashboard, which identified patients with an active DOAC prescription and an ICD-9/10 code for cirrhosis. Patients with an ICD-9/10 code for cirrhosis and prescribed a DOAC were screened for full study inclusion. Patient data were collected from the MEDVAMC Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) electronic health record (EHR). The research study was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board and the VA Office of Research and Development.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint for the study was all-cause bleeding. The secondary endpoints for the study were major bleeding and failed efficacy. Major bleeding was defined using the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) 2005 definition: fatal bleeding, symptomatic bleeding in a critical organ area (ie, intracranial, intraspinal, intraocular, retroperitoneal, intraarticular, pericardial, or intramuscular with compartment syndrome), or bleeding causing a fall in hemoglobin level of > 2 g/dL or leading to the transfusion of ≥ 2 units of red cells.6 Failed efficacy was a combination endpoint that included development of VTE, stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), and/or death. A prespecified subgroup analysis was conducted at the end of the study period to analyze trends in the DOAC and warfarin groups with respect to all-cause bleeding. All-cause bleeding risk was stratified by weight, BMI, Child-Turcotte-Pugh score, MELD score, presence of gastric and/or esophageal varices, active malignancies, percentage of time within therapeutic INR range in the warfarin group, indications for anticoagulation, and antiplatelet, NSAID, PPI, and H2RA therapy.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Continuous data were analyzed using the Student t test, and categorical data were analyzed using the Fisher exact test. Previous studies determined an all-cause bleeding rate of 10 to 17% for warfarin compared with 5% for DOACs.7,8 To detect a 12% difference in the all-cause bleeding rate between DOACs and warfarin, 212 patients would be needed to achieve 80% power at an α level of 0.05.

Results

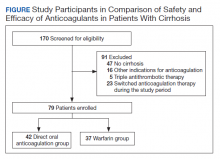

A total of 170 patients were screened, and after applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 79 patients were enrolled in the study (Figure). The DOAC group included 42 patients, and the warfarin group included 37 patients. In the DOAC group, 69.1% (n = 29) of patients were taking apixaban, 21.4% (n = 9) rivaroxaban, and 9.5% (n = 4) dabigatran. There were no patients prescribed edoxaban during the study period.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the 2 groups except for Child-Turcotte-Pugh score, MELD score, mean INR, and number of days on anticoagulation therapy (Table 1). Most of the patients were male (98.7%), and the mean age was 71 years. The most common causes of cirrhosis were viral (29.1%), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (24.1%), multiple causes (22.8%), and alcohol (21.5%). Sixty-two patients (78.5%) had a NVAF indication for anticoagulation. The average CHA2DS2-VASc score was 3.7. Aspirin was prescribed in 51.9% (n = 41) of patients, and PPIs were prescribed in 48.1% (n = 38) of patients. At inclusion, esophageal varices were present in 13 patients and active malignancies were present in 6 patients.

Statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics were found between mean INR, Child-Turcotte-Pugh scores, MELD scores, and number of days on anticoagulant therapy. The mean INR was 1.3 in the DOAC group compared with 2.1 in the warfarin group (P = .0001). Eighty-one percent (n = 34) of patients in the DOAC group had a Child-Turcotte-Pugh score of A compared with 43.2% (n = 16) of patients in the warfarin group (P = .0009). Eight patients in the DOAC group had a Child-Turcotte-Pugh score of B compared with 19 patients in the warfarin group (P = .004). The mean MELD score was 9.4 in the DOAC group compared with 16.3 in the warfarin group (P = .0001). The mean days on anticoagulant therapy was 500.4 days for the DOAC group compared with 1,652.4 days for the warfarin group (P = .0001).

Safety Outcome

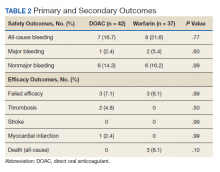

The primary outcome comparing all-cause bleeding rates between patients on DOACs compared with warfarin are listed in Table 2. With respect to the primary outcome, 7 (16.7%) patients on DOACs experienced a bleeding event compared with 8 (21.6%) patients on warfarin (P = .77). No statistically significant differences were detected between the DOAC and warfarin groups with respect to all-cause bleeding. Seven bleeding events occurred in the DOAC group; 1 met the qualification for major bleeding with a suspected gastrointestinal (GI) bleed.6 The other 6 bleeding episodes in the DOAC group consisted of hematoma, epistaxis, hematuria, and hematochezia. Eight bleeding events occurred in the warfarin group; 2 met the qualification for major bleeding with an intracranial hemorrhage and upper GI bleed.6 The other 6 bleeding episodes in the warfarin group consisted of epistaxis, bleeding gums, hematuria, and hematochezia. There were no statistically significant differences between the rates of major bleeding and nonmajor bleeding between the DOAC and warfarin groups.

Efficacy Outcomes

There were 3 events in the DOAC group and 3 events in the warfarin group (P = .99). In the DOAC group, 2 patients experienced a pulmonary embolism, and 1 patient experienced a MI. In the warfarin group, 3 patients died (end-stage heart failure, unknown cause due to death at an outside hospital, and sepsis/organ failure). There were no statistically significant differences between the composite endpoint of failed efficacy or the individual endpoints of VTE, stroke, MI, and death.

Subgroup Analysis

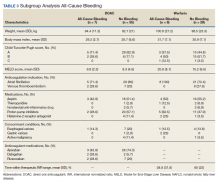

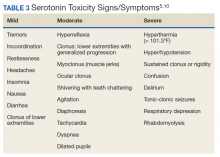

A prespecified subgroup analysis was conducted to determine risk factors for all-cause bleeding within each treatment group (Table 3). No significant trends were observed in the following risk factors: Child-Turcotte-Pugh score, indication for anticoagulation, use of NSAIDs, PPIs or H2RAs, presence of gastric or esophageal varices, active malignancies, and time within therapeutic INR range in the warfarin group. Patients with bleeding events had slightly increased weight and BMI vs patients without bleeding events. Within the warfarin group, patients with bleeding events had slightly elevated MELD scores compared to patients without bleeding events. There was an equal balance of patients prescribed aspirin therapy between the groups with and without bleeding events. Overall, no significant risk factors were identified for all-cause bleeding.

Discussion

Initially, patients with cirrhosis were excluded from DOAC trials due to concerns for increased bleeding risk with hepatically eliminated medications. New retrospective research has concluded that in patients with cirrhosis, DOACs have similar or lower bleeding rates when compared directly to warfarin.9,10

In this study, no statistically significant differences were detected between the primary and secondary outcomes of all-cause bleeding, major bleeding, or failed efficacy. Subgroup analysis did not identify any significant risk factors with respect to all-cause bleeding among patients in the DOAC and warfarin groups. To meet 80% power, 212 patients needed to be enrolled in the study; however, only 79 patients were enrolled, and power was not met. The results of this study should be interpreted cautiously as hypothesis-generating due to the small sample size. Strengths of this study include similar baseline characteristics between the DOAC and warfarin groups, 4-year length of retrospective data review, and availability of both inpatient and outpatient EHR limiting the amount of missing data points.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the groups except for mean INR, Child-Turcotte-Pugh score, MELD score, and number of days on anticoagulation therapy. The difference in mean INR between groups is expected as patients in the warfarin group have a goal INR of 2 to 3 to maintain therapeutic efficacy and safety. INR is not used as a marker of efficacy or safety with DOACs; therefore, a consistent elevation in INR is not expected. Child- Turcotte-Pugh scores are calculated using INR levels.11 When calculating the score, patients with an INR < 1.7 receive 1 point; patients with an INR between 1.7 and 2.3 receive 2 points.11 Therefore, patients in the warfarin group will have artificially inflated Child-Turcotte-Pugh scores as this group has goal INR levels of 2 to 3. This makes Child-Turcotte-Pugh scores unreliable markers of disease severity in patients using warfarin therapy. When the INR scores for patients prescribed warfarin were replaced with values < 1.7, the statistical difference disappeared between the warfarin and DOAC groups. The same effect is seen on MELD scores for patients prescribed warfarin therapy. The MELD score is calculated using INR levels.12 MELD scores also will be artificially elevated in patients prescribed warfarin therapy due to the INR elevation to between 2 and 3. When MELD scores for patients prescribed warfarin were replaced with values similar to those in the DOAC group, the statistical difference disappeared between the warfarin and DOAC groups.

The last statistically significant difference was found in number of days on anticoagulant therapy. This difference was expected as warfarin is the standard of care for anticoagulation treatment in patients with cirrhosis. The first DOAC, dabigatran, was not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration until 2010.13 DOACs have only recently been used in patients with cirrhosis accounting for the statistically significant difference in days on anticoagulation therapy between the warfarin and DOAC groups.

Limitations

The inability to meet power or evaluate adherence and appropriate renal dose adjustments for DOACs limited this study. This study was conducted at a single center in a predominantly male veteran population and therefore may not be generalizable to other populations. A majority of patients in the DOAC group were prescribed apixaban (69.1%), which may have affected the overall rate of major bleeding in the DOAC group. Pivotal trials of apixaban have shown a consistent decreased risk of major bleeding in patients with NVAF or VTE when compared with warfarin.14,15 Therefore, the results of this study may not be generalizable to all DOACs.

An inherent limitation of this study was the inability to collect data verifying adherence in the DOAC group. However, in the warfarin group, percentage of time within the therapeutic INR range of 2 to 3 was collected. While not a direct marker of adherence, this does allow for limited evaluation of therapeutic efficacy and safety within the warfarin group. Last, proper dosing of DOACs in patients with and without adequate renal function was not evaluated in this study.

Conclusions

The results of this study are consistent with other retrospective research and literature reviews. There were no statistically significant differences identified between the rates of all-cause bleeding, major bleeding, and failed efficacy between the DOAC and warfarin groups. DOACs may be a safe alternative to warfarin in patients with cirrhosis requiring anticoagulation for NVAF or VTE, but large randomized trials are required to confirm these results.

1. Qamar A, Vaduganathan M, Greenberger NJ, Giugliano RP. Oral anticoagulation in patients with liver disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2162-2175. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.03.023

2. Priyanka P, Kupec JT, Krafft M, Shah NA, Reynolds GJ. Newer oral anticoagulants in the treatment of acute portal vein thrombosis in patients with and without cirrhosis. Int J Hepatol. 2018;2018:8432781. Published 2018 Jun 5. doi:10.1155/2018/8432781

3. Intagliata NM, Henry ZH, Maitland H, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants in cirrhosis patients pose similar risks of bleeding when compared to traditional anticoagulation. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(6):1721-1727. doi:10.1007/s10620-015-4012-2

4. Hum J, Shatzel JJ, Jou JH, Deloughery TG. The efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants vs traditional anticoagulants in cirrhosis. Eur J Haematol. 2017;98(4):393-397. doi:10.1111/ejh.12844

5. Goriacko P, Veltri KT. Safety of direct oral anticoagulants vs warfarin in patients with chronic liver disease and atrial fibrillation. Eur J Haematol. 2018;100(5):488-493. doi:10.1111/ejh.13045

6. Schulman S, Kearon C; Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(4):692-694. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01204.x

7. Rubboli A, Becattini C, Verheugt FW. Incidence, clinical impact and risk of bleeding during oral anticoagulation therapy. World J Cardiol. 2011;3(11):351-358. doi:10.4330/wjc.v3.i11.351

8. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-962. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0

9. Hoolwerf EW, Kraaijpoel N, Büller HR, van Es N. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with liver cirrhosis: A systematic review. Thromb Res. 2018;170:102-108. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2018.08.011

10. Steuber TD, Howard ML, Nisly SA. Direct oral anticoagulants in chronic liver disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(10):1042-1049. doi:10.1177/1060028019841582

11. Janevska D, Chaloska-Ivanova V, Janevski V. Hepatocellular carcinoma: risk factors, diagnosis and treatment. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2015;3(4):732-736. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2015.111

12. Singal AK, Kamath PS. Model for End-Stage Liver Disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2013;3(1):50-60. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2012.11.002

13. Joppa SA, Salciccioli J, Adamski J, et al. A practical review of the emerging direct anticoagulants, laboratory monitoring, and reversal agents. J Clin Med. 2018;7(2):29. Published 2018 Feb 11. doi:10.3390/jcm7020029

14. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):981-992. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1107039

15. Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(9):799-808. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1302507

Coagulation in patients with cirrhosis is a complicated area of evolving research. Patients with cirrhosis were originally thought to be naturally anticoagulated due to the decreased production of clotting factors and platelets, combined with an increased international normalized ratio (INR).1 New data have shown that patients with cirrhosis are at a concomitant risk of bleeding and thrombosis due to increased platelet aggregation, decreased fibrinolysis, and decreased production of natural anticoagulants such as protein C and antithrombin.1 Traditionally, patients with cirrhosis needing anticoagulation therapy for comorbid conditions, such as nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) or venous thromboembolism (VTE) were placed on warfarin therapy. Managing warfarin in patients with cirrhosis poses a challenge to clinicians due to the many food and drug interactions, narrow therapeutic index, and complications with maintaining a therapeutic INR.1

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have several benefits over warfarin therapy, including convenience, decreased monitoring, decreased drug and dietary restrictions, and faster onset of action.2 Conversely, DOACs undergo extensive hepatic metabolism giving rise to concerns about supratherapeutic drug levels and increased bleeding rates in patients with liver dysfunction.1 Consequently, patients with cirrhosis were excluded from the pivotal trials establishing DOACs for NVAF and VTE treatment. Exclusion of these patients in major clinical trials alongside the challenges of managing warfarin warrant an evaluation of the efficacy and safety of DOACs in patients with cirrhosis.

Recent retrospective studies have examined the use of DOACs in patients with cirrhosis and found favorable results. A retrospective chart review by Intagliata and colleagues consisting of 39 patients with cirrhosis using either a DOAC or warfarin found similar rates of all-cause bleeding and major bleeding between the 2 groups.3 A retrospective cohort study by Hum and colleagues consisting of 45 patients with cirrhosis compared the use of DOACs with warfarin or low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH).4 Hum and colleagues found patients prescribed a DOAC had significantly fewer major bleeding events than did patients using warfarin or LMWH.4 The largest retrospective cohort study consisted of 233 patients with chronic liver disease and found no differences among all-cause bleeding and major bleeding rates between patients using DOACs compared with those of patients using warfarin.5

The purpose of this research is to evaluate the safety and efficacy of DOACs in veteran patients with cirrhosis compared with patients using warfarin.

Methods

A retrospective single-center chart review was conducted at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, between October 31, 2014 and October 31, 2018. Patients included in the study were adults aged ≥ 18 years with a diagnosis of cirrhosis and prescribed any of the following oral anticoagulants: apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, rivaroxaban, or warfarin. Patients prescribed apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban were collectively grouped into the DOAC group, while patients prescribed warfarin were classified as the standard of care comparator group.

A diagnosis of cirrhosis was confirmed using a combination of the codes from the ninth and tenth editions of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) for cirrhosis, documentation of diagnostic confirmation by clinicians from the gastroenterology or hepatology services, and positive liver biopsy result. Liver function tests, liver ultrasound results, and FibroSure biomarker assays were used to aid in confirming the diagnosis of cirrhosis but were not considered definitive. Patients were excluded from the trial if they had indications for anticoagulation other than NVAF and VTE and/or were prescribed triple antithrombotic therapy (dual antiplatelet therapy plus an anticoagulant). Patients who switched anticoagulant therapy during the trial period (ie, switched from warfarin to a DOAC) were also excluded from the analysis.

Patient demographic characteristics that were collected included weight; body mass index (BMI); etiology of cirrhosis; Child-Turcotte-Pugh, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), and CHA2DS2-VASc score; concomitant antiplatelet, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), proton pump inhibitor (PPI), and histamine-2 receptor antagonist

Two patient lists were used to identify patients for inclusion in the warfarin arm. The first patient list was generated using the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Cirrhosis Tracker, which identified patients with an ICD-9/10 code for cirrhosis and an INR laboratory value. Patients generated from the VA Cirrhosis Tracker with an INR > 1.5 were screened for a warfarin prescription and then evaluated for full study inclusion. The second patient list was generated using the VA Advanced Liver Disease Dashboard which identified patients with ICD-9/10 codes for advanced liver disease and an active warfarin prescription. Patients with an active warfarin prescription were then evaluated for full study inclusion. A single patient list was generated to identify patients for inclusion in the DOAC arm. This patient list was generated using the VA DOAC dashboard, which identified patients with an active DOAC prescription and an ICD-9/10 code for cirrhosis. Patients with an ICD-9/10 code for cirrhosis and prescribed a DOAC were screened for full study inclusion. Patient data were collected from the MEDVAMC Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) electronic health record (EHR). The research study was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board and the VA Office of Research and Development.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint for the study was all-cause bleeding. The secondary endpoints for the study were major bleeding and failed efficacy. Major bleeding was defined using the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) 2005 definition: fatal bleeding, symptomatic bleeding in a critical organ area (ie, intracranial, intraspinal, intraocular, retroperitoneal, intraarticular, pericardial, or intramuscular with compartment syndrome), or bleeding causing a fall in hemoglobin level of > 2 g/dL or leading to the transfusion of ≥ 2 units of red cells.6 Failed efficacy was a combination endpoint that included development of VTE, stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), and/or death. A prespecified subgroup analysis was conducted at the end of the study period to analyze trends in the DOAC and warfarin groups with respect to all-cause bleeding. All-cause bleeding risk was stratified by weight, BMI, Child-Turcotte-Pugh score, MELD score, presence of gastric and/or esophageal varices, active malignancies, percentage of time within therapeutic INR range in the warfarin group, indications for anticoagulation, and antiplatelet, NSAID, PPI, and H2RA therapy.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Continuous data were analyzed using the Student t test, and categorical data were analyzed using the Fisher exact test. Previous studies determined an all-cause bleeding rate of 10 to 17% for warfarin compared with 5% for DOACs.7,8 To detect a 12% difference in the all-cause bleeding rate between DOACs and warfarin, 212 patients would be needed to achieve 80% power at an α level of 0.05.

Results

A total of 170 patients were screened, and after applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 79 patients were enrolled in the study (Figure). The DOAC group included 42 patients, and the warfarin group included 37 patients. In the DOAC group, 69.1% (n = 29) of patients were taking apixaban, 21.4% (n = 9) rivaroxaban, and 9.5% (n = 4) dabigatran. There were no patients prescribed edoxaban during the study period.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the 2 groups except for Child-Turcotte-Pugh score, MELD score, mean INR, and number of days on anticoagulation therapy (Table 1). Most of the patients were male (98.7%), and the mean age was 71 years. The most common causes of cirrhosis were viral (29.1%), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (24.1%), multiple causes (22.8%), and alcohol (21.5%). Sixty-two patients (78.5%) had a NVAF indication for anticoagulation. The average CHA2DS2-VASc score was 3.7. Aspirin was prescribed in 51.9% (n = 41) of patients, and PPIs were prescribed in 48.1% (n = 38) of patients. At inclusion, esophageal varices were present in 13 patients and active malignancies were present in 6 patients.

Statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics were found between mean INR, Child-Turcotte-Pugh scores, MELD scores, and number of days on anticoagulant therapy. The mean INR was 1.3 in the DOAC group compared with 2.1 in the warfarin group (P = .0001). Eighty-one percent (n = 34) of patients in the DOAC group had a Child-Turcotte-Pugh score of A compared with 43.2% (n = 16) of patients in the warfarin group (P = .0009). Eight patients in the DOAC group had a Child-Turcotte-Pugh score of B compared with 19 patients in the warfarin group (P = .004). The mean MELD score was 9.4 in the DOAC group compared with 16.3 in the warfarin group (P = .0001). The mean days on anticoagulant therapy was 500.4 days for the DOAC group compared with 1,652.4 days for the warfarin group (P = .0001).

Safety Outcome

The primary outcome comparing all-cause bleeding rates between patients on DOACs compared with warfarin are listed in Table 2. With respect to the primary outcome, 7 (16.7%) patients on DOACs experienced a bleeding event compared with 8 (21.6%) patients on warfarin (P = .77). No statistically significant differences were detected between the DOAC and warfarin groups with respect to all-cause bleeding. Seven bleeding events occurred in the DOAC group; 1 met the qualification for major bleeding with a suspected gastrointestinal (GI) bleed.6 The other 6 bleeding episodes in the DOAC group consisted of hematoma, epistaxis, hematuria, and hematochezia. Eight bleeding events occurred in the warfarin group; 2 met the qualification for major bleeding with an intracranial hemorrhage and upper GI bleed.6 The other 6 bleeding episodes in the warfarin group consisted of epistaxis, bleeding gums, hematuria, and hematochezia. There were no statistically significant differences between the rates of major bleeding and nonmajor bleeding between the DOAC and warfarin groups.

Efficacy Outcomes

There were 3 events in the DOAC group and 3 events in the warfarin group (P = .99). In the DOAC group, 2 patients experienced a pulmonary embolism, and 1 patient experienced a MI. In the warfarin group, 3 patients died (end-stage heart failure, unknown cause due to death at an outside hospital, and sepsis/organ failure). There were no statistically significant differences between the composite endpoint of failed efficacy or the individual endpoints of VTE, stroke, MI, and death.

Subgroup Analysis

A prespecified subgroup analysis was conducted to determine risk factors for all-cause bleeding within each treatment group (Table 3). No significant trends were observed in the following risk factors: Child-Turcotte-Pugh score, indication for anticoagulation, use of NSAIDs, PPIs or H2RAs, presence of gastric or esophageal varices, active malignancies, and time within therapeutic INR range in the warfarin group. Patients with bleeding events had slightly increased weight and BMI vs patients without bleeding events. Within the warfarin group, patients with bleeding events had slightly elevated MELD scores compared to patients without bleeding events. There was an equal balance of patients prescribed aspirin therapy between the groups with and without bleeding events. Overall, no significant risk factors were identified for all-cause bleeding.

Discussion

Initially, patients with cirrhosis were excluded from DOAC trials due to concerns for increased bleeding risk with hepatically eliminated medications. New retrospective research has concluded that in patients with cirrhosis, DOACs have similar or lower bleeding rates when compared directly to warfarin.9,10

In this study, no statistically significant differences were detected between the primary and secondary outcomes of all-cause bleeding, major bleeding, or failed efficacy. Subgroup analysis did not identify any significant risk factors with respect to all-cause bleeding among patients in the DOAC and warfarin groups. To meet 80% power, 212 patients needed to be enrolled in the study; however, only 79 patients were enrolled, and power was not met. The results of this study should be interpreted cautiously as hypothesis-generating due to the small sample size. Strengths of this study include similar baseline characteristics between the DOAC and warfarin groups, 4-year length of retrospective data review, and availability of both inpatient and outpatient EHR limiting the amount of missing data points.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the groups except for mean INR, Child-Turcotte-Pugh score, MELD score, and number of days on anticoagulation therapy. The difference in mean INR between groups is expected as patients in the warfarin group have a goal INR of 2 to 3 to maintain therapeutic efficacy and safety. INR is not used as a marker of efficacy or safety with DOACs; therefore, a consistent elevation in INR is not expected. Child- Turcotte-Pugh scores are calculated using INR levels.11 When calculating the score, patients with an INR < 1.7 receive 1 point; patients with an INR between 1.7 and 2.3 receive 2 points.11 Therefore, patients in the warfarin group will have artificially inflated Child-Turcotte-Pugh scores as this group has goal INR levels of 2 to 3. This makes Child-Turcotte-Pugh scores unreliable markers of disease severity in patients using warfarin therapy. When the INR scores for patients prescribed warfarin were replaced with values < 1.7, the statistical difference disappeared between the warfarin and DOAC groups. The same effect is seen on MELD scores for patients prescribed warfarin therapy. The MELD score is calculated using INR levels.12 MELD scores also will be artificially elevated in patients prescribed warfarin therapy due to the INR elevation to between 2 and 3. When MELD scores for patients prescribed warfarin were replaced with values similar to those in the DOAC group, the statistical difference disappeared between the warfarin and DOAC groups.

The last statistically significant difference was found in number of days on anticoagulant therapy. This difference was expected as warfarin is the standard of care for anticoagulation treatment in patients with cirrhosis. The first DOAC, dabigatran, was not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration until 2010.13 DOACs have only recently been used in patients with cirrhosis accounting for the statistically significant difference in days on anticoagulation therapy between the warfarin and DOAC groups.

Limitations

The inability to meet power or evaluate adherence and appropriate renal dose adjustments for DOACs limited this study. This study was conducted at a single center in a predominantly male veteran population and therefore may not be generalizable to other populations. A majority of patients in the DOAC group were prescribed apixaban (69.1%), which may have affected the overall rate of major bleeding in the DOAC group. Pivotal trials of apixaban have shown a consistent decreased risk of major bleeding in patients with NVAF or VTE when compared with warfarin.14,15 Therefore, the results of this study may not be generalizable to all DOACs.

An inherent limitation of this study was the inability to collect data verifying adherence in the DOAC group. However, in the warfarin group, percentage of time within the therapeutic INR range of 2 to 3 was collected. While not a direct marker of adherence, this does allow for limited evaluation of therapeutic efficacy and safety within the warfarin group. Last, proper dosing of DOACs in patients with and without adequate renal function was not evaluated in this study.

Conclusions

The results of this study are consistent with other retrospective research and literature reviews. There were no statistically significant differences identified between the rates of all-cause bleeding, major bleeding, and failed efficacy between the DOAC and warfarin groups. DOACs may be a safe alternative to warfarin in patients with cirrhosis requiring anticoagulation for NVAF or VTE, but large randomized trials are required to confirm these results.

Coagulation in patients with cirrhosis is a complicated area of evolving research. Patients with cirrhosis were originally thought to be naturally anticoagulated due to the decreased production of clotting factors and platelets, combined with an increased international normalized ratio (INR).1 New data have shown that patients with cirrhosis are at a concomitant risk of bleeding and thrombosis due to increased platelet aggregation, decreased fibrinolysis, and decreased production of natural anticoagulants such as protein C and antithrombin.1 Traditionally, patients with cirrhosis needing anticoagulation therapy for comorbid conditions, such as nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) or venous thromboembolism (VTE) were placed on warfarin therapy. Managing warfarin in patients with cirrhosis poses a challenge to clinicians due to the many food and drug interactions, narrow therapeutic index, and complications with maintaining a therapeutic INR.1

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have several benefits over warfarin therapy, including convenience, decreased monitoring, decreased drug and dietary restrictions, and faster onset of action.2 Conversely, DOACs undergo extensive hepatic metabolism giving rise to concerns about supratherapeutic drug levels and increased bleeding rates in patients with liver dysfunction.1 Consequently, patients with cirrhosis were excluded from the pivotal trials establishing DOACs for NVAF and VTE treatment. Exclusion of these patients in major clinical trials alongside the challenges of managing warfarin warrant an evaluation of the efficacy and safety of DOACs in patients with cirrhosis.

Recent retrospective studies have examined the use of DOACs in patients with cirrhosis and found favorable results. A retrospective chart review by Intagliata and colleagues consisting of 39 patients with cirrhosis using either a DOAC or warfarin found similar rates of all-cause bleeding and major bleeding between the 2 groups.3 A retrospective cohort study by Hum and colleagues consisting of 45 patients with cirrhosis compared the use of DOACs with warfarin or low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH).4 Hum and colleagues found patients prescribed a DOAC had significantly fewer major bleeding events than did patients using warfarin or LMWH.4 The largest retrospective cohort study consisted of 233 patients with chronic liver disease and found no differences among all-cause bleeding and major bleeding rates between patients using DOACs compared with those of patients using warfarin.5

The purpose of this research is to evaluate the safety and efficacy of DOACs in veteran patients with cirrhosis compared with patients using warfarin.

Methods

A retrospective single-center chart review was conducted at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, Texas, between October 31, 2014 and October 31, 2018. Patients included in the study were adults aged ≥ 18 years with a diagnosis of cirrhosis and prescribed any of the following oral anticoagulants: apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, rivaroxaban, or warfarin. Patients prescribed apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban were collectively grouped into the DOAC group, while patients prescribed warfarin were classified as the standard of care comparator group.

A diagnosis of cirrhosis was confirmed using a combination of the codes from the ninth and tenth editions of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) for cirrhosis, documentation of diagnostic confirmation by clinicians from the gastroenterology or hepatology services, and positive liver biopsy result. Liver function tests, liver ultrasound results, and FibroSure biomarker assays were used to aid in confirming the diagnosis of cirrhosis but were not considered definitive. Patients were excluded from the trial if they had indications for anticoagulation other than NVAF and VTE and/or were prescribed triple antithrombotic therapy (dual antiplatelet therapy plus an anticoagulant). Patients who switched anticoagulant therapy during the trial period (ie, switched from warfarin to a DOAC) were also excluded from the analysis.

Patient demographic characteristics that were collected included weight; body mass index (BMI); etiology of cirrhosis; Child-Turcotte-Pugh, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), and CHA2DS2-VASc score; concomitant antiplatelet, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), proton pump inhibitor (PPI), and histamine-2 receptor antagonist

Two patient lists were used to identify patients for inclusion in the warfarin arm. The first patient list was generated using the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Cirrhosis Tracker, which identified patients with an ICD-9/10 code for cirrhosis and an INR laboratory value. Patients generated from the VA Cirrhosis Tracker with an INR > 1.5 were screened for a warfarin prescription and then evaluated for full study inclusion. The second patient list was generated using the VA Advanced Liver Disease Dashboard which identified patients with ICD-9/10 codes for advanced liver disease and an active warfarin prescription. Patients with an active warfarin prescription were then evaluated for full study inclusion. A single patient list was generated to identify patients for inclusion in the DOAC arm. This patient list was generated using the VA DOAC dashboard, which identified patients with an active DOAC prescription and an ICD-9/10 code for cirrhosis. Patients with an ICD-9/10 code for cirrhosis and prescribed a DOAC were screened for full study inclusion. Patient data were collected from the MEDVAMC Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) electronic health record (EHR). The research study was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board and the VA Office of Research and Development.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint for the study was all-cause bleeding. The secondary endpoints for the study were major bleeding and failed efficacy. Major bleeding was defined using the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) 2005 definition: fatal bleeding, symptomatic bleeding in a critical organ area (ie, intracranial, intraspinal, intraocular, retroperitoneal, intraarticular, pericardial, or intramuscular with compartment syndrome), or bleeding causing a fall in hemoglobin level of > 2 g/dL or leading to the transfusion of ≥ 2 units of red cells.6 Failed efficacy was a combination endpoint that included development of VTE, stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), and/or death. A prespecified subgroup analysis was conducted at the end of the study period to analyze trends in the DOAC and warfarin groups with respect to all-cause bleeding. All-cause bleeding risk was stratified by weight, BMI, Child-Turcotte-Pugh score, MELD score, presence of gastric and/or esophageal varices, active malignancies, percentage of time within therapeutic INR range in the warfarin group, indications for anticoagulation, and antiplatelet, NSAID, PPI, and H2RA therapy.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Continuous data were analyzed using the Student t test, and categorical data were analyzed using the Fisher exact test. Previous studies determined an all-cause bleeding rate of 10 to 17% for warfarin compared with 5% for DOACs.7,8 To detect a 12% difference in the all-cause bleeding rate between DOACs and warfarin, 212 patients would be needed to achieve 80% power at an α level of 0.05.

Results

A total of 170 patients were screened, and after applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 79 patients were enrolled in the study (Figure). The DOAC group included 42 patients, and the warfarin group included 37 patients. In the DOAC group, 69.1% (n = 29) of patients were taking apixaban, 21.4% (n = 9) rivaroxaban, and 9.5% (n = 4) dabigatran. There were no patients prescribed edoxaban during the study period.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the 2 groups except for Child-Turcotte-Pugh score, MELD score, mean INR, and number of days on anticoagulation therapy (Table 1). Most of the patients were male (98.7%), and the mean age was 71 years. The most common causes of cirrhosis were viral (29.1%), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (24.1%), multiple causes (22.8%), and alcohol (21.5%). Sixty-two patients (78.5%) had a NVAF indication for anticoagulation. The average CHA2DS2-VASc score was 3.7. Aspirin was prescribed in 51.9% (n = 41) of patients, and PPIs were prescribed in 48.1% (n = 38) of patients. At inclusion, esophageal varices were present in 13 patients and active malignancies were present in 6 patients.

Statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics were found between mean INR, Child-Turcotte-Pugh scores, MELD scores, and number of days on anticoagulant therapy. The mean INR was 1.3 in the DOAC group compared with 2.1 in the warfarin group (P = .0001). Eighty-one percent (n = 34) of patients in the DOAC group had a Child-Turcotte-Pugh score of A compared with 43.2% (n = 16) of patients in the warfarin group (P = .0009). Eight patients in the DOAC group had a Child-Turcotte-Pugh score of B compared with 19 patients in the warfarin group (P = .004). The mean MELD score was 9.4 in the DOAC group compared with 16.3 in the warfarin group (P = .0001). The mean days on anticoagulant therapy was 500.4 days for the DOAC group compared with 1,652.4 days for the warfarin group (P = .0001).

Safety Outcome

The primary outcome comparing all-cause bleeding rates between patients on DOACs compared with warfarin are listed in Table 2. With respect to the primary outcome, 7 (16.7%) patients on DOACs experienced a bleeding event compared with 8 (21.6%) patients on warfarin (P = .77). No statistically significant differences were detected between the DOAC and warfarin groups with respect to all-cause bleeding. Seven bleeding events occurred in the DOAC group; 1 met the qualification for major bleeding with a suspected gastrointestinal (GI) bleed.6 The other 6 bleeding episodes in the DOAC group consisted of hematoma, epistaxis, hematuria, and hematochezia. Eight bleeding events occurred in the warfarin group; 2 met the qualification for major bleeding with an intracranial hemorrhage and upper GI bleed.6 The other 6 bleeding episodes in the warfarin group consisted of epistaxis, bleeding gums, hematuria, and hematochezia. There were no statistically significant differences between the rates of major bleeding and nonmajor bleeding between the DOAC and warfarin groups.

Efficacy Outcomes

There were 3 events in the DOAC group and 3 events in the warfarin group (P = .99). In the DOAC group, 2 patients experienced a pulmonary embolism, and 1 patient experienced a MI. In the warfarin group, 3 patients died (end-stage heart failure, unknown cause due to death at an outside hospital, and sepsis/organ failure). There were no statistically significant differences between the composite endpoint of failed efficacy or the individual endpoints of VTE, stroke, MI, and death.

Subgroup Analysis

A prespecified subgroup analysis was conducted to determine risk factors for all-cause bleeding within each treatment group (Table 3). No significant trends were observed in the following risk factors: Child-Turcotte-Pugh score, indication for anticoagulation, use of NSAIDs, PPIs or H2RAs, presence of gastric or esophageal varices, active malignancies, and time within therapeutic INR range in the warfarin group. Patients with bleeding events had slightly increased weight and BMI vs patients without bleeding events. Within the warfarin group, patients with bleeding events had slightly elevated MELD scores compared to patients without bleeding events. There was an equal balance of patients prescribed aspirin therapy between the groups with and without bleeding events. Overall, no significant risk factors were identified for all-cause bleeding.

Discussion

Initially, patients with cirrhosis were excluded from DOAC trials due to concerns for increased bleeding risk with hepatically eliminated medications. New retrospective research has concluded that in patients with cirrhosis, DOACs have similar or lower bleeding rates when compared directly to warfarin.9,10

In this study, no statistically significant differences were detected between the primary and secondary outcomes of all-cause bleeding, major bleeding, or failed efficacy. Subgroup analysis did not identify any significant risk factors with respect to all-cause bleeding among patients in the DOAC and warfarin groups. To meet 80% power, 212 patients needed to be enrolled in the study; however, only 79 patients were enrolled, and power was not met. The results of this study should be interpreted cautiously as hypothesis-generating due to the small sample size. Strengths of this study include similar baseline characteristics between the DOAC and warfarin groups, 4-year length of retrospective data review, and availability of both inpatient and outpatient EHR limiting the amount of missing data points.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the groups except for mean INR, Child-Turcotte-Pugh score, MELD score, and number of days on anticoagulation therapy. The difference in mean INR between groups is expected as patients in the warfarin group have a goal INR of 2 to 3 to maintain therapeutic efficacy and safety. INR is not used as a marker of efficacy or safety with DOACs; therefore, a consistent elevation in INR is not expected. Child- Turcotte-Pugh scores are calculated using INR levels.11 When calculating the score, patients with an INR < 1.7 receive 1 point; patients with an INR between 1.7 and 2.3 receive 2 points.11 Therefore, patients in the warfarin group will have artificially inflated Child-Turcotte-Pugh scores as this group has goal INR levels of 2 to 3. This makes Child-Turcotte-Pugh scores unreliable markers of disease severity in patients using warfarin therapy. When the INR scores for patients prescribed warfarin were replaced with values < 1.7, the statistical difference disappeared between the warfarin and DOAC groups. The same effect is seen on MELD scores for patients prescribed warfarin therapy. The MELD score is calculated using INR levels.12 MELD scores also will be artificially elevated in patients prescribed warfarin therapy due to the INR elevation to between 2 and 3. When MELD scores for patients prescribed warfarin were replaced with values similar to those in the DOAC group, the statistical difference disappeared between the warfarin and DOAC groups.

The last statistically significant difference was found in number of days on anticoagulant therapy. This difference was expected as warfarin is the standard of care for anticoagulation treatment in patients with cirrhosis. The first DOAC, dabigatran, was not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration until 2010.13 DOACs have only recently been used in patients with cirrhosis accounting for the statistically significant difference in days on anticoagulation therapy between the warfarin and DOAC groups.

Limitations

The inability to meet power or evaluate adherence and appropriate renal dose adjustments for DOACs limited this study. This study was conducted at a single center in a predominantly male veteran population and therefore may not be generalizable to other populations. A majority of patients in the DOAC group were prescribed apixaban (69.1%), which may have affected the overall rate of major bleeding in the DOAC group. Pivotal trials of apixaban have shown a consistent decreased risk of major bleeding in patients with NVAF or VTE when compared with warfarin.14,15 Therefore, the results of this study may not be generalizable to all DOACs.

An inherent limitation of this study was the inability to collect data verifying adherence in the DOAC group. However, in the warfarin group, percentage of time within the therapeutic INR range of 2 to 3 was collected. While not a direct marker of adherence, this does allow for limited evaluation of therapeutic efficacy and safety within the warfarin group. Last, proper dosing of DOACs in patients with and without adequate renal function was not evaluated in this study.

Conclusions

The results of this study are consistent with other retrospective research and literature reviews. There were no statistically significant differences identified between the rates of all-cause bleeding, major bleeding, and failed efficacy between the DOAC and warfarin groups. DOACs may be a safe alternative to warfarin in patients with cirrhosis requiring anticoagulation for NVAF or VTE, but large randomized trials are required to confirm these results.

1. Qamar A, Vaduganathan M, Greenberger NJ, Giugliano RP. Oral anticoagulation in patients with liver disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2162-2175. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.03.023

2. Priyanka P, Kupec JT, Krafft M, Shah NA, Reynolds GJ. Newer oral anticoagulants in the treatment of acute portal vein thrombosis in patients with and without cirrhosis. Int J Hepatol. 2018;2018:8432781. Published 2018 Jun 5. doi:10.1155/2018/8432781

3. Intagliata NM, Henry ZH, Maitland H, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants in cirrhosis patients pose similar risks of bleeding when compared to traditional anticoagulation. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(6):1721-1727. doi:10.1007/s10620-015-4012-2

4. Hum J, Shatzel JJ, Jou JH, Deloughery TG. The efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants vs traditional anticoagulants in cirrhosis. Eur J Haematol. 2017;98(4):393-397. doi:10.1111/ejh.12844

5. Goriacko P, Veltri KT. Safety of direct oral anticoagulants vs warfarin in patients with chronic liver disease and atrial fibrillation. Eur J Haematol. 2018;100(5):488-493. doi:10.1111/ejh.13045

6. Schulman S, Kearon C; Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(4):692-694. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01204.x

7. Rubboli A, Becattini C, Verheugt FW. Incidence, clinical impact and risk of bleeding during oral anticoagulation therapy. World J Cardiol. 2011;3(11):351-358. doi:10.4330/wjc.v3.i11.351

8. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-962. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0

9. Hoolwerf EW, Kraaijpoel N, Büller HR, van Es N. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with liver cirrhosis: A systematic review. Thromb Res. 2018;170:102-108. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2018.08.011

10. Steuber TD, Howard ML, Nisly SA. Direct oral anticoagulants in chronic liver disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(10):1042-1049. doi:10.1177/1060028019841582

11. Janevska D, Chaloska-Ivanova V, Janevski V. Hepatocellular carcinoma: risk factors, diagnosis and treatment. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2015;3(4):732-736. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2015.111

12. Singal AK, Kamath PS. Model for End-Stage Liver Disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2013;3(1):50-60. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2012.11.002

13. Joppa SA, Salciccioli J, Adamski J, et al. A practical review of the emerging direct anticoagulants, laboratory monitoring, and reversal agents. J Clin Med. 2018;7(2):29. Published 2018 Feb 11. doi:10.3390/jcm7020029

14. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):981-992. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1107039

15. Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(9):799-808. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1302507

1. Qamar A, Vaduganathan M, Greenberger NJ, Giugliano RP. Oral anticoagulation in patients with liver disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):2162-2175. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.03.023

2. Priyanka P, Kupec JT, Krafft M, Shah NA, Reynolds GJ. Newer oral anticoagulants in the treatment of acute portal vein thrombosis in patients with and without cirrhosis. Int J Hepatol. 2018;2018:8432781. Published 2018 Jun 5. doi:10.1155/2018/8432781

3. Intagliata NM, Henry ZH, Maitland H, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants in cirrhosis patients pose similar risks of bleeding when compared to traditional anticoagulation. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(6):1721-1727. doi:10.1007/s10620-015-4012-2

4. Hum J, Shatzel JJ, Jou JH, Deloughery TG. The efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants vs traditional anticoagulants in cirrhosis. Eur J Haematol. 2017;98(4):393-397. doi:10.1111/ejh.12844

5. Goriacko P, Veltri KT. Safety of direct oral anticoagulants vs warfarin in patients with chronic liver disease and atrial fibrillation. Eur J Haematol. 2018;100(5):488-493. doi:10.1111/ejh.13045

6. Schulman S, Kearon C; Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(4):692-694. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01204.x

7. Rubboli A, Becattini C, Verheugt FW. Incidence, clinical impact and risk of bleeding during oral anticoagulation therapy. World J Cardiol. 2011;3(11):351-358. doi:10.4330/wjc.v3.i11.351

8. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-962. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0

9. Hoolwerf EW, Kraaijpoel N, Büller HR, van Es N. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with liver cirrhosis: A systematic review. Thromb Res. 2018;170:102-108. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2018.08.011

10. Steuber TD, Howard ML, Nisly SA. Direct oral anticoagulants in chronic liver disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(10):1042-1049. doi:10.1177/1060028019841582

11. Janevska D, Chaloska-Ivanova V, Janevski V. Hepatocellular carcinoma: risk factors, diagnosis and treatment. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2015;3(4):732-736. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2015.111

12. Singal AK, Kamath PS. Model for End-Stage Liver Disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2013;3(1):50-60. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2012.11.002

13. Joppa SA, Salciccioli J, Adamski J, et al. A practical review of the emerging direct anticoagulants, laboratory monitoring, and reversal agents. J Clin Med. 2018;7(2):29. Published 2018 Feb 11. doi:10.3390/jcm7020029

14. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):981-992. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1107039

15. Agnelli G, Buller HR, Cohen A, et al. Oral apixaban for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(9):799-808. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1302507

Multidisciplinary Transitional Pain Service for the Veteran Population

Despite advancements in techniques, postsurgical pain continues to be a prominent part of the patient experience. Often this experience can lead to developing chronic postsurgical pain that interferes with quality of life after the expected time to recovery.1-3 As many as 14% of patients who undergo surgery without any history of opioid use develop chronic opioid use that persists after recovery from their operation.4-8 For patients with existing chronic opioid use or a history of substance use disorder (SUD), surgeons, primary care providers, or addiction providers often do not provide sufficient presurgical planning or postsurgical coordination of care. This lack of pain care coordination can increase the risk of inadequate pain control, opioid use escalation, or SUD relapse after surgery.

Convincing arguments have been made that a perioperative surgical home can improve significantly the quality of perioperative care.9-14 This report describes our experience implementing a perioperative surgical home at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Salt Lake City VA Medical Center (SLCVAMC), focusing on pain management extending from the preoperative period until 6 months or more after surgery. This type of Transitional Pain Service (TPS) has been described previously.15-17 Our service differs from those described previously by enrolling all patients before surgery rather than select postsurgical enrollment of only patients with a history of opioid use or SUD or patients who struggle with persistent postsurgical pain.

Methods

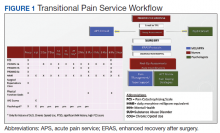

In January 2018, we developed and implemented a new TPS at the SLCVAMC. The transitional pain team consisted of an anesthesiologist with specialization in acute pain management, a nurse practitioner (NP) with experience in both acute and chronic pain management, 2 nurse care coordinators, and a psychologist (Figure 1). Before implementation, a needs assessment took place with these key stakeholders and others at SLCVAMC to identify the following specific goals of the TPS: (1) reduce pain through pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions; (2) eliminate new chronic opioid use in previously nonopioid user (NOU) patients; (3) address chronic opioid use in previous chronic opioid users (COUs) by providing support for opioid taper and alternative analgesic therapies for their chronic pain conditions; and (4) improve continuity of care by close coordination with the surgical team, primary care providers (PCPs), and mental health or chronic pain providers as needed.

Once these TPS goals were defined, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) guided the implementation. CFIR is a theory-based implementation framework consisting of 5 domains: intervention characteristics, inner setting, outer setting, characteristics of individuals, and process. These domains were used to identify barriers and facilitators during the early implementation process and helped refine TPS as it was put into clinical practice.

Patient Selection

During the initial implementation of TPS, enrollment was limited to patients scheduled for elective primary or revision knee, hip, or shoulder replacement as well as rotator cuff repair surgery. But as the TPS workflow became established after iterative refinement, we expanded the program to enroll patients with established risk factors for OUD having other types of surgery (Table 1). The diagnosis of risk factors, such as history of SUD, chronic opioid use, or significant mental health disorders (ie, history of suicidal ideation or attempt, posttraumatic stress disorder, and inpatient psychiatric care) were confirmed through both in-person interviews and electronic health record (EHR) documentation. The overall goal was to identify all at-risk patients as soon as they were indicated for surgery, to allow time for evaluation, education, developing an individualized pain plan, and opioid taper prior to surgery if indicated.

Preoperative Procedures

Once identified, patients were contacted by a TPS team member and invited to attend a onetime 90-minute presurgical expectations class held at SLCVAMC. The education curriculum was developed by the whole team, and classes were taught primarily by the TPS psychologist. The class included education about expectations for postoperative pain, available analgesic therapies, opioid education, appropriate use of opioids, and the effect of psychological factors on pain. Pain coping strategies were introduced using a mindfulness-based intervention (MBI) and the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) matrix. Classes were offered multiple times a week to help maximize convenience for patients and were separate from the anesthesia preoperative evaluation. Patients attended class only once. High-risk patients (patients with chronic opioid therapy, recent history of or current SUDs, significant comorbid mental health issues) were encouraged to attend this class one-on-one with the TPS psychologist rather than in the group setting, so individual attention to mental health and SUD issues could be addressed directly.

Baseline history, morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD), and patient-reported outcomes using measures from the Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement System (PROMIS) for pain intensity (PROMIS 3a), pain interference (PROMIS 6b), and physical function (PROMIS 8b), and a pain-catastrophizing scale (PCS) score were obtained on all patients.18 PROMIS measures are validated questionnaires developed with the National Institutes of Health to standardize and quantify patient-reported outcomes in many domains.19 Patients with a history of SUD or COU met with the anesthesiologist and/or NP, and a personalized pain plan was developed that included preoperative opioid taper, buprenorphine use strategy, or opioid-free strategies.

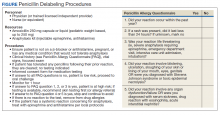

Hospital Procedures

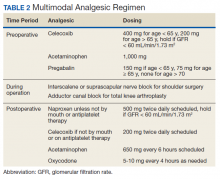

On the day of surgery, the TPS team met with the patient preoperatively and implemented an individualized pain plan that included multimodal analgesic techniques with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, gabapentinoids, and regional anesthesia, where appropriate (Table 2). Enhanced recovery after surgery protocols were developed in conjunction with the surgeons to include local infiltration analgesia by the surgeon, postoperative multimodal analgesic strategies, and intensive physical therapy starting the day of surgery for inpatient procedures.

After surgery, the TPS team followed up with patients daily and provided recommendations for analgesic therapies. Patients were offered daily sessions with the psychologist to reinforce and practice nonpharmacologic pain-coping strategies, such as meditation and relaxation. Prior to patient discharge, the TPS team provided recommendations for discharge medications and an opioid taper plan. For some patients taking buprenorphine before surgery who had stopped this therapy prior to or during their hospital stay, TPS providers transitioned them back to buprenorphine before discharge.

Postoperative Procedures

Patients were called by the nurse care coordinators at postdischarge days 2, 7, 10, 14, 21, 28, and then monthly for ≥ 6 months. For patients who had not stopped opioid use or returned to their preoperative baseline opioid dose, weekly calls were made until opioid taper goals were achieved. At each call, nurses collected PROMIS scores for the previous 24 hours, the most recent 24-hour MEDD, the date of last opioid use, and the number of remaining opioid tablets after opioid cessation. In addition, nurses provided active listening and supportive care and encouragement as well as care coordination for issues related to rehabilitation facilities, physical therapy, transportation, medication questions, and wound questions. Nurses notified the anesthesiologist or NP when patients were unable to taper opioid use or had poor pain control as indicated by their PROMIS scores, opioid use, or directly expressed by the patient.

The TPS team prescribed alternative analgesic therapies, opioid taper plans, and communicated with surgeons and primary care providers if limited continued opioid therapy was recommended. Individual sessions with the psychologist were available to patients after discharge with a focus on ACT-matrix therapy and consultation with long-term mental health and/or substance abuse providers as indicated. Frequent communication and care coordination were maintained with the surgical team, the PCP, and other providers on the mental health or chronic pain services. This care coordination often included postsurgical joint clinic appointments in which TPS providers and nurses would be present with the surgeon or the PCP.

For patients with inadequately treated chronic pain conditions or who required long-term opioid tapers, we developed a combined clinic with the TPS and Anesthesia Chronic Pain group. This clinic allows patients to be seen by both services in the same setting, allowing a warm handoff by TPS to the chronic pain team.

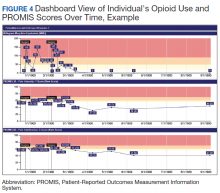

Heath and Decision Support Tools

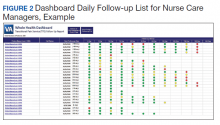

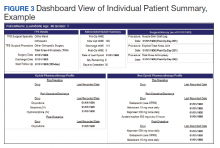

An electronic dashboard registry of surgical episodes managed by TPS was developed to achieve clinical, administrative, and quality improvement goals. The dashboard registry consists of surgical episode data, opioid doses, patient-reported outcomes, and clinical decision-making processes. Custom-built note templates capture pertinent data through embedded data labels, called health factors. Data are captured as part of routine clinical care, recorded in Computerized Patient Record System as health factors. They are available in the VA Corporate Data Warehouse as structured data. Workflows are executed daily to keep the dashboard registry current, clean, and able to process new data. Information displays direct daily clinical workflow and support point-of-care clinical decision making (Figures 2, 3, and 4). Data are aggregated across patient-care encounters and allow nurse care coordinators to concisely review pertinent patient data prior to delivering care. These data include surgical history, comorbidities, timeline of opioid use, and PROMIS scores during their course of recovery. This system allows TPS to optimize care delivery by providing longitudinal data across the surgical episode, thereby reducing the time needed to review records. Secondary purposes of captured data include measuring clinic performance and quality improvement to improve care delivery.

Results

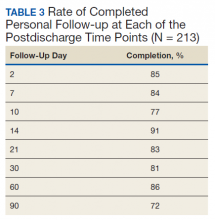

The TPS intervention was implemented January 1, 2018. Two-hundred thirteen patients were enrolled between January and December 2018, which included 60 (28%) patients with a history of chronic opioid use and 153 (72%) patients who were considered opioid naïve. A total of 99% of patients had ≥ 1 successful follow-up within 14 days after discharge, 96% had ≥ 1 follow-up between 14 and 30 days after surgery, and 72% had completed personal follow-up 90 days after discharge (Table 3). For patients who TPS was unable to contact in person or by phone, 90-day MEDD was obtained using prescription and Controlled Substance Database reviews. The protocol for this retrospective analysis was approved by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board and the VA Research Review Committee.

By 90 days after surgery, 26 (43.3%) COUs were off opioids completely, 17 (28.3%) had decreased their opioid dose from their preoperative baseline MEDD (120 [SD, 108] vs 55 [SD, 45]), 14 (23.3%) returned to their baseline dose, and 3 (5%) increased from their baseline dose. Of the 153 patients who were NOUs before surgery, only 1 (0.7%) was taking opioids after 90 days. TPS continued to work closely with the patient and their PCP and that patient was finally able to stop opioid use 262 days after discharge. Ten patients had an additional surgery within 90 days of the initial surgery. Of these, 6 were COU, of whom 3 stopped all opioids by 90 days from their original surgery, 2 had no change in MEDD at 90 days, and 1 had a lower MEDD at 90 days. Of the 4 NOU who had additional surgery, all were off opioids by 90 days from the original surgery.

Although difficult to quantify, a meaningful outcome of TPS has been to improve satisfaction substantially among health care providers caring for complex patients at risk for chronic opioid abuse. This group includes the many members of the surgical team, PCPs, and addiction specialists who appreciate the close care coordination and assistance in caring for patients with difficult issues, especially with opioid tapers or SUDs. We also have noticed changes in prescribing practices among surgeons and PCPs for their patients who are not part of TPS.

Discussion

With any new clinical service, there are obstacles and challenges. TPS requires a considerable investment in personnel, and currently no mechanism is in place for obtaining payment for many of the provided services. We were fortunate the VA Whole Health Initiative, the VA Office of Rural Health, and the VA Centers of Innovation provided support for the development, implementation, and pilot evaluation of TPS. After we presented our initial results to hospital leadership, we also received hospital support to expand TPS service to include a total of 4 nurse care coordinators and 2 psychologists. We are currently performing a cost analysis of the service but recognize that this model may be difficult to reproduce at other institutions without a change in reimbursement standards.

Developing a working relationship with the surgical and primary care services required a concerted effort from the TPS team and a number of months to become effective. As most veterans receive primary care, mental health care, and surgical care within the VA system, this model lends itself to close care coordination. Initially there was skepticism about TPS recommendations to reduce opioid use, especially from PCPs who had cared for complex patients over many years. But this uncertainty went away as we showed evidence of close patient follow-up and detailed communication. TPS soon became the designated service for both primary care and surgical providers who were otherwise uncomfortable with how to approach opioid tapers and nonopioid pain strategies. In fact, a substantial portion of our referrals now come directly from the PCP who is referring a high-risk patient for evaluation for surgery rather than from the surgeons, and joint visits with TPS and primary care have become commonplace.

Challenges abound when working with patients with substance abuse history, opioid use history, high anxiety, significant pain catastrophizing, and those who have had previous negative experiences with surgery. We have found that the most important facet of our service comes from the amount of time and effort team members, especially the nurses, spend helping patients. Much of the nurses' work focuses on nonpain-related issues, such as assisting patients with finding transportation, housing issues, questions about medications, help scheduling appointments, etc. Through this concerted effort, patients gain trust in TPS providers and are willing to listen to and experiment with our recommendations. Many patients who were initially extremely unreceptive to the presurgery education asked for our support weeks after surgery to help with postsurgery pain.

Another challenge we continue to experience comes from the success of the program.

Conclusions

The multidisciplinary TPS supports greater preoperative to postoperative longitudinal care for surgical patients. This endeavor has resulted in better patient preparation before surgery and improved care coordination after surgery, with specific improvements in appropriate use of opioid medications and smooth transitions of care for patients with ongoing and complex needs. Development of sophisticated note templates and customized health information technology allows for accurate follow-through and data gathering for quality improvement, facilitating data-driven improvements and proving value to the facility.

Given that TPS is a multidisciplinary program with multiple interventions, it is difficult to pinpoint which specific aspects of TPS are most effective in achieving success. For example, although we have little doubt that the work our psychologists do with our patients is beneficial and even essential for the success we have had with some of our most difficult patients, it is less clear whether it matters if they use mindfulness, ACT matrix, or cognitive behavioral therapy. We think that an important part of TPS is the frequent human interaction with a caring individual. Therefore, as TPS continues to grow, maintaining the ability to provide frequent personal interaction is a priority.

The role of opioids in acute pain deserves further scrutiny. In 2018, with TPS use of opioids after orthopedic surgery decreased by > 40% from the previous year. Despite this more restricted use of opioids, pain interference and physical function scores indicated that surgical patients do not seem to experience increased pain or reduced physical function. In addition, stopping opioid use for COUs did not seem to affect the quality of recovery, pain, or physical function. Future prospective controlled studies of TPS are needed to confirm these findings and identify which aspects of TPS are most effective in improving functional recovery of patients. Also, more evidence is needed to determine the appropriateness or need for opioids in acute postsurgical pain.

TPS has expanded to include all surgical specialties. Given the high burden and limited resources, we have chosen to focus on patients at higher risk for chronic postsurgical pain by type of surgery (eg, thoracotomy, open abdominal, limb amputation, major joint surgery) and/or history of substance abuse or chronic opioid use. To better direct scarce resources where it would be of most benefit, we are now enrolling only NOUs without other risk factors postoperatively if they request a refill of opioids or are otherwise struggling with pain control after surgery. Whether this approach affects the success we had in the first year in preventing new COUs after surgery remains to be seen.

It is unlikely that any single model of a perioperative surgical home will fit the needs of the many different types of medical systems that exist. The TPS model fits well in large hospital systems, like the VA, where patients receive most of their care within the same system. However, it seems to us that the optimal TPS program in any health system will provide education, support, and care coordination beginning preoperatively to prepare the patient for surgery and then to facilitate care coordination to transition patients back to their PCPs or on to specialized chronic care.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Candice Harmon, RN; David Merrill, RN; Amy Beckstead, RN, who have provided invaluable assistance with establishing the TPS program at the VA Salt Lake City and helping with the evaluation process.

Funding for the implementation and evaluation of the TPS was received from the VA Whole Health Initiative, the VA Center of Innovation, the VA Office of Rural Health, and National Institutes of Health Grant UL1TR002538.